Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

PhishNet: A Real-Time, Scalable Ensemble Framework for Smishing Attack Detection Using Transformers and LLMs

1 Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Computing and Information Technology, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, 21589, Saudi Arabia

2 Computer Science Department, College of Computer Science and Engineering, Taibah University, Yanbu, 46522, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Abeer Alhuzali. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Enhancing AI Applications through NLP and LLM Integration)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069491

Received 24 June 2025; Accepted 28 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

The surge in smishing attacks underscores the urgent need for robust, real-time detection systems powered by advanced deep learning models. This paper introduces PhishNet, a novel ensemble learning framework that integrates transformer-based models (RoBERTa) and large language models (LLMs) (GPT-OSS 120B, LLaMA3.3 70B, and Qwen3 32B) to enhance smishing detection performance significantly. To mitigate class imbalance, we apply synthetic data augmentation using T5 and leverage various text preprocessing techniques. Our system employs a dual-layer voting mechanism: weighted majority voting among LLMs and a final ensemble vote to classify messages as ham, spam, or smishing. Experimental results show an average accuracy improvement from 96% to 98.5% compared to the best standalone transformer, and from 93% to 98.5% when compared to LLMs across datasets. Furthermore, we present a real-time, user-friendly application to operationalize our detection model for practical use. PhishNet demonstrates superior scalability, usability, and detection accuracy, filling critical gaps in current smishing detection methodologies.Keywords

Phishing attacks remain one of the most pervasive cybersecurity threats, often exploiting user trust to gain unauthorized access to sensitive information [1–3]. Among these, smishing—phishing via SMS—has emerged as a particularly deceptive attack vector [4]. Unlike email, SMS messages have a significantly higher open rate, with over 90% opened within three seconds, making smishing a preferred method for cybercriminals [5]. These messages often impersonate trusted entities, prompting users to click on malicious links or divulge private data. The growing reliance on smartphones and the general public’s lack of cybersecurity expertise further exacerbate the threat.

Despite growing research efforts in smishing detection, several limitations persist. First, many existing solutions depend on static rule-based systems or traditional models that fail to adapt to modern, sophisticated attack strategies [6,7]. Second, while deep learning has shown promise in cybersecurity, its use in smishing detection—particularly through transformer models and large language models (LLMs)—remains underutilized [8,9]. Third, most approaches lack scalable and user-friendly implementations suitable for widespread adoption [10,11].

To address these gaps, this study introduces PhishNet, an ensemble-based framework that combines the predictive strengths of transformer models and LLMs to detect smishing messages in real time. By integrating RoBERTa with state-of-the-art LLMs and leveraging ensemble learning techniques, our system enhances detection robustness and classification accuracy. PhishNet goes beyond classification by providing users with immediate, actionable guidance depending on the message type—whether ham, spam, or smishing.

Research Questions. This study is guided by four key research questions that address the technical, methodological, and practical aspects of building an effective smishing detection system:

• RQ1: Which transformer-based model is most effective for smishing detection? Transformer architectures such as BERT, RoBERTa, and DistilBERT have demonstrated strong performance in natural language processing tasks, including spam and phishing detection [7,12,13]. However, their comparative effectiveness in the specific context of smishing (SMS-based phishing) remains underexplored. This question examines which model provides the optimal balance of precision, recall, and overall accuracy in identifying malicious SMS content. To address this question, we performed a comprehensive evaluation of the models through rigorous experimentation, with detailed results presented in Sections 3.2 and 4.3.

• RQ2: What is the impact of text preprocessing on model performance? Text preprocessing plays a crucial role in text classification tasks. This question explores whether conventional text-cleaning methods—such as lowercasing, removal of special characters, and stopword filtering—enhance the performance of transformer-based models in detecting smishing [7,8,12]. It also assesses if such preprocessing introduces any trade-offs, such as information loss or diminished model generalization. We investigated this issue and provided a detailed quantitative analysis and results in Section 4.3.

• RQ3: How does prompt engineering affect the classification performance of LLMs? Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-OSS 120B and LLaMA3.3 70B are capable of few-shot and zero-shot learning without the need for fine-tuning. This question examines how different prompting strategies (e.g., zero-shot vs. few-shot) impact LLM performance in classifying SMS messages [11,14]. It also considers how prompt design influences classification accuracy, especially in low-resource or imbalanced data scenarios [9,10]. We employed two prompting techniques and provided a detailed discussion of their effects in Section 4.4.

• RQ4: Can ensemble learning of transformers and LLMs outperform standalone models? While individual models provide robust predictions, combining them through ensemble methods may lead to improved robustness and generalization. This question investigates whether an ensemble approach—merging the outputs of transformer-based models and LLMs using majority or weighted voting—yields superior results in terms of F1-score and real-time performance, compared to using each model in isolation [12,13,15,16]. We examined this question by comparing the detection accuracy of the standalone models and our ensemble approach, as detailed in Section 4.5.

Contributions. To address the aforementioned research questions, this study presents the following key contributions, which advance the state-of-the-art in smishing detection through both technical innovation and practical implementation:

• We propose PhishNet, an ensemble-based detection system that integrates transformer-based models (specifically RoBERTa) with large language models (GPT-OSS 120B, LLaMA3.3 70B, and Qwen3 32B). This hybrid approach leverages the structured contextual understanding of transformers and the generalization capabilities of LLMs to enhance classification accuracy for SMS-based phishing (smishing) detection.

• We conduct a comprehensive evaluation and statistical analysis of three transformer architectures—BERT, RoBERTa, and DistilBERT—across multiple metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. The analysis identifies RoBERTa as the most effective standalone model for smishing classification.

• We systematically investigate how conventional text-preprocessing techniques (e.g., lowercasing, punctuation removal, stopword filtering) influence transformer model performance. Our findings reveal that these methods do not universally improve accuracy and can sometimes obscure contextual information critical for detecting subtle smishing cues.

• We evaluate zero-shot and few-shot prompting techniques to examine their effectiveness in enabling LLMs to classify SMS content without task-specific fine-tuning. Results show that few-shot prompting yields better performance across all metrics, highlighting the importance of context-rich examples in guiding LLM predictions.

• We develop a two-layer ensemble mechanism: (1) a weighted majority voting strategy among LLMs based on confidence scores, and (2) a final majority vote combining LLM output with RoBERTa’s prediction. This architecture significantly improves robustness, yielding an average accuracy improvement from 96% to 98.5% compared to the best standalone transformer, and from 93% to 98.5% when compared to LLMs across datasets.

• To promote practical adoption, we implement PhishNet as a mobile-ready application using FlutterFlow and Firebase. The app provides real-time SMS classification, actionable feedback for users, and educational insights to raise smishing awareness among non-experts.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews relevant literature on smishing detection and ensemble learning approaches. Section 3 presents the proposed methodology, including model architecture, dataset preprocessing, and ensemble strategy. Section 4 discusses the experimental setup and evaluates the performance of individual models and the ensemble framework. Section 5 details the implementation of the PhishNet application, while Section 6 outlines the testing procedures and usability evaluation. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

Extensive research has addressed phishing and smishing detection using various machine learning, deep learning, and large language model-based approaches. This section reviews prior work, grouped into four main categories based on methodology.

Traditional Machine Learning Approaches. Early efforts in phishing detection predominantly relied on classical machine learning models such as Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Random Forests [17,18]. Meléndez et al. [6] and Alhuzali et al. [19] performed a comparative evaluation of these models and found that while traditional classifiers offer reasonable performance, they are often outperformed by more advanced transformer-based models, especially in terms of contextual understanding and adaptability to new phishing patterns.

Transformer-Based Deep Learning Models. Transformer architectures have demonstrated significant improvements in phishing and spam detection tasks [20,21]. Jamal et al. [12] introduced the IPSDM model, a BERT-based classifier fine-tuned for phishing, spam, and ham detection using the Adaptive Synthetic (ADASYN) technique for handling class imbalance. Uddin et al. [7] utilized RoBERTa in conjunction with explainable AI techniques (e.g., LIME and Transformers Interpret) to enhance interpretability while maintaining high accuracy in SMS spam detection.

Ensemble Learning Techniques. Combining multiple models has proven effective in enhancing robustness and generalization. Ghourabi and Alohaly [13] utilized transformer-based embeddings from BERT, RoBERTa, and DistilBERT, and ensembled them with classifiers such as Random Forest and SVM, resulting in improved spam classification accuracy. Bilgen and Kaya [15] proposed EGMA, a hybrid model combining Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), and autoencoders through majority voting, achieving over 99% accuracy across diverse datasets. Pendie [16] showed that an ensemble of GPT-2 with LSTM and CNN outperformed standalone models in phishing detection, particularly under class imbalance conditions.

Large Language Models (LLMs) and Prompt Engineering. LLMs have recently gained traction for phishing and smishing detection due to their few-shot and zero-shot capabilities. Koide et al. [11] developed ChatSpamDetector, which utilized GPT-4 and structured prompting with chain-of-thought reasoning to achieve a 99.7% classification accuracy on phishing emails. Trad and Chehab [14] analyzed the trade-offs between fine-tuning and prompt engineering, demonstrating that fine-tuning leads to higher precision in imbalanced datasets, while prompting allows faster deployment. Lee and Han [10] proposed KorSmishing, a Korean-centric LLM-based framework combining GPT-4o for pseudo-labeling with QLoRA-fine-tuned models, achieving state-of-the-art performance and low computational cost. Tan et al. [9] introduced ScamGPT-J, which mimics scammer behavior using generative LLMs and offers similarity-based output explanations to help users assess potential scams. Desolda et al. [22] introduced APOLLO, a GPT-4o-based phishing detector that achieved up to 99% accuracy and produced explanations rated more trustworthy and understandable than standard browser warnings.

Despite the progress across these categories, most existing approaches either focus on a single model or lack real-time, user-accessible implementation. PhishNet addresses these gaps by integrating transformer models and LLMs in a unified ensemble framework and deploying the system through a publicly accessible, user-friendly application.

Our approach utilizes several transformer-based deep learning models using an ensemble learning approach for smishing detection. Specifically, we use three pre-trained transformer-based models, including BERT, RoBERTa, and DistilBERT, and three LLMs, OpenAI GPT-OSS 120B, LLaMA3.3 70B, and Qwen3 32B. Since the selected transformer models are architecturally similar, we perform several experiments to select a candidate model to use in PhishNet. For the LLMs, PhishNet combines their responses by performing weighted majority voting based on the confidence score of each LLM. To ensemble the classification results of the LLMs and the best-performing transformer model, we employ a simple ensemble learning approach based on a majority voting strategy to output a single classification result for each message. The following explains our methodology.

Dataset1: We use the SMS Phishing dataset for machine learning and pattern recognition [23], which meets our requirements of containing smishing, spam, and ham messages, being sufficiently large for analysis, and written in English. It includes

Dataset2: To assess our approach on additional dataset and to address the lack of suitable public datasets meeting our requirements listed above, we curated a custom collection of

3.2 Experiments of Transformer-Based Models

We consider three widely used transformer-based language models—BERT, RoBERTa, and DistilBERT—due to their proven effectiveness in phishing attack detection [19]. The BERT language representation model employs a transformer-based architecture and has been pretrained for various text-related applications. Its bidirectional attention mechanism enables BERT to comprehend complex relationships between words by considering context from both the left and right sides of a sentence. This capability enhances its grasp of language nuances. Using a Masked Language Model (MLM) approach, BERT infers original words from context by replacing specific words with a unique token (MASK) [12]. RoBERTa, or Robustly Optimized BERT approach, is an improved version of BERT. It enhances the performance by enabling larger batch sizes and training on longer sequences while prioritizing the encoder for text classification tasks [12]. DistilBERT is a streamlined version of BERT designed to offer comparable performance at a smaller size and faster speed.

Although these models share the same underlying transformer encoder architecture, they differ in performance, which is key in building a real-time detection application. Consequently, our approach finds the best-performing transformer and considers it as a sole transformer representative in our ensemble, prioritizing empirical performance and architectural complementarity with the selected LLMs. While adding more transformer models in our ensemble could increase diversity, our focus is on maximizing the overall ensemble’s effectiveness through well-justified, high-performing components.

To determine the most suitable transformer model for our ensemble model, we conduct a comparative evaluation and statistical analysis of these three models under consistent training and evaluation conditions, with and without preprocessing steps, which involve converting all alphabetic characters to lowercase, replacing all non-alphanumeric characters with spaces, and removing extra spaces and stopwords (i.e., words that do not affect the sentence’s meaning, such as “a” and “the”).

3.3 Experiments of Large Language Models

The introduction of pre-trained models has laid the foundation for modern Large Language Models (LLMs). LLMs are deep learning models trained on a massive amount of unstructured data to mimic human responses. They utilize massive datasets and have billions of parameters to enhance performance across multiple language tasks [28]. Some of the most popular LLMs are GPT-4.1 by OpenAI [29], BART by Facebook AI [30], T5 (text-to-text transfer transformer) by Google [24], and LLaMA by Meta [31].

We selected three recent, powerful, and open-source LLMs—OpenAI GPT-OSS 120B [32], LLaMA3.3 70B Versatile [33], and Qwen3 32B [34]—known for their strong reasoning capabilities. Some of these models have demonstrated exceptional performance in phishing detection, as evidenced by prior research [9–11,35]. We evaluated the models on the same test set of both datasets discussed in Section 3.1. Our system prompts the LLMs to classify each message as spam, ham, or smishing using two prompting techniques: zero-shot and few-shot learning. For a single classification of the message, our approach uses a weighted majority voting strategy (will be discussed in Section 3.3.2).

We incorporate two of the widely used prompt engineering techniques in many phishing detection approaches [14]: zero and few-shot learning. The prompts’ development underwent multiple cycles of experimentation. Through this process, we attempted to optimize the prompt structure and content that consistently delivers the best detection accuracy for our use cases. Specifically, in each cycle, we run the two prompts against a sample of messages from the test datasets. Then, we adjust the prompts to improve true positive rates and suppress false alarms.

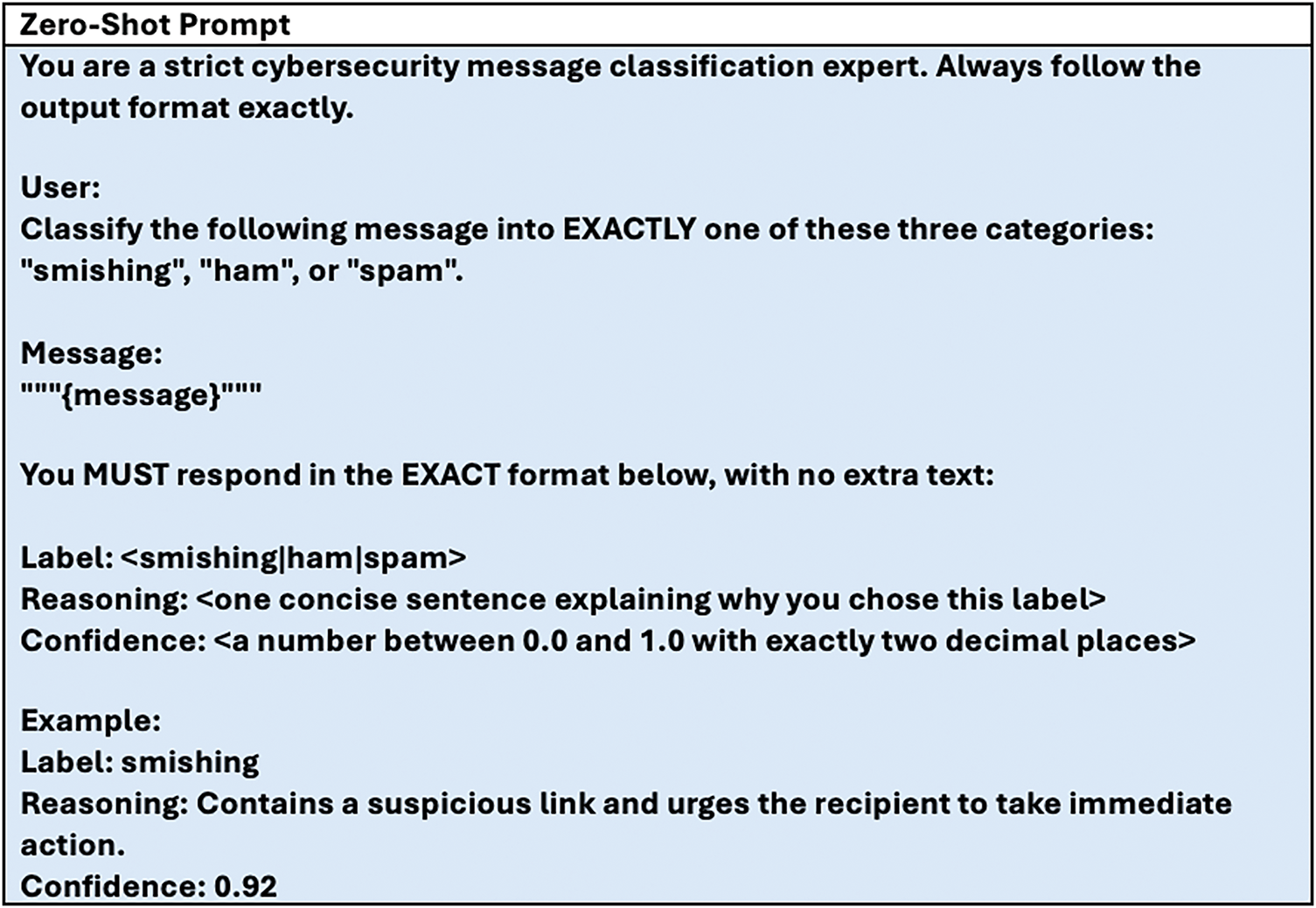

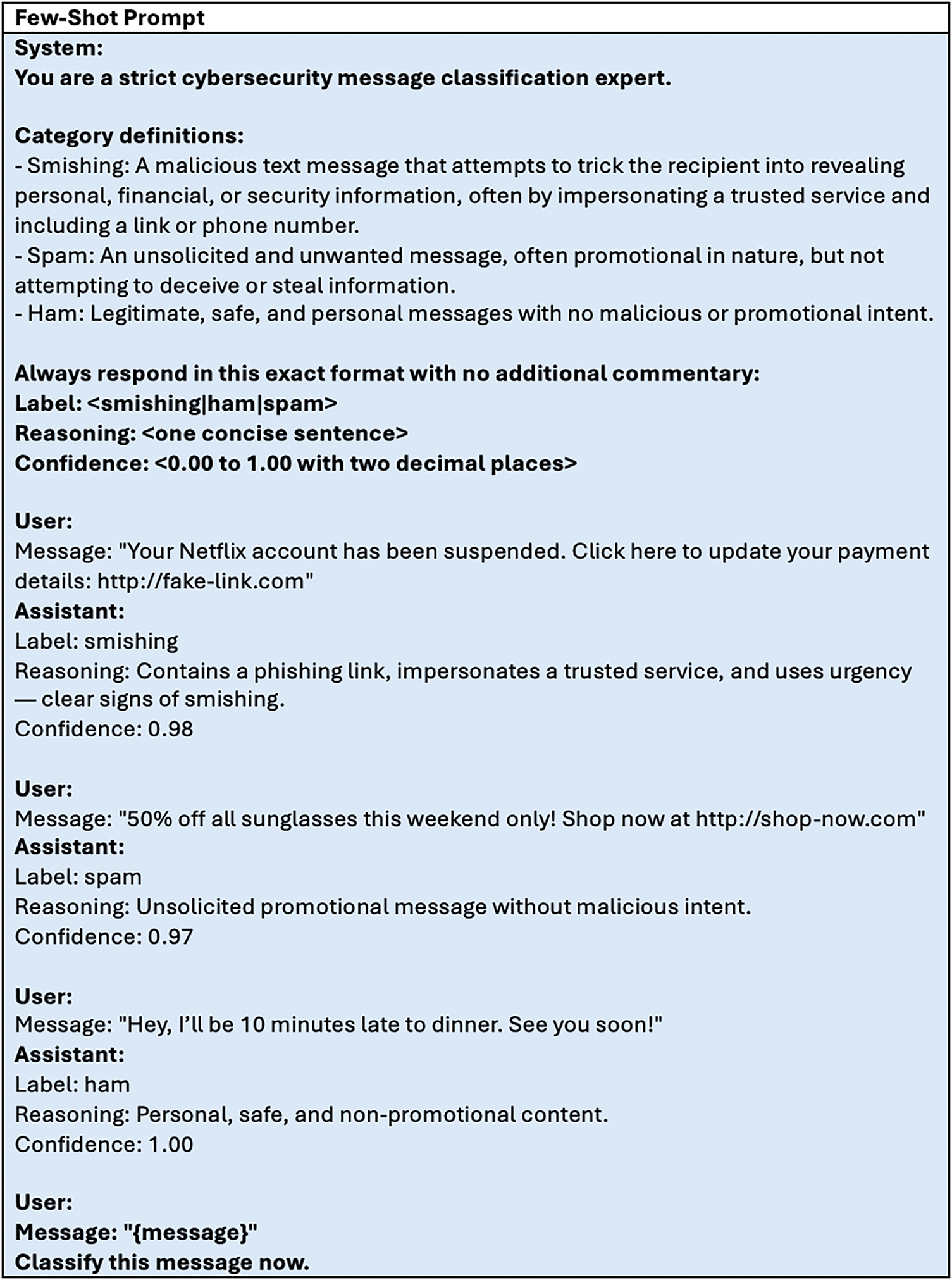

Zero-shot learning is a prompting technique where a model is instructed to perform a task without providing any examples or demonstrations and generate a response. It relies on the LLMs’ pre-trained knowledge. We created a zero-shot prompt for multiclass text classification as illustrated in Fig. 1. On the other hand, few-shot learning is a technique that involves giving the model a task description and a few input-output pair examples to guide its predictions. These examples, usually fewer than ten, help the model understand the desired format, context, or pattern for generating output. We evaluated our system using this prompt technique to understand its effect on the overall performance of the LLMs. The few-shot prompt utilized in our approach is illustrated in Fig. 2, which has examples of the three classifications.

Figure 1: Zero-shot learning prompt used in PhishNet

Figure 2: Few-shot learning prompt used in PhishNet

3.3.2 Weighted Majority Voting

Our weighted majority voting strategy combines predictions from each LLM by weighting each model’s vote according to its confidence score. Formally, let M be the set of models, C the set of possible classes, and

For example, if for a message, the

•

•

Since 1.6 > 0.6, the message is classified as spam.

Ensemble learning involves combining predictions from multiple models to produce a single final output that is more accurate and reliable. The ensemble can be based on various techniques, such as voting-based (e.g., majority vote) and stacking-based. Our ensemble approach combines predictions from the best-performing transformer model and multiple LLMs through majority voting. The transformer model receives equal voting weight to the collective LLM decision (where individual LLM votes are weighted as described in Section 3.3.2). Final classification follows these rules: (1) if all models agree, that label is selected; (2) in case of disagreement, the majority classification is chosen; and (3) tie-breaking prioritizes the transformer model’s prediction, as our evaluation (Section 4.3) demonstrates its superior accuracy over individual LLMs. The LLM consensus is always derived from the LLMs’ weighted majority voting output before being compared with the transformer’s prediction.

All experiments were carried out on Google Colab using Python 3, running on a Google Compute Engine backend equipped with a Tensor Processing Unit (TPU). LLMs were invoked using Groq cloud APIs [36]. We split the datasets into 80% for training and 20% for testing. For Dataset1, the test set comprised

To assess the performance of the models developed for smishing detection, several standard classification evaluation metrics were used: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. These metrics provide a comprehensive understanding of how well each model performs across the different message categories: ham, spam, and smishing.

• Accuracy: measures the overall model correctness by calculating the ratio of correctly predicted instances to the total number of instances.

• Precision: is the ratio of true positive predictions to the total predicted positives. High precision for a class means that the prediction is likely to be correct, thus reducing false positives.

• Recall: measures the ability of the model to identify all relevant instances correctly. A high recall value indicates that the model can detect most of the actual smishing messages, reducing false negatives.

• F1-score: is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, ideal for uneven class distribution as it considers both false positives and false negatives.

4.3 Transformer-Based Models Experimental Results

To answer RQ1 (best-performing transformer model for smishing attack detection), we evaluate and compare the performance of the three models with and without text preprocessing to assess the models’ detection accuracy. For all models, the same training procedure is applied consistently in both experiments. We first perform 5-fold cross-validation to evaluate stability and generalization, followed by training on the entire training set and final evaluation on a 20% hold-out test split. Each model is fine-tuned with a learning rate of 2e–5, a batch size of 16 for both training and evaluation, and for 3 epochs, using a weight decay of 0.01. A total of 500 warm-up steps is included to stabilize training. Evaluation and checkpoint saving are performed every 10 steps, and the best-performing checkpoint is automatically restored at the end of training. Importantly, all layers of the pre-trained models are fine-tuned, with no layers frozen during training to allow the models to fully adapt to our specific datasets. Model performance is reported on the 20% hold-out test set.

After testing the model with and without text preprocessing, we evaluate its performance to determine the impact of the preprocessing on the overall accuracy of the models, which addresses RQ2. Table 1 summarizes the transformers’ classification results and inference time. Note that the misclassification counts and inference times with preprocessing are very similar to those without preprocessing; for clarity, only the latter are reported in Table 1. In addition, for each class, FN indicates the total number of false negatives, while FP represents the total number of instances misclassified as any of the other classes. For example, for the ham class in BERT on Dataset2, we report 1 FN and 32 FPs, meaning that 1 ham message was incorrectly classified as non-ham (false negative) and 32 ham messages were misclassified as either spam or smish.

BERT model was evaluated on both unprocessed and preprocessed text to assess the impact of preprocessing on classification performance. BERT demonstrated moderate performance on Dataset1, achieving an overall accuracy of 85% both with and without message preprocessing, as illustrated in Table 1. Classification of ham messages was near-perfect with precision and recall reaching 97%–100%. Spam detection yielded a balanced F1-score of 81% in both settings. The most challenging category for BERT was smishing, where recall dropped to 32%–30% and the F1-score remained low at 37%. A considerable number of smishing instances were misclassified as ham or spam (477 FN, 110 FP without preprocessing), indicating difficulty in identifying subtle phishing cues in messages. On Dataset2, BERT performed substantially better (reaching 94% accuracy) in both text processing cases. Precision and recall were near-perfect for spam (F1-score: 100%), while ham and smishing detection also remained strong with F1-scores of 92%. The total inference time for all messages in the test set was moderate, averaging around 0.015 s per message for Dataset1 and 0.013 for Dataset2, which is acceptable for real-time systems.

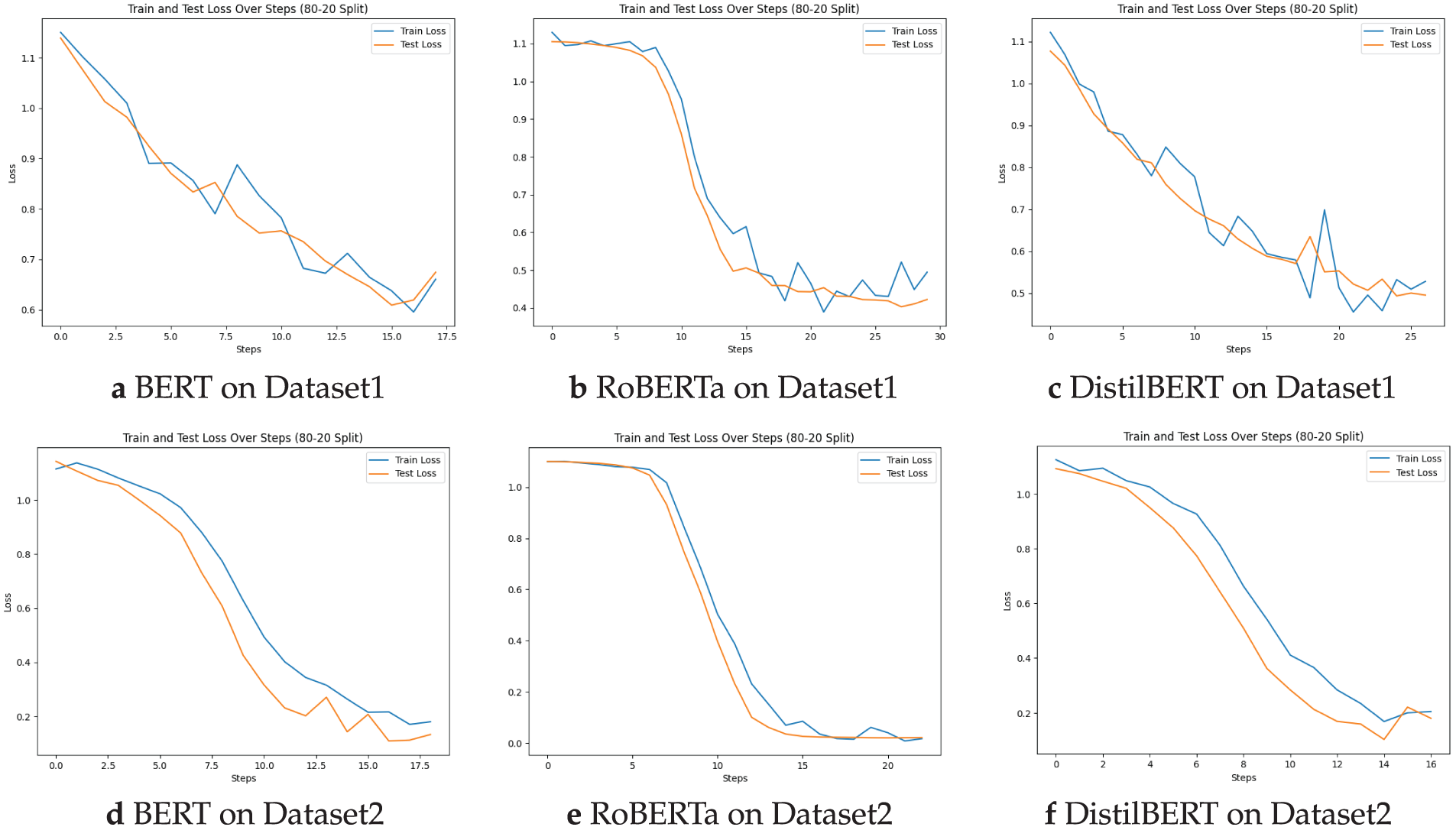

Training and testing loss curves for both datasets in both settings indicate stable learning and good generalization. Fig. 3a,d shows the train and test loss plots for the model in the unprocessed text case on Dataset1 and Dataset2, respectively. These results suggest that message preprocessing did not substantially alter the classification performance of BERT. The model’s contextual embeddings can capture sufficient semantic features from raw, unprocessed text. The model can be refined to distinguish spam and smishing messages more effectively.

Figure 3: Transformers training and testing performance plot without preprocessing on Datasets 1 and 2

As shown in Table 1, RoBERTa achieved the highest multi-class classification accuracy among the evaluated models on both datasets. Specifically, on Dataset1, the model performance improved slightly from 91% with preprocessing to 92% without. For ham detection, RoBERTa maintained extremely high precision and recall (both at 99% and 98%), and smishing classification was strong, with an F1-score of 0.87 in both configurations. Spam detection, however, remained an issue, with a recall of 35% and an F1-score of only 46% regardless of preprocessing. Most misclassifications occurred in the spam and smishing classes (i.e., 466 FN spam messages and 294 FP of incorrectly labeled smishing messages as other classes without preprocessing). On Dataset2, RoBERTa achieved near-perfect results, reaching 99% accuracy with preprocessing and a perfect 100% without it. In summary, the model achieved precision, recall, and F1-scores of at least 99% in the three classes, which indicates its superior ability to distinguish between ham, spam, and smishing in a cleaner dataset. Inference time averaged 0.016 s per message for Dataset1 and 0.010 s for Dataset2, making it the fastest transformer in the group.

Training and test loss plots of the RoBERTa model on Dataset1 (Fig. 3b) and Dataset2 (Fig. 3e) demonstrate a steady decrease in both training and testing loss, suggesting that the model is learning effectively and generalizing well to unseen data. Overall, the model shows robust performance for most classes, and the preprocessing provided limited benefit for RoBERTa, likely because its robust tokenization effectively handles raw text.

As shown in Table 1, the DistilBERT model performed slightly below RoBERTa on Dataset1, achieving 89% accuracy with and without preprocessing, excelling in ham classification (96% F1-score) and showing moderate smishing detection (precision = 70%, recall = 96%, F1 = 85%). Spam classification was more challenging (precision = 80%, recall = 22%, F1 = 26%) in both settings. The confusion matrix analysis revealed 522 FN spam messages and 294 FP smishing misclassifications. On Dataset2, DistilBERT achived better accuracy in both cases (93%), with perfect recall for ham and high scores for spam (F1-score: 0.99). Smishing detection had a lower recall (83%–82%) compared to RoBERTa and BERT, although precision remained high (99%–100%). DistilBERT has the next fastest inference time, at 0.013 s per message, for both datasets, after RoBERTa.

Training and testing loss plots for Dataset1 and Dataset2 in Fig. 3c and 3f, respectively, demonstrate a steady decrease, indicating that the model is learning effectively. The results also show that preprocessing provided limited benefit, and the model shows comparable performance to BERT for all classes.

4.3.4 Statistical Analysis of Model Performance

To further examine the models’ performance, we evaluated them statistically using the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and Friedman tests. The evaluation procedure involved reading the models’ K-Fold results (accuracy and macro-F1), followed by computing the confidence intervals (95% CI) for both metrics to capture the reliability of performance estimates, and finally, applying the Friedman tests for statistical performance comparison for all models.

For Dataset1, the models demonstrated moderate performance with statistically indistinguishable results. BERT achieved the highest mean accuracy (0.753, 95% CI [0.7192, 0.7877]) and Macro-F1 (0.679, CI [0.6221, 0.7376]), followed closely by DistilBERT (accuracy: 0.737, CI [0.7008, 0.7747]; Macro-F1: 0.661, CI [0.5929, 0.7288]) and RoBERTa (accuracy: 0.729, CI [0.7006, 0.7578]; Macro-F1: 0.636, CI [0.5828, 0.6898]). Friedman tests confirmed no significant differences in accuracy (

On Dataset2, all models exhibited near-perfect performance with accuracy and Macro-F1 scores exceeding 98.7% and tight confidence intervals. Specifically, for accuracy, BERT’s mean score was 0.988 (95% CI: 0.9775–1.0000), RoBERTa slightly outperformed with 0.989 (95% CI: 0.9825–0.9967), and DistilBERT followed closely at 0.987 (95% CI: 0.9776–0.9974). The results were mirrored in the Macro-F1 metric, where BERT reached 0.988 (95% CI: 0.9774–1.0000), RoBERTa obtained 0.989 (95% CI: 0.9824–0.9967), and DistilBERT scored 0.987 (95% CI: 0.9775–0.9973). The Friedman tests again showed no significant differences (accuracy:

Figure 4: Statistical analysis results of the 95% confidence interval and p-values of the models

4.3.5 Best-Performing Transformer Model

The statistical analysis discussed in Section 4.3.4 revealed no statistically significant differences between the models across these datasets. However, selecting the most suitable deployment model should consider additional factors beyond statistical equivalence. Our evaluation of the transformer models (Section 4.3) showed that RoBERTa achieved strong performance without text preprocessing on both datasets (accuracy 92% on Dataset1, 100% on Dataset2), particularly for ham classification. Detailed performance results on a hold-out testing set are presented in Table 1, providing further insight into each model’s strengths and weaknesses. Despite the high overall accuracy, all models consistently struggled to distinguish between spam and smishing messages, likely due to the inherent similarities in patterns between these classes. Additionally, inference time plays a crucial role in model selection for real-time applications such as PhishNet. RoBERTa had the fastest inference time on both datasets.

These key findings address the research questions RQ1 and RQ2. RoBERTa emerges as the optimal model for smishing detection, demonstrating the highest overall accuracy while maintaining balanced performance across all classes in both datasets (RQ1). Text preprocessing provided no significant accuracy improvements across any model, which indicates that transformer architectures effectively extract meaningful patterns from raw text (RQ2). These results suggest that future work should focus on enhancing model discrimination between spam and smishing, rather than text preprocessing optimizations.

To address our RQ3 (effect of prompt engineering on LLMs’ performance), we instruct the three LLMs to classify messages in the testing sets:

Table 2 presents the performance results of each LLM in the smishing attack detection task, utilizing zero-shot and few-shot prompting. Across both datasets, GPT-OSS consistently achieved the highest performance in all metrics, with accuracy and F1-scores reaching 0.94 and 0.96 on Dataset1 and 0.92 on Dataset2 using the few-shot prompting technique. LLaMA3.3 showed moderate zero-shot performance but improved substantially with few-shot learning, particularly on Dataset2 (accuracy/F1 = 0.91/0.91). Qwen3 maintained stable zero-shot results but exhibited limited or negative gains in few-shot learning, which could indicate weaker in-context learning capabilities of the model. Generally, few-shot prompting boosted the performance of GPT-OSS and LLaMA3.3 but had inconsistent effects on Qwen3. These improvements came at the cost of increased runtime. Specifically, in few-shot experiments, the models took a longer time to classify messages across both datasets. The overall processing time was higher for Dataset1 compared to Dataset2, which is consistent with their sizes (Dataset1 has 2371 messages, while Dataset2 has 600). Generally, GPT-OSS demonstrated the most robust and adaptable performance, especially in cases where accuracy and generalization are critical. The LLMs generally performed well in this task and could be further enhanced through additional prompting techniques or models’ fine-tuning to improve their domain adaptation.

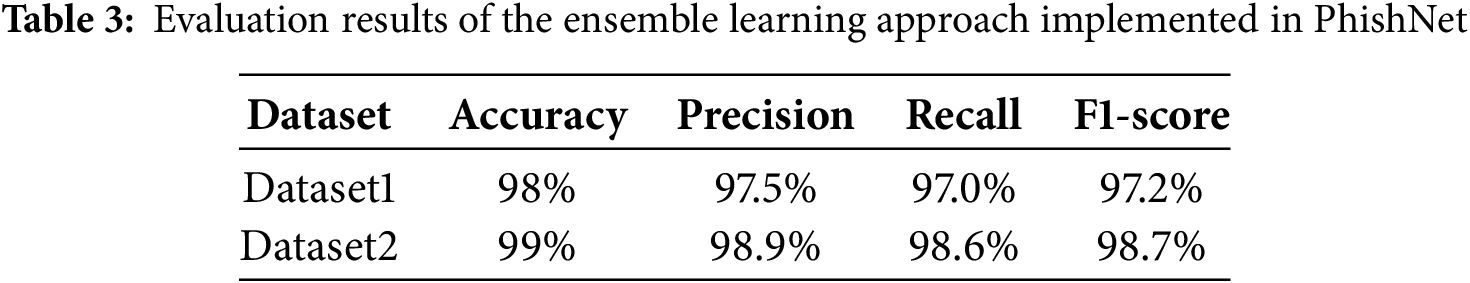

4.5 Ensemble Learning Model Results

Previous experiments identified RoBERTa as a strong baseline for smishing attack detection, achieving 92% accuracy on Dataset1 and 100% on Dataset2. Its strength lies in robust classification of ham messages and effective handling of spam and smishing messages. The LLMs achieved comparable results (94% accuracy using few-shot on Dataset1 and 92% on Dataset2). To address the complementary strengths and weaknesses of individual models, we implemented an ensemble learning approach that combines RoBERTa with the three LLMs through a majority voting strategy, as detailed in Section 3.4. Table 3 reports the performance of this ensemble on the 20% test split of both datasets. The ensemble model achieved 98% and 99% accuracy on Datasets 1 and 2, which is an improvement over both RoBERTa and the LLM ensemble when used individually. In addition, the ensemble model demonstrated balanced precision, recall, and F1-scores, confirming its robustness across both datasets. These results highlight that the LLM ensemble can effectively complement RoBERTa by reducing errors in more challenging data, as in Dataset1.

Inference efficiency is also an important factor to consider for real-time applications. For the larger dataset (Dataset1), Table 2 reported that the 3 LLMs produced classifications for the 2371 messages in the test set in 2 h 23 min 3 s using few-shot prompting. The time per classification is

Our approach advances smishing detection by integrating state-of-the-art NLP techniques with practical usability, establishing a foundation for future AI-driven cybersecurity tools. Nonetheless, our ensemble learning approach has limitations. Specifically, our evaluation relies on a limited number of datasets, primarily due to the lack of recent multiclass smishing datasets and the computational demands of fine-tuning and inference with large-scale open-source LLMs. As BERT base, RoBERTa, and DistilBERT were originally pre-trained on English-only corpora and are not optimized for handling non-English languages, we restricted our dataset selection to English messages. To enhance generalizability, future work could expand this scope to larger, multilingual datasets and various LLMs and transformers. Furthermore, this study does not examine adversarial attacks on LLMs, which remains an important direction for extended research. Adversarial attacks on LLMs aim to exploit weaknesses in models’ prompting or training to influence model behavior, which could lead to privacy violations, harmful results, or other security vulnerabilities.

5 PhishNet Development and Implementation Details

This section outlines how PhishNet was transformed from a conceptual framework into a fully functional smishing detection system. The implementation integrates three major components: the front-end interface, the back-end infrastructure, and the AI-powered classification engine. These elements work in tandem to deliver a scalable, responsive, and privacy-aware mobile application:

• Front-End Development: The front-end allows users to interact with the application through intuitive graphical interfaces. It was developed using FlutterFlow [38], a low-code platform built on top of the Flutter framework. This enables rapid prototyping and cross-platform compatibility. Users can register, submit SMS messages for analysis, view historical results, and receive actionable feedback through a clean and accessible design.

• Back-End Infrastructure: The back-end is responsible for secure data storage and communication with the AI engine. We utilize Cloud Firestore [39], a scalable NoSQL database service provided by Firebase, to store user data, including registration information and analyzed SMS content. The system ensures asynchronous communication and real-time updates through Firebase’s native APIs.

• AI Model Integration: The AI classification component consists of two layers (ensemble model): (1) transformer-based models for baseline classification, and (2) large language models (LLMs) integrated via the Groq API. The backend communicates with the AI layer using Flask [40], a lightweight and reliable web framework for Python. Flask handles incoming requests, invokes the appropriate model inference pipeline, and returns results to the application front-end.

PhishNet app begins with a welcome page offering login, signup, or guest access options as shown in Fig. 5a. Users can access the main analysis page, as shown in Fig. 5b, where they can input text for smishing detection. The result page displays the analysis outcomes with guidance on handling potential threats (refer to Fig. 5c). Users can manage their information through the profile page (Fig. 5d), review past analyses via the History page (Fig. 5e), and access an additional educational content through the awareness page (Fig. 5f).

Figure 5: Selected PhishNet application user interfaces

5.2 Privacy and Regulatory Compliance

Since PhishNet processes sensitive content from users’ SMS messages, its design adheres to internationally recognized data protection regulations. In particular, we consider the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [41] and the NIST Special Publication 800-63B guidelines for digital identity and authentication [42]. Under GDPR, SMS content containing names, phone numbers, or links may constitute personal data. To ensure compliance, the system applies the principles of data minimization, explicit user consent, and secure data handling. All data in transit is encrypted using HTTPS, and access control is enforced using Firebase Authentication and role-based permissions. Additionally, NIST 800-63B provides specific guidance on secure authentication mechanisms and SMS-based communications. In line with these recommendations, PhishNet avoids persistent storage of SMS content except when maintaining a history of analyzed messages for the user (refer to Fig. 5e). Even in such cases, users retain complete control, with the ability to delete the entire history or remove individual messages. All message analysis continues to occur in a secure execution environment. Future releases of PhishNet will include privacy-enhancing technologies such as differential privacy and formal auditing for regulatory compliance.

Three types of testing were performed on PhishNet to thoroughly validate its functionality and usability: unit testing, integration testing, and usability testing.

Unit testing focuses on verifying the functionality of internal components, such as the database interactions, in isolation. It ensures that each module or unit functions correctly under specified conditions. It was performed on two main components: the AI classification model and the back-end system. AI model testing was performed and explained in Section 4.3. Back-end testing validates data insertion and retrieval functionalities, including user registration, profile modification, and text message submission, which was evaluated through direct interface observation and backend changes. All operations were error-free, and the retrieved data matched expectations in structure and content.

Integration testing involves examining the application’s components to identify issues in their interactions. To conduct this testing, we performed the following scenario: a user submits a message, which is stored in the database with a pending status. The server routes the message to the AI model for classification, and upon receiving a response, updates the database with a new analyzed status. No anomalies were found, indicating proper integration and functionality of all system components.

Usability testing evaluates user interactions, satisfaction, and usability challenges. A total of ten participants, representing a diverse group of users with varying degrees of technical expertise, participated in the usability testing. Each participant was asked to complete nine unified tasks using the application, including user registration, submitting a text message for analysis, reviewing results and recommendations, navigating to the about us page, view and modify user profile, explore the analysis history page, and logging in and out of the app. During each session, participants were observed to assess task completion rates, time taken for each task, and any errors or confusions encountered. Upon completing the tasks, users filled out a feedback form based on the System Usability Scale (SUS) and provided qualitative comments regarding their experience.

Participants could complete tasks with minimal variation in performance. We found that the system required the most user effort during the initial registration process (i.e., # of clicks ranges from 7 to 8 and task duration was 1–3 min). Navigation tasks, such as viewing the user profile, are generally efficient (<= 1 min completion time). Message analysis typically took 2–3 clicks in <= 2 min. Most users completed all assigned tasks without requiring external assistance. The average SUS score was 84 out of 100, indicating strong usability. Users highlighted the logical flow of message submission and analysis, as well as the usefulness of the classification results and follow-up guidance. Some minor suggestions were offered to enhance user experience, such as providing visual confirmation upon successful message submission and improving the visibility of historical message records. Overall, the usability testing confirmed that the application is accessible to non-technical users and successfully communicates its core purpose.

In this study, we propose an ensemble-based deep learning framework for detecting smishing attacks, integrating a transformer model and large language models to enhance classification robustness. Our experiments revealed that RoBERTa outperformed BERT and DistilBERT in accuracy, while LLMs, despite their computational cost, provided complementary strengths through weighted majority voting. Key contributions include: (1) Addressing class imbalance via T5-generated synthetic samples improved minority-class recognition without overfitting. (2) Combining transformer models with LLMs via majority voting enhanced detection reliability, particularly in edge cases. (3) We developed an accessible application to empower end users with real-time smishing detection, bridging the gap between research and usability.

This work can be enhanced by applying different prompt engineering techniques. Additionally, various ensemble learning models can be employed. More datasets can be used to assess the model’s robustness. Furthermore, we intend to conduct pilot deployments and usability studies with broader user groups to determine real-world performance, scalability, and adoption.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical and financial support provided by DSR.

Funding Statement: This project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under Grant No. (GPIP: 1074-612-2024).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Abeer Alhuzali, Qamar AL-Qahtani, Asmaa Niyazi, and Lama Alshehri; methodology, Abeer Alhuzali, Qamar AL-Qahtani, Asmaa Niyazi, and Lama Alshehri; software, Abeer Alhuzali, Qamar AL-Qahtani, Asmaa Niyazi, and Lama Alshehri; validation, Abeer Alhuzali, Qamar AL-Qahtani, Asmaa Niyazi, and Lama Alshehri; formal analysis, Abeer Alhuzali, Qamar AL-Qahtani, Asmaa Niyazi, and Lama Alshehri; investigation, Abeer Alhuzali, Qamar AL-Qahtani, Asmaa Niyazi, and Lama Alshehri; writing—original draft preparation, Abeer Alhuzali, Qamar AL-Qahtani, Asmaa Niyazi, Lama Alshehri, and Fatemah Alharbi; writing—review and editing, Abeer Alhuzali and Fatemah Alharbi; visualization, Abeer Alhuzali, Qamar AL-Qahtani, Asmaa Niyazi, and Lama Alshehri; supervision, Abeer Alhuzali; project administration, Abeer Alhuzali; funding acquisition, Abeer Alhuzali. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Dataset1 is publicly available; Dataset2 is available upon request.

Ethics Approval: This study used only publicly available system datasets and did not involve human participants, animals, or sensitive personal data. All methods complied with relevant guidelines and regulations, and no ethical concerns are associated with this work.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Alabdan R. Phishing attacks survey: types, vectors, and technical approaches. Future Internet. 2020;12(10):168. doi:10.3390/fi12100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Alkhalil Z, Hewage C, Nawaf L, Khan I. Phishing attacks: a recent comprehensive study and a new anatomy. Front Comput Sci. 2021;3:563060. doi:10.3389/fcomp.2021.563060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Chiew KL, Yong KSC, Tan CL. A survey of phishing attacks: their types, vectors and technical approaches. Exp Syst Appl. 2018;106(4):1–20. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2018.03.050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Rahman ML, Timko D, Wali H, Neupane A. Users really do respond to smishing. In: Proceedings of the Thirteenth ACM Conference on Data and Application Security and Privacy; 2023 Apr 24–26; Charlotte, NC, USA. p. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

5. Wahsheh HAM, Al-Zahrani MS. Lightweight cryptographic and artificial intelligence models for anti-smishing. In: Proceedings of International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Intelligent Systems. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 483–96. [Google Scholar]

6. Meléndez R, Ptaszynski M, Masui F. Comparative investigation of traditional machine-learning models and transformer models for phishing email detection. Electronics. 2024;13(24):4877. doi:10.3390/electronics13244877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Uddin MA, Islam MN, Maglaras L, Janicke H, Sarker IH. ExplainableDetector: exploring transformer-based language modeling approach for SMS spam detection with explainability analysis. arXiv:2405.08026. 2024. [Google Scholar]

8. Mehmood MK, Arshad H, Alawida M, Mehmood A. Enhancing smishing detection: a deep learning approach for improved accuracy and reduced false positives. IEEE Access. 2024;12(2):137176–93. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3463871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Tan XW, See K, Kok S. ScamGPT-J: inside the scammer’s mind, a generative ai-based approach toward combating messaging scams. In: Forty-Fifth International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS); 2024 Dec 15–18; Bangkok, Thailand. [Google Scholar]

10. Lee Y, Han D. KorSmishing explainer: a korean-centric LLM-based framework for smishing detection and explanation generation. In: Dernoncourt F, Preoţiuc-Pietro D, Shimorina A, editors. Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: Industry Track; Miami, FL, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2024. p. 642–56. [Google Scholar]

11. Koide T, Fukushi N, Nakano H, Chiba D. ChatSpamDetector: leveraging large language models for effective phishing email detection; 2024. arXiv:2402.18093. 2024. [Google Scholar]

12. Jamal S, Wimmer H, Sarker IH. An improved transformer-based model for detecting phishing, spam and ham emails: a large language model approach. Secur Privacy. 2024;7(5):e402. doi:10.1002/spy2.402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ghourabi A, Alohaly M. Enhancing spam message classification and detection using transformer-based embedding and ensemble learning. Sensors. 2023;23(8):3861. doi:10.3390/s23083861. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Trad F, Chehab A. Prompt engineering or fine-tuning? A case study on phishing detection with large language models. Mach Learn Knowl Extr. 2024;6(1):367–84. doi:10.3390/make6010018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Bilgen Y, Kaya M. EGMA: ensemble learning-based hybrid model approach for spam detection. Appl Sci. 2024;14(21):9669. doi:10.3390/app14219669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Pendie GB. A transformer model approach for robust phishing detection [dissertation]. Washington, DC, USA: George Washington University; 2024. [Google Scholar]

17. Karim A, Shahroz M, Mustofa K, Belhaouari SB, Joga SRK. Phishing detection system through hybrid machine learning based on URL. IEEE Access. 2023;11(3):36805–22. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3252366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Alamri Z, Alhuzali A, Alsulami B, Alghazzawi D. Enhanced phishing website detection using optimized ensemble stacking models. Intl J Adv Comput Sci Appl. 2025;16(8):1031–46. [Google Scholar]

19. Alhuzali A, Alloqmani A, Aljabri M, Alharbi F. In-depth analysis of phishing email detection: evaluating the performance of machine learning and deep learning models across multiple datasets. Appl Sci. 2025;15(6):3396. doi:10.3390/app15063396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Majgave AB, Gavankar NL. Automatic Phishing website detection and prevention model using transformer deep belief network. Comput Secur. 2024;147(23):104071. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2024.104071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Do NQ, Selamat A, Fujita H, Krejcar O. An integrated model based on deep learning classifiers and pre-trained transformer for phishing URL detection. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2024;161(5):269–85. doi:10.1016/j.future.2024.06.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Desolda G, Greco F, Vigano L. APOLLO: a GPT-based tool to detect phishing emails and generate explanations that warn users. Proc ACM Hum-Comput Interact. 2025;9(4):EICS003. doi:10.1145/3733049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Mishra S, Soni D. SMS phishing dataset for machine learning and pattern recognition. In: Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Soft Computing and Pattern Recognition (SoCPaR 2022). Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2023. p. 597–604. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-27524-1_57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Raffel C, Shazeer N, Roberts A, Lee K, Narang S, Matena M, et al. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. J Mach Learn Res. 2020;21(140):1–67. [Google Scholar]

25. Timko D, Rahman ML. Smishing dataset I: phishing SMS dataset from Smishtank.com. In: CODASPY ’24: Proceedings of the Fourteenth ACM Conference on Data and Application Security and Privacy. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2024. p. 289–94. [Google Scholar]

26. Almeida T, Hidalgo J. SMS spam collection [Dataset]. UCI Machine Learning Repository; 2011. doi:10.24432/C5CC84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Faker: a python package that generates fake data [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 5]. Available from: https://faker.readthedocs.io/en/master/. [Google Scholar]

28. LLM training: a guide to machine learning engineering [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.run.ai/guides/machine-learning-engineering/llm-training. [Google Scholar]

29. OpenAI. GPT-4.1 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 8]. Available from: https://platform.openai.com/docs/models/gpt-4.1. [Google Scholar]

30. Lewis M, Liu Y, Goyal N, Ghazvininejad M, Mohamed A, Levy O, et al. BART: denoising sequence-to-sequence pre-training for natural language generation, translation, and comprehension. In: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL); 2020 Jul 5–10; Online. p. 7871–80. [Google Scholar]

31. Touvron H, Lavril T, Izacard G, Martinet X, Lachaux MA, Lacroix T, et al. LLaMA: open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv:2302.13971. 2023. [Google Scholar]

32. GroqCloud. GPT OSS 120B [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 8]. Available from: https://console.groq.com/docs/model/openai/gpt-oss-120b. [Google Scholar]

33. GroqCloud. Llama 3.3 70B [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 8]. Available from: https://console.groq.com/docs/model/llama-3.3-70b-versatile. [Google Scholar]

34. GroqCloud. Qwen3-32B [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 8]. Available from: https://console.groq.com/docs/model/qwen/qwen3-32b. [Google Scholar]

35. Ai L, Kumarage T, Bhattacharjee A, Liu Z, Hui Z, Davinroy M, et al. Defending against social engineering attacks in the age of LLMs. In: Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2024 Nov 12–16; Miami, FL, USA. p. 12880–902. [Google Scholar]

36. GroqInc. Groq Cloud API documentation [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 8]. Available from: https://groq.com/. [Google Scholar]

37. Pedregosa F, Varoquaux G, Gramfort A, Michel V, Thirion B, Grisel O, et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in python. J Machine Learning Res. 2011;12:2825–30. [Google Scholar]

38. Flutterflow.io [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 4]. Available from: https://www.flutterflow.io/. [Google Scholar]

39. Firestore [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 4]. Available from: https://firebase.google.com/docs/firestore. [Google Scholar]

40. Ronacher A. Flask: a python microframework for web development. Pallets projects; Version 3.1.1. [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2025 Jun 8]. Available from: https://flask.palletsprojects.com/. [Google Scholar]

41. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European parliament and of the council (General Data Protection Regulation) [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2025 Aug 5]. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj. [Google Scholar]

42. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Digital identity guidelines: authentication and lifecycle management. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: NIST; 2020. No. SP 800-63B. doi:10.6028/NIST.SP.800-63b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools