Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Novel Unsupervised Structural Attack and Defense for Graph Classification

1 School of Computer Science & Technology, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing, 100081, China

2 School of Computing, Institute of Science Tokyo, Tokyo, 152-8550, Japan

* Corresponding Author: Zhiwei Zhang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Deep Learning and Neural Networks: Architectures, Applications, and Challenges)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068590

Received 01 June 2025; Accepted 08 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have proven highly effective for graph classification across diverse fields such as social networks, bioinformatics, and finance, due to their capability to learn complex graph structures. However, despite their success, GNNs remain vulnerable to adversarial attacks that can significantly degrade their classification accuracy. Existing adversarial attack strategies primarily rely on label information to guide the attacks, which limits their applicability in scenarios where such information is scarce or unavailable. This paper introduces an innovative unsupervised attack method for graph classification, which operates without relying on label information, thereby enhancing its applicability in a broad range of scenarios. Specifically, our method first leverages a graph contrastive learning loss to learn high-quality graph embeddings by comparing different stochastic augmented views of the graphs. To effectively perturb the graphs, we then introduce an implicit estimator that measures the impact of various modifications on graph structures. The proposed strategy identifies and flips edges with the top-K highest scores, determined by the estimator, to maximize the degradation of the model’s performance. In addition, to defend against such attack, we propose a lightweight regularization-based defense mechanism that is specifically tailored to mitigate the structural perturbations introduced by our attack strategy. It enhances model robustness by enforcing embedding consistency and edge-level smoothness during training. We conduct experiments on six public TU graph classification datasets: NCI1, NCI109, Mutagenicity, ENZYMES, COLLAB, and DBLP_v1, to evaluate the effectiveness of our attack and defense strategies. Under an attack budget of 3, the maximum reduction in model accuracy reaches 6.67% on the Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) and 11.67% on the Graph Attention Network (GAT) across different datasets, indicating that our unsupervised method induces degradation comparable to state-of-the-art supervised attacks. Meanwhile, our defense achieves the highest accuracy recovery of 3.89% (GCN) and 5.00% (GAT), demonstrating improved robustness against structural perturbations.Keywords

Graph structures are fundamental to a wide range of real-world applications, including social networks [1], bioinformatics [2], communication networks [3], and chemical structures [4]. GNNs have shown outstanding performance across these fields due to their ability to capture both the structural and attribute information. In such cases, the task of graph classification [5–7], aiming to assign entire graphs to predefined categories, has been rapidly developed, supporting a wide range of complex applications.

However, recent research has shown that GNNs are vulnerable to adversarial attacks [8–13], where minor modifications to the graph, such as adding or removing edges or nodes, can cause significant performance degradation. For example, in drug discovery, competitors demonstrating vulnerabilities in the rival company’s model may damage the company’s reputation and hinder its drug development, thereby providing a competitive advantage [14]. In this case, attackers can subtly alter the connections or attributes within molecular structures. Such alterations can mislead the model into misclassifying toxic or harmful molecules as benign. This has the potential not only to derail drug development efforts but also to pose significant risks to human health in both clinical trials and practical applications. Therefore, graph evasion attacks not only threaten the robustness of the model but could also have severe consequences in real-world applications. Research on graph evasion attacks targeting graph classification tasks based on GNN models is particularly important.

In the evolution of adversarial research on GNNs, node-level tasks have received considerable attention, while studies on graph classification tasks are relatively scarce. Current attack methods for graph classification generally require direct or indirect access to graph label information to guide the adversarial training process. In white-box attacks, the gradient-based Gradargmax [15] method not only relies on label information from the dataset but also needs access to the target GNN’s parameters for backpropagation. In black box attacks, although it is not necessary to know the parameters of GNN and the true labels in the dataset, it is still necessary to query the model to obtain hard label information (i.e., know the predicted label of the model, but not the prediction probability related to that label). For example, Mu et al. [16] proposed a method that relies on hard-label information to guide the optimization process. RL-S2V [15] and Rewatt [17] based on reinforcement learning require label information to verify the success of the attack and determine the reward value. The dependence of all these methods on label information limits their practical applicability in real-world scenarios because, in practice, graph-structured data are typically easy to obtain, while reliable labels are often scarce due to annotation costs, privacy concerns, or regulatory constraints.

Recently, since labels are difficult to acquire, contrastive learning, as a novel unsupervised learning framework [18], exhibits performance comparable to supervised learning. As a self-supervised framework, graph contrastive learning encourages the model to learn highly discriminative embeddings that capture rich information of structural relationships. Due to the implicit “identifying differences” goal in contrastive learning training, the model is more sensitive to targeted perturbations, which are distinct from the normal noise of random data augmentation. This enhanced sensitivity provides an basis for guiding attacks because it can effectively identify perturbations that may most damage the core structural properties of the graph. However, graph contrastive learning in an unsupervised attack [19] for graph classification is a non-trivial task. Unlike continuous data in images, graphs are discrete, and how to utilize the results of contrastive learning to modify graph data for an effective attack is a challenge. In addition, our goal is to modify the graph so that it can affect the prediction results of downstream tasks. Therefore, an essential challenge is determining how to effectively evaluate the quality of the attacked graph.

To address these challenges, we propose a new unsupervised attack approach for graph classification, which leverages contrastive learning techniques to learn graph embeddings. Specifically, our method first utilizes graph contrastive learning models to extract representations of graphs. We generate different graph views using data augmentation, convert them into embeddings through a graph encoder, and employ a contrastive loss that encourages high similarity between views of the same graph, while reducing similarity across views from different graphs. Then, we propose an implicit estimator to measure the impact of various possible graph attacks (insert or delete edges) on graph classification. Finally, we alter the edges with the top-K highest scores from the estimator, effectively attacking the graph and consequently reducing the performance of graph classification.

In addition to the attack strategy, we further propose a lightweight defense mechanism that is specifically tailored to mitigate the structural perturbations introduced by our attack. Specifically, we introduce two regularization objectives: one promotes local smoothness between connected nodes, while the other encourages consistency between graph embeddings before and after perturbation. These terms can be seamlessly integrated into existing GNN training pipelines and yield significant defense gains.

The main contributions are as follows.

• We formulate a novel research problem: performing unsupervised evasion attacks and corresponding defense for graph classification tasks in a fully label-free setting. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work to address this problem and propose an effective framework under such constraints.

• We introduce an unsupervised method based on graph contrastive learning for conducting adversarial attacks in graph classification tasks.

• We propose an implicit estimator to measure the effects of graph modifications and perturb the graph via the estimator, thus degrading the overall performance of graph classification.

• We further design a tailored defense strategy consisting of two regularization objectives—edge-level smoothness and embedding-level consistency—that specifically mitigate the effects introduced by our proposed attack.

• Experiments on six public graph classification datasets show that our unsupervised method achieves competitive performance compared to state-of-the-art supervised attacks, and the proposed defense effectively mitigates the impact of our attack.

In the domain of graph adversarial attacks, these attacks can generally be divided into two main types based on the stage at which they occur: evasion attacks and poisoning attacks [20,21]. Since most attacks on graph classification are evasion attacks, we primarily elaborate on evasion attacks and briefly introduce poisoning attacks.

Evasion Attacks for GNNs. In evasion attacks, the model’s training parameters are assumed to remain unchanged. The attacker aims to generate adversarial samples that target the already trained model. This type of attack alters only the test data, without necessitating model retraining. Given our focus on this paradigm, we provide a targeted comparison of representative evasion attacks for graph-level classification in Table 1. The selection of methods is guided by the following inclusion criteria: we consider only attacks at the graph-level (excluding node-level and edge-level), operating under the evasion setting (excluding poisoning attacks), and select fundamental and representative methods from different attack strategies.

Dai et al. [15] provided a significant starting point for researching evasion attacks on GNNs by introducing RL-S2V, which is suitable for black-box attacks. Additionally, Ma et al. [17] proposed another reinforcement learning-based method, ReWatt. However, reinforcement learning-based methods are computationally intensive and often struggle to adapt to varying attack budgets. Diverging from the above two methods, Mu et al. [16] proposed an optimization-based approach in a black-box context, designing a symbolic stochastic gradient descent algorithm with guaranteed convergence. Wan et al. [22] proposed GRABNEL, a Bayesian optimization-based attack method that effectively misleads graph classification models under limited query budgets. Dai et al. [15] also introduced Gradargmax for white-box attacks, which greedily selects edges based on gradient information, though its performance in graph evasion attack tasks is average. Zhang et al. [23] designed a projection sorting method based on mutual information in the white-box attack scenario, which adapts to changes in the attack budget and requires prior knowledge of the node’s embedding and labels.

It’s worth noting that the aforementioned methods all require direct or indirect access to label information, which is often impractical in many real-world scenarios. Therefore, we focus on attack research solely based on raw graph data.

Poisoning Attacks for GNNs. In poisoning attacks, it is assumed that the attacker has the capability to modify the training data. The goal of a poisoning attack is to tamper with the learning algorithm itself by polluting the data it learns from, rather than exploiting vulnerabilities in an already trained model. Similar to evasion attacks, research on poisoning attacks [24–27] primarily focuses on labeled data. Zhang et al. [28] proposed an unsupervised poisoning attack targeting node classification in contrastive learning models. Their method performs attacks during the pretraining phase by leveraging gradient information to degrade the quality of node representations, and is specifically designed for downstream node classification tasks. In contrast, our work focuses on evasion attacks for graph classification, where the attacker perturbs the graph structure at test time without interfering with the training process. Our method employs contrastive learning and an implicit estimator to guide the attack, making it fundamentally different from Zhang et al. [28] in both task setting and attack paradigm.

3 Preliminaries and Problem Formulation

A graph set

Given a set of graphs

where

To achieve this, a loss function L is applied to quantify the discrepancy between the predicted and true labels. For each graph

where

GNNs are deep learning models designed specifically for graph-structured data. The fundamental concept behind GNNs is updating node representations via a message-passing mechanism. A typical GNN layer can be expressed as:

where

After propagating through L layers, a graph-level representation is obtained by aggregating the node-level embeddings through a readout function:

where L refers to the final layer of the GNN. The readout function is typically implemented using average, sum, or max pooling to capture global graph-level information effectively.

Attacker’s Knowledge and Capability. This paper focuses on evasion attacks against GNNs under a strict black-box setting. The attacker is assumed to have no access to the target model

Adversary’s Objective. The adversary’s objective is to subtly modify the graph structure (e.g., by adding or removing edges) without access to label information, aiming to degrade classification performance.

Generally, the objective of a non-targeted evasion attack on the victim model

G represents the original graph and G′ represents the modified graph after the attack.

As described in Section 3.1, GNNs derive graph-level representations through global pooling, which are then used to predict graph labels. The performance of graph classification depends on the quality of these representations, which aim to preserve key structural properties of the original graph in a lower-dimensional space. Therefore, if two graphs belong to different categories in the original space, their representations in the embedded space are likely to show significant differences. This difference also serves as a critical basis for machine learning models to distinguish between different categories.

Hence, in the absence of classification labels, we study a quantitative method to evaluate the similarity of graph embeddings before and after an attack. For vector representations, we can measure differences in magnitude and direction using Euclidean and cosine distances, respectively. However, since Euclidean distance is unbounded and highly sensitive to the scale of embedding vectors, it might overly emphasize changes in magnitude while neglecting significant structural changes. Therefore, we choose cosine distance as the primary metric for measuring differences between two graph embeddings.

Cosine distance focuses on the direction rather than the magnitude of vectors. By predicting cosine distance, we can more accurately capture and quantify changes in the direction of embedding representations caused by graph modifications, thereby identifying which modifications have the greatest impact on the graph embeddings.

Given this, our primary attack strategy revolves around maximizing the cosine distance between the embeddings before and after graph modifications. Since we do not have access to the target model or classification label information, we train an unsupervised model, parameterized by

The cosine distance between two graph representations is calculated as follows:

By the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality, the cosine similarity term

To achieve the above objective, after training the proxy model using contrastive learning, we train an implicit estimator to evaluate the impact of different edge modifications. We then rank these impact values to select the edges for modification, thereby maximizing the cosine distance by Eq. (6).

Defender’s Objective. In response to the adversary’s goal of degrading graph classification performance by introducing structure-level perturbations under a black-box, label-free setting, the defender aims to train a graph neural network model that is robust to such modifications. The objective is to ensure stable graph-level representations and accurate classification even when the graph structure is slightly perturbed.

Given an attacked graph G′, the defender’s objective is to maximize the classification accuracy of the model:

Our proposed method includes three stages: proxy model training, attack model training and attack execution. The detailed workflow of these stages is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Overview of the attack workflow. Steps ①, ②, and ③ correspond to our method’s three stages. The function

① Proxy Model Training Stage: To effectively train the proxy model without graph labels, we adopt graph contrastive learning to extract representations of graphs, as detailed in Section 4.2.

② Attack Model Training Stage: We introduce an implicit estimator to identify the most influential edges for the attack. Specifically, the estimator is trained to predict the impact of each edge modification (i.e., adding or removing edges) on the cosine distance between graph embeddings. This enables us to quantify how much each edge modification affects the graph’s classification performance, allowing for a more effective attack, as outlined in Section 4.3.

③ Attack Execution Stage: Once the estimator is trained, we use it to compute impact scores for each potential edge modification in the attacked graph. We then rank all edges based on these scores and select the top-K edges (where K is determined by the attack budget). These top-ranked edges are either added or removed, depending on their original presence in the graph. This process ensures that the most impactful modifications are made within the specified attack budget, maximizing the effectiveness of the attack, as described in Section 4.4.

4.2 Proxy Model Training Stage

In this stage, our goal is to train a proxy model capable of obtaining graph representations. We employ a GNN model [29] as the proxy model. Given that we do not have access to graph labels, we employ the graph contrastive learning technique from GraphCL [30] to pre-train GNNs.

To adapt contrastive learning to discrete graph-structured data, we use four stochastic graph augmentation strategies: node dropping, edge perturbation, subgraph sampling, and feature masking. These augmentations operate on the structural and attribute levels of graphs, generating diverse but semantically consistent views. They simulate perturbations that preserve the underlying semantics while introducing discrete variations to the graph topology or features. This is essential for contrastive learning on graphs, which lack the continuous spatial structure of images or text.

During the training phase, for each original graph, we randomly select two of the four augmentation techniques to obtain two perturbed versions of the same graph. These augmented graphs are then passed through a GNN with shared parameters to obtain their corresponding representations

The model is trained to maximize the similarity between the representations of positive pairs while pushing apart those of negative pairs in the latent space. This is achieved using the following loss:

where M represents the total number of graphs;

This training process encourages the model to learn highly discriminative embeddings with a deep understanding of structural relationships. The model becomes inherently more sensitive to abnormal, targeted perturbations that deviate from this learned distribution of “normal” noise. This enhanced sensitivity provides the foundation for our attack, as it allows the subsequent stages to effectively identify perturbations that can maximally disrupt the graph’s core structural properties.

4.3 Attack Model Training Stage

At this stage, we propose an implicit estimator to evaluate the impact of edge modifications on the graph-level representations. This impact is quantified by calculating the cosine distance between graph representations before and after the modifications.

For each potential edge in the graph, we construct its embedding by concatenating

This edge is then flipped—if it exists, the edge is removed; if not, the edge is added—resulting in an attacked graph

We compute the cosine distance

Here,

In our study, we employ the GNN model trained from contrastive learning to generate graph representations. Then the attack of a single edge will only cause a small change in the representation of the graph before and after the attack. As shown in Fig. 2, we present the distribution of cosine distances

Figure 2: The distribution of

Since only one edge is flipped at a time, the cosine distance between the graph embeddings before and after the modification remains very small. To ensure stable and efficient training of the neural network, we apply a scaling factor

Therefore, the loss function of estimator is computed by:

In the third stage, we leverage the trained estimator to predict the impact of modifying various edges on the overall graph features, aiming to execute an unsupervised attack by flipping the most critical edges.

Specifically, for each graph G, we rank all potential edges

It is important to note that we perform K modifications according to the specified attack budget. Previous research by [23] has demonstrated that the baseline graph for evaluating attack benefits should always be fixed to the clean graph, rather than any modified version. Therefore, given an attack budget K (i.e.,

where

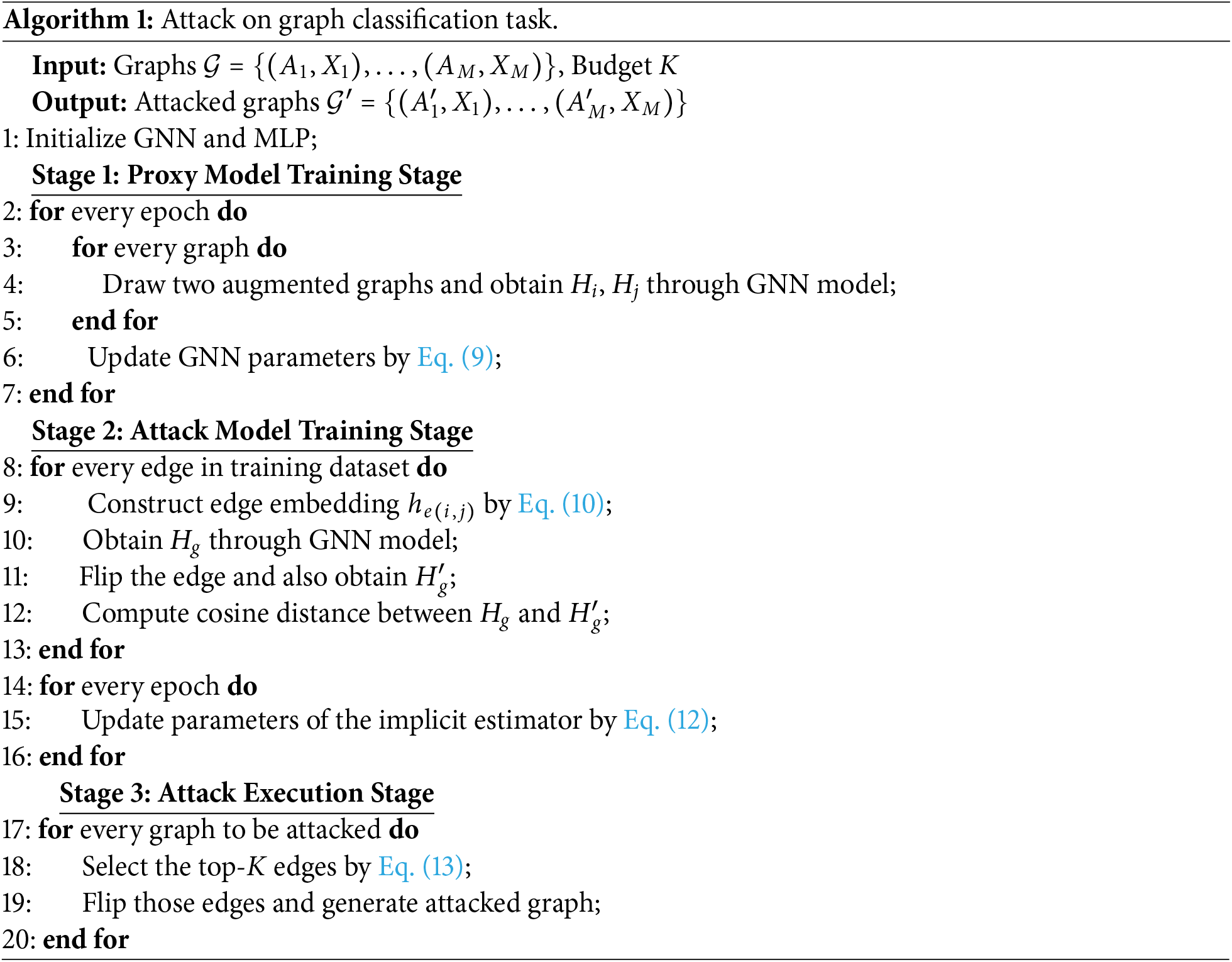

We summarized the overall process of our attack algorithm in Algorithm 1. Our attack method is divided into three stages, used to generate poisoned graphs. Firstly, during the training phase of the proxy model (lines 3–7), we perform data augmentation on each graph, then use the GNN to extract the embedding representation of the graph, and update the parameters of the GNN based on the contrastive loss. Next, in the attack model training phase (lines 8–12), we use the graph comparison learning model trained in the first stage to construct embedded representations of each edge as input, and calculate the cosine distance of the graph representation before and after edge flipping as labels to train the estimator. Finally, during the attack execution phase (lines 13–15), we feed each edge of the graph to be attacked into an estimator, and based on the score predicted by the estimator, select the top-K most critical edges for flipping to generate the attacked graph.

Time complexity: Our time complexity mainly depends on the model used for training, and our model uses a 3-layer GNN and a 2-layer MLP, so the time complexity is not high. Space complexity: As we calculate the score for each edge in the graph, the memory requirement is

To mitigate the impact of such attacks, we introduce two regularization terms that target both global and local vulnerabilities in the model’s representation space:

• Graph embedding consistency loss: This term directly constrains the change in global graph embeddings before and after small structural perturbations. It enforces representational stability by minimizing the directional deviation between the original and perturbed embeddings, which helps preserve prediction reliability under attack.

• Edge-level smoothness loss: This term reduces sensitivity to local perturbations by limiting the distance between embeddings of connected node pairs. This suppresses the amplification of perturbation effects during message passing and enhances local consistency in the learned representation.

These two objectives address different aspects of robustness: one at the global (graph-level) scale and the other at the local (edge-level) scale. Their combination yields a more comprehensive defense mechanism without introducing structural assumptions or modifying the model architecture.

5.1 Graph Embedding Consistency Loss

Considering that the core goal of the attack is to maximize the cosine distance between the graph embeddings before and after the perturbation, we propose a graph embedding invariance regularization term as a direct constraint on the robustness of structural perturbations. Specifically, during training, for each input graph G, we randomly add and remove edges with a fixed probability

where

5.2 Edge-Level Smoothness Loss

We know from the structure of the GNN model that graph embedding is generally obtained by readout of node embedding. Our attack method affects graph embedding and also causes fluctuations in local node representation. To this end, we introduce a edge-level smoothing regularization term to limit the distance between nodes on the connecting edge in the representation space and reduce the amplification effect caused by local changes in the structure. The specific form is as follows:

The final training objective jointly optimizes for classification accuracy and robustness under structural perturbations:

Here,

These two regularization objectives are designed to be complementary, forming a multi-scale defense mechanism. The

This defense strategy proactively simulates structural perturbations during training and guides the model to learn representations that are resilient to both local edge manipulations and global structural shifts. It is label-independent and thus compatible with unsupervised or contrastive pretraining settings. Our method effectively reduces performance degradation under the proposed attack.

This subsection elaborately details the experimental setup, encompassing the datasets used, baseline methods for comparison, and hyper-parameter settings.

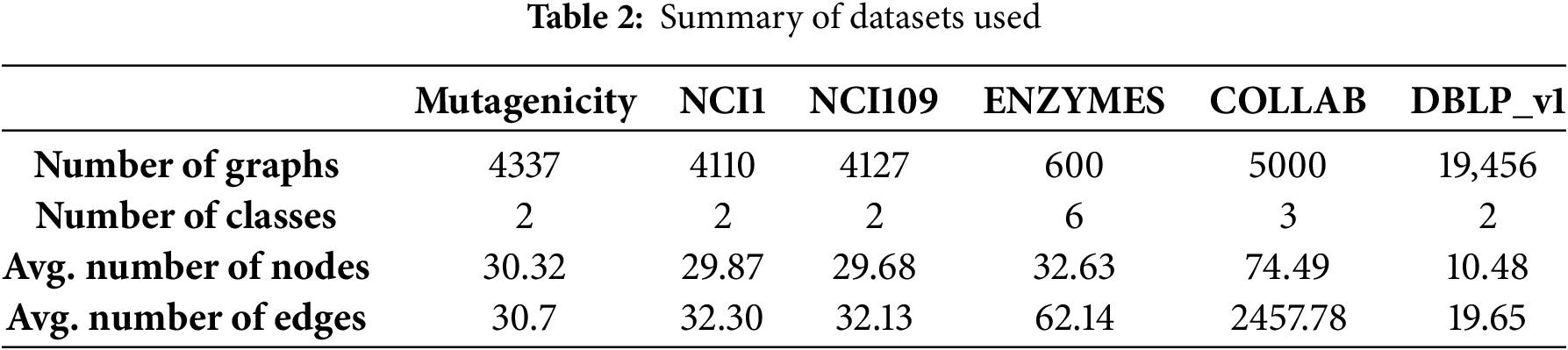

Datasets

To thoroughly evaluate our unsupervised attack method, we select six public datasets from bioinformatics, cheminformatics, and social networks: NCI1, NCI109, Mutagenicity, ENZYMES, COLLAB, and DBLP_v1. These datasets span diverse domains and differ in graph size, edge density, and classification complexity, allowing for a comprehensive assessment of attack generalizability across heterogeneous graph structures. A summary of these datasets is in Table 2. All datasets are split into training, validation, and test sets with a ratio of 8:1:1. Each evaluation is conducted using 10-fold cross-validation, and the average classification accuracy is reported.

• NCI1: This dataset includes 4110 chemical compounds, each represented in graph form, with nodes indicating atoms and edges signifying bonds. The goal is to classify these compounds based on their biological activity against non-small cell lung cancer and ovarian cancer cell lines.

• Mutagenicity: This dataset comprises 4337 chemical compounds, each labeled for its mutagenic or non-mutagenic properties. It serves as a crucial dataset for assessing the relationship between chemical structures and biological activity.

• ENZYMES: A protein structures dataset, consisting of 600 graphs, each representing the 3D structure of a protein. Each graph is classified into one of six different types of enzymes.

• NCI109: Provided by the National Cancer Institute, consisting of 4127 chemical compounds, mainly used in cancer-related research.

• COLLAB: A scientific collaboration dataset consisting of ego-networks of researchers from High Energy Physics, Condensed Matter Physics, and Astro Physics. The task is to classify each ego-network into one of these three fields.

• DBLP_v1: A citation graph dataset, where each graph represents a paper and its reference structure. The task is to classify each graph into either the database/data mining (DBDM) or computer vision/pattern recognition (CVPR) field.

Baseline. For the graph classification task in the unsupervised setting, there is no directly comparable existing work. Therefore, we design two baseline methods: a random attack and a degree-based attack. In the domain of supervised models, our comparative analysis is expanded to include the typical method GradArgmax, the state-of-the-art method Projective Ranking, and the black-box attack method ReWatt. The introduction of baselines is as follows:

• Unattacked. The GNN model is trained on without attacked graphs.

• Degree. This method inserts or removes edges between nodes with the highest degrees.

• Random. The GNN model is trained on poisoned graphs with randomly attacked edges.

• GradArgmax [15]. Select the edge with the largest absolute value of gradient to flip.

• Rewatt [17]. ReWatt performs structural attacks by applying rewiring operations and utilizes reinforcement learning to identify the optimal rewiring strategies.

• Projective Ranking [23]. Using mutual information, it sorts and evaluates the attack benefits of each disturbance to obtain effective attack strategies.

Hyper-Parameter Setting. For the baselines, we adhere to their default hyper-parameter settings. For our method, the GNN proxy model consists of three Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN) layers, each followed by a ReLU activation. The hidden dimension is set to 128, and a final global mean pooling is used as the readout function. The MLP-based implicit estimator includes two fully connected layers with hidden sizes of 128 and 64, respectively, using ReLU activations. The attack budget, denoted as budget, is crucial in determining the extent of modifications allowed in our attack strategy. We have considered multiple values for this parameter to assess its impact on the overall performance. Unless otherwise specified, we set the budget values to 1, 2, and 3. These values represent the number of edges that can be added or removed in the graph during the attack process.

Apart from the baseline hyper-parameters and the attack budget, several other hyper-parameters have been taken into account, including a learning rate of 0.001, 100 training epochs, and a batch size of 256. For defense,

6.2.1 Attacking Unsupervised Models

We first conduct attack tests on unsupervised graph embeddings. Specifically, we attack the graph contrastive learning proxy model proposed in the paper and assess the attack performance by training a predictor for downstream graph classification tasks. Given the unavailability of label information in unsupervised attack scenarios, we benchmark against random attacks due to the impracticality of conventional methods.

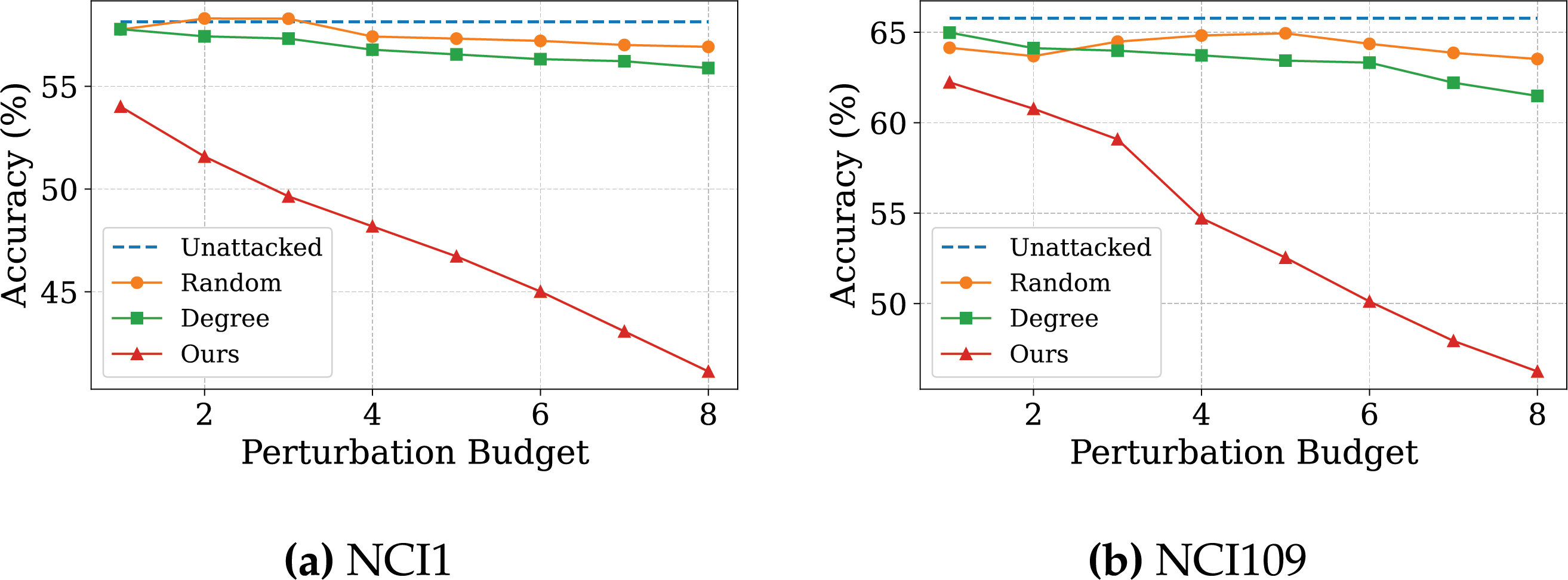

Fig. 3a–f illustrates the impact of our method on graph contrastive learning models under different attack budgets. With increasing attack budgets, the Random method exhibits minimal overall variation. Compared to the random attack, the Degree method achieves better overall attack performance, indicating that perturbations guided by structural information can be more destructive. However, this method relies solely on node degree—a static structural statistic—to select attack targets, without considering the role of edges in representation learning and decision-making within the model. As a result, it lacks guidance from the model’s behavior and remains limited in attack efficiency.

Figure 3: The impact of attack budget on unsupervised task performance

In contrast, our proposed method evaluates the impact of perturbation edges on the model’s embeddings, enabling it to accurately identify critical structures that significantly influence node representations. By prioritizing perturbations on these structures, our method achieves substantially improved attack performance.

6.2.2 Attacking Supervised Models

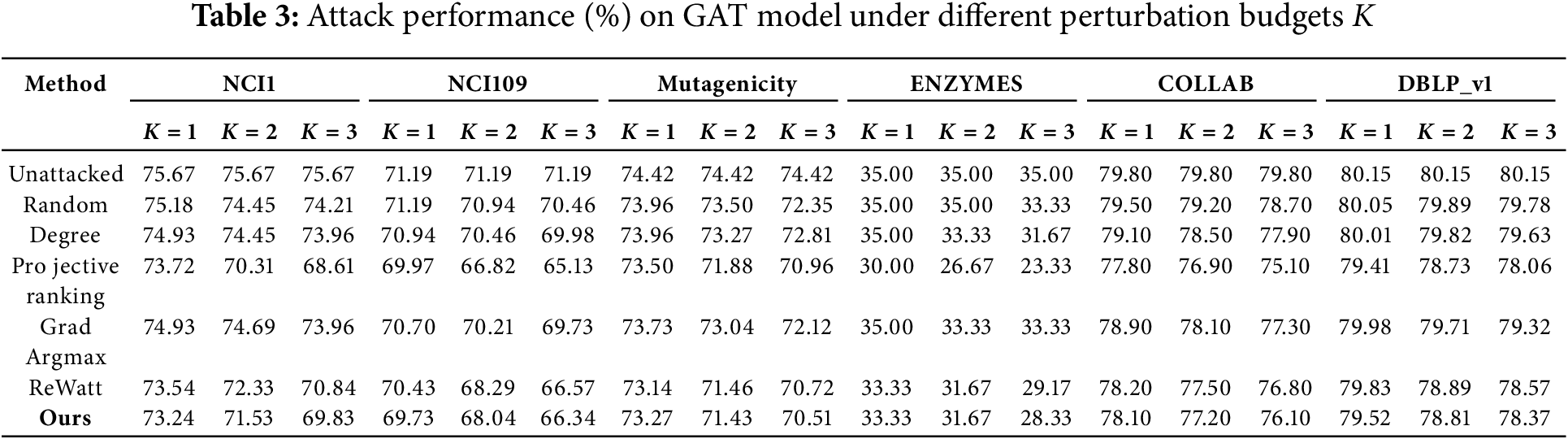

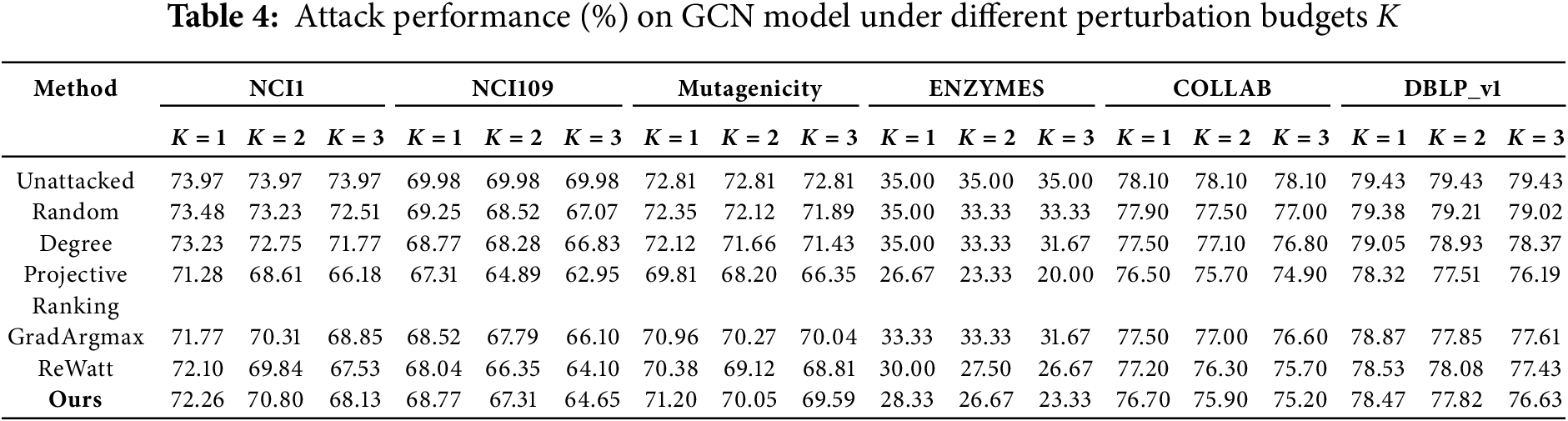

Tables 3 and 4 provide a detailed comparison of our attack method against other techniques in supervised tasks on GAT model and GCN model. Both the GAT and GCN models adopt a three-layer architecture and employ a fully connected layer to produce the final class predictions. It is observed that our approach significantly outperforms the Random method and Degree methods, which is consistent with the performance when attacking unsupervised models.

Compared to the GradArgmax method, our approach consistently outperforms GradArgmax in attacks on the GAT model across multiple datasets and varying attack budgets. In attacks on the GCN model, although GradArgmax performs well on the NCI1, NCI109, and Mutagenicity datasets under lower attack budgets, as the attack budget increases, our method gradually surpasses it, demonstrating superior robustness.

Compared to Projective Ranking and ReWatt, our method exhibits a similarly effective reduction in model performance by strategically identifying and modifying critical edges. While Projective Ranking slightly outperforms our method in some cases, it does so at the cost of requiring access to the model’s predictive probability distribution. Similarly, ReWatt requires label information to construct the reward function for reinforcement learning. These dependencies may constrain their applicability in practical scenarios where these data are unavailable. In contrast, our method operates independently of these constraints, offering a more universally applicable and streamlined attack strategy.

Meanwhile, the results of Tables 3 and 4 also indicate that although the proxy encoder is instantiated using GIN, the perturbed edges it identifies target structurally salient regions in the graph that influence global semantics. These critical edges remain impactful when transferred to different GNN architectures such as GAT and GCN. This suggests that our estimator captures transferable perturbation signals in the embedding space, rather than model-specific mechanisms.

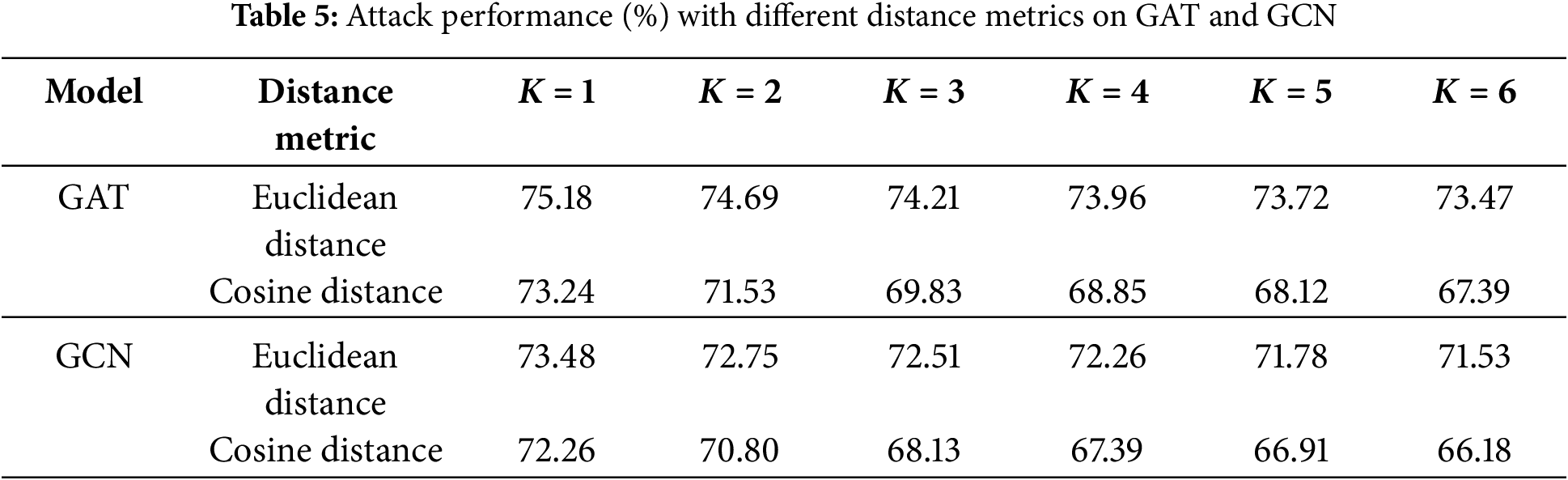

6.2.3 Quantitative Justification for Cosine Distance

While we hypothesize that cosine distance is qualitatively superior for capturing meaningful changes in graph embeddings, a formal quantitative justification is necessary. To provide this, we conducted a direct quantitative analysis comparing the efficacy of attacks guided by cosine distance versus Euclidean distance on both the GAT and GCN models using the NCI dataset.

The results presented in Table 5 provide decisive quantitative evidence. For the GAT model under an attack budget of

This stark quantitative difference strongly supports our initial hypothesis. Euclidean distance, which captures the magnitude discrepancy between embedding vectors, appears less effective in detecting subtle yet semantically meaningful changes in the representation space. In contrast, cosine distance, by focusing exclusively on directional deviation, serves as a more reliable and sensitive measure for identifying structural perturbations that are most detrimental to a GNN’s classification performance. Accordingly, we adopt cosine distance as the similarity metric in our estimator.

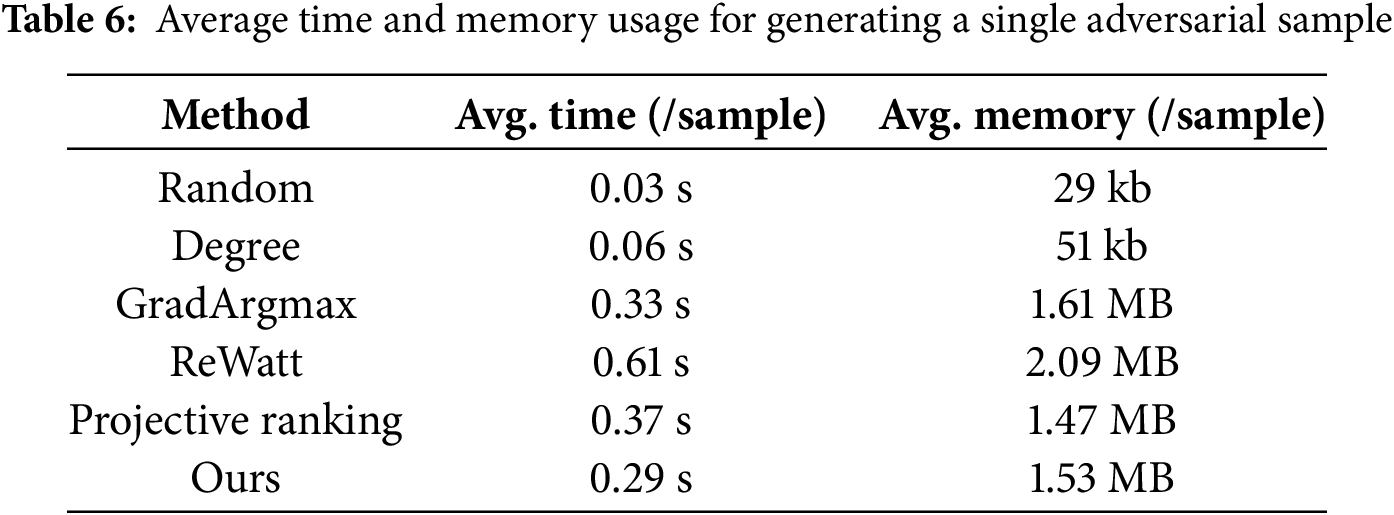

6.2.4 Efficiency Analysis of Sample Generation

To assess the computational efficiency of our proposed attack, we benchmark the average runtime and memory usage required to generate a single adversarial sample on the large-scale COLLAB dataset.

As shown in Table 6, although the runtime and memory overhead incurred by Random and Degree are minimal, their attack effectiveness remains consistently poor, offering little practical or comparative value. Excluding these simplistic baselines, our method achieves the lowest runtime among representative learning-based approaches, with memory usage comparable to other methods and only slightly higher than that of GradArgmax. These results validate the scalability of our method on large graphs, demonstrating its competitive efficiency.

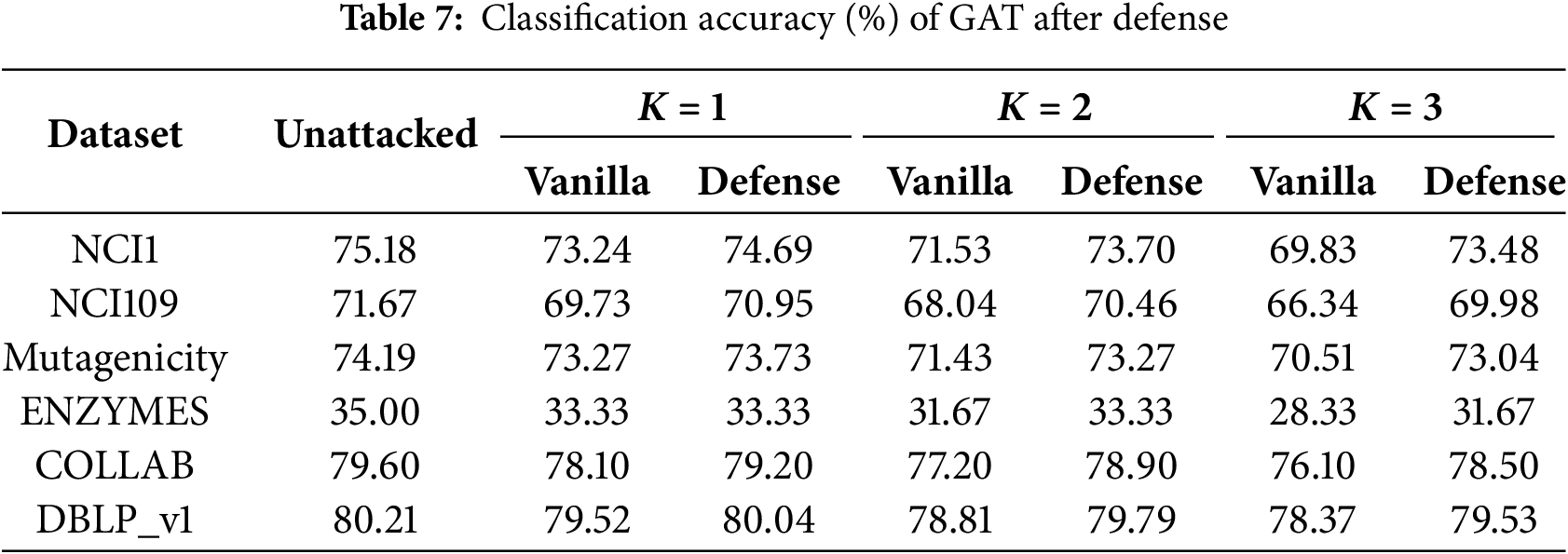

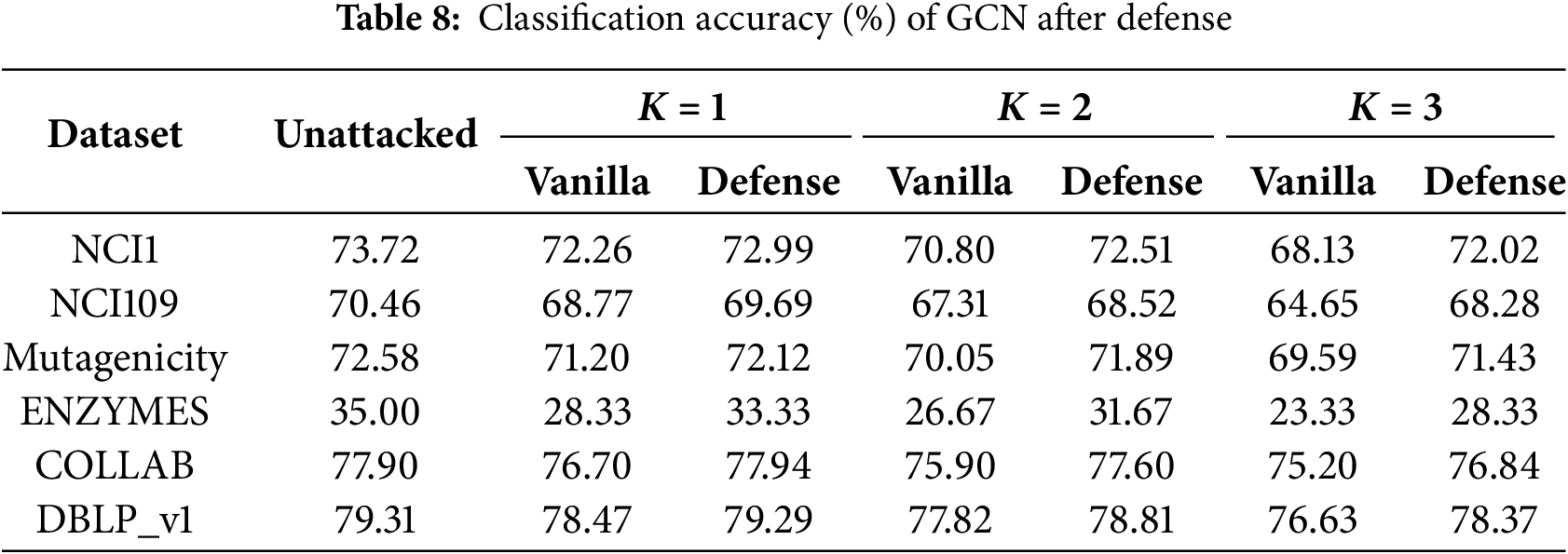

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed defense mechanism, we conduct experiments on six datasets. Each model is trained with and without our defense strategy. The test accuracy after attack on GAT and GCN is reported in Tables 7 and 8.

The results demonstrate that the proposed defense significantly improves the robustness of the trained models. As

6.3.2 Ablation Study of Defense

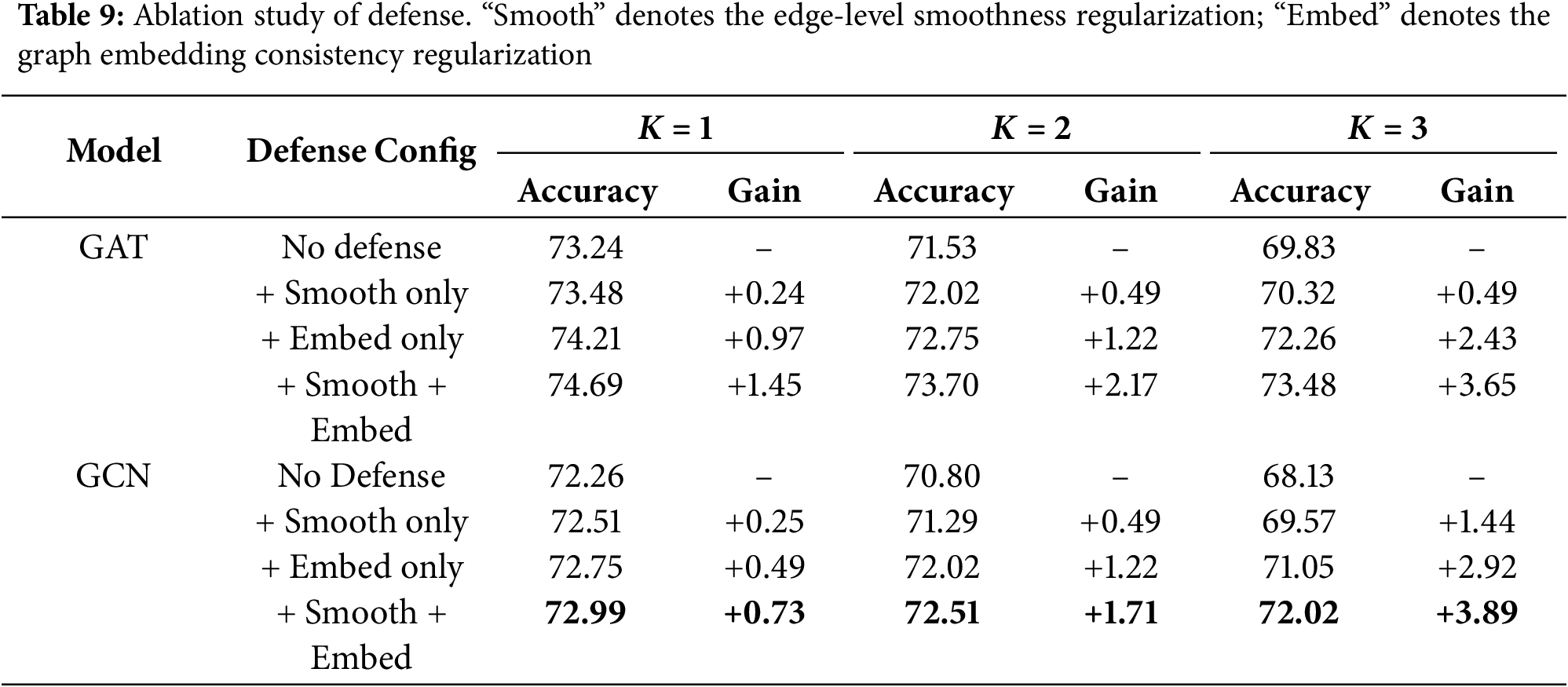

To further investigate the contributions of each component in our proposed defense, we conduct ablation studies on the NCI1 dataset, using both GCN and GAT models. Specifically, we evaluate the effectiveness of each individual regularization term: (1) the edge-level smoothness loss and (2) the graph embedding consistency loss. The classification accuracy under different attack budgets is reported in Table 9.

The results demonstrate that both regularization terms contribute positively to model robustness. For both architectures, adding only the graph embedding consistency regularizer yields a more substantial improvement than the edge-level smoothness term, particularly under stronger attacks (

In this work, we introduce an unsupervised method utilizing graph contrastive learning to perform adversarial attacks in graph classification tasks in the absence of graph labels. We also propose an implicit estimator to measure the impacts of different graph modifications and flip the edges with the top-K scores from the estimator, thereby degrading the overall performance of graph classification. Our experiments across diverse datasets, such as NCI1, NCI109, Mutagenicity, and ENZYMES, show the effectiveness of our method in decreasing graph classification accuracy.

To mitigate such attacks, we further design a lightweight defense mechanism that incorporates edge-level smoothness and graph embedding-level consistency regularization. This defense strategy can be seamlessly integrated into standard GNN training pipelines and shows strong robustness against our structure perturbations with minimal impact on clean accuracy. Although the design is tailored to our specific threat model, the proposed regularization framework enhances overall robustness and may offer partial resilience against other evasion attacks. It is important to note, however, that poisoning attacks during training differ fundamentally from evasion attacks in both their execution and objectives. Poisoning attacks aim to corrupt the learning process itself by injecting malicious data, thereby globally degrading model performance. Since our defense is applied during training on assumed clean data, it is not designed for the poisoning attack paradigm, and its applicability under such scenarios requires further research.

Moreover, our method is inherently model-agnostic and transferable across different GNN architectures. It does not rely on label information, model gradients, or prediction probabilities, making it applicable in both white-box and black-box settings. In experiments, although the proxy model is trained using a GIN encoder, the resulting perturbations effectively degrade the performance of other architectures such as GCN and GAT. Additionally, since the attack operates solely on the graph structure and features, it has potential to generalize to other domains.

From a deployment perspective, our attack is well-suited for real-world test-time scenarios where the adversary can modify the input graph before or during inference. Its reliance solely on structural and feature-level information—without requiring access to training data, labels, or model gradients—makes it easily automated, and stealthy. Nonetheless, in domains with strict topological constraints, the feasibility of structural perturbations may be limited. On the defense side, the proposed regularization-based mechanism is computationally efficient and generalizable, though it may introduce slight training overhead and require tuning to balance robustness with clean performance.

In future work, we plan to explore adaptive adversarial and defense strategies for dynamic or temporal graphs, where the structure evolves over time. Although our current method is designed for static graphs, its core components, namely the contrastive learning-based encoder, edge impact estimator, and regularization-based defense, are modular and can be extended to dynamic settings. For instance, in snapshot-based temporal scenarios, attack estimation and regularization can be applied to each graph state independently or with temporal coherence constraints. However, dynamic graphs introduce unique challenges such as temporal consistency, structural drift, and evolving semantics, which require further investigation to fully adapt both attack and defense mechanisms.

Acknowledgement: We sincerely thank Beijing Institute of Technology for providing support for the completion of this research.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2024YFE0209000), the NSFC (Grant No. U23B2019).

Author Contributions: Yadong Wang: Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing— original draft; Zhiwei Zhang: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing—review & editing; Pengpeng Qiao: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing; Ye Yuan: Funding acquisition, Project administration; Guoren Wang: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The benchmark datasets used in the manuscript are open to the public. All datasets can be found at https://chrsmrrs.github.io/datasets/docs/datasets/ (accessed on 07 September 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: One of the co-authors, Prof. Guoren Wang, serves as an Editor-in-Chief of Computers, Materials & Continua. The manuscript was submitted through the journal’s standard online system. According to the journal’s author guidelines, any submission involving a journal editor as a co-author will be handled by another editor with the least potential conflict of interest to ensure a fair review process. Additionally, this manuscript is submitted to a special issue, and we confirm that there is no conflict of interest with any guest editors of the issue.

References

1. Qiu J, Dong Y, Ma H, Li J, Wang K, Tang J. Network embedding as matrix factorization: unifying DeepWalk, LINE, PTE, and node2vec. In: Proceedings of the Eleventh ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining; 2018 Feb 5–9; Marina Del Rey, CA, USA: ACM. p. 459–67. doi:10.1145/3159652.3159706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Stokes JM, Yang K, Swanson K, Jin W, Cubillos-Ruiz A, Donghia NM, et al. A deep learning approach to antibiotic discovery. Cell. 2020;180(4):688–702.e13. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.01.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. You X, Wang CX, Huang J, Gao X, Zhang Z, Wang M, et al. Towards 6G wireless communication networks: vision, enabling technologies, and new paradigm shifts. Sci China Inf Sci. 2020;64(1):110301. doi:10.1007/s11432-020-2955-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Jin W, Barzilay R, Jaakkola T. Junction tree variational autoencoder for molecular graph generation. In: Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning. Stockholm, Sweden; 2018. [Google Scholar]

5. Zhang M, Cui Z, Neumann M, Chen Y. An end-to-end deep learning architecture for graph classification. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. New Orleans, LA, USA; 2018. 32 p. doi:10.1609/aaai.v32i1.11782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Lee JB, Rossi R, Kong X. Graph classification using structural attention. In: Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining. London, UK: ACM; 2018 Aug 19–23. p. 1666–74. doi:10.1145/3219819.3219980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wu J, Pan S, Zhu X, Zhang C, Yu PS. Multiple structure-view learning for graph classification. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2018;29(7):3236–51. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2017.2703832. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang H, Zheng T, Gao J, Miao C, Su L, Li Y, et al. Data poisoning attack against knowledge graph embedding. In: International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2019 Aug 10–16; Macao, China; 2019. p. 4853–59. [Google Scholar]

9. Zhu G, Chen M, Yuan C, Huang Y. Simple and efficient partial graph adversarial attack: a new perspective. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2024;36(8):4245–59. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2024.3364972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang A, Ma J. DefenseVGAE: defending against adversarial attacks on graph data via a variational graph autoencoder. In: Advanced Intelligent Computing Technology and Applications, ICIC 2024. Singapore: Springer; 2024. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-5591-2_27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Qiao P, Zhang Z, Li Z, Zhang Y, Bian K, Li Y, et al. TAG: joint triple-hierarchical attention and GCN for review-based social recommender system. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2023;35(10):9904–19. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2022.3194952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ou W, Yao Y, Xiong J, Wu Y, Deng X, Gou J, et al. Spectral adversarial attack on graph via node injection. Neural Netw. 2025;184:107046. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2024.107046. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Liu X, Huang JJ, Zhao W, Wang Z, Chen Z, Pan Y. SPA: a poisoning attack framework for graph neural networks through searching and pairing. Mach Learn. 2025;114(1):14. doi:10.1007/s10994-024-06706-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Xiong Z, Wang D, Liu X, Zhong F, Wan X, Li X, et al. Pushing the boundaries of molecular representation for drug discovery with the graph attention mechanism. J Med Chem. 2020;63(16):8749–60. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00959. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Dai H, Li H, Tian T, Huang X, Wang L, Zhu J, et al. Adversarial attack on graph structured data. In: Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning. Stockholm, Sweden; 2018. p. 1115–24. [Google Scholar]

16. Mu J, Wang B, Li Q, Sun K, Xu M, Liu Z. A hard label black-box adversarial attack against graph neural networks. In: CCS ’21: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2021 Nov 15–19; Virtual Event, Republic of Korea. p. 108–25. [Google Scholar]

17. Ma Y, Wang S, Derr T, Wu L, Tang J. Graph adversarial attack via rewiring. In: Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining; 2021 Aug 14–18; Virtual Event, Singapore. p. 1161–9. doi:10.1145/3447548.3467416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Qiu J, Chen Q, Dong Y, Zhang J, Yang H, Ding M, et al. GCC: graph contrastive coding for graph neural network pre-training. In: Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining; 2020 Jul 6–20; Virtual Event, CA, USA: ACM. p. 1150–60. doi:10.1145/3394486.3403168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Mohammed GB. Enhanced SCADA IDS security by using MSOM hybrid unsupervised algorithm. Int J Web-Based Learn Teach Technol. 2022;17(2):1–9. doi:10.4018/IJWLTT.20220301.oa2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Sun L, Dou Y, Yang C, Zhang K, Wang J, Yu PS, et al. Adversarial attack and defense on graph data: a survey. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2023;35(8):7693–711. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2022.3201243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Jin W, Li Y, Xu H, Wang Y, Ji S, Aggarwal C, et al. Adversarial attacks and defenses on graphs. ACM SIGKDD Explor Newsletter. 2021;22(2):19–34. doi:10.1145/3447556.3447566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wan X, Kenlay H, Ru B, Blaas A, Osborne MA, Dong X. Adversarial attacks on graph classification via Bayesian optimisation. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2022;34:6983–96. [Google Scholar]

23. Zhang H, Yuan X, Zhou C, Pan S. Projective ranking-based GNN evasion attacks. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2022:1–14. doi:10.1109/tkde.2022.3219209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zügner D, Akbarnejad A, Günnemann S. Adversarial attacks on neural networks for graph data. In: Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining; 2018 Aug 19–23; London, UK: ACM. p. 2847–56. doi:10.1145/3219819.3220078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Takahashi T. Indirect adversarial attacks via poisoning neighbors for graph convolutional networks. In: 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data); 2019 December 9–12; Los Angeles, CA, USA: IEEE. p. 1395–400. doi:10.1109/BigData47090.2019.9006004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Tang X, Li Y, Sun Y, Yao H, Mitra P, Wang S. Transferring robustness for graph neural network against poisoning attacks. In: Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining. Houston, TX, USA: ACM; 2020. p. 600–8. doi:10.1145/3336191.3371851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Bojchevski A, Günnemann S. Adversarial attacks on node embeddings via graph poisoning. In: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning. Long Beach, CA, USA; 2019 [Google Scholar]

28. Zhang S, Chen H, Sun X, Li Y, Xu G. Unsupervised graph poisoning attack via contrastive loss back-propagation. In: Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2022; 2022 Apr 25–29; Virtual Event. Lyon, France: ACM. p. 1322–30. doi:10.1145/3485447.3512179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Xu K, Hu W, Leskovec J, Jegelka S. How powerful are graph neural networks? In: International Conference on Learning Representations; 2019 May 6–9; New Orleans, LA, USA. [Google Scholar]

30. You Y, Chen T, Sui Y, Chen T, Wang Z, Shen Y. Graph contrastive learning with augmentations. In: Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2020 Dec 6–12; Vancouver, BC, Canada: ACM. p. 5812–23. doi:10.5555/3495724.3496212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Paszke A, Gross S, Massa F, Lerer A, Bradbury J, Chanan G, et al. PyTorch: an imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2019;32:8026–37. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools