Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Impact of Data Processing Techniques on AI Models for Attack-Based Imbalanced and Encrypted Traffic within IoT Environments

1 Department of Cyber Security, Kookmin University, Seoul, 02707, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Information Security, Cryptography and Mathematics, Kookmin University, Seoul, 02707, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Hwankuk Kim. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Intelligence and Security Enhancement for Internet of Things)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069608

Received 26 June 2025; Accepted 19 August 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

With the increasing emphasis on personal information protection, encryption through security protocols has emerged as a critical requirement in data transmission and reception processes. Nevertheless, IoT ecosystems comprise heterogeneous networks where outdated systems coexist with the latest devices, spanning a range of devices from non-encrypted ones to fully encrypted ones. Given the limited visibility into payloads in this context, this study investigates AI-based attack detection methods that leverage encrypted traffic metadata, eliminating the need for decryption and minimizing system performance degradation—especially in light of these heterogeneous devices. Using the UNSW-NB15 and CICIoT-2023 dataset, encrypted and unencrypted traffic were categorized according to security protocol, and AI-based intrusion detection experiments were conducted for each traffic type based on metadata. To mitigate the problem of class imbalance, eight different data sampling techniques were applied. The effectiveness of these sampling techniques was then comparatively analyzed using two ensemble models and three Deep Learning (DL) models from various perspectives. The experimental results confirmed that metadata-based attack detection is feasible using only encrypted traffic. In the UNSW-NB15 dataset, the f1-score of encrypted traffic was approximately 0.98, which is 4.3% higher than that of unencrypted traffic (approximately 0.94). In addition, analysis of the encrypted traffic in the CICIoT-2023 dataset using the same method showed a significantly lower f1-score of roughly 0.43, indicating that the quality of the dataset and the preprocessing approach have a substantial impact on detection performance. Furthermore, when data sampling techniques were applied to encrypted traffic, the recall in the UNSW-NB15 (Encrypted) dataset improved by up to 23.0%, and in the CICIoT-2023 (Encrypted) dataset by 20.26%, showing a similar level of improvement. Notably, in CICIoT-2023, f1-score and Receiver Operation Characteristic-Area Under the Curve (ROC-AUC) increased by 59.0% and 55.94%, respectively. These results suggest that data sampling can have a positive effect even in encrypted environments. However, the extent of the improvement may vary depending on data quality, model architecture, and sampling strategy.Keywords

As concerns over personal data protection grow, the network paradigm is shifting toward enhanced data protection through the application of security protocols during data transmission and reception. Not only in traditional wired and wireless communication systems, but also in evolving communication environments such as IoT and 5th Generation Mobile Networks (5G), plaintext data is increasingly being transformed into encrypted formats. Furthermore, the emergence of cloud computing and big data has led to service expansion, making encryption of network traffic essential to prevent data breaches during storage and transmission. However, the IoT environment represents a heterogeneous network that spans from outdated legacy devices to the latest devices. Many of these devices are unable to support encryption properly due to performance limitations or cost constraints. In such encrypted IoT environments, where encryption status may vary, there is a growing need for AI-based attack detection that operates without decryption by utilizing metadata from encrypted traffic.

The cyber threats posed by encryption. With changes in the communication environment, hackers are increasingly exploiting encrypted communication services and infrastructure to conceal their attacks and evade detection techniques. Cyberattacks that exploit encryption technologies to evade conventional plaintext-based detection methods and legacy security appliances are continuously on the rise. As reported in SonicWall’s 2024 Threat Analysis Report, cyberattacks using encrypted communication in the Asia region have increased by 117% year-over-year. Transport Layer Security (TLS) provides additional security for web sessions and internet communications, but attackers are increasingly using this security protocol to hide malware, ransomware, zero-day attacks, and more. Traditional firewalls and other traditional security controls lack the capacity or processing power to detect, inspect, and mitigate threats transmitted over HTTP traffic, making it a highly effective means for attackers to execute and deploy attacks [1].

Analyzing encrypted traffic through metadata without decryption. As encrypted traffic becomes increasingly prevalent, it has become crucial to establish countermeasures that can address emerging types of cyber threats. Two primary approaches can be considered to address this challenge. The first approach involves decrypting the encrypted traffic, analyzing the data, and subsequently re-encrypting it. The second strategy entails analyzing the metadata of encrypted traffic without the need for decryption [2]. The first approach, which involves decrypting encrypted traffic to detect cyber threats, presents legal challenges related to privacy protection and introduces substantial computational overhead due to the processes of decryption and re-encryption. As a result, an increasing number of studies are exploring methods that utilize only metadata from encrypted traffic for AI-based analysis without decryption [3–7]. Since this approach enables the extraction of essential information without decrypting the encrypted data, it reduces both legal risks and system performance burdens.

Technical challenges. First, difficulty in collecting encrypted traffic and utilizing it for research. Network traffic analysis using AI has been ongoing since the 1990s, with studies based on datasets such as KDDCUP99 [8] and NSL-KDD [9], which have facilitated a range of subsequent research and validation efforts. However, studies specifically targeting encrypted traffic have only just begun in earnest within the past five to ten years, making it difficult to secure validated datasets. At present, there are two approaches for applying AI to encrypted traffic. The first involves extracting necessary data by identifying security protocols from existing verified network traffic datasets. The second approach entails generating encrypted traffic directly and using it for analysis. Conducting research and experiments under the current conditions, where encrypted traffic data is limited, presents multiple constraints. Second, class imbalance and data scarcity issues. Compared to unencrypted traffic, encrypted traffic is relatively limited in volume. Furthermore, there is a pronounced class imbalance within encrypted traffic, where attack traffic occurs far less frequently than normal traffic. This imbalance can make it difficult to get enough training data to train AI models, which can negatively impact learning performance.

This thesis makes the following key contributions.

• Constructed and preprocessed encrypted traffic using two public datasets to make them suitable.

– In the UNSW-NB15 dataset, traffic was categorized into encrypted and unencrypted based on security protocols and service.

– In the CICIoT-2023 dataset, TLS-based traffic was identified, and features such as cipher suite and TLS payload length were directly extracted from raw pcap files.

• Empirically demonstrated that metadata-based attack detection is feasible even with encrypted traffic.

– In the UNSW-NB15 dataset, the f1-score for encrypted traffic was approximately 0.98, which is 4.3% higher than that of unencrypted traffic (approximately 0.94), indicating that effective detection is possible without decryption.

• Verified that data sampling techniques can be effective in improving detection performance, even in encrypted environments with different characteristics.

– In the encrypted traffic of UNSW-NB15 increased by 23.0% and 20.26%, respectively, f1-score improved by up to 59.0% and ROC-AUC increased by 55.94%.

2.1 Encrypted Traffic and Metadata

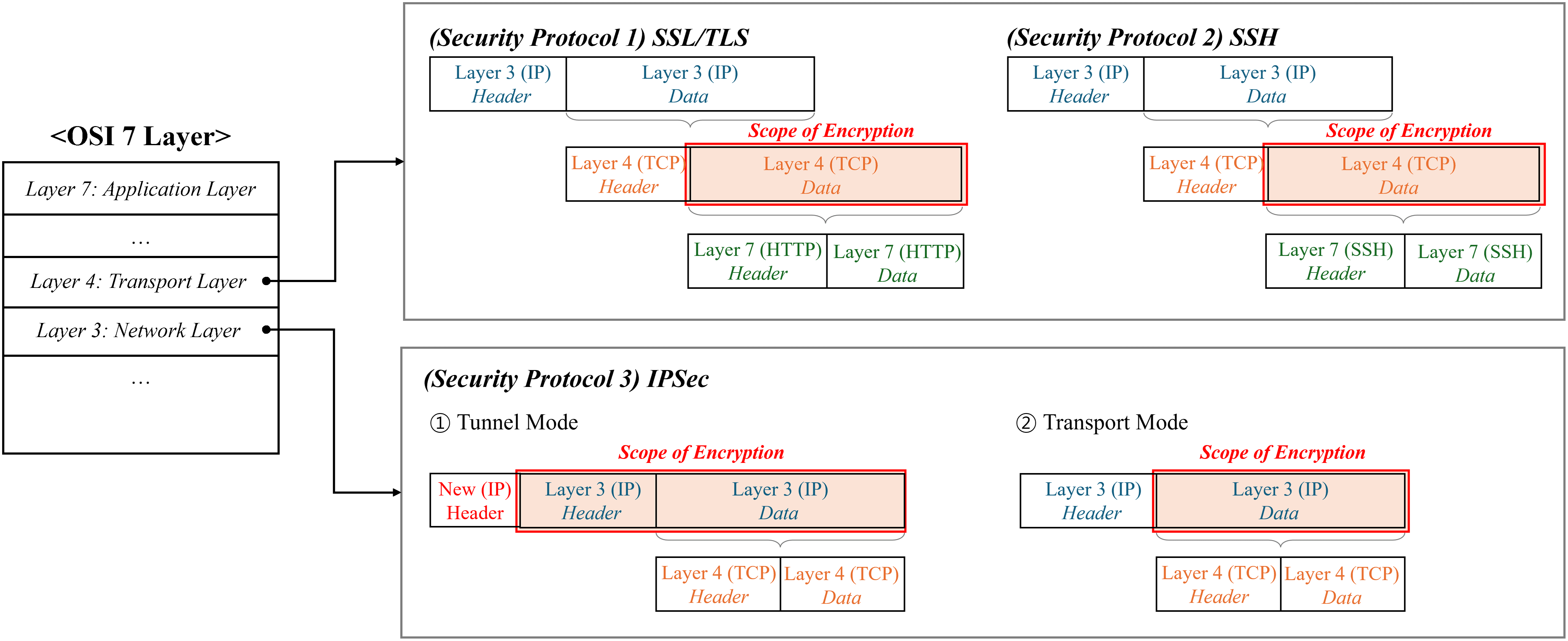

Scope of encryption by security protocol. Encrypted traffic employs security protocols to obscure packet fields that may contain personal information, thereby preventing data leakage during transmission. In contrast, unencrypted traffic does not employ any security protocols, which means that personally identifiable information within the packet is transmitted in plaintext, significantly increasing the risk of data leakage during transmission. As shown in Fig. 1, the extent of encryption applied to a packet varies depending on the evolution and type of security protocol used. For example, Internet Protocol Security (IPSec) functions at the network layer (Layer 3) and offers two modes of operation: tunnel mode and transport mode. In tunnel mode, the entire IP packet—including both the IP header and the IP data—is encrypted, and a new external IP header is then added. In contrast, transport mode leaves the original IP header unencrypted while encrypting only the IP data, which includes TCP header and TCP data. On the other hand, Secure Sockets Layer (SSL)/TLS and Secure Shell (SSH) are representative security protocols that operate at the application layer (Layer 7). These protocols typically encrypt the TCP data (e.g., HTTP or SSH headers and data) while excluding the TCP header from encryption. This research defines encrypted traffic specifically as traffic protected by security protocols like SSL/TLS and SSH, which encrypt the TCP data but retain the TCP header in an unencrypted form. In this study, we limit our analysis to encrypted traffic. This is to ensure that our analysis is based on metadata such as unencrypted TCP headers in encrypted traffic.

Figure 1: Encryption scope of three security protocols: SSL/TLS, SSH, and IPSec

Definition of metadata. In encrypted traffic contexts, metadata can be broadly classified into two categories: IP/TCP header-based metadata and flow-level metadata. IP/TCP header-based metadata consists of information retrieved directly from individual packet headers or calculated based on the values within those headers. For instance, source and destination IP addresses, port numbers, protocol, and service types can be obtained from the IP header, whereas the TCP header provides values like window size and TCP flag status. In contrast, flow-level metadata is derived from aggregating several packets and generally captures the temporal and quantitative distribution of network traffic. Typical examples include the total number of packets, average delay, and the mean packet size between a source and destination. In this study, both types of metadata were used as features in experiments aimed at classifying encrypted traffic into normal and malicious categories.

2.2 Eight Data Sampling Techniques

The following terminology definitions apply to the data processing techniques used in this study. First, the minority class refers to the class within the dataset that contains relatively fewer samples. Second, the majority class denotes the class that contains the highest number of samples in the dataset. Third, borderline data indicates the region near the decision margin between different classes, where data samples are more likely to be misclassified.

Oversampling Techniques Oversampling is a technique used to artificially increase the number of samples in the minority class to balance the class distribution [10]. Representative techniques include Random Oversampling and Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE). Random Oversampling replicates existing samples from the minority class in order to match the sample count of the majority class at a 1:1 ratio [11]. SMOTE is a way to connect two neighboring pieces of data from a small number of classes with a line, and then generate the data at the center of that line. The neighboring data are identified using the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) algorithm. Like Random Oversampling, SMOTE also increases the number of minority class samples until the ratio between minority and majority classes reaches 1:1.

Under-sampling Techniques. Under-sampling is a technique that reduces the number of majority class samples to balance the class distribution [12]. Representative techniques include Random Under-sampling, Near Miss, Tomek Links (Tomek), and Edited Nearest Neighbors (ENN). Random Under-sampling achieves a 1:1 class ratio by randomly discarding samples from the majority class [13]. Near Miss retains only the majority class samples that are in close proximity to the minority class and removes the rest. The method adjusts the majority-to-minority class ratio to 1:1 through the removal of majority class data. Tomek identifies the closest pair of samples from different classes—known as Tomek—and removes the majority class sample in each data pair. Euclidean distance is used to compute the proximity between samples [14]. The process continues until class boundaries are well-defined, without enforcing a fixed sampling ratio. ENN removes majority class samples when they are outnumbered by samples from classes among their neighbors. The KNN algorithm is used to determine neighbors [15]. Like Tomek, majority class samples are continuously removed until class boundaries are sufficiently refined, without adhering to a fixed ratio.

Hybrid-sampling Technique. Hybrid-sampling refers to a method that integrates under-sampling and over-sampling strategies to capitalize on the advantages of each. The process begins by applying one of the two techniques for partial sampling, followed by the other to complete the data-balancing process [16]. Representative methods include SMOTE + Tomek and SMOTE + ENN. In the SMOTE + Tomek approach, synthetic minority class data is generated using SMOTE, after which borderline or noisy samples are removed using the Tomek method. During the data generation phase, the class ratio is adjusted to 1:1, while in the removal phase, the technique proceeds iteratively until class boundaries are well-defined, without enforcing a fixed ratio. SMOTE + ENN first generates minority class data using SMOTE, and subsequently eliminates ambiguous data near the boundary through the ENN technique. As with SMOTE + Tomek, the generation phase ensures a 1:1 class ratio, while the deletion phase is performed iteratively until boundaries are clear, without setting a fixed ratio. However, since ENN removes all neighboring samples belonging to the majority class, it tends to eliminate more data compared to the Tomek method.

3 Proposed Analysis Methodology

3.1 Design of Three Experiments for AI-Based Analysis of Encrypted Traffic

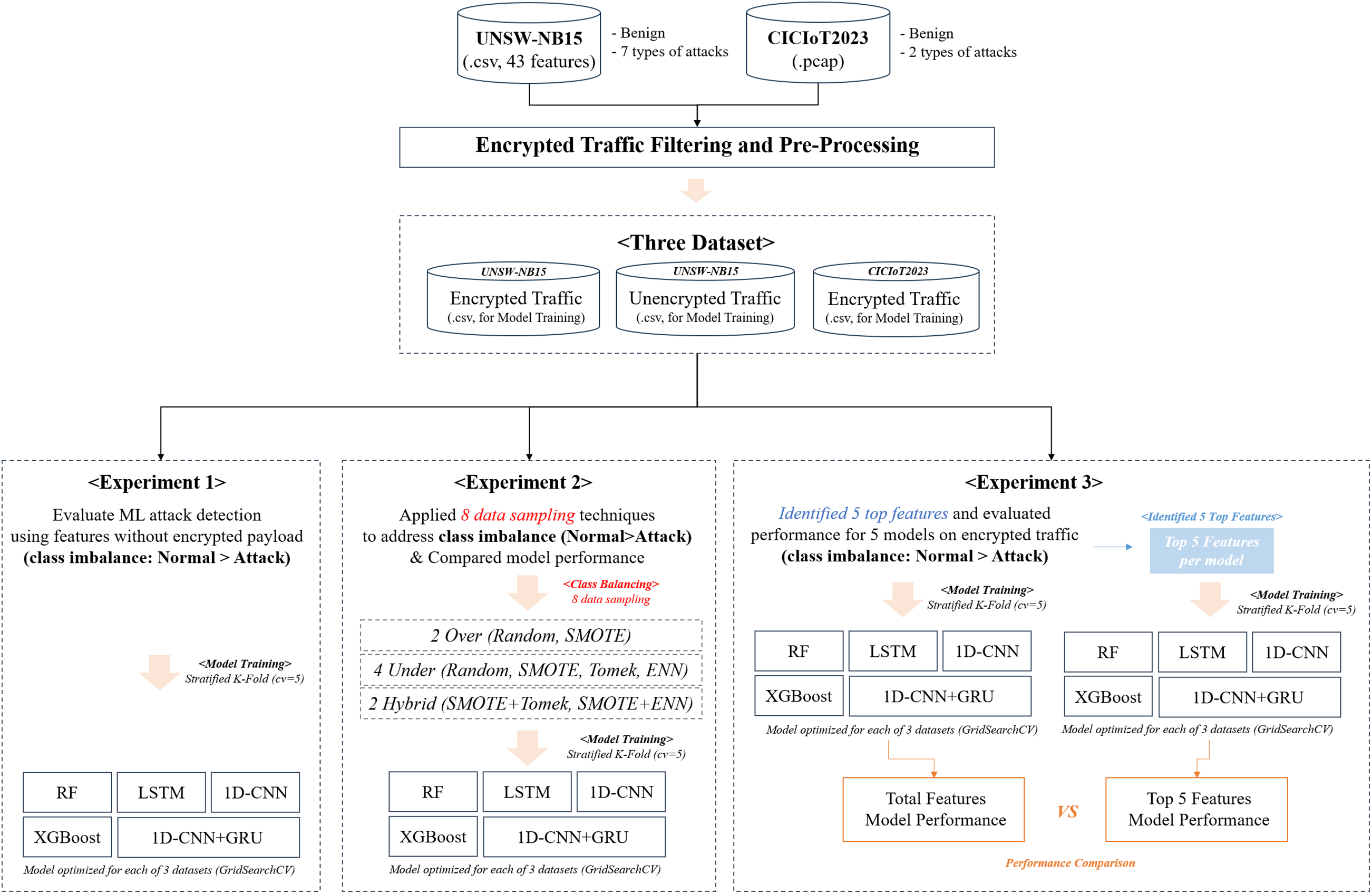

In overview of the proposed analysis method is presented in Fig. 2. First, encrypted traffic is filtered from the benchmark network traffic datasets, UNSW-NB15 and CICIoT-2023 (Section 3.2). Next, the common configuration settings used across the AI models and optimization techniques in this study are described (Section 3.3). Based on this experimental setup, three experiments were conducted using the filtered encrypted and unencrypted traffic from UNSW-NB15 and the encrypted traffic from CICIoT-2023. In the first experiment, we evaluated whether AI-based attack detection is feasible using only the metadata of encrypted traffic and analyzed the characteristics of each traffic type through data visualization. In the second experiment, we conducted a preliminary analysis of the impact of eight data sampling techniques on model performance, considering the class imbalance between attack and normal traffic that may occur in real-world network environments. The third experiment focused on encrypted traffic, identifying the top five features contributing to the detection of attack and normal traffic in each of the five AI models. We then analyzed how detection performance changed when using only these key features. Collectively, these three experiments serve as a preliminary investigation to verify the feasibility of AI-based attack detection in encrypted traffic environments.

Figure 2: Objectives and main procedures of the three experiments

3.2 Encrypted Traffic Filtering and Pre-Processing

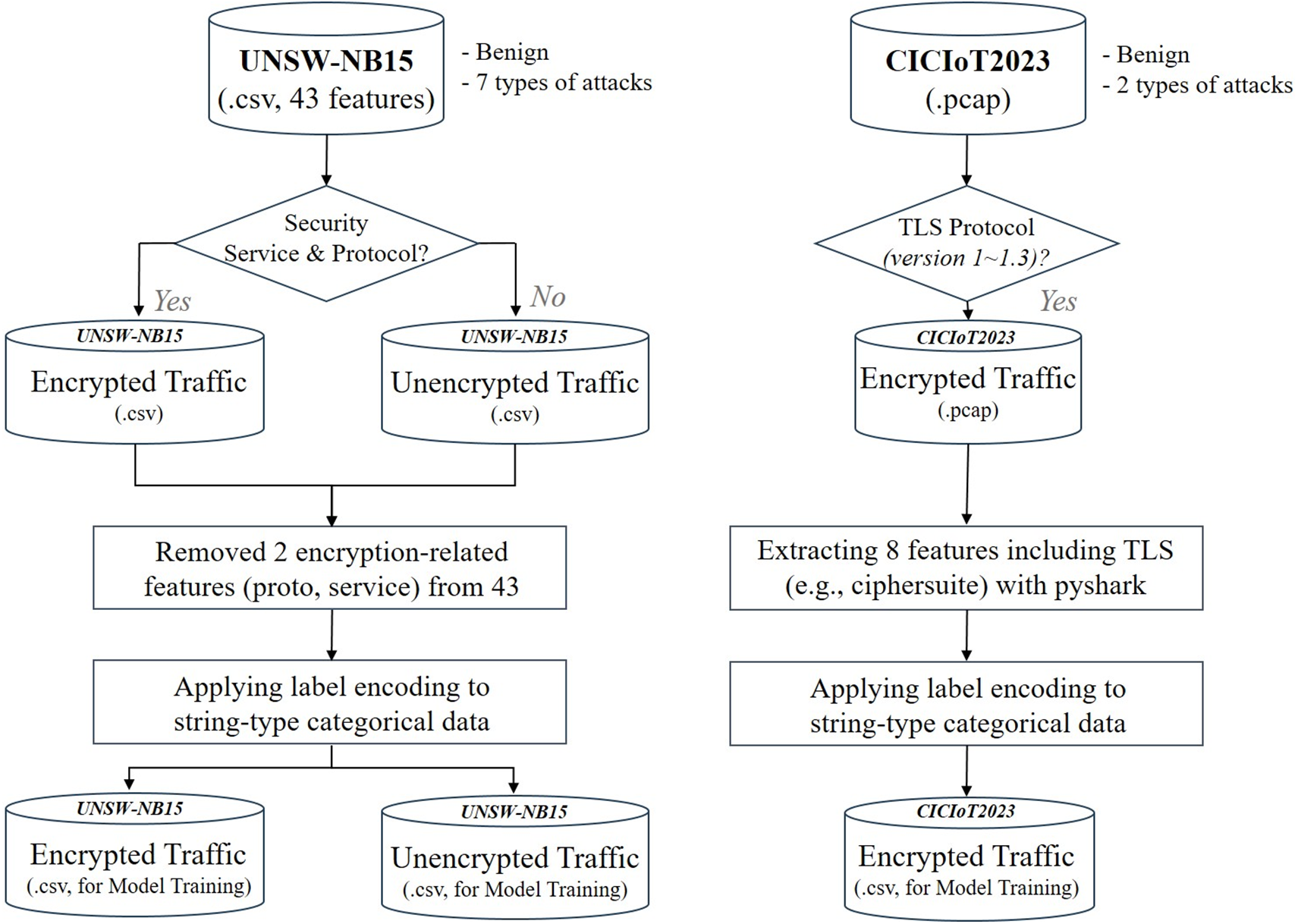

This study used tow publicly available network traffic datasets, UNSW-NB15 and CICIoT-2023, to conduct AI-based research on attack detection using metadata from encrypted traffic. This approach reflects recent research trends in encrypted traffic analysis, where data is selected based on security protocols [5,7,17–19]. In alignment with this trend, the present study also filtered encrypted traffic using information from security protocols and services. The dataset used is UNSW-NB15, developed in 2015 and cited more than 3985 times [20,21]. It includes traffic with security protocols and has been widely adopted for AI research on encrypted traffic [22–24]. Fig. 3 illustrates the preprocessing steps to model training, including the filtering of encrypted traffic for each dataset.

Figure 3: Overview of the proposed analysis methodology: encrypted traffic filtering, experiment 1 and experiment 2

The UNSW-NB15 dataset comprises various types of network traffic, including normal traffic as well as the following nine categories of attacks: Fuzzers, Analysis, Backdoors, DoS, Exploits, Generic, Reconnaissance, Shellcode, Worms. The dataset consists of a total of 49 features [12,21], among which 43 are derived from IP/TCP headers and flow-based metadata. It does not directly include the actual encrypted content of payloads; instead, it provides only two features that represent indirect information such as presence and length. Due to these characteristics, this study determined that the UNSW-NB15 dataset is suitable for the analysis of encrypted traffic and was thus selected for use.

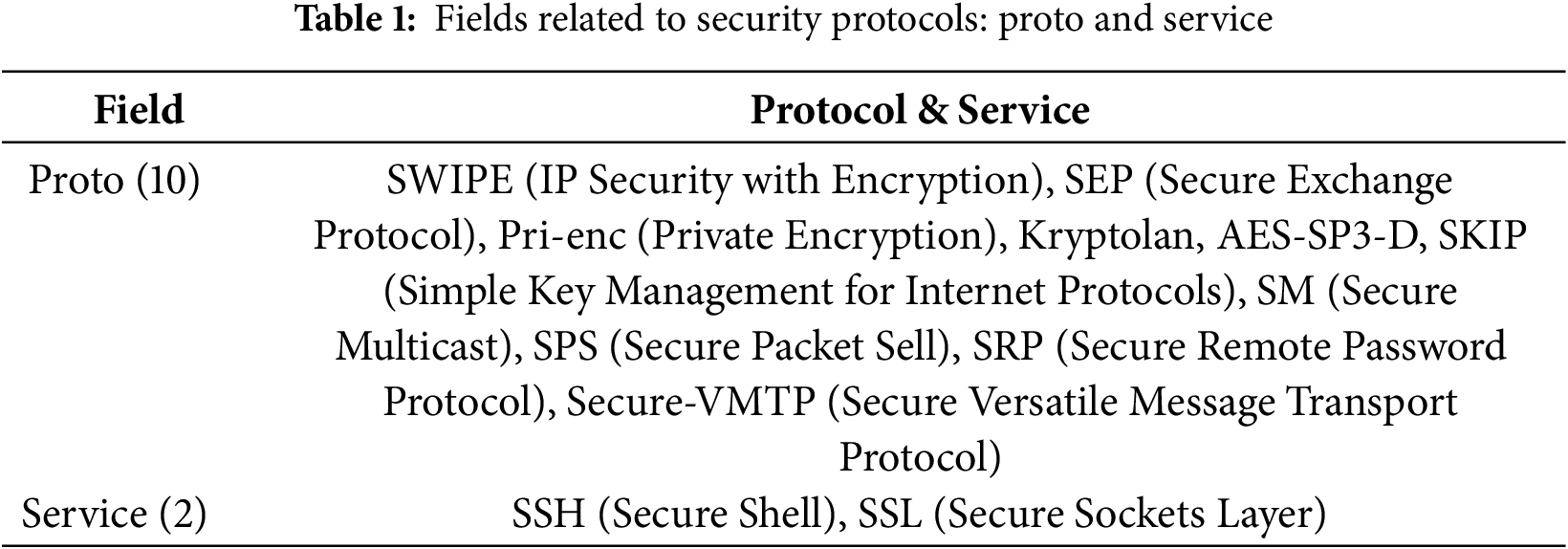

The UNSW-NB15 dataset contains two key features for identifying encrypted traffic: proto and service. The proto feature indicates the transport protocol used by the traffic, while the service feature denotes the type of network service associated with that traffic. Analysis of the proto feature revealed a total of 133 protocol types, among which 10 were identified as security-related protocols. Similarly, analysis of the service feature showed that out of 10 service types, two (SSH and SSL) were classified as secure services. A list of the security protocols and services is summarized in Table 1. Through this analysis, it was verified that the UNSW-NB15 dataset includes a mix of encrypted and unencrypted traffic. Encrypted traffic was filtered using the following criteria:

– Protocol-Based Filtering: If the proto value matched any of the 10 pre-identified security protocols, the corresponding entry was classified as encrypted traffic and extracted.

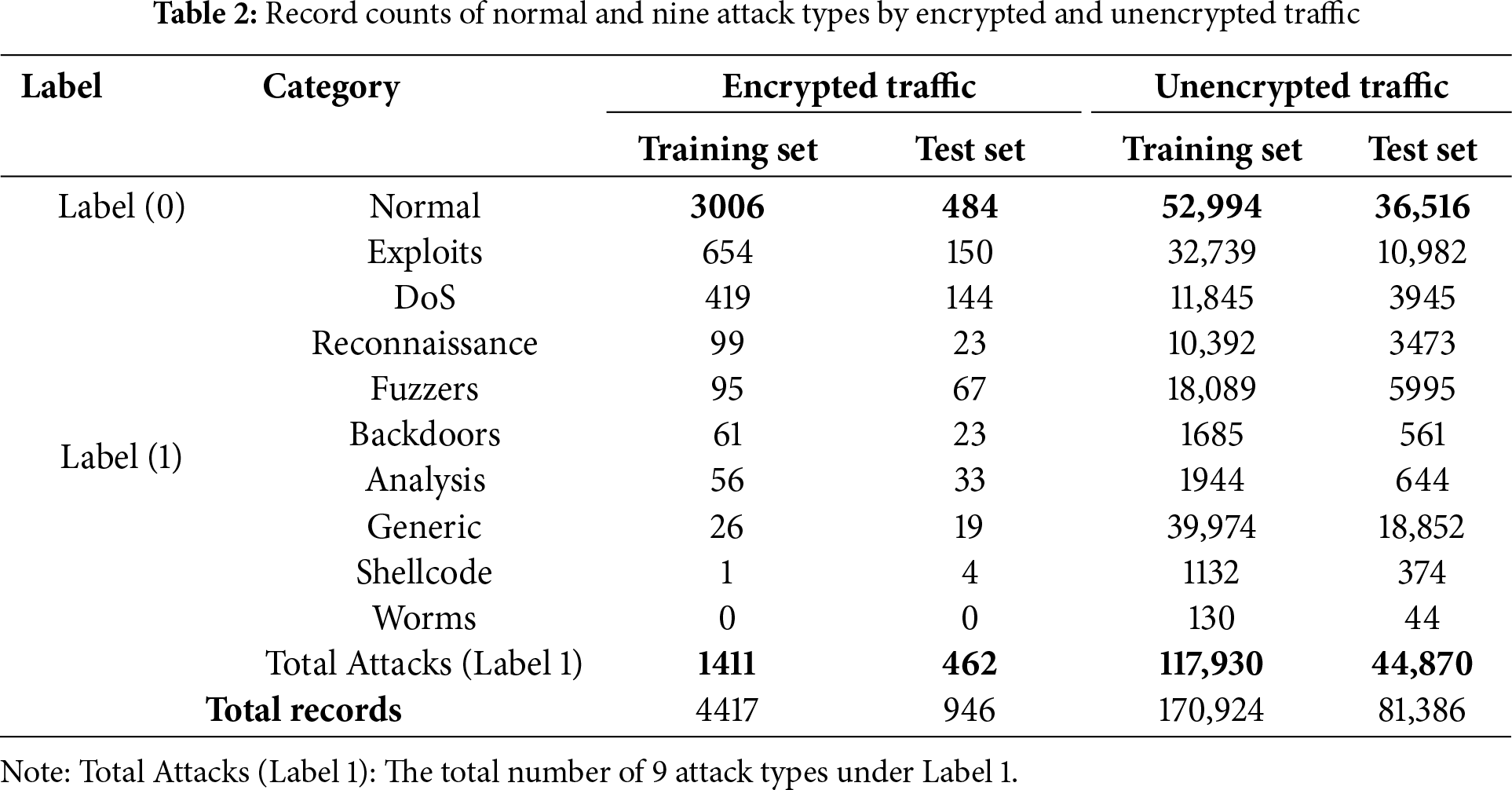

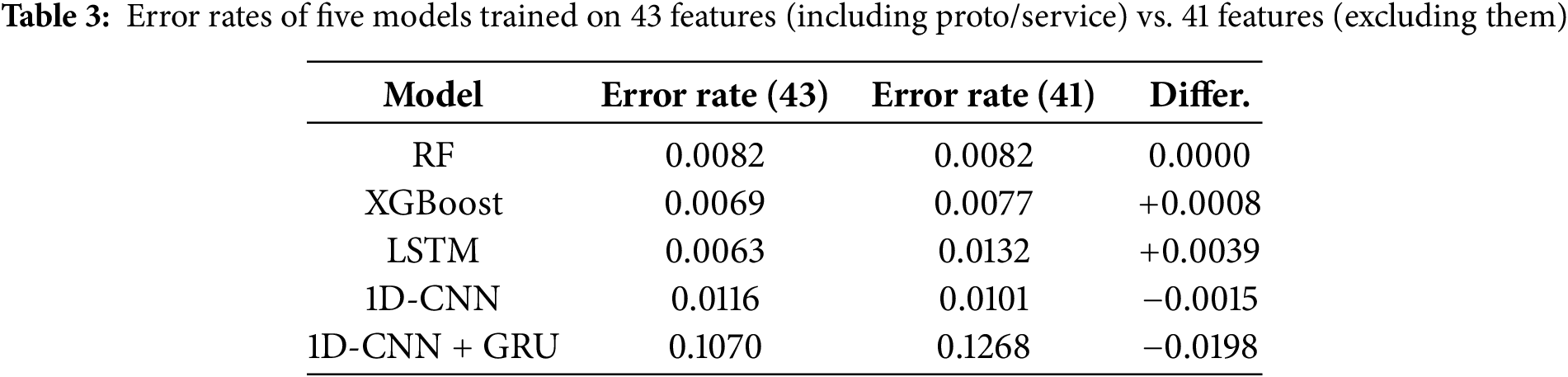

– Service-Based Filtering: Cases where a single network service is segmented and transmitted across multiple packets within a session were considered. Therefore, in instances where a secure service (SSH or SSL) appeared after a traffic segment marked with a—in the service field, the entire session was classified as encrypted traffic, and all associated traffic was extracted accordingly. Through this procedure, two sub-datasets were reconstructed: one consisting of encrypted traffic and the other of unencrypted traffic. The number of records for normal traffic and the nine attack types in each reconstructed sub-dataset is presented in Table 2. In addition, we trained five models using two features sets: one with all 43 features including the two features used to filter encrypted traffic (proto and service), and the other with those two features excluded (41 features). The resulting error rates were summarized in Table 3. The results showed that the Random Forest (RF) model was not affected, whereas the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and 1D Convolutional Neural Networks + Gated Recurrent Unit (1D-CNN + GRU) models experienced a performance degradation ranging from 0.0039 to 0.0198. Based on this finding, the proto and service features were excluded from the input features during model training. Furthermore, among the 41 features used for training, label encoding was applied to those containing string-type categorical data.

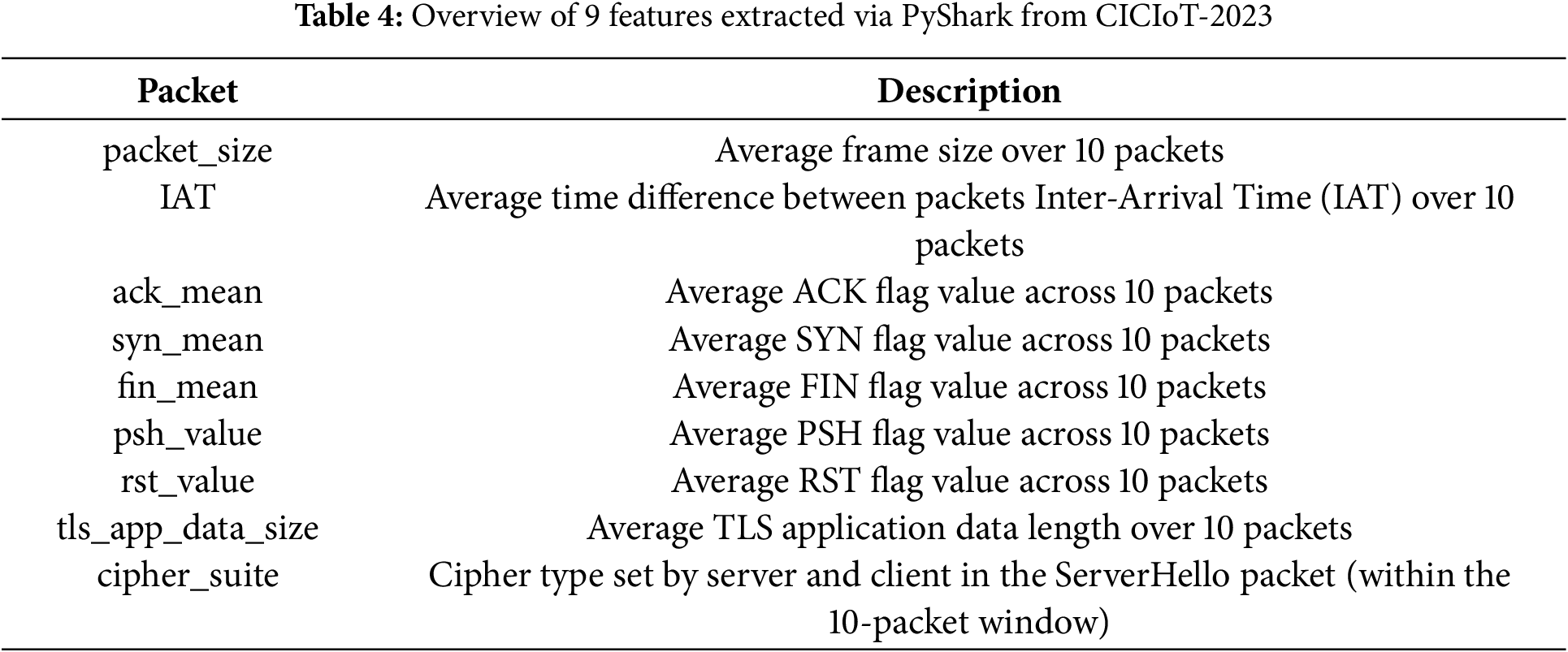

The second dataset used in this study is CICIoT-2023 [25], developed in 2023 and cited more than 564 times. This dataset consists of IoT attack traffic generated from 105 IoT devices. In particular, it includes traffic that uses TLS security protocols, ranging from TLSv1.0 to TLSv1.3. Therefore, CICIoT-2023 was selected to reflect encrypted traffic patterns that occur in heterogeneous IoT environments. The CICIoT-2023 dataset includes both normal traffic and seven attack categories: DDoS, DoS, Web-based, Reconnaissance, Spoofing, Mirai, and Brute Force. Among these, this study used two Web-based attacks-Browser Hijacking and SQL Injection-because they include encrypted attack traffic. This dataset provides both CSV and pcap files. To incorporate TLS protocol-related header information, specifically the “ciphersuite” field, we confirmed that the CSV files did not contain this field. Therefore, we extracted features directly from the pcap files using a sliding window approach based on 10 packets. Feature extraction was performed using the Python + Wireshark (PyShark) library. The remaining features were extracted using basic packet header information. A detailed description of the extracted features is provided in Table 4. To prepare the data for model training, label encoding was applied to string-type categorical features.

3.3 Selection, Optimization, and Evaluation of Five Machine Learning (ML) Models

This section describes the selection of AI models, model optimization procedures, and performance evaluation metrics used in the experiments. A total of five AI models were employed in this study. As shown in Table 2, the UNSW-NB15 dataset contains a significant class imbalance between attack and normal samples. To address this, ensemble-based models such as RF and Extreme Gradient Boost (XGBoost) were used. In addition, to evaluate the detection performance of DL models, we selected LSTM and 1D-CNN, which can accept feature inputs in CSV format. The 1D-CNN + GRU model, which has been proposed in prior intrusion detection research for encrypted environments, was also included for comparative analysis [22].

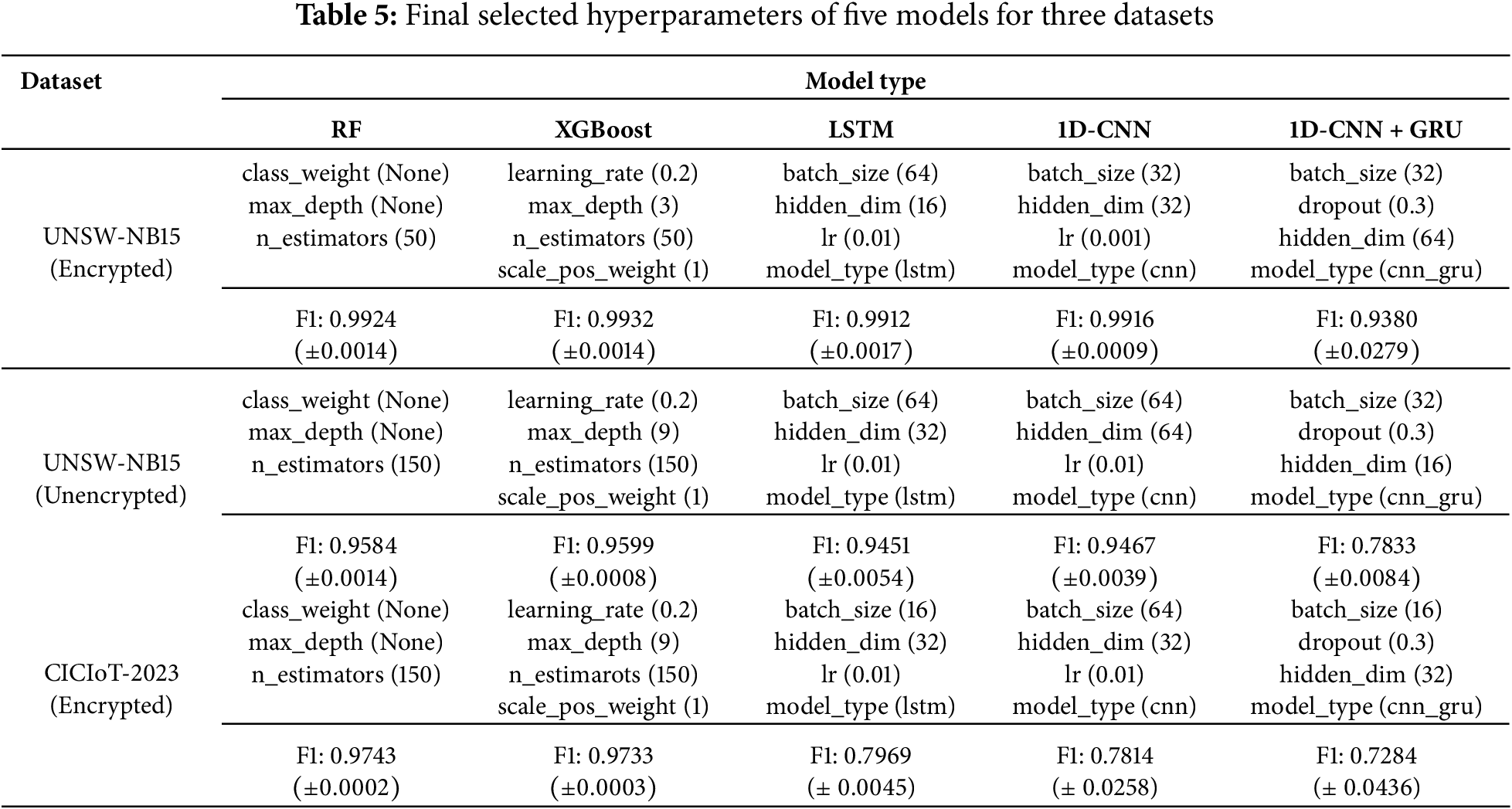

To ensure consistency across Experiments 1 to 3, hyperparameter tuning was conducted using GridSearchCV for each of the five models. Three datasets were used: UNSW-NB15 (Encrypted), UNSW-NB15 (Unencrypted), and CICIoT-2023 (Encrypted). To unify the number of training samples across experiments, all datasets were adjusted to match the smallest dataset, UNSW-NB15, resulting in 3006 normal and 1411 attack samples per experiment. Attack classes were defined as follows: for UNSW-NB15, all seven attack types were merged into a single label; for CICIoT-2023, two attack types were combined under label 1. Hyperparameter tuning was performed using GridSearchCV, and the best parameters were selected based on the highest f1-score to account for class imbalance. Stratified K-Fold cross-validation (cv = 5) was applied to calculate the average f1-score and confidence intervals for each model. The final hyperparameter settings are summarized in Table 5. The architecture, loss computation, and optimizer settings for the three DL models are provided in the Appendix Table A4.

The same Stratified K-fold approach was used for model performance evaluation to ensure consistency with the optimization procedure. This method provides more stable performance estimates than a single train/test split. Each model was trained and evaluated across five folds, and the average of the resulting five performance metrics was used as the final model performance. Confidence intervals were also computed from the results of the five trained models. The performance metrics used in this study include the following five, all derived from the confusion metrics, and are provided in Eqs. (1)–(4). In particular, due to the class-imbalanced nature of the datasets, precision, recall, and f1-score were emphasized. Accuracy and ROC-AUC were also considered to evaluate overall model performance and class discrimination capability.

4 Preliminary Experimental Results

4.1 Can AI Detect Attacks Using Only Metadata, without Decryption?

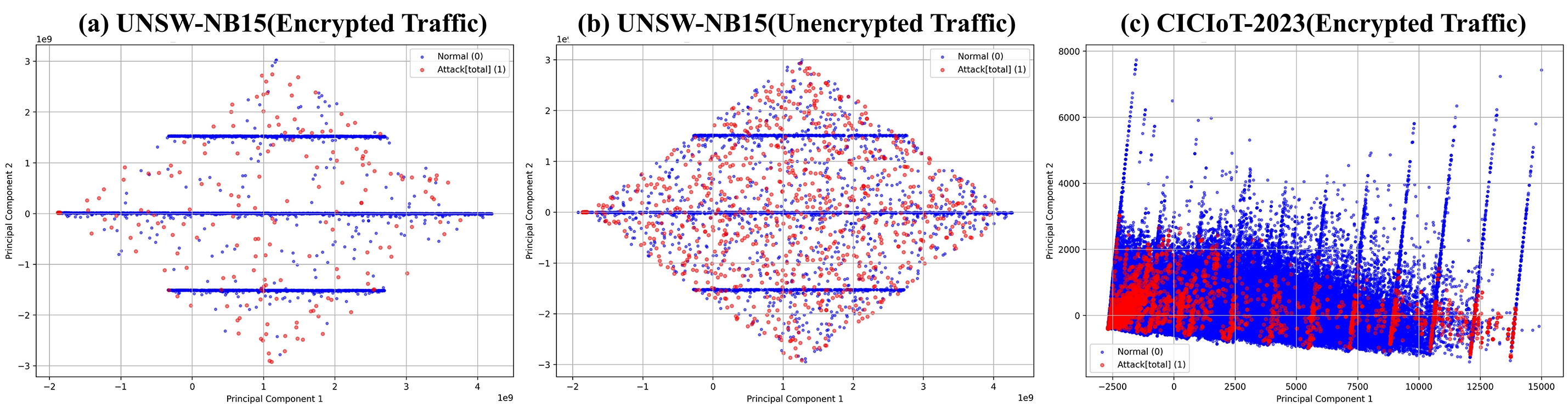

Before applying data sampling, we explored the feasibility of classifying encrypted traffic as normal or attack based on metadata alone, without decryption. Table 6 summarizes the classification performance on encrypted and unencrypted traffic from the UNSW dataset and encrypted traffic from the CICIoT-2023 dataset based on the baseline model without applying data sampling. Each classification result is the average of 5x cross-validation runs. Fig. 4 visualizes the data distribution using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to provide an overview of the structure of each dataset.

Figure 4: Visualization of normal (blue) and attack (red) data for three experimental datasets: (a) UNSW-NB15 (Encrypted), (b) UNSW-NB15 (Unencrypted), (c) CICIoT-2023 (Encrypted)

To evaluate the impact of encryption on classification performance, we compared encrypted and unencrypted traffic within the UNSW-NB15 dataset. We also wanted to generalize the patterns observed in encrypted traffic by comparing encrypted traffic from UNSW-NB15 and CICIoT-2023.

The encrypted traffic in the UNSW-NB15 dataset showed overall superior performance compared to the unencrypted traffic. The precision of the encrypted traffic was about 0.99, which is about 16.5% higher than the unencrypted traffic (about 0.85). Similarly, the recall of the encrypted traffic was also about 0.99, which is a 10.0% increase over the unencrypted traffic (about 0.90). The F1 score of the encrypted traffic was also about 0.98, which is higher than the unencrypted traffic (about 0.94), a difference of about 4.3%. These results indicate that both the detection accuracy and sensitivity of encrypted traffic are significantly improved.

Both the UNSW-NB15 and CICIoT-2023 datasets focused on encrypted network traffic, but there were notable differences in their performance metrics. The accuracy for the encrypted traffic in UNSW-NB15 was approximately 0.99, which was about 1.0% higher than that of CICIoT-2023, which was around 0.98. However, in terms of precision, UNSW-NB15 achieved about 0.99, while CICIoT-2023 showed a significantly lower value of about 0.76, representing a 23.2% difference. Recall also exhibited a substantial difference: UNSW-NB15 recorded about 0.99, whereas CICIoT-2023 reached only around 0.30, which was 69.7% lower. The f1-score was approximately 0.98 for UNSW-NB15 and around 0.43 for CICIoT-2023, showing a difference of about 56.1%.

These differences were likely due to the characteristics of each dataset and the way they were preprocessed. The CICIoT-2023 dataset involved feature extraction directly from raw pcap files, which meant it likely included more complex traffic patterns and noise that reflected real-world network environments. In contrast, the UNSW-NB15 dataset was provided in a preprocessed CSV format, meaning the data was more refined and structured, facilitating more effective model training. As a result, the CICIoT-2023 dataset not only suffered from information loss due to encryption but also from data imbalance and higher levels of noise, which likely contributed to its lower performance. In summary, differences in data preprocessing and feature extraction appeared to have had a significant impact on the model’s detection performance.

4.2 Can Data Sampling be Effective in Encrypted Traffic?

In this study, we apply eight data sampling techniques to address the problem of class imbalance in encrypted traffic and compare their performance to an unsampled baseline model. To evaluate the generalizability and effectiveness of these techniques, we apply the same sampling methods to unencrypted traffic and compare the results to those of encrypted traffic.

The performance evaluation is based on the change in accuracy, precision, recall, f1-score, and ROC-AUC. The impact of each sampling technique on the model performance is systematically analyzed.

Experiments are performed using both encrypted and unencrypted traffic from the UNSW-NB15 dataset and encrypted traffic from the CICIoT-2023 dataset. For UNSW-NB15, seven attack types are aggregated to perform binary classification, while for the CICIoT-2023 dataset, two attack types are combined. Stratified K-Fold cross-validation (cv = 5) is used for model training and evaluation, and each experimental configuration is repeated five times to ensure robustness and consistency. The average results are recorded. Ultimately, model performance results are aggregated to derive overall performance trends for each sampling technique. Sections 4.2.1, 4.2.2, and 4.2.3 present the results of applying eight data sampling techniques to UNSW-NB15 (Encrypted), UNSW-NB15 (Unencrypted), and CICIoT-2023 (Encrypted), respectively. Detailed numerical results for each of the five models are provided in the Appendix for each corresponding section.

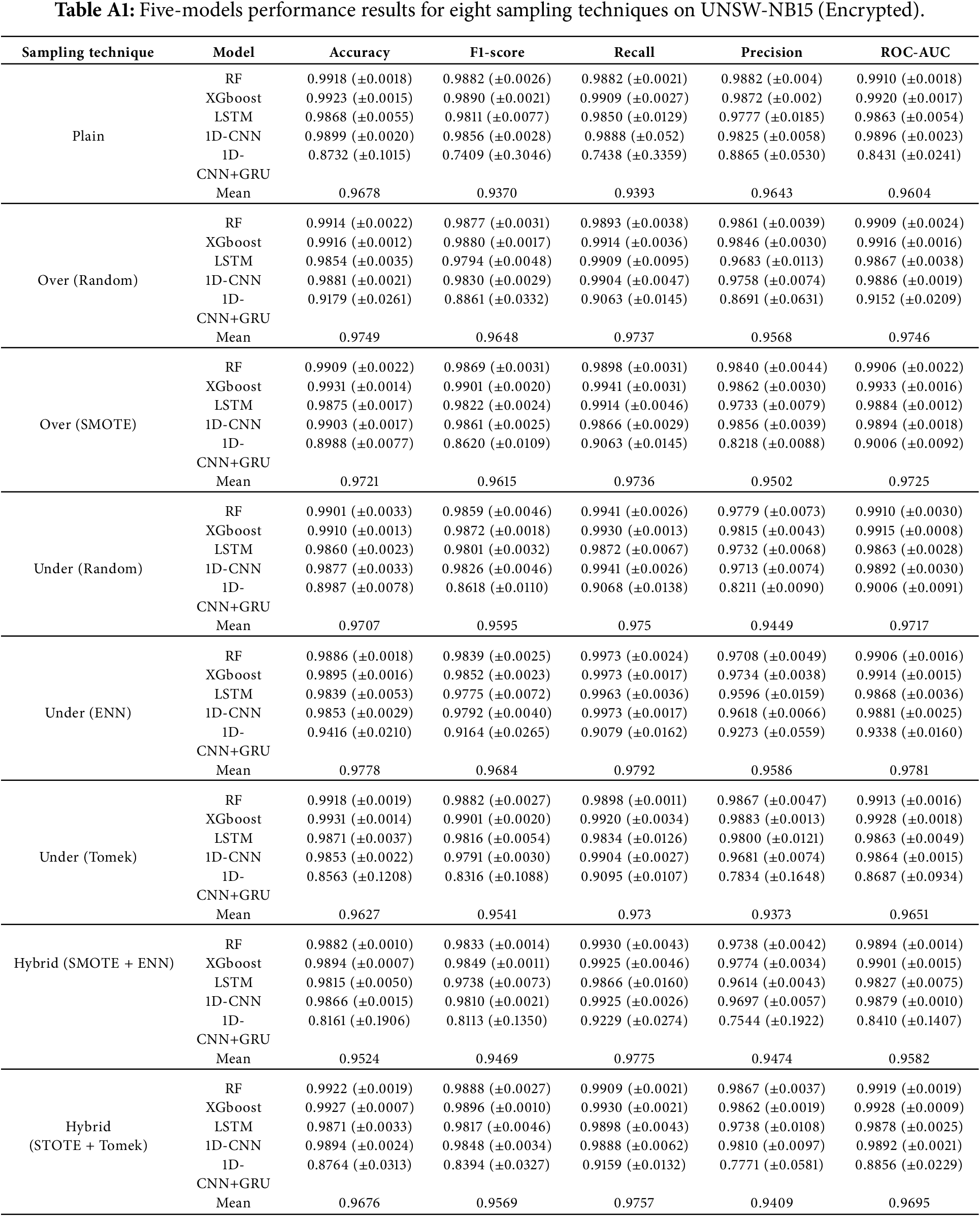

4.2.1 First Traffic Type: UNSW-NB15 (Encrypted Traffic)

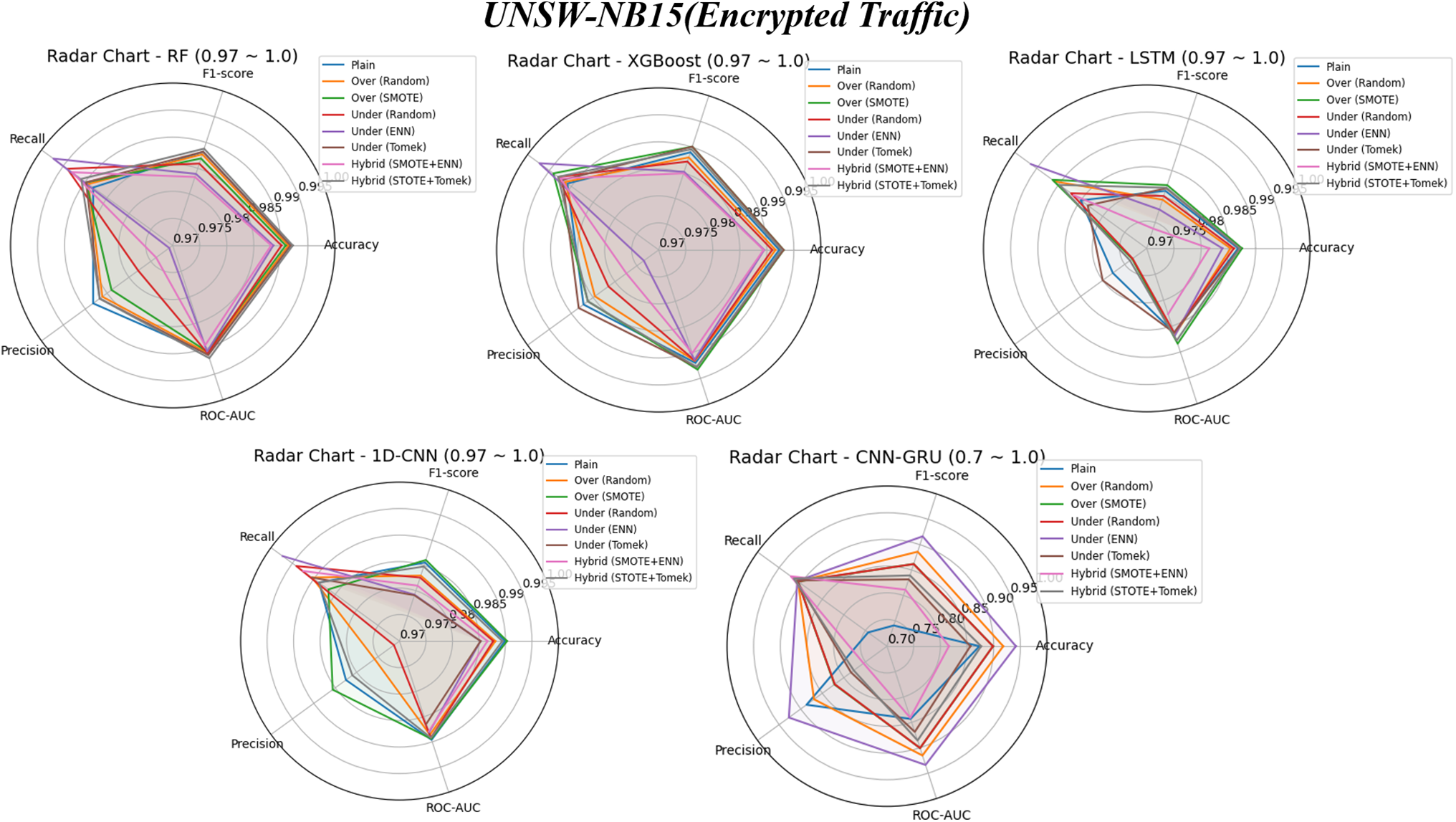

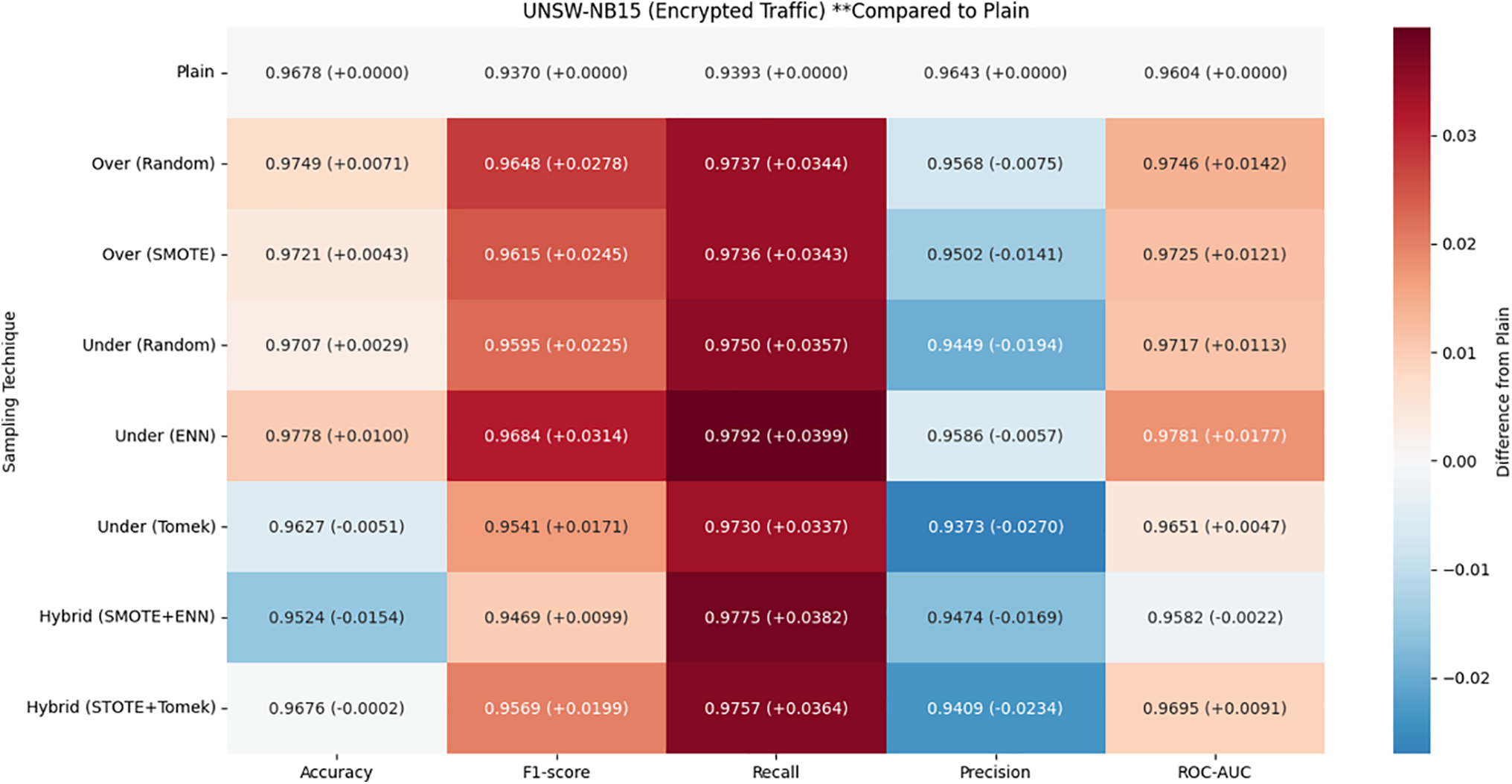

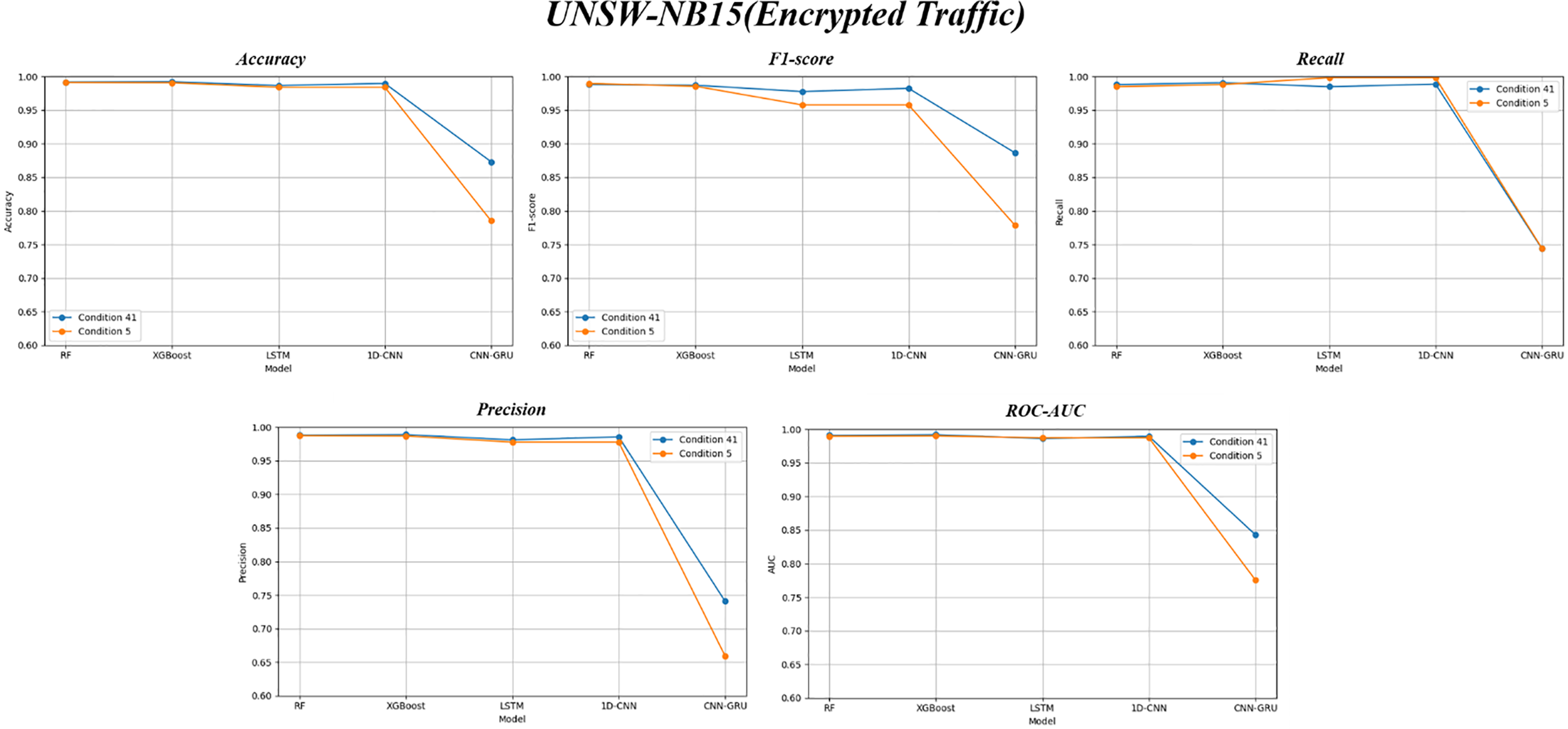

Figs. 5 and 6 visualize the variation in model performance by applying data sampling techniques to encrypted traffic from the UNSW-NB15 dataset.

Figure 5: Performance trends of five models on UNSW-NB15 (Encrypted): plain vs. eight data sampling methods

Figure 6: Average performance of five models on UNSW-NB15 (Encrypted): trends of five metrics across eight sampling methods

Fig. 5 summarizes the performance changes by model and visualizes the results using radar plots. The graphs highlight the noticeable changes in model performance when applying the undersampling-random, undersampling-ENN, and hybrid-SMOTE + ENN techniques compared to the plain (non-sampled). Among the models, 1D-CNN + GRU showed a relatively large performance variation across all sampling methods, including the three aforementioned techniques, indicating a high sensitivity to the sampling strategy. In particular, the 1D-CNN + GRU model achieved the highest performance when undersampling-ENN was applied, suggesting that this technique was the most effective for this model. A breakdown by performance metric showed that all models improved recall over the plain, with the XGBoost model showing the largest improvement at 23.0%, and the LSTM model showing the smallest improvement at 3.52%. Other models showed the following improvements 1D-CNN improved by 21.0%, RF by 4.24%, and 1D-CNN + GRU by 4.07%.

Fig. 6 is a heatmap visualization summarizing the impact of different sampling techniques on model performance. For each sampling method, we calculated the average performance across models and compared it to the baseline performance obtained without sampling. Overall, the four main performance metrics—accuracy, recall, f1-score, and ROC-AUC—showed consistent improvement across most sampling strategies, with the exception of Accuracy, which showed a slight downward trend. In particular, the undersampling-ENN technique showed the largest improvement in Recall at +4.25%, while undersampling-Tomek showed the smallest increase at +3.59%. Accuracy, on the other hand, tended to decrease for most sampling methods. The undersampling-Tomek technique saw the largest drop in accuracy at −2.8%, while undersampling-ENN saw the smallest drop at −0.59%.

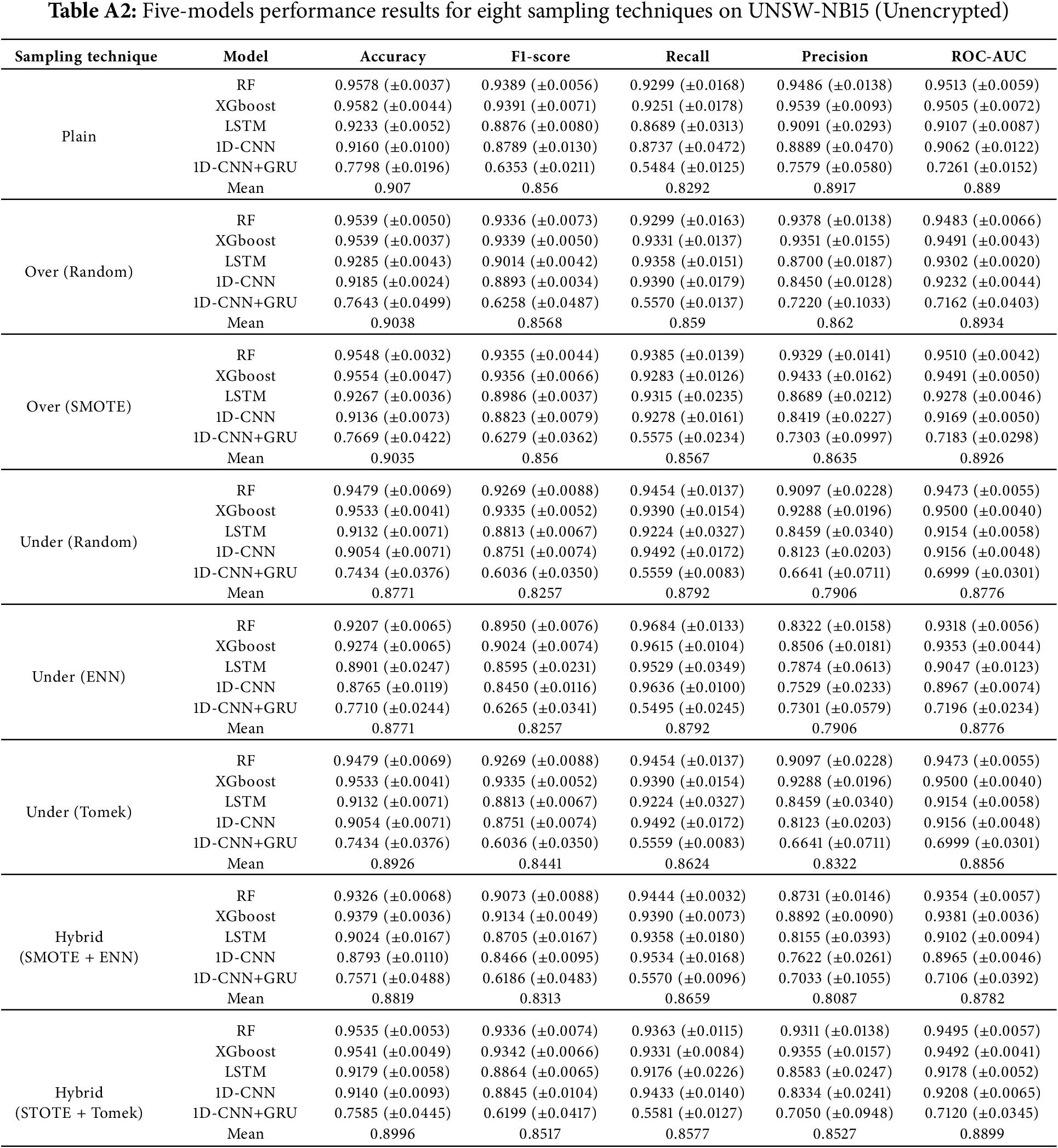

4.2.2 Second Traffic Type: UNSW-NB15 (Unencrypted Traffic)

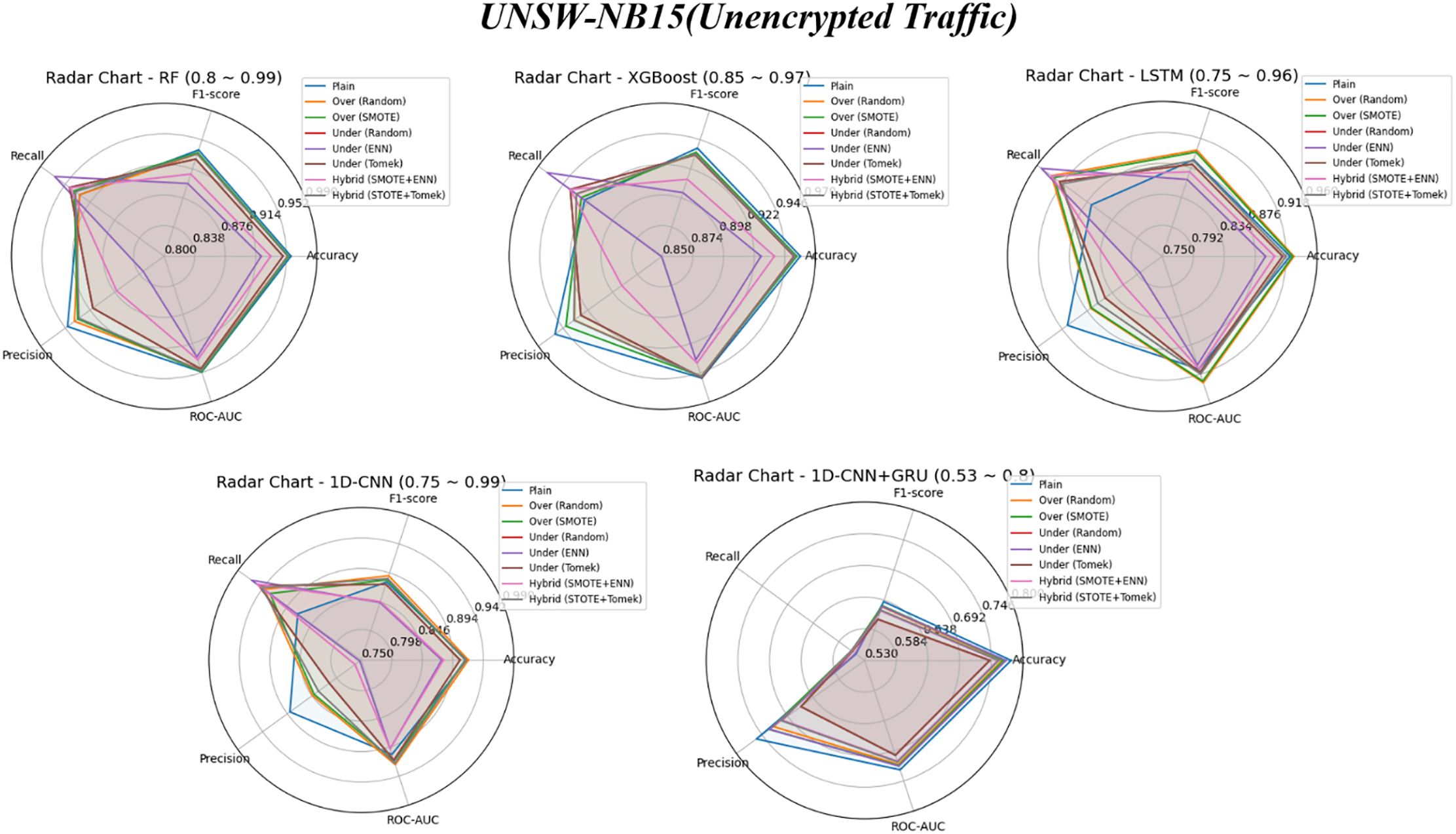

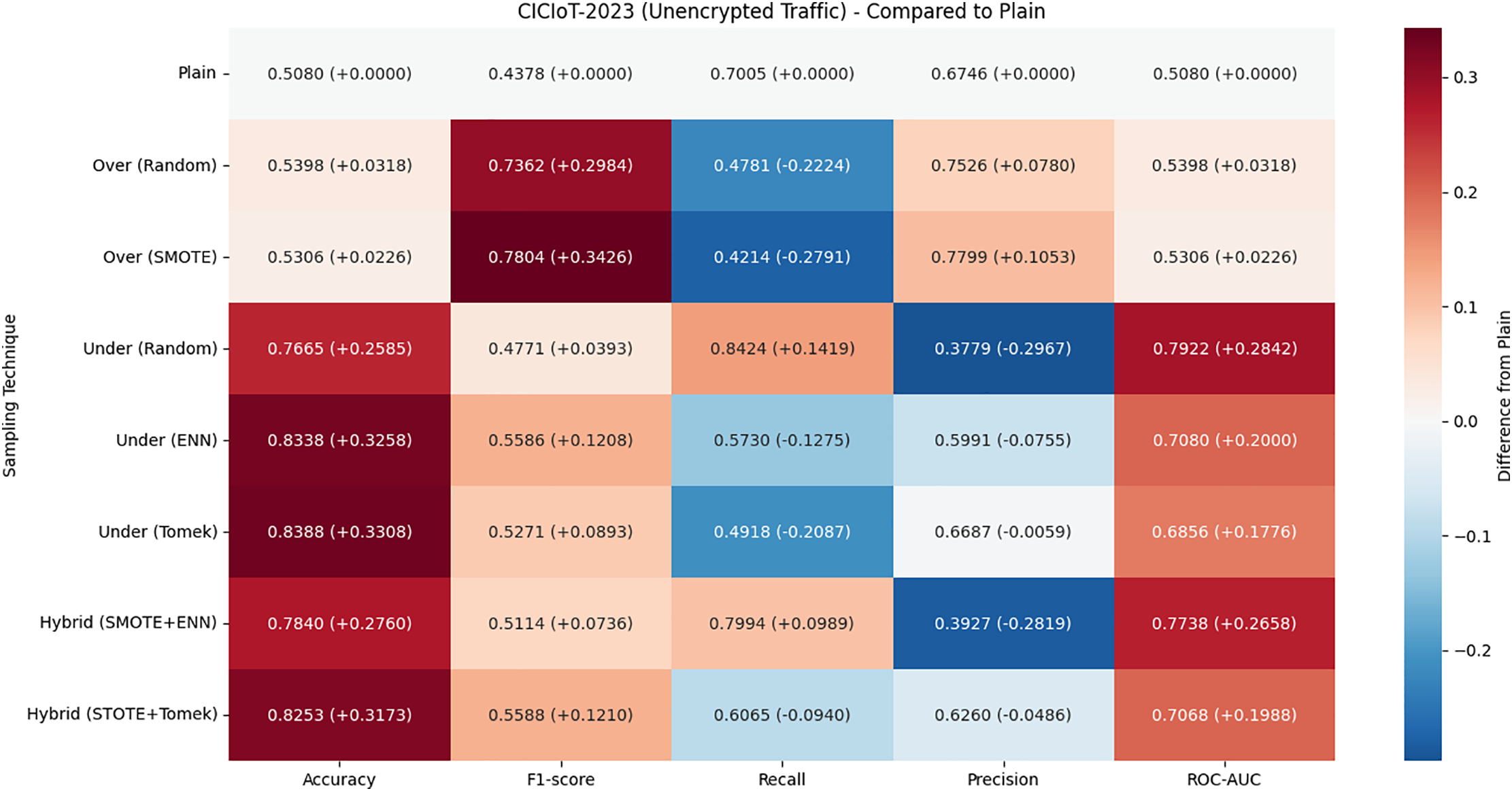

Figs. 7 and 8 show the variation in model performance as a result of applying data sampling techniques to unencrypted traffic from the UNSW-NB15 dataset.

Figure 7: Performance trends of five models on UNSW-NB15 (Unencrypted): plain vs. eight data sampling methods

Figure 8: Average performance of five models on UNSW-NB15 (Unencrypted): trends of five metrics across eight sampling methods

Fig. 7 summarizes the performance changes by model and visualizes the results using radar charts. The undersampling-ENN and hybrid-SMOTE + ENN techniques showed significant performance improvements over the baseline without sampling for the RF, XGBoost, LSTM, and 1D-CNN models. However, the 1D-CNN + GRU model showed only negligible performance changes, suggesting the limited effectiveness of these sampling methods on that architecture. Further analysis by performance metric showed that all models experienced a decrease in precision compared to the baseline without sampling. Specifically, the XGBoost model experienced the smallest decrease at about 2.8%, while the 1D-CNN model experienced the largest decrease at about 11.3%. Other models also experienced a decrease in precision: RF decreased by about 3.3%, LSTM by about 4.1%, and 1D-CNN + GRU by about 9.3%. These results indicate that overall, the application of sampling techniques had a negative impact on precision across models.

Fig. 8 presents a heatmap summarizing the performance variations resulting from the application of various sampling techniques. For each technique, the average performance across all models was computed and subsequently compared against the baseline average obtained from models trained without sampling. Among the evaluation metrics, Recall was the only metric that exhibited consistent improvement across all sampling methods. Specifically, the undersampling-Random technique yielded the highest increase in Recall (+6.03%), followed by undersampling-ENN (+5.88%), undersampling-Tomek (+4.62%), Hybrid-SMOTE+ENN (+4.07%), Oversampling-Random (+3.66%), hybrid-SMOTE+Tomek (+3.80%), and Oversampling-SMOTE (+3.32%). In contrast, Precision generally declined across most sampling techniques. The most significant degradations were observed for undersampling-Random (−11.34%), undersampling-ENN (−8.47%), and Hybrid-SMOTE+ENN (−9.31%). Meanwhile, Oversampling-Random (−0.84%) and Oversampling-SMOTE (−3.16%) exhibited relatively minor reductions in Precision, suggesting that these methods may be more appropriate in operational contexts where maintaining high precision is essential.

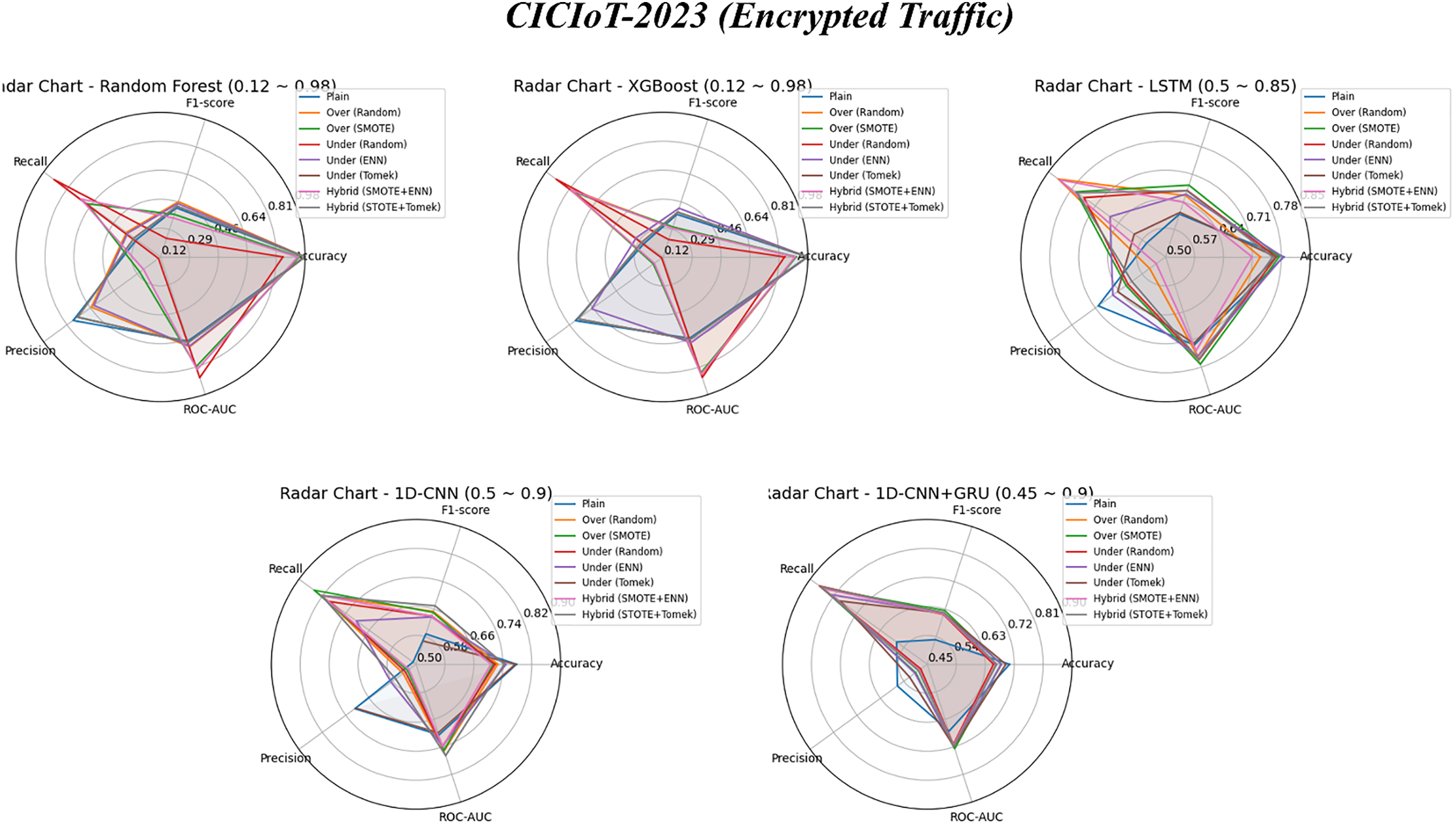

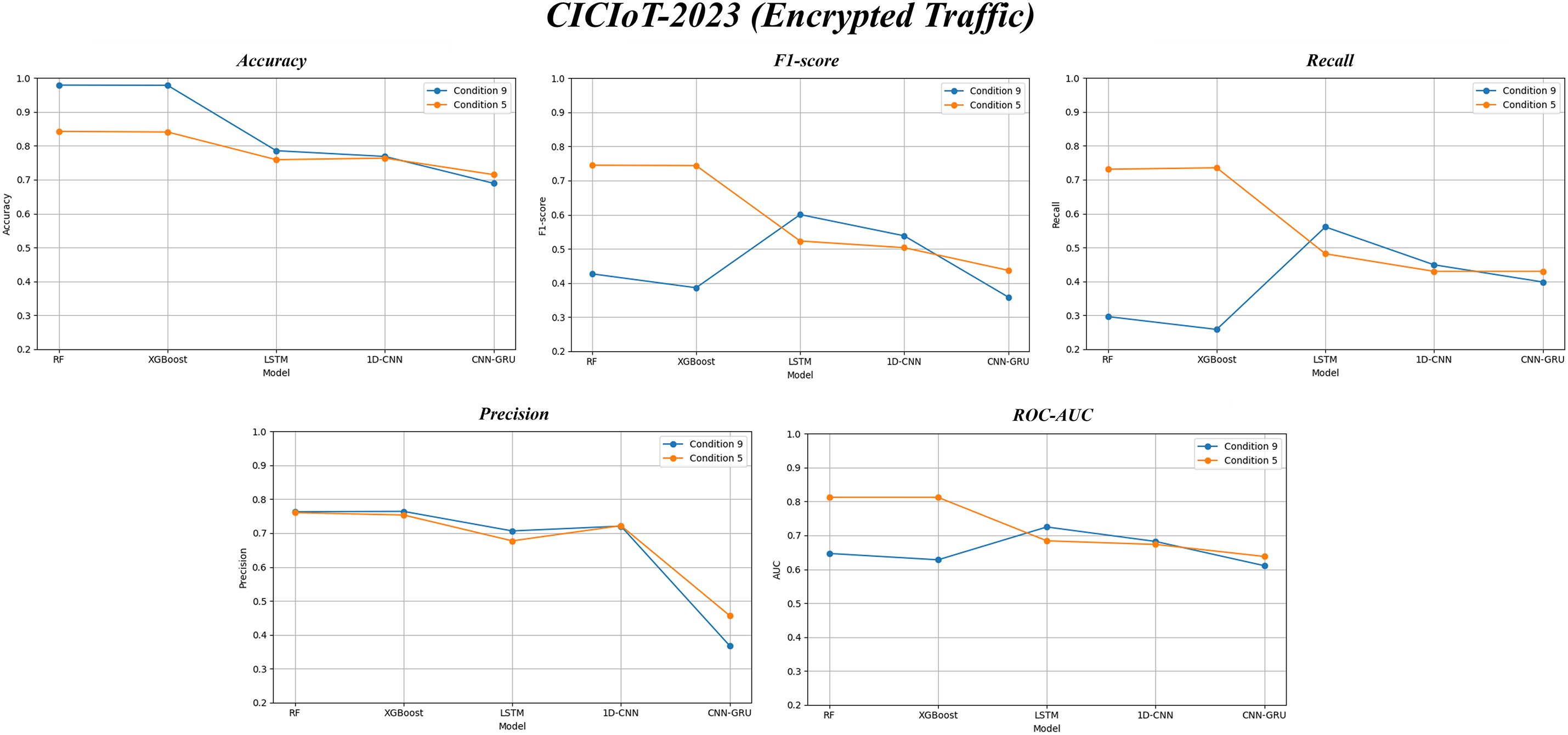

4.2.3 Third Traffic Type: CICIoT-2023 (Encrypted Traffic)

Figs. 9 and 10 visualize the impact of applying data sampling techniques on model performance using encrypted traffic from the UNSW-NB15 dataset.

Figure 9: Performance trends of five models on CICIoT-2023 (Encrypted): plain vs. eight data sampling methods

Figure 10: Average performance of five models on CICIoT-2023 (Encrypted): trends of five metrics across eight sampling methods

Fig. 9 summarizes the performance variation by model and shows it in the form of a radar chart. The oversampling-random and undersampling-random techniques showed a clear visual improvement in recall over the plain (non-sampled) for all models. When we analyzed recall at a granular metric level, the XGBoost model showed the highest improvement at +23.0%, while the LSTM model showed the lowest increase at +3.52%. Other models also showed improvement: 1D-CNN (+21.0%), followed by RF (+4.24%), and 1D-CNN + GRU (+4.07%).

Fig. 10 summarizes the performance changes by sampling technique and visualizes them using a heatmap. For each sampling technique, we calculated the average performance across models and compared it to the plain (non-sampled) model. Overall, the four performance metrics—precision, recall, f1-score, and ROC-AUC—showed improvement for most techniques except for precision. In particular, the undersampling-random method showed the largest improvements in recall (+20.26%) and ROC-AUC (+55.94%), indicating that it was effective in mitigating data imbalance. The oversampling-random method made a particularly positive contribution to improving f1 score (+59.0%) and precision (+8.75%), suggesting that it is suitable for scenarios that require a balance of sensitivity and precision.

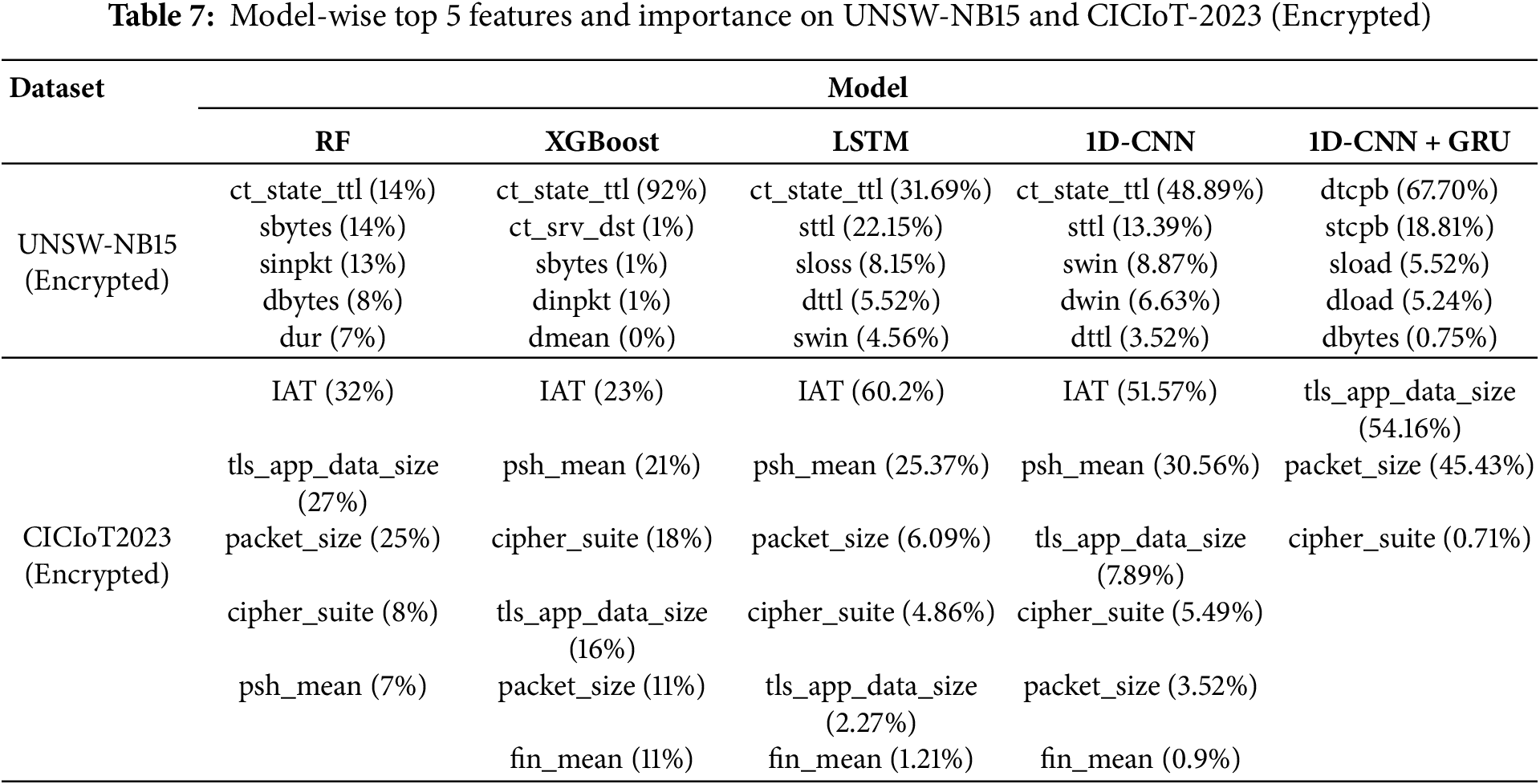

4.3 Which Features Attect the Performance of Encrypted Traffic Detection Models?

We trained five models using the encrypted traffic datasets UNSW-NB15 (Encrypted) and CICIoT-2023 (Encrypted). After training, we identified the features that each model considered most important during evaluation.

Table 7 shows the top 5 features selected by each model for both datasets based on training without applying any data sampling techniques. These features were determined based on their relative importance as evaluated by the models during training. Table 8 compares model performance metrics when using the full feature set and when using only the top five most important features. Initially, we trained and evaluated each model using the full feature set. During this training, we extracted the five most influential features for each model. Then, we reconstructed the datasets using only these top five features and retrained and reevaluated the same models to measure the difference in performance. Figs. 11 and 12 visualize the contribution score assigned to each of the top features selected by each model, providing insight into how each model weights the different input variables.

Figure 11: Comparison of five performance metrics between 5 and 41 features on UNSW-NB15 (Encrypted)

Figure 12: Comparison of five performance metrics between 5 and 9 features on CICIoT-2023 (Encrypted)

For the UNSW-NB15 encrypted dataset, four of the five models identified ct_state_ttl as one of the most important features. The exception was the 1D-CNN + GRU model, which prioritized TCP byte-related features such as dtcpb and stcpb.

For the CICIoT-2023 encrypted dataset, all five models considered tls_app_data to be an important feature during evaluation. In addition, four models (except 1D-CNN + GRU) considered IAT to be the most important feature. In contrast, the 1D-CNN + GRU model emphasized packet size as a key feature. These results suggest that different models rely on different feature types based on their architecture, and that DL models like 1D-CNN + GRU may learn different patterns than traditional ML models in terms of feature prioritization.

5.1 Scenario Exploration under Zero Visibility

Zero visibility refers to a condition where encryption prevents access to the packet payload or certain header information (e.g., IP or TCP), which limits traditional traffic analysis techniques. In this study, to simulate this zero-visibility scenario, we removed all IP and TCP-related features from encrypted traffic from the UNSW-NB15 dataset and instead selected 15 metadata-based features that are still accessible in an encrypted environment. These 15 features consist of only non-header-based statistical attributes such as packet size, inter-session arrival time, and number of packets sent. Our goal was to evaluate whether detection methods that rely only on these metadata are still effective under encryption constraints. To do this, we compared the selected features with the features that each model deemed important during training and evaluated their redundancy to determine the model’s dependence on the available features with zero visibility. The results of the comparison are summarized in Table 9.

The analysis showed that the RF model utilized 9 of the 15 selected metadata features as the most important, indicating a high reliance on statistical metadata and strong adaptability to conditions without visibility. In contrast, the 1D-CNN + GRU model identified only 1 of the 15 features as important, indicating a low tendency to rely on non-header features and potential limitations in highly encrypted scenarios. These results highlight that different model architectures rely on metadata to different degrees, and provide insights into their robustness and applicability in privacy-preserving or encrypted network environments.

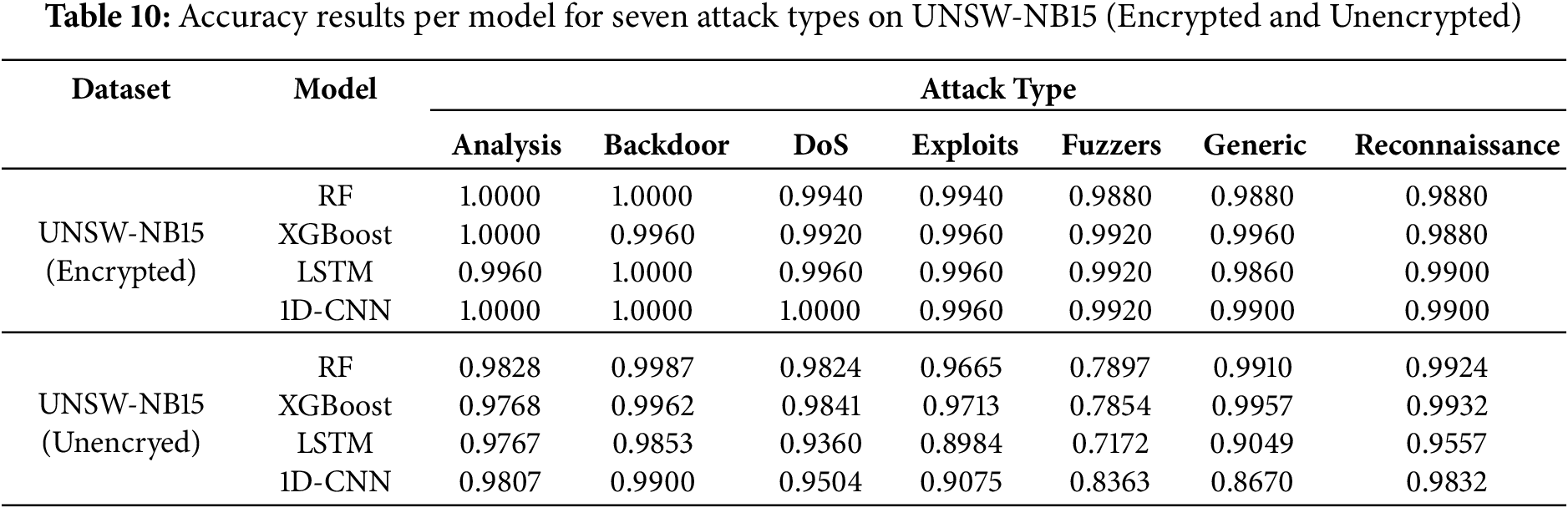

5.2 Accessing Attack Detectability

In this section, we evaluate detection accuracy by individual attack category to allow for a more granular analysis of detection performance for different attack types. In previous experiments, we evaluated model performance by aggregating multiple attacks, but this approach can obscure differences in detection effectiveness caused by differences in attack characteristics. Therefore, we analyzed the performance of four detection models for seven different attack types, and the results are summarized in Table 10.

In the case of encrypted traffic, analysis, backdoor, and dos attacks were detected with consistently high accuracy across all models, each scoring above 0.99, indicating stable and reliable detection. In contrast, generic and reconnaissance attacks performed slightly worse, with detection accuracies ranging from 0.98 to 0.99, suggesting that these attacks are relatively more difficult to detect in encrypted conditions. In the unencrypted traffic scenario, we observed an overall decrease in detection accuracy across all attack types, with the fuzzer attack type performing the worst, with all models achieving accuracy below 0.85. Similarly, Exploit attacks performed moderately well with an accuracy of 0.90 to 0.97 depending on the model.

These results suggest that detection models exhibit varying levels of robustness or vulnerability depending on the specific attack type, highlighting the need for customized detection strategies that are optimized for the characteristics of each attack class.

6.1 Research Trends in Acquiring Encrypted Traffic

To effectively apply AI-based detection methods in encrypted traffic environments, the development or acquisition of suitable datasets must come first. Although interest in encrypted traffic is growing and related research is actively progressing, practical limitations persist in acquiring high-quality datasets composed exclusively of encrypted traffic. Most publicly available network traffic datasets contain a mix of encrypted and unencrypted data. Therefore, to develop models specifically tailored for encrypted traffic, careful data selection, classification, and preprocessing are essential. Due to these limitations, researchers typically construct datasets using one of two approaches: (1) directly collecting and preprocessing traffic from real-world network environments without relying on public datasets, or (2) selecting only the traffic relevant to their research objectives from publicly available datasets and restructuring them accordingly.

When publicly available datasets lack the information required for a specific study, researchers opt to collect encrypted traffic themselves for experimental use. Currently, there are five representative studies that have generated encrypted traffic. First, Yang et al. (2021) constructed a dataset through the collection and filtering of traffic generated within the Sky Dome sandbox environment operated by QiAnXin Technology Research Institute [26]. Second, Fu et al. (2024) created their dataset using traffic captured from the vantage-G node of the Measurement and Analysis on the WIDE Internet project in Japan [3]. Third, Fu et al. (2022) developed their dataset for their research by extracting only the necessary traffic data from both attack samples and campus network captures [4]. Fourth, Canavese et al. (2022) constructed a dataset for their research using traffic generated by five web crawlers: Wget (v1.19), Wpull (v2.0.1), Curl (v7.55), GrabSite (v2.16), and HTTrack (v3.49.2) [6]. Fifth, Ucci et al. (2021) selected malware samples from three online malware analysis services—ANY.RUN, Hybrid Analysis, and Malware Traffic Analysis—and generated traffic based on those samples. The generated traffic was then utilized to construct a dataset for research purposes [2].

When publicly available datasets contain the information required for a particular study, only the encrypted traffic is extracted for use. Four publicly available datasets commonly used in encrypted network traffic research include NSL-KDD, CICIDS-2017, CTU-13, and CIRA-CIC-DoHBrw-2020 (DoH2020). The NSL-KDD dataset, in particular, has been employed in two studies. Wen Xu et al. (2021) [27] and Taimur Bakhshi et al. (2021) [22] extracted only the encrypted traffic data from the NSL-KDD dataset for use in their studies. To enhance the generalizability of their findings, Bakhshi et al. extracted encrypted traffic data from the UNSW-NB15 and CICIDS-2017 datasets in addition to the NSL-KDD dataset. The CICIDS-2017 dataset has also been employed in two studies. To enhance the generalizability of their findings, Bakhshi et al. (2021) [22] and Wang et al. (2022) [19] extracted only the encrypted traffic data from the CIC-IDS2017 dataset for their research. The CTU-13 dataset has been employed in four studies. Wu et al. (2024) [5], Yang et al. (2021) [28], Ibraheem et al. (2022) [7], and Long et al. (2023) [18] utilized only the encrypted traffic data extracted from the CTU-13 dataset in their respective studies. Zhangfa Wu et al. also extracted encrypted traffic from the DoH2020 dataset for use in their study [5]. There are two notable studies that employed the DoH2020 dataset. Wu et al. (2024) [5] and Moure-Garrido et al. (2023) [17] extracted encrypted traffic data from the DoH2020 dataset for analysis in their research.

6.2 Research Trends in AI-Based Detection Models for Encrypted Traffic

AI-based detection techniques, particularly ML and DL, have garnered significant attention in recent research on intrusion detection in encrypted network traffic. Models are utilized in DL-based detection techniques to automatically extract high-dimensional features from encrypted traffic, which are subsequently used to detect malicious activity. In contrast, ML-based detection approaches extract relatively simple and interpretable features using statistical or heuristic models, and use these to classify traffic as normal or anomalous.

When the data used in a study presents clearly defined features, or when resource constraints limit computational capacity, ML models are typically favored for intrusion detection tasks. In ML-based intrusion detection studies, two primary models have been predominantly utilized: the Graph-based model and the RF model. There are three notable studies that have implemented Graph-based models. First, Chuanpu Fu et al. (2024) proposed a clustering-based graph model to address the challenge of detecting previously unseen attack patterns [3]. Second, to address the performance degradation problem in malware detection, Fu et al. (2022) created the ST-Graph system, which integrates a graph-structured random walk model [4]. Third, in order to improve the low robustness of anomaly detection systems susceptible to poisoning attacks, Wu et al. (2024) proposed an online clustering Anomaly Detection Model based on Gaussian Mixture Models [5]. There are three notable studies that have employed RF models. First, Canavese et al. (2022) proposed a model for identifying traffic generation tools. They employed the RF model in their study to validate the performance of the dataset generated by the proposed model [6]. Second, Ibraheem et al. (2022) conducted a comparative analysis of the attack detection performance of various ML models, including RF, Support Vector Machine, Multi-Layer Perceptron, Naive Bayes, KNN, and Neural Network. Their results indicated that the RF model demonstrated the highest detection accuracy [7]. Third, Moure-Garrido et al. (2023) proposed a real-time malicious traffic detection technique based on statistical features. To verify the performance of the suggested method, they used the RF model [17].

When the target dataset is large-scale and exhibits complex patterns, DL models are generally adopted for intrusion detection. In DL-based detection research, three representative models—Autoencoder, Convolutional Neural Network, and Graph Neural Network—are widely utilized. There are four notable studies that have implemented Autoencoder models. First, Monroy et al. (2021) presented a detection framework based on Autoencoders to address the problem of restricted application of conventional detection methods in encrypted traffic [29]. Second, Long et al. (2023) proposed an anomaly detection framework that automatically extracts features based on an Auto Encoder (AE) model to address the resource burden associated with feature selection [18]. Third, Kim et al. (2024) suggested a method that leverages packet-level metadata that excludes skewed node-specific data. The AE model was used to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed solution [30]. Fourth, Wang et al. (2022) proposed a detection technique that integrates Federated Learning (FL) theory with a Convolutional Auto Encoder-based model to address the limitations arising from centralized data training [18]. There are four notable studies that have implemented CNN-based models. First, Bakhshi et al. (2021) compared the intrusion detection performance of standalone models—CNN, LSTM, RNN, and Gated Recurrent Unit—and hybrid models composed of these. Their findings indicated that the hybrid model combining CNN and GRU yielded the best performance [22]. Second, Yang et al. (2021) suggested a combined detection approach using a Term frequency-inverse Document Frequency model for text processing and a CNN model for traffic classification to address the low accuracy of prior detection systems [26]. Third, Yang et al. (2021) proposed a malicious traffic detection framework that fuses Deep Q-Network-Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Network with Residual Network—a CNN variant—aimed at solving the challenges of low detection accuracy and elevated false alarm rates in prior methods [28]. Fourth, Reddy et al. (2024) proposed a 1D-CNN model capable of detecting and classifying encrypted malicious traffic on mobile devices. There is one notable study that has implemented GNN-based models [31]. Yang et al. (2024) introduced a model integrating Transformer and GNN to improve upon the low accuracy problem associated with the conventional detection approaches [32].

This study investigated whether AI-based attack detection is feasible using only metadata from encrypted traffic in heterogeneous IoT environments, without requiring decryption. To this end, two public datasets, UNSW-NB15 and CICIoT-2023, were used to construct encrypted traffic, and five AI models were applied for detection experiments. The results showed that detection performance can be maintained or even improved in encrypted environments. Specifically, in the case of UNSW-NB15, the F1-score of encrypted traffic was 0.98, which was 4.3% higher than that of unencrypted traffic (0.94). In CICIoT-2023, applying data sampling techniques led to an f1-score improvement of up to 59.0% and a ROC-AUC increase of 55.94%.

These results indicate that data sampling techniques can be effective in improving detection performance, even in encrypted IoT traffic, as performance improvements were observed across two datasets with different characteristics. However, the degree of improvement varied depending on dataset quality, model architecture, and the choice of sampling strategy. Therefore, these factors should be carefully considered when applying sampling techniques to detection models.

This study is limited in that it was conducted using only the UNSW-NB15 and CICIoT-2023 datasets, and thus does not cover a wide range of encryption protocols or security environments. In particular, traffic characteristics resulting from advanced encryption protocols such as IPSec were not included. Additionally, although LSTM and 1D-CNN models are known to be utilized due to the nature of the sampling-based data structure. In future protocols, we plan to collect and analyze encrypted traffic generated by various security protocols and to reconstruct network traffic in a sequence-preserving format. This will enable the application of preprocessing and training architectures better suited for time-series models, with the goal of developing more generalized and particle detection systems.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2023-00235509, Development of security monitoring technology based network behavior against encrypted cyber threats in ICT convergence environment).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Yeasul Kim and Hwankuk Kim; methodology, Yeasul Kim and Hwankuk Kim; software, Chaeeun Won; validation, Yeasul Kim, Chaeeun Won, Hwankuk Kim; formal analysis, Yeasul Kim and Chaeeun Won; investigation, Yeasul Kim and Chaeeun Won; resources, Yeasul Kim and Chaeeun Won; data curation, Yeasul Kim and Chaeeun Won; writing—original draft preparation, Yeasul Kim and Chaeeun Won; writing—review and editing, Yeasul Kim and Chaeeun Won; visualization, Yeasul Kim and Chaeeun Won; supervision, Hwankuk Kim; project administration, Hwankuk Kim; funding acquisition, Hwankuk Kim. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A Detailed Performance of Each model for Eight Sampling Methods on the Three Datasets: The appendix includes the results of five models across eight data sampling methods for the three types of traffic introduced in Section 4.2: UNSW-NBA15 (Encrypted), UNSW-NB15 (Unencrypted), and CICIoT-2023 (Encrypted). Table A1 presents the results for UNSW-NB15 (Encrypted), Table A2 for UNSW-NB15 (Unencrypted), and Table A3 for CICIoT-2023.

Appendix B Implementation Details of DL Models: In this study, we used three DL-based models: LSTM, 1D-CNN, and 1D-CNN + GRU. The configuration details of each model-including the loss function, optimizer, and model architecture (model flow)-are summarized in Table A4. All DL models were implemented using the pytorch framework. In particular, the 1D-CNN + GRU model was implemented based on the 1D-CNN + GRU architecture proposed in previous studies [13].

References

1. SonicWall. Soicwall cyber threat report [Internet]. San Jose, CA, USA: SonicWall. [cited 2025 May 28]. Available from: https://www.sonicwall.com/resources/white-papers/2024-sonicwall-cyber-threat-report. [Google Scholar]

2. Ucci D, Sobrero F, Bisio F, Zorzino M. Near-real-time anomaly detection in encrypted traffic using machine learning techniques. In: 2021 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI); 2021 Dec 5–7; Orlando, FL, USA. p. 1–8. doi:10.1109/ssci50451.2021.9659955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Fu C, Li Q, Xu K. Flow interaction graph analysis: unknown encrypted malicious traffic detection. IEEE/ACM Trans Netw. 2024;32(4):2972–87. doi:10.1109/TNET.2024.3370851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Fu Z, Liu M, Qin Y, Zhang J, Zou Y, Yin Q, et al. Encrypted malware traffic detection via graph-based network analysis. In: Proceedings of the 25th International Symposium on Research in Attacks, Intrusions and Defenses; 2022 Oct 26–28; Limassol, Cyprus. p. 495–509. doi:10.1145/3545948.3545983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wu Z, Li H, Qian Y, Hua Y, Gan H. Poison-resilient anomaly detection: mitigating poisoning attacks in semi-supervised encrypted traffic anomaly detection. IEEE Trans Netw Sci Eng. 2024;11(5):4744–57. doi:10.1109/TNSE.2024.3397719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Canavese D, Regano L, Basile C, Ciravegna G, Lioy A. Encryption-agnostic classifiers of traffic originators and their application to anomaly detection. Comput Electr Eng. 2022;97(9):107621. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2021.107621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Ibraheem HR, Zaki ND, Al-mashhadani MI. Anomaly detection in encrypted HTTPS traffic using machine learning: a comparative analysis of feature selection techniques. Mesopotamian J Comput Sci. 2022;2022:18–28. doi:10.58496/mjcsc/2022/005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. McHugh J. Testing Intrusion detection systems: a critique of the 1998 and 1999 DARPA intrusion detection system evaluations as performed by Lincoln Laboratory. ACM Trans Inf Syst Secur. 2000;3(4):262–94. doi:10.1145/382912.382923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Tavallaee M, Bagheri E, Lu W, Ghorbani AA. A detailed analysis of the KDD CUP 99 data set. In: 2009 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence for Security and Defense Applications; 2009 Jul 8–10; Ottawa, ON, Canada. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/CISDA.2009.5356528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Mohammed R, Rawashdeh J, Abdullah M. Machine learning with oversampling and undersampling techniques: overview study and experimental results. In: 2020 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Systems (ICICS); 2020 Apr 7–9; Irbid, Jordan. p. 243–8. doi:10.1109/icics49469.2020.239556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zheng Z, Cai Y, Li Y. Oversampling method for imbalanced classification. Comput Inform. 2016;34(5):1017–37. [Google Scholar]

12. Moustafa N, Slay J. The evaluation of network anomaly detection systems: statistical analysis of the UNSW-NB15 data set and the comparison with the KDD99 data set. Inf Secur J A Glob Perspect. 2016;25(1–3):18–31. doi:10.1080/19393555.2015.1125974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Mishra S. Handling imbalanced data: SMOTE vs. random undersampling. Int Res J Eng Technol. 2017;4(8):317–20. [Google Scholar]

14. Tomek I. Two modifications of CNN. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern. 1976;SMC-6(11):769–72. doi:10.1109/TSMC.1976.4309452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wilson DL. Asymptotic properties of nearest neighbor rules using edited data. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern. 1972;SMC-2(3):408–21. doi:10.1109/TSMC.1972.4309137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Seiffert C, Khoshgoftaar TM, Van Hulse J. Hybrid sampling for imbalanced data. In: 2008 IEEE International Conference on Information Reuse and Integration; 2008 Jul 13–15; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 202–7. doi:10.1109/IRI.2008.4583030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Moure-Garrido M, Campo C, Garcia-Rubio C. Real time detection of malicious DoH traffic using statistical analysis. Comput Netw. 2023;234(4):109910. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2023.109910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Long G, Zhang Z. Deep encrypted traffic detection: an anomaly detection framework for encryption traffic based on parallel automatic feature extraction. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2023;2023(1):3316642. doi:10.1155/2023/3316642. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Wang Z, Wang P, Sun Z. SDN traffic anomaly detection method based on convolutional autoencoder and federated learning. In: GLOBECOM 2022—2022 IEEE Global Communications Conference; 2022 Dec 4–8; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. p. 4154–60. doi:10.1109/GLOBECOM48099.2022.10001438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. University of New South Wales. UNSW-NB15 dataset [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 28]. Available from: https://research.unsw.edu.au/projects/unsw-nb15-dataset. [Google Scholar]

21. Moustafa N, Slay J. UNSW-NB15: a comprehensive data set for network intrusion detection systems (UNSW-NB15 network data set). In: 2015 Military Communications and Information Systems Conference (MilCIS); 2015 Nov 10–12; Canberra, Australia. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/MilCIS.2015.7348942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Bakhshi T, Ghita B. Anomaly detection in encrypted Internet traffic using hybrid deep learning. Secur Commun Netw. 2021;2021(1):5363750. doi:10.1155/2021/5363750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Wang Z, Fok KW, Thing VLL. Machine learning for encrypted malicious traffic detection: approaches, datasets and comparative study. Comput Secur. 2022;113(5):102542. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2021.102542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ji IH, Lee JH, Kang MJ, Park WJ, Jeon SH, Seo JT. Artificial intelligence-based anomaly detection technology over encrypted traffic: a systematic literature review. Sensors. 2024;24(3):898. doi:10.3390/s24030898. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Neto ECP, Dadkhah S, Ferreira R, Zohourian A, Lu R, Ghorbani AA. CICIoT2023: a real-time dataset and benchmark for large-scale attacks in IoT environment. Sensors. 2023;23(13):5941. doi:10.3390/s23135941. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Yang H, He Q, Liu Z, Zhang Q. Malicious encryption traffic detection based on NLP. Secur Commun Netw. 2021;2021(1):9960822. doi:10.1155/2021/9960822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Xu W, Jang-Jaccard J, Singh A, Wei Y, Sabrina F. Improving performance of autoencoder-based network anomaly detection on NSL-KDD dataset. IEEE Access. 2021;9:140136–46. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3116612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Yang J, Liang G, Li B, Wen G, Gao T. A deep-learning- and reinforcement-learning-based system for encrypted network malicious traffic detection. Electron Lett. 2021;57(9):363–5. doi:10.1049/ell2.12125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Monroy SS, Gupta AK, Wahlstedt G. Detection of malicious DNS-over-HTTPS traffic: an anomaly detection approach using autoencoders. arXiv:2310.11325. 2023. [Google Scholar]

30. Kim MG, Kim H. Anomaly detection in imbalanced encrypted traffic with few packet metadata-based feature extraction. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;141(1):585–607. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.051221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Reddy PCS, Shirley Muller P, Koka N, Sharma S, Sharma V, Mukherjee N, et al. Detection of encrypted and malicious network traffic using deep learning. In: 2023 International Conference on Ambient Intelligence, Knowledge Informatics and Industrial Electronics (AIKIIE); 2023 Nov 2–3; Ballari, India. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/AIKIIE60097.2023.10390386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Yang J, Jiang X, Lei Y, Liang W, Ma Z, Li S. MTSecurity: privacy-preserving malicious traffic classification using graph neural network and transformer. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2024;21(3):3583–97. doi:10.1109/TNSM.2024.3383851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools