Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

GLAMSNet: A Gated-Linear Aspect-Aware Multimodal Sentiment Network with Alignment Supervision and External Knowledge Guidance

1 College of Artificial Intelligence & Computer Science, Xi’an University of Science and Technology, Xi’an, 710054, China

2 Institute of Systems Engineering, Macau University of Science and Technology, Macau, 999078, China

* Corresponding Authors: Yuze Xia. Email: ; Zhenhua Yu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Sentiment Analysis for Social Media Data: Lexicon-Based and Large Language Model Approaches)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 85(3), 5823-5845. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071656

Received 09 August 2025; Accepted 19 September 2025; Issue published 23 October 2025

Abstract

Multimodal Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis (MABSA) aims to detect sentiment polarity toward specific aspects by leveraging both textual and visual inputs. However, existing models suffer from weak aspect-image alignment, modality imbalance dominated by textual signals, and limited reasoning for implicit or ambiguous sentiments requiring external knowledge. To address these issues, we propose a unified framework named Gated-Linear Aspect-Aware Multimodal Sentiment Network (GLAMSNet). First of all, an input encoding module is employed to construct modality-specific and aspect-aware representations. Subsequently, we introduce an image–aspect correlation matching module to provide hierarchical supervision for visual-textual alignment. Building upon these components, we further design a Gated-Linear Aspect-Aware Fusion (GLAF) module to enhance aspect-aware representation learning by adaptively filtering irrelevant textual information and refining semantic alignment under aspect guidance. Additionally, an External Language Model Knowledge-Guided mechanism is integrated to incorporate sentiment-aware prior knowledge from GPT-4o, enabling robust semantic reasoning especially under noisy or ambiguous inputs. Experimental studies conducted based on Twitter-15 and Twitter-17 datasets demonstrate that the proposed model outperforms most state-of-the-art methods, achieving 79.36% accuracy and 74.72% F1-score, and 74.31% accuracy and 72.01% F1-score, respectively.Keywords

Aspect-based Sentiment Analysis (ABSA) [1] has emerged as a critical subtask in sentiment analysis, and it provides fine-grained predictions by identifying the sentiment polarity toward specific aspect terms within a sentence. Unlike traditional sentence-level sentiment classification, which assigns a global label to an entire sentence or document, ABSA explicitly focuses on the sentiment expressed toward individual targets, such as product features, named entities, or events. Neural network models for ABSA, such as Attention-based LSTM with Aspect Embedding (ATAE-LSTM) [2] and Interactive Attention Network (IAN) [3], employ target-aware attention mechanisms to capture sentiment-bearing expressions relevant to a given aspect. While the early methods have significantly advanced fine-grained sentiment modeling, their exclusive dependence on textual data reduces performance in cases of ambiguous expressions, sarcasm, or contextually ambiguous language. Furthermore, pre-trained language models like Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) [4] and Bidirectional and Auto-Regressive Transformers (BART) [5] have enhanced contextual understanding in pure-text settings, it is still of great difficulty in resolving sentiment cues with the requirements of commonsense reasoning. Such constraints are especially critical in informal or multimodal settings [6,7], where relying exclusively on textual data can compromise sentiment inference accuracy.

Multimodal Aspect-based Sentiment Analysis (MABSA) [8] becomes a promising direction with its capability in integrating both textual and visual modalities to enhance sentiment comprehension. This paradigm is of increasing relevance in dealing the information on platforms such as Twitter and Instagram, in which the users post comments frequently including images that convey rich emotional signals. MABSA is also considered as an important application scenario in the broader domain of affective computing [9,10], where understanding sentiment across heterogeneous modalities is essential for developing emotionally intelligent AI systems. Multimodal Interactive Memory Network (MIMN) [11] and Target-oriented Multimodal BERT (TomBERT) [12] demonstrate that it can boost sentiment prediction performance by incorporating visual cues into aspect-aware textual representations, particularly in case of involving subtle emotional indicators or ambiguous expressions. Subsequent models, such as Entity Sensitive Attention and Fusion Network (ESAFN) [13], further advance cross-modal interaction by modeling target-image relevance through attention mechanisms or alignment strategies. Recent studies have incorporated external knowledge, such as commonsense or affective cues, to further enhance multimodal sentiment reasoning.

Building on these advances, several recent multimodal aspect-based sentiment analysis models have explored complementary strategies, yet several important gaps remain to be addressed. The Hierarchical Interactive Multimodal Transformer (HIMT) [14] strengthens image–text interactions through hierarchical cross-modal attention; however, it does not impose explicit aspect–region supervision, thus attention can drift to salient but aspect-irrelevant regions when visual evidence is weak or ambiguous. The Knowledge-Enhanced Fusion framework (KEF) [15] enriches textual semantics with external commonsense, but its fusion remains predominantly text-led, leaving modality imbalance unresolved when visual cues are informative. The global-local features fusion with co-attention (GLFFCA) [16] captures interactions at multiple scales, but its reliance on implicit attention weights limits interpretability and does not provide stable alignment signals under noisy inputs. Taken together, these observations indicate that robust aspect–region alignment, balanced fusion, and stronger reasoning for ambiguous content remain open issues.

Therefore, we summarize three key challenges that remain unsolved in MABSA: (1) insufficient aspect–region alignment, (2) modality imbalance in fusion, and (3) lack of semantic reasoning for vague or shifted inputs requiring external priors. These issues hinder performance in weak-signal or ambiguous scenarios. To address them, we propose GLAMSNet, integrating alignment supervision, aspect-aware gated fusion, and large language model-guided sentiment reasoning. The significance of this study lies on that GLAMSNet unifies hierarchical visual-textual alignment, gated aspect-aware fusion, and external language model guidance for precise, interpretable multimodal sentiment modeling. It effectively handles weak, conflicting, or noisy multimodal signals, substantially improving accuracy and robustness in real-world scenarios.

The major contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) We introduce a hierarchical correspondence framework to align aspect terms with visual regions at coarse and fine granularities, enabling the model to focus on aspect-relevant regions, filter noise, and produce interpretable visualizations.

(2) We propose the Gated-Linear Aspect-Aware Fusion (GLAF) module, which adaptively modulates aspect-aware textual features by semantic relevance, suppressing noisy or weakly aligned signals and enhancing fine-grained sentiment reasoning. The ReLU-based linear attention is extended to multimodal sentiment analysis for efficient aspect-aware cross-modal modeling.

(3) We integrate external generative guidance from large language models (e.g., GPT-4o) to provide auxiliary sentiment predictions and embedding-level cues, improving inference under vague or noisy conditions and enhancing robustness on challenging multimodal inputs.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related works in text-based ABSA, multimodal sentiment analysis, and advances in knowledge integration and cross-modal alignment. Section 3 presents the GLAMSNet model with three core functions—modality-specific representation with supervised alignment, aspect-aware fusion via a gated-linear mechanism, and incorporation of external sentiment knowledge for enhanced reasoning—implemented through four modules. Section 4 reports experimental results, and Section 5 concludes with future research directions.

2.1 Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis

Aspect-based sentiment analysis (ABSA) [1] has been extensively explored within the textual modality, and existing methods primarily focus on modeling the interaction between aspect terms and their surrounding context. For instance, Recurrent Attention Memory Network (RAM) [17] employs a multi-hop memory mechanism to iteratively refine sentiment understanding, thereby improving robustness in complex sentence structures. Transformation Network (TNet) [18] introduces a context-preserving transformation mechanism to mitigate semantic drift during feature projection. Building upon these foundations, Multi-Grained Attention Network (MGAN) [19] proposes a hierarchical alignment strategy that aligns fine-grained aspect representations with coarse-grained sentence semantics.

While most research of ABSA concentrate on textual data, several studies explored vision-only sentiment classification. For example, Res-Aspect [20] introduces an aspect-aware visual attention mechanism to identify sentiment-relevant regions within an image based on a given aspect. By leveraging convolutional features and object-level cues, the model attempts to infer aspect-specific sentiment without textual input. However, vision-only methods face inherent limitations: visual semantics are frequently ambiguous, and the absence of textual context often leads to misinterpretation—particularly in abstract or symbolic imagery. These challenges underscore the requirement for multimodal frameworks [21] that jointly leverage complementary information from both text and image for more accurate and robust aspect-level sentiment analysis.

2.2 Multimodal Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis

To overcome limitations of unimodal approaches, multimodal aspect-based sentiment analysis (MABSA) [8] integrates text and image for richer sentiment understanding. Multimodal Interactive Memory Network (MIMN) [11] adopts dynamic memory for aspect-guided interaction, and Entity Sensitive Attention and Fusion Network (ESAFN) [13] uses selective attention to highlight relevant regions. Vision-and-Language BERT (ViLBERT) [22] enables co-attentional encoding of both modalities, while Target-oriented Multimodal BERT (TomBERT) [12] incorporates target-specific attention but lacks explicit alignment. Caption-Transformer BERT (CapTrBERT) [23] and the Recurrent Attention Network [24] further enhances fusion via auxiliary captions, saliency maps, or hierarchical interaction. However, most methods remain limited by static or text-biased fusion, reducing robustness under modality imbalance or implicit sentiment cues.

A considerable body of research has also followed the BERT-family combined with convolutional/ region-based vision backbones in MABSA. TomBERT [12] represents one of the earliest attempts, in which contextualized embeddings from BERT [4] are combined with global image features derived from a convolutional neural network, demonstrating the benefits of pre-trained transformers in capturing textual nuance. However, the reliance on global visual descriptors limited its ability to capture fine-grained sentiment cues. To address this issue, MIMN [11] subsequently introduced a multi-interactive memory network that jointly models textual and visual information under aspect supervision, using multi-hop memory updates to refine cross-modal representations. While effective, it relied on global ResNet features and thus lacks region-level alignment. Furthermore, ESAFN [13] incorporates explicit structure-aware attention to strengthen cross-modal interactions, ensuring that BERT-derived textual features are more directly matched with aspect-relevant image regions.

Recent models focus on finer-grained multimodal interaction. HIMT [14] enhances multi-level semantic alignment between aspect terms and visual content, while KEF [15] incorporates commonsense knowledge to support sentiment reasoning. Within the same BERT + CNN lineage, KEF employs knowledge-enhanced fusion to refine semantic correspondence between aspect terms and visual objects, while HIMT develops hierarchical alignment strategies that progressively link coarse-grained and fine-grained features across modalities. These advances collectively demonstrate that BERT-family text encoders, when paired with region-level visual representations, form a powerful yet flexible backbone for multimodal sentiment classification. Nonetheless, existing methods often rely on co-attention or memory units alone, which struggle to fully resolve modality imbalance and ambiguities in implicit sentiment expressions.

Overall, the BERT + CNN paradigm has become a central stream in multimodal aspect-based sentiment analysis. By combining contextualized textual embeddings from BERT-family encoders with convolutional or region-level visual features, these models demonstrate clear advantages in aligning aspect-aware semantics with visual evidence. Nevertheless, persistent challenges remain within this stream: early works such as TomBERT [12] depend on global CNN features and are unable to capture fine-grained cues; MIMN [11] introduce memory-based cross-modal interaction but is limited by its reliance on ResNet-level global representations; and more recent frameworks such as ESAFN [13], HIMT [14], and KEF [15] enhance alignment or incorporate external knowledge, yet they still struggled to overcome modality imbalance and implicit sentiment ambiguity. Taken together, this lineage underscores both the promise and the limitations of BERT + CNN approaches, stressing the requirement for unified solutions that can effectively tackle the challenges of supervised alignment, adaptive fusion, and knowledge-guided reasoning.

To enhance interpretability and target-aware reasoning, Face-Sensitive Image-to-Emotional-Text Translation (FITE) [25] aligns facial expressions with emotional text for cross-modal grounding, while the Affective Region Recognition and Fusion Network (ARFN) [26] applies region-level filtering to improve robustness under visual noise. The Global–Local Feature Fusion Network with Co-Attention (GLFFCA) [16] leverages gated fusion and contrastive learning for image–text alignment, yet remains largely aspect-agnostic. Multimodal Dual Cause Analysis (MDCA) [27] introduces causal reasoning via vision–language pretraining but lacks mechanisms to explicitly inject LLM-based sentiment predictions into the decision process. Most recently, the Prompt-guided Dual Query and Span-based Aspect Modeling (DQPSA) framework [28] enhances target-specific alignment by combining prompt-driven visual grounding with energy-based span prediction, offering a unified and task-aware solution to multimodal aspect-based sentiment analysis. Efficient Multimodal Transformer with Dual-Level Feature Restoration (EMT-DLFR) [29] and Modality-Invariant Contrastive Learning (MICL) [30] improve robustness under modality incompleteness, core challenges in alignment, fusion, and reasoning remain.

Beyond sentiment classification, related research in multimodal recommender systems has also demonstrated the benefits of combining affective cues from text and images. For instance, a study to explore how visual sentiment embedded in product images, together with textual sentiment in user reviews, can be fused within a context-aware collaborative filtering framework to enhance recommendation accuracy [31]. Although the objective differs from aspect-based sentiment classification, both domains share the insight that textual and visual modalities provide complementary emotional information. This cross-domain evidence further underscores the importance of multimodal fusion and motivates our work, which extends the paradigm by focusing on fine-grained aspect–region alignment, adaptive fusion, and external knowledge guidance for robust sentiment reasoning.

Despite these advancements, current MABSA [8] models still suffer from three recurrent limitations: (1) the absence of supervised alignment between aspect terms and visual regions, (2) insufficient modeling of aspect-aware dynamic fusion, and (3) underutilization of external reasoning capabilities, especially those enabled by modern LLMs. These challenges highlight the need for a more unified and interpretable framework that can simultaneously address cross-modal alignment, fusion adaptability, and knowledge-guided reasoning.

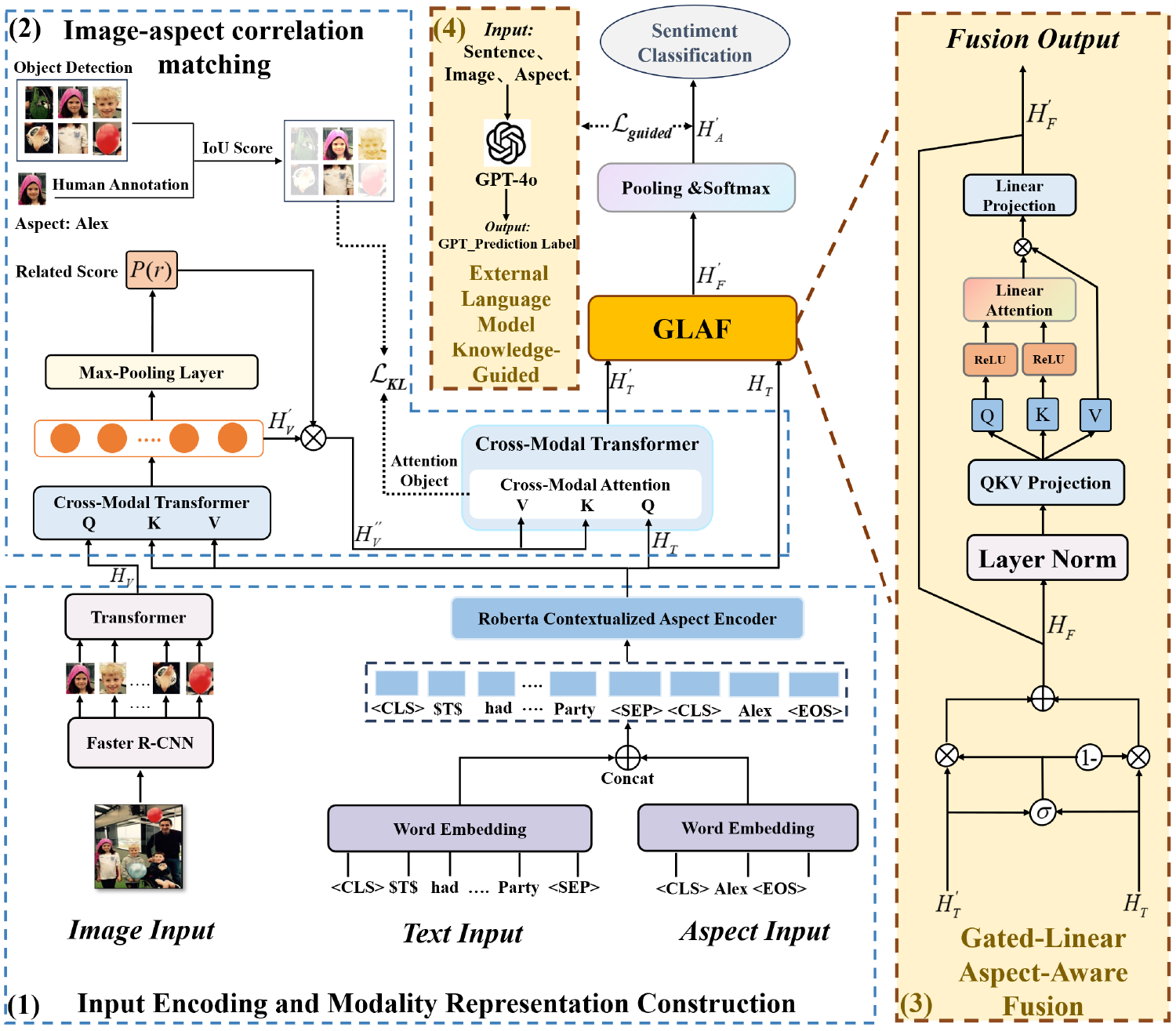

In this study, we propose a unified framework named Gated-Linear Aspect-Aware Multimodal Sentiment Network (GLAMSNet), as illustrated in Fig. 1:

Figure 1: An overview of the GLAMSNet architecture

The proposed framework comprises four modules: (1) Input Encoding and Modality Representation Construction, (2) Image–Aspect Correlation Matching, (3) Gated-Linear Aspect-Aware Fusion (GLAF), and (4) External Language Model Knowledge-Guided. The fused representation is then fed into a sentiment classification layer for aspect-level polarity prediction. The first two modules (Sections 3.2 and 3.3) address insufficient aspect–region alignment by constructing aspect-aware unimodal features and applying hierarchical alignment supervision. The GLAF module (Section 3.4) suppresses irrelevant textual information and refines features based on aspect semantics, while the External Knowledge-Guided (Section 3.5) incorporates sentiment priors from large language models to enhance reasoning under complex inputs.

Given a text sequence of n words S = (w1, w2, … , wn) and its associated image V, as well as a specific aspect A = (a1, a2, …, am), m implies the length of aspesct phrase. Particularly, we assume that all aspect entities (i.e., words or phrases) in S have been provided. The specific aspect is assigned a label y ∈ {negative, neutral, positive}. Formally, given a training dataset comprising D instances, each sample includes a triplet X = (S, V, A), where the model is expected to infer the sentiment polarity corresponding to the specified aspect term within the multimodal context. The objective is to learn a function capable of predicting aspect-level sentiment for multimodal samples.

3.2 Input Encoding and Modality Representation Construction

Let us consider a sample set with each sample represented as a triplet (S, V, A), which consists of a textual input, a paired image, and a set of aspect terms. In this module, we independently encode the textual and visual modalities to obtain modality-specific representations that serve as the input for downstream reasoning modules.

In the proposed framework, we adopt RoBERTa [32] as the textual encoder and Faster R-CNN [33] as the visual backbone. This choice is motivated by following the requirements of multimodal aspect-based sentiment analysis. The textual inputs in the applied datasets (e.g., Twitter-15 and Twitter-17 datasets) are typically short, noisy, and lack grammatical regularity, which demands a backbone capable of stable representation learning under limited data conditions.

On the textual side, RoBERTa [32], a robustly optimized variant of BERT [4], has demonstrated strong contextual modeling and reliable fine-tuning in low-resource sentiment tasks. By contrast, Decoding-enhanced BERT with Disentangled Attention (DeBERTa) [34] achieves gains on large-scale benchmarks but usually requires abundant data to exploit its disentangled attention fully. When applied to small and noisy corpora such as Twitter, DeBERTa [34] often suffers from unstable convergence and overfitting, whereas RoBERTa [32] provides proven robustness.

On the visual side, sentiment cues are often localized in specific regions, such as faces, trophies, or symbolic objects, rather than spread across the entire image. Faster R-CNN [33] is particularly suitable for this scenario because its region proposal mechanism yields object-level features that align naturally with aspect–image correspondence. In contrast, patch-based encoders such as the Vision Transformer (ViT) [35] or holistic vision–language models such as Contrastive Language–Image Pre-training (CLIP) [36] and Bootstrapping Language–Image Pre-training (BLIP) [37] primarily produce global embeddings that dilute fine-grained sentiment cues, thereby limiting their effectiveness in aspect-level alignment.

Another key consideration is efficiency and compatibility. Pre-extracted region proposals from Faster R-CNN [33] enable efficient training on a single GPU, avoiding the latency and memory overhead of large vision–language frameworks. More importantly, the discrete region-level features extracted by Faster R-CNN [33] and the stable token representations produced by RoBERTa [32] provide complementary granularity that aligns naturally with our Gated-Linear Aspect-Aware Fusion (GLAF) and alignment objectives, both of which require fine-grained and structurally consistent inputs to achieve effective cross-modal integration. In contrast, global embeddings generated by models such as ViT [35], CLIP [36], or BLIP [37] are less amenable to alignment-based supervision, while DeBERTa’s [34] instability on small and noisy corpora undermines downstream fusion. Therefore, the combination of RoBERTa [32] and Faster R-CNN [33] provides both efficiency and natural compatibility with GLAF and alignment-driven optimization, making it a well-suited backbone for our framework.

3.2.2 Textual Modality Encoder

We utilize a pretrained RoBERTa language model [32] to encode the input sentence in an aspect-aware manner. For the original input sentence S and an aspect term am ∈ A, a modified sequence S′ is constructed by concatenating the aspect term with a masked version of the sentence, separated by a special delimiter:

where Smasked is derived by replacing the aspect span am in S with a placeholder token. The token [SEP] is a special separator symbol used in RoBERTa to mark boundaries between different segments. The function Concat (·) denotes the token-level sequence concatenation (not embedding concatenation), and the square brackets [·] indicate token sequences rather than scalar values or mathematical sets.

The resulting sequence S′ is then encoded to produce contextualized token embeddings:

where HT serves as the aspect-aware textual embedding for subsequent cross-modal reasoning modules, h is the hidden dimension, and l is the input length. All visual and textual feature matrices are organized in a column-wise format, and each column represents a single token or region embedding vector of dimension ℎ.

To extract region-level visual features relevant to the aspect, a pretrained object detection model named Faster R-CNN [33] is used to process the input image V. The detector identifies the top K regions with the highest confidence scores, Subsequently, the detected object proposals are ranked based on their category-wise confidence scores, and the top 100 proposals are retained to preserve finer-grained objects, thereby facilitating precise alignment with aspect targets. Let R, R ∈

In order to capture the inter-object dependencies, the regional feature matrix R is projected and subsequently input into a Transformer encoder, producing object-level visual representations:

where WR ∈

3.3 Image–Aspect Correlation Matching

In multimodal aspect-based sentiment analysis, not all images are semantically aligned with the aspect under discussion in the text. In other words, some visual content may be unrelated or even with semantic noise, thereby degrading classification performance if they are fused indiscriminately. In this study, an image–aspect relevance module [38] is introduced to evaluate the semantic relatedness between the image and a given aspect. This module provides two levels of alignment supervision—coarse-grained image-aspect relevance and fine-grained region-level attention refinement—to guide the model in suppressing irrelevant visual content and attending to sentiment-relevant regions.

3.3.1 Coarse-Grained Image-Aspect Relevance

Let us start with the construction of visual representations that are guided by the aspect-aware textual semantics. We adopt a Cross-Modal Transformer layer [39] to model the interaction between the aspect and the image, which regards image representation HV as queries, and contextualized aspect representations HT as keys and values as follows:

where

To assess whether the image is semantically relevant to the aspect, we apply max-pooling to the visual representation

The aggregated vector hv is subsequently fed into a binary classifier to compute the relevance score P (r) ∈ (0, 1), which represents the probability that the image is semantically aligned with the current aspect:

where Wr ∈

A high relevance score indicates that the visual content provides meaningful context for the given aspect, while a low score suggests semantic misalignment. This scalar value P (r) serves as the global relevance signal and would be utilized in subsequent gating to suppress noisy or unrelated visual information during fusion.

While cross-modal fusion enables rich semantic interactions, irrelevant or noisy visual information may still introduce confusion if indiscriminately combined with textual representations. we leverage the scalar relevance score P (r) ∈ (0, 1) to suppress uninformative or misleading visual content. The score is then broadcast and expanded to match the shape of the visual representation

where ⊙ denotes the Hadamard (element-wise) product.

When P (r) is approaximate to 0 (indicating low image-aspect relevance), the visual signal is effectively suppressed. Conversely, when P (r) approaches to 1, the model retains full visual representation. This gated modulation acts as a soft attention filter, allowing the model to downweight noisy or irrelevant visual cues while preserving informative regions for downstream fusion.

To estimate semantic relevance between an image and a given aspect, we follow the coarse-grained region-aspect alignment [38], using manually annotated relevance tags to supervise visual–textual correspondence. The predicted relevance score P (r) is optimized with binary cross-entropy loss:

where M denotes the number of training samples with relevance annotations; k denote the k-th training instance. A higher penalty is imposed when the model predicts high relevance scores for semantically unrelated image–aspect pairs, or low scores for relevant pairs. This loss supervision guides the model to distinguish informative visual signals from noisy or irrelevant content.

3.3.2 Fine-Grained Region-Level Attention Refinement

While the visual modality provides abundant contextual signals for multimodal sentiment analysis, the sentiment expressed toward a given aspect is usually grounded in specific regions of the image rather than the entire visual scene. To be specific, for an individual mentioned in the text, the associated image may contain unrelated elements such as background objects, surrounding people, or environmental noise.

In this part, we employ a region alignment supervision module [38] to compute attention over localized image regions and optimize it toward a ground-truth alignment distribution based on manually annotated aspect-relevant regions. Through this supervision, the model is encouraged to focus on semantically relevant regions while suppressing noisy or unrelated visual content, thereby enhancing aspect-aware representation learning.

Cross-Modal Transformer layer [39] is applied to obtain the aspect-aware attention distribution over 100 object proposals from Faster R-CNN. We use the representation of the first token in the aspect input

where

We denote the attention weights from the i-th head of the CrossModal Transformer as Di. To obtain the final attention distribution across the K candidate regions, we compute the mean of all m attention heads, resulting in

To supervise the attention mechanism in learning semantically meaningful region-aspect alignments, we leverage the ground-truth (GT) bounding boxes that is manually annotated by human experts [40,41]. These GT regions serve as soft alignment references, enabling the model to calibrate its attention distribution toward sentiment-relevant visual areas. For each training instance, we construct the alignment distribution based on the degree of spatial overlap between the detected candidate regions and the annotated GT box. We construct the supervised alignment distribution α∈K by computing the Intersection over Union (IoU) between each of the K = 100 candidate regions—extracted from image V using Faster R-CNN—and the ground-truth (GT) bounding box BGT. For the i-th region Bi, we calculate its IoU score with BGT, denoted as si = IoU(Bi, BGT). If si exceeds a predefined threshold τ = 0.5, it is retained; otherwise, it is set to zero. The generated alignment distribution α serves as a soft supervision signal to guide the model’s region-level attention mechanism toward aspect-relevant visual regions.

To strengthen the alignment between the model-generated attention distribution D and the human-annotated alignment distribution α, we adopt the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence as the training objective. The region-level alignment loss is formally defined as:

where N is the number of aspect–image samples for region-level alignment training, we use manually annotated supervision with global image–aspect relevance labels and fine-grained bounding boxes to guide attention learning. These annotations help the model distinguish sentiment-relevant regions from noise, providing structured guidance for cross-modal alignment.

However, while the alignment module improves aspect–region correspondence, it lacks a fine-grained fusion of textual and image-derived aspect features. To address this, we introduce the Gated-Linear Aspect-Aware Fusion (GLAF) module, which adaptively integrates multimodal cues based on aspect relevance.

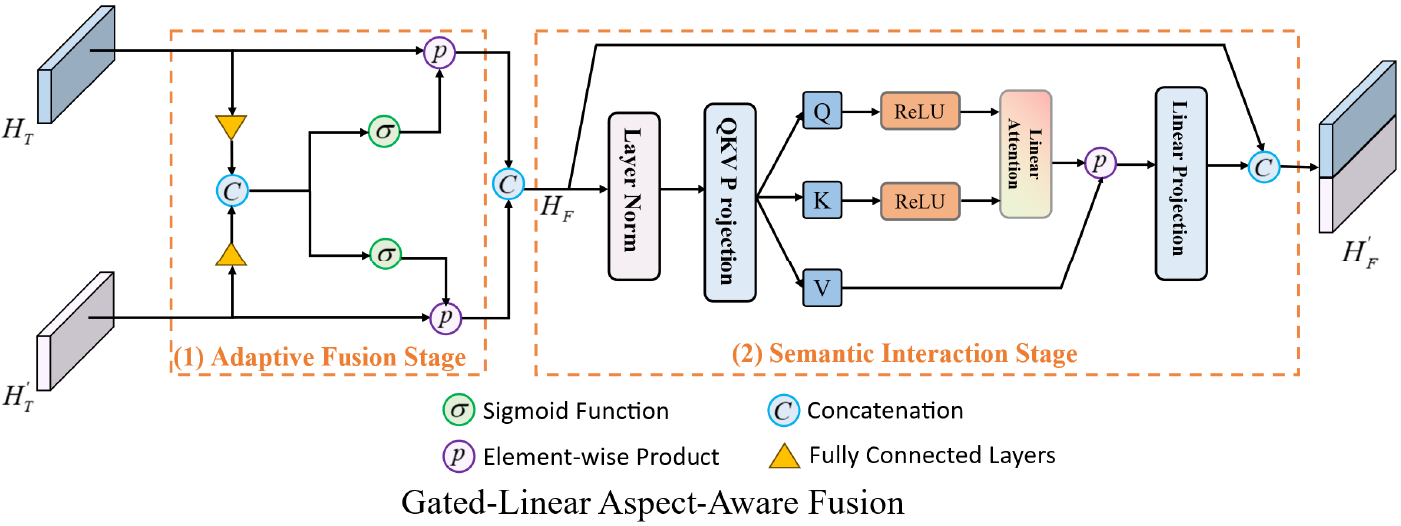

3.4 Gated-Linear Aspect-Aware Fusion

To improve aspect-aware representations and suppress noisy textual tokens, we propose the Gated-Linear Aspect-Aware Fusion (GLAF) module. Unlike standard cross-modal fusion, GLAF applies aspect-guided filtering within the textual modality, followed by lightweight attention-based refinement, enabling distilled sentiment-relevant signals and strengthened aspect-aware dependencies, as shown in Fig. 2. It operates in two stages: the Adaptive Fusion Stage uses gating to modulate textual token contributions based on the aspect vector, enhancing relevant features; the Semantic Interaction Stage refines the fused representation through aspect-aware cross-modal interactions, capturing nuanced sentiment cues from both modalities.

Figure 2: Overview of the gated-linear aspect-aware fusion

Before describing the details of GLAF, we clarify the notations used in this section to avoid ambiguity. Specifically, HT denotes the aspect-aware textual embedding obtained from the RoBERTa encoder (Eq. (2)), while

The rationale for using the image-based aspect representation

To dynamically regulate the contribution of different textual features under aspect guidance, we develop a gating-based adaptive fusion strategy. Specifically, given the aspect-aware textual representation HT and the generated image-based aspect representation

where W1, W2 ∈

The gating coefficient G ∈ (0, 1) indicates the contribution degree of the visual modality to the fusion representation. This gating formulation is a widely adopted linear gating strategy commonly used in multimodal representation learning [16]. Based on the gating matrix G, the fused representation is computed as:

This fusion mechanism allows the model to automatically adjust the relative contributions of individual textual tokens according to their aspect relevance, effectively mitigating the impact of noisy or irrelevant textual signals.

3.4.2 Semantic Interaction Stage

Although the gating-based fusion mechanism adaptively regulates token contributions based on aspect relevance, it does not explicitly model fine-grained semantic dependencies across the fused sequence. To address this, we propose a lightweight semantic interaction module based on multi-head linear attention, building upon ReLU-based linear attention [42] with structural simplification and reduced computational overhead. Specifically, we remove the softmax in self-attention and replace it with ReLU-activated queries and keys for more efficient, stable computation. This design reduces numerical instability and strengthens cross-modal semantic interaction without overfitting to dominant features, while a residual connection preserves original fused features for fine-grained refinement guided by learned attention weights.

Let HF denote the fused representation obtained from the previous stage, we project HF into the query, key, and value spaces as follows:

where WQ, WK, WV ∈

The ReLU activation introduces non-linearity and enhances the representation capacity. These projected matrices are then fed into a linear attention layer to compute contextualized embeddings, which are subsequently used for sentiment classification.

Next, the attention weights are computed using a linear normalization strategy. Specifically, we define the unnormalized attention matrix as QKT. The normalized attention weights are calculated as:

where Qi ∈

The attention-weighted representation is computed as:

where

This semantic interaction mechanism enables to model fine-grained global dependencies across tokens within the fused representation

The fused representation is fed into a sentiment classification layer. For aspect-level prediction, we apply mean pooling over token-level representations, a common method in sentence representation learning [4,32] for effectively aggregating embeddings.

The resulting vector

where P (y│X) ∈

3.5 External Language Model Knowledge-Guided

Although multimodal models can infer aspect-level sentiment from joint text–image representations, predictions often suffer from instability due to limited training data and semantic inconsistencies, especially with low-quality images or ambiguous text. While GLAF mitigates modality imbalance and improves fusion, it still relies only on observed inputs and lacks deeper reasoning under weak or conflicting signals. To address this, we introduce an external language model knowledge-guided mechanism that uses large-scale generative models to provide complementary sentiment priors, enhancing training supervision, representation learning, and semantic alignment for better generalization.

3.5.1 Sentiment Label Prediction and Embedding

To incorporate external sentiment supervision at the aspect level, we reformulate the original dataset into an aspect-specific instance structure. While each original sample is defined as a triplet X = (S, V, A). Specifically, we query the LLM to infer a sentiment polarity label yGPT ∈ {0, 1, 2} for each training sample based solely on its textual input. These predicted labels are then mapped into a continuous vector space via a learnable embedding function Emb: ℤ →

3.5.2 External Sentiment Label Generation

To obtain high-quality sentiment supervision signals, we leverage the reasoning capabilities of a pretrained large language model (GPT-4o) to generate auxiliary sentiment labels for each training instance. For a given sample X = (S, V, A), a carefully designed prompt is constructed and fed into GPT-4o to infer a sentiment polarity label: yGPT ∈ {negative, neutral, positive}.

Inspired by the prompt-based causal reasoning design in Multimodal Dual Cause Analysis (MDCA) [27], we design a set of structured prompt templates to elicit aspect-level sentiment understanding from the LLM.

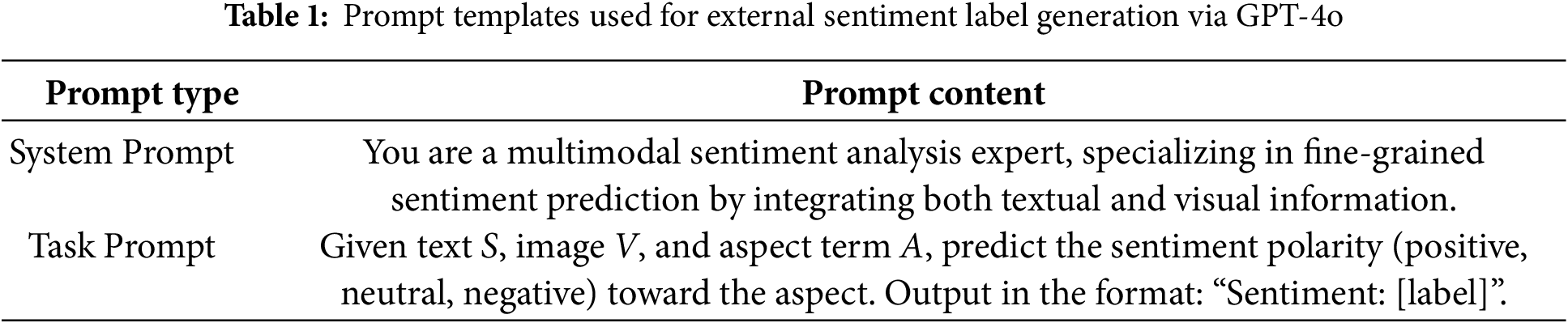

The prompt templates include a system prompt, defining the LLM’s role as a multimodal sentiment analysis expert, and a task prompt, providing text and visual context for aspect-level sentiment prediction. Table 1 shows representative examples illustrating their structural diversity and task relevance.

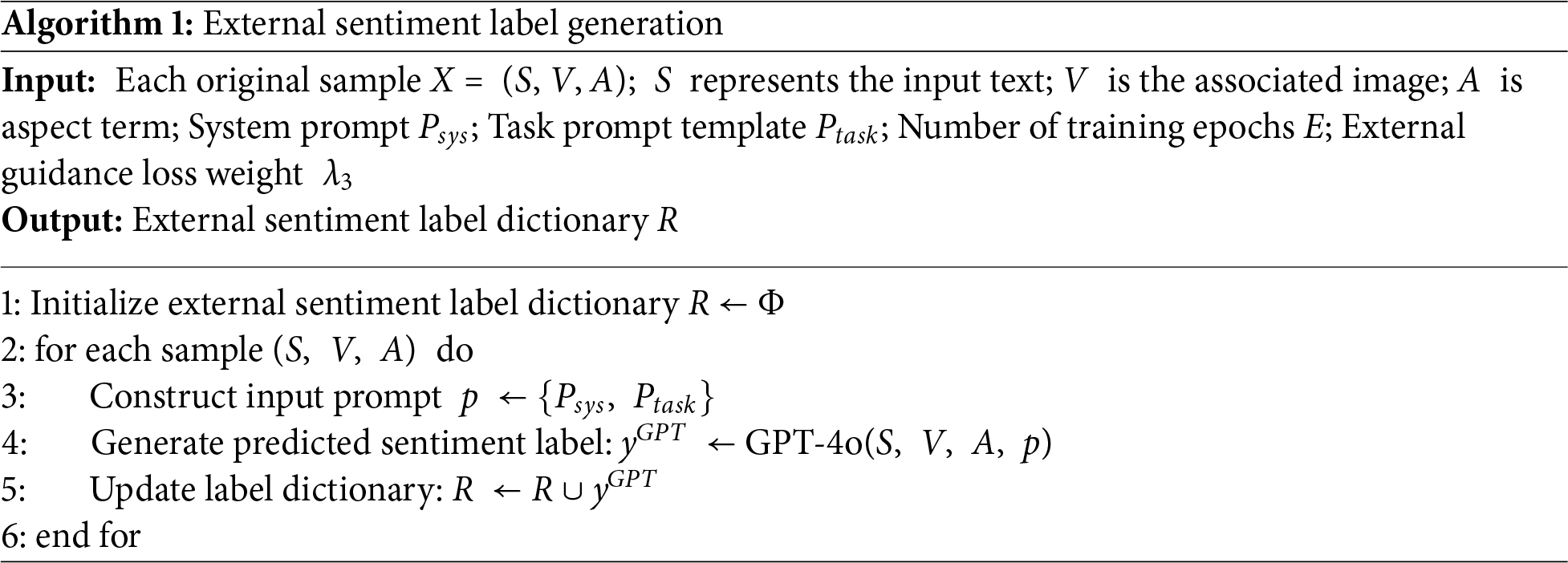

For each training sample, the overall procedure for external sentiment label generation via GPT-4o is formally in Algorithm 1.

Specifically, a combined system and task prompt is constructed based on the input text, image, and aspect term, and subsequently fed into GPT-4o to generate a predicted sentiment label. The resulting label is stored in an external sentiment label repository, which serves as prior supervision for downstream knowledge-guided training.

3.5.3 Sentiment Representation Alignment Loss and Joint Optimization

In the multimodal fusion stage, the Gated-Linear Aspect-Aware Fusion (GLAF) module generates a fused sentiment representation

This loss encourages the model to produce sentiment representations that are semantically aligned with external guidance, thereby leveraging high-level knowledge to improve robustness and accuracy during multimodal fusion. This design bridges implicit commonsense reasoning from LLMs with low-level multimodal representations, enabling the model to handle sentiment ambiguity more effectively.

We employ a multi-task training strategy integrating image–aspect relevance prediction, region-level alignment, sentiment classification, and external knowledge guidance to fully exploit multimodal signals at multiple granularities and enhance generalization via language model priors.

The overall training objective is formulated as a weighted sum of all sub-losses:

where

The coefficients λ1, λ2, λ3 are hyperparameters that control the relative contribution of each auxiliary loss. These values are selected based on validation performance to ensure that the auxiliary objectives enhance—but do not overpower—the primary sentiment classification task.

4 Experimental Results and Analysis

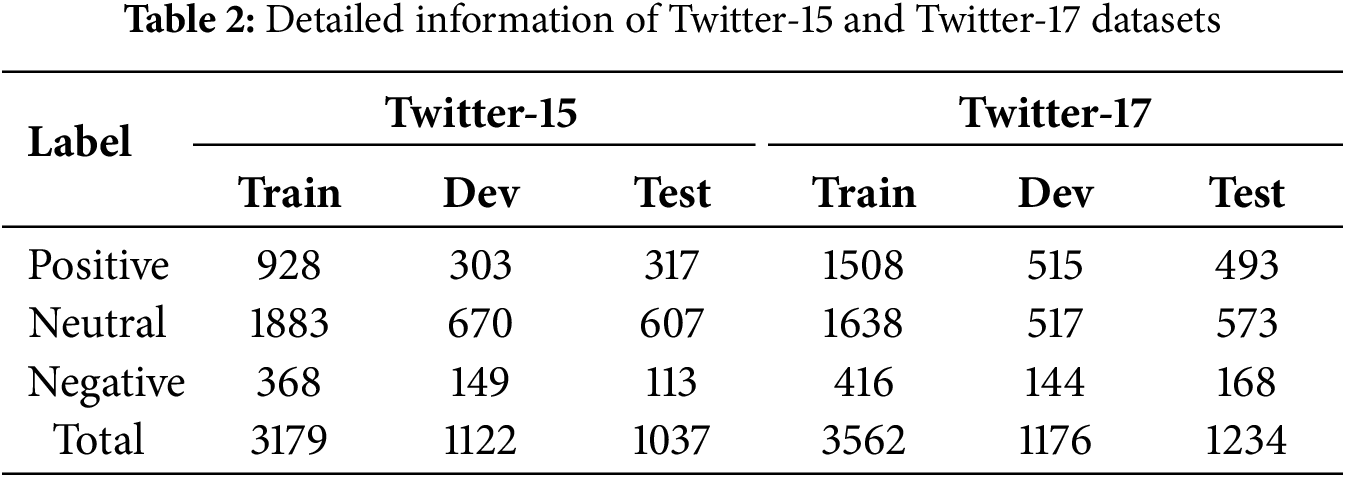

In this study, experiments are conducted on the widely used Twitter-15 [43] and Twitter-17 [44] datasets, where each multimodal tweet comprises a textual post, a corresponding image, one or more aspect terms, and sentiment labels (negative, neutral, positive) for each aspect, as detailed in Table 2.

4.2 Hyperparameter Settings and Evaluation Metrics

We use the pre-trained RoBERTa model with 24 layers, a hidden size of 1024, and 355 million parameters for textual and aspect representations, and Faster R-CNN to extract 100 region-of-interest features with a dimensionality of 2048 from images. Optimization uses BertAdam with learning rates of 1 × 10−5 for sentiment classification, 1 × 10−6 for visual region alignment, and 5 × 10−6 for external knowledge guidance, with a warmup proportion of 0.1. Training runs for 9 epochs with a batch size of 32 on a 32 GB NVIDIA V100 GPU. Performance is evaluated on the test set using Accuracy and Macro-F1 for baseline comparison.

To assess the performance of aspect-based sentiment classification, we compare the proposed model with three categories of baseline models: image-only models, text-only models, and multimodal models.

Image-only model: Res-Aspect [20] uses ResNet and BERT to extract visual and textual features.

Text-only models: Representative examples include MGAN [19] with multi-granularity attention, BERT [4] and BART [5] as pre-trained language models for sentiment prediction, ATAE-LSTM [2] and IAN [3] with attention-based aspect modeling, RAM [17] using weighted memory, and TNet [18] applying CNN layers to extract salient features.

Multimodal models: Multimodal models integrate textual and visual features through attention, memory, or knowledge-enhanced mechanisms for sentiment classification. Examples include cross-modal attention networks such as Res-MGAN and Res-BERT, memory-based architectures like MIMN [11], entity-sensitive fusion models such as ESAFN [13], and pre-trained vision–language transformers like TomBERT [12] and ViLBERT [22]. Other approaches enhance visual grounding or sentiment cues via caption-based modeling in CapTrBERT [23], saliency detection in SaliencyBERT [22], semantic gap reduction in HIMT [14], knowledge integration in KEF [15], facial expression cues in FITE [25], emotional region detection in ARFN [26], and global–local feature fusion with co-attention in GLFFCA [16]. More recent advances include MDCA [27], which formulates MABSA as dual-cause analysis guided by large language model reasoning, and DQPSA [28], which leverages dual-query prompting with an energy-based expert mechanism.

We conduct several comparative experiments based on the benchmark datasets, Twitter-15 and Twitter-17, to assess the effectiveness of the proposed Gated-Linear Aspect-Aware Multimodal Sentiment Network (GLAMSNet).

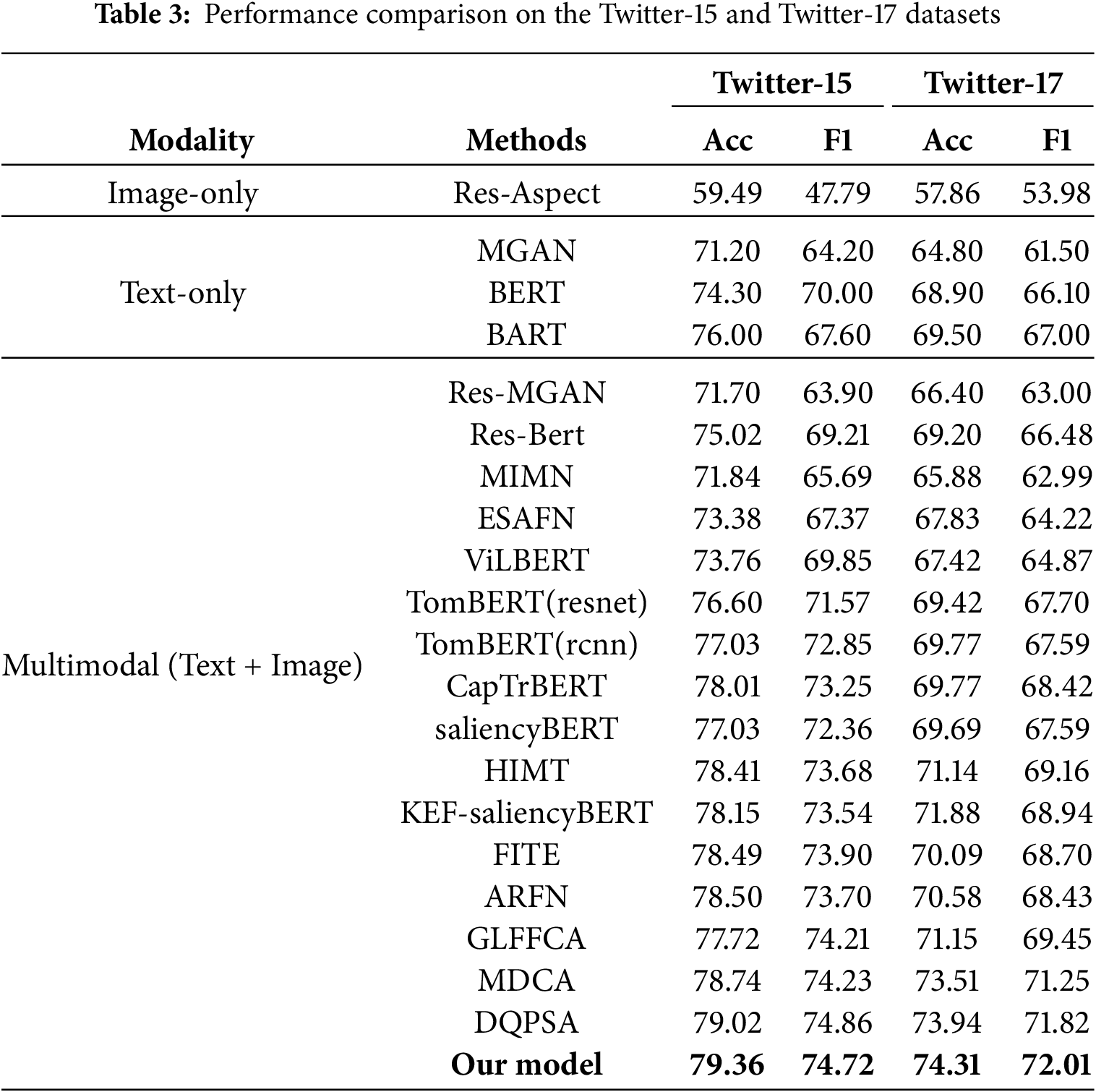

The bold entries in Table 3 indicate the optimal results of the obtained evaluations. Table 3 provides a performance comparison for the proposed GLAMSNet with several representative baseline models on the Twitter-15 and Twitter-17 datasets, with evaluations based on Accuracy (Acc) and Macro-F1 Score (F1). The baselines encompass text-only, image-only, and multimodal approaches. To ensure equitable comparison, all models are assessed under identical experimental settings.

The results show that GLAMSNet consistently outperforms most existing methods on both datasets. Compared with the strongest baseline group (GLFFCA, MDCA, and DQPSA) [16,27,28], our model yields further improvements. Specifically, GLAMSNet achieves F1 gains of 0.51% on Twitter-15 and 2.56% on Twitter-17 compared with GLFFCA [16], while also surpassing the more recent MDCA [27]and DQPSA [28]. MDCA frames MABSA as dual-cause analysis with large language model prompting, reaching 78.74% accuracy and 74.23% F1 on Twitter-15, and 73.51% accuracy and 71.25% F1 on Twitter-17. DQPSA introduces a dual-query prompt with an energy-based expert mechanism and delivers 79.02% accuracy and 74.86% F1 on Twitter-15, and 73.94% accuracy and 71.82% F1 on Twitter-17. Despite their competitiveness, GLAMSNet consistently surpasses both, achieving margins of 0.34%–0.82% in accuracy and 0.28%–1.20% in F1. This confirms the effectiveness of combining hierarchical alignment supervision, gated-linear aspect-aware fusion, multi-head linear attention, and external knowledge guidance into a unified framework.

Finally, EMT-DLFR [29] introduces efficient multimodal transformers with dual-level feature restoration for video-based sentiment analysis. As it addresses different modalities and datasets, direct comparison is infeasible. Nevertheless, its global–local fusion and restoration strategies provide promising directions for extending GLAMSNet to video sentiment analysis in future work.

4.4.2 Model Performance Analysis

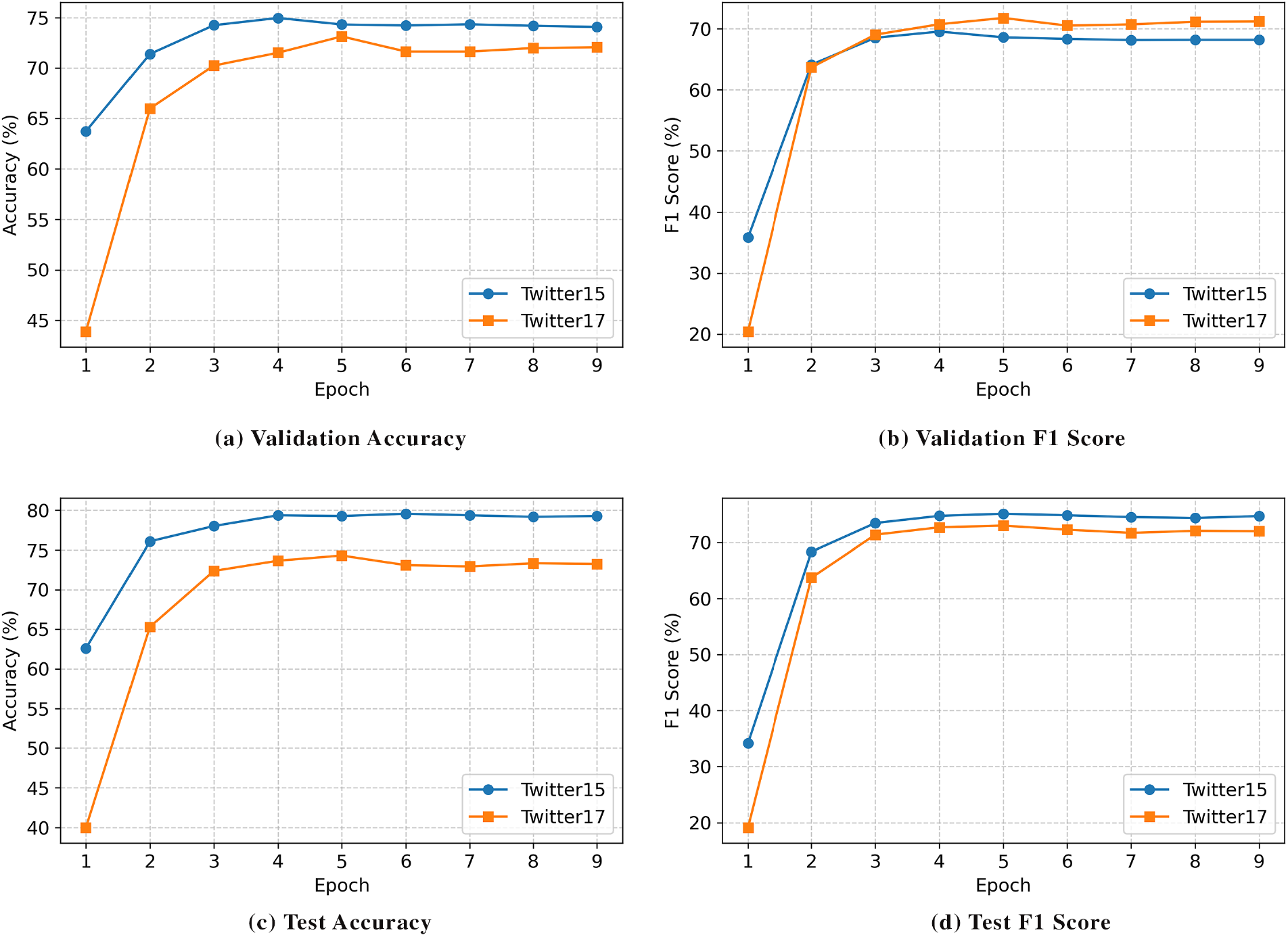

To evaluate GLAMSNet’s performance, we track Accuracy and Macro-F1 across epochs 0–8 on the validation and test sets of Twitter-15 and Twitter-17, as shown in Fig. 3. On validation sets, accuracy rises rapidly in early epochs—63.73% to 74.96% on Twitter-15 and 43.88% to 73.13% on Twitter-17—before stabilizing, with similar trends in F1 scores. On test sets, accuracy peaks at 79.56% for Twitter-15 and 74.31% for Twitter-17, while F1 reaches 75.14% and 73.02%, respectively, maintaining stable performance thereafter. GLAMSNet converges slightly faster on Twitter-15, but its peak results on Twitter-17 demonstrate adaptability to complex data. These trends confirm the effectiveness of the GLAF module and external guidance in achieving robust, high-accuracy sentiment prediction.

Figure 3: Performance of GLAMSNet on Twitter-15 and Twitter-17 across training epochs

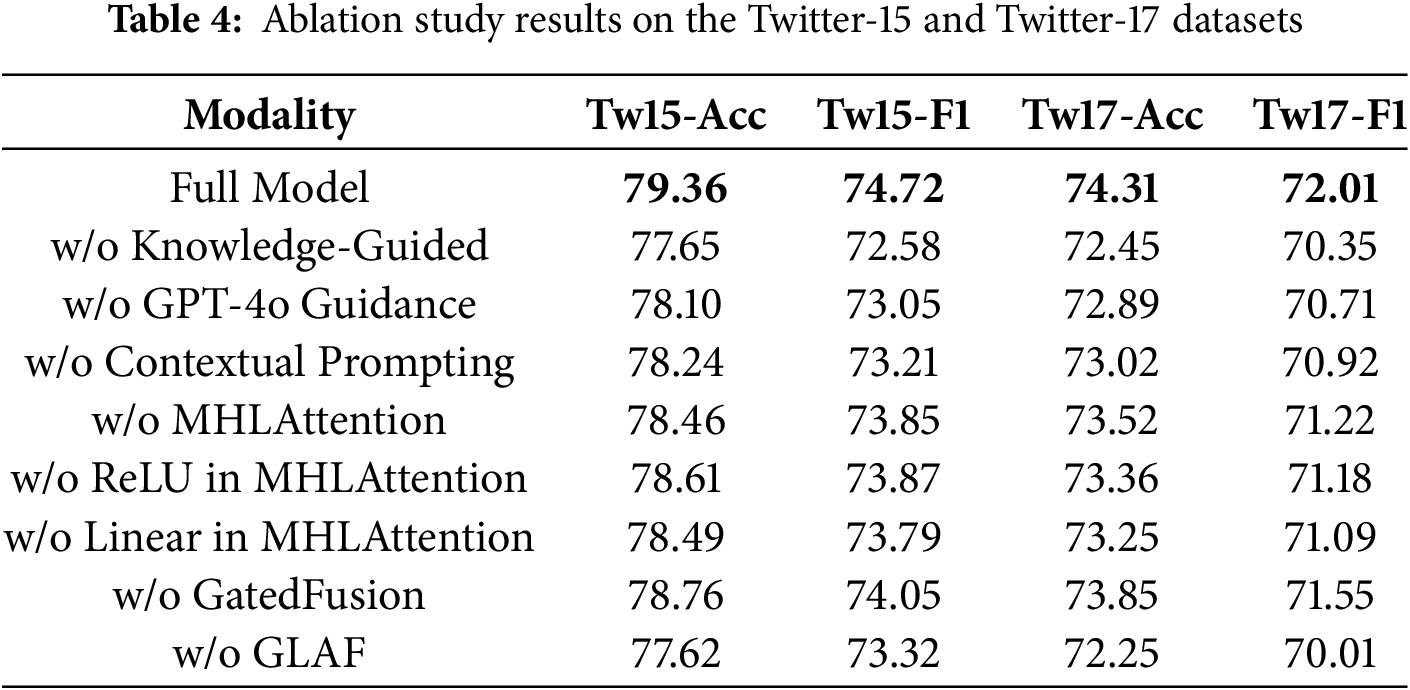

To validate the contribution of each component in GLAMSNet, we perform ablation studies on Twitter-15 and Twitter-17 by removing Knowledge-Guided, MHLAttention, GatedFusion, and GLAF modules individually. As shown in Table 4, “w/o Knowledge-Guided” excludes external knowledge guidance, “w/o MHLAttention” replaces it with standard Transformer self-attention, and “w/o GatedFusion” adopts the baseline gate-based fusion from the first-stage architecture without our enhanced design, while the “Full Model” denotes the complete architecture. In addition, we include fine-grained variants to analyze subcomponents: “w/o ReLU in MHLAttention” and “w/o Linear in MHLAttention” ablate the activation and projection operations within the linear attention module, respectively; “w/o Contextual Prompting” removes the contextualized prompt design for external knowledge guidance; and “w/o GPT-4o Guidance” substitutes GPT-4o–derived priors with outputs from GPT-2.

The ablation studies demonstrate the effectiveness of key components. First, removing the Knowledge-Guided module reduces accuracy by 1.71 points and F1-score by 2.14 points on Twitter-15, and 1.86 and 1.66 points on Twitter-17, confirming the value of GPT-predicted sentiment priors. In addition, replacing GPT-4o with GPT-2 as the external knowledge source reduces accuracy by 1.26 points and F1-score by 1.43 points on Twitter-15, while removing contextual prompting decreases accuracy by 1.12 points and F1-score by 1.09 points on Twitter-17, further demonstrating the necessity of both high-quality external knowledge and effective prompt design. Second, replacing the Multi-Head Linear Attention module decreases performance by 0.79 to 0.90 points, and removing either the ReLU or Linear transformation within this module causes additional drops of about 0.9 to 1.1 points, underscoring the importance of both activation and projection operations. Third, removing the Gated Fusion module leads to drops of 0.46 to 0.67 points, reflecting its role in balancing cross-modal information. Most significantly, ablating the Gated-Linear Aspect-Aware Fusion module causes the largest declines (2.00 to 2.40 points), underscoring its importance in mitigating aspect-image misalignment, particularly given that 58% of dataset images are aspect-irrelevant.

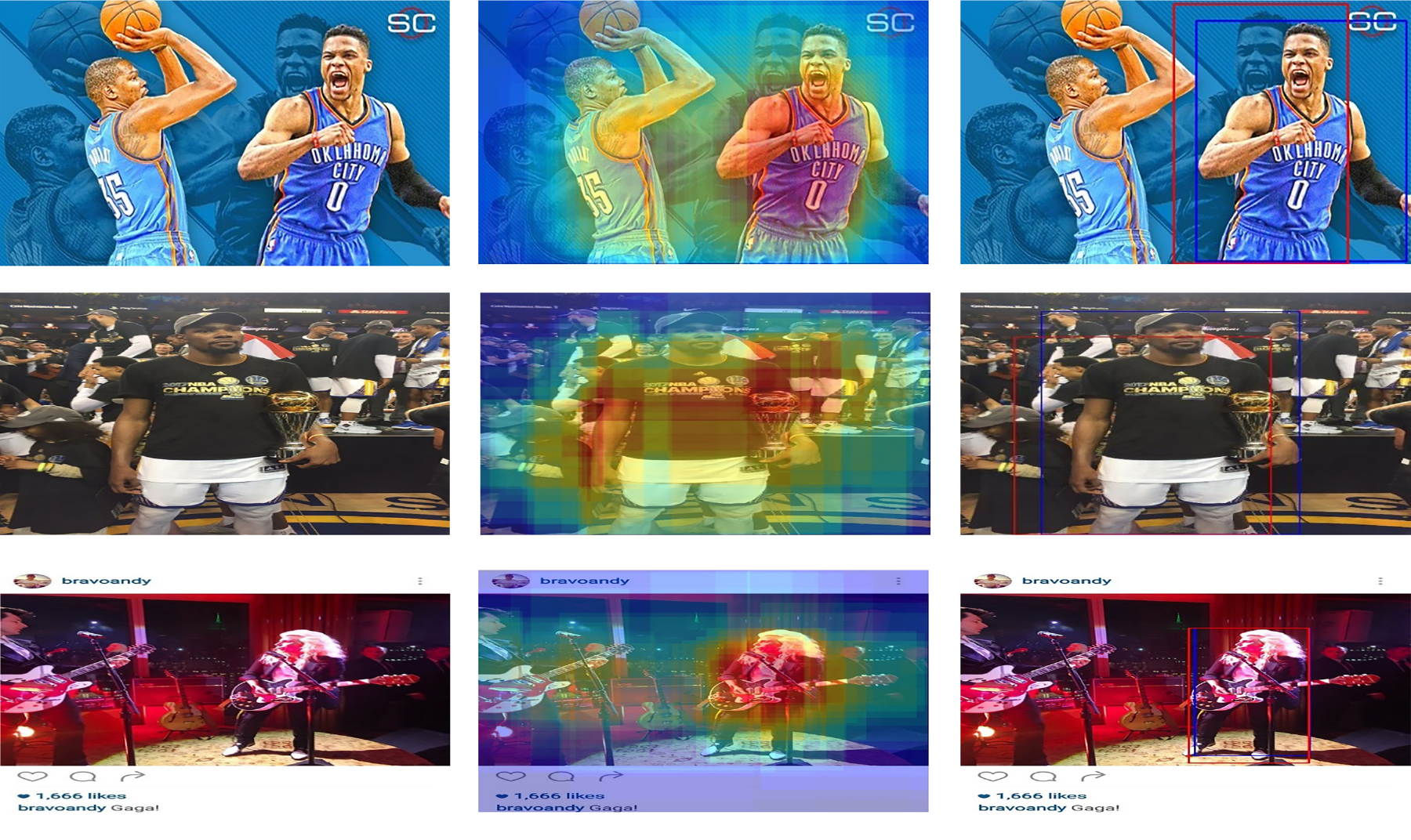

To evaluate GLAMSNet’s region selection and prediction in MASC, we examine three samples from Twitter-15 and Twitter-17 covering athletic achievements, sports conflicts, and entertainment performances, representing different cross-modal alignment levels.

As shown in Fig. 4 (3 × 3 grid layout), each sample presents the original image, attention-weighted regions, and predicted (red) vs. ground-truth (blue) bounding boxes. The first row in Fig. 4 shows a sports achievement from Twitter-15, depicting Kevin Durant and Russell Westbrook in a high-scoring game. The attention map [45] focuses on faces and hand gestures but partially covers the background, resulting in an IoU of 0.617, indicating background interference in dynamic scenes. The second row shows a sports honor from Twitter-17, where Kevin Durant receives the NBA Championship and Finals MVP awards. The model attends to the player, trophy, and podium with minimal background noise, achieving an IoU of 0.722 and reliable spatial focus in positive scenarios. The third row presents an entertainment performance from Twitter-17, featuring Mark Ronson and Lady Gaga at the Met Gala. The model focuses on both performers and the central stage with little background attention, yielding an IoU of 0.895, which reflects precise spatial focus and strong cross-modal alignment for accurate sentiment localization.

Figure 4: Visual region analysis of GLAMSNet on Twitter-15 and Twitter-17

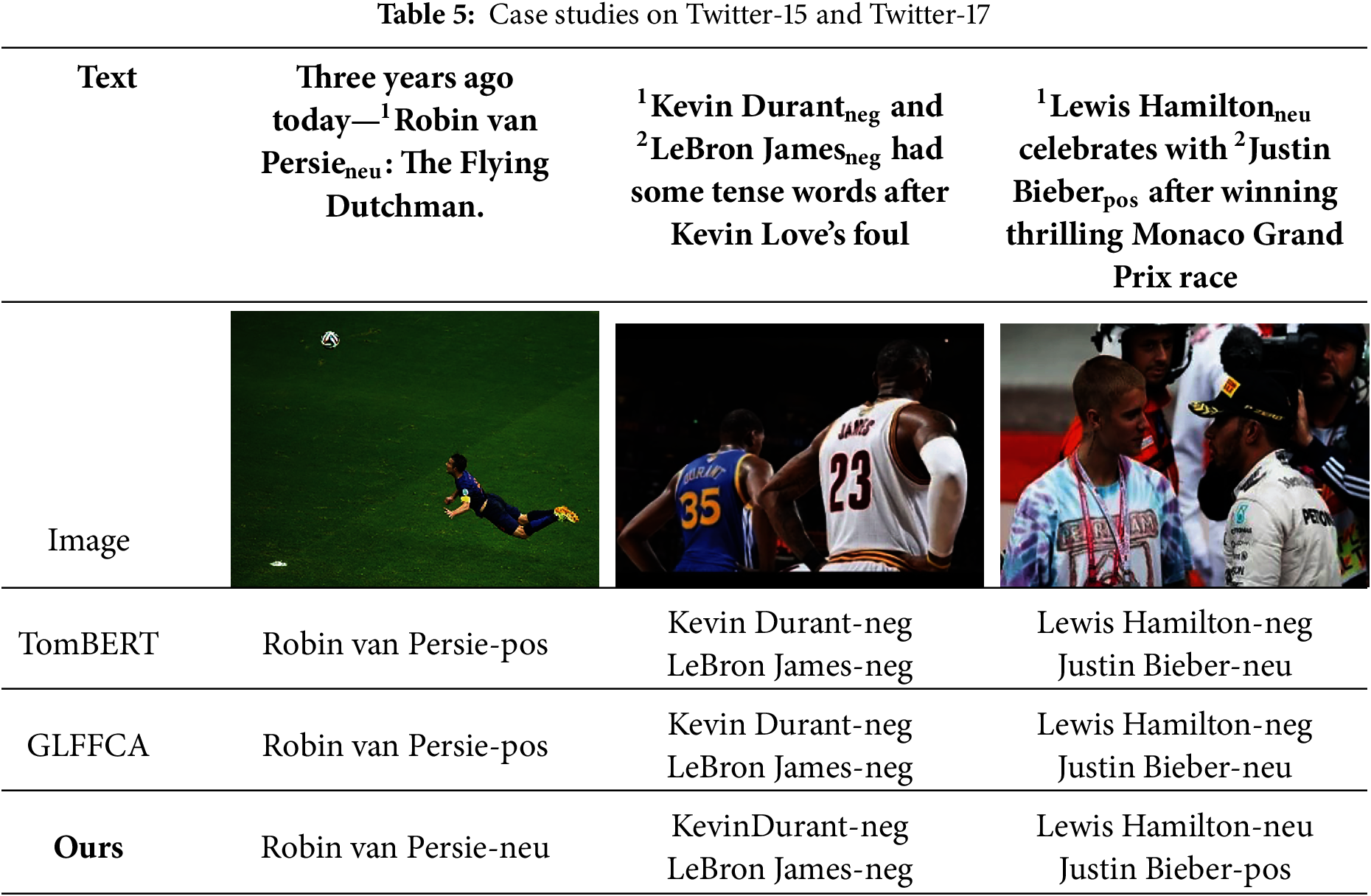

Three case studies compare our model with TomBERT [12] and GLFFCA [16] on textual–visual samples with multiple aspect sentiments, covering sports memorials, conflicts, and celebrations. These examples highlight the benefits of multimodal fusion and the limitations of baselines, as summarized in Table 5.

As shown in Table 5, three case studies compare our model with TomBERT [12] and GLFFCA [16]. In the sports memorial scenario, Robin van Persie’s “Flying Dutchman” goal is neutral but misclassified as positive by TomBERT and GLFFCA, whereas our model uses multimodal context to resolve the ambiguity. In the sports conflict scenario, a foul-induced confrontation between Kevin Durant and LeBron James is correctly predicted as negative by all models, with ours showing higher stability. In the event celebration scenario, Lewis Hamilton is neutral and Justin Bieber is positive; only our model correctly distinguishes both via fine-grained multimodal fusion. These cases confirm our approach’s effectiveness, with future work aimed at refining cross-modal attention for better generalization.

In this paper, we propose a unified framework for multimodal aspect-based sentiment analysis, named Gated-Linear Aspect-Aware Multimodal Sentiment Network (GLAMSNet), which is designed to address three key challenges in MABSA: insufficient aspect–image alignment, modality imbalance, and limited semantic reasoning. To this end, the model integrates hierarchical alignment supervision, aspect-aware gated fusion, and external language model guidance into a cohesive architecture. These components work collaboratively to enhance cross-modal interaction, improve representation quality, and enable more accurate and robust sentiment inference. Experimental results on Twitter-15 and Twitter-17 demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach, achieving 79.36% accuracy and 74.72% F1-score, and 74.31% accuracy and 72.01% F1-score, respectively—outperforming a range of strong baselines.

Despite its effectiveness, GLAMSNet relies on manual alignment annotations, limiting scalability in low-resource settings, and may be affected by noisy external knowledge that misleads sentiment inference. In future studies, we are interested in exploring self-supervised or weakly supervised alignment strategies, developing adaptive mechanisms to assess and calibrate the reliability of external knowledge sources, and further investigating the quality and controllability of knowledge generated by large language models.

Acknowledgement: The authors are deeply grateful to all team members involved in this research.

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by the National Nature Science Foundation of China under Grants 62476216 and 62273272, in part by the Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi Province under Grant 2024GX-YBXM-146, in part by the Scientific Research Program Funded by Education Department of Shaanxi Provincial Government under Grant 23JP091, and the Youth Innovation Team of Shaanxi Universities.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Dan Wang and Zhoubin Li; Methodology: Dan Wang, Zhoubin Li and Yuze Xia; Formal analysis and investigation: Dan Wang, Zhoubin Li and Yuze Xia; Writing—original draft preparation: Dan Wang and Zhoubin Li; Writing—review and editing: Dan Wang and Zhoubin Li; Funding acquisition: Dan Wang and Zhenhua Yu; Supervision: Zhenhua Yu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on reasonable request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Nazir A, Rao Y, Wu L, Sun L. Issues and challenges of aspect-based sentiment analysis: a comprehensive survey. IEEE Trans Affect Comput. 2022;13(2):845–63. doi:10.1109/TAFFC.2020.2970399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wang Y, Huang M, Zhu X, Zhao L. Attention-based LSTM for aspect-level sentiment classification. In: Proceedings of the 2016 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2016 Nov 1–5; Austin, TX, USA. p. 606–15. doi:10.18653/v1/d16-1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ma D, Li S, Zhang X, Wang H. Interactive attention networks for aspect-level sentiment classification. In: Proceedings of the 26th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2017 Aug 19–26; Melbourne, VIC, Australia. p. 4068–74. doi:10.24963/ijcai.2017/568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv:1810.04805. 2018. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1810.04805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Lewis M, Liu Y, Goyal N, Ghazvininejad M, Mohamed A, Levy O, et al. BART: denoising sequence-to-sequence pre-training for natural language generation, translation, and comprehension. arXiv:1910.13461. 2019. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1910.13461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Huang Y, Zhong H, Cheng C, Peng Y. Low-rank adapter layers and bidirectional gated feature fusion for multimodal hateful memes classification. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;84(1):1863–82. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.064734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Cao J, Wu J, Shang W, Wang C, Song K, Yi T, et al. Fake news detection based on cross-modal ambiguity computation and multi-scale feature fusion. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;83(2):2659–75. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.060025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhao T, Meng LA, Song D. Multimodal aspect-based sentiment analysis: a survey of tasks, methods, challenges and future directions. Inf Fusion. 2024;112(3):102552. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2024.102552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Shin J, Rahman W, Ahmed T, Mazrur B, Mia MM, Idress Ekfa R, et al. Exploring the effectiveness of machine learning and deep learning algorithms for sentiment analysis: a systematic literature review. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;84(3):4105–53. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.066910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Javed A, Shoaib M, Jaleel A, Deriche M, Nawaz S. X-OODM: leveraging explainable object-oriented design methodology for multi-domain sentiment analysis. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;82(3):4977–94. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.057359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Xu N, Mao W, Chen G. Multi-interactive memory network for aspect based multimodal sentiment analysis. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2019;33(1):371–8. doi:10.1609/aaai.v33i01.3301371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Yu J, Jiang J. Adapting BERT for target-oriented multimodal sentiment classification. In: Proceedings of the 28th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2019 Aug 10–16; Macao, China. p. 5408–14. doi:10.24963/ijcai.2019/751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Yu J, Jiang J, Xia R. Entity-sensitive attention and fusion network for entity-level multimodal sentiment classification. IEEE/ACM Trans Audio Speech Lang Process. 2020;28:429–39. doi:10.1109/TASLP.2019.2957872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yu J, Chen K, Xia R. Hierarchical interactive multimodal transformer for aspect-based multimodal sentiment analysis. IEEE Trans Affect Comput. 2023;14(3):1966–78. doi:10.1109/TAFFC.2022.3171091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhao F, Wu Z, Long S, Dai X, Huang S, Chen J. Learning from adjective-noun pairs: a knowledge-enhanced framework for target-oriented multimodal sentiment classification. In: Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computational Linguistics; 2022 Oct 12–17; Gyeongju, Republic of Korea. p. 6784–94. [Google Scholar]

16. Wang S, Cai G, Lv G. Aspect-level multimodal sentiment analysis based on co-attention fusion. Int J Data Sci Anal. 2025;20(2):903–16. doi:10.1007/s41060-023-00497-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chen P, Sun Z, Bing L, Yang W. Recurrent attention network on memory for aspect sentiment analysis. In: Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2017 Sep 7–11; Copenhagen, Denmark. p. 452–61. doi:10.18653/v1/d17-1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Li X, Bing L, Lam W, Shi B. Transformation networks for target-oriented sentiment classification. In: Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2018 Jul 15–20; Melbourne, Australia. p. 946–56. doi:10.18653/v1/p18-1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Fan F, Feng Y, Zhao D. Multi-grained attention network for aspect-level sentiment classification. In: Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2018 Oct 31–Nov 4; Brussels, Belgium. p. 3433–42. doi:10.18653/v1/d18-1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 770–8. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Li Y, Ding H, Lin Y, Feng X, Chang L. Multi-level textual-visual alignment and fusion network for multimodal aspect-based sentiment analysis. Artif Intell Rev. 2024;57(4):78. doi:10.1007/s10462-023-10685-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Lu J, Batra D, Parikh D, Lee S. ViLBERT: pretraining task-agnostic visiolinguistic representations for vision-and-language tasks. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2019;32:13–23. [Google Scholar]

23. Khan Z, Fu Y. Exploiting BERT for multimodal target sentiment classification through input space translation. In: Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2021 Oct 20–24; Virtual. p. 3034–42. doi:10.1145/3474085.3475692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wang J, Liu Z, Sheng V, Song Y, Qiu C. SaliencyBERT: recurrent attention network for target-oriented multimodal sentiment classification. In: Chinese Conference on Pattern Recognition and Computer Vision (PRCV); 2021 Oct 29–Nov 1; Beijing, China. p. 3–15. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-88010-1_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Yang H, Zhao Y, Qin B. Face-sensitive image-to-emotional-text cross-modal translation for multimodal aspect-based sentiment analysis. In: Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2022 Dec 7–11; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. p. 3324–35. doi:10.18653/v1/2022.emnlp-main.219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Jia L, Ma T, Rong H, Al-Nabhan N. Affective region recognition and fusion network for target-level multimodal sentiment classification. IEEE Trans Emerg Top Comput. 2024;12(3):688–99. doi:10.1109/TETC.2022.3231746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Fan R, He T, Chen M, Zhang M, Tu X, Dong M. Dual causes generation assisted model for multimodal aspect-based sentiment classification. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2025;36(5):9298–312. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2024.3415028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Peng T, Li Z, Wang P, Zhang L, Zhao H. A novel energy based model mechanism for multi-modal aspect-based sentiment analysis. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2024;38(17):18869–78. doi:10.1609/aaai.v38i17.29852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Sun L, Lian Z, Liu B, Tao J. Efficient multimodal transformer with dual-level feature restoration for robust multimodal sentiment analysis. IEEE Trans Affect Comput. 2024;15(1):309–25. doi:10.1109/TAFFC.2023.3274829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Liu R, Zuo H, Lian Z, Schuller BW, Li H. Contrastive learning based modality-invariant feature acquisition for robust multimodal emotion recognition with missing modalities. IEEE Trans Affect Comput. 2024;15(4):1856–73. doi:10.1109/TAFFC.2024.3378570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Wu LH. Exploit the visual sentiment of the item images to fuse with textual sentiment in context aware collaborative filtering. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;265(6):125970. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.125970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Liu Y, Ott M, Goyal N, Du J, Joshi M, Chen D, et al. RoBERTa: a robustly optimized BERT pretraining approach. arXiv:1907.11692. 2019. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1907.11692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ren S, He K, Girshick R, Sun J. Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017;39(6):1137–49. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2577031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. He P, Liu X, Gao J, Chen W. DeBERTa: decoding-enhanced BERT with disentangled attention. arXiv:2006.03654. 2020. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2006.03654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Dosovitskiy A, Beyer L, Kolesnikov A, Weissenborn D, Zhai X, Unterthiner T, et al. An image is worth 16 × 16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv:2010.11929. 2020. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2010.11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Radford A, Kim JW, Hallacy C, Ramesh A, Goh G, Agarwal S, et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. arXiv:2103.00020. 2021. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2103.00020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Li J, Li D, Xiong C, Hoi S. Blip: bootstrapping language-image pre-training for unified vision-language understanding and generation. In: International Conference on Machine learning; 2022 Jul 17–23; Baltimore, MD, USA. p. 12888–900. [Google Scholar]

38. Yu J, Wang J, Xia R, Li J. Targeted multimodal sentiment classification based on coarse-to-fine grained image-target matching. In: Proceedings of the 31st International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2022 Jul 23–29; Vienna, Austria. p. 4482–8. doi:10.24963/ijcai.2022/622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Tsai YH, Bai S, Liang PP, Kolter JZ, Morency LP, Salakhutdinov R. Multimodal transformer for unaligned multimodal language sequences. In: Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019 Jul 28–Aug 2; Florence, Italy. p. 6559–69. doi:10.18653/v1/p19-1656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Yu Z, Yu J, Xiang C, Zhao Z, Tian Q, Tao D. Rethinking diversified and discriminative proposal generation for visual grounding. In: Proceedings of the 27th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2018 Jul 13–19; Stockholm, Sweden. p. 1114–20. doi:10.24963/ijcai.2018/155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Lei J, Yu L, Berg T, Bansal M. TVQA+: spatio-temporal grounding for video question answering. In: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020 Jul 5–10; Online. p. 8211–25. doi:10.18653/v1/2020.acl-main.730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Cai H, Li J, Hu M, Gan C, Han S. EfficientViT: lightweight multi-scale attention for high-resolution dense prediction. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2023 Oct 1–6; Paris, France. p. 17256–67. doi:10.1109/iccv51070.2023.01587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Lu D, Neves L, Carvalho V, Zhang N, Ji H. Visual attention model for name tagging in multimodal social media. In: Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2018 Jul 15–20; Melbourne, Australia. p. 1990–9. doi:10.18653/v1/p18-1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Zhang Q, Fu J, Liu X, Huang X. Adaptive co-attention network for named entity recognition in tweets. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2018;32(1):5674–81. doi:10.1609/aaai.v32i1.11962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Leem S, Seo H. Attention guided CAM: visual explanations of vision transformer guided by self-attention. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2024;38(4):2956–64. doi:10.1609/aaai.v38i4.28077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools