Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Next-Generation Deep Learning Approaches for Kidney Tumor Image Analysis: Challenges, Clinical Applications, and Future Perspectives

1 Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, Jyothi Engineering College, Thrissur, 679531, India

2 Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, Karunya Institute of Technology and Sciences, Coimbatore, 641114, India

3 Department of Computer Science, University of Craiova, Craiova, 200585, Romania

* Corresponding Author: D. Jude Hemanth. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 4407-4440. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070689

Received 21 July 2025; Accepted 19 September 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

Integration of artificial intelligence in image processing methods has significantly improved the accuracy of the medical diagnostics pathway for early detection and analysis of kidney tumors. Computer-assisted image analysis can be an effective tool for early diagnosis of soft tissue tumors located remotely or in inaccessible anatomical locations. In this review, we discuss computer-based image processing methods using deep learning, convolutional neural networks (CNNs), radiomics, and transformer-based methods for kidney tumors. These techniques hold significant potential for automated segmentation, classification, and prognostic estimation with high accuracy, enabling more precise and personalized treatment planning. Special focus is given to Vision Transformers (ViTs), Explainable AI (XAI), Federated Learning (FL), and 3D kidney image analysis. Additionally, the strengths and limitations of the established models are compared with recent techniques to understand both clinical and computational challenges that remain unresolved. Finally, the future directions for enhancing diagnostic precision, streamlining physician workflows, and image-guided intervention for decision support are proposed.Keywords

Medical diagnosing systems use imaging modalities extensively for pre-processing medical images, as well as extracting relevant data from these images that is clinically useful. The sophisticated image processing techniques can enhance clinical diagnosis, treatment planning, and management of chronic illness based on the illustration of anatomical, physiological, and pathological changes in tissues [1]. Thus, image processing plays a vital role in detecting, documenting, and managing illness more objectively and precisely with more efficiency. In addition, image processing offers possibilities for conducting a quantitative assessment, predictive analytics, and pattern recognition by applying complex algorithms and computation, despite the simple visual inspection [2].

Medical imaging techniques are often non-invasive and can include Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), Computed Tomography (CT), and Positron Emission Tomography (PET) modalities that allow earlier stage detection of tumors [3,4]. In terms of detecting kidney tumors, it is a complex area due to the range of anatomical differences between patients and the imaging artifacts. Combining image processing with imaging would enable the detection of tumors in their earlier development, while overcoming the deviation due to anatomical variability in kidney radiological images. Furthermore, distinguishing benign renal masses and malignant tumors is equally important to avoid surgical mishaps. Detecting tumors early in their growth will impact the quality and continuity of care for cancer patients. Moreover, the earliest possible detection improves the treatment outcomes and survival chances. Further, precise detection of tumors is vital when planning treatment and further interventions. Additionally, accurate marking of tumors (e.g., delineation, staging, characterization) is essential for selecting an appropriate treatment plan and reducing the risk of recurrence.

Recent advancements in deep learning-based models for brain tumors with a spectrum of multi-modality MRI provide potentially useful foundational concepts for developing algorithms for kidney tumor imaging. Many issues within brain tumor segmentation have similarities to kidney tumor imaging, including the anatomical context complicating segmentation, distortion due to morphology differences, patient-specific variability expressed in different imaging presentations, and the criticality of accurate boundary detection in ascertaining tumor segmentation. Multi-modality practice that utilizes a variety of modalities acquired from imaging techniques that can include various MRI sequences, such as T1 and T2-weighted images, and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences, and adds the more complex agent-administered contrast to produce contrast-enhanced MRI sequences, is relevant to expanding the segmentation capabilities of MRI within neuro-oncology. Further innovations centered on new deep learning models, specifically CNNs, their emergence of Vision Transformers (ViTs), and the recent emergence of a hybrid model combining CNNs and ViTs have proven effective at differentiating the diverse features of MRI image data types. These models use advanced image fusion techniques at the pixel and feature level, adopt attention mechanisms for improving modality, and use contextual information in multimodal shapes that result in solid tumor delineation and accuracy. Meanwhile, if used with these multimodal fusion strategies and sophisticated architectural schemes, the findings could inform the integration of CT and MRI images for kidney tumor detection and account for anatomical complexity and segmentation robustness. Survey papers examining such brain tumor segmentation models illustrate the extent of achievement made and the various challenges with domain invariability and data sparsity, which are also related to kidney tumors [5–7].

Additionally, hyperparameter optimization for improving medical image classification performance provides a robust methodological rationale for applying optimized deep learning models to kidney tumor detection tasks. This complements the manuscript’s emphasis on fine-tuning pretrained architectures and supports the case for systematic optimization approaches that can enhance diagnostic accuracy and model generalizability [8]. One can leverage deep learning, particularly CNN and U-shaped neural network (U-Net) architectures, for medical image segmentation in forensic radiology. Their robust approach to biological profile estimation through bone image analysis reinforces the applicability of advanced segmentation techniques for precise tumor localization and characterization in kidney imaging [9]. Kidney tumors are often found incidentally during imaging for another issue, which is very common. An AI image processing tool can be helpful to ensure that no clinically significant lesions are being missed [10,11]. The review explores the developments in image processing based on deep learning for effective kidney tumor identification by considering technical aspects, clinical utility, and impact on patient care. Moreover, the effectiveness of modern methods that combine deep learning with other machine learning techniques, such as radiomics, and a range of hybrid methods, is discussed. Additionally, how the latest innovations, such as federated learning, XAI, and real-time processing, can solve the existing problems associated with kidney tumor diagnosis and improve kidney tumor diagnosis.

Search Strategy: An extensive literature search on PubMed, Scopus, IEEE Xplore, and Web of Science was conducted to identify studies with kidney tumor images using deep learning methods, from 2015 to June 2025. Search terms included terms for kidney tumor are kidney tumor, renal cell carcinoma, deep learning terms such as CNN, U-Net, etc., and imaging modalities in medicine, such as CT, MRI, and PET scans, using Boolean operations to narrow the search. There were no language restrictions, but only peer-reviewed original articles, reviews, and conference papers were included. Preprints and other non-peer-reviewed material were not included. A manual search was conducted on references, and duplicates were removed with the help of reference management software.

Inclusion/exclusion Criteria: Studies were included if they employed clinically relevant imaging modalities for kidney tumor examination, such as CT, MRI, and PET, for the detection, segmentation, classification, and/or characterization of benign or malignant lesions in the kidneys using deep learning approaches such as CNNs, Transformer architectures, or hybrid architectures. Peer-reviewed original research papers, systematic reviews, and conference papers published in scientific journals were considered. Studies reported performance metrics (e.g., sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, Dice coefficient, area under the curve (AUC) for comparability, written in English, and with no geographical restrictions. Studies were excluded when they did not examine kidney tumors, an unrelated pathology, or only approached using classical machine learning (ML) or traditional image analysis, not using a deep architecture. The studies were excluded if they did not provide relevant methodology or relevant performance metrics, were not peer-reviewed (e.g., preprint, editorial, opinion piece, abstract without full text), duplicates, or examined animal models or in vitro investigations without considering clinical imaging.

3 Deep Learning-Based Image Processing Approaches

Deep learning methods have been developed as a potent image processing method for kidney tumor detection, going beyond the state of the art, and offering improved accuracy, robustness, and clinical utility [12]. Deep learning works better than classical methods due to its ability to classify kidney tumors using CNNs, which can automatically learn and extract complex shapes and features, thereby leading to classifications of kidney lesions with accuracies not previously possible. In deep learning neural networks, spatio-temporal relationships in the medical images are automatically extracted, giving advantages for essential tasks such as classification, segmentation, detection, and image reconstruction [13].

One of the major advantages of deep learning is that manual feature construction is unnecessary. In traditional feature construction, the human expert must define and extract features manually. This requires many hours of work and the possibility of human error. The deep learning models learn the most relevant primary features from the training data and adapt to the various subtleties present in the images, as shown in Fig. 1. The figure illustrates a representative deep learning workflow for kidney tumor detection using CT/MRI images, starting with image preprocessing and enhancement. The enhanced images will be taken into a CNN for feature extraction and classification. Finally, the processed images will be subjected to postprocessing to produce elaborated outputs and reports. Additionally, deep learning algorithms can analyze their images at varying resolutions or scales, thus learning about the fine detail and the broader context available at the same time. That is useful tacitly because if these algorithms can operate at many different scales, they can learn spatially or build the relationship among the features, even when various diagnostic groups are present. This is valuable because spatially encoded information and improved accuracy in localizing diagnostic features enhance confidence in algorithmic predictions, thereby increasing their trustworthiness and credibility. With fully automated feature learning, deep learning offers the most objective and comprehensive understanding of the complexities of diagnostic interpretation and medical analytics.

Figure 1: Deep learning method for kidney tumor detection [13]

3.1 CNNs for Tumor Classification

CNNs have revolutionized medical image analysis, particularly in classifying kidney tumors, by making the process automated and highly accurate [14,15]. Unlike traditional algorithms that rely on manual feature engineering, CNNs learn features hierarchically from medical images. This ability allows CNNs to deduce and utilize complex feature patterns that traditional algorithms could never achieve [16,17]. CNN architectures or models are based on a human brain’s structure, consisting of a series of artificial neurons arranged in layers, which can be convolutional, pooling, or fully connected [16]. A representative CNN architecture applied to kidney tumor image analysis is shown in Fig. 2. The input consists of preprocessed CT or MRI scans that undergo multiple convolution layers and pooling to extract hierarchical features. Convolutional layers detect local patterns (e.g., edges, textures), while pooling layers reduce spatial dimensions for computational efficiency. Feature maps are progressively extracted, flattened, and passed through fully connected layers for classification and tumor subtype identification. The output represents the predicted presence and classification of kidney tumors. During training, CNN architectures learn to adjust their weights and biases to reduce prediction discrepancies from actual labels, thus approaching optimally recognized and classified kidney tumors [18]. There are trainable filters attached to each convolutional layer, allowing the CNN to automatically detect the essential features (for example, edges, textures, and shapes). Following the convolution operations, pooling layers allow spatial dimensions to be reduced, which significantly improves model computational efficiency, also conditionally stabilizing models [19,20].

Figure 2: A representative CNN architecture

A typical CNN architecture primarily consists of convolutional layers, which perform most (95%–99%) computations. These are followed by Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation functions, applied to introduce non-linearity into the computations [21,22]. Pooling layers are used to down-sample the feature maps, while fully connected layers assemble the extracted features to classify them like benign, malignant, or normal tissues [19,23]. The convolution operation itself computes the dot products between filter weights and specific image regions by sliding a filter across the image, which generates feature maps [23]. The number of channels determines the width of a layer and divides the feature maps into regions, enabling more specific assessments.

CNN-based classifiers consistently outperform standard methods in image classification, object detection, and segmentation, notably showing higher detection accuracy in kidney tumors [24,25]. They excel by learning spatial hierarchies, where initial layers identify basic patterns like edges, and subsequent layers learn increasingly abstract features [26–28]. Regularization techniques such as dropout, batch normalization, and weight decay are commonly employed to enhance generalization and mitigate overfitting. These classifiers are typically compiled with optimizers like Adam Optimizer, which utilize cross-entropy loss, and are evaluated based on accuracy, making them highly suitable for multi-class classification tasks [21]. Further performance gains can be achieved by fine-tuning pre-trained CNNs on massive datasets, leveraging knowledge acquired from broader image recognition tasks [22]. This approach significantly boosts their predictive capabilities, especially when limited medical imaging data is available.

Recent developments in deep learning have led to hybrid models, which often integrate elements like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) units into CNN architectures. This innovative combination allows these models to capture both spatial and temporal dependencies, leading to the learning of more comprehensive features [21]. CNNs are exceptionally useful in medical image analysis due to their unparalleled ability to automatically and adaptively learn spatial features across multiple hierarchical levels [29,30]. This inherent adaptability makes them indispensable tools for the nuanced and precise interpretation required in complex diagnostic scenarios, paving the way for even more sophisticated analyses in the future.

3.2 U-Net and Variants for Semantic Segmentation

U-Net is a CNN architecture that has rapidly risen to prominence with respect to medical image segmentation, especially for kidney tumor detection. U-Net was built for semantic segmentation, which classifies each pixel of an input image into a relevant category, for instance, as foreground or background [31]. A primary advantage of U-Net is that it generates accurate segmentation results with relatively few annotated training images, which is often a limitation in medical imaging datasets [32,33].

U-Net contains two types of paths: a contracting path (encoder) and an expansive path (decoder) [30]. The contracting path processes multiple layers of convolutions, followed by ReLU activation and max-pooling, to decrease the spatial resolution of the images simultaneously learning the hierarchy of features. Conversely, the expansive path performs up-sampling operations, recovering spatial information from the earlier layers to produce a new high-resolution segmentation map. One key characteristic of U-Net is that “skip connections” exist between each layer in the encoder and the same layer in the decoder. The model leverages these skip connections to retrieve very fine details that could easily be lost from the down-sampling operations, producing an accurate segment map [34,35]. A representative U-Net architecture is shown in Fig. 3. The figure illustrates the U-Net structure comprising an encoder (contracting path) and decoder (expanding path), with convolution, pooling, and up-sampling operations. Feature fusion across layers enhances segmentation accuracy, leading to a detailed output segmentation map. Here, the encoder compresses the image information and the decoder reconstructs it, enabling precise segmentation crucial for medical image analysis.

Figure 3: U-Net architecture for kidney image segmentation using encoder–decoder and feature fusion paths

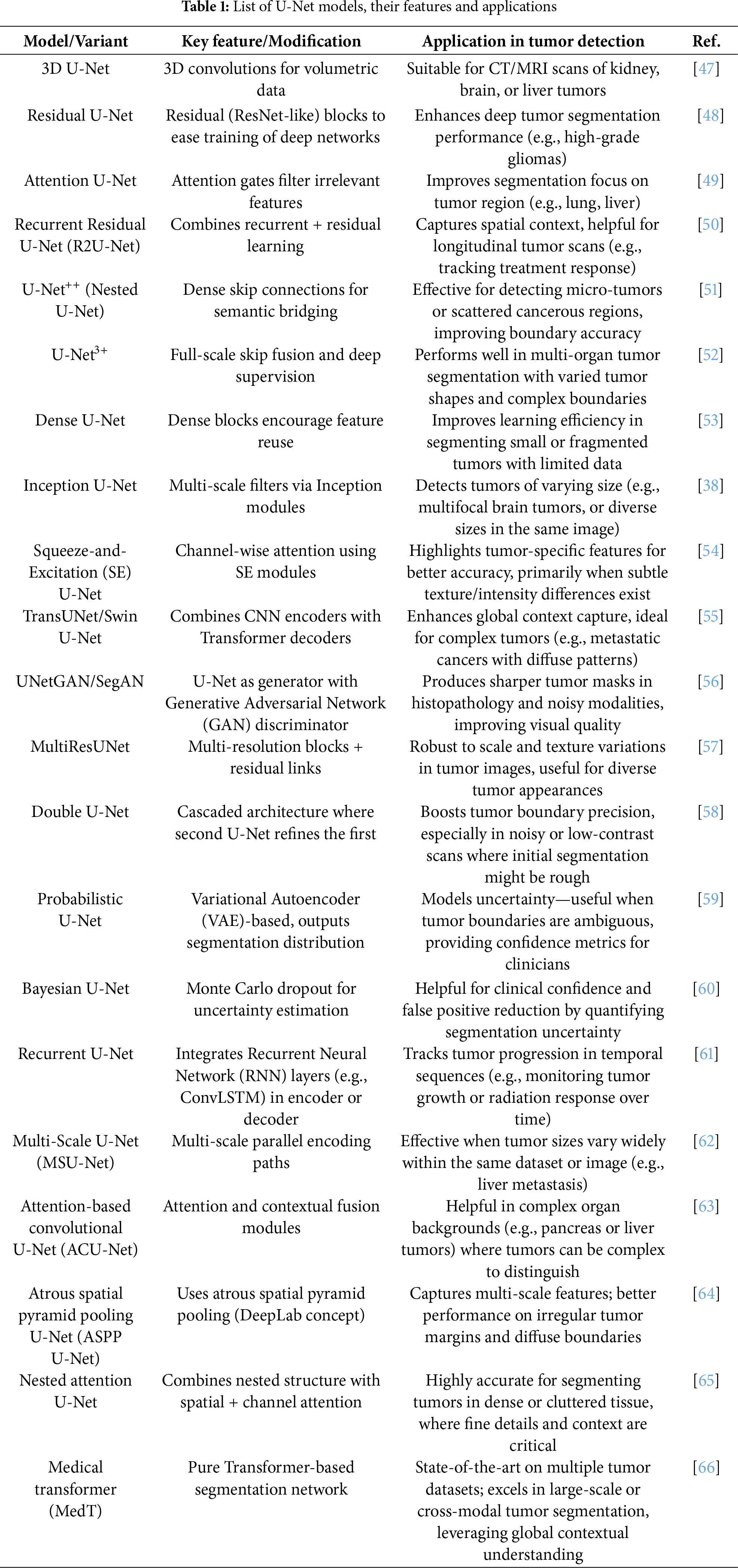

U-Net helps to achieve good accuracy on various segmentation tasks, but the primary reliance on convolutions limits the model’s potential to account for long-range dependencies and global contextual information [36,37]. These limitations have led to various architectural extensions to the U-Net. Attention U-Net incorporated an attention mechanism into the U-Net to accentuate relevant features and dampen any noise contributed by non-target objects in the background [36,38,39]. U-Net++ modified the skip connections to be dense connections with more than one output decoder path, which allowed for an enhanced feature fusion between multiple scales [39,40]. More variants, including MultiResUNet, add residual connections in order to both propagate features as well as learn more complicated patterns [31]. Seg-UNet uses elements of both U-Net and Novel Segmented Neural Network SegNet to combine the strengths of both [41]. Attention has also been used across many of these variants to identify how features are changed based on their relevance to the segmentation task [40]. Dropout and regularization loss methods have been included to mitigate overfitting, especially in scenarios with small datasets [42]. U-Net has demonstrated flexibility, with appropriate applications for many imaging types: CT, MRI, X-ray, and microscopy. U-Net can be applied to two-dimensional and three-dimensional tasks [43]. Variants of U-Net, and frameworks like 3D U-Net, allow for volumetric data processing which applies to full-body CT or MRI [44]. Existing frameworks like nnU-Net, a self-configuring framework, can automate changing network architectures and training configurations associated with each particular dataset to obtain accurate results [45,46]. Automation for architecture and training makes deployment more efficient and time-saving and is a crucial factor to consider for precise segmentation across many different tasks. Different U-Net models available for tumor detection are listed in Table 1.

Researchers have been developing hybrid U-Net models with Transformer models so that the latter can use local features while modeling global dependencies to overcome the limitations of local convolution. A vision transformer models long-range dependencies through self-attention which could be helpful for the local convolution operations of U-Net. Hybrid models such as UT-Net and UCTransNet [67] utilize transformer modules and attention-gated fusion modules, respectively, for feature representations and similarity of encoder and decoder feature maps.

3.3 Transfer Learning and Pretrained Models (ResNet, VGG, EfficientNet)

Transfer learning simply means taking a model trained for one task (source task) and starting to train a new but related task (target task) on the model. Transfer learning uses pre-trained models that are developed based on a large dataset, like kidney tumor detection, which is especially useful when there is very little labeled medical image data [68]. There are many models with varying complexities available, such as ResNet, Visual Geometry Group (VGG), and EfficientNet, that have been pre-trained on standard datasets like ImageNet, which can be used in kidney tumor detection, as shown in Fig. 4. These models will grasp and learn generalizable image features such as edges and textures, and then the model can be used for renal tumor detection [69,70]. Additionally, fine-tuning pre-trained models will also allow the model to learn the definitive features of kidney tumors and obtain better results even with mean or imbalanced datasets [71]. Double Contraction Layer U-Net (DC-UNet) and Dual-Path SENet Feature Fusion Block (CDSE-UNet) are state-of-the-art models for segmentation with deep learning. Both apply edge or contour detection mechanisms (e.g., Canny operator) in their workflow [72,73]. In general, DC-UNet achieves a significant performance improvement over the classical U-Net method. Pre-trained models does not require a new design or train a new model, and can save time. Therefore, utilizing pretrained models enables the researcher to benefit from previously built models instead of designing or creating new models [31].

Figure 4: Steps in transfer learning

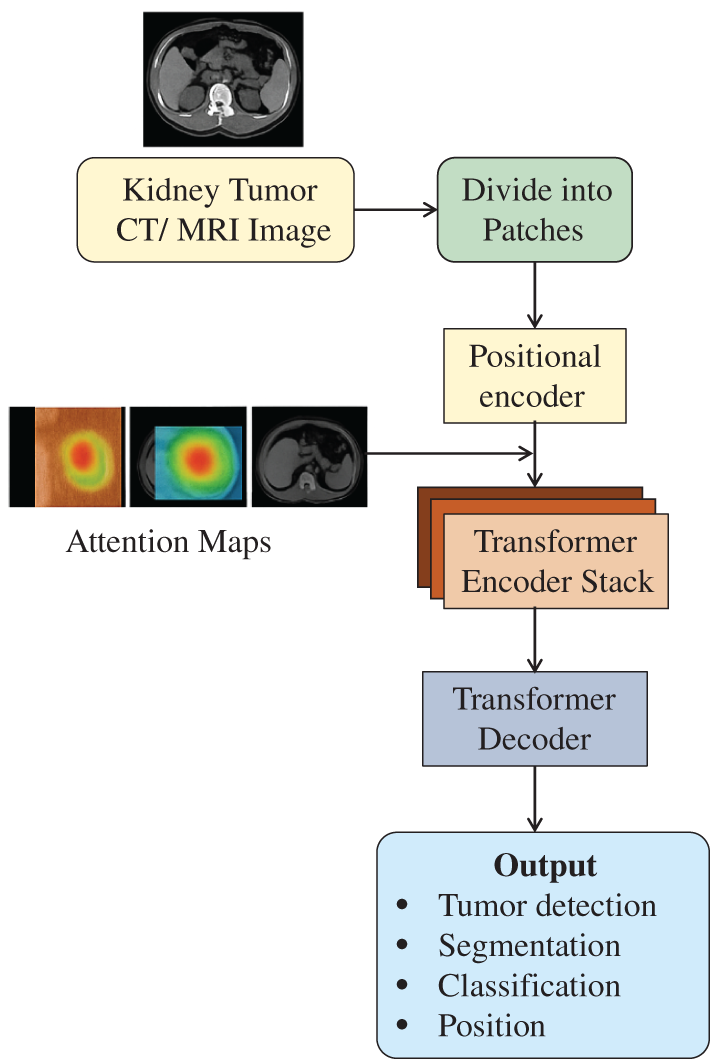

ViTs can significantly assist in identifying tumors in medical image analysis because they model long-range dependencies and long-context better than CNNs. ViTs segment an image as patches and apply a self-attention mechanism when processing them as token sequences [74], as shown in Fig. 5. The figure shows a ViT-based method for kidney tumor detection and segmentation from medical images. The process is initiated with a kidney scan from a patient (either a CT scan or an MRI, pre-processed to improve the quality of the image and enhance relevant anatomical features), and transformed patches of identical size are obtained from the improved image, from where the relevant embedding will be generated. Each patch is transformed into an embedding with a positional encoding, which retains the spatial context of different patches. Each embedding is concatenated and passes through a multi-head attention encoder, where each embedding is correlated to all other embeddings for both local detail and contextual features of the kidney region. The condensed encoding of the kidney region can then be passed through a feed-forward network and subsequently be generated through a decoder, retaining local and contextual information of the kidney region into a segmentation map. The segmentation map creates a new kidney tumor segmentation map, indicating the different tumor regions. The ultimate output is a detection result of the tumor and the resulting segmentation maps that define the tumor morphology in detail. Therefore, the ViT-based transfer encoder is a powerful tool to leverage numerous properties of an image from global context and local/cellular structure information, which provides better accuracy and advantages of relative visual interpretability to the analysis of the kidney tumor segmentation. Paraphernalia improve the performance of these types of models, and U-Net backbone models can be augmented effectively with ViTs within a single architecture. TransUNet, a model that derives an attention weight from a ViT architecture, allows the model to indicate the clinically relevant area while limiting the extent of the model’s attention to focus on irrelevant areas. Similar results when evaluating multiple resolutions for a task typically lead to good results. Applications of models based on leveraging ViTs are numerous and span any task of interest for medical imaging, such as segmentation, synthesis, or diagnosis [75,76]. The application mentioned above indicates that ViTs can achieve higher performance than CNNs on datasets with a large size. However, their requirement for large volumes of annotated data presents challenges in medical imaging, where data collection is constrained by cost and privacy considerations [77].

Figure 5: Vision Transformer (ViT) based architecture for kidney tumor detection from medical images

Hybrid architectures combining CNNs and ViTs are being explored to find a balance between local feature extraction and global context modelling. CNNs enable the capture of fine spatial details, and ViTs promote understanding at a larger context. Traditional image processing techniques, such as morphological operators, stain normalization, and noise filtering, also have a role to play in enhancing input data [78–80]. Combined with deep learning, these processes allow more robust and accurate tumor detection, especially when faced with lower-quality or limited-quality datasets. There has been a substantial increase in the quality and scale of digital pathology analysis using CNN-based models that explicitly learn complex image features from the data [81]. However, they learn from the associated data, and there is still a need for complementary solutions. Applying traditional approaches to deep learning systems can amplify system performance and interpretability [82,83].

3.4 Hybrid Approaches (Combining Deep Learning and Traditional Methods)

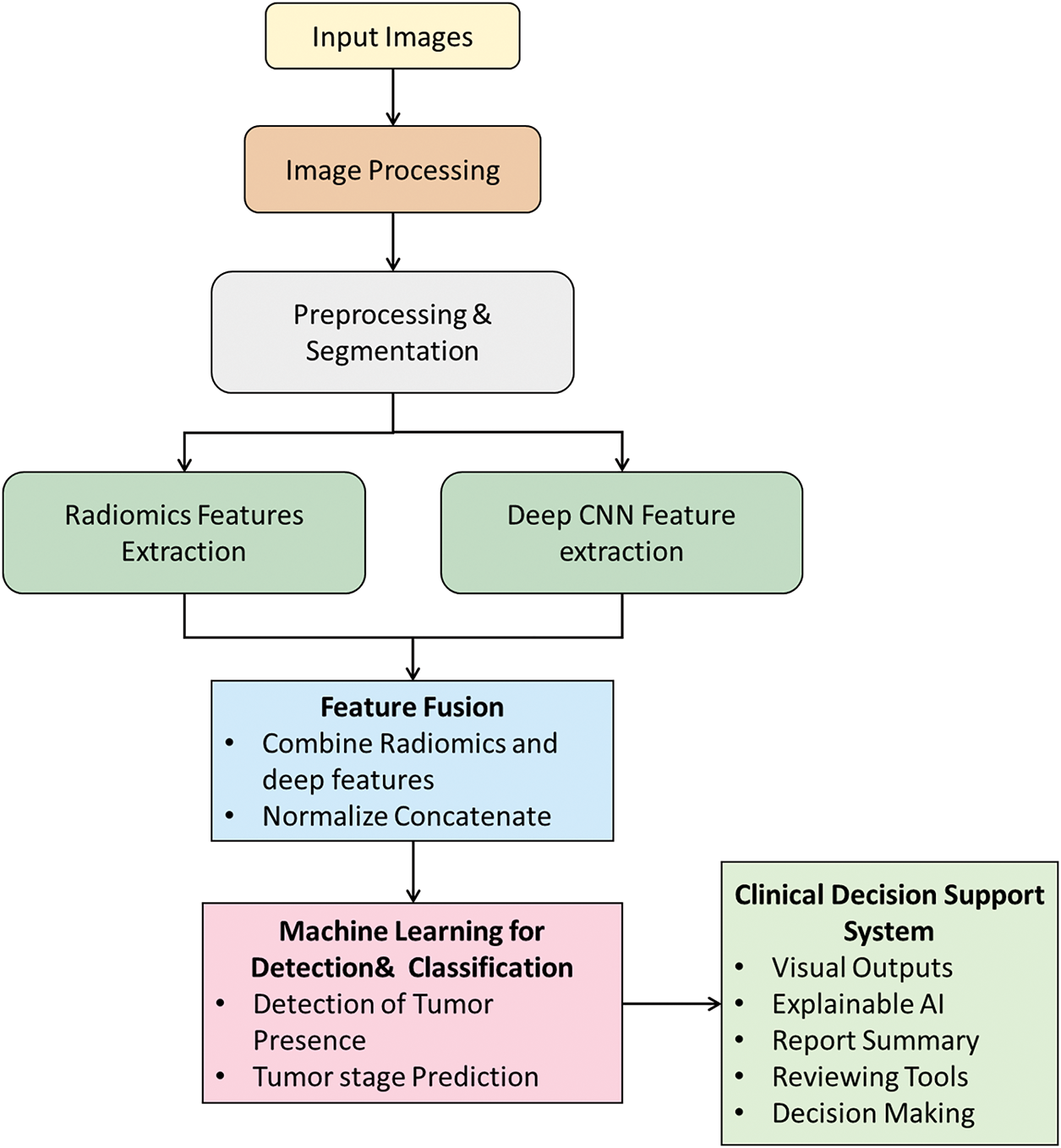

Hybrid AI systems for kidney tumor diagnostics are superior to deep learning methods in diagnostic accuracy and clinical trust. Hybrid methods combine the ability of deep learning to recognize patterns, while avoiding black box issues causing errors, and traditional image processing methods that incorporate human clinical knowledge and rationality. Traditional ML methods like support vector machines, decision trees, and random forests use handcrafted imaging features, like tumor size, shape, and texture, to provide explainable and clinically relevant results to practitioners. When traditional imaging features are combined using deep learning’s automated methods to extract higher-dimensional and complex features from imaging data provides a more advanced model to inherently identify and classify kidney tumors. A sample framework is shown in Fig. 6. The hybrid framework of the kidney tumor detection approach goes through image preprocessing and image segmentation, followed by input image preparation before identification. Radiomics features are extracted the use of image analysis methods, while deep features are extracted using a deep CNN. The radiomics features and deep features are normalized and concatenated to yield an overall feature set. Machine learning models utilize the fused features for accurate identification and classification of the tumor. An automated clinical decision support system provides interactive outputs (visuals), XAI, and tools for reporting and decision making.

Figure 6: Hybrid framework for kidney tumor detection, integrating traditional radiomics with deep learning for robust classification and clinical decision support

One prominent example is the hybridization pipeline of CNN-Radiomics fusion, in which deep CNNs, such as ResNet50, extract hierarchical image features that can then be fused with radiomic analysis of quantifiable features such as texture, shape, and wavelet features. The blending of both approaches improves classification accuracy, for example, between clear cell renal cell carcinoma and other forms of renal cell carcinoma, achieving up to 96% AUC performance and clinical interpretability with imaging biomarkers linked to pathologic features. Knowledge-guided deep learning would further enrich systems like these by using anatomical and physiological prior knowledge (for example, segmentation masks from dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI), resulting in anatomically improbable outputs and enhancing clinical confidence. Another hybrid model to combine the use of CNNs and Radiomics is a graph-based model, where spatial relationships among radiomic features are used. Those relationships are set up as respective nodes in graphs and quantified distances used in graph neural networks. Doing this enables a complete 3D understanding of the heterogeneity of the tumor, including its spatial relationships, which is critical for accurate diagnosis [13].

Clinical validations highlight the tangible benefits of hybrid AI systems. For example, research at Johns Hopkins demonstrated a 25% improvement in early detection of aggressive kidney tumors compared to CNN-only models [13]. These systems also incorporate rule-based constraints grounded in kidney anatomy to minimize diagnostic errors, thereby enhancing clinician confidence. Furthermore, the established and interpretable nature of radiomic modules facilitates regulatory approval processes, as seen in FDA-cleared hybrid platforms like Siemens’ syngo. via, which are already being used in clinical practice. Emerging advancements such as dynamic hybrid systems, which adaptively select analytic methods based on image quality, human-AI collaborative annotation workflows, and multiscale analysis combining organ-level and cellular-level features through attention mechanisms, have the potential to further elevate diagnostic precision and usability. For instance, a 2023 study at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center cited a 35% reduction in unnecessary biopsies, while maintaining perfect sensitivity for aggressive tumor detection with a hybrid model. The best hybrid systems will require structured implementations; integrating deep learning quality control with traditional Computer-Aided Diagnosis (CAD) systems, building tools to unify feature extraction, and including clinician-facing tools for interpretability [84].

3.5 3D Image Processing and Volumetric Analysis

Implementing three-dimensional (3D) image processing and volumetric analysis is an innovative development in kidney tumor detection that alters how kidney tumors are diagnosed and treated. This method provides information about the tumor comprehensively and accurately than 2D imaging. Though 2D images are clinically important, without volumetric data, it is difficult to assess location in space. With 3D imaging, one can do volumetry, visualize and comprehend anatomical relationships with adjacent vasculature and collecting systems with clarity, characterize lesions thoroughly through radiomic analyses, and, more importantly, conduct continuous and dynamic assessments over time. As we acquire modern CT and MRI examinations with isotropic voxels typically less than 1 mm³ and commonly 0.5 mm3, one can reconstruct the tumor margins with a precision in the sub-millimeter scale for surgical planning and margin assessment. Multiplanar reformatting offers additional interpretation of imaging datasets from many different planes and allows the operators to view details at any plane without losing quality across the entire 3D acquisition. Multi-planar reformatting also allows the accurate mapping from any anatomical site and provides accurate spatial measures of vessel-to-tumor distances to help plan potential complex tumor surgery while reducing intra-operative risks. The representative steps in 3D image processing and volumetric analysis are shown in Fig. 7. In a typical 3D image processing, the detection of kidney tumors involves obtaining MRI or CT images, image processing, and preprocessing, which includes steps such as attenuation and noise removal, intensity equalization and normalization, registration across modalities, and finally utilizing neural networks for segmentation of the tumor boundaries. Using neural networks results in a more reliable accuracy than traditional segmentation, particularly on images from different modalities, for segmenting the tumor accurately. Once 3D segmentation is completed, the geometric features can result in 3D measures/quantifications such as volume, surface area, and shape descriptors. Lastly, these features can be visualized, and the 3D feature quantification analyzed by the appropriate clinical reporting. Feature visualization of the kidney tumors may also be used for predictive modeling for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment.

Figure 7: 3D Image processing and volumetric analysis for kidney tumor detection

3D dynamic volumetric biomarkers of kidney tumors can be more sensitive and specific than traditional measures such as response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST). For instance, dynamic volumetric measures of enhancement kinetics can replicate tumor aggressiveness and grading conditions with an accuracy par with experts. Volume of necrotic core is an important metric of response to immunotherapy, and the degree of performance of segmentation to obtain necrotic core volume will often yield high overlap scores compared with a manual delineation performed by an expert. The clinical benefits of 3D volumetric imaging are diverse. Diagnostic sensitivity improves significantly, with the same ability to detect tumors of 1.5 mm3 as opposed to the 5 mm threshold with 2D imaging. Automated classification systems based on volumetric 3D imaging can give a high accuracy of lesions categorized as cystic [85]. Detailed fat quantification at very small volumes assists in distinguishing between a benign angiomyolipoma and a malignant renal cell carcinoma. Augmented reality navigation in the operating suite provides real-time 3D holographic projections of tumors and adjacent vasculature when planning surgical interventions. In laparoscopic partial nephrectomy with augmented reality navigation, it will incorporate enhanced guidance with real-time imaging, enabling precise targeting. Preoperative simulation of remnant kidney function with real-time volumetry during cryoablative procedures ensures adequate tumor coverage whilst preserving healthy tissue. Additionally, volumetric metrics show increasingly improved sensitivity for treatment response monitoring, with the ability to identify disease progression earlier than non-volumetric imaging.

The 3D imaging creates numerous computational hurdles for systems and scanners. The volume of data, with more than 4K × 4K × 2K resolution, is challenging regarding memory and processing requirements. Techniques such as patch-based processing and approach accelerated inference pipelines enable near real-time analysis of these large data sets, with processing times mainly under two seconds. Provided one has to keep all images on the same relative scale by employing normalization techniques to account for the differences in scanner hardware, and dealing with motion artifacts from free-breathing or non-sedated scans using shape deformation algorithms to normalize image sequences back to resting position.

New frontiers in kidney tumor imaging, including 4D modeling, incorporate spatial and temporal information to generate tumor growth models that capture respiratory motion in real time by utilizing innovative MRI sequences and reconstruction techniques. At the microscopic level, ultra-high-field MRI and phase-contrast CT allow microstructure imaging to map the texture and density, based on cell types of kidney tumors, facilitating new tumor characterization possibilities. There is also great potential for further refinement with theranostic strategies, such as radiotracer-volume fusion with PET/CT imaging, which improves specificity for targeting tumor locations for diagnosis and treatment. Biopsy procedures are being transformed using 3D probability maps that guide biopsies to the locations most likely to yield a diagnostic specimen.

3.6 Attention Mechanisms and Transformers in Medical Imaging

Attention mechanisms and transformer architectures, originally designed for natural language processing, are now radically advancing medical imaging for improved performance, interpretability, and understanding of complex medical data [86]. Attention mechanisms allow models to focus on an image’s most relevant and informative areas, akin to human visual attention. This selective focus is particularly useful in medical imaging, where important diagnostic information frequently lies in slight variations or is hidden in complex anatomical structures.

CNNs are functional in most scenarios, but their effectiveness in long-range spatial dependencies limits them. This is particularly common when assessing the location of larger tumors or when identifying more complex three-dimensional relationships among many different organs. The limitations of CNNs are most apparent in situations in which a true, full assessment of the image is required. For example, detecting the presence of small satellite tumors or subtle infiltrations beyond the kidney would require looking at the image in its entirety or through a view rather than observing a specific section (or patch) of the image. ViTs and their many adaptations to the medical domain (Swin-UNETR, TransMed, etc.) solve these challenges by modeling global interactions. Each voxel patch in the CT or MRI scan can self-attend to all other voxel patches. This unique vision enables the development of spatially distant but clinically relevant features to be synthesized in the model, such as the opportunity for the model to assess both perinephric tissue and intrarenal tumor characteristics simultaneously. This offers many other diagnostic lenses for assessment when compared to a CNN.

Another noteworthy development is the incorporation of cross-modality attention, which combines data across multiple imaging modalities (e.g., CT and MRI) and allows models to define weights with respect to each modality. The cross-modality frontiers demonstrated improved performance in complex tasks, such as kidney tumor subtype classification, with a reported accuracy (AUC) of as high as 94.2%. Furthermore, unlike black box algorithms, attention maps produced by the model visually explain how the model concluded by highlighting the image regions that had the most effect on predictions [87]. This attribute improves transparency and allows clinicians to visualize what features (e.g., enhancement patterns or textural abnormalities) contribute to their diagnosis, consequently allowing for more confident clinical decisions.

Comparative studies have demonstrated that transformer-based architectures consistently outperform CNNs in various aspects of kidney tumor analysis. For example, while a 3D U-Net CNN performs tumor segmentation with a Dice score of 0.83, the Swin-UNETR model improves this to 0.88 by better detecting small tumors. TransMed, which combines CT and MRI data, attains an AUC of 0.93 for tumor classification through effective multimodal fusion. The nnFormer model is promising in surgical planning, with a Dice score of 0.91 by accurately modeling complex vessel-tumor spatial relationships, which is critical for nephron-sparing surgeries. A sample framework is shown in Fig. 8, which illustrates the processing of kidney tumor CT or MRI images via a transformer-based neural network (transformer). The input image goes through partitioning (into patches) and positional encoding. The transformer encoder stack then utilizes attention approaches that yield attention maps depicting foci of importance, e.g., tumors. Finally, the transformer decoder generates outputs to detect, segment, classify, and locate tumors.

Figure 8: Schematic diagram showing the transformers integrated with an attention mechanism in kidney tumor detection

The remarkable advantages come with challenges for transformer models. The biggest challenge is identifying the accelerator demands. Modeling a single 3D kidney CT may require 24 GB of GPU memory for one scan, and this resource demand can restrict access in many clinical environments. Another challenge with transformers is that the models require larger annotated datasets, sometimes up to orders of magnitude larger than CNNs, to reach their full learning potential. This is often a difficult hurdle for the reverse image detection methods, as human annotations can be laborious and require trained expertise. Another challenging area is how, if there is misalignment between image slices (where images may look similar in appearance), these intra-slice indices can induce a drop in model accuracy, regardless of which axial, coronal, or sagittal image was included in the model. With the improvements in the computer architecture and more hospitals having access to various annotated datasets, accurate, interpretable, and flexible models may have profound effects on the future of clinical workflows and current practices for managing kidney cancer and other cancers.

4 Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

4.1 FL for Privacy-Preserving Tumor Detection

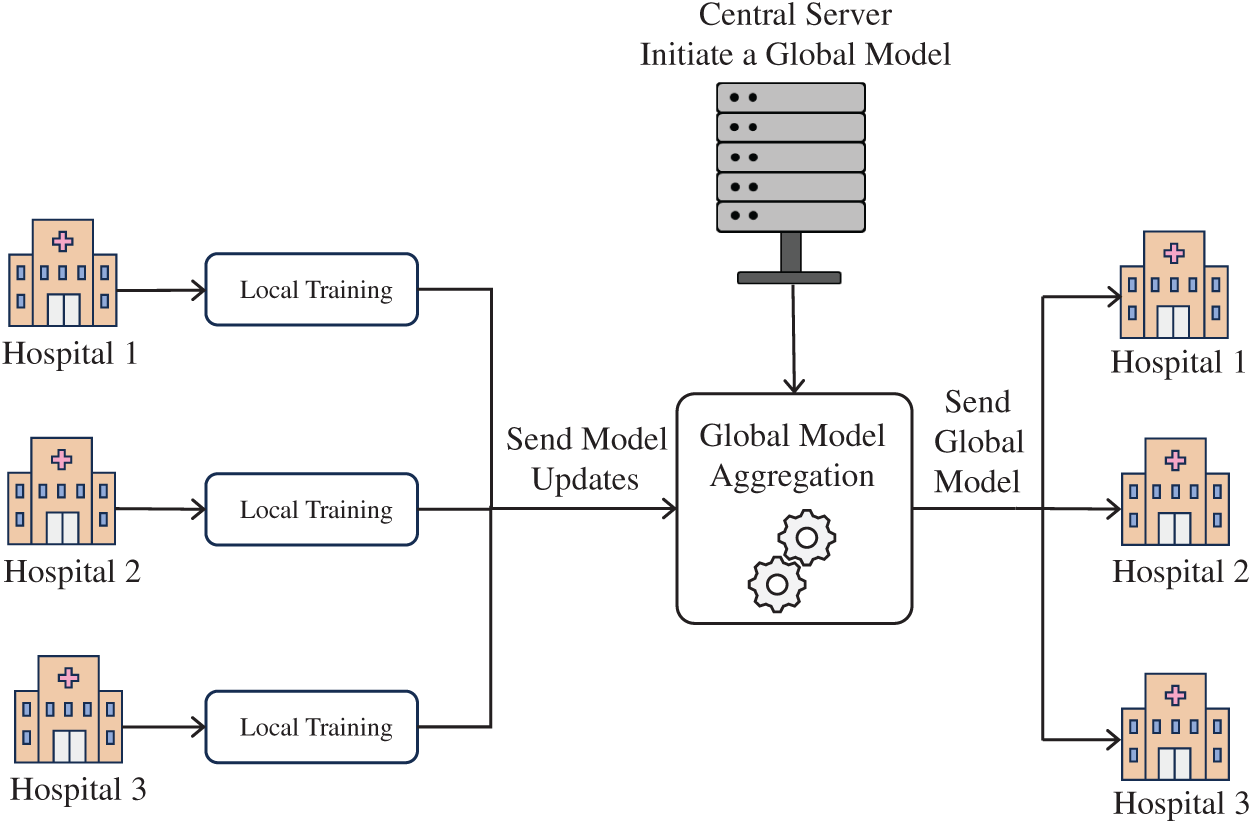

FL is increasingly recognized in healthcare settings where safeguarding patient privacy is crucial. In contrast to centralized training models that require pooling sensitive data at a single site, FL allows institutions to train models locally, sharing only encrypted updates such as weights or gradients. These updates are then aggregated through federated averaging to update a shared model, which is redistributed to all participating sites for continued training [88]. The representative FL framework is shown in Fig. 9, where several hospitals can cooperate to train a common AI model without exchanging patient data. Each hospital locally trains the model on its dataset to create local parameters/updates and shares those updates with the central federated server without sharing raw patient data. The federated server aggregates the local updates to bring together a global model. The improved global model is then returned to all participating hospitals, improving kidney tumor detection capability but not sharing specific patient data.

Figure 9: FL framework for kidney tumor detection

In kidney tumor analysis, FL has demonstrated notable effectiveness. A primary concern in FL is the diversity of data across sites, regarding imaging protocols, equipment, and patient populations. New FL approaches employ style transfer methods to limit these variations between sites. It is also possible to group institutions based on common characteristics, for example, adult vs. pediatric institutions, thereby building a more similar dataset for the model. Another aspect to make models more invariant and less biased is fairness-based aggregation (FBG) and differentially private FL [89]. While FL is designed to enhance privacy by keeping raw data local, it is not entirely immune to attacks. When using FL, one can identify the private patient data by analyzing the behavior of the model, even without direct access to the underlying raw data [90]. In addition, legal issues can prevent the adoption of FL, as there can be restrictions in a particular region for using medical imaging data as part of FL, even if the data are anonymized and approved for use [89].

FL is useful for tasks with limited or decentralized data, such as small hospitals or pediatric kidney tumor analysis. A cooperative model allows the models at or below the threshold to develop into complex and advanced models for quality diagnosis. The first step in FL deployment involves building up technical infrastructure. Container tools, such as Docker, can support local training. The following steps include establishing secure pathways for transmission and employing blockchain to support the verification and trustworthiness of the FL process. Once created, the system can be taken through a series of steps with multi-site trials and user evaluations by all possible clinicians on-chain. The practical and optimal goal focuses on deploying the FL research in a Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) system to monitor performance in real-time on a given population group. Applications such as swarm learning can be incorporated to eliminate the role and function of a central server. FL can help to develop partnerships across the globe for managing rare or complicated cases of kidney cancers. FL is still at a conceptual stage, and it has the potential to provide a model for innovation that protects privacy in a kidney cancer diagnosis.

4.2 XAI for Interpretable Diagnoses

The XAI is changing the way AI models detect and distinguish kidney tumors. Though deep learning models are effective in terms of accuracy, the opaque nature of accuracy-often referred to as the “black box” problem which can reduce clinical confidence and impede regulatory approvals. XAI attempts to correct this problem by producing interpretable and transparent decisions that build the confidence of health professionals and help meet regulatory demands [91]. In renal oncology, explainability is important in bridging the gap between automated prediction and clinical validation. For instance, by revealing how models differentiate oncocytomas from chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, XAI enables radiologists to better understand and confirm the outputs. Furthermore, it can help expose errors, especially when a model relies on artifacts or inappropriate anatomical features. Most importantly, interpretability tools can enhance treatment planning by showing the tumor features (e.g., enhancement features, margins, internal heterogeneity, etc.) that drive predictions of malignancy.

XAI can incorporate different strategies to enhance its interpretability. Images can be translated into visual tools and textual information, such as saliency maps, which show an image’s important regions of interest. Attention mechanisms can locate the most important slices in a 3D CT or MRI scan and help identify multifocal or heterogeneous tumors. There are quantitative strategies to assign importance scores to radiomic features (e.g., entropy, skewness, or texture) and give a measure of uncertainty for each prediction (e.g., 78% ± 5% confidence in clear cell RCC classification). Also, rule-based models can take the output of a neural network and relate it to logical conditions that approximate clinical guidelines. For example, if the tumor is predicted to have a high malignancy risk, it may be located in a cluster where >120 HU (Hounsfield Unit) enhancement and central necrosis overlap. These techniques fall into two different categories: model-specific and model-agnostic methods [92]. Model-specific techniques (e.g., integrated attention layers in CNNs) offer a form of built-in interpretability [93]. However, model-agnostic tools, like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations), can be applied regardless of the model type, providing post hoc explanations defining important feature contributions without altering the underlying architecture of the analytical framework, as shown in Fig. 10.

Figure 10: Representative architecture of XAI for interpretable diagnoses

Fig. 10 represents a model architecture for XAI in interpretable medical diagnoses. It takes multimodal data such as CT, MRI, ultrasound imaging, genomic, and clinical data at a preprocessing stage, providing better input for AI models. The AI system will use explainable features, including attention maps, that will allow the generation of interpretable outputs that visualize areas of interest and quantify the percentages that the model focused on, allowing for a certain level of transparency in decision-making. This workflow feeds into a clinical decision support system (decision support dashboards) to help with tumor staging, biopsy planning, and treatment decision-making, while incorporating measures for privacy and security to maintain fidelity, including differential privacy, homomorphic encryption, and FL.

Often, there is disagreement between human and machine reasoning, especially when saliency maps specify areas that radiologists are not interested in assessing. Furthermore, MRI-based radiomic interpretation is further complicated by the physical encapsulated mechanisms by which magnetic resonance signals are generated, making it more challenging and potentially less valid to verify or replicate model-focused areas in MRI images. A new potential concept, over-explanation, is emerging when the technological details of interpretation and explanation may distract the user from important clinical tasks and eventually lead to cognitive overload. Therefore, the design of XAI systems must be able to maximize or minimize the information and useful outputs appropriate to the expertise of the clinician and the context of the clinical workflow [94].

XAI is integral in enhancing diagnostic accuracy, supporting shared decision-making, and providing transparency in AI-assisted healthcare [95]. In the development of oncology treatment strategy, it offers valuable ancillary support in ways that require inherently sophisticated judgement of tumor biology and progression [96]. XAI enhances the trustworthiness of healthcare algorithms through transparency and accountability, which are vital for clinician trust [93]. It is important to emphasize that XAI is intended to complement the knowledge of medical experts, not replace it. When utilized properly, it can contribute to more informed decisions, improved communication among care teams, and ultimately better patient outcomes [97].

4.3 Integration with Multimodal Imaging

Multimodal imaging involves integrating data from various sources to provide a more comprehensive understanding of a patient’s condition, particularly for complex medical challenges like kidney tumor assessment. Beyond relying on a single imaging technique, information from CT, MRI, PET, and even non-imaging data such as genomics and clinical records is combined here. This approach is helpful when the individual modalities cannot provide substantial information, leading to more precise diagnoses, better characterization of tumors, and optimized treatment planning.

The process typically begins with data acquisition and preprocessing. Raw imaging data from each modality (CT, MRI, PET) undergoes specific preprocessing steps like noise reduction, intensity normalization, and image registration. This registration aligns all images to a common spatial frame, ensuring that corresponding anatomical regions across different scans precisely overlap. Simultaneously, non-imaging data, including genomic profiles, biomarker test results, and information from electronic health records (EHRs), is collected, standardized, and its relevant features are extracted. Once all data is preprocessed, the next stage is multimodal feature extraction and fusion. Various radiomic features (e.g., texture, shape, intensity, wavelet-based features) are extracted from each preprocessed imaging modality. Similar feature extraction occurs for genomic and clinical data. These diverse features are then combined through a process called feature fusion. This can involve simple concatenation (early fusion), combining predictions from separate models (late fusion), or more sophisticated deep learning architectures that learn to fuse features at different network layers (intermediate/hybrid fusion). The goal is to create a rich, integrated dataset that captures the full spectrum of available information. The fused data serves as input for the AI model training and prediction. A sophisticated AI model, often a deep learning architecture or an ensemble of ML classifiers, is trained on this combined feature set.

A multimodal AI model is designed to perform various critical tasks, including kidney tumor classification (e.g., distinguishing benign from malignant), tumor subtype prediction, predicting treatment responses, and prognosing patient outcomes. A sample framework is shown in Fig. 11. In Fig. 11, image inputs from multiple modalities go through data acquisition and preprocessing steps to guarantee quality and to ensure consistent measurements across modalities. After these steps, feature extraction is performed to obtain useful features from each modality. Non-imaging data is also extracted and fused with imaging features by feature fusion. The resulting dataset with both imaging and non-imaging features is used to train and test AI models to classify tumors and predict treatment responses. When different modalities are employed together, we can leverage the multimodal inputs to increase the accuracy of diagnosis, the precision of tumor characterization, and personalize treatment planning, with the ultimate goal of improving patient outcomes in kidney tumor treatment.

Figure 11: Integration of multimodal imaging for kidney tumor assessment

Finally, the AI’s predictions are channeled into clinical decision support and feedback. The integrated insights from the AI model, along with the raw imaging data and other clinical context, are presented to medical professionals such as radiologists and oncologists. Clinicians review these comprehensive insights to make more informed decisions regarding treatment planning and patient management for more precise diagnoses and tailored treatments. A crucial aspect of this stage is the feedback loop, where clinical outcomes and new patient data are continuously fed back into the AI model for retraining and refinement, ensuring the system continually learns and adapts to improve its performance over time.

4.4 Real-Time Processing and Edge Computing

The combination of real-time and edge processing can radically change kidney tumor diagnostics by enabling localized, efficient, and fast image analysis at the point of care. Real-time processing allows clinicians to get immediate diagnostic feedback right after the imaging, enabling them to perform timely clinical interventions and potentially improve clinical outcomes [98]. Edge computing does the computing as the data is created, and it can lower latency and high bandwidth transmission of medical images as it enables clinicians to analyze images without transmitting the medical images to a remote data center [99]. This technique is essential in under-resourced or rural environments where network capabilities are often limited or unreliable. Many such models cleared regulatory requirements. The US-FDA has approved multiple medical imaging devices that use ML, demonstrating the practicality and safety of utilizing AI-assisted real-time diagnoses within clinical environments [99]. Additionally, real-time edge processing can provide physical metrics, such as size, volume, and enhanced characteristics of tumors, during the imaging process; thus providing an efficient pathway to the clinician’s workflow and the diagnostic possibility [100]. Implementing edge computing for kidney tumor detection has many advantages. Edge-enabled devices, like portable ultrasound scanners or mobile CT/MRI workstations, can perform image processing on-device, providing immediate diagnostic feedback without reliance on cloud infrastructure. This process allows lower time-to-diagnosis and immediate clinical decision-making. Moreover, it provides data privacy and cybersecurity for sensitive medical data, which is paramount in healthcare.

Advances in hardware and the mass availability of graphics processing units (GPUs), field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs), and AI accelerators have made edge devices faster and have enabled them to handle complex deep learning algorithms. In conjunction with this, new AI models that are lightweight and optimized for low-power devices are resource-efficient and can achieve competitive inference without huge computation cost. Edge AI systems can handle a wide range of radiological modalities, such as X-ray, ultrasound, CT, and MRI, with the capacity for disease classification, localization, etc., in real time. AI-driven edge platforms can screen kidney images for neoplastic indicators and flag potentially malignant lesions. This capability improves the clinical workflow by allowing immediate triage and creates less workload for radiologists [101].

AI, intense learning models, is integral to kidney tumor diagnosis and management, as illustrated in Fig. 12. Typically, the process begins with gathering information using imaging (MRI and CT scans) and patient data (demographics, medical history, and symptoms). The AI, driven by deep learning, helps clinicians interpret these scans and accurately characterize the tumor size and stage. This interpretation helps them decide between active surveillance and initiation of one or more treatment options. AI can also help assess pathology information gathered from biopsy or surgical specimens to precisely deliver tumor subtype, size, and stage information. Refining deep learning into kidney tumor management increases one’s ability to customize treatment options, whether surveillance, ablation, systemic therapy, or even nephrectomy, and evaluate patient risk of recurrence, mortality, metastasis, or hospitalization. AI optimizes the workflow from detection to clinical outcomes, enabling providers to give more precise, timely, and individualized care in managing kidney tumors.

Figure 12: AI-driven workflow for kidney tumor detection and management: integrating imaging, patient data, and pathology with deep learning to guide diagnosis, treatment, and outcome prediction

U-Net and its variations, such as 3D U-Net, Attention U-Net, and Residual U-Net, have established themselves as the gold standard architectures for kidney tumor segmentation—in particular, volumetric imaging modalities like CT and MRI. With their encoder-decoder structures and skip connections, they effectively offer a precision of localization while predictably enabling context awareness, consistently producing high Dice scores typically between 0.85 and 0.92. These architectures require large annotated 3D datasets to provide such robust segmentation (e.g., datasets with multiple delineated images for each subject) and rely on a moderate amount of computing resources willing to sacrifice speed and efficiency in processing images, which is the basis of their efficacy. Attention mechanisms and residual blocks help to enhance the performance of U-Net by reducing distractions while segmenting between definitive tumor boundaries and subtle tumor lesions; thereby increasing accuracy during segmentation and improving training stability [102,103].

Transformer-based models such as TransUNet, Swin U-Net, and MedT present a distinct advantage in being able to encode both global and long-range dependencies from images represented by volumetric CT or MRI images of injured kidneys, particularly with tumors that are less conventional in either their shape or presentation. As a result, these models have reported state-of-the-art performance with Dice scores exceeding 0.90 in cases involving undeclared or incomplete MRI sequences (e.g., axial, sagittal, and coronal) or multi-modal imaging (e.g., CT and MRI). The performance has typically been highest with larger numbers of samples (e.g., patients) within a dataset. It would be confident in high-powered computing with available hardware, such as GPU memory to meet the extensive computing demand inherent with such approaches. The overall structure of their global contextual modeling is essential to identify metastatic or infiltrative tumors when they entail complex spatial relationships [104,105].

Hybrid CNN-Transformer models balance their use of CNNs for local feature extraction to act as efficient encoders and transformer networks as decoders. Hybrid models can provide significant practical value, as they allow for improved segmentation performance of kidney tumors vs. either a pure CNN or a pure transformer model. They can be used when one wants more than CNNs offer in terms of accuracy, while full transformer performance is not achievable. They are also very efficient for combining multi-scale and multi-modal imaging datasets. Thus, hybrid architectures have potential utility in research environments that are looking to push model development forward, while being alert to computational tools [106,107].

Generative adversarial network (GAN)-based models, such as UNetGAN and SegAN, enhance segmentation outputs by learning to generate sharper and more realistic tumor masks. This works very well in imaging contexts with noise or low contrast (e.g., low-dose CT scans). GANs are great at reducing artifacts that are often identifiable in scans and for creating visually appealing and interpretable outputs, which can be very important for clinical adoption of AI models. However, much like the previous models, they also entail complexity when trained and modeling instability that must be managed [102].

Uncertainty-aware networks, such as Probabilistic U-Net and Bayesian U-Net, provide segmentation predictions and quantify uncertainty to offer confidence estimates, which can be extremely important for clinical decision making. These architectures are most relevant when interpretability and risk assessment become essential, as would be the case for an ambiguous or borderline tumor that would benefit from a manual review combined with an automated review. The concerted use of uncertainty information can enable safer AI proliferation within clinical workflows by encoding a signal of reliability to predictions [108,109].

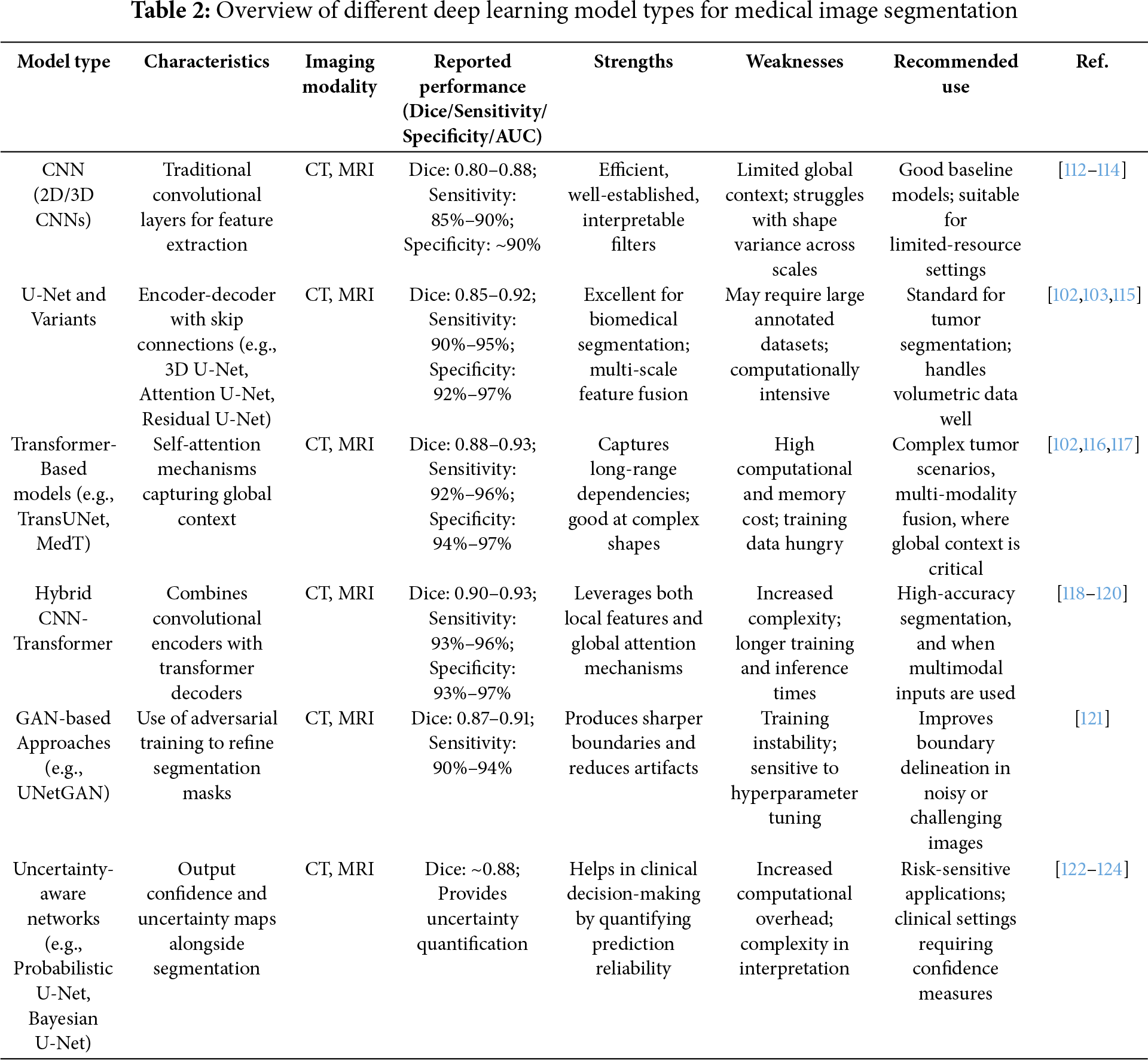

Additionally, recurrent and multi-scale networks, including R2U-Net and MSU-Net, consider temporal correlations and multi-scale variation. These models are especially relevant where longitudinal imaging studies would benefit from tracking tumor progression or time-based treatment response. They also perform well when there is a substantial change in size or texture of the tumors within the datasets, while assisting with multi-organ segmentation tasks where scale variance is a key challenge [110,111]. Table 2 consolidates the various deep learning models, their characteristics, limitations, and the suitability of the data type.

5 Clinical Applications and Challenges

AI, particularly deep learning, has enhanced the detection of kidney tumors and improved diagnostic accuracy while lessening clinical burden. CNNs are used to analyze CT and MRI scans to accurately identify tumors. Several studies that used architectures like Inception-v3 and ResNet discerned benign vs. malignant renal lesions, including tumors <4 cm, which achieved up to 95% sensitivity and high specificity with contrast-enhanced CT datasets. Results like these highlight AI’s capacity for early detection and individualizing care delivery. Although studies have provided promising results, several different barriers impede clinical implementation. One major problem is that the level of opacity of AI decision-making makes outputs difficult for clinicians to interpret [125]. Other barriers include limited diversity of datasets, due diligence standards, integration with hospital systems for existing PACS and EHRs, and navigating privacy laws (e.g., Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)). Also, historically poor infrastructure, lack of trained staff, time-consuming conversations of liability, and fears of clinicians losing their jobs have stalled implementation. Additionally, without intervention, biased datasets could worsen racially discriminatory diagnoses that limit treatment recommendations. Accountability, interpretability, fairness, and system security issues have become paramount concerns [126–128].

Trust from the patient perspective depends entirely on the AI outputs’ transparency and understandability. Ethical use of AI relies on adherence to principles of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice also implicate legal doctrine and data governance [129–131]. Patient anxiety needs to be coped with in advance, with clinicians, technologists, regulators, and patients working together to regulate the legal and ethical liability. The focus of the physician’s collaboration with AI should be to support clinical decision-making, rather than replacing them, and enhance workflows using features like heatmaps and reliability scores. AI can become a member of tumor boards and provide real-time updates supported by clinical review, with the potential for improved examination and accuracy, as well as efficiency of personalization.

Transitioning from research to the clinical realm is more complicated than it sounds. Developing an AI for rely-fit action by the agency or officials (FDA clearance; CE mark) requires multi-site testing, reliable results with generalizable performance developed, and evidence demonstrated—this process can take between 3–7 years (as opposed to a 1–2 year timeframe) and requires significant investment [132,133]. In the previously reported analysis, over 40% of FDA-cleared AI medical devices lack formal publication of clinical validation data. Adaptive AI systems may also face additional burdens, as significant updates post-deployment may be considered much better with no approval from the users (not necessarily users).

Integration into the IT ecosystem in hospitals is a different layer of complexity. AI must be integrated into PACS/Radiology Information System (RIS) or Electronic Medical Record (EMR) workflows. HIPAA/GDPR safeguards, system security, and hardware/network requirements can be costly, frequently underestimated, and often unavoidable in beginning research [134,135]. Infrastructure gaps between research and production are very common, particularly with respect to a lack of GPU clusters to develop & test the model, compliant data pipelines for conducting research, and high-speed secure storage. Also, integration-related expenses, including business analysis of the current PACS/RIS architectural model, could incur expenses of $25,000–$35,000, with overall integration costs often exceeding the initial AI development budget [136].

Workflow integration challenges are pervasive. AI output must be delivered at the right time and in the right manner without compromising a reporting path that is well-established and efficient. Disruptive delivery mechanisms, such as a product or a lack of interoperability across protocols and scanners, can halt meaningful deployment. Radiologists may need to review AI segmentations, which may slow overall turnaround time. Models trained on controlled datasets do not perform as well in heterogeneous, real-world imaging environments due to variability in factors such as quality, protocols, and ground truth labels [137,138]. Engaging clinical end users in the design stage, feedback loops, and use of trust-building design (explainable interfaces—overlays, probability maps) increase acceptance and trust in AI [139–141]. Bad reliability and capability, with little regard for the disruptions to established workflow in radiology, mean AI adoption is unlikely to occur.

Human factors are still vital. Radiologists must not only learn how to use AI tools, but also how to assess confidence scores or metrics of uncertainty. The training and support of users is critical. If the AI product does not align with workflows, it can initially lead to additional workload (and, in some cases, productivity drops over a 6–12 months). Only ~30% of Radiologists currently use AI, and over 70% of Radiologists report being reluctant to do so, indicating a “trough of disillusionment” in Gartner adoption curves. At-risk populations—to include individuals with burnout and alert fatigue—have significant risks in use, especially in high-volume settings [142,143].

In technical terms, transformer-based architectures (TransUNet, Swin-UNETR, nnFormer, TransMed) often surpass CNNs’ ability to detect small tumors and complicated tumor-vessel relationships. However, the high computational requirements (big GPUs/TPUs, large memory), long training times, and reliance on large annotated datasets mean they have yet to move into wider deployment. Inference will also take seconds to minutes when using volumetric datasets. At the production level, for resource-constrained settings, approaches such as model compression, mixed-precision inference, patch-wise processing, or transfer learning can help make deployment more tractable and maintain sufficient accuracy [144–148].

Generalizability is another large challenge. Many models are evaluated only internally, with very few external evaluation data collected from sites or scanners. The expected accuracy may decrease drastically since differences in manufacturer, field strength, or acquisition protocols result in domain shift. Multi-center datasets will allow for improved generalizability, but diversity in patient demographics, privacy-preserving FL training methods, and domain adaptation/harmonization methods will also facilitate better generalizability. Reporting both internal and external test performance as standard reporting will be advantageous [149–152].

The costs associated with deployment can be significant. Deploying an AI system in a very small clinic may cost between ~$250,000–$600,000 or ~$2–3.5 million for a multi-site system. Subsequently, there can be an annual burden of ~$15,000–$100,000 related to maintenance, retraining, and compliance-related fees. Most companies can recoup their investment after the second year; the true returns can often come in years 3–5, while the first two years can even induce negative Return on Investment (ROI). Only 86 randomized controlled trials of machine learning interventions have been published globally, while only 16 medical AI procedures have active billing codes. At present, the rate of success for real-world adoption of diagnostic AI has stalled at ~19% (documentation tools have rates closer to ~53%). Continuous monitoring is important to determine whether drift is occurring, and retraining requires competency that many institutional resources may not contain [153–156].

The involvement of clinicians at the outset, true human-centered design principles, accurate and explainable outputs, and comprehensive training basics will be paramount. Future studies should encompass more than simply accuracy; importantly, we need to measure impacts on workflow, measurement turnaround (or efficiency), radiologist satisfaction, and rates of error/rework. If we do not consider operational, regulatory, and human factors, even the most accurate AI models in kidney tumor imaging will stay within the experimental domain and not contribute to real-world clinical value.

6 Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Kidney tumor classification has evolved significantly, transitioning from traditional imaging modalities to advanced imaging and analytics powered by AI and deep learning. This shift has notably improved the completeness of the care cycle—encompassing early detection, appropriate treatment, and patient disposition—often beyond conventional measures, leading to greater operational efficiencies for both patients and healthcare systems. The performance of CNNs and U-Net-based approaches has been promising in tumor segmentation and lesion classification tasks. Integrating neural networks with radiomics has enabled the extracting of precise quantitative features from images, integrating imaging, genomic data, and clinical patient records to facilitate accurate personalized diagnostics. While initiatives like FL address data privacy concerns, other emerging methods facilitate interpretable models to augment clinical trust and confidence in these technologies. Despite many tangible advancements, challenges persist in dataset inconsistency, interpretability, regulatory uncertainty, and ethical dilemmas, which hinder the clinical adoption of these technologies.

To truly maximize the potential of AI for kidney tumor assessment, several key research questions must be addressed. One significant challenge lies in increasing the transferability and robustness of AI models. This heavily depends on training on diverse and large datasets representative of different populations, clinical scanning protocols, and rare tumor presentations. Transfer learning, domain adaptation, and self-supervised methods offer valuable opportunities to better generalize models and make them more robust to certain biases. Furthermore, targeting optimal data use and reduced annotation costs is important. Approaches including synthetic imaging, weak labeling, and active learning will reduce the reliance on extensively labeled datasets. When possible, applying standardized labeling protocols is also crucial to reducing variability and strengthening data accuracy. Additionally, including multiple modalities, such as scanned images, genomic signatures, and patient data, would enable a more comprehensive approach to clinical assessment. Incorporating temporal aspects into deep learning models, combining spatial dimensions with time, may be crucial across observational phases of monitoring and therapy, including assessing tumor development, treatment efficacy, and post-treatment relapse.

In recent years, transformer-based deep learning architectures have shown great potential in denoising, classifying, and segmenting images in clinical settings. Recently, the Transformer-based deep network models have been used for reducing noise in medical images, utilizing transformer architectures while preserving anatomical details. Noise and contamination in medical images can inhibit the detection of anomalous structures; in the case of imaging kidneys with tumors, neglecting the removal or suppression of noise in images can ultimately inhibit the integrity of tumor delineation during detection and segmentation and has the potential to mask or suppress the noise details present in images of fine tumor boundaries or minor texture details. Incorporating transformer denoising or denoising frameworks in automated pipelines for image analysis can theoretically improve the quality of images, which could hypothetically improve the predictive performance of models in their downstream tasks, including segmentation and classification of kidneys with tumors. The next logical step for the burgeoning field of medical imaging analysis utilizing transformers is to include and enhance the effects of clinical models already available, using a denoising approach in conjunction with transformers, to build clinically applicable kidney tumor analysis systems. Efforts are underway to improve models using attention mechanisms to reduce noise while enhancing certain features of renal tumors, hence integrating noise reduction, diminished noise images, and more pronounced roadmaps for automatic disease diagnostics.

Enhancing the ability of AI systems to justify their decisions is equally important in a clinical collaborative setting. While using attention mechanisms and visualization can enhance the transparency of the decision process, the next stage of development will require outputs closely linked to radiological findings and clinical indicators. Systems that augment, rather than displace, the role of radiologists will be critical for implementation in clinical practice. Developing practical tools for real-world use will also require models operating in resource-limited settings, such as mobile and bedside devices. Rigorous clinical trials will be an essential component of this stage to determine whether these technologies improve surgical accuracy or increase patient survival. With technical development, developing and enforcing a coherent framework to guide ethical and regulatory concerns for AI in healthcare is important. This framework should provide important guidance on accountability and bias, and inform adherence to data protection legislation. By coordinating various streams of research alongside responsible technology development and deployment (that respect equity), and fostering thoughtful partnerships with the healthcare workforce, AI can become equity-minded and integrated into a broader process for diagnosing and managing patients with kidney cancer. This approach will ultimately benefit patients worldwide.

Acknowledgement: NT acknowledges the management of Jyothi Engineering College, Cheruthuruty, for their support.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Neethu Rose Thomas and J. Anitha; Validation, Neethu Rose Thomas and J. Anitha; Investigation, Neethu Rose Thomas; Resources, Neethu Rose Thomas; Writing—original draft preparation, Neethu Rose Thomas; Writing—review and editing, Neethu Rose Thomas and J. Anitha; Visualization, Neethu Rose Thomas; Supervision, J. Anitha. Cristina Popirlan and Claudiu-Ionut Popirlan contributed equally to the conceptualisation, design, and critically revising the manuscript. D. Jude Hemanth provided expert guidance on AI-driven image processing techniques and deep learning model implementations. He aided in manuscript preparation, supervised the overall research progress, and finalized the article for submission. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Marias K. The constantly evolving role of medical image processing in oncology: from traditional medical image processing to imaging biomarkers and radiomics. J Imaging. 2021;7(8):124. doi:10.3390/jimaging7080124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Arabahmadi M, Farahbakhsh R, Rezazadeh J. Deep learning for smart healthcare-a survey on brain tumor detection from medical imaging. Sensors. 2022;22(5):1960. doi:10.3390/s22051960. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Nia NG, Kaplanoglu E, Nasab A. Evaluation of artificial intelligence techniques in disease diagnosis and prediction. Discov Artif Intell. 2023;3(1):5. doi:10.1007/s44163-023-00049-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Ali MB, Bai X, Gu IY, Berger MS, Jakola AS. A feasibility study on deep learning based brain tumor segmentation using 2D ellipse box areas. Sensors. 2022;22(14):5292. doi:10.3390/s22145292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Biratu ES, Schwenker F, Ayano YM, Debelee TG. A survey of brain tumor segmentation and classification algorithms. J Imaging. 2021;7(9):179. doi:10.3390/jimaging7090179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]