Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Syntax-Aware Hierarchical Attention Networks for Code Vulnerability Detection

School of Computer and Communication, Lanzhou University of Technology, Lanzhou, 730050, China

* Corresponding Author: Baofeng Duan. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069423

Received 23 June 2025; Accepted 24 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

In the context of modern software development characterized by increasing complexity and compressed development cycles, traditional static vulnerability detection methods face prominent challenges including high false positive rates and missed detections of complex logic due to their over-reliance on rule templates. This paper proposes a Syntax-Aware Hierarchical Attention Network (SAHAN) model, which achieves high-precision vulnerability detection through grammar-rule-driven multi-granularity code slicing and hierarchical semantic fusion mechanisms. The SAHAN model first generates Syntax Independent Units (SIUs), which slices the code based on Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) and predefined grammar rules, retaining vulnerability-sensitive contexts. Following this, through a hierarchical attention mechanism, the local syntax-aware layer encodes fine-grained patterns within SIUs, while the global semantic correlation layer captures vulnerability chains across SIUs, achieving synergistic modeling of syntax and semantics. Experiments show that on benchmark datasets like QEMU, SAHAN significantly improves detection performance by 4.8% to 13.1% on average compared to baseline models such as Devign and VulDeePecker.Keywords

With the acceleration of global digital transformation, software has become the core infrastructure for the operation of modern society. However, the rapid increase in software complexity and the continuous compression of development cycles have led to the frequent occurrence of security vulnerabilities, which pose a major threat to cybersecurity. According to the National Vulnerability Database (NVD) [1], as of March 2025, the cumulative number of Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) [2] recorded is up to 284,500. Once exploited by malicious attackers, these vulnerabilities can lead to a series of catastrophic consequences ranging from personal data leakage to the collapse of critical infrastructure such as power supply and public transportation systems.

Faced with such severe security challenges, traditional vulnerability detection methods have been difficult to meet the needs of complex software systems. In recent years, deep learning techniques have significantly improved the efficiency of vulnerability detection by learning vulnerability patterns from structured representations such as Abstract Syntax Trees (AST), Program Dependence Graph (PDG) and Control Flow Graphs (CFG). For example, SySeVR [3] uses program slicing technology to extract syntax-semantic features related to vulnerabilities from AST and PDG. Zhao et al. [4] added code block AST syntax structure information to CFG, while Zhang et al. [5] added control flow information based on AST to further enrich the syntactic features of code. The emergence of large language models (LLMs) has further driven changes in this field: With their powerful ability to understand context, LLMs can capture potential vulnerability semantic patterns from massive code corpora and even generate repair suggestions. However, as of now, LLMs are susceptible to data leakage and adversarial sample attacks during the process of code analysis, which limits their deployment in sensitive scenarios such as financial systems and industrial control.

Although deep learning-based vulnerability detection methods have made significant progress, they still have limitations in terms of efficiency and accuracy. For example, current vulnerability datasets (such as NVD) have issues such as high annotation noise and imbalanced distribution of vulnerability types, which lead to generalization challenges for models in real-world scenarios. Additionally, existing graph-based code representation methods contain a large number of irrelevant nodes, leading to models focusing too much on local features and ignoring global semantics.

To overcome these challenges, we propose a vulnerability detection method based on Syntax-Aware Hierarchical Attention Network (SAHAN). The core of this method involves generating Syntax Independent Units (SIUs) by independently slicing the AST. These slices rely on explicit syntactic features and do not require complex control flow or data flow analysis, thereby retaining critical context relevant to vulnerability patterns while incurring lower computational overhead compared to models based on complex graph structures. Next, the attention mechanism is applied to mitigate the limitations of syntax slicing in modeling long-range dependencies. Finally, the method adopts a hierarchical design: The local syntax-aware layer (Gated Recurrent Unit, GRU) encodes fine-grained patterns within SIUs (such as variable scopes and array accesses), while the global semantic correlation layer (Transformer) captures vulnerability chains across SIUs (such as resource leaks propagating across functions), achieving synergistic modeling of syntax and semantics. Experimental results show that our approach can more accurately detect vulnerabilities compared to baseline models.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

1. We use syntax-rule-based AST slicing without complex control flow or data flow analysis, which can bring lower computational costs compared to methods that rely on control flow or data flow.

2. We use a hierarchical design in our model, where low-level features generate local semantic representations to capture fine-grained patterns within individual syntax units, and high-level features generate global semantic representations to capture complex logic across multiple units.

3. We evaluated the effectiveness of our approach on public datasets, and experimental results clearly demonstrate the validity of our method.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 summarizes the existing work; Section 3 details our methodology; Section 4 describes the experimental setup. Section 5 analyzes the experimental results. Section 6 discusses limitations; Section 7 summarizes the thesis and looks forward to the future.

2.1 Traditional Vulnerability Detection Methods

Traditional static source code vulnerability detection methods mainly include rule-based approaches and classical machine learning methods.

Rule-based vulnerability detection methods rely on predefined rules and patterns to identify potential security vulnerabilities. These rules are typically manually written by security experts and cover known types of vulnerabilities and programming errors. Yamaguchi et al. [6] applied pattern matching techniques on Code Property Graph (CPG) to automatically detect common vulnerabilities in source code. Zheng et al. [7] constructed data flow graphs for program slicing, utilizing Graph Neural Networks (GNN) for representation learning to identify potential vulnerabilities.

A drawback of rule-based methods is that they may produce a high false positive rate because some legitimate code might be incorrectly flagged as vulnerable. The fundamental flaw of such methods lies in their inability to model the semantic context of code, allowing them to only detect known vulnerabilities with fixed patterns.

2.1.2 Classical Machine Learning Methods

Machine learning methods recognize vulnerabilities in code by learning features from annotated training data. These methods generally involve feature extraction, model training, and evaluation steps. Common algorithms include Decision Trees, Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Random Forests (RF). Medeiros et al. [8] evaluated dozens of classifiers including Random Forests and Naive Bayes, finding Logistic Regression to be the optimal classifier for the problems at hand. Chakraborty et al. [9] used models like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Random Forests to extract code features and predict the existence of vulnerabilities. Experimental results showed that this method could achieve high accuracy and F1 scores across different types of software programs. However, subsequent studies indicated that these pre-trained models do not perform well in real-world scenarios due to poor generalization across different datasets. Compared to rule-based methods, classical machine learning methods can automatically learn features, reducing the need for manual intervention. Nevertheless, the performance of these methods often depends on the quality of feature selection and the richness of the training data, and they may underperform when dealing with complex code structures.

2.2 Vulnerability Detection Based on Deep Learning

In recent years, deep learning-based vulnerability detection technologies have shown breakthrough potential, capable of more effectively capturing complex patterns and semantic information in code. Deep learning-based vulnerability detection primarily includes code sequence modeling, code graph structure modeling, and the use of pre-trained large models.

Code sequence modeling methods treat source code as sequential data, utilizing models such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) and Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTM) to capture contextual information within the code. Studies [10–14] are examples of vulnerability detection models based on code sequence modeling. A typical work is VulDeePecker [10], which generates token sequences from sliced code and uses Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) for vulnerability detection, improving accuracy. This method effectively handles sequential dependencies in code, thereby enhancing the accuracy of vulnerability detection. For instance, by converting code snippets into sequences, the model can learn relationships between different statements, thus identifying potential vulnerabilities. A recent study [15] proposed a cross-modal adversarial reprogramming method called Capture for software vulnerability detection. This method extracts structure-and type-aware token sequences by performing lexical parsing and linearization on the AST of source code, converts these sequences into perturbation images, and leverages pre-trained computer vision models for vulnerability detection. Experimental results show that Capture achieves detection accuracy comparable to state-of-the-art methods while having an advantage in training efficiency. It performs particularly well in terms of detection precision and F1 score, especially when the number of samples is limited. However, sequence models suffer from semantic biases due to ignoring syntax structures, in buffer overflow detection tasks, their false positive rate is 25% higher than that of graph models [16]. The fundamental issue lies in the inability of pure sequence modeling to effectively express syntactic constraints (such as bracket matching) in the code. Additionally, sequence models struggle with long-range dependency issues.

2.2.2 Code Graph Structure Modeling

Code graph structure modeling methods represent source code as a graph structure, leveraging technologies like GNN to capture syntactic and semantic information in the code. This approach efficiently handles complex structures in code, such as function calls, control flow, and data flow. By representing code as graphs, models can better understand the logical relationships within the code, thus enhancing vulnerability detection effectiveness. References [16–20] are examples of vulnerability detection methods based on code graph structure modeling. Zhou et al. [16] proposed a GNN-based vulnerability detection model called Devign, which transforms code into a graph structure to effectively capture syntactic and semantic information, thereby improving the accuracy and robustness of vulnerability detection. Wang et al. [17] adopted code graph embedding and graph self-supervised learning denoising to improve the accuracy and efficiency of code vulnerability detection. However, existing methods still face challenges; using graph structure modeling often requires complex control flow and data flow analysis, leading to significant computational overhead.

2.2.3 Pre-Trained Language Models

Pre-trained language models (e.g., CodeBERT [21], GraphCodeBERT [22]) learn general representations through massive code corpora, supporting zero-shot vulnerability detection. These models can capture deep semantic information in the code and perform excellently in various tasks. References [23–26] are examples of vulnerability detection methods combining LLMs. For example, LineVul [24] fine-tuned CodeBERT, achieving an F1 score of 0.82 in cross-project testing, a 30% improvement over traditional methods, demonstrating the effectiveness of LineVul. Recent work by Lu et al. [25] introduced the GRACE method, which combines graph structural information and context learning to enhance software vulnerability detection based on LLMs. Although LLMs show good generalization potential, they still face challenges such as privacy leaks and domain bias.

Existing vulnerability detection methods face a ternary constraint among detection accuracy, computational efficiency, and generalization ability. Rule-based and machine learning methods are limited by manually defined patterns, making it difficult to address new types of vulnerabilities; sequence models are lightweight but ignore structural semantics, while graph models are precise but computationally expensive. For example, models based on CPG or full AST, such as Devign [16] and IVDetect [27], require traversing complex control flows and data flows, causing graph sizes to grow exponentially with the amount of code. On the other hand, sequence models (e.g., VulDeePecker [10]) capture local contexts through sliding windows but are limited by window lengths, making it challenging to model global semantics across functions.

Additionally, existing methods exhibit imbalances in semantic granularity, some methods [10,28] focus excessively on fine-grained features (such as individual AST node types), leading to high false positive rates; while others [29,30] only model coarse-grained global representations, potentially missing complex logic vulnerabilities. To overcome these issues, several vulnerability detection methods using balanced semantic granularity have been proposed [3,31–33]. The SAHAN model proposed in this paper reduces computational costs compared to most graph-based models and effectively addresses the long-range dependency problems that sequence models struggle with.

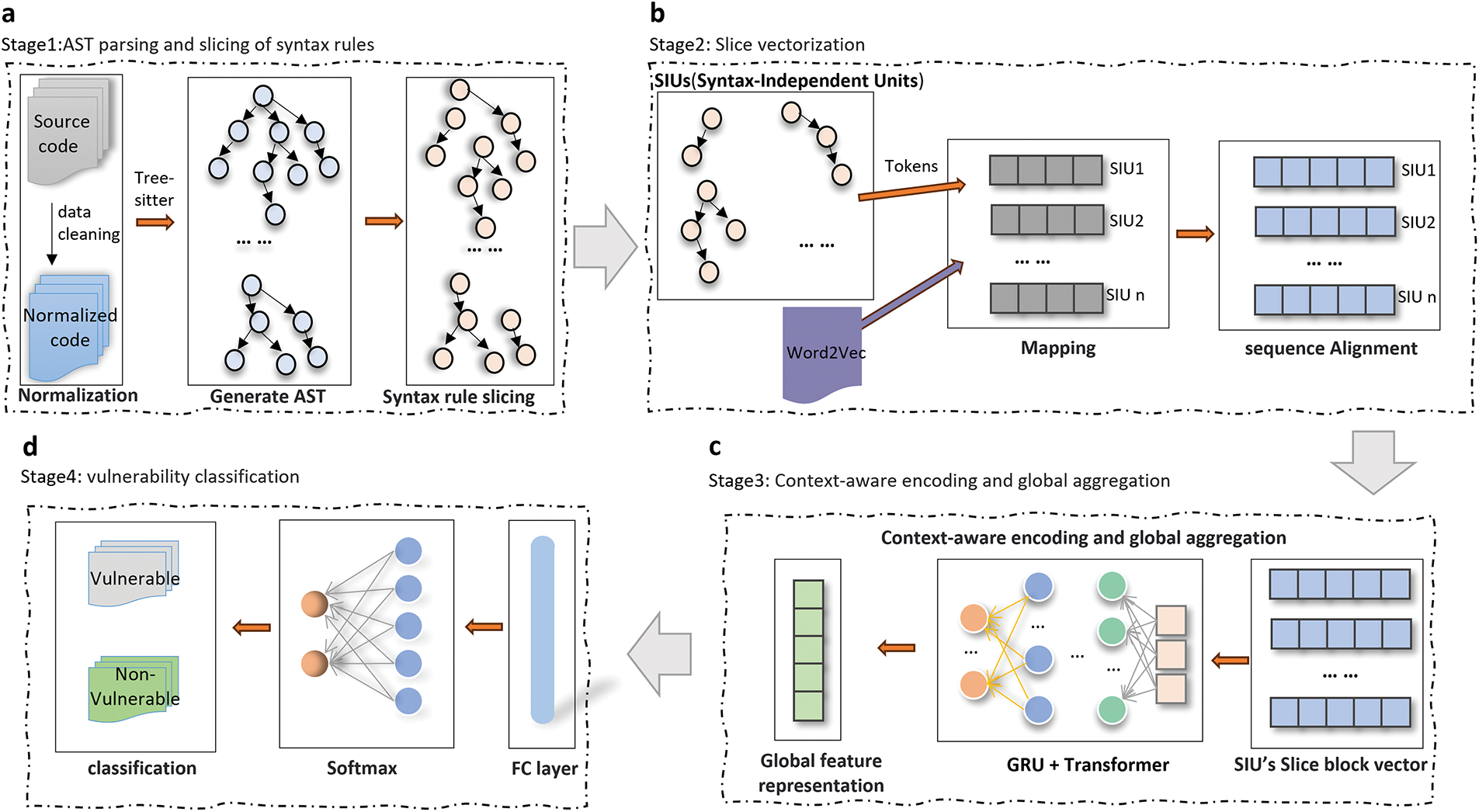

The SAHAN method we proposed primarily consists of four core stages: a. AST Parsing and Syntax-Rule-Based Slicing, b. Slice Vectorization, c. Context-Aware Encoding and Global Aggregation, d. Vulnerability Classification. The frame diagram of SAHAN’s method is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Framework diagram of the SAHAN vulnerability detection method

3.1 AST Parsing and Syntax-Rule-Based Slicing

The process of AST parsing and generating slices is shown in Stage 1 of Fig. 1. Before generating the AST, we preprocess the dataset to obtain standardized code snippets. The result of source code preprocessing is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Source code preprocessing

Tree-sitter [34] is an open-source parser generator tool and incremental parsing library that can generate AST and build efficient and flexible parsers for C/C++.

We use the Tree-sitter parser to convert standardized source code into an AST. This process is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Correspondence between source code and generated AST

Each AST node contains a syntax type (such as function_definition, if_statement) and text content (such as variable names, operators), and the complete tree structure is built through recursive traversal.

3.1.2 Syntax-Rule-Based Slicing

Existing AST-based slicing methods have shortcomings in controlling the slicing granularity. Fine-grained slicing methods rely on high-quality code slicing or annotations and are sensitive to noise. For example, VulDeePecker [10] slices the code into fine-grained Code Gadgets for extracting local semantics, but it may ignore the code context and global logic. On the other hand, coarse-grained slicing methods struggle to model long-range dependencies. Therefore, we use a syntax-rule-based AST slicing method that extracts program slices from the AST and can dynamically adjust the slicing depth. This method performs fine-grained slicing at critical vulnerability patterns (such as buffer operations) to capture local semantics. Each slice represents an Syntax Independent Unit, ensuring the maximum integrity of semantics. Additionally, by dividing the code into multiple levels using syntax rules (such as function level

Algorithm 1 describes the syntax-rule-based AST slicing method. The input is a set of functions F and predefined syntax rules R, and the output is S, which is the set of SIUs. The specific steps are as follows: First, initialize an empty set S to store syntax-independent units. Then, iterate through each function in the codebase. For each function, generate its AST. Next, iterate through the nodes of the generated AST. If a node meets the predefined syntax rules, perform slicing according to these rules and add the resulting slice to the set S. Finally, return the set S.

The definition of the SIU is as follows:

Definition 1 (Syntax-Independent Unit Based on Syntax-Rule Slicing, SIU). Given a set of functions

The syntax rules R guiding AST slicing (as referenced in Algorithm 1) are categorized into three levels, with specific rules detailed in Table 1.

Function-level rules. Focus on extracting complete function structures to preserve global semantic context.

Control flow level rules. Target critical control structures closely related to vulnerability patterns.

Data-operation level rules. Focus on fine-grained data interactions linked to common vulnerabilities (e.g., buffer overflows, null pointers).

These rules collectively guide the slicing process, ensuring that each SIU maintains semantic integrity while avoiding redundant nodes. The hierarchical design balances detailed feature capture (via data/control flow rules) and computational efficiency (via function-level scope control).

For the AST, each node represents a syntactic element in the code, containing rich syntactic and semantic information. The result of slicing the AST is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Syntax-rule-based slicing of the AST

Using this slicing method, SIUs can effectively capture the logical structure and semantic features of the code, balance the slicing granularity, and preserve semantic integrity.

Stage 2 of Fig. 1 shows the process of converting AST slice blocks into vector sequences, including lexical mapping and embedding results.

3.2.1 Serialization Representation

Mapping SIUs from AST slice blocks into index sequences involves the following steps:

Recursively traverse the SIUs. Start from the root node and perform a depth-first traversal to extract the syntax tokens of each SIU. If the node type is a syntactic structure (e.g., function_definition), retain its type name; if the node is a leaf node (such as variable names, operators), extract its text content.

Vocabulary Mapping. Use a pre-trained Word2Vec model to convert each token into an index. For known words, directly map them to the corresponding index in the vocabulary; for unknown words, assign a unified unknown word index “max_token + 1” (the vocabulary size is “max_token”, with starting index 1).

Sequence Alignment. Padding or truncation of SIU sequences of varying lengths to ensure uniform input dimensions.

Construct an embedding layer based on a pre-trained Word2Vec model to map index sequences to dense vectors, with the specific design as follows:

Embedding Matrix Construction. The dimension of the matrix is [vocab_size +1, embedding_dim], where vocab_size is the size of the Word2Vec vocabulary and embedding_dim is the vector dimension, which is set to 128. Load pre-trained vectors: the first vocab_size rows load pre-trained vectors to ensure that the model can utilize existing semantic information. The last row (index max_token + 1) is initialized as a zero vector, representing unknown words. This approach avoids introducing noise during training and provides a default configuration for unlogged words.

Embedding Layer Configuration. Use Embedding module to load the embedding matrix. This module can convert input index sequences into corresponding dense vector representations. During training, the Embedding module allows fine-tuning of the vectors for unknown words. This means that even if some words did not appear in the pre-training phase, the model can still adjust their representations based on contextual information, thereby improving the model’s generalization ability.

Through this design, the pre-trained embedding layer can effectively convert index sequences into dense vector representations. This method not only leverages pre-trained semantic information but also enhances the model’s adaptability to unknown words through fine-tuning mechanisms.

3.3 Context-Aware Encoding and Global Aggregation

Stage 3 of Fig. 1 shows the process of context-aware encoding and global aggregation. In this stage, the model performs context-aware encoding on the AST to further integrate and aggregate information from each SIU, capturing complex dependencies within code snippets.

In the first two stages, the model initially generates the AST and extracts SIUs (Stage 1), then slices and vectorizes the SIUs, converting them into dense vector representations (Stage 2). In Stage 3, through context-aware encoding and global aggregation, the model can effectively understand and represent the structure and semantics of the code.

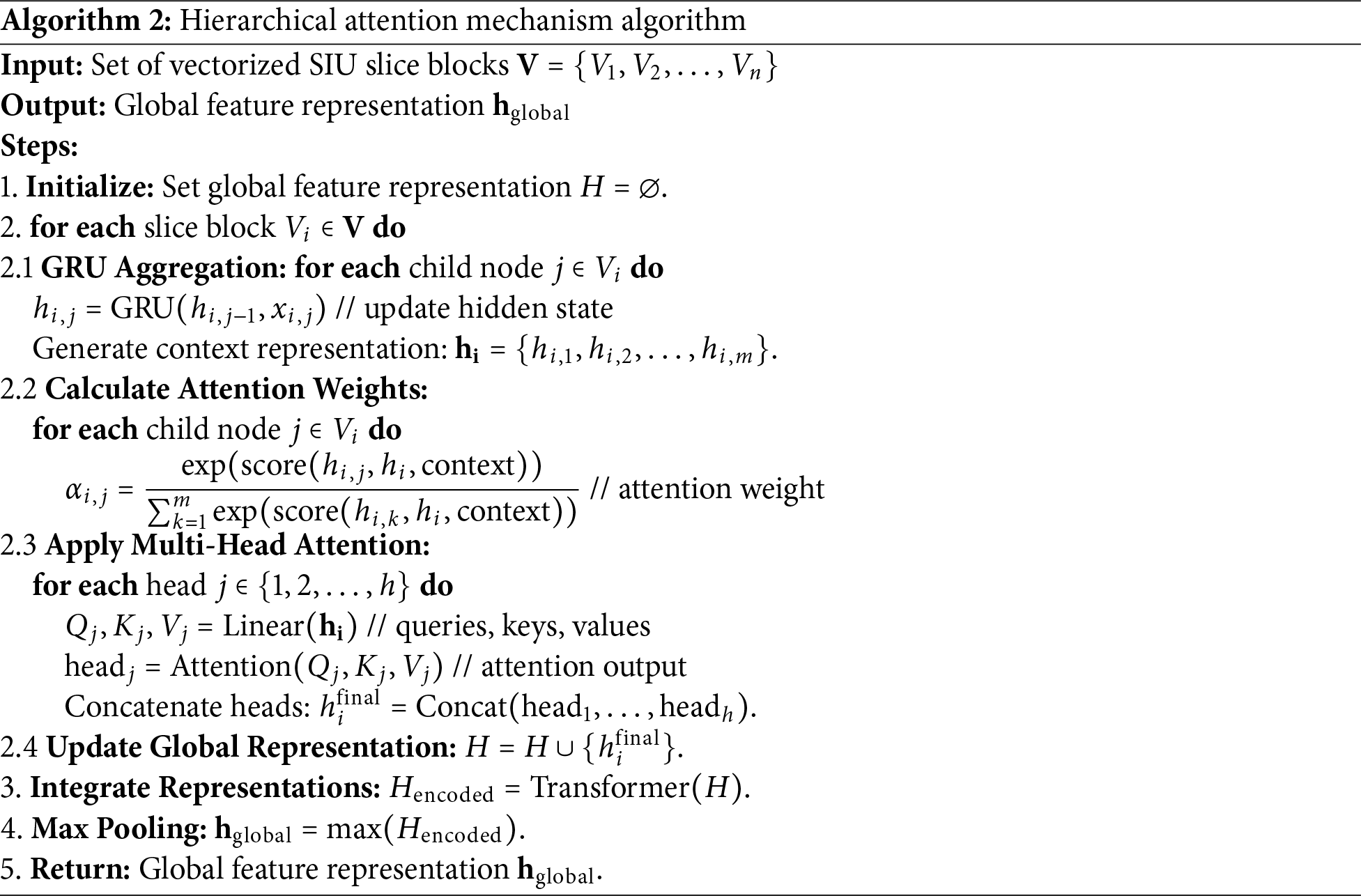

3.3.1 Hierarchical Attention Mechanism

The algorithm for aggregating SIU slice block information using a hierarchical attention mechanism is shown in Algorithm 2.

In Algorithm 2, the input is a set of vectorized SIU slice blocks, and the output is a global feature representation. The first step is initialization; In the second step, GRU aggregation is performed for each slice, then, attention weight is calculated, multi-head attention mechanism is applied, and global representation is updated. The third step integrates the representation information obtained in the second step; The fourth step is to extract global features by maximum pooling. Finally, returns the global feature.

Local Encoding (Within Unit). Use a GRU to recursively aggregate the information of child nodes within each slice block. GRUs can effectively capture dependencies and local structural features among child nodes, generating a context representation for each slice block. Through GRU’s gating mechanism, the model can selectively retain important information and suppress irrelevant noise. The algorithm for aggregating SIU slice block node information using GRUs is shown in Section 2.1 of Algorithm 2. Section 2.3 of Algorithm 2 describes applying a multi-head attention mechanism on top of GRU aggregation to weight important child nodes. By calculating the attention weights for each child node, the model can enhance the representation of key paths, ensuring that important information is highlighted in the context encoding. This mechanism helps capture complex dependencies and semantic information, enabling the model to better understand the logical structure of the code.

Global Aggregation (Across Units). In Steps 3 and 4 of Algorithm 2, we describe the process of global aggregation by integrating the representations of all SIU slice blocks through a Transformer encoder and extracting global features using max pooling. In step 3, the representation H of all slice blocks is entered into the multilayer Transformer encoder. The Transformer encoder uses a multi-head attention mechanism and feed-forward neural network to capture complex relationships and long-range dependencies between slices. Each layer of Transformer processes the input and learns higher-level feature representations, thereby enhancing the model’s expressive power.

In step 4, we apply max pooling to the encoded representations

3.3.2 Long-Range Dependency Enhancement

In the previous section, we discussed the hierarchical attention mechanism, which aggregates information from SIU slices and applies multi-head attention to weight the importance of child nodes. Building on this, we further enhance the capability to model long-range dependencies by employing a deep Transformer encoder.

To effectively capture complex dependencies across multiple SIU slice blocks, we use a 4-layer Transformer encoder to enhance the model’s expressive power. The deep structure is capable of capturing more complex features and long-range dependencies, improving the model’s performance. Each layer of the Transformer is designed to learn different levels of abstraction, enabling the model to understand the complex relationships within the code.

The combination of context-aware encoding and global aggregation enables the model to effectively model complex dependencies within code snippets, such as nested loops and inter-function calls. This capability is crucial for accurately capturing context-specific semantic patterns related to vulnerabilities. By combining these strategies, we have built a robust framework for modeling complex dependencies in code, ultimately achieving more accurate vulnerability detection.

3.4 Vulnerability Classification and Model Training

Stage 4 of Fig. 1 illustrates the overall structure of the vulnerability classification model. The following sections introduce the classifier design and training strategies.

In this study, we designed a classifier that maps global feature vectors to the vulnerability category space through a linear layer. First, we use a fully connected layer to map the feature vectors, which have undergone context-aware encoding and global aggregation, into the space of vulnerability categories. Next, the output dimension matches the number of categories, ensuring that each category corresponds to an independent confidence score. The Softmax activation function is applied to convert the output of the linear layer into a probability distribution. This ensures that the predicted probability for each category falls within the [0, 1] range, and the sum of probabilities for all categories equals 1, facilitating classification decisions.

To effectively train the model and improve its performance, we adopt the following training strategies:

We use the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate set to 0.001. Adam is an adaptive learning rate optimization algorithm suitable for handling sparse gradients. It balances gradient stability and convergence speed during training, allowing for rapid convergence in the early stages and stable optimization later on. It combines the advantages of momentum and Root Mean Square Propagation (RMSProp) by using independent learning rates for each parameter to enhance training efficiency.

We employ a dynamic trigger decay strategy based on validation set loss Reduce Learning Rate On Plateau (ReduceLROnPlateau). Specifically, when the validation set loss does not decrease for 5 consecutive epochs (patience = 5), the learning rate is reduced by a factor of 0.5 (factor = 0.5) to avoid getting stuck in local optima. This strategy dynamically decides the decay timing using following formula:

By doing so, the algorithm can automatically lower the learning rate when the performance on the validation set stagnates, avoiding local optima while maintaining sufficient optimization speed.

To comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness, robustness, and practicality of the SAHAN method, we conducted experimental validation around the following four core research questions:

RQ1: Effectiveness Validation. How effective is SAHAN in detecting vulnerabilities in source code?

RQ2: Module Contribution Analysis. How do the core modules of SAHAN impact overall performance?

RQ3: Computational Efficiency Validation. Does the computational overhead of SAHAN meet practical requirements?

RQ4: Cross-project Generalization Ability. Does SAHAN exhibit stable detection performance across different projects or in cross-project scenarios?

We used a widely adopted and validated open-source dataset, which includes the FFmpeg, QEMU, FFmpeg+QEMU [16], and ReVeal [9] datasets. These datasets are extensively used and recognized in the field of software vulnerability detection and program analysis. The number of projects and vulnerabilities in each dataset is shown in Table 2.

Before introducing the evaluation metrics, we first define four key terms to describe the relationship between predicted and actual class labels.

TP (True Positive). The sample is actually a positive class and is correctly predicted as a positive class by the model.

TN (True Negative). The sample is actually a negative class and is correctly predicted as a negative class by the model.

FP (False Positive). The sample is actually a negative class but is incorrectly predicted as a positive class by the model.

FN (False Negative). The sample is actually a positive class but is incorrectly predicted as a negative class by the model.

We use the following four metrics to evaluate our model’s performance, as they are widely applied in classification tasks and can comprehensively reflect the model’s performance. These metrics include Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 Score.

Accuracy measures the proportion of correct predictions out of all predictions made by the model. The calculation formula is:

Precision focuses on the accuracy of the model when predicting positive classes. The calculation formula is:

Recall assesses the model’s ability to identify actual positive samples. The calculation formula is:

F1 Score provides a balanced performance evaluation by considering both precision and recall. The calculation formula is:

In this section, we will provide a detailed description of the training process of SAHAN to facilitate model reproducibility. We use a Word2Vec pre-trained embedding layer with an embedding dimension of 128. The hierarchical attention part of the model employs a 256-dimensional GRU hidden layer and uses a 4-layer Transformer encoder with 8 heads. For the training strategy, we selected the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.001, a batch size of 16, and incorporated the aforementioned learning rate scheduler and early stopping mechanism for 200 iterations. All experiments were conducted in the following environment: CPU is Intel Xeon Silver 4214R @ 2.4 GHz, GPU is NVIDIA RTX 3090 Ti with 24 GB memory, software environment includes Ubuntu 22.04, Python 3.10, PyTorch 2.1.0, and CUDA 12.1.

In this part, we address the questions posed in Section 4.1 through experiments to validate the effectiveness and efficiency of our approach.

To evaluate the effectiveness of SAHAN, we selected the following baseline models: Transformer [35], VulDeePecker [10], Devign [16], SySeVR [3], ReVeal [11], GCL4SVD [17], GRACE [25], and Graph-BiLSTM [36].

The Transformer model can effectively capture long-range dependencies by processing input sequences in parallel.

VulDeePecker is a vulnerability detection model based on Code Gadgets and BiLSTM.

Devign is a vulnerability detection method that combines program graphs (AST + CFG + Data Flow Graph (DFG)) with GNN.

SySeVR is a vulnerability detection framework based on code slicing and CNN.

ReVeal is a context-sensitive vulnerability detection model based on Transformer.

GCL4SVD is a vulnerability detection method leveraging Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN) and self-confidence learning.

GRACE is a software vulnerability detection approach based on LLM, which integrates graph-structured information of code and utilizes contextual learning to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of vulnerability detection.

Graph-BiLSTM is a vulnerability detection model that combines graph structures with BiLSTM.

To ensure valid and interpretable performance comparisons, we selected baseline models based on three key criteria. We prioritized models with broad recognition in the field. Baselines such as Devign and VulDeePicker are widely cited as foundational works in deep learning-based vulnerability detection and represent classical technical paradigms. We focused on alignment with evaluation datasets. All selected baselines were evaluated on the same benchmark datasets (FFmpeg, QEMU, ReVeal) in their original studies, which ensures our performance comparisons are conducted under consistent data conditions. We also emphasized technical relevance. These baselines, like our proposed SAHAN, adopt deep learning architectures for code vulnerability analysis, allowing meaningful comparisons of core design choices rather than comparisons across incompatible frameworks.

Our experimental environment follows the training strategy described in Section 3.4 and the training details provided in Section 4.4. The experimental results are shown in Table 3. These results evaluate our method and other baseline models using four metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 Score. For baselines including Devign and VulDeePicker, Precision/Recall values are marked as ‘-’ since they are not reported in their original studies, and we were unable to derive them due to resource limitations in reimplementation.

From Table 3, it can be seen that the performance of the SAHAN method is superior to other baseline methods.

On the FFmpeg dataset, the Accuracy of the SAHAN method is 60.3%, which is an improvement of 8.7%, 6.8%, 5.8%, 10.8%, and 2.1% over the Transformer, LSTM, Devign, VulDeePecker, and GCL4SVD models, respectively. On the QEMU dataset, the Accuracy of the SAHAN method is 63.1%, which is an improvement of 5.6%, 4.1%, 4.8%, 13.1%, and 1.5% over the baseline models, respectively. On the FFmpeg+QEMU dataset, the Accuracy of the SAHAN method is 61.34%, which is an improvement of 4.45%, 11.43%, 13.49%, 0.27%, and 1.56% over the Devign, VulDeePecker, SySeVR, Reveal, and GRACE models, respectively.For the Reveal dataset, due to the imbalance in the distribution of vulnerabilities (with only about 10% of the data containing vulnerabilities), it is more appropriate to use the F1 score to evaluate model performance. The F1 score of the SAHAN method is 48.26%, which is higher by 14.35%, 32.09%, 17.52%, and 5.13% compared to the Devign, VulDeePecker, SySeVR, and GRACE models, respectively. However, it is lower by 21.34% compared to the Graph-BiLSTM model.

The above analysis demonstrates the effectiveness of the SAHAN method.

5.2 Module Contribution Analysis

We validated our core modules on the QEMU dataset. In the experiments, we separately evaluated the contributions of syntax slicing and the attention mechanism in SAHAN. The experimental results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4 shows that the syntax slicing method significantly contributes to improving model performance, resulting in a 3.72% increase in Accuracy and a 7.16% increase in the F1 score. The Transformer module demonstrates stronger feature extraction capabilities, contributing approximately a 4.36% increase in Accuracy and an 18.02% increase in the F1 score. The ablation study indicates that both the syntax slicing and Transformer modules make significant contributions to the model’s performance.

5.3 Computational Efficiency Validation

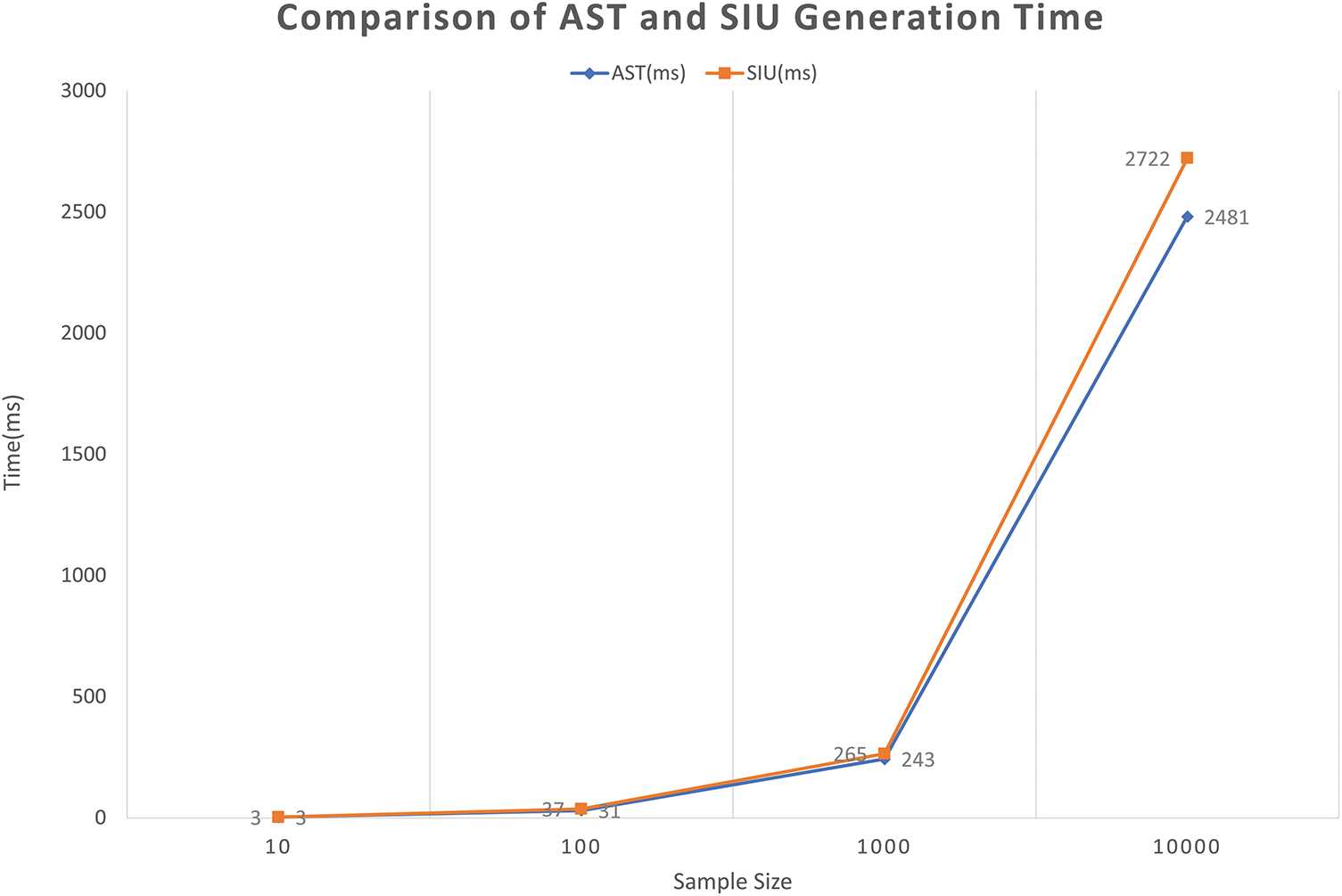

In this part, we first evaluate the time required to directly generate ASTs and to generate syntax slicing SIUs through experiments. The experimental data are the average values from ten trials. The dataset used for testing is QEMU. The experimental results are shown in Table 5.

As shown in Fig. 5, as the sample size increases from 10 to 10,000, the generation times for both AST and SIU exhibit an approximately linear growth trend. The AST generation time increases from 3 ms (for 10 samples) to 2481 ms (for 10,000 samples), while the SIU generation time increases from 3 ms (for 10 samples) to 2722 ms (for 10,000 samples). This indicates that at larger sample sizes (>10,000), the SIU generation time exceeds the AST parsing time. This difference is primarily due to the SIU method requiring the extraction of syntax slicing units, which introduces additional computational overhead.

Figure 5: Comparison of AST and SIU generation time

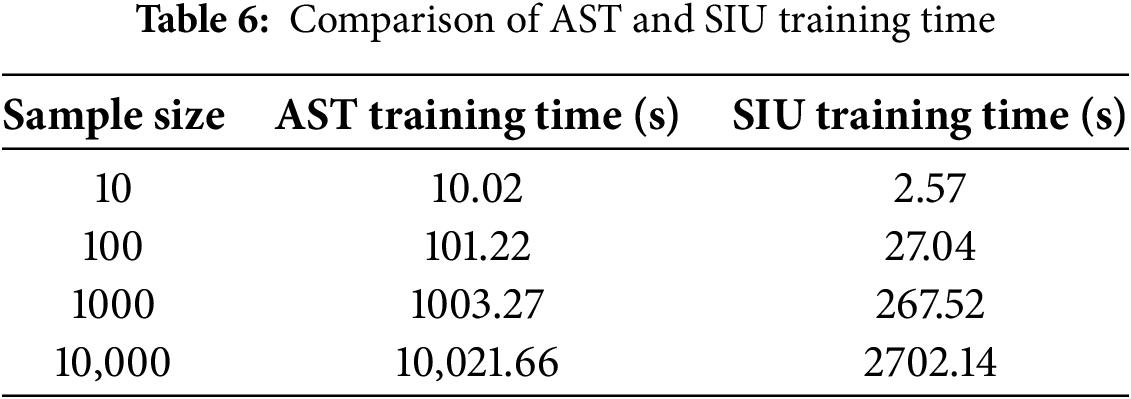

We then conducted validation experiments to assess the training time required. The time needed to train 10, 100, 1000, and 10,000 data samples is shown in Table 6. Our test samples were also taken from QEMU.

As shown in Fig. 6, as the sample size increases from 10 to 10,000, the AST training time grows from 10.02 s to 10,021.66 s, while the SIU training time increases from 2.57 s to 2702.14 s. The experiments indicate that the SIU method’s training time is approximately one-third (1/3.7) of the AST method’s training time. This demonstrates that the SIU training method is significantly more time-efficient than the AST method.

Figure 6: Comparison of AST and SIU training time

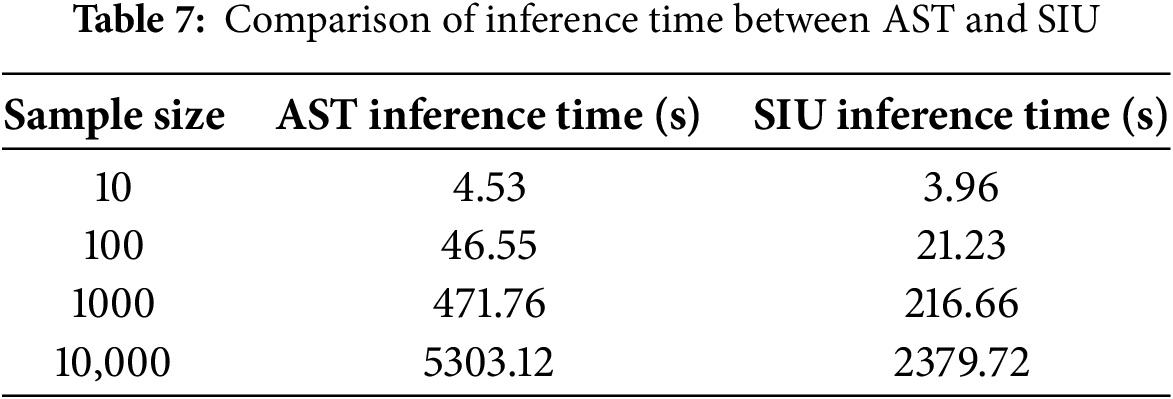

Building on the training time advantages of SIU (Table 6), we analyze the inference time to complete the efficiency validation.

Table 7 presents the inference latency of AST and SIU across sample sizes (10–10,000 samples, consistent with training experiments). Consistent with training phase results, SIU outperforms AST in inference efficiency. For 1000 samples, SIU’s inference time (216.66 s) is 46% of AST’s inference time (471.76 s), confirming SIU’s time-saving benefits persist in the prediction stage.

5.4 Cross-Project Generalization Ability

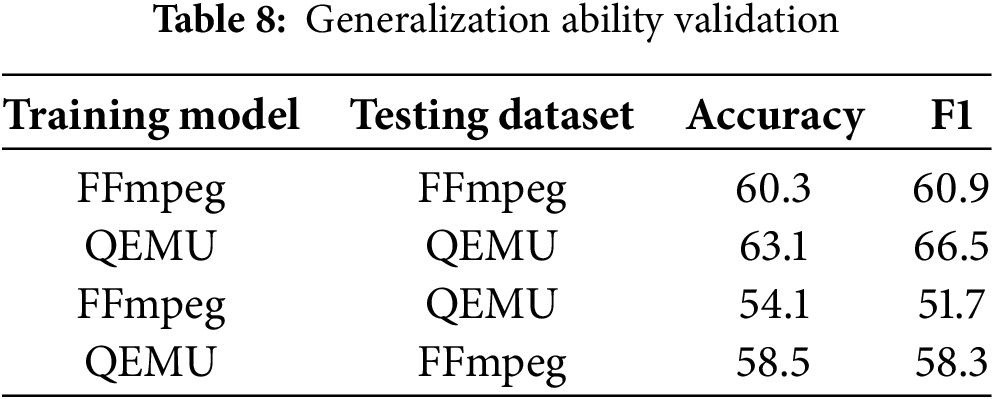

To validate the generalization ability, we used the FFmpeg and QEMU datasets. We trained models on the FFmpeg and QEMU datasets separately and then validated them on the QEMU and FFmpeg datasets, respectively. The results are shown in Table 8.

The experimental data show that the FFmpeg model’s Accuracy decreased by 6.2% and its F1 score decreased by 9.2% when tested on the QEMU dataset. Similarly, the QEMU model’s Accuracy decreased by 4.6% and its F1 score decreased by 8.2% when tested on the FFmpeg dataset. These experiments indicate that the generalization ability of the SAHAN model has limitations, suggesting that the cross-domain generalization capability of the current version of SAHAN needs to be improved.

In this study, although our model and methods have achieved certain results, there are still some limitations.

Dataset Limitations. The datasets used in this study are widely adopted and have a certain level of representativeness. However, the Reveal dataset suffers from class imbalance, which can affect the model’s generalization ability, leading to ineffective generalization in real-world scenarios. Additionally, our experiments are currently restricted to classic datasets (FFmpeg, QEMU, ReVeal), which may not fully reflect the characteristics of modern large-scale codebases and emerging vulnerability patterns, limiting the validation of the model’s scalability in newer scenarios.

Model Complexity and Computational Resources. We used a relatively complex model architecture, which can potentially lead to overfitting, especially when the amount of training data is insufficient. The complexity of the model might result in poor performance on unseen data. Additionally, due to limitations in computational resources, our experiments could only be conducted in a limited hardware environment. This may impact the training time and the depth of parameter tuning.

Adversarial Attack Vulnerability.The current SAHAN model does not explicitly account for adversarial attacks on code inputs (e.g., subtle code obfuscations, syntax-preserving modifications, or injection of misleading code patterns). Such attacks could alter the model’s perception of vulnerability-related features in AST slices, potentially reducing detection accuracy. Since our experiments were conducted on standard, non-adversarially modified datasets, the model’s robustness against maliciously perturbed code remains unvalidated.

Interpretability of Detection Results. SAHAN’s context-aware encoding and attention mechanisms lack sufficient interpretability. Unlike rule-based methods with explicit logic, they act as “black boxes”, making it hard to trace which AST slices or attention weights drive vulnerability predictions. This reduces trust in critical scenarios (e.g., high-security systems) where stakeholders need to understand the reasoning behind flagged vulnerabilities.

External Factors. In practical applications, the model’s performance may be influenced by external factors such as the quality and diversity of the data, environmental changes, etc. These factors were not fully considered in our experiments.

Addressing the ternary constraint problem among precision, efficiency, and generalization ability in existing vulnerability detection methods, we propose SAHAN model for vulnerability detection.This method combines context-aware encoding and hierarchical attention mechanisms, with its core contribution lying in efficiency-driven AST optimization. Specifically, it simplifies ASTs into SIU slices to reduce computational redundancy while retaining critical vulnerability-related features. This design not only improves the accuracy and efficiency of vulnerability detection but also makes the framework adaptable to resource-constrained scenarios. Additionally, it provides a scalable foundation for future research (e.g., extensions to multi-language code analysis or real-time vulnerability monitoring). Experimental results show that SAHAN performs well, demonstrating its potential in handling complex data structures.

The latest research [37] proposes a multimodal framework named FuSEVul, which innovatively fuses code semantic features with explanations generated by large language models to enhance vulnerability detection. It utilizes a code semantic encoder, an explanation generation and encoding module, and a self-attention fusion mechanism, and has shown good performance on multiple public datasets. While SAHAN currently focuses on AST-based optimization, future work could explore integrating similar cross-modal cues to further improve accuracy without sacrificing efficiency.

In the future, we plan to collect more diverse and balanced datasets (including modern benchmarks like MoreFixes and BigVul) to validate SAHAN’s scalability in large-scale, real-world codebases. We will explore more lightweight model architectures to reduce the risk of overfitting. Additionally, to address real-world applicability gaps, we will extend validation to proprietary codebases for business-logic vulnerabilities and multi-language code snippets simulating polyglot environments. We will optimize embedding methods by exploring the integration of sub-token and BPE embeddings to handle unknown word issues in large-scale or diverse code corpora, while optimizing their computational overhead to maintain the framework’s efficiency advantages. In addition, our method is only coarse-grained at the function level, and then we can consider line-level vulnerability precision location or multi-class vulnerability classification detection.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the research start-up funds for invited doctor of Lanzhou University of Technology under Grant 14/062402.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Yongbo Jiang, Shengnan Huang; data collection: Baofeng Duan, Shengnan Huang; analysis and interpretation of results: Yongbo Jiang, Tao Feng; writing original draft preparation: Baofeng Duan, Shengnan Huang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data underlying the results presented in this paper may be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). National vulnerability database [NVD] [Online]. Washington, DC, USA: U.S. Department of Commerce; 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 23]. Available from: https://nvd.nist.gov/. [Google Scholar]

2. CVE Mitre. Common vulnerabilities & exposures [CVE] [Online]; 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 23]. Available from: https://cve.miter.org/. [Google Scholar]

3. Li Z, Zou D, Xu S, Jin H, Zhu Y, Chen Z. SySeVR: a framework for using deep learning to detect software vulnerabilities. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2022;19(4):2244–58. doi:10.1109/TDSC.2021.3051525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhao Z, Yang B, Li G, Liu H, Jin Z. Precise learning of source code contextual semantics via hierarchical dependence structure and graph attention networks. J Syst Softw. 2022;184(1):111108. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2021.111108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhang H, Bi Y, Guo H, Sun W, Li J. ISVSF: intelligent vulnerability detection against Java via sentence-level pattern exploring. IEEE Syst J. 2022;16(1):1032–43. doi:10.1109/JSYST.2021.3072154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yamaguchi F, Golde N, Arp D, Rieck K. Modeling and discovering vulnerabilities with code property graphs. In: Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, 2014 May 18–21; Berkeley, CA, USA. p. 590–604. doi:10.1109/SP.2014.44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zheng W, Jiang Y, Su X. Vu1SPG: vulnerability detection based on slice property graph representation learning. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 32nd International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering (ISSRE); 2021 Oct 25–28; Wuhan, China. p. 457–67. doi:10.1109/ISSRE52982.2021.00054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Medeiros I, Neves NF, Correia M. Automatic detection and correction of web application vulnerabilities using data mining to predict false positives. In: Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on World Wide Web (WWW ’14); 2014 Apr 7–11; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 63–74. doi:10.1145/2566486.2568024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Chakraborty S, Krishna R, Ding Y, Ray B. Deep learning based vulnerability detection: are we there yet? IEEE Trans Softw Eng. 2022;48(9):3280–96. doi:10.1109/TSE.2021.3087402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Li Z, Zou D, Xu S, Ou X, Jin H, Wang S. VulDeePecker: a deep learning-based system for vulnerability detection. arXiv:1801.01681. 2018. doi:10.14722/ndss.2018.23158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Li X, Wang L, Xin Y, Yang Y, Tang Q, Chen Y. Automated software vulnerability detection based on hybrid neural network. Appl Sci. 2021;11(7):3201. doi:10.3390/app1107-3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Nguyen T, Le T, Nguyen K, de Vel O, Montague P, Grundy J, et al. Deep cost-sensitive Kernel machine for binary software vulnerability detection. In: Advances in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining: 24th Pacific-Asia Conference, PAKDD 2020. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag. p. 164–77. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-47436-2_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wu S, Wang C, Zeng J, Wu C. Vulnerability time series prediction based on multivariable LSTM. In: 2020 IEEE 14th International Conference on Anti-counterfeiting, Security, and Identification (ASID); 2020 Oct 30–Nov 1; Xiamen, China. p. 185–90. doi:10.1109/ASID50160.2020.9271730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Nguyen V, Le T, de Vel O, Montague P, Grundy J, Phung D. Dual-component deep domain adaptation: a new approach for cross project software vulnerability detection. Adv Knowl Discov Data Min. 2020;12084:699–711. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-47426-3_54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Tian Z, Qiu R, Teng Y, Sun J, Chen Y, Chen L. Towards cost-efficient vulnerability detection with cross-modal adversarial reprogramming. J Syst Softw. 2025;223(2):112365. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2025.112365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhou Y, Liu S, Siow J, Du X, Liu Y. Devign: effective vulnerability identification by learning comprehensive program semantics via graph neural networks. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (NeurIPS 2019). arXiv.1909.03496. 2019. [Google Scholar]

17. Wang Q, Li Z, Liang H, Pan X, Li H, Li T, et al. Graph confident learning for software vulnerability detection. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;133(C):108296. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2024.108-296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Tang M, Tang W, Gui Q, Hu J, Zhao M. A vulnerability detection algorithm based on residual graph attention networks for source code imbalance (RGAN). Expert Syst Appl. 2024;238(D):122216. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Tian Z, Tian B, Lv J, Chen Y, Chen L. Enhancing vulnerability detection via AST decomposition and neural sub-tree encoding. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;238(B):121865. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Shao M, Ding Y, Cao J, Li Y. GraphFVD: property graph-based fine-grained vulnerability detection. Comput Secur. 2025;151(3):104350. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2025.104350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Feng Z, Guo D, Tang D, Duan N, Feng X, Gong M, et al. CodeBERT: a pre-trained model for programming and natural languages. In: Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 1536–47. doi:10.18653/v1/2020.findings-emnlp.139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Guo D, Ren S, Lu S, Feng Z, Zhou M. GraphCodeBERT: pre-training code representations with data flow. arXiv:2009.08366. 2020. [Google Scholar]

23. Yang Y, Zhou X, Mao R, Xu J, Yang L, Zhang Y, et al. DLAP: a deep learning augmented large language model prompting framework for software vulnerability detection. J Syst Softw. 2025;219(9):112234. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2024.112234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Fu M, Tantithamthavorn C. LineVul: a transformer-based line-level vulnerability prediction. In: 2022 IEEE/ACM 19th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR); 2022 May 23–24; Pittsburgh, PA, USA. p. 608–20. doi:10.1145/3524842.3528452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Lu G, Ju X, Chen X, Pei W, Cai Z. GRACE: empowering LLM-based software vulnerability detection with graph structure and in-context learning. J Syst Softw. 2024;212(6):112031. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2024.112031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Choi R, Song Y, Jang M, Kim T, Ahn J, Im D. Smart contract vulnerability detection using large language models and graph structural analysis. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;83(1):785–801. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.061185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Li Y, Wang S, Nguyen TN. Vulnerability detection with fine-grained interpretations. In: Proceedings of the 29th ACM Joint Meeting on European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering (ESEC/FSE 2021); 2021 Aug 23–27; New York, NY, USA. p. 292–303. doi:10.1145/3468264.3468597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Fang Y, Han S, Huang C, Wu R. TAP: a static analysis model for PHP vulnerabilities based on token and deep learning technology. PLoS One. 2019;14(11):e0225196. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0225196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Chen H, Liu J, Liu R, Park N, Subrahmanian VS. VASE: a Twitter-based vulnerability analysis and score engine. In: 2019 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM). 2019 Nov 8–11; Beijing, China. p. 976–81. doi:10.1109/ICDM.2019.00110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Shen Y, Mariconti E, Vervier PA, Stringhini G. Tiresias: predicting security events through deep learning. In: Proceedings of the 2018 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS’18); 2018 Oct 15–19; Toronto, ON, Canada. p. 592–605. doi:10.1145/3243734.3243811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Wu Y, Zou D, Dou S, Yang W, Xu D, Jin H. VulCNN: an image-inspired scalable vulnerability detection system. In: 2022 IEEE/ACM 44th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE); 2022 May 25–27; Pittsburgh, PA, USA. p. 2365–76. doi:10.1145/3510003.3510229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Hanif H, Maffeis S. VulBerta: simplified source code pre-training for vulnerability detection. arXiv:2205.12424. 2022. [Google Scholar]

33. Zou D, Wang S, Xu S, Li Z, Jin H. μVulDeePecker: a deep learning-based system for multiclass vulnerability detection. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2021;18(5):2224–36. doi:10.1109/TDSC.2019.2942930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. GitHub. tree-sitter/tree-sitter. [cited 2025 Sep 23]. Available from: https://github.com/tree-sitter/tree-sitter. [Google Scholar]

35. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. arXiv:1706.03762. 2017. [Google Scholar]

36. Ge K, Han Q-B. Hidden code vulnerability detection: a study of the Graph-BiLSTM algorithm. Inf Softw Tech. 2024;175(4):107544. doi:10.1016/j.infsof.2024.107544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Tian Z, Li M, Sun J, Chen Y, Chen L. Enhancing vulnerability detection by fusing code semantic features with LLM-generated explanations. Inf Fusion. 2025;125(3):103450. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2025.103450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools