Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Multiaxial Fatigue Life Prediction of Metallic Specimens Using Deep Learning Algorithms

1 School of Mechanical, Electronic and Control Engineering, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, 100044, China

2 Locomotive & Car Research Institute, China Academy of Railway Sciences Corporation Limited, Beijing, 100081, China

3 CRRC Changchun Railway Vehicles Co., Ltd., Changchun, 130062, China

4 Chengdu EMU Depot, China Railway Chengdu Group Co., Ltd., Chengdu, 610057, China

* Corresponding Author: Zhiming Liu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068353

Received 26 May 2025; Accepted 16 July 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Accurately predicting fatigue life under multiaxial fatigue damage conditions is essential for ensuring the safety of critical components in service. However, due to the complexity of fatigue failure mechanisms, achieving accurate multiaxial fatigue life predictions remains challenging. Traditional multiaxial fatigue prediction models are often limited by specific material properties and loading conditions, making it difficult to maintain reliable life prediction results beyond these constraints. This paper presents a study on the impact of seven key feature quantities on multiaxial fatigue life, using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTM), and Fully Connected Neural Networks (FCNN) within a deep learning framework. Fatigue test results from eight metal specimens were analyzed to identify these feature quantities, which were then extracted as critical time-series features. Using a CNN-LSTM network, these features were combined to form a feature matrix, which was subsequently input into an FCNN to predict metal fatigue life. A comparison of the fatigue life prediction results from the STFAN model with those from traditional prediction models—namely, the equivalent strain method, the maximum shear strain method, and the critical plane method—shows that the majority of predictions for the five metal materials and various loading conditions based on the STFAN model fall within an error band of 1.5 times. Additionally, all data points are within an error band of 2 times. These findings indicate that the STFAN model provides superior prediction accuracy compared to the traditional models, highlighting its broad applicability and high precision.Keywords

The safety and fatigue reliability of engineering structural components are critical challenges that demand urgent attention. For uniaxial fatigue problems, many researchers have developed comprehensive fatigue models based on empirical evidence [1]. However, structural failure resulting from multiaxial fatigue loading is a widespread phenomenon in practical engineering [2]. Key components in industries such as aviation, aerospace, and rail transportation are frequently subjected to complex multiaxial fatigue loading, which can lead to structural failure [3]. Data show that up to 80

To advance the study of material life prediction models under multiaxial fatigue loading, researchers globally have classified these models into two categories based on their principles and methods, derived through experiments and theoretical analysis [14–17]. The first category includes methodologies leveraging machine learning models trained on loading data [18–20]. Machine learning algorithms provide an efficient and rapid approach to establishing mapping relationships. With capabilities for continuous learning and adaptive parameter updating, they enhance computational efficiency and reduce conventional calculation errors. Their accurate data processing and precise, reliable modeling methods make them dependable tools for predicting material fatigue life and analyzing fatigue failure [21]. In recent years, fully connected neural networks have been widely applied to uniaxial fatigue life prediction for diverse materials. Based on their investigation into the failure mechanisms of 316L steel under complex service environments, Srinivasan et al. employed Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) to establish complex functional mappings between variables (such as temperature) and fatigue life [22]. The work of Anastasios et al. demonstrated that with appropriate parameter settings and network architecture design, ANNs can predict fatigue life across the entire stress ratio range using only half the data required by conventional methods to construct multiple S-N curves. This enables more accurate life assessment and design work [23]. Addressing the fatigue life of metallic materials under mean stress, Barbosa et al. proposed an ANN-based probabilistic constant-life approach. This method achieves accurate predictions with minimal data, further validating the effectiveness of ANN methodologies [24]. Al-Assaf et al. experimentally and computationally demonstrated that ANNs for fatigue life prediction place high demands on model parameter settings, data quality, and purity; otherwise, they fail to ensure adequate accuracy and reliability of fitting results [25]. Furthermore, for fatigue analysis under random loading, ANN models—through rational input parameter design covering diverse materials and complex loading characteristics—maintain effectiveness and accuracy in predicting random loading fatigue life [26]. Jingye Yang et al. developed both semi-empirical and neural network models to study low-cycle fatigue behavior under non-proportional loading. Compared to the semi-empirical model, which has clear physical meaning but lower accuracy, the neural network more accurately captured the fatigue characteristics of materials under low-cycle fatigue loading, though it lacked corresponding physical interpretability [27]. However, such fully-connected neural network-based approaches for uniaxial fatigue life prediction are less suitable for multiaxial fatigue conditions. Building upon this research, scholars have proposed data-driven models applicable to multiaxial fatigue loading scenarios. Their aim is to develop a deep learning-based generic framework for predicting multiaxial fatigue life in metallic materials [28]. The application of machine learning to multiaxial fatigue life prediction enables the effective identification and optimization of damage coefficients, thereby facilitating the development of reliable fatigue life prediction models [29]. Yang et al. proposed a machine learning-based multiaxial fatigue life prediction model [30]. This model utilized a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural network to extract critical points from the load path, which were subsequently input into a Fully Connected Neural Network (FCNN). Similarly, Zheng et al. employed phase difference and normal and shear strain amplitude as inputs for a multiaxial fatigue prediction model [31,32]. They trained and tested their approach using fatigue data from pure titanium and titanium alloys. Their findings demonstrated that the proposed model outperformed conventional models based on physical mechanisms in predicting the fatigue life of titanium alloys. Zhan and Li integrated the theory of continuous medium damage mechanics (CDM) with machine learning to develop a predictive methodology for the lifespan of additively manufactured aerospace alloys [15]. This model was empirically validated through experimental testing. However, despite the success of machine learning in constructing multiaxial fatigue life prediction models and verifying their predictions with experimental data, certain limitations persist. Specifically, the selection of input feature parameters often neglects key loading parameters such as timing characteristics and amplitude. This omission prevents a comprehensive representation of the multiaxial fatigue loading process, resulting in discrepancies between predicted outcomes and experimental results.

Scholars have also focused on analyzing the fatigue failure mechanisms of metallic materials, aiming to develop fatigue life prediction methods grounded in physical mechanisms. The most widely used models in this domain include the Equivalent Strain Energy Density Method (ESM) [16], the Energy Method [33,34], and the Critical Plane Method [19]. In applying these models, specimens are defined as being subjected to multiaxial loading conditions, as is typical in standardized fatigue testing. The aforementioned fatigue life prediction models are established for metallic materials under multiaxial fatigue loading conditions. Corresponding predictive mapping frameworks between damage parameters and fatigue life are developed based on specific failure modes. These models not only predict the fatigue life of metallic materials but also elucidate the underlying multiaxial fatigue failure mechanisms.

(1) Equivalence Transformation Method. The Manson-Coffin equation is a well-established approach for predicting the uniaxial tensile fatigue life of materials, with a proven track record of reliability. Many researchers have extended this method to multiaxial fatigue life prediction for metallic materials by incorporating strain coefficients into the Manson-Coffin framework. For instance, Yang et al. conducted tensile and shear fatigue tests on the critical parts of bolted joints based on the equivalent structural stress method, derived the equivalent structural stress calculation model and finite element model that accurately characterize the stress state of bolted joints, and finally obtained the equivalent structural stress at the crack initiation site of bolted joints, indicating that the method can provide a reference for the design calibration and fatigue life prediction of bolted joints [35]. Li et al. established and determined a fatigue assessment framework for the dominant failure modes of rib-panel welded joints based on the equivalent structural stress method for evaluating the fatigue performance of rib-panel welded structures, and validated it with experimental data, which showed that the framework can accurately predict the main fatigue failure modes of welded joints [36]. While the equivalent strain method is effective for predicting uniaxial tensile fatigue life, it has several limitations. Notably, it lacks a direct mapping relationship between strain and life, disregards the interaction between stress and strain during deformation, fails to account for the material’s response along the loading path, and exhibits limited adaptability [29]. Consequently, when applied to multiaxial non-proportional loading conditions, the method often produces significant prediction deviations.

(2) Energy Method. To predict metal fatigue life, OSTERGREN applied the theory of calculating plastic work through stress-strain hysteresis loops, initially proposed by FELTNER [37,38]. Guard study further revealed an exponential relationship between crack life and the amount of plastic work performed, successfully extending this theory to multiaxial fatigue life prediction [39]. Considering the effects of mean stress and plasticity on the medium-high cycle uniaxial fatigue strength of common notched components, Benedetti refined and extended traditional elastoplastic methods, proposing a novel strain-energy-density-based fatigue criterion [40]. Gao et al. modified and generalized the conventional linear elastic strain energy density method by incorporating a novel exponential math model and material sensitivity parameters, significantly improving its applicability to medium-high cycle fatigue under wide stress ratios [41]. To address the unpredictability of failure locations and fatigue performance in aluminum alloy butt joints with fusion line defects under high-cycle fatigue, Chen established a defect competition behavior model based on linear elastic strain energy density. This model quantifies the effects of geometric parameters and residual stresses, with its accuracy validated through fatigue tests and finite element methods [42]. Sousa et al. developed a life prediction framework for bonded joints in composites and metals under medium-high cycle fatigue conditions using a strain energy density approach [43]. For thermo-mechanical fatigue life prediction, Sun et al. proposed a three-parameter power function equivalent energy method based on multiple conventional fatigue life prediction approaches. The validity of this method was verified through low-frequency fatigue test data of GH4133 material, demonstrating high computational accuracy and simultaneous fitting capability to fatigue test data at different strain ratios [44]. Although the energy method yields satisfactory predictions under uniaxial and multiaxial proportional loading conditions, its effectiveness varies depending on the specific energy form, applicable scenarios, and underlying physical mechanisms. For linear elastic strain energy methods: (1) These methods assume fully reversible energy dissipation. However, in medium/high-cycle fatigue, irreversible microscopic slip and dislocation motion occur [45], rendering elastic strain formulations inadequate for quantifying damage dissipation energy. (2) Formula modifications are required to characterize mean stress effects [46]. (3) Constrained by the macroscopic linear elasticity assumption, these methods fail in plasticity-dominated fatigue regimes [47]. For plastic strain energy methods: (1) As a scalar quantity, plastic work cannot fully capture fatigue damage mechanisms. (2) The approach neglects influences of mean stress and hydrostatic stress. (3) It becomes inappropriate when plastic strains are negligible [48].

(3) Critical Plane Method. The critical plane method, introduced by Brown and Miller integrates shear and normal strains within the plane of maximum shear strain [19]. Building on this foundation, Fatemi and Socie [20] proposed using stress instead of strain, enhancing the model’s utility. By incorporating a normal stress term, the method could account for the effects of additional reinforcement on fatigue life under low-circumferential fatigue conditions. To investigate proportional and non-proportional loading fatigue damage coefficients, Yakovchuk et al. compare the results of model calculations by Fatemi-Socie, Wang-Brown. with the experimental data obtained for 10 metal alloys and 6 multiaxial loading paths based on the theory of the critical plane method. The results show that the model correlates well with the experimental data for both proportional and non-proportional loading [49]. The critical plane method is widely used in the fatigue life calculation of metal materials. It reflects the microscopic mechanism of crack initiation and propagation to a certain extent, and the prediction results are good under non-proportional conditions of multi-axial loading. However, its applicability is also challenged under some special load conditions [50]. The study by Yang et al. integrates normal and shear stress failure criteria to implicitly capture phase-difference effects in non-proportional loading through multi-stress component combinations. This approach eliminates the dependency on explicit phase correction in conventional methods, providing a robust reference for life prediction of complex engineering components subjected to non-proportional loads [51]. Liu et al. proposed an enhanced critical plane approach for multiaxial fatigue life prediction by incorporating dynamic sensitivity coefficients, a shear stress intensification mechanism, and normal strain modification. This model accurately characterizes non-proportional additional hardening and crack propagation mechanisms, establishing a foundation for engineering applications in complex structural parts [52]. Qi et al. introduced the ratio of maximum shear stress amplitude to maximum normal stress amplitude, coupled with material fatigue parameters, to define distinct failure regimes on critical planes. Validated under multiaxial loading conditions including mean stresses, this model demonstrates superior prediction accuracy [53].

Although the critical plane approach demonstrates certain physical significance in damage parameter selection, its parameter determination has been controversial due to the lack of adherence to rigorous continuum mechanics theory. In recent years, some researchers have proposed the critical plane strain energy density method by integrating the advantages of energy-based methods and the critical plane approach [54–56]. Li et al. combined the critical plane method with strain energy density theory, introducing a damage proportionality model to simultaneously account for material failure modes and both normal and shear strain energy components. This provides a more comprehensive characterization of damage mechanisms under multiaxial loading [57]. Hao et al. improved the model by constructing a modified equivalent shear stress that incorporates a weighting function to characterize the influence of normal stress. The enhanced strain energy-based critical plane model effectively captures non-proportional additional hardening without requiring additional parameters [58].

This paper proposes a deep learning-based model for predicting the fatigue life of metals under multiaxial loading conditions. First, the key characteristic parameters influencing multiaxial fatigue were identified through an extensive review of the literature [30,59,60]. Next, timing data were selected based on the loading waveform and integrated with the characteristic parameters to create the model’s input data, encompassing both timing and loading features [61–63]. Finally, the optimal model parameters were determined through training, enabling the establishment of a comprehensive mapping relationship between the input features and fatigue life. This approach facilitates the accurate and reliable prediction of the fatigue life of metallic materials [64].

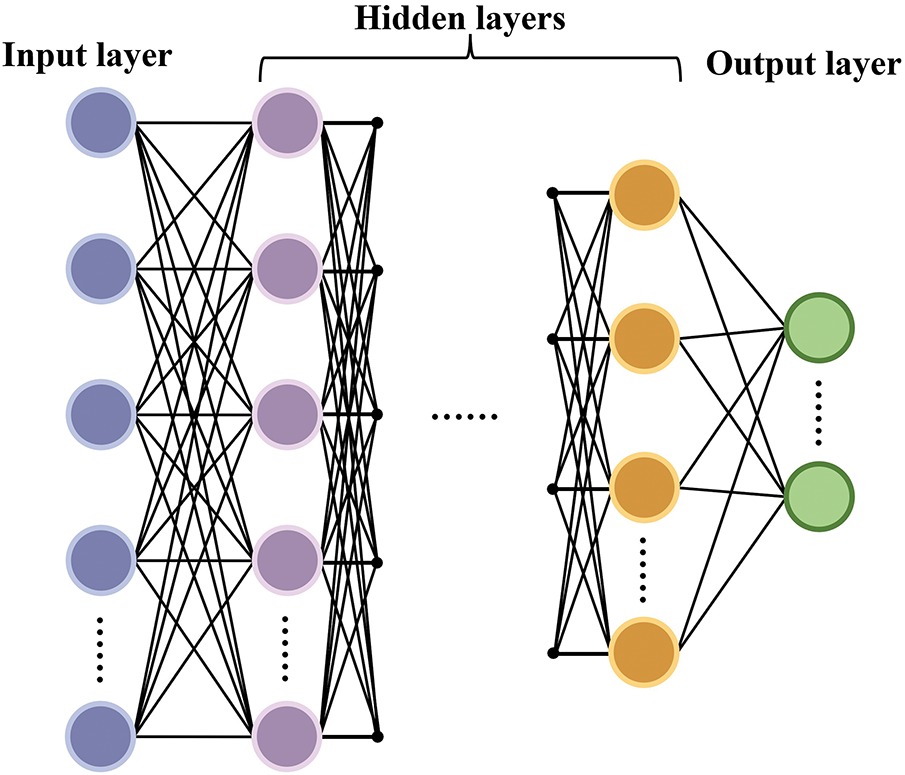

A fully connected neural network consists of three main layers: the input layer, hidden layers, and the output layer. This structure is depicted in Fig. 1. Through iterative training, the network learns a complex non-linear mapping between the input feature set (x) and the output (y), enabling accurate modeling of intricate relationships [30].

where

Figure 1: Diagram of fully connected neural network schematic

2.1 Fully Connected Neural Networks (FCNN)

where

2.2 Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

The primary structure of a convolutional Neural Network (CNN) consists of several key components: a convolutional layer, an activation function, a pooling layer, a fully connected layer, and an output layer. The structural configuration of the CNN model is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Diagram of convolutional neural network schematic

In Convolutional Neural Networks, the core operation is the accurate execution of the convolution process [65]. This is achieved through the use of a convolutional layer that scans each data value within the training or validation set. The activation function introduces nonlinearity to the model, enhancing the network’s ability to learn and predict complex relationships. The pooling layer reduces the spatial dimensions of the data, extracting key features for subsequent processing while also decreasing computational demands. Finally, the fully connected layer, typically located at the end of the network, integrates the distributed features into a unified representation.

2.3 Long Short-Term Memory Neural Network (LSTM)

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) is a special variant of the Recurrent Neural Network (RNN). The distinction between these two types of networks lies in their differing approaches to computing hidden states, with LSTM utilising specific functions to achieve this. The LSTM model is comprised of four primary structural components: the forget gate, input gate, state update, and output gate. The overall structure of the LSTM model is illustrated in Fig. 3. The forget gate will read the previous output, designated as ht-1, and the current input, denoted as x, and subsequently output the vector, designated as ft, following a nonlinear mapping operation (Eq. (3)). The input gate is comprised of two distinct phases. The initial phase entails the determination of the update state value through the application of a nonlinear mapping function. Secondly, the candidate parameter Ct is derived through the application of the activation function Tanh (Eqs. (4) and (5)). The objective of the state update is to transition Ct-1 to Ct (Eq. (6)).

Figure 3: Diagram of long short-term memory neural network schematic

The output gate is also composed of two processes. First, the output is determined using the sigmoid activation function. Then, the model state is processed through the Tanh activation function, and the resulting output is multiplied by the value from the previous step to produce the final output (Eqs. (7) and (8)).

2.4 Feature Parameter Selection

To investigate the effect of multiaxial loading on fatigue life, literature [66] presents experimental fatigue data from a selection of different materials. For the purpose of this study, eight materials—Haynes 188 [62], Titanium Alloy TC4 [64], 7075T651 [62], and LY12CZ [59] are selected for analysis. The characteristic coefficients representing the load are chosen for further examination.

The materials Haynes 188 and Titanium Alloy TC4 were subjected to stress-controlled testing, while 7075T651 and LY12CZ underwent strain-controlled testing. All materials were tested at ambient temperature, except for Haynes 188, which was tested at

The phase difference has been shown to significantly influence the fatigue life of metallic materials [67]. To investigate this effect, two materials Q235 [62] and Titanium Alloy TC4 [64] were selected for fatigue testing using strain-controlled conditions. Due to the presence of phase difference, the relationship between equivalent strain amplitude and fatigue life exhibits opposite trends for the two materials. With increasing equivalent strain amplitude and phase difference angle, the fatigue life of Q235 steel specimens monotonically decreases. Conversely, for Titanium Alloy TC4, larger phase difference angles result in fatigue life that exceeds that under in-phase loading conditions.

In this study, two materials Q235 and aluminum alloy 2A12 [63] were selected for analysis. These materials were subjected to different loading waveforms under strain-controlled conditions. The objective was to compare the fatigue life data obtained from the tests. The waveforms, which included sinusoidal, triangular, and square waveforms, were analyzed to determine their impact on the fatigue life of the metals.

To investigate the experimental fatigue life of metallic materials under different loading frequency ratios, two materials E335 [62] and PA38-T6Al [63] were selected for the study. The results show a positive correlation between fatigue life and loading frequency ratio. However, when the frequency ratio is below 1, the difference in fatigue life is either minimal or positive (for PA38-T6Al). Furthermore, it is shown that a small change in the frequency ratio can lead to a shift in the loading path.

In conclusion, the key factors influencing the fatigue life of metals have been identified, including amplitude, mean value, phase difference, loading waveform, and frequency ratio. Additionally, the critical timing points have been selected, which, together, form the input characteristic parameters for the model.

Generally, traditional fatigue prediction models focus on establishing a functional mapping relationship between damage parameters and fatigue life [68]. However, the function mapping for multiaxial fatigue is inherently complex, primarily due to the intricate microfatigue mechanisms involved. Deriving this relationship through straightforward logical deduction is a challenging task. Nonetheless, this complex mapping relationship can be effectively derived using machine learning techniques.

Fig. 4 illustrates the STFAN model for predicting the fatigue life of metallic materials using deep learning techniques. In this example, the model’s prediction process is demonstrated with a sinusoidal loading waveform.

Figure 4: Diagram of STFAN fatigue life prediction model

The following schematic illustrates the STFAN fatigue life prediction model. It is assumed that when the material is subjected to stress-controlled conditions, both the normal and shear stresses follow a sinusoidal waveform. The shape of the curves for these stresses may be influenced by the phase difference angle and the loading frequency ratio.

A series of data points are selected at equal intervals along the curve, based on a specific period, to form a feature matrix. This matrix serves as the input for both the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and the Long Short-Term Memory neural network (LSTM). The neural network then extracts the temporal characteristics of the multiaxial fatigue loading. The selected key parameters influencing the loading paths are used to create a new fatigue life prediction feature matrix, which serves as the input for the Fully Connected Neural Network (FCNN).

The newly developed feature matrix includes not only the time-series features of the fatigue loading condition but also key covariates that may influence the loading path, such as the phase difference angle and magnitude. Table 1 illustrates the parameters used during the model training process.

Currently, fatigue life prediction methods based on material physical mechanisms are widely used. These methods address the fatigue mechanisms under multiaxial loading conditions by establishing a mapping relationship between various damage coefficients and fatigue life. This approach is outlined in the referenced works [69]. Commonly used prediction models include the Equivalent Strain Method (ESM, Eqs. (9) and (10)), the Maximum Shear Strain Method (MSSM, Eq. (11)), and the Critical Plane Method, among others (FS, Eq. (12)) [17]. Their mathematical expressions are provided below:

The fatigue life of TC4 titanium alloy under different working conditions is predicted using fatigue life prediction methods based on physical mechanisms [64], as indicated by the test data for various fatigue loading conditions of TC4 titanium alloy material. The Equivalent Effect Strain Method (ESM), the Maximum Shear Strain Method (MSSM), and the Critical Plane Method (FS) are employed, in addition to the STFAN-based fatigue life prediction model using deep learning proposed in this paper. The relevant parameters, as illustrated in Eqs. (9)–(12) and Table 2, are used in the calculation of fatigue life using the physical mechanism-based methods. In contrast, the fatigue life prediction for the material using the deep learning method is computed by the model shown in Fig. 4. The multiaxial loading condition test life is presented as an error band diagram for comparative analysis with the fatigue life predicted by the four methods, as shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Diagram of prediction results of fatigue life prediction model based on physical mechanism are compared with those of STFAN model

In the Fig. 5, panels (a), (b), (c), and (d) present a comparative analysis of the prediction outcomes against the experimental results obtained using the Equivalent Strain Method (ESM), the Maximum Shear Strain Method (MSSM), the Critical Plane Method (FS), and the Deep Learning Model (STFAN), respectively. The black dotted line represents the 1.5 times error band, the black solid line represents the 2 times error band, the horizontal axis indicates the predicted fatigue life, and the vertical axis represents the true fatigue life of the material obtained from testing. The model’s prediction accuracy is considered satisfactory if the result falls within the specified error band. A higher level of accuracy is indicated when the result lies within the 1.5 times error band, and an even higher level of accuracy is indicated when the result falls on the fitted straight line [30].

As illustrated in Fig. 5a, the fatigue life prediction of TC4 using the ESM method is largely satisfactory for low-cycle fatigue with the data predominantly falling within the 2-fold error band. However, as the number of fatigue cycles increases (

Fig. 5c shows that the predicted fatigue life of TC4 using the FS method remains largely within the acceptable range, with most data points falling within the 2-fold error band. However, as the number of test cycles exceeds, some data points deviate from the 2-fold error band, suggesting potential inaccuracies in the prediction at this stage. As depicted in Fig. 5d, the projected fatigue life of TC4 using the STFAN model is generally accurate, with only a few data points falling outside the 2-fold error band, especially when the number of fatigue test cycles exceeds. In most cases, the prediction results fall within the 1.5-fold error band, demonstrating the model’s high accuracy and satisfactory performance. In particular, at low fatigue cycles (less than

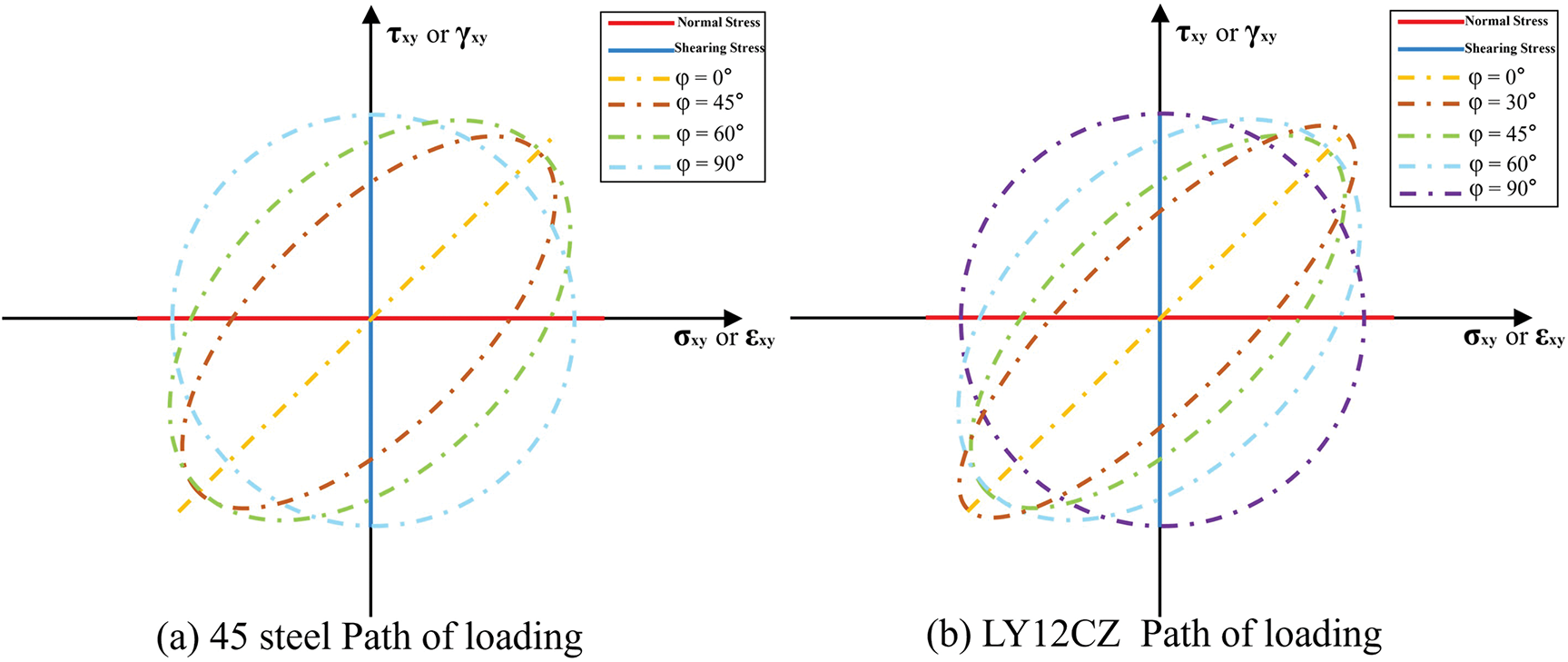

As shown in Fig. 5, the accuracy of the prediction results of the four material fatigue life prediction methods on TC4 titanium alloy is: STFAN > FS > ESM > MSSM. Notably, when the STFAN model is used to predict the fatigue life of TC4 material, some data points fall outside the 2-fold error band for low-cycle fatigue (less than cycles). However, the predictions tend to be conservative compared to the actual fatigue life test results. This raises the question of whether the model might have a tendency to provide conservative predictions with reduced accuracy under low-cycle fatigue conditions. The next phase of the study will address potential issues with the model and evaluate its generalization capacity, or its ability to make accurate predictions on datasets it has not encountered before. To this end, four different materials [59], each with distinct loading paths, have been selected for further analysis. The data have been divided into training, validation, and test sets to assess the accuracy of the STFAN model’s predictions for low-cycle fatigue. The loading paths of the test materials are illustrated in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Diagram of representative loading path of four kinds of material fatigue test process

Fig. 6 illustrates the relationship between the multiaxial fatigue loading path and the stress-strain response for four distinct materials. For 45 steel [61–63] and the aluminum alloys LY12CZ and 1Cr-Mo-V [59,62], three factors must be considered when examining the effects of multiaxial fatigue loading: uniaxial stress, torsion, and phase difference. In the case of material E335 [62], the loading frequency ratio, which varies between 0.25 and 6, must also be accounted for. Fig. 6a to c demonstrates how the material responds to uniaxial and torsional forces when the loading path is aligned with the coordinate axes, with a

As shown in Fig. 7, the fatigue loading conditions for 45 steel are relatively simple, as they consider only the effect of phase difference variations on the material’s fatigue life. The results of using the STFAN model to predict the material’s fatigue life are highly satisfactory, with most of the data falling within the range of the fitted straight line. The fatigue loading of LY12CZ material was analyzed with respect to its effect on the material’s fatigue life, considering phase differences ranging from

Figure 7: Diagram of 45 steel exists mean and non-proportional loading model prediction results

As shown in Fig. 8, the results of using the STFAN model to predict the material’s fatigue life are favorable. The data points align closely with the fitted straight line, with most falling within the 1.5 times error band, and all points within the 2 times error band. A comparative analysis of the fatigue loading conditions for 1Cr-Mo-V and LY12CZ materials reveals that the 1Cr-Mo-V material exhibits improved performance when the phase difference exceeds

Figure 8: Diagram of LY12CZ has mean and non-proportional loading model prediction results

As shown in Fig. 9, the results of using the STFAN model to predict the fatigue life of the 1Cr-Mo-V material are promising. A subset of the data points falls on the fitted straight line, the majority are within the 1.5-fold error band, and all data points lie within the 2-fold error band.

Figure 9: Diagram of 1Cr-Mo-V non-proportional loading model prediction results

Fig. 10 illustrates the multiaxial fatigue life error bands for material E335 under various loading ratios. The STFAN model demonstrates strong predictive capability for material E335 subjected to different fatigue loading conditions, including frequency ratios between 0.25 and 6 and phase difference angles of

Figure 10: Diagram of E335 non-proportional loading and variable load ratio model prediction results

The multiaxial fatigue prediction results of the above four materials show that the model has strong prediction ability under low cycle fatigue conditions.

Traditional multiaxial fatigue life prediction methods often lead to “distorted” predictions due to their limited focus on only part of the physical mechanisms influencing fatigue life—primarily the loading process. A critical factor that is frequently overlooked is the effect of load timing on fatigue life. To overcome the limitations of conventional methods, this study introduces a deep learning-based multiaxial fatigue prediction model (STFAN model) that simultaneously incorporates the physical mechanisms throughout the loading process and load sequence effects (the sequential coupling effect under non-proportional loading). The aim of this study is to assess the predictive accuracy of the proposed model by integrating key loading conditions from existing multiaxial fatigue studies. Five sets of fatigue test data from various materials were utilized, and the results confirm that the deep learning-based STFAN model demonstrates excellent predictive performance. This approach offers potential solutions to alleviate the industrial challenge of expensive full-scale fatigue testing for high-speed train components (e.g., wheelsets and bogies).

(1) The multiaxial fatigue life prediction model proposed in this paper leverages deep learning techniques and is applicable to a variety of common multiaxial loading conditions and their combinations, such as uniaxial and torsional loading. Additionally, it offers improved accuracy in predicting the fatigue life of materials subjected to both proportional and non-proportional loading paths.

(2) The model incorporates input parameters that simultaneously account for the load-time sequence characteristics, stress amplitude, mean value, frequency ratio, phase difference angle, and other key factors influencing the fatigue life of the material under multiaxial loading conditions. This comprehensive approach enables a more accurate representation of the material’s physical response to complex loading scenarios.

(3) The proposed prediction model is versatile and not restricted to specific materials or loading conditions. To evaluate its predictive capability, five distinct metal materials and various loading conditions were tested. The majority of the predicted data fell within 1.5 times the error band, and all data points remained within 2 times the error band, demonstrating the model’s strong predictive performance.

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge the support from the Key Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Science and Technology Research and Development Program Project of China Railway Group Co., Ltd.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by Key Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (U2368215) and the Science and Technology Research and Development Program Project of China Railway Group Co., Ltd. (N2023J056).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Jing Yang, Zhiming Liu, Beitong Li and Kaiyang Liu; methodology, Jing Yang, Xingchao Li and Zhongyao Wang; software, Xingchao Li; validation, Jing Yang, Zhiming Liu, Xingchao Li and Zhongyao Wang; formal analysis, Jing Yang; investigation, Jing Yang, Xingchao Li and Zhongyao Wang; resources, Zhiming Liu; data curation, Jing Yang; writing—original draft preparation, Jing Yang, Beitong Li, Kaiyang Liu and Wang Long; writing—review and editing, Zhiming Liu, Xingchao Li and Zhongyao Wang; visualization, Xingchao Li and Zhongyao Wang; supervision, Zhiming Liu; project administration, Zhiming Liu; funding acquisition, Zhiming Liu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data will be made available on request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

1. Rex AV, Paul SK, Singh A. The influence of equi-biaxial and uniaxial tensile pre-strain on the low cycle fatigue performance of the AA2024-T4 aluminium alloy. Int J Fatigue. 2023;173:107699. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2023.107699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Fatemi A, Molaei R, Phan N. Multiaxial fatigue of additive manufactured metals: performance, analysis, and applications. Int J Fatigue. 2020;134:105479. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2020.105479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Pagliari L, Concli F. A review of multiaxial low-cycle fatigue criteria for life prediction of metals. Int J Damage Mech. 2025;34(3):377–414. doi:10.1177/10567895241280788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Pineau A, Bathias C. Faigue of materials and structures: fundamentals. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley: London; 2010. [Google Scholar]

5. Fatemi A, Shamsaei N. Multiaxial fatigue: an overview and some approximation models for life estimation. Int J Fatigue. 2011;33(8):948–58. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2011.01.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Chen CY. Fatigue and fracture. Wuhan, China: Huazhong University of Science and Technology Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

7. Reis L, Li B, de Freitas M. Crack initiation and growth path under multiaxial fatigue loading in structural steels. Int J Fatigue. 2009;31(11–12):1660–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2009.01.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Chen X, Gao Q, Sun XF. Damage analysis of low-cycle fatigue under non-proportional loading. Int J Fatigue. 1994;16(3):221–5. doi:10.1016/0142-1123(94)90007-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Albinmousa J, Jahed H. Multiaxial effects on LCF behaviour and fatigue failure of AZ31B magnesium extrusion. Int J Fatigue. 2014;67:103–16. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2014.01.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Xiao L, Bai JL. Biaxial fatigue behavior and microscopic deformation mechanism of zircaloy-4,Biaxial fatigue deformation behavior of Zircaloy-4. Acta Metallurgica Sin. 2000;36(9):913–8. [Google Scholar]

11. Zhang J, Shi X, Bao R, Fei B. Tension-torsion high-cycle fatigue failure analysis of 2A12-T4 aluminum alloy with different stress ratios. Int J Fatigue. 2011;33(8):1066–74. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2010.12.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. McDiarmid DL. Fatigue under out-of-phase bending and torsion. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct. 1987;9(6):457–75. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2695.1987.tb00471.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Sonsino CM. Influence of material’s ductility and local deformation mode on multiaxial fatigue response. Int J Fatigue. 2011;33(8):930–47. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2011.01.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhao B, Song J, Xie L, Ma H, Li H, Ren J, et al. Multiaxial fatigue life prediction method based on the back-propagation neural network. Int J Fatigue. 2023;166(33):107274. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2022.107274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhan Z, Li H. A novel approach based on the elastoplastic fatigue damage and machine learning models for life prediction of aerospace alloy parts fabricated by additive manufacturing. Int J Fatigue. 2021;145(2):106089. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2020.106089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zamrik SY, Frishmuth RE. The effects of out-of-phase biaxial-strain cycling on low-cycle fatigue: experimental investigation shows a particular phase effect on crack growth and failure mode in the selected low-cycle-fatigue range. Exp Mech. 1973;13(5):204–8. doi:10.1007/bf02322654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Kanazawa K, Miller KJ, Brown MW. Low-cycle fatigue under out-of-phase loading conditions. J Eng Mater Technol. 1977;99(3):222–8. doi:10.1115/1.3443523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Brown MW, Miller KJ. High temperature low cycle biaxial fatigue of two steels. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct. 1979;1(2):217–29. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2695.1979.tb00379.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Brown MW, Miller KJ. A theory for fatigue failure under multiaxial stress-strain conditions. Proc Inst Mech Eng. 1973;187(1):745–55. doi:10.1243/pime_proc_1973_187_069_02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Fatemi A, Socie DF. A critical plane approach to multiaxial fatigue damage including out-of-phase loading. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct. 1988;11(3):149–65. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2695.1988.tb01169.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hamada A, Elyamny S, Abd-Elaziem W, Elkatatny S, Darwish MA, Sebaey TA, et al. Advancing fatigue life prediction with machine learning: a review. Mater Today Commun. 2025;43:111525. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2025.111525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Srinivasan VS, Valsan M, Bhanu Sankara Rao K, Mannan SL, Raj B. Low cycle fatigue and creep-fatigue interaction behavior of 316L(N) stainless steel and life prediction by artificial neural network approach. Int J Fatigue. 2003;25(12):1327–38. doi:10.1016/S0142-1123(03)00064-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Vassilopoulos AP, Georgopoulos EF, Dionysopoulos V. Artificial neural networks in spectrum fatigue life prediction of composite materials. Int J Fatigue. 2007;29(1):20–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2006.03.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Barbosa JF, Correia JAFO, Júnior RCSF, De Jesus AMP. Fatigue life prediction of metallic materials considering mean stress effects by means of an artificial neural network. Int J Fatigue. 2020;135:105527. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2020.105527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Al-Assaf Y, El Kadi H. Fatigue life prediction of unidirectional glass fiber/epoxy composite laminae using neural networks. Compos Struct. 2001;53(1):65–71. doi:10.1016/S0263-8223(00)00179-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ramachandra S, Durodola JF, Fellows NA, Gerguri S, Thite A. Experimental validation of an ANN model for random loading fatigue analysis. Int J Fatigue. 2019;126(31):112–21. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2019.04.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yang J, Kang G, Liu Y, Chen K, Kan Q. Life prediction for rate-dependent low-cycle fatigue of PA6 polymer considering ratchetting: semi-empirical model and neural network based approach. Int J Fatigue. 2020;136:105619. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2020.105619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Yang Y, Zhang B, Wu H, Zhang Y, Zhang H, Liu Y, et al. A deep learning approach for low-cycle fatigue life prediction under thermal-mechanical loading based on a novel neural network model. Eng Fract Mech. 2024;306:110239. doi:10.1016/j.engfracmech.2024.110239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Sun GQ, Shang DG, Wang Y. Research progress on fatigue behavior and life prediction under multiaxial loading for metals. J Mech Eng. 2021;57(16):153. doi:10.3901/jme.2021.16.153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Yang J, Kang G, Liu Y, Kan Q. A novel method of multiaxial fatigue life prediction based on deep learning. Int J Fatigue. 2021;151(4):106356. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2021.106356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zheng Z, Li X, Sun T, Huang Z, Xie C. Multiaxial fatigue life prediction of metals considering loading paths by image recognition and machine learning. Eng Fail Anal. 2023;143(4):106851. doi:10.1016/j.engfailanal.2022.106851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zheng ZG, Zhang J, Sun T, Xie CJ, Huang Z. Multi-axial fatigue life prediction of titanium alloy based on neural network of load phase difference. Chin J Nonferrous Met. 2023;33(3):781–91. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

33. Gan L, Wu H, Zhong Z. Multiaxial fatigue life prediction based on a simplified energy-based model. Int J Fatigue. 2021;144(12):106036. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2020.106036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Feng ES, Wang XG, Jiang C. A new multiaxial fatigue model for life prediction based on energy dissipation evaluation. Int J Fatigue. 2019;122:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2019.01.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Yang L, Yang B, Yang G, Jiang L, Xiao S, Zhu T. Fatigue evaluation method based on equivalent structural stress approach for bolted connections. Int J Fatigue. 2023;174(1442):107738. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2023.107738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Li J, Zhang Q, Bao Y, Zhu J, Chen L, Bu Y. An equivalent structural stress-based fatigue evaluation framework for rib-to-deck welded joints in orthotropic steel deck. Eng Struct. 2019;196(1):109304. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2019.109304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Ostergren WJ. A damage function and associated failure equations for predicting hold time and frequency effects in elevated temperature, low cycle fatigue. J Test Eval. 1976;4(5):327–39. doi:10.1520/jte10520j. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Feltner CE, Morrow JD. Microplastic strain hysteresis energy as a criterion for fatigue fracture. J Basic Eng. 1961;83(1):15–22. doi:10.1115/1.3658884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Garud YS. A new approach to the evaluation of fatigue under multiaxial loadings. J Eng Mater Technol. 1981;103(2):118–25. doi:10.1115/1.3224982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Benedetti M, Berto F, Le Bone L, Santus C. A novel Strain-Energy-Density based fatigue criterion accounting for mean stress and plasticity effects on the medium-to-high-cycle uniaxial fatigue strength of plain and notched components. Int J Fatigue. 2020;133(3):105397. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2019.105397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Gao F, Xie L, Liu T, Song B, Pang S, Wang X. An equivalent strain energy density model for fatigue life prediction under large compressive mean stress. Int J Fatigue. 2023;177(21):107899. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2023.107899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Chen Z, Wang P, Liu Y, Qian H. Analysis of high-cycle fatigue behavior for inherently defective butt joints using strain energy density method. Int J Fatigue. 2025;193:108770. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2024.108770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Sousa FC, Akhavan-Safar A, Carbas RJC, Marques WAS, da Silva LFM. A unified strain energy-based fatigue life prediction methodology for composite and metal adhesive joints: effects of adhesive, geometry and environment. Int J Fatigue. 2025;292(4):107899. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2024.112022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Sun JH, Yang ZC, Chen GB. Research on three-parameter power function equivalent energy method for high temperature strain fatigue. In: 2010 The 2nd International Conference on Industrial Mechatronics and Automation; 2010 May 30–31; Wuhan, China: IEEE; 2010. p. 84–7. doi:10.1109/ICINDMA.2010.5538086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Mughrabi H. Cyclic plasticity and fatigue of metals. J Phys IV France. 1993;3(C7):C7-659–68. doi:10.1051/jp4:19937105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Zhu S, Yue P, Correia J, Blason S, De Jesus A, Wang Q. Strain energy-based fatigue life prediction under variable amplitude loadings. Struct Eng Mech. 2018;66(2):151–60. doi:10.12989/sem.2018.66.2.151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Mi CJ, Hai Y, Xie X, Zhang D, Li YQ, Xiao YG, et al. A method for calculating the fatigue life of welds under pre-strain based on strain energy density. C.N. Patent No. CN 202310228999.4. [Google Scholar]

48. Ellyin F, Kujawski D. Plastic strain energy in fatigue failure. J Press Vessel Technol. 1984;106(4):342–7. doi:10.1115/1.3264362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Yakovchuk PV, Savchuk EV, Shukayev SM. Critical plane approach-based fatigue life prediction for multiaxial loading: a new model and its verification. Strength Mater. 2024;56(2):281–91. doi:10.1007/s11223-024-00647-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Karolczuk A, Macha E. A review of critical plane orientations in multiaxial fatigue failure criteria of metallic materials. Int J Fract. 2005;134(3):267–304. doi:10.1007/s10704-005-1088-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Yang J, Gong Y, Jiang L, Lin W, Liu H. A multi-axial and high-cycle fatigue life prediction model based on critical plane criterion. J Mater Res Technol. 2022;18:4549–63. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.04.069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Liu J, Ran Y, Wei Y, Zhang Z. A critical plane-based multiaxial fatigue life prediction method considering the material sensitivity and the shear stress. Int J Press Vessels Pip. 2021;194(1):104532. doi:10.1016/j.ijpvp.2021.104532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Qi X, Liu T, Shi X, Wang J, Zhang J, Fei B. A sectional critical plane model for multiaxial high-cycle fatigue life prediction. Fatigue Fract Eng Mat Struct. 2021;44(3):689–704. doi:10.1111/ffe.13386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Das J, Sivakumar SM. Multiaxial fatigue life prediction of a high temperature steam turbine rotor using a critical plane approach. Eng Fail Anal. 2000;7(5):347–58. doi:10.1016/S1350-6307(99)00025-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Park J, Nelson D. Evaluation of an energy-based approach and a critical plane approach for predicting constant amplitude multiaxial fatigue life. Int J Fatigue. 2000;22(1):23–39. doi:10.1016/S0142-1123(99)00111-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Chen Xu, Huang. A critical plane-strain energy density criterion for multiaxial low-cycle fatigue life under non-proportional loading. Fat Frac Eng Mat Struct. 1999;22(8):679–86. doi:10.1046/j.1460-2695.1999.00199.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Li H, Zhang J, Shen HZ, Wei XL. Multiaxial fatigue experiments and life prediction for silicone sealant bonding butt-joints. Theor Appl Fract Mech. 2019;103(7–9):102245. doi:10.1016/j.tafmec.2019.102245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Hao MF, Zhu SP, Xia FL. Multiaxial fatigue life evaluation using strain energy-based critical plane approach. Procedia Struct Integr. 2019;22(5):78–83. doi:10.1016/j.prostr.2020.01.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Zhang CC. High cycle fatigue life analysis of structure under complex stress field [MASC thesis]. Nanjing, China: Nanjing University of Astronautics; 2010. [Google Scholar]

60. Liu CC. Ultiaxial low cycle fatigue failure analysis and life prediction of 7075 aluminum alloy [MASC thesis]. Tianjin, China: Civil Aviation University of China; 2018. [Google Scholar]

61. Karolczuk A, Kluger K, Palin-Luc T. Fatigue failure probability estimation of the 7075-T651 aluminum alloy under multiaxial loading based on the life-dependent material parameters concept. Int J Fatigue. 2021;147:106174. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2021.106174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Arora P, Gupta SK, Samal MK, Chattopadhyay J. Validating generality of recently developed critical plane model for fatigue life assessments using multiaxial test database on seventeen different materials. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct. 2020;43(7):1327–52. doi:10.1111/ffe.13169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Liu B. Study on the failure of metal materials under tension-torsion composite stress conditions [MASC thesis]. Tianjin, China: Civil Aviation University of China; 2018. [Google Scholar]

64. Wu ZR, Hu XT, Song YD. Multiaxial fatigue life prediction for titanium alloy TC4 under proportional and nonproportional loading. Int J Fatigue. 2014;59(65):170–5. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2013.08.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Sun Y, Li S. Bearing fault diagnosis based on optimal convolution neural network. Measurement. 2022;190(18):110702. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2022.110702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Zhang J. Research on multiaxial fatigue life prediction model based on fully connected neural network [MASC thesis]. Nanning, China: Guangxi University; 2022. [Google Scholar]

67. Albinmousa J, Adinoyi MJ, Merah N. Multiaxial low-cycle-fatigue of stainless steel 410 alloy under proportional and non-proportional loading. Int J Press Vessels Pip. 2021;192:104393. doi:10.1016/j.ijpvp.2021.104393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Dong ZB, Wang CC, Li C. Review for research of fatigue life prediction of welded structures under complex loads and extreme environments. China Mech Eng. 2024;5:829–39. [Google Scholar]

69. Xu C, Liu G, Li Z, Huang Y. Multiaxial fatigue life prediction of tubular K-joints using an alternative structural stress approach. Ocean Eng. 2020;212:107598. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2020.107598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Foti P, Razavi N, Fatemi A, Berto F. Multiaxial fatigue of additively manufactured metallic components: a review of the failure mechanisms and fatigue life prediction methodologies. Prog Mater Sci. 2023;137:101126. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2023.101126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools