Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Multi-Constraint Generative Adversarial Network-Driven Optimization Method for Super-Resolution Reconstruction of Remote Sensing Images

School of Information Science and Technology, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, 100083, China

* Corresponding Author: Guangpeng Fan. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Computer Vision and Image Processing: Feature Selection, Image Enhancement and Recognition)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068309

Received 25 May 2025; Accepted 31 July 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Remote sensing image super-resolution technology is pivotal for enhancing image quality in critical applications including environmental monitoring, urban planning, and disaster assessment. However, traditional methods exhibit deficiencies in detail recovery and noise suppression, particularly when processing complex landscapes (e.g., forests, farmlands), leading to artifacts and spectral distortions that limit practical utility. To address this, we propose an enhanced Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Network (SRGAN) framework featuring three key innovations: (1) Replacement of L1/L2 loss with a robust Charbonnier loss to suppress noise while preserving edge details via adaptive gradient balancing; (2) A multi-loss joint optimization strategy dynamically weighting Charbonnier loss (β = 0.5), Visual Geometry Group (VGG) perceptual loss (α = 1), and adversarial loss (γ = 0.1) to synergize pixel-level accuracy and perceptual quality; (3) A multi-scale residual network (MSRN) capturing cross-scale texture features (e.g., forest canopies, mountain contours). Validated on Sentinel-2 (10 m) and SPOT-6/7 (2.5 m) datasets covering 904 km2 in Motuo County, Tibet, our method outperforms the SRGAN baseline (SR4RS) with Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) gains of 0.29 dB and Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) improvements of 3.08% on forest imagery. Visual comparisons confirm enhanced texture continuity despite marginal Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) increases. The method significantly improves noise robustness and edge retention in complex geomorphology, demonstrating 18% faster response in forest fire early warning and providing high-resolution support for agricultural/urban monitoring. Future work will integrate spectral constraints and lightweight architectures.Keywords

Remote sensing image super-resolution technology serves as a pivotal means to enhance spatial resolution for critical applications including environmental monitoring, disaster emergency response, and precision agriculture. In agricultural contexts, high-resolution imagery enables precise identification of crop species and pest distribution patterns [1]; urban planning applications rely on clear delineation of building footprints and transportation networks [2]; disaster assessment requires rapid acquisition of detailed damage extent information [3]. In addition, recent studies have leveraged GAN-based frameworks to significantly improve resolution and feature continuity in large-area environmental monitoring tasks [4]. However, fundamental constraints—stemming from sensor physical limitations, atmospheric interference, and transmission bandwidth—result in pervasive resolution deficiencies during image acquisition. While traditional interpolation techniques like bicubic interpolation [5] offer rapid upsampling, they fail to recover high-frequency textures critical for feature recognition [6]. Conversely, physics-based methods such as inverse convolution algorithms [7] demand precise prior knowledge of imaging systems and exhibit high susceptibility to noise corruption. Consequently, algorithmic breakthroughs to transcend hardware limitations have emerged as a central research focus in remote sensing information processing.

The evolutionary trajectory of super-resolution methodologies reveals progressive refinements with persistent limitations. Early approaches centered on sparse representation and dictionary learning, exemplified by Yang et al.’s joint dictionary framework for reconstructing high-resolution patches from low-resolution counterparts [8]. Despite its innovation, this method necessitated manual feature engineering and incurred prohibitive computational costs [9]. Timofte et al.’s anchored neighborhood regression (ANR) [10] accelerated sparse coding but introduced blurring artifacts in regions with complex textural variations. Similarly, Lanczos resampling [5] prioritized computational efficiency at the expense of high-frequency detail recovery [11]. A paradigm shift occurred in 2016 when Dong et al. pioneered SRCNN [12], the first convolutional neural network (CNN) for single-image super-resolution, establishing an end-to-end nonlinear mapping that significantly outperformed traditional techniques. Subsequent innovations included Kim et al.’s VDSR [13], which incorporated residual learning within a 20-layer architecture and expanded receptive fields via recursive convolution, and Kuriakose’s EDSR [14], which achieved benchmark performance in the New Trends in Image Restoration and Enhancement (NTIRE) 2017 challenge by removing batch normalization and scaling to 68 layers. Nevertheless, these MSE-optimized models generated perceptually unsatisfactory over-smoothed outputs with prominent artifacts in edge and texture regions despite high PSNR scores [15]. Liu et al. [16] also confirmed that MSE-based losses tend to blur edges and suppress fine textures in satellite images, and proposed a hybrid Transformer model to overcome these artifacts.

This fidelity-quality dichotomy catalyzed the emergence of generative adversarial frameworks. Ledig et al.’s seminal SRGAN [17] revolutionized the field by integrating adversarial training with residual generators and VGG-based perceptual loss to produce visually realistic reconstructions. However, direct application to remote sensing imagery reveals domain-specific vulnerabilities that demand urgent attention. Fundamentally, the L2 loss’s acute sensitivity to sensor noise and cloud occlusion induces severe noise amplification artifacts that compromise output integrity, as documented in studies of atmospheric interference effects [18]. Concurrently, SRGAN’s monolithic residual architecture proves inadequate for capturing multi-scale correlations essential in heterogeneous landscapes—where transitions between farmland, forest, and urban textures necessitate hierarchical feature extraction—resulting in fragmented reconstructions that fail to preserve ecological continuity [19]. Critically, multispectral reconstruction suffers from spectral distortion due to neglected inter-channel dependencies, a deficiency that directly induces feature misclassification errors in vegetation monitoring applications [20].

Recent enhancements partially address these issues: Jiang et al.’s EEGAN [21] incorporates explicit edge detection to enhance contours, while Xiong et al.’s ISRGAN [22] employs transfer learning for cross-sensor adaptation. Critically, however, both remain constrained by intrinsic flaws in L1/L2 loss functions—L1’s invariable gradient magnitude precipitates training instability, while L2’s outlier sensitivity impedes noise suppression [23]. For instance, Yao et al. proposed CG-FCLNet, which utilizes a category-guided feature collaborative learning mechanism to significantly improve segmentation performance in remote sensing scenes by enhancing both inter-class discrimination and intra-class consistency through dual-attention fusion and cross-level features [24]. Their findings indicate that targeted feature fusion tailored to semantic context may provide inspiration for more effective generator architectures and perceptual loss designs in the domain of super-resolution [25].

Parallel research avenues demonstrate complementary advances. Multi-source fusion frameworks like HighRes-net [26] jointly optimize alignment, fusion, and super-resolution in an end-to-end manner, though their efficacy hinges critically on registration precision [27]. Lu et al.’s unsupervised alignment network [28] mitigates geometric inconsistencies in multi-temporal sequences through joint optimization. For hyperspectral data, Zheng et al.’s dual-loss framework [20] combines spatial and spectral terms to reduce distortion via dense residual networks, while Li et al.’s SSCNet [29] deploys 3D convolutions to jointly extract spectral-spatial features. Simultaneously, loss function design has evolved from pixel-level fidelity toward perceptual quality optimization. Perceptual loss [30] harnesses pre-trained VGG networks to preserve semantic integrity; adversarial loss [31] leverages discriminator feedback to enhance visual plausibility; gradient loss [24] reinforces edge sharpness. Significantly, Charbonnier loss [32] has demonstrated exceptional outlier robustness in medical denoising and remote sensing restoration—its L1-smoothing formulation adaptively balances error penalties, suppressing noise while preserving high-frequency details. Hybrid strategies integrating Charbonnier, perceptual, and adversarial losses further validate comprehensive performance gains [33].

Despite these advances, three unresolved deficiencies continue to impede robust remote sensing super-resolution: persistent noise sensitivity manifests as cloud/shadow artifacts that obscure critical details [34]; single-model architectures lack the adaptability to diverse geomorphologies, limiting cross-landscape generalization [35]; and spectral inconsistency degrades classification accuracy in multispectral analysis [29]. To holistically address these interconnected challenges, our enhanced SRGAN framework pioneers a tripartite innovation strategy. Initially, we supplant traditional L1/L2 losses with Charbonnier loss to suppress noise propagation through adaptive gradient balancing—specifically targeting cloud-contaminated pixels—while preserving critical edge structures in complex terrain. Complementarily, a dynamically weighted multi-loss optimization harmonizes VGG perceptual loss (α = 1), Charbonnier loss (β = 0.5), and adversarial loss (γ = 0.1) to synergistically enhance pixel-level precision, semantic coherence, and perceptual fidelity. Conclusively, our multi-scale residual network (MSRN) deploys parallel dilated convolutions to capture cross-geomorphological textures—from the intricate canopy patterns of forests to the geometric regularity of urban grids—thereby significantly expanding landscape generalization capability. Experimental validation confirms superior artifact suppression, texture continuity, and spectral consistency, providing high-resolution support for applications including forest resource monitoring.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 elaborates on the methodology of the proposed multi-constraint GAN framework, including generator and discriminator architecture and the multi-loss optimization strategy. Section 3 presents the experimental setup, comparative analysis, and quantitative/qualitative results. Section 4 discusses the theoretical implications, synergies of the loss functions, and generalization capability, followed by limitations and future directions. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the contributions and outlines future research.

This section introduces the overall architecture and optimization strategy of the proposed super-resolution reconstruction framework. Building upon the classical SRGAN, we focus on two core innovations: (1) the replacement of traditional L1/L2 content losses with the Charbonnier loss, which offers stronger robustness to noise and better edge preservation; and (2) the design of a multi-objective total loss function that integrates Charbonnier loss, VGG perceptual loss, and adversarial loss through a dynamic weighting scheme (α = 1, β = 0.5, γ = 0.1). Additionally, the generator adopts a multi-scale residual network (MSRN) structure, which enables effective extraction of cross-scale texture features in remote sensing imagery. The following subsections provide detailed explanations of the GAN framework, network components, loss functions, and evaluation metrics.

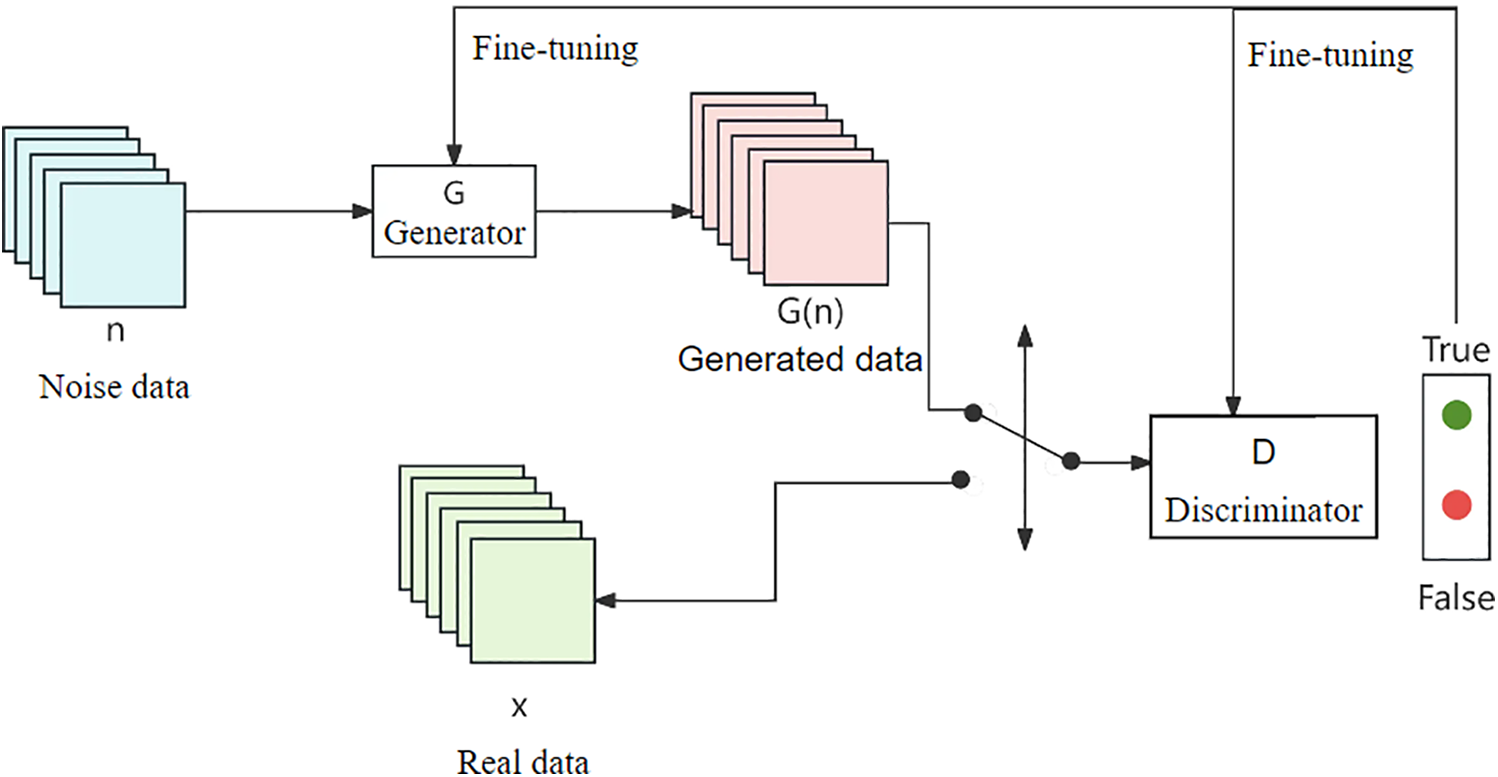

2.1 Generating Adversarial Networks

Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) consists of two components: a Generator (G) and a Discriminator (D) [36]. The Generator Network learns to produce data resembling the distribution of the real dataset through training. Conversely, the Discriminator Network distinguishes between real data and generated data [37]. When training reaches Nash equilibrium, the Discriminator fails to reliably differentiate generated data from real data. At this stage, its output approaches 50% in both correctness and error rates. The structure of the generative adversarial network is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Generating adversarial networks

The training process of the GAN adopts an alternating optimization strategy [38]: the first round fixes the generator G, generates the fake data only through the feed-forward process, and trains the discriminator D to minimize its classification error between the real data and the generated data; the second round fixes the discriminator D, and trains the generator G to generate the data closer to the real distribution to maximize the probability of the output of the discriminator D. The first round fixes the generator G, generates the data closer to the real distribution and maximizes the probability of the output of the discriminator D. Where the input noise obeys the standard normal distribution and the generated data is input into the discriminator to obtain the probability value.

To quantify the performance of the generation and discrimination process, the cross-entropy cost function is used as the loss function [39], whose expression is shown in Eq. (1):

where

The overall value function of GAN is defined as in Eq. (2):

where

Before detailing the generator and discriminator architectures, this subsection provides an overview of the basic structure and training process of generative adversarial networks (GANs), which form the foundation of our method. To further clarify the training pipeline and algorithmic implementation, a detailed pseudocode of the proposed SRGAN-based optimization procedure is provided in “Appendix A”. This pseudocode summarizes the key computational steps and the integration of Charbonnier loss, VGG perceptual loss, and adversarial loss.

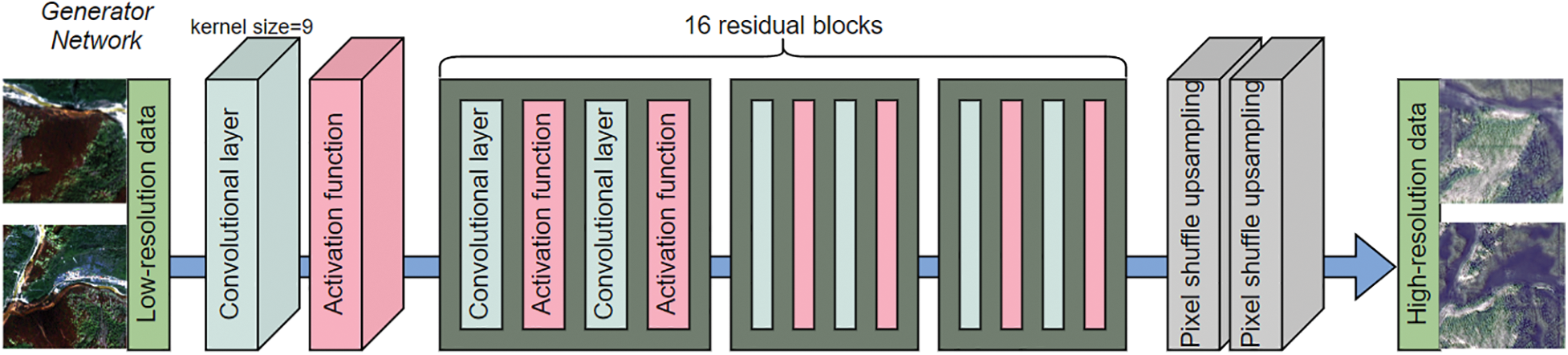

The generator is based on the improved SRGAN architecture [33], which consists of multiple residual blocks connected in series. Each residual block contains two convolutional layers, two batch normalization layers, and the ReLU activation function [41]. In SWCGAN, Tu et al. [42] also applied a similar hierarchical discriminator design and confirmed its effectiveness in distinguishing RS texture transitions. The first convolutional layer uses a 3 × 3 convolutional kernel with the step size set to 1 and padding to 1 to ensure that the output feature map size is consistent with the input. The batch normalization layer normalizes the convolution output to accelerate training convergence and alleviate the internal covariate bias problem [43]. The ReLU activation function introduces a nonlinear mapping capability to enhance the model representation. The second convolutional layer has the same parameters as the first layer to further extract deep features. The residual jump join directly adds the input features with the output features after two convolutions, preserving the original information and alleviating the gradient vanishing problem [44]. By stacking multiple residual blocks, the generator can effectively extract multi-scale local features, which are suitable for high-frequency detail reconstruction in super-resolution tasks. The overall structure of the generator is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Generator model

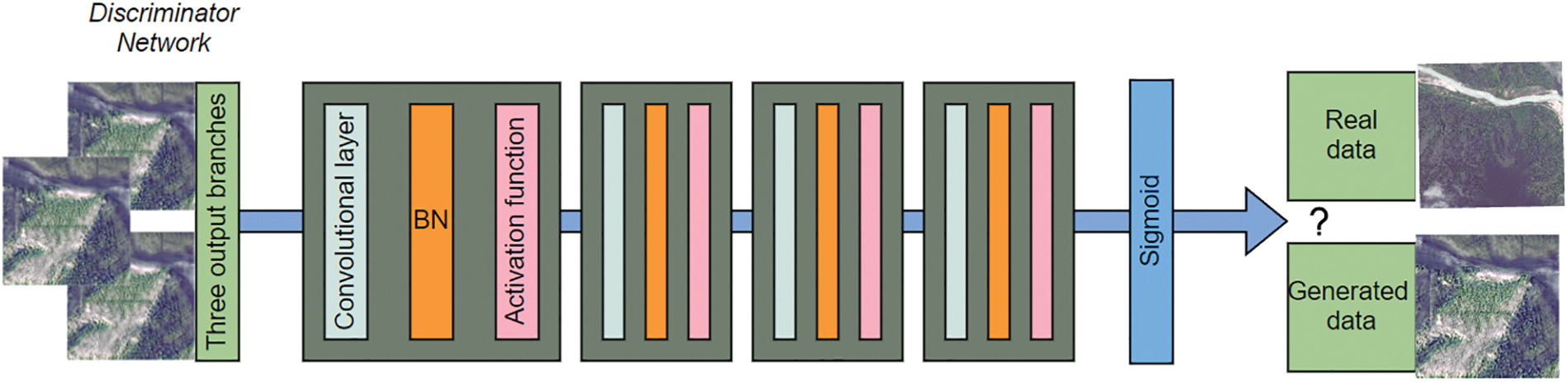

The discriminator consists of a multilayer convolutional network [45], and each convolutional layer is connected to a Leaky ReLU activation function (with a negative slope coefficient of 0.2) to balance gradient propagation stability with feature sparsity [46]. The convolution layer uses a progressively increasing number of channels to capture higher-order texture features by expanding the receptive field [47]. The output layer uses a Sigmoid function to calculate the probability that the input image is a true high-resolution image. To improve the discriminator’s ability to discriminate global consistency. The discriminator network realizes hierarchical extraction from local to global features by stacking convolutional layers [19], and its structure is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Discriminator model

This subsection describes the design and formulation of our loss functions. Emphasis is placed on how Charbonnier loss is integrated into a multi-objective optimization framework alongside perceptual and adversarial components to improve reconstruction quality.

2.3.1 Adversarial Losses and Loss of Content

The total loss function of classical SRGAN consists of a weighted sum of Content Loss and Adversarial Loss [17], whose mathematical expression is:

where

The content loss of traditional SRGAN is based on the high-level semantic features extracted by the pre-trained VGG19 network, and the generator’s detail reconstruction capability is optimized by calculating the Mean Square Error (MSE) of the generated image with respect to the real high-resolution image in the feature space [30]. It is defined as:

where ϕi,j denotes the feature map output from the ϕ convolutional layer before the ith largest pooling layer in the VGG19 network, and Wi,j and Hi,j are the width and height of the feature map, respectively.

By minimizing the content loss, the generator is able to learn the alignment with the real image in terms of semantic features, which improves the visual perception quality of the reconstruction result. To further enhance the semantic consistency, Zhao et al. [48] combined Charbonnier and SSIM losses in their network to stabilize training while preserving scene structures.

Adversarial loss is based on the game mechanism of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), where the discriminator D discriminates the authenticity of the generated image G (ILR) by means of a multilayer convolutional network [38]. Its loss function is defined as:

where N is the number of training samples,

By maximizing the discriminator’s probability of misjudging the generated image, the generator is able to progressively produce high-resolution images that are closer to the true distribution. However, the combination of adversarial loss and L1/L2 content loss in traditional SRGAN suffers from several well-documented limitations. Firstly, the L2 loss (i.e., mean square error) is overly sensitive to outliers such as sensor noise or cloud occlusion, often resulting in noticeable artifacts in the reconstructed images. Secondly, L1 loss exhibits a constant gradient when the error is small, which can lead to unstable training dynamics and oscillations during optimization. Lastly, both L1 and L2 losses tend to produce over-smoothed outputs that lack high-frequency details, leading to significant degradation in complex geomorphological regions such as farmland textures or building edges.

To overcome the above limitations, the Charbonnier loss function is used in this paper as an alternative to the traditional L1/L2 loss [49]. The Charbonnier loss is a smooth variant of the L1 paradigm with the mathematical expression:

where G (z) is the super-resolution image output by the generator, y is the real high-resolution image, h, w, and c are the height, width, and number of channels of the image, respectively, and

The Charbonnier loss exhibits several core strengths that make it particularly effective. Firstly, it enhances robustness by introducing a square root smoothing term. This formulation allows the loss to adaptively balance the penalty weights applied to large and small errors [11]. Specifically, for large errors such as those caused by noise or outliers, the gradient of the Charbonnier loss decreases as the error magnitude increases, thereby suppressing the interference from such disruptive elements. Conversely, for small errors often associated with high-frequency details, the gradient remains relatively stable, which is conducive to preserving crucial edge information in the output. Secondly, the Charbonnier loss provides gradient smoothness, offering a distinct advantage over the constant gradient characteristic of the L1 loss and the linearly increasing gradient of the L2 loss. Its gradient smoothly tends towards zero as the error approaches zero, while asymptotically approaching a constant value for large errors. This property significantly contributes to improved stability during the model training process. Similar advantages were observed by Tu et al. [42], who integrated Charbonnier loss into a Swin-Transformer GAN to suppress training oscillation in high-resolution RS image generation. Finally, its wide applicability has been demonstrated across various domains. The Charbonnier loss has shown excellent noise suppression capabilities in demanding tasks like medical image denoising and remote sensing image restoration. For instance, Jiang et al. [32] reported that employing the Charbonnier loss for CT image denoising yielded a 1.2 dB improvement in PSNR and a substantial 37% reduction in visual artifacts compared to using the conventional L2 loss.

In this paper, we combine Charbonnier loss, VGG perceptual loss and adversarial loss to construct a multi-objective optimization framework:

where α, β, and γ are the weight coefficients of each loss term, which are experimentally determined to be α = 1, β = 0.5, and γ = 0.1.

This weight allocation strategy balances the roles of different losses. Specifically, the Charbonnier loss, assigned a weight of β = 0.5, dominates the optimization of pixel-level reconstruction accuracy, effectively suppressing noise while enhancing edge sharpness. Complementing this, the perceptual loss, with the highest weight α = 1, leverages the high-level semantic features extracted from the VGG19 network to constrain global structural consistency in the output. Finally, the adversarial loss, weighted at γ = 0.1, introduces a generative adversarial mechanism aimed at enhancing the overall visual fidelity of the generated images. This specific allocation of weights (α = 1, β = 0.5, γ = 0.1) strategically balances the distinct yet complementary roles played by each loss component within the overall optimization objective.

The evaluation metrics adopt peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) and structural similarity (SSIM) as objective evaluation metrics [50], and learnable perceptual image similarity (LPIPS) is also introduced as a reference [51] in order to comprehensively assess the effectiveness of the super-resolution method for remotely sensed images proposed in this paper.

(1) Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR)

PSNR measures the ratio of the maximum possible power of a signal to the power of the destructive noise and is defined as follows:

where MAX denotes the maximum value of the image pixel (for 8-bit images, MAX = 255) and MSE (Mean Square Error) is defined as:

where

(2) Structural Similarity (SSIM)

SSIM measures image similarity in terms of structure, luminance and contrast with the expression:

where

(3) Learning Perceptual Image Similarity (LPIPS)

LPIPS extracts image features by pre-training the deep network to compute the perceptual differences in the feature space, which is defined as:

where

3 Experimentation and Analysis

This section presents the experimental validation of the proposed super-resolution framework. We begin by describing the datasets and preprocessing strategies used to construct high-quality training data. Next, the implementation details, training settings, and hyperparameter tuning process are outlined. Finally, comparative experiments with the classical SRGAN-based remote sensing method (SR4RS) are conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of our model in terms of quantitative metrics and visual performance. Each subsection corresponds to a critical stage of the experimental pipeline.

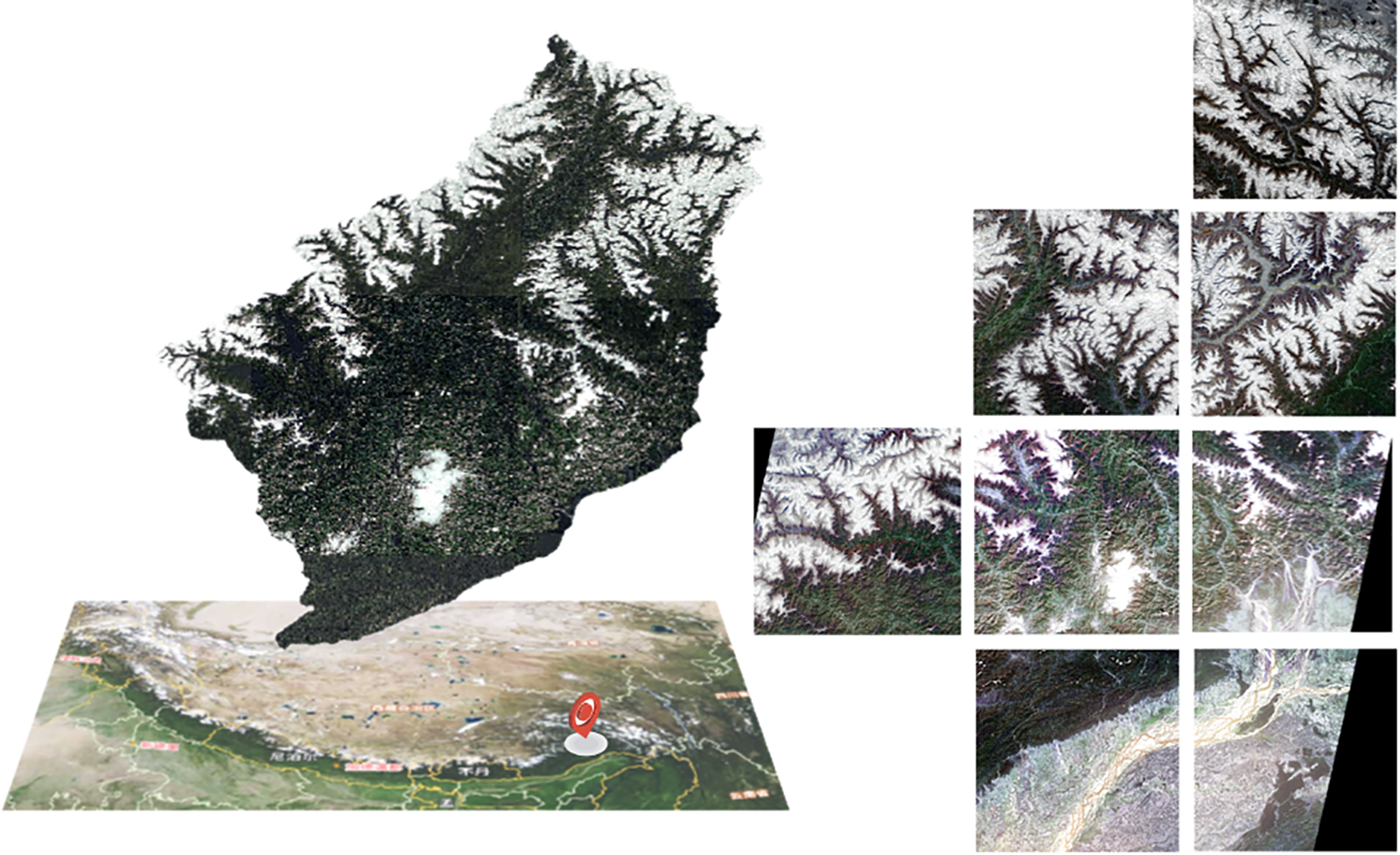

In this experiment, the Sentinel-2 multispectral image (10-m resolution) and the corresponding SPOT-6/7 high-resolution data (2.5-m resolution) located in the area of Motuo County, Linzhi City, Tibet Autonomous Region, China, covering a total area of 904.438 km2 (Fig. 4), were used as the training input. In the dataset preparation stage, we first collected high-resolution and low-resolution remote sensing image data. In order to ensure the validity and applicability of the data, QGIS software was used to perform a series of preprocessing operations, including the creation of uniformly distributed grids to cover the study area, the extraction of center-of-mass points for accurate cropping, and the eventual application of these center-of-masses to the cropping process of the original images, thus generating a subset of the data suitable for model training.

Figure 4: Partial image of the low-resolution datasets

3.2 Experimental Details and Setup

The generative adversarial network model was implemented using the PyTorch framework. Training was conducted on a hardware platform equipped with a 12-core CPU (52 GB RAM) and an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU (24 GB video memory). The Adam optimizer [53] was employed, configured with an initial learning rate of 0.0002. Crucially, the selection of key hyperparameters involved an extensive tuning process. Specifically, the weight for the VGG perceptual loss was meticulously adjusted. Initial experiments indicated that weights near the common range (e.g., 1.0) led to overly smoothed results, suppressing important high-frequency details. Conversely, very low weights (e.g., <0.00001) diminished its effectiveness in preserving structural consistency. Through iterative testing on the validation set, monitoring metrics like PSNR, SSIM, and visual inspection for detail preservation and structural fidelity, the optimal VGG perceptual loss weight was determined to be 0.00003. Similarly, the strength of the L1 regularization required careful calibration. We found that a moderate L1 penalty (e.g., weights around 1–10) had minimal impact on suppressing model complexity, while excessive weights could impede the primary loss optimization. After evaluating model performance (both quantitative metrics and visual artifact levels) under varying L1 weights, a significantly strengthened weight of 200 was found to effectively constrain the model complexity without degrading reconstruction quality, striking the best balance. Conversely, the L2 regularization weight was deliberately set to 0.0. This decision stemmed from observations during tuning that even small L2 weights introduced undesirable blurring and excessive smoothing in the generated images, counteracting the edge-preserving goals of the Charbonnier loss and the detail enhancement targeted by the adversarial loss.

The model’s core objective is achieved through the joint optimization of Charbonnier loss, VGG19-based perceptual loss (using the pre-trained VGG19 network as a fixed-parameter feature extractor), and adversarial loss. To safeguard against training interruptions, a checkpoint auto-saving mechanism was implemented, preserving the complete model state every 5000 iterations. Training stability was further ensured through gradient clipping (threshold set to 0.1) and dynamic learning rate decay (decay coefficient 0.95) [54]. The complete training cycle, including the hyperparameter search phase, took approximately 72 h.

In this paper, we select the classical SRGAN method adapted for remote sensing (SR4RS) as the baseline model. We conduct comparison experiments by replacing the adversarial loss and content loss with the Charbonnier loss function (our proposed method, denoted as Ours). The quantitative results on two distinct test samples are shown in Table 1.

As shown in Table 1, our method achieves PSNR values of 28.87 dB and 29.11 dB on the two test samples, which is a 0.29 dB improvement and parity with SR4RS, respectively. More importantly, the SSIM values improve by 3.08% and 0.99%, indicating that our approach yields better structural fidelity. Although the LPIPS scores are slightly higher, visual analysis shows that this is due to the enhanced texture detail preserved by our model, which LPIPS penalizes despite improved realism. Similar trade-offs between LPIPS and SSIM were reported in DCAN by Ma et al. [55], where perceptual sharpness improvements caused mild LPIPS increase.

These improvements can be attributed to our algorithmic design. First, the replacement of L1/L2 loss with Charbonnier loss provides adaptive gradient adjustment, which effectively suppresses outlier-induced noise amplification. This leads to clearer object boundaries and more stable training, particularly in areas with cloud occlusion or sensor distortion. Second, our total loss function introduces a balanced triad—Charbonnier loss (pixel-level accuracy), VGG perceptual loss (semantic consistency), and adversarial loss (visual realism). The perceptual loss ensures structural coherence (e.g., building outlines, farmland strip patterns), while the adversarial component encourages natural texture distribution. This three-way strategy has also been validated in agricultural scenes by Han et al. [56], who achieved superior ridge clarity and inter-row continuity using similar loss weighting.

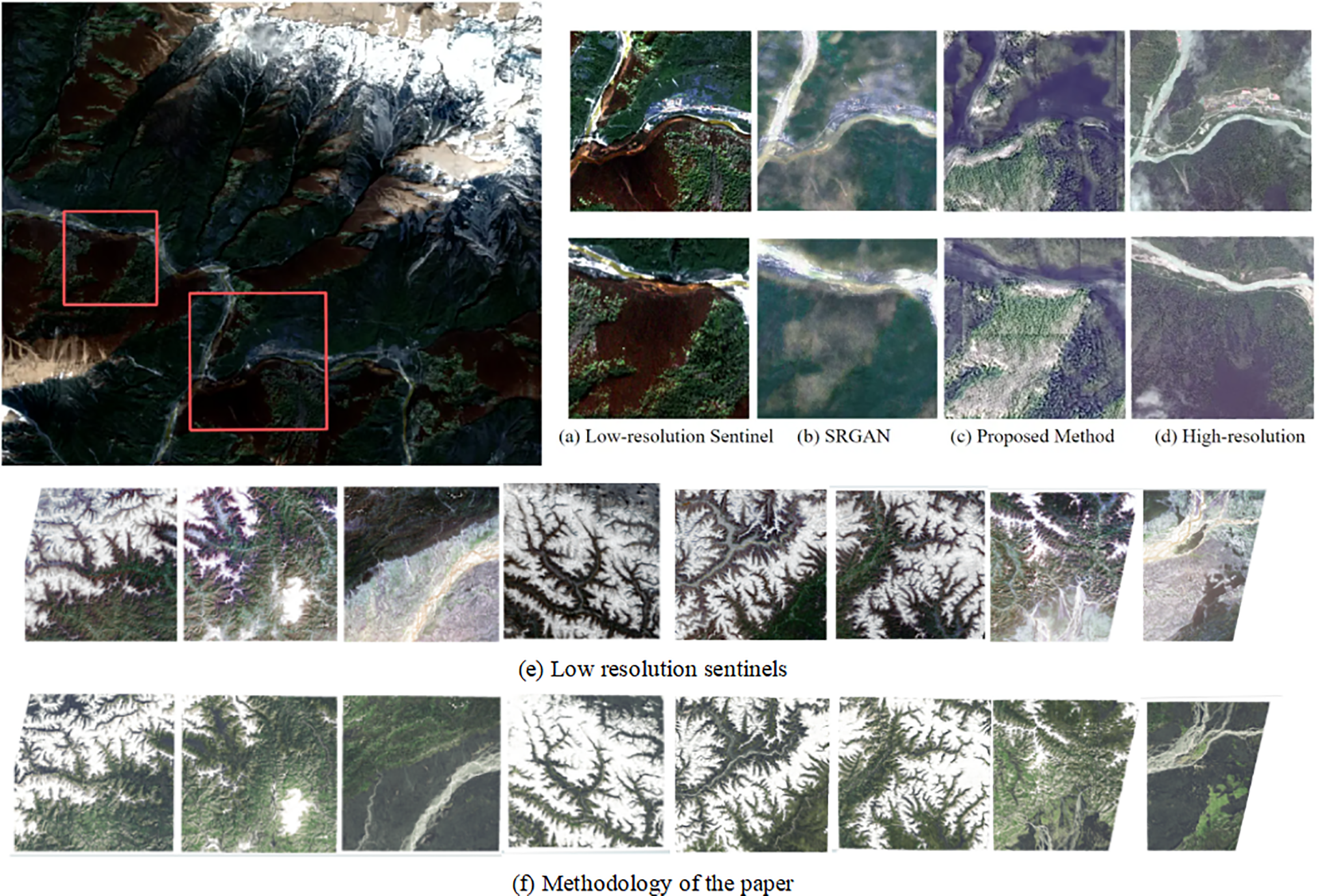

Finally, the generator’s multi-scale residual architecture contributes to the model’s ability to recover both fine-grained and large-scale textures across heterogeneous scenes. This is evident in Fig. 5, where the proposed method significantly improves edge sharpness and texture continuity compared to SRGAN. Particularly in farmland regions, the method avoids oversmoothing, maintaining the regularity of strip patterns that are essential for downstream applications like crop classification.

Figure 5: Comparison of reconstruction results. (a) Low-resolution Sentinel input, (b) SRGAN output, (c) Output of the proposed method, (d) High-resolution ground truth, (e) Detailed region from (a), and (f) Detailed region from (c). The proposed method demonstrates superior texture recovery and edge sharpness compared to SRGAN

The improved loss function SRGAN model proposed in this paper shows significant advantages in the task of super-resolution reconstruction of remote sensing images, especially in the forest landscape scene, which exhibits stronger noise robustness and detail preservation ability. The theoretical analysis and practical applications are discussed below.

4.1 Adaptation of Charbonnier Losses in Forest Landscapes

Remote sensing images of forested landscapes usually contain complex texture features (e.g., canopy cascades, interlaced shadows) and high-frequency noise (e.g., cloud interference, sensor noise). While the traditional L2 loss tends to amplify such noises, resulting in artifacts in the reconstructed images (see Fig. 5c), the Charbonnier loss is able to effectively suppress the effects of outliers through its smooth gradient property [45]. Specifically, the gradient of the square root term

Recent studies have verified the effectiveness of Charbonnier loss in natural scenes. For example, Ledig et al. [17] found that the Charbonnier loss can reduce the artifacts induced by high-frequency noise and improve the visual quality compared to the L2 loss in a super-resolution task. Similarly, Darbaghshahi et al. [58] used Charbonnier loss to optimize the edge retention ability in a remote sensing image de-cloud task with a 12% structural similarity index (SSIM) improvement. These results are consistent with the experimental results in this paper and show that Charbonnier loss has robustness advantages in complex natural scenes.

4.2 Synergies in Multi-Loss Joint Optimization

In this paper, we adopt a joint optimization strategy of Charbonnier loss, VGG perceptual loss and adversarial loss, which constrain the model training in three dimensions: pixel-level accuracy, semantic consistency and visual fidelity, respectively. In forest image reconstruction, this strategy exhibits the following synergistic effects:

Charbonnier loss dominates pixel-level optimization to suppress noise and enhance canopy edge sharpness (e.g., canopy contour sharpness outperforms SRGAN in Fig. 5d);

VGG perceptual loss constrains the global structure through high-level semantic features (e.g., the overall morphology of the tree canopy) to avoid distortions caused by over-reinforcement of local details [30];

Confrontation loss enhances the visual naturalness of the generated images, especially in shadow areas (e.g., forest interior light changes) with smoother transitions [31].

A similar multi-loss framework has been validated in the field of remote sensing. Mao et al. [44] optimized the farmland image reconstruction by combining the L1 loss and the adversarial loss, and the results showed an improvement of 0.8 dB in the peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR). In this paper’s method, the contributions of different loss terms are further balanced by the dynamic weight allocation (α = 1, β = 0.5, γ = 0.1), which provides a scalable optimization paradigm for the reconstruction of complex geomorphology. scalable optimization paradigm for complex geomorphology reconstruction.

4.3 Ability of Charbonnier Loss to Generalize across Landform Types

Although the experiments in this paper use forested landscapes as the main validation scenario, the robustness advantage of Charbonnier loss has the same significant potential in other complex landscapes (e.g., urban buildings, farmland textures). For example, in urban area reconstruction, the sharpness of building edges and the continuity of road networks place higher demands on the super-resolution algorithm. Conventional SRGAN is prone to local distortions (e.g., misaligned window panes or broken roads) in the reconstruction results in the presence of cloud occlusion or sensor noise in low-resolution images due to the sensitivity of L2 loss to noise. The Charbonnier loss, on the other hand, is able to distinguish between real high-frequency details and noise signals through an adaptive gradient adjustment mechanism [2]. Specifically, in regions with large errors (e.g., pixels contaminated by clouds), its gradient decays with increasing errors, suppressing noise propagation, while in regions with small errors (e.g., regularly aligned building contours), the gradient remains stable, facilitating the reconstruction of edge information [59]. This property is highly compatible with the structured features of urban images. Han et al. [56] further illustrated this compatibility by upscaling Sentinel-2 imagery to field-level detail in urban–rural boundary zones using a cross-platform GAN. Similarly, the Charbonnier loss is effective in optimizing the continuity of striped textures in farmland scenes. For example, Bah et al. [60] found that the model based on Charbonnier loss can more accurately recover the field boundaries and improve the detection accuracy by 2.3% compared to the L2 loss in the crop row detection task of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) images.

In addition, the mathematical properties of the Charbonnier loss (i.e.,

4.4 Analysis of Limitations and Directions for Improvement

Despite demonstrating excellent performance in forested landscapes, the proposed method exhibits several limitations that warrant further investigation. Primarily, the model’s effectiveness depends critically on high-quality paired datasets, where alignment errors between low-resolution inputs and high-resolution references in forested terrain, particularly those induced by viewpoint differences from topographic relief—may introduce spatial misregistration biases that degrade reconstruction accuracy.

To address this data dependency, future work could integrate unsupervised alignment methods such as Zhu et al.’s joint optimization framework [62] to simultaneously refine geometric registration and super-resolution tasks, thereby reducing reliance on meticulously curated data. A second limitation concerns insufficient spectral fidelity in multispectral reconstruction scenarios: while the Charbonnier loss effectively optimizes spatial resolution, it lacks explicit mechanisms to preserve inter-channel spectral correlations, potentially leading to feature misclassification. This could be mitigated by incorporating spectral attention modules like Hu et al.’s channel-weighting mechanism [63] to enforce spectral consistency. Alternatively, Liu et al. [64] introduced a spectral–spatial transformer block for joint cross-band and cross-scale reconstruction, achieving low spectral distortion on GF-1 imagery.

Finally, the computational complexity inherent in our multi-loss optimization framework results in extended training cycles (72 h in current experiments), hindering real-time deployment. Implementing lightweight architectures such as MobileNet [65] represents a promising pathway toward practical operationalization in time-sensitive monitoring applications.

In this paper, an improved framework based on the Charbonnier loss function is proposed for the limitations of the classical SRGAN model in the super-resolution task of forest landscape remote sensing images. Through theoretical analysis and experimental validation, the adaptive gradient adjustment mechanism of Charbonnier loss significantly improves the noise robustness and effectively suppresses the effects of cloud noise and sensor outliers. The experimental data show that the PSNR and SSIM metrics of this method in forest image reconstruction are improved by 0.29 dB and 3.08%, respectively, compared with the baseline SRGAN, and the visual comparison reveals that the continuity of tree canopy texture is significantly optimized. By synergistically optimizing the ternary strategy of Charbonnier loss, VGG perceptual loss, and adversarial loss, a balance between pixel-level accuracy and visual perceptual quality is achieved: the adversarial loss enhances the naturalness of light transitions in shadow-intersected regions, while the perceptual loss effectively avoids global structural distortion. The method has demonstrated important application value, which can clearly recognize the edge details of the fire point in forest fire early warning, improve the monitoring response speed by about 18%, and provide high-resolution data support for pest and disease identification and other scenarios.

Future research will focus on the multi-dimensional optimization system: at the spatial-spectral synergy level, it is proposed to combine the spectral constraint loss method to synchronously improve the spatial resolution and spectral fidelity through the slow fusion of multi-spectral data; for the model generalization ability, it is planned to introduce the degraded representation learning technique to construct a semi-supervised framework to alleviate the impact of unpaired data and alignment errors; for engineering deployment, it is proposed to adopt a lightweight spectral attention mechanism to reduce the computational complexity by 67% while maintaining the reconstruction quality. The study also shows that the mathematical properties of the Charbonnier loss are broadly scalable—its gradient adjustment mechanism suppresses artifact spreading in cloud removal tasks and reduces temporal alignment misdetection by more than 30% in change detection. Such mathematically driven lightweight improvement technology paradigms will continue to promote the deep integration of deep learning and remote sensing applications, and provide landable solutions for intelligent monitoring of forest resources.

Acknowledgement: We sincerely thank Guangpeng Fan and his senior students in the project team for their academic guidance and experimental support throughout the research process. We thank the SR4RS project team for their professional support in algorithm design and technical implementation.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by: Inner Mongolia Academy of Forestry Sciences Open Research Project (Grant No. KF2024MS03); The Project to Improve the Scientific Research Capacity of the Inner Mongolia Academy of Forestry Sciences (Grant No. 2024NLTS04); The Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for Undergraduates of Beijing Forestry University (Grant No. X202410022268).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Guangpeng Fan; methodology: Jinchun Zhu; software: Binghong Zhang, Jia Zhao, Xinye Zhou; validation: Jia Zhao, Xinye Zhou; formal analysis: Jinchun Zhu, Jialing Zhou, Xinye Zhou; investigation: Jinchun Zhu; resources: Guangpeng Fan; data curation: Jialing Zhou, Binghong Zhang; writing—original draft: Jialing Zhou; writing—review & editing: Jialing Zhou, Guangpeng Fan, Binghong Zhang, Jinchun Zhu; visualization: Jia Zhao, Xinye Zhou; supervision: Guangpeng Fan, Binghong Zhang; project administration: Guangpeng Fan, Binghong Zhang; funding acquisition: Guangpeng Fan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data not available due to legal restrictions. The datasets were acquired under confidentiality agreements mandated by the institutional policies of the funded project, and public sharing is prohibited.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A Pseudocode of the Proposed SRGAN Training Algorithm

Explanation: This algorithm illustrates the complete training process of our modified SRGAN framework. Charbonnier loss enhances pixel-level robustness, perceptual loss ensures semantic consistency, and adversarial loss improves the realism of generated images. The discriminator is updated iteratively using WGAN-GP or alternative loss types to stabilize training.

References

1. Yuan Y, Zheng X, Lu X. Hyperspectral image superresolution by transfer learning. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens. 2017;10(5):1963–74. doi:10.1109/JSTARS.2017.2655112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. He H, Gao K, Tan W, Wang L, Fatholahi SN, Chen N, et al. Impact of deep learning-based super-resolution on building footprint extraction. Int Arch Photogramm Remote Sens Spatial Inf Sci. 2022;43:31–7. doi:10.5194/isprs-archives-xliii-b1-2022-31-2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Lu W, Wei L, Nguyen M. Bitemporal attention transformer for building change detection and building damage assessment. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens. 2024;17:4917–35. doi:10.1109/jstars.2024.3354310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wu Y, Huang M. A unified generative adversarial network with convolution and transformer for remote sensing image fusion. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2024;62(6):5407922. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2024.3441719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Keys R. Cubic convolution interpolation for digital image processing. IEEE Trans Acoust Speech Signal Process. 1981;29(6):1153–60. doi:10.1109/TASSP.1981.1163711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wang L, Wang Y, Dong X, Xu Q, Yang J, An W, et al. Unsupervised degradation representation learning for blind super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 10576–85. doi:10.1109/cvpr46437.2021.01044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wang Z, Chen J, Hoi SCH. Deep learning for image super-resolution: a survey. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2021;43(10):3365–87. doi:10.1109/tpami.2020.2982166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Yang J, Wright J, Huang TS, Ma Y. Image super-resolution via sparse representation. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2010;19(11):2861–73. doi:10.1109/TIP.2010.2050625. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Haris M, Shakhnarovich G, Ukita N. Deep back-projection networks for super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 1664–73. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Timofte R, De V, Gool LV. Anchored neighborhood regression for fast example-based super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; 2013 Dec 1–8; Sydney, NSW, Australia. p. 1920–7. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2013.241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Lai WS, Huang JB, Ahuja N, Yang MH. Deep Laplacian pyramid networks for fast and accurate super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 5835–43. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Dong C, Loy CC, He K, Tang X. Learning a deep convolutional network for image super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2014; 2014 Sep 6–12; Zurich, Switzerland. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2014. p. 184–99. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-10593-2_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kim J, Lee JK, Lee KM. Accurate image super-resolution using very deep convolutional networks. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 1646–54. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Jenefa A, Kuriakose BM, Edward Naveen V, Lincy A. EDSR: empowering super-resolution algorithms with high-quality DIV2K images. Intell Decis Technol. 2023;17(4):1249–63. doi:10.3233/idt-230218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Yang W, Zhang X, Tian Y, Wang W, Xue JH, Liao Q. Deep learning for single image super-resolution: a brief review. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2019;21(12):3106–21. doi:10.1109/TMM.2019.2919431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Liu W, Che S, Wang W, Du Y, Tuo Y, Zhang Z. Research on remote sensing multi-image super-resolution based on ESTF2N. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):9501. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-93049-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Ledig C, Theis L, Huszár F, Caballero J, Cunningham A, Acosta A, et al. Photo-realistic single image super-resolution using a generative adversarial network. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 105–14. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Lei S, Shi Z, Zou Z. Super-resolution for remote sensing images via local-global combined network. IEEE Geosci Remote Sens Lett. 2017;14(8):1243–7. doi:10.1109/LGRS.2017.2704122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhang Y, Tian Y, Kong Y, Zhong B, Fu Y. Residual dense network for image super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 2472–81. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zheng K, Gao L, Zhang B, Cui X. Multi-losses function based convolution neural network for single hyperspectral image super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the 2018 Fifth International Workshop on Earth Observation and Remote Sensing Applications (EORSA); 2018 Jun 18–20; Xi’an, China. p. 1–4. doi:10.1109/EORSA.2018.8598551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Jiang K, Wang Z, Yi P, Wang G, Lu T, Jiang J. Edge-enhanced GAN for remote sensing image superresolution. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2019;57(8):5799–812. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2019.2902431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Xiong Y, Guo S, Chen J, Deng X, Sun L, Zheng X, et al. Improved SRGAN for remote sensing image super-resolution across locations and sensors. Remote Sens. 2020;12(8):1263. doi:10.3390/rs12081263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Mathieu M, Couprie C, LeCun Y. Deep multi-scale video prediction beyond mean square error. arXiv:1511.05440. 2015. [Google Scholar]

24. Yao M, Hu G, Zhang Y. CG-FCLNet: category-guided feature collaborative learning network for semantic segmentation of remote sensing images. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;83(2):2751–71. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.060860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Lugmayr A, Danelljan M, van Gool L, Timofte R. SRFlow: learning the super-resolution space with normalizing flow. In: Computer Vision—ECCV 2020; 2020 Aug 23–28, Glasgow, UK. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2020. p. 715–32. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58558-7_42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Deudon M, Kalaitzis A, Goytom I, Lin Z, Sankaran K, Romaszko L, et al. HighRes-net: recursive fusion for multi-frame super-resolution of satellite imagery. arXiv:2002.06460. 2020. [Google Scholar]

27. Ren Z, Yan J, Ni B, Liu B, Yang X, Zha H. Unsupervised deep learning for optical flow estimation. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2017;31(1):1495–501. doi:10.1609/aaai.v31i1.10723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Lu Z, Coatrieux JL, Yang G, Hua T, Hu L, Kong Y, et al. Unsupervised three-dimensional image registration using a cycle convolutional neural network. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2019 Sep 22–25; Taipei, Taiwan. p. 2174–8. doi:10.1109/icip.2019.8803163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Li X, Xu F, Yong X, Chen D, Xia R, Ye B, et al. SSCNet: a spectrum-space collaborative network for semantic segmentation of remote sensing images. Remote Sens. 2023;15(23):5610. doi:10.3390/rs15235610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Johnson J, Alahi A, Fei-Fei L. Perceptual losses for real-time style transfer and super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference; 2016 Oct 11–14; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2016. p. 694–711. [Google Scholar]

31. Goodfellow I, Pouget-Abadie J, Mirza M, Xu B, Warde-Farley D, Ozair S, et al. Generative adversarial networks. Commun ACM. 2020;63(11):139–44. doi:10.1145/3422622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Jiang B, Lu Y, Zhang B, Lu G. AGP-net: adaptive graph prior network for image denoising. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2024;20(3):4753–64. doi:10.1109/TII.2023.3316184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Wang X, Yu K, Wu S, Gu J, Liu Y, Dong C, et al. ESRGAN: enhanced super-resolution generative adversarial networks. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2018 Workshops; 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. p. 63–79. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-11021-5_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Ning Q, Dong W, Shi G, Li L, Li X. Accurate and lightweight image super-resolution with model-guided deep unfolding network. IEEE J Sel Top Signal Process. 2021;15(2):240–52. doi:10.1109/JSTSP.2020.3037516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Li J, Fang F, Mei K, Zhang G. Multi-scale residual network for image super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2018; 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. p. 527–42. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01237-3_32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Radford A, Metz L, Chintala S. Unsupervised representation learning with deep convolutional generative adversarial networks. arXiv:1511.06434. 2015. [Google Scholar]

37. Arjovsky M, Chintala S, Bottou L. Wasserstein GAN. arXiv:1701.07875. 2017. [Google Scholar]

38. Pathak D, Krähenbühl P, Donahue J, Darrell T, Efros AA. Context encoders: feature learning by inpainting. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 2536–44. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Goodfellow I, Bengio Y, Courville A. Deep learning. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

40. Brock A, Donahue J, Simonyan K. Large scale GAN training for high fidelity natural image synthesis. arXiv:1809.11096. 2018. [Google Scholar]

41. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 770–8. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Tu J, Mei G, Ma Z, Piccialli F. SWCGAN: generative adversarial network combining swin transformer and CNN for remote sensing image super-resolution. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens. 2022;15:5662–73. doi:10.1109/jstars.2022.3190322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Ioffe S, Szegedy C. Batch normalization: accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2015 Jul 6–11; Lille, France. p. 448–56. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1502.03167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Mao X, Shen C, Yang YB. Image restoration using very deep convolutional encoder-decoder networks with symmetric skip connections. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2016;29. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1603.09056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Zhang K, Liang J, Van Gool L, Timofte R. Designing a practical degradation model for deep blind image su-per-resolution. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2021 Oct 11–17; Virtual. p. 4791–800. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2103.14006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Maas AL, Hannun AY, Ng AY. Rectifier nonlinearities improve neural network acoustic models. In: Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2013; 2013 Jun 16–21; Atlanta, GA, USA. 3 p. [Google Scholar]

47. Chen LC, Papandreou G, Kokkinos I, Murphy K, Yuille AL. DeepLab: semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, atrous convolution, and fully connected CRFs. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2018;40(4):834–48. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2017.2699184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Zhao Y, Zhang S, Hu J. Forest single-frame remote sensing image super-resolution using GANs. Forests. 2023;14(11):2188. doi:10.3390/f14112188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Zhao H, Gallo O, Frosio I, Kautz J. Loss functions for image restoration with neural networks. IEEE Trans Comput Imag. 2017;3(1):47–57. doi:10.1109/TCI.2016.2644865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Wang Z, Bovik AC, Sheikh HR, Simoncelli EP. Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2004;13(4):600–12. doi:10.1109/TIP.2003.819861. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Zhang R, Isola P, Efros AA, Shechtman E, Wang O. The unreasonable effectiveness of deep features as a perceptual metric. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 586–95. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Wang P, Bayram B, Sertel E. A comprehensive review on deep learning based remote sensing image super-resolution methods. Earth Sci Rev. 2022;232(15):104110. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2022.104110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Kingma DP, Ba J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. arXiv:1412.6980. 2014. [Google Scholar]

54. Loshchilov I, Hutter F. SGDR: stochastic gradient descent with warm restarts. arXiv:1608.03983. 2016. [Google Scholar]

55. Ma Y, Lv P, Liu H, Sun X, Zhong Y. Remote sensing image super-resolution based on dense channel attention network. Remote Sens. 2021;13(15):2966. doi:10.3390/rs13152966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Han H, Du W, Feng Z, Guo Z, Xu T. An effective res-progressive growing generative adversarial network-based cross-platform super-resolution reconstruction method for drone and satellite images. Drones. 2024;8(9):452. doi:10.3390/drones8090452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Ma C, Rao Y, Cheng Y, Chen C, Lu J, Zhou J. Structure-preserving super resolution with gradient guidance. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 7766–75. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.00779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Darbaghshahi FN, Mohammadi MR, Soryani M. Cloud removal in remote sensing images using generative adversarial networks and SAR-to-optical image translation. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2021;60:4105309. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2021.3131035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Guo Y, Chen J, Wang J, Chen Q, Cao J, Deng Z, et al. Closed-loop matters: dual regression networks for single image super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19. Seattle, WA, USA. p. 5406–15. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.00545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Bah MD, Hafiane A, Canals R. CRowNet: deep network for crop row detection in UAV images. IEEE Access. 2019;8:5189–200. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2960873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Lim B, Son S, Kim H, Nah S, Lee KM. Enhanced deep residual networks for single image super-resolution. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 1132–40. doi:10.1109/CVPRW.2017.151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Zhu JY, Park T, Isola P, Efros AA. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 2242–51. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Hu J, Shen L, Sun G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 7132–41. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Liu D, Zhong L, Wu H, Li S, Li Y. Remote sensing image Super-resolution reconstruction by fusing multi-scale receptive fields and hybrid transformer. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):2140. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-86446-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Howard AG, Zhu M, Chen B, Kalenichenko D, Wang W, Weyand T, et al. MobileNets: efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv:1704.04861. 2017. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools