Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Federated Multi-Label Feature Selection via Dual-Layer Hybrid Breeding Cooperative Particle Swarm Optimization with Manifold and Sparsity Regularization

1 School of Computer Science, Hubei University of Technology, Wuhan, 430000, China

2 Hubei Provincial Key Laboratory of Green Intelligent Computing Power Network, Wuhan, 430000, China

* Corresponding Author: Huazhong Jin. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068044

Received 20 May 2025; Accepted 21 August 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Multi-label feature selection (MFS) is a crucial dimensionality reduction technique aimed at identifying informative features associated with multiple labels. However, traditional centralized methods face significant challenges in privacy-sensitive and distributed settings, often neglecting label dependencies and suffering from low computational efficiency. To address these issues, we introduce a novel framework, Fed-MFSDHBCPSO—federated MFS via dual-layer hybrid breeding cooperative particle swarm optimization algorithm with manifold and sparsity regularization (DHBCPSO-MSR). Leveraging the federated learning paradigm, Fed-MFSDHBCPSO allows clients to perform local feature selection (FS) using DHBCPSO-MSR. Locally selected feature subsets are encrypted with differential privacy (DP) and transmitted to a central server, where they are securely aggregated and refined through secure multi-party computation (SMPC) until global convergence is achieved. Within each client, DHBCPSO-MSR employs a dual-layer FS strategy. The inner layer constructs sample and label similarity graphs, generates Laplacian matrices to capture the manifold structure between samples and labels, and applies -norm regularization to sparsify the feature subset, yielding an optimized feature weight matrix. The outer layer uses a hybrid breeding cooperative particle swarm optimization algorithm to further refine the feature weight matrix and identify the optimal feature subset. The updated weight matrix is then fed back to the inner layer for further optimization. Comprehensive experiments on multiple real-world multi-label datasets demonstrate that Fed-MFSDHBCPSO consistently outperforms both centralized and federated baseline methods across several key evaluation metrics.Keywords

In recent years, rapid advancements in network and communication technologies have facilitated the integration of intelligent transportation systems, smart healthcare, and the Internet of Things (IoT), generating vast amounts of high-dimensional multi-label data. Applications such as image annotation, text classification, and personalized recommendation increasingly rely on multi-label learning, where instances can be associated with multiple labels—distinct from traditional single-label classification [1]. However, as data dimensionality grows, the presence of redundant and noisy features leads to the “curse of dimensionality,” which undermines training efficiency, heightens the risk of overfitting, and degrades generalization performance [2]. Consequently, effective feature selection (FS) in multi-label contexts has become a critical challenge.

With the rise of IoT, traditional centralized data processing faces issues such as high latency and privacy risks. To address the need for low-latency, localized processing, many IoT applications are adopting distributed architectures like edge computing [3] and Federated Learning (FL) [4]. Yet, federated settings pose significant problems for FS algorithms due to heterogeneous data distributions that are non-independent and identically distributed (non-IID), limited communication bandwidth, and strict privacy requirements. This calls for algorithms that not only preserve privacy and improve computational efficiency but also ensure effective and reliable FS.

In multi-label learning, the presence of strong inter-label dependencies significantly increases the complexity of FS. Existing methods typically employ first-order (independent labels), second-order (pairwise label relationships), or higher-order (complex dependency structures) strategies for FS [5], often augmented by advanced techniques such as Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [6], manifold learning [7], semi-supervised approaches [8], long short-term memory (LSTM) [9], and incremental learning [10] to enhance performance. Despite notable advancements, these methods continue to face considerable challenges in high-dimensional, non-IID data scenarios, including susceptibility to the local optima, low solution quality in multi-label feature selection (MFS), and limited generalizability.

To overcome these issues, researchers have explored meta-heuristic algorithms (MAs) such as Genetic Algorithms (GA) [11], Ant Colony Optimization algorithm (ACO) [12], and Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm (PSO) [13], which enhance global search capabilities and improve the stability of FS. Ye et al. [14] proposed the Hybrid Breeding Optimization algorithm (HBO), inspired by the heterosis theory of Chinese hybrid rice breeding. The algorithm partitions rice into three groups—maintainer, sterile, and restorers—based on fitness ranking, and these groups evolve cooperatively to produce superior offspring. This method has demonstrated strong performance in FS [13] and MFS tasks [15]. PSO, a well-established heuristic algorithm, is recognized for its robustness and rapid convergence, excelling in global search but often susceptible to being trapped in the local optima. Wang et al. [16] proposed a distance-based multi-objective PSO, which fully leverages PSO’s global search capability, incorporating adaptive distance and position update strategies to enhance optimization performance. Zhong et al. [17] introduced the self-adaptive competitive swarm optimizer, which exploits PSO’s global search advantage and combines parameter sorting and population reduction strategies to achieve superior performance across multiple benchmark and real-world problems. In contrast, the co-evolutionary mechanism of HBO refines the search trajectory, alleviating premature convergence and enhancing stability. The integration of these two algorithms provides a promising solution to enhance both the performance and stability of MFS models.

While recent efforts to integrate FL with MFS mainly utilize methods such as mutual information [18], fuzzy information theory [19], or causal inference [20], these approaches often fall short of fully capturing complex feature interactions and rely solely on the inherent data aggregation of FL for privacy protection. This is insufficient to safeguard sensitive information during large-scale transmission, leaving the system vulnerable to privacy breaches. Furthermore, most methods overlook local manifold structures and redundancy in high-dimensional data, leading to unstable performance under non-IID conditions.

To address these challenges, we propose Fed-MFSDHBCPSO—a novel framework for federated MFS, based on dual-layer hybrid breeding cooperative PSO with manifold and sparsity regularization (DHBCPSO-MSR). Built upon a FL architecture, Fed-MFSDHBCPSO integrates manifold regularization,

• We propose Fed-MFSDHBCPSO, a FL framework that enables privacy-preserving and efficient distributed MFS by executing DHBCPSO-MSR locally on each client, while integrating DP and SMPC to ensure encrypted transmission and secure aggregation.

• We propose DHBCPSO-MSR, a dual-layer MFS algorithm. The inner layer optimizes the FS weight matrix through manifold regularization and sparsity constraints on both samples and labels, enhancing feature discriminability. The outer layer further refines the weight matrix obtained from the inner layer using HBCPSO, ultimately achieving the optimal FS weight matrix.

• We propose HBCPSO, an algorithm inspired by the co-evolutionary mechanism of hybrid breeding optimization (HBO) based on heterosis theory. The population is divided into maintainer, sterile, and restorer lines based on fitness ranking, with each line optimized through co-evolution. PSO is applied within each line for global search. The optimal solution information is exchanged periodically among populations, resulting the generation of superior offspring. HBCPSO effectively avoids local sparsity traps and improves the global optimization of FS.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the related work, and Section 3 presents the proposed method in detail. Section 4 reports experimental results on real-world datasets to validate the effectiveness of the approach. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper.

Most early studies have focused on centralized MFS, while research on federated approaches for multi-label datasets remains limited. To date, only a few works have explored federated MFS. The following section reviews these studies.

2.1 Centralized Multi-Label Feature Selection

MFS methods are typically classified into two main categories: problem transformation and algorithm adaptation. Problem transformation approaches convert multi-label tasks into multiple single-label problems, enabling the application of traditional single-label FS techniques such as entropy-based label assignment (ELA), binary relevance (BR), and label powerset (LP) [23]. However, BR neglects the dependencies among labels, whereas LP often suffers from class imbalance and increased computational complexity.

Algorithm adaptation techniques overcome these limitations by directly extending single-label FS methods to handle multi-label data. Representative strategies include mutual information-based approaches for evaluating feature relevance and redundancy, as well as causal discovery frameworks for identifying causally informative features [24]. Moreover, MAs such as GA [11], ACO [12] and PSO [13] have been successfully employed to explore high-dimensional feature spaces.

Sparse learning has become a key focus in recent MFS research [25], with

2.2 Federated Multi-Label Feature Selection

Federated FS has recently advanced in both single-label and multi-label domains [31]. Inspired by the FL paradigm, existing methods are generally categorized into vertical and horizontal federated FS. Vertical FS applies when clients share the same instance IDs but possess different feature spaces [32], whereas horizontal FS is used when clients hold different data instances while sharing a common feature set [33].

Within horizontal federated MFS, Mahanipour and Khamfroush [18] introduced FMLFS, which employs information-theoretic measures to evaluate feature-label associations and mitigate redundancy. They further proposed a fuzzy logic-based approach that integrates reinforcement learning with ACO [19]. Similarly, Song et al. [20] developed FedCMFS, a causal federated MFS method incorporating three novel components to enhance the performance of FS. However, most existing methods rely solely on the inherent data-locality of FL for privacy protection, without incorporating more rigorous mechanisms such as DP or SMPC—leaving them susceptible to potential information leakage.

In this section, we provide a detailed introduction to Fed-MFSHBCPSO and the locally deployed DHBCPSO-MSR algorithm within the federated environment, along with an analysis of their privacy preservation, communication, and computational complexities. To ensure clarity and accuracy in presenting these details, in the preparation of this paper, AI tools (e.g., ChatGPT 4.1 and ChatGPT 5) are utilized for language polishing and structural adjustments.

3.1 A Dual-Layer Hybrid Breeding Cooperative Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm with Manifold and Sparsity Regularization (DHBCPSO-MSR)

This subsection introduces the DHBCPSO-MSR algorithm, which is executed by the client in the proposed Fed-MFSHBCPSO framework, including its inner modeling layer and outer optimization layer. The detailed flowchart of DHBCPSO-MSR is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: The flowchart of DHBCPSO-MSR

3.1.1 Inner Modeling Layer of DHBCPSO-MSR

Step 1: Initialization of input data. We Consider a multi-label dataset where

Step 2: Constructing the sample similarity graph. To preserve the local geometry of the data, we first construct the sample similarity graph. The similarity between samples is measured using a Gaussian heat kernel. The sample similarity matrix

where

Next, we construct the Laplacian matrix L = D − S, where D is the degree matrix, and the diagonal entries of D represent the degree of each sample (the number of connections to other samples).

The sample manifold regularization term

where

Step 3: Constructing the label similarity graph. To capture the global dependencies between labels, we construct the label similarity graph. The label similarity matrix

where

We then construct the Laplacian matrix

The label manifold regularization term

where

Step 4: Initialization of feature selection weight matrix W.The FS weight matrix

The W is then regularized using the

where

Step 5: Combined objective function. The overall optimization problem combines the loss, manifold regularization, label correlation regularization, and sparsity regularization terms. The combined objective function is shown in Eq. (7).

where

By minimizing this objective function, the algorithm jointly optimizes the FS weight matrix W and the embedding matrix F, selecting the most relevant features while preserving both sample and label dependencies. The optimization of W ensures FS, while F maps samples to the label space, and their joint optimization effectively captures both feature relevance and label structure.

3.1.2 Outer Optimization Layer of DHBCPSO-MSR

The outer optimization layer of DHBCPSO-MSR employs the HBCPSO algorithm to further optimize the FS weight matrix W obtained from the inner optimization layer. Based on the theory of heterosis, the HBCPSO algorithm adopts a three-line (maintainer, sterile, and restorer) co-evolution mechanism from HBO. Initially, the population is ranked based on fitness (calculated by Eq. (7)) and divided into three subgroups: the maintainer, sterile, and restorer lines. A PSO algorithm is then applied within each subgroup for global updates, including both velocity and position adjustments. After a fixed number of iterations, the best solutions from each subgroup exchange information periodically, guiding further optimization within the subgroups. Once the outer optimization layer updates the feature weight matrix

3.2 Federated Multi-Label Feature Selection via DHBCPSO-MSR (Fed-MFSDHBCPSO)

Centralized MFS methods face significant challenges in distributed environments: centralized approaches risk privacy breaches, while federated methods rely on FL’s inherent privacy guarantees, which are often insufficient. Moreover, limited data sharing hinders the capture of inter-feature correlations, causing convergence to the local optima and limiting the global performance of FS. To address these issues, we propose Fed-MFSDHBCPSO—a FL framework that integrates DHBCPSO-MSR, DP, and SMPC, enhanced with manifold regularization and sparsity constraints (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2: The architecture of the proposed Fed-MFSDHBCPSO: (a) Encrypt the optimal feature subset using DP. (b) Send the encrypted indices and weights to the server. (c) The server applies SMPC to securely aggregate and share encrypted results until global convergence, generating the global optimal feature weights and indices. (d) Distribute the aggregated weights back to clients

1) Client-side MFS process

Each client performs local FS using the following the following steps:

Step 1: Local data preprocessing. Clients load local datasets, initialize parameters, and perform data cleaning and normalization to ensure high-quality inputs.

Step 2: Local FS via DHBCPSO-MSR. Each client executes DHBCPSO-MSR, integrating an inner modeling layer with manifold construction and sparsity constraints, alongside an outer optimization layer driven by HBCPSO. This dual-layer algorithm ensures optimal feature subset selection that aligns with the client’s local data distribution.

Step 3: Privacy-preserving transmission. To ensure privacy, the selected feature weights and their corresponding indices are perturbed using a differential privacy (DP) mechanism before being transmitted to the central server, thereby achieving

where

Step 4: Local multi-label classification. Using the refined features, each client applies the multi-label k-nearest neighbors (ML-KNN) [19] for local multi-label classification. This decentralized approach minimizes communication overhead while ensuring data privacy.

2) Server-side dynamic collaborative optimization

The server implements a dynamic collaborative optimization strategy comprising the following steps:

Step 1: Key management. A public key infrastructure (PKI) is employed to securely distribute encryption keys, enabling end-to-end secure communication across the federated network.

Step 2: Feature aggregation and distribution.

(i) Secure aggregation via SMPC: Encrypted feature weights from clients are aggregated using SMPC, which ensures data privacy by allowing the server to compute aggregated feature weights without decryption. In this study, the SMPC protocol is simulated through a lightweight, custom implementation on the MATLAB platform. While standard secure computation frameworks such as CrypTen or PySyft are not utilized, our implementation adheres to core SMPC principles, enabling secure aggregation without decryption. This ensures that the server remains unable to access any client’s plaintext feature weights or index information during the aggregation process. The prototype is designed to evaluate the feasibility and computational efficiency of secure aggregation in resource-constrained edge computing environments.

(ii) Global feature weight computation: The global feature weight vector

where

Step 3: Global iterative optimization. The server iteratively aggregates encrypted feature weights using SMPC to update

In this framework, clients apply DP to perturb their feature weights for privacy, while the server aggregates encrypted feature weights securely using SMPC. This process ensures that no sensitive data is exposed during aggregation.

To thoroughly evaluate the practical applicability of the proposed method, we analyze the privacy preservation capability and computational complexity of Fed-MFSDHBCPSO.

3.3.1 Privacy Preservation Capability

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the server communicates exclusively with individual clients, preventing any direct client-to-client interaction. Throughout this process, feature weight results are exchanged while maintaining the confidentiality of sample data. Following the design of FL frameworks like FATE [34], communication is strictly confined to model parameters, ensuring that clients cannot access each other’s data distributions and thereby strengthening privacy protection. When feature names and their combinations are non-sensitive—for example, hospitals sharing disease-related attributes without disclosing individual patient information—Fed-MFSDHBCPSO effectively safeguards privacy. Clients may employ DP to secure data transmission, and the server utilizes SMPC to aggregate encrypted feature weights without decrypting them. Detailed cryptographic implementations are beyond the scope of this paper and will not be discussed further.

In the FL framework, Fed-MFSDHBCPSO ensures data privacy by restricting each communication round to essential interactions between the server and clients. Each round consists of three steps:

Step 1: Each client uploads the encrypted feature indices along with the weights of its locally selected optimal subset, avoiding the transmission of raw data or model parameters to ensure privacy and reduce communication overhead;

Step 2: The server aggregates the weights received from all clients and broadcasts the aggregated result to them;

Step 3: Clients perform local optimization based on the aggregated information and upload the encrypted updates back to the server.

Only D-dimensional indices and a small number of weight values are transmitted per round, resulting in low communication overhead relative to local computation. Moreover, since Fed-MFSDHBCPSO performs feature subset selection and compression locally at each client in advance, only highly condensed information is exchanged globally, further reducing overall communication cost.

3.3.3 Computational Complexity Analysis

The DHBCPSO-MSR algorithm minimizes computational overhead through efficient matrix operations and lightweight data structures, ensuring robust performance even on resource-constrained devices. The HBCPSO component further improves efficiency by leveraging parallel computation and dynamic task allocation tailored to device hardware. We utilize MATLAB’s parfor and parpool functions to parallelize particle evaluations, significantly accelerating the optimization process. Within the FL framework, all computations are performed locally on clients, reducing both data transmission and central processing overhead. To safeguard privacy, only feature weights are encrypted, further minimizing communication costs.

In Fed-MFSDHBCPSO, the total time complexity comprises both client-side and server-side components. On the client side, the inner modeling layer has a complexity of

demonstrating good scalability with respect to the number of clients and features. Although the client-side

In this section, we describe the experimental setup, compare the proposed Fed-MFSDHBCPSO with both centralized and federated approaches, and conduct a statistical significance analysis.

4.1.1 Federated Simulation and Dataset Description

In this study, the FL framework is simulated in a single-machine environment using multiprocessing, where each client independently loads its local data and performs FS. This setup closely mirrors real-world scenarios involving decentralized computation and data isolation.

To evaluate the performance of Fed-MFSDHBCPS, we simulate a FL environment using eight real-world datasets (see Table 1). To emulate non-IID conditions, we adopt a label distribution skew strategy [19], in which samples are grouped by label frequency and allocated to clients through stratified sampling. This approach produces imbalanced and heterogeneous multi-label distributions across clients, effectively capturing the statistical heterogeneity typical of edge devices.

In this paper, we utilize six standard multi-label evaluation metrics. Average Precision (AP) and Macro-F1 (MA) measure overall prediction accuracy (higher values are better), while Coverage (CV), Hamming Loss (HL), and Ranking Loss (RL) evaluate errors and ranking quality (lower values are better). Micro-F1 (MI) assesses global classification performance (higher values are better). AP calculates the average rank of labels for each instance, HL quantifies the discrepancy between the predicted and true label sets, and MA computes the average F1 score based on true positives, false positives, and false negatives for each instance. Further details on the definitions and computation methods are provided in [29].

4.1.3 Comparison Algorithms and Parameter Settings

We compare the proposed method with various centralized and federated MFS approaches. Recent federated MFS methods include FMLFS [18], Fuzzy FMFS [19], and FedCMFS [20], while centralized methods comprise deep learning-based MFS approaches such as LRDG [30] (referred to as Fed-LRDG in the federated setting), multi-objective optimization algorithms like MOEA/D [35] and NSGA-III [36] (referred to as Fed-MOEA/D and Fed-NSGA-III in the federated setting), as well as GLFS [37] and PDMFS [38]. Under federated learning settings, centralized methods are independently applied to each client, and results are averaged across clients, highlighting the limitations of centralized MFS and underscoring the advantages of federated methods in terms of privacy and collaboration. Parameter settings for these methods follow those reported in the original literature.

For Fed-MFSDHBCPSO, we adopt the parameter settings from [13]: population size = 30,100 iterations, and 30 runs. In the outer HBCPSO layer, the inertia weight decreases linearly from 0.9 to 0.2, with cognitive and social factors both set to 2.0, and maximum velocity set to 1.0. For the inner-layer optimization in Eq. (7), the parameters are

4.1.4 Experimental Environment

All experiments are conducted on a desktop computer running the Windows 10 operating system, equipped with a 13th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-13700KF processor @ 3.40GHz and 32 GB of memory. The software environment used for the experiments is MATLAB 2022.

4.2 Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

We conducte experiments with five clients and three datasets of varying sizes (Flags, Education, and Mediamill), selecting the final number of features according to the method in [39]. A sensitivity analysis of the hyperparameters

Figure 3: Parameter sensitivity analysis of the proposed method: (a) The impact of different

4.3 Comparative Analysis of Fed-MFSDHBCPSO with Centralized and Federated Approaches

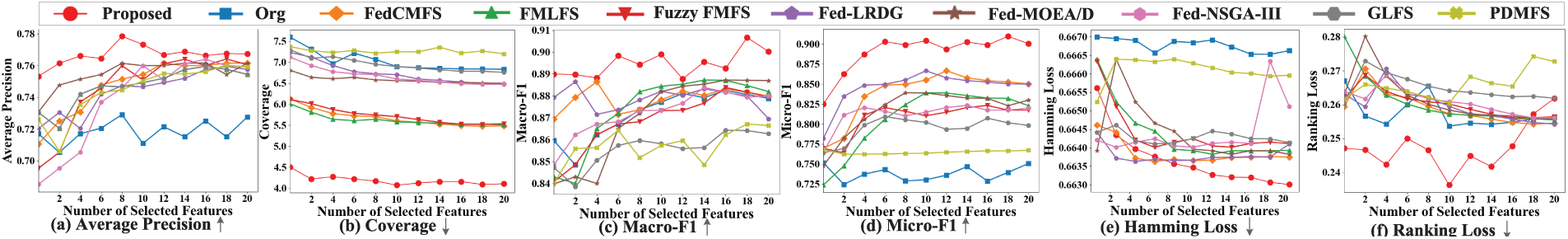

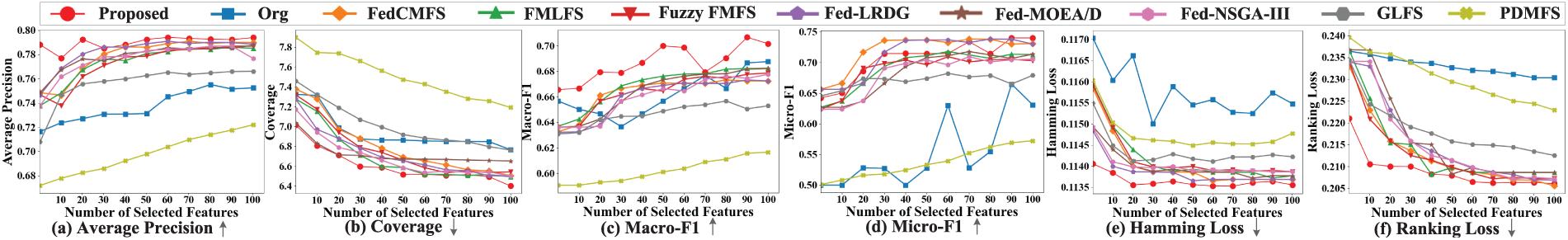

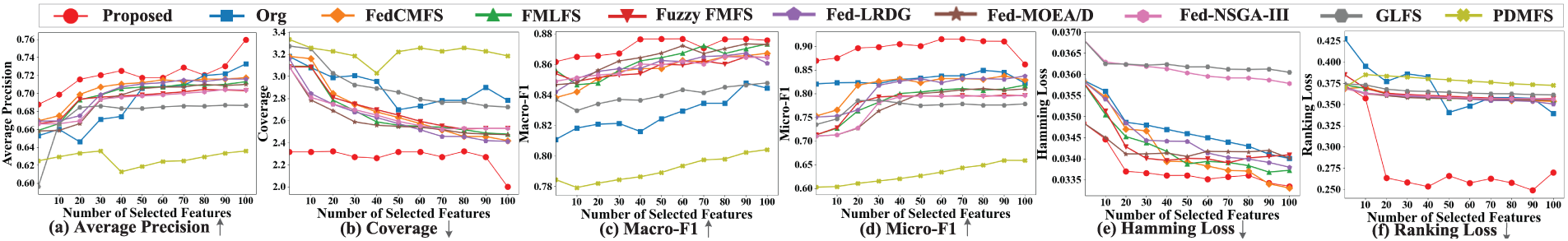

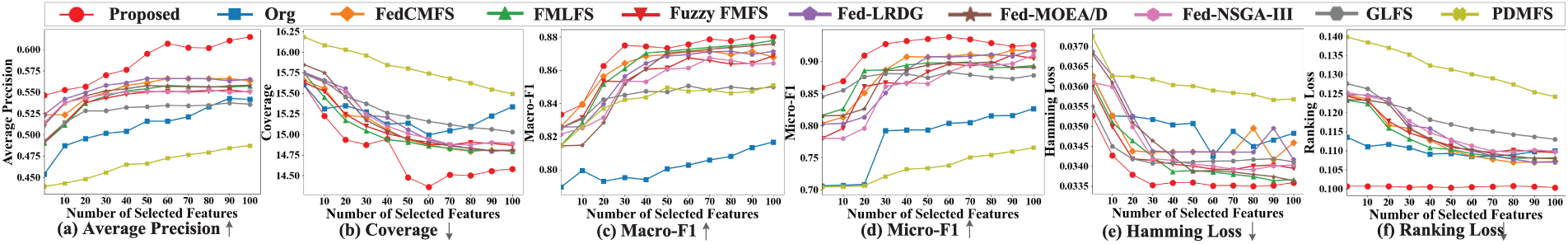

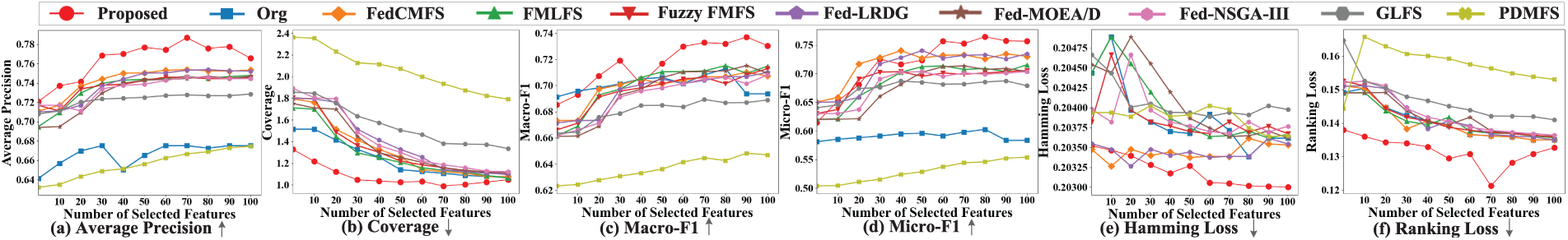

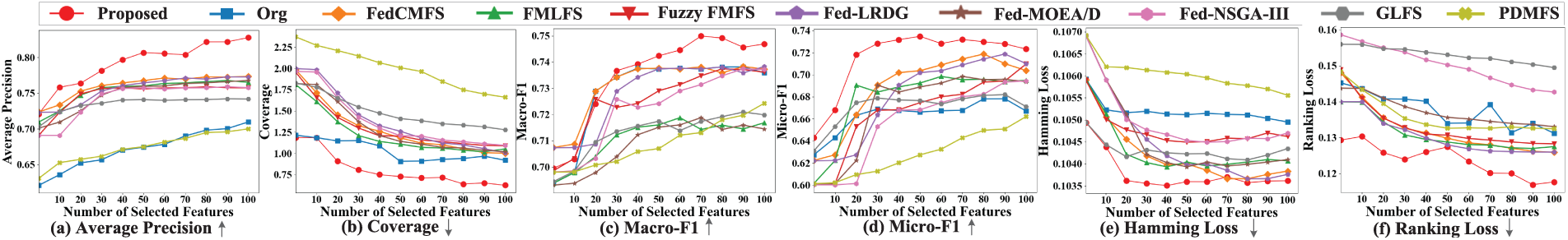

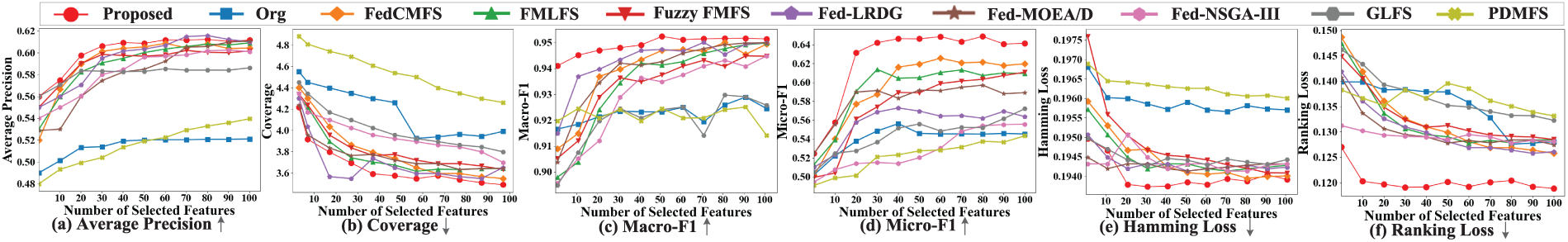

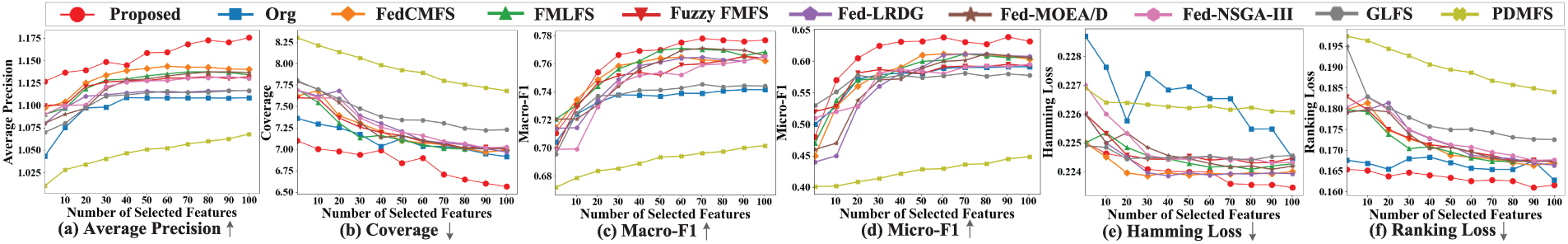

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, Figs. 4–11 compare it against the initial baseline, five recent centralized methods, and three federated MFS methods across eight datasets. The experiments are conducted with five clients, assessing performance across varying feature subsets. The results show that Fed-MFSDHBCPSO outperforms other methods on most datasets with only 10 features, including Mediamill, Image, Scene, Flag, and Education. On the Enron and Emotions datasets, Fed-MFSDHBCPSO, using 80 features, achieves comparable or superior Macro-F1, Micro-F1, and Hamming loss scores, while demonstrating more consistent performance across other metrics.

Figure 4: Performance comparison of different methods on the Flags dataset with varying numbers of features based on six metrics: (a) Average precision; (b) Coverage; (c) Macro-F1; (d) Micro-F1; (e) Hamming loss; (f) Ranking loss

Figure 5: Performance comparison of different methods on the VirusGo dataset with varying numbers of features based on six metrics: (a) Average precision; (b) Coverage; (c) Macro-F1; (d) Micro-F1; (e) Hamming loss; (f) Ranking loss

Figure 6: Performance comparison of different methods on the Emotions dataset with varying numbers of features based on six metrics: (a) Average precision; (b) Coverage; (c) Macro-F1; (d) Micro-F1; (e) Hamming loss; (f) Ranking loss

Figure 7: Performance comparison of different methods on the Enron dataset with varying numbers of features based on six metrics: (a) Average precision; (b) Coverage; (c) Macro-F1; (d) Micro-F1; (e) Hamming loss; (f) Ranking loss

Figure 8: Performance comparison of different methods on the Image dataset with varying numbers of features based on six metrics: (a) Average precision; (b) Coverage; (c) Macro-F1; (d) Micro-F1; (e) Hamming loss; (f) Ranking loss

Figure 9: Performance comparison of different methods on the Scene dataset with varying numbers of features based on six metrics: (a) Average precision; (b) Coverage; (c) Macro-F1; (d) Micro-F1; (e) Hamming loss; (f) Ranking loss

Figure 10: Performance comparison of different methods on the Education dataset with varying numbers of features based on six metrics: (a) Average precision; (b) Coverage; (c) Macro-F1; (d) Micro-F1; (e) Hamming loss; (f) Ranking loss

Figure 11: Performance comparison of different methods on the Mediamill dataset with varying numbers of features based on six metrics: (a) Average precision; (b) Coverage; (c) Macro-F1; (d) Micro-F1; (e) Hamming loss; (f) Ranking loss

These results indicate that the proposed method has minimal impact on communication overhead and model performance, despite the size of the feature set transmitted between clients and the edge server. It simultaneously enhances the effectiveness of the model, achieving an optimal balance between communication efficiency and predictive accuracy.

4.4 Comparison of Running Time for Different Methods

To evaluate the efficiency of the proposed method, we conducted a single federated iteration with five clients and compared the runtime of Fed-MFSDHBCPSO against several baseline methods, as presented in Table 2, where the bold values represent the best results. The results demonstrate that Fed-MFSDHBCPSO consistently achieves the shortest runtimes, particularly on large-scale datasets such as Mediamill, Enron, and Education. This superior efficiency stems from its dual-layer optimization, manifold regularization, sparsity constraints, and FL framework. In contrast, the Org method, which lacks FS, leads to significantly longer runtimes. Furthermore, methods such as Fed-LRDG, Fed-MOEA/D, Fed-NSGA-III, and PDMFS exhibit higher computational overhead on large datasets. Overall, Fed-MFSDHBCPSO delivers the best runtime efficiency among all evaluated algorithms.

To evaluate the contribution of each component, we conducted ablation experiments on five clients, determining the final number of selected features using the method in [39]. Four model variants were constructed by individually removing PSO (Proposed/PSO), HBO (Proposed/HBO), manifold regularization (i.e., removing Laplacian regularization, called Proposed/MR), and the sparsity constraint (Proposed/SC). In addition, we removed the inner optimization to create Fed-HBCPSO and compared it with Fed-NSGA-III and Fed-MOEA/D, using AP as the primary metric. As shown in Table 3, where the bold values indicate the best results. Excluding PSO or HBO led to significant performance degradation, while removing manifold regularization or the sparsity constraint also reduced accuracy and stability. Moreover, Fed-HBCPSO consistently outperformed Fed-NSGA-III and Fed-MOEA/D, benefiting from its three-population co-evolutionary mechanism, where sub-populations of varying quality periodically exchange best-solution information. This design effectively balances exploration and exploitation, avoids the local optima, and accelerates convergence. In contrast, the single-population strategies of NSGA-III and MOEA/D in federated settings struggle to maintain both diversity and precision, resulting in inferior performance. These findings demonstrate that all components are complementary and indispensable to the overall effectiveness of the proposed model.

4.6 Statistical Analysis of Significance

To assess the performance differences between Fed-MFSDHBCPSO and other comparison methods, we apply the Friedman test followed by the Nemenyi post-hoc test. As shown in Table 4, the Friedman statistics (

Following this, the Nemenyi post-hoc test is applied to identify which pairs of methods differ significantly. This test compares the mean ranks of the methods, where a lower rank indicates better performance. A significant difference between two methods is confirmed if the gap in their mean ranks exceeds the critical distance (CD), illustrated by the red line in the figure. The CD is computed as shown in Eq. (11).

where

Fig. 12 presents the results of the Nemenyi test, with the left side highlighting methods with superior performance rankings and the horizontal axis indicating the average ranks of these approaches. The differences in rankings between the proposed Fed-MFSDHBCPSO and FMLFS, PDMFS, and GLFS exceed the CD, demonstrating that Fed-MFSDHBCPSO significantly outperforms these methods. Conversely, the rankings of Fed-CFMS and Fuzzy FMFS lie within the CD threshold, indicating no statistically significant difference from Fed-MFSDHBCPSO. Nevertheless, Fed-MFSDHBCPSO consistently attains the highest rank, while Fed-CFMS and Fuzzy FMFS exhibit comparative.

Figure 12: Using the Nemenyi test to compare the performance of Fed-MFSDHBCPSO with other comparison methods on the following six metrics: (a) Average precision; (b) Hamming loss; (c) Coverage; (d) Macro-F1; (e) Micro-F1; (f) Ranking loss

This paper presents Fed-MFSDHBCPSO, a federated multi-label feature selection (MFS) framework based on the DHBCPSO-MSR algorithm. The framework integrates HBCPSO, differential privacy, secure multi-party computation, manifold regularization, and sparsity constraints to address high computational cost, low efficiency, and inadequate privacy protection in high-dimensional multi-label data. Fed-MFSDHBCPSO enables clients to perform local MFS with DHBCPSO-MSR, where the inner layer preserves manifold structure and sparsity via the

Acknowledgement: During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors also utilized AI tools (e.g., ChatGPT 4.1 and ChatGPT 5) for language polishing and structural adjustments. The authors have carefully reviewed and revised the output and accept full responsibility for all content.

Funding Statement: This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants U23A20318, 62376089, 62302153, and 62302154), the Key Research and Development Program of Hubei Province (Grant 2023BEB024), and the Scientific and Technological Innovation Team Program for Young and Middle-Aged Researchers in Hubei Higher Education Institutions (Grant T2023007).

Author Contributions: The authors’ contributions to the paper are as follows: Study conception and design: Songsong Zhang, Huazhong Jin, Zhiwei Ye; Data collection: Huazhong Jin, Zhiwei Ye, Songsong Zhang, Jia Yang, Jixin Zhang; Analysis and interpretation of results: Zhiwei Ye, Songsong Zhang, Xiao Zheng, Dongfang Wu; Draft manuscript preparation: Songsong Zhang, Dingfeng Song. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: This study uses datasets from two sources: the Mulan repository (https://mulan.sourceforge.net/datasets-mlc.html) (accessed on 20 August 2025) and a multi-label classification database (http://www.uco.es/kdis/mllresources/) (accessed on 20 August 2025). For additional information or data requests, please contact the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Li Y, Wang X, Yang X, Gao W, Ding W, Li T. Fusion-enhanced multi-label feature selection with sparse supplementation. Inf Fusion. 2025;117(3):102813. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2024.102813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Fan Y, Liu J, Tang J, Liu P, Lin Y, Du Y. Learning correlation information for multi-label feature selection. Pattern Recognit. 2024;145(8):109899. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2023.109899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Sharma M, Tomar A, Hazra A. Edge computing for industry 5.0: fundamental, applications and research challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(11):19070–93. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3359297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chen J, Yan H, Liu Z, Zhang M, Xiong H, Yu S. When federated learning meets privacy-preserving computation. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;56(12):1–36. doi:10.1145/3679013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Tarekegn AN, Giacobini M, Michalak K. A review of methods for imbalanced multi-label classification. Pattern Recognit. 2021;118:107965. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2021.107965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Maurya SK, Liu X, Murata T. Feature selection: key to enhance node classification with graph neural networks. CAAI Trans Intell Technol. 2023;8(1):14–28. doi:10.1049/cit2.12166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhang Y, Ma Y, Yang X. Multi-label feature selection based on logistic regression and manifold learning. Appl Intell. 2022;52(8):9256–73. doi:10.1007/s10489-021-03008-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Guo Z, Shen Y, Yang T, Li YJ, Deng Y, Qian Y. Semi-supervised feature selection based on fuzzy related family. Inf Sci. 2024;652(6):119660. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2023.119660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Pandithurai O, Venkataiah C, Tiwari S, Ramanjaneyulu N. DDoS attack prediction using a honey badger optimization algorithm based feature selection and Bi-LSTM in cloud environment. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;241(1):122544. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Gu S, Qian Y, Hou C. Incremental feature spaces learning with label scarcity. ACM Trans Knowl Discov Data (TKDD). 2022;16(6):1–26. doi:10.1145/3516368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Fang Y, Yao Y, Lin X, Wang J, Zhai H. A feature selection based on genetic algorithm for intrusion detection of industrial control systems. Comput Secur. 2024;139:103675. [Google Scholar]

12. Karimi F, Dowlatshahi MB, Hashemi A. SemiACO: a semi-supervised feature selection based on ant colony optimization. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;214(6):119130. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.119130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Mei M, Zhang S, Ye Z, Wang M, Zhou W, Yang J, et al. A cooperative hybrid breeding swarm intelligence algorithm for feature selection. Pattern Recognit. 2025;169(12):111901. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2025.111901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ye Z, Ma L, Chen H. A hybrid rice optimization algorithm. In: 2016 11th International Conference on Computer Science & Education (ICCSE); 2016 Aug 23–25; Nagoya, Japan: IEEE. p. 169–74. [Google Scholar]

15. Cai T, Ye C, Ye Z, Chen Z, Mei M, Zhang H, et al. Multi-label feature selection based on improved ant colony optimization algorithm with dynamic redundancy and label dependence. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;81(1):1157–75. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.055080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wang L, Hong L, Fu H, Cai Z, Zhong Y, Wang L. Adaptive distance-based multi-objective particle swarm optimization algorithm with simple position update. Swarm Evol Comput. 2025;94(5):101890. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2025.101890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhong R, Wang Z, Al-Shourbaji I, Houssein EH, Kachare PH, Jabbari A, et al. Self-adaptive competitive swarm optimizer: a memetic approach for global optimization and human-powered aircraft design. Memetic Comput. 2025;17(3):32. doi:10.1007/s12293-025-00465-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Mahanipour A, Khamfroush H. FMLFS: a federated multi-label feature selection based on information theory in IoT environment. In: 2024 IEEE International Conference on Smart Computing (SMARTCOMP); 2024 Jun 29–Jul 2; Osaka, Japan: IEEE. p. 166–73. [Google Scholar]

19. Mahanipour A, Khamfroush H. Fuzzy federated multi-label feature selection: reinforcement learning and ant colony optimization. In: 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData); 2024 Dec 15–18; Washington, DC, USA: IEEE. p. 7919–28. [Google Scholar]

20. Song Y, Cao D, Miao J, Yang S, Yu K. Causal multi-label feature selection in federated setting. arXiv:2403.06419. 2024. [Google Scholar]

21. Cheng Y, Li W, Qin S, Tu T. Differential privacy federated learning based on adaptive adjustment. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;82(3):4777–95. [Google Scholar]

22. Zhang C, Ekanut S, Zhen L, Li Z. Augmented multi-party computation against gradient leakage in federated learning. IEEE Trans Big Data. 2024;10(6):742–51. doi:10.1109/tbdata.2022.3208736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Gao C, Zhou J, Miao D, Yue X, Wan J. Granular-conditional-entropy-based attribute reduction for partially labeled data with proxy labels. Inf Sci. 2021;580(7):111–28. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2021.08.067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Dai J, Liu Q, Chen W, Zhang C. Multi-label feature selection based on fuzzy mutual information and orthogonal regression. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst. 2024;32(9):5136–48. doi:10.1109/tfuzz.2024.3415176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhang Y, Tang J, Cao Z, Chen H. Sparse multi-label feature selection via pseudo-label learning and dynamic graph constraints. Inf Fusion. 2025;118(5):102975. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2025.102975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Huang J, Li G, Huang Q, Wu X. Learning label-specific features and class-dependent labels for multi-label classification. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2016;28(12):3309–23. doi:10.1109/tkde.2016.2608339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Jian L, Li J, Shu K, Liu H. Multi-label informed feature selection. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-16); 2019 Jul 9–15; New York, NY, USA. p. 1627–33. [Google Scholar]

28. Sun Z, Chen Z, Liu J, Chen Y, Yu Y. Partial multi-label feature selection via low-rank and sparse factorization with manifold learning. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;296(8):111899. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.111899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhang J, Luo Z, Li C, Zhou C, Li S. Manifold regularized discriminative feature selection for multi-label learning. Pattern Recognit. 2019;95(9):136–50. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2019.06.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhang Y, Huo W, Tang J. Multi-label feature selection via latent representation learning and dynamic graph constraints. Pattern Recognit. 2024;151(2):110411. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2024.110411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Mahanipour A, Khamfroush H. Wrapper-based federated feature selection for IoT environments. In: 2023 International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC); 2023 Feb 20–22; Honolulu, HI, USA: IEEE. p. 214–9. [Google Scholar]

32. Feng S. Vertical federated learning-based feature selection with non-overlapping sample utilization. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;208(4):118097. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.118097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Wang Z, Chen Y, Cai Z, Heidari AA, Liu L, Chen H. Weighted mean of vectors algorithm with neighborhood information interaction and vertical and horizontal crossover mechanism for feature selection. Appl Intell. 2025;55(1):1–44. doi:10.1007/s10489-024-05889-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. de Greeff J, de Boer MHT, Hillerström FHJ, Bomhof H, Jorritsma W, Neerincx M. The FATE system: fair, transparent and explainable decision making. In: AAAI Spring Symposium: Combining Machine Learning with Knowledge Engineering; 2021 Mar 22–24; Palo Alto, CA, USA. p. 266–7. [Google Scholar]

35. Wang X, Zhao Y, Tang L, Yao X. MOEA/D with spatial-temporal topological tensor prediction for evolutionary dynamic multiobjective optimization. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2025;29(3):764–78. doi:10.1109/tevc.2024.3367747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Arya A, Gunarani GI, Rathinakumar V, Sharma A, Pati AK, Sethi KC. NSGA-III based optimization model for balancing time, cost, and quality in resource-constrained retrofitting projects. Asian J Civil Eng. 2024;25(7):5613–25. doi:10.1007/s42107-024-01133-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zhang J, Wu H, Jiang M, Liu J, Li S, Tang Y, et al. Group-preserving label-specific feature selection for multi-label learning. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;213:118861. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.118861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Miao J, Wang Y, Cheng Y, Chen F. Parallel dual-channel multi-label feature selection. Soft Comput. 2023;27(11):7115–30. doi:10.1007/s00500-023-07916-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Kashef S, Nezamabadi-Pour H, Nikpour B. Multilabel feature selection: a comprehensive review and guiding experiments. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Data Mining Knowl Discov. 2018;8(2):e1240. doi:10.1002/widm.1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools