Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

FMCSNet: Mobile Devices-Oriented Lightweight Multi-Scale Object Detection via Fast Multi-Scale Channel Shuffling Network Model

1 Hunan Intelligent Rehabilitation Robot and Auxiliary Equipment Engineering Technology Research Center, Changsha, 410004, China

2 College of Information Science and Engineering, Hunan Normal University, Changsha, 410081, China

* Corresponding Authors: Jinping Liu. Email: ; Pengfei Xu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Novel Methods for Image Classification, Object Detection, and Segmentation)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068818

Received 06 June 2025; Accepted 03 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

The ubiquity of mobile devices has driven advancements in mobile object detection. However, challenges in multi-scale object detection in open, complex environments persist due to limited computational resources. Traditional approaches like network compression, quantization, and lightweight design often sacrifice accuracy or feature representation robustness. This article introduces the Fast Multi-scale Channel Shuffling Network (FMCSNet), a novel lightweight detection model optimized for mobile devices. FMCSNet integrates a fully convolutional Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) module, offering global perception without significantly increasing parameters, effectively bridging the gap between CNNs and Vision Transformers. FMCSNet achieves a delicate balance between computation and accuracy mainly by two key modules: the ShiftMLP module, including a shift operation and an MLP module, and a Partial group Convolutional (PGConv) module, reducing computation while enhancing information exchange between channels. With a computational complexity of 1.4G FLOPs and 1.3M parameters, FMCSNet outperforms CNN-based and DWConv-based ShuffleNetv2 by 1% and 4.5% mAP on the Pascal VOC 2007 dataset, respectively. Additionally, FMCSNet achieves a mAP of 30.0 (0.5:0.95 IoU threshold) with only 2.5G FLOPs and 2.0M parameters. It achieves 32 FPS on low-performance i5-series CPUs, meeting real-time detection requirements. The versatility of the PGConv module’s adaptability across scenarios further highlights FMCSNet as a promising solution for real-time mobile object detection.Keywords

Object detection, a fundamental task in computer vision, aims to locate and identify objects within images or videos and has garnered significant attention from academia and industry. During the past decade, object detection technologies have been successfully applied in intelligent transportation, robotics systems, industrial inspection, UAV and remote sensing, and many other fields [1,2], with the rapid development of deep learning technologies and the computational power of hardware devices. As object detection moves from cloud-based platforms to mobile endpoints such as smartphones, in-vehicle computers, and smart sensors, real-time detection has become crucial. However, limited resources on mobile devices present significant challenges to the performance and deployment of object detection models.

Researchers have proposed various lightweight models to tackle the above challenges. In 2015, Redmon et al. [3] proposed YOLO v1 with a lightweight variant, Tiny-YOLO v1. While Tiny-YOLO v1 achieved a 3.4× speed improvement on the VOC2007 dataset, it incurred a 10.7% mAP reduction compared to YOLO v1. In addition, YOLO v1’s single-scale prediction box limits its adaptability to varying-scale objects. In the subsequent years, more lightweight models, such as SqueezeNet and MobileNetV1 [4] were proposed, which borrowed design concepts from the Inception network [5] and leveraged Depthwise Separable Convolution (DWConv) to reduce convolution operations, achieving only 1/8 to 1/9 of the original computational cost. In 2017, Zhang et al. proposed ShuffleNetv1 [6], which restructured the residual block by incorporating grouped convolution and channel shuffle operations to enable inter-group information exchange. It maintained a high TOP-1 classification accuracy of 73.7% on the ImageNet dataset while streamlining model complexity. Building upon this work, Ma et al. [7] proposed ShuffleNetv2, which divided input feature maps into two branches: one remained unaltered, while the other underwent convolution. The outputs were concatenated and processed through a Channel Shuffle operation, facilitating efficient information interaction. Although ShuffleNet leverages convolution and DWConv to reduce model complexity, the inherent limitations of convolutional networks in performing global feature processing persist.

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) often struggle to capture global features due to their localized nature. The self-attention mechanism addresses this by enabling adaptive attention across various locations, allowing effective handling of global features. In 2021, Dosovitskiy et al. [8] introduced the Vision Transformer (ViT) as an alternative to CNNs, significantly improving performance but at the cost of increased parameters and complexity, limiting deployment on mobile devices and reducing inference efficiency. The self-attention mechanism’s need to calculate attention weights between all locations further escalates computational complexity as input image sizes grow, constraining ViT’s scalability. To further mitigate network parameters, Touvron et al. [9] proposed the DelT model, which has about 5 to 6 million parameters with an accuracy slightly lower (3%) than MobileNetV3. MobileViT series models [10,11] focused on developing lightweight ViT models. MobileViTv2 and MobileViTv3 adopted a self-attention mechanism with linear complexity to improve inference speed. Despite these advancements, the extensive stacking of ViT modules in these models increases accuracy but fails to address the issue of substantial parameter counts. Furthermore, handling multi-scale objects often requires multiple inferences with input images of varying sizes, significantly increasing the computational and storage demands of the model.

Meanwhile, the YOLO series have become mainstream in industrial deployment due to their single-stage end-to-end architecture and real-time inference advantages. For instance, as reported by Wang et al. [12], YOLOv10 achieves 180 FPS. However, the loss of fine-grained features in deeper layers leads to high miss rates of small objects (e.g., only 19.8% AP for small objects on VisDrone [13]). Additionally, fixed pyramid structures exhibit limited adaptability to extreme scales, and complex scenes lead to notably elevated false positive rates with Zhang et al. reporting a 12.3% FP on the COCO dataset [14]. Specialized lightweight architectures, e.g., GhostNet-YOLO [15], EF-DETR [16], achieve efficient edge inference through parameter compression and hardware-aware designs. Yet, channel reduction induces multi-scale feature entanglement, especially, which will make an 8% recall drop in dense scenes [16] and degraded large-object detection performance, with Wu et al. reporting a 3.5% AP decline on the UAVDT [17] dataset.

This work aims to design a lightweight, mobile device-oriented, multi-scale object detection model leveraging DWConv, as seen in MobileNet. While DWConv reduces the number of parameters and computational complexity, it faces limitations in information exchange between channels. To address this, we design the Partial group Convolutional (PGConv) module as a substitute for DWConv, which can alleviate this problem. Additionally, to enhance the global perception capability of lightweight network models, we incorporate the ViT module, as seen in MobileViT, to improve model accuracy. However, for devices with lower computational power, achieving real-time inference is challenging. To overcome this, we replace the ViT module with a fully convolutional MLP module, which provides global perception with reduced computational demands. Furthermore, we integrate a Shift operation to enhance the model’s ability to learn translational invariance, forming the ShiftMLP module. The main contributions are as follows.

1. Addressing the limitation of DWConv: To overcome the restricted inter-channel information exchange in DWConv, we propose the PGConv module, which can effectively enhance channel communication while significantly reducing computational complexity.

2. Efficient global feature processing: We propose the ShiftMLP module as a partial substitute for the ViT module to address the high computational demands and parameter overhead of ViT. This adaptation improves the model’s ability to handle multi-scale objects and learn translational invariance, making it more suitable for real-time inference on mobile devices.

3. Flexible structural design: The proposed FMCSNet adopts a dual-branch structure, enabling flexible and effective selection of structural units. This design enhances the network’s ability to perceive multi-scale objects and capture multi-level image features, improving overall detection performance.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. Section 2 briefly reviews the principle of object detection with a literature review. Section 3 details the architecture of the proposed model and the comprised modules. Section 4 gives the detailed experimental validation and comparison results. Section 5 concludes the whole paper with possible further research directions.

2 Lightweight Multi-Scale Object Detection

In natural scenes, object sizes and positions vary due to camera distance and scene dynamics, making multi-scale techniques crucial for robust detection. As mobile devices gain prominence, lightweight models have become a research priority [18]. Significant progress has been made in addressing the demands for multi-scale processing and lightweight architectures. For instance, MobileNetV1 [4], introduced in 2017 for efficient mobile image classification. ShuffleNet [6] reduces complexity through channel shuffle operations, but this can lead to feature loss, hindering intricate feature representation. Similarly, YOLOv3-Tiny [19] achieves real-time detection with a grid-based approach but struggles with nuanced information in complex scenes, reducing its performance in highly intricate environments.

Although these models do not explicitly incorporate multi-scale techniques, the inherent nature of convolutional operations allows them to process input images of varying sizes. MobileNetV2 [10,11] introduced enhanced block structures and linear bottleneck architectures, significantly improving representational capabilities. While not a conventional multi-scale technique, it partially addresses feature processing at different scales. However, specialized tasks requiring high-level semantic information may still demand more sophisticated models.

As lightweight networks evolve, ongoing research is crucial to overcome model size limitations while achieving real-time performance and meeting diverse application needs. The self-attention mechanism has gained prominence in object detection, particularly in multi-scale scenarios, by dynamically capturing correlations across scales and enhancing semantic encoding. This mechanism has proven especially effective in lightweight models. Many self-attention mechanism-based multi-scale object detection models, such as FGDLAM&SCIF [20], MI-DETR [21], etc., have been proposed to better fuse multi-scale features and capture detailed contextual information. Lightweight models like EfficientDet-Lite [22] incorporate DWConv and lightweight attention mechanisms to reduce parameters and complexity. However, challenges remain, such as performance degradation when handling small objects and complex scenes. Recent state-of-the-art (SOTA) lightweight object detection models, such as YOLOX-Nano [23], PP-YOLO-Tiny [24], and Slim-YOLO-PR_KD [25], aim to balance accuracy and computational cost for mobile and edge deployments. These models employ techniques like decoupled detection heads, structural reparameterization, and lightweight feature fusion units to enhance detection performance while maintaining efficiency. They represent the forefront of lightweight object detection research and are included in our comparative experiments.

While DWConv is effective in reducing parameters and computational complexity, its reliance on small convolution kernels limits the receptive field, hindering its ability to capture nuanced high-level semantics in complex tasks. To address this, we propose the PGConv module as a replacement for DWConv. PGConv enhances the receptive field by dividing feature map channels into two parts: one undergoes convolution for feature extraction, while the other is combined with the convolved segment, enabling more effective processing of complex information. In ViTs, the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) module plays a pivotal role by nonlinearly mapping features to enhance the representation of intricate patterns and abstract features, facilitating the capture of semantic and spatial information. For mobile devices, we propose replacing the Transformer architecture in MobileViT with a redesigned MLP module. This module incorporates full convolution and Shift operations, forming the ShiftMLP module. Experimental results demonstrate that ShiftMLP effectively reduces model parameters and complexity while improving accuracy.

Mobile devices, with limited computational power, struggle with high-complexity models. To address this, we propose PGConv, a novel module that combines the strengths of DWConv and traditional convolution to enhance inter-channel information exchange while reducing parameters and computational complexity. In addition, a standard ViT model splits the input

We replace the ViT architecture with a fully convolutional MLP structure to enable global feature processing, addressing the limitations of traditional MLPs. By integrating Shift operations, the model enhances spatial transformation and learns translational invariance, crucial for generalization in multi-scale object detection. This combination improves computational efficiency and adaptability to complex data, boosting performance in multi-scale detection tasks.

To summarize, this article proposes the FMCSNet, which adopts a dual-branch structure to apply to complex scenes. The core idea is to use PGConv to extract local features of the image and then use the ShiftMLP module for global feature extraction, which enables us to extract valuable features better.

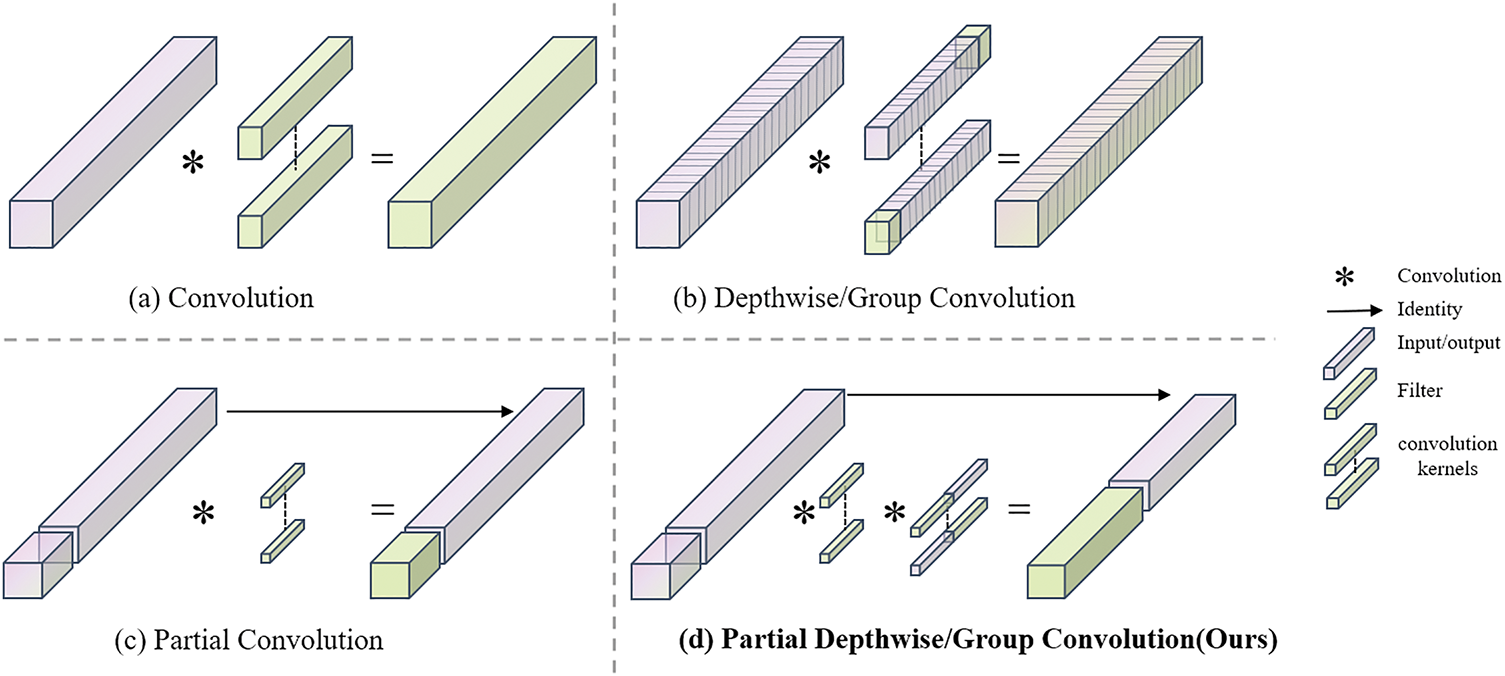

DWConvs are a popular variant of convolution (Conv), as illustrated in Fig. 1a, that has been widely used as a critical module in many neural networks. For the input

Figure 1: Our PGConv is fast and efficient with low FLOPs

Which is higher than the regular Conv, that is,

Note that

Since directly using DWConv instead of conventional Conv reduces accuracy, Chen et al. proposed PConv [26], as shown in Fig. 1c. PConv divides the input

where

To this end, we combined the advantages of the three to design PGConv, which divided the input

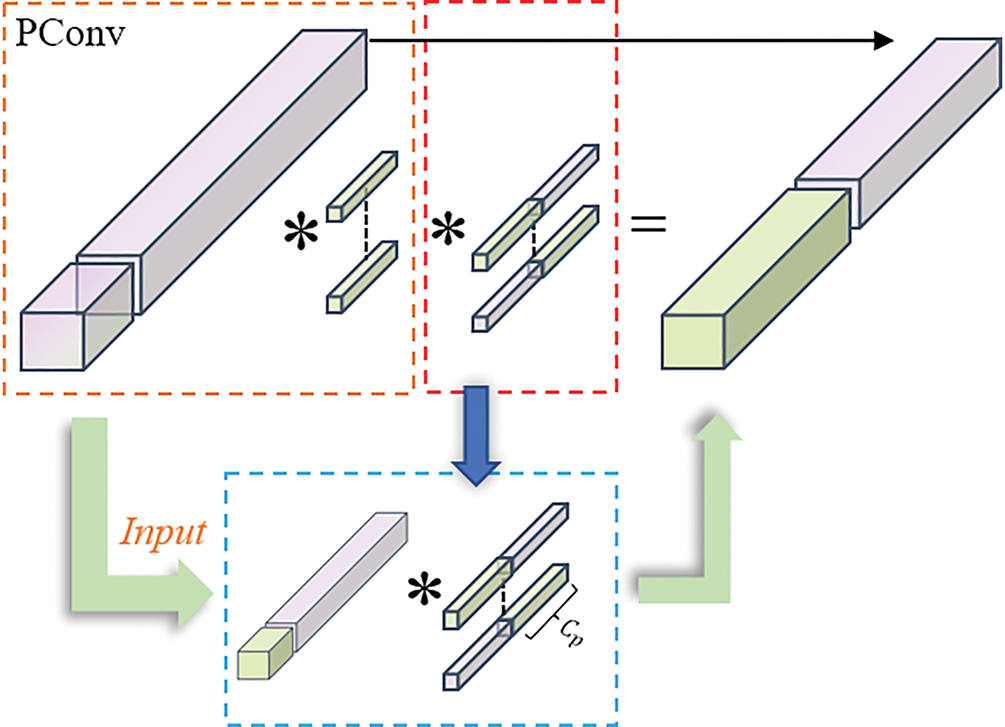

Our goal is to combine the idea of PConv (Fig. 1c) as a component of PGConv, as shown in Fig. 2. PGConv retains the parameter efficiency and computational simplicity of DWConv (Fig. 1b) while achieving feature extraction performance closer to full Conv (Fig. 1a).

Figure 2: Diagram of the PGConv process

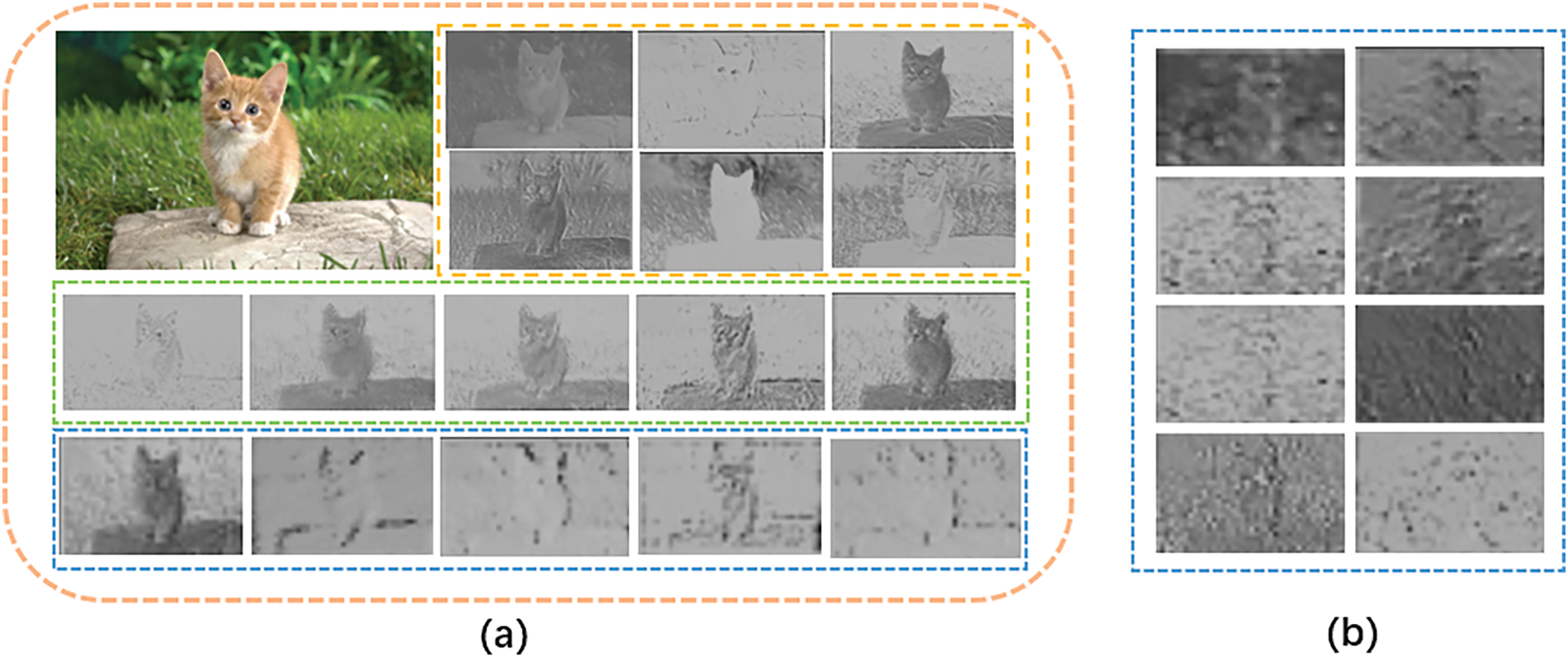

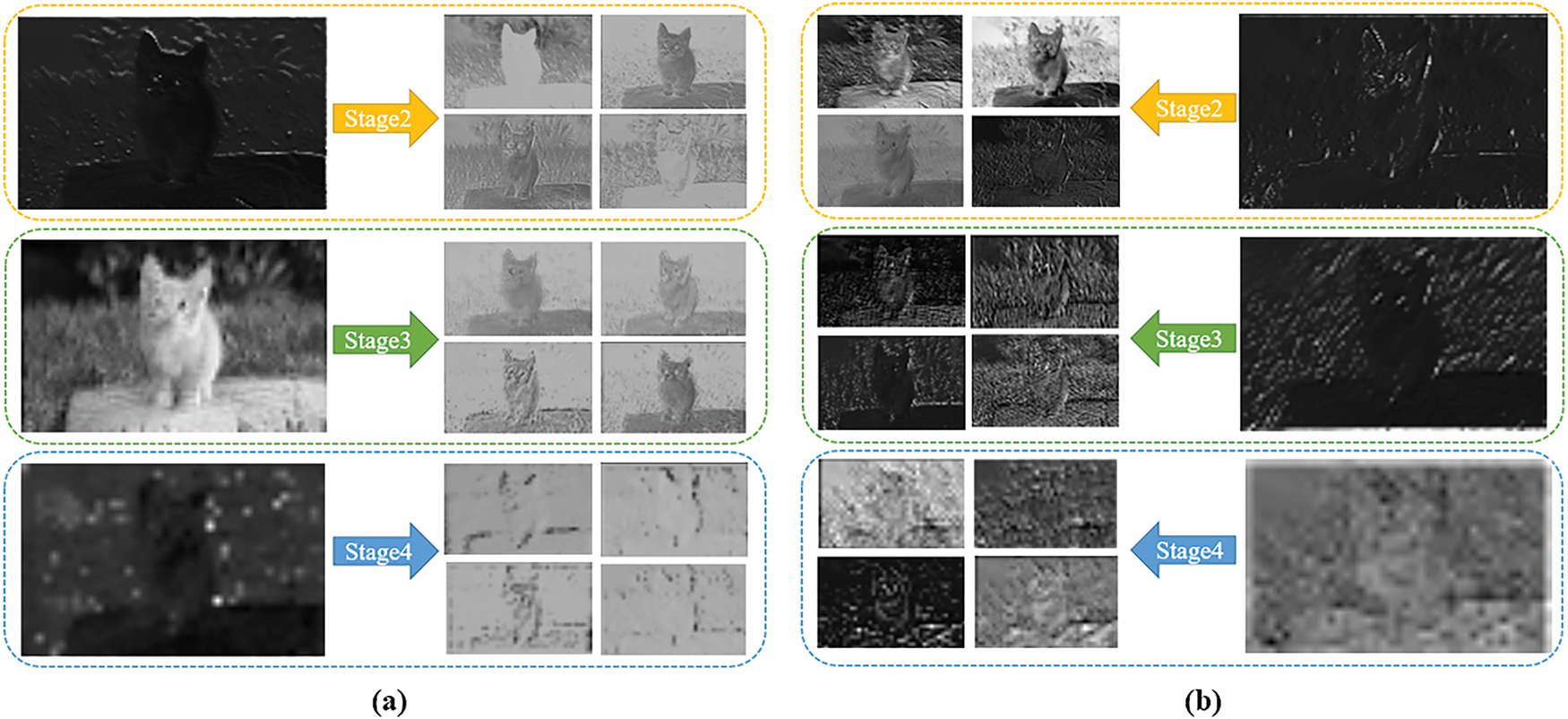

PGConv is applied at the beginning of each stage to effectively reduce the complexity of multi-scale feature maps, while PConv is used in intermediate stages to enhance accuracy. As shown in Fig. 3, the blue box represents the feature map of the third stage in the network, comparing the performance of PGConv in FMCSNet with DWConv in ShuffleNetv2. DWConv limits inter-channel information exchange, hindering the extraction of deeper features. In contrast, PGConv enables flexible transformations to align channels, perform deep convolutions, and facilitate inter-channel communication, minimizing channel separation. Without loss of generality, the input and output feature maps of this module maintain the same number of channels.

Figure 3: Feature map visualization. (a) FMCSNet middle layer feature map, the top left image is the input, the orange box is the feature map of Stage2, the green is the feature map of Stage3, and the blue is the feature map of Stage4. (b) ShuffleNetv2 intermediate layer

Replacing conventional Conv with PConv can effectively reduce FLOPs. However, experimental analysis on the Pascal VOC 2007 object detection task revealed limited improvement in detection performance, with low accuracy and difficulty in extracting deeper features. To address this, we redesigned the ratio factor, making it channel-dependent. Therefore, we redesigned the value of the ratio factor, which should be different for different channels. Thus, we found that the input channel

where

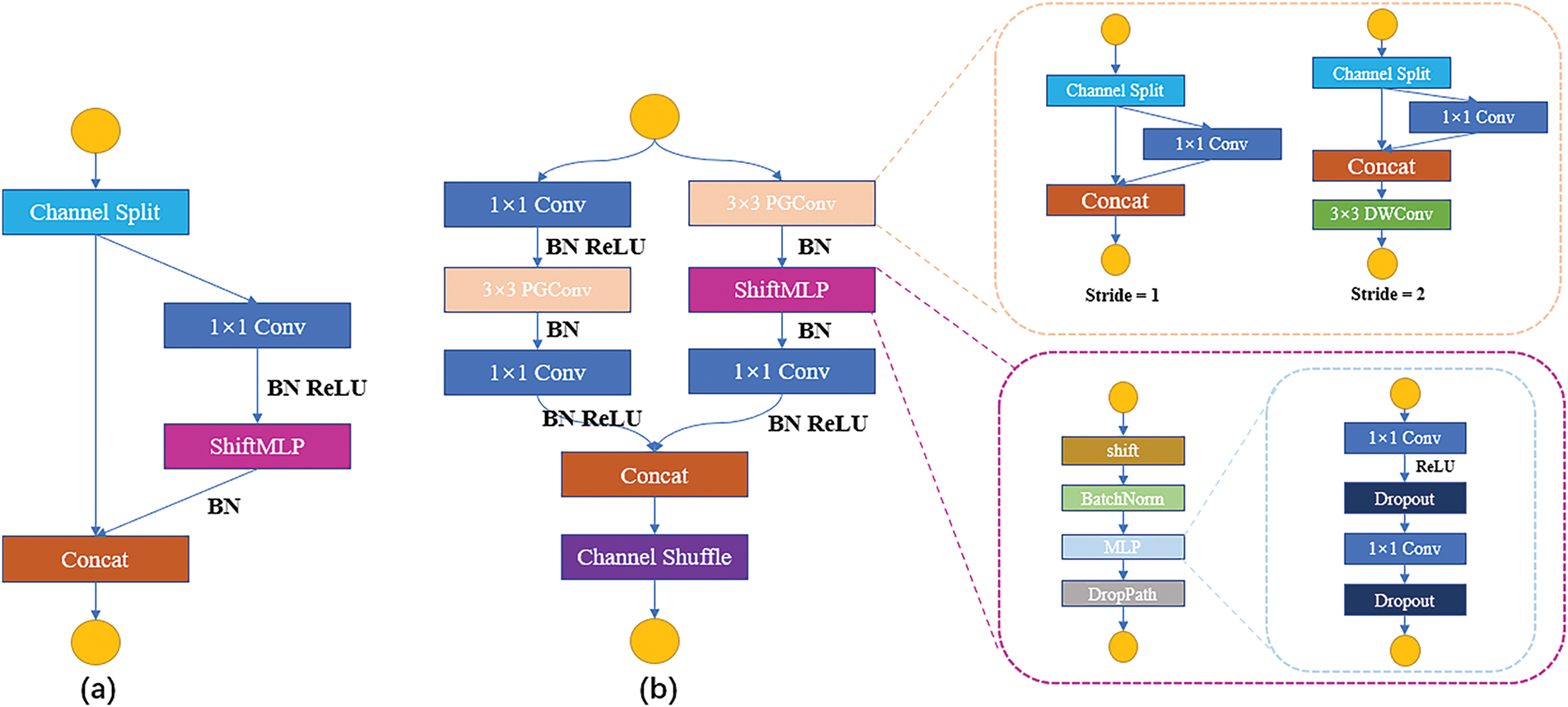

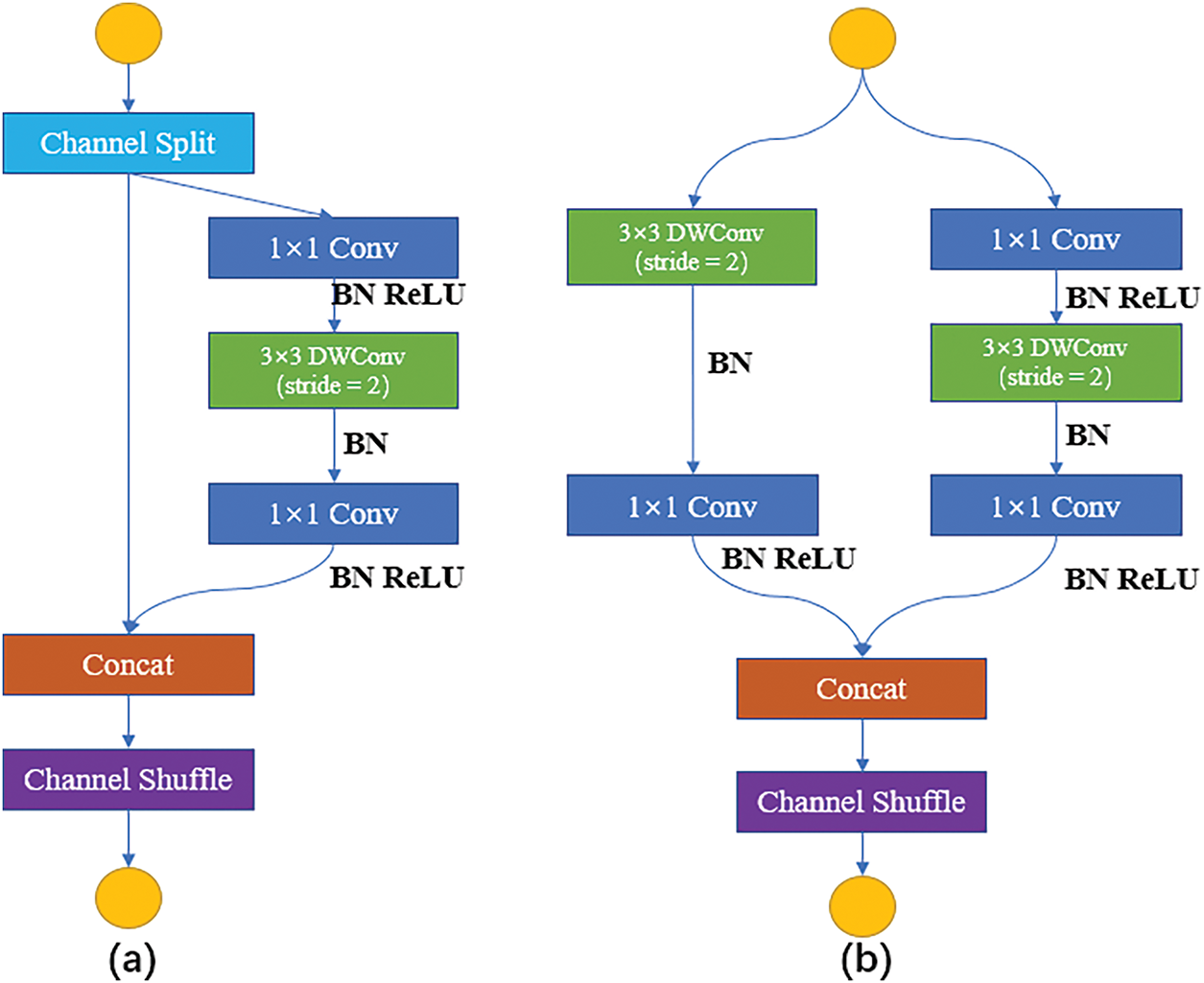

Self-attention mechanisms, such as those in ViT, enhance global perception by integrating contextual information from images, improving overall performance in computer vision tasks. However, standard ViTs are unsuitable for mobile devices due to their high computational demands. MobileViT addresses this with a linear Transformer optimized for mobile deployment, but it still faces challenges on lower-performance devices. To overcome these limitations, we propose replacing ViT in lightweight networks with a fully convolutional MLP. The detailed architecture of the proposed ShiftMLP module is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Building blocks of FMCSNet: (a) Lightweight layer basic unit of FMCSNet; (b) FMCSNet core unit. PGConv: PConv + GConv. ShiftMLP: Shift + MLP

A standard MLP uses fully connected layers, connecting each neuron to all neurons in the previous layer, which is computationally and memory intensive for capturing global features. While MLPs can model some global information, they are less efficient than convolutional networks at capturing local features and incur higher computational costs. The ShiftMLP module addresses this by sequentially stacking four components: Shift operation, layer normalization, MLP, and DropPath.

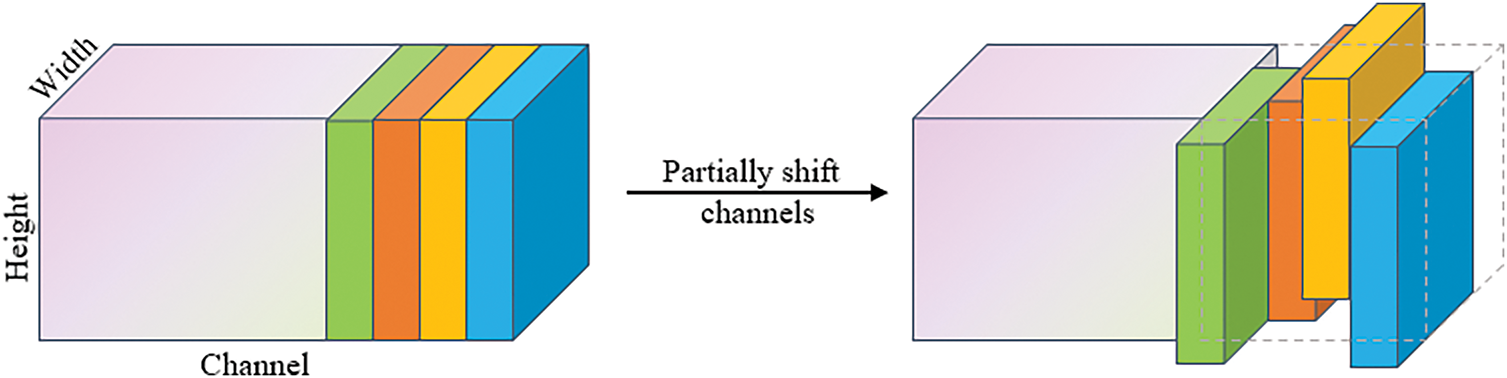

The shift operation has been well studied in CNNs, with various designs such as Active Shift [27] and sparse shift [28]. This work follows the partial Shift operation in TSM [29], as shown in Fig. 5. Given an input tensor, a small portion of the channels will move along four spatial directions, namely left, right, up, and down, while the remaining channels remain unchanged. Shift operation enhances translational invariance, improving spatial feature learning, especially in multi-scale object detection. By shifting features in four directions, the network can capture spatial relationships more effectively, which is crucial for detecting objects at various scales. This shifting operation, combined with the fully convolutional MLP, gives the network stronger generalization ability in multi-scale scenarios, enabling it to better handle variations in object size. Pixels outside the range after the shift are discarded, and empty pixels are zero-padded.

Figure 5: The shift operation

The Shift operation is highly efficient, requiring no parameters or arithmetic—only memory copying—making it more computationally efficient and easier to implement than self-attention mechanisms, and ideal for inference libraries like TensorRT. In this work, the shift step size is set to 1 pixel, balancing efficiency and performance. Combined with the fully convolutional MLP, the Shift operation improves the network’s generalization in multi-scale scenarios, enhancing its ability to handle object size variations.

Inspired by methods like TSM and MLP-Mixer [30], which enhance global feature learning through simple shifting operations and MLP architectures, the ShiftMLP module incorporates the Shift operation to improve adaptability to spatial transformations. This design is particularly effective for multi-scale object detection, where significant scale variations exist. In general, we assume the input features

where

Our work is related to the recent MLP variant, which proposes pure MLP-like architectures for image feature extraction, stepping away from the attention-based framework of ViT. For instance, MLP-Mixer [30] replaces the self-attention matrix with a token-mixing MLP to directly connect all spatial locations, maintaining accuracy while eliminating ViT’s dynamic nature. Subsequent work has investigated more MLP designs, such as spatial gated units or cyclic connections [31].

In our ShiftMLP module, we adopt a simple variant by replacing the linear layer with a 1 × 1 convolution, improving accuracy with minimal additional FLOPs. Compared to existing MLP approaches, ShiftMLP is simpler, more efficient, and capable of handling variable input sizes, overcoming the limitations of fixed linear weights in standard MLPs. Particularly on mobile devices, ShiftMLP achieves fast inference on low-power hardware while maintaining strong detection accuracy, making it well-suited for lightweight network architectures.

To address the limitations of mobile devices, we propose PGConv to reduce complexity and parameters with minimal accuracy loss, and ShiftMLP to enhance translational invariance and emulate ViT functionality efficiently. Additionally, a dual-branch structure improves multi-scale feature fusion and strengthens the network’s ability to capture multi-level image features.

Leverage the Channel Shuffle operation. We have designed FMCSBlock, starting from the design principle of Fig. 6a. It is a residual block [32]. In the residual branch, for

Figure 6: DWConv. (a) The basic units of ShuffleNet; (b) ShuffleNet downsamples (2×) cells

The overall FMCSNet architecture is listed in Table 1. The proposed network is mainly composed of three stages, and each stage comprises multiple FMCSBlock units. stride = 2 is adopted for the first building block of each stage. The other hyperparameters within a stage are kept constant while the output channels of the next stage are doubled. We set the number of bottleneck channels to 1/4 of the output channels of each FMCSBlock unit. The rest is similar to the ShuffleNetv2 network structure, where the number of channels in each block is scaled to generate networks of different complexity, labeled 0.5×, 1.0×, etc., as shown in Table 1. We aim to provide reference designs that are as simple as possible, although further tuning of hyperparameters may yield better results.

4 Experimental Validation and Result Discussions

This section presents the experimental results of FMCSNet on various datasets, with a detailed analysis of its performance on the Pascal VOC 2007 dataset [33] and Microsoft COCO dataset [34].

4.1 Dataset Description and Evaluation Metrics

Comparative experiments focus on the PGConv and ShiftMLP modules, evaluating their parameter selection schemes. Additionally, we compare FMCSNet with the latest methods. To further highlight the model’s strengths and weaknesses, we analyze feature map information at each stage, comparing FMCSNet with ShuffleNet. We evaluated FMCSNet against mainstream lightweight network models, using diverse metrics to assess their advantages and limitations.

To fully evaluate the performance of FMCSNet, we conducted experiments on both low-performance mobile devices and high-performance GPUs. Specifically, we tested the model on i5-series CPUs (low-performance) and NVIDIA GPUs (high-performance). On mobile devices with limited computational resources, FMCSNet achieved real-time inference (FPS ≥ 30), which is suitable for real-time object detection applications. While there was a slight trade-off in accuracy (e.g., accuracy loss of 1%–2%), the model still maintained an acceptable performance level due to its low computational cost (1.4G FLOPs) and small parameter size (1.3M parameters). This allowed FMCSNet to run efficiently on resource-constrained devices, ensuring fast inference times without heavily compromising accuracy.

• Pascal VOC 2007: The Pascal VOC 2007 dataset consists of images labeled across 20 object categories, including aero, bird, bottle, car, and train. It contains 5000 images split into training, validation, and testing sets. The dataset has become a standard in object detection research, offering a rich variety of objects in real-world conditions.

• Microsoft COCO: The Microsoft COCO dataset contains over 330,000 images across 80 object categories. It provides more challenging settings for object detection due to its large number of object instances and complex scenes. The dataset is also commonly used for multi-scale object detection tasks and is critical for evaluating the scalability of detection models.

To ensure the reproducibility of our results, we provide the detailed experimental setup used for training and evaluation of FMCSNet. The following configurations were applied across all experiments:

(1) Optimizer: We used the AdamW optimizer with an initial learning rate of 1 × 10−4.

(2) Learning Rate Scheduler: The learning rate decayed by a factor of 0.1 after every 10 epochs.

(3) Batch Size: A batch size of 32 was used for training.

(4) Epochs: The model was trained for a total of 100 epochs.

(5) Loss Function: Cross-entropy loss was used for classification tasks.

The training environment is a 15 vCPU Intel(R) Xeon(R) Platinum 8350C CPU @ 2.60 GHz, NVIDIA RTX4090(24G), 30G RAM, Python interpreter version 3.9, and a 15 VCPU Intel(R) Xeon(R) Platinum 8350C CPU @ 2.60 GHZ. The training was performed using CUDA 10.2 acceleration in Pytorch version 1.9.1. Meanwhile, we follow most of the training Settings and hyperparameters used in [35].

The main evaluation metrics are as follows:

(1) mAP: the average value of testing accuracy.

(2) AP50 and AP75: denote

(3) APs: Represents the AP measurement of a target box whose pixel area is less than 322.

(4) APm: Represents the AP measurement of the target box with a pixel area between 322~962.

(5) APl: Represents the AP measurement of a target box whose pixel area is larger than 962.

(6) FLOPs: A floating-point operation, that is, the amount of computation used to measure the complexity of an algorithm or model.

(7) Params: The number of parameters is related to the model’s size.

4.2 Experiments on Pascal VOC 2007

We trained the FMCSNet using the PyTorch framework on NVIDIA GPUs for 600 epochs, experimenting with image sizes of 416 × 416 and 320 × 320. Additionally, the experiments for this study were conducted on an i5 series CPU, which has lower performance than the Huawei P40 Kirin 900 chip. Regarding the optimizer, FMCSNet employs the AdamW optimizer, with hyperparameters and learning rate settings following the recommendations in the literature [7]. To ensure fair comparison, we excluded any additional acceleration effects, such as TensorRT acceleration. Table 2 presents a detailed evaluation of FMCSNet’s detection performance across various categories on the Pascal VOC 2007 dataset.

We also analyzed parameters and computational complexity of individual modules, as shown in Table 3. When testing with images of the same scale, our proposed PGConv effectively strikes a balance between traditional Conv and DWConv in terms of parameters and complexity. Furthermore, we compared PGConv with Conv and DWConv in terms of computational cost and parameters. In Table 3, we provide detailed FLOPs and parameter statistics for these modules. Specifically, under the same input conditions, PGConv reduces computational cost while maintaining high accuracy. These experiments demonstrate that FMCSNet achieves significant improvements in computational efficiency and parameter optimization.

4.2.1 Comparison with the SOTA Approaches

To comprehensively measure model performance, we employed a variety of different indicators. All comparison results are detailed in Table 4. As can be seen from Table 4, the proposed FMCSNet model, tested with an input size of 320 × 320, achieves an mAP of 37.6%, outperforming ShuffleNetv2 (35.4%) under the same input conditions. FMCSNet also demonstrates superior AP metrics across different IoU thresholds and object scales, including AP50 (57.7%), AP75 (39.3%), APs (11.1%), APm (18.1%), and APl (48.0%), indicating its robustness in detecting objects of varying sizes. Despite its competitive accuracy, FMCSNet maintains a low computational cost of 0.9G FLOPs and a minimal parameter count of 0.6M, making it highly efficient for resource-constrained environments. Furthermore, FMCSNet achieves real-time inference with an FPS of 32 on an i5-11400 CPU, surpassing all other models in terms of speed. Compared to EfficientNet, which achieves the highest mAP (46.8%) but requires 8.9G FLOPs and 11M parameters, FMCSNet offers a more balanced trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency. Similarly, while GhostNet exhibits the lowest computational cost (0.9G FLOPs) and parameter count (2.6M), its mAP (31.5%) and AP metrics are significantly lower than FMCSNet. MobileViTv3 achieves higher accuracy (mAP of 34.5%) but at the expense of increased complexity (12.9G FLOPs and 22.8M parameters), making it less suitable for mobile devices.

Although EfficientNet has higher accuracy than other models, its FLOPs reach nearly 9G, which is difficult to accept for mobile terminals. Although the FLOPs of GhostNet are only 0.9G, the detection effect is too low. The accuracy of MobileViTv3 decreases because the number of repetitions in each stage is set by 2, 2, 2, but even so, FLOPs reach nearly 13G, and the number of parameters reaches 22.8M. Therefore, it will lead to the inference that it is too slow when applied to mobile terminal object detection. Based on the above comprehensive considerations, ShuffleNetv2 heavily uses Conv and DWConv to reduce its FLOPs to 1.8G. Based on the above shortcomings, our FMCSNet performs very well. Because FMCSNet uses PGConv to replace the traditional Conv and DWConv, it reduces FLOPs and the number of parameters. Therefore, FMCSNet not only stands out in the number of parameters and complexity but also improves the accuracy. When

4.2.2 Feature Map Analysis of Each Stage

FMCSNet can improve the effect of small objects by 4.5%. The main reason is related to the information of the feature maps extracted at different stages. As shown in Fig. 7a, each stage’s extracted feature map information is displayed. It can be seen from the figure that the adoption of PGConv before the beginning of each stage has little impact on the following stages and the middle part of each stage. Fig. 7b shows the feature map extracted in each stage of ShuffleNetv2. Because ShuffleNet uses many DWConvs, the information exchange between its channels is limited, and the target with a pixel area less than

Figure 7: Feature maps of each stage. (a) FMCSNet. (b) ShuffleNetv2

4.2.3 PGConv Comparison Experiments

To further demonstrate the effectiveness of the PGConv module, we have integrated it into the ShuffleNetV2 network model. This integration involved replacing the original DWConv module with the PGConv module, thereby evaluating the effectiveness and versatility of PGConv. Through this experimental design, we can more comprehensively assess the performance and applicability of the PGConv module across different network architectures. At the same time, we adopt the scaling coefficient

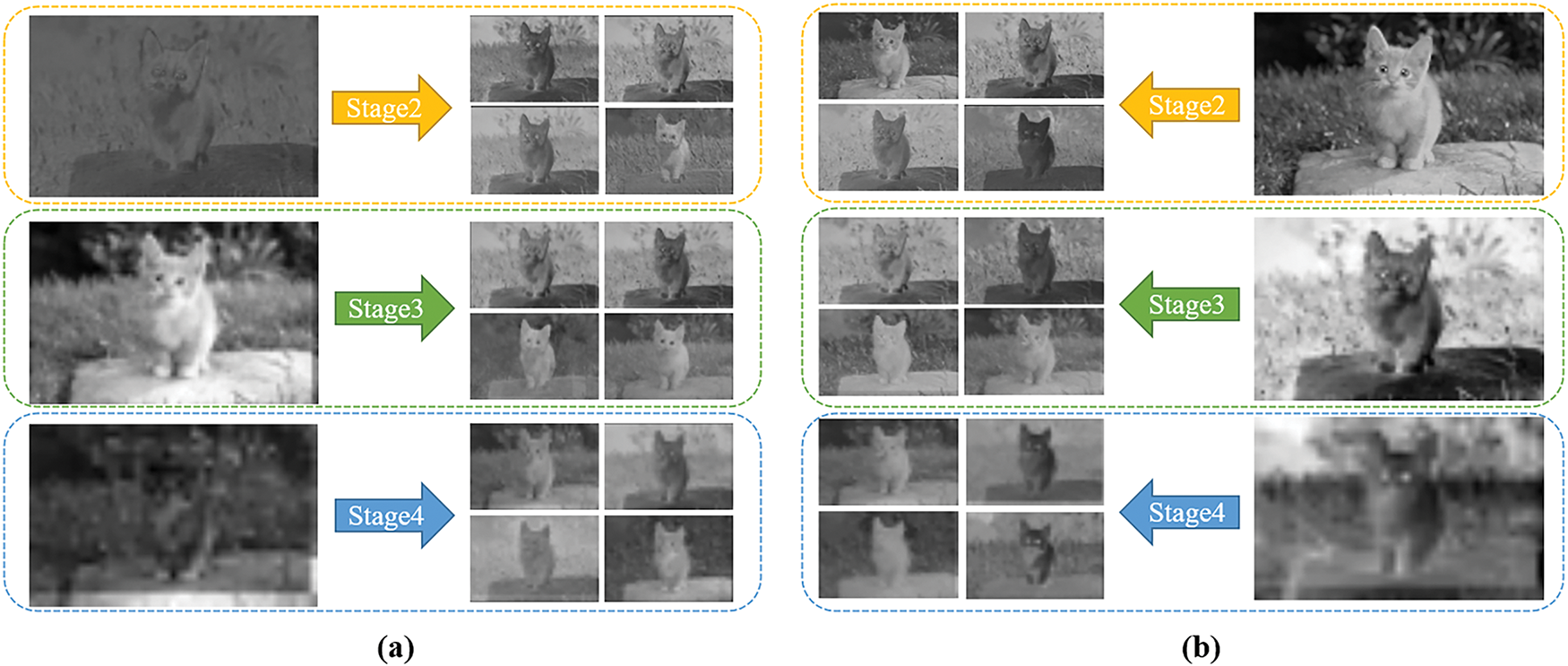

The experimental results are shown in Table 6. The direct replacement of DWConv with PGConv only slightly increases the FLOPs and parameters, but all other metrics increase, and the mAP increases from 40.9% to 41.2%. As shown in Fig. 8, the effect of using DWConv is compared with PGConv, and PGConv is used.

Figure 8: Feature map corresponding to Stage 4 in ShuffleNetv2 (a) pgconv version (b) dwconv version

4.2.4 ShiftMLP Comparison Experiments

To intuitively validate the capability of the ShiftMLP module in handling global features, we plan to conduct a series of experiments on the MobileViTv3 network. MobileViTv3 employs a linear complexity self-attention mechanism, known as the Linear Transformer, for efficient processing of global features. In our experiments, we will replace the Linear Transformer module in MobileViTv3 with ShiftMLP to handle these global features. As demonstrated in Table 7, the MobileViTv3 model, with ShiftMLP substituting for the Linear Transformer, significantly reduces its computational complexity to just 3.5G, and the model’s parameter size is also reduced to 4.6M. This indicates that ShiftMLP can serve as a more efficient solution for global feature processing.

Fig. 9 shows the feature map comparison of ShiftMLP and Linear Transformer in each stage of MobileViTv3, respectively. When ShiftMLP is used to replace Linear Transformer, the feature information displayed in each stage is similar. The effect of using ShiftMLP to process global feature information is slightly lower than that of using Linear Transformer to process global feature information. However, the FLOPs and parameters of ShiftMLP are much lower than those of Linear Transformer, so it is more appropriate to use ShiftMLP in lightweight network models. It is worth noting that for common-performance models with few parameters, the ShiftMLP module has comparable performance to the Transformer module. In contrast, for network models with a large number of parameters, the network model constructed by the Transformer module is better than other models in most cases.

Figure 9: Feature maps of each stage of MobileViTv3 using (a) ShiftMLP and (b) Linear Transformer module

4.3 Ablation Experiments on the COCO Dataset

To further validate the effectiveness of the FMCSNet, we conducted a series of ablation experiments on the Microsoft COCO [34] dataset. Additionally, we aim to apply this network to real-world scenarios in the final phase of our experiments. We used 118,000 images as the training set, 5000 as the validation set, and 40,000 as the test set. In evaluating model performance, we have chosen mAP (

According to the results in Table 8, several noteworthy observations were made. Specifically, incorporating only the PGConv module resulted in a 2.8-point increase in the mAP score, highlighting its significant contribution to the model’s overall performance. In contrast, if only the ShiftMLP module is used, the increase in mAP is just 0.5. Notably, these changes come with a minimal increase in computational overhead: FLOPs increased by only 0.04G, and Params increased by 0.14M. These results highlight FMCSNet’s ability to balance effectiveness and efficiency, especially when dealing with large-scale and complex datasets.

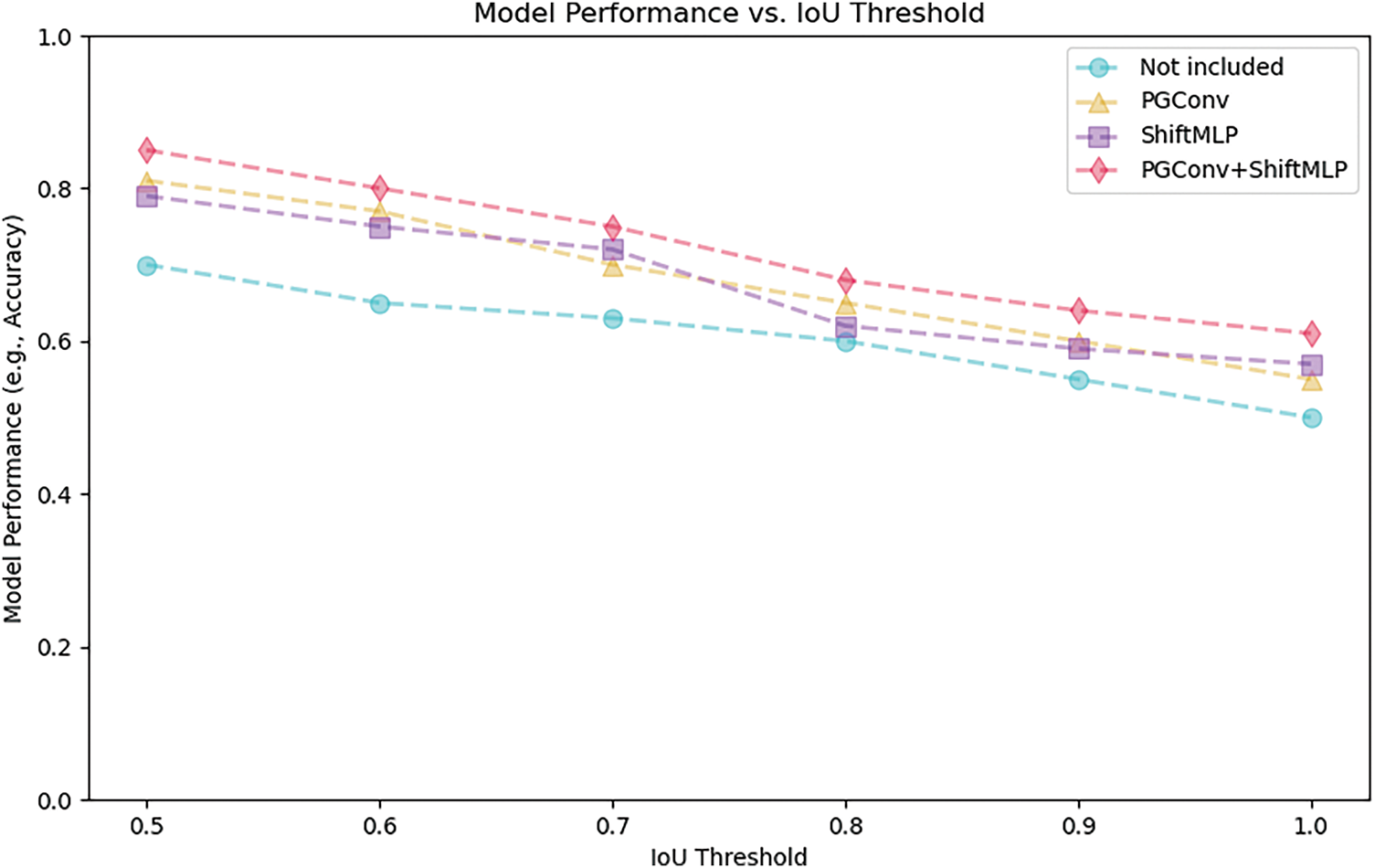

As illustrated in Fig. 10, we compared IoU thresholds on the COCO dataset. The results demonstrate that when both PGConv and ShiftMLP are employed simultaneously, the model maintains the highest accuracy across various threshold settings. This observation indicates that the combination of PGConv and ShiftMLP effectively enhances the precision of object detection under different threshold conditions.

Figure 10: IoU threshold plot

In summary, we conducted practical tests of the FMCSNet network model on the COCO dataset. We trained the model for 300 epochs using PyTorch on an NVIDIA GPU, employing the same parameter settings as used for the Pascal VOC 2007 dataset. The results of the experiment are presented in Table 9. The experimental results demonstrate that the FMCSNet model excels in accuracy, achieving a notable mAP of 30, while maintaining an optimal balance between FLOPs and parameter count (Params). These characteristics make FMCSNet highly suitable for mobile devices, offering both efficiency and precision. FMCSNet performs effectively across various platforms, from lower-performance mobile CPUs to higher-performance GPUs. On mobile devices, the model achieves real-time inference with a slight trade-off in accuracy, which remains acceptable for many real-time applications where speed is critical. Its low FLOPs and minimal parameter count ensure efficient operation on resource-constrained platforms without significant accuracy loss, making it ideal for mobile and edge devices requiring fast, real-time object detection.

Looking ahead, FMCSNet holds strong potential for extensive applications in the industrial sector, demonstrating its adaptability to real-world environments. As a general and efficient backbone network, FMCSNet can serve as a versatile solution for diverse object detection tasks. Further testing, as shown in Fig. 11, highlights its robustness and reliability across randomly selected images.

Figure 11: Illustrative detection results on the CPU

This work presents a novel lightweight detection model tailored for mobile devices called FMCSNet. FMCSNet leverages PGConv to replace DWConv and enhance inter-channel information exchange. To address the limitations of ViT on low-power devices, we propose ShiftMLP, a fully convolutional MLP with Shift operations, improving adaptability, translational invariance, and enabling real-time inference on mobile platforms. FMCSNet strikes a balance between computational efficiency and feature extraction, making it particularly effective for small object detection on resource-constrained platforms. Efficient feature fusion modules enhance detection capabilities without significantly increasing parameters, while lightweight attention mechanisms focus on critical information, reducing computational costs. In experiments, FMCSNet outperformed other lightweight models in small object detection tasks, validating its potential for real-world applications. Additionally, its compact structure and fast inference speed make it ideal for deployment on mobile devices. Looking forward, FMCSNet provides a promising foundation for lightweight multimodal networks, with potential extensions to image segmentation and natural language processing. Our ultimate goal is to develop a unified lightweight network for classification, segmentation, and detection tasks, and we remain committed to advancing research in efficient network architectures.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 62371187 and the Open Program of Hunan Intelligent Rehabilitation Robot and Auxiliary Equipment Engineering Technology Research Center under Grant No. 2024JS101.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Xianyi Liu and Jinping Liu; methodology, Lijuan Huang, Xianyi Liu, Jinping Liu and Pengfei Xu; software, Xianyi Liu and Jinping Liu; validation, Lijuan Huang and Pengfei Xu; investigation, Lijuan Huang, Xianyi Liu, Jinping Liu and Pengfei Xu; resources, Xianyi Liu; writing—original draft preparation, Xianyi Liu and Jinping Liu; writing—review and editing, Xianyi Liu and Jinping Liu; visualization, Lijuan Huang and Xianyi Liu; supervision, Jinping Liu; project administration, Jinping Liu; funding acquisition, Jinping Liu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The public datasets are used in this study, and the data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Jinping Liu or Pengfei Xu, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Jamali M, Davidsson P, Khoshkangini R, Ljungqvist MG, Mihailescu RC. Context in object detection: a systematic literature review. Artif Intell Rev. 2025;58(6):175. doi:10.1007/s10462-025-11186-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Leng J, Ye Y, Mo M, Gao C, Gan J, Xiao B, et al. Recent advances for aerial object detection: a survey. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;56(12):1–36. doi:10.1145/3664598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Howard AG, Zhu M, Chen B. Mobilenets: efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv:170404861. 2017. [Google Scholar]

4. Redmon J, Divvala S, Girshick R, Farhadi A. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 779–88. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Szegedy C, Vanhoucke V, Ioffe S, Shlens J, Wojna Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 2818–26. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhang X, Zhou X, Lin M, Sun J. ShuffleNet: an extremely efficient convolutional neural network for mobile devices. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 6848–56. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Ma N, Zhang X, Zheng HT, Sun J. ShuffleNet V2: practical guidelines for efficient CNN architecture design. In: Computer Vision—ECCV 2018. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 122–38. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01264-9_8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Dosovitskiy A, Beyer L, Kolesnikov A, Weissenborn D, Zhai X, Unterthiner T, et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv:2010.11929. 2020. [Google Scholar]

9. Touvron H, Cord M, Douze M, Massa F, Sablayrolles A, Jégou H. Training data-efficient image transformers & distillation through attention. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. Cambridge, UK: PMLR; 2021. p. 10347–57. [Google Scholar]

10. Mehta S, Rastegari M. Mobilevit: light-weight, general-purpose, and mobile-friendly vision transformer. arXiv:2110.02178. 2021. [Google Scholar]

11. Wadekar SN, Chaurasia A. Mobilevitv3: mobile-friendly vision transformer with simple and effective fusion of local, global and input features. arXiv: 220915159. 2022. [Google Scholar]

12. Wang A, Chen H, Liu L. YOLOv10: real-time end-to-end object detection. In: Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. Vancouver, BC, Canada: Curran Associates Inc.; 2025. p. 107984–8011. [Google Scholar]

13. Deng L, Luo S, He C, Xiao H, Wu H. Underwater small and occlusion object detection with feature fusi on and global context decoupling head-based YOLO. Multimed Syst. 2024;30(4):208. doi:10.1007/s00530-024-01410-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang TY, Li J, Chai J, Zhao ZQ, Tian WD. Improved YOLOv5 network with attention and context for small object detection. In: Intelligent computing methodologies. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 341–52. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-13832-4_29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Misbah M, Khan MU, Kaleem Z, Muqaibel A, Alam MZ, Liu R, et al. MSF-GhostNet: computationally efficient YOLO for detecting drones in low-light conditions. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens. 2024;18:3840–51. doi:10.1109/jstars.2024.3524379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Diwan T, Anirudh G, Tembhurne JV. Object detection using YOLO: challenges, architectural successors, datasets and applications. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023;82(6):9243–75. doi:10.1007/s11042-022-13644-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Liu Z, Zhang E, Ding Q, Liao W, Wu Z. An improved method for enhancing the accuracy and speed of dynamic object detection based on YOLOv8s. Sensors. 2024;25(1):85. doi:10.3390/s25010085. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Li S, Zhu Z, Sun H, Ning X, Dai G, Hu Y, et al. Toward high-accuracy and real-time two-stage small object detection on FPGA. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2024;34(9):8053–66. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2024.3385121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Redmon J, Farhadi A. Yolov3: an incremental improvement. arXiv:1804.02767. 2018. [Google Scholar]

20. Deng H, Wang C, Li C, Hao Z. Fine grained dual level attention mechanisms with spacial context information fusion for object detection. Pattern Anal Appl. 2024;27(3):75. doi:10.1007/s10044-024-01290-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Nan Z, Li X, Dai J, Xiang T. MI-DETR: an object detection model with multi-time inquiries mechanism. In: 2025 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2025 Jun 10–17; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 4703–12. doi:10.1109/CVPR52734.2025.00443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Tan M, Pang R, Le QV. EfficientDet: scalable and efficient object detection. In: 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 10778–87. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.01079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhong L, Tan H, Liao J. YOLOX-Nano: intelligent and efficient dish recognition system. In: 2022 7th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Signal Processing (ICSP); 2022 Apr 15–17; Xi’an, China. p. 1391–5. doi:10.1109/ICSP54964.2022.9778742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Vijayakumar A, Vairavasundaram S. YOLO-based object detection models: a review and its applications. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(35):83535–74. doi:10.1007/s11042-024-18872-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhang T, Zhao F, Zou Y, Zheng J. A lightweight real-time detection method of small objects for home service robots. Mach Vis Appl. 2024;35(6):129. doi:10.1007/s00138-024-01611-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Chen J, Kao SH, He H, Zhuo W, Wen S, Lee CH, et al. Run, don’t walk: chasing higher FLOPS for faster neural networks. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 12021–31. doi:10.1109/cvpr52729.2023.01157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Jeon Y, Kim J. Constructing fast network through deconstruction of convolution. Adv Neural Inform Process Syst. 2018;31:1–11. [Google Scholar]

28. Chen W, Xie D, Zhang Y, Pu S. All you need is a few shifts: designing efficient convolutional neural networks for image classification. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 7234–43. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2019.00741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Lin J, Gan C, Han S. TSM: temporal shift module for efficient video understanding. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 7082–92. doi:10.1109/iccv.2019.00718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Tolstikhin IO, Houlsby N, Kolesnikov A, Beyer L, Zhai X, Unterthiner T, et al. MLP-mixer: an all-mlp architecture for vision. Adv Neural Inform Process Syst. 2021;34:24261–22. [Google Scholar]

31. Chen S, Xie E, Ge C. Cyclemlp: a mlp-like architecture for dense prediction. arXiv:2107.10224; 2012. [Google Scholar]

32. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 770–8. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Everingham M, Van Gool L, Williams CKI, Winn J, Zisserman A. The pascal visual object classes (VOC) challenge. Int J Comput Vis. 2010;88(2):303–38. doi:10.1007/s11263-009-0275-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Lin T-Y, Maire M, Belongie S. Microsoft coco: common objects in context. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision-ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference; 2014 Sep 6–12; Zurich, Switzerland. p. 740–55. [Google Scholar]

35. Xie S, Girshick R, Dollár P, Tu Z, He K. Aggregated residual transformations for deep neural networks. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 5987–95. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Tan M, Le Q. Efficientnet: rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. Cambridge, UK: PMLR; 2019. p. 6105–14. [Google Scholar]

37. Ge Z, Liu S, Wang F, Li Z, Sun J. Yolox: exceeding yolo series in 2021. arXiv: 2107.08430; 2021. [Google Scholar]

38. Wang CY, Bochkovskiy A, Liao HM. YOLOv7: trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 7464–75. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.00721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Sandler M, Howard A, Zhu M, Zhmoginov A, Chen LC. MobileNetV2: inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 4510–20. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Mittal P. A comprehensive survey of deep learning-based lightweight object detection models for edge devices. Artif Intell Rev. 2024;57(9):242. doi:10.1007/s10462-024-10877-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools