Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Generative Steganography Based on Attraction-Matrix-Driven Gomoku Games

1 School of Cyber Science and Engineering, Wuxi University, Wuxi, 214105, China

2 School of Computer Science, School of Cyber Science and Engineering, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, 210044, China

* Corresponding Author: Chengsheng Yuan. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070158

Received 09 July 2025; Accepted 19 September 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Generative steganography uses generative stego images to transmit secret message. It also effectively defends against statistical steganalysis. However, most existing methods focus primarily on matching the feature distribution of training data, often neglecting the sequential continuity between moves in the game. This oversight can result in unnatural patterns that deviate from real user behavior, thereby reducing the security of the hidden communication. To address this issue, we design a Gomoku agent based on the AlphaZero algorithm. The model engages in self-play to generate a sequence of plausible moves. These moves form the basis of the stego images. We then apply an attraction matrix at each step. It guides the move selection so that the moves appear more natural. This method helps maintain logical flow between moves. It also extends the game length, which increases the embedding capacity. Next, we filter and prioritize the generated moves. The selected moves are embedded into a move pool. Secret message is mapped to these moves. It is then embedded step by step as the game progresses. The final move sequence constitutes a complete steganographic game record. The receiver can extract the secret message using this record and a predefined mapping rule. Experiments show that our method reaches a maximum embedding capacity of 223 bits per carrier. Detection accuracy is 0.500 under XuNet and 0.498 under YeNet. These results are equal to random guessing, showing strong imperceptibility. The proposed method demonstrates superior concealment, higher embedding capacity, and greater robustness against common image distortions and steganalysis attacks.Keywords

Steganography is a technique for covert communication [1], aiming to produce stego images imperceptible to human perception and statistical analysis, thereby enhancing security by concealing both the content and existence of information.

Recently, due to image steganography’s high embedding capacity and advancements in optimization algorithms and image processing techniques [2,3], image steganography has become a prominent research area within the broader field of information hiding. Traditional modification-based methods, such as Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) [4] and Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) [5], embed data by altering pixel values or frequency-domain coefficients. However, these methods often generate detectable statistical artifacts, making them susceptible to modern steganalysis techniques [6,7].

To address these issues, recent advancements in generative models have led to the emergence of generative steganography. This technique embeds secret message directly into the image generation process, producing stego images from scratch. By avoiding modifications to existing images, this approach enhances information concealment and reduces statistical detectability compared to traditional methods. Depending on how the secret message is embedded [8], generative stego images are typically classified as either pixel-based or latent-space-based methods.

Pixel-based generative steganography embeds secret message by generating images with specific pixel values [9–11]. These methods show a certain degree of resistance to statistical detection. However, they heavily rely on exact pixel values, which makes them vulnerable to modification-based attacks. In contrast, latent-space-based methods embed secret message within the latent space of generative networks [12–16]. These methods enhance robustness by avoiding direct manipulation of pixel values. Although the generated carriers statistically resemble the training data, they often lack meaningful semantic content. Furthermore, repeated transmission of such synthetic samples may raise suspicion, thereby limiting their practical applicability.

Researchers have increasingly explored behavioral steganography to address the limitations of conventional generative steganography. This emerging subfield generates stego images by mimicking realistic interactive behaviors, such as gameplay or social interactions. In doing so, it aims to enhance communication plausibility and reduce the likelihood of detection. Prior studies [17–21] have shown that these techniques can effectively evade conventional statistical steganalysis. However, a comprehensive analysis [17,22] reveals a significant limitation. Existing behavior-based systems are constrained to discrete environments and depend on limited action strategies. These constraints reduce encoding diversity and lead to repetitive behavioral patterns. Consequently, these systems encounter two major challenges. First, the embedding capacity of each carrier is inherently limited. Second, unrealistic behavioral patterns elevate the risk of anomaly detection, potentially compromising communication security.

This paper introduces a novel generative steganography approach that embeds secret message through Gomoku gameplay. In the embedding phase, a Gomoku-playing model translates secret message into game moves, enabling covert communication. During the extraction phase, the gameplay is reconstructed from images and decoded using predefined move-encoding rules. The main contributions of this work are as follows:

• A Steganographic Framework Based on Relative Move-Position Encoding: We propose a novel method that integrates steganography with Gomoku gameplay. The method embeds secret message by leveraging spatial dependencies between player moves. Unlike previous behavior-based methods [17,19], our method circumvents the constraints of fixed, discrete action spaces. Gomoku provides a significantly larger game tree, with approximately

• A Gomoku-Playing Model with Attraction Matrix: We design a Gomoku-playing model that combines a basic strategy network with an attraction matrix to balance gameplay authenticity and data embedding requirements. To minimize spatial bias when selecting suboptimal moves, the model first constructs a two-dimensional attraction field centered on previous moves. It then applies geometric constraints to guide the placement of subsequent moves. This design enhances the naturalness of gameplay and effectively conceals the steganographic channel, thereby improving the robustness and real-world applicability of the proposed approach.

Image generative steganography is an important subfield within information security. It embeds secret message using generative model. Unlike traditional steganographic techniques, this method embeds secret message directly into the input features of generative models. As a result, the models generate stego images that appear visually natural and realistic, effectively eliminating the statistical artifacts and reducing attackers’ suspicion.

According to recent studies [23], generative steganography can be broadly classified into two categories: pixel-defined generative steganography and latent-space-mapped generative steganography.

Pixel-defined generative steganography refers to methods that embed secret message directly into pixel values. Yang et al. [9] proposed a representative method based on Pixel Convolutional Neural Networks (PixelCNN). Their method models pixel dependencies by estimating the probability distribution of each pixel in the range [0, 255], conditioned on previously generated pixels. To embed data, they adopted a rejection sampling strategy. The process starts from the top-left corner of a blank image and proceeds pixel by pixel to the bottom-right. Appropriate pixel values are selected at each step based on the sampling rule, ultimately forming a complete stego image.

Building on the previous study, Zhang et al. [24] proposed Pixel-Stega, an enhanced method for pixel-defined generative steganography. This method replaces PixelCNN with the more advanced PixelCNN++. It also incorporates a sampling strategy based on arithmetic coding. In Pixel-Stega, secret message guide the generation of pixel values. This guidance is applied jointly with the predicted probability distribution for each pixel. The integration of arithmetic coding enables adaptive bit allocation. More bits are assigned to high-entropy regions, while fewer are allocated to low-entropy regions. This adaptive embedding strategy improves the visual quality of generated images. At the same time, it maintains a fixed payload, making the method practical for controlled steganographic communication.

Notably, pixel-defined generative steganography methods generate images entirely from scratch rather than modifying existing cover images. This characteristic makes them highly resistant to steganalysis techniques that rely on detecting statistical artifacts. However, these methods tend to suffer from limited robustness. The generated images are often vulnerable to distortion-based attacks during transmission.

Natural images exhibit complex, high-dimensional distributions. Neural networks can learn mappings between these image-space distributions and simpler latent distributions, such as high-dimensional Gaussian distributions [25]. Leveraging this insight, latent-space-based generative steganography establishes a correspondence between secret message and latent vectors. The secret message is first embedded into a latent representation, which is then used to generate the stego image.

For example, Liu et al. [26] embedded secret message into latent vectors and used diffusion models to generate stego images from these vectors. Su et al. [12] proposed a distribution-preserving data modulator. This modulator embeds secret messages while maintaining the original distribution, allowing imperceptible communication. They also introduced a generic secret message extractor to ensure reliable messages recovery. Similarly, Hu et al. [27] embedded secret message into low-dimensional noise vectors. These vectors were fed into a Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Network (DCGAN) to produce stego images. A convolutional neural network (CNN) was then used to extract and reconstruct the original messages.

Overall, latent-space-based approaches tend to exhibit greater robustness against perturbations, as they rely on sampling from latent distributions conditioned on the secret content [28,29]. However, these methods also have inherent limitations. Image distortions can induce latent vector drift, thereby reducing the accuracy of information extraction. Moreover, their embedding capacity is generally lower than that of pixel-defined methods.

Behavioral steganography is a technique that conceals secret message by designing specific behaviors or leveraging social attributes. Its primary goal is to produce covert actions that appear indistinguishable from normal behavior, thereby evading steganalysis. Depending on the application scenario, existing research in this field can be broadly classified into two categories: methods based on social network behavior and those based on game behavior. Both categories generate behavior sequences that conform to contextual rules. This method avoids directly modifying existing carriers and enhances the concealment of the secret message.

Steganography based on social network behaviors facilitates covert communication by encoding secret message within behavioral features. For instance, Zhang [30] introduced an innovative steganographic approach wherein participants exchange secret messages through the act of “liking” each other’s posts. Similarly, Wu et al. [31] employed undirected graphs to embed secret messages and directed graphs to represent network topology. Gilbert et al. [32] developed steganographic content that closely resembled authentic online conversations to conceal secret messages. These techniques leverage the high frequency and variability inherent in social interactions. Nonetheless, their data embedding capacity is frequently limited by platform regulations and the inherent difficulties in precisely modeling user behavior.

In contrast, game behavior steganography embeds secret message into in-game actions or states governed by game mechanics. For example, in bridge [33], Go [34], and maze games [35], secret message is conveyed through move choices and path planning. In chess [19], messages are embedded through piece positions and board colors. Tetris [36] maps its seven block shapes to the digits 0–6 for messages embedding. Minesweeper [37] and puzzle games [22,38] embed data through mine placements and puzzle shapes, respectively. These techniques take advantage of games’ complex structure and behavioral randomness to improve concealment. Nevertheless, they typically offer low embedding capacity. The applicability and generalizability of specific game environments often limit their real-world deployment.

Gomoku is a classic two-player, zero-sum board game. In the game, players place black and white stones on the intersections of a

Game-tree complexity analysis estimates Gomoku’s strategic space at approximately

Leveraging these characteristics, this study utilizes Gomoku game records as the carrier for information hiding. The overall framework of the proposed steganographic algorithm is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Overall framework of the proposed steganographic algorithm

As shown in Fig. 1, the proposed framework transforms Gomoku gameplay into a steganographic medium through three core modules: (1) the design of a Gomoku game model; (2) the generation of steganographic game records embedding secret message; (3) the extraction of secret message from the game records.

Gomoku gameplay exhibits strong local spatial correlation. Effective moves are typically concentrated around existing pieces on the board. However, empirical analysis shows that even after training, game models tend to generate spatially dispersed candidate moves when the optimal move is excluded. These moves often display spatial distributions that differ significantly from those observed in professional-level strategies. For example, in a specific board configuration, the top two optimal moves may have win rates of around

3.1.1 Basic Gomoku Game Network Construction

We trained a reinforcement learning-based neural network for Gomoku gameplay based on the project by Hu [39], capable of generating rule-compliant move strategies through extensive self-play simulations. This model serves as the foundation for enabling strategic communication via in-game actions.

The game environment is represented as a

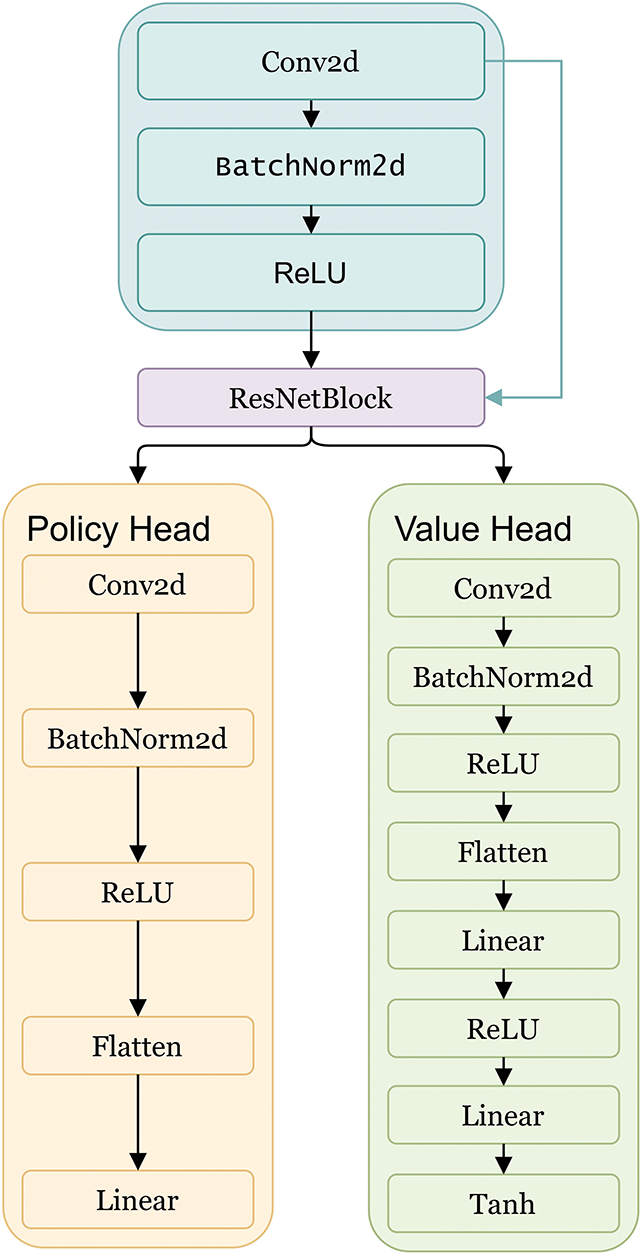

The model is trained using self-play reinforcement learning, combining policy gradient methods are combined with Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) to optimize move strategies through large-scale simulated gameplay. The overall system integrates a value network that estimates the probability of winning and a policy network that guides move selection. The model architecture is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Network architecture of the Gomoku game model

3.1.2 Attraction Matrix Construction

To mitigate game space anomalies induced by steganographic tasks, we introduce an attraction matrix mechanism to optimize the spatial distribution of candidate actions. The construction process comprises four sequential steps: (1) board state representation, (2) spatial influence modeling, (3) attraction value computation, and (4) candidate action optimization.

Step 1: Board State Representation

The algorithm begins by constructing a binary matrix T that captures the current game state. For a standard

Step 2: Spatial Influence Modeling

Based on the observation that effective Gomoku moves typically cluster around existing pieces, we define a spatial attraction decay function that assigns diminishing weights to positions at increasing distances from placed stones:

Here,

Step 3: Attraction Value Computation

For each board position

where the Manhattan distance metric is defined as:

Step 4: Candidate Action Optimization

The final step applies a two-stage optimization process to the candidate actions generated by the reinforcement learning model. First, a spatial validity filter removes any candidates corresponding to occupied positions (those with

where

3.2 Information Hiding Process

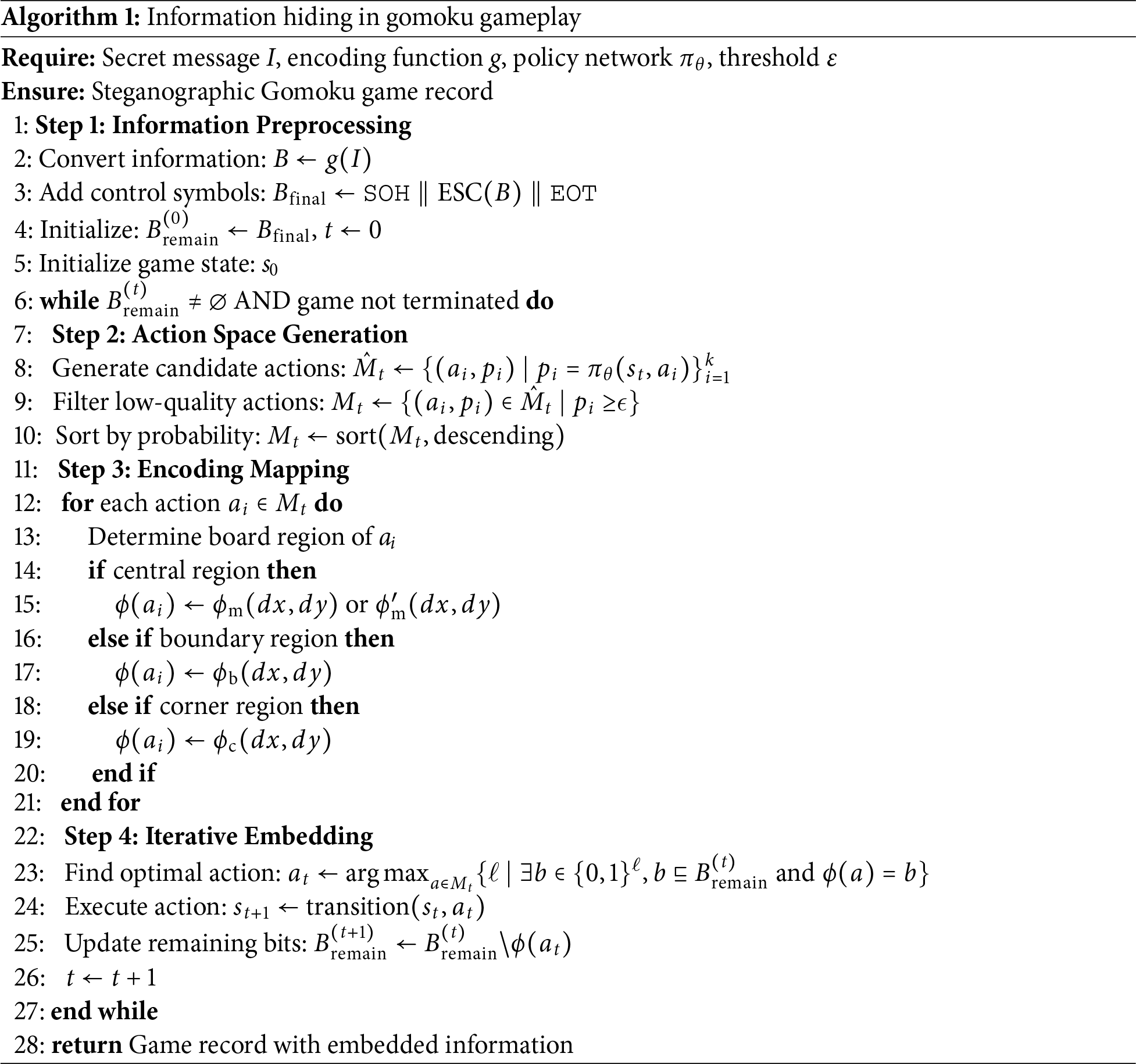

This method implements information-hiding by dynamically encoding move positions within Gomoku gameplay. The core process comprises four stages: information preprocessing, action space generation, encoding mapping, and iterative embedding. Each stage utilizes an optimized Gomoku model to ensure realistic gameplay and computational efficiency. The secret message, denoted by I, is converted into a binary sequence

Step 1: Information Preprocessing: The raw binary stream

Here, SOH indicates the message start, EOT marks the end, and ESC escapes reserved sequences. The final transmission sequence is constructed as:

where

Step 2: Action Space Generation: For each game state

where

Step 3: Encoding Mapping: We use the encoding function

Figure 3: Encoding layout in the central region

• Central Region Encoding: In order to maximize the coding capacity, the central region adopts a two-tier encoding scheme, where the encoding function

We first determine whether the relative move falls within the second outer layer surrounding the current position. If it does, we apply a 4-bit code. Otherwise, a 3-bit code is used, based on the eight cardinal and intercardinal directions from the current position: North (N), Northeast (NE), East (E), Southeast (SE), South (S), Southwest (SW), West (W), and Northwest (NW). The corresponding coding scheme is illustrated in Fig. 3.

• Boundary Region Encoding: For non-corner positions on the board edges, the encoding function

• Corner Region Encoding: For corner positions

Step 4: Iterative Embedding: Initialize

where

Algorithm 1 summarizes the complete information-hiding process, integrating all four steps into a unified workflow.

3.3 Extraction of Stone Coordinates in Gomoku

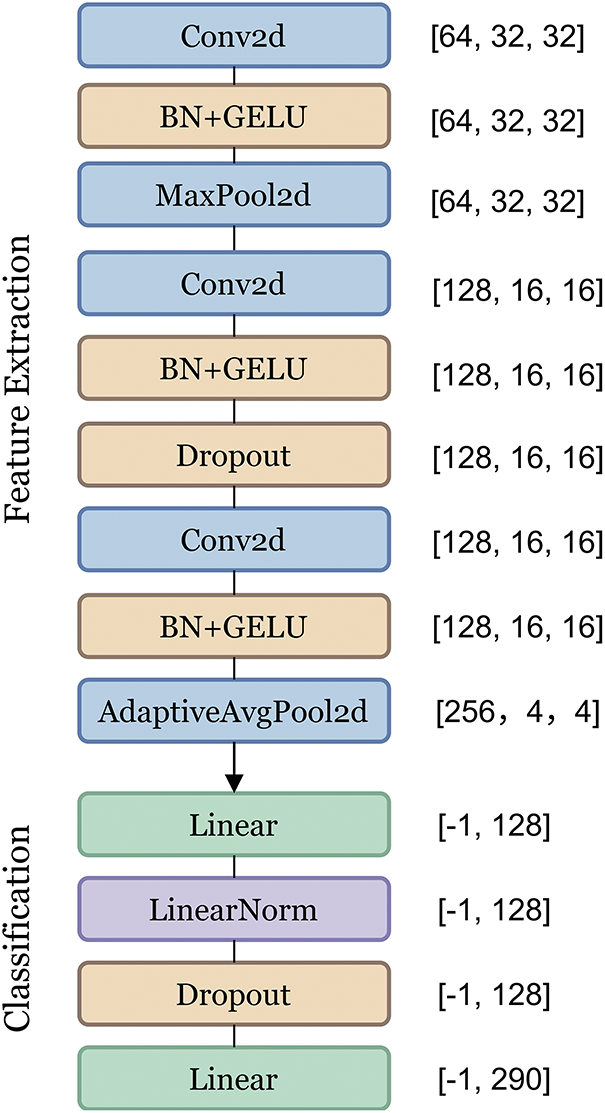

In this paper, we integrate color space analysis, Hough circle detection, and numeric label recognition to accurately extract information from Gomoku board images. Our proposed pipeline comprises three stages. First, we employ a board localization module based on HSV color space conversion, using experimentally optimized threshold values (H: 16–22, S: 50–255, V: 128–255) to robustly isolate the board region from the background. Second, we apply the Hough circle detection algorithm to identify and segment the game pieces. It employs an adaptive radius range (20–35 pixels at 800 dpi), enabling precise detection of stone regions. Third, we utilize a convolutional neural network (CNN) with multi-resolution feature fusion to recognize the numerical labels printed on the stones.

The CNN architecture follows a hierarchical design, as illustrated in Fig. 4. The feature extraction module comprises three convolutional blocks with progressively increasing channel sizes

Figure 4: Architecture of the Gomoku piece recognition network

The model is trained using the Adam optimizer with a cosine annealing learning rate schedule, starting at an initial learning rate of

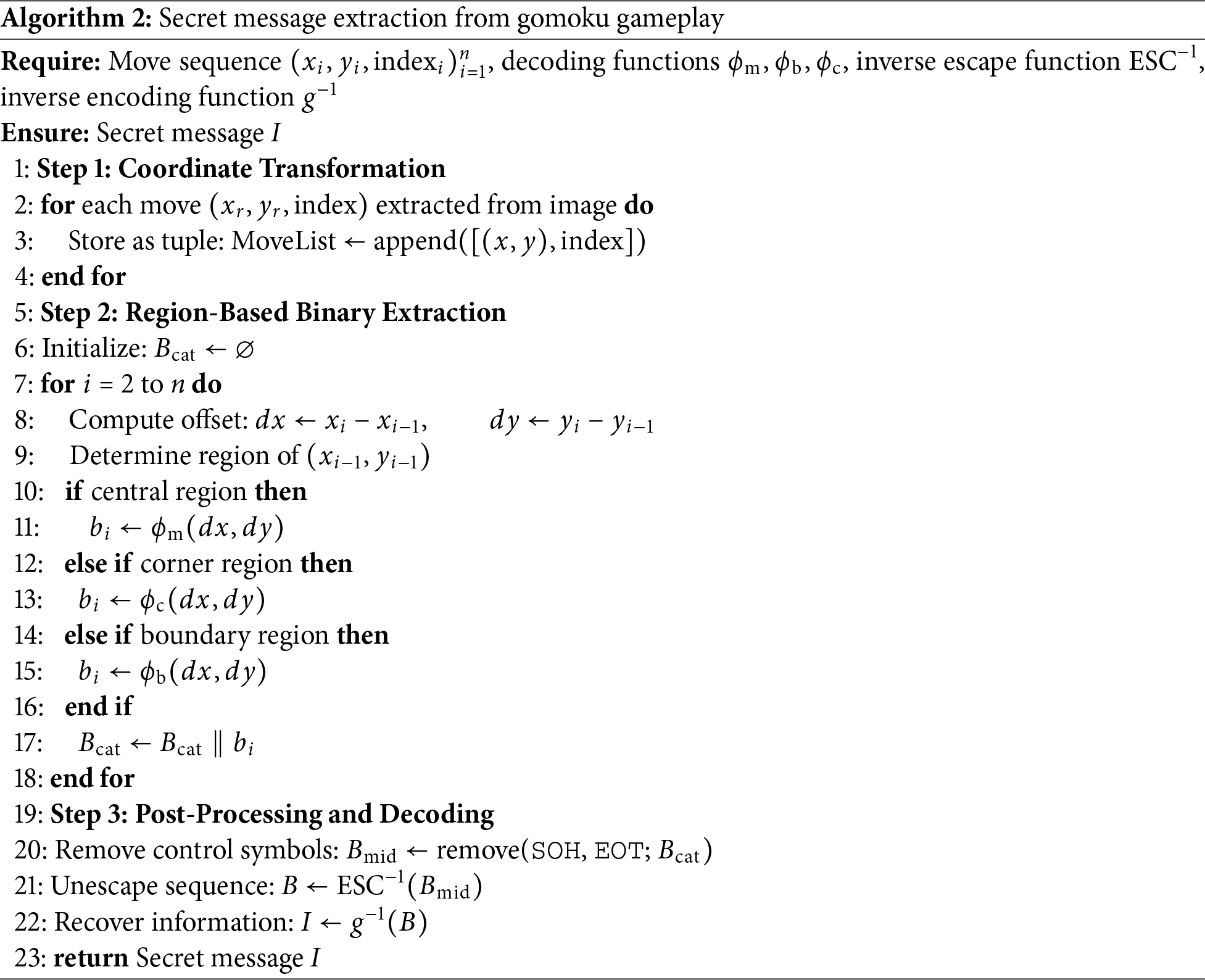

3.4 Secret Message Extraction Process

In the secret message extraction process, we include each stone’s position

Then, we use the positional differences

In this formulation,

After obtaining all binary codes, we concatenate them according to Eq. (18):

where

Next, we process

Subsequently, the inverse escape transformation is applied to recover the original binary message:

The experimental framework was implemented using Python 3.10 and the PyTorch 2.0.1 deep learning library. All experiments were conducted on a Tesla P4 GPU with 8 GB of memory. The Gomoku model was trained on

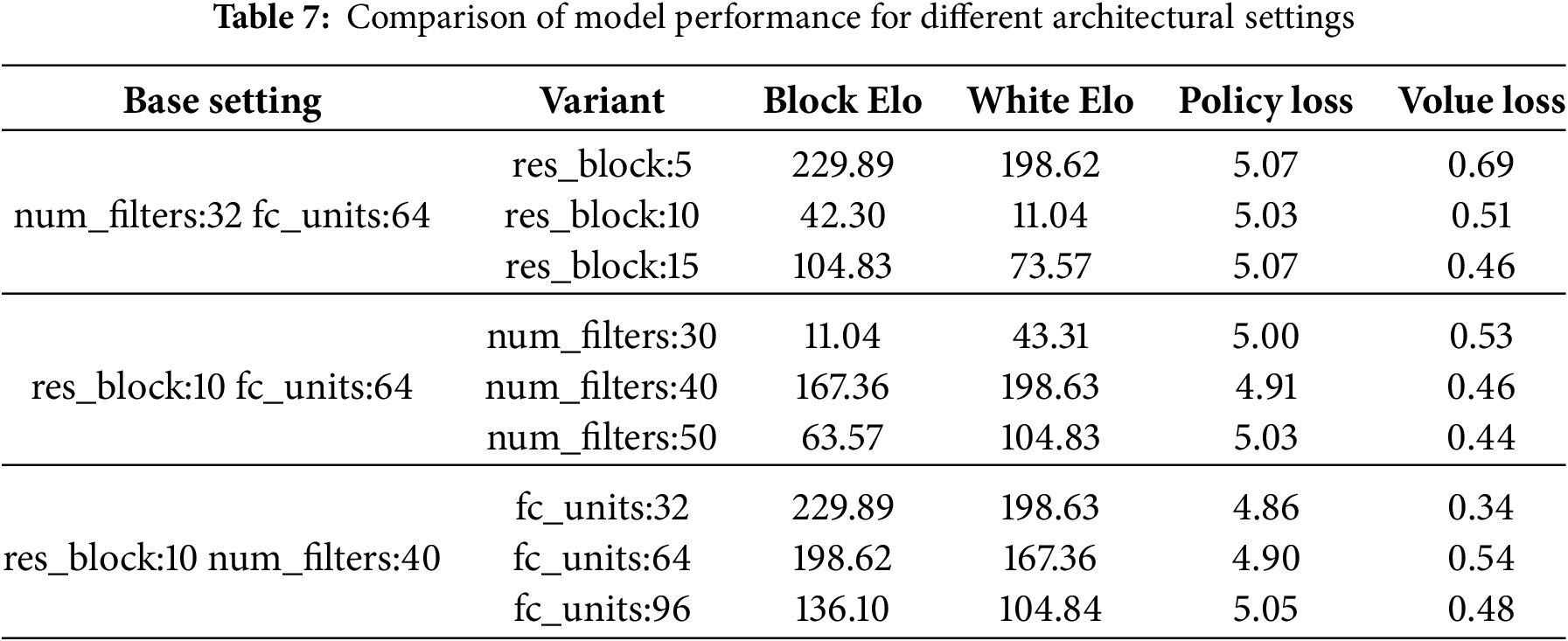

Embedding capacity, a key metric for evaluating information-hiding techniques, quantifies how much secret message can be embedded in a carrier medium. The embedding capacity of the proposed method is computed using Eq. (21):

where M denotes the total number of moves in the Gomoku game,

Based on our calculations, the maximum theoretical embedding capacity on a

Experimental results evaluating the embedding capacity of the proposed method are presented in Table 1.

Robustness is a fundamental metric for evaluating steganographic systems, reflecting their resilience to adversarial conditions based on the accuracy of covert information extraction. During transmission, stego images are frequently exposed to various perturbations, such as Gaussian noise, salt-and-pepper noise, and other forms of signal degradation. This section systematically evaluates the robustness of the proposed method through comparative experiments under a variety of attack scenarios. The proposed method demonstrates remarkable robustness by emphasizing the relative positional relationships between different operations rather than the specific pixels being modified. Furthermore, enhancing the system’s detection capabilities can further improve the robustness of the proposed method. The bit error rate (BER) serves as the primary evaluation metric and is mathematically defined as follows:

where

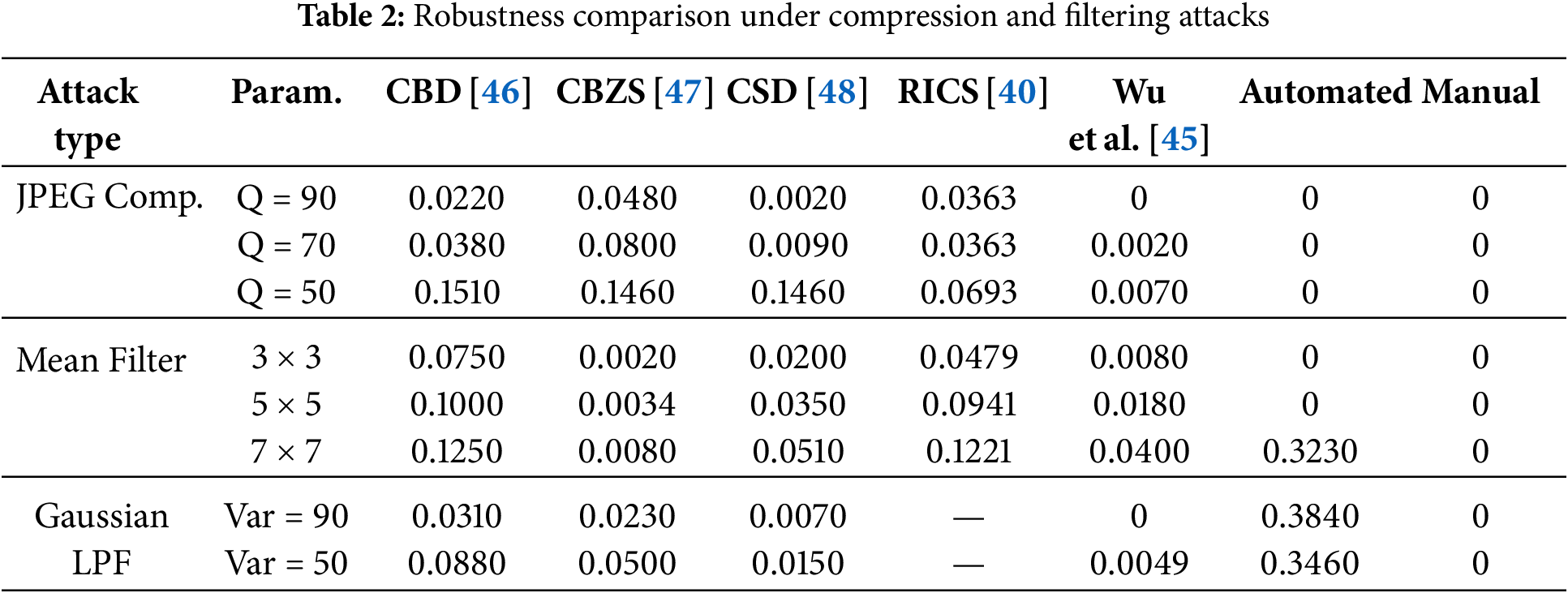

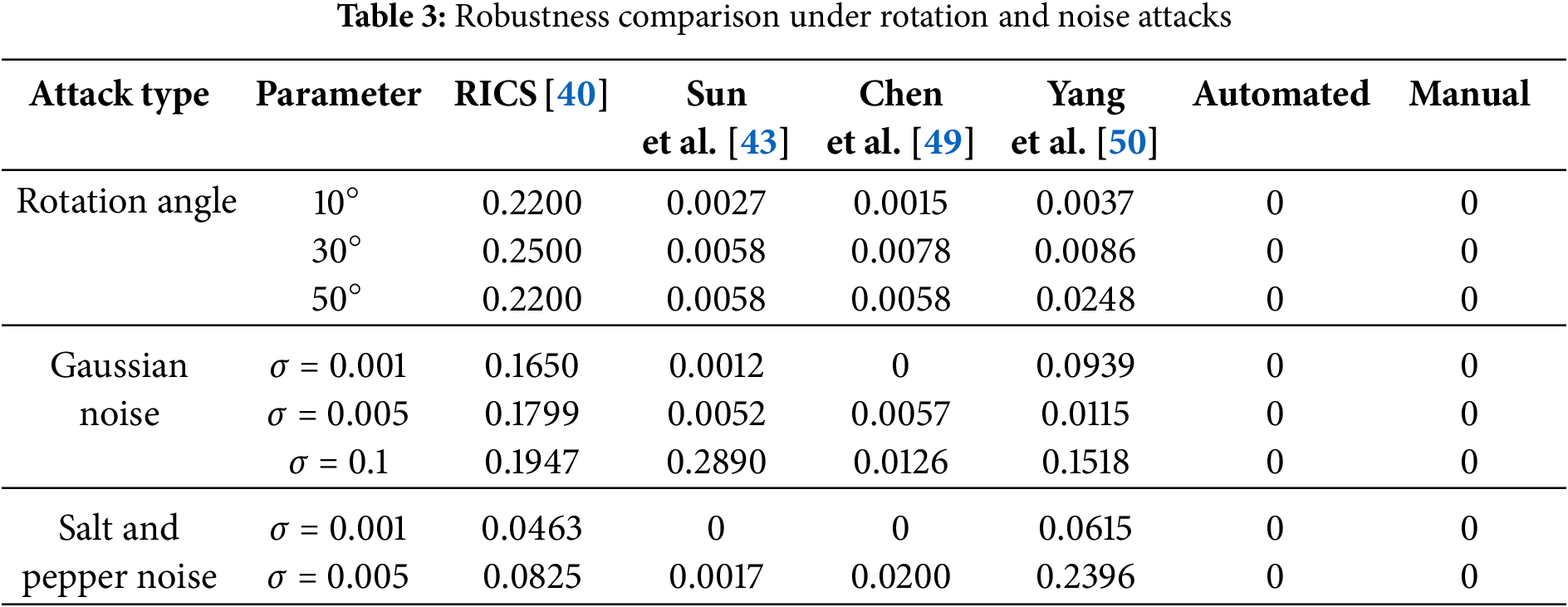

To comprehensively evaluate the robustness of the proposed method under adverse transmission conditions, we conducted extensive experiments involving various attack vectors, including JPEG compression, spatial filtering, geometric rotation, and additive noise injection. The comparative results, shown in Tables 2 and 3, benchmark the proposed method against representative methods: CBD [46], CBZS [47], CSD [48], RICS [40], and the methods proposed by Wu et al. [45], Sun et al. [43], Chen et al. [49], and Yang et al. [50].

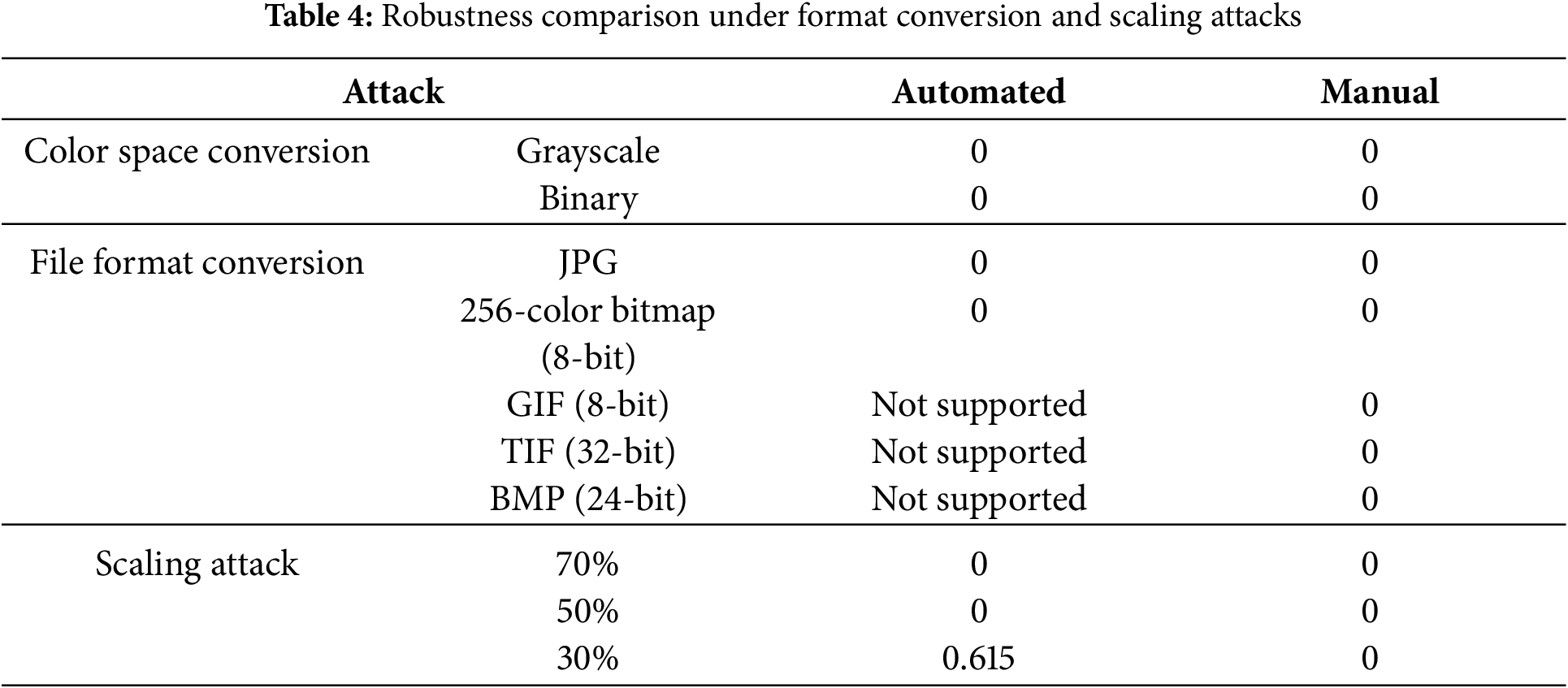

The results show that the proposed method achieves superior robustness across all tested attack scenarios. Furthermore, Table 4 demonstrates its stability under benign conditions such as lossless format conversion, confirming its practical robustness for real-world transmission environments.

4.2.1 Resistance to Image Processing Attacks

To mitigate potential recognition errors inherent in automated systems, a human-assisted correction mechanism was introduced as a post-processing step following the initial computer-based extraction. This hybrid approach allows for the evaluation of both fully automated performance and human-corrected outcomes, offering a more comprehensive assessment of the method’s practical applicability.

Table 2 presents the algorithm’s performance under JPEG compression, mean filtering, and Gaussian low-pass filtering.

Table 3 extends the evaluation to include geometric and noise-based attacks, comparing the proposed method’s performance with several existing approaches.

4.2.2 Resistance to Format Conversion Attacks

The format conversion experiments evaluated the robustness of the proposed method against color space transformations, file format conversions, and scaling attacks. As shown in Table 4, the method maintains a bit error rate (BER) of 0 when converting RGB images to grayscale or binary formats, and when converting PNG files to JPG, GIF, BMP, or TIF formats. In the scaling attack tests, images were resized to 30%, 50%, and 70% of their original dimensions to evaluate the accuracy of information extraction. The proposed method achieves a BER of 0 at both 50% and 70% scaling ratios. At the 30% scaling ratio, automated recognition results in a BER of 0.615, whereas human-assisted verification enables error-free extraction of the embedded information.

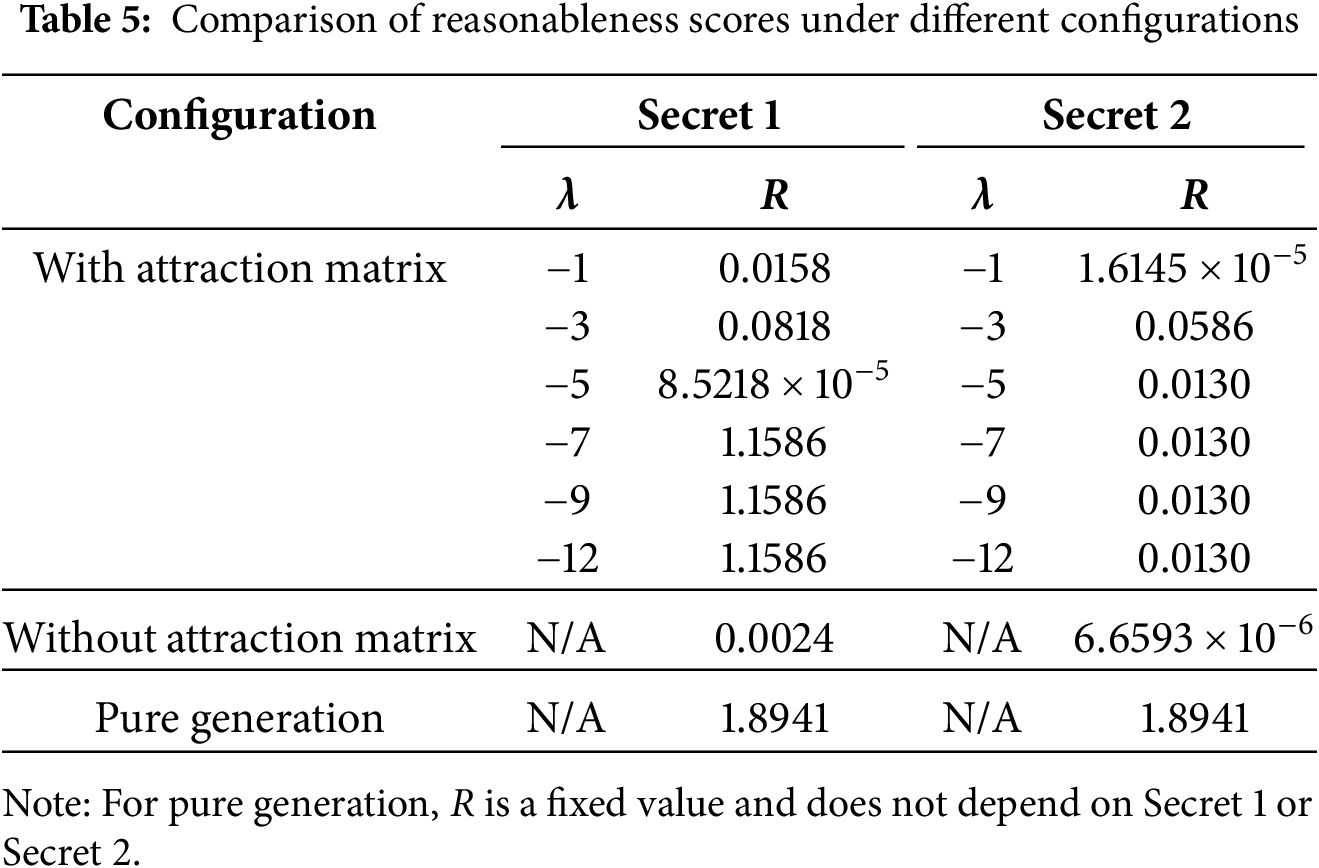

This subsection examines the influence of the attraction matrix mechanism and key neural network components on overall model performance. To evaluate the effect of the attraction matrix, we compare three configurations: purely generative gameplay, steganographic tasks with the attraction matrix, and steganographic tasks without it. The analysis considers variations in model reasonableness, embedding capacity, and the incidence of decision irregularities. Experimental results indicate that incorporating the attraction matrix substantially mitigates embedding capacity loss and reduces non-professional move patterns that arise under purely self-play conditions. Additionally, to assess the contribution of the neural network architecture, we perform ablation studies on critical structural parameters, including the number of residual blocks, the number of convolutional channels, and the size of fully connected layers, thereby confirming the role and effectiveness of each component.

4.3.1 Evaluation of Game Record Reasonableness

The reasonableness of generated game records under steganographic tasks is crucial for maintaining covert communication. In AlphaZero, the value head output represents the estimated winning probability of the current position. We use the following Eq. (23) to quantify the overall plausibility of the generated game record.

In this context, R represents the reasonableness score of a game record, N denotes the total number of moves, and

To evaluate the impact of the attraction matrix strength, we embed two textual excerpts from The Old Man and the Sea as the payload. Since the outcomes of the model training process remain within a fixed range, we select a representative set of values for the parameter

The experimental results indicate that incorporating steganographic tasks leads to a significant deviation in the reasonableness score compared to the purely generative model, suggesting that the payload disrupts the naturalness of gameplay. Introducing a moderate attraction matrix strength effectively mitigates this deviation, producing game records that more closely resemble standard gameplay. However, when the attraction matrix becomes excessively strong, the reasonableness score diverges from the baseline once again, implying that overly restrictive constraints introduce new patterns of unnatural behavior.

4.3.2 Evaluation of Decision Irregularities

Beyond average variations in winning probability, the model’s responsiveness to tactically critical positions serves as another key indicator of strategic reasonableness. In Gomoku, certain board patterns—such as “Open Three” and “Open Four”—represent critical tactical threats:

• Open Three: A pattern where three consecutive stones of the same color are aligned with two open ends. If left unaddressed, this often leads to an immediate win.

• Open Four: A pattern where four consecutive stones of the same color are aligned with two open ends. This configuration constitutes an immediate winning threat, as the player can win on the next move regardless of the opponent’s response.

In actual gameplay, players typically prioritize responding to such threats. Thus, frequent neglect of these patterns during steganographic encoding suggests a loss of strategic rationality and undermines trust in the generated records.

To quantify this, we introduce the metric Decision Irregularities (DI), which measures the total number of critical tactical errors made by the model during a game. After each game concludes, we retrospectively analyze the entire sequence of moves to identify scenarios where the board presents a decisive opportunity—specifically, an Open Three or Open Four situation. For each such scenario, if the model fails to select the move that would block the opponent’s imminent threat, we count this as an irregular decision. All such cases throughout the game are accumulated to compute the DI value. These counts serve as indicators of abnormal decision-making behavior under critical conditions. To further explore the trade-off between embedding capacity and move reasonableness, we also track the hidden payload capacity under identical experimental settings and analyze both metrics in parallel. The results are shown in Table 6.

Experimental results reveal that increasing attraction matrix strength significantly enhances the model’s embedding capacity. However, this comes at the cost of a higher frequency of ignored tactical patterns such as “Open Three” and “Open Four”. These findings suggest that while overly clustered moves enhance hiding performance, they impair the model’s strategic awareness and degrade overall gameplay quality.

Notably, when

Collectively, these results demonstrate that the attraction matrix serves a dual regulatory function in guiding move selection during information embedding. With proper tuning of the strength parameter

4.3.3 Evaluation of the AlphaZero Network

To ensure the effectiveness of the steganographic approach, it is essential to maintain robust model performance. A stronger Gomoku-playing model not only generates more optimal moves but also preserves the plausibility of gameplay, thereby reducing the risk of detection. Conversely, a weaker model is more likely to make unreasonable moves, compromising strategic integrity and increasing the likelihood of revealing the hidden information.

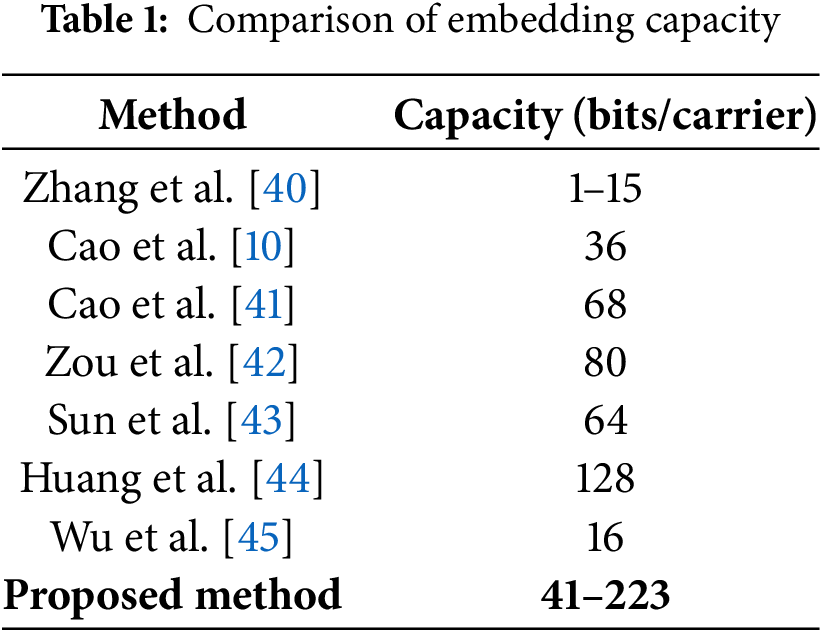

To better understand how architectural design influences model performance, we conducted a systematic investigation of key components in the AlphaZero neural network. Specifically, we examined three critical hyperparameters: the number of residual blocks, the number of convolutional filters, and the size of the fully connected layer. Each hyperparameter was varied independently using a one-factor-at-a-time experimental design, and the resulting configurations were evaluated based on playing strength, as measured by Elo ratings, and training loss metrics.

The Elo rating system, a standardized and extensively utilized framework, serves to quantify relative skill levels in board gameand analogous competitive domains. Its principal advantage lies in offering an equitable and objective means of comparison between competitors by condensing match outcomes into a singular rating value. These ratings are dynamically updated based on cumulative game results, thereby enabling the system to monitor fluctuations in actual playing strength over time. Denoting the current Elo ratings of models A and B as

If model A’s actual score in a match is

Here, K serves as a learning rate parameter, dynamically determined according to the current Elo score (following USCF rules):

Elevated Elo ratings indicate greater playing strength, thereby facilitating quantitative comparisons among various network architectures. Additionally, supplementary metrics such as policy loss and value loss were employed to assess the precision of action prediction and value estimation, respectively; lower values in these metrics correspond to improved model performance. In this study, the training dataset was generated by 20 parallel agents, each conducting 300 Monte Carlo simulations per move, with each model undergoing 30,000 training steps. The term Block Elo denotes the Elo rating for the black pieces, whereas White Elo refers to the Elo rating for the white pieces. The experimental findings are presented in Table 7.

The findings indicate that various network modules exert a substantial and intricate influence on the playing strength of the AlphaZero model. Performance does not exhibit a straightforward, monotonic improvement with increasing network depth or width; rather, it is essential to identify an optimal equilibrium among model capacity, training stability, and generalization capability.

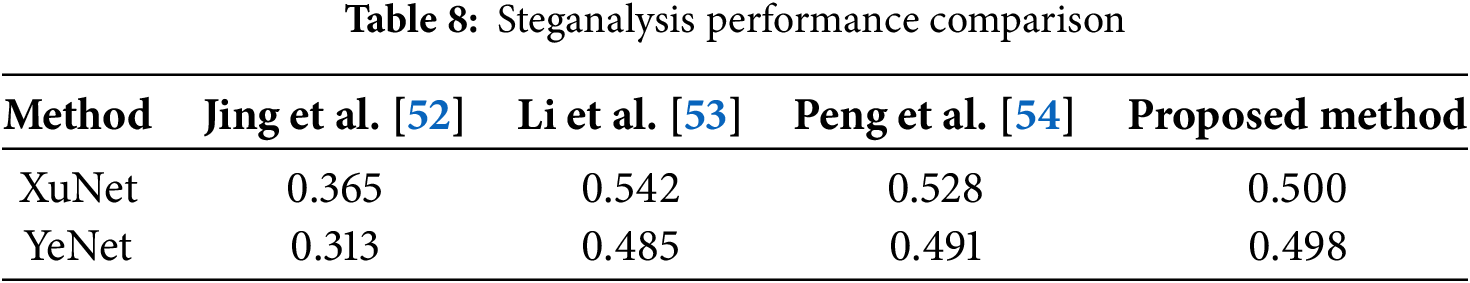

Steganographic security measures the resistance of stego images to detection by advanced steganalysis techniques. For images or videos embedding secret message, steganalysis examines pixel-level statistical features to detect the presence of concealed data. This study employs XuNet [51] and YeNet [7] to evaluate the steganalysis resistance of Gomoku board images embedded with secret message within image sequences. We prepared a cover dataset comprising 5000 distinct game images generated from multiple games without secret message, and a stego dataset consisting of 5000 board images from games containing embedded messages. These datasets were used to train XuNet and YeNet, with cover and stego images treated as separate classes.

The false alarm rate,

The miss detection rate,

The average decision error rate,

A

The proposed method embeds secret message in Gomoku move patterns rather than pixel values, resulting in minimal statistical anomalies detectable by conventional steganalysis models during training. Experimental results in Table 8 suggest that the proposed method exhibits notable resistance to steganalysis detection.

In this paper, we utilize a trained AlphaZero model to automate information hiding in Gomoku. The proposed method consists of four main components: (1) training the AlphaZero model, (2) integrating the base model with an attraction matrix, (3) generating steganographic game records, and (4) extracting secret messages based on the corresponding model rules and game records. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method generates game records consistent with typical human gameplay patterns, thereby reducing the likelihood of detection by adversaries. Furthermore, the method exhibits high embedding capacity, which can be further enhanced by improving the AlphaZero model’s performance. The integration of the attraction matrix module effectively mitigates the negative effects of steganographic constraints, which often cause stego game records to deviate from normal gameplay patterns. Additionally, the proposed method demonstrates strong robustness and security, indicating its potential for practical deployment.

Despite its effectiveness, the proposed method has several limitations. First, the attraction matrix functions as an external heuristic rather than a trainable component within the model. Integrating this mechanism directly into the AI agent could enable the model to optimize both embedding capacity and gameplay authenticity in a unified manner. Second, the framework has been evaluated primarily in offline settings and lacks adaptive capabilities for real-time applications. Future work should focus on developing efficient algorithms to support real-time encoding and transmission. Third, the proposed framework currently operates under the assumption of a perfect, noise-free communication channel. A crucial direction for future work is to investigate methods for enhancing the system’s robustness against channel noise, ensuring reliable data extraction even under adverse transmission conditions. These improvements would enhance the system’s applicability in dynamic, practical environments.

Acknowledgement: This paper is a collaborative effort of the five authors. We would like to express our gratitude for the fund support provided by the relevant project and thank all the experts who participated in the review process.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Wuxi “Taihu Light” Science and Technology Key Project (Basic Research) (K20241046); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 62102189, 62122032, 42305158); the Open Project of the National Engineering Research Center for Sensor Networks (2024YJZXKFKT02); and Wuxi University Research Start-up Fund for High-Level Talents (No. 2022r043).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Yi Cao, Chengsheng Yuan; data collection: Kuo Zhang, Linglong Zhu; analysis and interpretation of results: Kuo Zhang, Wentao Ge; draft manuscript preparation: Kuo Zhang, Wentao Ge, Linglong Zhu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The original test datasets used for XuNet and YeNet in this study are openly available via Google Drive at https://drive.google.com/file/d/16Ndnc1mS7vjYPu3wXYe4u_ZIWbUqBrGu/view?usp=drive_link (accessed on 18 September 2025). All other data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| BER | Bit Error Rate |

| Param. | Parameter |

| JPEG Comp. | JPEG compression |

| Gaussian LPF | Gaussian low-pass filtering |

References

1. Simmons GJ. The prisoners’ problem and the subliminal channel. In: Chaum D, editor. Advances in cryptology. Boston, MA, USA: Springer; 1984. p. 51–67. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-4730-9_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Jasim ZKJ, Kurnaz S. An improved image steganography security and capacity using ant colony algorithm optimization. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;80(3):4643–62. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.055195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Abd-El-Atty B. A robust medical image steganography approach based on particle swarm optimization algorithm and quantum walks. Neural Comput Applicat. 2023;35(1):773–85. doi:10.1007/s00521-022-07830-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. AbdelWahab OF, Hussein AI, Hamed HF, Kelash HM, Khalaf AA, Ali HM. Hiding data in images using steganography techniques with compression algorithms. TELKOMNIKA (Telecommunication Computing Electronics and Control). 2019;17(3):1168–75. doi:10.12928/telkomnika.v17i3.12230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Baby D, Thomas J, Augustine G, George E, Michael NR. A novel DWT based image securing method using steganography. Procedia Comput Sci. 2015;46(5):612–8. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2015.02.105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Weng S, Chen M, Yu L, Sun S. Lightweight and Effective Deep Image Steganalysis Network. IEEE Signal Process Lett. 2022;29(2):1888–92. doi:10.1109/lsp.2022.3201727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Ye J, Ni J, Yi Y. Deep learning hierarchical representations for image steganalysis. IEEE Transact Inform Foren Secur. 2017;12(11):2545–57. doi:10.1109/tifs.2017.2710946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Bui T, Agarwal S, Yu N, Collomosse J. Rosteals: robust steganography using autoencoder latent space. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 933–42. [Google Scholar]

9. Yang K, Chen K, Zhang W, Yu N. Provably secure generative steganography based on autoregressive model. In: International Workshop on Digital Watermarking. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018. p. 55–68. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-11389-6_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Cao Y, Zhou Z, Sun X, Gao C. Coverless information hiding based on the molecular structure images of material. Comput Mat Conti. 2018;54(2):197–207. [Google Scholar]

11. Ke Y, Zhang M, Liu J, Su T, Yang X. Generative steganography with Kerckhoffs’ principle. Multim Tools Applicat. 2019;78(10):13805–18. doi:10.1007/s11042-018-6640-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Su W, Ni J, Sun Y. StegaStyleGAN: towards generic and practical generative image steganography. In: Proceedings of the 38th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2024 Feb 20–27; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 240–8. [Google Scholar]

13. Zhou Z, Su Y, Li J, Yu K, Wu QJ, Fu Z, et al. Secret-to-image reversible transformation for generative steganography. IEEE Transact Depend Secure Comput. 2022;20(5):4118–34. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2022.3217661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Cao Y, Zhou Z, Chakraborty C, Wang M, Wu QJ, Sun X, et al. Generative steganography based on long readable text generation. IEEE Transact Computat Soc Syst. 2022;11(4):4584–94. doi:10.1109/tcss.2022.3174013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang X, Han S, Huang W, Fu D. A Generative image steganography based on disentangled attribute feature transformation and invertible mapping rule. Comput Mater Cont. 2025;83(1):1149–71. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.060876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang R, Zhu F, Liu J, Liu G. Depth-wise separable convolutions and multi-level pooling for an efficient spatial CNN-based steganalysis. IEEE Transact Inform Foren Secur. 2019;15:1138–50. doi:10.1109/tifs.2019.2936913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Shalu, Sharma Y. A review on game based steganography. In: 2019 International Conference on Intelligent Sustainable Systems (ICISS); 2019 Feb 21–22; Palladam, India. p. 286–90. [Google Scholar]

18. Kieu D, Wang ZH, Chang CH, Li MC. A sudoku based wet paper hiding scheme. Int J Smart Home. 2011;3(2):1–12. [Google Scholar]

19. Desoky A, Younis M. Chestega: chess steganography methodology. Secur Communicat Netw. 2009;2(6):555–66. doi:10.1002/sec.99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Cao Y, Ge W, Yuan C, Wang Q. Generative image steganography via encoding pose keypoints. Appl Sci. 2024;15(1):58. doi:10.3390/app15010058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Cao Y, Du Y, Ge W, Huang Y, Yuan C, Wang Q. Generative steganography based on the construction of chinese chess record. Electronics. 2025;14(3):451. doi:10.3390/electronics14030451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Seddik AH, Mohamed M, Hossam E. Coverless image steganography based on jigsaw puzzle image generation. Comput Mat Conti. 2021;67(2):2077–91. doi:10.32604/cmc.2021.015329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhou Z, Ding C, Li J, Peng F, Zhang X. Research on generative steganography. China J Comput. 2023;46(9):1855–87. [Google Scholar]

24. Zhang S, Yang Z, Tu H, Yang J, Huang Y. Pixel-Stega: generative image steganography based on autoregressive models. arXiv:2112.10945. 2021. [Google Scholar]

25. Kingma DP, Dhariwal P. Glow: generative flow with invertible 1 × 1 convolutions. In: Bengio S, Wallach H, Larochelle H, Grauman K, Cesa-Bianchi N, Garnett R, editors. Advances in neural information processing systems. Vol. 31. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2018. [Google Scholar]

26. Liu J, Ke Y, Zhang Z, Lei Y, Li J, Zhang M, et al. Recent advances of image steganography with generative adversarial networks. IEEE Access. 2020;8:60575–97. doi:10.1109/access.2020.2983175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Hu D, Wang L, Jiang W, Zheng S, Li B. A novel image steganography method via deep convolutional generative adversarial networks. IEEE Access. 2018;6:38303–14. doi:10.1109/access.2018.2852771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Yamni M, Karmouni H, Daoui A, ogri El O, Sayyouri M, Qjidaa H. Blind image zero-watermarking algorithm based on radial krawtchouk moments and chaotic system. In: 2020 International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Computer Vision (ISCV); 2020 Jun 9–11; Fez, Morocco. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

29. Yamni M, Karmouni H, Sayyouri M, Qjidaa H. Color stereo image zero-watermarking using quaternion radial tchebichef moments. In: 2020 International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Computer Vision (ISCV); 2020 Jun 9–11; Fez, Morocco. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

30. Zhang X. Behavior steganography in social network. In: Advances in Intelligent Information Hiding and Multimedia Signal Processing: Proceeding of the Twelfth International Conference on Intelligent Information Hiding and Multimedia Signal Processing; 2016 Nov 21–23; Kaohsiung, Taiwan. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2016. p. 21–3. [Google Scholar]

31. Wu H, Wang W, Dong J, Wang H. New graph-theoretic approach to social steganography. Electr Imag. 2019;31(5):1–7. doi:10.2352/issn.2470-1173.2019.5.mwsf-539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Gilbert E. Open book: a socially-inspired cloaking technique that uses lexical abstraction to transform messages. In: Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2015 Apr 18–23; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 477–86. [Google Scholar]

33. Murdoch SJ, Zieliński P. Covert channels for collusion in online computer games. In: International Workshop on Information Hiding. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2005. p. 355–69. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-30114-1_25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Hernandez-Castro JC, Blasco-Lopez I, Estevez-Tapiador JM, Ribagorda-Garnacho A. Steganography in games: a general methodology and its application to the game of Go. Comput Secur. 2006;25(1):64–71. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2005.12.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Lee HL, Lee CF, Chen LH. A perfect maze based steganographic method. J Syst Softw. 2010;83(12):2528–35. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2010.07.054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Ou ZH, Chen LH. A steganographic method based on tetris games. Inform Sci. 2014;276(2):343–53. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2013.12.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Mahato S, Yadav DK, Khan DA. A minesweeper game-based steganography scheme. J Inform Secur Applicat. 2017;32(3):1–14. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2016.11.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Farn EJ, Chen CC. Jigsaw puzzle images for steganography. Opt Eng. 2009;48(7):077006. doi:10.1117/1.3159872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Hu M. The art of reinforcement learning: fundamentals, mathematics, and implementation with python. New York, NY, USA: Apress; 2023 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 18]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-1-4842-9606-6. [Google Scholar]

40. Zhang X, Peng F, Long M. Robust coverless image steganography based on DCT and LDA topic classification. IEEE Transact Multim. 2018;20(12):3223–38. doi:10.1109/tmm.2018.2838334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Cao Y, Zhou Z, Yang CN, Sun X. Dynamic content selection framework applied to coverless information hiding. J Inter Technol. 2018;19(4):1179–86. doi:10.3966/160792642018081904020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Zou L, Sun J, Gao M, Wan W, Gupta BB. A novel coverless information hiding method based on the average pixel value of the sub-images. Multim Tools Applicat. 2019;78(7):7965–80. doi:10.1007/s11042-018-6444-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Sun Y, Liu J, Zhang R. A robust generative image steganography method based on guidance features in image synthesis. In: 2023 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME); 2023 Jul 10–14; Brisbane, QLD, Australia. p. 55–60. [Google Scholar]

44. Huang R, Lian C, Dai Z, Li Z, Ma Z. A novel hybrid image synthesis-mapping framework for steganography without embedding. IEEE Access. 2023;11:113176–88. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3324050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Wu J, Liu Y, Dai Z, Kang Z, Rahbar S, Jia Y. A coverless information hiding algorithm based on grayscale gradient co-occurrence matrix. IETE Techn Rev. 2018;35(sup1):23–33. doi:10.1080/02564602.2018.1531735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Singh S, Siddiqui TJ. A security enhanced robust steganography algorithm for data hiding. Int J Comput Sci Issues (IJCSI). 2012;9(3):131. [Google Scholar]

47. Bilal M, Imtiaz S, Abdul W, Ghouzali S, Asif S. Chaos based Zero-steganography algorithm. Multim Tools Applicat. 2014;72(2):1073–92. doi:10.1007/s11042-013-1415-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Wu J, Fei X, Wang N. Zero steganography algorithm research based on chaotic sequences and image DCT transform. Electr Measur Technol. 2017;40(5):174–9. [Google Scholar]

49. Chen X, Zhang Z, Qiu A, Xia Z, Xiong NN. Novel coverless steganography method based on image selection and StarGAN. IEEE Transact Netw Sci Eng. 2020;9(1):219–30. doi:10.1109/tnse.2020.3041529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Yang Z, Chen K, Zeng K, Zhang W, Yu N. Provably secure robust image steganography. IEEE Transact Multim. 2024;26:5040–53. doi:10.1109/tmm.2023.3330098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Xu G, Wu HZ, Shi YQ. Structural design of convolutional neural networks for steganalysis. IEEE Sig Process Lett. 2016;23(5):708–12. doi:10.1109/lsp.2016.2548421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Jing J, Deng X, Xu M, Wang J, Guan Z. Hinet: deep image hiding by invertible network. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2021 Oct 11–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 4733–42. [Google Scholar]

53. Li J, Niu K, Liao L, Wang L, Liu J, Lei Y, et al. A generative steganography method based on WGAN-GP. In: International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Security. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 386–97. [Google Scholar]

54. Peng F, Chen G, Long M. A robust coverless steganography based on generative adversarial networks and gradient descent approximation. IEEE Transact Circ Syst Video Technol. 2022;32(9):5817–29. doi:10.1109/tcsvt.2022.3161419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools