Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

HCL Net: Deep Learning for Accurate Classification of Honeycombing Lung and Ground Glass Opacity in CT Images

1 Department of Information Systems, Faculty of Computer Science and Information Technology, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

2 Department of Computing, University of Roehampton, Roehampton Lane, London, SW15 5PH, UK

3 Department of Biomedical Imaging, University Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

* Corresponding Authors: Hairul Aysa Abdul Halim Sithiq. Email: ; Liyana Shuib. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advancements in Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence for Pattern Detection and Predictive Analytics in Healthcare)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067781

Received 12 May 2025; Accepted 14 July 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Honeycombing Lung (HCL) is a chronic lung condition marked by advanced fibrosis, resulting in enlarged air spaces with thick fibrotic walls, which are visible on Computed Tomography (CT) scans. Differentiating between normal lung tissue, honeycombing lungs, and Ground Glass Opacity (GGO) in CT images is often challenging for radiologists and may lead to misinterpretations. Although earlier studies have proposed models to detect and classify HCL, many faced limitations such as high computational demands, lower accuracy, and difficulty distinguishing between HCL and GGO. CT images are highly effective for lung classification due to their high resolution, 3D visualization, and sensitivity to tissue density variations. This study introduces Honeycombing Lungs Network (HCL Net), a novel classification algorithm inspired by ResNet50V2 and enhanced to overcome the shortcomings of previous approaches. HCL Net incorporates additional residual blocks, refined preprocessing techniques, and selective parameter tuning to improve classification performance. The dataset, sourced from the University Malaya Medical Centre (UMMC) and verified by expert radiologists, consists of CT images of normal, honeycombing, and GGO lungs. Experimental evaluations across five assessments demonstrated that HCL Net achieved an outstanding classification accuracy of approximately 99.97%. It also recorded strong performance in other metrics, achieving 93% precision, 100% sensitivity, 89% specificity, and an AUC-ROC score of 97%. Comparative analysis with baseline feature engineering methods confirmed the superior efficacy of HCL Net. The model significantly reduces misclassification, particularly between honeycombing and GGO lungs, enhancing diagnostic precision and reliability in lung image analysis.Keywords

Honeycombing lung disease represents a terminal condition that can result in fatality. It is a pattern of lung damage seen in chronic lung conditions, characterized by clustered, irregular cystic spaces resembling a honeycomb on imaging studies [1]. This pattern arises from progressive fibrosis, where normal lung tissue is replaced by fibrotic scar tissue. Early diagnosis using CT scans is crucial for optimizing treatment options such as medication, pulmonary rehabilitation, supplemental oxygen, and, in severe cases, lung transplantation [2]. Radiologists rely on distinct visual lung patterns to identify honeycombing. However, its appearance can closely resemble Ground Glass Opacity (GGO), characterized by hazy grey areas on CT images [3,4]. Both honeycombing and GGO are associated with scarring, inflammation, and fluid accumulation, leading to similar appearances on CT scans, showing increased lung density and changes in lung tissue. GGO appears as a hazy opacity, while honeycombing displays clustered cystic spaces with fibrous bands. Distinguishing between the two solely based on imaging might not always be straightforward. The overlay of these diseases in diagnoses can sometimes lead to misdiagnosis, necessitating careful analysis and possibly additional diagnostic measures for accurate identification [5–7].

Radiologists traditionally examine CT scans to diagnose lung abnormalities [8–10], but manual interpretation is time-consuming and demands high precision [11–14]. Consequently, integrating precise diagnostic tools is vital to support radiologists, improve treatment outcomes, and reduce patient imaging requirements [15–18]. Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning, has emerged as a critical solution to automate and enhance diagnostic accuracy. Compared to conventional machine learning, deep learning efficiently processes large-scale datasets and excels in complex image interpretation tasks [19]. Deep learning, a specialized subset of AI within machine learning, has recently garnered attention for its exceptional performance in representation learning [20,21]. By automatically extracting features and patterns from medical images, deep learning models can accurately classify unseen data, proving advantageous for clinical applications.

Researchers worldwide have applied deep learning techniques such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to medical imaging tasks, achieving notable success [22]. CNNs are designed with layers such as convolutional, pooling, and fully connected layers, enabling automated feature extraction crucial for image classification and analysis [23]. Transfer learning, a method of leveraging pre-trained models, has become a standard practice to overcome the limitations of training deep models from scratch on small medical datasets. The focus of this research paper is on transfer learning, a deep learning technique used to classify normal lung, honeycombing lung, and ground glass opacity lung images. In this article, a specific type of deep learning neural network called ResNet50V2, a variant of the CNN, is employed. ResNet50V2, an upgraded version of ResNet50, shows improved performance compared to its original model [24]. ResNet, on the other hand, is a distinct CNN architecture introduced by Microsoft researchers in 2015 [25]. It was developed to tackle the challenge of training extremely deep neural networks. Its major innovation lies in the use of residual connections, also known as skip connections, allowing the network to learn residual functions rather than direct mappings. These skip connections facilitate gradient flow during training, alleviate the vanishing gradient problem, and enable the training of deeper networks. ResNet architectures typically consist of multiple residual blocks, each comprising convolutional layers, batch normalization, and skip connections that bypass one or more layers and directly connect the input to the output [26]. While CNN is a broad term for a class of deep learning models specifically designed for image analysis, ResNet represents a specific type of CNN architecture utilizing residual connections, particularly beneficial for training very deep networks. ResNet serves as a variant within the CNN domain, showcasing improved performance in handling deeper network architectures. However, the predominant applications of ResNet50V2 have been directed towards the classification of medical images related to breast cancer, pneumonia, and COVID-19 [27,28]. However, no documented research has specifically employed ResNet50V2 for the classification of lung diseases such as honeycombing and ground glass opacity. Furthermore, there is a limited body of research focusing on honeycombing and ground glass opacity patterns. The majority of studies have centered on lung cancers rather than broader lung diseases. Lung diseases encompass a range of conditions affecting the lungs, including Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), asthma, pulmonary fibrosis, pneumonia, and others [29], whereas lung cancers involve malignant tumor growths within the lungs. Despite both affecting pulmonary structures, they differ significantly in causes, symptoms, treatments, and prognoses. Previous research efforts predominantly utilized machine learning techniques for the classification of honeycombing lung diseases [30].

Most existing research focuses either on lung cancer or utilizes smaller datasets with limited verification, introducing potential biases. By contrast, this study introduces the HCL Net model, trained on extensively verified CT lung datasets annotated by expert radiologists from the University Malaya Medical Centre (UMMC). Importantly, the study emphasizes the challenges of differentiating between honeycombing and GGO, proposing solutions through intensive preprocessing, parameter tuning, and model customization. Therefore, the proposed model aims to pioneer honeycomb classification in future studies. Prior research heavily emphasized accuracy alone, which may introduce bias and misrepresent model performance. In response, the proposed evaluation includes a broader set of metrics such as precision, sensitivity, specificity, and AUC to offer a more comprehensive assessment. Another major limitation observed in past studies is the reliance on small datasets, which compromised the reliability and comparability of findings. Consequently, acquiring larger datasets is crucial for enhancing the model’s robustness and ensuring more reliable results.

Additionally, misclassification between HoneyCombing (HC) and Ground Glass Opacity (GGO) remains a common issue. Many previous studies relied on datasets like ImageNet, which may lack verified annotations. In contrast, the proposed model utilizes datasets that are rigorously annotated and verified by medical experts, ensuring higher accuracy and reliability. Thus, HCL Net, a pre-trained model based on ResNet50V2, is proposed as a benchmark for the classification of honeycombing lung patterns. Trained on a large, verified dataset, HCL Net aims to significantly enhance lung disease classification accuracy. By integrating multiple performance metrics beyond accuracy, the model strives to achieve a more effective and reliable classification outcome compared to existing deep learning classifiers, as supported by foundational studies. The major contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

• Introduction of HCL Net, a customized deep learning model for accurate HoneyCombing Lung (HCL) identification.

• Enhancement of ResNet50V2 architecture by adding additional residual blocks to overcome traditional model limitations.

• Application of intensive preprocessing techniques and hyperparameter tuning for optimal model performance.

• Use of rigorously verified datasets, ensuring the reliability of training and evaluation.

• Achievement of superior accuracy (99.97%), outperforming baseline methods and advancing lung disease classification research.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 discusses related work on lung classification. Section 3 describes the data collection and preprocessing. Section 4 presents the proposed model architecture. Section 5 discusses experimental evaluation and results. Section 6 concludes the study and outlines future work.

This section presents a comprehensive review of previous studies related to lung disease classification using machine learning and deep learning techniques. This review covers both early machine learning approaches and state-of-the-art deep learning methods, with particular emphasis on CNN based and transfer learning-based models.

2.1 Early Machine Learning Approaches for Lung Disease Classification

Medical image classification has rapidly advanced with the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning [31]. Initially, traditional machine learning algorithms such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs) were used. However, these methods struggled with larger datasets and complex diagnostic tasks due to their reliance on handcrafted features and limited generalization capability [32,33]. For example, Makaju et al. [34] used an SVM to classify lung cancer from CT scans, achieving 86.6% accuracy after resizing and grayscale the images. While this result was promising, the model’s dependence on handcrafted features risked losing subtle textural information crucial for diagnosis. Similarly, Jeyapaul et al. [35] combined SVM with segmentation techniques like K-means and Watershed, but achieved only 73% accuracy, highlighting the limitations of conventional methods in handling overlapping or poorly defined disease regions. Moreover, these studies typically focused on detecting a single disease type, lacking a generalizable framework for multi-class classification. These shortcomings led to a shift toward deep learning, which can extract discriminative features directly from raw images and better manage diagnostic complexity [36].

2.2 Deep Learning for Medical Imaging

For instance, Gao et al. [36] proposed a CNN-based framework to detect multiple lung abnormalities, including GGO, Reticular patterns, Honeycombing, and Emphysema. Although their model achieved a promising F-score of 0.908 for Ground Glass detection, the performance dropped considerably for Honeycombing lungs, suggesting that the model struggled with more complex or less frequent disease patterns. Similarly, Anthimopoulos et al. [37] implemented a convolutional neural network trained on 14,696 images spanning six types of lung diseases, resulting in an overall accuracy of 85.5%. In another study, Zhu et al. [38] utilized the CNN architecture to classify lung cancer by emphasizing the Region of Interest (ROI) containing lung nodules, achieving an accuracy of 92.74%. These studies highlight the effectiveness of deep learning in advancing lung disease classification, but they also expose key challenges, particularly in distinguishing visually similar abnormalities such as GGO and HC.

2.3 Honeycombing Lung and Ground Glass Opacity Detection

The HC and GGO lungs are progressive lung conditions that are frequently misdiagnosed due to their highly similar imaging characteristics. Early research efforts in this area faced notable challenges. Eğriboz et al. [39], for instance, developed a CNN-based model using a limited public dataset comprising only 170 images, resulting in a relatively low classification accuracy of 69%. To improve diagnostic performance, Cinar et al. [40] introduced a ResNet50-based model utilizing transfer learning techniques, achieving 97.22% accuracy in binary classification tasks focused on pneumonia detection. Li et al. [41] explored the use of an improved MobileNet architecture for honeycombing lung classification, achieving an impressive accuracy of 99.52%. Their study also emphasized MobileNet’s lightweight design and strong feature extraction capabilities, making it highly suitable for lung disease classification tasks. Chen et al. [42] developed a ResNet-based model specifically for lung disease detection, although the reported accuracy of 88.23% suggests room for improvement. Acar et al. [43] also applied transfer learning approaches, reaching a classification accuracy of 95%. Although these studies demonstrate significant advancements, many still encounter difficulties when differentiating between visually overlapping patterns like honeycombing and GGO, underlining the need for further refinement in model design and dataset composition.

2.4 ResNet-Based Applications in Medical Imaging

ResNet architecture has consistently demonstrated high effectiveness across diverse fields, particularly in medical image analysis. The foundational work by He et al. [25] introduced the ResNet model, which tackled the vanishing gradient issue commonly encountered in very deep neural networks. By incorporating residual connections, also known as shortcut paths and the architecture allows layers to learn identity mappings, making it easier to train deeper networks and improving overall performance in image recognition tasks. This innovation significantly improved the performance of deep architectures and set a new benchmark in image classification tasks, particularly through its success in the ImageNet competition. ResNet design has since become a widely adopted framework in various computer vision applications, including medical image analysis. Building upon this innovation, Wu et al. [44] applied the ResNet framework in the context of breast cancer diagnosis, attaining an AUC of 0.895, which highlighted the architecture’s capability in handling complex diagnostic tasks. Further exploring its potential, Showkat and Qureshi [45] implemented a pre-trained ResNet model to classify multiple lung conditions, specifically pneumonia, honeycombing, and ground glass opacity, using both Chest X-Ray (CXR) and CT imaging. Their model achieved an overall accuracy of 95%, alongside high precision and sensitivity scores, showcasing ResNet’s adaptability and strength in multi-disease detection settings. While these findings affirm the utility of ResNet-based models in medical domains, the need remains for models specifically designed to address nuanced patterns such as those present in honeycombing and GGO, where overlap in visual features often leads to diagnostic inaccuracies.

2.5 Comparative Analysis of Existing Models and the Proposed HCL Net

The studies summarized in Table 1 highlight notable advancements in medical image classification, spanning domains such as lung health monitoring, cancer detection, and infectious disease diagnosis. Models including CNNs, SVMs, and various iterations of ResNet have been employed with varying degrees of success. However, many of these studies exhibit certain limitations: inconsistent accuracy levels, limited focus on specific lung abnormalities, and a tendency to target single disease types. Such approaches may fall short when applied to real-world diagnostic scenarios involving coexisting or visually similar lung conditions, like honeycombing and ground glass opacity. In response to these challenges, the proposed HCL Net model introduces a more comprehensive solution. Built on a pre-trained ResNet50V2 backbone, HCL Net is specifically tailored for the classification of healthy lungs, honeycombing, and GGO patterns. It achieves an exceptional accuracy of 99.88%, along with high precision (0.9934), sensitivity (0.9965), and AUC (0.998), significantly outperforming prior models. This robust performance underscores the model’s capacity to effectively capture the subtle distinctions between overlapping pathological features, thereby addressing critical gaps left by earlier research.

The studies presented in Table 1 showcase commendable progress in medical image classification, addressing diverse domains including lung health, cancer detection, and infectious diseases. However, these endeavors exhibit certain limitations, including varying accuracies, a lack of comprehensive coverage for specific lung conditions, and reliance on diverse models such as CNN, SVM, and ResNet. Furthermore, some studies focus on single diseases, potentially neglecting the complexity of coexisting conditions. In response to these limitations, my proposed model, the HCL Net, aims to address these gaps by achieving a significantly high accuracy of 99.88% across multiple lung conditions, including healthy states, honeycombing, and ground glass opacity. Leveraging a pre-trained ResNet50v2, the HCL Net demonstrates superior precision, sensitivity, and overall robustness, offering a comprehensive solution to the identified shortcomings in the existing research landscape.

2.6 Motivation for Using Pre-Trained ResNet50V2

Compared to other architectures such as VGG16, VGG19, and Inception-V3, ResNet50V2 presents several distinct advantages that make it well-suited for this research. Its deeper architecture, supported by residual or skip connections, helps overcome the vanishing gradient problem [46], ensuring more stable training and improved generalization, critical features for complex medical imaging tasks [44,47]. Furthermore, ResNet50V2 has consistently demonstrated strong performance in classifying subtle and complex patterns in CT lung images, making it an ideal foundation for lung disease detection. Although VGG16 and VGG19 have produced acceptable results in earlier works [35], their lack of residual connections limits their effectiveness when scaled to deeper architectures. Inception-V3, while efficient and widely used for natural images, may not offer the same precision when applied to fine-grained patterns present in lung CT scans. As such, ResNet50V2 was selected for its superior architectural features and proven effectiveness in similar medical applications. To tailor the model specifically for this study, additional customized layers were incorporated into the pre-trained ResNet50V2, along with hyperparameter tuning. This modified version, named HCL Net, was designed to address the classification of three lung conditions: normal, honeycombing, and ground glass opacity. These enhancements significantly improved the model’s ability to discern subtle differences between similar lung patterns, notably reducing misclassification rates seen in earlier models [38,39,46]. By specifically targeting architectural limitations found in baseline models, HCL Net offers a more robust and accurate solution for medical image classification.

This study presents a deep learning-based model, HCL Net, designed for the classification of three types of lung conditions: normal, HC, and GGO using CT images. The architecture of this model is based on a fine-tuned ResNet50v2 backbone, enhanced with an additional convolutional block and customized skip connections, complemented by systematic preprocessing and regularization techniques. The following subsections provide a detailed description of the dataset, preprocessing, and model architecture.

The dataset employed to train and evaluate the suggested methods was sourced from the UMMC. It was acquired through collaboration with the hospital, involving relevant staff and a radiologist who was an integral part of the research team. It is important to note that no patients were directly affected, and the research aims to benefit a larger group of subjects. Prior to integration into the model, the dataset underwent a rigorous verification, labelling, and annotation process, overseen by a radiology expert from UMMC. The dataset consisted of 800 CT images each for normal lungs, Honeycomb lungs, and Ground Glass Opacity lungs, totaling 2400 CT images that were utilized and assessed in the proposed model. These datasets were utilized in their original, unprocessed state.

The dataset represents a group of patients aged between 40 and 80 years old with a 2:1 female predominance. Most of the patients had chronic cough, dyspnea with low lung volumes on radiograph and at least 1 episode of pneumonia requiring hospitalization at our center 1–2 years prior to having the CT scan. The working diagnosis in these patients going in for CT was either fibrotic-type nonspecific interstitial pneumonia or connective tissue-related interstitial lung disease. Many of the patients with nonspecific/mild/early CT findings, noncontributory history or laboratory findings usually responded to treatment for Non-Specific Interstitial Pneumonia (NSIP). There was a subset of patients with the fibrotic type NSIP pattern on CT who had occupational exposure to antigens.

The lung image dataset has been approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the UMMC. This approval is essential to ensure compliance with relevant regulations, adhere to widely accepted ethical standards, abide by institutional policies, and ensure adequate protection for research participants involved in this study.

3.2 Data Preprocessing and Augmentation

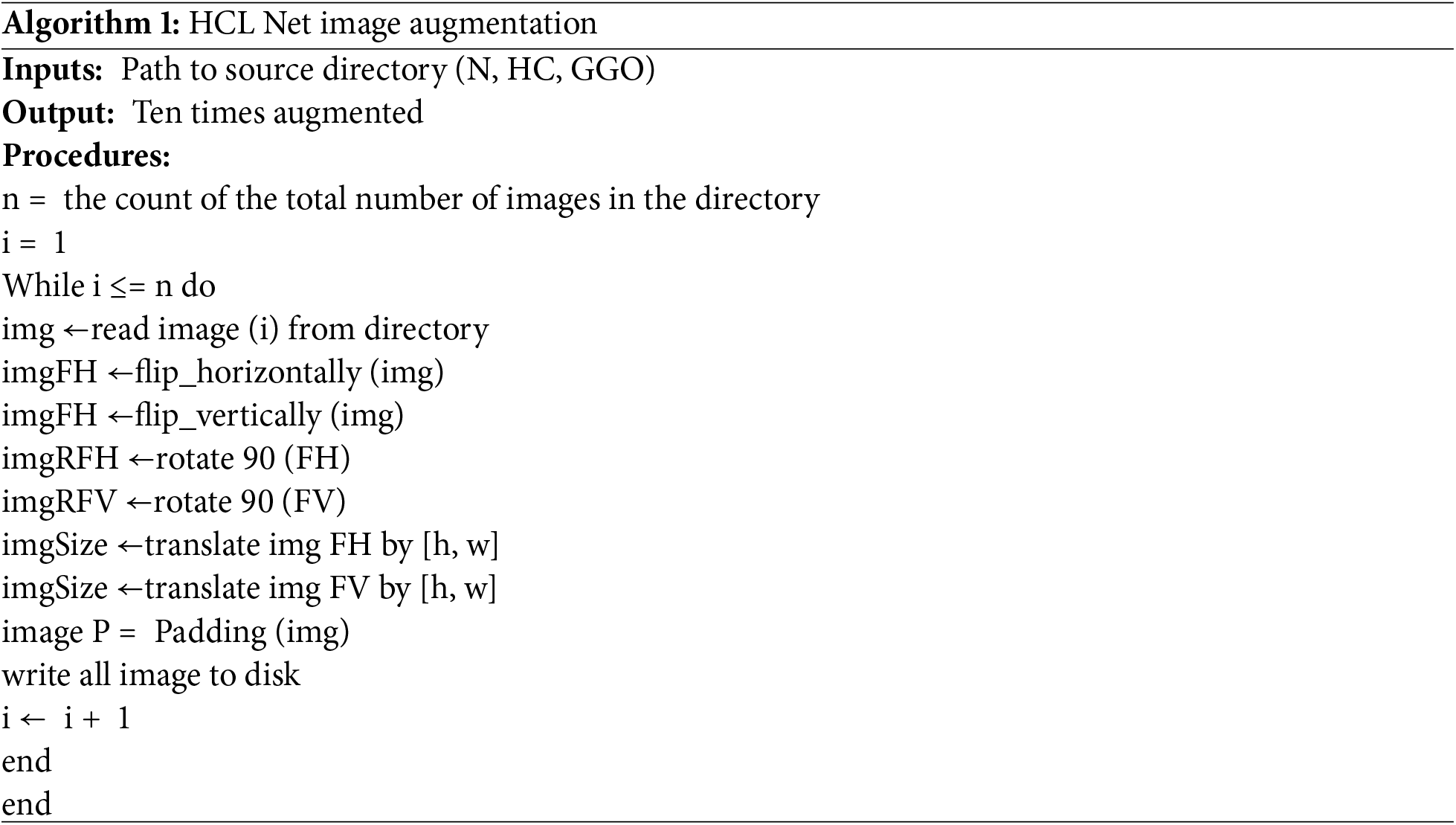

A crucial component of this study’s methodology is the preprocessing of the dataset, which significantly contributed to improved performance in the HCL Net model. In contrast to baseline studies that did not mention preprocessing steps, this study followed multiple preprocessing stages. All CT images were resized to 256 × 256 × 3 pixels, and pixel intensities were normalized to a [0, 1] range, which is essential for amplifying subtle differences between HC and GGO lungs [47]. Furthermore, data augmentation techniques were applied to enhance model generalization and to mitigate overfitting. Augmentation strategies included random rotation, horizontal flipping, and scaling. These techniques generated a broader variety of imaging conditions and anatomical orientations, increasing the diversity of the dataset and bolstering the model’s robustness. Algorithm 1 illustrates the data augmentation algorithm applied within the HCL Net model.

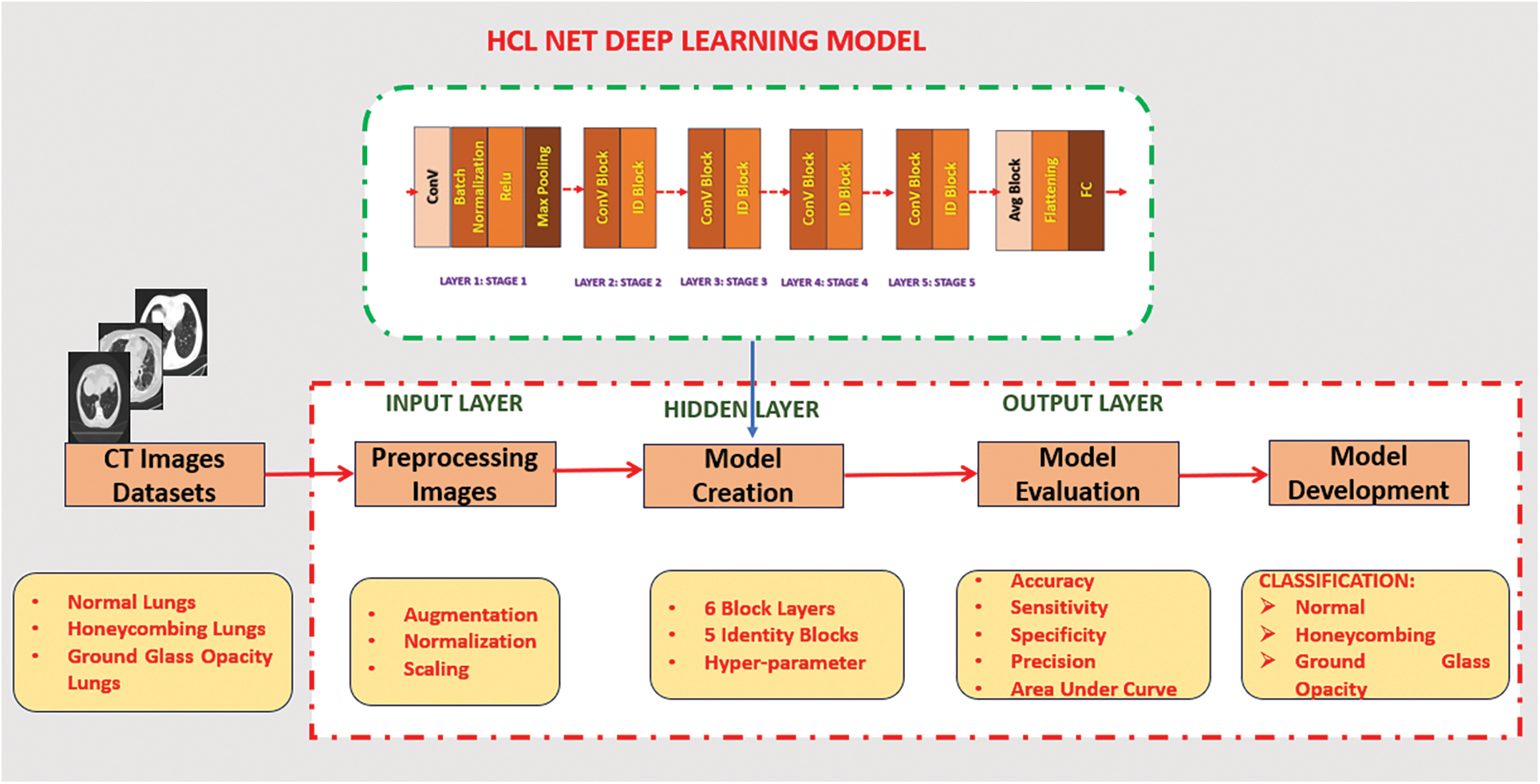

3.3 Proposed HCL Net Architecture

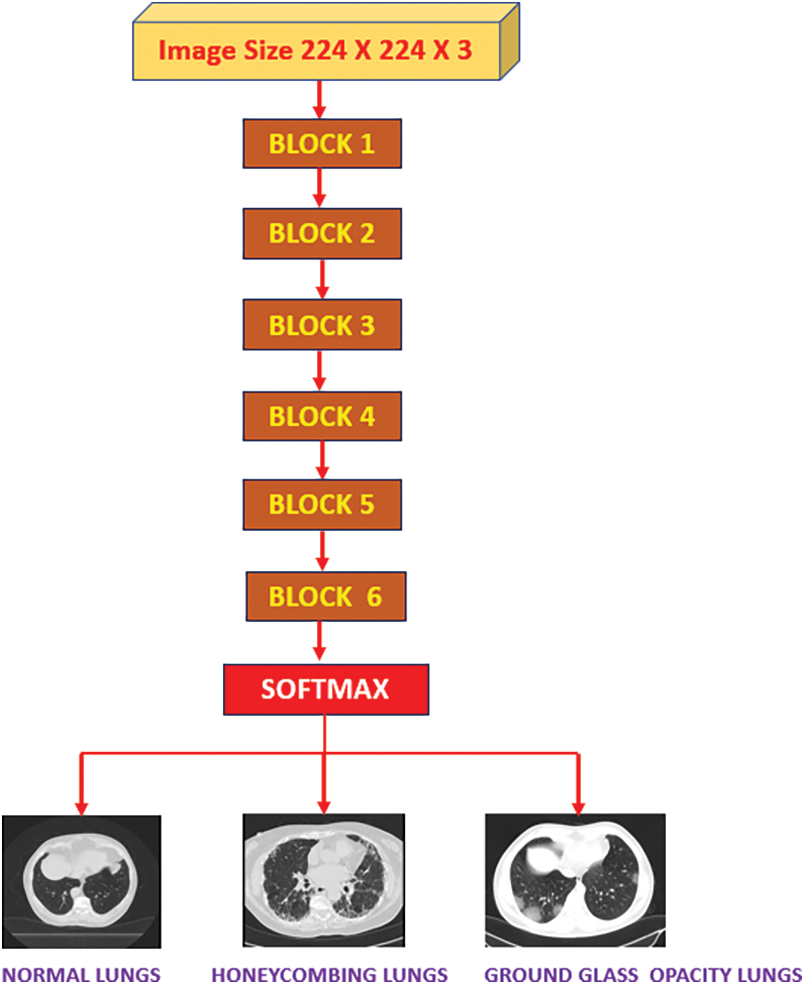

The architecture of HCL Net is an extension of the ResNet50v2 model, incorporating a sixth convolutional block. Each block consists of a sequence of convolutional layers, batch normalization, and activation functions. The additional block, which includes ten convolutional layers with ReLU activations, is specifically designed to capture the intricate patterns and textural nuances present in lung CT images. To prevent the vanishing gradient problem, the network integrates five residual skip connections [25]. These skip connections enable better gradient flow and facilitate the model’s ability to learn complex features. Fig. 1 illustrates the complete architecture of HCL Net, including all six convolutional blocks and the associated skip connections. The final classification layer configuration is discussed in detail in Section 3.4, where the transfer learning and layer freezing strategy are outlined.

Figure 1: HCL Net deep learning model

3.4 Residual Block Modification, Transfer Learning, and Layer Freezing Strategy

Critical preprocessing steps were implemented before classification to ensure uniform image quality and effective feature extraction. Initially, image normalization adjusted pixel values across all CT scan inputs to a consistent range of 0 to 255, followed by scaling to a 0–1 range. These steps improved clarity and consistency, which are essential for accurately distinguishing between visually similar conditions such as HC and GGO. The core of the HoneyCombing Lung Network (HCL Net) is constructed upon a pre-trained ResNet50v2 backbone, with convolutional layers designed to extract detailed image features necessary for accurate classification. The architecture comprises six blocks: Blocks 1 to 5 follow a consistent structure, while Block 6 integrates an additional 10 layers to enable deeper feature learning. Each block contains three convolutional layers supported by Batch Normalization (BN) and Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activations to stabilize and expedite training. The final SoftMax layer facilitates multiclass classification. A key architectural enhancement in HCL Net is the integration of Residual Blocks (RBs), which incorporate shortcut connections that bypass one or more layers. These connections mitigate the vanishing gradient problem and facilitate smoother gradient flow during training, enabling better convergence and learning of identity mappings [25]. This design allows the network to retain and reuse essential low-level features, improving its capacity to detect subtle differences between HC and GGO patterns.

Each residual block includes Batch Normalization, which helps maintain input stability across layers [48], and ReLU activation functions to promote effective nonlinear transformations. Together, these components enable the network to extract robust hierarchical features, supporting its resilience across diverse input variations. To further optimize model performance with limited data, transfer learning was adopted using weights pre-trained on the ImageNet dataset. This enables the reuse of generalized visual patterns while adapting the model to domain-specific features in CT images [49]. A layer freezing strategy was applied as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Freeze and unfreeze layers in the HCL Net Architecture

As shown in Fig. 2, the first three convolutional blocks are frozen, meaning their weights remain static during training to retain foundational feature representations. In contrast, the final three blocks are unfrozen, allowing for retraining and adjustment to specific features found in the target dataset. This selective fine-tuning balances the benefits of transfer learning with the flexibility required for accurate classification in medical imaging. Overall, the integration of residual connections, pre-trained knowledge, and a strategic freeze and unfreeze mechanism establishes HCL Net as a robust and computationally efficient architecture, well-suited for detecting and classifying complex lung conditions in CT scans.

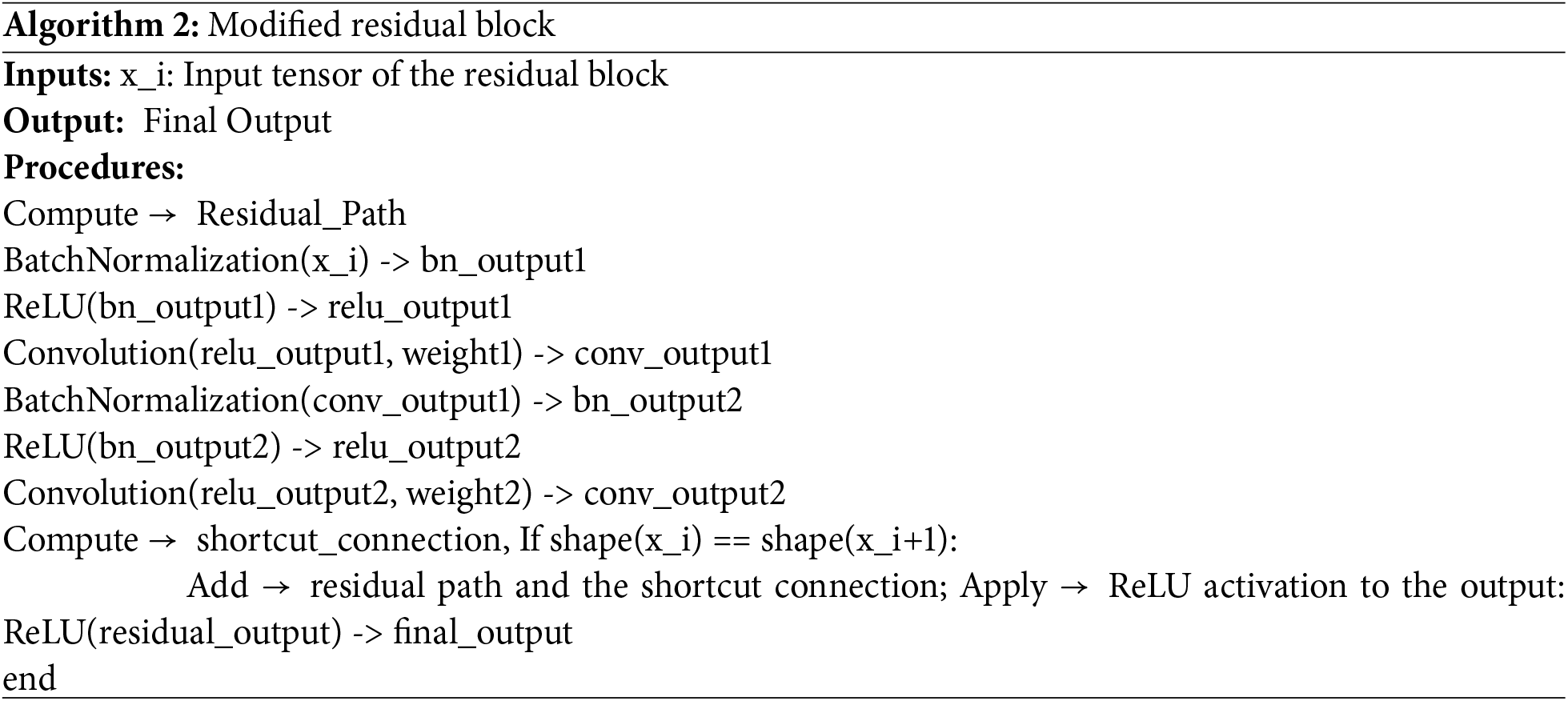

Residual Block Modification

HCL Net architecture employs Residual Blocks (RBs) as a foundational component to enhance training efficiency and classification performance. Specifically, the model utilizes four stacked residual blocks, each designed with shortcut connections that allow the network to bypass one or more convolutional layers. These connections are essential for addressing the vanishing gradient problem, which is common in deeper neural networks. By enabling the network to learn residual functions instead of directly modeling the target mapping, RBs significantly improve gradient flow, optimization, and convergence during training. As depicted in Fig. 3, a structural comparison is made between residual blocks used in conventional state-of-the-art models (a) and the proposed residual blocks in HCL Net (b). Unlike the standard design, the proposed residual blocks incorporate multiple BN layers, ReLU activation functions, and carefully tuned weight layers. This enhancement facilitates better stabilization of input distributions and supports more efficient nonlinear transformations at deeper layers. These modifications enable the model to capture intricate patterns in CT images, particularly when differentiating between HC and GGO lungs.

Figure 3: Residual block modification

Further illustrating this architectural advancement, Algorithm 2 outlines the algorithmic flow for the modified residual block construction. The process involves computing the residual path using a series of convolutional layers, applying multiple batch normalization (BN) and rectified linear unit (ReLU) layers, establishing a shortcut connection, merging it with the residual path, and applying a final activation function. This method ensures that essential spatial features are preserved and emphasized throughout the deeper network layers. This strategic use of enhanced residual blocks improves the model’s capacity to learn complex representations, thereby outperforming baseline architectures in the classification of chronic lung conditions. The efficacy of this approach aligns with findings in prior studies, such as [42], which emphasized the significance of hyperparameter optimization and residual network design in medical imaging applications.

3.5 Model Configuration and Training Strategy

This section details the activation functions, regularization techniques, and training configurations that contribute to the performance and stability of the HCL Net model.

The Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function,

3.5.2 Regularization and Dropout

To prevent overfitting and enhance the model’s generalization capability, L2 regularization was applied with a coefficient of 0.0002, a widely adopted technique in modern deep learning frameworks to penalize large weight values and reduce model complexity [52]. Dropout layers with a dropout rate of 0.3 were incorporated into the fully connected layers to randomly deactivate neurons during training, compelling the network to learn redundant and robust features [53]. As illustrated in Fig. 4, the selected dropout rate was determined based on validation set performance.

Figure 4: Dropout parameters

Studies suggest that dropout rates between 0.2 to 0.5 are commonly effective in reducing overfitting in deep learning models, especially for image classification tasks. This approach not only enhances model robustness but also prevents the network from relying too heavily on specific neurons, thereby encouraging general feature representation. BN was also employed extensively throughout the network, particularly within the Residual Blocks (RB), to stabilize input distributions across mini-batches and speed up the training process [54]. As shown in Fig. 5, BN helps maintain higher learning rates, reduces internal covariate shift, and contributes to overall model robustness and faster convergence. The integration of BN complements the dropout mechanism by further improving training stability and ensuring consistent activation distributions, which is essential in managing the high-dimensional input of CT lung images. Together, these techniques reinforce the model’s ability to generalize well to unseen data and support the reliable classification of lung conditions.

Figure 5: SoftMax activation function in HCL Net model

The training of HCL Net was conducted using the Adam optimizer, renowned for its efficiency and convergence speed in deep neural networks. Adam, or Adaptive Moment Estimation, adapts learning rates for each parameter, making it well-suited for image-based classification tasks [54]. A learning rate of 0.00001 was selected for this study to ensure gradual, stable updates to model weights and improved fine-tuning capabilities on the CT lung dataset. The model was trained using Sparse Categorical Cross-Entropy as the loss function, a widely used choice for multiclass classification tasks due to its ability to handle integer labels efficiently. This optimizer iteratively updates the model’s parameters to minimize the loss function, which in this case is particularly suited for multiclass problems involving image classification. Sparse Categorical Cross-Entropy is commonly favored in deep learning research due to its computational efficiency and accuracy in classifying discrete class labels in image-based tasks [55,48,49]. This loss function computes the divergence between the true class labels and the model’s predicted probabilities, ensuring accurate learning during training. The end-to-end prediction workflow, including the use of Global Average Pooling 2D and dropout adjustment, is illustrated in Algorithm 4, which highlights the multiclass classification pipeline of HCL Net. To evaluate model generalizability, training was conducted using a 70:30 split for training and validation datasets. Additionally, five-fold cross-validation was implemented. The model was trained for 50 epochs, with early stopping employed to halt training when no further improvement was observed in validation accuracy, thereby avoiding overfitting and reducing unnecessary computation.

To assess the performance of the models, six key evaluation metrics were employed: accuracy, precision, specificity, F1-score, sensitivity, and AUC-ROC. These metrics are particularly critical in medical imaging, where both false positives and false negatives must be minimized to support accurate diagnosis and clinical decision-making. Unlike some state-of-the-art studies that rely on limited evaluation criteria, this research adopts a comprehensive evaluation framework, ensuring a more nuanced understanding of model strengths and weaknesses. The inclusion of multiple metrics enables a holistic and multidimensional analysis of model performance, especially in the context of lung CT scan classification, where imbalanced datasets and subtle pathological differences (between honeycombing and ground glass opacity lungs) can skew single-metric interpretations. Recent studies have emphasized that over-reliance on accuracy alone may obscure clinically relevant shortcomings in model performance [56,57]. Hence, using a broader set of metrics not only strengthens model evaluation but also contributes to better optimization during training and enhances generalizability [58]. The following four subsections present a detailed analysis of these metrics across three different models CNN, ResNet50v2, and the proposed HCL Net by discussing their results and comparative performance. This structured analysis provides critical insights into the model’s effectiveness in handling complex lung conditions and reducing diagnostic error rates.

In this study, lung images were subjected to classification, aiming to enhance the categorization of normal, honeycombing lungs, and ground glass opacity. The evaluation involved the comparison of the HCL Net architecture model evaluated with the CNN model architecture and the ResNet50v2 architecture. The feature extraction process utilized the prebuilt ResNet50v2 model. Initially, pre-trained weights were loaded, and the network layers were kept trainable, enabling the model to adapt and learn new patterns from the provided previously unseen medical lung images. The results obtained from this process were then compared with the enhanced model. To assess the effectiveness of the proposed model, five performance metrics were employed for accuracy testing against the benchmark architectures. These metrics included the confusion matrix, 10-fold cross-validation, validation accuracy, multiple evaluation matrices, accuracy, and loss. These measures were utilized to gauge and compare the efficacy and performance of the proposed HCL Net architecture with the established benchmark models.

4.1 Experimental Results 1: Confusion Matrix

The confusion matrix is employed to assess the classification model’s performance, evaluating the baseline models (CNN and ResNet50V2) alongside the proposed HCL Net. In this study, the confusion matrix specifically focused on the classification of honeycombing (HC) lung and ground glass opacity (GGO) lung using three distinct models. These two selected datasets were scrutinized within the confusion matrix due to misclassifications observed in prior research. The confusion matrix serves as a visual representation of each model’s performance in distinguishing between the HC lung and the GGO lung. Table 2 displays the confusion matrices for CNN, ResNet50V2, and HCL Net.

The CNN model, in particular, shows difficulty in distinguishing between the two, with 250 GGO lung images incorrectly classified as HC lungs. This indicates that the CNN model may be insufficiently equipped to capture the subtle and complex patterns required to accurately distinguish between HC and GGO lung conditions. While it shows some sensitivity in detecting GGO lungs, its precision in identifying HC lungs is limited. The ResNet50V2 model performs notably better, with 600 true positives for HC lung, indicating an improved ability to identify HC lung images. However, it still misclassifies 58 GGO lung images as HC lung, and 92 HC lung images are incorrectly labeled as GGO lung. Although ResNet50V2 captures more complex features compared to CNN, it still struggles with accurately identifying all instances of GGO lungs. The HCL Net model shows the best performance among the three, with only minimal misclassifications: 6 GGO lung images misclassified as HC lung and 5 HC lung images mislabeled as GGO lung. This suggests that HCL Net can effectively distinguish between HC and GGO lung patterns, likely due to its advanced architecture and specialized training, which allow it to learn the subtle features characteristic of each condition.

In summary, the results demonstrate a clear improvement in classification accuracy from CNN to ResNet50V2 to HCL Net. The CNN model, being simpler, struggles with complex differentiations, resulting in more misclassifications. ResNet50V2 shows enhanced accuracy but still has limitations. HCL Net, with its deeper architecture, achieves the highest accuracy and reduces both false positives and false negatives, making it a promising option for clinical applications where precise lung condition classification is essential. This progression underscores the significance of using advanced architecture for complex medical image classification tasks.

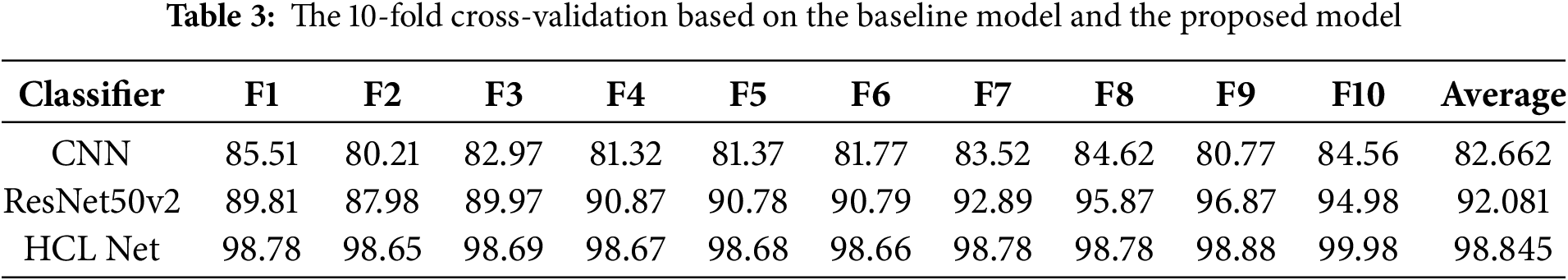

4.2 Experimental Result 2: 10-Fold Cross Validation

Due to previous research findings that highlighted frequent misclassifications between HC lungs and GGO lungs, this study places particular emphasis on evaluating and comparing the classification performance of three models: CNN, ResNet50V2, and the proposed HCL Net. Table 3 presents the prediction accuracy achieved by each classifier through a 10-fold cross-validation approach, enabling a robust comparison of their abilities to distinguish between HC lung and GGO lung.

The results indicate a progressive improvement in classification accuracy from CNN to ResNet50V2 and, ultimately, to HCL Net. Specifically, CNN yields an average accuracy of 82.66%, showing that while it has some capacity for classification, it struggles to differentiate between the intricate patterns of HC and GGO lungs consistently. This limitation is likely due to CNN’s simpler architecture, which lacks the depth necessary for capturing subtle image features that distinguish these lung conditions. The ResNet50V2 model shows a notable improvement, with an average accuracy of 92.08%. Its deeper architecture and residual connections help address some common issues in deep learning models, such as vanishing gradients, allowing it to learn more complex features. As a result, ResNet50V2 demonstrates enhanced accuracy in identifying HC and GGO lung images compared to CNN. However, despite its improvements, there remain instances of misclassification, indicating that further refinement is still needed.

The HCL Net model, designed specifically to enhance classification accuracy for HC and GGO lung images, achieves the highest average accuracy of 98.84%. This performance highlights its effectiveness in handling the subtle distinctions between HC and GGO lung features, as well as its ability to minimize both false positives and false negatives. HCL Net’s superior accuracy can be attributed to its specialized architecture, which integrates additional layers and optimized configurations tailored for this classification task. Overall, the analysis underscores the benefits of a more advanced and customized architecture, such as HCL Net, in achieving high accuracy in complex medical image classification tasks. The progression from CNN to HCL Net highlights the importance of architecture depth, residual connections, and customized layer arrangements in improving the model’s ability to discern between HC and GGO lung patterns accurately. These findings have significant implications for clinical applications, where reliable and precise classification of lung conditions is crucial for diagnosis and treatment planning.

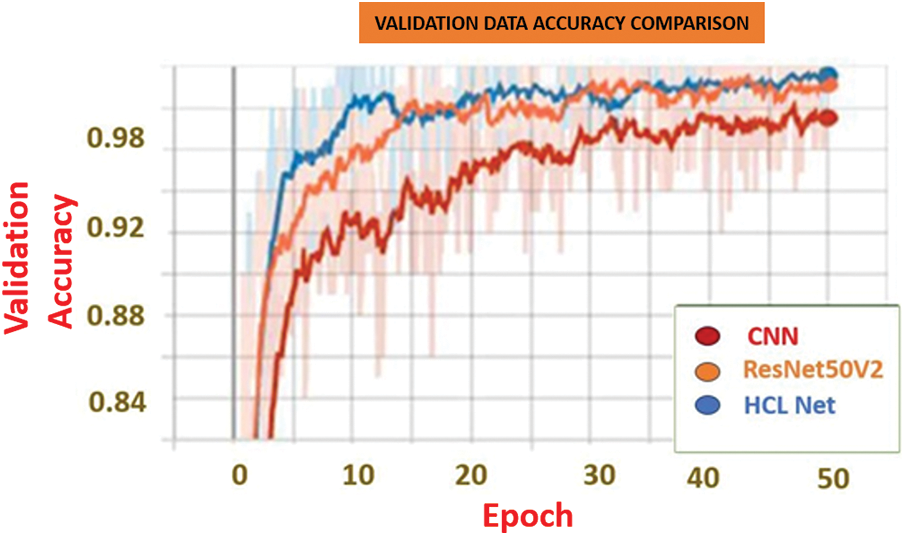

4.3 Experimental Result 3: Validation Accuracy

Fig. 6 highlights the validation accuracy of the three models, further illustrating the HCL Net’s performance advantage over CNN and ResNet50V2. The HCL Net achieved the highest validation accuracy at 99.78%, significantly outperforming ResNet50V2, which reached 95.75%, and CNN, which had an accuracy of 87.03%. This difference underscores HCL Net’s capacity for accurate classification in distinguishing honeycombing and ground glass opacity lung images.

Figure 6: Validation accuracy based on the baseline papers and the proposed model

4.4 Experimental Result 4: Multiple Evaluation Metrix

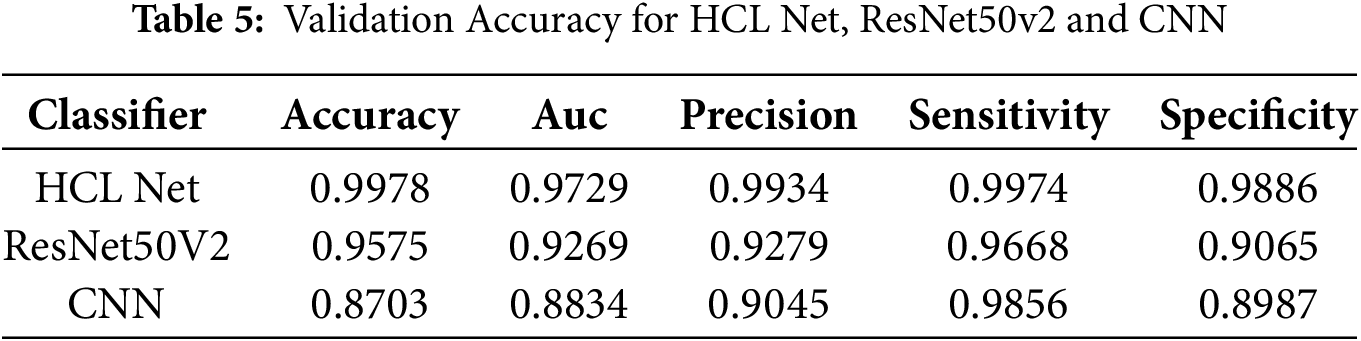

The training and validation results in Tables 4 and 5 provide a clear comparison of the performance metrics across the HCL Net, ResNet50V2, and CNN classifiers. The HCL Net demonstrates superior results in both training and validation, establishing its effectiveness in lung image classification compared to the other models.

In Table 4, which presents the training accuracy, HCL Net achieves the highest accuracy at 99.42%, with an impressive AUC of 0.9989, precision of 0.9934, sensitivity of 0.9968, and specificity of 0.9886. These metrics indicate that HCL Net performs well not only in distinguishing true positives but also in avoiding false positives, resulting in highly reliable classifications during training. The ResNet50V2 model, while also performing well, achieves a lower accuracy of 96.35% and AUC of 0.9291, showing a respectable but notably reduced classification capability. The CNN model further trails behind, with an accuracy of 89.6% and AUC of 0.9021, highlighting its comparatively limited effectiveness in learning the complex features necessary for accurate lung classification.

Table 5 reveals similar trends in validation performance, with HCL Net once again achieving the highest validation accuracy at 99.78% and a solid AUC of 0.9729. Its precision, sensitivity, and specificity remain high, indicating that the model maintains its performance when evaluated on unseen data. ResNet50V2, with a validation accuracy of 95.75% and AUC of 0.9269, performs reasonably well but does not match the robustness of HCL Net. CNN, with the lowest validation accuracy at 87.03% and AUC of 0.8834, exhibits limitations in generalizing to new data, which could lead to less reliable predictions in real-world applications. Overall, the tables underscore HCL Net’s enhanced capacity for lung classification, likely due to its advanced architecture, which includes additional residual blocks and refined parameter adjustments. These architectural improvements contribute to its superior ability to learn and generalize complex patterns, resulting in high precision and reliability in both training and validation stages. This comparative analysis reinforces HCL Net’s potential as a preferred model for accurately classifying lung conditions, especially in applications requiring precise and dependable results.

4.5 Experiment 5: Accuracy and Loss

The training process of the HCL Net model was meticulously designed to assess its performance through two fundamental metrics: accuracy and loss. These metrics serve as critical indicators of the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data, particularly in the context of distinguishing between normal lung tissue and various abnormalities.

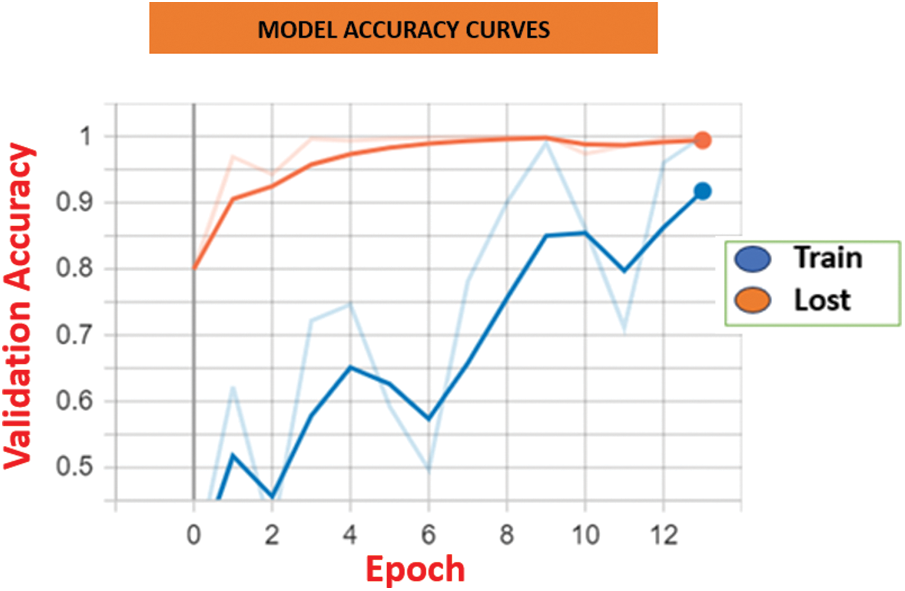

Fig. 7 illustrates the accuracy curves for both training and validation sets. The HCL Net showed a consistent upward trend in training accuracy and maintained a stable validation accuracy throughout the epochs. This indicates that the model not only learned effectively but also generalized well to unseen data. In contrast, baseline models exhibited slower accuracy gains and mild fluctuations in validation accuracy, suggesting potential overfitting or limited learning capacity.

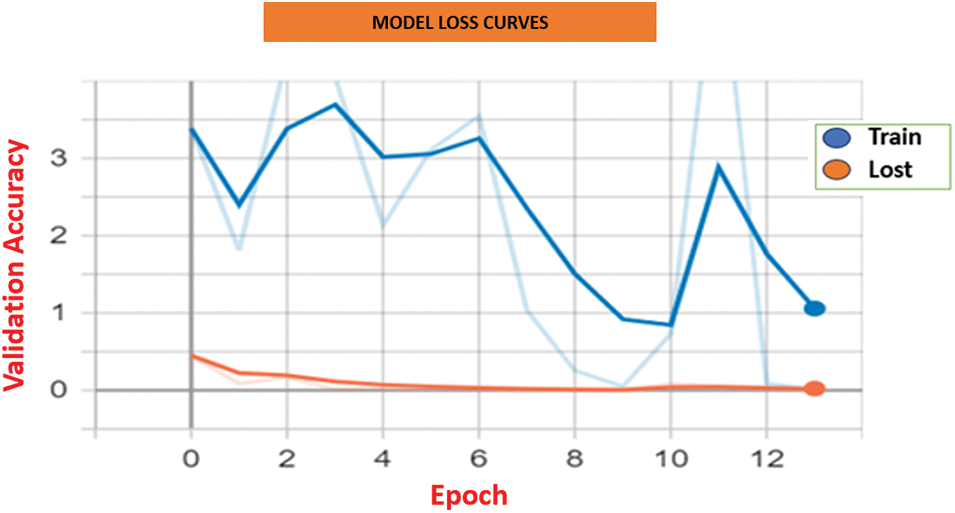

Figure 7: Model loss curves for HCL Net and baseline approaches

Fig. 8 displays the loss curves across the training epoch. HCL Net’s loss decreased steadily, with minimal variance between training and validation losses. This trend reflects efficient parameter tuning and reduced prediction errors as training progressed. On the other hand, baseline models showed less consistent loss reduction and occasional spikes, implying challenges in optimization or convergence. These results affirm the effectiveness of the residual block modifications, transfer learning, and the layer freezing strategy adopted in HCL Net. The use of well-tuned hyperparameters and deeper feature learning contributed significantly to the superior accuracy and lower loss values. Together, these findings emphasize the importance of architectural enhancements and training strategies in improving performance in medical image classification. In summary, the consistent improvements in both accuracy and loss validate the robustness of the HCL Net model and its applicability in clinical diagnostic tasks involving complex lung abnormalities.

Figure 8: Model Accuracy comparison between HCL Net and baseline approaches

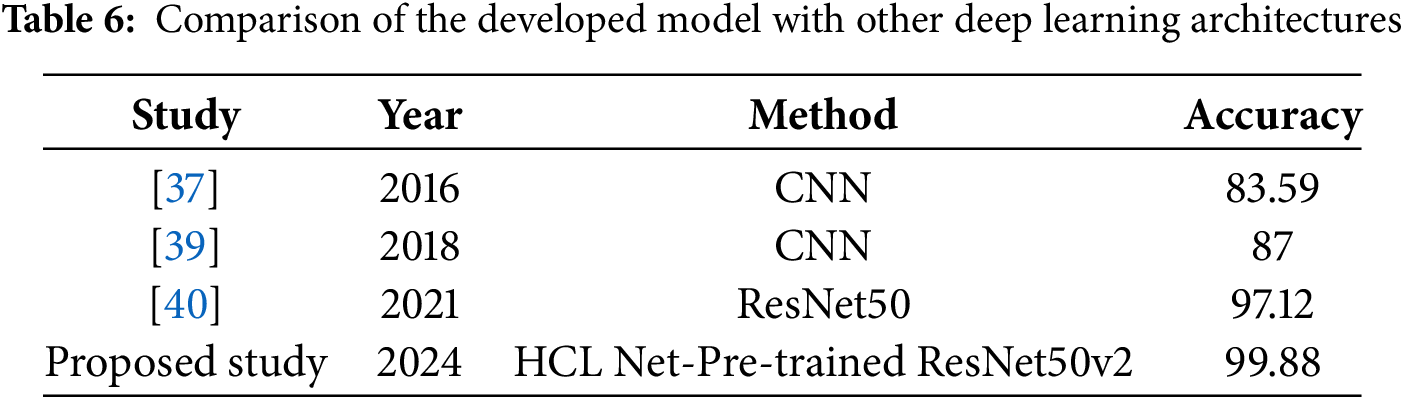

The primary objective of this study was to enhance the accuracy of honeycomb lung classification through the development of the HCL-Net model, utilizing a pre-trained ResNet50v2 architecture. This focus is particularly significant given the limited attention that honeycomb lung, a critical and often debilitating lung condition, has received in the realm of deep learning research. Most existing studies have predominantly concentrated on lung cancer, leaving a gap in the exploration of models specifically designed for other severe lung diseases. The introduction of HCL-Net represents a strategic effort to address the misclassification challenges encountered in previous research, particularly the confusion between honeycomb lungs and ground glass opacity. By tailoring the ResNet50v2 model for this specific classification task, HCL-Net aims to rectify the accuracy challenges that have hindered effective diagnosis in clinical settings. The promising results achieved in this study are underscored by the HCL-Net model’s performance, which reached an impressive accuracy rate of 99.88%, as shown in Table 6. This not only surpasses the accuracy rates of various baseline models but also demonstrates the potential of utilizing advanced deep learning techniques for precise disease classification. The findings highlight the efficacy of the HCL-Net model in distinguishing honeycomb lungs from other lung conditions, which is crucial for improving diagnostic outcomes and patient management. The significant improvement in accuracy compared to previous studies illustrates the model’s robustness and adaptability in learning the complex features associated with honeycomb lung pathology. This research contributes valuable insights into the application of deep learning in medical imaging, emphasizing the importance of focusing on underrepresented diseases within the field.

Looking ahead, there is a clear need for further refinement of the HCL-Net model to enhance its performance even further. Future studies could explore additional techniques such as data augmentation, fine-tuning of hyperparameters, or the incorporation of ensemble methods to bolster classification accuracy and reduce the likelihood of misclassifications. By continuing to advance the capabilities of deep learning models in the classification of honeycomb lungs and other similar conditions, we can better support clinical decision-making and improve patient outcomes.

In this study, a dataset obtained from UMMC was utilized, comprising 2400 CT images that include normal lungs, honeycombing lungs, and ground-glass opacity lungs. These raw images were subjected to pre-processing methods like image normalization, augmentation, and scaling before being rescaled to a size of 224 × 224 × 3. The dataset was divided into 70% and 20%. Optimizing HCL-Net involved fine-tuning its hyperparameters to achieve an optimal architecture for honeycombing classification. These hyperparameter values are crucial in governing the learning process, directly influencing various model parameters such as weights and biases, which in turn affect model performance. To enhance the accuracy of HCL-Net, the hyperparameter was fine-tuned. This process utilized random search optimization, which has been recommended by many researchers for its efficiency in exploring hyperparameters compared to grid search. Unlike grid search, random search optimizes by randomly selecting points in the hyperparameter space, making it easier and faster to implement. The strategy may lead to a less evenly spaced set of points, yet it enhances efficiency. For HCL-Net, random search optimization was conducted to identify the most suitable hyperparameters for honeycombing classification. The range of hyperparameters used in the random search optimization process is presented in Table 7.

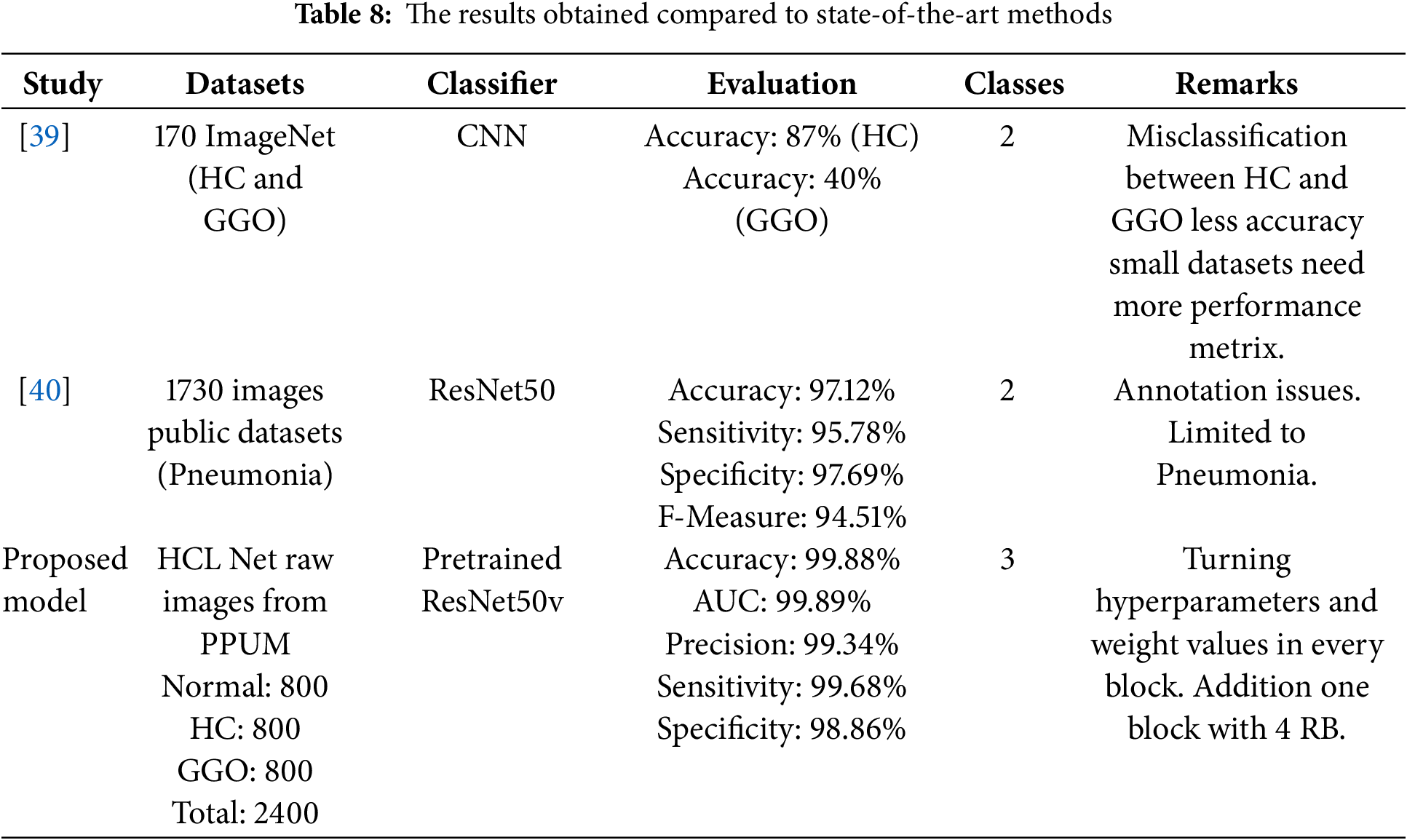

The HCL Net model demonstrated superior performance in accuracy compared to the methods outlined in Table 8, particularly in the context of the three-class classification task involving honeycomb lung, ground glass opacity, and normal lung tissue. This model achieved an impressive accuracy rate of 99.88%, a significant enhancement that can be attributed to the incorporation of additional layers and the meticulous tuning of hyperparameters, as discussed in earlier sections of the study. The effectiveness of HCL Net lies not only in its high accuracy but also in its ability to assist radiologists in accurately classifying honeycomb lung cases. Given the complexity and variability in imaging presentations of lung conditions, the model’s capability to correctly identify honeycomb lungs serves as a valuable tool in clinical practice. The exceptional accuracy achieved by HCL Net indicates its potential to reduce misdiagnosis, which can lead to better patient outcomes and more informed clinical decisions. Comparing the HCL Net results with state-of-the-art methods reveals notable differences. For instance, previous studies using CNNs and ResNet50v2 have reported lower accuracy rates, with some models struggling with high misclassification rates between honeycomb and ground glass opacity.

The HCL Net model’s architecture, which includes fine-tuning and the addition of an extra block with multiple residual blocks, contributes to its enhanced performance. This design choice effectively allows the model to learn complex patterns more efficiently, thereby addressing the shortcomings of earlier models, which were limited by smaller datasets and various annotation issues.

Moreover, the metrics presented in Table 8 highlight the holistic evaluation of HCL Net, showcasing not only accuracy but also other vital performance indicators such as precision, sensitivity, and specificity. These metrics collectively reinforce the model’s robustness and reliability in a clinical setting. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 99.89 further emphasizes the model’s exceptional ability to differentiate between the three classes effectively. In summary, the HCL Net model stands out as a powerful tool in the realm of medical imaging for lung disease classification. Its advanced architecture, coupled with rigorous hyperparameter optimization, has resulted in outstanding performance metrics, positioning it as a significant advancement in aiding radiologists in diagnosing and managing honeycomb lung and related conditions.

The primary objective of HCL Net is to classify normal lungs, honeycombing lungs, and ground glass opacity lungs by leveraging pre-trained feature extraction using ResNet50v2. Building upon the baseline ResNet50v2 architecture, additional layers were incorporated, and hyperparameters were fine-tuned. This improved architecture facilitated classification using both the CNN model and ResNet50v2, ultimately achieving the highest accuracy within the developed model. A new dataset, thoroughly validated by an expert and meticulously annotated, was created to ensure accuracy and flexibility for potentially automated labeling in future classification methods. This dataset, validated for accuracy and reliability, can be shared as a public benchmark, enabling future advancements by other researchers in the field. Moreover, future data augmentation of this dataset could yield similar results without compromising classification accuracy, thereby enhancing its quality. The enhanced HCL Net represents a tailored adaptation of the existing pre-trained model, ResNet50v2. While the baseline ResNet50v2 was trained on ImageNet, a collection of over 1000 diverse global objects, it was not originally designed for honeycomb lung classification. In contrast, HCL Net is specifically designed for multi-classification problems related to honeycombing. This specialization is a key factor contributing to its achievement of 99% accuracy. Furthermore, HCL Net allows for the use of specific image kernels for feature extraction, significantly improving training times by customizing image kernels at the convolutional layers of the model. This tailored approach enhances the model’s efficiency and effectiveness in classifying complex lung conditions.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: There is no funding statement available for this research.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design were carried out by Hairul Aysa Abdul Halim Sithiq, Muneer Ahmad and Liyana Shuib. Data collection was conducted by Hairul Aysa Abdul Halim Sithiq and Chermaine Deepa Antony. Analysis and interpretation of results were performed by Hairul Aysa Abdul Halim Sithiq, Muneer Ahmad and Liyana Shuib. The draft manuscript was prepared by Hairul Aysa Abdul Halim Sithiq, Muneer Ahmad and Liyana Shuib. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request.

Ethics Approval: This research project has obtained the ethical approval of the UMMC Ethics Committee (approval number IRB: 20241016-14314). The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The informed consent of the participants was obtained and the informed consent of the University Malaya Medical Centre, Malaysia (UMMC) hospital was obtained.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Johkoh T, Sakai F, Noma S, Akira M, Fujimoto K, Watadani T, et al. Honeycombing on CT; its definition, pathologic correlation, and future direction of its diagnosis. Eur J Radiol. 2014;83(1):27–31. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.05.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Wielpütz MO, Heußel CP, Herth FJ, Kauczor H-U. Radiological diagnosis in lung disease: factoring treatment options into the choice of diagnostic modality. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111(11):181. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2014.0181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Cozzi D, Cavigli E, Moroni C, Smorchkova O, Zantonelli G, Pradella S, et al. Ground-glass opacity (GGOa review of the differential diagnosis in the era of COVID-19. Jpn J Radiol. 2021;39(8):721–32. doi:10.1007/s11604-021-01120-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. El-Sherief AH, Gilman MD, Healey TT, Tambouret RH, Shepard J-AO, Abbott GF, et al. Clear vision through the haze: a practical approach to ground-glass opacity. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2014;43(3):140–58. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2014.01.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Aburto M, Herráez I, Iturbe D, Jiménez-Romero A. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: differential diagnosis. Med Sci. 2018;6(3):73. doi:10.3390/medsci6030073. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Gurkan CG, Karadogan D, Ufuk F, Cure O, Altinisik G. Management of patients with connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Turkish Thoracic J. 2021;22(4):346. doi:10.5152/TurkThoracJ.2021.20172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Oikonomou A, Mintzopoulou P, Tzouvelekis A, Zezos P, Zacharis G, Koutsopoulos A, et al. Pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: is the emphysema type associated with the pattern of fibrosis? World J Radiol. 2015;7(9):294. doi:10.4329/wjr.v7.i9.294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Frix A-N, Cousin F, Refaee T, Bottari F, Vaidyanathan A, Desir C, et al. Radiomics in lung diseases imaging: state-of-the-art for clinicians. J Pers Med. 2021;11(7):602. doi:10.3390/jpm11070602. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Monkam P, Qi S, Ma H, Gao W, Yao Y, Qian W. Detection and classification of pulmonary nodules using convolutional neural networks: a survey. IEEE Access. 2019;7:78075–91. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2920980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wang C, Elazab A, Wu J, Hu Q. Lung nodule classification using deep feature fusion in chest radiography. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2017;57(12):10–8. doi:10.1016/j.compmedimag.2016.11.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Mazurowski MA, Habas PA, Zurada JM, Lo JY, Baker JA, Tourassi GD. Training neural network classifiers for medical decision making: the effects of imbalanced datasets on classification performance. Neural Netw. 2008;21(2–3):427–36. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2007.12.031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Öztürk Ş. Class-driven content-based medical image retrieval using hash codes of deep features. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2021;68(2):102601. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2021.102601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Soni J, Ansari U, Sharma D, Soni S. Predictive data mining for medical diagnosis: an overview of heart disease prediction. Int J Comput Appl. 2011;17(8):43–8. [Google Scholar]

14. Yadav SS, Jadhav SM. Deep convolutional neural network based medical image classification for disease diagnosis. J Big Data. 2019;6(1):1–18. doi:10.1186/s40537-019-0276-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Gu Y, Chi J, Liu J, Yang L, Zhang B, Yu D, et al. A survey of computer-aided diagnosis of lung nodules from CT scans using deep learning. Comput Biol Med. 2021;137:104806. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104806. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Olayeye AK, Ukor OC, Aldakhil S, et al. Artificial Intelligence for Responsible Imaging (AIRIstreamlining radiology workflow, enhancing diagnostic accuracy, and reducing repeat scans. Radiology: Artificial Intelligence. 2025. doi:10.1001/jama.2025.0147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Umirzakova S, Ahmad S, Khan LU, Whangbo T. Medical image super-resolution for smart healthcare applications: a comprehensive survey. Inf Fusion. 2023;103(5):102075. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2023.102075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Wagholikar KB, Sundararajan V, Deshpande AW. Modeling paradigms for medical diagnostic decision support: a survey and future directions. J Med Syst. 2012;36:3029–49. doi:10.1007/s10916-011-9780-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Li M, Jiang Y, Zhang Y, Zhu H. Medical image analysis using deep learning algorithms. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1273253. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1273253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Astley JR, Wild JM, Tahir BA. Deep learning in structural and functional lung image analysis. British J Radiol. 2022;95(1132):20201107. doi:10.1259/bjr.20201107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Taye MM. Understanding of machine learning with deep learning: architectures, workflow, applications and future directions. Computers. 2023;12(5):91. doi:10.3390/computers12050091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Dack E, Christe A, Fontanellaz M, Brigato L, Heverhagen JT, Peters AA, et al. Artificial intelligence and interstitial lung disease: diagnosis and prognosis. Investig Radiol. 2023;58(8):602–9. doi:10.1097/RLI.0000000000000974. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Zhou W, Wang H, Wan Z. Ore image classification based on improved CNN. Comput Electr Eng. 2022;99:107819. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2022.107819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Halder A, Datta B. COVID-19 detection from lung CT-scan images using transfer learning approach. Mach Learn Sci Technol. 2021;2(4):045013. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2022.107819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Las Vegas, NV, USA. 2016. p. 770–8. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2022.107819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang F, Wang Q, Li H. Automatic segmentation of the gross target volume in non-small cell lung cancer using a modified version of resnet. Technol Cancer Res Treatment. 2020;19(3):1533033820947484. doi:10.1177/1533033820947484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhang S, Yuan G-C. Deep transfer learning for COVID-19 detection and lesion recognition using chest CT images. Comput Math Methods Med. 2022;2022:4509394. doi:10.1155/2022/4509394. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Malik H, Anees T. Bdcnet: multi-classification convolutional neural network model for classification of COVID-19, pneumonia, and lung cancer from chest radiographs. Multimed Syst. 2022;28(3):815–29. doi:10.1007/s00530-021-00878-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Choi JY, Rhee CK. Diagnosis and treatment of early chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD). J Clin Med. 2020;9(11):3426. doi:10.3390/jcm9113426. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Ohno Y, Aoyagi K, Takenaka D, Yoshikawa T, Ikezaki A, Fujisawa Y, et al. Machine learning for lung CT texture analysis: improvement of inter-observer agreement for radiological finding classification in patients with pulmonary diseases. Eur J Radiol. 2021;134:109410. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2020.109410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Lee J-G, Jun S, Cho Y-W, Lee H, Kim GB, Seo JB, et al. Deep learning in medical imaging: general overview. Korean J Radiol. 2017;18(4):570. doi:10.3348/kjr.2017.18.4.570. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Lundervold AS, Lundervold A. An overview of deep learning in medical imaging focusing on MRI. Zeitschrift Für Medizinische Physik. 2019;29(2):102–27. doi:10.1016/j.zemedi.2018.11.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Rundo L, Militello C. Image biomarkers and explainable AI: handcrafted features versus deep learned features. Eur Radiol Exp. 2024;8(1):130. doi:10.1186/s41747-024-00529-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Makaju S, Prasad P, Alsadoon A, Singh A, Elchouemi A. Lung cancer detection using CT scan images. Procedia Comput Sci. 2018;125(6):107–14. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2017.12.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Jeyapaul VH, Naidu L, Nehemiah HK, Sannasi G, Kannan A. Identification and classification of pulmonary nodule lung modality using digital computer. Appl Math Inf Sci. 2018;12(2):451–9. doi:10.18576/amis/120220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Gao L, Zhang L, Liu C, Wu S. Handling imbalanced medical image data: a deep-learning-based one-class classification approach. Artif Intell Med. 2020;108:101935. doi:10.1016/j.artmed.2020.101935. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Anthimopoulos M, Christodoulidis S, Ebner L, Christe A, Mougiakakou S. Lung pattern classification for interstitial lung diseases using a deep convolutional neural network. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 2016;35(5):1207–16. doi:10.1109/TMI.2016.2535865. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Zhu W, Liu C, Fan W, Xie X. Deeplung: 3D deep convolutional nets for automated pulmonary nodule detection and classification. arXiv:1709.05538. 2021. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1709.05538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Eğriboz E, Kaynar F, Albayrak SV, Müsellim B, Selçuk T. Finding and following of honeycombing regions in computed tomography lung images by deep learning. arXiv:1811.02651. 2018. [Google Scholar]

40. Çınar A, Yıldırım M, Eroğlu Y. Classification of pneumonia cell images using improved resnet50 model. Traitement Signal. 2021;38(1):165–73. doi:10.18280/ts.380117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Li G, Zhang HX, E. L, Zhang L, Li Y, Zhao JM. Recognition of honeycomb lung in CT images based on improved mobilenet model. Med Phys. 2021;48(8):4304–15. doi:10.1002/mp.14873. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Chen Y, Lin Y, Xu X, Ding J, Li C, Zeng Y, et al. Classification of lungs infected COVID-19 images based on inception-resnet. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2022;225(7):107053. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2022.107053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Acar E, Öztoprak B, Reşorlu M, Daş M, Yılmaz İ, Öztoprak İ. Efficiency of artificial intelligence in detecting COVID-19 pneumonia and other pneumonia causes by quantum fourier transform method. medRxiv. 2021;2020–12. doi:10.1101/2020.12.29.20248900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Wu N, Phang J, Park J, Shen Y, Huang Z, Zorin M, et al. Deep neural networks improve radiologists’ performance in breast cancer screening. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 2019;39(4):1184–94. doi:10.1109/TMI.2019.2945514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Showkat S, Qureshi S. Efficacy of transfer learning-based ResNet models in chest X-ray image classification for detecting covid-19 pneumonia. Chemometr Intell Lab Syst. 2022;224:104534. doi:10.1016/j.chemolab.2022.104534. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Shorten C, Khoshgoftaar TM. A survey on image data augmentation for deep learning. J Big Data. 2019;6(1):60. doi:10.1186/s40537-019-0197-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Ioffe S, Szegedy C. Batch normalization: accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. Brooklyn, NY, USA: PMLR; 2015. p. 448–56. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1502.03167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Yosinski J, Clune J, Bengio Y, Lipson H. How transferable are features in deep neural networks? In: Advances in neural information processing systems. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2014. Vol. 27, p. 3320–8. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1411.1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Nair V, Hinton GE. Rectified linear units improve restricted boltzmann machines. In: Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-10). Haifa, Israel; 2010. p. 807–14. doi:10.5555/3104322.3104425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Banerjee K, Gupta RR, Vyas K, Mishra B. Exploring alternatives to softmax function. arXiv:2011.11538. 2020. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2011.11538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Zhang X, Zheng Y, Lee H. Efficient L2 regularization techniques for deep learning models. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2018;27(4):1405–17. doi:10.1109/TIP.2018.2834561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Srivastava N, Hinton G, Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Salakhutdinov R. Dropout: a simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J Mach Learn Res. 2014;15:1929–58. doi:10.5555/2627435.2670313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Kingma DP, Ba J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. arXiv:1412.6980. 2015. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1412.6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Kim Y, Lee Y, Jeon M. Imbalanced image classification with complement cross-entropy. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2021;151(16):33–40. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2021.07.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Singh NP, Bapi RS, Vinod PK. Machine learning models to predict the progression from early to late stages of papillary renal cell carcinoma. Comput Biol Med. 2018;100(Suppl 17):92–9. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2018.06.030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Zhang K, Liu X, Xu J, Yuan J, Cai W, Chen T, et al. Deep-learning models for the detection and incidence prediction of chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes from retinal fundus images. Nat Biomed Eng. 2021;5(6):533–45. doi:10.1038/s41551-021-00745-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Gao XY, Amin Ali A, Shaban Hassan H, Anwar EM. Improving the accuracy for analyzing heart diseases prediction based on the ensemble method. Complexity. 2021;2021(1):6663455. doi:10.1155/2021/6663455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Huang Y, Liu Y, Steel PAD, Axsom KM, Lee JR, Tummalapalli SL, et al. Deep significance clustering: a novel approach for identifying risk-stratified and predictive patient subgroups. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28(12):2641–53. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocab203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools