Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

FeatherGuard: A Data-Driven Lightweight Error Protection Scheme for DNN Inference on Edge Devices

1 Department of Intelligent Semiconductors, Soongsil University, Seoul, 06978, Republic of Korea

2 School of Electronic Engineering, Soongsil University, Seoul, 06978, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Young Seo Lee. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069976

Received 04 July 2025; Accepted 20 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

There has been an increasing emphasis on performing deep neural network (DNN) inference locally on edge devices due to challenges such as network congestion and security concerns. However, as DRAM process technology continues to scale down, the bit-flip errors in the memory of edge devices become more frequent, thereby leading to substantial DNN inference accuracy loss. Though several techniques have been proposed to alleviate the accuracy loss in edge environments, they require complex computations and additional parity bits for error correction, thus resulting in significant performance and storage overheads. In this paper, we propose FeatherGuard, a data-driven lightweight error protection scheme for DNN inference on edge devices. FeatherGuard selectively protects critical bit positions (that have a significant impact on DNN inference accuracy) against bit-flip errors, by considering various DNN characteristics (e.g., data format, layer-wise weight distribution, actually stored logical values). Thus, it achieves high error tolerability during DNN inference. Since FeatherGuard reduces the bit-flip errors based on only a few simple arithmetic operations (e.g., NOT operations) without parity bits, it causes negligible performance overhead and no storage overhead. Our experimental results show that FeatherGuard improves the error tolerability by up to 6667 and 4000, compared to the conventional systems and the state-of-the-art error protection technique for edge environments, respectively.Keywords

Deep neural networks (DNNs) have shown remarkable capability in various domains such as image processing, speech recognition, and natural language processing. Recent DNN applications often contain a vast number of parameters (e.g., weights and biases) to achieve high accuracy, which requires massive computing resources for DNN inference [1–3]. To reduce the resource requirements, users on edge devices typically send requests for the inference of these applications to a centralized server, where sufficient computing resources are available. However, such centralized execution may cause several issues. First, data transmission between the centralized server and edge devices (i.e., inference requests and results) increases network traffic, which can cause network congestion. Second, the inference requests may include user’s private data, raising security concerns [4]. To alleviate these issues, there has been a growing emphasis on performing the inference of DNN applications locally on edge devices [5–7], as edge-based inference reduces latency, alleviates network congestion, and enhances data privacy. This trend is expected to expand further with emerging applications such as large on-device models, real-time sensing, and collaborative edge intelligence, which increasingly demand reliable and efficient local inference.

For DNN inference on edge devices, model parameters, such as weights, are initially loaded into the device’s main memory (specifically, DRAM). Since a DRAM cell stores data as charge within its capacitor, excessive charge loss can alter the stored value (i.e., bit-flip error). The charge loss becomes more severe at higher temperature due to the increased leakage current in the cell, which may cause more bit-flip errors [8–10]. Furthermore, as DRAM process technology scales down, the reduction in capacitor size of memory cells exacerbates the bit-flip errors [11]. Such bit-flip errors severely corrupt the values of the model parameters, thereby leading to substantial accuracy loss [12,13]; for example, in single-precision floating-point format, a single bit-flip error can change the value of the model parameter by up to

To alleviate the accuracy loss, it is crucial to mitigate bit-flip errors in the model parameters. Many studies have proposed error correction codes (ECCs), such as single error correction double error detection (SECDED) [14] and chipkill [15,16]. These ECCs effectively correct (or detect) bit-flip errors by leveraging parity bits. However, their correction process typically involves complex computations (e.g., polynomial operations over a Galois Field) along with data retrieval, leading to significant correction latency. Since the correction process lies on the critical path of the memory read operation, it causes significant performance overhead. In addition, the ECCs necessitate the additional storage of parity bits, resulting in storage overhead. Due to the performance and storage overheads, it is hard to deploy the ECCs on edge devices, which have strict real-time requirements and limited storage capacity. To reduce these overheads, several techniques have been proposed for resource-constrained edge devices [17,18]. Such techniques reduce bit-flip errors without parity bits based on simple operations, which provide a moderate level of error tolerability in DNN inference. However, with the recent increase in the occurrence of bit-flip errors [11], these techniques may no longer be sufficient for large DNN applications. More recent studies have proposed lightweight protection schemes for DNNs, including parity-based methods [19,20], redundancy- and importance-aware approaches [21–23], bit-level redundancy mechanisms [24], and attack-oriented defenses designed to mitigate targeted bit-flip errors [25]. While these methods improve reliability, they often incur storage overhead, focus on attack scenarios, or insufficiently address bit criticality, thereby limiting their applicability in resource and latency constrained edge environments.

In this paper, we propose FeatherGuard, a data-driven, lightweight error protection scheme designed to significantly enhance the error tolerability in DNN inference, without storage overhead. FeatherGuard strongly protects specific bit positions that have a significant impact on DNN inference accuracy against bit-flip errors, by considering various DNN characteristics (e.g., data format, layer-wise weight distribution, actually stored logical values). Thus, it achieves high error tolerability during DNN inference. The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

• FeatherGuard is a novel error protection scheme that selectively protects critical bits based on DNN-specific characteristics.

• Unlike conventional ECCs, FeatherGuard’s protection mechanism is based on simple inversion (a few NOT operations). This design has low computational requirements, resulting in negligible performance overhead.

• Furthermore, our scheme requires no parity bits, as data is restored by applying the same inversion operation twice. This enables a design with no storage overhead.

• Compared to prior techniques, FeatherGuard achieves substantially higher error tolerability by integrating layer-wise encoding/decoding and cell-aware inversion.

• We implement FeatherGuard within a memory controller to demonstrate its practicality for edge devices. We then evaluate its performance, power, and area overheads through a detailed analysis.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 examines the characteristics of DNN weights and their distribution across layers. Section 3 introduces the proposed FeatherGuard. In Section 4, we evaluate the improvement in reliability of FeatherGuard against the state-of-the-art technique. Finally, Section 5 presents related works and Section 6 concludes this paper.

Recent DNN applications generally have parameters (e.g., weights and biases) based on IEEE 754 single precision (FP32) format, which consists of a 1-bit sign, an 8-bit exponent, and a 23-bit mantissa. In the FP32 format, the magnitude of change in the parameter value due to a bit-flip error varies significantly depending on the bit position. In certain cases, the bit-flip error can drastically change the parameter value, resulting in severe accuracy loss. To quantitatively analyze the impact of bit-flip errors, we evaluate the accuracy loss caused by bit-flip errors at specific bit positions, in various DNNs.

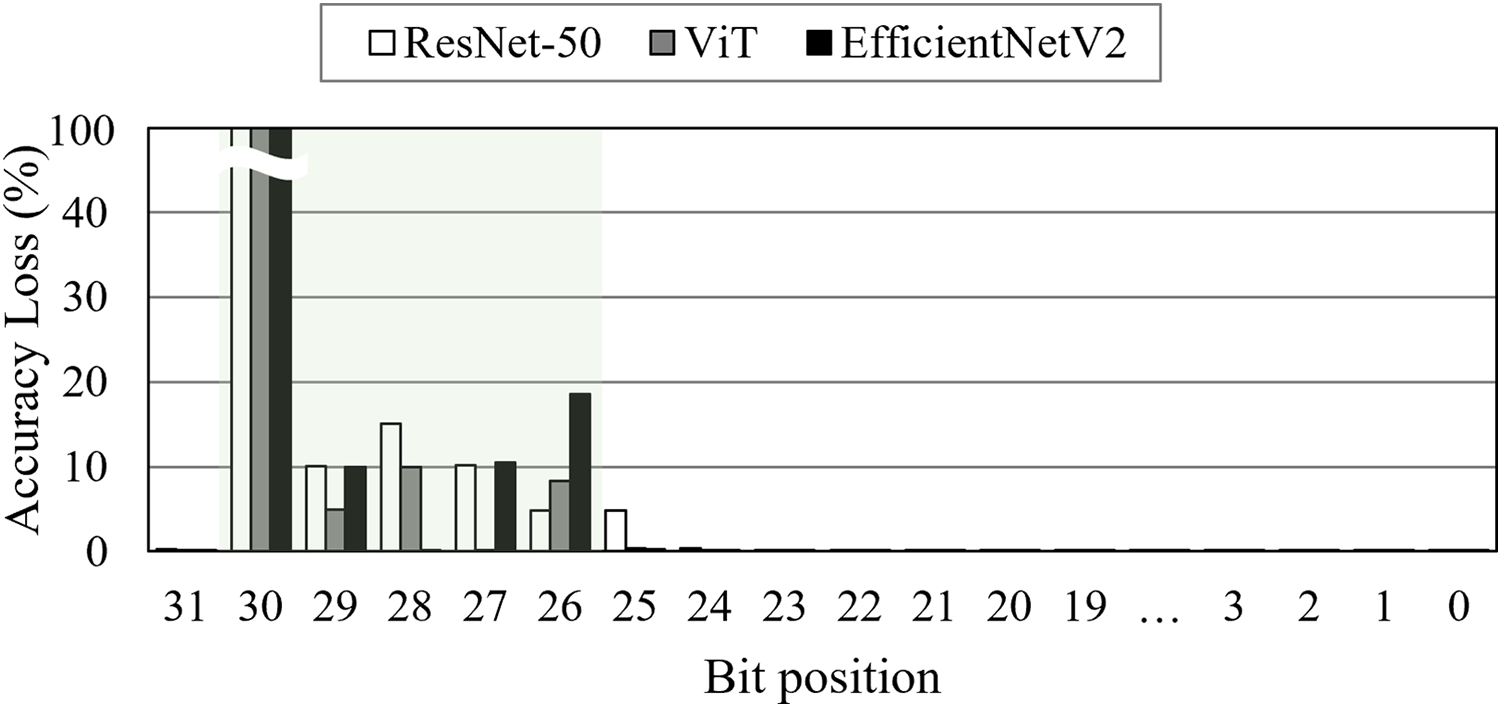

As shown in Fig. 1, the bit-flip errors at 30-

Figure 1: Accuracy loss caused by bit-flip errors depending on bit position. The bit-flip errors are injected at a 1e-5 bit error rate for each bit position

As a result, the bit-flip errors at 30-

2.2 Layer-Wise Weight Distribution

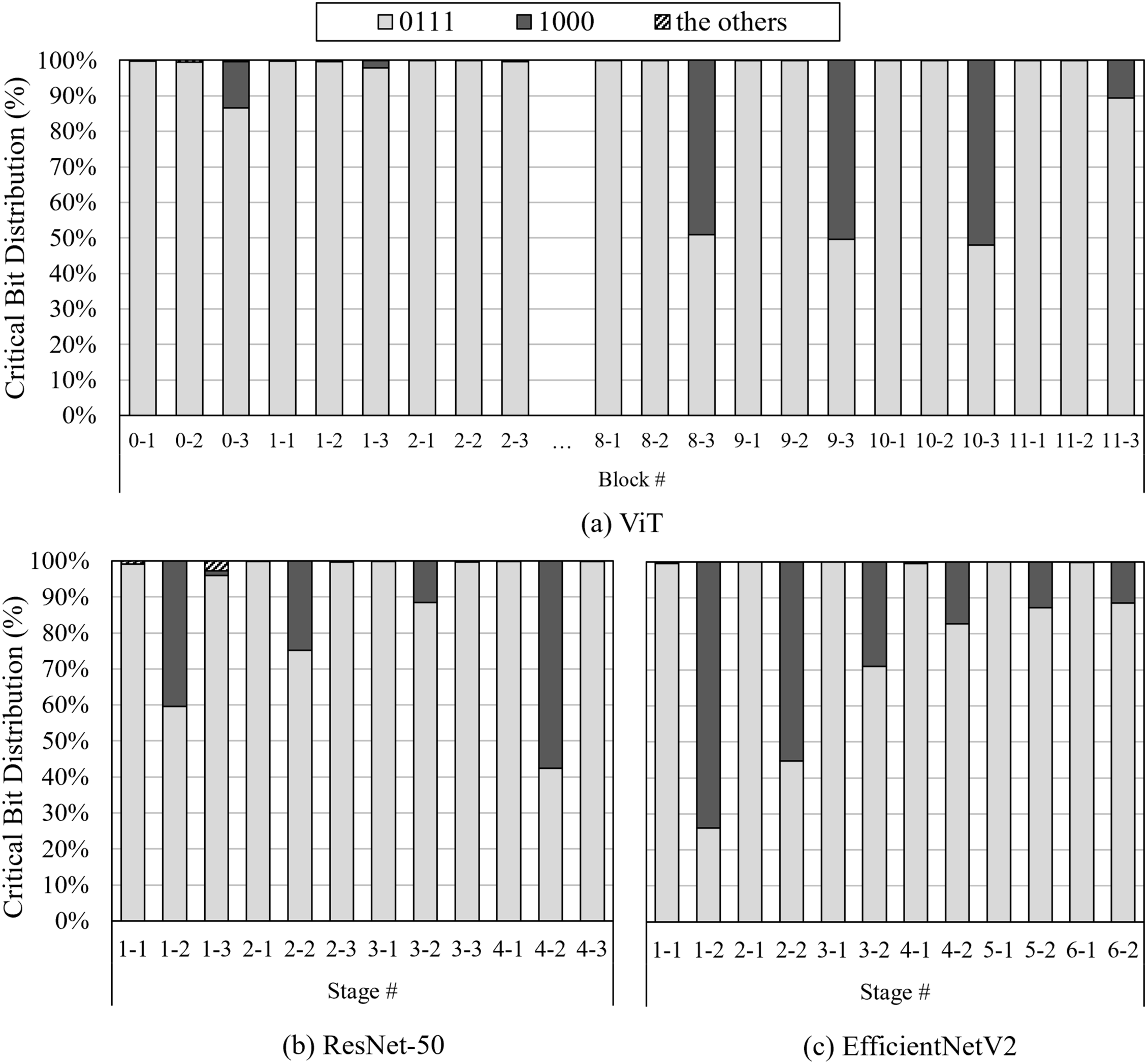

DNNs typically consist of multiple layers, where each layer performs a number of multiply-accumulate (MAC) operations on model parameters (e.g., weights, activations) and sequentially propagates the outputs to the next layer. To analyze the characteristics of different layers, we investigate the weight1 distribution across each layer in various DNNs. Fig. 2 shows the distribution of the CBs (defined in Section 2.1) in weight values across each stage/block; a stage/block refers to a group of multiple layers executing similar computational tasks.

Figure 2: Critical bit distribution across layers

As shown in Fig. 2, the distribution of the CBs varies across layers. Most layers predominantly have the CBs of 01112, since the majority of the weight values has the range of [−1, 1] in DNNs [17,18]. On the other hand, in certain layers, the CBs of 1000 constitute a significant portion in the distribution; in particular, the stage 1–2 in EfficientNetV2 has the CBs of 1000 in up to 74% of the distribution. These layers have a broader range of weight values compared to the other layers due to the following reasons. First, some layers may need to strongly reflect input features, leading to extremely large/small weight values. Second, the scale/shift factors in the normalization process can alter the range of weight values. Therefore, by leveraging the characteristic that the layers have different distributions of the CBs, it is necessary to adopt different error protection methods in a layer-wise manner, for high error tolerability in DNN inference.

To improve the overall error tolerability in DNN inference, we propose FeatherGuard, a data-driven lightweight error protection scheme, while not causing storage overhead. FeatherGuard strongly protects the CBs (defined in Section 2.1) in a layer-wise manner, leading to high error tolerability. Since FeatherGuard prevents bit-flip errors exploiting only a few simple operations without parity bits, it causes negligible performance overhead and no storage overhead.

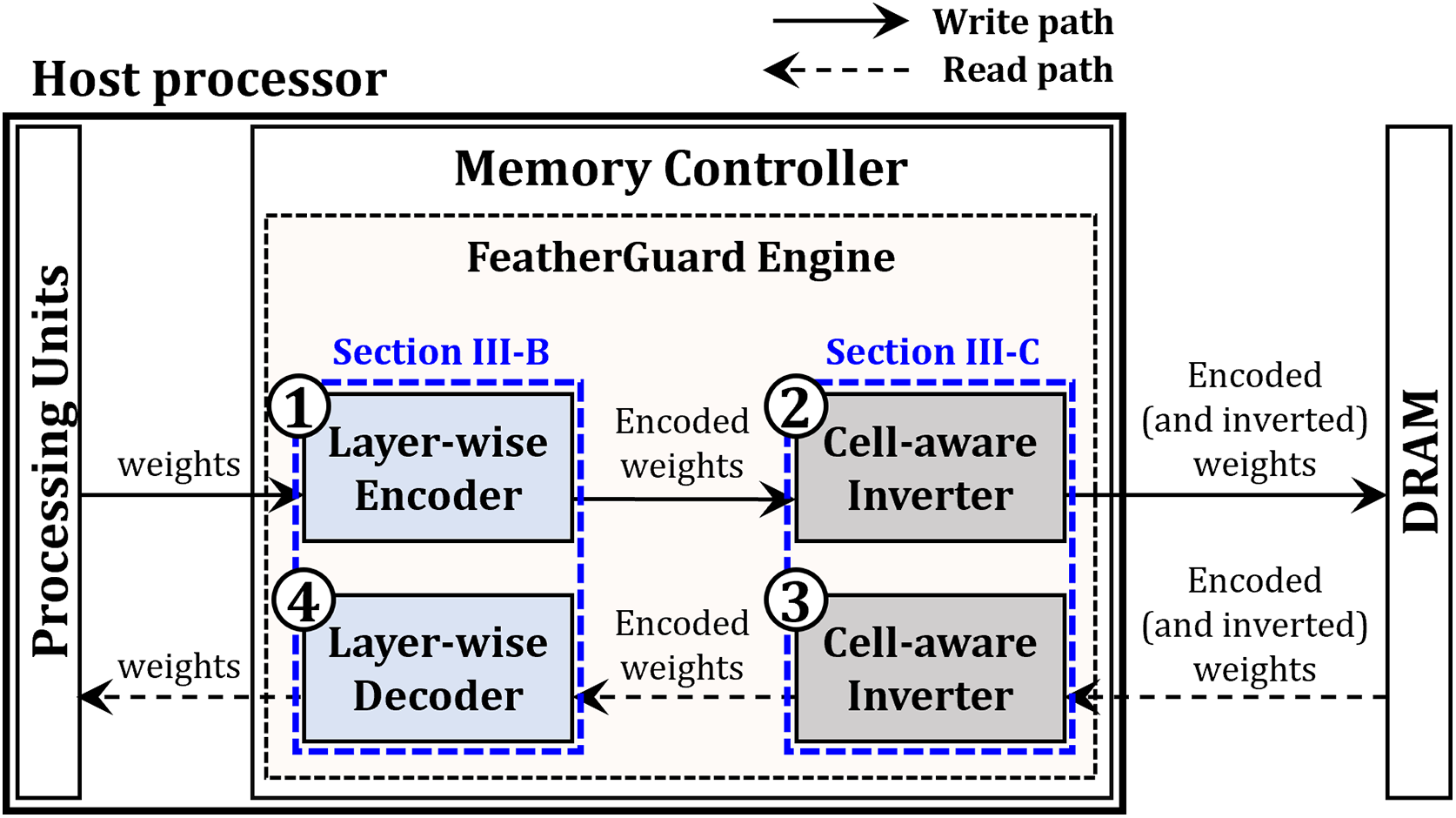

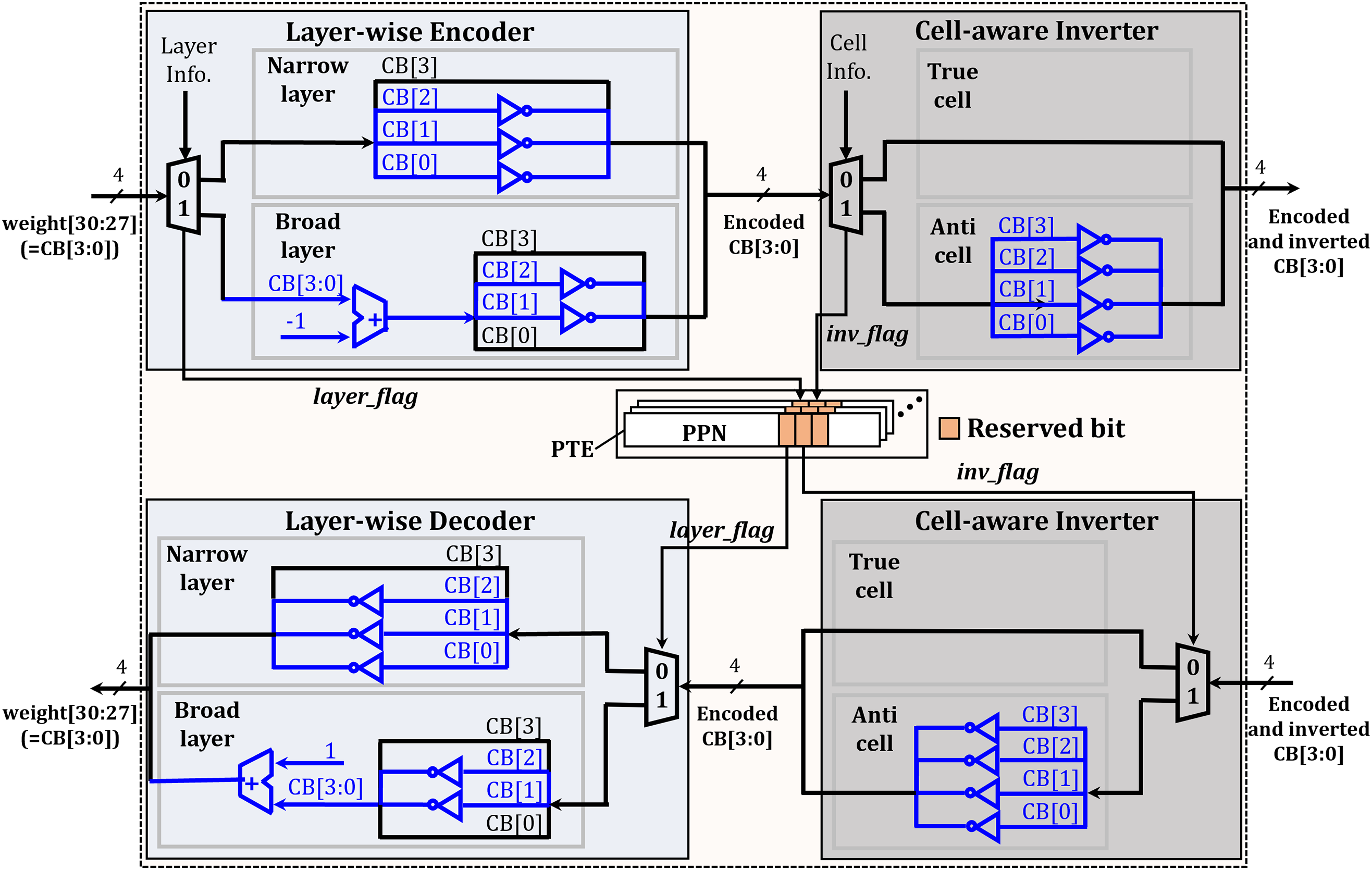

Fig. 3 depicts the overview of FeatherGuard, a technique proposed to protect CBs from bit-flip errors. It employs a two-part principle implemented within a FeatherGuard engine, which is integrated into the memory controller. First, a layer-wise encoder reduces the number of vulnerable bits by applying different encoding schemes based on the layer type. Second, a cell-aware inverter addresses the inverse bit-flip error that can occur in a certain type of memory cell, a concept further explained in Section 3.3. The overall processes of FeatherGuard are as follows (① to ④ in Fig. 3).

① When loading the weights of pre-trained DNN applications into the DRAM of edge devices, the layer-wise encoder adaptively encodes the weights; the detailed layer-wise encoding and decoding processes will be explained in Section 3.2.

② The cell-aware inverter selectively inverts the encoded weights depending on cell type (i.e., true or anti cell); the detailed inverting process will be explained in Section 3.3. The adaptively encoded (and inverted) weights are actually stored in DRAM.

③ During DNN inference, the weights adaptively encoded (and inverted) through ① to ② are loaded from DRAM to the FeatherGuard engine. The cell-aware inverter selectively performs inverting operations for the encoded and inverted weights.

④ Similar to the encoding process in ①, the layer-wise decoder adaptively decodes the encoded weights. Then, the original weights are transmitted to the processing units for performing DNN inference.

Figure 3: Overview of FeatherGuard

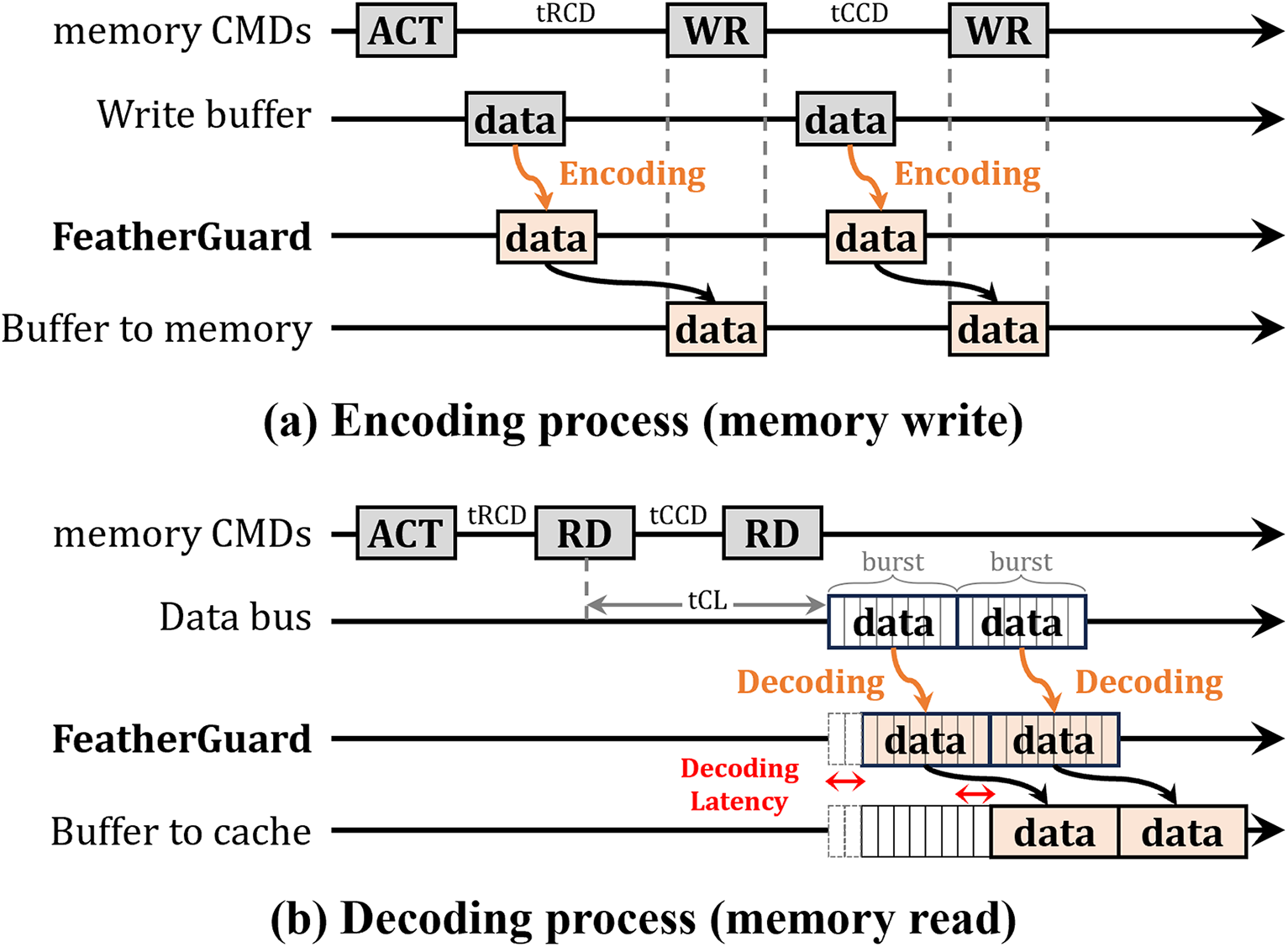

The FeatherGuard engine encodes and decodes the weights, without interfering with standard memory read and write operations. Fig. 4 illustrates the operational sequence of FeatherGuard engine during memory write and read operations. As shown in Fig. 4a, FeatherGuard encodes the data (i.e., weights) in the write buffer before transmitting the data to the memory. Since the data to be written to the memory is typically prepared in the write buffer prior to issuing a write (WR) memory command, FeatherGuard performs the encoding process transparently, without causing any additional latency. On the other hand, as shown in Fig. 4b, FeatherGuard decodes the data immediately after receiving it from the memory through burst transfers, which are commonly employed in DRAM read operations. Since all burst transfers associated with a single read (RD) memory command are completed before the data is forwarded to the upper-level memory structures such as caches, FeatherGuard performs decoding process in parallel with the burst transfers. Such parallelism minimizes the decoding latency, resulting in only negligible performance overhead.

Figure 4: Timing diagram of FeatherGuard extensions to DRAM operations

3.2 Layer-Wise Encoding/Decoding Process

The layer-wise encoder adaptively executes the encoding process for the weights, depending on the layer-wise weight distribution. We empirically classify the layers into two categories (i.e., narrow layer and broad layer), based on whether the proportion of 1000 CBs in each layer is below 10% or not. We consider layers with a proportion of 1000 CBs below 10% as narrow layers; otherwise, the layers are classified as broad layers. For both layers, the layer-wise encoder contributes to improved error tolerability by minimizing the number of 1s in CBs, since most bit-flip errors in capacitor-based memory occur from the charged state (logical ‘1’) to the discharged state (logical ‘0’) [28,29,17].

The upper-left region of Fig. 5 depicts the detailed process of the layer-wise encoder, for a single weight based on FP32 format. In the layer-wise encoder, only four CBs (i.e., CB[3:0] with position index) in the weight are encoded. Based on the layer information from pre-trained DNN applications, the layer-wise encoder classifies the layer as either narrow layer or broad layer. For narrow layers, the encoder reduces the number of 1s in CBs by inverting CB[2], CB[1], and CB[0], since narrow layers predominantly have the CBs of 0111. After encoding, the CBs (to be stored in DRAM) are changed from 0111 to 0000, completely eliminating the risk of bit-flip errors from 1 to 0. For broad layers, different encoding process is necessary to reduce the number of 1s in CBs. Since broad layers have a significant number of 1000 CBs as well as 0111 CBs, the same encoding processing as narrow layers may increase the number of 1s in CBs; inverting CB[2:0] of the 1000 CBs changes their value to 1111, which increases the bit-flip error probability. Thus, the layer-wise encoder subtracts the CBs by one through a simple adder, and then inverts only CB[2] and CB[1]. With this encoding process, the 0111 CBs are encoded to 0000, completely preventing bit-flip errors from 1 to 0. In addition, the 1000 CBs are encoded to 0001, which minimizes bit-flip error probability by reducing the number of 1s in CBs as much as possible. In this case, the encoder further contributes to improved error tolerability by eliminating 1s in CB[3], CB[2], and CB[1], since the bit-flip errors in these bits are relatively more likely to cause accuracy loss compared to the errors in CB[0], as shown in Fig. 1. As a result, the layer-wise encoder reduces the bit-flip error probability by eliminating 1s in the CBs as much as possible, thereby leading to high error tolerability for both layers. Moreover, the encoder only includes simple arithmetic operations (i.e., subtraction and inversion), resulting in negligible performance overhead.

Figure 5: Detailed design of the FeatherGuard engine

Since the CBs are encoded by different processes for each layer, the layer information should be stored to recover the original CBs. To avoid additional storage overhead for the layer information, we store a 1-bit layer_flag by exploiting the reserved bit field3 in the page table entry (PTE) (which is managed by a memory management unit) [34], as shown in Fig. 5. It is possible to manage the layer information at the page-level granularity, since the size of each layer is typically larger than the 4 KB page size; in recent DNN applications, each layer contains approximately 1 M parameters (4 MB size), on average (at least 1.5 K parameters (6 KB size) in the smallest layer).

In the decoding process as shown in the bottom-left region of Fig. 5, the layer-wise decoder operates in the reverse order of the encoder. The decoder restores the original CBs by reverting the CBs at the specific bit positions, based on the layer_flag stored in PTE; for broad layers, it additionally increments the reverted CBs by one. Thus, the layer-wise decoder restores the original CBs only exploiting the layer_flag, which does not require any parity bits. In addition, retrieving the flag does not cause additional performance overhead. The page translation process (from virtual address to physical address) should be performed before each memory access to DRAM, so that the flag for the corresponding page has already been available.

3.3 Cell-Aware Inverting Process

As explained in Section 3.2, the layer-wise encoder of FeatherGuard minimizes the number of 1s in CBs to reduce bit-flip errors, since the bit-flip errors from 1 to 0 in DRAM cells occur from the charged state (logical ‘1’) to the discharged state (logical ‘0’). However, the charged state of a DRAM cell does not always correspond to a logical ‘1’. In modern DRAM architectures, memory cells are classified as either true cells or anti cells, depending on the relations between the charged states and corresponding logical values. A true cell stores a logical ‘1’ as a charged state and a logical ‘0’ as a discharged state, whereas an anti cell stores these logical values in the opposite manner [35]. The primary reason for distinguishing between true and anti cells in DRAM is to reduce coupling interference between adjacent cells sense amplifiers [35–37], which helps improve signal integrity and stability during memory access. Thus, FeatherGuard considers the actual logical values stored in memory cells to effectively enable the layer-wise encoder operation, thereby leading to improved error tolerability.

As shown in the upper-right region of Fig. 5, the operation of the cell-aware inverter is quite simple. According to several studies on DRAM profiling and physical-level characterization [35,38,39], it is possible to distinguish the memory cells as either true cells or anti cells based on the physical address. Based on cell information (either true cells or anti cells), the cell-aware inverter selectively performs the inversion operations for the CBs encoded by the layer-wise encoder. For true cells, the encoded CBs remain unchanged, since the layer-wise encoder reduces the bit-flip errors for the true cells (from 1 to 0). On the other hand, for anti cells, all the encoded CBs are inverted, which minimizes the number of 0s (maximizes the number of 1s), thereby reducing the bit-flip errors from 0 to 1.

Though the cell information (either true cells or anti cells) is distinguished based on the physical address, identifying this information for every memory access may incur additional performance overhead. To avoid such overhead, we also store a 1-bit inv_flag in the reserved bit field in the PTE, similar to the layer-wise encoding process. The cell information can be managed at the page-level granularity, since the size of the true/anti cell regions exceeds the 4 KB page size. In general, the regions of true/anti cells are organized at the granularity of 512 rows (e.g., 1 MB size for the off-the-shelf DRAM in edge environments [40]); the distribution of true/anti cells varies depending on DRAM vendors, though.

As shown in the bottom-right region of Fig. 5, when loading the weights from DRAM, the cell-aware inverter selectively performs the inversion operations based on the inv_flag stored in PTE. The inverter reverts the encoded (and inverted) CBs only for anti cells by exploiting the inv_flag, which does not require any parity bits. In addition, retrieving the inv_flag does not introduce additional performance overhead due to the same reason as layer_flag.

3.4 Enhanced Reliability via FeatherGuard

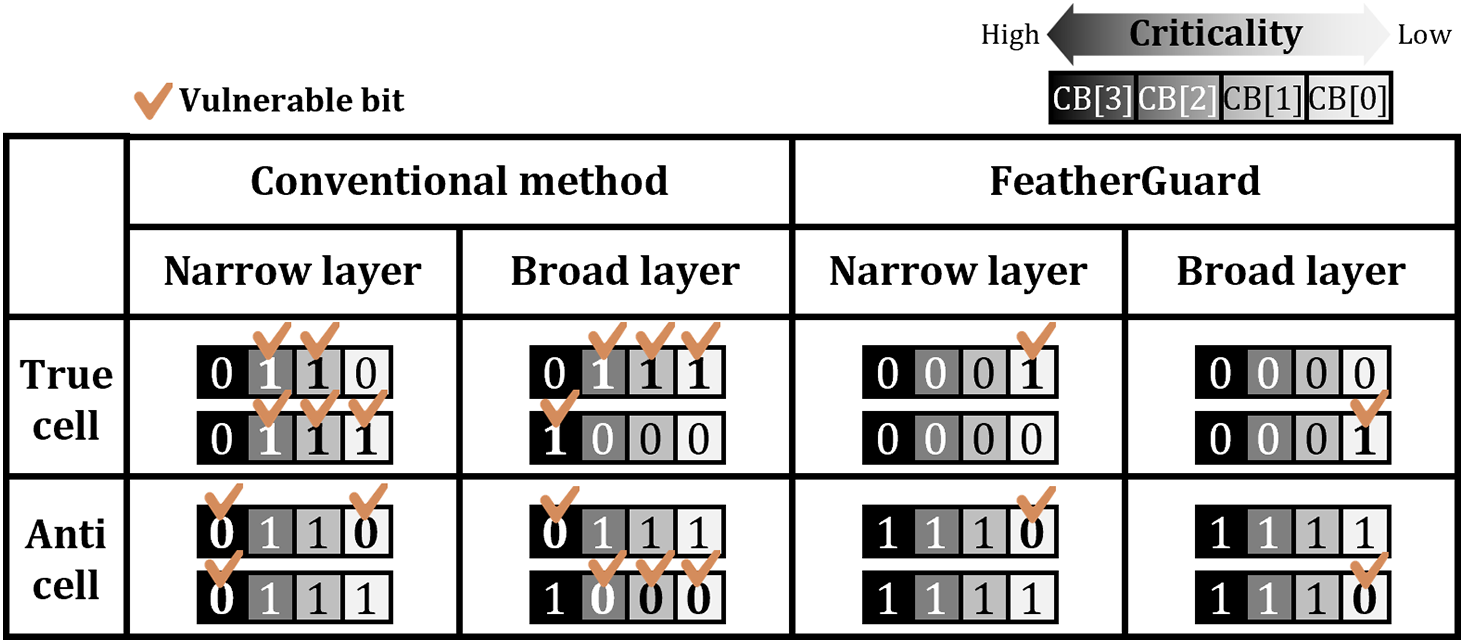

Fig. 6 describes the logical values of CBs (actually stored in DRAM) for representative cases, across different layer types (i.e., narrow and broad layers) and cell types (i.e., true and anti cells). In the conventional method (which directly stores the CBs in DRAM, without any encoding), there are a large number of vulnerable bits in CBs, regardless of the layer type and the cell type. In particular, for broad layers, CB[3] (which is the most critical bit as explained in Section 2.1) is vulnerable to bit-flip errors. Thus, the bit-flip errors in these vulnerable bits reduce error tolerability in DNN inference, which may cause severe accuracy loss. On the other hand, FeatherGuard significantly reduces the number of vulnerable bits in CBs across all cases (up to one vulnerable bit in each representative case). In each case, the only vulnerable bit is CB[0], which is the least critical bit in CBs. Since FeatherGuard strongly protects the CBs across all cases through layer-wise encoding/decoding process and cell-aware inverting process, it significantly enhances error tolerability in DNN inference.

Figure 6: Improved error tolerability of CBs stored in DRAM

We evaluate FeatherGuard in terms of the error tolerability, compared to the 1) no protection and 2) ZEM [17]. Since DRAMs deployed in edge environments (e.g., low power double data rate (LPDDR)) are typically not integrated with system-level ECCs (on host processor side) due to capacity constraints, we consider no protection as our baseline. In addition, we compare FeatherGuard with ZEM [17], a state-of-the-art lightweight ECC scheme designed for edge environments, while not incurring additional storage overhead. For evaluation, we employ three DNN models: ResNet-50 [41], vision transformer (ViT) [42], and EfficientNetV2 [43]. We utilize a transformer model (i.e., ViT) and convolutional neural network models (i.e., ResNet-50 and EfficientNetV2), which are representative in computer vision domain on edge environments. We select the models for computer vision domain, since they are more common than those for natural language processing domain, in edge environments where real-time processing, low-latency response, and on-device sensor integration are required.

To quantitatively analyze the error tolerability, we evaluate the tolerable bit error rate (BER) through random injection of bit-flip errors. We inject the bit-flip errors uniformly and independently across all DRAM cells at a fixed BER, assuming that all DRAM cells are equally susceptible to bit-flip errors; note such random-based error injection method has been widely exploited [44,45]. Then, we identify the maximum tolerable BER while maintaining acceptable inference accuracy4 by gradually increasing the BER over a wide range. This BER sweep methodology provides a comprehensive and realistic evaluation, as it implicitly accounts for diverse error conditions observed in real DRAM systems (e.g., temperature variation, reduced operating voltages, and device aging). A higher maximum tolerable BER indicates enhanced error tolerability. In addition, we evaluate the error tolerability across 20 iterations, due to the random injection of bit-flip errors.

To evaluate the performance, power, and area overheads of FeatherGuard, we utilize OpenRoad Flow [47]. We implement the FeatherGuard Engine in Verilog HDL and then synthesize them with the ASAP 7nm FinFET design kit [48]. According to the implementation results, the FeatherGuard Engine takes only one cycle to execute layer-wise encoding and decoding process (explained in Section 3.2) and cell-aware inverting process (explained in Section 3.3), thanks to the simple arithmetic operations (i.e., addition/subtraction and inversion operations).

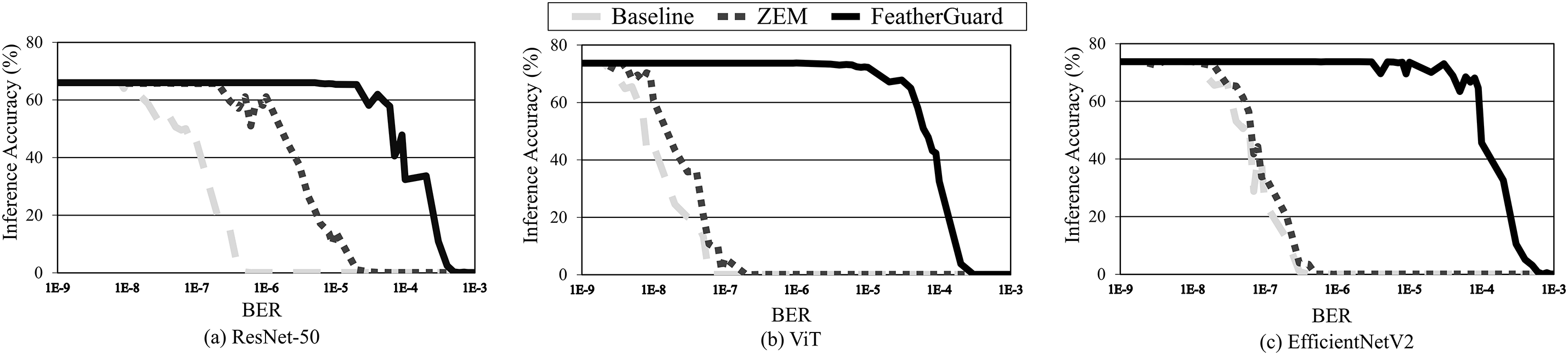

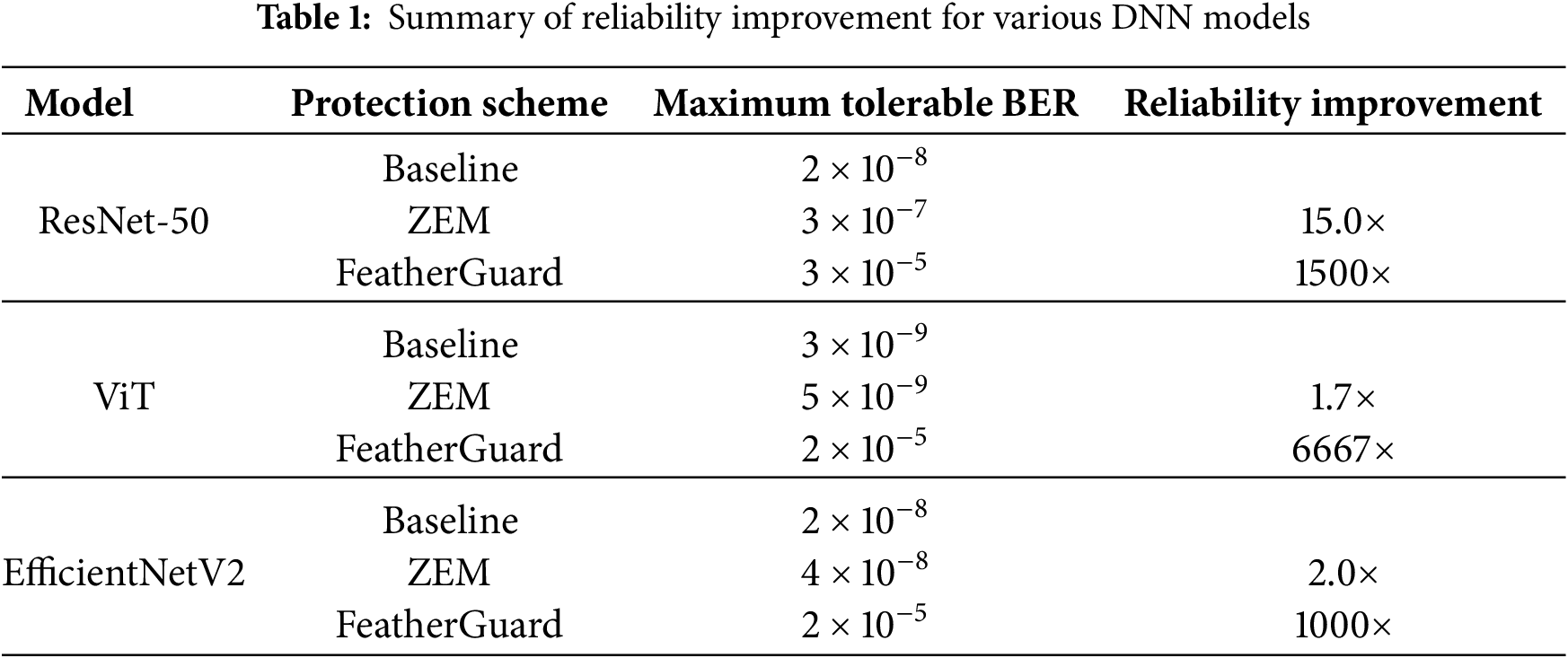

Fig. 7 depicts the impact of bit-flip errors on the accuracy in a mixed cell environment (i.e., true cell:anti cell = 50:50), which is a typical configuration in DRAM [49]. Table 1 summarizes the maximum tolerable BER depending on the protection schemes across DNN models, corresponding to the results in Fig. 7. As shown in Table 1, FeatherGuard has 1000–6667

Figure 7: Accuracy loss depending on bit error rates in a mixed cell environment

Interestingly, according to the experimental results, ZEM (the state-of-the-art lightweight ECC scheme) provides extremely slight improvement (1.7–2.0

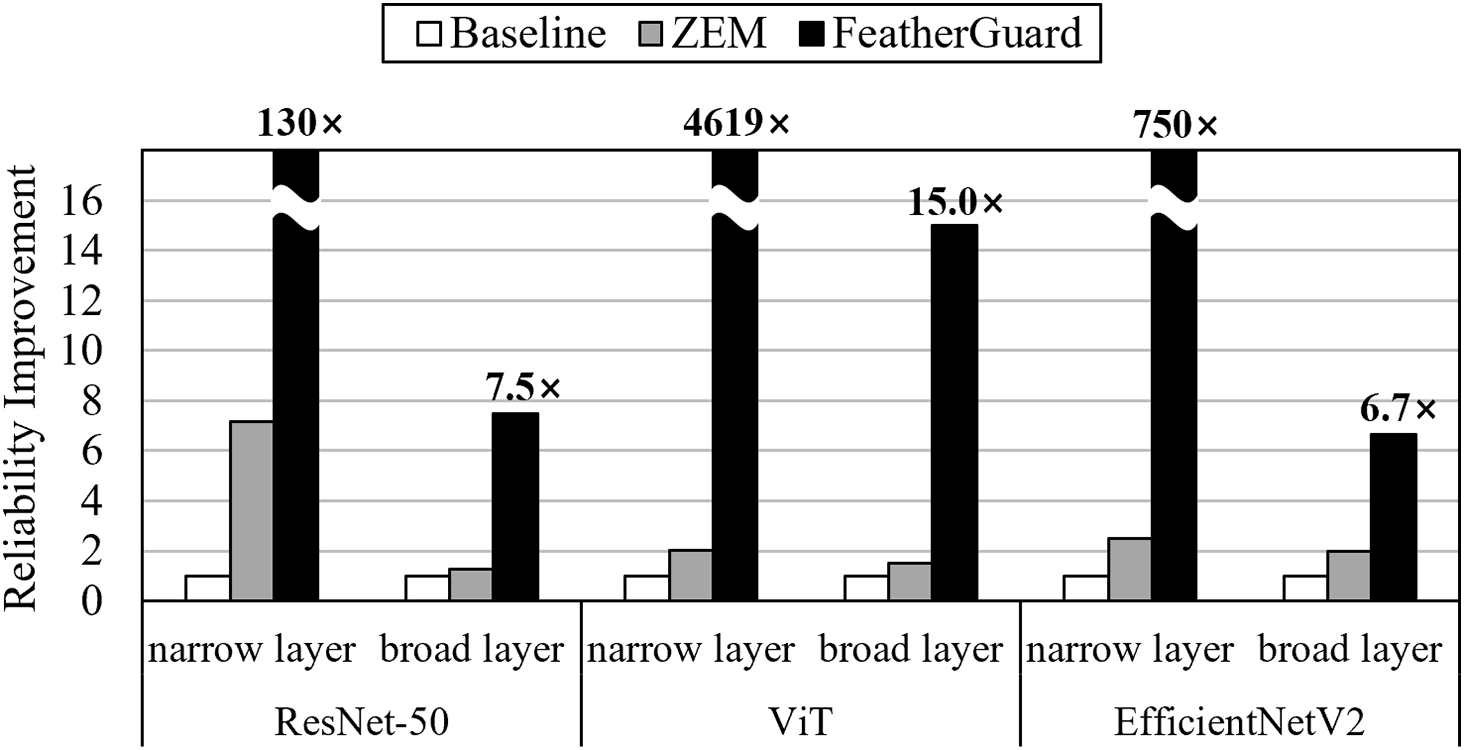

Fig. 8 shows the reliability improvement achieved in both narrow and broad layers. For narrow layers, FeatherGuard improves the reliability by 130–4619

Figure 8: Reliability improvement in narrow and broad layers across DNN models

4.2.2 Reliability Depending on Anti Cell Ratio

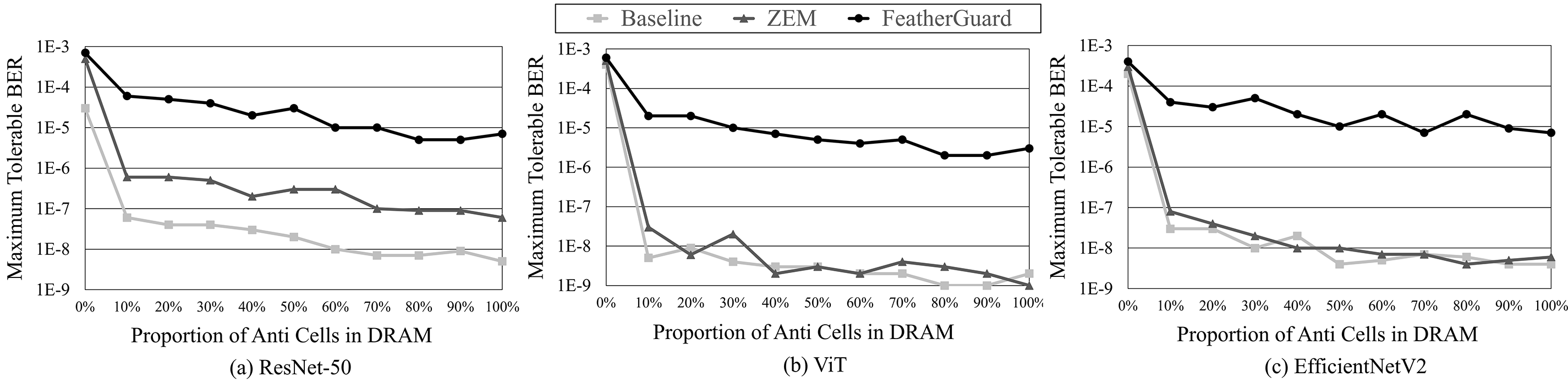

Since the anti cell proportion varies across DRAM vendors [36], we evaluate the sensitivity of anti cell proportion to error tolerability for verifying the effectiveness of FeatherGuard. Fig. 9 shows the maximum tolerable BER depending on the proportion of anti cells in DRAM. In all cases, FeatherGuard provides significantly higher error tolerability compared to the baseline and ZEM. FeatherGuard reduces bit-flip errors in both true and anti cells, by considering the actually stored logical values in DRAM, thereby leading to high error tolerability. Even in case that the proportion of anti cells is 0% (100% true cells) in DRAM, FeatherGuard has 1.5–23.3

Figure 9: Error tolerability depending on the proportion of anti cells in DRAM

4.2.3 Area and Power Overheads

According to the implementation results for FeatherGuard, the area (required for 16 instances of the circuit shown in Fig. 5, considering the memory burst) is only 0.0003 mm2. Since the area of memory controller in an off-the-shelf mobile CPU is approximately 5.76 mm2 [50], the area overhead introduced by FeatherGuard is negligible, accounting for 0.005% of the entire memory controller. Moreover, the power consumption is 1.4 mW, which causes negligible power overhead compared to the total power consumption (i.e., 80 W thermal design power) of the mobile CPU [50].

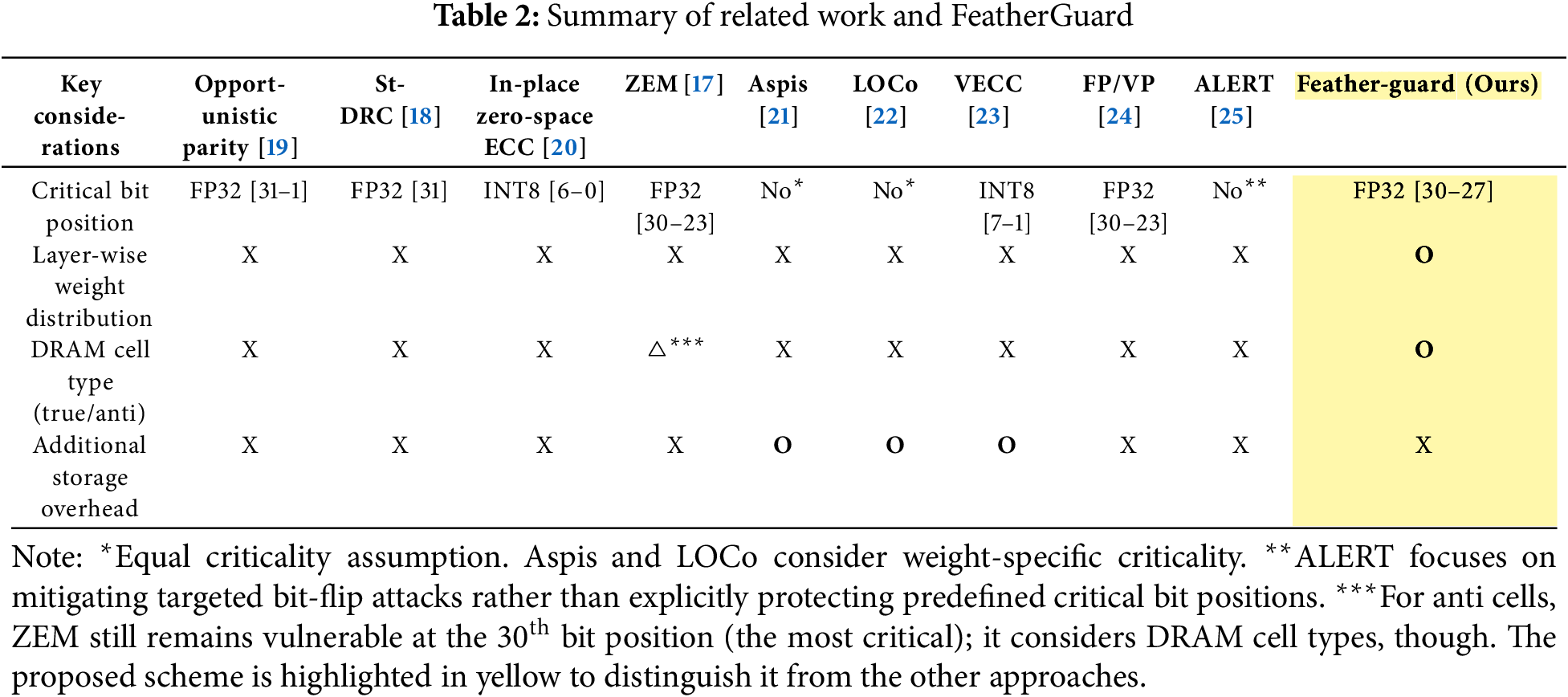

Many previous studies have proposed lightweight error protection techniques to mitigate the bit-flip errors for edge environments, while not causing additional storage overhead. Table 2 describes recent lightweight error protection techniques to mitigate the bit-flip errors for edge environments. Burel et al. proposed opportunistic parity [19], which protects the upper 31 bits (i.e., 31-

On the other hand, there have been several studies to improve DRAM reliability in edge environments. with a modest amount of storage overhead [21–23]. A. Schmedding et al. proposed Aspis [21], which selectively protects the weights based on their importance scores. It redundantly stores specific weights three times, which introduces a moderate amount of storage overhead. When the bit-flip errors occur, it corrects the corrupted value exploiting majority voting across the three copies, achieving high error tolerability. Hong et al. also proposed LOCo [22], which strongly protects specific weights by redundantly storing them. It reduces the additional storage overhead by applying a lightweight compression technique to the duplicated weights. In addition, Hsieh et al. proposed VECC [23], which protects the specific bit positions of the DNN weights by dynamically adopting ECCs. When the logical values at the specific bit positions are identical, it compresses these bits to reduce storage overhead. Otherwise, it applies ECCs to the logical values at the specific bit positions, which causes additional storage overhead due to the parity bits of ECCs. Furthermore, Catalán et al. [24] explored bit-level redundancy in CNNs and ViTs. They proposed continuous (fixed protection, FP) and discontinuous (variable protection, VP) critical bit (30-

To achieve high error tolerability during DNN inference, we propose FeatherGuard, a data-driven lightweight scheme for edge environments. FeatherGuard strongly protects the CBs against bit-flip errors by considering the layer-wise weight distribution and actually stored logical values in DRAM, which in turn achieves high error tolerability during DNN inference. It encodes the CBs exploiting only simple addition/subtraction and inversion operations without parity bits, resulting in negligible performance overhead and no storage overhead. Our results show that FeatherGuard achieves the error tolerability by up to 6667

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank Soongsil University for covering the Article Processing Charges (APC) of this article. Following are results of a study on the “Convergence and Open sharing System” Project, supported by the Ministry of Education and National Research Foundation of Korea.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Dong Hyun Lee and Young Seo Lee; methodology, Dong Hyun Lee; validation, Dong Hyun Lee and Na Kyung Lee; writing—original draft preparation, Dong Hyun Lee; writing—review and editing, Young Seo Lee; supervision, Young Seo Lee. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report the present study.

1In this paper, the weights in DNNs refer to all DNN parameters except for activations.

2The CBs of 0111 indicate that the corresponding weight value has a range of −2 to −2−15 and 2−15 to 2.

3Typically, the representative instruction set architectures (ISAs) in edge environments support the reserved bits in their PTEs for software-defined use [30]. For example, ARMv8-A and RISC-V provide 4 and 10 reserved bits, respectively. Note leveraging the reserved bits in the PTEs has been widely adopted across a range of hardware platforms as well as operating systems [31–33].

4According to [46], an accuracy loss of up to 1% is acceptable for image classification tasks in data centers. Thus, in this paper, we define acceptable inference accuracy as up to a 1% drop from the baseline inference accuracy.

References

1. Li J, Zhao R, Huang JT, Gong Y. Learning small-size DNN with output-distribution-based criteria. In: INTERSPEECH 2014; 2014 Sep 14–18; Singapore. p. 1910–4. doi:10.21437/Interspeech.2014-432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Kolachina P, Cancedda N, Dymetman M, Venkatapathy S. Prediction of learning curves in machine translation. In: Proceedings of the 50th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2012. p. 22–30. [Google Scholar]

3. Li Y, Phanishayee A, Murray D, Kim NS. Doing more with less: training large DNN models on commodity servers for the masses. In: Proceedings of the Workshop on Hot Topics in Operating Systems; 2021 Jun 1–3; Ann Arbor, MI, USA. p. 119–27. doi:10.1145/3458336.3465289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Cao K, Liu Y, Meng G, Sun Q. An overview on edge computing research. IEEE Access. 2020;8:85714–28. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2991734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Shuvo MMH, Islam SK, Cheng J, Morshed BI. Efficient acceleration of deep learning inference on resource-constrained edge devices: a review. Proc IEEE. 2023;111(1):42–91. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2022.3226481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Hussain H, Tamizharasan P, Rahul C. Design possibilities and challenges of DNN models: a review on the perspective of end devices. Artif Intell Rev. 2022;55(7):5109–67. doi:10.1007/s10462-022-10138-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li E, Zeng L, Zhou Z, Chen X. Edge AI: on-demand accelerating deep neural network inference via edge computing. IEEE Trans Wireless Commun. 2019;19(1):447–57. doi:10.1109/TWC.2019.2946140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Schroeder B, Pinheiro E, Weber WD. DRAM errors in the wild: a large-scale field study. ACM SIGMETRICS Perform Eval Rev. 2009;37(1):193–204. doi:10.1145/2492101.1555372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Hamamoto T, Sugiura S, Sawada S. On the retention time distribution of dynamic random access memory (DRAM). IEEE Trans Electron Devices. 1998;45(6):1300–9. doi:10.1109/16.678551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Al-Ars Z, van de Goor AJ, Braun J, Richter D. Simulation based analysis of temperature effect on the faulty behavior of embedded drams. In: Proceedings International Test Conference 2001 (Cat. No. 01CH37260). New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2001. p. 783–92. doi:10.1109/TEST.2001.966700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Gong SL, Kim J, Erez M. DRAM scaling error evaluation model using various retention time. In: 2017 47th Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks Workshops (DSN-W). New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 177–83. doi:10.1109/DSN-W.2017.48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Arechiga AP, Michaels AJ. The effect of weight errors on neural networks. In: 2018 IEEE 8th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC). New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 190–6. doi:10.1109/CCWC.2018.8301749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Restrepo-Calle F, Martínez-Álvarez A, Cuenca-Asensi S, Jimeno-Morenilla A. Selective SWIFT-R: a flexible software-based technique for soft error mitigation in low-cost embedded systems. J Electron Test. 2013;29(6):825–38. doi:10.1007/s10836-013-5416-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. JEDEC. DDR5 SDRAM [Internet] 2024. [cited 2025 Oct 15]. Available from: https://www.jedec.org/standards-documents/docs/jesd79-5c01. [Google Scholar]

15. Dell TJ. A white paper on the benefits of chipkill-correct ECC for PC server main memory. IBM Microelectron Div. 1997;11(1–23):5–7. [Google Scholar]

16. Li S, Chen K, Hsieh MY, Muralimanohar N, Kersey CD, Brockman JB, et al. System implications of memory reliability in exascale computing. In: Proceedings of 2011 International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis; 2011 Nov 12–18; Seatle, WA, USA. p. 1–12. doi:10.1145/2063384.2063445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Nguyen DT, Ho NM, Le MS, Wong WF, Chang IJ. ZEM: zero-cycle bit-masking module for deep learning refresh-less DRAM. IEEE Access. 2021;9:93723–33. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3088893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Nguyen DT, Ho NM, Chang IJ. St-DRC: stretchable DRAM refresh controller with no parity-overhead error correction scheme for energy-efficient DNNs. In: Proceedings of the 56th Annual Design Automation Conference 2019; 2019 Jun 2–6; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 1–6. doi:10.1145/3316781.3317915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Burel S, Evans A, Anghel L. Zero-overhead protection for cnn weights. In: 2021 IEEE International Symposium on Defect and Fault Tolerance in VLSI and Nanotechnology Systems (DFT). New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/DFT52944.2021.9568363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Guan H, Ning L, Lin Z, Shen X, Zhou H, Lim SH. In-place zero-space memory protection for cnn. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. Vol. 32. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

21. Schmedding A, Yang L, Jog A, Smirni E. Aspis: lightweight neural network protection against soft errors. In: 2024 IEEE 35th International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering (ISSRE). New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 248–59. doi:10.1109/ISSRE62328.2024.00036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Hong JY, Kim S, Jang JW, Yang JS. LOCo: LPDDR optimization with compression and IECC scheme for DNN inference. In: Proceedings of the 29th ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Low Power Electronics and Design; 2024 Aug 5–7; Newport Beach, CA, USA. p. 1–6. doi:10.1145/3665314.3670812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Hsieh TF, Li JF, Lai JS, Lo CY, Kwai DM, Chou YF. Refresh power reduction of DRAMs in DNN systems using hybrid voting and ECC method. In: 2020 IEEE International Test Conference in Asia (ITC-Asia). New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 41–6. doi:10.1109/ITC-Asia51099.2020.00019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Catalán I, Flich J, Hernández C. Exploiting neural networks bit-level redundancy to mitigate the impact of faults at inference. J Supercomput. 2025;81(1):183. doi:10.1007/s11227-024-06693-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wei X, Wang X, Yan Y, Jiang N, Yue H. ALERT: a lightweight defense mechanism for enhancing DNN robustness against T-BFA. J Syst Archit. 2024;152(5):103160. doi:10.1016/j.sysarc.2024.103160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Verbraeken J, Wolting M, Katzy J, Kloppenburg J, Verbelen T, Rellermeyer JS. A survey on distributed machine learning. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR). 2020;53(2):1–33. doi:10.1145/3377454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Liu Y, Liu S, Wang Y, Lombardi F, Han J. A survey of stochastic computing neural networks for machine learning applications. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2021;32(7):2809–24. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2020.3009047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Kraft K, Sudarshan C, Mathew DM, Weis C, Wehn N, Jung M. Improving the error behavior of DRAM by exploiting its Z-channel property. In: 2018 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE). New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 1492–5. doi:10.23919/DATE.2018.8342249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Yu J, Aflatooni K. Leakage current in dram memory cell. In: 2006 16th Biennial University/Government/Industry Microelectronics Symposium. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2006. p. 191–4. doi:10.1109/UGIM.2006.4286380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Waterman A, Asanović K, Hauser J. The RISC-V instruction set manual, volume II: privileged architecture [Internet]; 2021. Version 20211203. [cited 2025 Oct 15]. Available from: https://riscv.org/specifications/privileged-isa/. [Google Scholar]

31. Ainsworth S, Jones TM. Compendia: Reducing virtual-memory costs via selective densification. In: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM SIGPLAN International Symposium on Memory Management; 2021 Jun 22; Online. p. 52–65. doi:10.1145/3459898.3463902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wang Z, Liu L, Xiao L. iSwap: a new memory page swap mechanism for reducing ineffective I/O operations in cloud environments. ACM Trans Archit Code Optim. 2024;21(3):1–24. doi:10.1145/3653302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Delshadtehrani L, Canakci S, Egele M, Joshi A. Sealpk: sealable protection keys for risc-v. In: 2021 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE). New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 1278–81. doi:10.23919/DATE51398.2021.9473932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Intel 64 and IA-32 architectures software developer manuals. Vol. 4; 2024 [Internet]. [cited Oct 15]. Available from: https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/developer/articles/technical/intel-sdm.html. [Google Scholar]

35. Liu J, Jaiyen B, Kim Y, Wilkerson C, Mutlu O. An experimental study of data retention behavior in modern DRAM devices: implications for retention time profiling mechanisms. ACM SIGARCH Comput Archit News. 2013;41(3):60–71. doi:10.1145/2508148.2485928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kim Y, Daly R, Kim J, Fallin C, Lee JH, Lee D, et al. Flipping bits in memory without accessing them: an experimental study of DRAM disturbance errors. ACM SIGARCH Comput Archit News. 2014;42(3):361–72. doi:10.1145/2678373.2665726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Patel M, Kim JS, Hassan H, Mutlu O. Understanding and modeling on-die error correction in modern DRAM: an experimental study using real devices. In: 2019 49th Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks (DSN). New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 13–25. doi:10.1109/DSN.2019.00017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Kim DH, Song B, Ha Ahn, Ko W, Do S, Cho S, et al. A 16Gb 9.5 Gb/s/pin LPDDR5X SDRAM with low-power schemes exploiting dynamic voltage-frequency scaling and offset-calibrated readout sense amplifiers in a fourth generation 10nm DRAM process. In: 2022 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC). New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2022. Vol. 65. p. 448–50. doi:10.1109/ISSCC42614.2022.9731537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Seo Y, Choi J, Cho S, Han H, Kim W, Ryu G, et al. 13.8 a 1a-nm 1.05 v 10.5 Gb/s/pin 16Gb LPDDR5 turbo DRAM with WCK correction strategy, a voltage-offset-calibrated receiver and parasitic capacitance reduction. In: 2024 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC). New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2024, 67, 246–8. doi:10.1109/ISSCC49657.2024.10454381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. JEDEC. Low power double data rate (LPDDR) 5/5X [Internet]; 2023 [cited 2025 Oct 15]. Available from: https://www.jedec.org/standards-documents/docs/jesd209-5c. [Google Scholar]

41. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 770–8. [Google Scholar]

42. Dosovitskiy A, Beyer L, Kolesnikov A, Weissenborn D, Zhai X, Unterthiner T, et al. An image is worth 16 x 16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale [Internet]. In: International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2021); Virtual: OpenReview.net; 2021 [cited 2025 Oct 16] Available from: https://openreview.net/forum?id=YicbFdNTTy. [Google Scholar]

43. Tan M, Le Q. Efficientnetv2: smaller models and faster training. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2021. p. 10096–106. [Google Scholar]

44. la Parra C De, Guntoro A, Kumar A. Efficient accuracy recovery in approximate neural networks by systematic error modelling. In: Proceedings of the 26th Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference; 2021 Jan 18–21; Tokyo Japan. p. 365–71. doi:10.1145/3394885.3431533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Guesmi A, Alouani I, Khasawneh KN, Baklouti M, Frikha T, Abid M, et al. Defensive approximation: securing CNNs using approximate computing. In: Proceedings of the 26th ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems; 2021 Apr 12–23; Online; 2021. p. 990–1003. doi:10.1145/3445814.3446747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Chen Y, Liu S, Lombardi F, Louri A. A technique for approximate communication in network-on-chips for image classification. IEEE Trans Emerg Top Comput. 2022;11(1):30–42. doi:10.1109/TETC.2022.3162165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Kahng AB, Spyrou T. The OpenROAD project: unleashing hardware innovation. In: Government Microcircuit Applications and Critical Technology Conference (GOMAC 2021). Virtual: GOMACTech; 2021. p. 1–6. Available from: https://vlsicad.ucsd.edu/Publications/Conferences/383/c383.pdf. [Google Scholar]

48. Clark LT, Vashishtha V, Shifren L, Gujja A, Sinha S, Cline B, et al. ASAP7: a 7-nm finFET predictive process design kit. Microelectron J. 2016;53(2):105–15. doi:10.1016/j.mejo.2016.04.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Wu XC, Sherwood T, Chong FT, Li Y. Protecting page tables from rowhammer attacks using monotonic pointers in dram true-cells. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems; 2019 Apr 13–17; Providence, RI, USA. p. 645–57. doi:10.1145/3297858.3304039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Qualcomm. Snapdragon X Elite X1E-84-100 processor [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 15]. Available from: https://www.qualcomm.com/snapdragon-x-elite. [Google Scholar]

51. Tambe T, Yang EY, Wan Z, Deng Y, Reddi VJ, Rush A, et al. Algorithm-hardware co-design of adaptive floating-point encodings for resilient deep learning inference. In: 2020 57th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC). New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/DAC18072.2020.9218516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Wang G, Wang G, Liang W, Lai J. Understanding weight similarity of neural networks via chain normalization rule and hypothesis-training-testing. arXiv:2208.04369. 2022. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools