Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Cognitive Erasure-Coded Data Update and Repair for Mitigating I/O Overhead

School of Cyberspace Security, Hainan University, Haikou, 570228, China

* Corresponding Author: Yi Wu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069910

Received 03 July 2025; Accepted 09 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

In erasure-coded storage systems, updating data requires parity maintenance, which often leads to significant I/O amplification due to “write-after-read” operations. Furthermore, scattered parity placement increases disk seek overhead during repair, resulting in degraded system performance. To address these challenges, this paper proposes a Cognitive Update and Repair Method (CURM) that leverages machine learning to classify files into write-only, read-only, and read-write categories, enabling tailored update and repair strategies. For write-only and read-write files, CURM employs a data-difference mechanism combined with fine-grained I/O scheduling to minimize redundant read operations and mitigate I/O amplification. For read-write files, CURM further reserves adjacent disk space near parity blocks, supporting parallel reads and reducing disk seek overhead during repair. We implement CURM in a prototype system, Cognitive Update and Repair File System (CURFS), and conduct extensive experiments using real-world Network File System (NFS) and Microsoft Research (MSR) workloads on a 25-node cluster. Experimental results demonstrate that CURM improves data update throughput by up to 82.52%, reduces recovery time by up to 47.47%, and decreases long-term storage overhead by more than 15% compared to state-of-the-art methods including Full Logging (FL), Parity Logging (PL), Parity Logging with Reserved space (PLR), and PARIX. These results validate the effectiveness of CURM in enhancing both update and repair performance, providing a scalable and efficient solution for large-scale erasure-coded storage systems.Keywords

With the advent of the big data era, storage systems continue to scale up, and component failures have become increasingly common [1,2]. To ensure data reliability, modern storage systems typically employ replication and erasure coding (EC) techniques for fault tolerance [3]. In replication-based storage systems, data are divided into multiple blocks, and several replicas are generated for each block. In contrast, EC encodes a specified number of data blocks to produce parity blocks [4]. When block loss occurs, the system can reconstruct the missing block using the remaining data and parity blocks [5–9]. EC provides fault tolerance equivalent to replication while significantly reducing storage overhead, making it widely adopted in large-scale storage systems [10,11].

However, EC inevitably introduces higher I/O overhead than replication, especially in small-block write scenarios [12,13]. This overhead arises because updating a single data block requires additional operations on the associated parity blocks. To ensure consistency, erasure-coded systems generally adopt either re-encoding-based updates (REBU) or parity-delta-based updates (PDBU) [14]. REBU regenerates parity blocks by combining new and unchanged data, whereas PDBU calculates a parity delta by comparing old and new data before updating. While PDBU reduces overhead relative to REBU, it still requires reading old data before each update, resulting in higher update latency under intensive write workloads.

To address these limitations, log-based strategies have been proposed. FL appends updated data and parity differences sequentially to reduce update latency, but incurs excessive disk seeks for sequential reads and recovery [15]. PL [16] balances updates and reads by combining in-place writes with parity logging. Further, SARepair [17] enhances multi-stripe recovery in RS-coded clusters by dynamically refining recovery strategies with rollback functionality. PLR [18] reduces repair overhead by reserving disk space adjacent to parity blocks, but this strategy significantly increases storage overhead. These studies show that existing approaches often trade off between update performance, repair efficiency, and storage overhead, but cannot achieve simultaneous optimization across all dimensions.

Motivated by these challenges, this study proposes the Cognitive Update and Repair Method (CURM) to minimize both update and repair costs in erasure-coded storage systems. CURM leverages machine learning to classify files into three categories—write-only, read-only, and read-write—and applies tailored strategies accordingly. For write-only and read-write files, CURM employs data differences rather than parity deltas to avoid redundant I/O and introduces fine-grained I/O scheduling to transform

• We design a decision-tree-based file classification mechanism that categorizes files into write-only, read-only, and read-write types, enabling CURM to apply differentiated update and repair strategies. This classification achieves a prediction accuracy of over 92% on real-world traces, providing a reliable foundation for tailored operations.

• We propose a fine-grained update method that leverages data differences and parallel I/O scheduling, which significantly reduces I/O amplification. Experimental results show that CURM improves update throughput by up to 82.52% over state-of-the-art methods.

• We introduce a selective space reservation strategy for read-write files, which enables parallel repair while minimizing disk seek overhead. This design reduces recovery time by up to 47.47% and decreases long-term storage overhead by more than 15% over existing strategies such as FL, PL, PLR, and PARIX.

Our study focuses on the update efficiency of erasure-coded data in intensive small-block data update scenarios and the repair efficiency after data updates. Since data updates require corresponding updates to the parity blocks, they result in additional communication and I/O overhead. In [18], the updating tasks are performed in batches. The storage system uses a real-time method for data updates and a delayed method for parity updates. The update requests in a batch can be merged to reduce the inter-rack traffic generated by parity updates. Similarly, in [19], a cross-rack parallel update strategy (GRPU) based on graph theory is proposed, where interrelated data blocks are strategically deployed on the same stripe or even the same rack, maximizing the benefits of local communication.

For I/O optimization, FL [14] employs a log-append-based strategy to update both data and parity, reducing seek overhead during updates. However, it incurs high seek overhead during data reads. In contrast, PL [16] employs in-place updates for data and log-based updates for parity blocks, effectively balancing data updates and reads. Erasure-Coded Multi-block Updates (ECMU) [20] selects suitable write strategies based on the update size in applications, using a parity delta-based approach for small-block updates to reduce I/O, while re-encoding is applied for large-block updates to minimize overhead. PARIX [21] combines replicas and erasure coding to transform “read-after-write” into “write-after-write” operations, reducing seek operations during data updates, although current methods still require additional I/O. Further, in [5], the authors propose an integer linear programming model for the edge data placement problem to minimize storage overhead in edge storage systems. However, the proposed optimal solution for the edge data placement problem suffers from scalability issues due to its computational complexity, limiting its practicality in large-scale deployments.

When components fail, storage systems need to repair updated data. In [22], a weighted flow network graph is constructed based on the mappings between files, stripes, and blocks. The Ford-Fulkerson algorithm is applied to determine the maximum flow, enabling parallel repair of lost data. SelectiveEC, introduced in [23], dynamically selects a set of repair jobs and optimally chooses source and target nodes for each reconstruction task, achieving load balancing of storage nodes under single-node failure. Additionally, reference [24] proposes constructing new stripes for updated data from the same or original stripe, minimizing the mixing of new and old data blocks within stripes and thereby reducing seek times. The PLR technique accelerates data access without reorganizing blocks, reducing disk fragmentation and minimizing seeks, though reserving space leads to increased storage overhead. In-network approaches are also explored. NetEC [4] proposes offloading erasure coding reconstruction tasks to programmable switches, improving reconstruction speed and reducing read latency. However, switch SRAM limitations and task concurrency challenges restrict its applicability in systems with frequent data updates and repairs. Similarly, reference [1] introduces Paint, a parallelized in-network aggregation mechanism for failure repair, which enhances throughput but faces scalability and I/O overhead issues in distributed environments. In [25], the authors propose elastic transformation, adjusting sub-packetization to balance repair bandwidth and minimize I/O overhead. However, managing sub-packetization becomes increasingly complex in systems with many nodes. An adaptive relaying scheme for streaming erasure codes is introduced in [26], which reduces latency and improves error correction in three-node networks but struggles with dynamic erasure patterns at a larger scale.

Recent advancements have explored hybrid approaches. Machine learning libraries [27] have been leveraged to accelerate EC encoding with minimal code changes, achieving a 1.75

While prior studies address various aspects of update and recovery in erasure-coded systems, they often fail to adapt to workload heterogeneity or incur a fixed overhead for all files, regardless of their access patterns. Most approaches assume uniform update behaviors and do not leverage file-level characteristics for optimization. Our proposed CURM addresses this gap by incorporating file-type-aware strategies and machine learning-driven classification to apply differentiated update and repair processes.

The principle of EC involves splitting the original data into smaller blocks and then generating additional pieces of information (parity) based on those blocks. The parity pieces are distributed across various storage nodes in the system alongside the original data blocks. In the event of a storage node failure or data loss, the system can reconstruct the missing or corrupted data by using the remaining data blocks and the parity information stored on other nodes. By having multiple redundant pieces distributed across the storage cluster, EC provides a high degree of fault tolerance. Maximum Distance Separable (MDS) codes are a specific class of EC schemes that plays a key role in ensuring data reliability and fault tolerance in storage systems. The principle of MDS codes revolves around maximizing the distance between codewords, which refers to the minimum number of changes (disk failures or data losses) required to transform one valid code word into another. Using a (

In this study, data reliability is enhanced through the use of Reed-Solomon (RS) codes, a subset of MDS codes known for their optimal error correction capabilities. The use of RS codes allows for cost-effective data reliability solutions, making them a popular choice for large-scale storage systems. RS coding involves arithmetic operations conducted in the Galois field GF(

Let

where

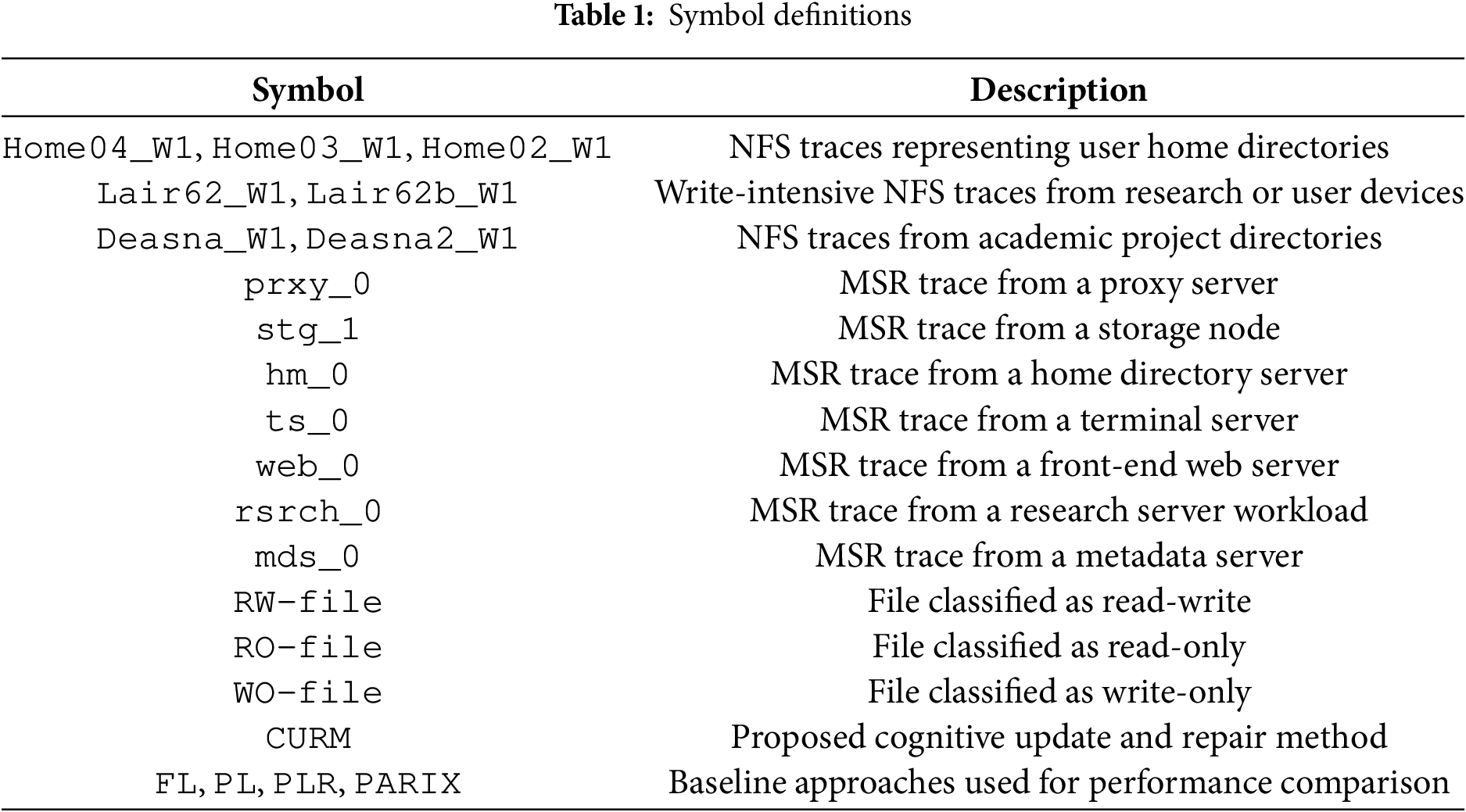

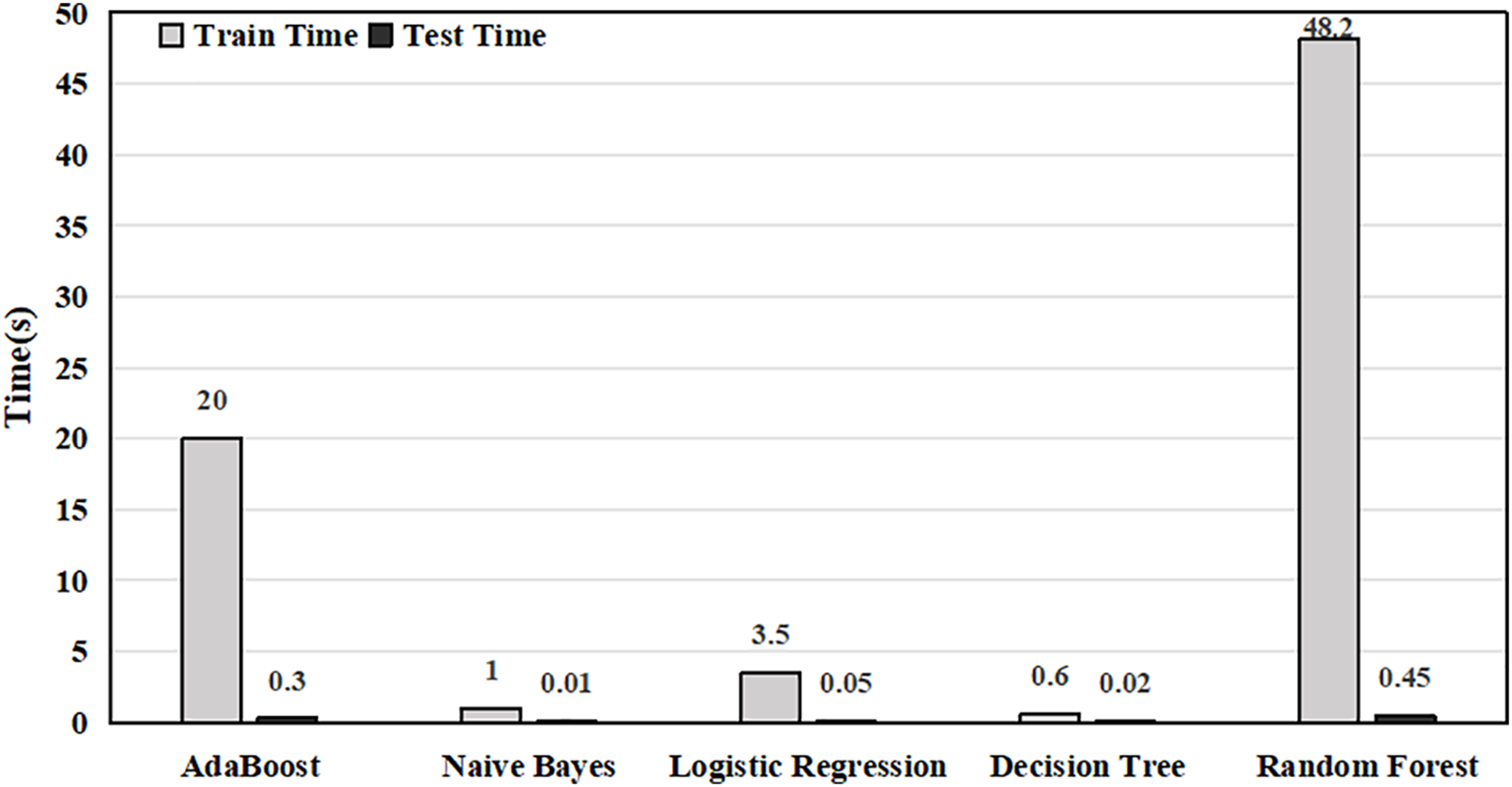

This study analyzes NFS traces [18] and MSR traces [30], provided by Harvard and Microsoft enterprise clusters, respectively. To facilitate interpretation of the figures in this section and subsequent analysis, Table 1 provides explanations for the figure-level notations used in NFS and MSR traces, including workload identifiers and classification labels. Fig. 1a illustrates the access distribution of the NFS trace. The write requests are categorized into update writes and non-update writes. Update write refers to the process of modifying existing data on a storage device. When new information is added, it is written to the storage device, replacing the previous version of the data. Non-update writes refer to write operations that do not modify existing data but instead involve writing new data to the storage device. The ratio of update writes is significantly higher than that of non-update writes. Fig. 1b shows the update size of the NFS trace. It can be seen that almost all update sizes are smaller than 128 KB. The dominant range is 8–128 KB. As depicted in Fig. 1c, update writes dominate the MSR traces, with an update write ratio exceeding 95% across all seven analyzed traces. Fig. 1d shows the distribution of access sizes in the MSR traces, revealing that access sizes are predominantly small, with the majority of requests being less than 128 KB. From the above analysis, we observe that small data updates are the dominant workload in these two real-world traces. Therefore, to optimize the overall performance of the storage system, improving the efficiency of small-block data updates is essential.

Figure 1: Access distribution of NFS and MSR traces

When selecting a classification algorithm, both traditional machine learning and advanced deep learning approaches could be considered. However, CURM requires frequent and sometimes near-real-time classification under dynamic workloads, where algorithms with high computational cost or inference latency are unsuitable. We therefore prioritize lightweight machine learning models to achieve the best balance between accuracy and efficiency.

Feature extraction is essential for ensuring both accuracy and interpretability. We select features under four principles: (i) low collection overhead—relying only on standard metadata and logs; (ii) temporal coverage—capturing both lifecycle stability and short-term locality; (iii) semantic discriminativeness—reflecting application intent; and (iv) orthogonality—ensuring complementary, non-redundant signals validated by information gain. Based on these principles, CURM employs seven features: 1) file type, 2) file age, 3) recency, 4) file size, 5) file owner, 6) recent access requests, and 7) access count. Each feature captures a distinct aspect of read/write behavior. File type and owner convey semantics, as logs or system files are typically write-heavy, while configuration files are read-dominant. Age and recency describe lifecycle and locality: younger or recently modified files are more likely to be write-intensive, whereas older and inactive files are often read-only. Size reflects access style—small files are frequently appended, while large files are mainly read sequentially. Recent requests capture short-term workload bursts, while access count reflects long-term tendencies. Together, these lightweight and complementary features enable the decision tree to learn interpretable rules that effectively separate write-only, read-only, and read-write files.

CURM classifies files into three categories: write-only, read-only, and read-write, with ground-truth labels derived from actual access traces. The classifier is trained on Harvard NFS and MSR Cambridge traces, totaling approximately 2.5 million file samples, randomly divided into 70% training and 30% testing sets. To ensure reproducibility, the decision tree is configured with Gini impurity as the splitting criterion, a maximum depth of 15 to control overfitting, a minimum of 2 samples for splitting, and 10 samples per leaf to avoid overly small nodes; all features are considered at each split.

Training proceeds via recursive partitioning: the algorithm evaluates splits for each feature, selects the one that maximizes impurity reduction, and continues until depth or size constraints are met. Each leaf node outputs one of the three classes. With this setup, the decision tree implemented in scikit-learn completes training on the entire dataset” within one second and achieves over 92% accuracy, with precision and recall further confirming robustness.

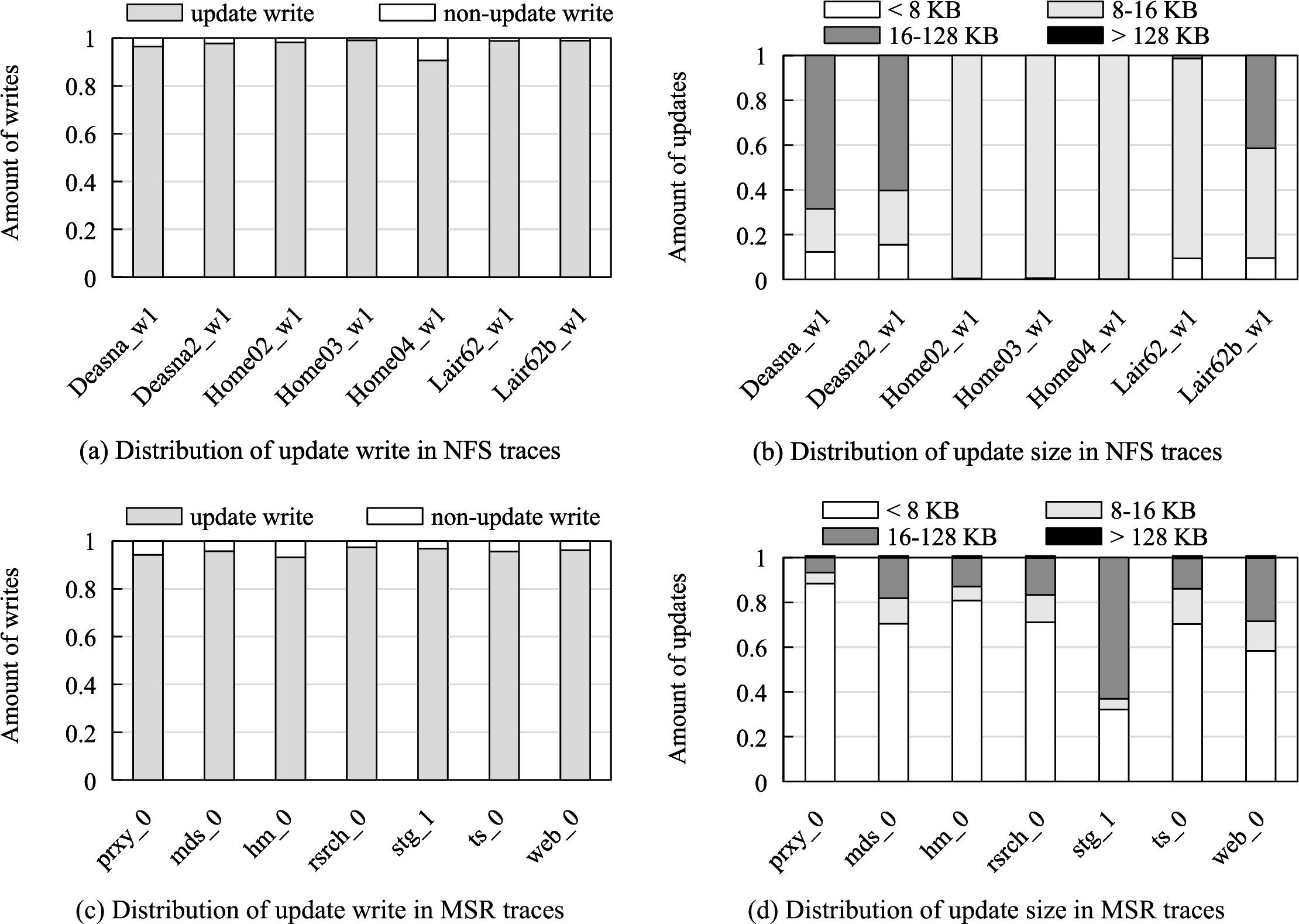

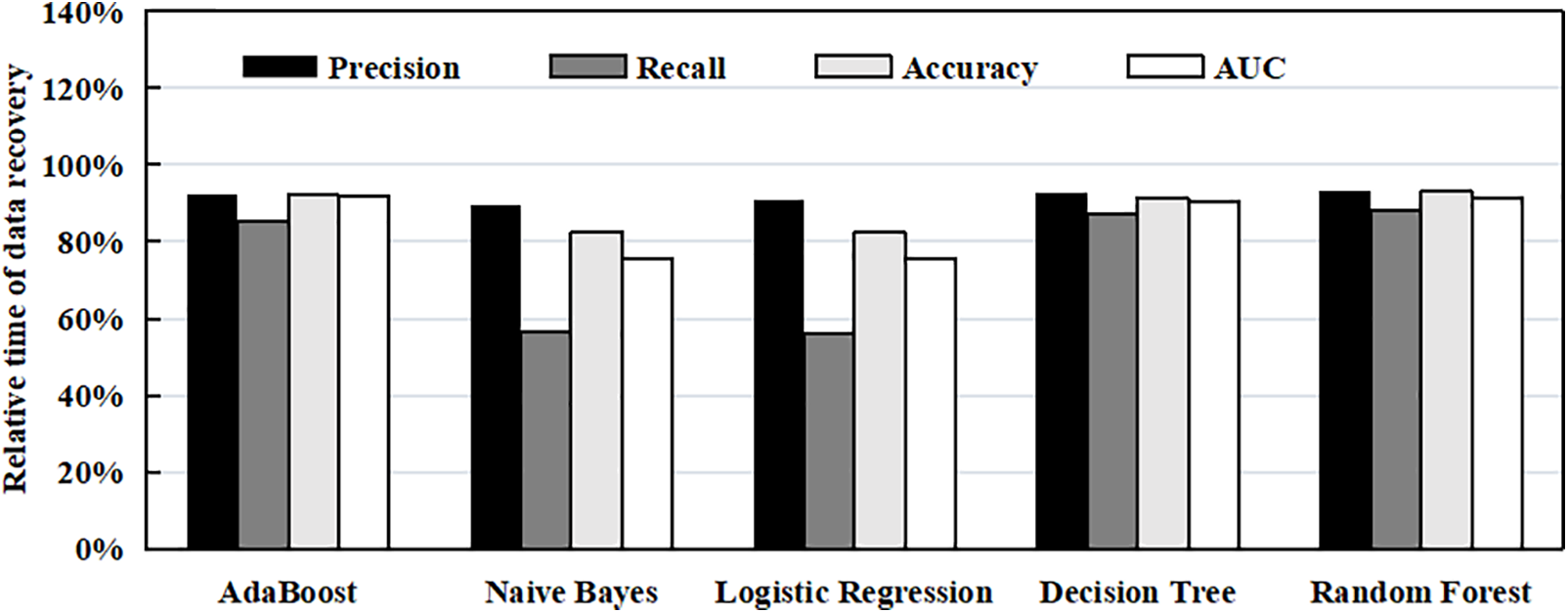

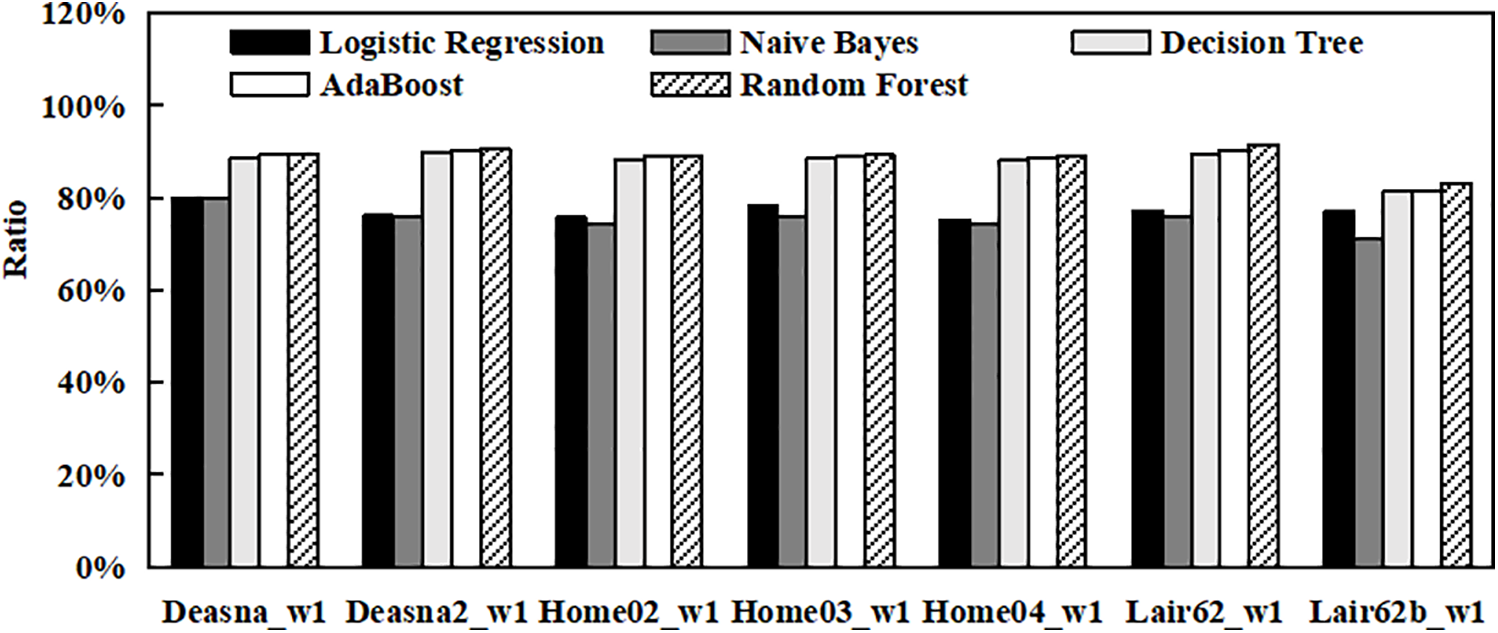

As shown in Fig. 2, the decision tree and random forest achieve the highest accuracy, with random forest slightly better. However, Fig. 3 shows that the decision tree trains in 0.6 s and tests in 0.02 s for ten thousand files, whereas random forest requires 48.2 s for training and 0.45 s for testing; AdaBoost is competitive but needs 20 s of training. Given that the accuracy gap compared with random forest is under 2%, its higher cost is unjustified. Deep learning models such as multilayer perceptrons and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) also offer strong accuracy in other domains but demand long training, large datasets, and significant resources. In CURM, where classification must be repeated frequently and with low latency, their overhead outweighs marginal accuracy gains. The decision tree therefore provides the most favorable trade-off and is adopted as the final classifier.

Figure 2: Metric values of all machine learning algorithms

Figure 3: Computation time of classification algorithms

Let

According to Eq. (2), we have

According to Eq. (3), we have

Eq. (4) shows that

PL is suitable for read-write files, as it can balance the updating and reading of data. FL is suitable for write-only files, as it can accelerate the writing of data. However, both PL and FL require performing a read-after-write operation for each small update. Based on Eq. (4), PL and FL can be optimized to reduce the I/O amplification.

According to Eq. (4), the data node should transmit data block

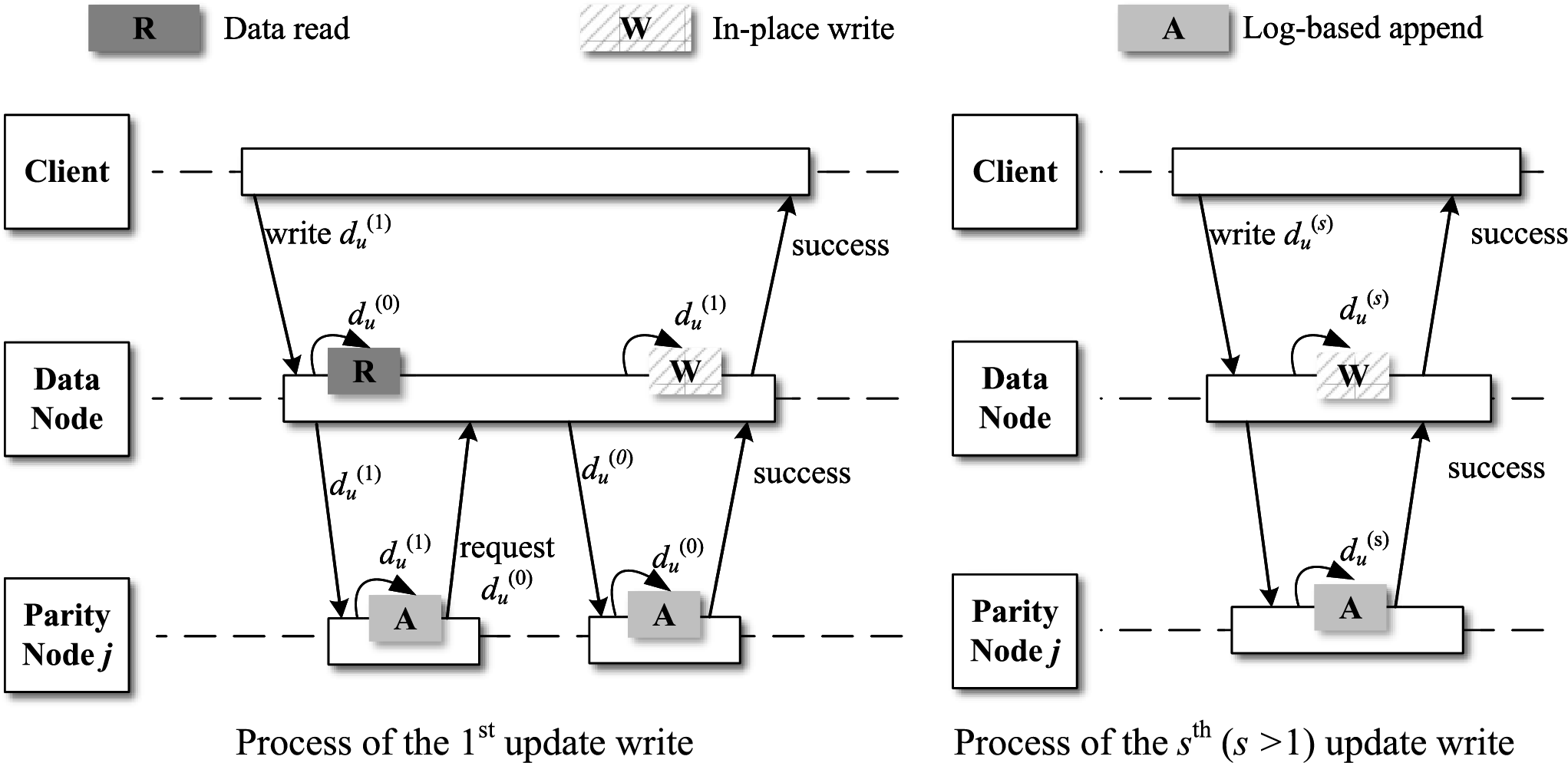

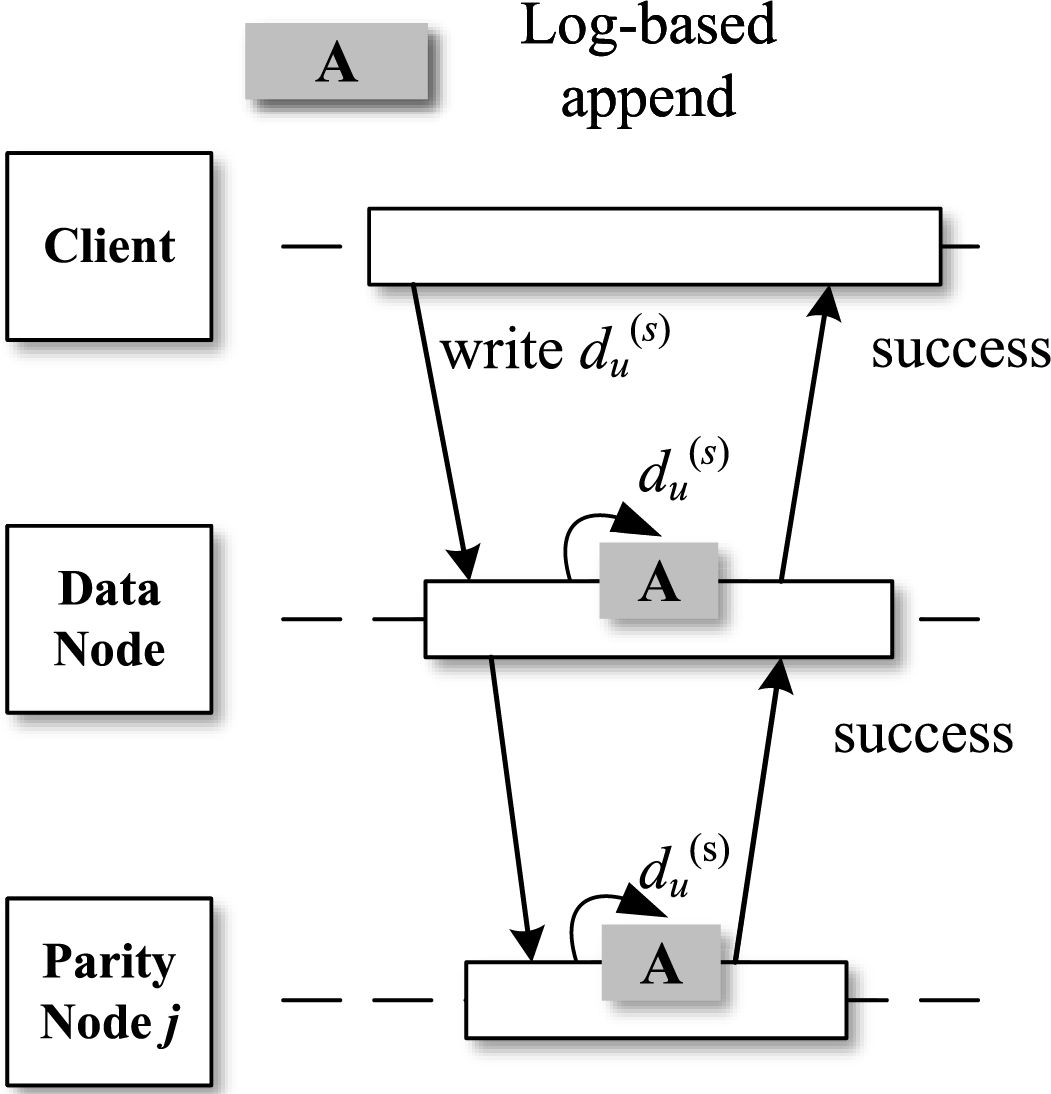

CURM introduces an enhanced update strategy grounded in PL, leveraging Eq. (4), specifically tailored for read-write files. The update workflow of the optimized PL (OPL) is illustrated in Fig. 4. Upon the initial write operation, the data node verifies the need for an update by consulting the label log. Given that the first data update lacks a corresponding entry in the log, the data node initiates by fetching the original data. When receiving

Figure 4: Process of OPL for read-write files

In FL, the original data is preserved and never overwritten. As a result, the storage system can access the original data from the data node to recover any lost data. This means that the data node only needs to transmit the updated data to the corresponding parity nodes

Figure 5: Process of OFL for write-only files

To further clarify the effectiveness of the fine-grained update mechanism under high-frequency small updates, we highlight that CURM reduces I/O amplification not only by avoiding repeated read-after-write operations but also by leveraging update logs and data difference computations. In scenarios with frequent small updates, traditional parity update mechanisms typically suffer from excessive disk I/O due to repeated reading of original data. CURM mitigates this by reusing cached or logged original data on data nodes and determining whether parity nodes require them, thereby minimizing unnecessary reads. Moreover, the use of Eq. (4) enables CURM to directly compute parity deltas from the current and initial data values, eliminating intermediate steps even when updates occur at high frequency. This design ensures that each small update only incurs one write to the parity node, rather than a full read-modify-write cycle. Consequently, CURM maintains low latency and high throughput even under intensive update workloads, as later verified in Section 6.2.

4.3 Reserving Space Based on Machine Learning

Fig. 6 illustrates update strategies for different methods. In the figure,

Figure 6: Update procedures

4.4 Data Recovery Based on Reserving Space

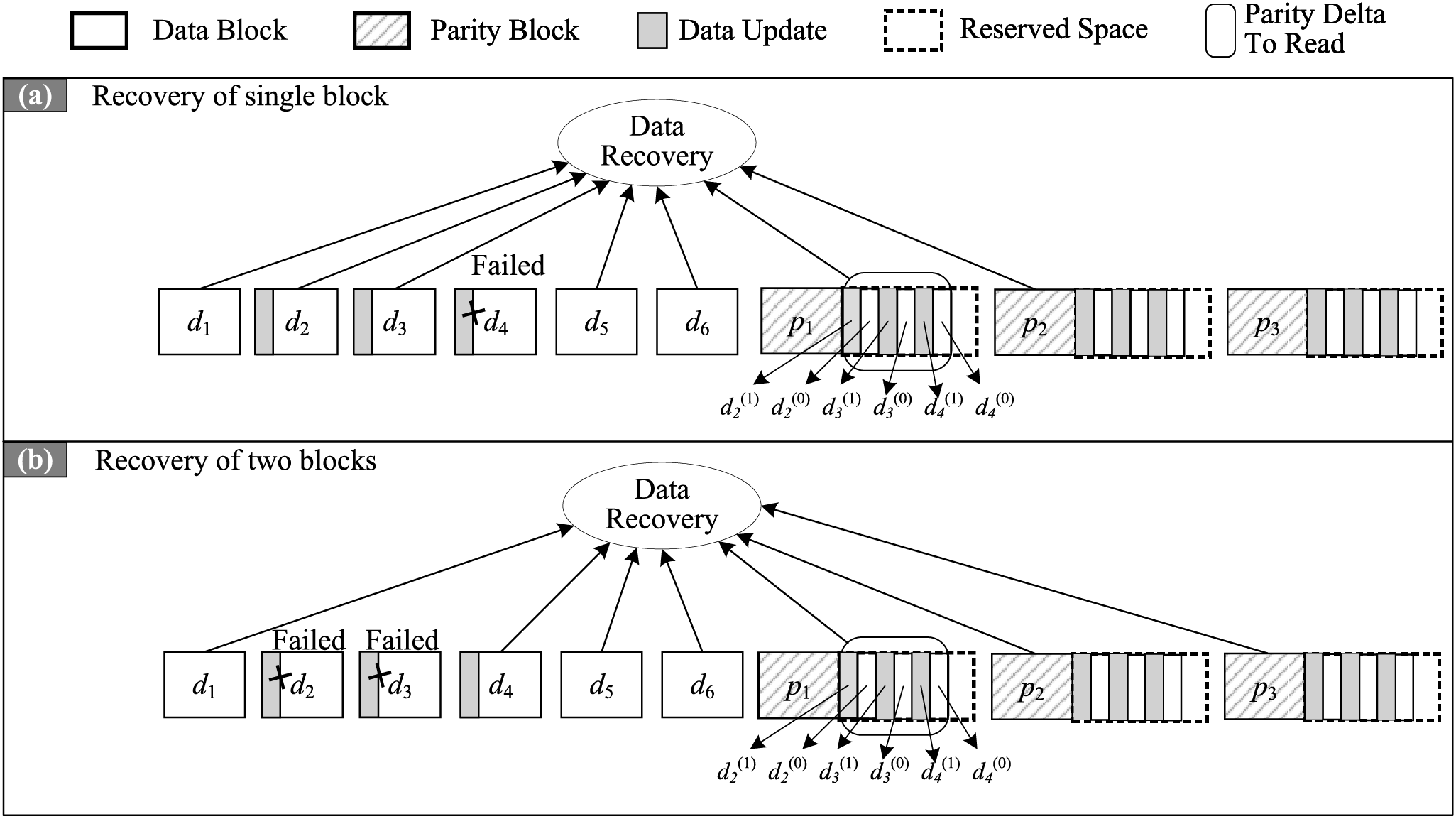

Fig. 7 depicts the data recovery procedure of CURM. Fig. 7a illustrates that when repairing the failed data block

Figure 7: Data recovery

5 Design of Prototype Storage System

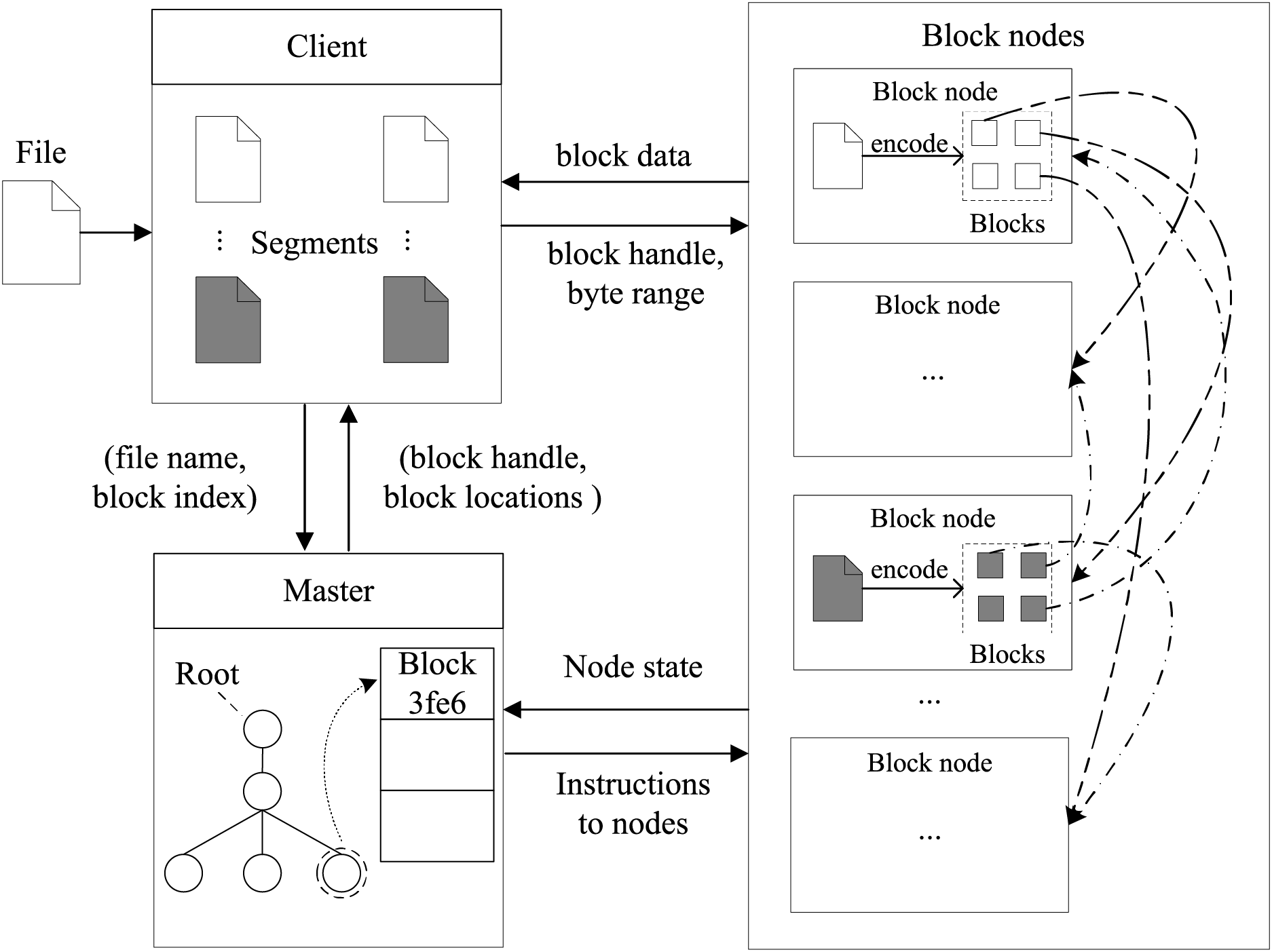

We design a prototype storage system named CURFS to evaluate the proposed methods, into which CURM is integrated for performance assessment. The architecture of CURFS is shown in Fig. 8. It contains a master, block nodes (data and parity nodes), and clients. The master maintains the namespace hierarchy of files and directories in the file system. It keeps track of the file names, directory structure, file sizes, access permissions, and other metadata information associated with each file. Any metadata operations such as file creation, deletion, renaming, or attribute updates are handled by the master. When a client application performs any metadata operation, it communicates with the master to update the metadata accordingly. The master stores metadata in memory for fast access and also periodically flushes it to disk for durability. It ensures that the metadata is consistent and up-to-date across all nodes in the system.

Figure 8: CURFS architecture

A block node is a critical component responsible for storing and managing the actual data chunks that make up the files stored in the distributed file system. The block node works in conjunction with the master and client applications to ensure efficient storage and retrieval of data in CURFS. The client acts as the intermediary between user applications and the distributed file system, enabling file I/O operations. During write operations, the client first partitions the file into chunks and interacts with the master to store metadata and identify the primary block node for each chunk. The client then sends each chunk to its assigned primary block node, which encodes the chunk into

The master assigns secondary block nodes to ensure balanced load distribution across the storage cluster. While primary and secondary block nodes are logical constructs rather than physical entities, they are purposefully defined to facilitate system operations and support load balancing. Any physical block node can serve as either a primary or secondary block node, depending on the segment it handles.

When a segment is read, the client first queries the master’s metadata daemon (MSD) to identify the primary block node. The client then sends a read request to the designated primary block node, which retrieves the local chunk and requests the remaining chunks from the secondary block nodes. These

The execution of write operations leads to a notable increase in the size of logs stored on data nodes and parity nodes. Once a node’s disk utilization or the reserved disk space hits a predefined threshold, asynchronous merge compactions are triggered. The compaction process offers the following benefits: 1) considerable reduction in the disk space consumed by logs, and 2) substantial decrease in the amount of data that must be read from logs, particularly during data recovery processes.

In summary, the prototype storage system described above provides the foundation for the subsequent evaluation of CURM. To ensure clarity and readability of this manuscript, we employed limited use of AI-assisted tools. During the preparation of this manuscript, ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA; https://openai.com (accessed on 13 September 2025)) was used only for language polishing. All scientific content, data analyses, and conclusions are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Our experiments are conducted on 25 physical nodes, each with dual Intel Xeon 4114 CPUs, 128 GB RAM, and six 4TB hard drives. We use an RS(6, 3) code to provide fault tolerance, and replay Harvard’s NFS traces [18] for evaluation. We compare CURM with four representative schemes—FL, PL, PLR, and PARIX—which aim to reduce I/O amplification and disk-seek overheads in erasure-coded storage via log-based updates, parity-difference computation, or reserved-space allocation. While these methods represent the direct lineage of work in I/O workflow optimization, we note that other recent state-of-the-art approaches have focused on complementary areas; for instance, Elastic Transformation [25] explores code parameter tuning, while Rethinking Erasure-Coding Libraries [27] focuses on computational acceleration. CURM differs by combining data-difference utilization with fine-grained scheduling and applying selective space reservation guided by file classification. This design highlights CURM’s comparability with existing methods and serves as the basis for the detailed evaluation presented in the following subsections.

Fig. 9 shows the accuracy of machine learning algorithms. Decision Tree, AdaBoost, and Random Forest consistently achieve high accuracies across all traces, approaching or exceeding 90% in most cases. Specifically, Decision Tree performs remarkably well, maintaining accuracies ranging from 88.71% to 89.61%. AdaBoost and Random Forest also demonstrate robust performance, with accuracies ranging between 88.78% and 91.4%. These results underscore the effectiveness of ensemble methods (AdaBoost and Random Forest) and decision-based algorithms (Decision Tree) in handling diverse I/O traces for file classification tasks.

Figure 9: Accuracy of machine learning algorithms

In contrast, Logistic Regression and Naive Bayes exhibit lower accuracies compared to the tree-based methods. Logistic Regression achieves accuracies between 75.66% and 80.02%, while Naive Bayes ranges from 71.02% to 80.01%.

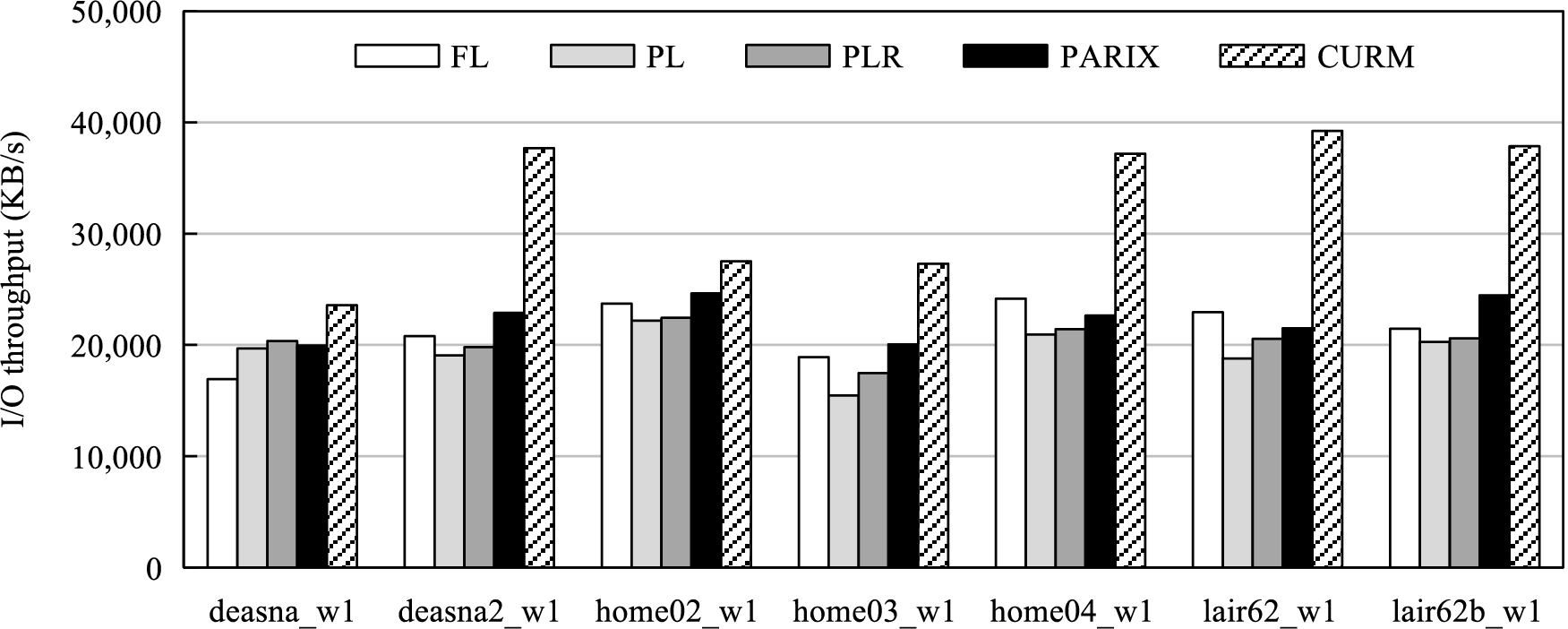

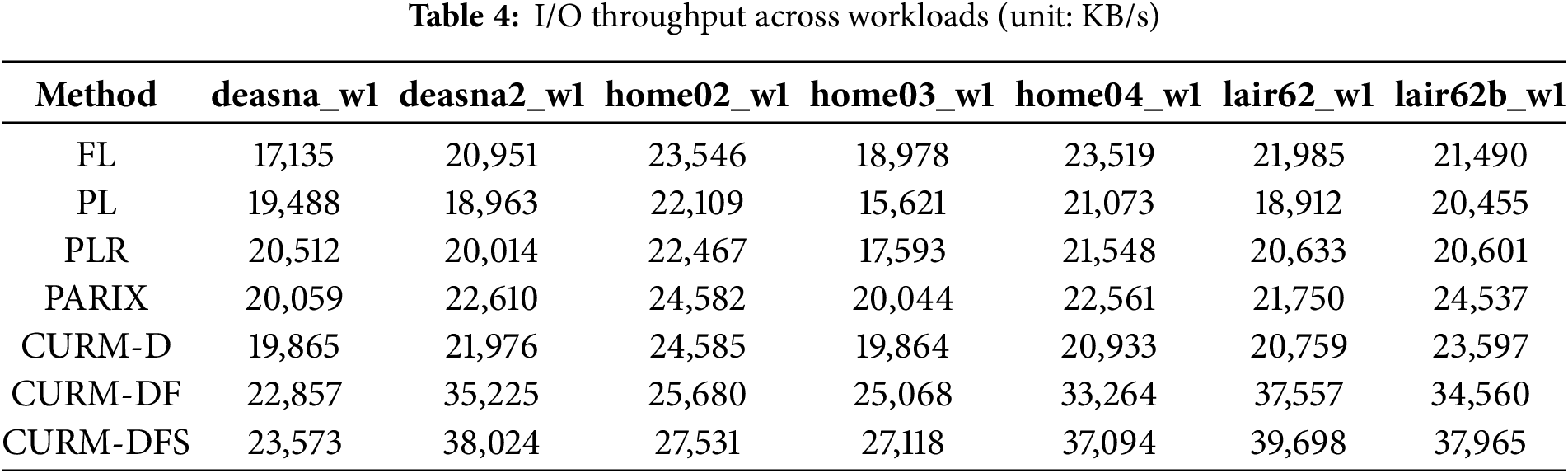

6.2 Evaluation of I/O Throughput

Fig. 10 shows the I/O throughput of FL, PL, PLR, PARIX, and CURM applied to seven I/O traces. FL consistently demonstrates moderate performance: it benefits from log-appended writes but suffers from slower reads due to frequent log seeks. PL exhibits more balanced performance by reducing the need for seek operations during reads, thereby mitigating some of FL’s drawbacks. PLR delivers throughput close to PL, as reserved contiguous space shortens seek distance during parity updates, while PARIX reduces logging overhead by adaptively recording only updated data values, yielding performance comparable to PL and PLR. Among all methods, CURM consistently achieves the highest throughput, especially in workloads with frequent small updates such as deasna2_w1, home04_w1, lair62_w1, and lair62b_w1. The primary reason for this superior performance stems from its fine-grained update mechanism described in Section 4.2. Unlike PL, which still requires a traditional “read-modify-write” cycle for each update, CURM leverages Eq. (4) to transform a series of

Figure 10: I/O throughput of update methods

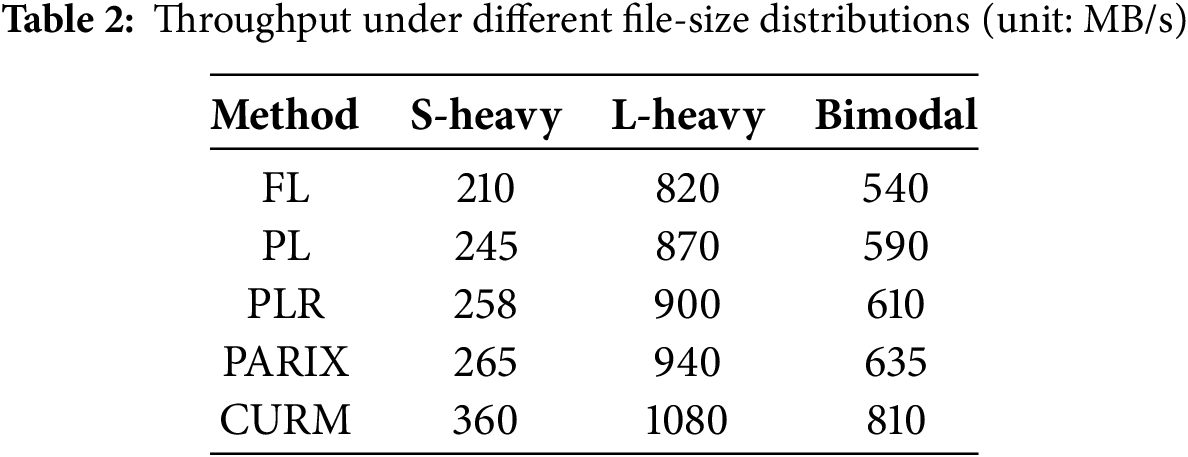

To further examine CURM’s universality, we introduce synthetic workloads with three representative file-size distributions, keeping the arrival process and read/write mix identical to the NFS traces. The profiles comprise S-Heavy (small files

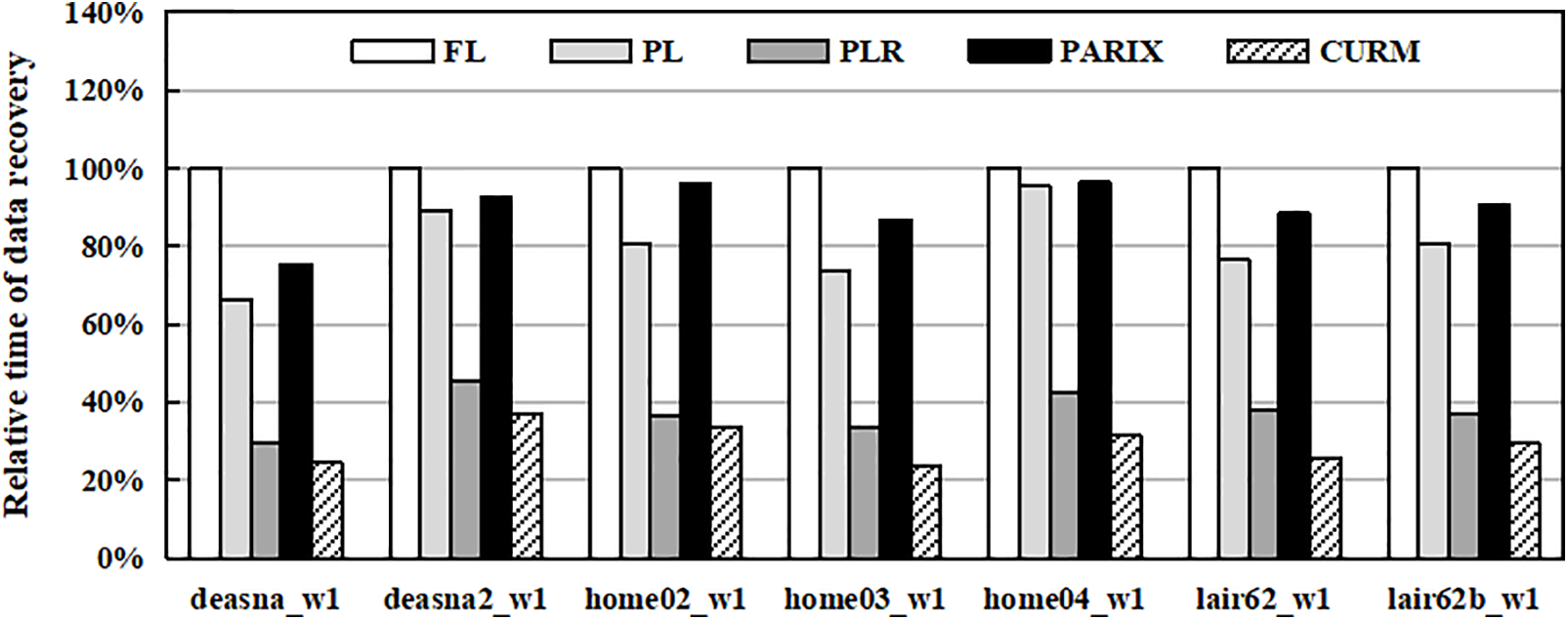

6.3 Evaluation of Data Recovery

Fig. 11 shows the relative recovery time compared to FL when the seven I/O traces are replayed. The experiments adopt a fault-injection approach to activate recovery. According to statistics from large-scale datacenters [31], single-block failures account for 98.08% of all cases, two-block failures for 1.87%, and three-block failures for 0.05%. To emulate realistic scenarios, our experiments follow the same proportions when injecting block failures. As the baseline, FL exhibits the slowest repair process due to frequent seek operations required to read scattered data from logs. PL improves repair efficiency by performing in-place updates for data, which balances write and read performance. PLR further optimizes recovery by reserving contiguous disk space, thereby reducing seek distances when accessing parity deltas. PARIX also leverages parity-difference computation, but its recovery process involves reading a larger volume of versioned data values, which slows recovery compared with PLR. Among all methods, CURM consistently achieves the fastest recovery performance, reducing repair time by up to 47.47% compared with PARIX. This significant advantage stems from CURM’s enhanced reserved space strategy (Section 4.4). While PLR effectively improves spatial locality by storing parity deltas, CURM goes further by also storing recent versions of updated data chunks within the reserved space on parity nodes. During reconstruction, these cached versions can be directly retrieved from one or two parity nodes instead of fetching data from all

Figure 11: Relative recovery time compared to FL

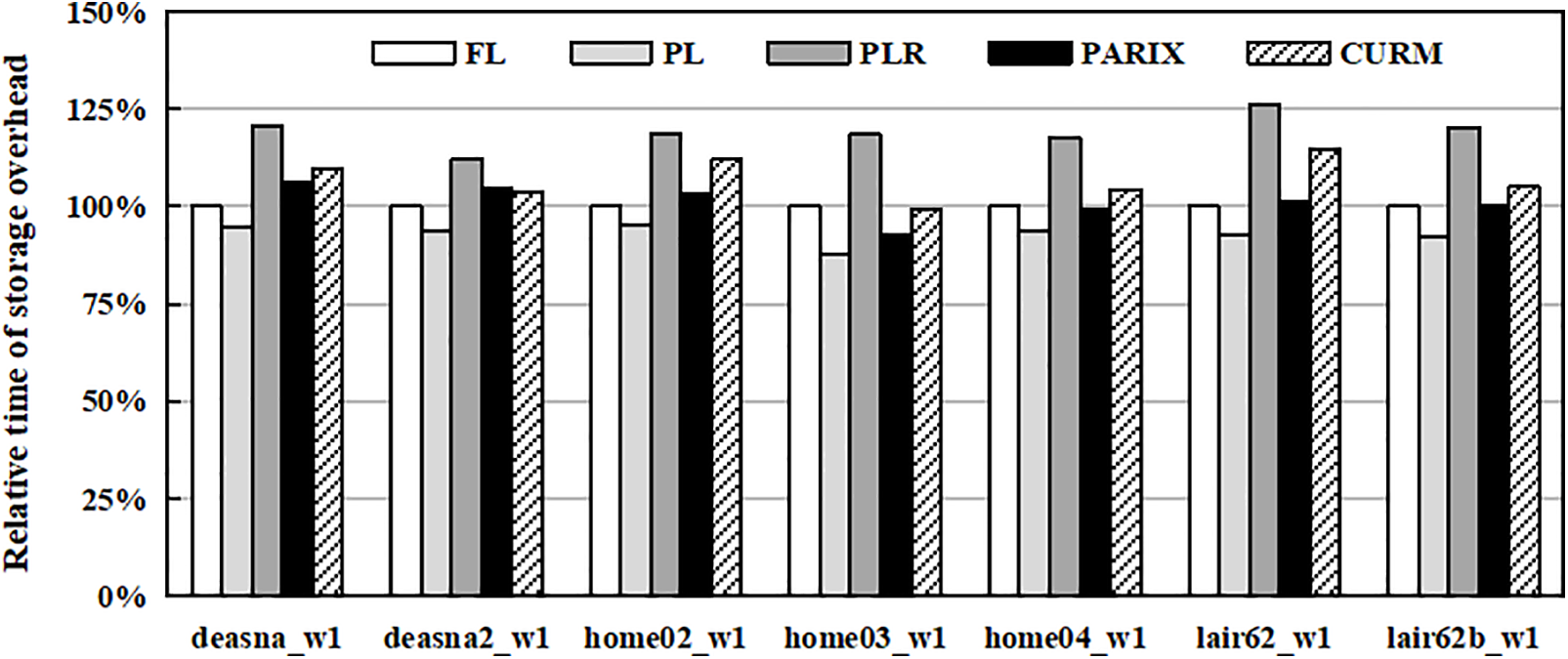

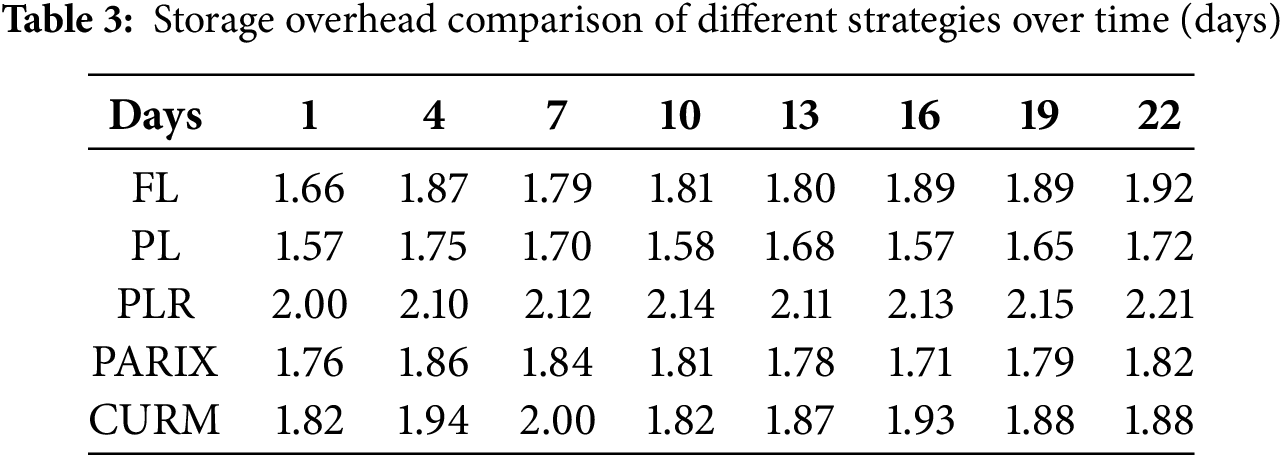

6.4 Evaluation of Storage Overhead

Fig. 12 illustrates the relative storage overhead of FL, PL, PLR, PARIX, and CURM, while Table 3 shows their long-term trends. FL incurs additional overhead because both data and parity deltas are appended to logs, causing continuous storage growth. For instance, the relative storage overhead of FL is 1.66 on Day 1, meaning that the consumed storage is about 1.66 times the size of the raw data, and it further increases to 1.92 by Day 22. PL reduces overhead by performing in-place updates for data and only logging parity, achieving consistently lower values than FL, with 1.57 on Day 1 and 1.72 on Day 22. PLR, by reserving contiguous disk space for future parity deltas, achieves efficient repair performance but introduces the highest storage overhead, remaining above 2.00 across all days. PARIX also increases storage usage because it maintains both original and updated data values at parity nodes, ranging from 1.76 on Day 1 to 1.82 on Day 22, which expands storage requirements compared with PL. In contrast, CURM achieves lower and more stable storage overhead across all traces, with values between 1.82 and 1.99 that remain close to PL and substantially lower than PLR. Its advantage arises from the combination of machine-learning-based file classification with selective space reservation, which ensures that only read-write files receive reserved space. This adaptive policy avoids the excessive and often unnecessary reservations seen in PLR while still preserving locality for frequently updated files. Moreover, CURM periodically reclaims and compacts unused logs, preventing long-term accumulation. Overall, Table 3 demonstrates that CURM not only provides efficient repair performance but also ensures sustainable storage management in long-term deployments.

Figure 12: Relative storage overhead compared to FL

6.5 Ablation Study on Key Strategies

Table 4 presents the I/O throughput results across workloads for different CURM variants. CURM-D refers to CURM with only data-difference utilization. CURM-DF represents CURM with both data-difference utilization and fine-grained I/O scheduling. CURM-DFS denotes the complete CURM, which integrates data-difference utilization, fine-grained scheduling, and selective space reservation.

The results reveal a clear progression in performance. Applying data-difference utilization alone, as in CURM-D, provides only marginal improvements over baseline schemes. This strategy eliminates the need to read the previous data version

In summary, the ablation study provides quantitative evidence that CURM’s performance improvements arise from the layered and synergistic contributions of its three strategies. Data-difference utilization establishes a necessary baseline by reducing redundant reads, fine-grained scheduling delivers the dominant throughput gains through intelligent orchestration, and selective space reservation adds complementary robustness by enhancing locality and ensuring long-term system stability.

6.6 Scalability Evaluation of CURM

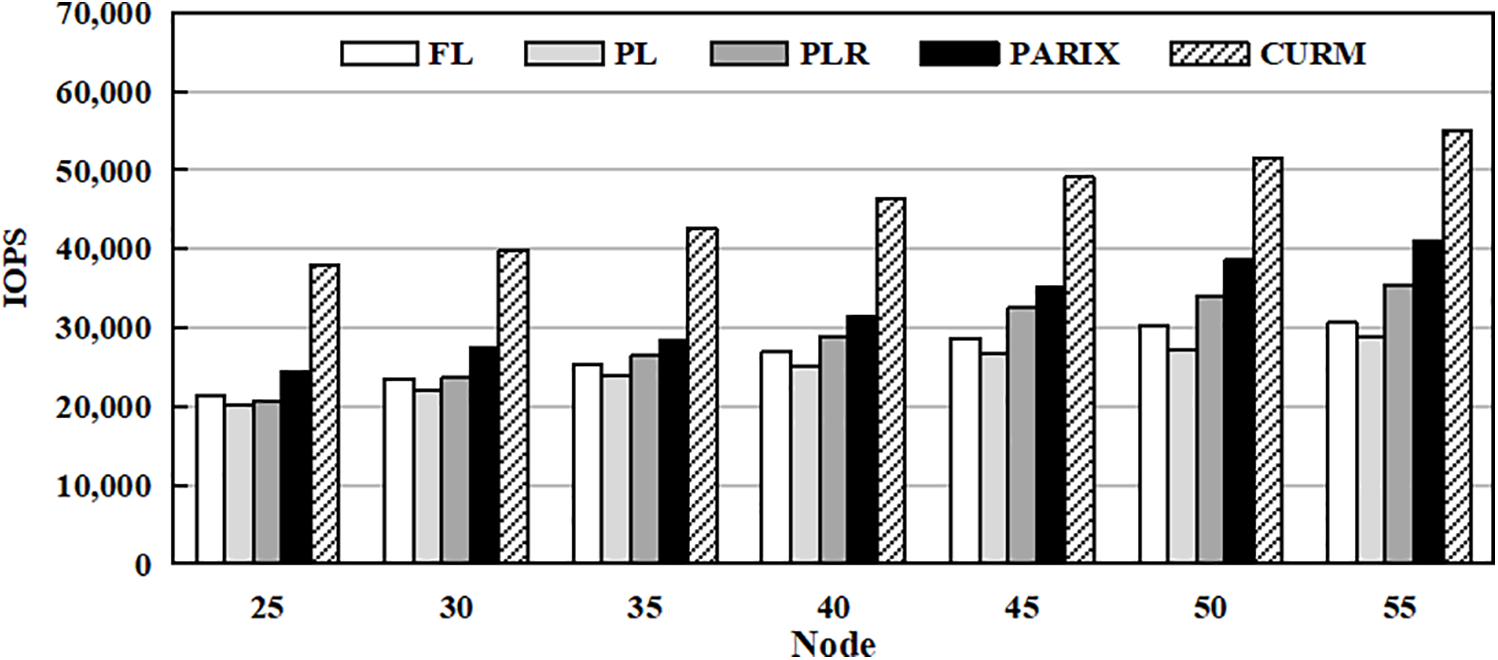

In this section, we evaluate the scalability of the Cognitive Update and Repair Method (CURM) by examining its performance as the number of nodes increases from 25 to 55. The evaluation focuses on I/O throughput, which is critical for assessing the ability of each method to handle growing storage scales. The results, summarized in Fig. 13, demonstrate that CURM sustains high throughput, enabled by its fine-grained I/O scheduling and task partitioning. These findings confirm that CURM remains robust and efficient in large-scale environments, highlighting its suitability for deployment in extensive storage systems.

Figure 13: Scalability comparison of different strategies in terms of I/O operations per second (IOPS)

6.7 Discussion of System Bottlenecks

Although the preceding experiments demonstrate the performance advantages of CURM, it is also important to consider the potential bottlenecks of the CURFS prototype under large-scale and high-concurrency scenarios. The decision-tree-based file classification remains lightweight and does not impose significant overhead, but system-level constraints may emerge. Network bandwidth can become saturated when scaling to hundreds of nodes, as cross-node communication is intrinsic to erasure-coded storage; CURM reduces redundant reads, yet aggregate traffic may still reach hardware limits. Disk contention may also appear with intensive parallel updates, where CURM’s fine-grained scheduling alleviates but cannot fully eliminate seek latency. Furthermore, metadata management overhead may grow with large numbers of classified files and reserved spaces, introducing potential latency. These factors suggest that while CURM’s relative advantages hold under scale-out conditions, absolute performance is bounded by hardware and network resources. Future work will extend CURFS with stress testing and concurrency benchmarks to quantify these bottlenecks and guide system-level optimizations.

In conclusion, this paper introduces CURM, a cognitive update and repair method for erasure-coded storage systems. By leveraging machine learning to classify files and employing tailored strategies for different file types (write-only, read-only, read-write), CURM significantly reduces I/O overhead during data updates and repair operations. Through efficient utilization of data differences and reserved disk space for parity blocks, CURM minimizes read-after-write operations and disk seek overhead, thereby improving both update and recovery performance. Experimental results demonstrate substantial performance gains compared to leading-edge approaches, validating CURM’s effectiveness in enhancing the efficiency and reliability of large-scale storage systems. Future work will explore extending CURM to multi-node failure recovery, stress testing under high-concurrency scenarios, and integrating system-level optimizations to further improve scalability and robustness in large-scale deployments.

Acknowledgement: We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Prof. Shudong Zhang for his invaluable guidance and support throughout this research. His insights and expertise greatly contributed to the development of our ideas, and we also acknowledge the use of ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI, San Francisco, USA; https://openai.com (accessed on 13 September 2025)) for limited language polishing during manuscript preparation. All scientific content and conclusions are entirely the responsibility of the authors.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62362019), the Natural Science Foundation of Hainan Province (Grant No. 624RC482), and the Hainan Provincial Higher Education Teaching Reform Research Project (Grant Hnjg2024-27).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Bing Wei: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. Ming Zhong: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing. Qian Chen: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing. Yi Wu: Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing. Yubin Li: Resources, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Yi Wu, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable for studies not involving humans or animals.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study

References

1. Xia J, Luo L, Sun B, Cheng G, Guo D. Parallelized in-network aggregation for failure repair in erasure-coded storage systems. IEEE/ACM Trans Netw. 2024;32(4):2888–903. doi:10.1109/tnet.2024.3367995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Shan Y, Chen K, Gong T, Zhou L, Zhou T, Wu Y. Geometric partitioning: explore the boundary of optimal erasure code repair. In: Proceedings of the ACM SIGOPS 28th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles; 2021 Oct 26–29; Online. p. 457–71. [Google Scholar]

3. Xu L, Lyu M, Li Z, Li C, Xu Y. A data layout and fast failure recovery scheme for distributed storage systems with mixed erasure codes. IEEE Trans Comput. 2021;71(8):1740–54. doi:10.1109/tc.2021.3105882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Qiao Y, Zhang M, Zhou Y, Kong X, Zhang H, Xu M, et al. NetEC: accelerating erasure coding reconstruction with in-network aggregation. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst. 2022;33(10):2571–83. doi:10.1109/tpds.2022.3145836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Jin H, Luo R, He Q, Wu S, Zeng Z, Xia X. Cost-effective data placement in edge storage systems with erasure code. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2022;16(2):1039–50. doi:10.1109/tsc.2022.3152849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhou H, Feng D, Hu Y. Bandwidth-aware scheduling repair techniques in erasure-coded clusters: design and analysis. IEEE Trans Parallel Distrib Syst. 2022;33(12):3333–48. doi:10.1109/tpds.2022.3153061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhou H, Feng D, Hu Y. Multi-level forwarding and scheduling repair technique in heterogeneous network for erasure-coded clusters. In: Proceedings of the 50th International Conference on Parallel Processing; 2021 Aug 9–12; Lemont, IL, USA. p. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

8. Wu S, Du Q, Lee PC, Li Y, Xu Y. Optimal data placement for stripe merging in locally repairable codes. In: IEEE INFOCOM 2022-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications; 2022 May 2–5; Online. p. 1669–78. [Google Scholar]

9. Li X, Cheng K, Tang K, Lee PC, Hu Y, Feng D, et al. ParaRC: embracing sub-packetization for repair parallelization in MSR-coded storage. In: Proceedings of the 21st USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies (FAST 23); 2023 Feb 21–23; Santa Clara, CA, USA. p. 17–32. [Google Scholar]

10. Tang J, Jalalzai MM, Feng C, Xiong Z, Zhang Y. Latency-aware task scheduling in software-defined edge and cloud computing with erasure-coded storage systems. IEEE Trans Cloud Comput. 2022;11(2):1575–90. doi:10.1109/tcc.2022.3149963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhou T, Tian C. Fast erasure coding for data storage: a comprehensive study of the acceleration techniques. ACM Trans Storage. 2020;16(1):1–24. doi:10.1145/3375554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Gong G, Shen Z, Wu S, Li X, Lee PC. Optimal rack-coordinated updates in erasure-coded data centers. In: IEEE INFOCOM 2021-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications; 2021 May 10-13; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

13. Deng S, Zhai Y, Wu D, Yue D, Fu X, He Y. A lightweight dynamic storage algorithm with adaptive encoding for energy internet. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2023;16(5):3115–28. doi:10.1109/tsc.2023.3262635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wei B, Wu J, Su X, Huang Q, Liu Y, Zhang F. Efficient erasure-coded data updates based on file class predictions and hybrid writes. Comput Electr Eng. 2022;104(6):108441. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2022.108441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Pei X, Wang Y, Ma X, Xu F. Efficient in-place update with grouped and pipelined data transmission in erasure-coded storage systems. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2017;69(11):24–40. doi:10.1016/j.future.2016.10.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhou H, Feng D. Stripe-schedule aware repair in erasure-coded clusters with heterogeneous star networks. ACM Trans Arch Code Optim. 2024;21(3):52. doi:10.1145/3664926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wei B, Shi J, Su X, Zhou L, Zhang S, Luo N, et al. Cognitive update and fast recovery using machine learning and parity delta shareability for erasure-coded storage systems. Res Sq. 2024. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-4400955/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Chan JCW, Ding Q, Lee PC, Chan HW. Parity logging with reserved space: towards efficient updates and recovery in erasure-coded clustered storage. In: Proceedings of the 12th USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies (FAST 14); 2014 Feb 17–20; Santa Clara, CA, USA. p. 163–76. [Google Scholar]

19. Shen Z, Lee PC. Cross-rack-aware updates in erasure-coded data centers. In: Proceedings of the 47th International Conference on Parallel Processing; 2018 Aug 13–16; Eugene, OR, USA. p. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

20. Liu Y, Wei B, Wu J, Xiao L. Erasure-coded multi-block updates based on hybrid writes and common XORs first. In: 2021 IEEE 39th International Conference on Computer Design (ICCD); 2021 Oct 27; Storrs, CT, USA. p. 472–79. [Google Scholar]

21. Li H, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Liu S, Li D, Liu L, et al. PARIX: speculative partial writes in erasure-coded systems. In: Proceedings of the 2017 USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC 17); 2017 Jul 12–14; Santa Clara, CA, USA. p. 581–7. [Google Scholar]

22. Zeng H, Zhang C, Wu C, Yang G, Li J, Xue G, et al. FAGR: an efficient file-aware graph recovery scheme for erasure coded cloud storage systems. In: 2020 IEEE 38th International Conference on Computer Design (ICCD); 2020 Oct 18–21; Hartford, CT, USA. p. 105–12. [Google Scholar]

23. Xu L, Lyu M, Li Q, Xie L, Xu Y. SelectiveEC: selective reconstruction in erasure-coded storage systems. In: 12th USENIX Workshop on Hot Topics in Storage and File Systems (HotStorage 20); 2020 Jul 13–14; Boston, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

24. Xu G, Feng D, Tan Z, Zhang X, Xu J, Shu X, et al. RFPL: a recovery friendly parity logging scheme for reducing small write penalty of SSD RAID. In: Proceedings of the 48th International Conference on Parallel Processing; 2019 Aug 5–8; Kyoto, Japan. p. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

25. Tang K, Cheng K, Chan HW, Li X, Lee PC, Hu Y, et al. Balancing repair bandwidth and sub-packetization in erasure-coded storage via elastic transformation. In: IEEE INFOCOM 2023-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications; 2023 May 17–20; New York, NY, USA. p. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

26. Facenda GK, Krishnan MN, Domanovitz E, Fong SL, Khisti A, Tan WT, et al. Adaptive relaying for streaming erasure codes in a three node relay network. IEEE Trans Inf Theory. 2023;69(7):4345–60. doi:10.1109/tit.2023.3254464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Hu J, Kosaian J, Rashmi KV. Rethinking erasure-coding libraries in the age of optimized machine learning. In: Proceedings of the 16th ACM Workshop on Hot Topics in Storage and File Systems; 2024 Jul 8–9; Santa Clara, CA, USA. p. 23–30. [Google Scholar]

28. Lan Y, Huang H, Huang Z, Chen Q, Wu S. ERBFT: improved asynchronous BFT with erasure code and verifiable random function. J Supercomputing. 2025;81(3):486. doi:10.1007/s11227-025-06995-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Pfister HD, Sprumont O, Zémor G. From bit to block: decoding on erasure channels. arXiv:2501.05748. 2025. [Google Scholar]

30. SNIA. MSR cambridge traces [Internet]. SNIA IOTTA persistent dataset; 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 2]. Available from: http://iotta.snia.org/traces/388/. [Google Scholar]

31. Xia M, Saxena M, Blaum M, Pease DA. A tale of two erasure codes in HDFS. In: Proceedings of the 13th USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies (FAST 15); 2015 Feb 16–19; Santa Clara, CA, USA. p. 213–26. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools