Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

P4LoF: Scheduling Loop-Free Multi-Flow Updates in Programmable Networks

1 Information Engineering University, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

2 National Key Laboratory of Advanced Communication Networks, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

3 Key Laboratory of Cyberspace Security, Ministry of Education, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

4 Purple Mountain Laboratories, Nanjing, 210000, China

* Corresponding Author: Le Tian. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069533

Received 25 June 2025; Accepted 28 August 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

The rapid growth of distributed data-centric applications and AI workloads increases demand for low-latency, high-throughput communication, necessitating frequent and flexible updates to network routing configurations. However, maintaining consistent forwarding states during these updates is challenging, particularly when rerouting multiple flows simultaneously. Existing approaches pay little attention to multi-flow update, where improper update sequences across data plane nodes may construct deadlock dependencies. Moreover, these methods typically involve excessive control-data plane interactions, incurring significant resource overhead and performance degradation. This paper presents P4LoF, an efficient loop-free update approach that enables the controller to reroute multiple flows through minimal interactions. P4LoF first utilizes a greedy-based algorithm to generate the shortest update dependency chain for the single-flow update. These chains are then dynamically merged into a dependency graph and resolved as a Shortest Common Super-sequence (SCS) problem to produce the update sequence of multi-flow update. To address deadlock dependencies in multi-flow updates, P4LoF builds a deadlock-fix forwarding model that leverages the flexible packet processing capabilities of the programmable data plane. Experimental results show that P4LoF reduces control-data plane interactions by at least 32.6% with modest overhead, while effectively guaranteeing loop-free consistency.Keywords

The rapid growth of distributed data-centric applications and AI workloads has led to a significant increase in communication traffic, placing immense demands on network infrastructure [1]. The performance of these systems relies on low-latency, high-throughput connectivity, making it essential to optimize resource utilization and operational agility. To meet these requirements, great efforts have been made to render communication networks more flexible and programmable, especially in the context of Software Defined Networking (SDN) architectures [2]. These technologies enable traffic routes to be adjusted in real time based on changing demands, including load balancing, traffic engineering, and fault recovery. However, this architectural programmability introduces critical challenges in maintaining operational consistency during updates. A primary concern arises when transitioning between routing configurations. The asynchronous and distributed nature of network devices can lead to temporary inconsistencies in their forwarding states [3,4]. For instance, during efforts to mitigate congestion or optimize paths, the controller implements new routing rules to replace outdated ones. Unfortunately, the absence of atomic synchronization across devices results in staggered rule activations: some nodes may adopt the new configuration while others continue to use outdated rules. These hybrid forwarding states can cause forwarding loops, leading to unexpected network performance degradation like packet loss, TCP reordering, and reduced reliability [3].

In recent years, researchers have investigated a variety of studies on how to consistently update network configurations. Existing solutions can be classified into three primary categories: two-phase update, ordering-based update, and time-based update. Reitblatt et al. [5] first propose the two-phase update solution that simultaneously maintains the initial and new configurations via packet tagging. Subsequent improvements in two-phase methodology [6,7] have primarily focused on mitigating inherent memory overheads caused by supplementary flow rules. In contrast, ordering-based update solutions eliminate requirements for packet labeling or costly TCAM memory consumption [8,9]. This paradigm achieves network path migration through strategic scheduling of configuration update sequences. Furthermore, unlike time-based update approaches [10,11] that rely on precise clock synchronization, ordering-based approaches gradually conduct rule updates among switches according to the scheduled update sequence. Therefore, the ordering-based multi-round update schemes have been widely studied and applied. These solutions can be briefly detailed as follows: the nodes arranged in the

However, existing ordering-based update approaches still encounter several critical challenges. First, while practical network updates often involve concurrent modifications to multiple flows [12], most previous studies primarily focus on maintaining consistency for single-flow updates [8,9,13]. For example, redistributing traffic in batches to individual servers in a Content Distribution Network [14] or redeploying a load balancing policy with a global network view in an SDN involves updating multiple flow rules. Second, the update process must minimize control-data plane interactions due to the inherent resource costs associated with switch reconfiguration and flow rules modifications. The controller should interact with the forwarding nodes as infrequently as possible to reduce the impact of the update process on the normal communication of the network. Third, considering the complexity of multi-flow update, the dependency of update sequences between nodes may constitute a deadlock [15,16]. The emergence of programmable data plane, enabled by domain-specific languages like P4 [17], offers promising solutions through flexible packet processing and fine-grained forwarding control [18]. This provides a possible solution to solve the update deadlock problem and makes update consistency guaranteed efficiently.

To address these problems, we propose P4LoF, an efficient loop-free update approach that reroutes multiple flows with minimal control-data plane interactions. First, we analyze the update dependency in the single-flow update scenario and build the shortest update dependency chain based on a greedy-based algorithm. Then, we analyze the complexity of multi-flow update and dynamically construct the dependency graph to compute the update sequences. To address the update deadlock dependencies in multi-flow update, we present a deadlock-fix forwarding model based on the flexible packet processing mechanism of the programmable data plane. Finally, we present the loop-free multi-round update plan based on the computed update sequence and the deadlock-fix forwarding model. We highlight the main contributions of our work as follows.

(1) We design a loop-free update solution, named P4LoF, which enables the controller to efficiently reroute multiple flows through minimal interactions with each switch in programmable networks.

(2) We propose a greedy-based algorithm to generate the shortest loop-free update dependency chain for each flow, then merge these chains into a dependency graph and solve it as a Shortest Common Super-sequence (SCS) problem to schedule loop-free multi-flow update.

(3) We present a deadlock-fix forwarding model to resolve deadlock dependencies of multi-flow update through consistent forwarding control.

(4) Based on real-world network topologies, we evaluate the update efficiency of P4LoF. Experimental results show that it significantly reduces the control-data plane interactions while guaranteeing the loop-free update consistency of multiple flows.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the detailed clarification and analysis of the loop-free consistency under the single-flow/multi-flow update scenarios which construct the motivation of this paper. Section 3 provides the design overview of our proposed loop-free update solution P4LoF. Section 4 presents the experimental investigation and Section 5 introduces related work. Section 6 gives the conclusion of this paper.

This section motivates the need for P4LoF by analyzing the loop-free update consistency through two practical example scenarios involving the rerouting of both single and multiple flows. The key notations involved in this paper are shown in Table 1.

Example 1: Loop-Free Consistency in Single-Flow Updates. Fig. 1 illustrates the importance of loop-free consistency when updating a single flow’s path. Flow

Figure 1: An example of the loop-free consistency update

However, network updates often experience delays and are unlikely to complete simultaneously. This lack of synchronization can create forwarding loops for flow

Example 2: Loop-Free Consistency of Multi-Flow Update. The update consistency constraint of flow

This section analyzes the challenge of maintaining loop-free consistency during flow rule updates. We highlight the update dependency problem in single-flow updates, where improper sequences can create transient loops. The analysis extends to multi-flow scenarios, showing how conflicting dependency chains can lead to NP-hard deadlocks that worsen update efficiency.

2.2.1 Loop-Free Consistency of Single-Flow Update

The rule update problem is essentially a path switching forwarding problem with the forwarding node as the basic update unit, and loop-free consistency is the basic property to maintain in this process. The rule update of flow

Definition 1: forwarding loop in single-flow update. Assume that the initial and final forwarding paths of flow

According to Definition 1, when both the old and new paths contain two nodes in the opposite order, to maintain the loop-free consistency property in the update process, the update scheme needs to ensure that node

2.2.2 Loop-Free Consistency of Multi-Flow Update

In a multi-flow update scenario, independent update paths can be managed using a single-flow update solution for parallel updates. However, if the paths intersect, it leads to an NP-hard problem due to potential conflicts in node update sequences between different flows [13]. We will define multi-flow update deadlock.

Definition 2: Multi-flow update deadlock dependency. Assume that there are no forwarding loops in the initial and final forwarding paths of each flow in the flow set F to be updated. If there exists a set of nodes

To address this problem, a simple solution is to use the flow rule as the basic update unit to complete updates to flow f and

However, such an update approach increases interactions between the switches and the controller, reducing update efficiency. To address this, we propose using forwarding nodes as the basic update unit, allowing the controller to update all relevant flow rules at each node in a single interaction. However, maintaining consistency during multi-flow updates is challenging, as simple ordering can lead to deadlocks. Thus, achieving loop-free updates for multiple flows involves solving two key problems.

This section clarifies the design details of P4LoF and its workflow depicted in Fig. 2. We first describe the loop-free consistency problem in the single-flow update scenarios, and then analyze the complexity of the multi-flow loop-free updates. Finally, the multi-flow loop-free update scheme is given.

Figure 2: The main workflow of P4LoF

3.1 Dependency Chain Generator for Single-Flow Update

In this paper, we design a dependency generating algorithm to obtain the minimal length of the dependency chain based on the greedy algorithm. The minimal represents that no node can improve its dependency without some other node getting worse. There are no loops in the initial forwarding path of flow

(1) Set the state of all nodes in the DAG to the initial state

(2) Traverse each node in the graph: For each node

(3) For each node

(4) Repeat (3) until the states of all nodes are set as

The dependency chain construction method allows nodes to be added only after their predecessor removes the initial forwarding rule, ensuring timely updates and minimal dependencies. In multi-flow updates, flows without intersecting dependencies can be updated in parallel using the dependency chain. However, due to complex dependencies, we dynamically create a multi-flow update dependency graph to enable loop-free updates.

3.2 Deadlock Detection and Removal for Multi-Flow Update

This section presents how P4LoF resolves the deadlock dependency in multi-flow updates. We first transform complex flow-level constraints into a dependency graph model where switches are aggregated into supernodes and dependency chains manifest as directed edges. Subsequently, we break detected loops through enforcing temporary P4-based forwarding rules to maintain consistency.

3.2.1 Dependency Graph Generator

Existing studies usually take flow rules as the basic update unit and formulate the update process as a series of LPs [8,19] (Linear programming): minimizing the communication amount and delay between the controller and switches as the objective, and the consistency update property as a constraint. From the analysis above for the flow

To address this problem, we replace those complex LPs with a dependency graph. In the single-flow update scenario, each node in the dependency chain is represented as the combination of node ID and flow ID, i.e.,

Further optimization in graph construction is achieved using a sliding window mechanism, which segments the sequence of switch-level update sets (supernodes) into smaller windows. Each window allows for incremental analysis of a subset of the graph, balancing computational latency and update efficiency. A larger window reduces control-data plane interactions by processing more supernodes in batches but increases computation time for resolving dependencies. Conversely, a smaller window allows for faster processing but leads to more frequent updates and coordination overhead. The window size can be dynamically adjusted based on real-time network conditions to optimize performance during low congestion or traffic bursts.

The sliding window size is dynamically adjusted in real-time to balance computational latency with update efficiency. In our implementation, we adjust the window size by simply adopting a threshold-based method. This adjustment strategy relies on three key network metrics: current network bandwidth utilization

When the network bandwidth utilization exceeds a predefined high threshold

After combining the constraints of each flow into a dependency graph and detecting the loop structures that constitute deadlocks from it, we need to fix those deadlocks to calculate the final global update sequence. For each deadlock

Also, to reduce the additional overhead caused by the deadlock-fix model, we carefully choose to cut off the one dependency chain that contains the least number of flows in the loop.

For each flow corresponding to the cropped

3.3 Loop-Free Multi-Flow Update

In practical networks, interactions between the control plane and the data plane require a certain resource cost. The more interactions the network has in the update process, the more it consumes switch resources. Besides, the time-consuming interaction process increases uncertainty and can further increase the security risk of network updates (e.g., rule loss, malicious tampering, etc.). Therefore, P4LoF needs to make each interaction cover as many nodes as possible to reduce resource consumption while ensuring the basic property of loop-free consistent updates.

3.3.1 Update Sequence Computing

We give some examples of dependency graph substructures shown in Fig. 3 to specify how we handle the multi-flow consistency update problem.

Figure 3: Dependency graph with different substructures. (a) Non-intersecting dependency; (b) Intersecting dependency w/o deadlock; (c) Deadlock dependency

Non-intersecting dependency. The dependency graph in Fig. 3a represents the update scenario where the consistency constraints of flow

Intersecting dependency without deadlock.The dependency graph in Fig. 3b represents the update scenario where the consistency constraints of the update process of flow

The problem of calculating the SCS of two sequences can be simply described as follows: given the sequences

where

Deadlock dependency. The dependency graph in Fig. 3c shows an update scenario where the consistency constraints of flows

3.3.2 Deadlock-Fix Forwarding Model

To address the problem of conflicting node update order during multi-flow update, we propose the P4-based Deadlock-fix forwarding model: first, the controller adds swTag tags to each flow in the dependency chain at the flow entry based on the dependency chains set that need to be eliminated in the dependency graph. These tags correspond to the individual node identifiers (like switch ID) in the dependency chain. Then, before sending the flow rules to be updated to the data plane, the controller preloads additional forwarding rules in each switching node corresponding to the swTag (Fig. 4) and specifies the outgoing port of each flow as the forwarding port before the update, to ensure a loop-free update of the flows. Finally, the controller loads new configurations to the data plane based on the calculated node update sequence to complete the update of the data plane. In addition, the deadlock-fix forwarding model sets a TTL value for these additional flow rules (Fig. 4a) to ensure that these rules can release the occupied switch storage resources in time after each node that constitutes the update deadlock finishes updating the flow rules.

Figure 4: Processing logic of the deadlock-fix forwarding model

In the P4-based programmable data plane, the packet parsing process is abstracted as a finite state machine, where each state node represents a field in the packet header and the edges represent a transition between states. The parser sequentially traverses the packet headers to extract field values during execution, which are processed using a predefined match-action table. The parsing process of P4LoF is represented by the parser graph in Fig. 4b. From the graph, it can be seen that for the set of eliminated dependency chains

(1) Processing of tagged traffic: swTag stores the identification (7 bits) of the nodes on the dependency chains

(2) Processing of untagged traffic: the same process as for IP packets in traditional networks, forwarding based on Layer 3 routing or Layer 2 switching flow rules (solid blue line in Fig. 4b), thus ensuring that the introduction of the deadlock-fix forwarding model does not affect the normal communication of other traffic in the network that is not involved in the update.

Based on the above-proposed construction and processing methods of the dependency graph, we set the update rounds of the network configuration as follows.

Round 0: dependency-free nodes. According to Definition 1, inconsistent updates only cause forwarding loops on links where old and new paths overlap. If node

Round

Rounds for multi-flow update deadlocks: none. By introducing additional forwarding rules to the loops that constitute the deadlock, we achieve sequential updating of each node in the deadlock while ensuring that each flow is forwarded without loops. The introduction of the additional forwarding mechanism destroys the original loop dependency structure of the deadlock and makes it degrade to a chain structure with weaker dependency among nodes, like Fig. 3a,b. Therefore, we can use the same method to handle these nodes and complete the update in the round

The update mechanism of P4LoF mainly consists of three core components: a greedy-based dependency chain generating algorithm for single flow update, an SCS-based update sequence scheduling for multi-flow update, and a forwarding model for handling deadlock update sequences. In this section, we present a comprehensive time complexity analysis of the former two algorithms and a memory complexity analysis of the forwarding model, which is conducted with additional flow rules on the data plane.

3.4.1 Time Complexity Analysis of Single-Flow Dependency Generation

The dependency generating algorithm aims to create a minimal-length update dependency chain for a single flow

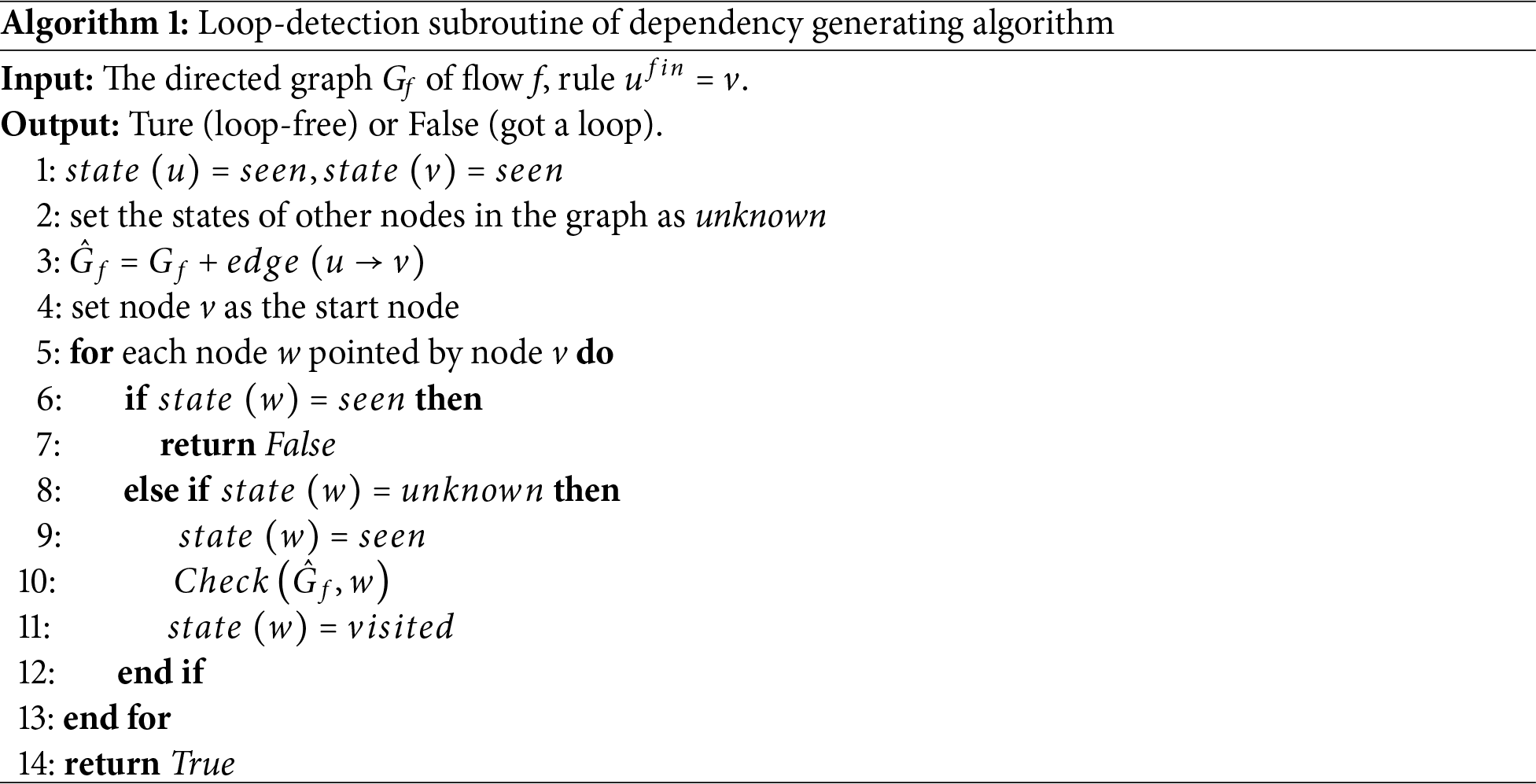

Loop-detection subroutine (Algorithm 1). Algorithm 1 performs a DFS-like traversal starting from

Main algorithm (dependency generating algorithm). In the second step of the main algorithm, we traverse all graph nodes and invoke Algorithm 1 for each. This results in

Although the time complexity of our dependency generating algorithm is theoretically high, it shows efficient performance in practice since real-world topologies usually exhibit short dependency chains. For instance, the evaluation results in Section 4.1 show that over 95% of dependency chains terminate within 5 hops across various topologies. Therefore, the time complexity can be simplified to

3.4.2 Time Complexity Analysis of Multi-Flow Scheduling

For scheduling the multi-flow update sequences with the dependency graph structure shown in Fig. 3b, P4LoF formulates the problem as calculating the SCS of a series of sequences. SCS is known to have a polynomial time algorithm if the number of input sequences is constant, and to be NP-hard if the number of input sequences is not constant [20]. By utilizing a sliding window (fixed update sequence length), P4LoF reduces the computational complexity of resolving the SCS problem from NP-hard to polynomial time. For the

3.4.3 Memory Complexity Analysis of the Deadlock-Fix Forwarding Model

To address the deadlock dependency constructed by conflicting update sequences, we propose the P4-based Deadlock-fix forwarding model. Deadlock-fix forwarding model introduces constant-time P4 operations, with memory complexity bounded by O(d) for d deadlocks in each window. Since each dependency deadlock is constructed by a series of dependency chains, the number of additional forwarding rules is linearly related to the sliding window size. Therefore, the memory complexity of the Deadlock-fix forwarding model is

In this section, we evaluate the effectiveness and performance of P4LoF based on real-world network topoologies. We implemented P4LoF with Python and P4. It currently supports deployment on the BMv2 model [22], a widely used software switch model for P4-based implementation. All experiments are conducted on LinuxOS (Ubuntu 20.04) with an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 5218 CPU@2.30 GHz and 256 GB RAM. Our code is publicly available at https://github.com/Arcents/p4lof (accessed on 10 August 2025).

Experiment setup. The experiments use four public topologies, including Ebone and Sprintlink from Rocketfuel [23], and Nobel and Germany50 from SNDlib [24] (shown in Table 2). In each experiment, we first take all Equal-Cost Multi-Path (ECMP) routes to the destination nodes as the initial network configuration. Then 50% of the routing weights are randomly modified. Finally, the routing paths are updated again using the ECMP algorithm and set as the final configuration.

Comparison methods. We evaluate P4LoF against state-of-the-art methods [6,8,25] that minimize control-data plane interactions. GRD [25] uses a heuristic based on solving the NP-hard problem of finding the maximum number of updatable switches per time slot to reduce control-data plane interactions. RMS [6] is A TCAM-free heuristic leveraging path reversal and merge optimization to minimize rule-update interactions while ensuring loop freedom. The work in [8] employs lazy cycle-breaking for loop-free updates. It has three variants: 1) OPT: Computes minimal-round schedules. 2) LP_OPT: Derives a theoretical lower bound using LP relaxation of the ILP. 3) Rounding: Develops a heuristic that rounds the fractional LP_OPT solution to achieve near-optimal schedules efficiently.

Evaluation metrics. Given N represents the number of flow rules to be updated. Let

(1) Memory overhead:

(2) Communication overhead:

(3) Time consumption: the time for constructing the dependency graph, the core algorithm of scheduling the update plan, and the total processing time (including topology parsing time).

We first evaluate the efficiency of P4LoF for single-flow update. Fig. 5 presents the experimental analysis of single-flow update dependency chains of P4LoF across four real-world topologies. The results demonstrate a sharp decline in dependency chain counts as chain length increases, demonstrating that the update dependencies of most flows are simple. Specifically, both Ebone (purple dashed line) and Nobel (blue solid line) exhibit near-zero dependency chains beyond length 6, while Germany50 (red solid line) achieves the same level at length 4. Sprintlink (green solid line) shows marginally longer chains due to its structural complexity yet maintains scalability within 5 hops. Notably, over 95% of chains terminate within

Figure 5: Experiment results of single-flow update

Fig. 6 presents comprehensive experimental results for multi-flow update across four network topologies, evaluating P4LoF’s performance through three critical metrics.

Figure 6: Experiment results of multi-flow update

Memory overhead. By integrating and optimizing the update sequence, P4LoF significantly reduces the number of flow rules that the switch needs to maintain during the update process. Additionally, to prevent deadlock when updating multiple flows, P4LoF installs a small number of extra forwarding rules in the switch. Fig. 6a quantifies this memory overhead as the ratio of additional flow rules to updated rules. As the sliding window size increases from 1 to 6, all topologies exhibit growth in memory overhead. Ebone incurs the steepest rise, surging from 2.8% to 18.9%, while Germany50 follows a similar trajectory from 1.7% to 14.1%. Nobel and Sprintlink maintain relatively conservative growth, stabilizing at 12.6% and 11.3% respectively at window size 6. This confirms that larger sliding windows necessitate more temporary rules to resolve deadlocks, with hierarchical topologies (e.g., Ebone) demanding higher TCAM utilization.

Communication overhead. Fig. 6b measures saved control-data plane interactions. Nobel consistently achieves the highest savings (70.1%–73.6%), demonstrating robust independence from window scaling. Ebone and Sprintlink maintain 63%–71% savings across all windows, with minor fluctuations linked to routing complexity. Germany50 shows the lowest but stable efficiency (32.6%–35.3%), indicating topology-dependent coordination costs. Notably, all topologies sustain 32.6% interaction savings—validating P4LoF’s core advantage in minimizing control-plane overhead. For the communication overhead in the data plane, the deadlock-fix forwarding model requires the addition of swTag tags containing the deadlock node identifier in the packet header. According to our design of swTag in Section 3.3.2, the length of each tag is only 1 byte. Experiments in various topologies show that the length of a single dependency chain does not exceed 3 in 90% of cases, and the corresponding deadlock-fix forwarding model adds no more than 3 bytes to the length of each tag in the packet header. In general, the packet size in normal network communication is not less than 64 bytes, then the additional bandwidth overhead added by the tag in the data plane is not more than 5% and will not affect the normal network communication.

Time consumption The execution time of the update algorithm should be considered, especially when the network has a low tolerance for update latency. Fig. 6c shows the relationship between window size and dependency generating time consumption. Germany50 exhibits the largest time consumption (<7.8 ms) among all topologies due to its high topology complexity. Other topologies maintain consistently low latency (1.7–3.4 ms ) across all window sizes and stabilize below 2.58 ms when the window size exceeds 4. P4LoF uses a greedy algorithm to construct the shortest length dependency chain between update nodes, which simplifies the computational complexity of subsequent update sequences.

Table 3 presents the time consumption of the core algorithm (i.e., resolving SCS and update dependencies) and total processing time. For the Germany50 topology with the highest network complexity, P4LoF can give the update sequence in 14.93 s in 90% of the experiments, including time consumption for parsing topologies. Meanwhile, for other network topologies with relatively simple structures, P4LoF can compute the node update sequence in 1.87 s. We also found that the core algorithm of P4LoF operates very quickly, taking less than 149 ms. However, parsing the network topologies requires significantly more time, leading to an overall time consumption measured in seconds. As can be seen in Table 3, for 90% of the experiments performed on topology Germany50, the execution time of the core algorithm is within 100 ms. For other network topologies, the core algorithm is able to give the update sequence for the multi-flow update within 28 ms, which is only 1.50% of the total running time of the update algorithm.

To evaluate the update efficiency of P4LoF, we conduct comparative experiments with state-of-the-art methods across various topology scales. Fig. 7 displays the experimental results for the simplest topology (Nobel) and the most complex topology (Sprintlink), respectively.

Figure 7: Update efficiency among varied topology scales

Experiment results in Fig. 7a illustrate significant performance variations among the evaluated schemes in the simple topology. The Rounding heuristic shows the highest median update rounds at 5.5, accompanied by substantial data dispersion, as indicated by its elongated whiskers and the presence of outliers. This suggests an unpredictable interaction overhead. In contrast, the P4LoF variants (MIN, MAX, and OPT denote adopting min/max/optimal sliding windows) achieve notably lower median values of 4.5, with compact interquartile ranges and minimal data spread, thereby highlighting their stable and consistent performance. Other methods, including GRD, RMS, OPT, and LP_OPT, cluster around similar quartiles with medians ranging from 3.5 to 4.5. However, their slightly wider distributions suggest marginally less consistency compared to the P4LoF variants. Overall, P4LoF demonstrates a robust efficiency in minimizing interactions in the control-data plane, with its sliding-window optimizations yielding reliable outcomes.

For the complex topology (Fig. 7b), the advantages of P4LoF become even more pronounced. The Rounding method again demonstrates the poorest performance, with a higher median of approximately 6.3 and a broader data spread. In contrast, P4LoF_MIN and P4LoF_OPT achieve the most efficient results, consistently maintaining minimal mean interaction counts of around 3.8. All P4LoF variants exhibit remarkable data homogeneity, reinforcing the method’s adaptability to intricate network structures. These patterns confirm that P4LoF’s optimal sliding-window configuration and deadlock-fix model significantly reduce interaction overhead, even in demanding topologies, outperforming both heuristic methods (GRD, RMS) and theoretical baselines (LP_OPT).

For loop-free consistency updating in programmable networks, the proposed research can be classified into three categories: two-phase update, ordering-based update, and time-based update.

Reitblatt et al. [5] first proposed a two-phase update (TP) scheme: By adding tags to each packet in a network, implement packets only according to the updated configuration before or after the flow rule configuration for forwarding, and will not appear at the same time, following the two configurations. This scheme makes programmers only need to focus on network status before and after the configuration updates, and have no need to worry about intermediate states that exist in violation of the consistency. The work in [7] further improved the scheme, eliminating the operation of adding labels to data packet headers, thus improving the network update efficiency. These update solutions can guarantee loop-free consistency in every intermediate state during network updating. However, such approaches and many subsequent studies based on them [18] have an inherent drawback: additional memory resource consumption (e.g., TCAM) is required to maintain both the old and new flow rules configuration at the same time [6]. Besides, since the old path is available in those approaches by default, they are not available for the update scenario with network link or node failure.

The ordering-based (OR) update solution converts the initial configuration of the data plane to the final configuration by calculating a specific update sequence of all the updating flow rules. Mahajan and Wattenhofer [26] first proposed a destination-based single-flow loop-freedom update scheme that emphasizes the inherent balance between the strength of consistency and the dependency of flow rules of different switching nodes. Unlike the TP updating plan, which adds flow rules to nodes, Ordering-based Update approaches [6,8,9] do not consume storage resources, but they also introduce a computational time bottleneck. Finding the fastest update solution was proved to be an NP-complete problem in [13]. Räcke et al. [8] propose a lazy cycle-breaking strategy which, by adding constraints lazily, dramatically improves update performance. Two strengths of loop-free updates are considered: strong loop-free consistency (the network is loop-free at any update stage) and relaxed loop-free consistency (only the forwarding path between source and destination nodes is required to be loop-free). It is shown that relaxed consistency can significantly improve the speed of network updates.

Time-based update approaches [10,11] provide the implementation flow consistency for the updating of new ideas. Such schemes utilize clock synchronization between switches to achieve a fine-grained arrangement of the updating process. These update plans can efficiently address the inconsistent update problems like forwarding loops, blackhole, and transient congestion [27]. However, this paradigm has extremely high requirements on the precision of clock synchronization between switches and is not applicable to actual deployment [28].

To address the forwarding loop inconsistencies during network configuration updates, this paper proposes an efficient loop-free update approach, P4LoF. It enables simultaneous rerouting of multiple flows with minimal control-data plane interactions. P4LoF constructs optimized update sequences by generating shortest per-flow dependency chains, merging them into a multi-flow update dependency graph, and solving it as an SCS problem. Furthermore, to address the multi-flow update deadlock dependencies, P4LoF builds a deadlock-fix model that provides consistent forwarding control based on the programmable data plane. Experimental results demonstrate that P4LoF can reduce the number of control-data plane interactions during updates by

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China under Grant 2022YFB2901501; and in part by the Science and Technology Innovation leading Talents Subsidy Project of Central Plains under Grant 244200510038.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Jiqiang Xia and Jianhua Peng; methodology, Jiqiang Xia and Qi Zhan; formal analysis, Yuxiang Hu; investigation, Jianhua Peng; writing—original draft preparation, Jiqiang Xia; writing—review and editing, Qi Zhan and Le Tian; supervision, Yuxiang Hu and Jianhua Peng; funding acquisition, Yuxiang Hu and Le Tian. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support this study are available from authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Le M, Huynh-The T, Do-Duy T, Vu TH, Hwang WJ, Pham QV. Applications of distributed machine learning for the internet-of-things: a comprehensive survey. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2025;27(2):1053–100. [Google Scholar]

2. McKeown N, Anderson T, Balakrishnan H, Parulkar G, Peterson L, Rexford J, et al. OpenFlow: enabling innovation in campus networks. SIGCOMM Comput Commun Rev. 2008;38(2):69–74. [Google Scholar]

3. Su J, Wang W, Liu C. A survey of control consistency in software-defined networking. CCF Trans Netw. 2019;2(3):137–52. doi:10.1007/s42045-019-00022-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Deb R, Roy S. A comprehensive survey of vulnerability and information security in SDN. Comput Netw. 2022;206(11):108802. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2022.108802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Reitblatt M, Foster N, Rexford J, Schlesinger C, Walker D. Abstractions for network update. In: Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM, 2012 Conference on Applications, Technologies, Architectures, and Protocols for Computer Communication, SIGCOMM ’12. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2012. p. 323–34. [Google Scholar]

6. Dolati M, Khonsari A, Ghaderi M. Minimizing update makespan in SDNs without TCAM overhead. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2022;19(2):1598–613. doi:10.1109/tnsm.2022.3146971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Namjoshi KS, Gheissi S, Sabnani K. Algorithms for in-place, consistent network update. In: Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM, 2024 Conference, ACM SIGCOMM ’24. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2024. p. 244–57. [Google Scholar]

8. Räcke H, Schmid S, Vintan R. Fast algorithms for loop-free network updates using linear programming and local search. In: IEEE INFOCOM 2024–-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications; 2024 May 20–23; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 1930–9. [Google Scholar]

9. Gao X, Majidi A, Gao Y, Wu G, Jahanbakhsh N, Kong L, et al. Nous: drop-freeness and duplicate-freeness for consistent updating in SDN multicast routing. IEEE/ACM Trans Netw. 2024;32(5):3685–98. doi:10.1109/tnet.2024.3404967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Hasan KF, Feng Y, Tian YC. Precise GNSS time synchronization with experimental validation in vehicular networks. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2023;20(3):3289–301. doi:10.1109/tnsm.2022.3228078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. He X, Zheng J, Dai H, Sun Y, Dou W, Chen G. Chronus+: minimizing switch buffer size during network updates in timed SDNs. In: IEEE 40th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems; 2020 Jul 8–10; Singapore. p. 377–87. [Google Scholar]

12. Larsen KG, Mariegaard A, Schmid S, Srba J. AllSynth: a BDD-based approach for network update synthesis. Sci Comput Program. 2023;230(C):102992. doi:10.1016/j.scico.2023.102992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Henzinger M, Paz A, Pourdamghani A, Schmid S. The augmentation-speed tradeoff for consistent network updates. In: Proceedings of the Symposium on SDN Research, SOSR ’22. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2022. p. 67–80. [Google Scholar]

14. Naeem MA, Ud Din I, Meng Y, Almogren A, Rodrigues JJPC. Centrality-based on-path caching strategies in NDN-based internet of things: a survey. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2025;27(4):2621–2657. doi:10.1109/COMST.2024.3493626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. He X, Zheng J, Dai H, Zhang C, Li G, Dou W, et al. Continuous network update with consistency guaranteed in software-defined networks. IEEE/ACM Trans Netw. 2022;30(3):1424–38. doi:10.1109/tnet.2022.3143700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Györgyi C, Larsen KG, Schmid S, Srba J. SyPer: synthesis of perfectly resilient local fast re-routing rules for highly dependable networks. In: IEEE INFOCOM 2024–-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications; 2024 May 20–23; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 2398–407. [Google Scholar]

17. Bosshart P, Daly D, Gibb G, Izzard M, McKeown N, Rexford J, et al. P4: programming protocol-independent packet processors. ACM SIGCOMM Comput Commun Rev. 2014;44(3):87–95. [Google Scholar]

18. Zhou Z, He M, Kellerer W, Blenk A, Foerster KT. P4Update: fast and locally verifiable consistent network updates in the P4 data plane. In: Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Emerging Networking EXperiments and Technologies, CoNEXT ’21. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2021. p. 175–90. [Google Scholar]

19. Pang Z, Huang X, Li Z, Zhang S, Xu Y, Wan H, et al. Flow scheduling for conflict-free network updates in time-sensitive software-defined networks. IEEE Trans Ind Inf. 2021;17(3):1668–78. doi:10.1109/tii.2020.2998224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Dudycz S, Ludwig A, Schmid S. Can’t touch this: consistent network updates for multiple policies. In: 46th Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks; 2016 Jun 28–Jul 1; Toulouse, France. p. 133–43. [Google Scholar]

21. Basta A, Blenk A, Dudycz S, Ludwig A, Schmid S. Efficient loop-free rerouting of multiple SDN flows. IEEE/ACM Trans Netw. 2018;26(2):948–61. doi:10.1109/tnet.2018.2810640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. P4-Language-Consortium. Behavioral model repository; 2014 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 4]. Available from: https://github.com/p4lang/behavioral-model. [Google Scholar]

23. Spring N, Mahajan R, Wetherall D, Anderson T. Measuring ISP topologies with Rocketfuel. IEEE/ACM Trans Netw. 2004;12(1):2–16. doi:10.1109/tnet.2003.822655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Orlowski S, Wessäly R, Pióro M, Tomaszewski A. SNDlib 1.0—survivable network design library. Networks. 2010;55(3):276–86. doi:10.1002/net.20371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Amiri SA, Ludwig A, Marcinkowski J, Schmid S. Transiently consistent SDN updates: being greedy is hard. In: Structural information and communication complexity. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2016. p. 391–406. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-48314-6_25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mahajan R, Wattenhofer R. On consistent updates in software defined networks. In: Proceedings of the Twelfth ACM Workshop on Hot Topics in Networks, HotNets-XII. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2013. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

27. Ceylan E, Chatterjee K, Schmid S, Svoboda J. Congestion-free rerouting of network flows: hardness and an FPT algorithm. In: 2024 IEEE Network Operations and Management Symposium; 2024 May 6–10; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

28. Chefrour D. Evolution of network time synchronization towards nanoseconds accuracy: a survey. Comput Commun. 2022;191(1):26–35. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2022.04.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools