Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

MewCDNet: A Wavelet-Based Multi-Scale Interaction Network for Efficient Remote Sensing Building Change Detection

1 School of Computer Science and Technology, Zhengzhou University of Light Industry, Zhengzhou, 450002, China

2 Department of Computing, Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, Suzhou, 215123, China

3 Department of Computer Science, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, L69 7ZX, UK

4 School of Software, Zhengzhou University of Light Industry, Zhengzhou, 450002, China

* Corresponding Author: Zuhe Li. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068162

Received 22 May 2025; Accepted 05 August 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Accurate and efficient detection of building changes in remote sensing imagery is crucial for urban planning, disaster emergency response, and resource management. However, existing methods face challenges such as spectral similarity between buildings and backgrounds, sensor variations, and insufficient computational efficiency. To address these challenges, this paper proposes a novel Multi-scale Efficient Wavelet-based Change Detection Network (MewCDNet), which integrates the advantages of Convolutional Neural Networks and Transformers, balances computational costs, and achieves high-performance building change detection. The network employs EfficientNet-B4 as the backbone for hierarchical feature extraction, integrates multi-level feature maps through a multi-scale fusion strategy, and incorporates two key modules: Cross-temporal Difference Detection (CTDD) and Cross-scale Wavelet Refinement (CSWR). CTDD adopts a dual-branch architecture that combines pixel-wise differencing with semantic-aware Euclidean distance weighting to enhance the distinction between true changes and background noise. CSWR integrates Haar-based Discrete Wavelet Transform with multi-head cross-attention mechanisms, enabling cross-scale feature fusion while significantly improving edge localization and suppressing spurious changes. Extensive experiments on four benchmark datasets demonstrate MewCDNet’s superiority over comparison methods: achieving F1 scores of 91.54% on LEVIR, 93.70% on WHUCD, and 64.96% on S2Looking for building change detection. Furthermore, MewCDNet exhibits optimal performance on the multi-class·SYSU dataset (F1: 82.71%), highlighting its exceptional generalization capability.Keywords

The accelerating urbanization process and escalating natural disaster occurrences have increased the demand for precise and efficient building change detection solutions [1]. As an important means of acquiring earth surface information, remote sensing technology provides abundant data for analyzing surface changes. Building change detection (BCD) is one of the key applications of remote sensing technology. Its core objective is to detect areas of building changes in bi-temporal images [2], playing a vital role in urban planning, disaster prevention, and resource management [3,4]. In recent years, with the rapid advancement of neural networks, deep learning technology has been widely applied to remote sensing image processing and analysis and has achieved remarkable results in improving the accuracy and efficiency of building change detection [5].

As remote sensing technology has advanced rapidly, both the resolution of remote sensing imagery and the volume of information they carry have seen significant increases. However, improving the accuracy of change detection remains a significant challenge [6]. Background elements in remote sensing images, such as vegetation, roads, and shadows, often exhibit spectral and textural similarities to buildings, making it difficult for models to accurately distinguish between buildings and backgrounds, resulting in false positives and missed detections [7]. Sensor discrepancies, resolution variations, and illumination differences can cause inconsistent feature representations of identical buildings across multi-temporal images, compromising change detection accuracy [8]. The performance of deep learning models varies across different scenarios and datasets. Moreover, processing high-resolution images demands substantial computational resources. Thus, improving computational efficiency while maintaining accuracy is an urgent issue to address [9].

In recent years, the design of deep learning-based change detection (CD) algorithms has primarily focused on two aspects: (1) efficient feature extraction; and (2) the design of difference calculation methods. Accurate and efficient identification of building features in bi-temporal imagery is a prerequisite for BCD [10]. Current mainstream feature extraction approaches can be broadly categorized into two types: using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) or Transformers as encoders. CNNs are widely used in image processing, where their convolutional layers excel at capturing texture and edge details of buildings in remote sensing images, demonstrating robust local feature extraction capabilities. Transformers, meanwhile, have emerged as a powerful alternative, leveraging self-attention mechanisms to model interactions between different image regions, thereby enhancing change detection accuracy. Several studies have successfully employed Transformers as encoders to extract features for bi-temporal remote sensing images, yielding impressive results. However, CNNs are limited in capturing long-range dependencies within images. Transformers can effectively capture global context, but they demand significant computational resources and depend on high-performance hardware for effective training.

Simply processing individual feature maps from different levels in change detection often fails to effectively utilize these features. Since feature maps at different levels capture information at varying scales, relying solely on features from one level can lead to the loss of critical multi-scale information [11]. Shallow feature maps preserve detailed information such as building edges and textures, while deep feature maps focus on abstract semantic information including overall building structures and layouts. Using only shallow features may result in incomplete building understanding, whereas exclusive reliance on deep features could miss important details. Consequently, integrating multi-scale features from different levels has become a key challenge in research [12]. In our model, a multi-scale fusion operation, implemented via a tailored strategy, effectively combines features from different network depths, providing richer and more comprehensive representations for downstream change detection tasks.

The difference calculation module performs change detection through subtraction and addition of bi-temporal feature maps. Pixel-wise subtraction enhances the contrast between change signals and background, facilitating subsequent threshold segmentation and change detection. However, this operation may amplify noise in bi-temporal images, increasing pseudo-change information. For instance, regions with no real changes may be falsely identified as changed areas in the difference image due to atmospheric conditions, variations in illumination, or sensor noise. Pixel-wise addition fuses feature maps from different temporal phases, intensifying common features in bi-temporal images. However, it struggles with complex change scenarios. When features in changed areas resemble background features, the addition operation may submerge these changed regions in the background, making foreground features difficult to detect. Therefore, designing a reasonable and efficient difference calculation method has become one of the key research focuses [13].

In this context, we proposed an innovative CD network named Multi-scale Efficient Wavelet-based Change Detection Network (MewCDNet). This network integrates the advantages of CNNs and Transformer, while maintaining a balance between model performance and computational efficiency. The encoder employs EfficientNet-B4 for hierarchical feature extraction, with a Multi-scale Feature Fusion (MFF) strategy integrating information from different depths. The fused feature maps are then fed into the Cross-temporal Difference Detection (CTDD) module to accurately identify building changes in bi-temporal images. Within the decoder, we designed a Cross-scale Wavelet Refinement (CSWR) module to achieve effective interaction between difference features at different scales and refine the difference feature maps.

Our specific contributions are as follows:

1. Cross-temporal Difference Detection (CTDD) Module: This dual-branch architecture combines pixel-wise differencing with semantic-aware Euclidean distance weighting to effectively distinguish authentic building changes from pseudo-changes caused by illumination variations or sensor errors, significantly enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio in change detection results.

2. Cross-scale Wavelet Refinement (CSWR) Module: By integrating Haar wavelet transform with a multi-head cross-attention mechanism enables cross-scale information interaction. Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) not only decouples frequency domain features of the difference feature maps but also performs lossless downsampling on them. This enhances edge localization accuracy while achieving a balance between model performance and computational efficiency.

3. Multi-scale Efficient Wavelet-based Change Detection Network (MewCDNet): With EfficientNet-B4 as the backbone, MewCDNet integrates the local feature extraction capability of CNNs with the global modeling advantages of Transformer. Through MFF strategies and frequency-domain optimization design, the model achieves high detection accuracy while balancing computational efficiency.

Deep learning methods have better scalability and adaptability when processing large-scale data, capable of handling remote sensing image data with different resolutions and types. Therefore, deep learning has demonstrated great potential and advantages in the field of remote sensing change detection, gradually becoming the mainstream method for CD. Current deep learning-based CD methods can be divided into three categories: 1. CNN-based methods; 2. Transformer-based methods; 3. Methods combining CNN and Transformer.

2.1 CNN-Based Change Detection

With the emergence and widespread application of deep learning in remote sensing change detection (RSCD) tasks, traditional methods relying on manual feature extraction and statistical models, such as Change Vector Analysis (CVA) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [14], are gradually attracting less attention from researchers. Deep learning models such as CNNs can automatically extract spatial features and semantic information from images through multi-layer convolutional and pooling operations, thereby capturing change information more effectively. This significantly reduces the laborious work of manual feature design while enabling learning of richer and more discriminative feature representations from large-scale data.

The introduction of CNN-based change detection methods further improves computational efficiency, detection accuracy, and robustness. Peng et al. [15] proposed an end-to-end change detection network (DDCNN) based on attention mechanisms and image differences. By introducing a dense attention method and a Difference Enhancement unit (DE), it effectively improves the ability to extract change features in bi-temporal optical remote sensing images. Dong et al. [16] proposed a new EfficientNet-based strategy called EfficientCD for remote sensing image change detection. By constructing a multi-level feature pyramid to enhance bi-temporal image feature representation, designing a parameter-free ChangeFPN architecture for cross-temporal feature interaction, and introducing a layer-wise decoding module based on Euclidean distance to accurately extract difference features. Huang et al. [17] proposed a lightweight remote sensing change detection network called MFCF-Net. It enhances feature representation by integrating adjacent layer features through the Adjacent Layer Enhancement Module (ALEM), and combines dense skip connections with cross-attention mechanisms to achieve global correlation of multi-scale spatial features. This significantly reduces edge blurring and small target omission issues. Wei et al. [18] proposed the CDNeXt framework. It queries and reconstructs spatial perspective dependencies and temporal style correlations of bi-temporal features through the Temporal-Spatial Interactive Attention Module (TIAM), effectively reducing false detections caused by geometric perspective rotation and temporal style differences. Additionally, researchers have explored combining frequency domain information with spatial information to enhance feature learning capabilities. Ma et al. [19] proposed a Dual-Domain Learning Network (DDLNet). It extracts frequency domain components of bi-temporal images through a Frequency Enhancement Module (FEM) based on Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) to enhance change features, combines with a Spatial Restoration Module (SRM) that cross-temporally and cross-scale fuses spatiotemporal features to reconstruct spatial details, achieving optimized balance between accuracy and efficiency. Li et al. [20] proposed a Diffusion-driven Spatial-Frequency Interaction method (DSFI-CD). This method generates pseudo-images through a Conditional Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (DDPM) to enhance sample diversity, designs a Joint Decoupling module (JD) to fuse multi-source features, and combines a Spatial-Frequency Interaction module (SFI) with an Edge Enhancement module (EE) to achieve high-precision detection of change region boundaries in remote sensing images and improve model robustness in complex scenarios.

CNN-based BCD methods can effectively identify building changes in images through their powerful feature extraction capabilities, especially for high-resolution remote sensing images with complex backgrounds and subtle changes. Their main advantages lie in automated feature learning and end-to-end training, which significantly simplify the manual feature extraction processes required in traditional image processing methods. However, due to their reliance on local feature representations, CNN-based methods often face limitations when handling large-scale data and modeling long-range dependencies.

2.2 Transformer-Based Change Detection

In recent years, the application of Transformer models has expanded from natural language processing to computer vision tasks, owing to their powerful self-attention mechanisms and strong capability in modeling global dependencies. Unlike traditional CNN models, Transformers are capable of modeling long-range contextual relationships in spatial and temporal domains. In RSCD tasks, they can more effectively capture spatial features and temporal information compared to CNN-based approaches.

By incorporating self-attention mechanisms, Transformers not only enhance the identification capability of change regions but also effectively process large-scale data in complex environments, demonstrating superior performance. Bandara and Patel [21] proposed ChangeFormer, which extracts multi-scale features from bi-temporal images through a hierarchical Transformer encoder, combines with a lightweight MLP decoder to fuse difference features, avoids reliance on traditional convolutional networks, and efficiently models long-range spatiotemporal contextual information using self-attention mechanisms. Zhang et al. [22] proposed SwinSUNet, a pure Transformer-based RSCD network. Using Swin Transformer blocks as basic units, it constructs a Siamese U-shaped encoder-decoder network. The network extracts multi-scale features through hierarchical Swin Transformers and progressively recovers change information using Upsampling and Merging (UM) blocks, effectively addressing the limitations of CNNs in spatiotemporal global information extraction.

To combine CNN’s powerful local feature extraction capability and Transformer’s excellent global feature capturing ability for more comprehensive image content understanding and improved change detection accuracy, researchers have begun focusing on CNN + Transformer hybrid models. Li et al. [23] proposed a hybrid model TransUNetCD combining Transformer and UNet. The model extracts global contextual information through a Transformer encoder and restores local spatial information through a UNet decoder, achieving precise localization. By introducing a Difference Enhancement Module (DEM) to weight change maps, the network’s learning capability is improved. Sun et al. [24] similarly integrated transformers into the UNet encoder stage and proposed FENET-UEVTS. The network introduces Spatial-Channel Attention Mechanism (SCAM), U-shaped Residual Module (USRM), Strengthened Feature Extraction Module (SFEM), and Self-Attention Feature Fusion Module (SAFFM), improving detection capabilities for irregular buildings and adjacent building changes. Zhang et al. [25] proposed a change detection model based on bi-temporal feature alignment, namely BiFA. This model achieves channel alignment via the Bi-temporal Interaction (BI) module and pixel-level spatial offset estimation through the Difference Flow Field Alignment module (ADFF). Furthermore, it integrates an Implicit Neural Alignment Decoder (IND) for continuous multi-scale feature representation. Xie et al. [26] proposed a Multi-scale Interaction Fusion Network (MIFNet). This network employs an early feature fusion strategy and a Cross-layer Collaborative Perception Module (CLCA) to avoid isolation of bi-temporal information. Additionally, it incorporates a Dual Complementary Attention (DCA) mechanism to integrate spatiotemporal features. Furthermore, it optimizes cross-layer information transmission through a combination of global information collection and multi-level feature embedding mechanisms. Yang et al. [27] proposed an Enhanced Hybrid CNN-Transformer Network (EHCTNet). This network integrates local and global features through a dual-branch architecture. It incorporates several novel components, including Head Residual Fast Fourier Transform (HFFT), Kolmogorov-Arnold Network-based Channel-Spatial Attention (CKSA), and Backward Residual Fast Fourier Transform (BFFT). These components facilitate multi-scale feature extraction and optimize semantic difference information in the frequency domain, leading to significant improvements in recall rate and continuity for change detection in remote sensing images. Liu [28] proposed a RSCD network based on a multi-scale Transformer, namely MSTransCDNet. By introducing multi-scale key-value vectors to construct multi-scale multi-head attention units, it can extract multi-scale features with rich spatial context information, effectively addressing the issue of change detection for multi-scale targets and irregular geometric structures.

Transformer-based BCD methods address the limitations of traditional CNN models in long-range dependency modeling through self-attention mechanisms. This advancement significantly improves the accuracy in detecting changed building regions in complex scenes. Compared with CNNs, Transformers can capture the spatiotemporal contextual information of bi-temporal images from a global perspective, effectively reducing false positives caused by geometric distortions, illumination variations, and background interference. In recent years, researchers have further optimized model performance by developing hybrid architectures that fuse Transformers with CNNs, thereby combining the advantages of local feature extraction and global semantic modeling. However, these hybrid models also face several challenges. The combination of CNNs and Transformers often leads to high computational cost and increased model complexity. Additionally, these models may suffer from limited generalization capability, particularly when faced with insufficient training data. Integrating the two architectures requires careful design to ensure effective feature fusion and model training.

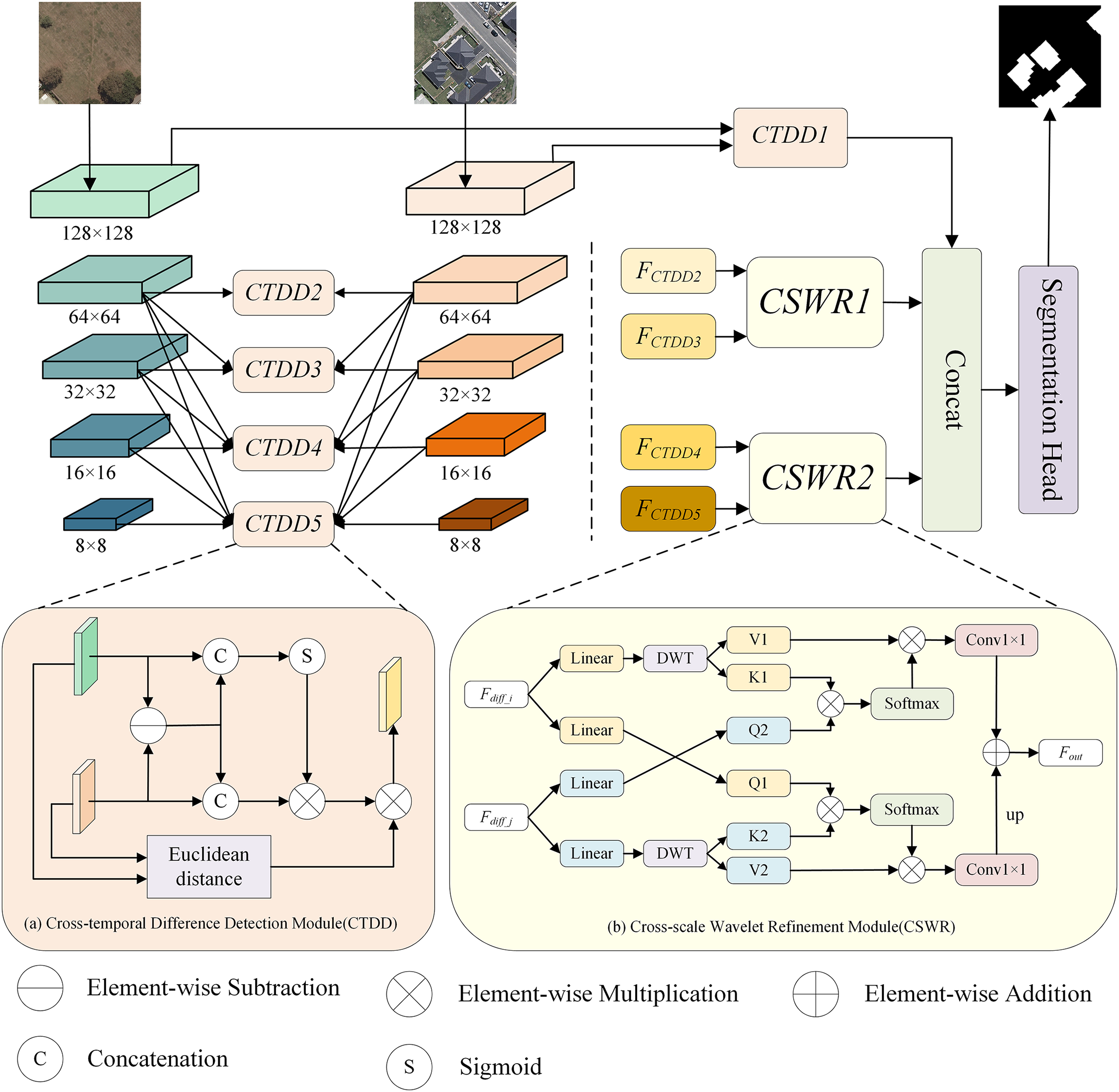

In this section, we detail the MewCDNet model. As shown in Fig. 1, the overall architecture mainly consists of EfficientNet feature extraction, CTDD, and CSWR. First, the model performs efficient feature extraction using EfficientNet-B4. Then, the extracted multi-level feature maps are further processed through MFF strategy. Next, the CTDD module is utilized to detect change information in the fused multi-level bi-temporal image features. Finally, the CSWR module is employed to achieve information interaction between different-scale change feature maps and further refines the change feature maps.

Figure 1: The overall framework of MewCDNet and two key modules: (a) Cross-temporal Difference Detection Module (CTDD): We introduce CTDD after multi-scale feature fusion to detect differences in bi-temporal feature maps; (b) Cross-scale Wavelet Refinement Module (CSWR): After difference detection, CSWR is introduced to promote information interaction between feature maps of different scales

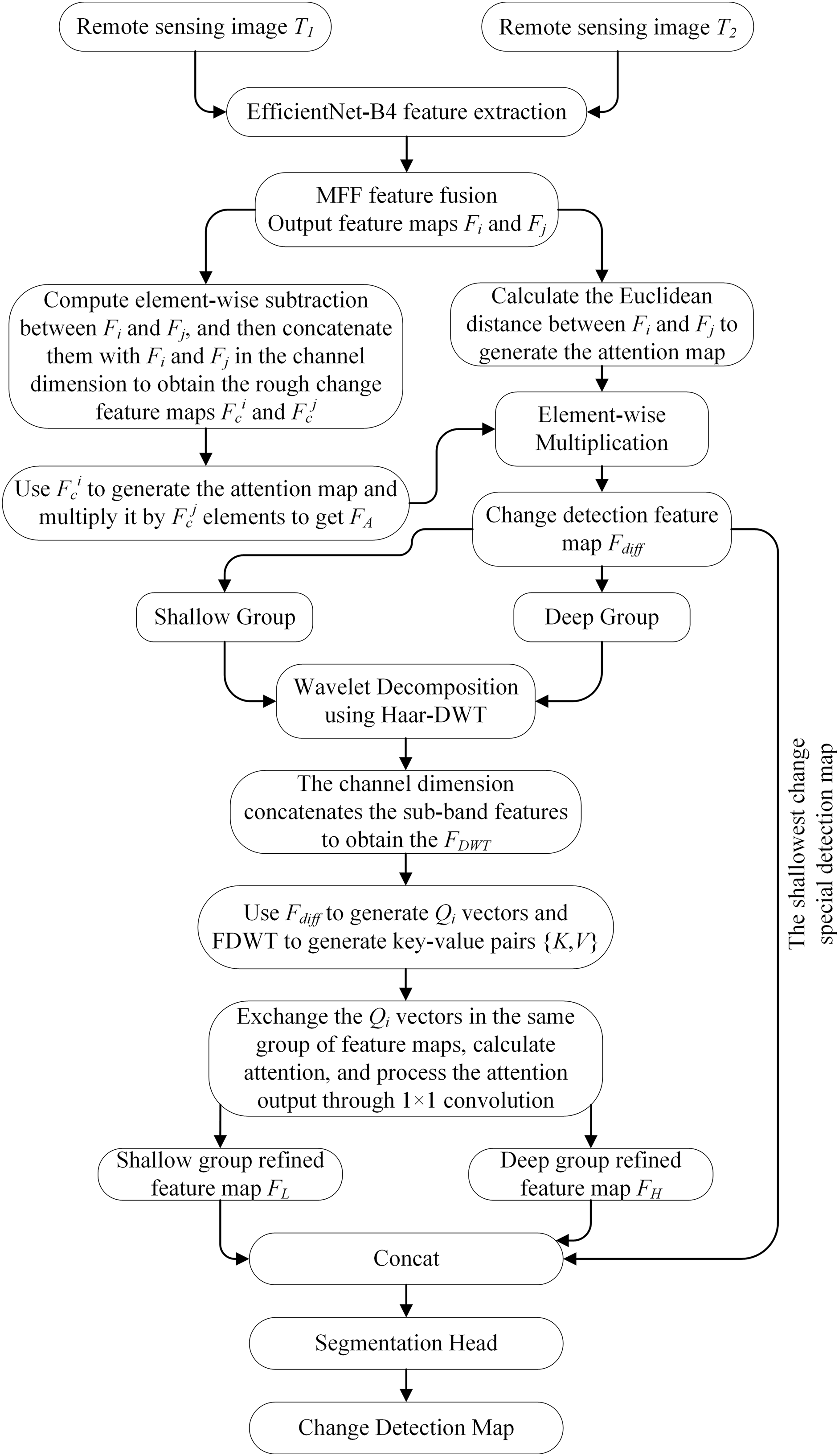

In this paper, we propose MewCDNet, a CNN-Transformer integrated BCD network. The flowchart of MewCDNet is shown in Fig. 2. The network adopts a dual-stream encoder-decoder architecture, using EfficientNet-B4 with shared weights as the feature extraction backbone to efficiently capture multi-level building features from bi-temporal remote sensing images. To address the representational discrepancy between shallow high-resolution features and deep semantic features, we propose a four-level progressive hierarchical feature fusion strategy to achieve layered feature fusion, which enhances global context awareness while preserving edge details. The CTDD module first uses depthwise separable convolutions to jointly encode feature differences and original features, generating enhanced residual representations. Then, it introduces a spatial attention weight map based on Euclidean distance for pixel-level weighting, effectively suppressing pseudo-difference signals caused by illumination changes or registration errors. To further optimize the interaction capability of multi-scale change feature maps, the network employs Haar-based discrete wavelet transform to decouple features into low-frequency structural components and high-frequency detail components, enabling cross-scale feature information interaction through multi-head cross-attention. Through the coordinated design of hierarchical feature fusion, difference enhancement, and frequency-domain optimization, this architecture significantly improves detection accuracy and robustness for building changes in complex scenarios.

Figure 2: Flowchart of MewCDNet

MewCDNet systematically integrates MFF mechanisms in the encoder stages, enhancing the model’s ability to capture multi-granularity building features through hierarchical feature fusion. By introducing a dual-stream cooperative difference detection method, it reduces interference from pseudo-changes. Additionally, the innovative incorporation of wavelet transform enables feature decoupling and lossless downsampling, significantly reducing the spatial dimensions of feature maps while preserving both high- and low-frequency information. In addition to improving change detection accuracy, it effectively controls the computational load of multi-head cross-attention.

In the field of RSCD, Transformer-based backbones are increasingly becoming mainstream solutions. These models establish long-range dependencies between image patches through self-attention mechanisms, effectively capturing global contextual information, which theoretically provides favorable conditions for identifying complex land cover change patterns. However, when applied to high-resolution remote sensing image processing, standard Vision Transformer architectures exhibit notable limitations: the time complexity of their self-attention mechanisms grows quadratically with input size, leading to prohibitively high computational costs when processing large-format remote sensing imagery.

This study adopts EfficientNet as the feature extraction backbone network, primarily due to its balanced combination of computational efficiency and multi-scale feature modeling capabilities. Compared to Transformer architectures, EfficientNet leverages neural architecture search-optimized compound scaling strategies and lightweight MBConv modules, significantly reducing computational resource consumption while adaptively fusing shallow details with deep semantic features. Its depthwise separable convolutions and channel attention mechanisms effectively address representation challenges arising from diverse building scales and complex boundaries in remote sensing imagery. Additionally, the model’s strong inductive bias helps mitigate overfitting risks with limited annotated data availability, providing a more robust feature foundation for change detection tasks. The structure of EfficientNet-B4 is shown in Table 1.

After completing multi-level feature extraction, this study introduces the MFF strategy. This strategy adaptively fuses high-resolution detail information (e.g., building edge textures) from shallow network layers with low-resolution semantic features (such as overall structural context) from deep network layers through a cross-level feature complementation mechanism. This approach effectively mitigates information attenuation caused by progressive downsampling.

3.3 Cross-Temporal Difference Detection Module

The CTDD module is a crucial component of MewCDNet, designed to detect building changes in bi-temporal feature maps. Its structure is illustrated in Fig. 1a. The CTDD module receives feature maps from various levels after multi-scale fusion and divides them into two branches for detection operations. Branch 1: It first performs pixel-wise subtraction between bi-temporal features

Next,

The second branch constructs discriminative logic from a physical perspective. It calculates the Euclidean distance between

Branch 1 focuses on precise spatial localization by employing a dynamic attention mechanism to separate target changes from background interference. Branch 2 employs a parameterized Euclidean distance to compute nonlinear mapping distances between bi-temporal features. This design effectively differentiates structural changes in buildings from fluctuations in illumination or color, balances multi-scale responses, and enables robust detection of both small-scale targets and large-scale changes. The two branches achieve collaborative optimization through feature multiplication, with Branch 1 providing pixel-level change candidate regions and Branch 2 validating the change rationality from a physical perspective.

3.4 Cross-Scale Wavelet Refinement Module

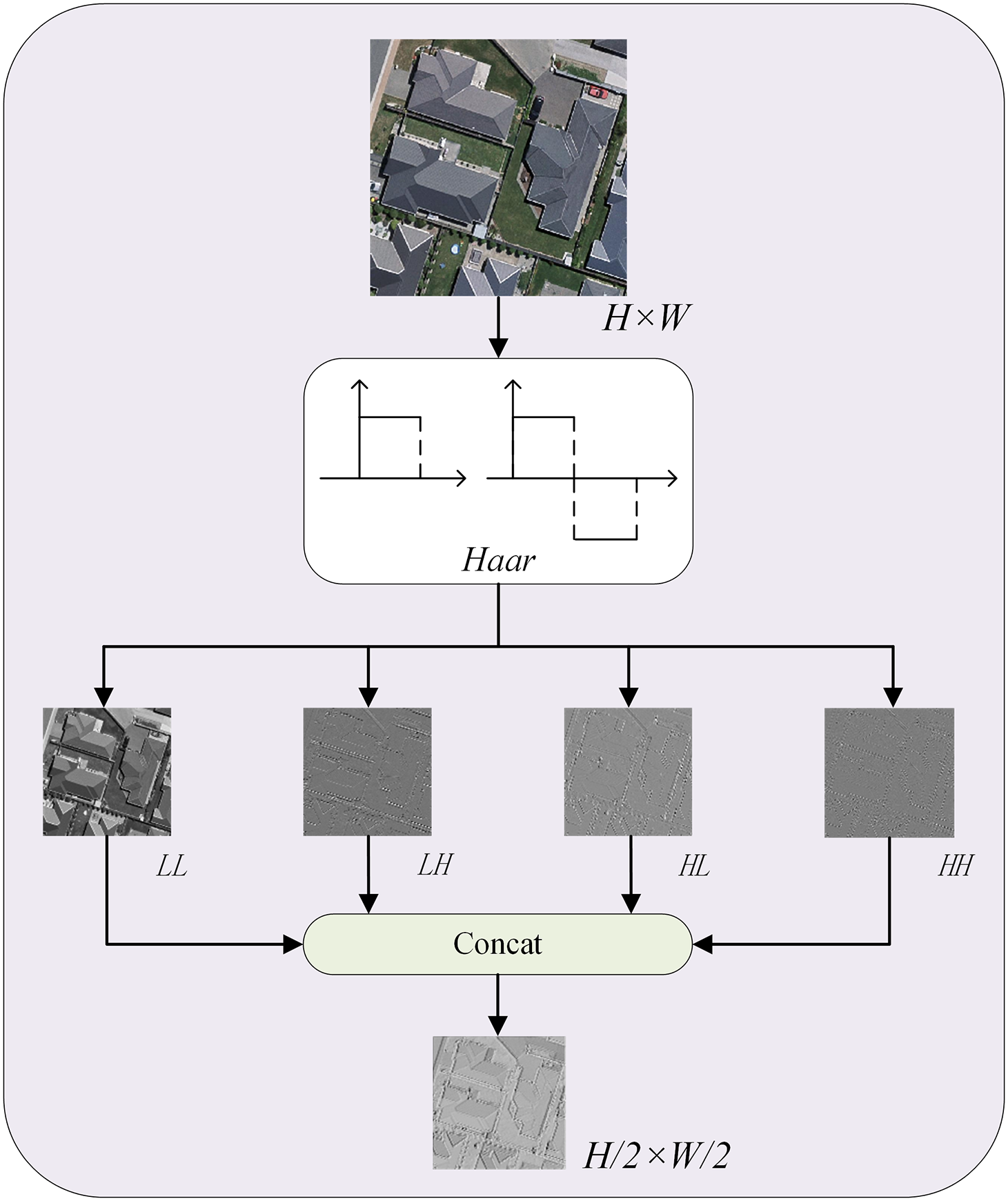

To address the semantic gap and edge blurring issues in the decoding process, we propose the CSWR module, whose structure is illustrated in Fig. 1b. This module performs refined cross-scale fusion of building change features through frequency-domain feature decoupling and multi-head cross-attention mechanisms. CSWR integrates wavelet transform into the attention computation pipeline, effectively decoupling low-frequency structural features from high-frequency texture variations. This significantly enhances the completeness of multi-scale feature fusion and improves edge consistency.

Compared to other frequency-domain transform methods, Haar wavelets employ the simplest orthogonal basis, requiring only addition, subtraction, and scalar multiplication operations. When processing 256 × 256 resolution images, their computational complexity is significantly lower than that of Daubechies wavelets with longer filters requiring floating-point convolutions, effectively alleviating the hardware burden for high-resolution remote sensing image processing. Furthermore, the rectangular impulse response of the Haar wavelet inherently functions as a first-order differentiator, providing a stronger response to the characteristic right angled of buildings. During decomposition, the horizontal and vertical high-frequency subbands extract edge features in their respective directions, while the diagonal high-frequency subband effectively isolates diagonal noise. This substantially enhances the feature signal-to-noise ratio, thereby providing more precise edge information for subsequent feature processing.

First, the four-level change feature maps are divided into two groups: the two low-level layers form as one group and two high-level layers form another, which are then input into CSWR module. To reduce the computational cost of multi-head cross-attention, a Haar-based DWT is applied to perform feature decoupling and downsampling on the input change map

Figure 3: Feature decoupler with Haar wavelet operator DWT

The

Finally,

Unlike traditional decoders that rely on layer-wise upsampling, the proposed method enables cross-scale information interaction through multi-head cross-attention and achieves deep coupling between spatial and frequency-domain features. DWT enhances directional-sensitive feature representation via frequency subband reorganization, while the attention mechanism introduces spatial adaptivity during reconstruction, effectively suppressing aliasing artifacts commonly observed in traditional inverse transforms. Moreover, DWT reduces computational overhead by performing lossless downsampling. Traditional self-attention complexity is

4.1 Experimental Setup and Details

LEVIR Dataset [29]: LEVIR is a building change detection dataset released by Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA, containing 637 pairs of high-resolution satellite images (1024 × 1024 pixels) with temporal coverage from 2002 to 2018, covering different areas of multiple cities in the United States. Each image pair has a temporal gap of approximately 5–14 years, annotated with binary masks indicating building construction, demolition, or no change. During training, the data were cropped to 256 × 256 pixels, with 7120 pairs for training, 1024 for validation, and 2048 for testing.

WHUCD Dataset [30]: WHUCD was developed by the Wuhan University team, it includes high-resolution aerial image pairs from 2006 to 2012, with a spatial resolution of 0.075 m per pixel. It covers around 20.5 square kilometers of an urban area and has detailed annotations for over 3000 building change samples, such as new construction, demolition, and renovation. The images are cut into 256 × 256-pixel patches. During the experiment, 6095 pairs are used for training, 737 for validation, and 787 for testing.

S2Looking Dataset [31]: S2Looking is a building change detection dataset focused on large perspective differences, jointly released by the Chinese University of Hong Kong and other institutions. It contains 5000 pairs of oblique-view satellite images (1024 × 1024 pixels), covering 60 rural and suburban areas worldwide, spanning from 2017 to 2020. Annotations include building change areas and their bounding boxes, emphasizing geometric distortions and occlusions caused by different shooting angles. By simulating real-world satellite observation conditions, this dataset promotes the study of model robustness under non-orthographic imaging and is divided into 56,000 training pairs, 8000 validation pairs, and 16,000 testing pairs.

SYSU Dataset [32]: SYSU contains 20,000 pairs of multi-temporal remote sensing images with dimensions of 256 × 256. The images have spatial resolutions ranging from 0.5 to 5 m, spanning from 2000 to 2018, covering urban-rural transition zones, farmland, forests, and partial urban areas. The annotations include semantic changes of multiple land cover types such as buildings, roads, vegetation, and water bodies, not limited to single-category building changes. By integrating multi-source data and complex scene interference, the dataset aims to validate models’ ability to extract heterogeneous data features and perform multi-target joint change detection. The data is divided into standard proportions: training set (60%), validation set (20%), and test set (20%).

The four datasets have been divided into training, validation, and test sets, and all compared models, including ours, follow this setting to ensure a consistent benchmark. To enhance the reliability of the results, future experiments can use K-Fold cross-validation, that is, the entire dataset is divided into K spatial blocks (such as K = 5). In each iteration, one block is used as a test set, and the remaining K − 1 blocks are used for model training and internal validation, ensuring that all geographical units participate in training and evaluation. This method will provide a robust statistical estimate of the performance of the model in different geographical contexts while maintaining spatial integrity.

The proposed model is implemented using Python 3.8 and PyTorch 2.0.0 framework on Ubuntu 20.04 LTS operating system. The main Python libraries used include: NumPy, PIL, Torchvision, TIMM, and Matplotlib. Training and inference are performed on an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU with 24 GB memory and GPU acceleration is performed using CUDA 11.8.

We applied extensive data augmentation techniques during training to enhance the model’s generalization ability. The overall process is shown in Fig. 4. Specifically, we used random horizontal flipping, random cropping (within 30 pixels of the original image borders), random rotation (with a probability of 0.2 and an angle range of [−15°, 15°]), and color jittering (random adjustments to brightness, contrast, saturation, and sharpness). Additionally, we introduced salt-and-pepper noise to the label images to simulate annotation noise and improve robustness. We designed an adapted Mosaic augmentation for change detection: with a probability of 0.75, we combined four training samples by cropping random quadrants from each and concatenating them into a single composite image. This helps the model learn to recognize changes at various scales and contexts. For testing, we only resized the images to 256 × 256 and normalized them. All input images were normalized to the range [−1, 1] using a mean and standard deviation of 0.5 for each channel.

Figure 4: Flowchart of data preprocessing

We adopted the AdamW optimizer with a weight decay of 0.0025 and an initial learning rate of 0.0005. The batch size was set to 16, and the model was trained for 80 epochs. The model weights corresponding to the best Intersection over Union (IoU) on the validation set were saved for subsequent testing.

To effectively evaluate the performance of our model, we employed multiple evaluation metrics, including F1-score (F1), Precision (Pre.), Recall (Rec.), and Intersection over Union (IoU).

To evaluate the performance of MewCDNet, we compared it with CD models using different architectures, including pure CNNs, pure Transformers, and hybrid CNN-Transformer approaches. Experimental results show that MewCDNet achieves strong performance in terms of cross-scenario generalization (91.54% F1 on LEVIR dataset) and robustness against complex interference (3.25% IoU improvement on S2Looking dataset), particularly demonstrating superior feature discrimination in handling small-scale building changes (93.70% F1 on WHUCD dataset) and large viewpoint variations (64.96% F1 on S2Looking dataset). To further assess the model’s generalization capability, we conducted non-building change detection on the SYSU dataset, where our model also outperformed other methods.

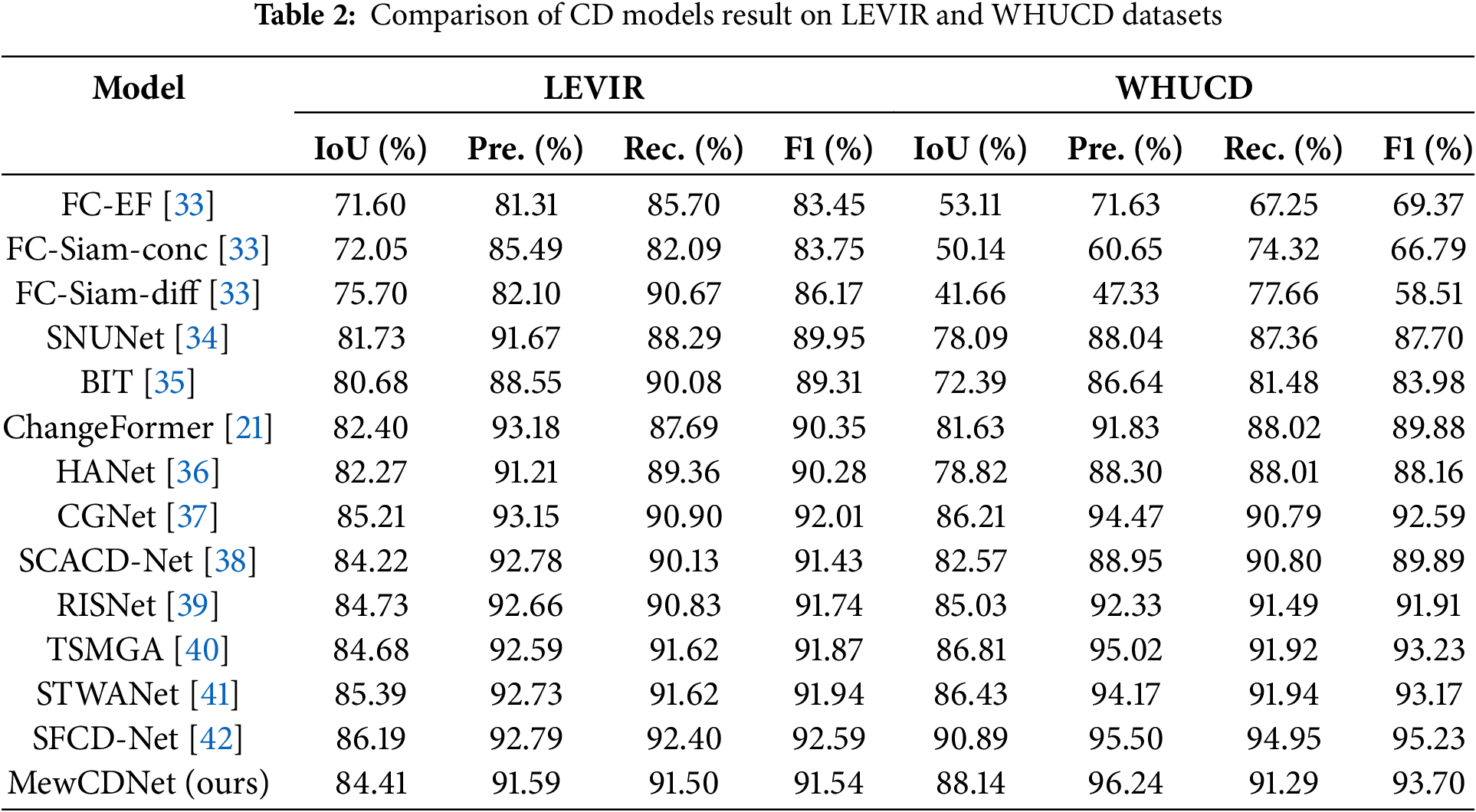

Table 2 presents a quantitative comparison of MewCDNet with other methods on the LEVIR and WHUCD datasets. The experimental results show that MewCDNet demonstrates strong overall performance on both datasets. On the LEVIR dataset, MewCDNet achieves an F1 score of 91.54%. Although slightly lower than STWANet and SFCD-Net, its recall rate is close to STWANet and significantly outperforms other hybrid architecture models. This shows a more balanced ability to capture true change regions in complex scenes. It also indicates the model can balance missed and false detections in long-term urban changes. Notably, on the WHUCD dataset, MewCDNet leads all comparison models except SFCD-Net with an F1 score of 93.70% and an IoU of 88.14%, confirming its effectiveness in suppressing false detections in small-scale building changes. Overall, MewCDNet balances detection accuracy and stability across datasets, showing significant advantages in BCD.

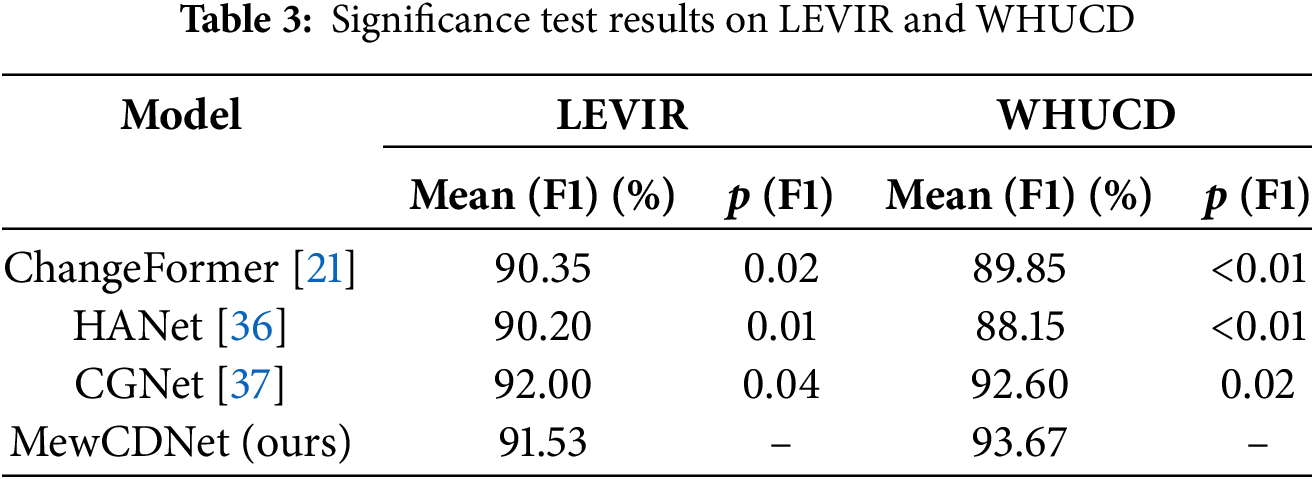

To verify that the performance improvements of MewCDNet are statistically significant, we performed paired t-tests on the F1 scores. For the LEVIR and WHUCD datasets, we compared the F1 scores of MewCDNet with those of three baseline models. The null hypothesis (H0) assumed no significant difference between the average F1 scores of MewCDNet and those of the baseline models. The alternative hypothesis (H1) posited that MewCDNet’s average F1 score was significantly higher. The significance level (α) was set to 0.05. The paired t-test results are summarized in Table 3. On the LEVIR dataset, MewCDNet exhibited significant improvements over ChangeFormer (p = 0.02) and HANet (p = 0.01). On the WHUCD dataset, MewCDNet achieved an average F1 score of 93.67%, and the p-values for comparisons with all three baselines were below the 0.05 threshold. These results provide strong statistical evidence of MewCDNet’s superiority on the WHUCD dataset, effectively ruling out random variations as the cause. Overall, these statistical tests reinforce the conclusion that MewCDNet delivers robust improvements over baseline methods.

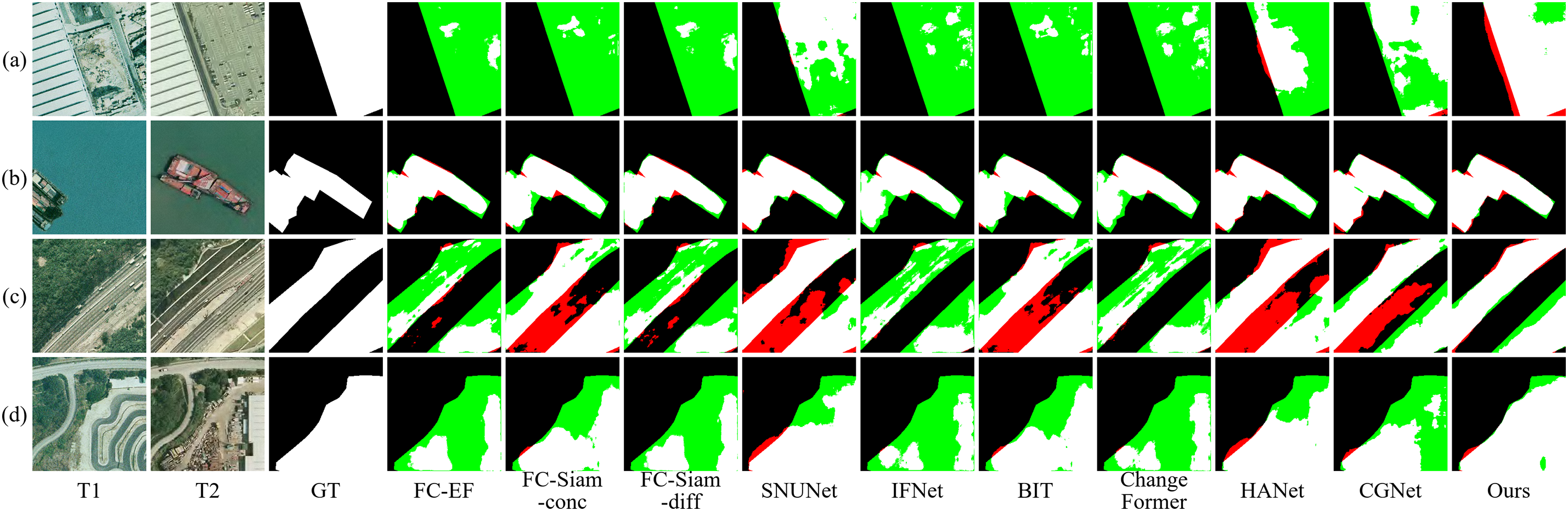

Figs. 5 and 6 present the visualized change detection results on the LEVIR and WHUCD datasets, where black indicates unchanged areas, white denotes true changes, red represents false positives, and green highlights false negatives. The visual comparisons reveal that MewCDNet exhibits significant advantages in detecting both dense clusters of new buildings and large-scale change regions, with only minimal proportions of red and green pixels. Specifically, in the examples of dense new building constructions shown in Figs. 5a,b and 6c,d, although the T1 phase images have fewer interference factors, the chromatic similarity between non-building change areas and target buildings in the T2 phase causes false positives in models like FC-EF and BIT. As shown in Figs. 5d and 6b, some baseline models mistakenly identify road expansions as building changes, highlighting the limitations of traditional methods in semantic-level discrimination. In contrast, MewCDNet accurately detects changed regions and precisely determines whether the changes pertain to buildings. The visual results provide strong evidence of MewCDNet’s technical advantages in both change detection and semantic recognition.

Figure 5: Visualization results on LEVIR dataset. The four pairs of bi-temporal images used for visualization are denoted as (a–d)

Figure 6: Visualization results on WHUCD dataset. The four pairs of bi-temporal images used for visualization are denoted as (a–d)

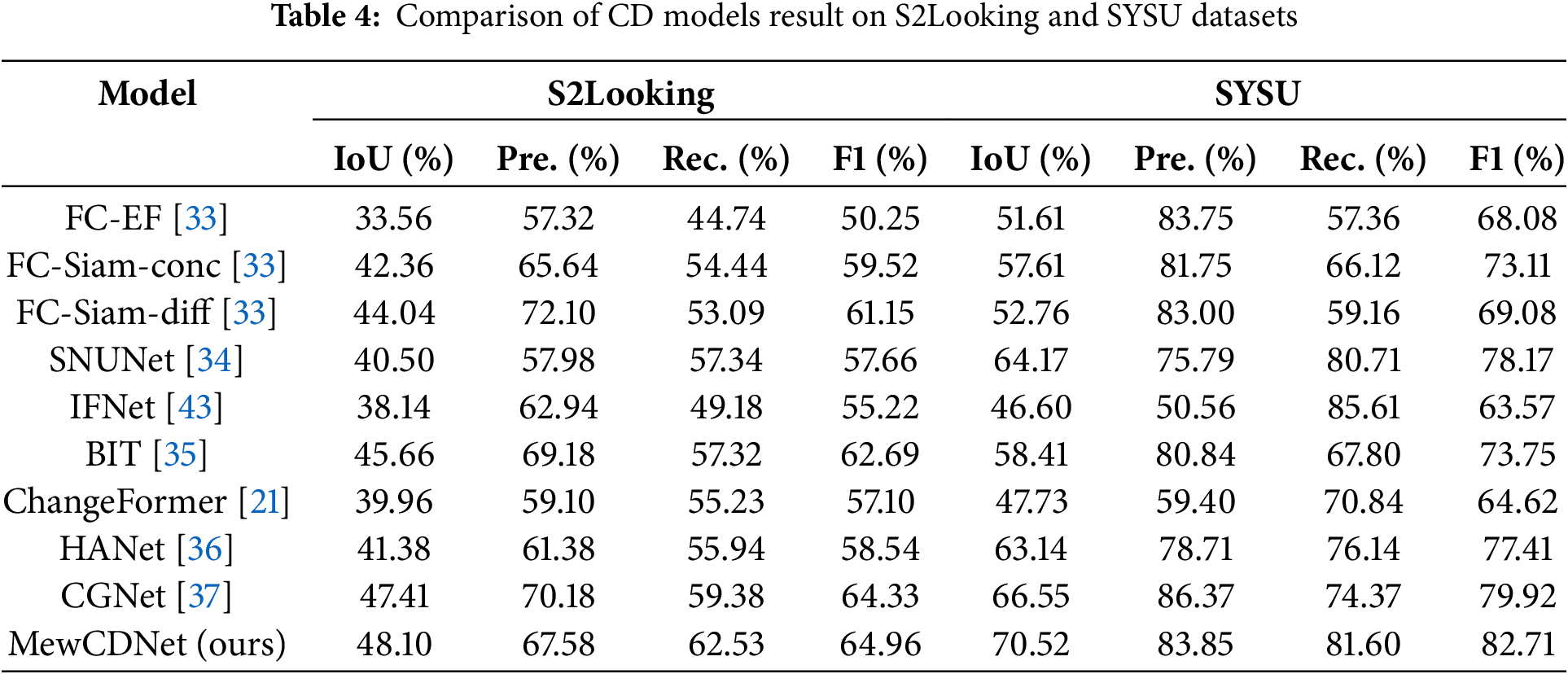

Table 4 presents the quantitative comparison of MewCDNet against other methods on the S2Looking and SYSU datasets. The S2Looking dataset focuses on extreme perspective differences and geometric distortions, which impose significant robustness challenges on change detection models. On this dataset, MewCDNet achieves an F1 score of 64.96% and an IoU of 48.10%, significantly outperforming all competing models. Specifically, its IoU is 0.69% higher than that of the second-best CGNet (47.41%). This result underscores MewCDNet’s superiority in pixel-level change region coverage, particularly in oblique-view scenarios with blurred building boundaries, where the IoU improvement demonstrates practical significance.

To further validate the cross-scene generalization capability of MewCDNet, we conducted experiments on the multi-source, multi-class SYSU dataset, which includes annotations for changes in buildings, roads, vegetation, and other land cover types. MewCDNet performed strongly in this task, achieving an IoU of 70.52% and an F1 score of 82.71%, outperforming all competing models. Specifically, it surpasses the second-best model, CGNet, by 3.97% in IoU and 2.79% in F1, and significantly outperforms the pure Transformer-based model ChangeFormer. The high IoU reflects precise coverage of multi-class change regions. Compared to the BIT model, MewCDNet’s F1 score is 8.96% higher than BIT’s (73.75%), highlighting its capability to distinguish complex land cover types, such as regions where farmland and buildings intersect.

Compared to the LEVIR and WHUCD datasets, the S2Looking poses greater challenges, as evidenced by the increased presence of red and green regions in the visualization results. Specifically, as shown in Fig. 7a,d, due to indistinct building features, even without interference factors in the T2 phase images, other models’ predictions exhibit large voids areas. In Fig. 7b, where the changed regions are relatively small, models such as BIT and ChangeFormer produce extensive false detections. Compared to other models, MewCDNet produces fewer false positives and false negatives in the visualization results, demonstrating its superior ability to identify building boundaries and structural information, thereby mitigating the issue of void predictions.

Figure 7: Visualization results on S2Looking dataset. The four pairs of bi-temporal images used for visualization are denoted as (a–d)

The SYSU dataset is also a challenging benchmark for change detection, as visualizations reveal extensive missed detections and false positives. To assess MewCDNet’s generalization capability, we evaluated it on the complete multi-class change detection task, rather than on a subset focused solely on building changes. In Fig. 8a, low-contrast change regions cause other models to miss large portions of the altered areas. In Fig. 8c, some parallel roads in road expansion scenes are misclassified as new buildings by several baseline models. Fig. 8d illustrates irregular change boundaries and composite changes involving two categories, which significantly increase the detection difficulty and result in extensive voids in the predictions of IFNet and CGNet. Overall, the visualizations of MewCDNet are clearly superior, demonstrating its strong performance in multi-type change detection and confirming its cross-scene robustness.

Figure 8: Visualization results on SYSU dataset. The four pairs of bi-temporal images used for visualization are denoted as (a–d)

Notably, the SYSU dataset encompasses a wide range of land cover changes, including alterations in vegetation, roads, water bodies, and buildings. MewCDNet’s strong performance on this dataset suggests its potential for adaptation to general land cover change detection tasks. Its ability to integrate multi-scale features and maintain robustness against complex background variations makes it a promising candidate for broader applications beyond building-specific change detection. With appropriate retraining and fine-tuning on datasets targeting other land cover types, MewCDNet could effectively detect changes across diverse land cover categories, thereby further extending its utility in remote sensing image analysis.

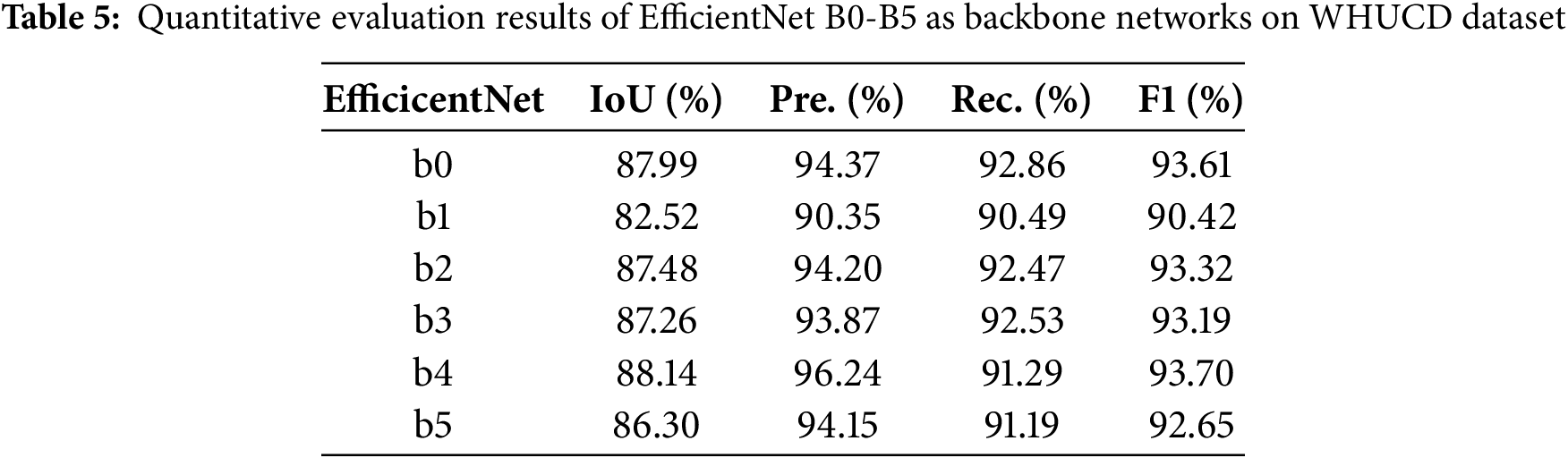

We conducted systematic architectural comparison experiments using EfficientNet models ranging from B0 to B5. EfficientNet scales depth, width, and resolution uniformly via compound coefficients, with significant variations in computational complexity and feature representation among different versions. Given B7’s extreme computational demands and diminishing returns, we evaluated B0-B5 as the backbone. The results are shown in Table 5. The results showed that EfficientNet-B4 offered the best balance for building change detection, achieving the highest IoU (88.14%) and F1 score (93.70%). Performance initially improves with increasing model size but declines beyond B4, indicating diminishing returns. Considering accuracy and efficiency, EfficientNet-B4 was chosen as the backbone feature extractor, providing the most discriminative multi-scale features for the change detection task.

While Transformer encoders excel at capturing global context through self-attention mechanisms, they often require substantially more computational resources, especially when processing high-resolution remote sensing images. EfficientNet-B4, with its optimized compound scaling strategy and lightweight MBConv modules, achieves a better trade-off between feature representation and computational cost. Considering accuracy, efficiency, and the practical demands of processing large-format remote sensing imagery, EfficientNet-B4 was chosen as the backbone, providing the most discriminative multi-scale features for the change detection task.

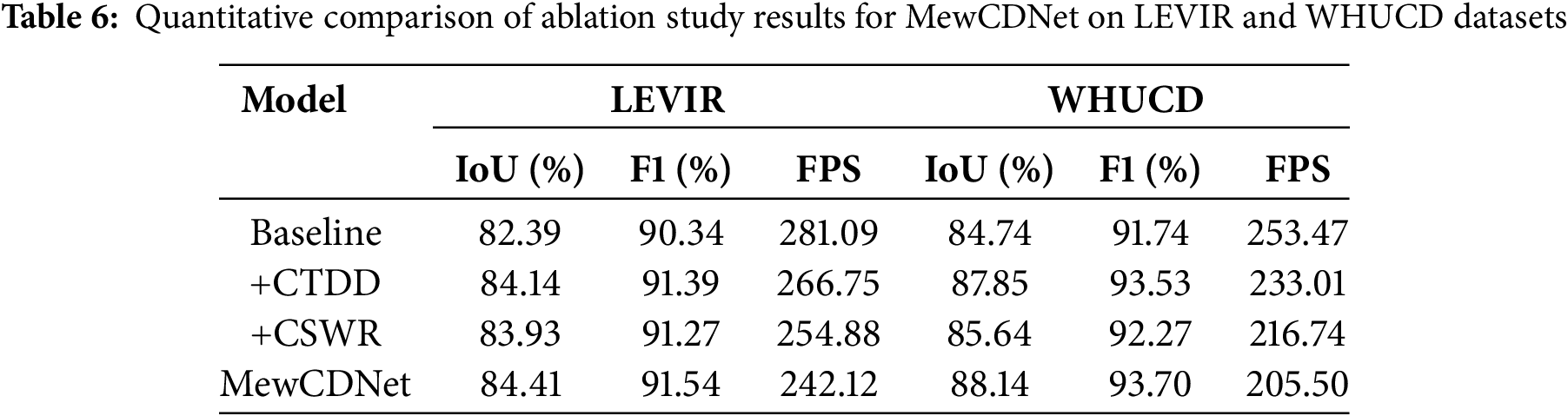

To validate the effectiveness of core modules in MewCDNet and their impact on computational efficiency, this section conducts systematic ablation experiments on LEVIR and WHUCD datasets. The results are shown in Table 6. By progressively adding modules, the experiments quantitatively analyze each component’s contribution to model performance and evaluate the computational overhead introduced by each module. By comparing performance differences across configurations, this section thoroughly investigates the importance of CTDD and CSWR in change detection and reveals how their collaborative optimization enhances performance in BCD tasks.

The CTDD module, through a dual-stream cooperative design, significantly enhances the model’s ability to discriminate true building changes. The pixel-wise difference branch captures pixel-level candidate regions, while the Euclidean distance branch suppresses false detections through physically meaningful verification. Experiments show that on the LEVIR and WHUCD datasets, CTDD improves IoU by 1.75% and 3.11%, respectively, and F1 by 1.05% and 1.79%. This confirms its robustness to complex interferences and its effectiveness in mitigating pseudo-changes caused by illumination and registration errors in high-resolution images.

The CSWR module innovatively integrates Haar wavelet transforms with cross-scale cross-attention mechanisms, enhancing edge localization accuracy through frequency decoupling. DWT preserves both high- and low-frequency information while reducing computational complexity. The cross-attention mechanism strengthens semantic links across multi-scale features. Experiments show it boosts LEVIR’s IoU from 82.39% to 83.93% and WHUCD’s from 84.74% to 85.64%. It also improves boundary consistency in dense building scenarios.

The synergy between CTDD and CSWR achieves performance breakthroughs. CTDD provides high-confidence change regions, while CSWR optimizes localization through frequency-domain refinement. The combined model excels across all datasets. Meanwhile, CSWR’s wavelet downsampling reduces attention computation costs, ensuring model efficiency. This architecture, combining temporal modeling and frequency optimization, balances detection accuracy in complex scenarios with engineering practicality, offering an efficient solution for real-time change monitoring of high-resolution remote sensing imagery.

In addition to IoU and F1 metrics, we evaluated the inference speed, measured in frames per second (FPS), of different module configurations on two datasets. As expected, the baseline model achieved the highest FPS owing to its architectural simplicity. The addition of the CTDD and CSWR modules—particularly CSWR with its cross-attention mechanism—increased computational overhead, thereby reducing the FPS. Although the complete MewCDNet, incorporating both CTDD and CSWR, achieves the lowest FPS, this reduction in speed is justified by its significant improvement in detection accuracy. MewCDNet effectively balances high accuracy with computational efficiency.

As shown in Fig. 9, we selected two cases each of building demolition and new construction from the WHUCD dataset for comparative analysis. In the demolition scenarios depicted in Fig. 9a,b, the high similarity between ground colors in demolition areas and original buildings causes baseline models and single-module experiments to exhibit varying degrees of missed detections. Notably, building shadows in the T1 phase imagery of Fig. 9a significantly increase detection difficulty, whereas the dual-module collaborative processing substantially improves recognition accuracy in shadowed regions. In the new construction examples shown in Fig. 9c,d, although the overall detection difficulty is lower, false detections occur in small local areas due to chromatic similarity between backgrounds and buildings. The visualization results demonstrate that the combined modules effectively reduce both false positives and missed detections.

Figure 9: Ablation study visualizations on WHUCD dataset. The four pairs of bi-temporal images used for visualization are denoted as (a–d)

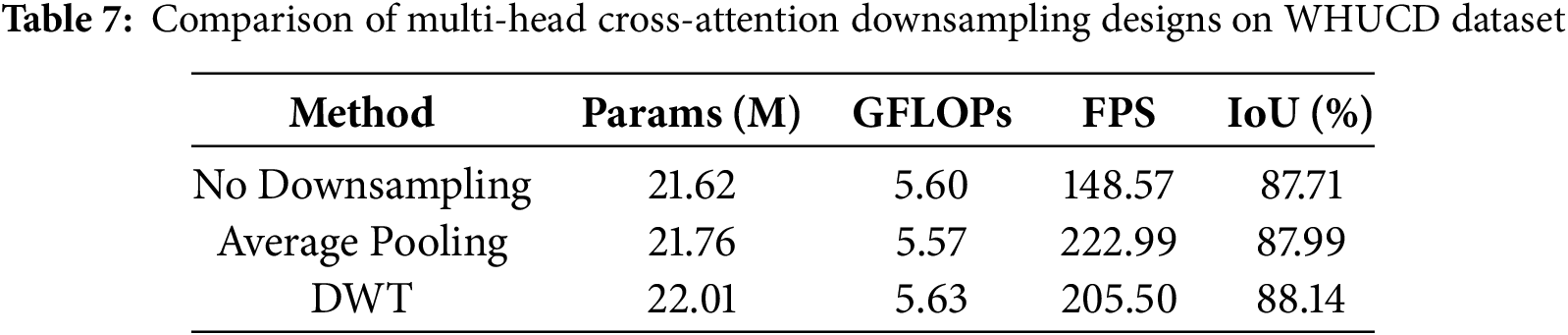

Table 7 systematically compares three CSWR variants based on multi-head cross-attention mechanisms in terms of model parameters, computational complexity (GFLOPs), inference speed (FPS), and change detection performance (IoU): no downsampling, average pooling downsampling, and DWT lossless downsampling. Compared to the no-downsampling method, adding downsampling increases the number of parameters; however, average pooling reduces GFLOPs by 0.30 and slightly improves FPS. With DWT downsampling, both parameters and GFLOPs increase because feature maps are decoupled into four frequency subbands during downsampling, and multi-channel feature recombination further adds to the computational complexity. Consequently, the FPS of the full model using DWT is lower than when using average pooling. Despite this increased computational cost, change detection performance improves by 0.43% compared to no downsampling, with only a modest increase in parameters. Importantly, the FPS achieved with DWT downsampling remains within practical limits. This indicates that the frequency-domain decoupling method achieves finer semantic boundaries at a manageable computational cost.

To address the challenges of insufficient change feature representation, boundary blurring, and prediction holes in current remote sensing image building change detection tasks, this paper proposes a deep learning framework named MewCDNet, which integrates CNN and Transformer architectures. Specifically, MewCDNet employs EfficientNet-B4 to extract features from bi-temporal images, and utilizes MFF to integrate feature maps from different levels. We design the CTDD and CSWR modules. The CTDD module enhances the model’s ability to distinguish pseudo-changes by combining pixel-level difference operations with semantically aware Euclidean distance weighting. The CSWR module integrates the Haar wavelet transform with a multi-head cross-attention mechanism to reduce computational overhead while improving edge localization accuracy. MewCDNet significantly improves detection performance in scenarios involving small-scale targets, large viewpoint variations, and complex backgrounds. For instance, on the LEVIR dataset, MewCDNet achieves an F1 score of 91.54% and an IoU of 84.41%. On the WHUCD dataset, it attains an F1 score of 93.70% and an IoU of 88.14%. Ablation studies on the LEVIR and WHUCD datasets confirm the synergistic effects of the CTDD and CSWR modules in suppressing noise and refining boundaries.

In real-world applications, MewCDNet holds great potential for urban planning, disaster and emergency response, and resource management. Future work will explore synergistic integration with advanced technologies such as big data analytics, the Internet of Things (IoT), and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to enhance the system’s performance and expand its application scope. Specifically, big data analytics can be leveraged to train more robust models on large-scale heterogeneous datasets, while IoT devices can provide real-time data streams for dynamic change monitoring. Furthermore, GIS integration will enable sophisticated spatial analysis and intuitive data visualization, facilitating applications like urban expansion tracking and environmental change assessment. Additionally, we plan to explore more advanced feature extraction backbones, incorporate temporal information from multiple time points, integrate multi-modal data, and optimize the model for edge device deployment. These directions could further enhance MewCDNet’s performance and broaden its applicability.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This paper was supported by the Henan Province Key R&D Project under Grant 241111210400, the Henan Provincial Science and Technology Research Project under Grants 252102211047, 252102211062, 252102211055 and 232102210069, the Jiangsu Provincial Scheme Double Initiative Plan JSS-CBS20230474, the XJTLU RDF-21-02-008, the Science and Technology Innovation Project of Zhengzhou University of Light Industry under Grant 23XNKJTD0205, and the Higher Education Teaching Reform Research and Practice Project of Henan Province under Grant 2024SJGLX0126.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Jia Liu and Hao Chen; methodology, Jia Liu, Hao Chen and Hang Gu; software, Zuhe Li and Haoran Chen; validation, Yushan Pan and Haoran Chen; formal analysis, Hao Chen and Hang Gu; investigation, Erlin Tian and Min Huang; resources, Jia Liu and Erlin Tian; data curation, Erlin Tian and Min Huang; writing—original draft preparation, Hao Chen and Hang Gu; writing—review and editing, Zuhe Li; visualization, Hang Gu and Yushan Pan; supervision, Jia Liu and Zuhe Li; project administration, Jia Liu and Zuhe Li; funding acquisition, Jia Liu and Zuhe Li. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this study are publicly available in the LEVIR Dataset at https://justchenhao.github.io/LEVIR (accessed on 01 August 2025) and the WHUCD Dataset at https://gpcv.whu.edu.cn/data/building_dataset.html (accessed on 01 August 2025) and the S2Looking Dataset at https://github.com/S2Looking/Dataset (accessed on 01 August 2025) and the SYSU Dataset at https://github.com/liumency/SYSU-CD (accessed on 01 August 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Liu C, Chen K, Zhang H, Qi Z, Zou Z, Shi Z. Change-agent: toward interactive comprehensive remote sensing change interpretation and analysis. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2024;62:5635616. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2024.3425815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Woodcock CE, Loveland TR, Herold M, Bauer ME. Transitioning from change detection to monitoring with remote sensing: a paradigm shift. Remote Sens Environ. 2020;238(18):111558. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2019.111558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zheng Z, Zhong Y, Wang J, Ma A, Zhang L. Building damage assessment for rapid disaster response with a deep object-based semantic change detection framework: from natural disasters to man-made disasters. Remote Sens Environ. 2021;265(1):112636. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2021.112636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhu Q, Guo X, Deng W, Shi S, Guan Q, Zhong Y, et al. Land-use/land-cover change detection based on a Siamese global learning framework for high spatial resolution remote sensing imagery. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens. 2022;184(14):63–78. doi:10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2021.12.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Liu J, Xu R, Duan Y, Guo T, Shi G, Luo F. MDGF-CD: land-cover change detection with multi-level DiffFormer feature grouping fusion for VHR remote sensing images. Inf Fusion. 2025;120(13):103110. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2025.103110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Gao T, Xia S, Liu M, Zhang J, Chen T, Li Z. MSNet: multi-scale network for object detection in remote sensing images. Pattern Recognit. 2025;158(21):110983. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2024.110983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Chen H, Li W, Shi Z. Adversarial instance augmentation for building change detection in remote sensing images. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2022;60:1–16. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2021.3066802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li X, Du Z, Huang Y, Tan Z. A deep translation (GAN) based change detection network for optical and SAR remote sensing images. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens. 2021;179(3):14–34. doi:10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2021.07.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jiang W, Sun Y, Lei L, Kuang G, Ji K. Change detection of multisource remote sensing images: a review. Int J Digit Earth. 2024;17(1):2398051. doi:10.1080/17538947.2024.2398051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Dai Y, Shen L, Wang Y, Liu S, Li Z. A lightweight dual-branch network for building change detection in remote sensing images integrating cross-scale coupling and boundary constraint. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2024;62(5):1–15. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2024.3441944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Liu Y, Zhang K, Guan C, Zhang S, Li H, Wan W. Building change detection in earthquake: a multiscale interaction network with offset calibration and a dataset. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2024;62(2):3438290–17. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2024.3438290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Huang Z, Qiu H, Hou M, Yu Z, Wang S, Li X. MCECF: a multiscale complementary enhanced context fusion network for remote sensing change detection. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2025;63:1–14. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2025.3556237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Jiang S, Lin H, Ren H, Hu Z, Weng L, Xia M. MDANet: a high-resolution city change detection network based on difference and attention mechanisms under multi-scale feature fusion. Remote Sens. 2024;16(8):1387. doi:10.3390/rs16081387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang Y, Wang M, Hao Z, Wang Q, Wang Q, Ye Y. MSGFNet: multi-scale gated fusion network for remote sensing image change detection. Remote Sens. 2024;16(3):572. doi:10.3390/rs16030572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Peng X, Zhong R, Li Z, Li Q. Optical remote sensing image change detection based on attention mechanism and image difference. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2021;59(9):7296–307. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2020.3033009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Dong S, Zhu Y, Chen G, Meng X. EfficientCD: a new strategy for change detection based with bi-temporal layers exchanged. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2024;62:1–13. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2024.3433014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Huang B, Xu Y, Zhang F. Remote-sensing image change detection based on adjacent-level feature fusion and dense skip connections. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens. 2024;17:7014–28. doi:10.1109/JSTARS.2024.3374290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Wei J, Sun K, Li W, Li W, Gao S, Miao S, et al. Robust change detection for remote sensing images based on temporospatial interactive attention module. Int J Appl Earth Obs Geoinf. 2024;128(10):103767. doi:10.1016/j.jag.2024.103767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ma X, Yang J, Che R, Zhang H, Zhang W. DDLNet: boosting remote sensing change detection with dual-domain learning. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME); 2024 Jul 15–19; Niagara Falls, ON, Canada. doi:10.1109/ICME57554.2024.10688140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Li X, Tan Y, Liu K, Wang X, Zhou X. DSFI-CD: diffusion-guided spatial-frequency-domain information interaction for remote sensing image change detection. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2025;63(5):1–18. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2025.3544402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Bandara WGC, Patel VM. A transformer-based Siamese network for change detection. In: Proceedings of the IGARSS 2022—2022 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium; 2022 Jul 17–22; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. doi:10.1109/IGARSS46834.2022.9883686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang C, Wang L, Cheng S, Li Y. SwinSUNet: pure transformer network for remote sensing image change detection. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2022;60:1–13. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2022.3160007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Li Q, Zhong R, Du X, Du Y. TransUNetCD: a hybrid transformer network for change detection in optical remote-sensing images. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2022;60:1–19. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2022.3169479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Sun Y, Zhao Y, Han X, Gao W, Hu Y, Zhang Y. A feature enhancement network combining UNet and vision transformer for building change detection in high-resolution remote sensing images. Neural Comput Appl. 2024;37(3):1429–56. doi:10.1007/s00521-024-10666-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhang H, Chen H, Zhou C, Chen K, Liu C, Zou Z, et al. BiFA: remote sensing image change detection with bitemporal feature alignment. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2024;62(5):1–17. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2024.3376673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Xie W, Shao W, Li D, Li Y, Fang L. MIFNet: multi-scale interaction fusion network for remote sensing image change detection. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2024;35(3):2725–39. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2024.3494820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yang J, Wan H, Shang Z. EHCTNet: enhanced hybrid of CNN and transforme network for remote sensing image change detection. arXiv:2501.01238. 2025. [Google Scholar]

28. Liu M. MSTransCDNet: a remote sensing image change detection method with multi-scale transformer. J Appl Remote Sens. 2025;19(1):018503. doi:10.1117/1.JRS.19.018503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Chen H, Shi Z. A spatial-temporal attention-based method and a new dataset for remote sensing image change detection. Remote Sens. 2020;12(10):1662. doi:10.3390/rs12101662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Ji S, Wei S, Lu M. Fully convolutional networks for multisource building extraction from an open aerial and satellite imagery data set. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2019;57(1):574–86. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2018.2858817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Shen L, Lu Y, Chen H, Wei H, Xie D, Yue J, et al. S2Looking: a satellite side-looking dataset for building change detection. Remote Sens. 2021;13(24):5094. doi:10.3390/rs13245094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Shi Q, Liu M, Li S, Liu X, Wang F, Zhang L. A deeply supervised attention metric-based network and an open aerial image dataset for remote sensing change detection. IEEE Remote Sens. 2021;60:1–16. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2021.3085870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Daudt RC, Saux BL, Boulch A. Fully convolutional siamese networks for change detection. In: Proceedings of the 2018 25th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2018 Oct 7–10; Athens, Greece. doi:10.1109/ICIP.2018.8451652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Fang S, Li K, Shao J, Li Z. SNUNet-CD: a densely connected siamese network for change detection of VHR images. IEEE Geosci Remote Sens Lett. 2021;19:1–5. doi:10.1109/LGRS.2021.3056416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Chen H, Qi Z, Shi Z. Remote sensing image change detection with transformers. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2021;60:1–14. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2021.3095166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Han C, Wu C, Guo H, Hu M, Chen H. HANet: a hierarchical attention network for change detection with bitemporal very-high-resolution remote sensing images. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens. 2024;16:3867–78. doi:10.1109/JSTARS.2023.3264802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Han C, Wu C, Guo H, Hu M, Li J, Chen H. Change guiding network: incorporating change prior to guide change detection in remote sensing imagery. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens. 2024;16:8395–407. doi:10.1109/JSTARS.2023.3310208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Yan W, Cao L, Yan P, Zhu C, Wang M. Remote sensing image change detection based on swin transformer and cross-attention mechanism. Earth Sci Inform. 2024;18(1):106. doi:10.1007/s12145-024-01523-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Chong Y, Ge X, Pan S. RISNet: robust ill-posed solver for remote sensing image change detection. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens. 2025;18(5):7625–43. doi:10.1109/JSTARS.2025.3541260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhang X, Yuan G, Hua Z, Li J. TSMGA: temporal-spatial multiscale graph attention network for remote sensing change detection. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens. 2025;18:3696–712. doi:10.1109/JSTARS.2025.3526785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Zhang X, Dong K, Cheng D, Hua Z, Li J. STWANet: spatio-temporal wavelet attention aggregation network for remote sensing change detection. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens. 2025;18:8813–30. doi:10.1109/JSTARS.2025.3551093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Zhang D, Wang F, Ning L, Zhao Z, Gao J, Li X. Integrating SAM with feature interaction for remote sensing change detection. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2024;62:1–11. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2024.3483775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Zhang C, Yue P, Tapete D, Jiang L, Shangguan B, Huang L, et al. A deeply supervised image fusion network for change detection in high resolution bi-temporal remote sensing images. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens. 2020;166:183–200. doi:10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2020.06.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools