Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

LLM-KE: An Ontology-Aware LLM Methodology for Military Domain Knowledge Extraction

1 Military Intelligence, Department of Information and Communication Command, National University of Defense Technology, Changsha, 410000, China

2 Military Intelligence, Department of Information and Communication Command, Information Support Force Engineering University, Wuhan, 430000, China

* Corresponding Author: Yongqi Wen. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068670

Received 03 June 2025; Accepted 09 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Since Google introduced the concept of Knowledge Graphs (KGs) in 2012, their construction technologies have evolved into a comprehensive methodological framework encompassing knowledge acquisition, extraction, representation, modeling, fusion, computation, and storage. Within this framework, knowledge extraction, as the core component, directly determines KG quality. In military domains, traditional manual curation models face efficiency constraints due to data fragmentation, complex knowledge architectures, and confidentiality protocols. Meanwhile, crowdsourced ontology construction approaches from general domains prove non-transferable, while human-crafted ontologies struggle with generalization deficiencies. To address these challenges, this study proposes an Ontology-Aware LLM Methodology for Military Domain Knowledge Extraction (LLM-KE). This approach leverages the deep semantic comprehension capabilities of Large Language Models (LLMs) to simulate human experts’ cognitive processes in crowdsourced ontology construction, enabling automated extraction of military textual knowledge. It concurrently enhances knowledge processing efficiency and improves KG completeness. Empirical analysis demonstrates that this method effectively resolves scalability and dynamic adaptation challenges in military KG construction, establishing a novel technological pathway for advancing military intelligence development.Keywords

Since Google first proposed the concept of “Knowledge Graph (KG)” in 2012, various industries have continuously explored methodologies for constructing their own knowledge graphs. To date, the technologies for KG construction have matured into a well-established technical framework [1]. A complete knowledge graph construction process typically includes the following steps: knowledge acquisition → knowledge extraction → knowledge representation → knowledge modeling → knowledge fusion → knowledge computation → knowledge storage. Knowledge extraction, as a crucial step in the construction of knowledge graphs, directly determines the quality of the graph’s construction.

In the military domain, due to confidentiality issues, data storage is often decentralized, and the knowledge system is complex. Relying solely on manual organization makes it difficult to improve the management efficiency of military knowledge. As a result, many researchers are actively exploring methods for constructing knowledge graphs in the military domain. In this process, knowledge extraction in the military domain is often a critical challenge. First, the military knowledge system cannot be constructed into an ontology through the “crowdsourcing method” as in general domains. Second, manually constructed knowledge ontologies face limitations in terms of generalization.

To address the above issues, the military knowledge extraction method based on LLM ontology awareness proposed in this paper leverages the text comprehension ability of large language models. It simulates the process of human crowdsourcing for constructing knowledge ontologies specifically for military domain texts. On one hand, it enhances the efficiency of knowledge extraction in the military domain using large language models, and on the other hand, it improves the completeness of military domain knowledge graphs.

2.1 Military Knowledge Extraction Research Advances

As a typical vertical domain knowledge graph, the construction of military domain knowledge graphs usually follows a top-down paradigm: First, domain experts collaboratively develop the military ontology layer, systematically defining entity types, relationship types, and attribute constraints to form a domain knowledge template. Then, based on the predefined ontology, a structured annotated corpus is constructed, and a weakly supervised learning mechanism is employed to train a deep neural network model, ultimately achieving the automated mapping of unstructured military texts to the knowledge graph data layer. This method, through the bidirectional coupling of expert knowledge and data-driven approaches, effectively ensures the normativity and semantic consistency of the military knowledge system. However, there is still room for optimization in terms of dynamic knowledge updating and cross-domain transfer.

Recent representative studies include Yuan et al. from the Army Engineering University [2] built a system framework for knowledge extraction in the command and control support domain, and they have preliminarily achieved the full lifecycle of knowledge extraction from “ontology modeling,” “corpus annotation,” “named entity recognition” to “relationship extraction.” Wang et al. from the Jiangsu Automation Research Institute [3] addressed issues such as the loose structure of military equipment databases, which are difficult to utilize effectively, leading to inefficiency and chaotic management. They proposed an entity-relationship extraction method based on CRF and syntactic parse trees. Through training with massive data, they optimized the military knowledge graph construction method, improving the single-algorithm extraction method to a ternary data extraction approach, and completed the military equipment graph construction. Experimental results showed that the accuracy of this method can reach 72%, and after incorporating a confidence model, the accuracy increased by 12.6%, with an overall evaluation accuracy of 78.11%.

2.2 LLM-Enhanced Military Knowledge Extraction Research Advances

In the traditional knowledge graph construction paradigm, Named Entity Recognition (NER) is a core task of knowledge extraction, aiming to locate and classify predefined entity types from unstructured texts. General domain NER models typically focus on basic categories such as people, organizations, and geographical entities, with their performance heavily reliant on large-scale manually annotated corpora. However, this paradigm faces domain adaptation challenges: The inherent tension between the continuously evolving nature of domain-specific knowledge architectures and the scarcity of high-quality annotated datasets, making traditional supervised learning methods unable to meet the dual demands of timeliness and coverage of knowledge in vertical domains such as military and healthcare.

Generative artificial intelligence technologies, represented by GPT [4,5] and Deepseek [6,7], have introduced new solutions for the NER task. Notable studies include: Wang et al. from Peking University and Zhejiang University [8], who jointly proposed GPT-NER. On one hand, they improved the generalization of knowledge extraction by converting the NER sequence labeling task into a text generation task. On the other hand, after entity extraction, they alleviated the low extraction accuracy caused by hallucinations in LLMs by incorporating a self-validation strategy. Sergey et al. from Allen AI Lab [9] designed an innovative prompt strategy for the biomedical field, which improved the F1 score of GPT-4 by 15% across six publicly available NER test datasets, and in some cases, the knowledge extraction performance even surpassed that of language models fine-tuned with supervision. Ashok et al. from Carnegie Mellon University [10] proposed the PromptNER method, which, with only a few-shot prompt, enables LLMs to generate a potential entity list based on the given text and automatically link it to predefined entity types. This method achieved an 11% F1 score improvement on the CoNLL dataset.

2.2.2 LLM-Enhanced KG Embedding

The main task of Knowledge Graph Embedding (KGE) is to map each recognized entity and relation into a low-dimensional vector space. These embeddings contain both semantic and structural information of the knowledge graph and can be used for various tasks such as question answering [11], knowledge reasoning [12], and knowledge recommendation [13]. Traditional knowledge graph embedding methods primarily rely on the structural information of the knowledge graph to optimize the embedding scoring function, such as TransE [14] and DisMult [15]. However, these approaches exhibit persistent challenges in effectively characterizing unseen entities and long-tail relational patterns, particularly pronounced in scenarios with constrained availability of structured training data [16,17].

To address the aforementioned issues, Wang et al. [18] proposed a unified model for knowledge embedding and pre-trained language representation called KEPLER. This model uses a pretrained language model (PLM) to encode textual entity descriptions as its embedding vectors, and then jointly optimizes the knowledge embedding (KE) and language modeling objectives. Zhang et al. from the MOE Key Laboratory of Computer Language at Peking University [19] proposed a training framework called Pretrain-KGE, which includes three stages: semantic-based fine-tuning of the pre-trained language model, knowledge extraction, and word embedding. Experimental results demonstrated that this training framework can improve knowledge embedding issues under few-shot conditions.

By combining the current research status of knowledge extraction technology in the military domain with LLM-enhanced knowledge extraction technology, the following conclusions can be drawn:

1. Scarcity of Supervised Data. Traditional supervised learning-based knowledge extraction models often rely heavily on the scale and quality of annotated datasets. However, data in the military domain is characterized by high sensitivity, resulting in an extreme scarcity of available annotated corpora, which significantly constrains the performance of knowledge extraction models.

2. The Contradiction between the Dynamics of Domain Knowledge and Model Adaptability. Knowledge in the military domain updates rapidly (such as the iteration of new equipment and tactical theories), while supervised learning-based knowledge extraction models often require significant data annotation and model training costs to continuously adapt to the evolving domain knowledge.

3. Research on LLM-Enhanced Knowledge Extraction Is Still in Its Early Stages. Most studies on LLM-enhanced knowledge extraction in general domains primarily explore the prompt layer and have not yet formed a mature research paradigm. The extraction effectiveness in the military domain has not yet reached a usable state.

To address the aforementioned issues and technical bottlenecks, the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

1. A basic framework for the military knowledge extraction method based on LLM ontology awareness has been established, providing a new research paradigm for enhancing knowledge extraction in the military domain through LLMs.

2. A multi-agent collaborative dynamic ontology construction mechanism based on LLM has been designed. By creating a multi-agent collaboration model (such as expert roles in military equipment and combat command) and a phased iterative validation process, the mechanism achieves automated aggregation and dynamic updating of knowledge ontologies, significantly enhancing the ontology’s adaptability to emerging military terminology.

3. Through prompt engineering, automated knowledge extraction in the military domain based on LLM has been achieved under unsupervised learning conditions, ensuring extraction efficiency while attaining performance comparable to supervised learning models.

In general, to build a highly flexible knowledge graph, the first step is to establish a comprehensive ontology [20]. This ontology then serves as a foundation for progressively enriching the knowledge graph with data from other collection channels as needed. The traditional paradigm for knowledge graph construction involves directly collecting manually edited knowledge graph corpora. However, this crowdsourcing approach is often costly and inefficient [21]. Therefore, we introduce Large Language Model (LLM) Agent technology to reduce the costs associated with crowdsourcing.

The basic framework of the military knowledge extraction method based on LLM ontology awareness proposed in this study (named LLM-KE) is shown in Fig. 1. Its architecture consists of four core modules arranged in a bottom-up manner: domain corpus collection layer, ontology awareness layer, knowledge extraction layer, and annotation generation layer, forming a progressive knowledge transformation mechanism among the layers.

Figure 1: Basic Framework for LLM Ontology-Aware Military Domain Knowledge Extraction Method (LLM-KE)

3.1.1 Domain Corpus Collection Layer

A multi-source heterogeneous data collection strategy is employed to systematically gather unstructured text data from specialized domains, including weaponry parameters, logistics support procedures, and military policies and regulations, thereby constructing a seed corpus that is representative of the domain. Through data cleaning and standardization, a small sample data foundation covering the core dimensions of military knowledge is formed.

3.1.2 Ontology Awareness Layer (Phase 1)

Constructing a Multi-Agent Collaborative Ontology Construction Mechanism:

1. Dynamic Definition of Expert Roles (e.g., specialists in military equipment, combat command, and logistics management) via military text embeddings and latent space clustering, eliminating the need for manual preset roles;

2. Designing a phased knowledge distillation process that simulates crowdsourced knowledge discovery through multi-round “hypothesis-validation-iteration” mechanisms;

3. Employing a hierarchical clustering algorithm to perform consistency checks on LLM-generated “entity-relation” outputs, ultimately forming an ontology model layer aligned with military domain characteristics.

3.1.3 Knowledge Extraction Layer (Phase 2)

Based on the established military ontology model layer, a dynamic role-switching mechanism is implemented:

1. Transforming domain ontology entity types into semantic constraint templates that are understandable by the LLM;

2. Using the few-shot learning paradigm to design entity recognition prompting engineering [22], dynamically adjusting the temperature coefficient to balance entity recall and precision;

3. Introducing an attention mechanism to enhance the model’s semantic sensitivity to military terminology, enabling the batch extraction of structured knowledge from large-scale tactical documents, operational regulations, and other texts.

3.1.4 Annotation Generation Layer

A standardized annotation template library (The example fragment is shown in Table 1) is constructed to achieve efficient annotation through the following technical pathways:

1. Designing an annotation instruction framework based on ontology constraints to ensure that the annotation format strictly aligns with the domain knowledge graph schema;

2. Developing an annotation quality assessment module that uses a cross-validation mechanism to filter out noise annotations generated by the LLM;

3. Establishing an automated annotation pipeline that supports multi-threaded parallel processing and incremental data updates, significantly enhancing the efficiency of knowledge transformation from military texts.

Though the LLM ontology-aware military domain knowledge extraction methodology illustrated in Fig. 1 largely adheres to conventional knowledge graph construction workflows, its superiority lies in automating traditionally expert-dependent procedures via large language models. This approach reduces manual effort while preserving KG professionalism and generalization. Concurrently, several critical technical challenges persist in the methodology depicted in Fig. 1. The following elaborates on these challenges and their corresponding solutions proposed in this study.

3.2.1 LLM-Based Multi-Agent Collaborative Ontological Perception

Role Cognition Model for LLM-Based Agents. To enhance the generalizability of LLM role configuration, military text embeddings are first incorporated followed by latent space feature clustering to define expert roles. The role feature space is defined as

where

The softmax function in Eq. (1) is chosen because it naturally models a probability distribution over potential roles given the input text and a specific role embedding. By using the concatenation

Subsequently, an attention masking mechanism is employed to constrain the LLM’s focus on domain-specific semantic comprehension:

where

Eq. (2) employs a self-attention mechanism, a widely adopted and theoretically sound component in large language models. The key innovation here is the dynamic generation of query

Distributed LLM-Agent Collaborative Entity Extraction. By establishing role cognition models for LLM agents, multiple agents can be configured to assume expert roles across various domains, such as military equipment specialists, operational command experts, and logistics support professionals. When processing lengthy textual inputs, these domain-specific LLM agents can either handle distinct text segments or focus on different entity types within the same text. For instance, military equipment specialists may concentrate on identifying weapon systems and technical specifications, while operational command experts might prioritize tactical patterns and command hierarchies.

Multiple LLM agents perform parallel extraction of domain-specific entities and relations from the given text. Each LLM agent

where

The use of multiple LLM agents for parallel entity extraction, formalized by

Military Knowledge Ontology Aggregation. After extracting several entities, it is necessary to further aggregate them through hierarchical clustering. The goal is to merge similar entities extracted by different LLM experts to eliminate redundancy and construct a consistent knowledge ontology. The process of ontology aggregation can be expressed mathematically as:

where

Eq. (4) represents a commonly used distance metric for hierarchical clustering. The term

Following the aforementioned methodology, domain-specific knowledge ontologies can be derived directly from arbitrary domain-agnostic textual data.

3.2.2 . Ontology-Based Military Knowledge Extraction

Crafting precise prompts for Large Language Models to generate content that aligns with human preferences for specific tasks and scenarios is a process known as prompt engineering [23,24]. Designing a comprehensive prompt is highly beneficial for enhancing an LLM’s ability to accomplish a given task. Our prompt construction approach was adapted from the framework established by Zhao et al. [25], with the detailed implementation procedure outlined below.

To achieve precise constraints on the task roles, task content, and output format of large language models (LLMs), this study constructs standardized prompt templates through prompt engineering. Specifically, the prompt design is developed from the following three dimensions:

1. Task Role Constraints. Injecting domain-specific expert cognitive patterns into LLMs. For example, in the military domain, roles such as “weapon equipment analyst” and “operational command expert” are defined.

2. Task Content Guidance. Clarifying the task objectives and processing requirements for input data to ensure that LLMs focus on key information. For instance, for named entity recognition tasks, the prompt specifies a detailed list of entity types (such as equipment names, combat units) and their semantic boundaries.

3. Output Format Standardization. Designing structured output templates to specify the format and organization of LLM-generated results. For example, using JSON or triple formats to output entity-relation pairs to enhance compatibility and processing efficiency in downstream tasks.

Following the aforementioned methodology, prompts were designed at the knowledge extraction layer illustrated in Fig. 1, as presented in Table 2.

3.3.1 Purpose of the Experiment

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the Ontology-Aware LLM Methodology for Military Domain Knowledge Extraction (LLM-KE) proposed in this paper, the following experiments are designed to verify three key scientific questions:

1. Comparison of Ontology Construction Capabilities. The comparison of ontology construction capabilities focuses on two aspects: (1) to verify whether the ontology awareness layer of LLM-KE proposed in this paper can achieve the level of manual ontology construction based on the seven-step method, thereby validating its effectiveness; and (2) to compare LLM-KE with state-of-the-art research works such as LLMs4OL [26] to validate its technical advancement.

2. Comparison of Extraction Performance. To evaluate whether LLM-KE can achieve extraction accuracy comparable to current mainstream military knowledge extraction methods while maintaining extraction efficiency.

3. Evaluation of Dynamic Ontology Adaptability. Military domain knowledge ontologies exhibit significant dynamic evolution characteristics, requiring continuous updates to their structure in response to the introduction of new equipment (e.g., hypersonic weapons), the iteration of tactical theories (e.g., multi-domain operations), and changes in the international strategic environment. Traditional manual ontology maintenance models face three major challenges: (1) lag in knowledge updates; (2) high costs of version iteration; (3) risk of cross-domain knowledge conflicts. Therefore, it is also necessary to examine the adaptability of LLM-KE to dynamic ontology scenarios.

3.3.2 . Datasets and Evaluation Methods

This study uses the same military domain dataset as in reference [27]. The dataset consists of 50 randomly selected military scenarios and battle case texts (approximately 320,000 characters) that have been manually annotated, covering 6105 annotated military text entities.

To evaluate the ontology construction capabilities of LLM-KE, we adopted the seven-step method for military domain ontology construction as described in reference [4]. Based on the aforementioned military texts (5 documents randomly selected), we constructed a knowledge ontology that includes 11 entity types: combat forces, countries, military types, equipment names, equipment types, equipment parameters, facility names, facility types, combat times, combat areas, and combat environments, as shown in Table 3. The quality of the ontology and its alignment with manually constructed ontologies were assessed using domain expert consistency metrics. The evaluation metrics are ontology coverage and redundancy, calculated as follows:

where

To evaluate the knowledge extraction capabilities of LLM-KE in the military domain, we assessed precision (

where

To evaluate the dynamic ontology adaptability of LLM-KE, we used the BiGRU-MTATT knowledge extraction method described in reference [27] to re-extract entities from the original corpus based on the entity types listed in Table 3, and compared the results with those of the method proposed in this paper.

4.1 Comparison of Ontology Construction Capabilities

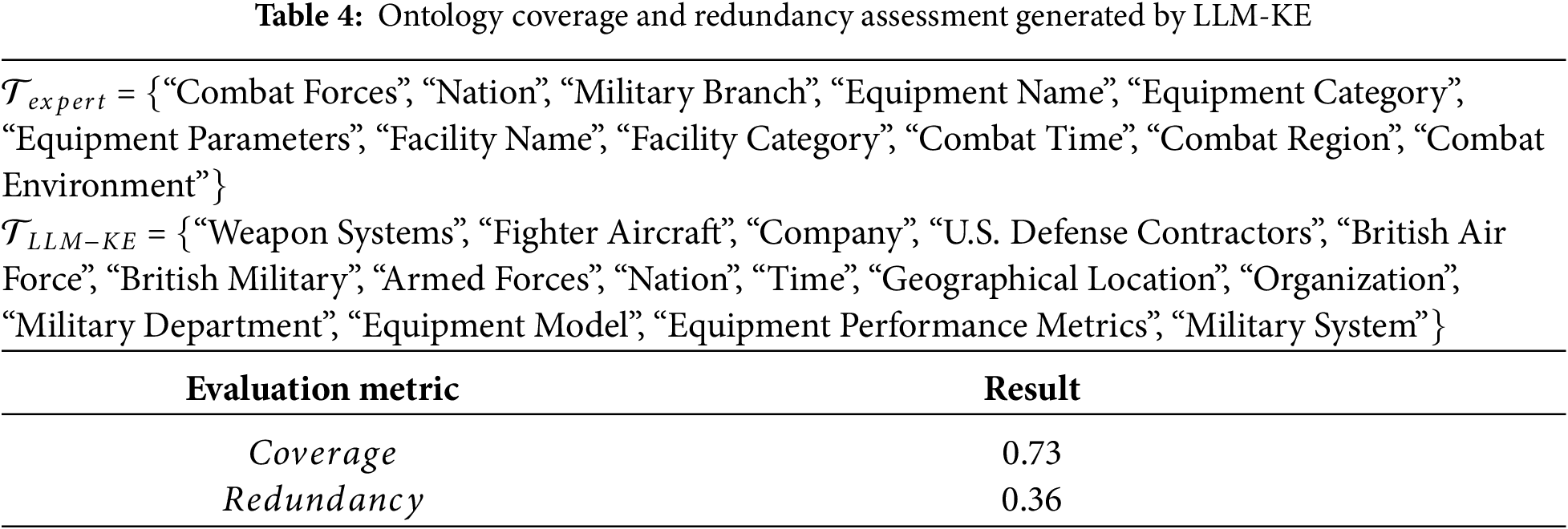

Five randomly selected documents were used as input for LLM-KE. The ontology generated by LLM-KE was evaluated using the ontology coverage and redundancy metrics provided in Section 3.3.2. The generated results and evaluation scores are shown in Table 4.

The experimental results in Table 4 show that LLM-KE can generate a knowledge ontology that closely aligns with the expectations of domain experts, even in a completely unsupervised setting, using only a small-scale corpus.

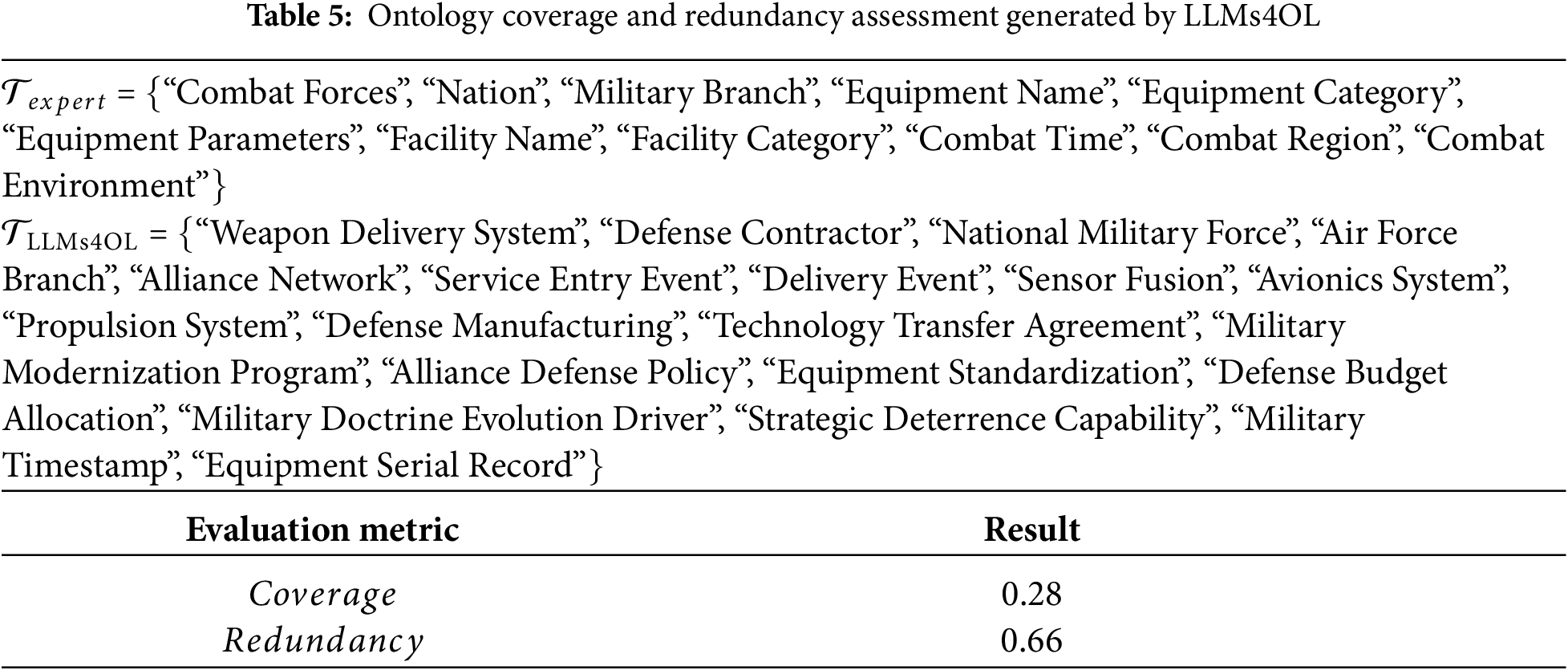

To further evaluate the technical advancement of LLM-KE, a comparative analysis was conducted between LLM-KE and the state-of-the-art research work (LLMs4OL [26]). The same evaluation metrics as Formulas (5) and (6) were adopted to assess ontology coverage and redundancy. The generated knowledge ontology results and evaluation scores are presented in Table 5.

The experimental results in Table 5 indicate that LLMs4OL [26] demonstrates domain-specific expertise in military ontology comprehension. However, it was observed to deviate significantly from human-expert-defined ontologies in the military ontology generation scenarios established in this study. This suggests that the ontology aggregation capacity of LLMs4OL remains misaligned with human preferences in the patent domain.

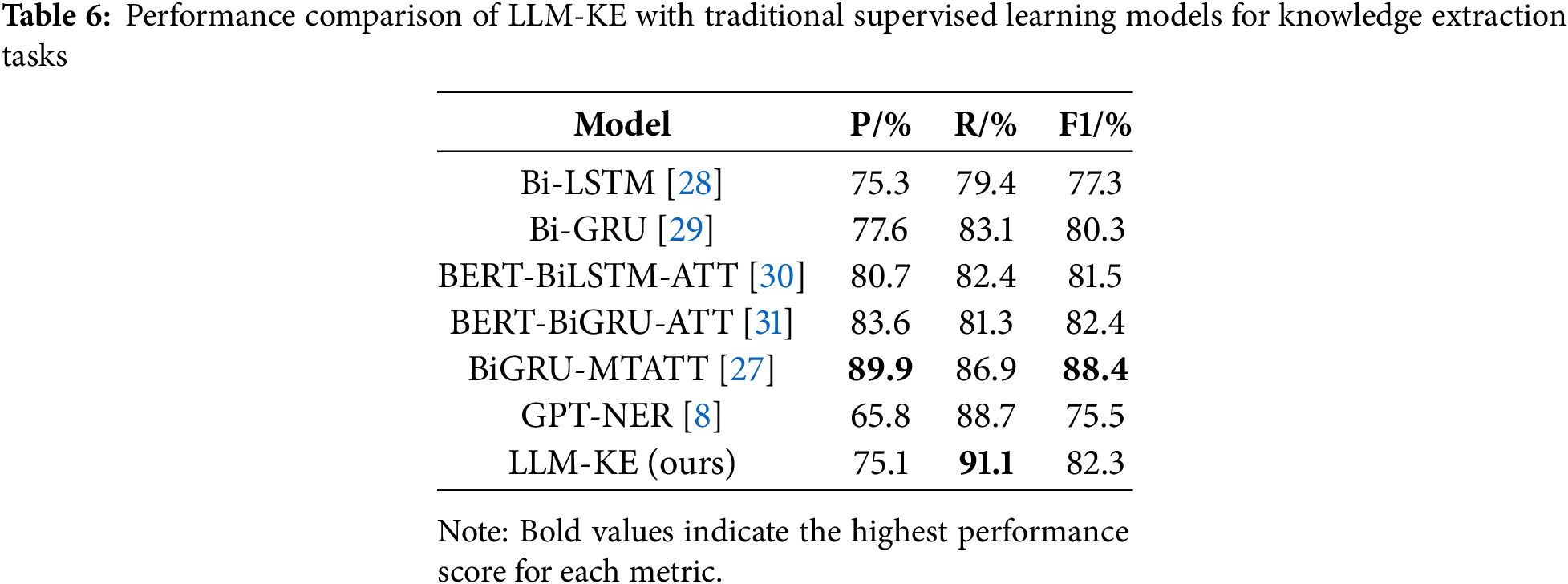

4.2 Comparison of Knowledge Extraction Performance

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the fully unsupervised method LLM-KE proposed in this paper for military domain knowledge extraction, we selected five classic supervised learning models as benchmark comparisons: Bi-LSTM [28], Bi-GRU [29], BERT-BiLSTM-ATT [30], BERT-BiGRU-ATT [31], and BiGRU-MTATT [27]. The two types of methods exhibit significant differences in data dependency, training mechanisms, and inference capabilities. Furthermore, we also selected the GPT-NER [8] method, a representative unsupervised learning approach in general domains, for comparative analysis.

For the experimental data settings of the supervised learning models: 6105 manually annotated military text samples were used, and the data were randomly divided into a training set (80%) and a validation set (20%).

For the experimental settings of the unsupervised LLM-KE: LLM-KE does not require manually annotated data and relies solely on the inference capabilities of the large language model (Deepseek-r1:671B, as selected in this study) to complete knowledge extraction. Following the process outlined in Fig. 1, knowledge extraction is automated through the domain corpus collection layer, ontology perception layer, knowledge extraction layer, and annotation generation layer. The performance comparison results of LLM-KE and traditional supervised learning models in the knowledge extraction task are shown in Table 6.

The experimental results in Table 6 lead to the following conclusions: (1) The proposed LLM-KE achieves an accuracy of 75.1% in the knowledge extraction task, which is only at the lowest level of traditional supervised learning models. This result indicates that relying solely on zero-shot prompts to guide the large language model (Deepseek-r1:671B) for inference still has certain limitations in entity recognition and boundary determination in the military domain, particularly in handling complex semantics or polysemous entities, where misjudgments are more likely to occur. (2) The recall rate of LLM-KE reaches 91.1%, significantly higher than that of traditional supervised learning models. This excellent performance is mainly attributed to the strong contextual understanding capability of Deepseek-r1:671B, which excels in capturing long-distance dependencies and implicit semantics, thereby effectively reducing the phenomenon of missed entity detections. (3) In the comparative experiments, the F1 score of LLM-KE is at a moderate level, reflecting its ability to balance precision and recall. Although its precision is relatively low, the high recall rate ensures that its overall performance remains competitive, especially in unsupervised scenarios, where it demonstrates good application potential. (4) As shown in the comparative results with GPT-NER [8], although GPT-NER demonstrates superior recall, its failure to emphasize the importance of ontology construction during military domain knowledge extraction leads to suboptimal precision, resulting in a lower F1 score.

In summary, LLM-KE exhibits a significant advantage in recall in the knowledge extraction task, but there is still room for improvement in terms of precision. Future work can focus on optimizing prompt engineering or introducing a small amount of labeled data to further enhance its performance.

4.3 Evaluation of Dynamic Ontology Adaptability

Based on the military domain knowledge ontology constructed using the seven-step method (as shown in Table 3), five documents were randomly selected from the original corpus. These documents were manually annotated to create a test dataset of 1000 data points, which was used to simulate the dynamic updating process of the knowledge ontology.

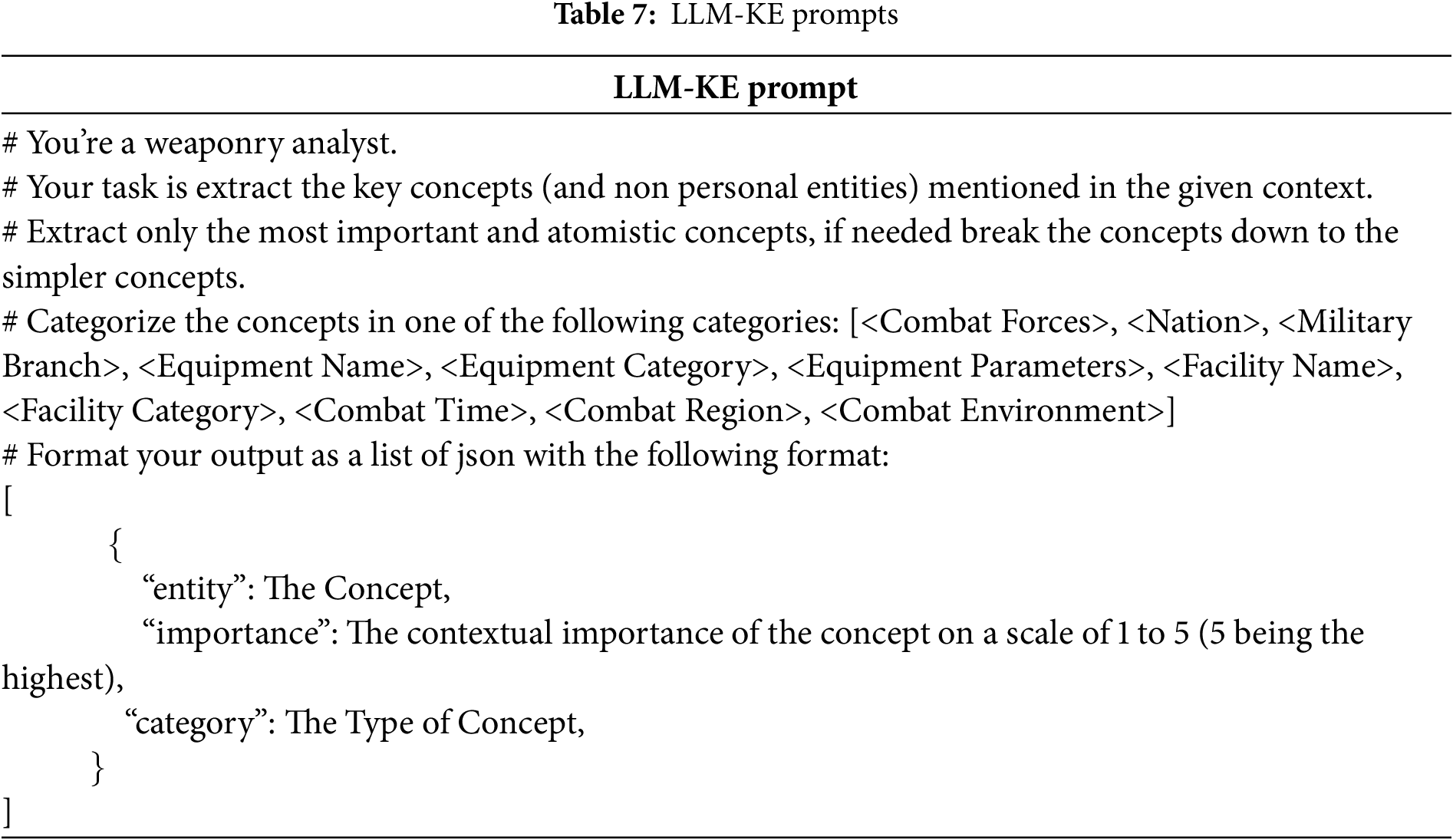

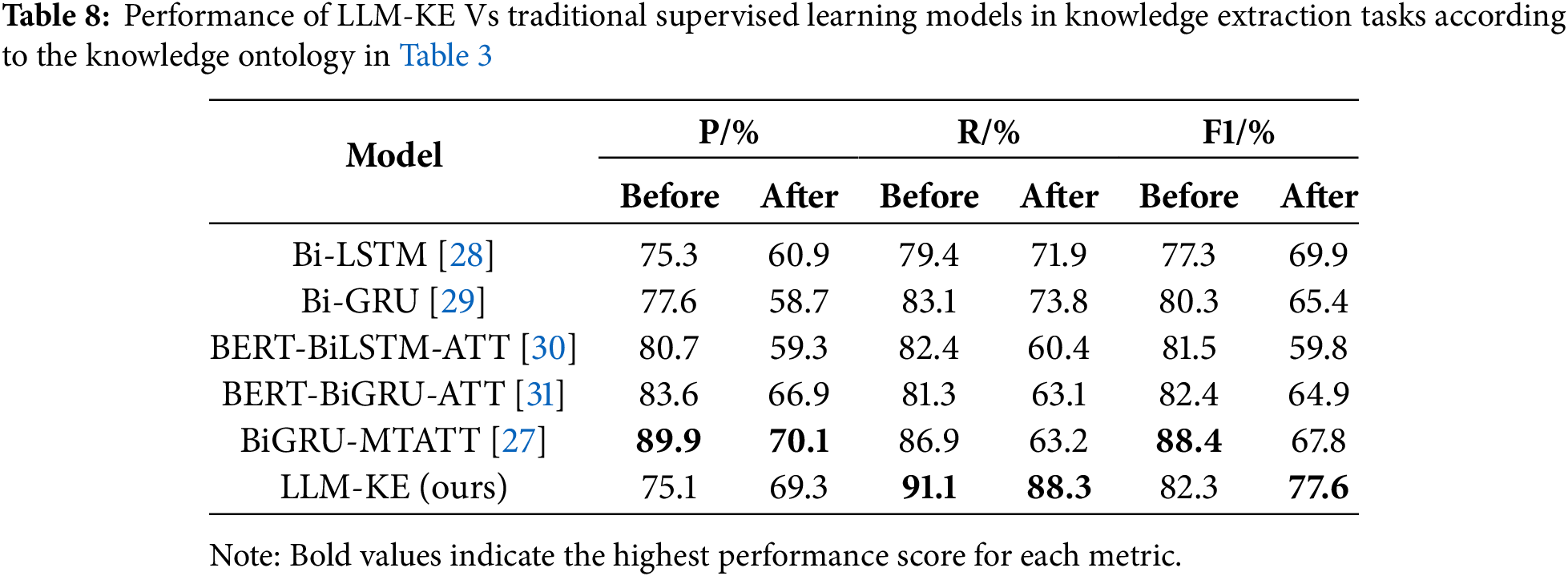

In the comparative experiments, the knowledge extraction prompts for LLM-KE were modified as shown in Table 7. The supervised learning models listed in Table 6 were still trained and validated using an 80:20 split of the training and validation sets. The test results are shown in Table 8.

The experimental results in Table 8 lead to the following conclusions: Under dynamic ontology conditions, the performance of traditional supervised learning models significantly declines in terms of precision (P), recall (R), and F1 score (all F1 scores drop below 70). This decline is likely due to the insufficient amount of labeled data available for supervised learning. In practical military scenarios, the amount of labeled data available for training may be even more limited. In contrast, the impact of dynamic ontology on LLM-KE is minimal (F1 score decreases by only 4.7 points), indicating that LLM-KE has stronger adaptability under dynamic ontology conditions.

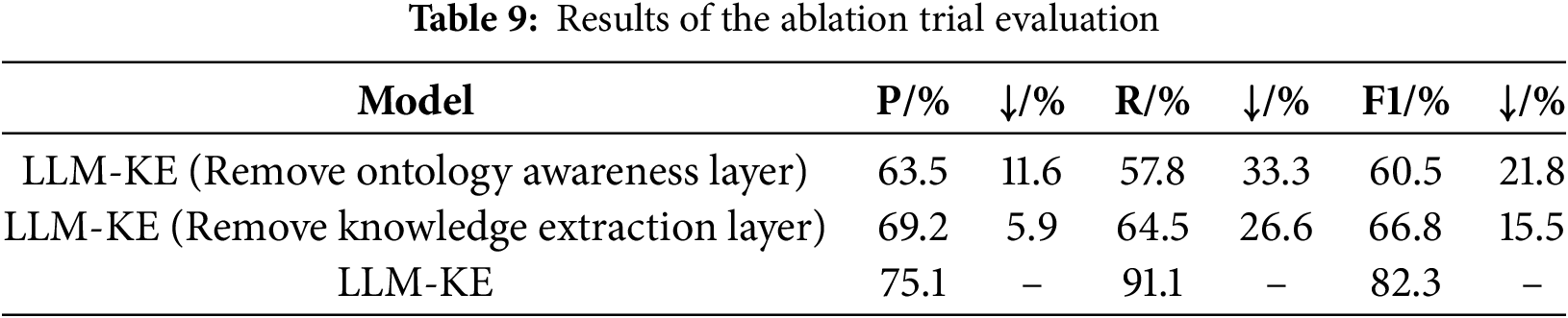

To evaluate the overall effectiveness of the proposed LLM-KE framework, an importance assessment was conducted on the ontology perception layer and the knowledge extraction layer. Specifically, the evaluation method described in Section 4.2 was used after separately removing the ontology perception layer and the knowledge extraction layer (by removing the extraction prompt constraints). The results are shown in Table 9.

The analysis of Table 9 shows that when the ontology perception layer and the knowledge extraction layer are separately removed, the performance of LLM-KE significantly declines in terms of precision (P), recall (R), and F1 score. Notably, the performance of knowledge extraction is particularly sensitive to the presence of the ontology perception layer.

This study addresses core issues in knowledge extraction across various domains, including the scarcity of supervised data, insufficient dynamic adaptability, and the immature application of Large Language Model (LLM)-enhanced techniques. We propose a knowledge extraction method based on an LLM with ontology awareness. By leveraging zero-shot learning and advanced prompt engineering, our framework, LLM-KE, achieves extraction performance comparable to traditional supervised learning models, even in the complete absence of annotated corpora. This success validates the potential of LLMs in mitigating data dependency and establishes a reusable, generalizable methodology for the automated construction of domain-specific knowledge graphs.

While our initial validation focused on the complex military domain—a challenging environment due to its highly specialized terminology and data scarcity—the underlying principles of LLM-KE are designed for cross-domain applicability. The core innovation lies in its ability to adapt to new domains without the need for extensive retraining or fine-tuning, simply by modifying the prompt to define the new ontology. This adaptability makes the framework an ideal candidate for deployment in a wide range of fields, such as:

• Medical science: Extracting relationships between diseases, symptoms, and treatments from clinical notes.

• LegalTech: Identifying key entities and clauses in legal documents to build a knowledge graph of case law.

• Financial analysis: Extracting market trends and relationships between companies from financial reports.

Despite these preliminary achievements, the task of robust knowledge extraction still presents several challenges that require further exploration in future research:

• Improving Extraction Accuracy and Adaptability: While our zero-shot approach is effective, the accuracy of LLM-based knowledge extraction can be further enhanced. We need to explore regular incremental learning or continuous fine-tuning mechanisms to boost the LLM’s knowledge inference capabilities and ensure its performance remains high as domain knowledge evolves.

• Automating Data Annotation: Future work will investigate research paradigms for expanding supervised datasets through automatic annotation by LLMs. This will significantly reduce the high annotation costs of traditional supervised learning models and accelerate the development of more accurate, domain-specific models.

• Multimodal Knowledge Fusion: Our future research will focus on multimodal knowledge fusion and expansion. By integrating heterogeneous data sources—such as images, sensor data, and spatiotemporal logs—we will study the collaborative mechanisms between LLMs and multimodal models. This will extend the coverage of knowledge graphs from text to a joint representation of “text-image-spatiotemporal” dimensions, providing a more comprehensive understanding of complex domains.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their gratitude to three scholars from the Information Support Force Engineering University for providing the dataset used in this study.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Yu Tao, Ruopeng Yang; data collection: Xiaolei Gu; analysis and interpretation of results: Yihao Zhong, Kaige Jiao; draft manuscript preparation: Yu Tao and Yongqi Wen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. China National Institute of Electronic Technology Standardization. Knowledge graph standardization white paper. Beijing, China: China National Institute of Electronic Technology Standardization; 2019.(In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

2. Yuan Q, Du X, Ma H. Research on framework of knowledge extraction system in the field of command and control support. Modern Electron Techniq. 2022;45(5):117–21, (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

3. Wang Y, Wu Z. Military equipment knowledge graph construction based on entity relationship extraction. Modern Electron Techniq. 2024;47(15):163–8. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

4. Brown TB, Mann B, Ryder N. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in neural information processing systems. In: Proceedings of the 34th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2020 Dec 6–12; Vancouver, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

5. OpenAI, Achiam J, Adler S. GPT-4 technical report. arXiv:2303.08774. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. DeepSeek-AI, Liu A, Feng B. DeepSeek-V2: a strong, economical, and efficient mixture-of-experts language model. arXiv:2405.04434. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2405.04434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Dai D, Deng C, Zhao C. DeepSeekMoE: towards ultimate expert specialization in mixture-of-experts language models. arXiv:2401.06066. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2401.06066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang S, Sun X, Li X, Ouyang R, Wu F, Zhang T, et al. GPT-NER: named entity recognition via large language models. arXiv:2304.10428. 2023. [Google Scholar]

9. Munnangi M, Feldman S, Wallace BC, Amir S, Hope T, Naik A. On-the-fly definition augmentation of LLMs for biomedical NER. arXiv: 2404.00152. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2404.00152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ashok D, Lipton ZC. PromptNER: prompting for named entity recognition. arXiv:2305.15444. 2023. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2305.15444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhu R, Liu B, Tian Q. Knowledge graph based question-answering model with subgraph retrieval optimization. Comput Operation Res. 2025;177(36):106995. doi:10.1016/j.cor.2025.106995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang G, Liu J, Zhou G, Zhao K, Xie Z, Huang B. Question-directed reasoning with relation-aware graph attention network for complex question answering over knowledge graph. IEEE/ACM Trans Audio Speech Lang Process. 2024;32(1):1915–27. doi:10.1109/TASLP.2024.3375631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wang H, Zhang F, Xie X, Guo M. DKN: deep knowledge-aware network for news recommendation. arXiv: 1801.08284. 2018. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1801.08284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Bordes A, Usunier N, Garcia-Duran A, Weston J, Yakhnenko O. Translating embeddings for modeling multi-relational Data. In: Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2012 Dec 3–6; Lake Tahoe, NV, USA. [Google Scholar]

15. Yang B, tau YW, He X, Gao J, Deng L. Embedding entities and relations for learning and inference in knowledge bases. arXiv:1412.6575. 2014. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1412.6575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ma R, Gao B, Wang W, Wang L, Wang X, Zhao L. MHEC: one-shot relational learning of knowledge graphs completion based on multi-hop information enhancement. Neurocomputing. 2025;614(10):128760. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2024.128760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang P, Han J, Li C, Pan R. Logic attention based neighborhood aggregation for inductive knowledge graph embedding. arXiv:1811.01399. 2020. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1811.01399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Wang X, Gao T, Zhu Z. KEPLER: a unified model for knowledge embedding and pre-trained language representation. Trans Assoc Comput Linguistics. 2021;9(11):176–94. doi:10.1162/tacl_a_00360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhang Z, Liu X, Zhang Y, Su Q, Sun X, He B. Pretrain-KGE: learning knowledge representation from pretrained language models. In: Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP; 2020 Nov 16–20; Virtual. p. 259–66. doi:10.18653/v1/2020.findings-emnlp.25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Gutierrez C, Sequeda JF. Knowledge graphs. Commun ACM. 2021;64(3):96–104. doi:10.1145/3418294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Paulheim H. How much is a triple? Estimating the cost of knowledge graph creation. In: Proceedings of the ISWC, 2018 Posters & Demonstrations, Industry and Blue Sky Ideas Tracks Co-Located with 17th International Semantic Web Conference; 2018 Oct 8–12; Monterey, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

22. Wei J, Wang X, Schuurmans D, Bosma M, Chi E, Ichter B, et al. Chain of thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2022;35:24824–37. [Google Scholar]

23. Liu V, Chilton LB. Design guidelines for prompt engineering text-to-image generative models. arXiv:2109.06977. 2023. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2109.06977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. White J, Fu Q, Hays S. A prompt pattern catalog to enhance prompt engineering with ChatGPT. arXiv:2302.11382. 2023. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2302.11382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhao WX, Zhou K, Li J. A survey of large language models. arXiv: 2303.18223. 2025. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2303.18223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Giglou HB, D’Souza J, Aue S. Large language models for ontology learning. arXiv: 2307.16648. 2023. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2307.16648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. LU Y, Yang R, Yin C, Lu W, Shi Z. Military entity relation extraction method combining pre-trained model with attention mechanism. J Inform Eng Univ. 2022;23(1):108–14. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

28. Chen K, Jia J. Network evasion detection with Bi-LSTM model. arXiv:2502.10624. 2025. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2502.1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Bhushan RC, Donthi RK, Chilukuri Y, Srinivasarao U, Swetha P. Biomedical named entity recognition using improved green anaconda-assisted Bi-GRU-based hierarchical ResNet model. BMC Bioinform. 2025;26(1):34. doi:10.1186/s12859-024-06008-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Daiyi L, Yaofeng T, Xiangsheng Z, Yangming Z, Zongmin M. End-to-end Chinese entity recognition based on BERT-BiLSTM-ATT-CRF. ZTE Communi. 2022;20(S1):27. doi:10.23919/ccc63176.2024.10662414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhao D, Chen X, Chen Y. Named entity recognition for Chinese texts on marine coral reef ecosystems based on the BERT-BiGRU-Att-CRF model. Appl Sci. 2024;14(13):5743. doi:10.3390/app14135743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools