Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Coupled Effects of Single-Vacancy Defect Positions on the Mechanical Properties and Electronic Structure of Aluminum Crystals

1 Department of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering, Hetao College, Bayannur, 015000, China

2 Science and Technology Office, Hetao College, Bayannur, 015000, China

3 School of Energy Power and Mechanical Engineering, North China Electric Power University, No. 2 Beinong Road, Beijing, 102206, China

* Corresponding Author: Gang Huang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071320

Received 05 August 2025; Accepted 08 October 2025; Issue published 10 November 2025

Abstract

Vacancy defects, as fundamental disruptions in metallic lattices, play an important role in shaping the mechanical and electronic properties of aluminum crystals. However, the influence of vacancy position under coupled thermomechanical fields remains insufficiently understood. In this study, transmission and scanning electron microscopy were employed to observe dislocation structures and grain boundary heterogeneities in processed aluminum alloys, suggesting stress concentrations and microstructural inhomogeneities associated with vacancy accumulation. To complement these observations, first-principles calculations and molecular dynamics simulations were conducted for seven single-vacancy configurations in face-centered cubic aluminum. The stress response, total energy, density of states (DOS), and differential charge density were examined under varying compressive strain (ε = 0–0.1) and temperature (0–600 K). The results indicate that face-centered vacancies tend to reduce mechanical strength and perturb electronic states near the Fermi level, whereas corner and edge vacancies appear to have weaker effects. Elevated temperatures may partially restore electronic uniformity through thermal excitation. Overall, these findings suggest that vacancy position exerts a critical but position-dependent influence on coupled structure-property relationships, offering theoretical insights and preliminary experimental support for defect-engineered aluminum alloy design.Keywords

Aluminum and its alloys are widely employed in aerospace, automotive, and transportation owing to their low density, high specific strength, and excellent corrosion resistance [1–3]. For load-bearing aerospace components in particular, the combination of light weight, strength, and corrosion resistance makes Al-based alloys prime candidates for advanced structural applications [4,5]. As performance requirements continue to rise, alloy development increasingly centers on microstructural design. Numerous studies have shown that strategies such as grain refinement, precipitation hardening, and the introduction of nanoscale precipitates can substantially improve strength and ductility in Al alloys [6,7], underscoring the pivotal role of microstructural control.

In metallic crystals, common point defects include vacancies, interstitials, and substitutional solutes [8]. A vacancy—i.e., a missing lattice atom—typically induces local lattice contraction and tensile stress fields; oversized interstitials cause local expansion and compressive stresses; and substitutional atoms generate elastic distortions due to size mismatch. First-principles studies have shown that vacancies in aluminum lead to appreciable volumetric contraction [9], perturb the surrounding electron density, and modify band structures, thereby influencing charge transport. For example, increasing vacancy concentration has been calculated to raise the electrical resistivity [10]. Substitutional solutes can introduce impurity states and alter the electronic density of states (DOS) near the Fermi level, affecting both electrical and thermal transport [11].

Point defects also play central roles in plastic deformation and fatigue. Vacancies and impurities affect dislocation motion and creep: under high-temperature creep conditions, vacancies facilitate dislocation climb and reduce flow stress [12], while solute atmospheres (Cottrell atmospheres) can pin dislocations and enhance strength. Theoretical modeling further indicates that excess vacancies strongly impact aging behavior and precipitation strengthening in aluminum alloys [13]. Although macroscopic fatigue cracks often nucleate at inclusions or interfaces, clusters of point defects may act as local stress concentrators that promote microcrack initiation [14]. In addition, point defects scatter electrons and phonons, thereby increasing electrical resistivity [15] and decreasing thermal conductivity [16].

Despite these advances, a systematic understanding of the coupled influence of point defects on structure-property relationships remains incomplete. In particular, the combined effects of defect position, applied stress, and temperature have received limited attention. For instance, vacancy formation energetics near grain boundaries differ from those in the bulk, indicating a strong position dependence [17], yet many prior studies assume spatially uniform defect distributions. Moreover, the temperature dependence of vacancy formation free energy is nonlinear [18], and strain further modifies defect energetics. Comprehensive first-principles investigations that concurrently treat defect position, strain, and temperature are still scarce, posing a key challenge for predictive alloy design.

To address this gap, we employ density functional theory (DFT) to systematically examine single-atom vacancies at distinct spatial positions in aluminum crystals. Seven vacancy configurations are constructed in a 2 × 2 × 2 face-centered cubic (FCC) supercell and evaluated under compressive strains (ε = 0–0.10) and at representative temperatures (0, 298, 450, and 600 K). We analyze the corresponding stress responses, vacancy formation energies, total-energy evolution, electronic DOS, and differential charge densities to elucidate how defect location governs structural stability and electronic properties under coupled strain-temperature fields. The results provide mechanistic insight into defect behavior under multi-physics interactions and offer theoretical guidance for defect-engineered optimization of aluminum-alloy performance.

2 Experimental and Computational Methods

The specimens were prepared from Fe-rich Fe-Al based alloy. Mechanical thinning was sequentially conducted using 120, 200, 500, 1000, and 2400 grit SiC abrasive papers, followed by punching into ϕ3 mm round disks with a final thickness of 50–60 μm. Electro-polishing was performed using a dual-jet setup with 4% nitric acid in ethanol as the electrolyte. Microstructural characterization was carried out using a 200 kV transmission electron microscope (Fischione M3000, with annular dark-field capability) to analyze dislocation configurations. After re-polishing and etching the samples for approximately 1 min in the same solution, surface morphology and grain structures were examined using a scanning electron microscope (FEI Gemini 500).

These experimental steps provided insight into the micro and mesoscopic features of the Fe-rich Fe-Al based alloy, such as dislocation density, grain size distribution, and boundary characteristics, which served as references for the theoretical modeling and simulation.

2.2 Defect Modeling in FCC Aluminum Supercell

A 2 × 2 × 2 FCC aluminum supercell comprising 32 atoms was constructed as the base model for defect simulations. This supercell, composed of eight conventional FCC unit cells, offers periodicity and symmetry suitable for simulating the local perturbations induced by point defects.

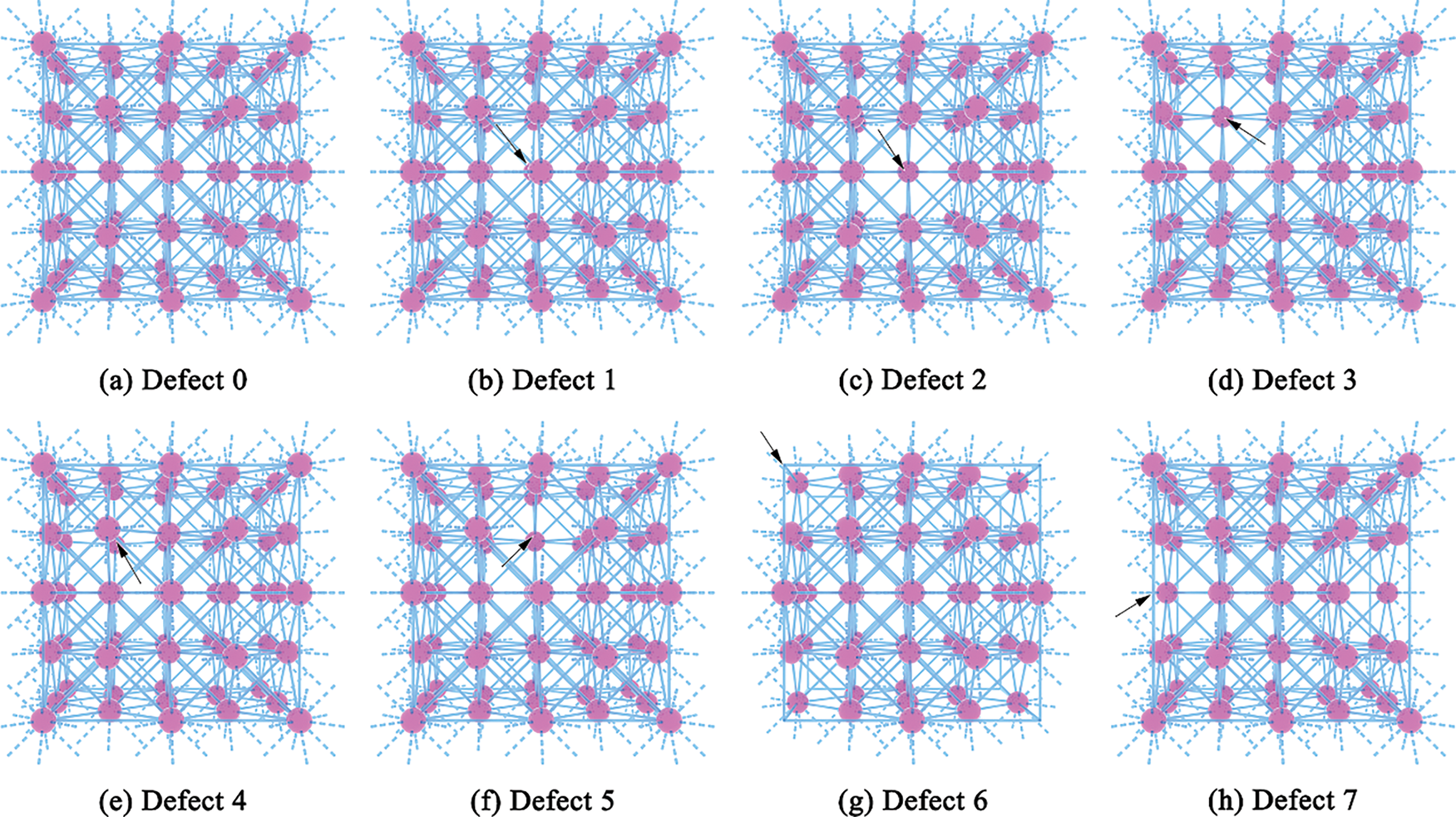

To comprehensively assess the influence of single-vacancy position on material behavior, seven vacancy-defective models (Defect 1 to Defect 7) were designed by removing a single Al atom from different positions in the supercell. The perfect crystal without any defects was labeled as Defect 0. The defect configurations, illustrated in Fig. 1, are defined as follows:

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of defect location

Defect 1: Vacancy at the center of the supercell, corresponding to a corner atom shared by eight unit cells.

Defect 2: Vacancy at a corner site shared by four front-surface unit cells.

Defect 3: Vacancy at a face-centered position in the top-left unit cell near the front surface.

Defect 4: Vacancy at a face-centered site shared by two unit cells at the upper-left of the supercell.

Defect 5: Vacancy at a face-centered position shared by two top-layer unit cells near the front surface.

Defect 6: Vacancy at a top-left corner site of one unit cell on the front surface.

Defect 7: Vacancy at a corner shared by two adjacent unit cells on the left-front edge.

These configurations were selected to cover common spatial vacancy positions in FCC structures, enabling a systematic investigation of how symmetry and position influence mechanical response, electronic density of states (DOS), band structures, and total energy evolution.

2.3 Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Initial structure relaxation and thermal stability assessment were performed using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations via the Forcite module in Materials Studio. The simulations used the COMPASS III force field [19] and were conducted under an NVT ensemble [20] with an initial temperature of 2 K. Atomic velocities were assigned randomly and controlled via a velocity rescaling thermostat. The simulation time step was 1 fs, with a total simulation time of 500 ps.

All periodic supercells used in this work were subject to periodic boundary conditions (PBC) in all three Cartesian directions, unless otherwise stated. For first-principles calculations (DFT), each 2 × 2 × 2 FCC supercell was treated with full 3D periodicity; volume and cell shape were controlled according to the applied strain.

Temperature-dependent structure evolution of the seven defective models was simulated to evaluate their thermal response and dynamic stability across a temperature range (0–600 K).

2.4 Density Functional Theory Calculations

Following MD relaxation, first-principles DFT calculations were conducted using the CASTEP module to evaluate the mechanical and electronic properties of each defect model under compressive strains (ε = 0–0.1) and four temperature settings (0, 298, 450, 600 K). The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the revised Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (RPBE) functional [21,22] was employed to treat exchange–correlation effects. Ultrasoft pseudopotentials [23] were used to represent the electron–ion interaction, and the plane-wave cutoff energy was set to 330 eV.

The Brillouin zone was sampled using an 11 × 11 × 11 Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid [24]. Structural optimization was performed using the Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (BFGS) algorithm [25]. The convergence criteria were set to: total energy variation <1 × 10−5 eV/atom, maximum atomic displacement <0.001 Å, residual stress <0.05 GPa, and Hellmann-Feynman force <0.03 eV/Å. All calculations included spin polarization to accurately account for the magnetic and electronic behavior of vacancy-containing structures.

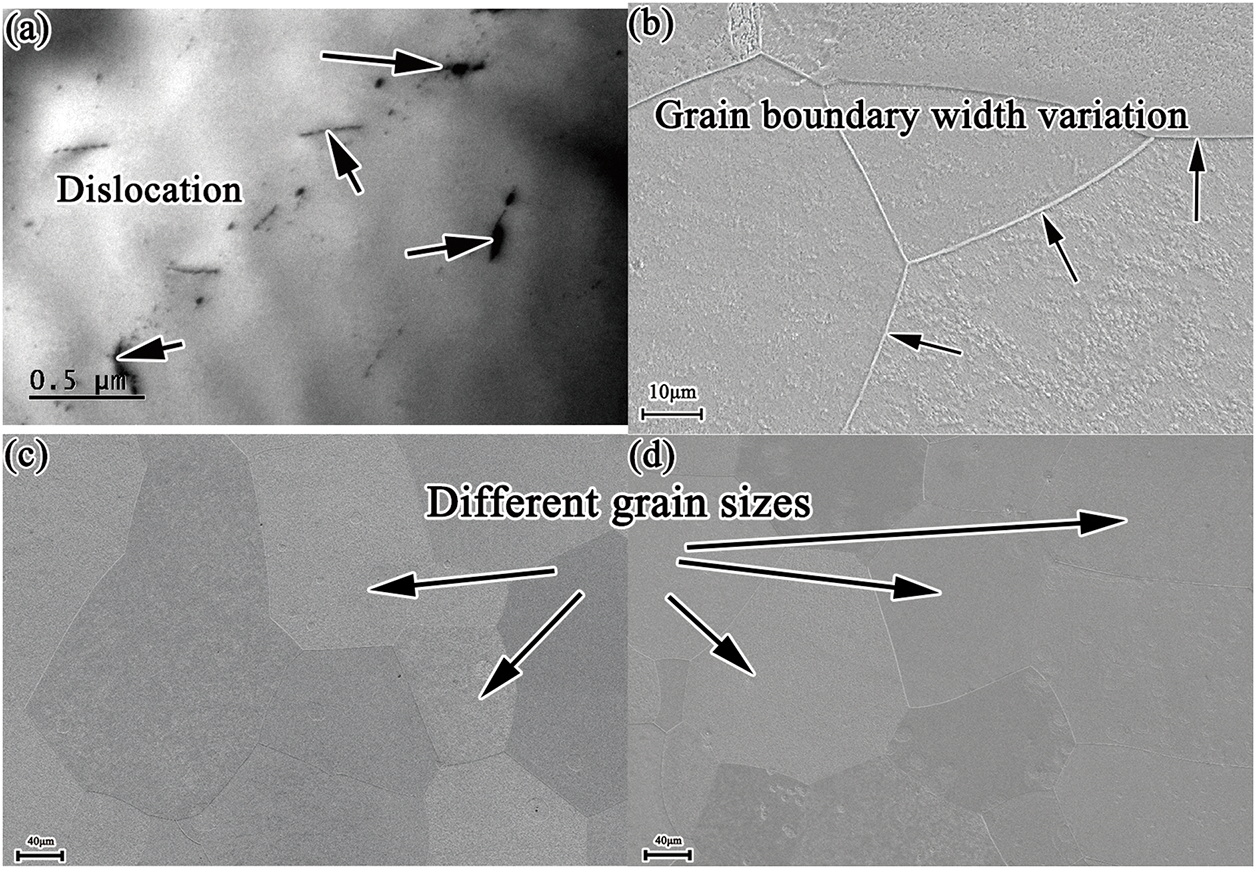

3.1 Microstructural Observation of Vacancy-Induced Defects

Fig. 2 illustrates the micro and mesoscale structural features observed in the Fe-rich Fe–Al alloy samples. The dark-field TEM image in Fig. 2a shows a relatively high density of dislocations, suggesting localized lattice strain at the atomic scale. SEM images in Fig. 2b–d reveal heterogeneous grain sizes and variations in grain boundary widths, indicating non-uniform structural characteristics across different regions

Figure 2: Micro and mesoscale structural changes induced by crystal defects: (a) High dislocation density; (b) Variation in grain boundary width; (c,d) Differences in grain size

These experimental observations imply that vacancy-type defects may contribute to mesoscale inhomogeneities by generating local stress fields. The presence of dislocation tangles and irregular grain boundaries is consistent with defect-induced perturbations of internal stress states, although additional quantitative characterization would be required to establish a direct causal relationship. Taken together, these findings support the relevance of simulating vacancy configurations and emphasize the role of spatial position in modulating the impact of defects on mechanical properties.

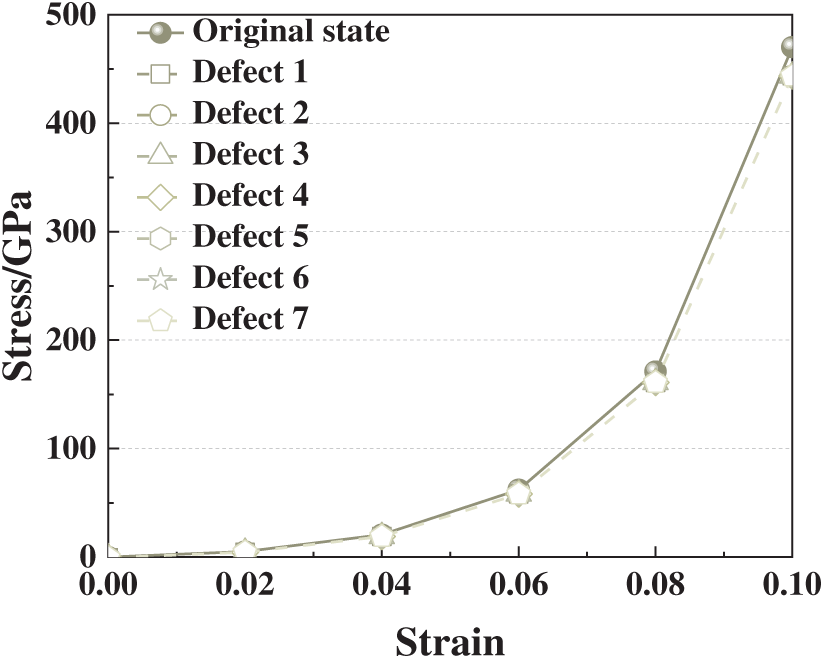

3.2 Stress-Strain Behavior of Defective Aluminum Crystals

Fig. 3 presents the compressive stress-strain (σ-ε) curves of aluminum crystals with different single-vacancy configurations over the strain range ε = 0–0.10. At small strains (ε < 0.06), all models display nearly overlapping linear-elastic responses, indicating that isolated vacancies exert negligible influence on the initial elastic regime, which is dominated by the bulk crystal framework.

Figure 3: Stress-strain curves of aluminum crystals with different single-atom vacancy defects under compressive strain (ε = 0–0.1)

Beyond ε ≈ 0.06, however, the responses begin to diverge. Vacancy models 3, 4, and 5 exhibit markedly reduced peak stresses compared with the defect-free crystal (Defect 0) and other configurations. These sites correspond to face-centered positions with high atomic coordination, which play a critical role in lattice load transfer. Removing atoms from such sites disrupts local bonding, induces stress concentration, and facilitates early structural instability under compression. In contrast, vacancies located at corners or boundary sites (Defects 1, 2, 6, and 7), which have lower coordination, exert minimal influence on load distribution and yield stress-strain curves comparable to the pristine crystal. These results demonstrate that not only the presence but also the location of a vacancy is decisive in governing strength degradation: face-centered vacancies are especially detrimental, whereas corner or boundary vacancies are relatively benign. This positional sensitivity highlights the mechanistic role of lattice symmetry and coordination in defect-induced weakening of metallic crystals.

To further assess the reliability of these results, we compared them with recent molecular dynamics (MD) studies. Das et al. [26] reported that defect-free crystals consistently exhibit higher strength than those containing single vacancies, while clustered vacancies lead to further reductions in load-bearing capacity. This trend aligns well with our first-principles calculations, where the introduction of single vacancies reduces theoretical strength and alters electronic bonding characteristics. Although the absolute compressive strength in our calculations (>500 GPa) is far higher than MD predictions, this discrepancy reflects methodological differences: our unit-cell DFT models capture idealized theoretical limits and exclude mechanisms such as dislocation motion or plastic slip, whereas the MD simulations incorporate larger supercells and better approximate real microstructural plasticity. Importantly, the weakening trend is consistent across both approaches, reinforcing the robustness of our conclusions while clarifying that the reported values should be interpreted as upper-bound theoretical strengths rather than experimental equivalents.

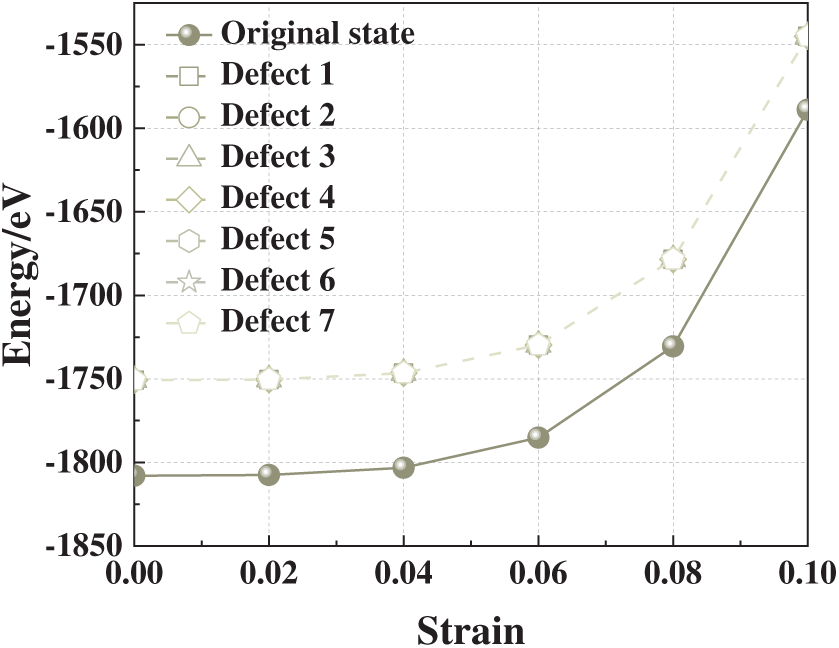

3.3 Strain-Dependent Total Energy Evolution

Fig. 4 shows the evolution of total energy for each defect model as a function of compressive strain. At zero strain (ε = 0), all vacancy-containing models possess higher total energies than the defect-free crystal (−1807.99 eV), with an average of −1750.78 eV. This difference corresponds to the vacancy formation energy and reflects the intrinsic thermodynamic destabilization associated with lattice disruption.

Figure 4: Total energy-strain curves of aluminum crystals with different single-atom vacancy defects under compressive strain

Within the elastic regime (ε < 0.06), total energy increases smoothly and nearly uniformly across all models, consistent with homogeneous elastic energy storage. Beyond ε ≈ 0.06, however, the trajectories of face-centered vacancy models (Defects 3–5) begin to diverge, rising more steeply and reaching higher energy levels under continued loading. This behavior suggests enhanced local atomic rearrangements and bond distortions in these configurations, indicative of incipient structural instability.

At ε = 0.10, the total energies of Defects 3–5 substantially exceed those of the other vacancy configurations, implying pronounced thermodynamic destabilization under high compressive strain. These observations are consistent with the stress-strain results and highlight the critical role of vacancy position in amplifying strain-energy accumulation. Taken together, the analysis indicates that face-centered vacancies, due to their high coordination and central role in lattice connectivity, are particularly detrimental to mechanical stability, whereas corner or boundary vacancies exert comparatively minor effects.

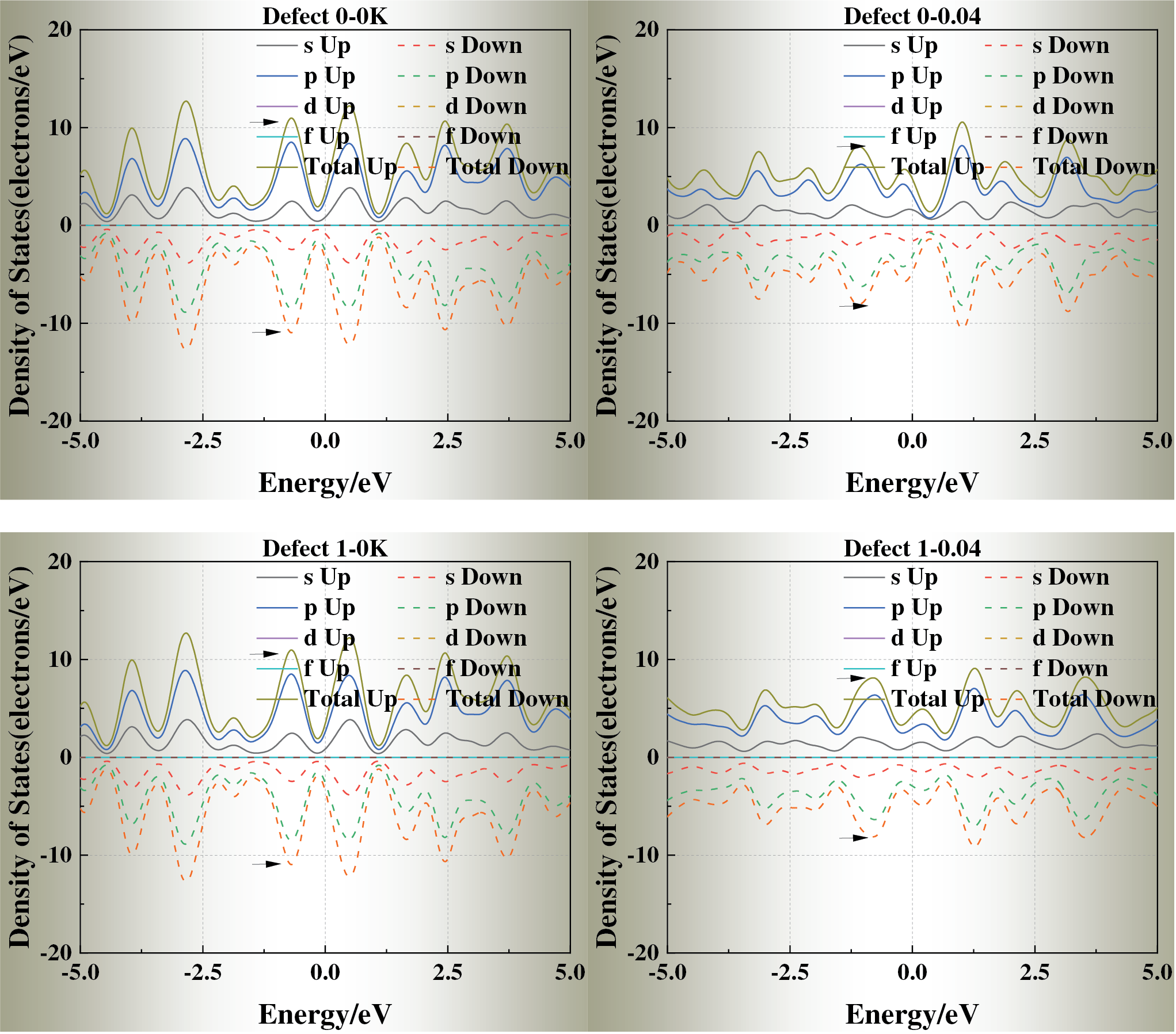

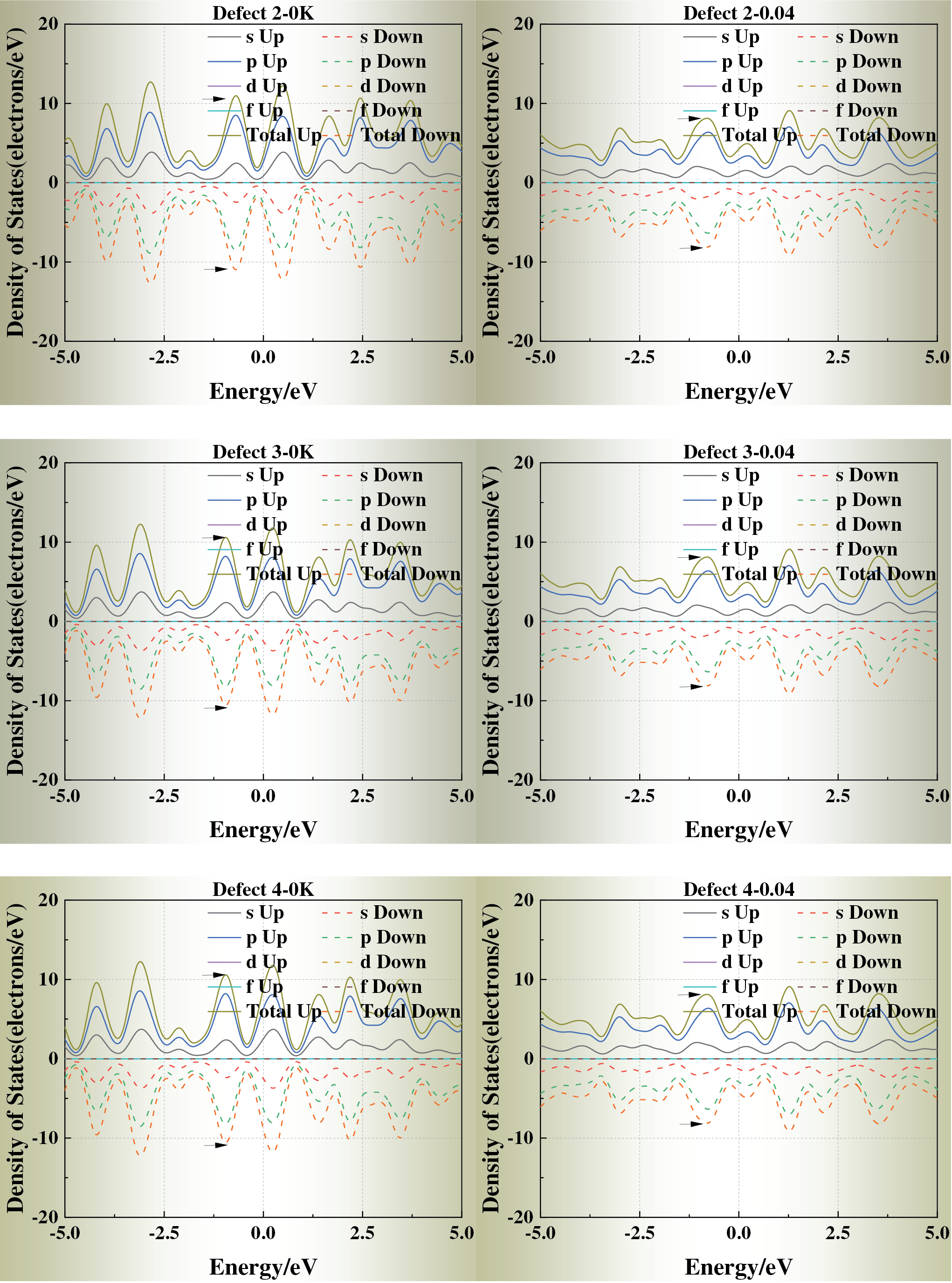

3.4 Strain-Dependent Electronic Density of States (DOS)

Fig. 5 displays the density of states (DOS) of each defect model at ε = 0 and ε = 0.04. With increasing strain, the DOS peaks near the Fermi level generally broaden and decrease in intensity, suggesting reduced electron localization and modified metallic bonding under stress-induced perturbations. For Defects 1, 2, 6, and 7, the DOS profiles remain close to that of the defect-free crystal, indicating that corner and edge vacancies exert only a minor influence on the electronic structure.

Figure 5: Density of states (DOS) of defective aluminum crystals under strain levels ε = 0 and ε = 0.04

In contrast, Defects 3, 4, and 5 exhibit pronounced alterations near the Fermi energy: the principal DOS peak shifts toward the Fermi level, and additional localized states emerge under strain. These changes suggest enhanced redistribution of electronic density and potential electron localization, arising from the disruption of the local potential field by face-centered vacancies with high coordination.

Taken together, these results indicate a clear coupling between mechanical strain and electronic structure. The presence and spatial position of vacancies modulate electron mobility and local conductivity by altering the DOS near the Fermi level, thereby linking lattice defects with stress-dependent electronic responses in aluminum crystals.

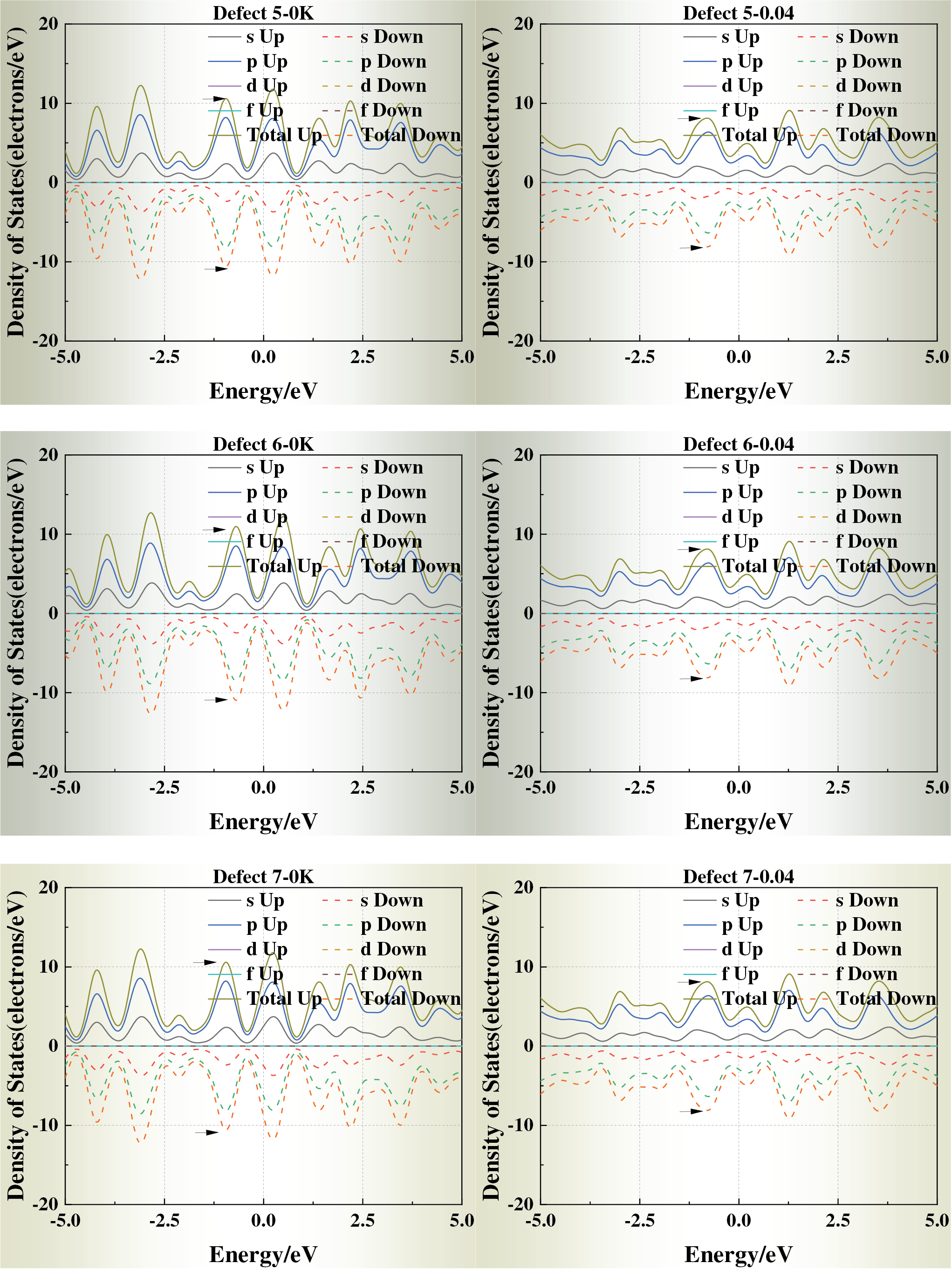

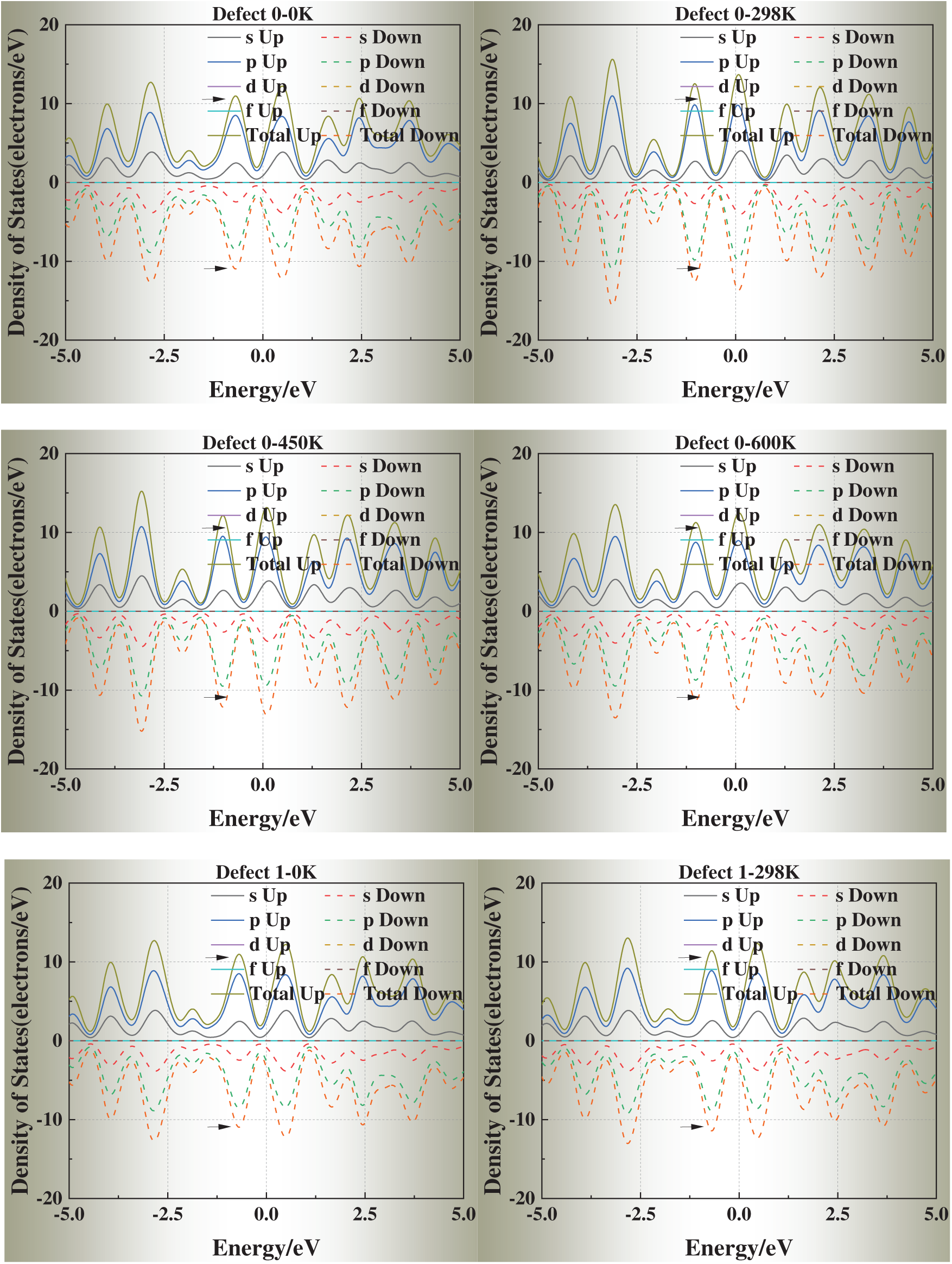

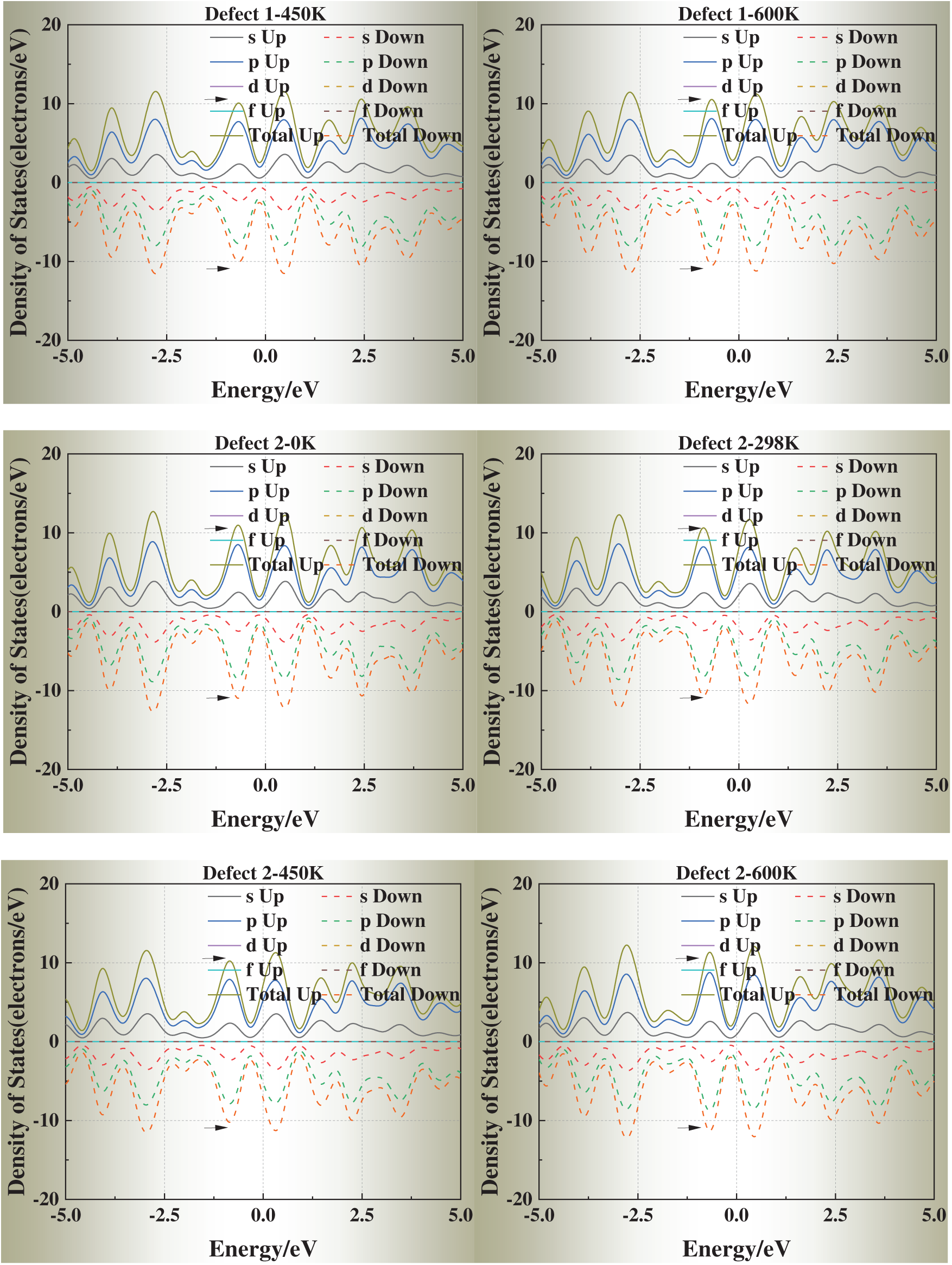

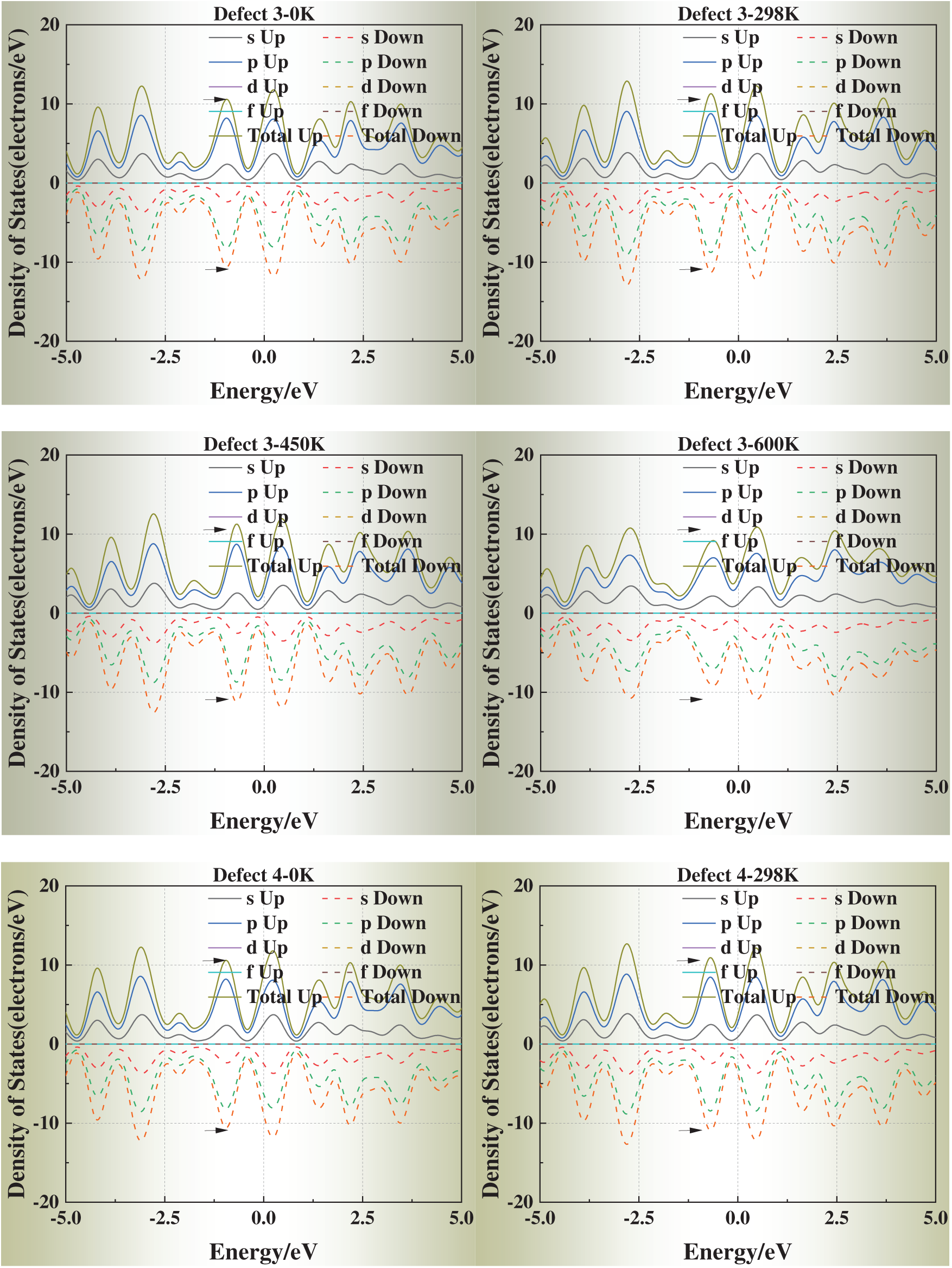

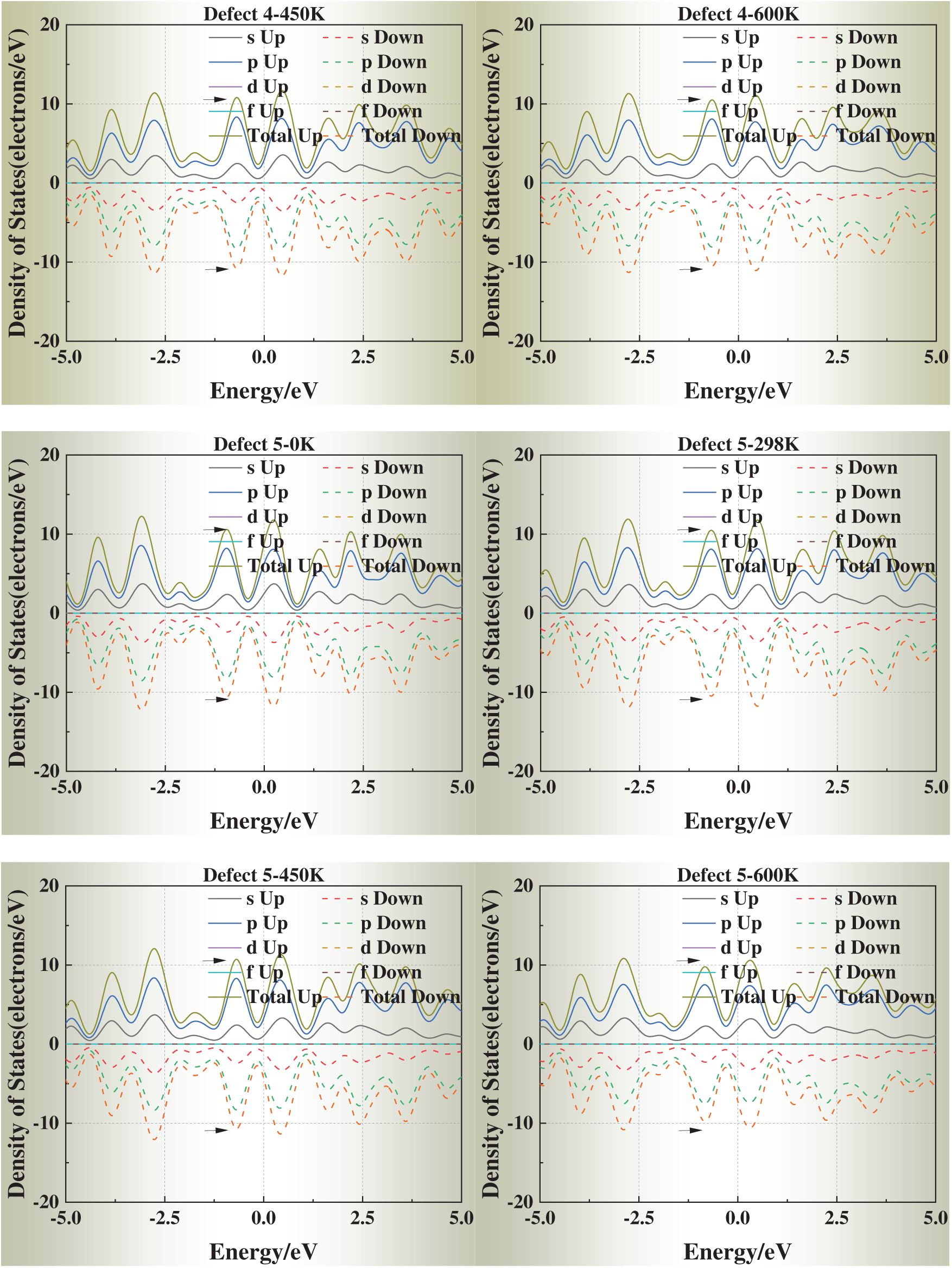

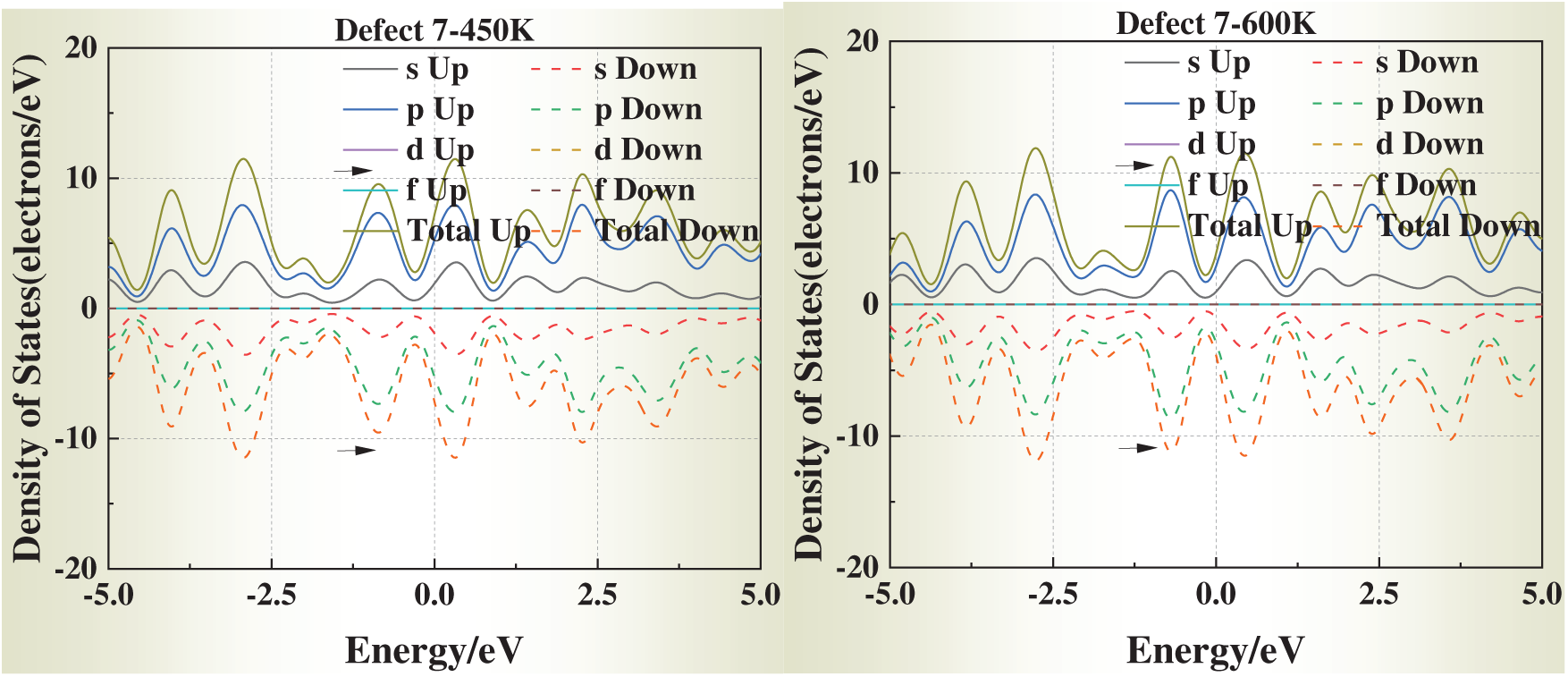

3.5 Temperature-Dependent DOS Evolution

We selected simulation temperatures of 0, 298, 450, and 600 K to capture three representative regimes of physical and engineering relevance. Specifically, 0 K serves as the ground-state DFT reference, providing a baseline for static relaxation and defect energetics. The 298 K condition reflects room-temperature behavior, enabling direct comparison with typical experimental conditions. The elevated temperatures of 450 and 600 K were chosen to explore thermally activated vacancy mobility and the temperature dependence of vacancy formation energies and electronic structure, while still remaining well below the melting point of aluminum (933 K) so that the system preserves its crystalline state. In addition, these temperature ranges correspond to annealing and processing windows commonly employed in aluminum metallurgy, thereby ensuring both scientific rigor and practical relevance.

Fig. 6 presents the DOS of defective aluminum crystals at four temperatures (0, 298, 450, and 600 K). Compared with strain, temperature exerts a more moderate influence on the electronic structure. Across all models, the DOS peaks near the Fermi level exhibit slight shifts toward it, while the overall curve shape remains essentially unchanged. This trend suggests that thermal excitation facilitates carrier activation but does not fundamentally alter the underlying band structure.

Figure 6: Density of states (DOS) of defective aluminum crystals at different temperatures (0, 298, 450, 600 K)

Notably, for Defects 3–5, the DOS profiles gradually approach that of the defect-free crystal at elevated temperatures. This apparent “DOS recovery” implies that thermal excitation may help redistribute electronic states and partially offset the perturbations introduced by face-centered vacancies, consistent with a thermally assisted relaxation of local lattice distortions.

These results indicate that temperature plays a stabilizing role in the electronic transport properties of defective aluminum, particularly by mitigating the severe electronic perturbations induced by highly coordinated vacancy sites.

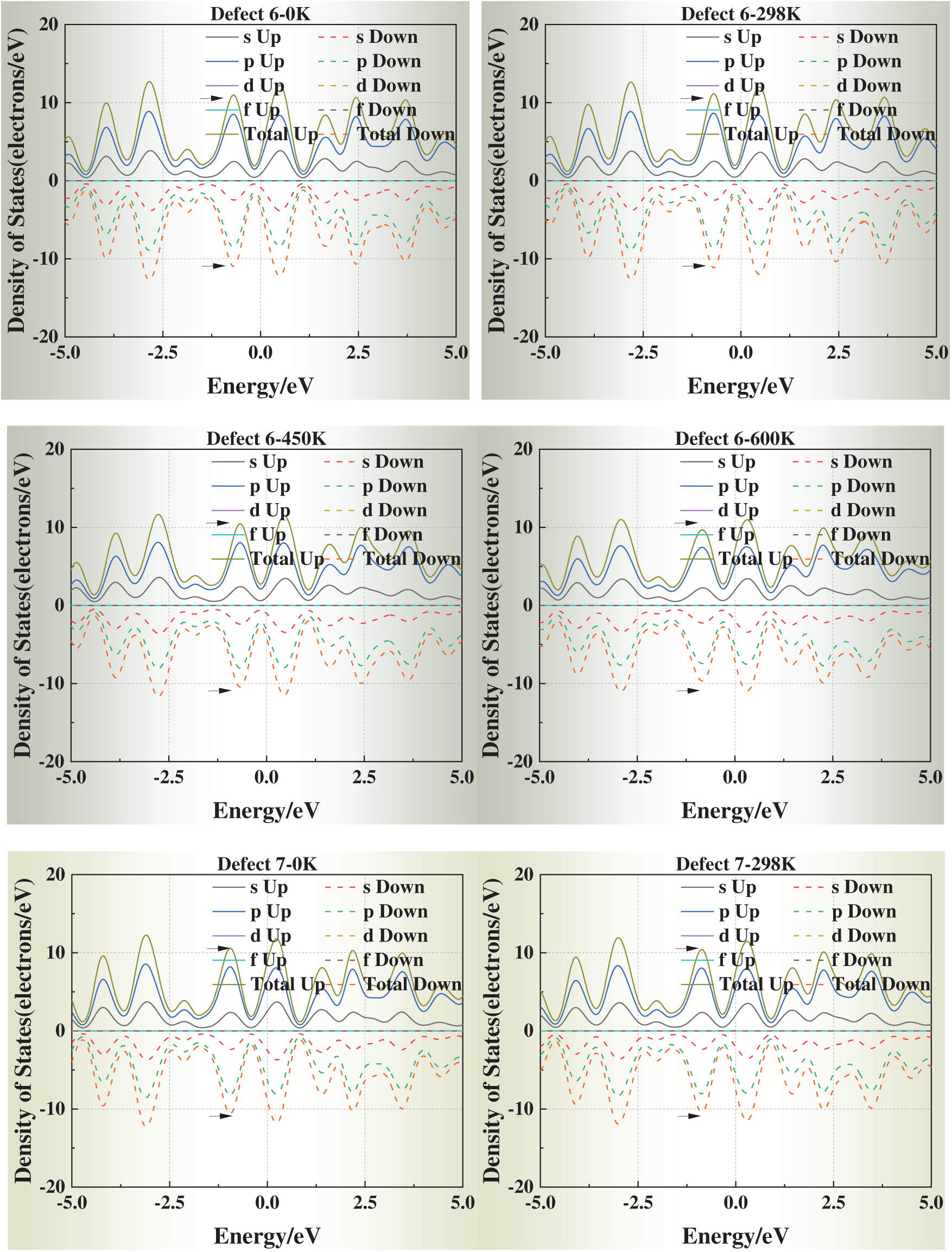

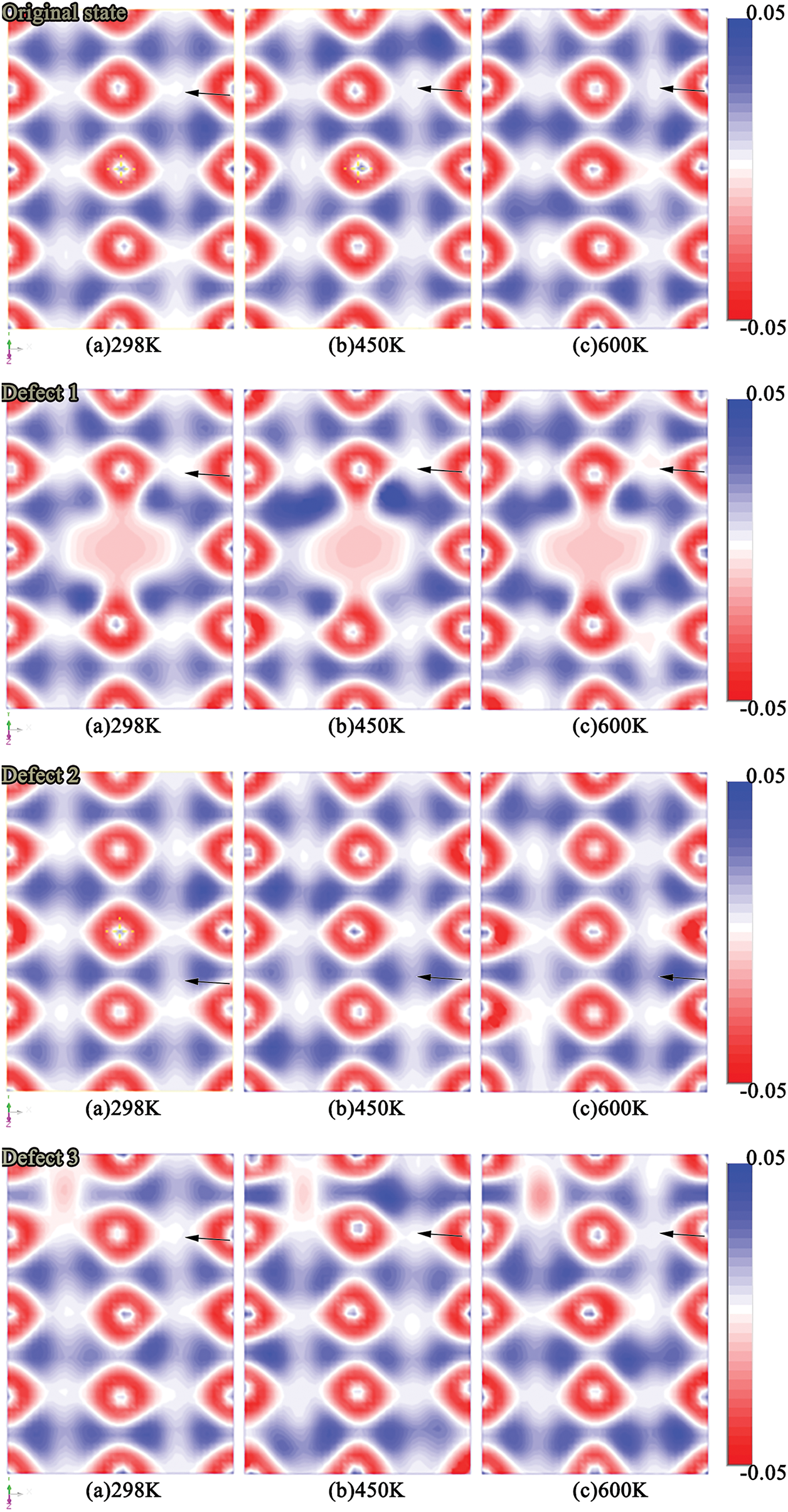

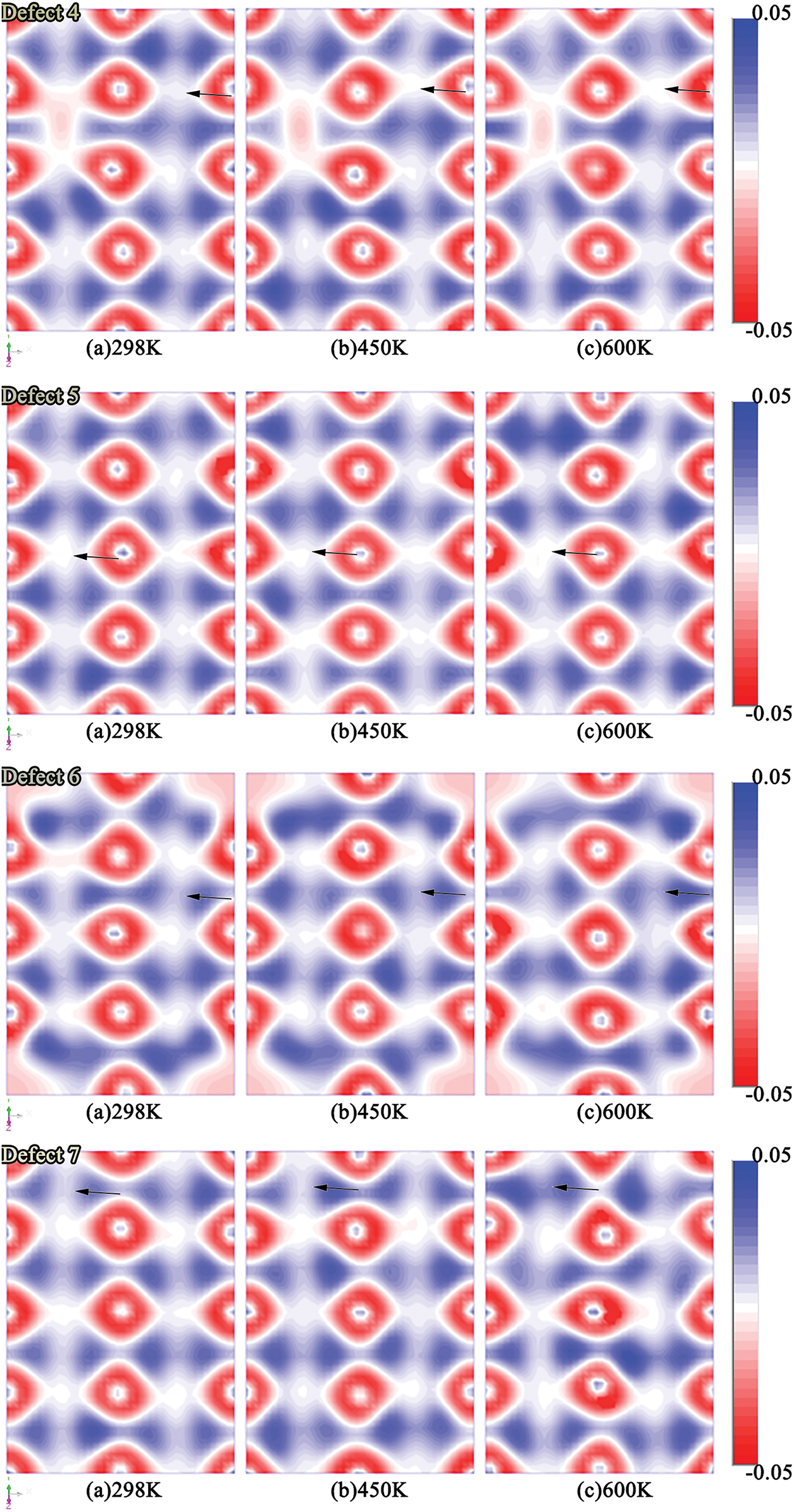

3.6 Temperature-Dependent Differential Charge Density

Fig. 7 illustrates the differential charge density distributions of all vacancy models under increasing temperature. In all cases, vacancies induce localized electron cloud depletion, indicating disruption of shared orbitals and weakened chemical bonding. These charge-depleted regions correspond to reduced bond strength and may serve as sites of mechanical brittleness.

Figure 7: Differential charge density distributions for different vacancy configurations under varying temperatures

With increasing temperature, the differential charge maps exhibit enhanced electron redistribution and smoother contour profiles. This trend suggests that thermal excitation promotes electron delocalization and orbital reorganization, thereby partially mitigating the vacancy-induced electronic perturbations. Such behavior is consistent with the “DOS recovery” observed in Fig. 6. Among all models, face-centered vacancies (Defects 3–5) display the most pronounced charge redistribution, underscoring their dominant role in destabilizing the local electronic environment due to their high coordination and central lattice connectivity.

The mechanistic interpretation of these findings can be summarized on three levels. First, the stress-strain results show that defects generally reduce load-bearing capacity by altering local atomic arrangements and bond networks, creating stress concentration sites where external loads are prematurely released, thus lowering yield strength and fracture strain. This is consistent with classical solid mechanics, which recognizes microstructural defects as preferred crack initiation sources.

Second, analysis of the energy-strain curves indicates that defective systems accumulate distortion energy more rapidly than the defect-free structure. This reflects the loss of lattice symmetry and uniform bonding, which leads to shallower local potential energy surfaces and facilitates atomic rearrangements such as slip or fracture under strain.

Third, electronic-structure analysis provides additional insight. The DOS results reveal that vacancies introduce localized states near the Fermi level, which can act as scattering centers that impede electron transport while simultaneously weakening chemical bonds. At elevated temperatures, thermal excitation enhances the occupation of these states, intensifying lattice softening and electronic instability.

In summary, the detrimental effects of vacancies operate through coupled mechanical and electronic mechanisms: mechanically by stress concentration and distortion energy, and electronically by state localization and bond weakening. This dual pathway explains the observed reduction in strength and stability in our simulations. By integrating structural, energetic, and electronic perspectives, the present work not only reports numerical results but also uncovers the physical mechanisms of defect-induced degradation, thereby offering theoretical guidance for defect engineering and microstructural optimization in aluminum alloys.

This study systematically examined the coupled effects of vacancy position on the mechanical and electronic behavior of aluminum crystals under stress and temperature fields, integrating experimental characterization with first-principles simulations. The main findings are as follows:

1. Mechanical response is vacancy-position dependent. Under high compressive strain (ε > 0.06), face-centered vacancies markedly reduce peak stress and structural stability, while corner and edge vacancies have comparatively minor effects.

2. Vacancies destabilize lattice energetics. All defective models exhibit higher total energies than the defect-free crystal, with face-centered sites showing the most rapid energy accumulation and strongest tendency toward instability.

3. Strain and temperature jointly modulate electronic states. Strain suppresses DOS near the Fermi level, weakening metallicity, whereas elevated temperatures partially restore DOS peaks and promote charge redistribution, suggesting a thermally assisted mitigation of vacancy-induced perturbations.

4. Experimental observations support simulation trends. Experimental observations show tendencies that are generally consistent with the simulation trends. TEM and SEM reveal dislocation tangles and heterogeneous grain boundaries that may be associated with vacancy-induced stress concentrations, thereby providing indicative—though not yet conclusive—mesoscopic validation of the computational results.

Potential applications. These mechanistic insights are relevant for defect engineering in aluminum alloys, including (i) tailoring precipitation and aging behavior via vacancy-mediated solute transport, (ii) controlling defect populations in additive manufacturing and rapid solidification, (iii) designing radiation-tolerant materials through vacancy clustering and sink engineering, and (iv) tuning electrical/thermal transport in Al conductors by manipulating vacancy distributions.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Research Project on Strengthening the Construction of an Important Ecological Security Barrier in Northern China by Higher Education Institutions in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (STAQZX202313), and the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Education Science ‘14th Five-Year Plan’ 2024 Annual Research Project (NGJGH2024635).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Gang Huang and Binchang Ma; methodology, Binchang Ma; software, Binchang Ma; validation, Gang Huang, Xinhai Yu and Binchang Ma; writing—original draft preparation, Binchang Ma; writing—review and editing, Gang Huang; visualization, Xinhai Yu; funding acquisition, Binchang Ma and Xinhai Yu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Novelty and Significance: The present work provides a systematic first-principles (DFT) investigation of single-vacancy effects in FCC aluminum, explicitly considering vacancy position within a representative supercell and its coupling with strain and temperature (0–600 K). By integrating vacancy formation energies, stress-strain responses, total-energy evolution, and electronic-structure diagnostics (DOS and differential charge density), the study offers the following key novelties:

I) Position sensitivity. Demonstration of how vacancy location (bulk, near-surface, or near-grain boundary equivalents) governs both mechanical response and electronic redistribution under coupled strain-temperature fields.

II) Mechanistic insight. Identification that vacancy-induced stress localization and charge redistribution depend strongly on site symmetry and compressive loading, highlighting the interplay between lattice coordination and defect energetics.

III) Cross-method validation. Combination of DFT with atomistic MD comparisons to distinguish intrinsic electronic/atomic-scale effects from size-dependent collective mechanisms such as dislocation nucleation.

Collectively, these results advance a mechanistic understanding of point-defect behavior in aluminum and provide atomistic guidance for defect-engineering strategies to optimize strength, ductility, and transport properties in Al-based alloys.

References

1. Omiyale BO, Olugbade TO, Abioye TE, Farayibi PK. Wire arc additive manufacturing of aluminium alloys for aerospace and automotive applications: a review. Mater Sci Technol. 2022;38(7):391–408. doi:10.1080/02670836.2022.2045549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Karaoğlu SY, Karaoğlu S, Ünal İ. Aerospace industry and aluminum metal matrix composites. Int J Aviat Sci Technol. 2021;2(02):73–81. [Google Scholar]

3. Yong Y. Research on properties and applications of new lightweight aluminum alloy materials. Highlights Sci Eng Technol. 2024;84:99–107. doi:10.54097/yd6e9h95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Li G, Chi W, Wang W, Liu X, Tu H, Long X. High cycle fatigue behavior of additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V alloy with HIP treatment at elevated temperatures. Int J Fatigue. 2024;184(5):108287. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2024.108287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wickramasinghe KC, Sasahara H, Usui M. Performance evaluation of a sustainable metal working fluid applied to machine Inconel 718 and AISI 304 with minimum quantity lubrication. J Adv Mech Des Syst Manuf. 2021;15(4):JAMDSM0046. doi:10.1299/jamdsm.2021jamdsm0046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Dai S, Khan MA, Liao L, Zhang X, Zhao D, Wang H, et al. Effect of hot extrusion, novel stepwise-rolling, and heat treatment on microstructure, mechanical properties, and precipitate chemistry of ultra-high strength Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy. J Alloys Compd. 2025;1010(6):177910. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2024.177910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhou Y, Yang J, Song K, Yang S, Zhu Q, Peng X, et al. Effect of annealing temperature on dual-structure coexisting precipitates in Cu–2.18Fe–0.03P alloy and softening mechanism at high temperature. J Mater Sci. 2022;57(44):20815–32. doi:10.1007/s10853-022-07910-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Xu N, Qi X, Shen Z, Hu L, Lv J, Zhong Y, et al. Point defects in metal halide perovskites. Nat Rev Phys. 2025;7(10):1–11. doi:10.1038/s42254-025-00861-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Li Y, Wang Q, Zhang H, Zhu H, Wang M, Wang H. Role of solute atoms and vacancy in hydrogen embrittlement mechanism of aluminum: a first-principles study. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2023;48(11):4516–28. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.10.257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhao B, Du Y, Yan Z, Rao L, Chen G, Yuan M, et al. Structural defects in phase-regulated high-entropy oxides toward superior microwave absorption properties. Adv Funct Mater. 2023;33(1):2209924. doi:10.1002/adfm.202209924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zunger A, Malyi OI. Understanding doping of quantum materials. Chem Rev. 2021;121(5):3031–60. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Fang X. Mechanical tailoring of dislocations in ceramics at room temperature: a perspective. J Am Ceram Soc. 2024;107(3):1425–47. [Google Scholar]

13. Wang Y, Wu X, Cao L, Tong X, Zou Y, Zhu Q, et al. Effect of Ag on aging precipitation behavior and mechanical properties of aluminum alloy 7075. Mater Sci Eng A. 2021;804(4):140515. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2020.140515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Huang Z, Li X, Wen D, Guo Q, Wang A, Dong J, et al. Crack initiation and propagation dominated by strain localization in quasi-single crystal and poly-crystalline of a Ni-based complex concentrated alloy. Mater Charact. 2023;201(13):112973. doi:10.1016/j.matchar.2023.112973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhou ZZ, Yan YC, Yang XL, Xia Y, Wang GY, Lu X, et al. Anomalous lattice thermal conductivity driven by all-scale electron-phonon scattering in bulk semiconductors. Phys Rev B. 2023;107(19):195113. doi:10.1103/physrevb.107.195113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Qian X, Zhou J, Chen G. Phonon-engineered extreme thermal conductivity materials. Nat Mater. 2021;20(9):1188–202. doi:10.1038/s41563-021-00918-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Moia D, Maier J. Ion transport, defect chemistry, and the device physics of hybrid perovskite solar cells. ACS Energy Lett. 2021;6(4):1566–76. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.1c00227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Mosquera-Lois I, Kavanagh SR, Klarbring J, Tolborg K, Walsh A. Imperfections are not 0 K: free energy of point defects in crystals. Chem Soc Rev. 2023;52(17):5812–26. doi:10.1039/d3cs00432e. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Akkermans RLC, Spenley NA, Robertson SH. COMPASS III: automated fitting workflows and extension to ionic liquids. Mol Simul. 2021;47(7):540–51. doi:10.1080/08927022.2020.1808215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kalibaeva G, Ferrario M, Ciccotti G. Constant pressure-constant temperature molecular dynamics: a correct constrained NPT ensemble using the molecular virial. Mol Phys. 2003;101(6):765–78. doi:10.1080/0026897021000044025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;77(18):3865. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.77.3865. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Xu X, Goddard WAIII. The extended Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functional with improved accuracy for thermodynamic and electronic properties of molecular systems. J Chem Phys. 2004;121(9):4068–82. doi:10.1063/1.1771632. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Vanderbilt D. Soft self-consistent pseudopotentials in a generalized eigenvalue formalism. Phys Rev B. 1990;41(11):7892. doi:10.1103/physrevb.41.7892. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Monkhorst HJ, Pack JD. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys Rev B. 1976;13(12):5188. doi:10.1103/physrevb.13.5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Pfrommer BG, Côté M, Louie SG, Cohen ML. Relaxation of crystals with the quasi-Newton method. J Comput Phys. 1997;131(1):233–40. doi:10.1006/jcph.1996.5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Das DK, Kumar B. Mechanical properties of aluminium-graphene core shell nanocomposite: a molecular dynamics simulation study. Diam Relat Mater. 2025;152(11):111981. doi:10.1016/j.diamond.2025.111981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools