Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Gradient-Guided Assembly Instruction Relocation for Adversarial Attacks Against Binary Code Similarity Detection

Key Laboratory of Cyberspace Security, Ministry of Education, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

* Corresponding Author: Ran Wei. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069562

Received 26 June 2025; Accepted 02 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Transformer-based models have significantly advanced binary code similarity detection (BCSD) by leveraging their semantic encoding capabilities for efficient function matching across diverse compilation settings. Although adversarial examples can strategically undermine the accuracy of BCSD models and protect critical code, existing techniques predominantly depend on inserting artificial instructions, which incur high computational costs and offer limited diversity of perturbations. To address these limitations, we propose AIMA, a novel gradient-guided assembly instruction relocation method. Our method decouples the detection model into tokenization, embedding, and encoding layers to enable efficient gradient computation. Since token IDs of instructions are discrete and non-differentiable, we compute gradients in the continuous embedding space to evaluate the influence of each token. The most critical tokens are identified by calculating the norm of their embedding gradients. We then establish a mapping between instructions and their corresponding tokens to aggregate token-level importance into instruction-level significance. To maximize adversarial impact, a sliding window algorithm selects the most influential contiguous segments for relocation, ensuring optimal perturbation with minimal length. This approach efficiently locates critical code regions without expensive search operations. The selected segments are relocated outside their original function boundaries via a jump mechanism, which preserves runtime control flow and functionality while introducing “deletion” effects in the static instruction sequence. Extensive experiments show that AIMA reduces similarity scores by up to 35.8% in state-of-the-art BCSD models. When incorporated into training data, it also enhances model robustness, achieving a 5.9% improvement in AUROC.Keywords

Deep learning models have been increasingly applied to Binary Code Similarity Detection (BCSD). BCSD measures similarity between binary code snippets based on their instruction sequences and has become fundamental for vulnerability discovery [1], software plagiarism analysis [2], patch analysis [3], and software supply chain analysis [4]. With the success of Transformer models in natural language processing (NLP), researchers have recognized structural and semantic parallels between assembly language and natural language. Consequently, BERT-based (Transformer encoder) models have been widely adopted for BCSD tasks, with models like jTrans [5]and CLAP [6] achieving state-of-the-art (SOTA) performance in detecting functional similarities among binary programs.

However, deep learning models exhibit inherent fragility and susceptibility to adversarial attacks—a phenomenon extensively documented in computer vision [7–9]. Enhancing the robustness of BCSD models is therefore critically important. As demonstrated in prior work [10,11], adversarial examples play a crucial role in evaluating and improving model robustness. By comparing predictions on adversarial vs. original inputs, these examples reveal vulnerabilities in decision-making processes. Furthermore, incorporating adversarial examples into training data enhances model generalization and perturbation resistance.

Current research on adversarial examples in code-related domains primarily focuses on source-level and binary-level modifications. Source-level techniques employ variable renaming or dead code insertion [11,12], while binary-level approaches either modify non-code regions of PE/ELF files (e.g., metadata or padding areas) [13–15] or inject trigger instructions into function bodies (e.g., PELICAN [16]). These methods provide valuable insights but exhibit significant limitations: 1) Source-level modifications are often stripped during compilation; 2) File-level perturbations don’t affect code segments; 3) Trigger injection requires extensive search spaces to construct target instructions, resulting in low efficiency.

To address these limitations, we propose AIMA (Assembly Instruction Movement Adversary), an innovative assembly instruction movement adversary method. The core innovation lies in our gradient-based identification of critical instruction segments, where we use the

Furthermore, Assembly files as compilation outputs retain comprehensive symbolic information [17,18]. Assembly-level instruction relocation leverages identified critical segments to move them outside function bodies via jump mechanisms, preserving control flow and introducing “deletion” effects at the instruction sequence level.

By integrating these techniques, AIMA demonstrates superior performance in functional equivalence, stealth, and operational efficiency compared to conventional methods. Our experimental results show a reduction in similarity scores by up to 35.8% and a 5.9% improvement in AUROC when adversarial examples are incorporated into training data. The mean space and runtime overhead of the samples is 1.061 and 1.035.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

1. Gradient-Based Identification of Critical Instruction Segments: This gradient-guided approach enables precise identification of key instructions affecting model similarity judgments. By focusing on these critical segments, AIMA achieves higher efficiency and effectiveness in adversarial example generation.

2. Assembly-Level Instruction Relocation Strategy: This strategy not only preserves functionality but also introduces “deletion” effects at the instruction sequence level. Compared to conventional approaches, this method eliminates the need for constructing perturbation instructions within large search spaces, thereby enhancing generation efficiency and stealth.

3. Prototype System Implementation (AIMA): We have designed and implemented AIMA as an end-to-end system that identifies critical instruction segments via gradient-based importance analysis, performs precise code relocation using jump table mechanisms, and generates adversarial binaries with controllable overhead.

4. Open Research Initiative: To facilitate reproducibility and advance research in binary analysis security, we have publicly released the source code of AIMA on GitHub1. This initiative encourages further exploration and development in secure binary analysis systems.

2.1 Binary Code Similarity Detection

As a fundamental technique in software security, BCSD measures the functional similarity between binary code fragments based on their instruction sequences. BCSD has critical applications in vulnerability discovery [19], malware analysis [20], software plagiarism detection [21], patch analysis [22], and supply chain security [23].

Deep learning techniques have been widely adopted in BCSD. Inspired by the success of Transformer models in Natural Language Processing (NLP), recent approaches exploit the structural and semantic parallels between assembly language and natural language. This paradigm shift has led to the widespread adoption of BERT-based architectures, resulting in notable models such as Palmtree [24], UniASM [4], BinBERT [2], jTrans [5], and CLAP [6].

Among these, jTrans and CLAP represent significant advancements. jTrans introduces jump-aware representations and embeds control flow information via specialized pre-training [5]. CLAP, built on RoBERTa with 110M parameters, employs instruction embedding, address rebasing, WordPiece tokenization, and jump relationship modeling [6]. Both exhibit excellent performance in binary similarity detection and thus serve as the adversarial baselines in this study.

2.2 Adversarial Example Generation

Research on adversarial example generation in code-related domains has primarily focused on three distinct levels of manipulation: source code-level transformations, binary file-level modifications, and function-level modification.

Source Code-Level Adversarial Examples. These approaches generate adversarial examples by modifying program source code. Notable methods include MHM [10], CARROT [12], and ALERT [11], which typically employ a two-phase methodology: (1) defining semantics-preserving transformation rules (e.g., identifier renaming, dead code insertion); (2) identifying target locations where these rules are applied, and optimizing the perturbations using feedback from model predictions.

Binary File-Level Adversarial Examples. At the binary level, researchers have targeted non-code regions of PE/ELF files [13–15], by employing optimization techniques to perturb metadata or padding sections to evade detection systems like MalConv. For example, Demetrio et al. [25] demonstrated that strategic modifications to DOS headers or section gaps could effectively deceive CNN-based classifiers that process binary files as raw byte streams.

Function-Level Adversarial Techniques. These approaches primarily involves the careful injection of specifically designed redundant code sequences into function bodies. PELICAN [16] introduces an advanced approach through the construction of backdoor triggers,which is carefully crafted instruction sequences. When the tirgger is injected, it cause BCSD models to misclassify the modified functions.

Overall, the three categories of adversarial methods exhibit significant limitations when applied to BCSD tasks. Source code-level approaches have limited impact on the resulting binary’s instruction sequences, as variable names are discarded during compilation and redundant instructions (e.g., dead code) may be optimized away by the compiler. Binary file-level methods preserve program functionality by modifying only non-code regions (e.g., headers, padding), but they fail to perturb actual function instructions. Consequently, they are unlikely to evade function-level BCSD models. Instruction injection techniques face two major challenges: (1) the enormous search space required to identify effective trigger patterns, and (2) the high computational overhead of micro-execution verification needed to ensure functional and semantic correctness. These limitations motivate us to propose a new approach.

Deep learning models exhibit inherent fragility and susceptibility to adversarial attacks, a phenomenon that has been extensively documented in computer vision and NLP [7,8,26]. However, BCSD differs from NLP tasks.

BCSD models typically rely on disassembled instructions to evaluate functional similarity. Nevertheless, there exist fundamental distinctions between assembly operands/opcodes and natural language words:

1. Lack of Semantic Diversity in Assembly Instructions: NLP adversarial attacks (e.g., character substitution or synonym replacement) exploit lexical richness and semantic flexibility. Assembly instructions, however, feature rigid syntax and unambiguous semantics [27], with no genuine synonyms between instructions. This prevents direct transfer of NLP adversarial techniques.

2. Data-Dependent Instruction Semantics: Unlike NLP words carrying intrinsic meaning, assembly instructions (e.g., mov, jmp) derive semantics from runtime values of their operands (registers/memory addresses), which function as “pronouns” [28]. For instance, in Linux’s Procedure Linkage Table (PLT) mechanism, the instruction jmp [Addr] redirects control flow based on the memory value at Addr, enabling dynamic binding.

Regarding adversarial perceptibility, binary code differs significantly from natural language: about natural language sensitivity, removing words often creates grammatical errors or semantic inconsistencies easily detectable by humans. But in binary opacity, users primarily evaluate programs through input/output behavior, file size, and execution time. Internal implementation changes (e.g., instruction reordering) remain imperceptible if functionality is preserved. Compiler causes identical source code to yield functionally equivalent but instructionally distinct binaries under different compilation options [1]. This diversity further obscures such modifications.

Traditional software adversarial methods, inspired by image/NLP domains, perform gradient-based synonym substitution or modify non-critical bytes. However, binary code demands specialized approaches due to its unique characteristics. Crucially, assembly files—as intermediate representations in compilation—retain rich symbolic information [29]. This enables relocating instruction segments outside function bodies while maintaining functionality through:

1. Symbolic Binding: Assemblers (as) and linkers (ld) resolve symbols to memory addresses during compilation [30].

2. Control Flow Preservation: jump instructions redirect execution to/from relocated segments.

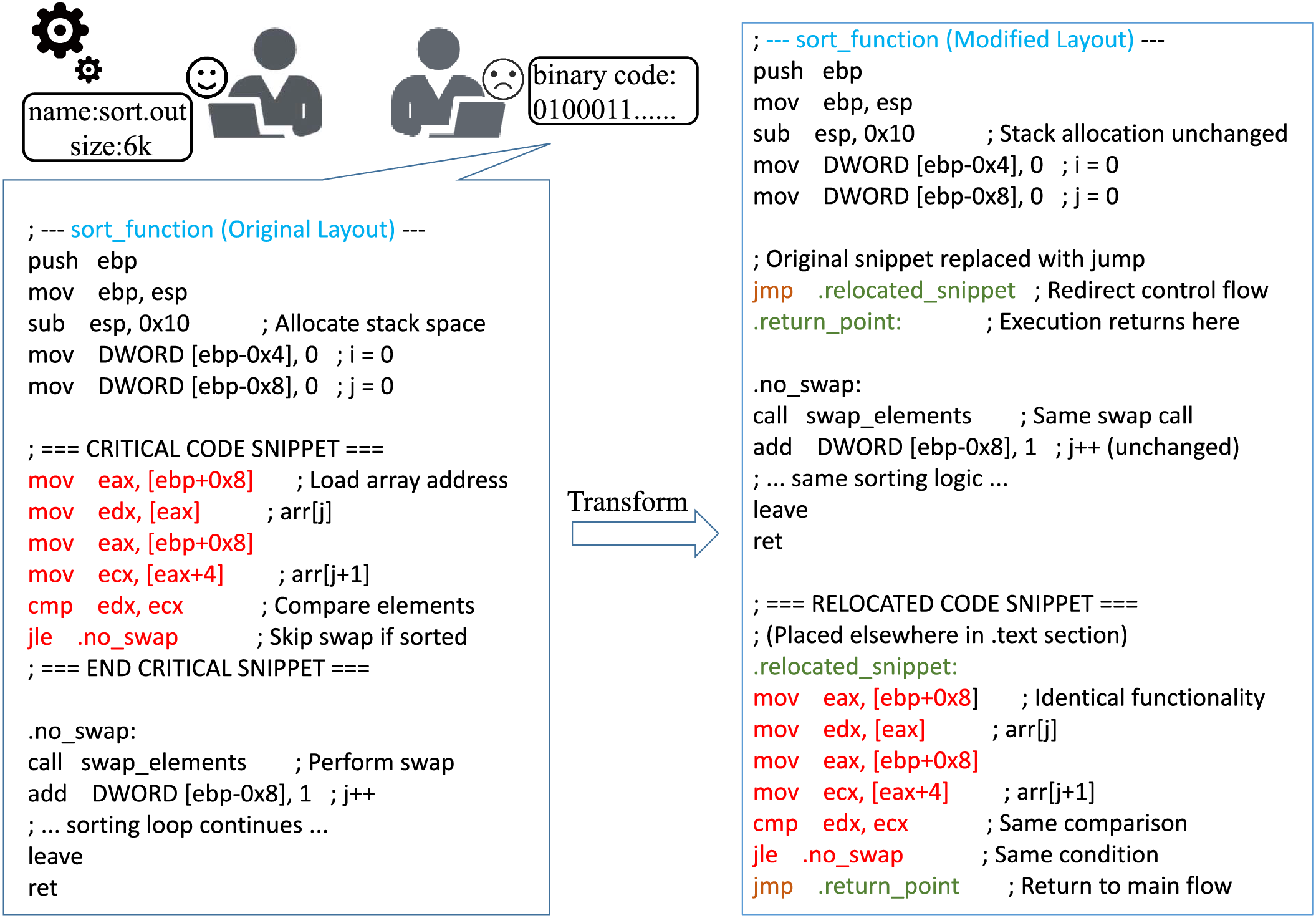

Therefore, we propose a novel adversarial method. As shown in Fig. 1, by using gradient-based importance to identify critical segments and moving them outside function bodies, we circumvent the limitation of searching for semantically equivalent instructions,avoid inefficient trigger generation, leverage indirect jumps for runtime adaptability (e.g., memory-dereferenced targets), and maintain functionality with minimal overhead (

Figure 1: An illustrative example of motivation: Key instruction segments are relocated outside the function body while maintaining functional correctness through jump-based redirection. This induces a “deletion” effect at the instruction sequence level in static disassembly views

We propose an adversarial method against Transformer-based BCSD models. The core insight involves relocating critical instruction sequences from their original function bodies to alternative code sections, creating a “deletion” effect in static disassembly views while preserving runtime functionality.

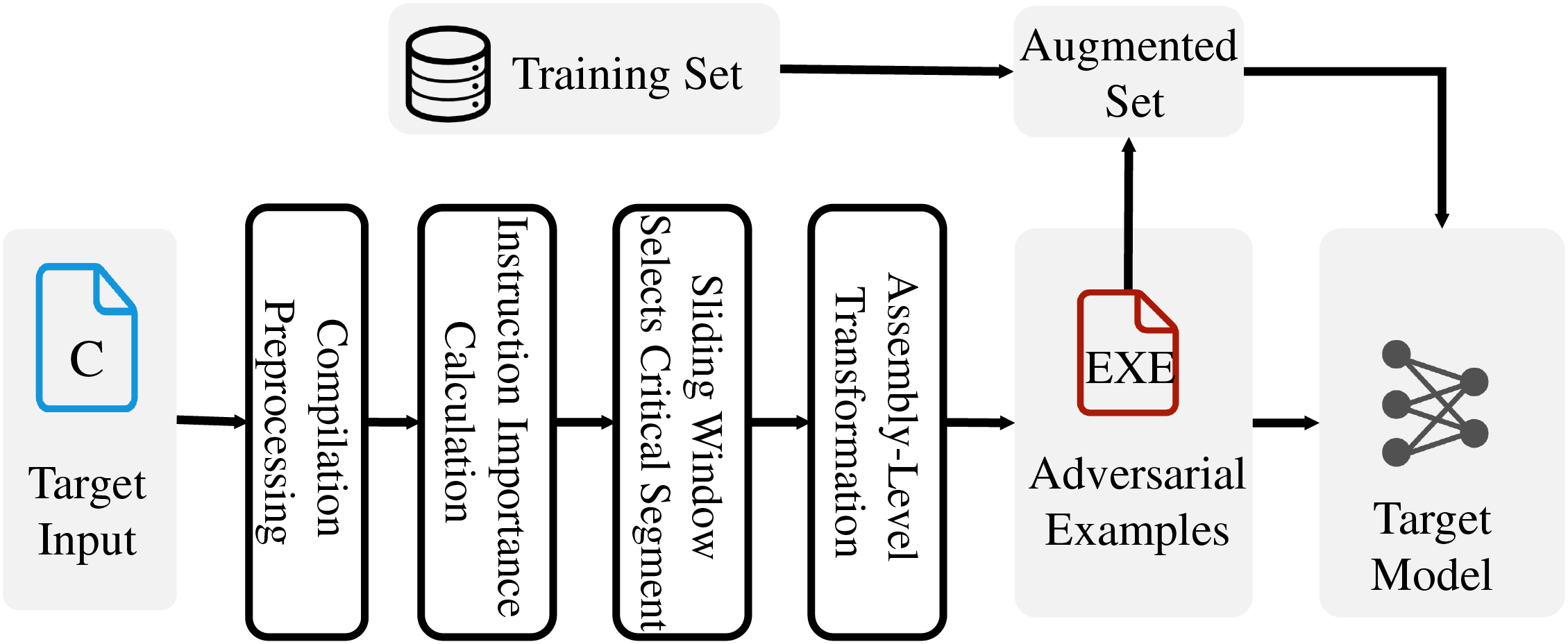

We design AIMA (Assembly Instruction Movement Adversary), with the workflow illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Overview of AIMA

The first stage, Compilation Preprocessing, involves compiling source code into assembly files (.s/.asm) with full symbolic information while simultaneously generating object files (.o) to serve as inputs for BCSD models.

The second stage, Instruction Importance Calculation, computes token-level importance using embedding gradients and aggregates these scores to determine instruction-level significance. This gradient-based attribution identifies semantically critical instructions that maximally influence similarity judgments.

The third stage, Sliding Window Selects Critical Segments, employs a variable-size sliding window to identify optimal relocation segments through cumulative importance summation. This approach addresses the limitation of single-instruction perturbations by selecting contiguous blocks that collectively maximize impact.

The final stage, Assembly-Level Transformation, performs the actual code modification: removing target segments from assembly files, inserting jump table-based redirection logic, and reassembling the modified assembly into adversarial binaries. The jump table mechanism dynamically redirects control flow during execution while appearing as static jumps in disassembly views.

Our approach initiates by compiling C source files into two complementary artifacts: Assembly files(.s/.asm) containing symbolic information for subsequent instruction relocation; Object files (.o) serving as inputs to BCSD models for embedding generation and gradient computation

Crucially, the instruction sequences in assembly files maintain strict one-to-one correspondence with disassembled views of object files (processed by tools like IDA Pro). This alignment enables precise mapping between tokens generated during BCSD model tokenization and their originating assembly instructions—a critical prerequisite for targeted instruction manipulation.

To address complications introduced by compiler-generated auxiliary data, we implement strategic compilation options with GCC that streamline assembly output: -masm=intel: Enforces Intel syntax for consistent disassembly representation -fno-asynchronous-unwind-tables: Suppresses exception handling metadata -fcf-protection=none: Prevents insertion of control-flow integrity instructions -fno-dwarf2-cfi-asm: Eliminates DWARF debugging directives

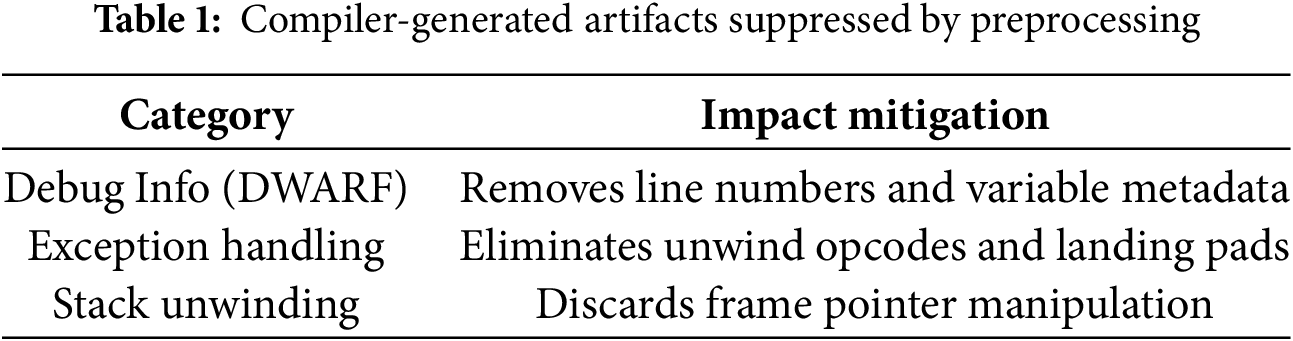

These optimizations specifically target three categories of non-essential elements (in Table 1) that complicate instruction relocation:

This curated compilation strategy yields assembly files containing only semantically essential instructions, significantly simplifying subsequent relocation operations while preserving the structural integrity required for precise adversarial transformations.

4.3 Gradient-Based Importance Computation for Assembly Instructions

BCSD models typically standardize disassembled instruction sequences by replacing immediates, addresses, and other operands with symbolic placeholders (e.g., [IMM], [ADDR]) before tokenization. Tokenization strategies vary across SOTA approaches: Whole-instruction tokenization [4,31], Opcode-operand separation [2,5], Fine-grained tokenization [24]. To bridge the granularity gap between instruction-level operations and token-based analysis, we establish a mapping

4.3.1 Function Embedding Generation in BERT-Based Models

For a binary function F with token sequence

The embedding process involves: Token Embeddings:

After processing through N Transformer layers, the output vector at the [CLS] position is extracted as the function embedding:

4.3.2 Gradient Computation in Embedding Space

In BERT-based BCSD models, binary functions are first tokenized into discrete token sequences

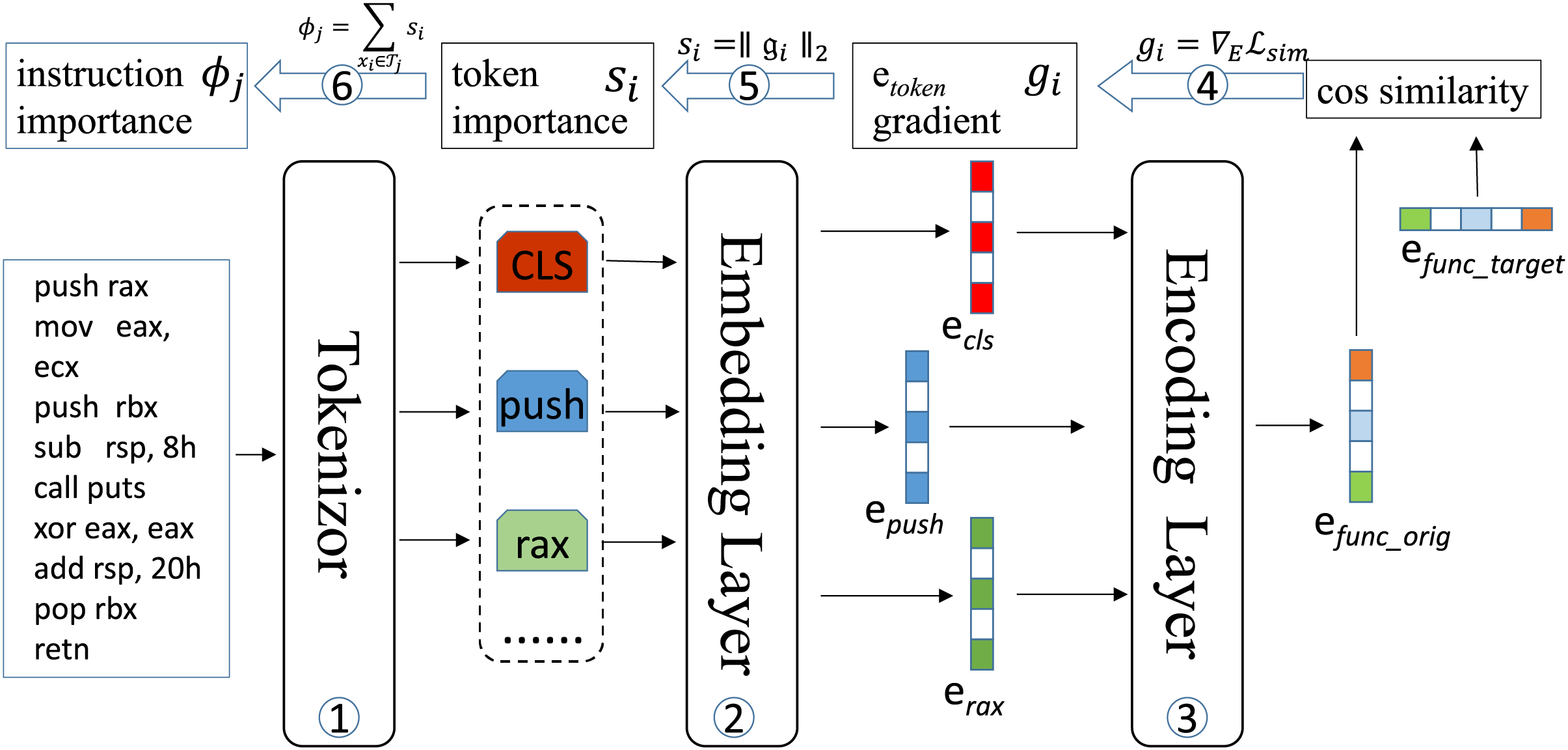

To enable efficient gradient computation while maintaining model integrity, we redesign the BERT architecture using a decoupled computation paradigm. As illustrated in Fig. 3, this involves partitioning the model into two isolated computational units:

Figure 3: Workflow for assembly instruction importance computation: BERT model decoupled into embedding and encoder modules; (1) Assembly instructions tokenized into discrete tokens; (2) Discrete tokens mapped to continuous embedding space; (3) Function embeddings computed through encoder processing; (4) Similarity loss backpropagated to compute token embedding gradients; (5) Caculate the

1. Embedding Module (

where

2. Encoder Module (

We map token IDs

we make a Loss Definition, for original function

As shown in Fig. 3, we employ gradient attribution to identify tokens critical for similarity decisions. First, we compute gradients with respect to token embeddings

This measures sensitivity of similarity loss to embedding perturbations. Then, compute the

Higher

4.3.3 Instruction-Level Importance Aggregation

Token importance scores are aggregated to the instruction level via mapping

The resulting

4.4 Sliding Window Selection for Critical Instruction Segments

Experimental analysis reveals that perturbing single instructions yields insufficient similarity reduction, necessitating the relocation of contiguous instruction blocks to achieve the target threshold

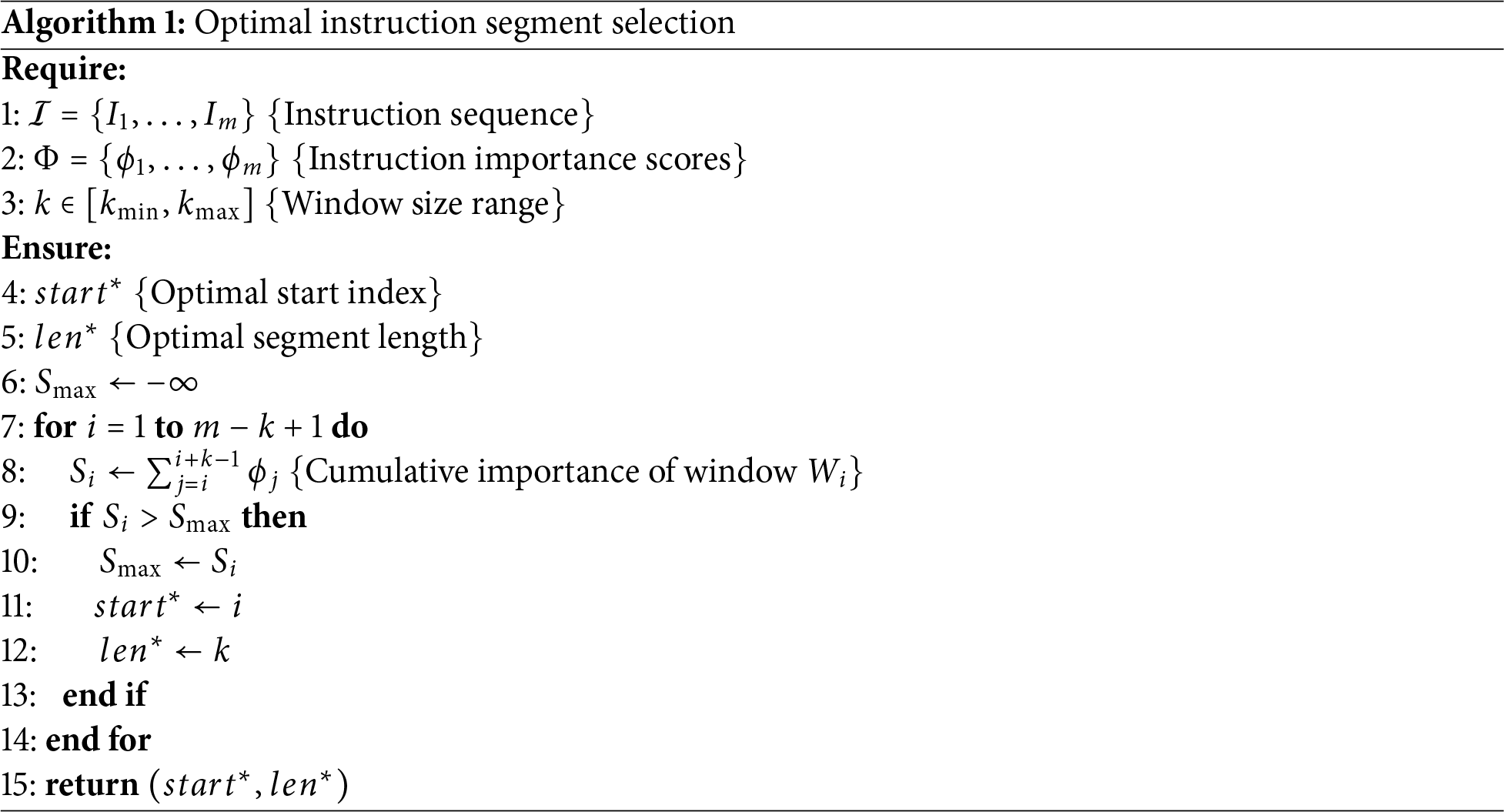

The algorithm identifies the optimal contiguous instruction segment for relocation through three key steps:

1. Initialization (Line 6): Set

2. Sliding Window Search (Lines 7–14): For each possible window of size

• Compute cumulative importance

• Update

3. Output (Line 15): Return the optimal segment

The algorithm identifies the maximally impactful contiguous segment of

where the selected segment

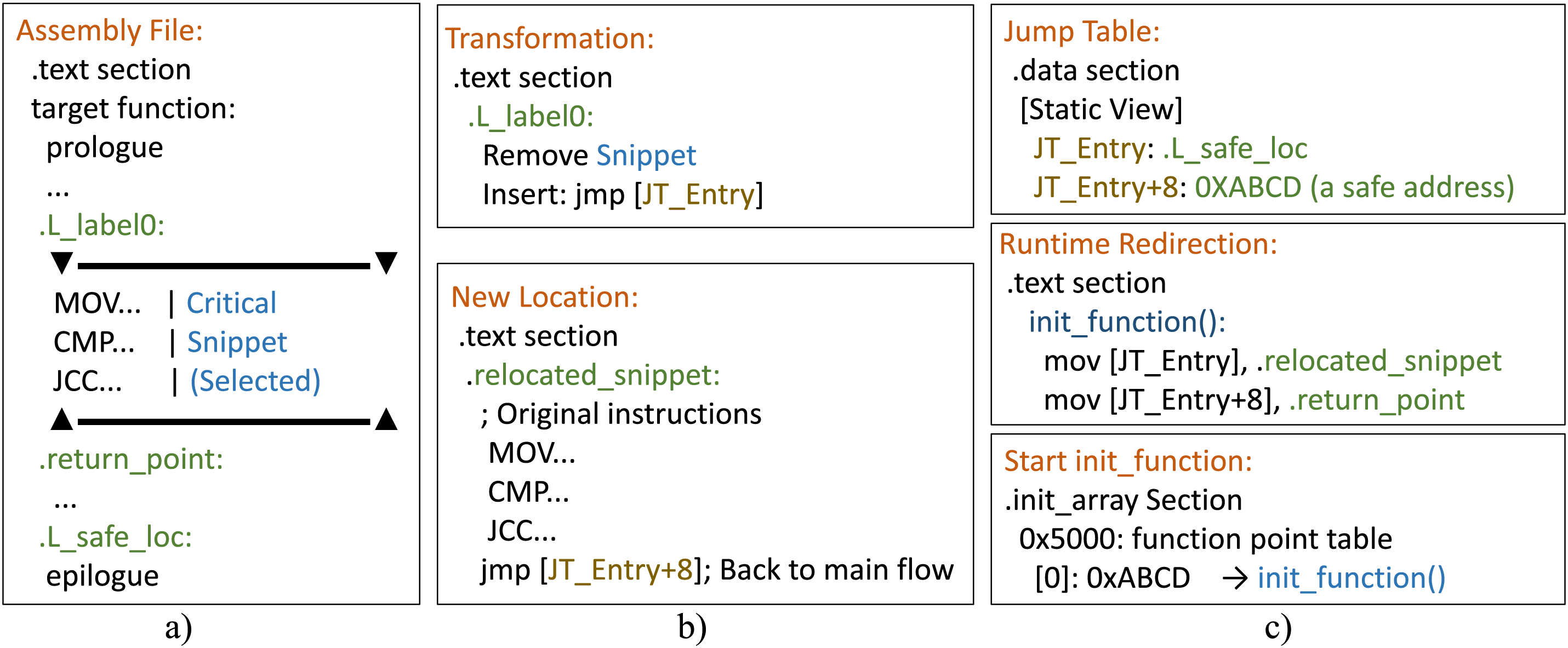

4.5 Assembly-Level Transformation

After identifying the critical instruction segment

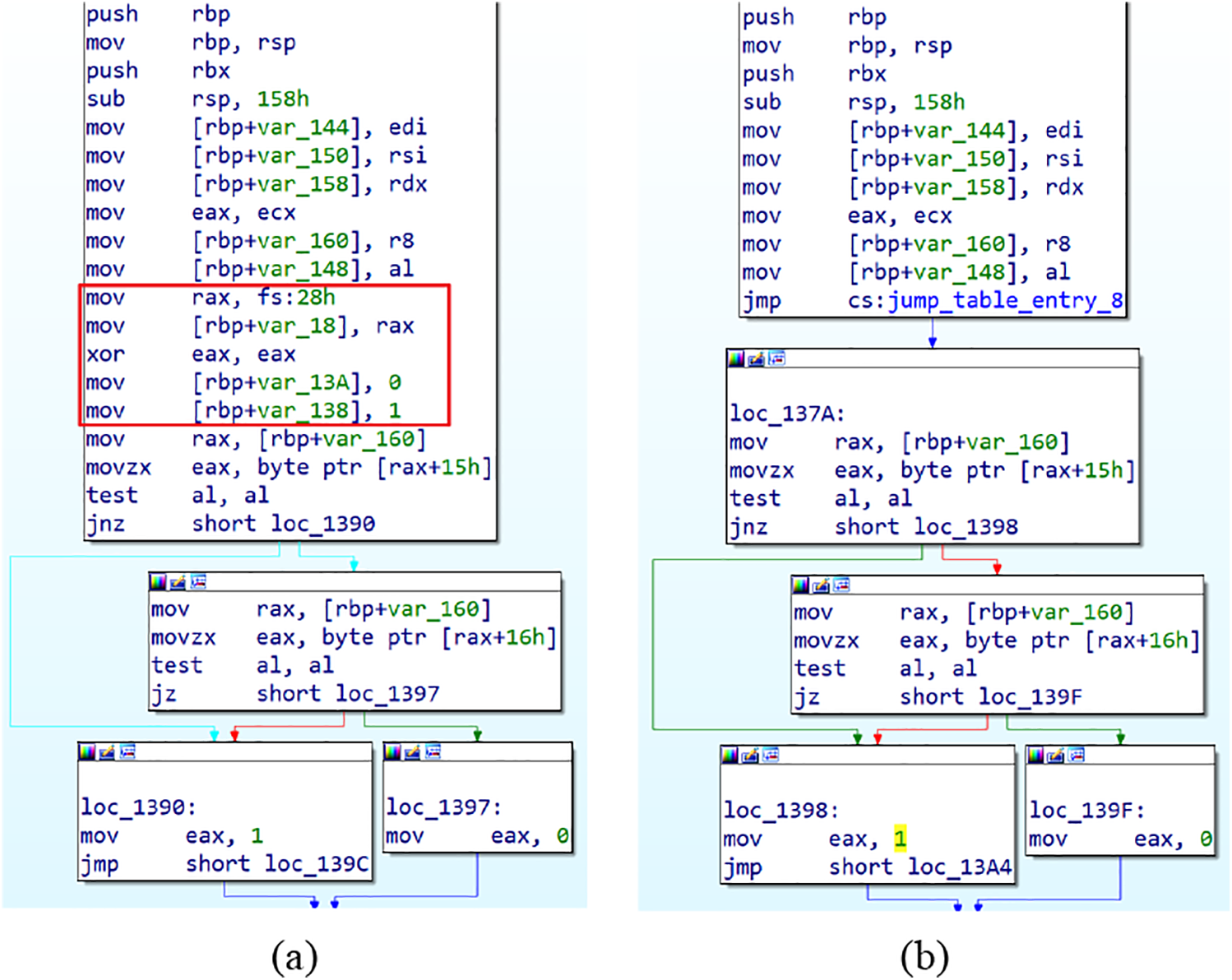

Figure 4: Instruction transfer mechanism: (a) Original function sequence with critical segment

When disassembling binary files, there are two disassembly methods: one is Linear Sweep, which processes instructions sequentially and continues past unconditional jumps, and the other is Recursive Descent, which traces control flow (branches/jumps/calls) and incorporates jump targets into function boundaries. Direct relative jumps (e.g., jmp <offset>) are vulnerable to reconstruction by reverse engineering tools (e.g., IDA Pro) using Recursive Descent.

To prevent the transferred code from being recovered by disassembly tools, we implement an evasion-proof transfer mechanism, as shown in Fig. 4c:

1. Indirect Jump: which utilizes memory-indirect mode (e.g., jmp [JT_Entry]) to redirect execution flow during runtime.

2. Dual-Value Jump Table: in the static view, points to an internal label (e.g.,.L_safe_loc), but during runtime execution, redirects to a transferred code segment.

3. Return Jump Repair: Insert jmp [JT_Return] at segment end. Initialize to safe address, runtime target to original return point.

4. Dynamic Initialization:

__attribute__((constructor))

void init_function() {

JT_Entry = &transferred_segment;

JT_Return = &original_ret_addr;

}

5. ELF Integration: Place init_function pointer in.init_array,and loader executes during program initialization.

This multi-stage approach ensures removed instructions appear disconnected from the original function in static analysis while maintaining full runtime functionality through position-transparent execution.

This section systematically evaluates AIMA through four research questions:

RQ1: Do adversarial examples preserve functionality? (Section 5.1)

RQ2: How effective is instruction relocation in evading BCSD models? (Section 5.2)

RQ3: Which critical instruction segment identification method maximizes attack efficacy? (Section 5.3)

RQ4: Can gradient-guided adversarial examples enhance model robustness? (Section 5.4)

All experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6330 CPU @ 2.00 GHz, 128 GB DDR4 RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU (24 GB GDDR6X VRAM), running Ubuntu 22.04 LTS. The GCC-9.4 compiler was used for code compilation and adversarial example generation.

Dataset. We selected the GNU coreutils toolset as the experimental benchmark. As a widely adopted open-source utility collection, coreutils is commonly included in training datasets for code similarity detection tasks. Prior studies confirm that SOTA BCSD models achieve high recognition accuracy (typically >85%) on functions within this benchmark [5]. This ensures observed performance changes stem from adversarial perturbations rather than model unfamiliarity with target functions.

5.1 Functional Correctness of Adversarial Examples

This section addresses RQ1: Do adversarial examples preserve functionality?

We evaluated 91 utilities from GNU Coreutils-8.30 (including ls, cat, and dd) compiled with GCC 9.4 under -c -O0 optimization. This process generated 1411 functions containing 137,861 assembly instructions.

Throughout the experiment, we produced 364 executable binaries. All adversarial variants maintained full functional equivalence with originals, exhibiting no runtime crashes or behavioral deviations. Comprehensive memory analysis using Valgrind confirmed the absence of memory leaks or corruption.

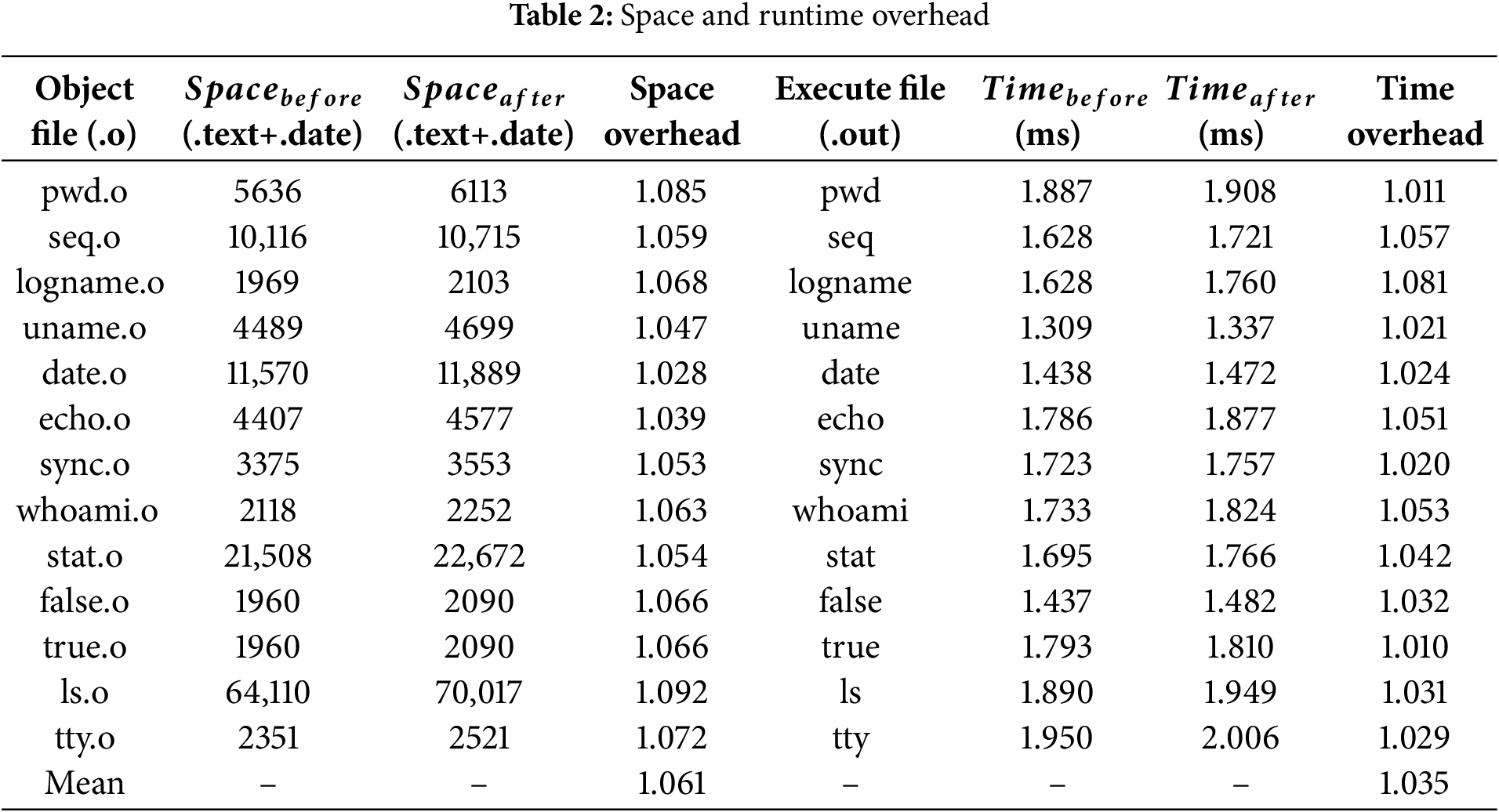

5.1.1 Space and Runtime Overhead Characteristics

Space overhead is one of the primary costs introduced by our method. Instruction relocation results in increased binary size due to the addition of jump instructions in the .text section and the allocation of jump tables in the .data section. To quantify this overhead, we used the size tool to measure the sizes of the .text and .data sections of both the original and adversarial binaries, and compared them statistically. The results show that the average size overhead for the .text section is 1.076, for the .data section it is 1.307, and the overall binary size overhead is 1.06.

Runtime overhead is another key performance cost. The execution time increases due to the additional instruction jumps and access to the jump tables. We measured the runtime overhead by executing 13 representative utilities (e.g., ls, false) with empty arguments over 10,000 iterations. As shown in Table 2, the mean execution latency increased by 3.5%.

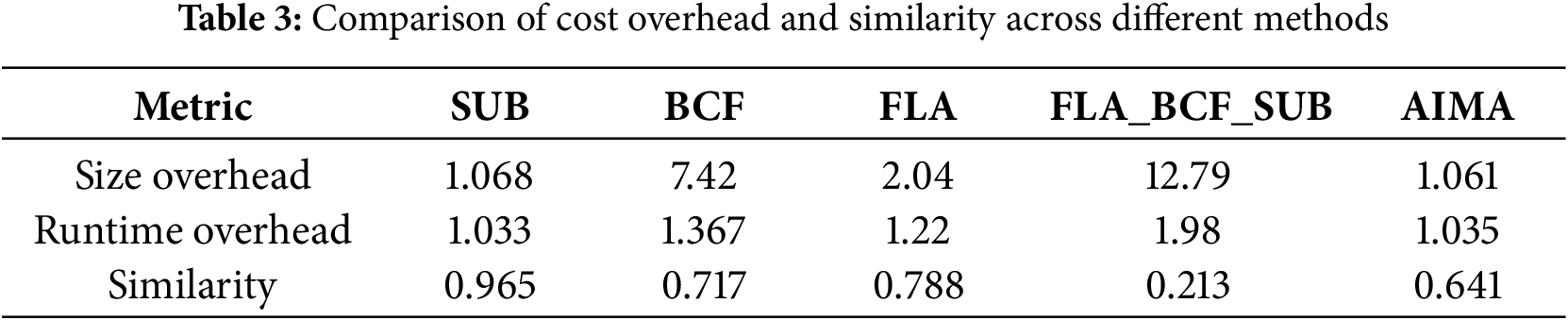

5.1.2 Comparative Analysis with OLLVM Obfuscation

We conducted a comparative analysis with OLLVM [32], a prominent obfuscation framework employing techniques including control flow flattening (FLA), bogus control flow (BCF), and instruction substitution (SUB). These methods were applied both individually and in combination (FLA_BCF_SUB) to the same 1411 functions.

The function size was measured using objdump, and runtime overhead was evaluated using the same methodology as described in the previous section. Similarity between the original and obfuscated functions was assessed using the jTrans and CLAP models, and the average similarity score was computed. The results are presented in Table 3.

• Size Overhead: OLLVM’s BCF and hybrid modes caused substantial bloat (7.42

• Runtime Overhead: OLLVM introduced 1.03

• Similarity: SUB replaces arithmetic/logical operations with semantically equivalent alternatives. Since Transformer architectures encode operational semantics rather than specific opcodes, this yields high similarity scores (0.965). BCF and FLA reorganize basic block sequencing while preserving original instructions within blocks. Transformer models exhibit inherent robustness to such structural permutations through self-attention mechanisms, resulting in limited similarity reduction (0.717–0.788). FLA+BCF+SUB combines these techniques, achieving significantly lower similarity (0.213) at the cost of exponential overhead (12.79

5.1.3 Effectiveness of Assembly Instruction Relocation

We implement instruction relocation through a jump table mechanism that preserves program functionality while concealing critical code segments moved from function bodies. This approach ensures: 1) semantic equivalence through dynamic redirection, 2) evasion of static analysis detection, and 3) compatibility with Binary Code Similarity Detection (BCSD) models.

Fig. 5 demonstrates this technique applied to the do_copy function in Coreutils’ cp utility. The IDA Pro disassembly view reveals:

• Original critical instructions (int the red boxes) removed from the function body

• Control flow redirected via jmp [jump_table_entry_8] (offset loc_137a)

• Seamless continuation at loc_137a post-relocation

Figure 5: Disassembly comparison: (a) Original do_copy function; (b) Adversarial variant with removed instructions.The red boxes indicate the removed instruction segments

Notably, the relocated instructions maintain identical opcode sequences while being logically disconnected from the original function body in static views. This confirms our method’s capability to induce semantic perturbations without altering runtime behavior.

Answer to RQ1: AIMA achieves functional preservation with significantly lower overhead than traditional obfuscation techniques, particularly in size-constrained and performance-sensitive environments.

5.2 Effectiveness of Adversarial Examples

This section addresses RQ2: How effective is instruction relocation in evading BCSD models?

Target Model: We selected jTrans and CLAP as primary adversarial targets. Both employ Transformer-based architectures and achieve state-of-the-art performance in BCSD.

Adversarial Examples Generation: The adversarial examples were generated from 1411 distinct functions compiled from GNU Coreutils 8.30. For each function

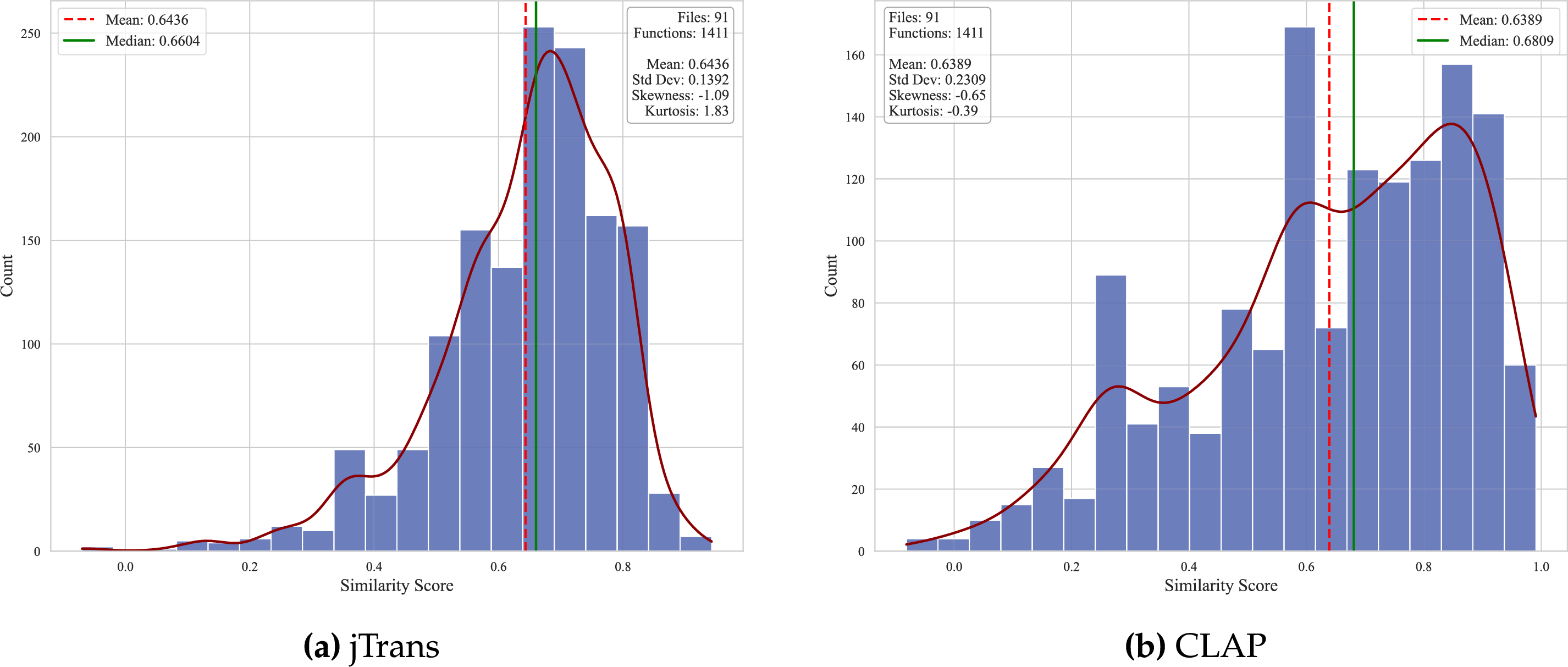

Figure 6: Distribution of similarity scores between original and adversarial examples

Attack Impact Metric: The fundamental measure of attack success is similarity reduction

The adversarial attacks demonstrate significant effectiveness across both models:

• High-Impact Attacks: 20.1% of samples achieved >50% similarity reduction (

• Moderate Impact Dominance: 59.7% of samples achieved 20%–50% similarity reduction (

• Attack-Resistant Cases: 20.3% of samples showed limited reduction (

The method effectively reduces similarity scores in 64.4% (jTrans) and 63.7% (CLAP) of samples, with 20.1% achieving high-impact reduction (

5.2.2 Relationship between Similarity and Sliding Window Ratio

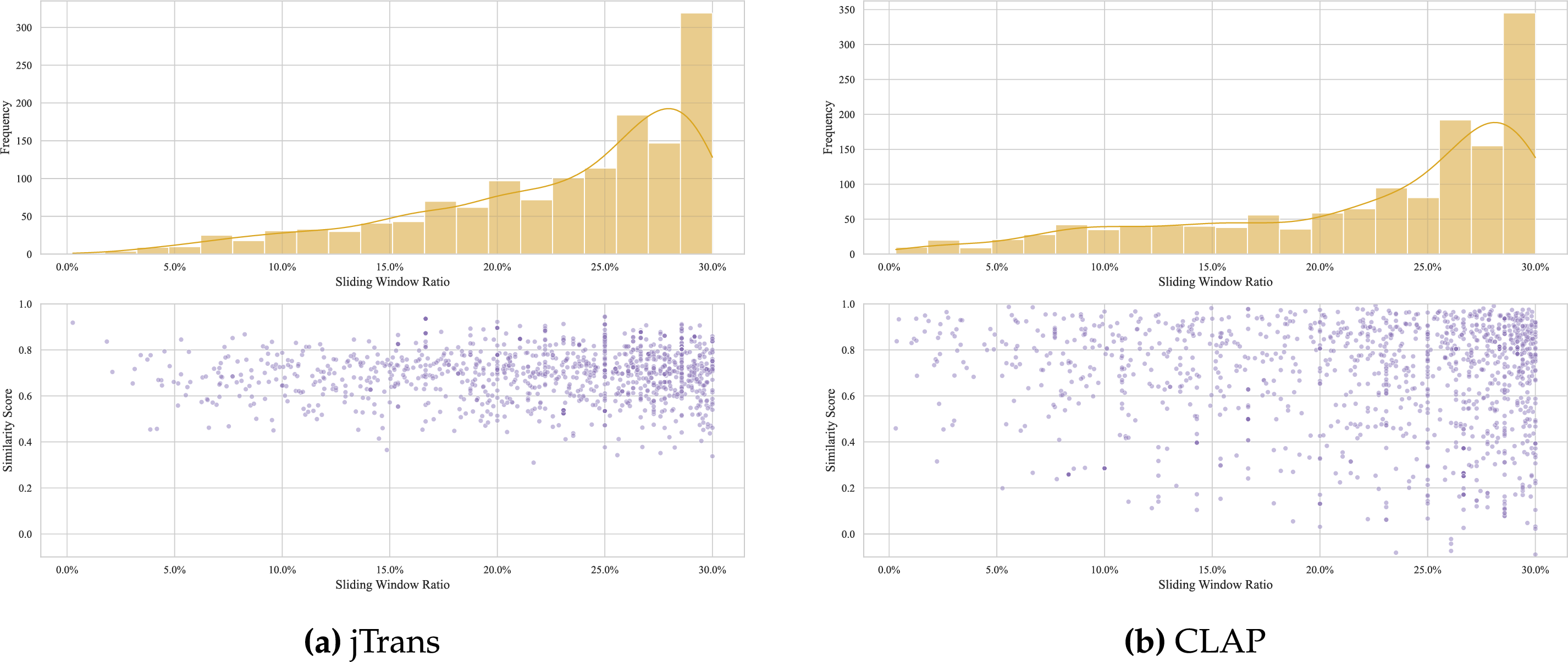

In this experiment, we generated adversarial examples across all possible window sizes ranging from 1 to 0.3 L (where L represents function length). For each function, we selected the window ratio yielding the maximum similarity reduction as the optimal perturbation. Fig. 7 presents the distribution of these optimal window ratios across the dataset, revealing a non-uniform distribution pattern:

Figure 7: Optimal perturbation window ratio distribution and corresponding similarity reduction

Analysis shows a pronounced concentration in the 24%–30% window ratio range (cumulative 54.9% occurrence), with peak density at 27%–30% (35.5%). Crucially, the 24%–27% window ratio achieved the lowest mean similarity (0.578), indicating optimal attack efficacy. This distribution demonstrates two key phenomena:

1. Nonlinear efficacy: While larger windows generally increase similarity reduction (mean similarity decreases from 0.770 at 0%–3% to 0.578 at 24%–27%), the 27%–30% window shows reduced effectiveness (mean similarity 0.709), revealing a saturation point beyond 27%.

2. Efficacy-reversal boundary: Optimal perturbation occurs at 24%–27% window ratio (min similarity 0.578), not at the maximum allowed 30% ratio. This suggests functional over-perturbation beyond critical thresholds may diminish attack effectiveness.

Thus, we conclude that while larger perturbation windows generally enhance attack effectiveness, the relationship is non-monotonic with diminishing returns beyond critical thresholds (

5.2.3 Function Search Evaluation

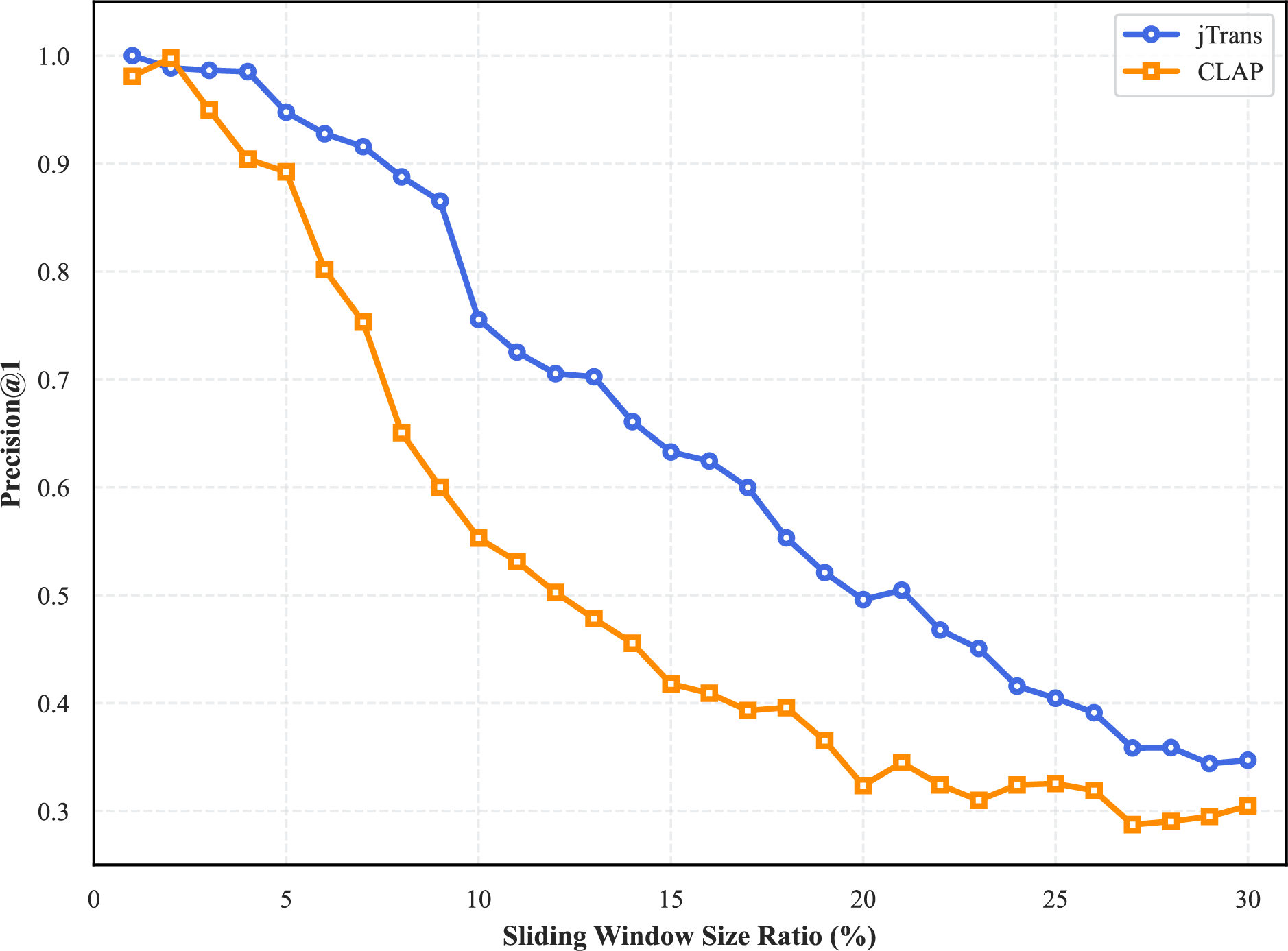

To assess the real-world impact of adversarial examples, we conducted function search experiments as follows. First, we compiled the original Coreutils binaries (GCC 9.4, -O0) with debug symbols and generated adversarial variants across relocation window sizes ranging from 1% to 30% of function instruction length. We then established ground truth mapping through 1:1 function correspondence using symbol tables. After stripping debug symbols to simulate production environments, we executed similarity searches from original to adversarial examples (function matching task). Performance was evaluated using Precision@1, defined as the proportion of queries where the correct match ranked first in the results.

Fig. 8 demonstrates statistically significant degradation in search accuracy. At maximum attack strength (30% window size), Precision@1 of jTrans decreased to 0.347 (65.3% reduction from baseline 1.0), and CLAP decreased to 0.29, confirming AIMA’s practical threat to binary analysis workflows.

Figure 8: Function search accuracy (Precision@1) under varying sliding window size ratio

Answer to RQ2: Adversarial examples significantly reduce similarity scores in both models (mean

5.3 Comparative Analysis of Token Saliency Methods

This section addresses RQ3: Which critical instruction segment identification method maximizes attack efficacy?

Identifying an efficient instruction saliency evaluation method is crucial for AIMA’s adversarial example generation. To this end, this section comparatively analyzes three importance assessment approaches:

1. Gradient-based attribution [33]

2. Attention-weight aggregation [34]

3. Gradient-embedding dot product [34]

In BERT-based models, the attention mechanism computes association weights between all tokens (including the [CLS] token) [35,36]. Through these attention operations, the [CLS] token interacts with all other tokens in the sequence, progressively integrating global information.

To calculate the attention weights of the [CLS] token (position 0) with respect to all other tokens (using a single attention head as an example):

where

The contextual representation of the [CLS] token is then derived as a weighted sum of the value vectors:

Attention layers assign weights to each input token which are often interpreted as indicators of contextual semantic importance. However, the explanatory power of attention weights remains debated in NLP literature [37–39].

Gradient-embedding dot product [34] calculate the dot product of the gradient vector

The magnitude of

To systematically evaluate token importance estimation strategies, we compare three established techniques with random token selection serving as the baseline. This comparison addresses whether attention mechanisms reliably identify semantically critical instructions in assembly code.

For each function, we generated adversarial examples across relocation window sizes ranging from 1% to 30% of total instructions (1% increments). At each window size

To quantify the differences in function similarity across mechanisms, we computed descriptive statistics and summarize them in Table 5. The table reports the mean similarity, standard deviation (Std Dev), median, and range (min–max) for each mechanism.

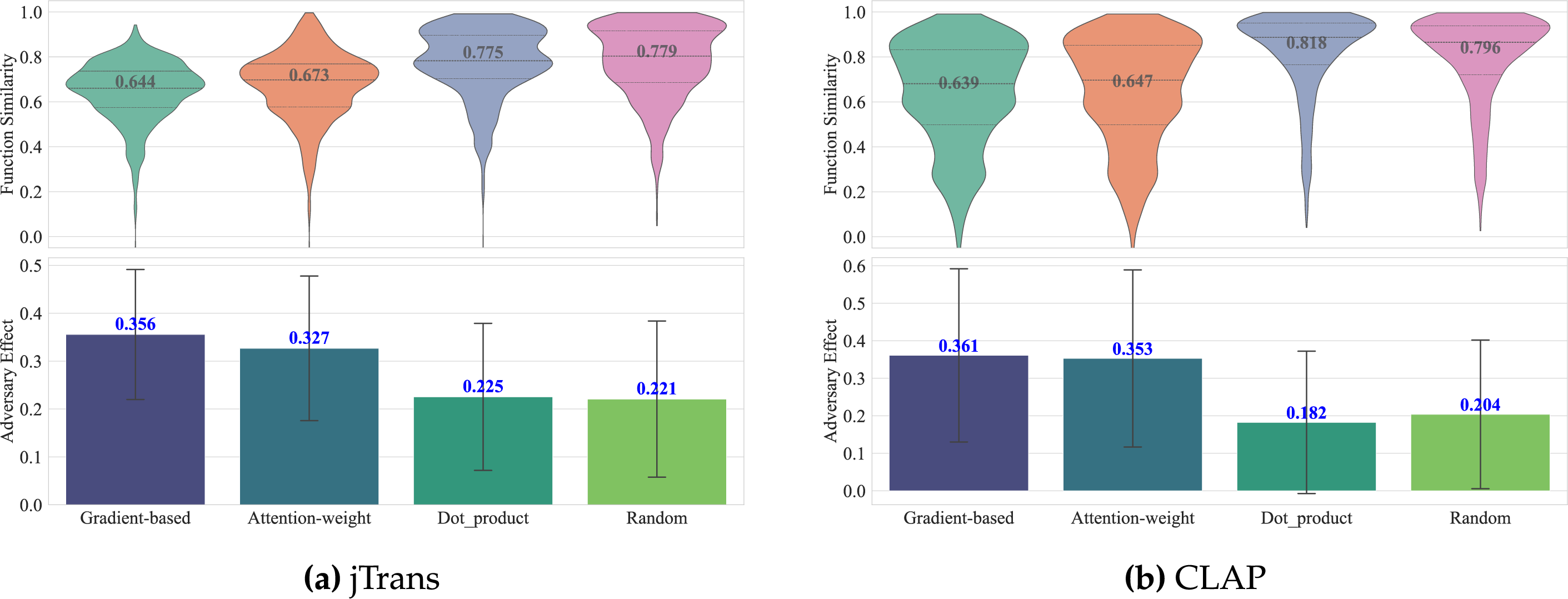

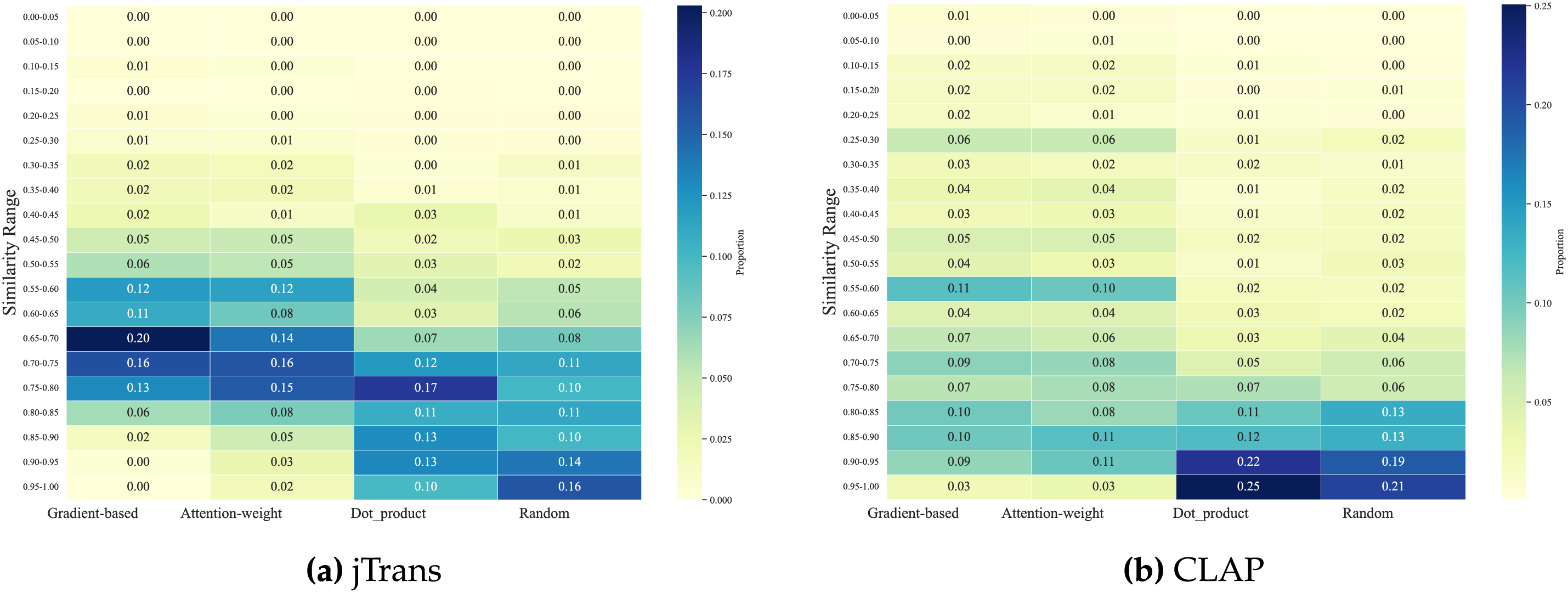

ANOVA confirmed significant differences between methods (

Fig. 9 details the similarity distributions across saliency methods, with Fig. 10 further revealing distribution patterns. Gradient-based attribution demonstrates the highest effectiveness, attention-weight shows moderate efficacy, while both dot_product and random baselines exhibit minimal effectiveness.

Figure 9: Distribution of similarity scores across saliency methods

Figure 10: Proportional distribution of similarity scores across saliency methods

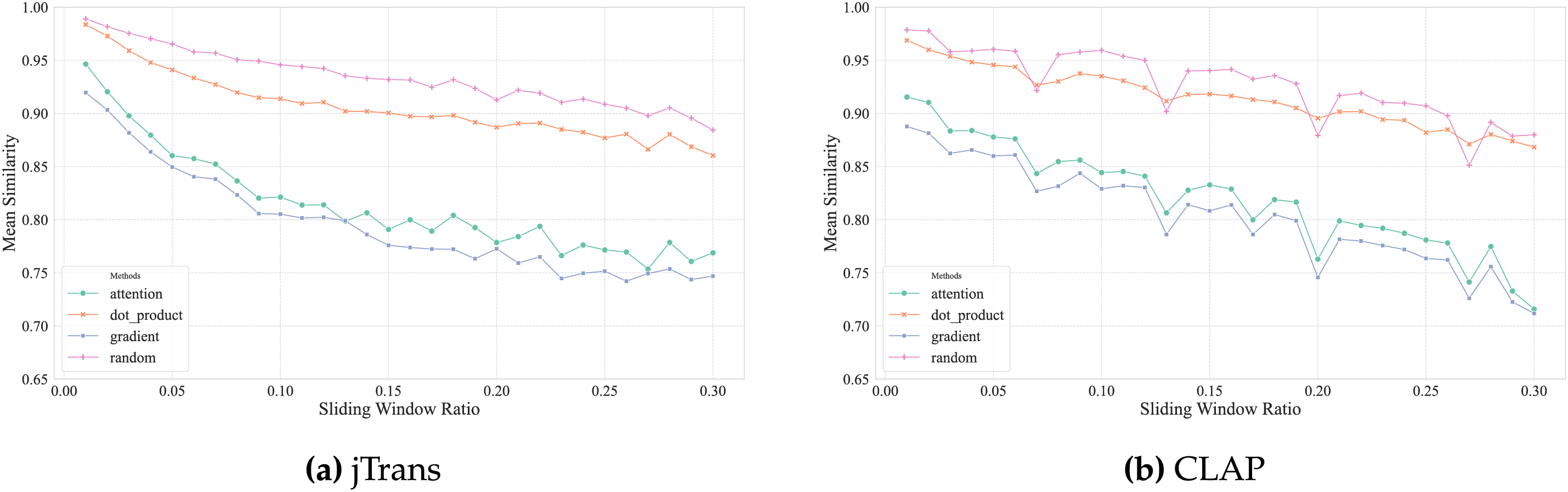

During experimentation, we systematically recorded similarity scores of adversarial examples generated across sliding window sizes ranging from 1% to 30% of function length. Fig. 11 illustrates the relationship between similarity reduction and window size ratio for four saliency methods.

Figure 11: Mean similarity under varying window ratio by saliency method

Gradient-based attribution (blue curve) consistently achieves the lowest similarity scores. This confirms its superiority in identifying semantically critical instructions.

Attention-weight aggregation (green curve) shows competitive but inferior effectiveness, maintaining a 0.05–0.12 similarity gap vs. gradient-based methods.

Gradient-embedding dot product (orange curve) and random selection (pink curve) perform significantly worse (similarity >0.86), indicating their inadequacy for adversarial targeting.

Answer to RQ3: These results demonstrate that gradient-based attribution most effectively identifies critical instructions for similarity reduction, while attention-based methods provide competitive alternatives. The weak performance of dot-product and random approaches underscores the importance of theoretically grounded saliency measures.

5.4 Model Robustness Enhancement

This section addresses RQ4: Can gradient-guided adversarial examples enhance model robustness?

Dataset and Task: We evaluate our approach on the BCSD task using Coreutils-8.30 benchmark dataset. This dataset contains 29,993 function pairs compiled with 4 optimization levels (O0-O3). The task requires determining whether two binary functions originate from the same source code (positive pairs) or different source code (negative pairs).

Evaluation Metric: We adopt Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC) as our primary evaluation metric due to its threshold-agnostic nature and ability to comprehensively evaluate model discrimination capability under adversarial conditions.

Test Models: Base Model–the standard jTrans and CLAP architecture, and Robust Model–the adversarially trained jTrans and CLAP variant.

For each target function in the Coreutils dataset, we generated adversarial examples using the AIMA method. These adversarial examples were incorporated into the training set alongside original functions.

The Baseline models were fine-tuned using the augmented dataset. The adversarial training objective was defined as:

where

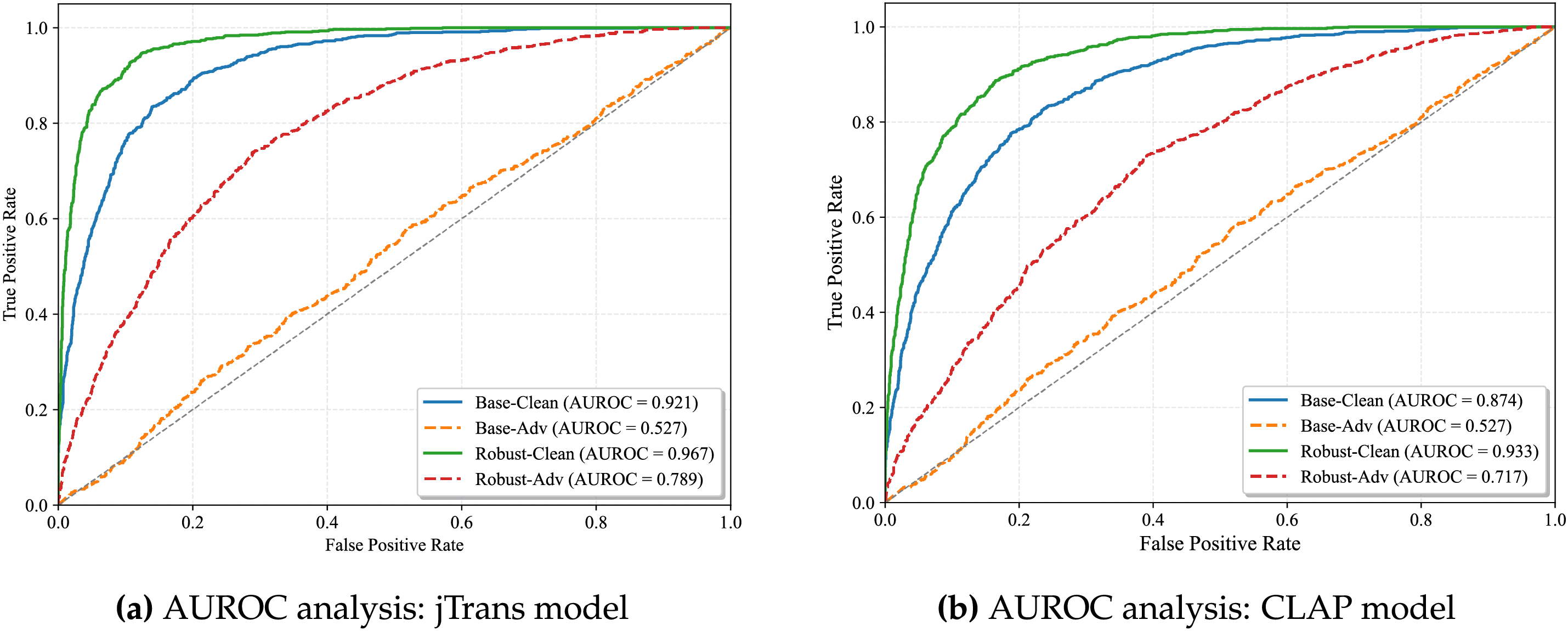

Experimental Results: Table 6 summarizes the AUROC performance across all experimental conditions. Our robust model demonstrates significant improvements in adversarial robustness while maintaining competitive performance on clean data.

Base models exhibit significant AUROC degradation under attack (jTrans:

Figure 12: Adversarial robustness evaluation: AUROC curves under clean and adversarial conditions

Answer to RQ4: Adversarial training significantly enhances resilience for both models. CLAP shows higher clean-data improvement (+6.8% vs. +5.0%), while jTrans achieves greater relative robustness gain (66.5% vs. 54.8%). This demonstrates AIMA’s effectiveness in enhancing state-of-the-art BCSD models.

Although this work primarily targets Transformer-based BCSD models,such as jTrans and CLAP, the core idea of gradient-guided critical segment identification is inherently generalizable to other deep learning architectures. The vulnerability of deep neural networks to gradient-based adversarial attacks has been widely observed across domains, including computer vision and natural language processing, suggesting that such susceptibility is not limited to a specific model family.

Our approach builds on two fundamental principles that are largely architecture-agnostic. First, gradient sensitivity: in any differentiable model—whether RNN, CNN, or GNN—the gradients with respect to input embeddings can serve as indicators of feature importance. This enables the identification of semantically critical components in the input. Second, semantic-preserving perturbation: by performing assembly-level code relocation, our method decouples the adversarial process from model internals. The modifications occur at the structural level of the binary, preserving runtime behavior while subtly altering the representation seen by the model.

Given the superior performance and growing dominance of Transformer models in BCSD tasks, we focus our empirical evaluation on this architecture. However, the underlying mechanism—identifying sensitive input regions via gradient analysis and applying semantics-preserving transformations—is not exclusive to Transformers. In future work, we will extend this investigation to CNN-, RNN-, and GNN-based BCSD systems, and explore defense strategies against such architecture-agnostic adversarial attacks.

This paper introduces AIMA—a novel approach for generating adversarial examples against Transformer-based BCSD models via assembly-level instruction relocation. We establish the first semantics-preserving adversarial methodology operating at the assembly intermediate representation level, enabling functional-equivalent perturbations through gradient-guided critical segment relocation. The core innovation involves a jump table mechanism that maintains runtime functionality while inducing static-view “deletion” effects. Furthermore, we explore how the generated adversarial examples can be leveraged within an adversarial training paradigm to enhance model robustness. Extensive validation shows AIMA reduces similarity scores by up to 35.8% in state-of-the-art BCSD models while improving robustness by 5.9% AUROC when integrated into training workflows.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by Key Laboratory of Cyberspace Security, Ministry of Education, China.

Author Contributions: Ran Wei: Software, Formal Analysis, Writing—Original Draft. Hui Shu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Review & Editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The source code, datasets, and preprocessed binaries used in this study are publicly available at: https://github.com/xiazixiazi/AIMA (accessed on 01 September 2025).

Ethics Approval: This research does not involve human participants or animals. Ethical approval is not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1https://github.com/xiazixiazi/AIMA (accessed on 01 September 2025)

References

1. Haq IU, Caballero J. A survey of binary code similarity. ACM Comput Surv. 2022;54(3):1–38. doi:10.1145/3446371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Artuso F, Mormando M, Di Luna GA, Querzoni L. Binbert: binary code understanding with a fine-tunable and execution-aware transformer. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2025;22(1):308–26. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2024.3397660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Flake H. Structural comparison of executable objects. In: Detection of Intrusions and Malware & Vulnerability Assessment, GI SIG SIDAR Workshop, DIMVA 2004. Dortmund, Germany: GI; 2004. p. 61–73. [Google Scholar]

4. Gu Y, Shu H, Kang F, Hu F. Uniasm: binary code similarity detection without fine-tuning. Neurocomputing. 2025;630(11):129646. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2025.129646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wang H, Qu W, Katz G, Zhu W, Gao Z, Qiu H, et al. jTrans: jump-aware transformer for binary code similarity detection. In: Proceedings of the 31st ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis; 2022 Jul 18–22; Virtual. p. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

6. Wang H, Gao Z, Zhang C, Sha Z, Sun M, Zhou Y, et al. CLAP: learning transferable binary code representations with natural language supervision. In: Proceedings of the 33rd ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis; 2024 Sep 16–20; Vienna, Austria. p. 503–15. [Google Scholar]

7. Kurakin A, Goodfellow IJ, Bengio S. Adversarial examples in the physical world. In: Artificial intelligence safety and security. Boca Raton, FL, USA: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2018. p. 99–112. [Google Scholar]

8. Yan M, Chen J, Cao X, Wu Z, Kang Y, Wang Z. Revisiting deep neural network test coverage from the test effectiveness perspective. J Softw Evolut Process. 2024;36(4):e2561. doi:10.1002/smr.2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Shen Q, Chen J, Zhang JM, Wang H, Liu S, Tian M. Natural test generation for precise testing of question answering software. In: Proceedings of the 37th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering; 2022 Oct 10–14; Rochester, MI, USA. p. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

10. Zhang H, Li Z, Li G, Ma L, Liu Y, Jin Z. Generating adversarial examples for holding robustness of source code processing models. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(1):1169–76. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i01.5469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yang Z, Shi J, He J, Lo D. Natural attack for pre-trained models of code. In: Proceedings of the 44th International Conference on Software Engineering; 2022 May 21–29; Pittsburgh, PA, USA. p. 1482–93. [Google Scholar]

12. Zhang H, Fu Z, Li G, Ma L, Zhao Z, Yang H, et al. Towards robustness of deep program processing models—detection, estimation, and enhancement. ACM Transact Softw Eng Methodol (TOSEM). 2022;31(3):1–40. doi:10.1145/3511887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ling X, Wu L, Zhang J, Qu Z, Deng W, Chen X, et al. Adversarial attacks against Windows PE malware detection: a survey of the state-of-the-art. Comput Secur. 2023;128:103134. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2023.103134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Qiao Y, Zhang W, Tian Z, Yang LT, Liu Y, Alazab M. Adversarial malware sample generation method based on the prototype of deep learning detector. Comput Secur. 2022;119:102762. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2022.102762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Lucas K, Sharif M, Bauer L, Reiter MK, Shintre S. Malware makeover: breaking ml-based static analysis by modifying executable bytes. In: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2021 Jun 7–11; Virtual. p. 744–58. [Google Scholar]

16. Zhang Z, Tao G, Shen G, An S, Xu Q, Liu Y, et al. PELICAN: exploiting backdoors of naturally trained deep learning models in binary code analysis. In: 32nd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 23); 2023 Aug 9–11; Anaheim, CA, USA. p. 2365–82. [Google Scholar]

17. Linn C, Debray S. Obfuscation of executable code to improve resistance to static disassembly. In: Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2003 Oct 27–30; Washington, DC, USA. p. 290–9. [Google Scholar]

18. Meng X, Miller BP. Binary code is not easy. In: Proceedings of the 25th International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis; 2016 Jul 18–20; Saarbrücken, Germany. p. 24–35. [Google Scholar]

19. Chandramohan M, Xue Y, Xu Z, Liu Y, Cho CY, Tan HBK. Bingo: cross-architecture cross-os binary search. In: Proceedings of the 2016 24th ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Foundations of Software Engineering; 2016 Nov 13–18; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 678–89. [Google Scholar]

20. Bensaoud A, Kalita J, Bensaoud M. A survey of malware detection using deep learning. Mach Learn Applicat. 2024;16(21):100546. doi:10.1016/j.mlwa.2024.100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Feng Q, Wang M, Zhang M, Zhou R, Henderson A, Yin H. Extracting conditional formulas for cross-platform bug search. In: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2017 Apr 2–6; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. p. 346–59. [Google Scholar]

22. Kargén U, Shahmehri N. Towards robust instruction-level trace alignment of binary code. In: 2017 32nd IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering (ASE); 2017 Oct 30–Nov 3; Urbana, IL, USA. p. 342–52. [Google Scholar]

23. Ren X, Ho M, Ming J, Lei Y, Li L. Unleashing the hidden power of compiler optimization on binary code difference: an empirical study. In: Proceedings of the 42nd ACM SIGPLAN International Conference on Programming Language Design and Implementation; 2021 Jun 20–25; Virtual. p. 142–57. [Google Scholar]

24. Li X, Qu Y, Yin H. PalmTree: learning an assembly language model for instruction embedding. In: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security CCS ’21; 2021 Nov 15–19; Virtual. p. 3236–51. [Google Scholar]

25. Demetrio L, Coull SE, Biggio B, Lagorio G, Armando A, Roli F. Adversarial exemples: a survey and experimental evaluation of practical attacks on machine learning for windows malware detection. ACM Transact Priv Secur (TOPS). 2021;24(4):1–31. doi:10.1145/3473039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wang Z, You H, Chen J, Zhang Y, Dong X, Zhang W. Prioritizing test inputs for deep neural networks via mutation analysis. In: 2021 IEEE/ACM 43rd International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE); 2021 May 22–30; Madrid, Spain. p. 397–409. [Google Scholar]

27. Hyde R. The art of assembly language. San Francisco, CA, USA: No Starch Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

28. He H, Lin X, Weng Z, Zhao R, Gan S, Chen L, et al. Code is not natural language: unlock the power of semantics-oriented graph representation for binary code similarity detection. In: 33rd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 24); 2024 Aug 14–16; Philadelphia, PA, USA; 2024. [Google Scholar]

29. Aho AV, Lam MS, Sethi R, Ullman JD. Compilers: principles, techniques, and tools. Boston, MA, USA: Addison-Wesley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

30. Stallman RM. Using and porting the GNU compiler collection. Vol. 86. Boston, MA, USA: Free Software Foundation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

31. Massarelli L, Di Luna GA, Petroni F, Baldoni R, Querzoni L. Safe: self-attentive function embeddings for binary similarity. In: International Conference on Detection of Intrusions and Malware, and Vulnerability Assessment. Cham, Swizerland: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 309–29. [Google Scholar]

32. Junod P, Rinaldini J, Wehrli J, Michielin J. Obfuscator-LLVM–software protection for the masses. In: 2015 IEEE/ACM 1st International Workshop on Software Protection; 2015 May 19–19; Florence, Italy. p. 3–9. doi:10.1109/spro.2015.10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zou A, Wang Z, Carlini N, Nasr M, Kolter JZ, Fredrikson M. Universal and transferable adversarial attacks on aligned language models. arXiv:2307.15043. 2023. [Google Scholar]

34. Clark K, Khandelwal U, Levy O, Manning CD. What does bert look at? An analysis of bert’s attention. arXiv:1906.04341. 2019. [Google Scholar]

35. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. In: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS’17); 2017 Dec 4–9; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 6000–10. [Google Scholar]

36. Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In: Burstein J, Doran C, Solorio T, editors. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers); 2019 Jun 2–7; Minneapolis, MN, USA. p. 4171–86. [Google Scholar]

37. Bastings J, Filippova K. The elephant in the interpretability room: why use attention as explanation when we have saliency methods? arXiv:2010.05607. 2020. [Google Scholar]

38. Jain S, Wallace BC. Attention is not explanation. arXiv:1902.10186. 2019. [Google Scholar]

39. Wiegreffe S, Pinter Y. Attention is not not explanation. arXiv:1908.04626. 2019. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools