Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Deep Learning Framework for Heart Disease Prediction with Explainable Artificial Intelligence

1 International Graduate School of AI, National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, Douliu, 64002, Taiwan

2 School of Computing and Information Science, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, CB11PT, UK

3 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, COMSATS University Islamabad, Islamabad, 44000, Pakistan

4 Department of Biomedical Technology, College of Applied Medical Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh, 11633, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Authors: Nadeem Javaid. Email: ; Nabil Alrajeh. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071215

Received 02 August 2025; Accepted 10 September 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Heart disease remains a leading cause of mortality worldwide, emphasizing the urgent need for reliable and interpretable predictive models to support early diagnosis and timely intervention. However, existing Deep Learning (DL) approaches often face several limitations, including inefficient feature extraction, class imbalance, suboptimal classification performance, and limited interpretability, which collectively hinder their deployment in clinical settings. To address these challenges, we propose a novel DL framework for heart disease prediction that integrates a comprehensive preprocessing pipeline with an advanced classification architecture. The preprocessing stage involves label encoding and feature scaling. To address the issue of class imbalance inherent in the personal key indicators of the heart disease dataset, the localized random affine shadowsampling technique is employed, which enhances minority class representation while minimizing overfitting. At the core of the framework lies the Deep Residual Network (DeepResNet), which employs hierarchical residual transformations to facilitate efficient feature extraction and capture complex, non-linear relationships in the data. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed model significantly outperforms existing techniques, achieving improvements of 3.26% in accuracy, 3.16% in area under the receiver operating characteristics, 1.09% in recall, and 1.07% in F1-score. Furthermore, robustness is validated using 10-fold cross-validation, confirming the model’s generalizability across diverse data distributions. Moreover, model interpretability is ensured through the integration of Shapley additive explanations and local interpretable model-agnostic explanations, offering valuable insights into the contribution of individual features to model predictions. Overall, the proposed DL framework presents a robust, interpretable, and clinically applicable solution for heart disease prediction.Keywords

Heart disease remains a significant universal health dilemma and is the leading cause of mortality across both developed and developing nations. The World Health Organization notes that cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of many deaths in the world, claiming about 17.9 million lives annually, a figure that accounts for 32% of deaths that occur globally. The prevalent heart disease [1,2] is usually caused by demeanors of life composed of sparse food, insufficient exercise, smoking of tobacco, excessive drinking, and so forth. The symptoms are commonly ignored or misrepresented in their earlier stages, which causes the problem to go undetected in time to prevent it [3].

Conventional diagnostic methods, including electrocardiograms, echocardiography, and stress testing, are effective but often costly, time-consuming, and dependent on clinical expertise. In addition, it is especially difficult to detect cases of a mild or non-symptomatic nature and therefore respond to them in time, with worse results. There is thus a pressing need for scalable, accessible, and accurate predictive models that can identify high-risk individuals before the disease reaches an advanced stage.

However, Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) have emerged as powerful tools in the sphere of medical diagnosis and risk prediction because it is possible to analyze complicated patterns in big data in healthcare. ML models such as support vector machines [4], decision trees [5], and ensemble methods have demonstrated success in structured clinical datasets, while DL architectures offer end-to-end feature learning capabilities suitable for high-dimensional data. Despite their promise, many existing approaches suffer from critical issues such as class imbalance, insufficient feature extraction, overfitting, and lack of interpretability. These limitations restrict their adoption in clinical practice, where trust, transparency, and generalizability are essential for supporting decision-making and improving patient care.

The authors in [6] present a healthcare system to predict the condition of patients with heart disease using ML and cloud computing. The evaluation of the model is based on quality-of-service parameters. To validate the models, a 5-Fold Cross-Validation (5-FCV) technique is used. The cloud-based healthcare systems face the issue of device latency.

The authors in [7] propose a hybrid model to detect heart disease at an early stage. ML algorithms are used for predicting the disease. For feature selection, the genetic algorithm and data balancing Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) are used. The proposed model achieved an accuracy of 86.6% when using Random Forest (RF).

The model proposed in [8] uses sensor and electronic data. The proposed system is based on ensemble DL for disease prediction. Feature fusion and information techniques are used for feature selection. The authors in [9] proposed a model using diverse datasets. The Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) and relief approaches are used to select the relevant features. A hybrid technique with traditional, boosting, and bagging models is used for the prediction of disease.

In [10], the authors introduced an ML model for predicting heart disease. The datasets are obtained from the Kaggle and UCI repositories. A feature selection approach is utilized to extract significant features, and a sampling strategy is employed to balance the dataset. Ensemble learning classifiers are used to predict heart disease.

In this study, the primary objective is to efficiently predict heart disease using an advanced DL-based framework. One of the key contributions of this framework is the integration of Localized Random Affine Shadowsampling (LoRAS), an oversampling method that reduces overfitting and improves class balance by preserving the underlying structure of the minority class. Additionally, a novel model, Deep Residual Network (DeepResNet), is also proposed in this framework, such that it takes the form of structured probabilistic modeling and hierarchical residual transformations to successfully recover the latent patterns in the data. To guarantee reliability and generalizability of the DeepResNet model with various data distributions, 10-FCV will be utilized. Furthermore, two eXplainable Artificial Intelligence (AI) methods, Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), are included to make the proposed model more interpretable and help to obtain an understanding of the model’s decision-making process.

2 Proposed Deep Learning Framework

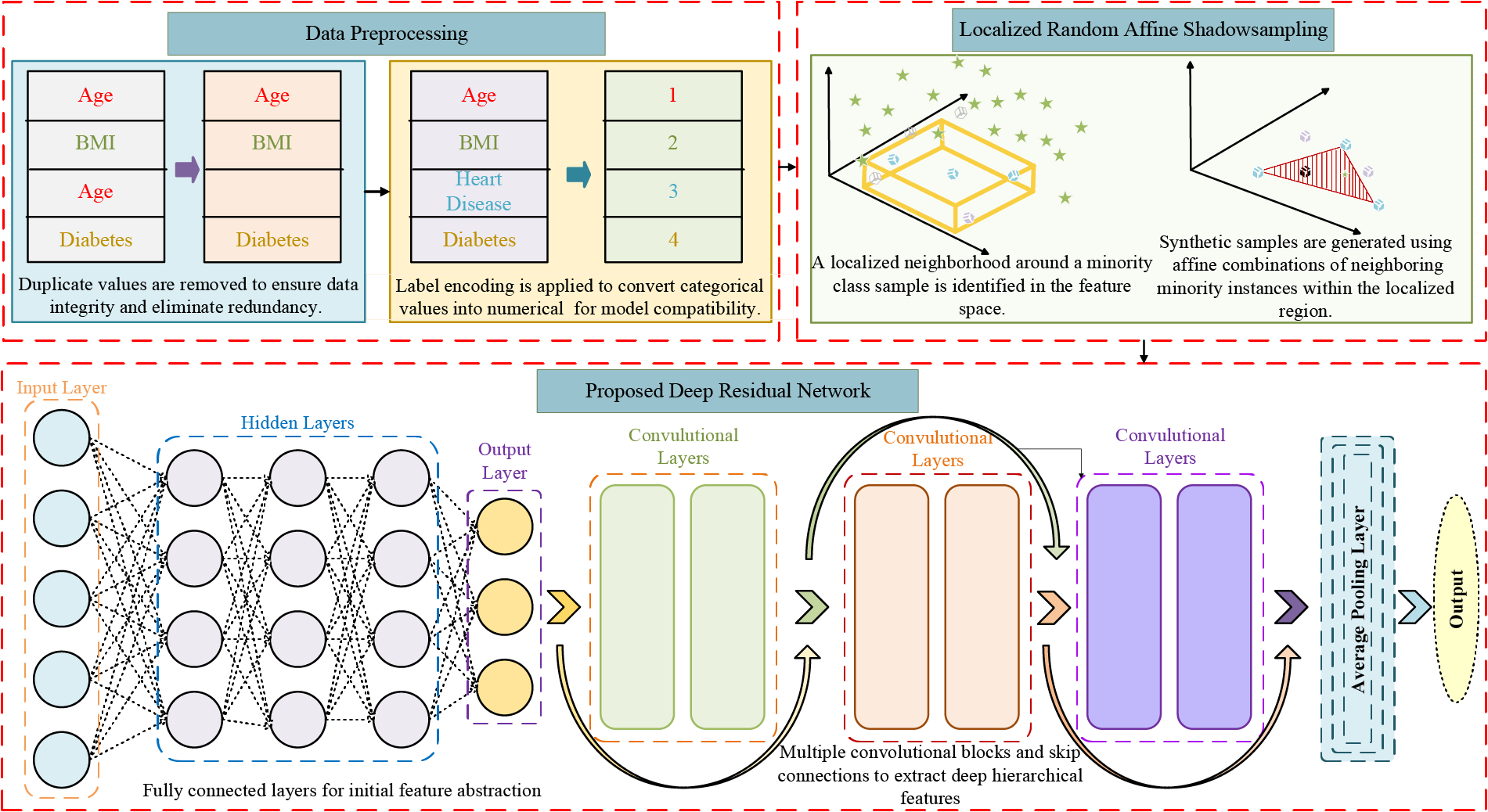

The proposed DL framework model follows a systematic structure that begins with data preprocessing. Firstly, categorical variables are transformed into numerical representations to ensure compatibility with DL frameworks. Secondly, features are normalized using standard scaling. Lastly, irrelevant or sensitive features are excluded to maintain ethical standards and reduce prediction bias in healthcare applications. Then, to tackle class imbalance, the LoRAS technique is employed, which generates synthetic samples through localized perturbations while preserving the distribution of the minority class. The core of the DL framework is a novel DeepResNet, which integrates hierarchical residual transformations to extract deep patterns and improve classification accuracy for heart disease prediction. Fig. 1 shows the complete working of the proposed framework.

Figure 1: Proposed deep learning framework for accurate heart disease prediction

2.1 Description of Personal Key Indicators of Heart Disease Dataset

We used the Personal Key Indicators of Heart Disease dataset, a core component of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), one of the largest health-related surveys in the United States of America. The dataset was collected in 2020 and consists of self-reported responses from around 400,000 residents of the USA regarding their health, lifestyle choices, and medical issues [11]. It has 319,795 occurrences and 18 attributes, including demographics, health conditions, and behavioral aspects. Heart Disease is a binary target variable; Class 1 represents those who have been diagnosed with heart disease, and Class 0 represents those who are healthy. The class imbalance in the BRFSS is one of its main problems; the percentage of individuals with heart disease diagnoses is significantly lower. The dataset has four numerical (decimal), five categorical (string), and nine boolean features.

Upon examination of the dataset, some notable patterns and correlations become apparent. Although there is no direct correlation between alcohol consumption and heart disease, smoking is closely associated with the disease. Heart disease is more common in men than in women, indicating that there are gender disparities. On the other hand, heart disease is far more common among those who have difficulty in walking. Age is also a significant factor because heart disease is more prevalent in people over 40. The same is true for physical inactivity, which is a major risk factor; sedentary individuals are more likely to get heart disease sooner than active people. Among the most significant predictors of heart disease in this dataset are comorbid disorders such as stroke, skin cancer, diabetes, and smoking history, and additional analysis shows their significant impact. These findings also support known medical research and make the dataset a valuable source for healthcare analytics, epidemiological research, and predictive modeling aimed at the early identification and prevention of heart disease.

The dataset was cleaned up to increase the results of the model by converting the categorical type variables to numerical methods that can be used by deep-learning models. Categorical variables like Smoking, HeartDisease, AlcoholDrinking, Stroke, Sex, PhysicalActivity, DiffWalking, Asthma, KidneyDisease, and SkinCancer were coded as 1 when the answer was Yes and 0 when the answer was No. Categorical variables, i.e., multi-class items, like Diabetic, were coded as 1 and 0 to represent Yes and No and any other items. The ordinal relationships between the AgeCategory and GenHealth features were coded numerically, with the relationship between AgeCategory and age ranges being represented by the following equivalences: Young, Middle-Aged, and Old corresponded to 1 (1–15), 2 (16–30), and 3 (31–58), respectively, and Old-Aged was translated to age 58 or older. The GenHealth feature was mapped to integers assigned the value 5-Excellent. As an additional data preparation process before model training, the features and target variable were scaled using the standard scaler. This step involved applying the scaler to the training data and then using it on both the training and test datasets, ensuring that all features are standardized and that no single feature carries significantly more weight than others due to differing ranges. These preprocessing procedures make the data set suitable for the format and magnitude of the DL implementation.

There is an ethical issue with the race feature that is explicitly excluded when performing our analysis, since it introduces some prejudices into the predictive model. The inclusion of race as a predictor can only create unavoidable gaps in healthcare determination instead of normalizing risks in an objective clinical manner. Rather, those aspects of clinical significance are targeted that have a direct relation to risk of heart diseases, i.e., age, smoking, and physical activity.

where X′ represents the dataset after removing the race feature. Additionally, to manage computational constraints and optimize training efficiency, a subset of 50,000 instances is selected for experimentation, ensuring a balance between dataset diversity and computational feasibility.

2.3 Data Balancing Using Localized Random Affine Shadowsampling

LoRAS is a synthetic data oversampling technique tailored to address class imbalance by producing high-quality minority class samples while preserving local data structures. For each minority class instance

where

2.4 Newly Proposed Deep Residual Network for Heart Disease Prediction

The proposed DeepResNet is a DL architecture that combines structured probabilistic modeling with residual learning to capture high-dimensional dependencies while ensuring stable gradient propagation across layers. Compared to the commonly used Deep Neural Networks (DNNs), which still take advantage of only deterministic transformation, DeepResNet incorporates the energy-based probabilistic representation of features and combines the hierarchical residual blocks. This design enables the model to learn meaningful latent representations while preserving critical information flow, ultimately enhancing classification performance in complex medical datasets such as the personal key indicators of the heart disease dataset. Let the training dataset consist of N samples, where each instance is denoted as

where

where

where

The residual learning block is defined as:

where

where

where

DeepResNet combines the ideas of probabilistic modeling and residual learning to yield a flexible and interpretable DL architecture that can capture rich feature interactions and achieve high predictive performance in classifying heart disease.

The novelty of the proposed DeepResNet lies in the integration of energy-based probabilistic modeling with residual learning. Unlike conventional ResNet architectures that rely solely on deterministic transformations through stacked convolutional and residual blocks, DeepResNet first projects the input into a structured probabilistic space using an RBM-inspired energy formulation. This probabilistic representation enables the model to capture high-dimensional dependencies and latent feature interactions that deterministic residual networks are unable to explicitly model. Once these latent probabilistic features are obtained, they are further refined through hierarchical residual blocks, which ensure stable gradient propagation and efficient feature reuse. In this way, the residual component contributes to optimization stability and depth scalability, while the probabilistic component contributes to richer representation learning. It is important to emphasize that, unlike classical RBMs, which are pretrained separately in an unsupervised manner, the proposed DeepResNet does not perform standalone pretraining for the probabilistic layer. Instead, the energy-based feature representation is optimized jointly with the residual convolutional and dense layers within a single end-to-end training pipeline. During backpropagation, the gradients of the free-energy-based transformation are updated simultaneously with the residual parameters, thereby ensuring that the probabilistic features are directly aligned with the supervised classification objective rather than being detached as a pretraining stage. This dual mechanism allows DeepResNet to not only preserve the advantages of ResNet but also extend it by embedding meaningful latent representations into the learning process. In contrast to standard ResNet, which relies purely on deterministic residual mappings, DeepResNet explicitly models latent dependencies through its probabilistic component, leading to enhanced feature expressiveness, improved optimization stability, and superior performance on complex medical datasets. These distinctions highlight the incremental yet significant advantages of the proposed framework over conventional ResNet architectures.

The objective of the DeepResNet model is to enhance the classifier accuracy of heart disease detection through the adoption of the deep probabilistic framework and residual learning. Several classification measures are used to assess the DeepResNet’s performance in detail. To ensure reliable validation, experiments are conducted on Google Colab utilizing a computational configuration that consists of an Intel Core i5-7300U CPU working at 2.71 GHz, 8 GB of RAM, and Windows 11 Pro running on a 64-bit operating system. This experimental environment provides a reliable framework to assess the effectiveness and scalability of the proposed DeepResNet model when tested with real-world data.

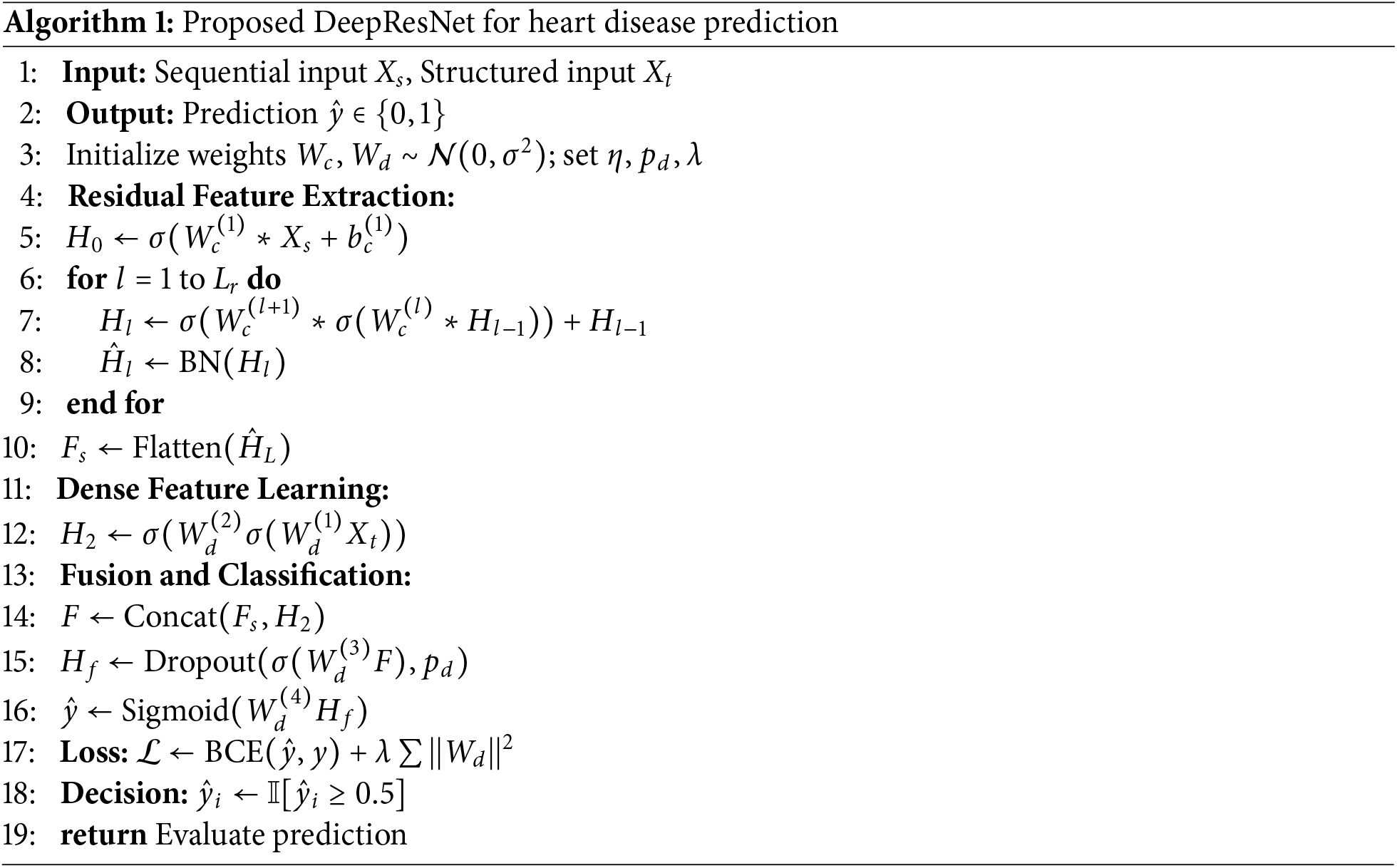

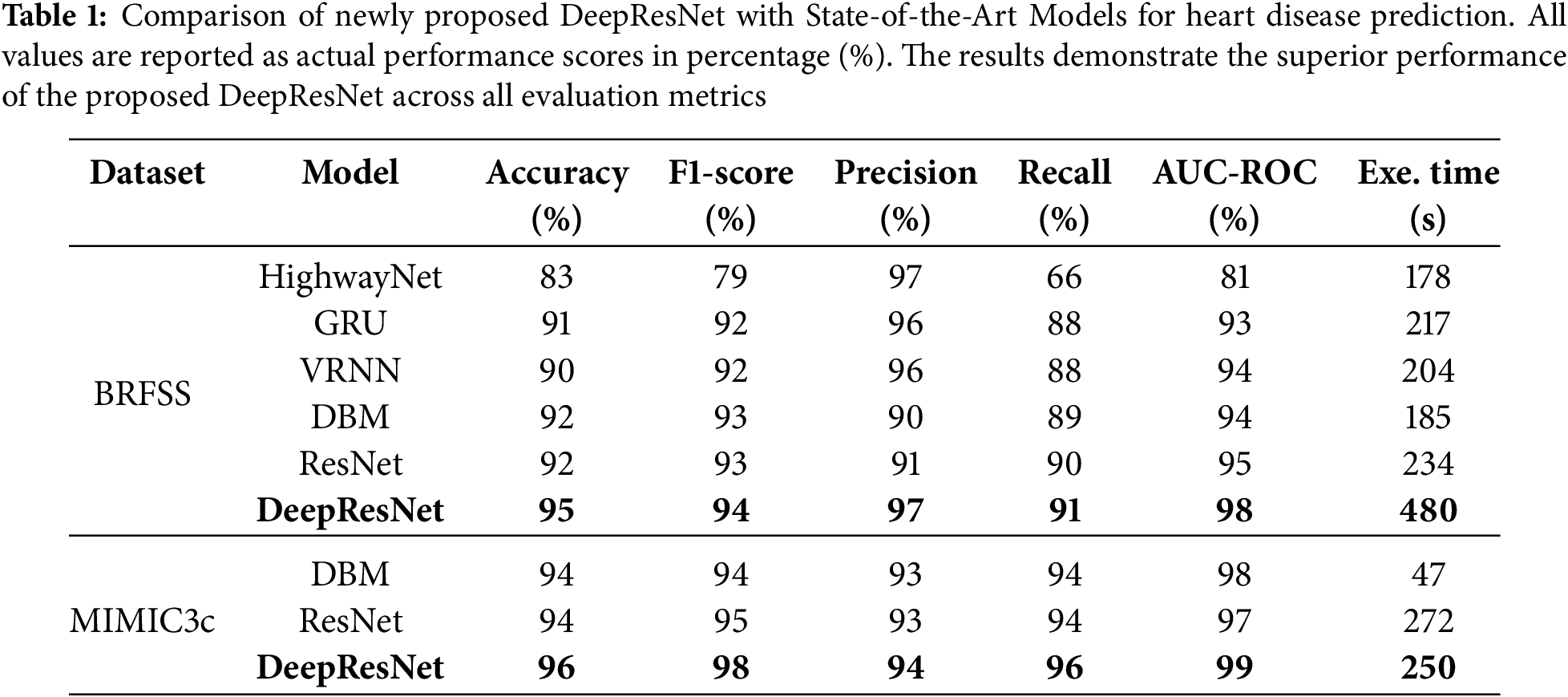

3.1 Performance Analysis of DeepResNet Model

Comparison of heart disease predictor models indicates that the DeepResNet model is the best model for heart disease prediction as compared to the other models in all the measures of evaluation. With an accuracy rate of 95%, as shown in Table 1, DeepResNet significantly outperforms Highway Network (Highway Net) at 83%, Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) at 91%, Vanilla Recurrent Neural Network (VRNN) at 90%, Deep Boltzmann Machine (DBM) at 92%, and even Residual Network (ResNet) at 92% on the BRFSS dataset. The reason for this improvement is DeepResNet’s ability to use its residual learning architecture to identify hierarchical features and integrate a probabilistic feature extraction mechanism. Unlike traditional deep networks that only use deterministic transformations, DeepResNet leverages structured latent space modeling to improve its capacity to identify complex patterns in the data. DBM and ResNet perform significantly poorer in classification and have inefficient feature propagation because of their limited capacity to preserve low-level features while processing deeper layers.

The MIMIC3c [13] dataset shown in Table 1 has 28 features and 58,976 instances, and we used 15,000 of these instances for training to ensure sufficient time management. DeepResNet recorded the best results in its accuracy of 96%, F1-score of 98%, precision of 94%, recall of 96%, and AUC-ROC of 99% as compared to DBM and ResNet. Whereas the baseline models showed satisfactory results, DeepResNet served up better results regularly on all the evaluation metrics. The execution time of the model on the chosen 15,000 instances took 250 s, which is quite a satisfactory balance between a satisfactory performance and a low computational cost. Overall, our model has outstanding results on both the BRFSS and MIMIC3c datasets, outperforming the other models at all levels of measurement and having competitive computational costs.

Additionally, the discussion is also provided regarding the CPU and memory consumption of baseline and proposed DeepResNet models, comprising DeepResNet, ResNet, and DBM. The DeepResNet consumes 81% of a CPU, which is similar to ResNet with 80% and a bit higher than DBM with 81.8. In terms of memory consumption, DeepResNet occupies 2.14 GB, which is more than ResNet with 1.75 GB and DBM with 2.05 GB. These findings show that the DeepResNet model is not as resource hungry as baseline models, though its memory consumption is somewhat higher compared to the other models. This data provides insights into the resource readings required to run the model and add efficiencies to the way it is being calculated.

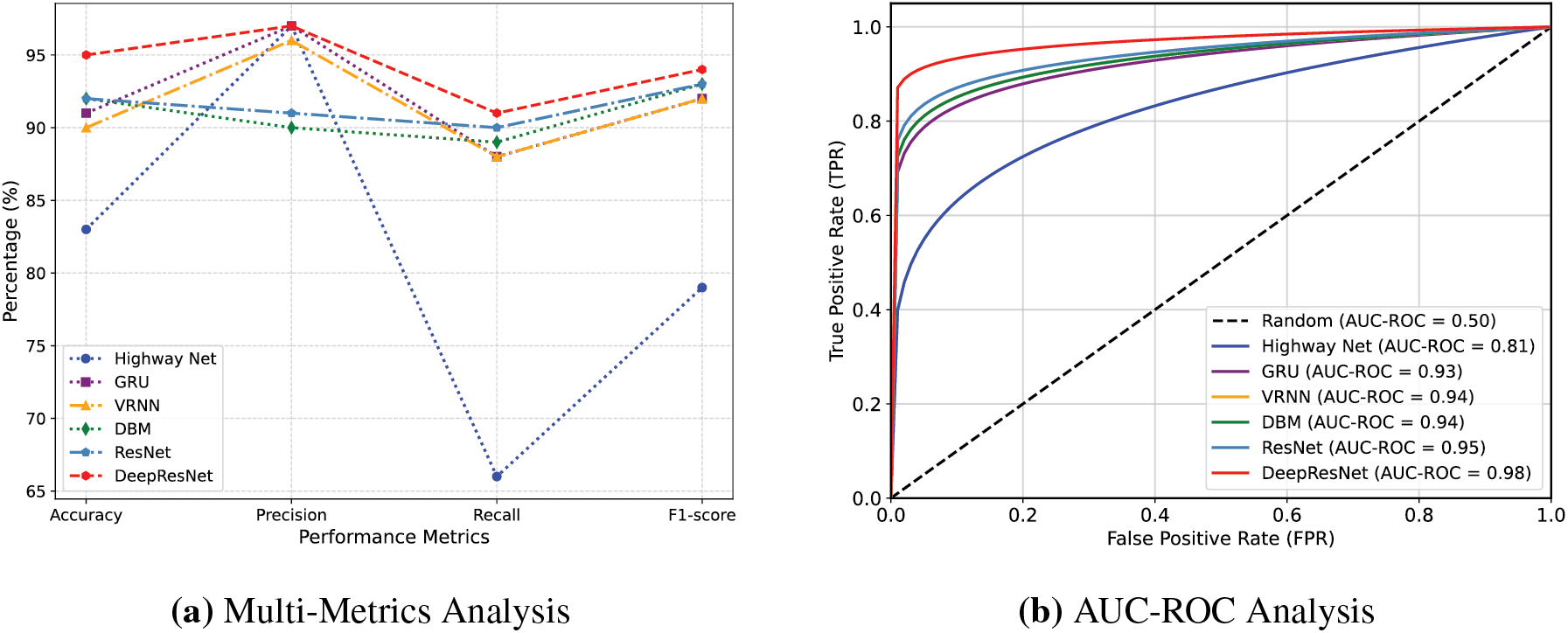

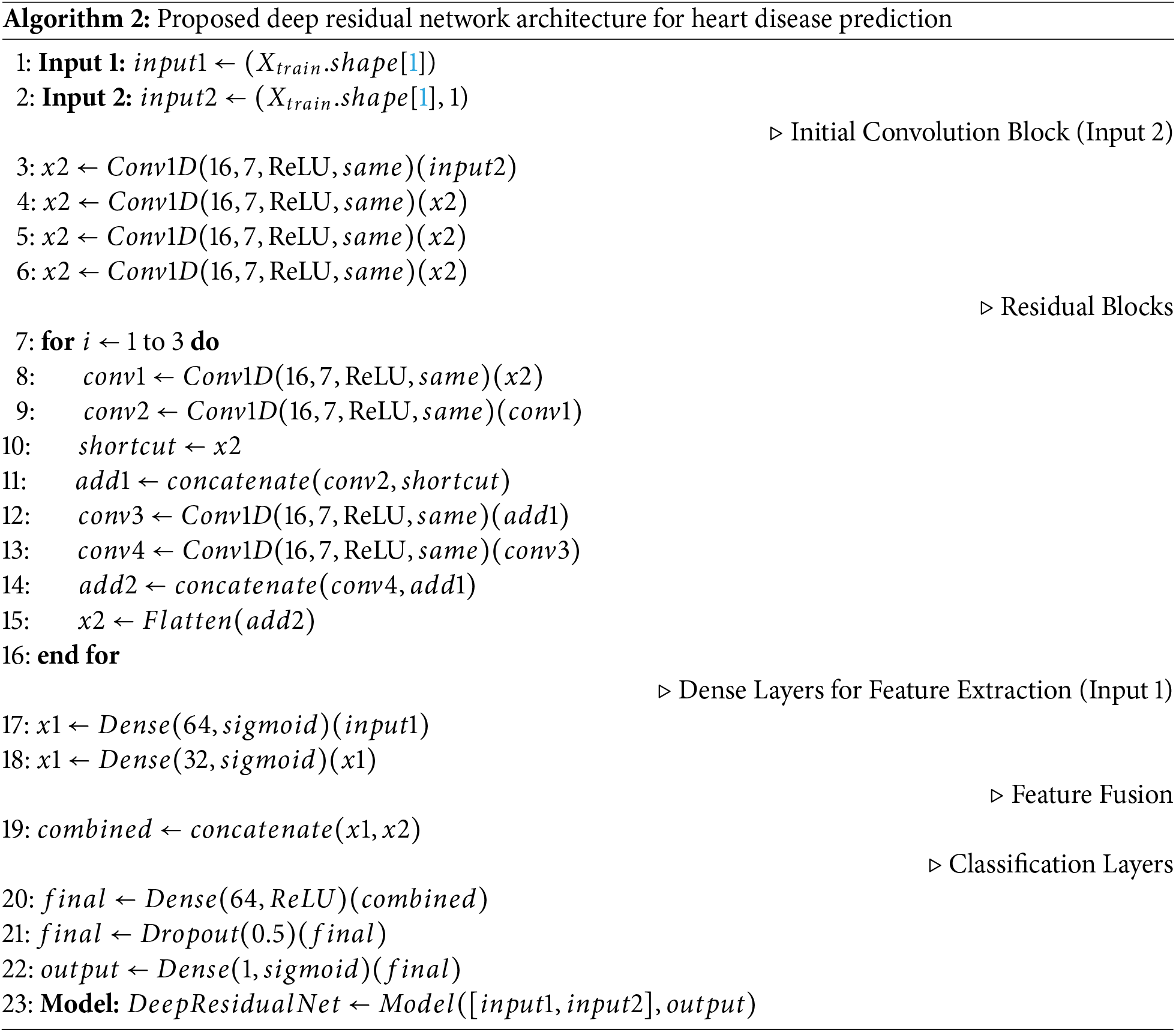

Predicting heart disease cases is highly reliable due to the precision values, which show the DeepResNet’s ability to reduce False Positives (FPs). DeepResNet performs well at distinguishing True Positives (TPs) cases, with the highest precision of 97% as shown in Fig. 2a. HighwayNet likewise reaches 97% precision, but its statistics are misleading because it lowers false alerts at the expense of identifying real heart disease cases, as seen by its recall falling to 66%. This imbalance makes it unsuitable for medical contexts where missing actual patients poses a significantly greater risk than a higher FP rate. While both VRNN and GRU achieve 96% precision, their 88% recall is lower. Conversely, DeepResNet continues to have excellent recall and high precision. With a 91% recall, DeepResNet outperforms all other models, with ResNet ranking in second at 90% and DBM at 89%. The recall measure assesses the DeepResNet’s ability to accurately identify people with heart disease. In medical diagnostics, where cases that remain unreported can have serious implications, DeepResNet’s stronger recall ensures that it lowers FNs. Despite their capacity to learn intricate feature representations, DBM and VRNN are limited in their ability to differentiate between borderline cases of heart disease because these models rely on conventional feature extraction methods that do not have residual connectivity, which makes it difficult for them to learn important spatial and structural information from previous layers. The F1-score of DeepResNet, which balances precision and recall, achieves a maximum value of 94%, as shown in Table 1. Although HighwayNet is accurate, its inability to discover enough positive cases makes it unreliable. This fact is demonstrated by its significantly lower F1-score of 79%, which shows that it is unable to maintain a good balance between precision and recall. Even though VRNN and GRU maintain a high F1-score of 92%, their recall limits hinder them from achieving the optimal balance between precision and recall. With F1-scores above 92%, the intense comparison between DBM, ResNet, and DeepResNet suggests that these models are fundamentally better suited for structured medical data where feature capture is essential, as shown in Fig. 2a. The strength of DeepResNet, however, is its hierarchical handling of feature dependencies without permitting gradient deterioration, ensuring that significant patterns for heart disease classification remain visible at deeper levels. The architecture of DeepResNet is described in Algorithm 2. The model utilizes the ReLU activation function in convolutional layers to introduce non-linearity and prevent vanishing gradients, while the sigmoid function is used in the final layer for binary classification to output probabilities between 0 and 1, which is suitable for heart disease prediction. The convolutional layers were activated by ReLU to provide non-linearity and alleviate the vanishing gradient issue. In trial runs, ReLU is seen to have performed better compared to other activation functions like Tanh or Leaky ReLU and is faster in training and performance. The Adam optimizer is selected for its adaptive learning capability, with a learning rate of 0.001 to ensure stable convergence. The learning rate was chosen relying on the empirical outcome of initial trials. A learning rate of 0.001 was selected due to a satisfactory trade-off between the speed of training and training stability. Using smaller values like 0.0001 produced slower convergence, whereas larger values of 0.01 produced unstable training in initial testing. Thus, 0.001 was the best parameter value for the DeepResNet architecture in performance and convergence. Binary crossentropy is employed as the loss function due to the binary nature of the classification task. A prediction threshold of 0.5 is used to determine class membership. The network consists of 4 convolutional layers and 3 residual blocks, each designed to capture deep features while maintaining gradient flow. A kernel size of 7 and 16 filters is used to extract spatial features. The fully connected part of the model comprises 3 dense layers with 64, 32, and 1 neurons, respectively, and includes a dropout rate of 0.5 to reduce overfitting. To avoid the overfitting problem during the model training phase using the relatively imbalanced dataset, the dropout rate of 0.5 was selected. According to the results of the cross-validation, this dropout rate helped maintain a balance between retaining sufficient network capacity and applying regularization. Smaller rates of 0.3 had no significant effects in preventing overfitting, whereas larger rates of 0.07 made the model underfit. Training is performed using a batch size of 32 for 20 epochs, ensuring sufficient learning while maintaining computational efficiency. The batch size was also optimized at 32, by observing the effects on training time and performance. A smaller batch size of 16 resulted in more variance in the gradient updates, which resulted in less stable convergence. In contrast, larger batch sizes of 64 did not demonstrate a significant difference in model performance, but the computational cost was increased. Hence, a batch size of 32 was revealed to be the optimal compromise between modeling precision and training speed. With an Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristics Curve (AUC-ROC) score of 98%, the model maintains greater discrimination between positive and negative cases across all probability thresholds. The AUC-ROC curve in Fig. 2b further illustrates DeepResNet’s ability to classify patients with and without heart disease, outperforming ResNet at 95%, DBM at 94%, VRNN at 94%, and GRU at 93%. HighwayNet performance, which displays an AUC-ROC of 81%, indicates that it struggles to maintain a stable classification boundary and is prone to misclassification errors at different sensitivity thresholds. Because of its probabilistic feature extraction mechanism, which improves the model’s capacity to generalize outside of training data while preventing overfitting, the DeepResNet architecture is able to sustain a high AUC-ROC score, as seen in Fig. 2. The slight drop in AUC-ROC for DBM and VRNN suggests that while these models perform well at default thresholds, their decision boundaries are less stable when evaluated at various probability thresholds, making them less reliable for clinical decision-making in the real world, where probability calibration is necessary.

Figure 2: Comparative analysis of baseline and proposed DeepResNet models

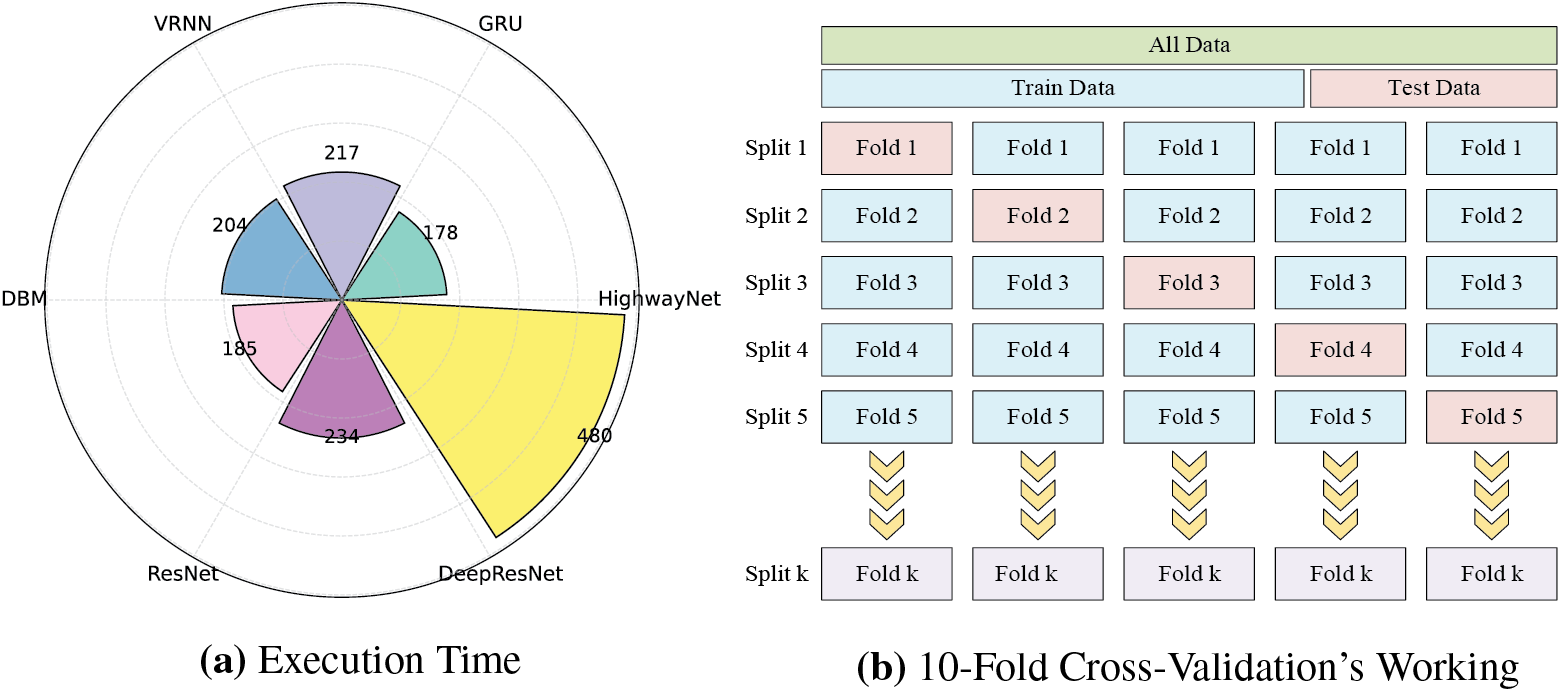

Fig. 3a shows an execution time analysis of the trade-off between predictive performance and computational efficiency. DeepResNet takes longer than ResNet, DBM, VRNN, and GRU, with 480 s. While this longer processing time can seem to be a drawback, it is directly caused by DeepResNet’s deeper architecture, which combines structured probabilistic learning and residual feature transformation. To improve the learning of intricate patterns in data, the feature learning process utilizes multiple hierarchical layers, which increases computational complexity. However, in medical applications where diagnostic accuracy is critical, a little longer execution time is a justified trade-off for improved predictive capability. ResNet performs worse in classification than DeepResNets despite being faster with 234 s due to its absence of a probabilistic feature representation strategy, which compromises prediction adaptability. For critical diagnostic tasks where reducing FNs is the primary goal, DBM, VRNN, and GRU are less suitable due to their lower classification reliability.

Figure 3: Execution time comparison baseline and proposed models and working of 10-Fold Cross-Validation

3.2 Performance Analysis of Data Balancing

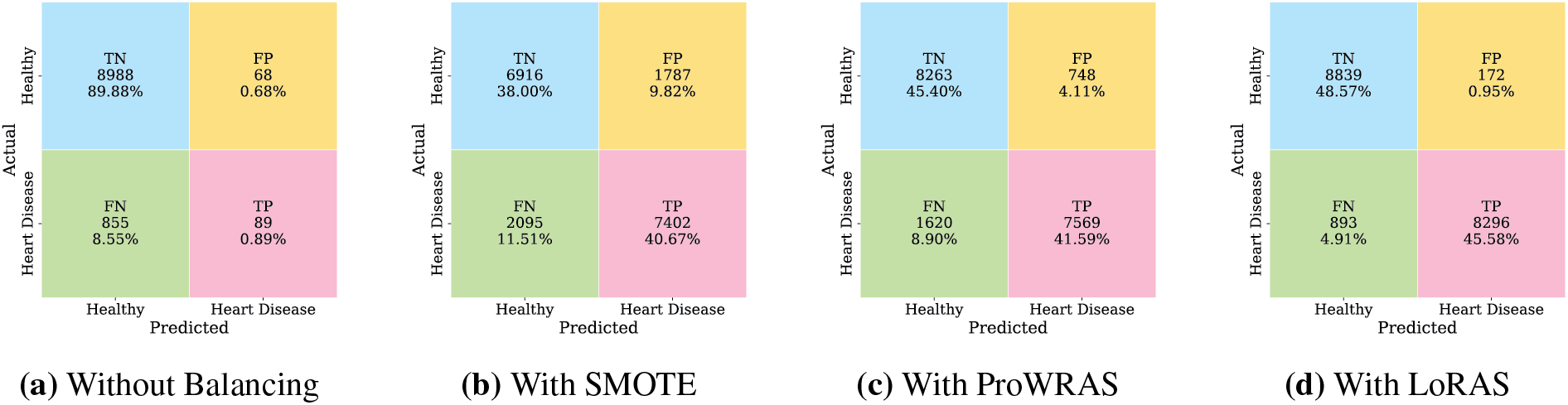

Fig. 4 presents the comparative performance of the proposed DeepResNet model under four different data balancing conditions, visualized using confusion matrices. Fig. 4a illustrates the results of the proposed model without balancing. The model achieves a True Negative (TN) count of 8988 (

Figure 4: Performance comparison of DeepResNet with different data balancing techniques

It is important to highlight that, while Fig. 4 presents the confusion matrix analysis of the proposed DeepResNet under different balancing strategies, all baseline models, including HighwayNet, GRU, and VRNN, are consistently trained and evaluated using the LoRAS-balanced dataset. The performance metrics of these baselines reported in Table 1 are therefore obtained under the same data distribution as the proposed model, ensuring fairness and consistency in comparative evaluation.

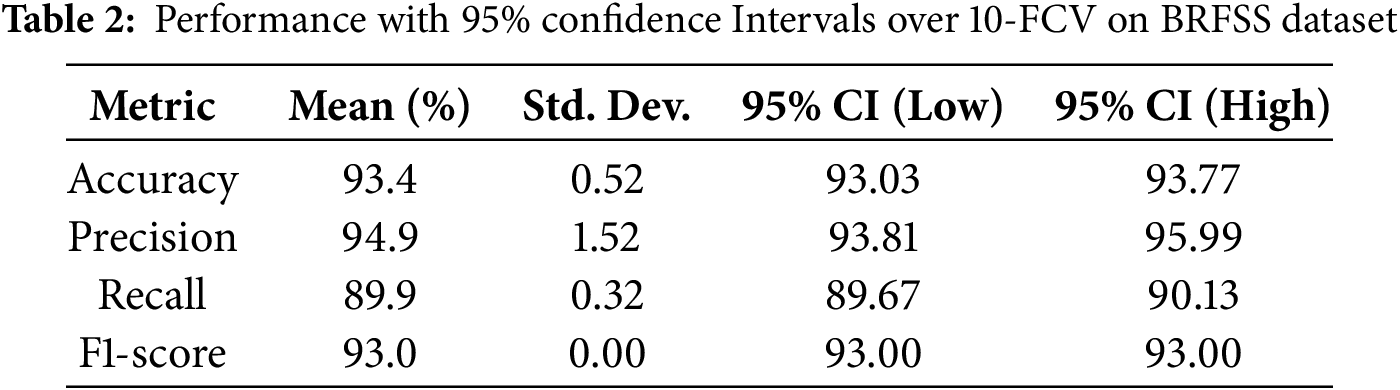

K-FCV is a robust model evaluation technique that enhances generalization by minimizing overfitting to a specific training set. The dataset is separated into K folds of equal size. The model is tested on the one remaining fold [14] after the training on K-1 folds. This procedure is carried out K times, using every instance for both training and testing, with each fold serving as the testing set once. Fig. 3b shows the complete working of K-FCV. A precise evaluation of the model’s performance is provided by the final performance metrics, which are produced by averaging the outcomes from each iteration. Particularly helpful in scenarios when data is limited, K-FCV maximizes the samples without needing an additional validation set.

The model shows consistently high performance at every fold. In Fold 1, the model achieved a recall of 89%, an F1-score of 93%, a precision of 98%, and an accuracy of 94%. Similarly, in Fold 2, recall improved slightly to 90%, while the F1-score and accuracy remained at 93% and 94%, respectively, and precision was 97%. There are uniform findings of Fold 3-8, with 90% recall and 93% F1-score. The degree of precision is less by 4%, and the accuracy is tame at 93%. Fold 9 experienced a slight gain in accuracy by 94% and retained the unaltered values of recall and F1-score. Fold 10 likewise indicated comparable results: 90% recall, 93% F1-score, 96% precision, and 94% accuracy. On the whole, the means with standard deviation on all folds are 90% recall, 93% F1-score, 96% precision, and 94% accuracy, which demonstrates the robustness of the model and its high sensitivity and balanced predictive performance on varying data subsets.

The performance of the DeepResNet model with K-Fold Cross-Validation (KFCV) is provided in Table 2. The average accuracy of the model was 93.4% with a small standard deviation of (93.03% to 93.77%), which means that the model has consistency in accuracy. The specificity was 94.9% with a range of between 93.81% and 95.99%; thus, it had a strong positive predictive value. The recall ability was really high, 89.9 percent, and its confidence interval was narrow (89.67 percent to 90.13 percent). The F1-score held steady at 93.0% with no variance, which was an indication of a balanced trade-off with the values of precision and recall. The general outcomes of our research prove the validity and validation of the DeepResNet model for predicting heart disease on the BRFSS dataset Interpretability of Deep Residual Network with Local.

3.4 Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations

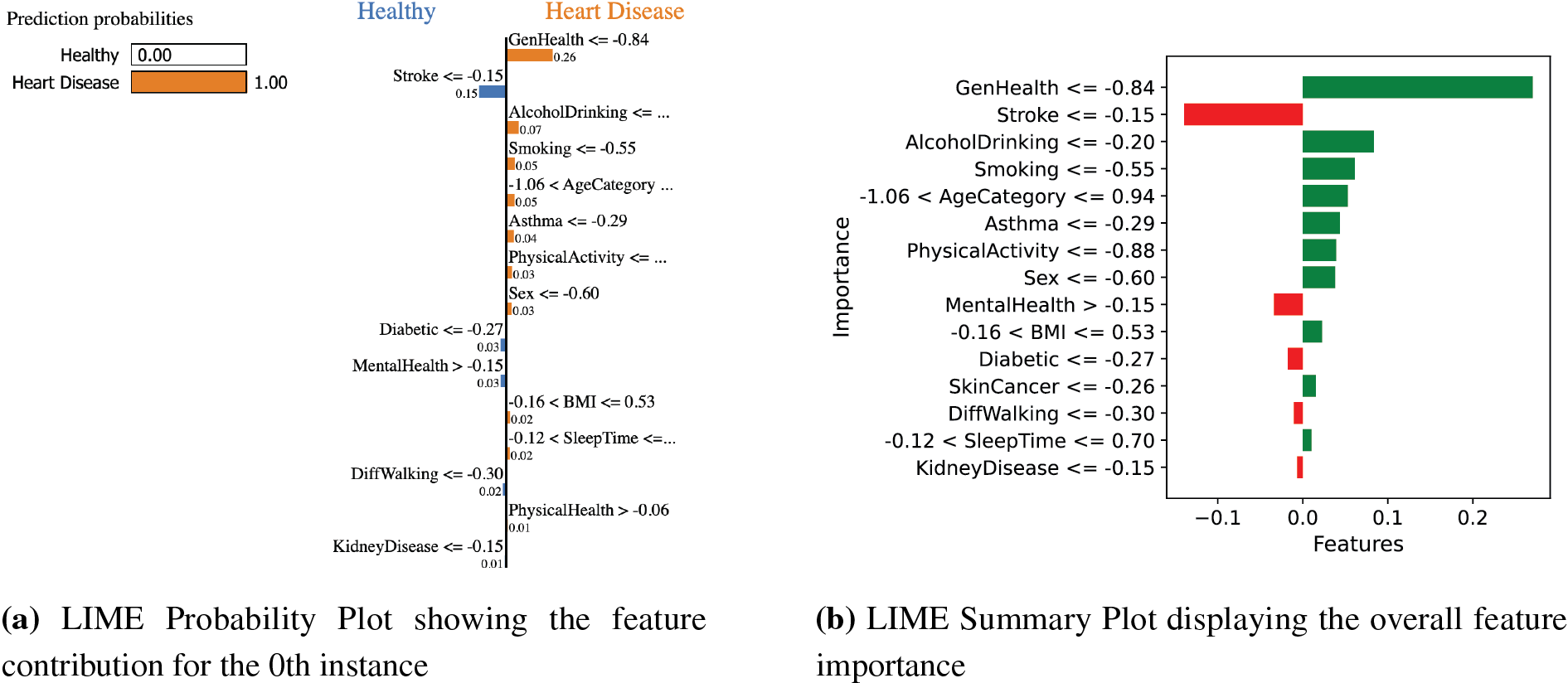

The LIME technique employs locally interpretable models to approximate DeepResNet predictions, offering transparency in DL models often regarded as black boxes [15]. In the context of heart disease, LIME highlights the contribution of key features, ensuring interpretability and aligning predictions with medical knowledge, as shown in Fig. 5. Fig. 5a highlights the feature contributions, and Fig. 5b is the summary plot of DeepResNet’s prediction by displaying the LIME probability for the

Figure 5: LIME visualizations: Probability plot showing feature contributions for the

The summary plot in Fig. 5b demonstrates that the model correctly prioritizes key medical indications and identifies instances where additional studies into the logic of the model can be necessary to preserve the clinical validity and interpretability of the prediction. The LIME explanation was produced with 500 perturbations an the scaled training data as the background dataset. In all the explanations, the 15 best features were chosen to help us understand the way this model makes its decisions. This set of features was considered so as to focus on interpretability versus detail.

3.5 Explainability of Deep Residual Network with SHapley Additive exPlanations

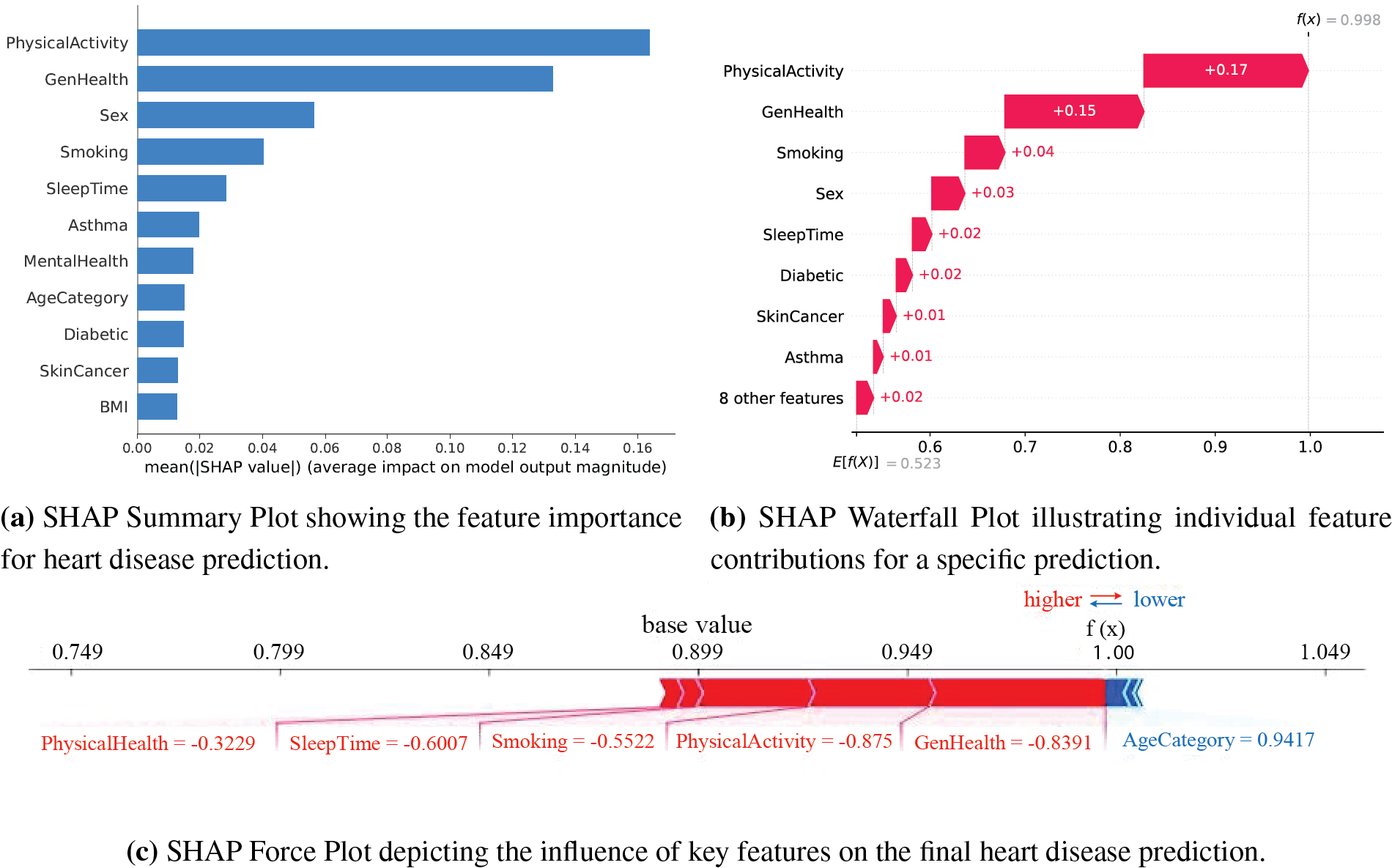

The popular interpretability technique SHAP, which is based on cooperative game theory, makes sure that the model identifies clinically meaningful risk factors. By calculating the marginal effect of each feature across all possible combinations, SHAP seeks to equally distribute each feature’s contribution to a DeepResNet’s prediction, guaranteeing consistency and global interpretability. This approach is especially helpful in healthcare applications where model transparency is crucial for trust and decision-making [16]. This study uses SHAP to examine the impact of different features in the prediction of heart disease. By analyzing both local and global feature attributions, SHAP allows us to identify potential biases and validate the accuracy of the DeepResNet’s predictions, as seen in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: SHAP visualizations illustrating feature importance, individual contributions, and the influence of key features on heart disease predictions

The summary bar plot in Fig. 6a shows the relative importance of every feature for DeepResNet predictions based on its average absolute SHAP values. PhysicalActivity with a large contribution suggests that higher levels of physical activity are associated with decreased risk. The most important finding confirmed by GenHealth is that self-reported poor overall health significantly increases the risk of heart disease. Another significant factor that has an adverse effect and increases the risk of heart disease is smoking. MentalHealth also matters, most likely because it has an indirect impact on lifestyle decisions like smoking and exercise. SleepTime has an effect as well, suggesting that a shorter sleep duration is linked to a higher risk. AgeCategory’s inclusion in the summary plot validates the medical assumption that elderly people are more likely to have heart disease.

The SHAP waterfall plot in Fig. 6b illustrates individual feature values shifting predictions closer to or farther away from a classification of heart disease for a specific instance. GenHealth and PhysicalActivity have the highest impact in a given context when their values of +0.17 and +0.15 indicate frequent physical activity and excellent health, which lowers the risk of heart disease. The impacts of smoking, sleep patterns, and physical health are further reinforced when their values align with healthy practices. However, the moderately favorable impacts of AgeCategory and MentalHealth shift the prediction in the direction of a higher risk of heart disease. According to this instance-level analysis, model choices are influenced by the interaction between different health indicators, ensuring that clinically significant elements are correctly prioritized.

The SHAP force plot in Fig. 6c provides a dynamic depiction of the interactions between several variables that result in the final prediction. The base value of 1.00 displays the average prediction probability across all features, whereas the colored bars indicate the size and direction of feature contributions for a particular instance. Physical activity and GenHealth have a major impact on reducing the risk of heart disease when their results indicate favorable health. Both smoking and sleep duration have adverse effects, indicating that a history of smoking-related inactivity and adequate sleep reduces the risk of heart disease. SHAP explanations were computed by using the KernelExplainer on a background dataset of 1000 randomly picked test samples. This subset was selected with the purpose of decreasing computational cost. The SHAP values were calculated on the top 10 most significant characteristics, as they helped to provide the best insight into the model predictions.

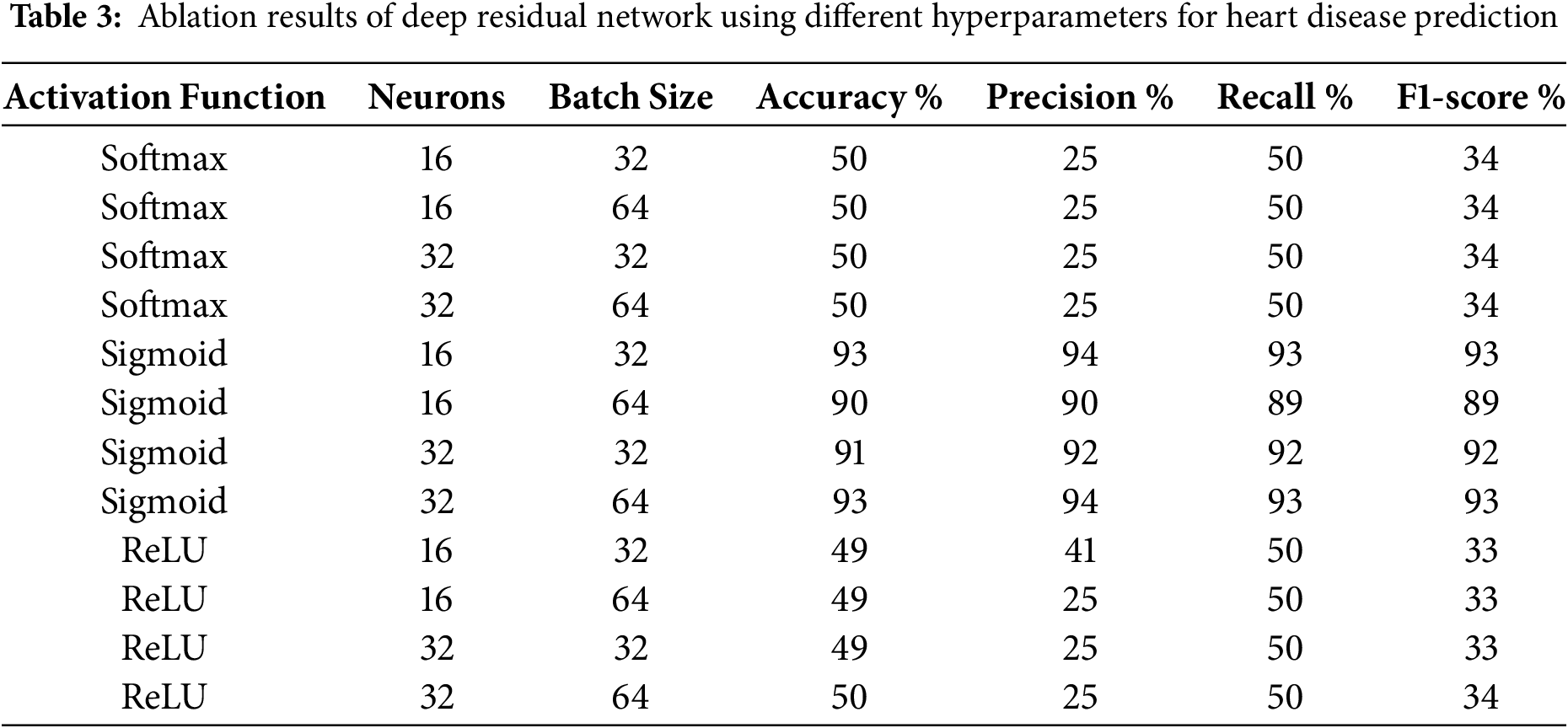

The ablation study is conducted to evaluate the impact of features and DeepResNet prediction components [17]. The performance of DeepResNet for heart disease prediction is compared in Table 3 with different activation functions, value counts, and batch size configurations. A significant finding drawn from these results is the significant diversity in activation function performance. The accuracy values for extitSoftmax and ReLU activations range from 49% to 50%, precision values range from 25% to 41%, and F1-scores are consistently low at 33% to 34%, which indicates ongoing poor performance. This poor performance is likely due to the nature of these activation functions in binary classification situations. Softmax is typically more appropriate for multi-class classification tasks than binary techniques since it normalizes probability across numerous classes. This can lead to less-than-ideal decision boundaries in a binary context. The loss of gradient information in some neurons is a further indication of dead neurons, which happens when negative values are mapped to zero, hindering learning. These activation functions are not suitable for this task, as evidenced by the consistently poor results across batch sizes and neuron counts.

Sigmoid activation works much better, achieving up to 93% accuracy with batch sizes of 32 and 64. With 16 or 32 neurons and a batch size of 32 or 64, the accuracy approaches 93%, the precision and recall are stable at 93% to 94%, and the F1-score remains consistently high as shown in Table 1. This evidence indicates that the sigmoid function, which generates values between 0 and 1, works better for binary classification problems like heart disease prediction. The model’s improved recall indicates that it is correctly identifying more positive cases, which is crucial for medical diagnostics because it can have major consequences if actual cases of heart disease are not detected. Batch size has an impact on the performance of model optimization as well; large batches of 64 can introduce more variance in gradient updates, whereas smaller batches of 32 have greater generalization. The consistency of results across different neuron counts further supports the durability of the sigmoid-based arrangement. These results emphasize the importance of selecting the right activation function for binary classification problems. Sigmoid activation ensures consistent learning and precisely calibrated probability results, unlike Softmax and ReLU, which cannot establish effective decision bounds.

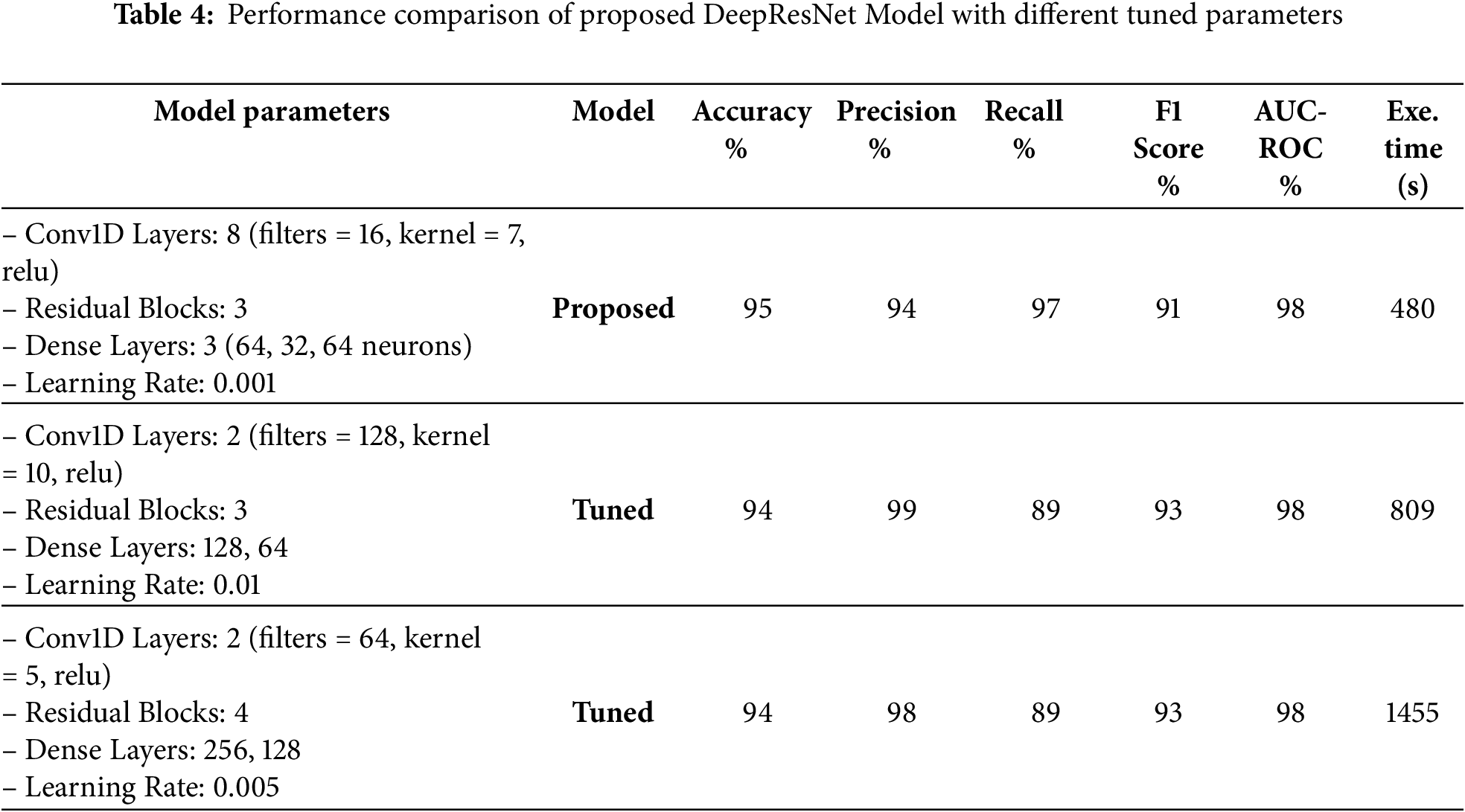

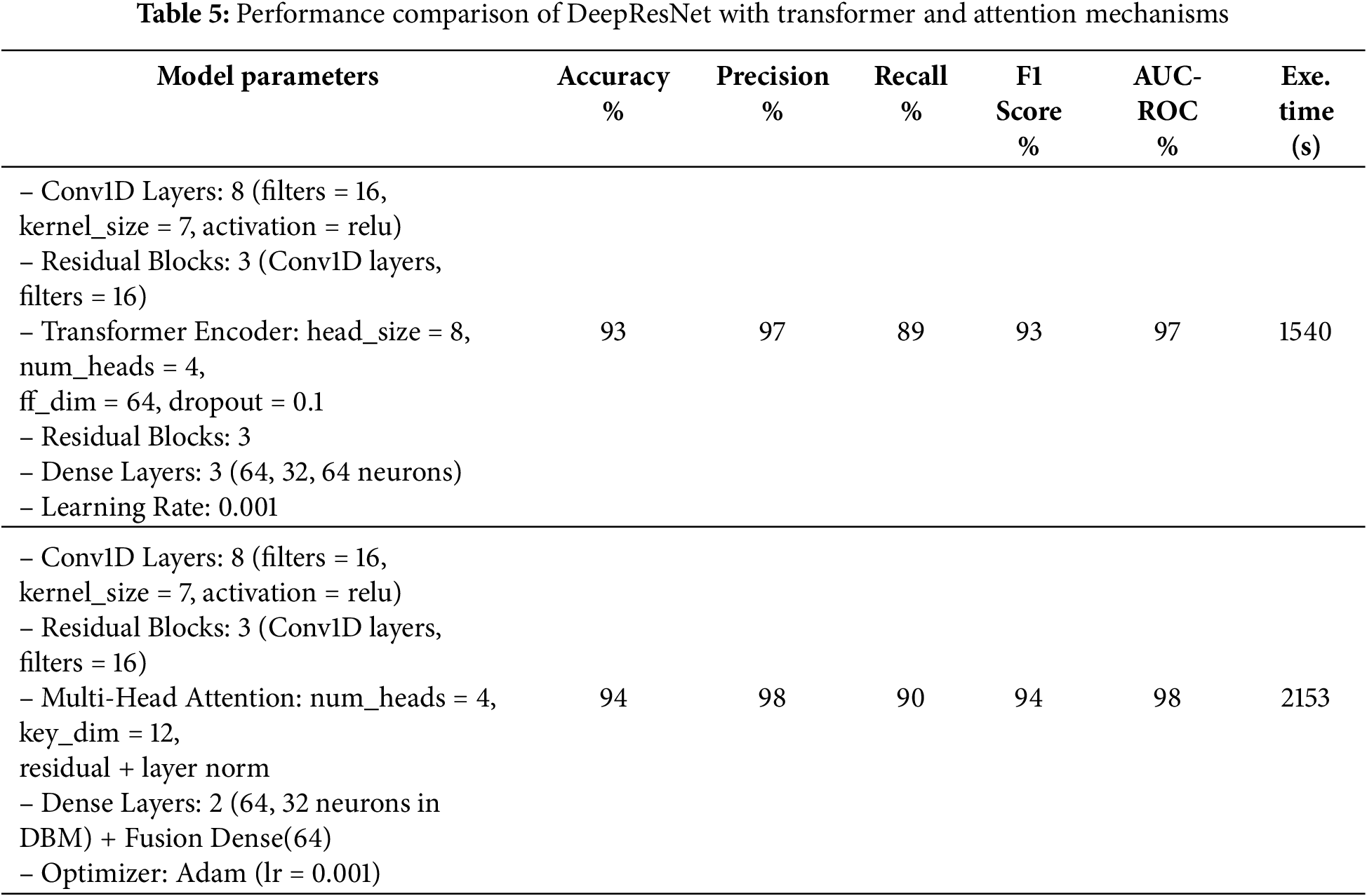

Table 4 provides the comparison of the DeepResNet model in terms of filter, kernel, and the number of residual blocks. The proposed model has 8 Conv1D layers and 16 filters, a 7-kernel, and 3 residual blocks, yielding 95% accuracy and 98% AUC-ROC. The tuned models experiment with changes like 2 Conv1D layers and a number of filters as 128 with a kernel size of 10, which increased the precisions to 99 but slightly decreased the accuracies to 94%. A slightly different architecture (64 filters and a kernel of 5 in 4 blocks of residuals) achieved a similar performance of 94%. Although these tuned models are an improvement in particular metrics, they have the shortcomings of an increased execution time, as the second tuned model takes 809 s and the third tuned model takes 1455 s. The number of epochs is set to 20, the batch size to 32, and the dropout rate to 0.5 throughout. The results indicate the tradeoff of performance when changing the parameters of the model to achieve a greater computational efficiency. Table 5 shows the comparison of the DeepResNet model to transformers and Attention mechanisms when used in various configurations. The first model is combined with a DeepResNet, DBM-style feature extraction, and Transformer Encoder layers, which provide 93% accuracy, 97% precision, and 89% recall. The second model provides a combination of DeepResNet and Multi-Head Attention layers and obtained 94% accuracy, 98% precision, and 90% recall. Although both models achieved better results in precision and recall, the second model with multi-head attention shows a slightly better result, which demonstrates that modern attention mechanisms are effective in the enhancement of model performance. However, both models are computationally demanding to use as compared to the proposed DeepResNet model, which takes 480 s to train. The Multi-Head Attention model requires 2153 s, whereas using the Transformer Encoder requires 1540 s, two modern techniques that are more demanding in terms of computational cost. Despite these improvements in precision and recall, the original DeepResNet model offers the best balance, achieving superior detection performance with significantly lower execution time, making it the most efficient choice.

This study presented a DL framework that builds on the major weaknesses of the current models of predicting heart diseases, such as limited feature learning, imbalance in the classes, poor classification accuracy, and uninterpretable nature of performance. In the DL framework, a new model called DeepResNet is developed that consists of hierarchical residual transformations and performs better in the area of feature learning. The DL framework includes LoRAS to overcome class imbalance and minimize overfitting. Through comprehensive experimental evaluation, DeepResNet outperformed several state-of-the-art models, achieving an F1-score of 94%, accuracy of 95%, precision of 97%, recall of 91%, and an AUC-ROC of 98%. To ensure the robustness and generalizability of the DeepResNet model across various data splits, 10-FCV was conducted. Additionally, the integration of SHAP and LIME offered distinct perspectives on feature contributions, enhancing the interpretability of the model. Overall, the results demonstrate that DeepResNet, as part of the proposed DL framework, offers a highly accurate and transparent solution for AI-driven heart disease prediction.

Although the proposed model demonstrates promising performance, several limitations remain. First, the framework has not been evaluated using state-of-the-art DL architectures or ensemble approaches, which could potentially yield superior predictive accuracy. Second, the current study does not incorporate federated learning, thereby overlooking privacy-preserving and decentralized training across multiple healthcare institutions. Third, clinical validation through feedback from medical professionals and domain experts is absent, restricting the evaluation of the real-world relevance of the model’s explanations. Lastly, the study does not explicitly address critical aspects of data privacy, bias, and fairness, which are essential for the reliable deployment of predictive models in healthcare practice.

Future studies can be conducted using state-of-the-art DL architectures with and without ensemble modeling to enhance heart disease prediction further. Furthermore, federated learning incorporation is the next solution that shows excellent prospects in privacy-preserving and decentralized training of models using different datasets, which ensures that medically sensitive data is not disclosed. Next, we will aim to explore the feasibility of federated learning in the context of heterogeneous data distribution, such as changes in patient demographics and clinical settings. In addition, we plan to incorporate feedback from clinicians and domain experts to evaluate the real-world relevance of the model’s explanations. Finally, the practical applicability of the model in a healthcare setting will be increased by the work aimed at optimizing the model performance to be used in real-time during clinical interaction and considering the problem of data privacy, bias, and fairness.

Acknowledgement: The authors extend their appreciation to the Ongoing Research Funding Program for Project number (ORF-2025-648), at King Saud University for supporting this research project.

Funding Statement: This project is funded by Ongoing Research Funding Program for Project number (ORF-2025-648), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: Muhammad Adil: Writing original draft, Methodology, Validation; Nadeem Javaid: Supervision, Visualization, Conceptualization; Imran Ahmed: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation; Abrar Ahmed: Funding, Resources, Validation; Nabil Alrajeh: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data curation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Pytlak, K. (2020). Personal key indicators of heart disease. Kaggle. Available at: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/kamilpytlak/personal-key-indicators-of-heart-disease (accessed on 03 September 2025). Scarlat, A. (n.d.). MIMIC3c aggregated data. Kaggle. Available at: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/drscarlat/mimic3c/data (accessed on 03 September 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ma CY, Luo YM, Zhang TY, Hao YD, Xie XQ, Liu XW, et al. Predicting coronary heart disease in Chinese diabetics using machine learning. Comput Biol Med. 2024;169(7):107952. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.107952. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Ramesh B, Lakshmanna K. Multi head deep neural network prediction methodology for high-risk cardiovascular disease on diabetes mellitus. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2023;137(3):2513–28. doi:10.32604/cmes.2023.028944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ahmad M, Alfayad M, Aftab S, Khan MA, Fatima A, Shoaib B, et al. Data and machine learning fusion architecture for cardiovascular disease prediction. Comput Mater Contin. 2021;69(2):2717–31. doi:10.32604/cmc.2021.019013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Nadeem MW, Goh HG, Khan MA, Hussain M, Mushtaq MF. Fusion-based machine learning architecture for heart disease prediction. Comput Mater Contin. 2021;67(2):2481–96. doi:10.32604/cmc.2021.014649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Arifuddin A, Buana GS, Vinarti RA, Djunaidy A. Performance comparison of decision tree and support vector machine algorithms for heart failure prediction. Procedia Comput Sci. 2024;234(1):628–36. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2024.03.048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Rani P, Kumar R, Ahmed NM, Jain A. A decision support system for heart disease prediction based upon machine learning. J Reliable Intelligent Environ. 2021;7(3):263–75. doi:10.1007/S40860-021-00133-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Shorewala V. Early detection of coronary heart disease using ensemble techniques. Inform Med Unlocked. 2021;26(6):100655. doi:10.1016/j.imu.2021.100655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ghosh P, Azam S, Jonkman M, Karim A, Shamrat FJ, Ignatious E, et al. Efficient prediction of cardiovascular disease using machine learning algorithms with relief and LASSO feature selection techniques. IEEE Access. 2021;9:19304–26. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3053759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Lakshmanarao A, Srisaila A, Kiran TS. Heart disease prediction using feature selection and ensemble learning techniques. In: 2021 Third International Conference on Intelligent Communication Technologies and Virtual Mobile Networks (ICICV); 2021 Feb 4–6; Tirunelveli, India. IEEE; 2021. p. 994–8. doi:10.1109/ICICV50876.2021.9388482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Rath A, Mishra D, Panda G, Satapathy SC. Heart disease detection using deep learning methods from imbalanced ECG samples. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2021;68(7):102820. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2021.102820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Pytlak K. Personal key indicators of heart disease. Kaggle. 2020 [cited 2025 Sep 3]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/kamilpytlak/personal-key-indicators-of-heart-disease. [Google Scholar]

12. Wang J, Xu M, Wang H, Zhang J. Classification of imbalanced data by using the SMOTE algorithm and locally linear embedding. In: 2006 8th International Conference on Signal Processing; 2006 Nov 16–20; Guilin, China. IEEE. doi:10.1109/ICOSP.2006.345752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Scarlat A. MIMIC3c aggregated data. Kaggle. (n.d.) [cited 2025 Sep 3]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/drscarlat/mimic3c/data. [Google Scholar]

14. Shaheen I, Javaid N, Rahim A, Alrajeh N, Kumar N. Empowering early predictions: a paradigm shift in diabetes risk assessment with Deep Active Learning. Knowl Based Syst. 2025;315(4):113284. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2025.113284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ferdowsi M, Hasan MM, Habib W. Responsible AI for cardiovascular disease detection: towards a privacy-preserving and interpretable model. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2024;254:108289. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2024.108289. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Khan H, Javaid N, Bashir T, Ali Z, Khan FA, Pamucar D. A novel deep gated network model for explainable diabetes mellitus prediction at early stages. Knowl Based Syst. 2025;328(4):114178. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2025.114178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. O’Keefe EL, Sturgess JE, O’Keefe JH, Gupta S, Lavie CJ. Prevention and treatment of atrial fibrillation via risk factor modification. Am J Cardiol. 2021;160(suppl_1):46–52. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2021.08.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools