Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Study on Improving the Accuracy of Semantic Segmentation for Autonomous Driving

Department of Mechanical Engineering, Kanagawa University, Yokohama, 2218686, Kanagawa, Japan

* Corresponding Author: Bin Zhang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Deep Learning: Emerging Trends, Applications and Research Challenges for Image Recognition)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.069979

Received 04 July 2025; Accepted 17 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

This study aimed to enhance the performance of semantic segmentation for autonomous driving by improving the 2DPASS model. Two novel improvements were proposed and implemented in this paper: dynamically adjusting the loss function ratio and integrating an attention mechanism (CBAM). First, the loss function weights were adjusted dynamically. The grid search method is used for deciding the best ratio of 7:3. It gives greater emphasis to the cross-entropy loss, which resulted in better segmentation performance. Second, CBAM was applied at different layers of the 2D encoder. Heatmap analysis revealed that introducing it after the second block of 2D image encoding produced the most effective enhancement of important feature representation. The training epoch was chosen for optimizing the best value by experiments, which improved model convergence and overall accuracy. To evaluate the proposed approach, experiments were conducted based on the SemanticKITTI database. The results showed that the improved model achieved higher segmentation accuracy by 64.31%, improved 11.47% in mIoU compared with the conventional 2DPASS model (baseline: 52.84%). It was more effective at detecting small and distant objects and clearly identifying boundaries between different classes. Issues such as noise and variations in data distribution affected its accuracy, indicating the need for further refinement. Overall, the proposed improvements to the 2DPASS model demonstrated the potential to advance semantic segmentation technology and contributed to a more reliable perception of complex, dynamic environments in autonomous vehicles. Accurate segmentation enhances the vehicle’s ability to distinguish different objects, and this improvement directly supports safer navigation, robust decision-making, and efficient path planning, making it highly applicable to real-world deployment of autonomous systems in urban and highway settings.Keywords

In recent years, autonomous driving technology has made remarkable progress, and it is widely expected to significantly enhance traffic safety and convenience. Autonomous driving is classified into levels from 0 to 5 according to its functionality and autonomy, with Level 5 aiming for full automation. Currently, many companies are developing technologies targeting Level 3 and above. Among them, Levels 4 and 5 are characterized by the ability to operate fully autonomously under specific conditions, eliminating the need for human driver intervention. This technology is expected to greatly reduce traffic accidents and improve the efficiency of transportation [1,2]. In autonomous driving, it is crucial for vehicles to accurately perceive their surrounding environment [3]. Among the various perception technologies, “semantic segmentation” is drawing particular attention [4]. Semantic segmentation refers to the technique of analyzing data collected by sensors such as cameras and LiDAR to label each part of an image or point cloud with categories like “road,” “pedestrian,” “vehicle,” and “traffic light”. This enables autonomous vehicles to accurately understand their surroundings and operate safely. Furthermore, in addition to conventional segmentation using 2D images, research on “3D semantic segmentation,” which utilizes 3D point cloud data, has rapidly advanced in recent years [5]. This technology allows for a three-dimensional understanding of the environment and enables high-precision object recognition even in complex urban areas or congested road conditions. By further improving the accuracy and efficiency of this technology, it is expected to greatly accelerate the adoption and safety enhancement of autonomous driving systems.

Semantic segmentation is a technique that assigns semantic meaning to each pixel in an image to identify objects. This technology is expected to have applications in various fields, such as autonomous driving and medical diagnostics. It is mainly classified into three types, each serving different applications: (1) Panoptic Segmentation [6]: A combination of semantic segmentation and instance segmentation that labels every pixel in the image and individually recognizes countable objects. Although still under development, it is attracting attention for future advancements and applications. (2) Semantic Segmentation [7]: Assigns labels to each pixel in an image, grouping pixels of the same class together. It is widely used in autonomous vehicles, smartphones, manufacturing plants, and medical fields to support tasks where object recognition is beneficial. (3) Instance Segmentation [8]: Identifies individual objects in an image and distinguishes between different instances within the same class. It performs both object localization and classification. Autonomous driving technology evolves by integrating object detection with semantic segmentation. This combination allows vehicles to grasp their environment in detail, directly contributing to improved safety. For example, on highways, accurately identifying lanes and junctions enables vehicles to maintain an appropriate speed and safely change lanes. In parking lots, recognizing parking spaces and obstacles allows for autonomous parking, reducing the driver’s burden. Semantic segmentation is utilized as a fundamental technology enabling autonomous vehicles to operate safely and efficiently in diverse environments. In autonomous driving, semantic segmentation serves as a core technology that allows vehicles to understand their surroundings in detail and accurately recognize roads and obstacles. Current technology still faces challenges in recognizing environments under complex conditions. Severe weather conditions, such as rain, fog, or nighttime visibility degradation, can significantly lower the performance of semantic segmentation. Tracking dynamic objects and interacting with pedestrians or other vehicles still lack sufficient recognition accuracy, indicating the need for further improvement [9,10]. Current state-of-the-art methods for semantic segmentation, like KPConv [11], RandLA-Net [12], or Cylinder3D [13], showed great performances in accuracy. They still have limitations like KPConv lacks appearance priors, and this method can be confused on semantically ambiguous classes that look distinct in images. Computational cost may prevent deployment unless compressed. RandLA-Net has excellent efficiency but can lose small/thin object detail from random sampling, which harms safety-critical detections (e.g., pedestrians, poles). As for Cylinder3D, voxel/cylinder quantization trades fine detail for structured context, and it is also heavier to run. While it has a high mIoU on benchmarks, it can still misclassify thin or texture-dependent classes that 2D images disambiguate. None of these methods inherently leverages rich appearance cues from cameras during training. 2DPASS [14] injects 2D image priors into 3D networks via distillation, improving semantic separability for classes that geometry alone struggles with. It is robust to misalignment, degraded images, and domain shifts, and that distills into efficient backbones offers the most practical path to combine SOTA geometric modeling with appearance priors for real-world autonomous driving. The current 2DPASS framework relies on raw 2D feature maps that may contain redundant or noisy information. This can weaken the quality of knowledge transferred to the 3D backbone, leading to less discriminative features during semantic segmentation. Small or thin objects (e.g., poles, pedestrians) and visually ambiguous classes are more likely to be misrepresented, while irrelevant regions such as background clutter or lighting artifacts may dominate the feature space. As a result, 2DPASS still has limitations on highlighting truly informative semantic cues, reducing its robustness in complex real-world driving scenarios.

The aim of this research was to enhance autonomous driving technology by achieving accurate recognition and analysis of the surrounding environment through semantic segmentation. Specifically, we sought to improve upon the 2DPASS model by integrating 3D LiDAR data and 2D camera images to achieve high-accuracy semantic segmentation even in dynamic and complex environments. Dynamically adjusting the loss function ratio is applied, and an attention module was incorporated into the model to enhance important features and improve overall performance. This study aimed to contribute to the development of safe and highly reliable autonomous driving technologies.

In Section 1, we present the research background information, review the previous literature, and indicate the contributions of our study. The remaining sections are structured as follows. Section 2 shows the current construction of the 2DPASS model and presents the methodology of our contributions in improving the model. The results and discussion are presented in Section 3. The main findings are summarized in the last section.

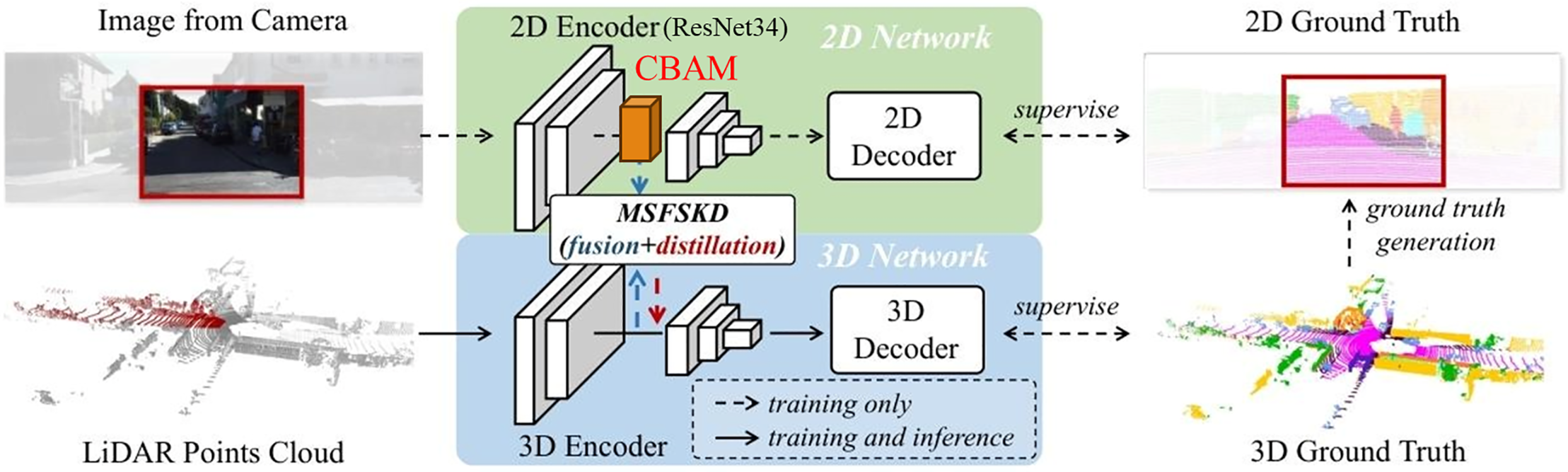

Based on the 2DPASS model, this study proposes several improvements aimed at enhancing its performance. First, the loss function was adjusted to improve segmentation accuracy. Second, an attention mechanism—Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) [15]—was introduced, and two application strategies were compared: applying CBAM uniformly across all layers and applying it selectively to specific layers. In addition, the training epoch was modified to maximize learning effectiveness. As a result, heatmap analysis revealed that introducing CBAM after the second block of the 2D image Encoder (ResNet34) was the most effective approach. The proposed architecture of improved 2DPASS is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Architecture of improved 2DPASS

2.1 Basic 2D-Pass Model for Semantic Segmentation

In conventional multimodal semantic segmentation approaches, the use of both LiDAR point cloud data and camera images has been mainstream. However, several issues have been identified with these methods. The first issue is the high requirement for consistency between the two modalities. Specifically, differences in fields of view (FOV) and misalignment of sensor placements can lead to a mismatch between some point clouds and the corresponding image regions, resulting in missing or misaligned information. The second issue lies in the increased computational cost during the inference phase, as both types of data must be processed simultaneously, making the approach unsuitable for real-time applications. In the case of single-modality methods, the sparsity of LiDAR data and the lack of texture information also limit model performance.

To address these challenges, 2DPASS (2D Priors Assisted Semantic Segmentation) is proposed. This method leverages rich semantic information from 2D images during the training phase to enhance the accuracy of 3D point cloud segmentation. Meanwhile, during inference, only LiDAR data is used, which reduces computational cost and avoids problems related to data alignment. Furthermore, an innovative technique known as Multi-Scale Fusion and Single-Knowledge Distillation (MSFSKD) is introduced to effectively transfer knowledge from 2D images to the 3D model. This approach not only integrates the features of both modalities but also preserves their unique characteristics, minimizing loss of information. As a result, the proposed 2DPASS achieved great performance on large-scale datasets such as SemanticKITTI [16] and nuScenes [17], demonstrating significant improvements in semantic segmentation accuracy compared to conventional methods.

2DPASS presents a new framework that overcomes the limitations of existing multimodal and single-modal approaches, opening new possibilities in 3D semantic segmentation. It takes input of a 2D image captured by a camera and a 3D point cloud captured by a LiDAR sensor. The 2D image is processed by a 2D encoder that extracts rich semantic and structural information, while the 3D point cloud is processed by a 3D encoder that captures geometric structure and sparse 3D features. Each encoder generates modality-specific features. These features are then fused using a module called MSFSKD (Multi-Scale Fusion and Single-Knowledge Distillation) [14]. In this process, the high-resolution semantic information learned by the 2D network is referenced by the 3D network. Subsequently, the 2D and 3D decoders generate their respective outputs. The 2D decoder produces the semantic segmentation result for the image, supervised by the 2D ground truth, while the 3D decoder outputs class labels for each point in the point cloud, supervised by the 3D ground truth. During training, the 2D and 3D networks operate collaboratively; however, during inference, only the 3D network is used. This design enables high-accuracy semantic segmentation while significantly reducing the computational cost at inference time. The process begins with feature extraction from both the 2D and 3D networks. These features are merged through a fusion operation, resulting in a new unified representation. The fused features are then passed through a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) for dimensionality reduction and information extraction. Various computational strategies are employed to maximize the complementary information between the 2D and 3D modalities. The fused features are further processed by a 2D learner, which feeds enhanced feature feedback back into the 3D feature space. This allows the 3D network to integrate semantic knowledge from the 2D network while reinforcing its own geometric representation, ultimately generating a new set of enriched 3D features. These enhanced features are passed to a classifier, which produces the final 3D semantic segmentation result. In addition, the fused 2D-3D features are also input into a classifier to generate a fusion-based prediction. KL divergence is introduced to minimize the distributional gap between the 3D prediction and the fusion prediction, promoting effective knowledge distillation. This KL divergence is only applied during training and is not used in inference. Ultimately, MSFSKD functions as a powerful module that effectively integrates and complements the strengths of both 2D and 3D features, significantly improving the performance of 3D semantic segmentation. This design enables the 2DPASS framework to achieve high accuracy and efficiency that surpasses conventional approaches. 2DPASS significantly outperforms baseline models in terms of 3D semantic segmentation accuracy.

In the baseline models, frequent misclassifications were observed for small objects (e.g., bicycles and pedestrians) and distant objects (e.g., trucks and vegetation), with particularly noticeable issues around object boundaries. In contrast, 2DPASS overcomes these challenges by integrating the rich semantic information available from 2D images. Specifically, it improves recognition accuracy for small objects and object boundaries and reduces class confusion between buildings and vegetation. Additionally, accurate segmentation results are achieved even for sparse point cloud data representing distant objects.

2.2 Optimization of Loss Function

Since the loss function defines the direction in which the model learns, the design and configuration of the loss function directly impact model performance. When combining multiple loss components, the weighting (or ratio) assigned to each loss term can significantly influence the balance of learning and overall accuracy. In this study, we aimed to further improve the semantic segmentation performance of the 2DPASS model by adjusting the ratio of its loss function components. In the original configuration, the

This adjustment allowed the cross-entropy loss to have a greater influence on the overall training process, effectively steering the model toward improved segmentation accuracy. Meanwhile,

2.3 Application of the Attention Module

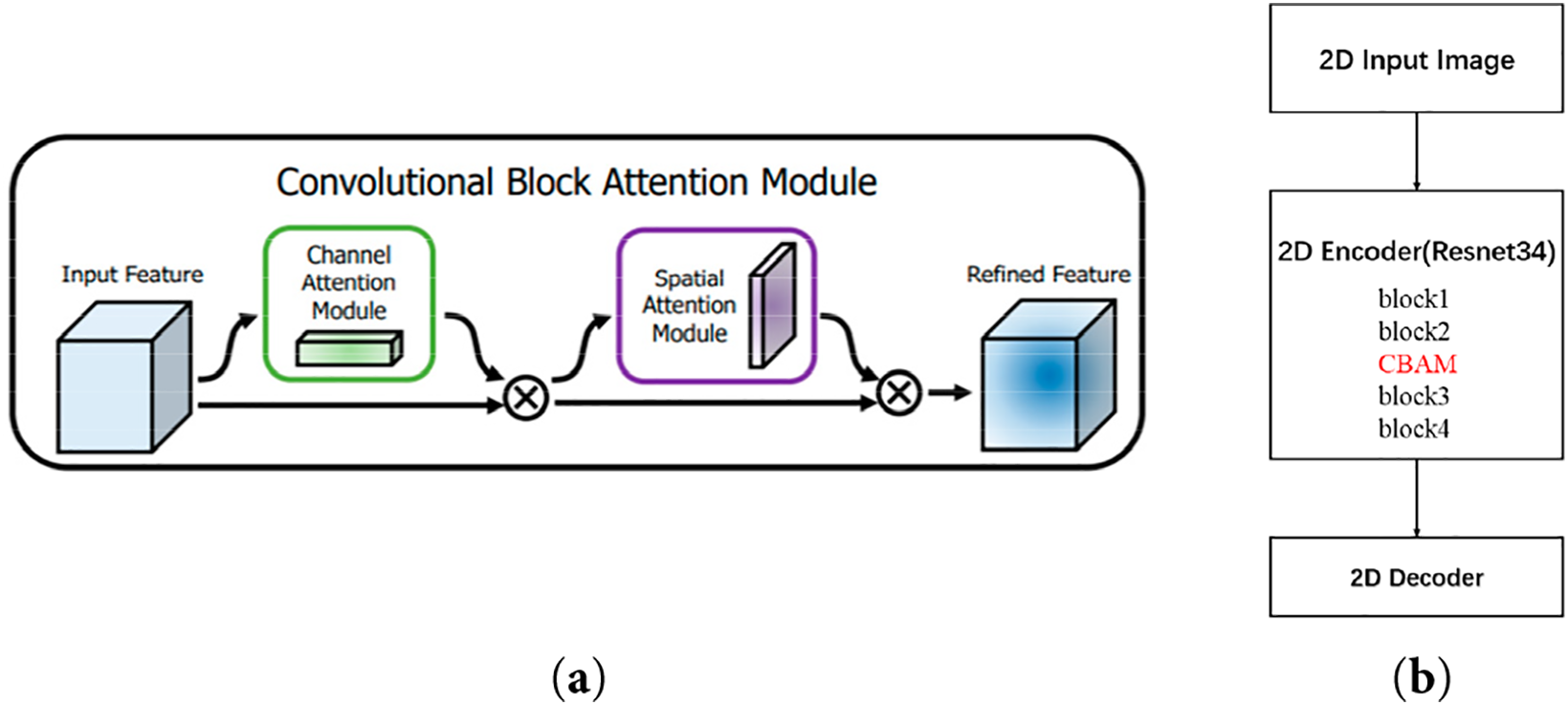

CBAM is an attention mechanism designed for convolutional neural networks (CNNs). CBAM enhances the representational power of the model by effectively learning attention maps along both spatial and channel dimensions. The processing flow of CBAM is shown in Fig. 2a. CBAM consists primarily of two components: channel-wise attention and spatial attention. The channel-wise attention mechanism extracts information across the channel dimension, emphasizing the more informative channels. This enables the network to adaptively assign weights to different features based on their relevance. The spatial attention mechanism captures spatial structures and applies attention to different locations within the feature map, allowing the model to consider contextual relationships over a broader spatial area. By combining these two mechanisms, CBAM can be integrated into various layers or blocks of a network, enabling adaptive and flexible attention application to important features in the data. As a result, it is expected to enhance overall model performance. CBAM showed better performances in expressiveness (better than SE attention blocks [19], since it adds spatial attention), efficiency (lighter than BAM or Transformers-based attention [20,21]), and practical applicability (plug-in friendly for 2DPASS training). This makes it especially effective at refining 2D priors for cross-modal distillation into LiDAR semantic segmentation. In this study, CBAM was introduced after the second layer of the 2D encoder within the 2DPASS model. This position was chosen because the 2D encoder plays a critical role in extracting rich semantic information from 2D images, and by the end of the second layer, local features of the input image have already been sufficiently captured. By applying CBAM at this stage, attention is added to the extracted semantic features in both the channel and spatial dimensions, further emphasizing the most relevant information. Moreover, applying CBAM after the second layer aligns with the design goal of enhancing feature representations at an intermediate stage of the information flow while maintaining a relatively low computational cost. This refinement improves the quality of features passed from the 2D encoder to the 3D encoder, thereby contributing to the overall enhancement of semantic segmentation performance through integrated 2D and 3D processing. The modified 2DPASS architecture incorporating CBAM is shown in Fig. 2b.

Figure 2: Modified 2DPASS by adding CBAM module. (a): CBAM module [15]; (b): Modified 2D encoder

2.4 Heatmap for Feature Visualization

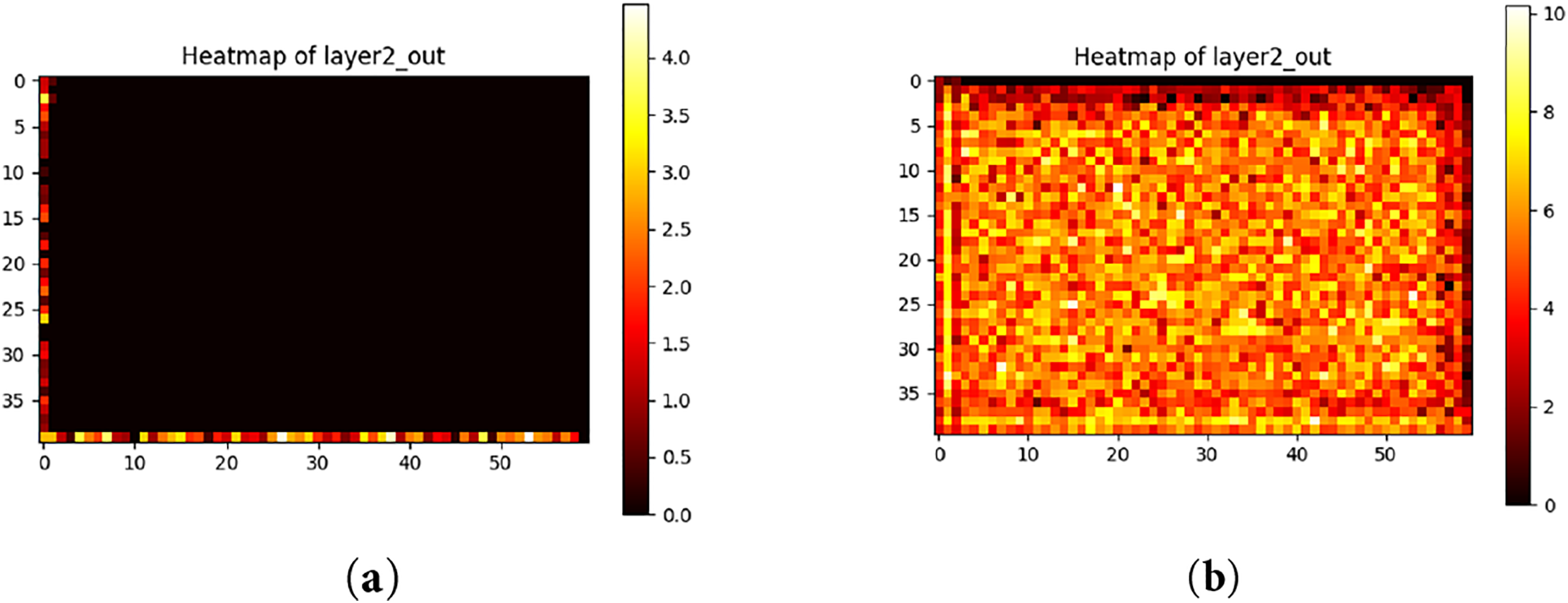

A heatmap is a visualization tool used to highlight data characteristics, particularly in deep learning, where it serves to illustrate which parts of the input data the model focuses on. In typical heatmaps, regions of high attention are shown in warm colors such as red or yellow, while regions of low attention are represented in cool colors such as blue or green. This visualization method allows intuitive understanding of the features or areas the model deems important. In this study, heatmaps were utilized to specifically evaluate the effects of integrating the CBAM into the 2DPASS model. This was motivated by the need to visually confirm how CBAM allocates attention to features through its combination of channel and spatial attention mechanisms. When CBAM was applied at different layers of the 2D encoder, heatmaps provided a valuable means of determining which layer most effectively enhanced feature representations. Moreover, heatmaps allow for detailed analysis of the model’s internal behavior and the attention patterns learned during training. Through this analysis, we were able to investigate how CBAM contributes to improving semantic segmentation accuracy. By identifying the optimal layer or position for CBAM integration, heatmaps offered critical insights for further enhancing the overall performance of the model.

Fig. 3a illustrates the activation features of the second block in 2D image encoding (ResNet34) without the application of CBAM. In this case, while some regions show localized activation, the overall density remains low, as shown by the black area being big, indicating that the conventional model is not effectively capturing the critical features of the input data at this step. This will lead to missed segmentation since the features of the targets have disappeared. In contrast, Fig. 3b shows the heatmap of activation features with CBAM applied to the second block. It is evident that the density of activated features is significantly higher, demonstrating that the attention mechanisms—both channel-wise and spatial—introduced by CBAM effectively enhance the model’s understanding of the input. Notably, Fig. 3b exhibits widespread high-density activation (colorful area), suggesting that the model is better able to emphasize important regions and features relevant to semantic segmentation. These results indicate that integrating CBAM at a specific layer (i.e., the layer after the second block in 2D image encoding) plays a crucial role in improving overall segmentation accuracy.

Figure 3: View of the heatmap. (a) Heatmap without using CBAM; (b) Heatmap when using CBAM

SemanticKITTI, which contains large-scale point cloud data acquired from LiDAR sensors mounted on autonomous vehicles, is provided as an extended version of the KITTI Vision Benchmark Suite. It consists of 11 sequences for training and 11 sequences for testing. These datasets are annotated with labels for 19 semantic classes, including vehicles, pedestrians, roads, buildings, and vegetation, which appear in various driving scenarios. SemanticKITTI is widely used as a standard benchmark for evaluating semantic segmentation of LiDAR point clouds. Each frame includes 3D coordinates, reflectance intensity, and the corresponding class label. Due to the large volume of data, the dataset not only enables comprehensive evaluation of model performance but also facilitates training for improving generalization capabilities in complex real-world scenarios. During our training process, 19,130 scans are used for training, and 4071 scans for validation. During the testing process, 20,351 scans are used to evaluate the performance of trained models. The number of training epochs is set to 80 to provide the model with more training iterations, allowing it to gain a deeper understanding of the features within the data set. This is particularly important in the 2DPASS framework, which involves a complex learning process that integrates two different modalities: 2D images and 3D point cloud data. Such integration requires adequate training time to achieve effective feature fusion. By increasing the number of epochs, the model’s ability to capture the diverse characteristics present in the dataset is expected to improve, thereby enabling higher-precision semantic segmentation. However, excessively increasing the number of epochs raises the risk of overfitting, making it crucial to strike a proper balance. In this study, 100 epochs are trained for the model, and 80 epochs were selected as an optimal setting that provides sufficient learning while avoiding overfitting through experiments.

Mean Intersection over Union (

where

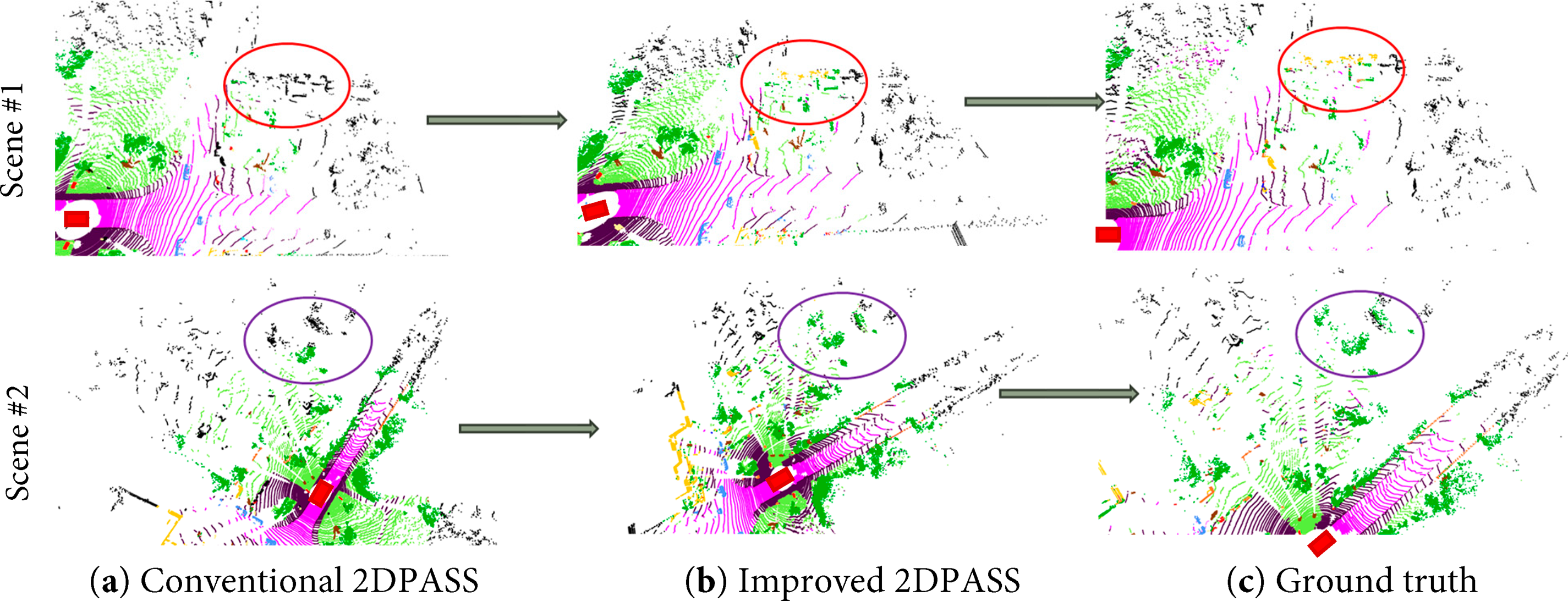

The semantic segmentation results of different scenes are shown in Fig. 4. The red rectangles in the figure show the positions of the autonomous vehicle (self-position), black points show the positions that failed to be segmented, and colored points show different segmentation results (e.g., roads are shown as pink points). The segmentation results are similar around the autonomous vehicle, as shown that the areas are similar in Fig. 4a–c, for both scene #1 and scene #2. There are still some differences, especially in the relatively distant regions, as shown in the circle lines. In the results shown in Fig. 4a, misclassifications are particularly noticeable in distant regions and along object boundaries (especially the area circled by the red line in scene #1 and the area circled by the purple line in scene #2), leading to an overall impression of ambiguous class separation. In contrast, Fig. 4b demonstrates more accurate class assignments compared to Fig. 4a, with clearer delineation between objects and background, especially along class boundaries (different classes are segmented and showed in different colors, as shown in the area circled by the red line in scene #1 and the area circled by the purple line in scene #2). Fig. 4c visualizes the ground truth labels, where classes such as road, vegetation, and buildings are accurately segmented. The output in Fig. 4b closely approximates the ground truth shown in Fig. 4c (especially the area circled by the red line in scene #1 and the area circled by the purple line in scene #2), although there are still some regions where the prediction does not fully match the ground truth. This indicates room for further improvement in segmentation accuracy.

Figure 4: Modified 2DPASS by adding the CBAM module

The accuracies of different classes by using different models are shown in Table 1. The proposed method shows the best accuracy in mIoU (64.31%), improved 11.47% from the baseline (52.84%). Its standard deviation decreases from 27.28% to 26.55%, showing the results are more clustered around the mean value of the data set, indicating that the proposed method has a small degree of dispersion, high data consistency, and a more concentrated and stable distribution. The accuracy for all classes is improved, and 15 classes in 19 show the best performances. The class of motorcycle shows the best improvement (+36.05%), and classes of bicycle (+20.3%), truck (+30.57%), person (+20.96%), bicyclist (+20.91%), and parking (+20.46%) also show great improvements. These results show the effects of optimization of the loss function, application of CBMA (especially for large objects like trucks), and the choice of optimal training epochs. Other-ground (+0.73%) shows the least improvement since the features are too few to handle for recognition. Above all, the proposed model has better performance with conventional 2DPASS models.

The inference time for the proposed model is almost the same as that of the conventional 2DPASS. Since optimization of the loss function does not add any new computations and adjusting training epochs only influences training time, the inference time is only influenced by applying CBAM modules. The feature map resolution of where we added the CBAM module is low, the increase in computational cost is small, and the number of parameters also changes slightly; the total inference time increased by only 1%–3% during the testing process, compared with the conventional 2DPASS model (44 ms). Compared with the improvements in accuracy, the proposal method strikes a balance between accuracy and efficiency.

Although the proposed method significantly improves mean IoU and per-class accuracy, several limitations remain. First, robustness to noise and distribution shift is still limited. The refined model, while effective under standard conditions, may struggle in complex real-world settings such as adverse weather or unconventional road layouts. This is primarily due to insufficient exposure to diverse training scenarios and the absence of explicit robustness-enhancing mechanisms such as uncertainty modeling or domain adaptation. Second, extreme class imbalance continues to hinder model generalization. Rare categories such as motorcyclist (2.21%) and other-ground (0.78%) remain poorly recognized, indicating severe under-learning caused by scarce or visually nonsalient samples. Despite overall gains, the model’s representational capacity is biased toward frequently occurring classes, leading to large inter-class performance gaps. Third, individual enhancement strategies show selective effectiveness. For instance, applying CBAM to every layer decreases accuracy for large objects like trucks and buses, demonstrating that uniform attention application may introduce feature redundancy or interfere with hierarchical abstraction. Hence, optimal performance depends on carefully targeted integration rather than universal use. Finally, prediction stability across categories remains uneven. Some classes still exhibit frequent false positives or negatives, reflecting unbalanced attention and over-reliance on dominant features. Therefore, the proposed improvements successfully enhance overall performance but reveal persistent challenges in robustness, class balance, and consistency—issues that warrant further study through adaptive re-weighting, multimodal fusion, and uncertainty-aware training frameworks.

Improving semantic segmentation accuracy and decreasing inference time are two of the most challenging aspects in developing autonomous vehicles. Current researchers are trying to apply complex deep learning models to show state-of-the-art performances in accuracy, but their practicality is usually not sufficient. In this study, we proposed several enhancement methods to improve the performance of semantic segmentation based on the light-architecture 2DPASS model and experimentally verified their effectiveness in accuracy and in real-time performance. Two important modifications were implemented: adjusting the loss function ratio and applying the attention mechanism (CBAM). By adjusting the loss function ratio to 7:3, we placed greater emphasis on the cross-entropy loss, leading to further improvements in segmentation accuracy. We proposed applying CBAM individually to different layers, and through heatmap analysis, confirmed that applying CBAM after the second layer in 2D encoding shows the best results. The training epoch number is set to 80 for optimization of model convergence and performance. It achieved higher segmentation accuracy by 64.31%, improved 11.47% in mIoU compared with the conventional 2DPASS model (baseline: 52.84%). The inference time remains almost the same, well within real-time requirements. The results of this study contribute to the advancement of semantic segmentation technology and lay the groundwork for future improvements for real-world environment perception in autonomous driving. It directly translates into safer, more reliable, and scalable autonomous driving systems capable of operating in the complexity of real-world environments.

Future work will focus on the following tasks. (1) Expanding Data Diversity: To enhance the generalization ability of the model, it is necessary to collect and utilize a more diverse dataset for training. We will scan data under varying lighting conditions and environmental settings to make our database adapt to real-world scenarios, as well as combine other databases like nuScenes. (2) Optimization of Model Architecture: Incorporating attention mechanisms like CBAM in a 3D backbone may lead to improved segmentation accuracy. The development of lightweight models with computational efficiency in mind will be essential. (3) Integration of Multimodal Information: The fusion of other kinds of sensor information, like ultrasonic sensors and Radar sensors, can improve the robustness of the model. Make sure the inference process works well, even if some sensors cannot scan the environment in real time.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Bin Zhang; methodology, Bin Zhang and Zhancheng Xu; software, Zhancheng Xu; validation, Zhancheng Xu; formal analysis, Bin Zhang and Zhancheng Xu; investigation, Zhancheng Xu; resources, Bin Zhang and Zhancheng Xu; data curation, Zhancheng Xu; writing—original draft preparation, Zhancheng Xu; writing—review and editing, Bin Zhang; visualization, Zhancheng Xu; supervision, Bin Zhang; project administration, Bin Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhang T, Sun Y, Wang Y, Li B, Tian Y, Wang FY. A survey of vehicle dynamics modeling methods for autonomous racing: theoretical models, physical/virtual platforms, and perspectives. IEEE Trans Intell Veh. 2024;9(3):4312–34. doi:10.1109/TIV.2024.3351131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. McKinsey Center for Future Mobility. New twists in the electric-vehicle transition: a consumer perspective [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 04]. Available from: https://www.mckinsey.com/features/mckinsey-center-for-future-mobility/our-insights/new-twists-in-the-electric-vehicle-transition-a-consumer-perspective#/. [Google Scholar]

3. Qiu Y, Lu Y, Wang Y, Yang C. Visual perception challenges in adverse weather for autonomous vehicles: a review of rain and fog impacts. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 7th Information Technology, Networking, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (ITNEC); 2024 Sep 20–22; Chongqing, China. p. 1342–48. doi:10.1109/ITNEC60942.2024.10733168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ding L, Sun H, Fan S, Ma S, Gu S, Ma C. Urban scenes dynamic adaptation semantic segmentation for autonomous driving. In: Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Electrical, Mechanical and Computer Engineering (ICEMCE); 2024 Oct 25–27; Xi'an, China. p. 2086–89. doi:10.1109/ICEMCE64157.2024.10862292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yang K, Bi S, Dong M. Lightningnet: fast and accurate semantic segmentation for autonomous driving based on 3D LIDAR point cloud. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME); 2020 Jul 6–10; London, UK. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICME46284.2020.9102769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Sirohi K, Mohan R, Büscher D, Burgard W, Valada A. EfficientLPS: efficient LiDAR panoptic segmentation. IEEE Trans Robot. 2022;38(3):1894–914. doi:10.1109/TRO.2021.3122069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Ibrahem H, Salem A, Kang H-S. Seg2Depth: semi-supervised depth estimation for autonomous vehicles using semantic segmentation and single vanishing point fusion. IEEE Trans Intell Veh. 2025;10(4):2195–205. doi:10.1109/TIV.2024.3370930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Gao J, Zhang C, Fan J, Wu J, Tian W, Chu H. Vehicle instance segmentation and prediction in bird’s-eye-view for autonomous driving. In: Proceedings of the 2024 8th CAA International Conference on Vehicular Control and Intelligence (CVCI); 2024 Oct 25–27; Chongqing, China. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/CVCI63518.2024.10830208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Leilabadi SH, Schmidt S. In-depth analysis of autonomous vehicle collisions in California. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC); 2019 Oct 27–30; Auckland, New Zealand. p. 889–93. doi:10.1109/ITSC.2019.8916775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ngo K-VH, Nguyen HK. Developing a deep learning-based embedded system to detect adverse weather conditions for autonomous vehicles. In: Proceedings of the 2024 RIVF International Conference on Computing and Communication Technologies (RIVF); 2024 Dec 21–23; Danang, Vietnam. p. 297–301. doi:10.1109/RIVF64335.2024.11009034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Thomas H, Qi CR, Deschaud JE, Marcotegui B, Goulette F, Guibas L. KPConv: flexible and deformable convolution for point clouds. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 6410–9. [Google Scholar]

12. Hu Q, Yang B, Xie L, Rosa S, Guo Y, Wang Z. RandLA-Net: efficient semantic segmentation of large-scale point clouds. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 11105–14. [Google Scholar]

13. Zhu X, Zhou H, Wang T, Hong F, Ma Y, Li W. Cylindrical and asymmetrical 3D convolution networks for LiDAR segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 9934–43. [Google Scholar]

14. Yan X, Gao J, Zheng C, Zheng C, Zhang R, Cui S, et al. 2DPASS: 2D priors assisted semantic segmentation on LiDAR point clouds. arXiv:2207.04397. 2022. [Google Scholar]

15. Woo S, Park J, Lee J-Y, Kweon I-S. CBAM: convolutional block attention module. arXiv:1807.06521. 2018. [Google Scholar]

16. SemanticKITTI: a dataset for semantic scene understanding using LiDAR sequences. [cited on 2025 Jul 4]. Available from: https://semantic-kitti.org/index.html. [Google Scholar]

17. NuScenes by Motional. [cited on 2025 Jul 04]. Available from: https://www.nuscenes.org/. [Google Scholar]

18. Tuning the hyper-parameters of an estimator. [cited on 2025 Jul 4]. Available from: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/grid_search.html. [Google Scholar]

19. Hu J, Shen L, Albanie S, Sun G, Wu E. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2020;42(8):2011–23. doi:10.1109/tpami.2019.2913372. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Park J, Woo S, Lee J-Y, Kweon IS. BAM: bottleneck attention module. arXiv:1807.06514. 2018. [Google Scholar]

21. Yang G, Tang H, Ding M, Sebe N, Ricci E. Transformer-based attention networks for continuous pixel-wise prediction. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 16249–59. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools