Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

FedCW: Client Selection with Adaptive Weight in Heterogeneous Federated Learning

1 School of Computer Science, Torrens University Australia, Sydney, NSW 2007, Australia

2 School of Computer Science, The University of Sydney, Camperdown, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia

3 College of Economics and Management, Taizhou University, Taizhou, 225300, China

* Corresponding Author: Jinhai Li. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in AI Techniques in Convergence ICT)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069873

Received 02 July 2025; Accepted 29 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

With the increasing complexity of vehicular networks and the proliferation of connected vehicles, Federated Learning (FL) has emerged as a critical framework for decentralized model training while preserving data privacy. However, efficient client selection and adaptive weight allocation in heterogeneous and non-IID environments remain challenging. To address these issues, we propose Federated Learning with Client Selection and Adaptive Weighting (FedCW), a novel algorithm that leverages adaptive client selection and dynamic weight allocation for optimizing model convergence in real-time vehicular networks. FedCW selects clients based on their Euclidean distance from the global model and dynamically adjusts aggregation weights to optimize both data diversity and model convergence. Experimental results show that FedCW significantly outperforms existing FL algorithms such as FedAvg, FedProx, and SCAFFOLD, particularly in non-IID settings, achieving faster convergence, higher accuracy, and reduced communication overhead. These findings demonstrate that FedCW provides an effective solution for enhancing the performance of FL in heterogeneous, edge-based computing environments.Keywords

Federated Learning (FL) [1] has emerged as a promising paradigm to enable distributed model training across multiple devices without the need to centralize data [2]. This characteristic is especially appealing in vehicular networks, where data privacy and communication costs are significant concerns [3,4]. With an increasing number of connected vehicles, FL can provide an efficient solution to collaboratively train models, such as those needed for traffic prediction, autonomous driving, and vehicular safety, while preserving individual data privacy [5]. The decentralized nature of FL reduces the risk of data breaches and ensures that sensitive information remains on local devices, which is particularly important for vehicular networks, where data privacy regulations are stringent, and the costs of data transmission are high [6]. However, the inherent heterogeneity in vehicular data and the variance in computational capabilities across different clients pose significant challenges to conventional FL algorithms [7–9].

A fundamental issue faced by traditional FL algorithms in vehicular networks is their inability to effectively address the heterogeneity of data and client capabilities. The variability in data distribution across clients, which is frequently non-independent and non-identically distributed (Non-IID), can significantly impede convergence and lead to biased global models [10–12]. In vehicular networks, data collected by individual vehicles may differ markedly due to factors such as geographic location, driving behavior, and environmental conditions, further complicating the learning process. Additionally, the random selection of clients without accounting for their potential contributions, coupled with static weight allocation that disregards clients’ relevance to the global model, exacerbates these challenges, particularly in resource-constrained vehicular contexts [13,14]. Consequently, the global model may converge slowly or fail to generalize effectively across all clients, resulting in suboptimal performance in real-world deployments. These challenges underscore a significant research gap in the domain of FL for vehicular networks. In Federated Learning, two central problems are client selection and the appropriate distribution of aggregation weights, particularly in heterogeneous environments where devices have diverse computational capacities and data distributions. The challenge of client selection lies in determining which edge devices should participate in each training round, as involving all clients can be computationally expensive and inefficient. Similarly, the aggregation of model updates must reflect the varying importance of contributions from different clients, considering that clients with more representative data or superior computational resources should have a greater influence on the global model. Fundamentally, both issues revolve around the optimal allocation of weights: client selection can be interpreted as assigning binary weights (0 or 1) to clients to determine their participation, while weight aggregation entails determining the proportional contribution of each client’s update. Studies have shown that unbalanced client participation and inappropriate weighting can detrimentally impact model convergence and accuracy. However, existing methods often treat client selection and weight aggregation independently, resulting in suboptimal outcomes that fail to capitalize on the interconnected nature of these processes. A holistic approach that jointly optimizes both client selection and weight aggregation could yield more efficient and accurate federated learning in heterogeneous edge environments.

In this paper, we aim to unify these two subproblems by presenting a new algorithm, FedCW (Federated Learning with Client Selection and Adaptive Weighting). This algorithm enhances Federated Learning in two key stages: client selection and weight allocation. we calculate the Euclidean distance between each client’s local model and the global model, prioritizing clients with greater divergence for selection. By dynamically adjusting the number of clients involved in each round and allocating weights based on both data volume and model divergence, the algorithm ensures that clients contributing more significant updates have a larger impact on the global model. This integrated approach simultaneously addresses both challenges, optimizing the learning process and improving global model convergence in heterogeneous federated learning environments. To validate our approach, we conduct experiments on various datasets, including MNIST, CIFAR-10, ImageNet-100, and CelebA. We evaluate the performance of FedCW against state-of-the-art algorithms. The experimental results demonstrate that FedCW significantly improves global model accuracy and convergence speed, especially in non-IID data scenarios. In the following, we provide a summary of contributions:

• We integrate client selection and weight allocation into a unified optimization framework for Federated Learning. This approach effectively addresses the interdependent challenges of heterogeneous client environments, improving both the efficiency and accuracy of model training.

• We introduce a novel client selection mechanism that prioritizes clients with diverse updates based on their Euclidean distance from the global model. Simultaneously, FedCW dynamically adjusts aggregation weights according to both data volume and model divergence, enhancing model convergence and generalization in non-IID environments.

• We demonstrate that FedCW significantly outperforms existing algorithms through extensive experiments. Our method achieves faster convergence, higher model accuracy, and reduced communication overhead, particularly in non-IID federated learning scenarios.

Client selection and weight allocation are considered open optimization problems in federated learning (FL), driven by the constraints of limited bandwidth and the necessity for selected participation in training. The problem of client selection is regarded as an ongoing optimization challenge within the FL process. Initial discussions on client selection, such as those by [15], introduced the concept of selecting clients based on their resource efficiency to enhance training convergence and model accuracy. This client selection paradigm has been foundational, sparking widespread research into optimizing FL with heterogeneous resources. However, choosing clients based merely on performance metrics such as speed or computational resources might lead to biases, potentially compromising data diversity. This challenge was addressed by [16], who provided a convergence analysis for client selection, advocating for a balanced approach that considers both computational and communication efficiencies. Further developments by [17] introduced a hybrid FL mechanism that aims to increase the number of participating clients and thus improve the accuracy of the aggregated model by enhancing the diversity of client data used during training. On the other hand, reference [18] explored dynamic data profiling to optimize client selection further, suggesting that understanding data characteristics dynamically could lead to more informed client choices in FL environments. Additionally, recent studies have proposed various frameworks to refine client selection further. For instance, reference [19]’s VFedCS framework focuses on optimizing client selection to manage the volatility and dynamic nature of client availability and resource allocation in federated settings. At the same time, recent vehicular/ITS surveys observe that most systems still decouple the decision of who participates from how much their updates should count during aggregation, which can entrench selection bias under non-IID and volatile participation [20,21].

Several algorithms have been developed to improve the aggregation phase in federated learning. Reference [22] proposed FedProx, which introduces a proximal term to the objective function, mitigating the impact of local updates diverging from the global model. This modification leads to more robust convergence in heterogeneous environments compared to FedAvg, particularly when devices perform a variable amount of local work. To tackle the client-drift problem caused by non-IID data, reference [23] introduced SCAFFOLD, which incorporates control variates to correct local updates. By reducing the variance of updates, SCAFFOLD improves the accuracy of the global model while requiring fewer communication rounds. In the domain of adaptive optimization, reference [24] presented FedOpt, which applies server-side optimization techniques such as Adam and Yogi during the aggregation process, leading to better performance in heterogeneous client environments. Additionally, reference [11] proposed FedNova, which normalizes local updates to eliminate objective inconsistency, ensuring that the global model converges to a solution of the correct objective function despite differences in local workloads. Reference [25] introduced FedMA, a novel aggregation technique that constructs a global model by matching and averaging neurons across layers of client models, effectively aligning the structure of local neural networks. This method enhances performance and reduces communication costs, particularly for complex neural network architectures such as CNNs and LSTMs. Nevertheless, these aggregation methods typically assume uniform or data-size-proportional weights and random/greedy participation, which implicitly presumes representativeness of the selected clients; vehicular studies indicate this assumption often breaks under mobility, skewed labels, and intermittent connectivity [20,21].

Security-oriented ITS works adopt FL for intrusion detection in in-/inter-vehicle networks, confirming feasibility but also revealing robustness and privacy tensions when participation is static and weights are near-uniform [26,27]. Resource-latency studies in vehicular edge computing (VEC) emphasize that client scheduling/offloading co-determines both spectral efficiency and learning dynamics; misaligned aggregation can offset scheduling benefits [28,29]. Communication-efficient FL with gradient quantization and DRL-based compression reduces bandwidth, yet injects additional noise/bias that calls for adaptive weighting and selection to prevent oscillation under harsh non-IID [30]. Application-driven ITS systems—traffic management and mobility/location prediction—report gains with FL but still rely on static participation and weighting, limiting resilience to churn and distribution drift [31,32].

Across client selection, aggregation, and vehicular deployments, three gaps emerge: (i) selection-aggregation decoupling—who participates is decided without calibrating how strongly their updates should influence the global model; (ii) sensitivity to non-IID and volatility—static policies amplify bias when participation is skewed or data distributions drift; (iii) engineering blind spots—scheduling/offloading and compression alter update statistics, yet server-side aggregation remains oblivious to these shifts.

Although the aforementioned works focus on client selection or weight allocation, they treat these as separate issues rather than addressing them as a unified problem. In this paper, we integrate both subproblems into a global optimization framework and propose the FedCW algorithm, which simultaneously tackles both challenges. Through extensive experiments, we compare our method with several of the aforementioned algorithms and demonstrate that FedCW effectively improves global accuracy and accelerates convergence.

Training Process

FL involves multiple clients that train on locally generated data and periodically communicate with a global server to aggregate models. Specifically, the training process in each round comprises the following steps:

• Initialize (Round 0): The global model is initialized on the server side and then distributed to all participating clients.

• Client Selection and Model Distribution: The server selects the client according to the provided client model and information, and sends the aggregated global model to the selected client.

• Local Training: Each selected client trains the received global model on their local data. This step involves running several epochs of training to adjust the model parameters based on the client’s unique data distribution.

• Model Transmission: each client sends their updated local model back to the server after local training.

• Model Aggregation: The server receives the successfully returned model and aggregates the updates to the new global model based on this algorithm.

• Repeat Process: The new round of training begins with the client selection step, repeating steps 2 to 5 until the desired convergence or accuracy is achieved.

To graphically understand FL’s training process, we refer the reader to the Fig, which demonstrates each step of the training process through examples.

Global Objective

In the standard FL framework, our objective is to minimize the global loss function

where

In our proposed method, the weights

where

where:

•

•

•

•

5 Client Selection with Adaptive Weight in FL

In this section, we introduce an enhanced FL algorithm. It can be conceptually divided into two stages: client selection and weight allocation. Algorithm 1 illustrates the operational procedure of our method. In the following, we will elucidate how Euclidean distances influence client selection and weight Allocation; we will also discuss how these elements integrate to form a cohesive whole.

5.1 Euclidean Distance Calculation

The server typically possesses significantly greater computational power and better resource allocation than individual clients. This enables efficient execution of complex mathematical computations, especially when involving multiple clients. Furthermore, performing these calculations on the server side also reduces the communication overhead by eliminating the need to transmit the computed distances. Therefore, starting from Round 1, server will compute the Euclidean distance from each client model to the current global model once the server receives and aggregates the models from all participating clients. The calculation is formulated as follows:

The equation defined above calculates the Euclidean distance

•

•

After the calculation is complete, the server will sort the

In this approach, we select clients based on a descending order of their Euclidean distance from the global model. Intuitively, selecting clients with the greatest divergence from the global model (i.e., the largest Euclidean distance) can introduce more information and data diversity. This is beneficial for the global model as it aids in learning and adapting to a broader data distribution, thereby reducing the risk of over-fitting. By prioritizing clients whose models significantly differ from the global model, each iteration can incorporate more substantial updates, potentially allowing the global model to adapt more quickly to the entire data distribution. We introduce a decay function to dynamically adjust the number of clients selected in each round. The decay function allows the algorithm to adjust the number of participating clients dynamically based on the progress of training or the performance of clients. This method can specifically increase or decrease the number of clients involved in training at different stages to meet the needs of the model during the training process. Given an initial selection fraction

Adjusting the number of participating clients can more effectively utilize limited computational and communication resources. Initially, more clients may need to be involved to enhance the diversity of the model, while later in training, the number might be reduced to concentrate resources on optimizing a model that is nearing convergence. This method, compared to randomly selecting a fixed number of clients, improves the algorithm’s adaptability to different training stages and network conditions, particularly when facing non-IID data distributions. Let N be the total number of clients. The number of clients selected in round

where

To ensure the robustness and efficacy of the algorithm, especially when the total number of clients N is large and the proportion

In the FedAvg algorithm, the aggregation formula for updating the global model is traditionally given by:

This formula ensures that each client’s contribution to the global model is weighted by the proportion of data they hold relative to the total dataset. However, the sheer volume of data does not always reflect a client’s potential impact on the model. Therefore, in our algorithm, the weight allocation formula is modified as follows:

•

•

•

• K is the number of participating clients.

Then the global model parameters are updated as follows:

This weight allocation formula not only considers the volume of data each client contributes but also the divergence of each client’s model from the global model. It introduces a corrective mechanism that allows models with greater Euclidean distances (i.e., more divergent client models) to have a more significant voice in the aggregation process. By employing an exponential function regulated by

When

When

This method of weight allocation can enhance the robustness and generalization ability of the global model in federated learning. It ensures that all relevant characteristics, such as data volume and model uniqueness, are appropriately considered in weighting each client’s contribution. This method is particularly effective in heterogeneous environments, as client data distributions and system characteristics often vary greatly in reality. We will demonstrate this in the experiments.

5.4 Synergy of Client Selection and Weight Allocation

In this algorithm, client selection and weight allocation are two interdependent components that together determine the efficiency and quality of the global model updates. They are less effective when existing alone while these components can be understood independently. And they complement each other when integrated, achieving optimal learning outcomes.

Limitations of Client Selection: Client selection alone, without appropriate weight allocation, may lead to an over-reliance on certain clients’ data. Particularly in scenarios where client data is highly imbalanced, selecting clients with larger data volumes can result in a model bias towards these clients’ characteristics, overlooking other important but smaller data volume clients. Purely basing client selection on criteria such as data volume or update frequency may neglect the differences between client models and the global model, which is detrimental to capturing the diversity of data across the entire network.

Limitations of Weight Allocation: If there is only weight allocation without an effective client selection mechanism, then weights might be allocated to clients that contribute minimally to model updates. For instance, clients with minimal divergence from the global model might receive higher weights, but these minor updates may not be sufficient to significantly enhance the model. Relying solely on weight allocation to handle all clients can lead to inefficient computations, especially when the number of clients is very large, resulting in significant computational and communication overhead that is largely unnecessary.

Client selection can reduce the number of clients that need to be processed each round, thereby reducing computational and communication burdens. On the other hand, weight allocation ensures that the maximum learning benefit is extracted from these selected clients, particularly by weighting updates from those clients who differ significantly from the global model, thereby accelerating model convergence. This combined strategy effectively learns from the data across the entire network, avoiding model over-fitting to specific client data and thus improving the model’s performance on unseen data.

FedCW requires each selected client to send its local model parameters to the server as in standard FL. The server computes the Euclidean distance

5.6 Security and Privacy Considerations

While FedCW demonstrates clear advantages in convergence and communication efficiency, its deployment in real-world vehicular networks also raises important concerns related to security, privacy, and system-level robustness. In particular, the Euclidean distance ranking strategy, although effective for selecting diverse clients, may inadvertently expose distributional characteristics of local model updates, thereby creating potential side-channel privacy risks. To mitigate this, future implementations of FedCW could be combined with secure aggregation protocols or differential privacy mechanisms that protect individual updates while still allowing the server to compute distance-based rankings. Another issue is the vulnerability of distance-based selection and adaptive weighting to malicious or Byzantine clients, who may inject manipulated updates to distort the aggregation process. Addressing this challenge requires the integration of anomaly detection techniques or Byzantine-resilient aggregation rules that can identify and suppress adversarial contributions without significantly increasing communication overhead. Beyond adversarial risks, large-scale vehicular deployments often encounter system bottlenecks such as channel congestion, synchronization delays, and frequent client churn, which can compromise the effectiveness of synchronous distance-based selection. To address these challenges, FedCW can be extended with asynchronous update strategies or hierarchical aggregation frameworks, where edge servers first coordinate subsets of vehicles before forwarding updates to the global server, thereby reducing latency and improving scalability.

The hyperparameters

Notation and update rule.

Let

The server performs the update

where

Assumption 1 (Smoothness): Each

Consequently, the global objective

Assumption 2 (Bounded gradients and variance): There exists

Let

Assumption 3 (Selection/weighting and local-drift bias): Define the conditional-mean decomposition at the server point

where

Step 1: Descent lemma (exact algebra, no convexity).

By L-smoothness of F and the update (11),

Step 2: Decompose

From (15), write

Then

Taking conditional expectation given

Using Young’s inequality

Multiplying (19) by

Step 3: Bound the quadratic term

From (18) and

Taking expectation and using (14),

Step 4: One-step expected descent inequality.

Taking expectation of (17) and substituting (22) and (24),

Group coefficients of each term:

Step 5: Stepsize choice and telescoping.

Choose a constant stepsize satisfying

Then (26) becomes

Summing (28) over

Using

Theorem 1 (Stationarity with selection/weighting bias): Under (12)–(16) and

Remark 1 (Interpretation and roles of

Corollary 1 (Convex case): If, additionally, F is convex and

Additional nonconvex result: iteration complexity and neighborhood size

Goal.

We turn (30) into an explicit iteration complexity statement under nonconvexity by optimizing the stepsize. Let

Optimizing the constant stepsize.

For fixed T, the right-hand side of (32) as a function of

Ignoring the box constraint momentarily, the unconstrained minimizer solves

If

where

Reaching an

Given a target

we need

Hence, under nonconvexity and stochasticity, FedCW attains an

When

If (34) violates the box constraint, set

which shows

Diminishing stepsizes.

Alternatively, choosing

again saturating at the bias floor B.

Remark 2 (Practical knobs): The bias floor

In this section, we will introduce the experiment setup and the results.

The experiments were conducted on a machine equipped with an AMD Ryzen 5600X processor, 32 GB DDR4 RAM, a 1 TB SSD, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4070ti super GPU. The experimental environment was set up using Python 3.8, with machine learning frameworks TensorFlow 2.5 and PyTorch 1.9 employed for implementing and training neural networks. We also used CUDA 11.8 with cuDNN support, and fixed random seeds (set to 42) for NumPy, PyTorch, and TensorFlow to ensure reproducibility. These tools and hardware configurations provided an efficient environment to conduct the experiments and analyze the results.

We utilized the LEAF framework [33], which is a benchmarking framework for learning in federated settings. LEAF provides tools and datasets for various applications, including federated learning, multi-task learning, meta-learning. This framework allowed us to simulate realistic federated environments and evaluate the performance of FedCW and baseline algorithms under different data distributions and client behaviors.

We evaluated FedCW on four image classification tasks using the MNIST, CIFAR-10, ImageNet-100, and CelebA datasets. To simulate different degrees of Non-IID across clients, we used a Dirichlet distribution to partition the data. Specifically, the training data for each dataset was divided among clients by sampling from a Dirichlet distribution with varying concentration parameters (

In our experiments, we focused on full client participation for each communication round. We compared FedCW with several popular baselines, including FedAvg, FedProx, SCAFFOLD, FedOpt, FedNova, and FedMA, across all datasets. Each algorithm was implemented using the same neural network architectures to ensure fair and consistent comparisons. The hyperparameters for each method, such as learning rate, batch size, and number of communication rounds, were tuned empirically based on prior experience. For FedCW specifically, we report the exact values used for

6.2.1 Accuracy and Communication Efficiency Comparison

Table 1 shows the performance of FedCW across all four datasets (MNIST, CIFAR-10, ImageNet-100, and CelebA) in terms of communication overhead, computation time, FLOPs, and accuracy. On the MNIST dataset, FedCW achieves a communication overhead of 198.6 MB, a 35% reduction compared to FedAvg’s 305.3 MB. Similar reductions are seen on CIFAR-10 (401.8 MB for FedCW vs. 603.2 MB for FedAvg, a 33% decrease). This substantial reduction is due to FedCW’s selective client participation strategy based on Euclidean distance, which prioritizes clients contributing the most valuable updates, thus minimizing unnecessary data exchange.

In terms of computation time, FedCW completes training faster; on MNIST, it takes 4173.25 s, a 17% reduction from FedAvg’s 5025.6 s. This speed-up comes from focusing only on clients whose updates are most informative, enhancing convergence and reducing the need for prolonged training. Furthermore, FedCW demonstrates computational efficiency with a 9.4% reduction in FLOPs on MNIST compared to FedAvg, owing to its ability to learn quickly from divergent updates and avoid redundant computations.

The higher accuracy achieved by FedCW—92.27% on MNIST, which is 1.84% higher than FedAvg—is attributed to its dynamic client selection process. By selecting clients that provide the most significant contributions to the model, FedCW maintains robustness, especially in non-IID data scenarios. In contrast, other algorithms like FedAvg involve random client selection, which may include clients with less impactful updates, resulting in slower convergence and lower accuracy. Thus, FedCW’s strategic client selection and efficient aggregation contribute to its superior performance.

6.2.2 Ablation Study on FedCW Components

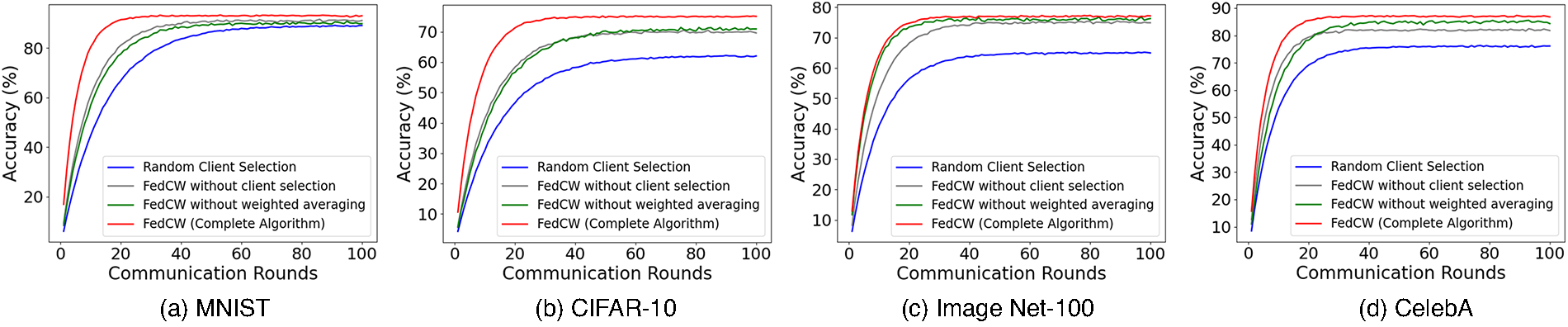

The plot in Fig. 1 illustrates the results of an ablation study comparing different versions of the FedCW algorithm over 100 communication rounds. It includes the complete FedCW algorithm and versions where client selection or weighted averaging is removed, as well as a baseline random client selection. From the plot, the complete FedCW algorithm achieves the highest accuracy, starting at around 67% and steadily rising to the capped maximum of 95%. In comparison, the version of FedCW without weighted averaging starts lower, around 65%, and improves more slowly, ultimately plateauing below 90%. Similarly, the version without client selection performs better than random selection but still underperforms compared to the complete FedCW algorithm, showing the importance of both components. Random client selection achieves the lowest accuracy, indicating that without any strategic selection mechanism, the model struggles to achieve high accuracy, with slower improvements over the rounds.

Figure 1: Impact of different components on FedCW performance. Different lines shows the performance of FedCW when key components such as client selection and weighted averaging are removed

The superior performance of FedCW can be attributed to two key components: client selection and weighted averaging. The client selection strategy, which prioritizes clients with the most informative updates, ensures that each round of communication focuses on maximizing the global model’s progress. By selecting clients with more divergent local data, the algorithm captures a wider range of variations in the dataset, leading to faster convergence. The weighted averaging mechanism dynamically adjusts the importance of client contributions based on their relevance, ensuring that significant updates have a larger impact on the global model. This helps maintain balance and avoids overfitting to any particular subset of clients, which is crucial in non-IID federated learning environments where client data distributions are heterogeneous. In contrast, removing these components diminishes the model’s ability to effectively utilize client data, resulting in slower convergence and lower final accuracy, as shown by the other lines in the plot. Overall, FedCW’s combination of these strategies allows it to leverage diverse and non-IID data efficiently, leading to faster convergence and higher overall performance compared to ablated versions of the algorithm.

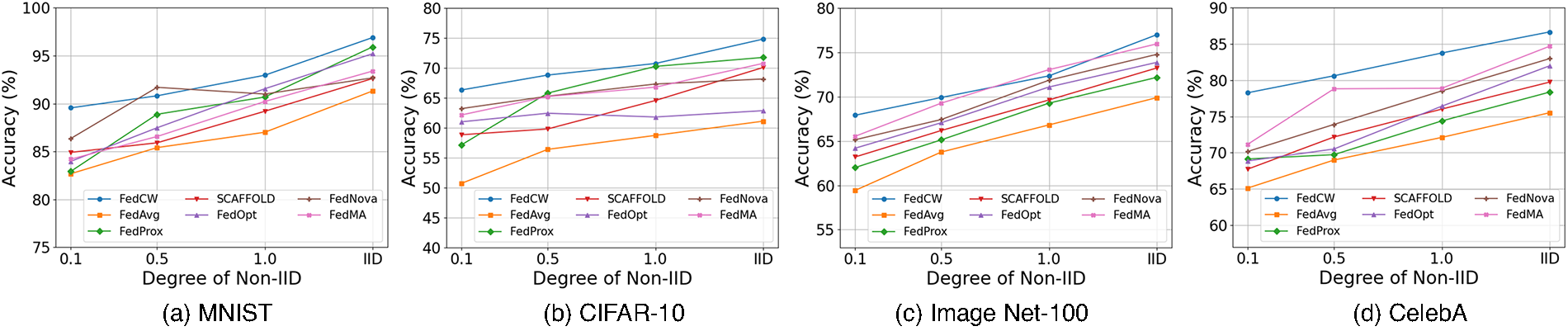

6.2.3 Impact of Non-IID Data Distribution on Algorithm Performance

The experimental results illustrated in Fig. 2 demonstrate the robustness and adaptability of the FedCW algorithm across multiple datasets. The goal of this experiment was to assess the performance of FedCW under different levels of Non-IID data distributions. As observed, FedCW consistently outperforms the baseline algorithms such as FedAvg, FedProx, SCAFFOLD, FedOpt, FedNova, and FedMA across all degrees of Non-IID. For example, in the MNIST dataset, FedCW reaches an accuracy of 97% under IID conditions, while FedAvg only achieves 91.5%. A similar trend can be observed across other datasets like CIFAR-10, where FedCW outperforms FedAvg significantly, achieving 75% accuracy compared to 60% for FedAvg under IID conditions. These results also highlight the intrinsic relationship between non-IID distributions, convergence, and communication overhead. As the degree of non-IID increases (lower

Figure 2: Accuracy of federated learning algorithms under varying degrees of Non-IID Data. The degrees of Non-IID are controlled by four different values of the dirichlet distribution’s concentration parameter (

6.2.4 Convergence Speed Comparison across Algorithms

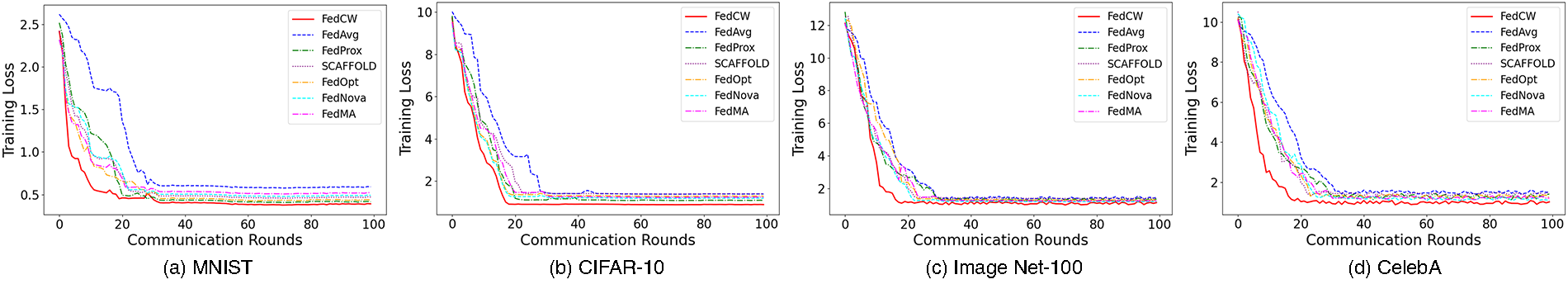

In this experiment, we compare the convergence speed of several federated learning algorithms, including FedCW, FedAvg, FedProx, SCAFFOLD, FedOpt, FedNova, and FedMA, by tracking their training loss over 100 communication rounds on the MNIST dataset. As illustrated in Fig. 3, FedCW demonstrates the fastest convergence, rapidly reducing its training loss to around 0.5 within the first 10 rounds and maintaining a stable performance throughout the remaining rounds on the MNIST dataset. This behavior is attributable to its client selection strategy and dynamic weighted averaging, which ensures that the most informative clients are selected, and their updates are efficiently aggregated. FedProx and FedMA follow in terms of convergence speed, with FedProx benefiting from the addition of a proximal term that stabilizes local updates in non-IID environments, leading to faster convergence compared to FedAvg. FedMA, with its layer-wise neuron matching, also performs well by preserving more structural information during aggregation, thereby reducing the loss more effectively than the other methods. SCAFFOLD exhibits a slightly slower convergence than FedCW and FedProx, although it manages to address client drift by utilizing control variates. FedOpt and FedNova show moderate improvements over FedAvg but are slower than FedCW due to their simpler aggregation mechanisms. FedAvg, as the baseline, has the slowest convergence, as it relies on random client selection and equal-weight averaging, which are less effective in non-IID settings. In several other data sets, the experimental results show similar characteristics. The results highlight the importance of sophisticated client selection and weighted aggregation strategies, as seen in FedCW, in achieving faster convergence, especially in heterogeneous federated learning environments.

Figure 3: Convergence speed of algorithms (Training Loss vs. Communication Rounds)

6.2.5 Effect of Client Participation on Accuracy

As previously discussed, client selection and weight allocation are fundamentally the same problem. Therefore, the FedCW algorithm, which addresses both issues simultaneously, demonstrates a significant advantage over other algorithms. Fig. 4 clearly reveal this. The results from the experiment testing the impact of varying client numbers on accuracy reveal that FedCW consistently achieves superior performance compared to other algorithms across different datasets, including MNIST, CelebA, CIFAR-10, and ImageNet-100. As the number of clients increases, FedCW is better able to aggregate diverse and representative data, allowing the model to generalize more effectively and maintain high accuracy. In contrast, algorithms like FedAvg, which use simple averaging across all clients, struggle to maintain high accuracy as the number of clients increases, particularly in non-IID settings. FedProx, SCAFFOLD, FedOpt, FedNova, and FedMA also benefit from their respective aggregation and optimization strategies, but none match FedCW’s ability to handle a large number of clients while maintaining robust performance. FedCW’s ability to adaptively adjust weight allocation during aggregation ensures that the most valuable updates are emphasized, further enhancing the model’s convergence speed and overall accuracy. This makes FedCW particularly advantageous in federated learning environments with a varying number of participating clients.

Figure 4: Accuracy vs. number of clients across multiple datasets. Each bar represents the performance of different algorithms, including FedCW, FedAvg, FedProx, SCAFFOLD, FedOpt, FedNova, and FedMA

In this paper, we proposed FedCW. It is an algorithm designed to simultaneously address the challenges of client selection and weight allocation in heterogeneous Federated Learning (FL) environments. Our approach leverages digital twins to assist in real-time computation offloading, while selecting clients based on their Euclidean distance from the global model and dynamically adjusting aggregation weights to balance data volume and model divergence. Through extensive experiments, we demonstrated that FedCW significantly improves model accuracy and reduces convergence time compared to existing methods such as FedAvg, FedProx, and SCAFFOLD, particularly in non-IID settings. In the future, further work can focus on enhancing the adaptability of FedCW to even more dynamic edge environments and exploring more advanced techniques for optimizing resource allocation in large-scale FL systems.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Haotian Wu and Jiaming Pei; methodology, Haotian Wu; software, Haotian Wu; validation, Haotian Wu; formal analysis, Haotian Wu; investigation, Haotian Wu; resources, Jinhai Li; data curation, Jinhai Li; writing—original draft preparation, Haotian Wu and Jiaming Pei; writing—review and editing, Haotian Wu and Jiaming Pei; visualization, Haotian Wu; supervision, Jiaming Pei and Jinhai Li; project administration, Jinhai Li; funding acquisition, Jinhai Li. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. McMahan B, Moore E, Ramage D, Hampson S, Arcas BA. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In: Artificial intelligence and statistics. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2017. p. 1273–82. [Google Scholar]

2. Tang F, Mao B, Kato N, Gui G. Comprehensive survey on machine learning in vehicular network: technology, applications and challenges. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2021;23(3):2027–57. [Google Scholar]

3. Posner J, Tseng L, Aloqaily M, Jararweh Y. Federated learning in vehicular networks: opportunities and solutions. IEEE Netw. 2021;35(2):152–9. doi:10.1109/mnet.011.2000430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Pei J, Li W, Mumtaz S. From routine to reflection: pruning neural networks in communication-efficient federated learning. IEEE Trans Artifi Intell. 2024:1–10. doi:10.1109/tai.2024.3462300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Elbir AM, Soner B, Çöleri S, Gündüz D, Bennis M. Federated learning in vehicular networks. In: 2022 IEEE International Mediterranean Conference on Communications and Networking (MeditCom); 2022 Sep 5–8; Athens, Greece. p. 72–7. [Google Scholar]

6. Lai C, Lu R, Zheng D, Shen X. Security and privacy challenges in 5G-enabled vehicular networks. IEEE Netw. 2020;34(2):37–45. doi:10.1109/mnet.001.1900220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li T, Sahu AK, Talwalkar A, Smith V. Federated learning: challenges, methods, and future directions. IEEE Signal Proc Mag. 2020;37(3):50–60. doi:10.1109/msp.2020.2975749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kairouz P, McMahan HB, Avent B, Bellet A, Bennis M, Bhagoji AN, et al. Advances and open problems in federated learning. Found Trends® Mach Learn. 2021;14(1–2):1–210. [Google Scholar]

9. Pei J. F3: fair federated learning framework with adaptive regularization. Knowl Based Syst. 2025;316(1–2):113392. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2025.113392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Yang Q, Liu Y, Chen T, Tong Y. Federated machine learning: concept and applications. ACM Trans Intell Syst Technol. 2019;10(2):1–19. doi:10.1145/3298981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wang J, Liu Q, Liang H, Joshi G, Poor HV. Tackling the objective inconsistency problem in heterogeneous federated optimization. Adv Neural Inf Proc Syst. 2020;33:7611–23. [Google Scholar]

12. Pei J, Omar M, Dabel MMA, Mumtaz S, Liu W. Federated few-shot learning with intelligent transportation cross-regional adaptation. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2025:1–10. doi:10.1109/tits.2025.3563928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Shi W, Cao J, Zhang Q, Li Y, Xu L. Edge computing: vision and challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2016;3(5):637–46. doi:10.1109/jiot.2016.2579198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Pei J, Li J, Song Z, Dabel MMA, Alenazi MJF, Zhang S, et al. Neuro-VAE-symbolic dynamic traffic management. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2025:1–10. doi:10.1109/tits.2025.3571210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Nishio T, Yonetani R. Client selection for federated learning with heterogeneous resources in mobile edge. In: ICC 2019—2019 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC); 2019 May 20–24; Shanghai, China. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

16. Cho YJ, Wang J, Joshi G. Client selection in federated learning: convergence analysis and power-of-choice selection strategies. arXiv:2010.01243. 2020. [Google Scholar]

17. Yoshida N, Nishio T, Morikura M, Yamamoto K, Yonetani R. Hybrid-FL for wireless networks: cooperative learning mechanism using non-IID data. In: ICC 2020—2020 IEEE International Conference On Communications (ICC); 2020 Jun 7–11; Online. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

18. Wu W, He L, Lin W, Maple C. FedProf: selective federated learning with representation profiling. arXiv:2102.01733. 2021. [Google Scholar]

19. Shi F, Hu C, Lin W, Fan L, Huang T, Wu W. VFedCS: optimizing client selection for volatile federated learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(24):24995–5010. doi:10.1109/jiot.2022.3195073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhang R, Mao J, Wang H, Li B, Cheng X, Yang L. A survey on federated learning in intelligent transportation systems. IEEE Trans Intell Vehicles. 2025;10(5):3043–59. doi:10.1109/tiv.2024.3446319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Maroua D. A state-of-the-art on federated learning for vehicular communications. Veh Commun. 2024;45(3):100709. doi:10.1016/j.vehcom.2023.100709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Li T, Sahu AK, Zaheer M, Sanjabi M, Talwalkar A, Smith V. Federated optimization in heterogeneous networks. Proc of Mach Learn and Syst. 2020;2:429–50. [Google Scholar]

23. Karimireddy SP, Kale S, Mohri M, Reddi S, Stich S, Suresh AT. Scaffold: stochastic controlled averaging for federated learning. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2020. p. 5132–43. [Google Scholar]

24. Reddi S, Charles Z, Zaheer M, Garrett Z, Rush K, Konečnỳ J, et al. Adaptive federated optimization. arXiv:2003.00295. 2020. [Google Scholar]

25. Wang H, Yurochkin M, Sun Y, Papailiopoulos D, Khazaeni Y. Federated learning with matched averaging. arXiv:2002.06440. 2020. [Google Scholar]

26. Huang K, Xian R, Xian M, Wang H, Ni L. A comprehensive intrusion detection method for the internet of vehicles based on federated learning architecture. Comput Secur. 2024;147:104067. [Google Scholar]

27. Althunayyan M, Javed A, Rana O. A robust multi-stage intrusion detection system for in-vehicle network security using hierarchical federated learning. Veh Commun. 2024;49(6):100837. doi:10.1016/j.vehcom.2024.100837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Hasan MK, Jahan N, Nazri MZA, Islam S, Khan MA, Alzahrani AI, et al. Federated learning for computational offloading and resource management of vehicular edge computing in 6G-V2X network. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2024;70(1):3827–47. doi:10.1109/tce.2024.3357530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Yan J, Chen T, Sun Y, Nan Z, Zhou S, Niu Z. Dynamic scheduling for vehicle-to-vehicle communications enhanced federated learning. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. 2025. doi:10.1109/twc.2025.3573048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhang C, Zhang W, Wu Q, Fan P, Fan Q, Wang J, et al. Distributed deep reinforcement learning based gradient quantization for federated learning enabled vehicle edge computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(5):4899–913. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3447036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Alqubaysi T, Asmari AFA, Alanazi F, Almutairi A, Armghan A. Federated learning-based predictive traffic management using a contained privacy-preserving scheme for autonomous vehicles. Sensors. 2025;25(4):1116. doi:10.3390/s25041116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Ali W, Din IU, Almogren A, Rodrigues JJ. Federated learning-based privacy-aware location prediction model for internet of vehicular things. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2024;74(2):1968–78. doi:10.1109/tvt.2024.3368439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Caldas S, Duddu SMK, Wu P, Li T, Konečnỳ J, McMahan HB, et al. Leaf: a benchmark for federated settings. arXiv:1812.01097. 2018. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools