Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Joint Optimization Model for Device Selection and Power Allocation under Dynamic Uncertain Environments

1 Shanxi Key Laboratory of Big Data Analysis and Parallel Computing, Taiyuan University of Science and Technology, Taiyuan, 030024, China

2 School of Artificial Intelligence and Big Data, Henan University of Technology, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

* Corresponding Authors: Xingjuan Cai. Email: ; Maoqing Zhang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Edge Computing and Artificial Intelligence in Smart Environment)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070592

Received 19 July 2025; Accepted 22 September 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Federated Learning (FL) provides an effective framework for efficient processing in vehicular edge computing. However, the dynamic and uncertain communication environment, along with the performance variations of vehicular devices, affect the distribution and uploading processes of model parameters. In FL-assisted Internet of Vehicles (IoV) scenarios, challenges such as data heterogeneity, limited device resources, and unstable communication environments become increasingly prominent. These issues necessitate intelligent vehicle selection schemes to enhance training efficiency. Given this context, we propose a new scenario involving FL-assisted IoV systems under dynamic and uncertain communication conditions, and develop a dynamic interval multi-objective optimization algorithm to jointly optimize various factors including training experiments, system energy consumption, and bandwidth utilization to meet multi-criteria resource optimization requirements. For the problem at hand, we design a dynamic interval multi-objective optimization algorithm based on interval overlap detection. Simulation results demonstrate that our method outperforms other solutions in terms of accuracy, training cost, and server utilization. It effectively enhances training efficiency under wireless channel environments while rationally utilizing bandwidth resources, thus possessing significant scientific value and application potential in the field of IoV.Keywords

In recent years, with the continuous advancement of wireless communication technologies and intelligent transportation systems, the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) has progressively emerged as a critical infrastructure for the development of smart cities [1]. The IoV facilitates information coordination and resource sharing among traffic participants through various communication modalities, including vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V), vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I), and vehicle-to-cloud (V2C) interactions [2–4]. This integration has propelled the implementation of functionalities such as autonomous driving, route optimization, and intelligent scheduling, significantly enhancing traffic safety and efficiency while contributing to the reduction of overall carbon emissions. Despite the immense application potential of the Internet of Vehicles (IoV), its highly distributed nature, pronounced temporal variability, and resource heterogeneity present numerous pressing challenges [5–7]. In particular, ensuring the system’s learning and collaborative capabilities in dynamic environments—characterized by uneven data distribution, constrained communication bandwidth, and frequent fluctuations in vehicular resource states—emerges as a critical issue [8].

To address the aforementioned challenges, Federated Learning (FL), as a distributed machine learning framework, offers an effective solution for Internet of Vehicles (IoV) systems [9]. Unlike traditional centralized learning methods, federated learning (FL) enables vehicles to train on private data locally and only upload model parameters to a central server for aggregation, thereby effectively preserving user privacy and reducing data transmission overhead [10,11]. However, the high dynamism of the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) introduces novel challenges to the federated learning (FL) training process: wireless channel quality is susceptible to environmental fluctuations, resulting in unstable bandwidth resources that affect the upload rate of model parameters; significant heterogeneity in computational capabilities, battery status, and data distribution among vehicles further exacerbates the non-iid nature of the training process [12–16]. Moreover, the volatility of communication and computational resources renders the latency, energy consumption, and convergence of model training unpredictable, thereby severely constraining the performance of federated learning in practical Internet of Vehicles (IoV) scenarios [17,18].

Current research predominantly focuses on singular optimization objectives, such as minimizing training latency or energy consumption, and fails to comprehensively balance the complex dependencies and mutual constraints among multiple optimization goals [19,20]. In the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) environment, wireless communication bandwidth exhibits dynamic variations influenced by environmental factors. Such fluctuations directly impact data transmission rates, thereby affecting the latency, energy consumption, and communication efficiency of Federated Learning (FL) training [21]. Consequently, optimizing device selection and resource allocation under dynamically uncertain conditions constitutes a critical challenge. Specifically, bandwidth variability induces instability in wireless channel quality, causing fluctuations in FL parameter transmission rates and consequently influencing training convergence speed; constrained computational resources impose mutual restrictions between computation and communication latency, rendering the optimization of training latency a pivotal issue; power limitations of IoV devices result in significant disparities in inter-device energy consumption, necessitating further investigation into minimizing system energy consumption while maintaining training efficiency [22,23]. Moreover, FL training encompasses multiple conflicting optimization objectives—such as training latency, energy consumption, and bandwidth utilization—posing ongoing challenges for joint optimization within a dynamic multi-objective optimization framework [24].

The high degree of dynamism in the IoV environment manifests at multiple levels: channel state and bandwidth resources fluctuate with changes in network load, interference intensity, and physical distance [25]; computational resources and energy levels of vehicles continuously vary over time; the volume and quality of data collected by on-board devices also exhibit dynamic changes due to differing geographical locations and task periods [26]. These factors collectively result in significant interval-based fluctuations in key performance indicators of federated training—training latency, system energy consumption, and communication efficiency. Traditional optimization methods based on deterministic modeling struggle to address such a complex and uncertain operational environment. Although existing methods have made progress in device selection and resource allocation, most rely on static or deterministic modeling and cannot effectively handle the dynamic uncertainties of bandwidth, energy, and computation in IoV. Some studies address single objectives such as latency or energy, but lack systematic modeling of multi-objective dependencies. To this end, this paper proposes a joint optimization model under a dynamic interval multi-objective framework, with detection and response mechanisms to improve the stability and adaptability of federated learning in dynamic uncertain environments.

To this end, this paper focuses on the optimization problem of device selection and resource allocation during the federated learning training process in the Internet of Vehicles (IoV), with the main contributions summarized as follows:

(1) A modeling framework oriented towards dynamic interval multi-objective optimization is proposed. In the model construction, the interval fluctuation characteristics of communication bandwidth, computational resources, and energy consumption constraints within the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) across different time periods were thoroughly considered. Training latency, system energy consumption, and bandwidth utilization were designated as primary optimization objectives, leading to the establishment of a resource-aware optimization model characterized by dynamic uncertainty features.

(2) The utilization of intervals to characterize the dynamic variations of resource metrics provides a more realistic and uncertainty-aware quantitative approach for model construction and optimization, enabling the model to better accommodate the dynamic fluctuations of resources within the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) environment. Through dynamic interval modeling, it is possible to accurately delineate the fluctuation ranges of various resource indicators in the IoV context, thereby facilitating the joint optimization of device selection strategies and communication power allocation schemes. This ensures that the model maintains robust adaptability and resilience in highly variable environments.

(3) To solve the proposed model, a novel dynamic interval multi-objective evolutionary algorithm is introduced, incorporating an innovative environmental detection mechanism and response mechanism for optimization. This approach addresses the solution aspect of the constructed model by designing a new algorithm aimed at identifying the optimal or satisfactory solutions of the model. The environmental detection and response mechanisms within the algorithm are specifically developed to better accommodate the dynamic interval characteristics inherent in the model, thereby effectively deriving strategies that satisfy multi-objective optimization criteria under dynamically changing environments.

The organizational structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 reviews the related work on device selection and power allocation in federated learning, as well as studies on dynamic interval algorithms. Section 3 delineates the details of the proposed model. Section 4 elaborates on the specifics of the proposed algorithm. In Section 5, the performance of the proposed model and the designed solution algorithm is evaluated and analyzed. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

2.1 Device Selection and Power Allocation in Federated Learning

In dynamic and uncertain edge computing environments, resource constraints and device heterogeneity constitute critical challenges for federated learning. The joint optimization of resource allocation and device selection not only enhances system adaptability and stability but also significantly improves training efficiency, reduces energy consumption, and minimizes communication overhead. Therefore, the effective implementation of resource allocation and device selection has emerged as a pivotal research focus in contemporary federated learning studies. However, existing approaches often address these two aspects separately, which limits their ability to achieve balanced optimization under highly dynamic and uncertain conditions.

In recent years, numerous studies have proposed targeted resource allocation and device selection strategies for practical application scenarios such as vehicular networks, aiming to optimize energy consumption management and communication efficiency in federated learning. To enhance algorithm convergence speed, Chang et al. [25] investigated the impact of pruning strategies on federated learning performance and proposed the VFed-AMP method, which integrates adaptive pruning, vehicle selection, and resource allocation into a joint optimization framework. Addressing the issue of unfair bandwidth resource distribution among clients engaged in federated learning, Xiong and Guo [26] developed a contribution calculation strategy based on Shapley values and designed a client selection scheme combined with model contribution metrics alongside wireless resource allocation methods. Under constrained bandwidth conditions, this approach improves global model convergence speed and accuracy by reducing training and aggregation frequency for low-contribution clients while increasing bandwidth allocation for high-contribution clients. To tackle challenges posed by vehicle mobility and high resource overhead in vehicular federated learning, Wang et al. [27] proposed a two-tier multi-access edge computing-assisted vehicular network framework that incorporates a node selection algorithm supporting dynamic vehicle participation and a distributed resource allocation strategy grounded in multi-agent reinforcement learning, thereby reducing the overall resource overhead during the federated learning process. Yuan et al. [28] integrated a vehicle selection and resource allocation mechanism based on deep deterministic policy gradient, modeling the vehicle selection and resource allocation problem as a Markov decision process. They employed deep reinforcement learning techniques for policy optimization and designed a hierarchical federated learning algorithm, which enhanced resource utilization in vehicular networks and mitigated the impact of resource constraints on federated learning performance.

Due to the high energy consumption inherent in the training process, issues such as training interruptions and system stability degradation frequently occur. In response, some researchers have proposed various resource management and scheduling strategies aimed at optimizing energy efficiency. To address energy consumption management in federated learning systems within Internet of Things (IoT) scenarios, Yao and Ansari [29] formulated a joint modeling of CPU frequency and power control as a nonlinear programming problem, with the objective of minimizing overall energy consumption. Under the constraint of meeting model training time requirements, this approach provides an efficient energy optimization strategy for federated learning applications on resource-constrained devices in edge computing environments. Yu et al. [30] introduced a novel approach to enhance overall system efficiency and stability by proposing a resource-aware client selection and resource allocation algorithm. This method adopts a synergistic management perspective of energy and latency, allocating resources based on device CPU frequency and transmission power to optimize the trade-off between maximizing the number of participating clients and minimizing total energy consumption. In federated learning applications involving unmanned systems, the limited battery capacity of micro unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) imposes operational bottlenecks during practical missions. Wen et al. [31] specifically proposed a joint optimization scheduling and wireless resource allocation strategy to enhance the sustained operational capability of UAVs engaged in collaborative tasks, thereby significantly improving overall mission completion efficiency. To mitigate issues arising from client devices in wireless communication systems being unable to continuously participate in federated learning due to energy constraints or communication interference, Hamdi et al. [32] developed an integrated optimization framework combining energy management with user scheduling, which enhances communication system stability and robustness throughout the federated learning process. To optimize federated learning performance under non-independent and identically distributed (non-IID) data scenarios, Yin et al. [33] constructed a Stackelberg game-based model incorporating an adaptive covariance matrix strategy; through joint optimization of wireless resource allocation and client scheduling, this approach effectively alleviates communication latency challenges inherent in non-IID data settings. Zheng et al. [34] proposed the FedAEB framework designed to optimize participation energy consumption among heterogeneous devices; leveraging deep reinforcement learning models for joint client selection and resource scheduling optimization enables dynamic balancing between training performance and communication energy consumption, thereby enhancing both stability and energy efficiency ratios of federated learning within heterogeneous edge environments.

Other researchers have integrated client selection with bandwidth optimization strategies [35] to maximize the utilization of communication resources. Addressing potential communication bottlenecks arising from high-density device access, Huang et al. [36] modeled user selection and bandwidth allocation as a joint optimization problem and devised a rational bandwidth allocation strategy; this approach concurrently enhances communication efficiency under constrained wireless spectrum resources. Nguyen et al. [37] proposed a two-hop communication protocol supporting dynamic resource allocation, optimizing resource distribution schemes within bandwidth-limited networks to enable greater client participation in federated learning training, thereby improving model generalization and fairness. Ji et al. [38] developed a scheduling mechanism incorporating the concept of virtual energy queues; through joint optimization of edge device selection and bandwidth allocation, their method ensures that federated learning systems in edge computing environments maintain favorable long-term average costs under stringent energy budget and latency constraints. To elevate the intelligence level of client selection and resource scheduling in federated learning, Zhang et al. [39] introduced a distributed resource collaborative allocation framework based on multi-agent reinforcement learning. This framework leverages cooperative decision-making among edge servers to optimize client selection and resource scheduling, demonstrating superior adaptability and performance in complex dynamic network environments.

However, the current research on device selection and resource allocation methods is still in its infancy. Although existing studies have demonstrated certain advantages in reducing communication overhead and enhancing training efficiency, they struggle to ensure the stability of model training under uncertain communication conditions characterized by unstable communication links and dynamically changing channel states. Additionally, the model training process often overlooks devices with constrained resources or uneven data distribution, leading to imbalanced resource allocation and compromised fairness in device participation, which in turn introduces biases in the training outcomes. Therefore, this paper constructs a joint optimization model from the perspectives of uncertain communication resources and device participation fairness, aiming to enhance the stability and fairness of federated learning in complex real-world environments.

2.2 Dynamic Range Multi-Objective Optimization Algorithm

Dynamic interval multi-objective optimization algorithms have numerous practical applications in real-world scenarios. Taking unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) path planning [40] as an example, a critical challenge lies in evading hazardous sources. Since acquiring the precise locations of these hazards is often prohibitively costly or infeasible, decision-makers typically only possess approximate range information regarding the hazards. Such range data are generally represented in the form of intervals, which dynamically vary in response to environmental changes, thereby rendering the optimization problem more complex and uncertain. Consequently, these problems are formulated as Dynamic Interval Multi-Objective Optimization Problems (DI-MOPs) [41]. The formal definition is presented in Eq. (1)

Among them,

Definition 1: The order relation between the objective values

Otherwise,

Definition 2: Using interval notation to represent “

If

Definition 3: Dynamic Interval Pareto Optimal Set (DIPOS). A solution is considered non-dominated if no other solution dominates it. The set of Pareto solutions comprises all Pareto optimal solutions at any given time. Consequently, the complete non-dominated solution set is referred to as DIPOS, which is mathematically expressed as:

Definition 4: Dynamic Interval Pareto Optimal Front (DIPOF). The set of vectors formed by the mapping of all Pareto optimal solutions in the objective space is defined as the DIPOF, expressed as follows:

Definitions 1 and 2 elucidate the internal relationships within DI-MOPs. Definition 1 introduces the concept of uncertain Pareto dominance

Based on the aforementioned definitions, the characteristics of dynamic interval multi-objective optimization problems can be summarized as follows: (1) the objective functions contain parameters; (2) these parameters are represented as interval vectors; (3) the interval vectors vary over time. This distinctive feature endows dynamic interval multi-objective optimization problems with heightened uncertainty and dynamism. The objective functions depend not only on decision variables but also on parameters expressed as intervals, encapsulating uncertainty, and these parameters evolve temporally. Consequently, the optimal solution set undergoes numerical variations and may exhibit diversified distributions influenced by the width of the intervals, reflecting different degrees of uncertainty. Conventional static multi-objective optimization methodologies often fail to accommodate such dynamic and uncertain environments effectively. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop algorithmic frameworks capable of dynamically detecting environmental changes, forecasting trends, and adaptively adjusting search strategies. Simultaneously, evaluation criteria must integrate interval uncertainty factors to ensure convergence, distribution uniformity, and robustness of the solution set.

To make the above mathematical definitions more intuitive, we provide a brief explanation here. In dynamic interval multi-objective optimization, each objective value is not a fixed number but an interval that changes with time. Interval dominance indicates whether the performance of one solution is consistently better than another across the entire interval range. The Dynamic Interval Pareto Optimal Set (DIPOS) can be regarded as the collection of all solutions that are not dominated under such interval comparisons, while the Dynamic Interval Pareto Optimal Front (DIPOF) represents their mapping in the objective space. Intuitively, this means that even if the exact values of objectives are uncertain, the optimization still seeks solutions that remain competitive across possible variations.

In recent years, an increasing number of researchers have proposed various effective and competitive DMOEAs to address DMOPs. However, when the problem objective values exhibit interval characteristics, it transitions into DI-MOPs. Conventional DMOEAs primarily focus on change detection and response mechanisms, designed specifically for DMOPs with precise values. In the context of imprecise DMOPs, Gong et al. [41] introduced a co-evolutionary algorithm for dynamic interval multi-objective optimization problems based on similarity, which collaboratively evolves decision variables by grouping based on the similarity between decision variables and interval parameters, and detects changes in the Pareto front of the optimization problem at an early stage. Nevertheless, this approach primarily emphasizes the similarity of interval variables during the optimization process and does not fully explore the impact of interval characteristics on the accuracy of change detection. Additionally, the high computational complexity of its co-evolutionary mechanism limits the algorithm’s applicability to high-dimensional problems. Xu et al. [42] proposed a reinforcement learning-based dynamic interval multi-objective optimization algorithm, utilizing internal interval similarity to detect the severity of changes within intervals and embedding Q-learning to select the optimal change response method to adapt to new environments. Although this study incorporates a reinforcement learning mechanism to enhance adaptability, its change detection relies on the measurement of internal interval characteristics, which may struggle to cope with complex environments characterized by diverse changing patterns. Furthermore, the method primarily focuses on change detection and lacks optimization of response mechanisms tailored to the characteristics of DI-MOPs, failing to propose efficient adjustment strategies better suited to such problems. Overall, research on DI-MOPs remains relatively limited, with existing methods falling short in change detection and response mechanisms. Specifically, accurately detecting dynamic changes in interval objectives and designing efficient response mechanisms to adapt to various types of environmental changes remain unresolved issues. Therefore, this paper conducts in-depth research on change detection and response mechanisms, integrating the characteristics of interval objectives to address the shortcomings of current studies.

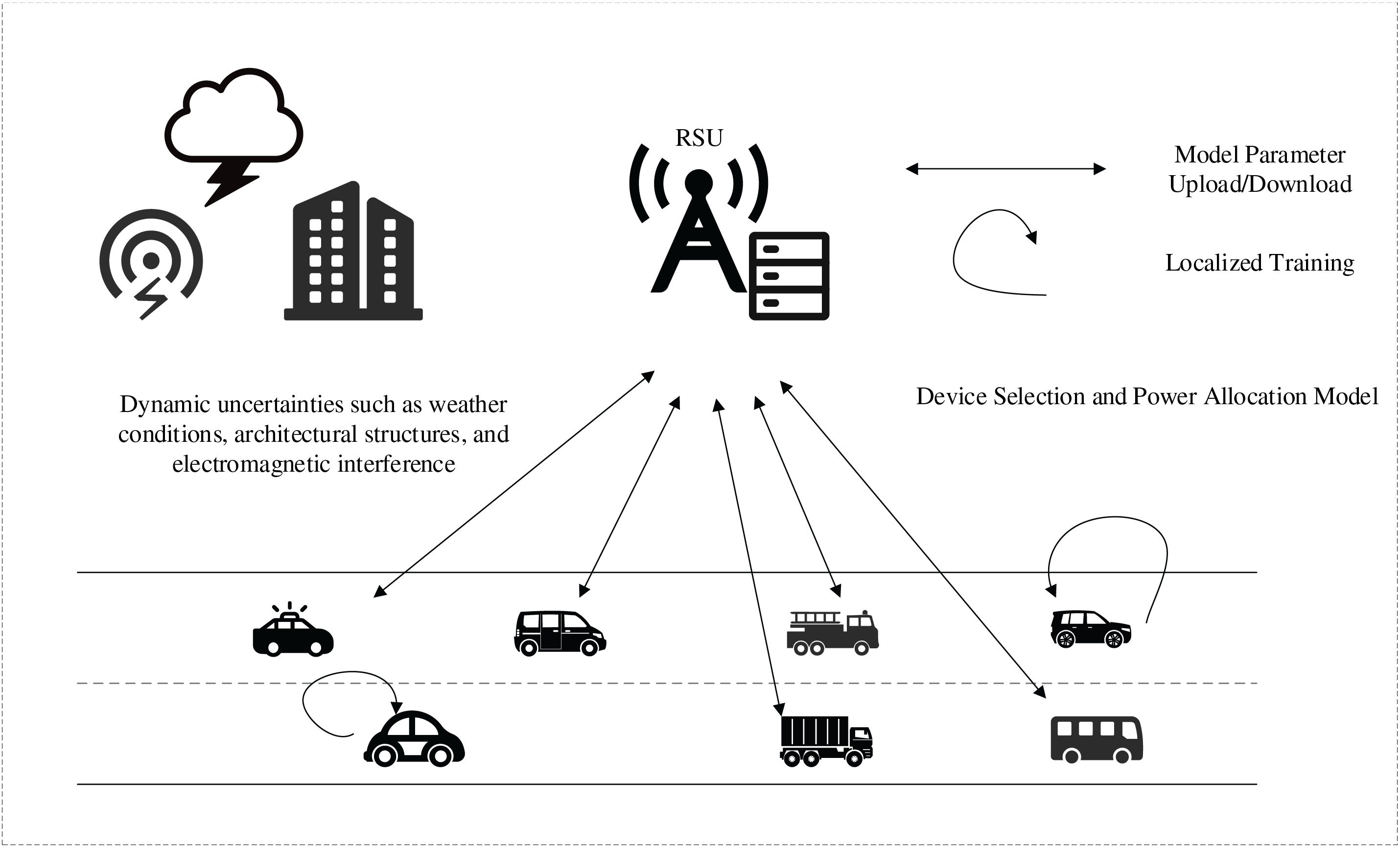

This chapter focuses on a resource-aware collaborative control system composed of a parameter central server (CS) and multiple mobile vehicles (MVs). A resource-aware collaborative control system is developed and investigated. In this system, each mobile vehicle (MV) possesses a locally acquired dataset

Figure 1: FL-assisted IoV collaborative training framework

To achieve joint optimization of device selection and bandwidth allocation, this paper introduces decision variables

Based on the aforementioned modeling framework, this study conducts an in-depth modeling and optimization of the federated learning process in the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) environment from three perspectives: first, considering latency performance jointly determined by computational capability and communication conditions; second, quantifying energy consumption during model training and data transmission; third, evaluating the effective utilization of bandwidth resources, upon which a system optimization model is constructed.

3.1 Objective Function I: Training Latency

In the practical deployment of federated learning (FL) systems, the constraint imposed by device resource allocation on training efficiency is primarily manifested in the two core stages of distributed computing: local model training and global model aggregation. Each mobile terminal leverages its own computational capacity to process local data and obtain corresponding parameter updates through localized training. Due to heterogeneity in processing capabilities and data scale among terminals, the time required for local training varies accordingly, thereby directly reflecting the degree of alignment between computational resources and data volume. The latency of local training has become a critical metric for evaluating the overall efficiency of FL systems, necessitating further optimization. Let

In the deployment of Federated Learning (FL) on mobile devices with limited communication bandwidth, the constrained network capacity and the number of participating vehicles may exacerbate communication bottlenecks. The frequent exchange of model parameters between Mobile Vehicles (MVs) and the Central Server (CS) increases the communication load. Due to the limited communication capabilities of mobile terminals, uploading locally trained model parameters to the CS incurs significant communication latency. (Compared to the uplink transmission from MVs, the communication cost for downloading models from the CS is negligible.) Therefore, the uplink transmission rate of model parameters for the

here,

Define the total delay of vehicle

Therefore, the target latency interval for the entire system is denoted as

3.2 Objective Function II: System Energy Consumption

In federated learning (FL) systems, vehicles participate as edge computing devices in model training, where energy consumption has consistently been a critical factor affecting both efficiency and sustainability. As key participants in FL, the energy consumption of vehicles can be categorized into two primary components: first, the energy expenditure during local data training, which predominantly arises from the utilization of onboard computational resources such as processors and memory hardware during the execution of model training tasks; second, the energy consumed during parameter transmission, wherein substantial communication bandwidth and power are required when vehicles upload locally trained model parameters to cloud servers or receive updated parameters from them.

Specifically, the training energy consumption of vehicle

here,

Communication energy consumption is defined as the product of transmission power and transmission delay, that is:

Therefore, the total energy consumption of vehicle

The system’s energy consumption target range is

3.3 Objective Function III: Bandwidth Utilization Rate

Under the increasingly constrained wireless resources, efficient bandwidth resource management plays a decisive role in ensuring the overall performance of federated learning systems. This model establishes a refined set of quantitative metrics aimed at optimizing bandwidth utilization. Taking into account fluctuations in channel state information, dynamic variations in network load, and the impact of time-varying channels caused by vehicular mobility, the bandwidth utilization rate of vehicle

The overall system bandwidth utilization range can be defined as the summation of the utilization rates of individual vehicles:

In each round of the federated learning (FL) system, the objective is to select vehicles that meet the following criteria: firstly, the training latency should be minimized, encompassing both computational delay and transmission delay, to ensure training efficiency; secondly, system energy consumption must be reduced as much as possible, including energy expenditure during training and transmission, in order to prolong battery life and decrease resource utilization; finally, bandwidth utilization should be maximized, defined as the ratio of allocated bandwidth to total available bandwidth for each vehicle, thereby optimizing wireless resource usage. Given that the proposed model incorporates these three concurrently optimized objectives, the problem is formulated as a dynamic interval multi-objective optimization model. The work presented in this chapter aims to reduce overall federated model training latency and energy consumption through optimization while maintaining satisfactory performance. Specifically, the model comprises three optimization objectives along with associated constraints.

Among them, the first constraint stipulates the selection state

4.1 A Severity-Based Response Mechanism for Switching in Dynamic Interval Multi-Objective Optimization (SRM-SEC)

4.1.1 Classification of Severity of Change

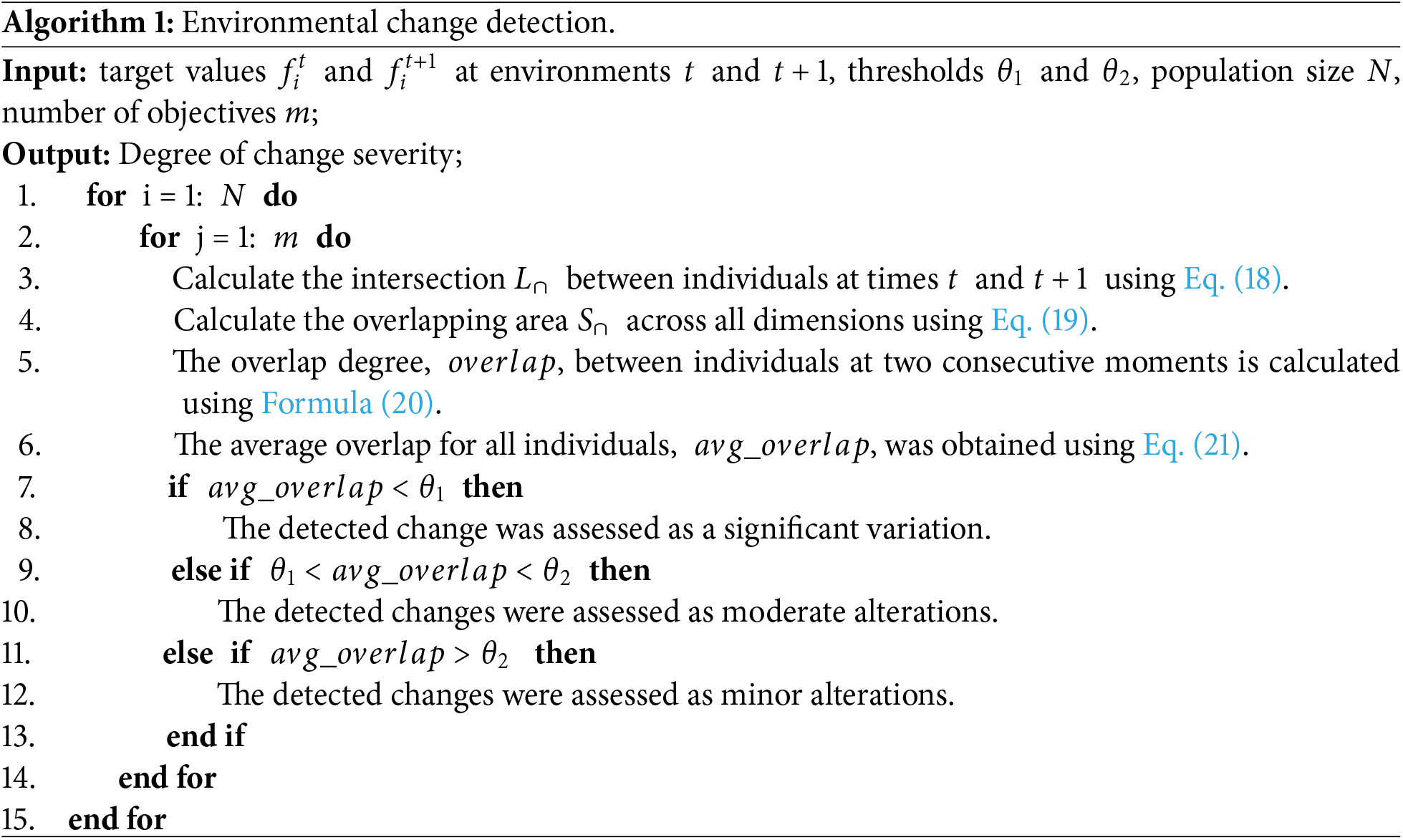

In addressing Dynamic Interval Multi-Objective Problems (DI-MOPs), the precise identification of environmental changes is of paramount importance. Consequently, when environmental alterations occur, it is necessary to assess their severity and adjust the response strategies according to the varying intensities of subsequent state changes. Given that the objective functions in dynamic interval problems are represented by interval values, the severity of changes is defined based on the degree of interval overlap, thereby enabling a more accurate detection of environmental variations.

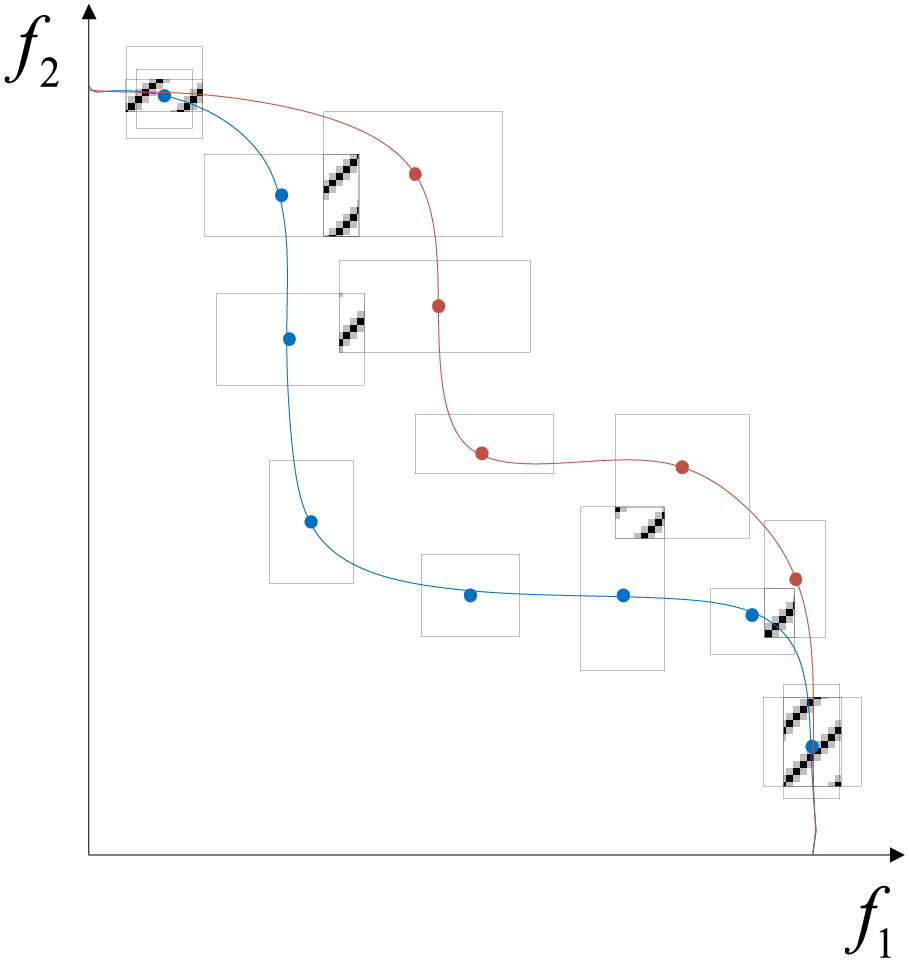

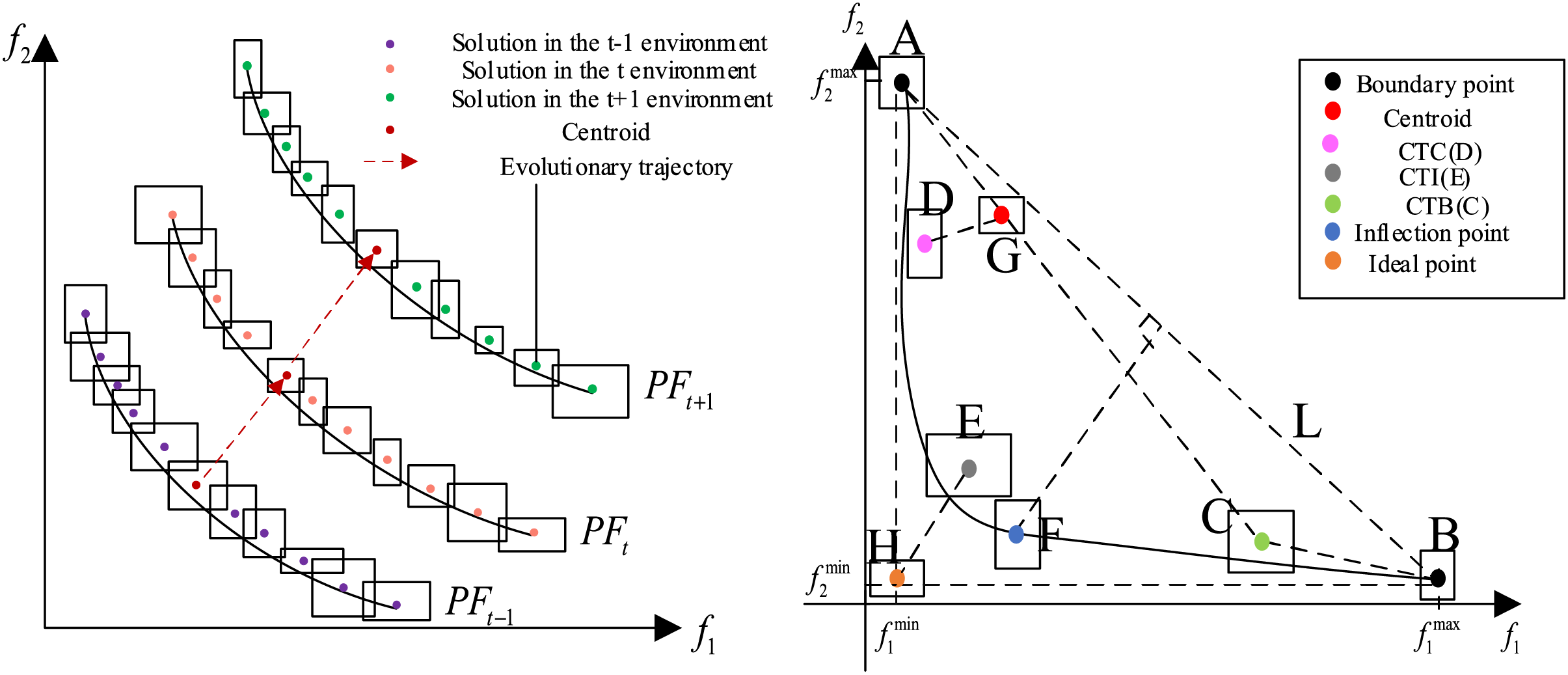

The environmental change detection operator designed in this section is illustrated in Fig. 2. The detection strategy involves computing the objective function values of each individual within the population under environment

wherein,

here,

Figure 2: Environment change detection operator

Algorithm 1 delineates the detailed procedure for environmental change detection. It employs the objective values at environment

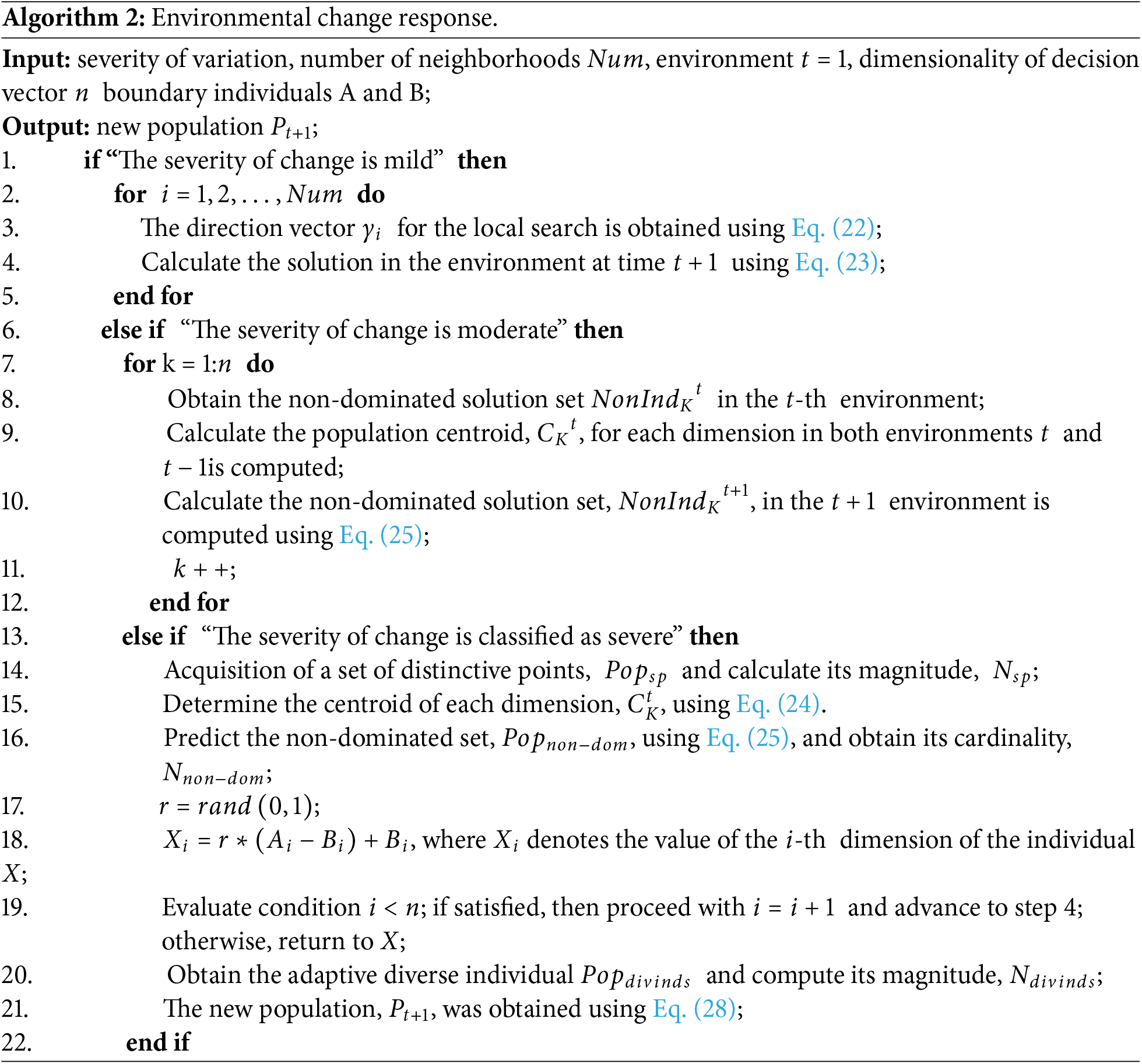

4.1.2 Response to Environmental Change

Upon detection of environmental changes, effective response measures should be promptly implemented to track the evolving Pareto front. An exemplary dynamic response mechanism must be capable of reinitializing a well-distributed population within the new environment, thereby approximating the updated Pareto Optimal Front (POF). This study employs the environmental detection operator

In scenarios characterized by minor changes, local search techniques are employed to adapt efficiently. This approach aims to guide individuals within the population toward proximal local optima, thereby expediting convergence. When addressing environmental shifts, local search effectively steers the population toward promising new search directions, particularly under subtle perturbations. By applying local search post-environmental change, a greater number of individuals exhibiting strong convergence and diversity can be identified, enhancing both the algorithm’s convergence performance and its responsiveness to environmental dynamics. Typically, the local search strategy leverages each solution to identify and update the optimal individuals within the population, optimizing overall population performance. The direction of local search is determined stochastically; a random value between 0 and 1 is generated using Eq. (22), which dictates the directional vector for local exploration.

The intensity of environmental change is modeled as a random variable following a normal distribution and is combined with a directional vector to guide the evolution of individuals within the search space, thereby enhancing the algorithm’s adaptability to environmental variations. Eq. (23) provides a detailed description of the generation method for individuals in the new environment.

wherein,

For moderate environmental changes, an interval prediction mechanism based on feedforward centroids is employed to guide the population in adapting to new environments. In dynamic environments, real-time performance and computational efficiency are critical considerations. Due to the high computational cost of nonlinear predictive models, their practicality in dynamic settings is limited; in contrast, linear predictive models demonstrate significant advantages in computational efficiency. They can complete prediction tasks within a short timeframe and rapidly respond to environmental changes, thereby better satisfying the stringent real-time requirements imposed by dynamic environments. Consequently, linear interval prediction mechanisms are more suitable for implementation in dynamic contexts. Moreover, this strategy selection is grounded in the observed phenomenon that when population trends remain relatively stable, guiding the entire population toward more optimal directions through feedforward centroid prediction can reduce unnecessary individual reinitializations.

The feedforward centroid method is a commonly utilized environmental change response mechanism in Dynamic Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithms (DMOEAs), designed to predict the evolutionary trend of the entire population. This approach involves considering the entire population during prediction, which includes not only nondominated individuals that significantly contribute to the optimization process but also a large number of redundant individuals with minimal impact on optimization direction and outcomes. The presence of these redundant individuals may interfere with prediction accuracy, increase computational resource consumption, and degrade predictive precision. Therefore, employing feedforward centroid prediction exclusively on nondominated individuals eliminates interference from redundant individuals, reduces computational resource wastage, and enhances prediction accuracy. The specific prediction process is expressed by the following formula:

wherein,

In Fig. 3, rectangles represent individuals in environments

Figure 3: Interval prediction mechanism based on feedforward centroid

In the face of drastic environmental changes, strategies based on direct memory often become inapplicable, as historical information fails to effectively guide the search for new Pareto optimal sets (POS) under such conditions. Conversely, a special-point-based interval prediction scheme is proposed to more accurately direct the population’s migration toward potential regions of the new POS. Special points play a pivotal role in the evolutionary process by providing critical information about the objective space, thereby facilitating more efficient exploration of the solution space and preventing entrapment in local optima or divergence from the global optimum. Furthermore, the utilization of a set of special points enhances population diversity. In novel environments, individuals derived through mapping from these special points can constitute part of the initial population, while additional individuals are generated randomly, thereby further enriching population diversity.

The special point set comprises five distinct types of points: boundary points, points close to the boundary (CTB), points close to the center (CTC), points close to the ideal solution (CTI), and inflection points. As illustrated on the right side of Fig. 3, various special points are marked within the population composed of interval individuals represented by rectangular centers. Two boundary points, A and B, jointly constitute the extremal line L. Points H and C do not belong to the special point set; they are solely utilized for obtaining CTI and CTC. Specifically, C denotes the center point, D represents CTC, H symbolizes the ideal point, E corresponds to CTI, and G indicates CTB. The extremal line L can be expressed as:

Assuming the coordinates of point K are

Among all non-dominated solutions, the point farthest from the extreme value line is designated as the inflection point. According to Eq. (27), point F exhibits the greatest distance to line L and is thus identified as the inflection point. Under conditions of abrupt variation, a special point set

In summary, both the employed feedforward center prediction and the special point set-based prediction mechanisms are predicated on interval values, utilizing the midpoint of each dimensional interval to represent individuals for prediction purposes. This approach is particularly suited to environments characterized by high uncertainty, as it not only preserves population diversity but also delivers high-quality predictive solutions, thereby mitigating premature convergence to local optima.

4.2 Overall Framework of the Algorithm

In Dynamic Interval Multi-Objective Problems (DI-MOPs), the objective function values are consistently constrained within dynamically varying interval ranges, which adjust in response to environmental changes. This indicates that the problem inherently possesses significant evolutionary and dynamic characteristics. To address this feature, the present study proposes a dynamic interval multi-objective optimization algorithm based on environmental change detection to efficiently handle DI-MOPs.

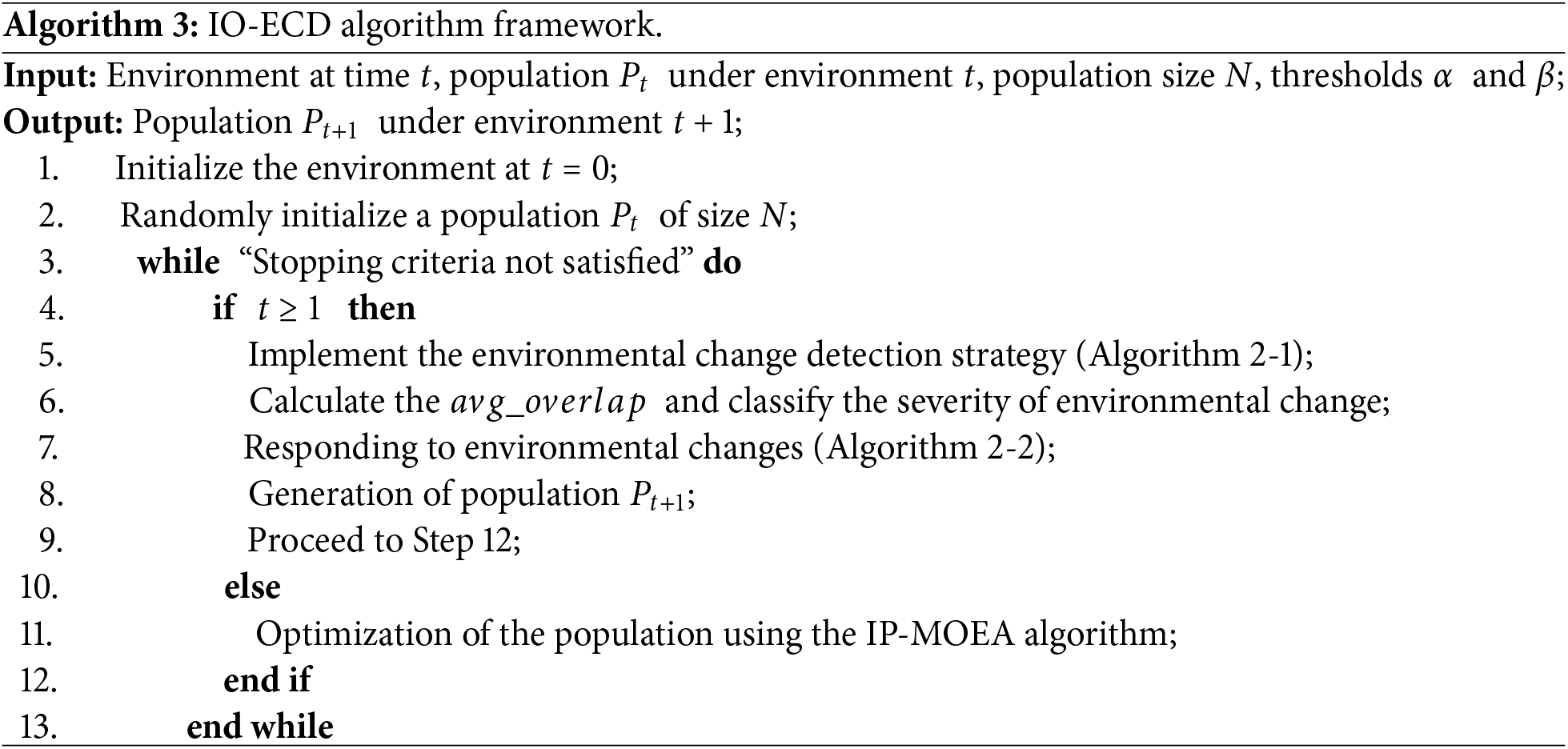

The proposed algorithmic framework is delineated in Algorithm 3. The initial population is randomly generated within the first environment. While the termination criterion remains unmet, a strategy based on interval overlap is employed from the second environment onward to detect environmental changes, categorizing the severity of changes into three levels: minor, moderate, and severe. Corresponding adaptive responses are implemented for each change type. For minor changes, given the relatively small magnitude of environmental variation and the preservation of population structure adaptability, local search techniques are utilized to finely adjust individual positions, thereby enhancing solution quality without necessitating extensive population restructuring. In the case of moderate changes, although population stability persists to some extent, simple local search proves insufficient to track dynamic trends; thus, a feedforward center-point interval prediction method is adopted to effectively estimate the evolutionary direction toward optimal solutions, guiding the population toward superior solution regions while minimizing unnecessary reinitialization. Under severe environmental fluctuations, historical population information becomes significantly less reliable and may even misdirect search trajectories; consequently, a specialized point set is employed to provide more instructive search guidance and augment directional diversity. This algorithm not only circumvents premature convergence to local optima but also accelerates convergence speed by promptly capturing dynamic variations and steering the population toward Pareto-optimal solutions more expeditiously, thereby furnishing improved initial populations for subsequent iterations. The new initial populations undergo optimization via an Imprecision-Propagating Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm (IP-MOEA), facilitating convergence toward true Pareto-optimal fronts. This iterative process continues until termination conditions are satisfied. Ultimately, a comprehensive set of nondominated solutions is outputted as the optimal solution set for Dynamic Interactive Multi-Objective Problems (DI-MOPs).

5.1 Simulation Experimental Platform and Parameter Configuration

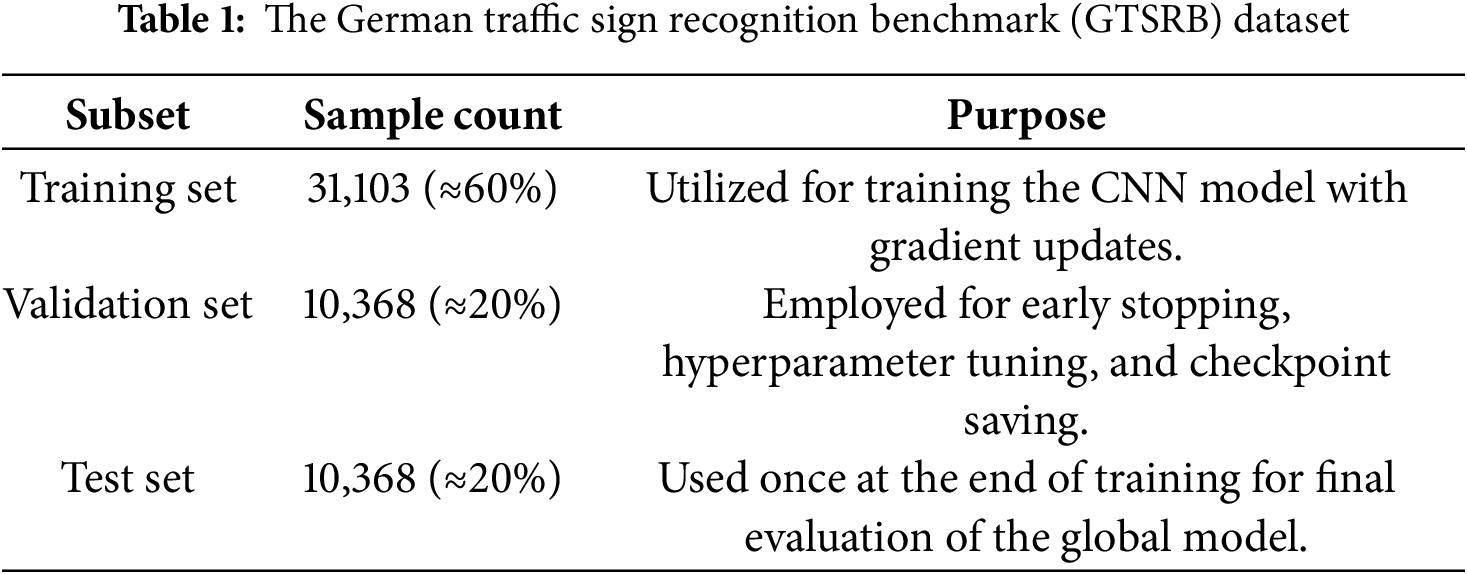

This chapter focuses on a federated learning-based convolutional neural network (CNN) model within the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) context, aiming to achieve effective traffic sign recognition. The experiments utilize the German Traffic Sign Recognition Benchmark (GTSRB) dataset, which comprises a total of 51,839 traffic sign images, each with a resolution of 30 × 30 pixels [41]. During the data pre-processing phase, the dataset is divided into mutually exclusive subsets with a ratio of 60%, 20%, and 20%, corresponding to the training set, validation set, and test set, respectively, with the detailed data allocation shown in Table 1. The training set is solely used for gradient updates; the validation set is employed for early stopping, hyperparameter tuning, and model checkpoint saving; and the test set is used once at the end of the entire training process to evaluate the performance of the global model.

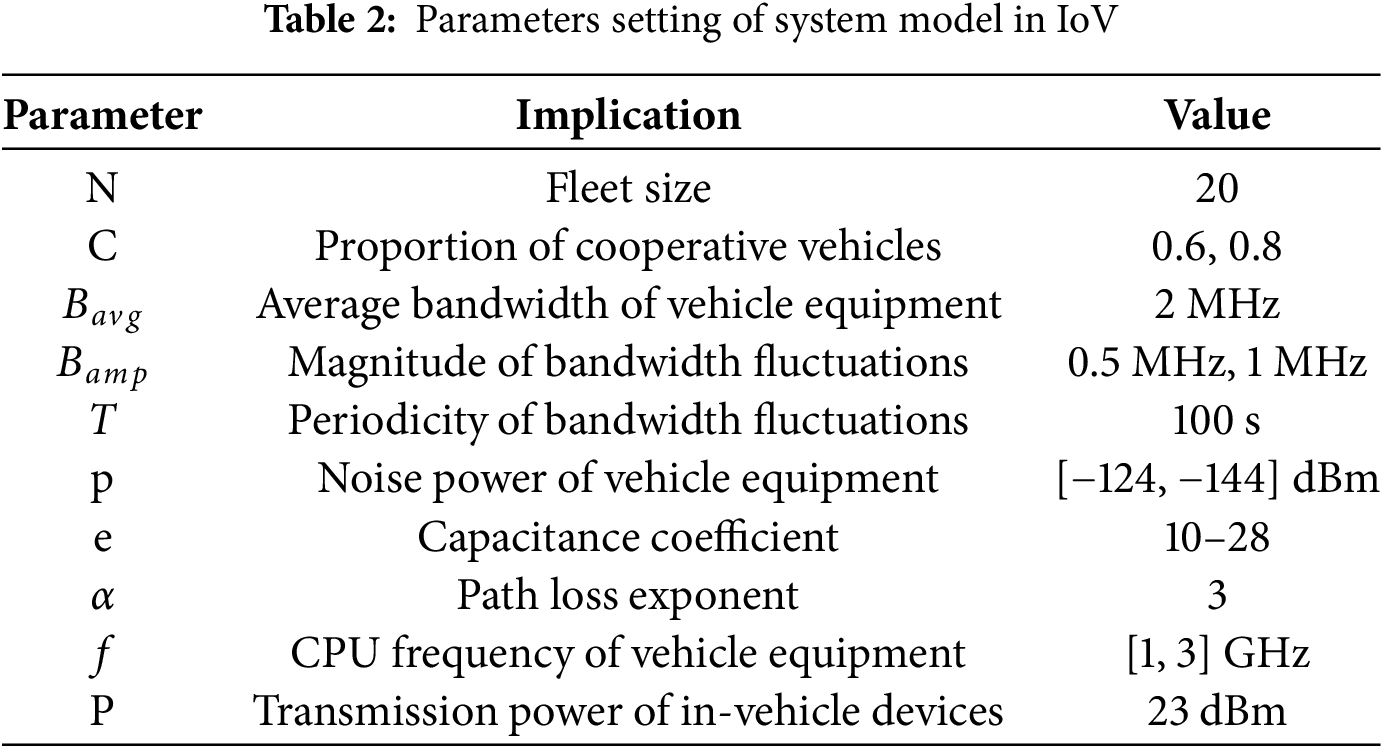

Additionally, modeling was conducted using Python, while Matlab was employed for model resolution. All simulations were implemented on the MATLAB R2019a platform, where the proposed dynamic interval multi-objective optimization algorithm and comparison algorithms were coded and executed under the same computational settings. The optimization process was carried out using customized MATLAB scripts with integrated optimization toolboxes to ensure reproducibility. Key parameters such as population size, iteration limits, and termination conditions were set uniformly across experiments to provide a fair comparison. To facilitate a more comprehensive analysis of system performance, experiments were designed under varying parameter configurations. The vehicle pool size was set to 20, with cooperative vehicle ratios established at 0.6 and 0.8. The average bandwidth of the vehicular devices was configured at 2 MHz, with bandwidth fluctuation amplitudes set at 0.5 and 1 MHz, respectively. Herein, the bandwidth is defined as an interval parameter that varies with environmental conditions, and is calculated as follows:

The environment step size is set to

5.2 Comparative Analysis of Algorithmic Model Performance

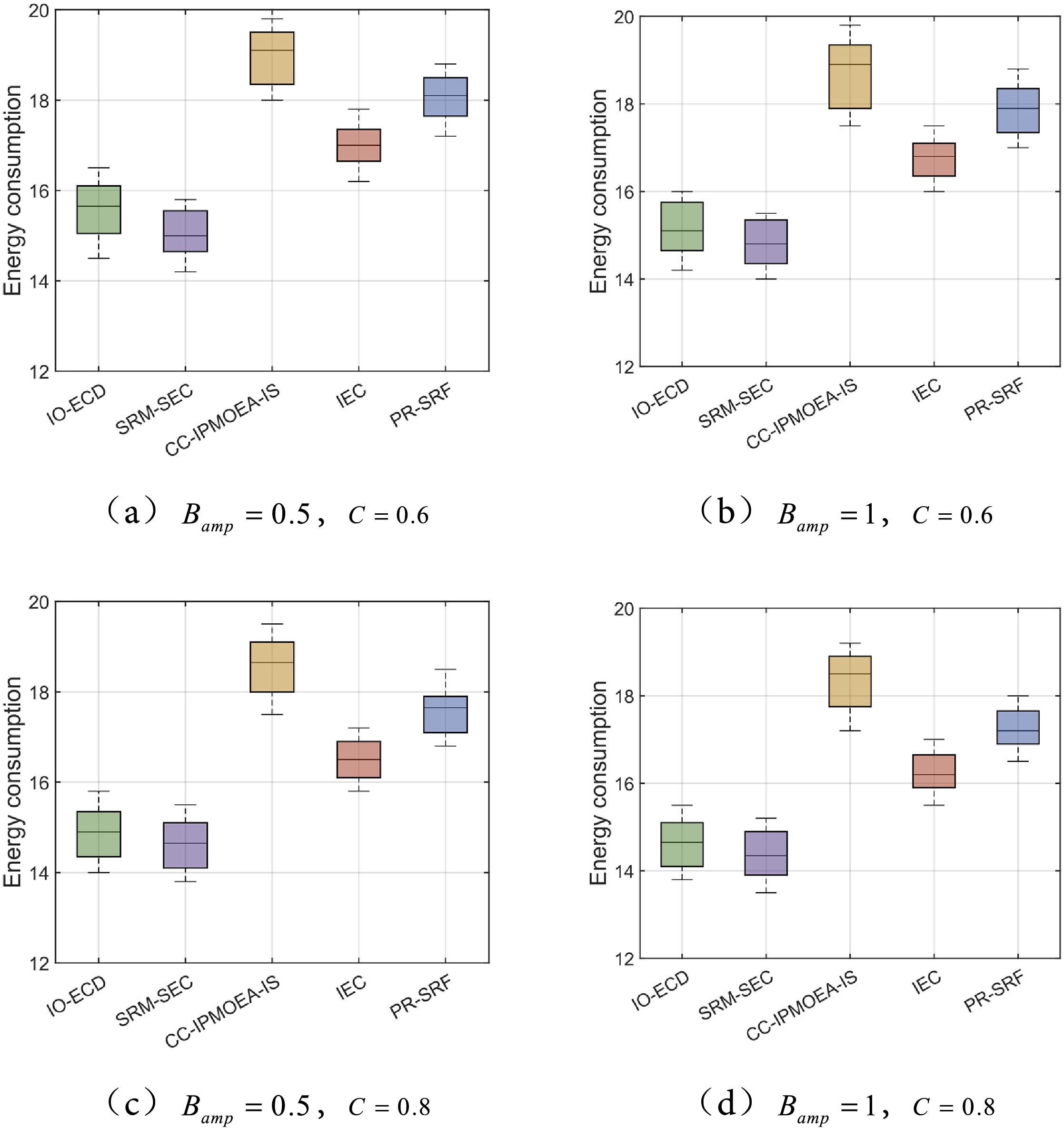

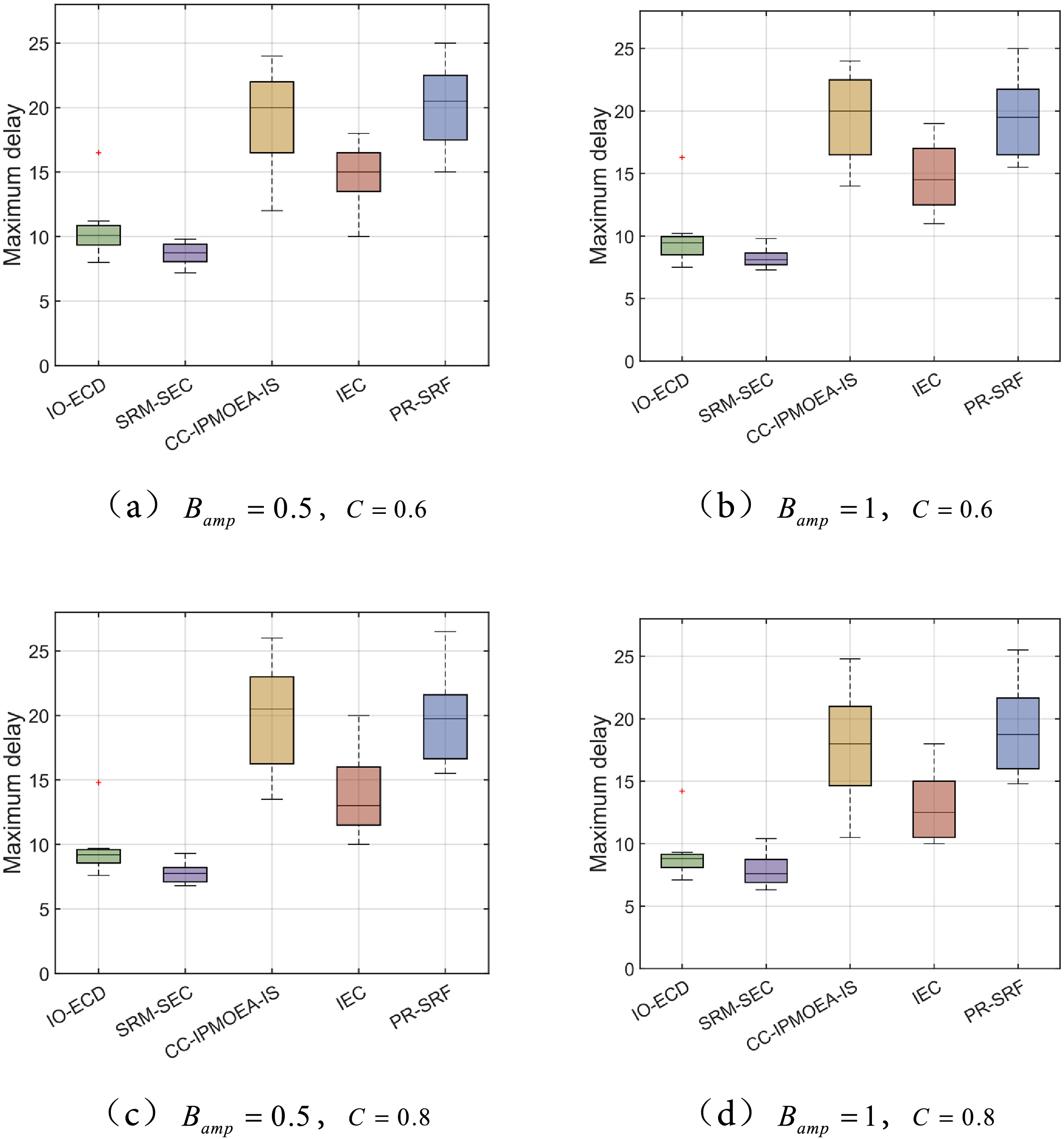

This section constructs a simulation scenario for federated learning (FL) collaborative training among vehicles on an urban road. The experimental area is modeled as a straight road segment measuring 1 km in length and 20 m in width, with the server deployed at the central position of the road to optimize communication coverage. Figs. 4 and 5 respectively present box plots illustrating the time delay and energy consumption obtained by the two algorithms proposed herein, IO-ECD and SRM-SEC, alongside three other state-of-the-art algorithms: CC-IPMOEA-IS, IEC, and PR-SRF, during the model-solving process.

Figure 4: Five algorithms obtain the boxplot of time delay under different parameter settings

Figure 5: Five algorithms obtain the boxplot of energy consumption under different parameter settings

As illustrated in Fig. 4, with the increase in the amplitude of bandwidth fluctuations, the latency performance of all algorithms during the solution process exhibits an optimization trend, among which the SRM-SEC algorithm demonstrates the most pronounced improvement. This phenomenon can be attributed to the algorithm’s heightened sensitivity to environmental variations, enabling it to more effectively perceive dynamic changes in bandwidth and thereby mitigate the escalation of maximum latency to a certain extent. Furthermore, an increase in the proportion of participating vehicles also exerts a positive influence on maximum latency, with all five algorithms showing a downward trend in latency under this condition. Taking IO-ECD as an example, when a higher vehicle selection ratio is employed, the algorithm can more precisely search for optimal solutions that satisfy low-latency constraints through effective filtering of uncertain solutions. A comprehensive analysis of each algorithm’s performance in terms of convergence speed and solution diversity under multiple parameter configurations yields the following ranking: SRM-SEC > IO-ECD > IEC > CC-IPMOEA-IS > PR-SRF.

Fig. 5 illustrates the energy consumption performance of various comparative algorithms under conditions of fluctuating bandwith amplitude and varying proportions of cooperative vehicles. It is evident from the figure that all algorithms demonstrate robust stability across different configurations. In terms of performance ranking, SRM-SEC consistently occupies the leading position, followed sequentially by IO-ECD, IEC, CC-IPMOEA-IS, and PR-SRF. Notably, compared to IO-ECD, the SRM-SEC algorithm incorporates an analysis of distributional discrepancies arising from environmental variations, thereby enhancing its sensitivity and granularity in detecting environmental changes. Building upon this foundation, SRM-SEC further implements a multi-strategy response mechanism, endowing it with superior adaptability in maintaining solution convergence, diversity, and feasibility. Experimental results substantiate that the proposed method achieves an optimal balance between energy consumption control and performance retention, thereby validating its efficacy and practical applicability.

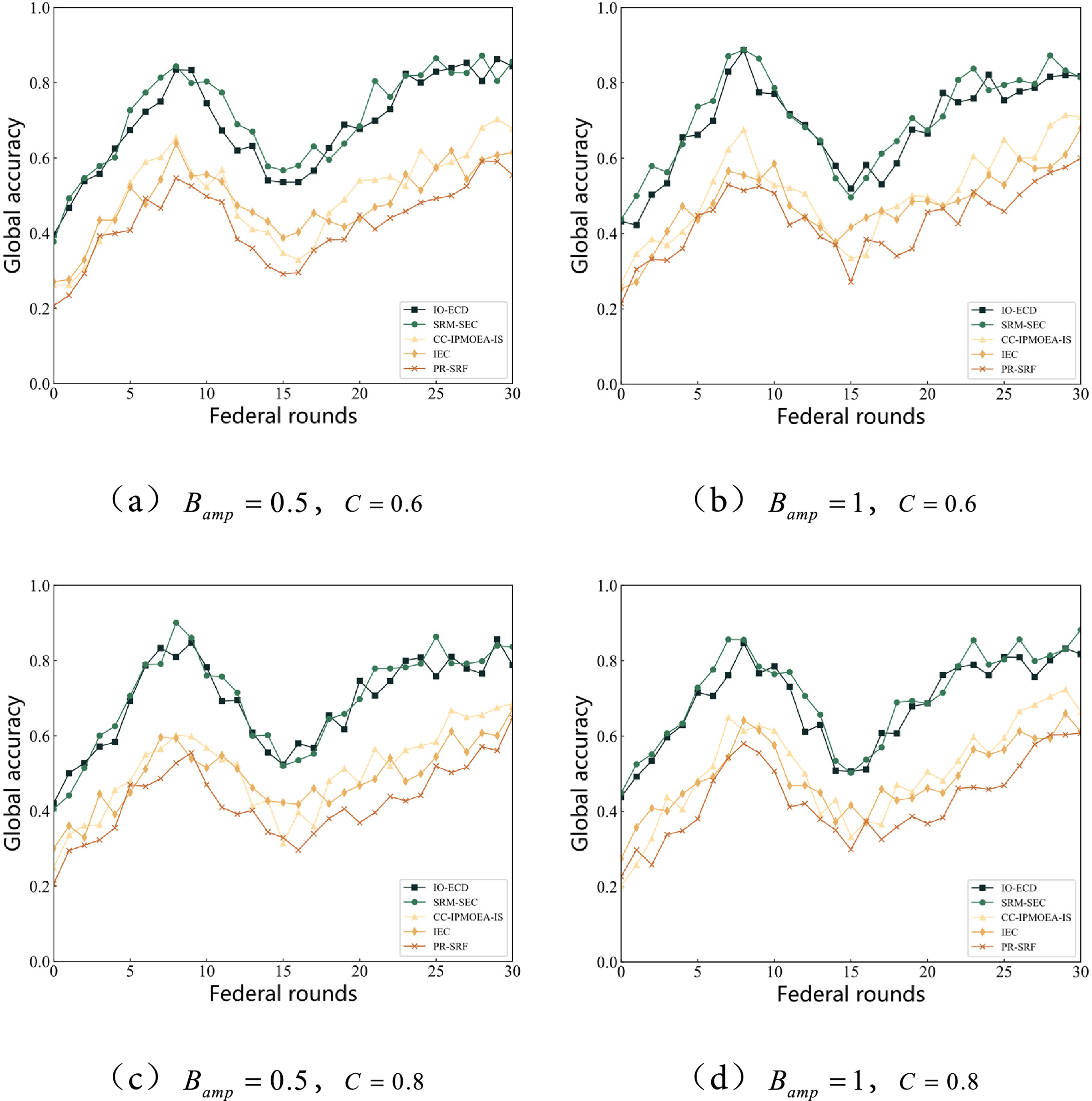

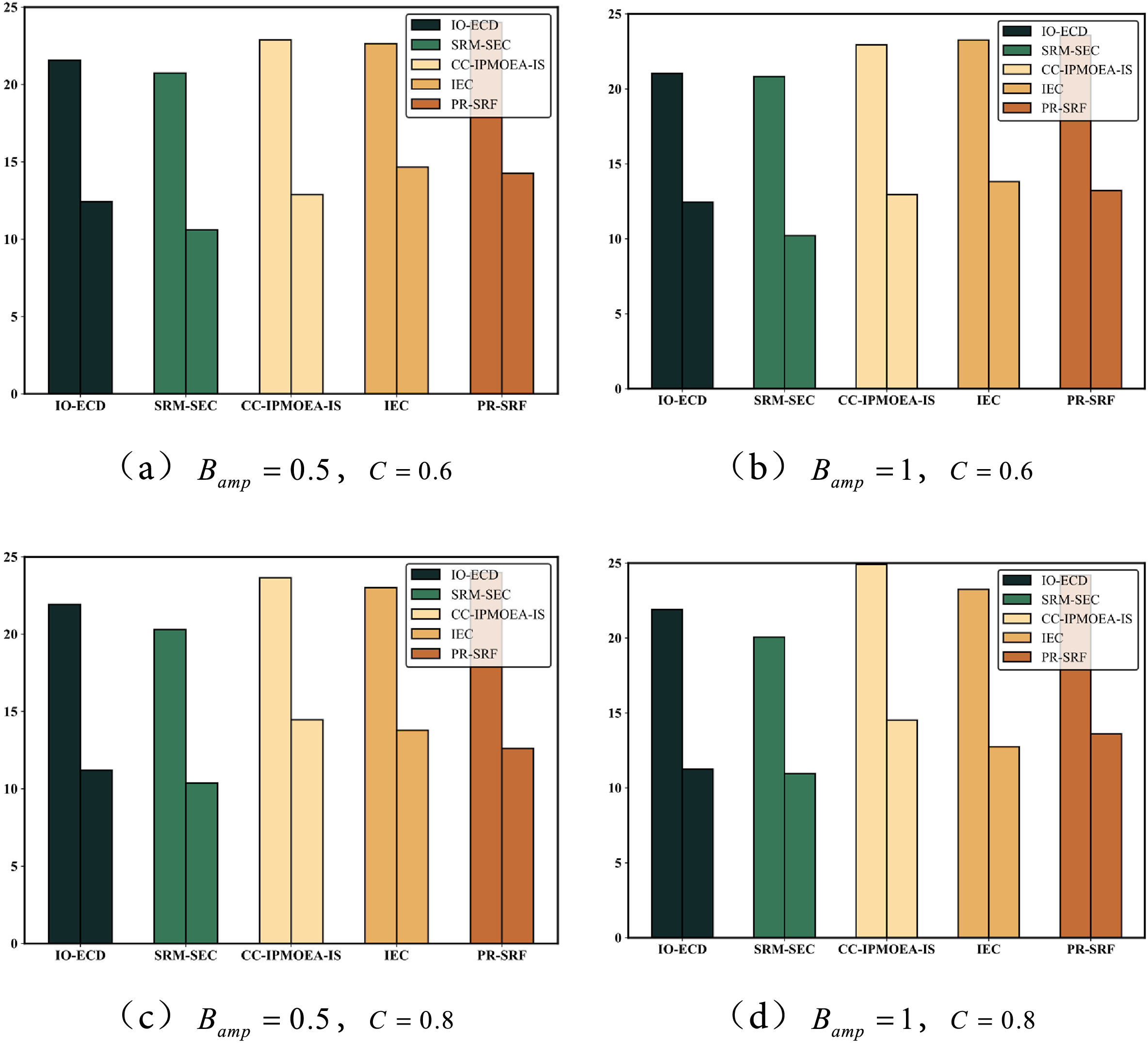

To comprehensively evaluate the optimization performance of the proposed algorithm in device selection and power allocation, the experiments conducted a comparative analysis across three dimensions: model training latency, energy consumption, and global model accuracy. Figs. 6 and 7 respectively illustrate the performance of five algorithms in these three aspects. The superior performance of SRM-SEC can be directly attributed to its adaptive response mechanism (Algorithm 2), which dynamically adjusts search strategies based on the detected severity of environmental changes. This mechanism reduces unnecessary reinitialization in stable settings and prevents premature convergence in highly dynamic environments, thereby improving both convergence speed and global accuracy.

Figure 6: The accuracy convergence trend of the five algorithms is obtained under different parameter settings

Figure 7: The results of maximum time delay and average energy consumption obtained by five algorithms when solving the model with different parameter Settings

In federated learning, the concept of federated rounds refers to the iterative communication cycles between the central server and participating devices. During each round, devices perform local training on their private datasets and then upload model updates to the server, which aggregates them into a global model. Thus, the number of federated rounds reflects the progress of collaborative training and is closely associated with the convergence speed of the system. Global accuracy measures the performance of the aggregated global model on a unified test dataset. It reflects how well the model generalizes across heterogeneous devices and varying data distributions. In Figs. 6 and 7, we evaluate the proposed method in terms of both the required number of federated rounds to achieve convergence and the final global accuracy. The results demonstrate that our model reduces the number of rounds needed while maintaining higher accuracy, highlighting its efficiency in handling dynamic uncertain environments.

Fig. 6 illustrates the convergence trends of various algorithms in the tasks of device selection and power allocation. The results indicate that the IO-ECD and SRM-SEC algorithms demonstrate superior convergence performance, exhibiting stable and rapid convergence capabilities across different proportions of cooperative vehicles and varying bandwidth fluctuation amplitudes. Notably, the SRM-SEC algorithm maintains exceptionally high convergence efficiency even under conditions of significant bandwidth variability, underscoring its robust adaptability to dynamic network environments. In contrast, the other three algorithms do not exhibit marked differences in convergence performance; however, both CC-IPMOEA-IS and PR-SRF algorithms display pronounced fluctuations during training, indicating weaker stability. This instability likely stems from deficiencies in their objective function modeling or environmental variation handling strategies, resulting in reduced adaptability of the search process to uncertainty perturbations and consequently impairing their ultimate convergence outcomes.

Fig. 7 illustrates the overall performance of five comparative algorithms at the 100th round of federated training, focusing on two core metrics: maximum latency and average energy consumption. As depicted, both IO-ECD and SRM-SEC demonstrate high stability across these two dimensions. Specifically, SRM-SEC achieves superior results in latency and energy consumption due to its enhanced sensitivity to environmental variations. Conversely, the IO-ECD algorithm effectively mitigates response delays caused by environmental changes through a refined response mechanism. Additionally, although PR-SRF exhibits slightly inferior performance compared to IEC in terms of latency and energy consumption, it maintains a certain advantage in environmental adaptability while concurrently detecting changes. In summary, the two algorithms proposed herein exhibit robust adaptability when confronting complex environmental dynamics, with SRM-SEC particularly demonstrating more prominent comprehensive performance during the model solving phase.

Figs. 4–7 present the performance comparison of the proposed SRM-SEC algorithm with baseline methods in terms of federated rounds and global accuracy. The results clearly show that SRM-SEC converges faster, requiring fewer federated rounds to achieve stable accuracy. This advantage is attributed to its severity-based adaptive response mechanism, which enables the algorithm to dynamically adjust its search strategy depending on the intensity of environmental changes. Under highly dynamic and uncertain conditions, SRM-SEC maintains population diversity and prevents premature convergence, while in relatively stable scenarios it accelerates convergence by exploiting historical information more efficiently. Consequently, SRM-SEC achieves consistently higher global accuracy across different parameter settings, demonstrating its robustness and adaptability to dynamic interval environments.

This chapter, grounded in the practical application scenarios of the Internet of Vehicles (IoV), addresses the dynamic uncertainties inherent in wireless channel environments and resource allocation challenges. By jointly considering vehicle selection and power allocation as optimization variables, a dynamic interval multi-objective optimization model is established with latency, energy consumption, and bandwidth utilization as the three optimization objectives. To solve the federated learning device selection and power allocation optimization problem under dynamic uncertain environments, the SRM-SEC algorithm is proposed and systematically validated through simulation experiments. Experimental results demonstrate that SRM-SEC maintains stable optimization performance under highly dynamic uncertain scenarios—such as high-speed vehicular mobility and sudden interference—where its unique response mechanism effectively prevents premature convergence and ensures fairness in resource allocation. Furthermore, in complex environments characterized by non-periodic variations, SRM-SEC exhibits enhanced adaptability, continuously optimizing federated learning device selection and power allocation strategies. Therefore, this algorithm provides an efficient and reliable solution for dynamic resource management in IoV systems, possessing significant practical application value.

In summary, the practicality of IoV systems depends on their capability for resource scheduling and learning efficiency within complex dynamic environments. Dynamic interval modeling not only adequately captures environmental uncertainties but also offers a theoretical foundation and constraint formulation for multi-objective optimization algorithms. By integrating dynamic interval theory with multi-objective optimization techniques, the proposed model and algorithm effectively enhance the deployment efficiency of federated learning in IoV as well as resource utilization levels, thereby demonstrating the necessity and practical significance of dynamic interval modeling in optimizing real-world intelligent systems. Although the proposed method demonstrates significant improvements in accuracy and efficiency, its scalability to very large-scale IoV systems may be affected by increased computational cost and communication overhead. Future work will focus on designing lightweight optimization strategies to further enhance scalability and reduce system overhead.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank Dr. Tianhao Zhao for his guidance on technical aspects and Professor Zhihua Cui for his guidance on both theoretical and practical aspects.

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by the Central Guidance for Local Science and Technology Development Funds under Grant No. YDZJSX2025D049; Shanxi Provincial Graduate Innovation Research Program under Grant No. 2024KY652.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Bohui Li and Xingjuan Cai; methodology, Bohui Li; software, Bohui Li; validation, Bohui Li, Bin Wang and Linjie Wu; formal analysis, Bohui Li and Maoqing Zhang; investigation, Bohui Li; resources, Bohui Li; data curation, Bohui Li; writing—original draft preparation, Bohui Li; writing—review and editing, Bohui Li and Bin Wang; visualization, Bohui Li; supervision, Xingjuan Cai; project administration, Xingjuan Cai; funding acquisition, Xingjuan Cai. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants or animals.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhang J, Zhang Z, Cai X, Cai J, Chen J. An interval evolutionary algorithm based on dynamic relation adjustment strategy for many-objective problems. Swarm Evol Comput. 2025;93(4):101853. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2025.101853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Kaur G, Grewal SK. Aggregation techniques in wireless communication using federated learning: a survey. Int J Wirel Mob Comput. 2024;26(2):115–26. doi:10.1504/ijwmc.2024.137135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Gao T, Jin X. Group-based federated knowledge distillation intrusion detection. Int J Soft Eng Knowl Eng. 2024;34(8):1251–79. doi:10.1142/s0218194024500190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Li K, Jin N, Tang J, Cao Y. Modified artificial bee colony based on random neighbourhood. Int J Comput Sci Math. 2024;20(3):188–96. doi:10.1504/ijcsm.2024.142730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wen J, Cui Z, Zhang H, Chen J. A many-objective joint device selection and aggregation scheme for federated learning in IoV. ACM Trans Sen Netw. 2024:3701035. doi:10.1145/3701035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Xiao S, Wang W. Dual model surrogate-assist evolutionary algorithm for expensive multi-objective optimisation. Int J Bio Inspired Comput. 2024;23(4):236–44. doi:10.1504/ijbic.2024.139276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhao J, Li W, Liu H, Yu P, Li H, Wen Z. An enhanced genetic algorithm for computation task offloading in MEC scenario. Int J Wirel Mob Comput. 2023;25(2):118–27. doi:10.1504/ijwmc.2023.133059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Cai J, Chen B, Wen J, Cui Z, Chen J, Zhang W. A joint vehicular device scheduling and uncertain resource management scheme for Federated Learning in Internet of Vehicles. Inf Sci. 2025;690(6):121552. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2024.121552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Cai X, Li J, Ma J, Zhang Z, Xu Q, Zhang W, et al. Interval many-objective evolutionary algorithm guided by dynamic dual-sequence mechanism. Swarm Evol Comput. 2025;94(4):101870. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2025.101870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Hu G, Zhu D, Shen J, Hu J, Han J, Li T. FedBeam: reliable incentive mechanisms for federated learning in UAV-enabled Internet of vehicles. Drones. 2024;8(10):567. doi:10.3390/drones8100567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Liu Y, Liu D, Khoukhi L, Wang B, Zhang L, Xu Y. Energy-efficient device selection and resource allocation for edge-driven hierarchical federated learning. Results Eng. 2025;27(4):105992. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2025.105992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Xing L, Cui J, Gao J, Deng K, Wu H, Ma H. Octopus: knapsack model-driven federated learning client selection in Internet of vehicles. Pervasive Mob Comput. 2025;111(8):102063. doi:10.1016/j.pmcj.2025.102063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Cui Z, Jin Y, Zhang Z, Xie L, Chen J. An interval multi-objective optimization algorithm based on elite genetic strategy. Inf Sci. 2023;648(2):119533. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2023.119533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Raza A, Badidi E. A trust-based client selection framework for federated learning in the Internet of vehicles. In: 2025 International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing (IWCMC); 2025 May 12–16. Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates: IEEE; 2025. doi:10.1109/IWCMC65282.2025.11059592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Li D, Wang L, Geng S, Hu Y, Li H, Tu J. A constrained multi-objective evolutionary algorithm based on dynamic clustering strategy. Int J Complex Appl Sci Technol. 2024;1(1):10068604. doi:10.1504/ijcast.2024.10068604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wen J, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Cui Z, Cai X, Chen J. Resource-aware multi-criteria vehicle participation for federated learning in Internet of vehicles. Inf Sci. 2024;664(12):120344. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2024.120344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang L, Zhou W, Xu H, Li L, Cai L, Zhou X. Research on task offloading optimization strategies for vehicular networks based on game theory and deep reinforcement learning. Front Phys. 2023;11:1292702. doi:10.3389/fphy.2023.1292702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhang Z, Wu L, He D, Li J, Lu N, Wei X. Using third-party auditor to help federated learning: an efficient Byzantine-robust federated learning. IEEE Trans Sustain Comput. 2024;9(6):848–61. doi:10.1109/TSUSC.2024.3379440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Qiang X, Chang Z, Hu Y, Liu L, Hämäläinen T. Adaptive and parallel split federated learning in vehicular edge computing. IEEE Internet Things J Forthcoming. 2024. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3479158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wu L, Zhao T, Cai X, Cui Z, Chen J. Dynamic multi-objective optimization for uncertain order insertion green shop production scheduling. Appl Soft Comput. 2025;182(2):113573. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2025.113573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang Q, Furqan MD, Nutzhat T, Machida F, Andrade E. Dependability of UAV-based networks and computing systems: a survey. arXiv:2506.16786. 2025. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2506.16786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhao H, Geng L, Feng W, Zhou C. Client selection and resource scheduling in reliable federated learning for UAV-assisted vehicular networks. Chin J Aeronaut. 2024;37(9):328–46. doi:10.1016/j.cja.2024.06.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Chang X, Obaidat MS, Xue X, Ma J, Duan X. Mobility-aware vehicle selection strategy for federated learning in the Internet of vehicles. In: 2024 International Conference on Communications, Computing, Cybersecurity, and Informatics (CCCI); 2016 Oct 16–18. Beijing, China: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ccci61916.2024.10736472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Liu J, Chang Z, Liang YC. Age-based device selection and transmit power optimization in over-the-air federated learning. arXiv:2501.01828. 2025. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2501.01828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Chang X, Obaidat MS, Ma J, Xue X, Yu Y, Wu X. Efficient federated learning via adaptive model pruning for Internet of vehicles with a constrained latency. IEEE Trans Sustain Comput. 2024;10(2):300–16. doi:10.1109/TSUSC.2024.3441658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Xiong G, Guo J. Contribution-based resource allocation for effective federated learning in UAV-assisted edge networks. Sensors. 2024;24(20):6711. doi:10.3390/s24206711. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Wang G, Xu F, Zhang H, Zhao C. Joint resource management for mobility supported federated learning in Internet of Vehicles. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2022;129(2):199–211. doi:10.1016/j.future.2021.11.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Yuan T, Chen L, Jiang Y, Chen H, Gong W, Gu Y. Resource management and optimization in Internet of vehicles for hierarchical federated learning. IEEE Access. 2024;12:158174–88. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3486775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Yao J, Ansari N. Enhancing federated learning in fog-aided IoT by CPU frequency and wireless power control. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020;8(5):3438–45. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2020.3022590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Yu L, Albelaihi R, Sun X, Ansari N, Devetsikiotis M. Jointly optimizing client selection and resource management in wireless federated learning for Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(6):4385–95. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2021.3103715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Wen W, Jia Y, Xia W. Joint scheduling and resource allocation for federated learning in SWIPT-enabled micro UAV swarm networks. China Commun. 2022;19(1):119–35. doi:10.23919/jcc.2022.01.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Hamdi R, Chen M, Ben Said A, Qaraqe M, Poor HV. Federated learning over energy harvesting wireless networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;9(1):92–103. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2021.3089054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Yin T, Li L, Lin W, Ni T, Liu Y, Xu H, et al. Joint client scheduling and wireless resource allocation for heterogeneous federated edge learning with non-IID data. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2024;73(4):5742–54. doi:10.1109/TVT.2023.3333329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zheng F, Sun Y, Ni B. FedAEB: deep reinforcement learning based joint client selection and resource allocation strategy for heterogeneous federated learning. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2024;73(6):8835–46. doi:10.1109/TVT.2024.3359860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Ko H, Lee J, Seo S, Pack S, Leung VCM. Joint client selection and bandwidth allocation algorithm for federated learning. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2023;22(6):3380–90. doi:10.1109/TMC.2021.3136611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Huang W, Yang Y, Chen M, Liu C, Feng C, Poor HV. Wireless network optimization for federated learning with model compression in hybrid VLC/RF systems. Entropy. 2021;23(11):1413. doi:10.3390/e23111413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Nguyen TV, Ho ND, Hoang HT, Do CD, Wong KS. Toward efficient hierarchical federated learning design over multi-hop wireless communications networks. IEEE Access. 2022;10(4):111910–22. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3215758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Ji X, Tian J, Zhang H, Wu D, Li T. Joint device selection and bandwidth allocation for cost-efficient federated learning in industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;10(10):9148–60. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2022.3233595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zhang W, Yang D, Wu W, Peng H, Zhang N, Zhang H, et al. Optimizing federated learning in distributed industrial IoT: a multi-agent approach. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. 2021;39(12):3688–703. doi:10.1109/JSAC.2021.3118352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zheng A, Li B, Zheng M, Zhong H. Multi-objective UAV trajectory planning in uncertain environment. Symmetry. 2021;13(11):2160. doi:10.3390/sym13112160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Gong D, Xu B, Zhang Y, Guo Y, Yang S. A similarity-based cooperative co-evolutionary algorithm for dynamic interval multiobjective optimization problems. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2019;24(1):142–56. doi:10.1109/TEVC.2019.2912204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Xu Y, Song Y, Pi D, Chen Y, Qin S, Zhang X, et al. A reinforcement learning-based multi-objective optimization in an interval and dynamic environment. Knowl Based Syst. 2023;280(2):111019. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2023.111019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Cai X, Li B, Wu L, Chang T, Zhang W, Chen J. A dynamic interval multi-objective optimization algorithm based on environmental change detection. Inf Sci. 2025;694(1):121690. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2024.121690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools