Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Deep Learning for Brain Tumor Segmentation and Classification: A Systematic Review of Methods and Trends

Centre of Real Time Computer Systems, Kaunas University of Technology, Kaunas, 44249, Lithuania

* Corresponding Author: Robertas Damaševičius. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Emerging Trends and Applications of Deep Learning for Biomedical Signal and Image Processing)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-41. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069721

Received 29 June 2025; Accepted 11 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

This systematic review aims to comprehensively examine and compare deep learning methods for brain tumor segmentation and classification using MRI and other imaging modalities, focusing on recent trends from 2022 to 2025. The primary objective is to evaluate methodological advancements, model performance, dataset usage, and existing challenges in developing clinically robust AI systems. We included peer-reviewed journal articles and high-impact conference papers published between 2022 and 2025, written in English, that proposed or evaluated deep learning methods for brain tumor segmentation and/or classification. Excluded were non-open-access publications, books, and non-English articles. A structured search was conducted across Scopus, Google Scholar, Wiley, and Taylor & Francis, with the last search performed in August 2025. Risk of bias was not formally quantified but considered during full-text screening based on dataset diversity, validation methods, and availability of performance metrics. We used narrative synthesis and tabular benchmarking to compare performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, Dice score) across model types (CNN, Transformer, Hybrid), imaging modalities, and datasets. A total of 49 studies were included (43 journal articles and 6 conference papers). These studies spanned over 9 public datasets (e.g., BraTS, Figshare, REMBRANDT, MOLAB) and utilized a range of imaging modalities, predominantly MRI. Hybrid models, especially ResViT and UNetFormer, consistently achieved high performance, with classification accuracy exceeding 98% and segmentation Dice scores above 0.90 across multiple studies. Transformers and hybrid architectures showed increasing adoption post-2023. Many studies lacked external validation and were evaluated only on a few benchmark datasets, raising concerns about generalizability and dataset bias. Few studies addressed clinical interpretability or uncertainty quantification. Despite promising results, particularly for hybrid deep learning models, widespread clinical adoption remains limited due to lack of validation, interpretability concerns, and real-world deployment barriers.Keywords

Brain tumors are among the most complex and life-threatening disorders of the central nervous system (CNS), constituting approximately 85%–90% of all primary CNS neoplasms [1]. Their impact is particularly severe in pediatric populations, where they remain a leading cause of cancer-related mortality and long-term neurological morbidity [2]. Prognosis and treatment planning are heavily dependent on tumor-specific characteristics, including anatomical location, histological type, growth dynamics, and volume. Consequently, early and accurate diagnosis is critical for improving clinical outcomes.

Recognizing the biological heterogeneity of brain tumors, the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced a revised tumor classification system in 2021, delineating over 200 tumor entities based on histopathological, morphological, and molecular features [3]. While this classification enhances diagnostic precision, it also increases the cognitive and diagnostic burden on clinicians, particularly when detecting small, ambiguous, or early-stage tumors that require time-intensive histopathological confirmation [4,5].

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is the current gold standard for brain tumor detection and monitoring due to its high spatial resolution, multiplanar capability, and superior soft tissue contrast [6]. MRI enables comprehensive anatomical visualization, accurate delineation of tumor margins, and improved identification of neuroanatomical landmarks, all of which are essential for effective surgical planning and treatment decision-making [7]. In comparison to other imaging modalities such as computed tomography, MRI offers higher sensitivity and specificity for brain pathology [8]. However, interpreting multimodal MRI scans remains a labor-intensive and highly specialized task that demands significant radiological expertise [9].

The increasing complexity of imaging data and diagnostic protocols has prompted the development of computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) systems that aim to support clinicians by automating repetitive and subjective tasks. Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning (DL), have enabled these systems to detect subtle, non-obvious features, reduce inter-observer variability, and process large-scale imaging data rapidly and consistently [10]. These capabilities are especially valuable for brain tumor diagnostics, where minor variations in tumor appearance may correspond to different prognoses or therapeutic strategies. AI-powered CAD tools not only assist in early detection but also enable the possibility of scalable, reproducible diagnostic workflows, fueled by large and diverse medical imaging datasets.

Among AI methods, deep learning has emerged as a particularly powerful paradigm for automating brain tumor segmentation and classification. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Transformer-based architectures have demonstrated remarkable performance in extracting spatial and contextual features from MRI scans [11,12]. These architectures offer a potential solution to many challenges faced by clinicians, including reducing diagnostic delay, increasing reproducibility, and enhancing the precision of treatment planning. Moreover, their capacity for end-to-end learning allows for seamless integration from raw imaging data to diagnostic outputs.

Despite these advances, the field faces several critical challenges. The vast and rapidly evolving body of research makes it difficult to establish consensus on the best-performing models, optimal dataset usage, and standardized evaluation metrics. Furthermore, issues related to model generalization, interpretability, and computational feasibility continue to limit clinical adoption [13,14]. Many models are trained and validated on curated datasets under idealized conditions, which may not translate to real-world clinical environments.

Over the last decade, significant research has focused on enhancing brain tumor diagnosis through the integration of advanced imaging modalities and deep learning techniques [15,16]. Studies have explored a wide spectrum of approaches, ranging from novel model architectures to iterative refinements of established methods, aimed at improving accuracy, reliability, and robustness in both classification and segmentation tasks [17–20].

To systematically understand these developments and guide future research, this review investigates and compares recent deep learning methods for brain tumor segmentation and classification. It places particular emphasis on model types, dataset usage, performance metrics, and the emerging role of attention-based and hybrid CNN-Transformer architectures. Through this, we aim to identify methodological trends, highlight unresolved challenges, and provide insight into the path toward clinically robust and trustworthy AI systems in neuro-oncology.

Recent review papers underscore the rapid and multifaceted development of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) methods in brain tumor classification and diagnosis. These works highlight the shift from traditional manual techniques to automated, high-accuracy computational pipelines using radiological imaging, especially MRI. Several studies reviewed the performance of ML models like support vector machines, random forests, and deep neural networks in classifying brain tumors, including gliomas and craniopharyngiomas, with high sensitivity and specificity [21]. Transfer learning has also emerged as a dominant theme, especially in adapting CNN-based models across heterogeneous MRI datasets to improve generalization and reduce data dependency [22]. Bibliometric analyses reveal a sharp rise in publications post-2020, with strong institutional collaborations and increasing emphasis on interpretability, multi-class classification, and radiomic feature extraction [23–25]. Additionally, domain-specific reviews suggest that DL techniques hold promise in neurosurgical workflows and radiogenomic correlation, though challenges remain in dataset standardization, external validation, and clinical integration [26–29].

The primary motivation of this study is to conduct a comprehensive and systematic literature review on deep learning-based methods for brain tumor segmentation and classification, with a focus on understanding methodological trends, dataset usage, performance benchmarks, and unresolved challenges. In contrast to previous surveys, this review places equal emphasis on both classification and segmentation perspectives, providing a holistic view of the pipeline from image acquisition to diagnostic inference. The key contributions of this review are summarized as follows:

• A comparative analysis of publicly available datasets with modality, size, and annotation characteristics.

• A performance benchmarking of state-of-the-art methods in terms of accuracy, Dice score, and other evaluation metrics.

• An exploration of current limitations related to data quality, model generalization, interpretability, and computational complexity.

• A set of recommendations and open challenges aimed at guiding future research toward clinically viable and trustworthy deep learning models.

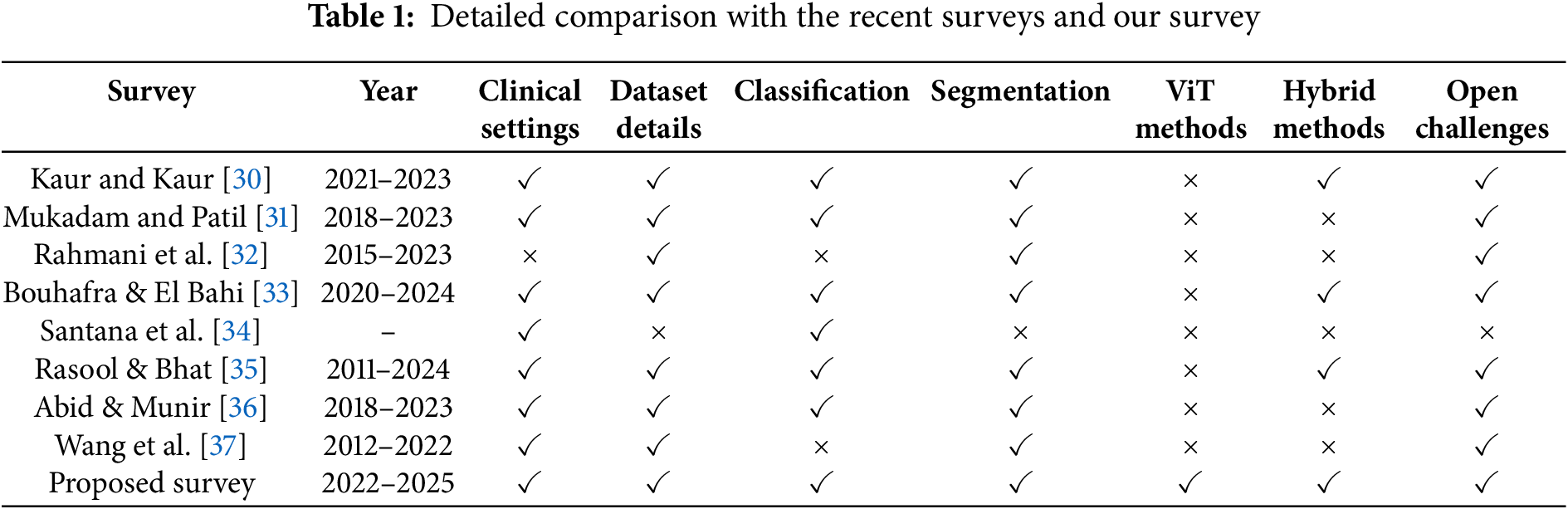

There are a number of review papers on various types of artificial intelligence applied to brain tumor detection but there are no review papers that analyze new methods such as Vision Transformer, hybrid methods, clinical imaging methods that are applicable to brain tumor segmentation and classification together or a review of the available clinical datasets in the field. In Table 1, we explored the comparison among our survey and recent conducted surveys based on publication year, clinical settings, tasks such as classification and segmentation, methods like ViT, Hybrid methods, and open challenges.

Kaur and Kaur [30] provided a systematic review focused on the deployment of deep learning for multi-organ cancer diagnosis of both classification and segmentation uses in clinical settings. It provided an expansive review to detail the datasets used, and explained hybrid approaches including ensemble of deep learning models. However, it did not examine Vision Transformer (ViT) methods. Notably, this study identified and explained multiple open challenges for using deep learning in clinical cancer diagnostics including dataset imbalance and model generalization challenges.

Mukadam and Patil [31] provided a comprehensive survey on machine learning and computer vision methods for cancer classification. Their review highlighted clinical applications and described datasets in detail. While classification and segmentation were discussed, it did not consider Vision Transformer methods or hybrid methods with multiple models. However, the study successfully highlighted many open challenges specific to simplifying traditional ML methods to fit complex medical imaging.

Rahmani et al. [32] only address medical image segmentation and deep learning. While their review is target-oriented (tumors, vessels, pathological structures), which makes it deeply technical, it is not explicitly tied to clinical applications. It provided relevant information and completely outlined the datasets and techniques related to segmentation, while classification and Vision Transformer methods were not the focus. Hybrid methods were also not a central aspect. It importantly contained an outline of a number of open challenges in relation to target complexity and segmentation accuracy within the medical domain.

Bouhafra and El Bahi [33] represented one of the newest and elaborate reviews to trace recent brain tumor detection and classification based on MRI images. It’s strong application-to-clinical basis and contained details of datasets and deep learning approaches for classification and segmentation. Although ViT methods were not the focus, it did mention some hybrid methods which included features of transfer learning or attention mechanisms. It also, like all surveys, outlined numerous open challenges such as model interpretability, variability in datasets, needing large annotated datasets etc.

Santana et al. [34] involved a large period, focused exclusively on machine learning for classification of brain tumors. The authors discussed clinical world relevance and used datasets appropriately, but exclude segmentation of tumors and higher-level Vision Transformer methods. They also did not consider hybrid methods. Another key point, this review does not highlight open challenges; therefore, it is probably the least forward-looking review of those part of this SLR.

Rasool and Bhat [35] provided a thorough review focusing on machine learning and deep learning applications in brain tumor detection from MRI. This review show a long-lasting evolution of techniques. Classification and segmentation tasks are well covered in the review also the datasets used are well elaborated the article. A clear omission are Vision Transformers, however hybrid methods are included in the survey. The discussion provided the authors demonstrated their ambition in presenting several open challenges, such as heterogeneity of tumor cells, model robustness, and annotation biases.

Abid and Munir [36] reviewed the application of deep learning technique’s in brain tumor segmentation, classification, and prediction. It details clinical applications and provides in-depth information on datasets. While the survey does not involve Vision Transformer techniques, it focuses on the use of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) in hybrid models to improve case diagnosis. The study mentions several important open challenges, recommending improvement in generalizing models within the oncology context, as well as some data-related issues associated with MRI acquisition and quality.

Wang et al. [37] consider the segmentation of meningiomas using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), based on MRI images. The study possesses a strong clinical foundation and includes discussion on datasets in detail, however, focus is only on segmentation, not classification of brain tumors. While there is no mention of Vision Transformers, hybrid methods that use CNN’s can help clinically relevant outcomes but health matters can be complex in different patients. The study illustrates important open challenges to improve segmentation, such as: variability of MRI images, patient heterogeneity of meningiomas and impact of diverse datasets; and importance of multisequence MRI may help better inform models.

Our systematic review includes a comprehensive and prospective breadth, which spans brain tumor segmentation tasks, brain tumor classification tasks with equal analytical rigor, and takes a look at state-of-the-art deep learning methods that have emerged recently between 2022 and 2025 such as ViT3D, ResViT, UNetFormer, and TECNN that incorporate attention, global context and hybrid CNN-Transformer to be either considered individually earlier or not at all. Our review also includes the increasing trend toward multimodal fusion and providing a note on the new norms regarding the integration of MRI, PET, and clinical metadata in DL pipelines. Our SLR also uniquely articulates the relative progress across datasets by consistently benchmarking results from a temporal perspective highlighting changing usage patterns, the inclusion of MOLAB and REMBRANDT datasets and their lack of consideration in previous reviews. This review relates a simplified and consolidated comparison Table 1, but goes further by clarifying methodological innovations, empirical dataset trends, and clinical usability issues therefore providing a novel, timely read for navigating towards more, robust, and clinically useful brain tumor diagnosis systems.

The objective of this SLR was to identify the most effective methods for the classification and segmentation of brain tumors using deep learning. Based on SLR, literature review was conducted to evaluate the various studies in accordance with a predetermined standard criterion. All of the data were arranged and analyzed to provide more compelling, rational, and conclusive responses to the research question only after the SLR. This subsequent review concentrated solely on the contributions made to the diagnosis of brain tumors, in addition to the identification of highly current research on deep learning techniques.

The systematic review of literature follows strict PRISMA rules to provide clear, frequent and detailed reporting processes. The review is structure based on a clear framework and addresses the formulated research questions regarding deep learning methods for brain tumor classification and segmentation. The first step of the SLR is to establish an evaluation framework to determine the strategy for qualitative assessment. The strategy is divided into three phases: planning, data selection and evaluation. During the evaluation phase, the collected studies are evaluated in detail to determine whether the evaluation is included or excluded.

3.2 Formulated Research Questions

The current works on deep learning methods for brain tumor segmentation and classification are to be thoroughly and transparently examined, and this methodological approach is utilized to achieve this. The whole study is guided by the research questions, which focus on the fundamental components of deep learning applications in brain tumor diagnostics. As a result, the primary goal of this review is to address the research concerns as described below:

• R1: Which type of image modality is suitable with deep learning for accurate diagnosis?

• R2: What datasets are widely used for brain tumor segmentation and classification in deep learning?

• R3: What deep learning techniques are frequently employed for diagnosing brain tumors?

• R4: What are limitations and key highlights associated with methods?

• R5: What accuracy is achieved by the methods for brain tumor diagnosis?

The application of systematic methodology and strategic development significantly influences the efficiency of extracting relevant and valuable content from the literature. Brain tumor studies contain a considerable body of literature on segmentation, classification, and detection techniques using deep learning; therefore, it is a vast and rapid domain. To effectively manage the information, we refined the search strategy to include only literature that is highly relevant to our research questions. The search is created using the Boolean operations such as ‘AND’ and ‘OR’ and after that the query is optimized by adding the topic related terms and narrow, to ensure the obtained articles are highly relevant for the comprehensive review, as shown in Fig. 1. The investigation focused on information related to brain tumor, including risk factors and other pertinent variables, as well as deep learning methods for brain tumor recognition. The criteria for selecting the literature utilized in this paper are as follows:

• Direct relevance to the formulated research questions.

• Terms specifically associated with the recognition of brain tumor through deep learning methodologies.

• The logical operators (“AND,” “OR”) are systematically applied between the keywords to enhance the effectiveness of the search string.

Figure 1: Systematic review workflow

The formulated query is fallow as Brain tumor AND (“Hybrid models” OR “ViT” OR “Hybrid CNN-Transformer”) AND (“MRI segmentation” OR “MRI classification”) AND (“Glioma” OR “Meningioma” OR “Pituitary tumor”) AND (“Dice coefficient” OR “IoU”). Fig. 1 illustrates the scheme of the search strategy adopted in this systematic review.

The initial search query for brain tumor segmentation and recognition using deep learning techniques is conducted in several highly regarded academic databases, including Scopus, Google Scholar, Taylor & Francis, and Wiley. The Scopus database is a widely recognized and extensive peer-reviewed literature indexing source that is widely used in a variety of disciplines, such as medicine, science, and technology. Therefore, it is well-deserved when extracting serious studies on the application of deep learning in medical. Many academic works, including reports, and journal articles, are collected by Google Scholar, which encompasses the majority of materials in all sciences. By publishing some of the most esteemed journals in the health sciences and related computational methods, Wiley assurances that the user will receive valuable and trustworthy references that are subject to a rigorous peer-review process. Taylor & Francis has achieved global recognition for its publication of rigorous studies in artificial intelligence and healthcare, which has allowed it to operate as a highly innovative and credible research medium. The optimized query was used to filter fundamental research materials on the subject, and subsequently, selection criteria were employed to conduct a systematic analysis of relevant articles.

3.5 Initial Selection Criteria

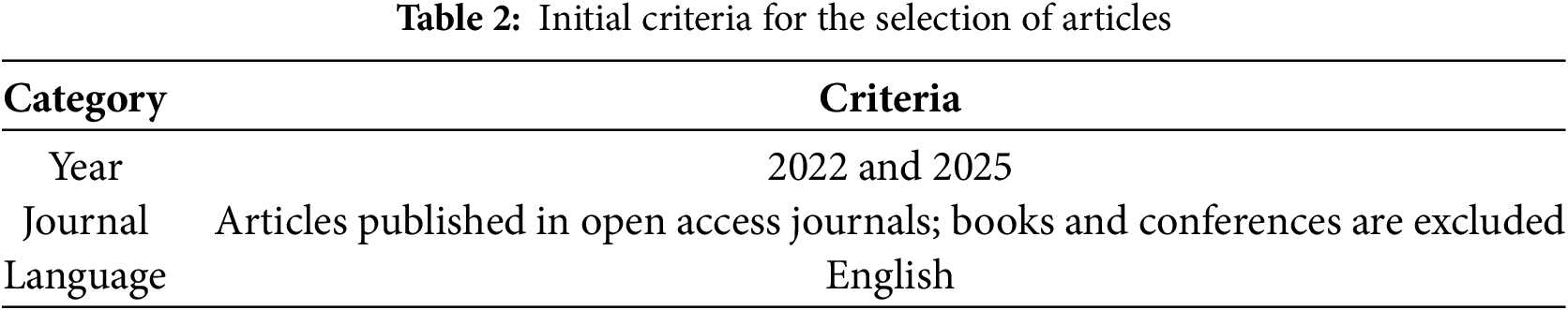

The primary selection of research articles considered several key criteria: publication language, open access articles, range of publication year, and relevance to the research topic. To effectively conduct an analysis, journal articles are primarily considered if they are published in English language. Research conducted between the years 2022 and 2025 is emphasized to have current advancements in thought. While, it was terrific if selected articles aligned closely with primary search strings as mentioned in the search strategy to have relevance to the area of interest. Table 2 described the initial criteria.

3.6 Selection and Evaluation Process

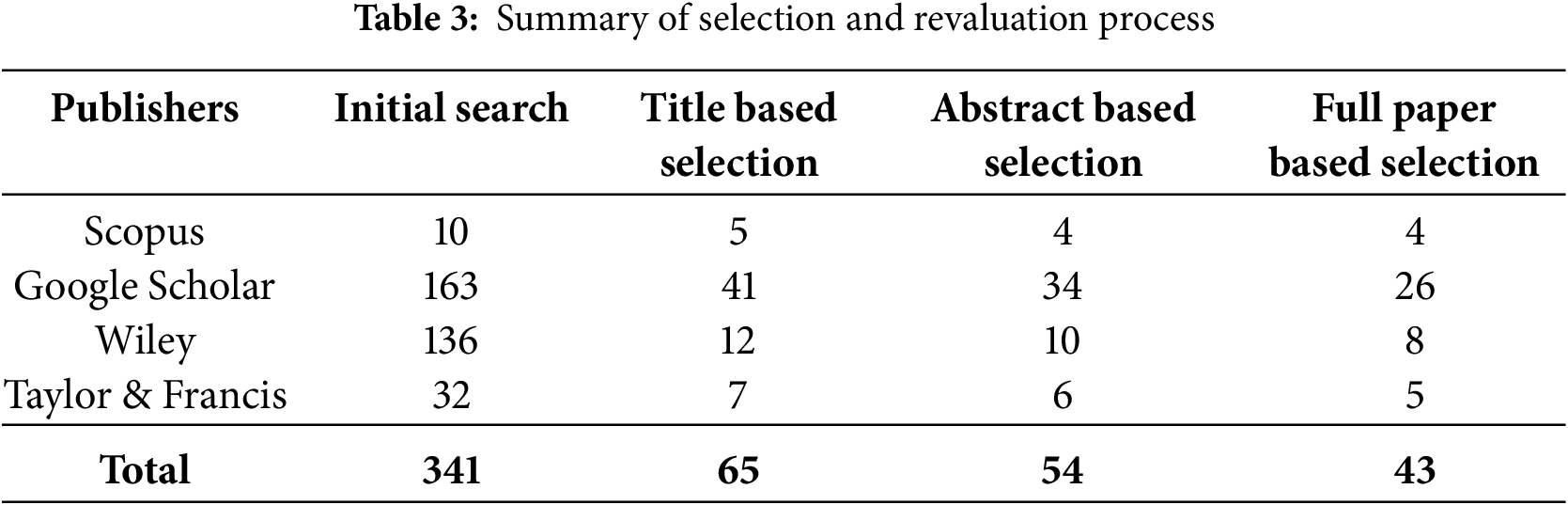

In selection and evaluation process, 341 articles are identified in the initial search based on the query. The selected articles are further filter based on the relevance of title and 65 are considered the best match of title with the objectives. 4 articles from the scopus, 32, 10, and 6 articles from the google scholar, Wiley, and taylor & Francis are selected based on the abstract. In the last, 54 articles thoroughly analyze and 43 articles are selected in the final phase for the literature review, as shown in Table 3. Conversely, 6 conferences from the CVPR and AAAI articles are added.

Fig. 2 presents the Prisma diagram of the systemic literature review process. According to the figure, the review starts with the Identification Phase, which involves the retrieval, from various databases including Scopus, google scholar, Wiley, and Taylor & Francis. This resulted in 341 total identified records. Six studies obtained at the high-caliber conferences CVPR and AAAI, both known for disseminating impactful and broadly-applicable research in computer vision and AI, were also included.

Figure 2: PRISMA diagram for the systemic literature review on brain tumor classification and segmentation using deep learning

In the screening process, rigorous filtering is performed to remove the articles that are not align with research questions. In the first filtering level, studies are filtered 276 records, based on Duplicate records studies not relevant or implication of the research objectives, not an Open Access publication, reports consisting of Conference papers, Studies in a foreign language other than English, and if years for the studies would not fall within the years of 2022–2025. After applying this process, 65 records is remaining.

In the second phase of screening, the abstracts of each of the studies remaining in the review process needed to be examined for relevancy. 11 studies are removed such as 1 from Scopus, 7 from Google Scholar, 2 from Wiley, and 1 from Taylor & Francis. Removing the 11 studies from the review ensured the full text review would only include studies that fully met the core research requirements. Following this review phase, 54 studies remained moving into the final review phase. The final phase of filtering is based on is the full article selection, which consisted of critically assessing the full text of the studies remaining. At this phase, 11 additional studies were removed, ensuring the articles considered for review are the highest quality, most relevant, and the most accessible studies. Following this review, 43 studies were selected from the databases along with 6 additional studies from the CVPR and AAAI conferences.

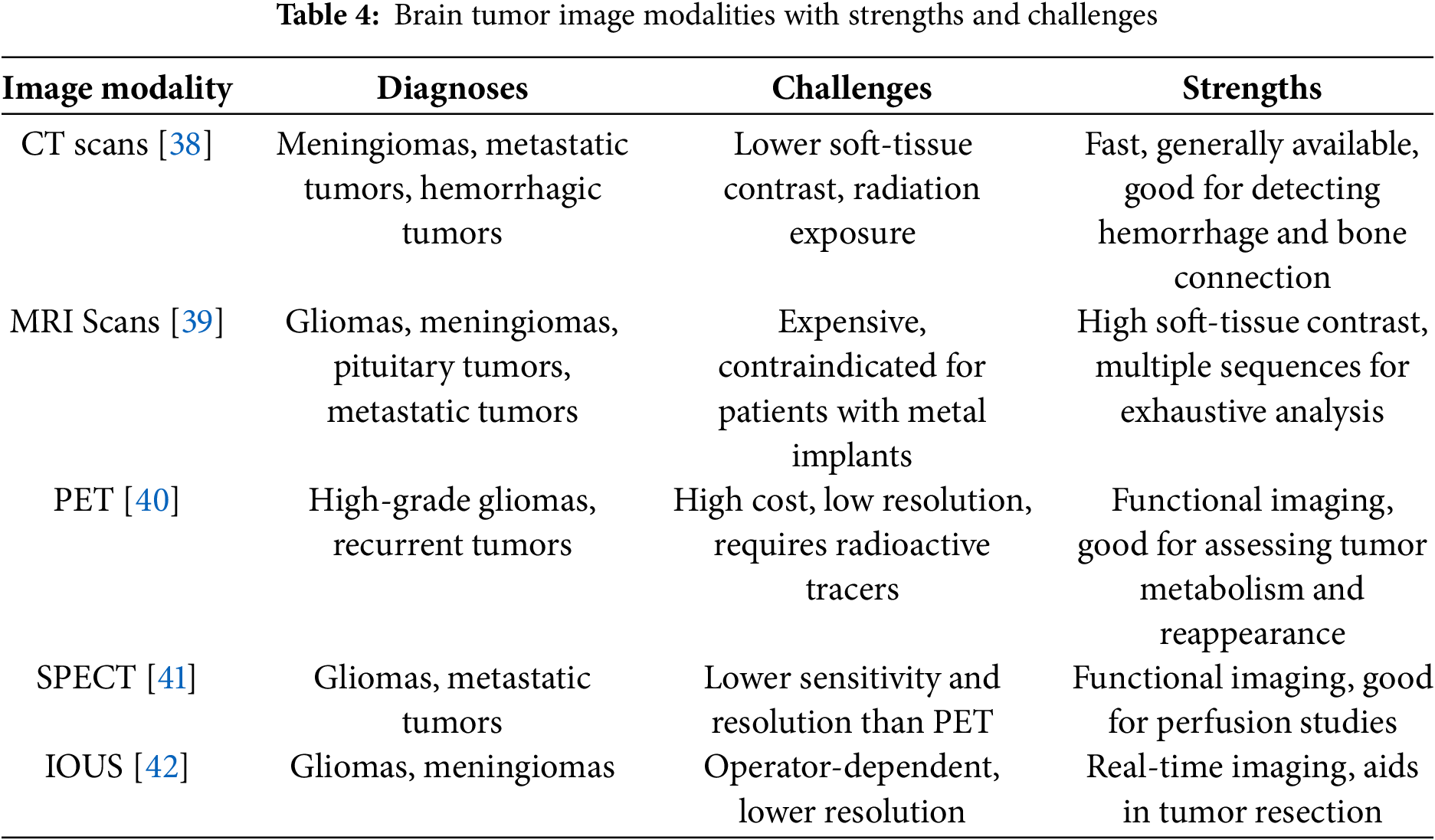

4.1 Image Modalities for Brain Tumor

The process of diagnosing and classifying brain tumor includes a variety of different imaging modalities, each providing a unique insight into the features of the tumor. Accurate imaging is a vital component of the process for early detection, treatment planning, and for monitoring tumor progression. A multitude of imaging methods exist that are used both to identify the location of the tumor as well as assess features such as metabolic activity, vascularity, and infiltration features into the nearby brain parenchyma. These modalities include the traditional anatomical images like MRI and CT scans and the advanced functional images such as PET and SPECT. Ultrasound imaging modalities can also be used intra-operatively that can assist in tumor resection events by neurosurgeons. Each of the imaging methods carry unique strengths and weaknesses and a multimodal approach is often warranted in conjunction with clinically obtaining all required information on tumor evaluation. The strength, challenges, and diagnoses for each image modality is described in Table 4.

4.1.1 Computed Tomography (CT-Scans)

CT scans [38] are frequently the initial imaging modality used in emergency situations due to their rapidity and accessibility. They offer exceptional information on bone involvement, hemorrhage, and calcifications. Contrast-enhanced CT scans enhance tumor visualization by identifying regions with aberrant vascularity. It is helpful for the visualization of tumors, including meningiomas and tumor metastases; however, it is less effective in individual between tumor types or providing specific information about the tumor’s features due to its lower soft-tissue contrast than MRI.

4.1.2 Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI-Scans)

Magnetic resonance imaging [39] is considered as the benchmark for seeing brain malignancies due to its superior soft-tissue contrast and capacity to delineate brain structures with precision. Aside from being non-invasive and devoid of ionizing radiation, repeated MRI scans are considered safe. Diverse MRI sequences provide distinct information about the tumor’s features. T1-weighted (T1W) imaging is very effective for depicting the anatomical architecture of the brain. T1-weighted imaging may sometimes be beneficial for visualizing regions of bleeding or malignancies containing fat. T2-weighted (T2W) imaging is effective for evaluating edema and defining the amount of tumor infiltration. Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) imaging is very effective for depicting peritumoral edema since it suppresses the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) signal in the images. Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) identifies highly cellular tumors and ischemia alterations in the brain, while perfusion-weighted imaging (PWI) MRI quantifies blood flow inside tumors, aiding in the variation of high-grade gliomas from low-grade gliomas. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) assesses the molecular makeup of brain tissue, which may sometimes aid in separating various forms of brain cancers. MRI is commonly used for the imaging of gliomas, meningiomas, pituitary tumors, and metastatic brain cancers.

4.1.3 Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) [40] imaging is a non-invasive technology that evaluates the functional activity of metabolites in brain tumors. Metabolically active tumor cells often exhibit elevated glucose absorption, which may be observed and evaluated by fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET imaging. Other specialized PET imaging techniques used in research include fluorothymidine (FLT), fluoro-ethyl-tyrosine (FET), and alpha-methyl-tyrosine (MET)-PET, along with additional radiotracers that exhibit increased selectivity for brain malignancies. It is an effective technique for classifying gliomas, individual between tumor development and therapy-induced necrosis, and offering insights for modifying treatment. This method has drawbacks such as expense, inadequate spatial resolution, and reliance on radioactive tracers.

4.1.4 Single-Photon Emission Computer Tomography (SPECT)

Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) [41] imaging utilizes radiolabeled tracers to assess tumor structure. Similar to PET, It is very effective in separating among benign and malignant tumors and assessing cerebral perfusion. It is more widely accessible than PET; yet, it has lesser sensitivity and resolution, making it less often used for the diagnosis of primary malignancies.

4.1.5 Intraoperative Ultrasound (IOUS)

Ultrasound [42] is often used in brain tumor procedures to facilitate the resection of tumor tissue. It offers intraoperative imaging to aid neurosurgeons in discriminating the tumor from healthy brain tissue. It is not used for preoperative imaging. IOUS enhances surgical accuracy and the amount of resection, particularly for gliomas, which often need more extensive and complex dissections than benign tumors. The drawbacks of ultrasonography include its dependence on the operator and often worse image resolution compared to MRI scans.

Fig. 3 highlights the predominance of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as the preferred imaging modality in brain tumor segmentation and classification studies, being used in 38 out of the 43 reviewed works. This dominance is attributed to MRI’s superior soft tissue contrast, multiplanar acquisition capabilities, and lack of ionizing radiation, which makes it particularly suitable for capturing complex brain anatomy. In contrast, computed tomography (CT) was utilized in only 6 studies, primarily in cases involving hemorrhagic or calcified lesions. Functional imaging modalities such as positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) appeared in 4 and 2 studies, respectively, indicating a limited but emerging role in assessing tumor metabolism and perfusion. Intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS), used in just 3 studies, offers real-time assistance during tumor resection but remains underrepresented in segmentation-focused research. Overall, the chart underscores the centrality of MRI and suggests opportunities for multi-modal fusion with underused modalities to enrich diagnostic and prognostic modeling.

Figure 3: Frequency of different imaging modalities used in brain tumor segmentation and classification studies

4.2 Publically Available Datasets

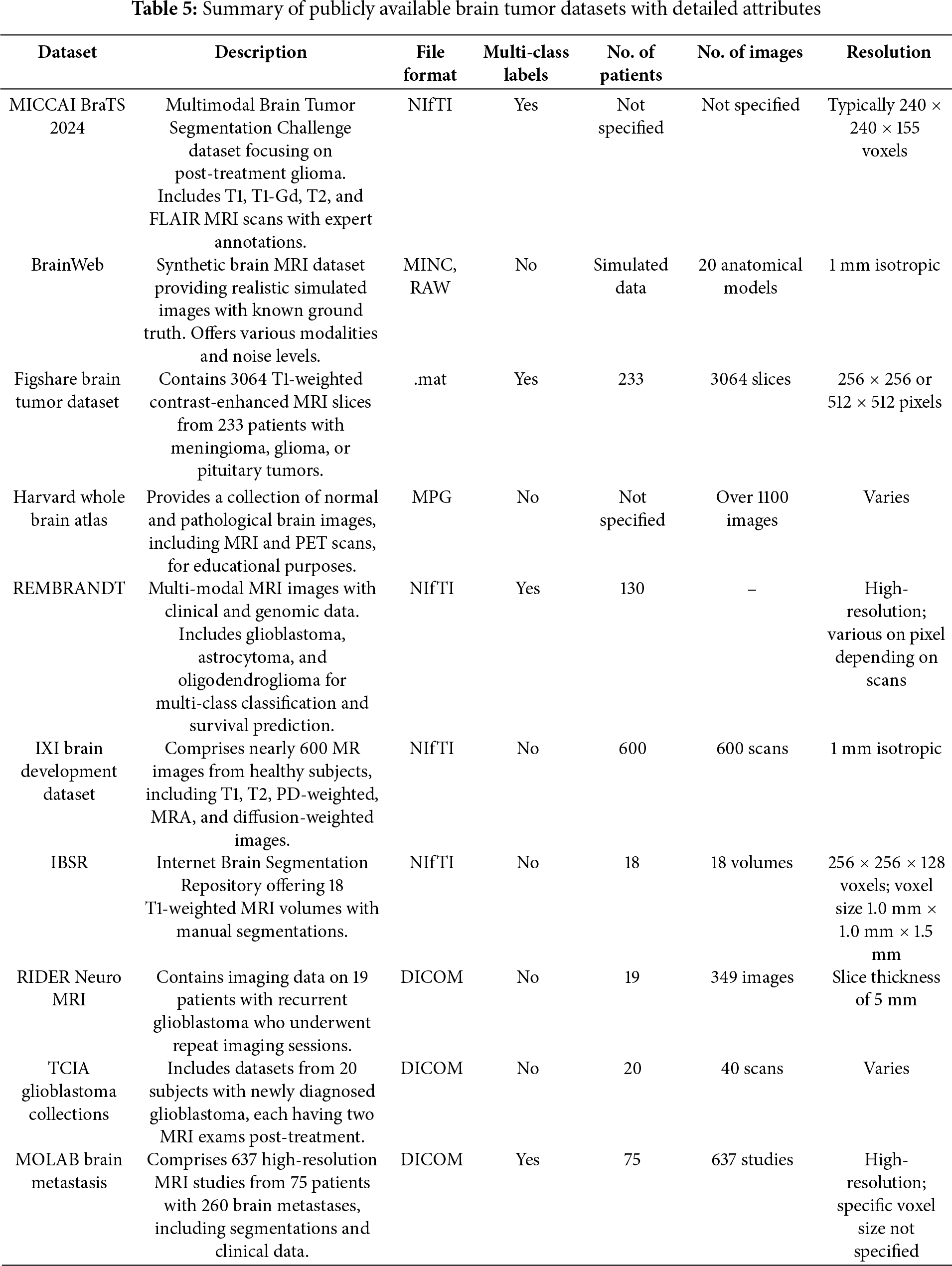

The detection and classification of brain tumors is essential in medical imaging, aiding in diagnostic and therapy planning for brain tumors. Researchers use benchmark datasets recognized as standard within the discipline. Benchmarks serve as definitive assessment criteria for algorithms and models. The datasets differ in imaging modality, tumor class quantity, and the intended purpose of segmentation or classification. Table 5 presents public datasets famous in the literature for brain tumor segmentation and classification and Fig. 4 presented the visual characteristics of each dataset.

Figure 4: Sample images for each dataset for visual characteristics

The BraTS dataset [43] is one of the most extensive and commonly utilized datasets for brain tumor segmentation. The dataset has been released annually since 2012 and contains multi-parametric MRI scans (T1, T1c, T2, and FLAIR) of glioblastoma and lower-grade gliomas. The dataset contains hand-segmented tumor regions, which include the enhancing tumor, peritumoral edema, and necrotic and non-enhancing tumor core. The BraTS dataset has a primary task of segmentation, making it a great resource to develop deep-learning-based medical image analysis and it is an essential dataset for deep-learning approaches.

The Figshare Brain Tumor Dataset [44] is a publicly accessible dataset that can be used for classification. This T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI image dataset is categorized into three types of brain tumors: glioma, meningioma, and pituitary tumor. The dataset is useful for researchers undertaking classification tasks in order to classify and identify the type of brain tumor.

4.2.3 TCGA-GBM and TCGA-LGG Dataset

The Cancer Genome Atlas–Glioblastoma Multiforme and Lower-Grade Glioma repositories [45] include MRI scans of patients with brain tumors that also contain genetic information. These repositories have been utilized for segmentation and classification tasks, as utilizing imaging features and genetic mutations in gliomas is an area of research.

The REMBRANDT (Repository of Molecular Brain Neoplasia Data) dataset [46] includes multi-modal MRI images as well as clinical data. It is primarily applied for research on brain tumors classifications and survival prediction. The dataset includes glioblastomas, astrocytomas, and oligodendrogliomas which lends itself to multi-class classification studies.

The MoLAB Brain Metastasis dataset [47], created by the Mathematical Oncology Laboratory (MoLAB), is a remarkable achievement in neuro-oncology and medical imaging. It contains 637 high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies from 75 patients with a total of 260 brain metastasis (BM) lesions. It also includes semi-automatic segmentations of 593 BMs across both pre and post-contrast T1-weighted sequences and is, therefore, of significant utility for diagnostic and longitudinal studies. Along with the imaging assessment, there is detailed clinical data provided alongside the imaging data for each patient. It also includes several morphological measurements and a plethora of radiomic features extracted from the segmented lesions. These qualities make this dataset particularly useful for the development and validation of automated algorithms for BM detection and segmentation to assess disease progression and help plan treatment.

BrainWeb [48] is a brain MRI dataset designed to facilitate research and assessment in medical imaging. The images are generated to be accurately simulated brain images with known ground truth, which provides an advantageous opportunity to validate and benchmark image processing algorithms such as segmentation, registration, and classification. It is particularly useful for development of machine learning and deep learning models where ground truth needs to be precise because the generation of the images occurs in a controlled environment and the brain structures are clearly delineated anatomically before generating the images. The dataset is composed of multiple imaging modalities and noisy images to replicate real-world imaging experiences. The multiple imaging modalities and noises add to the usefulness of the BrainWeb dataset as a testing and comparison tool for algorithms.

4.2.7 Harvard Whole Brain Atlas Dataset

The Harvard Whole Brain Atlas [49] is an extensive online atlas that contains a variety of human brain images, both diseased and normal. The goal of the source is to promote education and research in neuroanatomy and neuropathology. The atlases intended user group includes clinicians, researchers and students. Not only does the atlas provide a variety of human brain MRIs, but also the publication contains PET and CT scans and provided specific anatomical information. The source contains descriptive images of the human brain related to both structure and function. The breadth, scope, publicly available nature all provide a valuable dataset to support validation and development of imaging tools.

4.2.8 IXI Brain Development Dataset

The IXI Brain Development Dataset [50] is a collection made as part of the Information eXtraction from Images (IXI) project to support automated image analysis, mainly of healthy people from three hospitals in London. There are over 600 MRI scans of healthy people embedded into the dataset. The dataset provides T1-weighted, T2-weighted, proton density (PD), and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). The dataset represents a good neural mapping sample of normal human brain anatomy at various ages. The IXI Dataset is widely used for brain development studies, for registration tasks, and in training machine learning models, especially, predicting age and some aspects of brain morphometry.

The RIDER Neuro MRI dataset [51] is included as part of The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA). The RIDER Neuro MRI dataset contains MRI T1-weighted contrast-enhanced (T1-CE) scans and interventions in 19 patients with recurrent glioblastoma. The dataset formally supports research in treatment response evaluation, imaging biomarker development, and reproducibility. The dataset provides high quality standardized imaging for longitudinal studies in clinical research while evaluating imaging algorithms. Due to the clinically relevant database—and that the dataset is in TCIA—the RIDER dataset can advance certain aspects of further research related to quantitative imaging and radiogenomic aspects associated with brain tumor progression and monitoring therapy.

The distribution of usage for the most prominent publicly available datasets for brain tumor classification and segmentation as outlined in the Fig. 5. The BraTS dataset clearly leads the way with approximately 52% of the dataset usage, which fits well considering that it is the gold standard dataset for brain tumor segmentation challenges due to its assimilation of multi-modal MRI and annotations from experts in the field. The FigShare dataset is next with approximately 36% of usage, which is largely in support of classification tasks for glioma, meningioma, and pituitary tumors. The TCGA-GBM/LGG datasets collectively contribute 5% of the dataset usage value in terms of their imaging and their genetic information. The REMBRANDT dataset versions for 4% of the usage and provides a combination of MRI imaging and clinical data for multi-class classification and survival studies. The MOLAB dataset is a newer option that is considered by capturing many more detailed features on patients who have brain metastasis and is currently used about 3%, highlighting its iterative potential in more narrow segmentation tasks.

Figure 5: Distribution of Most used datasets for the brain tumor classification and Segmentation

4.3 Preprocessing and Data Augmentation in Brain Imaging

The efficacy of deep learning models in the classification and segmentation of brain tumors is greatly impacted by the quality and diversity of the training data [52]. Medical image datasets, especially brain tumor datasets, face several challenges such as class imbalance, limited annotated samples, noise, and variability in acquisition protocols. Preprocessing and data augmentation strategies are commonly used throughout the model training pipeline as a preventative and enhancement approach [53].

Preprocessing: Preprocessing [54] seeks to improve the quality of the input data by decreasing noise, normalizing image intensities, and aligning anatomical features. This includes techniques such as skull stripping, intensity normalization, bias field correction, image resizing, and registration. For example, intensity normalization adjusts image intensities across different acquisition protocols so that the images fall within a common intensity range, helping the deep learning model generalize better across varied inputs. Similarly, bias field correction addresses spatial intensity inhomogeneities in MRI scans, improving the contrast between tumor and normal tissue.

Data augmentation: This technique enhances the training dataset by employing label-preserving transformations such as rotations, flipping, scaling, cropping, elastic deformations, and contrast adjustments [55]. These transformations simulate clinical variations, leading to more robust and generalized deep learning models. Elastic deformations, for instance, mimic anatomical variability, while rotation and flipping mitigate spatial orientation biases.

The integration of both preprocessing and augmentation techniques has been shown to improve model performance across numerous studies. These strategies not only standardize inputs and enhance data variability but also help reduce overfitting, accelerate convergence, and enable models to learn more invariant and discriminative features. For brain tumor segmentation, preprocessing provides a standardized representation of tumor boundaries, while augmentation introduces diverse variations for improved pattern recognition across spatial contexts. Additionally, advanced augmentation methods such as adversarial augmentation, mixup, and generative models like GANs are increasingly used in low-data conditions. These approaches contribute not only to data augmentation but also to regularization, thereby enabling deep learning models to generalize better on unseen patient data. The common techniques are describe in Table 6.

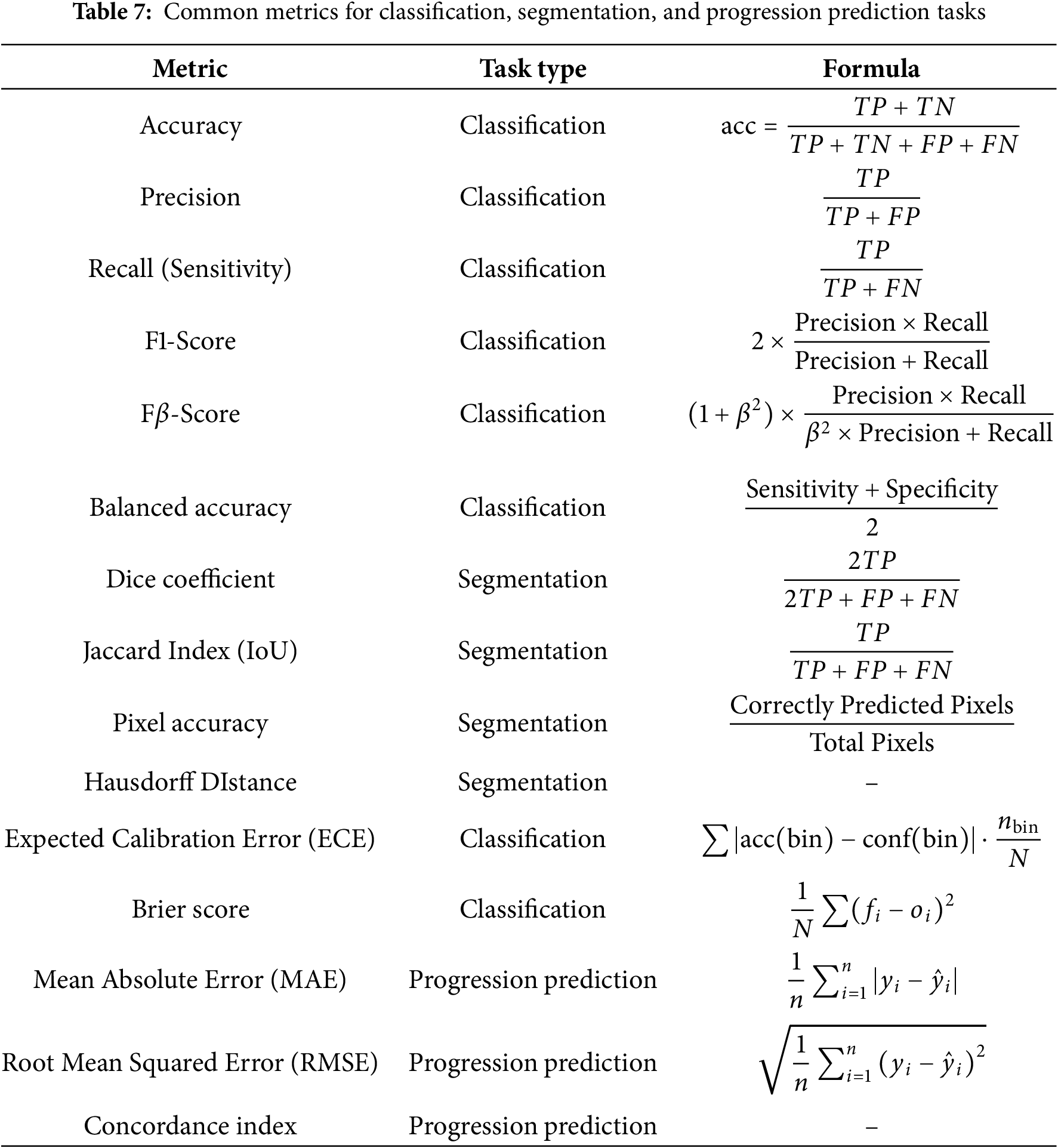

Evaluation metrics are a critical resource for providing actionable feedback and information to improve models when developing deep learning models. The evaluation metrics are particularly important when evaluating and interpreting model performance for different tasks. All the evaluation metrics, accuracy is the most widely used particularly in brain tumor classification tasks, since it is a straightforward measure of the correct predictions to total predictions. Table 7 described the evaluation metrics.

4.5 Deep Learning Architectures

Fig. 6 presents a taxonomy of deep learning methods used in brain tumor detection and segmentation. The taxonomy categorizes methods into four major groups: convolutional neural network (CNN)-based models, transformer-based architectures, hybrid models that integrate both CNNs and attention mechanisms, and multimodal or ensemble models. CNN-based approaches, such as U-Net, ResNet, and DenseNet, have been foundational in tumor segmentation tasks due to their ability to learn spatial hierarchies and extract robust features from MRI images [3,56,57]. Transformer-based models, inspired by advances in natural language processing, introduce global attention and have shown promising results in recent years with architectures like ViT, Swin-T, and UNetFormer [58–60]. Hybrid models combine the strengths of CNNs with attention-based transformers to overcome the limitations of each approach individually, enabling improved performance in complex multimodal datasets [61–63]. Finally, multimodal and ensemble methods leverage the integration of MRI with PET, CT, or clinical metadata to provide a richer and more holistic input space for classification or segmentation models [10,64]. These models often incorporate explainable AI components to increase transparency and support clinical decision-making. The evolution and diversification of these architectures reflect a growing sophistication in the computational handling of brain tumors, with research shifting toward more integrated, explainable, and patient-specific AI solutions.

Figure 6: Taxonomy of deep learning methods

Multimodal models take advantage of complementary data there is anatomical data through MRI, metabolic data through PET, and clinical metadata, all of which help improve and increase the accuracy of classification and segmentation. The recent literature shows that these integrative frameworks can not only achieve better accuracy and Dice score than unimodal models but can also enhance the ability to support survival predictions and treatment planning for patients. The work of [65] discusses the clear utility of adding radiomics and metadata into attention-guided 3D CNNs, which leads to more reliable prognostications. Moreover, these models can generalize better across different clinical scenarios, ultimately leading to more dependable prognostications. This research is also consistent with the shift towards precision medicine and supports the advancement of AI systems that are explainable as well as clinically robust.

Fig. 7 illustrates the evolution of deep learning techniques applied to brain tumor segmentation and classification between 2022 and 2025. The timeline begins in 2022 with the widespread adoption of convolutional neural networks (CNNs), particularly architectures like VGG, ResNet, and U-Net, which demonstrated strong performance in both segmentation and classification tasks. In 2023, the field progressed with the emergence of hybrid models that combined CNNs with attention mechanisms and early forms of self-supervised learning. This year also marked the initial deployment of Vision Transformers (ViTs), which brought global attention capabilities to medical image analysis. The trend continued into 2024, with increased interest in three-dimensional ViT models (e.g., ViT3D) and ensemble strategies such as ResViT and UNetFormer, offering state-of-the-art results on benchmark datasets. By 2025, research shifted toward integrating multimodal imaging (e.g., MRI with PET or clinical metadata) and enhancing interpretability through explainable AI frameworks. The timeline reflects a clear trajectory toward deeper, more integrated, and clinically aligned architectures for automated brain tumor analysis.

Figure 7: Timeline of the evolution of deep learning techniques for brain tumor analysis (2022–2025). Key milestones include the rise of CNNs, the introduction of Vision Transformers, and the emergence of multimodal and explainable architectures

4.6 Deep Learning Methods for Brain Tumor Classification

The reviewed literature on deep learning methods for brain tumor classification reveals a rich diversity of approaches, which can broadly be grouped into four categories: Transformer-based models, CNN-based architectures, hybrid deep learning frameworks, and classical machine learning models with hand-crafted features.

Transformer-based models (e.g., FT-ViT [66], RanMerFormer [58], ViT with residuals [67]) are gaining attention due to their ability to capture long-range dependencies and context-aware features. These models consistently report high classification accuracy, often exceeding 95%. For instance, Asiri et al. [66] achieved 98.13% accuracy using a fine-tuned ViT model. However, such models remain computationally expensive and are sensitive to dataset size and diversity, raising concerns about generalizability. The performance drops in studies involving small or imbalanced datasets, as observed by Sharma and Verma [67].

Hybrid deep learning models, which fuse CNNs with Transformers or other optimization modules, have shown the highest performance across various studies. Notably, the ResViT model by Karagoz et al. [61] achieved 98.53% accuracy using self-supervised learning, and the TECNN by Aloraini et al. [62] reached 99.10%. These methods benefit from combining local (CNN) and global (Transformer) features and often incorporate auxiliary tasks or optimization algorithms (e.g., Bayesian optimization [68]). Despite excellent accuracy (often >98%), they are limited by computational complexity and long inference times, which hinder real-time clinical deployment.

Ensemble and fusion-based approaches also demonstrate strong classification performance. Methods like those by Zebari et al. [69], Khan et al. [70], and Nassar et al. [71] combine outputs of multiple CNNs or integrate deep learning with machine learning classifiers (e.g., SVM, Random Forest). These frameworks provide robustness and high accuracy (up to 99.77%), yet they often require manual configuration, careful feature selection, and ensemble voting schemes, which may reduce explainability and add computational burden.

Classical machine learning models with hand-crafted feature extraction techniques (e.g., GLCM, DWT, PCA) remain popular in low-resource settings. Studies like those by Saad et al. [72], Ghahramani and Shiri [73], and Dheepak et al. [74] show accuracy

A key observation is the widespread dependence on the Figshare and BraTS datasets, often focusing on the same three tumor types (glioma, meningioma, pituitary). This creates a risk of overfitting and poor generalization to rare tumors and clinically diverse populations. Additionally, most studies report high classification accuracy in controlled benchmark conditions, but few validate on real-world, multi-center clinical data.

Another insight is the increasing shift towards models that integrate auxiliary clinical information (e.g., patient metadata, tumor grade), as seen in the work by Mazher et al. [65], which introduces a survival prediction framework. This trend highlights the growing demand for models that go beyond simple diagnosis to support decision-making in treatment planning and prognosis.

A comparison study is shown in Table 8 for the classification of brain tumor reviewed studies. From this table,the benchmarking results make evident that hybrid deep learning models that combined CNNs with Transformer-based architecture are always able to outperform CNN models only or classical machine learning methods in terms of accuracy in identifying brain tumors. Hybrid models, particularly ResViT and TECNN hybrid models, as well as models that used ensemble-based pipelines, were frequently trusted to return accuracy performance > 98%, denoting their ability to extract both local and global features that corresponded with the variability observed in tumor types. Ensemble models were quite complex, but showed extreme resilience and little variability in their performance. Non-ensemble pure CNN models still performed very well, looked very similar to performance shown with the hybrid models; however, generally, the pure CNN models, while still robust and highly accurate, were not as sensitive to imbalance dataset and models were found to be sensitive on input pre-processing.

Fig. 8 illustrates the distribution of classification errors for deep learning models applied to brain tumor detection and classification, where the error is computed as the complement of reported accuracy (i.e.,

Figure 8: Histogram of classification errors (100-accuracy) for deep learning models used in brain tumor detection and classification. The x-axis is shown on a logarithmic scale to highlight differences among top-performing models. The red dashed line indicates the mean error (3.15%), while the shaded band shows the 95% confidence interval (1.14%–5.17%)

Fig. 9 presents a bubble plot analyzing the relationship between dataset size and the reported accuracy of brain tumor classification models. The horizontal axis is plotted on a logarithmic scale to accommodate the wide range of dataset sizes, while the vertical axis reflects model accuracy. Each bubble corresponds to a specific deep learning model, with the bubble’s size indicating its publication year (larger bubbles represent more recent models), and its color denoting the architecture type—CNN (blue), Transformer (green), or Hybrid (orange). The visualization reveals that hybrid models tend to achieve the highest accuracy even on medium-sized datasets, while CNN-based models maintain strong performance across smaller datasets. Transformer-based models exhibit a broader range of accuracy and are typically applied to larger datasets. This plot provides insight into how model complexity and data scale influence classification performance in recent literature.

Figure 9: Bubble plot showing the relationship between dataset size (log scale) and classification accuracy of various deep learning models for brain tumor diagnosis. Each bubble represents a model, with its size corresponding to publication year (larger bubbles = more recent models), and color indicating the model type: CNN, Transformer, or Hybrid

Fig. 10 presents a box plot summarizing the distribution of classification accuracy across different deep learning model categories employed for brain tumor diagnosis. The four groups—CNN, Transformer, Hybrid, and Ensemble—are compared based on reported accuracy metrics from published studies. The ensemble-based methods achieve the highest and most consistent classification accuracy, with minimal variability. Hybrid models (which combine CNNs and transformers or other optimization techniques) also show high performance with a tight distribution, indicating robustness across different settings. In contrast, transformer-based models exhibit a broader accuracy range, reflecting both emerging potential and instability in performance. CNN-based models remain competitive, but their performance distribution includes a few lower-scoring instances, possibly due to limitations in feature abstraction when used standalone.

Figure 10: Box plot showing the accuracy distribution of deep learning models by architecture type. Hybrid and ensemble-based models demonstrate higher median accuracy and lower variability, while transformer-based models exhibit more diverse performance outcomes

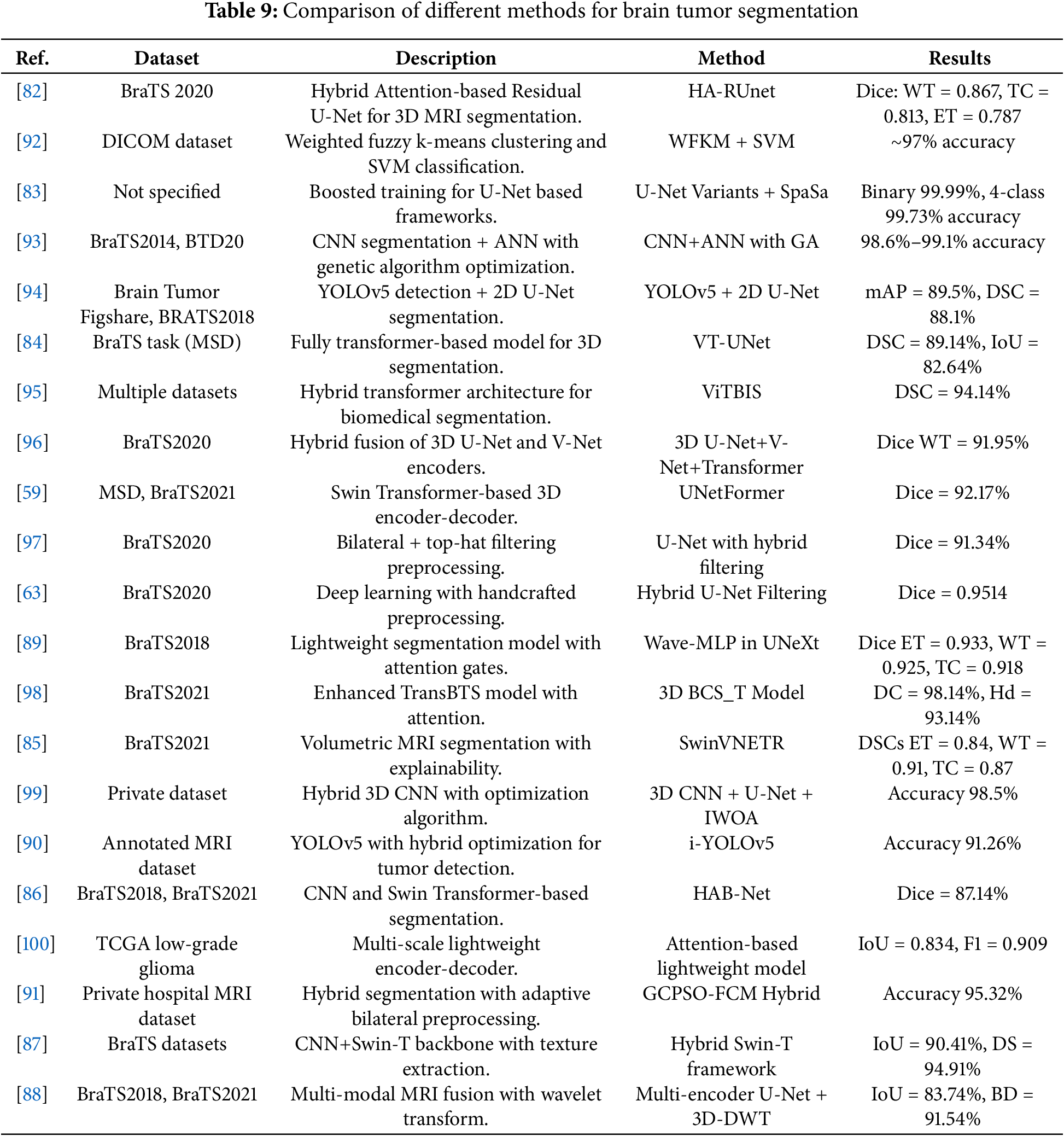

4.7 Deep Learning Methods for Brain Tumor Segmentation

The reviewed studies on deep learning-based brain tumor segmentation highlight significant progress through the use of advanced architectures, multi-modal inputs, and optimization strategies. These methods can be grouped into four major categories: (1) Hybrid U-Net and CNN architectures, (2) Transformer-based volumetric models, (3) Multi-modal fusion and attention-enhanced designs, and (4) Lightweight or optimization-driven frameworks.

1. Hybrid U-Net and CNN architectures remain foundational in segmentation research. Enhanced versions such as HA-RUnet [82] and U-Net variants [83] incorporate attention gates, residual blocks, and novel optimization strategies (e.g., SpaSa) to boost segmentation accuracy on benchmark datasets like BraTS. Dice scores over 0.85 for whole tumor (WT), tumor core (TC), and enhancing tumor (ET) regions were commonly reported. However, these approaches often sacrifice spatial resolution due to input resizing and may lack robustness to variations in real-world MRI protocols.

2. Transformer-based volumetric models (e.g., VT-UNet [84], UNetFormer [59], SwinVNETR [85]) leverage global context modeling through self-attention and hierarchical encoding, and have demonstrated competitive performance on 3D datasets. These models preserve spatial integrity across slices and enhance tumor boundary precision. For example, VT-UNet retains 3D inputs and reports state-of-the-art Dice scores with a relatively small model size. Despite these advantages, transformer-based methods are resource-intensive and require substantial memory and computational power, potentially limiting real-time deployment in clinical settings.

3. Multi-modal fusion and attention-enhanced designs combine MRI sequences (T1, T2, FLAIR, T1ce) with mechanisms like coordinate attention [86], boundary modules, and semantic skip connections [63,87]. These models often report superior segmentation metrics by capturing complementary information from different modalities. For instance, Pan et al. [88] used a wavelet-based multi-encoder U-Net with global context modules and achieved high Dice scores across tumor subregions. Nevertheless, reliance on full multi-modal datasets poses challenges in environments with limited imaging availability or incomplete scans.

4. Lightweight and optimization-driven frameworks, including Wave-MLP [89], i-YOLOV5 [90], and GCPSO-FCM [91], target real-time applicability and deployment in low-resource settings. These models reduce parameter count and training time while maintaining high accuracy, often above 90%. Despite their computational efficiency, such methods may struggle with more complex spatial structures or generalized segmentation across varying datasets due to the exclusion of volumetric context or simplified preprocessing.

Across all categories, a consistent theme is the trade-off between segmentation accuracy, computational cost, and clinical applicability. Multi-stage and hybrid pipelines integrating CNNs, transformers, optimization algorithms, and handcrafted preprocessing (e.g., bilateral filtering, wavelet transforms) tend to yield the highest performance but at the expense of model interpretability and speed. Moreover, while most studies report strong performance on BraTS datasets, validation on external, real-world, heterogeneous data remains sparse.

The summary of all the reviewed articles for the segmentation of brain tumors are shown in Table 9. This table shows segmentation benchmarking in which hybrid architectures produce the best performance considering all architectures used in segmentation. Ultimately, hybrid architectures that employed both CNN encoders and Transformer-base architectures such as SwinVNETR, UNetFormer, and ViTBIS were always better for comprehensive datasets than models such as VT-UNet, 3D U-Net provided accuracy, especially when contextual and global attention were added. Any lightweight architecture including Wave-MLP and i-YOLOV5 was faster, but accuracy was the trade-off; lightweight architectures have limits and are better suited for slow inference environments with limited MIPS. All segmentation architectures with highest approximation search-based performance tended to use some type of multi-modal inputs and depending on when the architecture was published some built in attention mechanism. It would seem there is a tendency to return to integrative and context based architectures.

Fig. 11 shows the range of deep learning techniques applied to classification and segmentation tasks for brain tumors as analyzed from the articles in this review. Based on the analysis, CNN-based methods had the largest share for classification, which reflects their historical position to excel at medical image analysis. Techniques based on ViT models, while newer, had a sizeable share, which alludes to their growing adoption rate, possibly because of improved global feature extraction capabilities compared to CNN-based methods. Hybrid models combining CNNs with transformer architectures showed a roughly equal share between classification and segmentation tasks, possibly indicating versatility in either task. Even though few studies employed ensemble models, it was interesting that most of those models were utilized for classification tasks. It indicates an increased interest in improving classification through model aggregation. While segmentation tasks may have increased attention, it is clear that classification tasks remain the dominant focus of the majority of uses of these deep learning techniques.

Figure 11: Count of reviewed articles using deep learning techniques for the classification and segmentation

Fig. 12 illustrates the distribution of segmentation errors for various deep learning models applied to brain tumor segmentation tasks. The errors are calculated as the complement of the reported Dice similarity coefficients or segmentation accuracies (i.e.,

Figure 12: Histogram of segmentation errors (100-Dice score or accuracy) for deep learning methods used in brain tumor segmentation. A logarithmic scale is applied to the x-axis to emphasize error variation among high-performing models. The dashed vertical line represents the mean segmentation error (5.14%), while the shaded region corresponds to the 95% confidence interval (3.30%–6.98%)

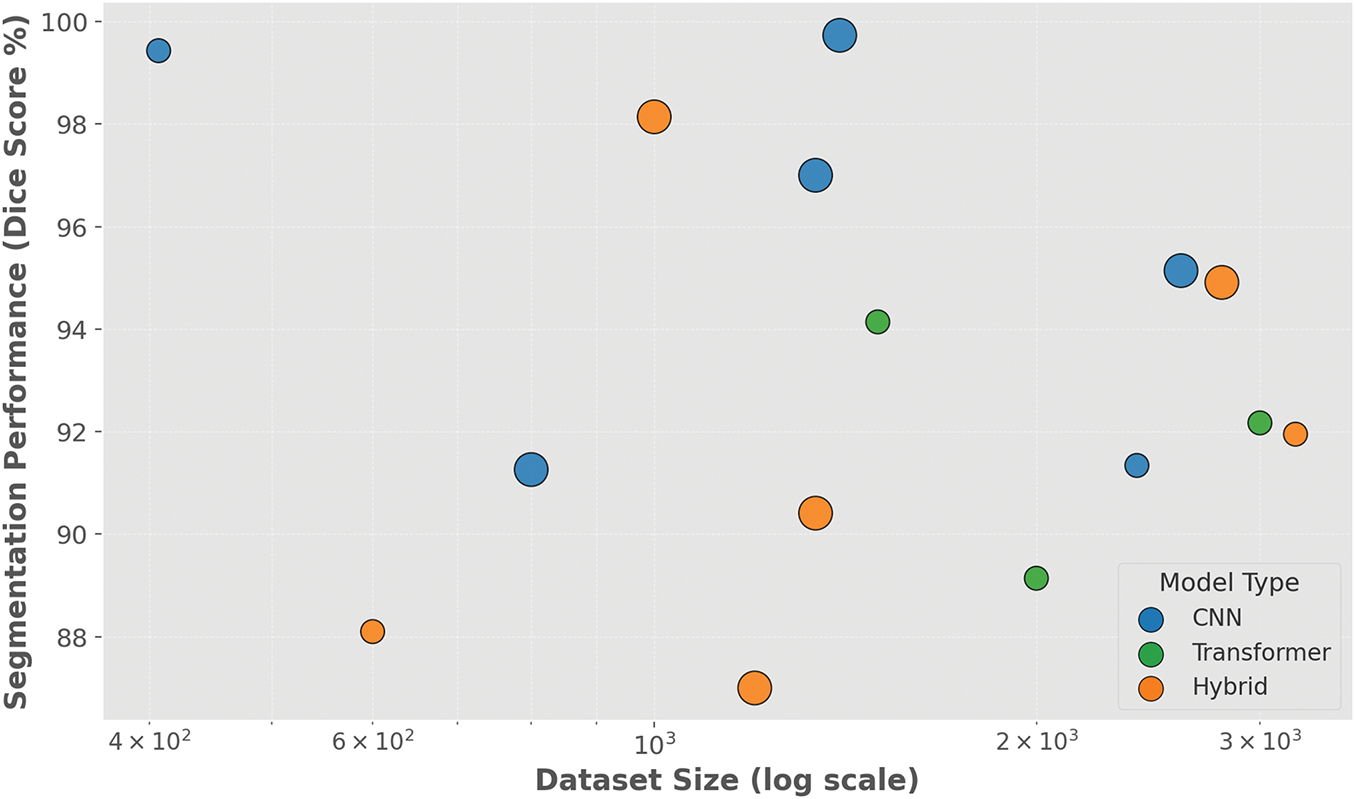

Fig. 13 displays a bubble plot that visualizes the relationship between dataset size and segmentation performance, measured using Dice similarity coefficient (DSC), across recent deep learning models for brain tumor segmentation. The x-axis employs a logarithmic scale to represent the varying dataset sizes, while the y-axis shows segmentation performance in percentage form. Each bubble corresponds to a distinct model, with its size reflecting the year of publication and its color indicating the model type: CNN (blue), Transformer (green), or Hybrid (orange). The plot reveals that most models maintain high segmentation accuracy (above 90%) regardless of dataset scale, although hybrid architectures are notably prominent in achieving Dice scores exceeding 95%. The largest bubbles representing the most recent work also tend to lie in the upper right, suggesting a positive trend in both dataset scale and segmentation quality over time.

Figure 13: Bubble plot illustrating the relationship between dataset size (log scale) and segmentation performance (Dice score) of deep learning models used in brain tumor segmentation. Each bubble represents a published model, with size proportional to publication year (newer models appear larger), and color indicating model architecture: CNN (blue), Transformer (green), or Hybrid (orange)

Fig. 14 presents a box plot summarizing the distribution of segmentation accuracy—reported as Dice similarity coefficient (DSC) or equivalent metrics—across four major deep learning architecture types used for brain tumor segmentation: CNN, Transformer, Hybrid, and Ensemble-based models. CNN-based models demonstrate robust performance with a median segmentation accuracy of 95.32%, and upper whiskers approaching 99.73%, reflecting their well-established reliability in medical image segmentation tasks. Hybrid models—which integrate CNNs with transformers or optimization techniques—also show consistently high accuracy with a wider range, including top-performing models reaching near-perfect segmentation results. In contrast, Transformer-based models show greater variability, with performance ranging from 84% to 94.14%, suggesting that while promising, these architectures are still maturing in this domain. Although only a few ensemble-based segmentation approaches were identified, they exhibit exceptionally high accuracy with minimal variance. This comparative view highlights that hybrid and ensemble strategies currently lead in segmentation reliability, while transformers hold potential for future optimization.

Figure 14: Box plot illustrating segmentation accuracy (Dice coefficient or equivalent percentage) of deep learning models categorized by architecture type. CNN and hybrid methods show high and consistent performance, while transformer-based models reveal greater performance variability

Within the landscape of deep learning applications for brain tumor analysis, many similar sequential thematic trends have evolved and emerged that indicate the maturing but challenging nature of the field. Most overtly apparent is the transition from traditional CNN-based models to hybrid models, such as those integrated with ViTs or attention models. Hybrid approaches permeate the current literature, due to their ability to utilize both spatial locality from CNNs and global context from Transformers, often generating superior performance such as 98% and above classification accuracy, Dice scores above 95% in segmentation. In the segmentation domain, U-Net variants remain the back-bone architecture, however, they are often improved upon through attention gates, boundary-aware modules, and wavelet transformations to boost performance. particularly on BraTS datasets. Transformer-based volumetric models such as VT-UNet and SwinVNETR report state-of-the-art results by maintaining 3D spatial information; however, associated costs and resource concerns, similar to CNNs or hybrid architectures, remain a significant barrier to translation. Emerging frameworks like (Wave-MLP and i-YOLOV5) aim to broaden the design space to facilitate better performance in terms of computational efficiency to support more deployment options; however, the results are often lacking in multi-modal datasets. Therefore key research gaps now exist: (i) develop models with training across multi-institution multimodal demographically broad datasets; (ii) develop explainable AI systems that cultivate clinicians trust; (iii) computational efficiencies of hybrid models; and (iv) integrate multi-modal imaging and patient-specific metadata for holistic patient-centered decisions. Development of clinical tools out of high performing methods will require addressing these gaps

Although classification and segmentation models are both important in analysis of brain tumors, their aims, challenges, and clinical uses are inherently different. Classification models primarily focus on predicting tumor type such as glioma, meningioma, pituitary, or other attributes such as tumor grade or patient prognosis. Classification models are usually assessed using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, and are intended to assist diagnostic and therapeutic decisions in clinical practices. Segmentation models, on the other hand, aim to highlight the tumor region extent spatially, within an imaging volume, allowing for surgical navigation, radiotherapy planning, or volumetric measurement. Segmentation results are often evaluated using Dice coefficient, Jaccard index, and Hausdorff distance. While classification models may typically face class imbalances and domain shift, segmentation models may false to spatial consistency in 3D volumes, computational intensity, and heterogeneity of morphology. In addition to classification and segmentation, hybrid and ensemble learning architectures are gaining importance in both domains. Their utility is expected to differ based on task complexity and dataset details. A comprehensive understanding of the differences in segmentation and classifications tasks is vital for creating effective deep learning solutions targeted at specific clinical needs.

4.8 Uncertainty Quantification in Brain Tumor Diagnosis Models

In the context of clinical decision-making, the reliability of DL models is of paramount importance. While recent advances in CNNs, ViTs, and hybrid architectures have demonstrated high predictive accuracy for brain tumor segmentation and classification, there remains a critical gap in the integration of uncertainty quantification (UQ) [101,102]. This omission poses substantial risks in real-world medical settings, where a confidently incorrect prediction can have more deleterious consequences than a cautious, uncertain one. Therefore, equipping DL models with the ability to express uncertainty is essential for interpretable clinical deployment.

Uncertainty quantification refers to the process of estimating the confidence associated with a model’s prediction [103]. In the domain of medical imaging, UQ has the potential to enhance diagnostic transparency, flag ambiguous regions for further expert review, and support risk-aware decision support systems. Several methodological frameworks have been proposed in recent literature to incorporate UQ into DL pipelines for brain tumor segmentation and classification. Among them, Monte Carlo (dropout applies stochastic dropout layers at inference time, enabling the estimation of predictive variance through repeated forward passes) [104]. Bayesian neural networks (BNNs) can learn distributions over network weights to quantify uncertainty and improve robustness of brain tumor segmentation for transparency [105]. Deep ensembles represent another widely adopted strategy, wherein multiple independently trained models are aggregated to approximate posterior predictive distributions, thus capturing both model and data uncertainty [106–108]. Evidential deep learning employs Dirichlet distributions to infer uncertainty in a single forward pass, offering a computationally efficient and interpretable framework for interpretable brain tumor segmentation [109,110].

In the context of brain tumor imaging, uncertainty quantification has been explored in several segmentation studies, particularly to assess confidence in tumor boundary delineation and to guide radiologists toward regions of high ambiguity [101]. Incorporating UQ into classification models can improve the robustness of diagnostic outputs and help mitigate overfitting, particularly in the presence of class imbalance and domain shift [111]. Despite these advances, our systematic review reveals that only a minority of studies in the brain tumor analysis literature explicitly incorporate uncertainty estimation techniques. Most models report deterministic accuracy metrics without addressing confidence calibration or failure detection. This oversight undermines the clinical readiness of otherwise high-performing models. As highlighted in recent literature [112], the incorporation of calibrated uncertainty estimates should be regarded as a standard component of trustworthy medical AI systems.

4.9 Answers to Research Questions

R1: Which type of image modality is suitable with deep learning for accurate diagnosis?

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) remains the most suitable and widely utilized imaging modality in deep learning-based brain tumor analysis due to its superior soft tissue contrast and non-invasive nature. Among MRI sequences, T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and FLAIR (Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery) are most frequently adopted. These sequences provide complementary information: T1 captures anatomical structure, T2 highlights fluid content, and FLAIR suppresses cerebrospinal fluid, aiding lesion visibility. Recent studies have also explored the use of PET and multi-modal inputs, though MRI remains dominant in both segmentation and classification tasks.

R2: What datasets are widely used for brain tumor segmentation and classification in deep learning?

The BraTS (Brain Tumor Segmentation Challenge) datasets are by far the most frequently cited benchmark in the literature. Available annually since 2012, BraTS provides multimodal MRI scans (T1, T2, T1-CE, and FLAIR) along with expert-labeled tumor segmentations. Other popular datasets include Figshare for classification tasks, the Internet Brain Segmentation Repository (IBSR), and the IXI dataset for structural brain imaging. Synthetic datasets such as BrainWeb are also used for validation and early-stage experiments. However, the field still lacks large, diverse, and fully annotated datasets for rare tumor types and pediatric populations.

R3: What deep learning techniques are frequently employed for diagnosing brain tumors?

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are the backbone of most deep learning models for both classification and segmentation tasks. Variants such as U-Net and its 3D and attention-enhanced extensions dominate segmentation studies. More recently, Transformer-based models and hybrid CNN-Transformer architectures have gained traction due to their ability to model long-range dependencies. Ensemble techniques, combining multiple models or learning strategies, are also employed to improve robustness and accuracy. Optimization methods, attention mechanisms, and transfer learning are frequently integrated to enhance performance and generalization.

R4: What are limitations and key highlights associated with methods?

Despite significant advances, major limitations persist. Chief among them is the reliance on 2D slice-based approaches, which ignore the spatial coherence of 3D volumetric data. Many models are computationally expensive and require high-end GPUs, making real-time clinical deployment difficult. Additionally, most models function as black boxes with limited explainability, posing trust and accountability challenges in healthcare. Nevertheless, key highlights include high Dice scores (

R5: What accuracy is achieved by the methods for brain tumor diagnosis?

The majority of recent studies report classification accuracy ranging from 95% to 99.8%, especially when using hybrid CNN-transformer architectures or ensemble strategies. For segmentation tasks, Dice similarity coefficients (DSC) typically range between 88% and 95%, with some hybrid models achieving up to 98%. While these results are promising on benchmark datasets like BraTS and Figshare, real-world performance often degrades due to domain shift, class imbalance, and imaging variability. Therefore, despite excellent reported metrics, generalization to heterogeneous clinical environments remains an open challenge. Although accuracy is still commonly reported metric in brain tumor classification, it is usually inadequate in healthcare. This inadequacy is present as it relates to class imbalance. Therefore, sensitivity, specificity, precision, F1-score, and AUC must also be reported for the purpose of effective diagnosis. In the case of segmentation tasks, Dice coefficient and IoU are also important for assessing spatial overlap of predicted and ground truth masks.

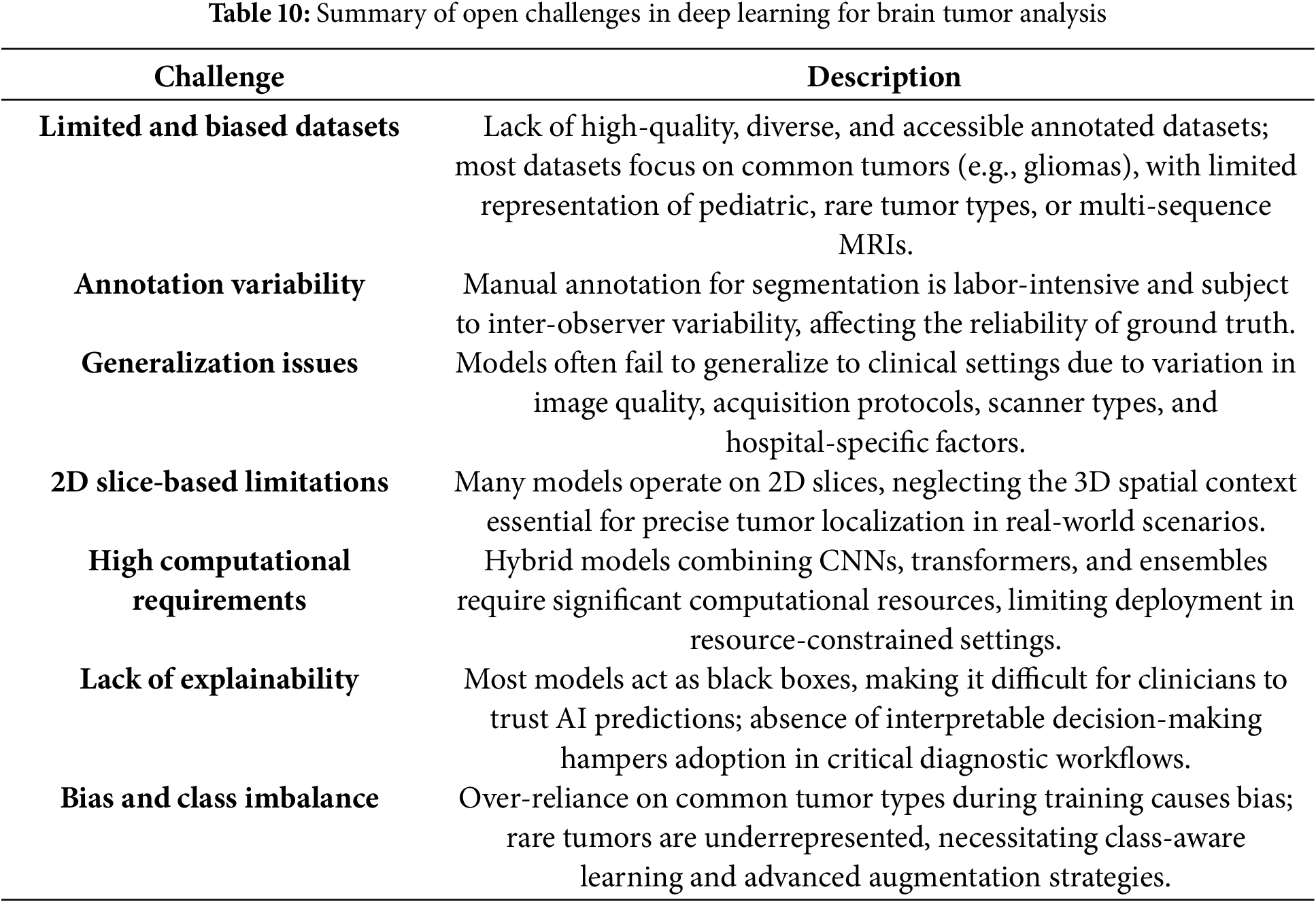

Considering the significant progress achieved with deep learning for the segmentation and classification of brain tumors, there are still numerous unresolved questions that limit the full integration of these systems into clinical settings (Table 10). One of the more significant areas of concern among the questions to be considered is the absence of high-quality annotated datasets which are both reliable and accessible. The sample diversity, class distribution, and differences in image acquisition methodologies of the majority of publicly available datasets are all limitations. For example, datasets that are frequently employed, such as BraTS or Figshare, concentrate on the most common kinds of cerebral neoplasm, and the rare, pediatric, and diverse MRI sequences are not given sufficient attention. The manual annotation process, particularly in the context of segmentation models, is labor-intensive and time-consuming, and it is possible that there will be variability among observers, which could potentially harm the reliability of genuine ground truth data. The generalizability of deep learning models is another area of concern. Many conceptual models will exhibit exceptional performance on benchmark datasets; however, they will ultimately struggle to sustain this level of performance when utilizing other clinical data sources. The performance of models can be vastly inconsistent due to variations in the quality of image texture, the types of scanners used, and the changes that occur in various clinical areas within hospitals.

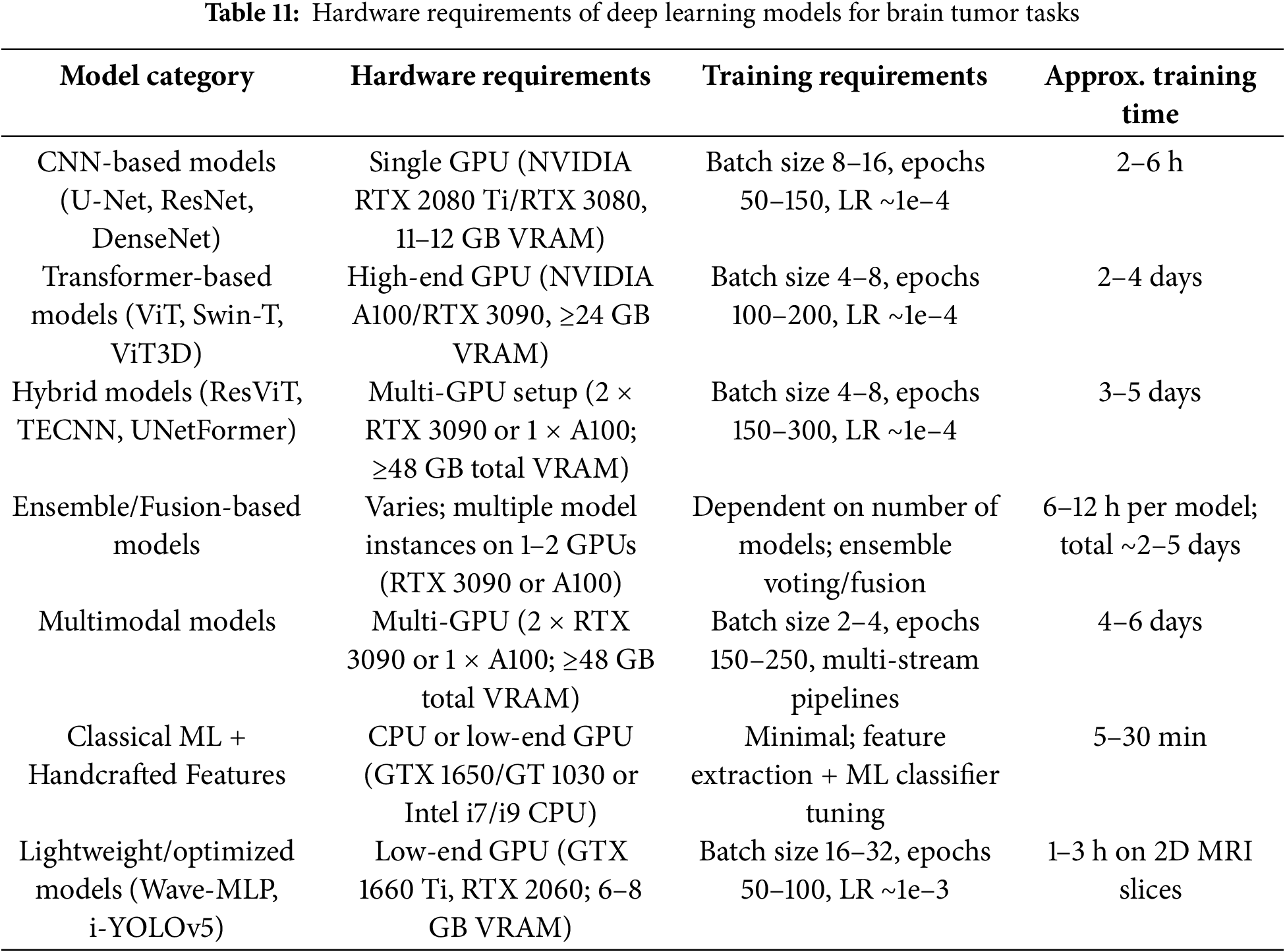

The majority of the models lack consideration for the spatial context of three-dimensional (3D) volumetric data, resulting in the use of slice-based processing in a two-dimensional (2D) format. This approach is presently proving to be problematic in the context of tumor localization and segmentation in real-world settings. The models and their structure, which encompass state-of-the-art models, are complex due to a compute requirement that may obstruct clinical utility. The utilization of hybrid architectures and the combination of CNNs, transformers, attention, and ensemble strategies frequently demands costly, high-performance hardware with extended training and inference periods as shown in Table 11. Therefore, hybrid architectures may not be practicable or beneficial for deployment in regions with significant constraints on real-time decision-making and computational resources. The need for hybrid architectures that are compatible with computational constraints and have lighter models, as well as acceptable accuracy levels, is becoming increasingly apparent. Interpretability and trust in predictions made by artificial intelligence (AI) continue to be of interest when contemplating the attribute. The majority of model architectures can be defined as “black boxes,” with little information regarding the process by which they construct their decisions. The healthcare community finds it exceedingly challenging to establish trust in and implement the use of these AI tools for critical workflows in diagnostic procedures due to their lack of explainability. It is crucial to note that the visual or logical conclusion based on the prediction in the clinic, below an AI system used in the identification of an impactful diagnosis (such as a brain tumor), is not explained. In addition to the development of explainable AI (XAI) models, the resolution of these AI risk issues compels the establishment of additional evidence for fidelity, as well as the provision of meaningful intuitive feedback, as trust in the healthcare community is established. Yet additional obstacles to progress are demonstrated by the class imbalance and the restricted emphasis on numerous uncommon tumor types. The majority of research is conducted on gliomas, meningiomas, and pituitary tumors, while rare but potentially significant forms of tumors, such as chordomas, medulloblastomas, or CNS lymphomas, are rarely, if ever, examined. Two barriers to effectiveness are imposed by low representation for rare tumors: the initial inherent bias during training and the narrowing of inclusion in diagnostic able categories. In what will undoubtedly necessitate users to establish an acceptable balance between datasets, consider class-aware learning or specific models such as focal loss functions or respondents of data augmentation that consciously avoid biases in underrepresented use cases.

A new area of research in brain tumor analysis is so-called federated learning, which lets decentralized institutions share knowledge to collaboratively train deep learning models, while preserving the privacy of patient data as institutional data remains anchored to that institution. This approach can help overcome barriers related to privacy, data governance, and institutional silos, all key limitations to the current clinical AI pipelines. A promising new step forward arises from the integration of large language models (LLMs) such as GPT-based architectures—into multimodal diagnostic frameworks which allow radiological imaging and textual clinical reports to work together. This creates opportunities for improved interpretability and more informed clinical reasoning about the context of diagnostic intentions. These results begin to illustrate a shift toward a more secure, collaborative, and explainable AI that more closely aligns with clinical requirements for deployment.

4.11 Domain Generalization and External Validation Issues