Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Motion In-Betweening via Frequency-Domain Diffusion Model

1 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, 730070, China

2 Department of Computer and Information Science, Southwest University, Chongqing, 400715, China

* Corresponding Author: Ying Qi. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068247

Received 23 May 2025; Accepted 17 July 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Human motion modeling is a core technology in computer animation, game development, and human-computer interaction. In particular, generating natural and coherent in-between motion using only the initial and terminal frames remains a fundamental yet unresolved challenge. Existing methods typically rely on dense keyframe inputs or complex prior structures, making it difficult to balance motion quality and plausibility under conditions such as sparse constraints, long-term dependencies, and diverse motion styles. To address this, we propose a motion generation framework based on a frequency-domain diffusion model, which aims to better model complex motion distributions and enhance generation stability under sparse conditions. Our method maps motion sequences to the frequency domain via the Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT), enabling more effective modeling of low-frequency motion structures while suppressing high-frequency noise. A denoising network based on self-attention is introduced to capture long-range temporal dependencies and improve global structural awareness. Additionally, a multi-objective loss function is employed to jointly optimize motion smoothness, pose diversity, and anatomical consistency, enhancing the realism and physical plausibility of the generated sequences. Comparative experiments on the Human3.6M and LaFAN1 datasets demonstrate that our method outperforms state-of-the-art approaches across multiple performance metrics, showing stronger capabilities in generating intermediate motion frames. This research offers a new perspective and methodology for human motion generation and holds promise for applications in character animation, game development, and virtual interaction.Keywords

With the rapid development of virtual reality, computer animation, and the digital game industry, the importance of human motion modeling has become increasingly prominent [1,2]. Accurately and efficiently generating realistic and natural human motion sequences has emerged as a key technology for enhancing the immersive experience of digital content.

Human motion modeling can be categorized into several directions based on different research objectives, including motion synthesis, motion prediction, and motion interpolation. Among these, motion interpolation constitutes a fundamental yet challenging task [3]: it aims to generate continuous and natural in-between motion sequences given only sparse conditions, such as the initial and terminal frames. This task is widely employed in practical applications like character animation and motion completion. For instance, in animation production, animators typically design only the key poses [4], with the remaining frames generated via interpolation algorithms and subsequent manual refinement to complete the desired motion transitions. In game development, interpolation techniques are often used to connect predefined motion clips, enabling diverse character behaviors and seamless transitions, thereby enhancing overall immersion and expressiveness.

To address the aforementioned challenges, researchers have proposed various interpolation strategies, from rule-driven methods to deep generative models, yet the quality bottleneck in sparse keyframe scenarios remains unresolved. Early methods like linear interpolation [5,6] and trajectory planning are simple and low-cost, but their underlying linear assumptions prevent them from capturing the non-linear coordination between joints, resulting in transitional motions that lack dynamic variation and expressiveness. With the advancement of deep learning, data-driven generative models have become the mainstream approach. Although Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) [7,8] can produce sharper details, their training process is unstable and prone to mode collapse, and they lack fine-grained control over the overall motion structure. Variational Autoencoder (VAE) [9,10] aim to improve in-betweening by modeling the latent distribution of motion, but their generated results often lack sufficient dynamic variation and rhythmic hierarchy, leading to indistinct dynamic features. Transformer-based temporal model [11,12] leverage global attention to capture long-range dependencies and excel at full sequence prediction. However, when anchored only by start and end frames, the attention mechanism lacks reliable constraints, often resulting in style convergence, significant local deformations, or discontinuities in motion. In summary, these methods struggle to simultaneously guarantee naturalness, stability, and structural coherence in interpolation tasks characterized by sparse keyframes, long sequences, and high diversity demands.

Synthesizing existing research reveals that although various generative models have made progress in specific areas, they commonly face a bottleneck when handling sparse keyframe interpolation tasks. The fundamental reason lies in the coexistence of information sparsity inherent to the task and the high complexity of motion data itself. The task typically relies on only sparse keyframe inputs, requiring the generation of complete, natural motion sequences from extremely limited information. Human motion data, often represented as the 3D coordinates of multiple joints per frame, is characterized by high dimensionality, complex multi-joint coordination, and intricate temporal dependencies. This requires a generative model not only to reconstruct spatial structures but also to capture dynamic changes across frames. For longer sequences or more complex actions, problems such as noise propagation and motion discontinuities become more pronounced, placing even greater demands on the model’s capabilities. Therefore, the core challenge of motion interpolation lies in simultaneously achieving naturalness, coherence, and structural plausibility under these sparse conditions.

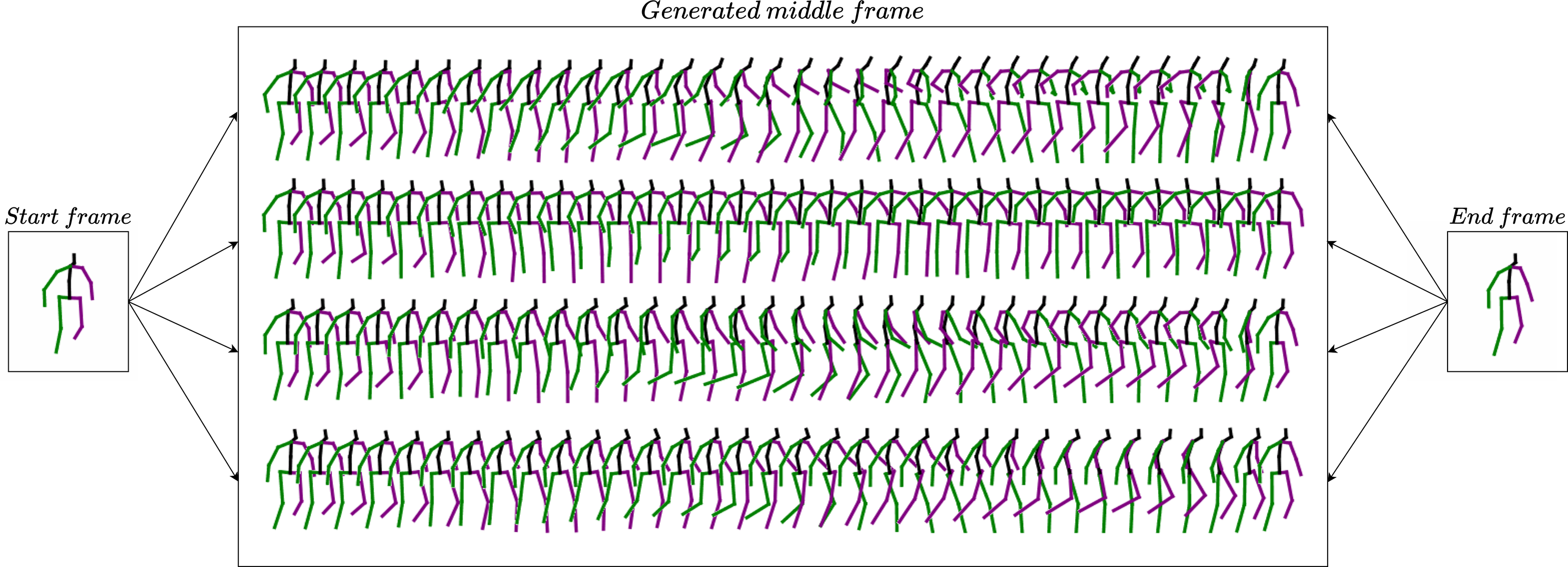

To better address the challenges of human motion interpolation under sparse conditions, this paper constructs a suitable framework by combining frequency-domain modeling with a diffusion-based generative mechanism. As an emerging generative paradigm, diffusion models learn the data distribution through a progressive denoising process, offering inherent training stability and high-quality generation capabilities [13,14], which are well-suited for interpolation tasks that demand strong structural coherence. Our approach, grounded in diffusion modeling, progressively recovers an intermediate motion sequence from random noise while adhering to keyframe constraints, demonstrating the ability to model high-dimensional and complex motion distributions. Given that human motion data is predominantly composed of low-frequency components, with high-frequency parts often corresponding to local perturbations and noise, we introduce the Discrete Cosine Transform to map motion sequences into the frequency domain. This approach not only compresses redundant dimensions but also reinforces the modeling of global motion trends, thereby enhancing the coherence and stability of the generated results. Furthermore, a denoising network built with a self-attention mechanism is employed to improve the model’s perception of sequential structure and dynamics. Concurrently, a multi-objective loss function is designed to optimize for smoothness, diversity, and structural consistency. The entire generation process, constrained by keyframes, progressively samples from noise to create a complete sequence, enabling the generation of natural, stable, and structurally plausible human motion even under sparse conditions, as visually demonstrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Demonstration of diverse motion in-betweening. Given a single pair of start and end frames (left and right), our model synthesizes multiple, physically plausible and distinct motion sequences (center)

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

• We propose a human motion interpolation framework based on a frequency-domain diffusion model that can generate natural, coherent, and physically plausible intermediate motion sequences given only the start and end frames.

• The integration of the Discrete Cosine Transform for frequency-domain modeling with a self-attention-based denoising network, which enhances the model’s ability to capture long-term dependencies and improves the stability of generated sequences.

• A multi-objective loss function that jointly optimizes the generation process for motion smoothness, pose diversity, and anatomical consistency.

Experiments on the Human3.6M and LaFAN1 datasets demonstrate that our proposed method outperforms current state-of-the-art approaches on several key metrics, exhibiting excellent generation quality and structural control. This work provides a new modeling paradigm for motion generation under sparse conditions and is broadly applicable to practical scenarios such as virtual human animation, game character synthesis, and human-computer interaction systems.

2.1 Models for Motion Generation

In recent years, data-driven deep generative models have made significant strides in the field of human motion synthesis. Different model paradigms have demonstrated distinct characteristics and limitations in generation tasks.

GANs [15] are renowned for producing sharp, detail-rich samples through a zero-sum game between a generator and a discriminator [7,8]. Their main advantage lies in avoiding the blurring effect caused by traditional loss functions like L2 loss. However, the training process of GANs is notoriously challenging, often facing issues such as gradient vanishing and mode collapse, which leads to insufficient diversity in the generated results [16]. Furthermore, their one-shot generation nature makes it difficult to directly capture and maintain complex long-term temporal dependencies.

VAEs [17] learn a regularized latent space through an encoder-decoder architecture, from which new motions can be generated by sampling [18,19]. The training of VAEs is relatively stable, and they can learn smooth latent representations. However, their core Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO) loss, in its effort to ensure a regularized latent distribution, often comes at the cost of reconstruction fidelity, leading to overly-smoothed outputs that lack high-frequency details and dynamic expressiveness [10].

Flow-Based Models [20] utilize a series of invertible transformations to precisely fit the true data distribution, thereby enabling the computation of exact likelihoods. While this gives them a theoretical advantage in probability density estimation, their architectural design (e.g., the invertibility constraint) is typically more complex than that of GANs and VAEs, and they face significant computational overhead when dealing with high-dimensional data.

Transformer-Based Models [21,22] have come to dominate sequence modeling tasks thanks to their powerful self-attention mechanism. They can effectively capture long-range dependencies in sequences, making them excel in motion generation tasks that require understanding global context. However, their performance is highly dependent on the quality and density of the input sequence; when faced with sparse conditions, how to effectively constrain their powerful attention mechanism becomes a new challenge.

Motion in-betweening is a fundamental yet highly challenging branch of motion generation [1]. The task is essentially to find a plausible path on a high-dimensional, non-linear pose manifold that connects two sparse keypoints (the start and end frames). The existence of an infinite number of possible transitions between two points makes this a classic ill-posed problem.

Early research primarily employed geometric or physics-based methods, such as linear interpolation [23] or dynamic planning [5,6]. Although simple to implement, these methods typically operate in Euclidean space, ignoring the rotational properties of poses and skeletal constraints, which often leads to visual artifacts like foot-skating and unnatural limb lengths.

With the rise of deep learning, researchers have attempted to apply mainstream generative models to this task. However, the inherent weaknesses of these models are amplified when faced with the sparse constraints of motion in-betweening. For GANs, the weak conditioning signal (only start and end frames) is insufficient to effectively guide the generation process, leading to intermediate frames that are nearly unconstrained and often resulting in chaotic or incoherent motions. For VAEs, their inherent tendency to regress towards the mean is particularly detrimental in interpolation tasks, as it erases all potential vivid details and generates a simplistic, averaged transition that lacks expressiveness.

To address these challenges, researchers have designed various specialized models. For example, Qin et al. [12] leveraged the powerful context modeling capabilities of Transformers, but their attention mechanism can still lose focus without intermediate anchors, leading to motion drift. The CVAE-based scheme by Ren et al. [9] can enhance diversity but remains limited by the inherent smoothing problem of VAEs. Hong et al. [24] tackled the long-horizon problem by predicting intermediate keyframes—an effective strategy, but one that introduces an additional prediction stage and may restrict the freedom of non-key frames.

In summary, existing methods for motion in-betweening have not yet found an ideal balance, struggling to simultaneously satisfy the three core requirements of physical realism, motion diversity, and structural coherence over long-horizon transitions.

2.3 Diffusion Models for Motion Generation

Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs) [25] offer a novel path to overcome the aforementioned difficulties. These models generate data by learning the reverse of a diffusion process, progressively denoising a sample from pure Gaussian noise back to a target sample. This mechanism grants them several key advantages: firstly, their training process is highly stable, avoiding the adversarial training challenges of GANs; secondly, they can fit complex data distributions with high fidelity, achieving superior generation quality and diversity compared to traditional VAEs.

The effectiveness of diffusion models in the domain of human motion generation has been widely validated. From general-purpose high-quality motion synthesis [13], to text-driven motion generation [14], and physics-constrained realistic motion simulation [26], diffusion models have consistently demonstrated State-of-the-Art (SOTA) performance. Therefore, with their powerful distribution-fitting capabilities and robustness to sparse conditions, diffusion models offer a highly promising technical path to solve the long-standing challenges of generation quality and diversity in motion in-betweening tasks.

2.4 Frequency-Domain Diffusion Models

Beyond architectural advancements, another emerging research direction seeks to enhance the performance of diffusion models by incorporating a frequency-domain perspective. Recently, a multitude of works have explored this direction within the fields of image and video generation. For example, FreeU [27] introduces a frequency-domain reweighting mechanism during inference to modulate the U-Net’s feature maps for improved image fidelity. DNI [28] proposes a spectral decomposition of the initial noise via adaptive filters to enable more flexible video editing. FlexiEdit [29] utilizes frequency-aware optimization to suppress high-frequency components in specific regions for better image layout editing. Furthermore, to enhance the temporal consistency of generated videos, FRAG [30] and FreeInit [31] have explored approaches from the perspectives of frequency-domain grouping and optimizing the low-frequency components of noise, respectively. Collectively, these works demonstrate the immense potential of frequency-domain operations in improving the quality and temporal coherence of generated content.

However, these cutting-edge explorations are largely confined to editing or optimizing existing visual content. A research gap remains in applying frequency-domain modeling as a core mechanism for end-to-end sequence generation from pure noise, especially for the task of motion in-betweening under extremely sparse conditions. The work presented in this paper aims to fill this gap, systematically investigating how frequency-domain representations can empower diffusion models to tackle the core challenges of motion interpolation.

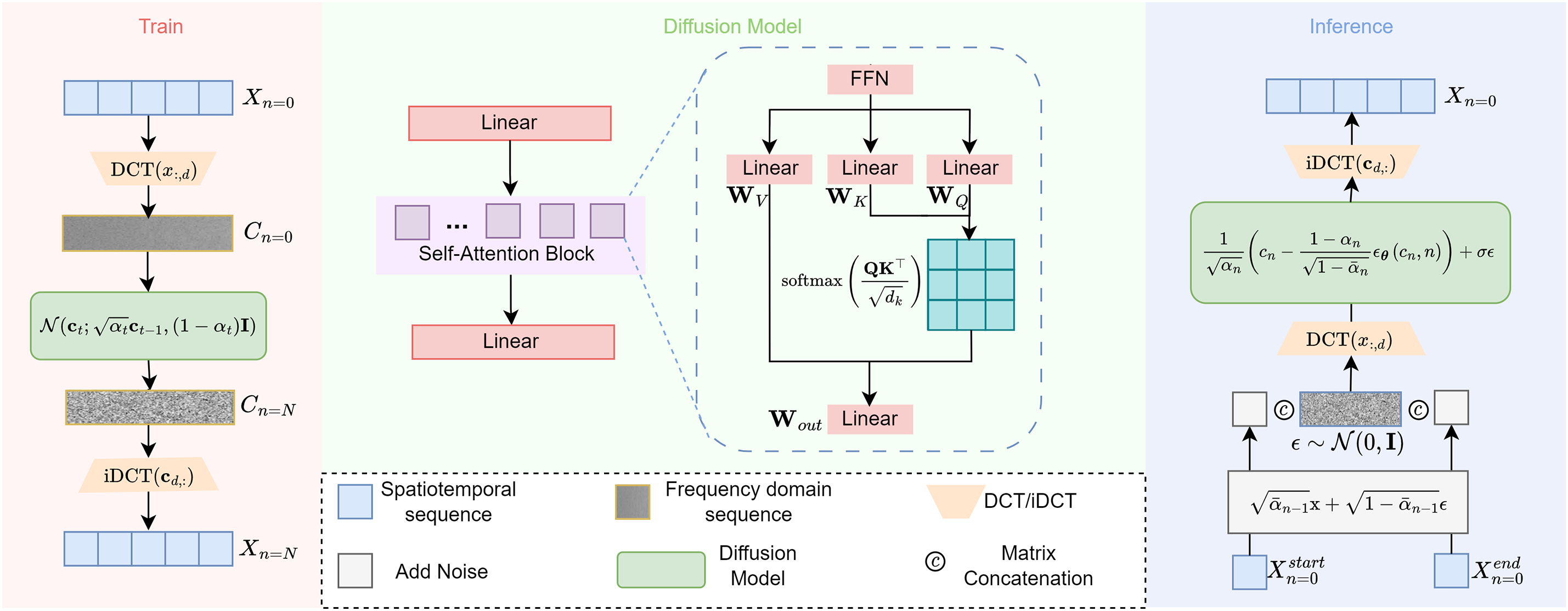

Given the initial frame

The proposed diffusion process consists of two main phases, as illustrated in Fig. 2. A key aspect of our framework is performing the diffusion process in the frequency domain, which allows for a more robust handling of long-term temporal structures in motion data. During the training phase, we apply noise addition and removal processes in the frequency domain after performing DCT on the complete action sequences. At each denoising time step, we calculate multiple losses on the spatiotemporal domain sequence obtained through iDCT. In the inference phase, we implement conditional generation using implicit guidance: we manually add the noise intensity corresponding to the current time step to the start and end frames, while the intermediate frames are obtained from the previous denoising network step. For each time step, the denoising network’s input is obtained by concatenating these two components. We have named our model FreqDiffusionBridge.

Figure 2: Overview of the proposed diffusion model. Left panel shows the training stage, right panel illustrates the sampling stage, and the central section details the denoising network architecture

DCT/iDCT Transformation: As motion data is inherently a time-series signal with strong structural properties, analyzing it from a frequency-domain perspective offers significant advantages. Human motion is naturally composed of dominant, low-frequency components that define the overall trajectory and primary actions, alongside high-frequency components that represent subtle gestures or noise. By transforming the motion sequence into the frequency domain, we can effectively decouple these elements. This allows the model to focus on learning the crucial low-frequency structures, which is essential for maintaining long-term coherence and smoothness, while simultaneously being more robust to high-frequency noise. This principle is why we adopt the DCT as a foundational step in our pipeline.

Given the high dimensionality of motion sequences, dimensionality reduction is essential for efficient processing. The adoption of DCT transformation not only addresses this challenge but also brings multiple advantages to motion sequence processing. DCT effectively decomposes temporal sequences into frequency components, allowing the model to focus on essential motion patterns while naturally filtering out high-frequency noise. This frequency-domain representation is particularly beneficial for human motion as it captures both the dominant low-frequency movement patterns and subtle motion details at different temporal scales. Moreover, by processing signals in the frequency domain, the model can better handle the periodic nature of human movements and long-term dependencies in action sequences. Specifically, for each coordinate component of every joint, we perform a one-dimensional DCT along the time dimension. Given an action sequence

the original action sequence is converted into a frequency domain representation

During generation, we invert the DCT coefficients from the frequency domain to reconstruct the motion sequence in the time domain. For this purpose, we perform the inverse DCT (iDCT) on the DCT coefficients. For each dimension

through the iDCT, we convert the frequency domain representation

Self-Attention Mechanism: Conventional diffusion approaches commonly adopt a U-Net architecture for the denoising network. However, this convolution-based architecture requires padding or cropping when applied to variable-length sequence data like human motion. To effectively capture long-term temporal dependencies in action sequences, we adopt linear layers composed of self-attention mechanisms as the denoising network. Compared to traditional deep network structures, linear layers have lower computational complexity, and the self-attention mechanism can capture correlations across the entire sequence globally.

The denoising network takes the noisy DCT coefficients

To make the model aware of the current noise level, the integer timestep

where

The self-attention process begins by projecting the input sequence

In this mechanism, these three matrices serve distinct roles. The

Next, we compute the attention scores, which determine how much focus each frame should place on every other frame. This is done by calculating the dot product of the Query and Key matrices. The result is scaled and passed through a softmax function to obtain the final attention weights. These weights are then used to create a weighted sum of the Value vectors:

where

Finally, this contextually-enriched representation

where

Diffusion Process: In diffusion frameworks, input data is progressively corrupted with noise during the forward pass, and the model is trained to iteratively remove this noise in the reverse pass, restoring the original data distribution. In training, entire motion sequences undergo noise perturbation and subsequent denoising to approximate the target data distribution.

The forward diffusion process is defined as:

where

During the training phase, our objective is to guide the model to capture the data distribution so that it can generate realistic action sequences from noise, as illustrated in Fig. 3. Adhering to the DDPM protocol, we sample Gaussian noise

where

where

Figure 3: In the training phase, we perform DCT operation on the complete action sequence to achieve spectrum conversion, and then perform denoising steps at each time step to capture the overall distribution of motion

In most conditional diffusion models, the denoising process is explicitly guided by external control signals, such as text, pose, or image features. These signals are injected via architectural mechanisms like cross-attention or FiLM layers. The conditional denoising sampling process typically follows:

where

In contrast, our method tackles a more challenging scenario: we utilize an unconditional diffusion model, yet aim to achieve conditionally guided action sequence generation. That is, we do not embed the given start and end frames (

This implicit conditioning approach is inherently more difficult than conventional methods, as the model must infer the temporal evolution from sparse keyframe constraints without access to explicit embeddings or attention mechanisms. To clarify the distinction, we contrast the conventional and our implicit guidance approaches:

• Explicit conditioning (conventional):

where the conditioning vector

• Implicit guidance (ours): The denoising network

This design allows us to retain the simplicity and generalization power of unconditional diffusion models, while still producing coherent, physically plausible sequences aligned with the sparse keyframe constraints.

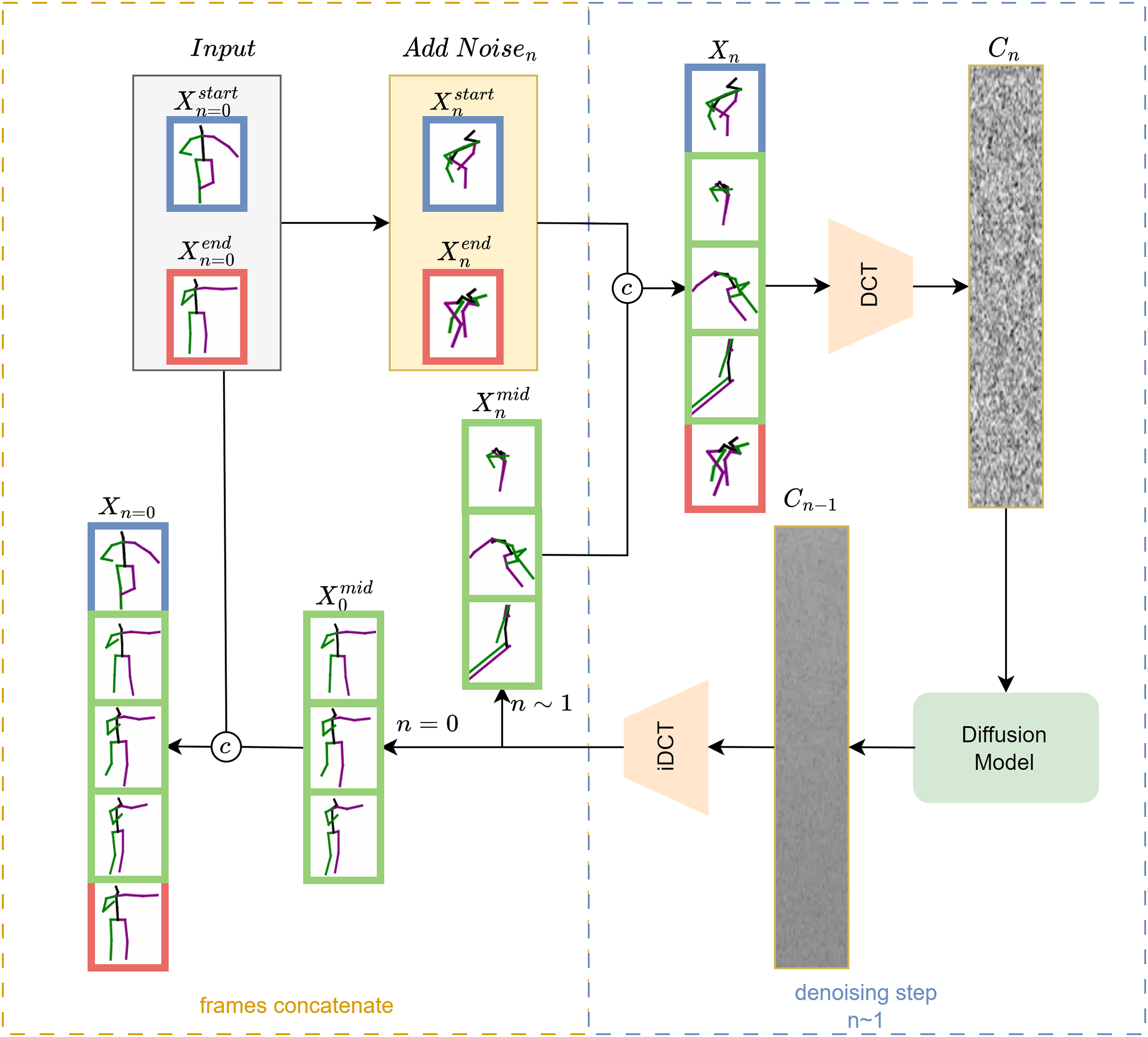

The detailed inference process proceeds as follows:

As our method utilizes an unconditional diffusion backbone, the key to conditional generation lies in carefully constructing the input tensor

To achieve this consistency, we apply noise to the original clean start and end frames in accordance with the diffusion schedule, precisely matching the noise level of the current timestep. We accomplish this by applying the official forward process (q-sample) formula from the DDPM framework [25]. This step is not an arbitrary perturbation; it is a mathematically grounded procedure that guarantees the resulting noised boundary frames have the correct statistical distribution for a given timestep.

The noised boundary frames,

This data manipulation step is the core of our implicit guidance strategy. By consistently providing the network with a fully noised sequence where the boundaries are anchored to the ground truth, we effectively steer the unconditional model to generate a coherent intermediate trajectory that honors the given conditions.

For the intermediate frames, the process is initialized at step N by sampling from a standard Gaussian distribution,

Since we choose to perform diffusion inference in the frequency domain, the denoised sequences must undergo an iDCT to be concatenated. At each denoising time step, the network input is the full sequence formed by concatenating the start frame, the intermediate frames, and the end frame:

At each time step

The entire inference process is summarized visually in Fig. 4, highlighting the temporal integration of keyframes with intermediate frames at each denoising step.

Figure 4: At each denoising time step, the noise in the middle frame is predicted by the denoising network. The noise intensity of the starting and ending frames is manually controlled to maintain consistency with the middle frame. These frames are then concatenated (denoted as ©) to form the input for the next time step of the denoising network

While the simple noise prediction loss (

Beyond plausibility, another key goal is to ensure generative diversity and combat mode collapse, a common failure mode in generative models. To this end, we incorporate a diversity loss (

Noise Prediction: We employ the DDPM’s

where

We incorporate a diversity-promoting regularizer that penalizes similarity among generated motion sequences, thereby discouraging mode collapse and ensuring a wide range of outputs. It does this by calculating the average difference between different generated samples, ensuring that the generated results have sufficient diversity:

in this context, N represents the total number of synthesized samples, and

The smoothness loss is used to ensure that the generated action sequences remain smooth and continuous over time, preventing unnatural abrupt changes in the generated sequences. It does this by calculating the differences between adjacent time frames, encouraging the frames in the sequence to transition gradually.

The bone length loss is used to ensure that the generated action sequences are physically plausible by maintaining the consistency of human bone lengths. It does this by constraining the distances between pairs of joints connected by bones, ensuring they are close to predefined bone lengths.

In this equation, T indicates the total frame count of the motion sequence, and

To ensure biomechanically plausible joint rotations and prevent unrealistic joint twisting, we introduce a bone angle loss based on joint-wise maximum angular limits:

Here, T indicates the sequence’s frame count,

In the end, the model’s training aims to optimize every facet of the synthesized motion sequences by combining all the loss functions with appropriate weights.

where

Our implementation is based on the PyTorch framework. During training, we set the number of denoising steps to 1000, the learning rate to

In evaluating the performance of generated motion sequences, five key metrics are employed to comprehensively analyze the model’s capabilities. L2P quantifies spatial discrepancies between generated and reference motions by computing the Euclidean distance for each corresponding joint, thereby gauging the model’s accuracy in reproducing motion trajectories. L2Q focuses on the evaluation of motion poses, utilizing quaternions to represent joint rotations and calculating the error in each frame’s pose between generated and ground-truth sequences [34]. NPSS (Normalized Power Spectrum Similarity) [1,35] emphasizes frequency-domain analysis by comparing the dynamic characteristics of generated motions with real ones, revealing whether the rhythm and variation of the generated movements are natural and smooth. APD (Average Pairwise Diversity) highlights the diversity among generated motions, assessing the model’s ability to avoid mode collapse by evaluating the differences between multiple generated sequences. Finally, ADE (Average Displacement Error) [36] offers a global perspective, measuring the overall deviation of generated motion sequences relative to reference trajectories. To harmonize datasets with differing scales and feature units, we apply normalization to the motion data prior to evaluation, thereby enhancing the generality and comparability of the results.

We compare our work against a suite of classical and state-of-the-art baselines, which are grouped by their underlying architecture. These include the GAN-based Two-stage [8], which employs a conditional GAN for pose sequence generation. The Transformer-based methods we evaluate are

Our approach is benchmarked against multiple top-tier baselines on two large-scale datasets: Human3.6M and LAFAN1. The quantitative results for generating intermediate frames of varying lengths (30, 50, and 100) are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. In these tables, we highlight the best-performing method for each metric in bold and the second-best in underline. For deterministic models like

The results across both datasets demonstrate the superior performance of our proposed method. On Human3.6M, our model achieves the best results on nearly all error-based metrics (ADE, L2P, L2Q) across all sequence lengths, indicating high accuracy in pose and trajectory generation. While Stitching-CVAE shows higher diversity (APD), our model provides a better balance of diversity and accuracy. This strength is particularly evident in the NPSS metric, where our results are consistently among the top, signifying that the generated motions are spectrally similar to real human movements. On the LAFAN1 dataset, which features more diverse and complex motions, our model continues to excel, particularly in pose accuracy (L2P, L2Q), significantly outperforming other methods. These comprehensive results confirm that our framework can generate motion sequences that are not only physically plausible and accurate but also diverse and natural, maintaining high effectiveness across different datasets and sequence lengths.

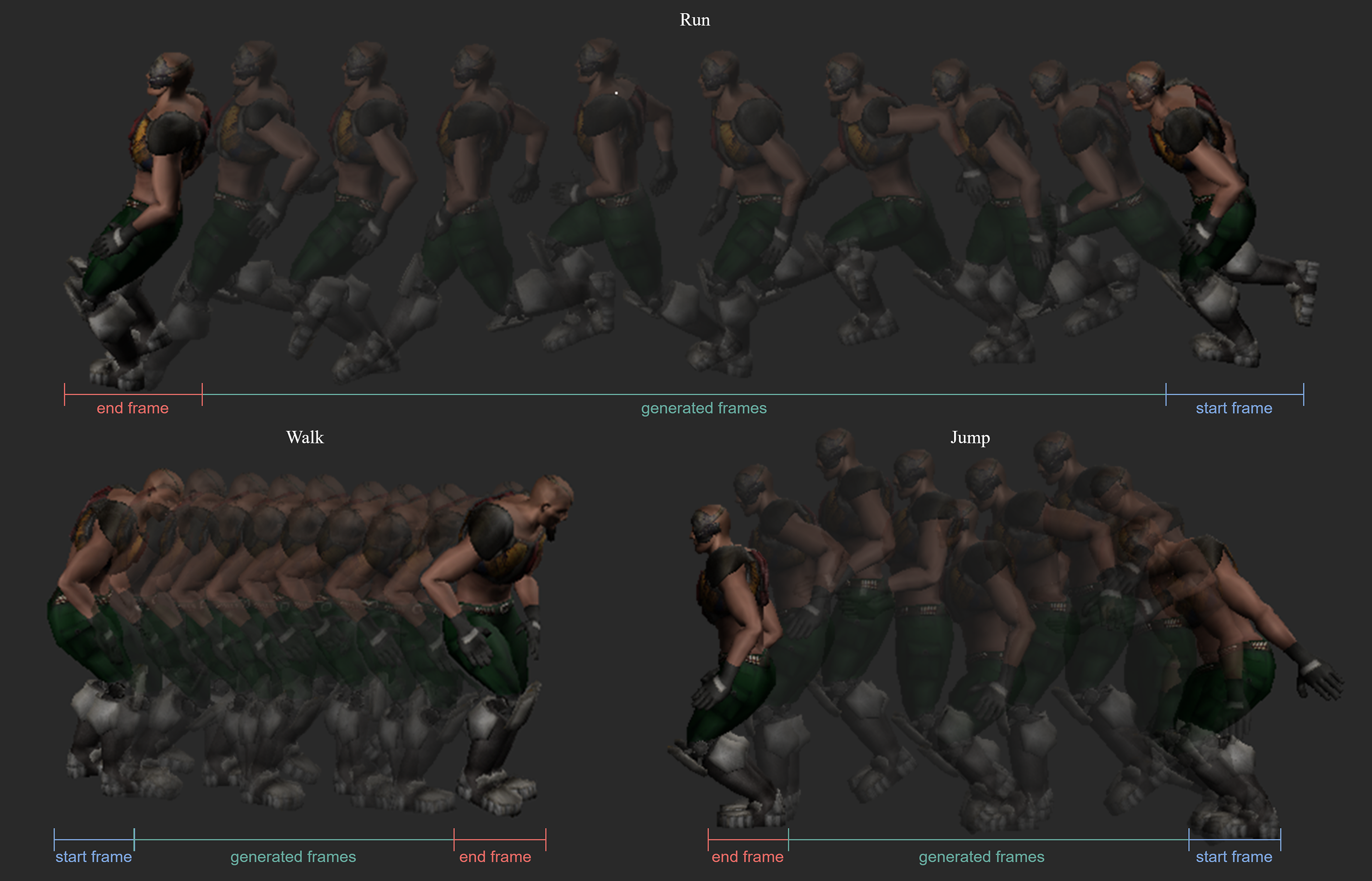

As shown in the tables, for the task of intermediate frame generation, our method outperforms existing methods on most metrics, especially on the NPSS metric. This demonstrates that our model can more accurately capture the original data distribution and generate more realistic intermediate frame sequences. Meanwhile, our results on APD are second only to the current best model, indicating that our method can generate diverse results while maintaining authenticity, as illustrated in Fig. 5. Notably, we also tested our model under a scenario with 100 frames, revealing that it remains highly effective across sequences of moderate to extended length.

Figure 5: Visualization results. We selected four actions from the Human3.6M dataset, each of which generates 118 intermediate frames through a start frame and a stop frame. We sampled every 5 frames and presented two different generated sequences for each action. Our framework synthesizes long-horizon motion sequences that are both diverse and plausible

In addition to quantitative metrics, we provide a qualitative analysis to visually assess the quality and practical utility of our generated motions. To validate our method’s applicability in standard animation pipelines, the output motion data from our model was directly imported into the industry-standard software Autodesk MotionBuilder and rendered on a 3D character, as shown in Fig. 6. These results highlight our model’s ability to produce high-fidelity and physically coherent motions for various activities.

Figure 6: Qualitative results of our motion in-betweening method on the LaFAN1 dataset. To demonstrate practical applicability, the generated motion trajectories for three actions (Run, Walk, and Jump) were imported into Autodesk MotionBuilder and rendered on a 3D character model. Given only the start and end poses, our model synthesizes smooth and physically plausible intermediate motions

For the Run sequence, our model generates a dynamic and consistent running cycle, where the coordination of limbs and the forward lean of the torso appear natural. In the Walk example, the trajectory shows a stable gait without noticeable artifacts such as foot-sliding, and the subtle vertical oscillations of the body are captured realistically. In the more complex Jump motion, our model successfully synthesizes an explosive take-off and a controlled landing, with the character’s center of mass following a plausible ballistic arc. Overall, these visualizations corroborate our quantitative findings, demonstrating that our framework can generate motion sequences that are not only accurate but also aesthetically pleasing and physically sound.

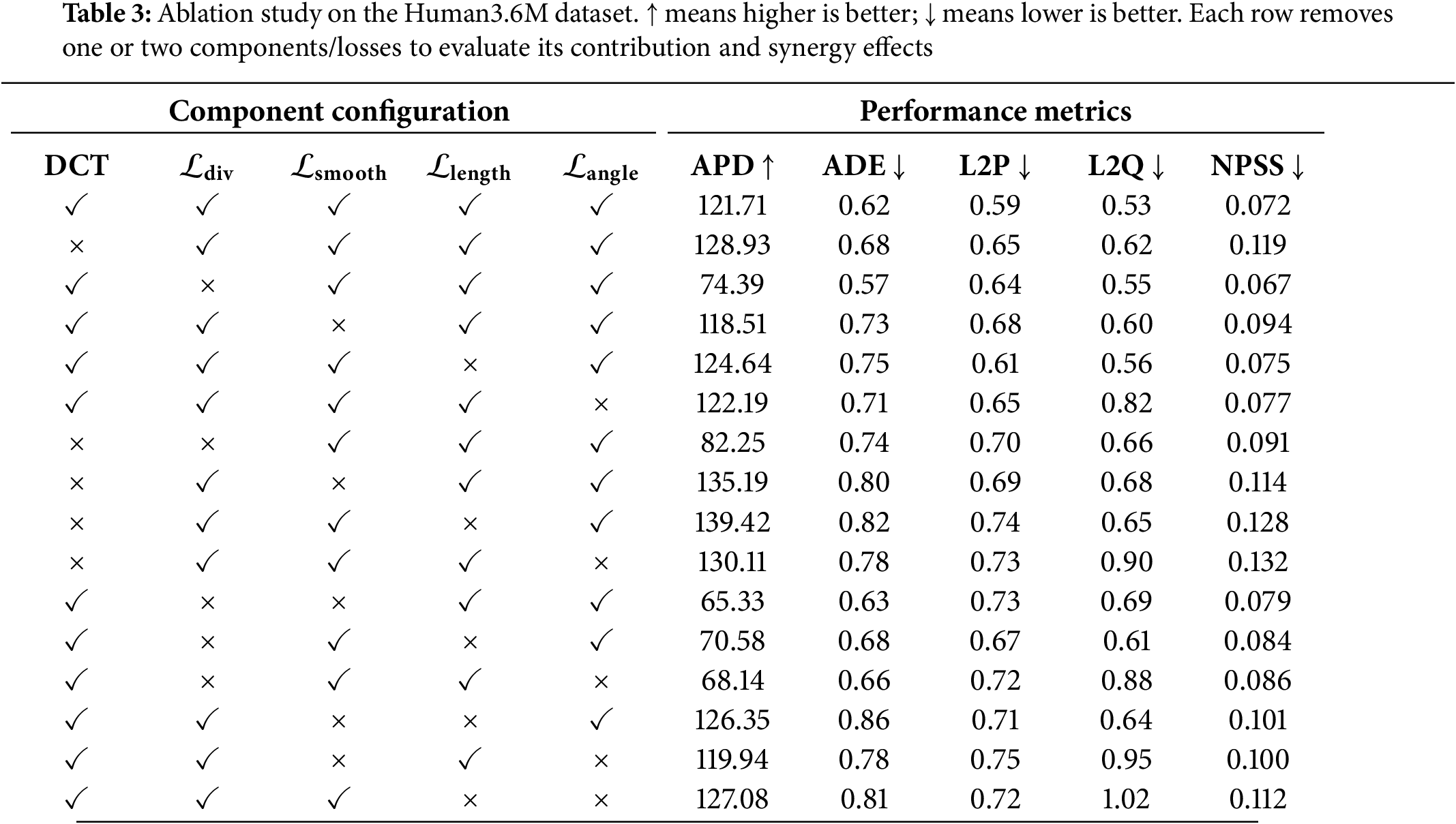

Ablation experiments were performed on the Human3.6M dataset to isolate and quantify the impact of each model module. Table 3 reports the outcomes of our ablation experiments. The table rows detail these experiments, with each row representing a different variant of the full model where one or more components have been disabled to evaluate their contributions.

The introduction of DCT plays a crucial role in our model. By mapping the action sequences into the spectral domain, DCT helps reduce high-frequency noise and eliminate jitter in the generated sequences, thereby enhancing the smoothness and naturalness of the generated actions. As shown in Table 3, removing DCT leads to significant drops in several evaluation metrics. While the increase in APD somewhat indicates that the absence of high-dimensional data can affect the diversity of the generated sequences, leading to a slight enhancement in diversity, the increases in ADE, L2P, and L2Q suggest a decline in the accuracy of position and pose predictions. The rise in NPSS indicates a reduced similarity between the spectral characteristics of the generated and real actions.

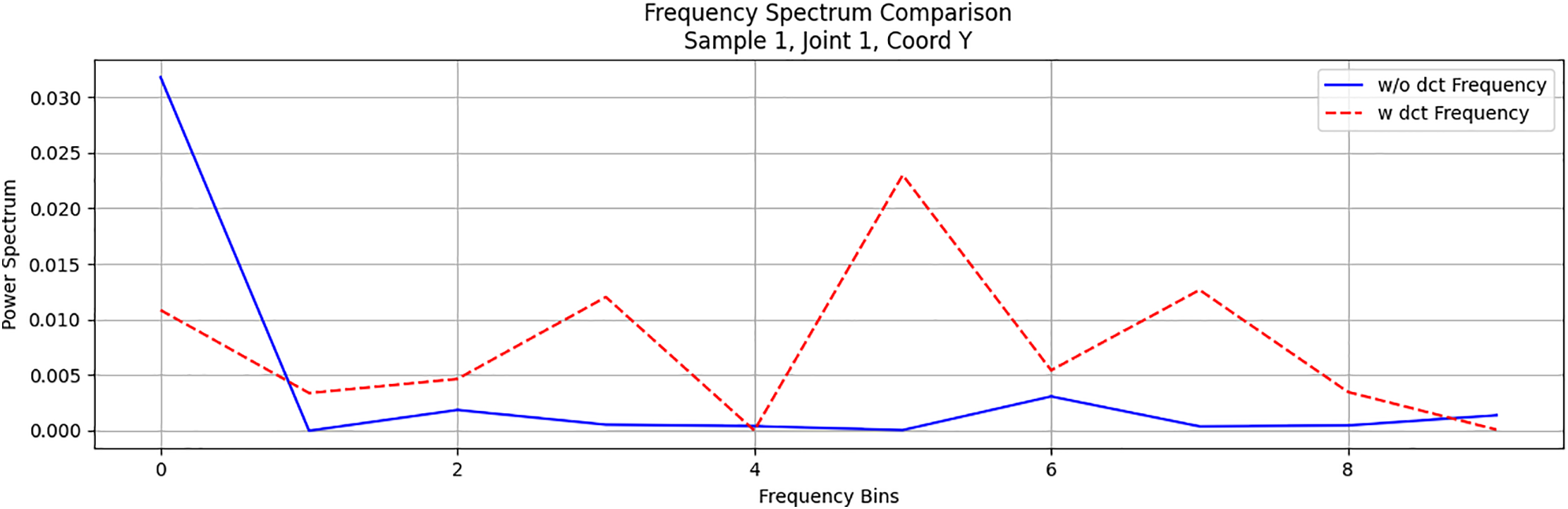

To further assess the impact of DCT preprocessing, we examined the power spectral distribution of the DCT-processed sequences. As shown in Fig. 7, after applying DCT, the model’s power spectrum distribution becomes more uniform in the low-frequency region, effectively covering the entire low-frequency range. This indicates that DCT preprocessing aids the model in capturing the characteristics of motion sequences in the low-frequency band, leading to a smoother and more natural overall distribution of the generated results in the frequency domain. It also avoids the issue of local frequency components being overly concentrated. This result underscores the significant role of DCT in boosting the model’s capacity to extract spectral characteristics of motion.

Figure 7: The comparison of the spectrograms of motion sequences generated with and without DCT shows that the sequences generated using DCT exhibit improved performance across different frequency bands

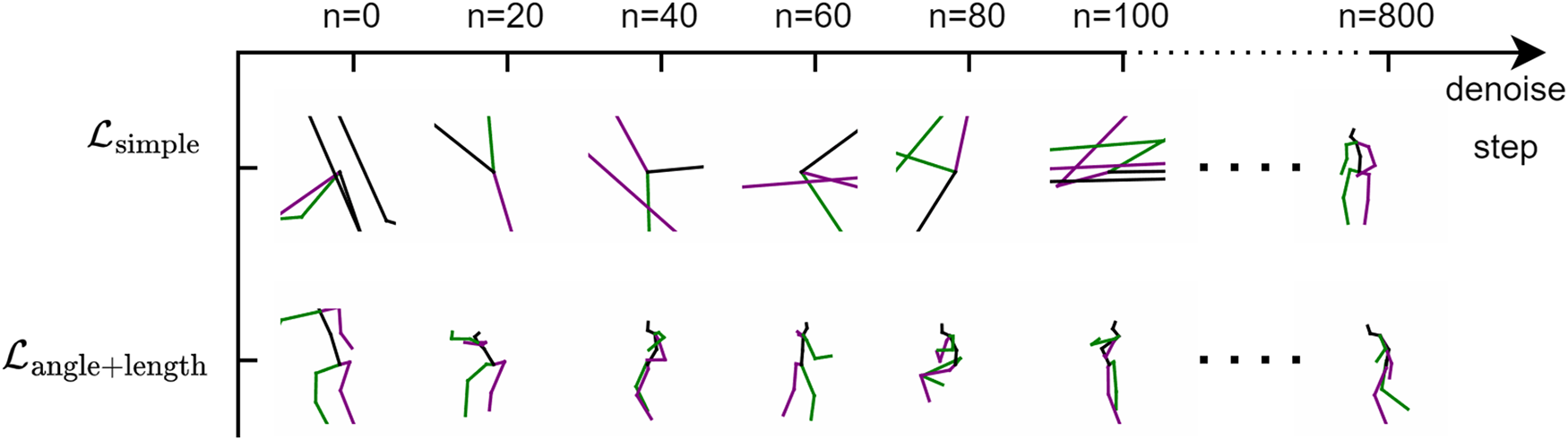

To foster varied outputs, the diversity loss maximizes the mean pairwise distance among generated sequences. After removing the diversity loss, while some accuracy metrics may improve, the significant decrease in APD indicates that this loss is crucial for maintaining the richness and diversity of the generated actions. Without the diversity loss, the model tends to generate more consistent and homogeneous sequences, which, although performing better on certain metrics, limits overall generation quality and diversity. Although removing the bone length loss and bone angle loss does not significantly improve the evaluation metrics, we observed during the model training process that these two losses significantly enhance the convergence speed of the model and improve generation quality in the early stages of training. Fig. 8 compares the motion sequences produced by models incorporating or omitting bone length and angle penalties at the same training epoch. The model incorporating bone length and angle losses generates more stable and natural sequences, whereas the model lacking these losses exhibits more anomalies and unreasonable poses in the generated sequences.

Figure 8: After incorporating the physical structure losses

The ablation study provides clear insights into the distinct role of each component and their interplay. The single-component results confirm foundational contributions: removing the DCT transformation significantly degrades motion accuracy and spectral consistency (NPSS), highlighting its crucial role in establishing a stable feature space, while removing the diversity loss term leads to a drastic drop in APD, confirming its necessity for preventing mode collapse.

Furthermore, the study reveals complex interactions when components are removed simultaneously. For instance, removing both bone length and angle losses results in a disproportionate increase in pose rotation errors (L2Q), demonstrating that these physical constraints work synergistically to ensure anatomical plausibility. Conversely, other combinations highlight critical trade-offs; removing both the diversity and angle constraints, for example, yields poses that, while less varied, lose significant rotational realism, underscoring the delicate balance required to generate outputs that are both diverse and physically correct.

While the proposed frequency-domain diffusion model achieves competitive results on the motion in-betweening task, we acknowledge that it has several limitations, which in turn point to promising directions for future research. First, the model’s generalization capability requires further investigation. Although it performs well on the Human3.6M and LaFAN1 datasets, its generation quality may degrade for out-of-distribution (OOD) motions not seen during training, such as professional acrobatics or highly stylized dance forms. Second, regarding inference efficiency, our method shares the inherent limitations of diffusion models. Although we already employ DDIM [32] to accelerate the sampling process by reducing the number of denoising steps from 1000 to 100, this iterative procedure still incurs considerable computational cost. This makes the current model challenging to deploy in real-time applications that require instantaneous feedback, such as interactive games or live virtual avatar driving. Furthermore, the current model’s generation process is conditioned solely on the start and end keyframes, lacking higher-level controllability; for instance, it cannot be guided by semantic information such as textual descriptions or musical rhythms. Finally, the quality of the generated motion is, to some extent, dependent on the quality of the input keyframes, and the model’s output may be unpredictable when given unreasonable or physically impossible start and end poses. Future work could explore avenues to address these limitations, such as enhancing the model’s generalization, investigating more efficient sampling techniques like consistency models, and integrating multi-modal conditioning.

In this work, we introduced a novel frequency-domain diffusion model for the task of human motion in-betweening. By operating in the frequency domain via the Discrete Cosine Transform, employing a self-attention-based denoising network, and designing a multi-objective loss function, our method effectively generates high-quality, natural, and physically plausible motion sequences from only start and end frames. The superiority of this framework is validated by comprehensive experiments on the Human3.6M and LaFAN1 datasets. The quantitative results demonstrate that our method achieves state-of-the-art performance on key error-based metrics, such as L2P and L2Q, while maintaining a strong balance between generation diversity (APD) and spectral realism (NPSS). This research confirms the significant potential of leveraging frequency-domain representations within diffusion models and offers a robust solution for creative applications in animation and virtual reality.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72161034).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Qiang Zhang, Shuo Feng and Ying Qi; methodology, Shuo Feng, Shanxiong Chen and Teng Wan; software, Shuo Feng and Shanxiong Chen; validation, Shanxiong Chen and Teng Wan; formal analysis, Shuo Feng and Shanxiong Chen; investigation, Shuo Feng, Shanxiong Chen and Teng Wan; resources, Qiang Zhang and Ying Qi; data curation, Shuo Feng and Shanxiong Chen; writing—original draft preparation, Shuo Feng and Teng Wan; writing—review and editing, Qiang Zhang, Shanxiong Chen and Ying Qi; visualization, Shuo Feng and Teng Wan; supervision, Qiang Zhang and Ying Qi; project administration, Qiang Zhang and Ying Qi; funding acquisition, Qiang Zhang and Ying Qi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The Human3.6M dataset used in this study is publicly available at http://vision.imar.ro/human3.6m/ (accessed on 11 July 2025). The LAFAN1 dataset is publicly available at https://github.com/ubisoft/ubisoft-laforge-animation-dataset (accessed on 11 July 2025). Other data generated during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Holden D, Saito J, Komura T. A deep learning framework for character motion synthesis and editing. ACM Trans Graph (TOG). 2016;35(4):1–11. doi:10.1145/2897824.2925975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Li H, Liu H, Zhao W, Liu H. The human motion behavior recognition by deep learning approach and the internet of things. Int J Interact Multimed Artif Intell. 2024;8(7):55–65. [Google Scholar]

3. Pavllo D, Feichtenhofer C, Auli M, Grangier D. Modeling human motion with quaternion-based neural networks. Int J Comput Vis. 2020;128(4):855–72. doi:10.1007/s11263-019-01245-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Holden D, Komura T, Saito J. Phase-functioned neural networks for character control. ACM Trans Graph (TOG). 2017;36(4):1–13. doi:10.1145/3072959.3073663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Chai J, Hodgins JK. Performance animation from low-dimensional control signals. ACM Trans Graph (TOG). 2005;24(3):686–96. doi:10.1145/1073204.1073248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Harvey FG, Pal C. Recurrent transition networks for character locomotion. In: SIGGRAPH Asia 2018 Technical Briefs; 2018 Dec 4–7; Tokyo, Japan. p. 1–4. doi:10.1145/3283254.3283277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Barsoum E, Kender J, Liu Z. HP-GAN: probabilistic 3D human motion prediction via GAN. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 1418–27. [Google Scholar]

8. Cai H, Bai C, Tai YW, Tang CK. Deep video generation, prediction and completion of human action sequences. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. p. 366–82. [Google Scholar]

9. Ren T, Yu J, Guo S, Ma Y, Ouyang Y, Zeng Z, et al. Diverse motion in-betweening from sparse keyframes with dual posture stitching. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph. 2024;31(2):1402–13. doi:10.1109/tvcg.2024.3363457. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Cai Y, Wang Y, Zhu Y, Cham TJ, Cai J, Yuan J, et al. A unified 3D human motion synthesis model via conditional variational auto-encoder. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2021 Oct 11–17; Montreal, BC, Canada. p. 11645–55. [Google Scholar]

11. Oreshkin BN, Valkanas A, Harvey FG, Ménard LS, Bocquelet F, Coates MJ. Motion in-betweening via deep Δ-interpolator. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph. 2023;30(8):5693–704. doi:10.1109/tvcg.2023.3309107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Qin J, Zheng Y, Zhou K. Motion in-betweening via two-stage transformers. ACM Trans Graph. 2022;41(6):184–1. doi:10.1145/3550454.3555454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Tevet G, Raab S, Gordon B, Shafir Y, Cohen-Or D, Bermano AH. Human motion diffusion model. arXiv:2209.14916. 2022. [Google Scholar]

14. Zhang M, Cai Z, Pan L, Hong F, Guo X, Yang L, et al. Motiondiffuse: text-driven human motion generation with diffusion model. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2024;46(6):4115–28. doi:10.1109/tpami.2024.3355414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Goodfellow I, Pouget-Abadie J, Mirza M, Xu B, Warde-Farley D, Ozair S, et al. Generative adversarial networks. Commun ACM. 2020;63(11):139–44. doi:10.1145/3422622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Gui LY, Wang YX, Liang X, Moura JM. Adversarial geometry-aware human motion prediction. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. p. 786–803. [Google Scholar]

17. Kingma DP, Welling M. Auto-encoding variational bayes. In: 2nd International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR2014); 2014 Apr 14–16; Banff, AB, Canada. [Google Scholar]

18. Komura T, Habibie I, Holden D, Schwarz J, Yearsley J. A recurrent variational autoencoder for human motion synthesis. In: The 28th British Machine Vision Conference; 2017 Sep 4–7; London, UK. 119 p. [Google Scholar]

19. Walker J, Doersch C, Gupta A, Hebert M. An uncertain future: forecasting from static images using variational autoencoders. In: Computer Vision-ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Springer; 2016. p. 835–51. [Google Scholar]

20. Yin W, Yin H, Kragic D, Björkman M. Graph-based normalizing flow for human motion generation and reconstruction. In: 2021 30th IEEE International Conference on Robot & Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN); 2021 Aug 8–12; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 641–8. [Google Scholar]

21. Petrovich M, Black MJ, Varol G. Temos: generating diverse human motions from textual descriptions. In: European Conference on Computer Vision; 2022 Oct 23–27; Tel Aviv, Israel. p. 480–97. [Google Scholar]

22. Ahn H, Ha T, Choi Y, Yoo H, Oh S. Text2action: generative adversarial synthesis from language to action. In: 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2018 May 21–25; Brisbane, QSL, Australia. p. 5915–20. [Google Scholar]

23. Harvey FG, Yurick M, Nowrouzezahrai D, Pal C. Robust motion in-betweening. ACM Trans Graph (TOG). 2020;39(4):60–1. doi:10.1145/3386569.3392480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Hong S, Kim H, Cho K, Noh J. Long-term motion in-betweening via keyframe prediction. Comput Graph Forum. 2024;43:e15171. [Google Scholar]

25. Ho J, Jain A, Abbeel P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Adv Neural Inf Proc Syst. 2020;33:6840–51. [Google Scholar]

26. Yuan Y, Song J, Iqbal U, Vahdat A, Kautz J. Physdiff: physics-guided human motion diffusion model. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2023 Oct 1–6; Paris, France. p. 16010–21. [Google Scholar]

27. Si C, Huang Z, Jiang Y, Liu Z. FreeU: free lunch in diffusion U-Net. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 4733–43. [Google Scholar]

28. Yoon S, Koo G, Hong JW, Yoo CD. DNI: dilutional noise initialization for diffusion video editing. In: European Conference on Computer Vision; 2024 Sep 29–Oct 4; Milan, Italy. p. 180–95. [Google Scholar]

29. Koo G, Yoon S, Hong JW, Yoo CD. Flexiedit: frequency-aware latent refinement for enhanced non-rigid editing. In: European Conference on Computer Vision; 2024 Sep 29–Oct 4; Milan, Italy. p. 363–79. [Google Scholar]

30. Yoon S, Koo G, Kim G, Yoo CD. FRAG: frequency adapting group for diffusion video editing. arXiv:2406.06044. 2024. [Google Scholar]

31. Wu T, Si C, Jiang Y, Huang Z, Liu Z. FreeInit: bridging initialization gap in video diffusion models. In: European Conference on Computer Vision; 2024 Sep 29–Oct 4; Milan, Italy. p. 378–94. [Google Scholar]

32. Song J, Meng C, Ermon S. Denoising diffusion implicit models. arXiv:2010.02502. 2020. [Google Scholar]

33. Ionescu C, Papava D, Olaru V, Sminchisescu C. Human3.6M: large scale datasets and predictive methods for 3D human sensing in natural environments. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2013;36(7):1325–39. doi:10.1109/tpami.2013.248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Martinez J, Black MJ, Romero J. On human motion prediction using recurrent neural networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 2891–900. [Google Scholar]

35. Gopalakrishnan A, Mali A, Kifer D, Giles L, Ororbia AG. A neural temporal model for human motion prediction. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2019 Jun 16–17; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 12116–25. [Google Scholar]

36. Ghosh P, Song J, Aksan E, Hilliges O. Learning human motion models for long-term predictions. In: 2017 International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV); 2017 Oct 10–12; Qingdao, China. p. 458–66. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools