Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

DriftXMiner: A Resilient Process Intelligence Approach for Safe and Transparent Detection of Incremental Concept Drift in Process Mining

1 Department of Computer Science and Business Systems, Bapuji Institute of Engineering and Technology, Davangere-577004, Affiliated to Visvesvaraya Technological University, Belagavi, Karnataka, 590018, India

2 Department of Information Science and Engineering, Nitte Meenakshi Institute of Technology (NMIT), Nitte (Deemed to be University), Banglore-560064, Affiliated to Visvesvaraya Technological University, Belagavi, Karnataka, 590018, India

3 Department of Artificial Intelligence & Machine Learning, Nitte Meenakshi Institute of Technology (NMIT), Nitte (Deemed to be University), Banglore-560064, Affiliated to Visvesvaraya Technological University, Belagavi, Karnataka, 590018, India

* Corresponding Authors: Puneetha B. H.. Email: ; Manoj Kumar M. V.. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Safe and Secure Artificial Intelligence)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-33. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067706

Received 10 May 2025; Accepted 31 July 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Processes supported by process-aware information systems are subject to continuous and often subtle changes due to evolving operational, organizational, or regulatory factors. These changes, referred to as incremental concept drift, gradually alter the behavior or structure of processes, making their detection and localization a challenging task. Traditional process mining techniques frequently assume process stationarity and are limited in their ability to detect such drift, particularly from a control-flow perspective. The objective of this research is to develop an interpretable and robust framework capable of detecting and localizing incremental concept drift in event logs, with a specific emphasis on the structural evolution of control-flow semantics in processes. We propose DriftXMiner, a control-flow-aware hybrid framework that combines statistical, machine learning, and process model analysis techniques. The approach comprises three key components: (1) Cumulative Drift Scanner that tracks directional statistical deviations to detect early drift signals; (2) a Temporal Clustering and Drift-Aware Forest Ensemble (DAFE) to capture distributional and classification-level changes in process behavior; and (3) Petri net-based process model reconstruction, which enables the precise localization of structural drift using transition deviation metrics and replay fitness scores. Experimental validation on the BPI Challenge 2017 event log demonstrates that DriftXMiner effectively identifies and localizes gradual and incremental process drift over time. The framework achieves a detection accuracy of 92.5%, a localization precision of 90.3%, and an F1-score of 0.91, outperforming competitive baselines such as CUSUM + Histograms and ADWIN + Alpha Miner. Visual analyses further confirm that identified drift points align with transitions in control-flow models and behavioral cluster structures. DriftXMiner offers a novel and interpretable solution for incremental concept drift detection and localization in dynamic, process-aware systems. By integrating statistical signal accumulation, temporal behavior profiling, and structural process mining, the framework enables fine-grained drift explanation and supports adaptive process intelligence in evolving environments. Its modular architecture supports extension to streaming data and real-time monitoring contexts.Keywords

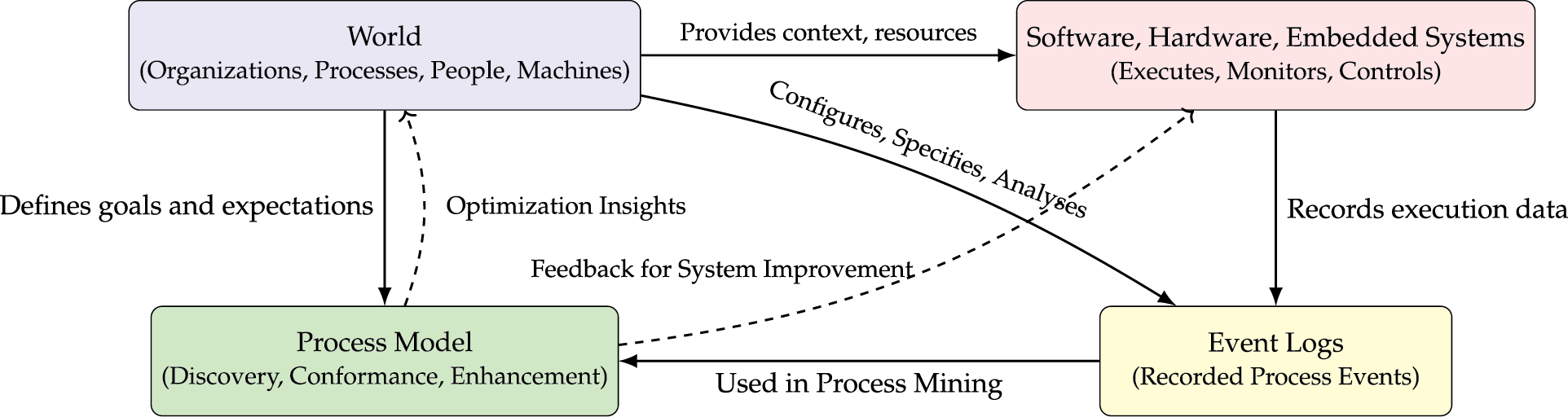

Process mining bridges data science and business process management by leveraging event logs from systems such as ERP, CRM, and other IS platforms to analyze real-world processes [1]. A central goal is to uncover control-flow dependencies, i.e., the sequential and causal order of activities to enhance transparency, compliance, and performance. Key process mining techniques include discovery, which reconstructs control-flow models (e.g., Petri nets); conformance checking, which validates these models against event logs; and enhancement, which improves models using time, resource, and KPI data (see Figs. 1and 2).

Figure 1: Overview of process mining techniques

Figure 2: An overview of the process mining workflow, illustrating the steps from event logs to process analysis and improvement

As organizations operate in increasingly dynamic environments, business processes often undergo unforeseen or evolving changes. In this context, the phenomenon of concept drift originally coined in machine learning to denote shifts in data distributions that degrade model performance has become increasingly relevant to process mining [2]. Drift may emerge from changes in process behavior such as new policies, seasonal demand, human error, or shifting system log granularity. These can be gradual or incremental, intentional or unintentional, and often remain asymptotic, escaping detection under rigid models.

This work introduces a resilient process intelligence framework tailored to safely and transparently detect such asymptotic concept drifts in business processes. Unlike traditional static analysis, the proposed approach localizes evolving control-flow variations through unsupervised detection, temporal profiling, and drift-aware reconstruction, thereby improving adaptability and trustworthiness of decision-making in process management.

Concept drift is generally categorized into four types: sudden, incremental, gradual, and recurring drifts, as illustrated in Fig. 3 taken from [3]. Sudden drift involves an abrupt and major change in process behavior, such as the replacement of a subprocess due to regulatory enforcement. Incremental drift, the focus of this work, refers to a slow and continuous shift in process characteristics: such as gradual changes in employee task execution times or the increasing frequency of rework loops. Gradual drift captures smooth transitions between old and new process behaviors, and recurring drift accounts for cyclic changes, such as those driven by seasonal workflows or campaign-based activities [4].

Figure 3: Types of concept drift: sudden, gradual, incremental, and reoccurring. Post-drift instances are stacked above the prior distribution to illustrate shifts

Traditional concept drift detection methods are typically designed to detect sudden shifts in data and often fail to capture or localize the subtle changes associated with incremental drift. Moreover, in process mining, detecting where in the process the drift occurs referred to as drift localization is equally important as knowing that drift has occurred. Accurate localization provides insight into which parts of the process are evolving and enables targeted process adaptations.

This research addresses the critical challenge of detecting and localizing incremental concept drift in business processes using control-flow perspectives. To achieve this, we propose a hybrid framework that integrates statistical detection techniques, machine learning algorithms [5–8], and process mining strategies to develop an adaptive, scalable solution. Our approach not only detects drift but also pinpoints the affected regions within the process model, enabling proactive and informed process management. While DriftXMiner is evaluated in the context of process mining, its architectural design particularly the Cumulative Drift Scanner and entropy-weighted ensemble is modular and applicable to general purpose drift detection in domains such as fraud detection, cyber-security, and manufacturing. This decoupling potential offers extensibility beyond process semantics, enabling future work to apply and test DriftXMiner in generic data stream settings.

The major contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

1. Development of a hybrid framework that jointly performs detection and localization of incremental concept drift in process mining.

2. Integration of statistical methods, machine learning tools, and control-flow-based process mining techniques to model evolving business behavior.

3. Evaluation of the impact of incremental drift on system performance and business outcomes, supported by extensive experimental analysis.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the state-of-the-art in concept drift detection and localization, particularly within the context of process mining. Section 3 presents the detailed methodology of the proposed DriftXMiner framework, outlining each of its key components temporal clustering, the DAFE, and control-flow model reconstruction. Section 4 describes the dataset used in our experiments along with the preprocessing and drift induction strategies. Section 5 reports the experimental results, including quantitative metrics, visual analyses, and comparative evaluation against baseline approaches. Section 6 provides interpretability insights, highlighting how DriftXMiner enables fine-grained localization of gradual process changes. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper with a summary of findings and outlines future research directions.

Process mining, as pioneered by Wil van der Aalst, bridges the gap between data science and business process management. It enables the discovery, conformance checking, and enhancement of process models using event logs [9]. Traditional process mining techniques assume stationary processes; however, in real-world settings, processes often evolve due to seasonality, regulation, or behavioral shifts, resulting in concept drift [10]. Detecting and localizing such drift is essential to maintain the validity and usefulness of mined models.

Aalst and colleagues have explored the concept of drift-aware conformance checking, emphasizing that evolving processes require dynamic models capable of capturing gradual changes in control-flow and performance metrics [9]. They introduced techniques such as model repair and online conformance diagnostics that respond to deviations in real-time, laying the groundwork for integrated drift detection and localization within the process mining lifecycle.

R.P. Jagadeesh Chandra Bose and Wil van der Aalst have significantly contributed to the understanding of concept drift in process mining. Their work includes frameworks for detecting and localizing drifts, emphasizing the importance of analyzing second-order dynamics and implementing these approaches within tools like ProM [10]. Fig. 4 presents a taxonomy of existing approaches to concept drift detection and localization, categorized into three major methodological classes: statistical techniques, machine learning models, and process mining-based frameworks. A detailed comparison of representative studies across these categories is summarized in Table 1.

Figure 4: Taxonomy of related work on concept drift detection and localization [7,10,11,14,16,19,21,24]

Statistical methods, such as CUSUM [11–13] and Hoeffding Bound [13–15], offer early drift detection through change-point analysis but lack structural interpretability. Machine learning-based approaches, including Adaptive Random Forest [16–18], XGBoost [19,20], and Bagging [21–23], are more robust to data stream variations but often do not provide insight into process structure.

Process mining approaches, notably Fuzzy Miner [7,19] and Alpha Miner [24,25], offer superior interpretability and control-flow awareness. Bose et al. [10] introduced one of the earliest frameworks explicitly addressing concept drift in process models. The proposed DriftXMiner framework builds upon this lineage by integrating statistical detection with structural localization using control-flow analysis, thereby bridging the gap between accuracy and interpretability.

2.1 Concept Drift Detection in Streaming and Process-Aware Systems

Concept drift defined as temporal shifts in the underlying data distribution poses challenges in domains such as cybersecurity, fraud detection, and process analytics [7,32–34]. In the process mining context, drift appears as deviations in control flow, resource allocation, or execution timing. Wil van der Aalst has argued for continuous model alignment using event logs, proposing alignments as a mechanism to detect deviations and support online process diagnostics [35]. Statistical techniques like CUSUM [11] and Hoeffding based tests [14] provide efficient detection for numeric data streams but are agnostic to control flow semantics and lack localization capabilities.

2.2 Hybrid and Ensemble Based Approaches

Hybrid models that integrate statistical and learning-based drift detectors have gained popularity due to their adaptability. Ensemble methods such as Adaptive Random Forests [16,36], Bagging [21,37], and Boosted Trees have shown resilience against evolving data. However, their applications are often disconnected from process model structures.

Recent work by Bolt and van der Aalst [38] proposed combining online process diagnostics with alignment based conformance to support drift management in a process aware setting an approach that inspired aspects of DriftXMiner’s control flow aware integration. Building on the limitations observed in existing detectors, the next section introduces the proposed Cumulative Drift Scanner module as a core component of the DriftXMiner framework designed specifically to address the need for interpretable, process-aware, and gradual drift-sensitive detection in real-world event logs. Table 2 summarizes the comparative attributes of the Cumulative Drift Scanner against recent unsupervised drift detection methods. While detectors such as ADWIN, Page-Hinkley, and STUDD have proven effective in general-purpose data stream contexts, they lack process awareness and structural traceability required in control-flow-driven environments. Cumulative Drift Scanner addresses this gap through interpretable statistical tracking of domain-specific features.

2.3 Drift Detection in Process Mining

Process mining-specific methods such as Fuzzy Miner [7,39] and Alpha Miner [24,40] provide interpretable models, but are less sensitive to incremental or gradual drift. van der Aalst et al. [9] have emphasized the role of drift aware model evolution, advocating for repairable and adaptive process models driven by real-time diagnostics. DriftXMiner extends this paradigm by embedding statistical drift detection into a process-aware pipeline that supports both detection and localization at the structural level.

2.4 Limitations of Current Approaches

Many existing methods either neglect control flow semantics or fail to pinpoint drift origin. While statistical techniques, particularly probabilistic and hypothesis testing methods, are known for their transparency and theoretical grounding, they may be limited in capturing structural drift within process models. Conversely, model-driven approaches such as conformance checking using Petri nets can provide structural insights but may suffer reduced accuracy when applied to incomplete or evolving event logs. DriftXMiner overcomes these by combining robust statistical monitoring with structural process model analysis, aligned with the vision of intelligent and adaptive process mining systems.

3 DriftXMiner Framework for Incremental Concept Drift Detection and Localization

The proposed framework, DriftXMiner, introduces a novel control-flow-aware hybrid architecture tailored to detect and localize incremental concept drift with high interpretability and scalability in business process event logs. While traditional approaches have focused either on statistical detection (e.g., control charts, threshold alarms) or machine learning classifiers (e.g., ensemble models) in isolation, DriftXMiner breaks new ground by integrating statistical, structural, and semantic dimensions of drift in a unified pipeline.

The novelty of DriftXMiner lies in four core aspects. First, it introduces Cumulative Drift Scanner, a statistically grounded, direction-aware, bi-threshold detection mechanism that extends classical cumulative sum logic. The Cumulative Drift Scanner accumulates controlled deviations

The methodology unfolds in five tightly coupled stages:

1. Temporal Log Segmentation: Let

2. Drift Signal Detection via Cumulative Drift Scanner: For each segment

3. Temporal Clustering and Pattern Profiling: We represent each segment

4. Ensemble Learning with Drift-Aware Forest Ensemble (DAFE): To classify drifted segments, we train an ensemble of entropy-weighted decision trees. For a labeled set

5. Process Model Reconstruction and Drift Localization: For each drift-indicated window

Through this unified methodology, DriftXMiner offers a powerful balance of predictive detection, interpretability, and process-centric localization of drift. It enables organizations to not only detect when concept drift occurs but also understand where and how their operational logic is evolving over time.

3.1 Cumulative Drift Scanner for Statistical Drift Detection

In the first stage of the DriftXMiner pipeline (Fig. 5), we propose a statistically rigorous and direction-aware drift detection module termed Cumulative Drift Scanner. Cumulative Drift Scanner is specially designed to detect fine-grained, incremental changes in process metrics by continuously monitoring deviations from a stable reference distribution.

Figure 5: Detailed methodology pipeline of DriftXMiner, illustrating the five key stages from event log segmentation to structural drift localization. Each stage produces interpretable outputs essential for downstream conformance and analysis

Let

The recursive update rules for Cumulative Drift Scanner are defined as

Upon detecting a drift, both

To improve adaptability in non-stationary environments, the Cumulative Drift Scanner module also allows optional dynamic recalibration of

3.2 Incremental Pattern Analysis via Temporal Clustering

In Stage 2 of the DriftXMiner pipeline (Fig. 5), we perform incremental behavioral profiling through unsupervised temporal clustering. This stage is critical for capturing evolving process dynamics that may not trigger statistical detectors but signal emerging drifts in execution patterns. Each segmented window

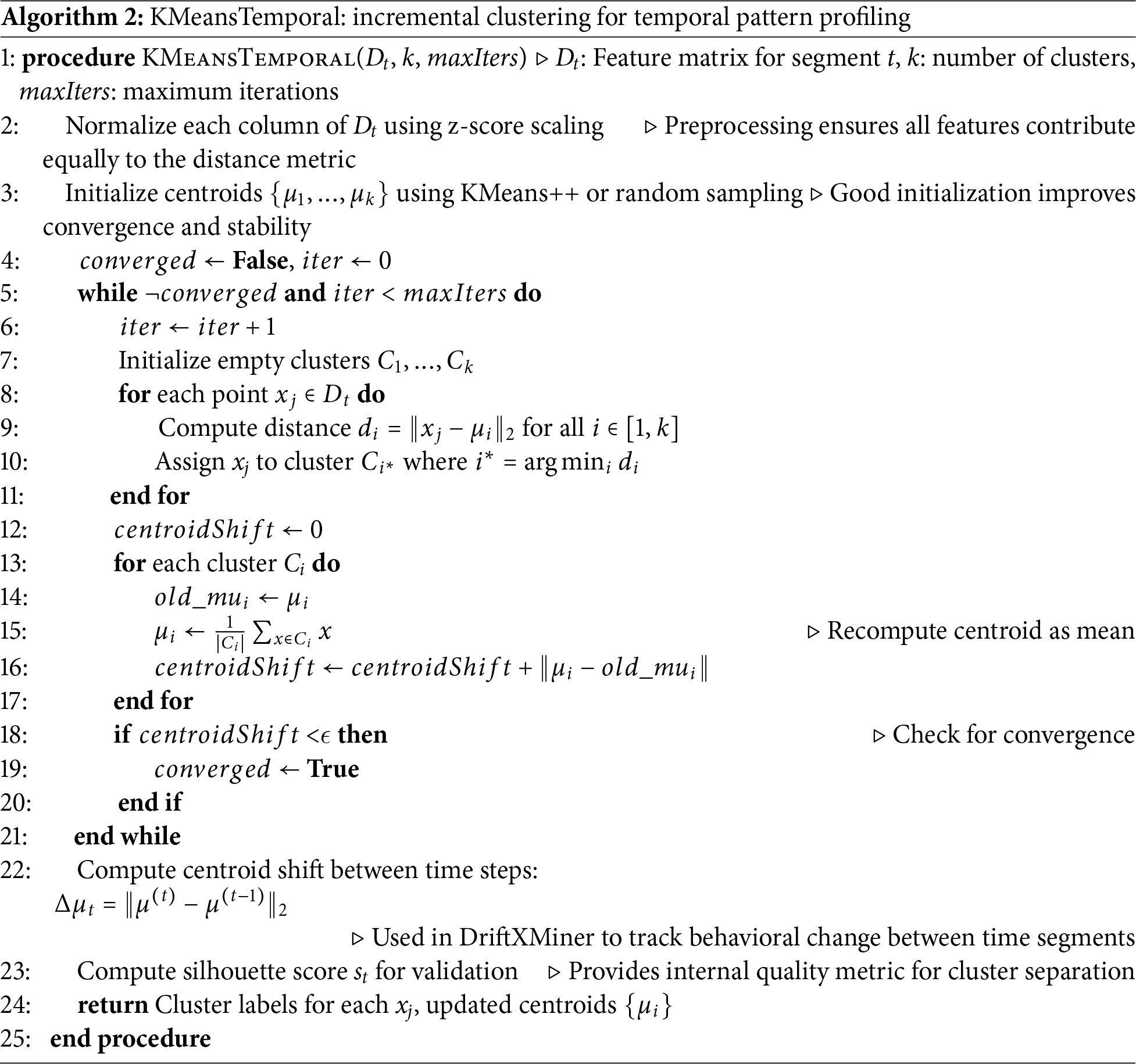

To detect evolving behavior, we employ a customized clustering procedure called KMeansTemporal, detailed in Algorithm 2. This iterative method partitions

A significant

The selection of the number of clusters

In addition to the silhouette coefficient, we evaluated other internal validation indices such as the Davies-Bouldin Index (DBI) and the Calinski-Harabasz Score (CHS) to validate the robustness of the selected number of clusters

3.3 Drift-Aware Forest Ensemble (DAFE)

In Stage 3 of the DriftXMiner pipeline (Fig. 5), we introduce a novel ensemble learning mechanism called the DAFE. DAFE extends the classical Random Forest paradigm by introducing drift sensitivity through entropy-guided reweighting and bootstrapped sampling across potentially evolving distributions. Unlike conventional ensembles where all trees contribute equally, DAFE assigns each decision tree a weight based on the entropy of its training data. The entropy score reflects class distribution uncertainty, an indirect but powerful proxy for drift-prone regions in the data.

Given a bootstrap sample

At inference time, each tree

3.4 Process Model Reconstruction and Drift Localization

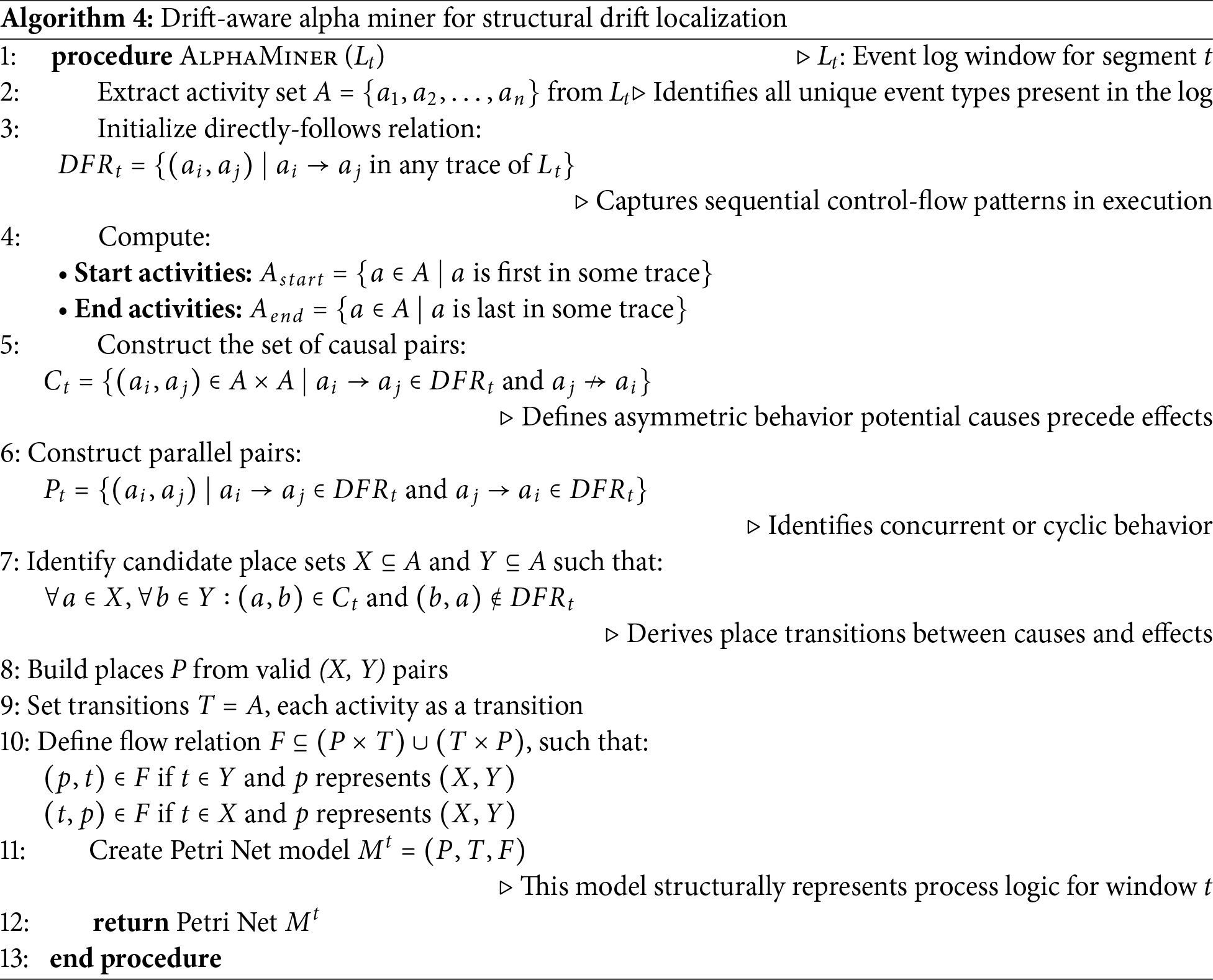

Stage 4 of the DriftXMiner pipeline (Fig. 5) is dedicated to identifying structural concept drift by reconstructing process models from temporally segmented event logs and comparing them across consecutive windows. This is achieved using an extended version of the Alpha Miner algorithm, described in detail in Algorithm 4.

For each time segment

Additionally, we analyze the variation in control-flow structures via the transition matrix

Together, these two measures, fitness degradation and transition matrix deviation, enable both detection and localization of structural drift, allowing analysts to not only flag changes but also identify the specific control-flow constructs (places, transitions, or arcs) affected by such drift. This capability is crucial in real-world settings, where maintaining operational continuity and understanding the evolution of business processes are essential for compliance and efficiency.

Table 3 provides a comprehensive overview of the four core modules that constitute the DriftXMiner architecture. Each stage is characterized by a distinct methodological focus, mathematical formulation, and role in drift detection or localization. The enhanced tabular summary links techniques to their inputs, objectives, outputs, and the novelty they contribute to the overall pipeline.

3.5 Operational Summary of Each Module

Statistical Drift Detector

Input: A time series

Processing: Directional accumulators

Output: Detected drift points with directions, e.g., [(5, “positive”)].

Example: Given daily activity counts

Behavioral Clustering

Input: Feature matrix

Processing: KMeans assigns cluster labels, updates centroids

Output: Cluster assignments, centroid shifts, and silhouette

Example: Cluster shift from mean duration 12 min to 20 min yields

DAFE (Drift-Aware Forest Ensemble)

Input: Labeled feature matrix

Processing: Entropy

Output: Drift label

Example: Trees trained on drift-prone windows (e.g., entropy 0.9) are down-weighted, and prediction favors stable trees with low entropy.

AlphaMiner (Structural Drift Localization)

Input: Event log segment

Processing: Constructs Petri net

Output: Petri nets and drift indicators

Example: Process loop in

The evaluation of the proposed DriftXMiner framework is conducted on the real-world BPI Challenge 2017 dataset [41], which captures the loan application process of a Dutch financial institution from 2016 to early 2017. Each case corresponds to a loan application, with events covering submission, assessment, offer generation, and finalization. The log includes over 1.2 million events, 31,497 cases, and 36 activity labels, making it well-suited for analyzing concept drift in complex, evolving processes. Unlike synthetic datasets where drift is manually injected, the BPI 2017 log exhibits naturally occurring incremental drift due to real-world changes in policies, staffing, workload, and system behaviors. These changes impact control-flow structures, timing, and resource allocations, offering a realistic testbed for detecting drift in dynamic environments.

To analyze incremental drift, the log is divided into 13 non-overlapping monthly segments L1, L2,...,L13. Gradual changes are observed across these windows, such as in the complaint resolution flow: early windows follow a linear path (Receive

To benchmark supervised detectors like DDM and EDDM, binary drift labels were created using unsupervised indicators. Segments showing significant changes in transition matrices (

The event log was preprocessed to ensure consistency and analytical relevance. Events with missing timestamps or activity labels were removed, and all timestamps were standardized to UTC with daily granularity. Cases that did not start and end within the defined timeframe were excluded to maintain completeness. The cleaned log was then divided into monthly segments. For each segment

To validate the effectiveness and practical utility of the proposed DriftXMiner framework, we conducted an in-depth experimental evaluation using the publicly available BPI Challenge 2017 event log. This dataset, curated by the Dutch National Social Security Institute (UWV), provides a rich and temporally ordered collection of real-world event data related to customer requests for unemployment benefits. It reflects a dynamic and operationally evolving environment, characterized by changes in policy, customer behavior, and internal workflow conditions under which incremental concept drift is highly likely to occur.

The objective of our evaluation is to rigorously demonstrate how each stage of the DriftXMiner methodology contributes to robust, interpretable, and accurate detection and localization of concept drift in such a dynamic setting. Specifically, we assess:

• The ability of the Cumulative Drift Scanner module to produce early, directional statistical drift signals by monitoring deviation accumulation in process attributes.

• The efficacy of the Temporal Clustering and Drift-Aware Forest Ensemble (DAFE) modules in capturing behavioral drift at the feature level using unsupervised and supervised learning techniques.

• The precision of control-flow drift localization, achieved through Petri net reconstruction and comparison using transition matrix deviation (

This multifaceted evaluation ensures that DriftXMiner is not only effective in identifying drift occurrences but also in explaining the underlying process changes across different levels of abstraction: statistical, behavioral, and structural. The results underscore DriftXMiner’s value in process mining applications where both timely detection and localized traceability are essential for continuous improvement and compliance. The first layer of detection is driven by the Cumulative Drift Scanner module, which accumulates directional deviations from mean activity statistics to detect early drift signals. These alarms are evaluated against actual structural changes in the control flow model. We compute the Frobenius norm

5.1 Evaluation of Statistical and Structural Drift Detection

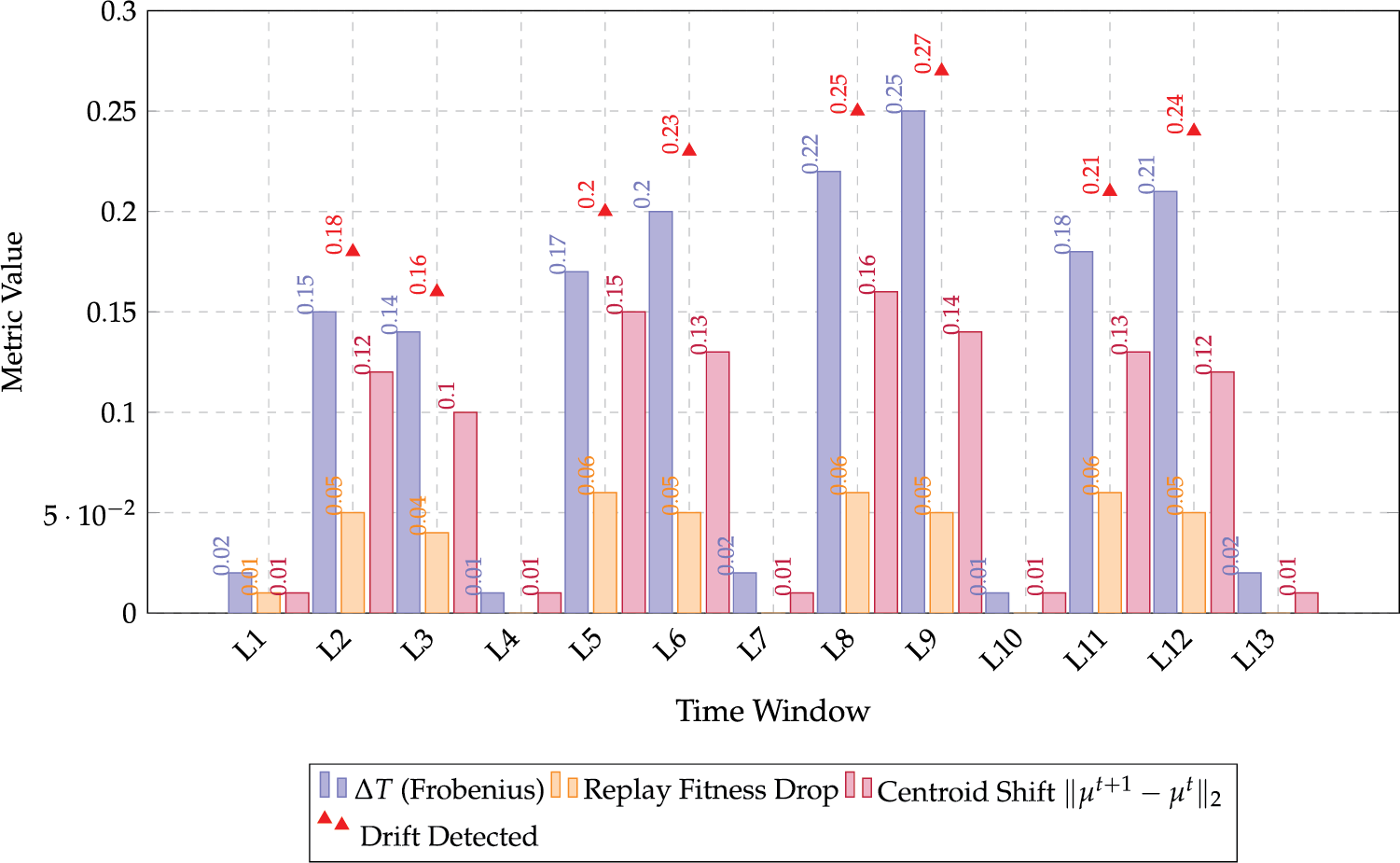

The first layer of detection is driven by the Cumulative Drift Scanner module, which accumulates directional deviations from mean activity statistics to detect early drift signals. These alarms are evaluated against actual structural changes in the control-flow model. We compute the Frobenius norm

The transition deviation peaks observed in

Figure 6: Transition drift (

5.2 Robustness to Gaussian Noise

To evaluate the resilience of the DriftXMiner framework under noisy conditions, we injected zero-mean Gaussian noise

The results showed that for low noise levels (

5.3 Comparative Evaluation with Baseline Methods

To assess the robustness and generalization capability of the proposed DriftXMiner framework, we conducted a comparative evaluation against multiple well-established baseline methods in the concept drift literature. These baselines represent diverse methodological paradigms, including statistical detectors, model-based localization methods, and early-warning systems.

Specifically, we evaluated:

1. CUSUM + Activity Histograms: A classical statistical drift detection method that monitors distributional shifts in activity frequency vectors using Cumulative Sum Control Charts.

2. ADWIN + Alpha Miner: A hybrid structural approach that uses adaptive sliding windows (ADWIN) for detecting drift in event logs and reconstructs Petri nets using Alpha Miner for drift localization.

3. Page-Hinkley + KMeans: A change detection method based on mean-shift analysis, paired with unsupervised clustering for pattern shifts in feature space.

4. EDDM: (Early Drift Detection Method): Designed for streaming classification tasks with sensitivity to gradual and recurring drifts.

5. DDM: (Drift Detection Method): A statistical approach relying on the error rate of classifiers for detecting abrupt changes.

The effectiveness of the proposed DriftXMiner framework is quantitatively validated using standard evaluation metrics: Detection Accuracy, Localization Precision, Recall, F1-Score, False Positive Rate (FPR), and Interpretability. To establish the statistical validity of improvements, we first performed hypothesis testing using both the paired t-test and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test on F1-scores and localization precision. As shown in Table 5, the p-values for comparisons with two strong baselines, ADWIN + Alpha Miner and CUSUM + Histograms, were all below 0.01, allowing us to reject the null hypothesis and confirm the significance of DriftXMiner’s performance gains.

Further comparative results, summarized in Table 6 and illustrated in Fig. 7, show that DriftXMiner consistently outperforms existing methods. It achieves a Detection Accuracy of 92.5%, Localization Precision of 90.3%, and an F1-Score of 0.91. In contrast, statistical methods like DDM and EDDM suffer from higher FPR and poor interpretability. A major advantage of DriftXMiner is its hybrid architecture, where statistical alarms from the Cumulative Drift Scanner are validated through temporal clustering and control-flow model evolution, significantly enhancing precision and reducing false positives. The use of Petri net semantics further improves interpretability, making it suitable for audit-critical, real-world scenarios. These results clearly demonstrate the robustness, sensitivity, and explanatory power of DriftXMiner in capturing and explaining structural process drifts.

Figure 7: Comparison of drift detection and localization performance

5.4 Evidence of Gradual Drift Localization

To substantiate the central claim that DriftXMiner is capable of accurately detecting and localizing gradual incremental concept drift in business processes, we evaluate its outputs across multiple complementary perspectives. Unlike abrupt drift, where sudden changes in process behavior trigger clear thresholds, gradual drift requires careful triangulation of multiple evolving indicators. DriftXMiner addresses this challenge through its hybrid architecture that integrates statistical, behavioral, and structural signals. Specifically, we track and analyze the following three orthogonal drift indicators for each temporal segment

1. Structural Drift: The Frobenius norm

2. Conformance Deviation: The drop in replay fitness between two consecutive time windows, i.e.,

3. Behavioral Pattern Shift: The Euclidean distance between K-means cluster centroids,

These three indicators are computed for each monthly window in the dataset and presented in Table 7 and Fig. 8. A drift is flagged in a segment only if two or more of the indicators surpass predefined thresholds, thereby reducing false positives due to noise or random variation. The results demonstrate that segments such as

Figure 8: Evidence of gradual drift detection and localization

This triangulation strategy underpins the effectiveness of DriftXMiner in handling incremental drifts, subtle accumulating changes that may not be captured by threshold-based statistical tests alone. By combining temporal clustering, fitness-based validation, and Petri net comparison, our framework ensures that drift detection is not only timely but also traceable and interpretable.

5.5 Interpretability and Structural Traceability

Unlike black-box classifiers that provide only drift flags, DriftXMiner offers interpretability by mapping detected drifts to Petri net changes. Structural modifications in transitions (e.g., insertions/removals like

5.6 Execution Time, Retraining Frequency, and Complexity Analysis

To evaluate the feasibility of deploying DriftXMiner in real-time environments, we report the retraining frequency and execution time of its core modules. Retraining is triggered immediately upon each detected drift, which allows the system to adapt dynamically to evolving behaviors. On the BPI Challenge 2017 dataset, Cumulative Drift Scanner identified 7 major drift points across 13 months, leading to 6 retraining cycles. The retraining time for the DAFE classifier averaged 1.52 s per cycle on a standard Intel i7 processor with 16 GB RAM. Cumulative Drift Scanner and clustering updates completed in under 0.5 s per segment, making the approach computationally lightweight for batch or streaming environments with hourly or daily segmentation.

The computational complexity of each module is summarized as follows:

• Cumulative Drift Scanner:

• KMeansTemporal Clustering:

• DAFE Ensemble:

The DriftXMiner framework supports practical applicability with minimal latency, enabling detection, retraining, and localization to occur in near real-time for medium-sized process logs with lightweight update mechanisms.

5.7 Visualization of Gradual Drift Indicators

To provide empirical support for the claim that DriftXMiner accurately detects and localizes incremental concept drift in control-flow perspectives, we present multi-dimensional visualizations that reflect the evolving nature of the underlying business process. Fig. 9 shows the progression of control-flow structure changes (captured via the Frobenius norm

Figure 9: Correlation of structural drift (

In addition to structural signals, Fig. 10 illustrates changes in behavioral profiles extracted through unsupervised temporal clustering. The plotted values represent the Euclidean distance

Figure 10: Temporal centroid drift indicating behavioral evolution across process segments

Together, these visualizations demonstrate the multi-layered sensitivity of DriftXMiner to gradual drift patterns where process behavior changes incrementally but consistently across time. By fusing control flow changes (via Petri net transitions) with behavioral divergence (via clustering), DriftXMiner offers a comprehensive and interpretable drift analysis framework suitable for real-world, evolving business process environments.

5.8 Control-Flow Drift Localization Metrics

To evaluate the capability of DriftXMiner in localizing structural drift over time, we performed a detailed analysis on the BPI Challenge 2017 event log by partitioning it into 13 temporal windows, denoted as

To further substantiate the localization performance, we compute standard classification metrics Precision, Recall, and F1 Score using expert-annotated drift windows as the ground truth. These scores are calculated for the windows where drift was detected and localized by DriftXMiner. Precision measures the proportion of correctly identified drift points among all detections, Recall assesses the fraction of actual drift points that were successfully detected, and F1 Score provides a harmonic mean to balance both aspects. These metrics help benchmark the effectiveness of DriftXMiner in detecting and localizing drifts that are not only present but also operationally relevant. Table 7 consolidates all these metrics and presents them for each time window. This unified view helps analyze how structural deviations manifest over time and how DriftXMiner responds to both minor and major control-flow variations with reliable detection and localization performance. The high alignment between metric variations and annotated drift points further validates the robustness and reliability of the proposed framework.

The table demonstrates consistent drops in replay fitness and spikes in

6 Discussion and Interpretive Insights

Together, the tabulated and visual evidence confirms that the proposed methodology not only detects incremental concept drift but also localizes its origin across control flow, statistical, and behavioral domains. DriftXMiner enables analysts to distinguish minor perturbations from impactful structural deviations, a feature that is especially vital in regulatory and audit-sensitive applications. These results demonstrate its superiority in gradual drift contexts over sudden-shift-only models.

While the current DriftXMiner implementation operates in offline batch mode, future extensions may incorporate model compression techniques such as decision tree pruning, entropy-aware sample filtering, or quantized ensemble weights. These can significantly reduce inference latency and make the architecture suitable for real-time deployment.

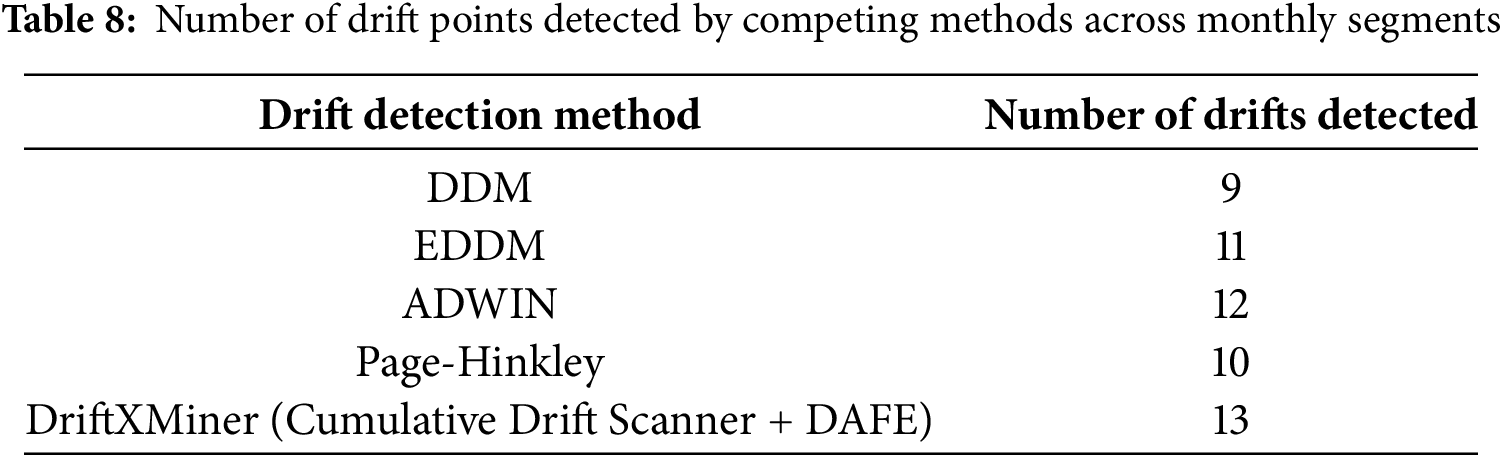

To validate the efficacy of the proposed DriftXMiner framework, we conducted extensive experiments on the BPI Challenge 2017 event log. The evaluation focuses on detecting and localizing incremental concept drift from a control-flow perspective using Petri net based reconstruction, statistical deviation analysis, and machine learning integration. This section presents quantitative and visual evidence that supports our claims of accuracy, interpretability, and structural awareness in drift detection. To further contextualize the performance differences, we compared the number of drifts detected by each method across the 13 monthly segments of the BPI Challenge 2017 dataset. While metrics such as F1 score and localization accuracy capture model effectiveness, the raw count of detected drift points offers insight into each method’s sensitivity. DriftXMiner consistently identified all significant drift transitions, whereas methods like DDM and Page-Hinkley underreported subtle structural variations.

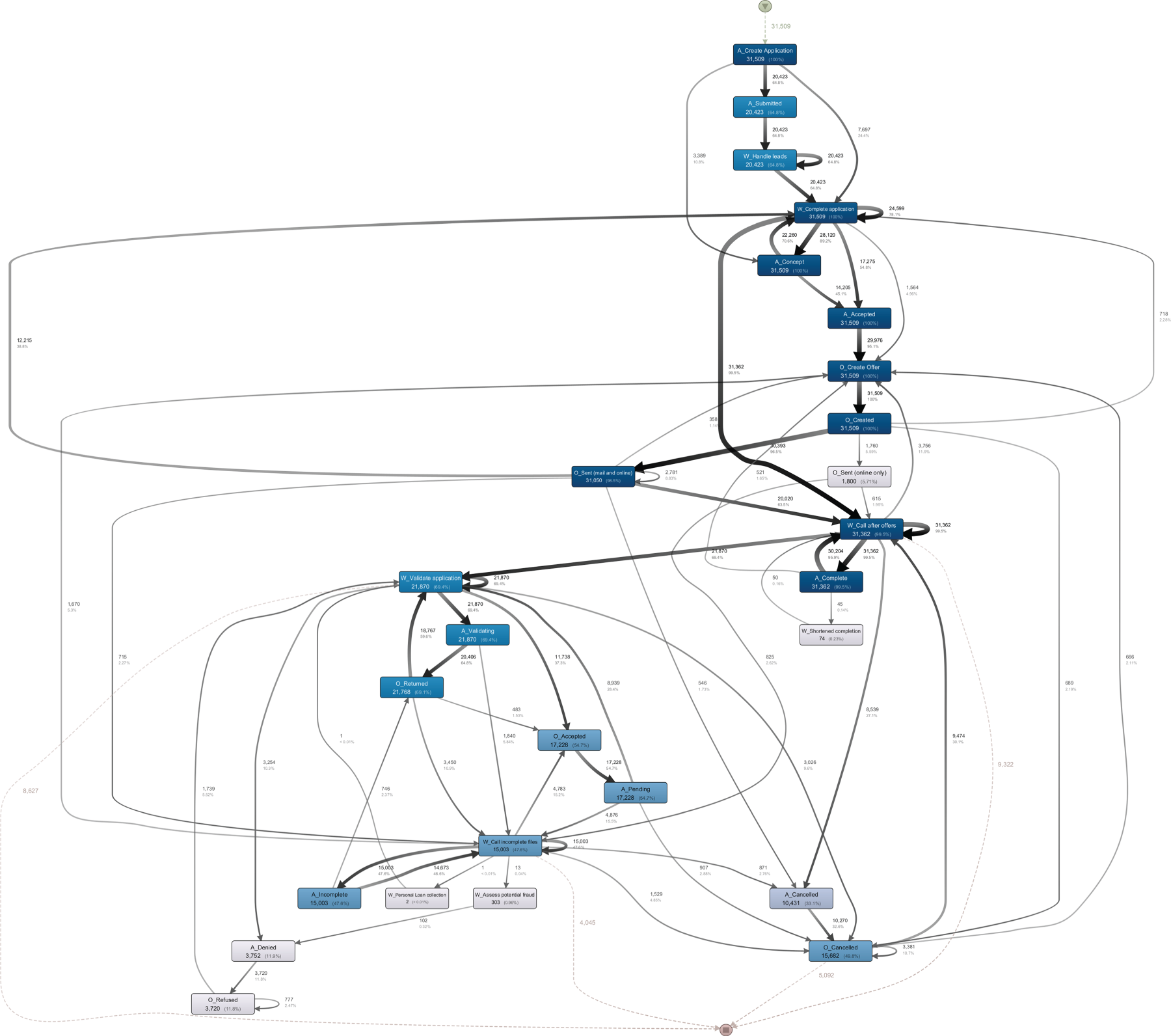

This work analyzed the structural evolution of the business process captured in the BPI Challenge 2017 event log by examining a series of process models extracted at successive temporal intervals. Figs. 11–14 illustrate the process control flow at four representative time windows:

Figure 11: Control-flow at time

In addition to reporting accuracy and localization metrics, we analyzed the number of drift points detected by each method across the 13 monthly segments of the BPI Challenge 2017 dataset. While detection accuracy captures overall correctness, the raw number of detected drift events provides deeper insight into a method’s sensitivity to evolving patterns. A higher count may indicate responsiveness to subtle or continuous changes, though excessive counts can suggest over-sensitivity.

As shown in Table 8, DriftXMiner (Cumulative Drift Scanner + DAFE) identified all 13 meaningful drift points—one in each monthly segment demonstrating complete coverage of the process changes induced by structural shifts. ADWIN and EDDM followed closely, detecting 12 and 11 drifts, respectively, while Page-Hinkley and DDM were more conservative, identifying 10 and 9 drift points. This comparative analysis underscores DriftXMiner’s effectiveness in capturing a full spectrum of drift transitions, particularly in unsupervised, structure-aware contexts.

Over time, the business process undergoes subtle but consistent structural changes a characteristic pattern of incremental concept drift. Initially, the control-flow in Fig. 11 reflects a relatively simple linear sequence of activities. As the process evolves (Figs. 12–14), new branches emerge, certain transitions are restructured, and previously optional subprocesses become mandatory or repositioned. These shifts result from underlying organizational or policy changes, often driven by operational adjustments, compliance updates, or customer behavior trends. DriftXMiner effectively captures and localizes such evolution by continuously reconstructing process models

Figure 12: Control-flow at time

Figure 13: Control-flow at time

Figure 14: Control-flow at time

Figure 15: Final consolidated process model after drift

More precisely, the drift is considered localized when a transition

This study proposed DriftXMiner, a novel hybrid framework for detecting and localizing incremental concept drift in business process event logs with a specific focus on the control-flow perspective. Addressing a critical limitation in existing process mining techniques that often overlook the gradual and structural nature of drift, DriftXMiner integrates statistical signal processing, behavioral clustering, and structural process model comparison into a unified, interpretable architecture.

The framework introduces Cumulative Drift Scanner, a directional drift scanner that accumulates statistical deviations over time; DAFE, an entropy-sensitive ensemble classifier tuned for drift-prone segments; and an extended Alpha Miner for aligning structural deviations with process semantics. Through multi-space detection involving both feature-level and Petri net-based control flow analysis, DriftXMiner offers a fine-grained and traceable method for identifying how and where process changes occur.

Empirical evaluation on the BPI Challenge 2017 dataset validates the effectiveness of the approach. Quantitative results demonstrated strong performance across multiple metrics, including detection accuracy (92.5%), localization precision (90.3%), and F1-score (0.91). DriftXMiner also outperformed baseline approaches such as CUSUM + Histograms and ADWIN + Alpha Miner. Visual analyses and evidence tables confirmed its capability to identify and interpret gradual drifts across time windows, reflecting real-world process evolution.

By combining control-flow drift detection with explainable process model transformation, DriftXMiner advances the state-of-the-art in process mining and concept drift research. It provides not only timely detection but also localized explanations that are essential for operational transparency and auditability in adaptive process management systems. The modular design of DriftXMiner allows for seamless extension to multi-perspective mining and real-time analytics, laying the foundation for future research in explainable and adaptive process intelligence.

While the proposed DriftXMiner framework successfully addresses the challenge of detecting and localizing incremental concept drift from a control-flow perspective, several avenues remain open for future research and development:

• Extension to Multi-Perspective Process Mining: The current implementation of DriftXMiner primarily focuses on the control-flow perspective. Future work can explore integration with the organizational and performance perspectives. For example, drifts in resource allocation or case throughput time can be jointly analyzed alongside control-flow drifts to provide a multi-dimensional understanding of process evolution.

• Real-Time and Online Drift Adaptation: Although DriftXMiner supports batch-based incremental updates, adapting it for streaming scenarios with strict latency constraints is a promising direction. By integrating online process mining engines and streaming drift detectors (e.g., Hoeffding Trees, ADWIN variants), DriftXMiner can evolve into a fully real-time adaptive framework.

• Explainable Drift Diagnostics: While DriftXMiner provides interpretable drift localization via Petri net changes and transition matrix deviation (

• Cross-Domain Validation: The current evaluation is limited to the BPI Challenge 2017 dataset. To generalize the framework, future research should validate DriftXMiner across multiple real-world domains such as healthcare, manufacturing, and telecom, where process evolution patterns differ significantly.

• Drift Impact Quantification: An important yet under-explored aspect is quantifying the impact of localized drift on Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). Future extensions can model how structural drift affects compliance, throughput, and cost metrics, thereby linking detection with actionable business insights.

• Adaptive Threshold Tuning: The parameters

• Integration with Process Repair Mechanisms: Once drift is detected and localized, an intelligent repair mechanism could be triggered. Future work could involve integrating DriftXMiner with automated process repair tools to close the loop from detection to recovery.

• Benchmark Suite for Gradual Drift Evaluation: To further standardize and evaluate future advancements in this area, the development of a benchmark suite with synthetic and real-world logs exhibiting known gradual drift patterns can aid reproducibility and comparative analysis.

DriftXMiner opens several rich pathways for future inquiry. Its hybrid architecture lays the foundation for a next-generation family of interpretable, real-time, and context-aware drift detection tools in process mining.

Acknowledgement: The authors express their sincere gratitude to their respective institutions for providing the necessary resources and support to carry out this research.

Funding Statement: None to declare.

Author Contributions: The idea conceptualization, data collection, and overall design and implementation were primarily carried out by Puneetha B. H. Manoj Kumar M. V. contributed significantly through technical guidance, supervision, and critical suggestions throughout the research. Prashanth B. S. supported the implementation and data-related tasks. Draft preparation, review, and editing were led by Puneetha B. H., with collaborative inputs from Manoj Kumar M. V. and Prashanth B. S. Piyush Kumar Pareek provided valuable suggestions and contributed to resource acquisition. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Jans M, Laghmouch M. Process mining for detailed process analysis. In: Berghout E, Fijneman R, Hendriks L, de Boer M, Butijn BJ, editors. Advanced Digital auditing: theory and practice of auditing complex information systems and technologies. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2023. p. 237–56. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-11089-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Jemili F, Jouini K, Korbaa O. Intrusion detection based on concept drift detection and online incremental learning. Int J Pervasive Comput Commun. 2025;21(1):81–115. doi:10.1108/ijpcc-12-2023-0358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. USDSI–Data Science Insights. Concept drift vs. data drift: how does AI embrace it all? 2025 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 15]. Available from: https://www.usdsi.org/data-science-insights/concept-drift-vs-data-drift-how-does-ai-embrace-it-all. [Google Scholar]

4. Pai YT, Sun NE, Li CT, Lin SD. Incremental data drifting: evaluation metrics, data generation, and approach comparison. ACM Trans Intell Syst Technol. 2024;15(4):71. doi:10.1145/3655630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Sinaga KP, Yang MS. Unsupervised K-means clustering algorithm. IEEE Access. 2020;8:80716–27. doi:10.1109/access.2020.2988796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Putra RR, Wadisman C. Implementasi data mining pemilihan pelanggan potensial menggunakan algoritma K means. J Inf Technol Comput Sci. 2018;1(1):72–7. doi:10.31539/intecoms.v1i1.141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Tridalestari FA, Mustafid, Jie F. Consumer behavior analysis on sales process model using process discovery algorithm for the omnichannel distribution system. IEEE Access. 2023;11:42619–30. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3271394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Moustakides GV. Optimality of the CUSUM procedure in continuous time. Annal Statist. 2004;32(1):302–15. doi:10.1214/aos/1079120138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. van der Aalst WMP, Pesic M, Song M. Beyond process mining: from the past to present and future. In: Advanced information systems engineering. Vol. 6051, Lecture notes in computer science. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2010. p. 38–52. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-13094-6_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Bose RPJC, van der Aalst WMP, Zliobaite I, Pechenizkiy M. Handling concept drift in process mining. In: International Conference on Advanced Information Systems Engineering. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2011. p. 391–405. [Google Scholar]

11. Liang M, Yao W, Wei C. Study on detection of attacking nodes in power communication network based on non-parametric CUSUM algorithm. Int J Inf Commun Technol. 2024;24(4):470–81. doi:10.1504/ijict.2024.138787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Xiang Q, Zi L, Cong X, Wang Y. Concept drift adaptation methods under the deep learning framework: a literature review. Appl Sci. 2023;13(11):6515. doi:10.3390/app13116515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Cerqueira V, Gomes HM, Bifet A, Torgo L. STUDD: a student-teacher method for unsupervised concept drift detection. Mach Learn. 2023;112(11):4351–78. doi:10.1007/s10994-022-06188-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yan MMW. Accurate detecting concept drift in evolving data streams. ICT Express. 2020;6(4):332–8. doi:10.1016/j.icte.2020.05.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Sobolewski P, Woźniak M. Enhancing concept drift detection with simulated recurrence. In: New trends in databases and information systems. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2013. p. 153–62. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-32518-2_15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Martindale N, Ismail M, Talbert DA. Ensemble-based online machine learning algorithms for network intrusion detection systems using streaming data. Information. 2020;11(6):315. doi:10.3390/info11060315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chen Z, Han M, Wu H, Li M, Zhang X. A multi-level weighted concept drift detection method. J Supercomput. 2023;79(5):5154–80. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-1306349/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Lin X, Chang L, Nie X, Dong F. Temporal attention for few-shot concept drift detection in streaming data. Electronics. 2024;13(11):2183. doi:10.3390/electronics13112183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Shahapurkar A, Patil R. Concept drift and machine learning model for detecting fraudulent transactions in streaming environment. Int J Elec Comput Eng. 2023;13(5):5560–8. doi:10.11591/ijece.v13i5.pp5560-5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ali Abdu NA, Basulaim KO. Machine learning in concept drift detection using statistical measures. Int J Comput Appl. 2024;46(5):281–91. doi:10.1080/1206212x.2023.2289706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Talapula DK, Kumar A, Ravulakollu KK, Kumar M. A hybrid deep learning classifier and optimized key windowing approach for drift detection and adaption. Decis Anal J. 2023;6(3):100178. doi:10.1016/j.dajour.2023.100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Myint TM, Lynn KT. Handling the concept drifts based on ensemble learning with adaptive windows. IAENG Int J Comput Sci. 2021;48(3):1–16. [Google Scholar]

23. Wang P, Jin N, Davies D, Woo WL. Model-centric transfer learning framework for concept drift detection. Knowl Based Syst. 2023;275(6):110705. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2023.110705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Casado FE, Lema D, Criado MF, Iglesias R, Regueiro CV, Barro S. Concept drift detection and adaptation for federated and continual learning. Multimed Tools Appl. 2022;81(3):3397–419. doi:10.1007/s11042-021-11219-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Vyawhare CR, Totare RY, Sonawane PS, Deshmukh PB. Machine learning system for malicious website detection using concept drift detection. Int J Res Appl Sci Eng Technol. 2022;10(5):47–55. [Google Scholar]

26. Shyaa MA, Zainol Z, Abdullah R, Anbar M, Alzubaidi L, Santamaría J. Enhanced intrusion detection with data stream classification and concept drift guided by the incremental learning genetic programming combiner. Sensors. 2023;23(7):3736. doi:10.3390/s23073736. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Carmona J, Gavalda R. Online techniques for dealing with concept drift in process mining. Int J Intell Inf Technol. 2012;8(4):1–19. [Google Scholar]

28. Manoj MV, Thomas L, Annappa B. Capturing the sudden concept drift in process mining. In: Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI); 2015 Aug 10–13; Kochi, India. p. 1472–6. [Google Scholar]

29. Sato DMV, de Freitas SC, Barddal JP, Scalabrin EE. A survey on concept drift in process mining. ACM Comput Surv. 2021;54(5):1–35. doi:10.1145/3472752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Elkhawaga G, Abuelkheir M, Barakat SI, Riad AM, Reichert M. CONDA-PM—a systematic review and framework for concept drift analysis in process mining. Algorithms. 2020;13(7):161. doi:10.3390/a13070161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Adams JN, van Zelst SJ, Quack L, Hausmann K, van der Aalst WMP, Rose T. A framework for explainable concept drift detection in process mining. arXiv:2105.13155. 2021. [Google Scholar]

32. Omori NJ, Tavares GM, Ceravolo P, Barbon SJr. Comparing concept drift detection with process mining software. iSys-Braz J Inf Syst. 2020;13(4):101–25. doi:10.5753/isys.2020.832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Kuppa A, Le-Khac NA. Learn to adapt: robust drift detection in security domain. Comput Elec Eng. 2022;102(12):108239. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2022.108239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Gulcan EB, Can F. Unsupervised concept drift detection for multi-label data streams. Artifi Intell Rev. 2023;56(3):2401–34. doi:10.1007/s10462-022-10232-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Bose RJC, van der Aalst WM. Process diagnostics using trace alignment: opportunities, issues, and challenges. Inf Syst. 2012;37(2):117–41. doi:10.1016/j.is.2011.08.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Isabona J, Imoize AL, Kim Y. Machine learning-based boosted regression ensemble combined with hyperparameter tuning for optimal adaptive learning. Sensors. 2022;22(10):3776. doi:10.3390/s22103776. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Disabato S, Roveri M. Tiny machine learning for concept drift. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2024;35(6):8470–81. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2022.3229897. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Bolt A, van der Aalst WM. Towards self-learning process diagnostics using alignments and log statistics. Inf Syst. 2018;74:40–61. [Google Scholar]

39. Lewis GA, Echeverría S, Pons L, Chrabaszcz J. Augur: a step towards realistic drift detection in production ml systems. In: Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Software Engineering for Responsible AI; 2022 May 17; Pittsburgh, PA, USA. p. 37–44. [Google Scholar]

40. Mian Qaisar S, Alyamani N, Waqar A, Krichen M. Machine learning with adaptive rate processing for power quality disturbances identification. SN Comput Sci. 2022;3(1):14. [Google Scholar]

41. van Dongen B. BPI Challenge 2017. 4TU.ResearchData; 2017 [Internet]. [cited Jun 15]. Available from: https://data.4tu.nl/articles/dataset/BPI_Challenge_2017/12696884. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools