Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

DRL-Based Cross-Regional Computation Offloading Algorithm

1 School of Information Science and Engineering, Shenyang Ligong University, Shenyang, 110159, China

2 Shen Kan Engineering and Technology Corporation, MCC., Shenyang, 110015, China

* Corresponding Author: Bo Qian. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069108

Received 15 June 2025; Accepted 19 August 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

In the field of edge computing, achieving low-latency computational task offloading with limited resources is a critical research challenge, particularly in resource-constrained and latency-sensitive vehicular network environments where rapid response is mandatory for safety-critical applications. In scenarios where edge servers are sparsely deployed, the lack of coordination and information sharing often leads to load imbalance, thereby increasing system latency. Furthermore, in regions without edge server coverage, tasks must be processed locally, which further exacerbates latency issues. To address these challenges, we propose a novel and efficient Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL)-based approach aimed at minimizing average task latency. The proposed method incorporates three offloading strategies: local computation, direct offloading to the edge server in local region, and device-to-device (D2D)-assisted offloading to edge servers in other regions. We formulate the task offloading process as a complex latency minimization optimization problem. To solve it, we propose an advanced algorithm based on the Dueling Double Deep Q-Network (D3QN) architecture and incorporating the Prioritized Experience Replay (PER) mechanism. Experimental results demonstrate that, compared with existing offloading algorithms, the proposed method significantly reduces average task latency, enhances user experience, and offers an effective strategy for latency optimization in future edge computing systems under dynamic workloads.Keywords

Over the past few decades, with the rapid development of advanced communication technologies such as 5G, there has been a clear trend toward intelligent development of vehicular equipment, accompanied by a continuous increase in the number of connected vehicular network devices, generating massive amounts of data. This exponential growth in data volume has imposed higher demands on the processing capabilities of Internet of Vehicles (IoV) devices. As cloud computing can provide centralized computing power and storage capabilities through remote servers, Mobile Cloud Computing (MCC) can partially compensate for the computational limitations of terminal devices [1]. However, latency issues persist in transmitting to these distant servers. In 2014, the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) introduced Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) technology, which deploys data processing tasks closer to the data source, significantly reducing network latency and optimizing bandwidth usage [2], thereby greatly enhancing service efficiency and user experience [3].

Although edge computing provides optimized computational resources for vehicular terminals, the diversity and wide geographic distribution of edge environments present significant challenges for efficient resource allocation. In particular, in regions with sparse edge server deployment, the lack of a unified coordination framework leads to inefficient resource utilization and load imbalance. Especially in areas completely devoid of edge coverage, tasks are forced to be processed locally, further exacerbating latency issues. Additionally, the dynamic nature of network conditions and the diversity of task types significantly increase the complexity of the offloading process. These heterogeneity and dynamic features necessitate that offloading strategies possess both cross-regional coordination capabilities and dynamic adaptability to ensure low-latency and high-efficiency operational requirements, which is particularly critical for the real-time response of safety-critical applications.

Given the challenges mentioned above, traditional distributed algorithms may struggle to achieve optimization, especially in dynamically changing network environments. However, Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) [4] can provide a powerful solution by learning optimal behavior strategies to dynamically adjust computation offloading decisions.

Building on this technical advantage, this study deeply integrates the DRL framework with cross-region offloading scenarios, proposing a DRL-based Cross-Region Task Offloading Method aimed at reducing the average task offloading latency of the system in dynamic environments. The proposed method integrates three offloading strategies: local computation, direct offloading to the edge server in local region, and Device-to-Device (D2D) [5] assisted offloading to edge servers in other regions. We formulate the task offloading problem as an optimization problem aiming to minimize the average task offloading latency of the system. To address this problem, we design an algorithm based on the Dueling Double Deep Q-Network (D3QN) architecture and incorporating the Prioritized Experience Replay (PER) mechanism (P-D3QN). Leveraging the technical advantages of DRL, we can dynamically select optimal offloading strategies based on real-time network conditions and task characteristics, thereby effectively reducing the average task processing latency of the system.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

1. For the vehicular network system model, we design a task offloading strategy that aims to minimize the average task latency across the system. The task offloading process is formulated as an optimization problem, considering three offloading approaches: local computation, direct offloading to the edge server in local region, and D2D assisted offloading to edge servers in other regions, with the objective of reducing overall offloading latency.

2. We transform the proposed optimization problem into an offloading decision-making problem under dynamic environments. By modeling the offloading process as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) and defining a latency-aware reward function, we aim to minimize offloading latency.

3. The proposed algorithm based on P-D3QN effectively solves this optimization problem. The algorithm enables efficient and rapid determination of optimal offloading strategies according to different tasks, thereby significantly enhancing overall system performance.

4. Extensive simulations are conducted to evaluate the convergence behavior of the proposed algorithm. Moreover, we assess the proposed method in terms of average task latency and compare it with existing baseline approaches. The results demonstrate the superiority of the proposed approach in reducing system latency.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. The related work is introduced in Section 2. System modeling and problem formulation are presented in Section 3. In Section 4, we transform the optimization problem into an MDP model and propose an algorithm based on P-D3QN. The simulation results are discussed in Section 5. The Section 6 concludes the paper.

In the field of edge computing offloading, existing research has primarily focused on optimizing task scheduling and resource allocation to reduce processing latency and improve resource utilization. However, with the expansion of network scale and the increasing complexity of tasks, edge computing environments have become highly dynamic and heterogeneous. The uncertainty in the distribution of terminal devices, task types, computational demands, and network conditions renders traditional offloading strategies insufficient to adapt to such complex and evolving scenarios. Therefore, designing an efficient and flexible task offloading algorithm that can operate effectively in dynamic and heterogeneous edge environments has become a critical and challenging research problem.

To optimize the performance of edge computing offloading, researchers have proposed a variety of approaches from different perspectives.

In some studies, game theory and optimization theory have been widely applied to address the task offloading problem. For instance, the authors in [6] adopted a resource competition game perspective, focusing on the utilization of idle devices and user self-interested behavior in dynamic environments. By employing potential game theory, they proved the existence of a Nash equilibrium and designed a lightweight algorithm to assist users in determining optimal offloading strategies. Similarly, the interaction between cloud service providers and edge server owners was modeled as a Stackelberg game in [7]. By determining optimal payment schemes and computation offloading strategies, the model aimed to maximize individual utility while mitigating base station overload. The authors in [8] proposed a non-destructive task reconstruction algorithm and solved it using convex optimization theory to maximize offloading benefits.

Other studies have explored heuristic-based approaches. For example, the authors in [9] proposed an event-triggered dynamic task allocation algorithm that integrates linear programming and binary particle swarm optimization. This method effectively balances multiple constraints—such as service delay, quality degradation, and edge server capacity—and enhances overall system performance. In a similar vein, the authors in [10,11] employed genetic algorithms and greedy algorithms, respectively, to optimize task offloading decisions. The authors in [12] transformed the computation offloading problem into an integer linear programming problem to optimize offloading overhead.

Existing methods often exhibit limited real-time responsiveness and adaptability in highly dynamic edge computing environments. For example, approaches based on game theory and optimization frameworks typically rely on strong assumptions, making them less effective in coping with rapid changes in network conditions, device workloads, and task demands. This can lead to increased latency in offloading decisions. Furthermore, most existing studies primarily focus on task offloading within localized regions, without fully addressing the challenges posed by cross-regional scenarios—such as insufficient edge server coverage and increased communication distance—which introduce additional latency and further complicate the offloading process.

In recent years, DRL has emerged as a prominent research focus in the field of computation offloading due to its strong adaptability and generalization capabilities in dynamic environments. By continuously interacting with the environment and learning from historical data, DRL can dynamically adjust offloading strategies, demonstrating enhanced flexibility and responsiveness in complex and rapidly changing edge computing scenarios. For instance, the authors in [13] modeled the computation offloading problem as a partially observable Markov decision process (POMDP), and incorporated game-theoretic concepts and Nash equilibrium to design an efficient decision-making mechanism based on policy gradient DRL methods. Similarly, the computation offloading process in heterogeneous edge computing environments was formulated as a long-term performance optimization problem with multiple objectives and constraints, which was solved using the Asynchronous Advantage Actor-Critic (A3C) algorithm for policy search [14]. However, existing DRL-based approaches still have limitations, as they rarely consider scenarios with sparsely distributed or insufficiently covered edge servers.

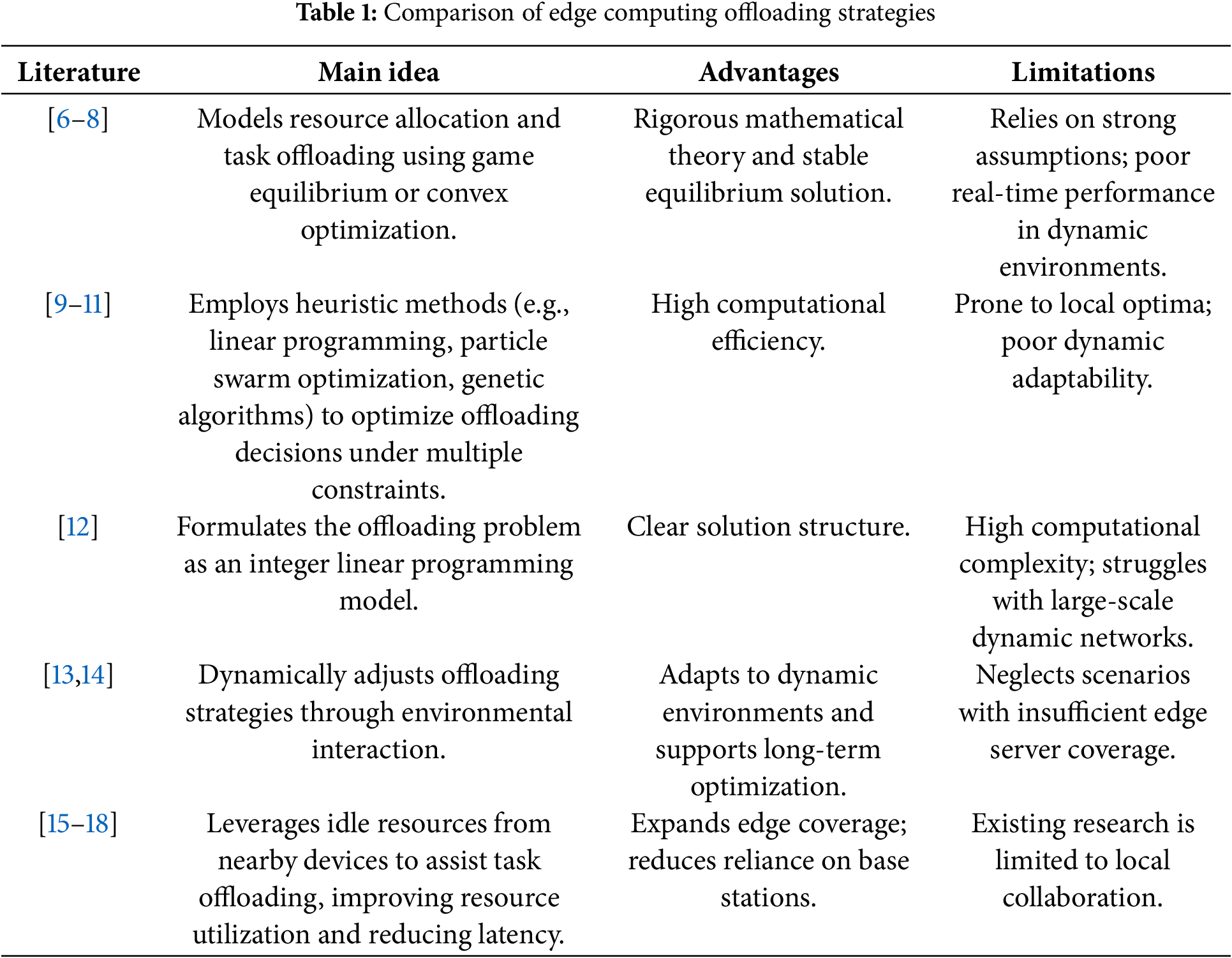

Meanwhile, D2D communication technology, as an innovative communication paradigm, offers new opportunities for computation offloading in edge computing environments. A system framework integrating D2D communication with MEC was proposed, wherein resource-constrained devices can offload their computation-intensive tasks to one or more idle neighboring devices, thereby improving resource utilization and reducing task execution latency [15]. Similarly, the authors in [16] introduced a D2D-based service sharing approach that enables users with insufficient local processing capabilities to acquire service applications from nearby qualified peers, allowing for partial local task execution. Furthermore, the study in [17,18] also employed D2D communication for task distribution, further demonstrating the potential of D2D in edge computing offloading scenarios. However, most existing studies focus on task collaboration among locally adjacent devices, without fully exploring the potential of cross-regional D2D communication. This limitation leads to low resource utilization in areas with insufficient edge server coverage. Moreover, the inherent dynamics of D2D networks and the instability of peer-to-peer connections pose additional challenges, making traditional offloading strategies less effective in such complex network environments. These challenges highlight the urgent need for an innovative offloading solution that combines the advantages of D2D communication with intelligent decision-making techniques to enable more efficient and flexible cross-region computation offloading. A comparative analysis of major computation offloading schemes is presented in Table 1.

To address these challenges, this study proposes a DRL-based cross-region computation offloading algorithm that incorporates D2D communication to mitigate the problem of insufficient edge server coverage. In the proposed algorithm, DRL continuously interacts with the environment to collect real-time information on network conditions, device load, and task requirements, enabling dynamic adjustment of offloading decisions. Meanwhile, the integration of D2D communication allows terminal vehicles to collaborate with neighboring devices and offload computational tasks to edge servers located in other regions, thereby enhancing the utilization of available resources. By leveraging this innovative strategy, the proposed algorithm not only addresses the challenge of limited edge server coverage in certain areas but also significantly reduces overall system latency, achieving intelligent and efficient cross-region computation offloading.

3 System Model and Problem Formulation

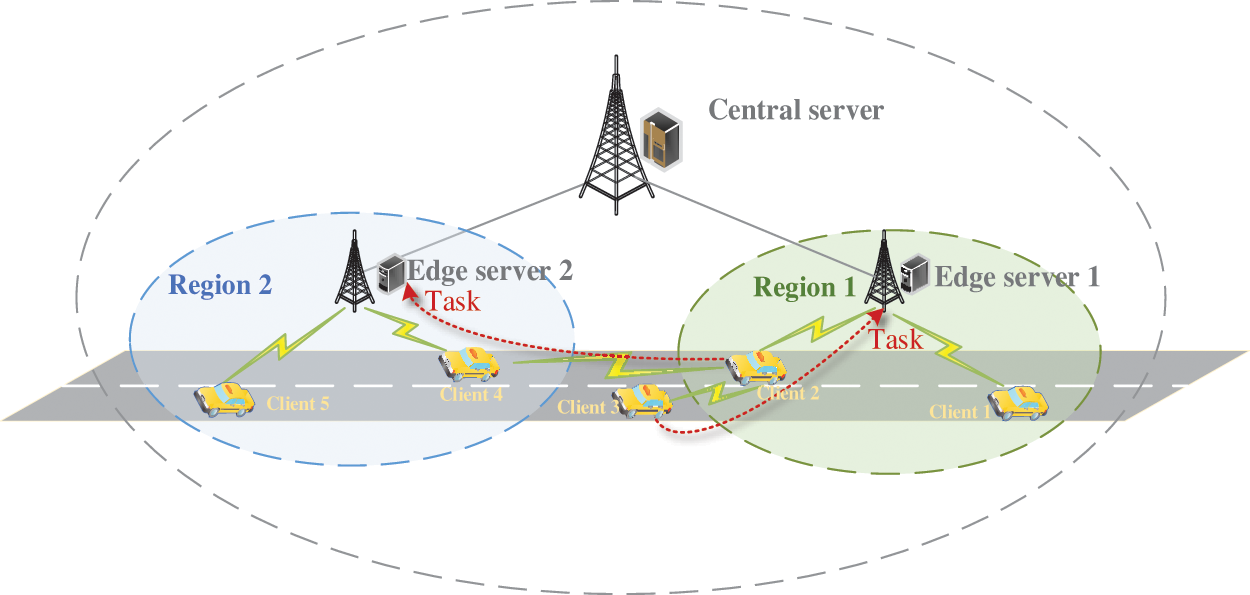

To investigate the task offloading latency minimization problem in vehicular networks, this paper constructs a computational offloading system model for IoV, as illustrated in Fig. 1: the edge layer and the terminal layer. The edge layer consists of a central server and M edge servers. All edge servers are equipped with equivalent computational capacities and wireless communication capabilities, enabling them to provide effective computational offloading services to vehicular users within their coverage areas. The central server is positioned at the center of the system and is connected to the edge servers via high-speed optical fibers. Its primary role is to manage resource information of the whole network and to make offloading decisions based on this information.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of cross-regional edge offloading system

The terminal layer is composed of N terminal vehicles that are unevenly distributed across the system’s coverage area. Each vehicle has a computation-intensive task that needs to be processed. Terminal vehicles have the option either to process these tasks locally or to offload them to the edge server in local region. Additionally, the system supports D2D communication, allowing terminal vehicles to offload tasks to the edge servers located in other regions via D2D technology, thereby further reducing computational latency. As shown in Fig. 1,

Assume that the set of edge nodes is defined as

In the proposed system, the communication links between terminal vehicles and edge servers operate on different frequencies from the D2D links. Both links utilize Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiple Access (OFDMA) [19] technology for spectrum resource allocation, with strict orthogonal subcarrier isolation design effectively mitigating inter-channel interference, thereby enhancing the system's communication efficiency and stability.

According to Shanno’s formula [20], the data transmission rate from terminal vehicle

where

Similarly, the data transmission rate when terminal vehicle

where

In scenarios where the network conditions are poor, edge servers are busy, or when a terminal vehicle is far from an edge server and there are no other terminal vehicles nearby to act as relays, the terminal vehicle can opt to execute computational tasks locally. At time

3.3 Direct Edge Offloading Model

The edge computing delay comprises four parts: the uplink transmission delay when offloading tasks to the edge server, the queuing delay at the edge server, the computation delay needed to process the task at the edge server, and the downlink transmission delay when the results are sent back. Typically, since the amount of data sent back is small, this part of the transmission delay can often be omitted. Therefore, this model only considers the first three parts of the delay. Thus, at time

In the direct edge offloading model,

3.4 D2D-Assisted Offloading Model

When a terminal vehicle

In the D2D-assisted offloading model,

To minimize the average task delay, we construct an objective function as expressed by Eq. (9).

Within the environment for task offloading and computation decision-making, the variable

Constraints:

Binary Variables:

Channel Gain Constraints: For all operational of any vehicle

Offloading Decision: For each vehicle

Resource Utilization Constraints: The sum of resources used by all tasks at an edge server should not exceed its total available resources:

Distance Constraints 1: The distance from the terminal vehicle

Distance Constraints 2: The distance between the terminal vehicle

In MEC environments, task arrivals and network state variations can occur on a millisecond timescale, imposing stringent requirements on the real-time responsiveness of optimization algorithms. Traditional methods struggle to cope with such rapidly changing scenarios, such as linear programming and integer programming. Specifically, parameters like task loads at end devices and channel conditions are highly time-varying. To accommodate these fluctuations, conventional algorithms typically require re-solving the optimization problem from scratch, resulting in substantial computational delays that hinder real-time decision-making. Additionally, in complex and dynamic network environments, historical experiences often contain valuable insights that can guide future decisions. However, traditional optimization approaches lack learning capabilities and are therefore incapable of leveraging past data to improve performance over time.

In contrast, DRL combines the decision-making strengths of reinforcement learning with the representational power of deep neural networks, effectively addressing the limitations of traditional methods. DRL not only adapts to dynamic network conditions in real time but also manages high-dimensional state and action spaces, making it an efficient and flexible solution for task offloading and computational optimization. By continuously interacting with the environment, DRL agents can learn from historical offloading data and incrementally refine their policies, thereby enhancing system performance under uncertainty and variability.

Based on this analysis, we formulate the task offloading and computational optimization problem as an MDP model, transforming the original complex optimization into a sequential decision-making task. A DRL-based algorithm is then applied to derive the optimal offloading strategy. This approach not only supports real-time decision-making but also leverages historical data to provide an intelligent, adaptive solution for resource allocation and task scheduling in highly dynamic MEC environments.

4 DRL-Based Cross-Regional Computation Offloading Algorithm

4.1 Deep Reinforcement Learning Framework

This section solves the proposed optimization problem by applying DRL. First, we formulate the optimization problem as an MDP model. The three elements of the MDP model are the state space, action space, and reward function, specifically designed as follows.

State Space S: The optimization focus of this algorithm is latency, characterized by the volume of data of tasks awaiting execution by each terminal vehicle within the system and their computational intensity, which dynamically reflects real-time task load and network conditions to provide inputs for decision-making. Thus, the state of this system is defined as Eq. (16).

Action Space A: An action represents the offloading decision of a terminal vehicle, with the action at time slot

Reward Function: The core objective of the proposed algorithm is to assist mobile terminals in rapidly completing offloading tasks for various applications by selecting appropriate offloading modes, with the ultimate goal of minimizing the system-wide average task latency. Since the objective of reinforcement learning is to maximize cumulative rewards, the reward function is defined as the negative value of latency, as shown in Eq. (18). This design ensures the agent achieves latency minimization by pursuing higher rewards. Through exploring high-reward strategies, the agent gradually converges to the optimal offloading solution.

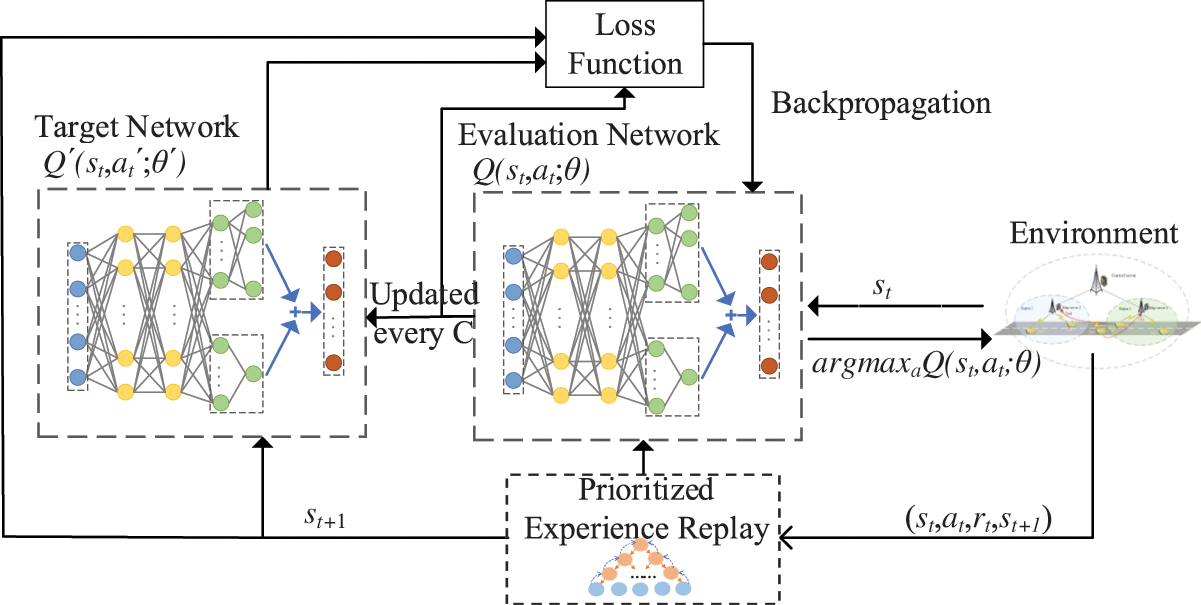

The P-D3QN algorithm framework is shown in Fig. 2. By constructing reasonable state space, action space and reward function, the agent can continuously interact with and learn from the environment, and obtain the optimal offloading strategy through iterative training with reward feedback mechanism. During training, the algorithm employs an

Figure 2: P-D3QN algorithm process

In this offloading scheme, the action space includes multiple offloading methods and multiple offloading targets to choose from. This multi-option design significantly expands the action space. It is worth noting that using average task latency as the optimization objective leads to relatively small Q-value ranges, where the differences between Q-values of different actions are also small. This characteristic exacerbates the inherent overestimation issue in conventional Deep Q-Networks (DQN).

To address these challenges, we propose a computational offloading algorithm based on the D3QN framework [22]. As shown in Fig. 2, D3QN introduces a dual-network architecture comprising an evaluation network and a target network, effectively decoupling action selection from target Q-value estimation. This architecture mitigates overestimation errors and improves training stability. Through the D3QN architecture, the system can more accurately evaluate the true value of each offloading option, enabling more effective delay-minimization decisions. Specifically, the evaluation network

Moreover, we integrate a PER mechanism [23] into the D3QN framework. By prioritizing the training of high-error experience samples, the decision accuracy can be improved, making it more adaptable to environmental dynamics. Given the dynamic nature of D2D link quality and the fluctuating loads on edge servers, this adaptability is crucial.

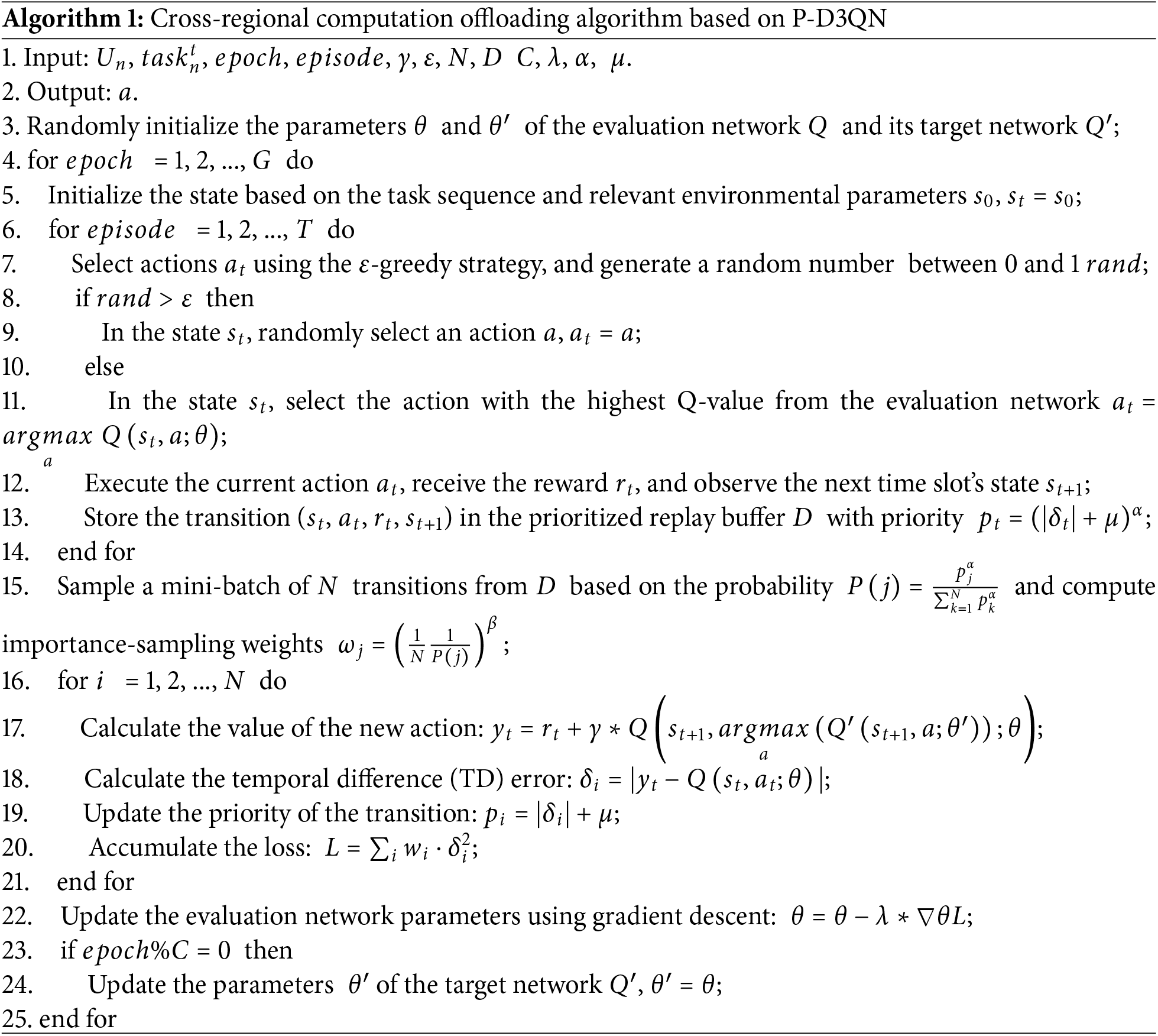

The pseudocode in Algorithm 1 outlines the core workflow of the algorithm. The inputs of the algorithm include the set of terminal vehicles

5 Simulation and Results Analysis

To validate the performance of the algorithm, this paper utilizes Python and conducts simulation tests under the PyTorch framework for the proposed algorithm. The simulation setup includes one central server, two edge servers, and several terminal vehicles. The effective communication range of the edge servers is set to 100 m, and the effective communication distance for D2D mode is also set at 100 m. The distance between the edge servers and the road is set at 10 meters, with mobile terminals randomly distributed within this area. The system parameters are configured as follows. The computational capacity of the edge server is set within the range of 4 to 10 GHz, and the computational capacity of the terminal device is fixed at 1 GHz. The communication bandwidth of the cellular link is set to 2 MHz, and the communication bandwidth of the D2D link is also set to 2 MHz. The transmit power of the terminal device is specified as 0.5 W, with a path loss factor of 4 and a noise power spectral density of −174 dBm/Hz. The task data volume size ranges from 100 to 900 KB, and the computational task intensity is defined within the range of 100 to 200 cycles per bit.

In the proposed task offloading scheme based on P-D3QN, the exploration rate is set to 0.05, the learning rate is configured as

5.2 Algorithm Convergence Analysis

This section verifies the convergence of the algorithm proposed in this paper by analyzing the changes in loss values and cumulative system rewards during the algorithm’s training process. The experimental setup ten terminal users who are randomly distributed within the system’s management range.

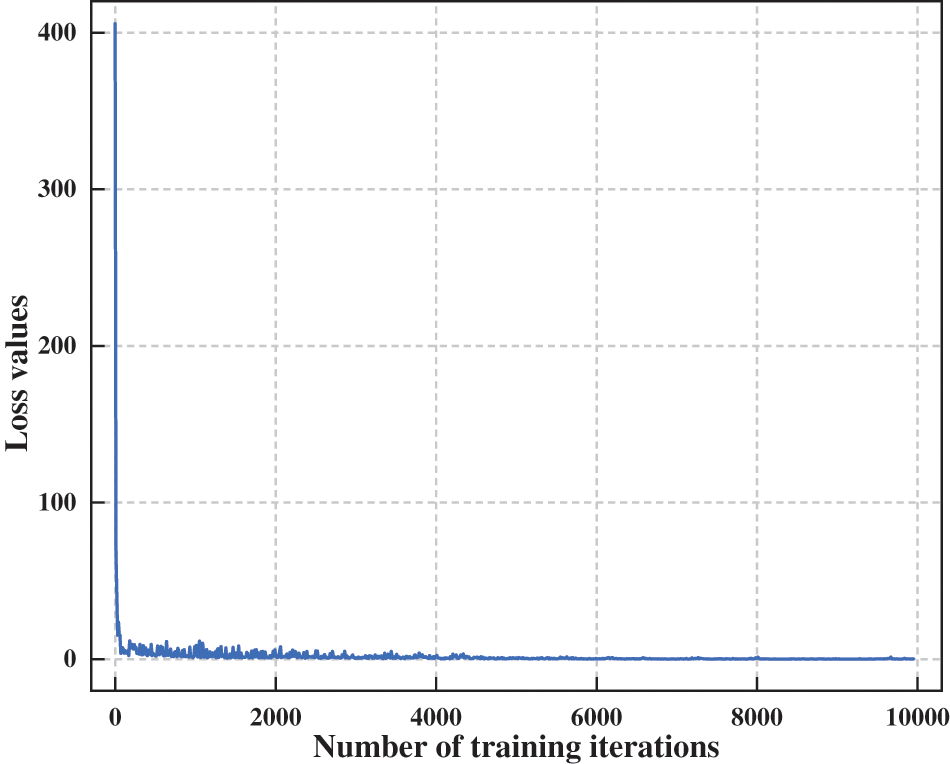

Fig. 3 illustrates the relationship between the algorithm's loss values and the number of training iterations. It is evident that the algorithm converges quickly during the early stages of training, with the loss value rapidly decreasing from 400 and approaching 0. This indicates that the algorithm’s design and parameter selection are effective, enabling it to quickly reduce errors and accelerate the learning process. As the number of training iterations approaches 4300, the loss values become stable, suggesting that the proposed algorithm begins to reach a state of convergence. There are no longer significant fluctuations, which is crucial for ensuring the reliability of the model in practical applications.

Figure 3: Variation of loss with training iterations

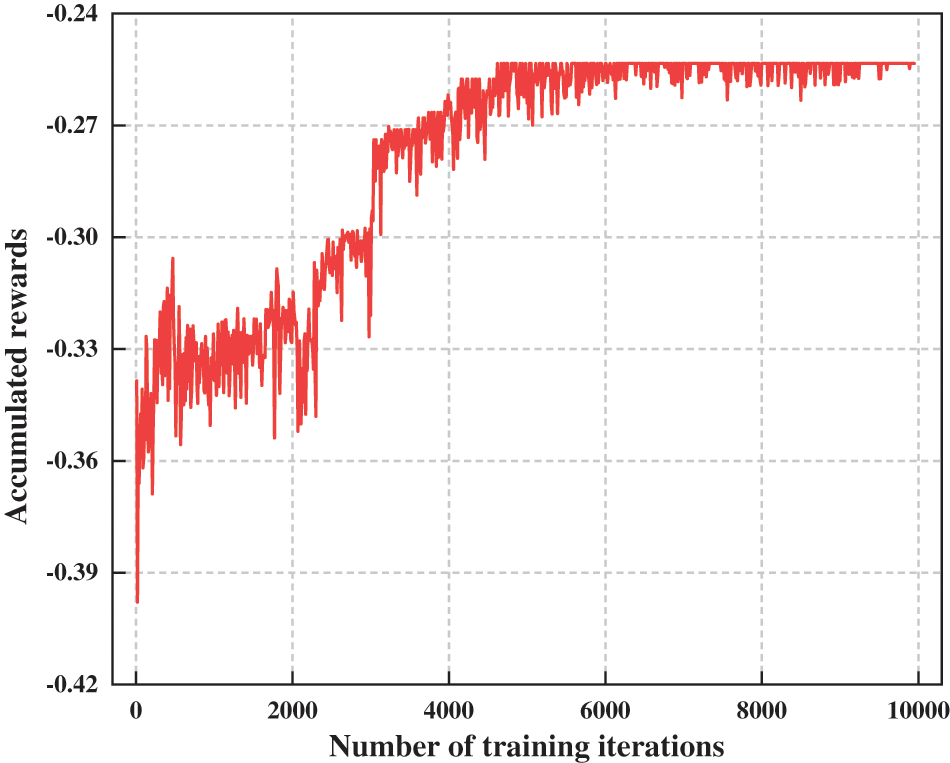

Fig. 4 shows the changes in the cumulative rewards as a function of training iterations. In the initial stage, since the algorithm makes decisions randomly, the accumulated rewards are small. As the number of training iterations increases, the cumulative rewards gradually increase, indicating that the algorithm is effectively solving problems and improving system performance through continuous learning and adjusting decision strategies. By the time the training count reaches 4300, the cumulative rewards reach their maximum value, and the algorithm has learned the optimal offloading strategy. The cumulative rewards fluctuate around this optimal point and gradually stabilize.

Figure 4: The variation of accumulated rewards with training frequency

To validate the effectiveness of the algorithm proposed in this paper, it is compared with four other offloading algorithms.

ND: Similar to the scheme in reference [24], it does not support D2D communication mode. Terminal users within the coverage of the edge server can offload tasks to that server, while users outside the coverage must perform computations locally.

DF: Supports D2D communication mode, where terminal users prioritize offloading tasks to the nearest edge server.

RC: Terminal users randomly choose their offloading destination, whether it be local computing or to a particular edge server.

LC: Does not support offloading services, and users can only compute locally.

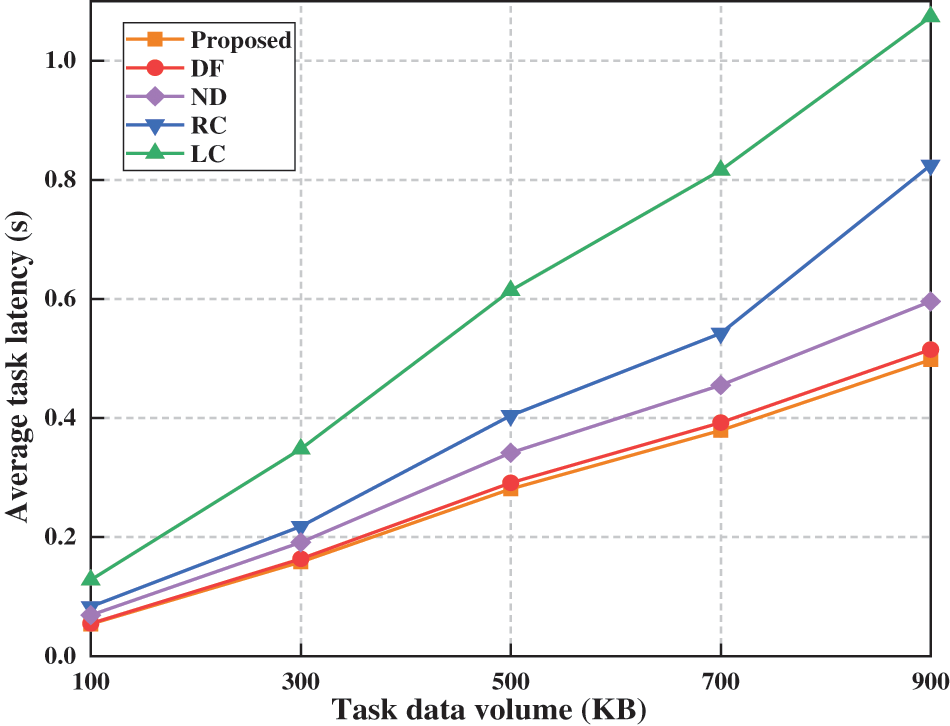

Fig. 5 shows the relationship between average task latency and task data volume when there are 10 terminal users and the computation frequency is 10 GHz. As task data volume increases, latency rises for all algorithms. The LC algorithm, relying solely on local computing, performs worst due to limited terminal capabilities, exhibiting the highest and fastest-growing latency. Our proposed algorithm possesses outstanding learning and exploration capabilities, allowing it to identify the optimal offloading strategy under certain constraints and minimize average task latency. Compared to DF and RC algorithms, the advantage of our proposed algorithm lies in its strong learning and optimization capabilities. While ND also has search capabilities, its lack of D2D communication restricts service coverage, making it inferior to both our method and even DF, which lacks search entirely.

Figure 5: Impact of task data volume on average task latency

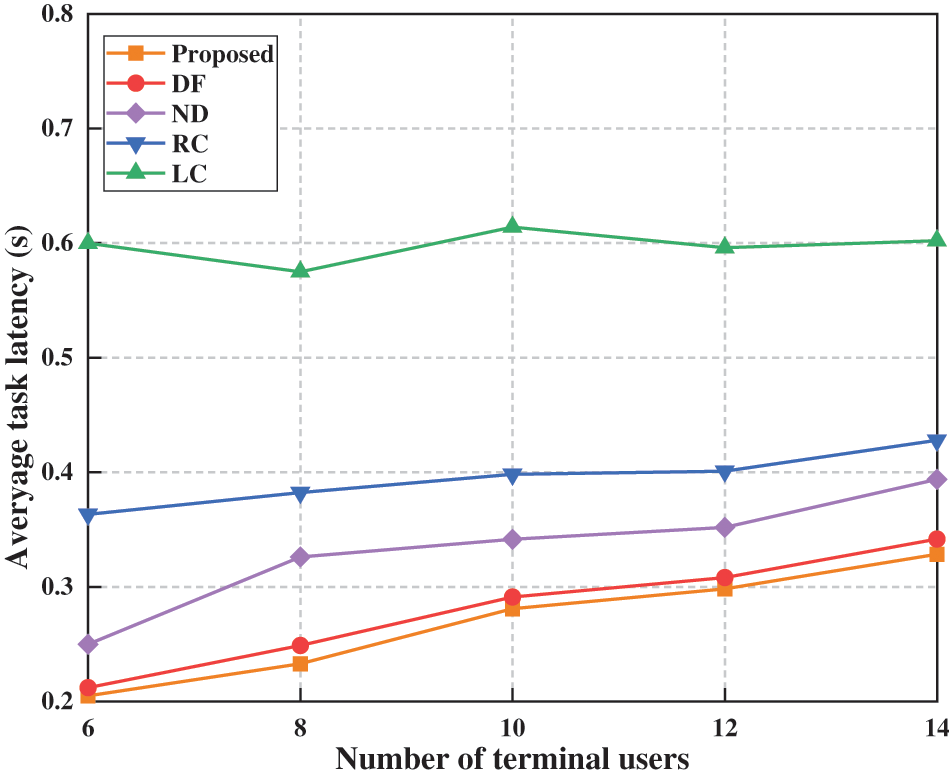

Fig. 6 shows the relationship between average task latency and the number of terminal users, given an average task data volume of 500 KB and an edge server computation frequency of 10 GHz. The results illustrate that as the number of terminal users increases, so does the number of tasks awaiting execution. Except for the LC algorithm, the average task latency of other algorithms exhibits an upward trend. As the LC algorithm does not compete for computing resources of edge servers and tasks are handled individually by users, its average task latency is almost unaffected by the increase in number of terminal users, though it has a high average task latency. The RC method performs slightly better than LC. Although the ND algorithm can search for optimal strategies, its lack of D2D offloading prevents it from serving users outside coverage areas. Thus, while ND outperforms RC, it still falls short of our proposed algorithm. The DF algorithm uses proximity-based offloading to maximize edge server resource utilization, but without cross-regional load balancing, its performance lags behind ours. Our algorithm achieves the lowest average task latency, demonstrating the best overall performance.

Figure 6: Impact of user numbers on average task latency

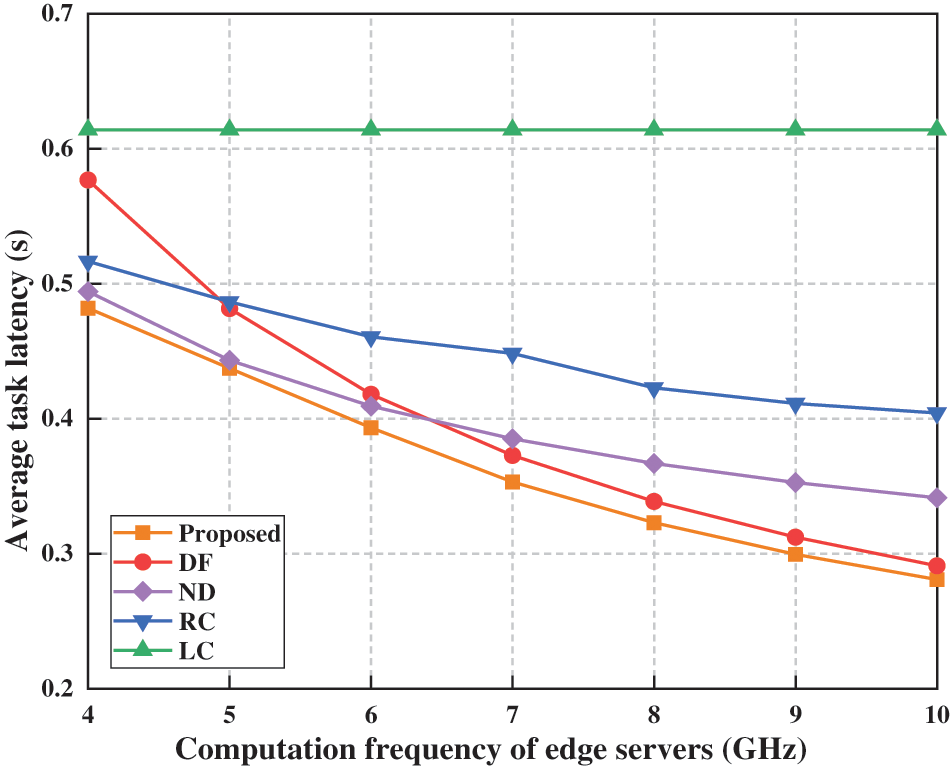

Fig. 7 displays the relationship between average task latency and the computation frequency of edge servers when there are 10 terminal users and the average task data volume is 500 KB. The graph reveals that, except for the LC algorithm, the average task latency of the other algorithms decreases as the computational power of the edge server increases. This reduction in latency occurs because an increase in computation frequency enables the edge server to provide more computational resources, subsequently shortening the processing time of tasks and reducing the overall average task latency. The LC algorithm, which does not utilize edge server resources, is unaffected by changes in the computation frequency of the edge server and exhibits the highest average task latency. When the computational frequency is at 4 GHz, due to the limited computing capacity of the edge server, the DF, which offloads all tasks to the nearest server, demonstrates a higher average task latency than both the RC and ND algorithms, and the advantage over the LC algorithm is not significant. However, as the computation frequency increases, the performance of the DF rapidly improves, surpassing the RC at 5 GHz and the ND at 7 GHz. The proposed algorithm dynamically adjusts its offloading strategies based on fluctuations in available computing resources, consistently outperforming the other algorithms.

Figure 7: Impact of MEC computing frequency on average task latency

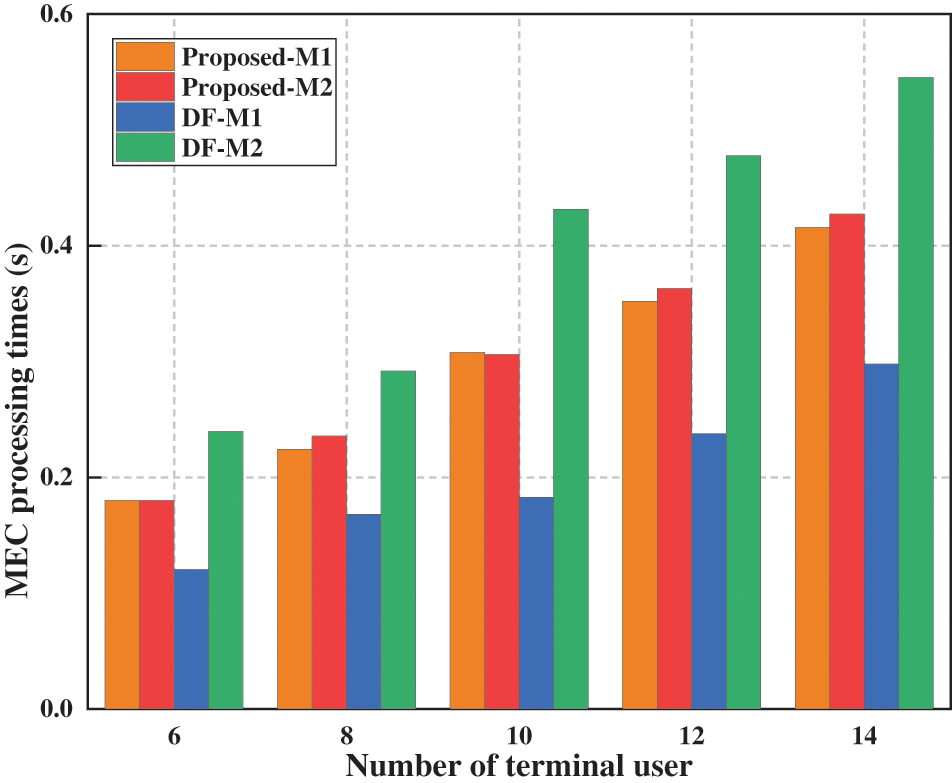

Fig. 8 illustrates the relationship between MEC processing times and the number of terminal users, given an average task data volume of 500 KB and an edge server computation frequency of 10 GHz. As the number of terminal users increases, the MEC processing time rises correspondingly due to the growing number of tasks that edge servers need to handle. Due to the uneven distribution of terminal users, different edge servers serve varying numbers of users. In the DF, where tasks are offloaded to the nearest edge server, a large number of tasks are offloaded to edge server M2, where they compete for computing resources, leading to long load times and increased queuing delays. Meanwhile, edge server M1 processes fewer tasks, resulting in a waste of computing resources. In contrast, the proposed algorithm achieves a more balanced processing time between edge servers M1 and M2. This is due to the algorithm's capability to offload computing tasks across regions, which balances the load across different edge servers and fully utilizes their computing resources, thereby effectively reducing the average task latency of the system.

Figure 8: Impact of the number of terminal user on MEC processing latency

From the analysis above, it can be seen that the algorithm our proposed significantly improves the overall performance of the edge computing environment compared to several other algorithms by implementing cross-regional task offloading. The key advantage of this algorithm is that it is not limited to offloading tasks to the physically nearest edge server; rather, it takes into account the current load and computing capacities of all available edge servers across the network, thus selecting the optimal server for task processing. This strategy optimizes resource allocation and significantly reduces task processing times, balances server loads, and improves system response times. Due to these performance enhancements, the algorithm our proposed is particularly suitable for use in environments with dense user bases and high service demands, such as large event venues or complex industrial applications.

This paper shows that the proposed algorithm significantly enhances edge computing by intelligently selecting different offloading modes to optimize system performance. Unlike traditional methods focused on proximity, our proposed algorithm considers server workloads and computational capacities, ensuring efficient task distribution without overloading any server. This leads to faster processing and better response times, especially in high-demand scenarios, making the algorithm our proposed a potentially robust solution for future edge computing enhancements. Although the proposed method demonstrates good performance under the given experimental conditions, there are still some limitations. For example, the study is validated only in environments with a limited number of regions and servers, and future work could expand to larger-scale networks and more complex scenarios.

Acknowledgement: We are grateful to all the colleagues and supporters during the writing of this paper. Special thanks to Ying Song, Yuanyuan Zhang, Xinyue Sun, and Meiran Li for their contributions to this paper. They provided valuable suggestions during the writing process, which helped improve the quality of the paper. We sincerely appreciate their selfless dedication and professional expertise, which were key factors in the successful completion of this research. We thank Kimberly Moravec, PhD, from Liwen Bianji (Edanz) (www.liwenbianji.cn/) for editing the structure of a draft of this manuscript.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62202215), Liaoning Province Applied Basic Research Program (Youth Special Project, 2023JH2/101600038), Shenyang Youth Science and Technology Innovation Talent Support Program (RC220458), Guangxuan Program of Shenyang Ligong University (SYLUGXRC202216), the Basic Research Special Funds for Undergraduate Universities in Liaoning Province (LJ212410144067), the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (2024-MS-113), and the science and technology funds from Liaoning Education Department (LJKZ0242).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Lincong Zhang; data collection: Yuqing Liu; analysis and interpretation of results: Kefeng Wei; draft manuscript preparation: Lincong Zhang, Yuqing Liu, Weinan Zhao and Bo Qian. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Jin X, Hua W, Wang Z, Chen Y. A survey of research on computation offloading in mobile cloud computing. Wirel Netw. 2022;28(4):1563–85. doi:10.1007/s11276-022-02920-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Taheri-abed S, Eftekhari Moghadam AM, Rezvani MH. Machine learning-based computation offloading in edge and fog: a systematic review. Clust Comput. 2023;26(5):3113–44. doi:10.1007/s10586-023-04100-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Sha K, Yang TA, Wei W, Davari S. A survey of edge computing-based designs for IoT security. Digit Commun Netw. 2020;6(2):195–202. doi:10.1016/j.dcan.2019.08.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ma G, Wang X, Hu M, Ouyang W, Chen X, Li Y. DRL-based computation offloading with queue stability for vehicular-cloud-assisted mobile edge computing systems. IEEE Trans Intell Veh. 2023;8(4):2797–809. doi:10.1109/TIV.2022.3225147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Gao X, Wang X, Qian Z. Probabilistic caching strategy and TinyML-based trajectory planning in UAV-assisted cellular IoT system. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(12):21227–38. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3360444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yang Y, Long C, Wu J, Peng S, Li B. D2D-enabled mobile-edge computation offloading for multiuser IoT network. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;8(16):12490–504. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2021.3068722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Liu Y, Xu C, Zhan Y, Liu Z, Guan J, Zhang H. Incentive mechanism for computation offloading using edge computing: a Stackelberg game approach. Comput Netw. 2017;129(5):399–409. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2017.03.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Feng C, Han P, Zhang X, Zhang Q, Zong Y, Liu Y, et al. Cost-minimized computation offloading of online multifunction services in collaborative edge-cloud networks. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manage. 2023;20(1):292–304. doi:10.1109/tnsm.2022.3201048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhu C, Tao J, Pastor G, Xiao Y, Ji Y, Zhou Q, et al. Folo: latency and quality optimized task allocation in vehicular fog computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019;6(3):4150–61. doi:10.1109/jiot.2018.2875520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Chakraborty S, Mazumdar K. Sustainable task offloading decision using genetic algorithm in sensor mobile edge computing. J King Saud Univ-Comput Inf Sci. 2022;34(4):1552–68. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2022.02.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wei F, Chen S, Zou W. A greedy algorithm for task offloading in mobile edge computing system. China Commun. 2018;15(11):149–57. doi:10.1109/cc.2018.8543056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Feng C, Han P, Zhang X, Zhang Q, Liu Y, Guo L. Dependency-aware task reconfiguration and offloading in multi-access edge cloud networks. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2024;23(10):9271–88. doi:10.1109/TMC.2024.3360978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhan Y, Guo S, Li P, Zhang J. A deep reinforcement learning based offloading game in edge computing. IEEE Trans Comput. 2020;69(6):883–93. doi:10.1109/TC.2020.2969148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Qi Q, Wang J, Ma Z, Sun H, Cao Y, Zhang L, et al. Knowledge-driven service offloading decision for vehicular edge computing: a deep reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2019;68(5):4192–203. doi:10.1109/TVT.2019.2894437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Li Y, Xu G, Ge J, Liu P, Fu X, Jin Z. Jointly optimizing helpers selection and resource allocation in D2D mobile edge computing, Seoul, Republic of Korea. In: 2020 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC); 2020 May 25–28, 2020; Seoul, Republic of Korea. doi:10.1109/wcnc45663.2020.9120538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zeng H, Li X, Bi S, Lin X. Delay-sensitive task offloading with D2D service-sharing in mobile edge computing networks. IEEE Wirel Commun Lett. 2022;11(3):607–11. doi:10.1109/LWC.2021.3138507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang X, Ye J, Lui JCS. Joint D2D collaboration and task offloading for edge computing: a mean field graph approach. In: 2021 IEEE/ACM 29th International Symposium on Quality of Service (IWQOS); 2021 Jun 25–28; Tokyo, Japan. doi:10.1109/IWQOS52092.2021.9521271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Jiang W, Feng D, Sun Y, Feng G, Wang Z, Xia XG. Joint computation offloading and resource allocation for D2D-assisted mobile edge computing. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2023;16(3):1949–63. doi:10.1109/TSC.2022.3190276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Nguyen PX, Tran DH, Onireti O, Tin PT, Nguyen SQ, Chatzinotas S, et al. Backscatter-assisted data offloading in OFDMA-based wireless-powered mobile edge computing for IoT networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;8(11):9233–43. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3057360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Luo Z, Dai X. Reinforcement learning-based computation offloading in edge computing: principles, methods. challenges. Alex Eng J. 2024;108(6):89–107. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2024.07.049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Tang Q, Li B, Yang HH, Li Y, He S, Yang K. Delay and load fairness optimization with queuing model in multi-AAV assisted MEC: a deep reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manage. 2025;22(2):1247–58. doi:10.1109/TNSM.2024.3520632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhong J, Chen X, Jiao L. A fair energy-efficient offloading scheme for heterogeneous fog-enabled IoT using D3QN. In: 2023 15th International Conference on Communication Software and Networks (ICCSN); 2023 Jul 21–23; Shenyang, China, p. 47–52. doi:10.1109/ICCSN57992.2023.10297384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Xu C, Zhang P, Yu H, Li Y. D3QN-based multi-priority computation offloading for time-sensitive and interference-limited industrial wireless networks. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2024;73(9):13682–93. doi:10.1109/TVT.2024.3387567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ma X, Zhou A, Zhang S, Wang S. Cooperative service caching and workload scheduling in mobile edge computing. In: IEEE INFOCOM 2020—IEEE Conference on Computer Communications; 2020 Jul 6–9; Toronto, ON, Canada, p. 2076–85. doi:10.1109/infocom41043.2020.9155455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools