Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Deep Learning-Enhanced Human Sensing with Channel State Information: A Survey

School of Information and Communication Engineering, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, 611731, China

* Corresponding Author: Yin Zhang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071047

Received 30 July 2025; Accepted 29 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

With the growing advancement of wireless communication technologies, WiFi-based human sensing has gained increasing attention as a non-intrusive and device-free solution. Among the available signal types, Channel State Information (CSI) offers fine-grained temporal, frequency, and spatial insights into multipath propagation, making it a crucial data source for human-centric sensing. Recently, the integration of deep learning has significantly improved the robustness and automation of feature extraction from CSI in complex environments. This paper provides a comprehensive review of deep learning-enhanced human sensing based on CSI. We first outline mainstream CSI acquisition tools and their hardware specifications, then provide a detailed discussion of preprocessing methods such as denoising, time–frequency transformation, data segmentation, and augmentation. Subsequently, we categorize deep learning approaches according to sensing tasks—namely detection, localization, and recognition—and highlight representative models across application scenarios. Finally, we examine key challenges including domain generalization, multi-user interference, and limited data availability, and we propose future research directions involving lightweight model deployment, multimodal data fusion, and semantic-level sensing.Keywords

Driven by rapid developments in wireless communication technologies, WiFi has evolved from a medium for network access into a versatile platform for human sensing applications [1,2]. Compared to traditional sensing modalities such as cameras and infrared sensors, WiFi offers several compelling advantages, including wide coverage, low power consumption, and minimal deployment cost. These features position WiFi as a promising foundation for large-scale, contactless sensing systems [3,4]. Consequently, its application scope has expanded beyond connectivity to encompass a wide range of sensing tasks such as human detection [5–7], indoor localization [8,9], and posture recognition [10–12], transforming it into a practical tool for passive human behavior analysis [2].

At the core of WiFi-based sensing lies Channel State Information (CSI), a physical-layer metric that characterizes the impact of multipath propagation, fading, and reflection on wireless signal transmission [13]. Unlike the coarse-grained Received Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI), CSI captures detailed amplitude and phase variations across subcarriers. For instance, within a 20 MHz bandwidth, CSI can record the frequency response of up to 56 subcarriers [14]. Importantly, CSI is highly sensitive to even minor human motions, enabling the detection of subtle activities such as breathing and hand gestures [2,15].

Recent advances in deep learning have further unlocked the potential of CSI for human sensing [16]. Traditional methods often rely on handcrafted features (e.g., energy spectra, Doppler shifts), but these features often fail to generalize across dynamic environments. In contrast, deep learning models can autonomously learn spatio-temporal-frequency representations from raw CSI data, enhancing both accuracy and adaptability [17–20]. For example, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) are effective in extracting spatial patterns across antennas [21,22], while Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), particularly Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) models, are adept at modeling temporal dependencies within CSI sequences [23,24]. These architectures demonstrate resilience to environmental changes such as furniture rearrangement and multipath interference. Moreover, these models are scalable and support deployment across diverse application scenarios [15].

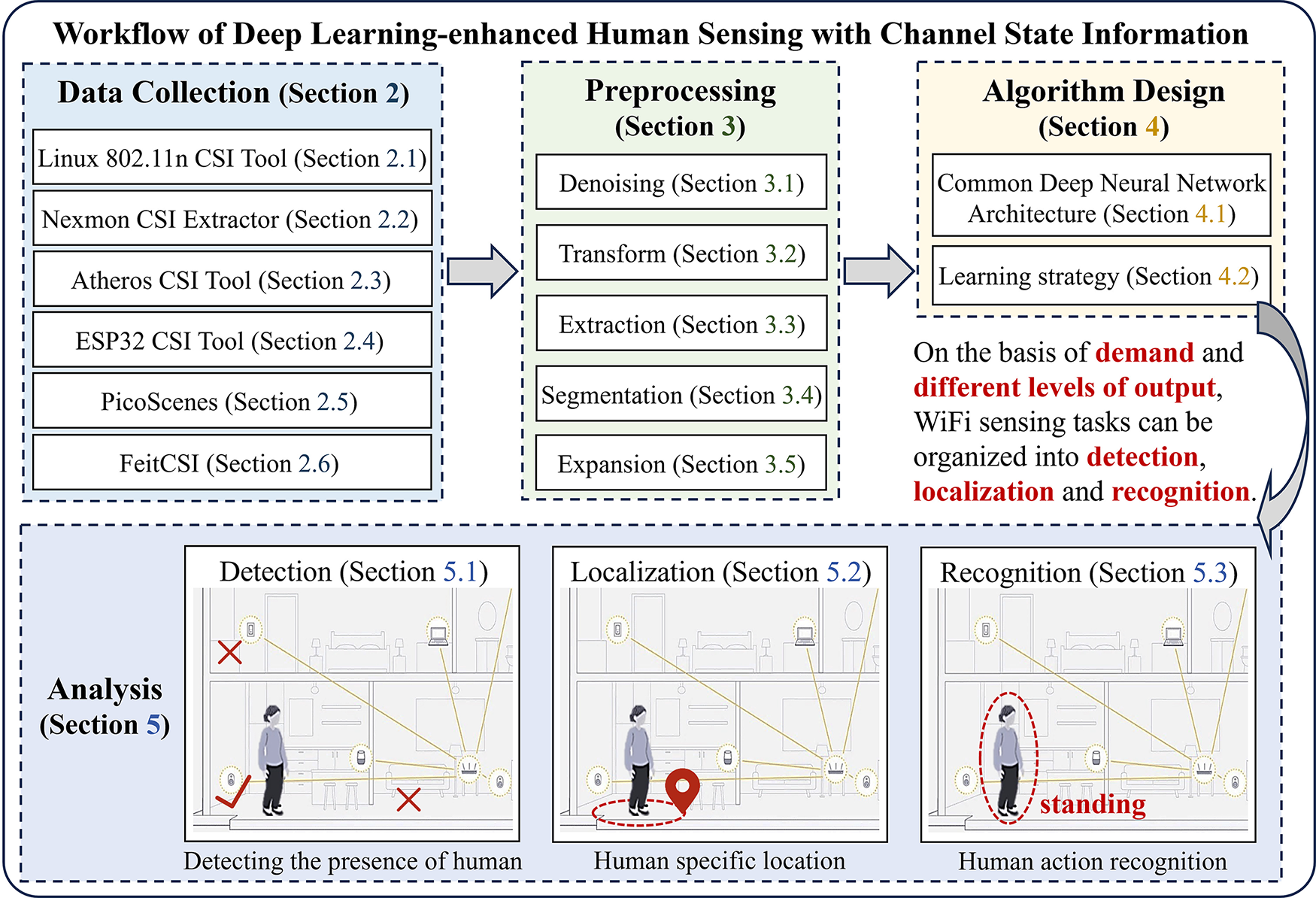

As illustrated in Fig. 1, a typical deep learning-enhanced human sensing pipeline comprises four stages: CSI data acquisition, preprocessing, algorithm design, and sensing analysis. Each stage plays a critical role in determining system performance:

• Data acquisition: Collecting raw CSI signals using tools such as the Intel 5300 NIC or ESP32-based platforms.

• Preprocessing: Denoising, calibrating, and transforming CSI into structured inputs suitable for learning models.

• Algorithm design: Employing deep learning architectures to extract meaningful features for target sensing tasks.

• Sensing analysis: Generating application-specific outputs such as presence detection (whether a person is present), localization (where the person is), and activity recognition (what the person is doing).

Figure 1: Workflow of deep learning-enhanced human sensing with CSI

Following this framework, this paper systematically reviews recent advancements in deep learning-enhanced human sensing using CSI. The main contributions are as follows:

• We present a structured and comprehensive overview of the CSI-based sensing pipeline, from data collection to task-specific analysis.

• We categorize and summarize representative deep learning methods according to sensing granularity: detection, localization, and recognition.

• We identify key technical challenges and outline promising research directions, including lightweight inference models, multimodal data fusion, and semantic-level understanding.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces common CSI data acquisition tools; Section 3 details preprocessing techniques; Section 4 discusses deep learning-based modeling strategies; Section 5 categorizes existing methods by sensing tasks; Section 6 highlights current challenges and future research opportunities; and Section 7 concludes the paper.

In deep learning-based human sensing systems, the quality of CSI acquisition plays a pivotal role in determining the overall performance of downstream models. Despite growing academic and industrial interest in WiFi-based human sensing, several practical challenges persist. These include the limited CSI accessibility from Commercial Off-The-Shelf (COTS) devices and the trade-off between measurement accuracy and deployment scalability. As such, selecting appropriate CSI extraction tools is a critical first step in building reliable sensing systems.

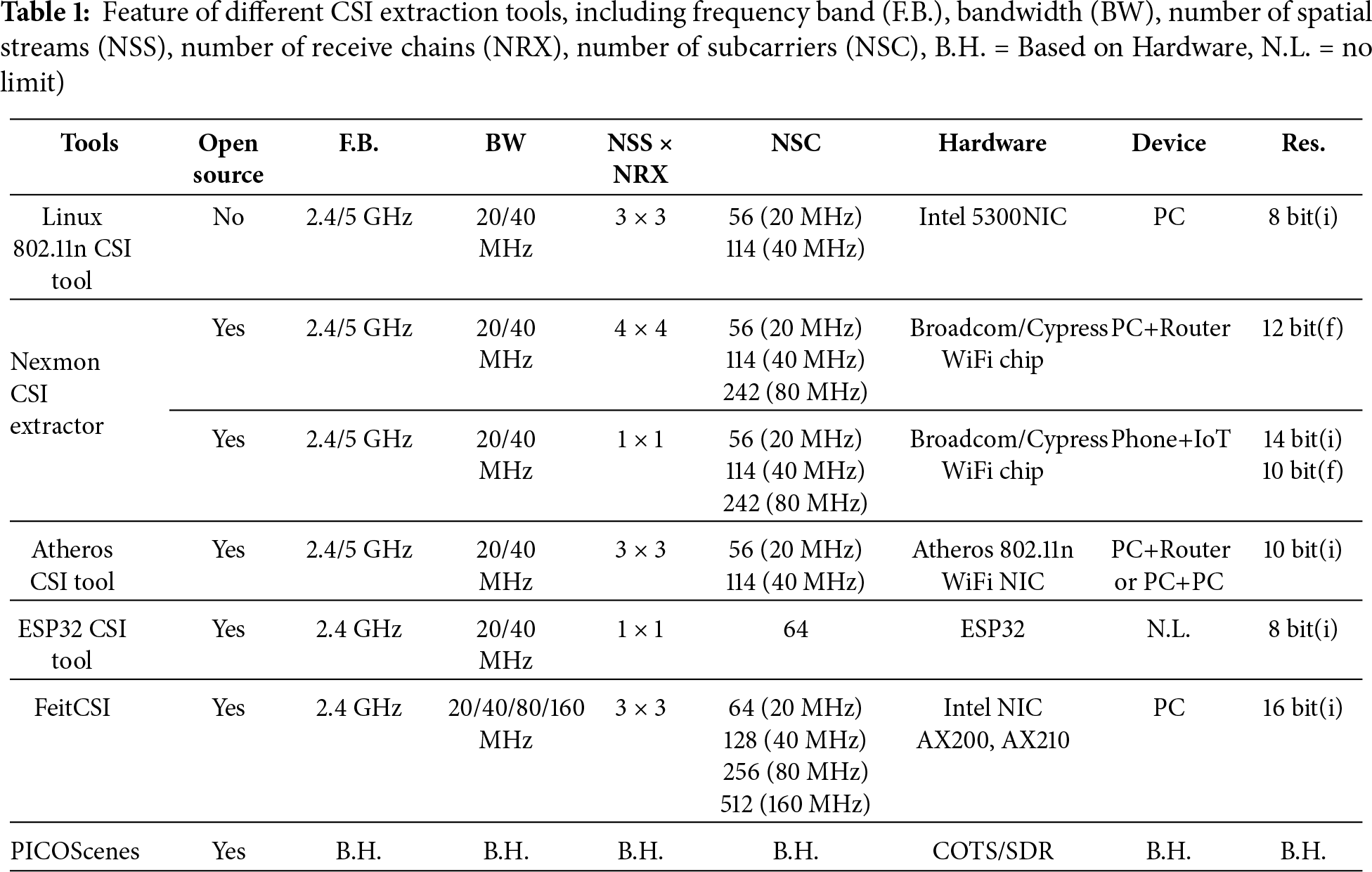

This section provides a systematic review of commonly used CSI acquisition tools, highlighting their hardware configurations, signal resolution, and application scenarios. Table 1 summarizes key specifications such as frequency bands, bandwidths, spatial stream support, subcarrier resolution, and platform compatibility.

CSI extraction tools can be broadly categorized into three types based on their underlying platform and design philosophy:

• Network Interface Card (NIC) driver-based tools: Network Interface Card (NIC) driver-based tools: Tools such as the Intel 5300 CSI Tool [25] and the Atheros CSI Tool [26] extract CSI via modified NIC drivers and are widely used in academic research. They provide stable sampling rates and well-documented data formats but are limited by hardware compatibility and poor scalability.

• Embedded platform-based tools: Embedded platform-based tools: Examples include the Nexmon CSI Extractor [27] and the ESP32 CSI Tool [28], which are designed for lightweight deployment on mobile or edge devices. These tools provide enhanced flexibility and cost-efficiency, although they generally require firmware modifications and offer lower sampling precision.

• Next-generation and high-resolution tools: Next-generation and high-resolution tools: Tools such as FeitCSI [29] and PicoScenes [30] are developed to support high-resolution, wide-bandwidth CSI acquisition compatible with modern WiFi standards. They enable advanced applications such as micro-motion analysis and WiFi imaging but may demand higher hardware and computational resources.

Developed for research use, this tool supports CSI extraction under the IEEE 802.11n standard, offering up to

Based on Broadcom/Cypress chipsets, this tool supports bandwidths up to 80 MHz and MIMO configurations up to

Utilizing the ath9k driver, this tool extracts CSI on Atheros NICs without requiring firmware modifications. It supports up to

Designed for edge applications, this tool enables low-cost CSI collection directly from ESP32 chips. Supporting up to 64 subcarriers at 20/40 MHz, it provides real-time data transmission via serial or SD card interfaces. Its primary strengths are low power consumption and ease of deployment in smart home environments. However, limited processing capability and sampling rates constrain its application in high-resolution sensing tasks.

As the first open-source tool supporting Intel AX200/AX210 NICs, FeitCSI operates across 2.4, 5, and 6 GHz bands, with bandwidths up to 160 MHz. It captures up to 512 subcarriers with 16-bit signed integer precision, offering high sampling fidelity. This tool is especially suited for tasks requiring fine temporal or spectral resolution, such as respiration monitoring or gesture recognition.

PicoScenes is a flexible CSI acquisition platform supporting both commercial NICs and software-defined radios (e.g., USRP, HackRF). It offers advanced functionalities such as synchronized multi-device acquisition, dynamic packet injection, and real-time CSI visualization. Its plugin-based architecture enables customization for a wide range of Integrated Sensing and Communication (ISAC) applications.

Raw CSI data is often subject to various distortions and noise arising from environmental dynamics, hardware limitations, and measurement inconsistencies. These include amplitude fluctuations, phase offsets, and temporal misalignments, all of which can severely degrade the performance of deep learning models if not addressed. The primary objective of preprocessing is therefore to transform raw CSI into a structured and noise-reduced format that preserves task-relevant information while enhancing feature discriminability.

This section categorizes and describes mainstream preprocessing techniques, including signal denoising, time–frequency transformation, dimensionality reduction, segmentation, and data augmentation.

Denoising is a critical step in mitigating noise introduced by channel variability [31], hardware artifacts [32], and environmental interference. Common sources of distortion [26] include Carrier Frequency Offset (CFO), Sampling Time Offset (STO), and Packet Detection Delay (PDD), which manifest as random fluctuations in amplitude and phase. Several approaches have been proposed to suppress such noise:

CSI ratio-based denoising [33]: This technique leverages the noise correlation between antennas on the same receiver. By computing the amplitude ratio between CSI streams from different antennas, high-frequency noise components and phase biases can be effectively cancelled. This approach has been widely adopted in tasks such as fall detection [32] and respiration monitoring [34], where it enhances the signal-to-noise ratio by isolating dynamic motion-induced variations from static multipath reflections.

Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) [35]: DWT decomposes CSI signals into multiple frequency components using wavelet basis functions [36], enabling localized thresholding of high-frequency noise [32] while preserving key temporal and spectral structures. This method is particularly effective in detecting abrupt changes caused by events [32,36,37] such as falls or sudden gestures, as it maintains sharp transitions in the signal while removing low-level background interference.

Deep learning-based denoising: Recent studies have employed end-to-end denoising networks—such as autoencoders or residual CNN [38]—to learn the distribution of noise patterns directly from CSI data. For instance, residual autoencoders [39] have demonstrated effectiveness in stabilizing CSI phase sequences and concurrently extracting discriminative features during denoising, making them suitable for frequency-division duplexing systems [40].

Human activities often induce non-stationary frequency components in CSI streams due to micro-Doppler effects. To capture these dynamic variations [15], time–frequency analysis techniques are employed:

Fourier-based methods: Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) is used to derive the power spectral density (PSD) of CSI sequences, which is effective for extracting low-frequency physiological signals [41] such as respiration or heart rate. However, traditional FFT loses temporal localization. To address this limitation, the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) applies a sliding window to balance time and frequency resolution, thereby generating spectrograms that reveal temporal activity patterns [28,36,37,42].

Wavelet-based methods: Unlike STFT, which uses a fixed time–frequency resolution, wavelet transforms provide adaptive resolution based on signal frequency [43]. Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) enables multi-resolution decomposition and supports hierarchical feature extraction [44], while Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT) generates time-frequency matrices [45] that visualize frequency content as temporally varying patterns—particularly useful for fast motions such as hand gestures [32,39,46,47].

CSI data contains strong inter-subcarrier correlations, especially between adjacent subcarriers [48]. Directly using high-dimensional raw data introduces redundancy and computational overhead. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [49] projects CSI data onto orthogonal components that capture the maximum variance. In practice, the first few components are often sufficient to retain over 90% of the signal’s energy, offering a compact and noise-resistant representation for motion-related features [37,47,50–52]. Additional methods include Local Linear Embedding (LLE) [53], Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) [54], and subcarrier selection based on correlation thresholds [32]. These techniques are applied based on specific sensing objectives and data characteristics, with the shared goal of compressing input while minimizing information loss.

Because CSI data is collected as continuous streams, identifying meaningful action segments is essential for accurate recognition. The choice of segmentation strategy [15] significantly affects temporal consistency and label alignment:

Fixed window segmentation: This method divides the CSI stream into non-overlapping segments of uniform length. It is simple and efficient but assumes that actions are of consistent duration [55]. When action boundaries fall within a window, segmentation errors may occur and degrade model performance.

Sliding window segmentation: Overlapping windows with adjustable stride allow better alignment with variable-length actions [56]. This approach also increases the number of training samples and captures contextual transitions between motion states. Adaptive versions detect activity boundaries based on statistical changes in CSI variance, offering improved temporal localization in scenarios such as fall detection [57] or continuous activity monitoring [58,59].

CSI datasets are often limited by high acquisition costs [36] and class imbalance [60], particularly for rare or short-duration activities [61,62] (e.g., falls, gestures). Data augmentation [63] enhances model robustness and generalization by expanding training samples through synthetic or transformed instances:

• Traditional augmentation: These methods include sequence recombination, signal interpolation, Gaussian noise injection, and label mixing [63] (e.g., mixup and cutmix). They are computationally efficient and suitable for edge deployment [64]. However, they generate only limited sample diversity [36].

• Intelligent generation schemes [65]: These schemes leverage the representational power of neural networks to learn the probability distribution of original data and generate synthetic data highly similar to real samples [61]. Generative models such as Variational Autoencoder (VAE) [66] and Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) are used to learn the underlying data distribution and generate realistic CSI samples. For example, domain-adaptive GAN can synthesize cross-environment data, while autoencoders reconstruct virtual samples with diverse but consistent patterns. These methods are particularly valuable for few-shot learning and cross-domain generalization [9,67,68].

The design of deep learning models is central to the effectiveness of CSI-based human sensing systems. Channel State Information inherently contains rich spatio-temporal and spectral characteristics, typically represented as a three-dimensional tensor with dimensions corresponding to time, subcarriers, and antennas. A well-designed model must therefore capture temporal dynamics, frequency-specific features, and spatial correlations to extract meaningful patterns for downstream sensing tasks.

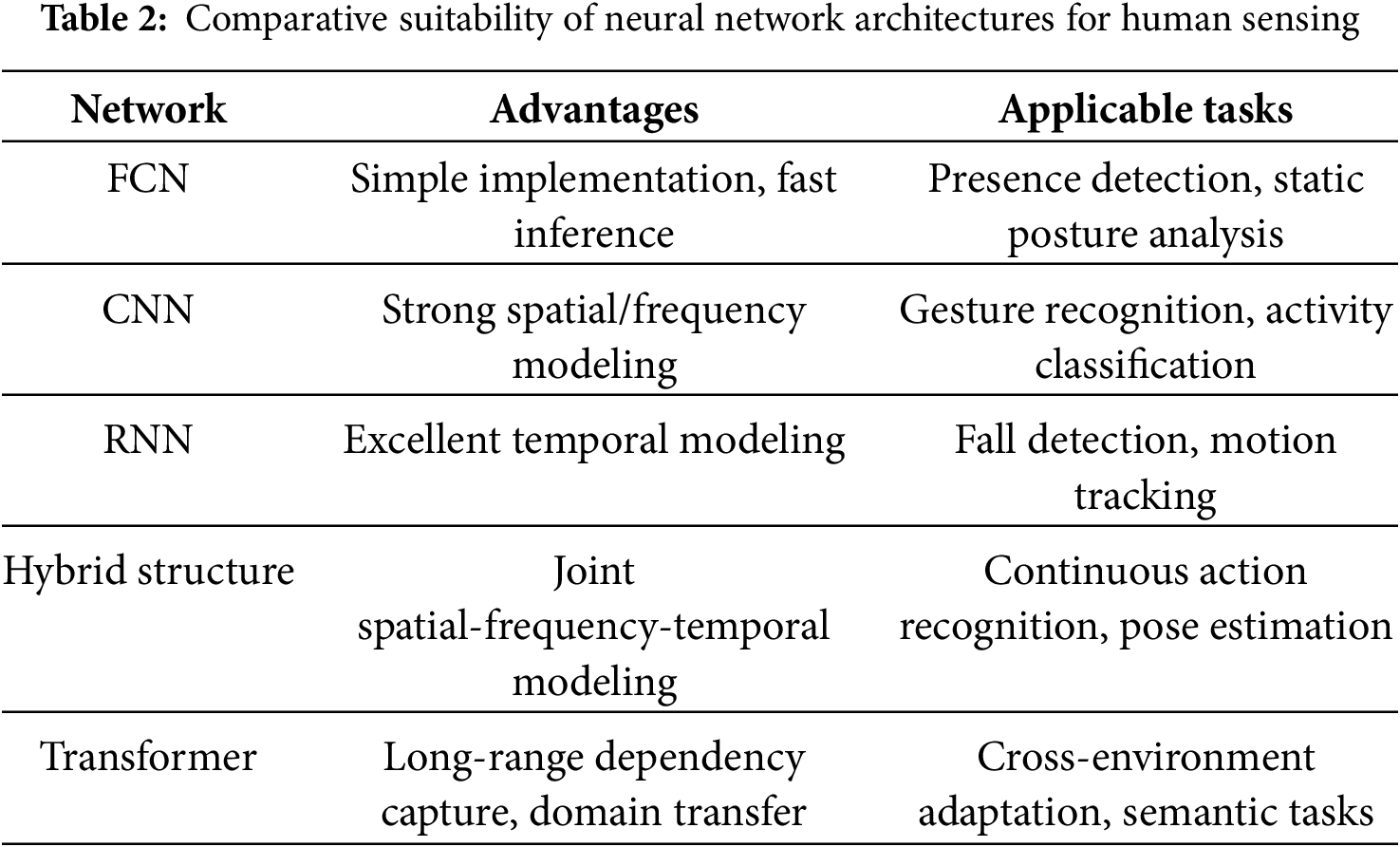

This section presents a structured overview of deep learning architectures for human sensing, categorized by model types, followed by a discussion of their suitability for specific tasks such as detection, localization, and recognition.

4.1 Common Deep Learning Neural Network Architecture

Fully Connected Network (FCN): The fully connected network (such as the multi-layer perceptron MLP) is one of the earliest structures applied to CSI perception. This type of model flattens the CSI sequence into a one-dimensional vector for input, and learns the high-level mapping between signals and behaviors [69,70]. For example, For example, Fang et al. combined CSI amplitude and phase into complex features and realized human presence detection using an MLP [5]. However, such structures ignore the spatial and frequency structures of CSI—flattening three-dimensional data into one-dimensional vectors will lose the frequency correlation between subcarriers and the spatial correlation between antennas, resulting in poor generalization ability in complex environments, which is mainly used for small-scale scenario verification [10,63,71].

Convolutional Neural Network (CNN): CNN extracts local frequency patterns and spatial features in CSI through the local receptive field and weight sharing mechanisms, which is particularly suitable for the case where the input is a CSI spectrogram (such as STFT/CWT heatmap), and has shown outstanding performance in human activity recognition [10,32]. For example, the IDSDL system designed by Hu et al. uses CNN to learn the multipath fuzzy components of CSI phase, achieving high-precision human detection in Non-Line-of-Sight (NLOS) environments [72]; Liu et al. adopt a parallel CNN architecture to simultaneously capture the temporal, frequency, and spatial dimensional information of CSI, improving the robustness of real-time occupancy detection [6]. The limitation of CNN lies in its weak ability to handle long-term temporal dependencies, which requires further optimization in combination with temporal networks.

Recurrent Neural Network (RNN): RNN processes the temporal dynamics of CSI through hidden state memory mechanisms, enabling the extraction of temporal dependency features from continuous CSI data. Typical examples include the Bi-LSTM, which captures action information from both past and future sequences, and the Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), which reduces computational complexity while maintaining modeling capability for real-time applications. Compared with CNN, RNN demonstrates superior performance in tasks such as fall detection and trajectory tracking [31,71]. For instance, Chu et al. used an LSTM to extract temporal features from CSI phase differences and combined it with a CNN to construct the spatio-temporal network C-MuRP, achieving multi-room human presence detection [73]; Ding et al. designed a deep recurrent network to process CSI time series, enhancing model adaptability in cross-scenario activity recognition [71]. However, RNN suffers from high computational complexity, necessitating careful selection of sequence length to balance accuracy and efficiency.

Hybrid Architectures: To model spatial and temporal features simultaneously, researchers have proposed hybrid structures combine CNN with RNN or multi-branch networks. Sheng et al. proposed a model combining CNN with Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM), where the front-end CNN extracts frequency image features and the back-end LSTM captures temporal dependencies, improving classification accuracy in complex activity recognition [74]. Li et al. designed the Two-stream Convolution-Enhanced Transformer (THAT) model. It processes channel and temporal features through a two-stream structure, incorporates multi-scale convolutions to expand the receptive field, and achieves high-precision human pose recognition [11].

Transformer-Based Models: Inspired by natural language processing, Transformer architectures have been introduced to address the limitations of CNN and RNN in capturing long-range dependencies. The self-attention mechanism dynamically weights features across time steps and subcarriers, enabling the model to focus on subtle yet critical motion cues. The multi-head attention structure is suitable for modeling multi-channel and multi-band CSI structures. Transformer shows significant potential in cross-domain migration, few-shot recognition, and other fields, though its training cost is relatively high.

Table 2 summarizes the applicability of different neural network architectures to human perception tasks. This table helps guide architecture selection according to task types (such as presence detection, fall recognition, or domain adaptation).

4.2 Learning Strategies and Training Methods

The choice of learning strategy significantly influences the adaptability, robustness, and data efficiency of CSI-based human sensing systems. Depending on the availability of labeled data, the complexity of sensing environments, and the desired generalization performance, researchers have explored various paradigms including supervised learning, unsupervised and self-supervised learning, transfer learning, and meta-learning:

Supervised Learning: Supervised learning guides models to learn the mapping between CSI and action labels using annotated data, and is currently the mainstream paradigm for Human Sensing. Its main advantage lies in the ability to learn complex patterns from large volumes of labeled data—for example, distinguishing subtle differences between falls and normal activities. The CSITime, for instance, achieves fine-grained classification of human activities through supervised learning [63]. However, this approach relies heavily on high-quality annotated datasets. In localization tasks, for example, fingerprinting requires extensive site surveys, resulting in significant costs [75]. Moreover, models trained in this way are prone to overfitting to specific environments, leading to reduced generalization performance in new scenarios [5]. To address this issue, researchers have introduced domain adaptation techniques. For example, the D-Fi system employs Domain-Adversarial Neural Networks (DANN) to minimize distribution discrepancies between source and target domains, thereby enhancing the environmental transferability of localization models [76].

Unsupervised and Self-Supervised Learning: Unsupervised learning eliminates the need for labeled data by uncovering the intrinsic structure of CSI, enabling feature clustering in data-scarce scenarios. For example, the WiSOM system proposed by Salman et al. employs a Self-Organizing Map (SOM) network to perform unsupervised clustering of CSI data, thereby achieving occupancy detection in smart buildings [77]. Similarly, the MaskFi model designed by Yang et al. masks parts of the CSI features to force the network to learn cross-modal (WiFi and vision) representations, thus improving the generalization of activity recognition under unlabeled conditions [78]. I-Sample [64] is a generation framework based on intermediate samples that addresses unsupervised domain adaptation for WiFi-based human activity recognition (HAR).Self-supervised learning, on the other hand, leverages pretext tasks—such as sequence reconstruction or feature contrast—to automatically learn effective representations from unlabeled data. For instance, the AutoFi system employs a geometric structure loss to guide the self-supervised module, thereby reducing dependence on manual annotations [79].

Transfer Learning: Transfer learning addresses cross-environment challenges by transferring knowledge from a source domain (e.g., a labeled laboratory setting) to a target domain (e.g., a newly deployed home environment). For instance, the CrossCount system proposed by Khan et al. leverages a pre-trained model for crowd counting in target rooms, requiring only minimal new data for fine-tuning [80]. Similarly, Xiao et al. developed a transfer learning framework based on Gram Angular Field (GASF) images, enabling the migration of CSI-based indoor localization models from the source environment to the target environment and thereby reducing the need for redundant retraining [81]. Common transfer strategies include pre-training and fine-tuning, as well as feature transfer. The key lies in identifying domain-invariant features that can be shared across domains, such as phase difference patterns in CSI induced by human activities.

Meta-Learning: Meta-learning endows models with the ability to “learn how to learn,” making them particularly effective in few-shot scenarios. The DASECount model combines meta-learning with few-shot learning (FSL) to achieve sample-efficient crowd counting across different domains [58]. Similarly, Zhang et al. proposed CSI-GDAM, which constructs an activity association graph using graph neural networks and employs meta-learning to optimize graph convolution parameters, enabling the recognition of new activity categories with only a few samples [82]. In meta-learning, the fundamental unit is the task; by learning generalizable strategies across multiple meta-training tasks, the model can rapidly adapt to meta-testing tasks such as activity recognition in new environments. For example, the AFSL-HAR model designed by Wang et al. integrates a feature generation network (FWGAN) to enhance the robustness of activity recognition in few-shot settings [83].

The analysis of human sensing tasks should be conducted based on hierarchical output objectives—ranging from binary detection determining human presence to spatial coordinate localization and further to posture recognition identifying specific actions, forming a perception system that progresses from macroscopic to microscopic levels. Following this logical framework, this section systematically examines the classification of WiFi sensing tasks enhanced by deep learning: first, it dissects fundamental sensing tasks such as human presence detection and crowd counting, exploring how to capture the existential characteristics of human activities through variations in CSI signals; then, it delves into localization and tracking tasks, analyzing how deep learning overcomes the accuracy limitations of traditional wireless positioning and achieves dynamic trajectory modeling; finally, it focuses on action and posture recognition tasks, revealing the feature learning mechanisms of models for human motion patterns at varying scales.

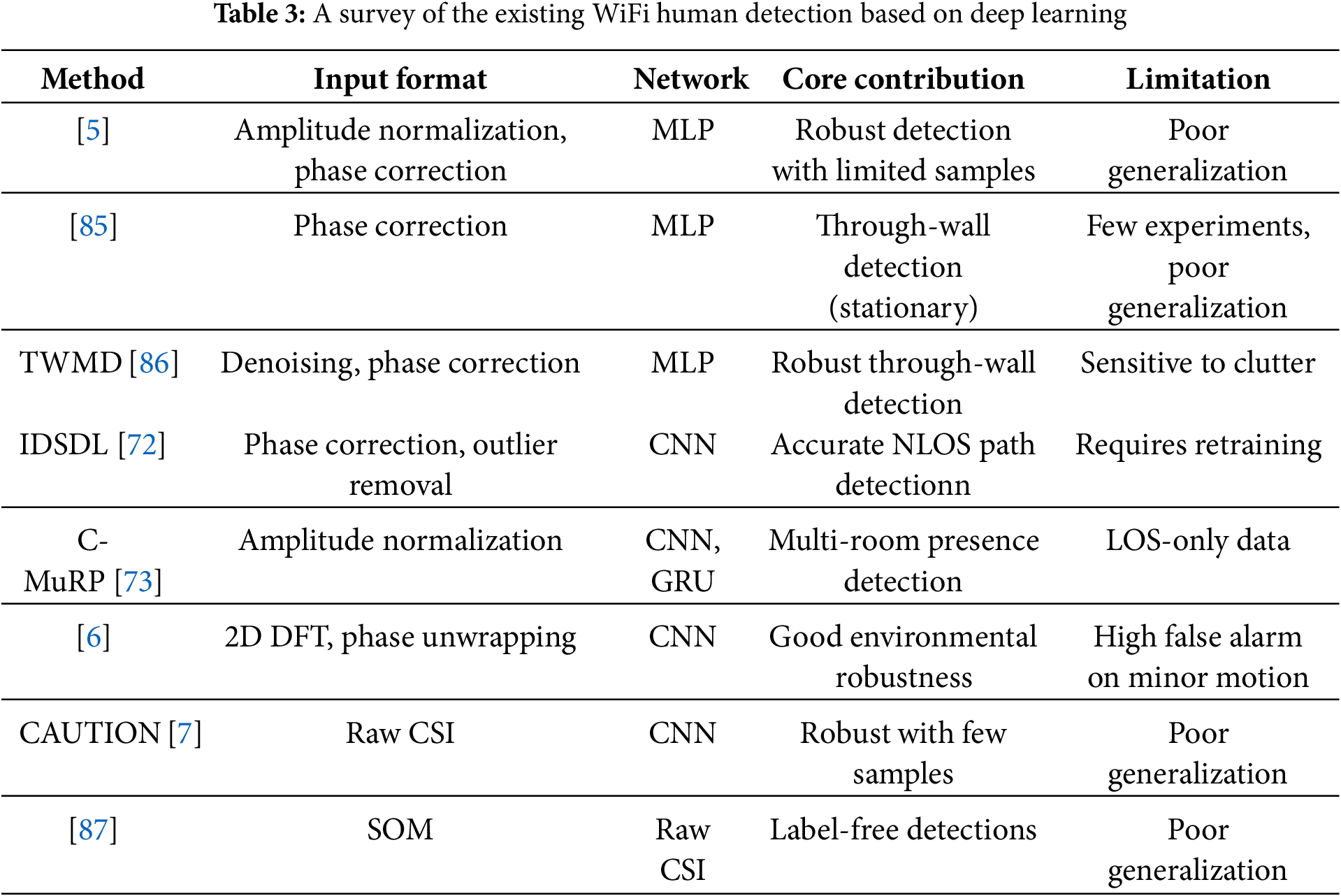

The detection task focuses on the presence judgment of human bodies or the estimation of the number of people within the sensing area, and its core is to capture the channel disturbances caused by human bodies through the changes in CSI signals. According to the task granularity, it can be divided into two categories: human presence detection (such as intrusion recognition [58,73,83] and health monitoring [6]) and crowd counting [84] (such as traffic statistics in public places), both of which rely on the ability of deep learning to recognize abnormal patterns of CSI.

Human presence detection differentiates between “occupied” and “unoccupied” states by analyzing dynamic changes in CSI amplitude or phase differences. Fang et al. first applied an MLP to this task, combining CSI amplitude and phase into complex features to classify human presence in office environments [5]. However, this method is significantly affected by multipath interference in through-wall scenarios. Yuan et al.’s through-wall detection system combines the smoothed MUSIC algorithm to estimate signal Time of Flight (ToF), enabling the identification of stationary humans behind walls via MLP [85]. The TWMD algorithm leverages temporal and subcarrier correlations in CSI to extract multi-dimensional features, enabling detection of both stationary and moving targets even through glass or brick walls [86].

Given the multi-dimensional nature of CSI, CNN have become the mainstream approach: The IDSDL system decomposes CSI phase components and applies a CNN to learn multipath features, thereby improving detection accuracy in NLOS scenarios [72]. Liu et al. adopted a parallel CNN architecture to simultaneously capture temporal, frequency, and spatial information from CSI, providing a real-time occupancy detection solution for libraries and apartments [6]. Chu et al. [73] proposed C-MuRP, a multi-room detection system integrating CNN and GRU, which enhances accuracy through spatio-temporal features and voting mechanisms. To address the annotation cost of supervised learning, Wang et al. developed the CAUTION system, which uses few-shot learning to extract gait features from limited CSI samples and combines intrusion thresholds for robust identity recognition and intrusion detection [7]. Additionally, Zhang et al. [87] introduced an unsupervised detection method based on Self-Organizing Map (SOM) neural networks to tackle data labeling challenges and achieve high accuracy in intrusion detection. Table 3 summarizes key deep learning-based approaches for WiFi human detection. These methods vary in model architecture and input format, with notable differences in environmental robustness and generalization ability.

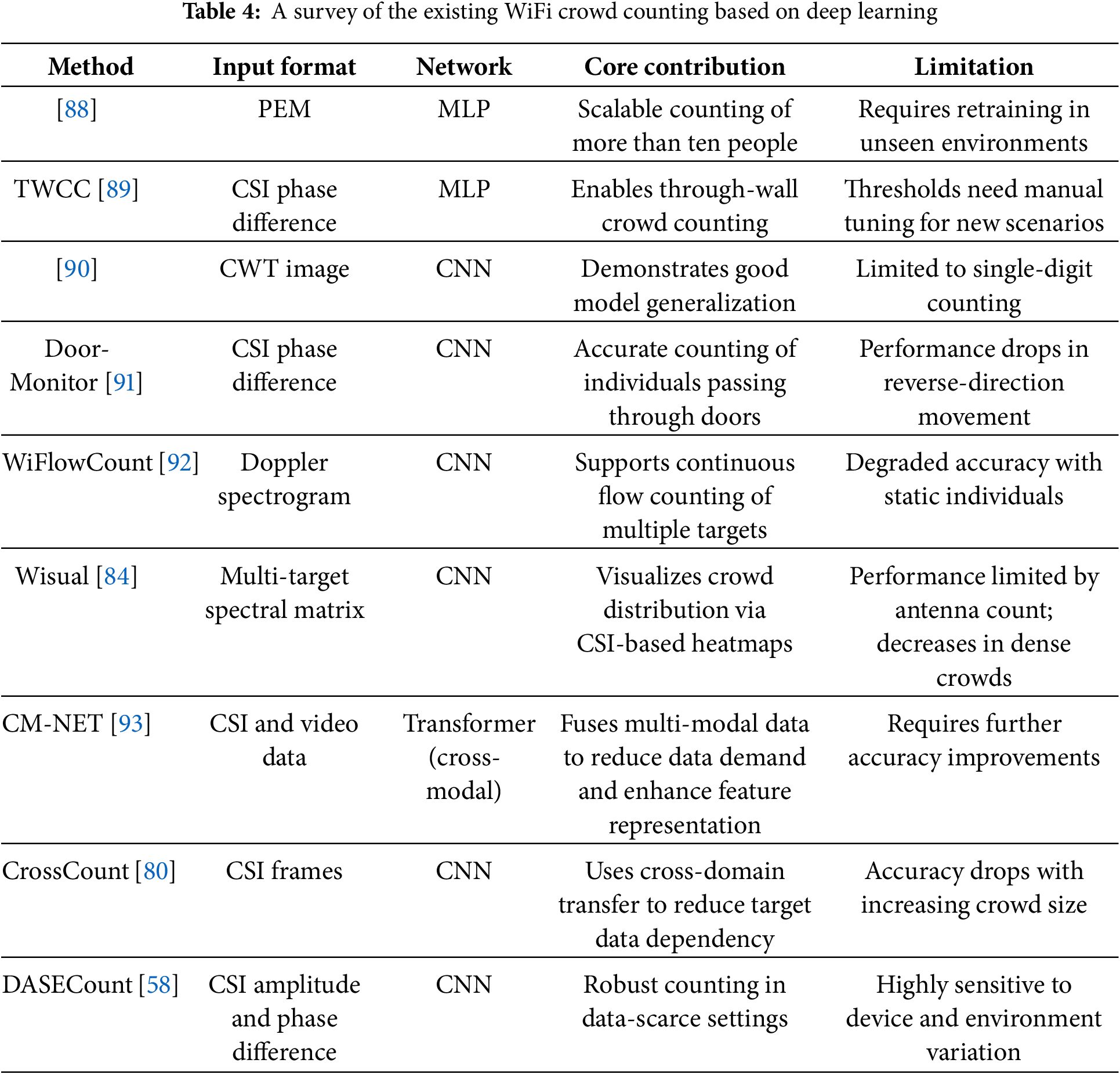

Crowd counting, as an advanced task of presence detection, requires estimating the number of people by analyzing the collective disturbances in CSI signals, facing dual challenges of multi-user signal aliasing and dynamic environmental changes. In early studies, Zhou et al. [88] extracted the percentage of non-zero elements in CSI subcarriers (PEM) as features and used MLP to achieve crowd counting for groups of over ten people. The TWCC system integrates four-dimensional features including time domain and subcarrier domain, completing crowd statistics in through-wall scenarios via neural networks, but requires manual adjustment of threshold parameters [89].

CNN schemes based on time-frequency analysis demonstrate higher accuracy: Shi et al. generated CWT images from CSI through continuous wavelet transform and input them into CNN to predict the number of individuals in elevator scenarios [90]. Yang et al.’s Door-Monitor system combines STFT with CNN to identify the sequence of multiple people passing through doors via spectrogram features [91]. The WiFlowCount system proposed by Zhou et al. [92] estimates the number of moving individuals by optimally rotating and segmenting Doppler shift spectrograms, but fails to detect stationary ones. The Wisual method by Ma et al. [84] innovatively integrates spatial (Angle of Arrival (AoA)), ToF, and Frequency of Change (FoC) domain features of CSI reflection paths to construct a Joint Multi-Feature Parameter (JMFP) spectral matrix, achieving crowd density estimation and path differentiation through 3-D CNN. It also completes Wi-Fi imaging based on 2-D MUSIC algorithm to visualize indoor personnel distribution.

In recent years, end-to-end and multimodal models have become research hotspots. The CM-NET model proposed by Guo et al. [93] fuses video and CSI data, leveraging Transformer and knowledge distillation techniques. It uses soft labels generated by visual networks to guide training, effectively compensating for the counting performance fluctuations caused by personnel position changes in single CSI. In terms of cross-domain adaptability, the CrossCount system by Khan and Ho [80] achieves target-domain adaptation of source environment pre-trained models through transfer learning. DASECount by Hou et al. combines few-shot learning with knowledge distillation to realize sample-efficient crowd counting in scenarios such as offices and lecture halls [58], providing new ideas for engineering applications in complex environments. Table 4 classifies and summarizes recent deep learning-based WiFi crowd counting tasks.

Localization aims to determine the spatial coordinates or trajectories of the human body, relying on the fingerprint characteristics of CSI in spatial positions—CSI amplitude and phase distributions are unique at different locations. Deep learning breaks through the accuracy limitations of RSSI-based localization by learning the mapping between CSI fingerprints and positions. Localization can be divided into static localization [94–96] and dynamic tracking [97,98].

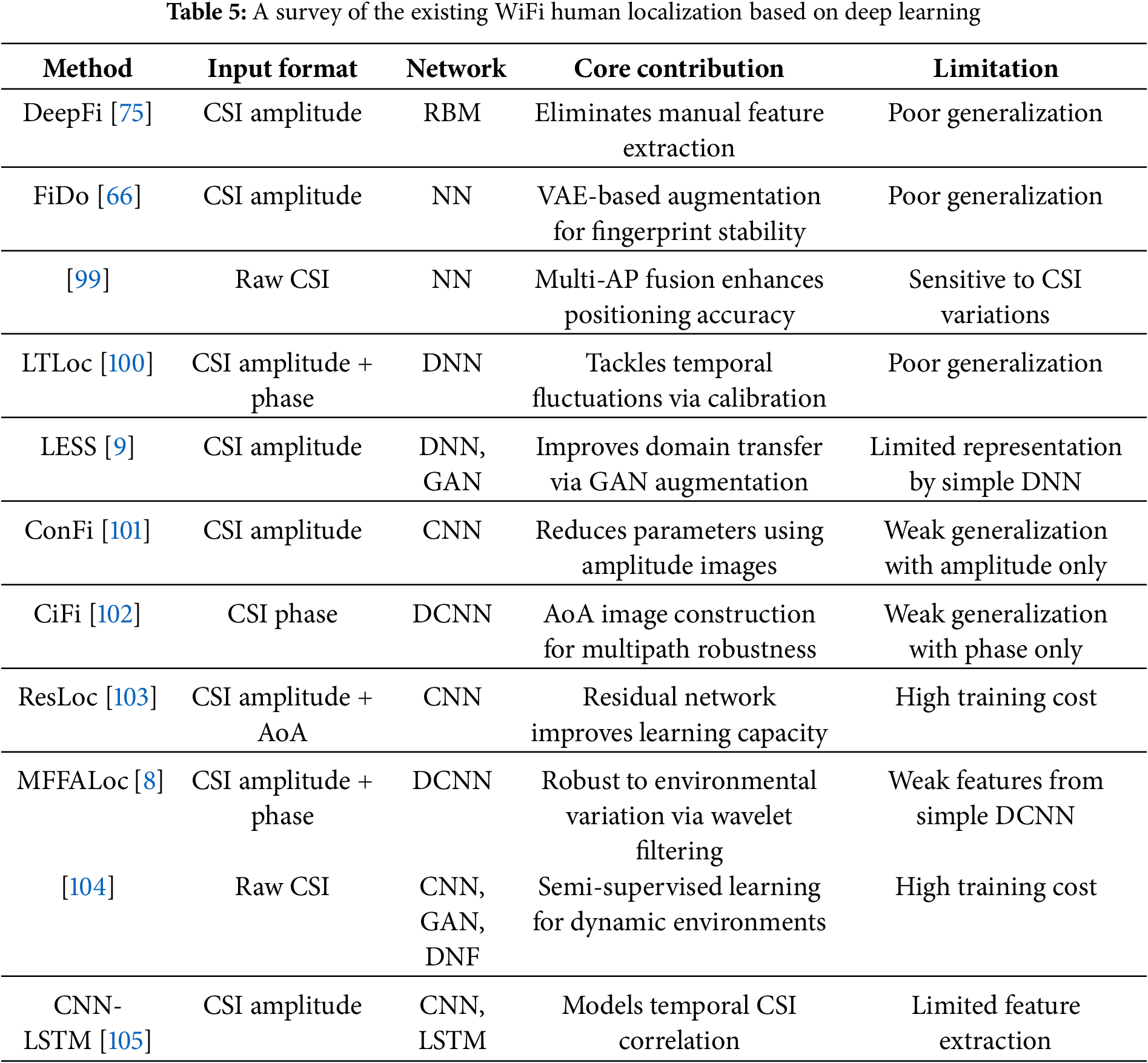

Deep learning-driven fingerprint localization began with the DeepFi model, which uses Restricted Boltzmann Machine (RBM) to learn the nonlinear relationship between CSI amplitude fingerprints and locations [75], albeit with high parameter training costs. Chen et al. [66] proposed the FiDo system achieving sub-meter localization accuracy and addressing inconsistencies of WiFi fingerprints across users. Gönültaş et al. [99] introduced a localization model for WLAN MIMO-OFDM systems that improves accuracy by combining multiple Access Points (APs) without requiring precise synchronization. Li and Rao [100] used adaptive Deep Neural Network (DNN) to tackle temporal variations in CSI fingerprint databases, while Zhang et al. [9] proposed LESS, a novel adaptive fingerprint localization method with minimal site surveys that addresses environmental migration from a domain relationship perspective, employing GANs to generate data and enhance transferability. Chen et al.’s ConFi algorithm converts CSI amplitude into images and uses CNN for sub-meter localization [101]; Wang et al.’s CiFi system estimates AoA from CSI phase to construct AoA images fed into deep CNN, maintaining robustness in multipath environments [102].

To address environmental dynamics, hybrid architectures and transfer learning are widely applied: the ResLoc system uses deep residual networks to process bimodal CSI tensors, improving localization accuracy in laboratory and corridor scenarios [103]; MFFALoc combines multi-feature fusion and domain adaptation techniques via CNN to learn cross-environment shared features [8]. Cui et al. [104] proposed a robust localization model using Deep Neural Forest (DNF), transferring learned knowledge from source to target environments to solve cross-environment device-free localization. Hoang et al.’s CNN-LSTM model enhances historical temporal information with LSTM, improving localization stability in office environments [105]. Table 5 presents representative deep learning-based approaches for WiFi human localization. These works vary in terms of network structures, and adaptability to complex indoor environments.

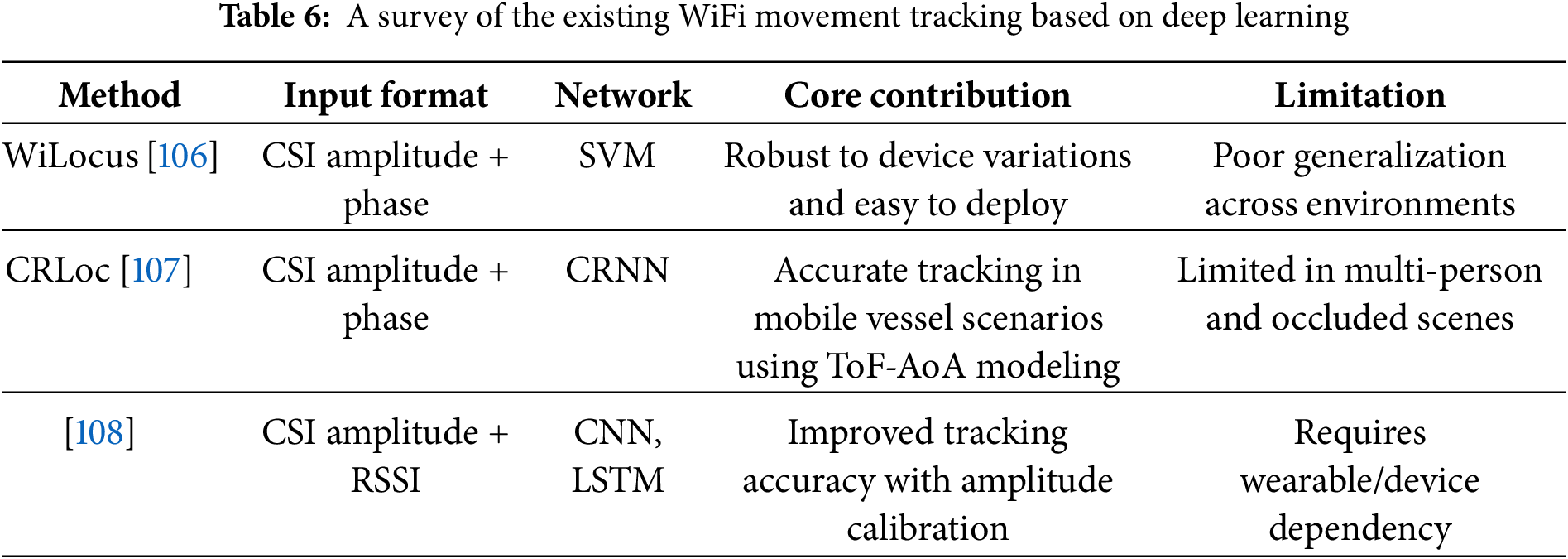

Movement tracking builds on localization by recording human trajectories in real-time, requiring simultaneous handling of spatial coordinates and temporal dynamics. The WiLocus system uses machine learning to classify behaviors such as “passing through doors” and “entering rooms,” constructing movement trajectories [106]; The CRLoc system targets mobile ship environments. It employs a convolutional recurrent neural network (CRNN) to suppress noise and interference, and combines it with variational Bayesian algorithms to estimate multipath parameters for precise human tracking [107]. Chen et al. [108] proposed a deep spatiotemporal neural network integrating RSSI and CSI data, extracting spatial features via CNN and temporal features via LSTM, achieving device-free target following in corridor scenarios. Currently, deep learning-based movement tracking research is limited, partly because traditional methods are still prevalent—for example, Qian et al. [109] proposed an algorithm combining AoA, ToF, and Doppler Frequency Shift (DFS) for joint estimation of movement trajectories without using deep neural networks; some neural network-based methods [110] focus on improving localization accuracy first, then obtaining trajectories via Bayesian filtering. Table 6 categorizes and summarizes recent deep learning CSI movement tracking studies.

The recognition task is one of the most complex categories in human body perception, requiring the model to identify specific actions or postures from CSI. According to the activity scale, it can be divided into large-scale actions (such as walking and falling) [50,111] and small-scale actions (such as gestures and breathing [112]). The core difference lies in the amplitude and frequency characteristics of signal disturbance.

Large-scale actions (such as sitting down and falling) cause strong disturbances to CSI, and deep learning mainly addresses the problems of cross-environmental generalization and few-shot learning. Adversarial networks and meta-learning are the mainstream solutions: The adversarial network designed by Jiang et al. learns CSI features independent of the environment through the game between the feature extractor and the domain discriminator [113]; Xiao et al.’s CsiGAN combines semi-supervised GAN and CycleGAN to generate target domain samples to enhance the generalization ability of the classifier [67].

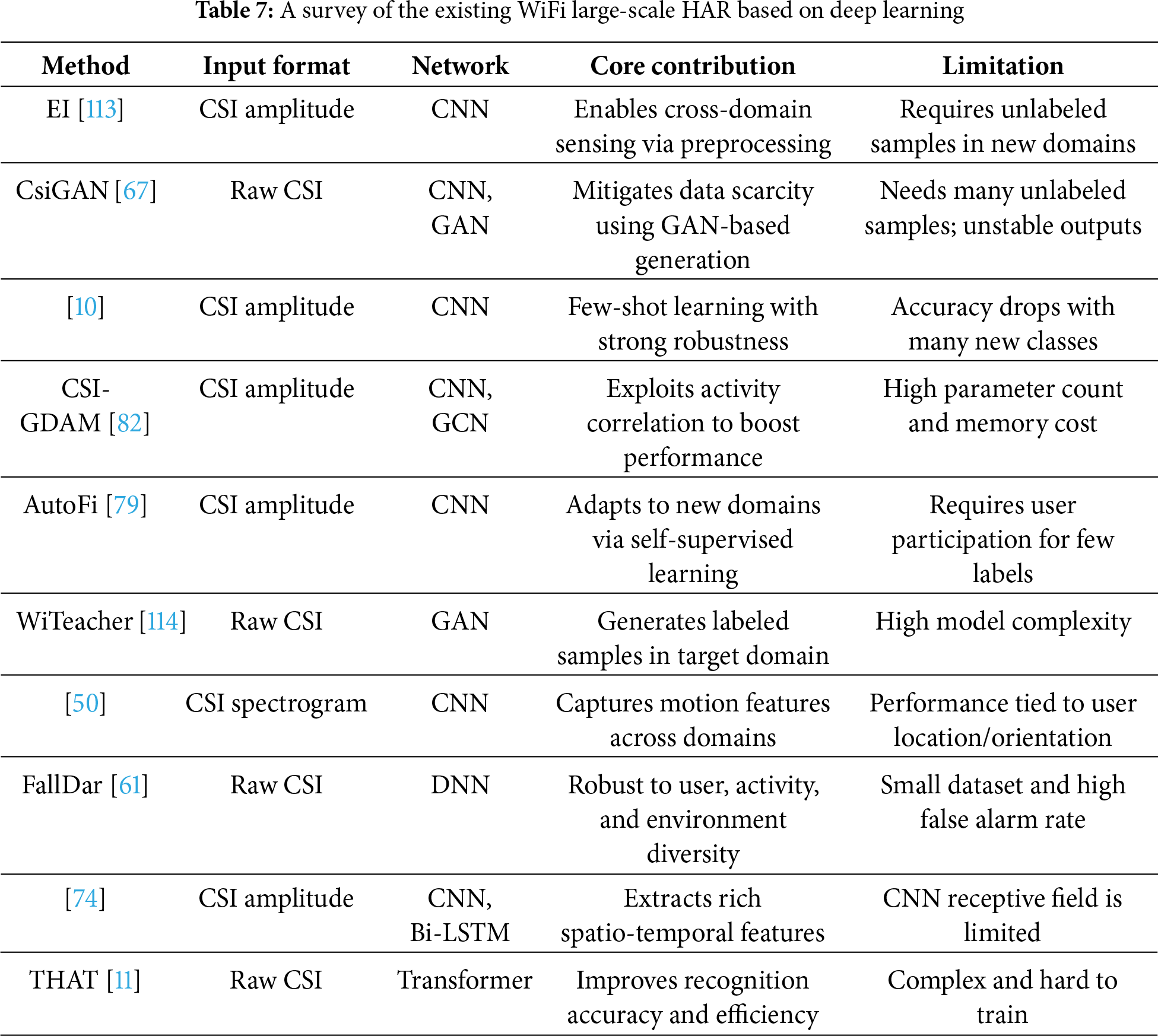

Meta-learning has outstanding performance in few-shot scenarios: CSI-GDAM proposed by Zhang et al. uses graph neural networks to construct activity correlation graphs and optimizes graph convolution parameters through meta-learning [82]; AFSL-HAR by Wang et al. combines the feature generation network (FWGAN) to improve robustness in the recognition of new action categories [83]. The hybrid architecture fuses spatio-temporal features: hybrid structure combine CNN with Bi-LSTM by Sheng et al. first extracts CSI spatial features and then captures action timing through bidirectional LSTM, which is suitable for complex activity classification [74]; THAT model processes channel and time features through a two-stream Transformer to achieve high-precision posture recognition [11]. Table 7 summarizes the existing work on applying deep learning to the field of large-scale human activity recognition.

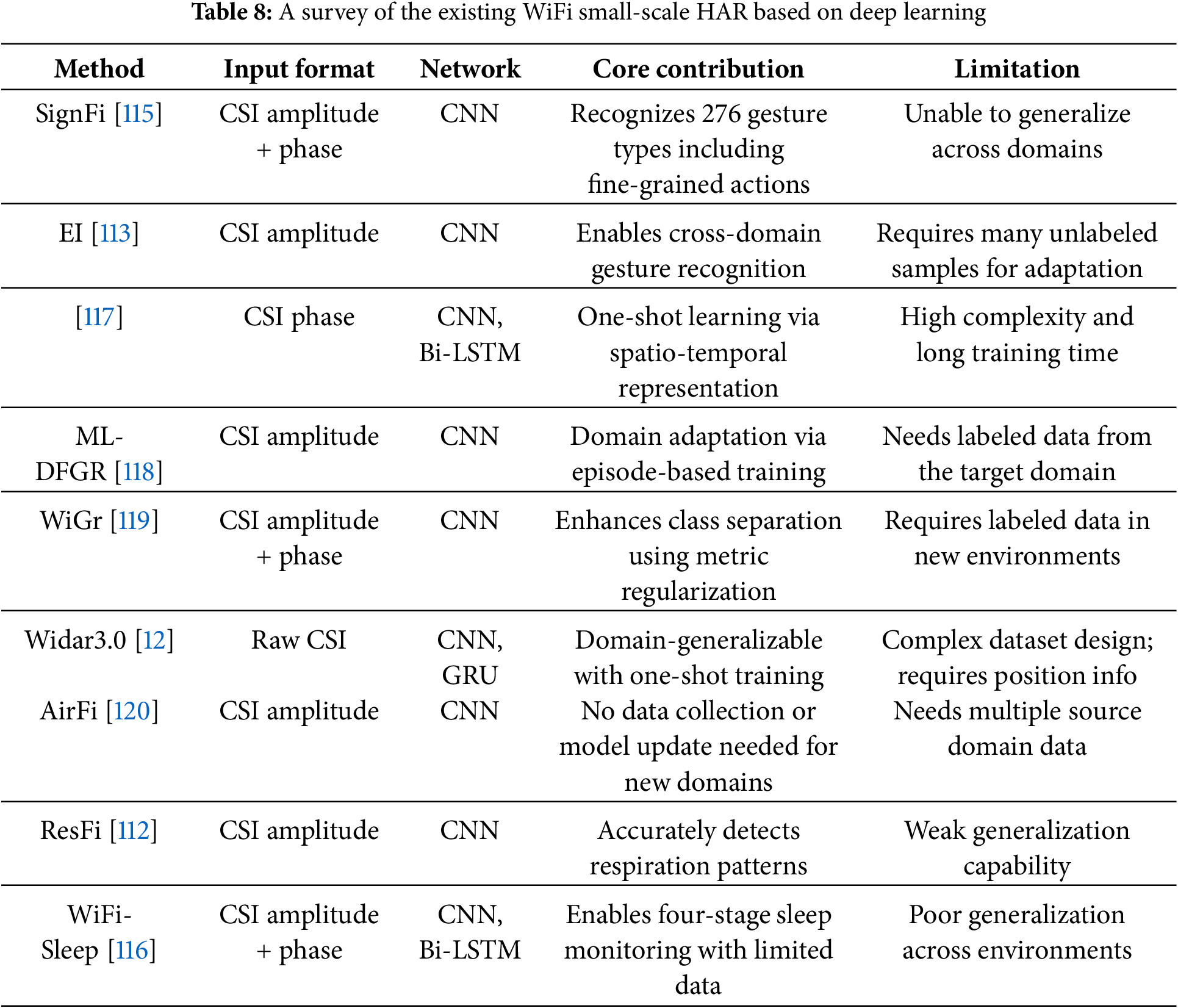

Compared with large-scale actions, small-scale activities (such as breathing and gestures) cause CSI disturbances with lower signal-to-noise ratios, which are easily masked by background noise, placing higher demands on data resolution and model sensitivity. In gesture recognition tasks, CNN is often combined with spectrograms: The SignFi system by MA et al. converts CSI into images and uses CNN to recognize 276 types of gestures [115]; Zhang et al.’s Widar3.0 estimates the Body Velocity Profile (BVP) and inputs it into hybrid architecture with CNN and GRU to achieve cross-domain gesture recognition [12].

Physiological signal monitoring is another research focus: The ResFi system processes CSI amplitude using a CNN and achieves 96.05% accuracy in breathing detection [112]; WiFi-sleep uses CNN and BiLSTM to classify four sleep stages with an average recognition rate of 94.80% [116]. A key challenge is improving the signal-to-noise ratio of micro-motions. For example, CSI fluctuations caused by breathing are easily masked by environmental noise, requiring denoising algorithms (e.g., wavelet transform) and high-resolution CSI acquisition tools (e.g., FeitCSI). Table 8 summarizes the existing work on applying deep learning to the field of small-scale WiFi human activity recognition.

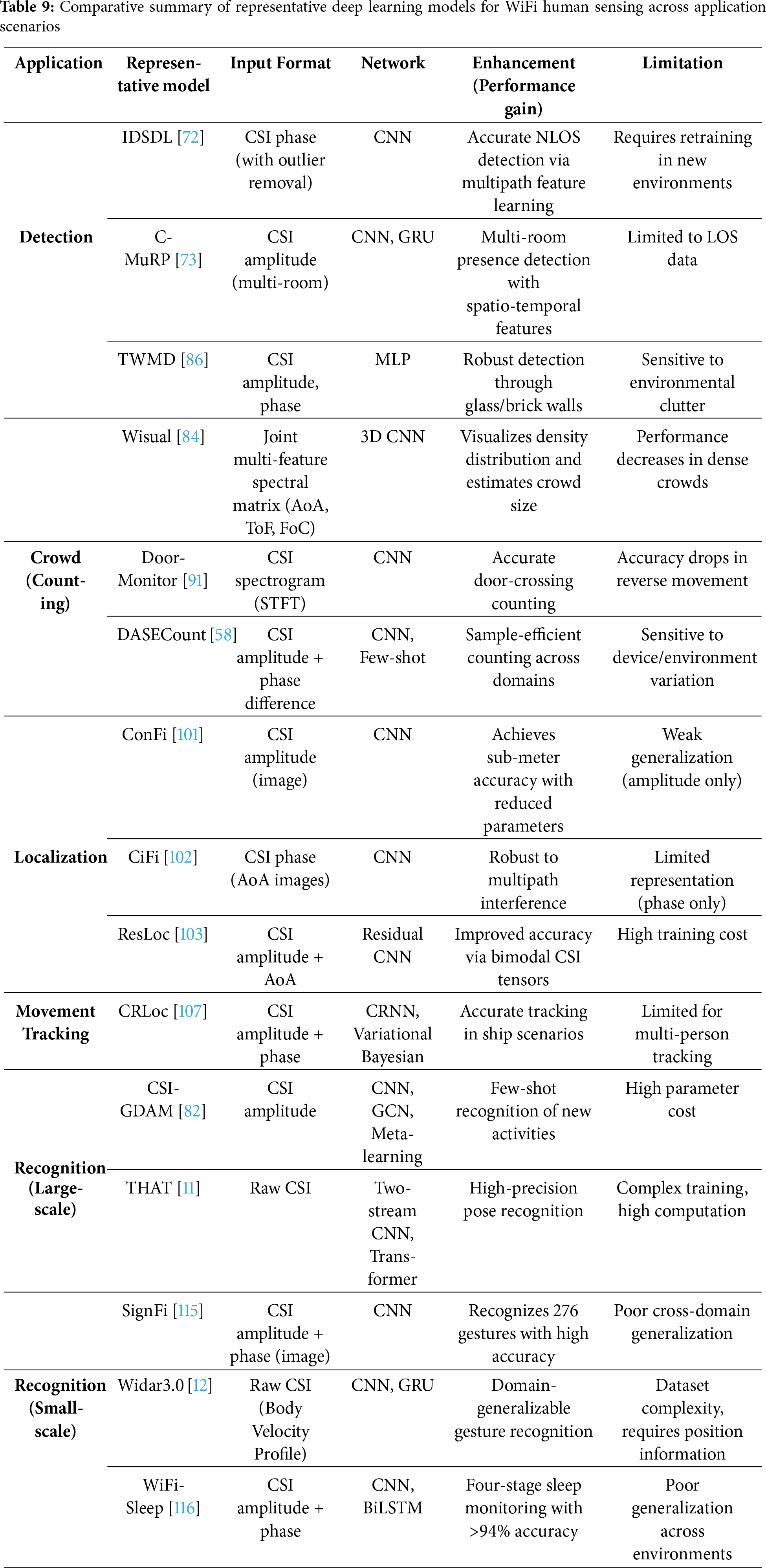

To provide a holistic view, we further summarize representative deep learning models across different human sensing tasks in Table 9. While task-specific methods detailed, Table 9 offers a unified comparison highlighting the enhanced sensing capability in various application scenarios. The table presents input formats, network architectures, performance improvements, and known limitations, thereby allowing readers to clearly observe how deep learning contributes to robustness, accuracy, and adaptability across detection, localization, and recognition tasks.

As shown in Table 9, deep learning has significantly advanced CSI-based human sensing by enhancing robustness in NLOS scenarios, enabling cross-domain recognition, and improving fine-grained localization accuracy. However, despite these achievements, practical deployment still faces challenges such as cross-environment generalization and multi-user interference, which are discussed in the following section on limitations and future trends.

6 Limitations and Future Trend

Although deep learning has substantially improved the performance of human sensing systems, several challenges still hinder its practical deployment. This section analyzes technical bottlenecks from the perspectives of data, models, and hardware, and outlines future research directions based on emerging trends.

Lack of standardized datasets and evaluation metrics: Most existing studies [10,73,89,113] rely on self-collected datasets, which differ substantially in acquisition environments, hardware platforms, numbers of participants, and activity definitions. These discrepancies make it extremely difficult to conduct fair quantitative comparisons across models. Moreover, the absence of unified labeling protocols and widely accepted evaluation metrics further limits reproducibility, as performance measures such as accuracy or F1-scores reported in one setting are often not directly comparable to those obtained in another. This issue is particularly severe for low-probability or safety-critical events such as falls or sudden stops, where collecting large-scale, high-quality samples is resource-intensive.

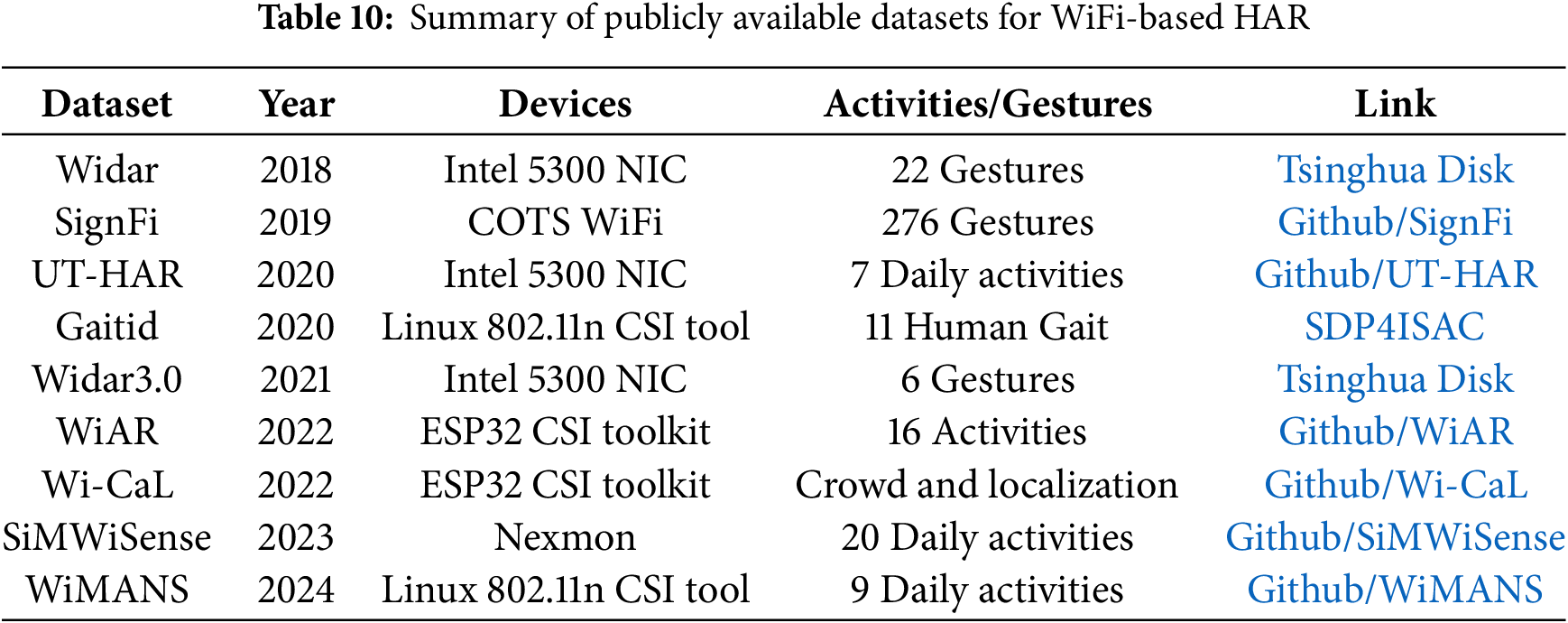

Several public datasets have been released for WiFi-based HAR, as summarized in Table 10. These datasets include Widar, Widar3.0, SignFi, UT-HAR, and others, covering tasks such as gesture recognition, daily activities, sleep monitoring, and fall detection. However, as shown in the table, they differ significantly in terms of activity categories, number of participants, hardware platforms, and data availability. Consequently, while these resources are valuable for advancing research, the lack of a unified and comprehensive benchmark still hinders reproducibility and fair cross-model comparison.

Signal interference in multi-user environments: In scenarios involving multiple users, CSI signals often interfere with one another [90], making it difficult to control variables such as user count, action types, and spatial layouts [84]. As the number of users increases, the complexity of activity combinations grows exponentially, requiring manual annotations that cover various interactions (e.g., collaboration, occlusion). However, most current studies [74] are limited to simplified settings with single-user activities and lack standardized annotation frameworks for multi-user scenarios, resulting in annotation costs that scale poorly with the number of users. More importantly, such interference directly degrades sensing accuracy, as overlapping motion patterns are difficult to separate, resulting in reduced recognition and localization accuracy in realistic crowded environments.

Robustness and generalization: Deep learning models [58,99,107,121] often struggle to maintain robustness under varying environmental conditions such as lighting, background noise, and spatial configurations. This is largely because training datasets are usually collected from constrained settings and specific populations, making it difficult for models to generalize to unseen environments or user groups. Furthermore, sampling bias can cause models to perform well on specific demographics or scenarios while degrading in others, limiting their applicability in diverse real-world settings. In particular, sensing accuracy in cluttered or non-line-of-sight (NLOS) environments is severely affected by multipath propagation and temporal variations (e.g., furniture re-arrangements, doors opening/closing). Location dependence further exacerbates this problem, as most CSI-based HAR models rely on site-specific fingerprints and thus suffer significant accuracy degradation when deployed in new environments. For fine-grained tasks such as respiration monitoring and gesture recognition, low signal-to-noise ratios further exacerbate recognition errors, highlighting the need for robust feature representations and adaptive learning strategies to sustain performance in complex scenarios.

Privacy and security: CSI inherently encodes sensitive information, such as spatial position and physiological traits (e.g., posture inferred from phase differences [122]), yet existing deep learning models lack sufficient resilience against adversarial attacks. For example, attackers can manipulate CSI phase information with crafted interference signals, producing incorrect outputs such as false location predictions. Traditional adversarial training techniques [123] are often ineffective against such phase-specific attacks, compromising the model’s robustness in privacy-critical applications. Moreover, to improve sensing accuracy, deep learning models typically exploit fine-grained CSI features (e.g., subcarrier-level phase differences), which may inadvertently reveal user-identifiable traits such as gait patterns [124], raising concerns over the balance between sensing accuracy and privacy protection.

Deployment complexity: Large model sizes and reliance on complex preprocessing make real-world deployment challenging. CSI extraction is currently supported only by a limited range of WiFi chipsets (e.g., Intel 5300 [1]), while edge devices like ESP32 lack sufficient computational capacity to run deep learning models efficiently [28]. Additionally, CSI acquisition often depends on proprietary drivers or custom firmware, further impeding large-scale deployment and system integration.

Source datasets and codes: Open-access datasets and code repositories are crucial for improving reproducibility and comparability in deep learning–enhanced human sensing research. Public availability of raw CSI datasets and well-documented implementations allows researchers to validate previous findings, accelerate algorithm development, and reduce redundant efforts. Furthermore, accessible resources contribute to the gradual establishment of common benchmarks, which can enhance cross-study comparability. An open ecosystem of datasets and codes not only fosters academic collaboration but also facilitates technology transfer toward practical applications.

Lightweight models and on-device deployment: Adopting lightweight deep neural networks is a key direction to enable practical deployment. These models aim to capture the complex spatio-temporal characteristics of WiFi signals while maintaining high accuracy in tasks such as activity recognition and pose estimation. Future work should also develop task-specific evaluation methodologies to ensure model reliability and adaptability in real-world settings, paving the way for integration into edge-intelligent applications.

Multimodal fusion and scene collaboration: Multimodal fusion can be implemented at three levels—data, feature, and decision. At the data level, signals from heterogeneous sensors such as WiFi, vision, and infrared are integrated; at the feature level, cross-modal abstract representations are combined; and at the decision level, complementary outputs are fused to enhance robustness. This approach strengthens the model’s adaptability to complex environments by leveraging multi-dimensional information, enabling high-precision sensing in real-world scenarios.

LLM-assisted semantic understanding: Current human sensing systems primarily focus on low-level activity recognition (e.g., walking, sitting, falling) and lack the capacity for high-level semantic reasoning. The emergence of large language models (LLMs) offers new opportunities to bridge the gap toward high-level semantic understanding. By treating intermediate outputs such as activity labels, locations, and movement trajectories as contextual inputs, LLMs can infer higher-level user intent (e.g., “preparing breakfast,” “leaving home”). This shift from signal-level to semantic-level understanding enables more intuitive human–computer interaction, particularly in smart home and eldercare applications. Future research may explore prompt engineering, reasoning chain construction, and few-shot semantic alignment to drive deeper integration between LLMs and human sensing systems.

This review has systematically examined deep learning-enhanced human sensing using CSI, covering key components including signal acquisition tools, data preprocessing techniques, and representative neural network architectures. We categorized and analyzed existing works based on three major sensing tasks: detection, localization, and recognition. Finally, we discussed critical technical bottlenecks, with particular emphasis on multi-user signal processing and environmental generalization. Looking ahead, open-source datasets, lightweight network architectures, and multimodal fusion techniques are expected to play central roles in advancing this field.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank University of Electronic Science and Technology of China.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under grant U23A20310.

Author Contributions: Binglei Yue, Aili Jiang, Chun Yang, Junwei Lei and Heng Liu: Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Review and Editing, Visualization. Yin Zhang: Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision, Funding. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ma Y, Zhou G, Wang S. WiFi sensing with channel state information: a survey. ACM Comput Surveys (CSUR). 2019;52(3):1–36. doi:10.1145/3310194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Yang J, Chen X. Toward ubiquitous sensing: researchers turn WiFi signals into human activity patterns. Patterns. 2023;4(3):100707. doi:10.1016/j.patter.2023.100707. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Shao Z, Cheng G, Ma J, Wang Z, Wang J, Li D. Real-time and accurate UAV pedestrian detection for social distancing monitoring in COVID-19 pandemic. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2021;24:2069–83. doi:10.1109/tmm.2021.3075566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Meng Z, Xia X, Xu R, Liu W, Ma J. HYDRO-3D: hybrid object detection and tracking for cooperative perception using 3D LiDAR. IEEE Trans Intell Veh. 2023;8(8):4069–80. doi:10.1109/tiv.2023.3282567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Fang SH, Li CC, Lu WC, Xu Z, Chien YR. Enhanced device-free human detection: efficient learning from phase and amplitude of channel state information. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2019;68(3):3048–51. doi:10.1109/tvt.2019.2892563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Liu Y, Wang T, Jiang Y, Chen B. Harvesting ambient RF for presence detection through deep learning. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2020;33(4):1571–83. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2020.3042908. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Wang D, Yang J, Cui W, Xie L, Sun S. CAUTION: a Robust WiFi-based human authentication system via few-shot open-set recognition. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(18):17323–33. doi:10.1109/jiot.2022.3156099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Rao X, Luo Z, Luo Y, Yi Y, Lei G, Cao Y. MFFALoc: CSI-based multifeatures fusion adaptive device-free passive indoor fingerprinting localization. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;11(8):14100–14. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3339797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhang L, Wu S, Zhang T, Zhang Q. Learning to locate: adaptive fingerprint-based localization with few-shot relation learning in dynamic indoor environments. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. 2023;22(8):5253–64. doi:10.1109/twc.2022.3232858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang Y, Wang X, Wang Y, Chen H. Human activity recognition across scenes and categories based on CSI. IEEE Trans Mobile Comput. 2020;21(7):2411–20. doi:10.1109/tmc.2020.3041756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Li B, Cui W, Wang W, Zhang L, Chen Z, Wu M. Two-stream convolution augmented transformer for human activity recognition. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2021;35(1):286–93. doi:10.1609/aaai.v35i1.16103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang Y, Zheng Y, Qian K, Zhang G, Liu Y, Wu C, et al. Widar3.0: zero-effort cross-domain gesture recognition with Wi-Fi. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2021;44(11):8671–88. doi:10.1109/tpami.2021.3105387. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Ahmadipour M, Kobayashi M, Wigger M, Caire G. An information-theoretic approach to joint sensing and communication. IEEE Trans Inf Theory. 2022;70(2):1124–46. doi:10.1109/tit.2022.3176139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Liu J, Liu H, Chen Y, Wang Y, Wang C. Wireless sensing for human activity: a survey. IEEE Commun Surveys Tutorials. 2019;22(3):1629–45. [Google Scholar]

15. Chen C, Zhou G, Lin Y. Cross-domain WiFi sensing with channel state information: a survey. ACM Comput Surveys. 2023;55(11):1–37. doi:10.1145/3570325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Li H, Ota K, Dong M. Learning IoT in edge: deep learning for the Internet of Things with edge computing. IEEE Netw. 2018;32(1):96–101. doi:10.1109/mnet.2018.1700202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang X, Wang X, Mao S. RF sensing in the Internet of Things: a general deep learning framework. IEEE Commun Magaz. 2018;56(9):62–7. doi:10.1109/mcom.2018.1701277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ahmed HFT, Ahmad H, Aravind CV. Device free human gesture recognition using Wi-Fi CSI: a survey. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2020;87(6):103281. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2019.103281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Schmidhuber J. Deep learning in neural networks: an overview. Neural Netw. 2015;61(3):85–117. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2014.09.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Zappone A, Di Renzo M, Debbah M. Wireless networks design in the era of deep learning: model-based, AI-based, or both? IEEE Trans Commun. 2019;67(10):7331–76. doi:10.1109/tcomm.2019.2924010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Yang J, Chen X, Zou H, Wang D, Xu Q, Xie L. EfficientFi: toward large-scale lightweight WiFi sensing via CSI compression. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(15):13086–95. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3139958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Nirmal I, Khamis A, Hassan M, Hu W, Zhu X. Deep learning for radio-based human sensing: recent advances and future directions. IEEE Commun Surveys Tutorials. 2021;23(2):995–1019. [Google Scholar]

23. Yang J, Chen X, Zou H, Lu CX, Wang D, Sun S, et al. SenseFi: a library and benchmark on deep-learning-empowered WiFi human sensing. Patterns. 2023;4(3):100707. doi:10.1016/j.patter.2023.100703. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Davaslioglu K, Soltani S, Erpek T, Sagduyu YE. DeepWiFi: cognitive WiFi with deep learning. IEEE Trans Mobile Comput. 2019;20(2):429–44. doi:10.1109/tmc.2019.2949815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Halperin D, Hu W, Sheth A, Wetherall D. Tool release: gathering 802.11 n traces with channel state information. ACM SIGCOMM Comput Commun Rev. 2011;41(1):53. [Google Scholar]

26. Xie Y, Li Z, Li M. Precise power delay profiling with commodity WiFi. In: Proceedings of the 21st Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking; 2015 Sep 7–11; Paris, France. p. 53–64. [Google Scholar]

27. Gringoli F, Schulz M, Link J, Hollick M. Free your CSI: a channel state information extraction platform for modern Wi-Fi chipsets. In: Proceedings of the 13th International Workshop on Wireless Network Testbeds, Experimental Evaluation & Characterization; 2019 Oct 25; Los Cabos, Mexico. p. 21–8. [Google Scholar]

28. Hernandez SM, Bulut E. Lightweight and standalone IoT based WiFi sensing for active repositioning and mobility. In: 2020 IEEE 21st International Symposium on “A World of Wireless, Mobile and Multimedia Networks”(WoWMoM); 2020 Aug 31–Sep 3; Cork, Ireland. p. 277–86. [Google Scholar]

29. Hutar M, Brida P, FeitCSI JM. Feitcsi, the 802.11 csi tool [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Sep 28]. Available from: https://feitcsi.kuskosoft.com. [Google Scholar]

30. Jiang Z, Luan TH, Ren X, Lv D, Hao H, Wang J, et al. Eliminating the barriers: demystifying Wi-Fi baseband design and introducing the PicoScenes Wi-Fi sensing platform. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;9(6):4476–96. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3104666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ding J, Wang Y. WiFi CSI-based human activity recognition using deep recurrent neural network. IEEE Access. 2019;7:174257–69. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2956952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Chen Y, Wei Y, Pang D, Xue G. A deep learning approach based on continuous wavelet transform towards fall detection. In: International Conference on Wireless Algorithms, Systems, and Applications. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2022. p. 206–17. [Google Scholar]

33. Zeng Y, Wu D, Xiong J, Zhang D. Boosting WiFi sensing performance via CSI ratio. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2020;20(1):62–70. doi:10.1109/mprv.2020.3041024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Liu J, Zeng Y, Gu T, Wang L, Zhang D. WiPhone: smartphone-based respiration monitoring using ambient reflected WiFi signals. Proc ACM Interact Mobile Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2021;5(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

35. Sardy S, Tseng P, Bruce A. Robust wavelet denoising. IEEE Trans Signal Process. 2001;49(6):1146–52. doi:10.1109/78.923297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Wen X, Song X, Zheng Z, Wang B, Guo Y. A multi-class dataset expansion method for Wi-Fi-based fall detection. In: 2022 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Biomedical Conference (IMBioC); 2022 May 16–18; Suzhou, China. p. 195–7. [Google Scholar]

37. Palipana S, Rojas D, Agrawal P, Pesch D. FallDeFi: ubiquitous fall detection using commodity Wi-Fi devices. Proc ACM Interact Mobile Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2018;1:1–25. [Google Scholar]

38. Zhang K, Zuo W, Chen Y, Meng D, Zhang L. Beyond a gaussian denoiser: residual learning of deep cnn for image denoising. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2017;26(7):3142–55. doi:10.1109/tip.2017.2662206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Ye H, Gao F, Qian J, Wang H, Li GY. Deep learning-based denoise network for CSI feedback in FDD massive MIMO systems. IEEE Commun Letters. 2020;24(8):1742–6. doi:10.1109/lcomm.2020.2989499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Rizzello V, Utschick W. Learning the CSI denoising and feedback without supervision. In: 2021 IEEE 22nd International Workshop on Signal Processing Advances in Wireless Communications (SPAWC); 2021 Sep 27–30; Lucca, Italy: IEEE. p. 16–20. doi:10.1109/spawc51858.2021.9593213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Wang X, Yang C, Mao S. PhaseBeat: exploiting CSI phase data for vital sign monitoring with commodity WiFi devices. In: 2017 IEEE 37th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS); 2017 Jun 5–8; Atlanta, GA, USA. p. 1230–9. [Google Scholar]

42. Tao M, Li X, Wei W, Yuan H. Jointly optimization for activity recognition in secure IoT-enabled elderly care applications. Appl Soft Comput. 2021;99(3):106788. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2020.106788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Bruns A. Fourier-, Hilbert- and wavelet-based signal analysis: are they really different approaches? J Neurosci Methods. 2004;137(2):321–32. doi:10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.03.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Akansu AN, Haddad RA. Multiresolution signal decomposition: transforms, subbands, and wavelets. Boston, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

45. Liu L, Hsu H. Inversion and normalization of time-frequency transform. In: 2011 International Conference on Multimedia Technology; 2011 Jul 26–28; Hangzhou, China. p. 2164–8. [Google Scholar]

46. Tahir A, Ahmad J, Shah SA, Morison G, Skelton DA, Larijani H, et al. WiFreeze: multiresolution scalograms for freezing of gait detection in Parkinson’s leveraging 5G spectrum with deep learning. Electronics. 2019;8(12):1433. doi:10.3390/electronics8121433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Shah SA, Ahmad J, Masood F, Shah SY, Pervaiz H, Taylor W, et al. Privacy-preserving wandering behavior sensing in dementia patients using modified logistic and dynamic Newton Leipnik maps. IEEE Sensors J. 2020;21(3):3669–79. doi:10.1109/jsen.2020.3022564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Wang Y, Wu K, Ni LM. Wifall: device-free fall detection by wireless networks. IEEE Trans Mobile Comput. 2016;16(2):581–94. doi:10.1109/infocom.2014.6847948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Shlens J. A tutorial on principal component analysis. arXiv:1404.1100. 2014. [Google Scholar]

50. Nakamura T, Bouazizi M, Yamamoto K, Ohtsuki T. Wi-Fi-based fall detection using spectrogram image of channel state information. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(18):17220–34. doi:10.1109/jiot.2022.3152315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Wang W, Liu AX, Shahzad M, Ling K, Lu S. Understanding and modeling of wifi signal based human activity recognition. In: Proceedings of the 21st Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking; 2015 Sep 7–11; Paris, France. p. 65–76. [Google Scholar]

52. Wang W, Liu AX, Shahzad M. Gait recognition using wifi signals. In: Proceedings of the 2016 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing; 2016 Sep 12–16; Heidelberg, Germany. p. 363–73. [Google Scholar]

53. Zhang Y, Wang W, Xu C, Qin J, Yu S, Zhang Y. SICD: novel single-access-point indoor localization based on CSI-MIMO with dimensionality reduction. Sensors. 2021;21(4):1325. doi:10.3390/s21041325. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Song Q, Guo S, Liu X, Yang Y. CSI amplitude fingerprinting-based NB-IoT indoor localization. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017;5(3):1494–504. doi:10.1109/jiot.2017.2782479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Haque KF, Zhang M, Restuccia F. Simwisense: simultaneous multi-subject activity classification through Wi-Fi signals. In: 2023 IEEE 24th International Symposium on a World of Wireless, Mobile and Multimedia Networks (WoWMoM); 2023 Jun 12–15; Boston, MA, USA. p. 46–55. [Google Scholar]

56. Cheng X, Huang B. CSI-based human continuous activity recognition using GMM-HMM. IEEE Sensors J. 2022;22(19):18709–17. doi:10.1109/jsen.2022.3198248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Zhang D, Wang H, Wang Y, Ma J. Anti-fall: a non-intrusive and real-time fall detector leveraging CSI from commodity WiFi devices. In: International Conference on Smart Homes and Health Telematics. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2015. p. 181–93. [Google Scholar]

58. Hou H, Bi S, Zheng L, Lin X, Wu Y, Quan Z. DASECount: domain-agnostic sample-efficient wireless indoor crowd counting via few-shot learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;10(8):7038–50. doi:10.1109/jiot.2022.3228557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Tao M, Li X, Xie R, Ding K. Pedestrian identification and tracking within adaptive collaboration edge computing. In: 2023 26th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design (CSCWD); 2023 May 24–26; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. p. 1124–9. [Google Scholar]

60. Liu H, Long M, Wang J, Jordan M. Transferable adversarial training: a general approach to adapting deep classifiers. In: International Conference on Machine Learning; 2019 Jun 9–15; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 4013–22. [Google Scholar]

61. Yang Z, Zhang Y, Zhang Q. Rethinking fall detection with Wi-Fi. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2022;22(10):6126–43. doi:10.1109/tmc.2022.3188779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Zou H, Chen CL, Li M, Yang J, Zhou Y, Xie L, et al. Adversarial learning-enabled automatic WiFi indoor radio map construction and adaptation with mobile robot. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020;7(8):6946–54. doi:10.1109/jiot.2020.2979413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Yadav SK, Sai S, Gundewar A, Rathore H, Tiwari K, Pandey HM, et al. CSITime: privacy-preserving human activity recognition using WiFi channel state information. Neural Netw. 2022;146(11):11–21. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2021.11.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Zhou Z, Wang F, Gong W. i-Sample: augment domain adversarial adaptation models for WiFi-based HAR. ACM Trans Sensor Netw. 2024;20(2):1–20. doi:10.1145/3616494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Creswell A, White T, Dumoulin V, Arulkumaran K, Sengupta B, Bharath AA. Generative adversarial networks: an overview. IEEE Signal Process Magaz. 2018;35(1):53–65. doi:10.1109/msp.2017.2765202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Chen X, Li H, Zhou C, Liu X, Wu D, Dudek G. Fido: ubiquitous fine-grained wifi-based localization for unlabelled users via domain adaptation. In: Proceedings of The Web Conference 2020; 2020 Apr 20–24; Taipei, Taiwan. p. 23–33. [Google Scholar]

67. Xiao C, Han D, Ma Y, Qin Z. CsiGAN: robust channel state information-based activity recognition with GANs. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019;6(6):10191–204. doi:10.1109/jiot.2019.2936580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Karras T, Laine S, Aila T. A style-based generator architecture for generative adversarial networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 4401–10. [Google Scholar]

69. Liu S, Zhao Y, Chen B. WiCount: a deep learning approach for crowd counting using WiFi signals. In: 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Parallel and Distributed Processing with Applications and 2017 IEEE International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing and Communications (ISPA/IUCC); 2017 Dec 12–15; Guangzhou, China. p. 967–74. [Google Scholar]

70. Zhang J, Tang Z, Li M, Fang D, Nurmi P, Wang Z. CrossSense: towards cross-site and large-scale WiFi sensing. In: Proceedings of the 24th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking; 2024 Nov 18–22; New Delhi, India. p. 305–20. [Google Scholar]

71. Ding X, Jiang T, Zhong Y, Huang Y, Li Z. Wi-Fi-based location-independent human activity recognition via meta learning. Sensors. 2021;21(8):2654. doi:10.3390/s21082654. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Hu Y, Bai F, Yang X, Liu Y. IDSDL: a sensitive intrusion detection system based on deep learning. EURASIP J Wirel Commun Netw. 2021;2021(1):95. doi:10.1186/s13638-021-01900-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Chu FY, Chiu CJ, Hsiao AH, Feng KT, Tseng PH. WiFi CSI-based device-free multi-room presence detection using conditional recurrent network. In: 2021 IEEE 93rd Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2021-Spring); 2021 Apr 25–28; Helsinki, Finland. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

74. Sheng B, Xiao F, Sha L, Sun L. Deep spatial-temporal model based cross-scene action recognition using commodity WiFi. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020;7(4):3592–601. doi:10.1109/jiot.2020.2973272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Wang X, Gao L, Mao S, Pandey S. DeepFi: deep learning for indoor fingerprinting using channel state information. In: 2015 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC); 2015 Mar 9–12; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 1666–71. [Google Scholar]

76. Liu W, Dun Z. D-Fi: domain adversarial neural network based CSI fingerprint indoor localization. J Inf Intell. 2023;1(2):104–14. doi:10.1016/j.jiixd.2023.04.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Salman M, Caceres-Najarro LA, Seo YD, Noh Y. WiSOM: WiFi-enabled self-adaptive system for monitoring the occupancy in smart buildings. Energy. 2024;294(5):130420. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.130420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Yang J, Tang S, Xu Y, Zhou Y, Xie L. Maskfi: unsupervised learning of wifi and vision representations for multimodal human activity recognition. arXiv:2402.19258. 2024. [Google Scholar]

79. Yang J, Chen X, Zou H, Wang D, Xie L. Autofi: toward automatic wi-fi human sensing via geometric self-supervised learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;10(8):7416–25. doi:10.1109/jiot.2022.3228820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Khan D, Ho IWH. CrossCount: efficient device-free crowd counting by leveraging transfer learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;10(5):4049–58. doi:10.1109/jiot.2022.3171449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Xiao X, Yan J. A transfer learning based CSI indoor localization using GASF image construction. In: 2023 International Conference on Computer, Information and Telecommunication Systems (CITS); 2023 Jul 10–12; Genoa, Italy. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

82. Zhang Y, Chen Y, Wang Y, Liu Q, Cheng A. CSI-based human activity recognition with graph few-shot learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;9(6):4139–51. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3103073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Wang Y, Yao L, Wang Y, Zhang Y. Robust CSI-based human activity recognition with augment few shot learning. IEEE Sensors J. 2021;21(21):24297–308. doi:10.1109/jsen.2021.3111030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Ma X, Xi W, Zhao X, Chen Z, Zhang H, Zhao J. Wisual: indoor crowd density estimation and distribution visualization using Wi-Fi. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;9(12):10077–92. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3119542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Yuan Z, Wu S, Yang X, He A. Device-free stationary human detection with wifi in through-the-wall scenarios. In: International Conference on Wireless and Satellite Systems. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2019. p. 201–8. [Google Scholar]

86. Yang X, Wu S, Zhou M, Xie L, Wang J, He W. Indoor through-the-wall passive human target detection with WiFi. In: 2019 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps); 2019 Dec 9–13; Waikoloa, HI, USA. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/gcwkshps45667.2019.9024327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Zhang Y, Wang X, Wen J, Zhu X. WiFi-based non-contact human presence detection technology. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):3605. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-54077-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Zhou R, Lu X, Fu Y, Tang M. Device-free crowd counting with WiFi channel state information and deep neural networks. Wirel Netw. 2020;26(5):3495–506. doi:10.1007/s11276-020-02274-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

89. Guo Z, Xiao F, Sheng B, Sun L, Yu S. TWCC: a robust through-the-wall crowd counting system using ambient WiFi signals. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2022;71(4):4198–211. doi:10.1109/tvt.2022.3140305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Shi W, Tahir U, Zhang H, Zhao J. Design and implementation of non-intrusive stationary occupancy count in elevator with wifi. In: International Conference on Broadband Communications, Networks and Systems. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2019. p. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

91. Yang Y, Cao J, Liu X, Liu X. Door-monitor: counting in-and-out visitors with COTS WiFi devices. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019;7(3):1704–17. doi:10.1109/jiot.2019.2953713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

92. Zhou R, Gong Z, Lu X, Fu Y. WiFlowCount: device-free people flow counting by exploiting doppler effect in commodity WiFi. IEEE Syst J. 2020;14(4):4919–30. doi:10.1109/jsyst.2019.2961735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Guo J, Gu X, Liu Z, Ji M, Wang J, Yin X, et al. CM-NET: cross-modal learning network for CSI-based indoor people counting in internet of things. Electronics. 2022;11(24):4113. doi:10.3390/electronics11244113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Huynh MK, Nguyen DA. A research on automated guided vehicle indoor localization system via CSI. In: 2019 International Conference on System Science and Engineering (ICSSE); 2019 Jul 20–21; Dong Hoi, Vietnam. p. 581–5. [Google Scholar]

95. Berruet B, Baala O, Caminada A, Guillet V. DelFin: a deep learning based CSI fingerprinting indoor localization in IoT context. In: 2018 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN); 2018 Sep 24–27; Nantes, France. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

96. Liu H, Yang J, Sidhom S, Wang Y, Chen Y, Ye F. Accurate WiFi based localization for smartphones using peer assistance. IEEE Trans Mobile Comput. 2013;13(10):2199–214. doi:10.1109/tmc.2013.140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

97. Kotaru M, Katti S. Position tracking for virtual reality using commodity WiFi. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 68–78. [Google Scholar]

98. Lin CL, Chang WJ, Tu GH. Wi-Fi-based tracking of human walking for home health monitoring. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;9(11):8935–42. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3118429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

99. Gönültaş E, Lei E, Langerman J, Huang H, Studer C. CSI-based multi-antenna and multi-point indoor positioning using probability fusion. IEEE Trans Wirel Commun. 2021;21(4):2162–76. doi:10.1109/twc.2021.3109789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

100. Li Z, Rao X. Toward long-term effective and robust device-free indoor localization via channel state information. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;9(5):3599–611. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3098019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

101. Chen H, Zhang Y, Li W, Tao X, Zhang P. ConFi: convolutional neural networks based indoor Wi-Fi localization using channel state information. IEEE Access. 2017;5:18066–74. doi:10.1109/access.2017.2749516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

102. Wang X, Wang X, Mao S. Deep convolutional neural networks for indoor localization with CSI images. IEEE Trans Netw Sci Eng. 2018;7(1):316–27. doi:10.1109/tnse.2018.2871165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

103. Wang X, Wang X, Mao S. Indoor fingerprinting with bimodal CSI tensors: a deep residual sharing learning approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020;8(6):4498–513. doi:10.1109/jiot.2020.3026608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

104. Cui W, Zhang L, Li B, Chen Z, Wu M, Li X, et al. Semi-supervised deep adversarial forest for cross-environment localization. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2022;71(9):10215–9. doi:10.1109/tvt.2022.3182039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

105. Hoang MT, Yuen B, Ren K, Dong X, Lu T, Westendorp R, et al. A CNN-LSTM quantifier for single access point CSI indoor localization. arXiv:2005.06394. 2020. [Google Scholar]

106. Yang G. WiLocus: CSI based human tracking system in indoor environment. In: 2016 Eighth International Conference on Measuring Technology and Mechatronics Automation (ICMTMA); 2016 Mar 11–12; Macau, China. p. 915–8. [Google Scholar]

107. Liu K, Yang W, Chen M, Zheng K, Zeng X, Zhang S, et al. Deep-learning-based wireless human motion tracking for mobile ship environments. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(23):24186–98. doi:10.1109/jiot.2022.3189698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

108. Chen CL, Ko CH, Wu SH, Tseng HS, Chang RY. Device-free target following with deep spatial and temporal structures of CSI. J Signal Process Syst. 2023;95(11):1327–40. doi:10.1007/s11265-023-01862-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

109. Qian K, Wu C, Zhang Y, Zhang G, Yang Z, Liu Y. Widar2.0: passive human tracking with a single Wi-Fi link. In: Proceedings of the 16th Annual International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications, and Services; 2018 Jun 10–15; Munich, Germany. p. 350–61. [Google Scholar]

110. Shi S, Sigg S, Chen L, Ji Y. Accurate location tracking from CSI-based passive device-free probabilistic fingerprinting. IEEE Trans Vehi Technol. 2018;67(6):5217–30. doi:10.1109/tvt.2018.2810307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

111. Hussain Z, Sheng QZ, Zhang WE. A review and categorization of techniques on device-free human activity recognition. J Netw Comput Appl. 2020;167:102738. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2020.102738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

112. Hu J, Yang J, Ong JB, Wang D, ResFi Xie L. WiFi-enabled device-free respiration detection based on deep learning. In: 2022 IEEE 17th International Conference on Control & Automation (ICCA); 2022 Jun 27–30; Naples, Italy. p. 510–5. [Google Scholar]

113. Jiang W, Miao C, Ma F, Yao S, Wang Y, Yuan Y, et al. Towards environment independent device free human activity recognition. In: Proceedings of the 24th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking; 2018 Oct 29–Nov 2; New Delhi, India. p. 289–304. [Google Scholar]

114. Xiao C, Lei Y, Liu C, Wu J. Mean teacher-based cross-domain activity recognition using WiFi signals. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;10(14):12787–97. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3256324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

115. Ma Y, Zhou G, Wang S, Zhao H, Jung W. SignFi: sign language recognition using WiFi. Proc ACM Interact Mob Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2018;2:1–21. [Google Scholar]

116. Yu B, Wang Y, Niu K, Zeng Y, Gu T, Wang L, et al. WiFi-sleep: sleep stage monitoring using commodity Wi-Fi devices. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;8(18):13900–13. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3068798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

117. Yang J, Zou H, Zhou Y, Xie L. Learning gestures from WiFi: a siamese recurrent convolutional architecture. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019;6(6):10763–72. doi:10.1109/jiot.2019.2941527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

118. Ma X, Zhao Y, Zhang L, Gao Q, Pan M, Wang J. Practical device-free gesture recognition using WiFi signals based on metalearning. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2019;16(1):228–37. doi:10.1109/tii.2019.2909877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

119. Zhang X, Tang C, Yin K, Ni Q. WiFi-based cross-domain gesture recognition via modified prototypical networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;9(11):8584–96. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3114309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

120. Wang D, Yang J, Cui W, Xie L, Sun S. AirFi: empowering WiFi-based passive human gesture recognition to unseen environment via domain generalization. IEEE Trans Mobile Comput. 2022;23(2):1156–68. doi:10.1109/tmc.2022.3230665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

121. Abuhoureyah FS, Wong YC. Location independent human activity recognition using self-training CSI-based techniques for wireless sensor networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(14):27419–34. doi:10.1109/jiot.2025.3565384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

122. Zhou S, Zhang W, Peng D, Liu Y, Liao X, Jiang H. Adversarial WiFi sensing for privacy preservation of human behaviors. IEEE Commun Letters. 2019;24(2):259–63. doi:10.1109/lcomm.2019.2952844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

123. Liu J, Xiao C, Cui K, Han J, Xu X, Ren K. Behavior privacy preserving in RF sensing. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2022;20(1):784–96. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2022.3143880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]