Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

EGOP: A Server-Side Enhanced Architecture to Eliminate End-to-End Latency Caused by GOP Length in Live Streaming

1 School of Computer Science, Xi’an Polytechnic University, Xi’an, 710048, China

2 Institute of Artificial Intelligence, Zhengzhou Xinda Institute of Advanced Technology, Zhengzhou, 450000, China

* Corresponding Author: Tao Wu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-27. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068160

Received 22 May 2025; Accepted 19 August 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Over the past few years, video live streaming has gained immense popularity as a leading internet application. In current solutions offered by cloud service providers, the Group of Pictures (GOP) length of the video source often significantly impacts end-to-end (E2E) latency. However, designing an optimized GOP structure to reduce this effect remains a significant challenge. This paper presents two key contributions. First, it explores how the GOP length at the video source influences E2E latency in mainstream cloud streaming services. Experimental results reveal that the mean E2E latency increases linearly with longer GOP lengths. Second, this paper proposes EGOP (an Enhanced GOP structure) that can be implemented in streaming media servers. Experiments demonstrate that EGOP maintains a consistent E2E latency, unaffected by the GOP length of the video source. Specifically, even with a GOP length of 10 s, the E2E latency remains at 1.35 s, achieving a reduction of 6.98 s compared to Volcano-Engine (the live streaming service provider for TikTok). This makes EGOP a promising solution for low-latency live streaming.Keywords

Today, the emergence of advanced networking technologies like 5G [1] and 6G [2], alongside the rapid growth of Over-The-Top (OTT) [3] content services (e.g., TikTok, YouTube, Bilibili, Douyin), and the increasing user preference for internet-based video over traditional television, have made video streaming the dominant internet traffic. Statistics reveal that live streaming drives peak internet usage in the United States, and this trend is just beginning. In 2024, the top ten traffic peak days were linked to live streaming events [4].

This paper focuses on the real-time demands of live streaming, where users are highly sensitive to end-to-end (E2E [5]) latency [6]—the delay between a video scene’s occurrence and its display on a user’s screen. To ensure a high-quality experience, live streaming platforms must deliver low-latency, stable video services. E2E latency is influenced by factors like encoding, transmission, buffering, and decoding, with the Group of Pictures (GOP) [7] length during video encoding being a critical element.

As illustrated in Fig. 1, a live streaming video source is a continuous sequence of GOPs. A typical GOP begins with an I-frame (intracoded frame) [8], followed by P-frames (predicted frames) [9] or B-frames (bidirectional predicted frames) [9]. Due to latency introduced by B-frames at both encoder and decoder ends, live streaming often uses only I-frames and P-frames. Since GOPs are processed independently, current systems manage operations at the GOP level [10].

Figure 1: GOP structure of video source

To address the need for users to join live streams with minimal latency, live streaming systems often recommend a maximum GOP length. This helps ensure that viewers do not encounter significant E2E latency when accessing a stream. In practice, many live streaming platforms advocate for a GOP size of 2 s. However, in scenarios demanding ultra-low latency for frequent interactions between hosts and viewers, a shorter GOP size may be necessary. For instance, Alibaba-Cloud’s live streaming service suggests a GOP length of 1 s, Tencent-Cloud recommends a keyframe interval of 1 or 2 s during streaming, and Volcano-Engine (the service provider for TikTok) advises setting the GOP length to 1 or 2 s.

Some solutions, such as LL-DASH [11] and HESP [12], have attempted to address this issue. They involve creating multiple streams on the server side: one with a shorter GOP for new users and another with a longer GOP for existing users, allowing a switch between them. While innovative, these methods have limitations for large-scale commercial use. First, they raise computational and bandwidth costs by generating and transmitting multiple streams with different GOP sizes across server nodes, while managing dual streams for one channel adds complexity and reduces reliability. Second, they can lower encoding efficiency for videos with little or no global motion. Finally, these solutions mainly focus on reducing the impact of GOP length on E2E latency, rather than eliminating it entirely.

We introduce a novel approach called Enhanced GOP Structure (EGOP). Unlike conventional GOP, EGOP not only includes key elements like I-frames and P-frames but also integrates image data for each frame, as shown in Fig. 2. EGOP-based streaming servers offer several benefits. First, by allowing access to the current frame at any time, EGOP ensures superior E2E latency stability compared to existing cloud-based live streaming services. Second, the average E2E latency of EGOP is significantly lower than that of cloud streaming. Lastly, EGOP is fully compatible with current live streaming environments, requiring no modifications to traditional streaming clients.

Figure 2: Overview of EGOP-Based streaming server

Our main contributions are as follows:

• We provide a detailed analysis of the challenges faced by major Chinese cloud-based live streaming providers [13], highlighting how E2E latency is consistently affected by the GOP length of the video source.

• We present the design of EGOP and explain how it effectively reduces the impact of video source GOP length on E2E latency.

• We evaluate the performance of an EGOP-based streaming media server. The results demonstrate that our solution achieves a mean E2E latency of approximately 1.35 s across various GOP lengths, with minimal correlation between GOP length and mean E2E latency. Specifically, when the GOP length at the video source is 10 s, the mean E2E latency is reduced by 6.93, 9.04, and 13.17 s compared to Volcano-Engine, Alibaba-Cloud, and Tencent-Cloud live streaming services, respectively.

• We conducted comparative experiments with LL-DASH and WebRTC [14], EGOP achieves a maximum mean E2E latency reduction of 10.566 s compared to LL-DASH and 4.965 s compared to WebRTC.

2.1 Cloud-Based Live Streaming

As a pivotal application of cloud computing technology, cloud-based live streaming leverages cloud infrastructure [15] to enable real-time transmission, storage, and distribution of video streams. Through its distributed architecture, the cloud live streaming platform efficiently handles video data acquisition, encoding, transmission, and playback. This setup ensures high-quality and low-latency live streaming experiences, even under conditions of large-scale concurrent access [16].

To ensure generality, we selected three prominent Chinese commercial cloud live streaming platforms: Alibaba-Cloud, Tencent-Cloud, and Volcano-Engine (see Table 1). For our experiments, we configured the setup using the RTMP protocol with H.264 [17] for video pushing and adopted HTTP-FLV [18] with H.264 for live content streaming. To maintain compatibility in this study, the output video stream of EGOP is formatted in HTTP-FLV, as demonstrated in the provided sample code.

HTTP-FLV is a video streaming format based on the HTTP protocol, widely used in low-latency live streaming scenarios. By encapsulating FLV [19] within HTTP, it facilitates rapid video transmission, making it a preferred choice for real-time streaming platforms. Its low-latency characteristic ensures excellent performance in interactive live broadcasts. Currently, major platforms such as Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok), Kuaishou, and Douyu employ the HTTP-FLV format for live streaming. In this study, EGOP also adopts this format.

High frame rates [20] (typically, 30 frames per second suffice for representing motion, though fast-changing content may require 60 FPS) and high-resolution uncompressed video data demand significant bandwidth, often exceeding the capacity of public networks. Compression is therefore essential. Several standards, such as MPEG [21], H.264, H.265 [22], and AV1 [23], enable comparable image quality with fewer bits.

H.264, also known as AVC [24], is a widely recognized video encoding standard that employs both intra-frame and inter-frame compression techniques. It achieves high efficiency through predictive coding and transform coding [25]. This standard offers remarkable adaptability, supporting a broad range of resolutions and bitrates, and is extensively used in video conferencing, streaming, and broadcasting. In our study, we consistently utilize H.264 for video encoding.

E2E latency in cloud-based live streaming refers to the total delay incurred during the entire process, from content capture, encoding, and transmission to decoding and rendering on the user’s device. It serves as a critical metric for evaluating the smoothness and responsiveness of the live streaming experience.

Fig. 3 depicts the primary process for measuring E2E latency. We employed Open Broadcaster Software (OBS), one of the most popular streaming tools, to push video sources. OBS offers flexibility in adjusting GOP length and supports concurrent streaming. For playback of the live video stream, we used the open-source FFMPEG suite. Notably, both streaming and playback were conducted on the same personal computer (PC), enabling a direct comparison of the time difference between the video source capture window and the live stream playback window, thus facilitating accurate E2E latency measurement.

Figure 3: The methodology used to measure E2E latency

To achieve low E2E latency, cloud streaming providers often require users to set a smaller GOP size. This is because the streaming server must transmit all video frames from the latest GOP to new viewers. Upon receiving the first frame, the user must decode and display it immediately. However, subsequent frames received from the server are placed into the playback buffer. In the worst-case scenario, E2E latency increases by the full GOP duration. For instance, with a GOP size of 8 s, the streaming server may have already cached 7.9 s of the latest GOP. When a new viewer joins, the server sends all 7.9 s of cached video frames, and the viewer begins playback from the first frame of the GOP. Consequently, the E2E latency is extended by nearly the entire GOP size, i.e., 7.9 s. In practice, to mitigate latency in live streaming, providers often recommend setting the GOP size to 1 s.

Current cloud-based streaming platforms attempt to minimize the impact of video source GOP length on E2E latency by enforcing a smaller GOP size, thereby achieving lower latency. However, this approach does not fully eliminate the issue. Therefore, developing an enhanced solution to completely remove the influence of the video source’s GOP length on live stream E2E latency remains a critical need.

2.5 Pearson Correlation Analysis

Pearson correlation analysis [26] is a widely adopted statistical method for evaluating the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two variables. In this study, we employed the Pearson correlation coefficient [27] to investigate the relationship between GOP length at the video source and E2E latency. The formula for calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient is given in Eq. (1).

where

The value of

•

•

•

Research on low-latency streaming technology has driven the development of efficient streaming server solutions, particularly for the gaming and interactive streaming industries. Recent studies have predominantly focused on video transmission optimization [28] and GOP-related optimizations.

In the domain of video streaming transmission optimization, significant efforts have been made to improve the overall quality of experience (QoE). Yang et al. [29] proposed a novel distributed HTTP live streaming rate control mechanism. Their Distributed Multisource Rate Control Algorithm (DMRCA) enables both video providers and consumers to dynamically select the optimal stream rate independently, without the need for centralized control. Wang et al. [30] introduced DeeProphet, a system designed to enhance low-latency live streaming performance through accurate bandwidth prediction. DeeProphet leverages TCP state information to detect intervals between consecutive packet transmissions, thereby collecting reliable bandwidth samples. It robustly estimates segment-level bandwidth by filtering out noise samples and predicts significant changes and uncertain fluctuations in future bandwidth using time-series analysis and machine learning-based approaches. Compared to state-of-the-art low-latency adaptive bitrate (ABR) algorithms, DeeProphet improves the overall QoE by 39.5%. Additionally, Niu et al. [31] developed a dual-buffer nonlinear model that provides a more objective and accurate evaluation of stalling in HTTP-FLV live streaming videos.

DASH-IF et al. [11] proposed Low-Latency DASH (LL-DASH), introducing the concept of chunks, which divide traditional DASH segments into smaller units. These finer-grained chunks can be downloaded and buffered by the browser using HTTP/1.1 chunked transfer encoding, even before the complete segment is generated, thereby reducing live streaming latency. While this approach resolves the issue of segments being unusable by clients during their generation, the E2E latency remains limited by the GOP length at the video source.

Pieter-Jan et al. [12] introduced HESP, a protocol that employs two streams for each video source: an initialization stream and a continuation stream. The initialization stream consists solely of I-frames, allowing new viewers to join at any time. Subsequently, viewers are switched to the continuation stream, which can be encoded with a larger GOP size.

Unlike LL-DASH, EGOP is built on the HTTP-FLV protocol, enabling live video streaming to users without relying on segment-based transmission. Moreover, EGOP eliminates the impact of GOP length at the video source on E2E latency by utilizing an auxiliary decoder, a minimal buffer, and a temporary encoder. In contrast, LL-DASH has yet to address the latency issues caused by GOP length.

The primary distinction between EGOP and HESP lies in their design and implementation. HESP is a proprietary commercial streaming protocol that achieves low-latency live streaming by combining two video streams, necessitating licensing and support from the HESP Alliance. Conversely, EGOP is based on RTMP and HTTP-FLV, ensuring compatibility with existing live streaming ecosystems without the need for auxiliary streams or additional infrastructure.

The proposed EGOP reduces E2E latency by leveraging an auxiliary decoder to build a small cache during streaming and using this cache with a temporary encoder to return the current frame upon a new playback request, thereby avoiding the need to retransmit the entire GOP.

EGOP effectively tackles the challenge of balancing low-latency live streaming with large GOP sizes at video sources, without modifying the existing transmission methods of the video source. Most live streaming platforms that rely on RTMP and HTTP-FLV can benefit from this approach. To the best of our knowledge, no prior work has implemented a similar method.

4 Impact of GOP Length on Cloud-Based Live Streaming E2E Latency

To gain a deeper understanding of how video source GOP length affects the E2E latency of mainstream cloud-based streaming platforms, we conducted a two-part evaluation. This evaluation examines the fluctuations in E2E latency under a fixed GOP length and analyzes the impact of varying GOP lengths on E2E latency.

To investigate the effect of GOP length on E2E latency in traditional cloud-based live streaming, we selected three commercial cloud streaming providers—Alibaba Cloud, Tencent Cloud, and Volcano Engine—to construct our dataset. As illustrated in Fig. 3, we collected E2E latency data using the following procedure: First, we set the GOP length of the video source to 1 s in the OBS software and initiated the stream. Then, for each streaming platform, we used FFmpeg to play 150 live streams and record the corresponding E2E latency. Subsequently, we adjusted the GOP length to 2 s and repeated the process. This procedure was iterated until the GOP length reached 10 s (Note: Alibaba Cloud rejects video streams when the GOP length exceeds 10 seconds; therefore, in this study, the maximum GOP length was limited to 10 s.) Through this method, we compiled a comprehensive dataset. Our dataset has been made publicly available on GitHub (https://github.com/zhoukunpeng504/EGOP-dataset) (accessed on 18 August 2025).

4.2 Fluctuations in E2E Latency

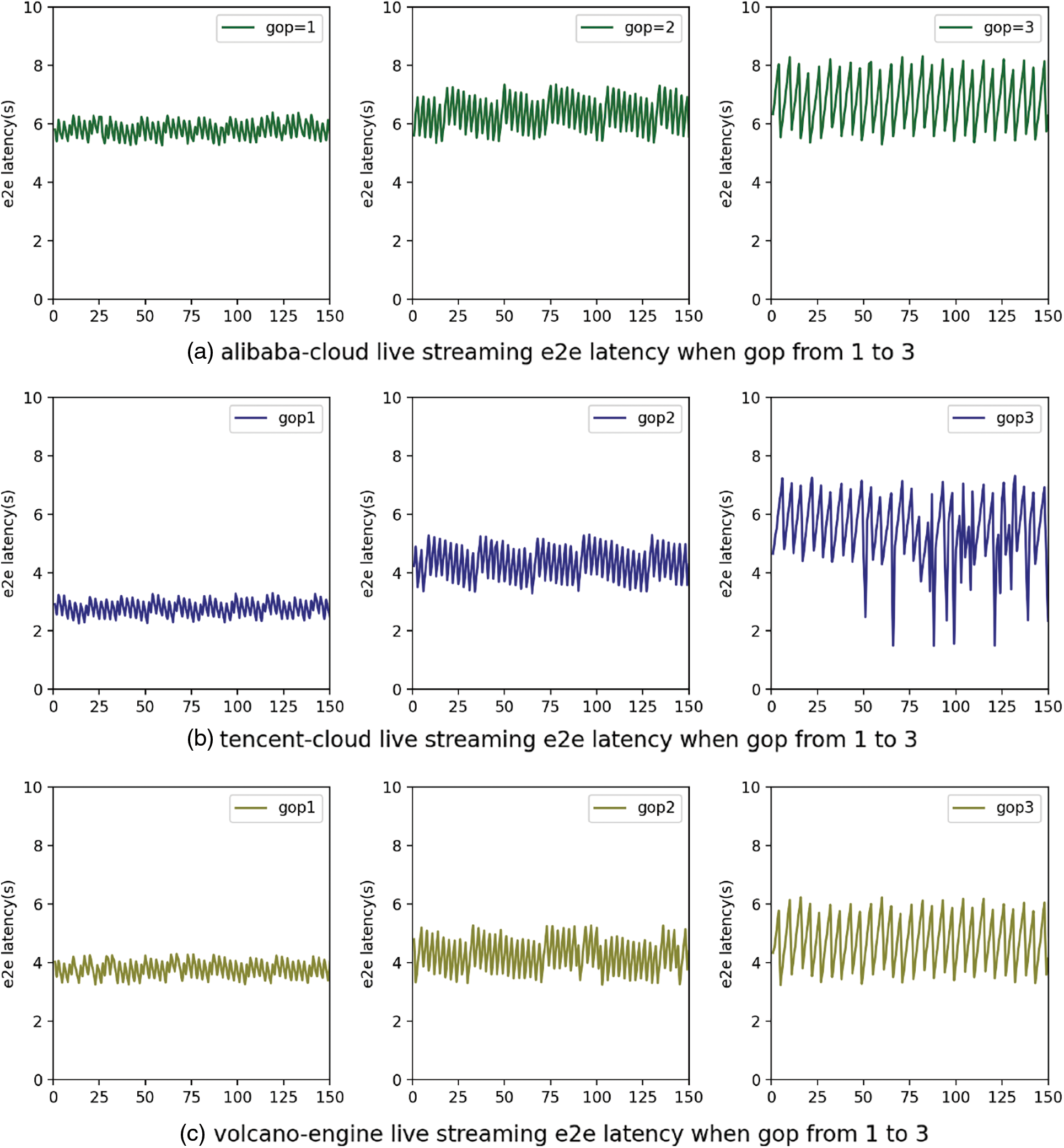

To evaluate the variability of E2E latency under fixed GOP lengths, we analyzed the results of 150 E2E latency measurements for video source GOP lengths of 1, 2, and 3 s.

Fig. 4 illustrates the performance of various cloud streaming platforms under fixed GOP lengths. We observed that the E2E latency data exhibit fluctuations within a specific range across all platforms, including Alibaba-Cloud, Tencent-Cloud, and Volcano-Engine. Furthermore, Fig. 4a–c reveals that, while the fluctuation ranges vary among cloud service providers for the same GOP length, the range of fluctuation tends to increase significantly as the GOP length increases.

Figure 4: E2E latency performance of different cloud-based live streaming platforms with GOP lengths set to 1, 2, or 3 s, featuring 150 E2E latency data points for each configuration

The underlying cause of the inherent fluctuations in E2E latency in traditional cloud-based live streaming platforms lies in the requirement for the streaming server to transmit the complete cached GOP [32] when a viewer joins a stream. Without the entire GOP, the viewer cannot decode the video frames correctly. Typically, the first frame received by the client upon playback is the initial frame of the current GOP, known as the I-frame. As illustrated in Fig. 5a, when the cached GOP length is short, the E2E latency tends to be near the lower bound of the fluctuation range. Conversely, as depicted in Fig. 5b, when the GOP length is longer, the E2E latency often approaches the upper bound of the fluctuation range.

Figure 5: Video frames received by viewers when joining cloud-based live streaming at different time points

As shown in Fig. 4, an increase in GOP length is associated with a corresponding rise in E2E latency, suggesting a potential relationship between these two factors. A comprehensive analysis of the impact of varying GOP lengths on latency will be provided in the subsequent subsection.

4.3 Impact of GOP Length Variation on Mean E2E Latency

Referring to Section 4.2, in traditional cloud-based live streaming platforms, although the GOP length at the video source remains constant, the measured E2E latency exhibits fluctuations within a specific range. To provide a more accurate evaluation of E2E latency, we define

Here,

Fig. 6 presents the variation in mean E2E latency for three major cloud-based live streaming platforms as the GOP length ranges from 1 to 10. The horizontal axis indicates the GOP length at the video source (in seconds), while the vertical axis represents the mean E2E latency (in seconds). The results demonstrate that, for each cloud streaming provider, the mean E2E latency consistently increases with longer GOP lengths. To quantitatively evaluate this relationship, we computed the Pearson correlation coefficient, with the results summarized in Table 2. The table indicates a strong positive linear correlation between the GOP length at the video source and the mean E2E latency.

Figure 6: Mean E2E latency across various cloud-based live streaming platforms. (a), (b), and (c) illustrate the mean E2E latency for Alibaba-Cloud, Tencent-Cloud, and Volcano-Engine, respectively, under different GOP lengths at the video source

Furthermore, we explore the relationship between GOP length and mean E2E latency using unary linear regression analysis [33]. Eq. (3) models the relationship between GOP length (

Our analysis confirms a strong positive linear correlation between mean E2E latency and GOP length at the video source across these cloud-based live streaming platforms. As GOP length increases, the mean E2E latency rises significantly.

Here, we analyzed the impact of GOP length at the video source on the E2E latency of cloud-based live streaming platforms. Before delving into the detailed description of EGOP, we outline the primary design objectives of EGOP as follows:

• To reduce fluctuations in E2E latency

• To achieve superior E2E latency performance, ensuring that E2E latency remains independent of GOP length.

As discussed in Section 4, for current live streaming services offered by cloud providers [34], both the stability and the average value of E2E latency are significantly affected by the GOP length at the video source. Therefore, exploring methods to mitigate or even eliminate this dependency is of great importance and poses a substantial challenge.

In a conventional GOP, only video frames are included. In contrast, the EGOP structure incorporates corresponding image data for each frame, as illustrated in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Comparison between EGOP and GOP. EGOP includes additional image information for each frame compared to GOP.

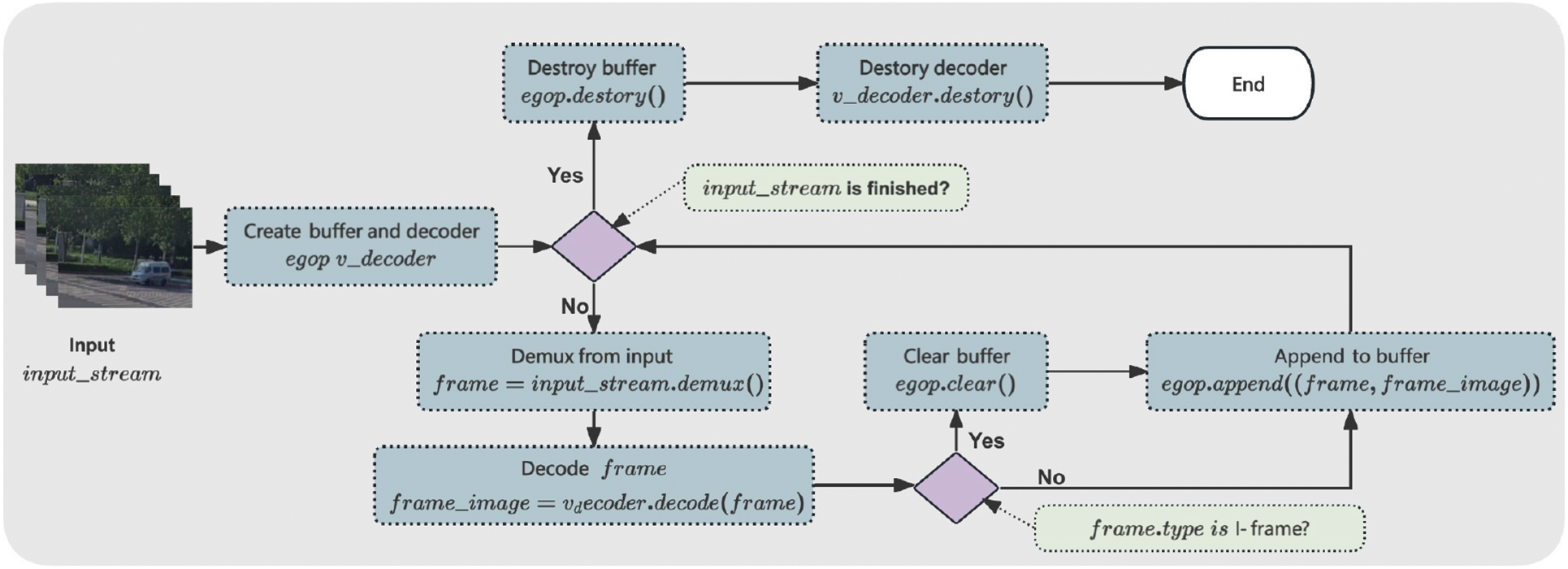

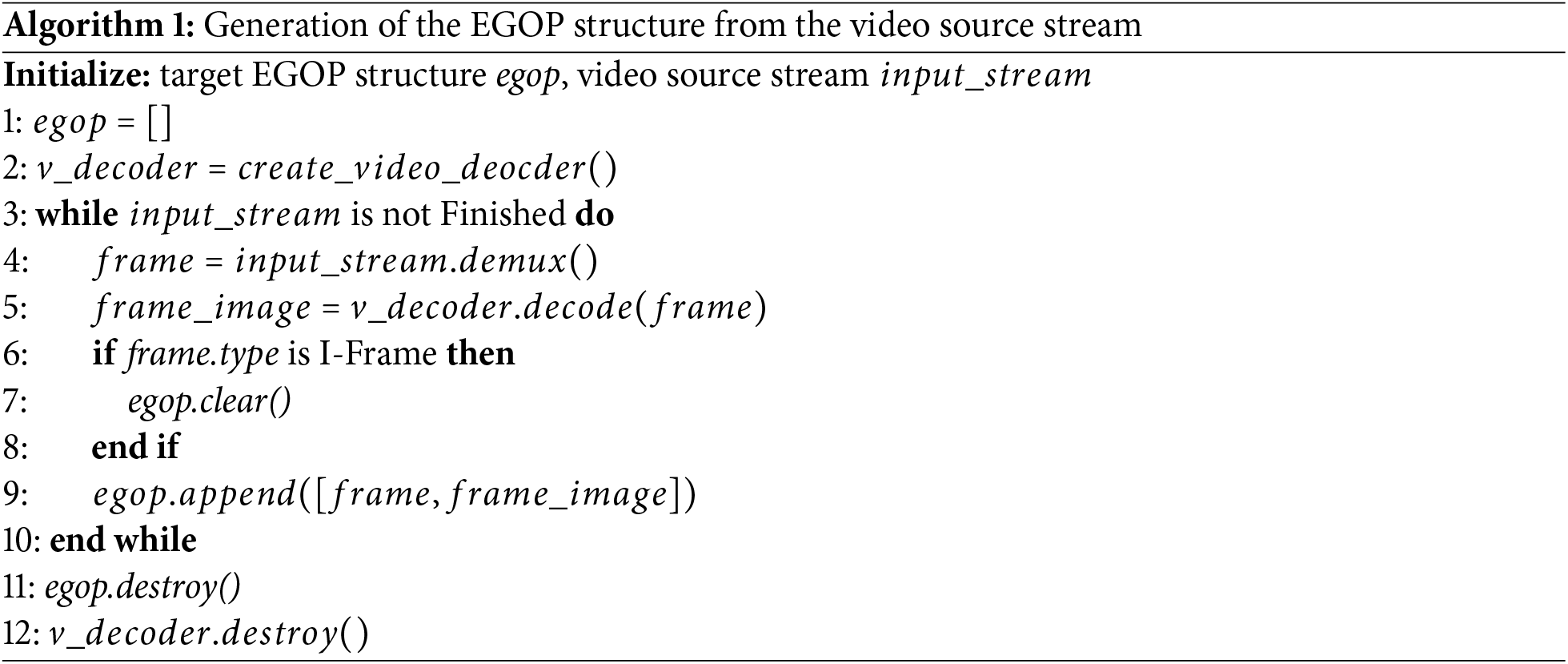

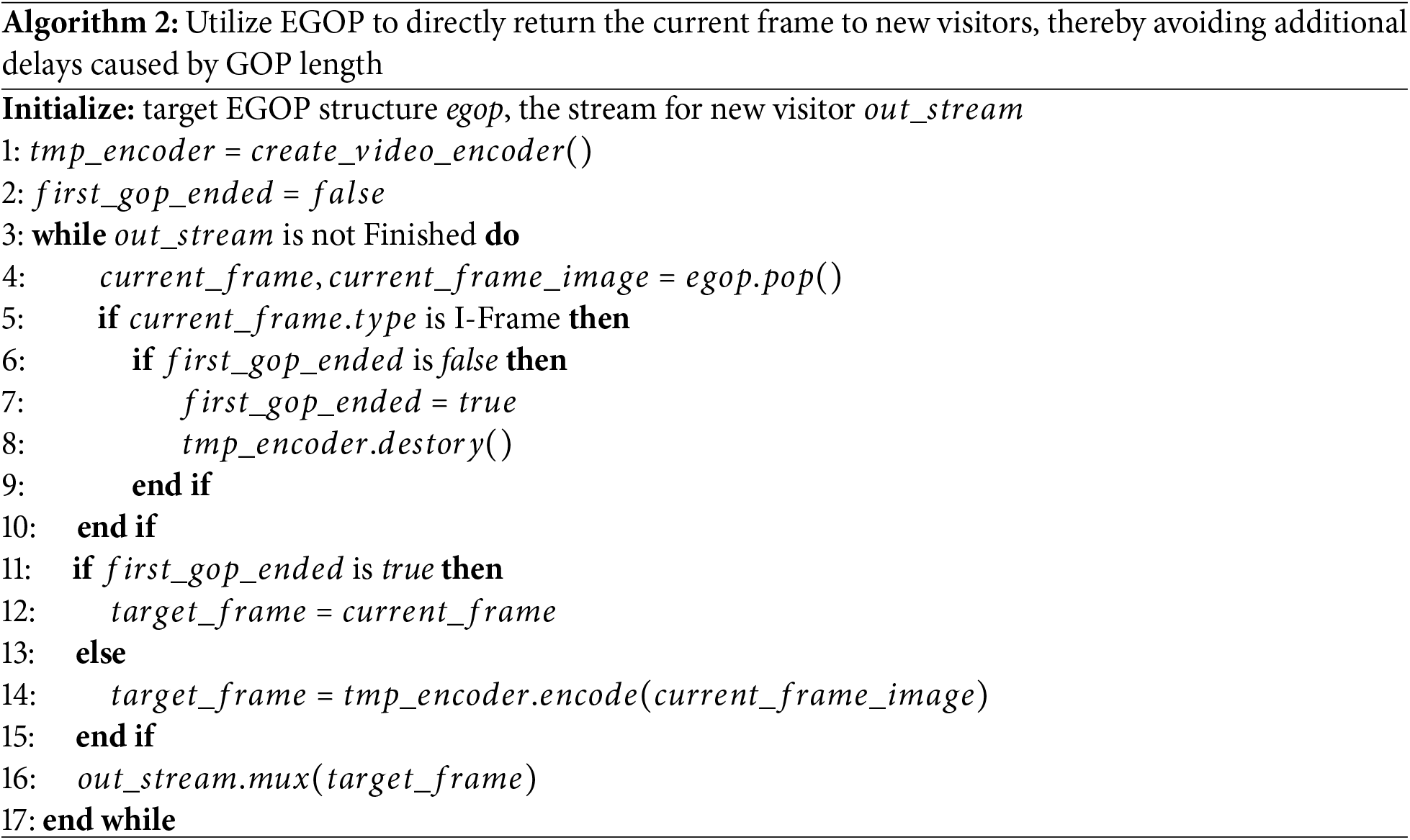

As outlined in Algorithm 1 and illustrated in Fig. 8, the construction of EGOP requires an auxiliary decoder and a minimal memory buffer. The EGOP is constructed through the following steps:

Figure 8: Flowchart of the EGOP construction process

(1) Upon receiving the video stream (denoted as

(2) For each new frame received (denoted as

(3) If the frame is an I-frame, the

The

5.3 Frame Generation with EGOP

By leveraging the image information associated with each frame in the EGOP structure, we enhance the process by which the streaming server delivers frames to new viewers upon joining. EGOP delivers video frames sequentially to new viewers, as described in Algorithm 2. A temporary encoder is instantiated for each playback request and is terminated upon receiving the first I-frame from the memory buffer (denoted as

To aid in understanding Algorithm 2, we will detail the step-by-step process of generating the first I-frame and subsequent frames using EGOP when a new visitor arrives and both the current and next frames are P-frames (as shown in Fig. 9).

Figure 9: When the current frame is

1. The EGOP-based streaming service receives a new request and creates a video stream object named

2. The streaming service creates a temporary encoder named

3. The streaming service retrieves the current frame (

4. The type of current frame is obtained using the

5. The

6. The streaming service retrieves the next frame (

7. The

8. The

9. The streaming service retrieves the next frame (

10. The

11. The

12. The streaming service retrieves the next frame (

13. The

14. The

5.4 How EGOP Reduces E2E Latency

This innovation ensures nearly constant E2E latency for video stream requests at any time, with the underlying principle as follows:

We define the GOP length of the video source as

As shown in Fig. 10, if a new viewer requests a video stream at time

If the video stream is requested at time

Figure 10: EGOP structure and its practical application example. Viewer A begins requesting the live stream at time

Similarly, if the video stream is requested at time

If a video stream is requested at time

When a new viewer joins, EGOP can instantly deliver the current frame without needing to transmit the entire cached GOP, thus avoiding the additional E2E latency resulting from the video source’s GOP length. However, theoretical justification alone is inadequate.Its outstanding performance is showcased through experimental data in Section 6.3.

5.5 Privacy and Security Protection

Due to the integration of a temporary decoder in EGOP (as detailed in Algorithm 1), a limited number of recent user video frames are briefly retained within EGOP. To safeguard security and privacy, EGOP adheres to the following design principles:

• In single-process implementations, EGOP’s data are stored exclusively in runtime memory and are strictly prohibited from being written to any form of persistent external storage. The implementation employed in this study complies with this principle.

• For distributed implementations where distributed memory (e.g., Redis [36]) is required, the following conditions must be met:

– The distributed memory must be protected with robust encryption mechanisms.

– EGOP’s data must be stored in an encrypted format.

– Memory blocks must support automatic expiration to ensure that data are automatically deleted immediately after a user terminates their video stream.

Here, we assess the performance of the EGOP design with a focus on E2E latency metrics. We begin by outlining the experimental setup employed to acquire the dataset. Subsequently, we provide a detailed evaluation to determine whether EGOP’s E2E latency surpasses that of existing solutions.

To assess the performance of EGOP, we developed a lightweight HTTP-FLV streaming service based on the EGOP framework. The source code for this implementation is publicly available on GitHub (https://github.com/zhoukunpeng504/EGOP-stream-server) (accessed on 18 August 2025). This service enables video stream pushing via RTMP [37] and supports playback of live video streams through HTTP-FLV.

We evaluated the E2E latency using the methodology outlined in Section 4.1. Initially, we configured the GOP length to 1 s in OBS and initiated the video stream push. The live stream was played 150 times, with E2E latency recorded for each session. Subsequently, the GOP length was adjusted to 2 s, and the live stream was played an additional 150 times, with latency measurements collected again. This procedure was repeated incrementally until the GOP length reached 10 s, resulting in a comprehensive dataset.

6.2 Fluctuations in E2E Latency

The primary question addressed in this subsection is whether the E2E latency fluctuations of the EGOP-based streaming service outperform those of traditional cloud-based streaming platforms.

To address this question, we analyzed the E2E latency data of the EGOP-based streaming server with GOP lengths set to 1, 2, and 3 s at the video source, as illustrated in Figs. 4 and 11. Our observations indicate that, with a GOP length of 1 s, the E2E latency data exhibited greater stability compared to that of traditional cloud-based live streaming services. Moreover, this stability was consistently maintained even when the GOP length was increased to 2 or 3 s.

Figure 11: E2E latency performance of the EGOP-based streaming server. (a) displays the E2E latency data for 150 trials when the GOP length of the video source is 1 s. (b) and (c) depict the E2E latency data for GOP lengths of 2 and 3 s, respectively

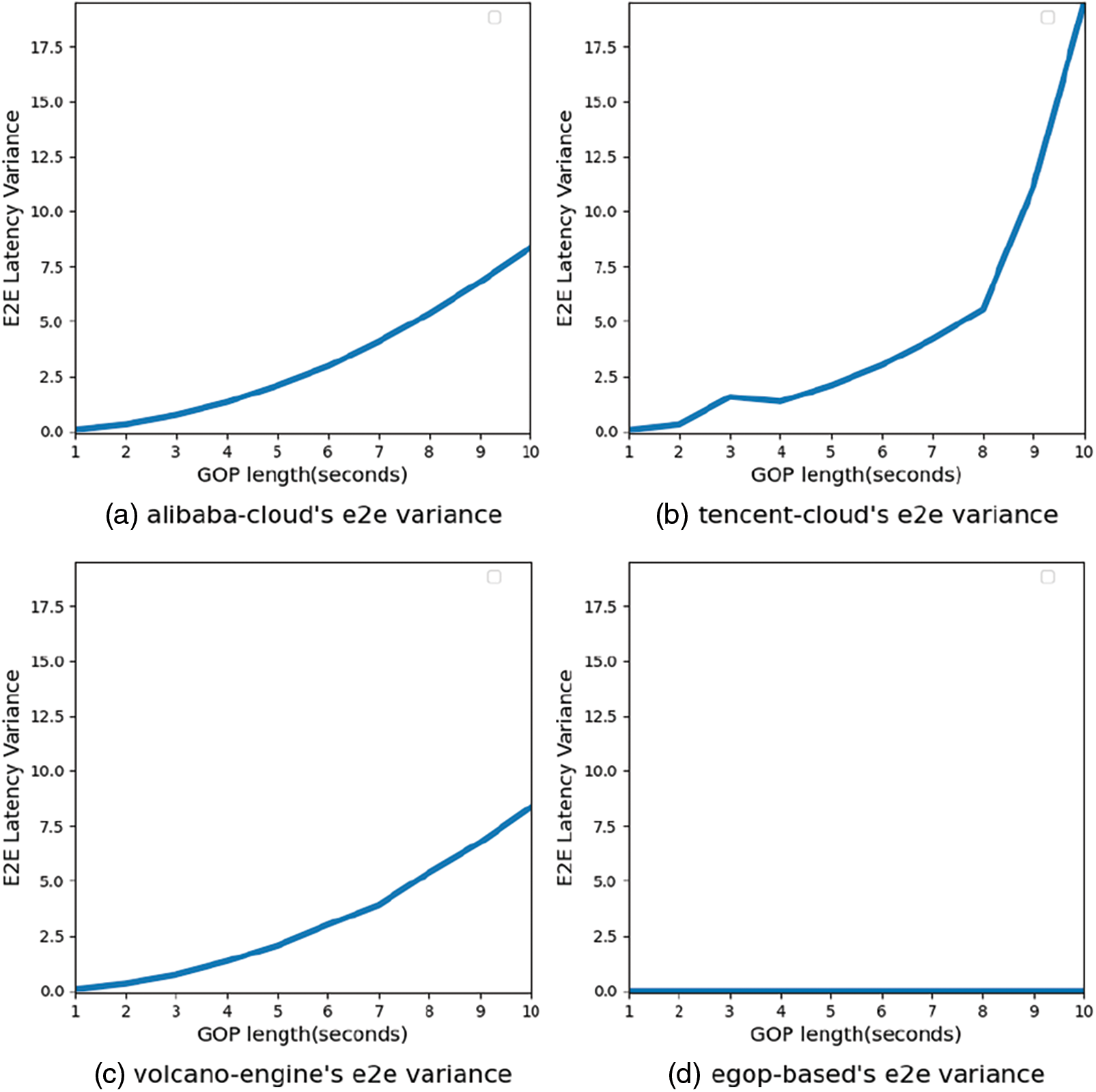

To further evaluate the stability of E2E latency between the EGOP-based service and traditional cloud-based live streaming platforms, we quantified the variance [38] of E2E latency, denoted as

This variance (

Fig. 12 and Table 3 present the E2E latency variance for major cloud-based live streaming platforms alongside our proposed EGOP-based streaming solution. It is evident that the E2E latency variance varies significantly across different cloud streaming platforms. In all evaluated scenarios, the EGOP-based live streaming system demonstrates substantially lower E2E latency variance compared to traditional cloud-based providers. Moreover, the EGOP-based solution proposed in this study maintains a variance close to zero across all GOP lengths at the video source, indicating exceptional stability in performance.

Figure 12: Variance of E2E latency performance for mainstream cloud-based live streaming platforms and the EGOP-based streaming server proposed. (a) Variance of E2E latency for Alibaba Cloud live streaming at different video source GOP lengths. (b), (c), and (d) correspond to Tencent Cloud, Volcano Engine, and the proposed EGOP-based live streaming, respectively

These results confirm that the E2E latency stability of the EGOP-based system significantly surpasses that of cloud-based live streaming platforms (e.g., Alibaba Cloud, Tencent Cloud, and Volcano Engine). This superior performance is attributed to the innovative design of the EGOP-based streaming server, which leverages the EGOP structure to enable instantaneous retrieval of the current frame at any given moment. Consequently, it eliminates the need to retrieve an entire cached GOP, thereby avoiding additional delays caused by GOP length at the streaming source and ensuring consistent performance.

6.3 Impact of GOP Length Variation on Mean E2E Latency

As illustrated in Fig. 11, our initial observations suggest that the E2E latency of the EGOP-based system is largely insensitive to variations in GOP length. This finding prompts the question of whether EGOP can maintain nearly identical E2E latency across arbitrary GOP lengths. Addressing this question will further reinforce our confidence in the substantial potential of EGOP to minimize E2E latency effectively.

To further explore the influence of the video source’s GOP length, we analyzed the mean E2E latency values across various GOP configurations. As presented in Table 4, it is evident that EGOP achieves lower E2E latency compared to cloud-based streaming solutions for shorter GOP lengths at the video source. This advantage becomes more pronounced as the GOP length increases. Additionally, we observed that the mean E2E latency of EGOP remains consistently stable at approximately 1.35 s.

We employed linear regression to model the relationship between mean E2E latency and GOP length, where

The results confirm that variations in GOP length at the video source have negligible impact on the mean E2E latency of EGOP. Consequently, EGOP exhibits superior low-latency performance compared to existing cloud-based solutions.

6.4 Comparative Analysis with LL-DASH and WebRTC

To acquire comparative data on the low-latency performance of LL-DASH, WebRTC, and EGOP, we conducted E2E latency experiments for both LL-DASH and WebRTC. The experimental setup closely aligns with the methodology outlined in Section 4.1, with the key difference being the playback mechanisms: LL-DASH utilizes dash.js [39] for live stream playback, whereas WebRTC is implemented using TCPlayer [40]. Detailed information regarding the LL-DASH and WebRTC providers is presented in Table 5.

Table 6 presents a comparison of the mean E2E latency for EGOP, LL-DASH, and WebRTC across varying GOP lengths. EGOP consistently outperforms both LL-DASH and WebRTC at all GOP evaluated lengths, achieving a maximum latency reduction of 10.566 s compared to LL-DASH and 4.965 s compared to WebRTC.

As described in Section 5.3 and Algorithm 2, when a new viewer joins a live stream and the current frame is a P-frame, EGOP employs a temporary encoder to re-encode this P-frame as an I-frame. Subsequently, it encodes all consecutive P-frames until the next I-frame is encountered.

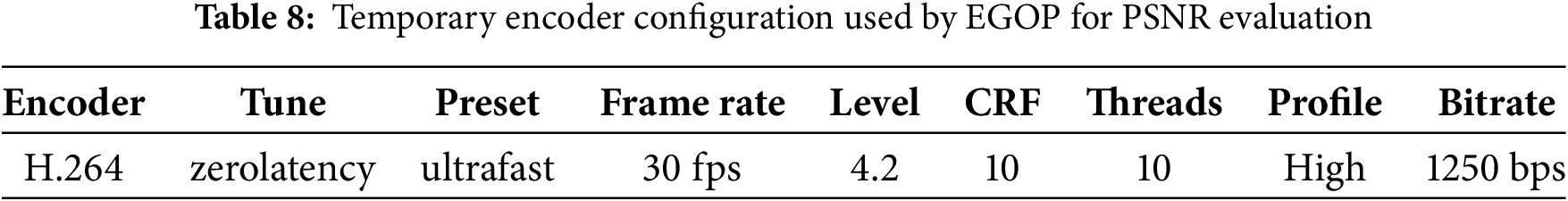

To assess the impact of this encoding strategy on video quality, we used the video sources listed in Table 7 to simulate a scenario in which a user joins at the first P-frame. The configuration of the temporary encoder utilized by EGOP is detailed in Table 8.

Fig. 13 illustrates the PSNR variations across 1799 video frames generated by EGOP under the evaluated conditions. We observed that the PSNR for frames 1 to 299 is approximately 60 dB, with an average PSNR of 62.945 dB during this period. For frames 300 to 1799, the PSNR remains consistently at 100 dB.

Figure 13: PSNR variation across 1799 video frames generated by EGOP for new viewers. A PSNR value of 100 dB indicates that the image is identical to the original

Since images are considered visually indistinguishable from the original when the PSNR exceeds 50 dB, we conclude that EGOP does not compromise the quality of the live stream during its operation.

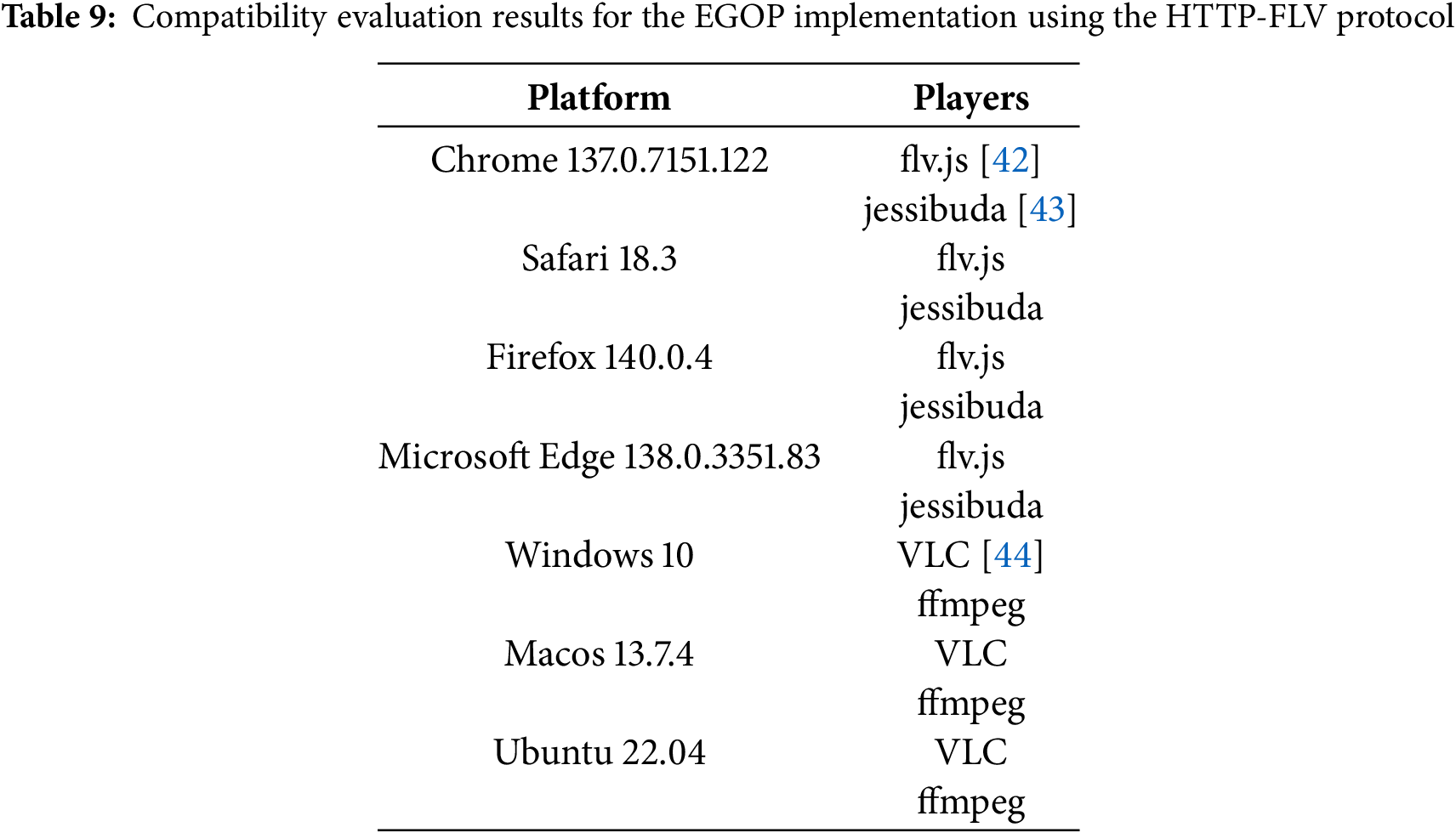

6.6 Player Compatibility Evaluation

The EGOP-based streaming server implementation used in this study outputs live streams in HTTP-FLV format. Due to the high compatibility of HTTP-FLV, all players listed in Table 9 were subjected to compatibility testing.

Given the widespread support for HTTP-FLV among cloud-based live streaming providers in China, it is theoretically expected that all modern browsers and FFmpeg-based players will pass compatibility testing.

6.7 Computational and Storage Overhead Analysis

As described in Section 5.2, EGOP requires additional decoding operations, leading to increased computational and storage overhead. To quantify these overheads, we deployed our EGOP server program on a Linux server using Docker (Docker image: zhoukunpeng505/egop_rtmp:2025-0711, available on Docker Hub) and monitored its CPU and memory usage in a real-world scenario.

The server configuration is detailed in Table 10, while the core configuration for OBS streaming is presented in Table 11. The experiment proceeded as follows: We first started the server program, and one minute later, OBS began pushing the video stream. At the fourth minute, the first viewer started playing the live stream; by the seventh minute, a second viewer joined the stream; at the tenth minute, both viewers simultaneously stopped playback; and the experiment concluded at the thirteenth minute. The experimental data are illustrated in Fig. 14.

Figure 14: CPU and memory overhead of the EGOP-based streaming server during video stream pushing and live stream playback. (a) represents the CPU overhead, and (b) represents the memory overhead. The short-term peaks within the red box indicate the additional CPU and memory overhead introduced by

We observed that after OBS began streaming, both CPU and memory overheads increased significantly. Each viewer playing the live stream incurs additional overhead, which dissipates automatically once the viewer leaves.

By analyzing the raw experimental data from the first to the fourth minute and from the tenth to the thirteenth minute, we calculated the average CPU and memory overhead of Algorithm 1 during the pushing of a 1080p video stream, as shown in Eq. (12).

As shown in Fig. 14, brief peaks in CPU and memory usage occur when new viewers join, attributed to the CPU and memory consumption during the operation of

Although EGOP introduces a small amount of additional CPU and memory overhead, this can be further mitigated by using efficient programming languages and hardware decoding techniques. We plan to focus on minimizing these overheads in future work.

The evaluation results of the EGOP-based streaming server can be summarized as follows:

With a fixed GOP length, the E2E latency remains stable, with variance approaching zero. This stability surpasses that of cloud-based live streaming solutions.

When the GOP length varies, the mean E2E latency remains constant at approximately 1.35 s, unaffected by changes in GOP length, ensuring superior real-time performance compared to cloud-based live streaming solutions.

In experiments conducted with EGOP, each 1080p video source incurs a CPU overhead of 0.516 cores and a memory overhead of 0.039 GB. Considering the significant improvements in low-latency performance, EGOP demonstrates substantial engineering potential.

We provide a Python-based implementation of EGOP, supporting video stream pushing via OBS and playback through the HTTP-FLV protocol. The code is open-source on GitHub (https://github.com/zhoukunpeng504/EGOP-stream-server) (accessed on 18 August 2025). To facilitate rapid deployment and reproducibility, a Docker image is also available (https://hub.docker.com/r/zhoukunpeng505/egop_rtmp) (accessed on 18 August 2025).

This implementation includes the complete workflows described in Algorithms 1 and 2, with all code publicly accessible. We recommend using this implementation as a reference for adapting existing streaming infrastructures to mitigate additional E2E latency caused by GOP length on the publishing side.

7.2 Building a Scalable EGOP Application

When applying EGOP to live streaming scenarios with large-scale audience loads, we recommend adopting the architecture depicted in Fig. 15. This design helps mitigate potential performance bottlenecks while ensuring on-demand scalability. The core components of this architecture are described below:

Figure 15: Architecture of EGOP for large-scale load scenarios

• Scalable Decoding Service: This service delivers general decoding capabilities for the

• Redis Cluster: This cluster offers high concurrency and substantial storage capacity. It supports Algorithm 1 in writing EGOP data and Algorithm 2 in reading EGOP data, achieved through a multi-instance deployment of Redis for enhanced performance and reliability.

• Scalable RTMP Service: This service enables users to push video sources via the RTMP protocol. Deployed in multiple instances with a unified access point, it fully implements Algorithm 1, supported by the scalable decoding service and the Redis distributed memory cluster for seamless operation.

• Scalable Encoding Service: This service provides general encoding capabilities for the

• Scalable HTTP-FLV Service: This service supports the HTTP-FLV protocol and is designed to handle large-scale audience loads. It utilizes the capabilities of the scalable encoding service and the Redis cluster to fully implement Algorithm 2. Deployed in multiple instances, it provides a unified access point via a load balancer to ensure optimal accessibility.

EGOP introduces the decoder

In this research, EGOP is implemented only for the HTTP-FLV live streaming protocol based on Algorithms 1 and 2, without adaptation for other protocols such as WebRTC or LL-HLS. However, theoretically, these algorithms have the potential to integrate with other video streaming protocols and reduce E2E latency. This issue will be explored further in future research.

In this paper, we conducted an in-depth investigation into the performance of prominent cloud-based live streaming platforms in China, uncovering notable variations in E2E latency across different GOP lengths. Building on these insights, we introduced the EGOP structure as a novel solution and validated its efficacy through rigorous experimentation. The key findings from our research are summarized as follows:

• For cloud-based live streaming services, including platforms such as Alibaba-Cloud, Tencent-Cloud, and Volcano-Engine, E2E latency demonstrates inconsistent behavior at fixed GOP lengths, characterized by significant fluctuations. Furthermore, as GOP length increases, the average E2E latency rises correspondingly, exhibiting a clear linear positive correlation.

• In contrast, live streaming services leveraging the EGOP structure achieve remarkable stability in E2E latency at fixed GOP lengths, with variance approaching zero, thereby surpassing the consistency of conventional cloud-based solutions. Additionally, when GOP length varies, the mean E2E latency remains steady at approximately 1.35 s, unaffected by alterations in the video source’s GOP configuration. This insensitivity to GOP length changes ensures superior real-time performance compared to traditional cloud-based live streaming systems.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work described in this article was partially supported by Henan Province Major Science and Technology Project (241100210100).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceive the study and write the manuscript: Kunpeng Zhou, review the manuscript: Tao Wu, manage the funding: Jia Zhang, collect and analysis the data: Jia Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in GitHub at https://github.com/zhoukunpeng504/EGOP-dataset (accessed on 01 January 2025). The code supporting the findings of this study is openly available on GitHub at https://github.com/zhoukunpeng504/EGOP-stream-server (accessed on 01 January 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Magnaghi M, Ghezzi A, Rangone A. 5G is not just another G: a review of the 5G business model and ecosystem challenges. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2025;215(1):124121. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2025.124121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Guo YJ, Guo CA, Li M, Latva-aho M. Antenna technologies for 6G-advances and challenges. IEEE Trans Antennas Propag. 2025. doi:10.1109/tap.2025.3550434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Khanna P, Sehgal R, Gupta A, Dubey AM, Srivastava R. Over-the-top (OTT) platforms: a review, synthesis and research directions. Market Intell Plann. 2025;43(2):323–48. doi:10.1108/MIP-03-2023-0122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Rosenthal K. The 2025 global internet phenomena report; 2025. [cited 2025 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.applogicnetworks.com/blog/the-2025-global-internet-phenomena-report. [Google Scholar]

5. Sun L, Zong T, Wang S, Liu Y, Wang Y. Towards optimal low-latency live video streaming. IEEE/ACM Transact Netw. 2021;29(5):2327–38. doi:10.1109/tnet.2021.3087625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wang H, Zhang X, Chen H, Xu Y, Ma Z. Inferring end-to-end latency in live videos. IEEE Transact Broadcast. 2021;68(2):517–29. doi:10.1109/tbc.2021.3071060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Sujatha G, Devipriya A, Brindha D, Premalatha G. An efficient Cloud Storage Model for GOP-Level Video deduplication using adaptive GOP structure. Cybernet Syst. 2023;15(4):1–26. doi:10.1080/01969722.2023.2176665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Akcay MN, Kara B, Begen AC, Ahsan S, Curcio ID, Kammachi-Sreedhar K, et al. Quality upshifting with auxiliary i-frame splicing. In: 2023 15th International Conference on Quality of Multimedia Experience (QoMEX). Ghent, Belgium: IEEE; 2023. p. 119–22. [Google Scholar]

9. Pourreza R, Cohen T. Extending neural p-frame codecs for b-frame coding. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. Montreal, QC, Canada: IEEE; 2021. p. 6680–9. [Google Scholar]

10. Zhou Y, Xu G, Tang K, Tian L, Sun Y. Video coding optimization in AVS2. Inform Process Manag. 2022;59(2):102808. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2021.102808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. DASH-IF and DVB. Low-latency Modes for DASH; 2019. [cited 2025 Jan 22]. Available from: https://dashif.org/news/low-latency-dash/. [Google Scholar]

12. Speelmans PJ. HESP - high efficiency streaming protocol. Internet Engineering Task Force; 2024. draft-theo-hesp-06. Work in Progress. [cited 2025 Jan 22]. Available from: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/draft-theo-hesp/06/. [Google Scholar]

13. Kumar T, Sharma P, Tanwar J, Alsghier H, Bhushan S, Alhumyani H, et al. Cloud-based video streaming services: trends, challenges, and opportunities. CAAI Transact Intell Technol. 2024;9(2):265–85. doi:10.1049/cit2.12299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Jansen B, Goodwin T, Gupta V, Kuipers F, Zussman G. Performance evaluation of WebRTC-based video conferencing. ACM SIGMETRICS Perform Evaluat Rev. 2018;45(3):56–68. doi:10.1145/3199524.3199534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Toka L, Dobreff G, Haja D, Szalay M. Predicting cloud-native application failures based on monitoring data of cloud infrastructure. In: 2021 IFIP/IEEE International Symposium on Integrated Network Management (IM). Bordeaux, France: IEEE; 2021. p. 842–7. [Google Scholar]

16. Chen W, Yang T. A recommendation system of personalized resource reliability for online teaching system under large-scale user access. Mobile Netw Applicat. 2023;28(3):983–94. doi:10.1007/s11036-023-02194-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. El-Mowafy M, Gharghory SM, Abo-Elsoud M, Obayya M, Allah MF. Chaos based encryption technique for compressed h264/avc videos. IEEE Access. 2022;10:124002–16. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3223355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Niu D, Cheng G, Chen Z, Qiu X. Video stalling identification for web live streaming under HTTP-FLV. Comput Netw. 2024;254(9):110714. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2024.110714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Adobe. FLV File Format; 2023 [Online]. [cited 2025 Aug 18]. Available from: https://www.adobe.com/creativecloud/file-types/video/container/flv.html. [Google Scholar]

20. Hunt B, Coole J, Brenes D, Kortum A, Mitbander R, Vohra I, et al. High frame rate video mosaicking microendoscope to image large regions of intact tissue with subcellular resolution. Biomed Optics Express. 2021;12(5):2800–12. doi:10.1364/boe.425527. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Boyce JM, Doré R, Dziembowski A, Fleureau J, Jung J, Kroon B, et al. MPEG immersive video coding standard. Proc IEEE. 2021;109(9):1521–36. doi:10.1109/jproc.2021.3062590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Yuan H, Wang Q, Liu Q, Huo J, Li P. Hybrid distortion-based rate-distortion optimization and rate control for H. 265/HEVC. IEEE Transact Cons Elect. 2021;67(2):97–106. doi:10.1109/tce.2021.3065636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Han J, Li B, Mukherjee D, Chiang CH, Grange A, Chen C, et al. A technical overview of AV1. Proc IEEE. 2021;109(9):1435–62. doi:10.1109/jproc.2021.3058584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Bross B, Chen J, Ohm JR, Sullivan GJ, Wang YK. Developments in international video coding standardization after AVC, with an overview of versatile video coding (VVC). Proce IEEE. 2021;109(9):1463–93. doi:10.1109/jproc.2020.3043399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Chen Y, Murherjee D, Han J, Grange A, Xu Y, Liu Z, et al. An overview of core coding tools in the AV1 video codec. In: 2018 picture coding symposium (PCS). San Francisco, CA, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 41–5. [Google Scholar]

26. Li R, Gospodarik C. The impact of digital economy on economic growth based on pearson correlation test analysis. In: International Conference on Cognitive based Information Processing and Applications (CIPA 2021) Volume 2. Singapore: Springer; 2021. p. 19–27. [Google Scholar]

27. Šverko Z, Vrankić M, Vlahinić S, Rogelj P. Complex Pearson correlation coefficient for EEG connectivity analysis. Sensors. 2022;22(4):1477. doi:10.3390/s22041477. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Ji Z, Hu C, Jia X, Chen Y. Research on dynamic optimization strategy for cross-platform video transmission quality based on deep learning. Artif Intell Mach Learn Rev. 2024;5(4):69–82. doi:10.69987/aimlr.2024.50406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Yang S, Fang C, Zhong L, Wang M, Zhou Z, Xiao H, et al. A novel distributed multi-source optimal rate control solution for HTTP live video streaming. IEEE Trans Broadcast. 2024 Sep;70(3):792–807. doi:10.1109/tbc.2024.3391051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Wei X, Zhou M, Kwong S, Yuan H, Wang S, Zhu G, et al. Reinforcement learning-based QoE-oriented dynamic adaptive streaming framework. Inf Sci. 2021;569(5):786–803. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2021.05.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Niu D, Cheng G, Chen Z. TDS-KRFI: reference frame identification for live web streaming toward HTTP flash video protocol. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2023;20(4):4198–215. doi:10.1109/tnsm.2023.3282563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Chen C, Yin W, Huang Z, Shi S. AGiLE: enhancing adaptive GOP in live video streaming. In: Proceedings of the 15th ACM Multimedia Systems Conference; 2024 Apr 15–18; Bari, Italy. p. 34–44. [Google Scholar]

33. Jia C, Ge Y. A resisting gross errors capability study of robust estimation of unary linear regression method. Communicat Statist-Simul Computat. 2017;46(2):815–22. doi:10.1080/03610918.2014.963608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Borra P. An overview of cloud computing and leading cloud service providers. Int J Comput Eng Technol. 2024;15:122–33. [Google Scholar]

35. Kränzler M, Herglotz C, Kaup A. A comprehensive review of software and hardware energy efficiency of video decoders. In: 2024 Picture Coding Symposium (PCS). Taichung, Taiwan: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

36. Sanfilippo S. Redis: a persistent database; 2009. [cited 2025 Jul 15]. Available from: https://redis.io/. [Google Scholar]

37. Hasana N, Lindawati L, Halimatussa’diyah R. Analisis QoS video dan audio streaming dengan RTMP (real time messaging protokol). Jetri J Ilm Tek Elektro. 2020;18(1):77–90. [Google Scholar]

38. Jones GP, Stambaugh C, Stambaugh N, Huber KE. Analysis of variance. Translat Radiat Oncol. 2023;18(1):171–7. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-88423-5.00041-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Forum DI. dash.js; 2023. [cited 2025 Jul 12]. Available from: https://github.com/Dash-Industry-Forum/dash.js. [Google Scholar]

40. Tencent Cloud. TCPlayer Integration Guide; 2025. [cited 2025 Jul 15]. Available from: https://www.tencentcloud.com/zh/document/product/266/33977. [Google Scholar]

41. BytePlus. BytePlus MediaLive | Video Platform; 2025. [cited 2025 Jul 12]. Available from: https://www.byteplus.com/en/product/medialive. [Google Scholar]

42. xqq. flv.js; 2018. [cited 2025 Jul 15]. Available from: https://github.com/bilibili/flv.js. [Google Scholar]

43. Jessibuda. Jessibuda; 2023. [cited 2025 Jul 15]. Available from: https://github.com/jessibuda. [Google Scholar]

44. VideoLAN Project. VideoLAN–Free multimedia solutions; 2025. [cited 2025 Jul 18]. Available from: https://www.videolan.org/. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools