Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Transforming Healthcare with State-of-the-Art Medical-LLMs: A Comprehensive Evaluation of Current Advances Using Benchmarking Framework

1 Department of Computer Science, SNEC, University of Calcutta, Kolkata, 700073, India

2 Department of Computer Science, PRTGC, West Bengal State University, Barasat, 700126, India

3 Department of Computer Science & Engineering, The Neotia University, Kolkata, 743368, India

4 Department of Computer Science & Engineering, University College of Science and Technology, University of Calcutta, Kolkata, 700009, India

5 Department of Food Science, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, 1165, Denmark

6 Department of Computer Science, Illinois Institute of Technology, 10 West 35th Street, Chicago, IL 60616, USA

7 Department of Computer Science, San Francisco State University, 1600 Holloway Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94132, USA

* Corresponding Author: Dipanwita Chakraborty Bhattacharya. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-56. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070507

Received 17 July 2025; Accepted 16 September 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

The emergence of Medical Large Language Models has significantly transformed healthcare. Medical Large Language Models (Med-LLMs) serve as transformative tools that enhance clinical practice through applications in decision support, documentation, and diagnostics. This evaluation examines the performance of leading Med-LLMs, including GPT-4Med, Med-PaLM, MEDITRON, PubMedGPT, and MedAlpaca, across diverse medical datasets. It provides graphical comparisons of their effectiveness in distinct healthcare domains. The study introduces a domain-specific categorization system that aligns these models with optimal applications in clinical decision-making, documentation, drug discovery, research, patient interaction, and public health. The paper addresses deployment challenges of Medical-LLMs, emphasizing trustworthiness and explainability as essential requirements for healthcare AI. It presents current evaluation techniques that improve model transparency in high-stakes medical contexts and analyzes regulatory frameworks using benchmarking datasets such as MedQA, MedMCQA, PubMedQA, and MIMIC. By identifying ongoing challenges in bias mitigation, reliability, and ethical compliance, this work serves as a resource for selecting appropriate Med-LLMs and outlines future directions in the field. This analysis offers a roadmap for developing Med-LLMs that balance technological innovation with the trust and transparency required for clinical integration, a perspective often overlooked in existing literature.Keywords

Large Language Models (LLMs) have garnered the majority of attention in healthcare AI research due to their unparalleled ability to process, generate, and contextualize natural language. Natural language is the primary medium of medical knowledge exchange [1]. While other paradigms such as federated learning have shown promise for preserving privacy and mitigating risks such as model poisoning in distributed healthcare settings [2–6], and Explainable AI (XAI) [7–9], Agentic AI [10,11], and traditional machine learning approaches continue to play important roles in specialized applications, LLMs offer a unifying capability. They can seamlessly integrate clinical text, patient records, and biomedical literature, enabling a wide range of applications, from decision support to patient communication. Their pretraining on massive, diverse corpora enables them to generalize across domains with minimal task-specific tuning, providing a practical edge over more narrowly focused methods. Consequently, while federated learning and explainable AI address specific challenges such as privacy and interpretability, LLMs have become the central focus due to their versatility, scalability, and translational potential across nearly every aspect of healthcare delivery. To foster the integration of LLMs into real-world healthcare and to overcome regulatory hurdles, this work also emphasizes the complementary role of paradigms such as Explainable AI in enabling safe, interpretable, and trustworthy clinical decision-making. LLMs may thus be envisioned as the “brain” for medical knowledge and reasoning, with Federated Learning, Explainable AI, and Agentic AI serving as supportive technologies that enhance privacy, trust, and practical deployment in healthcare.

In 2024, according to the study in MedRxiv [12] out of 28,180 AI-related healthcare publications indexed in PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 15 September 2025)), 1693 were identified as mature, with 1551 selected for detailed analysis. Notably, 479 publications (30.9%) employed Large Language Models (LLMs), surpassing traditional deep learning models (372 publications). The use of text data also rose significantly, accounting for 33.1% (525 publications) of the total, reflecting a growing shift toward LLM-driven research in healthcare—particularly for educational and administrative applications. Leveraging domain-specific data, medical LLMs can assist in diverse tasks such as medical note generation, patient interaction, and medical question answering (QA) [13]. One significant opportunity offered by medical LLMs lies in automating medical documentation. For instance, HEAL, a 13B-parameter model [14], excels in generating physician-quality SOAP notes directly from patient-doctor interactions, significantly reducing the administrative burden on healthcare professionals. Similarly, retrieval-augmented models like JMLR improve factual accuracy in medical QA by integrating domain-specific retrievers, ensuring that responses are both contextually relevant and grounded in credible data [15]. Such innovations promise to enhance efficiency and precision in clinical workflows. Multimodal Medical LLMs integrate diverse inputs such as text, images, and EHR data for holistic reasoning such as Med-PaLM Multimodal [16]. Another key advancement is the introduction of multilingual medical LLMs, such as BiMediX [17], which addresses the linguistic diversity in healthcare. By supporting seamless interaction in both English and Arabic, BiMediX caters to underrepresented populations, bridging gaps in access to medical knowledge and services [18]. Agentic Medical LLMs like ArgMed-Agents [19] act as autonomous clinical assistants that perform multi-step reasoning and decision support.

The adoption of LLMs in healthcare is not without challenges, such as ensuring reliability, minimizing biases, and addressing ethical concerns. Despite these advancements, medical LLMs face significant challenges. One of the critical issues is the potential for generating hallucinated or inaccurate information, which can lead to adverse clinical outcomes [20]. Some state-of-the-art models such as JMLR [15] and BiMediX require careful evaluation to ensure their recommendations align with established medical guidelines [21,22]. Another concern is the bias inherent in training data, which may disproportionately affect certain demographics, exacerbating health disparities [23]. Ethical considerations such as patient data privacy and model transparency remain pivotal in clinical adoption [24]. A crucial aspect of deploying LLMs in medicine is interpretability, which ensures that healthcare professionals can understand and trust model-generated outputs. Deep learning models typically operate as black boxes, in contrast to traditional rule-based systems, which makes understanding the rationale behind their specific predictions challenging. This lack of transparency raises concerns about patient safety, accountability, and clinical decision-making [25]. Techniques such as attention visualization, saliency mapping, and explainable AI (XAI) frameworks can enhance interpretability by providing insights into how models process medical information [26]. Ensuring that LLMs offer clear and justifiable outputs is essential for regulatory compliance, ethical considerations, and broader acceptance in clinical practice. Addressing these challenges requires a multi-faceted approach, combining advancements in model architectures, robust evaluation frameworks, and interdisciplinary collaboration. As medical LLMs continue to evolve, they offer an exciting frontier for improving healthcare delivery while underscoring the need for careful implementation and oversight.

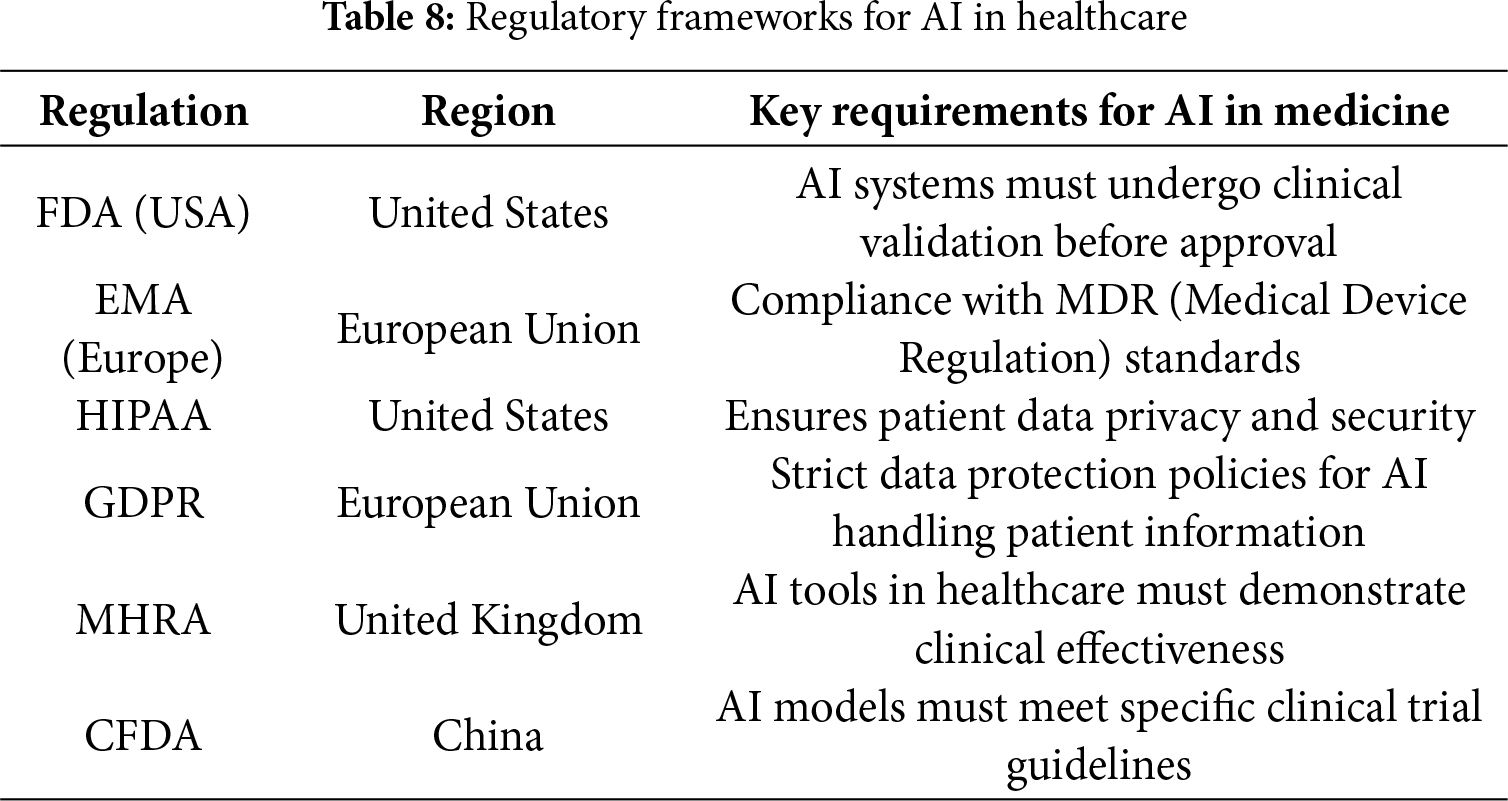

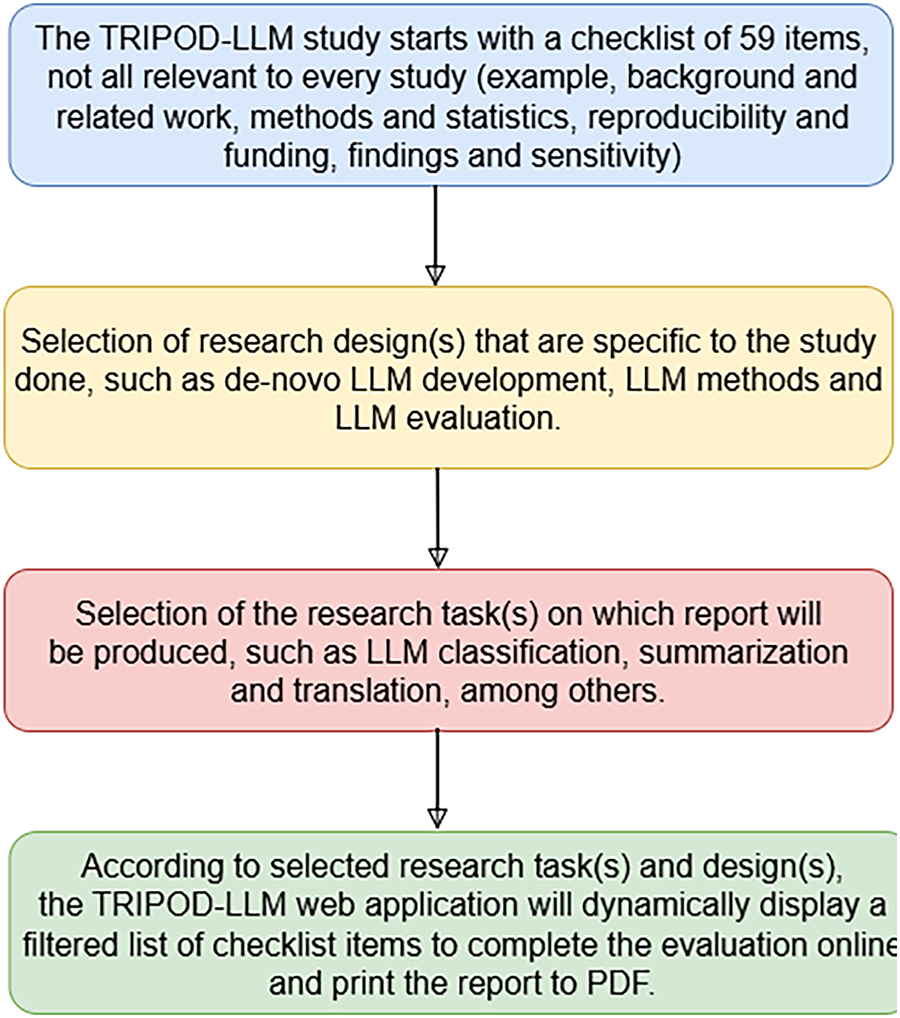

While numerous surveys published in 2024–2025 [24,27–31] explore the development, architecture, and clinical applications of Medical Large Language Models (Med-LLMs), a critical gap remains in evaluating these models from the perspective of real-world deployment readiness. Existing reviews largely focus on performance metrics from static benchmarks and NLP tasks—such as clinical summarization and question answering—but do not examine challenges related to regulatory compliance, Electronic Health Record (EHR) integration, explainability, or safety in clinical workflows. Based on the of recent literature, no existing paper systematically addresses Med-LLM evaluation through the lens of clinical risk, operational deployment barriers, and alignment with global regulatory standards (e.g., FDA, HIPAA, EU AI Act, WHO ethics).

To address this gap, this work provides the following key contributions:

• In this work, the transformation of LLM to Medical LLMs, evolution of Med-LLMs are traced and framing of LLMs as a paradigm shift in the digital healthcare ecosystem has been exhibited.

• This paper analyzes the state-of-the-art Med-LLMs by their underlying architecture, clinical tasks, and benchmark performance.

• Different evaluation techniques has been discussed, how current models are assessed using real-world criteria, going beyond accuracy to include robustness, hallucination risk, factual consistency, and clinician alignment.

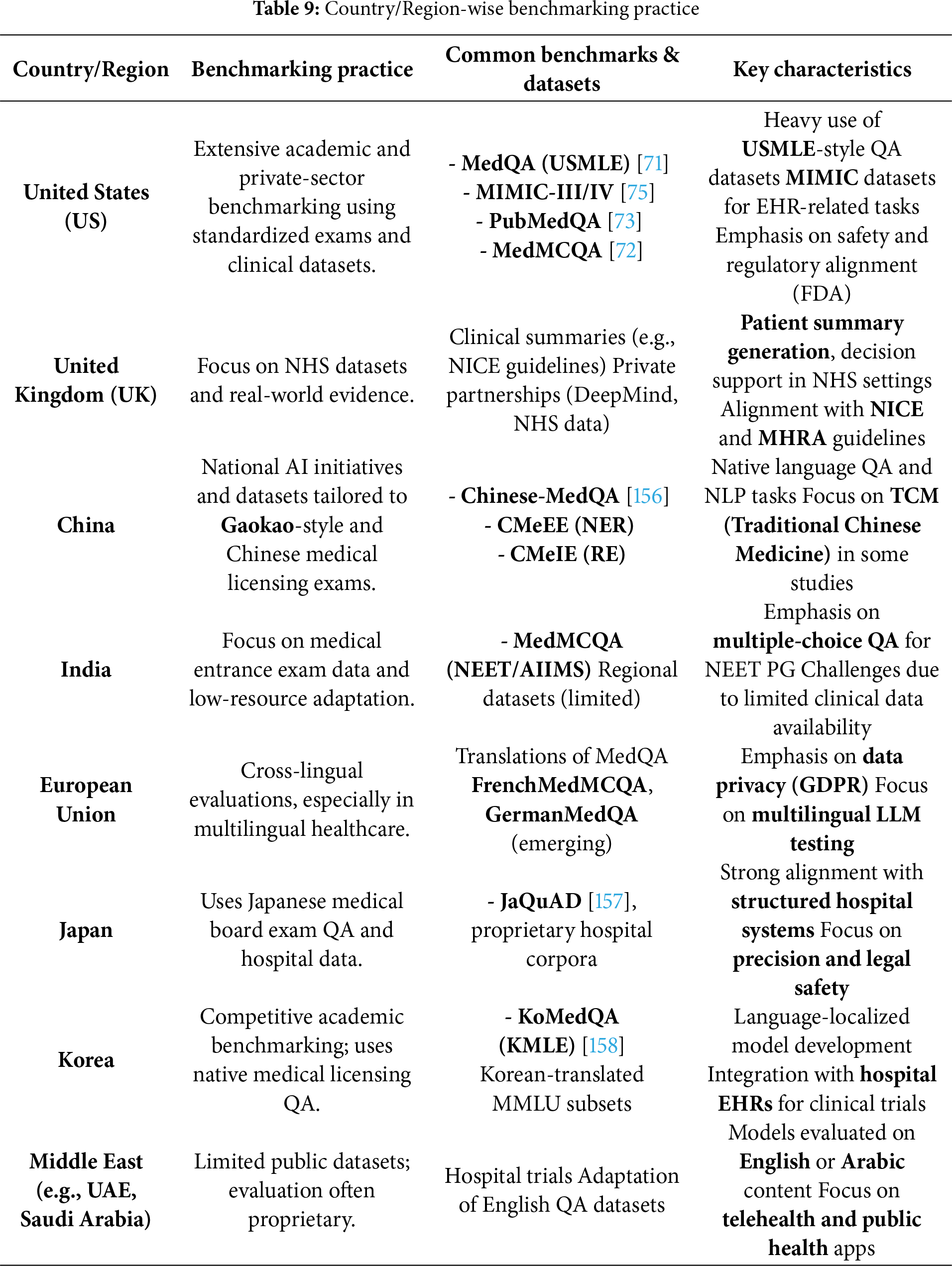

• This paper synthesizes international regulations and ethical frameworks to examine the deployment readiness of Med-LLMs and the benchmarking practices of different countries around the world.

• The major deployment barriers—including technical, regulatory, and infrastructural challenges are identified in this work with the future direction and scope in this research domain.

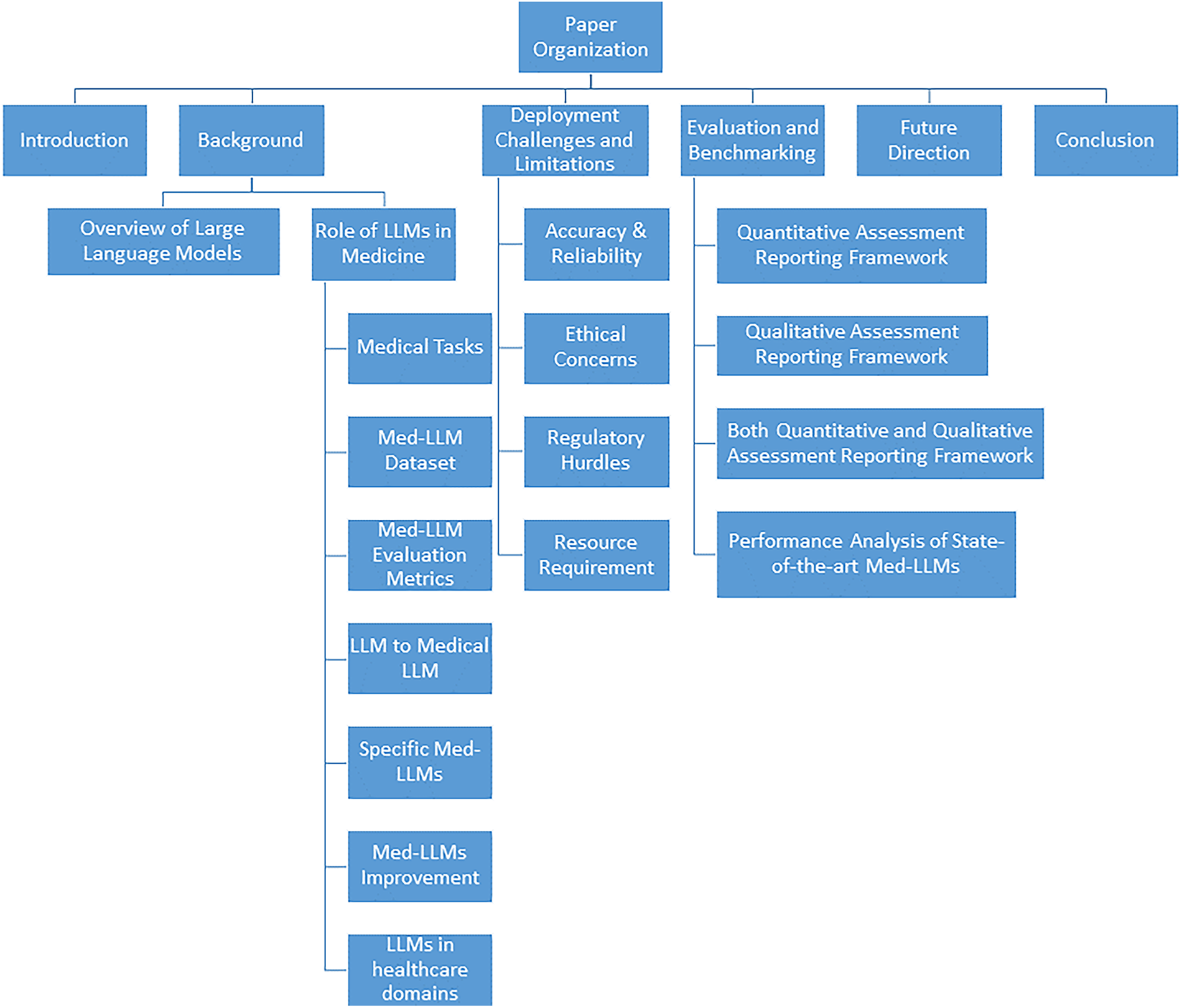

This paper leads to a valuable insight of the architectural evolution of Med-LLMs, the current state of real-world readiness, and the practical scope and limitations that must be addressed for safe and effective deployment in clinical settings. The organization of this paper is captured in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: A comprehensive study of Medical-LLMs, its deployment challenges and benchmarking techniques towards providing transparency

2.1 Overview of Large Language Models

Large Language Models (LLMs) are advanced AI systems built on deep learning techniques and trained on vast collections of text data to comprehend and produce natural language. These models, which utilize transformer-based architectures like GPT [14], BERT [18,32], and LLaMA [33–35], have shown remarkable capabilities in various language tasks including answering questions, creating summaries, translating text, and engaging in conversations. Through self-attention mechanisms and extensive pre-training combined with specialized fine-tuning, LLMs can grasp intricate patterns in meaning, grammar, and context within language. Recent developments have introduced Multimodal LLMs [36–39], which extend beyond text processing to integrate and understand multiple data types simultaneously, including images, audio, and video alongside textual information. These models can analyze medical images, interpret diagnostic scans, and correlate visual findings with clinical text, significantly expanding their utility in healthcare applications. Similarly, Multilingual [40,41] LLMs have been developed to process and generate content across multiple languages, breaking down language barriers in global healthcare delivery and enabling cross-cultural medical communication and research. Within healthcare, LLMs are being adapted through training on medical literature, patient records, clinical documentation, and specialized healthcare datasets to tackle medical applications such as supporting clinical decisions, automating medical documentation, facilitating patient communications, and enhancing medical training. The integration of multimodal capabilities allows these systems to process medical imaging data, laboratory results, and clinical photographs alongside textual information, while multilingual capabilities enable them to serve diverse patient populations and facilitate international medical collaboration. Advanced variants like Med-PaLM, BioMistral, Med-GPT, and BiMediX (as illustrated in Table 1)—which incorporate instruction-following capabilities, multiple languages, and various data types—have broadened the potential uses of LLMs in medical settings. These specialized systems, known as Medical LLMs (Med-LLMs), prioritize key aspects like task-specific optimization, safety protocols, accuracy, and interpretability in their development and assessment. While LLMs continue to advance rapidly and expand the possibilities for medical AI applications, they also present ongoing challenges related to dependability, addressing bias, and practical implementation in healthcare environments.

Model Architecture

The Transformer technology brings new possibilities to handling sequence-to-sequence tasks such as machine translation. Transformer models have developed at an extraordinary rate in recent times through growth to large parameter spaces. The models contain parameter counts ranging from billions to hundreds of billions [14,15]. The fundamental parts of the transformer design have the following features:

1. Encoder-Decoder Structure: The Transformer functions as two separate systems, processing input sequences through an encoder while producing output sequences through a decoder. This design enables flexible input-output mappings, which benefits translations and other related tasks.

2. Self-Attention Mechanism: Self-attention allows each input token to compute attention scores with all other tokens in the sequence. The model performs self-attention operations across multiple projection layers simultaneously, capturing intricate relationships within the input [18].

3. Positional Encoding: Since standard transformer operations lack an inherent understanding of sequence order, positional encoding plays a critical role. Common methods include sinusoidal encodings, learned embeddings, and more advanced techniques like rotary and hybrid encodings [20].

4. Residual Connections and Layer Normalization: Residual connections mitigate the vanishing gradient problem, ensuring stable model updates during training. After each residual connection, layer normalization improves model convergence, stability, and training efficiency [22].

a) Discussion on Pre-Training Stage: During LLM pre-training a model learns from basic text training before getting specific application tasks. Pre-training allows models to extract fundamental language patterns before fine-tuning for domain-specific tasks [42,43]. The following are commonly used pre-training tasks:

i Next Word Prediction (NWP): NWP is a core language modeling task where the model predicts the next word based on preceding words [13,44]. This is a crucial step in training LLMs as it helps models understand contextual dependencies in text [45].

ii Masked Language Modeling (MLM): MLM, as used in BERT, trains a model to predict masked words in a given sentence, enhancing its understanding of syntactic and semantic relationships [32,46,47].

iii Replaced Token Detection (RTD): RTD enables models to distinguish between naturally occurring tokens and deliberately replaced ones, improving their ability to detect subtle shifts in meaning [48–50].

iv Next Sentence Prediction (NSP): NSP helps models capture sentence coherence by predicting whether a given sentence logically follows the previous one. This aids in discourse-level understanding.

v Sentence Order Prediction (SOP): SOP refines a model’s ability to maintain narrative structure by ensuring correct sentence sequencing, which is beneficial for processing long-form medical texts [33,51].

b) Discussion on Fine-Tuning Stage: Fine-tuning adapts pre-trained models for specific tasks using domain-specific data [52–55]. The major fine-tuning techniques are:

i Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT): SFT improves LLMs by training them on labeled datasets, ensuring they perform well on specific downstream tasks [56,57]. This is widely used in healthcare applications.

ii Instruction Fine-Tuning (IFT): IFT enhances models by training them on instruction-based datasets, allowing them to generalize across multiple tasks [36,58,59]. This technique has been effective in aligning models with human preferences.

iii Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT): Fine-tuning becomes computationally efficient through PEFT, which modifies only a small portion of model parameters rather than the entire model [18,60,61]. This technique is critical for deploying LLMs in resource-constrained environments.

c) Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF): LLMs undergo additional refinement through RLHF, where human evaluators assess and guide model responses to enhance accuracy and alignment with expert knowledge. This ensures that the models remain reliable in high-stakes applications such as healthcare.

d) In-Context Learning (ICL): By offering a few examples within the input prompt, ICL enables LLMs to adapt across different tasks without requiring explicit fine-tuning. This is particularly useful in medical question-answering applications.

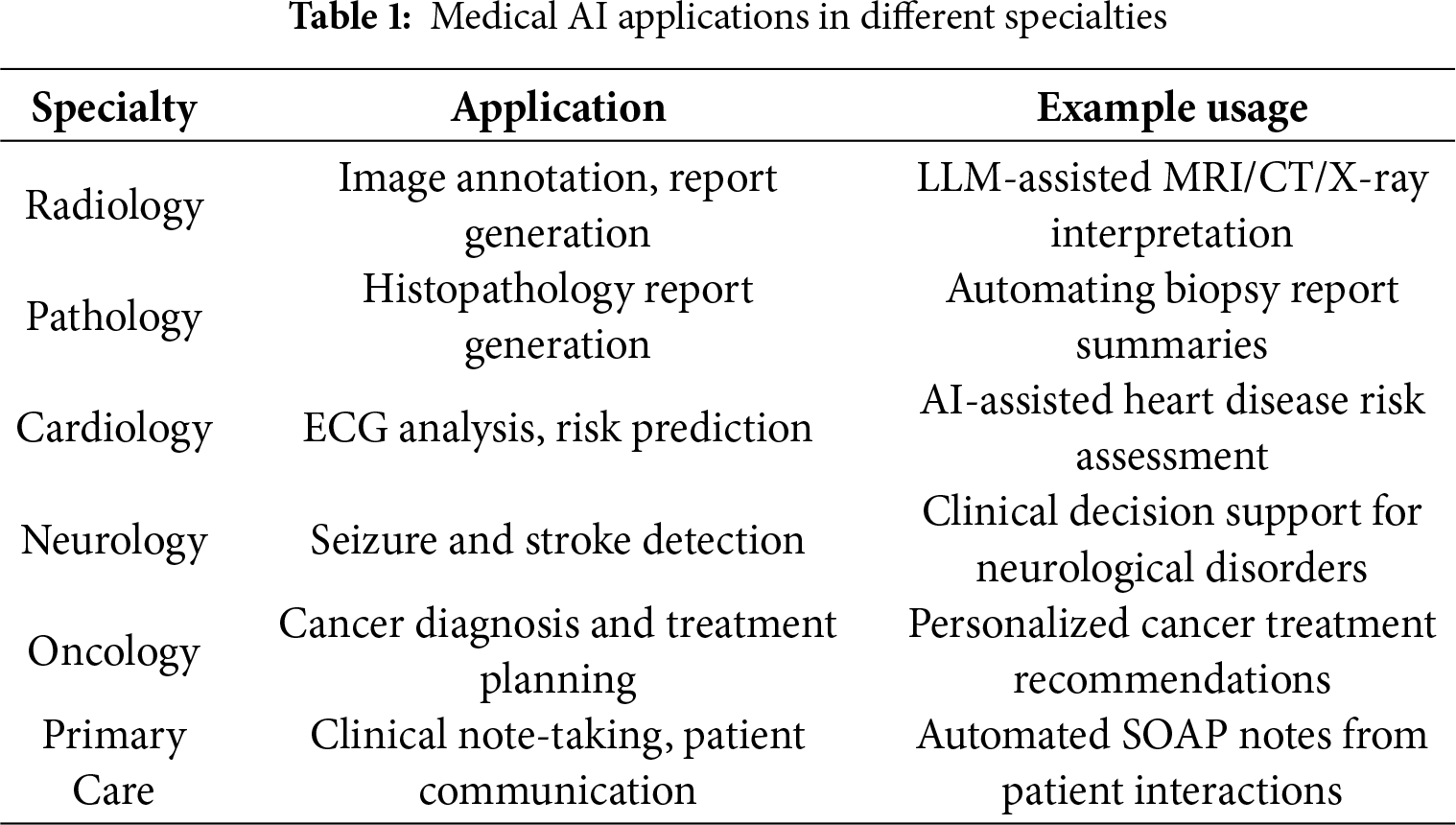

Large Language Models play a pivotal role across multiple domains of healthcare, including clinical decision support, medical documentation, patient communication, biomedical research, and education, by enabling advanced reasoning over vast medical knowledge sources. LLMs, when integrated with EHR data—including clinical notes, lab reports, medical images, and patient interactions—can support radiology, pathology, and clinical planning according to Table 1, enabling AI-driven applications such as diagnosis, prognosis, surgical assistance, telehealth, and hospital guidance as demonstrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: LLM in healthcare

2.2.1 NLP Tasks under Medical Domain

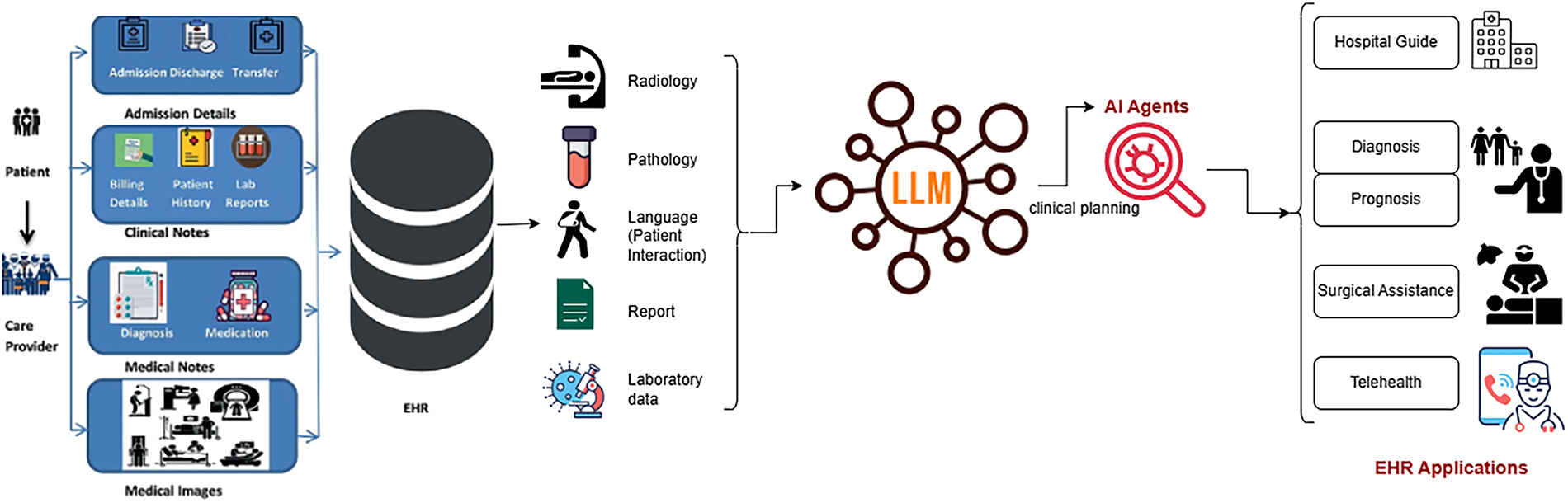

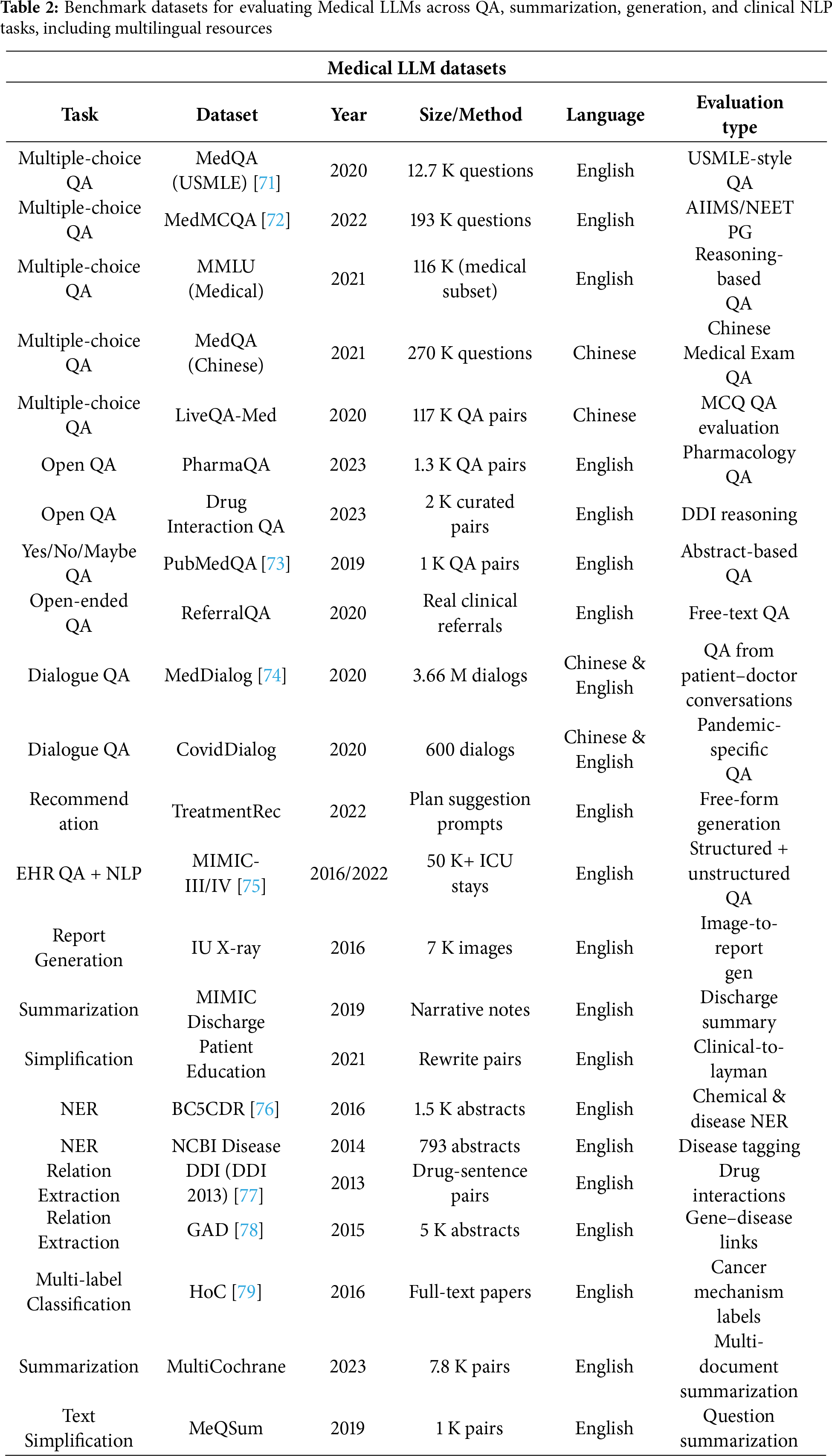

NLP is used to extract medical data (Med-IE), answer medical questions (Med-QA) [45], recognize medical relationships (Med-NLI), and generate medical texts (Med-Gen) [62]. Some medical NLP datasets have been mentioned in Table 2.

1. Medical Information Extraction: Medical Information Extraction (Med-IE) helps to find important medical details from all types of healthcare records without structure [63]. The effort aims to convert text data from medical information into organized forms ready for analysis through decision support tools and research programs [42].

2. Medical Question Answering: Through the Medical Question Answering (Med-QA) task, users build artificial intelligence systems (especially LLMs) to process medical questions from different stakeholders [64]. The system needs structured and unstructured medical data like healthcare records to create precise and dependable responses [65].

3. Medical Natural Language Inference: Medical Natural Language Inference (Med-NLI) is designed to evaluate medical text relationships [59]. The system needs to stay balanced when assessing one segment against another [66]. This task forms a sub-domain within Natural Language Processing where it is referred to as Recognizing Textual Entailment (RTE) [67].

This section seeks to gather and present important medical datasets for language models. The research includes basic dataset information such as publication year, data size, medical task, and available language versions. Medical datasets serve a dual purpose for Med-LLMs by making available expert-level knowledge for training and testing these systems against specific clinical tasks [68]. The rapid development of LLMs in recent years’ achievements drives a strong need for large and well-organized datasets, especially in intelligent medical research [69,70].

While most benchmarks such as MedQA [71] and NEET are limited to multiple-choice or exam-style QA, newer benchmarks are emerging to capture real-world tasks like summarization and patient communication. Datasets such as MIMIC-III/IV [75] for clinical note summarization, MedDialog [74] for doctor–patient dialogues, and HealthSearchQA for consumer-friendly explanations are increasingly being used to evaluate models on tasks beyond QA, aligning more closely with clinical practice.

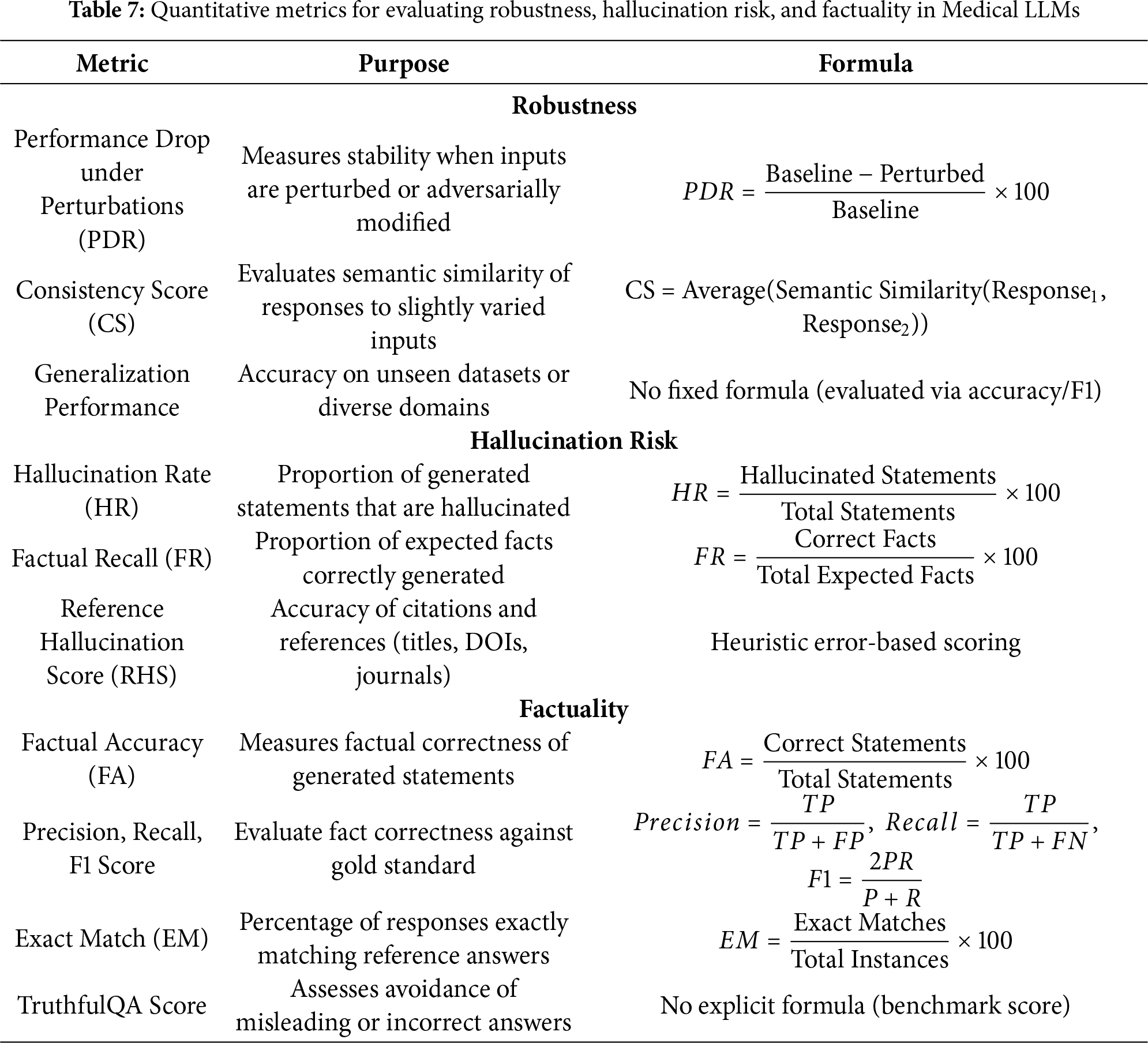

2.2.3 Med-LLM Evaluation Metrics

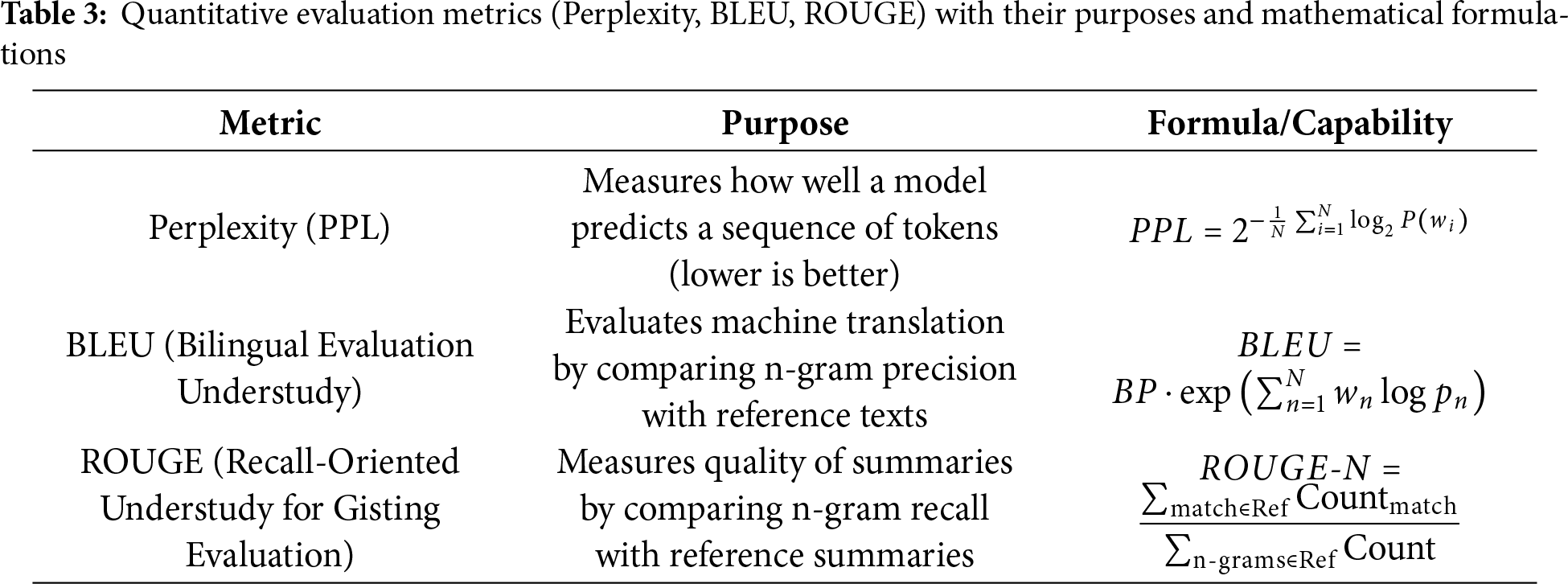

1) Quantitative Evaluation Metrics: The detailed key metrics used for evaluation are listed below:

• Perplexity: Perplexity serves as a basic standard to check how well a probability model predicts input samples. Higher prediction certainty in turn reduces a model’s perplexity score [22].

• ROUGE: A test of text similarity measures how many overlapping units (such as n-grams or chunks) exist between generated output and reference content. ROUGE offers several variants for evaluating text overlaps from its primary four assessments: ROUGE-N, ROUGE-L, ROUGE-W, and ROUGE-SU [18].

• BLEU: According to BLEU analysis, a translation’s similarity to multiple reference translations establishes its effectiveness. A translation quality should repeat small word groupings in the target language just like what appears in available reference texts [80].

However, BLEU [81] and ROUGE [82] summarized in Table 3 continue to be widely applied for evaluating Med-LLM outputs,their reliance on exact n-gram matches has been shown to inadequately capture semantic equivalence, particularly in the presence of medical synonyms, abbreviations, and clinically critical paraphrases. For example, terms such as “myocardial infarction” and “heart attack” or “acetylsalicylic acid” and “aspirin” are semantically equivalent but are penalized under n-gram-based scoring schemes. These challenges necessitate the adoption of more sophisticated evaluation methods that better capture semantic and clinical correctness. Recent works have explored the following approaches:

• Embedding-based semantic metrics: BERTScore leverages contextual embeddings to evaluate semantic similarity beyond surface form matching, thus addressing terminological variability more effectively [83].

• Ontology-aware evaluation: Resources such as the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) have been employed to normalize entity variation and align synonymous medical expressions across outputs, improving evaluation in terminology-rich clinical contexts [84].

• Task-specific factuality metrics: PlainQAFact introduces a factuality evaluation benchmark for medical summarization, where factual questions are automatically generated from model outputs and verified against source documents, providing stronger alignment with expert judgments [85].

Together, these approaches demonstrate that while BLEU and ROUGE remain useful for comparability, future evaluation of Med-LLMs requires the integration of semantic, ontology-aware, and task-specific metrics to more accurately assess clinical utility.

2) Qualitative Evaluation Metrics: In NLP settings, qualitative evaluations help analyze how humans interpret language output instead of using numerical scores [32]. Human experts use their evaluation skills to examine LLM results because quantitative metrics depend on numerical value measurements. Here are some common qualitative evaluation approaches:

• Human Evaluation: Expert evaluators examine generated text against criteria that measure readability, organized flow, writing quality, topic match, and accurate information [63].

• Error Analysis: Researchers study all system mistakes to identify its effective aspects and problem areas. System errors also need to discover strengths and weaknesses, which guides us in updating the model [64].

• Case Studies: A deep study of how systems perform in real-world scenarios shows what problems arise when dealing with unique situations that statistics cannot detect [86].

• User Feedback: Researchers need to talk with users who use LLM applications to learn if they get helpful responses that help them perform tasks [87].

• Thematic Analysis: The analysis studies how LLMs process language context to create accurate meaning [59].

• Aesthetic Judgments: This is hard to assign numbers to how well generated text looks when read [65].

• Ethical and Societal Impact Assessment: Studies both ethical issues and social outcomes of LLM system functions [25].

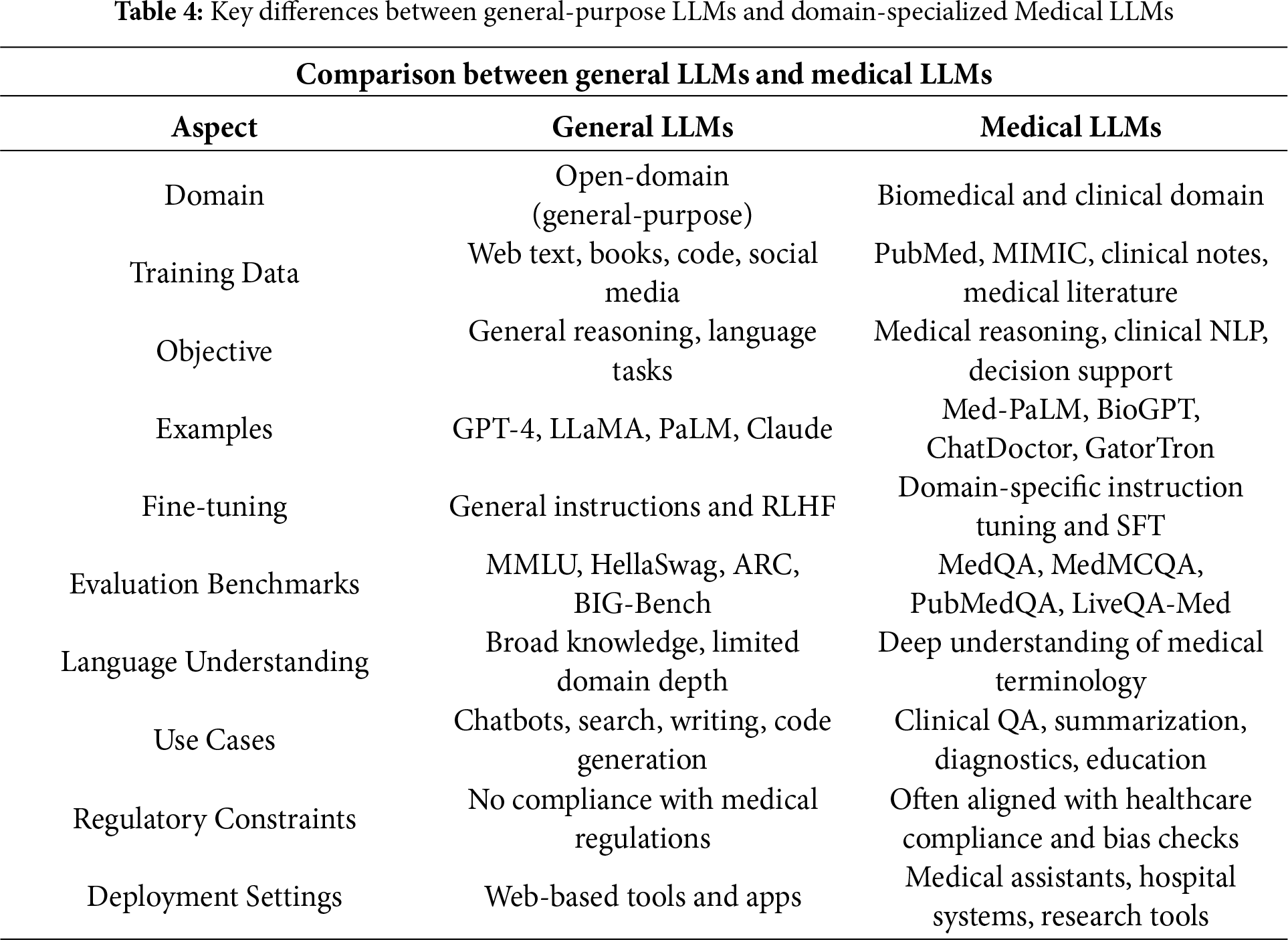

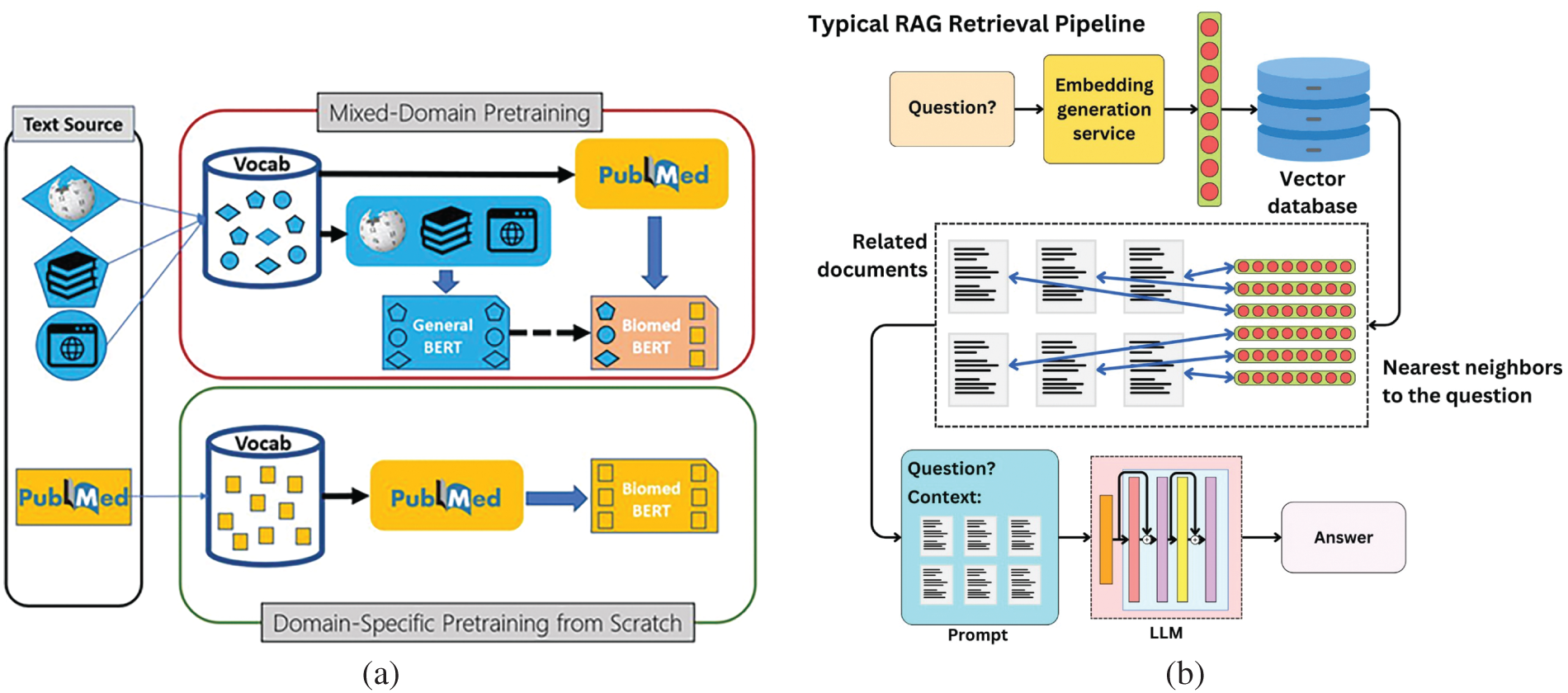

The procedure to enhance a basic large language model into a medical LLM, key differences stated in Table 4, entails complex techniques that surpass basic parameter tuning. The overall process contains a multi-step approach: methods use prompt engineering, medical training, and Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) [54,59].

• Prompt Engineering: Building prompts to ensure the model generates medical responses that align with healthcare standards [32]. The initial stage designs medical-specific prompts that feature structured instructions, real medical context, and predefined response patterns. Prompts guide the model to diagnose based on symptoms, recommend treatments, and simplify complex medical processes for human understanding [64].

• Medical-Specific Fine-Tuning: Choosing high-quality medical datasets begins with clinical notes, textbooks, anonymized patient records, and peer-reviewed research. The dataset must cover essential topics such as pathology, pharmacology, anatomy, diagnostics, therapeutic procedures, and patient treatment [63]. Proper fine-tuning enhances the model’s ability to provide accurate and reliable medical recommendations [66].

• Medical-Specific RAG: Developing a medical RAG system requires integrating retrieval mechanisms to access precise medical information efficiently. The system enables the model to fetch details from up-to-date medical sources, improving accuracy and reliability [65]. By combining generative capabilities with real-time retrieval from trusted databases, LLMs can produce more evidence-based responses [42].

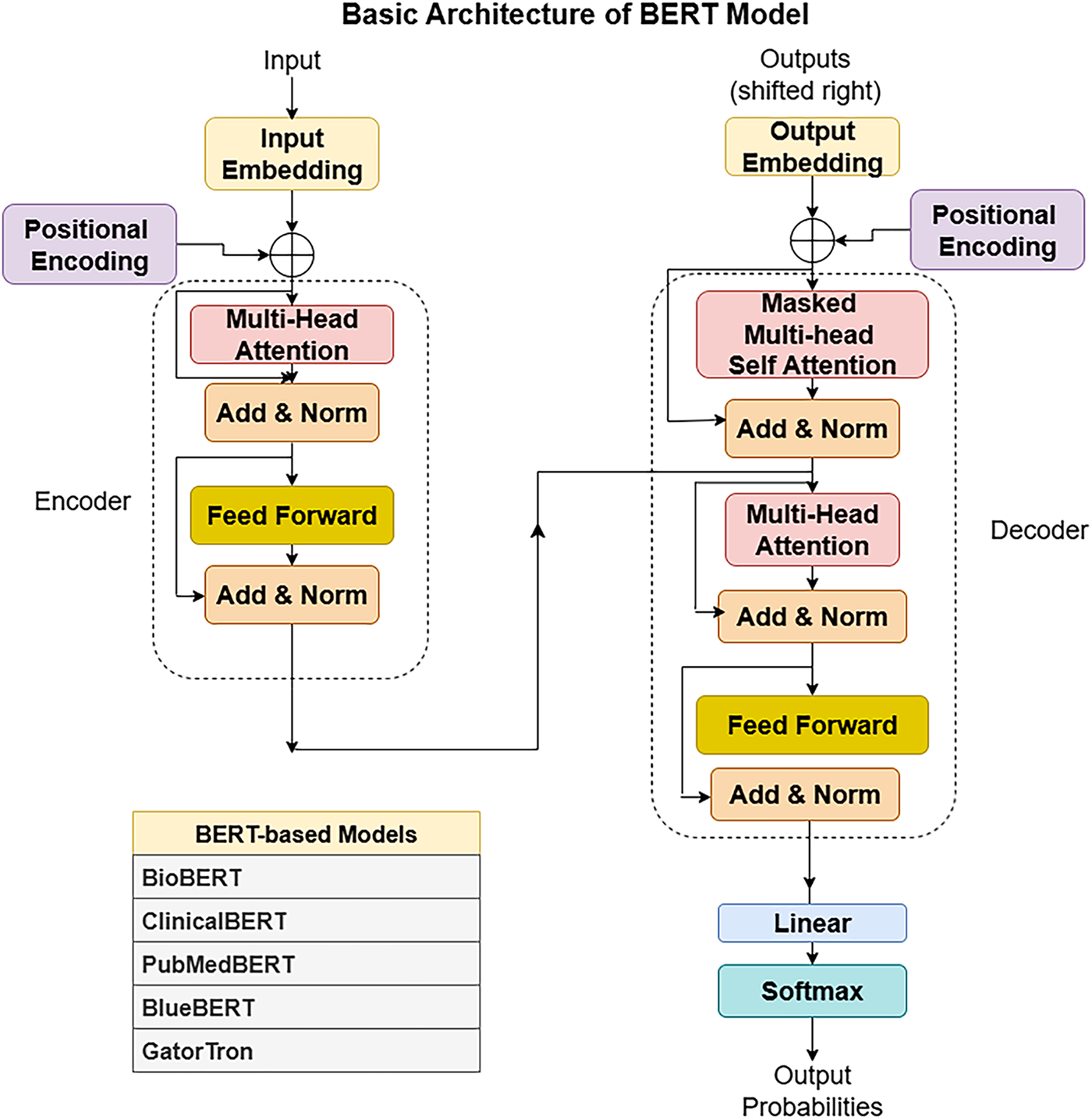

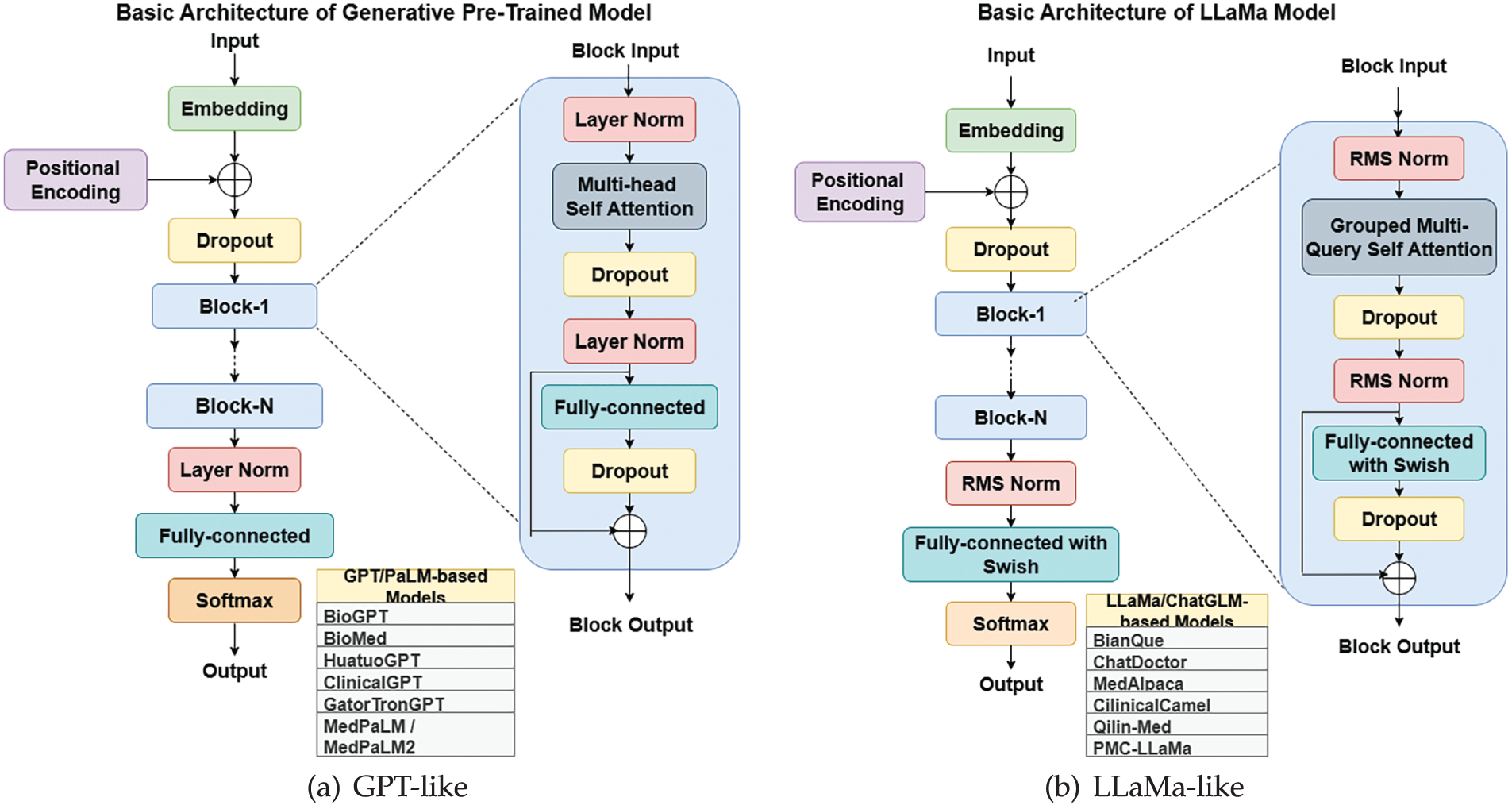

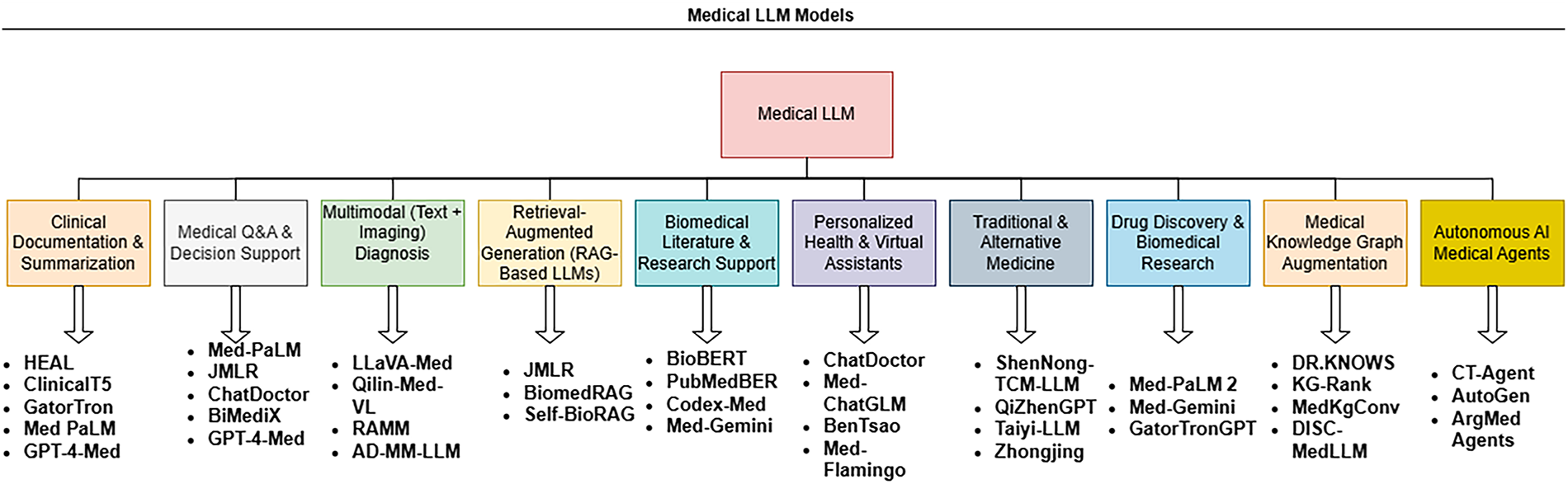

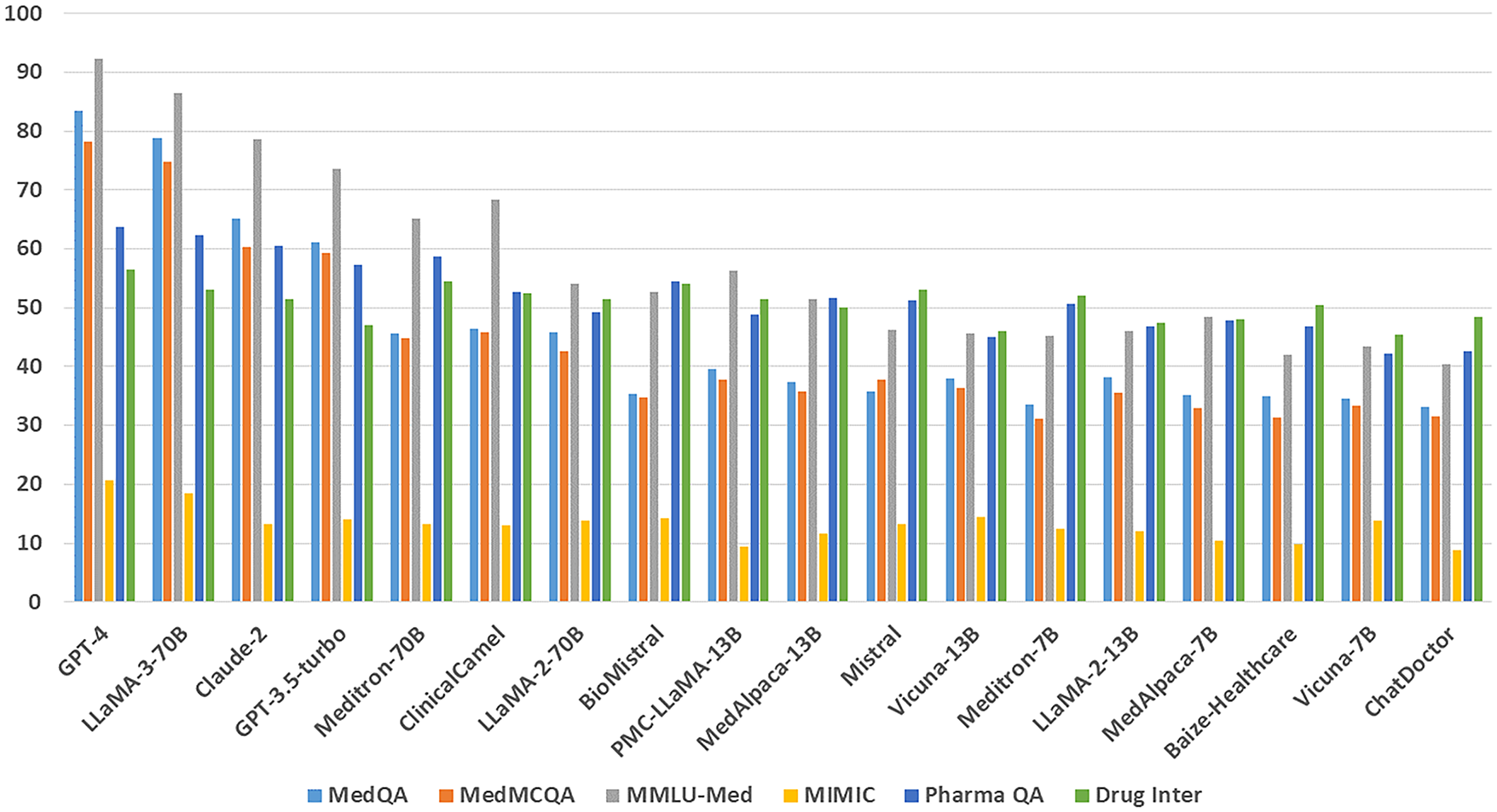

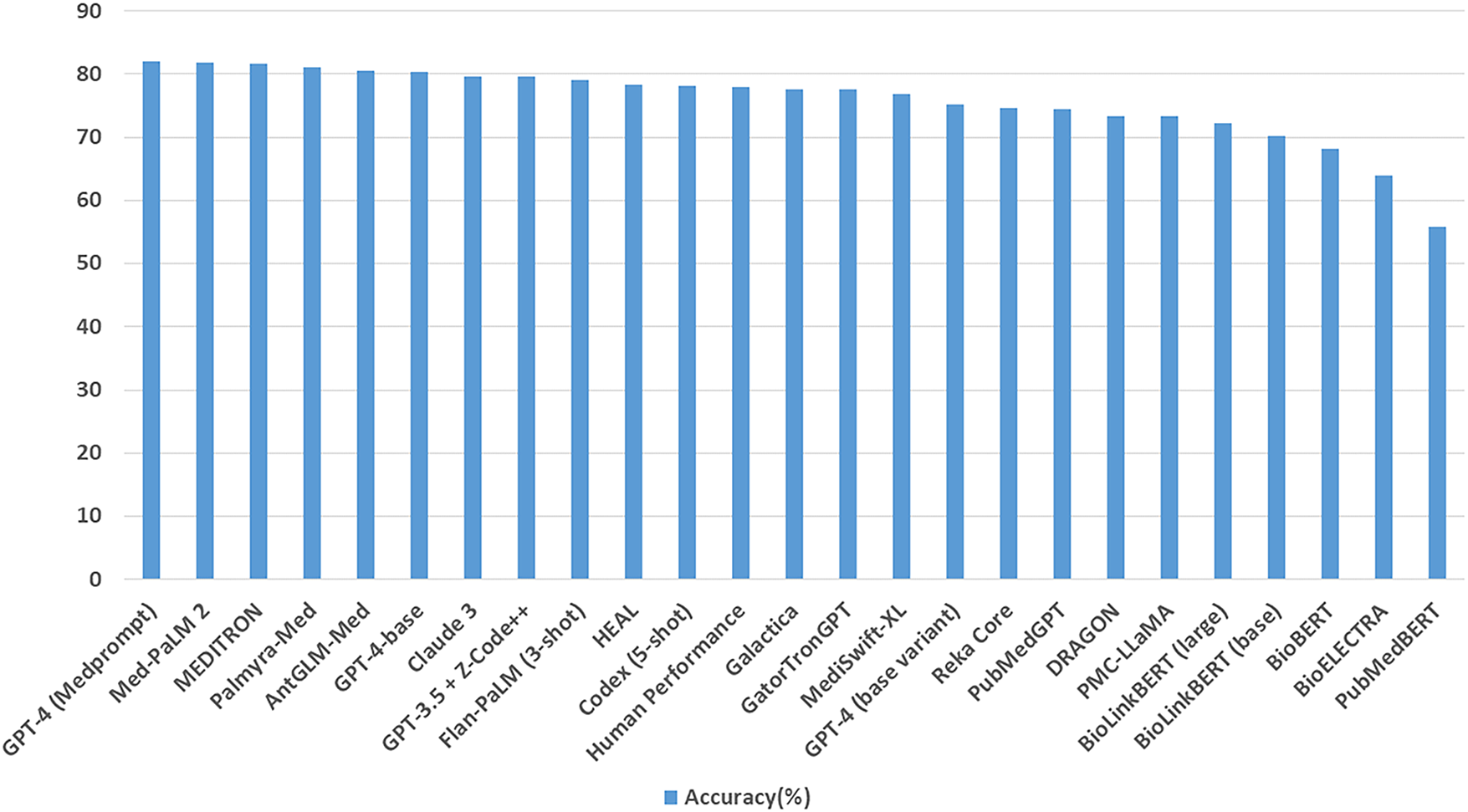

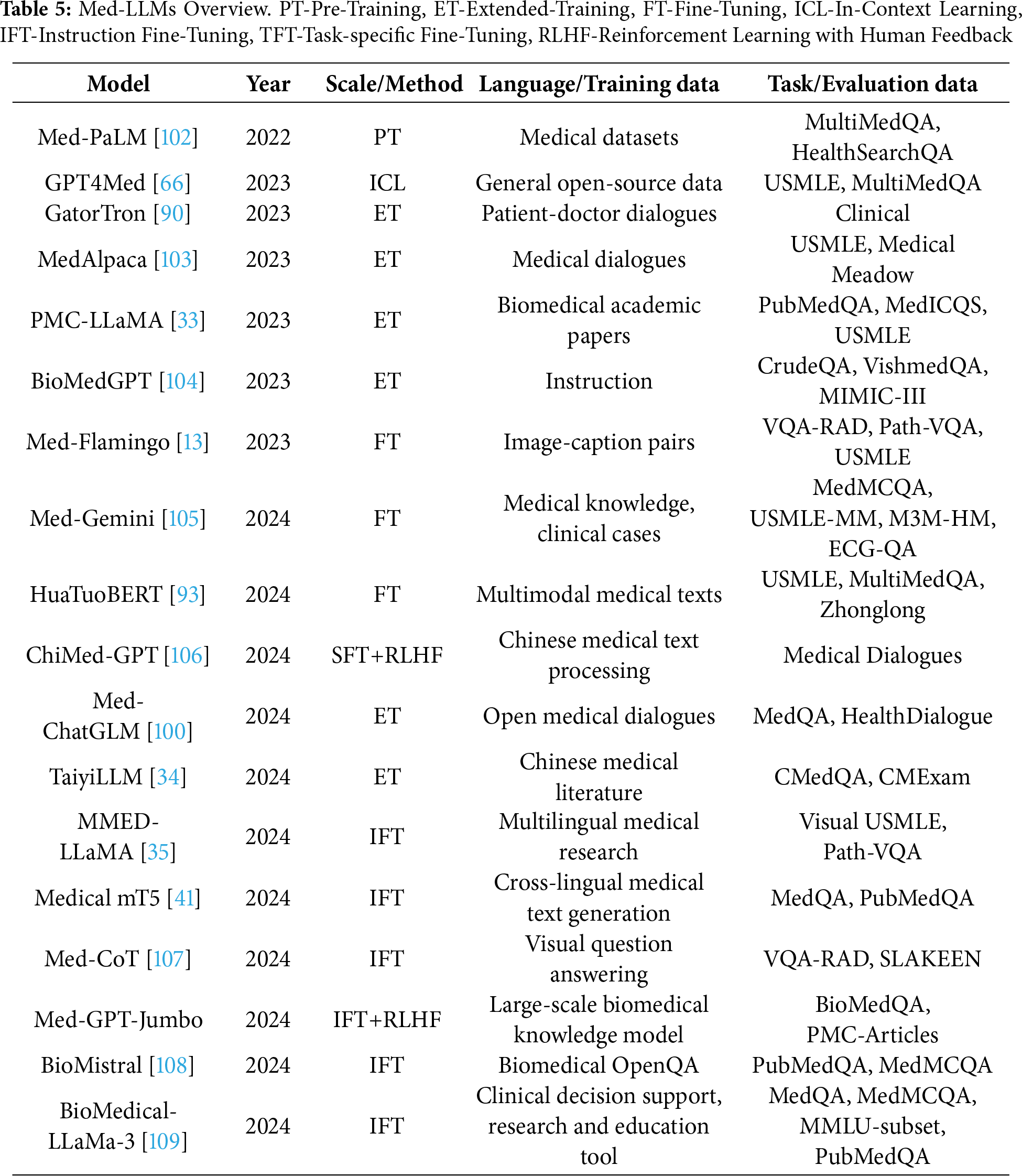

Training Techniques Medical LLMs including Med-PALM,Codex-Med, and MedAlpaca have delivered healthcare progress while focusing on distinct design features with their specialized structures and operational abilities which are mentioned in the Table 5. Medical LLMs were systematically grouped into BERT-based, GPT-based [88], and LLaMA-based [89] families, enabling a structured comparison of their design and performance characteristics highlighted in Figs. 3, 4.

Figure 3: BERT architecture

Figure 4: Rise of Medical-LLM from basic architecture of LLMs

A. BERT-Based Models

• BioBERT: BioBERT functions as a BERT variant adapted to process medical and biological text. The system focuses on enhancing medical and biological content comprehension beyond standard text processing designs [32].

• PubMedBERT: PubMedBERT trains a BERT model using abstracts found in PubMed and the architecture is. This approach shows strong results when processing biomedical publications, especially during literature analysis, retrieval, and abstraction tasks [18].

• GatorTron: GatorTron is a large language model developed for various tasks in the medical domain. Research shows this model successfully processes medical documents while producing excellent results [90].

• ClinicalT5: ClinicalT5 uses T5 technology to process clinical healthcare data. This system supports both clinical text generation and documentation summarization. It processes medical records, generates professional reports, creates patient summaries, and supports doctors in medical decision-making [91].

B. GPT/MedPaLM Based Models

• Med-PaLM: Med-PaLM is a language model developed for medical use cases. It undergoes extensive medical data training to assist healthcare professionals with text generation and data retrieval tasks [92].

• GPT-4-Med: GPT-4-Med is an adaptation of GPT-4 for specialized medical applications. It processes complex medical records and generates high-quality medical reports [66].

• BianQue: BianQue is designed to analyze medical text and retrieve medical information for various healthcare applications [62].

• Med-PaLM 2: Med-PaLM 2 is an upgraded version of Med-PaLM, offering improved performance in medical documentation and information extraction [54].

• GatorTronGPT: GatorTronGPT is a medical-oriented extension of GatorTron. It is optimized for medical text generation and information retrieval, producing comprehensive reports and assisting doctors in clinical decision-making [90].

• HuatuoGPT: HuatuoGPT is a medical language model used by doctors for generating detailed medical reports and aiding in clinical decisions [93].

• MedicalGPT: MedicalGPT is a multi-purpose medical LLM that assists in generating comprehensive reports, supporting healthcare providers in decision-making, and facilitating patient interactions [94].

• QiZhenGPT: QiZhenGPT is specialized in Traditional Chinese Medicine diagnostics and treatment planning. It helps physicians detect diseases, recommend therapies, and educate patients about preventive healthcare [95].

• HuatuoGPT-II: HuatuoGPT-II is an improved version of HuatuoGPT, optimized for more reliable and precise medical applications [93].

• Codex-Med: The Codex-Med medical variant delivers extensive medical reports and selects relevant clinical data for processing [96].

• Galactica: Galactica demonstrates strong performance in handling complex medical and scientific content across multiple fields [97].

C. LLaMa/ChatGLM Based Models

• Meditron: Meditron [98] is an open-source suite of multimodal foundation models built on Meta LLaMA, tailored for medical applications such as clinical decision support and diagnosis. Developed through collaboration between EPFL, Yale School of Medicine, and humanitarian organizations like the ICRC, it is trained on curated medical datasets with clinician input, ensuring domain alignment. Notably, the release of LLaMA-3[8B]-MeditronV1.0 demonstrated state-of-the-art performance within its parameter class on benchmarks such as MedQA and MedMCQA, highlighting its impact, particularly for low-resource healthcare settings.

• ChatDoctor: ChatDoctor allows AI-powered medical consultations, providing symptom-based recommendations as initial medical guidance [99].

• BenTsao: BenTsao enhances healthcare system operations by efficiently processing medical text and extracting relevant information [64].

• PMC-LLaMA: PMC-LLaMA is trained on research findings from PubMed Central. Its specialized functions facilitate medical literature searches and biomedical text generation [33].

• Med-ChatGLM: Med-ChatGLM is designed for patient interaction, offering tailored health recommendations and tracking ongoing treatments through user feedback [100].

• Med-Flamingo: Med-Flamingo is designed to support medical systems by generating detailed reports and assisting healthcare professionals in treatment decisions [13].

• ShenNong-TCM-LLM: ShenNong-TCM-LLM focuses on Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). It assists practitioners in diagnosing and recommending herbal treatments based on TCM principles [101].

D. Bilingual Model

• Taiyi-LLM: Taiyi-LLM specializes in Traditional Chinese Medicine, identifying medical conditions and recommending herbal remedies while educating patients on TCM practices [34].

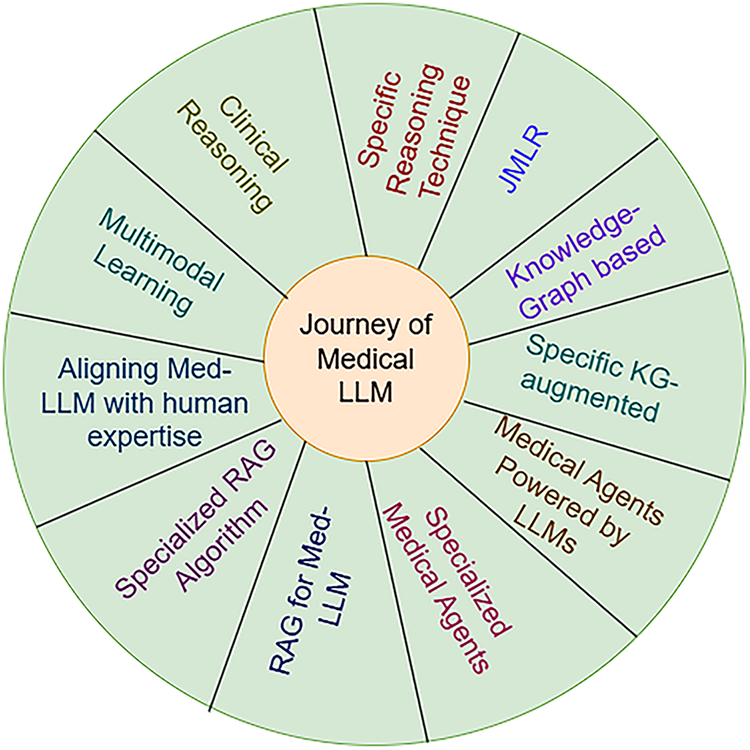

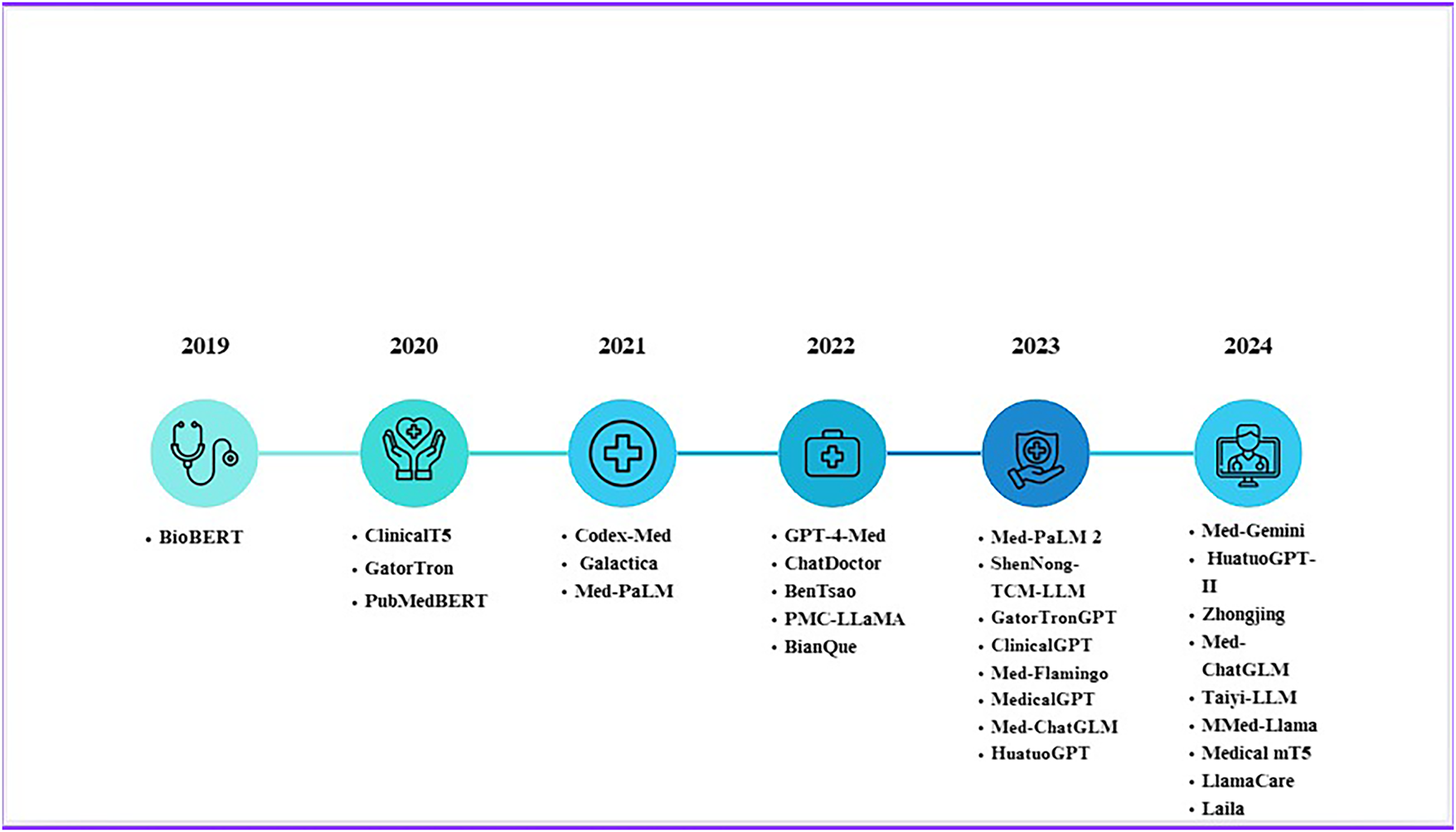

The development of medical large language models (LLMs) has advanced through distinct stages as demonstrated in Fig. 5. Initial applications from 2020 to 2022 addressed clinical reasoning by answering medical examination questions and supporting diagnostic reasoning. Subsequently, from 2021 to 2023, LLMs integrated knowledge graphs and structured biomedical data networks to improve factual accuracy. The emergence of retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) between 2022 and 2023 enabled models to access external sources such as PubMed and electronic health records (EHRs), enhancing output reliability. Joint Medical LLM and Retrieval Training (JMLR, 2023–2024) further refined this process by optimizing both the retriever, which locates relevant data, and the generator, which produces responses, to ensure evidence aligned with clinical reasoning. Most recently, domain-specific RAG (2023–2024) restricted retrieval to trusted biomedical datasets, and multimodal RAG (2024–2025) has begun integrating text, imaging, and structured EHR data to provide more comprehensive clinical decision support. Emerging directions include the development of medical agents (2024–2025), which equip LLMs with planning, reasoning, and task-execution capabilities within clinical workflows. There is also growing emphasis on aligning LLMs with human expertise (2024–2025) through physician-in-the-loop evaluation, reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF), and consensus-driven fine-tuning to ensure outputs are safe, trustworthy, and clinically actionable.

Figure 5: Structural Improvements over Medical LLMs

1. Medical Large Language Models (Med-LLMs) and Clinical Reasoning

Through clinical reasoning, LLMs demonstrate their ability to replicate and assist medical professionals in making decisions [110], similar to how a human doctor applies logical reasoning [54,66].

(a) General Algorithm: When someone works through a series of mental connections, they follow a Chain-of-Thought process, which helps them systematically analyze problems and responsibilities [25]. A healthcare model follows structured steps to break down complex medical questions, assess possible solutions, eliminate incorrect options based on prior knowledge, and explain the final reasoning behind the decision [65].

(b) Specific Reasoning Techniques: The improvement of clinical reasoning of Med-LLMs depends on certain specialized approaches such as:

In-Context Padding (ICP): ICP recommends four actions to improve LLM reasoning in clinical settings [86]:

• The first step is to identify key medical terminology in clinical texts and determine the primary purpose of the document [59].

• The system retrieves important medical entities from knowledge graph (KG) databases based on relevant medical source information [42].

• The model generates both an answer and a detailed medical explanation to support clinical decision-making [87].

2. Joint Medical LLM and Retrieval Training (JMLR)

The JMLR approach stands apart from other Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) systems, which train their retrieval and LLM models separately, because it trains both elements together at the fine-tuning stage [15]. By training LLMs in synchronization with retrieval systems for medical guidelines, JMLR enhances decision-making in patient care while reducing computational requirements [42,65].

3. Knowledge Graph for Med-LLMs

Although LLMs excel at various tasks, they struggle with knowledge base limitations, such as fabricating information and lacking specialized domain expertise [65]. Knowledge graphs (KGs) store extensive structured data that LLMs can leverage to enhance their performance by retrieving precise and relevant medical knowledge [42].

(a) Standard Algorithms: Academic investigations have identified three fundamental approaches for combining knowledge graphs with large language models: establishing LLM-KG Connectivity and developing LLM-KG Compatibility. The implementation of KG-enhanced LLMs alongside LLM-augmented KGs creates complementary structural arrangements that mutually strengthen the capabilities and effectiveness of both knowledge graphs and large language models [66]. The synergized LLM+KG model strengthens the connection between LLMs and knowledge graphs to optimize both systems.

• Inference-Time KG Augmentation: With a retrieval system, the LLM incorporates relevant knowledge from the KG based on the surrounding data to improve performance. By leveraging external knowledge from structured databases, the model reduces the likelihood of generating erroneous outputs and enhances domain-specific responses [63].

• Training-Time KG Augmentation: The LLM undergoes specialized training that integrates natural language processing tasks with structured knowledge graph data. This training process enables the model to utilize KGs more effectively for improved decision-making [64].

4. Specific KG-Augmented Med-LLMs

Healthcare LLM systems achieve superior performance in medical tasks when they receive access to structured medical information. The following are medical applications of LLM systems after integrating medical knowledge graphs [65,111].

• DR.KNOWS: The clinical diagnostic standards form the foundation for introducing DR.KNOWS, which enhances LLMs’s diagnostic capacity. Medical data retrieval reaches new standards by merging medical knowledge graphs with the National Library of Medicine’s UMLS system. DR.KNOWS utilizes medical knowledge graphs to assist doctors in analyzing complex medical cases [42,112].

• KG-Rank: KG-Rank enhances LLM performance in handling medical question inconsistencies and mitigating information bias. This approach improves the accuracy of free-text medical question-answering through ranking and re-ranking techniques applied within a medical knowledge graph [45]. The knowledge graph provides foundational information by extracting relevant triplet data when processing specific medical queries.

• MedKgConv: Conventional dialogue generation models tend to produce repetitive and unengaging interactions. MedKgConv improves natural medical dialogue by integrating multiple pretrained language models with UMLS and utilizing the MedDialog-EN database [63].

• ChiMed: The ChiMed system prepares Chinese medicine datasets tailored for the Qilin-med framework. It integrates patient inquiries, textual data, knowledge graphs, and medical interaction transcripts to enhance multilingual medical comprehension [40].

• DISC-MedLLM: DISC-MedLLM developed a sample creation method guided by medical knowledge graphs to build supervised fine-tuning (SFT) datasets. This approach ensures that generated medical responses remain accurate and trustworthy. The system selects relevant triples from a medical knowledge base based on patient queries through a department-oriented approach [62].

5. Medical Agents Powered by LLMs

LLMs extend beyond text generation by serving as control systems for advanced autonomous AI agents at the forefront of artificial intelligence development [113]. This new AI model moves beyond passive question-answering systems to create active agents capable of handling complex medical tasks.

• Planning Component: AI agents require robust planning systems for strategic reasoning. This mechanism allows the agent to systematically decompose tasks into subtasks and make dynamic adjustments during execution, mimicking human-like problem-solving techniques [55].

• Memory Component: Autonomous medical AI systems need efficient memory architectures to ensure long-term data retention and retrieval. These systems go beyond temporary chatbot memory, incorporating stable data storage and knowledge retrieval mechanisms for improved performance [114].

• Tool Utilization: The integration of planning and memory allows AI systems to iteratively refine inputs and outputs within a given environment. By leveraging external tools, these systems develop adaptive strategies for specialized medical tasks while utilizing memory to execute complex plans [42].

• Evaluation: AgentBench provides a standardized framework for assessing how well large language models function in agent-based tasks. This platform evaluates AI performance across multiple domains, including medical knowledge management, interactive diagnostic reasoning, and clinical decision support [115].

6. Specialized Medical Agents

Several medical applications have been built using large language models as depicted in Fig. 6. These AI-driven medical agents are designed to work alongside healthcare providers, ensuring that critical human skills such as empathy, intuition, and patient-centered care are not lost [42].

• CT-Agent: CT-Agent represents an integration between advanced LLM capabilities and multi-agent systems to improve availability and efficiency in clinical settings. CT-Agent enhances clinical workflows by leveraging GPT-4, multi-agent architectures, and advanced reasoning technologies such as LEAST-TO-MOST and ReAct [113].

• AutoGen: The open-source framework AutoGen enables users to build highly efficient AI programs capable of handling mathematical problems, coding tasks, and online decision-making. AutoGen allows for the creation of multi-agent setups, where different agents collaborate dynamically to complete complex tasks [55].

• ArgMed-Agents: ArgMed-Agents supports medical professionals in making explainable clinical decisions by utilizing multiple AI agents. The system captures the steps of clinical reasoning and generates human-readable explanations. Through self-argumentation cycles guided by a structured reasoning mechanism, ArgMed-Agents models human-like clinical thought processes. The framework employs a directed graph to represent conflicting interactions between different medical concepts, enabling logical rule evaluation [19].

• MAD: The MAD framework is designed to enhance the factual accuracy of LLM-generated responses while optimizing cost, time, and accuracy trade-offs. This system operates through a debate-based platform, where competing AI models assess and refine responses. However, achieving optimal performance with MAD remains challenging due to its dependency on fine-tuned model adjustments and case-specific configurations [116].

Figure 6: Task-specific medical LLM models

7. RAG for Med-LLMs

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) represents an innovative machine learning framework that merges retrieval mechanisms with generative capabilities to improve both the precision and variety of produced responses. The methodology has attracted considerable interest within natural language processing circles, finding particular utility in conversational AI systems, platforms designed for answering questions, and tools that condense document content [42].

• Retrieval Component: The information retrieval process starts by accessing relevant data from extensive storage repositories. The system efficiently locates prior information by performing query-based searches against stored conversations, medical records, and scientific literature [65].

• Generation Component: After retrieving relevant data, a generative model synthesizes this context to formulate responses. The generation model significantly improves its accuracy when trained with retrieved medical knowledge, as it can leverage structured input to produce clinically relevant outputs [63].

• Component Integration: The model first integrates retrieved data with input queries and forwards this enhanced context to the generator. The retrieval and generation components then collaborate iteratively, refining both input context and output accuracy across multiple processing stages [64].

8. Specific RAG Algorithms

Combining external knowledge systems with generative models enables RAG to retrieve more precise information that matches user context better than standard systems [42,117] whose architecture has been shown in Fig. 7.

• Clinfo.ai: Clinfo.ai is an open-source WebApp that utilizes scientific literature to provide medical answers. It evaluates both information retrieval methods and summary generation techniques to assess retrieval-augmented LLM systems [55].

• Almanac: LLMs often produce incorrect or harmful outputs. Almanac addresses these limitations by connecting to medical databases, offering users medically verified guidelines and protocols [66].

• BiomedRAG: Unlike traditional retrieval augmentation approaches, BiomedRAG directly integrates retrieved documents into LLMs without applying cross-attention encoding. This design reduces noise in search results while maintaining the integrity of retrieved medical information [63].

• Self-BioRAG: Self-BioRAG is a framework for biomedical text processing that includes specialized explanation generation, domain-specific document retrieval, and self-reflection on model-generated outputs. It is trained on 84,000 biomedical instruction sets [64].

• ECG-RAG: ECG-RAG employs zero-shot retrieval-augmented diagnosis, accessing LLM knowledge while incorporating expert knowledge through specialized prompts [46].

• ChatENT: Standard LLMs suffer from unpredictable outputs, dependence on conditional guidance, and a tendency to generate misleading information. ChatENT refines parameter tuning for medical applications, improving accuracy and reliability [113].

• MIRAGE: MIRAGE evaluates medical RAG systems using a dataset of 7663 medical QA questions collected from five specialized medical datasets. It demonstrates superior performance compared to Chain-of-Thought prompting, GPT-3.5, Mixtral, and GPT-4, improving LLM reasoning capabilities [20].

• MedicineQA: Companies face challenges when applying LLMs in medical domains due to a lack of domain-specific medical knowledge. MedicineQA was developed to test LLMs in real-world medical scenarios, requiring them to retrieve and use evidence from medical datasets to answer questions accurately. It features 300 multi-turn question-answer dialogues [45].

Figure 7: Advancement in architecture of Med-LLMs. (a) RAG Architecture adapted from Microsoft Research Blog [118]; (b) Multi-Modal RAG Architecture adapted from the AI Edge [119]

9. Aligning Med-LLMs with Human Expertise

(a) General Algorithm: LLMs trained on vast text corpora have become the standard for numerous natural language processing applications. However, these state-of-the-art models often struggle with accurately interpreting human instructions, generating biased outputs, and producing incorrect responses due to limitations in their reasoning capabilities. Research groups worldwide are focusing on improving LLMs to better align with human expectations [42,64].

• Data: Developing high-quality training datasets at scale requires access to widely recognized language benchmarks and professional annotators. Advanced language models assist in crafting task-specific instructions to improve the dataset’s reliability and diversity [63].

• Training: Machine learning experts have devised optimization techniques that reduce data requirements while training LLMs to respond more effectively to human feedback. These methods enhance model adaptability and minimize computational overhead [65].

• Evaluation: Researchers have introduced multiple evaluation frameworks and automated testing methods to assess various aspects of LLM alignment, such as factual accuracy, response coherence, and bias mitigation [46].

(b) Specific Alignment Algorithm: Achieving human alignment in medical LLM development is essential, as it directly impacts patient safety and public trust in AI-driven healthcare systems. The following alignment approaches help ensure the safe and responsible deployment of medical LLMs [25,42].

• Safety Alignment: Conducting initial safety assessments is a critical step in developing Medical LLMs. These evaluations establish foundational safety protocols and alignment standards for medical AI applications, ensuring models provide reliable and non-harmful recommendations [65].

• SELF-ALIGN: Addressing the challenges of expensive human supervision and variable quality, the SELF-ALIGN method integrates principle-driven reasoning with LLM-generated refinements. This approach seeks to minimize human intervention while maximizing model reliability [63]. SELF-ALIGN consists of four key steps:

1. The system employs synthetic prompt creation techniques to increase prompt diversity.

2. It utilizes human-written instructions to generate structured responses.

3. The model incorporates self-alignment mechanisms to produce high-quality fine-tuning outcomes.

• EGR: Enhancing Generalization via Retrieval (EGR) optimizes LLMs by incorporating multiple prompt-generation strategies. This method is particularly effective when models are provided with limited input samples, ensuring robust performance despite constrained data availability [115].

10. Multimodal Learning

Multi-Modal Large Language Models (MM-LLMs) are sophisticated systems that can process diverse data types—text, images, audio, video, and sensor information [42]. By incorporating various sensory inputs, these models expand beyond traditional text-based language processing to improve contextual understanding [63]. In this context, Multi-modal fusion denotes the process of integration of multiple data types-such as clinical text, medical images, and structured records-into a single, cohesive model for comprehensive reasoning. In Medical LLMs, this fusion is typically realized through:

• Feature Concatenation (Early Fusion): Simply merging embeddings from different modalities into one vector prior to processing.

• Attention-Based Fusion: Leveraging cross-attention layers, where tokens from one modality selectively attend to elements in another, enabling context-driven intermodal grounding.

• Hierarchical Fusion: Combining modality-specific encoders followed by joint attention layers, facilitating alignment at multiple abstraction levels.

General Algorithms: MM-LLMs are designed to function as unified platforms that process multimedia data across various communication modalities, enabling deeper and more context-aware interactions. Several general-purpose MM-LLMs exemplify these capabilities [115].

• Med-PaLM Multimodal (Med-PaLM M): Med-PaLM M [16] is a generalist, multimodal extension of Google’s medical LLM, designed to process and interpret diverse biomedical data—such as clinical notes, images, and genomic inputs—within a single model framework. Evaluated on the MultiMedBench benchmark (14 tasks), it achieves performance competitive with or exceeding that of task-specific specialist models, often outperforming expert systems.

• PaLM-E: Developed under Google’s Pathways initiative, PaLM-E is designed to process multiple modalities, including visual and textual data. It generates content responses based on images and text-based instructions, enabling automatic image descriptions, visual question answering, and advanced reasoning without requiring extensive specialized training datasets [39].

• LLaVA: LLaVA integrates a vision encoder with a language decoder (Vicuna) to create a foundational vision-to-language MM-LLM. The model undergoes fine-tuning on 158,000 image-text pairs, sourced from the MS-COCO dataset, allowing it to perform visual reasoning and multimodal understanding tasks.

• mPLUG-OWL: In response to parameter flexibility challenges, researchers from Alibaba DAMO Academy introduced mPLUG-OWL. This model combines the ViT-L/14 visual encoder from CLIP with the LLaMA-7B language decoder from mPLUG, enhancing multimodal comprehension and response generation.

11. Specialized Multimodal Med-LLMs

Recent research extensively explores medical vision-language models [117,120] by analyzing multimodal medical datasets, architectural frameworks, and training methodologies [63].

• BiomedCLIP: BiomedCLIP [121] is a biomedical vision-language foundation model pretrained on PMC-15M, a dataset containing 15 million image–caption pairs from biomedical literature. It was trained using contrastive learning to align image and text modalities and demonstrates state-of-the-art performance across diverse biomedical vision tasks (e.g., retrieval, classification, VQA). Notably, it surpasses even specialized radiology models like BioViL on tasks such as pneumonia detection.

• MMed-RAG (Multimodal Retrieval-Augmented Generation): MMed-RAG [122] is a retrieval-augmented generation system tailored for medical vision-language models. It introduces several key enhancements—domain-aware retrieval selection, adaptive context calibration, and RAG-based preference finetuning—to improve factual alignment in responses. Across datasets spanning radiology, pathology, and ophthalmology, MMed-RAG achieves up to 43.8% improvement in factual accuracy, particularly in VQA and report generation tasks.

• V-RAG (Visual Retrieval-Augmented Generation): V-RAG [120] is a framework developed to mitigate hallucinations in medical multimodal LLMs by incorporating both textual and visual evidence in retrieval steps. Evaluations on chest X-ray captioning and VQA tasks show that V-RAG significantly reduces hallucination errors and improves entity-level accuracy compared to baseline RAG methods.

• AD-MM-LLM: This model leverages LLMs for embedding textual data while utilizing ConvNeXt to process medical images, specifically for Alzheimer’s disease detection [25].

• RAMM: RAMM introduces a hybrid training framework that retrieves and integrates medical text and image data during fine-tuning, addressing challenges posed by small biomedical datasets. The model leverages PubMed-based PMCPM data to create image-text pairs, using contrastive learning for pretraining [45].

• LLaVA-Med: LLaVA-Med exhibits strong performance across diverse medical communication scenarios. During training, it associates biomedical terminology with figures, captions and employs instruction-following data to facilitate open-ended semantic comprehension [42].

• Qilin-Med-VL: As the first Chinese vision-language medical model, Qilin-Med-VL integrates a vision transformer core with an LLM foundation. Its training dataset comprises 1 million image-text pairs, sourced from the ChiMed-VL corpus [40].

2.2.7 LLMs in Healthcare Domains

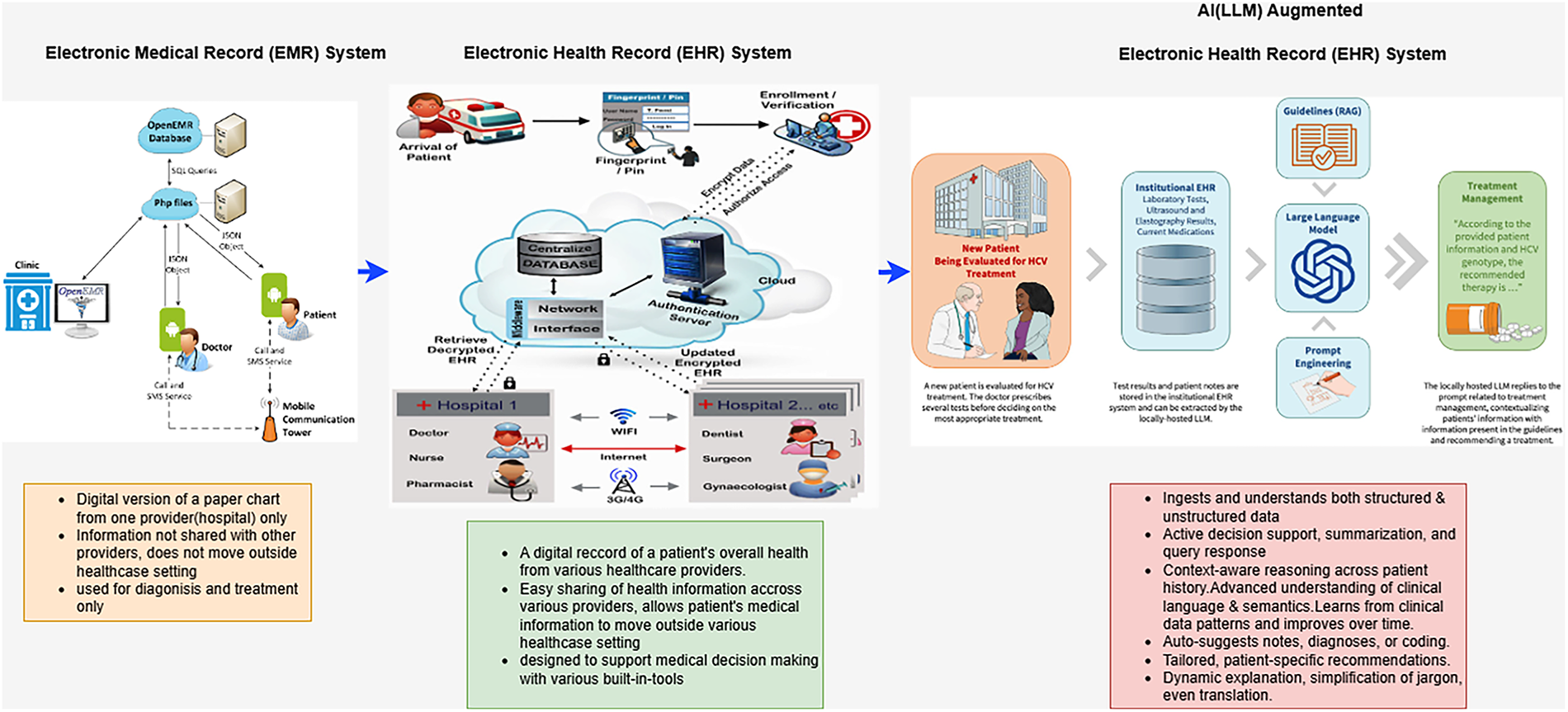

Large Language Models (LLMs) are transforming the entire medical field as exhibited in Fig. 8 by enhancing clinical decision-making, improving patient interaction, and accelerating biomedical research. These applications range from increasing diagnostic accuracy and automating documentation to expediting drug discovery. By leveraging structured reasoning and explainable AI techniques, medical LLMs provide healthcare professionals with more reliable and interpretable insights [42,63].

Figure 8: Transformation of Healthcare system

A. Clinical Decision Support

Clinical reasoning serves as the foundation of sound medical practice, equipping clinicians with the ability to diagnose accurately and implement effective management interventions [113,123]. It integrates theoretical knowledge, in-depth analysis, and contextual understanding to reach decisive conclusions and formulate optimal treatment plans. Med-LLMs enhance clinical decision support systems by providing data-driven insights that assist medical teams in making more informed treatment decisions. Specific applications include:

• Symptom Analysis: By analyzing symptom data from healthcare professionals or patients, Med-LLMs access extensive medical knowledge to propose potential diagnoses, assisting in the detection of rare or complex conditions [54].

• Risk Assessment: Med-LLMs evaluate patient demographics and health data to forecast potential medical risks, allowing healthcare teams to take preventive actions and develop personalized treatment plans [45,124].

• Treatment Recommendations: Based on a patient’s diagnosis, Med-LLMs suggest treatment plans that align with existing health guidelines and medication interactions, helping doctors optimize patient care [65].

With the increasing complexity of patient cases, particularly those involving multiple comorbidities and atypical presentations, advancements in AI and LLMs play a crucial role in refining clinical reasoning. The integration of LLMs into medical workflows enables physicians to navigate complex medical scenarios more effectively, ensuring high-quality patient care [65,115]. The following discussion explores the fundamental components, enablers, and emerging technologies that are reshaping clinical reasoning, with a particular focus on how AI and LLMs are driving these transformative changes.

Some Core Elements of Clinical Reasoning

Clinical reasoning can be categorized into two primary approaches: intuitive reasoning and analytical reasoning [65,115].

• Intuitive Reasoning: Commonly referred to as “System 1 thinking,” this approach heavily relies on pattern recognition and experiential knowledge. Clinicians use prior experiences and mental shortcuts to rapidly suggest possible diagnoses. While this method is fast and efficient, it is also prone to cognitive biases such as anchoring bias, confirmation bias, and the availability heuristic [113].

• Analytical Reasoning: Also known as “System 2 thinking,” this approach involves a more deliberate, systematic analysis of clinical data. It is particularly useful for complex or unfamiliar cases that require differential diagnosis, analysis of both favorable and unfavorable factors, and identification of gaps in available information to support accurate conclusions [64].

Both approaches are inherently interconnected. Experienced clinicians frequently alternate between intuitive and analytical reasoning—using the former to generate diagnostic hypotheses and the latter to validate and refine them. The synthesis of these modes results in a well-rounded diagnostic process that enhances reliability and minimizes diagnostic errors [42].

B. Medical Documentation, Summarization and Report Generation

The advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) and large language models (LLMs) has revolutionized medical documentation and summarization [125,126]. In the healthcare sector, Electronic Health Records (EHRs) serve as vital repositories of patient information, yet their vast and unstructured nature often hinders efficient retrieval and analysis. AI-driven models, particularly those leveraging advanced reasoning and summarization techniques, offer promising solutions for enhancing the accessibility and interpretability of EHRs [42,65].

Medical documentation demands precision and contextual understanding, making it a complex task for AI systems. Large language models, such as GPT-4, have demonstrated the capability to generate clinical notes, summarize patient histories, and assist in diagnostic reasoning. Research on diagnostic reasoning prompts for LLMs highlights how prompt engineering refines AI performance in clinical tasks. By structuring inputs with diagnostic reasoning frameworks, LLMs can produce more interpretable and clinically relevant outputs, improving trust and usability among healthcare professionals [54].

Efficient summarization of EHRs is essential for reducing clinicians’ cognitive load and ensuring timely decision-making. A knowledge-seed-based framework introduces a novel approach to guiding AI models in clinical reasoning. By integrating knowledge graphs and domain-specific insights, this method enhances the summarization process, ensuring that critical medical information is retained while minimizing redundancy. This structured approach aligns AI outputs with the cognitive pathways of clinicians, improving accuracy and reliability in medical decision-making [64].

One of the key challenges in AI-driven medical summarization is the interpretability of generated outputs. The ArgMed-Agents framework addresses this issue by employing argumentation-based reasoning. By engaging in self-argumentation and verifying clinical decisions through multi-agent interactions, this framework enhances the explainability of AI-generated summaries. Such systems not only improve accuracy but also foster greater trust among medical practitioners, ensuring that AI recommendations align with established medical knowledge [19].

Med-LLMs streamline clinical documentation by automating report generation, improving both speed and accuracy in medical record keeping.

• Automated Report Writing: Med-LLMs compile data from various medical sources to generate comprehensive reports, reducing manual workload. These systems can generate discharge summaries, radiology interpretations, pathology reports, and surgical notes [66].

• Customizable Templates: By integrating institutional reporting standards, Med-LLMs produce clinical reports that adhere to regulatory and professional guidelines, ensuring consistency and relevance [46].

• Consistency and Accuracy: Med-LLMs rely on extensive medical databases to maintain standardized and reliable documentation, minimizing errors and ensuring high-quality reporting [64].

Beyond documentation, AI is revolutionizing drug discovery and biomedical research by accelerating hypothesis generation, literature mining, and molecular simulations. Processing large-scale biomedical data, AI models can identify promising drug targets, analyze biomolecular interactions, and predict therapeutic efficacy. Advanced natural language processing (NLP) techniques enable researchers to extract critical insights from vast biomedical literature, leading to new discoveries and greater efficiency [45]. Moreover, AI-driven optimization in drug design and repurposing significantly reduces development time and costs, streamlining the drug discovery pipeline [46].

By making EHRs more actionable and facilitating innovation in drug discovery, AI is poised to transform healthcare delivery. Enhanced models can substantially reduce the time and effort required for documentation by leveraging structured reasoning, knowledge-based summarization, and explainability frameworks. As these capabilities continue to evolve, AI will play an increasingly critical role in augmenting medical decision-making, expediting biomedical research, and ultimately improving patient outcomes while optimizing healthcare workflows [115].

C. Drug Discovery and Biomedical Research

The introduction of artificial intelligence into drug discovery and biomedical research has significantly accelerated scientific discovery and hypothesis generation. The advent of large language models (LLMs) and advanced reasoning frameworks has fueled AI-driven approaches for mining vast biomedical literature, generating original hypotheses, and refining research methodologies. Several studies highlight the role of AI in biomedical research and clinical decision-making, with a focus on explainability, reasoning, and the organization of information retrieval [42,63].

In biomedical research, AI facilitates hypothesis generation and testing, expediting the research process. Knowledge-seed-based frameworks introduce structured methodologies to guide LLMs, integrating critical knowledge from clinical datasets to enhance reasoning. These frameworks are particularly relevant in drug discovery [127,128], aiding in the identification of molecular interactions, potential therapeutic targets, and drug-repurposing opportunities. By embedding both structured and unstructured biomedical knowledge, AI can bridge gaps in existing research and uncover new possibilities for pharmaceutical innovation [46].

Mining literature across vast biomedical databases would be infeasible without AI-driven automation. The ArgMed-Agents framework provides a structured clinical reasoning model using argumentation schemes, improving interpretability in decision-making. When applied to drug discovery, this approach enables AI to evaluate conflicting research, weigh evidence, and identify the most promising research avenues. Automated text-mining techniques further facilitate the extraction of key insights, allowing researchers to stay up-to-date with the latest scientific advancements [19].

One of the primary challenges in AI-driven research is ensuring the interpretability of generated insights. Studies on diagnostic reasoning prompts for LLMs demonstrate that structured prompts enhance AI reasoning capacities, improving alignment with expert decision-making processes. When applied to biomedical research, these structured reasoning methods enable AI to formulate hypotheses based on logical implications and supporting evidence, ensuring reliability and validity in generated outputs [54].

Additionally, AI has demonstrated significant success in drug repurposing by identifying new therapeutic applications for existing medications. By integrating structured reasoning techniques with knowledge-seed frameworks, AI models can make informed predictions regarding drug interactions, side effects, and mechanisms of action. Literature mining tools further enhance this process by cross-referencing studies on drug efficacy, thereby optimizing clinical trial design and drug development pipelines [45].

AI continues to expand its role in drug discovery and biomedical research, providing powerful tools for hypothesis generation, literature mining, and structured reasoning. Research indicates that AI-driven approaches enhance accuracy, explainability, and efficiency in biomedical research, ultimately leading to faster and more reliable scientific breakthroughs. As AI technology evolves, its capacity to address complex biomedical challenges will be crucial in shaping the future of healthcare and pharmaceutical innovation [115].

D. Patient Interaction and Health Education

Breakthroughs in artificial intelligence (AI) and large language models (LLMs) have dramatically reshaped the landscape of patient engagement and health-related educational approaches. The integration of chatbots and virtual health assistants into healthcare systems is increasingly undertaken to enhance patient engagement, provide medical guidance, and improve health literacy [129]. Recent studies illustrate how AI-driven clinical reasoning and argumentation frameworks contribute to developing more effective and explainable virtual health assistants [42,65].

LLMs have been employed to create conversational AI agents that assist patients with medical inquiries, appointment scheduling, and basic triage. The ArgMed-Agents framework provides an approach for enhancing AI-driven decision-making in virtual health assistants by leveraging argumentation schemes, allowing for more structured and transparent responses to patient concerns. Structured reasoning also helps mitigate misinformation and fosters greater trust in digital health interactions [19].

Health dietetics is a crucial aspect of preventive medicine, and AI-driven chatbots serve as personalized tutors, guiding patients toward healthier lifestyles. The knowledge-seed-based framework demonstrates how structured medical knowledge can enhance AI-powered reasoning, particularly in virtual health assistants. By tailoring health education materials to individual patient histories and risk factors, this approach improves adherence to medical advice and empowers patients to make informed health decisions [46].

Med-LLMs revolutionize medical education by providing interactive and efficient learning resources.

• Question-Answering Systems: Med-LLMs respond to medical queries with precise and evidence-based answers, improving access to expert-level knowledge for students and professionals [115].

• Simulation of Clinical Cases: Med-LLMs facilitate medical training by simulating patient cases, allowing students to practice diagnostic reasoning and treatment planning [20].

• Summarization of Research Papers: By continuously analyzing recent medical publications, Med-LLMs generate concise summaries that help students and researchers stay updated on the latest advancements [40].

One of the primary challenges in AI-based medical assistants is ensuring the interpretability of their recommendations. Studies on diagnostic reasoning prompts for LLMs emphasize the importance of structured prompts in improving AI-generated responses. Applying similar structured reasoning techniques in virtual health assistants ensures that patient information is communicated in a clear, simple, and easily understandable manner. Transparent information exchange fosters trust and acceptance of AI-driven healthcare assistants [54].

Despite these advancements, AI health assistants face several challenges, including biases in training data, risks of misinformation, and policy regulation concerns. Many of these issues can be mitigated through an argumentation-based reasoning framework that requires chatbots to ground their responses in evidence and comply with established medical guidelines. Additionally, real-time feedback mechanisms can refine chatbot interactions based on patient inputs, further enhancing their accuracy and reliability [45].

LLM-enabled chatbots and virtual health assistants are rapidly expanding their role in patient interaction and health education. The use of structured reasoning frameworks, knowledge-seed methodologies, and explainable AI techniques enables these tools to provide accurate, transparent, and personalized health guidance. As AI technologies continue to evolve, they will further empower patients by improving access to trustworthy health information, ultimately advancing healthcare outcomes and patient satisfaction [115].

Med-LLMs are opening new possibilities for integrating AI-driven robotics in medical training and clinical care.

• Personalized Surgical Planning: Med-LLMs develop customized surgical strategies based on a patient’s medical history and physiological characteristics [19]. Medical LLMs can contribute to personalized surgical planning by synthesizing multimodal patient data, including clinical notes, imaging reports, and laboratory findings, into coherent decision support. By reasoning over patient-specific factors and comparing them with prior clinical evidence, LLMs can generate tailored surgical strategies that align with individual anatomical and risk profiles. When integrated with multimodal models [16,121,122], they enable more precise preoperative guidance and support dynamic intraoperative decision-making.

• Robotic Training for Surgeons: In robotic surgical training, Medical LLMs serve as interactive tutors capable of delivering real-time, natural language guidance during simulation-based practice. They can summarize performance metrics such as errors, timing, and motion smoothness into actionable feedback, while also adapting training difficulty to a learner’s progress. This positions LLMs as valuable complements to robotic platforms, enhancing skill acquisition and ensuring evidence-based learning support. Med-LLMs support interactive procedural simulations, providing performance feedback to improve surgical training [65].

E. Public Health and Epidemiology

Public health and epidemiology are essential fields for monitoring, preventing, and controlling diseases at the population level. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and large language models (LLMs) has opened new avenues for real-time disease surveillance, predictive modeling, and informed decision-making. Recent studies highlight the role of AI-based clinical reasoning, literature mining, and structured argumentation frameworks in shaping public health strategies and epidemiological research [42,65].

The next frontier in disease surveillance involves AI-driven real-time data mining, which has the potential to revolutionize automated health monitoring. The knowledge-seed-based framework illustrates how structured knowledge generation enables AI to recognize sequential data patterns, trends, and anomalies within large datasets. Applied to epidemiological data, AI can help uncover emerging health threats, provide early outbreak warnings, and optimize responses to public health crises [46].

Timely access to relevant research on epidemic-prone diseases is crucial for epidemiologists in designing effective interventions. The ArgMed-Agents framework introduces an argumentation-based methodology that enhances AI-assisted literature mining for public health applications. AI systems can sift through vast biomedical research databases, extract critical findings, and synthesize evidence-based recommendations. This ensures that policymakers and researchers have the most up-to-date scientific knowledge to guide public health initiatives [19].

One of the primary challenges AI-powered public health initiatives face is ensuring transparency and explainability in decision-making. Studies on diagnostic reasoning prompts emphasize the importance of structured prompt engineering in guiding AI-generated recommendations. Implementing structured reasoning methods in public health models can enhance clarity and justification for policy decisions, including vaccination strategies, preventive programs, and epidemiological intervention plans [54].

By integrating AI-driven surveillance, literature mining, and structured reasoning, public health and epidemiology can leverage LLMs to improve decision-making, enhance early disease detection, and optimize intervention strategies. As AI technologies evolve, their ability to process and interpret large-scale epidemiological data will be instrumental in advancing global health security and public health preparedness [115].

3 Deployment Challenges and Limitations

Despite extensive research into LLM applications as shown in Fig. 9 in healthcare demonstrating their potential for improving diagnostics, patient management, and clinical decision-making, global adoption remains heavily concentrated in high-income countries like the United States and China [130]. This uneven distribution stems from significant deployment challenges including inadequate technological infrastructure, insufficient data governance frameworks, regulatory complexities, and concerns over bias and privacy [131]. While LLMs could potentially address healthcare inequalities in underserved regions of the Global South by automating patient screening and supporting frontline health workers (Fig. 2), barriers such as limited internet connectivity, computational resources, and quality training data prevent widespread implementation [131].

Figure 9: Evolution of Med LLMs from 2019 to 2024

While clinical reasoning is at the core of medical practice, various challenges contribute to diagnostic errors, delays, clinical incompetence, and potential patient harm:

• Cognitive Load: With the rapidly expanding body of medical knowledge and the vast amounts of patient data that must be assessed, clinicians often experience cognitive overload, increasing the risk of diagnostic errors [65].

• Diagnostic Uncertainty: Incomplete medical histories, ambiguous test results, and atypical presentations often introduce uncertainty into the diagnostic reasoning process, complicating decision-making [42].

• Cognitive Biases: Even experienced clinicians are prone to biases that distort their reasoning processes. These include anchoring bias, where clinicians become fixated on an initial diagnosis, and availability bias, where salient but irrelevant details disproportionately influence decisions [19].

• Time Constraints: In high-pressure environments such as emergency departments, clinicians may have limited time to reflect on complex cases thoroughly, increasing the likelihood of diagnostic errors [46].

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) have introduced transformative tools to support clinical reasoning. Large language models (LLMs) such as GPT-4 have demonstrated potential in improving diagnostic accuracy, facilitating information retrieval, and supporting clinical decision-making [54].

• Augmenting Differential Diagnosis: LLMs assist clinicians by generating comprehensive differential diagnoses based on vast medical knowledge and contextual awareness. For instance, AI models trained on medical datasets can recognize rare and atypical presentations, thereby reducing diagnostic uncertainty [45].

• Facilitating Information-Seeking: Tools such as MediQ leverage LLMs to generate follow-up questions and extract critical missing information during clinical interactions. This approach aligns with the sequential reasoning process clinicians follow in practice [113].

• Mitigating Cognitive Biases: AI-driven systems enhance diagnostic objectivity by synthesizing medical evidence and highlighting inconsistencies in reasoning. By surfacing overlooked differential diagnoses, these models help counteract cognitive biases such as premature closure and confirmation bias [115].

• Education and Training: LLMs provide valuable educational tools for medical trainees by simulating diagnostic reasoning processes. Interactive platforms guide learners through cases with structured explanations and real-time feedback, reinforcing clinical reasoning skills [64].

While AI presents significant opportunities for improving clinical reasoning, challenges remain. LLMs occasionally generate plausible but incorrect responses, and their reasoning processes are not always inherently transparent. Ensuring interpretability, trustworthiness, and ethical compliance—especially regarding patient privacy, data security, and equitable access—remains critical for their integration into clinical practice [115].

Clinical reasoning is an active and evolving skill set that plays a crucial role in patient care. Advances in AI and LLMs provide unique opportunities to enhance diagnostic accuracy and alleviate clinicians’ cognitive burden. However, careful consideration must be given to ensuring that these tools support, rather than replace, human judgment, empathy, and ethical responsibility. By addressing limitations and fostering collaboration between clinicians and AI systems, healthcare can advance in a manner that prioritizes patient-centered innovation [65].

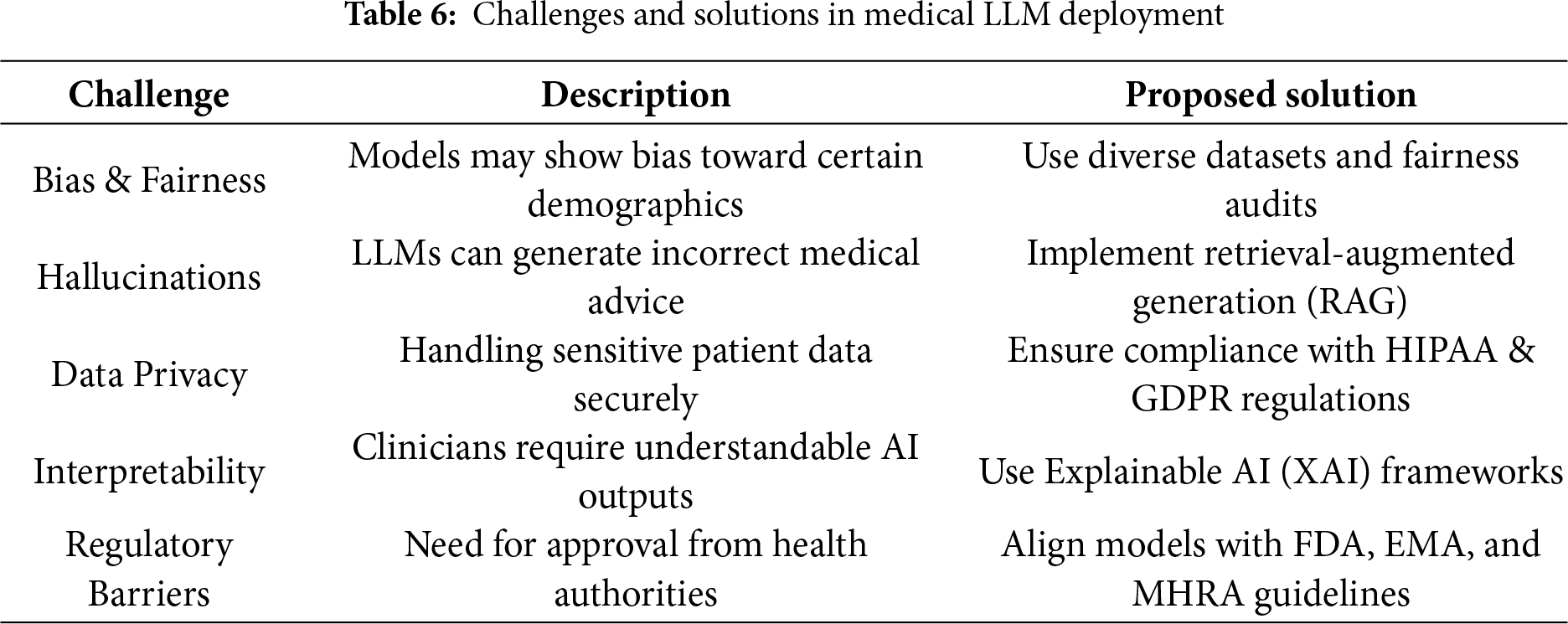

Providing accurate and interpretable medical documentation is a challenging task for AI systems. Large language models (LLMs) such as GPT-4 have demonstrated their ability to comprehend clinical notes, summarize patient histories, and assist in diagnostic reasoning. Research on diagnostic reasoning prompts for LLMs illustrates how prompt engineering can enhance AI performance in clinical settings. By structuring inputs based on diagnostic reasoning frameworks, LLMs generate more interpretable and clinically relevant outputs, improving trust and usability among healthcare professionals [54].