Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Model Construction for Complex and Heterogeneous Data of Urban Road Traffic Congestion

1 School of Economics and Management, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, 100044, China

2 School of Computer and Information Technology, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, 100044, China

3 School of Electronic and Information Engineering, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, 100044, China

* Corresponding Author: Minghao Zhu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069671

Received 27 June 2025; Accepted 26 September 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Urban traffic generates massive and diverse data, yet most systems remain fragmented. Current approaches to congestion management suffer from weak data consistency and poor scalability. This study addresses this gap by proposing the Urban Traffic Congestion Unified Metadata Model (UTC-UMM). The goal is to provide a standardized and extensible framework for describing, extracting, and storing multisource traffic data in smart cities. The model defines a two-tier specification that organizes nine core traffic resource classes. It employs an eXtensible Markup Language (XML) Schema that connects general elements with resource-specific elements. This design ensures both syntactic and semantic interoperability across siloed datasets. Extension principles allow new elements or constraints to be introduced without breaking backward compatibility. A distributed pipeline is implemented using Hadoop Distributed File System (HDFS) and HBase. It integrates computer vision for video and natural language processing for text to automate metadata extraction. Optimized row-key designs enable low-latency queries. Performance is tested with the Yahoo! Cloud Serving Benchmark (YCSB), which shows linear scalability and high throughput. The results demonstrate that UTC-UMM can unify heterogeneous traffic data while supporting real-time analytics. The discussion highlights its potential to improve data reuse, portability, and scalability in urban congestion studies. Future research will explore integration with association rule mining and advanced knowledge representation to capture richer spatiotemporal traffic patterns.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileWith the rapid growth of urbanization and the rising number of vehicles, traffic congestion in cities has become a critical problem. It causes economic losses, energy waste, and psychological stress. To address this issue, many scholars have studied traffic management optimization [1–3]. Most research emphasizes congestion detection and prediction. For example, Li et al. [4] proposed a method that uses features from traffic surveillance videos to estimate congestion levels more accurately. Chen et al. [5] developed PCNN, a deep convolutional neural network model, to capture periodic patterns in traffic data for short-term congestion prediction.

Traffic data in these studies show strong features of heterogeneity [6], multi-sourcing [7], and complexity [8]. Heterogeneity refers to diverse data formats. It includes structured data in databases, as well as semi-structured and unstructured data such as videos, text, and audio. Multi-sourcing means the data come from many origins. These include transport infrastructure, communication devices, and intelligent transportation systems. Complexity describes the intricate structure of traffic data. It contains both dynamic and static elements. These characteristics create challenges in research and practice. Problems include semantic inconsistency [9], format mismatch, and integration difficulty [10]. Knowledge graphs are widely used in smart cities and transportation. They support semantic unification and cross-domain reasoning. For example, Km4City [11] combines traffic facilities, events, and geography through ontologies and Resource Description Framework (RDF) triples. This allows semantic search and reasoning-based applications. Knowledge graphs provide rich semantic representation. They also support advanced reasoning. However, they require high costs in ontology design, data storage, and maintenance. To avoid these costs, some researchers propose metadata specifications [12,13]. These aim to solve semantic unification and reasoning issues. Yet, most specifications target specific data types, such as geospatial data [14] or meteorological data [15]. They cannot describe the full range of heterogeneous and complex traffic data. This lack of a unified description limits integration of multi-dimensional and cross-type data. It also restricts research on urban traffic congestion.

To address these challenges, we propose a metadata specification for heterogeneous and complex traffic data. The goal is to create a unified and standardized framework for describing urban road congestion data. This framework improves data interoperability and reusability. It also provides a standard basis for processing, storage, and analysis. In this way, data from different sources can be integrated and analyzed more effectively. Our main contributions are as follows:

• We design a unified metadata model for complex and heterogeneous traffic data. The model specifically addresses the multi-source and complex nature of congestion data. It provides the first unified description of nine core traffic data types. The framework combines a general metadata element set with resource-specific element sets. This resolves the limits of existing standards that often cover only one data type. In addition, we define extension principles and procedures. These allow new elements, code tables, or constraints to be added without breaking the core specification.

• We integrate metadata extraction with distributed storage technologies. The architecture is built on HDFS and HBase. It supports large-scale heterogeneous data processing. By applying computer vision, we automate metadata extraction from unstructured data. This makes real-time management and analysis of traffic data more practical and efficient.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The related work are introduced in Section 2. The design principles, model framework, and formalization are described in Section 3. Section 4 presents the metadata extraction process and demonstrates the model’s strong performance on HBase. Finally, Section 5 provides conclusions and future outlook.

Metadata is commonly defined as “data about data.” It provides the foundation for information management and data integration [16]. Widely used metadata standards include Dublin Core [17], ISO 19115 [18], and JATS [19]. Traffic metadata is a specialized form of metadata. It describes urban traffic information resources using metadata principles. In urban traffic, the big data era and the rise of smart city concepts [20] have produced vast amounts of data. These data include operational records, traffic processes, and management information. They come from transport infrastructure, communication devices, and intelligent transportation systems. As a result, traffic metadata has broad applications across many fields [21–24]. Bakirci [25] described wide application scenarios of traffic metadata on unmanned aerial vehicles in smart city environments.

The use of traffic metadata faces challenges. These challenges arise from diverse storage methods and complex data structures [26]. Traffic data include both dynamic and static elements. This makes it difficult to use and manage metadata effectively [11]. To address problems, researchers have studied extraction methods and application frameworks for traffic metadata worldwide.

In traffic metadata extraction, Zhao et al. [27] built a system for extraction and correction. They developed a vehicle metadata framework for traffic roads. This improved the quality of metadata extracted from surveillance videos. Bellini et al. [11] designed a system for data ingestion and coordination. The system managed data related to road maps, services, and traffic sensors. It handled both static and dynamic data from multiple sources. Gong et al. [28] proposed a method to collect and analyze metadata from Twitter. This supported spatiotemporal clustering algorithms for near real-time congestion detection. Das and Purves [29] created a model to extract location metadata from tweets. This offered a low-cost supplement to physical traffic infrastructure. These studies reduce some challenges in extracting traffic metadata. However, they mainly focus on single data types. They lack strong support for integrating diverse data in large-scale urban traffic systems.

The application framework for urban traffic metadata also faces challenges. It cannot handle multi-type data effectively. Qiao et al. [30] addressed the problem of isolated geographic data in cities. He proposed an XML-based web service solution. He also introduced a service model that integrates metadata with geographic data. Zhou et al. [31] applied metadata cataloging standards to video resources of the Qinghai-Tibet Railway surveillance system. This resolved inconsistencies in video descriptions. It also enabled fast retrieval, accurate targeting, and better sharing of video data. Research on single-type traffic data has made progress. However, little work addresses the integration of comprehensive urban traffic data.

From these studies, we identify two key problems. First, there is a lack of standardization across different types of data and applications. Second, there is insufficient consistency in the definition and description of metadata [32]. These problems limit the use of existing frameworks in large-scale traffic systems. To solve this, we propose a Hadoop-based framework for processing heterogeneous traffic data. We also introduce metadata standards for traffic big data. This framework provides an effective solution for extracting metadata from diverse urban traffic data.

3 Construction of Urban Traffic Road Metadata Model

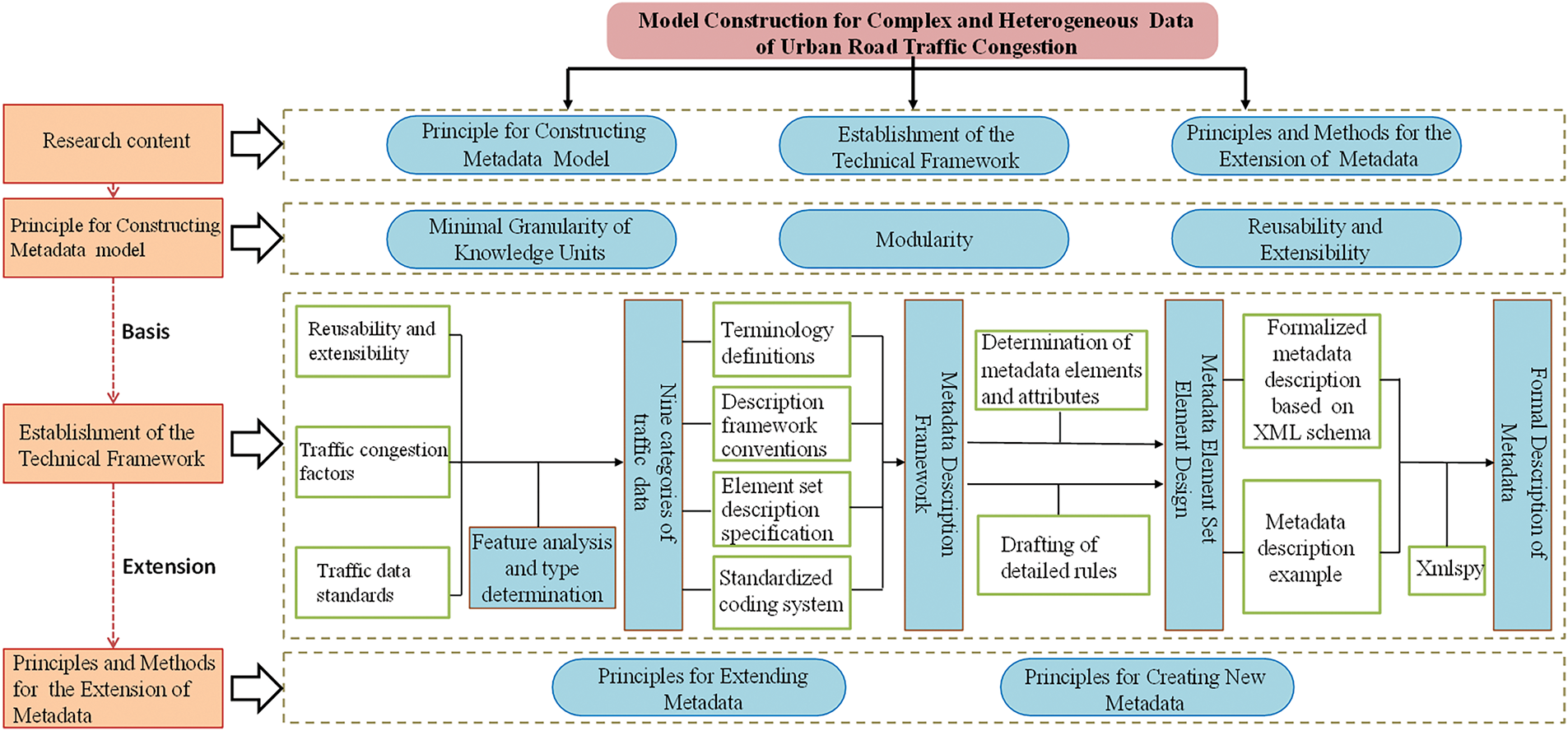

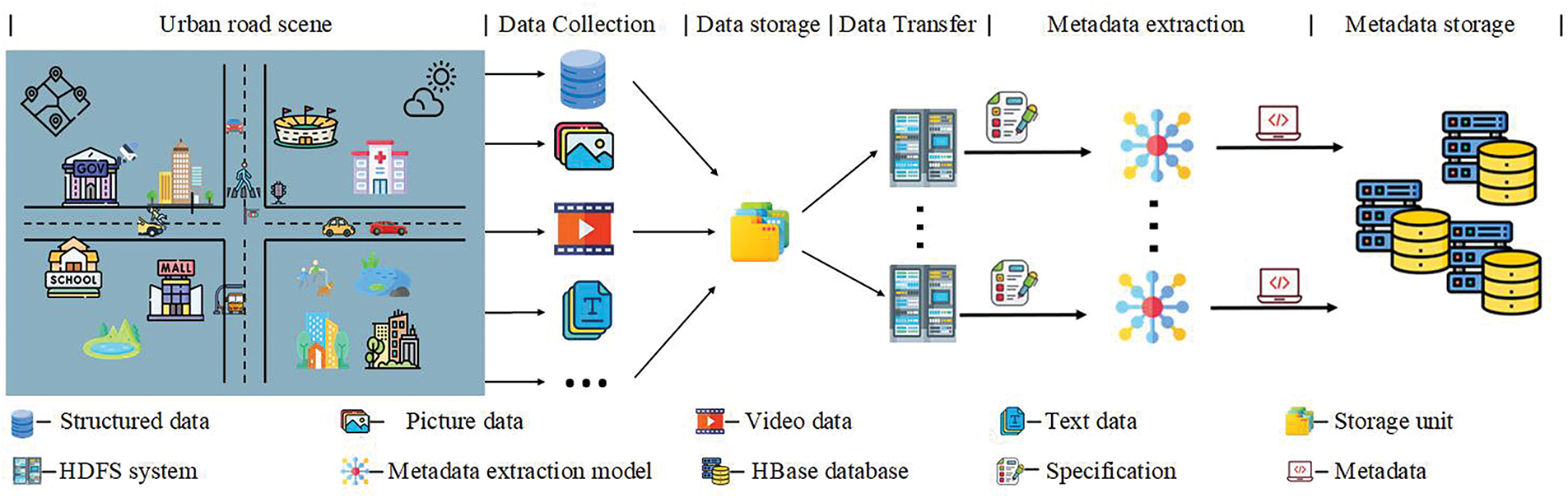

The construction of the metadata standard model is grounded in metadata theory. It applies an object-oriented modeling method to manage the complexity and heterogeneity of urban road traffic data. The framework is designed for both human use and computer processing. It supports multi-class, multi-source, and heterogeneous traffic data resources. The framework enables unified description, exchange, reuse, conversion, and integration of large-scale congestion data. This allows the aggregation and fusion of urban road traffic resources, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Urban road traffic metadata model construction process

3.1 Principles for Constructing the Urban Traffic Road Congestion Metadata Model

In data management, the FAIR guidelines [33] set out four key principles: findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability. They provide a roadmap for improving the reuse of data assets. In transportation, the growth of traffic big data and new technologies has increased the demand for fine-grained organization of information. Metadata descriptions have therefore moved toward greater detail and modularity. To build a metadata standard for multi-source and heterogeneous urban traffic data, and to comply with FAIR, we propose three principles:

• Minimal Granularity of Knowledge Units: Precise metadata comes from detailed description objects. Elements and attributes are defined at the finest level possible.

• Modularity: Traffic resources are divided into multiple entities. This allows flexible and associative descriptions. The framework includes three modules: general elements, a traffic-data element set, and a coding system.

• Reusability and Extensibility: The standard aligns with existing national and international norms. It also allows practical extension. General elements are reusable, and new traffic data types can inherit and extend the model.

3.2 Establishment of the Technical Framework

The process of constructing the urban road traffic metadata model framework involves four key steps: feature analysis and classification of traffic data, design of the metadata description framework, development of the metadata element set, and formal description of metadata.

3.2.1 Analysis and Determination of the Characteristics of Urban Traffic Congestion Data

To build a unified and general framework for urban traffic metadata, it is necessary to define the target data types. This process requires feature analysis and the identification of relevant traffic data. It includes the study of traffic features, congestion factors, and references to existing standards.

• Analyze flow, speed, temporal, incident, environmental, and infrastructure dimensions. Use structured, semi-structured, and unstructured sources, such as records, text, video, and audio. This reveals system mechanisms and supports a complete metadata standard.

• Group congestion causes into categories. These include demand and flow, infrastructure design, incidents, weather, socio-economic conditions, public transport quality, and traveler behavior. This guides traffic management strategies.

• Identify congestion-related data types and compare them with existing standards. Integrate useful parts. Where no direct standard exists, adapt similar formats and codes. Ground the specification in past research and actual data conditions.

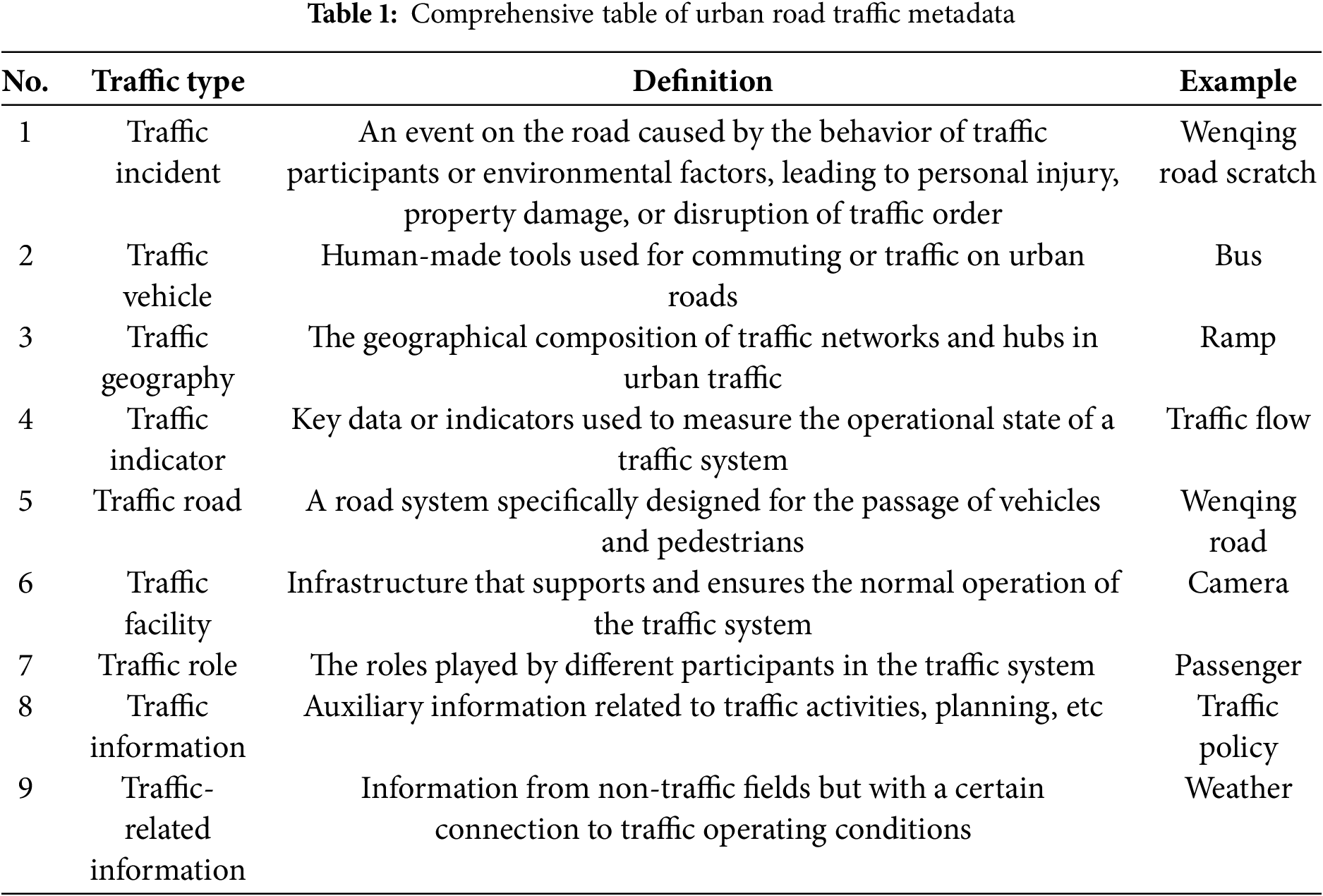

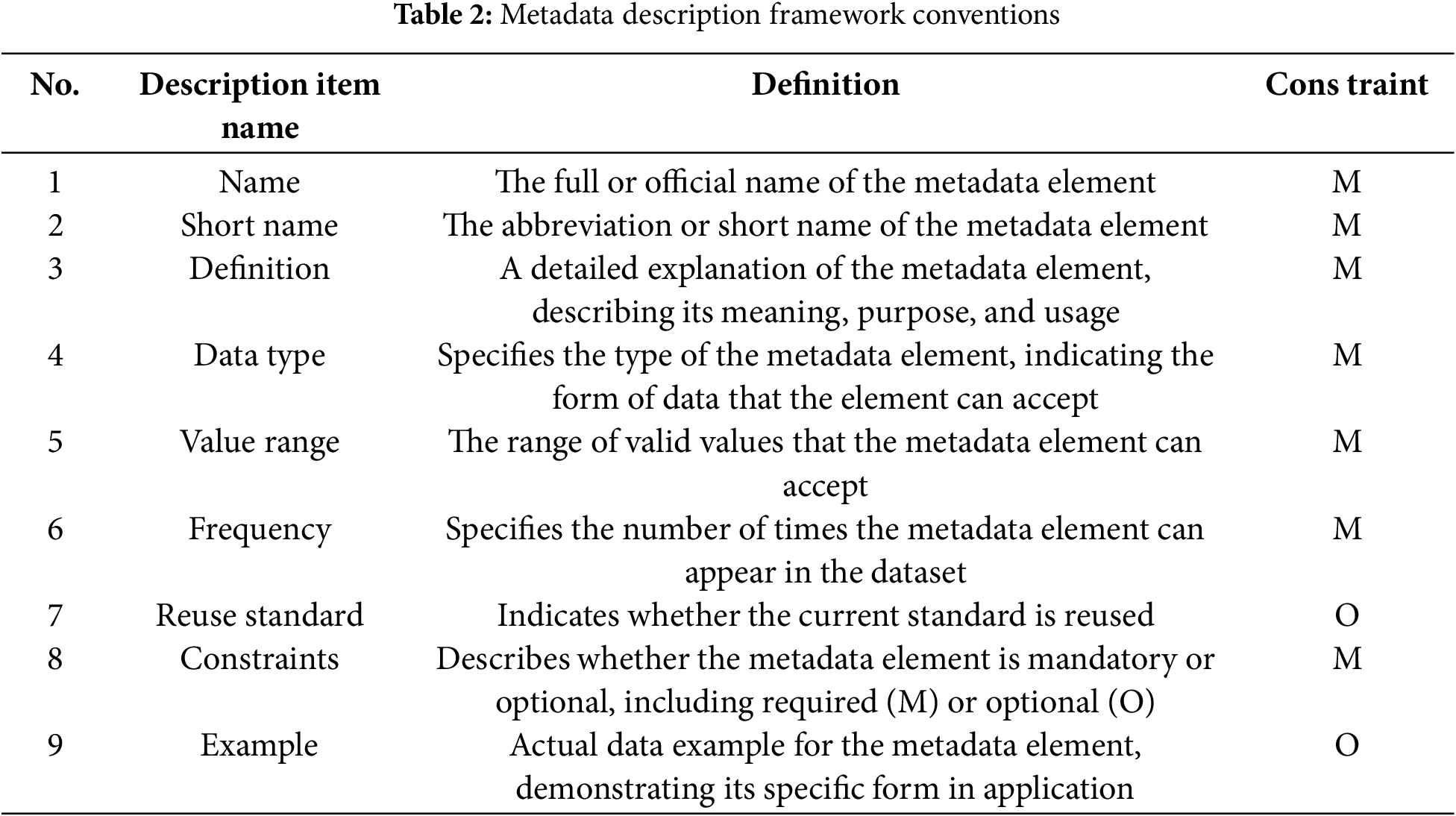

Based on this analysis, nine data resource types are selected. They include traffic accidents, traffic geography, transportation vehicles, traffic indicators, traffic roads, traffic facilities, traffic roles, traffic information, and traffic-related information, as shown in Table 1.

To present the semantic associations and constraints among these resources, we model the inter-entity relationships uniformly. Fig. 2 shows the overall network of the nine traffic data entities. The Appendix lists details of each relationship, including semantic meaning, domain, range, and cardinality constraints [34].

Figure 2: Diagram of the relationships among nine categories of data resources

As shown in Fig. 2, TRAFFIC_INCIDENT and TRAFFIC_ROAD entities are linked via the occurs_on relationship, indicating that a traffic incident has occurred on a specific road or segment. This explicit modeling approach lays the foundation for subsequent tasks such as automatic validation and semantic querying. Supplementary Table S39 further lists the English codes, semantic descriptions, domains/ranges, and cardinality constraints for each relationship, facilitating the implementation of structured constraints and ensuring consistency at the implementation level.

3.2.2 Metadata Description Framework Design

(1) Terminology Definitions

Terminology definitions clarify the terms and their meanings associated with the element attributes outlined in this specification. This step is crucial for ensuring consistency and eliminating ambiguity in metadata definitions for resource types. The terms in this document are explicitly defined to ensure clear and accurate practical application [35]. For example, a “metadata element” is the basic unit of metadata used to describe a particular characteristic of an information resource. A “metadata attribute” refers to information or data elements that describe the inherent characteristics of data, used for interpretation, classification, identification, and management. A “coding system” is a standardized method of identification, used to uniquely and meaningfully label information or entities.

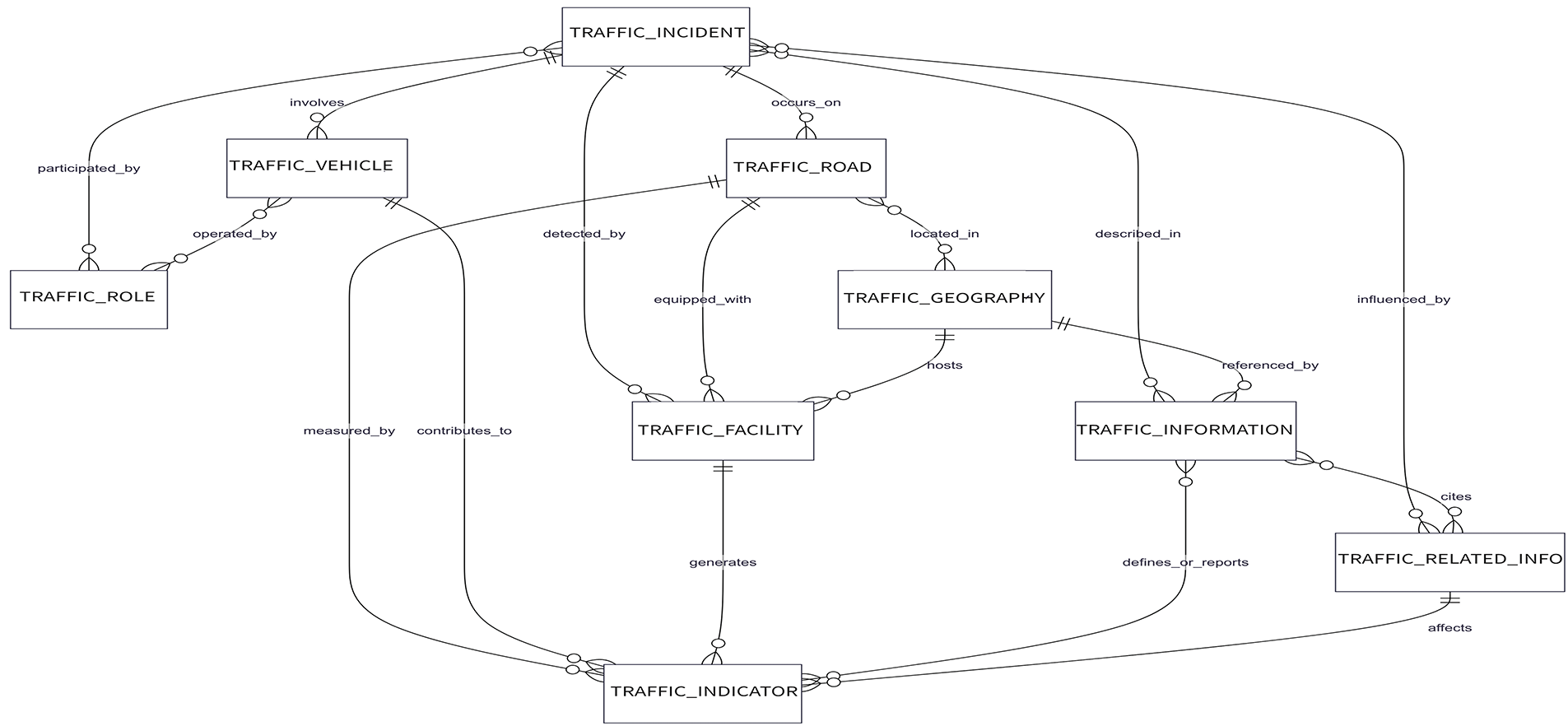

(2) Metadata Description Framework Conventions

The metadata description framework conventions form the core of the metadata system. These conventions are adapted from the metadata description methods in the Traffic Transportation Information Resource Catalog System, Part 3: Core Metadata [36]. As shown in Table 2, the framework conventions are described in nine aspects: name, short name, definition, data type, value domain, frequency, reuse standards, constraints, and examples. The definitions and constraints of each descriptive item are provided, including explanations and whether the item can have a null value. Required and optional values are denoted by M (Mandatory) and O (Optional), respectively.

It is important to follow these guidelines for the abbreviation rules of short names: 1) They must be unique within the scope of the standard. 2) For words with commonly used English abbreviations in international or industry contexts, use the standard English abbreviation. 3) The short name should be a seamless concatenation of the initials of the constituent words, with each initial capitalized.

(3) Description Standards for General Elements and Resource Metadata Element Sets

Building on the established metadata description framework conventions, the description standards for general elements and resource metadata element sets were further segmented and refined, general elements is shown in the Supplementary Table S10. And this process involved developing field structure specifications for both the metadata element set summary table and the detailed specification table for element descriptions.

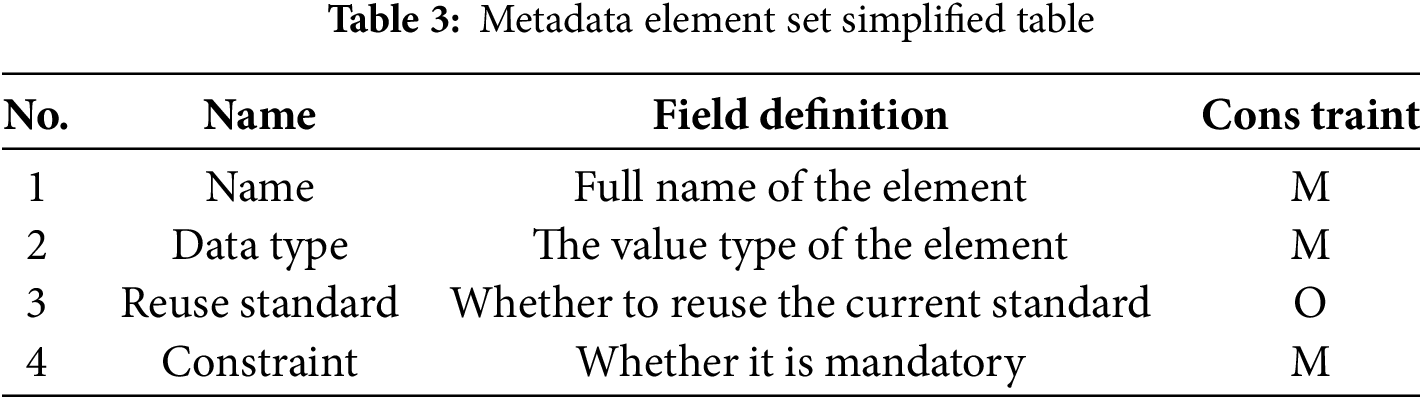

The metadata element set summary table provides a brief description of resources, allowing data users to gain an initial understanding. Specific descriptive items include name, reuse standards, and constraints, as shown in Table 3. And the complete content is shown in the Supplementary Tables S1–9.

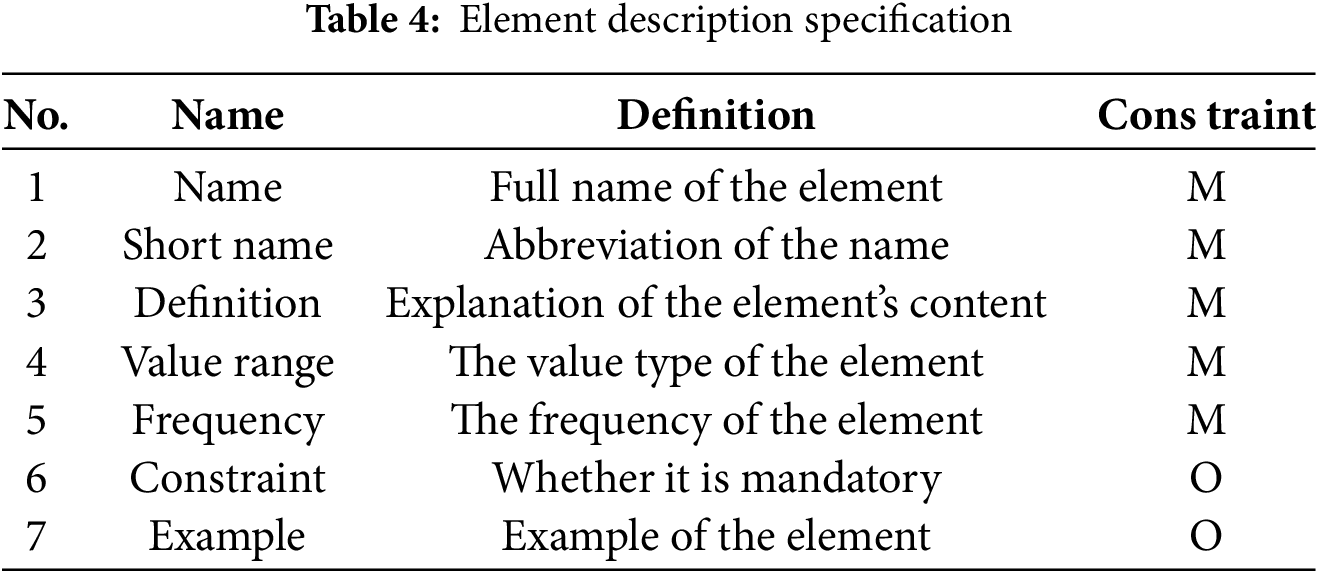

The detailed specification table expands upon the summary table by offering a more in-depth explanation of each metadata element. This ensures a clearer understanding of the elements’ purpose and functionality. Specific descriptive items include name, short name, definition, value domain, frequency, constraints, and examples, as shown in Table 4. And the complete content is shown in the Supplementary Tables S11–20.

(4) Standardized Coding System

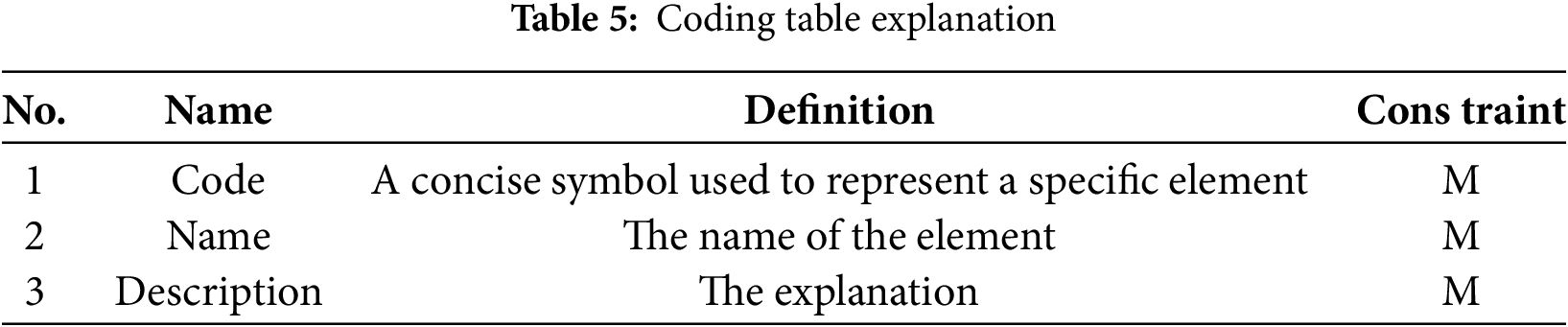

The “coding system” standardizes the value ranges of elements and attributes using controlled vocabularies or predefined name lists. By regulating these value ranges, the coding system offers several advantages, including uniqueness, conciseness, extensibility, consistency, and readability. The system consists of a standardized code list and its corresponding coding table, which organizes the codes and their definitions. As shown in Table 5, the descriptive items in the coding table include code, name, and description. The complete content is shown in the Supplementary Tables S21–38.

3.2.3 Metadata Element Set Element Design

Given the complexity and heterogeneity of data related to urban road traffic congestion, the design of metadata elements includes developing general elements, resource-specific elements, and attributes, along with compiling detailed specification tables for these components.

(1) Design of General Element Set

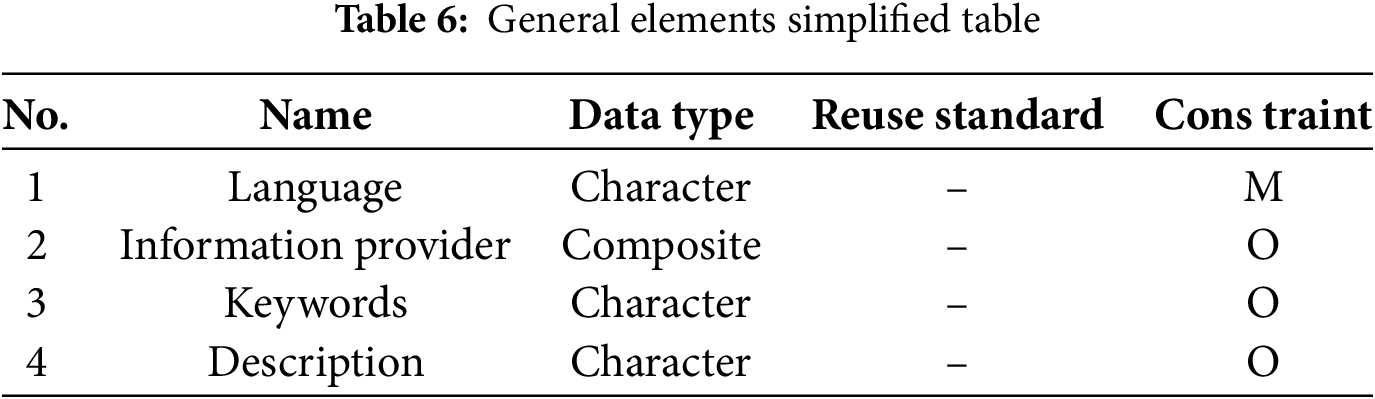

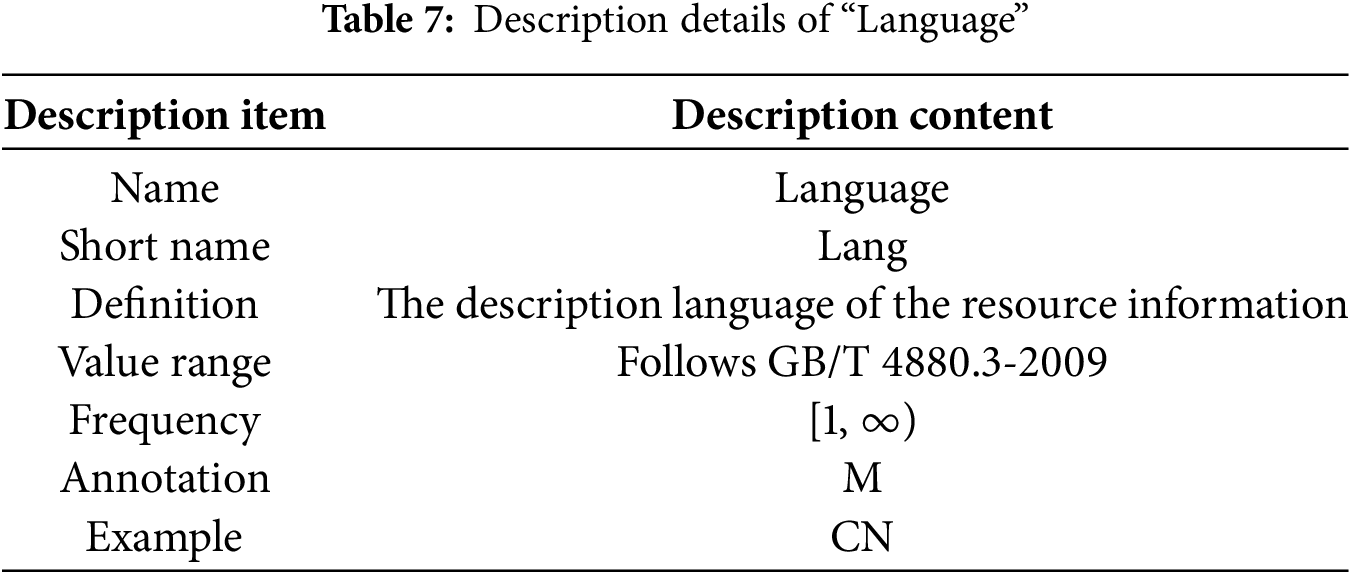

The design of the general metadata element set aims to ensure that its elements are both versatile and reusable, facilitating seamless integration with resource-specific element sets. After a thorough analysis of various resources, a set of general elements was identified. These elements are outlined in Table 6. Based on the confirmed elements, detailed specifications were compiled to ensure clarity, consistency, and practical applicability. For example, the element “Language” is a representative case, and its specifications are provided in Table 7.

(2) Design of Resource Metadata Element Set

Drawing on transportation-related research and national standards, the resource content is categorized and detailed. This ensures the designed elements comprehensively and accurately describe resources from multiple perspectives. Urban road traffic data metadata is classified into nine categories to capture the diversity of resource types.

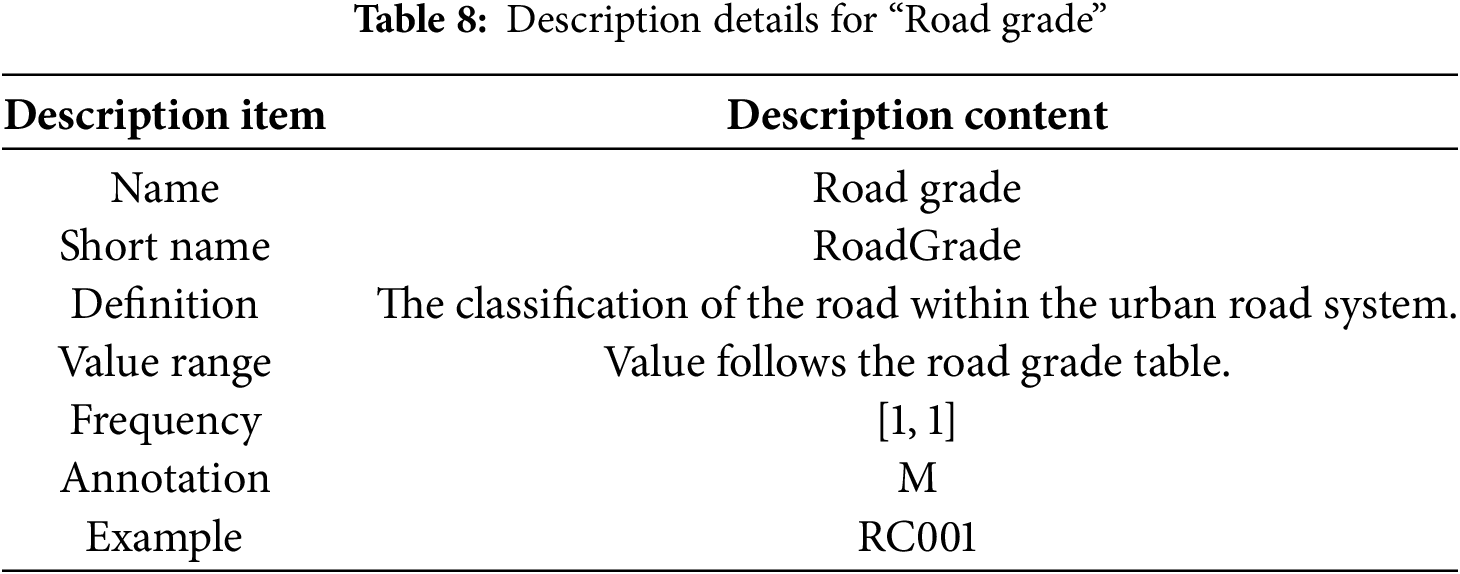

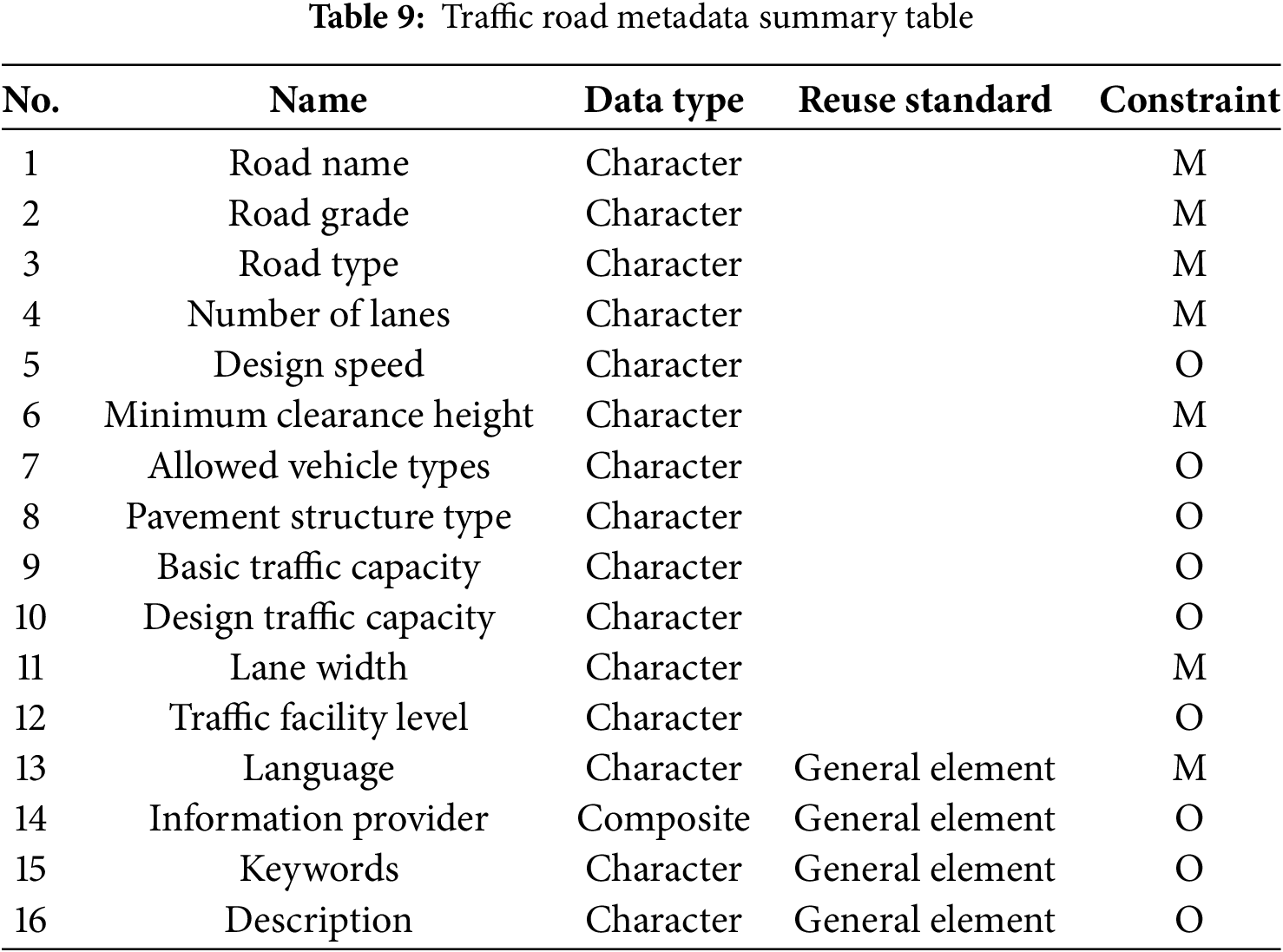

As shown in Tables 8 and 9, traffic road information resources are described using 18 elements, including Road Name, Road Grade, Road Type, pavement structure type, and others. The design distinguishes core elements, which capture the primary characteristics of the resource, from general elements that provide broader context. Building on this foundation, detailed field-level specifications are provided for each element—for example, the “Road Grade” element of the traffic-road resource is defined in the Element Specification Details table.

The value domain for this element is defined based on the Standards for Urban Comprehensive Transportation System Planning. This ensures consistency with established guidelines. Additionally, road category codes are created to facilitate standardization and clarity. For example, mixed-use lanes are assigned the code RT001.

(3) Code List

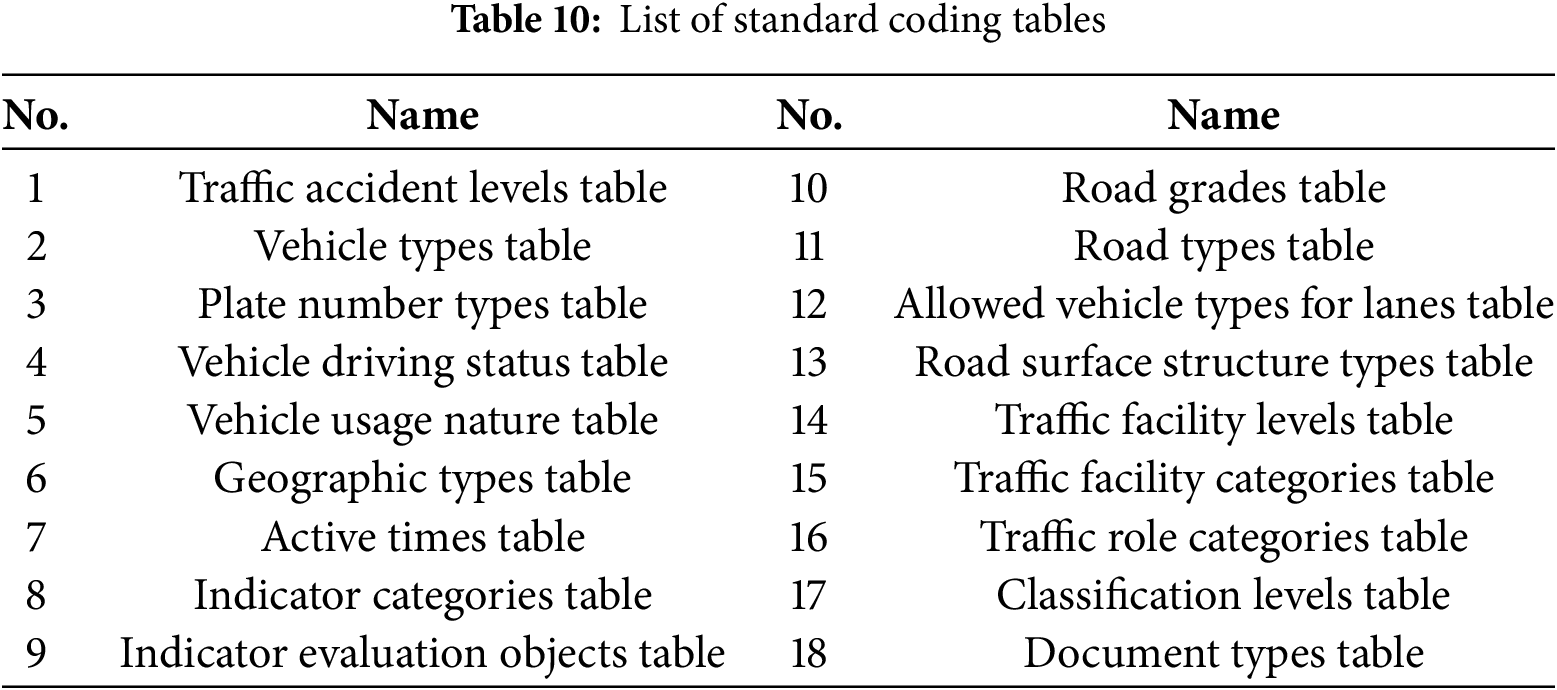

Based on the nine established categories of data resources and their metadata standards, standardized coding tables, such as the Traffic Accident Level Code Table, were developed to address value-related issues encountered during the process, as shown in Table 10. The coding standards are detailed in the appendix. By establishing a coding system, attribute value ranges and controlled vocabularies are effectively defined, making the creation of metadata more standardized and efficient.

3.2.4 Formal Description of Metadata

The formalized description of metadata is designed to represent its structure, content, semantics, and constraints in a precise manner. This ensures that computer systems can effectively interpret, process, and validate the metadata. XML and JSON are among the most commonly used languages for formalized descriptions. This standard adopts XML as the formalization language, given its flexibility and compatibility with metadata processing requirements.

XML provides a robust set of rules for defining semantic tags. This enables the transformation of metadata specifications into XML Schema description (XSD) files. These schema files encapsulate various types of resource metadata into XML files. They also facilitate automatic identification, interpretation, and validation by computer systems [37].

• Formalized Metadata Description Based on XML Schema: Using XMLSpy software, XML Schemas were created for the metadata describing the four categories of general elements and nine categories of resource data. The corresponding XSD files were generated.

• Metadata Description Example: Based on the compiled XML Schema, an XML data file was generated. This file contains specific metadata content for urban road traffic information resources.

3.3 Principles and Methods for the Extension of Urban Road Traffic Congestion Metadata

Urban traffic big data is large in volume, diverse in type, and time-sensitive. As regulations and standards evolve, metadata specifications must adapt as well. The principles and methods for metadata expansion are outlined below.

Permitted expansions to core metadata include: adding new metadata elements; adding new metadata entities; creating coding tables to replace free-text value domains; adding new coding table elements to extend existing domains; applying stricter optionality constraints; applying stricter maximum occurrence constraints; and narrowing value domains of existing metadata. Before expansion, existing metadata and their attributes must be reviewed. This ensures that essential metadata are not missing.

For each new metadata element, define its name, short name, definition, data type, value domain, maximum occurrences, and constraints. Provide examples where possible. For new coding tables and elements, specify the name, code, and description of each value.

Basic principles for creating new metadata are as follows:

• Select metadata according to resource characteristics and task complexity. Ensure that traffic information can support user needs in querying and extraction.

• Metadata must meet current transportation standards and anticipate future requirements. Referencing advanced industry standards is recommended.

• Added elements should follow hierarchical organization. If current metadata are insufficient, new ones may be created, and must not conflict with the names or definitions of existing elements or coding tables.

• New metadata may be composite, combining existing and new elements.

• Free-text value domains may be replaced by coding tables.

• Coding tables may be extended, provided they remain consistent with original rules.

• Value domains of existing elements may be narrowed.

• Stricter rules for optionality and maximum occurrences are allowed. For example, optional metadata may become mandatory, and unlimited elements may be restricted to one.

Following the establishment of the specifications, we outline the metadata extraction process within the Hadoop environment. The process, shown in Fig. 3, consists of two main steps: traffic data collection and storage, and the distributed extraction and storage of metadata.

Figure 3: Metadata extraction process

4.1 Data Collection and Storage

Urban road traffic data are collected in many forms, including flow records, video, images, and text. These data fall into two categories: structured and unstructured, each with different processing needs.

• Structured data can be stored directly in databases. It is represented logically in two-dimensional tables and requires no extra processing.

• Unstructured data have no fixed format, which makes them hard to standardize. They often require a specialized file system for storage. In this study, we store unstructured data in HDFS, while their metadata—such as location, size, and format—are stored in HBase.

4.2 Distributed Extraction and Storage of Metadata

After the data are ingested into HDFS, metadata are extracted with algorithms tailored to each data type and aligned with the previously defined schema. For traffic video streams, we employ YOLOv8 for object detection and SORT for online multi-object tracking, and then aggregate counts via a line-crossing strategy. For textual traffic reports, Jieba is used for word segmentation, while a BERT-based model performs syntactic parsing, named-entity recognition, and event extraction, such as controlled sections, incident start/end times, and locations. The resulting metadata are stored in HBase, with row keys engineered to match common query patterns and exposed through convenient access interfaces. The Rowkey is shown in the Supplementary Table S40.

4.3.1 Formal Description of Metadata

In this study, the Hadoop cluster server was deployed on Alibaba Cloud servers. The cloud server is configured with the following specifications: instance type: 2-core, 2 GB RAM, ecs.e series; system disk: ESSD Entry/dev/xvda 40 GB module properties; bandwidth: 3 Mbps; CPU: 2 cores; operating system: CentOS 7.9 64-bit Linux; memory: 2 GB. Furthermore, the relevant software versions utilized in the system include hbase-2.2.5, hadoop-2.8.5, apache-zookeeper-3.8.2.

To evaluate the performance of the aforementioned HBase database, YCSB plugin was employed for testing [38]. YCSB is a widely used benchmarking framework designed specifically to assess the performance of various large-scale cloud service database systems. The framework operates in two primary phases: the loading phase and the transaction phase, thereby determining the database system’s behavior under high-load conditions.

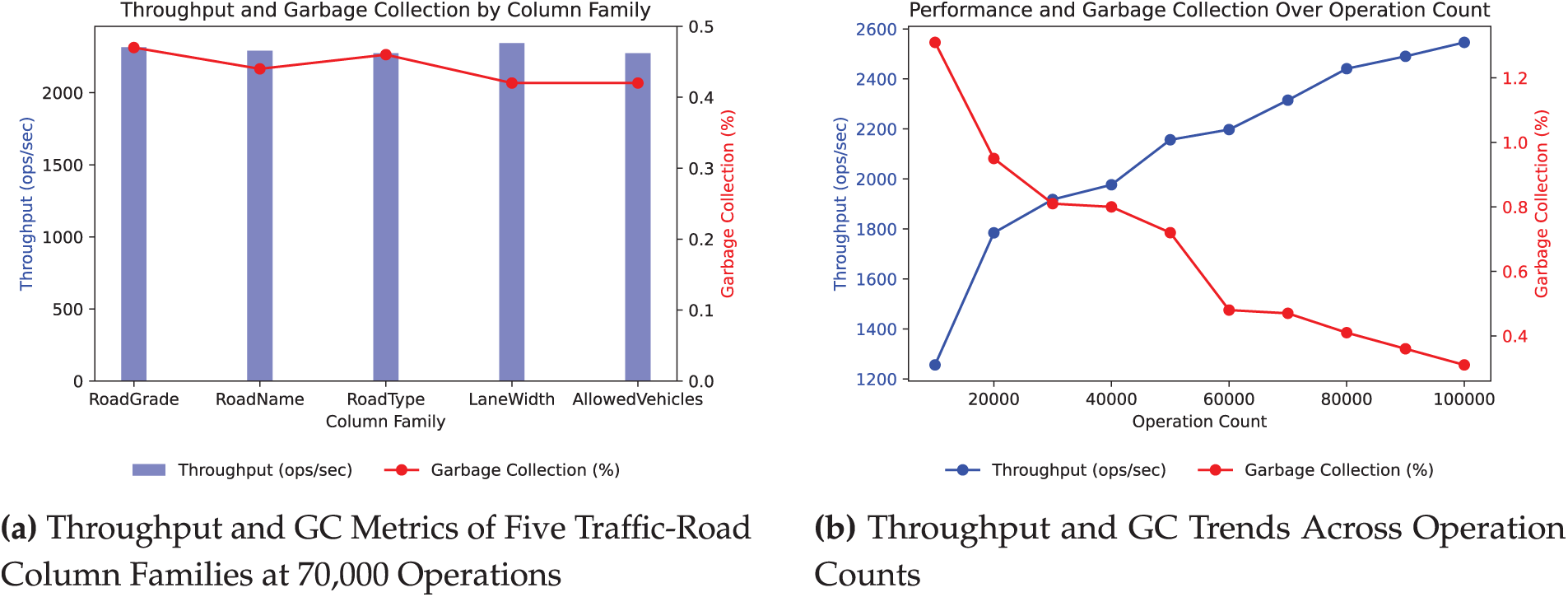

In this study, throughput and garbage collection (GC) are used as the metrics to evaluate HBase performance. GC is a memory management mechanism in the Java Virtual Machine. It reclaims unused memory automatically. This prevents memory leaks and improves memory efficiency. In YCSB performance metrics, GC is a key indicator. It affects both application responsiveness and throughput directly.

Using traffic roads as an example, we first set the number of operations to 70,000 and tested the column families ‘RoadGrade’, ‘RoadName’, ‘RoadType’, ‘LaneWidth’, and ‘AllowedVehicles’. As shown in Fig. 4a, the overall performance is satisfactory, with throughput ranging from 2250 to 2350 ops/sec, including both read and write operations. During the system’s runtime, 4.00% to 5.00% of the time was consumed by GC, indicating acceptable performance. Moreover, it can be observed that under the same number of operations, the overall performance differences among the various column families are minimal, remaining within a specific range.

Figure 4: Analysis of column family performance in Hbase

Building on this, the column family ’RoadGrade’ was selected for further testing by varying the number of operations to measure its performance under different load conditions. As illustrated in Fig. 4b, to a certain extent, as the number of operations increases, the system’s throughput consistently improves while garbage collection time decreases. These results demonstrate that the system exhibits excellent performance.

4.3.3 Coverage Evaluation and Comparisons

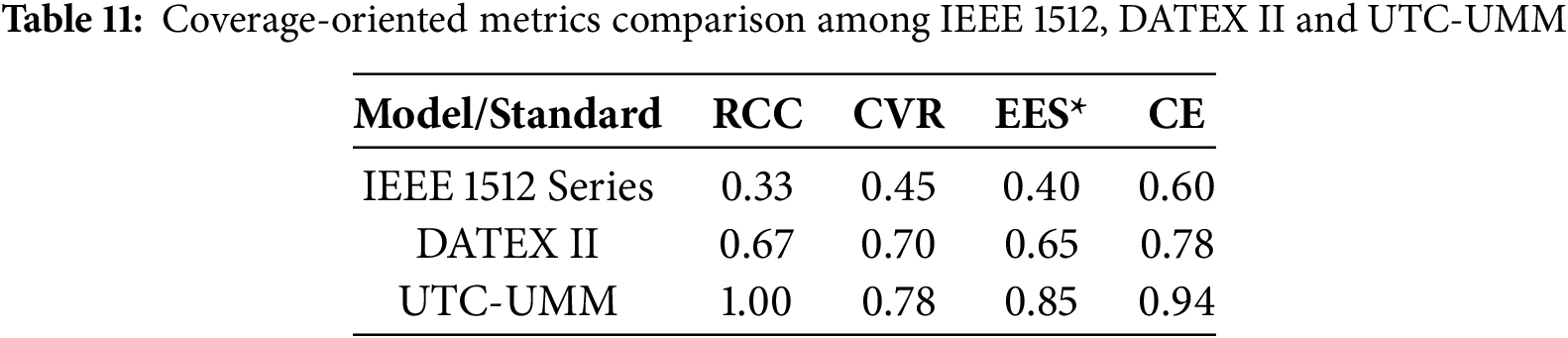

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed framework, we further quantified the extent to which UTC-UMM meets the requirements of the transportation domain and aligns with representative standards, comparing it against two existing models [39,40]. We defined four evaluation metrics: Resource-Class Coverage (RCC), Controlled Vocabulary Ratio (CVR), Extensibility Effort Score (EES), and Coverage Effectiveness (CE).

RCC is defined as:

CVR is defined as:

EES: This metric assesses the relative effort needed to extend the model to support a new data type, considering both the number of modification steps and the scope of the required changes. It is scored on a five point scale, with lower values indicating greater extensibility.

CE is computed as:

To ensure consistency, the EES was normalized to a 0-1 scale, denoted as EES*. The results for four metrics are shown in Table 11. UTC-UMM reaches an RCC of 1.0 across all nine core data domains, while the two baseline models cover only part of these classes. UTC-UMM also achieves a CVR of 0.78 and a CE of 0.94, both higher than the comparison standards. With a normalized EES of 0.85, UTC-UMM surpasses IEEE 1512 and DATEX II in extensibility. Overall, UTC-UMM shows stronger balance and effectiveness across four dimensions: coverage, standardization, extensibility, and operational performance.

4.3.4 Schema Validity and Coding Gains

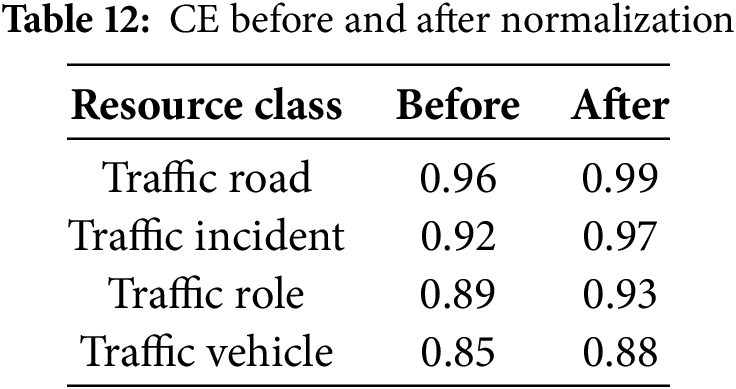

A supplementary validation experiment was conducted to assess the effectiveness of UTC-UMM’s schema constraints and controlled vocabularies. Four resource classes, Traffic Road, Traffic Incident, Traffic Role and Traffic Vehicle, were randomly sampled (100 records each). Raw metadata were first validated against XSD. Subsequently, the same records were normalized by mapping free-text values to standardized code tables, filling mandatory fields, and correcting format inconsistencies.

As shown in Table 12, CE improved markedly: Traffic Road rose from 0.96 to 0.99, Traffic Incident from 0.92 to 0.97, Traffic Role from 0.89 to 0.93, and Traffic Vehicle from 0.85 to 0.88. The most frequent initial errors involved uncontrolled values, missing mandatory items, and formatting mismatches. After normalization, these errors dropped to negligible levels.

This test highlights that, without additional algorithms or hardware, the UTC-UMM framework enhances metadata quality by enforcing semantic and syntactic consistency. Together with the performance results, it confirms both the scalability and the practical usability of the model.

This study addresses the complexity of urban-road congestion by introducing a unified metadata framework that covers nine core data domains, including accidents, roads, geography, vehicles, indicators, facilities, roles, traffic information, and related information. The framework applies a two-tier schema that links generic elements with resource-specific elements. It provides a complete specification that can describe structured, semi-structured, and unstructured data, and it reconciles semantic inconsistency and format heterogeneity.

The major finding is that UTC-UMM achieves broader coverage and better extensibility than existing standards. Previous studies often focused on single-type data, such as videos or relied on knowledge graphs that require high construction costs. In contrast, UTC-UMM integrates multiple heterogeneous sources within one consistent schema. Benchmark comparisons further show that it outperforms IEEE 1512 and DATEX II in coverage, controlled vocabulary use, and scalability. The results demonstrate that the model offers both technical feasibility and practical superiority.

Operational viability was confirmed on a cloud-based platform using the YCSB benchmark. Tests on five road column families sustained throughputs of 2250–2350 ops

Despite these promising results, several challenges remain. Future work will integrate traffic metadata with association rule mining to reveal spatio-temporal relationships among pedestrians, vehicles, and other entities. It will also focus on improving metadata extraction and quality control, expanding distributed storage and computing architectures, and designing a rule-based framework under spatio-temporal constraints. Through these efforts, the model can further support in-depth analysis of complex traffic phenomena.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to Letian Wang at Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing.

Funding Statement: This paper is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62172033).

Author Contributions: Jianchun Wen wrote the first draft of the manuscript; Bo Gao, Zhaojian Liu, and Xuehan Li revised the initial manuscript; Minghao Zhu designed the study question and supervised the research. All the authors analyzed the results, discussed this work, and commented on the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/cmc.2025.069671/s1.

References

1. Fujdiak R, Masek P, Mlynek P, Misurec J, Muthanna A. Advanced optimization method for improving the Urban traffic management. In: 2016 18th Conference of Open Innovations Association and Seminar on Information Security and Protection of Information Technology (FRUCT-ISPIT); 2016 Apr 18–22. St. Petersburg, Russia. p. 48–53. [Google Scholar]

2. Li X, Jing T, Wang X, Han D, Fan X, Dong H, et al. Two-stage offloading for an enhancing distributed vehicular edge computing and networks: model and algorithm. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2024;25(11):17744–614. doi:10.1109/tits.2024.3424852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Li X, Jing T, Li R, Wang X, Yan Y, Fan X, et al. Self-learning based dependable offloading optimization in semi-trusted vehicular edge computing and networks. IEEE Trans Vehicular Technol. 2025;74(5):8141–57. doi:10.1109/tvt.2025.3526696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Li J, Pang Y, Li X. Traffic congestion Net (TCNetan accurate traffic congestion level estimation method based on traffic surveillance video feature extraction. In: CICTP 2020; 2020 Aug 14–16; Xi’an, China. p. 1–12. doi:10.1061/9780784483053.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Chen M, Yu X, Liu Y. PCNN: deep convolutional networks for short-term traffic congestion prediction. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2018;19(11):3550–9. doi:10.1109/tits.2018.2835523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Guo S, Lin Y, Wan H, Li X, Cong G. Learning dynamics and heterogeneity of spatial-temporal graph data for traffic forecasting. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2022;34(11):5415–28. doi:10.1109/tkde.2021.3056502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Cui L, Deng Y, Bai Y, Peng Q. Beyond binary relationship: multivariant analysis between ride-hailing and public transit based on multi-sourcing data. Travel Behav Soc. 2025;38:100876. doi:10.1016/j.tbs.2024.100876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang J, Zhang C, Liu Y, Zhang Q. Traffic sensory data classification by quantifying scenario complexity. In: 2018 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV 2018); 2018 Jun 26–30; Suzhou, China. p. 1543–8. [Google Scholar]

9. Yang W, Zhu Q. Ontology-based semantic fusion of traffic information. In: 2012 International Conference on Computer Science and Service System; 2012 Aug 11–13; Nanjing, China. p. 769–72. [Google Scholar]

10. Cao M, Zhu W, Barth M. Mobile traffic surveillance system for dynamic roadway and vehicle traffic data integration. In: 14th International IEEE Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems, ITSC 2011; 2011 Oct 5–7; Washington, DC, USA. p. 771–6. [Google Scholar]

11. Bellini P, Benigni M, Billero R, Nesi P, Rauch N. Km4City ontology building vs data harvesting and cleaning for smart-city services. J Vis Lang Comput. 2014;25(6):827–39. doi:10.1016/j.jvlc.2014.10.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Van de Vyvere B, Colpaert P, Mannens E, Verborgh R. Open traffic lights: a strategy for publishing and preserving traffic lights data. In: WWW ’19: Companion Proceedings of the 2019 World Wide Web Conference; 2019 May 13–17; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 966–71. [Google Scholar]

13. Longhorn RA. Geospatial standards, interoperability, metadata semantics and spatial data infrastructure. In: NIEeS Workshop on Activating Metadata. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2005 Jul 6–7. p. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

14. Nogueras-Iso J, Zarazaga-Soria FJ, Muro-Medrano PR. Geographic information metadata for spatial data infrastructures: resources, interoperability and information retrieval. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

15. Muller CL, Chapman L, Grimmond C, Young DT, Cai XM. Toward a standardized metadata protocol for urban meteorological networks. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 2013;94(8):1161–85. doi:10.1175/bams-d-12-00096.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Mostafa A, Mokbel M. Towards open-source maps metadata. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2023. doi:10.1145/3589132.3625576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Kunze J, Baker T. The Dublin core metadata element set. Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF); 2007. doi:10.17487/RFC5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Karschnick O, Kruse FA, Töpker S, Riegel T, Eichler M, Behrens S. The UDK and ISO 19115 Standard. In: EnviroInfo. Santa Monica, CA, USA: Metropolis. 2003. p. 475–81. [Google Scholar]

19. Cuculovic M, Fondement F, Devanne M, Weber J, Hassenforder M. Semantics to the rescue of document-based XML diff: a JATS case study. Software Pract Exper. 2022;52(6):1496–516. doi:10.1002/spe.3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Silva BN, Khan M, Han K. Towards sustainable smart cities: a review of trends, architectures, components, and open challenges in smart cities. Sustain Cities Soc. 2018;38:697–713. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2018.01.053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hinz S, Lenhart D, Leitloff J. Traffic extraction and characterisation from optical remote sensing data. Photogrammetric Rec. 2008;23(124):424–40. doi:10.1111/j.1477-9730.2008.00497.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Gugulica M, Burghardt D. Mapping indicators of cultural ecosystem services use in urban green spaces based on text classification of geosocial media data. Ecosyst Serv. 2023;60:101508. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2022.101508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Pedersen KF, Torp K. Geolocating traffic signs using large imagery datasets. In: Proceedings of 17th International Symposium on Spatial and Temporal Databases, SSTD 2021. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2021. p. 34–43. [Google Scholar]

24. Yong-Kul K, Jin-Woo K, Doo-Kwon B. A traffic accident detection model using metadata registry. In: Fourth International Conference on Software Engineering Research, Management and Applications; 2006 Aug 9–11. Seattle, WA, USA. p. 255–9. [Google Scholar]

25. Bakirci M. Internet of Things-enabled unmanned aerial vehicles for real-time traffic mobility analysis in smart cities. Comput Electr Eng. 2025;123:110313. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2025.110313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Xu MY, Fang J, Tong YF. An intelligent adaptive spatiotemporal graph approach for GPS-data based travel time estimation. IEEE Intell Transp Syst Mag. 2022;14(5):222–37. doi:10.1109/mits.2021.3059796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhao X, Ma H, Zhang H, Tang Y, Fu G. Metadata extraction and correction for large-scale traffic surveillance videos. In: 2014 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data); 2014 Oct 27–30; Washington, DC, USA. p. 412–20. [Google Scholar]

28. Gong Y, Deng F, Sinnott RO. Identification of (near) real-time traffic congestion in the cities of Australia through Twitter. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2015. doi:10.1145/2811271.2811276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Das RD, Purves RS. Exploring the potential of Twitter to understand traffic events and their locations in greater Mumbai, India. India IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2020;21(12):5213–22. doi:10.1109/tits.2019.2950782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Qiao G, Wang W, Wu Z, Zhang J. Web service research of urban geographical data based on XML. In: 2006 6th International Conference on ITS Telecommunications; 2006 Jun 21–23; Chengdu, China. p. 214–7. [Google Scholar]

31. Zhou H, Jia L, Qin Y. Metadata specification of railway video information and its application in video monitoring system for Qinghai-Tibet railway. In: 2009 International Symposium on Computer Network and Multimedia Technology; 2009 Jan 18–20; Wuhan, China. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

32. Labetski A, Kumar K, Ledoux H, Stoter J. A metadata ADE for CityGML. Open Geospat Data Softw Stand. 2018;3(1):16. doi:10.1186/s40965-018-0057-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IJ, Appleton G, Axton M, Baak A, et al. The FAIR guiding principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci Data. 2016;3(1):1–9. doi:10.3233/ds-210047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhang M, Zhang X, Wang L, Han X, Xu D, Liu Y. Entity-relation joint extraction from urban planning standards without annotated data resources. Trans GIS. 2025;29(5):e70111. doi:10.1111/tgis.70111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Ulrich H, Kock-Schoppenhauer AK, Deppenwiese N, Gött R, Kern J, Lablans M, et al. Understanding the nature of metadata: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2022 Jan;24(1):e25440. [Google Scholar]

36. Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. Transportation information resource catalog system—part 3: core metadata. China Standards Press; 2020. Standard No.: JT/T 747.3; 2020. [cited 2025 Aug 25]. Available from: https://std.samr.gov.cn/hb/search/stdHBDetailed?id=BBF7535625AA2E1BE05397BE0A0A5DF9. [Google Scholar]

37. Gartner R. Metadata in the digital library: building an integrated strategy with XML. 1st ed. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2021. [Google Scholar]

38. Astrova I, Koschel A, Wellermann N, Klostermeyer P. Performance benchmarking of NewSQL databases with Yahoo Cloud serving Benchmark. In: Proceedings of the Future Technologies Conference. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 271–81. [Google Scholar]

39. Bounds MW III. IEEE 1512 family of standards. Space Commun. 2002;18(3–4):179–86. [Google Scholar]

40. Rinne M. Towards interoperable traffic data sources. In: 10th ITS European Congress, ERTICO–ITS Europe; 2014 Jun 16–19; Helsinki, Finland. SP 0018. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools