Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Dynamic Knowledge Graph Reasoning Based on Distributed Representation Learning

1 School of Information and Communication Engineering, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, 611731, China

2 School of Computer Science, Chengdu University of Information Technology, Chengdu, 610103, China

3 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, University of North Texas, Denton, TX 76207, USA

* Corresponding Authors: Jie Xu. Email: ; Du Xu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070493

Received 17 July 2025; Accepted 01 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Knowledge graphs often suffer from sparsity and incompleteness. Knowledge graph reasoning is an effective way to address these issues. Unlike static knowledge graph reasoning, which is invariant over time, dynamic knowledge graph reasoning is more challenging due to its temporal nature. In essence, within each time step in a dynamic knowledge graph, there exists structural dependencies among entities and relations, whereas between adjacent time steps, there exists temporal continuity. Based on these structural and temporal characteristics, we propose a model named “DKGR-DR” to learn distributed representations of entities and relations by combining recurrent neural networks and graph neural networks to capture structural dependencies and temporal continuity in DKGs. In addition, we construct a static attribute graph to represent entities’ inherent properties. DKGR-DR is capable of modeling both dynamic and static aspects of entities, enabling effective entity prediction and relation prediction. We conduct experiments on ICEWS05-15, ICEWS18, and ICEWS14 to demonstrate that DKGR-DR achieves competitive performance.Keywords

Since Google first introduced the concept of Knowledge Graphs (KG) in 2012 [1], they have been widely applied in various real-world scenarios. Despite their large scale, existing KGs still suffer from sparsity and incompleteness, with many implicit facts not directly represented [2]. Knowledge Graph Reasoning (KGR) aims to address these problems by inferring missing knowledge from known facts, thereby completing the KG.

However, most existing KGR approaches focus only on static knowledge graphs, assuming that facts do not change over time. This overlooks the temporal nature of knowledge. Time is critical in representing knowledge, as facts are often only valid during specific time periods. For instance, the fact (Country, president, Person) holds only for a certain term, and different individuals may hold the position before and after this period. Without temporal information, answering the question “Who is the president of a given country?” may lead to ambiguous or incorrect results. Therefore, it is essential to incorporate temporal dimensions into KG modeling.

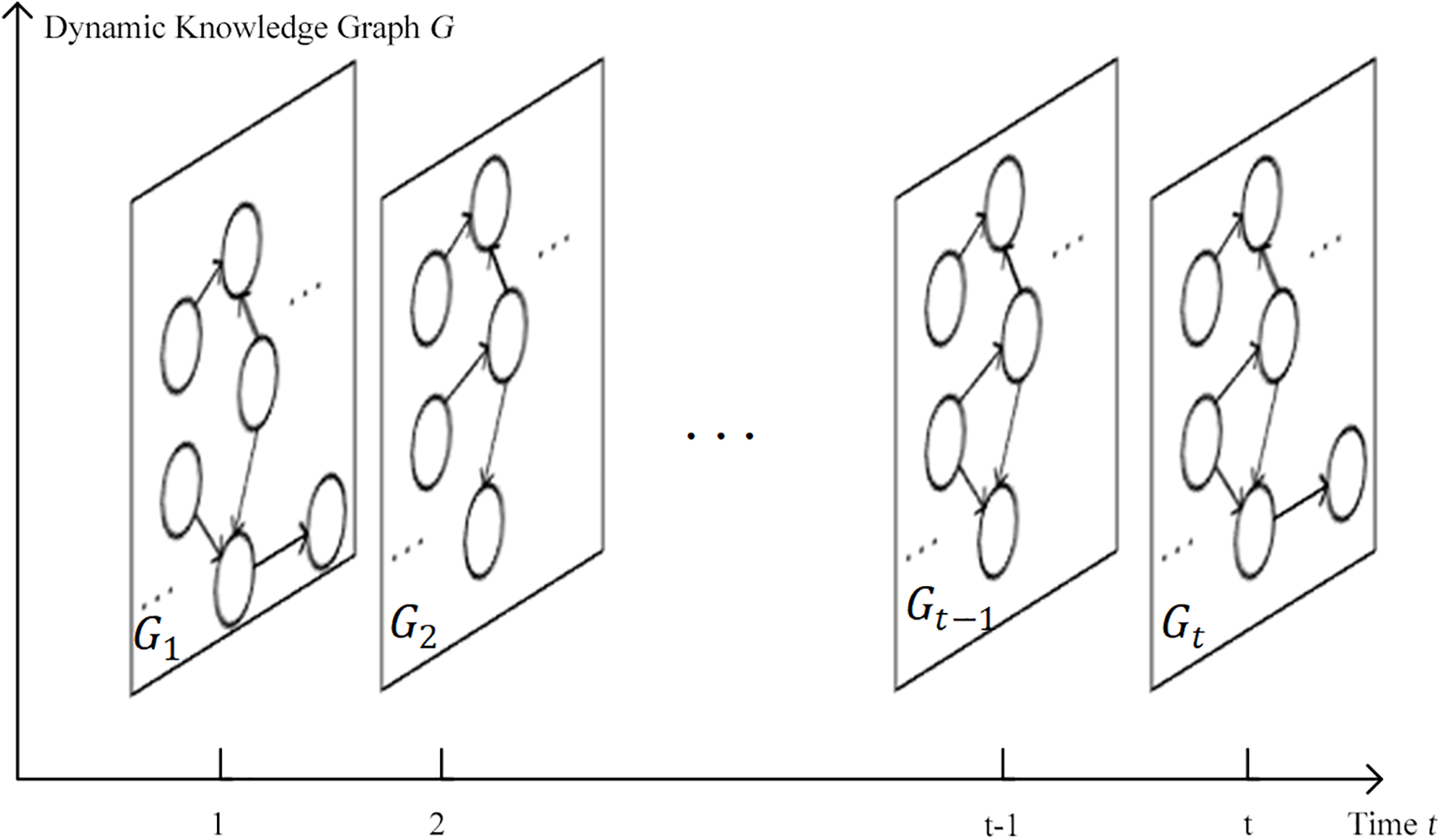

A Dynamic Knowledge Graph (DKG) can be regarded as a sequence of knowledge graphs evolving over time. As shown in Fig. 1, each timestamp corresponds to a distinct knowledge graph. A fact at time step

Figure 1: Illustration of a dynamic knowledge graph

• Entity Prediction: Given

• Relation Prediction: Given

Compared to static KGR, DKGR is more challenging due to the temporal changes in graph structure. MLPs [3] rely on logical rules and ignore temporal dynamics. TTransE [4] incorporates time into relation embeddings but follows the static reasoning paradigm of TransE [5], thus overlooking rich historical information. CyGNet [6] considers historical facts but only repeated ones. EvoKG [7] models both temporal and structural information but neglects static entity attributes. Both tensor decomposition-based and neural network-based DKGR models face limitations in representation capacity.

In this work, we model DKGs as a sequence of evolving knowledge graphs. At each time step, entities are connected by relations, forming a structure with strong dependencies. The graph structure encodes how entities are semantically linked through relations, and these dependencies provide essential contextual information for representation learning. Capturing such structural dependencies ensures that the learned embeddings reflect not only individual entities but also their interconnected roles in the knowledge graph. We refer to the sequential correlations of entity and relation representations across adjacent time steps as temporal continuity. Because the evolution of knowledge graphs typically follows smooth and progressive trends, modeling temporal continuity enables the representation learning process to capture dynamic patterns. In addition to temporal dynamics, we also consider static attributes of entities that do not change over time. These attributes, such as type, category, or descriptive features, serve as stable semantic signals that complement the dynamic structural and temporal information, thereby enhancing the expressiveness of the learned representations. Based on these ideas, we propose a distributed representation learning model called DKGR-DR, designed to effectively capture structural dependencies, temporal continuity, and static attributes for DKGR tasks.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

• We propose DKGR, a unified framework for both entity prediction and relation prediction tasks in dynamic knowledge graphs. The framework is composed of three major components: a representation learning module, a static attribute fusion module, and a prediction module, which work together to capture both temporal dynamics and static semantic information.

• To effectively model the evolving nature of knowledge graphs, we design a representation learning module that integrates recurrent neural networks with graph neural networks. This hybrid design enables the model to capture dynamic temporal dependencies through recurrent neural networks, while simultaneously learning static structural patterns of entities and relations from the graph topology using relational graph convolutional network.

• In order to enrich entity and relation representations with auxiliary information, we construct three types of static attribute graphs. These attribute graphs encode complementary semantic information such as entity categories, textual descriptions, and relation hierarchies, thereby providing additional contextual signals beyond the temporal interactions in the dynamic knowledge graph.

• We introduce a static attribute fusion module that leverages a relation-aware graph attention mechanism to integrate structural and attribute-based signals. By dynamically adjusting attention weights according to relation types, this module effectively balances heterogeneous sources of information, leading to more robust and expressive entity and relation representations.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related works on knowledge graph reasoning, highlighting the strengths and limitations of existing static and dynamic methods. Section 3 formulates the problem by introducing the task settings, notations, and objectives of entity and relation prediction in dynamic knowledge graphs. Section 4 presents the proposed DKGR-DR model in detail, including the representation learning module, the construction of static attribute graphs, and the relation-aware graph attention mechanism for attribute fusion. Section 5 reports the experimental setup, datasets, baselines, evaluation metrics, and results, along with ablation studies to validate the effectiveness of the model. Finally, Section 6 concludes the work by summarizing the key contributions.

Static knowledge graph reasoning methods can be broadly categorized into three classes. Translation-based models [5,8–12] model relations as translation operations in the embedding space, assuming that the tail entity should be close to the head entity after applying the relation-specific translation. Tensor decomposition-based models [13–17] reconstruct KGs by factorizing high-dimensional adjacency tensors into low-dimensional latent representations. Neural network-based models [18–21] directly learn a plausibility scoring function for factual triples using deep neural architectures. Beyond these general categories, several graph neural network approaches have been proposed for multi-relational graphs: Schlichtkrull et al. [22] introduced the Relational Graph Convolutional Network (R-GCN) tailored for KG structures, while Veličković et al. [23] proposed the Graph Attention Network (GAT), which leverages attention mechanisms to enhance representation learning on graph-structured data.

While static knowledge graph reasoning methods have achieved remarkable success in capturing structural dependencies within fixed relational data, they inherently overlook the temporal dimension of knowledge. However, in many real-world applications, facts are not static but evolve over time, with entities and relations continuously emerging, disappearing, or changing their states. To address this limitation, research has shifted toward dynamic knowledge graph (DKG) reasoning, which explicitly incorporates temporal information into the inference process.

Representative models have approached temporal knowledge graph reasoning from different perspectives. TTransE [4], as one of the earliest temporal extensions of TransE [5], augments the score function with temporal parameters to obtain time-aware embeddings. Building on this idea, HyTE [24] adapts the TransH [8] framework by projecting entities onto time-specific hyperplanes, thereby allowing the representation space to evolve with temporal contexts. DE-SimplE [25] further advances temporal modeling by encoding entities across multiple time steps using historical embeddings to capture long-term dependencies and entity evolution. These embedding-based extensions demonstrate the importance of explicitly incorporating temporal signals, but they remain limited in capturing complex structural patterns and often struggle with scalability.

Another line of research integrates sequential and recurrent architectures. TA-DistMult [26] employs recurrent neural networks to model temporal dependencies, enabling relation embeddings to adapt dynamically over time. RE-NET [27] extends this paradigm by sequentially encoding historical contexts of entities and relations, effectively leveraging temporal sequences to improve predictive performance. Complementary to these approaches, CyGNet [6] focuses on recurring temporal patterns in entity prediction, addressing the cyclic or periodic nature of temporal interactions. These models highlight the effectiveness of sequence modeling for temporal reasoning, yet they often overlook the integration of static semantic attributes and fine-grained relation-specific signals.

More recently, advanced frameworks have been proposed that combine temporal reasoning with attention or multimodal information. For example, TANGO [28] integrates graph convolutional and temporal convolutional networks with gating and attention mechanisms to jointly capture relational and temporal dynamics. In the financial domain, KGTransformer [29] applies attention-based GNNs to contextual signals for enhanced link prediction and investment strategies. TD-RKG [30] further explores dynamic fusion by integrating recurrent, implicit, and attention-based encoding to improve temporal reasoning. While these approaches achieve strong performance, they tend to treat structural information and static attributes in isolation, limiting the robustness and expressiveness of learned representations.

In summary, existing studies provide valuable strategies for incorporating temporal information into knowledge graph reasoning, ranging from temporal embedding extensions to recurrent architectures and attention-based models. However, most of them do not fully integrate temporal dynamics, graph structural patterns, and static semantic attributes in a unified framework. This gap motivates our proposed DKGR-DR, which leverages RNNs and GNNs for temporal and structural modeling, constructs multiple static attribute graphs, and introduces a relation-aware graph attention module to fuse heterogeneous information effectively.

A dynamic knowledge graph (DKG) can be represented as a sequence of static knowledge graphs:

We assume that reasoning over the facts at time

A representation learning algorithm aims to encode the historical knowledge graphs into distributed embeddings for entities and relations. Specifically, let

Based on these representations, we define two reasoning tasks:

• Task 1: Entity Prediction. Given a query triple

• Task 2: Relation Prediction. Given a query triple

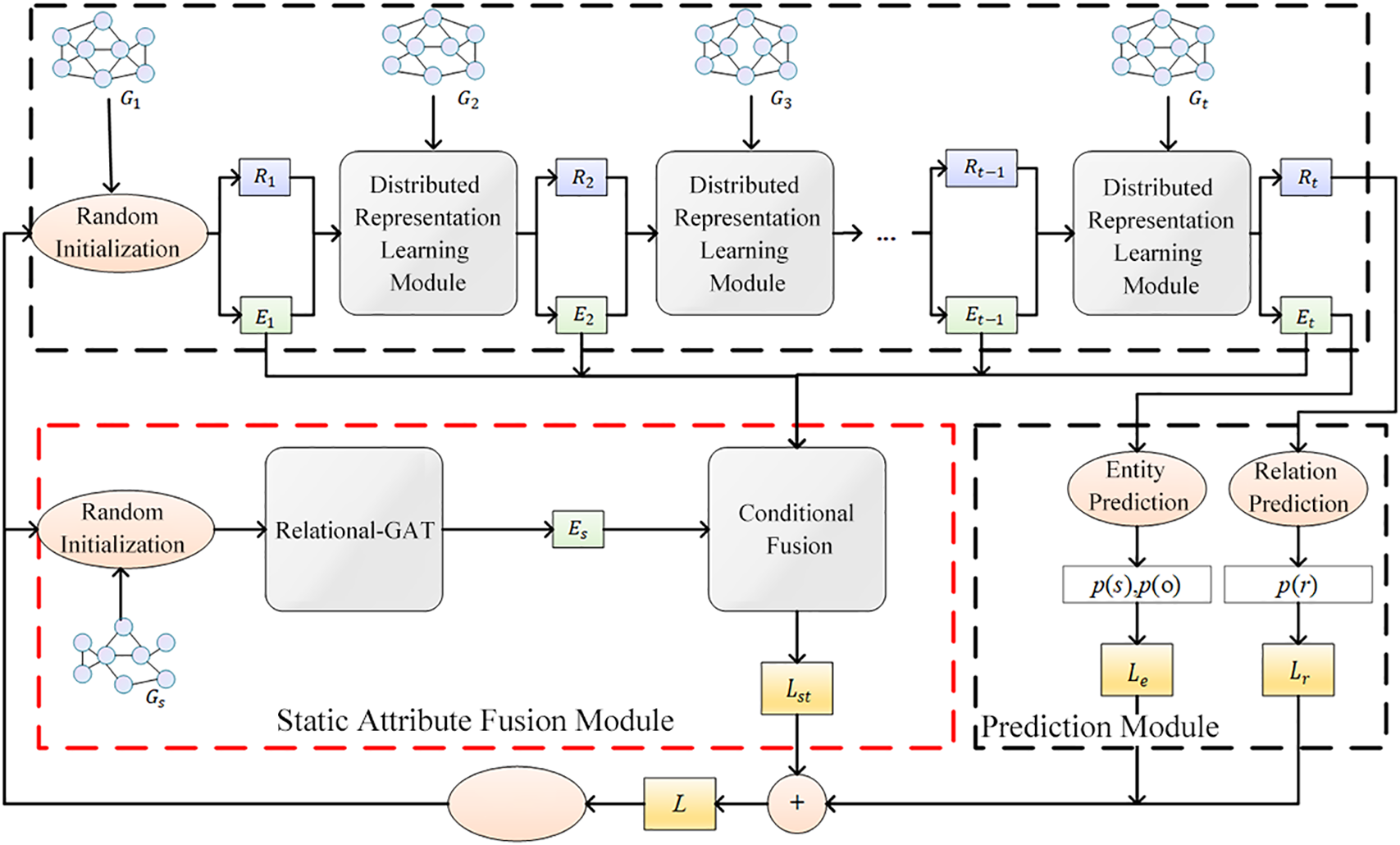

DKGR-DR models structural dependency, temporal continuity, and static attributes of entities for dynamic knowledge graph reasoning. It supports both entity prediction and relation prediction. As shown in Fig. 2, the model consists of a distributed representation learning module, a static attribute fusion module, and a prediction module.

Figure 2: Architecture of the DKGR-DR model

4.1 Distributed Representation Learning Module

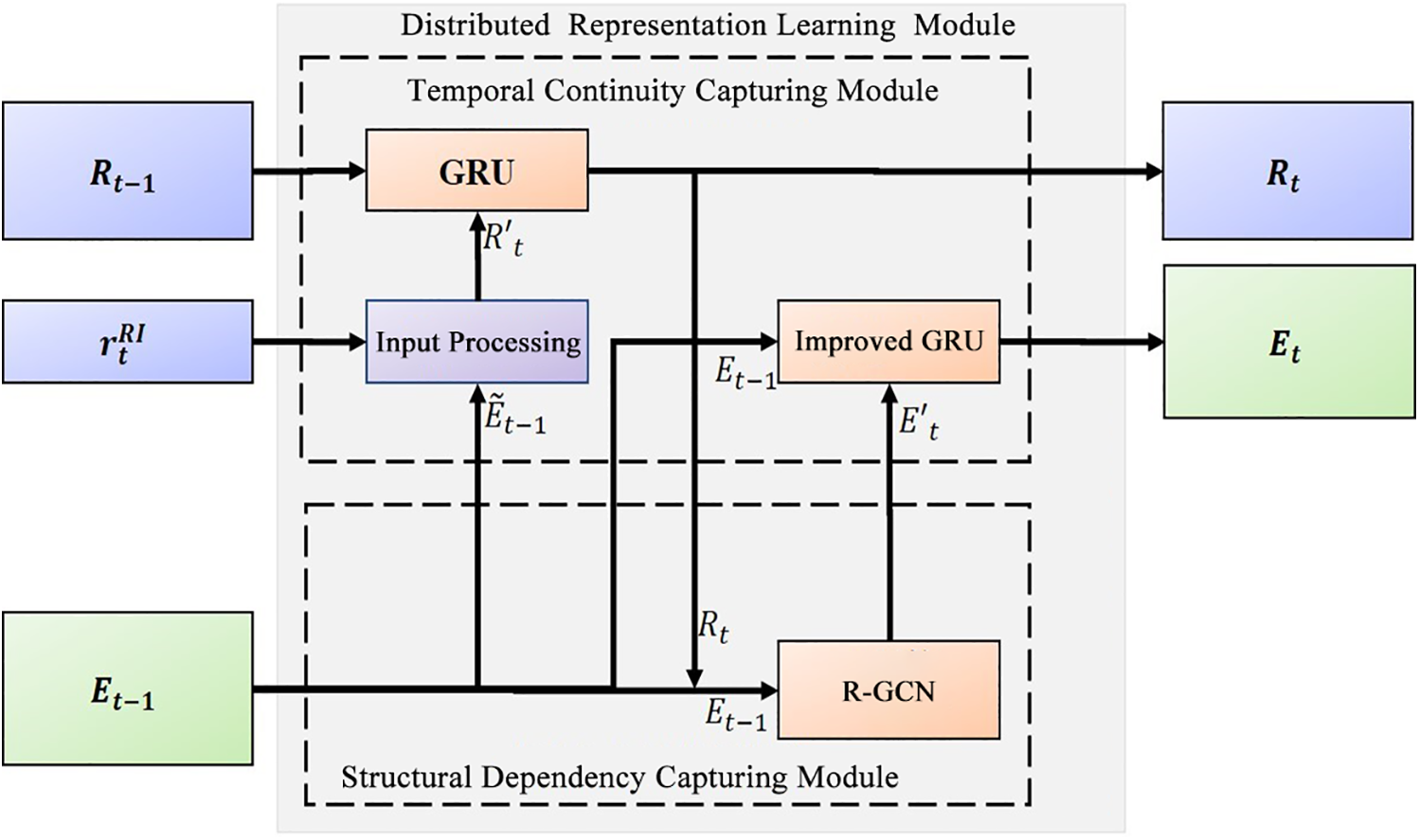

This module is designed to jointly capture the structural and temporal dynamics of dynamic knowledge graphs. Instead of treating each snapshot independently, DKGR-DR learns how entities and relations evolve over time while preserving graph connectivity information at each step. To achieve this, we combine recurrent neural networks with relational graph convolutional networks. This hybrid design allows the model to benefit from the complementary strengths of both sequence modeling and graph representation learning. The module structure is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Structure of the distributed representation module

In Fig. 3, the distributed embedding matrices of entities and relations at time step

1. Structure dependency capture module based on R-GCN. By feeding

2. Temporal continuity and relation learning module based on GRU. In Fig. 3,

3. Temporal continuity and entity learning module based on enhanced GRU. Similar to the GRU-based temporal continuity and relation learning module, the entity learning module takes

4.1.1 Structural Dependency Module

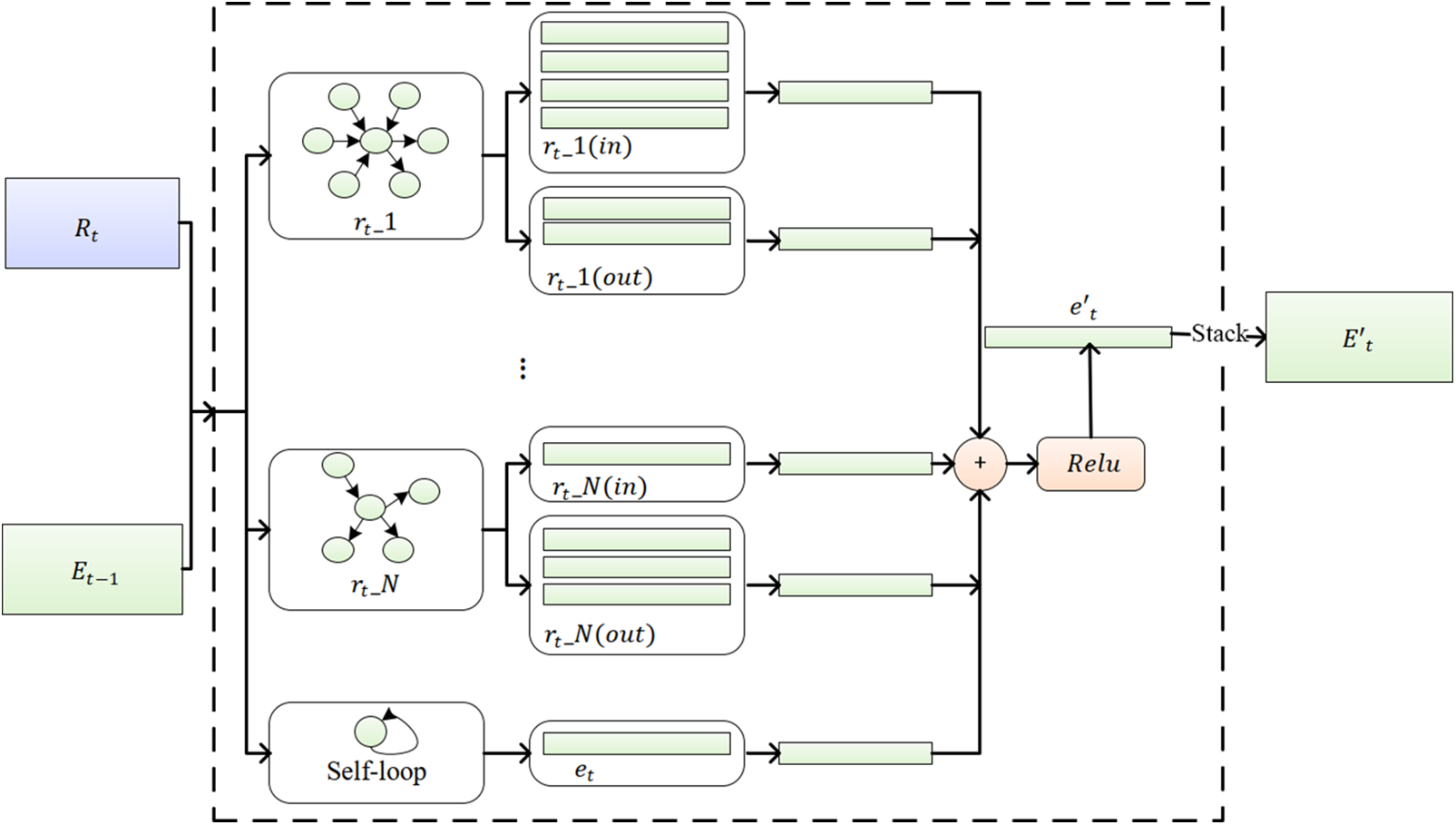

At each timestamp, entities interact through diverse relations, forming a graph structure that encodes local dependencies. We employ R-GCN to model these structural patterns. R-GCN explicitly distinguishes different relation types when aggregating neighborhood information, ensuring that semantic differences between relations (e.g., ally vs. attack) are preserved. Moreover, the self-loop mechanism ensures that even isolated entities can maintain meaningful representations. After several layers of R-GCN, we obtain a structurally enriched entity embedding matrix

As illustrated in Fig. 4, the input of the R-GCN-based structural dependency capturing module consists of the relation embedding matrix

Figure 4: Structure of the structural dependency module

Here,

From Eq. (3), it can be observed that R-GCN is able to aggregate relational information and update the feature vector of any entity, regardless of whether it serves as the head or the tail entity, because it explicitly distinguishes the directionality of relations. For entities that are not involved in any facts, namely those without neighboring entities, self-loop operations can still be applied to update their feature vectors. In practice, R-GCN derives new representations of entities at each time step based on the observed facts among them, while the self-loop operation can be regarded as a form of self-learning for entities.

By passing each entity in

4.1.2 Temporal Continuity Module

While R-GCN captures structural dependencies within a single snapshot, temporal reasoning requires tracking how entities and relations evolve over time. To this end, we design a temporal continuity module based on gated recurrent units (GRUs). For relations, the GRU takes as input both the aggregated embeddings of related entities from the previous timestamp and a learnable base embedding, enabling it to update relation states in a history-aware manner. For entities, we use a simplified GRU that adaptively blends past embeddings with current structural features, effectively controlling how much historical information is retained or forgotten. This mechanism allows the model to capture both short-term dynamics (e.g., sudden events) and long-term trends (e.g., stable alliances).

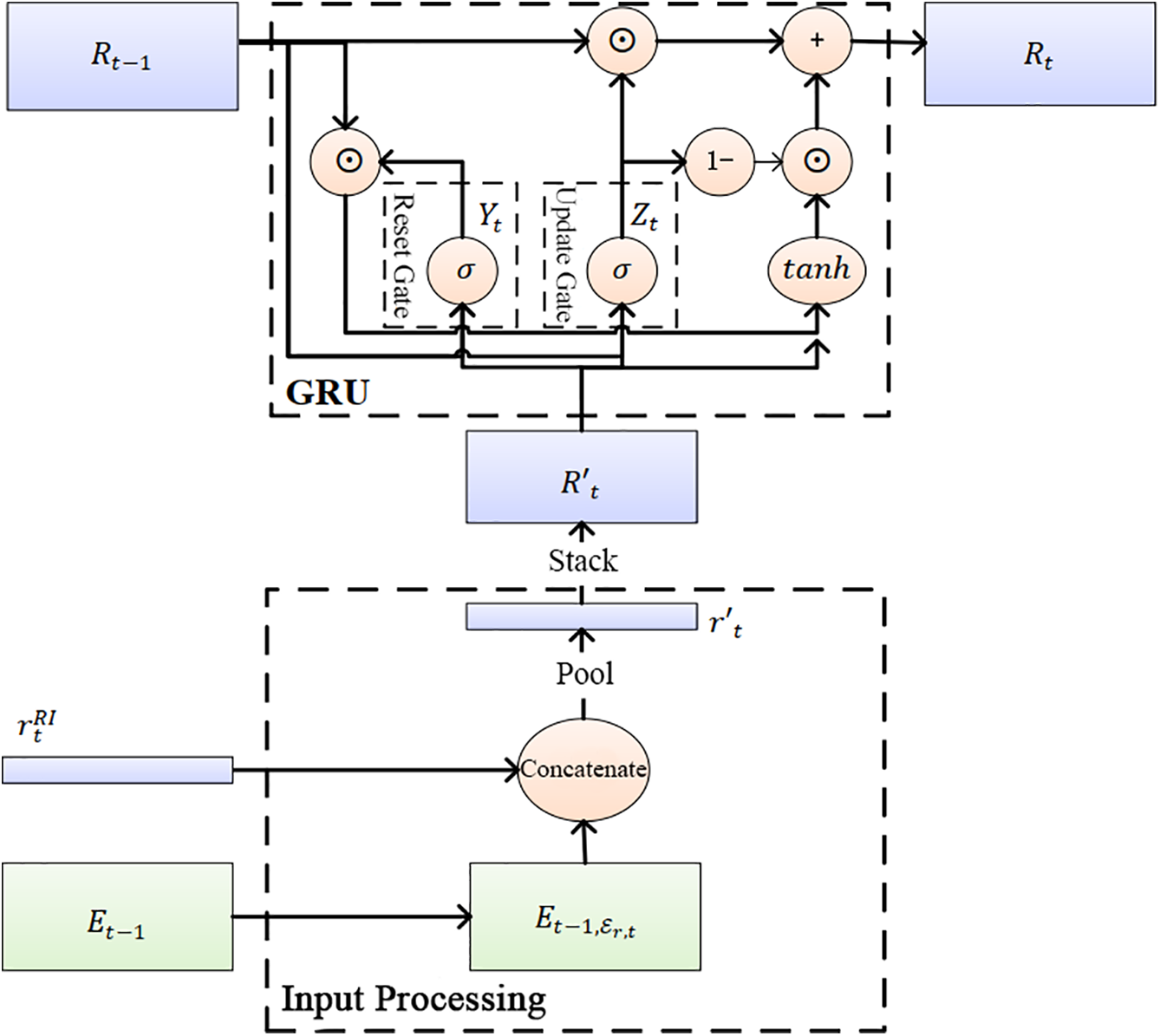

As shown in Fig. 5, the input processing module takes as input the distributed embedding matrix of entities

Figure 5: Structure of the temporal continuity module

Here,

The relation embeddings are updated as:

The output

Given that the entity set is usually orders of magnitude larger than the relation set and that entity representations exhibit relatively smooth temporal variations, employing a full GRU for all entities would lead to prohibitive computational cost and vanishing gradients. To mitigate those issues, we adopt a simplified GRU that retains only the update gate. This design effectively balances the preservation of historical information with the incorporation of current structural features, while maintaining training stability in large-scale dynamic knowledge graphs. Entity embeddings are updated using a simplified GRU with fewer parameters:

Here,

4.2 Static Attribute Fusion Module

Dynamic interactions alone may not fully capture the semantic characteristics of entities. For example, two countries with similar political systems may exhibit correlated behaviors even if they rarely co-occur in temporal graphs. To address this, we introduce a static attribute fusion module.

4.2.1 Static Attribute Graph Construction

We incorporate simple static attributes such as entity type and country. In ICEWS14, many entity names include country information (e.g., Government_(Nigeria)). Such entities are represented with type and country triples, e.g., (Government, isA, Government), (Government, country, Nigeria). For entities like France, we use (France, is, France). We construct a static attribute graph

4.2.2 Static Attribute Learning

To effectively learn from attribute graphs, we introduce a relation-aware graph attention network (Relational-GAT). Unlike conventional GATs that treat all edges equally, Relational-GAT dynamically adjusts attention scores based on relation types, thereby prioritizing more informative attribute connections. This produces enhanced static embeddings

Here,

When aggregating entity features, the Relational-GAT does not include an additional self-loop module for learning the entity’s own features. This is because, during the construction of

Here,

Unlike other graph neural networks that update only node representations while ignoring edge updates, the Relational-GAT-based static attribute capturing module not only formulates an update rule for entities but also designs a feed-forward neural network to update relation representations. The relation update uses a feedforward network:

In the equation,

Finally, DKGR-DR fuses static and dynamic representations in a principled manner. The key motivation is that static attributes provide stable semantic anchors, whereas dynamic embeddings capture time-sensitive interactions and may vary significantly across timestamps. Simply concatenating the two types of embeddings is insufficient, as this may lead to inconsistent representations where temporal fluctuations override static semantics. To address this issue, DKGR-DR enforces a geometric alignment constraint that regulates the angle between static and dynamic embeddings over time.

Concretely, the model encourages the dynamic embedding of an entity to remain close to its corresponding static embedding in the vector space, but without forcing them to be identical. This design ensures that while dynamic representations are free to evolve according to temporal signals (e.g., changing alliances or sudden events), they are still guided by invariant semantic properties (e.g., a country always being a government or belonging to a certain region). This balance improves robustness to noisy or sparse temporal interactions and enhances interpretability, because the dynamic embedding trajectories remain consistent with domain knowledge encoded in static attributes.

Formally, we constrain the angle between static and dynamic embeddings. Let

where

The cosine similarity between the static embedding

This guarantees that the two embeddings are never too far apart in angular space, even if the dynamic embedding drifts due to temporal changes. The corresponding fusion loss at time

where

Intuitively, static embeddings act as semantic “anchors,” preventing entity trajectories from drifting too far in representation space, whereas the gradual relaxation of constraints allows flexibility for temporal adaptation. As a result, the fusion mechanism enables DKGR-DR to capture both the stability of static knowledge and the variability of temporal dynamics within a unified framework.

4.3 Loss Function and Optimization

After obtaining the predicted probabilities for entity and relation predictions, we define the loss functions to optimize the model.

Entity prediction is treated as a multi-label classification problem. Let

where

Similarly, relation prediction is formulated as a multi-label classification problem. Let

where

Finally, the total loss function combines the entity prediction loss, relation prediction loss, and the static attribute fusion loss:

where

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed DKGR-DR model, we conduct comparative experiments against both static and dynamic knowledge graph reasoning models across three dynamic knowledge graph datasets. For code requests or further information, please contact the corresponding author.

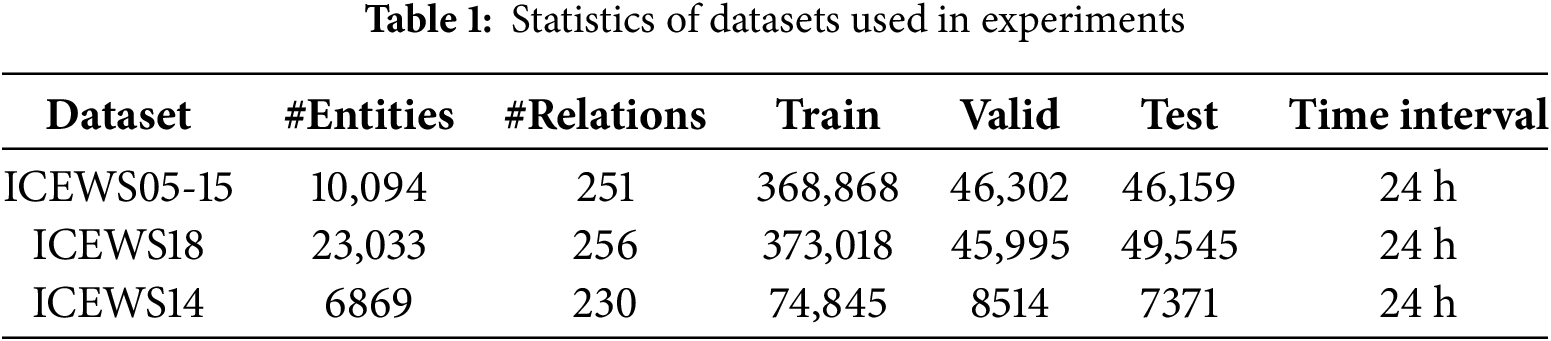

We utilize three publicly available dynamic knowledge graph datasets: ICEWS05-15, ICEWS18, and ICEWS14 [31]. Table 1 summarizes the statistics of these datasets. The time interval indicates that, at each time step, all events or states occurring on that day are recorded.

We employ standard evaluation metrics for knowledge graph reasoning: Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR) and Hits@N (N = 1, 3, 10). Mean Rank (MR) is generally considered less informative and is thus omitted.

5.1.3 Experimental Environment

All experiments are implemented in Python using the PyTorch framework. The hardware environment includes an AMD Ryzen 7 5800U processor with 16 cores at 1.90 GHz and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080 GPU.

The hyperparameters are set as follows: embedding dimension

5.2 Experimental Results and Analysis

To validate the effectiveness of DKGR-DR, we compare it with both static and dynamic knowledge graph reasoning models. Static models include ComplEx [16], R-GCN [22], ConvE [18], and RotatE [32]. Dynamic models encompass HyTE [24], TA-DistMult [26], RE-NET [27], CyGNet [6], T-GAP [33], EvoKG [7], TANGO [28], KGTransformer [29] and TD-RKG [30]. For models without publicly available code, we adopt the results reported in their respective papers.

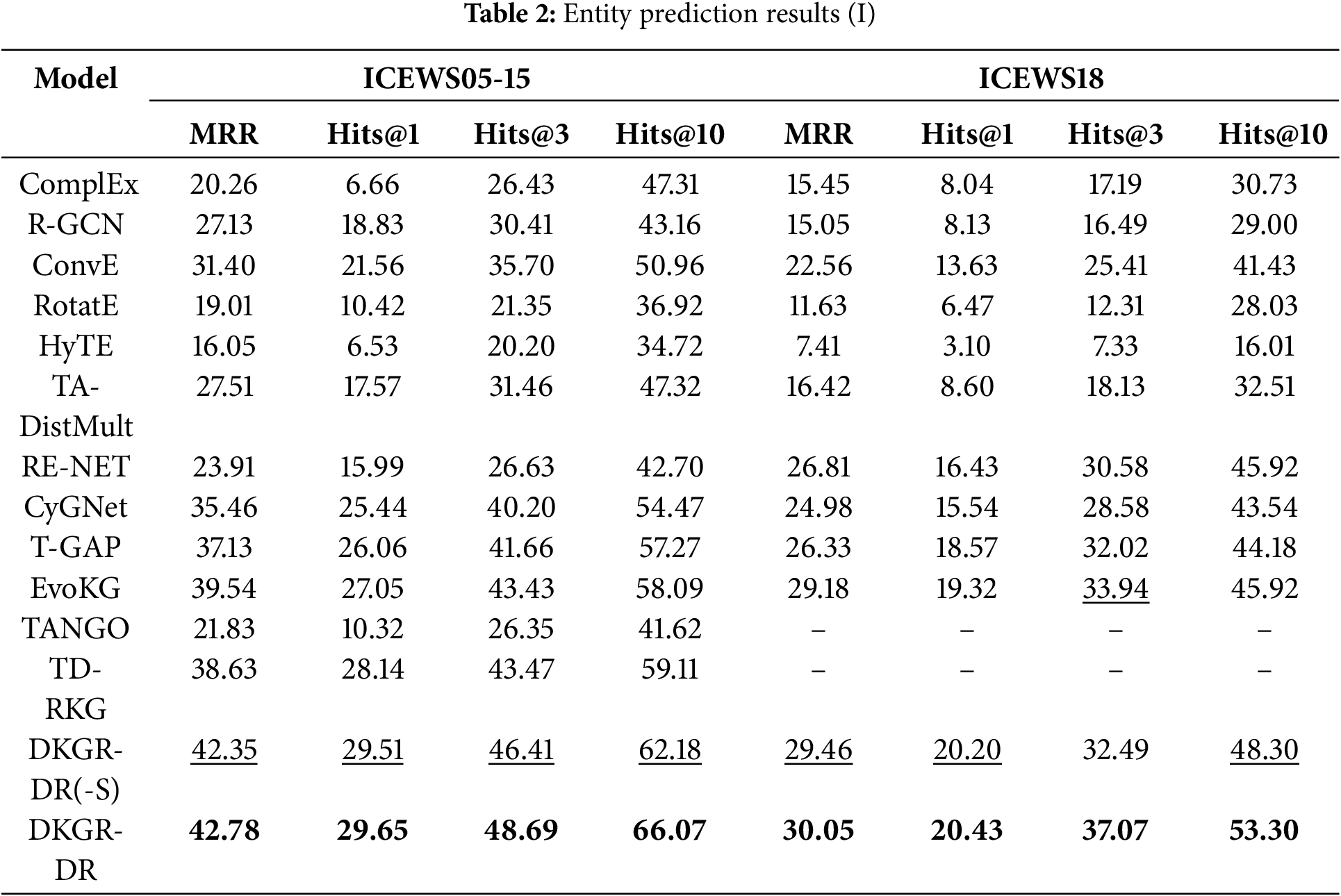

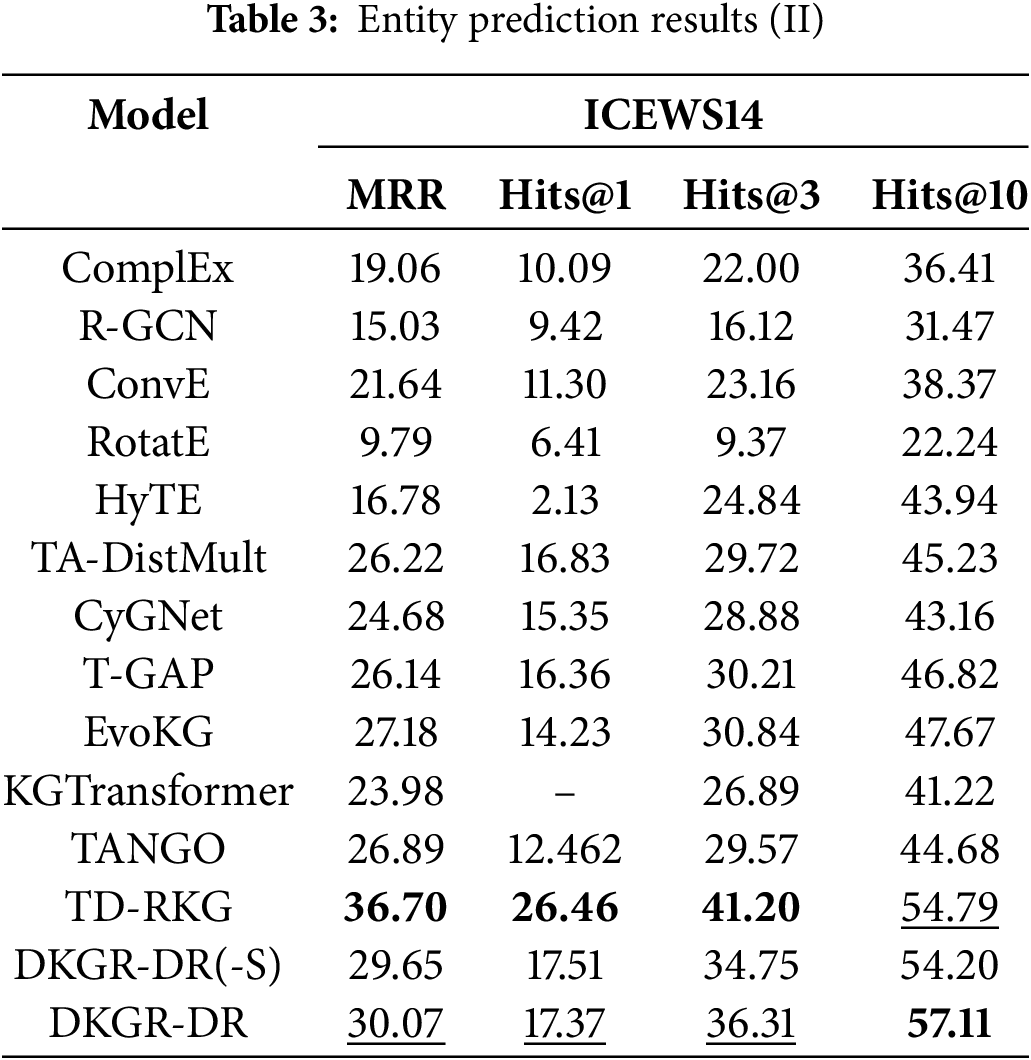

5.2.1 Entity Prediction Results

The results of the entity prediction task are presented in Tables 2 and 3. All evaluation metrics are reported as percentages, with the “%” symbol omitted for clarity. The best-performing results for each metric are shown in bold, while the second-best results are underlined. DKGR-DR(-S) denotes the variant of our model without the static attribute fusion module.

As shown in Table 2, the proposed DKGR-DR outperforms the baseline models on all evaluation metrics in ICEWS05-15 and ICEWS18. In particular, DKGR-DR demonstrates clear superiority over the four static reasoning models. This improvement can be attributed to the use of GRU and its modified variant within DKGR-DR, which effectively capture the temporal continuity between adjacent timestamps. It consistently outperforms other dynamic baselines. The model performs better on ICEWS05-15 compared to ICEWS18. This is because ICEWS05-15 contains knowledge graphs from 4017 timestamps—approximately ten times more than the other two datasets. The richer structural dependencies and temporal continuity allow DKGR-DR, through R-GCN, to better model entity representations.

As shown in Table 3, DKGR-DR achieves excellent results on ICEWS14 across most baselines. The model also surpasses the majority of dynamic reasoning models. As noted in [7], GRU addresses the inherent issues of gradient vanishing and explosion in traditional RNNs, leading to more stable training and improved performance. It is worth noting, however, that DKGR-DR performs worse than TD-RKG on the ICEWS14 dataset. This is likely due to the fact that ICEWS14 contains only one year of data, making it relatively sparse and lacking in clear temporal evolution patterns—conditions under which DKGR-DR’s dynamic modeling capabilities are less effective. In contrast, TD-RKG incorporates a dynamic global information attention layer that captures deeper semantic relationships across timestamps and entity types, allowing it to leverage more informative temporal cues in such sparse scenarios.

5.2.2 Relation Prediction Results

For the relation prediction task, only a subset of models from the entity prediction experiments were selected, as not all models are designed for relation prediction. We report the results using two evaluation metrics: MRR and Hits@10. Hits@1 and Hits@3 are excluded because the differences among models on these metrics are minimal and do not clearly distinguish model performance. Specifically, we select ConvE [18] and ConvTransE [34] from the static models, and RGCRN [35] from the dynamic models, and these models are more representative of their respective categories and share similarities with our proposed model. The experimental results are shown in Table 4.

As shown in Table 4, DKGR-DR achieves the best performance in terms of both MRR and Hits@10 across all four datasets. DKGR-DR(-S) ranks second in all cases. These results indicate that structural dependencies, temporal continuity, and static entity attributes all contribute positively to dynamic relation reasoning.

To evaluate the effectiveness of each neural network module in the DKGR-DR model, we designed ablation experiments by replacing individual modules.

In the encoder distributed representation learning unit, to capture structural dependencies among entities, we proposed an R-GCN-based structural dependency capturing module. To examine its contribution, we replaced this module with randomly initialized embedding vectors while keeping other settings unchanged, denoted as DKGR-DR(-RGCN).

To learn relation embeddings with temporal continuity, we proposed a GRU-based temporal continuity and relation learning module within the encoder. Under the same conditions, we replaced this module with a convolutional operation, denoted as DKGR-DR(-GRU).

After obtaining distributed representations of entities and relations, we designed a ConvE-based decoder. To verify its effectiveness, we replaced ConvE with a simple fully-connected layer while keeping other components unchanged, denoted as DKGR-DR(-ConvE).

Similarly, DKGR-DR(-S) denotes the variant of the model without incorporating the static view.

Among the three dynamic knowledge graph datasets—ICEWS14, ICEWS18 and ICEWS05-15—we chose ICEWS18 for the ablation experiments. Although ICEWS14 and ICEWS18 both record events within a single year with the same temporal granularity, ICEWS18 contains nearly four times more entities than ICEWS14. While ICEWS05-15 has almost as many facts as ICEWS18, it spans nearly 10 years, resulting in relatively few facts per timestamp. Therefore, ICEWS18 was used for the ablation experiments.

Using ICEWS18 as the ablation dataset, the results for the entity prediction task are presented in Table 5.

From the results in Table 5, several observations can be made. First, removing the R-GCN-based structural dependency module (DKGR-DR(-RGCN)) leads to the most significant performance drop across all metrics, highlighting the importance of capturing structural dependencies among entities. Second, omitting the GRU-based temporal continuity and relation learning module (DKGR-DR(-GRU)) also noticeably degrades performance, indicating that modeling temporal dynamics of relations is crucial for accurate prediction. Third, replacing the ConvE decoder with a simple fully-connected layer (DKGR-DR(-ConvE)) results in moderate performance decline, suggesting that the ConvE decoder effectively captures complex entity-relation interactions. Fourth, the variant without static view incorporation (DKGR-DR(-S)) exhibits lower Hits@3 and MRR compared to the full model, demonstrating that integrating static attributes helps stabilize entity representations and improve prediction accuracy.

Overall, the ablation study confirms that each module in DKGR-DR contributes positively to the model’s performance. The combination of structural dependency modeling, temporal continuity learning, relation-aware decoding, and static attribute integration enables the model to achieve the best results on ICEWS18, validating the of DKGR-DR design for dynamic knowledge graph reasoning.

This paper proposes a model, named DKGR-DR, which learns distributed representations of entities and relations by capturing three key properties of dynamic knowledge graphs (DKGs): structural dependencies, temporal continuity, and static entity attributes. To capture temporal continuity, we design an enhanced GRU network. Additionally, we construct three static attribute datasets and introduce a Relational-GAT network to model entity static attributes. Overall, the DKGR-DR model supports both entity prediction and relation prediction. We conduct comparative experiments on three widely used dynamic reasoning datasets. The experimental results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed model.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 62071098, U24B20128); Sichuan Science and Technology Program (Grant No. 2022YFG0319).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Qiuru Fu; methodology, Qiuru Fu, Shumao Zhang, Jie Xu and Du Xu; software, Qiuru Fu, Shumao Zhang and Shuang Zhou; validation, Shanchao Li and Du Xu; formal analysis, Qiuru Fu, Shanchao Li and Du Xu; investigation, Shumao Zhang, Shanchao Li and Du Xu; resources, Qiuru Fu; data curation, Qiuru Fu, Jie Xu and Changming Zhao; writing—original draft preparation, Qiuru Fu; writing—review and editing, Qiuru Fu, Shumao Zhang, Jie Xu and Changming Zhao; supervision, Jie Xu and Changming Zhao; project administration, Jie Xu, Changming Zhao and Du Xu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Singhal A. Introducing the knowledge graph: things, not strings; 2012 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 25]. Official Google Blog. Available from: https://www.blog.google/products/search/introducing-knowledge-graph-things-not. [Google Scholar]

2. Dong X, Gabrilovich E, Heitz G, Horn W, Lao N, Murphy K, et al. Knowledge vault: a web-scale approach to probabilistic knowledge fusion. In: Proceedings of the 20th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, KDD ’14. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2014. p. 601–10. doi:10.1145/2623330.2623623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Chekol M, Pirrò G, Schoenfisch J, Stuckenschmidt H. Marrying uncertainty and time in knowledge graphs. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2017;31(1):10495. doi:10.1609/aaai.v31i1.10495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Jiang T, Liu T, Ge T, Sha L, Chang B, Li S, et al. Towards time-aware knowledge graph completion. In: Proceedings of COLING 2016, the 26th International Conference on Computational Linguistics: Technical Papers. Osaka, Japan: The COLING 2016 Organizing Committee; 2016. p. 1715–24. [Google Scholar]

5. Bordes A, Usunier N, Garcia-Duran A, Weston J, Yakhnenko O. Translating embeddings for modeling multi-relational data. In: Burges CJ, Bottou L, Welling M, Ghahramani Z, Weinberger KQ, editors. Advances in neural information processing systems. San Francisco, CA, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2013. Vol. 26, p. 2787–95. doi:10.5555/2999792.2999923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhu C, Chen M, Fan C, Cheng G, Zhang Y. Learning from history: modeling temporal knowledge graphs with sequential copy-generation networks. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Washington, DC, USA: AAAI Press; 2021. Vol. 35, p. 4732–40. doi:10.1609/aaai.v35i5.16604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Park N, Liu F, Mehta P, Cristofor D, Faloutsos C, Dong Y. EvoKG: jointly modeling event time and network structure for reasoning over temporal knowledge graphs. In: Proceedings of the Fifteenth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining (WSDM ’22). New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2022. p. 794–803. doi:10.1145/3488560.3498451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang Z, Zhang J, Feng J, Chen Z. Knowledge graph embedding by translating on hyperplanes. In: AAAI’14: Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2014 Jul 27–31; Québec City, QC, Canada. p. 1112–9. doi:10.1609/aaai.v28i1.8870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Lin Y, Liu Z, Sun M, Liu Y, Zhu X. Learning entity and relation embeddings for knowledge graph completion. In: AAAI’15: Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2015 Jan 25–30; Austin, TX, USA. p. 2181–7. doi:10.1609/aaai.v29i1.9491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ji G, He S, Xu L, Liu K, Zhao J. Knowledge graph embedding via dynamic mapping matrix. In: Zong C, Strube M, editors. Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 7th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing. Beijing, China: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2015. p. 687–96. doi:10.3115/v1/P15-1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Xiao H, Huang M, Hao Y, Zhu X. TransA: an adaptive approach for knowledge graph embedding. arXiv:1509.05490. 2015. [Google Scholar]

12. Xiao H, Huang M, Zhu X. TransG: a generative model for knowledge graph embedding. In: Erk K, Smith NA, editors. Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Berlin, Germany: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2016. p. 2316–25. doi:10.18653/v1/P16-1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Nickel M, Tresp V, Kriegel HP. A three-way model for collective learning on multi-relational data. In: Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML’11. Madison, WI, USA: Omnipress; 2011. p. 809–16. doi:10.5555/3104482.3104584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yang B, Yih SWt, He X, Gao J, Deng L. Embedding entities and relations for learning and inference in knowledge Bases. arXiv.1412.6575. 2015. [Google Scholar]

15. Nickel M, Rosasco L, Poggio T. Holographic embeddings of knowledge graphs. In: AAAI’16: Proceedings of the Thirtieth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2016 Feb 12–17; Phoenix, AZ, USA. p. 1955–61. doi:10.5555/3016100.3016172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Trouillon T, Welbl J, Riedel S, Gaussier E, Bouchard G. Complex embeddings for simple link prediction. In: Balcan MF, Weinberger KQ, editors. Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning. New York, NY, USA: PMLR; 2016. Vol. 48, p. 2071–80. doi:10.5555/3045390.3045609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Liu H, Wu Y, Yang Y. Analogical inference for multi-relational embeddings. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. New York, NY, USA: PMLR; 2017. p. 2168–78. doi:10.5555/3305890.3305905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Dettmers T, Minervini P, Stenetorp P, Riedel S. Convolutional 2D knowledge graph embeddings. In: Proceedings of the Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirtieth Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference and Eighth AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence, AAAI’18/IAAI’18/EAAI’18. Washington, DC, USA: AAAI Press; 2018. p. 1811–8. doi:10.5555/3504035.3504256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Kazemi SM, Poole D. SimplE embedding for link prediction in knowledge graphs. In: Bengio S, Wallach H, Larochelle H, Grauman K, Cesa-Bianchi N, Garnett R, editors. Advances in neural information processing systems. San Francisco, CA, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2018. Vol. 31, p. 4289–300. doi:10.5555/3327144.3327341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Nguyen DQ, Vu T, Nguyen TD, Nguyen DQ, Phung D. A capsule network-based embedding model for knowledge graph completion and search personalization. In: Burstein J, Doran C, Solorio T, editors. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Minneapolis, MN, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019. p. 2180–9. doi:10.18653/v1/N19-1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Vashishth S, Sanyal S, Nitin V, Agrawal N, Talukdar P. InteractE: improving convolution-based knowledge graph embeddings by increasing feature interactions. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(3):3009–16. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i03.5694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Schlichtkrull M, Kipf TN, Bloem P, van den Berg R, Titov I, Welling M. Modeling relational data with graph convolutional networks. In: Gangemi A, Navigli R, Vidal ME, Hitzler P, Troncy R, Hollink L, et al. editors. The semantic web. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 593–607. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-93417-4_38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Veličković P, Casanova A, Liò P, Cucurull G, Romero A, Bengio Y. Graph attention networks. In: 6th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2018; 2018 Apr 30–May 3; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 1–12. doi:10.17863/CAM.48429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Dasgupta SS, Ray SN, Talukdar P. HyTE: hyperplane-based temporally aware knowledge graph embedding. In: Riloff E, Chiang D, Hockenmaier J, Tsujii J, editors. Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Brussels, Belgium: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2018. p. 2001–11. doi:10.18653/v1/D18-1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Goel R, Kazemi SM, Brubaker M, Poupart P. Diachronic embedding for temporal knowledge graph completion. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(4):3988–95. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i04.5815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. García-Durán A, Dumančić S, Niepert M. Learning sequence encoders for temporal knowledge graph completion. In: Riloff E, Chiang D, Hockenmaier J, Tsujii J, editors. Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Brussels, Belgium: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2018. p. 4816–21. doi:10.18653/v1/D18-1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Jin W, Qu M, Jin X, Ren X. Recurrent event network: autoregressive structure inferenceover temporal knowledge graphs. In: Webber B, Cohn T, He Y, Liu Y, editors. Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP). Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020. p. 6669–83. doi:10.18653/v1/2020.emnlp-main.541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Wang Z, Ding D, Ren M, Conti M. TANGO: a temporal spatial dynamic graph model for event prediction. Neurocomputing. 2023;542(1):126249. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2023.126249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Li XV, Sanna Passino F. FinDKG: dynamic knowledge graphs with large language models for detecting global trends in financial markets. In: Proceedings of the 5th ACM International Conference on AI in Finance, ICAIF ’24. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2024. p. 573–81. doi:10.1145/3677052.3698603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Chen H, Zhang M, Chen Z. Temporal knowledge graph reasoning based on dynamic fusion representation learning. Expert Syst. 2025;42(2):e13758. doi:10.1111/exsy.13758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Boschee E, Lautenschlager J, O’Brien S, Shellman S, Starz J, Ward M. ICEWS coded event data. Harvard Dataverse. 2015. doi:10.7910/DVN/28075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Sun Z, Deng ZH, Nie JY, Tang J. RotatE: knowledge graph embedding by relational rotation in complex space. arXiv.1902.10197. 2019. [Google Scholar]

33. Jung J, Jung J, Kang U. Learning to walk across time for interpretable temporal knowledge graph completion. In: Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, KDD ’21. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2021. p. 786–95. doi:10.1145/3447548.3467292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Shang C, Tang Y, Huang J, Bi J, He X, Zhou B. End-to-end structure-aware convolutional networks for knowledge base completion. In: Proceedings of the Thirty-Third AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirty-First Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference and Ninth AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence, AAAI’19/IAAI’19/EAAI’19. Washington, DC, USA: AAAI Press; 2019. p. 3060–7. doi:10.1609/aaai.v33i01.33013060. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Seo Y, Defferrard M, Vandergheynst P, Bresson X. Structured sequence modeling with graph convolutional recurrent networks. In: Neural Information Processing: 25th International Conference, ICONIP 2018. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2018. p. 362–73. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-04167-0_33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools