Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Validation of Contextual Model Principles through Rotated Images Interpretation

School of Computer Science, Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology (FEIT), University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, 2007, Australia

* Corresponding Author: Illia Khurtin. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.067481

Received 05 May 2025; Accepted 23 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

The field of artificial intelligence has advanced significantly in recent years, but achieving a human-like or Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) remains a theoretical challenge. One hypothesis suggests that a key issue is the formalisation of extracting meaning from information. Meaning emerges through a three-stage interpretative process, where the spectrum of possible interpretations is collapsed into a singular outcome by a particular context. However, this approach currently lacks practical grounding. In this research, we developed a model based on contexts, which applies interpretation principles to the visual information to address this gap. The field of computer vision and object recognition has progressed essentially with artificial neural networks, but these models struggle with geometrically transformed images, such as those that are rotated or shifted, limiting their robustness in real-world applications. Various approaches have been proposed to address this problem. Some of them (Hu moments, spatial transformers, capsule networks, attention and memory mechanisms) share a conceptual connection with the contextual model (CM) discussed in this study. This paper investigates whether CM principles are applicable for interpreting rotated images from the MNIST and Fashion MNIST datasets. The model was implemented in the Rust programming language. It consists of a contextual module and a convolutional neural network (CNN). The CM was trained on the rotated Mono Icons dataset, which is significantly different from the testing datasets. The CNN module was trained on the original MNIST and Fashion MNIST datasets for interpretation recognition. As a result, the CM was able to recognise the original datasets but encountered rotated images only during testing. The findings show that the model effectively interpreted transformed images by considering them in all available contexts and restoring their original form. This provides a practical foundation for further development of the contextual hypothesis and its relation to the AGI domain.Keywords

Despite significant progress in the field of artificial intelligence (AI) and its practical applications, uncovering the principles of a human-like, or (general), intelligence (AGI) remains a theoretical challenge. One of the key problems is understanding the meaning of information by humans, a question that dates back to ancient times. Aristotle suggested that people do not operate with phenomena as set of features but rather the situation in which those phenomena appear. In other words, the context in which the phenomenon is analysed is considered an integrative part of the information flow. Contemporary understanding of human information comprehension sets it as an active, three-stage procedure: sensory reception, cognitive processing, and synthesis of a holistic object representation. Perception involves detecting elements of external phenomena through the senses, interpreting them cognitively, and integrating them into a coherent, objective image. It is a subjective process, based on the observer’s prior experience. As a result, incoming information acquires meaning. Meaning exists only as potential prior to interpretation by the recipient. An informational message may contain multiple potential meanings until interpretation collapses them into one. The contextual model (CM) hypothesis [1] states that interpretation begins with transforming the incoming signal into an internal representation, which is then evaluated against mnemonic templates stored in memory. A detected congruence marks successful interpretation, indicating that the new input has been assimilated to a pre-existing cognitive prototype-meaning. In this way, the CM extracts meaning from the incoming information by transforming it into something previously memorised. Meaning is thus integrated with the transformation rules, which produce interpretation. These rules are combined into a context. Information is intrinsically asemantic and gains meaning only when processed within a particular interpretive context. Borrowing quantum-theoretic language, an incoming message has a superposition of all possible meanings. The application of a specific context collapses this spectrum to a single outcome. Consequently, identical data can yield distinct interpretations in different contexts. One of the first applications of this approach was Turing’s crib-based analysis of the Enigma code. However, empirical evidence supporting CM remains limited. This study aims to address this gap by developing and evaluating a programming model based on contextual principles that is capable of processing visual information from multiple viewpoints.

Computer vision has advanced significantly in recent years, particularly with artificial neural networks (ANNs). They have achieved notable progress in the field of object recognition [2–6], but still struggle with geometrically transformed images [7–9]. Various approaches have been proposed to improve this. Their advantages and disadvantages are discussed in detail in [10]. In this paper, we focus on Hu moments, spatial transformer networks (STNs), Capsule Networks (CapsNets), attention and memory mechanisms, as they are conceptually related to the CM discussed here.

Hu moments, introduced by Ming-Kuei Hu in 1962 [11], are based on scalar image descriptors computed from normalised central moments, which are invariant to image translation, rotation, and scaling. They are widely used as compact rotation-invariant features for shape and digit recognition tasks. Hu moments have been evaluated on MNIST and rotated variants to provide rotation-invariant descriptors and to complement learned features in subsequent classifiers [12]. Being combined with convolutional neural networks (CNNs), Hu moments significantly improved robustness to affine transformations [13]. However, the set of invariances is fixed by the predefined moment equations, addressing only affine changes. In contrast, CM learns transformation rules (contexts) directly from examples and can accommodate a broader class of conversions applied to any type of information, not only images.

STNs are based on the idea of recognising the transformation itself and restoring the original object [14]. A spatial transformation recognition module is implemented with the localisation network and a parameterised sampling grid. It is trained on transformations and performs a reversal operation. The module is placed in the architecture before the CNN, which then recognises the restored objects by their features. The model revealed essential improvements in the spatial transformation invariance of CNNs without a significant influence on the system performance. The drawback of the spatial transformers is that they can only recognise the specific affine transformations they were trained on [15]. Like STN, the CM described in this paper was able to recognise spatial transformations of the greyscale images. It learned a particular set of transformations and restored the original image for the subsequent recognition by a CNN. However, CM principles can be applied to arbitrary information, which relates to the theoretical questions of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) [1]. Context rules are applied as an atomic action and do not suffer from overtraining issues like STNs. Also, the same context can be used for the reverse transformation.

The main unit in CapsNets is a capsule [10,16]. It is a group of neurons, each activated by specific attributes of an object, such as its position, size, or colour. Formally, a capsule generates an activity vector, where each neuron corresponds to an instantiation parameter (e.g., hue). The length of the vector reflects the probability of the object’s presence in the input, while its orientation encodes the capsule’s properties. CapsNets replace scalar-output feature detectors with vector-output capsules and max-pooling with a routing-by-agreement mechanism. The independence of units ensures that agreement among multiple capsules significantly increases the probability of accurate detection. Higher-level capsules aggregate outputs from lower-level ones whose outputs cluster, driving them to output both a high probability of the object’s presence and a high-dimensional pose representation [17,18]. Traditional CNNs generalise poorly to unlearned viewpoints beyond translations [19,20]. Addressing other affine transformations using CNNs would require either exponentially increasing the feature detector grid size or scaling the training dataset size, making these methods impractical for larger problems. CapsNets utilize transformation matrices to model spatial relationships between object components, enabling recognition of the entire object even from its distributed representation [21]. Unlike STNs and CM, CapsNets can process segments and are subject to multiple transformations without their normalization [22]. Similar to CapsNets, which isolate calculations in capsules, CM does it in independent contexts. However, CM cannot yet recognise separated objects; instead, it restores the original object and the transformation applied to it.

A promising route to transformation-invariant visual understanding is offered by a relatively recent class of ANNs, inspired by biological visual systems, incorporating feedback connections [23], memory and attention mechanisms [24,25]. Attention highlights the most informative visual cues and suppresses irrelevant inputs, yielding more compact and robust internal representations. Memory-augmented networks retain previously acquired features while continually integrating new information about image transformations during successive training phases. These strategies are crucial for producing resilient representations in demanding applications such as few-shot learning [26]. Although these models frequently invoke the term ‘context’, its usage diverges from that in CM. ‘Context’ refers to selecting the most valuable subset of incoming data. In contrast, CM defines ‘context’ as the set of transformation rules employed to extract meaning and construct interpretive framework, rather than facilitating object recognition.

The CM discussed in this paper was combined with a CNN. It was implemented in the Rust programming language and validated on the MNIST [27] and Fashion MNIST [28] benchmark datasets. The CM module was responsible for transformation in contexts, while the CNN detected coherence with the pre-existing prototypes it was trained for. CM demonstrated context knowledge transfer, remaining independent of the incoming information. It was trained on one dataset and subsequently applied to interpret two other distinct datasets without modification. The CNN module, responsible for interpretation matching with memory, was adapted to accommodate the trained model for MNIST or Fashion MNIST. Beyond these immediate results, this work established a foundation for advancing CM principles toward AGI theory, providing a practical model for information interpretation across contexts.

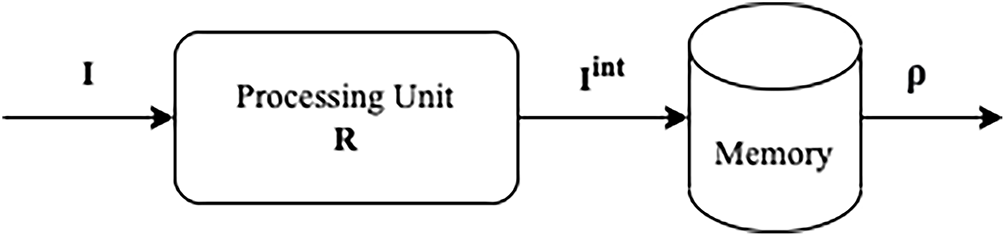

A. Redozubov formalized the process of information handling within CM [1]. The approach assumes that an informational message I can be decomposed into concepts c. The complete set of unique c forms a dictionary C. Then, I is a set of c with K elements: I = {ck}, where ck ∈ C, k ∈ 1..K. Replacing ck in the original message I with cj from the same C maps I to its interpretation Iint: I = {ck} → Iint = {cj}, ck, cj ∈ C. The collection of messages Ii and their corresponding Iiint constitutes the memory M of a subject S. Each memory element mi ∈ M is defined as a pair of the original message and its interpretation: m = (Ii, Iiint). M of S is formed during the learning phase. Since both Ii and Iiint consist of c, M can be separated into groups which associate sets of different concepts {c} from Ii with their interpreted concepts {cint}. Thus, the memory is mapped into a set of conversion rules: Rk = {(ck, cint)} across all Ii and Iiint in M. A consistent subset of R, referring to the same transformation, forms a context Cont. These contexts form a space of contexts {Conti} of S. Since multiple distinct messages I can correspond to the same interpretation Iint, the total number of unique interpreted elements is constrained by

Figure 1: Computational scheme of the context module

2.2 Contextual Model for Images Geometric Transformations

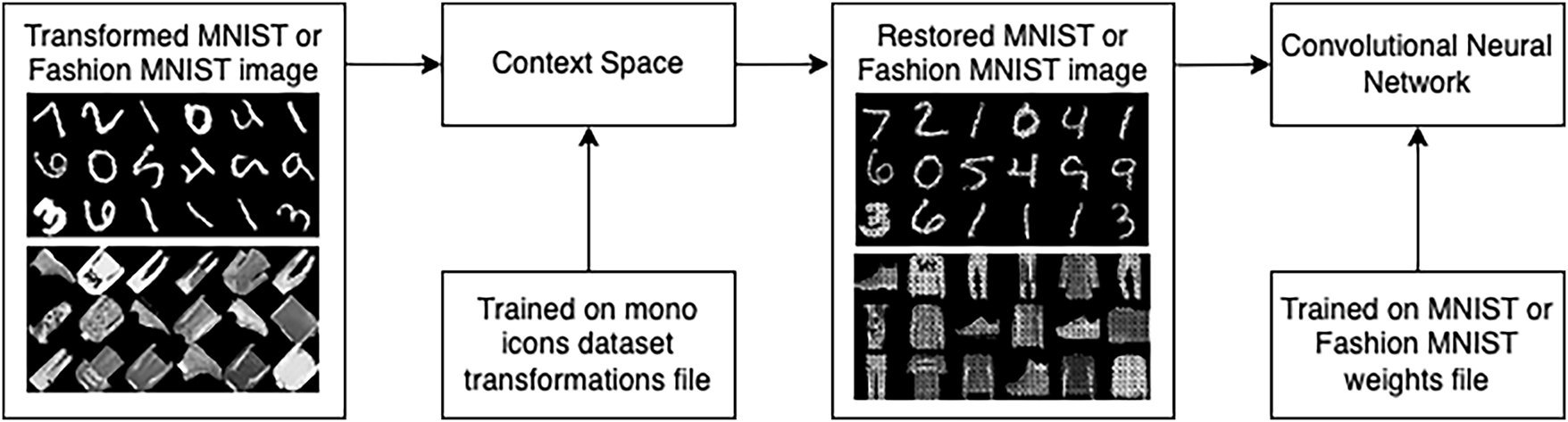

The CM implemented in this investigation operated by applying a set of geometric transformation rules to an input image, generating an interpretation that was recognised by a trained CNN. If a match was found, the corresponding context was selected as a “context-winner”. This process was repeated across multiple contexts, and the context-winner was updated if a better interpretation was identified. The design of the model is presented in Fig. 2. The interaction between the CM and the CNN was carried out using the MNIST data format. The CM output interpreted images as a 784 one-dimensional vector of pixels values (28 × 28 px = 784), which was then recognised by the CNN.

Figure 2: CM with integrated CNN

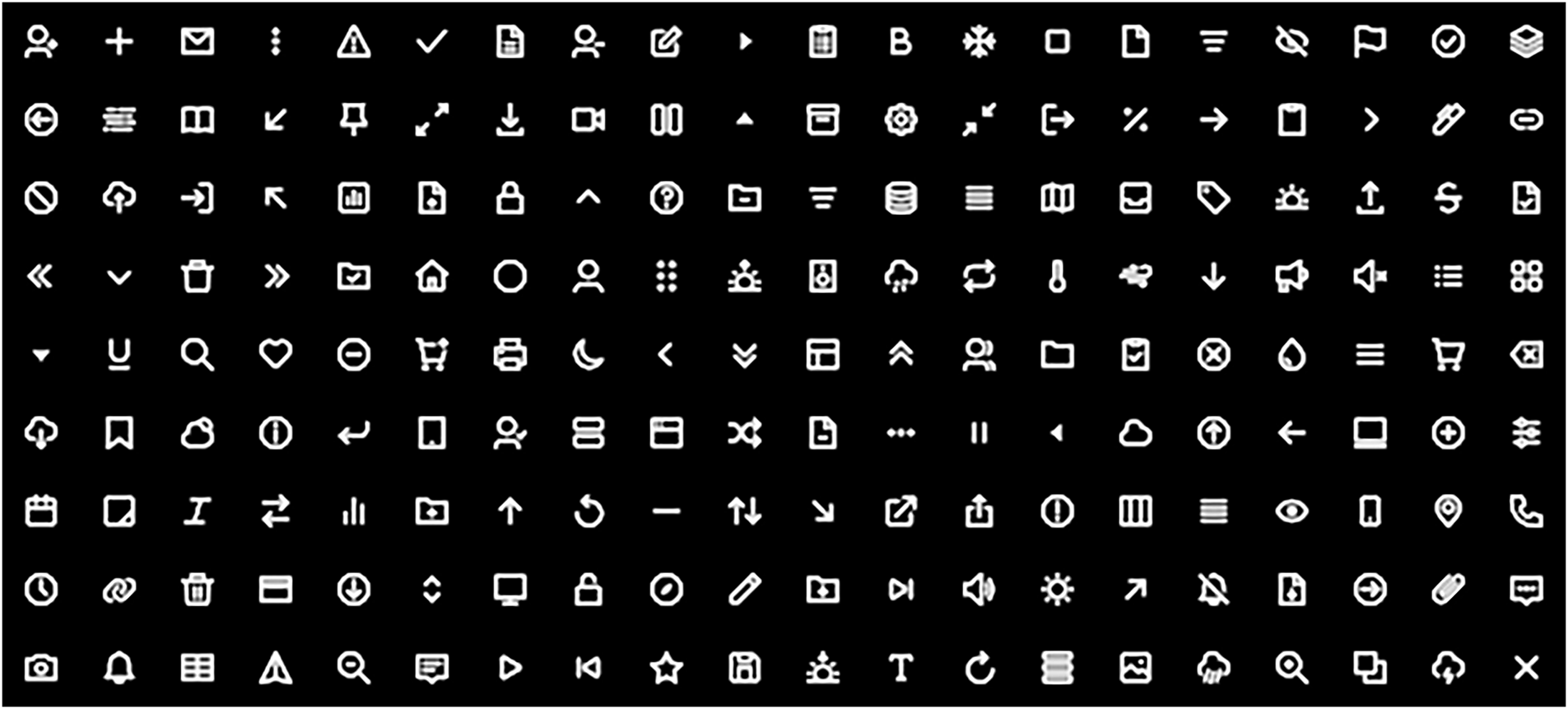

The CM was trained on the Mono Icons dataset, which is fundamentally different from MNIST and Fashion MNIST images. The dataset contains 180 grey images (Fig. 3), normalised to 28 × 28 px. Since this amount was insufficient to span variations across all pixels, we augmented the dataset to enable the CM to capture transformations across most pixels. As a result, in addition to the original set, every picture was rotated on

Figure 3: Mono icons dataset

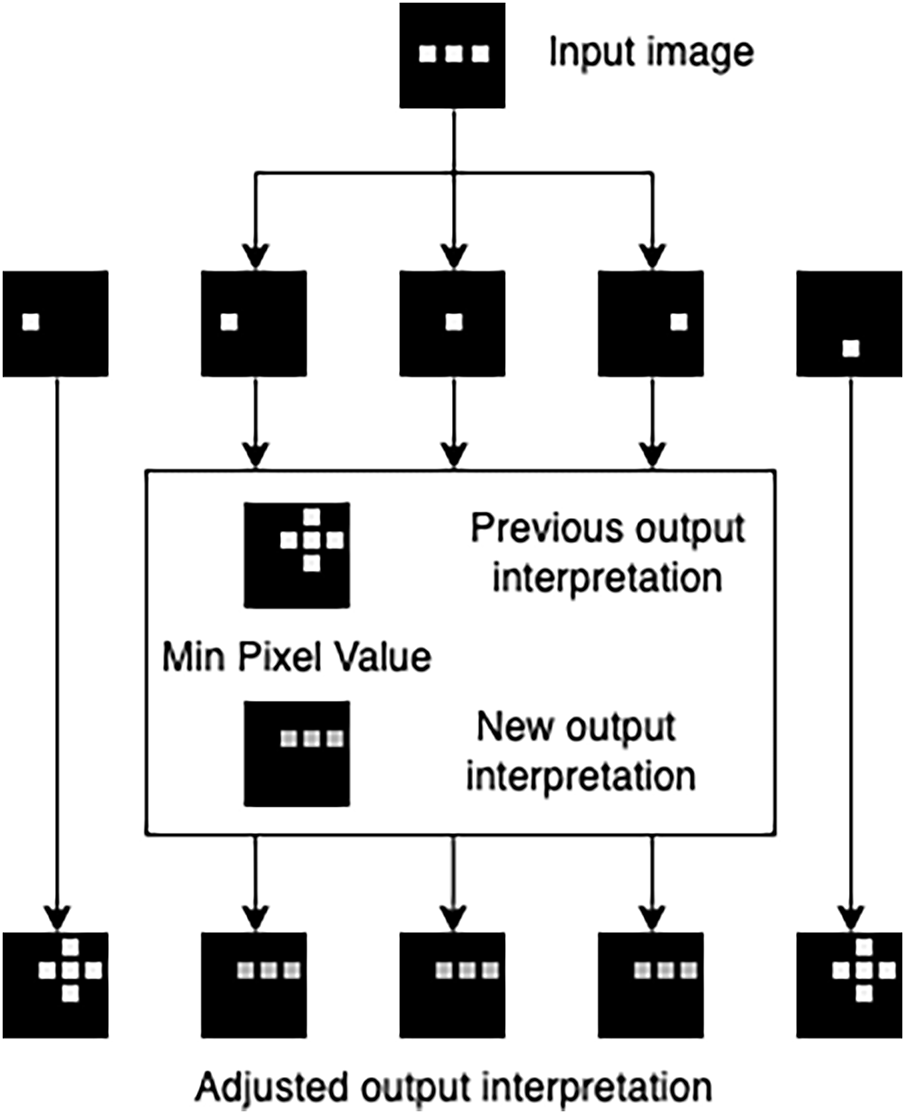

The logic for selecting transformation rules supported greyscale pixels. An input image was disassembled into pixels different from 0. Initially, every input pixel was mapped to all set pixels of the output image, as shown for x- and y-shifts in Fig. 4. With more examples, the rule was adjusted by removing extra output pixels, which had no relation to the transformed input pixel (Fig. 5). The model took the minimum value between the previously stored output pixel and the new incoming one. As a result, the more examples the CM processed, the clearer the rules became within contexts. Output pixels unrelated to the input (non-black) gradually received lower values (black). The augmented Mono Icons dataset essentially increased the number of examples. Applying the context for the backward transformation, the model instead took the maximum pixel value. Input pixels were rounded to the nearest threshold so that values within it were considered equal. The threshold was set to 5, meaning grayscale values (0–255) were grouped into 52 discrete levels. This hyperparameter reduced the number of transformation rules required.

Figure 4: Disassembling incoming image into pixels and setting initial shifted in x and y output interpretations for them

Figure 5: Adjusting shifted in x and y output interpretation on the following learning

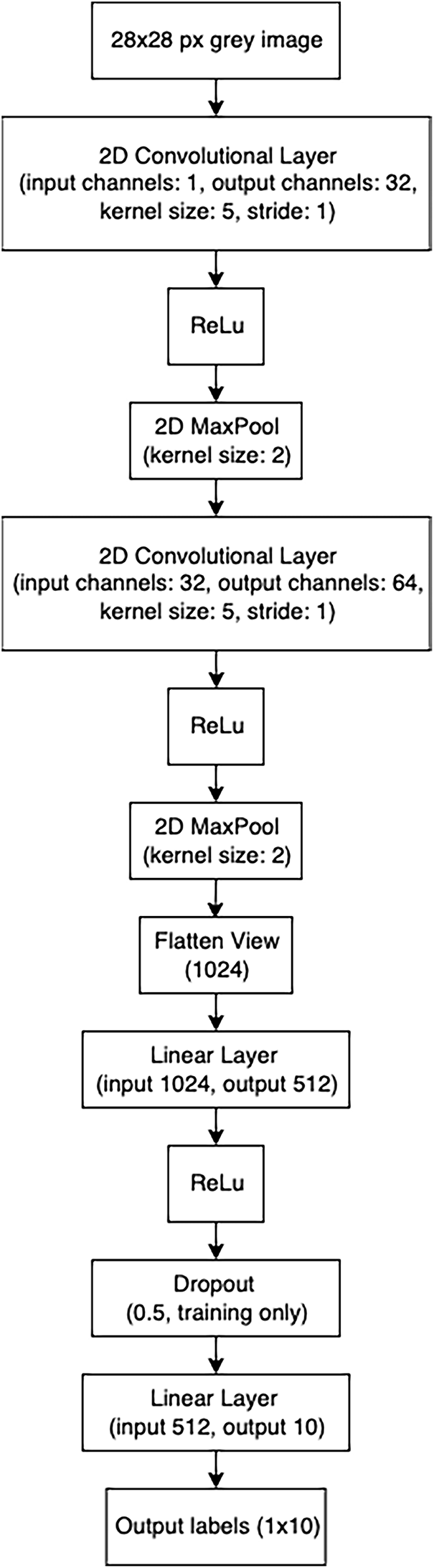

The CNN component in the model was used to find correlations with memory after interpretation (Fig. 2). It was implemented with the Rust PyTorch crate for machine learning tch v.0.1.7 [30]. The source code was built and run on Ubuntu v.24.04.3, compiler rustc v.1.89. The architecture of the CNN is shown in Fig. 6. The same design was used to train on both the MNIST and Fashion MNIST datasets, but the weights were saved in separate files. Testing was then performed on the respective test sets. The learning rate was set to 0.01, batch size to 1024, number of epochs to 20, and the optimiser was Adam. Then the test datasets were rotated by angles from the following set: 0,

Figure 6: CNN architecture

The full flow of CM testing is depicted in Fig. 2. Each context applied its transformation rules to the input image, generating an interpretation. This was then sent to the trained CNN module for recognition. If recognition was successful, the corresponding context was selected as the winner. The context-winner was then used for subsequent incoming image interpretations. If another context produced a better interpretation of a transformed image, the context-winner was updated. The models were tested with rotations only; shifts along the x- and y-axes were not applied, except in the case of one CM that was able to interpret them.

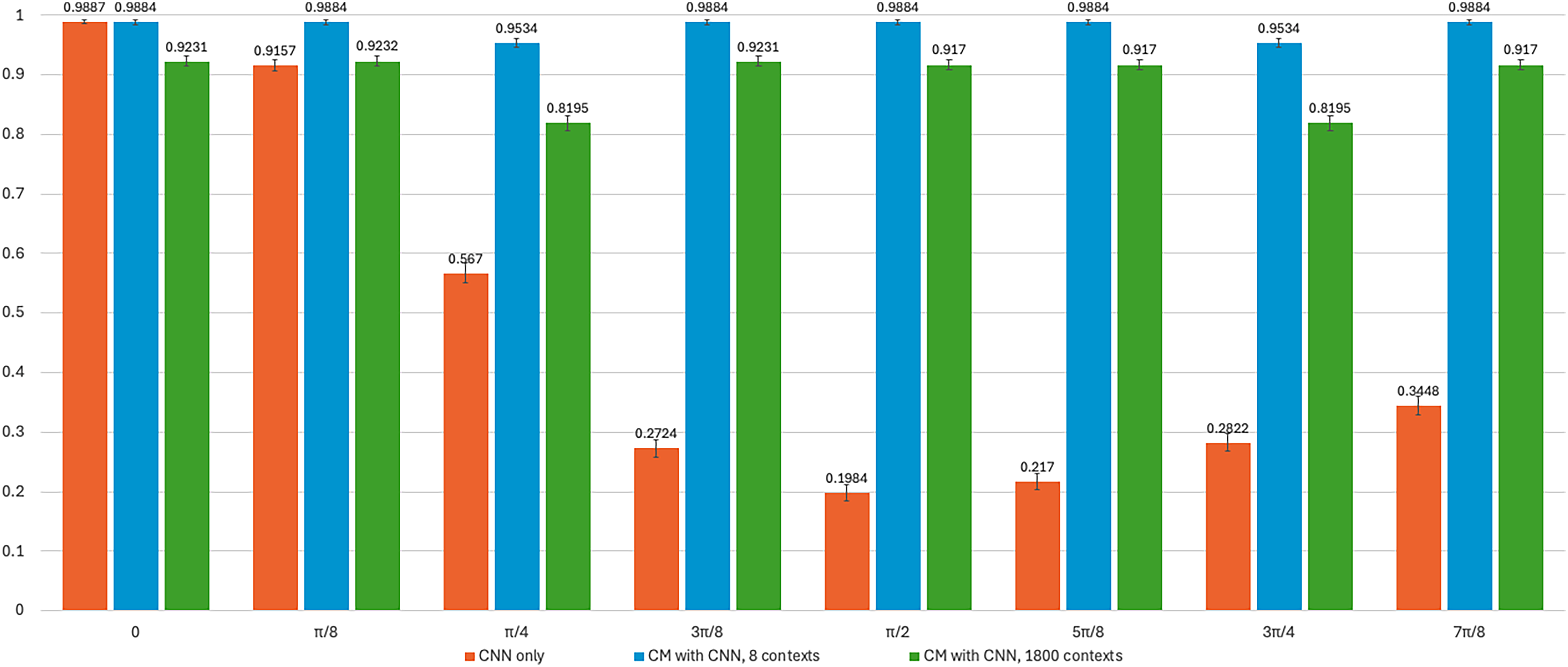

The CNN module (Figs. 2 and 6) was trained on the MNIST training dataset (60,000 examples) and then tested on the corresponding test dataset (10,000 examples). The recognition accuracy achieved was 0.9887 (113 errors out of 10,000). The trained weights were saved into a file and were used for all rotation tests. The recognition accuracy results for the MNIST test dataset rotated by 8 angles (0,

Figure 7: Accuracy achieved by the trained CNN, CM with 8 and 1800 contexts on the MNIST dataset

Fig. 7 shows that the CNN model was not invariant to rotations. Its recognition accuracy decreased substantially as the rotation angle increased, reaching a minimum of 0.1984 at

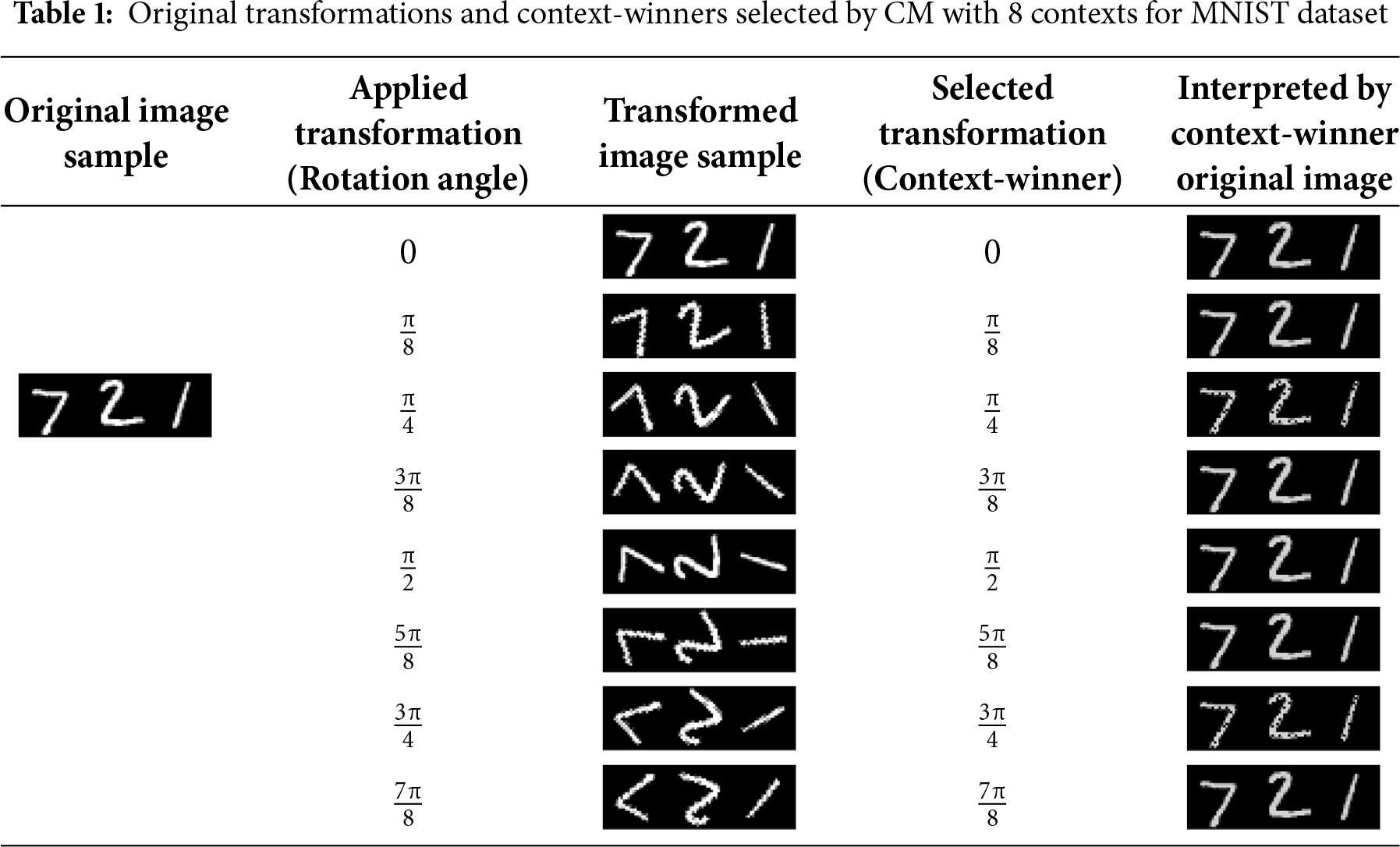

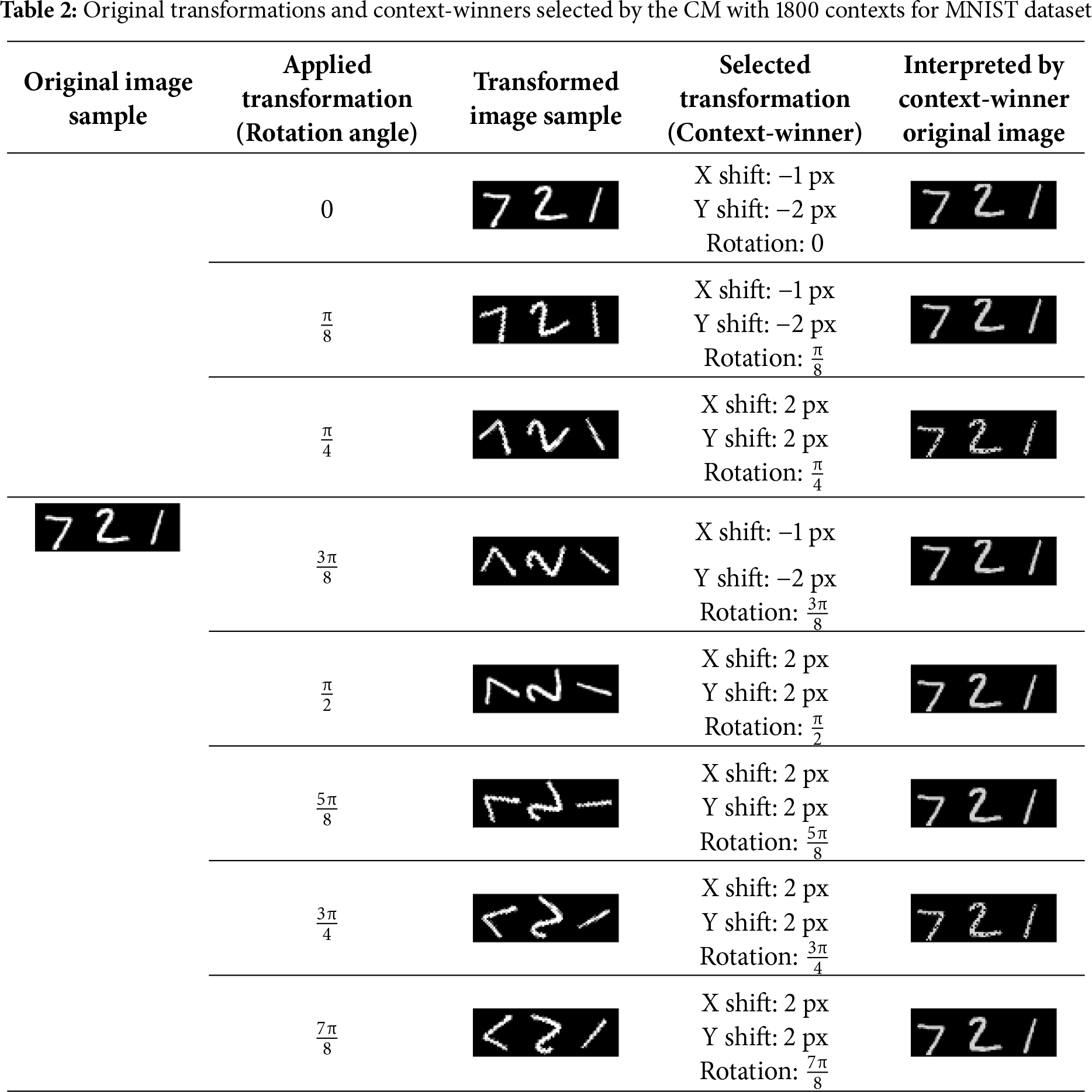

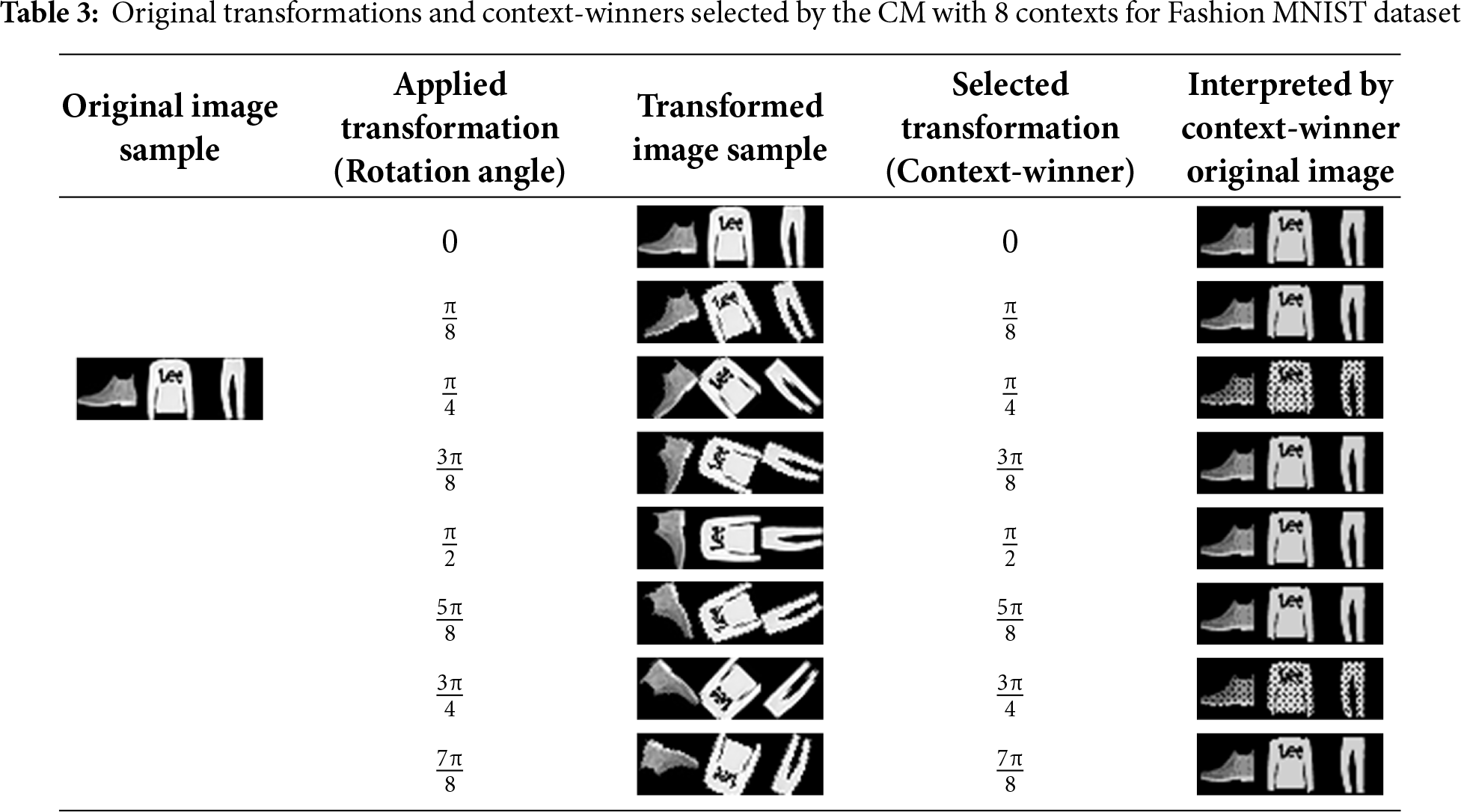

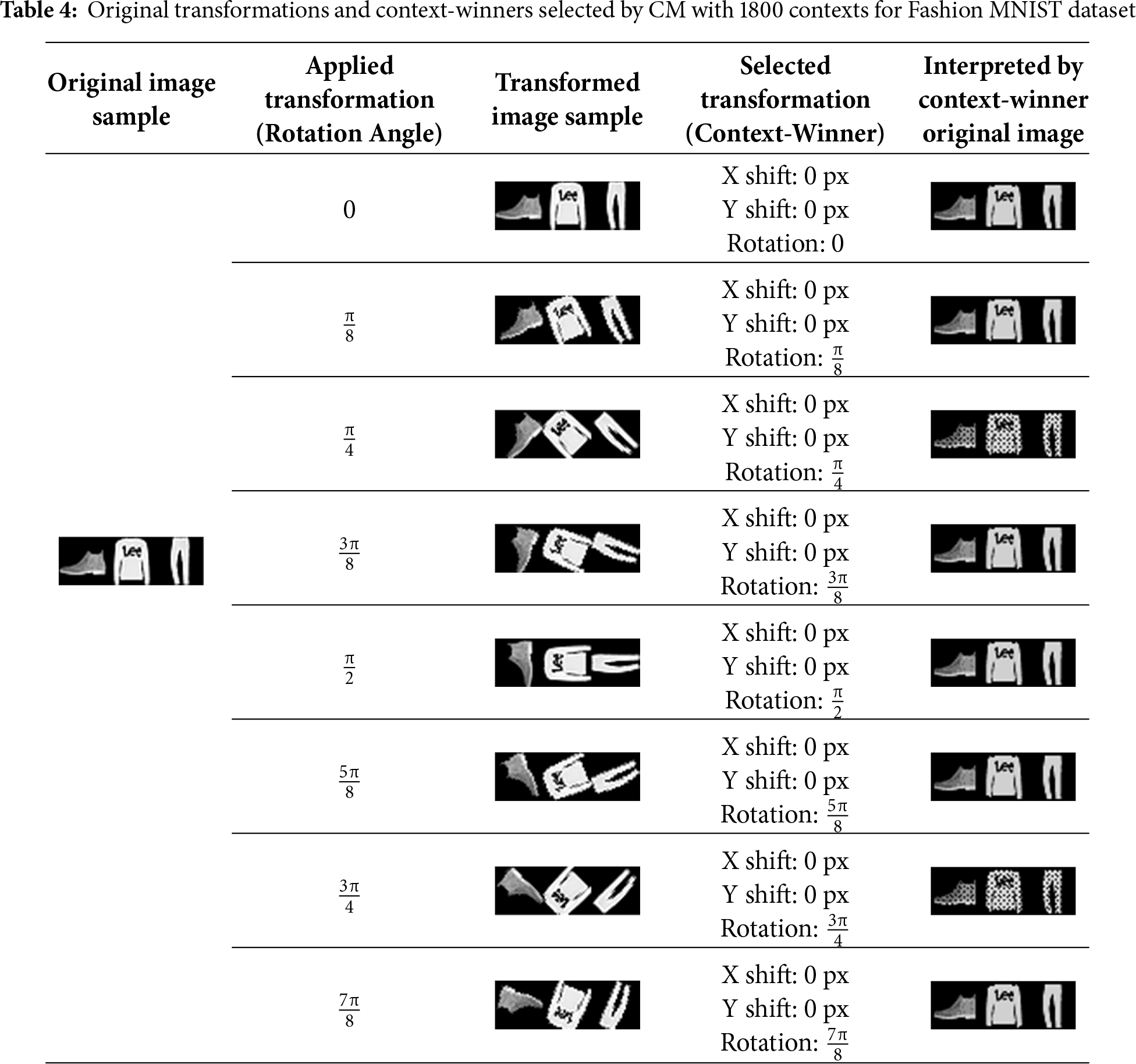

In addition to reconstructing the original images from their transformed inputs, the CM identified the specific transformation rules applied to the original object (context–winner). The results of the selected context-winners for CM trained with rotations only are displayed in Table 1.

The ‘Original image sample’ column contains the first 3 images from the MNIST test dataset as examples. The ‘Applied transformation’ column shows the angle to which the original image was rotated. The ‘Transformed image sample’ column contains the first 3 images from the MNIST test dataset rotated by the given angle. The ‘Selected transformation’ column depicts the context-winner chosen by the CM. Finally, the ‘Interpreted by context-winner original image’ column shows the interpretation rules applied by the selected context-winner to the first 3 rotated images from the MNIST test dataset. Similar results for the CM trained on both rotations and shifts are presented in Table 2.

The results in Tables 1 and 2 show that the CM correctly recognised the rotation angle. The model trained with the shifts (Table 2) introduced minor errors along the x- and y-axes, not exceeding 2 pixels (expected = 0). The interpreted images also exhibited some artefacts (missed pixels and loss of contrast), but they were not critical for subsequent recognition by the CNN module. This explains the high accuracy observed in the rotated tests where the CNN was augmented with the contextual module.

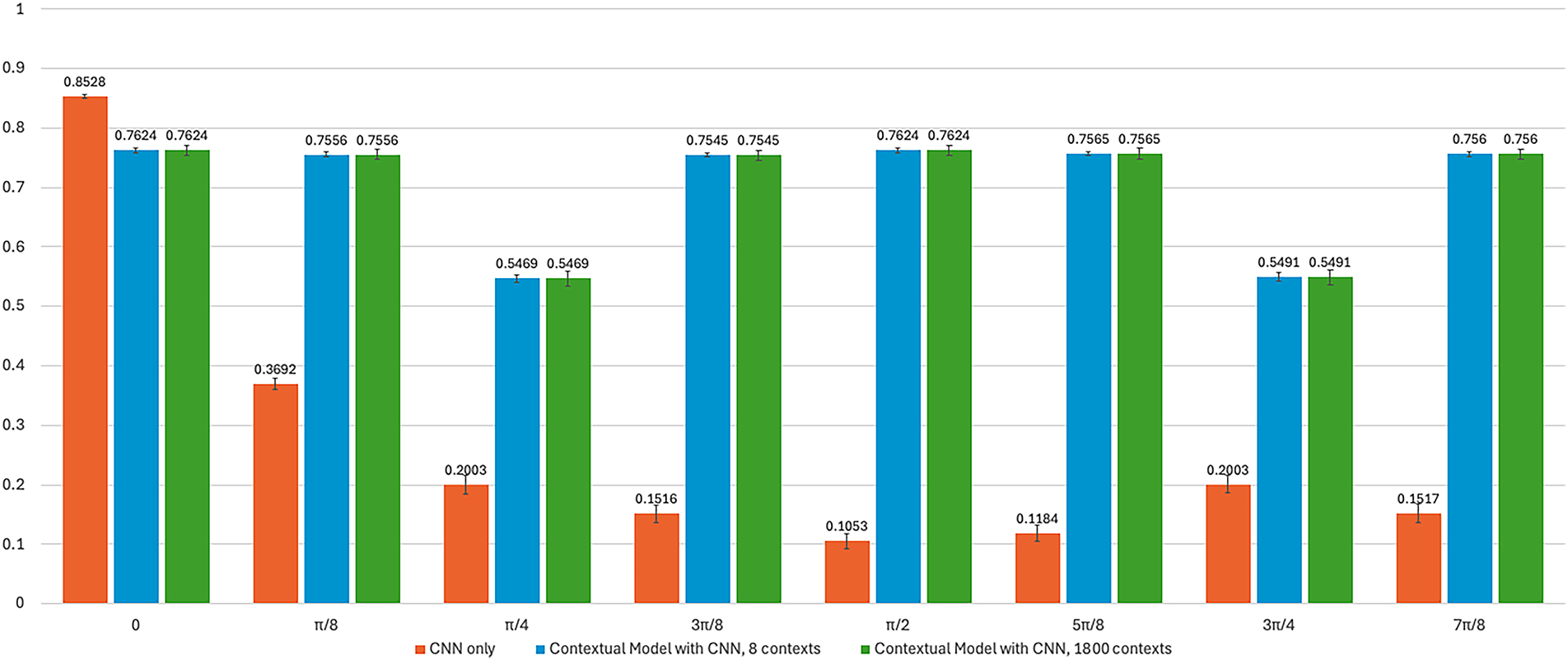

Similar results were obtained with the CNN module trained on the Fashion MNIST dataset, with no changes to its architecture (Fig. 6). The contextual module trained on the Mono icons dataset (Fig. 3) was also left unchanged. The CNN alone achieved an accuracy of 0.8528 on Fashion MNIST after training, as shown in Fig. 8 (CL is 99.9%). The CM achieved lower results on the same dataset for both 8 and 1800 contexts (0.7624), compared with the MNIST results (Fig. 7). However, rotated images drastically reduced the CNN’s accuracy, with a minimum of 0.1053 at

Figure 8: Accuracy achieved by the trained CNN, CM with 8 and 1800 contexts on the fashion MNIST dataset

The selected context-winners results for the CM on the Fashion MNIST dataset are displayed in Tables 3 and 4.

Both the 8 and 1800 contexts CMs correctly recognised the rotation angles. The 1800 contexts CM selected context-winners with x- and y-shifts equal to 0 (Table 4), in contrast to the MNIST results (Table 2). This can be explained by the fact that Fashion MNIST images occupy more space within 28 × 28 px field, and shifts therefore reduced recognition accuracy compared with MNIST images. The interpreted images for

4 Limitations and Recommendations

The CM introduced in this research is still in the conceptual stage and cannot yet compete with modern, fully developed models. This study focuses on validating the core principles of CM in order to provide practical grounding for the theoretical framework outlined in [1] and to establish a solid foundation for future investigations in the area of AGI. The transformation rules learning algorithm used in the model is basic and will need to be enhanced for practical applications. The images used in this investigation were selected from the widely adopted MNIST and Fashion MNIST datasets to demonstrate the capability of CM to process greyscale benchmark images when integrated with CNN. Nevertheless, several improvements could be made. Incorporating edge detection techniques would enable the model to handle colour images. Increasing image resolution could reduce the impact of pixel loss during rotation, resulting in smoother edges. Introducing controlled uncertainty into pixel interpretation may further refine the model, though this could also make results less predictable and harder to reproduce, presenting both challenges and opportunities for practical applications. Integrating CM with a CNN currently slows recognition, particularly when a large number of contexts are involved. This limitation could be mitigated by training the CM only on the necessary transformations and by improving both the rule-learning process and context-winner identification algorithms.

This investigation validated the theoretical principles of the CM in practice by restoring rotated images and selecting the appropriate context-winners in the test datasets. Its effectiveness was evaluated by enhancing the spatial invariance of a CNN to rotated images from the MNIST and Fashion MNIST datasets. The model was trained on a separate dataset of transformed images and successfully generalised to unseen rotations in different test datasets, demonstrating the contextual module’s independence from incoming information and, therefore, its ability to transfer context knowledge. These practical results in information interpretation through contexts provide a robust foundation for extrapolating CM principles toward AGI theory and for further investigation.

However, the study also revealed certain limitations. The model introduced artifacts in the interpreted images. Moreover, while it accurately identified the rotations applied to the original images, it exhibited minor uncertainty in detecting shifts along the x- and y-axes in the MNIST dataset. These areas require refinement for the CM to be suitable for practical application.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express sincere appreciation to Alexey Redozubov for his invaluable guidance and insightful discussions on interpreting the results for this paper. His support has been instrumental in shaping the direction of this research and enhancing the quality of the findings.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Illia Khurtin and Mukesh Prasad; methodology, Illia Khurtin; software, Illia Khurtin; validation, Illia Khurtin and Mukesh Prasad; formal analysis, Illia Khurtin; investigation, Illia Khurtin; resources, Illia Khurtin and Mukesh Prasad; data curation, Illia Khurtin; writing—original draft preparation, Illia Khurtin; writing—review and editing, Illia Khurtin and Mukesh Prasad; visualization, Illia Khurtin; supervision, Mukesh Prasad; project administration, Illia Khurtin; funding acquisition, Mukesh Prasad. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of manuscript

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, [Illia Khurtin], upon reasonable request. The source code of the model in the Rust language can be downloaded at: https://github.com/iluhakhurtin/CS_CNN_MNIST (accessed on 01 May 2025), commit hash 71bae4d, folder ‘mnist’.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| AGI | Artificial General Intelligence |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network(s) |

| CapsNet(s) | Capsule Network(s) |

| CL | Confidence Level |

| CM | Contextual Model |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network(s) |

| MNIST | Modified National Institute of Standards and Technology (dataset) |

| STN | Spatial Transformer Network(s) |

References

1. Redozubov A, Klepikov D. The meaning of things as a concept in a strong AI architecture. In: Artificial general intelligence. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 290–300. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-52152-3_30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Chakraborty S, Mali K. Applications of advanced machine intelligence in computer vision and object recognition: emerging research and opportunities. Hershey, PA, USA: Engineering Science Reference; 2020. [Google Scholar]

3. Egmont-Petersen M, de Ridder D, Handels H. Image processing with neural networks—a review. Pattern Recognit. 2002;35(10):2279–301. doi:10.1016/S0031-3203(01)00178-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Tasnim S, Qi W. Progress in object detection: an in-depth analysis of methods and use cases. Eur J Electr Eng Comput Sci. 2023;7(4):39–45. doi:10.24018/ejece.2023.7.4.537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Edozie E, Shuaibu AN, John UK, Sadiq BO. Comprehensive review of recent developments in visual object detection based on deep learning. Artif Intell Rev. 2025;58(9):277. doi:10.1007/s10462-025-11284-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Egipko V, Zhdanova M, Gapon N, Voronin VV, Semenishchev EA. Real-time deep learning-based object recognition in augmented reality. In: Proceedings of the Real-Time Processing of Image, Depth, and Video Information 2024; 2024 Apr 7–12; Strasbourg, France. p. 27. doi:10.1117/12.3024957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Cheng ZQ, Dai Q, Li H, Song J, Wu X, Hauptmann AG. Rethinking spatial invariance of convolutional networks for object counting. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 19606–16. doi:10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.01902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Tan Z, Dong G, Zhao C, Basu A. Affine-transformation-invariant image classification by differentiable arithmetic distribution module. In: Berretti S, Azari H, editors. Smart Multimedia. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2025. p. 78–90. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-82475-3_6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Cao J, Peng B, Gao M, Hao H, Li X, Mou H. Object detection based on CNN and vision-transformer: a survey. IET Comput Vis. 2025;19(1):e70028. doi:10.1049/cvi2.70028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Mumuni A, Mumuni F. CNN architectures for geometric transformation-invariant feature representation in computer vision: a review. SN Comput Sci. 2021;2(5):340. doi:10.1007/s42979-021-00735-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Hu MK. Visual pattern recognition by moment invariants. IRE Trans Inf Theory. 1962;8(2):179–87. doi:10.1109/TIT.1962.1057692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Hjouji A, EL-Mekkaoui J, Jourhmane M. Rotation scaling and translation invariants by a remediation of Hu’s invariant moments. Multimed Tools Appl. 2020;79(19):14225–63. doi:10.1007/s11042-020-08648-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. AbuRass S, Huneiti A, Belal M. Enhancing convolutional neural network using hu’s moments. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl. 2020;11(12):130–7. doi:10.14569/ijacsa.2020.0111216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Jaderberg M, Simonyan K, Zisserman A, Kavukcuoglu K. Spatial transformer networks. arXiv: 1506.02025. 2015. [Google Scholar]

15. Finnveden L, Jansson Y, Lindeberg T. Understanding when spatial transformer networks do not support invariance, and what to do about it. In: Proceedings of the 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR); 2021 Jan 10–15; Milan, Italy. p. 3427–34. doi:10.1109/icpr48806.2021.9412997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Hinton GE, Krizhevsky A, Wang SD. Transforming auto-encoders. In: Proceedings of the Artificial Neural Networks and Machine Learning—ICANN 2011; 2011 Jun 14–17; Espoo, Finland. p. 44–51. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-21735-7_6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. ZHang P, Wei P, Han SH. CapsNets algorithm. J Phys Conf Ser. 2020;1544(1):12030. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1544/1/012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Kwabena Patrick M, Felix Adekoya A, Abra Mighty A, Edward BY. Capsule networks—a survey. J King Saud Univ Comput Inf Sci. 2022;34(1):1295–310. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2019.09.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Özcan B, Kınlı F, Kıraç F. Generalization to unseen viewpoint images of objects via alleviated pose attentive capsule agreement. Neural Comput Appl. 2023;35(4):3521–36. doi:10.1007/s00521-022-07900-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Xu Y, Li Y, Shin BS. Medical image processing with contextual style transfer. Hum Centric Comput Inf Sci. 2020;10(1):46. doi:10.1186/s13673-020-00251-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. LaLonde R, Khosravan N, Bagci U. Deformable capsules for object detection. Adv Intell Syst. 2024;6(9):2400044. doi:10.1002/aisy.202400044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Babaei R, Pham H, Cheng S, Zhao S. EADR: entropy adjusted dynamic routing capsule networks. In: Proceedings of the 2025 59th Annual Conference on Information Sciences and Systems (CISS); 2025 Mar 19–21; Baltimore, MD, USA. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/CISS64860.2025.10944763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Jarvers C, Neumann H. Incorporating feedback in convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Cognitive Computational Neuroscience; 2019 Sep 13–16; Berlin, Germany. p. 395–8. doi:10.32470/ccn.2019.1191-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Itti L, Koch C. Computational modelling of visual attention. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2(3):194–203. doi:10.1038/35058500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Marblestone AH, Wayne G, Kording KP. Toward an integration of deep learning and neuroscience. Front Comput Neurosci. 2016;10(5):94. doi:10.3389/fncom.2016.00094. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Hu T, Yang P, Zhang C, Yu G, Mu Y, Snoek CGM. Attention-based multi-context guiding for few-shot semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the Thirty-Third AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-19); 2019 Jan 29–Feb 1; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 8441–8. doi:10.1609/aaai.v33i01.33018441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. LeCun Y, Cortes C, Burges CJC. The MNIST database of handwritten digits [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 May 1]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/hojjatk/mnist-dataset. [Google Scholar]

28. Xiao H, Rasul K, Vollgraf R. Fashion-MNIST: a novel image dataset for benchmarking machine learning algorithms. arXiv: 1708.07747. 2017. [Google Scholar]

29. Kang K, Shelley M, Sompolinsky H. Mexican hats and pinwheels in visual cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(5):2848–53. doi:10.1073/pnas.0138051100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Mazare L. Tch-rs [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 May 1]. Available from: https://crates.io/crates/tch/0.1.7. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools