Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Machine Intelligence for Mental Health Diagnosis: A Systematic Review of Methods, Algorithms, and Key Challenges

Chitkara University School of Engineering and Technology, Chitkara University, Baddi, 174103, Himachal Pradesh, India

* Corresponding Author: Ashutosh Kumar Dubey. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Medical Imaging Techniques Using Generative Artificial Intelligence)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-65. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.066990

Received 23 April 2025; Accepted 17 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Objective: The increasing global prevalence of mental health disorders highlights the urgent need for the development of innovative diagnostic methods. Conditions such as anxiety, depression, stress, bipolar disorder (BD), and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) frequently arise from the complex interplay of demographic, biological, and socioeconomic factors, resulting in aggravated symptoms. This review investigates machine intelligence approaches for the early detection and prediction of mental health conditions. Methods: The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) framework was employed to conduct a systematic review and analysis covering the period 2018 to 2025. The potential impact of machine intelligence methods was assessed by considering various strategies, hybridization of algorithms, tools, techniques, and datasets, and their applicability. Results: Through a systematic review of studies concentrating on the prediction and evaluation of mental disorders using machine intelligence algorithms, advancements, limitations, and gaps in current methodologies were highlighted. The datasets and tools utilized in these investigations were examined, offering a detailed overview of the status of computational models in understanding and diagnosing mental health disorders. Recent research indicated considerable improvements in diagnostic accuracy and treatment effectiveness, particularly for depression and anxiety, which have shown the greatest methodological diversity and notable advancements in machine intelligence. Conclusions: Despite these improvements, challenges persist, including the need for more diverse datasets, ethical issues surrounding data privacy and algorithmic bias, and obstacles to integrating these technologies into clinical settings. This synthesis emphasizes the transformative potential of machine intelligence in enhancing mental healthcare.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileIn today’s world, mental health issues are becoming increasingly widespread, showing up in various symptoms such as mood swings, depression, anxiety, stress, paranoia, and shifts in social and dietary patterns [1]. According to the World Health Organization, mental health continues to be one of the most neglected areas in public health, with an estimated one billion people worldwide experiencing a mental disorder [2]. This study investigates the intricate nature of mental disorders. It examines how emerging technologies, particularly artificial intelligence (AI) methods such as machine learning (ML) [3,4], deep learning (DL) [5], and nature-inspired algorithms [4–6], can support clinical decision-making. Recognizing the often ambiguous and uncertain nature of medical diagnosis and early prediction, this study seeks to bridge the existing gaps by uncovering further insights into the factors associated with mental illness and assessing the potential of machine intelligence algorithms for the early detection of mental disorders.

The rise of machine intelligence has instigated a substantial transformation in mental health care, moving from subjective and complex psychological diagnostics to data-driven methodologies [3–7]. These technologies, proficient in processing and analyzing large datasets from genetic, neuroimaging, and electronic health records, reveal patterns and predictors that were previously ignored by human analysts [8–11]. This review examines how computational models and algorithms are revolutionizing mental health care, providing hope for enhanced diagnostics and tailored treatment plans. However, while several reviews have examined the use of AI in mental health, most are focused either on specific disorders or on specific techniques. A clear synthesis across a wider range of disorders and machine intelligence paradigms is lacking. Additionally, many previous reviews fail to address the comparative evaluation of algorithmic performance, dataset diversity, and clinical applicability. This paper fills that gap by presenting a comprehensive, disorder-wise mapping of various machine intelligence models, including ML, DL, and nature-inspired algorithms, applied to six major mental disorders. It also introduces recent developments and evaluates methodological performance, dataset trends, and translational limitations, offering a broader, updated, and translationally impactful perspective.

The motivation for this comprehensive review is driven by the critical need to refine diagnostic precision and deepen our understanding of mental health disorders. Early detection and precise analysis of conditions such as anxiety, stress, depression, bipolar disorder (BD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are pivotal for improving treatment outcomes and quality of life. The primary goal of this study is to examine the development and results of various computational models, evaluate the effectiveness and precision of these models, investigate the datasets utilized, and identify trends and gaps.

Numerous machine intelligence techniques, including k-nearest neighbors (kNN), support vector machine (SVM) [12,13], random forests (RF) [14], decision tree (DT) [15,16], convolutional neural network (CNN) [14–17], as well as boosting, bagging methods, and nature-inspired optimization, have been investigated in relation to mental health disorders. These approaches provide a diverse array of methods for comprehending and tackling the intricacies of mental disorders, offering valuable insights into diagnosis, treatment, and management strategies [18–22]. Each algorithm makes a distinct contribution to the field, ranging from pattern recognition and predictive modeling to generating data-driven insights, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of addressing mental health challenges.

The study aim is to provide a systematic exploration of machine intelligence techniques applicability in the detection of mental health disorders. The objectives of this study are as under:

• To analyze various computational models and the development, application, and effectiveness of different machine intelligence algorithms (ML, DL, AI, and data-driven) within the realm of mental health.

• To evaluate the performance of these models considering varying conditions and parameters.

• To explore the datasets used and understand their scope, limitations, insights, and applicability.

• To highlight the advantages, challenges, and limitations and recognize areas that require further research to advance the field.

This study systematically reviewed each study and evaluated the methodologies employed, strategies adopted, outcomes achieved, and datasets used. This process offers a thorough overview of the existing landscape of computational models for understanding and diagnosing mental-health disorders. The goal is to bridge the gap between technological advancements and clinical practice. This review and analysis not only emphasize the significant potential of machine intelligence in transforming mental health care but also considers the challenges and ethical issues linked to its integration. Through this detailed exploration, this study contributes to ongoing efforts to improve accessibility, precision, and effectiveness of mental health care.

The distinct contribution of this review lies in its comprehensive, multi-dimensional analysis of machine intelligence applications across six major mental health disorders namely anxiety, depression, schizophrenia (SZ), BD, ASD, and AD. Unlike existing reviews, this study integrates conventional ML models, DL architectures, and nature-inspired optimization techniques, offering a comparative evaluation of their effectiveness, limitations, and use-case suitability. It also consolidates dataset trends from 2018 to 2025, highlighting their diversity, geographical distribution, and methodological relevance. Furthermore, the inclusion of collaboration networks and dataset method mappings add unique analytical value. By synthesizing technical performance, dataset availability, and translational challenges, this review offers a novel, systematized foundation to inform future research and real-world deployment of AI-driven mental health tools.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 addresses the research questions for review and mapping. Section 3 defines the scope, outlines the search strategy, specifies the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and details the categorization, data extraction, and analysis. Section 4 discusses and analyzes the methods employed to detect mental disorders, with each category of mental health examined individually. Section 5 provides an analysis based on the datasets accompanied by an in-depth discussion. Section 6 presents an overall discussion and analysis. Finally, Section 7 offers concluding remarks.

2 Review Question Mapping Method

This study focuses on analyzing research related to the detection of mental disorders, understanding various techniques, and the rationale behind their usage. This review and analysis attempt to exemplify the motivations for employing these methods, the experimental protocols used for validation, the parametric variations, and the challenges faced in these studies. The systematic review and meta-analysis are guided by the following mapping questions (MQs) and research questions (RQs), which are formulated to address specific aspects of this investigation.

The MQs and RQs are as follows:

MQ1: What is the publication status and article selection strategy employed for This study?

MQ2: What are the most commonly used machine intelligence algorithms for assessing mental health?

MQ3: How has the collaboration network among researchers in the field of machine intelligence for mental health diagnosis evolved from 2018 to 2025?

RQ1: What are the key methodological studies in the field of mental health?

This question addresses the methods currently used for detecting mental disorders, the primary factors contributing to successful mental health treatment, and how integrating various classifiers, including ML, DL, and other methodological approaches, affects model performance.

RQ2: What are the strengths and weaknesses of these specific methodologies?

This question examines the impacts of previous results and the major challenges encountered. Additionally, it explores the extent to which existing studies address the current challenges and implications in the field.

RQ3: Is the machine intelligence approach effective in identifying mental health issues?

This question investigates the challenges in developing machine intelligence for mental health, the impact of technological interventions on treatment, strategies for monitoring mental health, social media’s effects, and the potential benefits of machine intelligence. These findings emphasize the need for the effective integration of technology in understanding and treating mental health issues. Additionally, it explores how incorporating technology in monitoring progress can assist clinicians in decision-making.

RQ4: What is the current state of dataset availability in this domain?

This question explores the related datasets.

This section includes the scope definition, search strategy, inclusion/exclusion criteria, categorization, data extraction, and analysis.

3.1 MQ1: What is the Publication Status and Article Selection Strategy Employed for This Study?

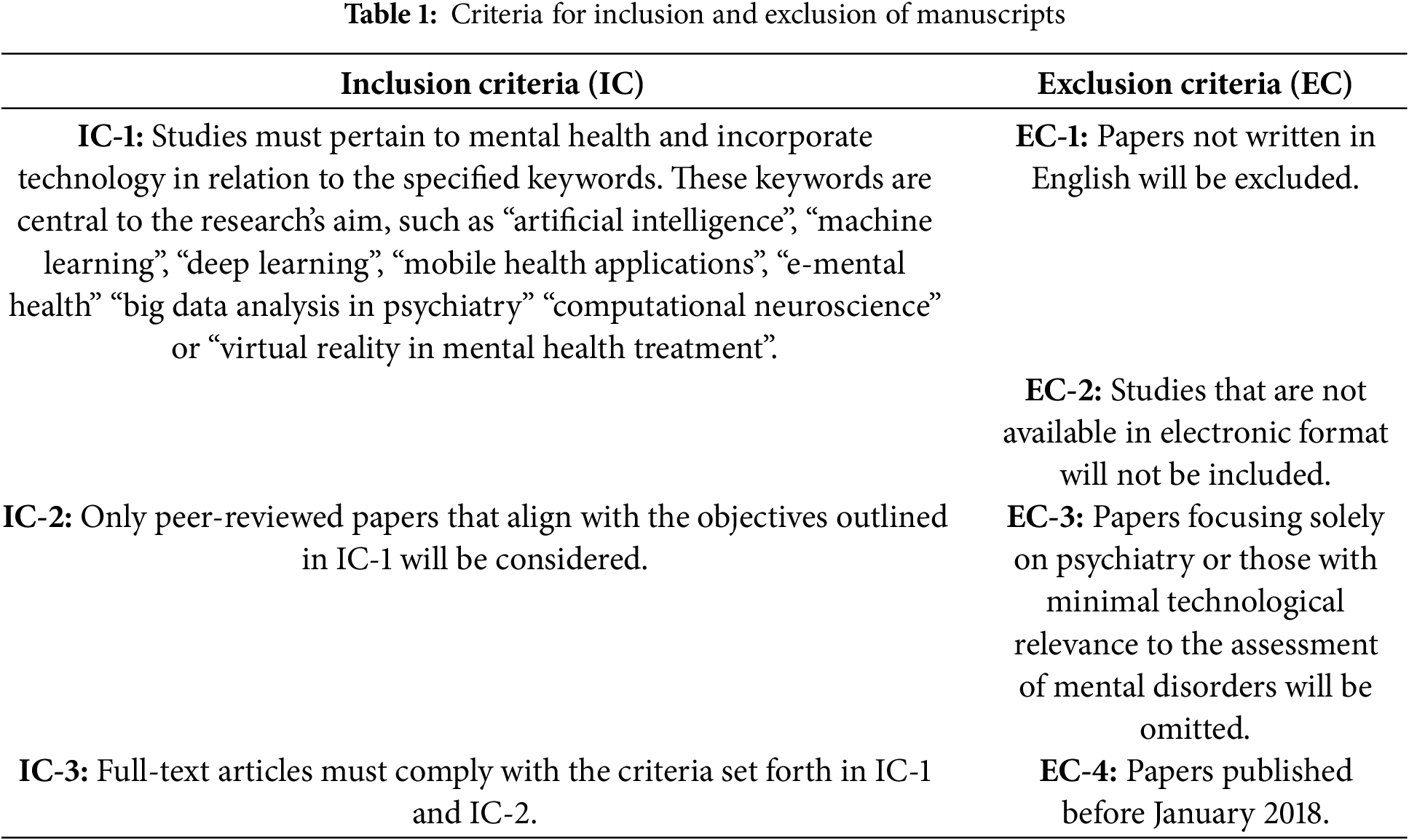

For this study, a total of 1011 papers were reviewed from various databases, including Google Scholar, PubMed, Springer, ScienceDirect, and IEEE Xplore. The publishers considered included Springer, Elsevier, IEEE, MDPI, Hindawi, Wiley, and Nature. The primary search targeted technological keywords such as “machine learning,” “deep learning,” “data mining,” “classification,” “clustering,” “nature-inspired algorithms,” and “big data.” Additionally, related terms about mental health such as depression, SZ, ASD, BD, AD, and anxiety/stress were also considered in the search strategy. Table 1 outlines the criteria for selecting manuscripts based on their relevance to mental health and technology, specifying required keywords like “artificial intelligence” and “machine learning.” It emphasizes the inclusion of peer-reviewed, full-text articles in English that are available electronically, while excluding non-English papers, those not in electronic format, and those without technological focus.

Fig. 1 presents a data collection chart (from January 2018 to June 2025) summarizing 187 papers concerning mental health categories. The papers were sourced from multiple publishers: 43 from IEEE, 53 from Elsevier, 36 from Springer, 12 from Wiley, 11 from MDPI, 9 from Hindawi, and 12 from Nature. Additionally, 11 papers were obtained from other publishers. The collection includes research papers addressing various mental disorders: 33 focus on anxiety and stress-related disorders, 49 on depression, 28 on SZ, 26 on ASD, 26 on BD, and 25 on AD. The latest trends, including studies from 2024 and 2025, have also been discussed and compared in the Discussion section.

Figure 1: Data collection chart from January 2018 to June 2025, summarizing the paper count (187) across different publishers and categories of mental health issues

A systematic and structured methodology for review has been established to conduct an exploratory study. The online database utilized facilitates the construction of a comprehensive corpus for the study. The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were adhered to in the selection of relevant studies [23]. The primary objective was to demonstrate application of this technology in the diagnosis, prediction, and detection of mental health disorders. The impetus for this exploratory study was to address the identified research gap. Key factors were recognized in the prediction and treatment of mental diseases. Fig. 2 presents the PRISMA flow diagram. The flow chart illustrates the process for selecting studies for inclusion in the review. The process began with 1011 records identified. After removing 205 duplicates, 806 records remained for screening. Following the exclusion of non-English papers, poster papers, and EC-2, 720 records were assessed for eligibility. Some reports could not be retrieved, leaving 613 for evaluation. After excluding EC-3, EC-4, and studies with incomplete results, 187 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final review.

Figure 2: Flowchart of the article selection strategy based on the PRISMA style

3.2 MQ2: What are the Most Commonly Used Machine Intelligence Algorithms for Assessing Mental Health?

Machine intelligence algorithms can be broadly categorized into several types on the basis of their learning approach, purpose, and application. Supervised learning algorithms learn from labeled training data, guiding the model to make predictions. Examples include linear regression (LR), logistic regression (LoR), SVM, kNN, DT, RF, gradient boosting machines, and neural networks (NNs) [24–28] (Fig. 3). Unsupervised learning algorithms, which include clustering and association, are used when the data have no labels. Notable methods here include K-means, fuzzy c-means, hierarchical clustering, and density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise [26–28]. Principal component analysis, singular value decomposition, and autoencoders also fall under this category [26–28]. Semi-supervised learning algorithms, such as self-training and co-training models, are trained on a combination of labeled and unlabeled data. These approaches are particularly useful when obtaining a fully labeled dataset is impractical or cost-prohibitive [26–28]. Reinforcement learning algorithms, such as Q-learning, state-action-reward-state-action, deep Q network, proximal policy optimization, and actor-critic methods, learn by interacting with an environment, using feedback from their actions and experiences [26–29]. DL algorithms, a subset of ML that uses NN with many layers (deep networks), include deep convolutional neural networks (DCNNs), and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), which feature long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, generative adversarial networks, and transformers [12–16]. Ensemble learning algorithms combine the predictions of several base estimators, such as bagging (bootstrap aggregating), boosting (e.g., AdaBoost, extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost)), and stacking [12–16], to improve generalizability and robustness. Evolutionary algorithms, including genetic algorithms (GA), particle swarm optimization, ant colony optimization, teaching–learning-based optimization, and artificial bee colony, utilize the principles of natural selection to iteratively select and modify populations of solutions [29,30]. Dimensionality reduction algorithms, which include feature selection techniques (filter, wrapper, and embedded methods) and feature extraction techniques (principal component analysis and t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding), reduce the number of random variables to consider [16–19]. This simplifies the complexity of the data, aiding in more efficient analysis and interpretation.

Figure 3: Taxonomy of machine intelligence algorithms by learning methodology and function

The predominance of algorithms such as SVM, CNN, and RF in mental health research is largely driven by the nature of the data and the diagnostic tasks involved. SVM is well-suited for high-dimensional datasets with limited samples, a common trait in Electroencephalogram (EEG) and questionnaire-based studies, due to its robustness in handling nonlinear separability and small-sample learning. CNNs excel in processing structured data like brain imaging magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), functional MRI (fMRI) and EEG signals by capturing spatial hierarchies and local patterns, making them ideal for diagnosing conditions like AD, SZ, and ASD. RF offers high interpretability and resistance to overfitting, particularly useful in scenarios involving heterogeneous or tabular data, such as clinical surveys and behavioral markers. These methods were frequently chosen across studies due to their favorable balance between accuracy, computational efficiency, and applicability to varied input modalities. Other models such as LSTM, LoR, kNN, or ensemble methods were included where temporal dynamics, interpretability, or ensemble robustness were required. Thus, the algorithm choices reflect their alignment with the specific nature of mental health data ranging from time-series and spatial data to text and behavioral features.

3.3 MQ3: How Has the Collaboration Network among Researchers in the Field of Machine Intelligence for Mental Health Diagnosis Evolved from 2018 to 2025?

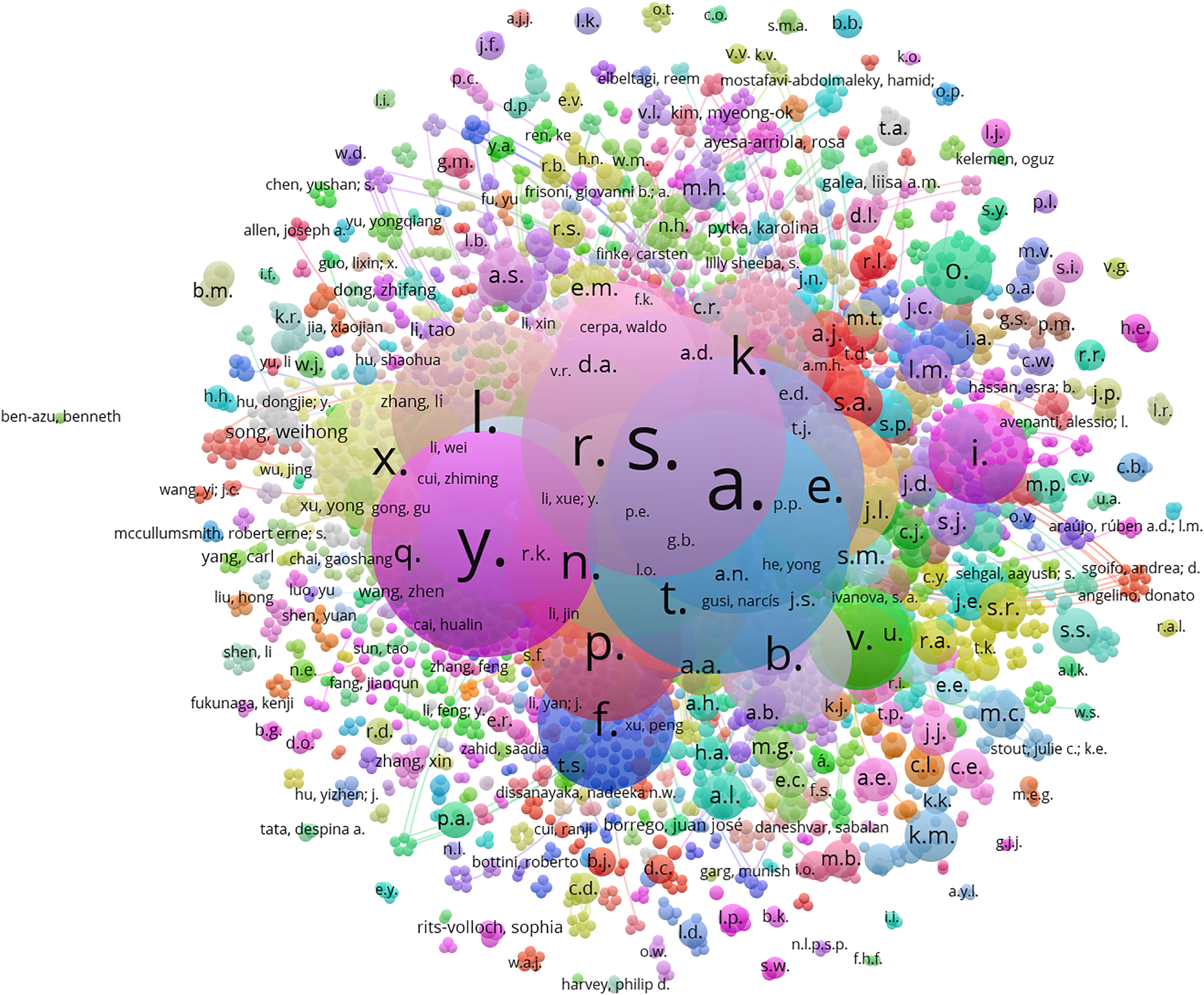

Figs. 4–6 were created using VOSviewer, drawing upon data from the Scopus database for network visualization. Fig. 4 presents a VOSviewer network visualization that demonstrates the linkages between researchers, signified by their respective names during 2018–2025. This is depicted through a color spectrum at the bottom. Each node symbolizes an individual researcher, with the node’s size reflecting their scholarly productivity or citation count. The interconnecting lines represent either collaborative efforts or citation relationships. The nodes’ color variations correspond to different years, illustrating the dynamic nature of collaborative networks over time.

Figure 4: VOSviewer network visualization showing the linkages between researchers, signified by their respective names, spanning from 2018–2025

Figure 5: Network of connections among researchers specializing in the diagnosis of mental health diseases

Figure 6: Interrelationships among various terms associated with AI in mental health

Fig. 5 illustrates the network of connections among researchers specializing in the diagnosis of mental health diseases. The nodes’ diverse colors denote clusters of researchers who frequently collaborate or are jointly cited, whereas the node size may signify the magnitude of their citations or their prominence in the field. The connections between names indicate coauthorship or other collaborative forms. The color gradient at the bottom of the figure, which ranges from 10–60, quantifies the researchers’ impact through their publication and citation counts.

Fig. 6 graphically depicts the interrelationships among various terms associated with AI in mental health. Central terms such as “machine learning,” “artificial intelligence,” “deep learning,” and “neural networks” are indicative of a focus on AI technologies. Adjacent terms reveal AI applications within mental health, covering specific conditions such as depression, anxiety, BD, and SZ. The diagram elucidates the interconnectedness of these topics within contemporary research, with larger nodes suggesting terms that appear more frequently within the scholarly literature, indicating a substantial focus on the application of AI in mental health diagnosis and treatment. The inclusion of terms such as “COVID-19” and “coronavirus disease 2019” signifies the pertinence and investigative interest at the juncture of AI and the pandemic’s effects on mental health. This map infers the application of ML techniques to comprehend and perhaps forecast mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Terms such as “anxiety,” “depression,” and “mental health” situated in proximity to “COVID-19” mirror an upswing in research exploring the pandemic’s impact on mental health disorders, employing AI as an analytical, diagnostic, and management tool. It encapsulates the interdisciplinary essence of contemporary research, bridging AI with healthcare challenges intensified by the pandemic.

The PRISMA framework has been used for the systematic review as it ensures methodological rigor by enforcing a standardized, multi-stage selection process covering identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion, aligned with predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria for mental health and machine intelligence studies. This structured approach minimizes selection bias, enables reproducible dataset and methodology mapping, and supports transparent reporting of algorithmic performance, dataset diversity, and clinical applicability. By clearly documenting each decision point, PRISMA strengthens the validity of comparative analyses across disorders and facilitates replication.

4.1 RQ1: What Are the Key Methodological Studies in the Field of Mental Health?

This section provides an analysis of the techniques utilized to identify mental disorders, with a focus on each mental health category individually. It further examines the crucial factors that contributed to successful mental health interventions and evaluates the effect of incorporating various classifiers, such as ML, DL, and other methodological approaches, on the performance of models. The mental disorders addressed include anxiety/stress, depression, SZ, BD, ASD, and AD.

To explore the application of machine intelligence in individual mental health conditions, the analysis begins with anxiety and stress. These conditions are among the most commonly reported and have received substantial attention in recent research due to their high prevalence and diverse data availability.

Recent developments in machine intelligence have enabled new strategies for the detection and treatment of mental health disorders. A variety of methods have been employed by researchers globally, including the analysis of electrocardiogram signals and the application of ML algorithms, to better comprehend and tackle the intricacies of mental health issues. This subsection presents prominent studies conducted between 2018 and 2021 that illustrate the advancements and variety within this domain, covering the technological aspects.

In 2018, R-R intervals from electrocardiogram signals were determined by Adheena et al. [31] using the Pan Tompkins method. The identification of anxious states was achieved with accuracies of 69.35% and 71.1% by employing the Kalman filter and SVM, respectively. In 2018, Višnjić et al. [32] found that higher anxiety levels were linked to being younger, texting frequently, and using the internet less, whereas increased stress was associated with making fewer calls and having more phone conversations. In the same year, Wang et al. [33] introduced a model to trigger emotions and pinpointed ideal EEG electrode sites, like Fp2, for evaluating the mental states of miners, leading to the creation of a smart helmet system for real-time monitoring. In 2019, Puli and Kushki [34] introduced a method for the prompt diagnosis and alleviation of negative outcomes from physical activity. By integrating accelerometry and heart rate signals through a novel multiple model Kalman-like filter, an accuracy of 93% was achieved in detecting arousal in children with ASD. Gavrilescu and Vizireanu [35] developed a method that combined active appearance models, an SVM, and a facial action coding system, achieving a 93% accuracy rate in differentiating healthy individuals and an 85% accuracy rate for major depressive disorder (MDD), posttraumatic stress disorder, or generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). Ramakrishnan et al. [36] reached a 96% accuracy in detecting stress conditions using SVMs trained on physiological data, while a DT that incorporated both physiological and self-reported data achieved an 84% accuracy in identifying high trait anxiety. Khouja et al. [37] reported that SVMs accurately identified stress with a 96% success rate. Increased computer use was linked to a slight rise in anxiety and depression risk during weekdays and weekends. Fathi et al. [38] developed a three-stage methodology for diagnosing social anxiety disorder, which included preprocessing steps such as feature selection, normalization, and anomaly detection. An adaptive network-based fuzzy inference system model demonstrated an accuracy of 98.67%, with sensitivity at 97.14% and specificity at 100%. Priya et al. [39] utilized DT, RF trees, naïve Bayes (NB), SVM, and kNN to forecast anxiety, depression, and stress levels using data from the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS21) questionnaire, achieving accuracies as high as 79.8%. Xie et al. [40] introduced an innovative method that combined the functional connectivity of brain networks with CNNs for detecting anxiety and depression through EEG, achieving a classification accuracy of 67.67%. Arsalan et al. [41] gathered EEG data from 28 participants over a three-minute period, extracted features in the time domain, applied a wrapper method for feature selection, and reached an accuracy of 78.5% in classifying anxiety using the RF classifier. In 2020, Chen et al. [42] conducted a survey with 78 couples experiencing recurrent miscarriages and 80 couples without, using a questionnaire. Their multiple regression analysis identified anxiety, stress, social support, and recurrent miscarriage as predictors of depressive symptoms, accounting for 62.9% of the variance. In 2021, Xiong et al. [43] developed YODA, a tool for predicting youth disorders through online questionnaires filled out by parents, using a feature ensemble-based Bayesian neural network (FE-BNN) to achieve area under the curve (AUCs) of 0.8683, 0.8769, and 0.9091 for separation, generalized, and social anxiety disorders, respectively. In 2021, Kruthika et al. [44] applied ML for predicting mental disorders, incorporating Indian classical ragas, with SVM emerging as the most effective classifier, achieving an accuracy of 87.23%. In 2021, Meyerbröker and Morina [45] reviewed the use of virtual reality in assessing and treating anxiety disorders, focusing on patient acceptance and therapist reluctance and their impact on the therapeutic alliance. In 2021, Sharma and Verbeke [46] analyzed biomarkers from 11,081 healthy Dutch citizens’ lifeline biobank data, reducing the dataset to 28 variables. Using ML, relationships among biomarkers and four anxiety disorders were explored, revealing significant but weak correlations (0.17 to 0.3).

Modern approaches to detecting anxiety and stress are increasingly incorporating physiological data, such as electrocardiogram (ECG) readings, along with behavioral patterns from technology use. ML and DL methods, including SVM and NNs, are utilized to examine these datasets, achieving significant accuracy in identifying stress and anxiety indicators. By combining multiple classifiers, the models’ performance is improved, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of mental states by considering both physiological and lifestyle elements. Effective treatment depends on early detection, personalized interventions, and ongoing monitoring, areas where these integrated technological methods can be crucial. These developments encourage a more proactive and individualized strategy for managing anxiety and stress, highlighting the vital role of multimodal data and sophisticated analytical models in enhancing mental health care.

While anxiety and stress have demonstrated strong correlations with behavioral and physiological indicators, depression presents a broader spectrum of symptoms and more heterogeneous data types. The following subsection delves into methodological developments aimed at diagnosing depression using multimodal datasets such as EEG, social media, and facial expression analysis.

In recent years, significant advancements have been made in the application of machine intelligence for diagnosing depression, employing various data sources and analytical techniques. Researchers have developed and validated multiple methods to enhance the detection and understanding of depression, ranging from the analysis of facial features and movements in videos to the utilization of EEG signals and social media data. This subsection summarizes key research findings from 2018 to 2021, highlighting the diverse approaches and technologies employed to assess depression severity, detect depressive symptoms, and predict treatment responses, thereby illustrating the potential of machine intelligence in mental health diagnostics.

In 2018, Wang et al. [47] collected videos from both depressed patients and a control group, utilizing SVMs to analyze facial features and movement variations. The results yielded a recall of 80.77%, precision of 77.75%, accuracy of 78.85%, and specificity of 76.92%. Cai et al. [48] developed a psychophysiological database comprising 213 subjects, including 92 depressed individuals and 121 healthy controls (HCs), recording EEG signals during both resting states and sound stimulation. Various techniques were used to extract features, with kNN achieving the highest accuracy of 79.27%. Jiang et al. [49] analyzed 170 native Chinese individuals, including 85 HCs and 85 depressed patients, and introduced an ensemble LoR model for detecting depression in speech (ELoRDD), which demonstrated favorable sensitivity and specificity ratios. Zhou et al. [50] proposed DepressNet, a deep regression network for assessing depression severity using facial data, which performed well on the Audiovisual Emotional Challenge (AVEC) 2013 and 2014 benchmark datasets, achieving a mean absolute error (MAE) of 6.21 and a root mean square error (RMSE) of 8.39. Wu et al. [51] recorded EEG responses to uplifting images and applied the conformal kernel SVM (CK-SVM) for participant-independent classification of MDD, achieving an accuracy of 83.64%, sensitivity of 87.50%, and specificity of 80.65%. Islam et al. [52] analyzed Facebook data using ML techniques, including DTs, SVMs, ensembles, and kNNs, with DT achieving the highest accuracy of 99%. In 2019, Li et al. [53] employed EEG data from a 128-channel HydroCel Geodesic sensor net for diagnosing depression, attaining an accuracy of 89.02% using an ensemble learning model and power spectral density features. Tadesse et al. [54] used ML and natural language processing (NLP) techniques, achieving optimal depression detection with an accuracy of 91% and an F1-score of 0.93 through a combination of features and multilayer perceptron (MLP) classifier. Ay et al. [55] introduced a hybrid model that combined LSTM and CNN architectures for detecting sadness in EEG signals, achieving notable accuracies of 99.12% for the right hemisphere and 97.66% for the left hemisphere. In 2020, Cai et al. [56] analyzed EEG signals from 86 depressed patients and 92 HCs using linear and nonlinear features along with GA for feature weighting, resulting in kNN achieving 86.98% accuracy. Wang et al. [57] proposed the use of Kinect, a cost-effective depth sensor, for nonintrusive, real-time detection of depression, reaching a classification accuracy of 93.75% across 95 subjects (43 depressed and 52 nondepressed). Wu et al. [58] introduced a DL approach for depression detection with heterogeneous data sources, using RNNs for 1453 active Facebook users, which achieved an F1-score of 76.9%, precision of 83.3%, and recall of 71.4%. Smith et al. [59] conducted semi-structured interviews, incorporating the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) with 46 older individuals, where SVM was used to analyze recorded interviews, correctly predicting high and low depression scores between 86% and 92%. In 2021, He et al. [60] introduced an integrated framework combining deep local global attention with CNNs, applied to the AVEC 2013 and 2014 datasets, achieving an RMSE of 8.39 and an MAE of 6.59 on AVEC 2013 and 8.30 and 6.51 on AVEC 2014. Zhou et al. [61] utilized term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) and multimodal features from tweets analyzed through linear discriminant analysis (LDA), LR, and Gaussian naive Bayes (GNB), with LDA achieving the highest precision (91.2%) and accuracy (90.4%) in depression detection. Seal et al. [62] introduced DeprNet, a CNN designed for EEG data classification in depression, achieving 99.37% accuracy and 0.999 AUC in record-wise splits, while subject-wise splits yielded an accuracy of 91.4% and an AUC of 0.956. Nemesure et al. [63] utilized 59 features from general health surveys to train a model for MDD and GAD among 4184 students, achieving AUCs of 0.73 for GAD patients and 0.67 for MDD patients. DeSouza et al. [64] recommended using NLP to analyze speech patterns in late-life depression, investigating differences from younger adults with depression and older adults with other conditions. Saeedi et al. [65] proposed a DL framework employing EEG data for automatic discrimination between MDD patients and HCs, achieving an accuracy of 99.24% with one-dimensional CNN-LSTM on effective connectivity images. Kong et al. [66] introduced a spatiotemporal graph convolutional network for the automatic diagnosis of MDD and predicting treatment response, demonstrating superior performance compared to other models.

Depression is diagnosed through clinical interviews and standardized questionnaires, with emerging methods leveraging ML to analyze speech patterns, physical activity, and social media usage for signs of depressive symptoms. DL models, including NLP and sentiment analysis, offer new avenues for identifying depression outside of traditional clinical settings, potentially reaching individuals earlier in their illness. Integrating these models with clinical data can increase diagnostic precision and guide the development of customized treatment plans, emphasizing the importance of early intervention, ongoing monitoring, and a holistic approach to care.

In contrast to depression, SZ is characterized by complex neurocognitive symptoms and often requires advanced neuroimaging and signal processing techniques for diagnosis. The next section explores how ML and DL methods have been applied to identify biomarkers and classify SZ cases.

The exploration of machine intelligence in diagnosing SZ has undergone significant advancements through diverse methodologies and data sources in recent years. Researchers have made strides in identifying biomarkers and symptoms of SZ with notable accuracy from wearable technology that captures autonomic behavior to advanced imaging techniques and EEG signal analysis. This summary encapsulates studies from 2018–2021 and highlights the application of ML algorithms such as SVMs, CNNs, and deep belief networks (DBNs) in distinguishing SZ patients from HCs. These studies not only highlight the potential for more accurate and early diagnosis but also demonstrate the evolving landscape of SZ research, where technology and medicine intersect to offer innovative solutions for mental health diagnostics.

In 2018, wearable technology was utilized by Cella et al. [67] for mobile health applications in patients with SZ. A link was established between parasympathetic dysregulation and symptom severity. The mHealth device effectively measured autonomic behavior and activity. In the same year, Chakraborty et al. [68] conducted interviews with 78 participants, achieving subjective rating predictions with an accuracy ranging from 61% to 85% based on openSMILE acoustic signals. The groups were distinguishable with an accuracy of 79% to 86% using supervised learning techniques. Mikolas et al. [69] employed brain fractional anisotropy data from 77 first-episode SZ patients and 77 age-matched controls, achieving a significant accuracy of 62.34% with a linear SVM in differentiating patients from controls. In 2019, Jahmunah et al. [70] introduced an automated diagnostic tool for evaluating EEG signals from both healthy and SZ subjects. The SVM with radial basis function (SVM-RBF) demonstrated superior performance, attaining an average value of 92.91%. Zhu et al. [71] investigated 960 individuals, finding a correlation between prenatal famine exposure and SZ, with a significant association of the rs2283291 genotype in males. Devia et al. [72] monitored EEG activity in SZ patients viewing nature scenes, achieving an overall accuracy of 71%, with 81% sensitivity for patients and 59% specificity for controls. Oh et al. [73] applied an eleven-layered CNN to analyze EEG signals from 14 healthy volunteers and 14 SZ patients, obtaining accuracies of 98.07% for non-subject-based testing and 81.26% for subject-based testing. Latha and Kavitha [74] analyzed SZ subjects using DBNs based on ventricular regions, achieving a high classification accuracy of 90% with segmented ventricles. The segmented ventricle images exhibited utility, achieving a high AUC (0.899). In 2020, Krishnan et al. [75] applied multivariate empirical mode decomposition to EEG data to evaluate entropy parameters, revealing significant differences between HCs and SZ patients using SVM-RBF, with a 93% F1-score and 0.9831 AUC. Siuly et al. [76] proposed an EEG-based system for SZ identification, achieving a 93.21% correct classification rate using empirical mode decomposition and ensemble bagged trees. Lei et al. [77] achieved 81% accuracy in SZ classification through ML on functional connectivity data from 295 patients and 452 healthy individuals, outperforming other methods. In 2020, Shalbaf et al. [78] attained a 98.6% accuracy in SZ diagnosis using a deep CNN with transfer learning on EEG data, surpassing other models. In 2021, Baygin et al. [79] introduced an innovative automated model for SZ detection through EEG signals, achieving high classification accuracies of 99.47% and 93.58% on two SZ databases. In 2021, Shi et al. [80] implemented multimodal imaging and multilevel characterization with a multiclassifier technique, reaching a classification accuracy of 83.49% for SZ patients and HCs using fMRI and static MRI data without global signal regression. Kadry et al. [81] proposed an automated SZ detection method using T1-weighted brain MRI scans, employing a pretrained visual geometry group (VGG16) and a slime mold algorithm for feature optimization, achieving an accuracy of 94.33% with SVM-C. Khare et al. [82] combined time-frequency analysis and a CNN for SZ detection, reaching an accuracy of 93.36% through the use of spectrograms and CNNs. Sharma et al. [83] introduced a computer-aided diagnosis method using single-channel EEG data for accurate SZ diagnosis, achieving maximum accuracies of 99.21% and 97.2% using wavelet-based features and SVM and kNN, respectively. Karthik et al. [84] identified seven biomarkers from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database for SZ and BD, with their proposed system achieving accuracies of 97.01% and 95.65% on the respective datasets, surpassing benchmark performance.

SZ detection relies primarily on psychiatric evaluations and the identification of characteristic symptoms, such as delusions and hallucinations. ML models have been applied to EEG and fMRI data to detect abnormalities in brain activity and structure associated with SZ. DL techniques, such as autoencoders and RNNs, have shown promise in identifying patterns indicative of the disorder, potentially leading to earlier diagnosis. Success in treatment hinges on early detection, integrated care approaches, and the personalized adjustment of therapeutic strategies, where AI can play a significant role in predicting treatment outcomes.

Moving from SZ, which typically emerges in early adulthood, the analysis now focuses on ASD, a condition with developmental origins. This section highlights how early screening and behavioral modeling through ML contribute to ASD diagnosis across different age groups.

4.1.4 Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

The application of machine intelligence in the diagnosis and understanding of ASD has advanced significantly in recent years, utilizing a diverse range of data types and analytical methods. EEG signal analysis, MRI imaging, and social media data have been employed by researchers to create models with high accuracy for detecting ASD across different age groups. These studies emphasize the potential of ML algorithms, including SVM, kNN, deep neural network (DNNs), and reinforcement learning, to provide personalized support and early intervention strategies, from early diagnosis in toddlers to screening in adults. This summary presents key contributions from 2018 to 2021, illustrating the varied approaches used to improve ASD diagnosis and understanding, including wearable technology for feature extraction and the development of cognitive computing-based learning models and optimization algorithms for screening. The evolving role of technology in advancing ASD care and research is highlighted.

In 2018, Ibrahim et al. [85] examined EEG feature extraction and classification for epilepsy and ASD. Utilizing various datasets, their methodology attained an accuracy of up to 94.6% through the discrete wavelet transform, Shannon entropy, and kNN algorithms. A cognitive computing-based learning model aimed at enhancing personalized education for ASD patients was proposed by Vijayan et al. [86]. This model employed reinforcement learning and a NN to identify and support autistic students through interactive chatbots and visual aids. Li et al. [87] applied multichannel CNNs along with a patch-level data-expanding technique to detect infants at risk for ASD, achieving an accuracy of 0.7624 on the National Database for Autism Research (NDAR) dataset. Further validation in at-risk infant populations was recommended. In 2019, Kong et al. [88] constructed an individual brain network for feature representation and implemented a deep NN for classification between ASD and typical controls (TC). Their method, using 3000 top features from T1-weighted MRI scans in the autism brain imaging data exchange (ABIDE I), achieved an accuracy of 90.39% and an AUC of 0.9738. In 2019, Akter et al. [89] utilized a Kaggle dataset containing 2009 records to suggest an early diagnosis model for ASD. By employing methods such as AdaBoost, flexible discriminant analysis, C5.0, and SVM, accuracies of 98.77%, 97.20%, 93.89%, and 98.36% were recorded for toddler, child, adolescent, and adult datasets, respectively. An ML model was introduced by Thabtah et al. [90] for screening ASD in adults and adolescents. Through LoR, the model reached accuracies of 99.91% for adults and 97.58% for adolescents. In 2019, Kou et al. [91] investigated 77 children and identified a lower visual preference for dynamic social stimuli as a potential biomarker for ASD in Chinese children. In 2020, Goel et al. [92] presented the modified grasshopper optimization algorithm (MGOA) for ASD screening across all life stages. Testing on datasets from children, adolescents, and adults, the approach utilizing the RF classifier achieved near-perfect accuracy, specificity, and sensitivity for ASD prediction at all developmental stages. In 2020, Yaneva et al. [93] assessed 31 participants with ASD and 40 HC, achieving an accuracy of 74% through LoR classifiers using gaze and non-gaze features. Caution was advised against web-search tasks for very young children due to the limited sample size. In 2020, Tang et al. [94] created a deep multimodal model utilizing two types of connectomic data derived from fMRI scans. Using the ABIDE dataset with 1035 subjects, their method achieved notable results, including a classification accuracy of 74%, a recall of 95%, and an F1-score of 0.805, surpassing unimodal approaches. In 2020, Brueggeman et al. [95] introduced force ASD, an ensemble classifier that integrates brain gene expression and network data. The reliability of prior predictors for estimating gene contributions to ASD etiology was demonstrated. In 2020, Wedyan et al. [96] analyzed thirty children, employing an SVM with features extracted using LDA. Among them, fifteen children were diagnosed with ASD, resulting in a sorting accuracy of 100% and an average accuracy of 93.8%. In 2020, Cantin-Garside et al. [97] implemented SVMs, kNN, and additional algorithms for ASD diagnosis, achieving 99.1% accuracy for individuals and 94.6% accuracy for groups, indicating excellent classification efficiency. In 2021, Negin et al. [98] proposed a nonintrusive vision-assisted technique utilizing YouTube videos for detecting ASD-related behaviors. The best accuracy (79%) was attained through the identification of the histogram of the optical flow descriptor. In 2021, Papakostas et al. [99] adopted an ML-based multimodal approach to evaluate children’s engagement. By employing various ML techniques and ensemble models, AdaBoost and DT reached an accuracy of 93.33% in assessing children’s engagement. In 2021, Akter et al. [100] utilized the Kaggle and University of California Irvine datasets for ASD across age groups. Their multimodel approach incorporated various ML algorithms, with LoR outperforming others. Accuracies of 100%, 99.32%, 94.33%, and 99.74% are achieved for toddlers, kids, teens, and adults, respectively. In 2021, Vakadkar et al. [101] used a toddler dataset from Kaggle, which achieved high accuracies with classifiers: LR (97.15%), NB (94.79%), SVM (93.84%), kNN (90.52%), and RFClassifier (81.52%). Large datasets enhance accuracy.

ASD detection methodologies typically incorporate behavioral assessments and developmental screenings during early childhood. Recent advancements have seen the application of ML algorithms to analyze genetic data, facial expressions, and speech patterns for identifying early signs of ASD. DL models, such as CNNs, have been utilized on neuroimaging data to reveal structural and functional differences in the brains of individuals with autism. These technological methods complement conventional diagnostic approaches, providing the potential for earlier and more accurate diagnoses, which are essential for implementing effective intervention strategies.

While ASD research emphasizes early developmental screening, BD studies often focus on mood fluctuation tracking and episodic pattern recognition. The subsequent section examines how data from neuroimaging, digital phenotyping, and EEG are used to distinguish BD from related mood disorders.

In recent years, substantial advancements have been achieved in the application of ML and data science techniques to enhance the diagnosis and understanding of BD. A variety of methodologies have been investigated, including MRI analysis, EEG data classification, digital phenotyping, and the utilization of NLP in healthcare records. These studies have contributed not only to the identification of biomarkers and the exploration of the neural and genetic foundations of BD but also to innovative methods for monitoring and predicting mood states in individuals with BD. This summary outlines key research efforts from 2018 to 2021, emphasizing how the integration of diverse data sources and advanced analytical techniques has improved the accuracy of BD diagnosis, provided insights into the pathophysiology of BD, and opened new pathways for personalized treatment strategies.

In 2018, Altamura et al. [102] employed 3 Tesla MRI to examine 171 subjects (114 BD and 57 HC). Psychotic BD patients demonstrated gray matter volume deficits in the left frontal and right temporoparietal cortices. The integration of multiple datasets may have affected the results. Alimardani et al. [103] induced steady-state visual evoked potentials in both schizophrenic and BD patients using a 16 Hz visual stimulus. EEG data were classified using various algorithms, with kNN achieving the highest accuracy of 91.30%. Satisfactory accuracies above 70% were maintained with reduced analysis times. Perez et al. [104] utilized a custom smartphone application involving 130 BD individuals and applied signature-based learning, which correctly categorized 75% of participants into the appropriate diagnostic groups and predicted over 70% of future mood evaluations, with an accuracy of 89%–98% among healthy participants. Manzan et al. [105] suggested using MLP networks with orthogonal bipolar vectors for pattern recognition, showing enhanced performance compared to traditional methods across the Iris, Semeion digit, and Australian sign language datasets. Johnson et al. [106] analyzed 29 HCs and 40 bipolar I patients, some of whom were rescanned during different mood states, employing the Montgomery-Asberg depression rating scale, the Young Mania rating scale (YMRS), and 3 Tesla MRI. A key limitation noted was the small sample size. In 2019, Farshad [107] applied the K-means data description method for internal fault detection on a 1000 km bipolar high-voltage direct current line, successfully identifying 4320 internal and 2816 external faults using local measurements. Abaeikoupaei and Al Osman [108] introduced an automatic ternary classification model for BD based on audio features, achieving an unweighted average recall of 59.3% with the stacked ensemble classifier on the test set. Chandran et al. [109] employed NLP to extract information about obsessive and compulsive symptoms from mental healthcare records, attaining precision and recall values of 0.77 and 0.67, respectively. Maes et al. [110] investigated biomarkers related to oxidative and nitrosative stress in individuals with MDD and BDs I and II, seeking to differentiate among these disorders. In 2020, Stanislaus et al. [111] studied 203 newly diagnosed BD patients, 54 unaffected relatives, and 109 HCs, finding significantly higher mood instability ratings in patients compared to HCs. The study noted a lower-than-expected number of unaffected relatives. Lee et al. [112] utilized data science techniques to identify significant single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with the classification of BDs I and II. A classifier using 42 single nucleotide polymorphisms achieved an AUC of 0.9574, resulting in a 3.46% increase in accuracy. Li et al. [113] combined voxel-based morphometry and regional homogeneity analyses with the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) for feature selection, achieving 87.5% accuracy with their SVM model in identifying BD patients. In 2021, Li et al. [114] developed a DL framework utilizing a CNN for the automatic diagnosis of first-episode psychosis (FEP), BD, and HCs based on structural MRI data. The CNN reached high accuracy (99.72%), precision (99.76%), recall (99.74%), and F1-score (99.75%) in distinguishing between FEP patients, BD patients, and HCs. Su et al. [115] utilized LASSO regression and ElasticNet regression to predict Hamilton depression rating scale (HAM-D) and YMRS scores for BD patients based on digital phenotyping data from 84 individuals, achieving prediction errors of 2.73 and 1.06 points for HAM-D and YMRS, respectively. Llamocca et al. [116] employed ML, including RF, DTs, LoR, and SVM, to classify states of BD using various data sources, with RF yielding the highest accuracy.

For BD, detection methods include clinical assessments, self-report questionnaires, and, increasingly, physiological data analysis through wearable technology. ML techniques, including SVMs and NNs, are employed to analyze patterns in mood fluctuations and sleep, offering potential for early detection and differentiation from other mood disorders. The integration of these classifiers with traditional diagnostic tools enhances accuracy and aids in developing personalized treatment strategies, focusing on medication management, psychotherapy, and lifestyle adjustments.

Unlike BD, which involves episodic mood variations, AD is a progressive neurodegenerative condition. The following discussion centers on the use of neuroimaging, biomarker analysis, and smart home data for early AD detection and monitoring.

In recent years, a wide range of ML and DL techniques have been applied to improve the diagnosis and understanding of AD. Studies have utilized various data types, including MRI and fMRI scans, smart home data, and even human plasma, to develop models capable of identifying AD and its stages with remarkable accuracy. From the use of DNN and RF for feature selection to the implementation of novel biomarkers and biosensors, researchers have made significant strides in enhancing AD diagnostics. This summary highlights key research from 2018–2021, highlighting the diversity of approaches and advancements in AD detection. These efforts not only demonstrate the potential for early and accurate diagnosis but also contribute to the development of personalized treatment strategies, indicating the critical role of technology in addressing this complex disease.

In 2018, a DNN and RF feature selection classification model was introduced by Amoroso et al. [117] for 240 subjects across four categories: AD, HC, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and cMCI. DNN results included recall values of (87.5%, 74.5%, 52.5%, 52.5%) and precision values of (27.5%, 34.3%, 52.5%, 51.2%). The fuzzy and RF models achieved notable recall values of (82.5%, 78.6%, 50%, and 55.9%, respectively) and precision values of (20%, 22.9%, 57.5%, and 47.9%, respectively). In the same year, regression models utilizing SmoteBOOST and a wrapper-based rapidly converging Gibb were developed by Alberdi et al. [118] for symptom prediction, focusing on smart home data of older adults from 2011 to 2016. A clinical assessment was introduced using an activity behavior algorithm to evaluate global cognition and mobility. Among the assessed models, RF exhibited the highest sensitivity (0.92) and F1-score (0.77), while MLP had the lowest values (0.71 sensitivity, 0.69 F1-score). Abd-Elminaam [119] proposed a child safety model in 2018 that employed smartphones equipped with near-field communication, quick response code readers, and optical character recognition features to prevent situations involving missing children, connecting to a cloud-based platform for Internet of Things data storage. An AD diagnosis model was proposed by Islam and Zhang [120] using a deep CNN with brain MRI data, identifying various disease stages, with ensemble networks achieving accuracies of 78% and 77%. In 2019, a DL model for AD and c-MCI diagnosis was developed by Basaia et al. [121] using CNNs on 3D T1-weighted MRI scans from Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative (ADNI) and institutional datasets, achieving 99% accuracy. A DL framework combining Three Dimensional (3D)-CNN and fully stacked bidirectional LSTM for enhanced AD diagnosis was developed by Feng et al. [122]. The average accuracies of baseline MRI and 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography data from the ADNI dataset were 94.82%, 86.36%, and 65.35%, respectively. In 2019, a nanoplasmonic biosensor utilizing gold nanorods and a chaotropic agent for ultrasensitive AD biomarker detection in human plasma was introduced by Kim et al. [123], which minimized overlapping protein levels to enhance diagnostic accuracy. Acharya et al. [124] proposed a computer-aided brain-diagnosis system for AD detection using MRI and shearlet transform in 2019, achieving accuracy rates of 94.54%, precision of 88.33%, and sensitivity of 96.30%. With a benchmark MRI database, it attained an accuracy of 98.48% and 100% precision. Li et al. [125] introduced a 4-dimensional DL model for AD detection in 2020, achieving accuracy exceeding 92% based on fMRI data. An unsupervised DL method for AD diagnosis utilizing CNN and MRI data was proposed by Bi et al. [126], with the leading model reaching an accuracy of up to 97.01%. A novel biomarker, three-dimensional tortuosity, was introduced by Barbará-Morales et al. [127], with an RF classifier achieving 86.66% accuracy. Al-Shoukry et al. [128] reviewed AD disease through MRI data and ML techniques, emphasizing biomarkers and neuroimaging studies. Ramzan et al. [129] investigated resting-state fMRI for classifying AD stages, achieving high accuracies with a fine-tuned ResNet 18 model. In 2021, Liu et al. [130] utilized open access series of imaging studies (OASIS) structural image data, applying depthwise separable convolution, with classification accuracies ranging from 78.02% to 93.02%. DEMentia NETwork (DEMNET) was presented by Murugan et al. [131] on ADNI data, achieving an overall accuracy of 95.23% and recommending testing on diverse datasets. A CNN and transfer learning approach was employed by Helaly et al. [132] for ADNI dataset classification, achieving accuracy rates of up to 97% using the enhanced VGG19 model.

ASD detection methodologies frequently incorporate behavioral assessments and developmental screenings during early childhood. Recent advancements involve the application of ML algorithms to analyze genetic data, facial expressions, and speech patterns for the identification of early signs of ASD. DL models, particularly CNNs, have been utilized on neuroimaging data to reveal structural and functional differences in the brains of individuals with autism. These technological approaches enhance traditional diagnostic methods, providing the potential for earlier and more accurate diagnoses, which is essential for the initiation of effective intervention strategies.

Although the reviewed techniques have shown substantial promise across multiple disorders, it is essential to examine the methodological limitations and potential biases that may affect their generalizability, interpretability, and clinical integration.

4.1.7 Limitations and Biases of the Chosen Methods

Despite their demonstrated effectiveness, the machine intelligence techniques reviewed—such as SVM, CNN, RF, and LSTM—have certain limitations and biases that may affect generalizability and interpretability in mental health diagnostics. A common concern is the data dependency and overfitting risk inherent in DL models, especially when trained on small or imbalanced datasets. CNNs and LSTMs, while powerful, often require extensive labeled data and may not generalize well across different populations or clinical settings without retraining.

SVM are effective in handling high-dimensional data but are sensitive to kernel choice and parameter tuning. They may also lack interpretability, making them less suitable for clinical decision-making in settings where explainability is critical. Similarly, RF, though robust and interpretable to a degree, can become computationally expensive and are prone to bias when trained on skewed datasets.

Moreover, algorithmic bias can arise when models reflect or amplify patterns in the training data, leading to disparities across demographic groups. This is particularly problematic in mental health, where symptoms manifest heterogeneously across age, gender, and cultural backgrounds. For example, if models are predominantly trained on data from one region or population, they may underperform in other contexts, leading to reduced diagnostic accuracy or missed cases.

Class imbalance, especially between healthy and affected cases, is another pervasive issue that skews model performance metrics. Models may achieve high overall accuracy while failing to detect minority classes such as rare or early-stage disorders. Additionally, lack of transparency in how some DL models derive their outputs makes it difficult to validate or interpret findings in a clinical setting.

Finally, many methods do not account for temporal dynamics of mental health states. Static models may overlook important longitudinal variations or transitions in patient conditions. Incorporating time-series models or hybrid frameworks may offer a path forward but also introduces added complexity and data requirements.

Addressing these limitations is essential for the ethical and effective deployment of machine intelligence in mental health care. Future efforts should prioritize model interpretability, bias mitigation, data diversity, and clinical validation.

With the methodological insights and challenges outlined, the next section provides a comparative evaluation of the strengths and weaknesses of the reviewed ML and DL techniques across anxiety, depression, and stress domains. This sets the stage for synthesizing best practices and identifying gaps for further exploration.

4.2 RQ2: What Are the Strengths and Weaknesses of These Specific Methodologies?

This section presents a comprehensive overview of recent studies that utilize ML and DL techniques for the detection and analysis of mental disorders, specifically focusing on anxiety, depression, and stress. Various methods, including SVM, LoR, DL, and other advanced algorithms, are encapsulated, showing their results, the datasets employed, and the targeted disease categories. Table 2 highlights the advantages and limitations of the respective studies, offering valuable insights into the current state of mental health diagnostics.

Table 2 provides an insightful overview of the progress made in applying ML and DL to diagnose mental health conditions, specifically anxiety, stress, and depression, throughout 2022–2023. This period has seen a diverse array of methodological approaches, ranging from traditional statistical models to advanced NN, applied to various data types and mental health issues. Despite notable achievements and advancements, challenges such as the necessity for larger sample sizes [133–136], the imperative to address bias [137–140], and the integration of these findings into clinical practice remain significant hurdles [141–143]. This not only underscores the immense potential that AI holds for enhancing mental health diagnostics but also emphasizes the ongoing need for further research to adapt these technological advancements for practical, real-world applications.

Several key benefits associated with these technological approaches in mental health diagnostics have been highlighted. High accuracy and precision in identifying conditions such as anxiety, stress, and depression are paramount for early detection and intervention. The application of diverse datasets, ranging from questionnaires and physiological signals to social media interactions, demonstrates the adaptability and versatility of ML models to various data inputs. These methodologies enable a deeper understanding of the intricate patterns and factors related to mental disorders, paving the way for more personalized and effective treatment plans. Furthermore, the integration of sophisticated computational models such as DL facilitates the processing of complex data structures, revealing subtle diagnostic nuances. The exploration of new biomarkers and the development of real-time monitoring systems underscore the innovative potential in preventative mental health care.

Among the algorithms that have demonstrated significant performance, SVM, DT, kNN, RF, and DL models, including CNNs and LSTM networks, have been particularly noteworthy. SVMs excel in classifying mental health conditions due to their effectiveness in managing high-dimensional data with limited training samples. DTs simplify the decision-making process, facilitating the clear identification of mental health indicators. The straightforward implementation and effectiveness of kNN in classification tasks, the improvement in prediction accuracy and mitigation of overfitting offered by RF, and the ability of DL models to extract complex patterns from extensive datasets all contribute to the depth, accuracy, and efficiency of mental health diagnostics.

The combined use of these algorithms presents a promising opportunity for the early identification and customized treatment of mental health disorders. Their application in various data analysis contexts—ranging from physiological monitoring to the analysis of textual and speech information—demonstrates the holistic approach to mental health diagnostics and the significant potential of ML in overcoming its fundamental challenges.

Table 3 illustrates how advanced computational techniques have facilitated a deeper comprehension of complex mental health disorders. For instance, the utilization of LDA to examine thousands of abstracts yields enhanced insights into the pathogenesis of AD, while the implementation of multiple classifiers, including kNN, achieves nearly perfect accuracy in diagnosing AD. This highlights the efficacy of integrating various algorithms to enhance diagnostic precision. The investigation of these computational models across different diseases underscores the versatility and adaptability of ML and DL techniques. For AD, innovative methodologies such as 3D-CNN models and SVMs in conjunction with extreme learning machine (ELM) demonstrate exhibit high effectiveness in identifying disease markers. In the context of ASD, multimodal and fusion techniques, including the integration of a CNN architecture with GA, highlight the effectiveness of combined models in improving diagnostic accuracy. For BD, the application of ensemble models and regression analyses presents new opportunities for identifying treatment targets and understanding disease biomarkers. Research on SZ benefits from the use of DL and ensemble methods, showing the potential for superior classification performance and the investigation of sensory changes and social skill impacts. Despite these promising developments, this study also identifies limitations in current research, such as small sample sizes, potential biases, and challenges in integrating findings into clinical practice. The need for larger, more diverse datasets and the validation of models across varied populations are recurring themes. This underscores the rapid advancements in machine intelligence applications for mental health diagnostics, providing insight into the future of personalized medicine and the ongoing challenge of translating these technological innovations into practical tools for clinicians and patients. This collective effort opens new pathways for early detection, enhanced understanding, and more effective treatment of mental health conditions.

4.3 RQ3: Is the Machine Intelligence Approach Effective in Identifying Mental Health Issues?

The recognition of machine intelligence’s effectiveness in identifying mental health issues has been growing, driven by advancements in algorithms, computational power, and the abundant availability of data. The development and utilization of machine intelligence models in mental health introduce several challenges, including data privacy issues, the requirement for large and diverse datasets to train algorithms effectively, and the integration of these technologies into clinical practice. Nonetheless, technological interventions have demonstrated encouraging results in mental health treatment, presenting new possibilities for diagnosis, monitoring, and therapy.

Machine intelligence has fundamentally changed how mental health conditions are identified, diagnosed, and treated. AI-driven tools and applications can analyze speech patterns, facial expressions, and social media activity to uncover early signs of issues such as depression, anxiety, and stress. These technologies enable the prompt identification of conditions that may not be noticeable to clinicians or patients, thereby facilitating timely intervention [57,61,84,132,133]. Wearable devices and mobile applications powered by AI algorithms are crucial for real-time mental health monitoring. They track physiological indicators [91,97,103], including heart rate variability [115,117], sleep patterns [127,143], and activity levels, providing insights into an individual’s mental state [152]. This continuous tracking allows for the recognition of patterns and triggers associated with mental health conditions, leading to tailored treatment strategies. Additionally, when social media data are analyzed using machine intelligence, it can offer valuable insights into an individual’s mental health. Techniques such as NLP and sentiment analysis can reveal mood changes and signs of depression or anxiety based on users’ posts and interactions [54,64,109]. However, this also brings up important concerns regarding privacy and the ethical use of data.

Fig. 7 illustrates the percentage distribution of methodological usage across various machine intelligence approaches applied in mental health diagnostics. It provides a clear proportional representation of each method’s contribution to the field, highlighting CNN and RF as some of the most frequently employed techniques. The figure also demonstrates the applicability of different methods across key aspects of mental health, including diagnosis, treatment planning, and monitoring. Each method, including SVM, DT, kNN, RF, CNN, LSTM, and LoR, is evaluated for its effectiveness in these areas, as indicated by their utility scores. Notably, CNN and LSTM networks demonstrate high utility across all three domains, underscoring their broad applicability and effectiveness in mental health diagnostics and care. This highlights the diverse capabilities of machine intelligence approaches in improving mental health services, from accurate diagnosis of conditions to the formulation of treatment plans and ongoing patient monitoring. Fig. 8 provides an analysis of methodological performance in cases of anxiety/stress and depression.

Figure 7: Methodological usage percentages and utility of machine intelligence approaches in mental health domains

Figure 8: Analysis of methodological performance in cases of anxiety/stress and depression

Fig. 9 shows the top 10 methods used across various disease categories, including AD, ASD, BD, and SZ. Each method is assessed on the basis of its accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score percentage, highlighting its effectiveness in diagnosing or studying these conditions. This clearly indicates the significant role of these computational techniques in enhancing diagnostic accuracy and efficiency, reflecting their potential to contribute to advanced and personalized mental health care solutions.

Figure 9: Analysis of methodological performance in patients with AD, ASD, BD, and SZ

The most effective machine intelligence algorithms for diagnosing mental health disorders have shown clear trends across conditions. For anxiety and stress, SVM, RF, and kNN excel on physiological and questionnaire-based data, while CNNs and LSTM networks lead in multimodal analysis combining EEG, behavioral, and usage data. For depression, CNNs, spatiotemporal deep models, and attention-based architectures are highly effective on EEG, facial video, and neuroimaging data, whereas transformers, hierarchical attention networks, and RF deliver strong results on text, speech, and social media datasets. SZ diagnosis benefits most from CNNs, DBNs, and hybrid EEG–MRI approaches. For ASD, CNNs, SVMs, and multimodal deep learning models on MRI, EEG, and behavioral data achieve good results with reinforcement learning and optimization algorithms improving early screening. BD detection leverages RF, SVM, and ensemble methods on EEG, MRI, and digital phenotyping data, while CNN-based models differentiate BD from related mood disorders with high precision. AD shows best results from CNNs, hybrid algorithms including LSTM, and ResNet-based transfer learning on MRI/fMRI, often paired with RF or ELM for feature selection. Overall, ensemble and hybrid pipelines that combine DL for complex signals with interpretable ML for structured data consistently outperform single-model approaches, offering superior accuracy and robustness.

4.4 Experimental Setup and Implementation Details

The reviewed studies employed a range of data preprocessing techniques depending on the data modality. Common steps included missing value imputation, outlier detection, data normalization, and feature scaling. Missing values were typically addressed using mean or median imputation for numerical features and mode imputation for categorical variables. In time-series and physiological datasets, outliers were identified using z-score thresholds or interquartile ranges and either excluded or capped. For neural signal data, preprocessing steps often included band-pass filtering, artifact rejection, and baseline correction. Imaging data were preprocessed using standardized pipelines such as skull stripping, intensity normalization, and spatial alignment. For textual data from social media, tokenization, stopword removal, and stemming/lemmatization were commonly applied.

4.4.2 Hyperparameter and Model Tuning

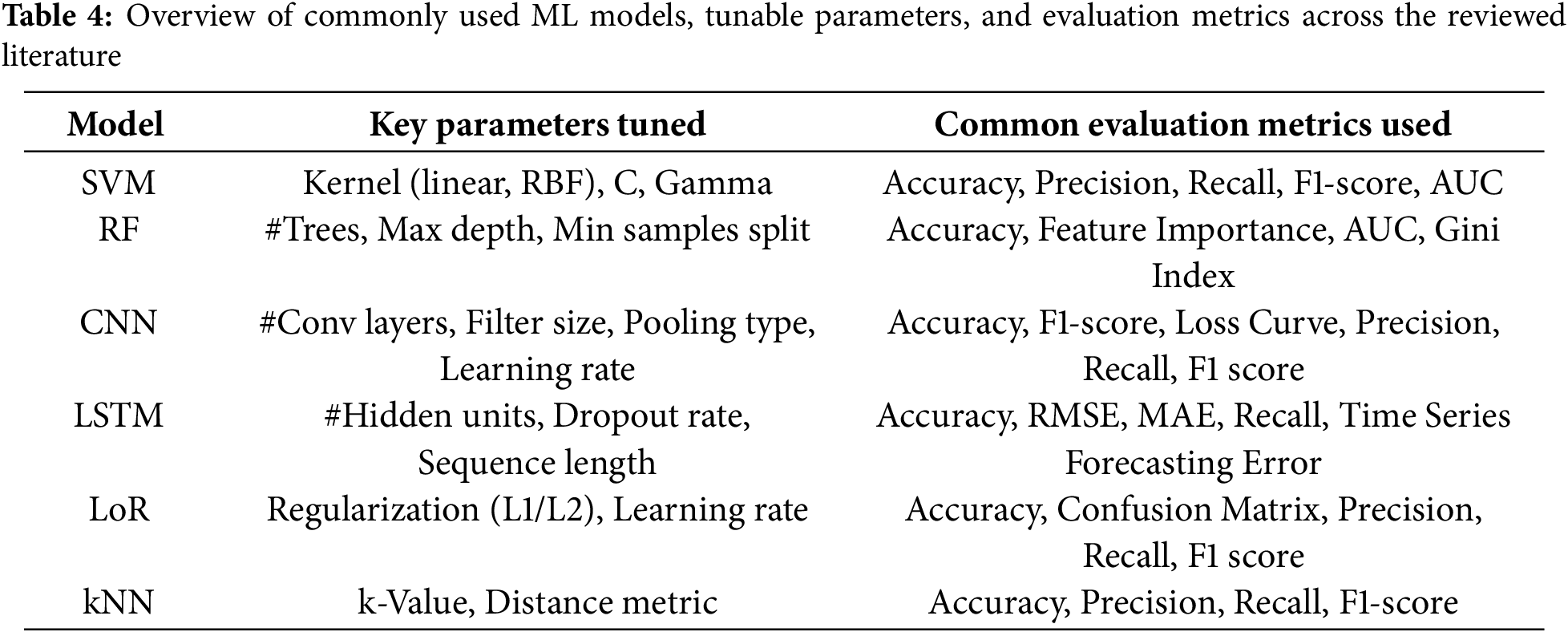

Parameter tuning was a key component in optimizing model performance across studies. For SVM, tuning involved selecting kernel functions and adjusting regularization and gamma values. RFs were optimized by adjusting the number of estimators, tree depth, and minimum samples per split. For CNN and LSTM models, hyperparameters such as the number of layers, filter size, learning rate, dropout rate, batch size, and optimizer were iteratively tuned using grid search, random search, or Bayesian optimization. Many studies reported employing early stopping and learning rate scheduling to prevent overfitting and improve generalization. Table 4 provides a consolidated list of the most common models reviewed, their tuned hyperparameters, and the evaluation metrics used across the reviewed literature. Since this review consolidated results from various published works, computational environments varied.

Validation strategies were critical in ensuring model reliability. Most studies employed k-fold cross-validation, with 5-fold and 10-fold setups being the most common. For DL models, hold-out validation and stratified splits were also used to preserve class distribution. Some studies also reported leave-one-subject-out cross-validation, especially in clinical or EEG datasets, to evaluate model robustness on unseen participants.

RQ4: What is the Current State of Dataset Availability in this Domain?

In this section, a variety of datasets pertaining to different mental illnesses is examined. These datasets were organized by type of disorder, including depression, SZ, AD, BD, ASD, and anxiety/stress-related issues (Table 5). They incorporate multiple data collection methods, such as clinical assessments, EEG recordings, video and audio analyses, as well as behavioral patterns observed on social media. The analysis of these datasets aimed to reveal the underlying patterns and indicators of disorders. This strategy sought to enhance the creation of more precise diagnostic tools and tailored treatment plans, utilizing advancements in machine intelligence to tackle the complexities associated with mental health conditions.

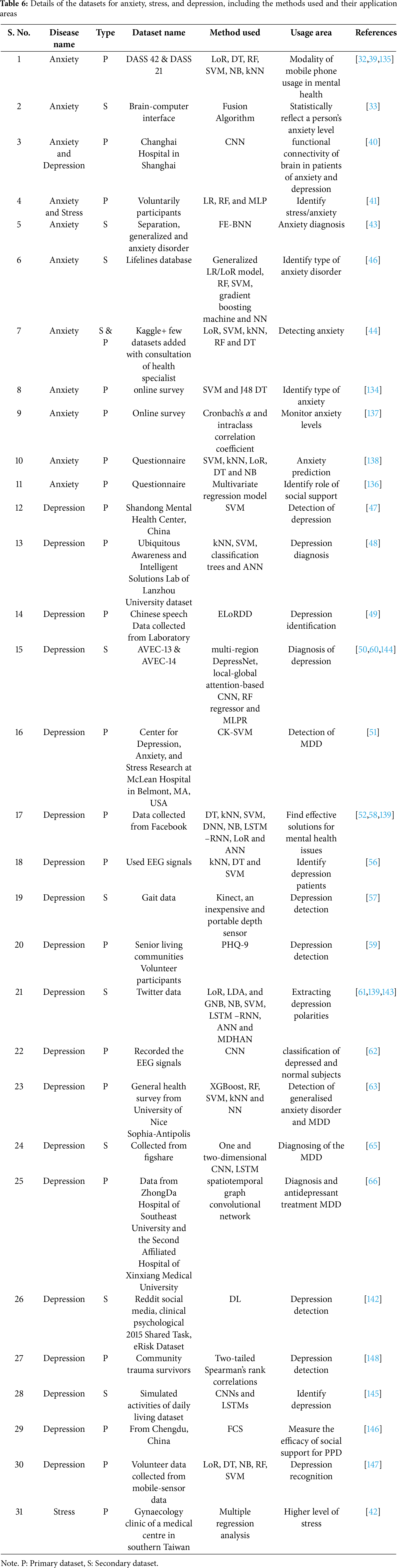

Table 6 presents a detailed overview of datasets concerning anxiety, stress, and depression, organized by type of disorder. It encompasses both primary and secondary datasets employed in various research efforts to comprehend and diagnose these mental health conditions. The methodologies applied include LoR, DT, RF, SVM, and CNN, showing the diverse analytical approaches utilized. Application areas range from mobile phone usage in mental health to the functional connectivity of the brain in individuals with anxiety and depression, as well as the detection of depression through gait data and social media behavior analysis. This highlights the interdisciplinary nature of contemporary mental health research, where datasets are derived not only from clinical and EEG recordings but also from digital footprints on social media and mobile sensor data, reflecting the evolving landscape of mental health diagnosis and monitoring. Table 7 enumerates the datasets for ASD, BD, SZ, and AD, demonstrating a variety of methods employed in their analysis and respective application areas. These datasets, gathered through both primary and secondary means, have been crucial in enhancing the understanding and diagnosis of these complex mental health conditions. Techniques such as DNN, RF, CNN, and LoR have been utilized for the analysis of these datasets. The application areas include predicting MCI and its progression to ADs, early diagnosis of ASD in infants, classifying BD based on psychosis, and assessing the severity of SZ symptoms. This illustrates the collaborative effort in mental health research, employing advanced computational methods to extract insights from varied data sources, ultimately aiming to enhance diagnostic accuracy and patient care.

Fig. 10 represents the relationships among mental disorders, the methods applied, and their usage counts, with each method. The methods include LoR, CNN, SVM, RF, kNN, and DT, which show their application across various disorders, such as anxiety, depression, AD, ASD, BD, and SZ.

Figure 10: Relationship between mental disorders and the usage count for the method applied