Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Network for Remote Sensing Images Based on Improved Residual Module and Attention Mechanism

1 School of Computer Science and Technology, Zhengzhou University of Light Industry, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

2 School of Information Engineering, Zhengzhou University of Technology, Zhengzhou, 450044, China

3 Digital and Intelligent Engineering Design Institute, SIPPR Engineering Group Co., Ltd., Zhengzhou, 450007, China

* Corresponding Author: Yong Gan. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Deep Learning and Neural Networks: Architectures, Applications, and Challenges)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.068880

Received 09 June 2025; Accepted 01 September 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

High-resolution remote sensing imagery is essential for critical applications such as precision agriculture, urban management planning, and military reconnaissance. Although significant progress has been made in single-image super-resolution (SISR) using generative adversarial networks (GANs), existing approaches still face challenges in recovering high-frequency details, effectively utilizing features, maintaining structural integrity, and ensuring training stability—particularly when dealing with the complex textures characteristic of remote sensing imagery. To address these limitations, this paper proposes the Improved Residual Module and Attention Mechanism Network (IRMANet), a novel architecture specifically designed for remote sensing image reconstruction. IRMANet builds upon the Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Network (SRGAN) framework and introduces several key innovations. First, the Enhanced Residual Unit (ERU) enhances feature reuse and stabilizes training through deep residual connections. Second, the Self-Attention Residual Block (SARB) incorporates a self-attention mechanism into the Improved Residual Module (IRM) to effectively model long-range dependencies and automatically emphasize salient features. Additionally, the IRM adopts a multi-scale feature fusion strategy to facilitate synergistic interactions between local detail and global semantic information. The effectiveness of each component is validated through ablation studies, while comprehensive comparative experiments on standard remote sensing datasets demonstrate that IRMANet significantly outperforms both the baseline and state-of-the-art methods in terms of perceptual quality and quantitative metrics. Specifically, compared to the baseline model, at a magnification factor of 2, IRMANet achieves an improvement of 0.24 dB in peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) and 0.54 in structural similarity index (SSIM); at a magnification factor of 4, it achieves gains of 0.22 dB in PSNR and 0.51 in SSIM. These results confirm that the proposed method effectively enhances detail representation and structural reconstruction accuracy in complex remote sensing scenarios, offering robust technical support for high-precision detection and identification of both military and civilian aircraft.Keywords

Remote sensing images, as the core data source of remote sensing technology, serve as a fundamental basis for remote sensing applications. These images not only provide researchers with abundant reference information but also facilitate a deeper understanding and analysis of various natural phenomena on Earth. Currently, remote sensing images are widely applied in smart city planning [1], military reconnaissance [2], target detection [3], scene categorization [4], and other fields. However, due to the multi-dimensional challenges inherent in the complex imaging process—including factors such as motion platform distortion, atmospheric turbulence, and sensor limitations—the acquired remote sensing images often suffer from insufficient spatial resolution. This limitation not only causes the loss of fine details but also reduces the accuracy of subsequent interpretation, making it difficult for existing data to meet the requirements of high-precision remote sensing analysis. To advance research in related fields, it is therefore imperative to investigate super-resolution (SR) reconstruction methods for remote sensing images. The aim of this study is to employ deep learning to reconstruct high-resolution (HR) images from low-resolution (LR) images in a cost-effective manner.

The rapid advancement of deep learning [5] techniques has driven significant progress in image SR research. In general, these methods can be categorized into two groups: convolutional neural network [6,7] (CNN)-based approaches and generative adversarial network [8,9] (GAN)-based approaches. The Super-Resolution Convolutional Neural Network (SRCNN), a three-layer fully convolutional architecture first introduced by Dong et al. [10], represented a breakthrough in applying CNNs to image SR and substantially improved reconstruction quality. Subsequently, Ledig et al. [11] introduced GANs into the super-resolution task. Although their proposed SRGAN underperformed CNN-based approaches in objective metrics such as PSNR, it demonstrated clear advantages in restoring perceptual visual quality through adversarial training. Later, Chen et al. [12] innovatively integrated the attention mechanism with the generator’s residual block structure to enhance detail reconstruction, enabling the network to focus more effectively on critical regions, thereby improving learning efficiency and further enhancing reconstruction quality.

Compared to other image types, remote sensing images are characterized by complex and variable texture distributions, large spatial dimensions, and rich detail information, which pose significant challenges for super-resolution reconstruction techniques in this domain. Although traditional approaches—such as bilinear interpolation [13]—and CNN-based methods have achieved notable success in natural image processing tasks, they often suffer from substantial cross-domain adaptability issues when applied to remote sensing image reconstruction [14]. These methods frequently struggle to accurately recover high-frequency details, leading to loss of fine textures, degradation of structural information, and blurred edges in the reconstructed images. In contrast, GANs have gained considerable attention in recent years due to their unique advantages in texture detail restoration and perceptual quality enhancement in image super-resolution tasks. By guiding the generator to approximate the true data distribution through adversarial loss, GANs are capable of effectively restoring high-frequency details and producing sharper, more realistic textures. This “fooling the eye” training paradigm provides GANs with strong adaptability for handling the complex structures and intricate texture representations typical of remote sensing images. Consequently, this paper adopts a GAN-based framework for the super-resolution reconstruction of remote sensing images, aiming to exploit its adversarial learning mechanism to enhance both perceptual quality and detail restoration in the reconstruction results.

Building on this foundation, this paper provides a systematic review of existing super-resolution reconstruction algorithms and, in response to the limitations of current methods in high-frequency detail recovery, feature utilization, and structural preservation, proposes a novel network model—IRMANet based on an improved residual module and attention mechanism. The proposed model is designed to simultaneously enhance the quality of reconstructed images and the stability of model training.

The following concisely describes the contributions of our study in this thesis:

1. Design of the Enhanced Residual Unit: The traditional residual blocks have been optimized by integrating deeper residual connections, which significantly enhances the model’s capability for feature extraction. This refinement enables the model to acquire a richer set of features from the input images.

2. Design of the Self-Attention Residual Block: In this work, we introduce an improved residual module that incorporates multi-convolutional stacking operations and a multi-scale feature fusion strategy within each module. This enhances the network’s capacity for detail recovery and multi-level feature extraction. Additionally, by combining the self-attention mechanism with the proposed residual module, we have constructed the Self-Attention Residual Block. This block allows the network to effectively capture long-range dependencies within images and focus on significant features. These improvements make the model more adept at handling complex structures and high-frequency details, thereby improving the quality of the generated images.

3. Demonstrated Performance Improvement: Extensive experimental validation confirms that the proposed network architecture achieves substantial improvements across multiple evaluation metrics (e.g., PSNR, SSIM). In particular, the network exhibits superior performance in detail restoration and overall image quality, consistently outperforming existing state-of-the-art methods.

The structure of the paper is as follows: While Section 3 provides a thorough explanation of the suggested approach and its elements, Section 2 examines relevant work. The dataset and evaluation measures utilized in the experiments are provided at Section 4, and the experimental results and analysis are provided in Section 5. The research is finally concluded in Section 6.

2.1 Super-Resolution Convolutional Neural Network

In the research progress of image SR based on deep learning, SRCNN proposed by Dong et al. [10] is groundbreaking. As a first step, this model builds an end-to-end convolutional neural network architecture, overcoming the performance limitation of conventional hand-crafted feature-based methods. To ensure that the input image attains sufficient spatial resolution and information before entering the neural network, the architecture first applies bicubic interpolation to pre-upsample the low-resolution image. This preprocessing step allows the network to work directly with images that already meet a certain resolution requirement. The SRCNN produces HR images that are noticeably superior to those produced by conventional techniques with respect to objective evaluation metrics and visual quality. Interestingly, the team’s subsequent Fast SRCNN (FSRCNN) [15] moves the bicubic interpolation to the end of the network, utilizes a transposed convolutional layer to achieve end-to-end learning, and simultaneously boosts computational efficiency by approximately 40% by reducing the filter size and adding more mapping layers without sacrificing model performance.

The Very Deep Super-Resolution (VDSR) introduced by Kim and colleagues [16] establishes a standard for residual learning in terms of model depth expansion. The model effectively addresses the issue of gradient disappearance of the deep network and expedites the training process by introducing residual learning into the construction of a 20-layer deep network. This allows the network to concentrate on learning the residual information between low-resolution and high-resolution images. The quality of reconstructed images is enhanced by its broad receptive field, which greatly enhances the capacity to acquire image context information. In order to creatively incorporate the channel attention mechanism into the picture super-resolution (SR) problem, Zhang et al. [17] suggested a deep residual network of Residual Channel Attention Network (RCAN) based on the residual channel attention mechanism. The network’s capacity to represent features and the quality of reconstructed images are both enhanced by the attention mechanism, which allows the network to adaptively learn the significance of each channel and better fuse the information from various channels. Since that time, enhancing the attention process has emerged as a key area of study for image super-resolution [18]. Zamir et al. [19] proposed the Multi-scale Information Distillation and Residual Network (MIRNet), which has demonstrated outstanding performance across a range of real-world image reconstruction tasks. This model preserves and enhances high-resolution features by constructing multi-scale residual blocks and incorporating a spatial-channel joint attention mechanism. Fueled by advances in deep learning, single-image super-resolution techniques have achieved substantial progress [20]. Behjati et al. [21] introduced the Directional Variance Attention-based Super-Resolution Network (DVAN), which employs a direction-aware mechanism to capture texture variations along different orientations within an image, significantly improving reconstruction quality. In addition, Wang et al. [22] proposed the Multi-scale Attention Network (MAN), which integrates large receptive field convolutional kernels with attention mechanisms to enhance the network’s ability to model texture and structural information, thereby offering new insights into the design of lightweight and efficient super-resolution models.

2.2 Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Network

Goodfellow et al. proposed GAN [23], which has since become a widely adopted deep learning model alongside CNNs. A discriminator (D) and a generator (G) are the two main parts of their architecture. The discriminator D attempts to discern between data produced by the generator G and real data, while the generator G strives to produce data that closely resembles real samples. Both networks continuously enhance their capabilities through an adversarial learning process: the generator G gets better at producing highly realistic outputs, while the discriminator D becomes better at recognizing synthetic data.

Ledig et al. [11] proposed SRGAN, which for the first time applies GAN to image SR tasks and introduces residual networks to extract features more efficiently. The model is based on the GAN architecture and contains both G and D as well. It takes LR as input and generates SR images after G. Then, the generated SR image along with the true HR is input to D, which extracts features layer by layer, calculates the probability that the generated image is judged to be the true image, and outputs the result. Subsequently, G’s weight parameters are updated based on the feedback from D. During training, G and D fight against each other and eventually reach a balance where G can generate SR images that are closer to the real image. Building upon the SRGAN, Wang et al. [24] proposed the Enhanced Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Network (ESRGAN). This method significantly improves the perceptual quality of reconstructed images by introducing residual channel attention blocks (RCAB) to enhance feature expression capabilities and replacing the traditional mean squared error (MSE) loss with a combination of perceptual loss and adversarial loss. To further enhance the robustness of GANs in real-image super-resolution tasks, Wang’s team [25] developed Real-ESRGAN, which incorporates more stable training strategies and improved perceptual loss functions, thereby enabling the model to demonstrate stronger adaptability when processing real-world degraded images. Xiong et al. [26] proposed an Improved Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Network (ISRGAN) to address the needs of cross-regional and cross-sensor remote sensing image super-resolution tasks. Additionally, Li et al. [27] developed an image super-resolution method based on a multi-scale dual attention mechanism, integrating spatial attention and channel attention modules into the generator to effectively enhance the network’s ability to model multi-scale details. Although existing methods have achieved promising results in processing natural images and some remote sensing image tasks, they still face significant challenges when dealing with remote sensing images that feature both rich high-frequency details and complex structures. These challenges include detail loss, edge blurring, and structural distortion. To address these issues and enhance the quality and stability of remote sensing image super-resolution reconstruction, this paper proposes the IRMANet.

The Transformer [28] architecture makes extensive use of Self-Attention [29], a powerful neural network component that was first introduced in the Natural Language Processing (NLP) discipline [30]. By determining the correlations between the elements of the input sequence and dynamically modifying the amount of attention given to each element, it effectively captures the dependencies between distant pixels in an image. The self-attention mechanism’s primary benefit is its capacity to process the input sequence in parallel, which greatly increases modeling efficiency and enhances the ability to model long-range dependencies.

Over the past few years, the self-attention mechanism has not only garnered remarkable achievements in natural language processing but has also become a staple in computer vision tasks. For instance, self-attention residual networks [31] have been devised to enhance face image super-resolution, while other studies have leveraged self-attention to boost the spatial resolution of solar and natural scene images [32,33]. These endeavors underscore the self-attention mechanism’s prowess in capturing long-range dependencies and refining detail restoration and image clarity. Motivated by these successes, we have integrated the self-attention mechanism into the realm of remote sensing image super-resolution reconstruction.

The IRMANet proposed in this paper mainly consists of the generator (G) and the discriminator (D). From a given LR input—

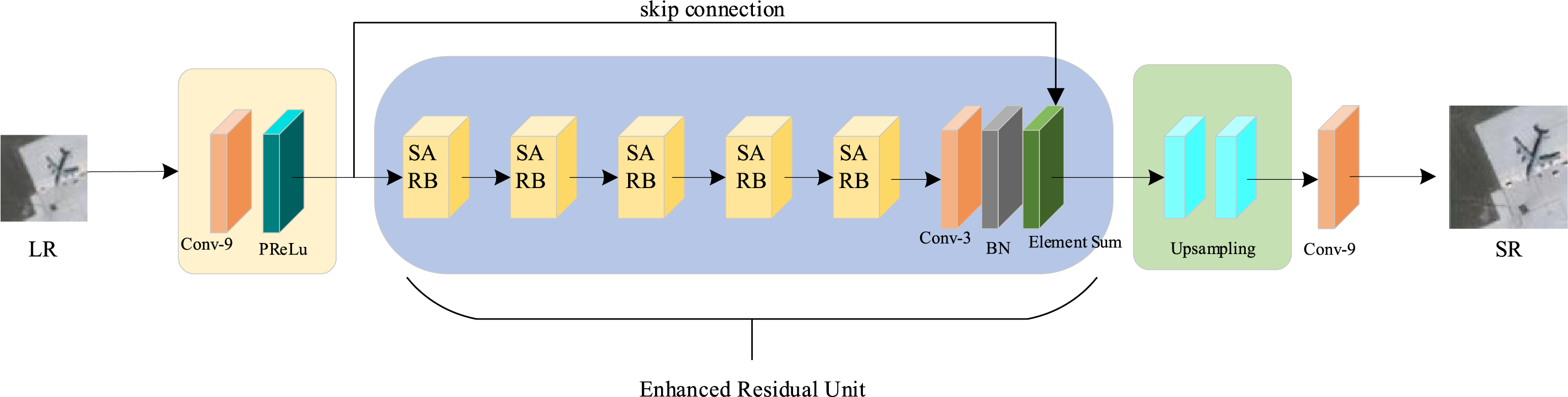

Figure 1: The generator network structure of IRMANet

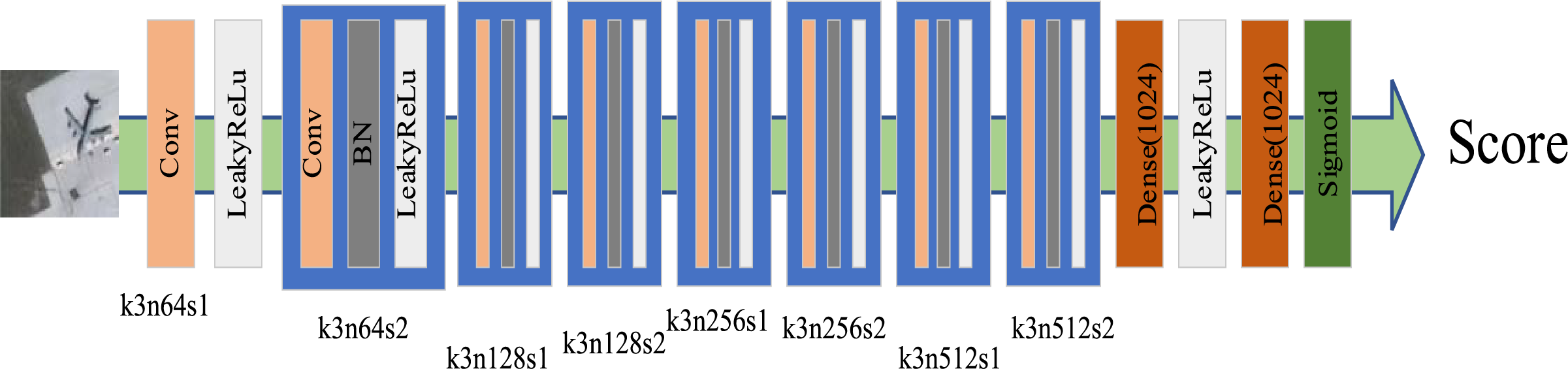

Figure 2: The discriminator network structure of IRMANet, where k, n, and s represent the size, number, and stride of the convolutional kernel, respectively

The main objective of the formulation is to make the SR image generated by G and the true HR image as similar as possible through min-max optimization. D is designed to differentiate the true HR image from the generated SR image, maximizing the probability that the true image will be correctly classified while minimizing the misclassification of the generated HR image probability. To make the generated image harder to distinguish, G attempts to deceive D. Through adversarial training, G enhances the image reconstruction quality by learning more realistic features of HR images.

The generator architecture of the network proposed in this paper is composed of four integral modules: a shallow feature extraction module, an improved residual block group, an upsampling module, and an image reconstruction module. We will subsequently elaborate on the functions and structures of these four modules.

In the shallow feature extraction module, low-resolution input images are first processed via a convolutional layer, which is specifically designed to extract fundamental features from the input data. This initial processing step serves as the foundation for subsequent feature enhancement and refinement within the network. The mathematical representation of this module can be expressed as:

here,

Subsequently, the core structure of the improved generator network, namely the Enhanced Residual Unit (ERU), is introduced. This unit is primarily utilized for deep feature extraction. Specifically, the ERU comprises five Self-Attention Residual Blocks (SARBs). Detailed information regarding the ERU will be elaborated in Section 3.2 of this part. The mathematical expression of this module is:

Among them,

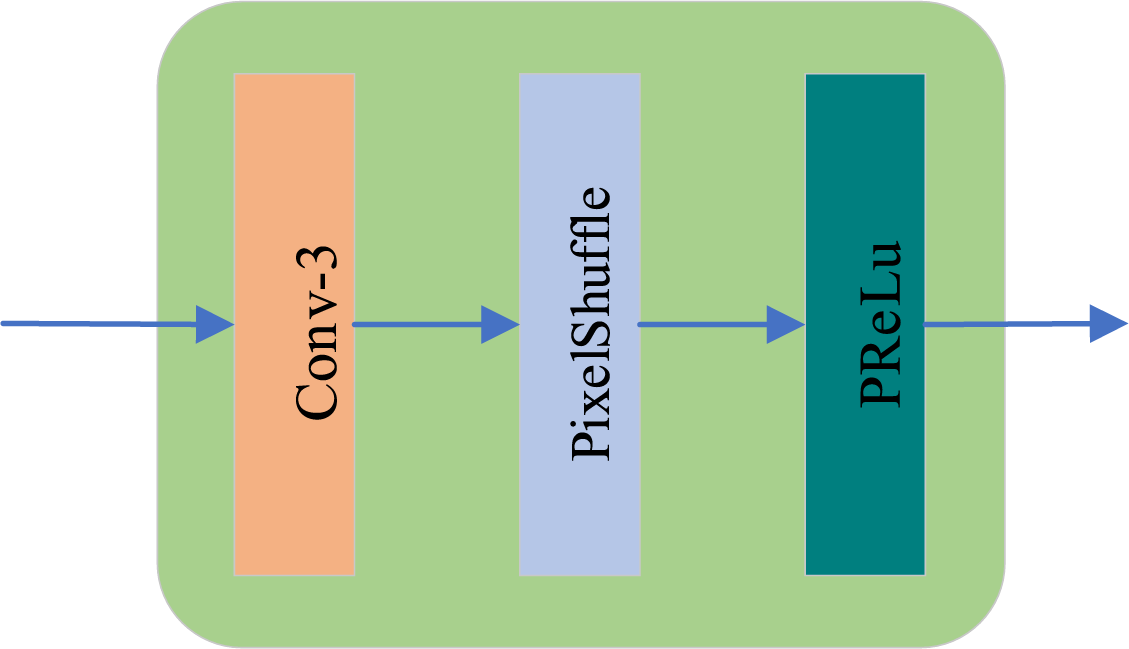

Figure 3: Upsampling structure diagram

We built and trained a discriminator network, whose precise architecture is described in Fig. 2, in order to successfully separate HR images from SR ones. We purposefully avoided the maximum pooling procedure and instead used the LeakyReLU [35] activation function across the network. This discriminator network’s training is intended to solve the maximizing problem given by Eq. (1). Similar to the VGG network, the network is made up of eight convolutional layers with a gradual rise in the number of 3 × 3 filter kernels. The number of filters starts at 64 and doubles with each layer, reaching 512. Strided convolution is used to decrease the spatial resolution if the number of feature maps doubles. After obtaining 512 feature maps, the network sequentially connects two dense layers as well as a final sigmoid activation function as a way of obtaining the probability values for sample classification.

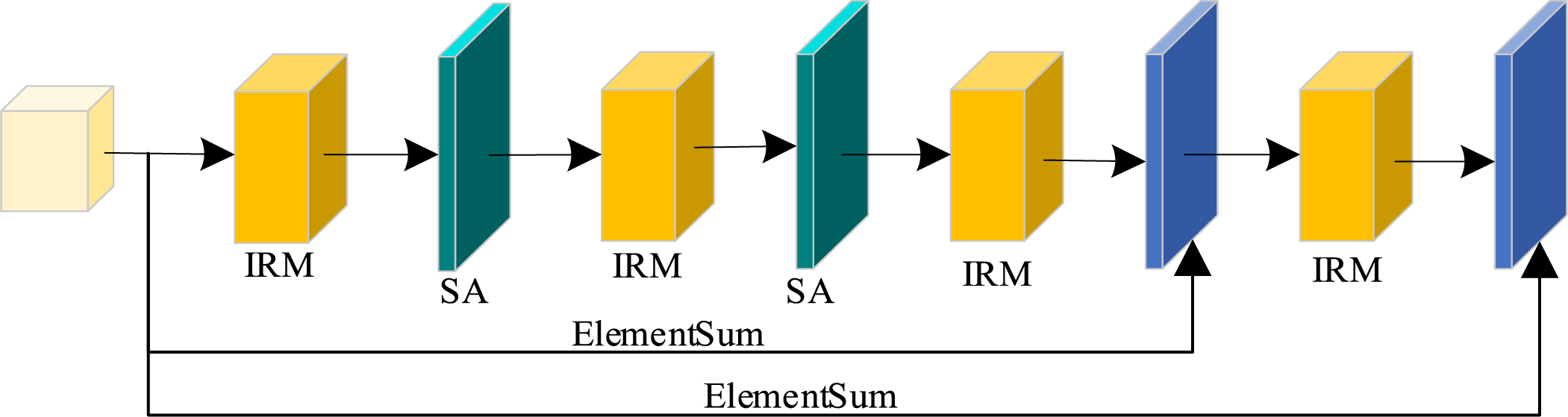

The residual blocks in SRGAN primarily consist of two 3 × 3 convolutional layers, a Batch Normalization (BatchNorm) layer [36], and a Parametric ReLU activation function [37]. Although this structure can learn the mapping between LR and HR images, it exhibits limited feature extraction capabilities. Furthermore, the inclusion of BatchNorm may introduce undesired normalization effects that hinder the network’s representational power. To overcome these limitations, this paper proposes the ERU, designed to improve feature learning capacity. ERU incorporates deeper and more flexible residual connection paths, which enhance feature propagation efficiency and the network’s nonlinear expressiveness. This design not only effectively alleviates the vanishing gradient problem commonly encountered in deep networks but also ensures that fine-grained image details are preserved and propagated to higher-level semantic features, thereby providing more realistic and context-aware support for the reconstruction of low-frequency components. In addition, considering the characteristics of remote sensing images—such as complex textures and varying target scales—the deep residual structure of ERU facilitates the joint extraction of global structural information and fine local textures. To further enhance the model’s ability to recover high-frequency details and maintain structural consistency, the SARB is integrated into the ERU. SARB consists of the IRM combined with self-attention mechanisms, as illustrated in Fig. 4. This structure facilitates the seamless integration of shallow network features and deep high-frequency features. It not only enhances the reconstruction of image edges but also accentuates the learning of key areas, thereby substantially elevating the overall image restoration quality.

Figure 4: The self-attentive residual block, SA denotes self-attention

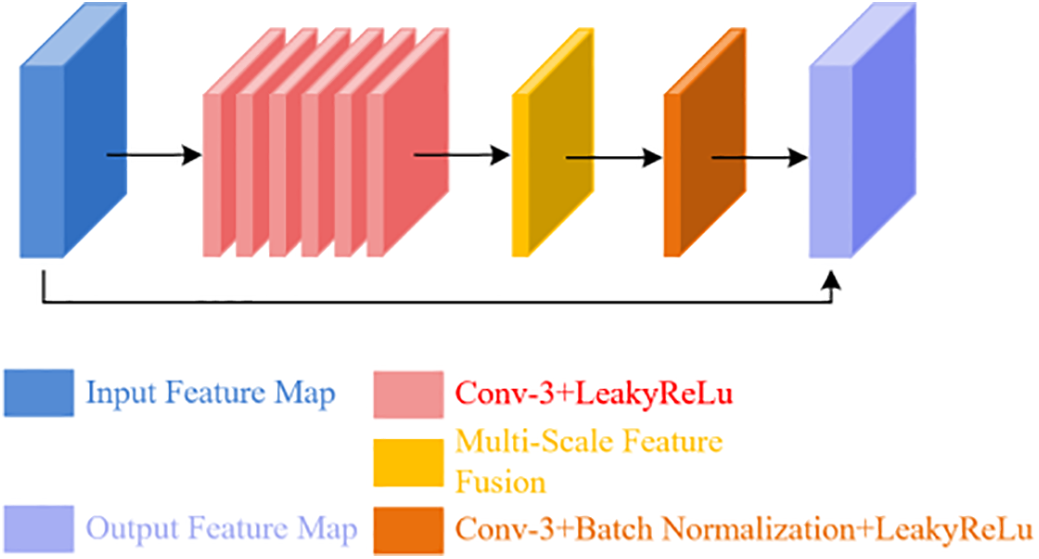

3.2.1 Improved Residual Module

Fig. 5 presents the architecture of the Improved Residual Module (IRM) proposed in this paper, which is designed to enhance feature extraction capabilities through a meticulously structured sequence of convolutional layers and activation functions. The IRM begins by applying multiple 3 × 3 convolutional layers followed by LeakyReLU activation functions to the input feature maps. This initial step is aimed at enhancing the nonlinear representation of features, thereby enriching the expressive power of the network. Subsequently, a multi-scale feature fusion mechanism is incorporated to capture contextual information across different receptive fields. This mechanism enables the network to perceive and integrate complex image content more effectively, which is crucial for handling the intricate textures and varying scales of objects commonly found in remote sensing images. The fused features are then refined through a combination of convolutional layers, BN and LeakyReLU activation functions. This refinement process not only stabilizes the training process but also accelerates convergence, ensuring that the network learns robust and meaningful representations. Finally, residual connections are employed to merge the input and output feature maps. This strategy ensures effective retention of information and efficient gradient propagation throughout the network, mitigating the risk of information loss during the deep learning process. The design of the IRM significantly boosts feature expression capabilities while maintaining a low computational overhead, providing a robust foundation for subsequent image reconstruction tasks. Compared to standard residual blocks, the IRM places a greater emphasis on integrating cross-scale texture and structural information. This characteristic makes the IRM particularly well-suited for remote sensing images, which often contain objects of varying sizes and complex textures. By effectively capturing and fusing these diverse features, the IRM lays a stable and efficient groundwork for subsequent integration with attention mechanisms, ultimately enhancing the overall performance of the super-resolution reconstruction process.

Figure 5: The improved residual module

3.2.2 Self-Attentive Residual Block

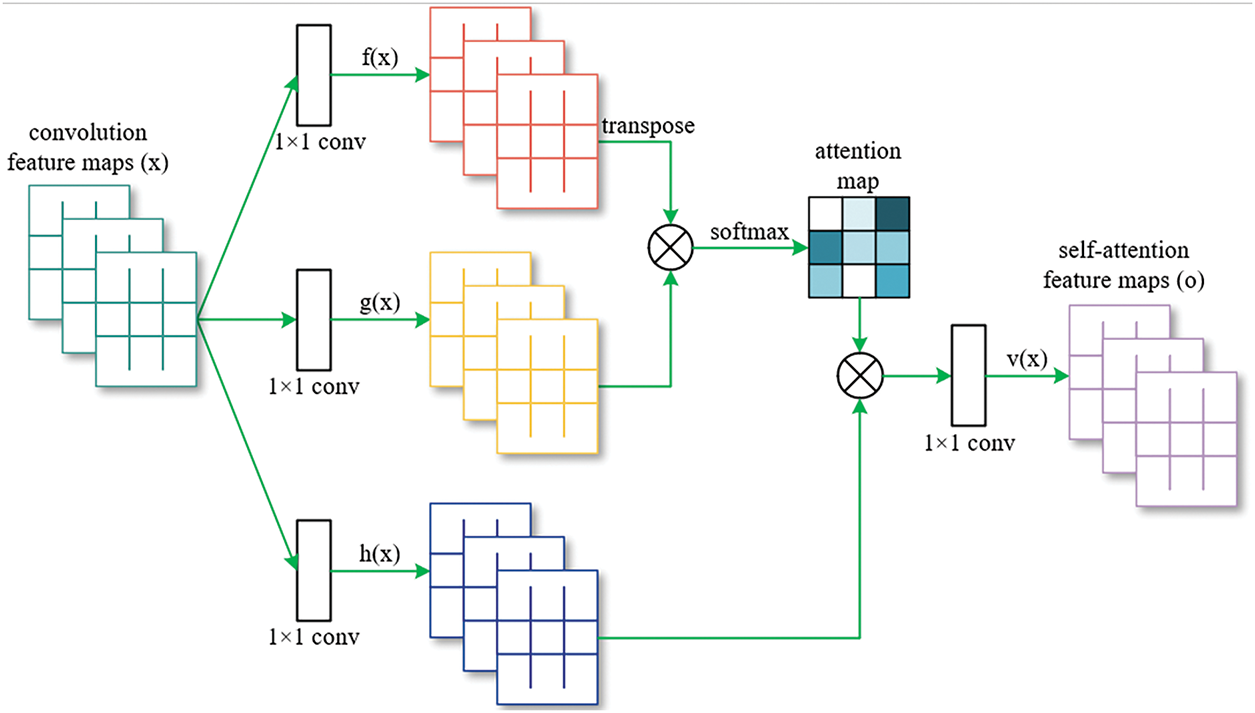

Traditional residual blocks primarily depend on local convolutional operations with a limited receptive field, which restricts their ability to effectively model dependencies between distant features. This limitation hampers the coordination of overall structural and textural modeling in image super-resolution tasks. In contrast, the self-attention mechanism, as illustrated in Fig. 6, possesses powerful global modeling capabilities. It enables the network to dynamically focus on key regions by calculating correlation weights between all spatial locations in the feature map, thereby enhancing the representation of key structures and textures. In this paper, we innovatively integrate the self-attention mechanism into the construction of the ERU and propose the SARB structure. Within this structure, IRM and self-attention layers are stacked alternately to achieve effective synergy between local feature extraction and global modeling. Ultimately, each path feature is fused via Element-wise Summation (EWS). This fusion strategy not only preserves the advantageous information from each path but also strengthens the global consistency and differentiation ability of the features, thereby significantly alleviating structural blurring and detail loss in image reconstruction. The proposed IRMANet is structurally tailored to the unique characteristics of remote sensing images. The ERU enhances the transmission of shallow details to higher-level semantic layers via residual connections, thereby improving the fidelity of features in deep networks. The IRM adopts a multi-scale feature fusion strategy that enables the model to capture contextual information at various scales. Combined with the self-attention mechanism within the SARB structure, the model significantly improves its ability to model long-range structural relationships. As a result, the network can precisely focus on key target regions in the image, even under challenging remote sensing conditions characterized by strong background interference and weak structural features. IRMANet thus demonstrates strong robustness and representational capacity, providing an effective, stable, and highly generalizable solution for high-quality remote sensing image reconstruction.

Figure 6: Self-attention mechanism structure. The symbol ⊗ denotes matrix multiplication and the softmax operation is performed on each row

In this paper, we improve the generator using a weighted loss function. Image loss, adversarial loss, perceptual loss and total variation (TV) loss are the four parts of the loss function. Eq. (6) below defines the generator’s total loss function:

where

Image loss, also known as MSE loss, is used to calculate the difference in pixel space between the created and target images, and picture quality is assessed by directly comparing the errors at the corresponding pixel points. Below is the calculation for its matching Formula (7):

The adversarial loss is utilized in this work to evaluate image quality and assist the generator create images that can mislead the discriminator. In particular, the SR image produced by the generator passes through the discriminator, which outputs a probability used to measure that it is a real image. In order to optimize the generator’s parameters and make it more difficult for the discriminator to differentiate among the generated image and true HR images that have greater perceptual quality, we apply Binary Cross-Entropy Loss [38] (BCE). The Formula (8) is used to calculate the adversarial loss.

In order to assess the differences between generated and target images, perceptual loss is usually calculated in the feature space of CNNs that have already been trained. The Visual Geometry Group (VGG) network is a common approach for doing so because it can effectively capture an image’s high-level semantic features. The VGG16 [39] model’s feature layers (up to 31 levels in this case) are used to extract picture characteristics in this research. The MSE [40] between the generated and target images in this feature space is then computed to quantitatively assess the difference. Eq. (9) provides a definition of perceptual loss.

Since most algorithms magnify the noise along with the resolution, even a small quantity of noise in the image can have a big effect on the reconstruction outcomes during super-resolution reconstruction. Thus, we present the TVLOSS [41] to preserve the image’s smoothness and minimize artifacts. By limiting the gradient fluctuation between nearby pixels, this loss lowers noise and promotes local image smoothness. Eq. (10) provides the calculation.

To balance the contribution of these loss terms in the training process, we finally determined the weighting values

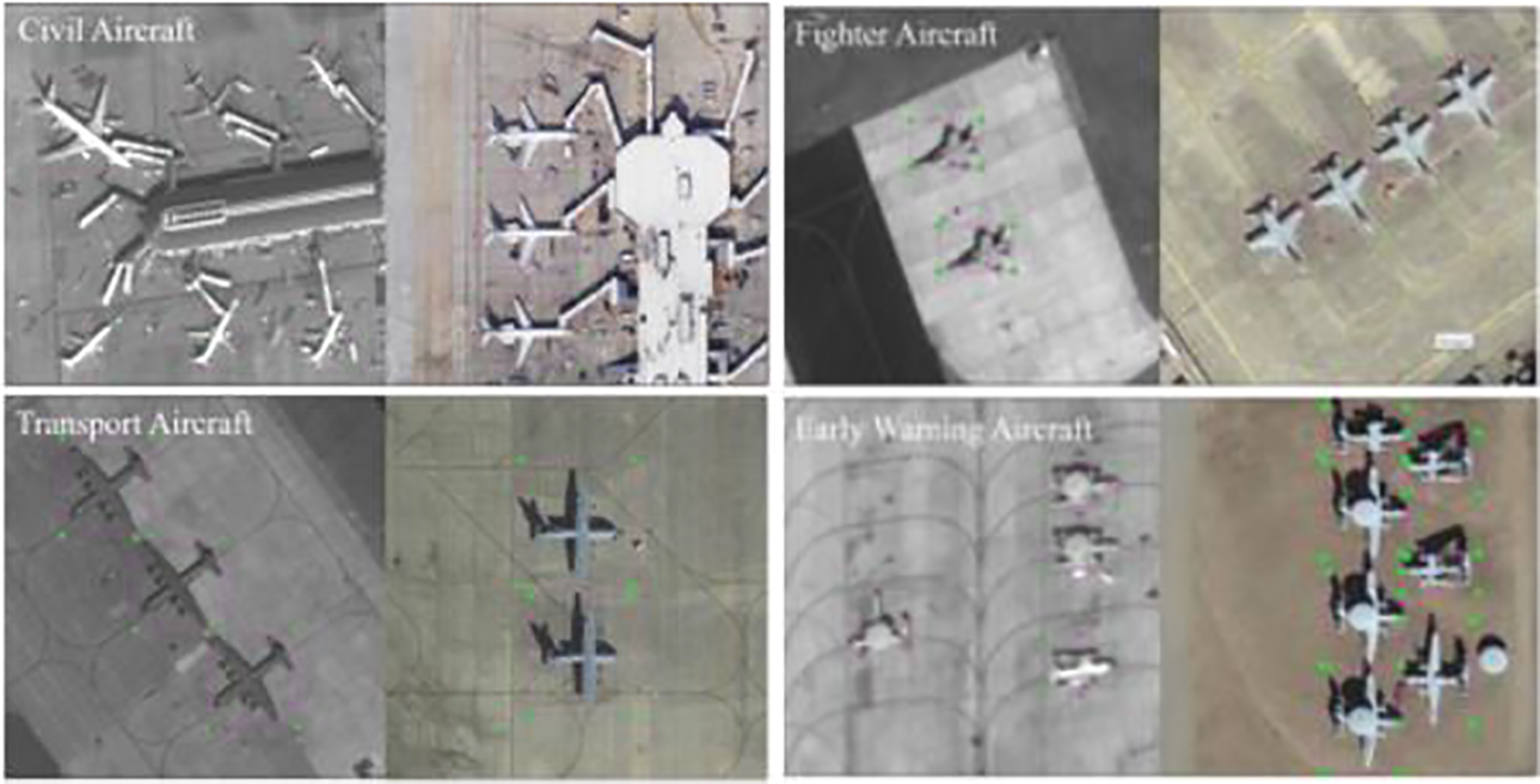

In this study, we used the CORS-ADD dataset [42] (Complex Optical Remote Sensing Aircraft Detection Dataset). This dataset consists of optical remote sensing images from multiple sources, including satellites and platforms such as WorldView-2, WorldView-3, Pleiades, Jilin-1, IKONOS, and Google Earth. It encompasses a diverse range of complex scenes and targets, including aprons, runways, aircraft carriers, ocean backgrounds, and aircraft in flight, providing a rich testing environment for super-resolution tasks in remote sensing imagery. The dataset comprises a total of 5486 manually annotated images, varying in size from 4 × 4 pixels to 240 × 240 pixels. During the training phase, we employed 3764 images from the training subset; for the testing phase, we used 1722 images from the testing subset. For detailed information on the data preprocessing procedures, please refer to Section 4.3, “Experimental Setup,” in the following text. Examples from the dataset are illustrated in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Example diagram of a dataset

Two criteria for assessing image quality are employed in this study: SSIM and PSNR.

PSNR, measured in decibels (dB), is a commonly used metric for evaluating image or video quality. The ratio of a signal’s maximum possible power to that of the noise is used to calculate PSNR [43]. In theory, better quality is reflected by a higher PSNR, which denotes a smaller deviation from the original image. PSNR is computed as follows (Eq. (11)):

where MAX is the image’s maximum pixel value, MSE stands for mean square error, and

SSIM is used to assess the similarity between real images and reconstructed super-resolution images. By contrasting the three essential elements: brightness, contrast, and structure, it measures the similarity between two images. In particular, the covariance between the two images is used to measure structural similarity. The brightness comparison is determined by the average intensity of the two images, while the contrast comparison is based on their standard deviation. SSIM combines these three components to create an overall similarity score, which has a range of 0 to 1 [44]. An original HR image and the reconstructed SR image are considered more similar when the SSIM value is nearer 1, indicating a more effective and visually accurate reconstruction. SSIM is calculated as follows (Eq. (12)):

where (

For the purposes of our research, we employed the deep learning framework PyTorch (version 1.10) and performed GPU-accelerated computations using an NVIDIA RTX 4090D (24 GB VRAM) with CUDA 11.3.

Before training, the image data were preprocessed by applying random cropping, central cropping, and random horizontal flipping to the training set images. These operations helped standardize input dimensions and enhance the model’s generalization capabilities. High-resolution images were additionally downscaled using bicubic interpolation to generate corresponding low-resolution inputs. The training process employed the Adam optimizer with a fixed learning rate of 0.0002 and was conducted over 200 epochs, with a batch size of 16. A random seed of 1029 was set to ensure reproducibility. For model saving, a dynamic strategy was adopted to balance storage efficiency and performance tracking. During the first 150 epochs, model weights were saved every 10 epochs to avoid storing unstable early models. In the final 50 epochs, the model was saved after each epoch to facilitate fine-grained comparisons and ensure that the best-performing model was retained as the network converged.

5 Experimental Results and Analysis

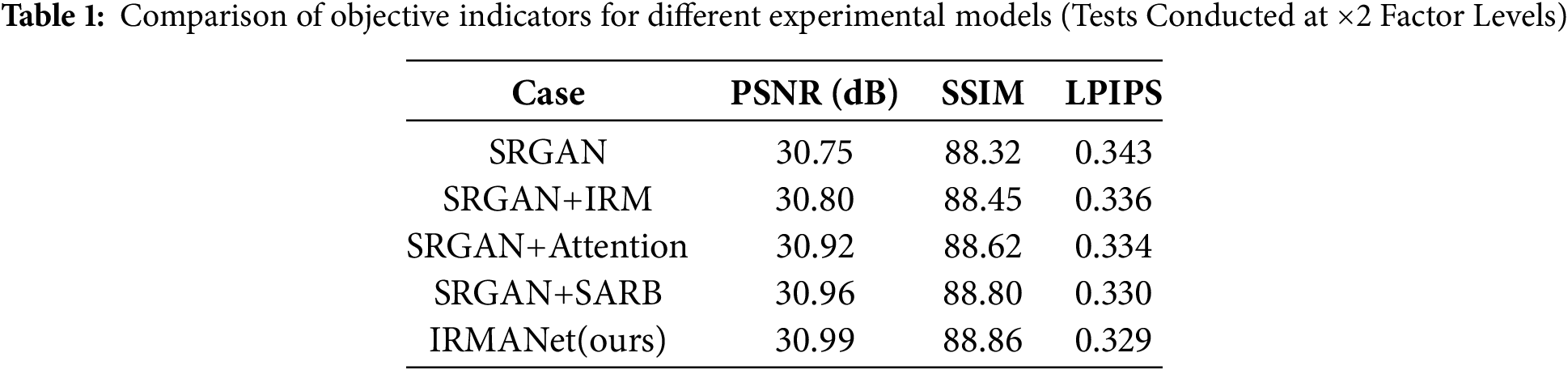

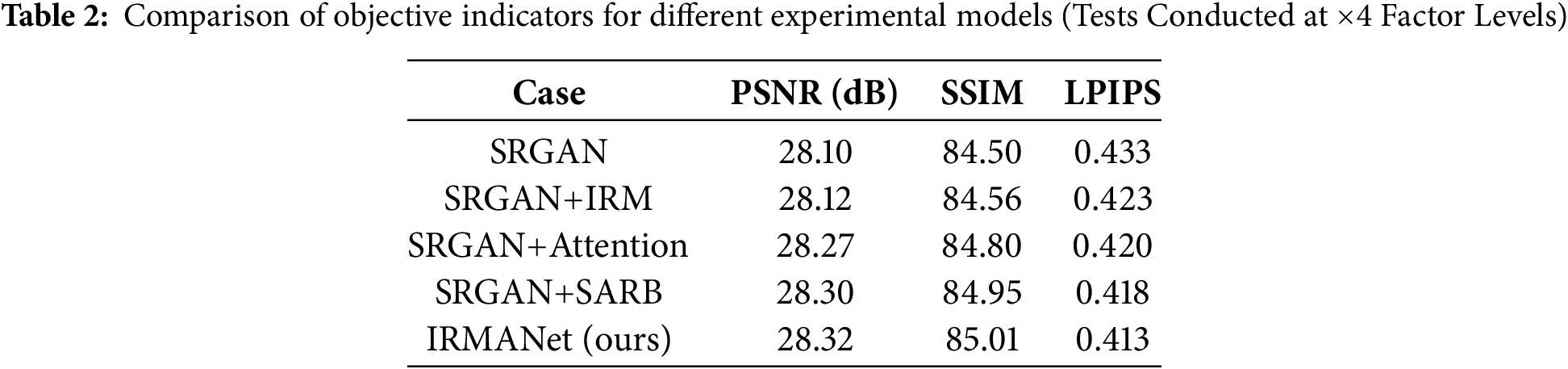

To thoroughly assess the contributions of each module in the proposed IRMANet model to the performance of remote sensing image super-resolution reconstruction, we conducted ablation experiments at ×2 and ×4 magnification factors. Five different models were compared: the basic SRGAN model, SRGAN + IRM, SRGAN + Attention, SRGAN + SARB, and the complete IRMANet model. We utilized peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR), structural similarity index (SSIM), and learned perceptual image patch similarity (LPIPS) as evaluation metrics. Higher PSNR and SSIM values indicate superior pixel-level and structural quality of the reconstructed images, while a lower LPIPS value suggests that the generated image is perceptually closer to the ground-truth image. The experimental results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. The results demonstrate that the incorporation of each module brings varying degrees of improvement to the model performance, regardless of the magnification factor (×2 or ×4), thereby validating their effectiveness in remote sensing image reconstruction tasks. Notably, although the IRM module alone shows limited performance gains, its combination with the self-attention mechanism to form the SARB module not only effectively mitigates the potential training instability associated with attention mechanisms but also exhibits significant synergy in high-frequency detail recovery and global structure modeling. This combination achieves better performance in the LPIPS metric. Ultimately, the IRMANet model outperforms all other variants in terms of PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS, showcasing its excellent reconstruction quality and perceptual performance. These experiments fully demonstrate the complementarity and synergy of the proposed modules in the remote sensing image super-resolution task, providing strong evidence for the rationality and effectiveness of the IRMANet architecture design.

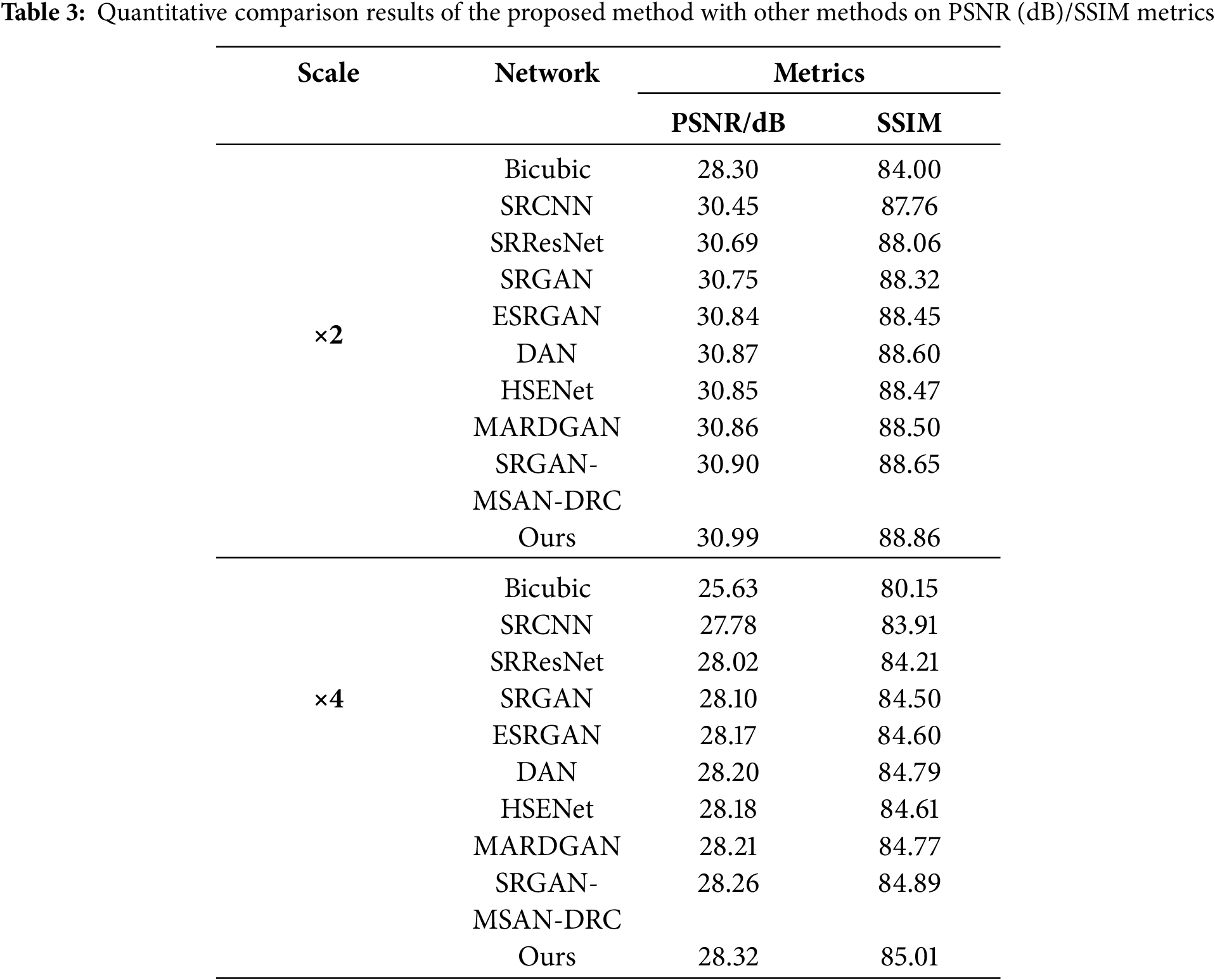

5.2 Comprehensive Evaluation Results

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed method, we conducted comparisons with several advanced super-resolution models, including the Bicubic interpolation algorithm [45], SRCNN [10], SRResNet [11], SRGAN [11], ESRGAN [24], DAN [46], HSENet [47], MARDGAN [27], and SRGAN-MSAN-DRC [48]. The Peak PSNR and SSIM were used as evaluation metrics to assess the performance of each model in the remote sensing image super-resolution task. To ensure a fair comparison, all models were trained according to the parameter settings specified in their original publications and evaluated under the same experimental conditions using the CORS-ADD dataset. The experimental results are presented in Table 3. As shown in the results, regardless of the reconstruction scale factor (×2 or ×4), the proposed method consistently achieves the highest performance in both PSNR and SSIM metrics. This demonstrates that our method provides superior reconstruction quality compared to existing state-of-the-art approaches.

In addition, to more intuitively demonstrate the performance of different models in remote sensing image reconstruction tasks, we selected typical samples from the test set and conducted visual analyses under the conditions of reconstruction scale factors of ×2 and ×4, respectively (as shown in Figs. 8 and 9). The experimental results show that IRMANet performs better in detail retention, edge clarity, and texture restoration. At a magnification of ×2, most methods can reconstruct the overall structure, but there are still significant differences in texture clarity and high-frequency detail restoration. The Bicubic interpolation method struggles to restore fine details, resulting in an overall blurry reconstruction. Although GAN-based models such as SRGAN, ESRGAN, and HSENet show certain visual improvements, they still exhibit issues such as inconsistent textures, structural distortions, or slight artifacts. In contrast, IRMANet demonstrates superior performance in edge preservation and local texture enhancement, effectively restoring key image details without introducing pseudo-textures. At a magnification of ×4, the differences among various methods become more pronounced. The reconstruction results of Bicubic interpolation and SRCNN are severely degraded, with blurred overall structures and significant loss of detail. While other GAN-based models have improved in detail sharpening, artifacts or structural distortions occur around fine structures such as aircraft wings. In contrast, IRMANet can maintain clear edges and a complete structure, and still effectively restore complex textures under large-scale magnification conditions, making the reconstruction effect more realistic and natural. This outstanding performance is attributed to the synergy among the various modules designed in this paper. The SARB not only enhances the model’s ability to model long-range dependencies but also adaptively focuses on key areas in the image. The ERU effectively alleviates the vanishing gradient problem through its deep connection mechanism, while ensuring the efficient propagation of shallow network features to higher-level semantics. This design enables effective modeling and high-quality reconstruction of the overall image features. Overall, our method, IRMANet, not only outperforms existing methods in objective metrics but also demonstrates excellent visual subjective effects, verifying its effectiveness in high-quality reconstruction of remote sensing images.

Figure 8: Visual comparison of reconstruction results from different models and corresponding HR reference images, the scale factor is ×2: (a) Original image; (b) HR; (c) Bicubic; (d) SRCNN; (e) SRResNet; (f) SRGAN; (g) ESRGAN; (h) DAN; (i) HSENet; (j) MARDGAN; (k) SRGAN-MSAN-DRC; (l) Ours

Figure 9: Visual comparison of reconstruction results from different models and corresponding HR reference images, the scale factor is ×4: (a) Original image; (b) HR; (c) Bicubic;(d) SRCNN; (e) SRResNet; (f) SRGAN; (g) ESRGAN; (h) DAN; (i) HSENet; (j) MARDGAN; (k) SRGAN-MSAN-DRC; (l) Ours

This paper introduces IRMANet, a generative adversarial network (GAN) model specifically designed for the super-resolution reconstruction of remote sensing images. This model overcomes the limitations of existing methods in high-frequency detail recovery, feature representation, and structural modeling by introducing an Enhanced Residual Unit (ERU). Through deep-level feature learning, it enhances the network’s information transmission capability, ensuring the effective fusion of shallow network features with deep high-frequency features. Building on this foundation, the Improved Residual Module (IRM) is integrated with a self-attention mechanism to construct the Self-Attention Residual Block (SARB). This design enables adaptive weighting of feature mappings, thereby significantly enhancing the model’s ability to model long-range dependencies and focus on key feature regions. Additionally, the multi-scale feature fusion strategy employed in IRM collaboratively optimizes the perception of high-frequency details and the retention of local information, leading to breakthroughs in texture clarity and structural consistency of the reconstructed images. Experimental results on remote sensing datasets demonstrate that IRMANet outperforms existing methods in both objective evaluation metrics (PSNR and SSIM) and subjective visual quality. The generated images effectively retain high-frequency details while restoring the overall structure, achieving a visually pleasing outcome. This method provides an effective and feasible solution for high-precision detection and identification of military and civil aircraft in complex environments. Despite the significant performance improvements achieved by IRMANet, its large number of parameters results in long training times and substantial computational overhead. Future work will therefore focus on optimizing the network structure to develop a more lightweight architecture, reducing computational costs and improving deployment efficiency. Additionally, we plan to extend IRMANet to multiple types of remote sensing image processing tasks, such as ground object classification and change detection. We will also explore its adaptability in cross-platform and large-scale remote sensing scenarios to further enhance the model’s practicality and generalization performance.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Henan Province Key R&D Program Project, “Research and Application Demonstration of Class II Superlattice Medium Wave High Temperature Infrared Detector Technology”, grant number 231111210400.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Yong Gan and Yifan Zhang; methodology, Yifan Zhang; validation, Yifan Zhang and Mengke Tang; formal analysis, Xinxin Gan; investigation, Yifan Zhang and Mengke Tang; data curation, Xinxin Gan; writing—original draft preparation, Yong Gan and Yifan Zhang; writing—review and editing, Yong Gan, Yifan Zhang, Mengke Tang and Xinxin Gan; visualization, Mengke Tang; supervision, Yong Gan and Xinxin Gan; project administration, Yong Gan and Xinxin Gan; funding acquisition, Yong Gan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Yong Gan, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Bonafoni S, Baldinelli G, Verducci P. Sustainable strategies for smart cities: analysis of the town development effect on surface urban heat island through remote sensing methodologies. Sustain Cities Soc. 2017;29(1):211–8. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2016.11.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zakiev E, Kozhakhmetov S. Prospects for using remote sensing data in the armed forces, other troops and military formations of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Vojnoteh Glas. 2021;69(1):196–229. doi:10.5937/vojtehg69-28698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Cheng G, Zhou P, Han J. Learning rotation-invariant convolutional neural networks for object detection in VHR optical remote sensing images. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2016;54(12):7405–15. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2016.2601622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Guo D, Xia Y, Luo X. Scene classification of remote sensing images based on saliency dual attention residual network. IEEE Access. 2020;8:6344–57. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2963769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. LeCun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G. Deep learning. Nature. 2015;521(7553):436–44. doi:10.1038/nature14539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Bai F, Lu W, Huang Y, Zha L, Yang J. Densely convolutional attention network for image super-resolution. Neurocomputing. 2019;368(3):25–33. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2019.08.070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Shi W, Caballero J, Huszár F, Totz J, Aitken AP, Bishop R, et al. Real-time single image and video super-resolution using an efficient sub-pixel convolutional neural network. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 1874–83. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang Z, Jiang K, Yi P, Han Z, He Z. Ultra-dense GAN for satellite imagery super-resolution. Neurocomputing. 2020;398(5):328–37. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2019.03.106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jiang K, Wang Z, Yi P, Wang G, Lu T, Jiang J. Edge-enhanced GAN for remote sensing image superresolution. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2019;57(8):5799–812. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2019.2902431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Dong C, Loy CC, He K, Tang X. Learning a deep convolutional network for image super-resolution. In: Computer vision—ECCV 2014. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2014. p. 184–99. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-10593-2_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Ledig C, Theis L, Huszár F, Caballero J, Cunningham A, Acosta A, et al. Photo-realistic single image super-resolution using a generative adversarial network. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 105–14. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Chen Y, Phonevilay V, Tao J, Chen X, Xia R, Zhang Q, et al. The face image super-resolution algorithm based on combined representation learning. Multimed Tools Appl. 2021;80(20):30839–61. doi:10.1007/s11042-020-09969-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Sa Y. Improved bilinear interpolation method for image fast processing. In: 2014 7th International Conference on Intelligent Computation Technology and Automation; 2014 Oct 25–26; Changsha, China: IEEE; 2014. p. 308–11. doi:10.1109/ICICTA.2014.82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Guo J, Lv F, Shen J, Liu J, Wang M. An improved generative adversarial network for remote sensing image super-resolution. IET Image Process. 2023;17(6):1852–63. doi:10.1049/ipr2.12760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Dong C, Loy CC, Tang X. Accelerating the super-resolution convolutional neural network. In: Computer vision—ECCV 2016. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 391–407. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46475-6_25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Kim J, Lee JK, Lee KM. Accurate image super-resolution using very deep convolutional networks. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 1646–54. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang Y, Li K, Li K, Wang L, Zhong B, Fu Y. Image super-resolution using very deep residual channel attention networks. In: Computer vision—ECCV 2018. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 294–310. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01234-2_18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Dai T, Cai J, Zhang Y, Xia ST, Zhang L. Second-order attention network for single image super-resolution. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 11057–66. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2019.01132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zamir SW, Arora A, Khan S, Hayat M, Khan FS, Yang MH, et al. Learning enriched features for real image restoration and enhancement. In: Computer vision—ECCV 2020. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 492–511. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58595-2_30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wang Y, Bashir SMA, Khan M, Ullah Q, Wang R, Song Y, et al. Remote sensing image super-resolution and object detection: benchmark and state of the art. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;197(3):116793. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.116793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Behjati P, Rodriguez P, Fernández C, Hupont I, Mehri A, Gonzàlez J. Single image super-resolution based on directional variance attention network. Pattern Recognit. 2023;133(2):108997. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2022.108997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wang Y, Li Y, Wang G, Liu X. Multi-scale attention network for single image super-resolution. In: 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2024 Jun 17–18; Seattle, WA, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 5950–60. doi:10.1109/CVPRW63382.2024.00602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Goodfellow IJ, Pouget-Abadie J, Mirza M, Xu B, Warde-Farley D, Ozair S, et al. Generative adversarial nets. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2020;2014(11):139–44. doi:10.1145/3422622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wang X, Yu K, Wu S, Gu J, Liu Y, Dong C, et al. ESRGAN: enhanced super-resolution generative adversarial networks. In: Computer Vision—ECCV 2018 Workshops. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 63–79. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-11021-5_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wang X, Xie L, Dong C, Shan Y. Real-ESRGAN: training real-world blind super-resolution with pure synthetic data. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW); 2021 Oct 11–17; Montreal, BC, Canada: IEEE; 2021. p. 1905–14. doi:10.1109/iccvw54120.2021.00217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Xiong Y, Guo S, Chen J, Deng X, Sun L, Zheng X, et al. Improved SRGAN for remote sensing image super-resolution across locations and sensors. Remote Sens. 2020;12(8):1263. doi:10.3390/rs12081263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Li HA, Wang D, Zhang J, Li Z, Ma T. Image super-resolution reconstruction based on multi-scale dual-attention. Connect Sci. 2023;35(1):2182487. doi:10.1080/09540091.2023.2182487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Han K, Wang Y, Chen H, Chen X, Guo J, Liu Z, et al. A survey on vision transformer. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2023;45(1):87–110. doi:10.1109/tpami.2022.3152247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Zhang H, Goodfellow I, Metaxas D, Odena A. Self-attention generative adversarial networks. In: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2019 Jun 9–15; Long Beach, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

30. Zhou M, Duan N, Liu S, Shum H-Y. Progress in neural NLP: modeling, learning, and reasoning. Engineering. 2020;6(3):275–90. doi:10.1016/j.eng.2019.12.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Liu QM, Jia RS, Zhao CY, Liu XY, Sun HM, Zhang XL. Face super-resolution reconstruction based on self-attention residual network. IEEE Access. 2019;8:4110–21. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2962790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Deng J, Song W, Liu D, Li Q, Lin G, Wang H. Improving the spatial resolution of solar images using generative adversarial network and self-attention mechanism. Astrophys J. 2021;923(1):76. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ac2aa2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Vo TN, Ngo BD, Bui LT. Super resolution using convolutional neural network and self-attention mechanism. In: 2024 RIVF International Conference on Computing and Communication Technologies (RIVF); 2024 Dec 21–23; Danang, Vietnam: IEEE; 2024. p. 366–71. doi:10.1109/RIVF64335.2024.11009104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Yu C, Pei H. Super-resolution reconstruction method of face image based on attention mechanism. IEEE Access. 2021;13(10):121250–60. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3070898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Radford A, Metz L, Chintala S. Unsupervised representation learning with deep convolutional generative adver-sarial networks. arXiv:1511.06434. 2015. [Google Scholar]

36. Ioffe S, Szegedy C. Batch normalization: accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covari-ate shift. In: Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning; 2015 Jul 7–11; Lille, Frence. [Google Scholar]

37. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Delving deep into rectifiers: surpassing human-level performance on ImageNet classification. In: 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2015 Dec 7–13; Santiago, Chile: IEEE; 2015. p. 1026–34. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2015.123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Ruby U, Theerthagiri P, Jacob IJ, Vamsidhar Y. Binary cross entropy with deep learning technique for Image classification. Int J Adv Trends Comput Sci Eng. 2020;9(4):5393–7. doi:10.30534/ijatcse/2020/175942020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Simonyan K, Zisserman A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv:1409.1556. 2014. [Google Scholar]

40. Marmolin H. Subjective MSE measures. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern. 1986;16(3):486–9. doi:10.1109/TSMC.1986.4308985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Chen M, Pu YF, Bai YC. Low-dose CT image denoising using residual convolutional network with fractional TV loss. Neurocomputing. 2021;452(4):510–20. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2020.10.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Shi T, Gong J, Jiang S, Zhi X, Bao G, Sun Y, et al. Complex optical remote-sensing aircraft detection dataset and benchmark. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2023;61:5612309. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2023.3283137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Korhonen J, You J. Peak signal-to-noise ratio revisited: is simple beautiful? In: 2012 Fourth International Workshop on Quality of Multimedia Experience; 2012 Jul 5–7; Melbourne, VIC, Australia: IEEE; 2012. p. 37–8. doi:10.1109/QoMEX.2012.6263880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Dosovitskiy A, Brox T. Generating images with perceptual similarity metrics based on deep networks. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2016;29:658–66. [Google Scholar]

45. Liu J, Gan Z, Zhu X. Directional bicubic interpolation—a new method of image super-resolution. In: Advances in Intelligent Systems Research; 2013 Nov 29–Dec 1; Guangzhou, China. doi:10.2991/icmt-13.2013.57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Huang Z, Li W, Li J, Zhou D. Dual-path attention network for single image super-resolution. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;169(1):114450. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2020.114450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Lei S, Shi Z. Hybrid-scale self-similarity exploitation for remote sensing image super-resolution. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2021;60:5401410. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2021.3069889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Hu W, Ju L, Du Y, Li Y. A super-resolution reconstruction model for remote sensing image based on generative adversarial networks. Remote Sens. 2024;16(8):1460. doi:10.3390/rs16081460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools