Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Composite Loss-Based Autoencoder for Accurate and Scalable Missing Data Imputation

Department of Computer Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Eskisehir Technical University, Eskisehir, 26555, Türkiye

* Corresponding Author: Cahit Perkgoz. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070381

Received 15 July 2025; Accepted 23 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Missing data presents a crucial challenge in data analysis, especially in high-dimensional datasets, where missing data often leads to biased conclusions and degraded model performance. In this study, we present a novel autoencoder-based imputation framework that integrates a composite loss function to enhance robustness and precision. The proposed loss combines (i) a guided, masked mean squared error focusing on missing entries; (ii) a noise-aware regularization term to improve resilience against data corruption; and (iii) a variance penalty to encourage expressive yet stable reconstructions. We evaluate the proposed model across four missingness mechanisms, such as Missing Completely at Random, Missing at Random, Missing Not at Random, and Missing Not at Random with quantile censorship, under systematically varied feature counts, sample sizes, and missingness ratios ranging from 5% to 60%. Four publicly available real-world datasets (Stroke Prediction, Pima Indians Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease, and Framingham Heart Study) were used, and the obtained results show that our proposed model consistently outperforms baseline methods, including traditional and deep learning-based techniques. An ablation study reveals the additive value of each component in the loss function. Additionally, we assessed the downstream utility of imputed data through classification tasks, where datasets imputed by the proposed method yielded the highest receiver operating characteristic area under the curve scores across all scenarios. The model demonstrates strong scalability and robustness, improving performance with larger datasets and higher feature counts. These results underscore the capacity of the proposed method to produce not only numerically accurate but also semantically useful imputations, making it a promising solution for robust data recovery in clinical applications.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileIn the current era, data are considered a critical asset in various fields, including healthcare, finance, robotics, industry, social sciences, and engineering. The increasing importance of data-based decision-making processes has increased the importance of reliable data sets, even those that contain incomplete information that may reduce analytical validity. However, real-world datasets frequently contain missing values, which pose considerable obstacles for data analysis, statistical modeling, and machine learning. As stated by [1], improper handling of missing data can lead to biased results and reduce model efficacy in regression and classification tasks. Missing data, first formalized in early statistical literature and now widely addressed in contemporary machine learning and epidemiological research, can arise through canonical mechanisms, commonly classified as Missing Completely at Random (MCAR), Missing at Random (MAR), and Missing Not at Random (MNAR) [2].

Researchers have therefore developed numerous imputation methods to overcome these challenges. These methods can be categorized into (i) conventional techniques such as mean, median, and mode imputation; Expectation-Maximization (EM) [3]; Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) [4]; k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) [5]; and regression-based methods [6] and (ii) modern techniques such as MissForest [7], matrix factorization methods [8,9], and a range of deep learning architectures [10] including Autoencoders [11], Denoising Autoencoders [12], Generative Adversarial Imputation Networks (GAIN) [13], Variational Autoencoders (VAE) [14], and Transformer-based models [15,16]. Although these modern techniques have substantially improved imputation performance on complex datasets, several challenges persist. One well-known limitation is the gap between minimizing reconstruction error and achieving high performance in downstream tasks, such as classification or regression. Furthermore, modern techniques require a considerable amount of data for effective generalization, restricting their applicability when sample sizes are small [17]. Besides, deep learning-based models tend to overfitting because of unsuccessful imputation which causes decreased robustness [17,18] and models may introduce bias due to inadequate missingness process, particularly under MNAR mechanisms [19]. Hence, there is a need for approaches that prevent overfitting under different missingness mechanisms.

To address these gaps, a novel and robust imputation approach across missingness mechanisms is proposed in this study. The proposed model is inspired by the Generative Adversarial Imputation Network developed by Yoon et al. [13], especially in its use of supporting signals to improve the imputation process. While several generative architectures such as GANs and diffusion models have been utilized to impute missing data, this study focus on an autoencoder-based approach since autoencoders present several advantages. First, they provide stable training dynamics for tabular datasets of moderate size, whereas GANs may suffer from mode collapse and diffusion models often require hundreds of denoising steps. Second, our guided loss function integrates the observation mask, hint matrix, and noise injection within the reconstruction objective, which is more direct to implement in an autoencoder framework than in adversarial or diffusion-based configuration. Third, autoencoders are computationally more efficient, while maintaining competitive downstream predictive performance. These characteristics make autoencoders a suitable backbone for developing robust, mask-aware imputation models in real-world tabular applications. However, instead of utilizing GAN architecture, our methodology is founded on an autoencoder framework and introduces a new effective loss function for missing data imputation. This loss function comprises three principal components: a Guided Masked Mean Squared Error (GM-MSE), which penalizes reconstruction errors exclusively on the missing entries, adhering to established practices in deep imputation frameworks [11]; a Noise Loss term, which deters the model from reproducing randomly introduced noise in the imputed areas, akin to denoising methodologies [12]; and a Variance Penalty, which fosters diversity in imputations and alleviates over-smoothing, addressing issues identified in over-regularized models [17]. Together, these components create a balanced objective that simultaneously encourages reliability to observed data, robustness to noise, and diversity in reasonable imputations.

Accordingly, we introduce the Guided Autoencoder (Guided_AE), an autoencoder-based architecture that combines noise-aware masking with the variance penalty to improve the reconstruction of missing values. We evaluate the model under MCAR, MAR, MNAR, and MNAR with quantile censorship (hereafter abbreviated as MNAR_QUANT) across missingness ratios of 5%, 15%, 25%, 40%, and 60%. The principal contributions of this work are:

• A new composite-loss autoencoder that unifies mask guidance, noise suppression, and variance control.

• A comprehensive evaluation spanning four missingness mechanisms, five missingness ratios, and four benchmark healthcare datasets.

• Evidence that the proposed model narrows the gap between reconstruction fidelity and downstream predictive accuracy, even with limited sample sizes.

Results show that Guided_AE consistently delivers strong performance, underscoring its potential for practical missing-data imputation.

Handling missing data has long been a central challenge in statistical modeling and machine learning, prompting the development of various imputation strategies tailored to different missingness mechanisms. According to Little and Rubin [1], these mechanisms are typically classified as MCAR, MAR, and MNAR. In the case of MCAR, the probability of missingness is unrelated to either observed or unobserved data, implying that the missingness introduces no bias. In the context of MAR, the probability of missingness may depend on the observed data but not on the missing values themselves, and each mechanism demands a specific imputation strategy. However, in the MNAR case, the probability of missingness is related to the unobserved data, making valid inference significantly more challenging without explicitly modeling the missingness mechanism. They also stated that the performance of imputation and inference methods is largely contingent on the missingness mechanism, and that methods such as maximum likelihood estimation and multiple imputation perform effectively under MAR and MCAR provided the imputation model is correctly specified. However, their effectiveness deteriorates substantially under MNAR, often resulting in biased estimates unless the missingness mechanism itself is explicitly modeled. To address the limitations mentioned above, multivariate approaches such as MICE have been proposed [4]. MICE models each variable conditionally using iterative regressions, allowing for uncertainty estimation by generating multiple imputations and pooling the results. However, it has been observed that its performance is limited in the presence of non-linear or highly complex inter-variable relationships. Non-parametric methods have also been explored, such as MissForest [7], which employs the Random Forest algorithm to iteratively impute missing values and has demonstrated improved performance on mixed-type data. However, it can be computationally expensive on large datasets and sensitive to hyperparameter tuning. Techniques such as Probabilistic Principal Component Analysis (PPCA) and Bayesian PCA [20] have also been explored for learning latent representations. However, these are linear modelling techniques, and their successes are dependent on the assumption of linearity. Matrix factorization [8] and spectral regularization [21] methods based on low-rank structures have been developed in recommendation systems and bioinformatics for missing value imputation. In contrast to these methods, the proposed approach does not rely on strict assumptions of linearity or low-rank structures, allowing it to capture non-linear dependencies that are prevalent in real-world datasets.

Several researchers have compared the effectiveness of imputation models [16,22,23]. For example, Jerez et al. compared several statistically based traditional methods (e.g., hot-deck imputation) with machine learning techniques (e.g., Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), Self-Organizing Maps (SOM), and KNN) [23]. They reported that the machine learning-based methods outperformed traditional statistical methods, particularly in complex datasets. According to Farhangfar et al., different imputation techniques may produce different results, and some may significantly affect classification errors [24]. They reported that the imputation method should be decided appropriately for each type of missing data. In 2011, Liew et al., concluded that none of the evaluated methods consistently outperformed the others across all scenarios, based on 19 different imputation algorithms [25]. They also noted that the effectiveness of an imputation strategy is highly dependent on the characteristics of the dataset. While these comparative studies provide valuable insights, they generally stop short of offering a unified evaluation framework that integrates both statistical and deep learning approaches. This study directly responds to that need by systematically benchmarking across diverse methods and controlled missingness scenarios.

In recent years, deep learning-based imputation methods have attracted researchers with an increasing interest [26]. However, existing studies often lack a comprehensive evaluation, with most approaches tested primarily under MCAR or MAR assumptions [27]. Furthermore, many studies did not specify or justify the missingness mechanisms used in their experimental setups. The more challenging MNAR remains significantly underexplored, despite real-world data being more likely to follow MNAR mechanism in the fields such as healthcare, finance, and social sciences [16,28,29]. Moreover, few studies systematically examine how imputation models perform across a range of missingness ratios. The existing studies do not address more realistic forms of data loss, such as quantile-based MNAR mechanisms or data censoring [30]. Existing benchmark studies often focus on a limited number of datasets. Besides, they compare a restricted number of models where to draw generalizable conclusions about model robustness across different types of missingness is difficult. Beyond tabular settings, recent studies have also addressed imputation in graph-structured data. Xia et al. [31] introduced the Attribute Imputation Autoencoder (AIAE), which utilizes dual encoders for structural and attribute information together with a spectral-entropy regularizer to alleviate oversmoothing, achieving state-of-the-art results on benchmark graph datasets. In addition, Xia et al. [32] presented the first comprehensive survey on incomplete graph learning, proposing a taxonomy of missingness types and outlining challenges such as the lack of standardized benchmarks and the need for scalable methods. These works highlight that robust imputation is also a pressing issue in structured domains like social networks and biological systems, further emphasizing the general importance of developing flexible and principled approaches to missing data. By contrast, the present framework explicitly incorporates a broader range of missingness mechanisms, including underexplored cases such as MNAR_QUANT, thereby enabling a more realistic and comprehensive comparison. This positions the study as a step toward bridging the fragmented findings in prior research. These gaps highlight the need for a comprehensive evaluation framework that incorporates multiple models and scenarios, compares traditional and deep learning approaches, and operates under various controlled missingness patterns and proportions.

Although several studies have been conducted on deep learning-based imputation, many of them also remain limited in the scope of their evaluations. For example, the results of the GAIN method, proposed by Yoon et al. [13], were explored by focusing primarily on MAR settings, without exploring MNAR scenarios or more complex data censoring conditions. Similarly, Somepalli et al. introduced SAINT, a Transformer-based model for tabular imputation, but tested it mainly under MCAR and MAR assumptions [33]. Eduardo and Nazábal proposed a variational autoencoder for imputing heterogeneous data; nevertheless, their experiments were conducted using synthetic MAR setups [14]. A score-based diffusion models for imputation was applied in [34] but not evaluated under MNAR conditions. The literature also lacks evaluations across a range of missingness ratios and realistic mechanisms, such as quantile-censored MNAR. These gaps underscore the need for a comprehensive, model-agnostic benchmarking framework that systematically compares both traditional and deep learning approaches across various missingness types and levels. In response to these limitations, this study proposes a comprehensive evaluation framework that benchmarks both traditional and modern imputation models under a wide range of missingness scenarios. Unlike prior studies, we explicitly simulate and test four missingness mechanisms, MCAR, MAR, MNAR, and MNAR_QUANT, across five missingness levels (5%, 15%, 25%, 40%, and 60%). The proposed Guided Autoencoder is compared against a diverse set of baseline methods, including MICE, MissForest, EM, Matrix Factorization, standard Autoencoder, VAE, GAIN, Denoising Autoencoder, and Transformer-based models. To the best of our knowledge, this is among the first studies to systematically evaluate deep learning–based imputation methods across all major missingness types, highlighting their strengths and limitations through both reconstruction error and downstream classification performance. While prior studies have contributed individual methodological advances, they often lack a critical synthesis across mechanisms, datasets, and evaluation metrics. The Guided Autoencoder not only builds upon ideas from GAN-based and denoising frameworks but also introduces a novel composite loss that explicitly balances fidelity, robustness, and diversity. This integrated perspective highlights both the connections with earlier approaches and the distinct contributions of the present work.

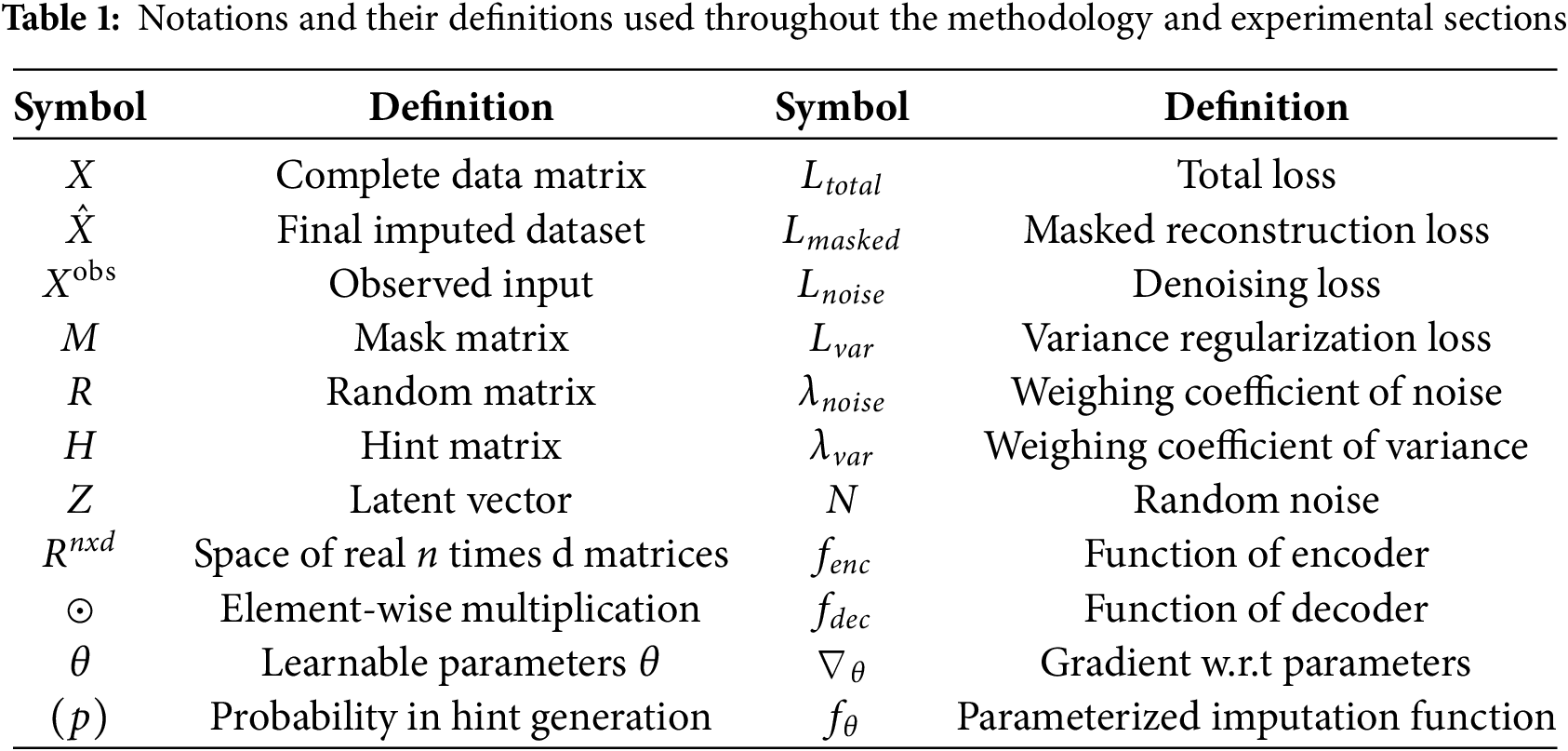

The notations and symbols used throughout the methodology and experimental sections of the paper is summarized in Table 1 below:

Let

where

Formally, we seek to learn a function

parameterized by

To support this learning, additional information is provided to the model in the form of a hint matrix

To encourage variability and prevent overfitting, random noise N ∈

where

This formulation is designed to accommodate various missingness mechanisms, including MCAR, MAR, and MNAR, as well as MNAR_QUANT, by simulating different mask matrices (M) under controlled experimental conditions. The goal is not only to achieve low reconstruction error on missing values but also to ensure that imputed data remain informative and predictive for downstream tasks, such as disease classification.

3.3 Guided Autoencoder Imputation

The objective of the proposed method is to integrate auxiliary information from three sources: a mask matrix indicating observed data, a random matrix introducing noise, and a partially revealing hint matrix. These components guide the decoder during the reconstruction phase. Let

The model comprises an encoder fenc and a decoder fdec: The encoder receives the channel-wise concatenation of the observed data

The decoder then reconstructs the full data matrix from this code, and a hint matrix H,

3.4 Masked Reconstruction Loss

The masked reconstruction loss is designed to ensure that the model focuses exclusively on imputing the missing entries, while preserving the integrity of the observed values. This selective emphasis prevents the network from altering known data points during training. The loss is computed as:

where X represents the original input matrix with missing values,

This formulation computes the mean squared error only over the missing elements, thus directing the optimization process to minimize reconstruction error specifically where values are imputed.

3.5 Noise-Aware Regularization

A noise-aware regularization term is introduced to prevent the model from overfitting to noise-driven patterns within the missing entries. This component discourages the model from reconstructing values that closely resemble the injected random noise, thereby reducing overconfidence in uncertain imputations. The noise regularization loss is defined as follows:

where N denotes a random noise matrix, in which each element is independently drawn from a predefined distribution (normal or uniform). This formulation ensures that the model avoids reproducing random noise in the imputed regions and encourages more meaningful reconstructions.

To prevent degenerate solutions such as collapsed or constant-valued outputs, a variance regularization term is incorporated into the objective function. This component is defined as

which penalizes low variance in the reconstructed data and encourages diverse imputations.

The overall model is trained by minimizing the total loss Ltotal using stochastic gradient descent. After training, the reconstructed matrix

The weighting coefficients

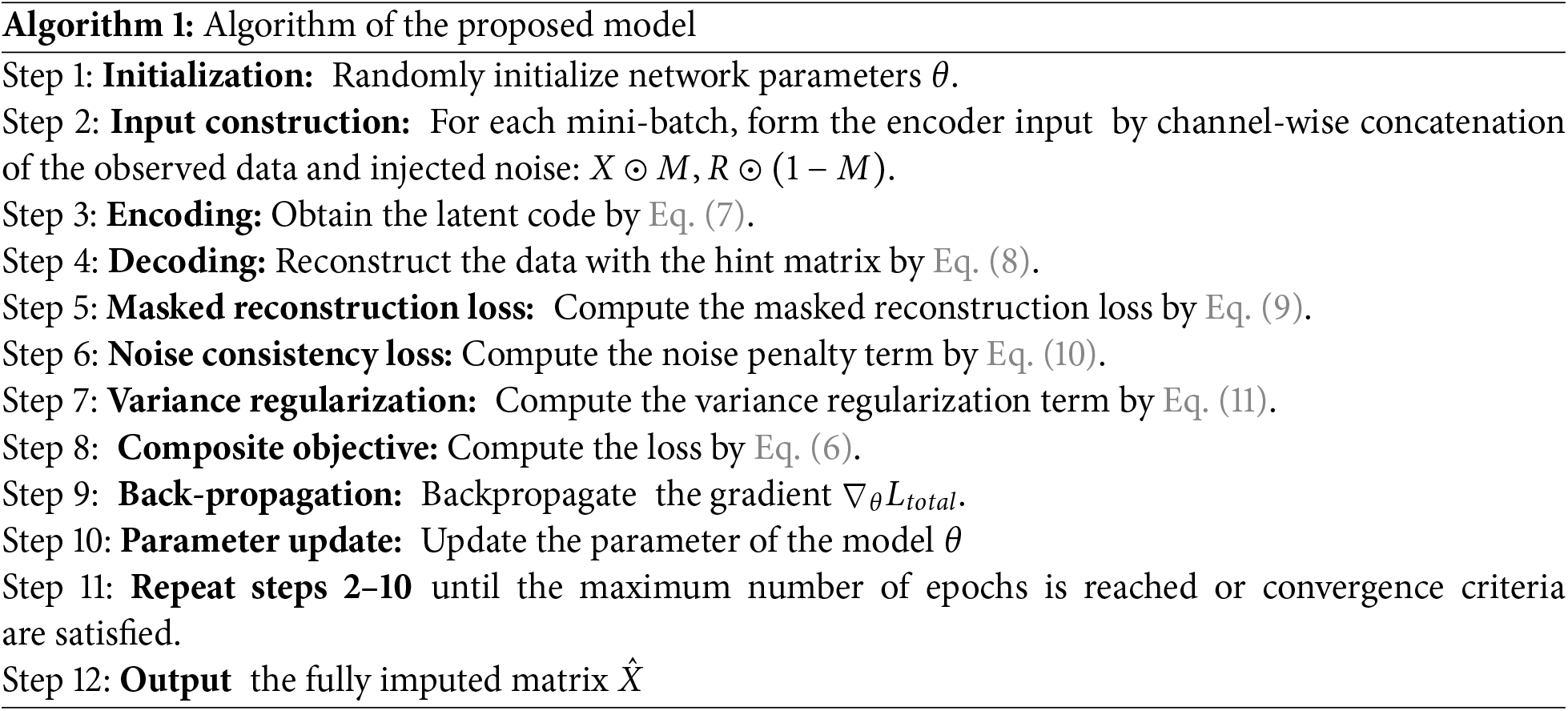

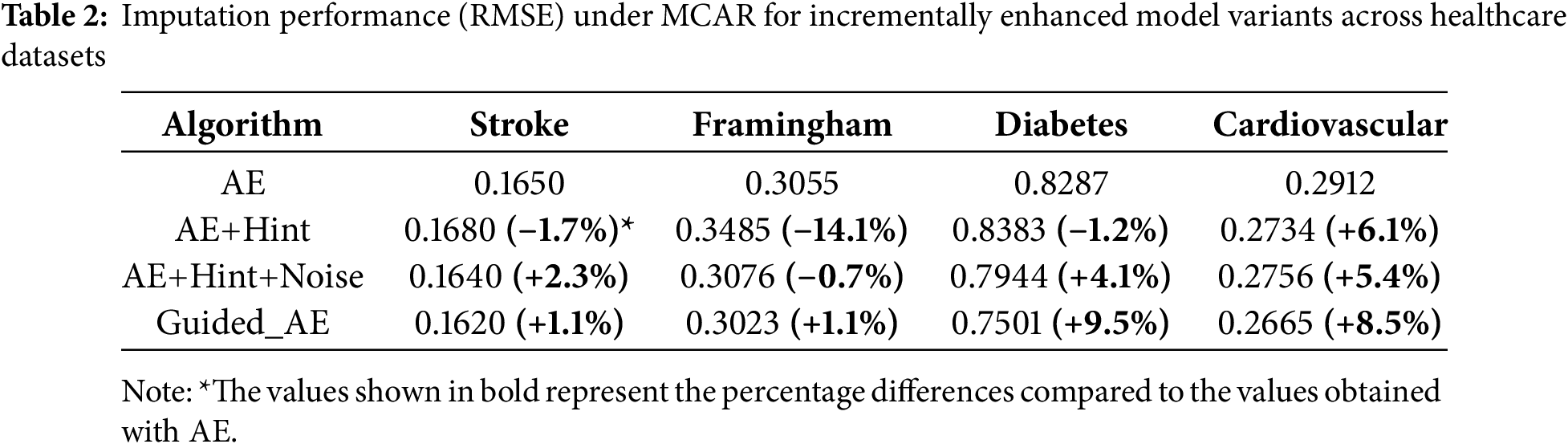

3.7 Proposed Model: Algorithmic Procedure and Flowchart

The proposed model follows an iterative training procedure designed to learn robust representations for missing data imputation. At each training step, the model leverages three key sources of information: the observed data entries, random noise injected into the missing positions, and a partially informative hint matrix that reveals a subset of the missingness pattern. The encoder receives a concatenation of these inputs and generates a latent representation that captures both the observed structure and the uncertainty in the data. The decoder then uses this latent code, along with the hint matrix, to reconstruct the full data matrix, including the imputed values. The training process is guided by a composite loss function that incorporates (i) a masked reconstruction loss applied only to the missing entries; (ii) a noise consistency loss which discourages the network from replicating random noise; and (iii) a variance regularization term which prevents the model from converging to trivial constant outputs. The training is performed using stochastic gradient descent, and the network parameters are updated iteratively to minimize the total loss. The data flow of the proposed model and the detailed training steps are outlined in the Algorithm 1 below.

The overall structure of the proposed model is depicted in Fig. 1 below.

Figure 1: Flowchart of the proposed guided autoencoder imputation model

4 Experimental Results and Discussions

Each dataset used in this study contains a target variable, enabling assessment of both the imputation quality and its impact on classification performance. Preprocessing tasks, including categorical feature encoding and standardization of continuous features, were conducted to ensure consistency across all models.

To benchmark the proposed method, we selected widely cited imputation algorithms that span diverse modelling assumptions: Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations, a regression-based iterative approach; MissForest, a non-parametric random-forest method; Expectation–Maximization, a likelihood-based technique; Matrix Factorization, which assumes a low-rank latent structure; and deep-learning based models such as standard Autoencoder, Variational Autoencoder, Denoising Autoencoder (DAE), Generative Adversarial Imputation Network, and a Transformer-based architecture.

All deep learning models, including the proposed Guided_AE, were implemented in PyTorch and trained using stochastic gradient descent. For fair comparison, the same network backbone was used across autoencoder-based methods, with modifications only to the loss functions and auxiliary mechanisms. Hyperparameters, including learning rate, batch size, and regularization coefficients (λnoise and λvar), were tuned via grid search on a validation split.

The experimental procedure proceeds in three phases. First, we performed a qualitative analysis to illustrate how the proposed model leverages the mask, noise, and hint signals (see Supplemental File 1 in Supplementary Materials). Second, we carried out a quantitative comparison on different datasets and performed a comparison with state-of-the-art imputation methods (Supplemental File 2). Finally, we evaluated the performance of the model across varying dataset sizes and feature dimensions (Supplemental File 3).

Each dataset was subjected to four simulated missingness mechanisms: MCAR, MAR, MNAR, and MNAR_QUANT with missingness ratios of 5%, 15%, 25%, 40%, and 60% introduced by randomly masking the data according to the selected mechanism. The original complete datasets were retained as ground truth to assess reconstruction accuracy, and each imputation experiment was repeated five times with different random seeds to compute average performance and promote its variability.

We reported root-mean-squared error (RMSE) for reconstruction accuracy and area under the ROC curve (ROC AUC) for downstream classification. To ensure robustness, all evaluations were repeated five times and the results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation across these repetitions.

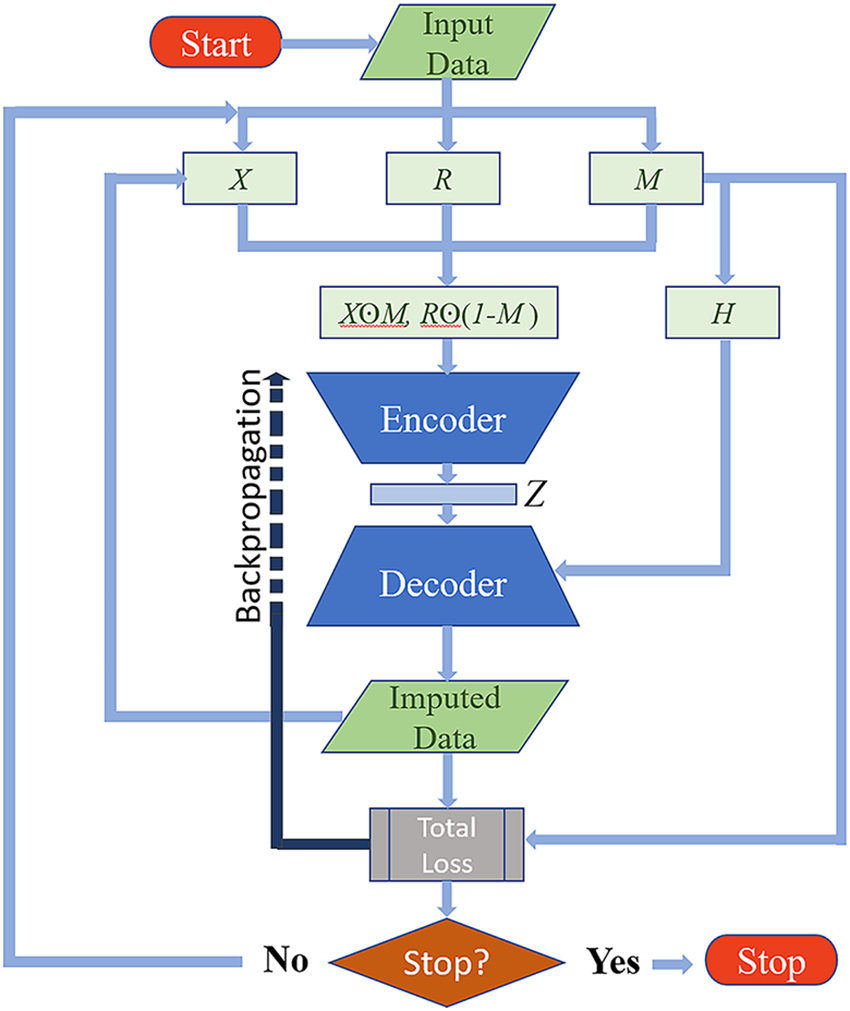

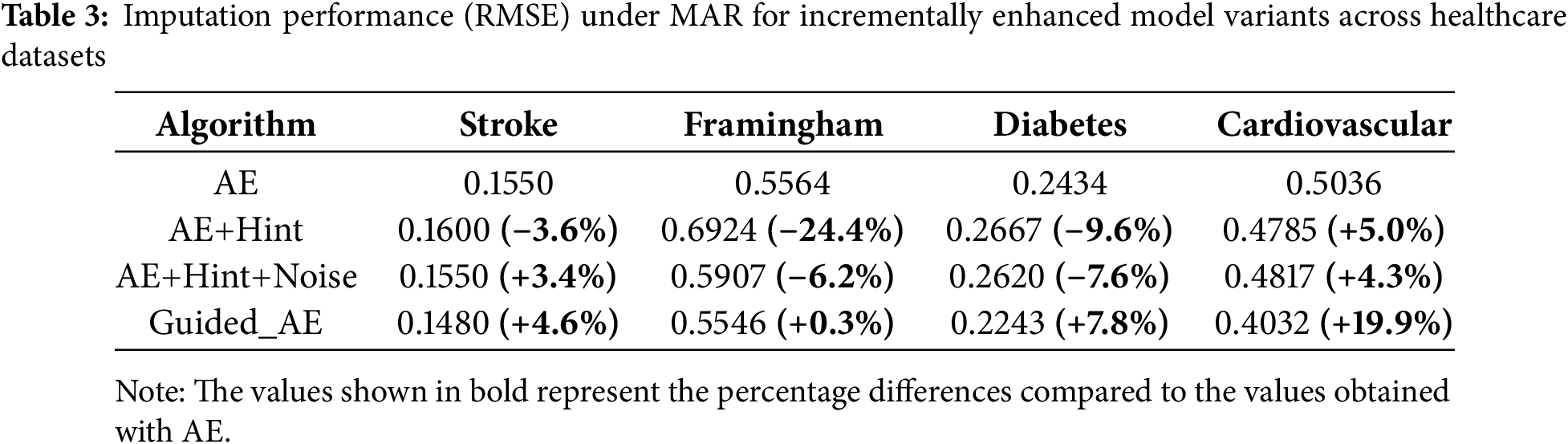

4.2 Effect of Model Components on Imputation Performance

The performance of the proposed framework arises from four critical elements: the autoencoder backbone, the masked-reconstruction loss (

Across all missingness mechanisms, we observe monotonic improvements in RMSE with each added component. Under MCAR (Table 2), the most straightforward missingness mechanism, Guided_AE consistently yields the lowest RMSE across all datasets. The most notable improvement is seen on the Diabetes dataset, where RMSE drops from 0.8287 (AE) to 0.7501 (Guided_AE), indicating a relative improvement of 9.5%. Similarly, on the Cardiovascular dataset, the full model improves RMSE by 8.5% over the baseline AE.

Under MAR (Table 3), where missingness depends on observed values, the advantages of the full model become even more evident. On the Cardiovascular dataset, the RMSE improves from 0.5036 (AE) to 0.4032 (Guided_AE), an enhancement of 19.9%, which is the highest observed gain across all settings. The Diabetes and Stroke datasets also show notable improvements, reflecting the capacity of the model to weight observed patterns effectively through the hint mechanism and noise-aware loss.

In the more complex MNAR setting (Table 4), where missingness depends on unobserved data, Guided_AE maintains superior performance, particularly on the Framingham and Cardiovascular datasets. For Framingham dataset, the RMSE improves from 0.5318 (AE) to 0.4665 (Guided_AE), a gain of over 12%. This is especially significant, as MNAR represents a setting where conventional imputation methods often fail due to their inability to model unobserved dependencies.

The MNAR_QUANT scenario (Table 5), which incorporates censorship based on quantiles, presents one of the most difficult imputation challenges. Nevertheless, Guided_AE continues to outperform all other variants. On the Stroke dataset, we observe a substantial 25.5% improvement over the baseline AE (from 0.1880 to 0.1400). Across all datasets, the final model consistently achieves the lowest RMSE, showcasing both robustness and flexibility under structured and non-random missingness conditions.

These results affirm the importance of each component in the model design. The hint matrix enables better estimation by incorporating auxiliary information about observed data; the noise penalty prevents the network from overfitting to corrupted or uncertain inputs; and the variance regularization term ensures non-trivial, expressive outputs. Full configuration (AE +

4.3 Model Performance Evaluation

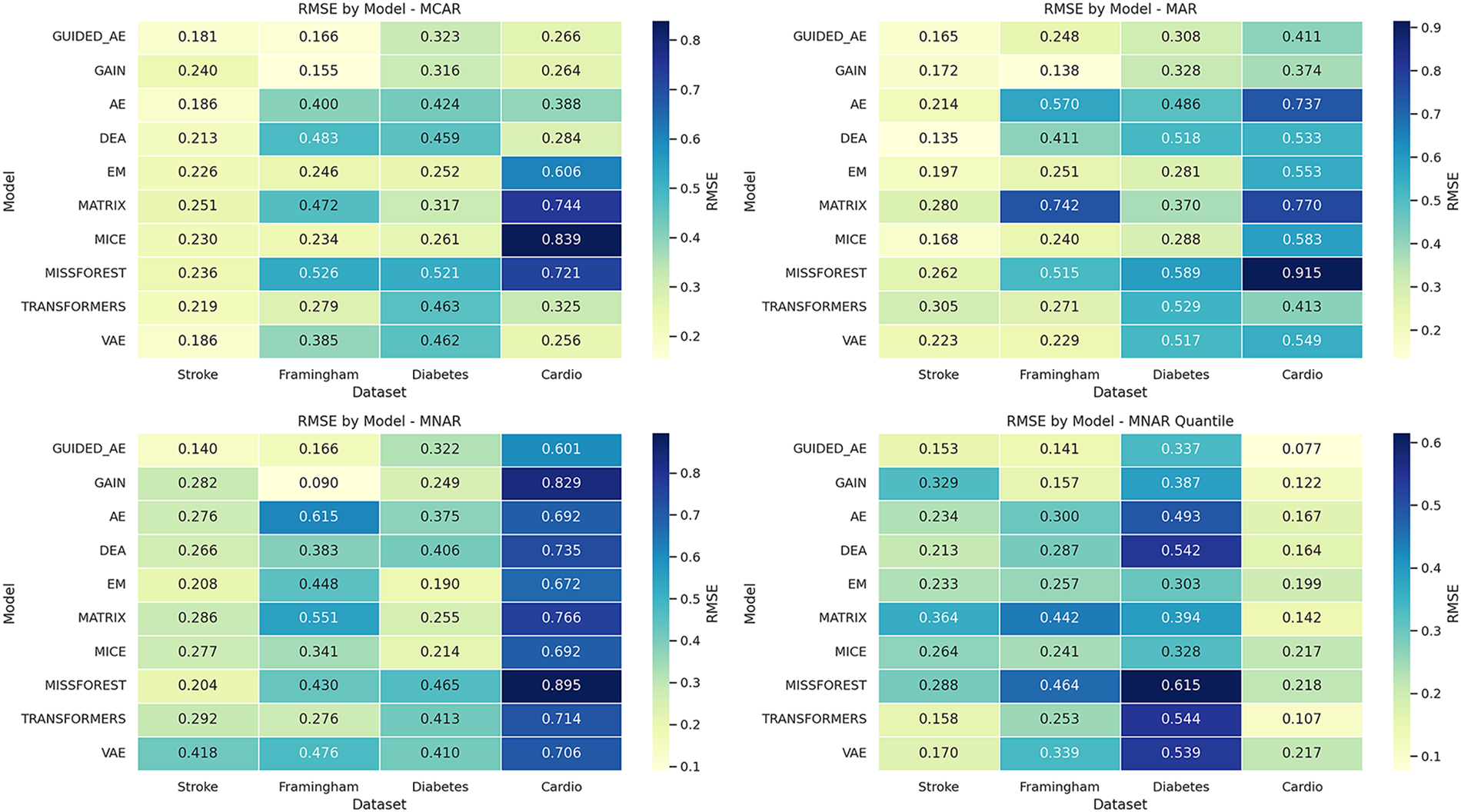

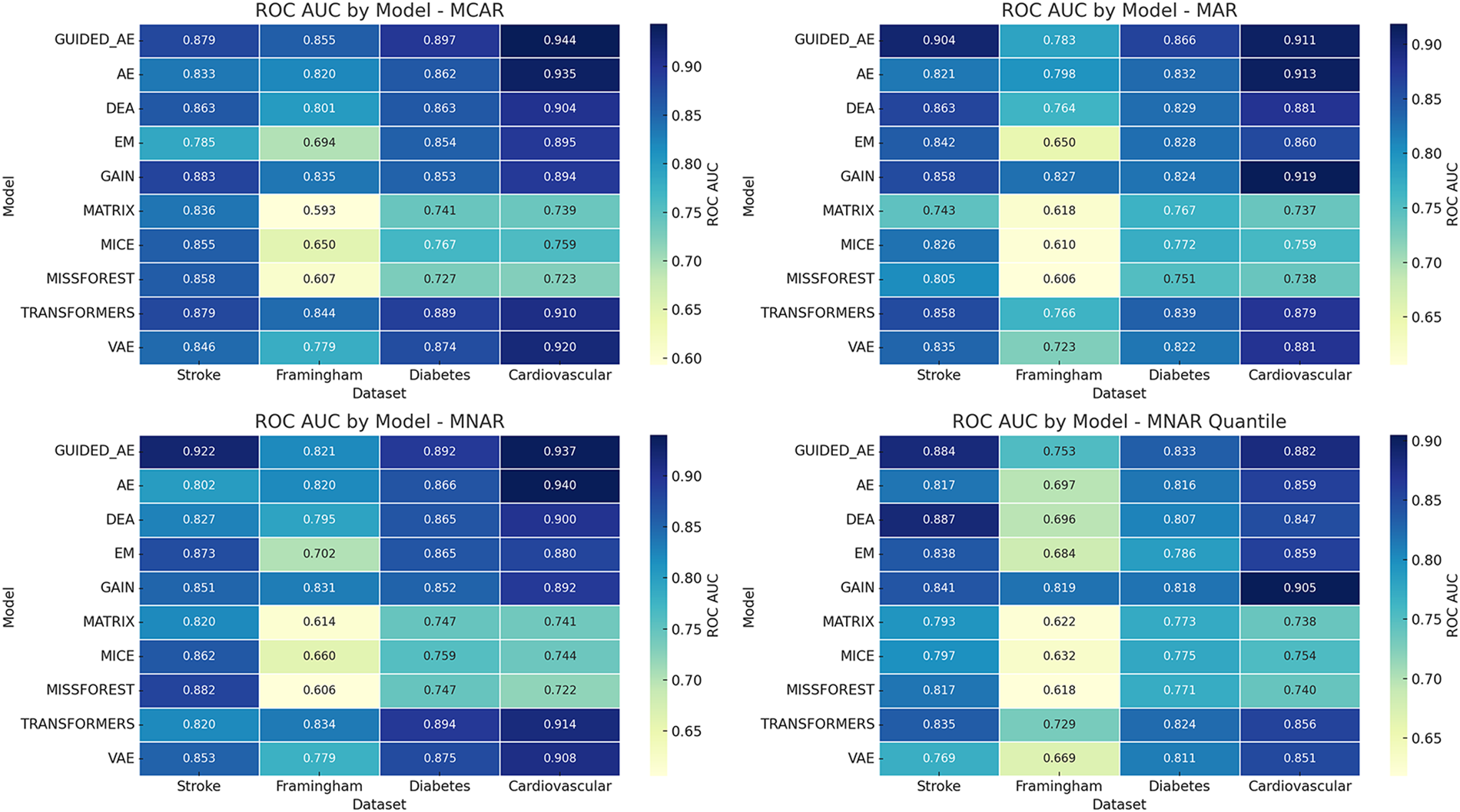

We next benchmarked the Guided Autoencoder under four simulated missingness mechanisms, including MCAR, MAR, MNAR, and MNAR_QUANT. Performance was benchmarked across four publicly available datasets: the Stroke Prediction dataset, the Framingham Heart Study dataset, the Pima Indians Diabetes dataset, and the Cardiovascular Disease dataset. For each dataset and missingness condition, the proposed model was compared to state-of-the-art imputation techniques, including AE, VAE, DAE, Transformer-based models, GAIN, MissForest, MICE, EM, and Matrix Factorization. The quantitative comparisons are shown in Fig. 2, where performance is measured using RMSE (reconstruction fidelity). These results along with Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (ROC AUC) scores (classification accuracy on the imputed data) are presented in tables in Supplementary File 4. All results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation across five runs.

Figure 2: Heatmap of RMSE for imputation models under varying missingness mechanisms across healthcare datasets

The proposed model achieved better results, providing an effective and extensible solution for missing data imputation in various contexts. By integrating hint-guided decoding, noise-aware regularization, and a masked reconstruction loss, the model achieves state-of-the-art results in both straightforward scenarios (e.g., MCAR and MAR) and challenging settings like MNAR and MNAR_QUANT. GAIN remains a strong competitor, surpassing the Guided Autoencoder on the Framingham dataset under MAR and MNAR, which underscores the strength of adversarial learning combined with hint signals. Traditional methods such as MICE, EM, and Matrix factorization demonstrated comparatively effective performance on the smaller diabetes dataset (~700 instances), probably due to that deep learning models cannot be trained adequately for this small number of datasets. This confirms that basic traditional methods can yield satisfactory results on small, well-structured datasets [23]. However, their significant deterioration in performance on larger and more complex datasets highlights their limited scalability and flexibility in adapting to real-world patterns of missingness. These findings confirm the robustness, adaptability, and exceptional generalization capabilities of the proposed model, making it appropriate for real-world dataset imputation tasks.

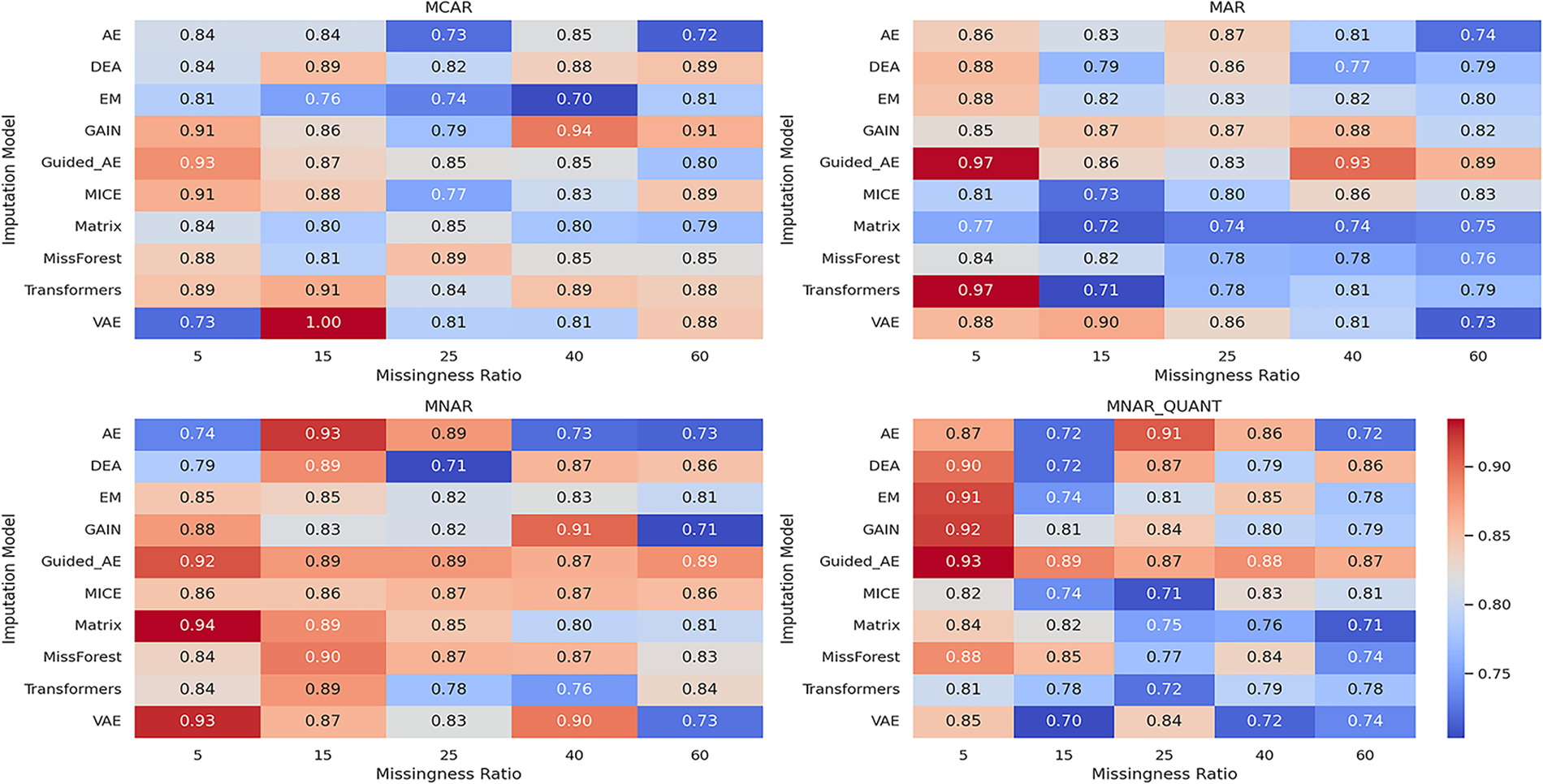

As mentioned above, to assess the classification performance after imputation, we computed the ROC AUC scores for all models across four real-world healthcare datasets under four missingness mechanisms shown in Fig. 3. The proposed model achieves the top score on three of the four datasets, most notably on the Cardiovascular dataset, where it records AUCs of 0.944 under MCAR and 0.934 under MNAR. This demonstrates strong predictive fidelity even under complex missingness structures. The sole exception is the Framingham dataset, where GAIN records 0.835 AUC under MCAR and 0.827 under MAR, marginally surpassing Guided_AE and underscoring the value of adversarial hint-based learning for certain feature configurations.

Figure 3: Heatmap of ROC AUC scores for imputation models under varying missingness mechanisms across healthcare datasets

Traditional methods like MissForest, MICE, and Matrix Factorization showed consistently lower ROC AUC values compared to deep learning-based models, especially under MAR and MNAR_QUANT on datasets with complex correlations (e.g., Cardiovascular). These results reinforce the value of hybrid deep learning architectures for producing high-fidelity imputations that support accurate downstream prediction under varying data incompleteness mechanisms [13,23].

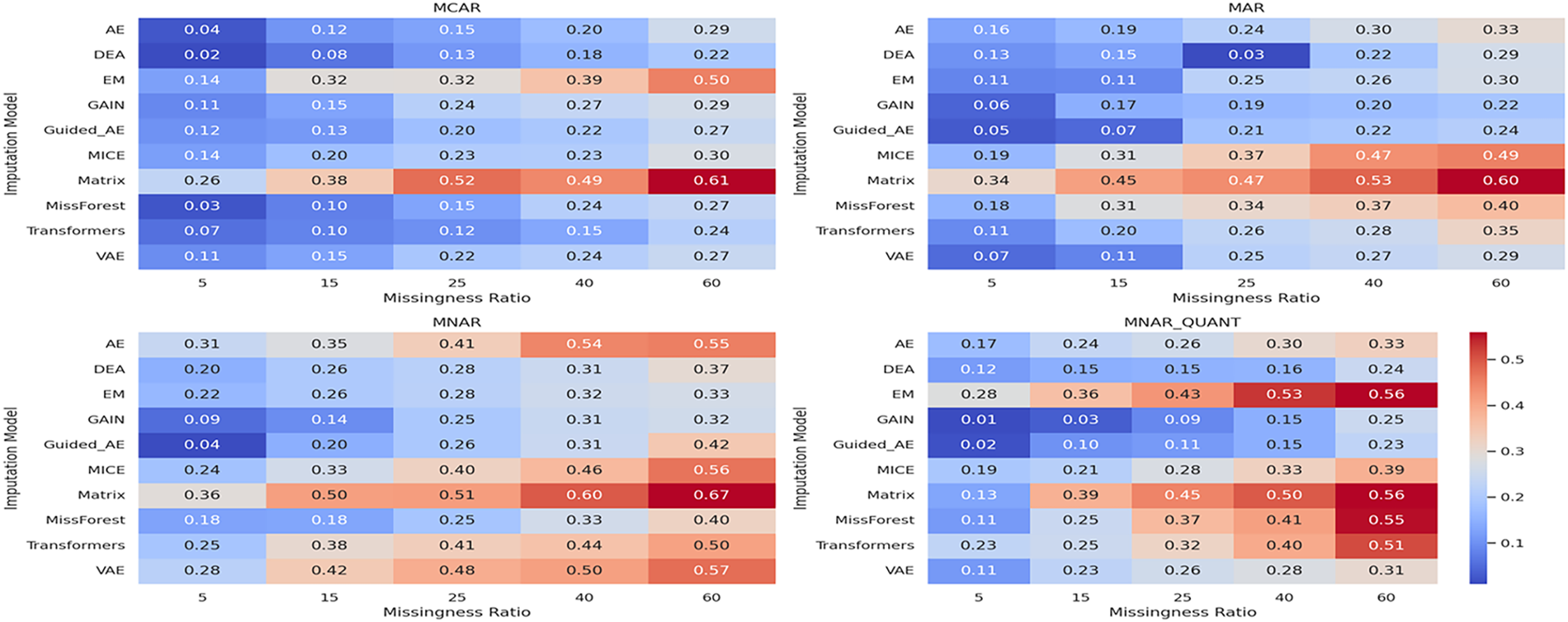

We further evaluated the performance of the proposed model across various missingness ratios. Specifically, we applied missingness ratios of 5%, 15%, 25%, 40%, and 60% to the Stroke Prediction dataset and assessed the resulting imputation and classification performance. Fig. 4 presents RMSE values, while Fig. 5 reports the area under the ROC curve for the corresponding downstream classification tasks across different data missingness types and ratios. Each heatmap subplot corresponds to a specific missingness mechanism. The proposed model demonstrates consistently low RMSE and high ROC AUC values with particularly strong performance under MNAR and MNAR_QUANT, indicating its robustness in both non-random and censored data scenarios. These results confirm the model’s ability to maintain reconstruction accuracy and predictive integrity even as the extent of data incompleteness increases. These visual representations facilitate a comparative analysis of algorithm robustness under varying degrees and patterns of data incompleteness.

Figure 4: Heatmap of RMSE for imputation models under varying missingness ratios (stroke prediction dataset)

Figure 5: Heatmap of ROC AUC scores for imputation models under varying missingness ratios (stroke prediction dataset)

The ROC AUC results demonstrate that the proposed model preserves predictive structure as effectively as the generative–adversarial baseline GAIN. Notably, the proposed model maintains low RMSE and high ROC AUC across all experimental settings, with particularly strong performance under MNAR and MNAR_QUANT, the two most challenging missingness mechanisms. In contrast, traditional models (e.g., EM, MICE) and simpler neural models (e.g., AE) suffer substantial degradation as missingness becomes non-random or structured. This confirms that our model not only reconstructs missing values effectively but also preserves meaningful structure relevant to downstream tasks.

To investigate how dataset size affects imputation performance, we conducted a series of experiments using varying sample sizes. Fig. 6 presents the RMSE for three models (AE, GAIN, and Guided_AE) on the Stroke dataset, with sample sizes ranging from 500 to 4000 instances. RMSE values are normalized within each mechanism to ensure comparability. As expected, imputation performance improves for all models as the dataset grows; however, Guided_AE exhibits the steepest decline in RMSE, particularly under more challenging mechanisms such as MNAR and MNAR_QUANT. This widening performance gap at larger sample sizes highlights the enhanced capacity of the model to leverage data richness. In contrast, under MCAR and MAR, the differences among models are relatively small, suggesting that simpler missingness structures can be effectively handled even by baseline autoencoders. Nonetheless, Guided_AE maintains a distinct advantage whenever missingness is driven by unobserved or censored values.

Figure 6: RMSE comparison across sample sizes under different missingness mechanisms (stroke prediction dataset)

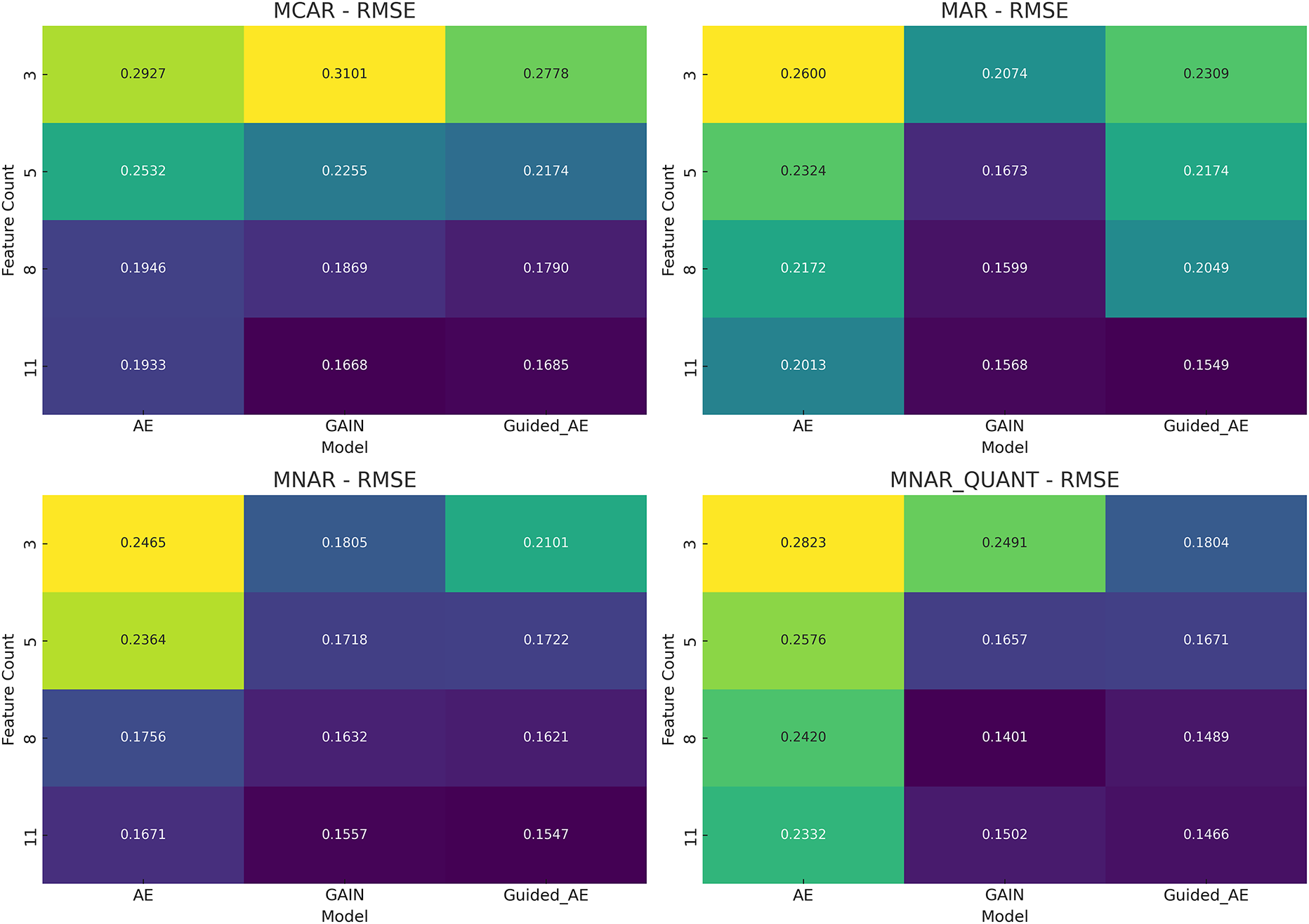

We have also employed experiments with different sizes of features in order to analyze imputation performance. The experiments have been conducted by the increasing number of features (3, 5, 8, and 11 features) under four missingness mechanisms: MCAR, MAR, MNAR, and MNAR_QUANT. It was observed that as the feature count increased, the Guided Autoencoder demonstrated a monotonic improvement in RMSE. This shows that the model scales effectively with richer feature sets. Under more challenging conditions, such as MNAR and MNAR_QUANT, the proposed model continues to show robustness and scalability.

These improvements demonstrate that the model generalizes well across different missing data mechanisms and is more effective than traditional approaches. The results obtained are displayed in Fig. 7, where darker cells indicate better performance (lower RMSE). Across every missingness mechanism, and especially under MNAR and MNAR_QUANT settings, the proposed model has consistently the best performance.

Figure 7: RMSE heatmap of imputation models across feature counts and missingness mechanisms (stroke prediction dataset)

The models are validated not only on synthetically masked datasets under MCAR, MAR, MNAR, and MNAR with quantile censorship mechanisms but also on publicly available datasets that contain naturally occurring missing values. In particular, two datasets which are considered which are the UCI Horse Colic dataset, a relatively small dataset with approximately 300 records, and the Adult Census dataset, a large-scale dataset with over 48,000 records. To strengthen the evaluation, we expanded both the set of baseline methods and the evaluation metrics. In addition to previously included approaches, we incorporated the k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) imputer as an additional non-parametric baseline. This broader baseline set ensures fair comparisons across statistical, ensemble-based, low-rank, and deep generative models. For evaluation, three complementary dimensions are considered: (i) Imputation quality, measured by MAE, RMSE, and Normalized RMSE (NRMSE); (ii) Downstream predictive performance, assessed with Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1 score, ROC-AUC, Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), and Brier score; and (iii) Computational efficiency, reported in terms of training time (s), imputation time (s), and peak memory usage (MB). All results are presented as mean ± standard deviation over multiple runs (10) to account for variability. This expanded evaluation framework provides a comprehensive and balanced view of both accuracy and efficiency of imputation methods across a wide range of conditions. The imputation quality results are presented below in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Imputation quality (RMSE, MAE, NRMSE) across UCI horse colic and adult census datasets

On the UCI Horse Colic dataset (≈300 records), MissForest and MICE achieved the best results, while Guided_AE remained competitive, highlighting the strength of ensemble-based approaches in small-sample scenarios. In contrast, on the Adult Census dataset (≈48,000 records), Guided_AE and GAIN clearly outperformed traditional methods, demonstrating the scalability of deep generative models to large and high-dimensional data. Overall, the findings suggest that MissForest is preferable for small datasets, whereas Guided_AE and GAIN provide superior performance on large-scale tabular data. Several evaluation metrics, including MAE, RMSE, and NRMSE, were utilized to ensure a comprehensive assessment of imputation quality. For evaluation, imputed values were compared against ground truth entries that were temporarily masked from the observed data, while truly missing entries were excluded from metric computation.

Fig. 9 displays the classification results obtained after imputation on both the UCI Horse Colic and Adult Census datasets. On the UCI dataset, MissForest and MICE achieved the strongest performance across Accuracy, F1, ROC AUC, and MCC, while also producing the lowest Brier scores, confirming their robustness under small sample conditions. Guided_AE and GAIN performed competitively but were slightly behind, whereas VAE and DAE consistently underperformed. On the Adult Census dataset, however, Guided_AE and GAIN outperformed all other methods, achieving the highest ROC AUC and MCC values with well-calibrated predictions as indicated by low Brier scores. Several complementary metrics were employed, including Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1, ROC AUC, MCC, and Brier, to capture not only discriminative ability but also calibration and robustness; in particular, MCC provides a balanced measure under class imbalance, while the Brier score evaluates the accuracy of probabilistic predictions.

Figure 9: Classification performance after imputation across UCI horse colic and adult census datasets

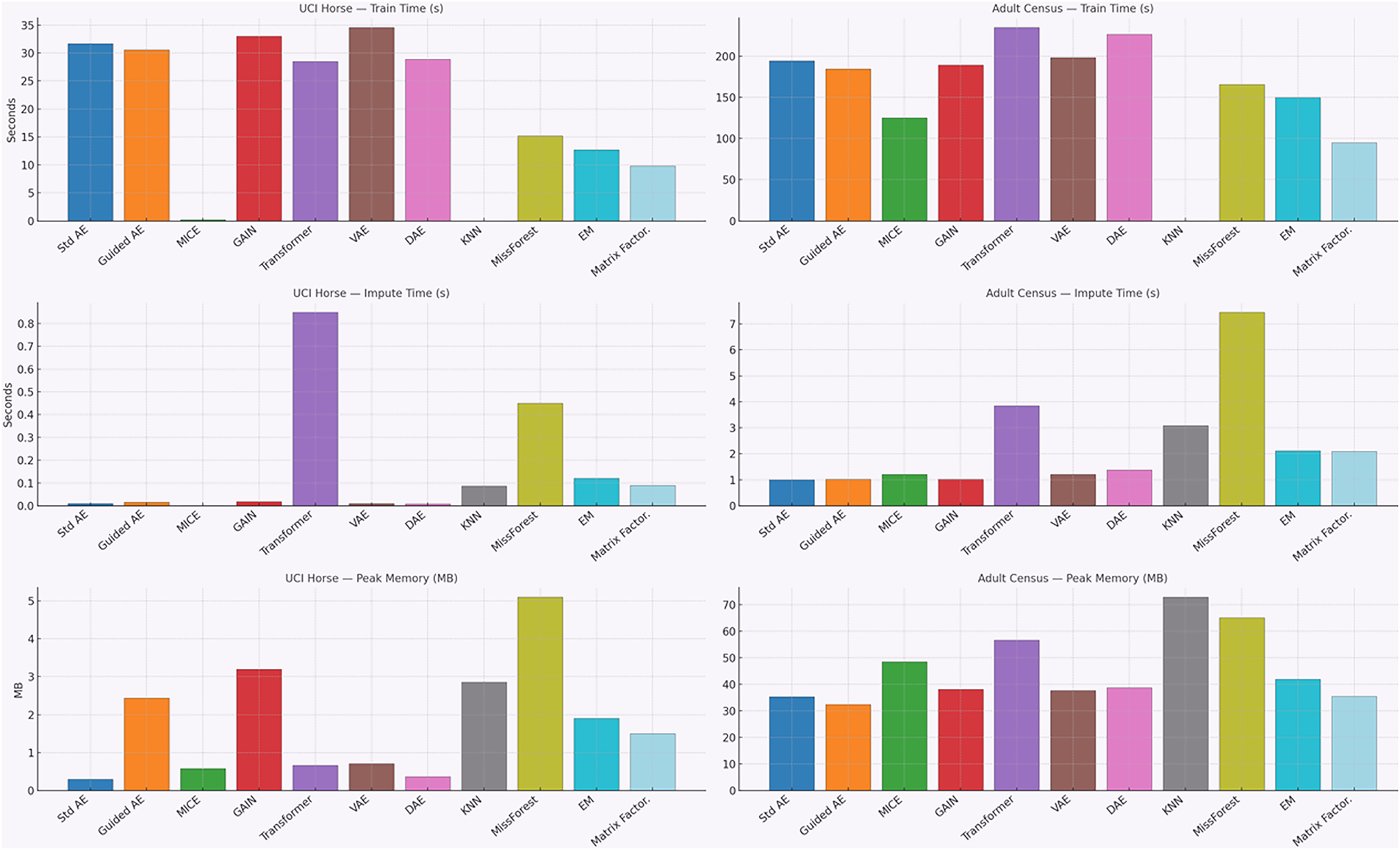

Fig. 10 shows the results of testing our model’s computational efficiency. We measured training time, imputation time, and peak memory. Each metric was averaged over 10 runs with standard deviation.

Figure 10: Computational efficiency of imputation models (training time, imputation time, and peak memory usage)

On the small UCI Horse dataset, classical methods trained the fastest, while deep models took more time. KNN had almost no training cost because it is an instance-based method that does not build a model, but it had slower imputation and higher memory use. On the Adult Census dataset, deep learning models needed much longer training. Imputation time also made the differences clear: MissForest and kNN were the slowest, and the Transformer used a substantial memory resource. In general, Guided_AE showed a balanced performance, with good accuracy, moderate training time, and medium memory usage.

5 Conclusion and Recommendations

A novel deep learning-based architecture, Guided_AE, for missing value imputation in high-dimensional healthcare datasets was presented in this study. A composite loss function was designed, which includes a guided masked mean squared error, a noise-aware regularization term, and a variance penalty. The guided masked mean squared error loss uses a binary mask to target only the missing entries, whereas the noise-aware regularization term enhances robustness by introducing stochastic noise into missing components during training, and the variance penalty term improves expressive reconstructions while suppressing trivial or degenerate outputs. This multi-component loss structure improves generalization across varying data conditions and enables the model to focus learning on the most uncertain parts of the input.

The model was evaluated systematically with varied sample size, feature dimensionality, and missingness ratio (ranging from 5% to 60%) under four representative missing data mechanisms (MCAR, MAR, MNAR, and MNAR_QUANT). Particularly in the MNAR and MNAR_QUANT scenarios, which are the most challenging conditions due to their non-random missingness patterns, the proposed model continuously outperformed baseline autoencoders and achieved competitive or superior performance compared to GAIN.

A downstream classification task involving diabetes diagnosis, cardiovascular risk assessment, Stroke Prediction, and Framingham Heart Study datasets was also conducted in order to assess the practical utility of the imputed data. The proposed model achieved the highest ROC AUC scores across all datasets, demonstrating its ability to preserve class-discriminative structure essential for clinical inference. Furthermore, the results show the generalization potential of the proposed model in terms of robustness and scalability because of that the RMSE performance improves with increasing data.

The results from both ablation studies and benchmarking against traditional and modern imputation algorithms emphasize the effectiveness of the proposed Guided_AE architecture. Notably, the model’s performance remains consistently strong across all forms of missingness, including the more complex MNAR scenarios. Heatmap visualizations and sample-size experiments further confirm that the model not only imputes accurately but also scales well with richer input dimensions and larger datasets. Although mid-sized datasets were used in this study, the model can be applied to larger real-world scale settings according to the trends of observed in the obtained results.

In conclusion, the proposed framework combines architectural innovation with a task-aware loss design to provide a scalable, principled, and high-performing approach to missing data imputation. The incorporation of the hint matrix and the variance penalty into the learning objective yields notable performance gains and enhanced robustness. As a future direction, we recommend extending this framework to handle longitudinal time series and multimodal clinical records, thereby facilitating its integration into practical, decision-support systems in healthcare settings.

Acknowledgement: This study is derived from Thierry Mugenzi’s Ph.D. thesis work at Eskisehir Technical University.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Cahit Perkgoz; methodology, Thierry Mugenzi and Cahit Perkgoz; software, Thierry Mugenzi; validation, Thierry Mugenzi and Cahit Perkgoz; formal analysis, Thierry Mugenzi; investigation, Thierry Mugenzi; resources, Cahit Perkgoz; data curation, Thierry Mugenzi; writing—original draft preparation, Thierry Mugenzi; writing—review and editing, Cahit Perkgoz; visualization, Thierry Mugenzi; supervision, Cahit Perkgoz. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available on Kaggle at: https://www.kaggle.com/fedesoriano/stroke-prediction-dataset (Stroke Prediction Dataset), accessed on 26 March 2025. https://www.kaggle.com/sulianova/cardiovasculardisease-dataset (Cardiovascular Disease Dataset), accessed on 29 March 2025. https://www.kaggle.com/uciml/pima-indians-diabetes-database (Pima Indians Diabetes Dataset), accessed on 11 December 2024. https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/dileep070/heart-disease-prediction-using-logistic-regression (Framingham Heart Study Dataset), accessed on 05 February 2025.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/cmc.2025.070381/s1.

References

1. Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2019. [Google Scholar]

2. Jakobsen JC, Gluud C, Wetterslev J, Winkel P. When and how should multiple imputation be used for handling missing data in randomised clinical trials—a practical guide with flowcharts. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):162. doi:10.1186/s12874-017-0442-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. J R Stat Soc Ser B Stat Methodol. 1977;39(1):1–22. doi:10.1111/j.2517-6161.1977.tb01600.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. Mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Soft. 2011;45(3):1–67. doi:10.18637/jss.v045.i03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Batista GE, Monard MC. A study of K-nearest neighbour as an imputation method. In: Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Health Information Systems; 2020 Oct 20–23; Amsterdam and Leiden, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

6. Arteaga F, Ferrer A. Framework for regression-based missing data imputation methods in on-line MSPC. J Chemom. 2005;19(8):439–47. doi:10.1002/cem.946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Stekhoven DJ, Bühlmann P. MissForest—non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(1):112–8. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btr597. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Mazumder R, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Spectral regularization algorithms for learning large incomplete matrices. J Mach Learn Res. 2010;11:2287–322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

9. Hwang WS, Li S, Kim SW, Lee K. Data imputation using a trust network for recommendation via matrix factorization. Comput Sci Inform Syst. 2018;15(2):347–68. doi:10.2298/csis170820003h. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Śmieja M, Struski Ł, Tabor J, Zieliński B, Spurek P. Processing of missing data by neural networks. In: Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems 31 (NeurIPS 2018); 2018 Dec 3–8; Montreal, QC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

11. Gondara L, Wang K. MIDA: multiple imputation using denoising autoencoders. In: Advances in knowledge discovery and data mining. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2018. p. 260–72. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-93040-4_21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Vincent P, Larochelle H, Bengio Y, Manzagol PA. Extracting and composing robust features with denoising autoencoders. In: Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2008 Jul 5–9; Helsinki, Finland. doi:10.1145/1390156.1390294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Yoon J, Jordon J, Schaar M. Gain: missing data imputation using generative adversarial nets. In: Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2018 Jul 10–15; Stockholm, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

14. Eduardo S, Nazábal A. Robust variational autoencoders for outlier detection and repair of mixed-type data. In: Proceedings of the Twenty Third International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics; 2020 Aug 26–28; Online. [Google Scholar]

15. Lotfipoor A, Patidar S, Jenkins DP. Transformer network for data imputation in electricity demand data. Energy Build. 2023;300:113675. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2023.113675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Waljee AK, Mukherjee A, Singal AG, Zhang Y, Warren J, Balis U, et al. Comparison of imputation methods for missing laboratory data in medicine. BMJ Open. 2013;3(8):e002847. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002847. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Mattei PA, Frellsen J. MIWAE: deep generative modelling and imputation of incomplete data sets. In: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2019 Jun 9–15; Long Beach, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

18. Che Z, Purushotham S, Cho K, Sontag D, Liu Y. Recurrent neural networks for multivariate time series with missing values. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):6085. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-24271-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Mohan K, Pearl J, Tian J. Graphical models for inference with missing data. In: Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems 26 (NIPS 2013); 2013 Dec 5–10; Lake Tahoe, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

20. Ilin A, Raiko T. Practical approaches to principal component analysis in the presence of missing values. J Mach Learn Res. 2010;11:1957–2000. [Google Scholar]

21. Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Wainwright M. Statistical learning with sparsity. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2015. doi:10.1201/b18401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Murthy VSVS, Kumar JNVRS. Missing data imputation: a systematic comparison of traditional, machine learning and deep learning approaches. In: 2025 International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT); 2025 Apr 23–25; Kirtipur, Nepal. doi:10.1109/ICICT64420.2025.11005380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Jerez JM, Molina I, García-Laencina PJ, Alba E, Ribelles N, Martín M, et al. Missing data imputation using statistical and machine learning methods in a real breast cancer problem. Artif Intell Med. 2010;50(2):105–15. doi:10.1016/j.artmed.2010.05.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Farhangfar A, Kurgan L, Dy J. Impact of imputation of missing values on classification error for discrete data. Pattern Recognit. 2008;41(12):3692–705. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2008.05.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Liew AW, Law NF, Yan H. Missing value imputation for gene expression data: computational techniques to recover missing data from available information. Brief Bioinform. 2011;12(5):498–513. doi:10.1093/bib/bbq080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Firdaus F, Islami A, Darmawahyuni A, Sapitri AI, Rachmatullah MN, Tutuko B, et al. A modified deep residual-convolutional neural network for accurate imputation of missing data. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;82(2):3419–41. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.055906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhou Y, Aryal S, Bouadjenek MR. Review for handling missing data with special missing mechanism. arXiv:2404.04905. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2404.04905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Arif Khan F, Herasymuk D, Protsiv N, Stoyanovich J. Still more shades of null: a benchmark for responsible missing value imputation. arXiv: 2409.07510. 2024 doi:10.48550/arXiv.2409.07510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Barrabés M, Perera M, Novelle Moriano V, Giró-I-Nieto X, Mas Montserrat D, Ioannidis AG. Advances in biomedical missing data imputation: a survey. IEEE Access. 2024;13:16918–32. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3516506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Jäger S, Allhorn A, Bießmann F. A benchmark for data imputation methods. Front Big Data. 2021;4:693674. doi:10.3389/fdata.2021.693674. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Xia R, Zhang C, Li A, Liu X, Yang B. Attribute imputation autoencoders for attribute-missing graphs. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;291:111583. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.111583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Xia R, Liu H, Li A, Liu X, Zhang Y, Zhang C, et al. Incomplete graph learning: a comprehensive survey. Neural Netw. 2025;190:107682. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2025.107682. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Somepalli G, Goldblum M, Schwarzschild A, Bruss CB, Goldstein T. Saint: improved neural networks for tabular data via row attention and contrastive pre-training. arXiv:2106.01342. 2021. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2106.01342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Tashiro Y, Song J, Song Y, Ermon S. CSDI: conditional score-based diffusion models for probabilistic time series imputation. In: Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems 34 (NeurIPS 2021); 2021 Dec 6–14; Virtual. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools