Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Conditional Generative Adversarial Network-Based Travel Route Recommendation

1 Department of Computer Engineering, Chung-Ang University, 84 Heukseok-ro, Seoul, 06974, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Artificial Intelligence, FPT University, Da Nang Campus, Da Nang, 550000, Vietnam

3 Jagiellonian Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (JAHCAI), Institute of Applied Computer Science, Jagiellonian University, Krakow, 30-348, Poland

4 Department of Information Technology, School of Information Technology, Halmstad University, Halmstad, 30118, Sweden

5 ALGORITMI Research Centre, School of Engineering, Universidade do Minho, Braga, 4710-057, Portugal

6 Department of Information Technology, Faculty of Engineering-Information Technology, Quang Binh University, Dong Hoi City, 510000, Vietnam

* Corresponding Author: Jason J. Jung. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-40. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070613

Received 20 July 2025; Accepted 28 August 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Recommending personalized travel routes from sparse, implicit feedback poses a significant challenge, as conventional systems often struggle with information overload and fail to capture the complex, sequential nature of user preferences. To address this, we propose a Conditional Generative Adversarial Network (CGAN) that generates diverse and highly relevant itineraries. Our approach begins by constructing a conditional vector that encapsulates a user’s profile. This vector uniquely fuses embeddings from a Heterogeneous Information Network (HIN) to model complex user-place-route relationships, a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) to capture sequential path dynamics, and Neural Collaborative Filtering (NCF) to incorporate collaborative signals from the wider user base. This comprehensive condition, further enhanced with features representing user interaction confidence and uncertainty, steers a CGAN stabilized by spectral normalization to generate high-fidelity latent route representations, effectively mitigating the data sparsity problem. Recommendations are then formulated using an Anchor-and-Expand algorithm, which selects relevant starting Points of Interest (POI) based on user history, then expands routes through latent similarity matching and geographic coherence optimization, culminating in Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP)-based route optimization for practical travel distances. Experiments on a real-world check-in dataset validate our model’s unique generative capability, achieving scores ranging from 0.163 to 0.305, and near-zero scores between 0.002 and 0.022. These results confirm the model’s success in generating novel travel routes by recommending new locations and sequences rather than replicating users’ past itineraries. This work provides a robust solution for personalized travel planning, capable of generating novel and compelling routes for both new and existing users by learning from collective travel intelligence.Keywords

Tourism represents one of the largest and fastest-growing industries in the world, driving the emergence of numerous online travel agencies such as Expedia, Klook, and TripAdvisor that provide comprehensive digital services. However, the proliferation of tourism products has led to an overwhelming overload of information, making it difficult for users to quickly find products of interest. A travel route recommendation system is an important tool for addressing this challenge. However, unlike conventional recommendation items, such as books or movies, travel routes have distinct properties that pose significant challenges for personalized recommendations.

• Travel data tends to be significantly sparser. This sparsity is particularly acute as the available data often consists of implicit feedback, such as check-in records or geotagged photos, which lack explicit ratings. This nature of data poses two fundamental challenges for recommendation: According to [1], there is an ambiguity in unobserved interactions, since we cannot be sure whether a non-interacted item is genuinely disliked or is a positive item that was never exposed to the user. Furthermore, as argued by [2], implicit feedback is highly susceptible to exposure bias, where a user’s interaction history is more a reflection of what they were exposed to, rather than their true, holistic preferences. This creates a self-reinforcing loop where renowned tourist spots are constantly overrepresented, hindering the discovery of new or niche locations.

• Routes are composite items composed of a sequence of individual places, meaning a deep understanding of the user-route relationship requires modeling the underlying places.

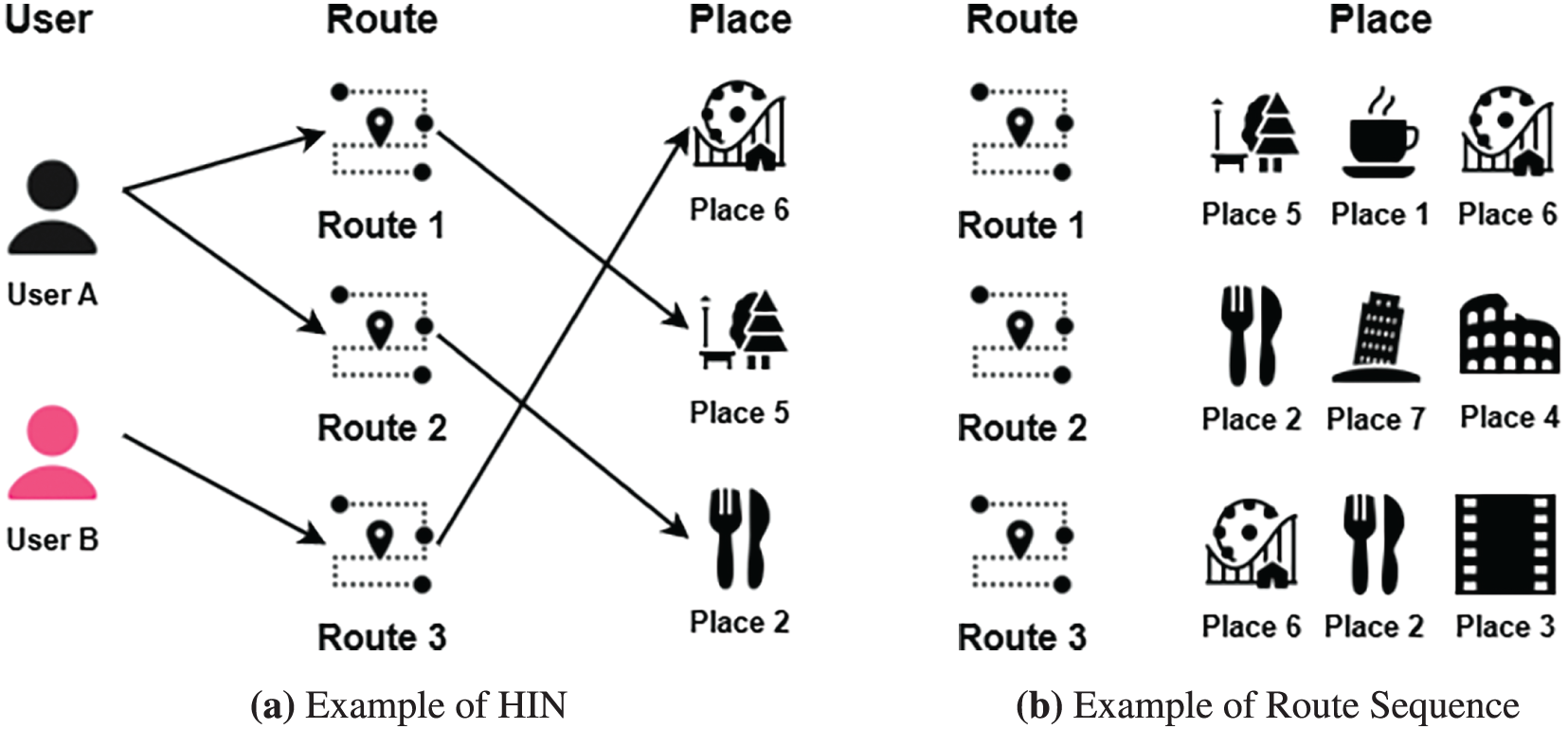

• Routes can be represented by a sequence of places, and users may define routes composed of the same places but in different orders, with different routes. For example, in Fig. 1b, two routes composed of the same places can be defined as different routes depending on the user. Therefore, this sequence is one of the important features of a route.

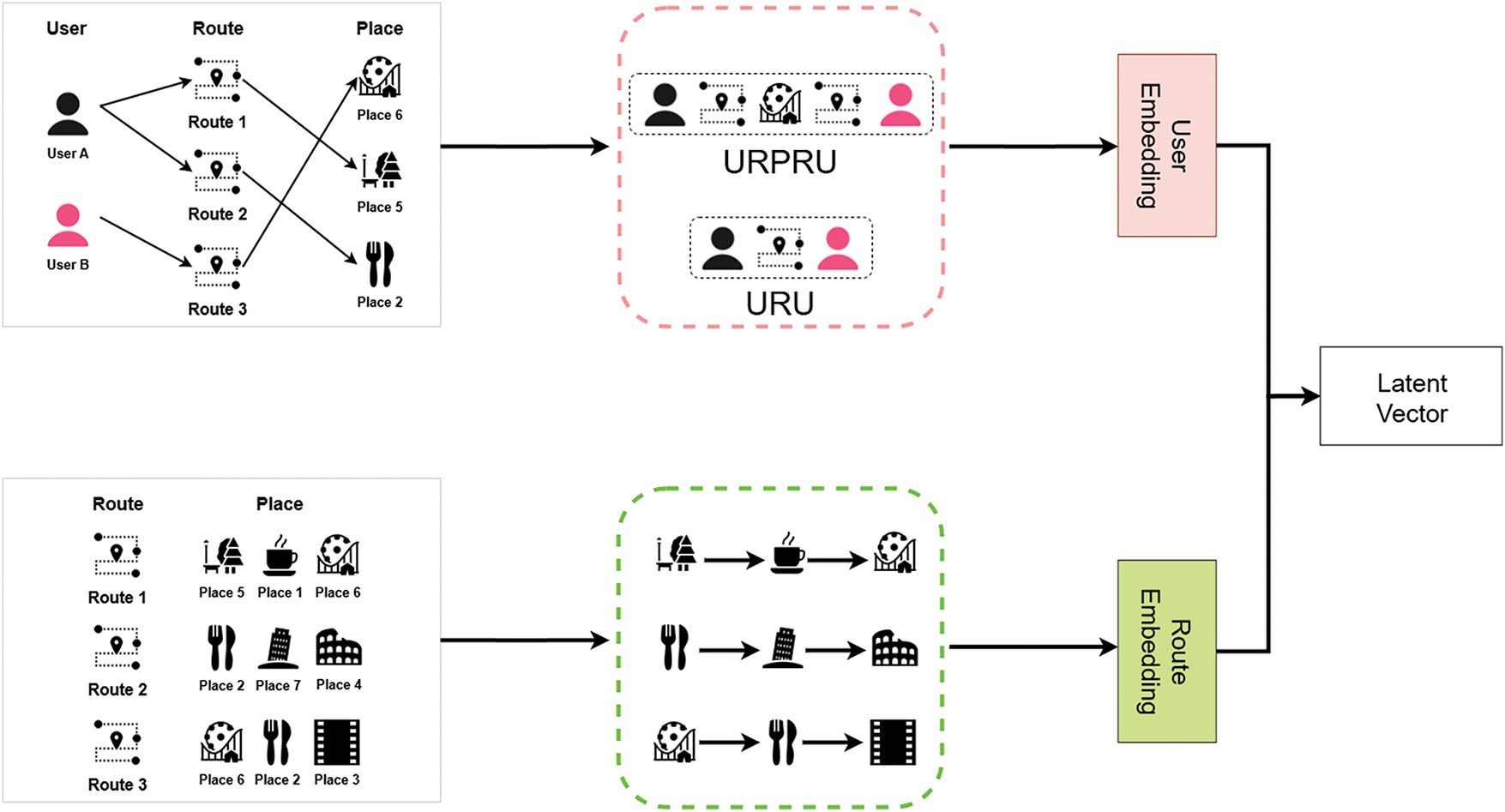

Figure 1: Conceptual diagram illustrating the Heterogeneous Information Network (HIN) and the sequential nature of routes. (a) An example of the HIN, which is modeled with users, routes, and places. User A (black icon) takes Route 1 and Route 2 to reach Place 5 (park) and Place 2 (restaurant). User B (pink icon) takes Route 3 to visit Place 6 (amusement park). (b) An example demonstrating that routes are represented as a sequence of places. Route 1 is composed of a park (Place 5), a cafe (Place 1), and an amusement park (Place 6). Route 2 consists of a restaurant (Place 2), and two tourist attractions (Place 7, Place 4). Route 3 is composed of an amusement park (Place 6), a restaurant (Place 2), and a movie theater (Place 3). (Icons by https://icons8.com/icons)

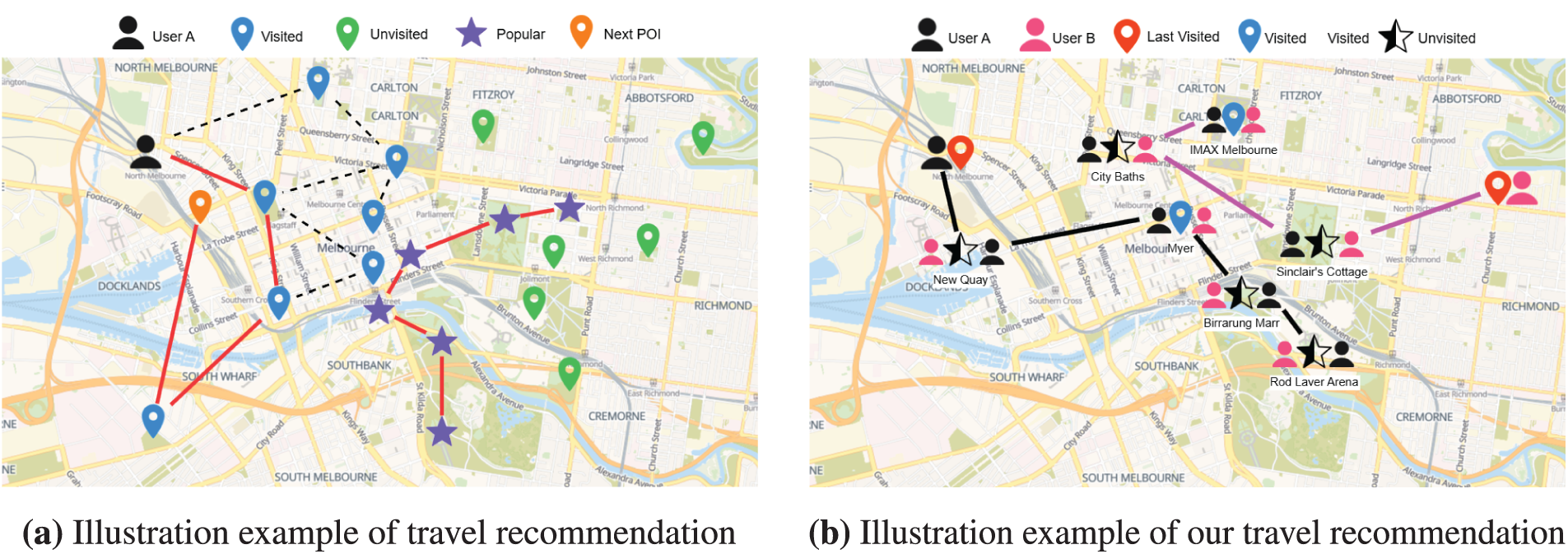

These challenges create a significant gap: the inability of conventional systems to generate truly novel yet relevant travel experiences. As illustrated in Fig. 2a, these systems often trap users in a ‘popularity’, either by suggesting minor extensions to their historical paths (e.g., from previously visited to a predicted next POI) or by recommending mainstream tourist routes composed exclusively of popular locations. This approach fails to facilitate new discovery of places, limiting users to a narrow subset of their potential interests.

Figure 2: Conceptual illustration of travel recommendation, comparing conventional methods with our proposed generative approach. (a) The limitations of conventional recommendation systems, which often trap users in a ‘popularity loop’ by suggesting routes based on past behavior or mainstream locations. The icons denote locations already visited by User A (blue pin), unvisited locations (green pin), popular tourist destinations (purple star), and a predicted next POI (orange pin). The black dashed line illustrates a minor extension based on a historical path. (b) Our proposed model’s ability to generate novel routes by synthesizing collective travel intelligence from multiple users. User A is represented by the black icon and User B by the pink icon. Red pins indicate the last visited POI for each respective user, while blue pins show locations visited by both. The half-filled stars represent places visited (filled half) or unvisited (empty half) by the corresponding user. (Map data: © OpenStreetMap contributors), (Icons by https://icons8.com/icons)

Previous research leveraging implicit feedback has approached the problem from several distinct paradigms. Optimization-based methods often frame the task as a variant of the orienteering problem, using behavioral signals such as POI visit duration to infer user interest [3] and photo metadata to estimate queuing times [4]. Meanwhile generative modeling approaches have employed Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) to learn complex trajectory distributions from historical travel patterns, creating synthetic yet realistic routes [5].

Despite these advances, existing methods often fail to holistically integrate multiple complex signals or lack sophisticated mechanisms to generate structured, sequential recommendations capable of addressing inherent data biases effectively.

To address these issues, we propose a travel route recommendation model that considers the characteristics of the relationship between users and routes, including places, and the features of routes represented as a sequence of places. Our primary motivation is to shift the paradigm from simple retrieval to true route generation, as illustrated in Fig. 2b. By learning from the collective travel patterns of all users, our system can synthesize entirely new routes that merges user’s personal history with destinations they have never visited but are contextually relevant based on the experiences of others. Specifically, our model utilizes latent vectors for user and route embeddings using HIN, RNN, and CGAN to effectively address the data sparsity issue related to the relationship between routes and users. The model adopts a HIN targeting users and routes, modeling the relationships between users and places they have experienced within routes. User characteristics are then extracted using meta-path-based embedding techniques. Additionally, route sequences are embedded using an embedding layer followed by an LSTM layer to capture sequential information, generating rich route embeddings based on sequences of places.

Fig. 1a illustrates an example of a HIN modeled with users, routes, and places, while a separate RNN captures the sequential nature of routes. Leveraging embeddings from these models, along with rich user profile vectors, a CGAN is trained to generate novel latent vectors representing personalized routes. Finally, these generated vectors are decoded into concrete POI sequences using an Anchor-and-Expand strategy, facilitating compelling recommendations while effectively mitigating data sparsity challenges.

The proposed analytical approach and recommendation system in this paper follow a generative learning paradigm that leverages historical travel patterns from multiple users to create novel route recommendations. Each user’s historical travel behavior is analyzed by identifying the sequence of visited POIs, forming distinct patterns that implicitly reflect their thematic preferences. The system incorporates thematic priority rankings and neural collaborative filtering by evaluating similarities among users based on visitation sequences and thematic preferences.

Our CGAN-based recommendation framework operates through a systematic learning process where historical travel data from existing users serves as training input for the generative model. The CGAN learns to capture the underlying patterns, thematic preferences, and sequential visitation behaviors from these diverse user profiles. Through this learning process, the model internalizes the complex relationships between POI characteristics, user preferences, and travel sequence patterns without simply replicating existing routes.

Once trained on the collective travel patterns of each user, the CGAN model generates entirely novel route recommendations for new users. Rather than directly recommending previously visited POIs from similar users, the system leverages the learned latent representations to synthesize completely new travel experiences. The model conditions the generation process on new user profile characteristics, enabling it to create personalized routes that align with their potential preferences while introducing POIs and sequences that have never been experienced by any user in the training set.

This generative approach represents a fundamental shift from traditional collaborative filtering methods. Instead of finding similar users and recommending their visited locations, the system uses the collective knowledge from the existing users to understand the underlying principles of travel preference formation and route construction. The trained CGAN then applies these learned principles to generate novel, coherent travel routes for new users that balance thematic consistency with exploration of entirely new destinations and sequences.

This integrative strategy significantly enhances recommendation novelty, diversity, and personalization by moving beyond the limitations of existing route reproduction to true route generation and discovery.

The main contributions are summarized as follows.

• We propose an advanced CGAN model capable of directly sampling route embeddings from conditional latent spaces. Unlike existing methods limited to rearranging known routes or place combinations, our model can generate entirely new, personalized travel routes that the user hasn’t experienced. By conditioning route generation on diverse inputs–including user characteristics, preferred themes, geographical focal points, historical visit patterns, and similarity information from related users–our CGAN approach allows sophisticated, personalized recommendations even under complex user scenarios. This significantly expands the recommendation scope beyond traditional methods by incorporating previously unvisited locations and novel route combinations.

• Our approach ensures diversity by actively avoiding repeated recommendations of overly frequent or popular themes. Instead, it combines known user preferences with previously unexplored themes, enabling users to experience novel and personalized travel routes beyond their prior travel history.

• We introduce a hybrid embedding strategy that comprehensively integrates relational contexts from a HIN, sequential travel patterns via RNN, and NCF. By conditioning recommendations explicitly on user-specific themes, actual historical visitation data, spatial proximity, and embedding-based similarity to other users, our system ensures highly accurate, practically relevant recommendations that reflect not only stated preferences but genuine behavioral patterns and contextual similarities.

Section 2 summarizes related work on travel route recommendation methodologies. Section 3 presents preliminary descriptions and the problem statement. Section 4 elaborates methodology of the proposed model. Experimental results are given in Section 5. Finally, we draw our conclusion, limitations and outlines future research direction in Section 6.

In this section, we will review prior research on three aspects related to the route recommendation process proposed in this study: HIN, RNN, GAN, and GNN.

2.1 Personalized Tour Recommendation

Various studies have proposed methods for recommending customized travel packages. For instance, PersonalTour, a multi-agent recommendation system, was designed to find suitable travel products based on user preferences [6]. To better analyze the unique features of travel packages compared to conventional items, the Tourist-Area-Season Topic (TAST) [7] model was introduced. This was later extended to the Tourist-Relation-Area-Season Topic (TRAST) [8] model to capture potential relationships between tourists within travel groups. Yu et al. suggested using location-based social networks to recommend personalized travel products, utilizing data from users’ social networks and applying a collaborative filtering approach to infer destination preferences [9].

Heterogeneous Information Network (HIN) [10] can model complex objects and their diverse relationships in recommendation systems. In this context, objects have different types, and links between objects represent various relationships [11]. Meta-path is an effective method within HIN for capturing intricate relationships among nodes [12].

Inspired by methods such as DeepWalk [13] and Node2vec [14], unsupervised heterogeneous graph embedding methods like Metapath2vec [15] and HIN2Vec [16] were designed and applied to create structural features in recommendation systems. HERec [17] uses meta-path-based random walks to generate object sequences, learns object embeddings using node2vec, and computes embedding similarities for recommendations. IF-BPR [18] utilizes meta-paths to identify implicit friends in social recommendation systems and designs a biased random walk method considering the noise in social relationships. HueRec [19] assumes that a user or item shares a common meaning under various meta-paths and learns integrated representations of users and items using all meta-paths. HetNERec [20] transforms heterogeneous networks into multiple sub-networks based on meta-paths and uses the learned embeddings for matrix factorization regularization.

With advancements in deep learning, neural network-based recommendation models have demonstrated enhanced performance due to their robust feature interaction capabilities and flexible architectural design. Heterogeneous Graph Neural Networks based on meta-path modeling effectively introduce prior knowledge from heterogeneous graphs and capture high-level semantic information [21]. MEIRec [22] aggregates heterogeneous neighbors along each meta-path and accumulates various meta-paths to obtain user embeddings and query embeddings. CDPRec [23] employs a meta-path-based random walker to extract homogenous graphs from heterogeneous graphs and concurrently trains multi-head attention and RNN for a sequential recommendation. MetaHIN [24] proposes a new meta-learning approach to leverage the capabilities of meta-learning at the model level and HIN at the data level for cold-start problems in recommendation systems.

In this study, we model the HIN that consists of users, routes, and places.To extract user features related to routes, we apply meta-path-based embedding methods to generate user embeddings.

The primary objective of GAN is to simultaneously train a generator that produces synthetic data and a discriminator that attempts to distinguish between real and synthetic data, to generate data indistinguishable from real instances. IRGAN [25] pioneered the integration of generative and discriminative models for information retrieval tasks. Subsequently, various recommendation systems based on GAN have been explored.

CFGAN [26] is an approach to recommendation systems based on GAN principles. Experiments have demonstrated that discrete sampling operations within the generator can hinder the discriminator’s ability to effectively differentiate between real and synthetic samples, especially in scenarios with sparse and discrete data. As a solution, CFGAN proposes vector-unit training, where the generator creates complete user history profiles, and the discriminator distinguishes between generated and real user profiles from the User-Item Rating Matrix (URM).

CAAE [27] employs two autoencoder based generators and utilizes the BPR loss in the discriminator to create realistic user and item embeddings, enabling the discriminator to distinguish between genuine and generated interactions.

RAGAN [28] and AugCF [29] aim to address data sparsity issues in the URM using GAN based approaches. RAGAN synthesizes user-profiles and interactions, effectively addressing the challenge of completing missing ratings within the URM. AugCF, based on CGAN, generates additional interaction data to enrich the original dataset. In AugCF, the generator takes various inputs and produces items for users based on specified criteria. The discriminator initially functions as a classifier and later transitions to a collaborative filtering model.

DeepTrip [5] proposed an adversarial neural network-based framework combining an encoder-decoder architecture to capture human mobility patterns. DeepTrip leverages an adversarial network to learn the implicit distribution of users’ sequential check-in data, effectively modeling the spatio-temporal constraints between POIs. The approach successfully captures non-linear and complex transition patterns inherent in trajectory data, demonstrating superior performance in recommending personalized trips and sequences of POIs.

Previous methods primarily optimize loss functions using GANs to alleviate data sparsity. In this study, we propose a novel CGAN-based approach that mitigates data sparsity and enhances recommendation accuracy by encoding comprehensive user and route characteristics into a latent embedding vector. Specifically, our method incorporates diverse user preferences and contextual route attributes to form enriched condition vectors, effectively capturing complex interactions between users and POIs.

Recent advancements in Graph Neural Network (GNNs) have provided powerful tools for solving complex transportation problems. For instance, Liu and Meidani [30] proposed a GNN-SDE to effectively estimate the shortest travel distance and recommend routes, particularly in large-scale networks under hazardous conditions like floods. Their approach formulates the problem as a node-level regression task, using the GNN to learn from topological features like node coordinates and edge weights to predict the shortest distance from a single source. The final route recommendation is then constructed as a post-processing step by identifying the path of minimum predicted distance, making it highly effective for emergency response and evacuation planning where speed is the primary objective.

While this GNN-based method demonstrates high efficiency and accuracy for shortest path optimization, our research addresses a different challenge: personalized route recommendation. Unlike the GNN-SDE model which focuses on single, physically optimal path based on distance or time, our study aims to generate routes tailored to individual user preferences and the contextual attributes of various points of interest. We leverage a Heterogeneous Information Network (HIN) to capture the complex relationships between users, routes, and places, and employ a novel CGAN-based approach to generate diverse and personalized travel suggestions. Thus, while Liu and Meidani’s work provides a solution for logistical optimization, our study focuses on the subjective and user-centric nature of travel recommendation.

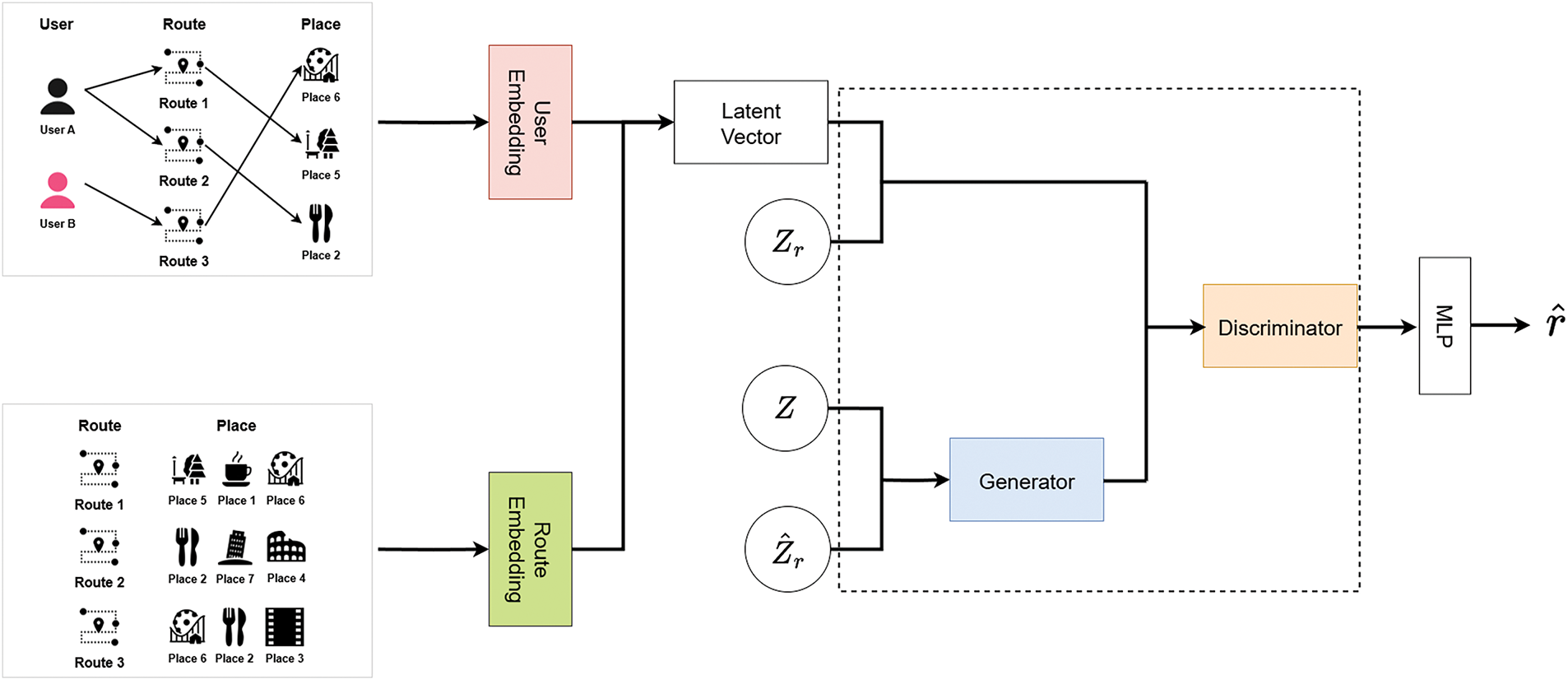

In this section, we introduce the core notation and formal definitions underpinning our route recommendation framework. Table 1 summarizes the notation of our paper. We then give three fundamental definitions: check-in records, check-in trajectory sequence, and generate route recommendation.

Definition 1. A check-in record is denoted by a tuple

Definition 2. For any user

Definition 3. Given the historical POI interactions

where

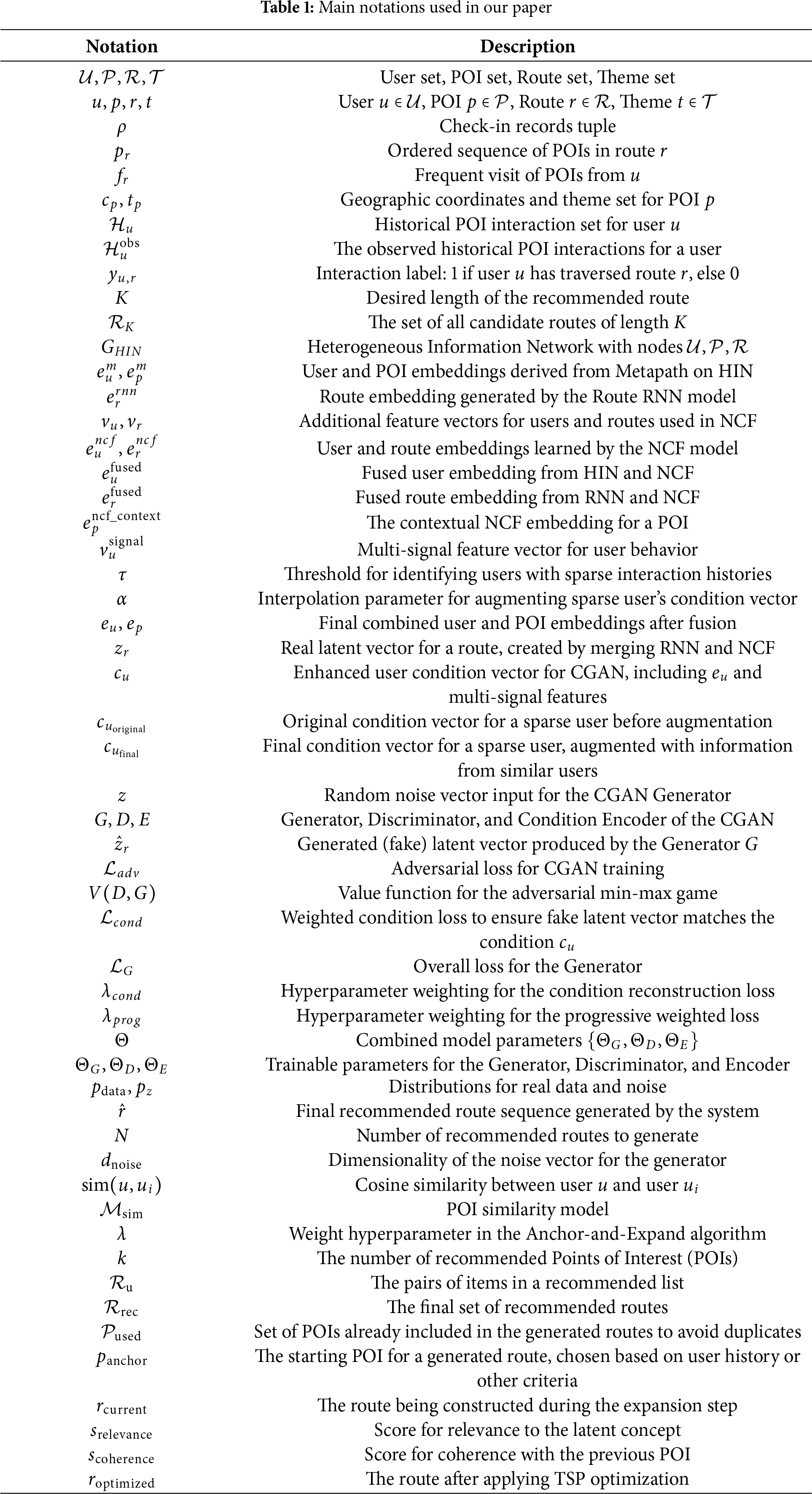

This section delineates the comprehensive methodology for our proposed travel route recommendation system. The core objective is to generate diverse, personalized, and practical travel itineraries by proficiently addressing the inherent challenges of data sparsity and the complex, sequential nature of user preferences. Our model is structured into three principal components, which are elaborated in the subsequent subsections:

1. Hybrid Multi-Source Representation Learning: We construct comprehensive representations for users, routes, and POIs by fusing embeddings from multiple information sources. This process is further enriched by incorporating a rich set of multi-signal features that capture interaction confidence, uncertainty, and behavioral patterns.

2. Conditional Route Generation via Spectrally Normalized CGAN: We employ an advanced CGAN, stabilized by spectral normalization and guided by a dedicated condition loss, to generate high-fidelity latent representations of travel routes tailored to individual user profiles.

3. Recommendation via Anchor-and-Expand Route Formulation: We introduce a novel decoding strategy, the Anchor-and-Expand algorithm, which translates the generated latent vectors into concrete and practical POI sequences by grounding recommendations in user history and optimizing for geographic coherence.

An overview of the proposed model’s architecture is depicted in Fig. 3

Figure 3: Framework of the proposed model (Icons by https://icons8.com/icons)

4.1 Hybrid Multi-Source Representation Learning

To effectively model the complex relationships between users, routes, and places, we first construct rich, multi-faceted representations for all entities. These representations serve as the foundational input for the subsequent generation model. The process for generating these representations is depicted in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Example of generating hybrid embeddings and the latent vector (Icons by https://icons8.com/icons)

The representation for each user

• Hybrid User Embedding: The core user embedding is created by fusing two distinct types of representations to capture both relational and collaborative signals.

– HIN-Based Relational Embedding: To model the structural relationships between entities, we construct a HIN comprising user, route, and place nodes. We define specific meta-paths, such as User-Route-Place-Route-User (URPRU) and User-Route-User (URU), to capture different semantic connections (e.g., users who visited routes with common places or users who visited the exact same route). We then employ the Metapath2Vec algorithm to perform random walks along these meta-paths, generating a relational embedding

– NCF-Based Collaborative Embedding: To incorporate collaborative signals from the broader user base, we utilize a Neural Collaborative Filtering (NCF) model. Our enhanced NCF model learns not only from user-route interactions but is also augmented with explicit features, including the user’s thematic profile and geographic center, and the route’s thematic composition and physical characteristics. This process yields a collaborative embedding

The fused user embedding is the concatenation of these two vectors:

• Multi-Signal Feature Vector: To move beyond static preferences, we engineer a feature vector that quantifies the dynamics and reliability of a user’s behavior. This vector includes:

– Interaction Confidence and Uncertainty: We compute a confidence score for user-POI interactions based on visit frequency, spatial consistency (i.e., re-visitation patterns), and geographic coherence (i.e., proximity to other visited POIs). We also model uncertainty by measuring preference variance across themes, data scarcity (total interaction count), and the variance in interaction confidence scores.

– Behavioral and Diversity Patterns: We analyze the user’s travel history to extract features such as theme transition stability, average route length, and visitation diversity (the ratio of unique themes/POIs visited to the total available). These features capture a user’s tendency toward exploration versus exploitation.

The representation for each route

• Hybrid Route Embedding: The core route embedding is created by fusing two distinct types of representations to capture both sequential and collaborative signals.

– RNN-Based Sequential Embedding: Since a route is fundamentally a sequence of places, we employ a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) with LSTM cells to model its sequential dynamics. Each route’s POI sequence is integer-encoded and padded to a uniform length before being fed into the LSTM, which generates a sequential embedding

– NCF-Based Collaborative Embedding: The identical NCF model described previously also learns a collaborative embedding for each route,

The fused route embedding is the concatenation of these two vectors:

where Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is applied to the RNN embedding for dimensionality reduction and noise filtering.

A rich POI representation,

• HIN-Based Structural Embedding: The Metapath2Vec model trained on the HIN provides a structural embedding for each POI, representing its role and relationships with users and routes within the entire information network.

• NCF-Based Contextual Embedding: To capture a POI’s function within actual itineraries, we derive a contextual embedding from the NCF model. This vector is computed as the mean of the NCF embeddings

The final POI embedding is the concatenation of these two vectors:

this hybrid embedding is used during the Anchor-and-Expand phase to calculate similarities.

4.1.4 Latent and Condition Vectors

With these components, we define the two primary inputs for CGAN:

1. Real Latent Vector: The ground-truth latent representation for a given route

2. Enhanced User Condition Vector: The condition vector that guides the generator is a comprehensive concatenation of the user’s fused embedding and multi-signal features:

4.1.5 Collaborative Augmentation for Sparse Users

To address the cold-start problem for users with sparse interaction histories, we introduce a collaborative augmentation mechanism. If a user’s interaction count falls below a predefined threshold

1. Identify the Top-K most similar users based on the cosine similarity of their explicit theme preference vectors.

2. Retrieve the enhanced condition vectors

3. The target user’s final, augmented condition vector,

where

4.2 Route Generation with Spectrally Normalized CGAN

The goal of our model is to learn a mapping from an enhanced user condition vector

Our CGAN architecture consists of a Generator, a Discriminator, and a Condition Encoder.

Generator: The generator’s G objective is to produce a realistic latent route vector

Discriminator: The objective of the discriminator D is to distinguish between real route latent

Condition Encoder: To ensure the generated route

4.2.2 Objective Functions and Training

The model is trained by optimizing a composite loss function.

Adversarial Loss: The model is trained through a standard min-max game between the generator and the discriminator. The objective function is defined as:

Condition Loss: To enforce conditional relevance, we penalize the generator if the latent vector it produces does not sufficiently encode the information from the condition vector. This is achieved by minimizing the Mean Squared Error (MSE) between the original condition vector and the one reconstructed by the condition encoder from the generated sample:

Overall Objective: The generator and condition encoder are jointly trained to minimize a weighted sum of the adversarial and condition losses, while the discriminator is trained to maximize the adversarial loss. The final loss for the generator is:

where

4.3 Anchor-and-Expand Algorithm

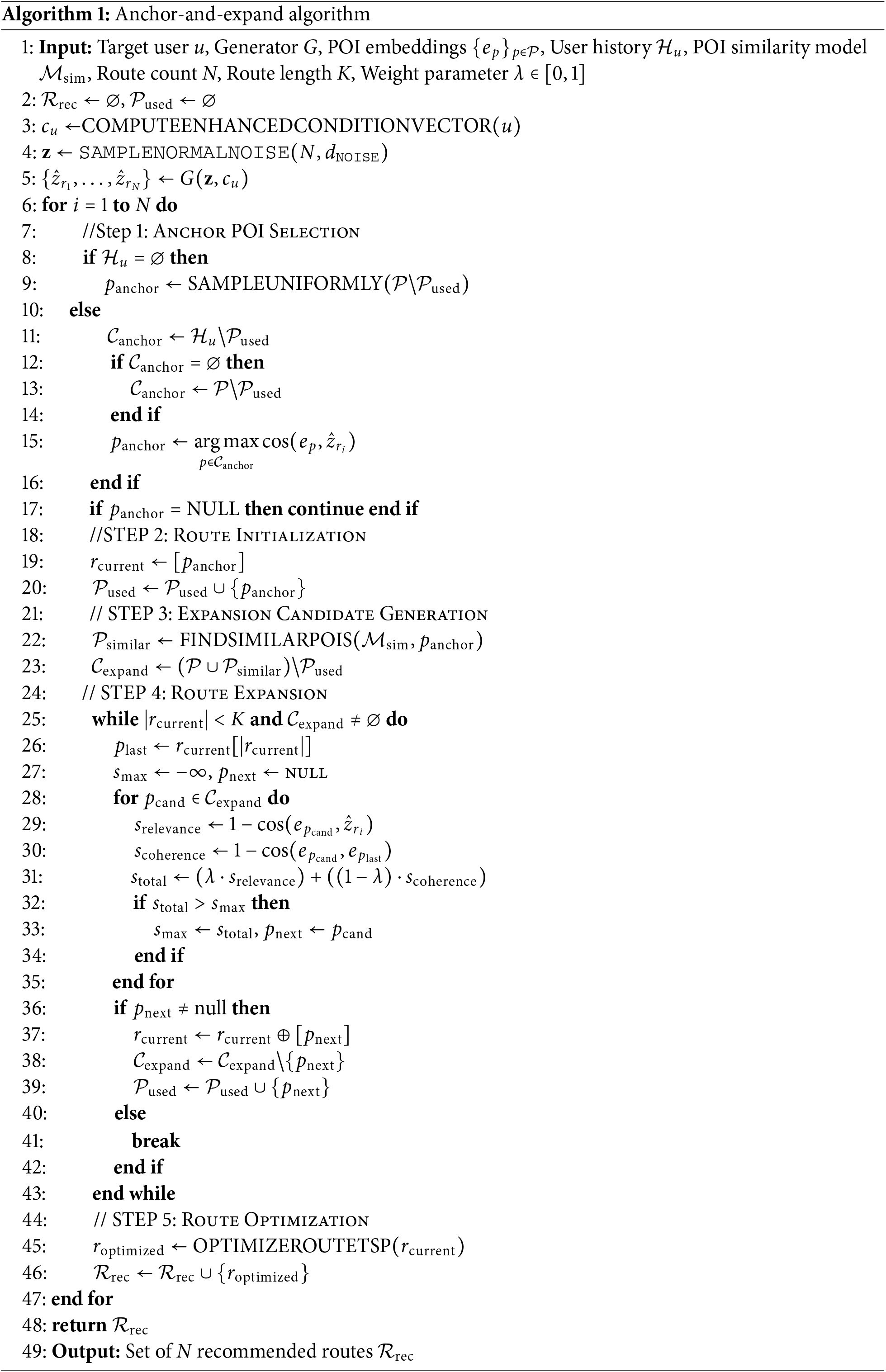

The final stage of our methodology involves translating the synthetic latent vectors produced by the CGAN into tangible and practical route recommendations. We utilize a novel Anchor-and-Expand algorithm, which ensures that recommendations are both personalized and coherent. The process is formally described in Algorithm 1.

A key contribution of this algorithm is its ability to address the cold-start problem, where effective recommendations must be generated for new users with none prior travel history. Our model tackles this by leveraging the collective travel patterns learned from data-rich users. For a new user, the system utilizes their explicitly stated thematic preferences and available demographic data to identify a cohort of existing users with similar profiles. By creating a synthesized profile that augments the new user’s sparse data with the rich, latent travel behaviors of this similar user group, the CGAN can generate a tailored latent vector even in the absence of historical data.

The algorithm initiates the recommendation process by generating a set of personalized latent route concepts, which is achieved by feeding the user’s unique ‘Collaborative Condition Vector’ into the pre-trained CGAN Generator. From there, the system employs an ‘Anchor-and-Expand’ strategy that adapts based on the user’s history. For an existing user with past travel data, each generated concept is first anchored to the most relevant Point of Interest (POI) from their actual travel history, ensuring the recommendation is grounded in their past, expressed behavior. Conversely, to address the cold-start problem for new users, the system first creates an enriched condition vector by identifying data-rich users with similar preferences and augmenting the new user’s sparse profile with their aggregated characteristics. Then, since the new user lacks a travel history, the initial anchor POIs for their recommendations are selected from the entire pool of valid POIs. Once the anchor POI is established for either user type, the algorithm expands the route by iteratively adding new POIs, selecting candidates that offer the best balance of relevance to the original latent concept and coherence with the previously added POI. This process ensures the final recommended route is not only optimized for the individual but is also logically connected.

This section presents a rigorous empirical evaluation of our proposed model. Our primary objectives are to: (I) assess the quality of the generated travel routes compared to the state-of-the-art methods; (II) validate the stability and robustness of the core CGAN component by examining its training dynamics and loss convergence; (III) analyze the fidelity and diversity of the generated routes by evaluating the latent space distribution and assessing performance across varying route lengths; and (IV) investigate the model’s effectiveness in addressing the cold-start problem by generating routes for users without travel history.

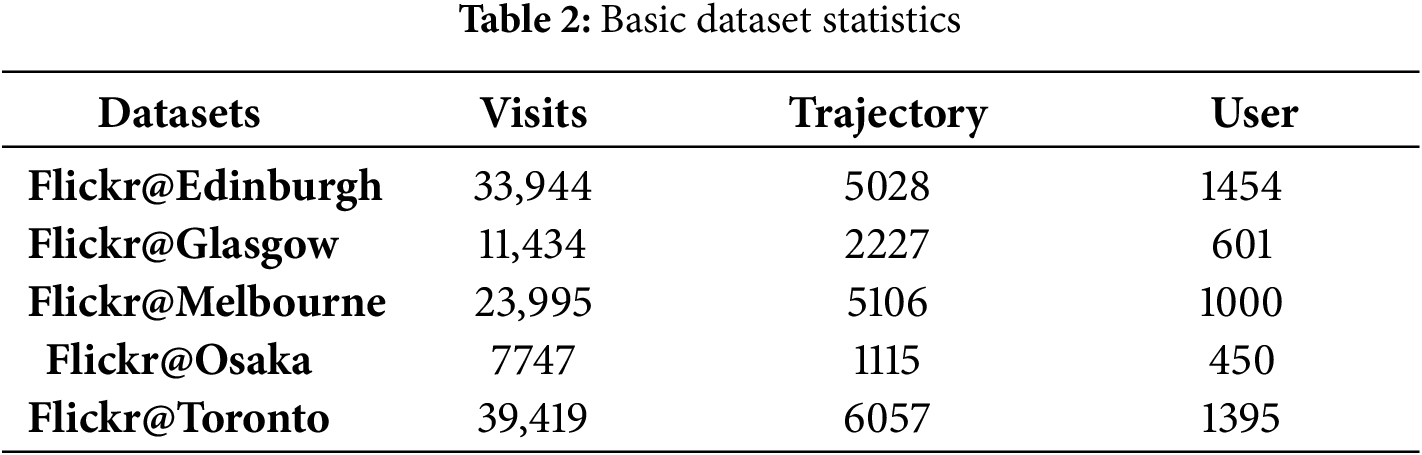

The datasets used in our experiments are shown in Table 2. The travel data in Edinburgh, Glasgow, Melbourne, Osaka, and Toronto were used in [31]. Each check-in is associated with GPS coordinates and some semantics (e.g., venue-categories).

Our experimental framework is built upon several key assumptions and is subject to certain constraints. We assume that the sequence of a user’s check-ins accurately reflects their actual travel path and that the thematic information and visit frequency of POIs are crucial indicators of latent user preferences. In line with the principles of implicit feedback, we treat unvisited POIs not as negative signals, but as potential positive candidates yet to be discovered by the user.

However, our study is constrained by the data’s lack of consistent temporal information, such as timeline of visiting or duration of stay, which were therefore excluded from our analysis. Furthermore, the dataset contains no explicit user feedback like ratings or reviews, forcing our model to rely entirely on the implicit signals derived from check-in histories.

(1) POIRank [32]: A two-stage method that first ranks POIs using RankSVM and then connects them into a trajectory based on their ranking scores.

(2) Markov and Markov-Rank [32]: Constructs a POI transition matrix and recommends trajectories based on Markov transitions and POI ranking.

(3) Path and Path-Rank [32]: Enhances Markov-based methods by using an integer linear program with sub-tour elimination constraints, adapted from the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP), to find the optimal path.

(4) DeepTrip [5]: A deep learning model that learns the implicit distribution of users’ sequential check-in data to capture complex spatio-temporal constraints and non-linear transition patterns between POIs.

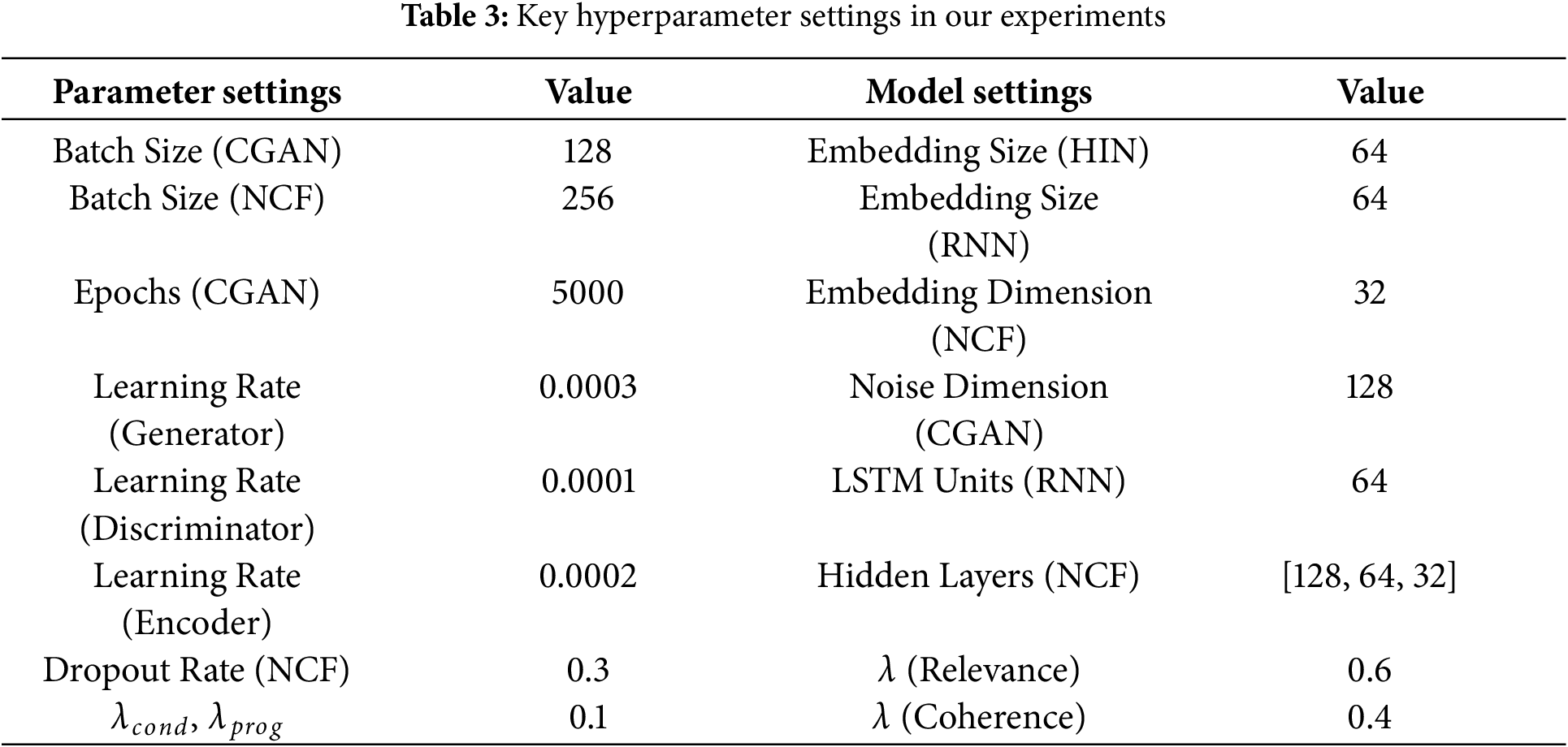

The proposed model was implemented on a machine with NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4080, Intel Core i7-13700F with 2.10 GHz, and 32 GB RAM. We use Windows 11 as an operating system. The implementation was developed in a Python 3.11.9 environment. Key libraries and their versions include: Pandas (2.2.3), NumPy (1.26.4), Scikit-learn (1.4.2), Tensorflow (2.12.0), NetworkX (3.3), Gensim (4.3.2), SciPy (1.10.1), Matplotlib (3.8.4), and Folium (0.16.0). The overall dataset was split into training (80%) and testing (20%) sets to ensure a robust evaluation of the model’s performance. The key hyperparameter settings used in our experiment is shown in Table 3.

To ensure the quality and relevance of the data for travel route recommendation, several preprocessing steps were performed:

1. First, we identified and excluded POIs associated with themes deemed irrelevant to tourism, such as ‘Office’, ‘Residential Accommodation’, ‘Vacant Land’, etc.

2. All data points corresponding to these excluded POIs, including their coordinates and visit frequencies, were subsequently excluded by the system.

3. Following this, we excluded user trajectories containing fewer than 3 distinct POIs to focus on meaningful travel sequences.

4. Finally, we constructed a comprehensive profile for each user by calculating the normalized visit frequency for every valid theme based on their historical check-ins. This process enriched the user profile with a quantitative measure of their thematic affinities, which was used as input for the recommendation models.

The overall model consists of five main neural network components: a Heterogeneous Information Network (HIN) for initial embeddings, a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) for sequence encoding, a Neural Collaborative Filtering (NCF) model for capturing user-item interactions, and a Conditional Generative Adversarial Network (CGAN) for generating new route recommendations, and an Anchor-and-Expand algorithm for translating generated latent vectors into tangible POI sequences.

• Heterogeneous Information Network (HIN): The HIN is constructed with three types of nodes: User, Route and Place. Edges are formed between users and the routes they have traversed (User-Route) and between routes and the POIs they contain (Route-Place). This structure creates a rich, multi-layered graph representing the complex relationships within the dataset. To learn node embeddings from this network, we utilize the Metapath2Vec algorithm. The selection of meta-paths is crucial as it defines the semantic relationships we aim to capture. We chose the following two schemas based on semantic meaningfulness and empirical validation:

(1) User-Route-Place-Route-User (URPRU): This primary meta-paths is designed to capture deep contextual similarities between users. By traversing from a user to a route they took, to the places within that route, and then back through another route to a different user, we can identify users who visit similar types of places, even if they haven’t visited the exact same ones. This captures shared interests in the underlying characteristics of the POIs, enabling the discovery of latent spatial preferences.

(2) User-Route-User (URU): This shorter meta-paths focuses on more direct user similarity. It identifies users who have embarked on the same routes, suggesting a higher degree of similarity in their travel behavior and preferences. This complements the URPRU schema by capturing explicit route-based similarities.

Next, we explain how meta-paths are sampled.

– Metapath Sampling: The embedding process is driven by meta-path-guided random walks with strict edge-type validation. For each node in the graph, we initiate 5 random walks, where the length of each walk is precisely determined by the length of the followed meta-path schema (e.g., 5 steps for URPRU). Unlike traditional random walks, these are constrained to follow the defined meta-path schemas through rigorous edge-type checking:

* Edge-Type Validation: When transitioning between node types (e.g., User

* Schema Adherence: Each walk must strictly follow the predefined node type sequence. Walks that cannot complete the meta-path due to missing connections are discarded to ensure semantic validity.

* Quality Control: A minimum count threshold is dynamically adjusted based on dataset size to balance vocabulary coverage and noise reduction.

This constrained sampling generates high-quality sequences of nodes that preserve the specific semantic relationships defined by our meta-paths. The sequences are then used to train a Word2Vec model with optimized hyperparameters: window size of 5, 10 training epochs, and 4 parallel workers. This produces semantically meaningful 64-dimensional embeddings for users and POIs.

Our implementation also includes comprehensive error handling for edge cases: (I) nodes with insufficient connections are assigned zero vectors as fallbacks, (II) empty meta-path generation triggers warning systems, and (III) the algorithm gracefully degrades performance rather than failing completely when encountering sparse connectivity patterns.

The random nature of the walk selection at each valid step ensures diverse exploration of the graph structure, while the meta-path constraints guarantee that the learned embeddings capture meaningful semantic relationships rather than arbitrary topological patterns.

• Route RNN: To encode the sequential nature of travel routes, we use an RNN with a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) layer. Each route, represented as a sequence of POI indices, is padded to a maximum length of 10 to ensure uniform input length. The model architecture is as follows:

(1) An embedding layer that maps the padded POI sequences into 64-dimensional vectors. This layer employs a masking mechanism to ensure that the padded zero-values are disregarded during subsequent computations, allowing the model to process variable-length sequences effectively.

(2) An LSTM layer with 64 units to process the sequence of embeddings.

(3) A dense output layer with 64 units and a linear activation function, producing a fixed-size latent vector for each route. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is then applied to these latent vectors with the number of components adaptively determined based on the statistical constraints of the data, ensuring mathematically valid dimensionality reduction. The optimal number of components is selected to respect both the target dimensionality and the intrinsic limitations imposed by the sample size and feature dimensionality of the training data.

The reason for applying PCA following the RNN embedding stage, rather than directly reducing the RNN’s output dimension, is rooted in a two-stage strategy designed to enhance the quality and robustness of the route representations. This approach first allows the RNN to learn a rich, high-dimensional latent representation, providing sufficient capacity to capture complex sequential dynamics. Subsequently, PCA serves as an unsupervised statistical method to optimally compress the learned embeddings while preserving the most informative variance components and filtering out noise-associated dimensions.

• Neural Collaborative Filtering (NCF): Our enhanced NCF model integrates both implicit feedback and explicit features.

– Inputs: The model takes four inputs: UserID, Route (Item) ID, a user feature vector, and a route feature vector. The user feature vector includes theme frequency vectors and geographical center coordinates. The route feature vector includes average theme vectors, POI count, and geographical information.

– Architecture: User and item IDs are first passed through separate embedding layers to create 32-dimensional latent vectors. These ID-based embeddings are then concatenated with their respective feature vectors. The resulting combined user and item vectors are concatenated and fed into an Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) consisting of three hidden dense layers with three ([128, 64, 32]) units and ReLU activation. A Dropout rate of 0.3 is applied after each hidden layer to prevent overfitting. The final output is a single node with a sigmoid activation for predicting the interaction probability.

• Conditional GAN (CGAN): The CGAN is responsible for generating new, personalized route latents. It consists of a Generator and a Discriminator.

– Generator: The generator takes a 128-dimensional random noise vector and a user condition vector as a input. These inputs are processed through separate branches, each containing a dense layer (256 units), batch normalization, and a LeakyReLU activation. The outputs are concatenated and passed through two additional blocks of Dense (512 units)

– Discriminator: The discriminator aims to distinguish real route latents from generated ones, conditioned on a user vector. Its inputs are a route latent vector and a user condition vector. To improve training stability, the model applies spectral normalization to its dense layers. The architecture is composed of two main blocks:

(1) Spectral Normalization (Dense (512))

(2) Spectral Normalization (Dense (256))

A final dense layer with a

• Anchor-and-Expand Algorithm: To translate the generated latent vectors from the CGAN into tangible POI sequences, we employ a novel Anchor-and-Expand algorithm. This process unfolds in three stages:

1. Latent Vector Generation: For a target user, the trained generator produces a set of personalized route latent vectors based on the user’s condition vector and random noise.

2. Anchor POI Selection: For each generated latent vector, an ‘Anchor’ POI is selected. This POI serves as the starting point for a new route. The anchor is chosen by identifying the POI from a pool of candidates (the user’s previously visited places or all valid POIs for cold-start users) whose embedding has the highest cosine similarity to the generated latent vector.

3. Iterative Route Expansion: Starting from the anchor POI, the route is iteratively expanded one POI at a time. In each step, the next POI is selected from a candidate pool of unvisited places. The selection is based on a scoring function that balances two criteria: (I) the cosine similarity between the candidate POIs embedding and the original generated latent vector (refers to relevance), and its similarity to the last POI added to the route (refers to coherence). After a full sequence is constructed, a Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP)-based optimization is applied to reorder the POIs for route efficiency.

To evaluate the performance of our model, we employed a comprehensive set of metrics designed to assess both traditional recommendation accuracy and the qualities of a generative system. For accuracy, we chose two metrics for performance comparison,

To quantitatively validate the core attributes of our generative CGAN model, we also assessed: Fréchet Distance (FD), Diversity, Novelty, and Serendipity.

Fréchet Distance measures the fidelity of the generated routes by calculating the similarity between the distribution of generated routes and real routes. A lower score indicates that the generated routes are structurally more authentic and closer to real-world travel data.

Diversity measures the variety within the set of recommended routes. This score reflects the unique characteristics of each city’s dataset, indicating how widely POIs are distributed in the learned embedding space. It is calculated as the average dissimilarity between all pairs of items in a recommended list

Novelty evaluates whether the system recommends new POIs that users have not previously visited. The novelty of a recommended list

Serendipity assesses the model’s ability to provide recommendations that are both unexpected and relevant. The serendipity scores validate that our model helps users make serendipitous discoveries. A common way to formalize serendipity is by combing relevance and unexpectedness.

5.7 Overall Performance Comparison

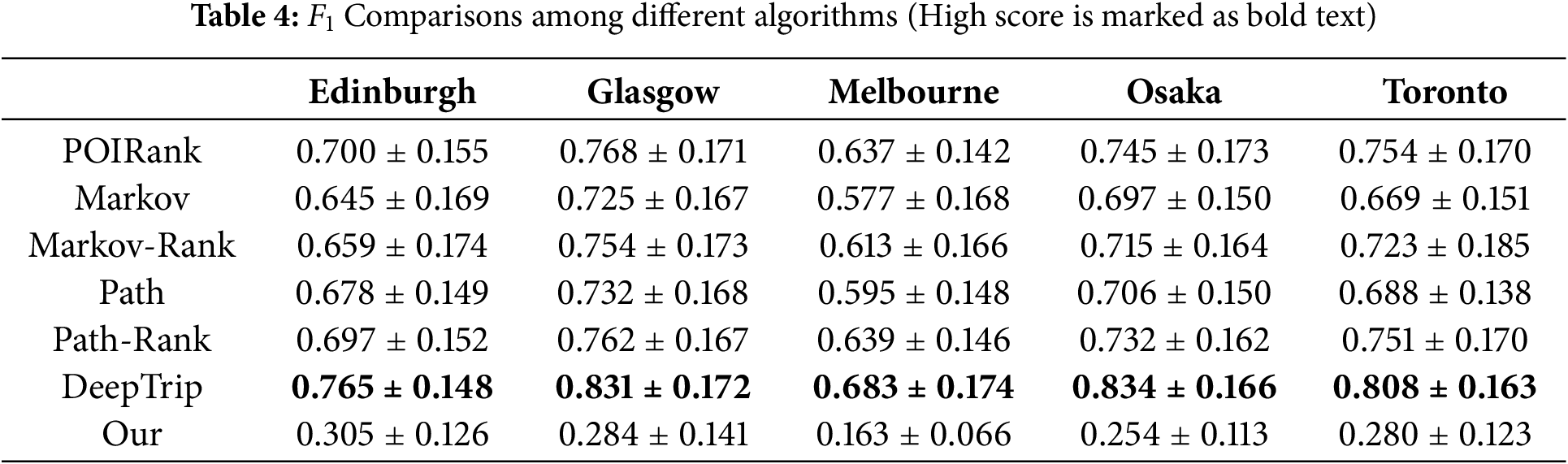

This experiment validates the performance of the proposed model in route recommendation by comparing it with state-of-the-art baseline models. The experimental evaluation reveals fundamentally different characteristics between our generative approach and existing recommendation systems, which are reflected in the evaluation metrics. The results of

(1) Our model achieved

The lower

Baseline methods achieved higher

(2) Our model demonstrated significantly lower

The

In contrast, baseline methods achieved high

(3) The lower performance on traditional metrics highlights a fundamental mismatch between evaluation paradigms for generative and recommendation systems:

• Traditional recommendation systems optimize for predicting users’ likely next actions based on historical patterns, making high

• As a generative system, our model explicitly aims to synthesize novel experiences that expand users’ travel horizons while respecting their thematic preferences, making low scores on historical-overlap metrics an indicator of success rather than failure.

(4) The experimental results provide compelling evidence that our model successfully fulfills its design objective of generating novel, personalized travel routes:

• Complete Route Novelty: Near-zero

• Thematic Coherence:

• Consistent Generative Behavior: The pattern of low traditional metrics but successful novel route generation is consistent across all five diverse geographic datasets.

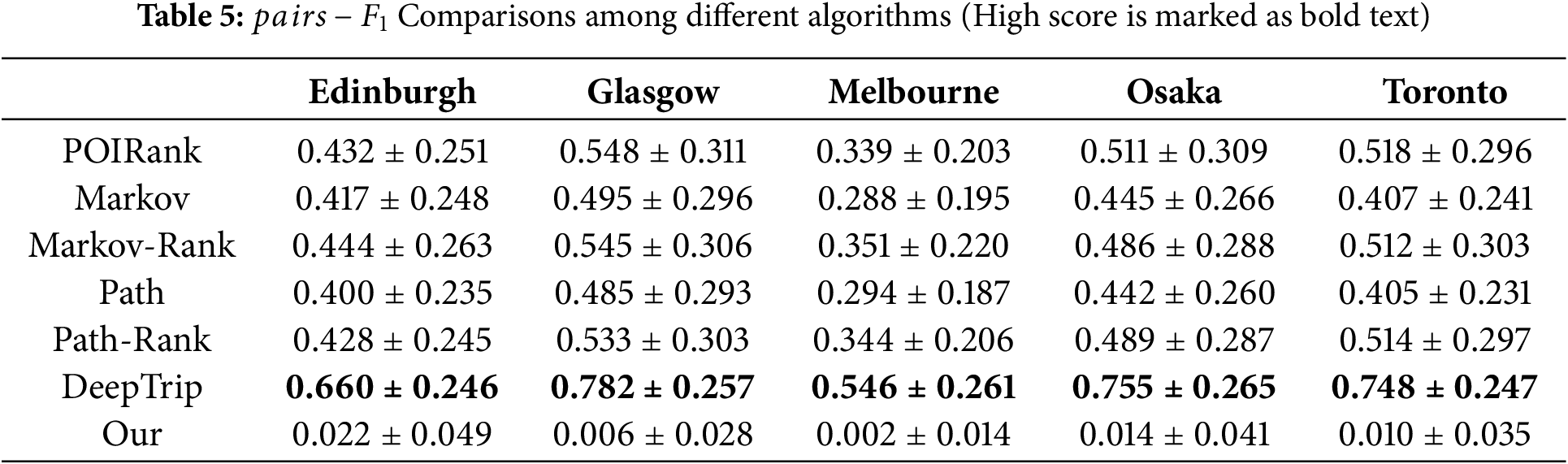

(5) To quantitatively validate that our CGAN was successfully trained as a generative model, we employed metrics to assess the core attributes of generated content: fidelity (Fréchet Distance), diversity, novelty, and serendipity. The results presented in Table 6, confirms that the model not only learned the underlying data distribution effectively but also excelled at creating new and meaningful travel experiences. These generative metrics strongly validate the effectiveness of our training process and model architecture:

• High-Fidelity Generation: The Fréchet Distance (FD) measures the similarity between the distribution of generated routes and real routes. A lower score indicates higher fidelity. Our model achieved consistently low FD scores across all datasets, with Osaka and Edinburgh demonstrating strong performance of 0.0176 and 0.0330 along with Glasgow, Toronto and Melbourne of 0.0332 to 0.0437. This confirms that our CGAN has successfully learned the underlying distribution of real-world travel data, generating routes that are structurally authentic.

• Diversity: The diversity metric reflects the variety within the set of recommended routes. This score is determined by the unique characteristics of each city’s dataset, reflecting how closely or widely its POIs are distributed in the learned embedding space. The results indicate that datasets with lower diversity scores, such as Glasgow, Osaka, and Melbourne range from 0.0889 to 0.1844, consists of POIs that are thematically similar and tightly clustered. In contrast, datasets with higher scores like Edinburgh and Toronto range from 0.2828 to 0.3238, feature more thematically distinct and dispersed POIs.

• Novelty and Serendipity: The scores for novelty ranging from 0.6955 to 0.8390 and serendipity ranging from 0.7169 to 0.9433 are crucial indicators of the model’s success. High novelty confirms that the system recommends new POIs that users have not previously visited. High serendipity indicates that the recommendations fulfill the core goal of helping users make serendipitous discoveries by recommending unexpected but relevant places.

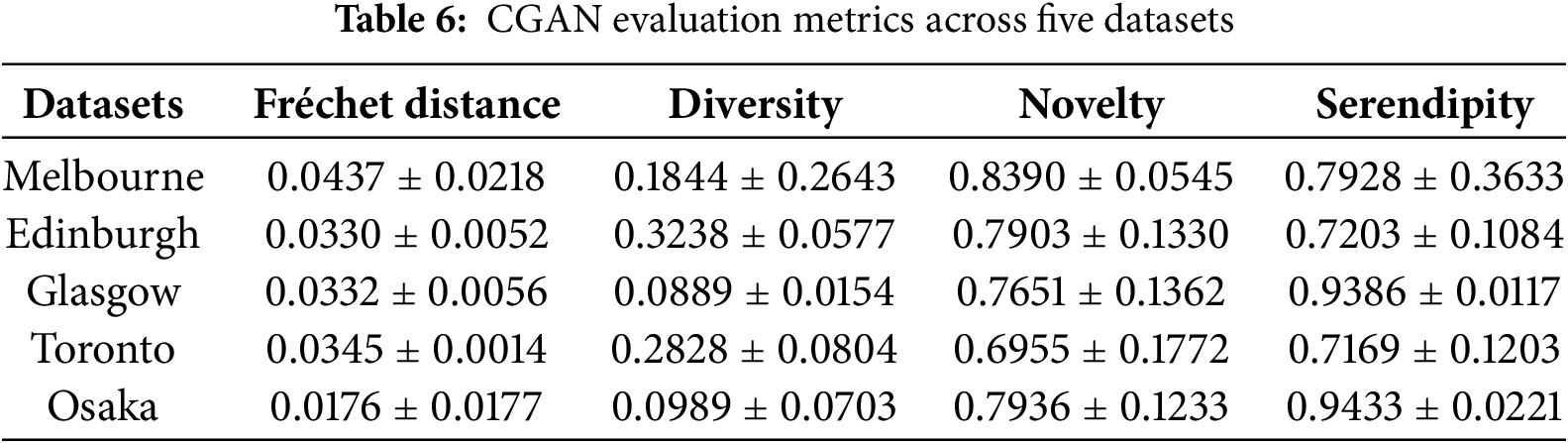

In this part, we provide a explanation results of baseline models: POIRank, Markov-Rank, Path-Rank, DeepTrip, and ours based on their respective trained models. We tested with Melbourne dataset. Fig. 5a is a route recommended by POIRank, Fig. 5b is a route recommended by Markov-Rank, Fig. 5c is a route recommended by Path-Rank, Fig. 5d is a route recommended by DeepTrip, and Fig. 5e is a generated route recommended with CGAN.

Figure 5: Recommendation results with different methods. (a) The result from POIRank, which recommends a route with diverse POIs but lacks novelty, including previously visited locations. The pink pin indicates the starting point, blue stars represent previously visited POIs, orange pins are the recommended POIs, the red pin is the destination, and the red line shows the recommended route. (b) The result from Markov-Rank, which provides a more natural path but is inefficient, forming a zig-zag pattern, and also fails to recommend novel places. The pink pin is the starting point, blue stars are previously visited POIs, orange pins are the recommended POIs, the red pin is the destination, and the red line shows the recommended route. (c) The result from Path-Rank, which, due to high computational complexity, fails to generate a complete route and recommends only two POIs. The pink pin is the starting point, blue stars are previously visited POIs, orange pins are the recommended POIs, the red pin is the destination, and the red line shows the recommended route. (d) The result from DeepTrip, which generates a realistic route (red line) but fails to provide a novel experience as it mirrors a route the user had previously taken (blue line). The pink pin is the starting point, blue stars are previously visited POIs, orange pins are the recommended POIs, and the red pin is the destination. (e) The result from our proposed CGAN model, which successfully generates a completely novel route. The pink pin is the starting point, the blue pin is the user’s last visited location, orange pins are the recommended novel POIs, and the red pin is the destination. The red line is the recommended route, and the black dotted line shows the path from the last visited location to the start of the new route. (Map data: © OpenStreetMap contributors), (Icons by https://icons8.com/icons)

POIRank as shown in Fig. 5a, utilizes RankSVM to learn features of individual POIs (e.g., category, popularity, distance) and connects the highest-scoring ones in sequence. This approach offers a chance to experience diverse locations by recommending POIs across various areas. However, it demonstrates a significant weakness in providing novel recommendations. Both the start and end points were places the user had already visited. Furthermore, the recommended route also included previously visited POIs, indicating an overall failure to introduce new experiences.

Markov-Rank as shown in Fig. 5b, improves upon POIRank by considering the transition probabilities between POIs, resulting in a more natural and realistic travel path. Nevertheless, it shares a similar limitation: the start and end points were again selected from the user’s visit history. Moreover, the path was observed to be inefficient, forming a zig-zag pattern across the city, which diminishes its practicality.

Path-Rank as shown in Fig. 5c, is designed to provide a highly optimized and practical route by incorporating sub-tour elimination constraints using Integer Linear Programming (ILP), which theoretically ensures an efficient, non-repeating path. In our experiment, however, the model failed to deliver on this promise. It recommended only two POIs, suggesting that it could not find an optimal long route within a reasonable time frame due to the high computational complexity of its constraints.

DeepTrip, as shown in Fig. 5d, deeply learns the sequential and spatio-temporal relationships between POIs. The recommended route, therefore, presents a smooth and consistent path with a natural and logical flow, successfully modeling realistic movement trajectories. Despite this realism, its critical weakness was its failure to provide a novel experience, as it had recommended places the user had already visited, also showed a route pattern (blue line) which user had went through.

In contrast, our CGAN model as shown in Fig. 5e, successfully generated a completely new route. It also shows the path from the user’s last visited location to the starting point of the recommended route (indicated by the dotted black line). Crucially, all POIs within the generated route were places the user had never visited before, demonstrating our model’s strength in creating genuinely novel and personalized travel experiences. This highlights a paradigm shift from route optimization to route generation, where metrics like

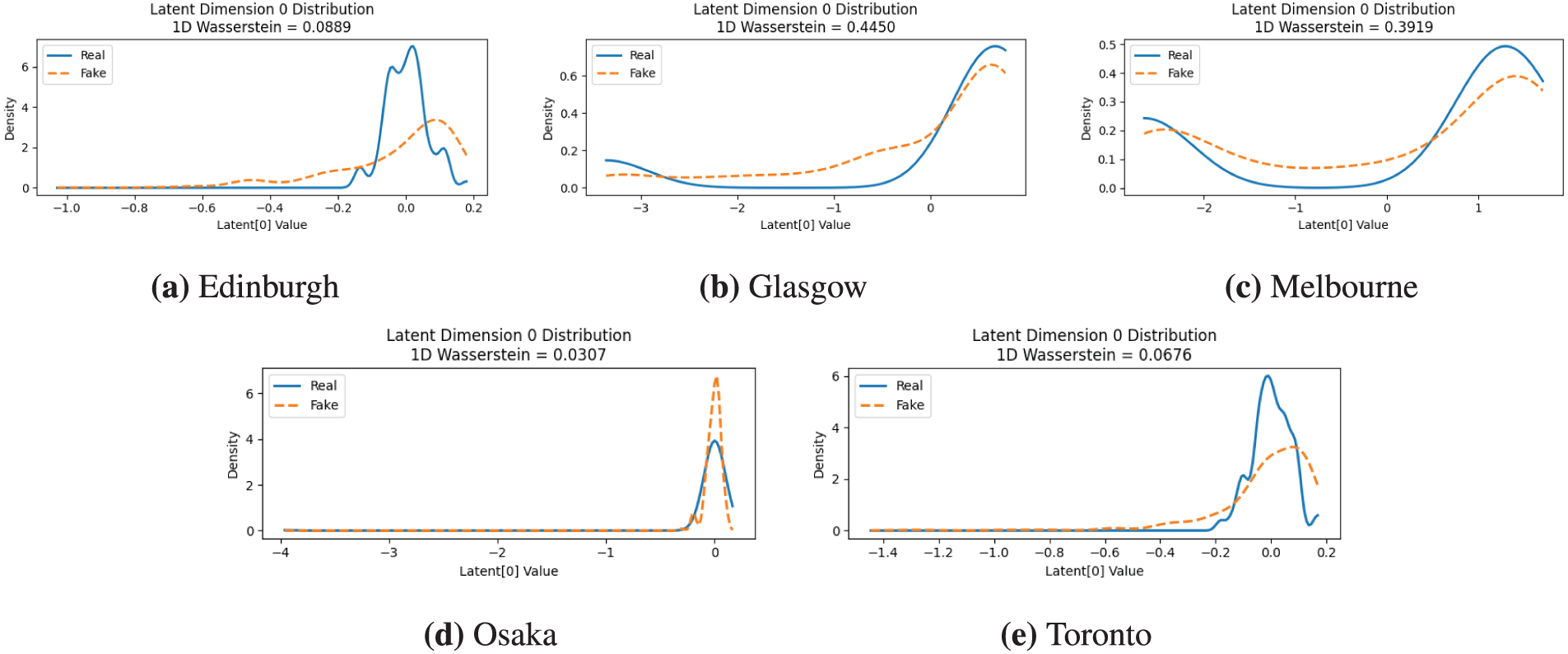

This section provides an in-depth analysis of the Conditional Generative Adversarial Network’s (CGAN) performance in learning the latent distribution of travel routes. A critical aspect of this evaluation is assessing the model’s ability to replicate the distribution of Latent Dimension 0. As established in our methodology, this dimension is not an arbitrary feature; it is the first Principal Component (PC1) derived from the Route RNN embeddings. Academically, PC1 is defined as the axis of maximum variance within the high-dimensional space of route embeddings. It represents the single most dominant structural pattern that distinguishes one route from another across the entire dataset. For instance, if the primary structural difference between routes in a city is their scale and density (e.g., short, dense urban paths or long, sprawling suburban tours), PC1 is precisely the variable that captures this fundamental characteristic. Therefore, the generator’s success in accurately modeling the distribution of Dimension 0 is a direct indicator of its ability to learn the most crucial structural essence of routes in a given city.

A comparative visualization of the real and generated (fake) distributions for Latent Dimension 0 is presented in Fig. 6, with the 1D Wasserstein distance offering a quantitative measure of similarity. The model demonstrates its highest fidelity on the Osaka, achieving a low Wasserstein distance of 0.0307. As seen in Fig. 6d, the generated distribution almost perfectly overlays, indicating a successful capture of the highly consistent structural pattern in Osaka’s routes. Toronto and Edinburgh also showed strong performance, with low Wasserstein distance of 0.0676 and 0.0889, respectively. In both cases (as shown in Fig. 6a,e), the generator identifies the primary mode of the real distribution, although the generated curves exhibit slightly broader variance and do not fully capture the sharpness of the real peaks. This suggests a successful approximation of the main pattern but with less precision on the finer statistical details. Conversely, the model faced greater challenges with the more complex distributions of Glasgow and Melbourne (as shown in Fig. 6b,c). The Melbourne presents a bimodal distribution, and while the generator correctly learns this bimodal nature; it struggles to perfectly align the location and density of its generated peeks, resulting in a Wasserstein distance of 0.3919. The Glasgow proved most challenging, yielding the highest Wasserstein distance of 0.4450. Here, the generator failed to replicate the sharp, skewed peak of the real distribution, producing a much flatter and more uniform curve instead.

Figure 6: Comparison of real and generated distributions for Latent Dimension 0. In each panel, the solid blue line represents the distribution from the real data, while the dashed orange line shows the distribution generated by the model. The 1D Wasserstein distance quantifies the similarity, with lower values indicating a better match. The panels display the results for five different cities: (a) Edinburgh, where the model captures the primary mode but with a broader variance (Wasserstein distance =

This discrepancy in performance highlights a key challenge inherent in generative models: the difficulty of accurately replicating complex, multi-modal, or sharply skewed data distributions, particularly when learning from sparse, implicit feedback. The generator’s struggles in the Melbourne and Glasgow datasets can be attributed to several interconnected factors:

• Data Heterogeneity and Sparsity: The Osaka, Toronto, and Edinburgh datasets likely feature more uniform and dominant travel patterns, resulting in a clearer, unimodal latent distribution that the generator can learn effectively. In contrast, the distribution in Melbourne and the sharp, skewed peak in Glasgow suggest more diverse and heterogeneous travel behaviors. When faced with such diverse patterns, especially with sparse implicit data [33] where no negative feedback is available, the generator may oversimplify the distribution, failing to capture all existing modes or smoothing out sharp peaks [34].

• Mode Collapse Tendencies: While spectral normalization [35] stabilizes training, it does not completely eliminate the risk of partial mode collapse [36], a common issue in GANs. In the Glasgow case, the generator’s failure to replicate the sharp peak, instead producing a flatter curve, is a classic symptom. It learns the general location of the data but fails to capture the high density of a specific, dominant pattern, opting for a safer, more averaged-out generation. Similarly for Melbourne, the generator identifies both modes but struggles with their precise shape and density, indicating difficulty in balancing its learning across multiple distinct data clusters.

• Limitations of the Conditional Vector: The conditional vector, though rich, compresses a user’s entire profile into a single, fixed-size representation [37]. This can act as an information bottleneck [38]. For users with highly varied or multi-modal preferences—which may be more prevalent in the complex Glasgow and Melbourne datasets–the vector might average out these nuances. As a result, the generator receives a blended signal that doesn’t provide enough specific guidance to reproduce the sharp, distinct features of the true data distribution.

To mitigate these challenges, future work could explore several advanced techniques. As will be detailed in Section 6, this includes adopting more sophisticated GAN architectures, refining the loss function to promote diversity, and employing hierarchical or autoregressive generation processes to better handle complex data structures.

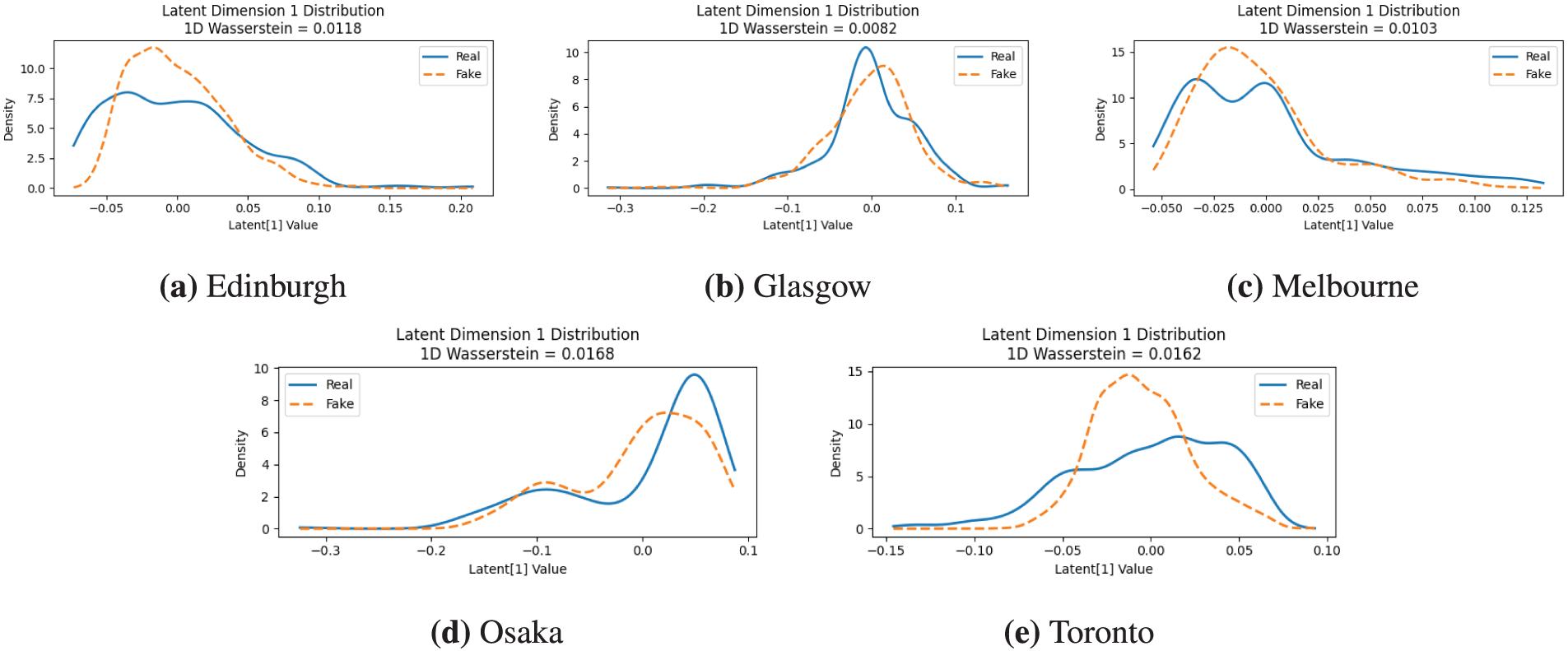

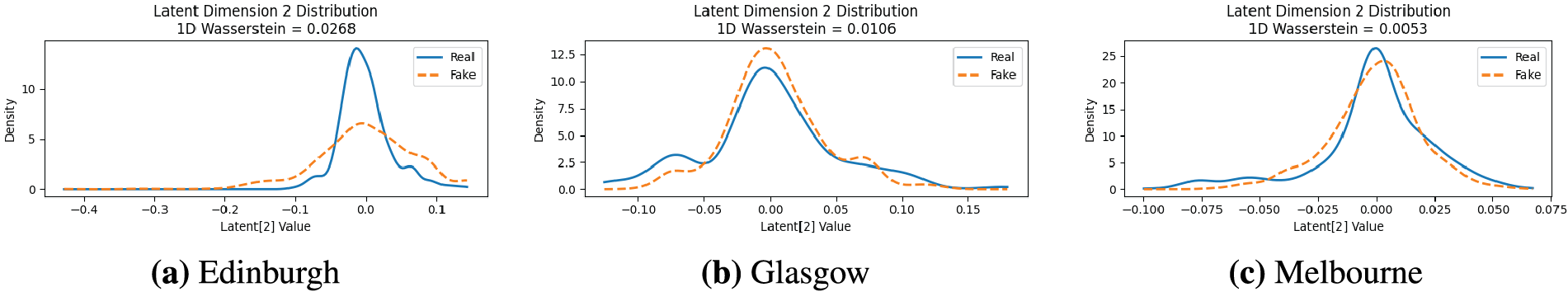

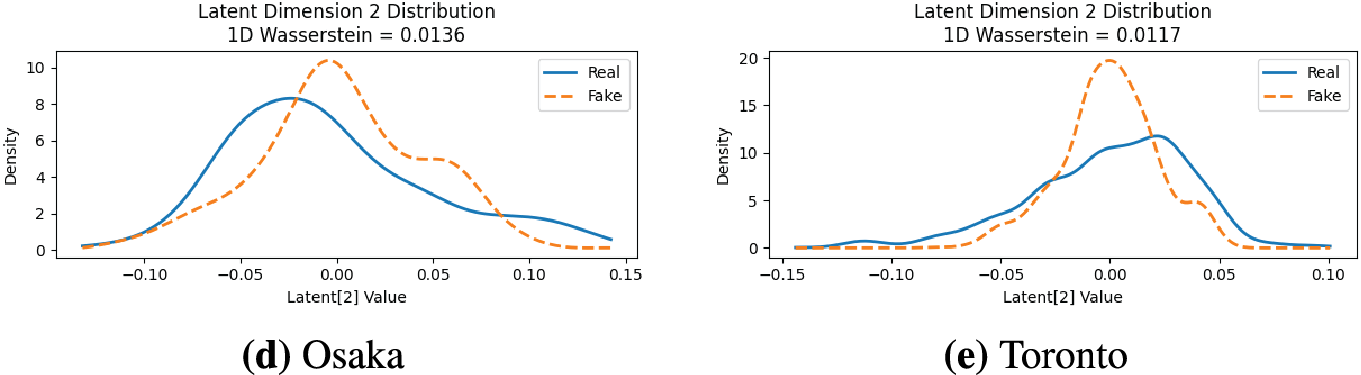

Beyond the primary component, we analyze Dimension 1 (the second Principal Component, PC2) to assess the model’s ability to capture secondary structural patterns. PC2 is defined as the axis orthogonal to PC1 that captures the maximum remaining variance. Its academic significance lies in representing the most prominent structural pattern that is uncorrelated with the primary pattern of PC1. PC1 captures a route’s scale and density, PC2 captures an independent characteristic such as its topology; distinguishing between circular routes and linear, one-way paths. As shown in Fig. 7, the CGAN demonstrated remarkable proficiency in modeling this second dimension. Notably, the model for Glasgow (as shown in Fig. 7b) achieved a low Wasserstein distance of 0.0082, with the generated distribution closely tracking the real data. Similarly, Edinburgh and Melbourne (as shown in Fig. 7a,c) demonstrate fidelity with Wasserstein distance of 0.0103 and 0.0118. Osaka and Toronto (as shown in Fig. 7d,e) also perform well, successfully capturing the general shape of their respective distributions, including the bimodal nature of the Osaka data.

Figure 7: Comparison of real and generated distributions for Latent Dimension 1. This dimension captures secondary structural patterns, such as a route’s topology. In each panel, the solid blue line represents the distribution from the real data, while the dashed orange line shows the distribution generated by the model. The 1D Wasserstein distance quantifies the similarity, with lower values indicating a better match. The panels display the results for five different cities: (a) Edinburgh, where the model demonstrates fidelity in capturing the distribution’s shape (Wasserstein distance = 0.0118). (b) Glasgow, where the generated distribution closely tracks the real data, achieving a very low Wasserstein distance of 0.0082. (c) Melbourne, also showing high fidelity between the real and generated distributions (Wasserstein distance = 0.0103). (d) Osaka, where the model successfully captures the bimodal nature of the real distribution (Wasserstein distance = 0.0168). (e) Toronto, where the generator also performs well in capturing the general shape of the distribution (Wasserstein distance = 0.0162)

Further, we evaluate the model’s performance on Dimension 2 (the third Principal Component, PC3). This dimension is defined as the axis orthogonal to both PC1 and PC2 that explains the next largest portion of variance. It captures the most significant structural difference among routes not already accounted for by the first two components, such as the tendency to pass through a specific central hub or the thematic consistency between a route’s start and end points. The model’s ability to learn this tertiary-level detail is confirmed in Fig. 8. The results showed strong performance, with Melbourne in Fig. 8c reaching Wasserstein distance of 0.0053, along with Glasgow 0.0106, Toronto 0.0117, Osaka 0.0136, Edinburgh 0.0268 (as shown in Fig. 8a,b,d,e).

Figure 8: Comparison of real and generated distributions for Latent Dimension 2. This dimension captures tertiary-level structural details, such as the tendency for a route to pass through a central hub. In each panel, the solid blue line represents the distribution from the real data, while the dashed orange line shows the distribution generated by the model. The 1D Wasserstein distance quantifies the similarity, with lower values indicating a better match. (a) Edinburgh, where the generator replicates the concentrated peak of the real distribution, resulting Wasserstein distance of 0.0268. (b) Glasgow, where the model successfully captures the primary peak but struggles to fully replicate the more subtle secondary modes of the complex real distribution (Wasserstein distance = 0.0106). (c) Melbourne, demonstrating the best performance, where the generated distribution almost perfectly overlays the sharp, narrow peak of the real data (Wasserstein distance = 0.0053). (d) Osaka, where the model correctly identifies the bimodal nature of the data but with minor inaccuracies in the location and density of the peaks (Wasserstein distance = 0.0136). (e) Toronto, where the model captures the general location of the distribution well, but represents it with a sharper peak compared to the broad, flat-topped shape of the real data (Wasserstein distance = 0.0117)

5.9.2 Effects of Hyperparameter in Generator Loss

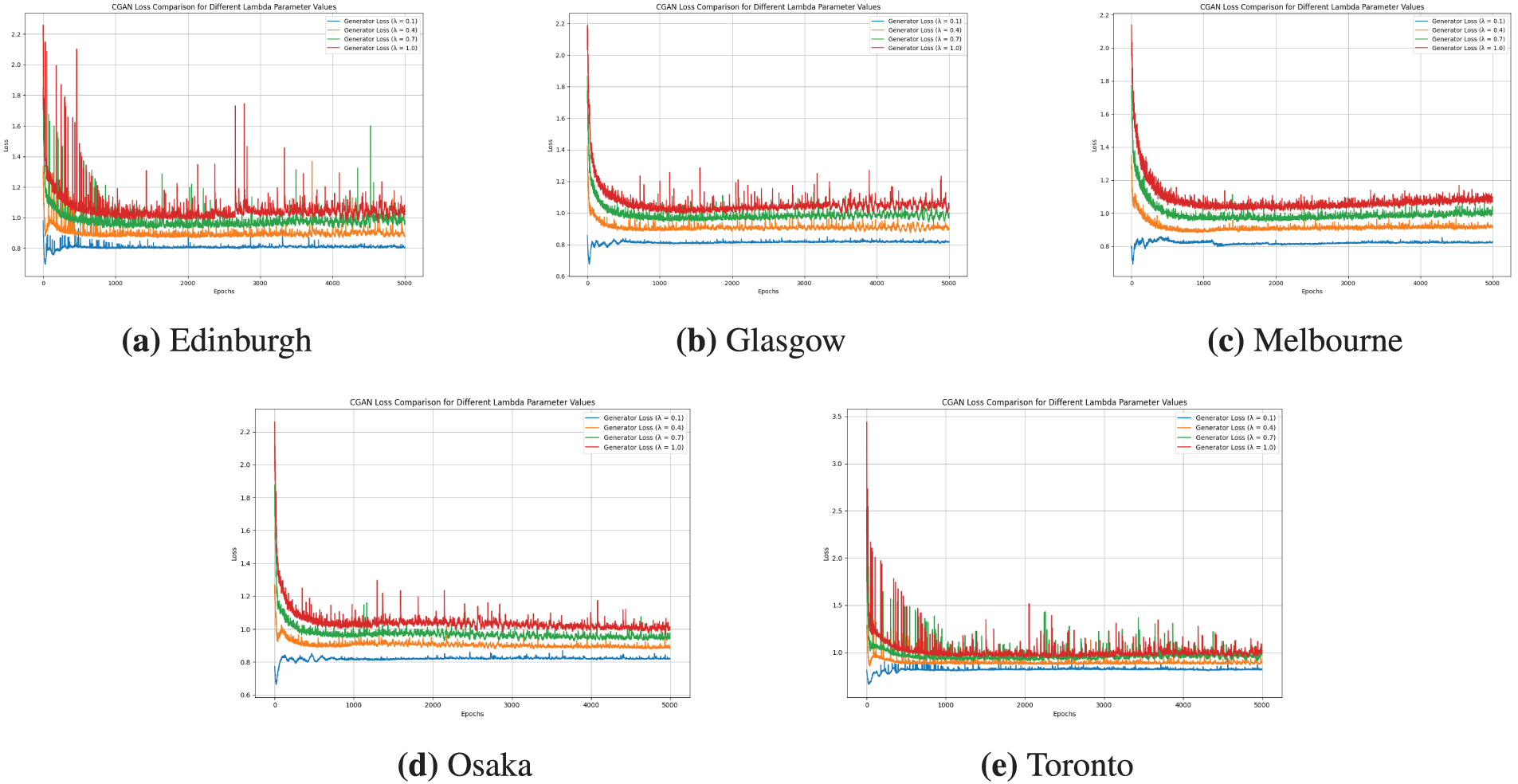

In our generator’s loss function as defined in the Eq. (8), the hyperparameters

This approach of equating the two hyperparameters was chosen for two primary reasons. First, it makes the hyperparameter search more tractable, avoiding a computationally expensive grid search across a two-dimensional space. Second, both

The results are presented in Fig. 9. A clear and consistent pattern emerged across all datasets.

Figure 9: Effect of the hyperparameter

Based on this empirical evidence, we selected hyperparameter as 0.1 for both

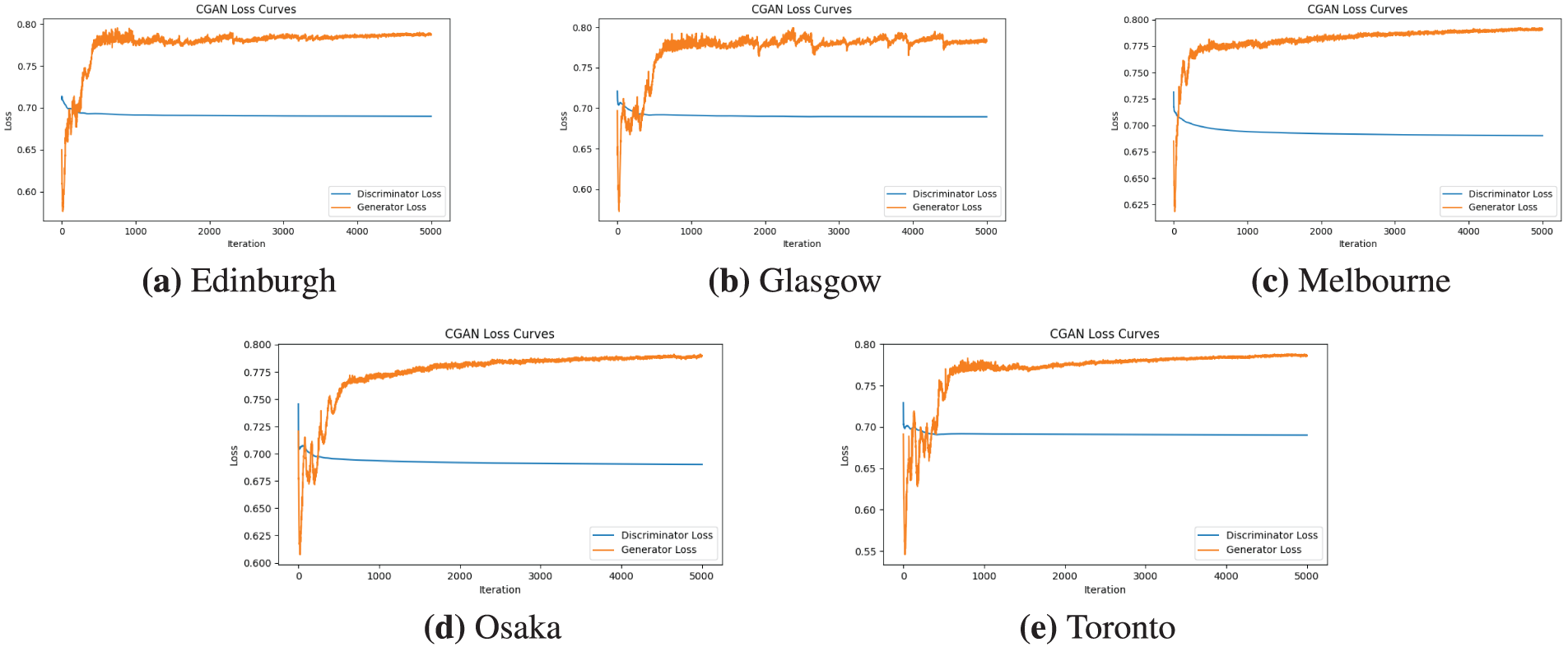

In addition to the quality of the latent space, the stability of the training process is a crucial indicator of the model’s robustness. We analyzed the training dynamics by examining the loss curves of the generator and discriminator across the five datasets, as presented in Fig. 10. A consistent pattern of stable convergence was observed in all cases, which is a hallmark of a well-behaved and effective Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) training process.

Figure 10: CGAN loss curves for the generator and discriminator, demonstrating training stability across five datasets: (a) Edinburgh, (b) Glasgow, (c) Melbourne, (d) Osaka, and (e) Toronto. For each dataset, the discriminator loss is represented by the blue line and the generator loss by the orange line. The plots consistently show stable convergence over 5000 iterations, with the discriminator loss settling around 0.69 and the generator loss around 0.78. This pattern indicates a well-balanced and robust adversarial training process, avoiding common issues like mode collapse

Across all datasets, the discriminator loss (the blue line) rapidly decreased from its initial state and converged to a stable value of approximately 0.69. This indicates that the discriminator quickly learns to effectively distinguish between real and generated route representations. Concurrently, the generator loss (the orange line) increased from a lower initial value and also stabilized approximately 0.78, reflecting the generator’s successful adaptation to the improving discriminator by producing increasingly plausible latent vectors.

Crucially, the convergence of both loss functions to stable equilibrium points, without divergence or erratic oscillations, confirmed that the model avoided common GAN training pitfalls such as mode collapse. This robust training stability can be attributed to key architectural choices in our model, particularly the use of Spectral Normalization in the discriminator, which effectively regularizes the training dynamics and ensures a balanced adversarial game between the two networks.

5.9.4 Latent Space Visualization via t-SNE

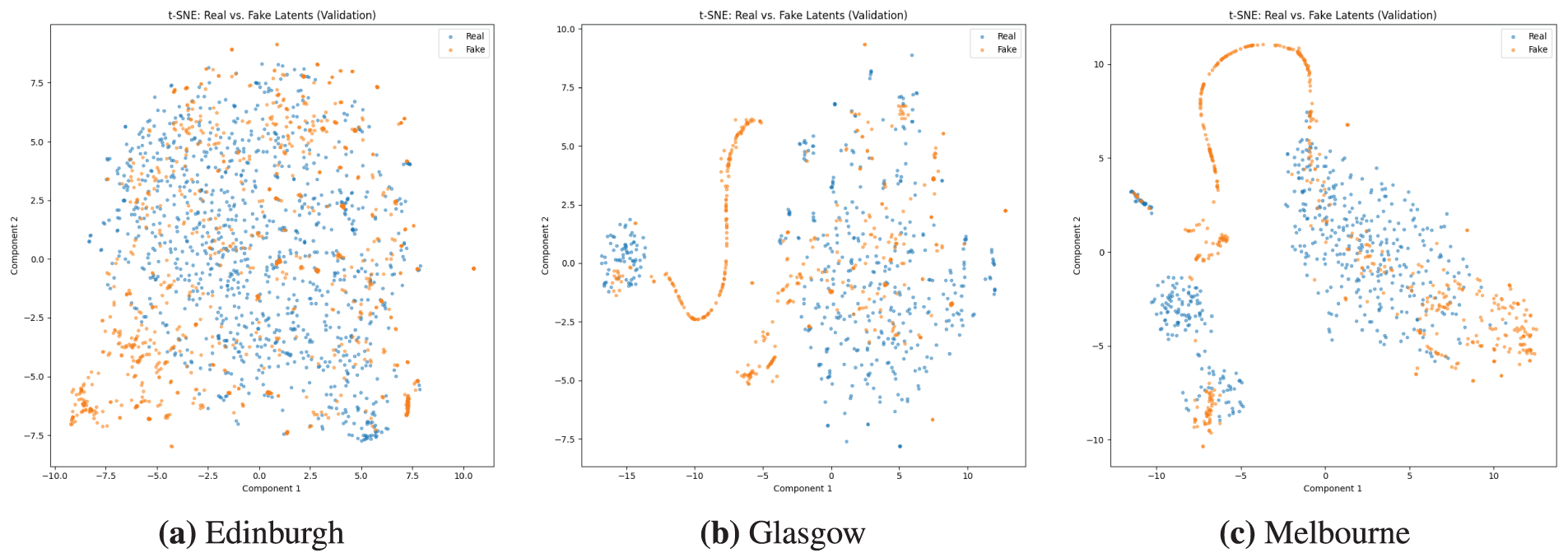

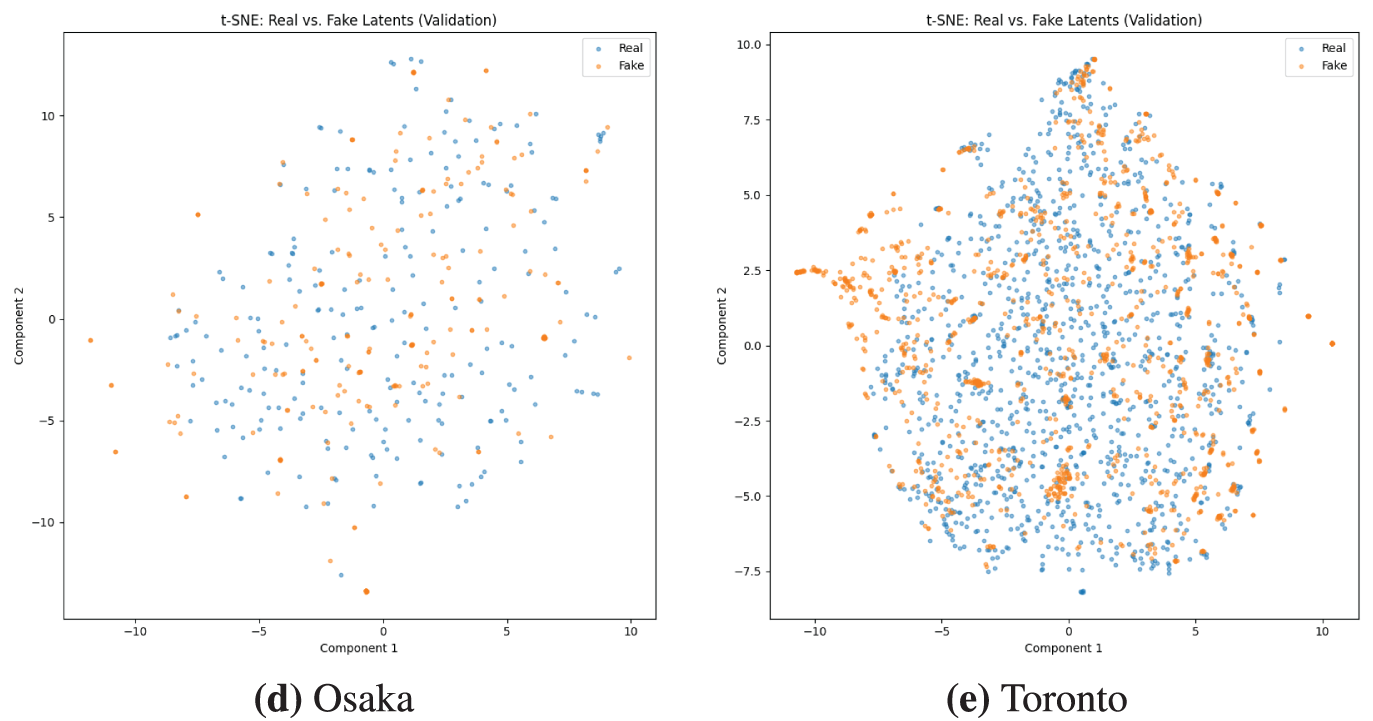

To qualitatively assess the fidelity and diversity of the generated route representations, we employ t-SNE (t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding) to visualize the high-dimensional latent space in two dimensions. This technique allows for a direct visual comparison between the distributions of real latent vectors from the dataset and the fake vectors produced by our CGAN generator. An ideal generator would produce a distribution of fake points (the orange dots) that is indistinguishable from the distribution of real points (the blue dots), meaning they should be well-mixed and occupy the same manifold.

The t-SNE visualizations for all five datasets are presented in Fig. 11. The results provide a nuanced view of the model’s performance, corroborating our quantitative findings from the latent dimension analysis. For Osaka and Toronto, the plots show a high degree of overlap and mixture between the real and generated data points. The two distributions are well-interspersed, indicating that the generator is successfully creating a diverse set of latent vectors that are structurally similar to the real ones. The Edinburgh plot also demonstrates a good mixture, though with some minor instances of generated clusters forming at the periphery of the real data distribution, suggesting a slightly less comprehensive but still effective capture of the data manifold.

Figure 11: A t-SNE visualization comparing the distributions of real (blue dots) and generated (orange dots) latent vectors from the validation set across five different datasets. A well-mixed distribution indicates that the generator is successfully capturing the diversity and structure of the real data manifold. The panels show the results for: (a) Edinburgh, which demonstrates a good mixture with some minor generated clusters on the periphery; (b) Glasgow, which reveals partial mode collapse, with generated samples forming a distinct arc-like artifact in a region not populated by real data; (c) Melbourne, shows evidence of partial mode collapse with dense, generated clusters and arcs outside the real data distribution; (d) Osaka, displays a high degree of overlap and interspersion between real and fake points ; and (e) Toronto, which also demonstrates a well-mixed distribution, indicating high-fidelity generation

Conversely, the visualizations for Melbourne and Glasgow reveal a more complex outcome. While the generator successfully populates the main clusters occupied by the real data, both plots exhibit clear evidence of partial mode collapse, where the generated samples form distinct, dense artifacts that are visible as arcs or isolated clusters in regions not populated by real data points. This phenomenon suggests that for datasets with more intricate underlying structures, the generator, while capable of learning the primary data modes, also tends to converge on and overproduce certain specific types of latent structures. This qualitative analysis confirms that the model’s performance is dataset-dependent, excelling where route patterns are more uniform and facing challenges with more heterogeneous distributions [39].

5.9.5 Diverse POI Recommendation

To assess the model’s capability to generate routes of varying lengths, we analyzed on the number of recommended Points of Interest (POIs), denoted by

The results as shown in Fig. 12, across all five datasets, performance generally degraded as the route length

Figure 12: Diverse POI recommendation. This presents a sensitivity analysis of the model’s performance based on the diverse number of POI recommendation (

While datasets for Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Toronto (as shown in Fig. 12a–c) show a relatively monotonic increase in FID with route length, an exception was observed in the Osaka and Melbourne datasets. In both cases, the model achieved a better FID score for routes of length

5.9.6 Ablation Study: Impact of Anchor-and-Expand Algorithm

To isolate the specific contribution of our proposed route generation strategy, we conducted a detailed ablation study on the Anchor-and-Expand algorithm. This experiment compares the performance of our model against a variant where the Anchor-and-Expand component is removed. In the simplified variant, routes are generated by directly selecting the top-K POIs that have the highest cosine similarity to the generated latent vector

The results from Fig. 13 reveal a critical trade-off inherent in the recommendation process. The model variant without the Anchor-and-Expand algorithm consistently achieved higher scores in both diversity and novelty. This is an expected outcome, as a less constrained decoding process naturally produces a wider and more unfamiliar range of POIs. However, this increase in raw novelty comes at a significant cost to the quality of the recommendation.

Figure 13: Ablation study on the impact of the Anchor-and-Expand algorithm. The charts compare the performance of the full model with the algorithm (blue bars) against a model variant without it (red bars). The results highlight a critical trade-off: while removing the algorithm leads to higher scores in diversity and novelty, its inclusion consistently and substantially boosts serendipity, demonstrating its essential role in generating high-quality, unexpectedly relevant user experiences. The performance comparison across the five city datasets is as follows: (a) For the Edinburgh dataset, including the algorithm changes the scores for Diversity from 0.491 to 0.349 and Novelty from 0.892 to 0.795, while increasing Serendipity from 0.541 to 0.681. (b) For the Glasgow dataset, the algorithm’s inclusion alters the scores for Diversity from 0.141 to 0.097 and Novelty from 0.878 to 0.819, while Serendipity improves from 0.895 to 0.927. (c) For the Melbourne dataset, there is a notable trade-off, with Diversity dropping from 0.621 to 0.143 and Novelty from 0.975 to 0.849, but Serendipity surging dramatically from 0.296 to 0.857. (d) For the Osaka dataset, Diversity decreases from 0.632 to 0.113 and Novelty from 0.898 to 0.834, in exchange for a significant increase in Serendipity from 0.563 to 0.941. (e) For the Toronto dataset, including the algorithm results in Diversity changing from 0.511 to 0.296 and Novelty from 0.896 to 0.807, while boosting the Serendipity score from 0.594 to 0.781

The most crucial finding of this study is the consistent and substantial outperformance of the model in terms of serendipity. Across all five datasets, the inclusion of the Anchor-and-Expand algorithm led to significantly higher serendipity scores. For instance, in the Melbourne dataset, the serendipity score surged from 0.296 to 0.857 with the algorithm, Osaka, increased from 0.563 to 0.941, Edinburgh increased from 0.541 to 0.681, Toronto increased from 0.594 to 0.781, and Glasgow increased from 0.895 to 0.927. This demonstrates that while the algorithm may slightly reduce the absolute novelty by grounding the route in a user’s history (the ‘Anchor’ step) and ensuring logical progression (the ‘Expand’ step), it is precisely this structured approach that transforms novel POIs into unexpectedly relevant discoveries. It effectively filters out irrelevant novelty, retaining only the suggestions that are both new and contextually coherent. Therefore, this ablation study validates that the Anchor-and-Expand algorithm is not merely an add-on but a core component that is essential for balancing exploration with personalization and generating practical, high-quality travel routes that lead to serendipitous user experiences.

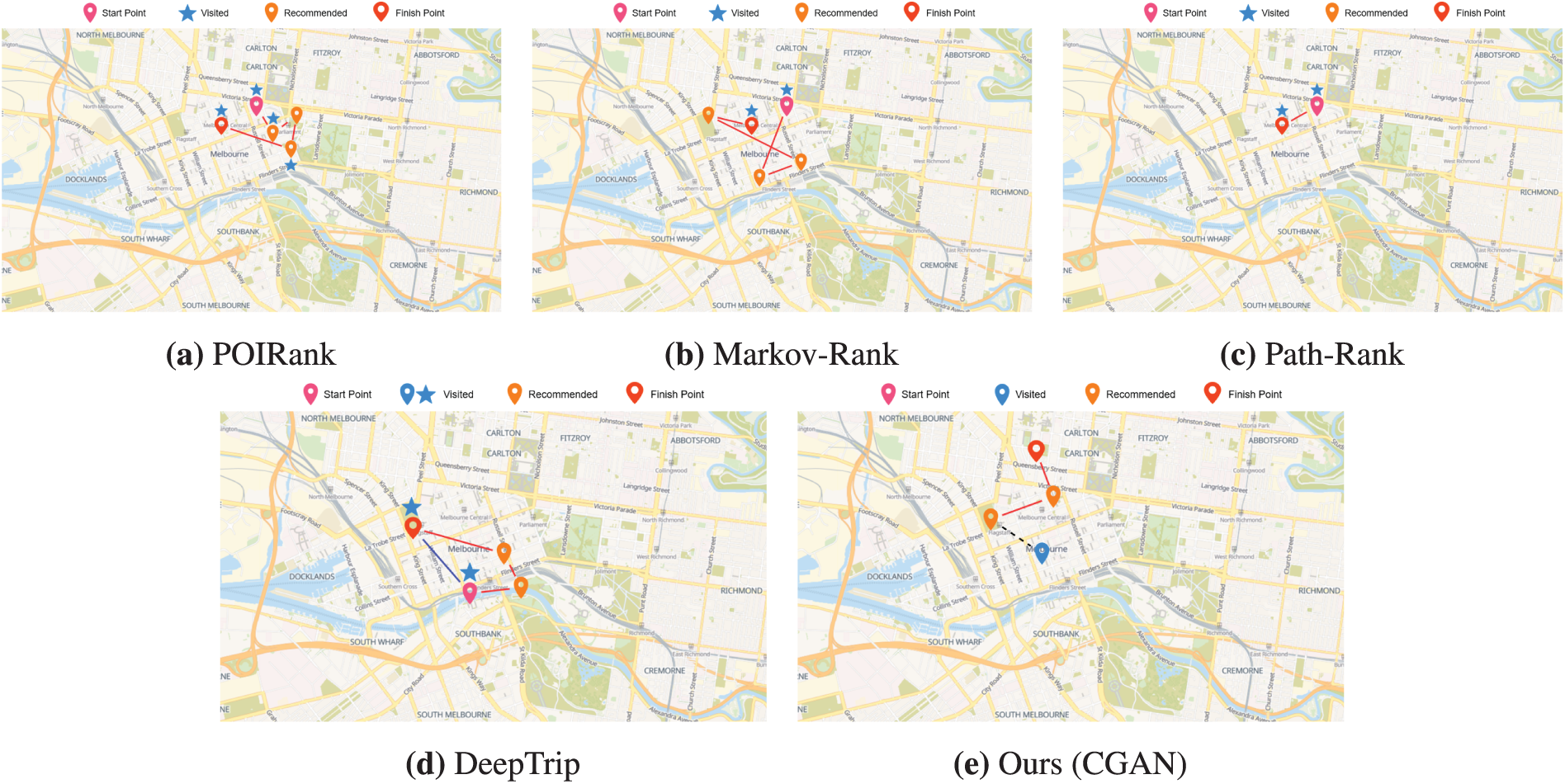

The results from Figs. 6–11 demonstrates that our model is well-trained to generate novel routes. Fig. 14 shows the generated route for the users with travel records from five datasets. And Fig. 15 shows the generated route for the cold-start user without travel records from five datasets.

Figure 14: Generated routes for users with travel records. This shows the results of generating three new routes, each consisting of three POIs, for users with existing travel records. The blue pin on the map indicates the user’s last visited location, and the black dotted line shows the path from this location to the starting point of a generated route. The recommended POIs are marked with red pins. The three generated routes are distinguished by red, green, and purple lines. All routes are efficiently constructed using an optimizer for the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP). Each panel displays the results for a different city: (a) Edinburgh, (b) Glasgow, (c) Melbourne, (d) Osaka, and (e) Toronto. (Map data: © OpenStreetMap contributors)

Figure 15: Generated routes for cold-start users without travel records. This shows the result of generating three routes, each composed of three POIs, for new users without any travel history. The three generated routes consist of POIs are connected by red, green, and blue lines. These routes are generated in an efficient and logical sequence by applying the haversine formula for geographical distances and an optimizer for the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP). Each panel displays the results for a different city: (a) Edinburgh, (b) Glasgow, (c) Melbourne, (d) Osaka, and (e) Toronto. (Map data: © OpenStreetMap contributors)

For Fig. 14 we generated 3 routes with 3 POIs from the user with travel records. The blue pin is the POI where the user last visited from their previous routes, and dotted line points to the first starting POI from each generated routes. Each of the routes are generated with different colors to connect POIs (red, green, and purple). Also, for Fig. 15, we generated a 3 routes with 3 POIs from the user without travel records. Each of the routes are generated with different colors to connect POIs (red, green, and blue).

The model has successfully generated routes by applying haversine formula to calculate geographical distances and an optimizer for the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) creating efficient and logically sequenced travel routes.

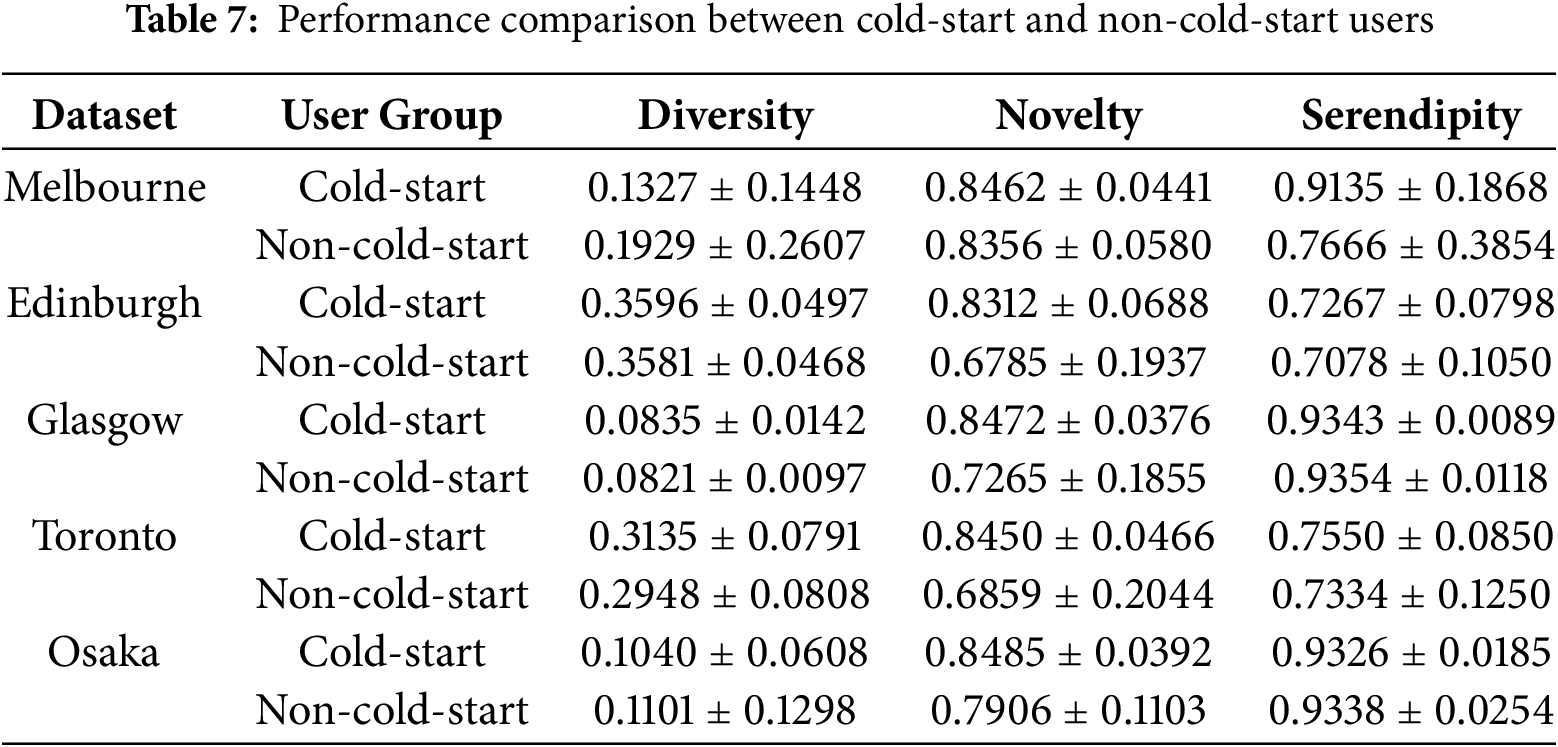

5.9.8 Cold-Start Performance Analysis