Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Compatible Remediation for Vulnerabilities in the Presence and Absence of Security Patches

1 College of Software, Northeastern University, Shenyang, 110169, China

2 National Frontiers Science Center for Industrial Intelligence and Systems Optimization, and Key Laboratory of Data Analytics and Optimization for Smart Industry, Northeastern University, Shenyang, 110169, China

* Corresponding Author: Zhiliang Zhu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068930

Received 10 June 2025; Accepted 22 July 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Vulnerabilities are a known problem in modern Open Source Software (OSS). Most developers often rely on third-party libraries to accelerate feature implementation. However, these libraries may contain vulnerabilities that attackers can exploit to propagate malicious code, posing security risks to dependent projects. Existing research addresses these challenges through Software Composition Analysis (SCA) for vulnerability detection and remediation. Nevertheless, current solutions may introduce additional issues, such as incompatibilities, dependency conflicts, and additional vulnerabilities. To address this, we propose Vulnerability Scan and Protection (), a robust solution for detection and remediation vulnerabilities in Java projects. Specifically, builds a fine-grained method graph to identify unreachable methods. The method graph is mapped to the project’s dependency tree, constructing a comprehensive vulnerability propagation graph that identifies unreachable vulnerable APIs and dependencies. Based on this analysis, we propose three solutions for vulnerability remediation: (1) Removing unreachable vulnerable dependencies, thereby resolving security risks and reducing maintenance overhead. (2) Upgrading vulnerable dependencies to the closest non-vulnerable versions, while pinning the versions of transitive dependencies introduced by the vulnerable dependency, in order to mitigate compatibility issues and prevent the introduction of new vulnerabilities. (3) Eliminating unreachable vulnerable APIs, particularly when security patches are either incompatible or absent. Experimental results show that these solutions effectively mitigate vulnerabilities and enhance the overall security of the project.Keywords

Nowadays, up to 80% of the code in commercial products comes from open-source components [1]. To reduce development costs, developers introduce third-party libraries (dependencies) and leverage their interfaces to quickly implement functions. For each dependency, it automatically introduces multiple transitive dependencies to support its functionality. Meanwhile, transitive dependencies with vulnerabilities are also automatically introduced. A recent study [2] analyzing 7666 popular projects identified 166,577 vulnerabilities, with 166,486 of them originating from dependencies. Among these, 136,559 vulnerabilities were found in transitive dependencies, while 29,927 were in direct dependencies. This result indicates that 99.94% of vulnerabilities stem from third-party libraries rather than the client code itself, and 82.02% of vulnerabilities reside in transitive dependencies. The complex relationships among dependencies pose significant challenges for vulnerability remediation. Therefore, when fixing vulnerabilities, it is crucial to consider these interdependencies; otherwise, it may lead to incompatibilities, dependency conflicts, or even introduce new vulnerabilities.

For vulnerability detection in dependencies, most tools rely on Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CPE) from public vulnerability databases such as the National Vulnerability Database (NVD). Dependencies that match the known vulnerabilities are classified as vulnerable dependencies. In terms of fixing, the common approach [3–5] is to upgrade the vulnerable dependencies to versions that have patched the vulnerabilities. However, existing methods have the following issues:

• False positives in vulnerability detection with software composition analysis (SCA). SCA is a technique used to generate a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM), which, in combination with public vulnerability databases, helps identify known vulnerable dependencies. Most SCA tools identify vulnerable dependencies based solely on CPE without verifying whether the vulnerable APIs are actually invoked in the project. However, this coarse-grained analysis approach often leads to false positives [6–8].

• Limitations of existing approaches to vulnerability mitigation via dependency upgrades. Existing research explores software vulnerability detection from various angles, yet often treats vulnerable dependencies in isolation. Reifer et al. [9] discussed COTS maintenance challenges without considering cascading effects among components. Chernis and Verma [10] applied machine learning for vulnerability detection but overlooked dependency relationships. Similarly, Guan et al. [11] and Hanif et al. [12] surveyed deep learning and vulnerability taxonomies, respectively, while treating dependencies as independent units. Despite their contributions, these studies share several limitations. First, upgrading a vulnerable dependency can introduce dependency conflict issues with other dependencies, potentially leading to system instability and functionality failures. Second, different versions of dependencies may introduce changes in functionality and APIs, requiring significant code refactoring and extensive testing. This not only increases the development workload but also introduces additional risks.

• Lack of effective solutions for vulnerabilities without available patches. When no patches are available for vulnerable dependencies, users face a difficult choice: either continue using the vulnerable version while awaiting a patch or migrate to an alternative dependency with similar functionality. However, both options can introduce additional risks and overhead. The lack of available patches may result from delayed maintenance, abandonment of the dependency, or the patch is incompatible with other dependencies, which are external factors beyond the control of developers and project management teams.

In this paper, our goal is to address the issues outlined above by evaluating the actual impact of vulnerable components on a project. However, we face the following challenges: (1) Balancing security and compatibility. Failing to fix vulnerable dependencies can lead to data breaches and system disruptions. Conversely, upgrading to patched versions may introduce compatibility issues due to changes in the code, potentially breaking functionality with existing dependencies. Striking a balance between security and compatibility while addressing vulnerabilities is a complex task that requires careful planning and execution. (2) Complexity of global optimization. Fixing vulnerable dependencies through version upgrades can introduce a range of unpredictable issues. A recommendation to upgrade a single vulnerable dependency may necessitate changes in the overall dependency tree, potentially introducing new vulnerabilities or dependency conflicts. Achieving global optimization involves addressing improvements across the entire system, not just isolated issues.

To fill the gap, we propose VulnScanPro, an automated approach for vulnerability detection and remediation, specifically designed to assess the impact of vulnerabilities. Our approach begins with constructing a fine-grained method graph using the static analysis tool slimming [13]. We then map this method graph onto the dependency tree to generate a vulnerability propagation graph, where method invocation relationships are translated into dependency relationships. Next, we annotate the vulnerability propagation graph with vulnerability information from OSSIndex [14]. To enhance vulnerability remediation, we propose three solutions.

• Solution 1: removing vulnerable unreachable dependencies. These are dependencies that are not invoked by the client. By eliminating them, we not only address security vulnerabilities but also reduce the maintenance burden on developers.

• Solutions 2: upgrading vulnerable dependencies to the closest non-vulnerable versions and pinning versions of transitive dependency. We propose upgrading to the most recent non-vulnerable versions of dependencies while pinning the versions of their transitive dependencies. Dependencies of semantic versioning closer to the vulnerable version are generally more compatible. Existing approaches typically focus only on upgrading the vulnerable dependency version, overlooking the fact that such upgrades may also change the versions of transitive dependencies, potentially introducing new vulnerabilities or causing dependency conflicts.

• Solution 3: eliminate unreachable vulnerability. For vulnerable dependencies with no available patches, we mitigate security risks by removing unreachable vulnerable APIs and generating a non-vulnerable version of the dependency.

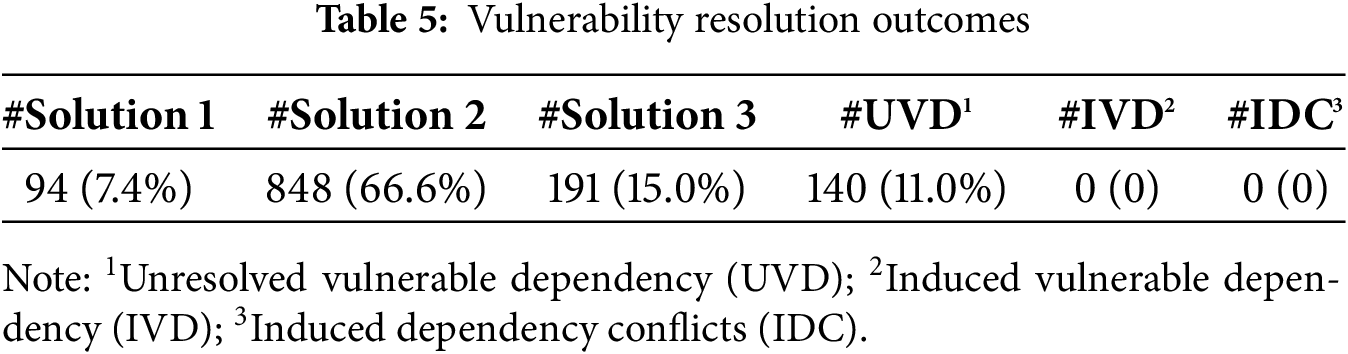

Experimental results show that, for 1273 vulnerabilities, solution 1 resolves 7.4%, solution 2 addresses 66.6% and solution 3 mitigates 15.0% of the security issues. In summary, we make the following contributions:

• We propose VulnScanPro, an automated and effective approach that can detect vulnerable dependencies and apply different solutions to remediate vulnerabilities, thereby enhancing software security and reducing maintenance costs for developers.

• We have implemented a visualization for reachable vulnerable APIs. When running VulnScanPro on the target project, a Vulnerability Detection Visualization.html file is generated, allowing developers to easily identify the vulnerable APIs along the vulnerability propagation path. In addition, we provide a reproduction package on our website (https://vulnscanpro.github.io/ (accessed on 09 June 2025)), which includes the datasets, an available tool, and raw experimental data, to support future research.

In recent years, security risks in Software Supply Chains (SSC) have garnered increasing attention. Ladisa et al. [15] proposed a comprehensive taxonomy of attacks targeting open-source software supply chains, providing a foundation for systematic classification and analysis. Ohm et al. [16] conducted a large-scale study of real-world incidents and compiled the “Backstabber’s Knife Collection,” which highlights the diverse attack vectors within OSS ecosystems. Reid et al. [17] emphasized the issue of orphan vulnerabilities that arise from the reuse of unmaintained code. Enck and Williams [18] summarized five key challenges based on feedback from industry and government stakeholders in securing the software supply chain. Vu et al. [19] investigated how source code repositories can be utilized to detect software supply chain attacks early. Tan et al. [20] conducted an exploratory analysis of deep learning frameworks, shedding light on the unique risks embedded in their supply chains. To understand the sources of vulnerabilities in SSC, existing studies have demonstrated that vulnerabilities can arise from including bloated or vulnerable dependencies [13,21]. More specifically, Gkortzis et al. [21] demonstrated that using dependencies, particularly through invocating APIs between packages, introduced vulnerabilities in the SSC. These studies confirm that security risks are present in all dependency networks. However, while they highlight that vulnerabilities can be inherited from upstream dependencies, they lack a deep and qualitative analysis of the various sources of vulnerabilities, such as direct dependencies, transitive dependencies, or the client program itself. To identify vulnerability, many software use Software Component Analysis (SCA) to manage third-party dependencies, which provides convenience in analyzing the vulnerability scope based on package-level dependency relations. Several SCA tools have been suggested including Eclipse Steady [22], Dependabot [23], OSSIndex [14], OWASP Dependency Check [24], etc. However, it has been proved that not all dependencies are actually used by the clients, especially for transitive dependencies [13,25,26]. Most of the security warnings produced by those tools are false-positive because the vulnerable function in the warned dependency is not used by the client [27,28]. Some studies [7,8] also investigated current industry-leading SCA tools, and showed that the package-level SCA is hard to detect all kinds of vulnerabilities and their accuracy is limited. In addition, existing works often recommend multiple patch versions for vulnerabilities, requiring manual verification by developers. However, recent studies have consistently demonstrated that compatibility issues frequently emerge when applying recommended patch versions to mitigate vulnerabilities in third-party libraries. For instance, Zhang et al. [3] proposed a remediation framework specifically designed for Java projects, revealing that many suggested upgrades lack backward compatibility and often disrupt existing functionalities. Similarly, Alfadel et al. [29] examined Dependabot’s usage and found that developers frequently ignore or postpone security pull requests due to concerns regarding integration failures and insufficient test assurances. Moreover, Pashchenko et al. [30] highlighted that not all transitive vulnerable dependencies are necessarily reachable or exploitable, indicating that indiscriminate patching without contextual analysis can induce unnecessary compatibility challenges. Complementing this perspective, Ponta et al. [22,31] demonstrated that patch recommendations based solely on metadata fail to capture the actual usage patterns of vulnerable components, thereby leading to ineffective or even detrimental upgrades. In contrast, our study focuses on a finer-grained, function-level analysis to detecting whether a vulnerability is propagated into client programs. Furthermore, we automate the patch version verification process, recommending only a single patch version to developers that is guaranteed to resolve the vulnerability without introducing incompatibility issues or dependency conflicts.

Existing research on vulnerability Remediation in SSC has primarily concentrated on analyzing the time and processes involved in releasing patches [32–34]. These studies have shown that vulnerabilities in libraries often remain unresolved in client programs for extended periods, typically taking anywhere from three to fifteen months to be addressed. In addition, automated program remediation, which aims to generate patches automatically [35,36], has attracted growing interest in recent years, with a significant exploration of its potential for resolving vulnerabilities [37,38]. However, existing vulnerability remediations primarily focus on fixing independent programs. In a Maven project’s dependency tree, modifying dependency versions can be challenging, especially when breaking changes are introduced in dependency updates. This often requires developers to address incompatible API invocations or module imports. Such challenges prevent client developers from easily upgrading or downgrading their dependencies. Additionally, existing research does not effectively handle scenarios where no patches are available, or where existing patches fail to resolve the vulnerability. In this study, we pin the automatic introduction of patch versions for transitive dependencies to resolve compatibility issues. For scenarios with no available patches or where patches introduce compatibility problems, we adopt mitigation solutions for vulnerability remediation by removing bloated code in the vulnerabilities, thereby reducing their propagation scope.

3 Preliminaries and Definitions

To describe the detection and remediation of vulnerable dependencies within Java projects, we present the key concepts for the analysis of a project p in the context of the set of its software dependencies, denoted as D.

Definition 1: Direct Dependency: A project p includes the set of direct dependencies,

Definition 2: Transitive Dependency: A project p includes a set of transitive dependencies,

Definition 3: Dependency Tree: The dependency tree of a project p relies on direct and transitive dependencies. The project p is the root node, and the edges represent dependency relationships between p and the dependencies in D. Fig. 1 shows the dependency tree of the project p. The project has three direct dependencies, as specified in its dependency configuration file, and three transitive dependencies. Dependencies d5 and d6 are transitively induced by d3, while d4 is induced by d1. It is important to note that all the bytecodes from these transitive dependencies will be included in the classpath of project p and packaged with it, even if they are not used by p.

Figure 1: Dependency tree

Definition 4: Vulnerability Propagation Graph: The vulnerability propagation graph is a directed graph that visually represents the usage relationships between dependencies in a project. A usage relationship exists if there is an edge in the dependency tree of project p, between p and dependency d, such that code of d is used, either directly or indirectly, by p. Fig. 2 illustrates a hypothetical example of the dependency usage tree of project p. Suppose that p directly invokes two sets of instructions from the direct dependency d1 and d2. The subset of instructions called within d2 also invokes instructions from d6. In this scenario, the used dependencies d1, d2, and d6 contain used code, while the remaining dependencies only include vulnerable code. Thus, dependencies d3, d4, and d5 are unreachable dependencies.

Figure 2: Vulnerability propagation graph

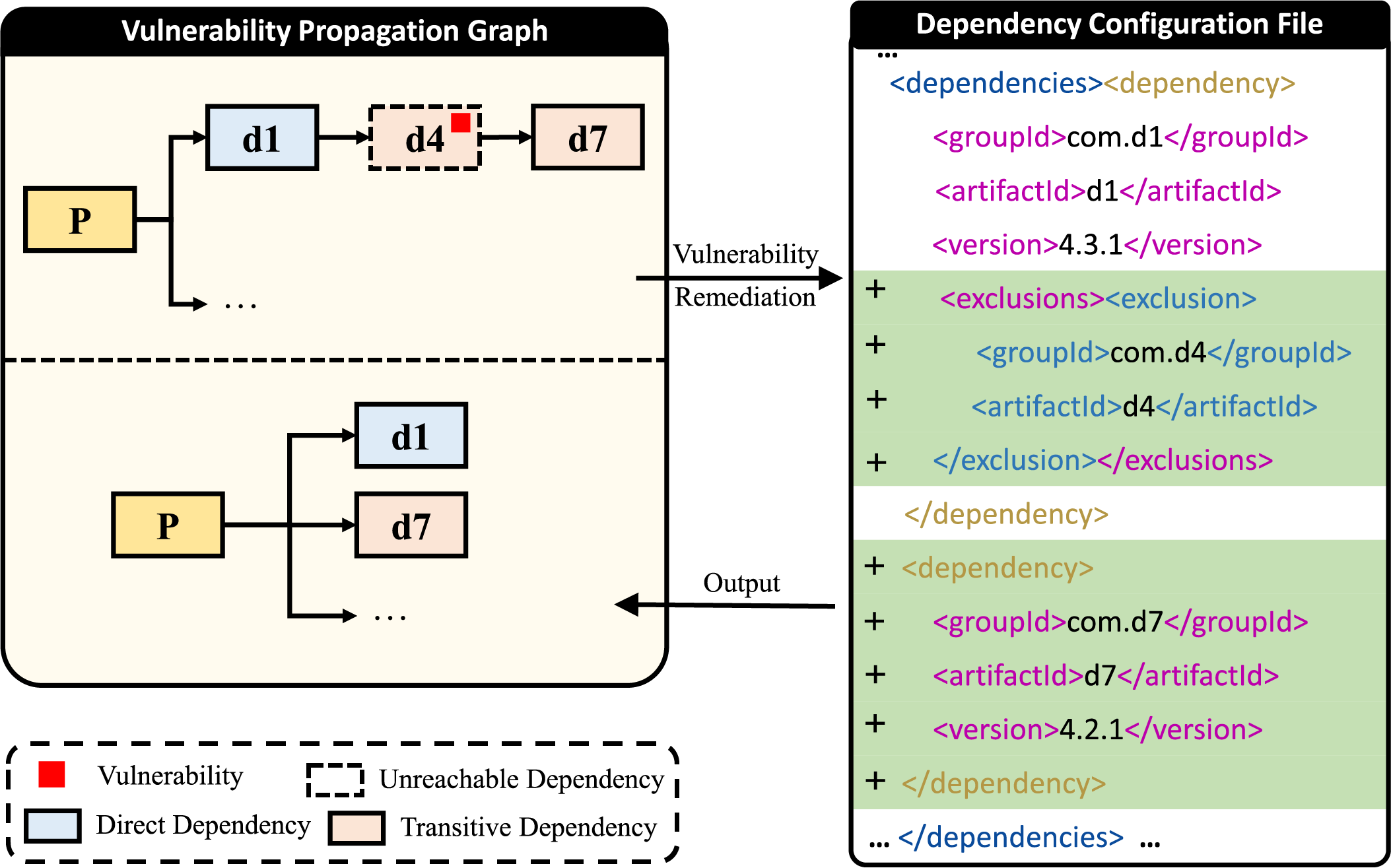

For vulnerability detection, it is relatively easy. Existing techniques match the CPE of each dependency in a Maven project p with vulnerability data from various databases, such as OSSIndex [14], GitHub Advisory DB [39], and Snyk Vulnerability DB [40]. Yet, vulnerability remediation is complex. Remediating vulnerabilities may lead to changes in the project’s dependency tree, potentially introducing new issues. Fig. 3 shows an example of vulnerability remediation through dependency upgrades. Developers can simply modify the version of the vulnerable dependency in the dependency configuration file to upgrade it to the closest non-vulnerable version. However, this results in changes to the dependency tree, which may introduce compatibility issues, dependency conflicts, and new vulnerable dependencies. This work investigates the evolution of vulnerable dependencies and proposes more effective methods for addressing them.

Figure 3: Mitigating vulnerabilities via dependency upgrades

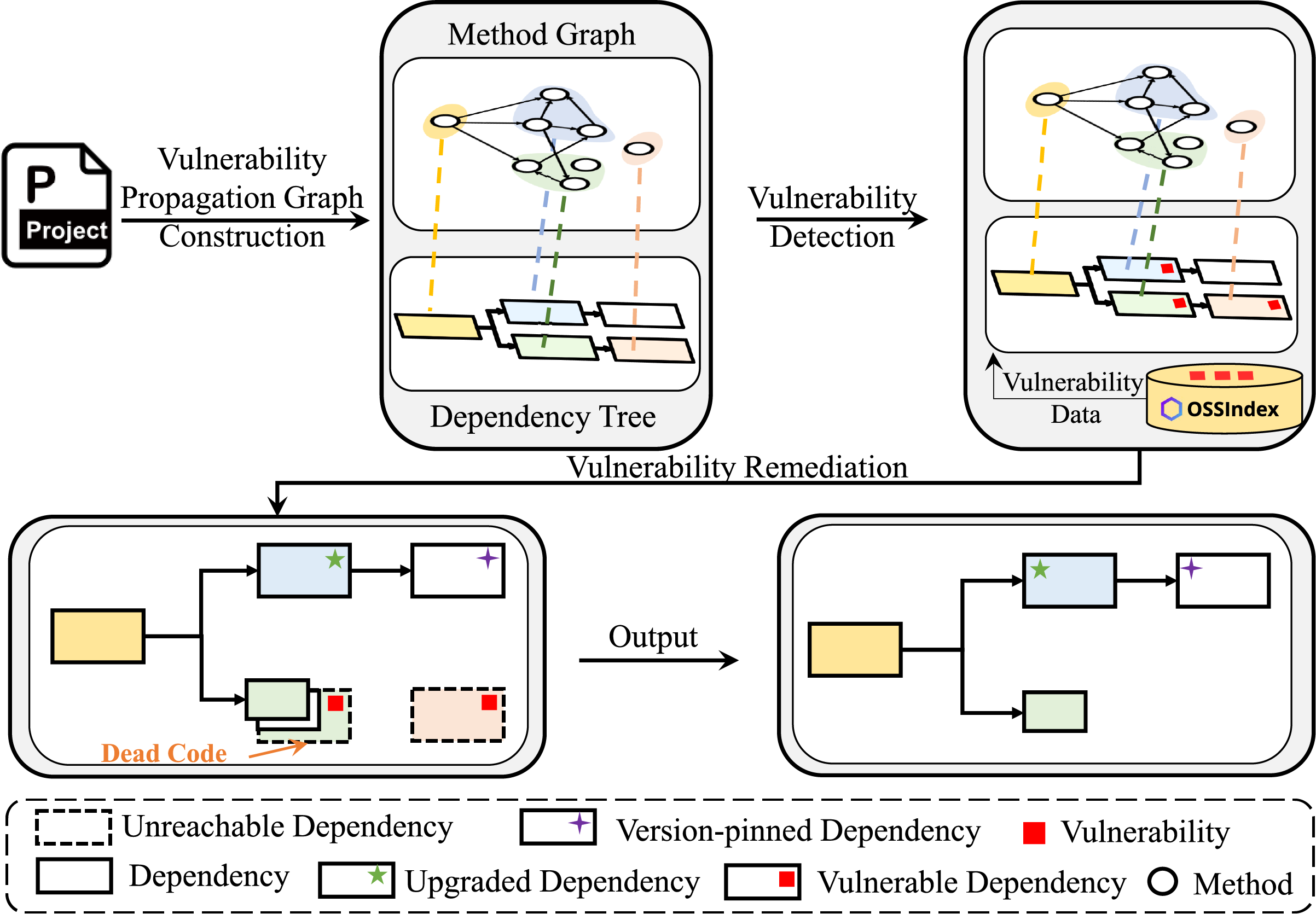

In this paper, we propose VulnScanPro to detect and remediate vulnerabilities. Fig. 4 presents an overview of our approach, which consists of three main components. (1) Vulnerability propagation graph construction. We construct a method graph. By mapping the method graph to the dependency tree, we construct a vulnerability propagation graph, where method-level call relationships are translated into actual dependency relationships, revealing the internal dependency structure of the project. (2) Vulnerability detection. This step matches the CPE of each dependency in a project with vulnerability data from OSSIndex [14] to identify known vulnerabilities. (3) Vulnerability remediation. Three solutions are employed to fix vulnerabilities. These processes enable VulnScanPro to efficiently detect and remediate vulnerabilities without introducing new issues.

Figure 4: Overview of VulnScanPro

4.1 Vulnerability Propagation Graph Construction

• Method Graph. We use the static analysis tool slimming [13] to construct the method graph for the project, which captures the call relationships between methods in Java projects. In this process, all methods defined within the program itself (excluding external dependencies) are treated as entry points. Each node in the graph represents a method, while edges denote the calling relationships between methods. The method graph represents the actual methods invoked and their interrelationships. This graph represents the potential function call paths that the project may traverse at runtime, serving as foundational data for reachability analysis and vulnerability remediation.

• Vulnerability Propagation Graph. VulnScanPro utilizes the existing tool [41] by executing the command (mvn dependency:tree), which extracts the complete dependency tree of the project, encompassing both direct and transitive dependencies. By mapping the nodes in the method graph to the corresponding dependencies in the dependency tree, VulnScanPro identifies which dependencies are actually invoked by the client. Dependencies that do not contain any nodes from the method graph are marked as unreachable. This identification of unreachable dependencies is crucial for effective vulnerability remediation: if a vulnerable dependency is identified as unreachable, it can be safely removed, thereby rapidly eliminating security risks without requiring complex vulnerability remediation actions.

VulnScanPro takes the Common Platform Enumeration (CPE) identifiers of all dependencies in the project’s dependency tree as input and queries OSSIndex [14] to determine whether they are linked to known vulnerabilities. The identified vulnerable dependencies are then annotated within the vulnerability propagation graph.

To address vulnerable dependencies, we propose three solutions:

• Removing vulnerable unreachable dependencies. VulnScanPro employs techniques compliant with dependency management principles to remove dependencies marked as both vulnerable and unreachable in the vulnerability propagation graph. For direct dependencies marked as vulnerable and unreachable, VulnScanPro removes the declaration of

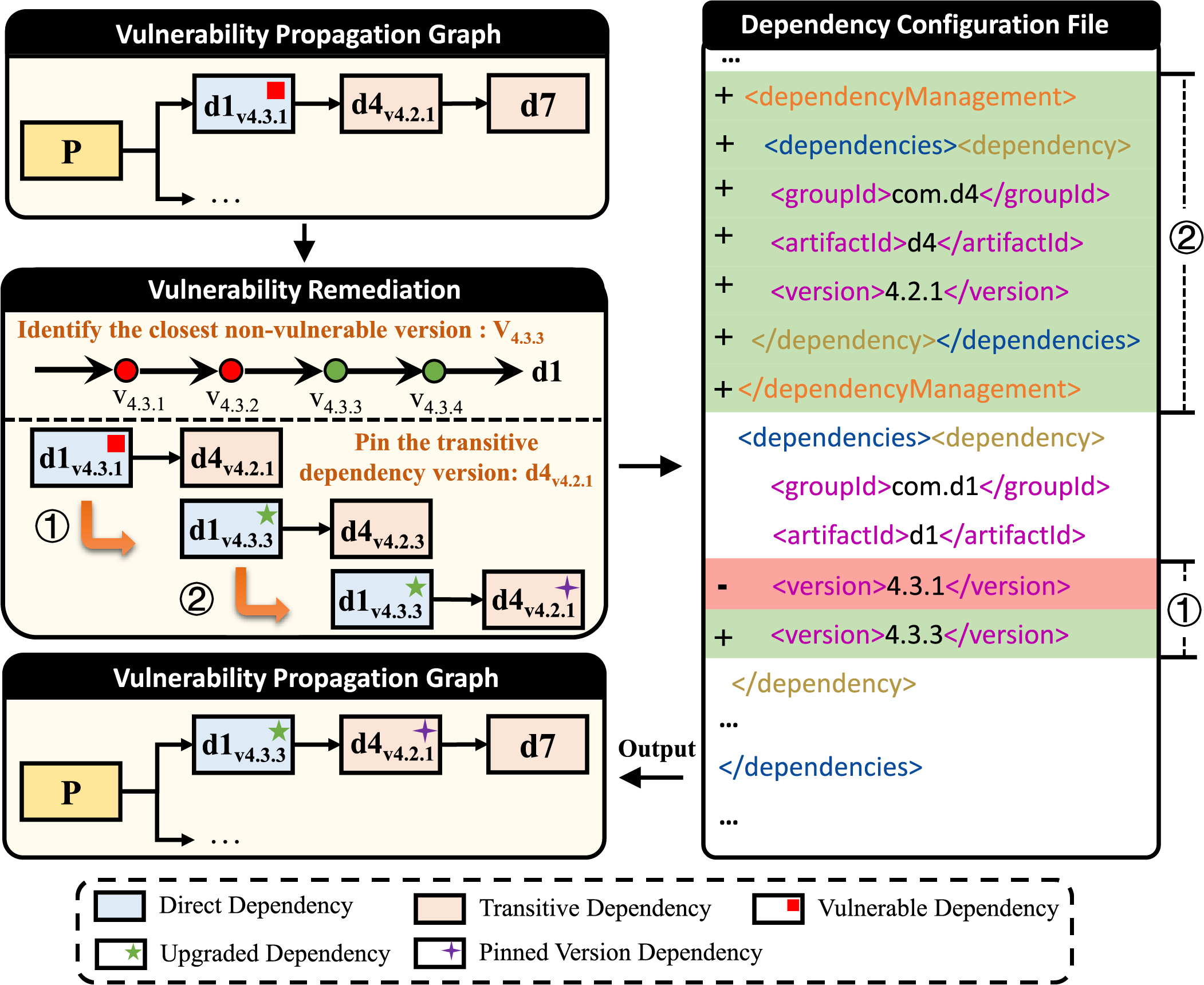

• Upgrading vulnerable dependencies to the closest non-vulnerable versions and pinning versions of transitive dependency. To enhance software compatibility after upgrading vulnerable dependencies, VulnScanPro selects the closest non-vulnerable version. This approach prioritizes versions that are as close as possible to the vulnerable version, as they are more likely to maintain compatibility with the existing code and dependency relationships. As shown in Fig. 7, this process is detailed. VulnScanPro identifies the closest non-vulnerable version of a dependency through the following tasks: (1) retrieve upgradable candidate versions. VulnScanPro queries the Maven Central Repository [43] for candidateVersions, a collection of versions released after the currently vulnerable version

• Eliminating unreachable vulnerability. This solution serves as a mitigation strategy for addressing vulnerable dependencies without available patches. Existing research [27] indicates that among 83,237 projects with vulnerable dependencies, only 35% of projects invoke the vulnerable APIs. For unreachable vulnerable APIs, VulnScanPro performs reachability analysis in the vulnerability propagation graph to eliminate unreachable vulnerabilities.

Figure 5: Eliminating vulnerable and unreachable direct dependencies

Figure 6: Eliminating vulnerable and unreachable transitive dependencies

Figure 7: Upgrade dependencies and pin transitive dependency versions

In this section, we aim to answer the following research questions:

• RQ1: What is the typical lifecycle duration of known vulnerabilities, and how does this motivate the need for automated remediation tools like VulnScanPro?

• RQ2: Is the vulnerability remediation approach of VulnScanPro effective in addressing identified vulnerabilities?

• RQ3: Is the vulnerability remediation approach of VulnScanPro secure?

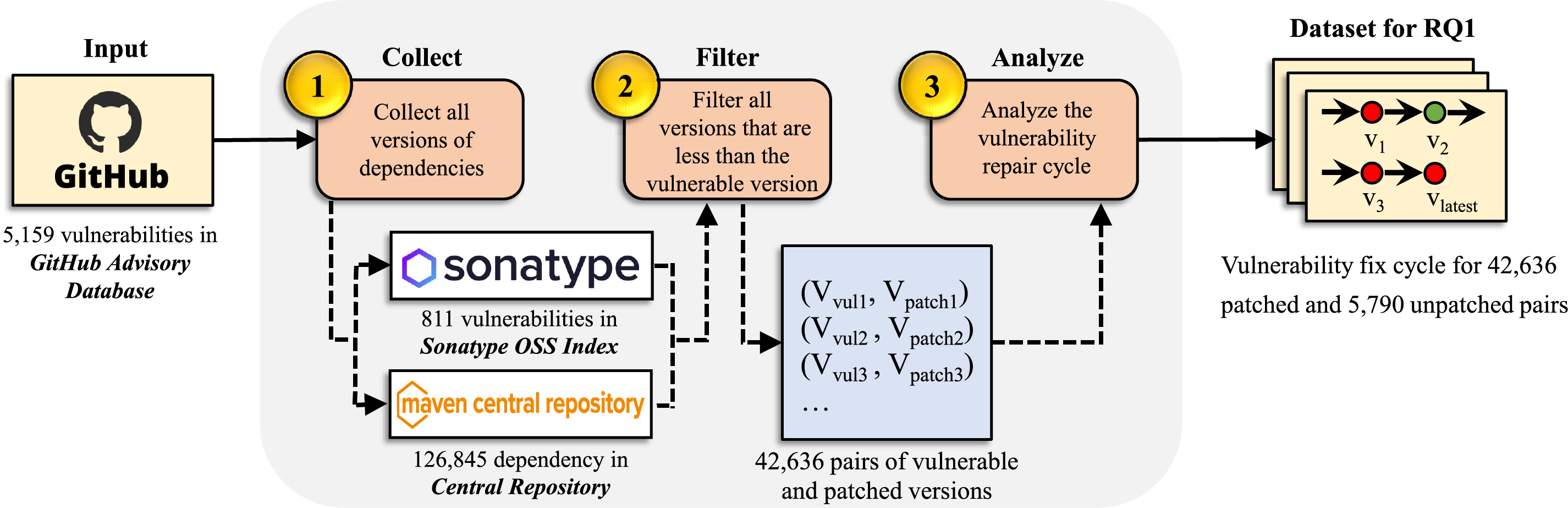

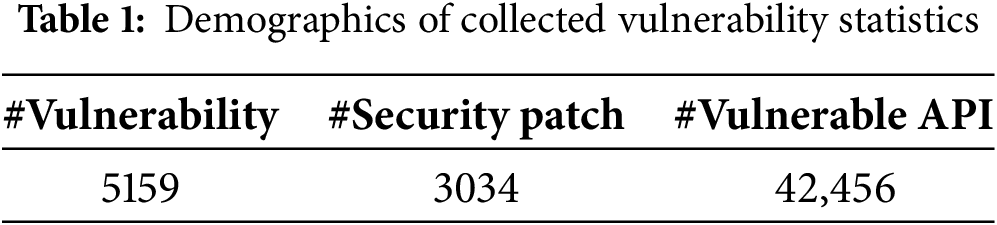

To analyze the vulnerability lifecycle, including introduction, exposure, and eventual remediation, we collected 5159 known Java-related vulnerabilities from the GitHub Advisory Database [39] as of 18 November 2024. Fig. 8 depicts the data collection pipeline. To ensure the representativeness of this vulnerability dataset, we conducted vulnerability statistics and the coverage rate of the OWASP Top 25 CWE [45]. Table 1 presents the demographics of the collected vulnerability statistics. It contains the number of vulnerabilities, the patches of vulnerabilities and the vulnerable APIs.

Figure 8: Overview of our data collection pipeline

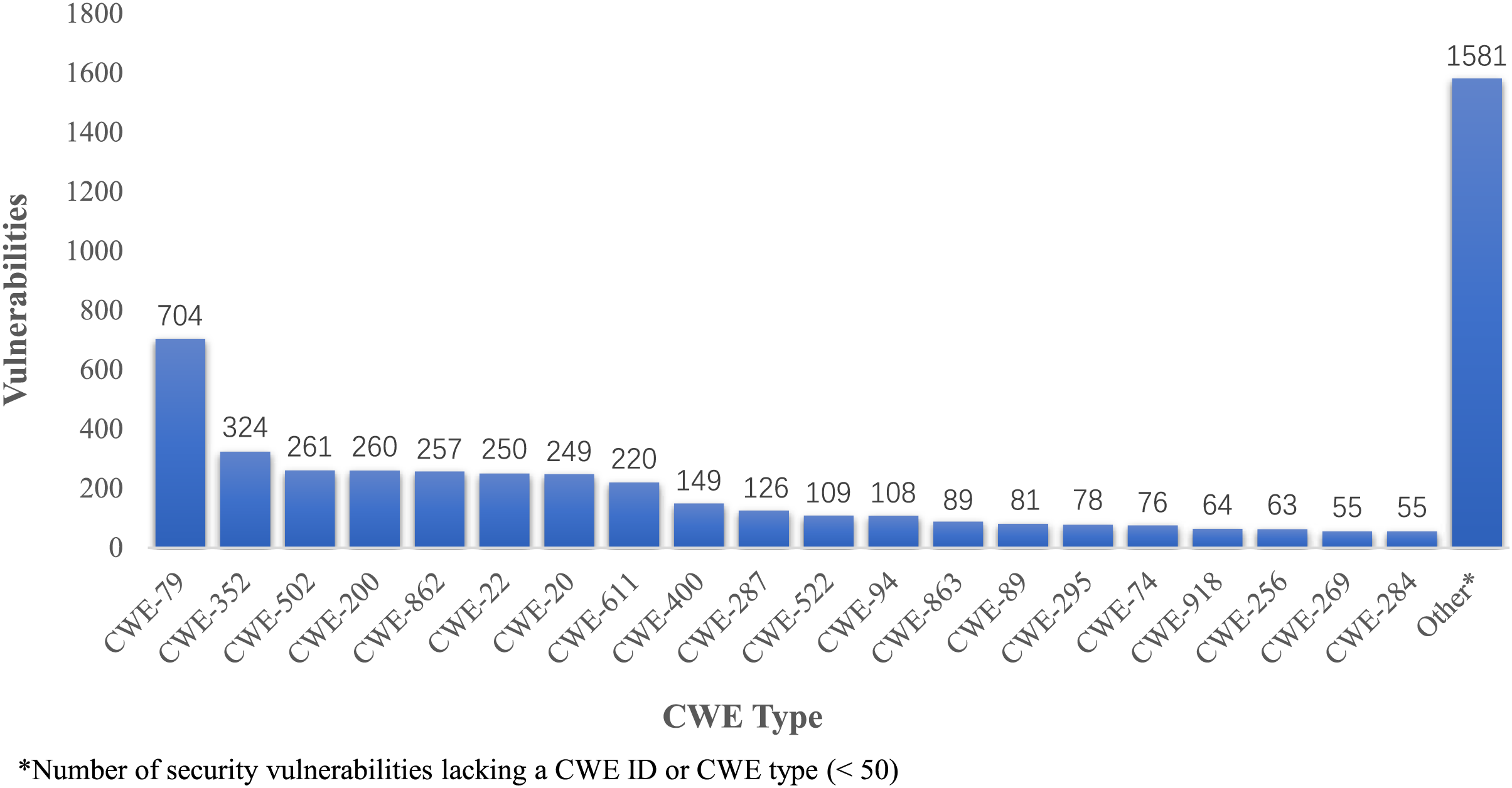

As depicted in Fig. 9, the 5159 vulnerabilities within our dataset are categorized under 229 types of Common Weakness Enumeration (CWE). Among these, the vulnerability type designated as CWE-79 is the most prevalent, accounting for 704 instances, which constitutes 14% of the total count. In addition, 2788 out of the 5159 identified vulnerabilities are classified within the scope of the 2023 CWE Top 25 Most Dangerous Software Weaknesses (CWE Top 25) [45], and all the CWE Types listed in the CWE Top 25 are included in our constructed dataset.

Figure 9: Distribution of vulnerabilities by CWE categories

To assess the lifecycle of known vulnerabilities (RQ1), it is essential to collect both the release dates of the vulnerabilities and their corresponding patches. Since the GitHub Advisory DB [39] provides limited information regarding the release dates of vulnerabilities and patches, we combine data from OSSIndex [14] and the Maven Central Repository [43] to collect the necessary release dates. We follow to collect this dataset.

❶ Collect. Our data collection pipeline begins with a list of vulnerable dependency from the GitHub Advisory DB. We found that only 811 dependencies were flagged as vulnerable in the OSSIndex. To further analyze, we collected all versions associated with the 811 vulnerable versions from central repository, resulting in a total of 126,845 versions, with the goal of identifying those closest to the vulnerable versions.

❷ Filter. The most vulnerabilities are fixed by upgrading to a patched version. We filter out all versions lower than the vulnerable version, resulting in 48,426 pairs. Among these, only 42,636 pairs have available patches.

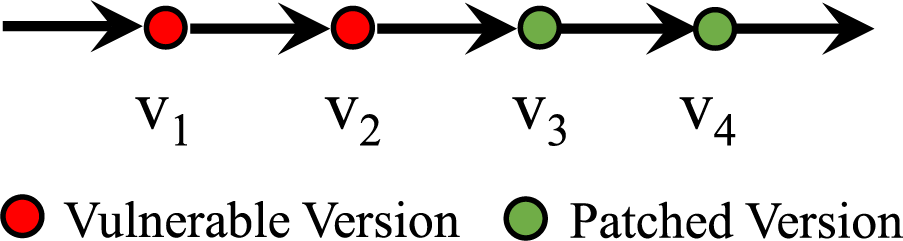

❸ Analyze. For vulnerabilities with available patches, the vulnerability lifecycle is defined as the duration between the release of the closest patched version and the release of the corresponding vulnerable version. In Fig. 10,

Figure 10: Vulnerabilities with patch

Figure 11: Vulnerabilities without patch

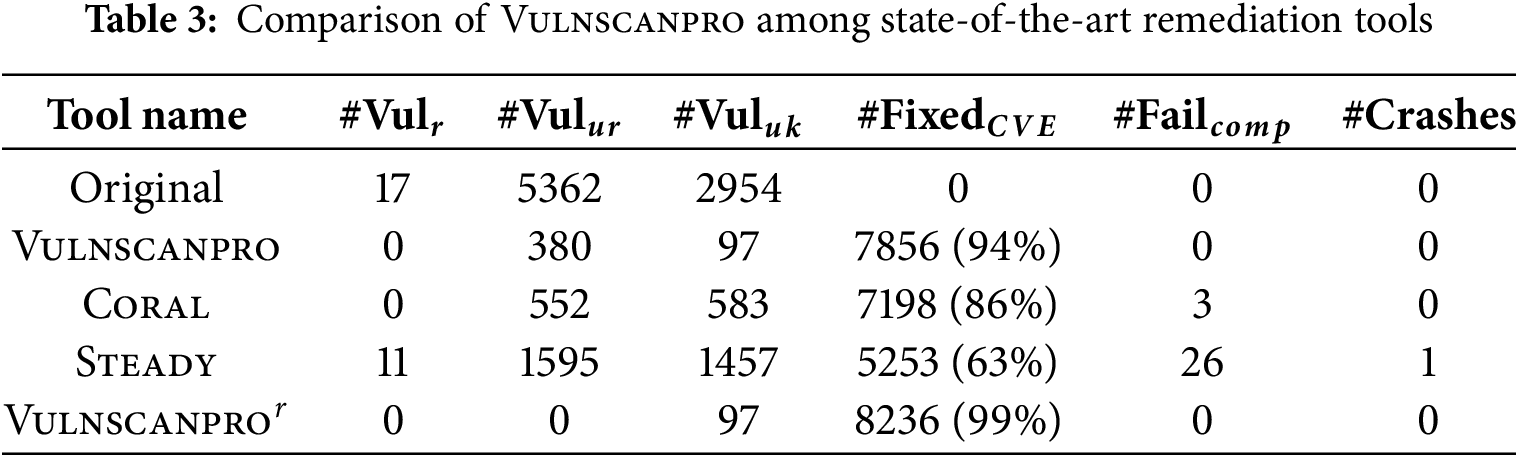

For evaluating the effectiveness of VulnScanPro in remediating vulnerabilities (RQ2). We compare VulnScanPro with two existing remediation tools, using coral’s dataset [3]. The dataset includes 301 projects, with 300 successfully built. To assess the security of VulnScanPro in remediating vulnerabilities (RQ3), we examine the potential introduction of new vulnerabilities and dependency conflicts in the fixed version, using another existing dataset [27]. The dataset includes 1256 projects, with 448 successfully built. The compilation task is the most crucial and difficult part, as it involves downloading dependencies, ensuring the correct version of Java, and maintaining the proper project state, i.e., the inability to download dependencies from private repositories.

5.2 RQ1:Vulnerability Lifecycle and Automation Need

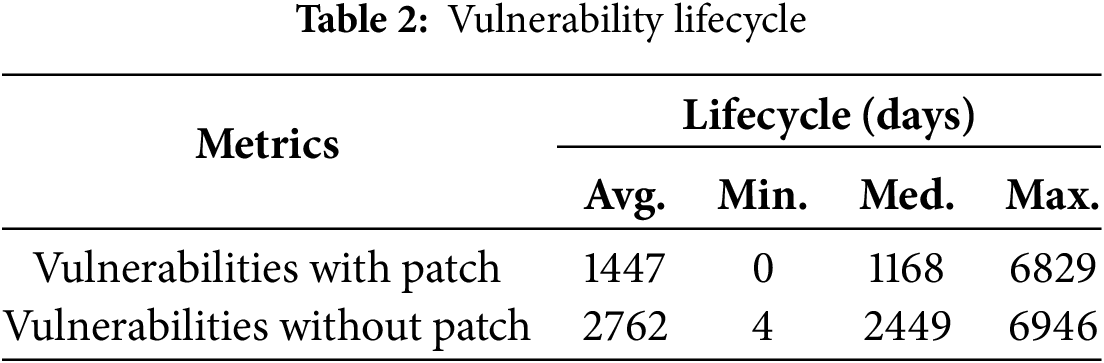

To investigate the persistence of vulnerabilities in software dependency ecosystems, we conducted a quantitative analysis of vulnerability lifecycles based on historical release and patch data. Specifically, we measured the lifecycle between the introduction of a vulnerable version and the release of a corresponding patched version, when available. The results are summarized in Table 2.

Vulnerabilities with available patches exhibit an average lifecycle of 1447 days and a median of 1168 days. In contrast, as of 18 November 2024, a total of 5790 known vulnerabilities remained unpatched, persisting for significantly longer durations, with an average of 2762 days and a median of 2449 days. These durations indicate that vulnerable versions frequently remain in circulation for several years, even when the issue is known. In extreme cases, the lifecycle exceeds 6900 days. This prolonged presence suggests that the impact of known vulnerabilities is not limited to isolated incidents but reflects a recurring and systemic challenge within software supply chains.

A long vulnerability lifecycle implies that systems remain exposed for extended periods, highlighting the need for automated remediation approaches like Vulnscanpro. Given the scale and complexity of modern dependency graphs, manual identification and mitigation of vulnerabilities is often infeasible. Automation offers the potential to continuously monitor dependencies, detect known vulnerabilities, and assist developers by recommending or applying fixes with minimal delay. By reducing the vulnerability lifecycle, such tools can enhance ecosystem resilience and minimize the attack surface associated with outdated or insecure components.

Answer to RQ1: Vulnerable dependency versions often persist in the ecosystem for several years, even when a patch is eventually released. This long lifecycle reflects structural challenges in manual vulnerability management. The prolonged exposure highlights the need for automated tools like Vulnscanpro, which can help detect and remediate vulnerable versions more efficiently. Automation is essential to reduce the time vulnerabilities remain unaddressed and to improve security at scale.

5.3 RQ2: Effectiveness of Vulnerability Remediation

In this research question, we compare the vulnerability remediation results of Vulnscanpro with coral and steady. The comparison was based on six metrics from coral: (1)

• Coral [3] is a remediation tool designed to address vulnerabilities in third-party libraries for Java projects. coral (ICSE 2023) balances the trade-off between compatibility and security during vulnerability remediation.

• Steady [22] is an open-source Software Composition Analysis (SCA) tool. steady refines the versioning of both direct and transitive dependencies to mitigate vulnerability risks through fine-grained analysis. Moreover, it leverages reachability analysis to filter out low-risk, unreachable CVEs from the remediation process.

The evaluation was conducted based on the remediated projects (the versions of dependencies adjusted by remediation tools in the dependency configuration file. VulnScanPro employs solutions 1 and 2 to remediate vulnerabilities. To demonstrate the effectiveness of solution 3, we introduce VulnScanPror, which resolves vulnerable dependencies with incompatible or no available patches. The comparison results with the remediation tools and baselines are provided in Table 3. The analysis of each metric is as follows:

• Remaining Reachable Vuls: Vulnscanpro eliminated all reachable CVEs. coral and steady have 0 and 11 reachable vulnerabilities, respectively. The existence of results with remaining reachable CVEs is consistent with previous study [3].

• Remaining Unreable and Unknown Vuls: VulnScanPro had significantly fewer unreachable and unknown vulnerabilities than the other tools, primarily due to the removal of unreachable vulnerable dependencies. However, 380 unreachable vulnerabilities remained after remediation, mainly because the client still uses parts of the vulnerable dependencies’ APIs. To further remediate vulnerabilities, we introduce VulnScanPror, which removes unreachable vulnerable APIs and declares the unreachable vulnerable dependencies in the dependency configuration file. Additionally, all versions of the 97 unknown vulnerabilities remained vulnerable.

• Compilation Failures: VulnScanPro is the only tool to achieve 0 compilation failures, due to three factors: (1) Removing bloated vulnerable dependencies. (2) Only removing bloated vulnerable code. Both bloated dependencies and code have no effect on the project’s actual functionality or compilation process [46]. (3) Pinning dependency versions. When upgrading a vulnerable dependency, we pin the versions of transitive dependencies introduced by the vulnerable dependency. Proper management of dependency versions avoids dependency conflicts and ensures stable behavior [47].

Answer to RQ2: VulnScanPro successfully fixed 94% of CVEs in the benchmark of Zhang et al. [3]. Compared to other tools, it fixed the most CVEs. Furthermore, VulnScanPro is the only tool to achieve 0 compilation failures. This demonstrates that VulnScanPro is a promising technique that advances the state-of-the-art in vulnerability remediation.

5.4 RQ3: Security of Vulnerability Remediation

This research question addresses an essential concern for developers: Does vulnerability fixing introduce new issues? We answer this question through the number of new vulnerabilities, new incompatible dependencies, and breaking changes introduced before and after vulnerability fixes across the evolution of the studied projects. We employ VulnScanPro on 448 successfully built projects, among which 200 projects contain 1273 vulnerable dependencies, while the remaining projects have no detected vulnerabilities. Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics of the vulnerable dependency analysis. In the dataset, the number of vulnerabilities in direct and transitive dependencies is 331 (26.0%) and 942 (74.0%), respectively, indicating that the majority of vulnerabilities reside in transitive dependencies. Fixing vulnerable direct dependencies alone addresses only a small portion of the security issues. Through reachability analysis on the method graph, only 63 (4.9%) reachable vulnerable APIs were identified. Although most vulnerable APIs are not invoked, risks remain because the classes associated with vulnerable dependencies are still loaded in the classpath. For example, CVE-2022-25845 in the Alibaba FastJSON library (version 1.2.80) allows exploitation of classpath objects with script-execution properties during JSON-to-Java object deserialization, even if these classes are not directly used by the application [27].

In Table 5, we present the outcomes of three different solutions for security of vulnerability remediation. The focus of this analysis is to determine how many vulnerabilities can be resolved without introducing new issues, specifically the number of induced break changes, vulnerable dependencies and dependency conflicts. Removing unreachable vulnerable dependencies (Solution 1) fixed 94 vulnerable dependencies, accounting for 7.4% of the total, while upgrading vulnerable dependencies to the closest non-vulnerable versions and pinning versions of transitive dependency (Solution 2) addressed 848 vulnerable dependencies, representing 66.6%, and eliminating unreachable vulnerable APIs (Solution 3), which fixed 191 vulnerable dependencies (15.0%), is a mitigation solution that may only reduce the spread of vulnerabilities rather than fully resolving them. These results demonstrate that while fixing vulnerabilities is achievable without compromising system stability, mitigation solutions like Solution 3 may provide limited effectiveness in completely addressing vulnerabilities. Notably, all versions of the 140 vulnerable dependencies are vulnerable.

Answer to RQ3: All three solutions demonstrate the ability to address vulnerabilities without introducing new issues. This highlights the feasibility of enhancing system security effectively while maintaining stability. The absence of induced new vulnerable dependencies and dependency conflicts across all solutions underscores a positive outcome in vulnerability management, providing confidence in the reliability of these approaches.

One potential threat to the validity of our study is the precision of bloated code detection. We utilized static analysis techniques to collect the necessary code from Maven projects, but static analysis may miss usages that rely on dynamic Java features, such as reflection or runtime code generation, leading to the incorrect reporting of used code as bloated. Another threat arises from the non-representativeness of the dataset, as our analysis primarily used open-source projects, with few industrial projects included. This limits the generalizability of our findings, as the characteristics of open-source code may differ significantly from those found in large-scale, proprietary systems. Additionally, performing static analysis on bytecode rather than source code introduces another limitation. For example, lombok is a dependency that manipulates bytecode at compile-time using annotations, generating boilerplate code like getters and setters. Since these annotations are not present in the bytecode, static analysis may falsely report dependency lombok as bloated, affecting our results’ precision.

VulnScanPro offers vulnerability detection and remediation without causing dependency conflicts, breaking compatibility, or introducing new vulnerabilities. Given that the average lifecycle of vulnerabilities exceeds 1400 days, there is an urgent need for automated tools like VulnScanPro to address these issues efficiently. Our evaluation demonstrates the tool’s effectiveness, successfully fixing 94.2% of vulnerabilities while maintaining a 100% compilation success rate. Furthermore, when focusing solely on safety, VulnScanPro is capable of resolving up to 98.8% of CVEs. Future work includes extending support to additional package managers such as npm and pip, as well as investigating developer behaviors related to security updates to better understand the barriers to timely dependency upgrades.

Acknowledgement: The authors express thanks to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.

Funding Statement: The work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62141210), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. N2217005), Open Fund of State Key Lab. for Novel Software Technology, Nanjing University (KFKT2021B01), and 111 Project (B16009).

Author Contributions: Both authors contributed equally in writing the manuscript. Xiaohu Song: Initial draft, data curation, comparative analysis, and thorough proofreading. Zhiliang Zhu: Draw figures, equations, critical analysis, and thorough proofreading. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly at: https://vulnscanpro.github.io/ (accessed on 09 June 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Pittenger M. Open source security analysis: the state of open source security in commercial applications. In: Technical report. Burlington, MA, USA: Black Duck Software; 2016. [Google Scholar]

2. Shen Y, Gao X, Sun H, Guo Y. Understanding vulnerabilities in software supply chains. Empir Softw Eng. 2025;30(1):1–38. doi:10.1007/s10664-024-10581-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhang L, Liu C, Xu Z, Chen S, Fan L, Zhao L, et al. Compatible remediation on vulnerabilities from third-party libraries for java projects. In: 2023 IEEE/ACM 45th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE); 2023 May 14–20; Melbourne, VIC, Australia. p. 2540–52. [Google Scholar]

4. Chakraborty S, Krishna R, Ding Y, Ray B. Deep learning based vulnerability detection: are we there yet? IEEE Trans Softw Eng. 2021;48(9):3280–96. doi:10.1109/tse.2021.3087402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ghaffarian SM, Shahriari HR. Software vulnerability analysis and discovery using machine-learning and data-mining techniques: a survey. ACM Comput Surv (CSUR). 2017;50(4):1–36. doi:10.1145/3092566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhang F, Fan L, Chen S, Cai M, Xu S, Zhao L. Does the vulnerability threaten our projects? automated vulnerable api detection for third-party libraries. IEEE Trans Softw Eng. 2024;50(11):2906–20. doi:10.1109/tse.2024.3454960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Dann A, Plate H, Hermann B, Ponta SE, Bodden E. Identifying challenges for oss vulnerability scanners—a study & test suite. IEEE Trans Softw Eng. 2021;48(9):3613–25. [Google Scholar]

8. Imtiaz N, Thorn S, Williams L. A comparative study of vulnerability reporting by software composition analysis tools. In: Proceedings of the 15th ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement (ESEM); 2021 Oct 11–15; Bari, Italy. p. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

9. Reifer DJ, Basili VR, Boehm BW, Clark B. Eight lessons learned during cots-based systems maintenance. IEEE Softw. 2003;20(5):94–6. doi:10.1109/ms.2003.1231161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Chernis B, Verma R. Machine learning methods for software vulnerability detection. In: Proceedings of the Fourth ACM International Workshop on Security and Privacy Analytics; 2018 Mar 19–21; Tempe, AZ, USA. p. 31–9. [Google Scholar]

11. Guan Z, Wang X, Xin W, Wang J, Zhang L. A survey on deep learning-based source code defect analysis. In: 2020 5th International Conference on Computer and Communication Systems (ICCCS); 2020 May 15–18; Shanghai, China. p. 167–71. [Google Scholar]

12. Hanif H, Md Nasir MHN, Ab Razak MF, Firdaus A, Anuar NB. The rise of software vulnerability: taxonomy of software vulnerabilities detection and machine learning approaches. J Netw Comput Appl. 2021;179(9):103009. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2021.103009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Song X, Wang Y, Cheng X, Liang G, Wang Q, Zhu Z. Efficiently trimming the fat: streamlining software dependencies with java reflection and dependency analysis. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM 46th International Conference on Software Engineering; 2024 Apr 14–20; Lisbon, Portugal. p. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

14. Sonatype oss index [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 10]. Available from: https://ossindex.sonatype.org/. [Google Scholar]

15. Ladisa P, Plate H, Martinez M, Barais O. Sok: Taxonomy of attacks on open-source software supply chains. In: 2023 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2023 May 21–25; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 1509–26. [Google Scholar]

16. Ohm M, Plate H, Sykosch A, Meier M. Backstabber’s knife collection: a review of open source software supply chain attacks. In: Detection of Intrusions and Malware, and Vulnerability Assessment: 17th International Conference, DIMVA 2020; 2020 Jun 24–26; Lisbon, Portugal. p. 23–43. [Google Scholar]

17. Reid D, Jahanshahi M, Mockus A. The extent of orphan vulnerabilities from code reuse in open source software. In: Proceedings of the 44th International Conference on Software Engineering; 2022 May 25–27; Pittsburgh, PA, USA. p. 2104–15. [Google Scholar]

18. Enck W, Williams L. Top five challenges in software supply chain security: observations from 30 industry and government organizations. IEEE Secur Priv. 2022;20(2):96–100. doi:10.1109/msec.2022.3142338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Vu DL, Pashchenko I, Massacci F, Plate H, Sabetta A. Towards using source code repositories to identify software supply chain attacks. In: Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2020 Nov 9–13; Online. p. 2093–5. [Google Scholar]

20. Tan X, Gao K, Zhou M, Zhang L. An exploratory study of deep learning supply chain. In: Proceedings of the 44th International Conference on Software Engineering, 2022 May 25–27; Pittsburgh, PA, USA. p. 86–98. [Google Scholar]

21. Gkortzis A, Feitosa D, Spinellis D. Software reuse cuts both ways: an empirical analysis of its relationship with security vulnerabilities. J Syst Softw. 2021;172(2):110653. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2020.110653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ponta SE, Plate H, Sabetta A. Detection, assessment and mitigation of vulnerabilities in open source dependencies. Empir Softw Eng. 2020;25(5):3175–215. doi:10.1007/s10664-020-09830-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Dependabot-core [Internet]. [cited 2025 June 10]. Available from: https://github.com/dependabot/dependabot-core. [Google Scholar]

24. Dependency check [Internet]. [cited 2025 June 10]. Available from: https://github.com/dependency-check/DependencyCheck. [Google Scholar]

25. Soto-Valero C, Durieux T, Baudry B. A longitudinal analysis of bloated java dependencies. In: Proceedings of the 29th ACM Joint Meeting on European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering; 2021 Aug 23–28; Athens, Greece. p. 1021–31. [Google Scholar]

26. Soto-Valero C, Harrand N, Monperrus M, Baudry B. A comprehensive study of bloated dependencies in the maven ecosystem. Empir Softw Eng. 2021;26(3):45. doi:10.1007/s10664-020-09914-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Abdollahpour MM, Dietrich J, Lam P. Enhancing security through modularization: A counterfactual analysis of vulnerability propagation and detection precision. In: 2024 IEEE International Conference on Source Code Analysis and Manipulation (SCAM); 2024 Oct 7–8; Flagstaff, AZ, USA. p. 94–105. [Google Scholar]

28. Zapata RE, Kula RG, Chinthanet B, Ishio T, Matsumoto K, Ihara A. Towards smoother library migrations: A look at vulnerable dependency migrations at function level for npm javascript packages. In: 2018 IEEE International Conference on Software Maintenance and Evolution (ICSME); 2018 Sep 23–29; Madrid, Spain. p. 559–63. [Google Scholar]

29. Alfadel M, Costa DE, Shihab E, Mkhallalati M. On the use of dependabot security pull requests. In: 2021 IEEE/ACM 18th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR); 2021 May 17–19; Madrid, Spain. p. 254–65. [Google Scholar]

30. Pashchenko I, Plate H, Ponta SE, Sabetta A, Massacci F. Vuln4real: a methodology for counting actually vulnerable dependencies. IEEE Trans Softw Eng. 2020;48(5):1592–609. doi:10.1109/tse.2020.3025443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ponta SE, Plate H, Sabetta A. Beyond metadata: Code-centric and usage-based analysis of known vulnerabilities in open-source software. In: 2018 IEEE International Conference on Software Maintenance and Evolution (ICSME); 2018 Sep 23–29; Madrid, Spain. p. 449–60. [Google Scholar]

32. Prana GAA, Sharma A, Shar LK, Foo D, Santosa AE, Sharma A, et al. Out of sight, out of mind? How vulnerable dependencies affect open-source projects. Empir Softw Eng. 2021;26(4):1–34. doi:10.1007/s10664-021-09959-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Kula RG, German DM, Ouni A, Ishio T, Inoue K. Do developers update their library dependencies? An empirical study on the impact of security advisories on library migration. Empir Softw Eng. 2018;23(1):384–417. doi:10.1007/s10664-017-9521-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Yasumatsu T, Watanabe T, Kanei F, Shioji E, Akiyama M, Mori T. Understanding the responsiveness of mobile app developers to software library updates. In: Proceedings of the Ninth ACM Conference on Data and Application Security and Privacy; 2019 Mar 25–27; Richardson, TX, USA. p. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

35. Goues CLe, Pradel M, Roychoudhury A. Automated program repair. Commun ACM. 2019;62(12):56–65. [Google Scholar]

36. Bui Q-C, Paramitha R, Vu D-L, Massacci F, Scandariato R. Apr4vul: an empirical study of automatic program repair techniques on real-world java vulnerabilities. Empir Softw Eng. 2024;29(1):18. doi:10.1007/s10664-023-10415-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Huang Z, Lie D, Tan G, Jaeger T. Using safety properties to generate vulnerability patches. In: 2019 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2019 May 19–23; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 539–54. [Google Scholar]

38. Gao X, Wang B, Duck GJ, Ji R, Xiong Y, Roychoudhury A. Beyond tests: program vulnerability repair via crash constraint extraction. ACM Trans Softw Eng Methodol (TOSEM). 2021;30(2):1–27. [Google Scholar]

39. Github advisory database [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 10]. Available from: https://github.com/advisories. [Google Scholar]

40. Snyk vulnerability database [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 10]. Available from: https://security.snyk.io/. [Google Scholar]

41. Maven dependency tree [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 10]. Available from: https://github.com/apache/maven-dependency-tree. [Google Scholar]

42. Dependency mechanism [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 10]. Available from: https://maven.apache.org/guides/introduction/introduction-to-dependency-mechanism.html. [Google Scholar]

43. Maven central repository [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 10]. Available from: https://central.sonatype.com/. [Google Scholar]

44. Apache maven artifact resolver [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 10]. Available from: https://maven.apache.org/resolver/. [Google Scholar]

45. 2023 cwe top 25 most dangerous software weaknesses [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 10]. Available from: https://cwe.mitre.org/top25/archive/2023/2023_top25_list.html. [Google Scholar]

46. Soto-Valero C, Durieux T, Harrand N, Baudry B. Coverage-based debloating for java bytecode. ACM Trans Softw Eng Methodol. 2023;32(2):1–34. doi:10.1145/3546948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Pom reference [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 10]. Available from: https://maven.apache.org/pom.html. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools