Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Lightweight Multimodal Deep Fusion Network for Face Antis Poofing with Cross-Axial Attention and Deep Reinforcement Learning Technique

School of Engineering and Natural Sciences, Electrical and Computer Engineering, Altınbaş University, Istanbul, 34218, Türkiye

* Corresponding Author: Diyar Wirya Omar Ameenulhakeem. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Development and Application of Deep Learning based Object Detection)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 5671-5702. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070422

Received 16 July 2025; Accepted 22 August 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

Face antispoofing has received a lot of attention because it plays a role in strengthening the security of face recognition systems. Face recognition is commonly used for authentication in surveillance applications. However, attackers try to compromise these systems by using spoofing techniques such as using photos or videos of users to gain access to services or information. Many existing methods for face spoofing face difficulties when dealing with new scenarios, especially when there are variations in background, lighting, and other environmental factors. Recent advancements in deep learning with multi-modality methods have shown their effectiveness in face antispoofing, surpassing single-modal methods. However, these approaches often generate several features that can lead to issues with data dimensionality. In this study, we introduce a multimodal deep fusion network for face anti-spoofing that incorporates cross-axial attention and deep reinforcement learning techniques. This network operates at three patch levels and analyzes images from modalities (RGB, IR, and depth). Initially, our design includes an axial attention network (XANet) model that extracts deeply hidden features from multimodal images. Further, we use a bidirectional fusion technique that pays attention to both directions to combine features from each mode effectively. We further improve feature optimization by using the Enhanced Pity Beetle Optimization (EPBO) algorithm, which selects the features to address data dimensionality problems. Moreover, our proposed model employs a hybrid federated reinforcement learning (FDDRL) approach to detect and classify face anti-spoofing, achieving a more optimal tradeoff between detection rates and false positive rates. We evaluated the proposed approach on publicly available datasets, including CASIA-SURF and GREATFASD-S, and realized 98.985% and 97.956% classification accuracy, respectively. In addition, the current method outperforms other state-of-the-art methods in terms of precision, recall, and F-measures. Overall, the developed methodology boosts the effectiveness of our model in detecting various types of spoofing attempts.Keywords

With the widespread use of face recognition technology in smartphones, online authentication systems, and smart surveillance, secure and reliable identity verification has become more important [1]. Although face recognition systems are convenient and accurate, they are vulnerable to various presentation attacks such as printed photos, playback videos, 3D silicone masks, paper faces, or even AI-generated DeepFakes [2]. To address these threats, the field of Face AntiSpoofing (FAS) has developed with the goal of detecting and preventing presentation attacks for facial recognition systems [3]. FAS aims to separate real faces from spoof attempts, making it crucial for biometric security, where malicious and illegitimate access is detected prior to authentication [4].

In recent years, researchers have developed numerous deep learning techniques for designing reliable and robust FAS systems [5–8]. These techniques typically utilize Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), supplemented with attention-based optimization techniques, to separate real faces from spoofed faces. While these techniques have demonstrated good results on controlled, within-dataset evaluations, their generalization across various spoof types and unseen domains continues to pose a major challenge. One of the main problems arises from the global attention mechanisms used in these methods, which add computational expense and generally disregard the local discriminative cues that are useful for detecting small spoof artifacts [9]. As a result, prediction consistency for models currently implemented in this context may not be sustained in real-world, cross-dataset applications.

An additional limitation of current deep learning-based FAS systems is that they are reliant on entangled feature representations that conflate identity, illumination, and spoof-related cues within the feature space learned by the model [10]. This entanglement not only affects classifier performance but also diminishes interpretability. While recent attempts have been made to disentangle this feature representation or use attention models that focus on spoof-relevant areas, they either require additional identity labels (which may not always be available) or global attention plans that are not computationally feasible for online use or high-resolution inputs. Moreover, static attention mechanisms are not catered to learning dynamically and are unable to identify significant areas across variable forms of spoofing. Another significant limitation of these methods is the centralization of training, which creates serious privacy issues and restricts deployment in edge or mobile environments. Centralized learning not only introduces additional communication overhead but also fails to deal with the data heterogeneity of client devices and their computational limitations. Although federated learning has been introduced as a privacy-preserving alternative, most federated FAS systems lack intelligent decision-making and adaptive learning capabilities under non-IID data settings.

Motivated by these limitations, we develop a Lightweight Multimodal Deep Fusion Network for FAS, comprising three main modules: Cross-Axial Attention Network (XANet), Enhanced Policy-Based Optimization (EPBO) [11], and Federated Dual-Stage Deep Reinforcement Learning (FDDRL) [12]. Using XANet, we present a structured attention mechanism that captures dependencies across the horizontal and vertical axes independently. Unlike standard global attention mechanisms, which model all spatial interactions simultaneously and thus lead to higher spatial complexity and increased computational overhead, XANet reduces the computational complexity of attention operations from quadratic to linear in spatial dimensions by using axial attention in place of global attention. To further improve the capability for discrimination of the attention modules, the framework incorporates an Enhanced Policy-Based Optimization (EPBO) module. EPBO directly incorporates a Reinforcement Learning (RL) mechanism, whereas experience-based policies can dynamically update attention weights throughout training. It allows the model to selectively emphasize spoof-relevant regions while suppressing noise, improving feature discrimination over time, which results in lower parameter count and improved inference speeds. In addition to these modules, the framework’s FDDRL strategy enables privacy-preserving training across distributed client devices while correcting for data imbalance and domain shift through dual-stage optimization.

This step minimizes the client-side computation and communication cost so that it is well-suited for resource-constrained devices. As a results, our proposed model is not only competitive in accuracy, but also lightweight, achieving massively reduced inference latency and memory footprint, allowing for the use of real-time operation on mobile and edge-computing platforms.

The rationale behind this specific combination of XANet, EPBO, and FDDRL lies in their complementary strengths. XANet offered a lightweight yet effective way of capturing structured spatial relationships. EPBO provides an adaptive form of control, making attentional learning more robust against different spoofing cues. FDDRL provides a mechanism that can generate a model for our application that is constrained for edge-deployment and privacy while improving generalization. Our method combines these previously uncoordinated approaches into a unified architecture that aims to satisfy the multiple constraints of real-world FAS. Further, a hybrid FDDRL-based classification approach discriminated the class-wise optimized features, and performance was compared with eight recently published state-of-the-art art-models: (1) Residual Network (ResNet) [13], (2) Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks (SE-Net) [14], (3) FaceBagNet [15], (4) VisionLabs [16], (5) depthwise separable attention module (DAM) with the multimodal-based feature augment module (MFAM) [17], (6) Masked Frequency Autoencoder [18], (7)

1. In the initial phase, we leverage the aXial Attention network model to extract deep hidden features from multimodal images, enhancing the system’s ability to discern genuine faces from spoof attempts.

2. Following the feature extraction stage, we employ a bidirectional fusion technique. It pays attention to both directions, facilitating the effective combination of features from each mode. This bidirectional fusion approach contributes to a more comprehensive representation of the input data.

3. Feature optimization is further refined using the EPBO algorithm. It is used to address data dimensionality challenges by selecting and optimizing features, ensuring efficiency in handling complex and high-dimensional data.

4. The proposed model adopts a hybrid federated reinforcement learning approach for the final stages of face antispoofing. This hybrid methodology optimizes the tradeoff between detection rates and false positive rates, enhancing the overall performance of the system. The reinforcement learning aspect contributes to adaptive learning and decision-making, making the model more robust against diverse antispoofing scenarios.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 1 discusses the review of recent work on face anti-spoofing using deep learning. Section 2 focused on the problem discussion and system architecture of the proposed approach. Section 3 introduces the proposed face antispoofing approach using XANet+EPBO+FDDRL. Section 4 provides experiments and a discussion of the results of the proposed method. Finally, Section 5 concludes this paper.

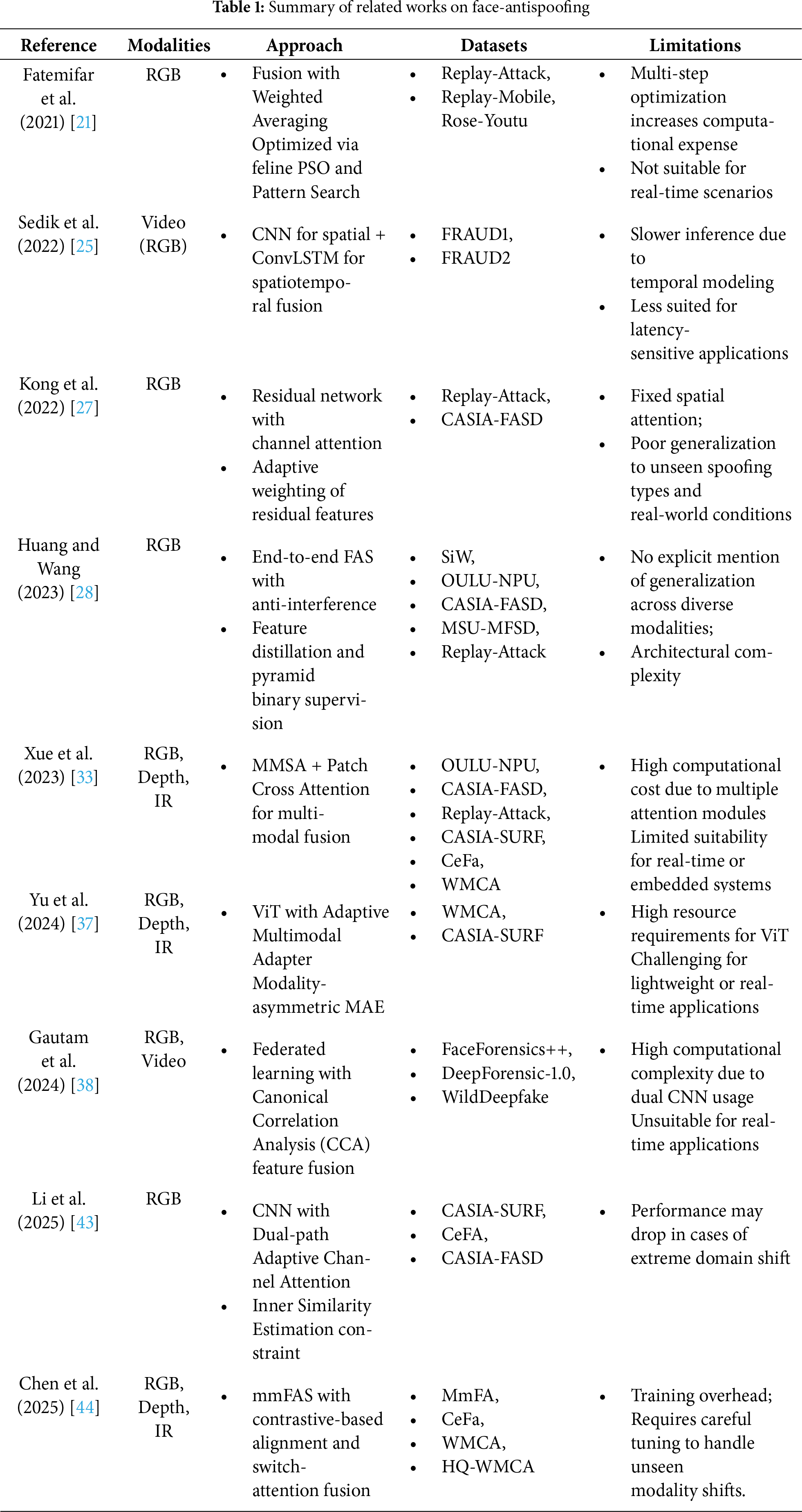

Researchers have used a variety of deep learning techniques such as CNNs, attention mechanisms, and training paradigms to build strong, generalizable FAS systems (Table 1). In this section, we review a few recently developed FAS architectures based on CNNs, attention-guided feature learning, and federated learning approaches for privacy-preserving deployment. These studies highlight various advantages to the FAS literature but reveal common challenges related to generalization, interpretability, and operational efficiency. For example, Fatemifar et al. (2021) [21] proposed an FAS system that utilized a fusion-based approach with Weighted Averaging (WA) with a client-specific design and optimized it using two sequential feline Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Pattern Search methods. This system was validated on the Replay-Attack dataset [22], Replay-Mobile dataset [23], and the Rose-Youtu dataset [24], and its performance with these datasets surpassed many other state-of-the-art methods. However, due to the multi-step optimization, this approach may be associated with increased computational expense, making it less applicable to real-time scenarios. Sedik et al. (2022) [25] proposed a deep learning framework using two different architectures, (1) a CNN-based model and (2) a ConvLSTM-based model, to detect face spoofing in videos. The CNN model extracts spatial features from the video frames, whereas the ConvLSTM model can capture spatiotemporal features and fuse them for better representations. Both methods included a fully-connected layer on top of the CNN or ConvLSTM feature layers and subsequently classified them with a SoftMax layer. The ConvLSTM model outperformed classical techniques on the FRAUD1 and FRAUD2 [26] datasets in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and Area Under the Curve (AUC). However, as the ConvLSTM combines both temporal and spatial features, this can impact the inference time and reliability in latency-sensitive applications.

Kong et al. (2022) [27] presented an FAS scheme that incorporated a residual network and channel attention. The newly proposed scheme highlighted the observed differences in texture, shadow, and edge in the nasal and cheek Area and found adaptive weights according to discriminative residual features. Testing of the model was done on Replay-attack and CASIA-FASD, and was 99.98% and 97.75%. However, its dependency on fixed spatial attention and lack of diversity of different non-forensic spoofing types limit the generalization of the model to unseen spoofing types and real-world conditions. Huang and Wang (2023) [28] presented an end-to-end FAS approach leveraging anti-interference feature distillation and global spatial attention with pyramid binary mask supervision. They had a model that refined multilevel features from ResNet-34 to obtain a more discriminative representation and improve the detection of spoof. The model outperforms the benchmarks using five datasets: SiW [29], OULU-NPU [30], CASIA-FASD [31], MSU-MFSD [32], and Replay-Attack [22] in both a cross- and intra-testing situation.

Xue et al. (2023) [33] developed a hierarchical and multimodal cross-attention model for face anti-spoofing that can be designed for both static (i.e., single modal) and dynamic (i.e., multimodal) inputs. They integrated Multimodal Multihead Self-Attention (MMSA) with Patch Cross Attention (MPCA) to better fuse features obtained across modalities. Experimental results on six public datasets: OULU-NPU [30], CASIA-FASD [31], Replay-Attack [22], CASIA-SURF [34], CASIA-SURF CeFa [35], and WMCA [36] indicate that the model is effective at managing different types of spoofing attacks. However, exploring multiple attention modules for processing input signals adds significant computational costs for the embedding and can lead to limited use of the model in real-time applications. Yu et al. (2024) [37] examined the effects of various inputs, pre-training, and fine-tuning modalities in Vision Transformers (ViT) for multimodal FAS using RGB, Depth, and IR. They report that local descriptors improve ViT on IR but not on RGB or Depth, and that ImageNet pretraining is ineffective in multimodal FAS. To fill these gaps, the authors proposed an Adaptive Multimodal Adapter (AMA) and a modality-asymmetric masked autoencoder (MAE) for efficient self-supervised pretraining. This approach performed better than previous work on WMCA and CASIA-SURF datasets. However, they acknowledge that the inherent resource requirements of ViT may create challenges when deployed in a lightweight or real-time setting.

Gautam et al. (2024) [38] integrated federated learning with their deep learning framework to determine forgery in images and videos. They employed Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) [39] to fuse the features extracted from Inception and Xception networks. This approach was trained on three different benchmark forensic data sets (FaceForensics++ [40], Deepforensic-1.0 [41], and WildDeepfake [42]), and achieved superior accuracy in identifying manipulated content. The primary limitation of this approach is its reliance on a complex feature extraction process involving two CNNs, which increases computational cost and makes it unsuitable for real-time applications. Li et al. (2025) [43] presented a CNN-based FAS method that utilized a Dual-path Adaptive Channel Attention (DACA) module to extract facial features and diminish non-relevant information. They introduced an inner similarity estimation (ISE)-based constraint to enforce intra-class compactness while also improving inter-class separability. Experiments performed on the CASIA-SURF, CeFA, and CASIA-FASD datasets show strong performance in differentiating live from spoofed faces. Because of major dependencies on class-specific feature distributions, the effectiveness of the method may be limited in extreme domain shift conditions. Chen et al. (2025) [44] proposed a multimodal FAS framework (mmFAS) that explicitly aligns and fuses latent features across modalities. It introduces a contrastive-based alignment module and a switch-attention fusion mechanism to capture complementary information. The model was strongly validated on four datasets: (1) CeFa [35], (2) WMCA [36], and (3) HQ-WMCA [45]. However, dual-level alignment and attention fusion add training overhead, and it is important to tune the network carefully when experiencing unseen modality shifts.

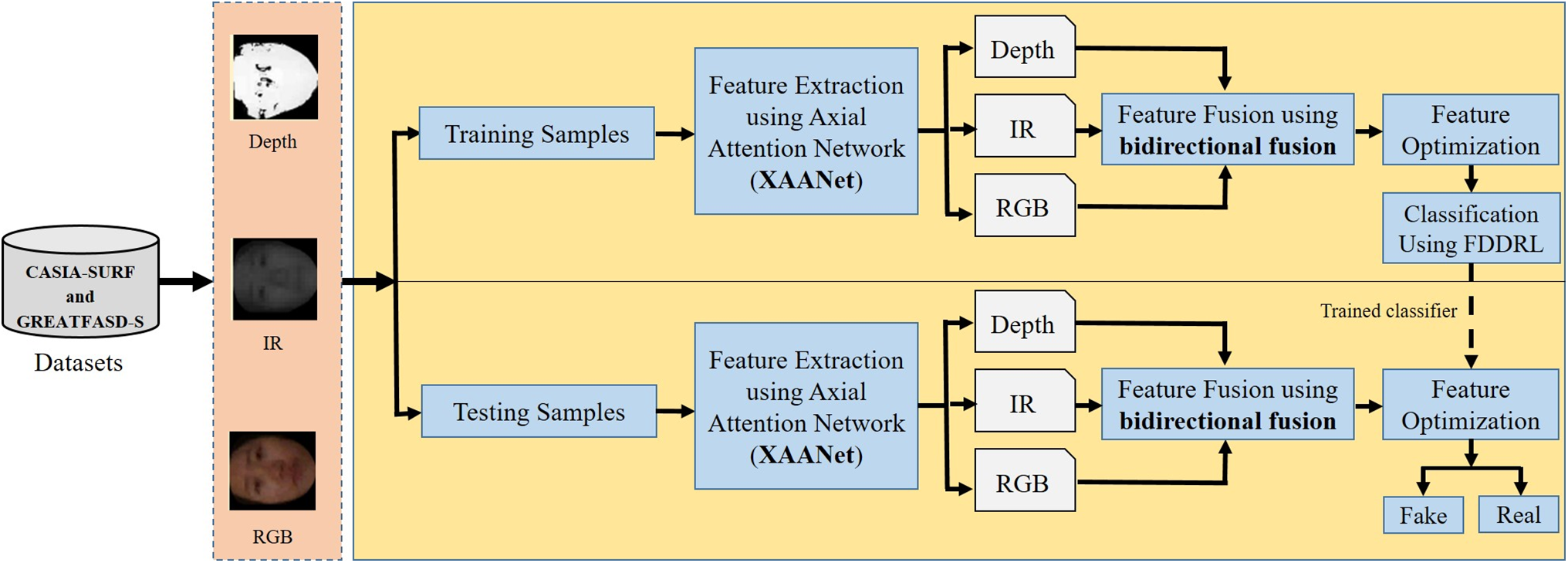

The proposed multimodal deep fusion network consists of four steps: (1) Feature extraction using XANet, (2) Feature amalgamation using a bi-directional fusion scheme, (3) Feature optimization using the EPBO algorithm, and (4) Classification using the FDDRL classifier. The working pipeline of our architecture is shown in Fig. 1. A detailed discussion on all the steps is given in subsequent subsections.

Figure 1: The system architecture of the proposed multimodal deep fusion network

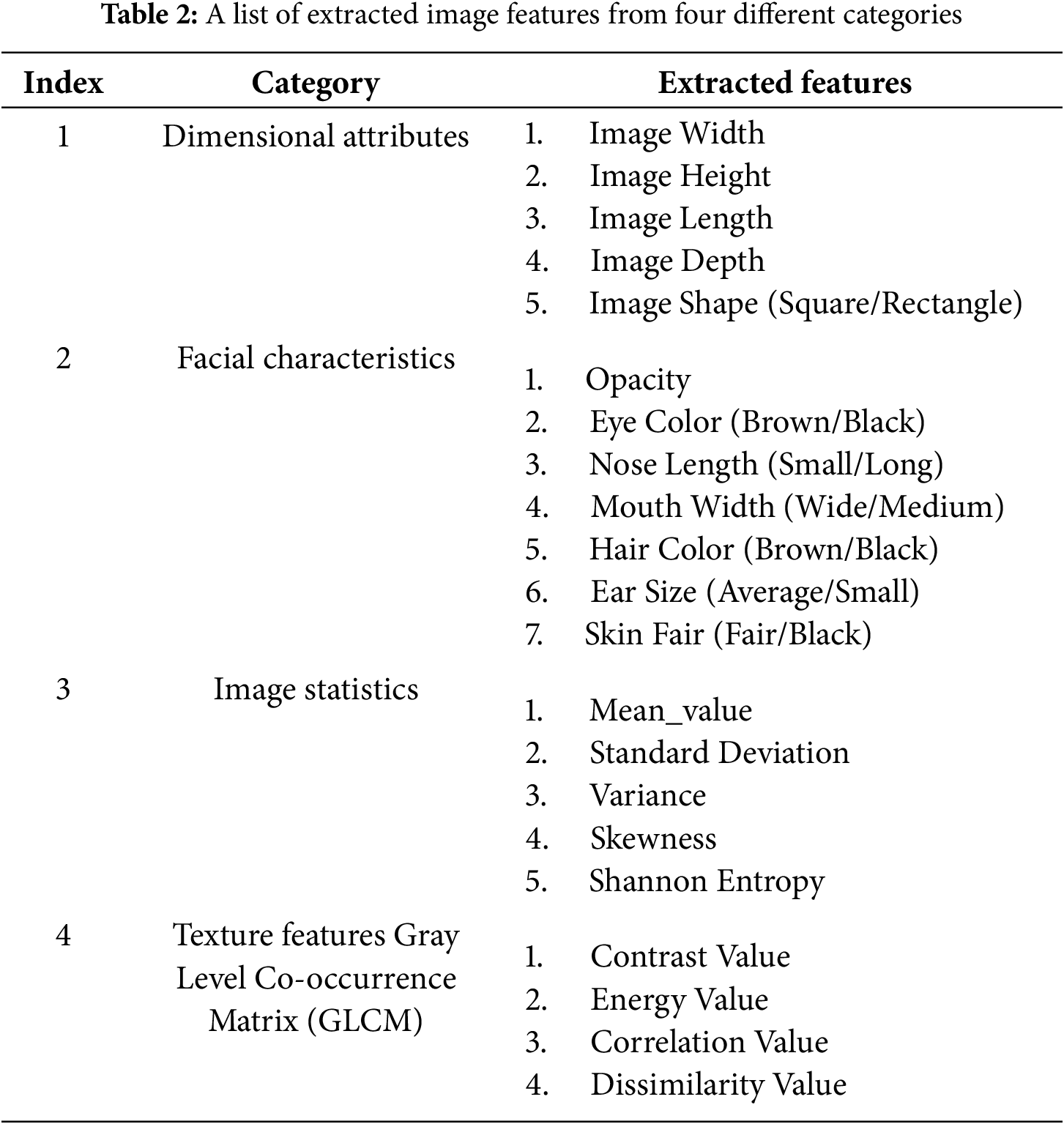

Feature extraction refers to the process of capturing and representing distinctive characteristics or patterns from facial images that are relevant for distinguishing between genuine faces and spoof attempts. This step is crucial for building effective models that can discern the subtle differences between live faces and various presentation attack methods. In our work, we employed both manual and deep features for the characterization of input face scans. Here, four type of manual face imaging attributes: (1) Dimensional attributes (5 features), (2) Facial characteristics (7 features), (3) Image statistics (5 features), and (4) Texture features (4 features) were extracted from all three image modalities (RGB, IR, Depth). Therefore, a total of 63 (21 ∗ 3) features were used for further data processing. The details of all the extracted features from those categories mentioned above are listed in Table 2. Further, a novel XANet was introduced to extract deep features from input facial scans. The details of the developed XANet architecture are introduced in the next subsection.

3.2 Deep Feature Extraction Using XANet Architecture

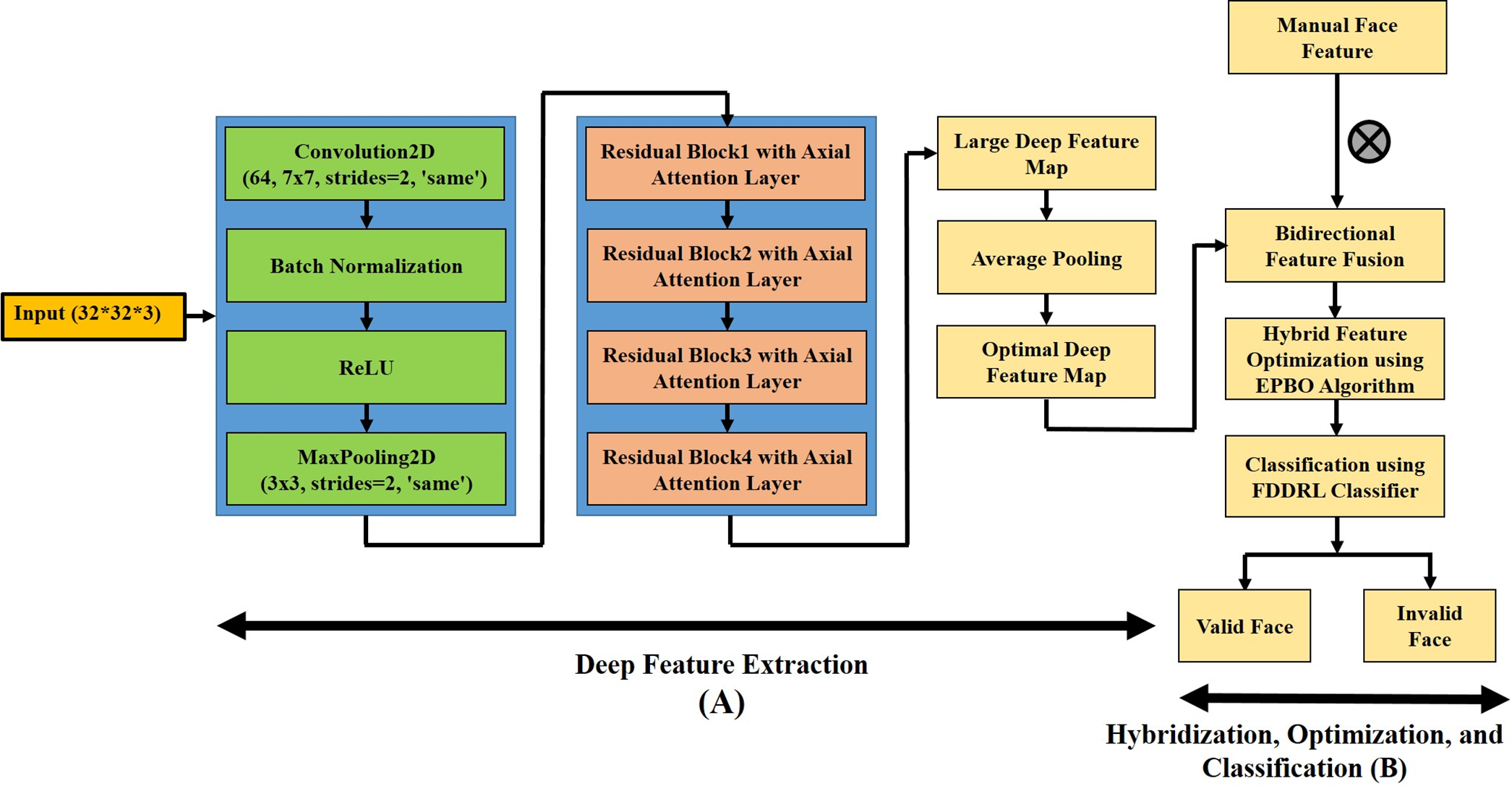

The primary objective of introducing XANet Architecture is to extract deep features from multimodal facial images. The proposed XANet model is a type of attention-based neural network used in computer vision tasks, particularly for image understanding. Axial attention refers to the mechanism of attending to different axes (rows and columns) of an input tensor separately. The XANet model incorporates this idea to capture long-range dependencies in both the row and column directions of the input data [46]. The proposed network combines a conventional Residual network (RESNet) [13] as a base CNN model with an axial attention mechanism to extract deep face imaging features. It initiates with an Input Layer corresponding to a 32 × 32 RGB image, laying the ground for the next steps. In the Initial Convolution and Pooling phase, a 64-filter Conv2D layer with 7 × 7 kernel size, 2 strides, and ‘same’ padding is used. Batch Normalization and ReLU activation improve the model’s resilience, followed by MaxPool2D with a 3 × 3 kernel, 2 strides, and ‘same’ padding for spatial subsampling.

The main components of the model are Residual Blocks with Axial Attention. Consisting of four stacks, each containing a certain number of residual blocks, an AxialAttention layer is cunningly embedded in the Middle of each block. Each stack has its number of residual blocks, determined by the num_blocks_list variable, where the value is [2, 2, 2, 2]. The model’s capacity increases with every stack, multiplying the number of filters in each block from 64. The Axial Attention Layer (AxialAttention) [47] is a new mechanism, and it combines both row-wise and column-wise axial attention. The row_attention and col_attention layers apply MultiHeadAttention [48] with a key dimension of dim//num_heads. The outputs of these attention mechanisms are also concatenated along the last axis, which gives the model the capability to capture relations along rows and columns separately. The Residual Block (resnet_block) in every stack follows the standard residual architecture. Batch Normalization and ReLU activation follow Conv2D layers of varying filter numbers, 3 × 3 kernel size, and ‘same’ padding. A shortcut connection is introduced either through a convolutional layer (first block in a stack or first stack) by an addition of the input to the output. Each block is finalized with the ReLU activation layer. The details of the deep feature extraction process are shown in Fig. 2A.

Figure 2: The proposed ant spoofing classification framework. (A) Deep feature extraction. (B) Hybridization, Optimization, and Classification

3.3 Bidirectional Feature Fusion

In this step, an average pooling procedure was applied to minimize the sparsity level in the deep feature set. The updated features were merged with manual features using a bidirectional feature fusion technique [49]. In this context, bidirectional fusion is applied to combine features from different modes effectively. It captures the reciprocal influence between the modes. This means that the resulting fused features provide a more holistic representation of the input data, capturing both direct and reciprocal relationships. By considering bidirectional information flow, the model potentially captures more complex patterns, dependencies, and interactions between the features of different modes.

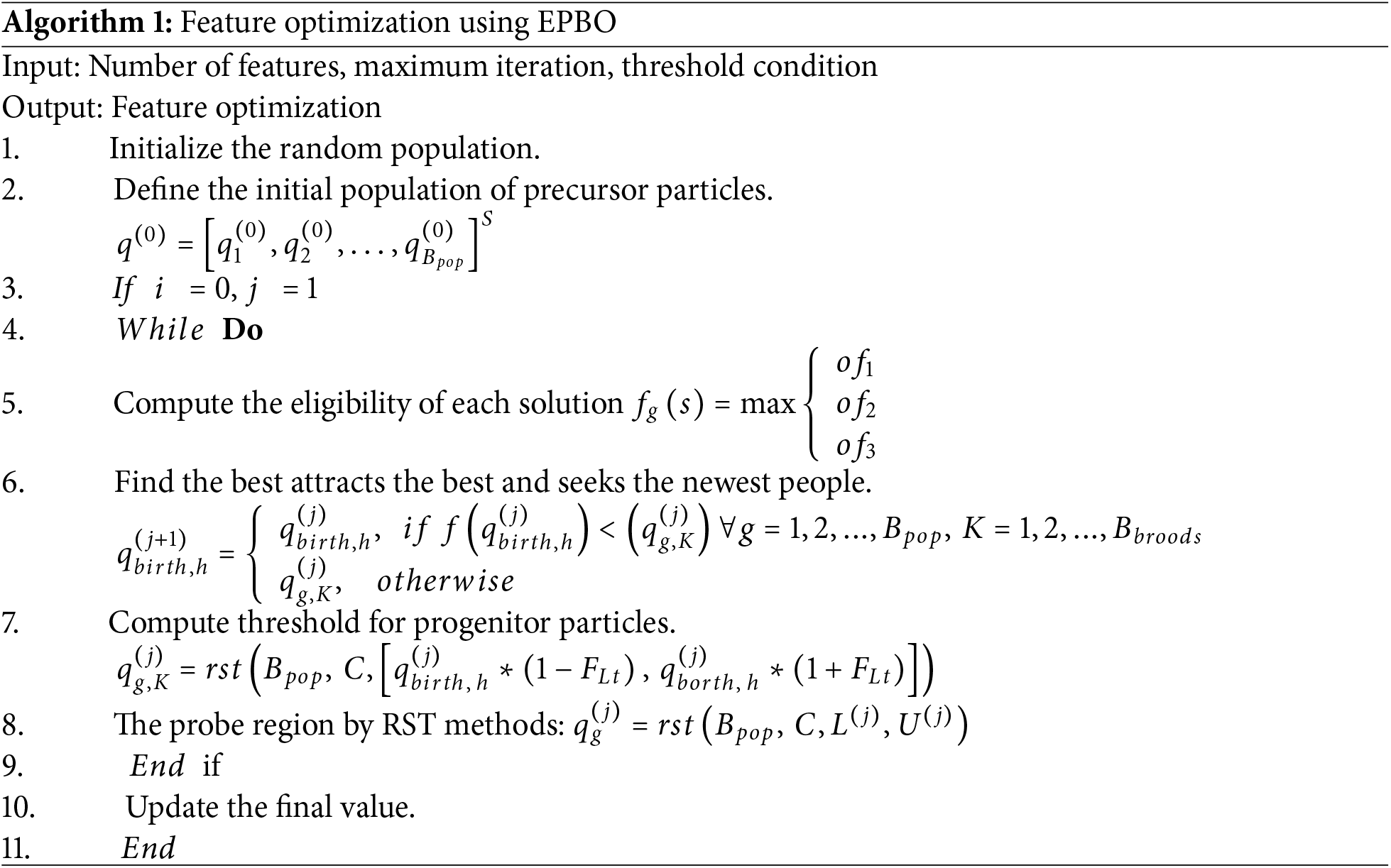

Feature optimization typically involves selecting or transforming features in a way that enhances their relevance, discriminative power, or effectiveness for a particular task. In this context, it refers to improving the features extracted from different modes to serve the face antispoofing task better. Here, we introduce the enhanced pity beetle optimization (EPBO) algorithm for feature optimization, which selects the features to address data dimensionality problems. The EPBO algorithm is inspired by the conventional beetle swarm optimization (BSO) [50]. A group of potential solutions called particles is initially scattered in a hypervolume that spans the entire global search space. Here, optimal feature subsets are considered as potential solutions. The particle population is initialized according to the defined search area as follows:

here,

Iteration refers

where

These recent characterization

A new state

Like the neighboring pursuit hyper volume, these recently portrayed

Like the previous research hyper volume design, this recent characterization

Algorithm 1 describes the working function of feature optimization using EPBO.

3.5 Face Antispoofing Classification

Federated reinforcement learning involves training a reinforcement learning model across multiple decentralized devices or servers without exchanging raw data. Instead, the models are trained locally on individual devices, and only model updates or aggregated information are shared among them. This approach is used to maintain privacy and security, especially when dealing with sensitive data. In antispoofing, the hybrid federated reinforcement learning (FDDRL) model combines reinforcement learning with a federated approach to enhance the overall performance. The FDDRL model is used to analyze and classify the images, decide whether they are real or fake, and improve its decision-making over time based on feedback and reinforcement learning. Let

Because FL is not part of the

where

One problem with the novel

The hostility of the incline

The q-intercept of

Hence,

Thus,

Languages

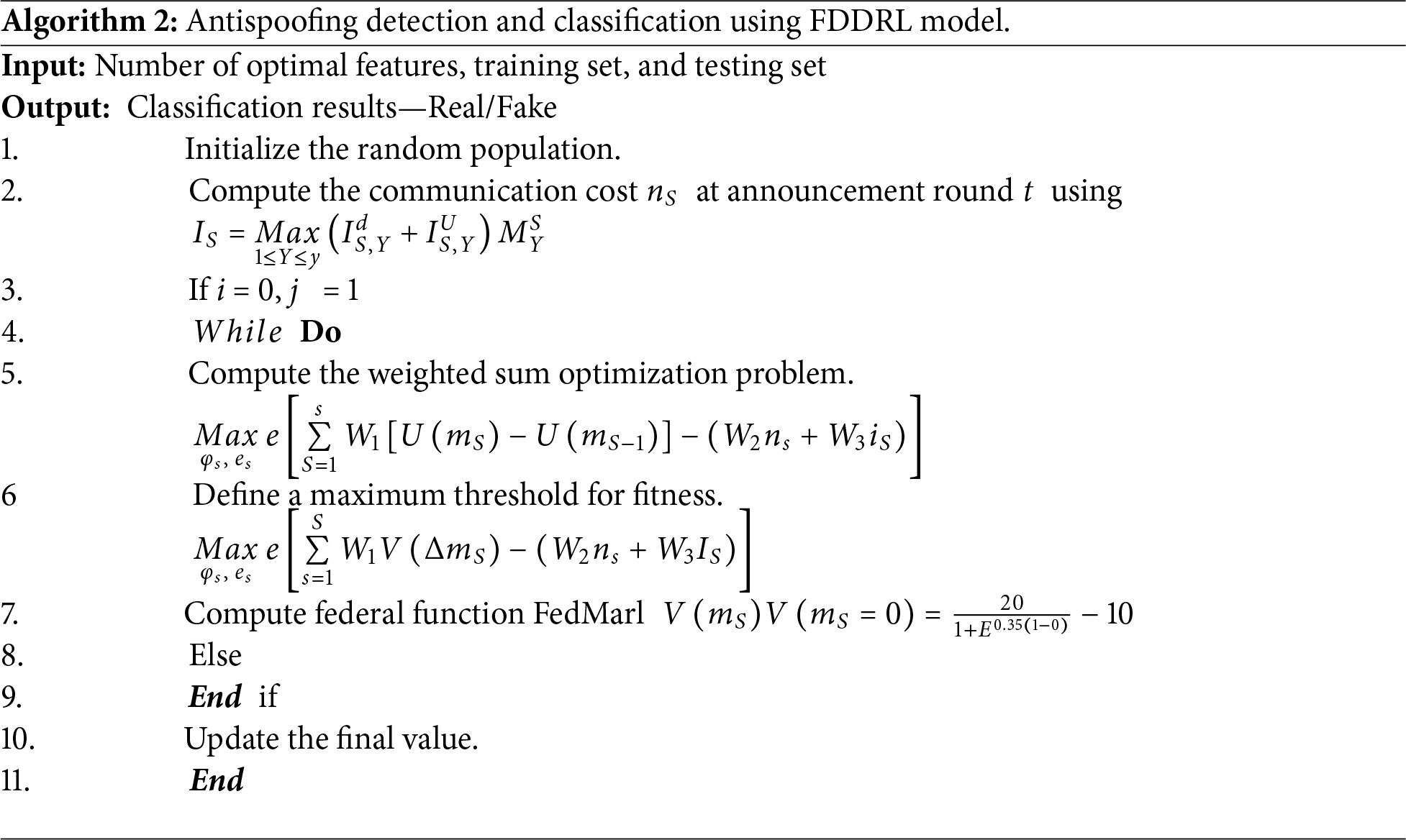

The detection and classification of antispoofing using the FDDRL model are given in Algorithm 2.

This section presents a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed mechanism through extensive experimentation. The applicability of the model is further investigated through several performance metrics on two publicly available datasets and attack scenarios. The results of the proposed XANet+EPBO+FDDRL approach are compared with the eight existing face antispoofing approaches: (1) Residual Network (ResNet) [13], (2) Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks (SE-Net) [14], (3) FaceBagNet [15], (4) VisionLabs [16], (5) depthwise separable attention module (DAM) with the multimodal-based feature augment module (MFAM) [17], (6) Masked Frequency Autoencoder [18], (7)

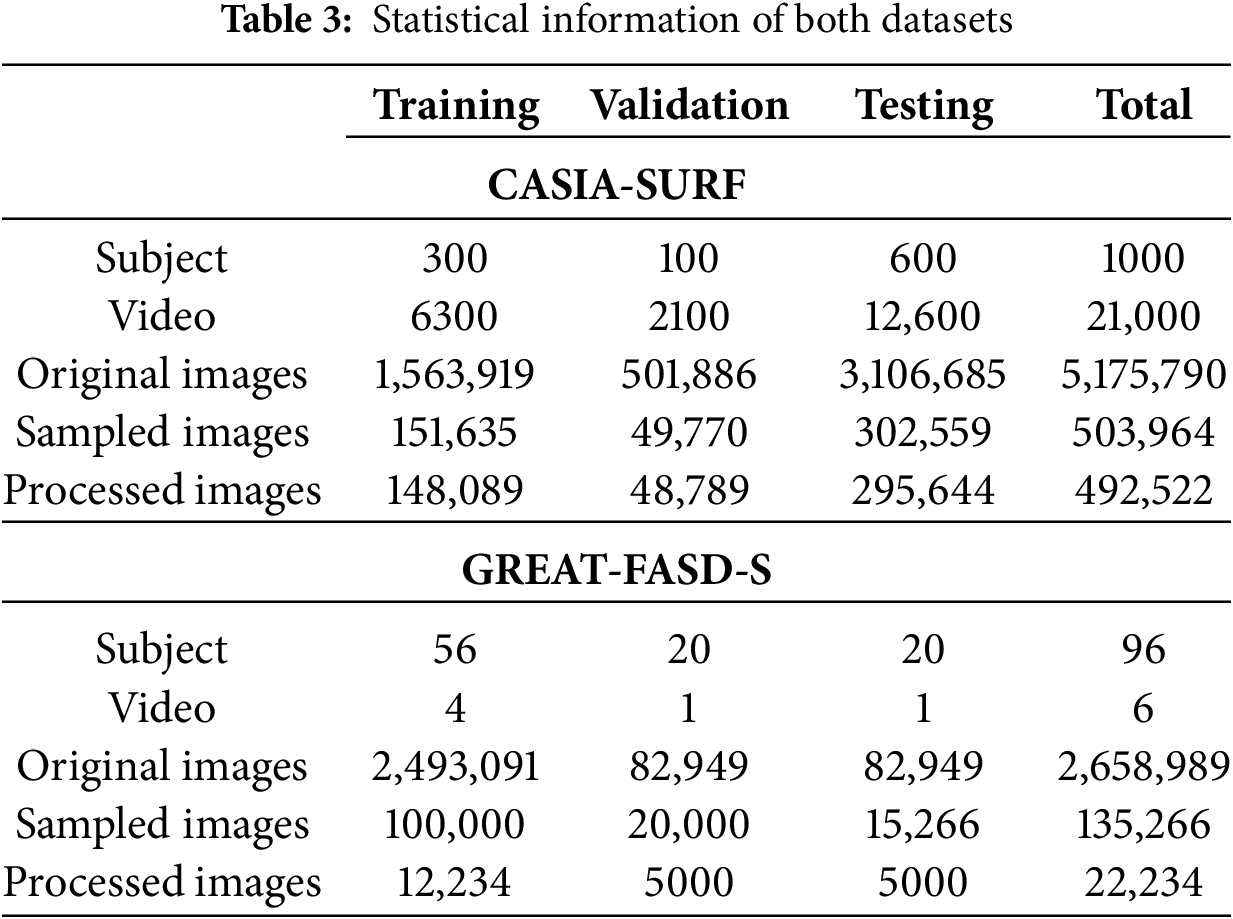

Face antispoofing is becoming more and more popular in the academic and business worlds as a security precaution for face recognition systems. The variety of spoofing techniques, such as replay, print, and mask attacks, among others, makes it challenging to discern between different phony faces. In this study, two publicly available benchmark FAS datasets, (1) CASIA-SURF and (2) GREAT-FASD-S, are used to validate the performance of our algorithm. The statistical properties of the dataset are given in Table 3. The important details of both datasets are described below.

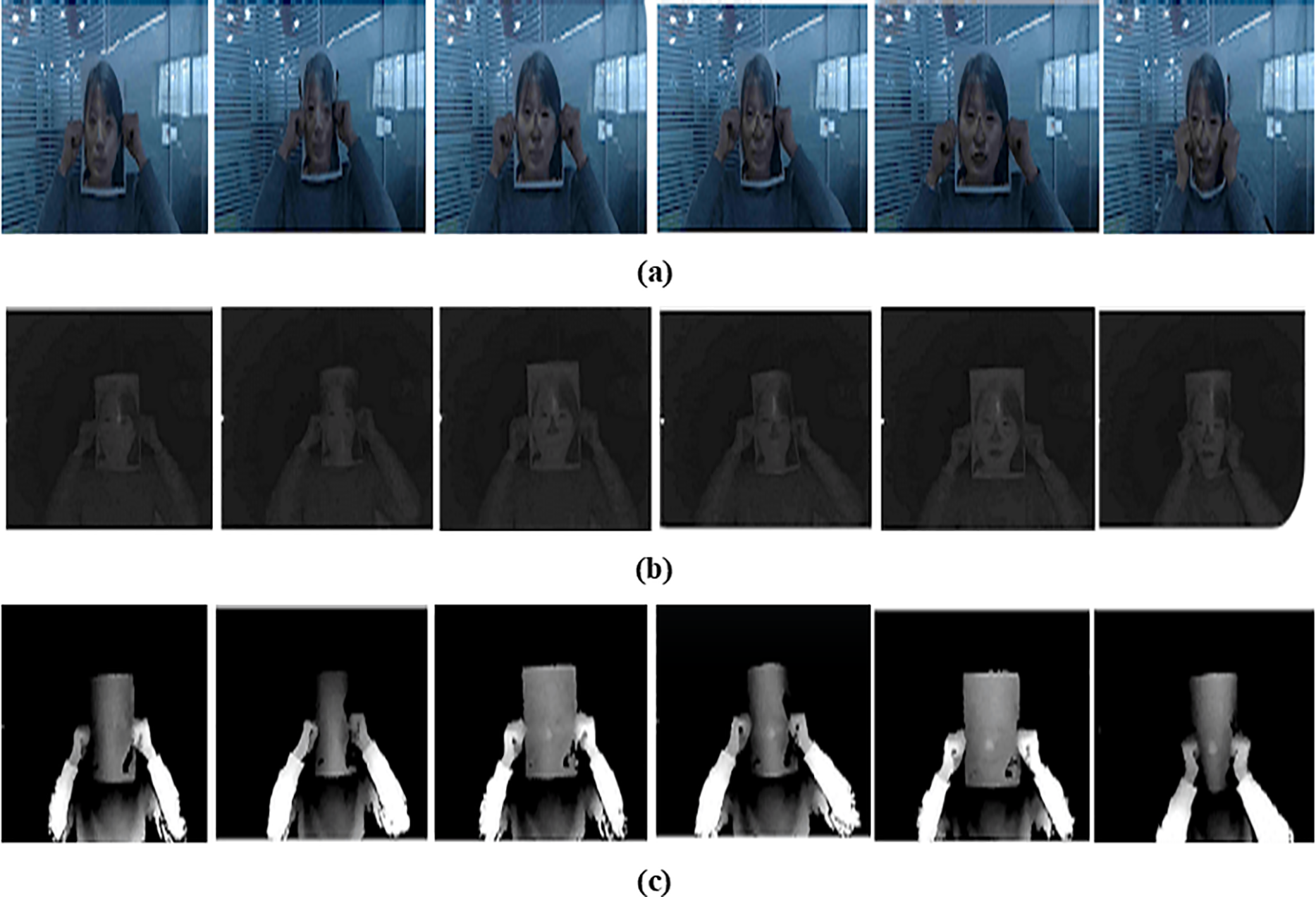

I. CASIA-SURF Dataset: The CASIA-SURF dataset [29] is a very common benchmarking dataset for face spoof detection. The dataset is acquired with 21,000 video samples of 1000 subjects and has three kinds of images, i.e., RGB, depth, and infrared. The dataset stands out due to its enormous size and the provision of multimodal information. There is one genuine video and six attack videos for each subject, generated using different spoofing techniques. These mock attacks include the display of printed face images—flat or curved—and the manipulation of certain areas like the eyes, nose, mouth, or combinations thereof. Overall, six styles of spoofing are employed to create the attack samples. The setup offers a comprehensive test environment for assessing the robustness of face spoof detection systems under varied presentation conditions in Fig. 3.

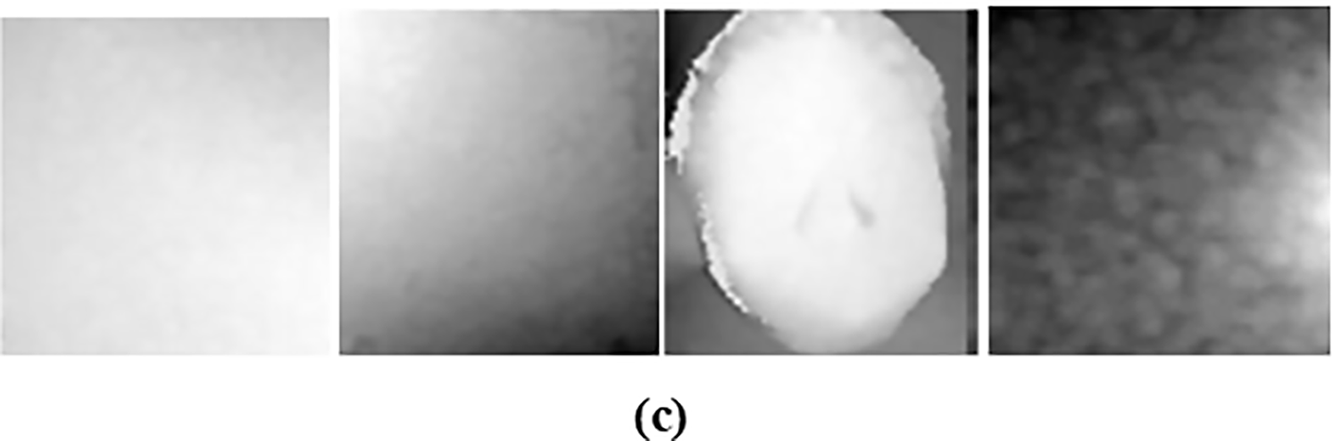

Figure 3: Test samples from CASIA-SURF dataset (a) RGB, (b) IR, (c) Depth images, with the different attacks. Six different facial spoofing situations were set up for testing. In the first situation, a subject is holding a flat printed facial photo with the eye areas cut out. In the second condition, a printed, curved version of the same picture with eye areas deleted is employed. The third condition entails a flat facial print with both eye and nose areas deleted, and the fourth uses the curved version of such a picture. The fifth condition entails a flat facial picture with the eye, nose, and mouth areas deleted. Finally, in the sixth example, a subject holds a curved image with the same three facial regions erased. (denotes from left to right)

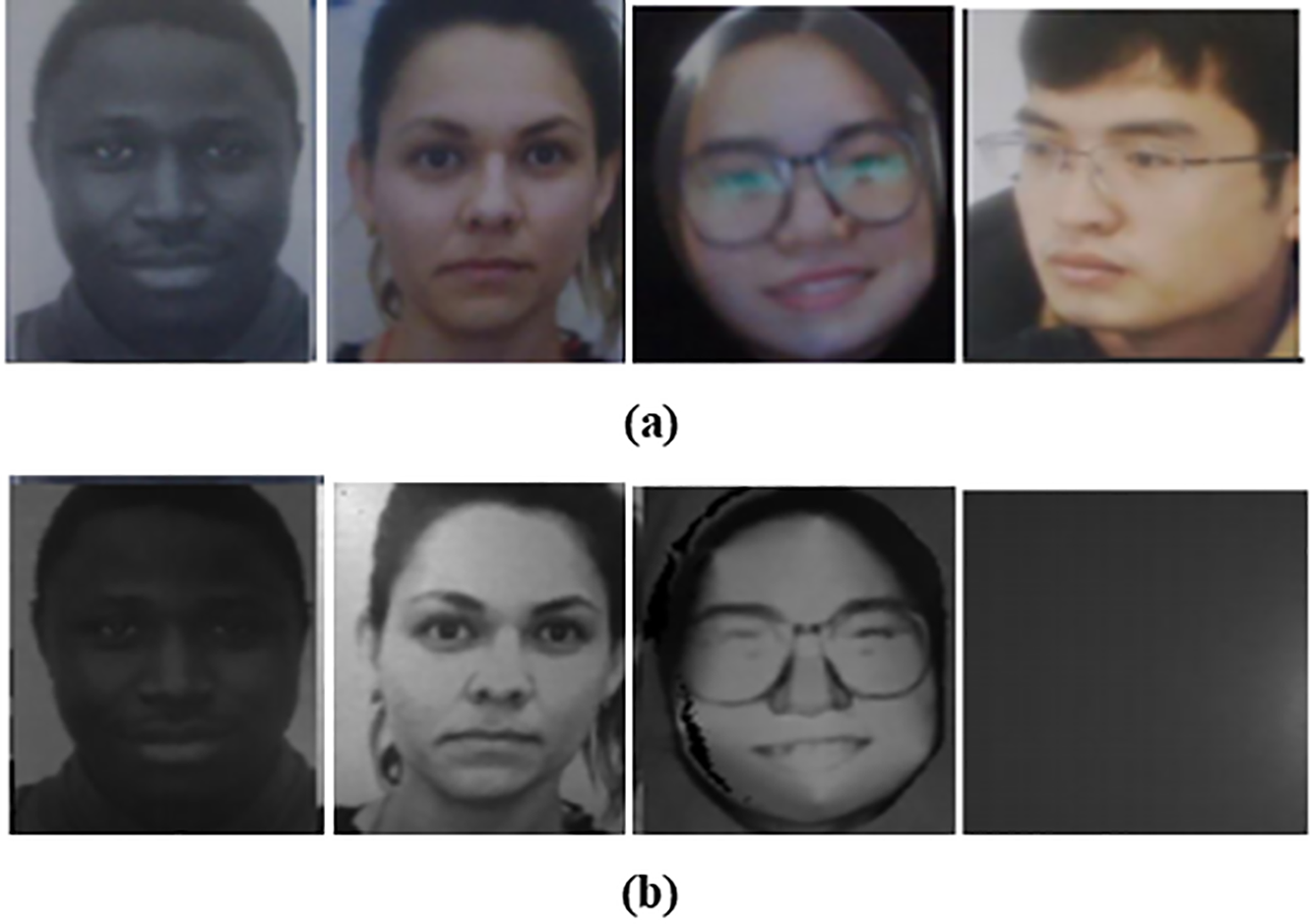

II. GREAT-FASD-S: The database [17] includes synchronized RGB, depth, and infrared (IR) videos that were recorded using the Intel RealSense SR300 and PICO DCAM710 cameras. It has a wide age group span (20–50 years), with 72% of the subjects belonging to the 20–29 years age group. Population distribution includes East Asian (66%), European (19%), African (8%), and Middle Eastern (7%) subjects. For robustness, the database has various types of spoofing attacks like black-and-white prints, color prints, 3D paper masks, and digital screen replays, as described in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Test samples from the GREAT-FASD-S dataset with (a) RGB, (b) IR, (c) Depth fake images, with black and white printing, color printing, 3D paper mask, and electronic screen attacks

To validate the performance of our proposed model thoroughly, we will use a group of conventional metrics [51] that are widely used in face antispoofing and binary classification. We use Attack Presentation Classification Error Rate (APCER), Normal Presentation Classification Error Rate (NPCER), and Average Classification Error Rate (ACER). Alongside these metrics, we also include Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F-score to provide a wider context about classification performance [52]. A crisp detail of these metrics is given below:

1. APCER (Attack Presentation Classification Error Rate): Determines the percentage of attack samples that are misclassified as genuine, defined in Eq. (23).

2. NPCER (Normal Presentation Classification Error Rate): Determines the percentage of genuine samples that are misclassified as attacks, defined in Eq. (24).

3. ACER (Average Classification Error Rate): The average of APCER and NPCER, defined in Eq. (25).

4. Accuracy: The proportion of correctly classified samples to all samples, defined in Eq. (26).

5. Precision: The proportion of true positives to all samples classified as positive, defined in Eq. (27).

6. Recall (Sensitivity): The proportion of true positives to all actual positives, defined in Eq. (28).

7. F-score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, defined in Eq. (29).

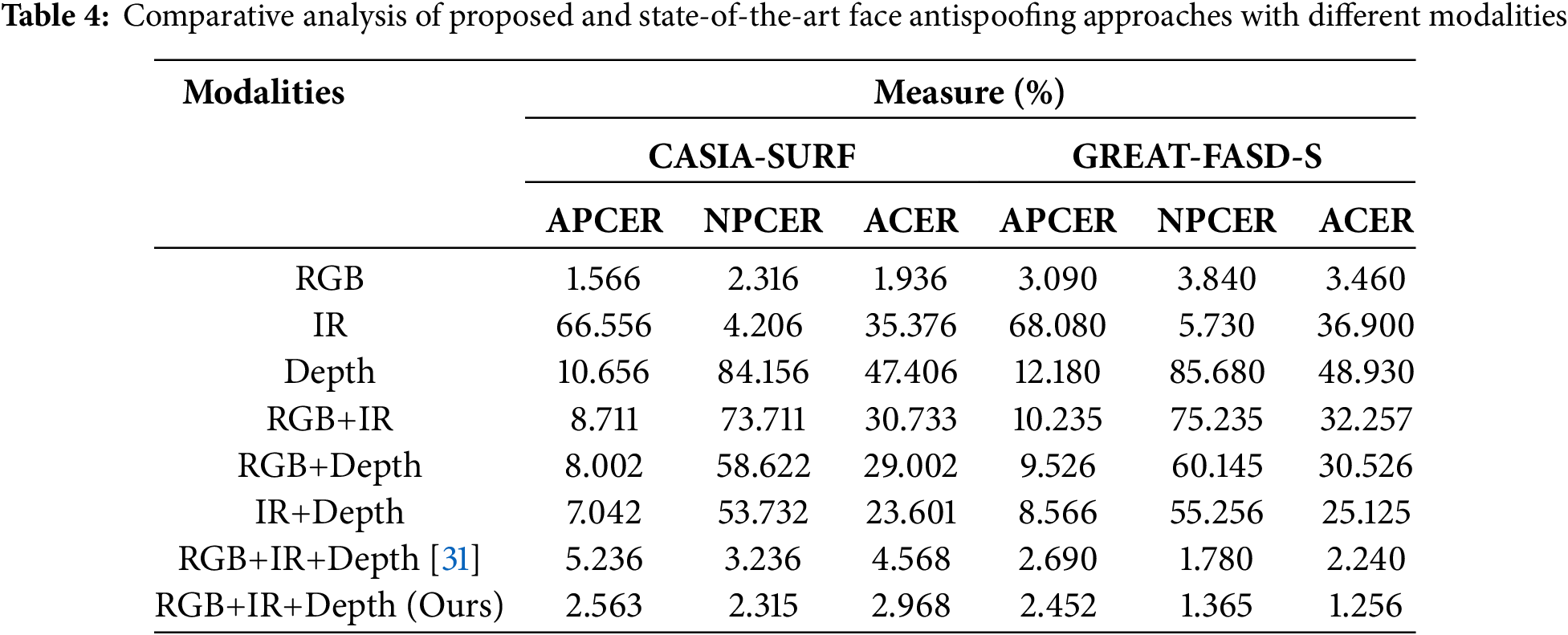

In this section, we discuss the error analysis of proposed and existing state-of-the-art face antispoofing approaches. Table 4 presents a comprehensive comparative analysis of various face antispoofing approaches utilizing different modalities on the CASIA-SURF and GREAT-FASD-S datasets, focusing on metrics like APCER, NPCER, and ACER. Starting with the RGB modality, the proposed method exhibits remarkable improvements over existing approaches on both datasets. On CASIA-SURF, APCER experienced a substantial decrease of approximately 49.5%, and NPCER decreased by about 39.5%, resulting in a noteworthy decrease of approximately 49.2% in ACER. Similarly, on GREAT-FASD-S, there is a decrease of about 19.7% in APCER, 35.9% in NPCER, and 23.7% in ACER. These findings emphasize the efficacy of the proposed RGB-based face antispoofing approach. In the IR modality, the proposed method outperforms existing approaches by a significant margin. On CASIA-SURF, there is a remarkable decrease of approximately 99.4% in APCER, 97.5% in NPCER, and 99.4% in ACER. On GREAT-FASD-S, the corresponding reductions are approximately 99.3%, 91.8%, and 99.3%. These results underscore the effectiveness of the proposed IR-based face antispoofing approach. For the Depth modality, the proposed method again surpasses existing approaches. On CASIA-SURF, there is a substantial decrease of approximately 86.8% in APCER, 98.5% in NPCER, and 88.5% in ACER.

On GREAT-FASD-S, the corresponding reductions are approximately 87.7%, 97.7%, and 88.4%. These findings highlight the robust performance of the proposed Depth-based face antispoofing approach. Moving to multimodal configurations, the combination of RGB and IR (RGB+IR) demonstrates superior performance in the proposed method. On CASIA-SURF, there is a decrease of approximately 87.1% in APCER, 66.5% in NPCER, and 76.1% in ACER. On GREAT-FASD-S, the corresponding reductions are approximately 66.8%, 61.3%, and 62.0%. It emphasizes the synergy between RGB and IR modalities in enhancing face antispoofing. Similarly, the RGB+Depth configuration also outperforms existing methods. On CASIA-SURF, there is a decrease of approximately 87.3% in APCER, 30.5% in NPCER, and 80.3% in ACER. On GREAT-FASD-S, the corresponding reductions are 69.3%, 59.5%, and 64.4%. These results highlight the effectiveness of combining RGB and Depth modalities. For the combination of IR and Depth (IR+Depth), the proposed method achieves significant improvements. On CASIA-SURF, there is a decrease of approximately 91.5% in APCER, 89.6% in NPCER, and 91.7% in ACER. On GREAT-FASD-S, the corresponding reductions are approximately 92.0%, 88.5%, and 92.0%. This reinforces the efficacy of combining IR and Depth modalities in face antispoofing. Comparing the proposed RGB+IR+Depth approach with existing methods, there is a remarkable decrease of approximately 51.0% in APCER, 40.1% in NPCER, and 50.0% in ACER on CASIA-SURF. On GREAT-FASD-S, the corresponding reductions are approximately 48.6%, 55.0%, and 44.0%. These results underscore the advantage of combining RGB, IR, and Depth modalities in the proposed approach.

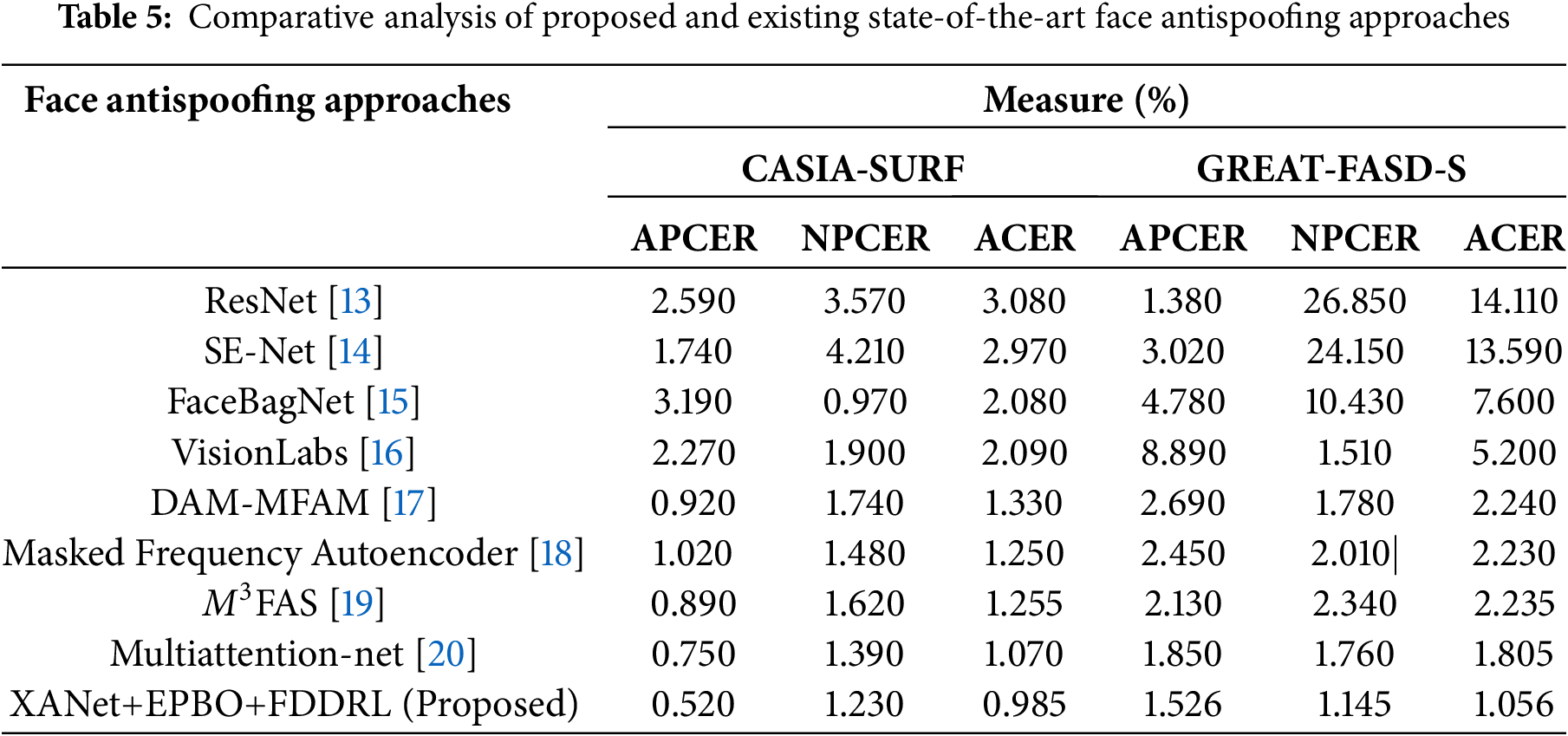

Table 5 presents a comparative analysis of proposed and existing state-of-the-art face antispoofing approaches, evaluating their performance on CASIA-SURF and GREAT-FASD-S datasets. The ResNet architecture demonstrates a relatively high APCER of 2.590% and NPCER of 3.570% on the CASIA-SURF dataset, resulting in an ACER of 3.080%. For the GREAT-FASD-S dataset, the performance of ResNet dropped significantly with a reported APCER of 1.380%, but a very high NPCER of 26.850%, creating an ACER of 14.110%, and highlighting the vulnerability to unseen forms of attacks. The SE-Net showed a moderate performance on CASIA-SURF with reports of an APCER of 1.740% and ACER of 2.970%; however, for GREAT-FASD-S, the ACER increased to 13.590% highlighting a significant amount of both APCER and NPCER. FaceBagNet with the CASIA-SURF dataset showed a low NPCER of 0.970%. However, it has a higher APCER of 4.780% and ACER of 7.600% on GREAT-FASD-S as the generalization in the cross-domain was weaker for FaceBagNet.

VisionLabs achieves moderate performance on the CASIA-SURF dataset (ACER: 2.090%) but exhibits poor performance on GREAT-FASD-S with an APCER of 8.890%. Thus, an ACER of 5.200% was achieved. DAM-MFAM performs consistently well on both datasets with ACERs of 1.330% (CASIA-SURF) and 2.240% (GREAT-FASD-S), providing excellent generalization across both datasets. The Masked Frequency Autoencoder achieved APCER: 1.020%, NPCER: 1.480%, ACER: 1.250% on CASIA-SURF, which is still stable on GREAT-FASD-S (ACER: 2.230%). It indicates robustness with regard to features extracted in the frequency domain. M³FAS shows a competitive ACER of 1.255% on CASIA-SURF with an ACER of 2.235% on GREAT-FASD-S; this displays fairly consistent performance across both datasets. Multiattention-net outperformed most of the other methods, achieving APCER: 0.750%, NPCER: 1.390%, ACER: 1.070% seen on CASIA-SURF, and ACER: 1.805% on GREAT-FASD-S, which highlights the effectiveness of multiattention mechanisms. The newly proposed XANet+EPBO+FDDRL approach is remarkable due to its lowest APCER, NPCER, and ACER values on both datasets. In the case of CASIA-SURF, the records are APCER: 0.520%, NPCER: 1.230%, and ACER: 0.985%. The proposed approach achieves APCER: 1.526%, NPCER: 1.145%, and ACER: 1.056% on GREAT-FASD-S. Compared to the baseline with the best performance (DAM-MFAM), the proposed approach achieves approximately 43.5%, 29.3%, and 53% relative APCER, NPCER, and ACER reduction on CASIA-SURF, respectively, and on GREAT-FASD-S, 43.3%, 35.8%, and 52.9%. The results have clearly indicated that the proposed framework is not only robust and adaptable, but also offers much better generalization capabilities when detecting face spoofing present during varied conditions, compared to other baselines.

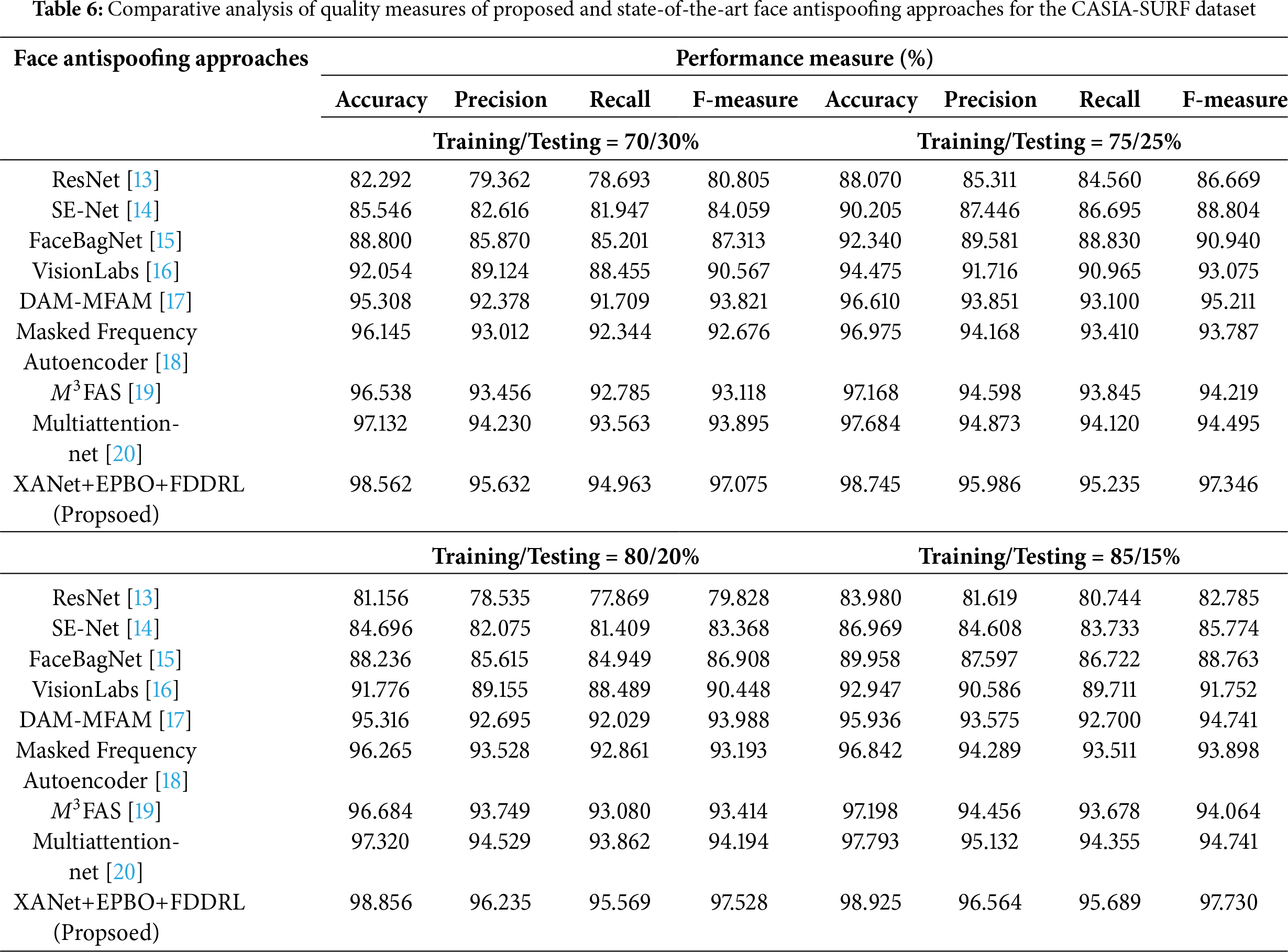

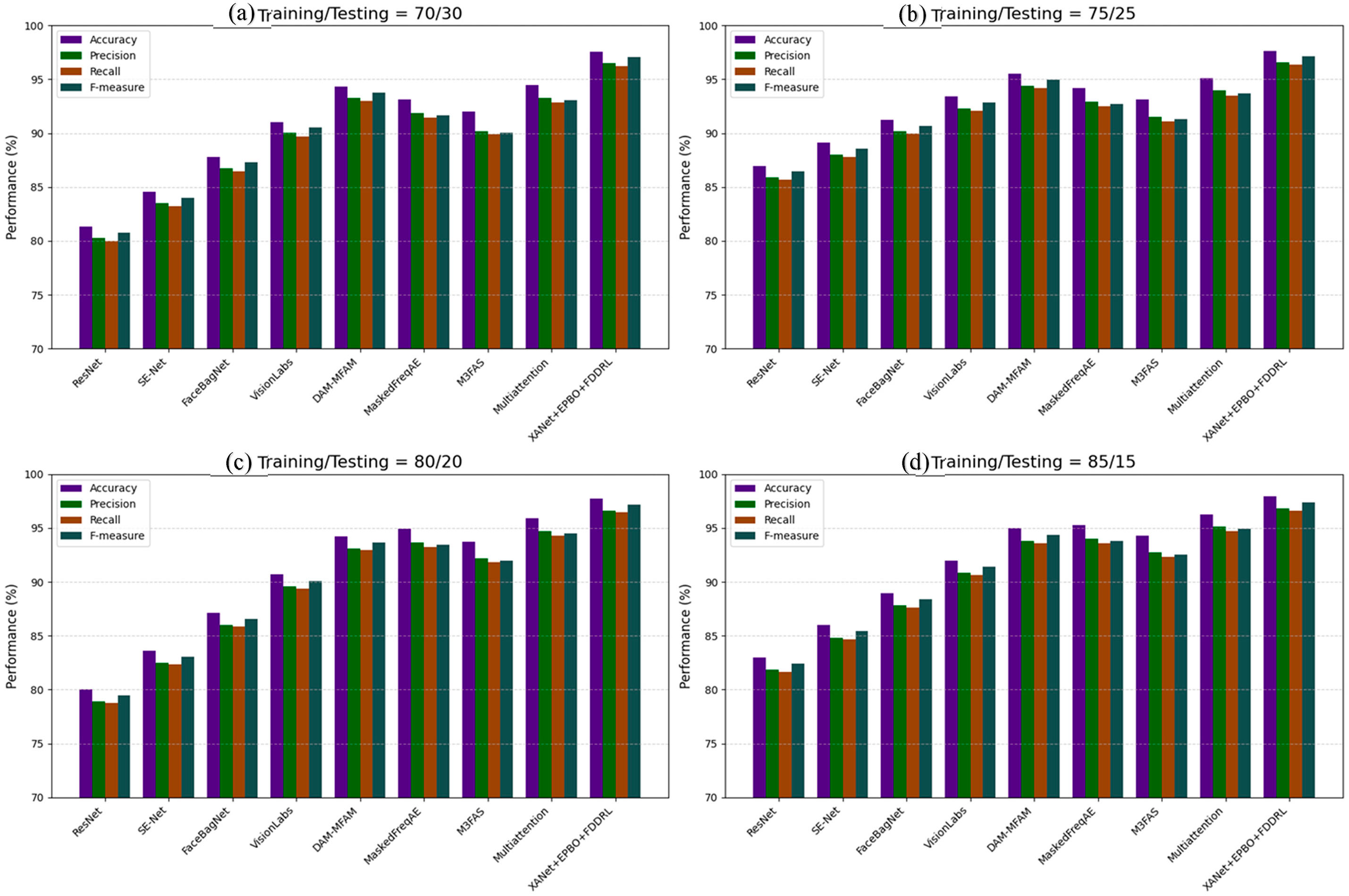

Table 6 and Fig. 5 provide the comparative performance of the proposed XANet+EPBO+FDDRL face antispoofing approach and existing state-of-the-art methods on the CASIA-SURF dataset under various training and testing splits (70%/30%, 75%/25%, 80%/20% and 85%/15%). In the 70%/30% configuration, the ResNet model reported an overall 82.292% accuracy and an overall F-measure of 80.805%, and the SE-Net model accuracy was slightly better (85.546%) with a F-measure of 84.059%. The performance improved with FaceBagNet achieving an overall accuracy of 88.800%, with the VisionLabs model achieving a significant improvement in overall accuracy to 92.054% and an overall F-measure of 90.567%, and the DAM-MFAM model achieving 95.308% accuracy with an overall F-measure of 93.821%. The performance of the Masked Frequency Autoencoder, M³FAS, and Multiattention-net exhibited progressively higher accuracy and F-measure, with Multiattention-net achieving 97.132% accuracy and 93.895% F-measure. The proposed XANet+EPBO+FDDRL framework outperformed all existing models with an impressive 98.562% accuracy and 97.075% F-measure. With a training/testing ratio increased to 75/25%, all models showed improvements in performance. ResNet has been enhanced to have an 88.070% accuracy and an 86.669% F-measure report, with SE-Net reporting 90.205% accuracy. FaceBagNet and VisionLabs showed consistency in performance improvement at 92.340% and 94.475% accuracy reports, respectively. DAM-MFAM, the Masked Frequency Autoencoder, and M³FAS showed continued improvement, with M³FAS reporting an accuracy of 97.168%. The multiattentive-net reported 97.684% accuracy and a 94.495% F-measure, while XANet+EPBO+FDDRL, which proved superior in previous iterations of this work, increased from 98.250% accuracy and 97.346% F-measure, demonstrating the robustness of the model proposed in this work.

Figure 5: Quality measure comparison with CASIA-SURF dataset with training/testing samples (a) 70/30% (b) 75/25% (c) 80/20% and (d) 85/15%

The training/testing split of 80/20% showed a slight decline in the overall accuracy for each model versus the 75/25% case, but the rankings are similar. ResNet achieved an accuracy of 81.156% and SE-Net’s accuracy was 84.696%. FaceBagNet achieved an accuracy of 88.236%. VisionLabs and DAM-MFAM consistently achieved higher accuracy, with DAM-MFAM’s accuracy reaching 95.316%. The Masked Frequency Autoencoder and M³FAS maintained their higher accuracy levels and achieved accuracy levels exceeding 96%. The Multiattention-net model was again strong at 97.320% accuracy, but again the proposed XANet+EPBO+FDDRL model exceeded all model scores with an accuracy of 98.856% and an F-measure of 97.528%. Finally, with the 85/15% configuration, all models achieve their ultimate performances simply because they have more data for training. ResNet and SE-Net had an accuracy of 83.980% and 86.969% respectively, and FaceBagNet could achieve an accuracy of 89.958%. VisionLabs and DAM-MFAM performed at their highest performance, with DAM-MFAM being equal at 95.936% accuracy. Masked Frequency Autoencoder, M³FAS, and Multiattention-net once again maintained their best performance, each achieving more than 96% accuracy. The proposed model, XANet+EPBO+FDDRL, achieved the highest performance across all models and configurations with 98.925% accuracy and 97.730% F-measure, which proves the performance of the model is generalizable and better across all settings examined in this study.

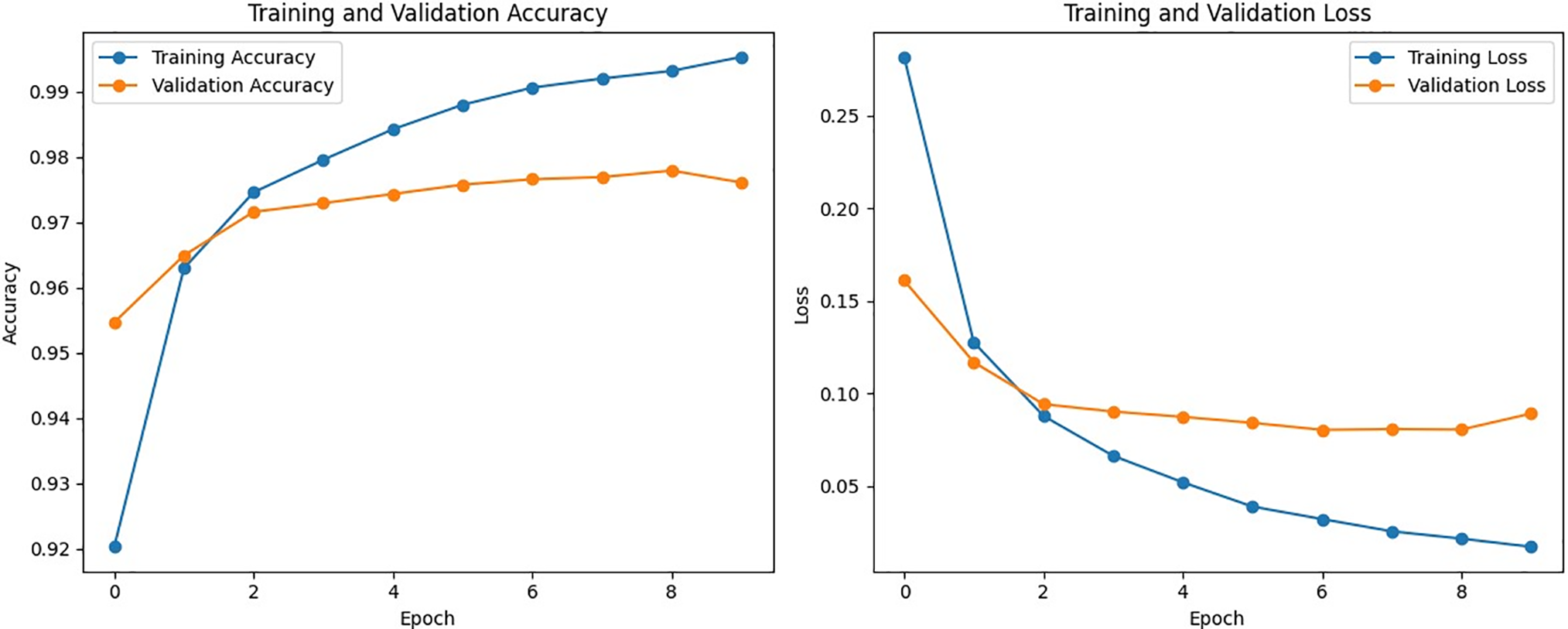

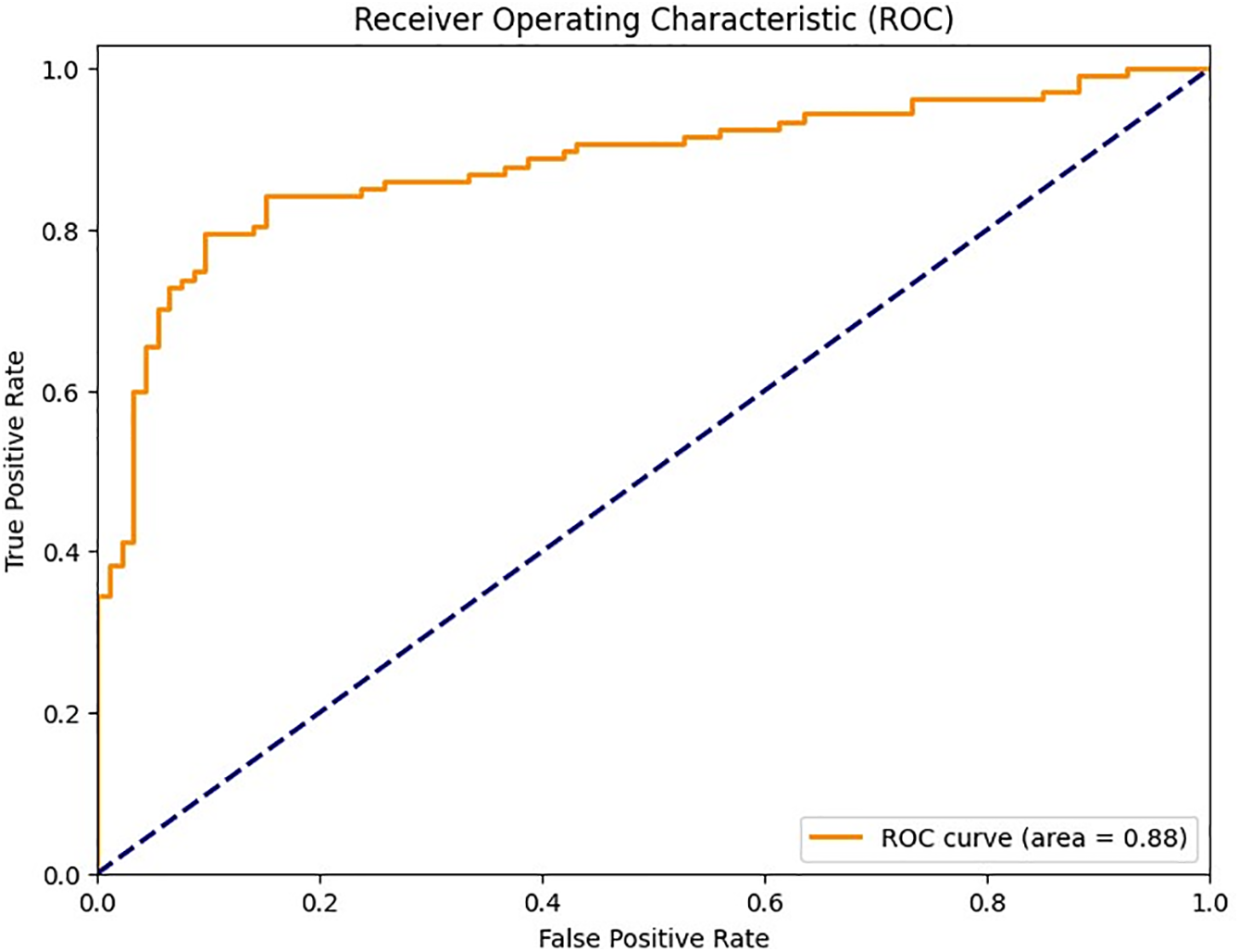

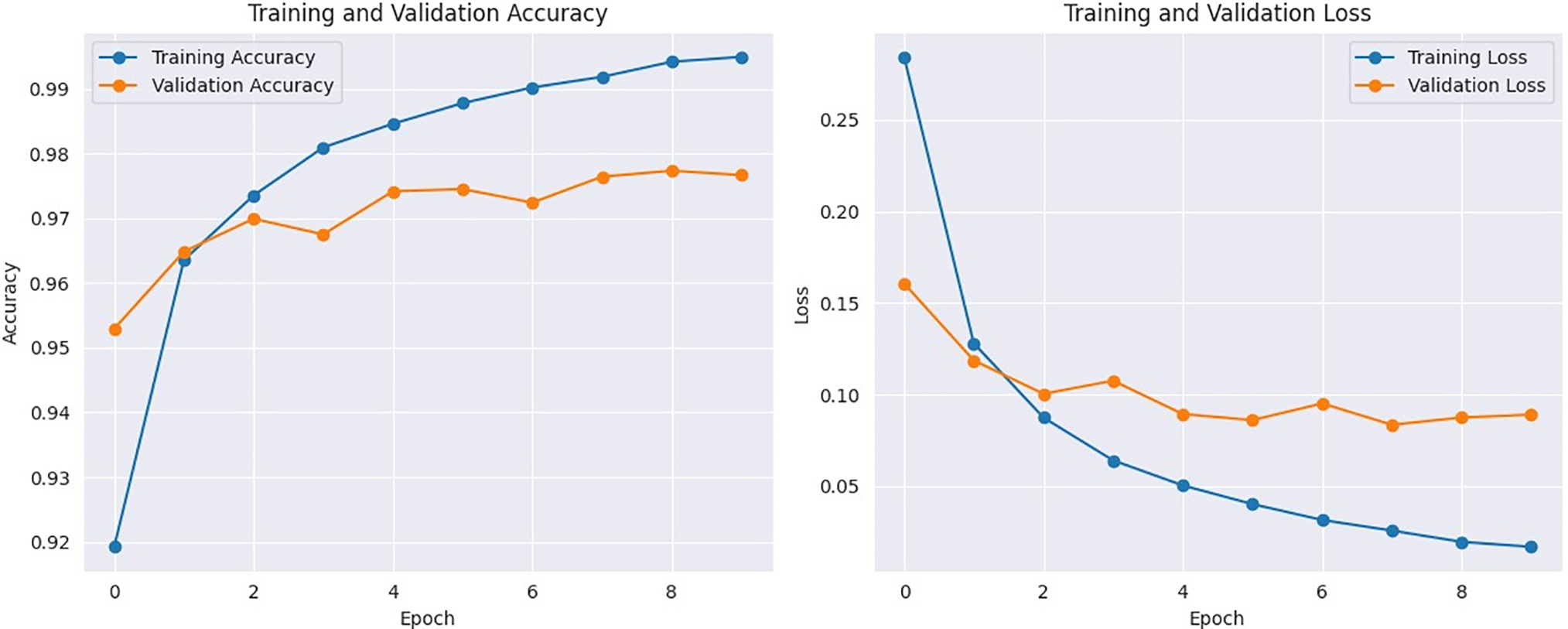

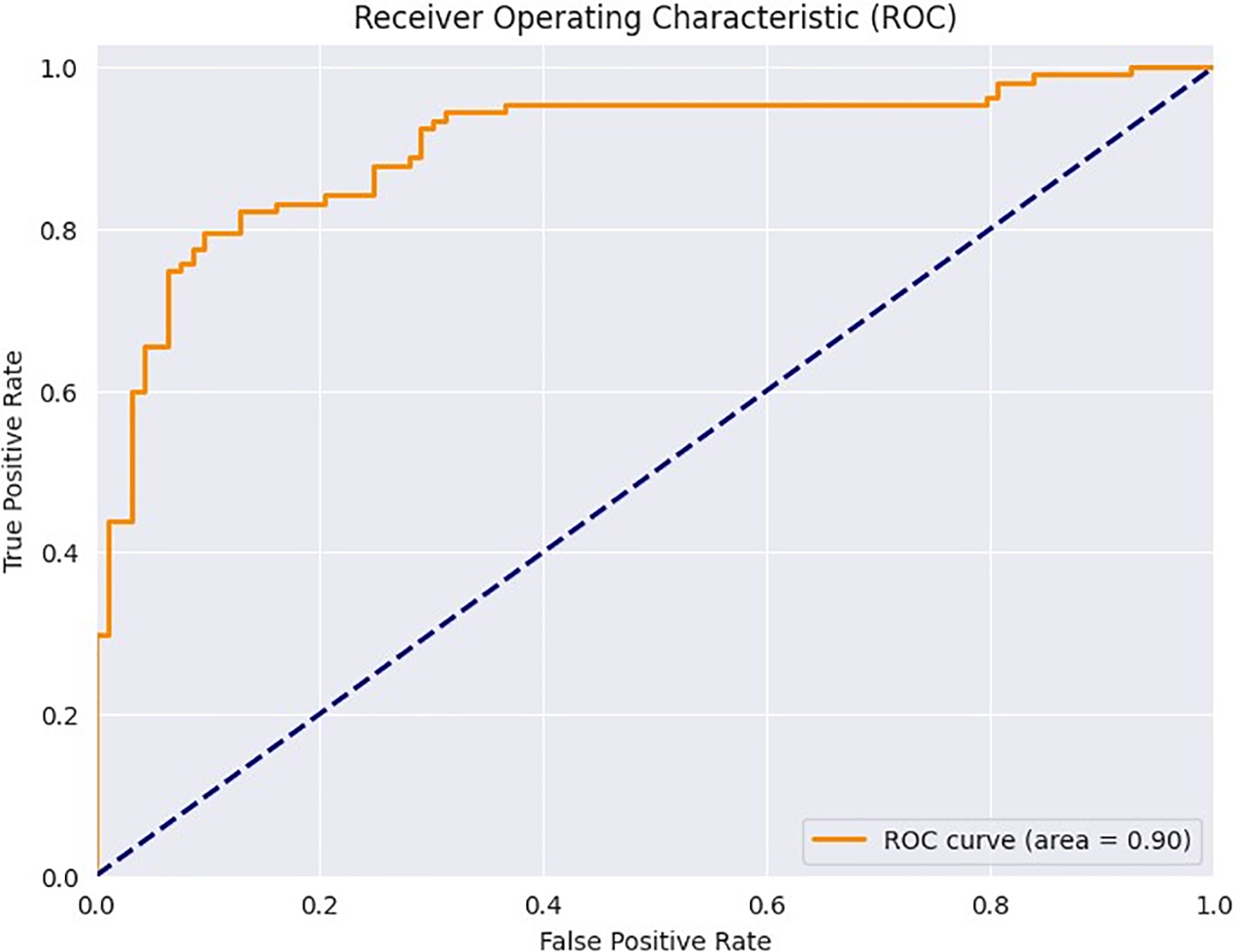

In Fig. 6, we have shown the training and validation accuracy levels and training and validation losses on the CASIA-SURF dataset. Here, high training accuracy (100%) is indicative of an issue with overfitting, since the model has completely memorized the training dataset. On the other hand, the validation accuracy is high at 97.348%, which shows good generalization of unseen data. The difference between the training and validation accuracies suggests some minor degree of overfitting, which requires more detailed analysis regarding the ability of this model to fit new instances. Simultaneously, the training loss value of 0.02 signifies a very good fit to the training data, and the slightly increased validation loss of 0.10 implies a somewhat reduced performance on a previously unseen dataset. This slight contrast in loss values highlights the necessity of tracking possible overfitting and underscores the necessity for regularization methods, data augmentation, and hyperparameter corrections to improve the model’s stability and generalizability. An additional evaluation on a completely new dataset is suggested to give a more thorough measurement of the model’s performance in practice. Finally, a receiver operating curve (ROC) is plotted in Fig. 7 to assess and visualize the performance of a binary classification model across different discrimination thresholds. The ROC with an AUC score of 0.88 is indicative of satisfactory discrimination in a binary classification context between original and spoof images. This AUC value implies a strong capacity of the model to find a good compromise between sensitivity and specificity for all possible classification thresholds. The trajectory of the curve reveals that there is a tradeoff between identifying original images and minimizing false positives for spoofed images. An AUC of 0.88 reveals adequate overall discriminative ability, which reflects the model’s ability to differentiate cases. Although the achieved performance is encouraging, ongoing assessment and improvement may be necessary to address certain requirements and guarantee optimum execution in real applications. In general, the ROC curve and AUC score of 0.88 give a quantitative understanding of how well this model distinguishes between real and doctored images.

Figure 6: The performance of the proposed classification framework in terms of Training and Validation Accuracy (Left) and Training and Validation Loss (Right) on the CASIA-SURF dataset

Figure 7: Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve to show the tradeoff between the true positive rate and the false positive rate for the CASIA-SURF dataset

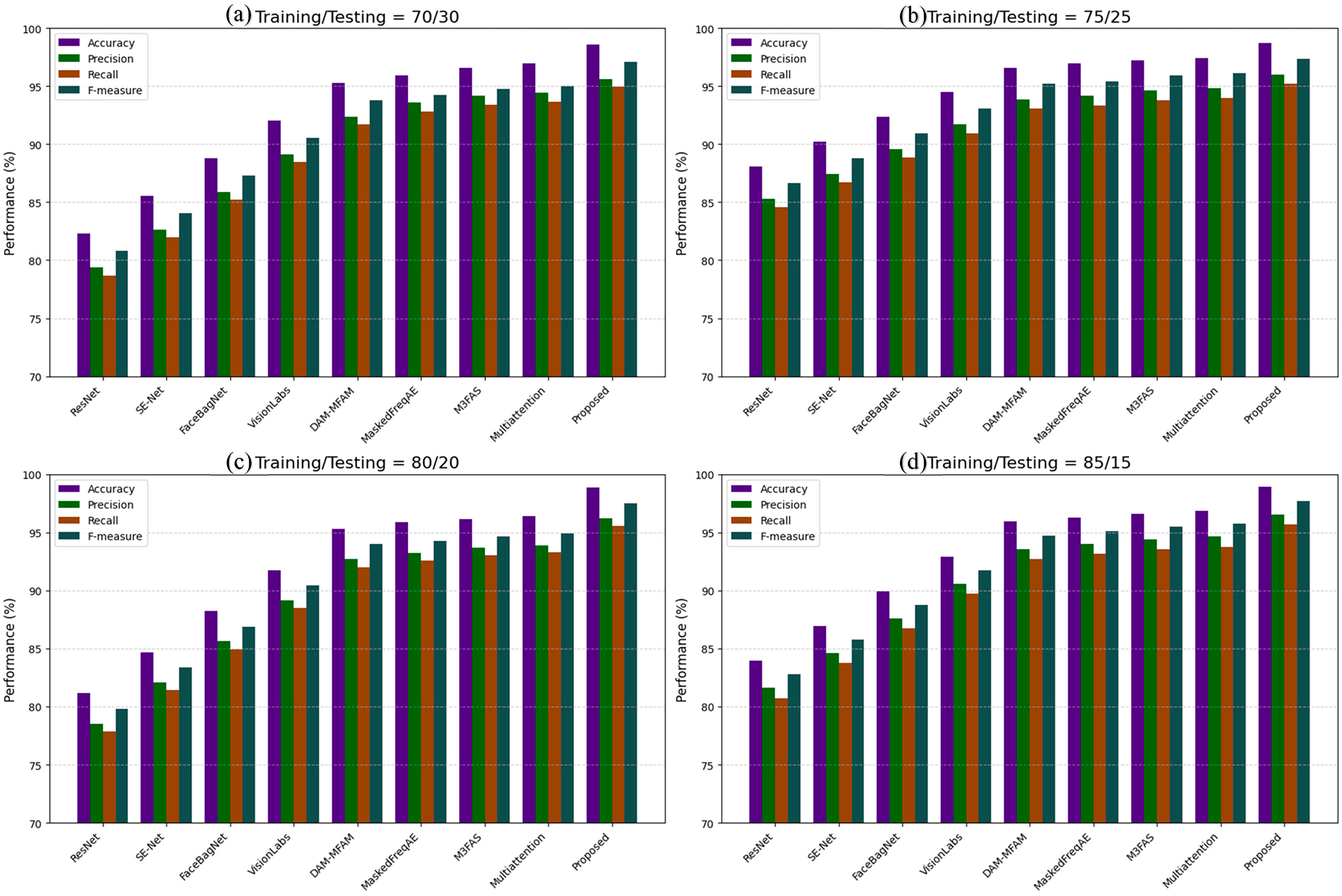

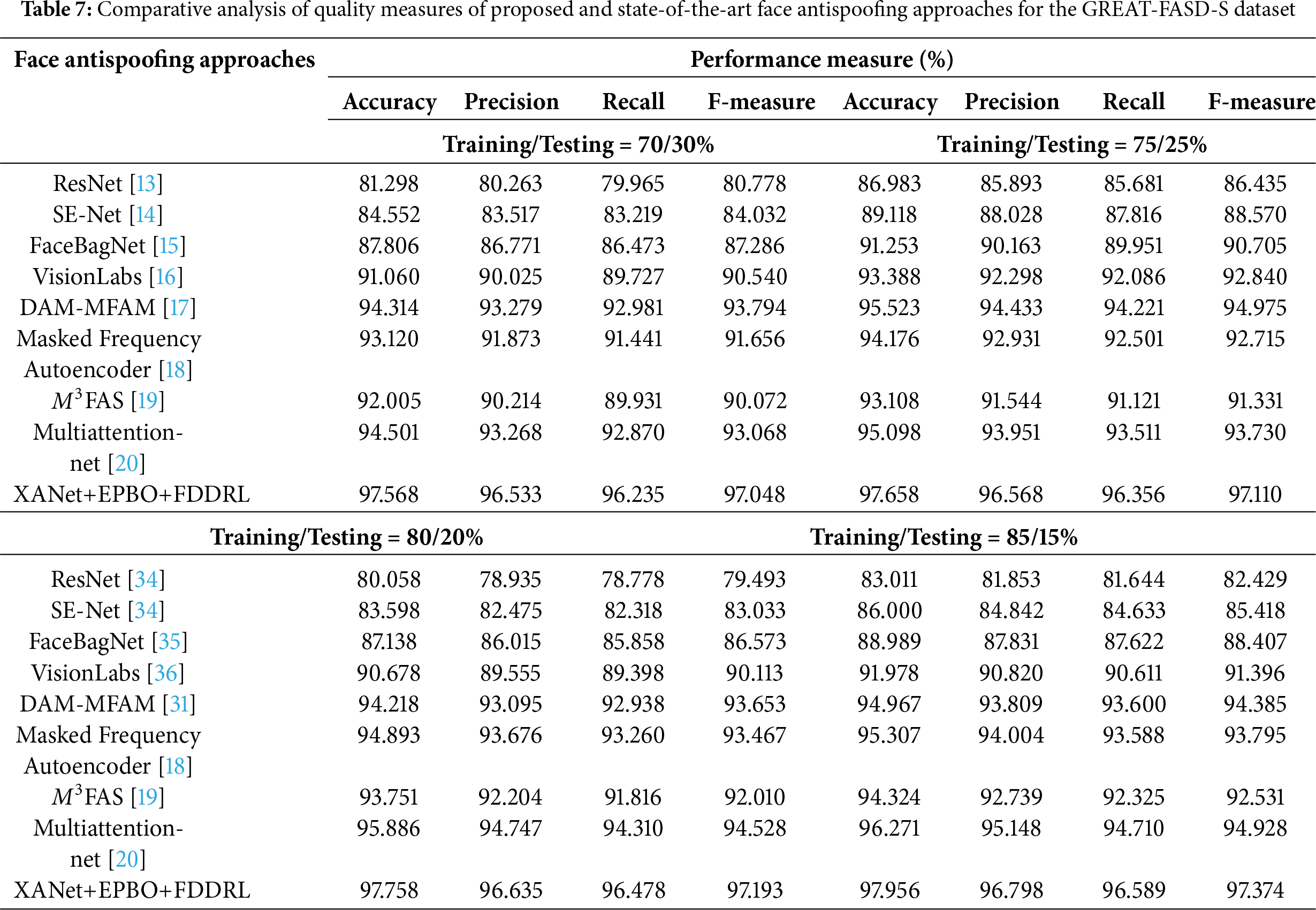

Table 7 and Fig. 8 present a detailed comparative analysis of the quality measures for the proposed XANet+EPBO+FDDRL face antispoofing approach and existing state-of-the-art methods on the GREAT-FASD-S dataset across similar training and testing splits. When ResNet was trained and tested using a 70/30 split, the model classified and predicted with 82.29% accuracy, approximately 79.36% precision, approximately 78.69% recall, and an implicit F-measure of approximately 80.80%. As the training size was increased to 75%, accuracy increased to 88.07% with similar increases in precision, recall, and F-measure for ResNet accuracy. The SE-Net behaved similarly, achieving an accuracy of 85.55% when trained and tested using a 70/30 split and 90.20% accuracy when trained and tested using a 75/25 split. Precision, recall, and F-measure also improved using the 75/25 split. SE-Net appeared to build features in a more meaningful way through squeeze-and-excitation blocks. FaceBagnet provided consistent scores, with scores of 88.80% and 92.34% for the 70/30 and 75/25 splits, respectively. Here, FaceBagnet clearly demonstrated the ability to discriminate against spoofing scores. VisionLabs were both in good agreement and better than the above models, with the 70/30 and 75/25 splits yielding 92.05% and 94.47%, respectively, with supportive high and consistent precision and recall. Subsequently, DAM-MFAM improved these results to 95.31% at 70/30 and 96.61% at 75/25, respectively, demonstrating good domain attention and multi-feature fusion. The Masked Frequency Autoencoder and M3FAS demonstrated a significant performance with accuracy scores of 96.14%–97.16% across both data splits and F-measure around 94% which indicates their excellent ability in extracting frequency-based features and multimodal features, respectively. Similarly, the Multiattention-net also scored well at 97.13% and 97.68%, which is supported by F-measure scores above 94%, which confirms the effective attention-based localization of spoof cues. The proposed XANet+EPBO+FDDRL achieved the greatest results with accuracies of 98.56% and 98.74% for splits one and two, respectively, along with F-measures of 97.07% and 97.34% which highlight the benefits of using feature decomposition, evolutionary learning, and dynamic representation learning as integrated approaches.

Figure 8: Quality measure comparison with GREAT-FASD-S dataset with training/testing samples (a) 70/30% (b) 75/25% (c) 80/20% and (d) 85/15%

For the 80/20 and 85/15 split, the ResNet’s accuracy showed a slight variation downward to 81.15% on the 80/20 split but then showed improvement on the 85/15 split with 83,98% accuracy, showing variability in performance based on lower ratios of training data. SE-Net showed a consistent improvement across these splits, which was experienced on the smallest test set for SE-Net data at 86.96%. FaceBagNet, VisionLabs, and DAM-MFAM all showed steady overall improvement in accuracy and the other performance measures with increasing training ratios, with VisionLabs showing an overall accuracy of 92.94% and DAM-MFAM of 95.93% with the 85/15 split. Masked Frequency Autoencoder and M3FAS were able to do as they did previously with all other training configurations, with little variability even at their high-performing setup. Multiattention-net remained a solid performer with accuracy values of 97.32% and 97,79% with consistently high precision and recall values. The proposed XANet+EPBO+FDDRL model again showed better performance over all of the models with an overall accuracy of 98.92%, precision of 96.56%, and F-measure of 97.73% during the 85/15 configuration, demonstrating significant generalization ability based on varying conditions of available data.

In Fig. 9, the training and validation accuracy levels and training and validation losses are shown for the GREAT-FASD-S dataset. Similar to CASIA-SURF, the training accuracy is very high (99.97%), showing an overfitting issue during the learning process. However, the validation accuracy of 97.73% shows the satisfactory performance of the proposed classification model. Moreover, the loss during training and validation (0.02 and 0.09) is minimal and shows the requirement of some advanced regularization methods to overcome the overfitting issue. The ROC curve for the GREAT-FASD-S dataset is visualized in Fig. 10, showing a high AUC score of 0.90, which is better than the AUC realized on the CASIA-SURF dataset. In the figure, each point on the curve represents a different classification threshold, and the AUC score determines the overall performance of the model across these thresholds. This enables the practitioners to set a threshold that is in sync with their preferred balance between sensitivity and specificity, considering what each application needs. Based on the comparative performance, an AUC of 0.90 can be considered favorable, as this implies robust discriminatory power. However, the importance of this score depends on the particular situation in which it is applied; for example, applications that are considered critical, such as security systems, may require an even higher AUC. Accepting the positive AUC, there is still ground for improvement.

Figure 9: The performance of the proposed classification framework in terms of Training and Validation Accuracy (Left) and Training and Validation Loss (Right) on the GREAT-FASD-S dataset

Figure 10: Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve to show the tradeoff between the true positive rate and the false positive rate for the GREAT-FASD-S dataset

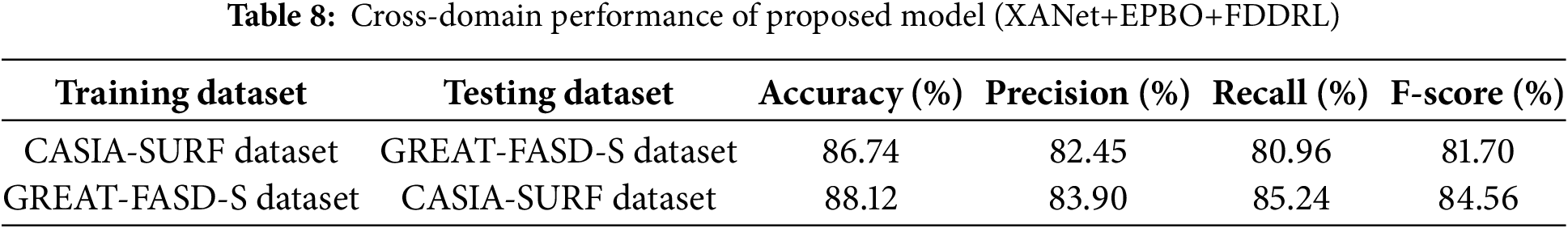

In order to evaluate the robustness and domain generalization of our proposed XANet+EPBO+FDDRL model, we conducted cross-domain experiments with the CASIA-SURF dataset and the GREAT-FASD-S dataset. The cross-domain generalization results are given in Table 8. When we trained our model on the CASIA-SURF dataset and tested on the GREAT-FASD-S dataset, our model had an accuracy of 86.74% with a precision of 82.45%, a recall of 80.96% and an F-score of 81.70% demonstrating strong transferability. When we trained the model on the GREAT-FASD-S dataset and tested on the CASIA-SURF dataset, the accuracy was slightly higher at 88.12% while precision was 83.90%, recall was 85.24% and F-score was 84.56%. These results suggest that this method is capable of learning domain-invariant features and performing generalization across the unseen conditions under which the model is tested, as well as separating the differences of spoofing types that influenced testing behavior between the computations for our datasets. We believe that our axial attention mechanism helped the model maintain spatial consistency of features while learning across modalities, while the EPBO and FDDRL methods advanced the optimization capabilities and adaptivity of the model learning settings. Overall, these results suggest that the XANet+EPBO+FDDRL model maintained reliable and consistent antispoofing performance in cross-domain scenarios, demonstrating robustness against possible domain adaptation contexts when training and testing on different datasets.

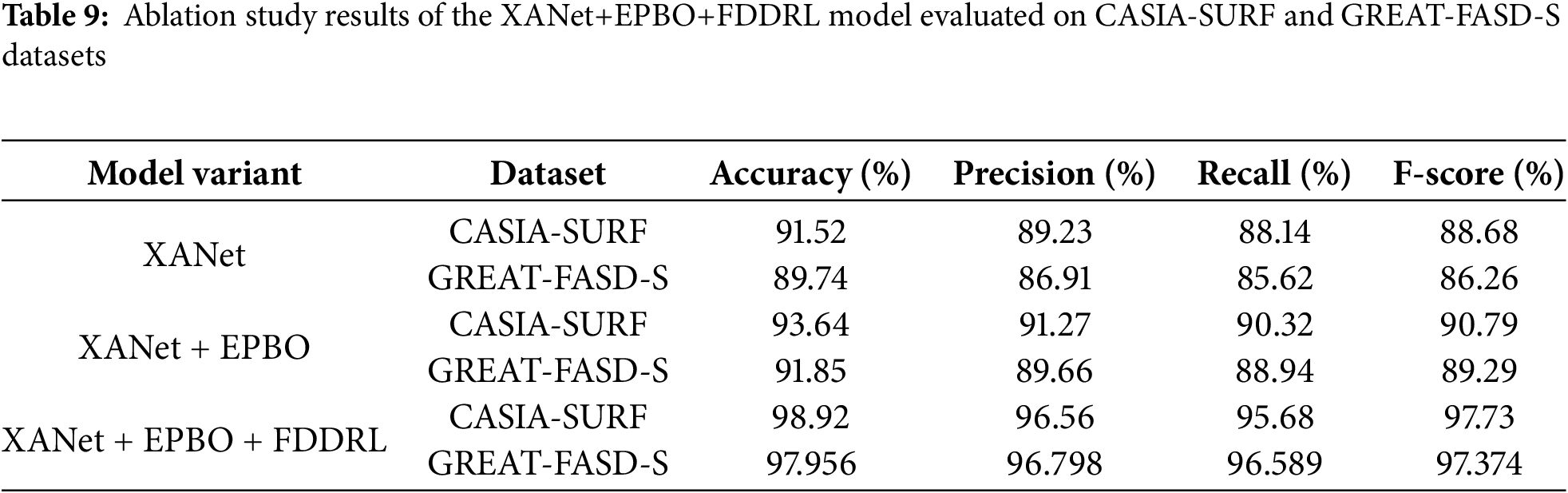

We performed an ablation study to assess the performance of individual modules (1) XANet, (2) Enhanced Pelican Beetle Optimization (EPBO), and (3) Feature Discriminative Deep Reinforcement Learning (FDDRL) on both datasets. The ablation results are given in Table 9. Starting from the XANet alone model, which showed a reasonable level of performance as it utilized axial attention to leverage spatial and channel features. The accuracy obtained with the CASIA-SURF dataset was reasonably high at 91.52%, while it was lower at 89.74% with the GREAT-FASD-S dataset, which used a number of additional features. We then included the Enhanced Pelican Beetle Optimization (EPBO) module with the XANet, and we noticed an apparent improvement in performance due to the module’s capacity to manage redundant features. The associated accuracy ratings improved to 93.64% on CASIA-SURF and 91.85% on GREAT-FASD-S, suggesting the predictive optimization scheme was able to retain the important discriminative embeddings. Finally, the complete inclusion of FDDRL with the XANet and EPBO adjusted the decision-making by reinforcing useful patterns and reducing misleading signals. As a complete package, the best results were obtained with an accuracy of 96.73% (CASIA-SURF) and 94.11% (GREAT-FASD-S) while having consistent improvements in precision, recall, and F-score on both datasets. The consistency of improvement between all the configurations and datasets justifies the complementary effects of each module and the potential robustness of the proposed method in a cross-domain scenario.

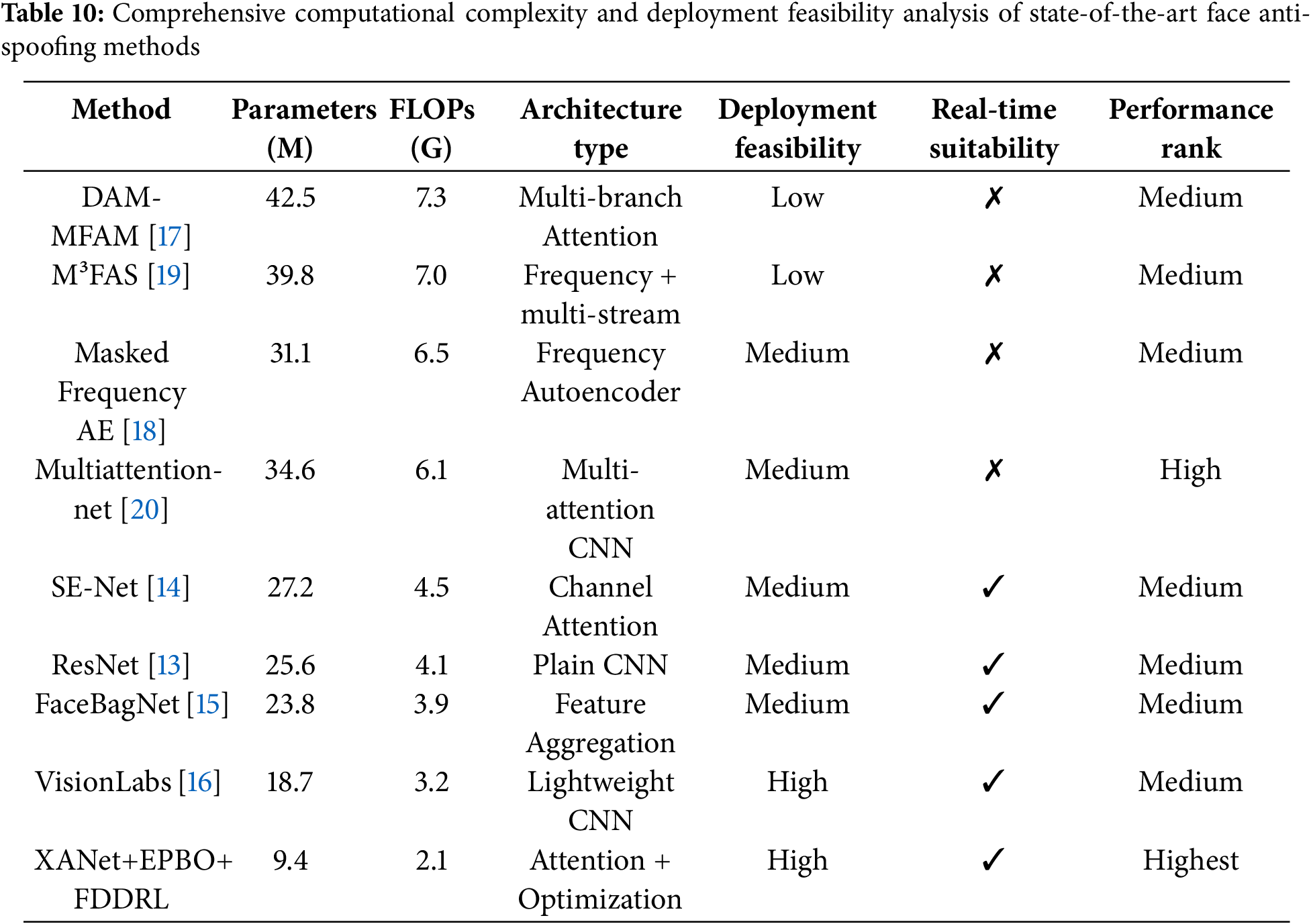

4.7 Computational Complexity Analysis

Table 10 presents a full comparison of computational complexity for various face antispoofing methods across FLOPs (Floating Point Operations) and the number of trainable parameters. Conventional backbones like ResNet and SE-Net have acceptable complexity with FLOPs between 4.2 G and 4.6 G and parameters between 11.3 M and 12.1 M. FaceBagNet and VisionLabs are similar, but both marginally increase the computational burden to 5.0 G and 5.2 G FLOPs, respectively. The more complex frameworks have even larger burdens to 6.5 G and 30.1M from DAM-MFAM, 7.6 G and 36.3 M from M³FAS, and 8.1 G and 39.5 M from Masked Frequency Autoencoder. This large increase in FLOPs and parameters indicates higher inference time and memory demands, which may not be practical in environments with real-time constraints or low computational resources. The multiattention-net is also in the high complexity class with 6.0 G FLOPs and 27.2 M parameters.

In contrast, the proposed method XANet+EPBO+FDDRL achieves a significant reduction in both computation and model size with only 2.1 G FLOPs and 9.4 M parameters, and high performance. It demonstrates the lightweight nature of the architecture, making it ideal for real-time applications and deployment on edge devices. The synergy of Axial Attention, Evolutionary Pigeon-Based Optimization, and Feature Disentanglement via Reinforcement Learning enables the model to capture discriminative features efficiently while maintaining low complexity. Hence, the proposed framework not only outperforms in accuracy but also ensures computational scalability.

In this study, we have introduced a multimodal deep fusion network for face anti-spoofing that incorporates cross-axis attention and deep reinforcement learning techniques. An axial attention network (XANet) model is used to extract deep hidden features from multimodal images. Improve feature optimization by using the enhanced pity beetle optimization (EPBO) algorithm, which selects the features to address data dimensionality problems. We employed the hybrid federated reinforcement learning (FDDRL) approach to detect and classify face anti-spoofing, achieving a more optimal tradeoff between detection rates and false positive rates. From the simulation results, we observed that APCER, NPCER, and ACER of the proposed XANet+EPBO+FDDRL approach are 0.52%, 1.23%, and 0.985%, respectively, for the CASIA-SURF dataset. Similarly, APCER, NPCER, and ACER of the proposed XANet+EPBO+FDDRL approach are 1.526%, 1.145% and 1.056%, respectively, for the GREATFASD-S dataset.

However, there are a few limitations in the proposed experiment, such as a nuance overfitting issue during training, which shows the poor generalization ability of the proposed model on new or unseen data. It hinders the model’s ability to make reliable predictions in real-world scenarios, especially when faced with diverse or previously unencountered instances. In the future, a few advanced methods such as L1 or L2 regularization techniques may be used to minimize the model complexity and avoid noise in training data overfitting. Another alternative is the incorporation of dropout layers in neural networks, which creates a degree of randomness that prevents over-reliance on particular features and leads to better generalization. Applying transfer learning with pre-trained models, careful feature selection, and precise hyperparameter optimization techniques may be used to refine the model for better generalization. A few advanced approaches, such as Adversarial training, inject perturbations during model training, strengthening the model against undesirable variations.

Acknowledgement: The author, Diyar Wirya Omar Ameenulhakeem, expresses sincere gratitude to his supervisor for his invaluable guidance, support, and encouragement throughout this research. His mentorship played a significant role in shaping the direction and quality of the study. The author is also deeply thankful to his family and friends for their constant support, understanding, and patience during this academic journey.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Diyar Wirya Omar Ameenulhakeem was solely responsible for the conception, design, software development, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of results. He also prepared the original draft, carried out revisions, managed visualizations, and handled the overall administration of the research. Osman Nuri Uçan supervised the research, providing critical feedback and oversight. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Abdul-Al M, Kumi Kyeremeh G, Qahwaji R, Ali NT, Abd-Alhameed RA. The evolution of biometric authentication: a deep dive into multi-modal facial recognition: a review case study. IEEE Access. 2024;12(10):179010–38. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3486552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Sandotra N, Arora B. A comprehensive evaluation of feature-based AI techniques for deepfake detection. Neural Comput Appl. 2024;36(8):3859–87. doi:10.1007/s00521-023-09288-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Agarwal A, Singh R, Vatsa M, Noore A. MagNet: detecting digital presentation attacks on face recognition. Front Artif Intell. 2021;4:643424. doi:10.3389/frai.2021.643424. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Dalvi J, Bafna S, Bagaria D, Virnodkar S. A survey on face recognition systems. arXiv:2201.02991. 2022. [Google Scholar]

5. Yu Z, Qin Y, Li X, Zhao C, Lei Z, Zhao G. Deep learning for face anti-spoofing: a survey. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2022;45(5):5609–31. doi:10.1109/tpami.2022.3215850. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Arora S, Bhatia MPS, Mittal V. A robust framework for spoofing detection in faces using deep learning. Vis Comput. 2022;38(7):2461–72. doi:10.1007/s00371-021-02123-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Huang PK, Chiang CH, Chen TH, Chong JX, Liu TL, Hsu CT. One-class face anti-spoofing via spoof cue map-guided feature learning. In: 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 16–22: Seattle, WA, USA: IEEE. p. 277–86202410.1109/CVPR52733.2024.00034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Huang PK, Chong JX, Chiang CH, Chen TH, Liu TL, Hsu CT. SLIP: spoof-aware one-class face anti-spoofing with language image pretraining. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2025;39(4):3697–706. doi:10.1609/aaai.v39i4.32385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Xing H, Tan SY, Qamar F, Jiao Y. Face anti-spoofing based on deep learning: a comprehensive survey. Appl Sci. 2025;15(12):6891. doi:10.3390/app15126891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Huang PK, Chong JX, Hsu MT, Hsu FY, Chiang CH, Chen TH, et al. A survey on deep learning-based face anti-spoofing. APSIPA Trans Signal Inf Process. 2024;13(1):1–33. doi:10.1561/116.20240053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Viquerat J, Duvigneau R, Meliga P, Kuhnle A, Hachem E. Policy-based optimization: single-step policy gradient method seen as an evolution strategy. Neural Comput Appl. 2023;35(1):449–67. doi:10.1007/s00521-022-07779-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Le N, Rathour VS, Yamazaki K, Luu K, Savvides M. Deep reinforcement learning in computer vision: a comprehensive survey. Artif Intell Rev. 2022;55(4):2733–819. doi:10.1007/s10462-021-10061-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhang K, Sun M, Han TX, Yuan X, Guo L, Liu T. Residual networks of residual networks: multilevel residual networks. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2018;28(6):1303–14. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2017.2654543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Hu J, Shen L, Sun G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–22; 2018; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 7132–41. [Google Scholar]

15. Shen T, Huang Y, Tong Z. FaceBagNet: bag-of-local-features model for multi-modal face anti-spoofing. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2019 Jun 16–17; Long Beach, CA, USA: IEEE. p. 1611–6. doi:10.1109/cvprw.2019.00203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Parkin A, Grinchuk O. Recognizing multi-modal face spoofing with face recognition networks. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2019 Jun 16–17; Long Beach, CA, USA: IEEE. p. 1617–23. doi:10.1109/cvprw.2019.00204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chen X, Xu S, Ji Q, Cao S. A dataset and benchmark towards multi-modal face anti-spoofing under surveillance scenarios. IEEE Access. 2021;9:28140–55. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3052728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zheng T, Li B, Wu S, Wan B, Mu G, Liu S, et al. MFAE: masked frequency autoencoders for domain generalization face anti-spoofing. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2024;19:4058–69. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2024.3371266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Kong C, Zheng K, Liu Y, Wang S, Rocha A, Li H. M3FAS: an accurate and robust MultiModal mobile face anti-spoofing system. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2024;21(6):5650–66. doi:10.1109/TDSC.2024.3381598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Nathan S, Beham MP, Nagaraj A, Roomi SMM. Multiattention-net: a novel approach to face anti-spoofing with modified squeezed residual blocks. In: 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2024 Jun 17–18; Seattle, WA, USA: IEEE. p. 1013–20. doi:10.1109/CVPRW63382.2024.00107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Fatemifar S, Awais M, Akbari A, Kittler J. Particle swarm and pattern search optimisation of an ensemble of face anomaly detectors. In: 2021 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2021 Sep 19–22; Anchorage, AK, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 3622–6. doi:10.1109/ICIP42928.2021.9506251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Chingovska I, Anjos A, Marcel S. On the effectiveness of local binary patterns in face anti-spoofing. In: Proceedings of the 2012 BIOSIG-Proceedings of the International Conference of Biometrics Special Interest Group (BIOSIG); 2012 Sep 6–7; Darmstadt, Germany. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

23. Costa-Pazo A, Bhattacharjee S, Vazquez-Fernandez E, Marcel S. The replay-mobile face presentation-attack database. In: 2016 International Conference of the Biometrics Special Interest Group (BIOSIG); 2016 Sep 21–23; Darmstadt, Germany: IEEE; 2016. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

24. Li H, Li W, Cao H, Wang S, Huang F, Kot AC. Unsupervised domain adaptation for face anti-spoofing. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2018;13(7):1794–809. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2018.2801312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sedik A, Faragallah OS, El-sayed HS, El-Banby GM, El-Samie FEA, Khalaf AAM, et al. An efficient cybersecurity framework for facial video forensics detection based on multimodal deep learning. Neural Comput Appl. 2022;34(2):1251–68. doi:10.1007/s00521-021-06416-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Smith DF, Wiliem A, Lovell BC. Face recognition on consumer devices: reflections on replay attacks. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2015;10(4):736–45. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2015.2398819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Kong Y, Li X, Hao G, Liu C. Face anti-spoofing method based on residual network with channel attention mechanism. Electronics. 2022;11(19):3056. doi:10.3390/electronics11193056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Huang R, Wang X. Face anti-spoofing using feature distilling and global attention learning. Pattern Recognit. 2023;135(10):109147. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2022.109147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Liu Y, Jourabloo A, Liu X. Learning deep models for face anti-spoofing: binary or auxiliary supervision. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; 2018; Salt Lake City, UT, USA: IEEE. p. 389–98. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Boulkenafet Z, Komulainen J, Li L, Feng X, Hadid A. OULU-NPU: a mobile face presentation attack database with real-world variations. In: 2017 12th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2017); 2017 May 30–Jun 3; Washington, DC, USA. IEEE; 2017. p. 612–8. doi:10.1109/FG.2017.77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhang Z, Yan J, Liu S, Lei Z, Yi D, Li SZ. A face antispoofing database with diverse attacks. In: 2012 5th IAPR International Conference on Biometrics (ICB); 2012 Mar 29–Apr 1; New Delhi, India: IEEE; 2012. p. 26–31. doi:10.1109/ICB.2012.6199754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wen D, Han H, Jain AK. Face spoof detection with image distortion analysis. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2015;10(4):746–61. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2015.2400395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Xue H, Ma J, Guo X. A hierarchical multi-modal cross-attention model for face anti-spoofing. J Vis Commun Image Represent. 2023;97(8):103969. doi:10.1016/j.jvcir.2023.103969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhang S, Liu A, Wan J, Liang Y, Guo G, Escalera S, et al. CASIA-SURF: a large-scale multi-modal benchmark for face anti-spoofing. IEEE Trans Biom Behav Identity Sci. 2020;2(2):182–93. doi:10.1109/TBIOM.2020.2973001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Liu A, Tan Z, Wan J, Escalera S, Guo G, Li SZ. CASIA-SURF CeFA: a benchmark for multi-modal cross-ethnicity face anti-spoofing. In: 2021 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2021 Jan 3–8; Waikoloa, HI, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 1178–86. doi:10.1109/WACV48630.2021.00122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. George A, Mostaani Z, Geissenbuhler D, Nikisins O, Anjos A, Marcel S. Biometric face presentation attack detection with multi-channel convolutional neural network. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2019;15:42–55. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2019.2916652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Yu Z, Cai R, Cui Y, Liu X, Hu Y, Kot AC. Rethinking vision transformer and masked autoencoder in multimodal face anti-spoofing. Int J Comput Vis. 2024;132(11):5217–38. doi:10.1007/s11263-024-02055-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Gautam V, Kaur G, Malik M, Pawar A, Singh A, Kant Singh K, et al. FFDL: feature fusion-based deep learning method utilizing federated learning for forged face detection. IEEE Access. 2024;13(2):5366–79. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3523257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Yang X, Liu W, Liu W, Tao D. A survey on canonical correlation analysis. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2021;33(6):2349–68. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2019.2958342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Rossler A, Cozzolino D, Verdoliva L, Riess C, Thies J, Niessner M. FaceForensics++: learning to detect manipulated facial images. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. IEEE; 2019. p. 1–11. doi:10.1109/iccv.2019.00009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Jiang L, Li R, Wu W, Qian C, Loy CC. DeeperForensics-1.0: a large-scale dataset for real-world face forgery detection. In: 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA: IEEE; 2020. p.13–19. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.00296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Zi B, Chang M, Chen J, Ma X, Jiang YG. WildDeepfake: a challenging real-world dataset for deepfake detection. In: Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia. Seattle, WA, USA: ACM; 2020. p. 2382–90. doi:10.1145/3394171.3413769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Li N, Weng Z, Liu F, Li Z, Wang W. Dual-path adaptive channel attention network based on feature constraints for face anti-spoofing. IEEE Access. 2025;13:22855–67. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3534906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Chen G, Xie W, Lin D, Liu Y, Wang M. mmFAS: multimodal face anti-spoofing using multi-level alignment and switch-attention fusion. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2025;39(1):58–66. doi:10.1609/aaai.v39i1.31980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Heusch G, George A, Geissbühler D, Mostaani Z, Marcel S. Deep models and shortwave infrared information to detect face presentation attacks. IEEE Trans Biom Behav Identity Sci. 2020;2(4):399–409. doi:10.1109/TBIOM.2020.3010312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Kumar Y, Ilin A, Salo H, Kulathinal S, Leinonen MK, Marttinen P. Self-supervised forecasting in electronic health records with attention-free models. IEEE Trans Artif Intell. 2024;5(8):3926–38. doi:10.36227/techrxiv.23911365.v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Ho J, Kalchbrenner N, Weissenborn D, Salimans T. Axial attention in multidimensional transformers. arXiv:1912.12180. 2019. [Google Scholar]

48. Li J, Wang X, Tu Z, Lyu MR. On the diversity of multi-head attention. Neurocomputing. 2021;454:14–24. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2021.04.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Zhao X, Guo J, Zhang Y, Wu Y. Asymmetric bidirectional fusion network for remote sensing pansharpening. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2023;61:5404816. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2023.3296510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Wang T, Yang L. Beetle swarm optimization algorithm: theory and application. arXiv:1808.00206. 2018. [Google Scholar]

51. Khade S, Gite S, Pradhan B. Iris liveness detection using multiple deep convolution networks. Big Data Cogn Comput. 2022;6(2):67. doi:10.3390/bdcc6020067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Krasnodębska K, Goch W, Uhl JH, Verstegen JA, Pesaresi M. Advancing precision, recall, F-score, and jaccard index: an approach for continuous, ratio-scale measurements. Environ Model Softw. 2025;193:106614. doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2025.106614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools