Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Multi-Stage Pipeline for Date Fruit Processing: Integrating YOLOv11 Detection, Classification, and Automated Counting

Department of Computer Engineering, College of Computer Sciences and Information Technology, King Faisal University, Al Ahsa, 31982, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Abid Iqbal. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-27. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070410

Received 15 July 2025; Accepted 03 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

In this study, an automated multimodal system for detecting, classifying, and dating fruit was developed using a two-stage YOLOv11 pipeline. In the first stage, the YOLOv11 detection model locates individual date fruits in real time by drawing bounding boxes around them. These bounding boxes are subsequently passed to a YOLOv11 classification model, which analyzes cropped images and assigns class labels. An additional counting module automatically tallies the detected fruits, offering a near-instantaneous estimation of quantity. The experimental results suggest high precision and recall for detection, high classification accuracy (across 15 classes), and near-perfect counting in real time. This paper presents a multi-stage pipeline for date fruit detection, classification, and automated counting, employing YOLOv11-based models to achieve high accuracy while maintaining real-time throughput. The results demonstrated that the detection precision exceeded 90%, the classification accuracy approached 92%, and the counting module correlated closely with the manual tallies. These findings confirm the potential of reducing manual labour and enhancing operational efficiency in post-harvesting processes. Future studies will include dataset expansion, user-centric interfaces, and integration with harvesting robotics.Keywords

The date fruit is a major stakeholder, and its significant role also contributes to the economies of various regions, particularly in places such as the Middle East and North Africa, where it serves as a stable crop and is an essential component of economic and cultural life. Moreover, the ideal hubs for date production significantly contribute to both local consumption and global exports due to their unique climate and soil conditions [1]. The global market demands vary based on population preferences, taste, mood, and cultivation techniques [2,3]. Traditional practices, while reliable for small-scale operations, rely heavily on manual labour and are inherently time-consuming, labour-intensive, and susceptible to errors [4]. Limitations in this domain have become increasingly prevalent in agricultural operations, and even minor defects or issues can cause substantial losses in financial, logistical, and resource terms [5].

In addition, the importance of optimizing the date fruit extraction process, from yield to packaging in the factory, extends the economic benefits. This helps enhance the efficiency of harvesting, packing, and sorting operations in the date fruit agricultural domain. It also contributes to reducing food loss worldwide and improving the sustainability of agrarian processes. Innovative solutions for enhancing agricultural productivity are emerging daily, which is crucial in addressing global challenges related to food security and environmental safety. Thus, modern technology is now recognized as a key intervention for streamlining processes, delivering good economic outcomes, and aligning with global sustainable development objectives in agriculture [6].

In recent years, advances in computer vision and deep learning techniques have opened up transformative possibilities to address challenges in agricultural processes [7]. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have become foundational in image analysis and recognition and have also emerged as cornerstones of farm applications, enabling tasks such as fruit detection, ripeness analysis, fruit assessment, and yield estimation [6,8]. These advancements reflect broader trends of artificial intelligence integration into agriculture, often referred to under the umbrella of “smart farming” [9]. Among object detection algorithms, the You Only Look Once (YOLO) family has gained significant recognition for its computational speed and accuracy. These characteristics are particularly suitable for the field of agricultural environments, where real-time processing and precision are paramount [10]. The latest iterations of YOLO have shown strong performance in detecting small and partially occluded objects, which is common in fields where fruits grow amid dense foliage. Therefore, YOLO is well-suited for dynamic and complex agricultural environments [11]. In the third stage, a counting module is employed to incrementally tally the fruits as they pass through a predefined Region of Interest (ROI) [12].

Although significant progress has been made in fruit detection and classification, a less explored yet equally critical aspect is real-time fruit counting [13]. An automated fruit counting system offers multiple benefits, including improved yield estimation, optimized resource allocation, and the elimination of repetitive tasks that require manual labor [14]. These types of systems should be integrated because they enable farmers and agribusinesses to make decisions based on data rather than intuition, allowing for accurate harvest planning and efficient supply chain management [12]. This study proposes a comprehensive multistage pipeline to enhance the efficiency and accuracy of date fruit processing. The pipeline begins with YOLOv11 detecting the date fruits. YOLOv11, a next-generation object detection algorithm, identifies the fruits and generates cropped bounding boxes as inputs for the next stage. These inputs are passed to a classification model that categorizes the date fruits based on visual features [15,16]. A counting module is employed in the third stage, which tallies the fruits incrementally as they cross the range of interest (ROI). This innovative counting mechanism not only ensures precise and accurate enumeration but also seamlessly integrates the detection and classification tasks by merging all tasks, for example, detection, classification, and counting, into a unified framework, which significantly reduces the manual intervention of labour, minimizes the probability of the error, and helps to enhance the scalability of the modern day field of agriculture. Furthermore, the need for precision and accuracy is something which is required, which is why the unique unified framework plays a vital role in enabling resource optimization and reducing the environmental footprint in farming operations by addressing the challenges of efficiency in sociability in the field of agriculture; the study also showcases the transformative potential of artificial intelligence in improving the shape of future farming and food systems around the globe [17].

Altaheri et al. [18] presented a real-time Date Fruit Classification System for Robotic Harvesting that utilizes VGG-16 and AlexNet architectures to identify date fruits for robotic harvesting. They used more than 8000 pictures in the dataset, along with the numerous groups they divided, which enabled the model to achieve outstanding accuracy and improve throughout training. These writers emphasized the requirement of accurate classification, therefore enhancing the dependability and efficiency of harvesting systems. The overlap between neighbouring maturity stages makes classifying date fruits somewhat challenging. To address these limitations, the authors of this paper suggested that further studies focus on increasing the dataset size using more varied and representative images. Moreover, it was observed that steps towards practical application were improving the model’s robustness to environmental changes and incorporating advanced preprocessing techniques. Using YOLO and EfficientNet models for Date Fruit Classification Based on Surface Quality in 2023, Albarrak et al. [19] published their work in the MDPI journal. This work sought to identify date fruits based on their surface quality using advanced deep learning architectures, including EfficientNet-B0, EfficientNet-B1, YOLOv5n, and YOLOv5m. Each category included 550 samples; hence, the dataset used guaranteed equitable representation of every class. The article emphasized the benefits of combining classification models, which would provide excellent accuracy in surface quality assessments. Still, the somewhat limited sample size—just 55 images per class—restricted the generalisability of the results. This paper proposes extending the dataset and utilizing real-time deployment strategies to validate the model’s effectiveness in real-world conditions, thereby overcoming these challenges and enhancing the model’s performance. Combining different models showed promise in boosting classification accuracy, particularly for uses demanding excellent dependability.

A deep learning model utilizing the MobileNetV2 architecture was employed to classify eight different types of date fruits commonly found in Saudi Arabia [19]. Their model achieved an accuracy of 99% by incorporating advanced preprocessing techniques, including image augmentation, decayed learning rate, model checkpointing, and hybrid weight adjustment. The study highlighted the effectiveness of MobileNetV2 in agricultural applications, outperforming other models, such as AlexNet, VGG16, InceptionV3, and ResNet, in terms of accuracy. ElHelew’s study aimed to classify date fruit quality (accepted or rejected) using machine learning technology to reduce cost, time, and improve the quality of the final product. The study utilized Convolutional Neural Network architectures (Inception-v3, Inception-ResNet-v2, VGG19) to classify three varieties of date fruit (Medjool, Saiedi, El-Wadi) into accepted and rejected samples. The Inception-ResNet-v2 model demonstrated the best performance, achieving an accuracy of 98.99% [20]. Nasiri’s work focused on automating the sorting of date fruits using deep learning techniques. By employing a CNN model, the study achieved an overall classification accuracy of 96.98%, demonstrating the potential of AI in enhancing the efficiency of date fruit sorting processes [21].

Ouhda et al. [22] proposed a clever decision support system for automated date fruit harvesting by 2023. It mixed K-means clustering for ripeness prediction with YOLOv8 for fruit recognition. The study utilized an 8079-photo collection of several Moroccan date variants, taken in a range of environmental settings. The system demonstrated the promise of YOLO-based architectures in precision agriculture, achieving an inference time of 0.015 s and a mean average precision (mAP) of 99.1%. The stability of the system in real-world situations was influenced by environmental factors, such as backdrop complexity and light fluctuations, thereby limiting its usefulness, despite achieving very high accuracy and efficiency. The authors emphasized the need to incorporate real-time capabilities for efficient integration into autonomous harvesting operations and enhance system flexibility to accommodate diverse field situations [22]. In the same year, Nadhif and Dwisnati conducted two similar investigations using deep learning methods to classify different types of dates. The initial attempt classified nine different kinds of date fruit using the MobileNetV2 architecture and CNNs. Comprising 1658 photos, the collection was split into training and testing subsets. With a small sample size, a 96% classification accuracy confirmed CNN-based methods’ potential for agricultural applications. Acknowledging that dataset constraints influence model generalisation [23], the authors proposed further enhancements via data expansion and architectural optimisation. Published under the same title, the authors’ second study built on their prior work by focusing on practical implementation methods for CNN-based classification systems. The paper utilized the same dataset and basic approach to enhance model performance by employing expanded assessment metrics and refined training procedures. Taken together, these studies demonstrated the potential of deep learning models for practical applications. They recommended further inquiry into multi-stage classification pipelines, real-time deployment, and integration with automated data processing systems [23].

Despite considerable progress in deep learning and computer vision for agricultural applications, fundamental deficiencies remain in the automation of date fruit processing. Most current research primarily focuses on discrete tasks, such as detection or classification, with little emphasis on cohesive, multi-stage systems that concurrently execute detection, classification, and real-time counting—an essential need for effective post-harvest automation. Moreover, existing techniques often encounter difficulties in challenging situations, such as obscured or overlapping fruits, significant lighting fluctuations, and congested backdrops, which are prevalent in real-world agricultural environments. Although several studies have demonstrated great accuracy with models like YOLOv5 and EfficientNet, they often rely on restricted or uniform datasets, which limit their applicability to varied orchard settings. The use of complex object identification models, such as YOLOv11, is mainly studied in the realm of date fruit processing, particularly in situations requiring high throughput and accuracy. There is a deficiency in domain adaptation techniques to guarantee model resilience across various geographic and climatic locations. Ultimately, real-time deployment options, such as mobile-compatible interfaces or interaction with mechanical harvesting systems, are hardly discussed, despite their significance in expanding smart agricultural technology. This work aims to address these gaps by presenting a comprehensive, real-time, and scalable pipeline that enhances the efficiency and accuracy of post-harvest fruit processing.

This study proposes an end-to-end framework for the automated identification, categorization, and counting of date fruits, encompassing model deployment, post-processing, and final integration. The approach was designed to guarantee scalability, precision, and real-time use in reasonable agricultural environments.

3.1 Image Acquisition and Pre-Capture Setup

The dataset used in this study was compiled from publicly available sources, primarily YouTube videos of real-world factory processing lines, rather than being captured using custom hardware. These videos inherently presented a wide range of practical complexities, such as varied lighting, conveyor motion, and fruit clustering. Roboflow’s built-in video frame extraction utility was employed to systematically extract frames at fixed intervals, ensuring consistent and representative coverage across the footage. During the annotation process, several key characteristics were emphasized:

Occlusion: Many frames included partially hidden or overlapping fruits, which were intentionally retained and labeled following robust annotation guidelines to reflect practical operational scenarios.

Orientation: Fruits appeared at various angles (top-down, side, oblique), as expected in conveyor-based imagery. These naturally occurring orientations enabled the model to generalize more effectively across real-world viewpoints.

Clustering: Scenes often contained large groups of date fruits in proximity, replicating post-harvest and packaging conditions. These complex cases were labelled comprehensively to train the model on non-trivial layouts.

Annotation Practice: Using Roboflow’s annotation interface, all visible instances of the class’ date’ were manually labelled, regardless of variety. The labelling process adhered to best practices, ensuring consistency and high-quality bounding boxes across occluded, rotated, or clustered fruit instances.

This strategy enabled us to create a detection dataset that closely mimics production-level complexity without requiring manual data capture, while maintaining strong annotation integrity.

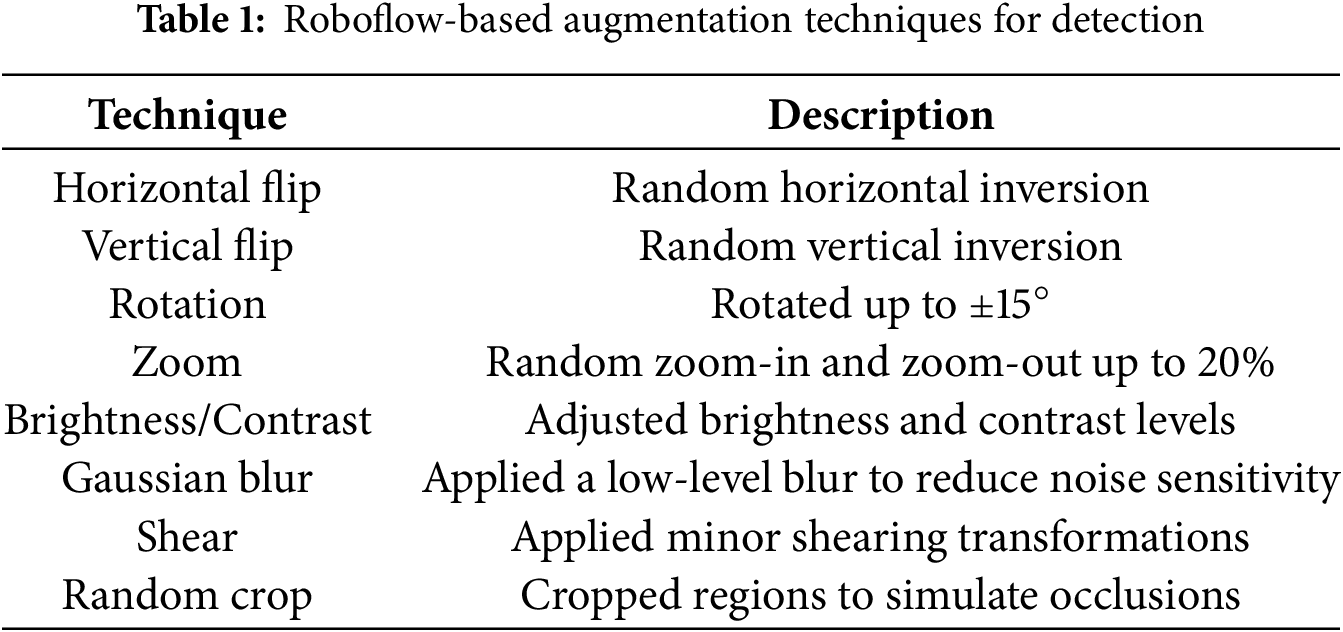

A comprehensive dataset of date fruit images and video frames was collected from available online platforms, including YouTube and Google Images. YouTube videos captured harvesting scenarios under varying illumination conditions, camera perspectives, and orchard arrangements. Frames were systematically extracted at fixed intervals using the Roboflow platform, ensuring coverage of diverse poses, occlusions, and seasonal interactions such as winter fruiting. Google Images contributed further variability by providing examples across a wide range of varieties and ripeness stages. In this segment, the objective was to detect the presence and location of date fruits within each image, while the Classification model determines the specific class. Therefore, all instances of dates were labeled using a single class tag, ‘date’, rather than distinguishing between types. This simplification is crucial in the detection phase, allowing for a pure focus on object localization under diverse environmental conditions. The detection dataset was uploaded and processed in Roboflow. All images were manually labeled with a single class name and date to mark the location of the fruit, without considering its variety. This was done on purpose to keep detection separate from classification and make the system more reliable in complex visual conditions. Roboflow was used to standardize image resolution, apply dataset augmentation, and export the annotated dataset in YOLOv11-compatible format. Table 1 outlines the exact configuration settings used within Roboflow during dataset preparation.

In total, 3227 images were collected and manually labelled for the detection model. These images were processed using the Roboflow augmentation engine to enhance robustness and generalizability. Table 2 summarises the augmentation techniques applied.

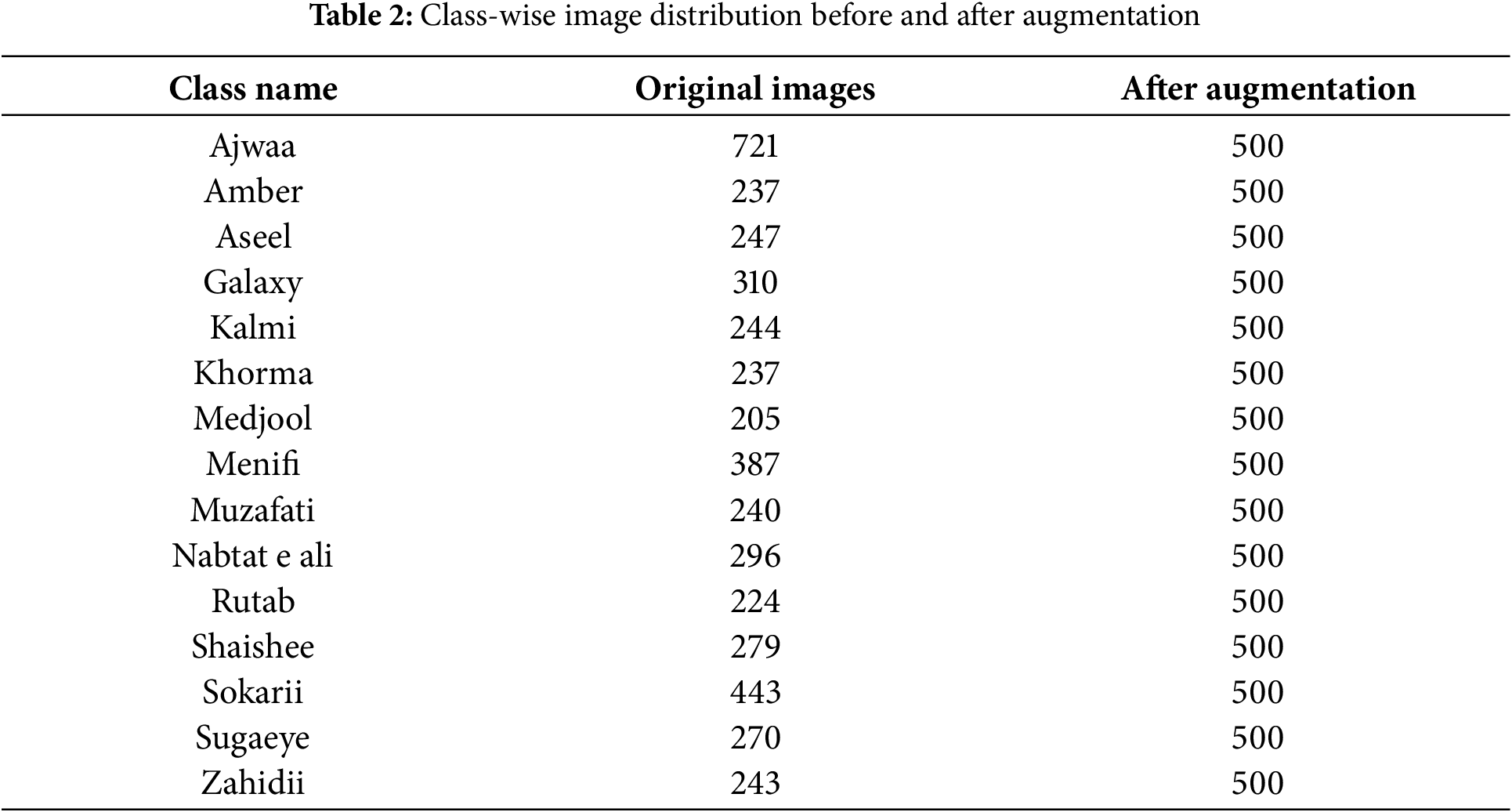

After the detection stage, where date fruits were marked with bounding boxes, the next step was to classify each fruit into one of 15 known varieties. The cropped bounding box areas were used as input for the classification model. Since the number of original samples for each class varied significantly, as shown in Table 2, the dataset was balanced to minimize bias during training. This was done by augmenting the data so that each class had exactly 500 images.

Python-based libraries such as ImageDataGenerator and Albumentations were employed to generate these additional samples. The augmentation strategies included random horizontal and vertical flips, brightness and contrast adjustments, affine transformations, colour jitter, and minor rotations. These transformations ensured that the classifier could generalize well across diverse fruit appearances, camera angles, and lighting conditions while maintaining equal representation for all classes.

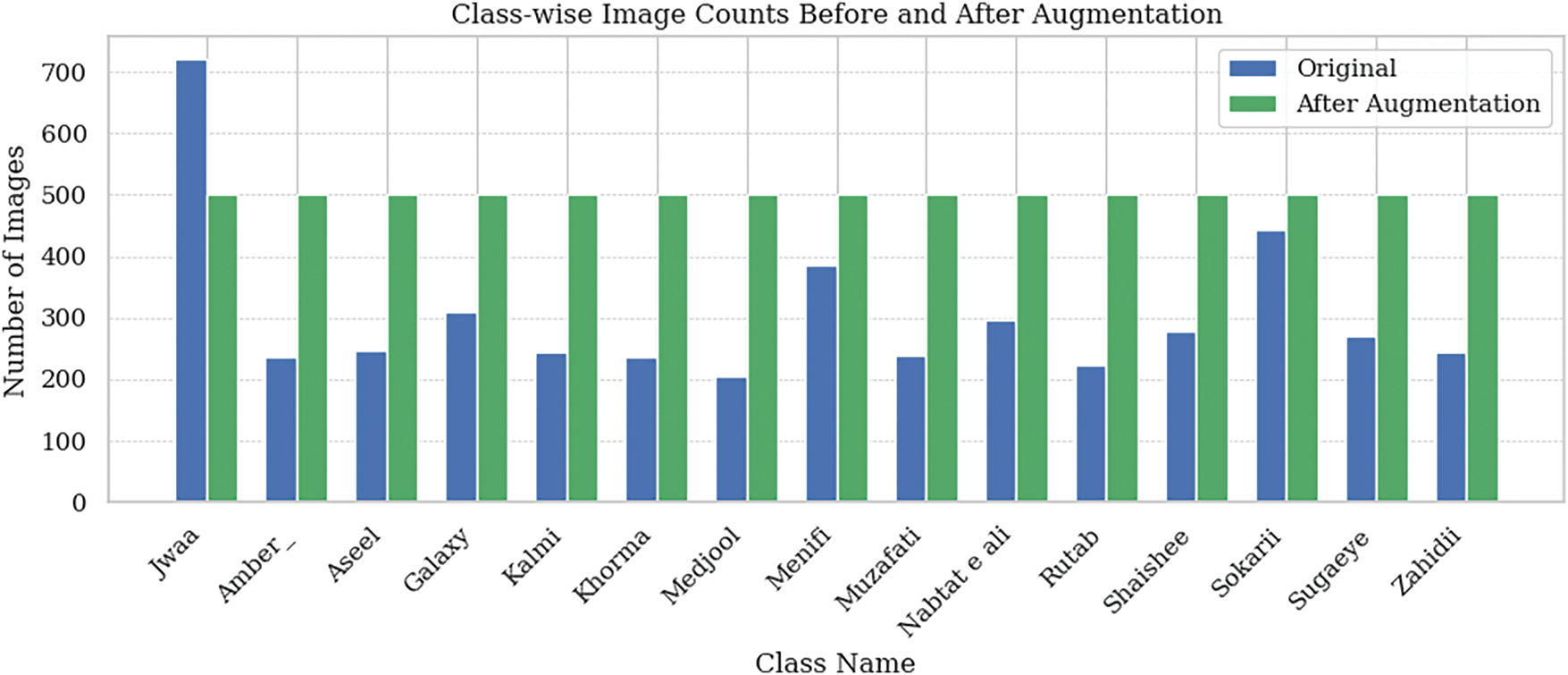

As shown in Fig. 1, the original dataset exhibits class imbalance, with certain classes, such as Ajwaa, having significantly more images than others, like Medjool or Khorma. To address this, data augmentation techniques were applied to underrepresented classes, resulting in a balanced dataset of 500 images per class.

Figure 1: Class-wise image counts before and after data augmentation for each date fruit class

Before training, every image underwent a well-regulated preprocessing chain. Assignment of boundary boxes and class labels matching fruit kind and ripeness degree generated hand comments. Several data augmentation techniques were employed to enhance generalizability and performance across various agricultural environments. These included adjusting brightness to reflect multiple lighting conditions, scaling and cropping to standardize item size, adding synthetic noise to simulate real-world faults, and introducing random rotations to evaluate numerous orientations. This augmentation method enhanced the model’s generalizability by reducing overfitting and increasing its sensitivity to visual fluctuations, leading to improved performance in real-world, dynamic field conditions.

In the initial phase of the proposed system, a single-class object identification module built on the YOLOv11 architecture searches and recognizes date fruits in every input frame. When the model detects a fruit, it generally labels it, assigns a confidence score, and creates bounding boxes around it. Due to its impressive speed-accuracy ratio and ability to detect small objects in a range of lighting and background conditions—qualities essential for practical use in real-world agricultural environments—YOLOv11 was selected [24].

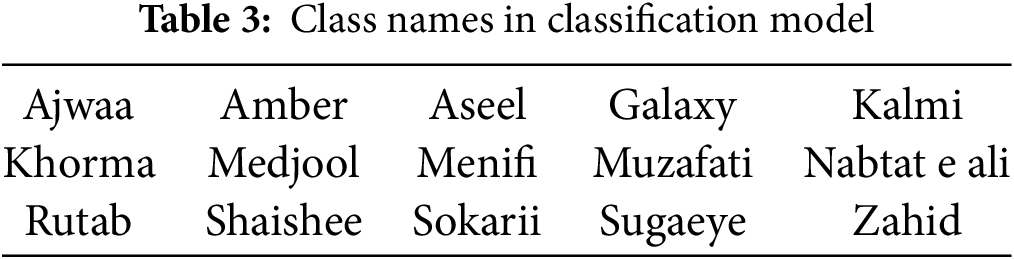

The cropped frames extracted by the Detection model, sent as bounding boxes, are then classified by the YOLOv11-based Classifier, YOLOv11-CLS. This algorithm classifies dates into the various 15 classes based on the features shown in Table 3. The unified framework, which consists of the multimodal model approach, ensures accurate detection and fine-grained classification by leveraging the YOLOv11’s advanced and enhanced capabilities for small object detection and recognition; the system has improved precision and recall and also showcased the robust performance in challenging the real-life scenarios such as detecting the overlapped date fruits and occluded objects, YOLOv11’s optimized architecture is known for the lightweight and real-time processing further enhanced its suitability for high-density environments and also enables its suitability for the right density environments and enables the efficient handling of complex datasets, this integration allows us to works tirelessly and reduce the computational over- head and also maintain the high accuracy and making it a reliable solution for the actual world application in the agricultural and beyond [25].

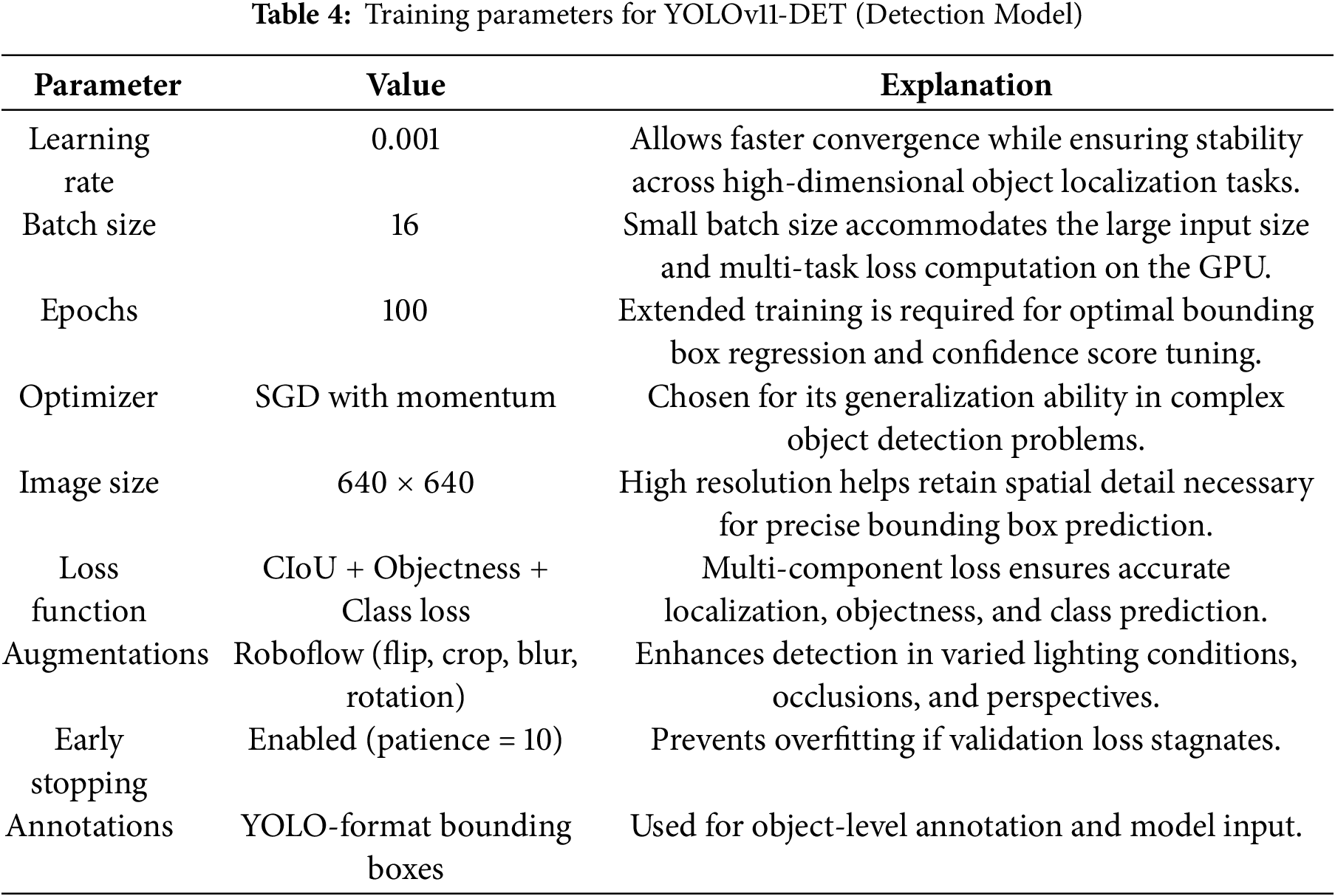

4.1 YOLOv11-DET: Detection Model Training Configuration

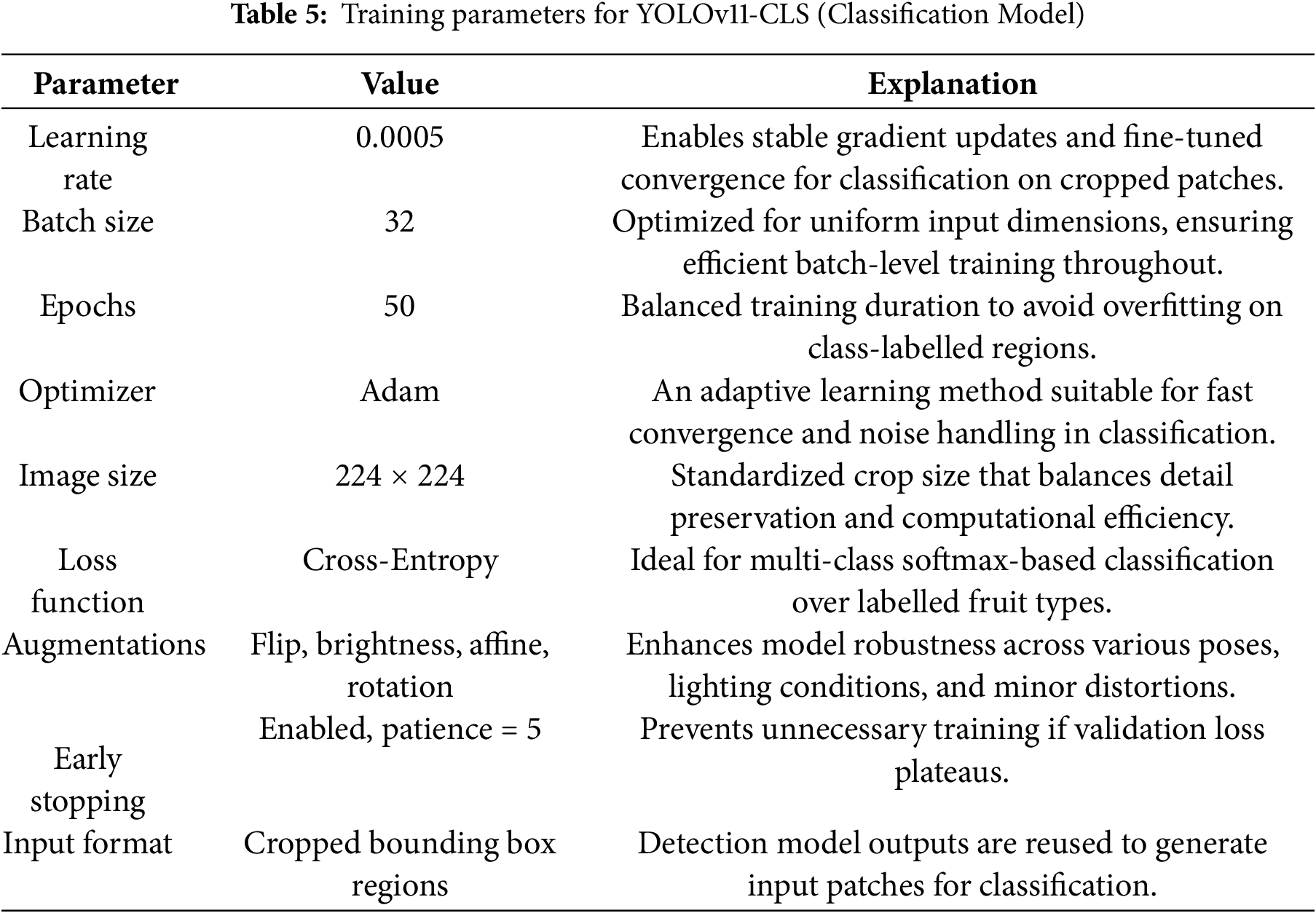

Two versions of the YOLOv11 model were trained separately for object detection and classification. Both use the same base architecture, but their training settings were adjusted to match the specific needs of each task. Table 4 outlines the parameters for the detection model, which is YOLOv11n, whereas Table 5 presents the training setup for the classification model YOLOv11n-CLS.

4.2 YOLOv11-CLS: Classification Model Training Configuration

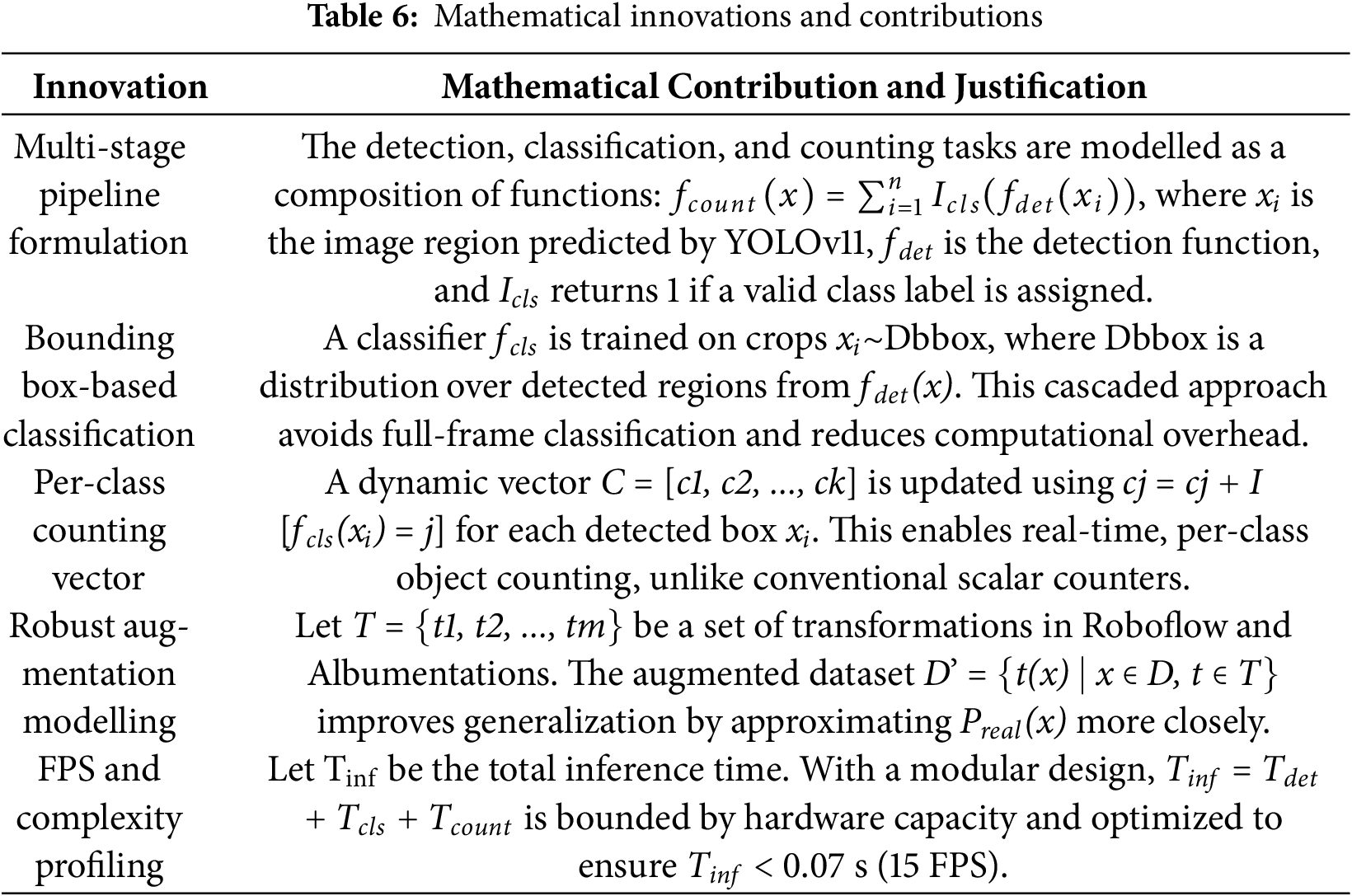

Our proposed system, as shown in Table 6, introduces mathematical rigor in linking the three submodules—detection, classification, and counting—into a cohesive, end-to-end differentiable pipeline. The detection module outputs bounding boxes, which are directly used to crop image patches for classification. Each classified patch updates a counter for its specific class in real time and unlike traditional object counters that only give a total number our system keeps a list of counts for each class so it can track inventory in detail and our augmentation method uses a planned set of image changes to make the data more like real-world conditions and for performance we measure the time each part of the system takes and make sure the whole pipeline runs within a set time limit while keeping a speed that works for real-time factory use These mathematical formulations collectively make the system more explainable, modular and generalizable, especially when adapted to new operational conditions.

4.3 Post-Processing and Counting

After the classification and the detection, there comes a specialized counting module, which is implemented to track and enumerate the detected fruits; this module employs a line-based tally mechanism and increases the counter whenever the bounding box crosses a predefined line or region of interest; the approach is effectively mitigated error in counting the overlapping fruits and also ensured to count accurately and reliability, the counting process seamlessly integrated the output of the detection and the classification as well, providing the finals results that included the bounding box for the detected fruits and acceptable grained class labels indicating the variety and ripeness and real-time cumulative counts displayed on the user’s interface for efficient monitoring and management.

All the models were trained on the Kaggle platform, utilizing CUDA for efficient parallelization. Extensive hyperparameter tuning was performed to optimize the key parameters, including learning rates for faster convergence, batch sizes to handle large datasets efficiently, and early stopping criteria to prevent overfitting. The validation sets are also applied to the unseen data to monitor the model’s performance and ensure that the models achieve high accuracy while maintaining the ability to generalize.

The pipeline implementation began with annotating the dataset using Roboflow to create a perfect dataset for training. The YOLOv11 detection model was trained using these annotations to achieve reliable fruit identification. The resulting bounding boxes were cropped and compiled into a secondary dataset that was subsequently used to train the YOLOv11-CLS classifier. The first step was to train both models on different datasets. This is because the detection model requires bounding box labeling and the classification model requires folder structure labeling after the model’s training stages; the models were integrated into a unified system where they work in a pipeline and after the pipeline was ready, then the it was tested on a video collected from the industry of the date fruit which evaluated the performance of the model as the pipeline and confirmed the accuracy and adaptability across various scenarios.

4.6 System Architecture and Module Interconnection

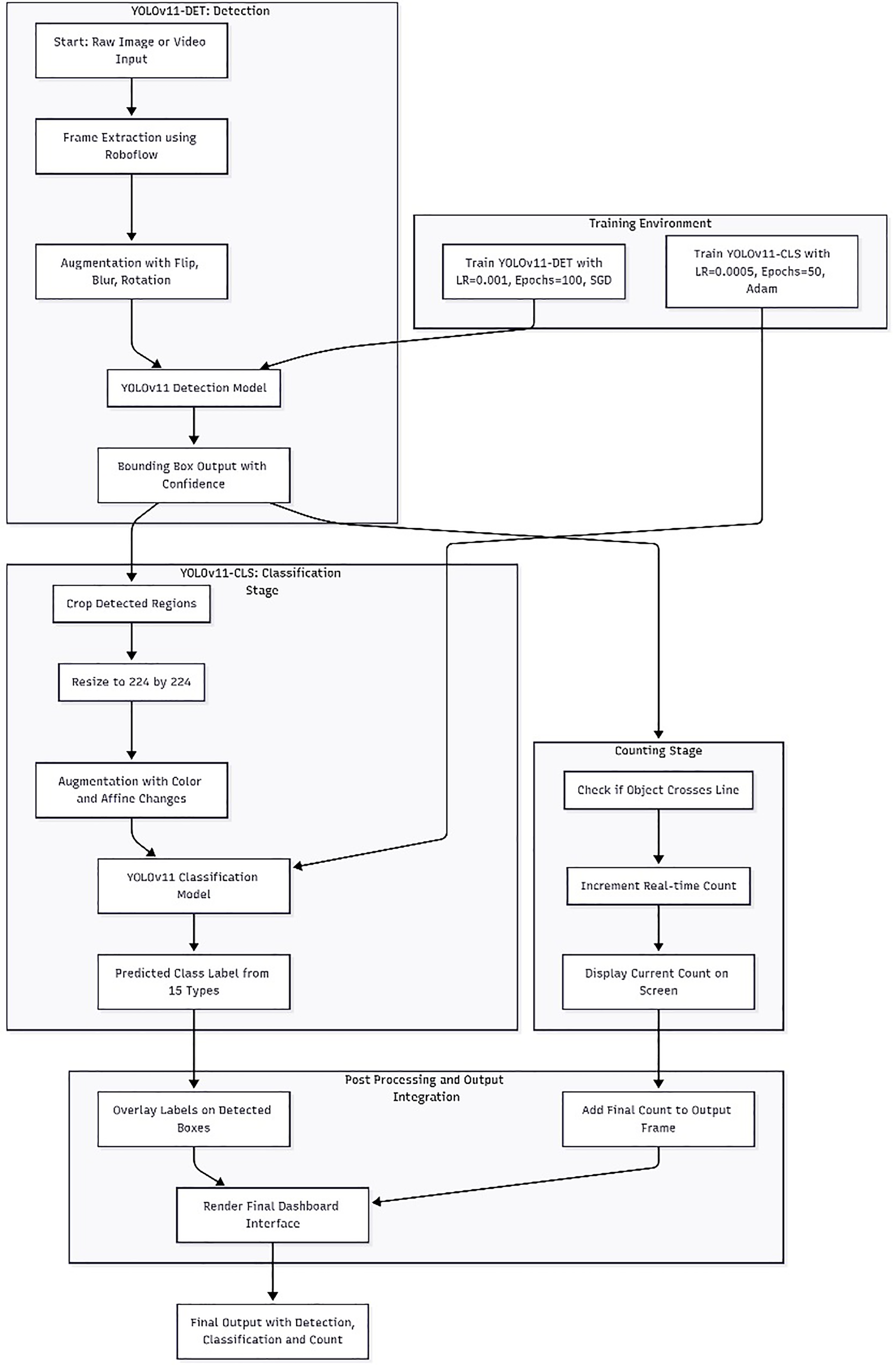

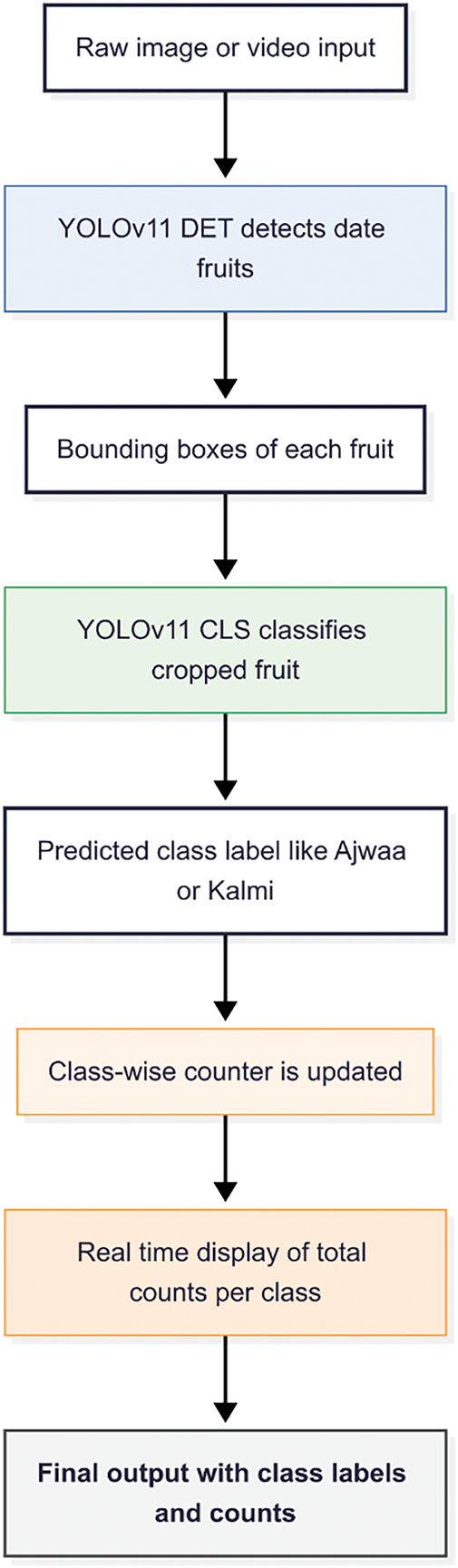

Fig. 2 shows the complete pipeline, starting from raw image or video input, where the YOLOv11 model first processes it to find all visible date fruits and draw bounding boxes around each one. These boxes are then passed to the YOLOv11-CLS model, which classifies each fruit into one of 15 predefined varieties after resizing and augmentation are applied. Simultaneously, a line-based counting module monitors the movement of each fruit and updates a class-wise tally in real-time. Finally, results are overlaid on a dashboard interface, which shows bounding boxes, predicted class labels, and cumulative counts.

Figure 2: End-to-end pipeline for date fruit processing, including detection, classification and counting modules

As seen in Fig. 3, the workflow is tightly integrated. Detection using YOLOv11-DET triggers the downstream processes. Each detected bounding box is cropped and passed into YOLOv11-CLS for class assignment. The predicted class is then sent to the counting module, which updates the appropriate counter based on object tracking and spatial line-crossing logic. This integration ensures the system provides accurate classification results and counts in real-time, allowing the modules to work together smoothly. The output is easy to understand and efficient to use.

Figure 3: Sequential relationship between detection, classification, and counting modules

5.1 YOLOv11 Comparison with Previous YOLO Models

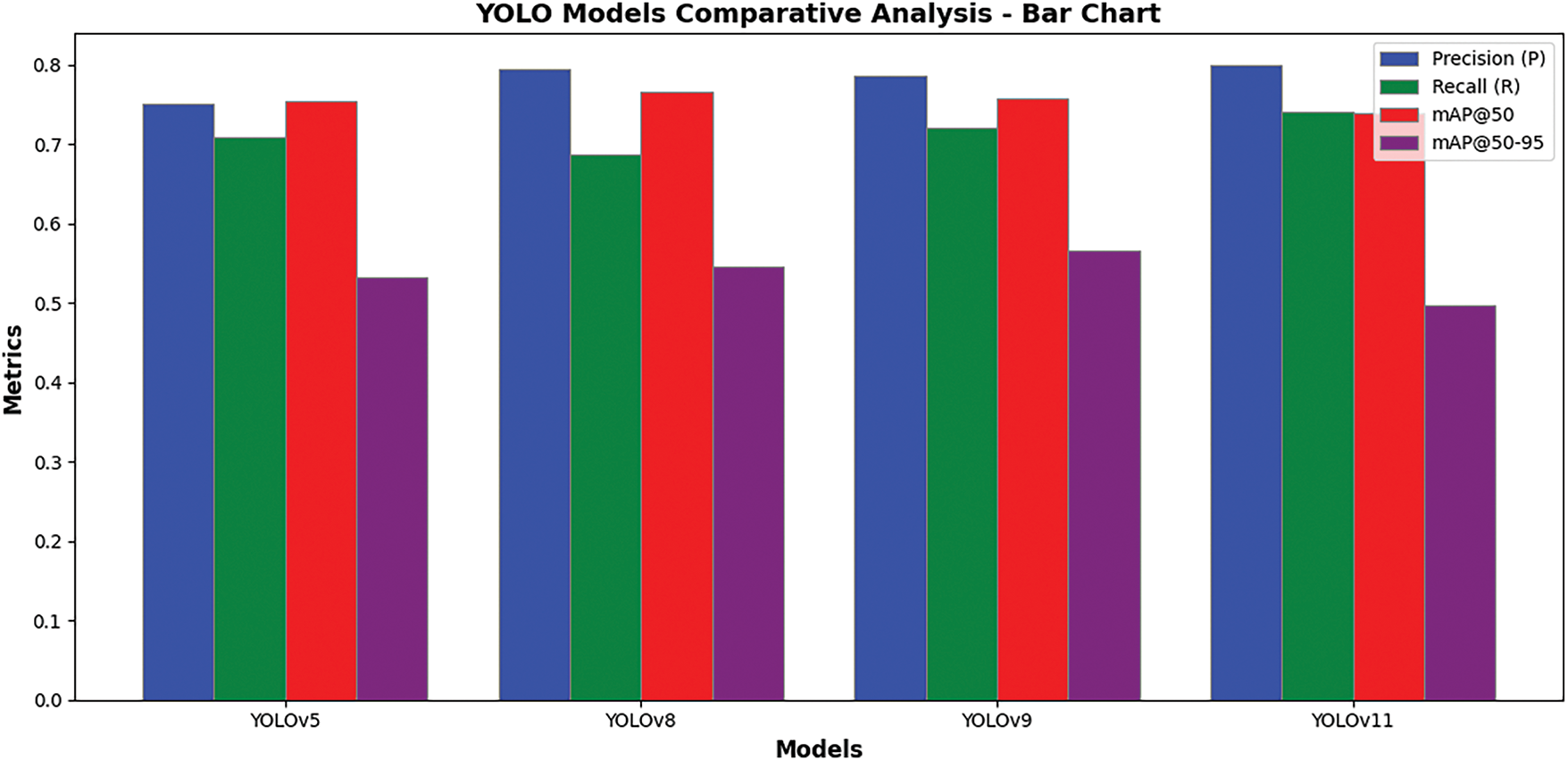

Designing the automatic date fruit processing system relied heavily on selecting the most effective detection model. Four state-of-the-art object recognition architectures—YOLOv5, YOLOv8, YOLOv9, and the most recent YOLOv11—were thoroughly compared to ensure excellent performance and reliability. With an eye toward real-world situations, such as orchard environments and conveyor-based processing systems, the assessment was based on fundamental performance metrics, including Precision, Recall, Mean Average Precision (mAP), and computing efficiency. Although YOLOv5 and YOLOv8 produced good and balanced results—offering a noteworthy trade-off between accuracy and inference speed—their general-purpose nature made them adequate but not outstanding for the complicated circumstances of agricultural jobs. Despite adding architectural improvements, YOLOv9 proved unable to recognize tiny objects and manage partial occlusions, which are common in tightly packed fruit configurations. These difficulties compromised its consistency in aesthetically demanding settings. By comparison, YOLOv11 showed better performance on all assessment criteria. It retained real-time inference skills without compromising accuracy, routinely displayed great precision and recall, and excelled at spotting tiny and partly veiled fruits. These benefits validated YOLOv11 as the most robust and suitable model for integration into the planned multimodal pipeline, thereby addressing the specific needs of high-density, real-time fruit processing.

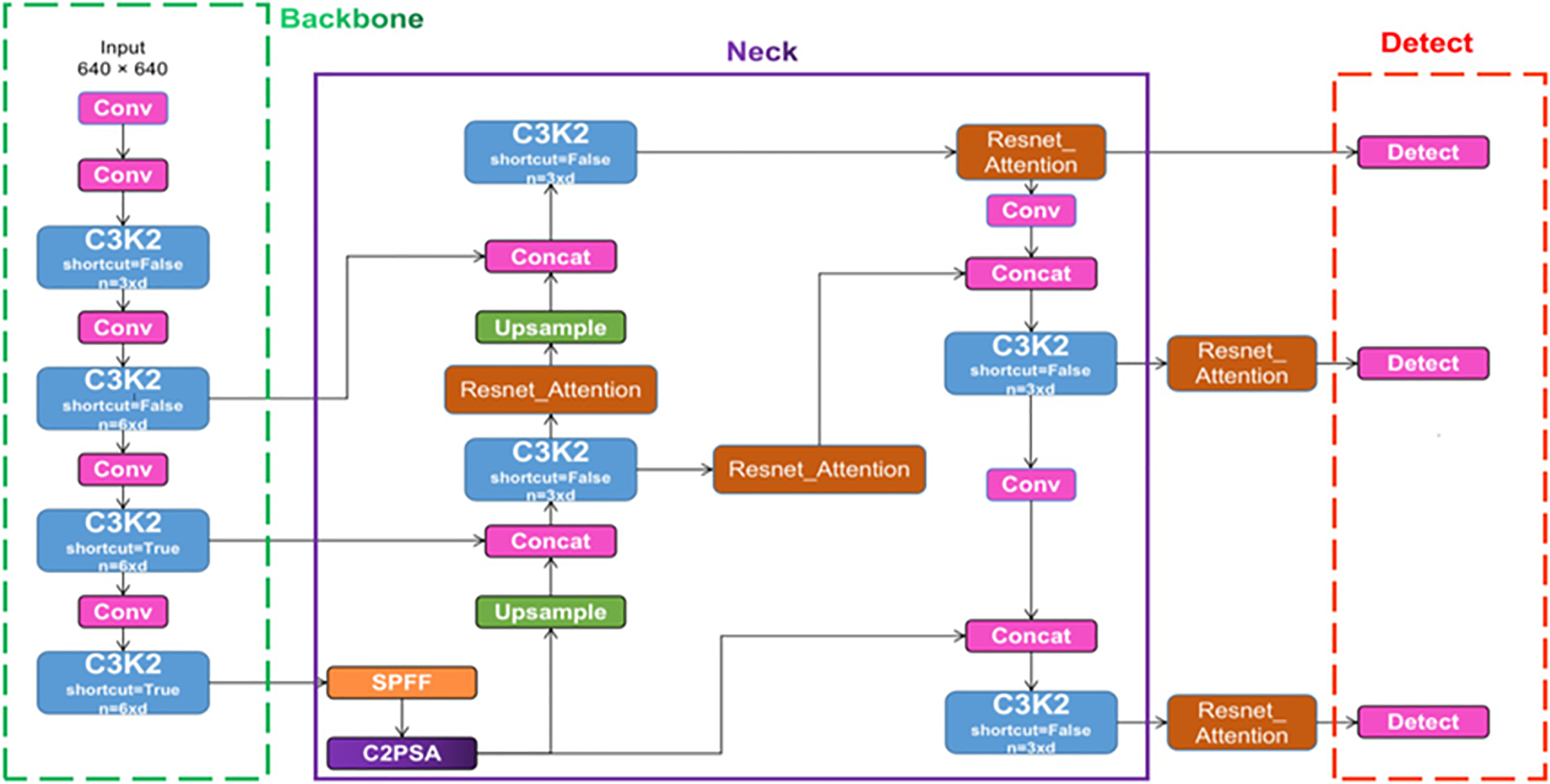

Based on essential performance measures, including precision, recall, mean Average Precision (mAP), and mAP@0.5, Fig. 4 presents a comparison of four advanced YOLO architectures: YOLOv5, YOLOv8, YOLOv9, and YOLOv11. The following bar chart makes a simple comparison abundantly evident: YOLOv11 outperforms its rivals across all assessed criteria. Underlining its resilience in challenging detection circumstances, including occlusions, tiny objects, and densely packed instances, YOLOv11 notably obtains the best accuracy and mAP values. A second line graph shows the performance evolution among models; YOLOv11 shows steady gains over previous iterations. Although YOLOv5 and YOLOv8 provide balanced performance, and YOLOv9 brings structural advancements, all three fall short in key areas, such as fine-scale object detection and efficient real-time inference capabilities, which are fundamental for automated agricultural systems. These relative analyses support the choice of YOLOv11 as the best-suited detection system for the intended use. These results confirmed that YOLOv11 is the optimal model for accurate and efficient detection. Therefore, the pipeline employed two distinct YOLOv11 models to handle detection and classification tasks effectively. The architecture of YOLOv11, as shown in Fig. 5, highlights its backbone, neck, and head components, which are optimized for small-object detection and real-time inference. Leveraging the architectural innovations of the model, the developed pipeline integrates two specialised YOLOv11 modules—one dedicated to object detection and the other to fine-grained classification—delivering high-precision, real-time results within the dynamic and highly populated environments of post-harvest fruit processing facilities.

Figure 4: Comparison of various YOLO models

Figure 5: YOLOv11 Architecture highlighting the backbone, neck, and head components

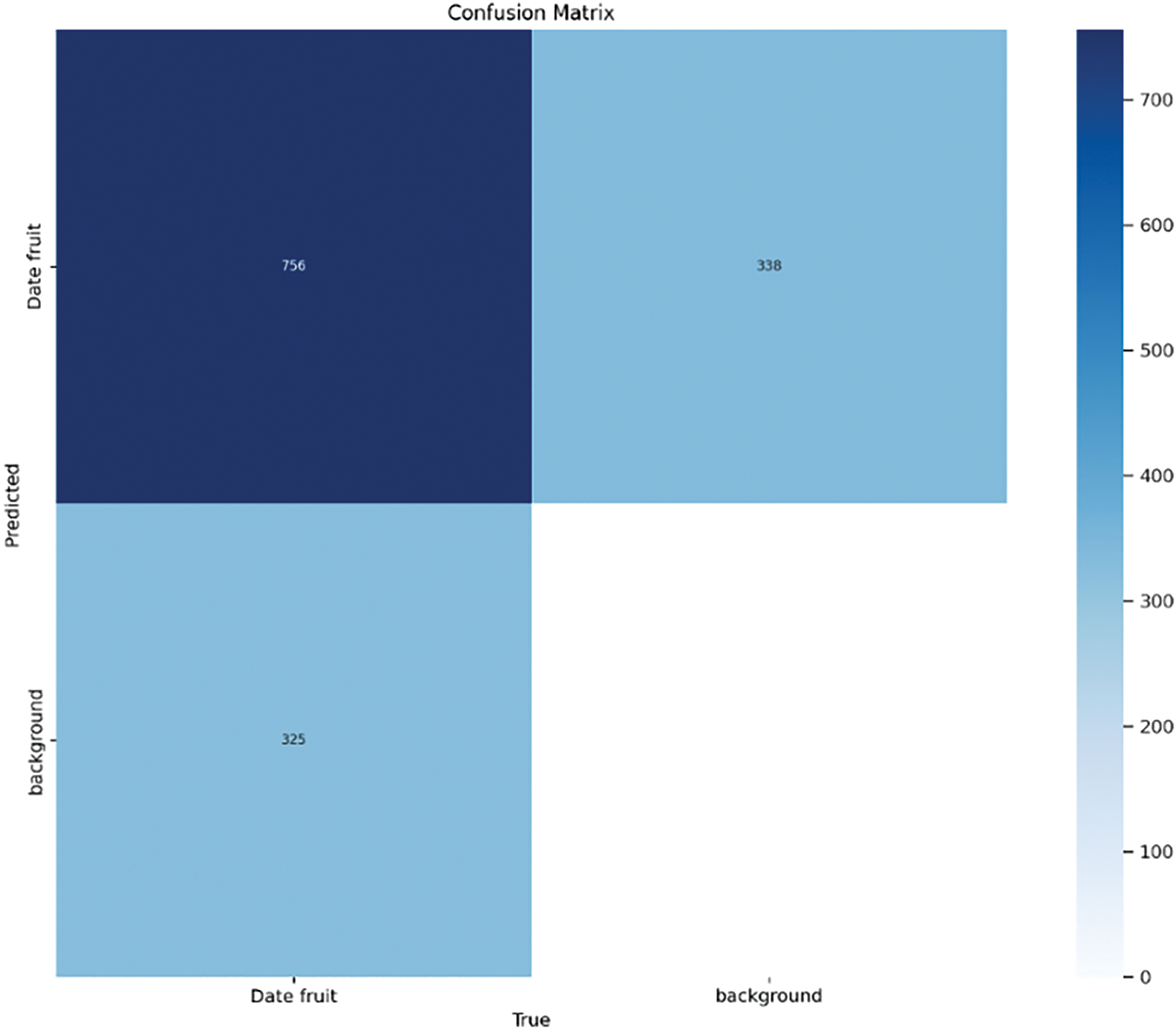

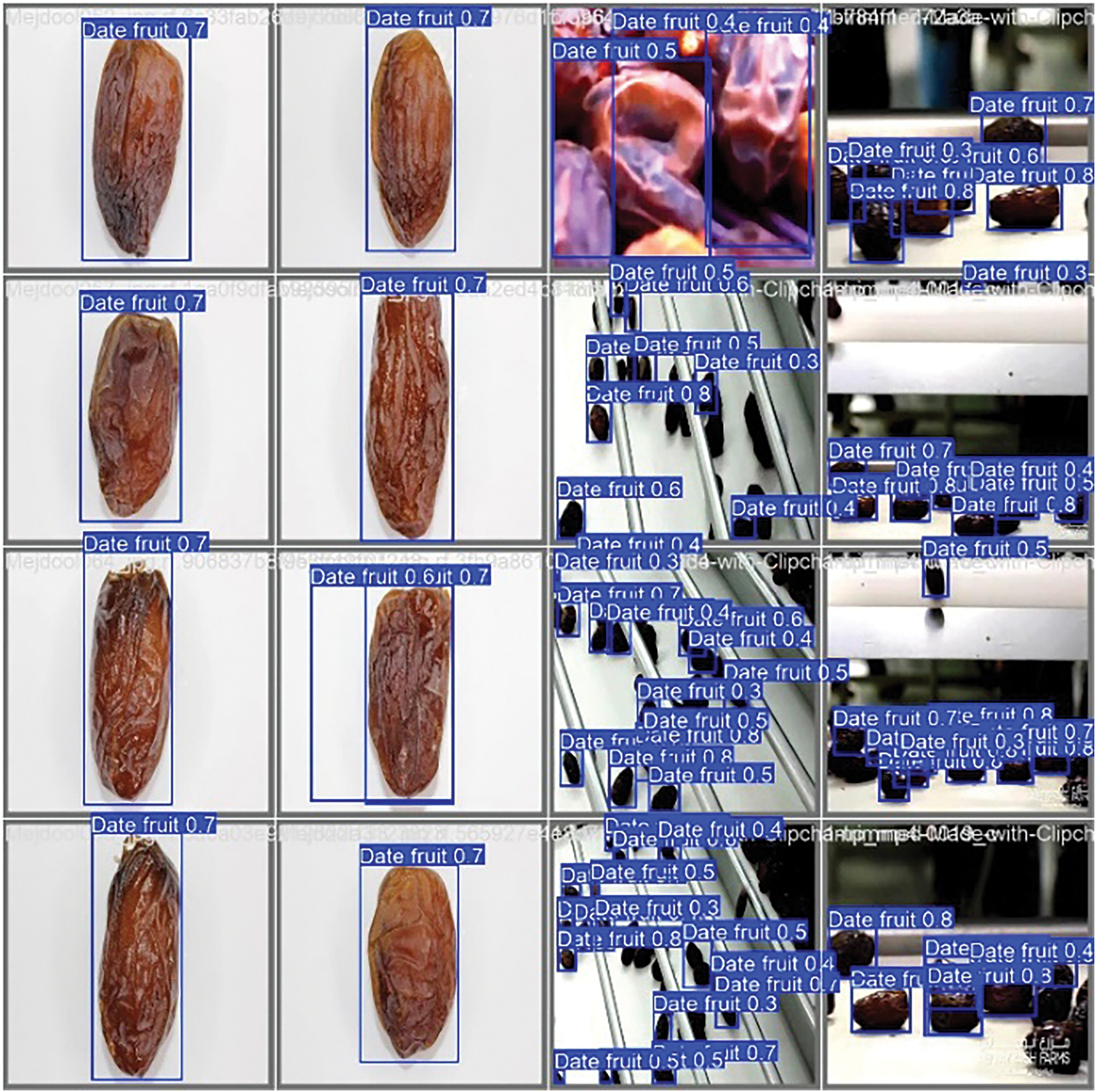

Reflecting its high accuracy in precisely detecting real positives while minimizing false detections, the YOLOv11-based detection model demonstrated excellent and consistent performance, with a precision exceeding 90% and a recall of 88%. These findings highlight how well the algorithm detects date fruits throughout a spectrum of intricate and changing visual situations. Figs. 6–13 indicate that the detection system regularly found and localized date fruits under various lighting conditions and within visually complex or crowded backdrops, thereby confirming its resilience in real-world agricultural settings. Furthermore, the confusion matrix for the detection test showed a significant number of false positives, suggesting a poor inclination of the model to misclassify non-date items as date fruits. This degree of precision substantially enhances the reliability of the overall automated processing system and supports the model’s extensive generalizing capability.

Figure 6: Confusion matrix for date detection

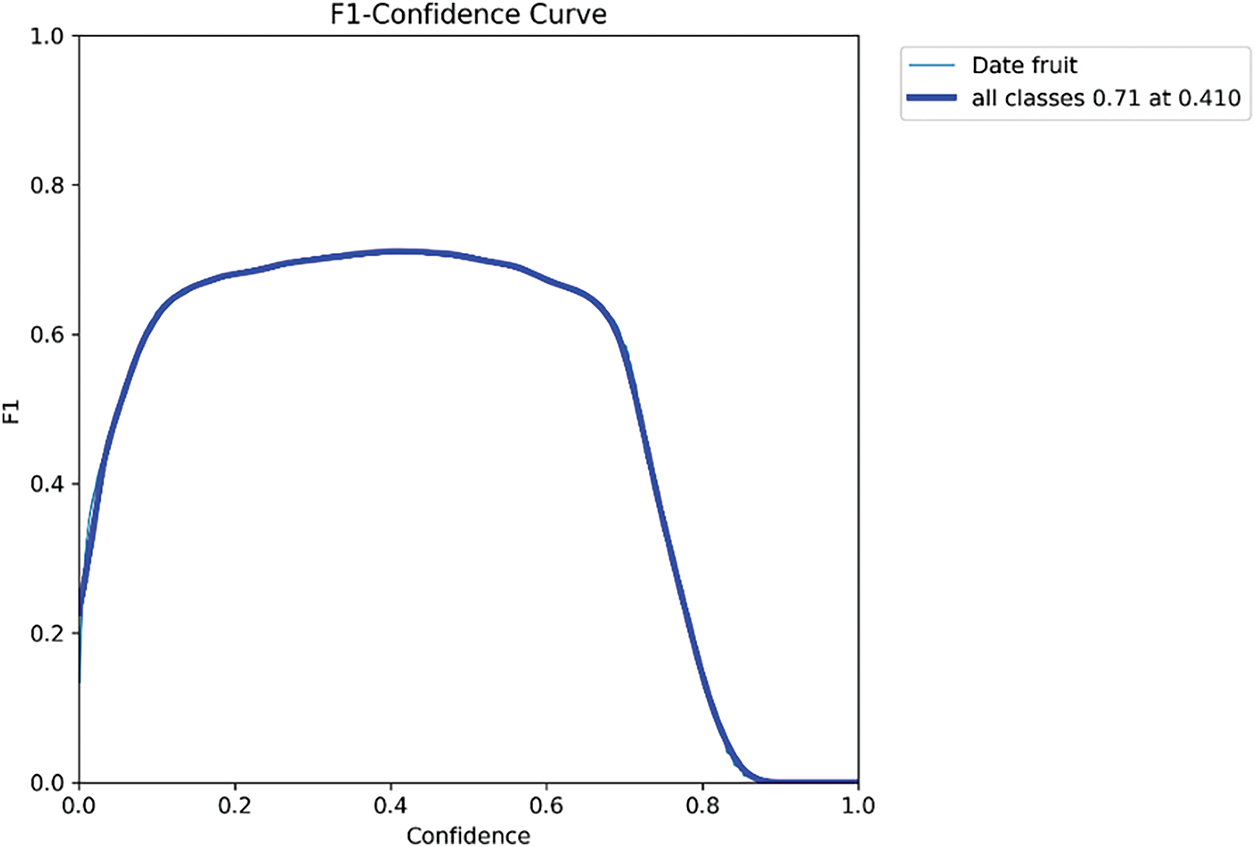

Figure 7: F1 Curve for date detection performance

Figure 8: Precision curve date detection performance

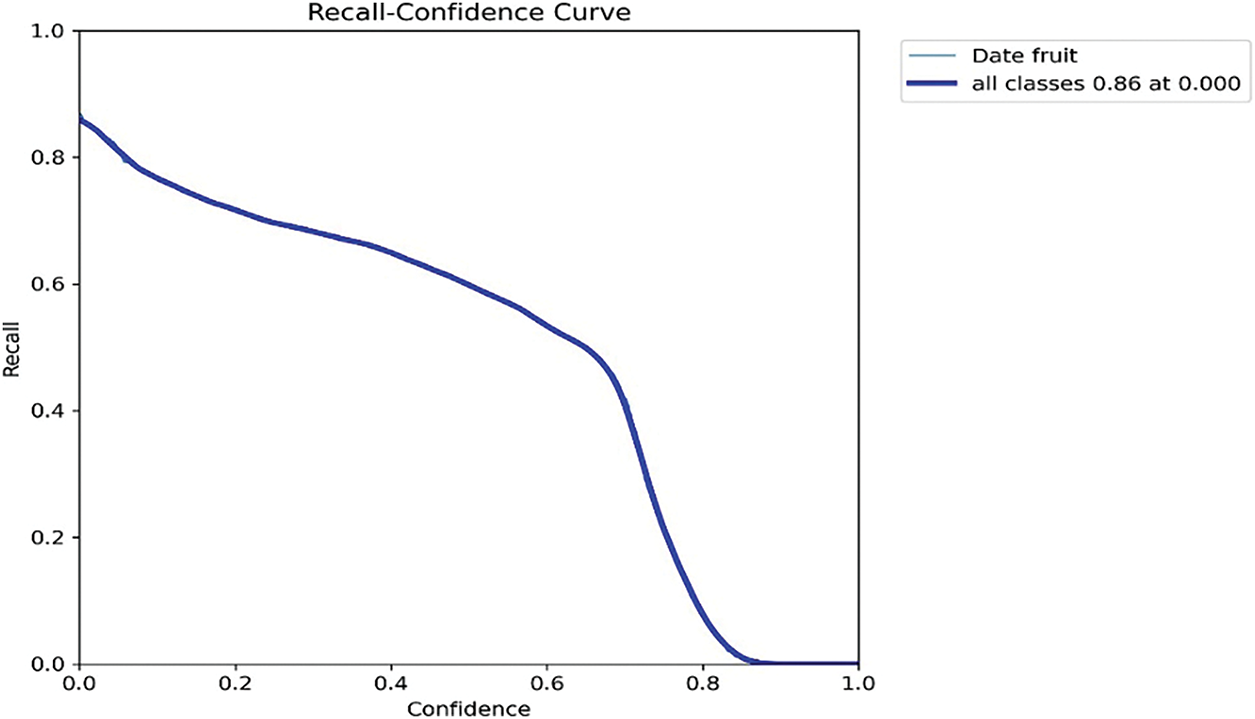

Figure 9: Recall curve for date detection performance

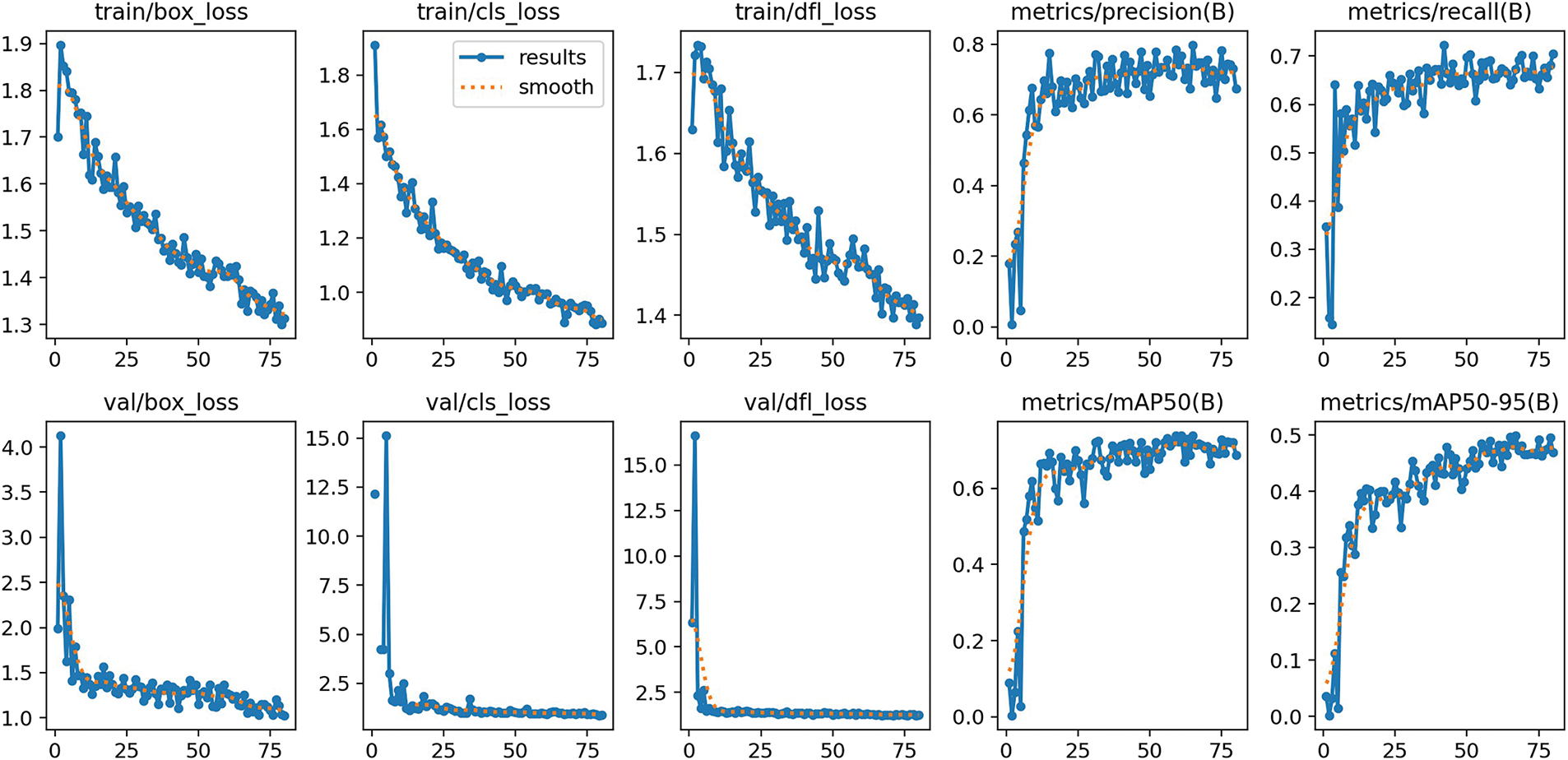

Figure 10: Results of the date detection model

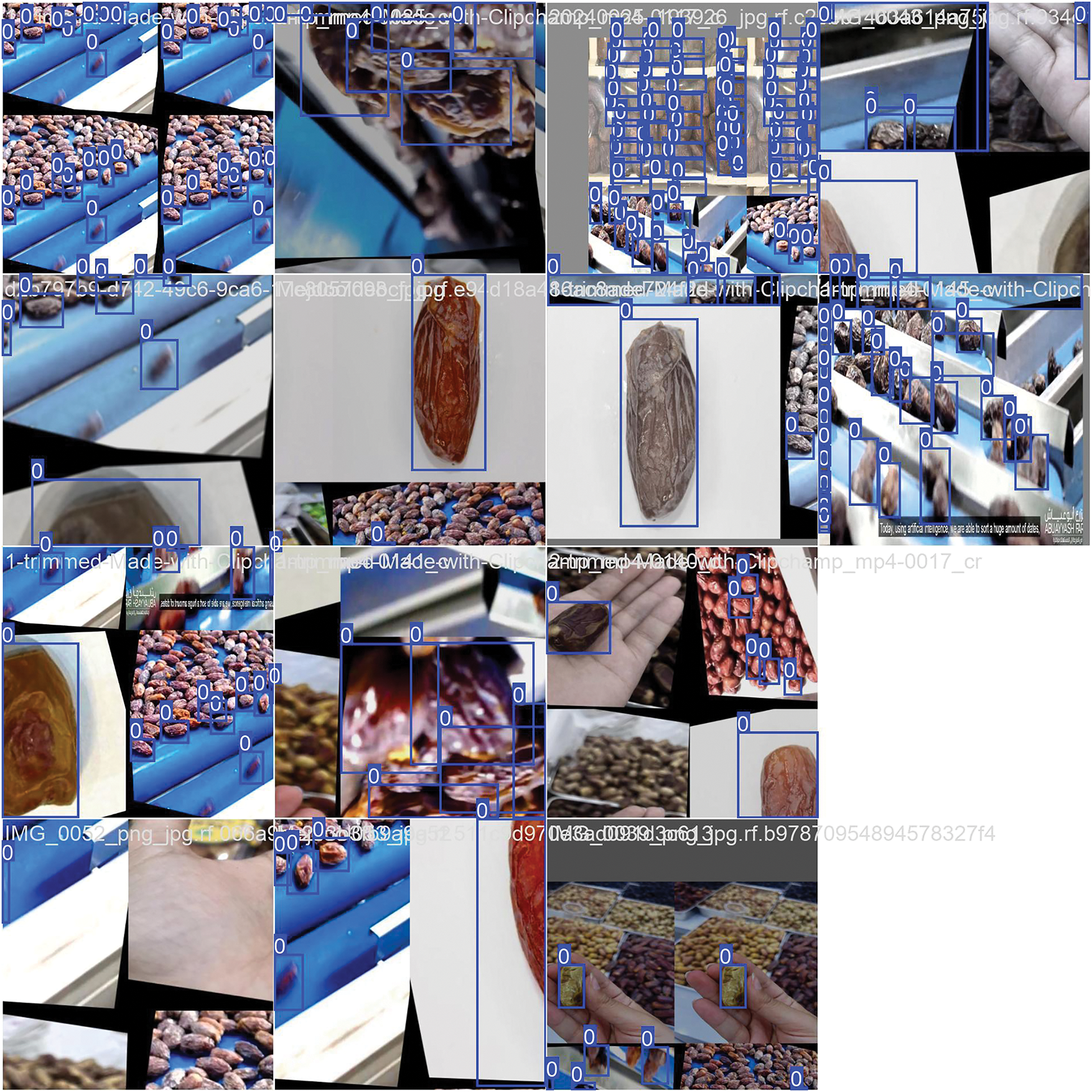

Figure 11: Training batch 0 for date detection

Figure 12: Validation batch 0 predictions for dates detection

Figure 13: Confusion matrix—Classification

Separating “Date Fruit” from “Background” categories, the confusion matrix provides a comprehensive evaluation of the binary classification performance of the YOLOv11 detection algorithm. The model demonstrated a high capacity to precisely categorize both fruit and non-fruit areas, as it correctly identified 784 true positives and 857 true negatives. By contrast, it noted 35 false negatives—where real fruits were missed—and 38 false positives—where background objects were wrongly identified as date fruits. These findings highlight the model’s excellent classification accuracy and its reliability in reducing both over- and under-detection in practical agricultural settings.

Fig. 7 shows the accuracy-recall curve for the YOLOv11 detection model evaluated across a range of confidence levels. With a confidence level of 0.41, the model achieved its highest F1-score of 0.71, implying an optimal balance between recall—correctly identifying true positives—and precision—minimizing false positives. This balance is crucial in practical settings where the dependability of performance relies on both sensitivity and accuracy. The continuous and smooth shape of the curve further supports the model’s consistent performance across various detection thresholds, thereby confirming its robustness and flexibility in demanding agricultural environments.

Fig. 8 shows the accuracy curve of the YOLOv11 detection model, assessed across various confidence levels. The accuracy of the model increases progressively as the confidence level rises, peaking at 1.0 at a threshold of 0.784. This trend highlights how effectively the model employs more stringent confidence criteria to minimize false positives. The model’s dependability in verifying detections with greater confidence is demonstrated by the rapid increase in accuracy at higher thresholds. In crucial agricultural settings, where sustaining workflow efficiency and guaranteeing dependable automation depend on minimising erroneous identifications, such conduct is very beneficial.

Fig. 9 illustrates the recall performance of the YOLOv11 detection model across various confidence levels. When the detection criteria are less strict, the model achieves its best recall at lower confidence levels, suggesting great sensitivity and the ability to identify most true positives. Recall falls gradually, however, as the confidence threshold rises; it reaches 0.06 with a threshold of 0.900. This pattern illustrates the typical precision-recall trade-off, where prioritizing forecast certainty reduces false positives but increases the likelihood of missing actual detections. Optimising the model to fit the particular sensitivity and tolerance criteria of a given agricultural application depends on an awareness of this link.

Over 75 epochs, Fig. 10 illustrates the training and validation performance of the YOLOv11 detection model, providing insight into the model’s learning development and generalization capabilities. Effective convergence is shown by a constant decreasing trend in the training losses: bounding box regression loss (box_loss), classification loss (cls_loss), and distribution focal loss (dfl_loss). Likewise, the validation losses dropped significantly in the early phases of training and eventually stabilised, suggesting that the model could generalise well to unprocessed data free from evidence of overfitting.

Essential performance measures confirm these results even more. After approximately thirty epochs, the classification accuracy reached 0.75 and the recall approached 0.70; both measures stabilized. With a mean average precision (mAP) at an IoU threshold of 0.5 exceeding 0.80, and mAP@0.5:0.95 nearing 0.60, the model also demonstrated excellent detection performance. These findings validate the dependability and resilience of YOLOv11 for real-time, high-precision identification in challenging and heavily crowded agricultural settings, like date fruit recognition in post-harvest conditions.

Fig. 11 presents a typical sample from Training Batch 0 used in the training phase of the YOLOv11 detection model. This batch comprises a diverse collection of annotated photographs designed to replicate the actual environments encountered in date fruit identification projects. To mark the existence and position of date fruits, each picture is painstakingly labelled with bounding boxes and a consistent class identification (“0”). The dataset covers a spectrum of environmental changes, including several points of view on dates fruits on conveyor belts, changing lighting conditions, intricate backdrops, occlusions, and cases of overlapping fruits. These demanding requirements are intentionally included to enhance the model’s exposure to real-world situations, thereby fostering stronger learning.

Including fruits in various sizes, orientations, and spatial configurations helps to strengthen a detection model further. The model achieves accurate object localization and class assignment solely through the quality and variation of the annotations. Therefore, particularly in high-throughput scenarios such as sorting and packaging lines, this training batch is crucial in enabling the model to generalize effectively across various agricultural conditions.

Fig. 12 depicts the efficacy of the YOLOv11 detection model on Validation Batch 0, including previously unencountered photos omitted from the training dataset. The model exhibits robust generalization skills by precisely recognizing and classifying date fruits in novel and visually varied environments. It reliably produces accurate bounding boxes, even in complicated settings including fluctuating illumination, partial obstructions, and intricate backgrounds, demonstrating its strong detection capabilities. The model’s remarkable accuracy in real-world conditions highlights its versatility and efficacy in extracting and interpreting spatial data crucial for object recognition. The model’s constant performance on unrefined data validates its dependability for real agricultural applications, such as automated sorting, quality evaluation, and post-harvest processing. These findings demonstrate the pipeline’s preparedness for use in dynamic, high-throughput settings characteristic of contemporary agricultural practices.

5.3 Classification Performance

Fig. 13 shows the confusion matrix for the YOLOv11-CLS classification module, which achieved an average classification accuracy above 92% across 15 different date fruit classifications. The strong diagonal dominance of the matrix underscores the model’s reliability in identifying visually similar fruit varieties and suggests a high degree of accurate predictions. Mainly restricted to classes with minute changes in visual features, such as colour, texture, or shape, minor misclassifications, which suggest that these errors come from natural inter-class similarities rather than model restrictions—rule here. Still, the classifier consistently demonstrates remarkable accuracy and recall across all categories, thereby reflecting its outstanding feature-extracting capacity and generalization ability.

These findings confirm the efficiency of the YOLOv11-ClS module in practical automated fruit sorting systems, where classification accuracy is vital. Furthermore, the confusion matrix is a valuable diagnostic tool that provides information for further optimisation using targeted data augmentation, enhanced class distribution, or sophisticated feature engineering.

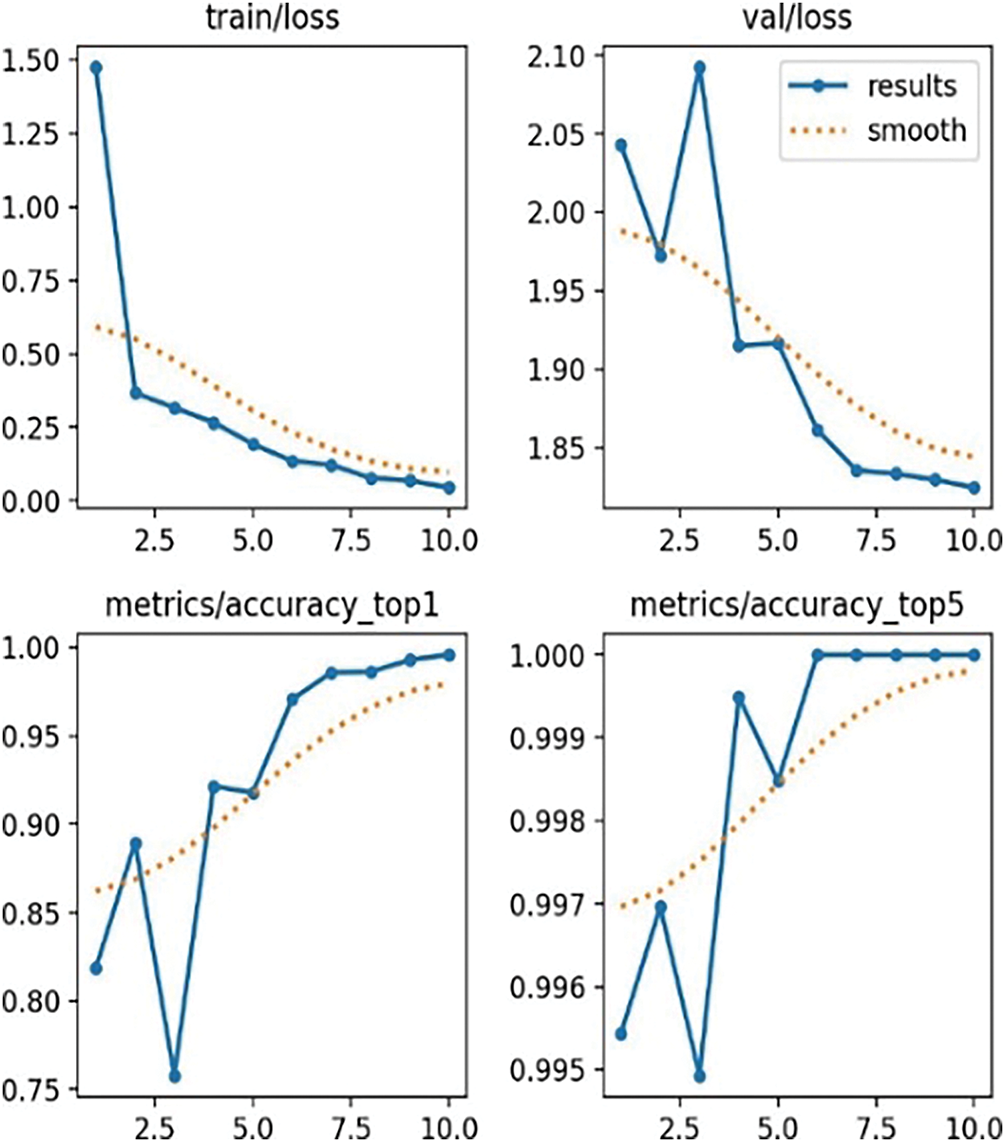

Fig. 14 illustrates the training and validation performance of the YOLOv11-CLS classification model, highlighting its progressive learning capacity and robust generalization throughout the epochs. A consistent downward trend in the training and validation loss curves suggests effective optimization and low symptoms of overfitting. This trend demonstrates the model’s ability to learn discriminative features without compromising its performance on unprocessed data. The top-1 and top-5 accuracy measures confirm even more the categorisation efficiency of the model. Top-1 accuracy rises rapidly, showing how well the algorithm forecasts the most likely class label. Especially, the Top-5 accuracy values 100%, indicating that the right class was nearly always included among the top five predictions—a crucial ability for differentiating various date fruit kinds with minor visual variations.

Figure 14: Classification model results

The convergence of loss and accuracy measures emphasises the strong discriminative power and general resilience of the model. These results confirm YOLOv11-CLS as a dependable and scalable solution for industrial-grade fruit categorization tasks, where variation and quality evaluation depend significantly on visual details in multiple fields.

Comprising all 15 date fruit types, Fig. 15 illustrates a representative subset of the training data used for the YOLOv11-ClS classification model. The images vary in key visual elements, such as size, colour, texture, and ripeness stages. This diversity is essential for the model to gain class-distinctive characteristics and to generalise effectively across a broad spectrum of real-world events. Especially in visually similar data types, the dataset exposes the model to intra-class variability and inter-class similarity, thereby improving resilience and discriminative capacity. Such variability underlies high classification accuracy and durability, particularly in industrial agricultural environments where exact variation detection is needed for sorting, grading, and quality control operations. This large and fully annotated dataset serves as the basis for a robust, scalable, and high-performance classification system, suitable for automated post-harvest fruit processing. Fig. 16 shows a validation photo sample used to assess the YOLOv11-CLS classification model performance. Every photo displays a different kind of date fruit, exactly matched in its suitable group. The collection comprises a diverse range of visual traits, including variations in shape, colour, and texture, to reflect the variety encountered in real agricultural settings.

Figure 15: Training images for classification training

Figure 16: Validation images for classification evaluation

By evaluating the model on these diverse and heretofore unprocessable images, we may better understand how faithfully it generalises outside of the training data. The strong and consistent performance of the model across all samples highlights its ability to discriminate even the most visually similar date fruit species regularly. In automated sorting and grading, this reliability is crucial when accuracy and consistency are required.

5.4 Counting Accuracy and Efficiency

This study mainly contributes to the efficient integration of a fruit counting module into the whole processing flow. As shown in Fig. 17, the line-based counting technique proved to be quite effective, yielding results that are pretty comparable to manual counts. Most test cases found that, that is, the difference between hand counting and the automated system’s exceptional accuracy was limited to one or two fruits. The module also meets the performance needs of industrial environments on a standard GPU, operating at a real-time speed of around 15–20 frames per second. A scalable and pragmatic solution for automated post-harvest fruit processing, the unified interface enables one workflow to effortlessly count, identify, and categorise. By reducing running costs and reliance on human effort, this approach offers a significant benefit for high-throughput agricultural activities.

Figure 17: Demonstration of the counting module in operation

Fig. 17 illustrates the operational counting module within a real-time industrial environment, where dates are conveyed along a conveyor belt. The system utilizes bounding boxes to identify and monitor each fruit individually as it traverses a designated line or region of interest. A digital counter accurately records each fruit that crosses the line in real-time. This visual illustration demonstrates the module’s accuracy in counting, even in tumultuous and unpredictable environments. It shows precise automation of essential fruit counting choreography through constant performance, despite motion blur, overlapping fruits, or partial occlusions. This reduces labour expenses and enhances workflow reliability, scalability, and efficiency in post-harvest operations inside agricultural processing facilities.

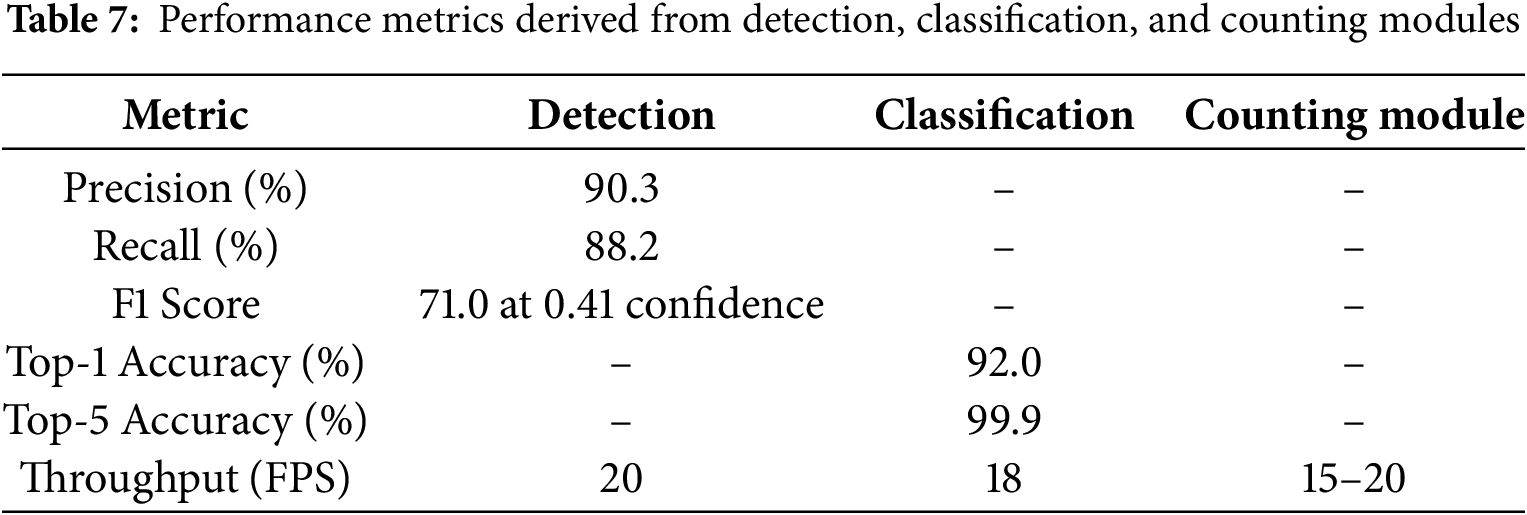

Table 7 presents a complete breakdown of significant performance measures—precision, recall, classification accuracy, and throughput (measured in frames per second, FPS)—offering a full picture of the system’s performance. These benchmarks taken together indicate the performance of the recommended pipeline under real-world agricultural conditions. Even in challenging surroundings, the excellent accuracy and recall ratings demonstrate the system’s dependability in correctly identifying and categorizing date fruits. Similarly, the high classification accuracy ensures its ability to separate 15 visually similar date fruit types with minimal error. Furthermore, the stated throughput indicates that the system runs almost in real-time, which supports its use in high-volume, fast-paced industrial environments. These findings generally highlight the system’s scalability, dependability, and suitability for use in pragmatic post-harvest automated systems.

Table 7 lists the fundamental performance measures of the YOLOv11-powered detection, classification, and counting systems forming the backbone of the automated date fruit processing pipeline. The outcomes clearly demonstrate the system’s dependability, precision, and real-time functionality in actual agricultural settings. Striking a good balance between precisely recognizing date fruits and minimizing both false positives and missed detections, the detection module achieved an impressive 90.3% accuracy and 88.2% recall. Reaching a high F1 score of 71.0% at a confidence level of 0.41, it maintained a processing speed of 20 FPS—fast enough for industrial applications. Delivering a top-1 accuracy of 92.0% and a near-perfect top-5 accuracy of 99.9%, the classification module likewise performed relatively well. This implies the algorithm could consistently differentiate among 15 physically similar types of fruit. Maintaining excellent efficiency without compromising accuracy, it ran at 18 FPS. Working at a rate of 15 to 20 FPS, the counting module was well-matched to the bits for detection and categorization. It often produced exact counts using a line-based tracking method, closely matching manual counts. Such traits are highly beneficial for high-throughput processing systems, where speed and accuracy are crucial. The results demonstrate the accuracy and efficiency of the system, as well as its scalability and practical application preparation. By automating the often time-consuming procedures of detection, classification, and counting, this multimodal pipeline offers a valuable and sensible answer for post-harvest tasks. The excellent performance of the system is attributed to intelligent data augmentation methods, meticulous hyperparameter tuning, and thorough data preparation, including accurate annotations. Though occasional misclassifications among physically similar fruit kinds offer an opportunity for improvement—possibly via domain adaptation or targeted data enrichment—the pipeline as a whole exhibits impressive robustness. This combined approach lays the foundation for major smart agriculture applications by considerably increasing the efficiency of modern date fruit processing facilities and offering a scalable, reasonably priced replacement for human labour.

This study presents a multi-stage pipeline for the identification, classification, and automated enumeration of date fruits, using YOLOv11-based models to provide real-time performance with excellent accuracy. The proposed system achieved a detection precision of over 90%, a classification accuracy of 92%, and a strong correlation between automated and human counting, validating its ability to reduce labour demands and enhance operational efficiency in post-harvest processes. Future efforts will focus on improving the system’s robustness in complex agricultural environments, addressing challenges such as dense fruit clusters, substantial light variations, and diverse orchard topographies. Domain adaptation procedures might enhance the model’s generalizability across various field situations, while expanding and diversifying the training dataset may diminish classification errors across visually similar fruit categories. The use of thermal or hyperspectral imaging is anticipated to provide a more profound comprehension of subtle variations in maturity. Furthermore, the creation of easy-to-use interfaces or mobile application integration may improve accessibility, allowing field operators to use the system with less technical knowledge. Integrating this pipeline with robotic harvesting arms presents a feasible path to a fully automated solution, capable of performing detection, classification, selection, and counting within a unified, end-to-end workflow, thereby enhancing the automation of intelligent agricultural systems.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia, Grant No. KFU250098.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Abid Iqbal, Ali S. Alzaharani; data collection: Abid Iqbal; analysis and interpretation of results: Abid Iqbal, Ali S. Alzaharani; draft manuscript preparation: Abid Iqbal, Ali S. Alzaharani. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used in this study, including both the detection and classification image sets, have been organized and securely stored on Kaggle. Due to data hosting limitations and licensing considerations from some public sources (e.g., Google Images, YouTube frames), the datasets are currently kept private. However, they can be made publicly accessible upon request. Researchers and practitioners interested in this topic are encouraged to contact the corresponding authors via the email addresses provided in the manuscript. Upon request, we will share the Kaggle links and relevant dataset documentation to support reproducibility and further research in the domain of agricultural visual recognition.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Baliga MS, Baliga BRV, Kandathil SM, Bhat HP, Vayalil PK. A review of the chemistry and pharmacology of the date fruits (Phoenix dactylifera L.). Food Res Int. 2011;44(7):1812–22. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2010.07.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Al-Khayri JM, Jain SM, Johnson DV. Date palm genetic resources and utilization. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

3. Jha K, Doshi A, Patel P, Shah M. A comprehensive review on automation in agriculture using artificial intelligence. Artif Intell Agric. 2019;2(3):1–12. doi:10.1016/j.aiia.2019.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mahmud MSA, Abidin MSZ, Emmanuel AA, Hasan HS. Robotics and automation in agriculture: present and future applications. Appl Model Simulation. 2020;4:130–40. [Google Scholar]

5. Yang X, Shu L, Chen J, Ferrag MA, Wu J, Nurellari E, et al. A survey on smart agriculture: development modes, technologies, and security and privacy challenges. IEEE/CAA J Autom Sinica. 2021;8(2):273–302. doi:10.1109/jas.2020.1003536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Kamilaris A, Prenafeta-Boldú FX. Deep learning in agriculture: a survey. Comput Electron Agric. 2018;147(2):70–90. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2018.02.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Deng L, Yu D. Deep learning: methods and applications. FNT Signal Processing. 2014;7(3–4):197–387. doi:10.1561/2000000039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ferentinos KP. Deep learning models for plant disease detection and diagnosis. Comput Electron Agric. 2018;145(6):311–8. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2018.01.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wolfert S, Ge L, Verdouw C, Bogaardt MJ. Big data in smart farming—a review. Agric Syst. 2017;153:69–80. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2017.01.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Xiao F, Wang H, Xu Y, Zhang R. Fruit detection and recognition based on deep learning for automatic harvesting: an overview and review. Agronomy. 2023;13(6):1625. doi:10.3390/agronomy13061625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Kanna SK, Ramalingam K, Pazhanivelan P, Jagadeeswaran R, Prabu PC. YOLO deep learning algorithm for object detection in agriculture: a review. J Agric Eng. 2024;55(4):97–111. doi:10.4081/jae.2024.1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Pawara P, Boshchenko A, Schomaker LRB, Wiering MA. Deep learning with data augmentation for fruit counting. In: Artificial intelligence and soft computing. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 203–14. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-61401-0_20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Darwin B, Dharmaraj P, Prince S, Popescu DE, Hemanth DJ. Recognition of bloom/yield in crop images using deep learning models for smart agriculture: a review. Agronomy. 2021;11(4):646. doi:10.3390/agronomy11040646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Shamshiri RR, Shafian S, Hameed IA, Grichar WJ. Precision agriculture: emerging technologies. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2024. [Google Scholar]

15. Gupta S, Tripathi AK. Fruit and vegetable disease detection and classification: recent trends, challenges, and future opportunities. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;133:108260. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2024.108260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Bai Y, Yu J, Yang S, Ning J. An improved YOLO algorithm for detecting flowers and fruits on strawberry seedlings. Biosyst Eng. 2024;237(13):1–12. doi:10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2023.11.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang Z, Ling Y, Wang X, Meng D, Nie L, An G, et al. An improved Faster R-CNN model for multi-object tomato maturity detection in complex scenarios. Ecol Inform. 2022;72(3):101886. doi:10.1016/j.ecoinf.2022.101886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Altaheri H, Alsulaiman M, Muhammad G. Date fruit classification for robotic harvesting in a natural environment using deep learning. IEEE Access. 2019;7:117115–33. doi:10.21227/x46j-sk98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Albarrak K, Gulzar Y, Hamid Y, Mehmood A, Soomro AB. A deep learning-based model for date fruit classification. Sustainability. 2022;14(10):6339. doi:10.3390/su14106339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. ElHelew W, Abo-Bbakr D, Zayan S, Mayhoub M. Classification of dates quality using deep learning technology based on captured images. Misr J Agric Eng. 2024;41(3):1–18. doi:10.21608/mjae.2024.286079.1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Nasiri A, Taheri-Garavand A, Zhang YD. Image-based deep learning automated sorting of date fruit. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2019;153(1):133–41. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2019.04.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ouhda M, Yousra Z, Aksasse B. Smart harvesting decision system for date fruit based on fruit detection and maturity analysis using YOLO and K-means segmentation. J Comput Sci. 2023;19(10):1242–52. doi:10.3844/jcssp.2023.1242.1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Nadhif MF, Dwiasnati S. Classification of date fruit types using CNN algorithm based on type. MALCOM Indones J Mach Learn Comput Sci. 2023;3(1):36–42. doi:10.57152/malcom.v3i1.724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Mu D, Guou Y, Wang W, Peng R, Guo C, Marinello F, et al. URT-YOLOv11: a large receptive field algorithm for detecting tomato ripening under different field conditions. Agriculture. 2025;15(10):1060. doi:10.3390/agriculture15101060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sharma A, Kumar V, Longchamps L. Comparative performance of YOLOv8, YOLOv9, YOLOv10, YOLOv11 and Faster R-CNN models for detection of multiple weed species. Smart Agric Technol. 2024;9:100648. doi:10.1016/j.atech.2024.100648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools