Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Privacy-Preserving Convolutional Neural Network Inference Framework for AIoT Applications

1 Information Center, Guizhou Power Grid Co., Ltd., Guiyang, 550003, China

2 State Key Laboratory of Public Big Data, College of Computer Science and Technology, Guizhou University, Guiyang, 550025, China

* Corresponding Author: Zhenyong Zhang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069404

Received 22 June 2025; Accepted 05 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

With the rapid development of the Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT), convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have demonstrated potential and remarkable performance in AIoT applications due to their excellent performance in various inference tasks. However, the users have concerns about privacy leakage for the use of AI and the performance and efficiency of computing on resource-constrained IoT edge devices. Therefore, this paper proposes an efficient privacy-preserving CNN framework (i.e., EPPA) based on the Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) scheme for AIoT application scenarios. In the plaintext domain, we verify schemes with different activation structures to determine the actual activation functions applicable to the corresponding ciphertext domain. Within the encryption domain, we integrate batch normalization (BN) into the convolutional layers to simplify the computation process. For nonlinear activation functions, we use composite polynomials for approximate calculation. Regarding the noise accumulation caused by homomorphic multiplication operations, we realize the refreshment of ciphertext noise through minimal “decryption-encryption” interactions, instead of adopting bootstrapping operations. Additionally, in practical implementation, we convert three-dimensional convolution into two-dimensional convolution to reduce the amount of computation in the encryption domain. Finally, we conduct extensive experiments on four IoT datasets, different CNN architectures, and two platforms with different resource configurations to evaluate the performance of EPPA in detail.Keywords

Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT) is a frontier technology that combines artificial intelligence and IoT closely, moving toward system-level intelligence. Its development cannot proceed without Edge Computing. Edge computing sends computing tasks to edge nodes, providing resource-constrained IoT devices with computing power that fits real scenarios better. This helps cut down data transmission delay, improves real-time response, and drives AIoT to develop into system-level intelligence. As a critical infrastructure, the AIoT interconnects existing and continuously advancing information and communication technologies with physical devices equipped with execution capabilities. It enables data sharing, conducts in-depth analysis and intelligent processing by leveraging AI techniques, and accomplishes specific services or tasks. With the rapid advancement of technology, the AIoTSys has captured widespread attention and generated substantial interest across diverse industries. The development of the AIoTSys can bring about numerous conveniences to various fields such as daily medical assistance, transportation, industrial manufacturing, education, and smart home living. Thao et al. [1] proposed a CNN-LSTM model for real-time AIoT systems, and independently classified the abnormal conditions of industrial diesel generators through supervised learning technology to improve the efficiency of maintenance services for industrial diesel generators. Chen et al. [2] applied MobileNet to IoT devices, enabling real-time and efficient detection of whether residents wear masks properly. Xu et al. [3] utilized machine learning technology in combination with wearable devices to predict the injury risks in football sports. Ferdowsi et al. [4] employed Deep Neural Network (DNN) to propose an edge analysis architecture, endowing the devices in intelligent transportation systems with powerful computer vision and signal processing capabilities, thereby demonstrating the contributions and great development potential of AIoTSys technology in multiple domains. Furthermore, the application of the AIoTSys in smart grids is also becoming increasingly prevalent. Zhang et al. [5] considered the development trends of machine learning applications in smart grids based on the IoT. Additionally, Zhang et al. [6] also pointed out that in the application of machine learning in smart grids, models such as those for solar/wind energy prediction are susceptible to adversarial attacks.

Neural network technology holds an unshakable position in the field of artificial intelligence and has profoundly transformed our understanding of information processing and pattern recognition. For instance, deep learning convolutional neural networks play a crucial role in image processing and data analysis within intelligent Internet of Things (IoT) systems. Zhao et al. [7] have analyzed the data of the elderly monitored remotely by means of deep convolutional neural networks to gain a better understanding of the health status of the elderly. Dwivedi et al. [8] utilized CNN biometric recognition technology empowered by the Internet of Things (IoT) to perform secure identity verification and recognition for transportation service personnel. Liu et al. [9] have simulated a computing-constrained environment using a Raspberry Pi and successfully implemented a lightweight neural network inference with privacy protection on medical datasets. These cases demonstrate the extensive cross-domain application value of neural network technology. Although the development of artificial intelligence technology has brought convenience in many fields, the accompanying issue of data privacy cannot be overlooked.

In 2022, the American company OpenAI first released the ChatGPT chatbot model. In 2024, a Chinese artificial intelligence technology company released the open-source and self-controllable Deepseek large model, which quickly attracted extensive attention and usage from a large number of Internet users upon its release. However, the issue of data privacy leakage brought about by artificial intelligence services has constantly worried global users. When the services used involve users’ sensitive information, ensuring the confidentiality of data is a crucial and indispensable part. In 2016, the European Union promulgated the “General Data Protection Regulation” [10] (GDPR), requiring enterprises to take relevant safeguard measures for personal data to protect it from leakage and unauthorized illegal use. Currently, due to the extensive deployment of AIoT devices, a large amount of data resources of sensitive information, such as video data, geographical location information, health data, and industrial production data, are being accumulated. Once these data are leaked or illegally exploited, they will not only seriously violate personal privacy rights but also potentially trigger a commercial data leakage crisis because of the huge potential commercial value of the data. In addition, as a typical application scenario of the integration of AIoT technology, autonomous driving, with its highly integrated sensors, communication modules, and software systems, has become a new target of cyberattacks. He et al. [11] pointed out that malicious attacks on autonomous driving systems may threaten the operational safety of vehicles and cause the leakage of sensitive information such as users’ travel trajectories and biometric features. Gozubuyuk et al. [12] emphasized that with the popularization of Internet-connected vehicles and autonomous driving technology, effectively ensuring user privacy and security while achieving intelligent travel has become a key issue that the industry urgently needs to address.

Problem Statement. An IoT server has a unique pre-trained neural network model W. Meanwhile, the IoT edge device with limited computing resources has its private data X. The IoT edge device needs to use the model W to conduct inference and prediction on the data X while ensuring the confidentiality of the data X. Therefore, in order to safeguard the privacy of the data and the correctness of model inference, FHE has become an effective solution. FHE supports directly performing relevant calculations on the encrypted private data X without decrypting it, without leaking any information about X. It effectively maintains data privacy and helps the AIoT achieve intelligent decision-making.

Therefore, in view of the requirements for high security, timeliness, and accuracy in AIoT, this paper combines FHE technology with convolutional neural networks and proposes a fully homomorphic encryption-based convolutional neural network model to serve inference on AIoT edge devices. Leveraging the high overall security of FHE, under the premise that model parameters and user data are protected, the inference efficiency of edge IoT devices is continuously optimized. The implementation of our EPPA involves the following two steps: (i) Securely deploying the CNN model on the IoT cloud server; (ii) Applying fully homomorphic encryption to client data and transmitting it to the cloud server to complete the full privacy-preserving inference. Our contributions are as follows:

• A privacy-preserving convolutional neural network inference (i.e., EPPA) based on the fully homomorphic encryption is proposed for AIoT application.

• In the encryption domain, we use composite polynomials to approximate the nonlinear activation functions, and integrate the BN layer into the convolutional layer. Besides, the ciphertext noise is refreshed through interactive decryption-encryption operations. More importantly, we convert the calculation of the three-dimensional convolution into the computation of a two-dimensional convolution to reduce the computation overhead.

• We conduct experiments on four IoT datasets and evaluate the performance of EPPA using four evaluation metrics. The Raspberry Pi is used as a resource-limited end to verify the feasibility of EPPA.

In this section, we first elaborate on some typical privacy-preserving neural network inference schemes based on FHE. Then, we introduce the related work of non-linear function calculations.

2.1 FHE-Based Secure Neural Network Inference

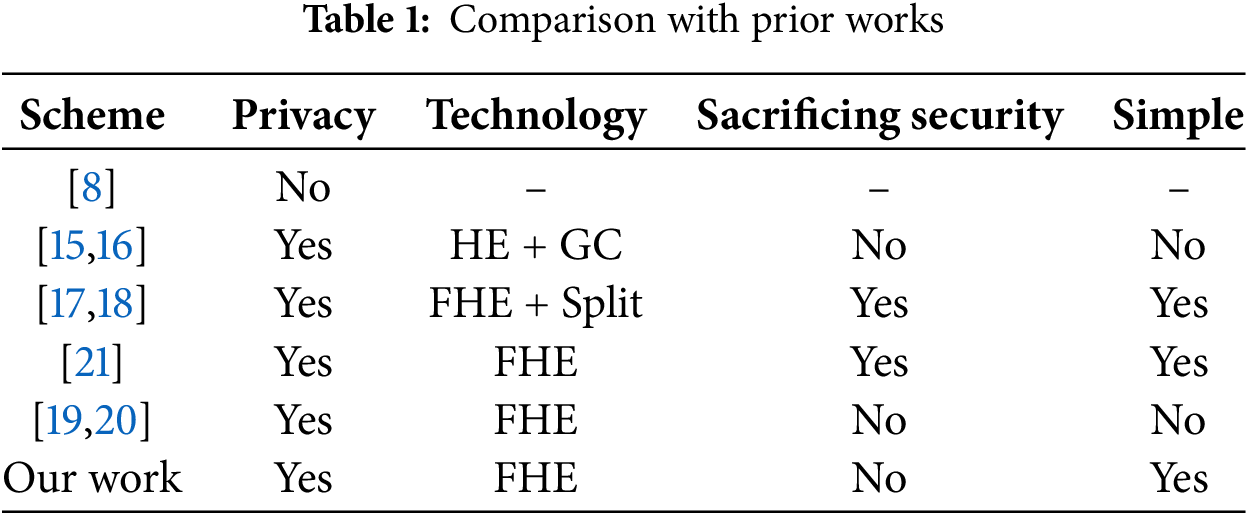

Despite plenty of works aiming to improve the performance of machine learning in IoT scenarios, privacy remains a critical factor that cannot be overlooked. As shown in Table 1, the scheme [13] achieves fast and secure 2PC inference based on FHE and SS. The scheme [14] uses HE and SS to realize privacy-preserving CNN inference and is the first to consider adversarial attacks under ciphertext. Although schemes [15,16] based on HE and GC can achieve secure CNN inference, they suffer from excessively high communication overhead. The schemes [17,18] adopting FHE and Split technology can improve inference efficiency but may expose partial model information, making them difficult to meet the requirements of high-security scenarios. The schemes [19,20] rely on bootstrapping operations for ciphertext noise refreshment, which is extremely inefficient and unfriendly to IoT devices with limited computational resources. Additionally, while the scheme [21] performs noise refreshment through communication and decryption, it poses a risk of leaking intermediate decryption results. In contrast, the scheme proposed in this paper only involves lightweight communication and encryption-decryption operations, achieving noise refreshment while ensuring security.

2.2 FHE-Based Computation of Non-Linear Functions

The existing schemes BFV [22] and CKKS [23] can easily implement the calculation of convolutional layers and fully connected layers, which belong to linear functions. However, the calculation of some non-linear functions still poses challenges. The common solutions for addressing this issue can use SS and GC, as seen in schemes [14,24]. Nevertheless, these solutions are unfriendly to be implemented with FHE. The scheme [16] replaces the ReLU activation function with a square function, and the scheme [20] approximates ReLU by using computation-friendly polynomial functions, which are both computation-friendly for FHE calculation. Our scheme also employs composite polynomials to achieve approximate computation of activation functions.

In this section, we introduce the preparatory knowledge related to EPPA, including the architecture of the convolutional neural network and the basic knowledge of CKKS.

Convolutional layers are a fundamental building block of convolutional neural networks (CNNs), designed to extract key features by sliding learnable convolution kernels over input tensor data. This process performs element-wise multiplications and additions between the kernels and the input. In this paper, a two-dimensional convolutional layer is employed to process image data. The details are given in Section 4.1.

Batch normalization (BN) addresses the issue of “internal covariate shift by standardizing the input data for each batch, thereby accelerating the training process of the model. Specifically, BN normalizes the data to a normal distribution with a mean of 0 and a variance of 1, ensuring that the inputs to neurons remain within a stable and optimal range. This technique also mitigates the problems of vanishing or exploding gradients to some extent. Additionally, BN acts as a regularizer, reducing the likelihood of overfitting.

The core role of activation functions is to introduce non-linearity, enhance the model’s ability to extract and express data features, and thus improve the model’s generalization capability in various classification tasks. This paper introduces two activation functions, ReLU and ReLU6, which are suitable for IoT edge devices with limited computational resources. While ReLU is computationally efficient, it may suffer from precision loss when encountering large activation values, particularly on mobile devices with low-precision hardware. As a variant of ReLU, ReLU6 restricts its output to the range of

After multiple rounds of convolution operations, the data is transformed into abstract multi-dimensional feature maps. By flattening these maps into a one-dimensional vector and connecting it to fully connected layers, a series of weight matrices and bias terms are used to associate the extracted features with the output classes. Finally, the Softmax operation converts the output vector into a probability distribution where all values sum to 1.

The CKKS fully homomorphic encryption is an encryption scheme with extremely high security and has been widely applied in privacy-preserving machine learning. It allows correct operations to be performed on the encrypted underlying messages without knowing the key. Its security relies on Ring Learning with Errors (RLWE) and is considered quantum-secure. CKKS supports approximate arithmetic operations on real and complex numbers. EPPA also uses the CKKS scheme [25]. The polynomial quotient ring

CKKS supports approximate operations, including homomorphic addition and multiplication. For plaintexts

where

4 Convolutional Neural Network Based on Fully Homomorphic Encryption

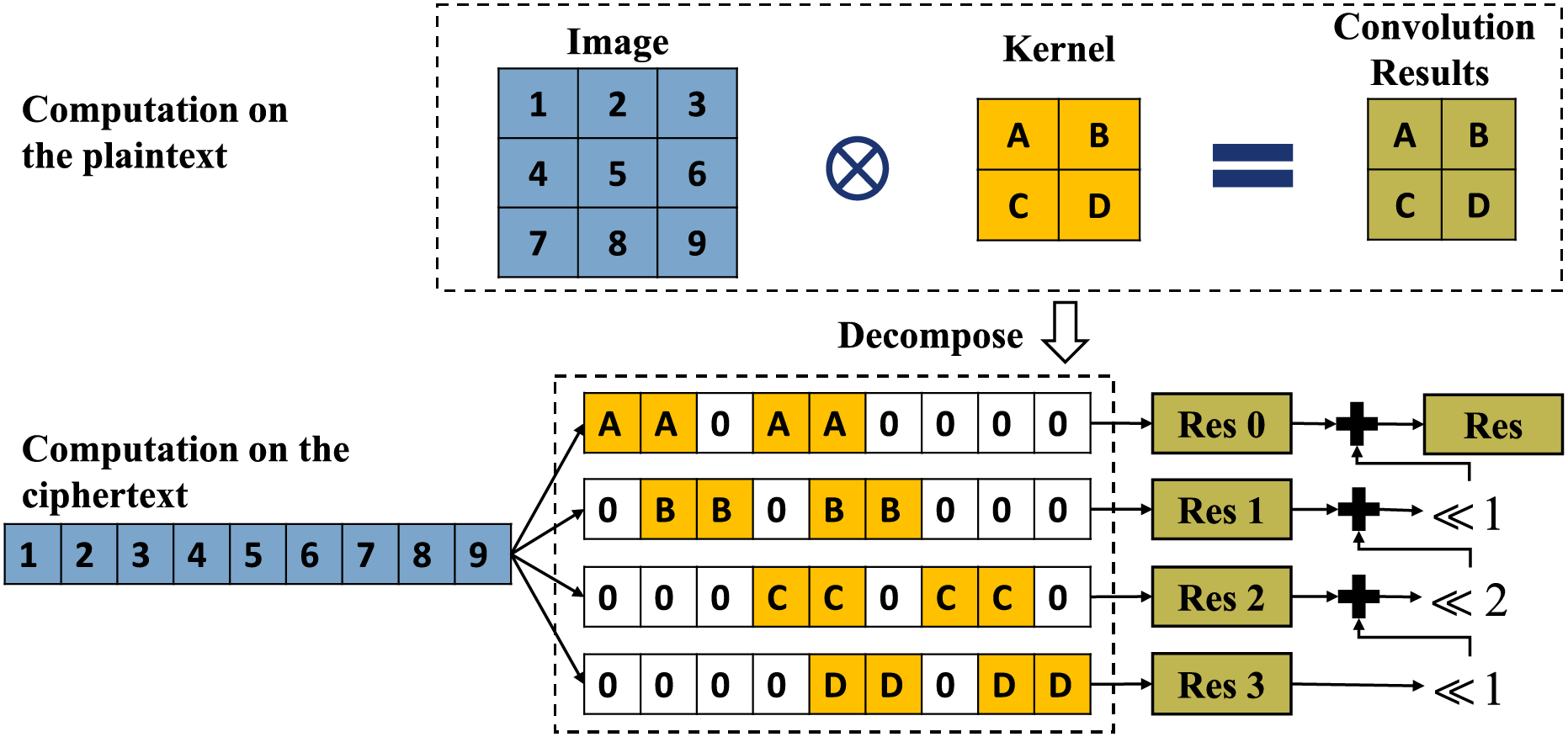

Given an input feature map

where

Figure 1: An example of the 2D convolution

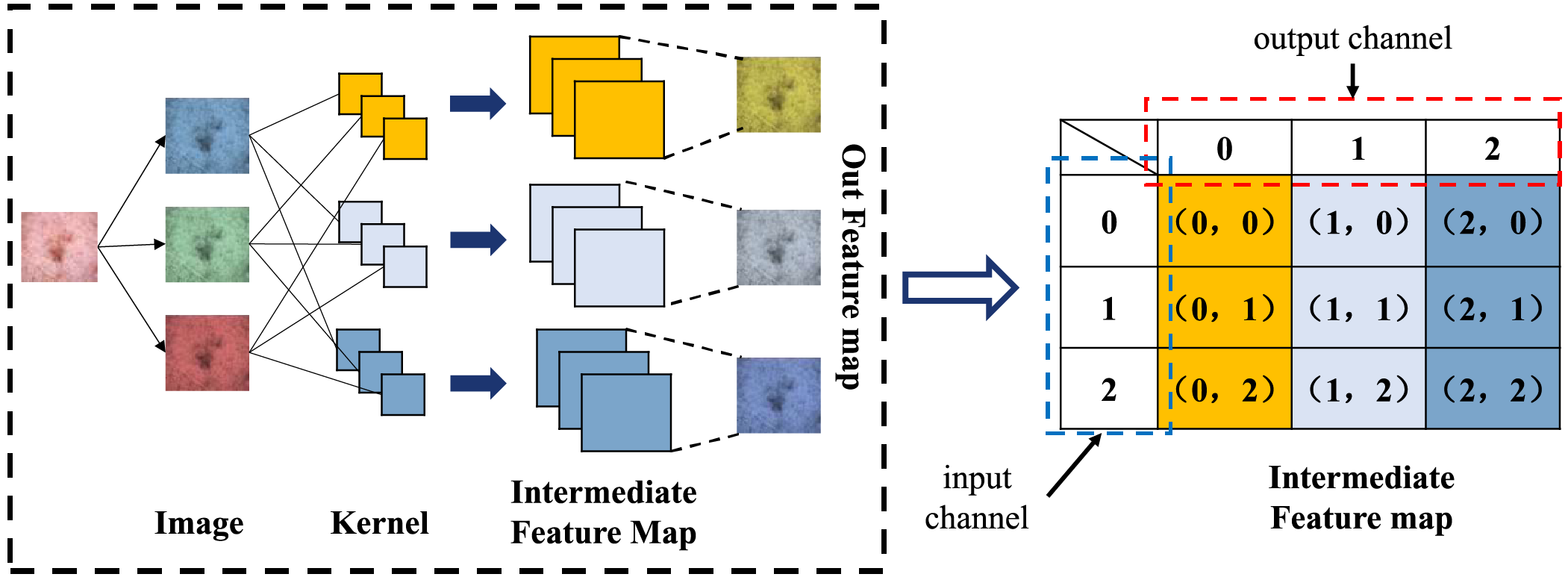

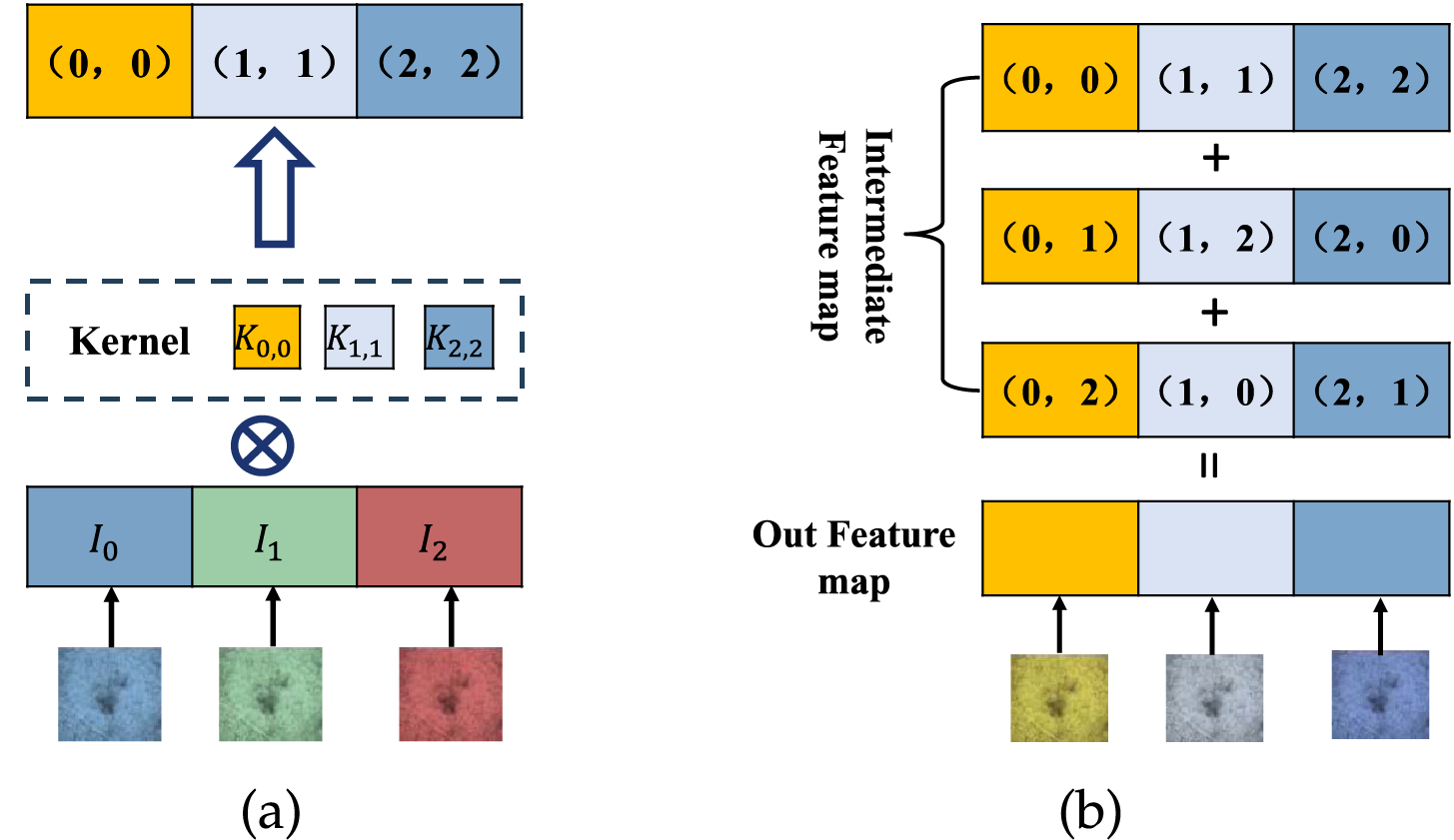

By focusing on the 3D convolution with CC′ kernels

where

Figure 2: An example of the 3D convolution

Figure 3: An example of batch convolution and sum of intermediate feature maps

In this study, we apply batch normalization immediately after each convolution operation to prevent extreme shifts in the feature distribution effectively. The formula of BN is:

where

where

4.3 Activation Function and Fully Connected Layer

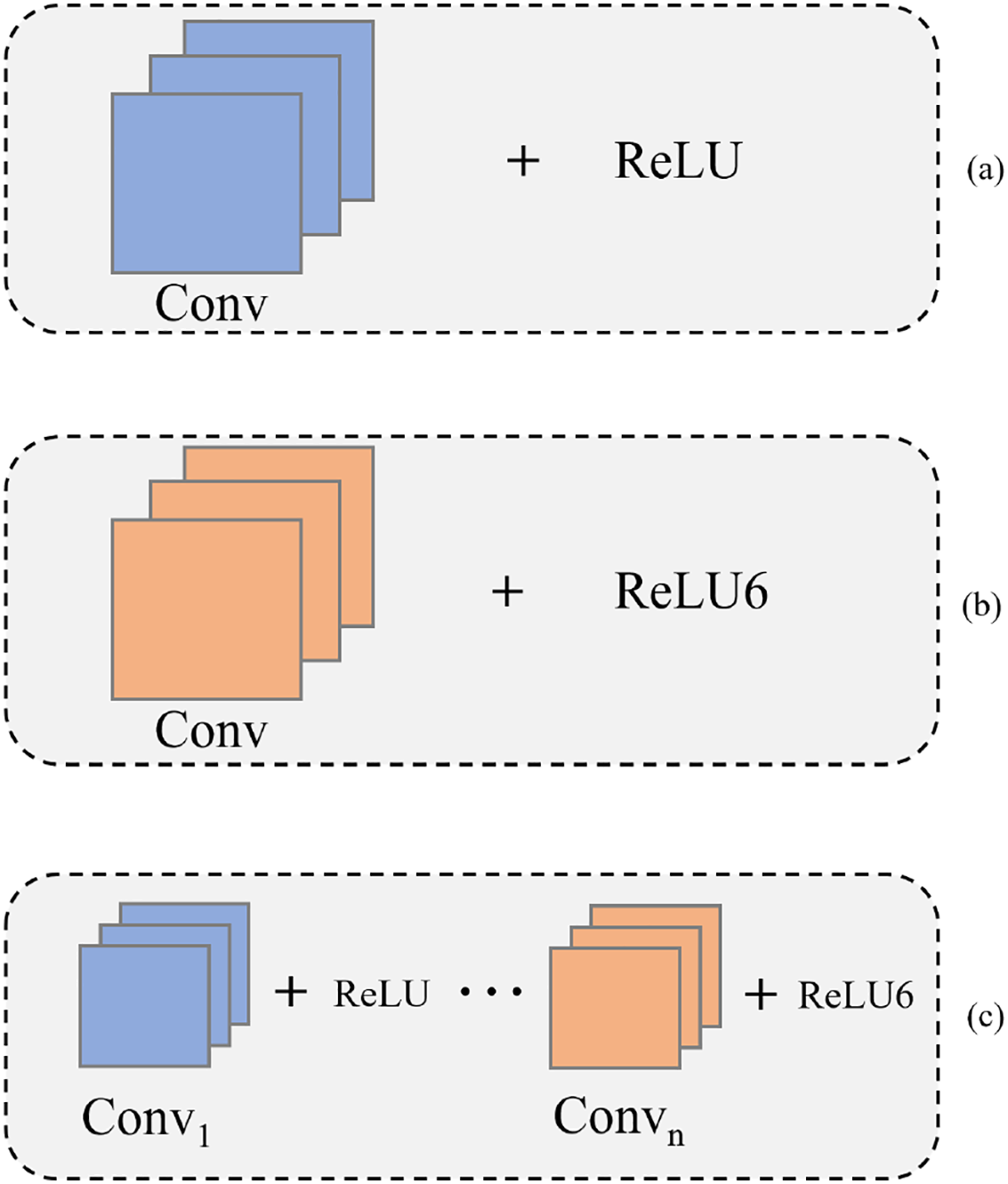

The ReLU activation function and its variant ReLU6 are defined by the formulas ReLU(x) = max(0, x) and ReLU6(x) = min(max(0, x), 6), respectively. ReLU6 restricts the output range by introducing an upper threshold. In this paper, we carefully design and compare three convolution-activation schemes combining ReLU and ReLU6. As shown in Fig. 4a, the first scheme is similar to most existing approaches, ReLU(Conv[x]), using ReLU as the activation function after all convolutional layers. The subsequent scheme employs ReLU6 after convolution in Fig. 4b, ReLU6(Conv[x]). The remaining scheme uses ReLU for shallow layers and ReLU6 for deep layers in Fig. 4c,

Figure 4: Performance Comparison of plaintext and ciphertext metrics

After being flattened into a one-dimensional vector by the Flatten layer, the computation of the fully connected layer (

In homomorphic encryption operations, noise refreshment is indispensable. Noise accumulates continuously after each homomorphic operation, and once it exceeds a certain threshold, it can lead to decryption failures or data errors. Therefore, noise reduction is required to control the noise level. Previously, noise was refreshed through bootstrapping operations, which introduce extremely high computational overhead, making it less suitable for computationally-constrained devices. Here, we implement noise refreshment through interactive decryption-encryption operations.

When the server obtains the ciphertext feature map

Upon receiving the ciphertext

Eventually, the server obtains the noise-refreshed ciphertext

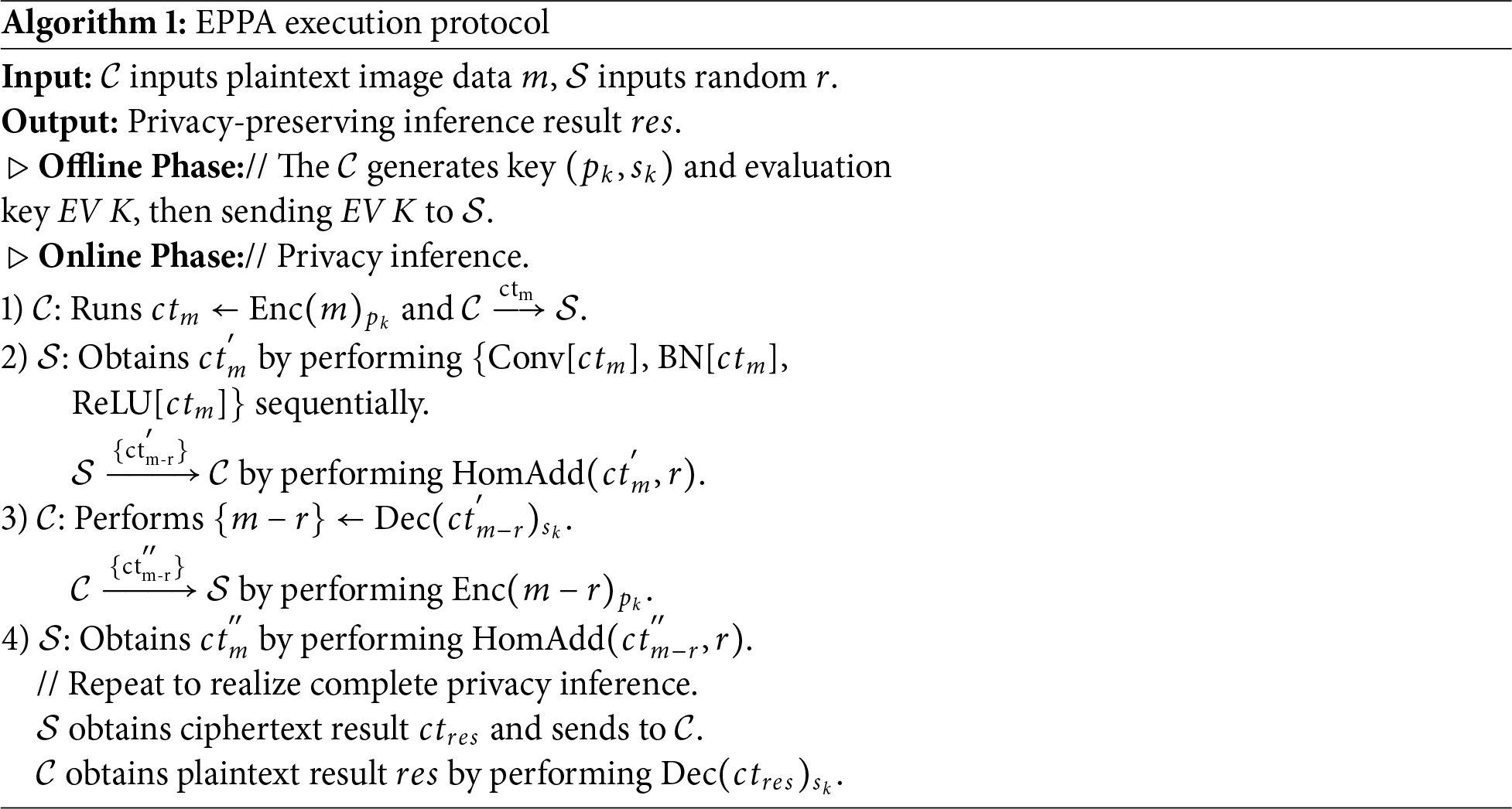

In order to better describe the execution process of the EPPA scheme, we elaborate in detail through Algorithm 1.

(1) Initialization: The client generates CKKS parameters, including the secret key

(2) Server-Side Computation: Upon receiving the ciphertext

(3) Client-Side Noise Refreshment: After receiving the ciphertext

(4) Server-Side Recovery: The server performs a homomorphic addition of r to the ciphertext

Repeat steps (2–4) to complete the full privacy-preserving inference process.

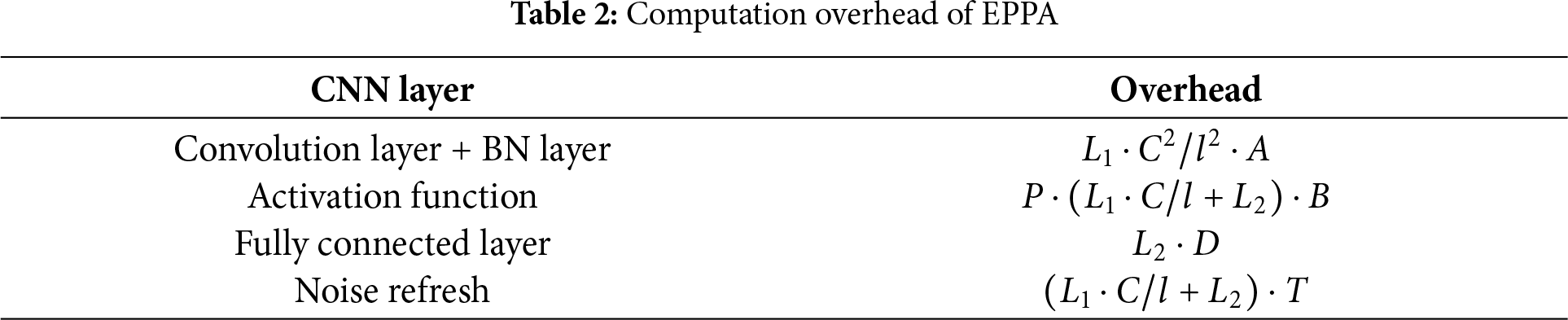

4.6 Computational Complexity Analysis

To clarify the computational performance of EPPA, we perform a layer-wise analysis of the computational cost in the CNN architecture.

We assume that each ciphertext can be stored in the feature maps of

5 Analysis of the Execution Protocol

This section is primarily on presenting an overview of the security of the EPPA. We provide a comprehensive security analysis of the EPPA protocol in an honest but curious model. The definition of privacy is given, and the following lemma is used in the execution protocol’s security.

Theorem 1: Our algorithm protects the privacy of data based on FHE. Under an honest and curious model, the adversary

Proof: A series of random variables will be simulated by the simulator

From what has been mentioned above, we have established the existence of a polynomial-time simulator

In the following section, we conduct extensive experiments to evaluate various indicators and the performance of EPPA. In the experiments, we use a computer equipped with an Intel Core i7-14700KF processor (3.40 GHz) and 32 GB of RAM to perform simulations in Golang. We have experimentally evaluated EPPA on five datasets, including two datasets for checking seatbelt usage in intelligent transportation, two datasets for detecting skin diseases in intelligent healthcare, and the remaining one dataset for inspecting product defects in intelligent manufacturing. Additionally, we conducted supplementary evaluation experiments on two seatbelt datasets using two Raspberry Pi models with different computing capabilities, namely Raspberry Pi 4B and Raspberry Pi 5. The configuration of Raspberry Pi 4B is as follows: the CPU is Broadcom BCM2711, which adopts a 64-bit quad-core ARM Cortex-A72 architecture with a main frequency of 1.5 GHz, the memory is 4 GB LPDDR4 RAM, and the operating system is Linux. The configuration of Raspberry Pi 5 is: a central processing unit of Broadcom BCM2712 D0, a 64-bit quad-core ARM Cortex-A76 architecture with a main frequency of 2.4 GHz; the memory is 4GB LPDDR4X-4267 RAM. the operating system is also Linux. As shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: EPPA implemented with the Raspberry Pi (as a resource-limited device)

6.1 Dataset and CNN Architecture Description

In the experimental evaluation, all the datasets we used were sourced from real-world scenarios, demonstrating the relevance of our model to practical applications. All datasets were evenly divided into training sets and test sets at a ratio of 8:2. The following is a detailed introduction:

• data Image Dataset (dID) [26]: This dataset contains a total of 1083 images, which are used to detect whether drivers are wearing seat belts while driving. It includes two categories: wearing a seat belt and not wearing a seat belt. All the images in this dataset were provided by Roboflow users.

• NEU Surface Defect Database (NSDD) [27]: It is a dataset specifically designed for the detection of metal surface defects. There are six defect categories in total, namely Rolled-in Scales (RS), Patches (Pa), Crazing (Cr), Pitted Surfaces (PS), Inclusions (In), and Scratches (Sc). Each category contains 300 grayscale images, making a total of 1800 images. This dataset is provided by Northeastern University.

• Skin-Disease-Dataset (SDD): This dataset contains a total of 1159 images, which were collected from the Internet. It encompasses a total of 8 categories of skin disease infections.

• Skin Disease Classification (SDC): This dataset consists of a total of 900 images, which are sourced from ISIC. It includes 9 categories of skin diseases. For the sake of convenience, we only selected 6 of these categories for experimental evaluation.

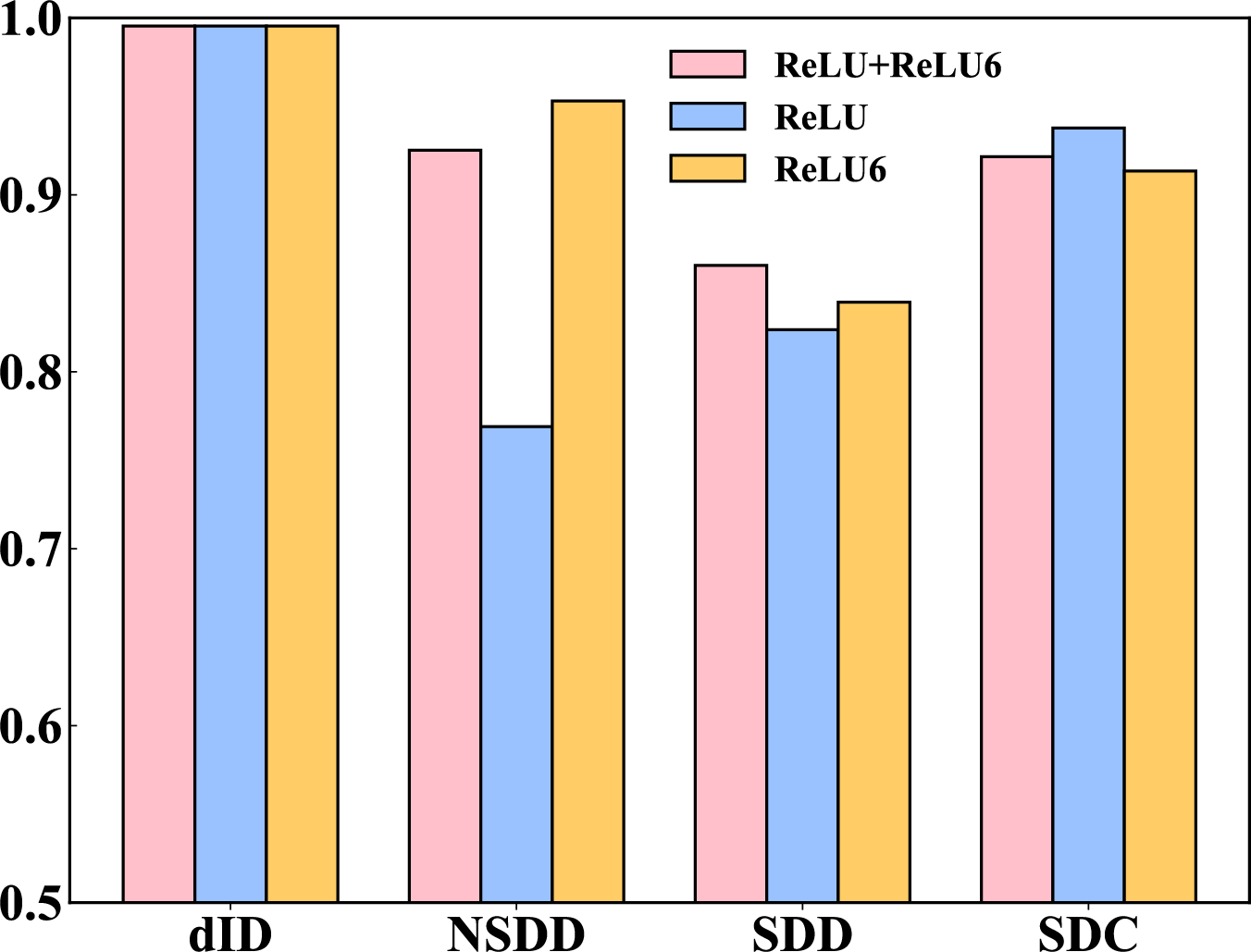

For three different plaintext convolution-activation schemes, we compared their accuracies to screen the corresponding convolution-activation structures for ciphertext. As shown in Fig. 6. When using ReLU, the accuracy on datasets dID and SDC reached 99.54% and 93.78%, respectively, but the performance on datasets NSDD and SDD was less optimistic, only achieving 76.91%, and 82.38%. In the subsequent deployment of ReLU6, the accuracies on datasets dID, NSDD, SDD, and SDC reached 99.54%, 95.31%, 83.94% and 91.35%, respectively. When adopting the ReLU+ReLU6 architecture, the accuracy on datasets dID and NSDD was comparable to that of the ReLU6 architecture, with slight improvements on datasets SDD and SDC. Given the relatively outstanding performance of ReLu+ReLu6 on the four datasets. Therefore, we adopted ReLU+ReLU6 as the activation function for the ciphertext inference.

Figure 6: Comparison of accuracy among different CNN architectures

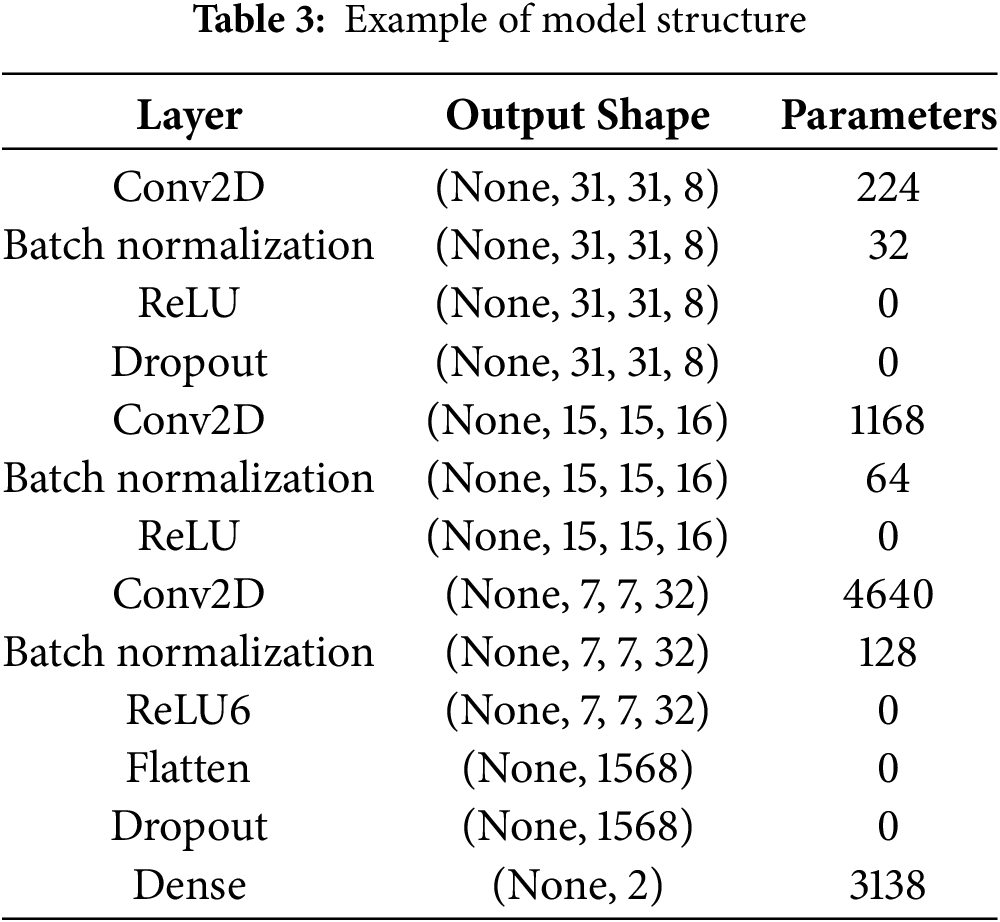

Subsequently, there is a detailed description of the architecture of the CNN classification model. In the initial two datasets (dID, NSDD), the CNN model is composed of three convolutional layers and one fully connected layer. Moreover, each convolutional layer contains 8, 16, and 32 convolutional kernels with a dimension of 3 × 3, respectively. We use the ReLU activation function after the initial two convolutional layers, and employ ReLU6 as the activation function after the last convolutional layer. In the field of intelligent healthcare, more precise and detailed classification and prediction results are required. Therefore, for the latter two datasets SDD and SDC, we use four convolutional layers for feature extraction, namely, an additional layer is added after the third convolutional layer, which contains 64 convolutional kernels. Similarly, ReLU is deployed after the first two convolutional layers, and ReLU6 is deployed after the remaining two convolutional layers. After each convolution, we use batch normalization to accelerate the convergence of the model. Additionally, we strategically introduce dropout after the first and final convolutional layers to improve the model’s generalization ability. The feature map is flattened into a one-dimensional vector and input into the fully connected layer to map to the classification result vector. In order to have a more intuitive understanding of the architecture of the classification model, we have presented the model architecture in plain text through the detailedly drawn Table 3.

In the image classification experiment, Accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score are used as evaluation indicators. Four factors (TP, TN, TF, and TN) are needed to calculate them. TP represents the number of samples correctly classified as positive, TN represents the number of samples correctly classified as negative, FP represents the number of negative samples misclassified as positive, and FN represents the number of positive samples misclassified as negative.

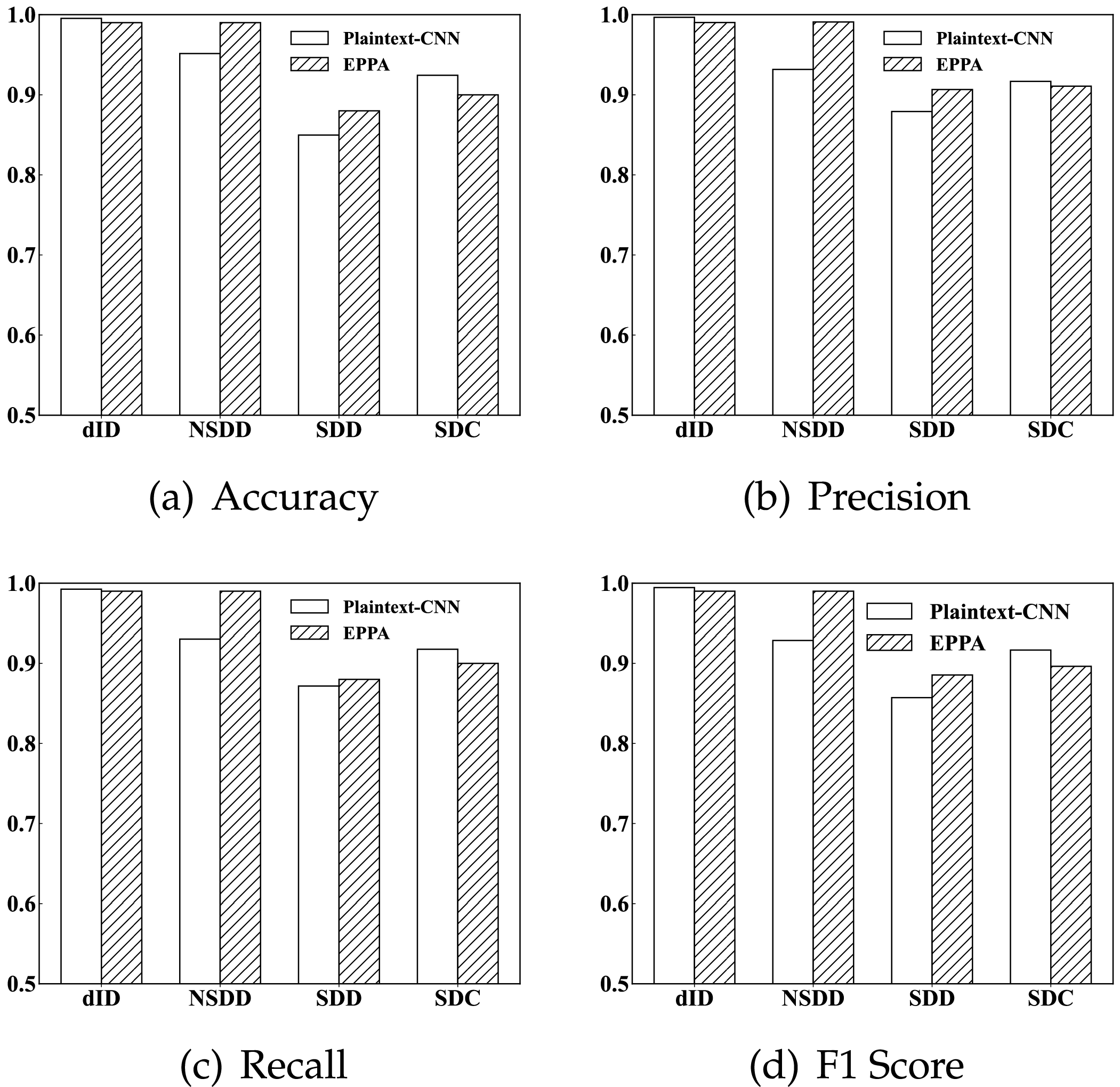

For each experimental dataset, we compared the average scores of each indicator in the plaintext and ciphertext states, respectively. As shown in Fig. 7. we demonstrate the effectiveness of EPPA through these indicators.

Figure 7: Performance comparison of plaintext and ciphertext metrics

Fig. 7a demonstrates the performance of EPPA in terms of accuracy. In the plaintext state, the dataset dID for intelligent transportation achieved a high accuracy of 99.54%. For the dataset NSDD, our scheme attained an accuracy of 95.14%, verifying its effectiveness in industrial inspection scenarios. In intelligent medical skin disease diagnosis, the datasets SDD and SDC achieved results of 84.97% and 92.43%, respectively, revealing the application potential of our scheme in the medical field. When converted to the ciphertext state, both the dID and NSDD datasets reached an accuracy of 99.00%. The SDD and SDC datasets achieved accuracies of 88.00% and 90.00%, respectively. These results indicate that our scheme exhibits comparable performance in plaintext and ciphertext states, further validating its accuracy and effectiveness.

Fig. 7b demonstrates the performance of EPPA in terms of precision. In the plaintext state, the SDD dataset achieves a precision of 86.90%, while the NSDD, dID, and SDC datasets reach 95.12%, 99.54%, and 92.65%, respectively. After conversion to the ciphertext state, the NSDD, dID, SDD, and SDC datasets achieve 99.09%, 99.02%, 90.65%, and 91.08% in precision, respectively. Overall, EPPA’s capability to predict positive samples is impressive.

Fig. 7c illustrates the performance of EPPA in terms of recall. In the plaintext state, the SDD dataset achieves a recall rate of 84.97%, while the NSDD, dID, and SDC datasets reach 95.14%, 99.54%, and 92.43%, respectively. After applying FHE technology, the recall rates of the NSDD, dID, and SDC datasets are 99.00%, 99.00%, and 90.00%, respectively, and that of the SDD dataset is 88.00%. These results demonstrate that our EPPA scheme exhibits excellent capability in covering positive samples.

Fig. 7d shows the F1 scores of EPPA on four datasets. The NSDD and dID datasets show excellent performance, with values of 95.11% and 99.54%, respectively. The SDC dataset also achieves a high score of 92.31%, while the final SDD dataset reaches 85.11% under our carefully designed model. After conversion to ciphertext using FHE technology, the NSDD and dID datasets still maintain outstanding performance at 99.01% and 99.00%, respectively, while the SDD and SDC datasets achieve scores of 88.54% and 89.63%, respectively. Although there is room for improvement, EPPA’s impressive F1 score performance on multiple IoT datasets is sufficient to highlight the applicability and potential of our scheme across multiple domains.

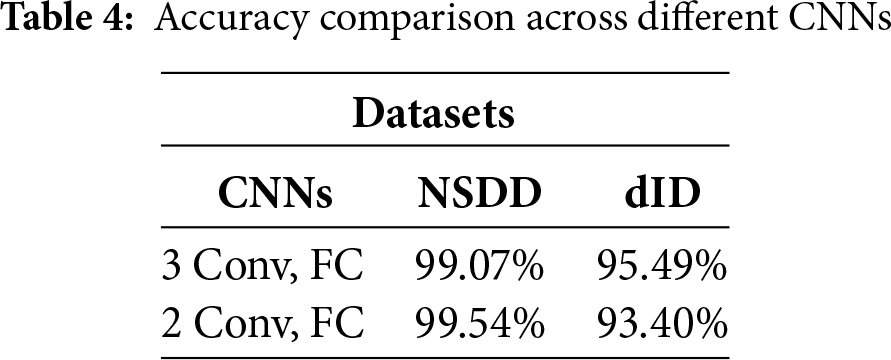

Additionally, we further evaluated the accuracy of EPPA under different CNN architectures on two distinct datasets, as shown in Table 4. Building upon the experiments with the previous activation structures, the first architecture consists of three convolutional layers followed by an FC layer, where ReLU activation is applied after the first two convolutional layers and ReLU6 is applied after the final convolutional layer. The second architecture applies ReLU activation after the first convolutional layer and ReLU6 after the final convolutional layer. Since the dID dataset contains only two classes, EPPA achieves high accuracy, reaching 99.07% and 99.54% under the two architectures, respectively. For the NSDD dataset, EPPA also demonstrates strong classification performance, achieving 95.49% and 93.40% accuracy, respectively.

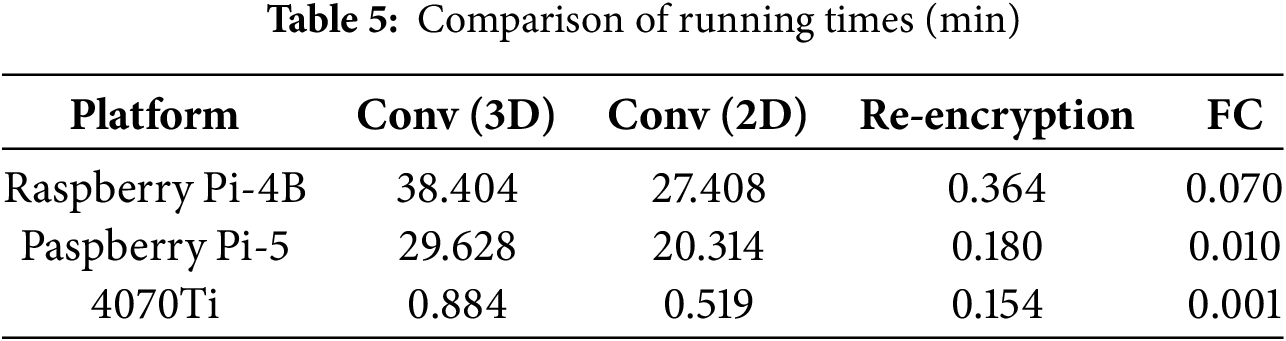

In addition, we compared the privacy inference times of each component of the model on the host computer (equipped with a 4070 Ti graphics card), Raspberry Pi 4B, and Raspberry Pi 5, as shown in Table 5. Due to the large number of parameters in the fully homomorphic encryption scheme, the overall running time is relatively slow. Obviously, compared with high-performance computing platforms, the running times of each component of the model on Raspberry Pi 4B and Raspberry Pi 5, which have limited hardware computing resources, are significantly longer in most cases. For ciphertext convolution operations, we compared 3D convolution and 2D convolution. For 3D convolution calculations, the host with 4070 Ti takes 0.884 min, Raspberry Pi 4B takes as long as 38.404 min, while Raspberry Pi 5 takes 29.628 min. For the converted 2D convolution, the host with 4070 Ti takes 0.519 min, Raspberry Pi 4B takes 27.408 min, and Raspberry Pi 5 takes 20.314 min. This acceleration is attributed to our conversion of 3D convolutions into 2D convolutions, which yields an approximate 1.7

In this paper, we propose an efficient privacy-preserving neural network inference scheme for AIoT applications based on FHE, named EPPA. In the non-ciphertext phase, we deploy ReLU and ReLU6 into the layers of varying depths for fully homomorphic inference in the encryption domain. After switching to the ciphertext phase, EPPA transforms 3D convolutions into 2D convolutions to reduce computational overhead, targeting resource-constrained edge computing devices. Additionally, EPPA integrates the computations of the BN layer into the convolutional layer to minimize extra overhead caused by homomorphic operations. For the non-linear part, EPPA uses composite polynomials for the approximated computation of activation functions. Finally, experimental evaluations on multiple IoT datasets verify the effectiveness of EPPA and its applicability in multi-scenario environments.

Although we have simulated privacy-preserving inference in AIoT scenarios using multiple datasets, there is still room for improvement in the performance of various metrics under both plaintext and ciphertext states. Meanwhile, we are aware that EPPA may have certain limitations when confronted with more complex and large-scale AIoT scenarios. Therefore, in the future, we plan to optimize EPPA from two aspects. On one hand, we will perform customized optimizations for large-scale ciphertext convolution operations to accelerate computation. On the other hand, we will balance the complexity and security of the FHE scheme to identify an FHE solution better suited to EPPA, thereby further improving its inference performance.

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge the support of the Intelligent Security Laboratory at Guizhou University for providing technical and equipment assistance during this research.

Funding Statement: This paper is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China No. 62362008 and the Major Scientific and Technological Special Project of Guizhou Province ([2024]014).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Haoran Wang, Shuhong Yang, Kuan Shao, Zhenyong Zhang; methodology, Haoran Wang, Shuhong Yang, Kuan Shao; software, Haoran Wang, Shuhong Yang, Kuan Shao; validation, Haoran Wang, Shuhong Yang, Kuan Shao, Tao Xiao; formal analysis, Haoran Wang, Shuhong Yang, Kuan Shao; investigation, Haoran Wang, Shuhong Yang, Kuan Shao; resources, Zhenyong Zhang; data curation, Zhenyong Zhang; writing—original draft preparation, Haoran Wang, Shuhong Yang, Zhenyong Zhang; writing—review and editing, Haoran Wang, Shuhong Yang, Zhenyong Zhang; visualization, Haoran Wang, Shuhong Yang, Zhenyong Zhang; supervision, Zhenyong Zhang; project administration, Haoran Wang, Zhenyong Zhang; funding acquisition, Haoran Wang, Zhenyong Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data openly available in a public repository. The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at [https://universe.roboflow.com/bassant/] (accessed on 04 September 2025) and [https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/] (accessed on 04 September 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Thao ND, Phuong NT, Cho M-Y. Real-time AIoT anomaly detection for industrial diesel generator based an efficient deep learning CNN-LSTM in industry 4.0. Internet Things. 2024;27(11):101280. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2024.101280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Chen Z, Cui J, Zhang Y. Efficient mask recognition based on MobileNet. In: 2023 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence of Things and Systems (AIoTSys); 2023 Oct 19–22;Xi’an, China. p. 194–7. [Google Scholar]

3. Xu S, Zhang X, Jin N. Soccer sports injury risk analysis and prediction by edge wearable devices and machine learning. In: 2023 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence of Things and Systems (AIoTSys); 2023 Oct 19–22;Xi’an, China. p. 38–43. [Google Scholar]

4. Ferdowsi A, Challita U, Saad W. Deep learning for reliable mobile edge analytics in intelligent transportation systems—an overview. IEEE Vehicular Technol Mag. 2019;14(1):62–70. doi:10.1109/mvt.2018.2883777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhang Z, Liu M, Sun M, Deng R, Cheng P, Niyato D, et al. Vulnerability of machine learning approaches applied in IoT-based smart grid: a review. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(11):18951–18975. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3349381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhang Z, Yang Z, Yau DKY, Tian Y, Ma J. Data security of machine learning applied in low-carbon smart grid: a formal model for the physics-constrained robustness. Appl Energy. 2023;347(1):121405. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.121405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhao R, Xie Y, He D, Choo K-KR, Jiang ZL. Practical privacy-preserving convolutional neural network inference framework with edge computing for health monitoring. IEEE Trans Netw Sci Eng. 2024;11(6):5995–6006. doi:10.1109/tnse.2024.3434643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Dwivedi R, Raman R, Sutaria KK, Rameshkumar SG, Srinivasan S, Babu TRG. IoT-enabled CNN biometrics for enhanced security and verification for smart transportation systems. In: 2024 1st International Conference on Innovative Sustainable Technologies for Energy, Mechatronics, and Smart Systems; 2024 Apr 26–27; Dehradun, India. [Google Scholar]

9. Liu X, Wu B, Yuan X, Yi X. Leia: a lightweight cryptographic neural network inference system at the edge. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2022;17:237–52. doi:10.1109/tifs.2021.3138611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. GDPR. General data protection regulation; 2018 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 4]. Available from: https://gdpr-info.eu. [Google Scholar]

11. He P, Duan H, Luo J. An integration tool of safety and security requirements for autonomous vehicles. In: 2023 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence of Things and Systems (AIoTSys); 2023 Oct 19–22; Xi’an, China. p. 118–24. [Google Scholar]

12. Gozubuyuk B, Bailey W, Everson D, Dong Z, Cheng L, Pesé MD. An overview of security in connected and autonomous vehicles. In: 2023 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence of Things and Systems (AIoTSys); 2023 Oct 19–22;Xi’an, China. p. 206–13. [Google Scholar]

13. Fu Y, Tong Yu, Ning Y, Xu T, Li M, Lin J, et al. Swift: fast secure neural network inference with fully homomorphic encryption. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2025;20:2793–806. doi:10.1109/tifs.2025.3547308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. He G, Ren Y, He G, Feng G, Zhang X. PPNNI: privacy-preserving neural network inference against adversarial example attack. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2024;17(6):4083–96. doi:10.1109/tsc.2024.3399648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Juvekar C, Vaikuntanathan V, Chandrakasan A. GAZELLE: a low latency framework for secure neural network inference. In: 27th USENIX security symposium (USENIX security 18); 2018 Aug 15–17; Baltimore, MD, USA. p. 1651–69. [Google Scholar]

16. Mishra P, Lehmkuhl R, Srinivasan A, Zheng W, Popa RA. Delphi: a cryptographic inference system for neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 2020 Workshop on Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning in Practice; 2020 Nov 9; Online. p. 27–30. [Google Scholar]

17. Pereteanu G, Alansary A, Passerat-Palmbach J. Split HE: fast secure inference combining split learning and homomorphic encryption. arXiv:2202.13351. 2022. [Google Scholar]

18. Lou Q, Feng B, Fox GC, Jiang L. Glyph: fast and accurately training deep neural networks on encrypted data. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2020;33:9193–202. [Google Scholar]

19. Lee J-W, Kang H, Lee Y, Choi W, Eom J, Deryabin M, et al. Privacy-preserving machine learning with fully homomorphic encryption for deep neural network. IEEE Access. 2022;10:30039–54. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3159694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kim D, Guyot C. Optimized privacy-preserving CNN inference with fully homomorphic encryption. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2023;18(11):2175–87. doi:10.1109/tifs.2023.3263631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Wu L, Fu S, Luo Y, Xu M. SecTCN: privacy-preserving short-term residential electrical load forecasting. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2024;20(2):2508–18. doi:10.1109/tii.2023.3292532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Fan J, Vercauteren F. Somewhat practical fully homomorphic encryption. Cryptol EPrint Arch, Paper. 2012/144, 2012. [cited 2025 Sep 4]. Available from: https://eprint.iacr.org/2012/144. [Google Scholar]

23. Cheon JH, Kim A, Kim M, Song Y. Homomorphic encryption for arithmetic of approximate numbers. In: Proceeding 23rd International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017. p. 409–37. [Google Scholar]

24. Yang X, Chen J, He K, Bai H, Wu C, Du R. Efficient privacy-preserving inference outsourcing for convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2023;18:4815–29. doi:10.1109/tifs.2023.3287072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Cheon JH, Han K, Kim A, Kim M, Song Y. A full RNS variant of approximate homomorphic encryption. In: Selected Areas in Cryptography-SAC 2018: 25th International Conference. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2018. p. 347–68. [Google Scholar]

26. Roboflow user, data image datase [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 14]. Available from: https://universe.roboflow.com/bassant/. [Google Scholar]

27. NEU surface defect database [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 14]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools