Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Q-Learning Improved Particle Swarm Optimization for Aircraft Pulsating Assembly Line Scheduling Problem Considering Skilled Operator Allocation

1 Henan Provincial Key Laboratory of Intelligent Manufacturing of Mechanical Equipment, Zhengzhou University of Light Industry, Zhengzhou, 450000, China

2 School of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering, Zhengzhou University of Light Industry, Zhengzhou, 450000, China

3COMAC Shanghai Aircraft Manufacturing Co., Ltd., Shanghai, 200000, China

* Corresponding Author: Hao Li. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Algorithms for Planning and Scheduling Problems)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-27. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069492

Received 24 June 2025; Accepted 04 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Aircraft assembly is characterized by stringent precedence constraints, limited resource availability, spatial restrictions, and a high degree of manual intervention. These factors lead to considerable variability in operator workloads and significantly increase the complexity of scheduling. To address this challenge, this study investigates the Aircraft Pulsating Assembly Line Scheduling Problem (APALSP) under skilled operator allocation, with the objective of minimizing assembly completion time. A mathematical model considering skilled operator allocation is developed, and a Q-Learning improved Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm (QLPSO) is proposed. In the algorithm design, a reverse scheduling strategy is adopted to effectively manage large-scale precedence constraints. Moreover, a reverse sequence encoding method is introduced to generate operation sequences, while a time decoding mechanism is employed to determine completion times. The problem is further reformulated as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) with explicitly defined state and action spaces. Within QLPSO, the Q-learning mechanism adaptively adjusts inertia weights and learning factors, thereby achieving a balance between exploration capability and convergence performance. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed approach, extensive computational experiments are conducted on benchmark instances of different scales, including small, medium, large, and ultra-large cases. The results demonstrate that QLPSO consistently delivers stable and high-quality solutions across all scenarios. In ultra-large-scale instances, it improves the best solution by 25.2% compared with the Genetic Algorithm (GA) and enhances the average solution by 16.9% over the Q-learning algorithm, showing clear advantages over the comparative methods. These findings not only confirm the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm but also provide valuable theoretical references and practical guidance for the intelligent scheduling optimization of aircraft pulsating assembly lines.Keywords

In the manufacturing of large aircraft, assembly operations account for approximately 50%~70% of total direct manufacturing costs, excluding production preparation and industrial equipment fabrication [1]. Automated and flexible assembly techniques have long been central to advances in aircraft production. Sub-assembly in aircraft manufacturing focuses on “partial manufacturing,” whereas final assembly represents the “integration of the entire aircraft”. The aircraft pulsating final assembly line is divided into stations according to the assembly outline, enabling the aircraft to move between stations with an inherent takt time, thereby improving assembly efficiency and shortening the production cycle. Among these, final assembly plays a pivotal role in determining both the production rate and overall product quality [2].

With growing demand for commercial, military, and general-aviation aircraft in China, developing assembly lines that are more cost-effective, efficient, and capable of ensuring high quality has become a strategic priority. Traditional fixed hangar-style assembly reveals significant limitations when confronted with increasingly complex aircraft designs and rising production volumes. Drawing on successful practices in the automotive industry, the aviation sector has begun to adopt mobile assembly methods. These are commonly categorized by automation level into “pulsating assembly lines” and “continuously moving assembly lines” [3]. In a pulsating assembly line, the assembly outline (AO, the smallest unit of task assignment in the production system) is distributed across a limited number of workstations. Each station is assigned a set of tasks to be completed within a fixed cycle; at the end of the cycle, the aircraft advances to the next station, yielding a stepwise, pulse-like movement. By contrast, a continuously moving assembly line operates with higher automation and a stable material supply: the aircraft moves at a constant speed while operators complete tasks sequentially. At present, aircraft pulse assembly lines are mainly constrained by multiple factors, including material supply, precedence relations among tasks, resource availability, spatial limitations, and operator collaboration. Materials are supplied by multiple vendors, and large commercial aircraft involve numerous and complex operational constraints. The resources primarily include tooling equipment and ordinary operator resources. Each operator occupies space within the aircraft section while working, and the execution of assembly tasks often requires the cooperation of multiple types and numbers of workers. Therefore, pulse final assembly lines have attracted extensive academic attention worldwide.

The workstation segmentation inherent to aircraft pulsating assembly lines gives rise to two major research topics: the “Aircraft Pulsating Assembly Line Balancing Problem (APALBP)” and the “Aircraft Pulsating Assembly Line Scheduling Problem (APALSP)”. The APALBP [4] focuses on distributing assembly tasks across stations to balance workload and minimize idle time. This problem has been widely studied in aircraft assembly and other manufacturing domains. For example, Bao et al. [5] developed an integer linear programming model and proposed a two-stage heuristic for balancing an aircraft final assembly line. Korivand et al. [6] introduced a framework for predicting human performance in human-robot teaming by integrating physiological data with Q-learning, achieving 95.45% accuracy; their findings offer insights relevant to resource and performance optimization in aircraft assembly. In contrast, the APALSP [7] addresses the allocation of resources and operators under spatial constraints, as well as the scheduling of task start and finish times to ensure timely assembly completion. The resources considered include various tool resources and different types of operators, each of whom occupies space within the aircraft sections. Owing to its diverse focus areas, APALSP has spawned several subproblems. Prior studies have examined related topics such as multi-operator parallel scheduling [8], multi-skilled operator allocation [9,10], multi-level operator assignment [11], scheduling with operator fatigue [12], workload-fluctuation scheduling [13], and human-robot collaborative scheduling [14]. The present research concentrates on one such subproblem: the aircraft pulsating assembly line scheduling problem with skilled operator allocation. The aircraft assembly process is subject to strict task sequencing constraints, and skilled workers impact the completion time of each task. Therefore, efficient operator scheduling [15] and task scheduling are crucial for improving assembly efficiency and reducing production costs.

Building on this literature, many studies emphasize operator allocation yet often treat operators as homogeneous resources. In practice, however, training skilled operators requires substantial investment, and their deployment directly affects assembly efficiency, product quality, and production stability. Skilled operators execute complex tasks more accurately and efficiently. Therefore, explicitly modeling skilled operators as a distinct resource within the scheduling process is both critical and challenging.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews APALSP from the perspectives of resource constraints and operator allocation. Section 3 details the problem statement and mathematical formulation. Section 4 presents the Q-Learning improved Particle Swarm Optimization (QLPSO) approach. Section 5 reports experimental validation on small-, medium-, large-, and ultra-large-scale test cases. Section 6 concludes the study and outlines avenues for future research.

The aircraft pulsating assembly line scheduling problem can be regarded as a variant of the project scheduling problem with unique constraints. It extends and generalizes the classical Resource-Constrained Project Scheduling Problem (RCPSP) [16]. As a key area in operations research, RCPSP has been extensively studied and is considered a mature topic in both modeling and algorithm development. Li et al. [17] proposed a proactive scheduling model for RCPSP, incorporating resource constraints, and solved it using a branch-and-bound algorithm. Their method outperformed CPLEX and traditional genetic algorithms. Liu et al. [18] introduced a bi-objective model for finance-based and resource-constrained robust project scheduling (FBRCRPSP). They developed an enhanced non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm (NSGA-II-LS), which efficiently explores the neighborhood space and performs well on small-scale instances. Currently, research in this area continues to evolve, providing valuable insights and decision-making support for project managers.

The Aircraft Pulsating Assembly Line Scheduling Problem (APALSP) remains in the early stages of academic exploration. This is largely due to the relatively late development of China’s aircraft manufacturing and assembly industry, where research across multiple dimensions is still emerging. Roussel et al. [19] conducted preliminary studies on design optimization for aircraft assembly lines. Traditionally, manufacturing systems are developed after the aircraft design is finalized, often resulting in suboptimal performance. To address this, the authors proposed integrating production system considerations into the early stages of aircraft design. They introduced a constraint programming encoding and an ε-constraint-based algorithm, which demonstrated significant potential. In parallel, Long et al. [20] investigated productivity prediction for aircraft final assembly lines. Their study compared three modeling approaches: a simulation-based prediction model, a representative regression model, and a machine learning model including multilayer perception, gradient boost regression tree and random forest. These methods were validated using a real-world final assembly line involving three types of aircraft, confirming their practical applicability. Both domestic and international scholars continue to focus on simulation and optimization studies of aircraft final assembly pulsating lines. These efforts aim to improve resource utilization and achieve better operational balance across production stages.

Research on the Aircraft Pulsating Assembly Line Scheduling Problem (APALSP) primarily focuses on resource constraints, as this is the most classical and fundamental modeling framework. Many researchers have conducted studies based on resource-constrained models, considering various tooling resources and operator resources, and some scholars have also taken spatial constraints into account. Cai et al. [21] addressed spatial constraints in the aircraft assembly process by formulating a mathematical model for sub-assembly scheduling. Their objective was to minimize total assembly duration while accounting for spatial limitations. To solve the model, they proposed an Improved Genetic Algorithm with Variable Neighborhood Search (IGA-VNS). Similarly, Wen et al. [7] applied a reinforcement learning-based genetic algorithm (QIGA) to handle multiple constraints in aircraft assembly scheduling. By integrating genetic algorithms with Markov decision models and dynamically adjusting parameters, the method enhanced the search efficiency. Experimental results demonstrated that the proposed algorithm significantly reduced total assembly time in large-scale aircraft assembly scenarios. Shan et al. [22] also focused on resource constraints but treated them as an objective function within the scheduling problem. They developed a comprehensive fitness function to evaluate resource balance in demand-driven scheduling and introduced an Adaptive Genetic Algorithm (GA) to address the problem. Further research has delved deeper into flexible resource allocation. Ren et al. [23] proposed a flexible resource investment model based on project splitting (FRIP_PS), which allows for dynamic resource allocation in final assembly scheduling. They embedded a heuristic method into a genetic algorithm to solve the problem efficiently. In subsequent work, Ren et al. [24] incorporated resource transfer times between stations into the scheduling model. Considering task precedence and resource limitations, they proposed a linear mathematical model aimed at minimizing total project completion time. A branch-and-bound embedded genetic algorithm was developed to solve this model. To address the challenges of multi-workstation parallel execution and the unavailability of line-end shared resources, Lu et al. [25] introduced a new variant of the scheduling problem: the Resource Investment Problem based on Project Splitting with Time Windows (RIPPS_TW). This model allows projects to be divided into sub-projects, enhancing scheduling flexibility. They also proposed a two-stage iterative loop algorithm and validated its effectiveness through experimental case studies. Borreguero et al. [26] developed a multi-mode resource-constrained project scheduling model that incorporates incompatibility constraints, resource limitations, and a large task volume. Using a constraint programming-based large neighborhood search algorithm, they achieved significantly better results compared to the company’s previously applied heuristics.

Focusing on resource constraints, both field research and literature reviews reveal an increasing emphasis on the allocation and arrangement of assembly line personnel in aircraft production. As a result, many scholars have explored workforce allocation in greater depth. Xin et al. [9] addressed the scheduling problem of moving production lines in aircraft assembly. They considered scenarios where multiple operators could jointly execute a task and developed a model for scheduling multi-operator parallel tasks. Their goal was to minimize total assembly completion time. They compared various heuristic algorithms with different rule sets and designed a genetic algorithm (GA) for performance benchmarking. Fang et al. [27] examined the allocation of workers across multi-level stations. Since certain specialized operators must shift between stations at fixed intervals, the objective was to minimize cycle time while balancing workloads. To tackle this, an improved non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm (NSGA-IV) was proposed. Some researchers take a more human-centered perspective. Arkhipov et al. [28] studied task allocation under both economic and ergonomic constraints, aiming to optimize task schedules. They proposed two models and validated them through a case study. Ottogalli et al. [29] used virtual reality (VR) to assess automated and semi-automated cargo handling processes, selecting the most efficient one. They also analyzed operator ergonomics in tight fuselage spaces, focusing on safe human-robot collaboration. Their results showed notable reductions in assembly time and labor costs. Human-robot collaboration has become a key research area. Wang et al. [14] emphasized that operator movements across stations, especially when skills differ, significantly affect final assembly efficiency. He introduced the dynamic worker allocation problem for aircraft final assembly (DWA-AFA) and proposed a human-machine collaborative optimization method (HMC-O). Tereshchuk et al. [30] developed a scheduling method for aircraft assembly involving multiple collaborative robots. They addressed the soft task priority constraint, which arises from tasks requiring different tools. Their multi-robot task allocation model reduced tool change time by incorporating priority constraints. A two-stage, data-driven approach was proposed to select task priorities, along with a soft-priority iterative auction strategy and machine learning-based scheduling. Guo [31] focused on coordinating tasks between human and robot teams (HRTs). He proposed a hybrid approach combining mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) and constraint programming (CP). The CP method outperformed others in solving real-world scheduling challenges in synchronized aircraft production and logistics.

Existing research on aircraft assembly line scheduling under resource constraints has provided a solid theoretical and algorithmic foundation. However, the critical role of operator allocation has not been fully addressed. Effective operator assignment can significantly enhance both the efficiency and quality of the assembly process. While numerous studies have examined scheduling and workforce allocation in aircraft assembly, further investigation is needed in areas such as operator allocation, multi-objective optimization, and dynamic scheduling. Building on this gap, the paper proposes a scheduling model for the Aircraft Pulsating Assembly Line Scheduling Problem considering skilled operator allocation, and design the QLPSO algorithm to solve it. This work aims to offer both theoretical insights and practical guidance for improving production efficiency in the manufacturing industry.

3 Problem Description and Formulation

An aircraft pulse assembly line refers to the process in which aircraft components enter the assembly workshop to complete all assembly tasks and testing until the completion of the test flight. An aircraft involves a large number of AO, each of which must strictly follow its precedence constraints. The execution of AO also requires specific resources, including various tooling resources and multiple operators. During task execution, operators occupy the space within the aircraft section, and the available space varies across different sections of the aircraft. Therefore, operator assignment must also strictly adhere to spatial constraints. These constraints affect total assembly time, restrict the number of operators, and make workforce allocation critical, as operator differences can significantly influence task durations.

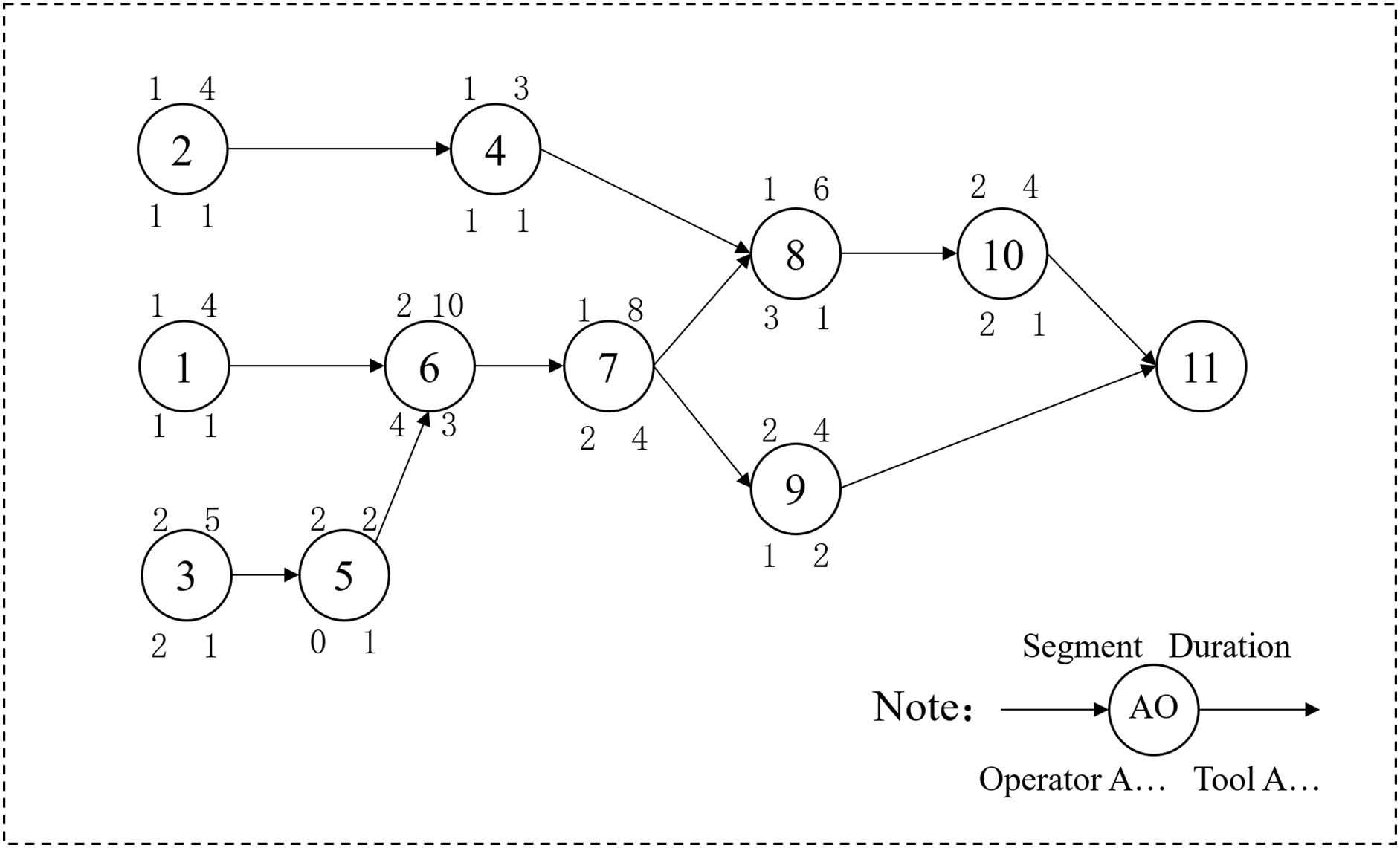

Therefore, solving such scheduling problems requires considering multiple factors, including AO precedence constraints, resource constraints, spatial constraints, and skilled worker allocation. The aircraft pulsating assembly line scheduling problem with skilled operator assignment can be defined as follows: After the aircraft’s tasks are divided across stations, each station contains a set of AO. Let there be a total of J AO, referred to as AO, within a station. Each AO is subject to precedence constraints based on the Operation Sequence Plan (OSP), which can be represented using an Activity on Node (AON) diagram [32]. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the AON diagram depicts not only the sequential relationships between AO but also includes segment information, task duration, and the required number of operators for each AO.

Figure 1: The activity on node (AON) for aircraft pulsating assembly line

Each segment within the assembly line is subject to a maximum capacity constraint, limiting the number of operators that can work in parallel within that segment. The duration refers to the time required to complete a specific AO, while the number of operators indicates the quantity of regular operators needed to perform the AO. Operators A and B are considered shared resources and are subject to maximum availability constraints. Skilled operators, on the other hand, can be flexibly assigned. Each AO requires at least one skilled operator to proceed under normal conditions. If two skilled operators are assigned to an AO, its duration is reduced by one-third. Assigning three skilled operators shortens the duration by half. However, allocating more than three skilled operators results in diminishing returns in efficiency, which is not considered in this study. The objective of this problem is to determine the optimal scheduling of AOs and the allocation of skilled and shared operators to minimize the total completion time.

The following symbols and their meanings are required to establish the mathematical model for the aircraft pulsating assembly line scheduling problem considering skilled operator allocation, as shown in Table 1.

The mathematical model for the aircraft pulsating assembly line scheduling problem considering skilled operator allocation, is as follows:

Objective:

subject to:

Objective function (1) represents the minimization of the total completion time of the aircraft assembly line. Constraint (2) represents that all AOs in the aircraft assembly line must be completed within the total completion time and cannot exceed the planned station cycle time; Constraint (3) represents that each AO must be completed within the specified time and cannot be overdue; Constraint (4) represents that each AO can only be assigned to one segment space within the station for execution; Constraints (5) and (6) represent the precedence constraints between AOs, where the start time of a succeeding AO cannot exceed the completion time of the preceding AO; Constraints (7) and (8) represent worker quantity constraints, meaning the total number of allocated operators cannot exceed the maximum number of operators available, where the former refers to regular operators and the latter refers to skilled operators; Constraints (9) and (10) represent that at any given time, each operator can only perform one AO; Constraint (11) represents resource constraints, meaning the resource demand for parallel AOs cannot exceed the total available resources; Constraint (12) represents skilled operator constraints, meaning the number of skilled operators assigned to each AO cannot exceed three; Constraint (13) represents skilled operator resource constraints, meaning the resource demand for AOs performed by skilled operators cannot exceed the total available resources; Constraint (14) represents space constraints, meaning the space occupied by regular and skilled operators cannot exceed the maximum capacity of the segment space.

4 Q-Learning Improved Particle Swarm Optimization

Swarm Intelligence (SI), a prominent branch of Artificial Intelligence (AI), is inspired by the collective behaviors of social organisms in nature. Among various SI algorithms, Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) stands out as one of the most widely applied and extensively studied paradigms [33]. Since its introduction in the 1990s, PSO has attracted considerable attention from both researchers and practitioners.

Despite its global search capability, PSO is prone to premature convergence in high-dimensional or complex problems and is highly sensitive to parameter settings. Reinforcement learning has been shown to alleviate these issues by adaptively tuning parameters and enhancing exploration [34]. In this study, we embed Q-learning, a model-free reinforcement learning algorithm, into PSO, enabling particles to dynamically adjust their strategies based on feedback. This integration improves convergence efficiency and increases the likelihood of attaining global or near-optimal solutions.

4.1 Design of Reverse Sequence Encoding

Due to the precedence constraints inherent in the aircraft pulsating assembly line scheduling problem, it is not feasible to generate a valid solution through purely random initialization. Instead, a priority sequence list must first be randomly generated. The value in this list represents the priority of each AO—the higher the value, the higher the AO’s priority, and the earlier it should be scheduled. This priority list serves as the basis for encoding the solution. For large-scale scheduling problems with complex precedence relationships, a forward scheduling approach is typically employed. This method requires strict adherence to AO dependencies: a AO can only be executed once all of its predecessor AO have been completed. Such tight constraints greatly increase the complexity of the scheduling algorithm. To address these challenges, some researchers have explored inverse sequence-based scheduling methods. For example, Guo et al. [35] proposed a genetic algorithm based on inverse sequence virtual components to solve complex product scheduling problems with tightly coupled constraints. Similarly, Wang [36] adopted an inverse sequence scheduling strategy, which first schedules root-node processes, followed by leaf-node processes. Their experimental results demonstrate that inverse sequence scheduling offers advantages in both computational efficiency and solution quality.

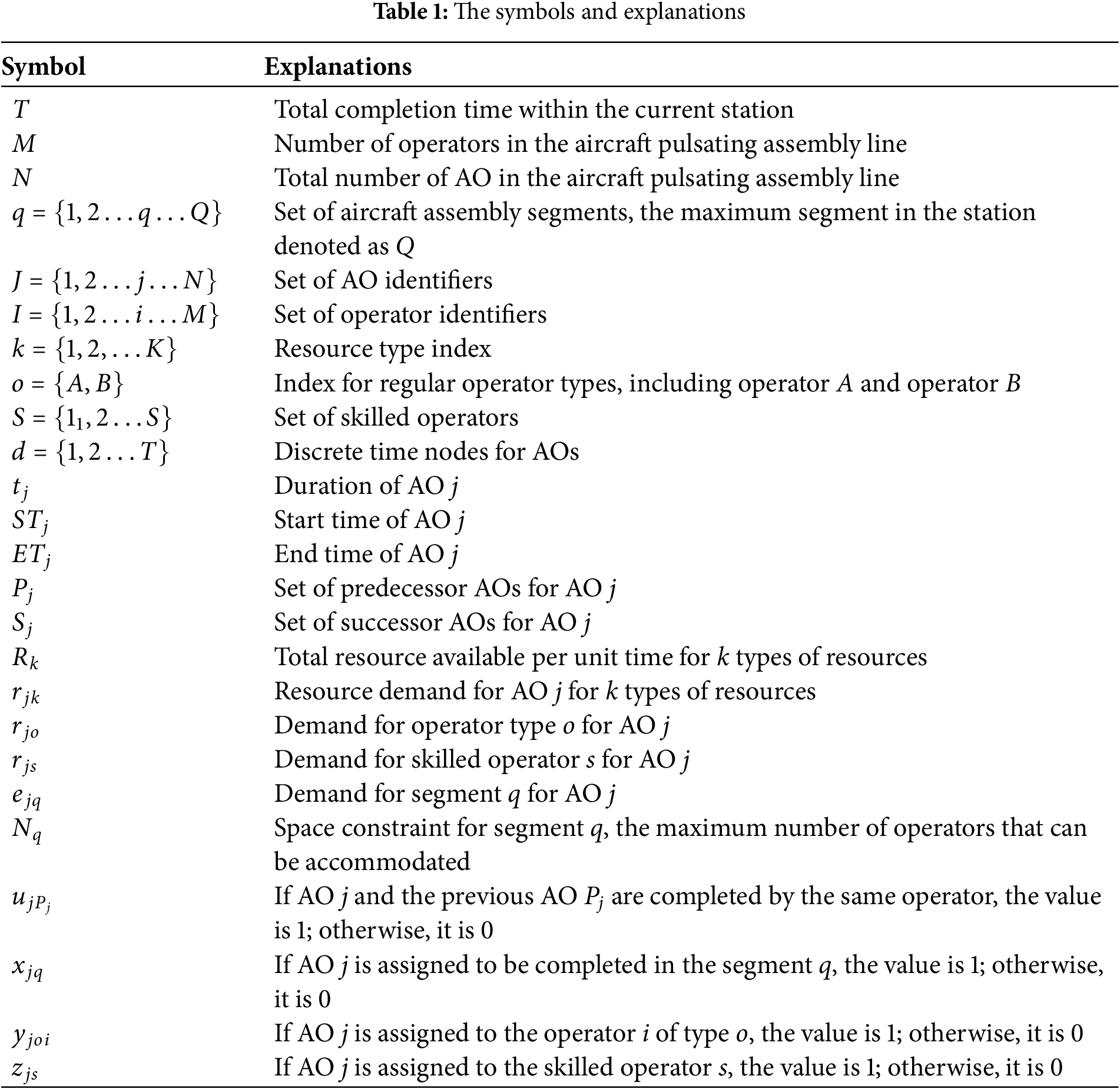

As illustrated in Fig. 2, a priority sequence value is randomly assigned to each AO. When a preceding AO is completed and multiple candidate AOs are eligible for execution, the selection is made based on their priority sequence values—the AO with the higher value is scheduled first. However, this encoding strategy necessitates repeated feasibility checks. For instance, suppose AO2, AO4, and AO8 have the highest priority sequence values. According to the priority principle, AO2 should be scheduled first, followed by AO4, and then AO8. Yet, since AO8 has an uncompleted predecessor (AO7), it cannot be executed immediately. Therefore, a predecessor check is required after each AO selection to ensure precedence

Figure 2: Sequential encoding based on priority sequence

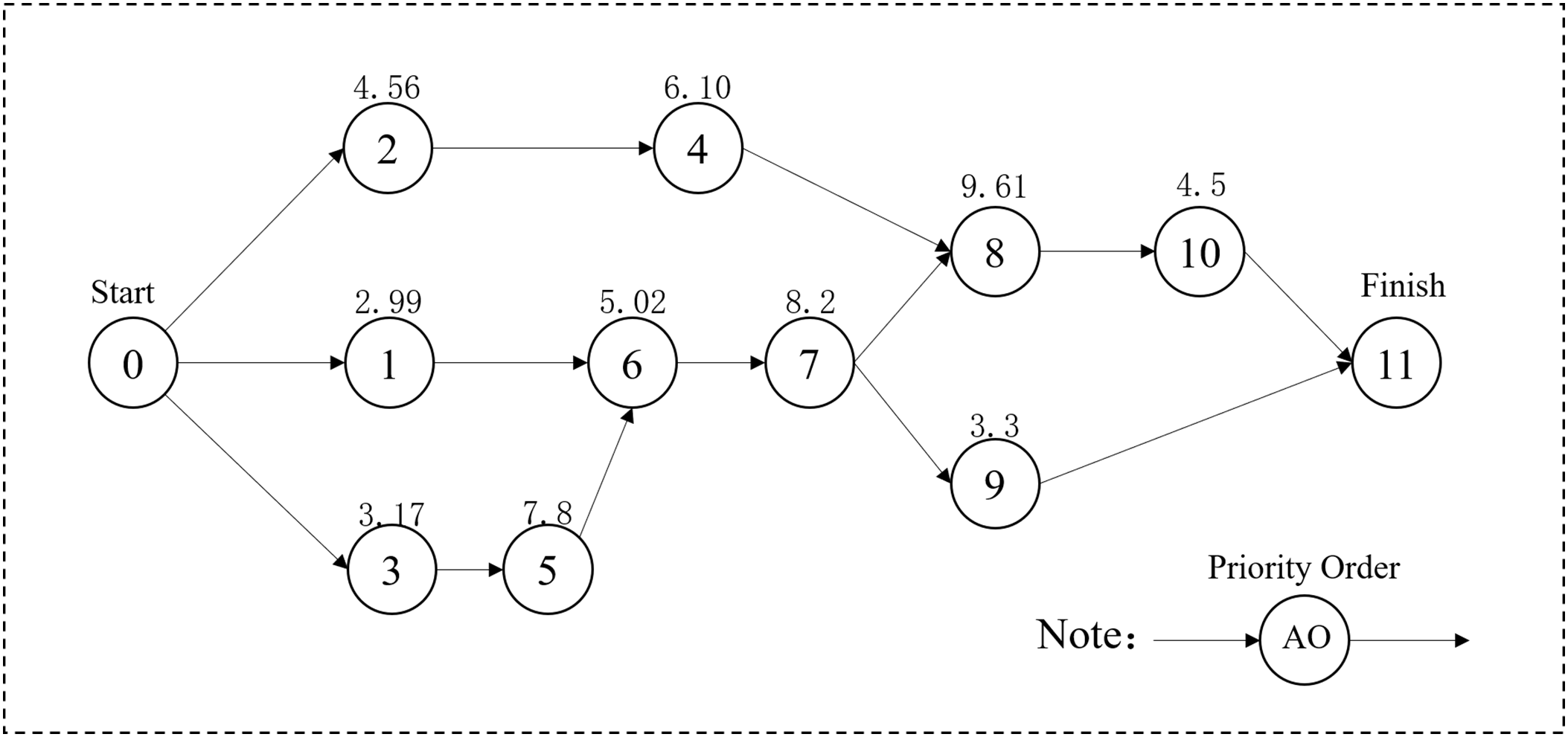

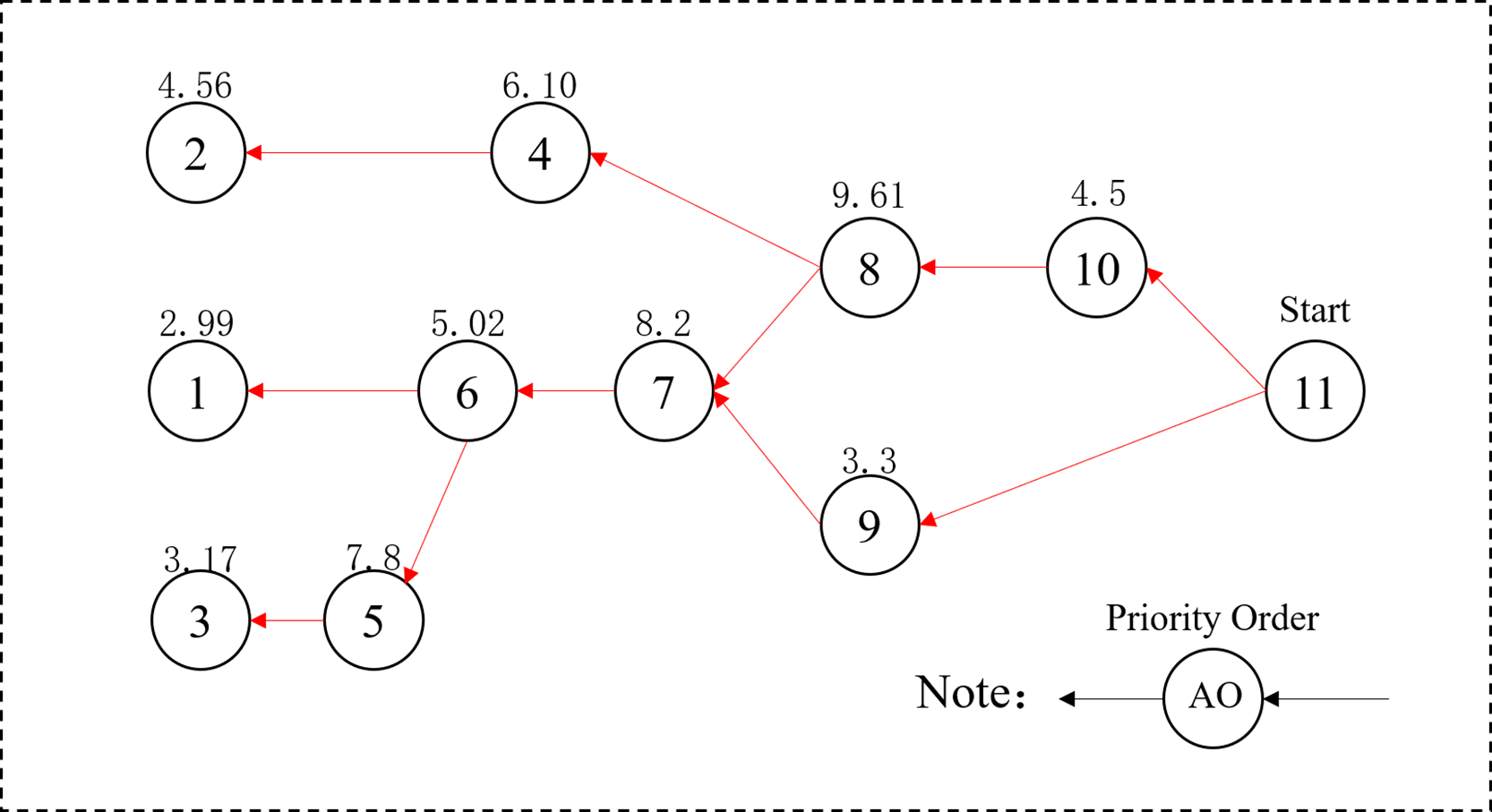

This article introduces an inverse sequence encoding method based on AO priority. It reverses the AO precedence constraints and considers only the immediate predecessor AO for each AO. Duplicate AO in the earlier sequence is removed, retaining only the final AO order. The resulting AO sequence is then reversed again to produce a feasible schedule that satisfies all priority constraints. For example, as shown in Fig. 3, the process begins with AO11. At each step, only the AO with a higher priority value is selected as the next in sequence. This process continues iteratively, resulting in a sequence of AOs with higher priority than AO11. Duplicate AOs appearing earlier in the sequence are removed, and each unique AO is retained to form a final sequence of 11 AOs. This sequence is then reversed to produce a valid solution that adheres to the AO priority constraints.

Figure 3: Reverse sequence encoding based on priority sequence

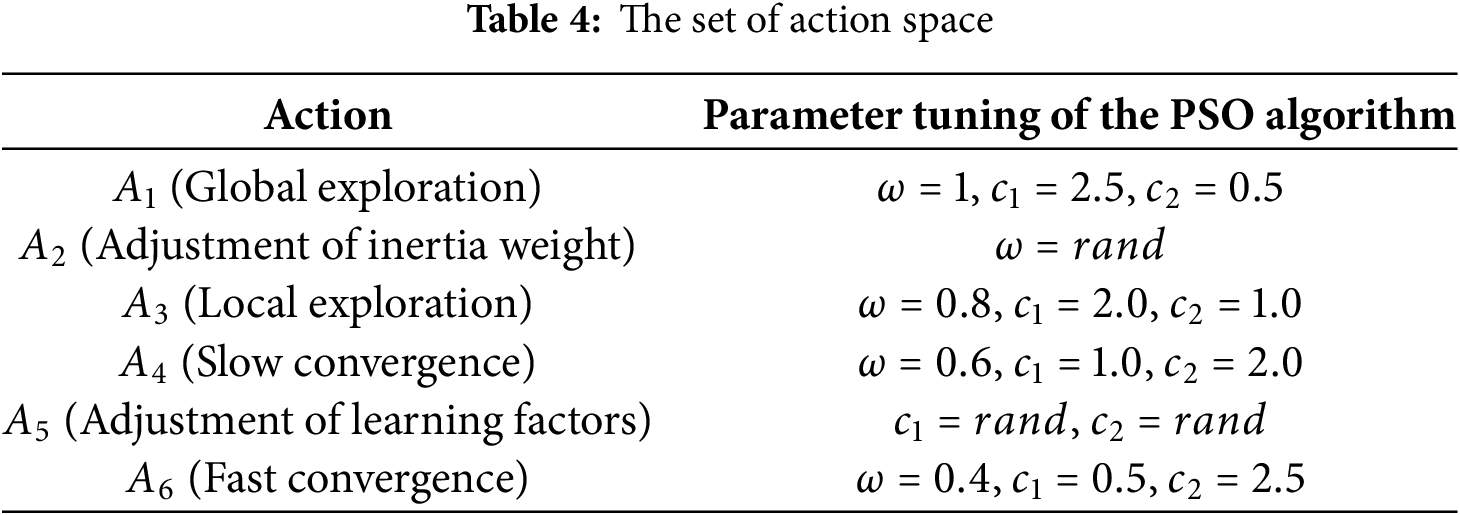

The mathematical model for the aircraft pulsating assembly line scheduling problem with skilled operator allocation employs Reverse Sequence Encoding based on priority sequences. As illustrated in Fig. 4, the encoding design consists of three layers. The first layer represents the priority sequence values, which correspond to positions in the particle swarm optimization (PSO) iteration. These values are generated randomly and used to construct the AO sequence. The second layer contains the velocity values of the particles, which are added to the priority sequence values to modify the AO sequence during the PSO update process. The third layer encodes the skilled operator assignments: one operator enables basic task execution, two operators reduce processing time by 1/3, and three operators reduce it by 1/2.

Figure 4: Encoding design of the aircraft pulsating assembly line scheduling problem

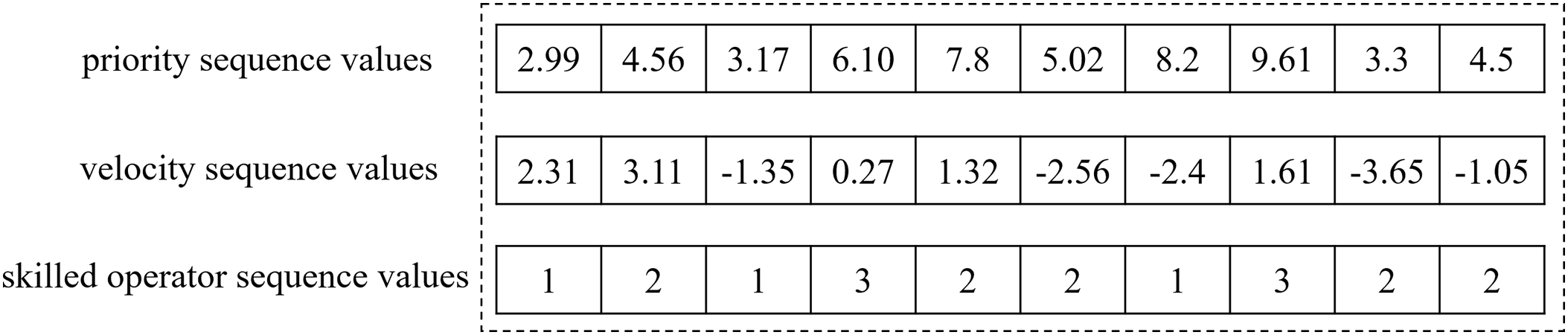

A comparative experiment was conducted using representative test cases from small-scale (20 AO), medium-scale (50 AO), large-scale (100 AO), and extra-large-scale (600 AO) AO sets. For each case, 50 independent runs of both Reverse Sequence Encoding and Sequential Encoding were executed. The solution times and results were recorded, as shown in Table 2. Both the minimum and average solution times for Reverse Sequence Encoding are consistently lower than those for Sequential Encoding. Furthermore, the time advantage of Reverse Sequence Encoding becomes more pronounced as the problem scale increases, highlighting its efficiency in handling larger instances. In terms of solution quality, Reverse Sequence Encoding also outperforms Sequential Encoding, albeit slightly. Overall, Reverse Sequence Encoding demonstrates superior algorithmic performance, particularly in obtaining near-optimal solutions within limited time. Therefore, only Reverse Sequence Encoding is employed in the experimental studies presented in Section 5.

The algorithm generates a corresponding AO sequence based on priority sequence values and calculates the completion time for that sequence. Given that AO across different sections of the aircraft pulsed assembly line can begin simultaneously, parallel execution must be considered—adding significant complexity to the decoding process. Additionally, resources are limited, so potential resource shortages must also be accounted for.

To address these challenges, the algorithm incorporates both time sequence checks and resource checks. AO are sorted based on an activity list. If both the Time Sequence Check and Resource Check are satisfied, the AO are executed in parallel. If not, the algorithm first verifies whether all predecessor AO of the current AO are completed. If not, it releases the predecessor and any incomplete AO before proceeding to the Resource Check. If available resources are insufficient, the algorithm releases and reallocates resources until the AO’s requirements are met, allowing execution to resume.

Moreover, each AO requires a different number of skilled operators, which are allocated according to the skilled operator sequence values. As each operator occupies spatial resources, a Spatial Check is also incorporated. Skilled operators, along with required operators A and B, consume space within each assembly section. Therefore, the total number of operators assigned to a AO must not exceed the section’s spatial capacity. If this limit is exceeded, AO execution is delayed. This scheduling process continues until all AO are completed, ultimately determining the total assembly line completion time.

The PSO algorithm simulates the predatory behavior of bird flocks by iteratively updating the position and velocity of each particle. It leverages the social interactions among particles to explore the search space and find optimal solutions. However, PSO often suffers from premature convergence, frequently becoming trapped in local optima. Furthermore, its performance is highly sensitive to parameter settings; improper configuration can result in slow convergence, reduced accuracy, or stagnation in suboptimal regions. To address these issues, Tanweer et al. [37] and Han et al. [38] introduced adaptive parameter tuning methods. Tanweer proposed two strategies: one involving the self-adjustment of the inertia weight, and another employing self-awareness mechanisms to enhance global search capability. Han tackled the problem of negative knowledge transfer by evaluating the quality of transferred knowledge, thereby improving adaptability. Although these approaches improved PSO performance, the algorithm still struggles with large-scale and complex instances, such as those encountered in aircraft pulsed assembly line scheduling.

With the advancement of artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies [39–41], researchers have increasingly explored hybrid approaches combining reinforcement learning (RL) with metaheuristic algorithms. Lu et al. [42] proposed an RL-based elite ion selection strategy to guide the particle update process, thereby enhancing performance. Wen et al. [7] applied a reinforcement learning-enhanced genetic algorithm to address multi-constraint scheduling in aircraft assembly, achieving notable results. Building on this foundation, the proposed approach proposes a reinforcement learning-based PSO algorithm, incorporating a Q-learning-driven parameter update mechanism. The algorithm dynamically adjusts the inertia weight and learning factors during iterations, promoting broader global exploration in the early stages and accelerating convergence in the later stages. By integrating Q-learning into the PSO framework, the proposed method aims to significantly improve the algorithm’s performance in solving complex scheduling problems.

The aircraft pulsating assembly line scheduling problem involves complex decision-making regarding AO precedence relationships, as well as the effects of resource and spatial constraints. These problems are characterized by temporality and randomness, making them well-suited to be modeled as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) for optimizing scheduling strategies. In this approach, the algorithm defines the state of the assembly line based on the current particle’s completion time and categorizes it into five discrete states. It then designs six possible actions, selecting different actions for each state during the iteration process. This framework allows the algorithm to effectively manage uncertainties inherent in the assembly process, enhancing the adaptability and robustness of the scheduling plan. As a result, the overall production efficiency of the aircraft pulsating assembly line is significantly improved.

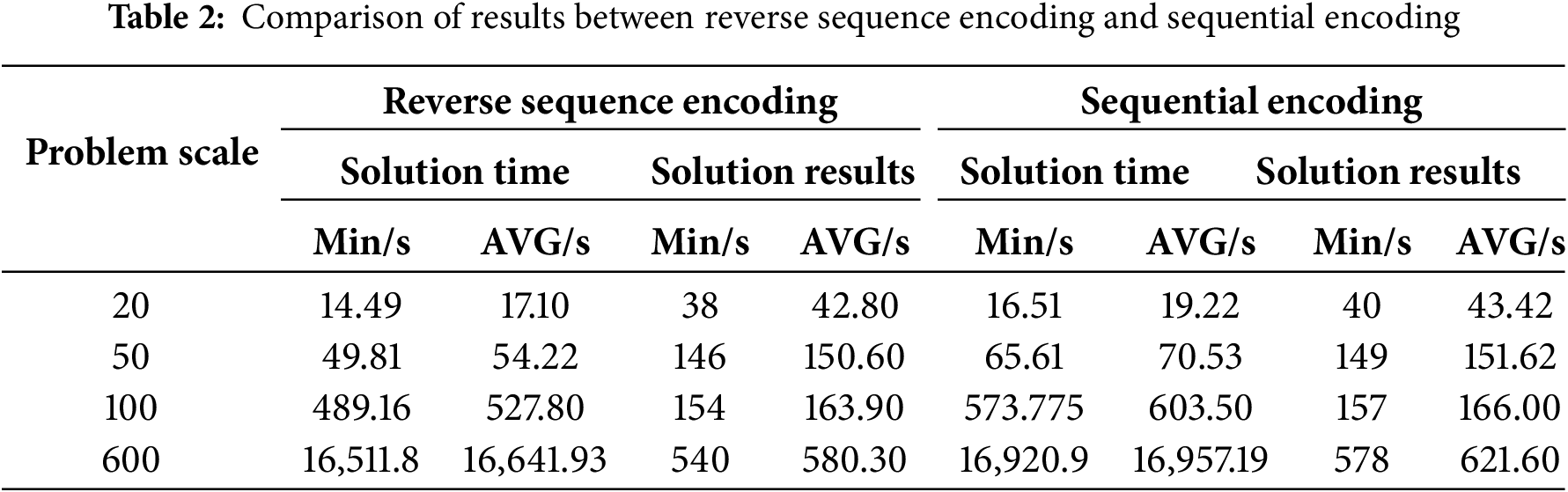

After modeling the aircraft pulsating assembly line scheduling problem as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), the algorithm takes the decoded completion time as the state variable. This completion time is divided into five discrete states for decision optimization. The algorithm obtains the completion time of 100 particle groups and calculates the average time

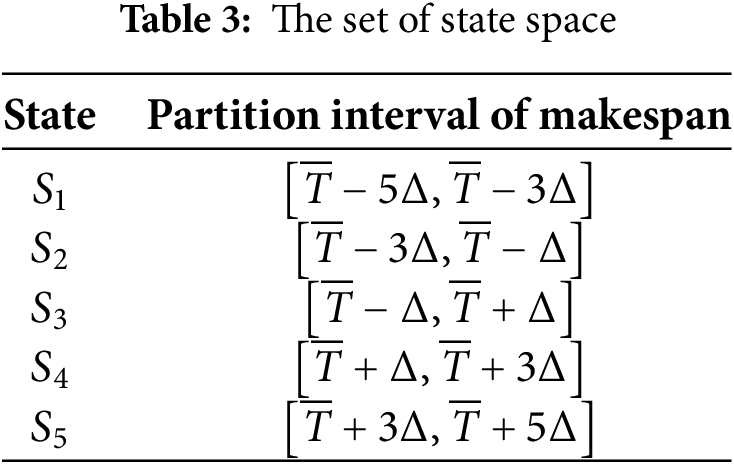

After modeling the aircraft pulsating assembly line scheduling problem as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), the algorithm needs to design the action space, which will influence the scheduling strategy and optimize the final completion time state. This approach combines the optimization idea of reinforcement learning and defines the following six actions. Each action affects the AO sequence and guides the completion time to transition to different states. The specific design is shown in Table 4.

4.3.4 Strategy Update Mechanism

After executing an action, the QL model will adjust the PSO parameters. The algorithm obtains the next generation of particles through the iterative update mechanism of PSO, calculates the completion time of each particle, and computes the corresponding reward based on the optimization objective. Here,

To achieve this optimization process, the QL model uses the basic Bellman iteration formula for updates. Using this formula, the current Q-value is updated based on the current reward obtained by the particle and the maximum Q-value in the next state, performing iterations in the QL model. Here,

4.3.5 QLPSO Algorithmic Strategies and Processes

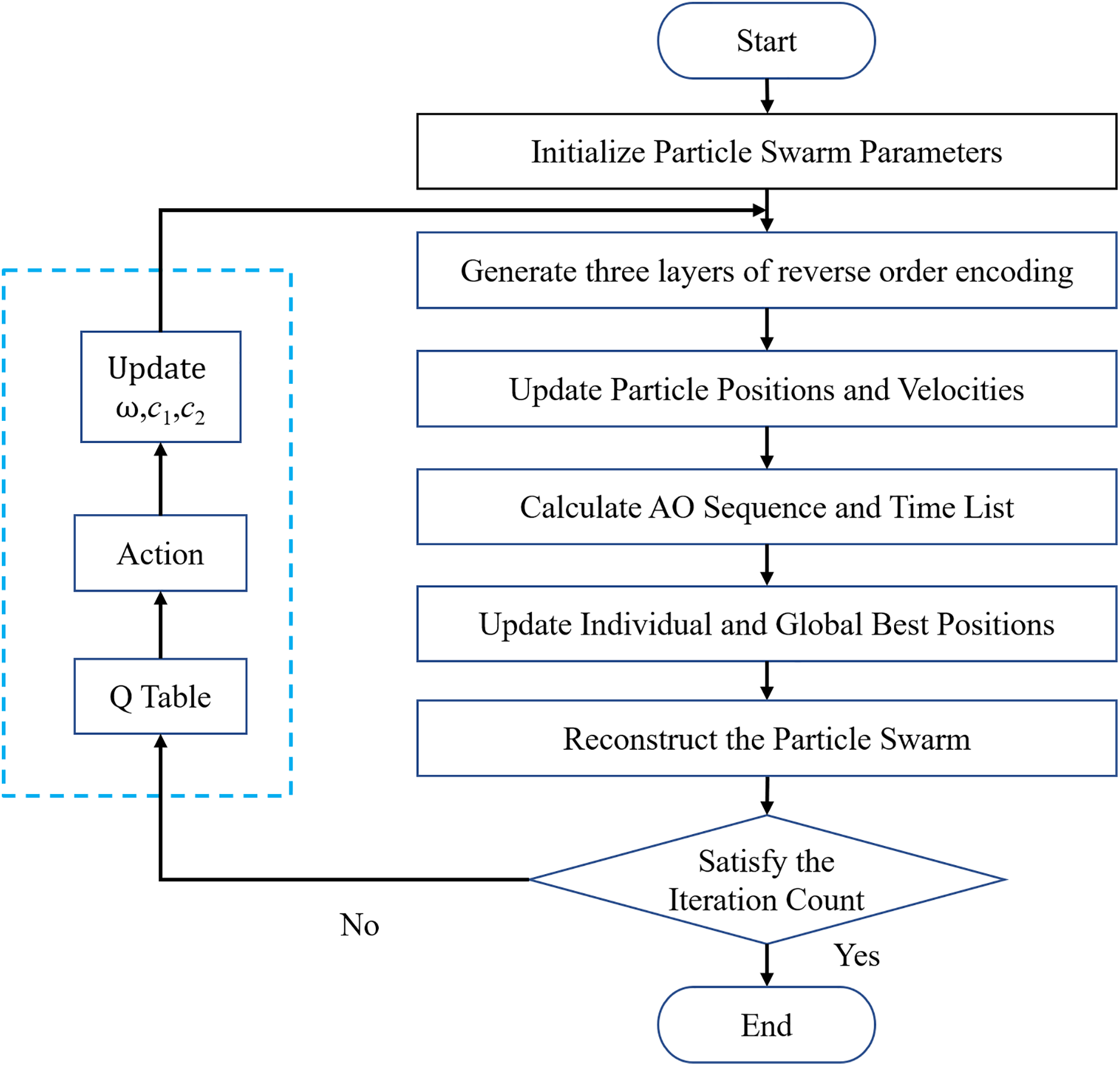

This study proposes the QLPSO algorithm, as illustrated in Fig. 5. The particle swarm parameters are initialized, and case data is read to generate parameters such as population size and the number of iterations. Each particle is encoded using a three-layer reverse order encoding scheme to represent feasible assembly sequences. Then, the particle positions and velocities are updated based on the standard Particle Swarm Optimization update rules. The AO sequences and their corresponding time lists are obtained through time decoding. The individual and global best positions are updated based on the final completion time. To avoid premature convergence, the population is reconstructed during the search process, retaining the top 60% of the population, while the remaining 40% is generated by new individuals for the next generation. Additionally, a Q-learning algorithm is employed to guide the dynamic adjustment of PSO parameters. The completion time of the current particle is used to obtain the corresponding state, update the Q-table, and apply a strategy to select actions that update the particle swarm parameters, continuing to the next generation. This adaptive mechanism balances global exploration and local exploitation, resulting in faster and more efficient scheduling optimization.

Figure 5: Encoding design of the aircraft pulsating assembly line scheduling problem

5 Experimental Results and Comparisons

This article focuses on the aircraft pulsating assembly line of a large commercial aircraft as the research object. A total of 32 AO are designed to evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed algorithm. The resource requirements for components, task durations, operator A, operator B, tool A, and tool B are randomly generated. As the task set is based on a small-scale case, only two segments of the assembly line are selected for the experiment. The task names are referenced from Citation [7]. The available resources include 12 operator A personnel, 14 operator B personnel, 9 skilled operators, and a maximum of 10 units each for tool A and tool B. Task precedence relationships are defined using data files from the Resource-Constrained Project Scheduling Problem (RCPSP) benchmark [43]. Detailed task and resource information is presented in Table 5.

The algorithm programming environment is Visual Studio, with the code written in C++. The running environment consists of an Intel i7-12700F 2.10 GHz CPU and 32 GB of memory. Since the configuration of parameters significantly affects the performance of the QLPSO algorithm, this approach first determines the parameter selection range, as shown in Table 6. Since the algorithm proposed uses the QL model to modify the inertia weight

Through experimental verification, the parameters selected are a population size of 200, 200 iterations, a maximum particle position (

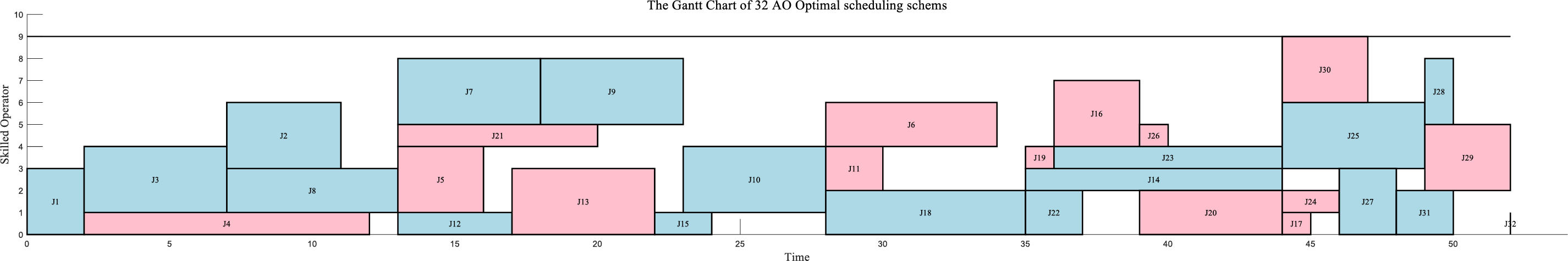

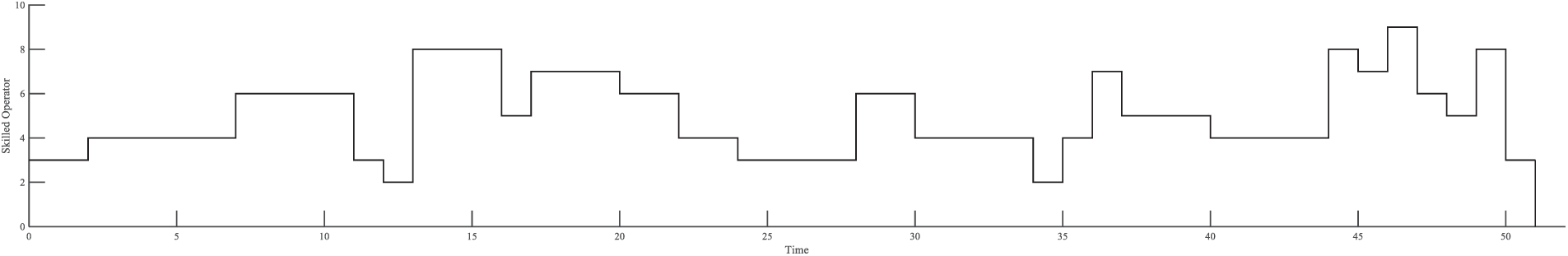

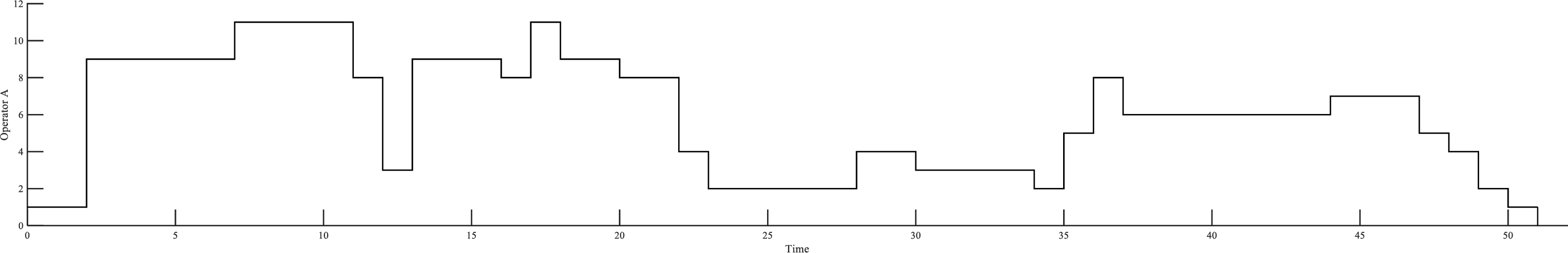

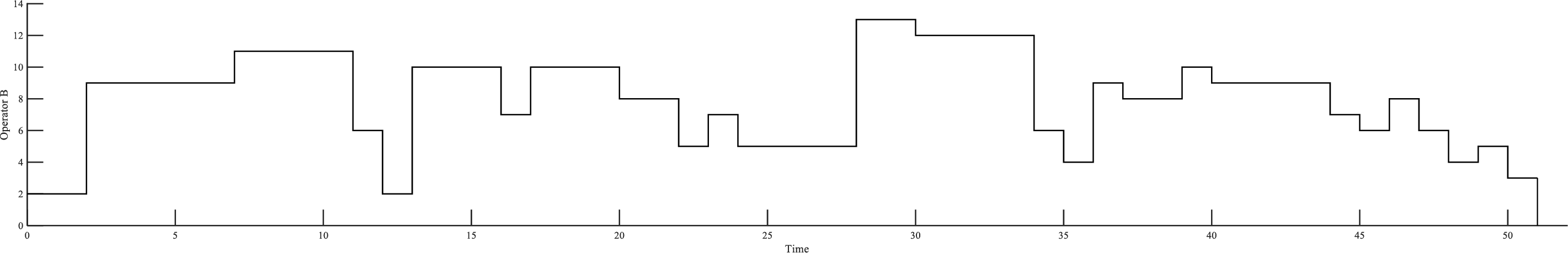

The QLPSO algorithm is employed in this study to solve the scheduling problem using the parameters described above. The results are illustrated in Fig. 6. The horizontal axis indicates the assembly time, while the vertical axis shows the allocation of skilled operators. Blue bars represent AO for Segment 1, and red bars represent AO for Segment 2. A higher vertical position corresponds to a greater number of operators assigned to a task. As shown in Fig. 6, the number of skilled operators allocated at any point does not exceed the total available. Figs. 7–9 further display the detailed allocation of skilled operators, as well as the individual schedules for Operator A and Operator B across different time intervals. These results demonstrate that operator assignments remain within capacity limits, confirming the feasibility and optimality of the solution under the defined constraints.

Figure 6: The Gantt chart of 32 AO optimal scheduling schemes for scheduling problem

Figure 7: Ladder diagram of skilled operator resource allocation

Figure 8: Ladder diagram of skilled Operator A resource allocation

Figure 9: Ladder diagram of skilled Operator B resource allocation

5.2 Comparison Algorithm Implementation

This study first reviewed relevant literature and then designed test cases of varying sizes: small-scale (20–30 AO), medium-scale (50–80 AO), large-scale (100–300 AO), and ultra-large-scale (600 AO). Six algorithms were evaluated: Genetic Algorithm (GA), Simulated Annealing (SA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization (APSO), Q-learning, and the Q-Learning improved Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm (QLPSO) proposed in this article. For small and medium-scale instances, 100 test runs were conducted for each algorithm. For large-scale and ultra-large-scale cases, 60 and 20 runs were performed, respectively. In this context, Gap represents the difference between each algorithm’s result and its optimal value. Here,

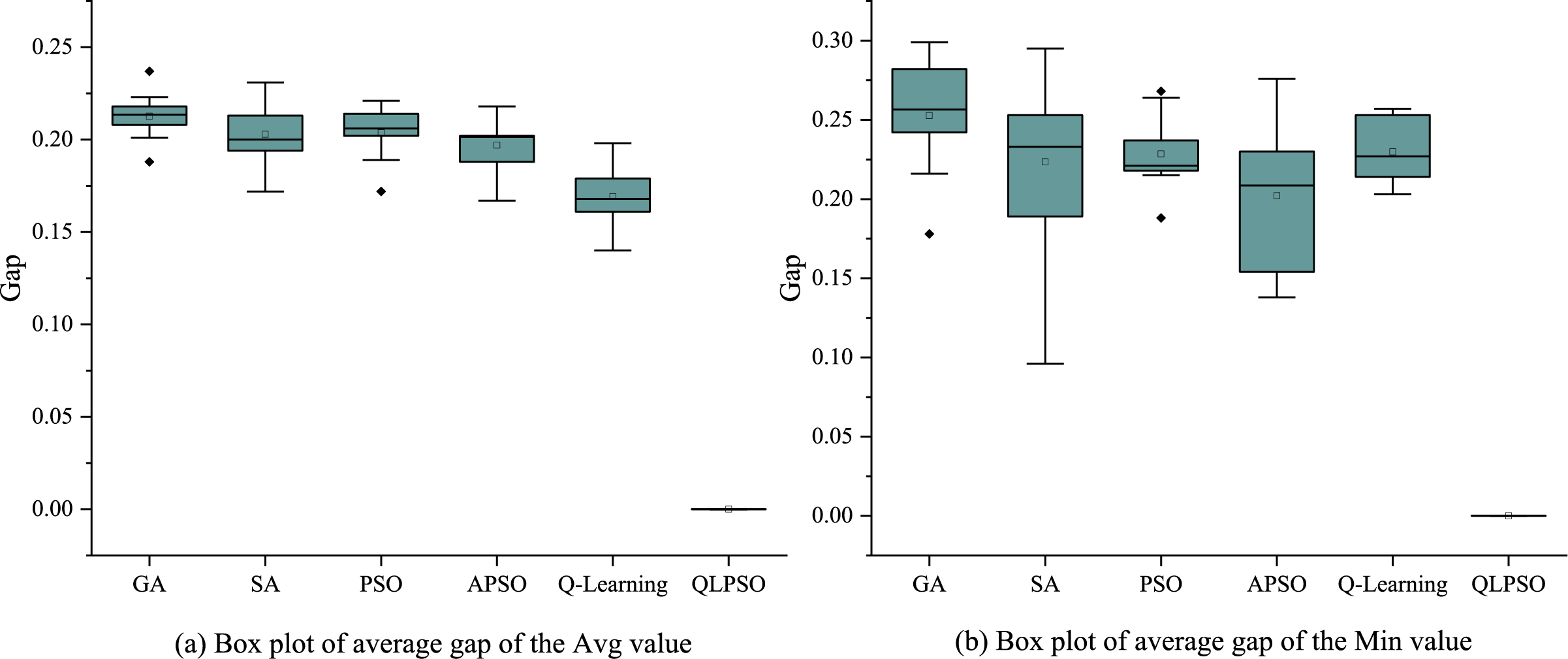

The average Gap for each scale is calculated, as the test cases vary across different scales. For example, the small-scale case involves 20 AO and 30 AO. Therefore, a box plot of Gap is drawn to more intuitively represent the algorithm’s performance. The optimal and average results for each set of test cases are summarized in the table below. In each case, the optimal result is highlighted in bold.

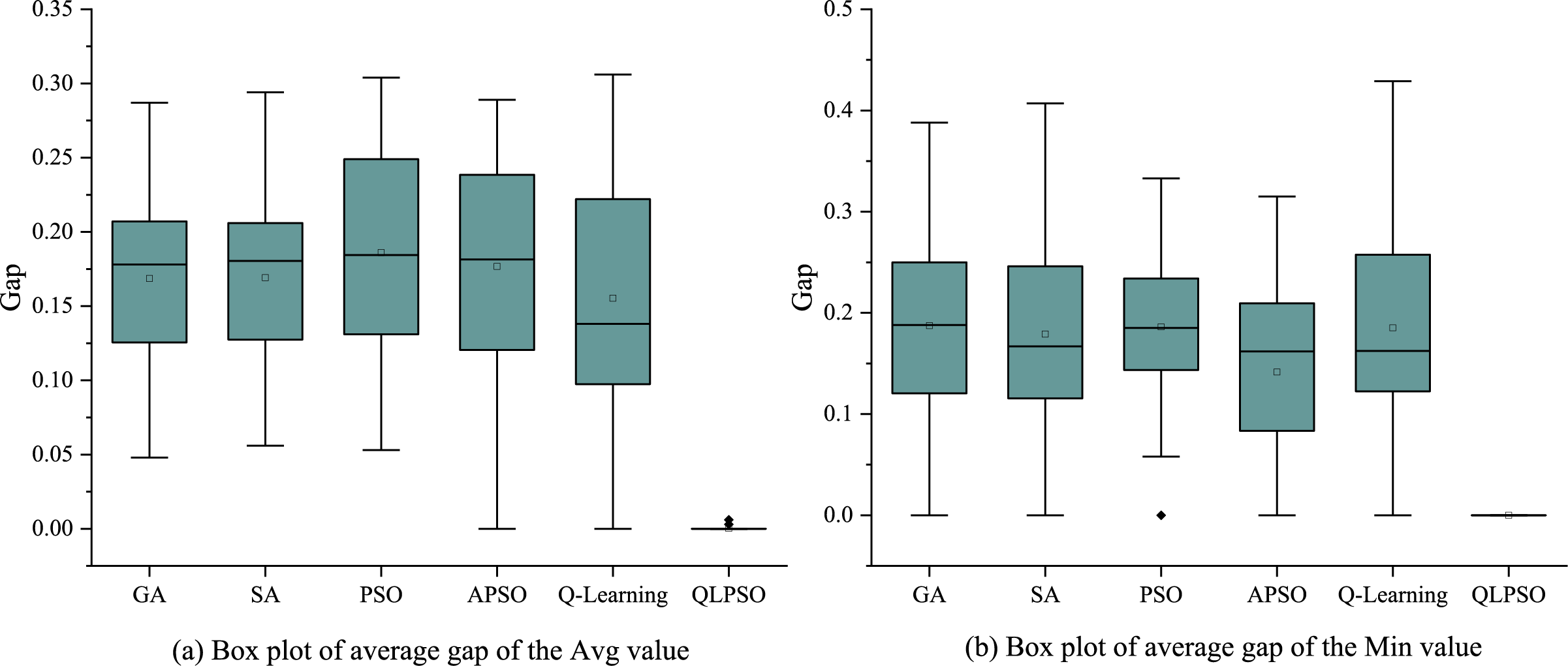

The experimental results reveal that the average Gap values obtained by GA, SA, and PSO are relatively high, indicating substantial deviations from the optimal solutions. Although APSO (Min) and Q-learning (Avg) achieve certain improvements, with average Gap values of 14.1% and 15.5%, their performance remains inconsistent across different test cases. By contrast, the proposed QLPSO algorithm demonstrates superior performance, frequently attaining the optimal solution in all 40 test cases. This advantage is further corroborated by the boxplot, Fig. 10 analysis, in which QLPSO exhibits extremely low variance, thereby confirming its high accuracy and remarkable stability. Overall, these findings suggest that QLPSO effectively integrates the strengths of PSO and Q-learning, providing a dynamic and adaptive approach that enhances both convergence speed and solution quality. A detailed comparison of the results is provided in Table 7.

Figure 10: Box plot of the gap value for small-scale (20–30) AO instances

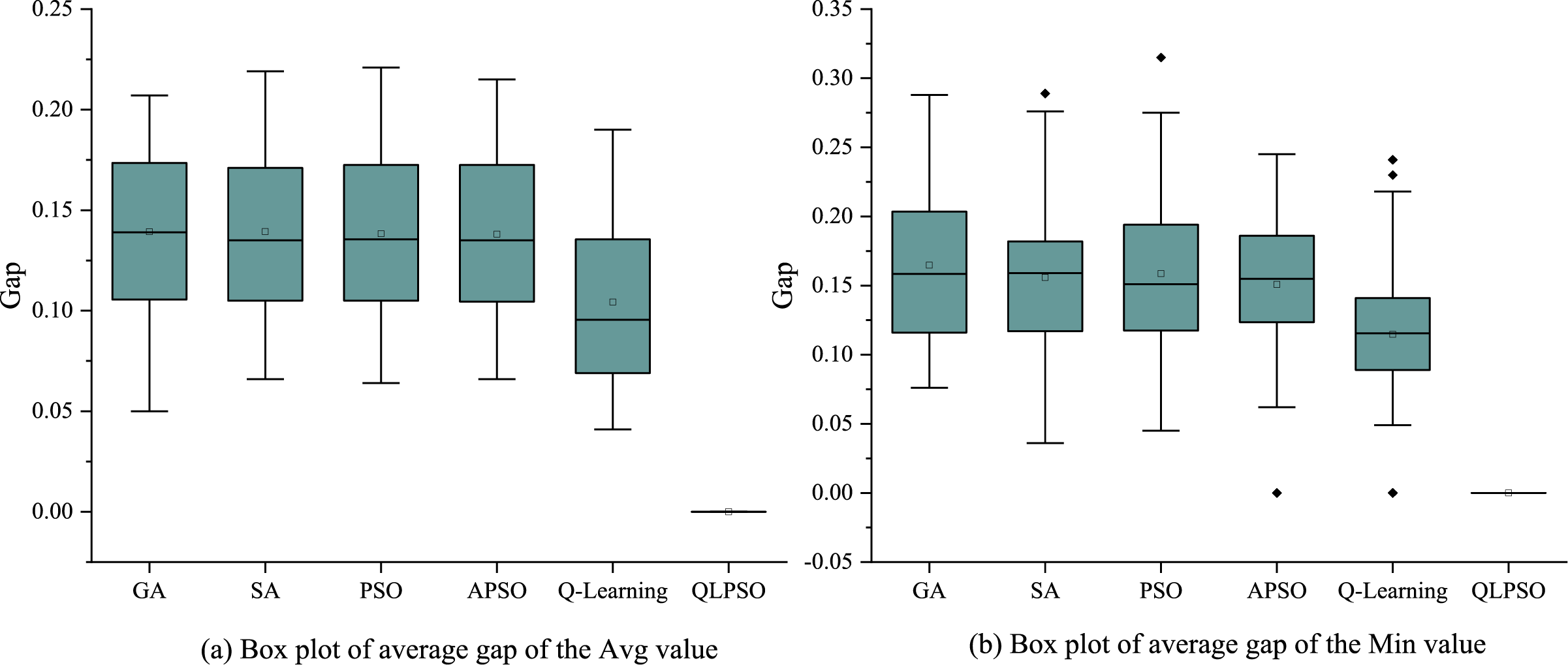

In the medium-scale test cases, the QLPSO algorithm continues to deliver the best overall performance. Traditional algorithms such as GA, SA, PSO, and APSO exhibit relatively high and widely distributed average Gap values, indicating significant performance variations across different instances and a noticeable deviation from the optimal solution. In contrast, the Q-learning algorithm demonstrates relatively better results, with average Gap values of 10.4% and 11.4%, respectively. Notably, QLPSO outperforms all other algorithms, consistently achieving optimal or near-optimal solutions across the given test cases. The box plot for the average Gap of Min value (Fig. 11b) shows a significantly tighter distribution, with values much closer to 0, further confirming the superior performance of QLPSO. This suggests that the algorithm is capable of finding the best possible solution in most cases, highlighting its stability and effectiveness. A detailed comparison of the results is presented in Table 8.

Figure 11: Box plot of the gap value for medium-scale (50–80) AO instances

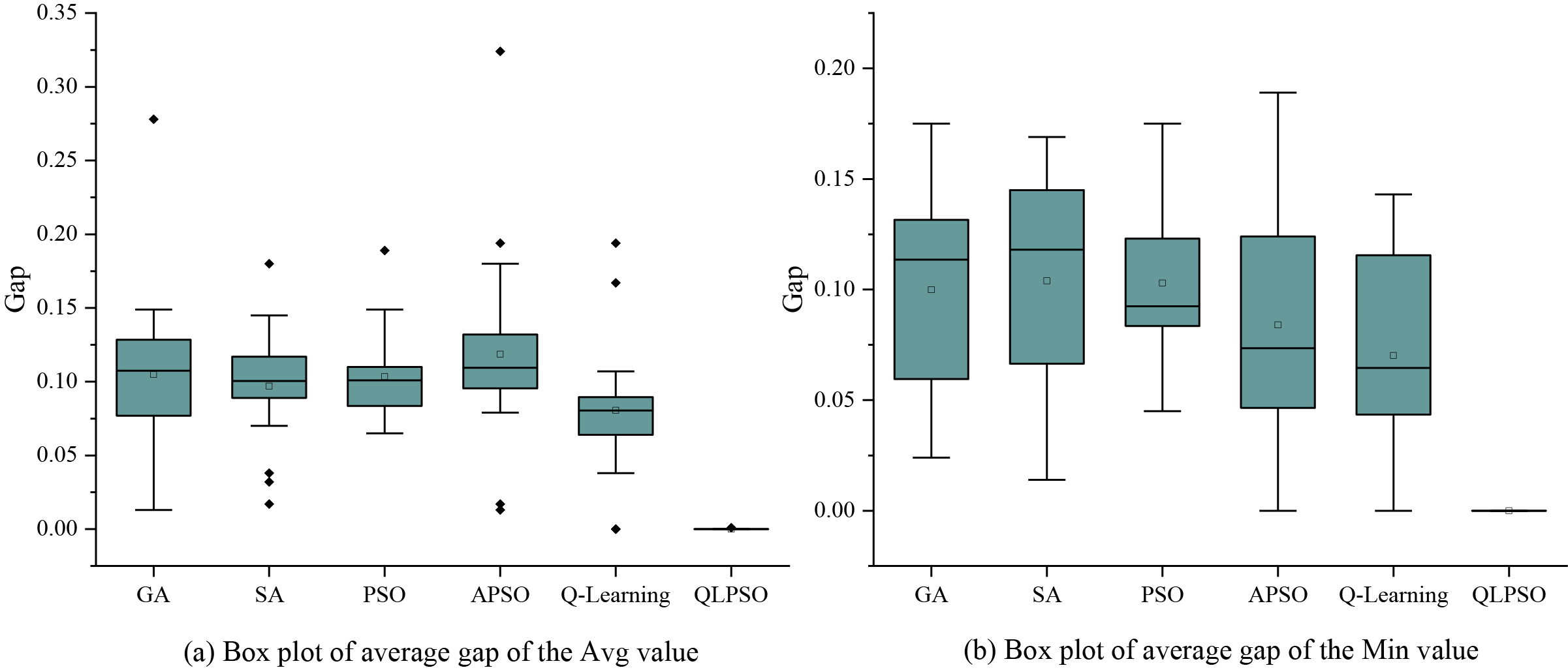

In the large-scale test cases, the comparison of algorithm performance on large-scale instances reveals significant differences in their ability to reach the optimal solution. QLPSO outperforms all other algorithms, with an average Gap of only 0.05% and a minimum Gap of 0, indicating its strong robustness and consistent ability to find near-optimal solutions. The Q-learning algorithm also performs well, with an average Gap of 7.2% for the minimum values, while other algorithms show higher average Gaps, around 10%, with greater variation, indicating poorer stability and a lower likelihood of finding the optimal solution. These results suggest that QLPSO improves both the quality and consistency of the solutions, demonstrating the best solution quality and the strongest stability. Overall, QLPSO exhibits the optimal solution quality and stability in large-scale test cases, with Q-learning in second place, while other methods are relatively inferior. A detailed comparison of the results is presented in Table 9 and Fig. 12.

Figure 12: Box plot of the gap value for large-scale (100–300) AO instances

In the ultra-large-scale test cases, In the results of the 600 AO cases, QLPSO consistently outperforms all other algorithms, with the average Gap of Avg value (0%) and the average Gap of Min value (0%), indicating its high stability in finding near-optimal or optimal solutions. Compared to the optimal value, QLPSO’s algorithm results are 25.2% better than those of the GA algorithm. Other algorithms exhibit significantly higher average Gaps (ranging from 16.9% to 25.2%) with a broader distribution, indicating that their solutions deviate more from the optimal solution and have poorer consistency. The box plot, Fig. 13, further confirms that QLPSO demonstrates stable algorithm performance, while the distribution range of other algorithms is much wider, indicating that their solutions are less consistent and less effective in large-scale scenarios. A detailed comparison of the results is presented in Table 10.

Figure 13: Box plot of the gap value for ultra-large-scale (600) AO instances

The experimental results across different test case scales consistently demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed QLPSO algorithm. In the small-scale test cases, QLPSO outperforms traditional algorithms such as GA, SA, PSO, and APSO, achieving the Avg and Min values, while exhibiting exceptional stability across all test cases. In the medium- and large-scale instances, QLPSO continues to deliver optimal or near-optimal solutions, with both the average Gap of the Avg value and the average Gap of the Min value lower than those of other algorithms, highlighting its robustness and consistent ability to find near-optimal solutions. The Q-learning algorithm also performs well but shows greater variation, with higher Gap values and lower consistency compared to QLPSO. In the ultra-large-scale test cases, involving 600 AO cases, QLPSO again demonstrates its exceptional stability and accuracy, achieving the best results with a Gap of 0% across all cases, 25.2% better than GA. The box plot analysis further emphasizes the superior consistency and performance of QLPSO, with a significantly tighter distribution compared to other algorithms. Overall, these results clearly indicate that QLPSO not only provides the best solution quality but also ensures the strongest stability across all scales, outperforming all other methods and offering a dynamic and adaptive approach that integrates the strengths of PSO and Q-learning.

This study presents a comprehensive study of the scheduling problem associated with aircraft pulsating assembly lines in the aircraft manufacturing industry. It systematically reviews relevant theories related to the resource-constrained project scheduling problem (RCPSP) and evaluates the current advancements in aircraft assembly line scheduling research. Building on this foundation, a scheduling model that integrates skilled operator allocation for the pulsating assembly line is proposed. To solve this model, a Q-Learning improved Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm is developed. The algorithm incorporates a Q-table and defines appropriate state and action spaces. The practical applicability and solution accuracy of the model are validated through real-world case studies. Finally, this paper outlines two key directions for future research in aircraft assembly line scheduling.

(1) The current model considers only the allocation of skilled operators and their impact on task durations. However, in real production environments, task durations are often subject to considerable uncertainty. Furthermore, operators differ in terms of types and skill levels, which further complicates the scheduling process. These factors introduce additional layers of complexity, posing significant challenges for future research on scheduling aircraft pulse assembly lines.

(2) Although the proposed QLPSO algorithm demonstrates strong performance in addressing the aircraft pulse assembly line scheduling problem, the application of reinforcement learning in this domain remains relatively limited. Furthermore, its implementation still requires further investigation. For example, the design of state and action spaces remains complex, and achieving an effective balance between exploration and exploitation continues to demand careful refinement and optimization. Future research could focus on developing more efficient algorithms or enhancing existing ones to improve both solution accuracy and computational efficiency.

In conclusion, this study provides both a theoretical foundation and a practical reference for optimizing scheduling in aircraft pulse assembly lines. It is hoped that future research will continue to build upon and further refine the findings presented herein.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to the professors for their valuable guidance and support throughout this research.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52475543), Natural Science Foundation of Henan (Grant No. 252300421101), Henan Province University Science and Technology Innovation Talent Support Plan (Grant No. 24HASTIT048), Science and Technology Innovation Team Project of Zhengzhou University of Light Industry (Grant No. 23XNKJTD0101).

Author Contributions: Xiaoyu Wen: Methodology, conceptualization, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, supervision. Haohao Liu: Methodology, data curation, validation, writing—original draft. Xinyu Zhang: Conceptualization, writing—review & editing. Haoqi Wang: Formal analysis, software, investigation. Yuyan Zhang: Methodology, investigation, validation. Guoyong Ye: Writing—review & editing, supervision. Hongwen Xing: Formal analysis, resources, investigation. Siren Liu: Data curation, resources, supervision. Hao Li: Project administration. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Hao Li], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhang H. Introduction of aircraft assembly equipment and suppliers. Aeronaut Manuf Technol. 2008;51(11):71–3. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1671-833X.2008.11.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zhang XW, Lü RQ, Du XC, Zhang JE. Research on simulation and optimization of aircraft assembly pulsating production line. J New Ind. 2023;13(12):87–95. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.2095-6649.2023.12.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Blanco D, Rubio EM, Agustina B, Marín MM, Camacho AM. Advanced procedures and scheduling for aircraft assembly processes: a systematic review approach. Procedia CIRP. 2024;126:817–22. doi:10.1016/j.procir.2024.08.264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Pan Z, Guo Y, Zha S, Zhang S, Wang B. Aircraft pulsating assembly line balancing problem based on hybrid algorithm. Comput Integr Manuf Syst. 2018;24(10):2436–47. Available from: http://www.cims-journal.cn/CN/10.13196/j.cims.2018.10.007. [Google Scholar]

5. Bao Z, Chen L, Qiu K. An aircraft final assembly line balancing problem considering resource constraints and parallel task scheduling. Comput Ind Eng. 2023;182(2):109436. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2023.109436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Korivand S, Galvani G, Ajoudani A, Gong J, Jalili N. Optimizing human-robot teaming performance through Q-learning-based task load adjustment and physiological data analysis. Sensors. 2024;24(9):2817. doi:10.3390/s24092817. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Wen X, Zhang X, Xing H, Ye G, Li H, Zhang Y, et al. An improved genetic algorithm based on reinforcement learning for aircraft assembly scheduling problem. Comput Ind Eng. 2024;193(4):110263. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2024.110263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zheng Q. Research on assembly operation scheduling problem of aircraft final assembly moving production line with multiple parallel operations [dissertation]. Shanghai, China: Shanghai Jiao Tong University; 2015. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

9. Xin B, Li Y, Yu J, Zhang J. An adaptive BPSO algorithm for multi-skilled workers assignment problem in aircraft assembly lines. Assem Autom. 2015;35(4):317–28. doi:10.1108/aa-06-2015-051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ma’ruf A, Gultom SUAM. Multi-skilled operator assignment model for long cycle time and low-volume assembly line: a case study of aircraft assembly line. In: Proceedings of the 6th Asia Pacific Conference on Manufacturing Systems and 4th International Manufacturing Engineering Conference; 2022 Oct 27; Surakarta, Indonesia. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2023. p. 195–204. doi:10.1007/978-981-99-1245-2_18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wang P, Pei F, Liu J, Guo H, Zhuang C. Assembly scheduling problem of complex products considering multi-skill level worker assignment. J Mech Eng. 2025;4:389–402. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

12. Allemang–Trivalle A, Donjat J, Bechu G, Coppin G, Chollet M, Klaproth OW, et al. Modeling fatigue in manual and robot-assisted work for operator 5.0. IISE Trans Occup Ergon Hum Factors. 2024;12(1–2):135–47. doi:10.1080/24725838.2024.2321460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Bruni ME, Beraldi P, Guerriero F, Pinto E. A heuristic approach for resource constrained project scheduling with uncertain activity durations. Comput Oper Res. 2011;38(9):1305–18. doi:10.1016/j.cor.2010.12.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang D, Qiao F, Guan L, Liu J, Ding C, Shi J. Human-machine collaborative optimization method for dynamic worker allocation in aircraft final assembly lines. Comput Ind Eng. 2024;194(3):110370. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2024.110370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Chen S, Zhang N, Wang A. Pulsating assembly production personnel scheduling technology based on improved genetic algorithm. In: 2022 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation (ICMA); 2022 Aug 7–10; Guilin, China. p. 1346–51. doi:10.1109/ICMA54519.2022.9856253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ding H, Zhuang C, Liu J. Extensions of the resource-constrained project scheduling problem. Autom Constr. 2023;153(14):104958. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2023.104958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Li X, He Z, Wang N. A branch-and-bound algorithm for the proactive resource-constrained project scheduling problem with a robustness maximization objective. Comput Oper Res. 2024;166(2):106623. doi:10.1016/j.cor.2024.106623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liu W, Zhang J, Liu C, Qu C. A bi-objective optimization for finance-based and resource-constrained robust project scheduling. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;231(1):120623. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.120623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Roussel S, Polacsek T, Chan A. Assembly line preliminary design optimization for an aircraft. In: The 29th International Conference on Principles and Practice of Constraint Programming; 2023 Aug 27–31; Toronto, ON, Canada. doi:10.4230/LIPIcs.CP.2023.32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Long T, Li Y, Chen J. Productivity prediction in aircraft final assembly lines: comparisons and insights in different productivity ranges. J Manuf Syst. 2022;62:377–89. doi:10.1016/j.jmsy.2021.12.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Cai W, Zhao Y, Chen HJ, Zhang J. Improved genetic algorithm variable neighborhood search for solving aircraft assembly line scheduling problem. Manuf Autom. 2021;43(4):69–73,89. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1009-0134.2021.04.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Shan S, Hu Z, Liu Z, Shi J, Wang L, Bi Z. An adaptive genetic algorithm for demand-driven and resource-constrained project scheduling in aircraft assembly. Inf Technol Manag. 2017;18(1):41–53. doi:10.1007/s10799-015-0223-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ren Y, Lu Z. A flexible resource investment problem based on project splitting for aircraft moving assembly line. Assem Autom. 2019;39(4):532–47. doi:10.1108/aa-09-2018-0126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ren Y, Lu Z, Liu X. A branch-and-bound embedded genetic algorithm for resource-constrained project scheduling problem with resource transfer time of aircraft moving assembly line. Optim Lett. 2020;14(8):2161–95. doi:10.1007/s11590-020-01542-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Lu Z, Ren Y, Wang L, Zhu H. A resource investment problem based on project splitting with time windows for aircraft moving assembly line. Comput Ind Eng. 2019;135(21–22):568–81. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2019.06.044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Borreguero Sanchidrián T, Portoleau T, Artigues C, García Sánchez A, Ortega Mier M, Lopez P. Large neighborhood search for an aeronautical assembly line time-constrained scheduling problem with multiple modes and a resource leveling objective. Ann Oper Res. 2024;338(1):13–40. doi:10.1007/s10479-023-05629-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Fang P, Yang J, Liao Q, Zhong RY, Jiang Y. Flexible worker allocation in aircraft final assembly line using multiobjective evolutionary algorithms. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2021;17(11):7468–78. doi:10.1109/TII.2021.3051896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Arkhipov D, Battaïa O, Cegarra J, Lazarev A. Operator assignment problem in aircraft assembly lines: a new planning approach taking into account economic and ergonomic constraints. Procedia CIRP. 2018;76(2):63–6. doi:10.1016/j.procir.2018.01.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ottogalli K, Rosquete D, Rojo J, Amundarain A, María Rodríguez J, Borro D. Virtual reality simulation of human-robot coexistence for an aircraft final assembly line: process evaluation and ergonomics assessment. Int J Comput Integr Manuf. 2021;34(9):975–95. doi:10.1080/0951192x.2021.1946855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Tereshchuk V, Bykov N, Pedigo S, Devasia S, Banerjee AG. A scheduling method for multi-robot assembly of aircraft structures with soft task precedence constraints. Robot Comput Integr Manuf. 2021;71(15–16):102154. doi:10.1016/j.rcim.2021.102154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Guo D. Fast scheduling of human-robot teams collaboration on synchronised production-logistics tasks in aircraft assembly. Robot Comput Integr Manuf. 2024;85(3):102620. doi:10.1016/j.rcim.2023.102620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Duan Q, Liao TW. Improved ant colony optimization algorithms for determining project critical paths. Autom Constr. 2010;19(6):676–93. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2010.02.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Gad AG. Particle swarm optimization algorithm and its applications: a systematic review. Arch Comput Meth Eng. 2022;29(5):2531–61. doi:10.1007/s11831-021-09694-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wang F, Wang X, Sun S. A reinforcement learning level-based particle swarm optimization algorithm for large-scale optimization. Inf Sci. 2022;602:298–312. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2022.04.053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Guo WF, Song YC, Zhou F, Lei Q, Lyu XF. Integrated scheduling algorithm of complex product with no-wait constraint based on reversed virtual component. Comput Integr Manuf Syst. 2020;26(12):3313–28. (In Chinese). doi:10.13196/j.cims.2020.12.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Wang Q. Research on integrated scheduling algorithm driven by inverse sequence dynamics [dissertation]. Harbin, China: Harbin University of Science and Technology; 2023. (In Chinese). doi:10.27063/d.cnki.ghlgu.2023.001088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Tanweer MR, Suresh S, Sundararajan N. Self regulating particle swarm optimization algorithm. Inf Sci. 2015;294(4):182–202. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2014.09.053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Han H, Bai X, Han H, Hou Y, Qiao J. Self-adjusting multitask particle swarm optimization. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2022;26(1):145–58. doi:10.1109/TEVC.2021.3098523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Arviv K, Stern H, Edan Y. Collaborative reinforcement learning for a two-robot job transfer flow-shop scheduling problem. Int J Prod Res. 2016;54(4):1196–209. doi:10.1080/00207543.2015.1057297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Chalmers E, Contreras EB, Robertson B, Luczak A, Gruber A. Learning to predict consequences as a method of knowledge transfer in reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2018;29(6):2259–70. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2017.2690910. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Park KT, Jeon SW, Noh SD. Digital twin application with horizontal coordination for reinforcement-learning-based production control in a re-entrant job shop. Int J Prod Res. 2022;60(7):2151–67. doi:10.1080/00207543.2021.1884309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Lu L, Zheng H, Jie J, Zhang M, Dai R. Reinforcement learning-based particle swarm optimization for sewage treatment control. Complex Intell Syst. 2021;7(5):2199–210. doi:10.1007/s40747-021-00395-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. The operations research & scheduling research data; 2025. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.projectmanagement.ugent.be/research/data. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools