Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Energy Optimization for Autonomous Mobile Robot Path Planning Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning

School of Computer Science, Jiangsu University of Science and Technology, Zhenjiang, 212100, China

* Corresponding Author: Longfei Gao. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068873

Received 09 June 2025; Accepted 18 August 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

At present, energy consumption is one of the main bottlenecks in autonomous mobile robot development. To address the challenge of high energy consumption in path planning for autonomous mobile robots navigating unknown and complex environments, this paper proposes an Attention-Enhanced Dueling Deep Q-Network (AD-Dueling DQN), which integrates a multi-head attention mechanism and a prioritized experience replay strategy into a Dueling-DQN reinforcement learning framework. A multi-objective reward function, centered on energy efficiency, is designed to comprehensively consider path length, terrain slope, motion smoothness, and obstacle avoidance, enabling optimal low-energy trajectory generation in 3D space from the source. The incorporation of a multi-head attention mechanism allows the model to dynamically focus on energy-critical state features—such as slope gradients and obstacle density—thereby significantly improving its ability to recognize and avoid energy-intensive paths. Additionally, the prioritized experience replay mechanism accelerates learning from key decision-making experiences, suppressing inefficient exploration and guiding the policy toward low-energy solutions more rapidly. The effectiveness of the proposed path planning algorithm is validated through simulation experiments conducted in multiple off-road scenarios. Results demonstrate that AD-Dueling DQN consistently achieves the lowest average energy consumption across all tested environments. Moreover, the proposed method exhibits faster convergence and greater training stability compared to baseline algorithms, highlighting its global optimization capability under energy-aware objectives in complex terrains. This study offers an efficient and scalable intelligent control strategy for the development of energy-conscious autonomous navigation systems.Keywords

With the rapid improvement of artificial intelligence, robotics and automation, autonomous mobile robots show a wide range of application prospects in the fields of industrial manufacturing, service, search and rescue, intelligent logistics, military reconnaissance and environmental monitoring [1]. Among them, path planning, as a core technology for realizing autonomous navigation and task execution, has become a research focus of academic and industrial attention [2]. However, robots often face rugged terrains, undulating ramps, and diverse obstacles in real-world deployments, as shown in Fig. 1, and path planning needs to strike a balance between efficiency, safety, and energy consumption. Optimization of energy consumption is especially critical for long-duration field exploration and rescue missions, which directly affects mission continuity and reliability. In the context of energy constraints and the increasing demand for sustainable development, energy-optimized path planning has become a key technical bottleneck that restricts the large-scale application of autonomous robots.

Figure 1: Robot operating in a complex environment

In recent years, path planning methods have evolved from classical algorithms to deep reinforcement learning (DRL) approaches [3]. Traditional algorithms such as Dijkstra [4], A* [5], and D* Lite [6] have been widely adopted. Dijkstra guarantees optimal paths [7], but suffers from high computational complexity [8]. A* improves efficiency by incorporating heuristic functions, making it effective in static environments, but its adaptability to dynamic or complex scenarios remains limited [9]. D* Lite supports dynamic re-planning and exhibits better adaptability [10], yet it still faces significant computational overhead in large-scale or continuous spaces [11].

With the rapid advancement of DRL its application in complex path planning has gained increasing attention [12]. For example, Hu et al. [13] proposed a DRL-based navigation approach that achieved autonomous navigation on flat terrains with dynamic obstacles. Zhang et al. [14] presented a hierarchical reinforcement learning framework for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, which integrates path planning and energy management to realize more optimal overall energy consumption control. Han et al. [15] employed Double Deep Q-Networks (Double DQN) to optimize the energy management strategy of hybrid tracked vehicles, demonstrating significantly improved fuel economy compared to conventional Q-learning and dynamic programming algorithms. Shu et al. [16] addressed the multi-agent path planning problem for unmanned aerial vehicles by introducing a deep reinforcement learning method incorporating an energy consumption model and attention mechanisms, which outperformed traditional heuristic and some reinforcement learning algorithms in terms of energy efficiency. Although the aforementioned studies have achieved certain degrees of energy optimization in various scenarios, most of them only focus on energy consumption or path distance optimization during local operations, lacking a coordinated planning framework for global path energy consumption and distance.

In contrast to the aforementioned approaches that focus solely on local energy consumption optimization, the Attention-Dueling DQN framework proposed in this paper dynamically balances path length and energy consumption at the global path level. By leveraging a multi-objective reward function and efficient state feature modeling, the algorithm is able to comprehensively consider overall energy consumption, distance, and obstacle avoidance during the optimization process, thereby yielding a more optimal global scheduling strategy. Although DRL techniques such as Dueling DQN, attention mechanisms, and prioritized experience replay (PER) have been extensively studied, most existing works tend to apply these methods in isolation and lack systematic integration and mechanism innovation tailored for energy-optimized path planning tasks. To address the energy optimization requirements of autonomous mobile robots operating in complex terrains, this paper proposes a unified Attention-Enhanced Dueling Deep Q-Network (AD-Dueling DQN) framework, which, for the first time, deeply integrates a multi-head attention mechanism with the Dueling DQN architecture and introduces an adaptive prioritized experience replay based on temporal-difference (TD) error. This effectively enhances the sampling efficiency of critical energy-related states and accelerates policy convergence.

Compared with existing methods, the main innovations of this paper are as follows:

• This work embeds multi-head attention not only at the feature input layer but also within the dueling branches, enabling explicit and dynamic modeling of energy-critical states and substantially improving sensitivity to energy consumption variations.

• A reward function is designed to prioritize energy consumption while also accounting for path smoothness, task completion, and obstacle avoidance, thus enhancing overall path planning performance.

• Experience replay sampling priorities are adaptively adjusted based on energy-related TD-error, which accelerates convergence toward lower energy policies and improves training stability and generalization through phased bias adjustment.

• The proposed algorithm exhibits robust energy optimization and generalization across complex terrains, indicating strong potential for real-world deployment.

The remainder of the paper is as follows: Section 2 presents related works. There was a comprehensive methodology in Section 3. A result analysis is provided in Section 4, and a conclusion is presented in Section 5.

Path planning for autonomous mobile robots can be modeled as an energy-aware Markov Decision Process (MDP) [17]. An MDP is formally defined as a five-tuple

During decision-making, the robot selects and executes an action according to its current policy, receives a reward

This process is centered around three core components: the action space, the state space, and the reward function, which together define the decision-making dynamics of the autonomous agent.

The traditional DQN predicts action-value functions (Q-values) using a single neural network architecture. However, this structure cannot effectively decouple the contributions of states and actions, which often leads to unstable action selection policies—particularly in complex terrain environments where state dynamics are highly nonlinear.

To address this limitation, the Dueling DQN architecture was proposed. This approach innovatively separates the estimation of the state value function and the advantage function [19], as shown in Eq. (2). This separation enables the network to more accurately evaluate the relative importance of different actions, making it particularly suitable for robotic navigation tasks involving complex and high-dimensional state representations.

Originally introduced in the field of natural language processing, the attention mechanism enables models to learn the relative importance of input features and focus on task-relevant information, thereby enhancing feature representation and decision accuracy [20]. In recent years, attention has been widely incorporated into reinforcement learning to improve perception, decision-making, and generalization capabilities.

In high-dimensional and dynamic environments, attention is particularly effective at extracting salient features from noisy and redundant inputs. By computing inter-feature dependencies and dynamically assigning weights, the attention mechanism guides the policy network to focus on critical information at each decision step [21]. Its mathematical formulation is as follows:

2.4 Prioritized Experience Replay

Traditional experience replay mechanisms, such as uniform replay, sample historical experiences randomly and equally during training, without differentiating between the importance of each sample. As a result, low-information or redundant experiences are repeatedly sampled, which slows convergence—particularly in complex and dynamic environments [22].

To address the inefficiency caused by indiscriminate sampling in conventional experience replay, PER was introduced [23]. The core idea of PER is to assign sampling priorities based on the TD error of each experience [24], thereby increasing the likelihood of replaying high-value experiences that are more informative for learning. The prioritization mechanism is formally defined in Eq. (4).

where

In this expression,

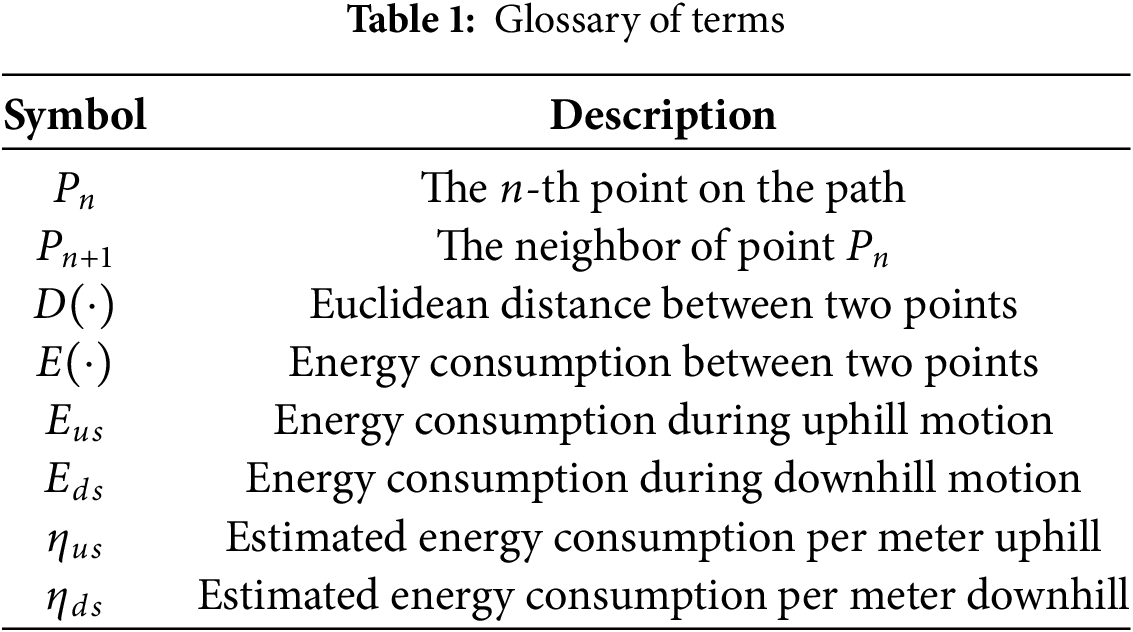

In energy-sensitive path planning, the shortest path does not necessarily yield the lowest energy consumption, especially in complex off-road terrains where uphill and downhill energy costs differ significantly. This study adopts the ECEM energy model proposed by Huang et al. [25], incorporating a slope-aware mechanism to refine energy estimation by accounting for both power demand and energy recovery, thereby enhancing the energy efficiency and accuracy of path planning in challenging terrains. Table 1 summarizes the model terms.

First, the distance D between consecutive path nodes is determined using the Euclidean geometry formula, as shown in Eq. (6).

Based on the fitted curve and the distance computation model described above, an energy consumption model between two points is constructed, as shown in Eq. (7). In this formulation,

In this formulation,

Here,

3 Energy-Efficient Path Planning for Autonomous Mobile Robots

3.1 State and Action Space Definition

(1) State Space.

In reinforcement learning-based path planning tasks, the state space must comprehensively capture the environmental information perceived by the autonomous robot. In this study, the state space

where

This compact yet comprehensive state representation provides the agent with both global navigation objectives and local perceptual awareness, facilitating robust and scalable policy learning across diverse simulated environments.

(2) Action Space.

The action space is discretized into six representative velocity vectors—forward, half-speed forward, left turn, slow left turn, right turn, and slow right turn—based on the kinematic constraints of the Pioneer 3-AT differential-drive robot, as defined in Eq. (12). Compared to continuous action spaces, discretization simplifies control and deployment, accelerates reinforcement learning convergence, and enhances policy stability. The choice of six discrete actions reflects the hardware constraints of the Pioneer 3-AT and balances maneuverability with control simplicity. This set covers typical navigation needs while supporting efficient learning and generalization.

The maximum wheel speed is set to

3.2 Design of an Energy-Dominant Multi-Objective Reward Function

This paper designs a multi-objective reward function that prioritizes energy consumption minimization while accounting for task completion, path smoothness, and obstacle avoidance.

The core structure is energy-driven and embeds the energy consumption per unit distance E (as defined in Eqs. (6)–(10)) as an immediate penalty term in the reward function. In the reward function, the energy consumption term

In addition to the energy-dominant term, the reward function incorporates several auxiliary objectives, including goal achievement, distance-to-goal minimization, path smoothness, time efficiency, and obstacle avoidance performance. Goal Achievement Reward

The reward

The path length penalty

To promote smoother motion trajectories, the reward function includes a path smoothness reward term

In order to encourage the robot to reach the goal as soon as possible and to avoid the strategy from getting stuck in a localized loop or a long trial, this paper adds the

where

When the distance sensor senses that the distance to an obstacle is too close, there is an obstacle proximity penalty term

In this formulation,

In summary, the complete immediate reward function

During the design of reward function weights, multiple parameter combinations were evaluated for energy consumption, path length, time efficiency, and obstacle avoidance. Specifically, energy weights of 30, 50, and 100; path length weights of 5, 10, and 20; time efficiency weights of 1.0, 5.0, and 10.0; and obstacle avoidance weights of 0.1, 0.5, and 1.0 were tested. For each configuration, full training and comparative experiments were conducted to comprehensively assess their impact on energy consumption, path quality, and convergence speed. Ultimately, the combination of an energy weight of 50, path length weight of 10, time efficiency weight of 5.0, and obstacle avoidance weight of 0.5 was selected, achieving a favorable balance between multi-objective performance and training convergence. It should be noted that a large-scale grid search was not conducted; instead, weights were determined through empirical tuning and comparative experiments.

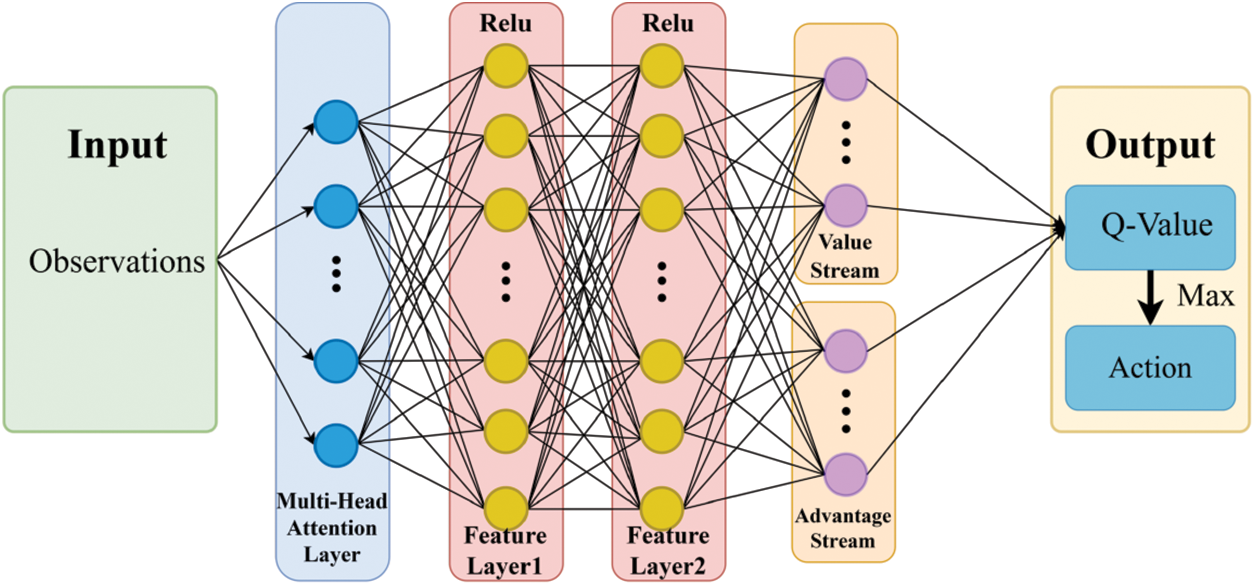

Traditional DQN and its variants treat all input state features equally, limiting their ability to identify key energy-related factors such as slope or obstacle density in high-dimensional tasks. To address this, a multi-head attention mechanism is introduced before the dueling architecture, independently modeling and weighting each state dimension. This enhances the model’s sensitivity and responsiveness to critical energy-related features.

Let the current state input be

Here,

In each attention head

LayerNorm(

The overall network architecture of the proposed AD-Dueling DQN algorithm is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Network architecture of the proposed AD-Dueling DQN algorithm

To enhance training efficiency and sample utilization in energy-aware path planning, a TD-error-based prioritized experience replay mechanism is adopted. Importance sampling weights are used to correct bias from non-uniform sampling.

The step size

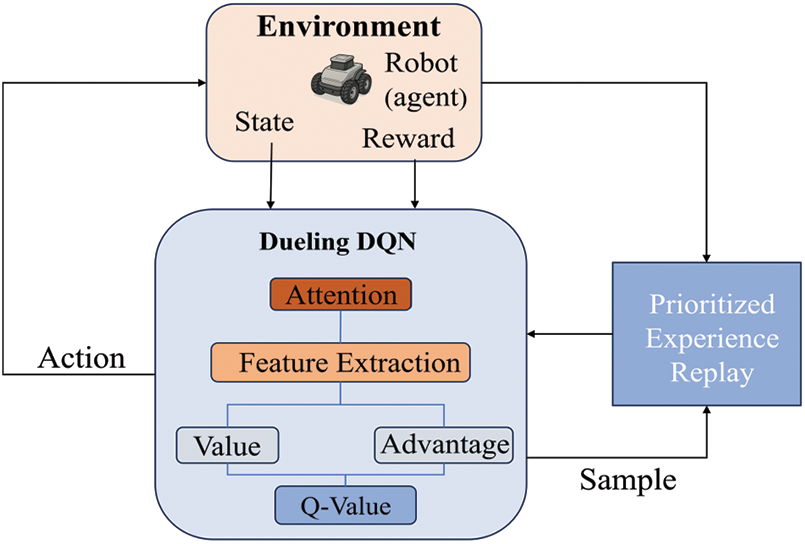

In summary, the path planning flowchart of the AD-Dueling DQN algorithm based on energy optimization is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Framework of the proposed AD-Dueling DQN-based path planning model

The overall procedure is summarized as follows:

1. Initialize the attention-based Dueling DQN and target network.

2. In each training episode, reset the environment and interact using the

3. Compute TD-error to assign priority and store experiences.

4. Sample mini-batches based on priority, extract salient features via multi-head attention, and update the network.

5. Update sample priorities and periodically synchronize the target network.

6. Output the optimized policy network.

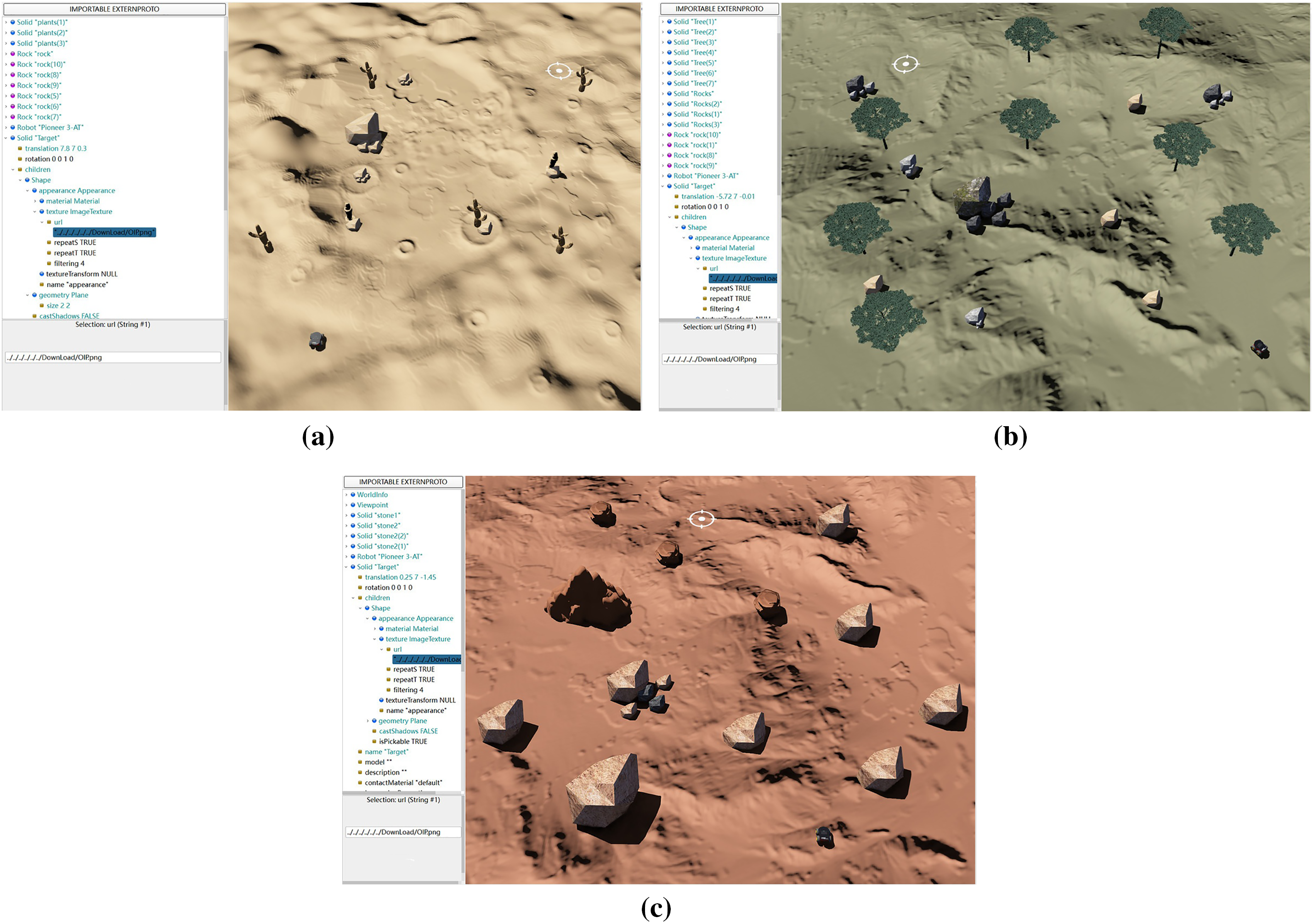

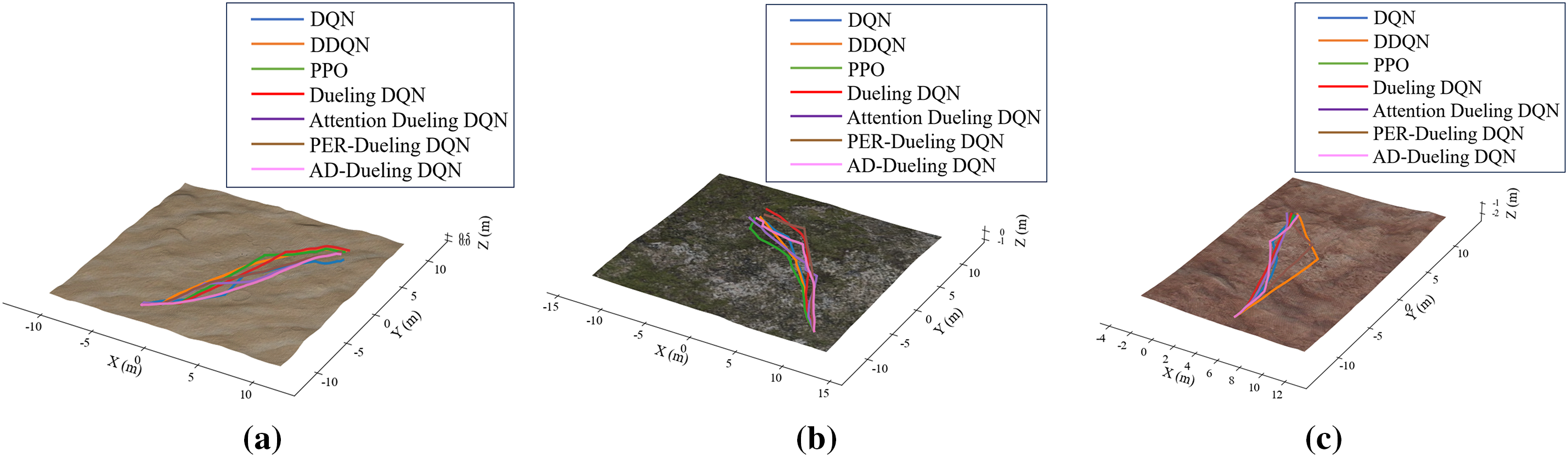

Three representative and challenging off-road simulation environments were constructed, as illustrated in Fig. 4. Environment (a) features sand dune undulations and sparse obstacles to evaluate path smoothness and slope awareness; Environment (b) consists of a dense hilly forest to test obstacle avoidance efficiency and robustness in constrained spaces; Environment (c) simulates complex rocky terrain to assess energy modeling and path stability.

Figure 4: Three representative off-road simulation environments constructed in Webots: (a) desert terrain; (b) forest terrain; (c) rocky terrain

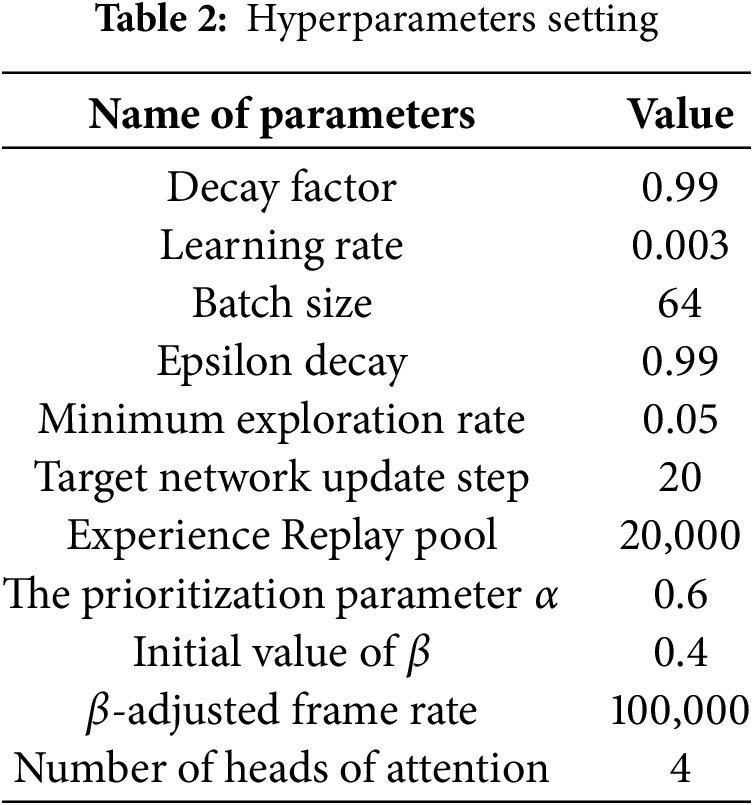

The AD-Dueling DQN algorithm involves several critical hyperparameters, with key settings summarized in Table 2. A high-fidelity mobile robot simulation platform was developed in Webots. The Pioneer 3-AT robot is equipped with distance, compass, touch, and GPS sensors. To realistically simulate sensor measurement errors and uncertainties present in real-world environments, Gaussian noise is added to sensor signals in the simulation. Training was conducted on an i7-13700H CPU and RTX 4060 GPU, taking about 10 h per environment.

The path planning performance of AD-Dueling DQN is evaluated using key indicators, including average path length, average energy consumption, and energy consumption improvement rate relative to other algorithms.

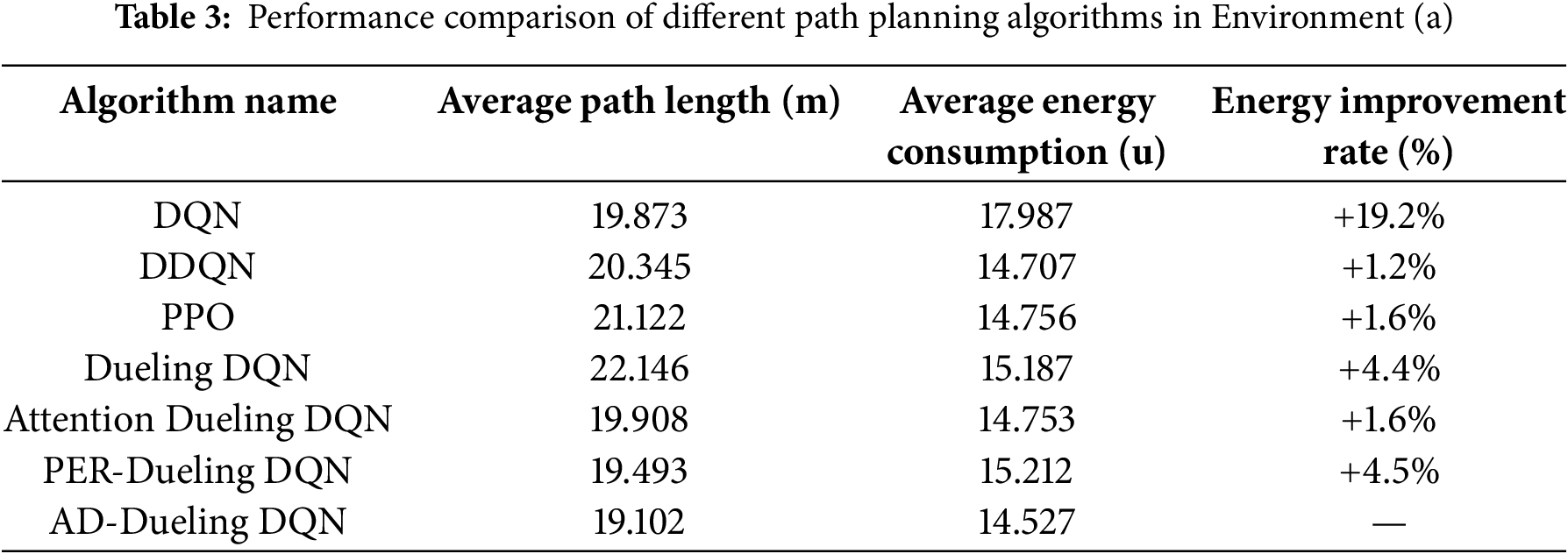

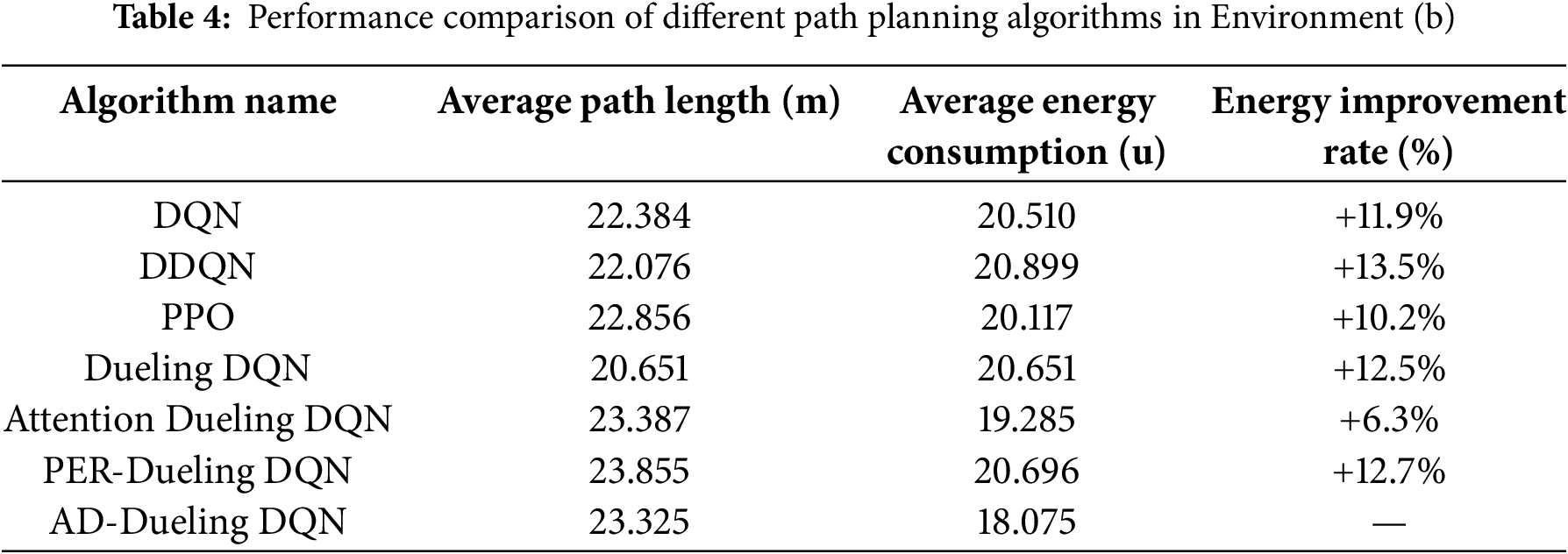

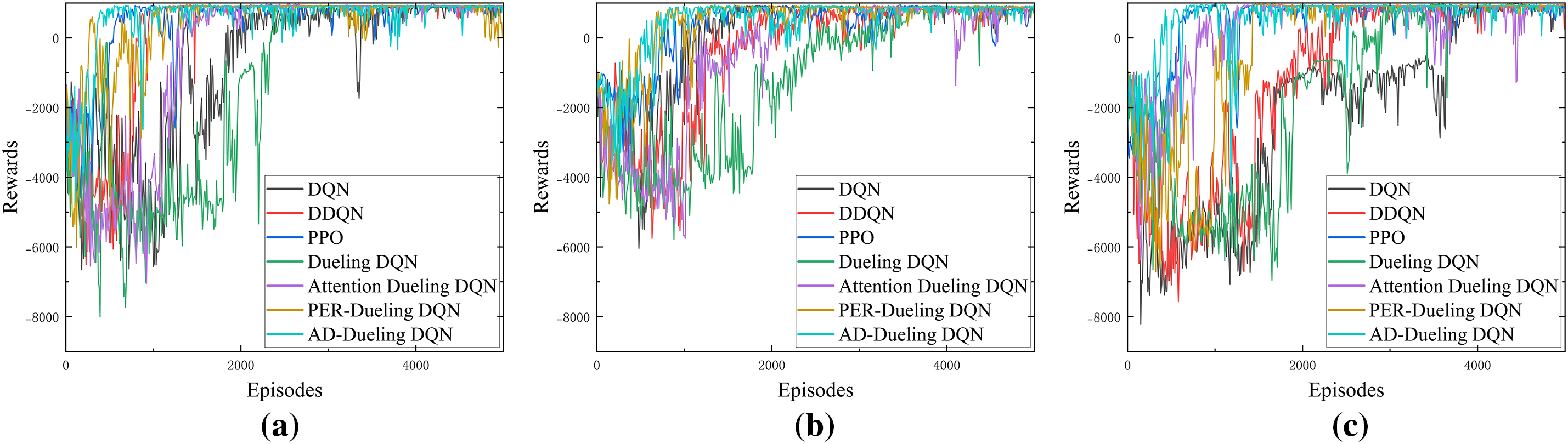

Tables 3–5 summarize the performance metrics of all baseline and ablation groups. DQN and DDQN are classical value-based reinforcement learning algorithms, while Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) is a widely used policy gradient method. DQN, DDQN, and PPO serve as baseline methods. Dueling DQN, Attention Dueling DQN, and PER-Dueling DQN serve as ablation groups, representing models without multi-head attention and PER, with only attention, or with only PER, respectively. AD-Dueling DQN integrates both modules as the complete model. The path planning results of AD-Dueling DQN, DQN, DDQN, PPO, Dueling DQN, Attention-Dueling DQN, and PER-Dueling DQN in three different off-road environments are illustrated in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Simulation results of all algorithms: (a) Environment a; (b) Environment b; (c) Environment c

The results demonstrate that the proposed AD-Dueling DQN consistently achieves the lowest average energy consumption across all environments, validating its superior energy optimization capability.

In Environment (a), AD-Dueling DQN achieves the lowest average energy consumption (14.527 u), with a 19.2% reduction compared to DQN and improvements of 1.2%, 1.6%, and 1.6% over DDQN, PPO, and Attention-Dueling DQN, respectively. Dueling DQN and PER-Dueling DQN perform moderately well but remain less efficient. AD-Dueling DQN also maintains an optimal balance between path length and energy consumption.

In Environment (b), AD-Dueling DQN again leads (18.075 u), with improvements of 11.9%–13% over DQN, DDQN, and Dueling DQN, and 12.7% over PER-Dueling DQN. Ablation studies confirm that both the attention mechanism and prioritized experience replay independently benefit energy optimization, with their combination yielding the best results. While PPO shows some advantage in path length, its energy optimization is inferior.

In Environment (c), all algorithms show lower energy consumption due to terrain, but AD-Dueling DQN still achieves the best performance (11.495 u), outperforming DQN and Attention Dueling DQN by 7.5% and 9.6%, respectively, and maintaining a low path length.

Overall, AD-Dueling DQN demonstrates superior generalization and stability across varied terrains, consistently outperforming DQN, DDQN, PPO, and all ablation variants. The synergy of multi-head attention and prioritized experience replay enables efficient, energy-saving path planning in complex environments, highlighting its practical value and application potential.

Fig. 6 illustrates the reward convergence of various algorithms across three representative environments. As shown in the figures, all algorithms experience substantial reward fluctuations during the initial 1000–1500 episodes. The baseline group (DQN, DDQN, PPO) exhibits marked instability and slower convergence, with wide reward distributions. In contrast, the ablation group (Dueling DQN, Attention Dueling DQN, PER-Dueling DQN) achieves faster and more stable convergence, particularly PER-Dueling DQN and AD-Dueling DQN, which rapidly attain positive rewards across all environments and maintain minimal post-convergence fluctuations, demonstrating superior stability and robustness. These advantages are further amplified in the Environment (b) and Environment (c) environments, where Dueling DQN and PER-Dueling DQN reach high reward levels within 2000 episodes, and AD-Dueling DQN consistently achieves the fastest and smoothest convergence. Overall, the baseline group performs significantly worse in complex environments, underscoring the superior generalization and policy performance of the ablation variants, especially AD-Dueling DQN.

Figure 6: Changes in the reward values of all algorithms during the training process: (a) Environment a; (b) Environment b; (c) Environment c

In summary, AD-Dueling DQN excels in energy optimization, convergence speed, stability, and adaptability, confirming its effectiveness for complex energy-sensitive path planning.

This paper proposes an AD-Dueling DQN to reduce energy consumption in robot path planning over complex terrains. Unlike prior methods, the proposed framework embeds multi-head attention into both the feature input and value estimation branches, enabling explicit and dynamic modeling of energy-critical states. Experience replay priorities are adaptively adjusted based on energy-related TD-errors, improving learning efficiency and sensitivity. An energy-aware multi-objective reward function guides the agent toward low-energy trajectories. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed method outperforms baseline and ablation models in adaptability and robustness. Although validated in simulation, the proposed method still faces challenges for real-world deployment, such as sensor noise and unmodeled dynamics, which are common in sim-to-real transfer. Future work will employ domain randomization or transfer learning to enhance adaptability.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contributions to this work as follows: study conception and design: Longfei Gao; data collection: Weidong Wang; analysis and interpretation of results: Dieyun Ke; draft manuscript preparation: Longfei Gao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the Longfei Gao.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Loganathan A, Ahmad NS. A systematic review on recent advances in autonomous mobile robot navigation. Eng Sci Technol Int J. 2023;40(2):101343. doi:10.1016/j.jestch.2023.101343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Jia L, Li J, Ni H, Zhang D. Autonomous mobile robot global path planning: a prior information-based particle swarm optimization approach. Control Theory Technol. 2023;21(2):173–89. doi:10.1007/s11768-023-00139-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Deguale DA, Yu L, Sinishaw ML, Li K. Enhancing stability and performance in mobile robot path planning with PMR-Dueling DQN algorithm. Sensors. 2024;24(5):1523. doi:10.3390/s24051523. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Cui J, Wu L, Huang X, Xu D, Liu C, Xiao W. Multi-strategy adaptable ant colony optimization algorithm and its application in robot path planning. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;288(23):111459. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.119410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ma Y, Zhao Y, Li Z, Yan X, Bi H, Krolczyk G. A new coverage path planning algorithm for unmanned surface mapping vehicle based on A-star based searching. Appl Ocean Res. 2022;123(3):103163. doi:10.1016/j.apor.2022.103163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Gao Y, Han Q, Feng S, Wang Z, Meng T, Yang J. Improvement and fusion of D* Lite algorithm and dynamic window approach for path planning in complex environments. Machines. 2024;12(8):525. doi:10.3390/machines12080525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Candra A, Budiman MA, Hartanto K. Dijkstra’s and A-star in finding the shortest path: a tutorial. In: 2020 International Conference on Data Science, Artificial Intelligence, and Business Analytics (DATABIA); 2020 Jul 16–17; Medan, Indonesia. p. 28–32. [Google Scholar]

8. Karur K, Sharma N, Dharmatti C, Siegel JE. A survey of path planning algorithms for mobile robots. Vehicles. 2021;3(3):448–68. doi:10.3390/vehicles3030027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Katona K, Neamah HA, Korondi P. Obstacle avoidance and path planning methods for autonomous navigation of mobile robot. Sensors. 2024;24(11):3573. doi:10.3390/s24113573. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Oral T, Polat F. MOD* Lite: an incremental path planning algorithm taking care of multiple objectives. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2015;46(1):245–57. doi:10.1109/tcyb.2015.2399616. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Zhu X, Yan B, Yue Y. Path planning and collision avoidance in unknown environments for USVs based on an improved D* Lite. Appl Sci. 2021;11(17):7863. doi:10.3390/app11177863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wang X, Wang S, Liang X, Zhao D, Huang J, Xu X, et al. Deep reinforcement learning: a survey. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2022;35(4):5064–78. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2022.3207346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Hu H, Zhang K, Tan AH, Ruan M, Agia C, Nejat G. A sim-to-real pipeline for deep reinforcement learning for autonomous robot navigation in cluttered rough terrain. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2021;6(4):6569–76. doi:10.1109/lra.2021.3093551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang Q, Wu K, Shi Y. Route planning and power management for PHEVs with reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2020;69(5):4751–62. doi:10.1109/tvt.2020.2979623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Han X, He H, Wu J, Peng J, Li Y. Energy management based on reinforcement learning with double deep Q-learning for a hybrid electric tracked vehicle. Appl Energy. 2019;254(1):113708. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.113708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Shu X, Lin A, Wen X. Energy-saving multi-agent deep reinforcement learning algorithm for drone routing problem. Sensors. 2024;24(20):6698. doi:10.3390/s24206698. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Xi M, Yang J, Wen J, Liu H, Li Y, Song HB. Comprehensive ocean information-enabled AUV path planning via reinforcement learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(18):17440–17451. doi:10.1109/jiot.2022.3155697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhang K, Yang Z, Başar T. Multi-agent reinforcement learning: a selective overview of theories and algorithms. In: Handbook of Reinforcement Learning and Control. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2021. p. 321–84. [Google Scholar]

19. Wang Z, Schaul T, Hessel M, Hasselt H, Lanctot M, Freitas N. Dueling network architectures for deep reinforcement learning. In: The 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning; 2016 Jun 19–24; New York, NY, USA. p. 1995–2003. [Google Scholar]

20. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. In: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2017; 2017 Dec 4–9; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

21. Dehimi NEH, Tolba Z. Attention mechanisms in deep learning: towards explainable artificial intelligence. In: 2024 6th International Conference on Pattern Analysis and Intelligent Systems (PAIS); 2024 Apr 24–25; EL OUED, Algeria. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

22. Hou Y, Liu L, Wei Q, Xu X, Chen C. A novel DDPG method with prioritized experience replay. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC); 2017 Oct 5–8; Banff, AB, Canada. p. 316–21. [Google Scholar]

23. Schaul T, Quan J, Antonoglou I, Silver D. Prioritized experience replay. arXiv:1511.05952. 2015. [Google Scholar]

24. Hassani H, Nikan S, Shami A. Traffic navigation via reinforcement learning with episodic-guided prioritized experience replay. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;137(2):109147. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2024.109147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Huang S, Wu X, Huang G. Deep reinforcement learning-based multi-objective path planning on the off-road terrain environment for ground vehicles. arXiv:2305.13783. 2023. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools