Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Synthetic Speech Detection Model Combining Local-Global Dependency

School of Computer Science and Technology, Shandong University of Technology, Zibo, 255000, China

* Corresponding Author: Wenhao Yuan. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069918

Received 03 July 2025; Accepted 01 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Synthetic speech detection is an essential task in the field of voice security, aimed at identifying deceptive voice attacks generated by text-to-speech (TTS) systems or voice conversion (VC) systems. In this paper, we propose a synthetic speech detection model called TFTransformer, which integrates both local and global features to enhance detection capabilities by effectively modeling local and global dependencies. Structurally, the model is divided into two main components: a front-end and a back-end. The front-end of the model uses a combination of SincLayer and two-dimensional (2D) convolution to extract high-level feature maps (HFM) containing local dependency of the input speech signals. The back-end uses time-frequency Transformer module to process these feature maps and further capture global dependency. Furthermore, we propose TFTransformer-SE, which incorporates a channel attention mechanism within the 2D convolutional blocks. This enhancement aims to more effectively capture local dependencies, thereby improving the model’s performance. The experiments were conducted on the ASVspoof 2021 LA dataset, and the results showed that the model achieved an equal error rate (EER) of 3.37% without data augmentation. Additionally, we evaluated the model using the ASVspoof 2019 LA dataset, achieving an EER of 0.84%, also without data augmentation. This demonstrates that combining local and global dependencies in the time-frequency domain can significantly improve detection accuracy.Keywords

The rise of Artificial Intelligence Generated Content (AIGC) has led to flourishing voice, image, and video generation technologies. This development has resulted in significant advances in generative speech in terms of humanization, realism, and naturalization. In particular, since 2022, the release and rapid rise in popularity of Chat generative pretrained Transformer (ChatGPT) has propelled the field of speech generation into the GPT era. However, this rapid development has concurrently introduced specific security risks, with the Automatic Speaker Verification (ASV) system [1–3] emerging as a primary target for speech spoofing attacks. With the continuous advancement of deep learning technologies, the development of speech synthesis and voice conversion techniques has enabled the generation of synthetic speech that is nearly indistinguishable from real speech. Attackers can use synthetic speech, which is false yet highly similar to real speech, to impersonate the target speaker, thereby posing a serious threat to the security of existing ASV systems. Therefore, enhancing the capability to detect synthetic speech has become a critical issue that needs to be addressed. In recent years, significant progress has been made in the development of synthetic speech detection technology, with various researchers conducting multi-perspective studies on the detection of different types of synthetic speech. Additionally, the combination of synthetic speech detection technology and deep learning has greatly promoted the development of the field of synthetic speech detection.

Liu et al. [4] argue that the discriminative information involved in speech synthesis and conversion is distributed across both local and global levels, such as unnatural stress and intonation (local level) as well as overly smoothed features (global level). Therefore, combining local and global dependencies can effectively enhance the anti-spoofing performance. Due to the strong locality of convolution layers and pooling layers [5–8], current systems based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have achieved relatively ideal results in extracting local dependency [9–13]. A classic model is LCNN-LSTM [14], which uses light convolutional neural networks (LCNN) to process the input features and then employs long short-term memory (LSTM) [15] layers to further process the extracted information. This model has now become one of the benchmark models for spoofing challenges [4]. The recently introduced AASIST model utilizes graph neural networks as back-end modules to process local features extracted by CNNs, and also demonstrates superior results [16]. The model utilizes graph attention to capture discriminative clues across frequency intervals and time positions. However, in order to reduce computational complexity, the constructed graph nodes are limited in number. This result in the loss of some spectrum-time information when the model aggregates feature maps along the frequency and time dimensions to extract time maps and spectrum maps, thereby affecting the acquisition of global dependencies. Therefore, in later models, such as the hybrid Transformer architecture proposed by Zaman et al. [17], the local feature maps extracted by CNN are directly input into a lightweight Transformer encoder to capture global dependencies [4,18,19]. SE-Rawformer also employs Transformer to process the output of CNN, and Transformer [20] has demonstrated superior results compared to other sequence models such as LSTM [21] through its self-attention mechanism. SE-Rawformer reshapes feature maps along the time and frequency dimensions into longer sequences, and subsequently employs a Transformer to capture global dependencies. However, this result in a significant increase in both computational and memory consumption. Furthermore, during the process of merging the time and frequency domains, some information regarding their individual features may be lost, which can adversely affect the overall performance of the model.

In order to further improve the effectiveness of speech recognition, we propose an innovative model called TFTransformer, which combines local and global time-frequency domain dependencies of speech signals. In the front-end of the model, SincLayer is first used to extract spectrotemporal features [22], thereby generating lower-level feature map (LFM). Then, LFM is processed through 2D convolution to extract high-level feature map (HFM) with local dependency. These feature maps can accurately capture local dependency in speech signals and provide a solid foundation for subsequent processing. Next, we use our proposed time-frequency Transformer module to process these feature maps, further capturing global dependency in the speech signal. The time-frequency Transformer consists of two independent Transformer modules that process features in the time domain and frequency domain, respectively. These two modules can effectively capture global dependency information in speech signals. In addition, to further enhance feature expression, we added a channel attention mechanism to the 2D convolution block to extract local dependency more accurately.

During the experiments, we first explored different combinations of the number of 2D convolution blocks and time-frequency Transformer modules to investigate the optimal structural configuration of the model. Through this process, we are able to find the optimal combination that maximizes performance while maintaining efficient computing. Next, we introduced the Res-SERes2Net block [8] with channel attention mechanism to replace the ResNet block [23], and explored the effectiveness of the Res-SERes2Net block on synthetic speech detection, and then compared the model with other existing synthetic speech detection models. Finally, to enhance the robustness of the model, we applied four data augmentation methods to the dataset, including adding colored noise (ACN), high-pass filtering (HPF), low-pass filtering (LPF), and gain (GAI). Through these comparative experiments, we were able to comprehensively evaluate the performance of TFTransformer under various conditions and further demonstrate its advantages in capturing both local and global dependencies in speech signals.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes end-to-end-based synthetic speech detection models. Section 3 introduces the model we proposed. Section 4 introduces the experimental setup and dataset. Section 5 analyzes and discusses the experimental results. Finally, we summarize this paper in Section 6.

2 End-to-End Synthetic Speech Detection Models

The end-to-end synthetic speech detection technology uses deep network models to directly process the time domain or frequency domain representations of raw speech signals [24], learning feature representations related to forged information and training classifiers.

This type of detection technology uses advanced signal processing and deep learning techniques to detect anomalies or inconsistencies related to voice spoofing attacks. For example, it uses Sinc filters and pre-trained models to extract speech features directly from raw speech signals, and employs CNN networks, ResNet networks, and graph attention networks for modeling and classification to determine whether the input voice is genuine or fabricated. The loss function of the model commonly uses the Binary Cross-Entropy loss (BCE) or the Weighted Cross-Entropy Loss (WCE) function. BCELoss is a widely used loss function in binary classification problems, and its calculation formula is as Eq. (1) follows:

Here, y is the true label (with values of 0 or 1), and p is the probability predicted by the model for class 1,

WCELoss is an extension of Cross-Entropy loss, introducing weights

Here,

Using the end-to-end structure to process raw speech waveform signals avoids the complex steps of preprocessing and feature extraction required in traditional speech signal processing. At the same time, the network is trained to adaptively learn the weights of the convolution kernels, thereby improving the model’s performance and generalization ability.

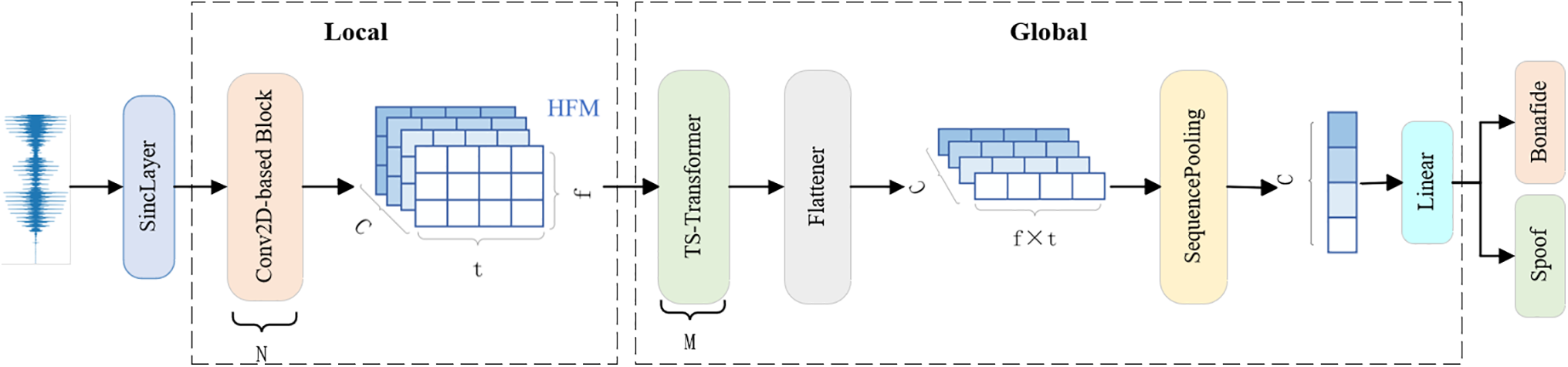

Our model employs a multi-level structure to fully capture local and global dependencies in speech signals. The overall architecture of the model is shown in Fig. 1, and it mainly consists of two core parts: The SincLayer and 2D convolution blocks for local dependency modeling, and time-frequency Transformer modules for global dependency modeling. In this way, our model can comprehensively consider local details and global dependency in speech signals, thereby improving the accuracy and robustness of speech recognition or classification.

Figure 1: Overall structure diagram of the proposed end-to-end model

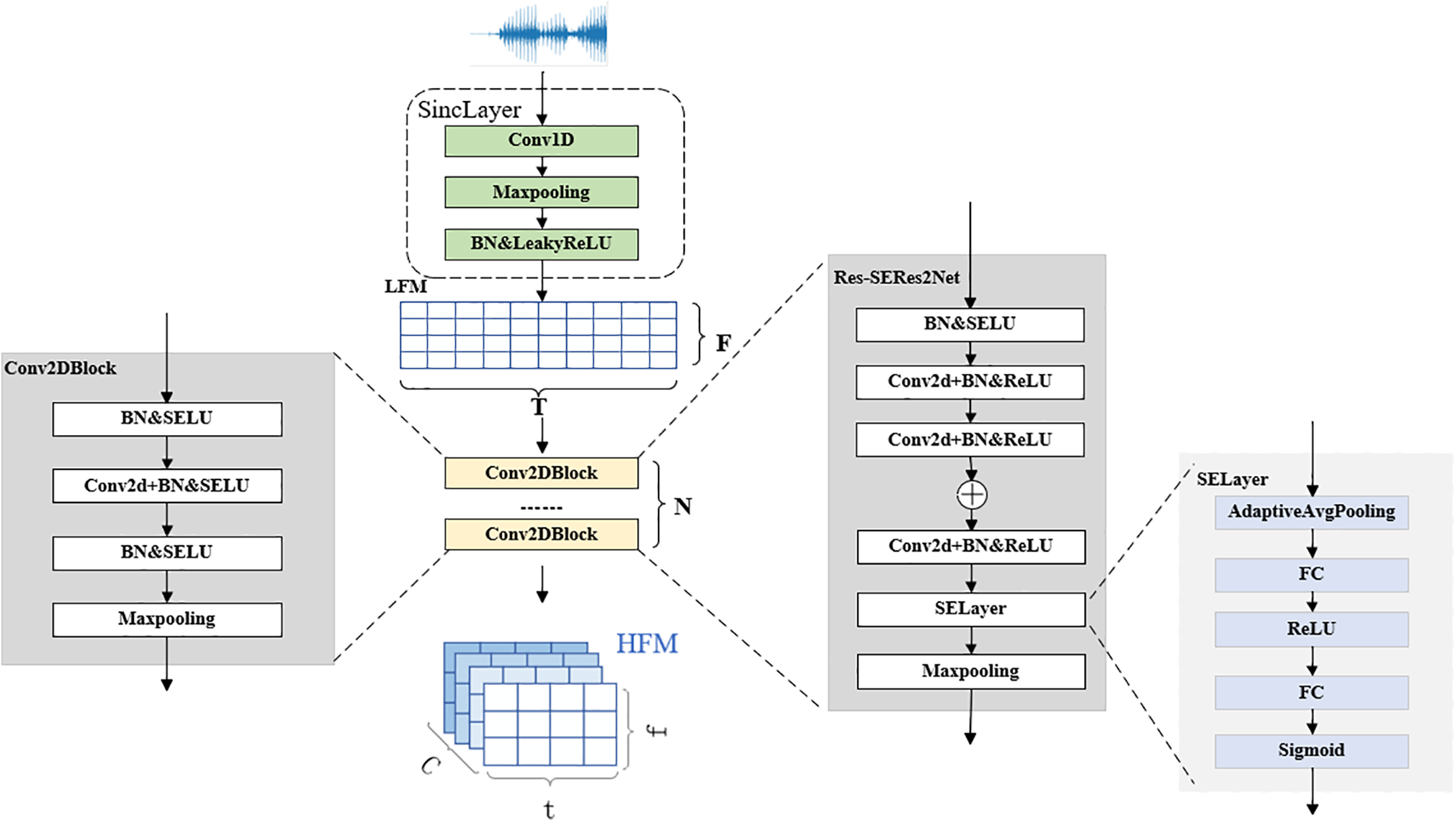

The structural diagram of this section is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Structure of the local dependency modeling

Local dependency modeling consists of SincLayer and 2D convolution blocks, which can efficiently extract audio features. We first use a SincLayer composed of a series of sinc functions and 1D convolutions to extract spectrotemporal features from the original waveform. As one of the core components, the SincLayer can perform frequency conversion, mapping Hertz frequencies to Mel frequencies. During initialization, it strictly checks the number of input channels to ensure that only single-channel inputs are processed, and enforces an odd number of convolution kernel sizes to ensure filter symmetry. A bandpass filter is generated through a series of frequency calculations and sinc functions, consisting of two low-pass filters, in the form of:

Here,

The input speech signal first enters the Sinc Layer to extract basic features, generating the LFM, denoted as

We introduce the channel attention mechanism into the 2D convolution block, namely the Res-SERes2Net block. The channel attention mechanism improves the model’s feature expression capabilities by adaptively adjusting the relationships between channels. Its core idea is to enhance the response to important features while suppressing irrelevant features by dynamically weighting the channels.

First, the channel attention mechanism compresses the spatial dimensions of the input feature map through global average pooling, compressing the spatial information of each channel into a global descriptor. The input signal for this stage is

Then, the channel attention mechanism dynamically generates a weight for each channel through a fully connected neural network. This neural network consists of two fully connected layers. The input C-dimensional vector passes through the first fully connected layer and outputs a smaller dimension (usually

Here,

Here,

The channel attention mechanism enhances the relationship between different convolution channels by adaptively adjusting the weights of each channel in the convolution layer, thereby improving the overall performance of the model while ensuring computational efficiency. By adding this mechanism, the model can more flexibly capture complex dependencies between signal channels, thereby improving its overall understanding and processing capabilities for speech signals.

3.2 Global Dependency Modeling

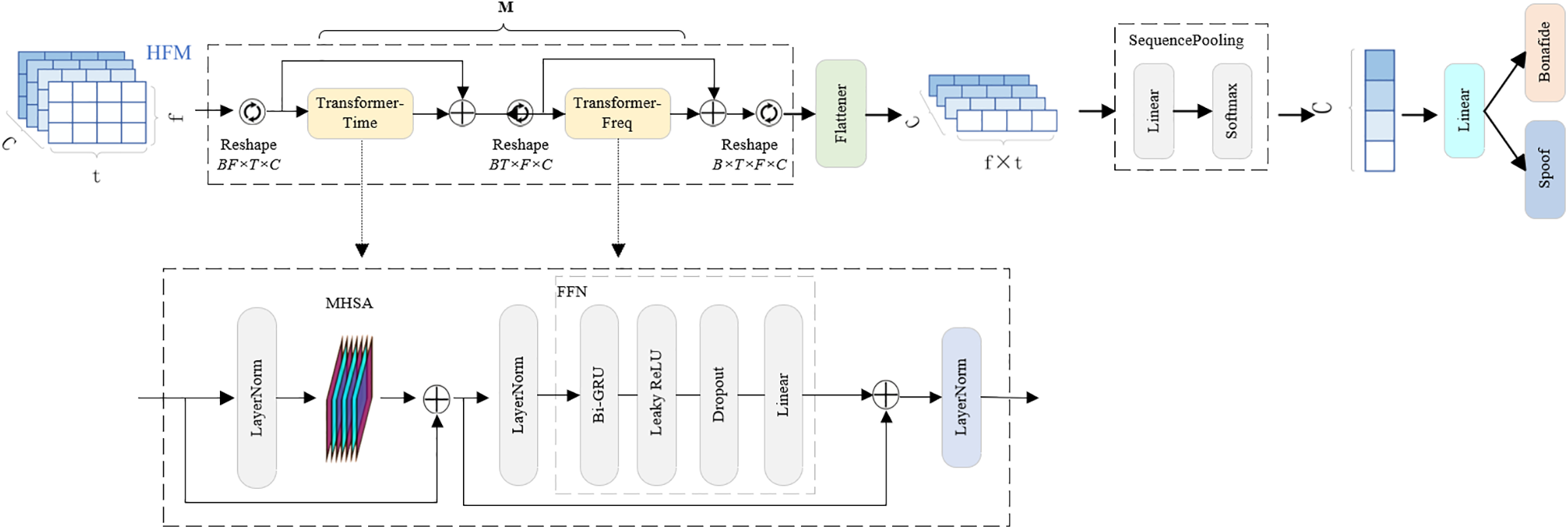

Transformer has demonstrated exceptional capabilities in handling long-term dependency, particularly in capturing global dependency. Therefore, in our model, we choose to use the Transformer module to effectively capture these global dependency. Through the self-attention mechanism, the Transformer can automatically learn the relationships between distant data points in long time series, making it a standard solution for many natural language processing and sequence modeling tasks. The specific structure of this part is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Structure of the global dependency modeling

This part uses multiple stacked time-frequency Transformer modules to form an encoder, which performs multiple rounds of feature extraction and enhancement on the input speech features. Each time-frequency Transformer modules includes two standard Transformer modules, a time Transformer and a frequency Transformer, each of which includes a multi-head self-attention mechanism and a feedforward neural network (FFN).

As shown in the figure, the input feature map

After the input feature map is processed independently by the time Transformer and frequency Transformer, the outputs of the two are fused using residual connections, and the final output

The extraction of global dependency combines multiple neural network modules to achieve efficient audio feature extraction and classification. This design can effectively extract time-domain and frequency-domain features from time series data, thereby enabling accurate category judgments.

During the training stage, speech is cropped or concatenated to fix a length of 4 s. We set the SincLayer with 70 filters and use fixed cut-in and cut-off in each filter. The AdamW [25] optimizer with a learning rate of 8 × 10−4 is used. We used BCELoss function and combined the ASVspoof 2021 LA training and development sets to train the model for 300 epochs. The training batch size is 16.

The dataset we used was from the ASVspoof challenge, which was jointly launched by renowned universities and international research institutions such as the University of Eastern Finland, the University of Edinburgh, and the National Institute of Informatics in Japan. The ASVspoof 2021 Challenge includes three types of tasks: Logical Access (LA), Physical Access (PA), and DeepFake (DF) [3]. The LA task is to detect spoofing attacks that are robust to the encoders and transmission channels of the ASV system, i.e., synthetic speech generated using text-to-speech, speech conversion, and other technologies is directly input into the ASV system. The PA task is to detect attacks on the physical access part of the ASV system, i.e., using recording playback technology to play back pre-recorded voice recordings of the target speaker. And the DF tasks are new tasks added in the 2021 season. DF tasks detect deceptive audio that is deceptive to the human auditory system rather than being limited to the ASV system. Similar to LA tasks, the speech data is generally deceptive speech generated by speech synthesis or speech conversion and may be compressed.

We evaluated the model using ASVspoof 2021 LA, whose training and development sets are derived from the training and development sets of the ASVspoof 2019 LA track. The LA training set has 20 speakers (8 male and 12 female), including 2580 segments of real speech and 22,800 segments of fake speech. The validation set has 20 speakers (8 male and 12 female), including 2548 segments of real speech and 22,296 segments of spoofed speech. The specific sample sizes for the training set, development set, and evaluation set are shown in Table 1. And the synthetic speech is generated by six types of spoofing attack algorithms.

All speech data used in this experiment was extracted from speech segments provided in the dataset, with each segment lasting 4 s. Segments shorter than 4 s were first copied and then extracted. The data was encoded in a standard 16-bit PCM format with a sampling rate of 16 kHz and compressed in FLAC format.

We compared the performance of models based on EER [2], which is one of the official metrics of the ASVspoof 2021 challenge. The lower the EER, the better the detection performance of the system; conversely, the higher the EER, the poorer the performance.

5 Experimental Results and Analysis

5.1 Model Structure Optimization and Combination Exploration

We first explored different combinations of N 2D convolutional blocks and M time-frequency Transformers to obtain the optimal model for capturing anti-spoofing local-global dependencies. The results show the best results for each training session.

First, we set M to 2, then change the value of N. The experimental results show that when the number of time-frequency transformers M is equal to 2, the best results are obtained with four two-dimensional convolution blocks. We then set M to 3 and N to 4 and 6. The experimental results for this section are shown in Table 2.

The experimental results show that the model with three time-frequency Transformer modules and six 2D convolution blocks performs best. Therefore, in subsequent experiments, we use two configurations: M = 2, N = 4 (TFTransformer-S) and M = 3, N = 6 (TFTransformer-L).

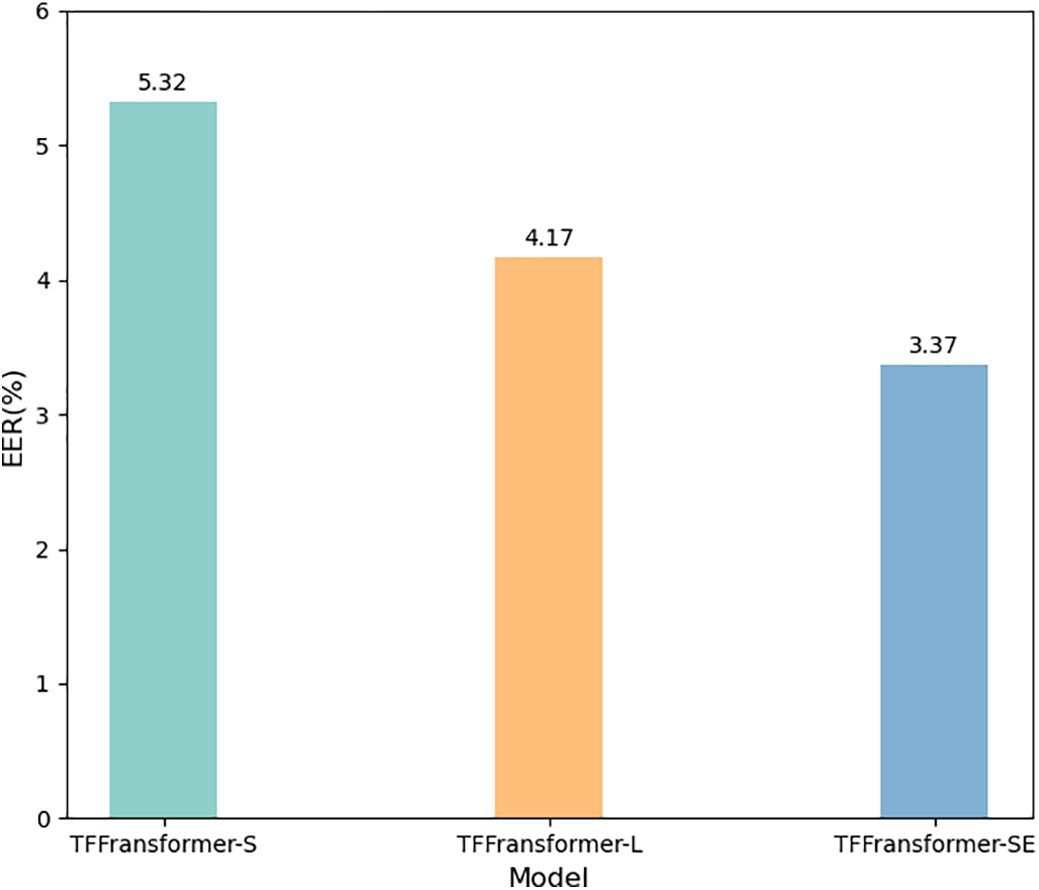

Considering the number of parameters and the complexity of the model, we replaced the ResNet block in TFTransformer-S with the Res-SERes2Net block, which incorporates a channel attention mechanism. We refer to this as TFTransformer-SE. We use ResNet blocks as the first block, first expanding the number of channels to 32, and then replacing the subsequent three ResNet blocks with three Res-SERes2Net blocks. After replacing the traditional ResNet module with the Res-SERes2Net module, the experimental results are shown in Fig. 4. It can be observed that the model performance has been significantly improved, demonstrating the best results.

Figure 4: Comparison of TFTransformer-SE results

In addition, we statistically analyzed the EER values during training. A total of 300 epochs were trained. As can be clearly seen from the figure, the EER values of TFTransformer-L and TFTransformer-S are mainly concentrated in the range of 10%–12%, while the EER values of TFTransformer-SE are concentrated in the range of 8%–10%. These results indicate that the Res-SERes2Net block with the channel attention mechanism significantly improves the model’s optimal detection performance compared to the traditional ResNet block. Throughout the training process, TFTransformer-SE’s average detection performance is superior to that of the other two models. TFTransformer-SE demonstrated more stable and lower EER values during training, indicating that the introduction of the channel attention mechanism effectively enhanced the model’s feature capture ability, enabling it to have stronger discrimination capabilities and helping it maintain efficient detection performance across a wider range of synthetic speech samples.

5.2 Comparison and Analysis with Existing Models

To facilitate fair comparison with prior works and better demonstrate the model’s robustness and generalization ability under diverse deception attacks, we also evaluated the model using the ASVspoof2019 LA dataset. The experimental results of this model compared with other existing models in recent years are shown in Table 3. The comparison results clearly show that TFTransformer-SE performs excellently and achieves satisfactory results. This also indicates that a synthetic speech detection model that combines local and global dependencies can effectively improve detection accuracy, demonstrating its potential in the field of synthetic speech detection.

5.3 Speech Data Augmentation Methods for Enhancing Model Robustness

In the experiment, we also investigated the impact of different DA methods on model detection performance. DA is one of the most commonly used techniques in the field of deep learning. It involves transforming or expanding limited speech data to increase the diversity and quantity of speech data for training. Using DA can alleviate the problem of overfitting and improve the robustness of the model.

In this experiment, we used four different speech enhancement methods for DA: ACN, HPF, LPF and GAI.

ACN is one of the most common speech enhancement methods in the field of synthetic speech detection. It involves mixing noise with the original clean speech to obtain speech with varying noise characteristics and intensity, thereby simulating real-world noisy environments to enhance the robustness of the spoof detection model to noise. The formula is expressed as follows:

Here,

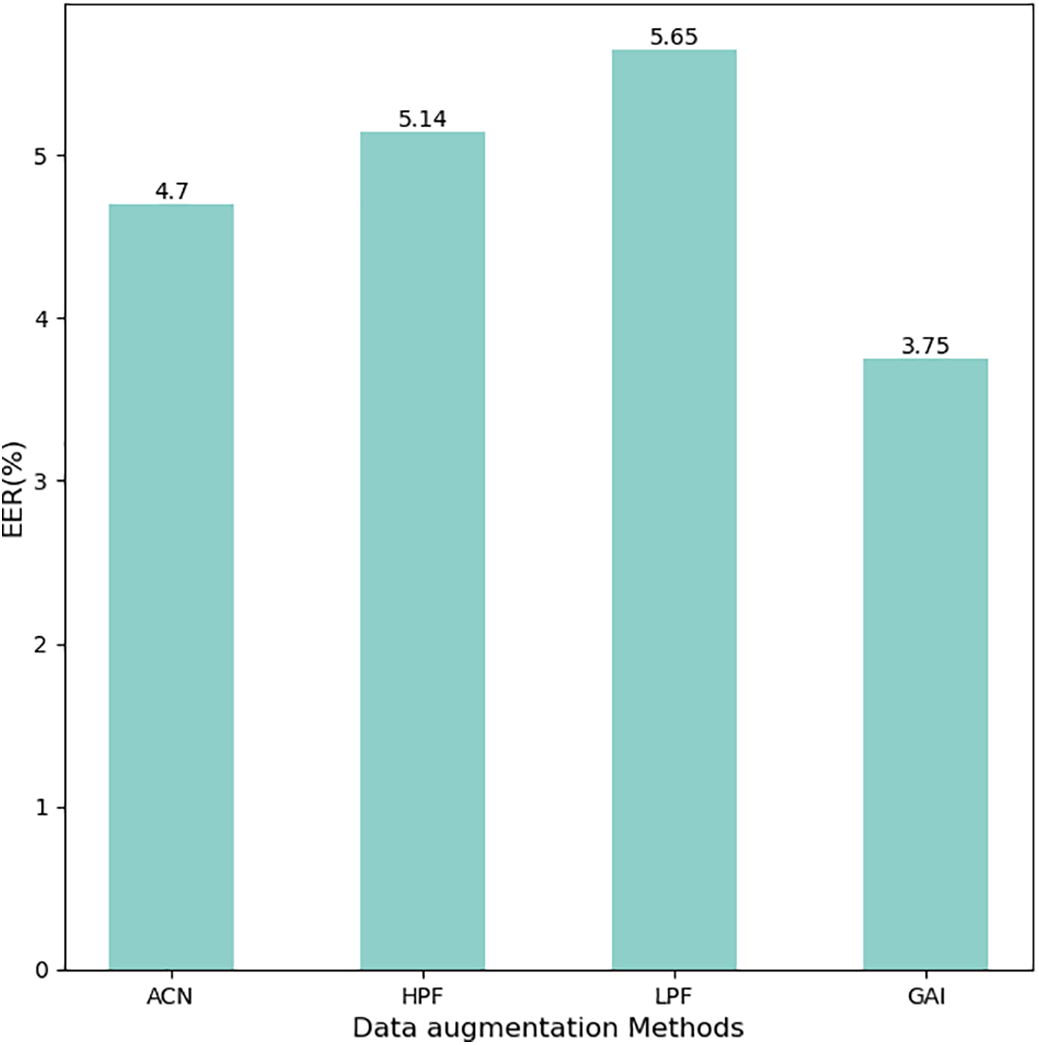

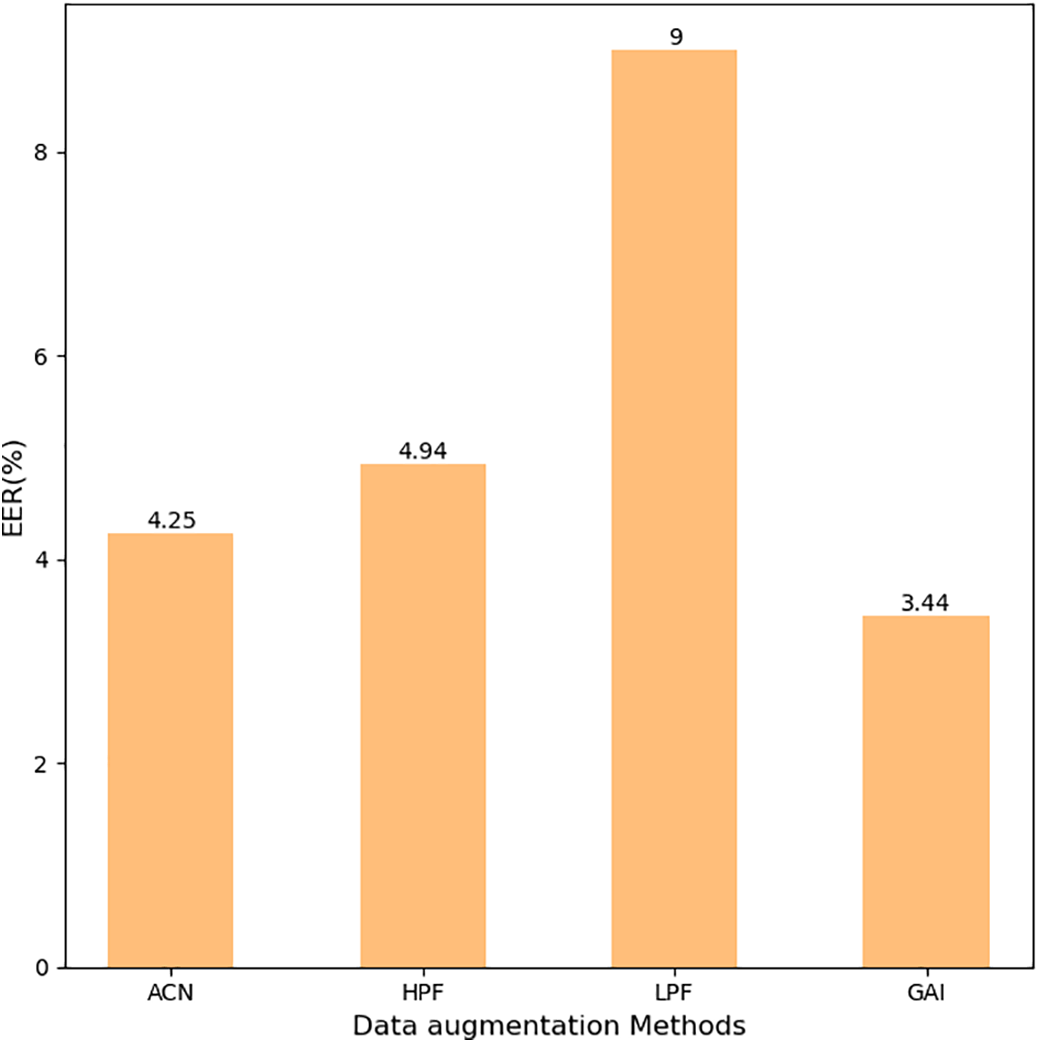

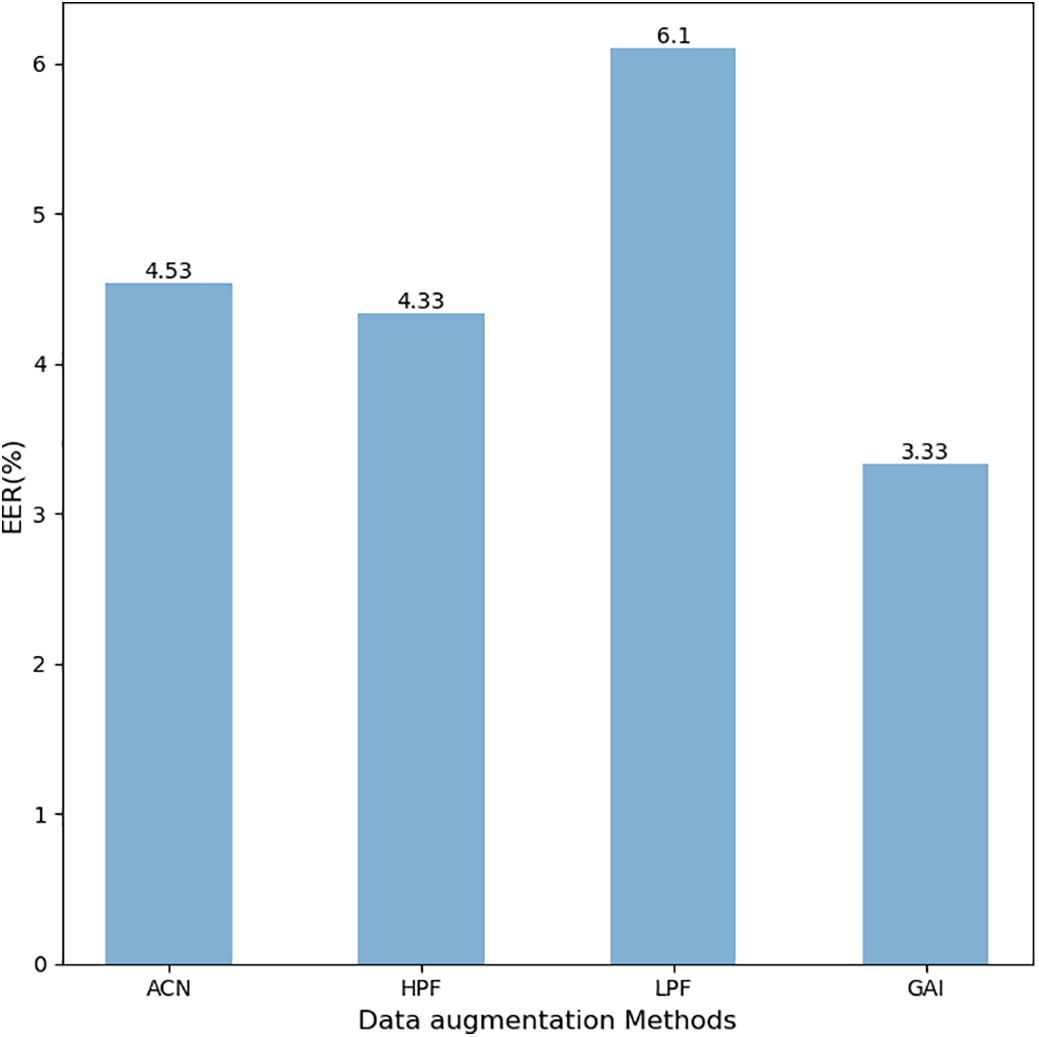

We set the application probability of these four speech enhancement methods to 0.5 to avoid over-determination or overfitting, ensuring balance and diversity in the experimental process. The experimental results are shown in Figs. 5–7.

Figure 5: Different DA methods in TFTransformer-S

Figure 6: Different DA methods in TFTransformer-L

Figure 7: Different DA methods in TFTransformer-SE

The results show that the LPF enhancement method has higher EER values than the models without data augmentation in all three models, and it is the worst of the four data augmentation methods in terms of detection performance. This result indicates that synthetic speech detection is less effective in the low-frequency range. Low-pass filters weaken the high-frequency components of the signal, which may cause the loss of key feature information of synthetic speech, making it difficult for the model to effectively identify synthetic speech in the low-frequency range. The detection performance of the two data augmentation methods, ACN and HPF, is similar. Among the three models, the detection performance of the GAI data augmentation method was the best, with an EER value of 3.33% in the TFTransformer-SE model. This indicates that the GAI augmentation method enhances the diversity and complexity of speech signals by adjusting the gain of the speech signal, thereby changing the volume or energy of the signal. This enables the model to better generalize and recognize different types of synthetic speech.

This paper proposes a new synthetic speech detection model named TFTransformer. This model innovatively combines local and global time-frequency domain dependencies of speech signals, aiming to reduce information loss and improve the accuracy of synthetic speech detection by more efficiently integrating the dependencies between local and global features.

The TFTransformer model adopts a novel structural design that emphasizes the time-frequency characteristics of speech signals. The front-end of the model uses SincLayer and 2D convolution blocks to extract deep features from the input speech signal, effectively capturing the detailed features of the speech signal and obtaining HFM with local dependency. Next, the global feature extraction component, composed of multiple time-frequency Transformer modules, is used to obtain global dependency. Each time-frequency Transformer block includes two standard Transformer modules, which process time-domain and frequency-domain features, respectively. Finally, the outputs of the two modules are fused through residual connections. This component can effectively and comprehensively capture global dependency in the time-frequency domain, thereby achieving more accurate detection results. To further enhance the model’s performance, we introduced the Res-SERes2Net block with channel attention mechanism into the 2D convolution block. This module adaptively adjusts the relationships between channels to improve the model’s feature expression capabilities, effectively enhancing the interconnectivity between convolution channels and more accurately extracting local dependency.

The experimental results demonstrate that the TFTransformer-SE model can significantly improve the performance of synthetic speech detection, achieving EER reductions of 0.84% and 3.37% on the ASVspoof 2019 LA and ASVspoof 2021 LA datasets, respectively. These results not only demonstrate the powerful potential of TFTransformer in synthetic speech detection tasks, but also prove that combining local and global dependencies can significantly improve detection accuracy, providing new ideas and technical paths for research in the field of speech security.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research is supported by project ZR2022MF330 supported by Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation and the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 61701286.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, software, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, Jiahui Song; validation, Yuepeng Zhang; conceptualization, methodology, supervision, Wenhao Yuan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in zenodo at https://zenodo.org/records/4837263 (accessed on 01 August 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wu Z, Kinnunen T, Evans N, Yamagishi J, Hanilçi C, Sahidullah M, et al. ASVspoof 2015: the first automatic speaker verification spoofing and countermeasures challenge. In: Interspeech 2015. Arlington, VA, USA: International Speech Communication Association; 2015. p. 2037–41. doi:10.21437/interspeech.2015-462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Nautsch A, Wang X, Evans N, Kinnunen TH, Vestman V, Todisco M, et al. ASVspoof 2019: spoofing countermeasures for the detection of synthesized, converted and replayed speech. IEEE Trans Biom Behav Identity Sci. 2021;3(2):252–65. doi:10.1109/tbiom.2021.3059479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Yamagishi J, Wang X, Todisco M, Sahidullah M, Patino J, Nautsch A, et al. ASVspoof 2021: accelerating progress in spoofed and deepfake speech detection. In: 2021 Edition of the Automatic Speaker Verification and Spoofing Countermeasures Challenge; 2021 Sep 16. Online. p. 47–54. doi:10.21437/asvspoof.2021-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Liu X, Liu M, Wang L, Lee KA, Zhang H, Dang J. Leveraging positional-related local global dependency for synthetic speech detection. In: ICASSP 2023—2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2023 Jun 4–10; Rhodes Island, Greece. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

5. Cai W, Wu H, Cai D, Li M. The DKU replay detection system for the ASVspoof 2019 challenge: on data augmentation, feature representation, classification, and fusion. In: Interspeech 2019. Arlington, VA, USA: International Speech Communication Association; 2019. p. 1023–27. doi:10.21437/interspeech.2019-1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yang Y, Wang H, Dinkel H, Chen Z, Wang S, Qian Y, et al. The SJTU robust anti-spoofing system for the ASVspoof 2019 challenge. In: Interspeech 2019. Arlington, VA, USA: International Speech Communication Association; 2019. p. 1038–42. doi:10.21437/interspeech.2019-2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li X, Li N, Weng C, Liu X, Su D, Yu D, et al. Replay and synthetic speech detection with Res2Net architecture. In: ICASSP 2021—2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2021 Jun 6–11; Toronto, ON, Canada. p. 6354–8. doi:10.1109/icassp39728.2021.9413828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li X, Wu X, Lu H, Liu X, Meng H. Channel-wise gated Res2Net: towards robust detection of synthetic speech attacks. In: Interspeech 2021. Arlington, VA, USA: International Speech Communication Association; 2021. p. 4314–8. doi:10.21437/interspeech.2021-2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhang Y, Jiang F, Duan Z. One-class learning towards synthetic voice spoofing detection. IEEE Signal Process Lett. 2021;28:937–41. doi:10.1109/lsp.2021.3076358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Chen X, Zhang Y, Zhu G, Duan Z. UR channel-robust synthetic speech detection system for ASVspoof 2021. In: 2021 Edition of the Automatic Speaker Verification and Spoofing Countermeasures Challenge; 2021 Sep 16; Online. p. 75–82. doi:10.21437/asvspoof.2021-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Ma X, Liang T, Zhang S, Huang S, He L. Improved lightcnn with attention modules for asv spoofing detection. In: 2021 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME); 2021 Jul 5–9; Shenzhen, China. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICME51207.2021.9428313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Lei Z, Yan H, Liu C, Ma M, Yang Y. Two-path GMM-ResNet and GMM-SENet for ASV spoofing detection. In: ICASSP 2022—2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2022 May 23–27; Singapore. p. 6377–81. doi:10.1109/ICASSP43922.2022.9746163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Tak H, Patino J, Todisco M, Nautsch A, Evans N, Larcher A. End-to-end anti-spoofing with RawNet2. In: ICASSP 2021—2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2021 Jun 6–11. Toronto, ON, Canada. p. 6369–73. doi:10.1109/ICASSP39728.2021.9414234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang X, Yamagishi J. A comparative study on recent neural spoofing countermeasures for synthetic speech detection. In: Interspeech 2021. Arlington, VA, USA: International Speech Communication Association; 2021. p. 4259–63. doi:10.21437/interspeech.2021-702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wang X, Yamagishi J, Todisco M, Delgado H, Nautsch A, Evans N, et al. ASVspoof 2019: a large-scale public database of synthesized, converted and replayed speech. Comput Speech Lang. 2020;64:101114. doi:10.1016/j.csl.2020.101114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Jung J, Heo H, Tak H, Shim H, Chung JS, Lee B, et al. Aasist: audio anti-spoofing using integrated spectrotemporal graph attention networks. In: ICASSP 2022—2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2022 May 22–27; Singapore. p. 6367–71. [Google Scholar]

17. Zaman K, Samiul IJAM, Sah M, Direkoglu C, Okada S, Unoki M. Hybrid transformer architectures with diverse audio features for deepfake speech classification. IEEE Access. 2024;12:149221–37. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3478731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Koizumi Y, Karita S, Wisdom S, Erdogan H, Hershey JR, Jones L, et al. DF-conformer: integrated architecture of conv-tasnet and conformer using linear complexity self-attention for speech enhancement. In: 2021 IEEE Workshop on Applications of Signal Processing to Audio and Acoustics (WASPAA); 2021 Oct 17–20; New Paltz, NY, USA. p. 161–5. doi:10.1109/WASPAA52581.2021.9632794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Chen S, Wu Y, Chen Z, Wu J, Li J, Yoshioka T, et al. Continuous speech separation with conformer. In: ICASSP 2021—2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2021 Jun 6–11; Toronto, ON, Canada. p. 5749–53. [Google Scholar]

20. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. In: 31st Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017); 2017 Dec 4–9; Long Beach, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

21. Li C, Yang F, Yang J. The role of long-term dependency in synthetic speech detection. IEEE Signal Process Lett. 2022;29:1142–6. doi:10.1109/lsp.2022.3169954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Jung JW, Kim SB, Shim HJ, Kim JH, Yu HJ. Improved RawNet with feature map scaling for text-independent speaker verification using raw waveforms. In: Interspeech 2020. Arlington, VA, USA: International Speech Communication Association; 2020. p. 1496–500. doi:10.21437/interspeech.2020-1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Identity mappings in deep residual networks. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

24. Hua G, Teoh ABJ, Zhang H. Towards end-to-end synthetic speech detection. IEEE Signal Process Lett. 2021;28:1265–9. doi:10.1109/lsp.2021.3089437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Loshchilov I, Hutter F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. In: International Conference on Learning Representations; 2019 May 6–9; New Orleans, LA, USA. [Google Scholar]

26. Todisco M, Wang X, Vestman V, Sahidullah M, Delgado H, Nautsch A, et al. ASVspoof 2019: future horizons in spoofed and fake audio detection. In: Interspeech 2019. Arlington, VA, USA: International Speech Communication Association; 2019. p. 1008–12. doi:10.21437/interspeech.2019-2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Das RK. Known-unknown data augmentation strategies for detection of logical access, physical access and speech deepfake attacks: ASVspoof 2021. In: 2021 Edition of the Automatic Speaker Verification and Spoofing Countermeasures Challenge; 2021 Sep 16; Online. p. 29–36. doi:10.21437/asvspoof.2021-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Cohen A, Rimon I, Aflalo E, Permuter HH. A study on data augmentation in voice anti-spoofing. Speech Commun. 2022;141:56–67. doi:10.1016/j.specom.2022.04.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Martín-Doas JM, Lvarez A. The vicomtech audio deepfake detection system based on wav2vec2 for the 2022 add challenge. In: ICASSP 2022—2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2022 May 23–27; Singapore. [Google Scholar]

30. Ding S, Zhang Y, Duan Z. SAMO: speaker attractor multi-center one-class learning for voice anti-spoofing. In: ICASSP 2023—2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2023 Jun 4–10. Rhodes Island, Greece. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/icassp49357.2023.10094704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Wang Z, Fu R, Wen Z, Xie Y, Liu Y, Wang X, et al. Generalized fake audio detection via deep stable learning. In: Interspeech 2024. Arlington, VA, USA: International Speech Communication Association; 2024. p. 4773–7. doi:10.21437/interspeech.2024-1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Chen C, Dai B, Bai B, Chen D. Deep correlation network for synthetic speech detection. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;154:111413. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools