Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Face-Pedestrian Joint Feature Modeling with Cross-Category Dynamic Matching for Occlusion-Robust Multi-Object Tracking

The School of Cryptography Engineering, Information Engineering University, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

* Corresponding Author: Hongshan Kong. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Secure & Intelligent Cloud-Edge Systems for Real-Time Object Detection and Tracking)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-31. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069078

Received 13 June 2025; Accepted 13 August 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

To address the issues of frequent identity switches (IDs) and degraded identification accuracy in multi object tracking (MOT) under complex occlusion scenarios, this study proposes an occlusion-robust tracking framework based on face-pedestrian joint feature modeling. By constructing a joint tracking model centered on “intra-class independent tracking + cross-category dynamic binding”, designing a multi-modal matching metric with spatio-temporal and appearance constraints, and innovatively introducing a cross-category feature mutual verification mechanism and a dual matching strategy, this work effectively resolves performance degradation in traditional single-category tracking methods caused by short-term occlusion, cross-camera tracking, and crowded environments. Experiments on the Chokepoint_Face_Pedestrian_Track test set demonstrate that in complex scenes, the proposed method improves Face-Pedestrian Matching F1 area under the curve (F1 AUC) by approximately 4 to 43 percentage points compared to several traditional methods. The joint tracking model achieves overall performance metrics of IDF1: 85.1825% and MOTA: 86.5956%, representing improvements of 0.91 and 0.06 percentage points, respectively, over the baseline model. Ablation studies confirm the effectiveness of key modules such as the Intersection over Area (IoA)/Intersection over Union (IoU) joint metric and dynamic threshold adjustment, validating the significant role of the cross-category identity matching mechanism in enhancing tracking stability. Our_model shows a 16.7% frame per second (FPS) drop vs. fairness of detection and re-identification in multiple object tracking (FairMOT), with its cross-category binding module adding aboute 10% overhead, yet maintains near-real-time performance for essential face-pedestrian tracking at small resolutions.Keywords

With the rapid advancement of intelligent surveillance and smart city construction, MOT technology has emerged as a core research focus within the computer vision domain. While existing deep learning-based tracking methods (e.g., DeepSORT [1], FairMOT [2]) have achieved significant progress on public datasets, they still encounter significant challenges such as frequent ID switches and degraded identity recognition performance in practical complex scenarios, particularly under circumstances involving pedestrians with similar attire and mutual occlusion [3]. Consequently, multi-object tracking in heavily occluded environments requires further investigation. Traditional pedestrian tracking methods primarily rely on pedestrian appearance features and motion models for data association [4]. However, their performance is constrained in the following scenarios:

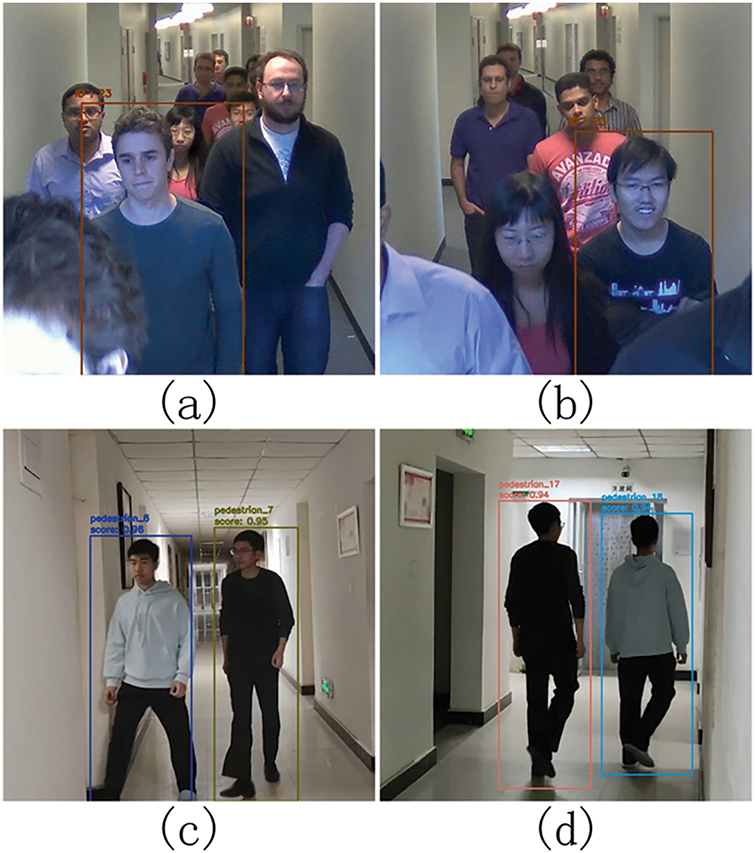

(1) Short-term occlusion: Occlusion leads to severe degradation of appearance features, reducing discriminability among pedestrians wearing similar clothing during intersections, as shown in Fig. 1a,b.

Figure 1: Illustration of complex scene. (a, b) Examples of short-term occlusion causing appearance feature degradation and reduced discriminability among pedestrians in similar clothing. (c, d) Examples of cross-camera tracking challenges due to significant appearance disparities under different viewpoints, highlighting the difficulty of establishing stable associations with unimodal features

(2) Cross-camera tracking: Significant disparities in pedestrian appearance under different viewpoints make it difficult to establish stable associations using only unimodal features, illustrated in Fig. 1c,d.

(3) Dynamic environments: Dynamic factors such as fluctuating pedestrian density and target deformation can invalidate fixed matching thresholds.

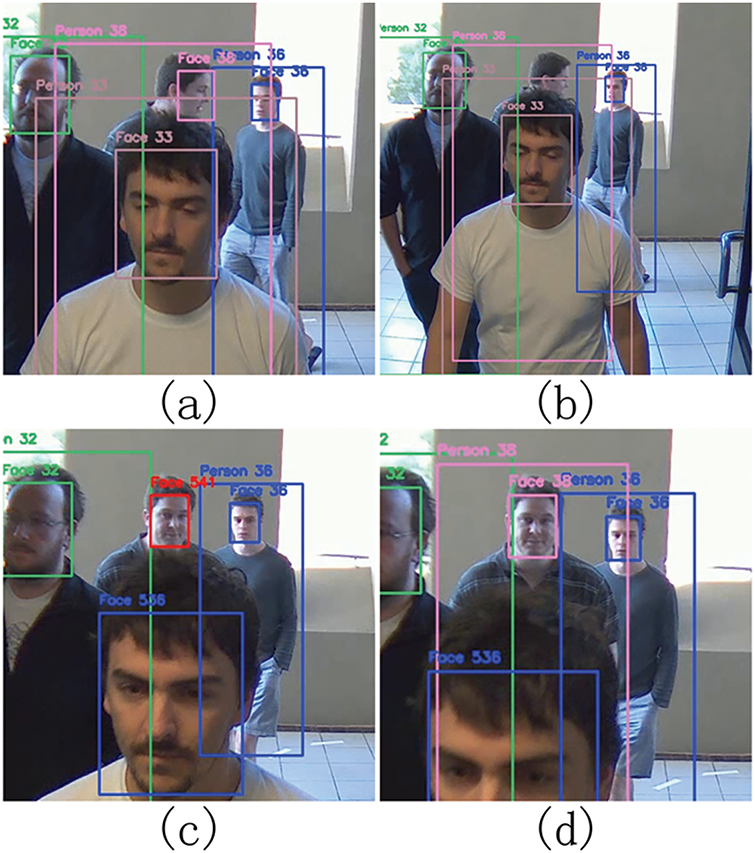

In crowded scenes, pedestrians are often partially or completely occluded, with the face typically remaining the only continuously visible part [5]. Pedestrian tracking, reliant on full-body or upper-body detection, is highly susceptible to detection failures under heavy occlusion. Conversely, face tracking focuses solely on the facial region, enabling consistent tracking even when most of the body is occluded, as depicted in Fig. 2. However, most existing works treat faces and pedestrians as independent detection targets, lacking an effective cross-category associationmechanism.

Figure 2: Illustration of Target ID correction. (a) Tracking example of pedestrian bounding box (ID 38) and face bounding box (ID 38), annotated by a pink box. (b) Tracking example of pedestrian bounding box (ID 38) with occluded face bounding box, annotated by a pink box. (c) Tracking example of face bounding box (ID 541) with occluded pedestrian bounding box, annotated by a red box. (d) Tracking example after ID correction, showing the correct association of the pedestrian bounding box (ID 38) and face bounding box (ID 38), annotated by a pink box

To address these limitations, this study proposes a face-pedestrian joint tracking approach featuring cross-category dynamic binding and occlusion-robust multi-target tracking, with main contributions including:

(1) Face-Pedestrian Joint Tracking Model: An enhanced model based on the FairMOT framework, centered on the principle of “intra-class independent tracking + cross-category dynamic binding.” This significantly mitigates tracking instability issues (frequent ID switches and trajectory fragmentation) encountered by traditional single-category pedestrian trackers in complex scenes.

(2) Multi-Modal Joint Matching Metric with Spatio-temporal and Appearance Constraints: ① Effectively suppresses cross-category mismatches in complex scenes by fusing historical centroid distance and spatial constraints (IoA/IoU); ② Introduces a cross-category feature mutual verification mechanism, utilizing historical feature pools for bidirectional face-pedestrian feature validation to enhance association reliability; ③ Proposes an occlusion-aware dynamic weighting strategy that adaptively adjusts the weights of spatio-temporal and appearance constraints based on environmental complexity.

(3) Face-Pedestrian Association via Dual Matching Strategy: ① Formulates a matching matrix integrating feature similarity and spatio-temporal constraints, transforming the cross-category association task into a rapidly solvable maximum-weighted bipartite matching problem; ② Establishes a bidirectional historical mapping mechanism with ID consistency correction and feature inheritance strategies, effectively overcoming frequent ID switches and degradation in identification rate caused by occlusion, thereby ensuring spatio-temporal continuity of cross-category trajectories.

(4) Dynamic Threshold Filtering Based on Environmental Complexity: Designs an environmental complexity-based assessment framework to realize adaptive dynamic threshold filtering, effectively resolving the adaptability limitations of fixed thresholds in dynamic scenes.

To validate the efficacy of the proposed method, comprehensive experiments were conducted on the annotated Chokepoint_Face_Pedestrian_Track test set.

(1) Face-Pedestrian Matching Experiment: In complex scenarios, our method demonstrated substantial improvement over traditional geometric matching and pure feature-based methods (FP, IoA, IoU), with F1 AUC enhancement ranging between approximately 4 and 43 percentage points, indicating stronger robustness and matching precision.

(2) Face-Pedestrian Matching Ablation Study: By incrementally incorporating functional modules (IoA-IoU joint metric, cross-category feature retrieval, spatial constraint, dynamic threshold adjustment, historical ID correction), the effectiveness of each module in optimizing face-pedestrian matching performance was individually verified.

(3) Multi-Face-Pedestrian Joint Tracking Experiment: Achieved overall performance metrics of IDF1: 85.1825% and MOTA: 86.5956%. Compared to the baseline model without the joint matching mechanism (IDF1: 84.2776%, MOTA: 86.5413%), this represents increases of 0.91 percentage points and 0.06 percentage points, respectively. The synchronized improvement in IDF1 and MOTA validates the contribution of the proposed cross-category identity matching mechanism to enhancing tracking performance.

(4) Real-Time Performance and Computational Cost Analysis: The computational efficiency analysis reveals that Our_model (without matching) exhibits a 16.7% FPS reduction compared to FairMOT’s single-category tracking, with the cross-category dynamic binding module introducing approximately 10% additional computational overhead. Nevertheless, Our_model maintains near-real-time performance with small-resolution inputs, achieving its essential cross-category face-pedestrian tracking capability at controlled computational costs.

As one of the core tasks in computer vision, MOT primarily revolves around detection, association, and feature representation. In recent years, with the advancement of deep learning techniques, MOT methods have gradually evolved into a diversified research framework centered on detection while integrating multiple technologies. The following discussion classifies and reviews existing methods from the perspectives of MOT technical paradigms and specific target tracking, while also summarizing commonly used object tracking datasets.

2.1 Classification of MOT Methods

2.1.1 Detection-Based MOT Methods

Tracking by Detection (TBD): Constructs trajectories via frame-wise detection and association. SORT [6] uses IoU for matching but suffers under occlusion. DeepSORT reduces ID switches via cascade matching and appearance features. ByteTrack [7] leverages low-confidence boxes for occlusion handling, while BoT-SORT [8] fuses motion/appearance data. TBD methods remain vulnerable to detection errors causing trajectory fragmentation.

Joint Detection and Tracking (JDT): End-to-end joint optimization. FairMOT employs a CenterNet-based dual-branch (detection/ReID) architecture. Chained-Tracker [9] formulates association as regression. JDT mitigates pipeline fragmentation but requires extensive training data.

2.1.2 Segmentation-Based MOT Methods

MOTS [10] pioneers mask-level tracking via Track-RCNN. PointTrack [11] treats pixels as point clouds, improving occlusion robustness through instance embeddings. However, segmentation methods rely on costly pixel-level annotations and exhibit high computational complexity.

2.1.3 Transformer-Based MOT Methods

In recent years, Transformer [12] has emerged as a research focus in MOT due to its global modeling capability. TransTrack [13] achieves unified modeling of detection and tracking through a query mechanism, while TrackFormer [14] employs an encoder-decoder framework to handle trajectory initialization and association. Although some Transformer-based MOT methods demonstrate superior performance in complex motion scenarios, their accuracy on conventional datasets remains inferior to optimized TBD methods such as OC-SORT [15]. Moreover, high-performance Transformer-based MOT approaches suffer from substantial computational overhead, while lightweight models exhibit significant accuracy degradation in complex environments, making them difficult to deploy on edge devices.

Face tracking aims to detect and track facial targets in video sequences, leveraging facial key points to enhance identity preservation. Shi et al. [16] proposed a fusion framework based on the MTCNN detector and an improved KCF tracker, establishing a “detection-tracking-redetection” loop mechanism. However, its multi-stage detection structure leads to insufficient real-time performance in high-density scenarios. Lin et al. [17] adopted RetinaFace to replace MTCNN and combined it with KCF for fast multi-face tracking, significantly improving processing efficiency. Qi et al. [18] enhanced YOLOv5 to design the YOLO5Face detector, introducing a Stem module to strengthen generalization capability and improving occlusion stability through landmark supervision. Jöchl and Uhl [19] proposed the FaceSORT model, integrating facial biometric features with visual appearance features, thereby enhancing robustness in occlusion and side-view scenarios. However, the sensitivity to biometric feature quality and adaptive parameter tuning remain areas for improvement. Current face tracking methods generally suffer from high dependency on frontal faces, performance degradation under extreme poses, and frequent ID switches in low-resolution scenarios.

Pedestrian head tracking focuses on detecting and continuously tracking head targets to address challenges such as occlusion and scale variation. Stewart et al. [20] developed an end-to-end detection framework based on Faster R-CNN but did not resolve high-density association issues. Sundararaman et al. [21] constructed the first large-scale head tracking dataset, CroHD, and proposed the HeadHunter-T framework. It employs a context-sensitive feature pyramid for optimized detection and combines particle filtering with histogram matching for tracking, achieving an IDF1 of 57.1% in occlusion scenarios. However, it underutilizes biometric features and relies on handcrafted features for appearance similarity modeling, leading to frequent ID switches under complex lighting conditions. Sun et al. [22] designed a multi-source information fusion network (MIFN) that integrates five sources (RGB + optical flow + depth + frame difference + density map) for end-to-end training, achieving a MOTA of 76.7% on the Cchead dataset (a 5.7% improvement over FairMOT). Overall, existing head trackers primarily rely on appearance features, lacking the strong discriminative power of facial biometrics. They exhibit significant shortcomings in occlusion robustness and adaptability to dynamic scenes, with prediction errors notably increasing during nonlinear motions such as sharp turns or evasive maneuvers in crowds.

Multi-modal joint tracking technology aims to enhance persistent target identity tracking in complex surveillance scenarios by fusing multi-modal biometric features. Current research suggests that collaborative modeling of target identity, behavior, and intention improves performance in multi-target tracking tasks under challenging conditions. Multi-modal identity inference (e.g., cross-camera re-identification based on skeletal pose or clothing attributes) serves as the foundation for resolving target ID switches. Behavior recognition (e.g., classifying walking/stationary states) provides dynamic constraints for trajectory motion models, while pedestrian intention prediction (e.g., crossing decisions) critically influences the reliability of long-term trajectory forecasting. Sharma et al. [23] highlight that integrating visual (RGB/IR), geometric (point cloud), and behavioral modalities (gait/hand gestures) enhances intention reasoning accuracy, with spatio-temporal graph networks further optimizing group trajectory modeling by incorporating scene semantics. Huang et al. [24] proposed a feature-level fusion approach, employing a concatenation strategy for facial and pedestrian features along with a maximum-value-based decision mechanism. However, their method requires manual alignment due to feature dimensionality discrepancies and exhibits limited robustness in occlusion scenarios. Li [25] developed a cross-camera system that leverages head features to assist ReID and face recognition, significantly reducing the missed detection rate through a parallel matching mechanism (where a match is confirmed upon the success of any single feature). Nevertheless, the field still faces challenges, including insufficient feature complementarity under occlusion, bottlenecks in cross-modal fusion, and high computational costs that hinder real-time performance.

Object tracking datasets can be categorized into single-object tracking (SOT) datasets and multi-object tracking (MOT) datasets based on the number of tracked targets.

The commonly used single target tracking data include OTB data set, VOT data set, GOT-10K data set, LaSOT data set, etc. The OTB [26,27] dataset pioneered this field, propelling early advancements in target tracking algorithms. The VOT [28,29] dataset, updated annually for the Visual Object Tracking competition, has expanded to include real-time, long-term, and RGBD tracking challenges. More recent contributions include GOT-10K [30], a large-scale dataset covering diverse scenarios with 1.5 million annotated bounding boxes, and LaSOT [31], featuring 1400 high-quality sequences with over 3.5 million densely annotated frames, each frame in the sequence was annotated manually, making LaSOT the largest annotation-intensive tracking benchmark of its time.

In the realm of multi-object tracking, the MOT series [32–34] has been instrumental. This series, evolving from MOT15 to MOT20, progressively introduced more complex scenarios, increased occlusions, and faster movement speeds. The STEP-ICCV21 dataset [35] advanced the field further by focusing on Multi-Object Tracking and Segmentation tasks. Additionally, the TAO VOS dataset [36] represents a significant contribution to large-scale video object segmentation and tracking, aimed at enhancing research in video understanding, particularly for long videos and extensive category ranges.

Table 1 presents a summary of the basic information for these datasets.

Publicly available face tracking datasets are limited, with MobiFace and Chokepoint being the most commonly used (see Table 2).

MobiFace, proposed by Lin et al. [37] in 2019, is a novel dataset for mobile face tracking and grouping, containing 80 unedited videos recorded via smartphone live streaming. It provides over 95,000 annotated bounding boxes.

The Chokepoint dataset, introduced by Wong et al. [38] in 2019, is designed for multi-face tracking. It comprises two scenarios recorded one month apart: Scenario 1 includes 25 individuals (19 male, 6 female), while Scenario 2 has 29 (23 male, 6 female). Three cameras were mounted above an office doorway, capturing 78 video sequences with 64,204 annotated face images (excluding 6 unlabeled sequences). The first 100 frames of each sequence are reserved for background modeling, with no foreground objects present.

While datasets for pedestrians, vehicles, and animals are relatively mature, face tracking datasets and evaluation metrics remain scarce. Even the widely used Chokepoint dataset only annotates eye trajectories for simple scenarios (single pedestrian per frame). Notably, its six complex sequences (“P2E_S5” and “P2L_S5”), featuring multiple pedestrians with mutual occlusion, lack annotations, highlighting the need for further refinement in face tracking datasets.

3.1 Face-pedestrian Joint Tracking Framework

3.1.1 Model Architecture Design

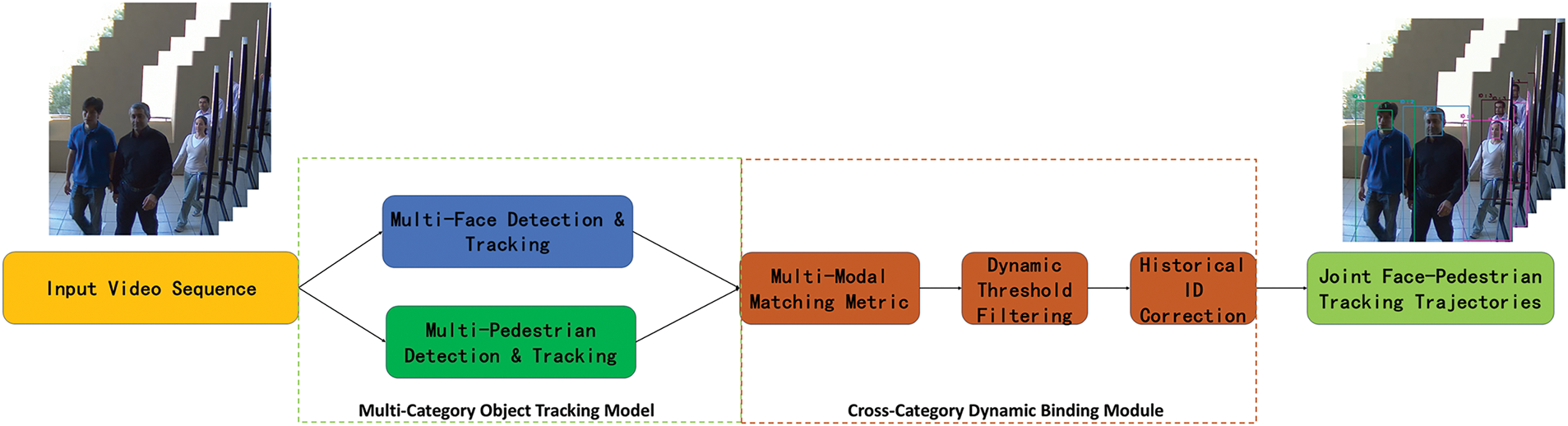

The proposed Face-Pedestrian Joint Tracking framework (Fig. 3) implements “intra-class independent tracking + cross-category dynamic binding”, Figs. 4 and 5 present the detailed architectural diagrams of intra-class independent tracking and cross-category dynamic binding, respectively. Based on an enhanced FairMOT architecture, it extends the detection head and increases feature channels to convert single-category tracking into multi-category tracking for faces and pedestrians. Cross-category dynamic binding then enables joint tracking through a joint matching mechanism. The architecture comprises two stages:

Figure 3: Face-pedestrian joint tracking framework

Figure 4: Intra-class independent tracking framework

Figure 5: Cross-category dynamic binding framework

(1) Intra-Class Independent Tracking

Face Tracking Branch: Facial features are extracted via the DLA-34 backbone network, outputting face bounding boxes

Pedestrian Tracking Branch: Using the shared DLA-34 backbone network, pedestrian features are extracted, outputting pedestrian bounding boxes

(2) Cross-Category ID Binding

Based on the spatio-temporal and appearance joint metric (detailed in Section 3.2), trajectories Tf and Tp are dynamically associated, outputting the bound joint trajectory

3.1.2 Face-Pedestrian Tracking Dataset Construction

Building upon the Chokepoint dataset, this work employs a combination of “automatic tracking” and “manual annotation” to label “face tracking” and “pedestrian tracking” data across 78 videos from Chokepoint, forming the Chokepoint_Face_Pedestrian_Track dataset. Of these, 72 videos represent simple scenes with minimal inter-pedestrian occlusion, as shown in Fig. 6a,b. The remaining 6 videos depict complex scenes with significant inter-pedestrian occlusion, as shown in Fig. 6c,d. The dataset comprises approximately 130,000 face tracking annotations and 160,000 pedestrian tracking annotations. These are divided into training, validation, and test sets using a 70%, 15%, 15% split. The statistical information of the Chokepoint_Face_Pedestrian_Track dataset is shown in Table 3. To evaluate the zero-shot tracking performance of Our joint tracking model, we constructed the Challenging Face_Pedestrian_Track Dataset. Compared to the Chokepoint_Face_Pedestrian_Track Dataset, the Challenging dataset contains numerous side-view and back-view scenarios where faces are partially visible or completely occluded, as illustrated in Fig. 7. The dataset statistics are presented in Table 4.

Figure 6: Scene examples from chokepoint dataset. (a, b) Examples of simple scenes in the chokepoint dataset. (c, d) Examples of complex scenes in the chokepoint dataset

Figure 7: Scene examples from challenging Face_Pedestrian_Track Dataset. (a) Example of multiple pedestrian targets in Scene 1 (front view). (b) Example of multiple pedestrian targets in Scene 1 (rear view), where the red bounding box represents the simulated face bounding box used for performance evaluation. (c) Example of multiple pedestrian targets in Scene 2 (front view). (d) Example of pedestrian targets in Scene 2 (side view), where the red bounding box represents the simulated face bounding box used for performance evaluation

Annotation Format:

cls_id obj_id center_x center_y width height

3.1.3 Loss Function Calculation

(1) Detection Task Loss Calculation

Heatmap Prediction: Detection head output channels match class count (e.g., one per pedestrian/face). CTFocalLoss is computed via pixel-wise cross-entropy over all classes, summed to a scalar.

where

Size/Offset Regression Loss: The regression losses for target size and center offset are calculated directly based on the locations of all positive samples:

where M denotes the total number of positive samples for both faces and pedestrians;

(2) ReID Task Loss Calculation

ID Feature Hybrid Learning: Pedestrian and face IDs share a unified global pool (e.g., pedestrians: 1–9, faces: 11–19). Cross-entropy loss uniformly distinguishes all ID features as independent classes.

where

(3) Total Loss Calculation

The total loss function is the weighted sum of the individual loss components:

where

The model training pipeline is illustrated in Fig. 8, and the training and validation loss curves are shown in Fig. 9. The primary focus of this study is to validate the effectiveness of the face-pedestrian joint matching method, rather than pursuing state-of-the-art (SOTA) model performance. Due to the relative scarcity of training datasets for face tracking tasks, the proposed method may exhibit limited generalization capability in scenarios with significant domain discrepancies.

Figure 8: Training pipeline for face-pedestrian tracking model

Figure 9: Training and validation loss curves for face-pedestrian tracking model

3.2 Face-Pedestrian Matching Method

To mitigate ID switches and trajectory fragmentation issues inherent in traditional single-category pedestrian tracking algorithms within complex scenarios like similar attire and mutual occlusion, this paper further optimizes the face-pedestrian matching strategy within the proposed joint detection and tracking framework. This is achieved by designing a multi-modal joint matching metric, establishing a dynamic threshold filtering mechanism, and utilizing the Hungarian algorithm to achieve global optimal matching for face-pedestrian pairs within a single frame.

3.2.1 Multi-Modal Joint Matching Metric

In complex MOT scenarios, occlusion and similar clothing degrade ReID features, causing ID switches. We propose a multi-modal matching metric with three mechanisms: (1) Spatio-Temporal Constraint: Combines centroid motion with IoA/IoU to suppress mismatches. (2) Cross-Category Feature Verification: Uses historical feature pool for bidirectional validation. (3) Dynamic Weighting: Adapts constraint weights to scene complexity.

After normalization:

where

(1) Weight Calculation Method

The empirical coefficients are set as

(2) Face-Pedestrian Centroid Motion Constraint

Here,

(3) Occlusion Level Assessment Method

The occlusion level

Spatial Occlusion Detection: Compute the maximum IoU (

where

Temporal Smoothing: Maintain a temporal smoothing window of length

For new tracks, the queue is initialized by repeating the current frame’s

3.2.2 Face-Pedestrian Association via Dual Matching Strategy

We propose a robust face-pedestrian matching method combining Hungarian algorithm-based maximum-weighted bipartite matching (using feature similarity and spatio-temporal constraints) with dynamic threshold filtering. The system adaptively adjusts thresholds via environmental complexity assessment to mitigate occlusion-induced ID switches, while employing bidirectional historical mapping for ID consistency and feature inheritance for unmatched targets to maintain trajectory continuity.

(1) Face-Pedestrian Matching via Hungarian Algorithm

Construct a cost matrix

Subject to the constraints:

The solution matrix

(2) Dynamic Joint Threshold Filtering Mechanism

An initial face-pedestrian match pair

where

(3) Historical ID Correction Mechanism

Maintain two bidirectional mapping tables to record historical associations:

Face-Dominated Correction: For a current matched pair

Pedestrian-Dominated Correction: For a current matched pair

The pseudo-code for the face-pedestrian association algorithm using the dual matching strategy is as Algorithm 1.

3.2.3 Dynamic Threshold Mechanism

To address the adaptability limitations of fixed matching thresholds in dynamic environments, this study designs an environmental complexity-based assessment framework to construct a threshold adaptation model. This model dynamically adjusts the multi-modal joint matching metric threshold based on real-time tracking conditions (specifically, pedestrian density and mutual occlusion within the current frame), thereby avoiding fragmented trajectories caused by excessively high thresholds in complex scenes or mismatches resulting from overly low thresholds in simple scenes.

(1) Dynamic Matching Threshold

The dynamic matching threshold

where

The scene complexity factor

where N is the total number of targets in the current frame.

The local density

where

where

(2) Dynamic Occlusion Threshold

The dynamic occlusion threshold

where

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, this study designs four experimental components: (1) Face-Pedestrian Matching Accuracy Test, (2) Face-Pedestrian Matching Ablation Study, (3) Face-Pedestrian Tracking Performance Evaluation, and (4) Real-Time Performance and Computational Cost Analysis. The first experiment evaluates the accuracy of the face-pedestrian matching component, while the second quantifies the contribution of individual modules in the matching approach. The third assesses the overall performance of the joint face-pedestrian tracking model, and the fourth systematically examines the computational efficiency through runtime and frame rate measurements. Experiments 1 and 2 adopt F1 AUC as the primary evaluation metric, Experiment 3 employs IDF1 and MOTA as key performance indicators, and Experiment 4 focuses on processing time and average FPS comparisons.

4.1 Face-Pedestrian Matching Accuracy Testing

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed face-pedestrian association matching method, an evaluation framework based on dual IoU thresholds was designed to quantify the face-pedestrian matching results.

4.1.1 Association Matching Strategy

This evaluation framework employs a dual-constraint Hungarian matching algorithm for association determination. A successful match is defined as follows:

where

4.1.3 Performance Quantitative Evaluation

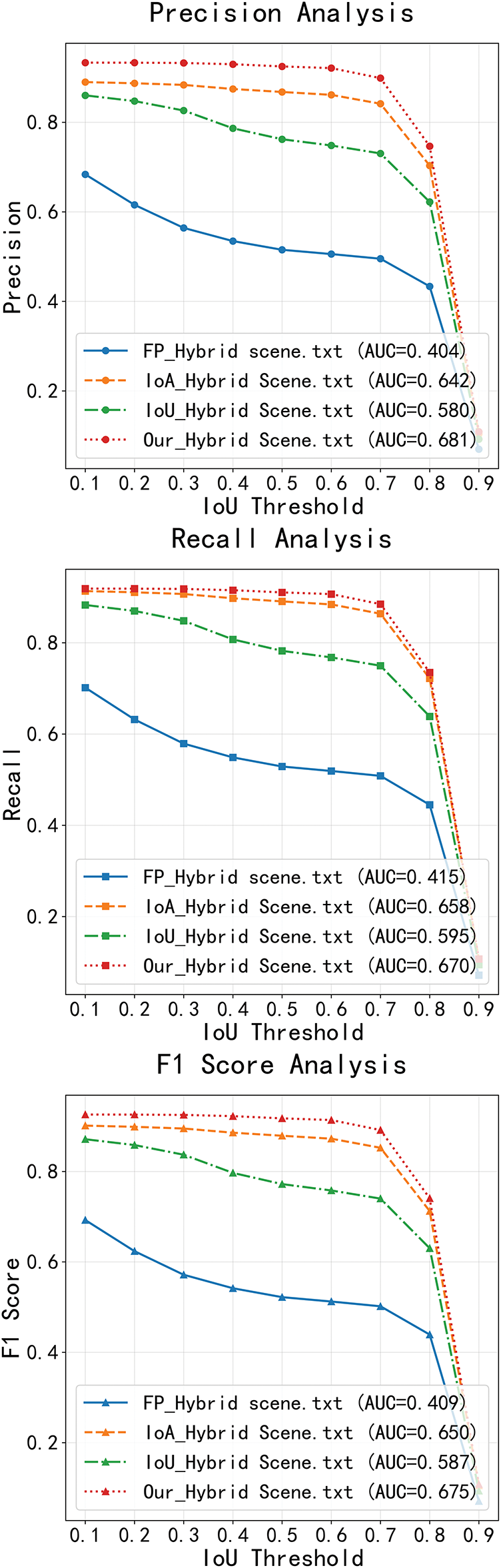

To overcome the limitations of single-threshold evaluation, this paper conducted multi-threshold testing within the range

The experiment was tested on 12 video sequences from the Chokepoint_Face_Pedestrian_Track test set. Among these, 9 represent simple scenes with minimal inter-pedestrian occlusion, and 3 represent complex scenes with significant inter-pedestrian occlusion. Test results are aggregated separately for each scene type. For an intuitive comparison of different methods’ performance across various metrics and thresholds, the AUC was employed for global performance assessment:

where

4.1.4 Performance Comparison of Face-Pedestrian Matching Methods

We evaluate four methods

Figure 10: Face-pedestrian matching performance comparison in simple scenes

Figure 11: Face-pedestrian matching performance comparison in complex scenes

Figure 12: Face-pedestrian matching performance comparison in hybrid scenes

Simple Scenes: Performance differences between methods are minimal. Our method achieves the highest F1 AUC (0.706), slightly outperforming IoA (0.705), FP (0.674), and IoU (0.697). All methods effectively balance Precision and Recall in simple scenes. Notably, IoA attains the best Recall AUC (0.726), while Our method demonstrates superior overall performance with balanced Precision (0.687) and Recall (0.725), highlighting its adaptability.

Complex Scenes: Our method exhibits significant advantages, with Precision AUC (0.676), Recall AUC (0.633), and F1 AUC (0.654) substantially exceeding other methods (e.g., FP achieves around only 0.225 for all metrics). Traditional methods (FP, IoA, IoU) perform poorly, with IoA (0.611) and IoU (0.511) outperforming FP but still lagging behind Our method, demonstrating its robustness in complex scenes.

Hybrid Scenes: Our method achieves the best performance across all metrics: Precision AUC (0.681), Recall AUC (0.670), and F1 AUC (0.675). While IoA shows competitive Recall AUC (0.658), its Precision (0.642) and F1 (0.650) remain inferior. Traditional methods (IoU, FP) exhibit inconsistent performance, performing well in simple but poorly in complex scenes, revealing their limited adaptability. This underscores the effectiveness of Our method’s multi-modal joint matching, dual matching strategy, and scene adaptation mechanisms for cross-scenario applications.

The results demonstrate Our method’s consistent superiority in simple, complex, and hybrid scenes. In complex scenes, it significantly outperforms geometric (IoA, IoU) and feature-based (FP) methods, with F1 AUC improvements ranging from 4 to 43 percentage points, validating its robustness and accuracy for face-pedestrian matching across diverse environments.

4.2 Face-Pedestrian Matching Ablation Study

The novelty of the proposed face-pedestrian matching method lies mainly in five key mechanisms: (1) Spatial matching based on IoA-IoU joint metric, denoted IoA-IoU. (2) Cross-category reverse feature retrieval strategy, denoted FPF (Face-Pedestrian Features). (3) Spatial constraint mechanism based on centroid distance, denoted CD (Centroid Distance). (4) Environment-aware dynamic threshold filtering method, denoted DT (Dynamic Threshold). (5) Target ID correction mechanism based on historical matching, denoted IDC (ID Correction). To validate the effectiveness of each module, an ablation analysis was performed using comprehensive testing on 9 simple scenes and 3 complex scenes. The five core components were systematically verified. Specific experimental results are shown in Fig. 13.

Figure 13: Ablation study on face-pedestrian matching in hybrid scenes

Analysis of the ablation results reveals:

IoA-IoU Joint Metric: Introducing this module significantly improved performance, increasing F1 AUC from the baseline of 0.58747 to 0.668036 (relative increase of 13.7%). This demonstrates that the IoA mechanism effectively alleviates the high sensitivity of single IoU to target deformation and occlusion, robustly validating the necessity of the joint metric strategy for spatial alignment.

FPF Module: Adding this module resulted in a marginal performance increase, with F1 AUC rising only by 0.00033 (0.668036

CD Module: Introducing this constraint increased F1 AUC by 0.001301 (0.668366

DT Module: Enabling this mechanism improved F1 AUC and Recall AUC, but caused a slight decrease in Precision AUC (–0.000198, 0.675589

IDC Module: Finally, adding this module for identity correction using historical matching information further enhances long-term identity consistency for face-pedestrian matching. Built upon the accumulation of all previous modules, it raises the final model’s F1 AUC to 0.67533 (+0.82% compared to without IDC), providing a solution to mitigate ID drift issues in cross-category tracking.

The proposed face-pedestrian matching framework systematically optimizes performance by integrating the IoA-IoU joint metric, FPF cross-category feature retrieval, CD spatial constraint, DT dynamic threshold, and IDC historical correction mechanisms. The ablation study indicates: IoA-IoU serves as the foundational module, contributing the primary performance gain (F1 AUC increase of 13.7%), robustly validating the joint metric’s effectiveness for spatial alignment. CD and IDC further enhance performance through spatial constraints and historical consistency optimization, enabling the final model to achieve an F1 AUC of 0.67533 (15% improvement over the baseline). FPF and DT modules, while providing smaller contributions, offer optimization direction for cross-category alignment and environmental adaptability.

4.3 Face-Pedestrian Tracking Model Performance Testing

This experiment is also conducted on the 12 video sequences from the Chokepoint_Face_Pedestrian_Track test set, systematically evaluating two model architectures:

Baseline Model: The “Face-Pedestrian Multi-Category Object Independent Tracking Model” without integrated identity association information. Its performance is tested separately for pedestrian and face tracking.

Our Model: The joint tracking model integrating the “Face-Pedestrian Cross-category Matching Mechanism.” Recognizing that pedestrian targets generally maintain detection and tracking continuity more effectively than faces in real-world scenarios, while also being more susceptible to occlusion in complex settings, this experiment focuses solely on evaluating the corrected pedestrian tracking results output by Our Model. This targeted evaluation aims to specifically validate the effectiveness of the proposed occlusion-handling ID correction mechanism.

The experimental design serves two primary verification objectives: (1) Assess the feasibility of the multi-category object independent tracking framework via performance evaluation of the baseline model. (2) Quantitatively analyze the optimization effect of the cross-category identity matching mechanism on tracking performance through comparative experiments with the baseline model.

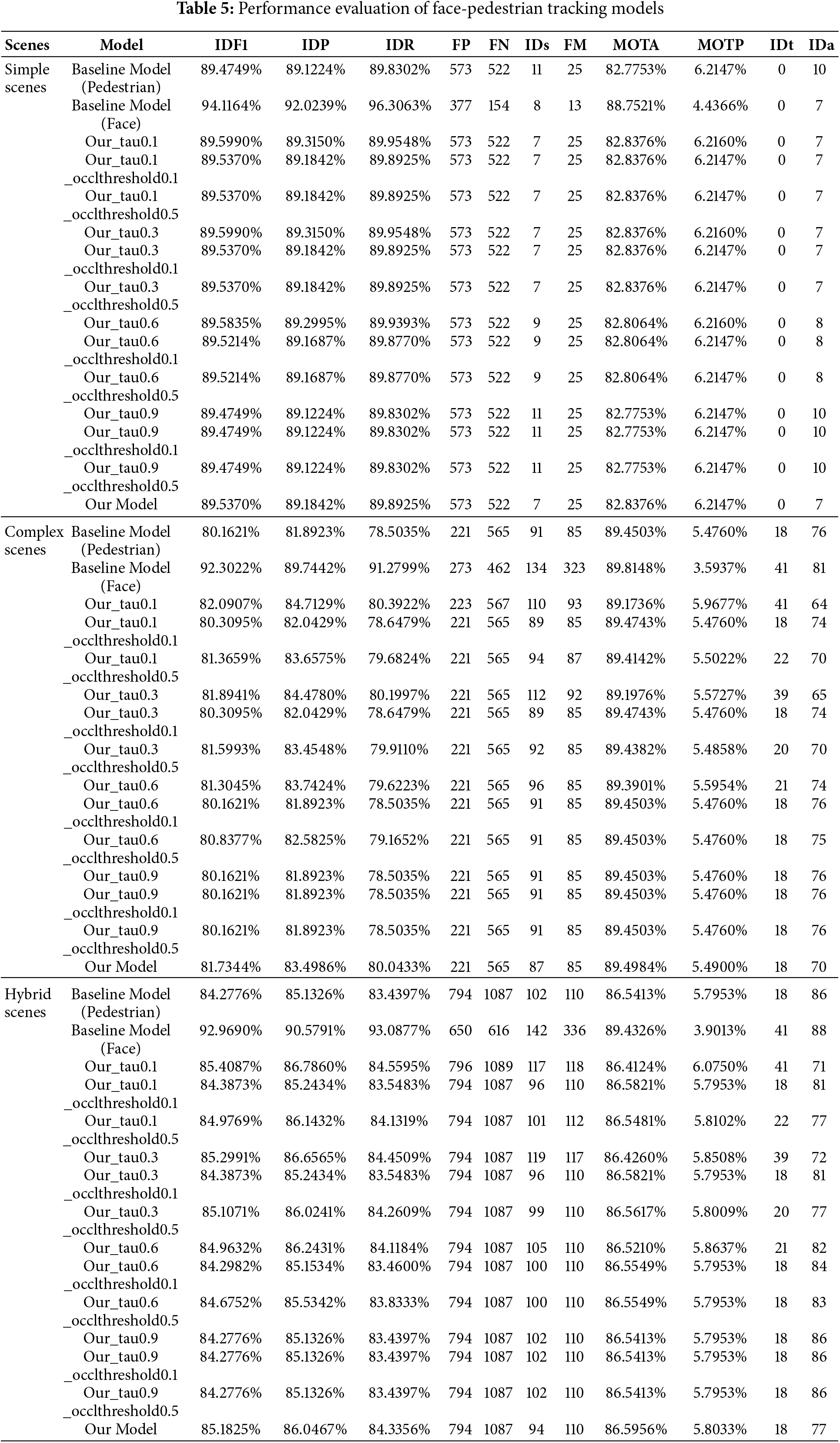

Performance evaluation follows the MOT Challenge standard evaluation protocol, employing a multi-dimensional assessment system. Core metrics include: IDF1: Comprehensively measures ID precision and recall. IDs: Specifically assesses target identity stability (number of identity switches). MOTA: Integrally reflects detection and tracking capability. MOTP: Quantifies trajectory localization precision. All metrics were calculated using the motmetrics toolkit. Results are presented in Table 5.

4.3.1 Validation of Multi-Category Object Independent Tracking Framework Feasibility

Results indicate that the baseline model (Baseline Model) achieved the following pedestrian tracking performance across different scenarios: Simple Scenes: IDF1: 89.4749%, MOTA: 82.7753%. Complex Scenes: IDF1: 80.1621%, MOTA: 89.4503%. Hybrid Scenes: IDF1: 84.2776%, MOTA: 86.5413%. Its face tracking performance was: Simple Scenes: IDF1: 94.1164%, MOTA: 88.7521%. Complex Scenes: IDF1: 92.3022%, MOTA: 89.8148%. Hybrid Scenes: IDF1: 92.9690%, MOTA: 89.4326%. These results validate the fundamental tracking capability of the proposed multi-category object independent tracking framework for both pedestrian and face targets. Note: The performance evaluation of Our Model is conducted only on the pedestrian tracking trajectories output by its cross-category association correction mechanism. Accordingly, for direct comparison, the performance metrics reported for the Baseline Model in the following sections pertain specifically to its pedestrian tracking results.

Comparison of Our Model results reveals that in all three scenarios, its IDF1 (89.5370%, 81.7344%, 85.1825%) and MOTA (82.8376%, 89.4984%, 86.5956%) metrics are superior to the corresponding values of the Baseline Model. This suggests room for improvement in the baseline model’s ability to maintain target identity consistency and trajectory continuity, thereby confirming the necessity of introducing the cross-category association mechanism.

It should be specifically noted that in the experimental test dataset, pedestrian targets predominantly exhibit frontal faces throughout the sequence, and the ground truth annotations for evaluating face tracking performance are based on ground truth face tracking data rather than ground truth object tracking data. Consequently, the face tracking results appear favorable. However, in cross-camera scenarios or situations where face detection and tracking are more challenging, standalone face tracking performance would decline significantly. For tracking pedestrian-like targets, whether employing face tracking or pedestrian tracking, the primary objective is to maintain target identity consistency and continuity. Since pedestrian tracking is less affected by camera angles (compared to face tracking, which requires near-frontal views), using ground truth pedestrian tracking annotations to evaluate algorithm performance is more reliable. Therefore, in the experiments, Our Model only presents test results based on the corrected pedestrian tracking data derived from the proposed method.

4.3.2 Optimization Effect of Cross-Category Identity Matching Mechanism

The core innovation of Our Model lies in effectively correcting trajectory interruptions and ID switches caused by single-modal occlusion or tracker limitations via the face-pedestrian association mechanism. To validate this ID correction mechanism, parameter combination experiments were conducted using face_matrix_tau (association confidence threshold) and occl_threshold (occlusion level threshold), with the filtering logic: reject a match pair if its association confidence is below face_matrix_tau or its occlusion level exceeds occl_threshold.

Analysis shows: When adjusting only face_matrix_tau, IDF1 exhibits an initial increase followed by a decrease as the threshold rises from 0.1 to 0.9 (e.g., in Hybrid Scenes, IDF1 peaked at 85.4087% when face_matrix_tau = 0.1 but declined towards baseline levels when face_matrix_tau > 0.6). This is attributed to low thresholds retaining excessive mismatches causing error propagation, while high thresholds over-filter valid matches. MOTA showed the opposite trend, peaking at 86.5413% (baseline level) when face_matrix_tau = 0.9. This highlights the inherent limitation of a single parameter in balancing identity consistency (IDF1) and tracking accuracy (MOTA).

Given that most mismatches occur in heavily occluded scenes, occl_threshold was introduced for joint filtering. In Complex Scenes, setting face_matrix_tau = 0.1 or 0.3 and occl_threshold = 0.1 reduced IDs from the baseline 91 to 89 and increased MOTA from 89.4503% to 89.4743%. The same settings in Hybrid Scenes reduced IDs by 6 (102

Our Model, utilizing a collaborative filtering mechanism that dynamically adjusts face_matrix_tau and occl_threshold, achieved an IDF1 of 85.1825% and MOTA of 86.5956% in Hybrid Scenes. This improves upon the Baseline Model by +0.91pp and +0.06pp on IDF1 and MOTA respectively, while reducing IDs to 94. Despite its weighted sum (IDF1 + MOTA = 171.7781%) being marginally lower than the best manual combination (171.8211%), the latter’s lower MOTA (86.4124% compared to baseline 86.5413%) compromised overall balance, whereas Our Model achieved a synchronous improvement in both IDF1 and MOTA over the baseline, demonstrating superior balance capability. These results demonstrate that the dynamic adaptation mechanism effectively tailors filtering strategies to task priorities: combinations favoring low thresholds enhance tracking performance, while single low face_matrix_tau filtering benefits long-term identity consistency.

Fig. 14 presents the tracking results on a subset of the test dataset. Specifically, Fig. 14a,c,e displays the tracking results of the Baseline Model in one simple and two complex scenarios, while Fig. 14b,d,f shows the corresponding results of Our Model. For clarity in evaluating tracking performance, relevant targets are annotated with color-coded bounding boxes. As seen in Fig. 14(a2,a4,a5), the Baseline Model assigns inconsistent IDs (21, 23, 24) to the same pedestrian, indicating severe ID_SWITCH. In contrast, Our Model maintains a consistent pedestrian ID (24) in the corresponding frames Fig. 14(b2,b4,b5). This is because, in the joint tracking framework, the face ID remains stable (e.g., ID 23 in Fig. 14(b1,b3)). When pedestrian tracking suffers from ID_SWITCH, the face ID consistency is leveraged to correct it. In Fig. 14(b2,b4,b5), when face and pedestrian detections are successfully matched, the system displays the pedestrian ID (24) by default. If matching fails or either detection is missing, the initial tracking ID (uncorrected) is shown instead. Thus, face IDs in Fig. 14b appear as both 23 and 24, though the underlying face ID is consistently 23—this visualization is used solely to illustrate the correction mechanism. Similarly, in complex scenarios (Fig. 14c–f), Our Model demonstrates clear advantages. For instance, in Fig. 14c, the Baseline Model assigns pedestrian IDs 31, 33, and 34, whereas Our Model corrects these to 49 and 52 (Fig. 14d). In Fig. 14, the Baseline Model produces IDs 12 and 15, while Our Model maintains ID 13 (Fig. 14f). These observations confirm that face information serves as a critical identity anchor in tracking scenarios. By associating stable face IDs with pedestrian tracking results, Our Model robustly mitigates frequent ID_SWITCH in the baseline approach, improving continuous tracking accuracy and identity consistency under challenges such as occlusion and deformation.

Figure 14: The side-by-side comparison visualizations of tracking results from the baseline model and our model

The core value of the proposed face-pedestrian joint framework lies in its complementary and synergistic mechanisms. Body tracking features exhibit superior robustness to viewpoint variations (e.g., side/back views) and partial occlusions compared to face tracking. When facial information degrades or fails due to occlusion or pose changes, body cues maintain tracking continuity and identity consistency. Compared to pedestrian tracking alone, in crowded environments, human bodies are often partially or fully occluded, whereas faces typically remain the only consistently visible feature. Crucially, the cross-category dynamic matching strategy adaptively selects optimal matching clues (face, body, or fused features) based on real-time confidence metrics (e.g., face detection quality, occlusion severity). This enables the model to leverage high-discriminability facial features when reliable, while seamlessly switching to robust body features or weighted fusion in challenging scenarios (e.g., severe occlusion or cross-camera views). Consequently, the framework achieves consistently stable tracking performance across diverse conditions, particularly in occlusion-prone and viewpoint-varying environments—a capability unattainable by unimodal approaches.

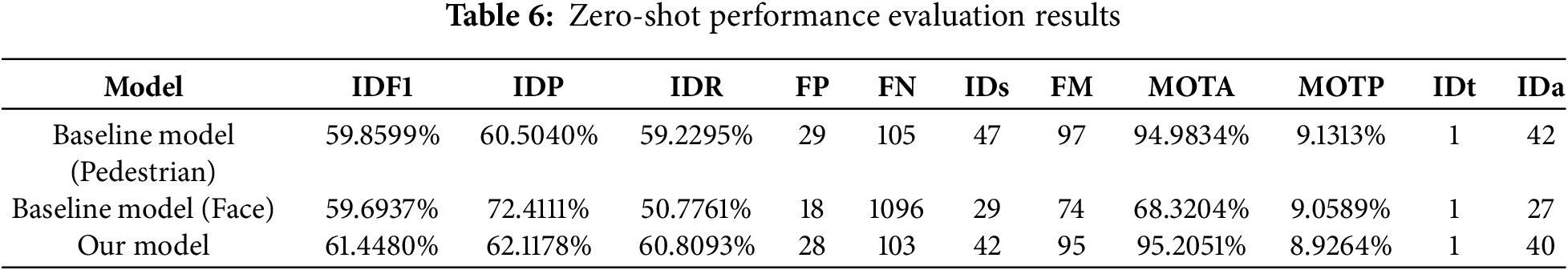

4.4 Zero-Shot Performance Evaluation of Face-Pedestrian Tracking Models

To further validate the advantages of the Our joint tracking model over standalone pedestrian tracking or standalone face tracking models in handling pedestrian viewpoint variations (e.g., side-view/back-view) and occlusion scenarios, this paper evaluates three models—Baseline Model (pedestrian), Baseline Model (face), and Our Model—on the Challenging Face_Pedestrian_Track Dataset. It should be noted that in the Challenging dataset, targets exhibit significant viewpoint variations in camera footage, with frequent side-view and back-view scenarios, resulting in some targets’ faces being undetectable or untrackable. To ensure a fair comparison of tracking performance across models, for side-view and back-view scenarios, even if faces cannot be detected or tracked by the model, simulated face tracking annotations are used as ground-truth face tracking annotations during performance evaluation. This ensures that the total number of targets (faces or pedestrians) in the ground-truth annotations remains consistent for all three models during evaluation. As shown in Fig. 7b,d, the test results for each model are presented in Table 6.

(1) Severe Limitations of Standalone Face Models

In critical scenarios such as side-view and back-view, the standalone face-tracking model (Baseline Model (face)) reveals fundamental flaws. It heavily relies on visible frontal faces; once the target turns sideways or away from the camera, causing face information to be lost, the model fails. This directly leads to catastrophic false negatives (FN = 1096, far exceeding the other two models), reflected in an extremely low identification recall rate (IDR = 50.7761%). Although its precision (IDP) is acceptable, the abysmal recall rate drags down its overall identification performance (lowest IDF1) and accuracy (MOTA = 68.3204%), indicating that the model cannot stably track targets under pose variations and lacks robustness.

(2) Significant Advantages of the Joint Model

The proposed face-pedestrian joint tracking model (Our Model) effectively overcomes the limitations of single-modality approaches by integrating face and pedestrian appearance information. It demonstrates exceptional performance in handling side-view and back-view scenarios: false negatives (FN = 103) are significantly lower than those of the face model and approach the level of the standalone pedestrian model; the identification recall rate (IDR = 60.8093%) is notably higher than that of the face model and slightly better than the pedestrian model, proving its ability to maintain tracking when targets are not facing the camera. Its comprehensive identification performance (IDF1 = 61.4480%) and overall accuracy (MOTA = 95.2051%) are the highest among the three. The key lies in the model’s ability to intelligently switch or fuse information sources (using faces for frontal views and pedestrian data for non-frontal views), ensuring trajectory continuity.

(3) Conclusions and Value

Experiments on the Challenging Dataset, which is rich in side-view and back-view challenges, clearly demonstrate that standalone face-tracking models suffer from severe flaws when target poses vary, lacking the robustness required for practical applications. In contrast, the proposed joint tracking model, through complementary fusion of face and pedestrian information, significantly improves tracking stability and continuity under viewpoint variations and occlusions, achieving optimal comprehensive performance. Its design strategy holds substantial practical value.

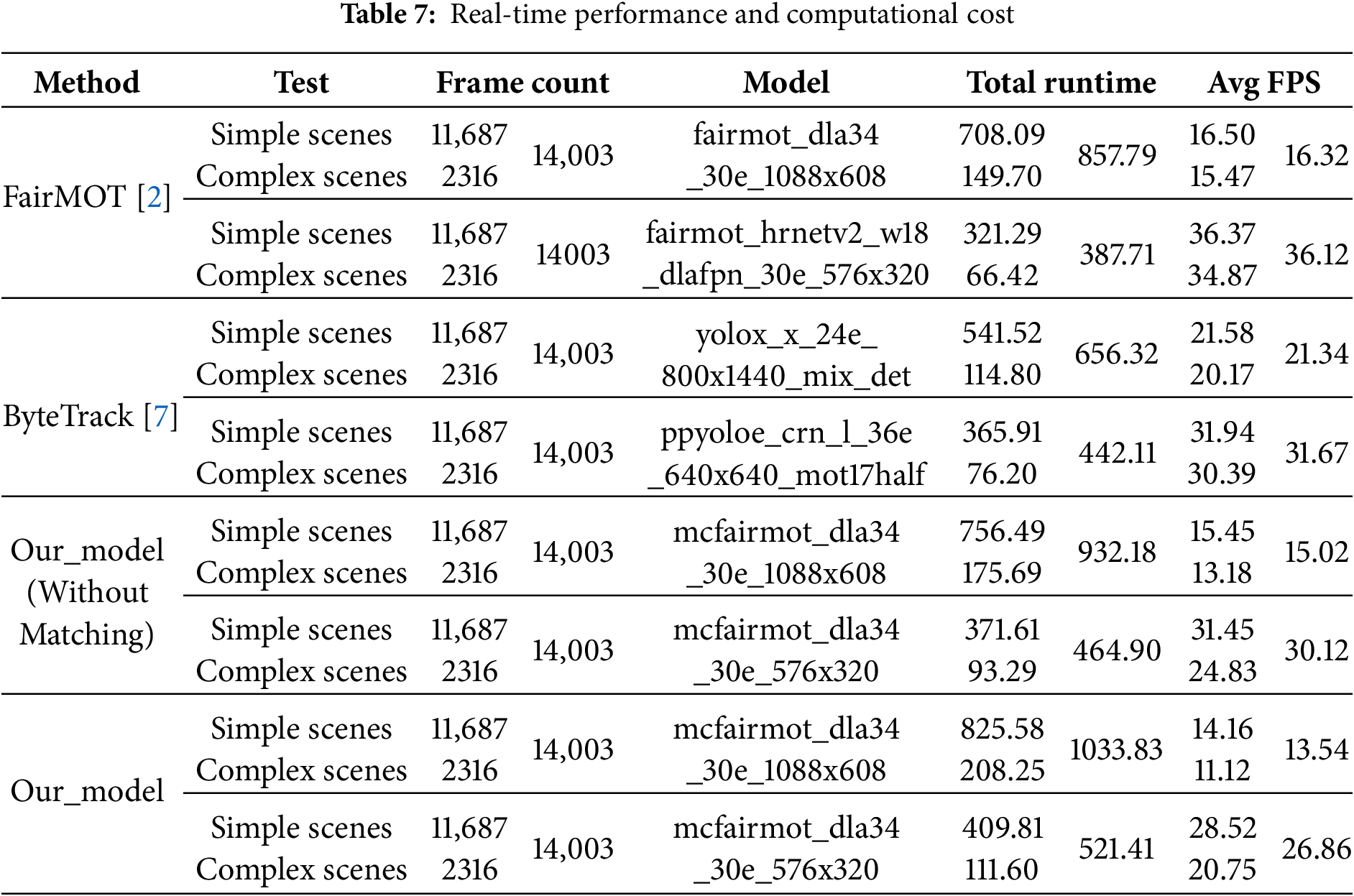

4.5 Real-Time Performance and Computational Cost Analysis

To evaluate the practical deployment costs of the proposed method, we conducted comparative experiments between Our_model and two representative tracking models: FairMOT (a JDE-based approach) and ByteTrack (an SDE-based approach). The evaluation was performed on the Chokepoint_Face_Pedestrian_Track dataset, consisting of 12 video sequences (9 simple scenes and 3 complex scenes). For each method, we tested both large-resolution and small-resolution model variants. Each video sequence was processed three times, with the total runtime calculated as the average across these trials.

We recorded two key metrics:

(1) Total runtime across all video sequences, including all computational overhead (system initialization, model loading, parameter initialization, data loading, preprocessing, model inference, post-processing, and result output)

(2) Average FPS, computed across all frames (including frames without targets)

For ablation analysis, Our_model (Without Face-Pedestrian Matching) refers to a modified version where the cross-category dynamic binding module was removed, retaining only the trained McFairmot model for separate face and pedestrian tracking.

Experimental Hardware Configuration:

CPU: Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-14700KF

GPU: NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 Ti (16GB VRAM)

System Memory: 48GB RAM

The comparative results (total runtime, average FPS, and performance across different scene types) are summarized in Table 7.

This study evaluates the real-time deployment performance of Our_model against representative tracking models (FairMOT and ByteTrack) on the Chokepoint_Face_Pedestrian_Track dataset. As shown in Table 7, the key results are as follows: With the small-resolution model (576

Further analysis reveals that our model’s unique cross-category dynamic binding module incurs quantifiable computational overhead. When this module is removed (denoted as Our_model (without matching)), the small-resolution model’s speed increases to 30.12 FPS (approximately 10.4% improvement), indicating that this feature currently contributes around 10% additional computational load. Compared to FairMOT’s small-resolution model at 36.12 FPS, Our_model (without matching) exhibits a 16.7% speed reduction. Notably, scene complexity significantly impacts Our_model’s performance (with frame rates dropping by approximately 27.2% from simple to complex scenes), a more pronounced decline than FairMOT’s 3.5% reduction, suggesting potential for improving algorithmic robustness in challenging environments. In summary, Our_model achieves its critical cross-category face-pedestrian tracking capability at a controlled speed cost (maintaining real-time performance with small-resolution inputs), demonstrating a reasonable trade-off between functional richness and computational expense. Excluding system initialization, model loading, and other overheads, its actual frame rate potential retains room for further optimization.

This study systematically addresses the challenge of multi-object tracking in complex occlusion scenarios by proposing an innovative solution based on joint face-pedestrian feature modeling. The developed cross-category dynamic binding framework and multi-modal joint matching metric system effectively overcome the performance limitations of conventional single-modality tracking methods in challenging scenarios involving occlusions and viewpoint variations. Experimental validation demonstrates that in face-pedestrian matching tasks, the proposed spatio-temporal-appearance joint constraint mechanism achieves up to 43 percentage points improvement in cross-category matching F1 AUC compared to certain conventional methods. Notably, ablation studies reveal that the IoA-IoU joint metric contributes 13.7% of the F1 AUC gain, while the dynamic threshold adjustment mechanism reduces IDs by 4.3% in complex scenes. In object tracking experiments, the dual matching strategy combined with dynamic threshold adjustment simultaneously improves both IDF1 and MOTA metrics compared to the baseline model, with IDF1 reaching 85.1825% in mixed scenarios, verifying the effectiveness of the cross-category identity correction mechanism. The computational efficiency analysis reveals that Our_model (without matching) exhibits a 16.7% FPS reduction compared to FairMOT’s single-category tracking, with the cross-category dynamic binding module introducing approximately 10% additional computational overhead. Nevertheless, Our_model maintains near-real-time performance with small-resolution inputs, achieving its crucial cross-category face-pedestrian tracking capability at controlled speed costs. These results provide practical technical support for intelligent surveillance and cross-camera tracking applications, demonstrating particular value for continuous identity verification in crowded areas. Future research will focus on optimizing the cross-category feature extraction network and exploring multi-dimensional feature fusionmechanisms to address more extreme occlusion scenarios.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the confidential research grant No. a8317.

Author Contributions: Qin Hu conceived the research, designed the study framework, collected the data, conducted the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. Hongshan Kong performed the data analysis and interpretation, as well as revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wojke N, Bewley A, Paulus D. Simple online and realtime tracking with a deep association metric. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2017 Sep 17–20; Beijing, China: IEEE. p. 3645–9. [Google Scholar]

2. Zhang Y, Wang C, Wang X, Zeng W, Liu W. Fairmot: on the fairness of detection and re-identification in multiple object tracking. Int J Comput Vis. 2021;129(11):3069–87. doi:10.1007/s11263-021-01513-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hu Y, Niu A, Sun J, Zhu Y, Yan Q, Dong W, et al. Dynamic center point learning for multiple object tracking under Severe occlusions. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;300(1–2):112130. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.112130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hassan S, Mujtaba G, Rajput A, Fatima N. Multi-object tracking: a systematic literature review. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(14):43439–92. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-17297-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Barquero G, Hupont I, Fernández Tena C. Rank-based verification for long-term face tracking in crowded scenes. IEEE Trans Biomet Behav Identity Sci. 2021;3(4):495–505. doi:10.1109/tbiom.2021.3099568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Bewley A, Ge Z, Ott L, Ramos F, Upcroft B. Simple online and realtime tracking. In: 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2016 Sep 25–28; Phoenix, AZ, USA. New York: IEEE; 2016. p. 3464–8. [Google Scholar]

7. Zhang Y, Sun P, Jiang Y, Yu D, Weng F, Yuan Z, et al. Bytetrack: multi-object tracking by associating every detection box. In: Computer Vision—ECCV 2022. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2022. p. 1–21 doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-20047-2_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Aharon N, Orfaig R, Bobrovsky BZ. Bot-sort: robust associations multi-pedestrian tracking. arXiv:2206.14651. 2022. [Google Scholar]

9. Peng J, Wang C, Wan F, Wu Y, Wang Y, Tai Y, et al. Chained-tracker: chaining paired attentive regression results for end-to-end joint multiple-object detection and tracking. In: Computer Vision–ECCV 2020. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 145–61. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-58548-8_9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Voigtlaender P, Krause M, Osep A, Luiten J, Sekar BBG, Geiger A, et al. MOTS: multi-object tracking and segmentation. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. New York: IEEE; 2019. p. 7934–43. [Google Scholar]

11. Xu Z, Zhang W, Tan X, Yang W, Huang H, Wen S, et al. Segment as points for efficient online multi-object tracking and segmentation. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference; 2020 Aug 23–28; Glasgow, UK. p. 264–81. [Google Scholar]

12. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2017;30:5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

13. Sun P, Cao J, Jiang Y, Zhang R, Xie E, Yuan Z, et al. Transtrack: multiple object tracking with transformer. arXiv:2012.15460. 2020. [Google Scholar]

14. Meinhardt T, Kirillov A, Leal-Taixé L, Feichtenhofer C. TrackFormer: multi-object tracking with transformers. In: 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. New York: IEEE; 2022. p. 8834–44. [Google Scholar]

15. Cao J, Pang J, Weng X, Khirodkar R, Kitani K. Observation-centric SORT: rethinking SORT for robust multi-object tracking. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. New York: IEEE; 2023. p. 9686–96. [Google Scholar]

16. Shi C, Li SC, Li L. Research on face detection and tracking algorithm based on MTCNN and improved KCF. In: Chinese. In: Proceedings of the 7th China Command and Control Conference. Beijing, China; 2019. [Google Scholar]

17. Lin ZB, Huang ZQ, Yan LM. Research on face detection and tracking algorithm Based on RetinaFace and KCF. Chin Electron Qual. 2021;9:59–64. [Google Scholar]

18. Qi D, Tan W, Yao Q, Liu J. YOLO5Face: why reinventing a face detector. In: Computer Vision–ECCV 2022 Workshops. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2023. p. 228–44. [Google Scholar]

19. Jöchl R, Uhl A. FaceSORT: a multi-face tracking method based on biometric and appearance features. arXiv:2501.11741. 2025. [Google Scholar]

20. Stewart R, Andriluka M, Ng AY. End-to-end people detection in crowded scenes. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. New York: IEEE; 2016. p. 2325–33. [Google Scholar]

21. Sundararaman R, De Almeida Braga C, Marchand E, Pettre J. Tracking pedestrian heads in dense crowd. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 3865–75. [Google Scholar]

22. Sun K, Wang X, Liu S, Zhao Q, Huang G, Liu C. Toward pedestrian head tracking: a benchmark dataset and an information fusion network. arXiv:2408.05877. 2024. [Google Scholar]

23. Sharma N, Dhiman C, Indu S. Pedestrian intention prediction for autonomous vehicles: a comprehensive survey. Neurocomputing. 2022;508(5):120–52. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2022.07.085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Huang X, Cai XD, Hu YL, Cao Y, Liu YZ. Target dynamic identification method based on feature fusion. Chin Video Eng. 2020;44(6):6–10,38. [Google Scholar]

25. Jin Li Y. Research on cross-camera target recognition and tracking method based on face and pedestrian features [Ph.D. dissertation]. Beijing, China: People’s Public Security University of China; 2022. [Google Scholar]

26. Wu Y, Lim J, Yang MH. Online object tracking: a benchmark. In: 2013 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2013 Jun 23–28; Portland, OR, USA. New York: IEEE; 2013. p. 2411–8. [Google Scholar]

27. Wu Y, Lim J, Yang M-H. Object tracking benchmark. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2015;37(9):1834–48. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2014.2388226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Kristan M, Matas J, Leonardis A, Felsberg M, Pflugfelder R, Kamarainen JK, et al. The seventh visual object tracking VOT2019 challenge results. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshop (ICCVW). Seoul, Republic of Korea; 2019. p. 2206–41. [Google Scholar]

29. Kristan M, Leonardis A, Matas J, Felsberg M, Pflugfelder R, Kämäräinen JK, et al. The eighth visual object tracking VOT2020 challenge results. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020 Workshops; 2020 Aug 23–28; Glasgow, UK. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 547–601. [Google Scholar]

30. Huang L, Zhao X, Huang K. Got-10k: a large high-diversity benchmark for generic object tracking in the wild. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2019;43(5):1562–77. doi:10.1109/tpami.2019.2957464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Fan H, Lin L, Yang F, Chu P, Deng G, Yu S, et al. LaSOT: a high-quality benchmark for large-scale single object tracking. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. New York: IEEE; 2019. p. 5369–78. [Google Scholar]

32. Leal-Taixé L, Milan A, Reid I, Roth S, Schindler K. Motchallenge 2015: towards a benchmark for multi-target tracking. arXiv:1504.01942. 2015. [Google Scholar]

33. Milan A, Leal-Taixé L, Reid I, Roth S, Schindler K. MOT16: a benchmark for multi-object tracking. arXiv:1603.00831. 2016. [Google Scholar]

34. Dendorfer P, Rezatofighi H, Milan A, Shi J, Cremers D, Reid I, et al. Mot20: a benchmark for multi object tracking in crowded scenes. arXiv:2003.09003. 2020. [Google Scholar]

35. Weber M, Xie J, Collins M, Zhu Y, Voigtlaender P, Adam H, et al. Step: segmenting and tracking every pixel. arXiv:2102.11859. 2021. [Google Scholar]

36. Voigtlaender P, Luo L, Yuan C, Jiang Y, Leibe B. Reducing the annotation effort for video object segmentation datasets. In: 2021 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2021 Jan 3–8; Waikoloa, HI, USA. New York: IEEE; 2021. p. 3059–68. [Google Scholar]

37. Lin Y, Cheng S, Shen J, Pantic M. MobiFace: a novel dataset for mobile face tracking in the wild. In: 2019 14th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2019); 2019 May 14–18; Lille, France: IEEE; 2019. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

38. Wong Y, Chen S, Mau S, Sanderson C, Lovell BC. Patch-based probabilistic image quality assessment for face selection and improved video-based face recognition. In: CVPR 2011 WORKSHOPS; 2011 Jun 20–25; Colorado Springs, CO, USA. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2011. p. 74–81. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools