Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Automatic Detection of Health-Related Rumors: A Dual-Graph Collaborative Reasoning Framework Based on Causal Logic and Knowledge Graph

College of Information Science and Engineering, Hunan Institute of Engineering, Xiangtan, 411228, China

* Corresponding Author: Haoran Lyu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Fake News Detection in the Era of Social Media and Generative AI)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-31. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068784

Received 06 June 2025; Accepted 19 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

With the widespread use of social media, the propagation of health-related rumors has become a significant public health threat. Existing methods for detecting health rumors predominantly rely on external knowledge or propagation structures, with only a few recent approaches attempting causal inference; however, these have not yet effectively integrated causal discovery with domain-specific knowledge graphs for detecting health rumors. In this study, we found that the combined use of causal discovery and domain-specific knowledge graphs can effectively identify implicit pseudo-causal logic embedded within texts, holding significant potential for health rumor detection. To this end, we propose CKDG—a dual-graph fusion framework based on causal logic and medical knowledge graphs. CKDG constructs a weighted causal graph to capture the implicit causal relationships in the text and introduces a medical knowledge graph to verify semantic consistency, thereby enhancing the ability to identify the misuse of professional terminology and pseudoscientific claims. In experiments conducted on a dataset comprising 8430 health rumors, CKDG achieved an accuracy of 91.28% and an F1 score of 90.38%, representing improvements of 5.11% and 3.29% over the best baseline, respectively. Our results indicate that the integrated use of causal discovery and domain-specific knowledge graphs offers significant advantages for health rumor detection systems. This method not only improves detection performance but also enhances the transparency and credibility of model decisions by tracing causal chains and sources of knowledge conflicts. We anticipate that this work will provide key technological support for the development of trustworthy health-information filtering systems, thereby improving the reliability of public health information on social media.Keywords

The Internet now serves as a primary source of health information, with nearly 90% of individuals turning to online searches when confronted with health concerns [1]. While this ease of access has reduced barriers to obtaining medical consultation [2], shortcomings within the regulatory framework for information have facilitated the rapid dissemination of health-related misinformation [3]. The World Health Organization has cautioned that such misinformation poses a significant threat to global public health security [3,4].

Existing rumor detection methods can be broadly categorized into three approaches: (1) semantic modeling using deep language models; (2) propagation network analysis that leverages the structure of social networks; and (3) methods that combine external knowledge reasoning or causal-driven approaches. The first two categories have made significant progress, yet they remain insufficient in health-related scenarios. Deep language models such as BERT and RoBERTa are capable of capturing rich semantic patterns; however, they lack the ability to verify the misuse of biomedical terminology or the logical consistency of medical statements [5,6]. Graph neural networks like TextGCN and Compare-GCN are effective at exploiting structural clues inherent in the online propagation of rumors, but they largely overlook the internal logic of the rumor content [7,8]. To address these shortcomings, recent work has begun exploring knowledge-driven and causal-driven methods [9–12]. Knowledge-based approaches enhance text representations by linking entities such as diseases, symptoms, and treatments to biomedical knowledge graphs, thereby introducing domain-specific prior knowledge. While these methods improve the identification of health-related concepts, they inherently model static associations and are unable to reveal the fictitious causal chains characteristic of many health rumors [13]. In contrast, causal-driven methods employ causal discovery or causal inference techniques to uncover underlying causal mechanisms and distinguish genuine causal relationships from spurious correlations [14]. However, in health-related contexts, these methods face two major challenges: (1) rumor texts are typically noisy and unstructured, rendering causal inference unreliable; and (2) without the support of domain knowledge, the inferred causal links may not be consistent with biomedical rationality. Consequently, a purely causal-based approach may misinterpret or overfit the rumor patterns when unconstrained by external knowledge. Although recent studies have attempted to optimize causal reasoning models for rumor detection [11], such efforts remain limited, with most research focusing on general social rumors rather than those specific to the health domain. Moreover, some recent studies have explored hybrid or multi-graph inference strategies that integrate heterogeneous information sources [10,13,15]. While these methods demonstrate the benefits of graph integration, they typically focus on combining social propagation graphs or multimodal graphs rather than jointly leveraging causal structures and biomedical knowledge. Thus, the feasibility and potential of unifying causal discovery with domain-specific knowledge for health rumor detection remain uncertain. In view of the recent progress in knowledge-driven and causal-driven approaches, we attempt to explore the feasibility of health rumor detection by integrating knowledge graphs with causal discovery methods.

Here, we propose a health rumor detection framework based on dual-graph fusion, termed CKDG. This framework establishes a collaborative reasoning architecture that integrates a causal graph with a knowledge graph, jointly modeling the implicit causal logic within text and an external medical knowledge verification mechanism, effectively mitigates the limitations of existing methods in capturing pseudo-causal relationships and in the appropriate usage of specialized terminology. Specifically, CKDG initially extracts medical entities from the text and constructs a weighted causal graph to quantify the strength of causal relationships among these entities. It then integrates the causal graph with a medical knowledge graph through a tailored knowledge-guided credibility estimation approach, wherein each causal edge is cross-validated against pre-validated knowledge within the medical graph. Finally, by fusing EGRET with a hierarchical pooling strategy, CKDG dynamically combines causal strength signals and knowledge verification cues, enabling multi-granularity reasoning that spans both local paths and global semantics.

In summary, our main contributions are as follows:

• We propose a dual-channel fusion framework, Causal Graph-Knowledge Graph, which, for the first time, jointly incorporates implicit causal logic and external domain knowledge into health rumor detection.

• We design a knowledge-guided causal strength estimation method, introducing an entity alignment strategy and a knowledge validation mechanism, which significantly correct causal direction misjudgments and enhance the discovery of implicit associations.

• We introduce an edge aggregated graph attention network and a hierarchical pooling strategy to achieve efficient fusion of complex causal topologies and knowledge validation signals, thereby improving the model’s robustness.

• On a dataset comprising 8430 health rumor instances, CKDG, when combined with the Chinese Medical Knowledge Graph (CMeKG), achieves an accuracy of 91.28% (an improvement of 5.11% over the best-performing baseline) and an F1 score of 90.38% (an improvement of 3.29% over the best-performing baseline), validating the effectiveness of dual-graph collaborative reasoning.

Rumor detection methods can be categorized from multiple perspectives. In this work, we focus on text-based approaches, incorporating causal graphs and knowledge graphs as key features. Therefore, we primarily discuss causality-based methods and approaches that leverage external knowledge.

Causal relationships characterize the logical connections between events or entities, and the causal semantics inherent in natural language have garnered significant scholarly attention. Extensive investigations have explored causal relations in natural language, yielding promising applications in text classification, word embeddings, and beyond. For example, reference [16] demonstrated that integrating the robustness and interpretability of models developed for natural language processing tasks. Similarly, reference [17] employed a causal perspective to construct graphs capturing user interactions and rumor propagation, while reference [18] applied causal intervention and reasoning approaches to mitigate biases between textual features and news labels. In the realm of fake news detection, reference [19] utilized counterfactual reasoning to address entity bias stemming from the uneven distribution of entities within texts. Collectively, these studies substantiate the feasibility and necessity of leveraging causal relationships to advance rumor detection methodologies.

Knowledge-based rumor detection methods can generally be categorized into two primary approaches. One approach focuses on fact verification by extracting and comparing triplet structures derived from knowledge graphs [7]. A unified framework has been developed to integrate fact-based and feature-based models by incorporating external fact-checking sources through model preference learning [20]. Another framework has been introduced to jointly model propagation dynamics and the structural relationships among entities in knowledge graphs [21]. Additionally, entity linking techniques have been employed to detect fake news by leveraging entity descriptions from external knowledge bases [22].

The second line of research emphasizes integrating social media responses with news content by leveraging external knowledge to identify key entities [23]. Additionally, several studies have investigated the incorporation of commonsense knowledge graphs, which encode complex conceptual relationships through structured representations [24]. These graphs have been shown to enhance performance in various downstream tasks, including open-domain conversations, question answering, sentiment analysis, and stance detection [25–27]. Furthermore, commonsense knowledge has proven effective in supporting tasks such as sarcasm detection, meme interpretation, and emotion recognition [28,29].

From extensive studies, it is evident that considerable progress has been achieved in the field of rumor detection. However, current approaches have not sufficiently addressed the relationships among entities or the impact of external knowledge on rumor detection. Indeed, knowledge serves as a paradigmatic standard for human judgment and plays a pivotal role in evaluating health-related rumors.

Causal reasoning mainly concerns (1) the existence of causal relations and (2) their strength. To capture both, CKDG integrates causal discovery, edge strength estimation, and a graph attention model that fuses causal signals with domain verification.

3.1 Causal Discovery via Greedy Fast Causal Inference (GFCI)

Causal discovery corresponds to the first class of causal reasoning problems. From a graph-based perspective, it refers to inferring causal structures from observational data. In CKDG, this translates to identifying directional links among biomedical entities extracted from rumor texts. To achieve this, we adopt the GFCI algorithm [30], a hybrid method that integrates constraint-based conditional independence testing and score-based structure search. Unlike conventional approaches that assume causal sufficiency, GFCI allows for the presence of latent confounders by generating a Partial Ancestral Graph (PAG), which flexibly represents plausible causal structures. Each PAG corresponds to a Markov equivalence class of DAGs compatible with the observed independence constraints, and may contain uncertain or bidirectional edges. This makes it particularly suitable for noisy and incomplete data derived from real-world texts.

3.2 Causal Strength Estimation

Causal strength estimation corresponds to the second class of causal reasoning problems, which aims to quantify the influence of each learned causal relationship—whether it is strong or weak. In our CKDG framework, we adopt the Average Treatment Effect (ATE) as the metric for causal strength. For a directed edge

3.3 Edge Aggregated Graph Attention Network (EGRET)

To effectively leverage both node-level and edge-level information in downstream classification, we utilize an EGRET [31]. EGRET extends traditional Graph Attention Networks (GAT) by incorporating edge features not only in attention score computation, but also in the message aggregation process. Formally, the attention coefficient

Our proposed health rumor detection framework, termed Causal-Knowledge Dual Graph (CKDG), identifies health-related misinformation by jointly modeling causal reasoning and biomedical knowledge validation within the text. The overall architecture is illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2.

Figure 1: Causal-knowledge dual graph integration framework. The left part shows the causal graph construction process from rumor texts using BioBERT and GFCI. The right part depicts the knowledge verification pipeline that aligns causal edges with entities in the medical knowledge graph, evaluates credibility based on alignment confidence and directionality, and enhances the dual-graph structure

Figure 2: Edge-enhanced dual graph fusion classifier framework. The classifier utilizes node features from BioBERT and knowledge graph embeddings, along with fused edge features comprising causal strength and credibility. Through an EGRET-based graph attention mechanism, these features are jointly processed to compute attention weights and node embeddings. A hierarchical pooling module aggregates graph semantics, followed by an MLP for rumor classification

Fig. 1 illustrates the complete architecture of the CKDG framework, which consists of two collaborative modules. In the left part (Module A), BioBERT is used to extract biomedical entities from rumor texts, followed by the construction of a causal graph through the GFCI algorithm and constraint-based filtering. In the right part (Module B), these causal edges are verified against a domain-specific knowledge graph using alignment strategies and semantic similarity. A credibility score is then computed for each edge based on its alignment quality and consistency with medical knowledge, which will be integrated into the final dual-graph representation.

Given a health-related statement

To achieve reliable prediction beyond shallow semantics, we construct a dual-graph representation

Our task is thus transformed into learning a function

4.2 Causal Graph Construction and Strength Estimation

As outlined in Section 3, we model both the existence and strength of causal relations. we next elaborate on their instantiation in the CKDG framework.

4.2.1 Causal Graph Construction

To construct the nodes of the causal diagram, semantic parsing and entity extraction are performed on health rumor texts. Given the characteristics of health rumors, this task is classified as a biomedical named entity recognition (BioNER) task. General pre-trained language models (e.g., BERT) exhibit significant limitations in recognizing specialized terminology due to a lack of domain adaptation. Therefore, we employ the BioBERT model [32], which has been re-trained on the PubMed corpus. Through a domain adaptive strategy, BioBERT improves the F1 score in the BioNER task by 0.62% compared to BERT (p < 0.05), making it well-suited for processing health rumors. Subsequently, we establish the edges of the graph. Considering that health-related rumors are filled with unverified, fragmented, and often deliberately misleading information, many confounding factors interfere with causal inference. For example, take the research question of whether smoking causes lung cancer [33]. In this scenario, we examine the possible causal relationship between smoking (T) and lung cancer (Y), where age acts as a confounding factor (c). Although comparing lung cancer rates between smokers and non-smokers may seem straightforward, However, age influ-ences both smoking and lung cancer. Specifically, older individuals are more likely to smoke and also face a significantly higher risk of developing cancer. Ignoring the effect of age may lead to misattributing its influence on lung cancer to smoking, thereby exaggerating the estimated causal effect. Inspired by Liu et al. [30], we adopt the GFCI algorithm [34] to uncover causal relationships among various factors. GFCI integrates scoring-based and constraint-based algorithms, combining the robust performance of scoring-based methods with the advantage of bypassing the constraint-based approach’s dependence on the assumption of causal sufficiency (i.e., the absence of unobserved confounders). Specifically, GFCI does not rely on the assumption of no latent confounders, making it well-suited for noisy, unstructured textual data such as health rumors. Detailed comparative experiments can be found in Section 5.2.4.

However, automatically generated causal graphs may include noisy edges that are inconsistent with established medical logic. To enhance the reliability of the causal graph, we introduce two constraint-based rules to filter out such edges:

a) Medical Logic Constraint: Certain entities and relations in the medical domain follow well-defined logical structures [35]. For example, we prohibit edges from symptom-type entities pointing to disease, drug, or treatment entities, as such directions contradict the inherent etiology-symptom logic in medical knowledge bases.

b) Temporal Constraint: Given that causes generally precede effects in time, and symptom descriptions are typically documented in chronological order, we use the temporal order of textual mentions as a constraint. If factor A appears after factor B in most cases, an edge from A to B is disallowed.

It is important to note that the temporal constraint does not imply the existence of an edge from B to A, as temporal precedence is not a sufficient condition for causality.

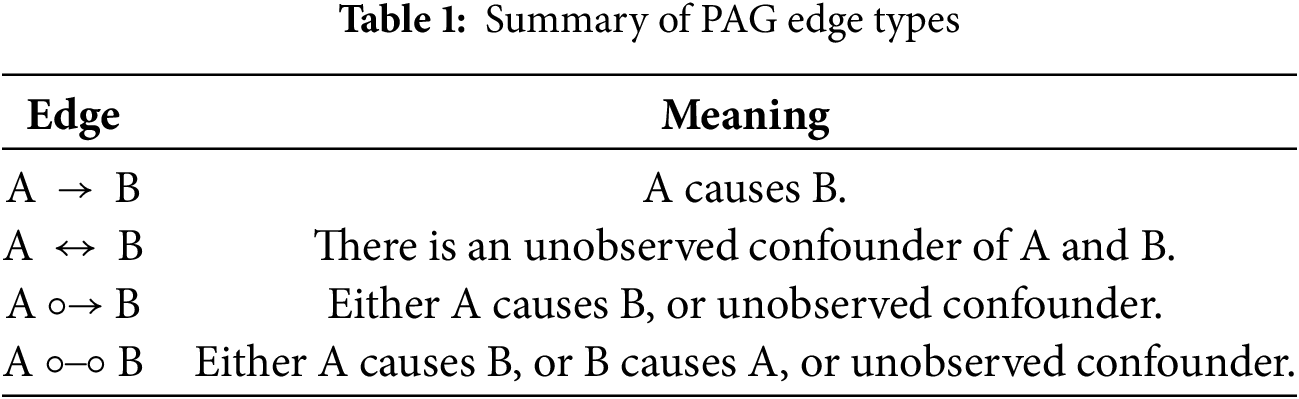

Table 1 summarizes four types of uncertain relations found in the PAG output by GFCI, which pose challenges for causal strength estimation and downstream tasks. Drawing on the probabilistic causal discovery framework of Liu et al. [30], we generate Q candidate causal graphs (Fig. 3). For each sampled graph, we retain deterministic edges

Figure 3: Overall pipeline of causal reasoning in CKDG. In the entity extraction phase, each circle represents a biomedical entity identified from the input rumor text. In the causal relation learning phase, directed and uncertain edges between entities are derived using the GFCI algorithm to construct a PAG, which includes four types of edges:

This multi-graph sampling strategy allows us to handle uncertainty in PAG edge types and obtain a robust estimation of possible causal structures before strength computation.

4.2.2 Causal Graph Strength Estimation

Once the causal structure is established, the next step is to assign edge weights to reflect how influential each causal factor is. Given the inherently noisy nature of the resulting causal graph, we refine the sampled causal graph by quantifying the strength of learned causal associations. Edges demonstrating substantial causal effects are assigned higher weights, while those corresponding to non-causal relationships or exhibiting negligible effects receive weights approaching zero. Intuitively, this strength characterizes the magnitude of the expected change in outcome Y in response to variations in the treatment variable T. For example, in the causal diagram from “smoking (T)

Here,

4.3 Knowledge Graph-Driven Causal Validation

Automatically inferred causal graphs may contain spurious or implausible edges. To enhance their reliability, we validate them using domain-specific knowledge.

This section aims to validate whether the causal relations identified in the causal graph

The objective of entity alignment is to match each entity

Figure 4: Illustration of the edge-level alignment between the causal graph and knowledge graph. Three alignment strategies—direct matching, multi-hop reasoning, and semantic similarity—are applied to verify the validity of causal edges. Each edge is then assigned to one of four verification scenarios based on its correspondence in the knowledge graph: positive, negative, ambiguous, or missing

a) Exact Matching: Entities with identical names are directly matched using a hash table. For these,

b) Fuzzy Matching: For unmatched entities, semantic similarity scores

c) Unaligned Tagging: Entities that remain unmatched after the above steps are labeled as “Missing”.

4.3.2 Knowledge-Guided Causal Credibility Estimation

After completing entity alignment, we estimate the credibility

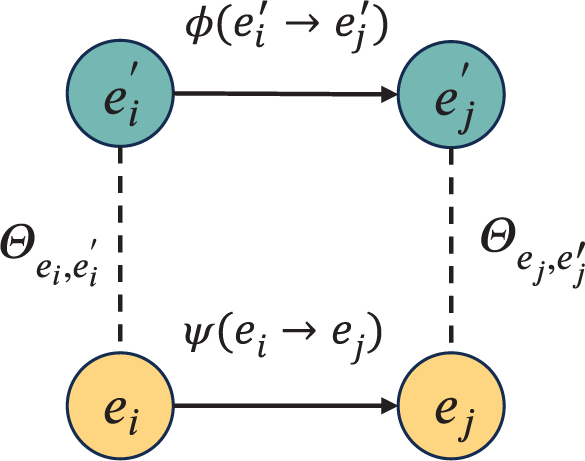

Figure 5: Minimal model in the causal credibility estimation task

Following the idea of gated mechanisms, we construct the credibility estimation function

Starting with a multiplicative gating structure, we formulate the function as

Accordingly, the complete credibility estimation function becomes:

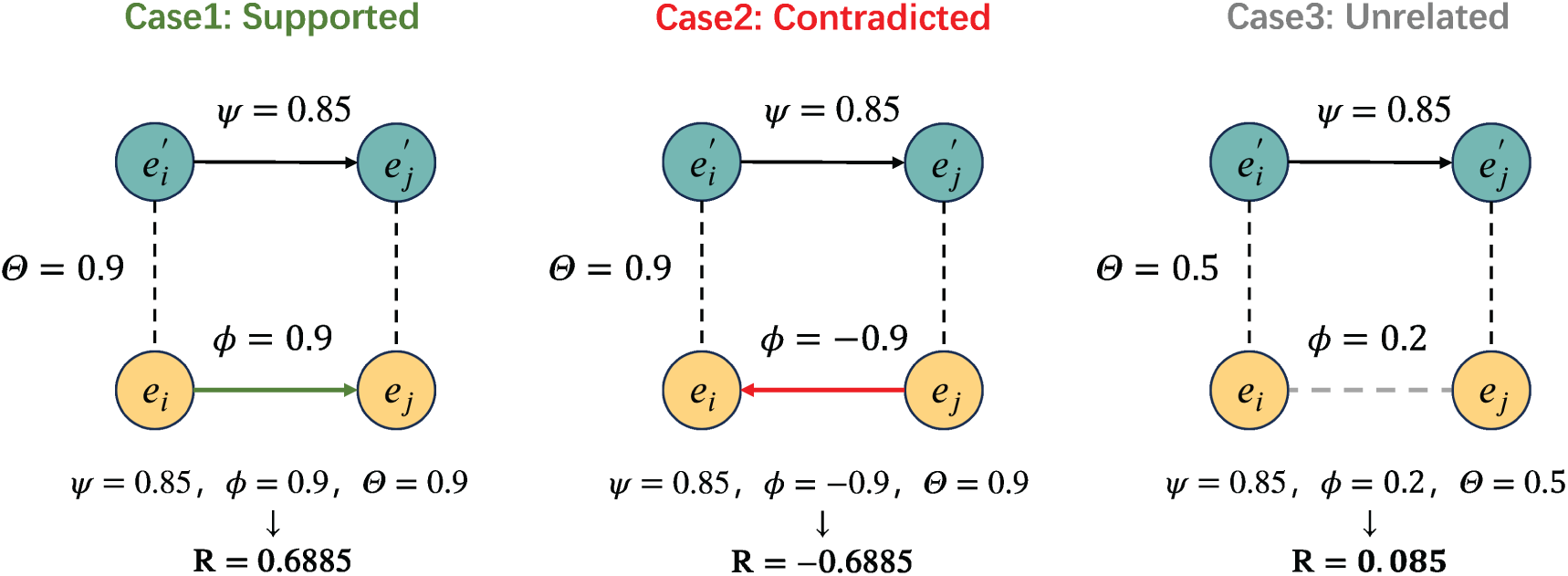

To better illustrate how the credibility function R modulates the original causal strength

Figure 6: Illustration of three typical cases in knowledge-guided credibility estimation. Case 1 (Support): when the causal claims align with biomedical knowledge (e.g., “Vitamin C can boost immunity”), a positive trustworthiness score is obtained. Case 2 (Contradiction): when the claims contradict established knowledge (e.g., “High doses of antibiotics can cure viral infections”), a negative trustworthiness score results. Case 3 (Irrelevant): when the claims lack clear support in the knowledge graph (e.g., “Ginkgo biloba cures all diseases”), the trustworthiness score approaches zero

In Case 1, the knowledge graph supports the same causal direction (i.e.,

In Case 2, a contradictory path exists in the knowledge graph (i.e.,

In Case 3, no valid path is found between

These examples demonstrate how our credibility estimation acts as a selective gate to suppress unreliable or unsupported causal edges, and to retain the ones consistent with external knowledge.

After designing the credibility function R, we further examine the determination of

Direct Relations: For a causal edge

When

Multi-Hop Paths: When a direct connection between two entities does not exist in the knowledge graph but a multi-hop path is available (e.g.,

a) Path Search: The search starts simultaneously from both

b) Path Filtering: Only paths with consistent directionality (e.g.,

Intuitively, multi-hop paths can reveal underlying indirect causal mechanisms, such as “virus infection

Among these,

Unrelatedness Test: When no explicit relation exists between the knowledge graph entities corresponding to a candidate causal edge, its credibility is dynamically adjusted based on the global coverage of the knowledge graph, as defined by the following formula:

where

Missing Entity Detection: The annotation of missing entities is performed by an upstream task. Here, we implement a penalty function for specific missing entities:

where

Integrated Credibility Computation: Considering that both a direct causal relation and multiple multi-hop paths may exist simultaneously between two entities, we integrate the final causal edge strength

Here,

Subsequently, the resulting

This refined graph integrates both data-driven causal discovery and knowledge-informed validation, forming a more trustworthy basis for downstream classification.

4.4 Edge-Enhanced Dual-Graph Fusion Classifier

In our graph

Fig. 2 details the EGRET-based dual-graph fusion classifier used in CKDG. It encodes both node features (from BioBERT and aligned TransE embeddings) and edge features (causal strength and credibility). The edge-enhanced attention mechanism enables the model to incorporate structural and semantic cues from both the causal graph and knowledge validation during message passing. The attention-weighted features are aggregated into a graph-level representation using a hierarchical pooling mechanism, which is then passed to a MLP classifier for final prediction.

Node Feature Encoding: As shown in Module A in Fig. 1, We utilize the final hidden states of BioBERT as the initial feature representation

Here,

Edge Feature Encoding: To reduce computational complexity in subsequent processes, we encode the causal strength

where

4.4.2 Edge-Enhanced Graph Attention Computation

Following the approach of EGRET, the attention score for each directed edge

By combining node embeddings with edge features, the attention mechanism is guided to focus on semantically consistent and structurally validated relations. Here,

To fully exploit the informative capacity of the edge features

Before aggregation, the edge features

To map the structural information of the graph into the classification space, we employ a MLP as the classifier. Given the hierarchical nature of graph-level semantics in the task of health rumor detection, node-level embeddings must first be aggregated into a graph-level representation. Inspired by the work of Lee et al. [37], we incorporate an attention pooling mechanism to dynamically capture the varying contributions of individual nodes. Specifically, for all node embeddings

where

This mechanism assigns greater importance to nodes with high causal strength, aligning with the task requirement of focusing on core causal chains in rumor detection. The graph-level embedding

where

The training objective of the model is jointly optimized via a multi-task loss, which consists of the primary classification loss, a knowledge consistency constraint, and a sparsity regularization term. The primary loss adopts the Label Smoothing Cross-Entropy (LS-CE) loss to mitigate the overconfidence problem caused by class imbalance by introducing a smoothing factor

where

where

The weight coefficients

4.5 Limitations and Discussion

Although the CKDG framework demonstrated outstanding performance in experiments, it still presents several inherent limitations that delineate the scope of the current study while also pointing to directions for future improvements.

Language and knowledge graph dependencies: The current CKDG is designed exclusively for Chinese health rumor detection, relying on language-specific resources such as the BioBERT model fine-tuned on Chinese biomedical texts and the CMeKG knowledge graph. This design choice inevitably limits its direct applicability to other languages. The entity extraction and semantic alignment modules are highly sensitive to linguistic features, and the knowledge validation process is also constrained by the coverage and structural patterns of CMeKG.

Generalization to multilingual and cross-domain scenarios: To enable CKDG to adapt to a wider range of environments, the following extensions can be considered. For multilingual adaptation, pre-trained cross-lingual models (such as mBERT or XLM-R) can be incorporated to support cross-lingual entity extraction and semantic similarity computation. Additionally, integrating multilingual or language-agnostic knowledge bases (such as UMLS or Wikidata) can provide the necessary domain information for knowledge verification in different languages. The causal discovery module (GFCI) relies solely on statistical correlation and is language-independent, so it can essentially remain unchanged. The primary challenge lies in achieving high-quality entity alignment and relation mapping across heterogeneous knowledge graphs.

Other considerations: Additionally, the computational complexity of causal discovery and graph inference is relatively high, which may affect real-time applications. Relevant experiments can be found in Section 5.2.8; moreover, the model relies on the coverage and accuracy of the underlying knowledge graph, and missing or erroneous knowledge could compromise the reliability of validation.

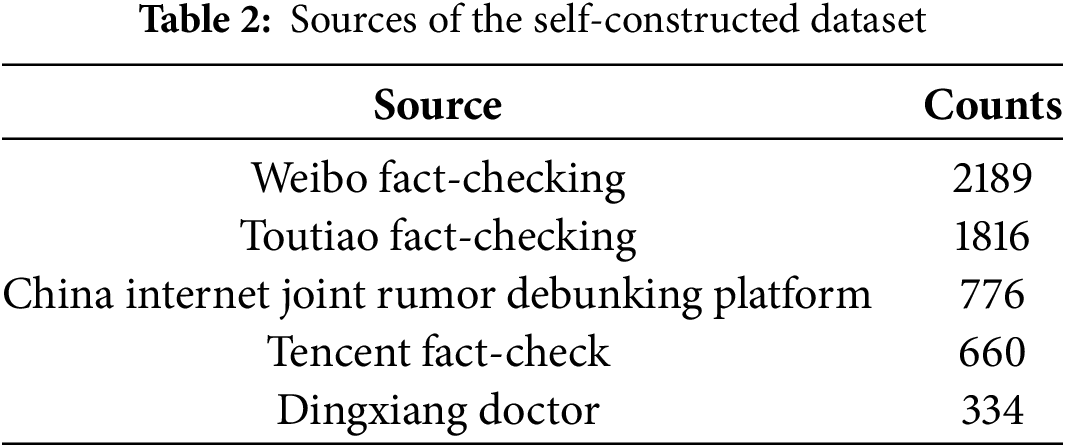

We conducted experiments using three datasets: the LTCR dataset1 [38], the COVID-19 Health Rumors (CHR) dataset2 [39], and a self-constructed multi-source health rumor dataset. The LTCR dataset comprises 2307 samples, including 1731 rumors, 516 non-rumors, and 60 unknown cases. The CHR dataset contains 408 samples, all of which are health-related rumors. To enhance the diversity and scale of the experimental data, we collected samples from multiple authoritative fact-checking platforms and constructed a novel health rumor dataset. The sources and statistics of each platform are detailed in Table 2. The veracity labels (rumor/non-rumor) were directly assigned by domain experts and editorial teams from these platforms, ensuring a high level of annotation accuracy and reliability. Additionally, to guarantee quality, we randomly selected 500 samples, which were independently reviewed by two authors alongside the original platform decisions. In the end, the self-built dataset comprises a total of 5775 samples, including 3954 rumors and 1821 non-rumors.

After merging the three datasets, we obtained a total of 8430 samples, consisting of 6093 rumors and 2337 non-rumors. We performed data preprocessing procedures including duplicate removal, word segmentation, and entity annotation based on BioBERT. The final dataset was split into training, validation, and test sets in a 7:2:1 ratio.

In addition, we conducted comparative experiments on the knowledge graph components using CMeKG and Disease-KB. CMeKG 2.0 is currently the largest publicly available Chinese medical knowledge graph, containing approximately 1.56 million medical knowledge triples. Disease-KB focuses on common disease-related information and includes approximately 310,000 relational entries.

We compare our framework against a broader set of baseline models from four categories.

Shallow models:

• SVM-BOW [40] employs a support vector machine classifier on bag-of-words features as a naive lexical baseline.

• RFC [41] leverages handcrafted features including structural and linguistic statistics via random forest classification.

• CSI [42] introduces a hybrid approach combining user behavior scoring with textual modeling.

Deep text-based models:

• GRU [43] uses gated recurrent units to capture temporal evolution in rumor sequences.

• TextCNN [44] and BiLSTM [45] are classical CNN and bidirectional LSTM architectures, respectively, used to encode local n-gram features and global dependencies.

• BERT [36] and BERT-LSTM [46] represent pre-trained transformer-based encoders fine-tuned for classification, where BERT-LSTM appends a recurrent classifier on top of contextual embeddings.

• RoBERTa [47] is a robustly optimized variant of BERT that removes the next sentence prediction objective and dynamically changes masking patterns, often leading to stronger contextual encoding performance.

Graph-based models:

• TextGCN [48] constructs a document-word graph and uses GCN for text classification.

• Compare-GCN [49] captures inter-document semantic differences through GCN variants.

• CRNN [50] combines convolution and recurrent layers to capture both local and sequential features.

• Bi-GCN [51] performs bidirectional graph propagation over rumor trees, modeling both top-down and bottom-up rumor diffusion.

Knowledge-based models:

• KCNN [52] incorporates commonsense knowledge embeddings into convolutional text encoders.

• B-TransE [53] aligns textual features with TransE-encoded knowledge triples.

• K-BERT [54] integrates triples from external knowledge bases into the attention flow of BERT via soft position constraints.

• R-GCN [55] applies relational GCNs over multi-relational knowledge graphs to enrich node-level representations.

We implemented our model using PyTorch 1.13.1 and conducted experiments on a server equipped with an Intel Xeon Platinum 8352V CPU (12 cores), 48 GB RAM, and dual NVIDIA RTX 3080 GPUs (20 GB VRAM each). Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 score were used as evaluation metrics to assess model performance.

For causal graph construction and strength estimation, the significance level was set to 0.05, with the number of iterations

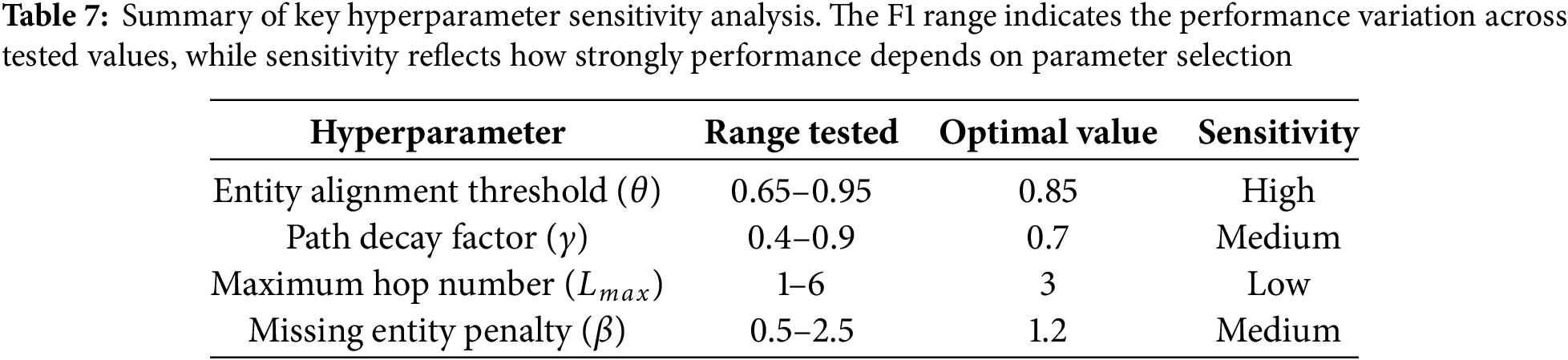

In knowledge graph-driven causal validation, the fuzzy matching threshold for entity alignment was set to

In the edge-enhanced dual-graph fusion classifier, node features were encoded using the hidden layer representations of BioBERT with dimensionality

The initial selection of these hyperparameter values was based on common practices in the relevant literature, preliminary experiments conducted on a reserved validation set, and the limitations imposed by our computational resources [10,11,13,14]. The sensitivity of these choices will be rigorously assessed in Section 5.2.8.

All models were trained using the Adam optimizer, with an initial learning rate

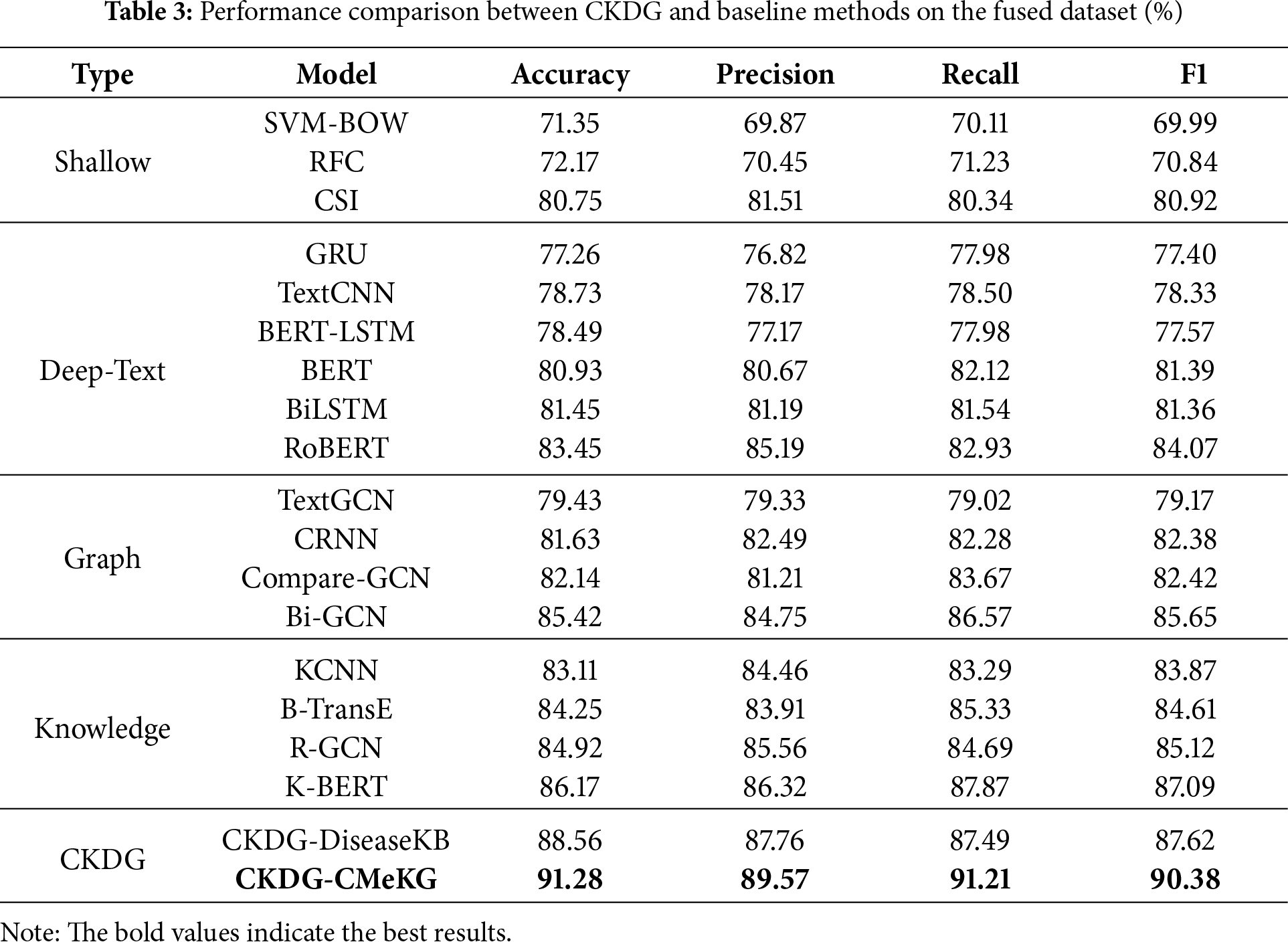

Table 3 summarizes the performance of CKDG and 18 baseline models across four categories. Overall, CKDG-CMeKG achieves the best results, with 91.28% accuracy and 90.38% F1-score, surpassing all shallow, deep text, graph-based, and knowledge-based baselines. The improvements over the strongest baseline model (K-BERT) reach 5.11% in accuracy and 3.29% in F1, demonstrating the effectiveness of our dual-graph reasoning mechanism.

Traditional shallow classifiers such as SVM-BOW and RFC show limited performance, with F1-scores around 70%. CSI, which combines user behavior with textual features, achieves a relatively strong 80.92% F1, outperforming many deep models. However, such models still fall short in handling implicit semantics or domain-specific logic, making them less suitable for complex rumor detection scenarios.

Deep learning methods based on sequential and transformer architectures yield moderate improvements. Models like GRU, BiLSTM, and TextCNN show similar performance levels, while BERT and RoBERTa significantly outperform them, with RoBERTa reaching 84.07% F1 and 83.45% accuracy. This suggests that pre-trained language models are more effective at capturing contextual nuances. Nonetheless, these methods rely solely on text and are insensitive to external knowledge or causal structure, which limits their interpretability and robustness.

Graph-based approaches provide stronger performance, especially in modeling structural patterns within rumor propagation or entity interactions. Compare-GCN and CRNN both exceed 82% F1, while Bi-GCN attains 85.65%, outperforming all non-knowledge-based models. These results demonstrate the benefits of structural representation learning, although such models still lack domain validation and may be misled by noise in graph construction.

Introducing external knowledge further improves results. Knowledge-based models like KCNN, R-GCN, and B-TransE all achieve F1 scores above 84%. K-BERT, which directly integrates medical triples into the attention mechanism, obtains 87.09% F1, outperforming both text-only and graph-based methods. This supports the hypothesis that health rumor detection benefits significantly from background knowledge. However, these models do not reason over causal relationships, and their decision process remains pattern-driven.

The CKDG variants demonstrate clear superiority. Even using the smaller Disease-KB, CKDG already surpasses K-BERT by more than 0.5% in F1. When integrated with CMeKG, CKDG achieves the highest performance across all metrics. The combination of BioBERT-based entity representation, GFCI-derived causal structure, credibility-weighted edge features, and EGRET-based attention enables CKDG to dynamically integrate causal reasoning with domain verification, suppressing spurious correlations and improving generalization to complex health misinformation.

Taken together, these results highlight that shallow and deep models capture surface patterns, graph models capture structural propagation, and knowledge models introduce domain priors. CKDG unifies all three aspects and advances the state-of-the-art via fine-grained causal and knowledge fusion.

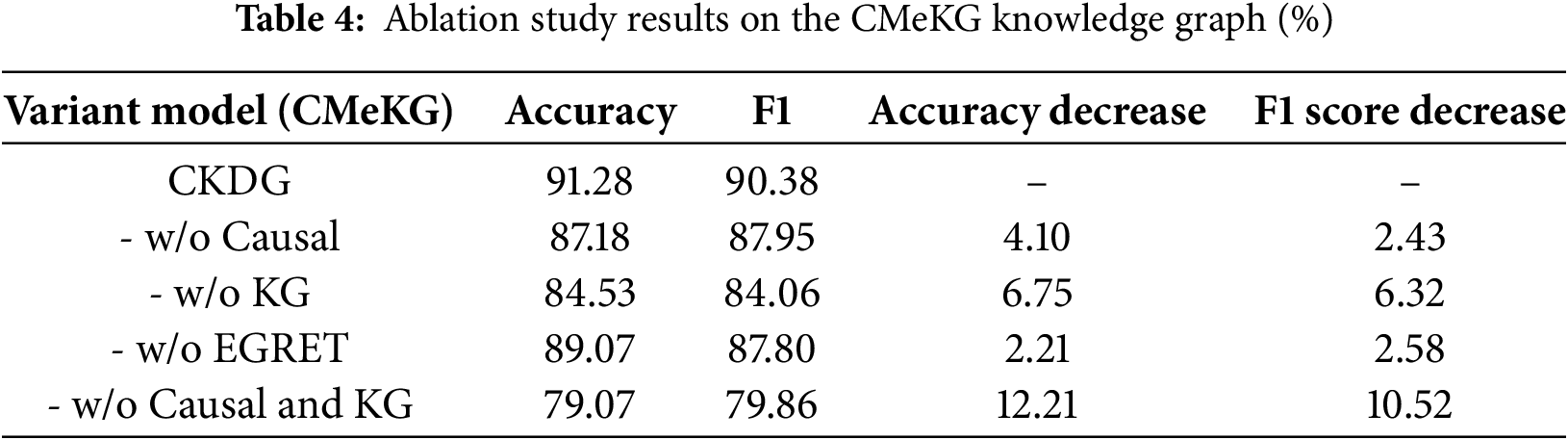

In this subsection, we conduct experiments to evaluate the effectiveness of each module within CKDG. Using the CMeKG knowledge graph consistently, we report the average performance over five runs on the test set. As shown in Table 4, removing the knowledge graph validation module (-w/o KG) results in a 6.75% drop in accuracy and a 6.32% decrease in F1-score, which we attribute to the model’s inability to filter out spurious causal relations that contradict established medical facts. This compromises its capacity to validate causal chains and renders it susceptible to data-driven pseudo-correlations, ultimately undermining detection reliability. Similarly, removing the causal inference module (-w/o Causal) leads to a 4.1% decrease in accuracy and a 2.43% decline in F1-score, highlighting the essential role of causal graph construction and strength estimation in capturing the latent causal logic within text; without it, the model struggles to differentiate between genuine and pseudo-causal relations implied in rumors. Moreover, excluding the edge-enhanced graph attention mechanism (-w/o EGRET) causes a 2.21% reduction in accuracy and a 2.58% drop in F1-score, demonstrating that dynamically integrating edge features and emphasizing edges with stronger causal strength can significantly enhance the model’s capacity to handle complex causal topologies.

Notably, when both the causal inference and knowledge graph validation modules are removed (-w/o Causal and KG), the model experiences a 12.21% decrease in accuracy and a 10.52% decline in F1-score, indicating a non-linear performance degradation that strongly supports the effectiveness of CKDG’s dual-graph fusion architecture.

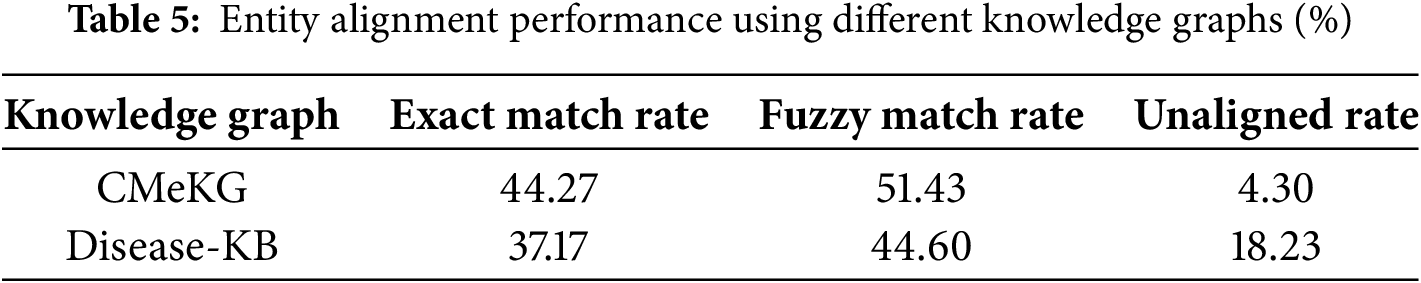

5.2.3 Impact of Different Knowledge Graphs

To assess the impact of different knowledge graphs, we evaluated the alignment performance using two distinct knowledge graphs, as presented in Table 5. A comparison with the results in Table 3 reveals that CKDG-CMeKG achieves a significantly higher alignment success rate (95.7% for exact and fuzzy matching combined) than CKDG-DiseaseKB (81.77%). We attribute this performance gap primarily to differences in the scale and coverage of the two knowledge graphs. CMeKG, as a large-scale medical knowledge graph, demonstrates clear advantages in both the breadth and depth of domain knowledge. In contrast, although DiseaseKB is tailored to a specific domain, its relatively limited size constrains its capacity to represent complex medical entities. These results underscore the substantial influence of knowledge graph selection on the performance of the CKDG framework.

5.2.4 Impact of Different Causal Discovery Algorithms

This experiment compares four causal discovery algorithms—GFCI, PC, PCMCI, and PCGCE. As shown in Table 6, CKDG-GFCI achieves a significantly higher accuracy (91.28%) and F1 score (90.38%) than other variants, highlighting the unique advantages of GFCI in handling unobserved confounders and nonlinear causal interactions in medical texts. The PC algorithm (CKDG-PC, F1 = 87.10%) fails to accommodate potential confounders in health rumors due to its reliance on the causal sufficiency assumption. PCMCI (CKDG-PCMCI, F1 = 88.08%) imposes temporal constraints that conflict with the non-temporal causal chains often present in textual data, thereby weakening its generalization capability. Although PCGCE (CKDG-PCGCE, F1 = 89.74%) enhances representation through latent space embedding, its strong dependence on prior knowledge limits its robustness in knowledge-sparse scenarios. The results demonstrate that GFCI, through a nonparametric framework and dynamic constraint rules, generates highly reliable causal paths under noisy conditions, offering optimal logical support for the model.

5.2.5 Impact of Text Length on Model Performance

To examine the impact of text length on model performance, we compared CKDG-CMeKG with representative baselines from each model family based on Table 3: CSI (shallow), RoBERTa (deep text), Bi-GCN (graph-based), and K-BERT (knowledge-based). The test set was partitioned by character count into four groups: short (0–20), medium (21–50), long (51–100), and ultra-long (>100) texts, each containing 70 samples. Evaluation was repeated five times, and averaged results are shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Accuracy and F1 scores of the best performing models for each category with different data volumes

CKDG achieves the best performance across all text lengths, with 86.12% accuracy and 85.59% F1 on short texts, and 90.76% accuracy and 90.03% F1 on ultra-long texts. The relatively strong results on short texts can be attributed to the presence of compact but informative medical terms, enabling CKDG’s dual-graph design to leverage localized causal links and knowledge validation. Despite this, its performance remains slightly lower compared to longer inputs, due to sparse entities and limited graph depth in short samples. On medium and long texts, CKDG shows substantial improvements as longer context allows for richer causal structure construction and credibility filtering. Notably, Bi-GCN benefits significantly from longer inputs, reaching 90.07% accuracy and 88.52% F1 on long texts—second only to CKDG—demonstrating the strength of bidirectional rumor tree modeling. However, its performance plateaus on ultra-long inputs due to information redundancy and graph over-smoothing.

K-BERT exhibits stable accuracy and F1 across all lengths (within a 5% range), confirming that incorporating structured knowledge contributes to robustness. Nonetheless, it lacks mechanisms for reasoning over causal inconsistencies, limiting its effectiveness in longer, more ambiguous inputs. RoBERTa shows relatively weaker performance throughout, particularly on short texts, likely due to its reliance on pure contextual embeddings without external knowledge or structure. CSI, despite being a shallow model, performs surprisingly well on short and medium texts, outperforming RoBERTa in F1. This suggests that behavior-aware heuristics still offer complementary cues in rumor detection, though their gains diminish on longer texts due to their limited semantic capacity.

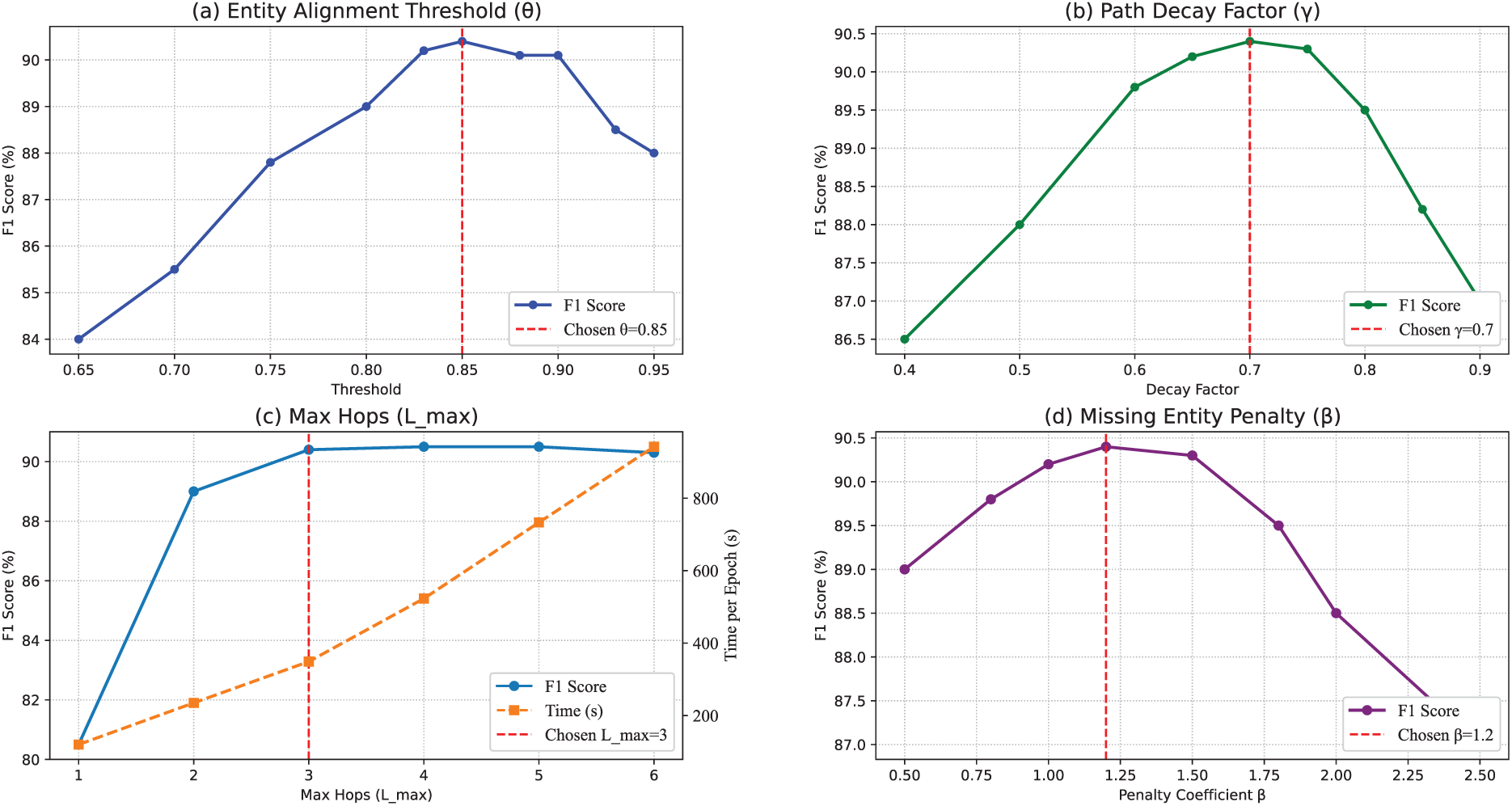

To evaluate the robustness of CKDG, we conducted sensitivity analysis on four key hyperparameters: entity alignment threshold (

Figure 8: Sensitivity analysis of key hyperparameters. (a) Entity alignment threshold (

The sensitivity analysis reveals three key patterns in how hyperparameters affect CKDG’s performance. First, the entity alignment threshold (

Overall, these findings demonstrate that CKDG maintains robust performance across reasonable hyperparameter choices, with particularly stable behavior in knowledge integration parameters (

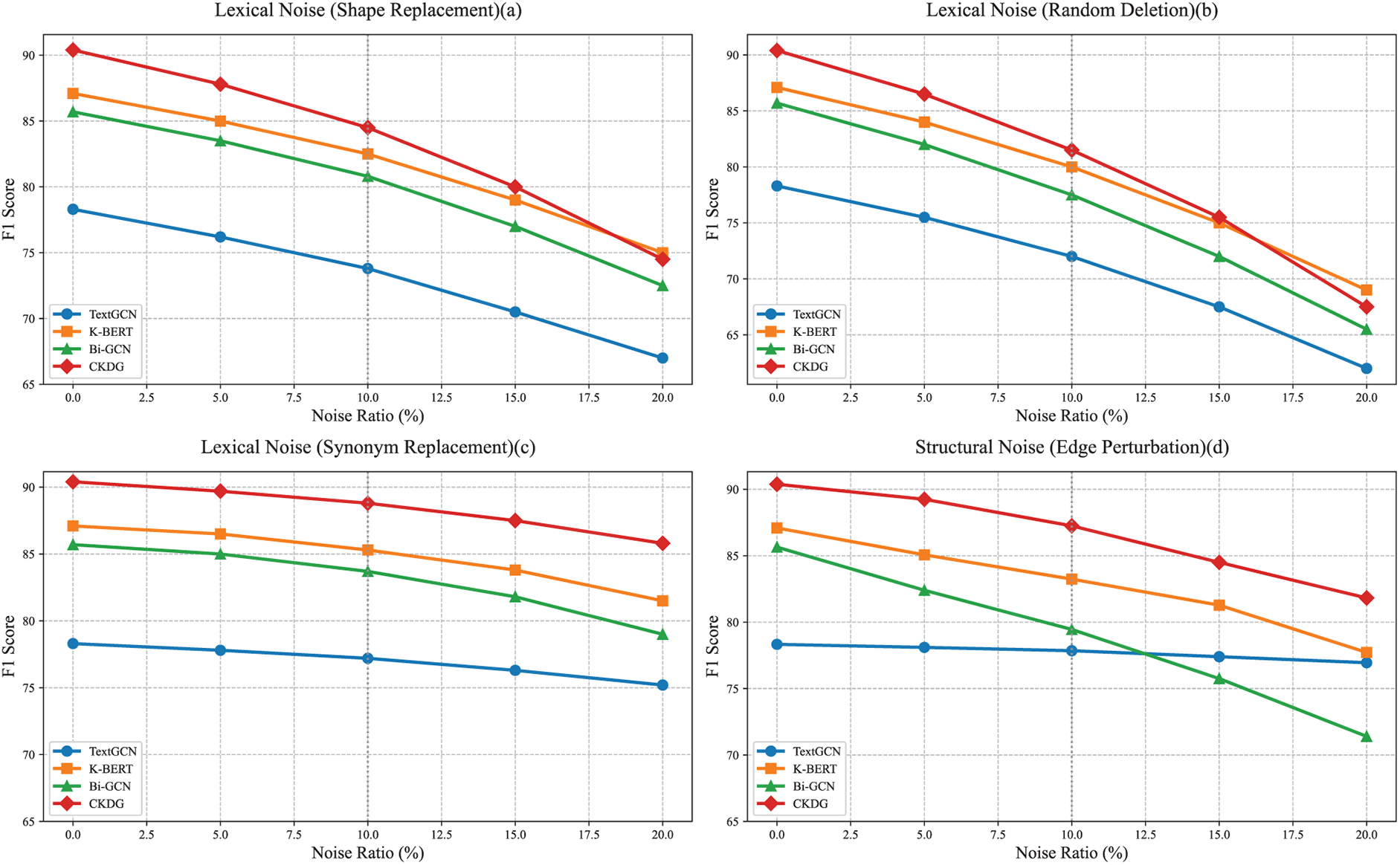

To evaluate the practicality of CKDG in real-world scenarios, we conducted robustness tests under two categories of noise conditions: Lexical Noise (text content perturbation) and Edge Perturbation (graph topology perturbation). Specifically, lexical noise comprises three types: Shape Replacement, Random Deletion, and Synonym Replacement3. For comparison, we selected three representative baseline models: TextGCN, K-BERT, and Bi-GCN. Noise was injected at rates of 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%, with each condition run 5 times on the test set, and the average results were recorded. The final data are presented in Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Robustness analysis under four types of noise: (a) shape substitution, (b) random deletion, (c) synonym substitution, and (d) structural noise. The x-axis represents the noise ratio, and the y-axis shows the F1-score

Experimental results indicate that different types of noise have distinct impacts on model performance. Lexical noise, shape replacement, and random deletion notably affect CKDG, with random deletion having the most significant impact. As the noise ratio increases, CKDG’s performance drops sharply from 90.4% to 67.5%. This is primarily attributed to CKDG’s reliance on BioBERT for extracting medical entities, where disruptions in the text directly impair the accuracy of entity recognition and subsequent graph construction. In contrast, synonym replacement has a relatively minor effect on CKDG, with performance declining only from 90.4% to 85.8%. This improvement is likely due to the integration of similarity calculations during the subsequent entity alignment step, which helps to mitigate the impact of changes in word meaning. For the baseline models, TextGCN, K-BERT, and Bi-GCN exhibit similar trends; however, CKDG consistently maintains a clear advantage across all noise levels, demonstrating its robustness in medical entity comprehension and graph structure reasoning.

In the Edge Perturbation experiment, CKDG’s performance decreased from 90.38% to 81.82%, a smaller decline compared to that caused by lexical noise. We believe this is primarily attributable to the design of the GFCI causal discovery algorithm, which permits the existence of unobserved confounders, thus mitigating the impact of graph structure perturbations on the model. In contrast, other baseline models, lacking a similar causal robustness mechanism, exhibit greater sensitivity to structural noise.

This experiment demonstrates that CKDG exhibits robust characteristics when confronted with both text content perturbations and graph structure disturbances: it is sensitive to highly disruptive lexical noise, such as random deletions, minimally affected by synonym substitutions, and possesses a certain tolerance for graph structure perturbations, making it appropriate for scenarios with stable input conditions.

5.2.8 Model-Level Efficiency Comparison

To comprehensively evaluate the computational characteristics of various rumor detection methods in practical deployment, we measured the inference efficiency and GPU memory usage of all models under uniform hardware(NVIDIA RTX 3080 GPU, 48 GB RAM) and consistent parameters(batch size = 16, sequence length = 128). Table 8 presents the average inference time per sample and the peak GPU memory consumption during the evaluation phase.

The results exhibit efficiency levels corresponding to the complexity of the model architectures. CKDG imposes the highest computational demand, requiring 41.75 ms per inference with a peak memory usage of 8245.33 MB. This overhead arises from its multi-stage process, including BioBERT-based entity extraction, GFCI-based causal discovery, medical knowledge validation using CMeKG, and EGRET dual graph inference. The peak memory consumption is primarily due to the persistent memory occupation by the medical knowledge graph and intermediate graph structures. Among the compared models, CSI is the most efficient due to its shallow architecture and feature-based design (4.20 ms per item, 187.50 MB). Moreover, RoBERTa, serving as an optimized Transformer encoder, also demonstrates excellent performance (7.85 ms per item, 2987.20 MB). Graph-based models (Bi-GCN) and knowledge-enhanced models (K-BERT) exhibit moderate efficiency, as their graph computations and knowledge injection mechanisms incur measurable additional overhead compared to purely text-based models.

The computational characteristics of each model reflect the inherent trade-off between architectural complexity and operational efficiency. Although CKDG demands higher resources, it prioritizes detection accuracy through explicit causal reasoning and knowledge verification—capabilities that are absent in more efficient models. Therefore, CKDG is particularly suitable for application scenarios that require extremely high accuracy and can accommodate batch processing or offline analysis. Therefore, we recommend that in practical deployments, CKDG is most appropriate for high-risk areas such as medical rumor detection, public health monitoring, or policy-related debunking, where the demands for accuracy and interpretability outweigh the computational costs. For real-time or resource-constrained environments (e.g., social media stream filtering), lighter models (such as RoBERTa or CSI) might be more optimal. Consequently, when the risk of misclassification is extremely high and computation can be allocated through offline or batch inference, CKDG should be considered a priority.

We selected a real-world health rumor case from the test set, as illustrated in Fig. 10. While baseline models such as Compare-GCN and RoBERT misclassified the instance as credible, our CKDG model successfully identified its pseudoscientific nature. As shown in Fig. 10, the causal graph construction module extracted four causal chains from the text and constructed a corresponding causal strength graph. Notably, the edge ionized water

Figure 10: Rumor content and causal graph after attention calculation

It is noteworthy4 that the downstream causal chain glutathione

5.3.2 Interpretability for End-Users

Beyond causal reasoning, CKDG can provide end-users (e.g., health professionals and regulators) with interpretable results by explicitly mapping low-credibility causal relations back to the original sentences. For example, in Fig. 11, the sentence “Recent studies show that drinking ionized water rich in antioxidants can boost glutathione levels in the body.” is linked to two causal edges (ionized water

Figure 11: Interpretability enhancement in case study. CKDG maps low-credibility causal edges (red dashed arrows) back to their original sentences, providing end-users with transparent explanations and evidence

To address the limitations of existing health rumor detection methods, particularly their reliance on label-specific features and their difficulty in identifying the misuse of medical knowledge and pseudoscientific logic, this paper proposes a dual-graph fusion framework (CKDG) that integrates causal reasoning with domain knowledge graphs. By constructing an interaction mechanism between implicit textual causal graphs and medical knowledge graphs, and incorporating an Edge Aggregated Graph Attention Network alongside a hierarchical pooling strategy, the model robustly captures complex causal topologies and domain logic within health rumors.

Experimental results on a dataset of 8430 health-related rumors demonstrate that CKDG, when combined with the CMeKG knowledge graph, achieves an accuracy of 91.28% and an F1 score of 90.38%, outperforming the best baseline by 5.11% and 3.29%, respectively. Ablation studies reveal that the knowledge verification and causal reasoning modules contribute accuracy gains of 6.75% and 4.1%, confirming the critical role of dual-graph synergy in suppressing spurious correlations.

Nonetheless, several limitations remain. First, the incomplete coverage of rare medical entities in current knowledge graphs may hinder the verification of unaligned concepts. Second, the construction of causal graphs relies on text extraction quality, posing challenges for handling ambiguous or redundant expressions. Third, the model’s computational complexity restricts its applicability in real-time detection scenarios. Moreover, the current framework is tailored to Chinese health rumor texts and Chinese medical knowledge graphs, which limits its generalizability to other languages and regions. To extend CKDG to multilingual settings, future work could incorporate pretrained cross-lingual language models such as mBERT or XLM-R to support entity extraction and alignment across languages. Additionally, integrating multilingual or language-agnostic knowledge bases like UMLS or Wikidata can provide broader domain coverage. The causal discovery module may also be adapted to handle semantic variations across languages by leveraging translation-invariant representations or universal embedding spaces. Future work will also explore lightweight graph reasoning algorithms, dynamic knowledge graph updates, multilingual adaptation, and multimodal data integration to further enhance model generalizability.

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by the College of Information Science and Engineering at Hunan Institute of Engineering and the HUGONG ACM Laboratory.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 2025JJ70105) and the Hunan Provincial College Students’ Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (Project No. S202411342056). The article processing charge (APC) was funded by the Project No. 2025JJ70105.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Haoran Lyu; Formal analysis, Ning Wang and Haoran Lyu; Funding acquisition, Ning Wang; Investigation, Haoran Lyu; Methodology, Ning Wang and Haoran Lyu; Software, Haoran Lyu; Supervision, Ning Wang; Visualization, Yuchen Fu; Writing—original draft, Haoran Lyu; Writing—review & editing, Yuchen Fu. All authors will be updated at each stage of manuscript processing, including submission, revision, and revision reminder, via emails from our system or the assigned Assistant Editor. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1https://github.com/Enderfga/DoubleCheck (accessed on 18 September 2025)

2https://github.com/Kelaxon/COVID19-Health-Rumor (accessed on 18 September 2025)

3https://github.com/One-sixth/HIT-IR-Lab-Tongyici-Cilin-Extended (accessed on 18 September 2025)

4The original data in this case was in Chinese. To facilitate reading, it has been translated into English.

References

1. “Cyberchondriacs” on the Rise? The Harris Poll; 2010 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 25]. Available from: https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/healthcare/cyberchondriacs-rise. [Google Scholar]

2. Chua AY, Banerjee S. To share or not to share: the role of epistemic belief in online health rumors. Int J Med Inform. 2017;108(6):36–41. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.08.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Yin M, Liu L, Cheng L, Li Z, Tu Y. A novel group multi-criteria sorting approach integrating social network analysis for ability assessment of health rumor-refutation accounts. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;238(2):121894. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Bhatnagar B, Office WP, Wadia R. Working together to tackle the “infodemic”. 2022 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/29-06-2020-working-together-to-tackle-the-infodemic-. [Google Scholar]

5. Guan R, Zhang H, Liang Y, Giunchiglia F, Huang L, Feng X. Deep feature-based text clustering and its explanation. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2022;34(8):3669–80. doi:10.1109/icde55515.2023.00362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yang Z, Lin J, Guo Z, Li Y, Li X, Li Q, et al. Towards rumor detection with multi-granularity evidences: a dataset and benchmark. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2024;36(11):7188–200. doi:10.1109/tkde.2024.3401700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Fionda V, Pirrò G. Fact checking via evidence patterns. In: Proceedings of the 27th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2018 Jul 13–19; Stockholm, Sweden. p. 3755–61. [Google Scholar]

8. Zhou X, Zafarani R. A survey of fake news: fundamental theories, detection methods, and opportunities. ACM Comput Surv. 2020;53(5):1–40. doi:10.1145/3395046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Li J, Li R, Ni S, Kao HY. EPRD: exploiting prior knowledge for evidence-providing automatic rumor detection. Neurocomputing. 2024;563(8):126935. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2023.126935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Haque A, Abulaish M. CARES: a commonsense knowledge-enriched and graph-based contextual learning approach for rumor detection on social media. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;266(2):125965. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.125965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yao X, Zhao Y, Gao N, Du H, Huang H. Causal related rumors controlling in social networks of multiple information. IEEE ACM Trans Netw. 2024;32(3):2085–98. doi:10.1109/tnet.2023.3337774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wang J, Qian S, Hu J, Dong W, Huang X, Hong R. End-to-end explainable fake news detection via evidence-claim variational causal inference. ACM Trans Inf Syst. 2025;43(4):1–26. doi:10.1145/3728462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhang Y, Huang S. Automatic rumor recognition for public health and safety: a strategy combining topic classification and multi-dimensional feature fusion. J King Saud Univ—Comput Inf Sci. 2024;36(5):102087. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2024.102087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Huang J, Cao D, Lin D. Leverage causal graphs and rumor-refuting texts for interpretable rumor analysis. In: ICASSP 2024—2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2024 Apr 14–19; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 9946–50. [Google Scholar]

15. Yuan X, Shu A, Wu Y, Liu J, Wang M, Liu J. MSSCR: multi-scale semantic collaborative reasoning model for explainable multimodal rumor detection. Neurocomputing. 2025;653(6380):131042. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2025.131042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Feder A, Keith KA, Manzoor E, Pryzant R, Sridhar D, Wood-Doughty Z, et al. Causal inference in natural language processing: estimation, prediction, interpretation and beyond. Trans Assoc Comput Linguist. 2022;10(1):1138–58. doi:10.1162/tacl_a_00511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang W, Zhong T, Li C, Zhang K, Zhou F. CausalRD: a causal view of rumor detection via eliminating popularity and conformity biases. In: IEEE INFOCOM 2022—IEEE Conference on Computer Communications. 2022 May 2–5; Online. p. 1369–78. [Google Scholar]

18. Chen Z, Hu L, Li W, Shao Y, Nie L. Causal intervention and counterfactual reasoning for multi-modal fake news detection. In: Rogers A, Boyd-Graber J, Okazaki N, editors. Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Toronto, ON, Canada: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2023. p. 627–38. [Google Scholar]

19. Sheng Q, Cao J, Li S, Wang D, Zhuang F. Generalizing to the future: mitigating entity bias in fake news detection. In: Proceedings of the 45th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2022. p. 2120–5. [Google Scholar]

20. Sheng Q, Zhang X, Cao J, Zhong L. Integrating pattern-and fact-based fake news detection via model preference learning. In: Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management; 2021 Nov 1–5; Onine. p. 1640–50. [Google Scholar]

21. Sun M, Zhang X, Zheng J, Ma G. DDGCN: dual dynamic graph convolutional networks for rumor detection on social media. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Vol. 36; Washington, DC, USA: AAAI; 2022. p. 4611–9. [Google Scholar]

22. Hu L, Yang T, Zhang L, Zhong W, Tang D, Shi C, et al. Compare to the knowledge: graph neural fake news detection with external knowledge. In: Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing; 2021 Aug 1–6; Online. p. 754–63. [Google Scholar]

23. Yang SH, Chen CC, Huang HH, Chen HH. Entity-aware dual co-attention network for fake news detection. arXiv:2302.03475. 2023. [Google Scholar]

24. Speer R, Chin J, Havasi C. ConceptNet 5.5: an open multilingual graph of general knowledge. In: Proceedings of the 31th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Vol. 31; 2017 Feb 4–9; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 4444–51. [Google Scholar]

25. Bauer L, Wang Y, Bansal M. Commonsense for generative multi-hop question answering tasks. arXiv:1809.06309. 2018. [Google Scholar]

26. Xie Y, Liu Z, Ma Z, Meng F, Xiao Y, Miao F, et al. Natural language processing with commonsense knowledge: a survey. arXiv:2108.04674. 2021. [Google Scholar]

27. Zhang H, Li Y, Zhu T, Li C. Commonsense-based adversarial learning framework for zero-shot stance detection. Neurocomputing. 2024;563(3):126943. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2023.126943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhong P, Wang D, Miao C. Knowledge-enriched transformer for emotion detection in textual conversations. arXiv:1909.10681. 2019. [Google Scholar]

29. Sharma S, Arora U, Akhtar MS, Chakraborty T. MEMEX: detecting explanatory evidence for memes via knowledge-enriched contextualization. arXiv:2305.15913. 2023. [Google Scholar]

30. Liu X, Yin D, Feng Y, Wu Y, Zhao D. Everything has a cause: leveraging causal inference in legal text analysis. arXiv:2104.09420. 2021. [Google Scholar]

31. Mahbub S, Bayzid MS. EGRET: edge aggregated graph attention networks and transfer learning improve protein-protein interaction site prediction. Brief Bioinform. 2022;23(2):bbab578. doi:10.1101/2020.11.07.372466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Lee J, Yoon W, Kim S, Kim D, Kim S, So CH, et al. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinform. 2019;36(4):1234–40. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btz682. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Pearl J, Mackenzie D. The book of why: the new science of cause and effect. London, UK: Penguin Books Limited; 2018. [Google Scholar]

34. Ogarrio JM, Spirtes P, Ramsey J. A hybrid causal search algorithm for latent variable models. In: Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Probabilistic Graphical Models; 2016. Vol. 52, p. 368–79. [Google Scholar]

35. Li L, Lian R, Lu H, Tang J. Document-level biomedical relation extraction based on multi-dimensional fusion information and multi-granularity logical reasoning. In: Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computational Linguistics; 2022 Oct 12–17; Gyeongju, Republic of Korea. p. 2098–107. [Google Scholar]

36. Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K. Bert: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, NAACL-HLT 2019; 2019 Jun 2–7; Minneapolis, MN, USA. p. 4171–86. [Google Scholar]

37. Lee J, Lee I, Kang J. Self-attention graph pooling. In: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2019 Jun 9–15; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 3734–43. [Google Scholar]

38. Ma Z, Liu M, Fang G, Shen Y. LTCR: long-text Chinese rumor detection dataset. arXiv:2306.07201. 2023. [Google Scholar]

39. Yang W, Wang S, Peng Z, Shi C, Ma X, Yang D. Know it to defeat it: exploring health rumor characteristics and debunking efforts on Chinese social media during COVID-19 crisis. arXiv:2109.12372. 2021. [Google Scholar]

40. Ma J, Gao W, Wong KF. Rumor detection on twitter with tree-structured recursive neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2018 Jul 15–20; Melbourne, VIC, Australia. p. 1980–9. [Google Scholar]

41. Kwon S, Cha M, Jung K, Chen W, Wang Y. Prominent features of rumor propagation in online social media. In: 2013 IEEE 13th International Conference on Data Mining; 2013 Dec 7–10; Dallas, TX, USA. p. 1103–8. [Google Scholar]

42. Ruchansky N, Seo S, Liu Y. CSI: a hybrid deep model for fake news detection. In: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management; 2017 Nov 6–10; Singapore. p. 797–806. [Google Scholar]

43. Zhou P, Qi Z, Zheng S, Xu J, Bao H, Xu B. Text classification improved by integrating bidirectional LSTM with two-dimensional max pooling. arXiv:1611.06639. 2016. [Google Scholar]

44. Chen YC, Liu ZY, Kao HY. IKM at SemEval-2017 Task 8: convolutional neural networks for stance detection and rumor verification. In: Proceedings of the 11th International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation (SemEval-2017); 2017 Aug 3–4; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 465–9. [Google Scholar]

45. Augenstein I, Rocktäschel T, Vlachos A, Bontcheva K. Stance detection with bidirectional conditional encoding. arXiv:1606.05464. 2016. [Google Scholar]

46. Wang J, Wang X, Yu A. Tackling misinformation in mobile social networks a BERT-LSTM approach for enhancing digital literacy. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):1118. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-4116981/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Liu Y, Ott M, Goyal N, Du J, Joshi M, Chen D, et al. RoBERTa: a robustly optimized BERT pretraining approach. arXiv:1907.11692. 2019. [Google Scholar]

48. Yao L, Mao C, Luo Y. Graph convolutional networks for text classification. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2019;33(1):7370–7. doi:10.1609/aaai.v33i01.33017370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Vashishth S, Sanyal S, Nitin V, Talukdar P. Composition-based multi-relational graph convolutional networks. arXiv:1911.03082. 2019. [Google Scholar]

50. Liu Y, Wu YF. Early detection of fake news on social media through propagation path classification with recurrent and convolutional networks. In: AAAI’18: AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2018 Feb 2–7; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 354–61. [Google Scholar]

51. Bian T, Xiao X, Xu T, Zhao P, Huang W, Rong Y, et al. Rumor detection on social media with bi-directional graph convolutional networks. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(1):549–56. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i01.5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Wang H, Zhang F, Xie X, Guo M. DKN: deep knowledge-aware network for news recommendation. In: Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference; 2018 Apr 23–27; Lyon, France. p. 1835–44. [Google Scholar]

53. Pan JZ, Pavlova S, Li C, Li N, Li Y, Liu J. Content based fake news detection using knowledge graphs. In: International Semantic Web Conference. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018. p. 669–83. [Google Scholar]

54. Liu W, Zhou P, Zhao Z, Wang Z, Ju Q, Deng H, et al. K-BERT: enabling language representation with knowledge graph. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(3):2901–8. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i03.5681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Schlichtkrull M, Kipf T, Bloem P, Berg RVD, Titov I, Welling M. Modeling relational data with graph convolutional networks. In: The Semantic Web (ESWC 2018). Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017. p. 593–607. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools