Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Ponzi Scheme Detection for Smart Contracts Based on Oversampling

1 State Key Laboratory of Public Big Data, Guizhou University, Guiyang, 550025, China

2 College of Computer Science and Technology, Guizhou University, Guiyang, 550025, China

3 Computer College, Weifang University of Science and Technology, Weifang, 262700, China

* Corresponding Author: Yuling Chen. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069152

Received 16 June 2025; Accepted 25 August 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

As blockchain technology rapidly evolves, smart contracts have seen widespread adoption in financial transactions and beyond. However, the growing prevalence of malicious Ponzi scheme contracts presents serious security threats to blockchain ecosystems. Although numerous detection techniques have been proposed, existing methods suffer from significant limitations, such as class imbalance and insufficient modeling of transaction-related semantic features. To address these challenges, this paper proposes an oversampling-based detection framework for Ponzi smart contracts. We enhance the Adaptive Synthetic Sampling (ADASYN) algorithm by incorporating sample proximity to decision boundaries and ensuring realistic sample distributions. This enhancement facilitates the generation of high-quality minority class samples and effectively mitigates class imbalance. In addition, we design a Contract Transaction Graph (CTG) construction algorithm to preserve key transactional semantics through feature extraction from contract code. A graph neural network (GNN) is then applied for classification. This study employs a publicly available dataset from the XBlock platform, consisting of 318 verified Ponzi contracts and 6498 benign contracts. Sourced from real Ethereum deployments, the dataset reflects diverse application scenarios and captures the varied characteristics of Ponzi schemes. Experimental results demonstrate that our approach achieves an accuracy of 96%, a recall of 92%, and an F1-score of 94% in detecting Ponzi contracts, outperforming state-of-the-art methods.Keywords

As a decentralized technology, blockchain has gained global recognition for its unique transparency, immutability, and anonymity [1,2]. The innovative utilization of smart contract technology is propelling blockchain into new developmental stages across various industries, such as finance, healthcare, the Internet of Things (IoT), and edge computing (EC) [3]. Ethereum, as the preeminent blockchain platform for smart contracts, holds the second-largest market capitalization in the cryptocurrency domain, surpassed only by Bitcoin. By automatically executing predefined contractual terms, smart contracts significantly reduce the dependence of trusted third parties in transactions, establishing a solid foundation for the continued expansion of the blockchain in industries.

However, while smart contracts facilitate financial innovation, they simultaneously introduce novel avenues for financial fraud, with Ponzi schemes leveraging smart contract functionality emerging as a particularly salient concern. As a classic financial fraud model, Ponzi schemes were first organized and carried out by Charles Ponzi in the early 20th century. Their core operational mechanism relies on using funds from new investors to pay returns to earlier ones, creating a false appearance of profitability to lure more investors into the scheme [4]. In blockchain environments, the automated execution of smart contracts enhances the concealment and deceptiveness of Ponzi schemes. For instance, TRM Labs’ (2022) investigative report on illicit cryptocurrency ecosystems reveals that blockchain-based Ponzi schemes predominantly exploit investor psychology by advertising unrealistic returns and employing hierarchical referral-based profit structures [5]. Participants earn rewards not only through direct referrals but also via tiered gains based on subsequent investments by recruited members. Such mechanisms have drawn global participation, resulting in approximately a

Recent scholarly efforts in detecting smart contract-based Ponzi schemes have predominantly concentrated on feature extraction methodologies operating at the bytecode and opcode levels. However, these features often fail to comprehensively or accurately capture the intrinsic characteristics of Ponzi schemes. Existing approaches inadequately leverage the rich semantic and syntactic information embedded in high-level programming languages, as well as complex control and data dependencies, resulting in detection models that struggle to identify the core logic of such frauds. Additionally, the vast and rapidly growing number of smart contracts on Ethereum, combined with the extremely low proportion of Ponzi scheme contracts, exacerbates class imbalance issues. Although traditional oversampling methods such as Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling Technique (SMOTE) and Adaptive Synthetic Sampling (ADASYN) [9] can partially alleviate class imbalance, they often generate minority-class samples that cluster around existing instances. This approach neglects critical boundary samples, thereby reducing the model’s discriminative ability. Effectively identifying limited Ponzi scheme contracts within massive datasets remains an unresolved challenge. Thus, it is essential to employ data science methodologies to develop efficient and precise detection models, enabling the effective identification and prevention of Ponzi schemes in Ethereum smart contracts.

To address issues of class imbalance, single-source feature extraction, and incomplete representation of transaction semantics in smart contracts, we propose an oversampling-based detection method. First, we apply oversampling techniques to balance the dataset between normal and Ponzi scheme samples. Then, we construct transaction graphs to remove redundant information and capture complex transaction relationships within smart contracts. Finally, we employ graph neural networks for feature extraction and classification to accurately identify Ponzi schemes. Our main contributions include:

• An improved ADASYN algorithm addressing limitations in handling class imbalance by considering both the proximity of generated samples to decision boundaries and their distribution in feature space, enhancing the model’s ability to identify critical boundary samples.

• A novel Contract Transaction Graph (CTG) construction method that transforms contract source code into graphs, removes redundancy, and captures comprehensive transaction-related semantics of smart contracts.

• Through rigorous comparative experiments and comprehensive statistical analysis, the proposed method demonstrates substantial improvements in performance indicators such as accuracy, recall, and F-score compared to traditional methods.

The subsequent sections of this paper are structured as follows. Section 2 provides a review of related research, while Section 3 introduces fundamental concepts. In Section 4, we elaborate on the design of our detection methodology. Section 5 presents an experimental analysis of the proposed method. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and discusses future research directions.

Ethereum stands as the leading platform for building and executing smart contracts, offering many unique advantages. It provides a rich and powerful set of application programming interfaces, giving developers convenient tools to efficiently create complex smart contracts. Within the Ethereum blockchain ecosystem, programming languages like Solidity have been used to successfully develop and deploy a vast number of decentralized applications. These applications are implemented as smart contracts, significantly broadening the application scenarios of blockchain technology. The Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) plays a crucial role in enabling Ethereum’s Turing-complete computational capabilities, primarily responsible for executing smart contract bytecode. Upon a smart contract being invoked, the EVM systematically carries out the specified actions and stack operations as defined by the contract’s instructions. Throughout this process, the EVM interacts closely with storage to read, store, and update data. Smart contracts are self-executing programs deployed on blockchain networks, engineered to automatically enforce predefined contractual terms upon the fulfillment of specified conditions. Unlike traditional contracts that rely on third-party intermediaries for execution, smart contracts operate autonomously through deterministic code. This approach delivers substantial benefits in operational efficiency, transactional transparency, and cryptographic security. Once deployed on a blockchain, smart contracts persist indefinitely, with state modifications permitted only through their predefined functions. This immutability ensures a high degree of tamper resistance and operational reliability, making them particularly suitable for decentralized finance (DeFi), digital asset management, and supply chain traceability applications.

However, this has also spurred the emergence of numerous Ponzi scheme contracts, prompting extensive research efforts to address their detection. This section centers on discussing detection methods for Ponzi schemes, which can be broadly classified into three categories: bytecode-based features, opcode-based features, and transaction-based features.

Bytecode Features. Bartoletti et al. [10] proposed using the normalized Levenshtein distance (NLD) to measure contract similarity, which calculates the number of character modifications needed to transform one bytecode into another for identifying Ponzi schemes. This approach aids in detecting Ponzi schemes by quantifying character-level modifications between bytecode sequences. Fan et al. [11] adopted a distinct strategy: they enriched their dataset by analyzing decentralized applications (DApps) and trained detection models using an ordered boosting algorithm. Their model mapped the frequency distributions of various opcodes in smart Ponzi schemes, DApp Ponzi schemes, and non-Ponzi schemes. However, this single-feature frequency analysis has limitations, as it does not reveal the directional impact of feature values on the model. Zheng et al. [12] proposed extracting features from multi-dimensional perspectives, including bytecode, semantics, and developer information, and applied machine learning methods for Ponzi scheme detection. Nevertheless, bytecode features may vary across different compiler versions and often fail to capture the semantic logic of contracts. To achieve more comprehensive feature representation, Zhang et al. [13] integrated user transaction information and opcode frequencies while extracting bytecode features, then introduced an improved LightGBM-based method for identifying smart contract Ponzi schemes. This approach significantly enhanced both model training speed and detection performance.

Opcode Features. Trozze et al. [14] focused on the frequency distribution of opcodes in DeFi project token smart contracts to detect securities violations. However, such techniques are constrained by their sole reliance on opcode frequency distributions, thereby failing to comprehensively and precisely characterize Ponzi schemes. Peng and Xiao [15] developed an efficient automatic detection model for smart Ponzi schemes by leveraging opcode functionalities. They systematically modeled these functionalities to enable detection at the initial deployment phase of smart contracts. Wang and Huang [16] adopted the N-gram algorithm to extract more comprehensive opcode features and introduced adaptive synthetic sampling techniques to tackle class imbalance issues. They eventually used an AdaBoost classifier for detecting fraudulent contracts.

Transaction Features. Chen et al. [17] put forward a transaction data-driven approach, which improves detection capabilities by extracting six new behavioral features. However, their feature importance analysis only included one behavioral feature. At the same time, Jung et al. [18] used the trans2vec network embedding algorithm to construct transaction networks from datasets and adopted one-class SVM for phishing contract classification. Similarly, Wu et al. [19] created a transaction record dataset, applied trans2vec for transaction network construction, and classified fraudulent contracts through one-class support vector machine (SVM). Hu et al. [20] developed 14 time-series features based on contract activity patterns and trained a long short-term memory (LSTM) network to identify contract types. Jin et al. [21] introduced a heterogeneous feature enhancement module that aggregates meta-path behavioral features from auxiliary heterogeneous interaction graphs into account nodes within homogeneous graphs for detection, capturing heterogeneous behavioral patterns. He et al. [22] proposed Ethereum-CTRF, which extracts lexical features, sequence features, and transaction features from contract code and applies simple random oversampling to build a multi-granularity network model. However, this approach has the risk of overfitting.

Despite progress in accuracy and efficiency for detecting Ponzi schemes in smart contracts, existing methods face several limitations hindering further performance improvements. First, they struggle to fully capture semantic information related to Ponzi schemes within smart contracts. While these methods can extract features from entire contracts, core characteristics of Ponzi schemes often manifest in unique transaction patterns that constitute only a small portion of the contract code. Non-transaction-related parts may introduce noise, disrupting the learning process and reducing detection effectiveness. Second, class imbalance further limits detection model performance, leading to inadequate recognition of minority class datasets. To tackle these challenges, this study puts forward an oversampling-based detection method. The aim is to boost the model’s recognition ability for Ponzi scheme contracts by balancing the class distribution of the dataset.

This section elaborates on the fundamental concepts of Ponzi schemes, ADASYN, and graph construction addressed in this research, with the aim of promoting a deeper comprehension of the detection methods proposed in the article.

3.1 Smart Contract Ponzi Scheme

Smart Ponzi schemes exploit the automated execution features of blockchain technology, using smart contracts on decentralized platforms to automate operations. This makes it harder to trace and monitor the scheme’s execution and fund flows. Smart contracts are essentially self-executing programs that automatically enforce the terms of a contract without intermediaries, thus greatly enhancing operational efficiency [7]. However, they also provide more covert methods for illicit activities. Scammers often disguise these schemes as fake financial investment platforms, gambling games, or other types of applications designed to attract users, convincing investors of high returns to lure them into investing.

The decentralized nature of blockchain eliminates reliance on centralized institutions, with all transaction records being stored in a distributed manner across network nodes, thereby ensuring data transparency and tamper-proof characteristics. This ensures data transparency and immutability, securing the safety and authenticity of transactions. Yet, this same feature also offers convenience to fraudsters. They exploit anonymity to hide their identities and evade regulation. Additionally, due to the irreversible nature of blockchain transactions, once funds are transferred to the scammer’s control, they are almost impossible to recover, leaving victims with few options for recourse. Compared to traditional Ponzi schemes, smart contract Ponzi schemes exhibit several distinctive features [6]. First, they utilize blockchain anonymity to keep the scammer’s identity concealed. Second, after deployment, smart contracts cannot be altered or halted, which adds stability to the fraudulent environment. Third, while the public and automatic execution of smart contract code theoretically increases transparency, in practice, this can mislead investors into believing in their safety, thereby lowering their guard and extending the duration of the scam.

ADASYN [23] is an advanced oversampling technique developed to tackle the issue of data imbalance in classification tasks. Its main idea is to dynamically adjust the strategy for generating synthetic samples, prioritizing the increase of minority class density near classification boundaries. This enhances a model’s ability to learn complex decision boundaries. As an advanced version of the SMOTE algorithm, ADASYN not only generates new samples through linear interpolation but also introduces an adaptive weighting mechanism based on classification difficulty. Initially, the method computes the density ratio of majority instances in the local vicinity of each minority sample, defined as the classification difficulty coefficient. Samples surrounded by more majority class samples are assigned higher weights and generate more synthetic samples. Conversely, simpler samples with concentrated distributions generate fewer. This approach focuses on areas with higher classification difficulty by analyzing local distribution characteristics of minority class samples. In the context of detecting Ponzi schemes, fraudulent contracts frequently share characteristics with legitimate ones in various features. Traditional uniform sampling methods may overlook these boundary samples due to identical time intervals between samplings. In contrast, ADASYN generates synthetic samples densely within risky neighborhoods through linear interpolation. This forces classifiers to recalibrate decision boundaries, significantly improving the recognition rate of high-risk samples. Compared to SMOTE, ADASYN’s advantage lies in its adaptive capability to data distribution [9]. By allocating weights, it reduces redundant replication of simple samples while enhancing sample density in boundary regions.

Graphs serve as fundamental data structures in computer science, employed to depict complex relationships among entities. Their core components consist of nodes and edges. Nodes represent entities or data objects, whereas edges illustrate the connections between these entities. This structural design is particularly well-suited for modeling many-to-many interaction patterns [24]. In the field of program analysis graph construction algorithms achieve deep analysis by abstracting source code into a graph structure. These algorithms typically follow three construction phases. First, functions and key variables are abstracted into nodes. Second, two types of connections are established: one is control flow edges, and the other is data flow edges. Finally, the algorithm integrates the syntactic semantics and dependencies of the program. Control flow edges are constructed based on the execution paths of the program while data flow edges are generated based on the definition and usage relationships between variables. Control flow graphs as a core tool in program analysis use basic blocks as their node units. A basic block refers to a linear sequence of code without jump instructions. The connections between edges reflect control transfer logic such as conditional branches and loop jumps fully presenting all possible execution paths of the program. Data flow graphs focus on the lifecycle of data within the program tracking the entire process of data storage.

In this section, we introduce the Ponzi scheme detection for smart contracts based on oversampling, a specific methodology leveraging oversampling techniques to identify Ponzi schemes in smart contracts. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the overall workflow of our approach comprises four stages.

Figure 1: Framework of the proposed method

1) Data Collection: Crawling smart contract source code and transaction information from https://etherscan.io/ (accessed on 24 August 2025). based on the contract address.

2) Sample Balancing: To tackle the challenge of learning from a limited number of samples in the dataset, we expand the quantity of smart contract Ponzi scheme samples through an enhanced ADASYN technique. This approach avoids ineffective identification by generating high-quality minority-class samples.

3) Contract Transaction Graph Construction: Through static analysis of smart contract source code, we extract fund management-related functions and variables to construct a Directed Graph of Contract (DGC). Next, we extract transaction-related semantic segments in two steps based on the transfer interface and transaction-related state variables. We remove redundant information to construct the Contract Transaction Graph (CTG), highlighting features critical for Ponzi scheme detection. This offers high-quality input for subsequent graph neural network training.

4) Model Detection: We utilize Graph Neural Networks (GNN) [25] to train and analyze the extracted CTG, thereby determining whether a contract belongs to the Ponzi scheme category.

This study collects smart contract source code through https://etherscan.io/ and retrieves all transaction records associated with specific contracts using a modified Ethereum client. To ensure data integrity and analytical reliability, the acquired transaction data undergoes a filtering process. Since certain transactions may fail due to

Given that the majority class dominates the sample set, minority samples are frequently neglected, resulting in a classifier biased towards the majority class with compromised performance. To tackle this imbalance issue, we improve the ADASYN oversampling algorithm for data processing.

In synthesizing new examples, two critical factors are considered: the proximity of these samples to the decision boundary and their distribution within the feature space. The proximity of generated samples to the decision boundary has a direct impact on the accuracy of the learned classification boundary. Meanwhile, how these samples are combined affects their distribution reasonableness in the feature space. Improper combination can result in sample concentration in non-representative areas, impacting the model’s generalization ability. Our enhanced ADASYN approach addresses these two critical aspects by generating synthetic samples in close proximity to the decision boundary, thereby strengthening the classifier’s discriminative capability. Furthermore, the method incorporates an optimized sample combination strategy that ensures a balanced distribution throughout the feature space, effectively avoiding excessive clustering in less informative regions. The main implementation process of this method is shown in Algorithm 1:

Define the original dataset G, the generated synthetic sample set

1) Determine the quantity of minority class samples Q requiring synthesis:

Here,

2) For each minority class sample

Here,

3) Normalize

4) Calculate the number of synthetic samples

5) Select secondary samples

Here,

6) Generate new samples

Here,

4.3 Contract Transaction Graph Construction

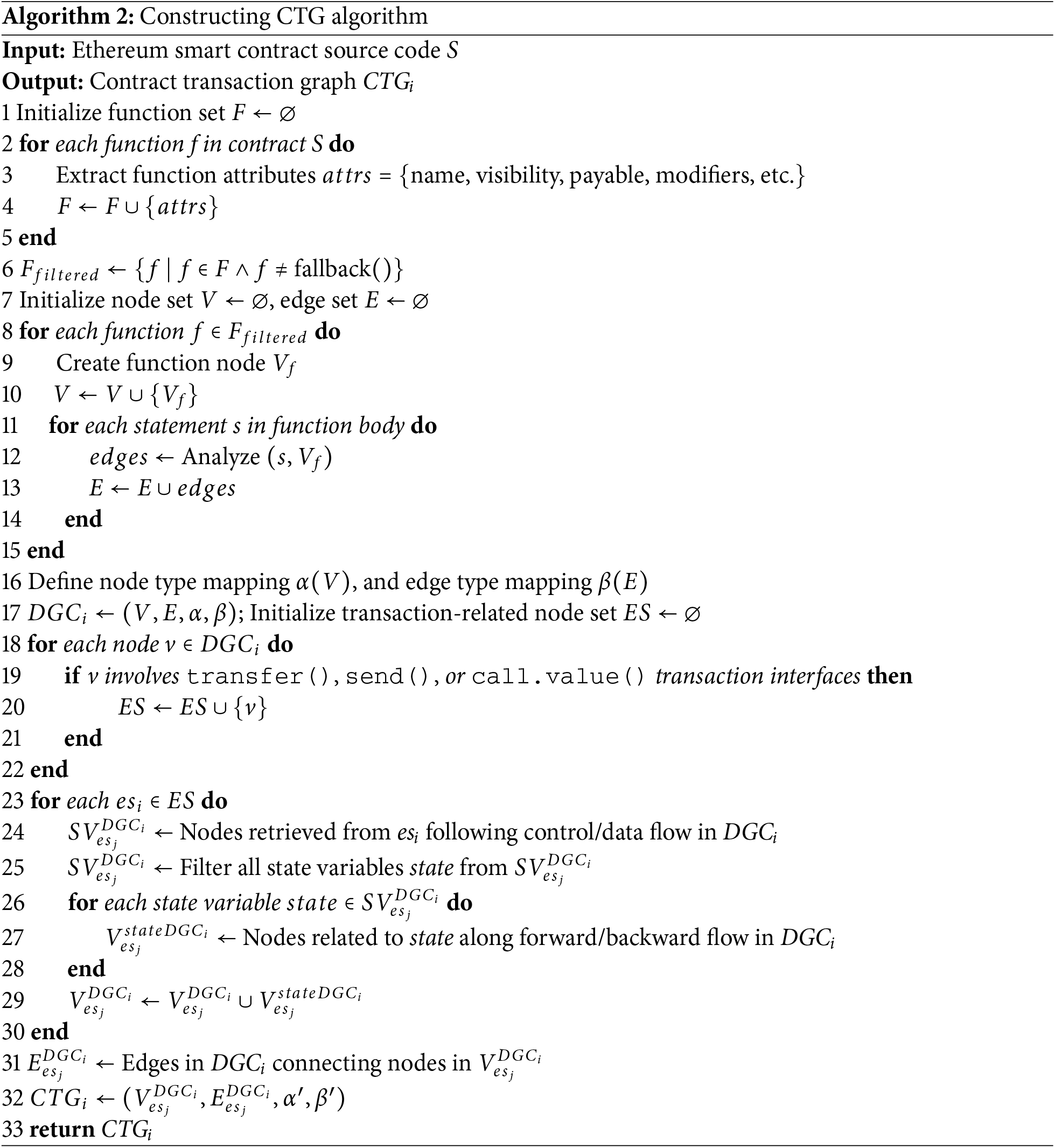

This section presents a comprehensive overview of the methodology for constructing transaction contract graphs and outlines the procedures involved in extracting transaction graphs. The construction process of CTG is presented in Algorithm 2. The overall architecture of this method includes the following four stages:

1) Static Analysis: To meet the requirements for generating a smart contract graph, we start with a static analysis of the source code. Our goal is to identify functions related to transaction and fund management operations and extract their various semantic relationships. From there, we can build a contract graph based on the results of this static analysis. Specifically, we initiate the analysis by examining the contract’s source code to gather essential function attributes, such as function names, visibility modifiers, and payable designations.

Notably, we exclude the

2) Graph Generation Phase: In the graph generation phase, we use the extracted function attributes and data dependencies to construct a contract graph. This simulation helps in understanding the behavior of anomalous contracts and triggers their functionalities. As shown in Lines 6 to 14 of Algorithm 2. We construct a directed contract graph, denoted as DGC and represented by

Node Representation. Nodes represent the key elements of the contract graph, including functions and variables. The contract graph comprises three types of nodes: core nodes, function nodes, and variable nodes. Table 1 details the classification of these three node types. Core nodes signify key variables or function calls related to Ponzi schemes. Function nodes represent functions that have not been extracted as core nodes. Variable nodes represent variables that have not been extracted as core nodes.

As illustrated in Fig. 2, this exemplifies a simplistic case of a Ponzi scheme contract. The contract embodies a quintessential Ponzi scheme framework, where returns promised to early investors are fulfilled primarily through capital inflows from subsequent investors, rather than from legitimate business operations or investment gains. Upon calling the

Figure 2: Ponzi scheme example

To facilitate the subsequent edge construction process, we have labeled each node with corresponding colors and sequence numbers in the figure.

Directed Edge Representation. To capture the rich semantic relationships between nodes, we define two levels of edge classification. Different nodes are connected based on static analysis of statement descriptions, with all edges categorized as either control flow or data flow. Table 2 details the types and semantics of these directed edges. Control flow edges represent program statements that describe contract execution paths. Data flow edges track variable usage, reflecting changes and movements of funds or account balances, including variable access or modification. S represents statements, code blocks and

Fig. 3a shows the contract graph constructed based on the Ponzi scheme contract example illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 3: Graph construction process and interpretability

3) Key Graph Information Extraction: During information propagation in graph neural networks, existing approaches often fail to adequately account for interference from transaction-irrelevant code segments. These segments may disrupt the model’s learning of Ponzi scheme-related features, ultimately compromising detection accuracy. Moreover, the varied structural compositions of graphs derived from different smart contract source codes pose challenges to the effectiveness of GNN training.

In Ponzi scheme detection, only transaction-relevant semantic information proves critical. To enhance detection accuracy and efficiency, we must eliminate irrelevant redundant information while preserving transaction-related semantics in the contract graph. This process not only highlights detection-critical information but also substantially reduces graph complexity by removing non-essential elements. The simplified graph representation enables GNNs to more effectively learn features vital for Ponzi scheme identification, thereby improving overall model performance. Based on the contract graph, we carry out two steps to extract transaction-related semantic segments. Corresponding to Lines 14 to 28 in Algorithm 2. In the first step, the transfer interface is employed as an extraction criterion for backward information retrieval, with the goal of identifying the nodes on which the transfer interface relies. In step two, we use the state variables identified in step one as criteria for forward and backward extraction, retaining the semantics of all state variables within functions dependent on transactions.

Step 1: Extraction Based on Transfer Interface. Smart contracts leverage the transfer interface to facilitate cryptocurrency transmission on blockchain platforms. The significance of this assertion resides not only in its semantic content but also in its profound connection to the execution context. By analyzing the transfer interface and its dependent code snippets, one can understand how the function implements the specific semantics of transactions. The transfer interface and its associated codes fully display the logic for executing fund transfers. Before invoking this interface, smart contracts usually perform a series of conditional checks, including permission verification, account status checks, and business rule constraints, among other control logics. Moreover, the input parameters of the transfer interface define the transaction recipient and amount. Thus, integrating the transfer operation with its associated data context can uncover how the semantics of transaction recipients and amounts are computed within the smart contract code. By combining the transfer statement with its dependent context, we can collect semantic information about the transfer’s execution and derive specific semantics related to the transaction recipient and amount. This approach ensures that important code snippets related to transactions are retained from the smart contract code to the greatest extent possible. We construct an extraction standard node set (Extract standard nodes) ES, which includes all nodes related to transaction operations, such as function calls like

Step 2: In smart contracts, state variables are stored on the blockchain and affect both current and future executions. When transactions rely on specific state variables, it is essential to extract the semantics of all transaction-related state variables—rather than merely those associated with the transfer interface in the first step. From the key information extracted in the first step, we have obtained all nodes related to the transfer interface, denoted as

This process not only includes semantic fragments directly related to the transfer interface but also considers the cross-transaction effects of state variables. The resulting CTG after extraction is shown in Fig. 3b.

4) Graph Embedding: Graph embedding, a crucial data preprocessing technique, plays a significant role in the field of graph data processing [26]. Its main function is to transform high-dimensional and sparsely featured graph data into low-dimensional, dense, and continuous vector representations. In practical applications, graph embedding techniques convert all nodes in a graph to their corresponding vector representations. This mapping allows the similarity between nodes to be effectively translated into distances or similarity measures between vectors. By utilizing this feature, graph embedding has become extensively applied across a range of graph-related activities, such as the visualization of graph data to provide clear and understandable representations of intricate structures; extracting features to uncover key information within graph data; aiding classification by accurately determining node categories based on vector features; and facilitating clustering by grouping nodes with similar characteristics.

After normalizing the contract graph, it encompasses features across both nodes and directed edges. These features are further consolidated into core node features and presented in text form. To prepare these features for input into neural networks, we use the word2vec [27] model to vectorize node and edge features, transforming textual features into low-dimensional vectors that meet the input data format requirements of neural networks. By concatenating the feature vectors of nodes and edges, we form the node feature vectors, completing the construction of CTG for subsequent model training.

Deep learning, leveraging its ability to automatically extract features from raw data, has demonstrated exceptional performance across diverse domains. However, traditional deep learning models are mainly limited to processing data in the form of vectors or matrices. On the other hand, GNNs possess unique advantages in handling graph-structured data, effectively modeling and analyzing complex relationships within graphs [25]. Based on this characteristic, this study utilizes graph-structured data constructed from smart contract transactions and implements an effective detection of Ponzi schemes through the GNN model.

Graph Embedding Learning. We utilize CTG as input to the GNN model, where the node feature matrix

where

where

where

After completing the graph embedding process, we utilize mean pooling to aggregate node features, yielding an overall graph representation.

Classification Detection. The classifier consists of a fully connected layer and a dropout layer. The fully connected layer is intended to learn intricate nonlinear interactions among input data features, which helps capture comprehensive feature representations and improve classification accuracy. Dropout layers randomly set neuron outputs to zero, effectively preventing model overfitting and enhancing generalization ability. In graph classification tasks, the global feature representation of a graph is input into the classifier. After processing through fully connected and dropout layers, the classifier outputs predicted class labels for the graphs. Using this approach, the model assesses whether a target smart contract constitutes a Ponzi scheme, thereby facilitating efficient identification of such schemes.

To enhance the interpretability of the model, this study incorporates GNNExplainer [28]. GNNExplainer is capable of automatically identifying and revealing the critical subgraph structures and node features that the model relies on when making predictions. The core idea of GNNExplainer is to extract the most influential subgraph and key node features by minimizing the entropy of the subgraph structure and feature subset while preserving the model’s original prediction. As a model-agnostic explanation technique, GNNExplainer can provide interpretability for any GNN-based model. When applied to the CTG constructed in this work, GNNExplainer effectively highlights which function nodes, variable nodes, and their dependencies play a decisive role in the model’s classification of a contract as a Ponzi scheme. The detailed procedure of the GNNExplainer subgraph extraction method is as follows:

Step 1: Initialization. Initialize the graph mask matrix and feature mask matrix to select important subgraph structures and node features.

Step 2: Input Data. Provide a trained GNN model along with its prediction results.

Step 3: Subgraph Generation. Adjust the graph mask to generate a subgraph that has the greatest impact on the GNN model’s prediction.

Step 4: Feature Selection. Input the trained GNN model and its prediction results.

Step 5: Objective Definition. For the target node

Step 6: Optimization Objective. Formalize the notion of “importance” by maximizing the mutual information between the subgraph and the prediction outcome.

Step 7: Explanation Output. The resulting subgraph structure is the explanation subgraph, representing the parts of the graph structure and features that the GNN model actually focuses on when making predictions.

Following the above steps, GNNExplainer extracts the subgraph from the CTG that truly influences the prediction outcome. This subgraph, referred to as the explanation subgraph, serves as an interpretation of the model’s decision. Taking a Ponzi scheme contract illustrated in Fig. 2 as an example, Fig. 3c presents the key subgraph identified by GNNExplainer. This subgraph refines the original transaction graph by retaining nodes and edges critical to the classification, including function nodes, variable nodes, and their dependency relationships, while filtering out redundant information to highlight the core logical pathways. Notably, the variable node “balance” represents a key factor reflecting the core mechanism of fund allocation and cyclical returns within the contract. These critical nodes and their relationships constitute essential criteria for identifying Ponzi schemes. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 3b, the explanation subgraph aligns closely with the model’s prediction, thereby validating the interpretability of the model’s decision process and the soundness of its rationale.

In this section, we perform experiments to assess the efficacy of our suggested detection approach. To ensure the reliability of the outcomes, these experiments utilize verified datasets. We begin by offering an overview of the experimental setup and evaluation criteria. Then, we present experiments utilizing our proposed approach for detecting Ponzi scheme smart contracts and compare its performance against other representative methods [29,16].

5.1 Experimental Setup and Evaluation Metrics

To ensure the reliability and timeliness of the dataset, this study employs a validated and labeled dataset sourced from the XBlock website, as cited in literature [12]. The dataset includes 318 Ponzi scheme contract addresses and 6498 legitimate contract addresses. Using the contract addresses in this dataset, we systematically retrieved the full source code of each contract and all associated transaction records from the Ethereum blockchain explorer.

The experiments were executed on a standalone workstation featuring an Intel Core i7 processor running at 2.9 GHz and 32 GB of RAM. The proposed detection model was developed and executed locally as a standalone offline analysis tool. It does not require on-chain deployment or rely on blockchain security protocols, making it well-suited for static analysis and Ponzi structure identification in smart contracts.

Regarding the experimental parameter settings, the configurations for each module are as follows: In the oversampling phase, the small constant parameter of the improved oversampling algorithm is set to

To conduct a comparative analysis with other typical Ponzi scheme detection methods, we evaluated the models using three key evaluation metrics: Precision, Recall, and the F1-score. The mathematical formulations for these metrics are presented in the following equations:

TP (True Positives) represents the number of contracts correctly identified as Ponzi schemes. FP (False Positives) indicates the number of normal contracts mistakenly classified as Ponzi schemes. FN (False Negatives) denotes the number of Ponzi scheme contracts incorrectly predicted as normal contracts.

5.2 Handling Imbalanced Classification

To assess the model’s effectiveness on imbalanced datasets and to confirm the efficacy of our oversampling algorithm in achieving sample balance, we applied various oversampling techniques to the dataset. We then performed a comparative analysis of the experimental outcomes, which are summarized in Table 3.

In this research, we utilized an enhanced version of the ADASYN algorithm to oversample the minority class instances within the training dataset. Our findings indicate that the conventional ADASYN method effectively creates new samples based on the minority class’s density distribution, aiding in reducing class imbalance issues. Nonetheless, our refined ADASYN approach significantly improved key performance metrics, including precision, recall, and F1-score, thereby validating the effectiveness of our proposed oversampling technique for minority class instances. Specifically, our enhanced algorithm not only addresses class imbalance but also strengthens the model’s ability to learn from minority class data. By optimizing the strategy for generating boundary samples, it further boosts overall classification performance. The substantial increase in recall indicates that the model has become more adept at identifying minority class samples. High precision also demonstrates that the model can accurately detect Ponzi scheme smart contracts—a critical attribute for real-world applications. Incorrect identification or failure to detect a Ponzi scheme could lead to substantial financial losses.

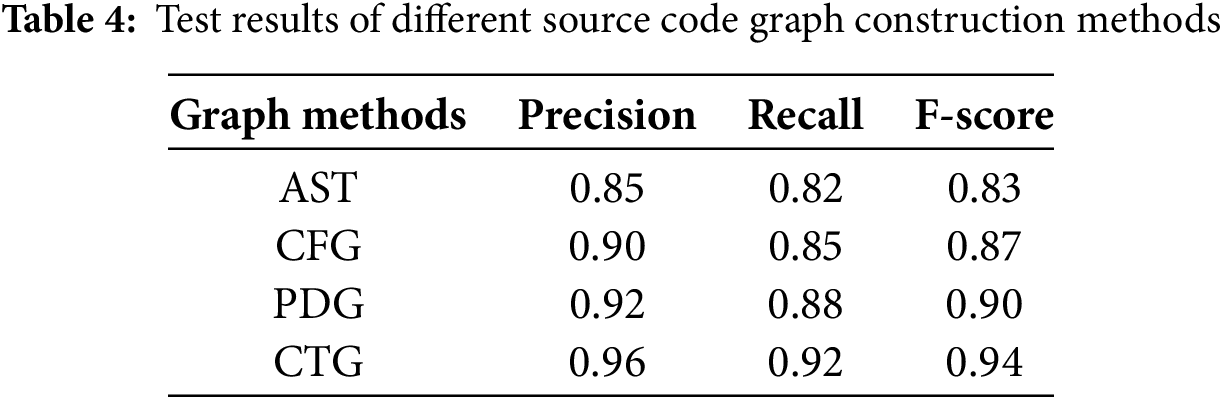

5.3 Different Source Code Graph Construction Methods

To assess the effectiveness of our proposed CTG composition method, we utilized several common code composition methods to re-compose and vectorize the representations of smart contracts. Under identical experimental conditions and training parameters, we fed the results into a detection model for training and testing. The detection outcomes were then compared with those obtained from our method, as shown in Table 4.

The experimental outcomes show that our proposed CTG method surpasses other approaches in performance. The Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) method delivered the weakest performance. Unlike other techniques, AST only captures static syntactic structures of code and fails to represent dynamic semantic information during program execution, such as critical control-flow and data-flow dependencies. Among other graph construction methods, the Program Dependence Graph (PDG) achieved higher accuracy, recall, and F1-score than the Control Flow Graph (CFG) by 2.2%, 3.6%, and 3.4%, respectively. This advantage likely stems from PDG’s ability to model both data-flow and control-flow dependencies, making it more effective for detecting Ponzi schemes in smart contracts, which requires identifying transaction-related patterns in source code. Our CTG method further surpasses common graph construction techniques. By eliminating redundant information and focusing on transaction-specific feature extraction, CTG generates a more targeted and comprehensive graph representation. This enables CTG to accurately capture key behavioral patterns associated with Ponzi schemes in smart contracts.

5.4 Efficiency of Different Methods

To further evaluate the effectiveness of our method in identifying Ponzi schemes within smart contracts and to achieve comprehensive validation,we compared our approach with notable methods from TxClass [20], MTCformer [29] and AdaBoost [16]. We selected precision, recall, and the F-score as metrics to measure model performance. The outcomes are illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Comparison with the existing methods

Our proposed method outperforms existing detection methods across all metrics. Specifically, the proposed method achieves a recall of 0.92, representing notable improvements over the values reported by TxClass (0.70), MTCformer (0.83), and AdaBoost (0.80), with relative increases of 31.4%, 10.8%, and 15%, respectively. This substantial performance gain highlights the strong practical value of our approach in the context of smart contract Ponzi scheme detection. From a practical deployment perspective, when analyzing 100 Ponzi contracts, our method is capable of identifying at least 22 more instances than TxClass, and 9 and 12 more cases than MTCformer and AdaBoost, respectively, demonstrating a significant improvement in detection efficiency. We attribute this enhanced performance to two primary factors. First, our approach builds a more extensive graph structure for representing code semantics. Second, by effectively extracting transaction-related key information, the graph structure can more accurately interpret transaction semantics. Additionally, looking at the comprehensive evaluation metric, the F1 score, our method also performs best among the four methods, further confirming its superiority in overall performance. The experimental outcomes indicate that our proposed method is both highly dependable and practically beneficial, providing a novel approach for detecting Ponzi schemes in smart contracts.

To address class imbalance and the challenge of fully expressing transaction semantics in smart contract Ponzi scheme detection, we proposed an oversampling-based detection method primarily targeting Ethereum smart contracts. First, we improved the ADASYN algorithm by integrating proximity to decision boundaries and distribution rationality in feature space, enhancing the identification of boundary samples and generating minority class samples to alleviate sample imbalance. Second, we designed a graph construction algorithm that includes various node and edge types, combined with key graph information extraction techniques to remove redundancy while retaining core transaction semantics. This achieves precise representation of smart contract transaction features. Finally, we utilized GNN combined with GAT for model training and detection, effectively extracting graph features. The experimental outcomes indicate that our method surpasses current advanced methods.

Nevertheless, this study has certain limitations. On the one hand, the accuracy of transaction semantics extraction remains suboptimal when portions of the source code are missing. On the other hand, the proposed method still faces challenges in terms of scalability and real-time applicability when processing large-scale smart contract data. These issues highlight promising directions for future research.

Currently, the proposed detection method is primarily based on offline analysis, relying on static analysis of smart contract source code and transaction graph construction. It does not yet support real-time detection. Given the dynamic and evolving nature of attacks in blockchain environments, real-time capability is crucial. Therefore, improving the framework’s real-time applicability will be an important direction for future research.

Future research will concentrate on developing real-time detection techniques for Ponzi schemes in smart contracts, as well as adapting the proposed method to accommodate other blockchain platforms, including Binance Smart Chain (BSC) and Solana. Through comprehensive analysis of diverse features, including opcodes and bytecode, we intend to strengthen the effectiveness and precision of fraud detection mechanisms. Our research primarily seeks to recognize abnormal execution behaviors and implement adaptive monitoring systems that can efficiently uncover suspicious Ponzi structures. Furthermore, we are committed to developing a highly adaptive and scalable detection framework to continuously address evolving fraudulent tactics, thereby providing stronger technical safeguards against smart contract-based financial fraud.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Key Project of Joint Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China “Research on Key Technologies and Demonstration Applications for Trusted and Secure Data Circulation and Trading” (U24A20241), the National Natural Science Foundation of China “Research on Trusted Theories and Key Technologies of Data Security Trading Based on Blockchain” (62202118), the Major Scientific and Technological Special Project of Guizhou Province ([2024]014), Scientific and Technological Research Projects from the Guizhou Education Department (Qian jiao ji [2023]003), the Hundred-Level Innovative Talent Project of the Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Department (Qiankehe Platform Talent-GCC[2023]018), the Major Project of Guizhou Province “Research and Application of Key Technologies for Trusted Large Models Oriented to Public Big Data” (Qiankehe Major Project [2024]003), and the Guizhou Province Computational Power Network Security Protection Science and Technology Innovation Talent Team (Qiankehe Talent CXTD[2025]029).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Yafei Liu; methodology, Yafei Liu, Yuling Chen; validation, Yuling Chen; formal analysis, Xuewei Wang; investigation, Yafei Liu; resources, Yafei Liu; data curation, Yafei Liu; writing—original draft preparation, Yafei Liu; writing—review and editing, Yafei Liu; visualization, Xuewei Wang, Chaoyue Tan; supervision, Yuxiang Yang, Chaoyue Tan; project administration, Yuxiang Yang; funding acquisition, Chaoyue Tan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in https://xblock.pro/#/dataset/25 (accessed on 24 August 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Yang Y, Chen Y, Liu Z, Tan C, Luo Y. Verifiable and redactable blockchain for internet of vehicles data sharing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(4):4249–61. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3483809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Chen Y, Li Y, Chen Q, Wang X, Li T, Tan C. Energy trading scheme based on consortium blockchain and game theory. Comput Stand Interf. 2023;84:103699. doi:10.1016/j.csi.2022.103699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Maurya V, Rishiwal V, Yadav M, Shiblee M, Yadav P, Agarwal U, et al. Blockchain-driven security for IoT networks: state-of-the-art, challenges and future directions. Peer Peer Netw Appl. 2025;18(1):1–35. doi:10.1007/s12083-024-01812-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Dymkov M, Gorgadze V, Karanyuk A, Barger A. Identifying and analyzing web3 protocols with Ponzi scheme features. In: 2024 6th International Conference on Blockchain Computing and Applications (BCCA); 2024 Nov 26–29; Dubai, United Arab Emirates. p. 794–800. [Google Scholar]

5. TRM Labs. Illicit Crypto Ecosystem Report; 2023 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 24]. Available from: https://www.trmlabs.com/report. [Google Scholar]

6. Agarwal U, Rishiwal V, Tanwar S, Yadav M. Blockchain and crypto forensics: investigating crypto frauds. Int J Netw Manag. 2024;34(2):e2255. doi:10.1002/nem.2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Luo B, Zhang Z, Wang Q, Ke A, Lu S, He B. AI-powered fraud detection in decentralized finance: a project life cycle perspective. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;57(4):1–38. doi:10.1145/3705296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Chen Y, Yang X, Li T, Ren Y, Long Y. A blockchain-empowered authentication scheme for worm detection in wireless sensor network. Digital Communicat Netw. 2024;10(2):265–72. doi:10.1016/j.dcan.2022.04.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Dey I, Pratap V. A comparative study of SMOTE, borderline-SMOTE, and ADASYN oversampling techniques using different classifiers. In: 2023 3rd International Conference on Smart Data Intelligence (ICSMDI); 2023 Mar 30–31; Trichy, India. p. 294–302. [Google Scholar]

10. Bartoletti M, Carta S, Cimoli T, Saia R. Dissecting Ponzi schemes on Ethereum: identification, analysis, and impact. Future Generat Comput Syst. 2020;102(3–4):259–77. doi:10.1016/j.future.2019.08.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Fan S, Fu S, Xu H, Cheng X. Al-SPSD: anti-leakage smart Ponzi schemes detection in blockchain. Inform Process Manag. 2021;58(4):102587. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2021.102587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zheng Z, Chen W, Zhong Z, Chen Z, Lu Y. Securing the ethereum from smart ponzi schemes: identification using static features. ACM Transact Softw Eng Methodol. 2023;32(5):1–28. doi:10.1145/3571847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhang Y, Yu W, Li Z, Raza S, Cao H. Detecting ethereum Ponzi schemes based on improved LightGBM algorithm. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst. 2021;9(2):624–37. doi:10.1109/tcss.2021.3088145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Trozze A, Kleinberg B, Davies T. Detecting DeFi securities violations from token smart contract code. Financ Innovat. 2024;10(1):1–35. doi:10.1186/s40854-023-00572-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Peng J, Xiao G. Detection of smart Ponzi schemes using opcode. In: Blockchain and trustworthy systems: second international conference, BlockSys 2020. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 192–204. [Google Scholar]

16. Wang M, Huang J. Detecting ethereum ponzi schemes through opcode context analysis and oversampling-based adaboost algorithm. Comput Syst Sci Eng. 2023;47(1):1023–42. doi:10.32604/csse.2023.039569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chen W, Zheng Z, Cui J, Ngai E, Zheng P, Zhou Y. Detecting ponzi schemes on ethereum: towards healthier blockchain technology. In: Proceedings of the 2018 world wide web conference; 2018 Apr 23–27; Lyon, France. p. 1409–18. [Google Scholar]

18. Jung E, Le Tilly M, Gehani A, Ge Y. Data mining-based ethereum fraud detection. In: 2019 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain (Blockchain); 2019 Jul 14–17; Atlanta, GA, USA. p. 266–73. [Google Scholar]

19. Wu J, Yuan Q, Lin D, You W, Chen W, Chen C, et al. Who are the phishers? Phishing scam detection on ethereum via network embedding. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Syst. 2020;52(2):1156–66. doi:10.1109/tsmc.2020.3016821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Hu T, Liu X, Chen T, Zhang X, Huang X, Niu W, et al. Transaction-based classification and detection approach for Ethereum smart contract. Inform Process Manag. 2021;58(2):102462. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2020.102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Jin C, Jin J, Zhou J, Wu J, Xuan Q. Heterogeneous feature augmentation for ponzi detection in ethereum. IEEE Transact Circuits Syst II Express Briefs. 2022;69(9):3919–23. doi:10.1109/tcsii.2022.3177898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. He X, Yang T, Chen L. CTRF: ethereum-based ponzi contract identification. Secur Commun Netw. 2022;2022(1):1554752. doi:10.1155/2022/1554752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. He H, Bai Y, Garcia EA, Li S. ADASYN: adaptive synthetic sampling approach for imbalanced learning. In: 2008 IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence); 2008 Jun 1–8; Hong Kong, China; 2008. p. 1322–8. [Google Scholar]

24. Anuyah S, Bolade V, Agbaakin O. Understanding graph databases: a comprehensive tutorial and survey. arXiv:2411.09999. 2024. [Google Scholar]

25. Shabani N, Wu J, Beheshti A, Sheng QZ, Foo J, Haghighi V, et al. A comprehensive survey on graph summarization with graph neural networks. IEEE Transact Artif Intell. 2024;5(8):3780–800. doi:10.1109/tai.2024.3350545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ge X, Wang YC, Wang B, Kuo CCJ. Knowledge graph embedding: an overview. APSIPA Trans Signal Inf Process. 2024;13(1):e1. doi:10.1561/116.00000065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Johnson SJ, Murty MR, Navakanth I. A detailed review on word embedding techniques with emphasis on word2vec. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(13):37979–8007. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-17007-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ying Z, Bourgeois D, You J, Zitnik M, Leskovec J. Gnnexplainer: generating explanations for graph neural networks. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc.; 2019. 829 p. [Google Scholar]

29. Chen Y, Dai H, Yu X, Hu W, Xie Z, Tan C. Improving Ponzi scheme contract detection using multi-channel TextCNN and transformer. Sensors. 2021;21(19):6417. doi:10.3390/s21196417. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools