Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Porosity-Impact Strength Relationship in Material Extrusion: Insights from MicroCT, and Computational Image Analysis

1 School of Engineering and Physical Sciences, Heriot-Watt University Malaysia, Putrajaya, 62200, Malaysia

2 School of Engineering and Physical Sciences, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, EH14 4AS, UK

3 Industrial Technology Division, Malaysian Nuclear Agency, Kajang, 43000, Malaysia

* Corresponding Author: Tze Chuen Yap. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Design, Optimisation and Applications of Additive Manufacturing Technologies)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070707

Received 22 July 2025; Accepted 23 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Additive Manufacturing, also known as 3D printing, has transformed conventional manufacturing by building objects layer by layer, with material extrusion or fused deposition modeling standing out as particularly popular. However, due to its manufacturing process and thermal nature, internal voids and pores are formed within the thermoplastic materials being fabricated, potentially leading to a decrease in mechanical properties. This paper discussed the effect of printing parameters on the porosity and the mechanical properties of the 3D printed polylactic acid (PLA) through micro-computed tomography (microCT), computational image analysis, and Charpy impact testing. The results for both tests were correlated to investigate the relationship between porosity and Charpy impact strength. PLA samples of 1 cm3 × 1 cm3 × 1 cm3 were 3D printed at printing temperatures of 180°C, 200°C, 220°C, and 240°C, and at printing speeds of 50, 80, and 110 mm/s, while porosity was measured from microCT-reconstructed data. Additionally, impact strength was assessed using a notched Charpy impact tester following ASTM D6610-18. In general, results show that higher printing temperatures and lower printing speeds reduced pore size by improving material flow and fusion, while also increasing impact strength due to better thermal bonding and interlayer adhesion. A maximum 36.8% reduction in mean pore size and a 114% improvement in impact strength were observed at 110 mm/s and 220°C. Conversely, increasing printing speed led to lower Charpy impact strength. Optimal impact behavior and minimal voids were observed at a printing temperature of 220°C and a printing speed of 50 mm/s.Keywords

The Fourth Industrial Revolution, Industry 4.0 (I4.0), signifies the merging of information and communication technologies (ICT) with the automation of machinery and manufacturing infrastructure on a broad scale to enhance industrial vitality. Within this paradigm, additive manufacturing (AM), colloquially known as 3D printing, has emerged as a pivotal component, revolutionizing traditional manufacturing processes by enabling layer-by-layer fabrication to produce advanced and custom-designed items. This technology not only facilitates intricate design realization but also streamlines production through the direct translation of digital models into physical objects, thereby redefining the boundaries of manufacturing efficiency and versatility [1].

Among various AM techniques, material extrusion (MEX/TRB-P), also known as fused deposition modeling (FDM), stands out for its widespread adoption and applicability [2]. By extruding thermoplastic filaments, this method enables rapid prototyping and production of diverse geometries with notable cost-effectiveness [3]. However, the optimization of printing parameters remains a critical issue to ensure the quality and reliability of printed components. One of the paramount concerns in extrusion 3D printing is the porosity, which can significantly compromise structural integrity and functional performance. Porosity results from incomplete fusion or air entrapment due to uncontrollable pressure after material deposition, as well as the choice of infill patterns during printing [4], remaining a pervasive challenge that necessitates investigation.

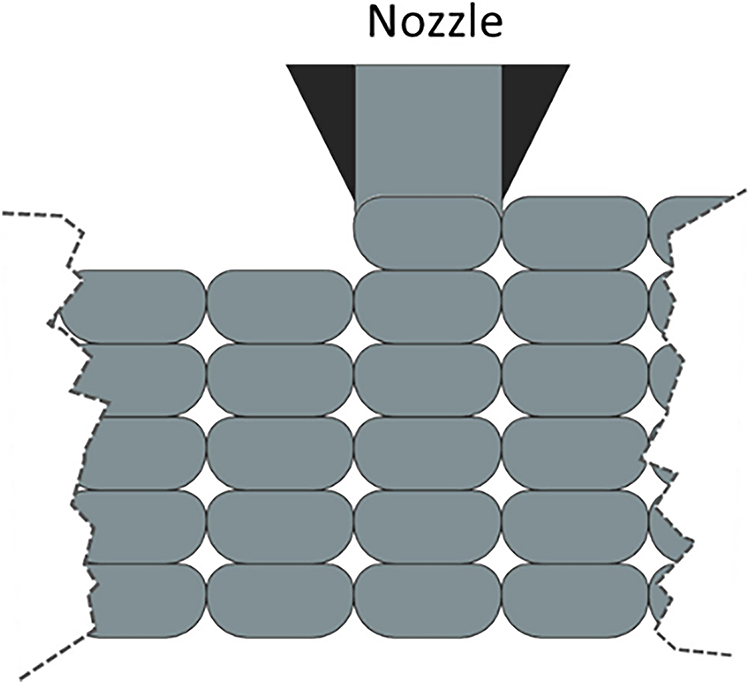

The resulting voids in 3D-printed materials have a significant impact on the quality and performance of the 3D-printed object. These voids are identified in three key regions within the structure of additively manufactured components: within the bulk material, between deposited layers, and at the fibre/matrix interface [5]. The fundamental cause of void formation is the uncontrollable pressure that occurs after the melted material leaves the printing head. The uncontrolled pressures with rapidly decreasing temperatures, can lead to insufficient bonding between material strands, as shown in Fig. 1. The cross-sectional shape of the material tracks deposited during printing, as well as the geometry and distribution of voids within MEX/TRB-P components are affected by parameters such as nozzle shape, material properties, temperature, flow rate, and deposition speed [4].

Figure 1: Formation of voids between material strands during material extrusion [6]

The mechanical properties of printed materials are another key factor in their suitability for various applications. While it is established that printing parameters impact mechanical properties [5,7–10]. The precise influence of these parameters on the underlying structural factors affecting mechanical properties remains unclear. This lack of clarity complicates the selection of printing parameters for achieving optimal mechanical properties [11]. Exploring the influence of printing parameters on mechanical performance and understanding the interplay between printing conditions and resultant porosity within printed objects becomes imperative to optimize material utilization and enhance component reliability.

Printing parameters such as infill density, printing temperature, and printing speed contribute to the formation and distribution of voids in 3D-printed parts. Direction-parallel patterns may have high density but could leave gaps in non-polygonal curvilinear layers, while contour-parallel patterns, tracing the perimeter, work well for such layers but might lead to voids within the contour due to filling challenges [12]. Higher printing speeds result in larger voids in polylactic acid (PLA) printed samples [13], whereas higher printing temperatures result in smaller voids and lower porosity [14].

Similarly, these printing parameters significantly influence the overall mechanical performance of 3D-printed PLA, with tensile strength decreasing at higher printing speeds [15]. In general, increasing printing speed during MEX 3D printing reduces voids between beads and contributes to a stronger printed part [16]. Opposite results were reported by Natarajan et al. [17], where they investigated the effect of printing speed and layer thickness on the mechanical properties of Acacia concinna-filled PLA. Their results showed that increasing printing speed reduced tensile, flexural, and impact strength. Furthermore, printing speed affects the cooling time and eventually affects the crystallinity of the printed part [16].

On the other hand, an increase in printing temperature results in an increase in tensile strength [14,16,18], bending strength [14], adhesion strength [19], strain at failure [20], wear resistance, and friction coefficient [21]. The correct extrusion or printing temperature is important to obtain good adhesion between the deposited beads, and high temperatures over the optimal limit reduce the strengths [16,22]. This suggests a strong dependence of the mechanical properties of printed samples on the printing temperature. However, research by Sultana et al. [23] indicates that the nozzle temperature and printing speed had relatively minor effects compared to other parameters, based on Analysis of variance (ANOVA) analysis, where the printing temperatures used were 180°C, 185°C, and 190°C, and the printing speeds were 10, 15, and 20 mm/s.

The presence of porosity significantly impacts the mechanical properties of 3D-printed samples, typically resulting in a weakening of the material. Variations in the size and shape of inter-bead pores are a crucial determinant of mechanical reliability. Several studies have investigated the relationship between porosity and impact strength in 3D-printed parts, showing that higher porosity content generally leads to decreased mechanical properties in the specimens, including tensile strength, Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio, compressive strength, and damping capacity [24]. The presence of porosity diminishes the mechanical properties of the specimens, as it initiates the failure process from the formation of voids.

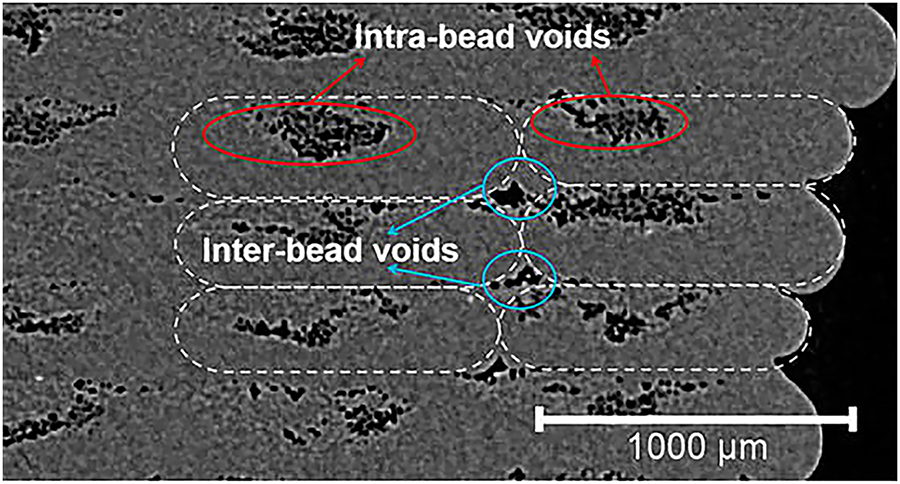

Micro-computed tomography (microCT) serves as a quantitative and qualitative tool to assess deviations from ideal geometry and to understand how printing parameters affect surface roughness and interior characteristics. This quality assessment ensures safety and performance requirements in 3D-printed objects [25]. In addition, microCT assists in the investigation of porosity, cell shape, and internal and external surface roughness in complex 3D-printed objects [26]. The technology quantifies porosity and provides information about overall structural integrity and the extent and distribution of interior defects (Fig. 2). The mircoCT technique has been used for void measurement of material extrusion 3D-printed parts [27–31].

Figure 2: Micro-CT image of printed objects containing different types of voids: intra-bead (red) and inter-bead (blue) voids [32]

The effect of printing parameters (nozzle temperature, printing speed, raster angle, infill density, bed temperature, and layer thickness) on the porosity, surface roughness, and dimensional accuracy of MEX 3D-printed PLA has been previously investigated [27]. In that study [27], the research team utilized an L25 Taguchi orthogonal array to investigate the interaction effects of the printing parameters on three responses. MicroCT was used to measure the porosity of the prints. However, due to the large number of results, only five samples of microCT results were presented, selected from the diagonal of the (5 × 5) 25 cases. As such, the direct relationship between individual printing parameters, such as nozzle temperature and porosity, was not explicitly discussed. Since the work focused on statistical analysis of the results, the understanding of how porosity is linked to single printing parameters remains limited. Furthermore, the study did not examine the mechanical properties of the 3D prints.

A similar L25 orthogonal array investigation with the same six printing parameters and three responses was repeated on ABS [28]. Based on the ANOVA, regression equations were formed for optimizing these quality features and enhancing the overall performance of 3D-printed parts. This work also focused on statistical analysis of the results and did not explicitly discuss the underlying mechanisms.

The mechanical properties, thermal properties, structural characteristics, dimensional variance, and porosity of ferronickel slag (FNS)-PLA composite with six different weight percentages of FNS [2,4–6,10,14] were investigated by Vidakis et al. [31]. The authors used microCT to measure the porosity in the 3D prints, and showed that the inclusion of FNS particles reduced the porosity of the 3D-printed samples. The porosity of the composite first decreased with increasing weight percentage of FNS until 5% and after 5% the porosity increased. Furthermore, when the porosity of the PLA composite was the lowest porosity (at PLA-5% FNS), the tensile, flexural, and impact strengths were optimal. Similar work was reported by Petousis et al., where the mechanical properties and porosity of 3D-printed material extrusion of recycled fine powder glass (RFPG)-PLA composites of different weight percentages were investigated [30]. MicroCT images revealed that the porosity decreased as the RFPG content increased from 0% to 6% and after 6%, the porosity increased. Similarly, the optimal Charpy impact strength, flexural strength, and tensile strength occurred when the porosity was the lowest (at 6% RFPG).

In a recent study, the linkage between printing parameters, voids, and tensile properties of MEX-printed PLA was investigated by Faizaan et al. [29]. The authors conducted two Taguchi L9 DOE experiments to investigate the effects of three printing parameters, where the first case consisted of nozzle diameter, layer thickness, and extrusion temperature, while the second case consisted of layer thickness, print speed, and number of top/bottom layers. MicroCT scans were acquired for samples with varying nozzle diameters printed at a constant layer thickness of 0.15 mm and for samples of varying layer thickness printed at a constant nozzle diameter of 0.6 mm. From the microCT results, the authors reported that the lower layer thicknesses and larger nozzle diameters generated fewer voids, and eventually the lower void content produced better tensile properties.

Although there is extensive research on the effects of printing parameters on porosity and the link between porosity and mechanical properties, few studies have specifically investigated the relationship between impact strength and porosity in MEX/TRB-P 3D-printed PLA at different printing parameters, measured via microCT. Moreover, existing research often overlooks the influence of printing parameters when assessing the influence of porosity on mechanical properties (environmentally, sustainability). As a result, the interactions between printing parameters, porosity characteristics, and impact performance are not fully understood. In this study, the porosity in MEX/TRB-P printed PLA parts at three printing speeds and four different temperatures is measured via micro-CT image analysis, and the Charpy impact strengths of the prints are determined through Charpy impact testing. The relationship between printing parameters (printing speed, printing temperature), porosity, and impact strength is then evaluated.

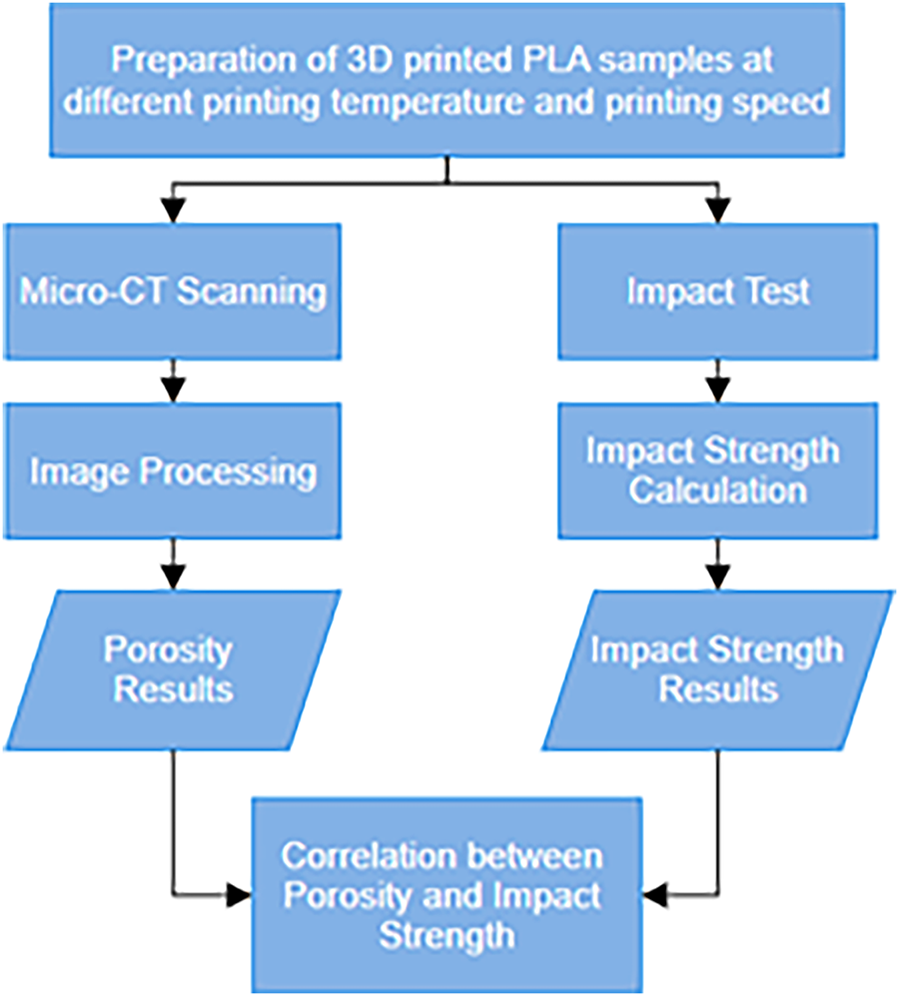

Fig. 3 shows the process, which begins with MEX/TRB-P 3D printing of PLA, where different printing parameters are systematically varied to observe their impact. Then, the specimens undergo two parallel assessments. The first involves the identification of voids within the 3D-printed samples using microCT scanning. In parallel, MEX/TRB-P-printed specimens are subjected to direct impact tests to evaluate the material’s impact strength. In the final stage, the identified voids and the results from the direct impact tests are correlated, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of how porosity relates to the impact strength of the 3D-printed specimens.

Figure 3: Flow chart of the experimental work

An UltiMaker 2+ 3D Printer was utilized for the printing process. This printer has a build volume of 223 mm × 220 mm × 205 mm with a nozzle diameter of 0.4 mm, and a maximum nozzle temperature of 260°C. The material selected for the investigation was polylactic acid (PLA) (Ultimaker, Zaltbommel, The Netherlands), with a filament diameter of 2.85 mm. The PLA filament has tensile modulus of 3250 ± 119 MPa (XY-Flat), a flexural modulus of 3019 ± 87 MPa, and a Charpy impact strength of 3.9 ± 0.4 kJ/m2 [33]. Other properties and the details of the manufacturer’s test method/standard are available in the manufacturer’s technical data sheet [33].

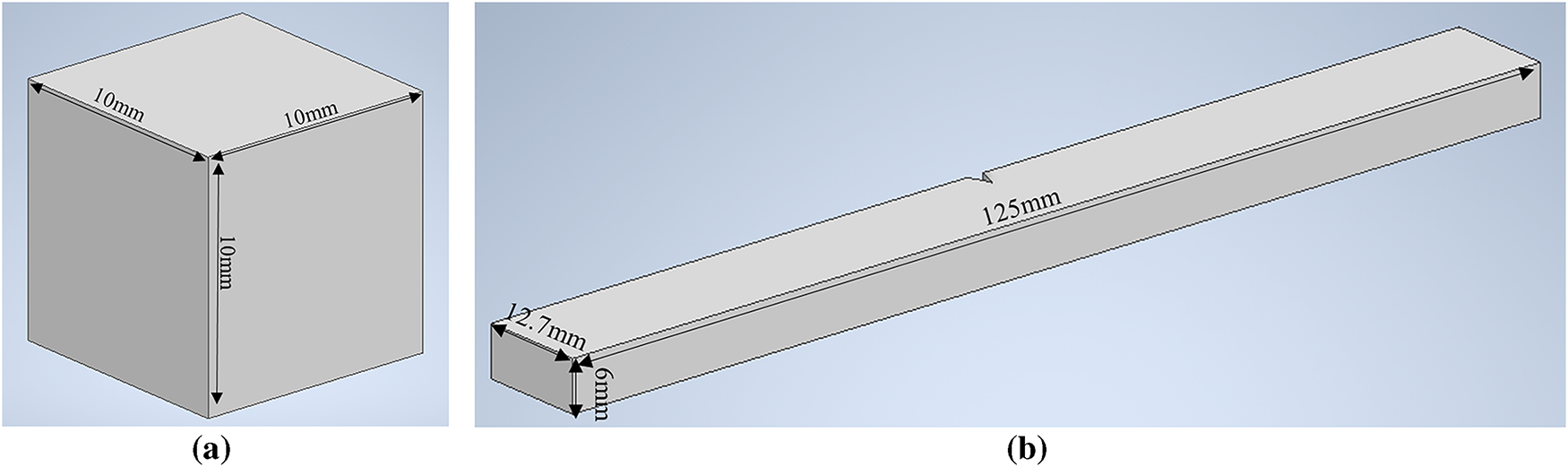

The Surface Tessellation Language (STL) file of 1 cm3 cube sample and impact test samples, according to ASTM D6110-18 [34], were created using Autodesk Inventor 2024, as shown in Fig. 4. The print path code and other parameters were generated using the slicing software UltiMaker CURA 5.4.0.

Figure 4: (a) 1 ∗ 1 ∗ 1 cm3 samples for micro-CT analysis and (b) 125 ∗ 12.7 ∗ 6 mm3 samples for ASTM D6110-18 impact test

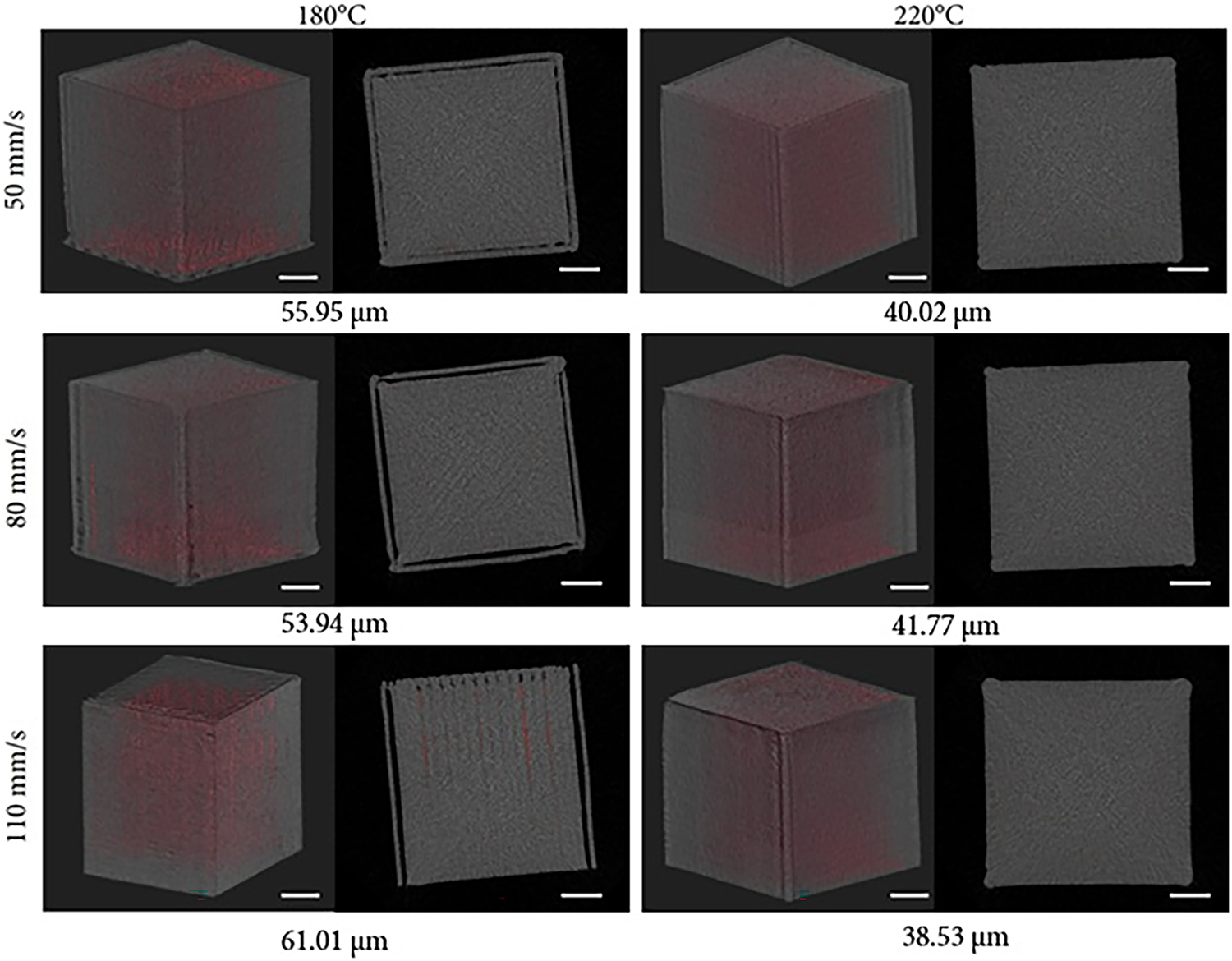

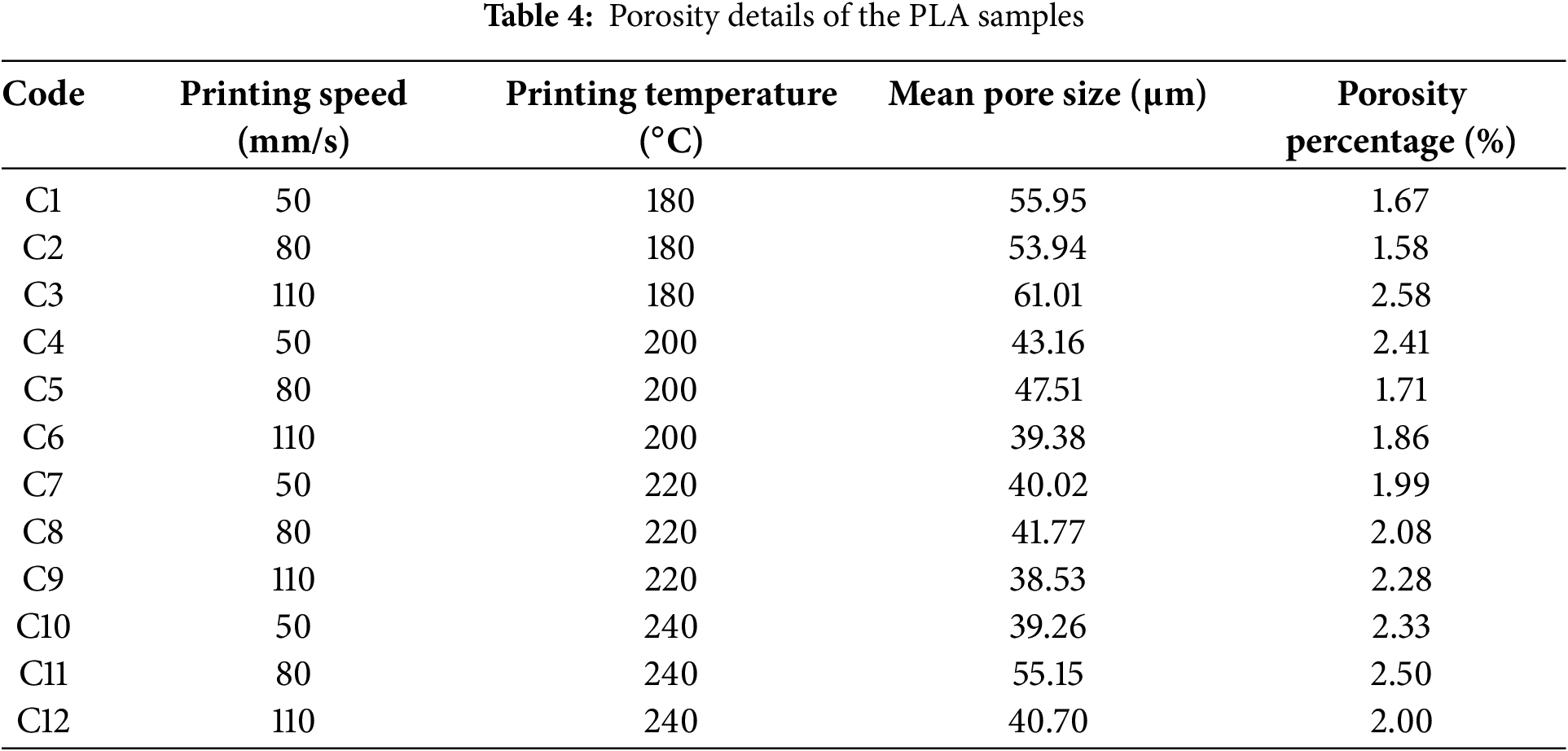

The investigation focused solely on varying the printing temperature and printing speed to study their effects on porosity and mechanical strength, while keeping other processing parameters constant. The fixed parameters are outlined in Table 1. A layer height of 0.1 mm was selected to reduce the void [27,29]. A flat build orientation was selected to optimise the impact strength [35]. The build plate temperature was set to 60°C, based on the recommended temperature range for PLA and our preliminary tests to obtain good first-layer adhesion. A raster angle of 45° was selected for optimal impact strength [36].

Based on the findings of a review study, the recommended extrusion temperature range for PLA parts falls between 180°C and 240°C [37]. At printing temperatures below 180°C, the PLA material does not fully reach its melting point [38]. The 3D printer utilized in this study has a default printing speed of 60 mm/s. Without altering any other printing parameters, the study commenced by exploring the minimum and maximum printing speeds achievable with this 3D printer. Hence, 1 cm3 cube samples were printed at each printing temperature ranging from 180°C to 240°C at intervals of 20°C, and printing speeds ranging from 50 to 110 mm/s at intervals of 30 mm/s, as shown in Table 2.

2.2 MicroCT Image Acquisition and Processing

MicroCT images were acquired using a SkyScan 1172 (Kontich, Belgium) at the Malaysian Nuclear Agency based on scanning parameters in Table 3. Following acquisition, the raw data were reconstructed into high-resolution images (13.07 μm voxel size) using NRecon Software, V1.6.10.4.

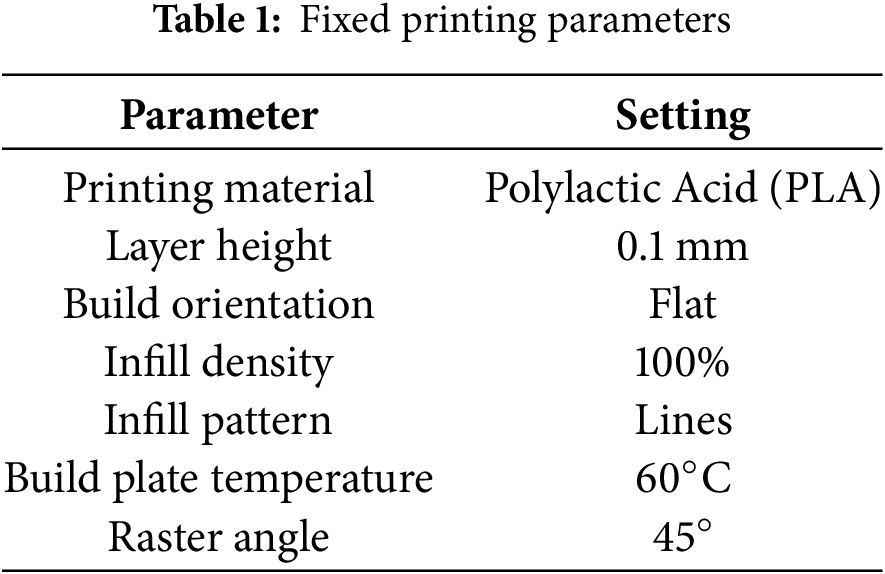

2.2.1 Computational Image Analysis

MicroCT images were analyzed using Python 3.8 libraries SimpleITK and scikit-image. First, noise in the images was reduced using a recursive Gaussian filter with a filter width of σ = 0.2 (Fig. 5a). Thereafter, the 3D-printed samples were segmented using Otsu’s method [39] (Fig. 5b), and all pores were closed by applying a morphological closing operation with a kernel radius size of 20 voxels (Fig. 5c). To exclude regions where the outer wall intersects with the infill that could bias the porosity measurements, the masked images were eroded using an iterative process to a final erosion of 50 voxels (Fig. 5d). A masked image was then created multiplying the filtered image by the segmented one (Fig. 5e) and porosity within the sample was segmented using a moments threshold image filter [40] on the masked image (Fig. 5f). The volume of the printed sample and the volume of the pores were then measured, and porosity was determined. Finally, the average pore size was evaluated using the BoneJ plugin [41] in Fiji [42].

Figure 5: Segmentation of 3D printed sample’s porosity. (a) Micro-CT image after noise filtering. (b) Segmented sample using Otsu’s method. (c) Binary mask after morphological closing. (d) Eroded mask. (e) Volume of interest analyzed. (f) Porosity within the 3D printed sample

The Charpy impact tests were performed using an impact tester machine (LY-XJL-22/50D Digital Impact Test Machine, Dongguan, China). Once the sample was positioned, the pendulum was raised to its initial position and securely fastened using the locking mechanism. The release energy and the speed were set in the digital display panel. Upon release, the pendulum traveled through the sample, causing it to fracture. The energy absorbed during this process was recorded from the digital display panel. This sequence was repeated for each sample to ensure consistent and reliable results. Charpy impact experiments for all the twelve sets, as reported in Table 2 were conducted and each impact test was repeated three times. The impact strength was calculated using Eq. (1) by dividing the energy absorbed, E (kJ), with the thickness, b (m), and the width of the sample, h (m) [43].

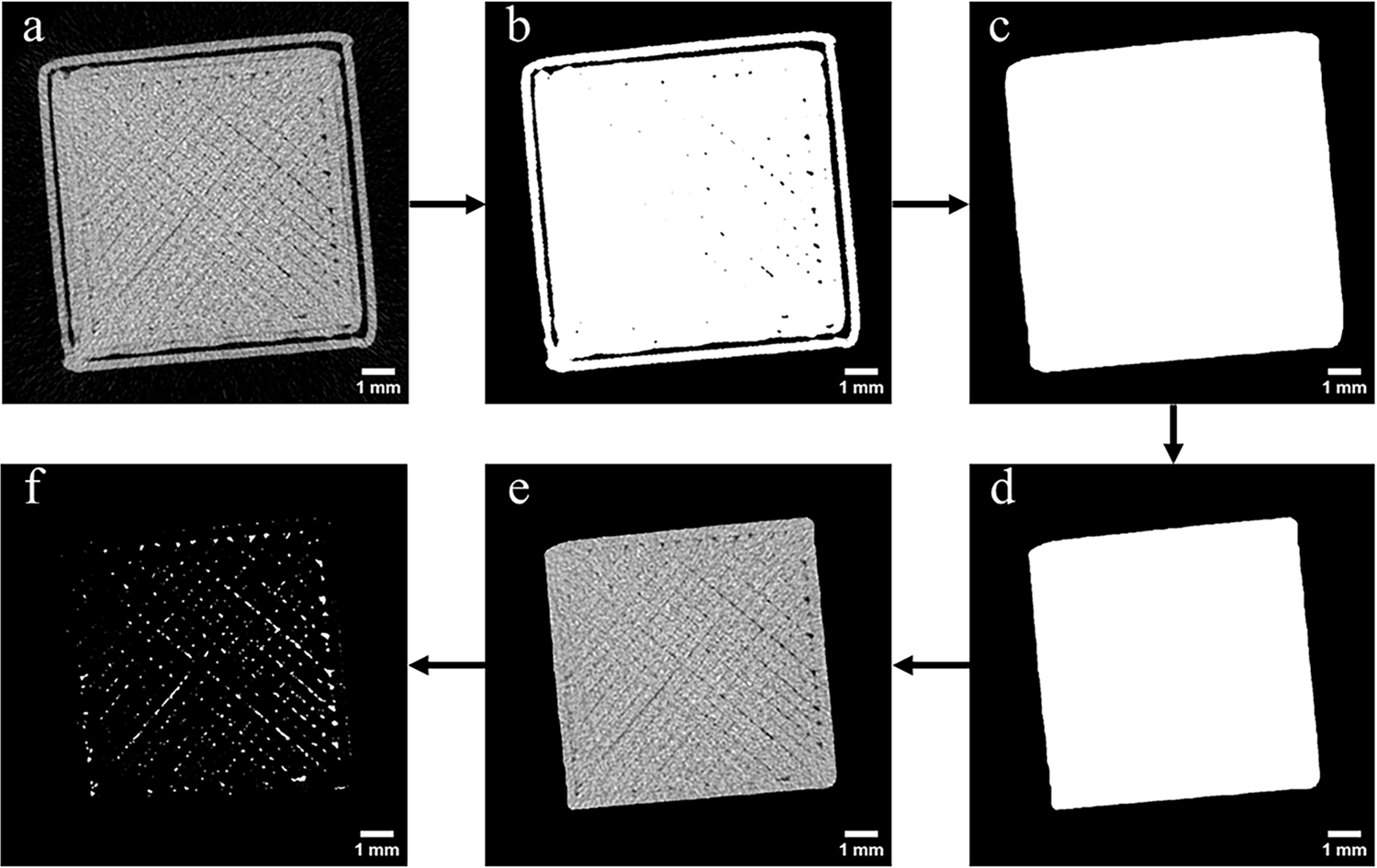

MicroCT images allowed visualization and quantification of porosity within the printed PLA samples in 3D (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: MicroCT images of PLA samples printed at 180°C and 220°C at increasing printing speeds (50, 80, and 110 mm/s). 3D visualization of the samples and representative cross-section are shown, with pore volume overlaid in red colour onto original images. Mean Pore Size (μm) is reported at the bottom of each sample. Please note porosity is represented for the analysed volume of interest as described in Section 2.2.1. Scale bars correspond to 2 mm

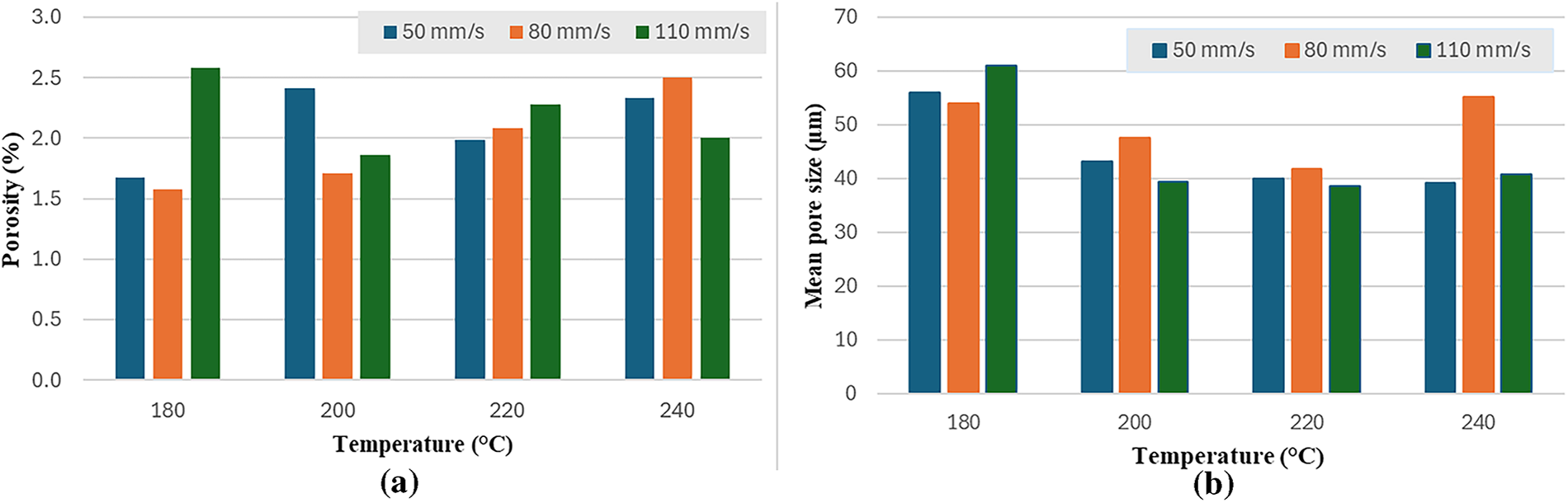

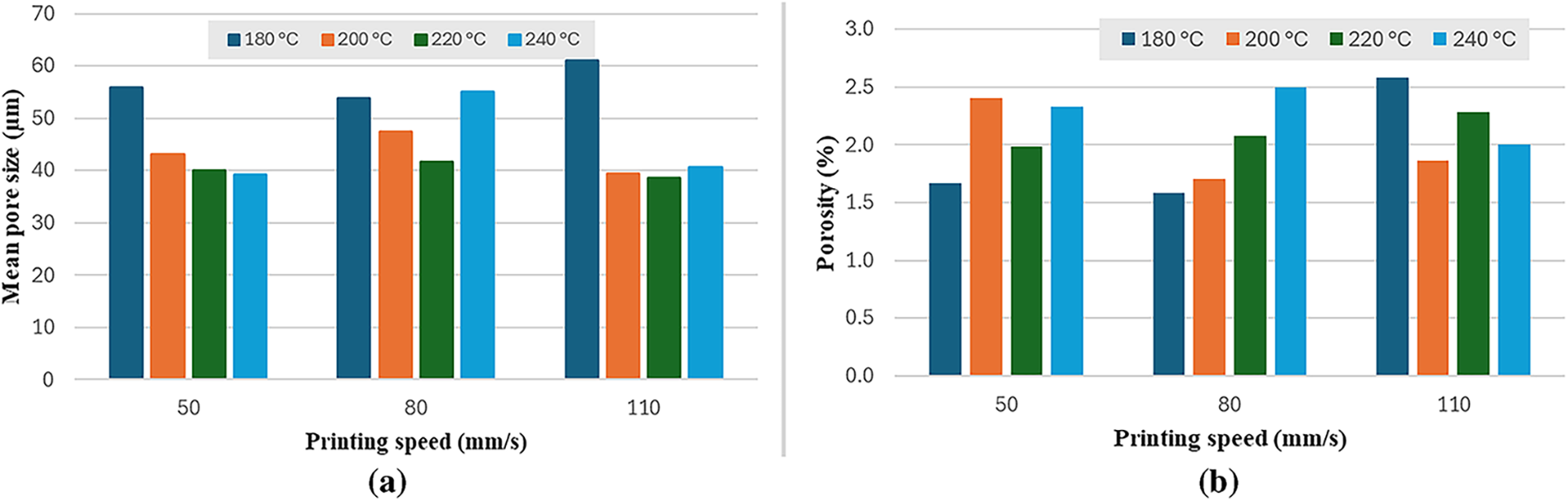

Table 4 provides a summary of the porosity details for the different samples, indicating how variations in printing temperature and printing speed impact porosity. The influence of the printing temperature on the porosity of printed PLA can be seen in Fig. 7. In general, the mean pore size decreased as the printing temperature increased from 180°C to 220°C, except at 50 mm/s. At 50 mm/s, the mean pore size decreased by 29.8% when the printing temperature increased from 180°C to 240°C, whereas at 80 and 110 mm/s, maximum reductions of 22.6% and 36.8% in mean pore size were obtained at 220°C. Beyond 220°C, the mean pore size increased. Similar observations were reported by Charlon et al. [19], where the porosity of MEX-printed polypropylene was reduced with the increase in printing temperature from 170°C to 180°C.

Figure 7: (a) Porosity and (b) mean pore size as a function of printing temperature

The highest percentage porosity was obtained at the lowest temperature and highest printing speed (180°C at 110 mm/s). As reported previously, the absorbed moisture in the PLA filament evaporated as steam during printing and created bubbles/voids in the MEX-manufactured part, and the porosity in the 3D-printed PLA is proportional to the storage relative humidity [44]. PLA absorbs water molecules when exposed to the ambient environment. When the printing temperature increases, the absorbed water in the PLA filament vaporizes into steam, leading to the formation of more bubbles/voids within the fabricated part. Furthermore, elevating the printing temperature raises the temperature of the molten material, resulting in a decrease in viscosity. The increase in printing temperature enhances the mobility of PLA polymer chains, facilitating the fusion between the layers [19]. The lower viscosity prevents the bubbles from coalescing into larger pores. As a result, although more voids were formed but they are smaller in mean pore size due to the higher viscosity of PLA, as observed in the current work.

In MEX/TRB-P 3D printing, bonding between filament layers can be categorized as in-layer and inter-layer bonding. In-layer bonding occurs between adjacent filaments within the same layer, while inter-layer bonding occurs between successive layers. As the melt is extruded from the nozzle, it undergoes convective cooling from the environment and conductive cooling from the previous layer [45]. The results obtained for printed PLA at a lower printing temperature in Fig. 7b are likely due to reduced adhesion between deposited filaments and layers [46], a similar observation was reported by Morales et al. [47]. Higher printing temperatures reduce interlayer voids by enhancing material fluidity, improving interaction between material chains, and decreasing discontinuities, thereby contributing to a denser and more structurally sound 3D-printed object, which reduces the inter-layer voids and thus reduces the mean pore size. Lower printing temperatures may lead to poor layer-to-layer bonding and increased void size due to incomplete melting of the material [48]. Furthermore, the printed PLA may not melt sufficiently to achieve the optimum viscosity, resulting in weak bonding between neighboring particles and layers [49].

The influence of the printing speed on the porosity of printed PLA can be seen in Fig. 8. As reported previously, the highest percentage of porosity was obtained at the highest printing speed (of 110 mm/s) and the lowest printing temperature (of 180°C). A similar trend was observed in previous work, where increasing the printing speed during MEX 3D printing reduced voids between beads [16]. Based on Fig. 8, the mean pore size initially increased with the increasing printing speed due to under-extrusion, where thermal shrinkage has occurred during the cooling of materials [50]. In general, the mean pore size increased with printing speed, until a certain point, beyond which it decreased. Similar results were reported previously, where a slower printing speed resulted in more contact between adjacent roads [13], and as such higher printing speed resulted in larger pores. In addition to the effects of interlayer adhesion and material compaction during the MEX printing process, printing speed also plays an important role in determining the density of MEX-fabricated parts. At lower printing speeds, the semi-molten polymer extruded from the nozzle has more time to spread and flow into the adjacent gaps and inter-filament voids before the semi-molten polymer solidifies. The improved wetting and filling behavior reduces the presence of porosity and micro-voids between deposited filaments. Consequently, components printed at lower speeds typically exhibit higher density and reduced porosity compared to those manufactured at higher printing speeds. As a result, the insufficient spreading and rapid solidification of the semi-molten polymer limit the chance of interfacial contact and void closure [51]. Therefore, lower printing speeds allow for better bonding between layers and provide sufficient time for material fusion.

Figure 8: (a) Porosity and (b) mean pore size as a function of printing speed

In contrast, higher printing speeds reduce extrusion volume and printing stability, which leads to rough fractured sections with substantial voids [52]. Furthermore, the volumetric flow rate from the nozzle does not scale linearly with printing speed [53]. Consequently, as printing speed increases, there is a reduced supply of materials through the nozzle, resulting in thinner extruded paths. As the printing speed increases, the complete extrusion of the material transpires before the onset of the thermal decomposition reaction initiated by the nozzle temperature [54].

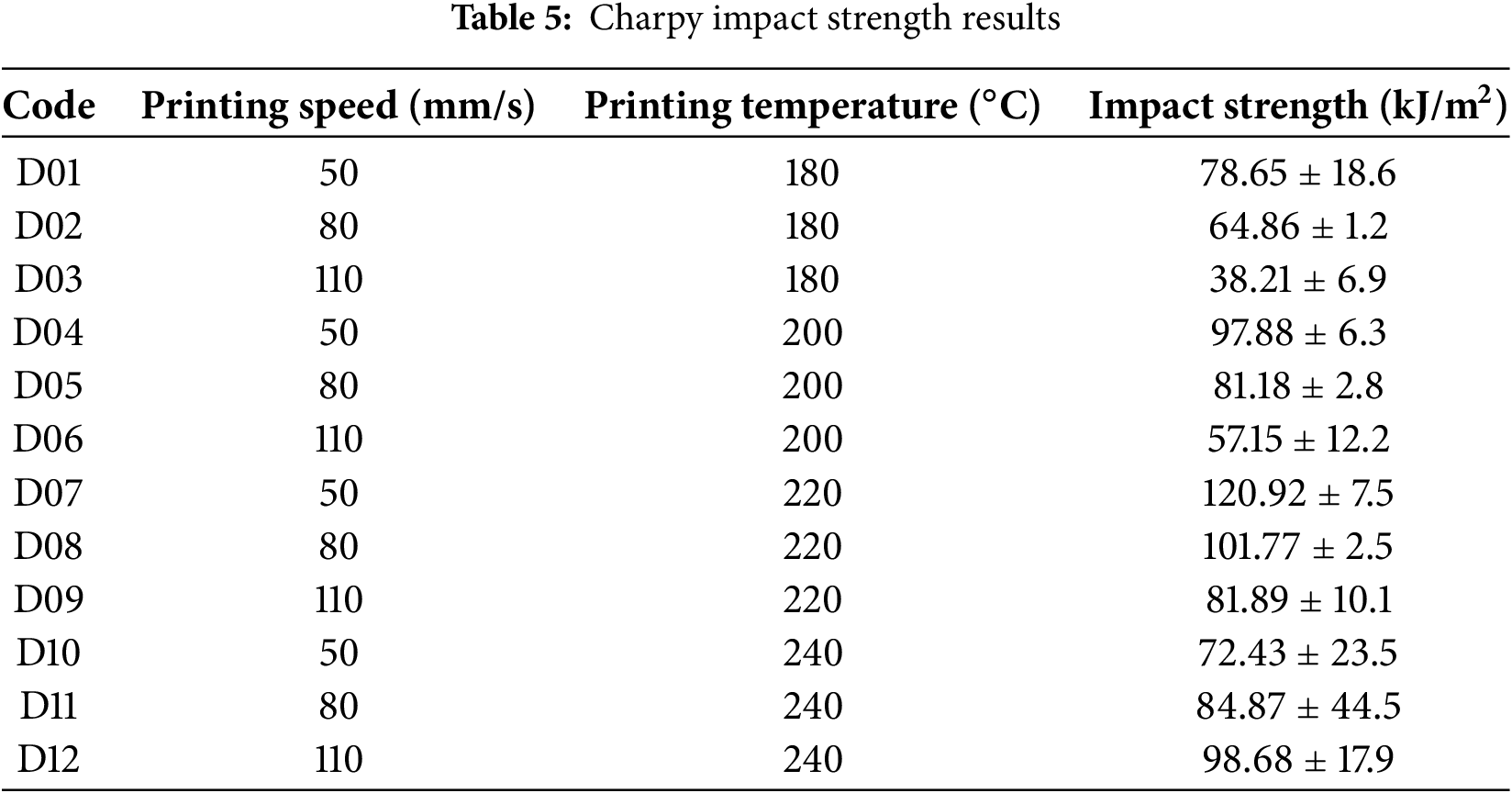

Table 5 provides the calculated average Charpy impact strength for the 3 printed PLA specimens at different printing temperatures and printing speeds, indicating the variations in printing parameters on impact strength. The results are illustrated in the graphs shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Charpy Impact strength of printed PLA specimens as a function of (a) printing speed (b) printing temperature

Fig. 9a shows the impact of increasing printing speed from 50 to 110 mm/s on Charpy impact strength at print temperatures of 180°C, 200°C, 220°C, and 240°C. Generally, as the printing speed increases, the impact strength of printed PLA decreases, except for the specimen printed at 240°C. Higher printing speed results in poor layer bonding performance due to the rapid cooling of the plastic, which results in insufficient temperature being applied to the extruded layer and poor adhesion to the layer underneath [55]. Hence, selecting a high printing speed can cause inadequate layer bonding, consequently diminishing the mechanical strength of the part [49].

However, when the printing temperature is excessively high at a low printing speed, the viscosity of the molten PLA decreases significantly. This reduced viscosity of molten PLA affects the dimensional stability of the deposited material. The low viscosity semi-molten PLA filament is subjected to undesired deformation such as spreading, sagging, or distortion before the semi-molten PLA fully solidify. Furthermore, a higher printing temperature increases the cooling and solidification time required for each deposited PLA layer, which may produce warping, deformation, and eventually affect the geometrical accuracy in the final component. On the other hand, at a printing temperature of 240°C, the impact strength of the manufactured parts increases with higher printing speeds. This improvement is likely contributed by a more balanced interaction between the flow of the molten PLA, solidification rate, and interlayer bonding, which reduces excessive heat accumulation while still maintaining adequate interlayer adhesion [49]. If the set temperature is too low at high speeds, the filament may not melt at a sufficient rate, leading to material getting stuck inside the nozzle and resulting in a higher viscosity melt than desired. Therefore, it can be concluded that the printing temperature and printing speed should be appropriately matched, where increasing the printing speed should also necessitate an increase in printing temperature to ensure the filament is fully melted before being deposited [49].

Fig. 9b illustrates the impact of increasing printing temperature from 180°C to 240°C on porosity at print speeds of 50, 80, and 110 mm/s. As the printing temperature increases from 180°C to 220°C, the impact strength of printed PLA increases. At 220°C, improvements in impact strength of 53.7%, 56.9%, and 114% were observed for samples printed at 50, 80, and 110 mm/s, respectively. After 220°C, the impact strengths for the samples printed at 50 and 80 mm/s were then reduced. At lower temperature, PLA polymer chains lack the necessary mobility to effectively diffuse across the interface [19]. At higher printing temperatures, the increased flow of melted resin from the printer nozzle leads to greater deviation, attributable to the decrease in shear viscosity [56]. Increasing the printing temperature led to stronger thermal bonding and stronger interlayer lamination, resulting in increased mechanical properties [22,57]. However, as the temperature of the nozzle rises, there is a promotion of reptation and entanglement among the polymer chains at the interface due to an increase in chain diffusion. Therefore, the impact strength of printed PLA was reduced after 220°C. Increasing the printing temperature has a significant impact on the viscosity of molten PLA. As the nozzle temperature rises, the viscosity of the molten PLA decreases. Consequently, this temperature-dependent behavior facilitates better diffusion of newly extruded PLA molecules into the underlying layer, which enhances the interlayer adhesion strength of the printed material [20]. Regarding adhesion strength, Sun et al. [46] and Sood et al. [58] suggest that increasing the printing temperature enhances the adhesion between layers. Fernandes et al. [59] observed that increasing printing temperature enhances the contact area between layers because the extruded material becomes oval from a circular shape as viscosity decreases with the rising printing temperature.

Higher printing temperatures during MEX/TRB-P resulted in increased crystallinity due to the reheating of previously deposited layers as new filaments were extruded [60]. The increase in PLA crystallinity correlates with changes in its mechanical properties, where an increase in the crystallinity of 3D-printed PLA corresponded to higher impact strength [61,62]. Hence, it can be concluded that the results depicted in Fig. 9, where printing temperature increases correspond to higher impact strength, are partially due to the increasing crystallinity.

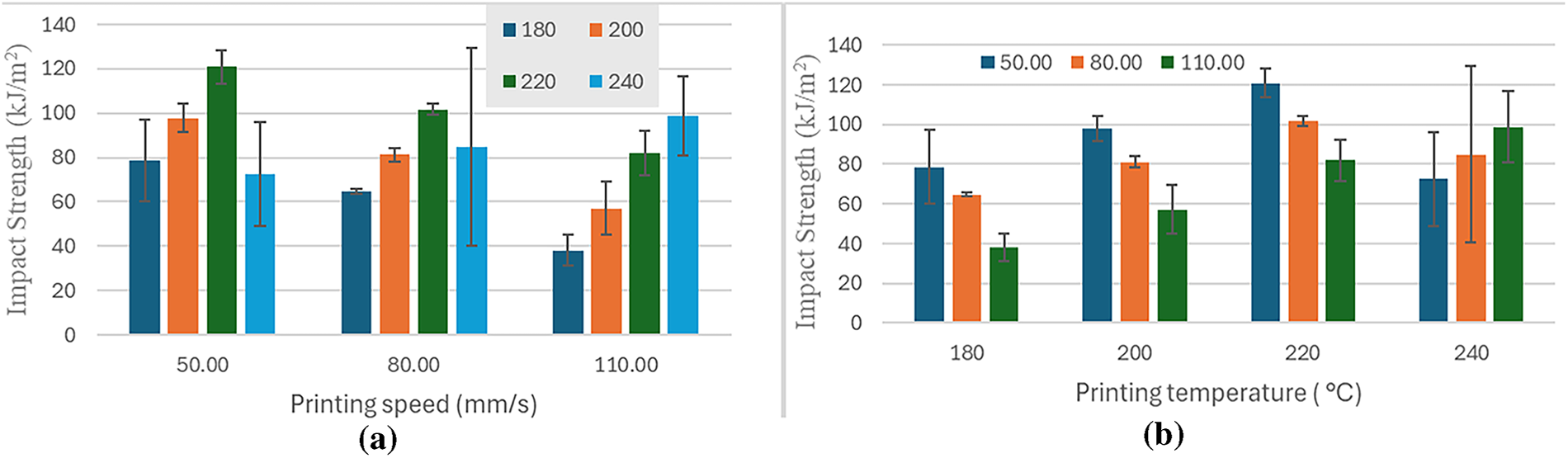

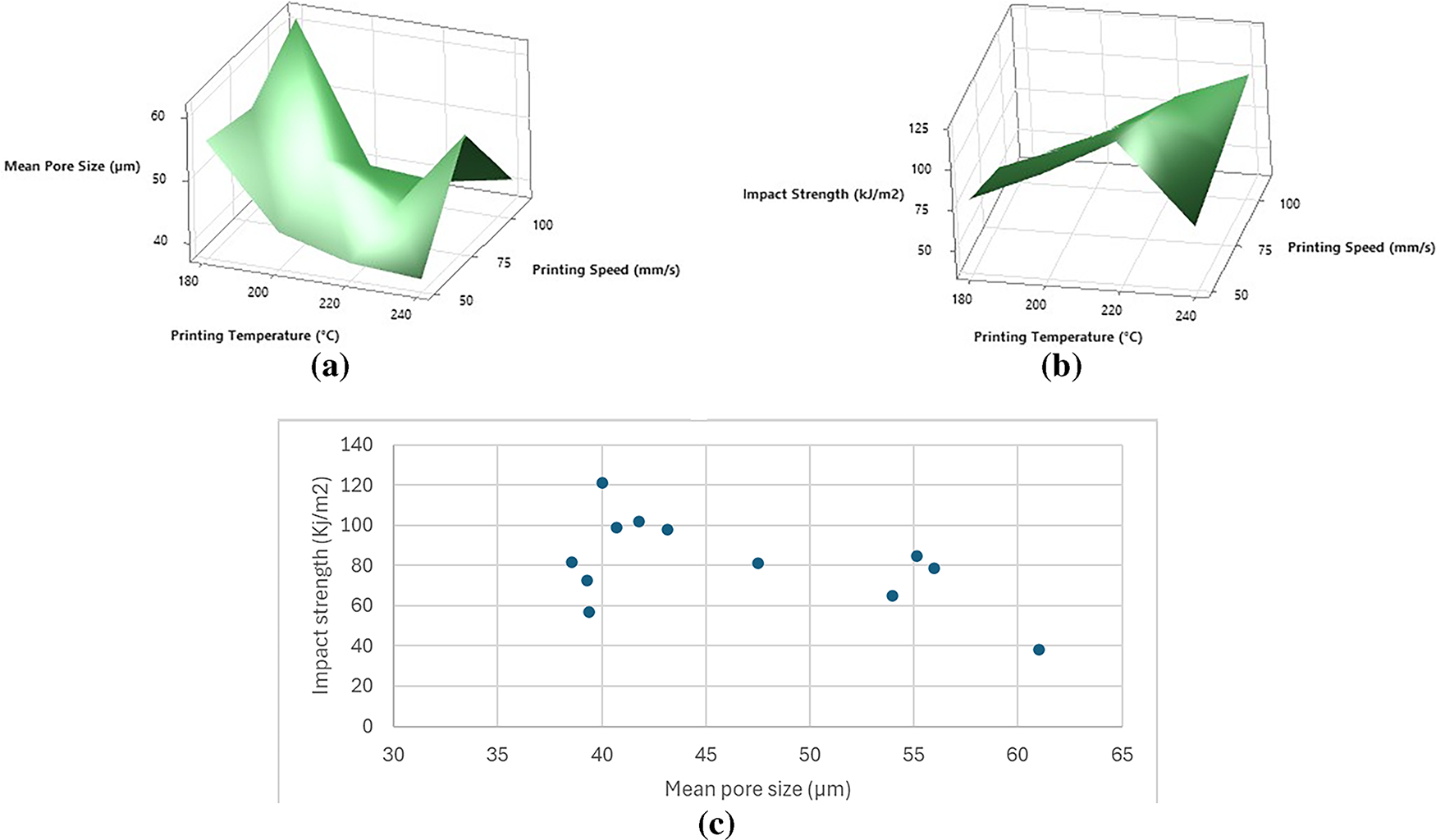

3.3 Correlation between Porosity and Charpy Impact Strength

The relationship between impact strength and mean pore size at different printing temperatures and printing speeds can be obtained from Fig. 10a,b. In general, the impact strength decreases as the mean pore size increases, as shown in Fig. 10c, except for the results at a printing temperature of 240°C. Several researchers observed the same effect of porosity on mechanical properties [8,63,64]. The voids in the printed PLA are the primary causes of the impact strength reduction observed in Fig. 8. Voids serve as stress concentration points within the printed PLA, facilitating the initiation of cracks that propagate to the nearby regions. Porosity is distributed at critical locations, and when load is applied, interlaminar cracks rapidly propagate due to the high interlayer porosity, leading to the separation of printed layers [6]. Tao et al. [65] stated that reducing the porosity of the cross-section led to increased density and enhanced force-bearing capacity of the part. Higher porosity diminishes the effective cross-sectional area of the material available to resist the applied load during impact. The impact strength of printed PLA decreases due to the presence of voids, as the material’s capacity to absorb impact energy is compromised [66].

Figure 10: (a) Porosity and (b) impact strength against printing temperature and printing speed, (c) Correlation between impact strength (kJ/m2) and mean pore size (μm)

At low printing temperatures, the printed PLA with low fluidity and high viscosity leads to inadequate bonding and increased porosity between the lines and layers of the molten polymer, which results in poor impact strength [67]. Conversely, with an increase in printing temperature, the viscosity of printed PLA decreases, which results in decreased mean pore size and therefore increased impact strength. When the printing speed increases, the porosity increases, while the impact strength decreases. This is because at high printing speed, rapid heat dissipation causes insufficient melting rate and reduces the fusion between layers [38]. Therefore, at a high printing temperature (220°C) and low printing speed (50 mm/s), the porosity of the printed PLA is reduced, and the impact strength is increased.

The results at printing temperatures of 180°C, 200°C, and 220°C are aligned with the trend of previous works. However, the results for a printing temperature of 240°C deviate from the trends observed, which show unpredictable and inconsistent results. There was a big range between the highest and lowest impact strength in the 240°C printed specimens. Tian et al. [68] corroborated this finding through experiments that PLA transitions into a liquid state at temperatures above 240°C, leading to uncontrolled flow from the nozzle and compromising printing precision. Printing PLA above its degradation temperature results in the material becoming increasingly brittle and less ductile over time [69]. Hence, the material tends to have lower viscosity, prolonging the cooling time, which can impact the degree of crystallinity. Additionally, at a very high printing temperature, adjacent particles and layers may be deposited before adequate cooling, affecting bonding between layers, which results in challenges in maintaining the dimensional stability of the printed part [49]. Similarly, Khosravani and Reinicke [70] suggested that thermal degradation within the extruder leads to the generation of gas, resulting in the formation of numerous trapped bubbles within the filament. This phenomenon may appear as a noticeable foaming effect. The upper layer of material fails to fully cool after melting when the printing temperature is excessively high, which introduces defects during the forming process. These defects diminish the mechanical properties of the sample.

In the present work, the effects of printing temperature and printing speed on the porosity and impact strength of material extrusion 3D printed PLA along with the relationship between porosity and Charpy impact strength, have been identified. MicroCT imaging and impact tests were conducted where the PLA specimens were printed at printing speeds ranging from 50 to 110 mm/s and printing temperatures ranging from 180°C to 220°C. Current work has led to the following conclusions:

• The printing temperature of 220°C and printing speed of 50 mm/s yielded the best impact behavior and a smaller mean pore size.

• Increasing the printing temperature caused the mean pore size of the printed PLA to decrease due to enhanced material fluidity and improved interaction between material chains.

• The same effect was observed when the print speed was decreased, where a low printing temperature allows enough time for material fusion.

• Increasing the printing temperature and decreasing the printing speed increases the impact strength due to better thermal bonding and enhanced interlayer adhesion strength.

• The impact strength decreases as the porosity increases. Higher porosity decreases the effective cross-sectional area of the material available to resist the applied load during impact.

• Results at 240°C are different from expectations due to material degradation and overheating, which introduce defects during the material deposition process.

Acknowledgement: The first author wishes to express his sincere appreciation to Heriot-Watt University Malaysia and the Malaysian Nuclear Agency for providing research support and essential laboratory equipment, which significantly contributed to the success of this study.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Tze Chuen Yap; methodology, Jia Yan Lim and Tze Chuen Yap; validation, Siti Madiha Muhammad Amir and Tze Chuen Yap; formal analysis, Jia Yan Lim and Tze Chuen Yap; investigation, Jia Yan Lim, Roslan Yahya and Marta Peña Fernández; resources, Siti Madiha Muhammad Amir and Tze Chuen Yap; data curation, Jia Yan Lim and Tze Chuen Yap; writing—original draft preparation, Jia Yan Lim and Tze Chuen Yap; writing—review and editing, Tze Chuen Yap, Marta Peña Fernández, Siti Madiha Muhammad Amir and Roslan Yahya; visualization, Jia Yan Lim, Marta Peña Fernández and Tze Chuen Yap; supervision, Siti Madiha Muhammad Amir and Tze Chuen Yap; project administration, Tze Chuen Yap. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Tze Chuen Yap, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Gibson I, Rosen D, Stucker B. Additive manufacturing technologies: 3D printing, rapid prototyping, and direct digital manufacturing. 2nd ed. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2015. 498 p. [Google Scholar]

2. Mwema FM, Akinlabi ET. Basics of fused deposition modelling (FDM). In: Fused deposition modeling: strategies for quality enhancement. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

3. Menezes PL, Misra M, Kumar P. Tribology of additively manufactured materials: fundamentals, modeling, and applications. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2022. 360 p. [Google Scholar]

4. Tao Y, Kong F, Li Z, Zhang J, Zhao X, Yin Q, et al. A review on voids of 3D printed parts by fused filament fabrication. J Mater Res Technol. 2021;15:4860–79. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2021.10.108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Al-Maharma AY, Patil SP, Markert B. Effects of porosity on the mechanical properties of additively manufactured components: a critical review. Mater Res Express. 2020;7(12):122001. doi:10.1088/2053-1591/abcc5d. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Tronvoll SA, Welo T, Elverum CW. The effects of voids on structural properties of fused deposition modelled parts: a probabilistic approach. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2018;97(9–12):3607–18. doi:10.1007/s00170-018-2148-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Perkins A, Yang W, Liu Y, Chen L, Yenusah C. Finite element analysis of the effect of porosity on the plasticity and damage behavior of Mg AZ31 and Al 6061 T651 alloys. ASME Int Mech Eng Congr Expo. 2020;9:9. doi:10.1115/IMECE2019-10672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang X, Zhao L, Fuh JYH, Lee HP. Effect of porosity on mechanical properties of 3D printed polymers: experiments and micromechanical modeling based on X-ray computed tomography analysis. Polymers. 2019;11(7):1154. doi:10.3390/polym11071154. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Muzli MF, Ismail KI, Yap TC. Effects of infill density and printing speed on the tensile behaviour of fused deposition modelling 3D printed PLA specimens. J Eng Technol Appl Phys. 2024;6(2):1–8. [Google Scholar]

10. Amirruddin MS, Ismail KI, Yap TC. Effect of layer thickness and raster angle on the tribological behavior of 3D printed materials. Mater Today Proc. 2022;48:1821–5. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2021.09.139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. von Windheim N, Collinson DW, Lau T, Brinson LC, Gall K. The influence of porosity, crystallinity and interlayer adhesion on the tensile strength of 3D printed polylactic acid (PLA). Rapid Prototyp J. 2021;27(7):1327–36. doi:10.1108/rpj-08-2020-0205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sun X, Mazur M, Cheng CT. A review of void reduction strategies in material extrusion-based additive manufacturing. Addit Manuf. 2023;67:103463. doi:10.1016/j.addma.2023.103463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Abbott AC, Tandon GP, Bradford RL, Koerner H, Baur JW. Process-structure-property effects on ABS bond strength in fused filament fabrication. Addit Manuf. 2018;19:29–38. doi:10.1016/j.addma.2017.11.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Fan C, Shan Z, Zou G, Zhan L, Yan D. Interfacial bonding mechanism and mechanical performance of continuous fiber reinforced composites in additive manufacturing. Chin J Mech. 2021;34(1):21. doi:10.1186/s10033-021-00538-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Miazio L. Impact of print speed on strength of samples printed in FDM technology. Agric Eng. 2019;23(2):33–8. doi:10.1515/agriceng-2019-0014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Abualbandora TA, Alshneeqat MG, Mourad AHI. Impact of 3D printing parameters of short carbon fiber reinforced polymer CFRP on the mechanical and failure performance: review and future perspective. Next Mater. 2025;8:100645. doi:10.1016/j.nxmate.2025.100645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Natarajan SM, Senthil S, Narayanasamy P. Investigation of mechanical properties of FDM-processed Acacia concinna–filled polylactic acid filament. Int J Polym Sci. 2022;2022:4761481. doi:10.1155/2022/4761481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Pang R, Lai MK, Ismail KI, Yap TC. Characterization of the dimensional precision, physical bonding, and tensile performance of 3D-printed PLA parts with different printing temperature. J Manuf Mater Process. 2024;8(2):56. doi:10.3390/jmmp8020056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Charlon S, Le Boterff J, Soulestin J. Fused filament fabrication of polypropylene: influence of the bead temperature on adhesion and porosity. Addit Manuf. 2021;38:101838. doi:10.1016/j.addma.2021.101838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Behzadnasab M, Yousefi A. Effects of 3D printer nozzle head temperature on the physical and mechanical properties of PLA based product. In: 12th International Seminar on Polymer Science and Technology (ISPST); 2016 Nov 2–5; Tehran, Iran: Islamic Azad University; 2016. p. 3–5. [Google Scholar]

21. Zainal MA, Ismail KI, Yap TC. Tribological properties of PLA 3D printed at different extrusion temperature. J Phys Conf Ser. 2023;2542(1):012001. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/2542/1/012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Pang R, Lai MK, Teo HH, Yap TC. Influence of temperature on interlayer adhesion and structural integrity in material extrusion: a comprehensive review. J Manuf Mater Process. 2025;9:196. doi:10.3390/jmmp9060196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Sultana J, Rahman MM, Wang Y, Ahmed A, Xiaohu C. Influences of 3D printing parameters on the mechanical properties of wood PLA filament: an experimental analysis by Taguchi method. Prog Addit Manuf. 2024;9(4):1239–51. doi:10.1007/s40964-023-00516-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Aqida SN, Ghazali MI, Hashim J. Effect of porosity on mechanical properties of metal matrix composite: an overview. J Teknol. 2004;40:17. doi:10.11113/jt.v40.395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Shelmerdine SC, Simcock IC, Hutchinson JC, Aughwane R, Melbourne A, Nikitichev DI, et al. 3D printing from microfocus computed tomography (micro-CT) in human specimens: education and future implications. Br J Radiol. 2018;91(1088):20180306. doi:10.1259/bjr.20180306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Du Plessis A, Yadroitsev I, Yadroitsava I, Le Roux SG. X-Ray microcomputed tomography in additive manufacturing: a review of the current technology and applications. 3D Print Addit Manuf. 2018;5(3):227–47. doi:10.1089/3dp.2018.0060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Vidakis N, David C, Petousis M, Sagris D, Mountakis N, Moutsopoulou A. The effect of six key process control parameters on the surface roughness, dimensional accuracy, and porosity in material extrusion 3D printing of polylactic acid: prediction models and optimization supported by robust design analysis. Adv Ind Manuf Eng. 2022;5:100104. doi:10.1016/j.aime.2022.100104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Vidakis N, David C, Petousis M, Sagris D, Mountakis N. Optimization of key quality indicators in material extrusion 3D printing of acrylonitrile butadiene styrene: the impact of critical process control parameters on the surface roughness, dimensional accuracy, and porosity. Mater Today Commun. 2023;34:105171. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2022.105171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Faizaan M, Shenoy BS, Nunna S, Mallya R, Rao US, Ramanath KC, et al. A study on the overall variance and void architecture on MEX-PLA tensile properties through printing parameter optimisation. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):1–12. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-87348-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Petousis M, Michailidis N, Kulas V, Papadakis V, Spiridaki M, Mountakis N, et al. Sustainability-driven additive manufacturing: implementation and content optimization of fine powder recycled glass in polylactic acid for material extrusion 3D printing. Int J Lightweight Mater Manuf. 2025;8(5):595–610. doi:10.1016/j.ijlmm.2025.02.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Vidakis N, Kalderis D, Michailidis N, Papadakis V, Mountakis N, Argyros A, et al. Environmentally friendly polylactic acid/ferronickel slag composite filaments for material extrusion 3D printing: a comprehensive optimization of the filler content. Mater Today Sustain. 2024;27:100881. doi:10.1016/j.mtsust.2024.100881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wu H, Chen X, Xu S, Zhao T. Evolution of manufacturing defects of 3D-printed thermoplastic composites with processing parameters: a Micro-CT analysis. Materials. 2023;16:6521. doi:10.3390/ma16196521. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Ultimaker. Technical Data Sheet: Ultimaker PLA [Internet]. Utrecht, The Netherlands: Ultimaker B.V; 2018 [cited 2025 May 1]. Available from: https://support.ultimaker.com/hc/en-us/articles/360011962720-Ultimaker-PLA-TDS. [Google Scholar]

34. ASTM D6110-18. Standard test method for determining the Charpy impact resistance of notched specimens of plastics. West Conshohocken, PA, USA: ASTM International; 2018. [Google Scholar]

35. Huang B, Meng S, He H, Jia Y, Xu Y, Huang H. Study of processing parameters in fused deposition modeling based on mechanical properties of acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene filament. Polym Eng Sci. 2019;59(1):120–8. doi:10.1002/pen.24875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Dziewit P, Rajkowski K, Płatek P. Effects of building orientation and raster angle on the mechanical properties of selected materials used in FFF techniques. Materials. 2024;17:6076. doi:10.3390/ma17246076. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Zharylkassyn B, Perveen A, Talamona D. Effect of process parameters and materials on the dimensional accuracy of FDM parts. Mater Today Proc. 2021;44:1307–11. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2020.11.332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Hsueh MH, Lai CJ, Wang SH, Zeng YS, Hsieh CH, Pan CY, et al. Effect of printing parameters on the thermal and mechanical properties of 3D-printed PLA and PETG, using fused deposition modeling. Polymers. 2021;13:1758. doi:10.3390/polym13111758. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Otsu N. A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. Trans Syst Man Cybern. 1979;9(1):62–6. doi:10.1109/TSMC.1979.4310076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Tsai WH. Moment-preserving thresholding: a new approach. Comput Vis Graph Image Process. 1985;29(3):377–93. doi:10.1016/0734-189X(85)90133-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Doube M, Klosowski MM, Arganda-Carreras I, Cordelières FP, Dougherty RP, Jackson JS, et al. BoneJ: free and extensible bone image analysis in ImageJ. Bone. 2010;47(6):1076–9. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2010.08.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9(7):676–82. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Tunçel O. Optimization of charpy impact strength of tough PLA samples produced by 3D printing using the taguchi method. Polymers. 2024;16:459. doi:10.3390/polym16040459. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Lendvai L, Fekete I, Jakab SK, Szarka G, Verebélyi K, Iván B. Influence of environmental humidity during filament storage on the structural and mechanical properties of material extrusion 3D-printed poly(lactic acid) parts. Results Eng. 2024;24:103013. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Lepoivre A, Boyard N, Levy A, Sobotka V. Heat transfer and adhesion study for the FFF additive manufacturing process. Procedia Manuf. 2020;47:948–55. doi:10.1016/j.promfg.2020.04.291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Sun Q, Rizvi GM, Bellehumeur CT, Gu P. Effect of processing conditions on the bonding quality of FDM polymer filaments. Rapid Prototyp J. 2008;14(2):72–80. doi:10.1108/13552540810862028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Morales NG, Fleck TJ, Rhoads JF. The effect of interlayer cooling on the mechanical properties of components printed via fused deposition. Addit Manuf. 2018;24:243–8. doi:10.1016/j.addma.2018.09.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Hsueh MH, Lai CJ, Liu KY, Chung CF, Wang SH, Pan CY, et al. Effects of printing temperature and filling percentage on the mechanical behavior of fused deposition molding technology components for 3D printing. Polymers. 2021;13:2910. doi:10.3390/polym13172910. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Abeykoon C, Sri-Amphorn P, Fernando A. Optimization of fused deposition modeling parameters for improved PLA and ABS 3D printed structures. Int J Lightweight Mater Manuf. 2020;3(3):284–97. doi:10.1016/j.ijlmm.2020.03.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Algarni M, Ghazali S. Comparative study of the sensitivity of PLA, ABS, PEEK, and PETG’s mechanical properties to FDM printing process parameters. Crystals. 2021;11:995. doi:10.3390/cryst11080995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Cardoso PHM, Coutinho RRTP, Drummond FR, da Conceição MN, Thiré RMSM. Evaluation of printing parameters on porosity and mechanical properties of 3D printed PLA/PBAT blend parts. Macromol Symp. 2020;394(1):2000157. doi:10.1002/masy.202000157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Tegegne WW. Effect of voids and printing parameters on the mechanical behavior of composite structure manufactured by 3D printing fused deposition modeling [master’s thesis]. Changsha, China: Central South University; 2021. [Google Scholar]

53. Loskot J, Jezbera D, Loskot R, Bušovský D, Barylski A, Glowka K, et al. Influence of print speed on the microstructure, morphology, and mechanical properties of 3D-printed PETG products. Polym Test. 2023;123:108055. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2023.108055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Yoo CJ, Shin BS, Kang BS, Yun DH, You DB, Hong SM. Manufacturing a porous structure according to the process parameters of functional 3D porous polymer printing technology based on a chemical blowing agent. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2017;229(1):012027. [Google Scholar]

55. Johansson F. Optimizing fused filament fabrication 3D printing for durability: tensile properties and layer bonding. Blekinge Inst Technol. 2016;26:952. [Google Scholar]

56. Akbaş OE, Hıra O, Hervan SZ, Samankan S, Altınkaynak A. Dimensional accuracy of FDM-printed polymer parts. Rapid Prototyp J. 2020;26(2):288–98. doi:10.1108/rpj-04-2019-0115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Tymrak BM, Kreiger M, Pearce JM. Mechanical properties of components fabricated with open-source 3-D printers under realistic environmental conditions. Mater Des. 2014;58:242–6. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2014.02.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Sood AK, Ohdar RK, Mahapatra SS. Experimental investigation and empirical modelling of FDM process for compressive strength improvement. J Adv Res. 2012;3(1):81–90. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2011.05.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Fernandes J, Deus AM, Reis L, Vaz MF, Leite M. Study of the influence of 3D printing parameters on the mechanical properties of PLA. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Progress in Additive Manufacturing; 2018 May 14–17. Singapore. [Google Scholar]

60. Drummer D, Cifuentes-Cuéllar S, Rietzel D. Suitability of PLA/TCP for fused deposition modeling. Rapid Prototyp J. 2012;18(6):500–7. doi:10.1108/13552541211272045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Benwood C, Anstey A, Andrzejewski J, Misra M, Mohanty AK. Improving the impact strength and heat resistance of 3D printed models: structure, property, and processing correlationships during fused deposition modeling (FDM) of poly(lactic acid). ACS Omega. 2018;3(4):4400–11. doi:10.1021/acsomega.8b00129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Wang L, Gramlich WM, Gardner DJ. Improving the impact strength of poly(lactic acid) (PLA) in fused layer modeling (FLM). Polymer. 2017;114:242–8. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2017.03.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Ning F, Cong W, Qiu J, Wei J, Wang S. Additive manufacturing of carbon fiber reinforced thermoplastic composites using fused deposition modeling. Compos B Eng. 2015;80:369–78. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2015.06.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Guo Y, Chen C, Wang Q, Liu M, Cao Y, Pan Y, et al. Effect of porosity on mechanical properties of porous tantalum scaffolds produced by electron beam powder bed fusion. Trans Nonferrous Met Soc China. 2022;32(9):2922–34. doi:10.1016/s1003-6326(22)65993-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Tao Y, Li P, Pan L. Improving tensile properties of polylactic acid parts by adjusting printing parameters of open source 3D printers. Mater Sci. 2020;26(1):83–7. doi:10.5755/j01.ms.26.1.20952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Kumar KR, Mohanavel V, Kiran K. Mechanical properties and characterization of polylactic acid/carbon fiber composite fabricated by fused deposition modeling. J Mater Eng Perform. 2022;31(6):4877–86. doi:10.1007/s11665-021-06566-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Valerga AP, Batista M, Salguero J, Girot F. Influence of PLA filament conditions on characteristics of FDM parts. Materials. 2018;11:1322. doi:10.3390/ma11081322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Tian X, Liu T, Yang C, Wang Q, Li D. Interface and performance of 3D printed continuous carbon fiber reinforced PLA composites. Appl Sci Manuf. 2016;88:198–205. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2016.05.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Pantani R, De Santis F, Sorrentino A, De Maio F, Titomanlio G. Crystallization kinetics of virgin and processed poly(lactic acid). Polym Degrad Stab. 2010;95(7):1148–59. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2010.04.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Khosravani MR, Reinicke T. On the use of X-ray computed tomography in assessment of 3D-printed components. J Nondestr Eval. 2020;39(4):1–17. doi:10.1007/s10921-021-00818-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools