Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

High-Dimensional Multi-Objective Computation Offloading for MEC in Serial Isomerism Tasks via Flexible Optimization Framework

School of Robotics and Automation, Hubei University of Automotive Technology, Shiyan, 442002, China

* Corresponding Author: Zheng Yao. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: IoT-assisted Network Information System)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068248

Received 23 May 2025; Accepted 22 August 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

As Internet of Things (IoT) applications expand, Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) has emerged as a promising architecture to overcome the real-time processing limitations of mobile devices. Edge-side computation offloading plays a pivotal role in MEC performance but remains challenging due to complex task topologies, conflicting objectives, and limited resources. This paper addresses high-dimensional multi-objective offloading for serial heterogeneous tasks in MEC. We jointly consider task heterogeneity, high-dimensional objectives, and flexible resource scheduling, modeling the problem as a Many-objective optimization. To solve it, we propose a flexible framework integrating an improved cooperative co-evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition (MOCC/D) and a flexible scheduling strategy. Experimental results on benchmark functions and simulation scenarios show that the proposed method outperforms existing approaches in both convergence and solution quality.Keywords

The Internet of Things (IoT) generates numerous high-density, low-latency tasks—such as augmented reality and gaming—on mobile devices [1,2]. However, limited computational power and energy severely constrain device performance [3,4], hindering IoT development. While cloud computing offers elastic resources [5], it suffers from latency and congestion due to long-distance transmission. Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) mitigates these issues by enabling low-latency, localized computation through edge servers [6]. Computation offloading, a core MEC component, poses significant challenges due to task dependencies, resource constraints, and conflicting objectives. Recent studies tackle challenges like complex task topologies and conflicting goals such as minimizing delay versus energy consumption [7,8]. Subtasks may have serial or parallel dependencies, requiring careful offloading decisions. Most research, however, focuses on low-dimensional problems and rarely considers scenarios with more than four objectives, common in real MEC systems. This gap motivates the need for scalable and robust offloading algorithms.

To tackle these challenges, this paper investigates high-dimensional multi-objective computation offloading for serial isomerism tasks, emphasizing serial task structure, multi-objective complexity, and flexible scheduling. We formulate the problem as a Many-objective optimization model and propose a hybrid framework integrating an improved MOCC/D algorithm with a task-aware scheduling strategy. Experiments on benchmarks and simulations validate the effectiveness of the proposed method over existing approaches. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows.

• We propose a flexible offloading model for MEC with serial isomerism tasks, tackling high-dimensional optimization across makespan, delay, energy consumption, and energy balance, while capturing task dependencies, resource heterogeneity, and objective conflicts.

• We propose a new offloading solution framework that integrates an improved MOCC/D algorithm with a flexible scheduling strategy. The MOCC/D incorporates decomposition-based co-evolution, cumulative-probability-guided mating selection, and HV-based evolution switching to improve search performance in high-dimensional spaces. The scheduling module introduces a task-aware double-layer encoding, greedy decoding, randomized initialization, and crossover operations tailored to serial task execution.

• Experimental results on benchmarks and simulations confirm that our approach outperforms existing methods in convergence, diversity, and resource efficiency for high-dimensional offloading tasks.

The paper has six sections: Section 2 reviews related work; Section 3 presents the model; Section 4 introduces the algorithm strategy; Section 5 shows experiments; Section 6 concludes the work.

2.1 Application Topology for Edge Computation Offloading

Application topologies in MEC offloading fall into two categories: full-offload and partial-offload. The full-offload model handles tightly coupled applications as a whole and is typically NP-hard [9], often solved via heuristics such as artificial fish swarm algorithms [10] or optimization of CPU frequency, transmission power, and UAV path planning [11]. Partial-offload divides tasks into subtasks, forming streaming or workflow structures. Prior work has explored parallel streaming under mobility reinforcement learning with energy harvesting [12], and dependency-aware grouping to reduce latency [13]. More recent approaches include distributed deep reinforcement learning for scalable offloading [14] and hybrid bio-inspired models for intrusion detection [15]. However, flexible offloading for serial isomerism tasks—sequential subtasks differing in type, load, and hardware compatibility—remains underexplored, especially in multi-user, multi-server MEC settings. This paper addresses this gap by jointly considering structural diversity and execution constraints in dynamic edge environments.

2.2 Optimization Objectives for Edge Computation Offloading

Computation offloading decisions often aim to minimize makespan, or balance makespan and energy. Wu et al. [16] proposed a layered algorithm to reduce total makespan, while Gorlatova et al. [17] used probabilistic modeling for makespan minimization. Time-delay constraints linked to deadlines were addressed by Meng et al. [18] through an online strategy maximizing deadline satisfaction, and by Verba et al. [19] with penalty terms for violations. To balance makespan and energy, Wang et al. [20] used a weighted sum objective solved via an improved genetic algorithm, and Li et al. [21] introduced a cooperative edge caching strategy. However, high-dimensional multi-objective computation offloading in MEC remains underexplored. We propose an intelligent offloading algorithm based on a flexible optimization framework, combining an improved multi-objective cooperative co-evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition (MOCC/D) with a flexible scheduling strategy. This hybrid framework offers enhanced exploration capabilities for solving high-dimensional multi-objective offloading problems.

In this section, we present a generic computation offloading system of serial isomerism tasks as illustrated in Fig. 1. The considered computation offloading system supports the cooperation among multiple edge servers and can be applied to the real-world scenario with highly random and dynamic request, e.g., smart transportation, smart buildings, smart home. This network is a powerful infrastructure to handle complex and changeable demand in IOT system.

Figure 1: The diagram of system model

The proposed offloading system adopts a hierarchical architecture comprising mobile terminals, a single wireless access point, and multiple edge servers. At the terminal layer, mobile devices are heterogeneous, large-scale, and geographically dispersed, functioning collectively in IoT applications where a single device failure may impact overall performance. Given the prevalence of latency-sensitive and computation-intensive tasks, energy-efficient management of low-battery devices is critical. These terminals generate workflows of serial isomerism tasks—subtasks that differ in type and resource demands but execute sequentially—modeled via function reference graphs to capture dependencies. At the wireless layer, communication between terminals and the access point uses Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiple Access (OFDMA), with negligible transmission loss due to the co-location of the access point and edge servers. At the edge layer, multiple servers collaboratively process offloaded tasks. Since each server supports only a subset of software types, verifying compatibility between subtasks and edge resources is essential. Therefore, an efficient and flexible scheduling strategy is needed to enable parallel execution of tasks.

In view of the above MEC architecture, mobile terminals of IoT system can be expressed as

where

Workflow applications of sequential chain can be expressed as

where

Edge server cluster can be expressed as

where

When

where

where

When

where

where

Makespan represents the total time to complete the task workflow, reflecting system efficiency and throughput. Minimizing makespan reduces processing time, improving resource utilization and performance. In contrast, time-delay measures the deviation from a task’s deadline, indicating the system’s ability to meet real-time requirements. Minimizing time-delay ensures timely execution and enhances user satisfaction by reducing deadline violations. These metrics provide a comprehensive view of time performance: makespan addresses global scheduling efficiency, while time-delay focuses on meeting individual task deadlines. Optimizing both simultaneously enables more effective time-related system performance.

The energy consumption of a mobile terminal includes both computational energy and communication energy, which are further divided into active and idle states. We consider energy usage comprehensively to optimize two critical system-level objectives: minimizing total energy consumption and ensuring energy balance across devices. The computing module of mobile terminal includes running and idle states, and the calculation of them is as follows:

where

The communication module of mobile terminal includes send, back and idle states, and the calculation of them is as follows:

where

Therefore, the total energy consumption

To achieve the purpose of prolonging the lifetime of IoT system, we introduce the high-dimensional multi-objective computation offloading problem in terms of combine makespan, time-delay, energy-consumption and energy-balance optimization objectives. The following optimization objectives are designed:

where

To address these challenges, we model the computation offloading problem as a Many-objective optimization task and propose an intelligent offloading algorithm based on a flexible optimization framework. The proposed MOCC/D incorporates cooperative co-evolution, cumulative probability-based mating selection, and multi-evolutionary switching using HV. The proposed flexible scheduling strategy feature a double-layer coding scheme, pluggable greedy decoding, randomized population initialization, and line-order crossover, to effectively solve the scheduling of serial isomerism tasks. Source code for the proposed framework is available at https://github.com/Changpuqing/CMC_MEC.git (accessed on 21 August 2025). The algorithm functions as an offline optimization engine, intended to be deployed on resource-relatively-abundant edge servers or cloudlets. Its purpose is to generate pre-computed task-offloading strategies or periodic resource allocation plans (e.g., re-optimized every few minutes or hours based on predicted network states and task loads) for the underlying terminal devices.

High-dimensional multi-objective problems with over four objectives challenge MOEAs due to poor convergence and rising computational complexity from many non-dominated solutions [22]. Although methods like MOEA/D [23], RVEA [24], BiGE [25], and MEMO [26], balancing convergence and diversity remains difficult. We propose MOCC/D, an improved cooperative co-evolution algorithm that decomposes the problem into single-objective subproblems to reduce complexity and enable subpopulation cooperation. A mating selection alternates between nearest and farthest individuals using cumulative probability to balance convergence and diversity. Two evolutionary strategies switch adaptively based on the hypervolume (HV) of an extra population to enhance convergence to the Pareto front.

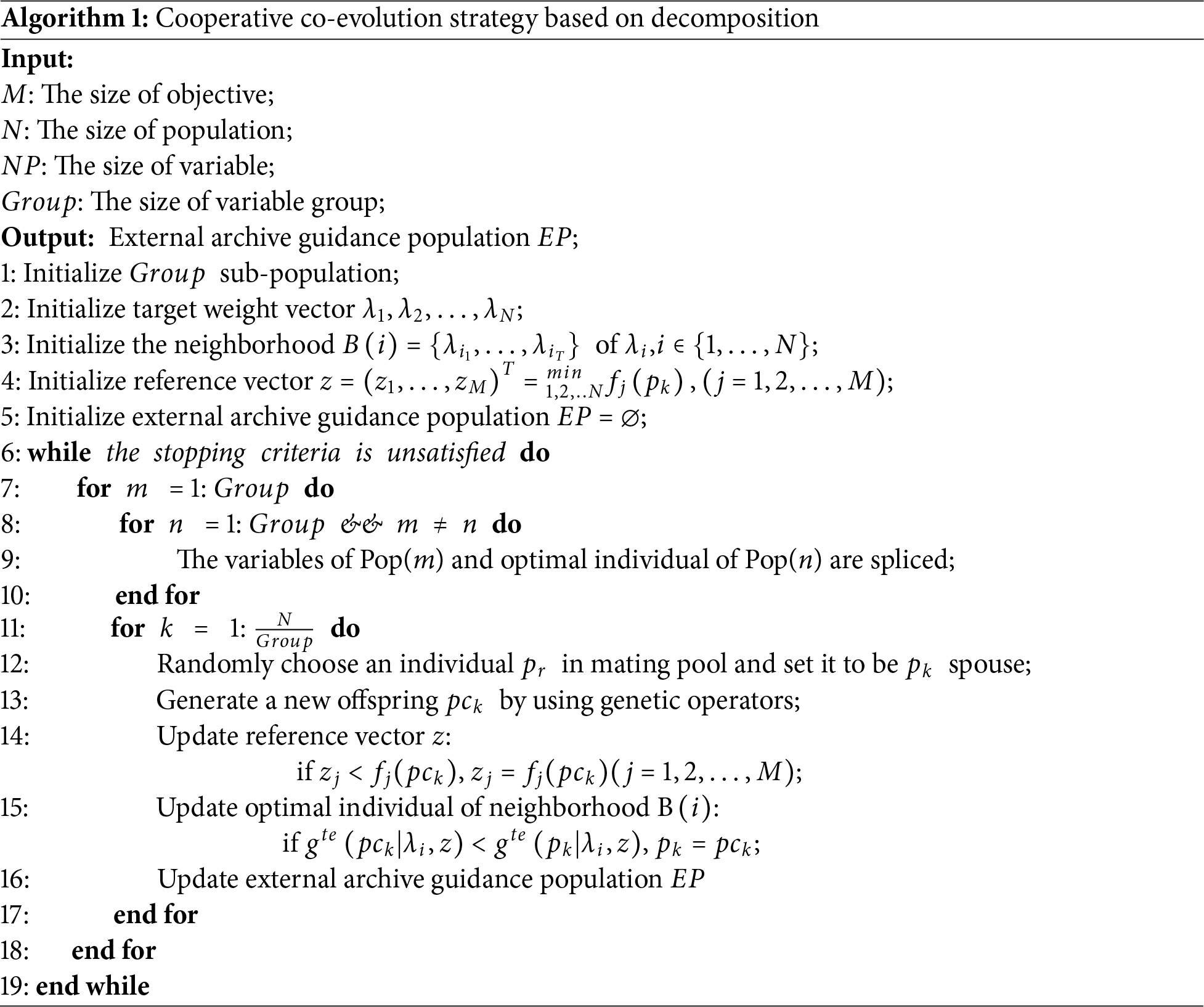

4.1.1 Cooperative Co-Evolution Strategy Based on Decomposition

The cooperative co-evolution strategy adopts a divide-and-conquer approach to significantly reduce the search space and computational complexity. Specifically, the complete variable set is divided into multiple segments, and the population is partitioned into corresponding subpopulations. Optimal individuals from each subpopulation are combined to form complete solutions for fitness evaluation. Subpopulations then evolve independently to generate new populations. To address multi-objective problems and further reduce computational complexity, a cooperative co-evolution strategy based on decomposition is designed. This transforms multiple objectives into a series of single-objective subproblems, enabling cooperation among subpopulations. Uniform weight vectors are generated using the simplex lattice method, each associated with a subproblem. Subproblems are evaluated via the Chebyshev scalarization function. Finally, Euclidean distances between weight vectors define neighborhoods, allowing subproblems to evolve independently. Algorithm 1 presents the pseudocode of this strategy.

The time complexity of the algorithm is approximately

4.1.2 Mating Individual Selection Strategy Based on Cumulative Probability

Subproblems traditionally select crossover partners randomly within their neighborhoods, making it difficult to balance convergence and diversity. To address this, we propose a mating selection strategy that alternates between the nearest and farthest individuals in the neighborhood. The nearest mating individual is chosen based on the smallest Euclidean distance, while the farthest is based on the largest distance. Additionally, a switching mechanism driven by cumulative probability controls the alternation. Fig. 2 illustrates this mating selection strategy.

Figure 2: The diagram of mating individual selection strategy based on cumulative probability

Specifically, the mathematical expression of the switching method based on cumulative probability is as follows:

where

where

where

4.1.3 Multi-Evolutionary Switching Strategy Based on HV

Cooperative co-evolution reduces search space and computational complexity but weakens local search. To better approach the Pareto front, we introduce a genetic evolution strategy based on cost values. An external population preserves non-dominated solutions, and switching between two evolutionary strategies is guided by its hypervolume (HV). When the non-dominated set exceeds capacity, a neighborhood screening strategy is applied. Fig. 3 illustrates this multi-evolutionary switching strategy.

Figure 3: The diagram of multi-evolutionary switching strategy based on HV

When the external population’s HV declines continuously past a threshold, the current strategy is deemed ineffective and switches to another. The mathematical form is:

where

where

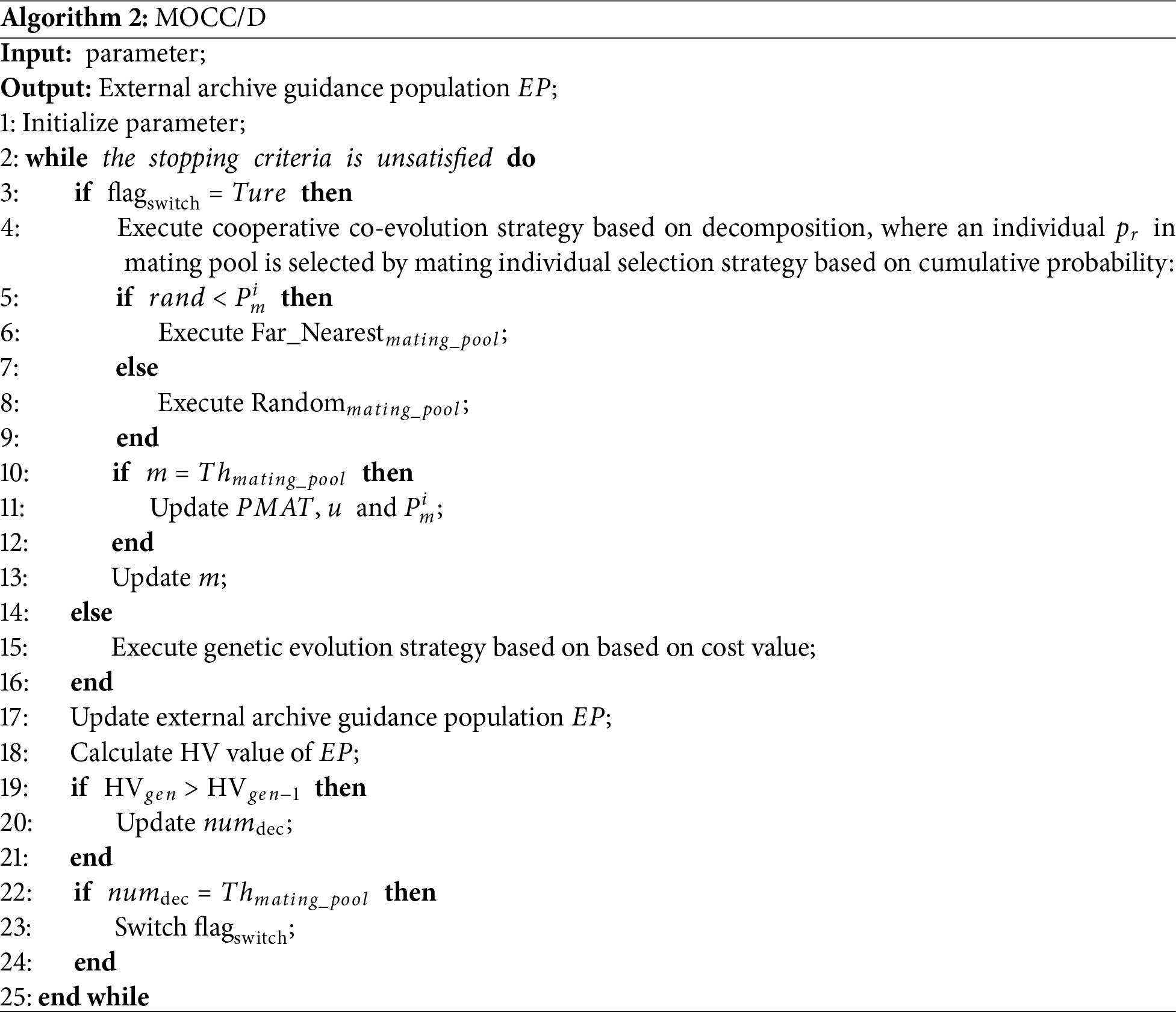

4.1.4 The Procedure of Proposed MOCC/D

In summary, MOCC/D consists of cooperative co-evolution strategy based on decomposition, mating individual selection strategy based on cumulative probability and multi-evolutionary switching strategy based on HV. The pseudocode of MOCC/D is as follows (Algorithm 2).

4.2 Flexible Scheduling Strategy

Furthermore, based on solving Many-objective optimization with MOCC/D, we proposed a flexible scheduling strategy, designing a double-layer coding strategy, a pluggable greedy decoding strategy, a randomized population initialization strategy, and a line order cross evolution strategy, which efficiently solves the flexible scheduling problem of serial isomerism tasks.

4.2.1 Double-Layer Coding Strategy

Unlike traditional chromosome coding, a double-layer coding strategy based on task ID and position order is proposed. Chromosomes are arranged by task ID and subtask order, defining execution sequence and positions. The task ID chromosome length equals the total number of subtasks; each gene’s integer indicates the task ID, and its appearance order determines subtask execution order. The position order chromosome, of the same length, encodes each subtask’s execution position within its feasible set, ensuring valid solutions. Fig. 4 illustrates a sequence: subtasks T21, T11, T31, T32, T41, T12, T22, T42 with execution positions VM3, VM4, VM1, VM3, VM2, VM4, VM2, VM1.

Figure 4: The diagram of double-layer coding strategy based on task ID and position order

4.2.2 Pluggable Greedy Decoding Strategy

To reduce the idle time of local terminals and edge servers and shorten the task execution time, a plug-in greedy decoding strategy is designed, which fetches the execution order and execution position of sub-tasks in turn, and then inserts the sub-tasks into the available execution position idle interval. Specifically, the previous sub-task end time of the same task ID (TP) and the previous sub-task end time of the same execution location (TM) are compared. If the time gap between TP and TM is greater than the execution time of the current sub-task and TM is greater than TP, the current sub-task can be inserted into the gap, and the start time is TM. Otherwise, the current sub-task cannot be inserted into the gap and the start time is TP.

4.2.3 Randomized Population Initialization Strategy

To ensure the diversity of individuals in the population, a randomized population initialization strategy is designed. Specifically, it supposes the chromosome length based on task ID is

4.2.4 Line Order Cross Evolution Strategy

To enhance the global convergence of the evolution strategy, the gene of task ID is defined as a dominant gene, and the gene of position order code is an invisible gene. The invisible gene is adjusted according to the change of the dominant gene. Therefore, the line order cross evolution strategy is adopted in the chromosome of the task ID. The specific steps are as follows. Firstly, it randomly generates two crossing positions and exchanges the fragments of two parent individuals between the two crossing positions. Secondly, it deletes the same gene in the original parent individual as the gene exchanged from another parent individual. Thirdly, from the first gene position, it fills in the remaining genes outside the two cross positions in turn.

To validate the proposed method for Many-objective optimization and computing offloading, benchmark function tests and simulation experiments were conducted. Experiments ran on MATLAB 2020b with an Intel i7-7700 CPU (3.6 GHz) and 16 GB RAM under Windows 10.

5.1 Benchmark Function Experiments

The MaF1–MaF6 benchmark functions from the CEC2018 competition were selected with 3, 5, and 7 objectives to represent Many-objective optimization problems. MaF1 and MaF2 feature rule-based frontiers; MaF3 and MaF4 have multi-modal frontiers; MaF5 presents unevenly distributed frontiers; and MaF6 involves degenerate convex frontiers. Evaluation uses IGD and HV metrics: HV measures convergence and diversity, while IGD assesses convergence and uniformity. IGD is defined as:

where

5.1.2 Simulation Results and Analysis

Experiments were run 30 times independently for fair comparison. Tables 2 and 3 present mean and variance results for IGD and HV metrics, with best performances highlighted. MOCC/D consistently outperforms four benchmark algorithms across most test cases. For MaF1 and MaF2 (regular fronts), MOCC/D excels at 3, 5, and 7 objectives, showing strong global and local search. For MaF3 and MaF4 (multi-modal fronts), MOCC/D leads at 3 objectives and remains competitive at higher dimensions, though MEMO slightly outperforms it at 5 and 7 objectives due to complex front adaptation. For MaF5 (uneven fronts), MOCC/D is less consistent, especially against MOEA/D, indicating challenges in maintaining diversity. For MaF6 (convex and degenerate fronts), MOCC/D performs best across all dimensions, demonstrating robustness. Overall, results validate MOCC/D’s effectiveness: decomposition-based co-evolution reduces complexity, cumulative-probability mating balances search, and HV-guided multi-evolution improves uniformity and Pareto proximity, confirming its competitive edge on diverse high-dimensional problems.

5.2 Model Simulation Experiment

Based on [27], we simulate realistic data for the MEC system. Firstly, 10 mobile terminals are randomly deployed in the communication network, with the computing capacity value ranges from 0.1 × 109 MIPS to 0.2 × 109 MIPS, the computing power value in the working state and idle state respectively ranges from 100 to 300 mW and 5 to 10 mW, the communication power value in the transmission state and idle state ranges from 50 to 150 mW and 8 to 15 mW, the remaining battery value ranges from 0.05 to 01 J and the network radius value from 10 to 100 m. Secondly, the number sub-task of workflow applications ranges from 3 to 7, the data volume value of sub-task ranges from 10 to 50 MB, the type of sub-task ranges from 1 to 5 and the time deadline of task ranges from 0.1 to 2 s. Finally, the communication network based on routing node is presented, with the fixed maximum channel bandwidth value of 5 × 106 HZ, the fixed channel noise power value of 10−13, the channel power gain value of 2 and the path loss objective value of 10−4. Meanwhile, 6 edge servers are randomly deployed in the routing node, with the computing capacity value ranges from 5 × 109 MIPS to 6 × 109 MIPS and the number of soft type ranges from 2 to 3.

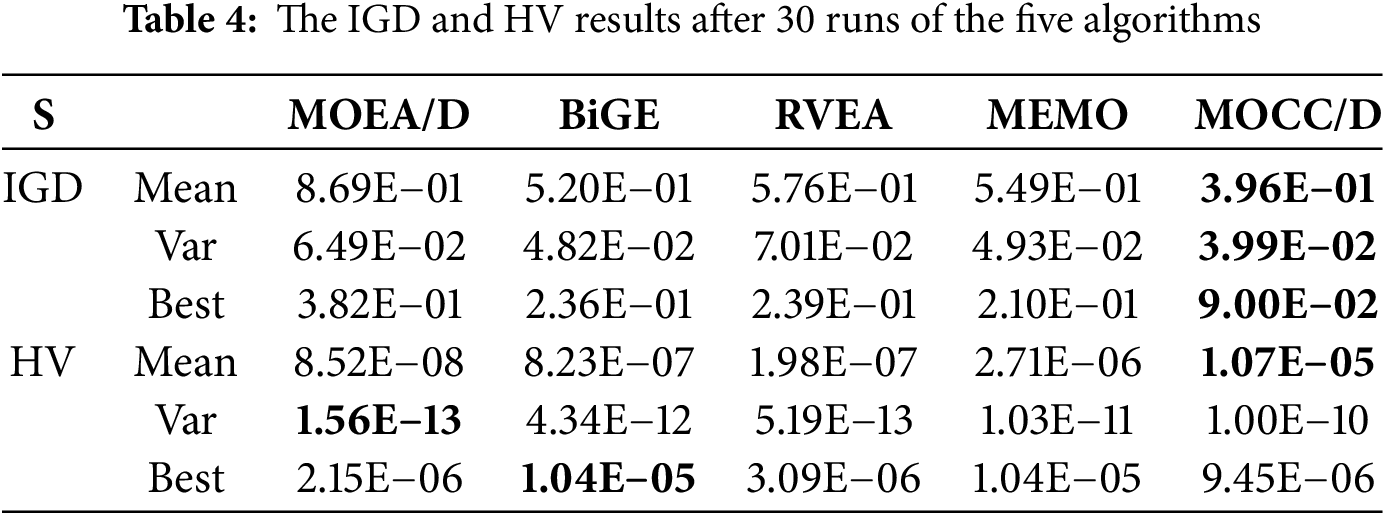

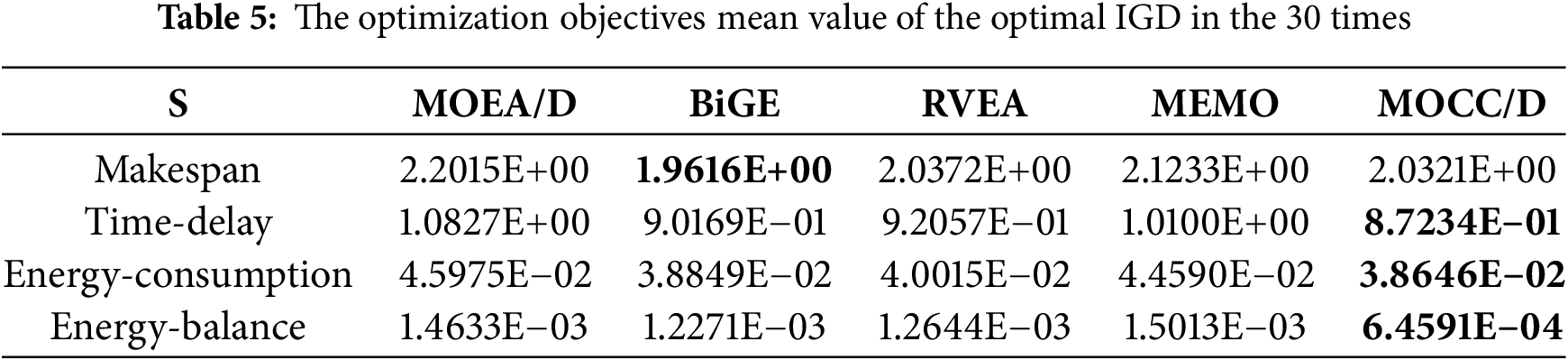

5.2.2 Model Solution Results and Analysis

For fair comparison, experiments were run 30 times independently. Table 4 and Fig. 5 show IGD and HV comparing MOCC/D with MOEA/D, RVEA, BiGE, and MEMO, with best results highlighted. MOCC/D outperforms all others in the multi-objective offloading model, improving mean IGD by 119.44%, 31.31%, 47.98%, and 38.64%, while reducing variance by 62.66%, 20.8%, 75.7%, and 23.56%. For HV, MOCC/D improves mean performance by 3, 2, 2, and 1 orders of magnitude, though variance is not always better. Overall, MOCC/D delivers solutions closer to the true Pareto front with more even distribution.

Figure 5: The IGD and HV box diagram after 30 runs of the five algorithms. (a) The IGD box diagram. (b) The HV box diagram

Table 5 shows the mean values of each objective for the IGD optimal runs over 30 iterations, with the best results highlighted. MOCC/D outperforms others in average delay, energy consumption, and energy balance, reducing delay by 24.11%, 5.11%, 6.12%, and 15.78%, and energy consumption by 18.96%, 1.11%, 4.0%, and 15.93%. Energy balance improves by 126.55%, 90.06%, 95.76%, and 130.77%. These results demonstrate MOCC/D’s suitability for time-sensitive MEC offloading, delivering accurate task matching and stable user experience. Its delay is only 3.6% higher than the optimal, which is acceptable. Overall, MOCC/D exhibits stronger global and local search performance than the four compared algorithms.

5.2.3 Model Parameter Analysis

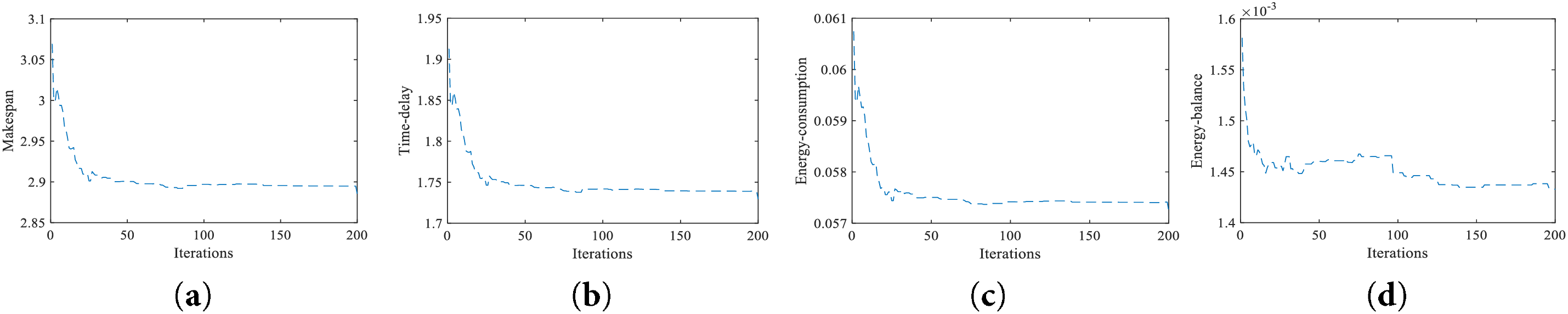

To analyze convergence, Fig. 6 shows the population evolution of model objectives using the proposed MOCC/D. Table 5 indicates good convergence, with makespan, time-delay, and energy consumption stabilizing after about 40 iterations, and energy balance stabilizing after approximately 125 iterations Fig. 6 shows the evolution of optimization objectives using the proposed MOCC/D algorithm. Makespan, time-delay, and energy consumption stabilize after about 40 iterations, while energy balance converges around 125 iterations, indicating good overall convergence.

Figure 6: The convergence analysis of model optimization objective. (a) Makespan. (b) Time-delay. (c) Energy-consumption. (d) Energy-balance

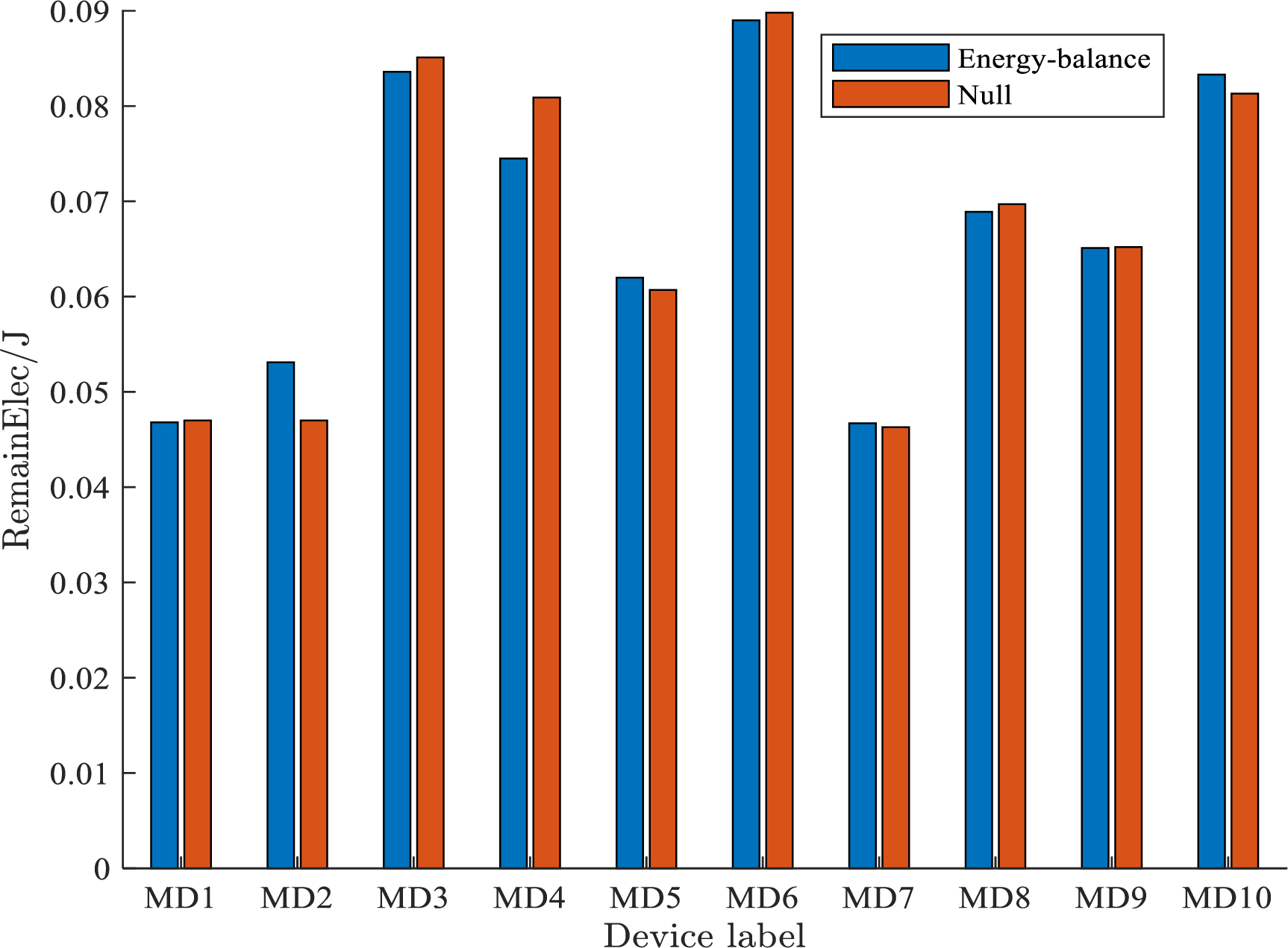

Fig. 7 illustrates the impact of the energy balance strategy on device battery levels. Without it, devices MD1, MD2, MD5, and MD7 experience significant depletion. With the strategy, the remaining energy of MD2, MD5, and MD7 improves by 12.98%, 2.14%, and 0.86%, respectively, effectively protecting low-energy nodes. Although MD1 shows a slight 0.42% drop, it remains within acceptable limits. Devices with higher initial energy—MD3, MD4, MD6, and MD8—show increases of 1.8%, 8.6%, 47.98%, and 0.9%, respectively. These results confirm that the strategy redistributes workload to balance energy consumption and prolong overall system lifetime.

Figure 7: The distribution of the terminals remaining battery under two conditions

This paper addresses high-dimensional multi-objective computation offloading in MEC for serial isomerism tasks, considering task characteristics, complex objectives, and flexible resource scheduling. We model the problem as a Many-objective optimization and propose an intelligent offloading algorithm within a flexible optimization framework, featuring an improved multi-objective cooperative co-evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition (MOCC/D) and a flexible scheduling strategy. Evaluation on benchmark functions and simulations demonstrates the superior performance of the proposed approach.

Acknowledgement: The authors are deeply grateful to all team members involved in this research.

Funding Statement: Funding: This work was supported by Youth Talent Project of Scientific Research Program of Hubei Provincial Department of Education under Grant Q20241809, Doctoral Scientific Research Foundation of Hubei University of Automotive Technology under Grant 202404.

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Zheng Yao; data collection: Zheng Yao and Puqing Chang; analysis and interpretation of results: Zheng Yao and Puqing Chang; draft manuscript preparation: Zheng Yao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhang Y, Cui X, Zhao Q. A multi-objective joint task offloading scheme for vehicular edge computing. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;84(2):2355–73. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.065430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Bhaskaran S, Muthuraman S. A comprehensive study of resource provisioning and optimization in edge computing. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;83(3):5037–70. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.062657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hasan MK, Jahan N, Ahmad Nazri MZ, Islam S, Khan MA, Alzahrani AI, et al. Federated learning for computational offloading and resource management of vehicular edge computing in 6G-V2X network. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2024;70(1):3827–47. doi:10.1109/TCE.2024.3357530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Dong S, Tang J, Abbas K, Hou R, Kamruzzaman J, Rutkowski L, et al. Task offloading strategies for mobile edge computing: a survey. Comput Netw. 2024;254(6):110791. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2024.110791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wu G, Chen X, Shen Y, Xu Z, Zhang H, Shen S, et al. Combining Lyapunov optimization with actor-critic networks for privacy-aware IIoT computation offloading. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(10):17437–52. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3357110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Patel M, Naughton B, Chan C, Sprecher N, Abeta S, Neal A. Mobile-edge computing—introductory technical white paper. In: Sophia antipolis. France: Mobile-Edge Computing (MEC) Industry Initiative; 2014. [Google Scholar]

7. Wu H, Lu Y, Ma H, Xing L, Deng K, Lu X. A survey on task type-based computation offloading in mobile edge networks. Ad Hoc Netw. 2025;169(2):103754. doi:10.1016/j.adhoc.2025.103754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang S, Yi N, Ma Y. A survey of computation offloading with task types. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2024;25(8):8313–33. doi:10.1109/TITS.2024.3410896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Li QP, Zhao JH, Gong Y. Computation offloading and resource management scheme in mobile edge computing. Telecommun Sci. 2019;35(3):36–46. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

10. Yang L, Zhang H, Li M, Guo J, Ji H. Mobile edge computing empowered energy efficient task offloading in 5G. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2018;67(7):6398–409. doi:10.1109/TVT.2018.2799620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhou F, Wu Y, Hu RQ, Qian Y. Computation rate maximization in UAV-enabled wireless-powered mobile-edge computing systems. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. 2018;36(9):1927–41. doi:10.1109/JSAC.2018.2864426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Min M, Xiao L, Chen Y, Cheng P, Wu D, Zhuang W. Learning-based computation offloading for IoT devices with energy harvesting. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2019;68(2):1930–41. doi:10.1109/TVT.2018.2890685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kang MC, Li X, Ji H, Zhang HL. Collaborative computation offloading exploring task dependencies in small cell networks. J Beijing Univ Posts Telecommun. 2021;44(1):72–8. (In Chinese). doi:10.13190/j.jbupt.2020-115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Darchini-Tabrizi M, Roudgar A, Entezari-Maleki R, Sousa L. Distributed deep reinforcement learning for independent task offloading in mobile edge computing. J Netw Comput Appl. 2025;240(6):104211. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2025.104211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Saheed YK, Abdulganiyu OH, Tchakoucht TA. Modified genetic algorithm and fine-tuned long short-term memory network for intrusion detection in the Internet of Things networks with edge capabilities. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;155(4):111434. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wu Y, Qian LP, Ni K, Zhang C, Shen X. Delay-minimization nonorthogonal multiple access enabled multi-user mobile edge computation offloading. IEEE J Sel Top Signal Process. 2019;13(3):392–407. doi:10.1109/JSTSP.2019.2893057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Gorlatova M, Inaltekin H, Chiang M. Characterizing task completion latencies in multi-point multi-quality fog computing systems. Comput Netw. 2020;181(6):107526. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2020.107526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Meng J, Tan H, Li XY, Han Z, Li B. Online deadline-aware task dispatching and scheduling in edge computing. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst. 2020;31(6):1270–86. doi:10.1109/TPDS.2019.2961905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Verba N, Chao KM, Lewandowski J, Shah N, James A, Tian F. Modeling industry 4.0 based fog computing environments for application analysis and deployment. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2019;91(1):48–60. doi:10.1016/j.future.2018.08.043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wang Y, Ge HB, Feng AQ. Computation offloading strategy in cloud-assisted mobile edge computing. Comput Eng. 2020;46(8):27–34. doi:10.1109/icccbda49378.2020.9095689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Li C, Zhang Y, Gao X, Luo Y. Energy-latency tradeoffs for edge caching and dynamic service migration based on DQN in mobile edge computing. J Parallel Distrib Comput. 2022;166(4):15–31. doi:10.1016/j.jpdc.2022.03.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Cao Y, Mao H. High-dimensional multi-objective optimization strategy based on directional search in decision space and sports training data simulation. Alex Eng J. 2022;61(1):159–73. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2021.04.077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhang Q, Li H. MOEA/D: a multiobjective evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2007;11(6):712–31. doi:10.1109/TEVC.2007.892759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Cheng R, Jin Y, Olhofer M, Sendhoff B. A reference vector guided evolutionary algorithm for many-objective optimization. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2016;20(5):773–91. doi:10.1109/TEVC.2016.2519378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Li M, Yang S, Liu X. Bi-goal evolution for many-objective optimization problems. Artif Intell. 2015;228:45–65. doi:10.1016/j.artint.2015.06.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Yuan J, Liu HL, Gu F. A cost value based evolutionary many-objective optimization algorithm with neighbor selection strategy. In: 2018 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC); 2018 Jul 8–13; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. doi:10.1109/CEC.2018.8477649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Rui L, Yang Y, Gao Z, Qiu X. Computation offloading in a mobile edge communication network: a joint transmission delay and energy consumption dynamic awareness mechanism. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019;6(6):10546–59. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2019.2939874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools