Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

When Large Language Models and Machine Learning Meet Multi-Criteria Decision Making: Fully Integrated Approach for Social Media Moderation

1 College of Computer, Information and Communications Technology, Cebu Technological University, Corner M.J. Cuenco Avenue & R. Palma St., Cebu City, 6000, Philippines

2 Center for Applied Mathematics and Operations Research, Cebu Technological University, Corne, M.J. Cuenco Avenue & R. Palma St., Cebu City, 6000, Philippines

3 Centre for Operational Research and Logistics, University of Portsmouth, Portland Building, Portland Street, Portsmouth, PO1 3AH, UK

* Corresponding Author: Lanndon Ocampo. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068104

Received 21 May 2025; Accepted 26 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

This study demonstrates a novel integration of large language models, machine learning, and multi-criteria decision-making to investigate self-moderation in small online communities, a topic under-explored compared to user behavior and platform-driven moderation on social media. The proposed methodological framework (1) utilizes large language models for social media post analysis and categorization, (2) employs k-means clustering for content characterization, and (3) incorporates the TODIM (Tomada de Decisão Interativa Multicritério) method to determine moderation strategies based on expert judgments. In general, the fully integrated framework leverages the strengths of these intelligent systems in a more systematic evaluation of large-scale decision problems. When applied in social media moderation, this approach promotes nuanced and context-sensitive self-moderation by taking into account factors such as cultural background and geographic location. The application of this framework is demonstrated within Facebook groups. Eight distinct content clusters encompassing safety, harassment, diversity, and misinformation are identified. Analysis revealed a preference for content removal across all clusters, suggesting a cautious approach towards potentially harmful content. However, the framework also highlights the use of other moderation actions, like account suspension, depending on the content category. These findings contribute to the growing body of research on self-moderation and offer valuable insights for creating safer and more inclusive online spaces within smaller communities.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileSocial media platforms have become an integral part of people’s daily lives, enabling them to connect, share, and create content [1]. These platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, blogs, and others, offer users avenues to share user-generated content (UGC), such as their thoughts, experiences, and emotions, and interact with a broader online community through posts, tweets, shares, likes, and reviews [2]. User-generated content is the lifeblood of social media, driving engagement and shaping how people communicate and interact online. The accessibility and convenience of social media platforms have significantly impacted the way people communicate, access information, and share UGC in today’s digital age [3]. However, the increase in the usage of social media platforms and the very notion of freedom of expression exercised in several democracies have also brought forth a range of challenges that can have adverse effects on users. These challenges include concerns about the quality of content, harmful online communications, and psychological or mental impacts on users [4,5]. As Internet usage continues to increase, so does the amount of personal information and data that is made available online, which can be out of one’s control [6]. The quality of content on these platforms is also a major concern, given the ease with which false or misleading information can be disseminated [4].

Users often rely on social media as a source of information, but the lack of regulation and fact-checking on these platforms raises concerns about the accuracy and reliability of the information shared [7,8]. In fact, during the COVID-19 pandemic, 80% of users encountered fake news about the outbreak, with social media companies removing 7 million fake news stories, 9 million pieces of content promoting extremist organizations, and 23 million instances of harmful online communication [9]. Additionally, harmful online communications such as cyberbullying, hate speech, and trolling have become prevalent on most platforms [5]. These actions can have a detrimental impact on the mental well-being of individuals who experience such negativity [9]. Furthermore, the psychological and mental impacts of social media usage have been a growing concern. Studies have shown that excessive use of social media is associated with lower psychological well-being. Such symptoms include increased feelings of loneliness and depression, reduced self-esteem, and heightened levels of anxiety. These symptoms are particularly concerning for young adults, who may already be experiencing mental health difficulties.

Another concern related to the impact of social media on mental health is the issue of body image problems, eating disorders, and self-esteem issues, especially among young women. Exposure to images promoting unrealistic body ideals can contribute to negative body image and an increased risk of developing eating disorder behaviors such as anorexia nervosa or bulimia. Thus, the bidirectional relationship between social media usage and psychological well-being suggests that these platforms can exacerbate mental health issues in vulnerable individuals. Additionally, social media platforms provide easy access to content related to suicide and self-harm, which can be particularly harmful to individuals who are already experiencing mental health difficulties. The availability and accessibility of such content can potentially increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among vulnerable individuals. Furthermore, the impact on mental health can also be indirect. For example, excessive use of social media can lead to decreased physical activity, as individuals spend more time online and less time engaging in physical activities. This harmful online behavior and communication can contribute to poor physical and mental health concerns [10,11]. As a result, users and institutions need to understand the implications of harmful online communication and the role of social media to navigate this ever-evolving digital landscape responsibly and effectively.

Thus, the agenda of mitigating harmful online communication and its adverse impacts on users’ well-being has become a prominent topic of discussion in the literature. One of the solutions that various studies have explored is the role of government and the enforcement of legislation, such as the inclusion of cyberbullying in the general anti-bullying laws (e.g., the Philippine Republic Act No. 10627) [12,13]. However, several studies have emphasized the greater role that private entities play, as they have the decisive power of intervention and the responsibility to provide a safe online environment for social media users [10,14]. They can perform counteractions such as deleting posts or blocking the user who developed them, a process known as content moderation.

Content moderation refers to assessing UGC published on social media sites and determining whether to retain or remove it [15]. Given the vast amount of UGC across various platforms, developing a type of content moderation that matches the scale of these platforms is of paramount significance [9]. Recent progress in artificial intelligence (AI), increased computational power, and enhanced capacity to manage vast amounts of data have paved the way for automating the detection of online content. The current automated systems, which utilize machine learning and deep neural networks to detect and classify harmful content, have considered accuracy, precision, and recall as performance metrics [9]. However, despite these advances, various studies have emphasized the importance of human moderation, especially in the context of hate speech, where perceptions of objectionable language vary depending on the user, geographic location, culture, and historical context (e.g., [9,16]). In particular, there has been limited exploration into content moderation within smaller communities (e.g., web communities, Facebook pages), especially in the context of developing economies where the dynamics of online interaction and community management may differ significantly from those in more established digital landscapes. Furthermore, manual moderation (e.g., self-moderation) within small online communities, where community members decide on content moderation and policy, remains a primary and more affordable alternative [17,18]. However, disagreements and biases may arise within these contexts regarding the effectiveness and fairness of self-moderation [9,19]. Factors such as power dynamics within the community, cultural norms, and individual biases can influence decisions on what content is deemed acceptable or objectionable [20]. These factors can lead to tensions and conflicts within the community, potentially undermining the effectiveness of self-moderation efforts and highlighting the need for further research and understanding in this area. Accordingly, within the context of small online communities, an effort to systematically identify self-moderation actions appropriate to the characteristics inherent in sensitive social media content is lacking, which essentially forms the gap in the literature that this work intends to bridge. This methodological outlook, particularly for self-moderation efforts prominent in small online communities, has not been thoroughly explored in previous studies.

In light of the gap outlined above, this study develops a methodological framework for self-moderation actions of sensitive social media content by answering the following research questions (RQs):

(RQ1): How can sensitive content on social media be systematically categorized into general types?

(RQ2): Building on the general types of sensitive content, how can they be characterized to capture their specific forms on social media?

(RQ3): From the resulting clusters of content with multiple underlying characteristics, how can self-moderation actions be appropriately identified?

1.3 Contributions of the Study

In light of the identified gap in the literature, this study presents a methodological framework grounded in expert systems and large language models (LLMs) that can inform self-moderation efforts of small online communities. The proposed framework consists of the following interrelated actions, which form the main advances from existing methods on self-moderation:

1. extracts types of sensitive content from social media posts,

2. uses LLMs to extract categories that represent a collective description of similar types from a vast number of sensitive content types,

3. employs LLMs to evaluate the degree to which a large number of social media posts fit the extracted categories in action (2),

4. performs characterization to create clusters with defined attributes, and

5. determines the moderation decisions for each cluster of social media posts.

Actions (1) to (3) employ LLMs in defining categories of social media posts through text analysis as they are powerful tools used to process, understand, and derive insights from large volumes of unstructured text data, enabling tasks such as sentiment analysis, topic modeling, and semantic search [21]. Thus, LLMs are becoming increasingly popular in academia and industry due to their exceptional performance across various applications (e.g., [22–23]), making it crucial to evaluate their impact not only on specific tasks but also on society as a whole, to better understand potential risks.

Action (4) characterizes social media posts based on their contextual sensitivity, which is crucial for refining moderation strategies, addressing specific types of harmful content in varied contexts, combating misinformation and hate speech, and promoting a safer, inclusive online space within communities. In this study, the characterization process is viewed as a clustering problem, where clustering serves as a technique to group observations, data points, or feature vectors that share common characteristics [24]. In the literature, various clustering methods have been deployed. One of the most prominent methods is the k-means clustering algorithm, considered one of the simplest, non-supervised learning algorithms [25]. The algorithm partitions through iterative steps until it reaches a local minimum [26]. It offers several advantages over alternative clustering methods, notably its simplicity, robustness, and high efficiency [27]. Due to these advantages, several studies in the literature have employed this method across various domains, including education, tourism, agriculture, and manufacturing, among others. Note that this list is not intended to be comprehensive. A recent review of the application of the k-means algorithm was presented by Ikotun et al. [28].

Action (5) determines the moderation decision of the categories defined by the clustering method, which can be viewed through the lens of a multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) problem, as it requires inputs from decision-makers in the decision-making process. This particular component of the proposed methodological framework advances the domain literature by incorporating expert judgments associated with their geographic, cultural, and historical make-ups, which may be more defined in smaller online communities. A comprehensive overview of the current state of this field is provided by Sahoo and Goswami [29]. Today, MCDM tools are crucial for solving numerous real-world decision-making problems that require the consideration of various criteria. Among the MCDM tools, the TODIM (Tomada de Decisão Interativa Multicritério) method, introduced by Gomes and Lima [30], distinguishes itself as a widely used discrete approach by incorporating group utility and individual regret—factors often neglected in traditional MCDM methods—making it suitable for both quantitative and qualitative criteria. The TODIM method utilizes a value function within the framework of prospect theory to determine the dominance degree of each alternative over the others with respect to various criteria. It is noteworthy that in recent years, the application of the TODIM method has gained prominence. Thus, in the context of this work, the attributes of the defined clusters, derived from the k-means algorithm, are taken into account to determine the type of moderation initiatives (considered alternatives) that should be implemented in each cluster. Due to the non-compensatory nature of the attributes, the TODIM method is deemed suitable for evaluating the moderation initiatives.

Succinctly, the proposed framework, which integrates LLMs, machine learning, and MCDM, provides a novel approach to characterizing UGC (i.e., social media posts) on various Facebook online communities into clusters and determining moderation decisions for these clusters based on their underlying attributes, thereby collectively contributing to the literature on self-moderation of small online communities.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses the related literature on the integration of AI into MCDM methods and their applications across various domains, while Section 3 presents the preliminary concepts of the k-means clustering algorithm and the TODIM method. Section 4 outlines the methodology of the proposed approach, while Section 5 presents the results of the analysis. Limitations of the study and the associated future work are outlined in Section 6. Finally, Section 7 presents some concluding remarks.

This section reviews the integration of AI into MCDM methods and their applications across various domains. In a rapidly modernized society, decision-making becomes increasingly complex. Various environmental and societal issues have emerged, but several related policies, priorities, goals, and socio-economic trade-offs remain unexplored [31]. Moreover, technological advancements continually introduce new capabilities across various fields, including manufacturing systems, information technology, education, and engineering [32,33]. Thus, such a challenging environment requires advanced tools and techniques to support decision analysis. In particular, MCDM methods are crucial for assisting decision-makers in addressing complex issues that involve numerous conflicting objectives and criteria [34]. This decision-making process is crucial in various fields, including manufacturing, education, engineering, healthcare, and information technology, where choices must be made by weighing multiple, often conflicting, criteria. In the context of social media, the prominent usage of MCDM techniques includes selection of social media platforms (e.g., [35]), evaluation of factors affecting social media behavior (e.g., [36]), analysis for factors for social media marketing strategies (e.g., [37]), and more recently, determining the level of sensitivity of social media content (e.g., [38]). While this list is not exhaustive, Sahoo and Goswami [29] provide a comprehensive review of MCDM applications and future directions across various domains. In line with this, numerous MCDM methods have been developed and can be classified into compensatory and non-compensatory methods. In compensatory methods, such as AHP (Analytic Hierarchy Process), SAW (Simple Additive Weighting), and TOPSIS (Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution), poor performance in one criterion can be offset by high performance in others. Conversely, in non-compensatory methods, e.g., PROMETHEE (Preference Ranking Organization METHod for Enrichment of Evaluations), ELECTRE (ELimination Et Choix Traduisant la REalité), and DRSA (Dominance-based Rough Set Approach), significant poor performance in any criterion cannot be offset by high performance in others, making each criterion independently critical.

The growing importance of MCDM techniques led to various integrations with other methods to augment its utility. In particular, due to the emergence of data-driven decision-making in the literature, the integration of MCDM and AI has become a prominent topic of discussion across various domains, particularly with the growth and advancement of these fields in recent years. More recently, Galamiton et al. [38] integrated MCDM and AI into their proposed overarching framework for predicting the intensity of sensitive social media content. They deployed LLMs in populating the evaluation matrix as the primary input for multi-criteria sorting—an MCDM problematique for sorting social media content into pre-ordered categories of intensity. Subsequently, the LLM-generated evaluation matrix and the resulting category assigned to each piece of content were used to train a prediction model, which was then deployed to a relatively large dataset of social media content. Aside from the preceding studies in the domain literature, various AI tools integrated into MCDM include machine learning algorithms, neural networks, genetic algorithms, multi-agent systems, predictive analytics, and natural language processing.

Notably, natural language processing has demonstrated substantial potential when combined with MCDM. Natural language processing tools facilitate the analysis of large volumes of textual data, extracting valuable patterns and insights that can guide decision-making [39,40]. In the context of social media, the common usage of natural language processing includes extracting feedback and reviews, providing recommendation systems, prioritizing posts, and classifying posts (e.g., [41]), among others. Over the years, large language models (LLMs) have become increasingly prominent and critical components of NLP. Models like OpenAI’s GPT-4, Google’s Gemini, Microsoft’s Copilot, and Meta AI have transformed the field by offering advanced capabilities in comprehending and generating human language. As one of the most commonly used LLM models, the usage and evaluation of GPT4 have become a prominent topic of discourse in the literature. Its application and implications have been explored in various domains, including medicine, education, business, cybersecurity, public health, and communication. Accordingly, the advantages of GPT lie in its ability to streamline and enhance technology research by leveraging its extensive knowledge base and advanced language processing capabilities to assist researchers in accessing information, analyzing data, and identifying trends or challenges [42]. Furthermore, GPT4 can efficiently synthesize and summarize relevant content, saving researchers time and effort while keeping them informed on the latest advancements. In three NLP tasks related to sense disambiguation of acronyms and symbols, semantic similarity, and relatedness, Liu et al. [43] evaluated the performance of LLMs, including GPT4. They found that LLMs outperformed previous machine learning approaches, with an accuracy of 95% in acronym and symbol sense disambiguation and over 70% in similarity and relatedness tasks. Oka et al. [44] supported this finding by conducting experiments to determine whether LLMs can replicate human scoring tasks. Their results suggest that human-model scoring achieves an inter-rater reliability of 0.63, which closely resembles the reliability of human-human scoring, ranging from 0.67 to 0.70. Driven by a series of investigations, Thelwall [45] communicated their observations by highlighting the capability of GPT4 in understanding and performing complex text processing tasks, in which GPT4 produces plausible responses. Based on these advantages, GPT4 can be a practical text analytics tool, particularly in evaluating a vast amount of text to generate trends, classifications, or categories, subscribing to those demonstrated by Galamiton et al. [38].

This section presents the preliminary concepts of the k-means algorithm and the TODIM method.

The k-means clustering is a prominent technique in the literature for grouping data points into

Definition 1: Considering a set of observations

here,

while the equivalence can be inferred from the identity presented as follows:

Rooted in Prospect Theory, TODIM captures the decision-maker’s perception of gains and losses for the evaluation of the alternatives. As such, the TODIM method, described by Gomes and Lima [30], is defined as follows.

Definition 2: Let

Step 1. Construct an evaluation matrix. Determine the performance value

Step 2. Calculate relative weights. For each

The reference criterion

Step 3. Calculate dominance degree. For each

where

Step 4. Obtain the overall dominance degree. For each

Step 5. Normalize the overall performance. For each

Step 6. Rank the alternatives. The alternatives are evaluated according to the values

This section presents the case study environment, data collection, and the proposed methodological framework for characterizing social media posts from various Facebook online communities into clusters and determining moderation decisions based on their underlying characteristics. The application of the proposed methodological framework is detailed in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: The proposed methodological framework

In the vast and diverse landscape of social media, public academic Facebook groups serve as pivotal hubs for knowledge dissemination, collaboration, and community engagement among stakeholders, including scholars, researchers, and students [47]. These groups harness the power of UGC to foster discussions, share insights, and build professional networks within specific academic domains. However, alongside the benefits of such platforms come significant content moderation challenges that demand nuanced approaches to maintaining a constructive and safe online environment [48,49].

This case study examines the operations of a public academic Facebook group established to facilitate scholarly discourse and knowledge sharing. The Facebook group currently has over 5000 followers, with an average of more than 20 weekly posts, and the majority of members, approximately 98%, are Filipinos. Members share research findings, current local and global academic news, and personal perspectives concerning university operations. Serving as a vibrant hub for academic discussions, sharing research insights, and seeking advice, the group faces increasing complexities due to its growing global audience and expanding UGC. The critical tasks are ensuring content quality, preventing misinformation, and managing harmful online communications. The research team tackles these challenges by leveraging a methodological framework integrating LLMs for text analysis. This approach helps identify sensitive content types, categorize posts based on their contextual sensitivity, and employ MCDM tools, such as the TODIM method, to determine appropriate moderation actions for each cluster with associated characteristics.

By combining AI-driven insights with human expertise, the group aims to enhance user experience, foster meaningful discussions, and mitigate the negative impacts of harmful online behaviors within its community, contributing to a safer and more productive digital space for academic discourse.

4.2 Application of the Proposed Methodological Framework

This section outlines a comprehensive approach to moderating sensitive content on social media. Phase I employs GPT4 to extract and categorize sensitive content in social media posts. Phase II utilizes k-means clustering to form clusters with specific characteristics. Phase III determines the appropriate moderation decisions for each cluster using the TODIM method.

Phase I consists of actions (1) to (3) defined in Section 1.3 that identify types of sensitive content in social media posts, utilize LLMs to derive categories that collectively describe similar types from a wide array of sensitive content types, and apply LLMs to assess how well a large volume of social media posts align with the defined categories. Phase II conducts characterization to form clusters with specific attributes through the k-means algorithm, while Phase III determines the moderation actions for each cluster of social media posts using the TODIM method. The steps of the three phases are detailed as follows.

Phase I. Employs GPT4 to identify and categorize sensitive content in social media posts.

Step 1. Identify the types of sensitive content. In this step, 52 Facebook posts containing sensitive content were randomly selected from Facebook posts under various discussion topics. Box 1 presents the generalized prompt fed into GPT4. The 52 randomly selected Facebook posts are shown in Table S1 of the Supplementary Materials.

Box 1: Generalized prompt for extracting types of sensitive content.

Please extract the types of sensitive content from the following post:

[Insert social media post]

For instance, using the following social media post:

Please extract the sensitive content from the following post:

“Our post recently that deals with LGBTQ+ Community and against

Sogiebill have been removed by facebook.

But we assure of this to them..No one is able to remove the

truth that is in us, the elect, for the Word of God will stand forever! Amen. (1Ptr.1:25)

No wonder, truly, we live in a day when people speak biblical truth is

considered a HATE SPEECH–even among those who profess Christ. ”

GPT4 generates the following response.

“This message touches on a contentious issue involving the intersection of freedom of speech, religious beliefs, and LGBTQ+ rights. Here are the sensitive elements it encompasses:

1. **Content Removal**: The post starts by noting that a previous message, which was critical of legislation related to LGBTQ+ rights (specifically mentioning the SOGIE Bill), was removed from Facebook. This raises questions about social media policies on content moderation and the balance between free expression and protection against hate speech.

2. **Expression of Belief**: The author asserts their commitment to what they perceive as the ““truth”” based on their religious convictions, emphasizing the permanence of their beliefs despite the removal of their post.

3. **Conflict Between Beliefs and Modern Sensibilities**: The message suggests a tension between expressing certain biblical interpretations and current societal norms regarding hate speech, particularly concerning LGBTQ+ issues.

4. **Citation of Scripture**: By quoting 1 Peter 1:25, the author grounds their argument in religious scripture, framing their perspective as not just personal opinion but as a matter of divine principle.

5. **Critique of Contemporary Discourse**: The statement implies a critique of contemporary discourse, suggesting that what they consider to be the expression of biblical truth is often labeled as hate speech, including by some within the Christian community.

This content is sensitive due to its engagement with complex and highly divisive topics, including the interpretation of religious texts in public discourse, LGBTQ+ rights, and the parameters of hate speech. The viewpoints expressed reflect the broader global debate over how societies balance freedom of speech with the protection of individuals from discrimination and harm.”

Using the sample prompt in Box 1, a list of 227 types of sensitive content was generated, as shown in Table S2 of the Supplementary Materials.

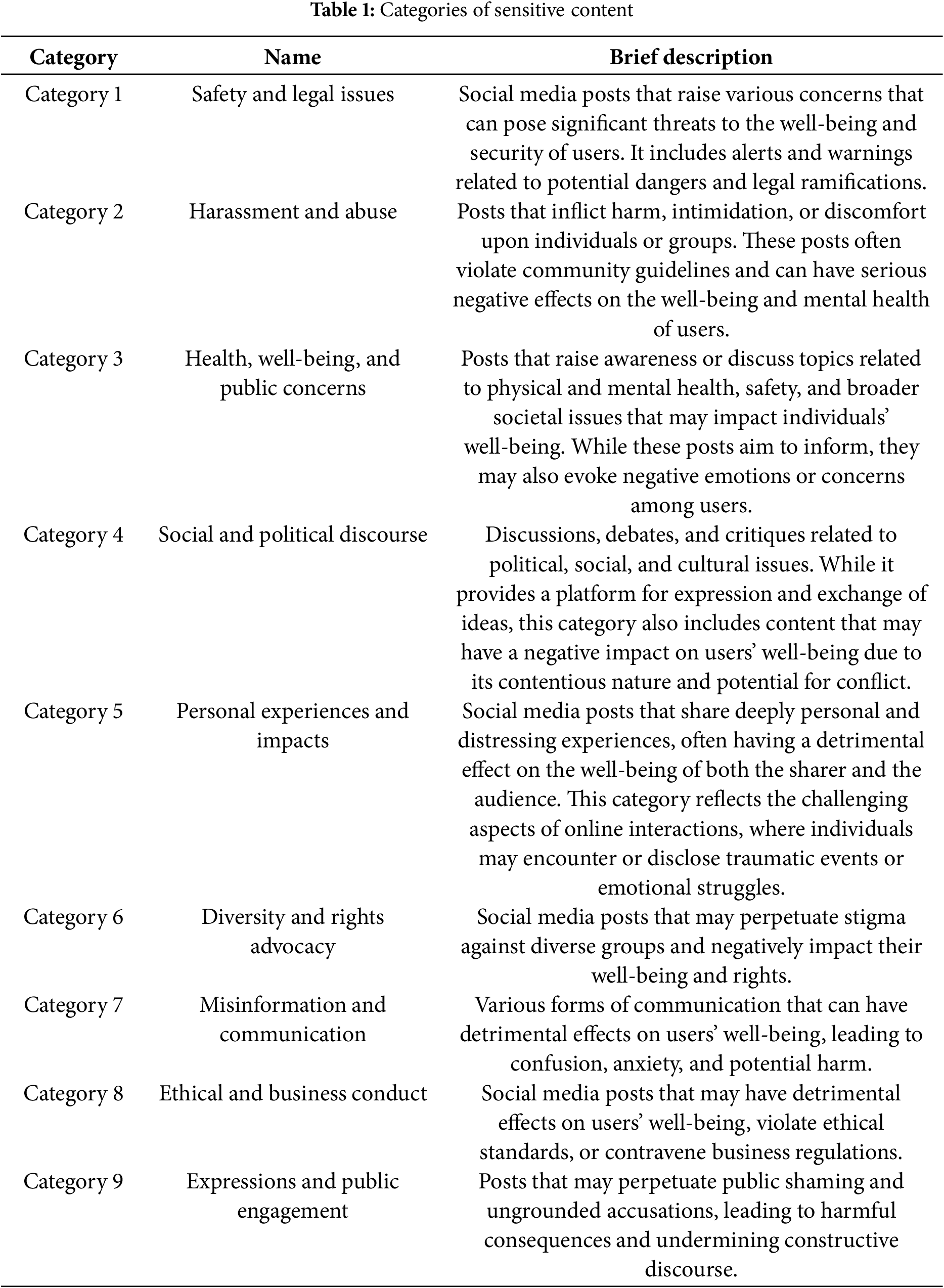

Step 2. Derive categories of the types of sensitive content. From the 227 types obtained in Step 1, Box 2 represents the prompt fed in GPT4, wherein nine unique categories were generated that collectively describe similar types of sensitive content. This compact list of categories prevents redundancy and ensures a more streamlined and efficient categorization process, facilitating better analysis and management of the sensitive content types identified. The list of categories and their corresponding brief description is shown in Table 1.

Box 2: Generalized prompt for creating clusters from the generated sensitive content.

Create clusters of the following types of sensitive content:

[Insert sensitive content types]

Step 3. Evaluate Facebook posts. In this step, 502 Facebook posts containing sensitive content were obtained randomly. Using the generated categories from Step 2, 502 Facebook posts were evaluated using the sample prompt in Box 3. Evaluation scores measuring the degree to which each post fit the corresponding categories were generated and are presented in Table S3 of the Supplementary Materials.

Box 3: Generalized prompt in evaluating Facebook posts containing sensitive content.

Given these categories:

[Insert the categories defined in Table 1]

From 0.000 to 1.000, 0.000 being the lowest and 1.000 being the highest, please rate the degree to which the following post demonstrates the provided categories, and generate a table indicating the scores:

[Insert Facebook post]

Phase II. Clustering using the k-means algorithm.

Step 4. Execute k-means clustering and determine the characteristics of the clusters. Using the equivalent crisp dataset from Step 3, k-means clustering was carried out to determine the clusters of posts and their corresponding characteristics. In RapidMiner® version 9.9, the Clustering (k-means) operator was applied to process the crisp dataset, with details found in the Supplementary Materials. Given Fig. 2, the lowest value of the Davies Bouldin Index was chosen to set the parameter

Figure 2: Davies Bouldin Index at various k values

Phase III. Ranking of moderation decisions using the TODIM method.

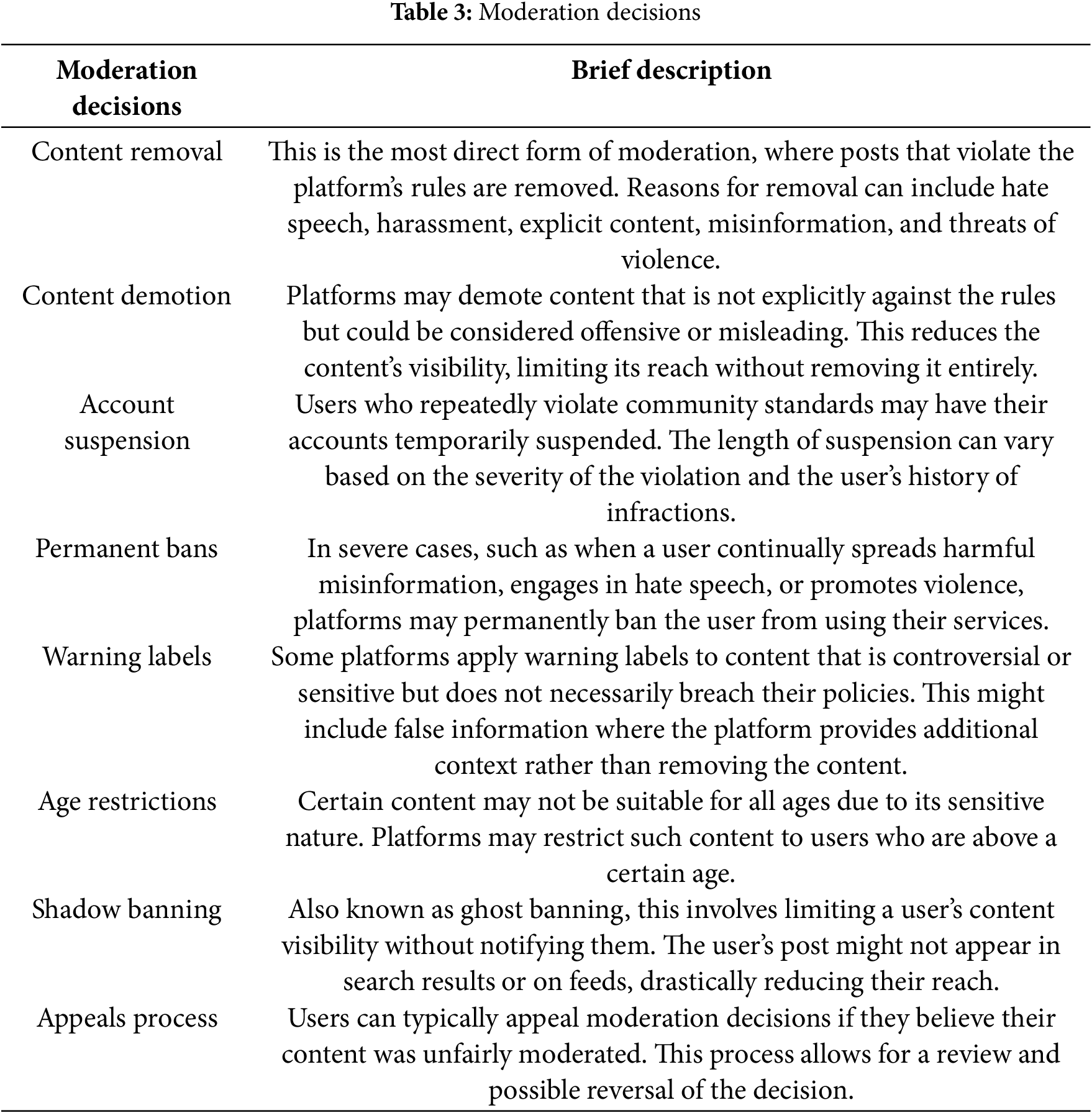

Step 5. Construct the evaluation matrix. Evaluation matrix for each cluster

Box 4: Generalized prompt in determining the list of moderation decisions for social media posts.

Different moderation punishment for social media sensitive content

[Insert sensitive content types]

Step 6. Determine the weights of the cluster characteristics using GPT4. First, each cluster was defined by providing a cluster name and its corresponding brief description, outlining its characteristics, using the prompt provided in Box 5.

Box 5: Generalized prompt in defining the name of each cluster.

How do you define in one word the sensitive content with the following characteristics:

[Insert the characteristics of the Cluster 3]

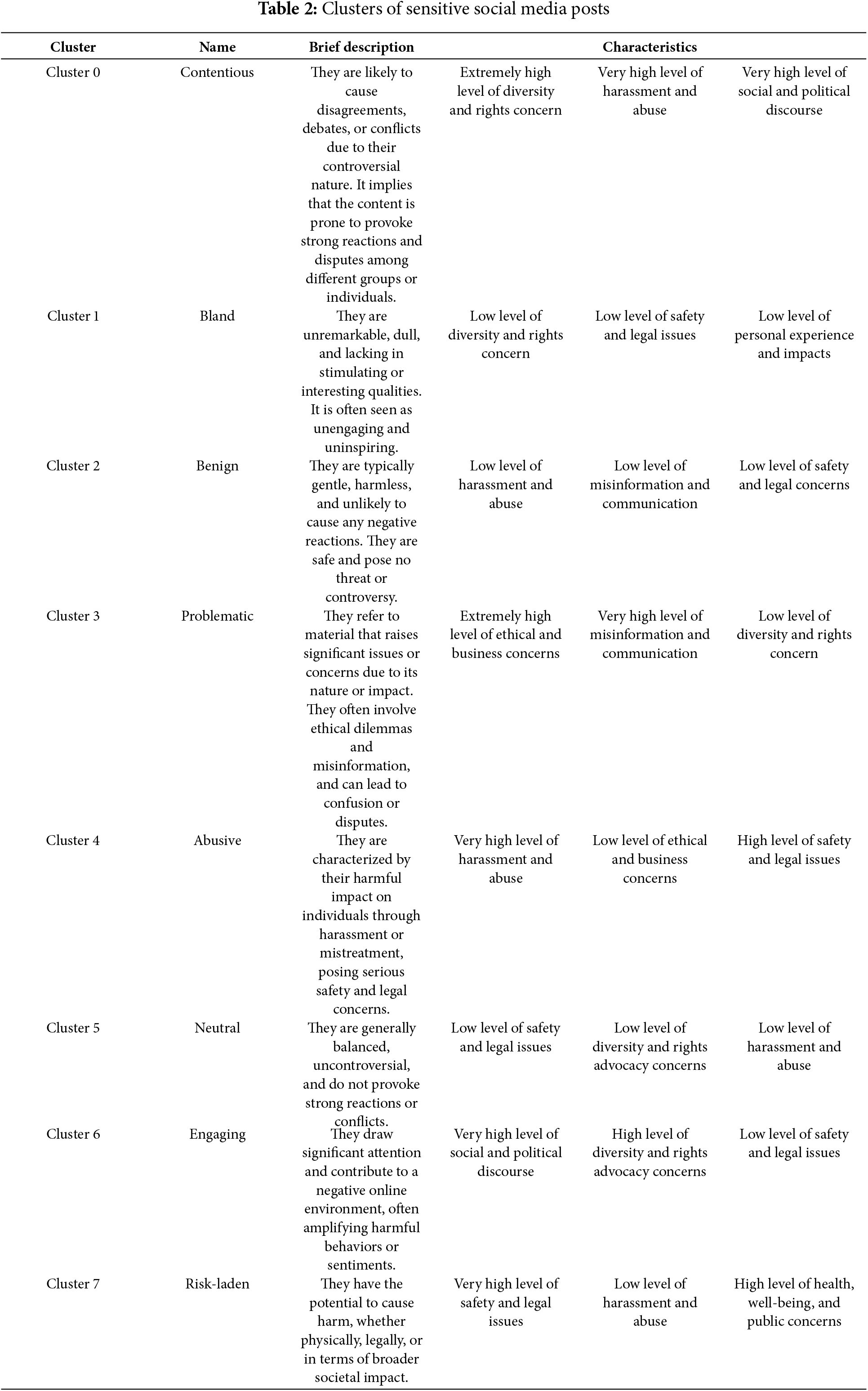

Then, in generating the brief description of each cluster, the prompt detailed in Box 6 was fed into GPT4. The details of each cluster are provided in Table 2.

Box 6: Generalized prompt for defining each cluster.

Define [generated cluster name].

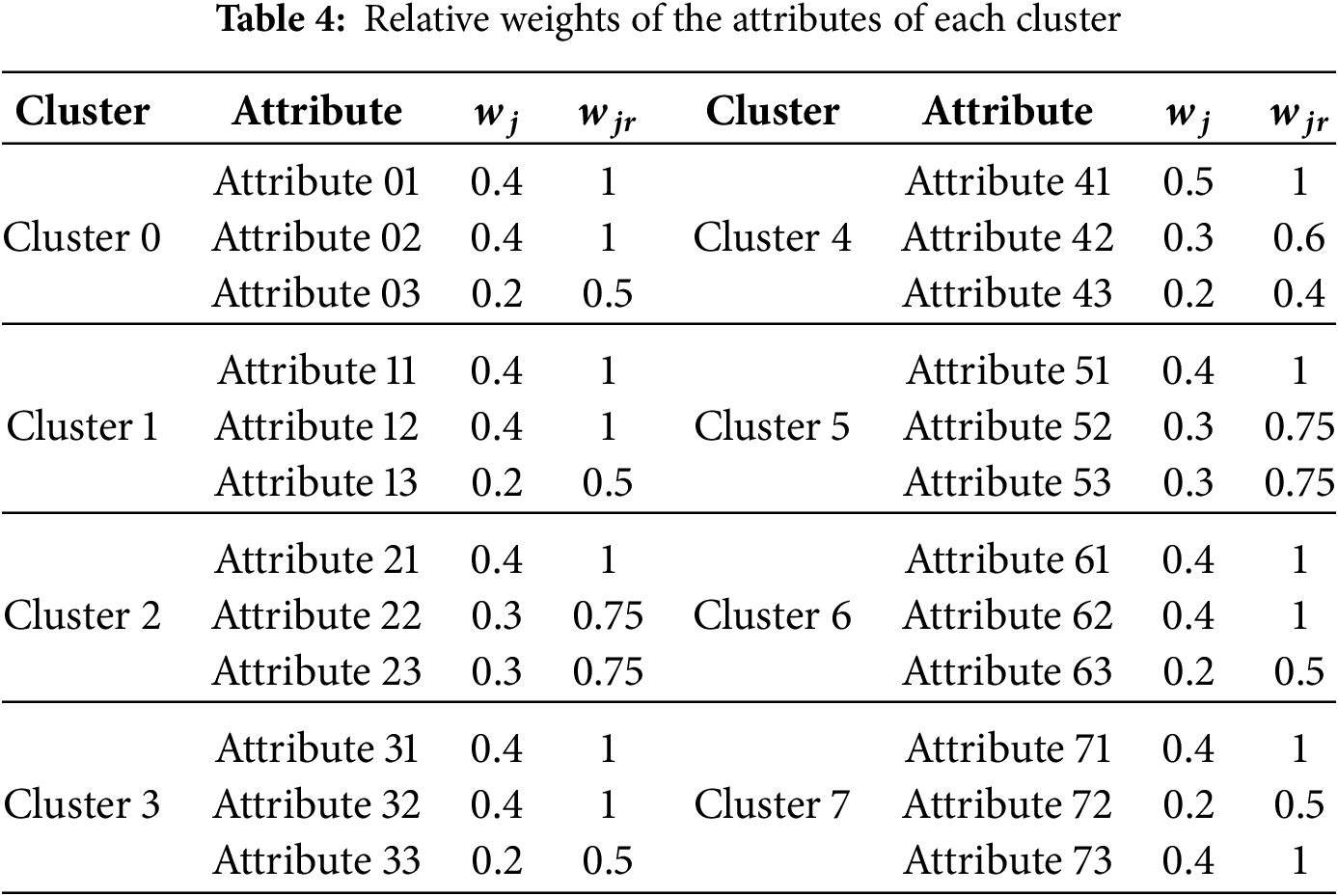

Lastly, using the sample prompt in Box 7, the weights, denoted as

Box 7: Generalized prompt in determining the weights of each attribute of the eight clusters.

What weight we must assign to the three characteristics of [insert the output of Box 5]. Total weights of the three characteristics should be equal to 1?

[Insert the characteristics of the output of Box 5]

Step 7. Calculate the relative weights of the cluster’s characteristics. The relative weights of each cluster attribute are obtained using Eq. (4). The result is illustrated in Table 4.

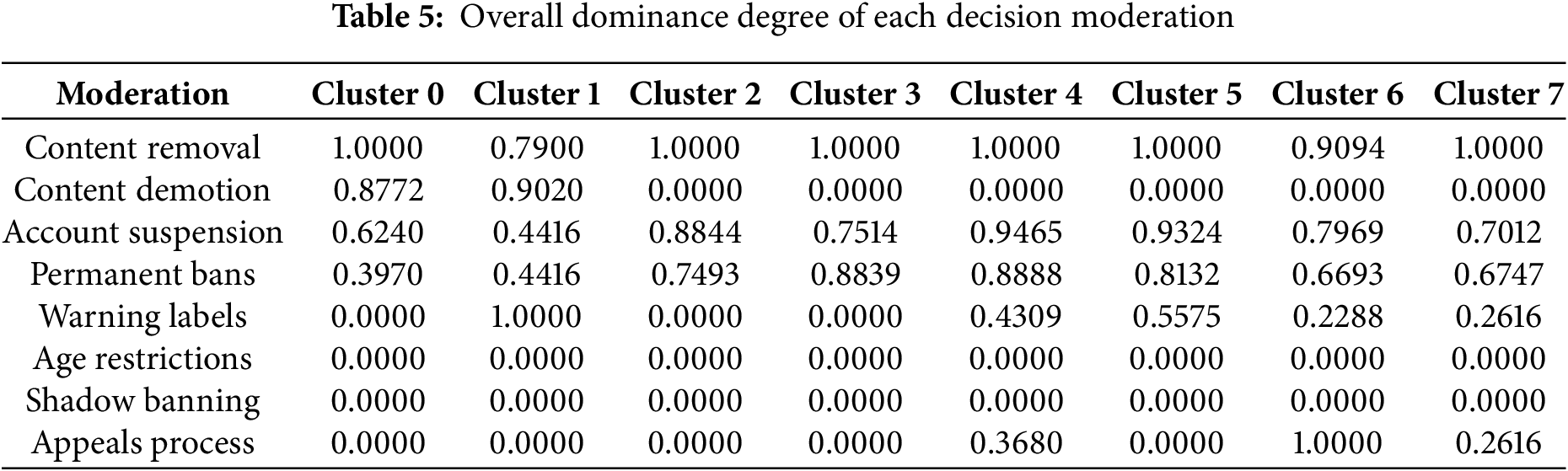

Step 8. Compute the overall dominance degree. First, the dominance degree of one moderation decision over the others is calculated using Eq. (5). Then, the overall dominance degree is calculated using Eq. (6), and the results are provided in Table 5.

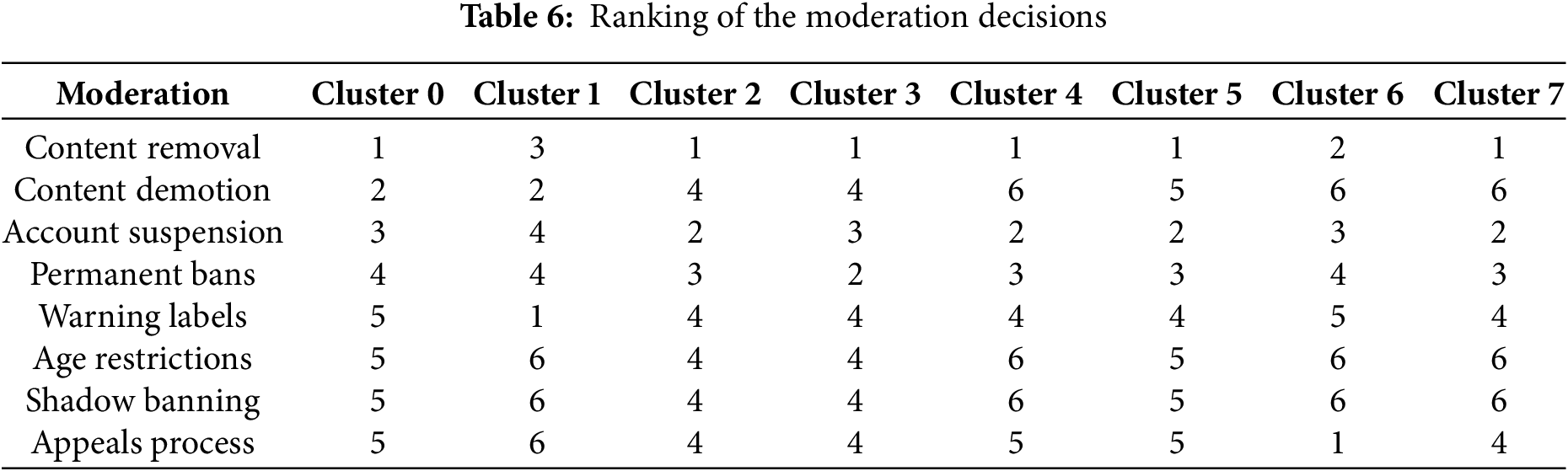

Step 9. Rank the moderation decisions. The moderation decisions are ranked based on their corresponding normalized overall dominance degree, denoted

Figure 3: Illustration of the moderation decisions ranking

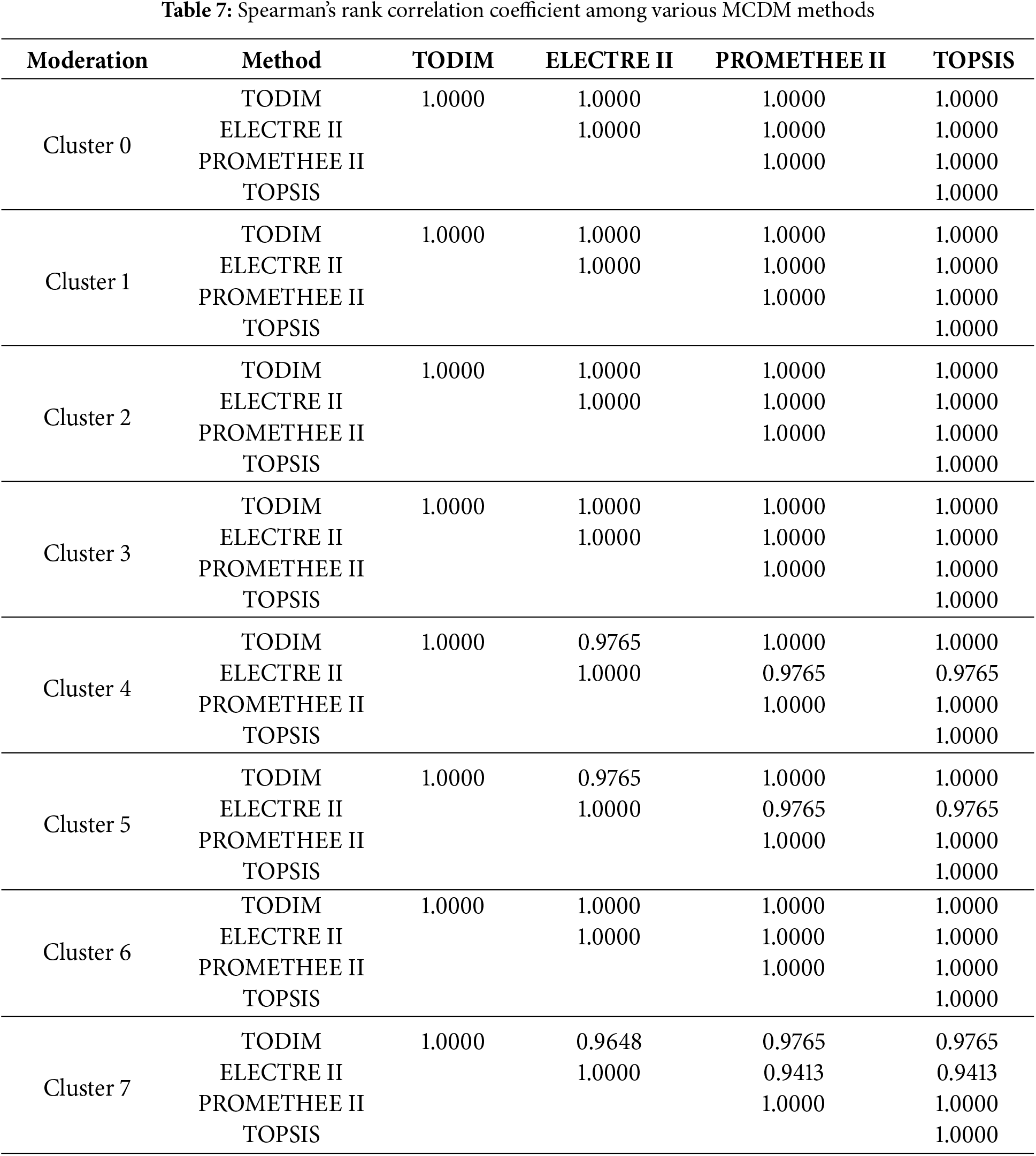

This section presents a comparative analysis to illustrate the performance of TODIM in comparison to other MCDM methods (i.e., ELECTRE II, PROMETHEE II, and TOPSIS) in ranking moderation decisions for the defined clusters of sensitive content, using the same priority weights for each characteristic per cluster (see Table 4). For brevity, the algorithms of other MCDM ranking methods are not discussed in this section. A comprehensive discussion of the algorithms is provided by Roy and Bertier [50] for ELECTRE II, Vincke and Brans [51] for PROMETHEE II, and Hwang and Yoon [52] for TOPSIS. The ranking result of employing these methods is shown in Fig. 4. The moderation decisions that rank first and last across the clusters remain the same among the methods under consideration. For instance, in Cluster 0, the four methods agree that Content Removal is the most appropriate moderation decision, while Shadow Banning, Age Restrictions, Warning Labels, and Appeals Process are tied as the least appropriate.

Figure 4: Comparison among various MCDM ranking methods

Moreover, we used Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient to assess the consistency of the ranking results across the different methods. The results revealed that the correlation between the rankings produced by TODIM and those produced by ELECTRE II, PROMETHEE II, and TOPSIS was consistently above 0.90, as presented in Table 7.

The high Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients indicate a strong agreement between the rankings of TODIM and those of ELECTRE II, PROMETHEE II, and TOPSIS. This result suggests that despite the different methodological approaches and underlying algorithms compared to other MCDM ranking tools, the proposed methodological framework is consistent and robust in identifying the most and least appropriate moderation decisions within the identified clusters of sensitive content.

Examining the nature of social media posts is crucial for designing measures to address specific problems, maintain digital order, protect individuals, and promote well-being. From randomly extracted social media posts, GPT4 generates nine categories spanning several domains. Safety and legal issues provide alerts and updates to protect public welfare, while measures addressing harassment and abusive posts work to create safer digital spaces. Health, well-being, and public concerns cover mental and physical health and substance abuse. Social and political discourse includes debates on current events and media criticism. Personal experiences and impacts share stories to connect and inspire. Diversity and rights advocacy promote equality and highlight issues of discrimination. Misinformation posts counter false information and educate users, while ethical and business conduct focuses on corporate responsibility and accountability. Lastly, expressions and public engagement foster cultural expression and community involvement. Due to the multidimensionality of social media posts, these categories are used as bases for evaluating a large number of social media posts to generate clusters with their corresponding characteristics. The k-means clustering yields the heatmap illustrated in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Heatmap of moderation strategies

The analysis provided in Fig. 5 reveals that there are eight identifiable clusters, namely: Cluster 0 as “contentious”, Cluster 1 as “bland”, Cluster 2 as “benign”, Cluster 3 as “problematic”, Cluster 4 as “abusive”, Cluster 5 as “neutral”, Cluster 6 as “engaging”, and Cluster 7 as “risk-laden”. “Contentious” content is characterized as having an extremely high level of diversity and rights advocacy (229.77% above average), a very high level of harassment and abuse (151.12% above average), and a very high level of political discourse (131.44% above average). Due to its controversial nature, this cluster is likely to spark disagreements, debates, or conflicts and is prone to provoking strong reactions and disputes among various groups and individuals. “Bland” content comprises a low level of diversity and rights advocacy (96.22% below average), a low level of safety and legal issues (83.92% below average), and a low level of personal experiences and impacts (77.21% below average). This cluster is perceived as unremarkable, commonly lacks stimulation or interest, and is often deemed unengaging and uninspiring. “Benign” content encompasses a low level of harassment and abuse (82.06% below average), a low level of misinformation and communication (77.31% below average), and a low level of safety and legal issues (75.63% below average). Characteristically, this cluster features gentle and harmless content, unlikely to cause adverse reactions, and is safe, posing no threat or controversy. “Problematic” content has an extremely high level of ethical and business concerns (237.81% above average), a very high level of misinformation and communication (157.34% below average), and a low level of diversity and rights advocacy (67.58% below average). It is firmly committed to integrity, transparency, and social justice. Thus, it promotes ethical practices, ensuring the accuracy and clarity of information, advancing equality and inclusivity, and often challenging unjust systems, thereby fostering a more informed and equitable society. “Abusive” content consists of a very high level of harassment and abuse (159.62% above average), a low level of ethical and business concerns (64.60% below average), and a high level of safety (60.21% above average). The content of this cluster strongly advocates for justice, integrity, and accountability. It is likely to actively highlight instances of misconduct, advocate for systemic changes to prevent harm, and promote ethical business practices and legal compliance, aiming to foster a safer and more equitable environment for all. “Neutral” content includes a low level of safety and legal issues (89.34% below average), a low level of diversity and rights advocacy (88.77% below average), and a low level of harassment and abuse (82.36% below average). This cluster would exhibit a strong commitment to social justice, inclusivity, and accountability and is likely to actively raise awareness about various forms of mistreatment, advocate for marginalized communities, promote legal protections, and push for systemic changes to create safer and more equitable environments for all individuals. “Engaging” content encompasses a very high level of social and political discourse (128.08% above average), a high level of diversity and rights advocacy (74.94% above average), and a low level of safety and legal issues (62.89% below average). Thus, this cluster draws significant attention and contributes to a hostile online environment, often amplifying harmful behaviors or sentiments. Lastly, “risk-laden” content comprises a very high level of safety and legal issues (121.34% above average), a low level of harassment and abuse (75.09% below average), and a high level of health, well-being, and public concerns (57.57% above average). Consequently, content here can potentially cause harm, whether physically, legally, or in terms of broader societal impact.

The results of TODIM associate appropriate moderation actions for each cluster. For instance, in the “contentious” cluster, content removal has the highest dominance degree among moderation strategies. Hence, with the extreme extent of a violation (i.e., hate speech, harassment, explicit content, misinformation, and threats), content removal emerges as the most appropriate action, followed by content demotion, account suspension, and permanent bans. For “bland” content, the most appropriate actions are warning labels, followed by content demotion and removal. On the other hand, for “benign” cluster, content removal is the most suitable moderation approach for content with extreme violations, followed by account suspension, then permanent bans, leading to age restrictions, an appeals process, warning labels, and shadow banning, with the minor action preferred. Moreover, the most appropriate actions for “problematic” content are content removal, permanent bans, and account suspension, while the least suitable choices are the appeals process, content demotion, warning labels, and shadow banning. Conversely, for “abusive content”, content removal is the most suitable moderation, followed by account suspension and permanent bans; consequently, minor action is taken with warning labels, an appeals process, shadow banning, and content demotion. In contrast, the “neutral” cluster suggests that content removal would be the worst possible action, followed by account suspension and permanent bans, while warning labels, an appeals process, age restrictions, and content demotion are the least likely choices. In “engaging” content, the first action to be addressed in worst-case scenarios is an appeals process, followed by content removal and account suspension. Meanwhile, permanent bans, warning labels, content demotion, and shadow banning are the least likely choices. Nevertheless, content removal is the most suitable course of action for “risk-laden” content in cases of extreme violation, followed by account suspension and permanent bans. Warning labels, an appeal process, content demotion, and age restrictions are the least severe options.

Concurrently, among the eight distinct clusters, six clusters, namely “contentious”, “benign”, “problematic”, “abusive”, “neutral”, and “risk-laden”, opted for content removal as the dominant action for an extreme violation. At the same time, the appeals process and shadow banning are consistently considered the least minor course of action. Meanwhile, permanent bans, account suspensions, and warning labels are the neutral course of action. The findings of this work have a practical contribution that can be embodied as a two-step process. Content moderators in Facebook groups, for instance, can evaluate each post according to the eight clusters of content identified in Phase II of the proposed framework. This process may involve a visual checklist that compares the characteristics of a given post with those of the clusters. Once content moderators can determine the appropriate cluster to which the post belongs, the findings in Phase III will offer guidance on the corresponding moderation actions. With appropriate mechanisms in place, this two-step process can be implemented in real-time, even in large datasets of social media posts. Meanwhile, a comparative analysis reveals that these findings are consistent with those of comparable MCDM methods, such as ELECTRE II, PROMETHEE II, and TOPSIS.

Finally, this work presents the first attempt to demonstrate a fully integrated framework that combines LLMs, machine learning, and MCDM. This novel attempt offers a more nuanced approach to leveraging the strengths of these intelligent systems in a systematic evaluation of decision problems, in general, and in content moderation decisions, in particular. Our proposed approach makes the following contributions within the domain of decision-making under multiple criteria. First, the decision elements (i.e., criteria and alternatives) are identified using LLMs, which are deemed appropriate for highly complex problems that require a more comprehensive list than human decision-makers may generate. Second, our approach leverages the strength of LLMs in text analytics tasks, which incorporates nuances associated with their extensive deep learning models pre-trained on vast amounts of data. When this capability is used to evaluate multiple alternatives across various criteria, it captures the nuances that human decision-makers often find difficult. In addition, the efficiency that LLMs offer in evaluating alternatives is extremely beneficial in large-scale MCDM problems, where evaluations via human judgment are nearly impossible due to high cognitive demands. Third, the sequential process of feeding an MCDM problem with results from machine learning algorithms (i.e., k-means clustering) and LLMs is first reported in this work. The list of criteria is obtained by machine learning, while LLMs determine their corresponding weights. Overall, the integration of LLMs, machine learning, and MCDM highlights a more systematic and efficient approach to complex, large-scale decision-making problems.

6 Limitations of the Study and Future Research

This work is not free from limitations, like other existing studies. First, the use of GPT4 in tasks associated with generating sensitive content types, categories of sensitive content, the evaluation of social media posts under the different categories, and the identification of moderation strategies has potential biases, detailed as follows:

(1) The massive training data of GPT4 contains historical, cultural, and societal bias, overrepresents Western or English-speaking perspectives, and underrepresents marginalized voices or low-resource languages.

(2) GPT4 may also misclassify neutral or context-specific content as overly positive or negative, which can lead to an underestimation of sarcasm, humor, or emotionally nuanced content.

(3) The responses of GPT4 may be susceptible to confirmation bias, amplifying patterns that frequently appear in the training data, thereby reinforcing popular opinions or dominant narratives, even if they seem inaccurate.

(4) Certain topics in social media posts considered in this work may be largely framed with a dominant cultural lens (e.g., American-centric views), which may not be relevant in other cultural frames.

(5) GPT4 may misinterpret non-English or code-switched text, potentially affecting the evaluation of social media posts across different categories.

Thus, the results of this work must be interpreted with caution in light of the aforementioned biases. While the insights we outlined may apply to a Philippine-based Facebook group in the case study due to the Western inclination of Philippine culture, the same may not be relevant in other cultures with different municipal laws on free speech in place. Thus, when the proposed methodological framework is adopted in future research, bias mitigation approaches such as human-in-the-loop validation, domain-specific fine-tuning for the social media group under consideration, and incorporating diverse training datasets may be implemented.

Second, the social media posts we extracted are those that comply with existing laws in the Philippines, such as cybercrime laws. These may not exist if tighter laws are in place; hence, the generation of categories and clusters is dependent on what the existing laws allow, making them context-dependent. Consequently, a different collection of social media posts in other regions may yield different categories and clusters, as well as associated moderation actions. Third, the moderation decisions identified for each cluster may depend on the focus group discussions of two experienced moderators. Future work may extend the evaluation by involving a larger group of moderators. Fourth, future research can expand the proposed methodological framework to other social media platforms, such as Twitter, YouTube, and Instagram, to assess its adaptability across different environments. Investigating the application of the framework to large datasets with imprecise data will test its robustness and scalability. Fifth, the evaluation of social media posts under different categories poses ambiguity and imprecision, which could be addressed by existing frameworks that handle data ambiguity and precision. In this view, future work could integrate advanced fuzzy set extensions (e.g., intuitionistic fuzzy sets) to enhance the precision of content categorization and moderation. Lastly, real-time moderation systems, cultural and regional impact studies, and the incorporation of user feedback will further refine the framework.

This study presents a novel methodological framework that augments self-moderation efforts within small online communities such as Facebook groups created for academic purposes. It utilizes LLMs (i.e., GPT4) for content analysis and categorization, coupled with a k-means clustering algorithm to characterize social media posts, and MCDM (i.e., TODIM) to determine appropriate moderation decisions for each content cluster. By leveraging LLMs for text analysis and incorporating clustering algorithms and expert judgments within the MCDM process, the proposed framework offers a more nuanced and context-sensitive approach to self-moderation. This framework offers a promising solution for creating safer and more inclusive online spaces within smaller communities, particularly in developing economies where community dynamics and management may differ from those in established online landscapes. Furthermore, the comparative analysis also shows that the proposed approach yields comparable results with other MCDM tools (i.e., ELECTRE II, PROMETHEE II, TOPSIS). Although these insights may contain idiosyncrasies, the findings from this study contribute to the growing body of research on self-moderation in online communities.

In the implementation of the proposed methodological framework, the 227 types of sensitive content determined by GPT4 can be grouped into nine categories: (1) safety and legal issues, (2) harassment and abuse, (3) health, well-being, and public concerns, (4) social and political discourse, (5) personal experiences and impacts, (6) diversity and rights advocacy, (7) misinformation and communication, (8) ethical and business conduct, and (9) expressions and public engagement. From 502 social media posts evaluated under the nine categories, eight distinct clusters of social media content were identified, including contentious, bland, benign, problematic, abusive, neutral, engaging, and risk-laden content. With eight possible moderation strategies elucidated by GPT4 (i.e., content removal, content demotion, account suspension, permanent bans, warning labels, age restrictions, shadow banning, and appeals process), TODIM identifies the priority moderation actions for each cluster. The analysis of moderation strategies revealed a clear preference for content removal across all clusters. This finding suggests a cautious approach by the platform, prioritizing the removal of potentially harmful content. However, the dominance scores assigned to other moderation actions, like account suspension and permanent bans, highlight a nuanced strategy that adapts based on the content cluster. These findings hold significant implications for social media platforms. By understanding the types of content within each cluster and the most effective moderation approaches, content moderators can create a more balanced online environment, one that ensures user safety while upholding freedom of expression.

Acknowledgement: The authors are grateful to the Office of the Vice-President for Research and Development of Cebu Technological University for funding this project.

Funding Statement: This work was partially funded by the Office of the Vice-President for Research and Development of Cebu Technological University.

Author Contributions: Noreen Fuentes—Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. Janeth Ugang—Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. Narcisan Galamiton—Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. Suzette Bacus—Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. Samantha Shane Evangelista—Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization. Fatima Maturan—Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization. Lanndon Ocampo—Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Project Administration. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are in the Supplementary Materials.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at .

References

1. Bentz N, Chase E, Deloach P. Social Media Debate Position 4: social media and information services. Internet Ref Serv Q. 2021;25(1–2):55–64. [Google Scholar]

2. Stasi ML. Social media platforms and content exposure: how to restore users’ control. Compet Regulation Netw Ind. 2019;20(1):86–110. doi:10.1177/1783591719847545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ponte C, Velicu A, Simões JA, Lampert C. Parental practices in the era of smartphones. In: Smartphone cultures. Routledge; 2017. p. 41–54. [Google Scholar]

4. Asyraff MA, Hanafiah MH, Zain NAM, Hariani D. Unboxing the paradox of social media user-generated content (UGC) information qualities and tourist behaviour: moderating effect of perceived travel risk. J Hospitality Tourism Insights. 2024;7(4):1809–30. doi:10.1108/jhti-02-2023-0072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Saura JR, Palacios-Marqués D, Ribeiro-Soriano D. Privacy concerns in social media UGC communities: understanding user behavior sentiments in complex networks. Inf Syst E-Bus Manag. 2025;23(1):125–45. doi:10.1007/s10257-023-00631-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Almansoori A, Alshamsi M, Abdallah S, Salloum SA. Analysis of cybercrime on social media platforms and its challenges. In: The International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Vision. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 615–25. [Google Scholar]

7. Huang W, Zhu S, Yao X. Destination image recognition and emotion analysis: evidence from user-generated content of online travel communities. Comput J. 2021;64(3):296–304. [Google Scholar]

8. Lam JM, Ismail H, Lee S. From desktop to destination: user-generated content platforms, co-created online experiences, destination image and satisfaction. J Destination Marketing Manag. 2020;18(5):100490. doi:10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Gongane VU, Munot MV, Anuse AD. Detection and moderation of detrimental content on social media platforms: current status and future directions. Soc Netw Anal Min. 2022;12(1):129. doi:10.1007/s13278-022-00951-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Einwiller SA, Kim S. How online content providers moderate user-generated content to prevent harmful online communication: an analysis of policies and their implementation. Policy Internet. 2020;12(2):184–206. doi:10.1002/poi3.239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Mars B, Gunnell D, Biddle L, Kidger J, Moran P, Winstone L, et al. Prospective associations between internet use and poor mental health: a population-based study. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0235889. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

12. Butrime E, Zuzeviciute V. Possible risks in social networks: awareness of future law-enforcement officers. In: Rocha Á, Adeli H, Reis L, Costanzo S, editors. Trends and Advances in Information Systems and Technologies. WorldCIST’18 2018. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. Vol. 746. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018. p. 264–76. [Google Scholar]

13. Edwards A, Webb H, Housley W, Beneito-Montagut R, Procter R, Jirotka M. Forecasting the governance of harmful social media communications: findings from the digital wildfire policy Delphi. Policing Soc. 2021;31(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

14. Taddeo M, Floridi L. The debate on the moral responsibilities of online service providers. Sci Eng Ethics. 2016;22:1575–603. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

15. Schintler LA, McNeely CL(Eds.). Encyclopedia of big data. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022. [Google Scholar]

16. Banaji S, Bhat R. Social media and hate. London, UK: Taylor & Francis; 2022. 140 p. [Google Scholar]

17. Kraut RE, Resnick P. Building successful online communities: evidence-based social design. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: MIT Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

18. Hwang S, Foote JD. Why do people participate in small online communities? Proc ACM Hum-Comput Interaction. 2021;5(CSCW2):1–25. [Google Scholar]

19. Chandrasekharan E, Samory M, Jhaver S, Charvat H, Bruckman A, Lampe C, et al. The Internet’s hidden rules: an empirical study of Reddit norm violations at micro, meso, and macro scales. Proc ACM Hum-Comput Interaction. 2018;2(CSCW):1–25. [Google Scholar]

20. Cai J, Wohn DY. After violation but before sanction: understanding volunteer moderators’ profiling processes toward violators in live streaming communities. Proc ACM Hum-comput Interaction. 2021;5(CSCW2):1–25. doi:10.1145/3479554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Mazzullo E, Bulut O, Wongvorachan T, Tan B. Learning analytics in the era of large language models. Analytics. 2023;2(4):877–98. [Google Scholar]

22. Meyer JG, Urbanowicz RJ, Martin PC, O’Connor K, Li R, Peng PC, et al. ChatGPT and large language models in academia: opportunities and challenges. BioData Min. 2023;16(1):20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

23. Chang Y, Wang X, Wang J, Wu Y, Yang L, Zhu K, et al. A survey on evaluation of large language models. ACM Trans Intell Syst Technol. 2024;15(3):1–45. [Google Scholar]

24. Talabis M, McPherson R, Miyamoto I, Martin J, Kaye D. Information security analytics. Oxford, UK: Syngress; 2015. [Google Scholar]

25. MacQueen J. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. Proc Fifth Berkeley Symp Math Statistics Probability. 1967 Jun;1(14):281–97. [Google Scholar]

26. Shang Q, Li H, Deng Y, Cheong KH. Compound credibility for conflicting evidence combination: an autoencoder-K-means approach. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybernetics Syst. 2021;52(9):5602–10. [Google Scholar]

27. Wu J. Advances in K-means clustering: a data mining thinking. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Science & Business Media; 2012. [Google Scholar]

28. Ikotun AM, Ezugwu AE, Abualigah L, Abuhaija B, Heming J. K-means clustering algorithms: a comprehensive review, variants analysis, and advances in the era of big data. Inf Sci. 2023;622:178–210. [Google Scholar]

29. Sahoo SK, Goswami SS. A comprehensive review of multiple criteria decision-making (MCDM) Methods: advancements, applications, and future directions. Decision Making Adv. 2023;1(1):25–48. [Google Scholar]

30. Gomes LFAM, Lima MMPP. TODIM: basics and application to multicriteria ranking of projects with environmental impacts. Found Comput Decis Sci. 1991;16(3–4):113–27. [Google Scholar]

31. Doumpos M, Grigoroudis E. Multicriteria decision aid and artificial intelligence: links, theory and applications. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2013. [Google Scholar]

32. Mindell DA, Reynolds E. The work of the future: building better jobs in an age of intelligent machines. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 2023. [Google Scholar]

33. Habbal A, Ali MK, Abuzaraida MA. Artificial Intelligence Trust, Risk and Security Management (AI TRiSMframeworks, applications, challenges and future research directions. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;240(4):122442. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Taherdoost H, Madanchian M. Multi-criteria decision making (MCDM) methods and concepts. Encyclopedia. 2023;3(1):77–87. [Google Scholar]

35. Bozdemir MKE, Alkan A. Selection of social media platforms using fuzzy PROMETHEE method with different scenario types. J Eng Studies Res. 2022;28(4):41–50. doi:10.29081/jesr.v28i4.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Abbas S, Alnoor A, Yin TS, Sadaa AM, Muhsen YR, Khaw KW, et al. Antecedents of trustworthiness of social commerce platforms: a case of rural communities using multi group SEM & MCDM methods. Electron Commer Res Appl. 2023;62:101322. [Google Scholar]

37. Jami Pour M, Hosseinzadeh M, Amoozad Mahdiraji H. Exploring and evaluating success factors of social media marketing strategy: a multi-dimensional-multi-criteria framework. Foresight. 2021;23(6):655–78. doi:10.1108/fs-01-2021-0005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Galamiton N, Bacus S, Fuentes N, Ugang J, Villarosa R, Wenceslao C, et al. Predictive modelling for sensitive social media contents using entropy-FlowSort and artificial neural networks initialized by large language models. Int J Comput Intell Syst. 2024;17(1):262. doi:10.1007/s44196-024-00668-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Hassani H, Beneki C, Unger S, Mazinani MT, Yeganegi MR. Text mining in big data analytics. Big Data Cogn Comput. 2020;4(1):1. [Google Scholar]

40. Zhang F, Song W. Product improvement in a big data environment: a novel method based on text mining and large group decision making. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;245:123015. [Google Scholar]

41. Mukhamediev RI, Yakunin K, Mussabayev R, Buldybayev T, Kuchin Y, Murzakhmetov S, et al. Classification of negative information on socially significant topics in mass media. Symmetry. 2020;12(12):1945. [Google Scholar]

42. Rice S, Crouse SR, Winter SR, Rice C. The advantages and limitations of using ChatGPT to enhance technological research. Technol Soc. 2024;76:102426. [Google Scholar]

43. Liu Y, Melton GB, Zhang R. Exploring large language models for acronym, symbol sense disambiguation, and semantic similarity and relatedness Assessment. AMIA Summits Transl Sci Proc. 2024;2024:324–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

44. Oka R, Kusumi T, Utsumi A. Performance evaluation of automated scoring for the descriptive similarity response task. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):6228. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

45. Thelwall M. ChatGPT for complex text evaluation tasks. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol. 2025;76(4):645–8. [Google Scholar]

46. Forgy EW. Cluster analysis of multivariate data: efficiency versus interpretability of classifications. Biometrics. 1965;21:768–9. [Google Scholar]

47. Cheng WWH, Lam ETH, Chiu DK. Social media as a platform in academic library marketing: a comparative study. J Acad Librariansh. 2020;46(5):102188. [Google Scholar]

48. De Gregorio G. Democratising online content moderation: a constitutional framework. Comput Law Secur Rev. 2020;36:105374. [Google Scholar]

49. Seering J. Reconsidering self-moderation: the role of research in supporting community-based models for online content moderation. Proc ACM Hum-Comput Interaction. 2020;4(CSCW2):1–28. doi:10.1145/3415178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Roy B, Bertier P. La méthode Electre II. Note De Travail. 1971;142:25. [Google Scholar]

51. Brans JP, Vincke P. Note—a preference ranking organisation method: (The PROMETHEE method for multiple criteria decision-making). Manage Sci. 1985;31(6):647–56. doi:10.1287/mnsc.31.6.647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Hwang CL, Yoon K. Multiple attribute decision making: methods and applications a state-of-the-art survey. Vol. 186. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Science & Business Media; 2012. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools